Paris Peace Conference (1919–1920) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Paris Peace Conference was a set of formal and informal diplomatic meetings in 1919 and 1920 after the end of

The second category, of New Guinea, Samoa, and South West Africa, were located so close to responsible supervisors that the mandates could hardly be given to anyone except Australia, New Zealand, and South Africa. Finally, the African colonies would need the careful supervision as "Class B" mandates, which could be provided only by experienced colonial powers: Britain, France, and Belgium although Italy and Portugal received small amounts of territory. Wilson and the others finally went along with the solution. The dominions received " Class C Mandates" to the colonies that they wanted. Japan obtained mandates over German possessions north of the

The second category, of New Guinea, Samoa, and South West Africa, were located so close to responsible supervisors that the mandates could hardly be given to anyone except Australia, New Zealand, and South Africa. Finally, the African colonies would need the careful supervision as "Class B" mandates, which could be provided only by experienced colonial powers: Britain, France, and Belgium although Italy and Portugal received small amounts of territory. Wilson and the others finally went along with the solution. The dominions received " Class C Mandates" to the colonies that they wanted. Japan obtained mandates over German possessions north of the

The maintenance of the unity, territories, and interests of the British Empire was an overarching concern for the British delegates to the conference, but they entered the conference with more specific goals with this order of priority:

* Ensuring the security of France

* Removing the threat of the

The maintenance of the unity, territories, and interests of the British Empire was an overarching concern for the British delegates to the conference, but they entered the conference with more specific goals with this order of priority:

* Ensuring the security of France

* Removing the threat of the

The dominion governments were not originally given separate invitations to the conference, and had been expected to send representatives as part of the British delegation.

Convinced that Canada had become a nation on the battlefields of Europe, Prime Minister

The dominion governments were not originally given separate invitations to the conference, and had been expected to send representatives as part of the British delegation.

Convinced that Canada had become a nation on the battlefields of Europe, Prime Minister

French Prime Minister

French Prime Minister

In 1914, Italy remained neutral despite the Triple Alliance with Germany and Austria-Hungary. In 1915, it joined the Allies to gain the territories promised by the

In 1914, Italy remained neutral despite the Triple Alliance with Germany and Austria-Hungary. In 1915, it joined the Allies to gain the territories promised by the

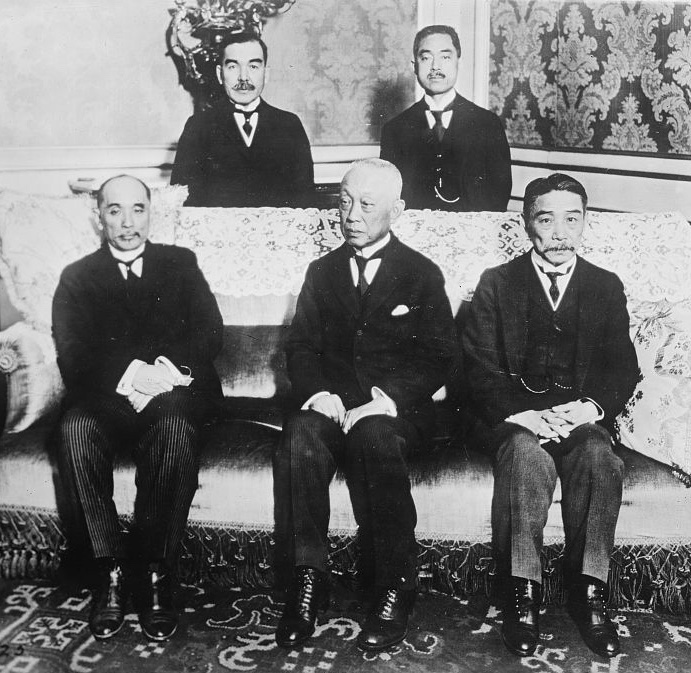

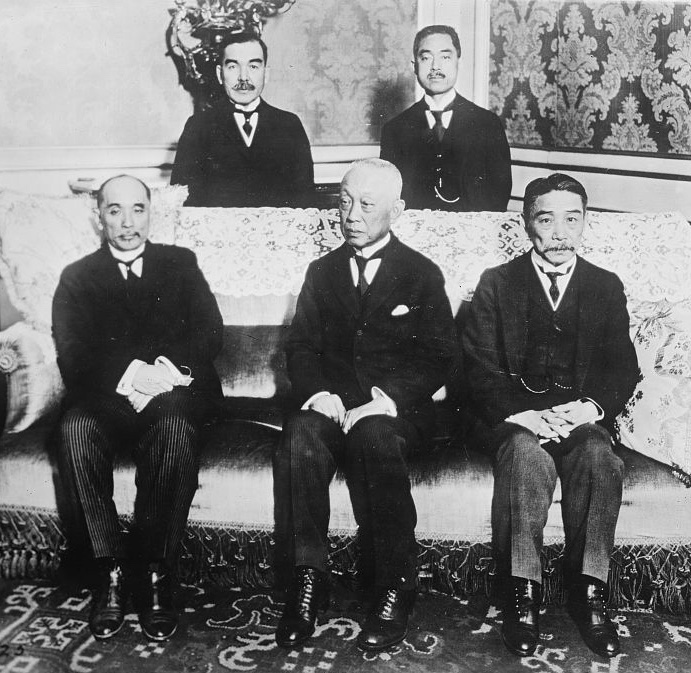

Japan sent a large delegation, headed by the former Prime Minister, Marquis

Japan sent a large delegation, headed by the former Prime Minister, Marquis

Until Wilson's arrival in Europe in December 1918, no sitting American president had ever visited the continent. Wilson's 1918

Until Wilson's arrival in Europe in December 1918, no sitting American president had ever visited the continent. Wilson's 1918

The three South Caucasian republics of

The three South Caucasian republics of

The February 1919 statement included the following main points: recognition of Jewish "title" over the land, a declaration of the borders (significantly larger than in the prior Sykes-Picot agreement), and League of Nations sovereignty under British mandate.Statement of the Zionist Organization regarding Palestine

The February 1919 statement included the following main points: recognition of Jewish "title" over the land, a declaration of the borders (significantly larger than in the prior Sykes-Picot agreement), and League of Nations sovereignty under British mandate.Statement of the Zionist Organization regarding Palestine

, 3 February 1919 An offshoot of the conference was convened at San Remo in 1920, leading to the creation of the

Writing the Great War - The Historiography of World War I from 1918 to the Present

' (2020); full coverage for major countries. *

excerpt and text search

* Dillon, Emile Joseph. ''The Inside Story of the Peace Conference'', (1920

online

* Dockrill, Michael, and John Fisher. ''The Paris Peace Conference, 1919: Peace Without Victory?'' (Springer, 2016). * Ferguson, Niall. ''The Pity of War: Explaining World War One'' (1999), economics issues at Paris pp 395–432 * Doumanis, Nicholas, ed. ''The Oxford Handbook of European History, 1914–1945'' (2016) ch 9. *

online free

* Henderson, W. O. "The Peace Settlement, 1919" ''History'' 26.101 (1941): 60–6

online

historiography * Henig, Ruth. ''Versailles and After: 1919–1933'' (2nd ed. 1995), 100 pages; brief introduction by scholar * {{Cite book , last= Hobsbawm , first= E. J. , author-link= Eric Hobsbawm , year= 1992 , title= Nations and Nationalism since 1780: Programme, Myth, Reality , edition=2nd , series=Canto , location= Cambridge , publisher=

full text online

* Dimitri Kitsikis, ''Le rôle des experts à la Conférence de la Paix de 1919'', Ottawa, éditions de l'université d'Ottawa, 1972. * Dimitri Kitsikis, ''Propagande et pressions en politique internationale. La Grèce et ses revendications à la Conférence de la Paix, 1919–1920'', Paris, Presses universitaires de France, 1963. * Knock, Thomas J. ''To End All Wars: Woodrow Wilson and the Quest for a New World Order'' (1995) * Lederer, Ivo J., ed. ''The Versailles Settlement—Was It Foredoomed to Failure?'' (1960) short excerpts from scholars * Lentin, Antony. ''Guilt at Versailles: Lloyd George and the Pre-history of Appeasement'' (1985) * Lentin, Antony. ''Lloyd George and the Lost Peace: From Versailles to Hitler, 1919–1940'' (2004) * {{cite book, last=Lloyd George, first=David, author-link=David Lloyd George, title=The Truth About the Peace Treaties (2 volumes), year=1938, publisher=Victor Gollancz Ltd, location=London * {{Cite book, last=Lundgren, first=Svante, chapter=, title=Why did the Assyrian lobbying at the Paris Peace Conference fail?, year=2020, location=, publisher=Chronos : Revue d'Histoire de l'Université de Balamand, pages=63–73, isbn=, url= * Macalister-Smith, Peter, Schwietzke, Joachim: ''Diplomatic Conferences and Congresses. A Bibliographical Compendium of State Practice 1642 to 1919'', W. Neugebauer, Graz, Feldkirch 2017, {{ISBN, 978-3-85376-325-4. * {{Cite book , last= McFadden , first= David W. , year= 1993 , title= Alternative Paths: Soviets and Americans, 1917–1920 , location= New York, NY , publisher=

online

* Mayer, Arno J., ''Politics and Diplomacy of Peacemaking: Containment and Counter-revolution at Versailles, 1918–1919'' (1967), leftist * Newton, Douglas. ''British Policy and the Weimar Republic, 1918–1919'' (1997). 484 pgs. * {{cite journal , last1 = Pellegrino , first1 = Anthony , last2 = Dean Lee , first2 = Christopher , last3 = Alex , year = 2012 , title = Historical Thinking through Classroom Simulation: 1919 Paris Peace Conference , journal = The Clearing House: A Journal of Educational Strategies, Issues and Ideas , volume = 85 , issue = 4, pages = 146–152 , doi = 10.1080/00098655.2012.659774 , s2cid = 142814294 * Roberts, Priscilla. "Wilson, Europe's Colonial Empires, and the Issue of Imperialism", in Ross A. Kennedy, ed., ''A Companion to Woodrow Wilson'' (2013) pp: 492–517. * Schwabe, Klaus. ''Woodrow Wilson, Revolutionary Germany, and Peacemaking, 1918–1919: Missionary Diplomacy and the Realities of Power'' (1985) * Sharp, Alan. ''The Versailles Settlement: Peacemaking after the First World War, 1919–1923'' (2nd ed. 2008) * {{cite journal , last1 = Sharp , first1 = Alan , year = 2005 , title = The Enforcement Of The Treaty Of Versailles, 1919–1923 , journal = Diplomacy and Statecraft , volume = 16 , issue = 3, pages = 423–438 , doi=10.1080/09592290500207677, s2cid = 154493814 * Naoko Shimazu (1998), ''Japan, Race and Equality'', Routledge, {{ISBN, 0-415-17207-1 * Steiner, Zara. ''The Lights that Failed: European International History 1919–1933'' (Oxford History of Modern Europe) (2007), pp 15–79; major scholarly work * {{cite journal , last1 = Trachtenberg , first1 = Marc , author-link = Marc Trachtenberg , year = 1979 , title = Reparations at the Paris Peace Conference , journal = The Journal of Modern History , volume = 51 , issue = 1, pages = 24–55 , jstor=1877867 , doi=10.1086/241847, s2cid = 145777701 * Walworth, Arthur. ''Wilson and His Peacemakers: American Diplomacy at the Paris Peace Conference, 1919'' (1986) 618pp * {{Cite book , last=Walworth , first=Arthur , title=Woodrow Wilson, Volume I, Volume II, publisher=Longmans, Green , year=1958 ; 904pp; full scale scholarly biography; winner of Pulitzer Prize

online free; 2nd ed. 1965

* Watson, David Robin. ''George Clemenceau: A Political Biography'' (1976) 463 pgs. * Xu, Guoqi. ''Asia and the Great War – A Shared History'' (Oxford UP, 2016

online

{Dead link, date=October 2022 , bot=InternetArchiveBot , fix-attempted=yes {{refend

Seating Plan of the Paris Peace Conference – UK Parliament Living Heritage

Frances Stevenson – Paris Peace Conference Diary – UK Parliament Living Heritage

Frances Stevenson – Paris Peace Conference ID Card – UK Parliament Living Heritage

* Sharp, Alan

The Paris Peace Conference and its Consequences

, in

1914–1918-online. International Encyclopedia of the First World War

Excerpts from the NFB documentary ''Paris 1919''

Sampling of maps

used by the American delegates held by th

American Geographical Society Library

UW Milwaukee {{Paris Peace Conference navbox, state=expanded {{World War I {{David Lloyd George {{Woodrow Wilson {{Authority control {{DEFAULTSORT:Paris Peace Conference (1919-1920) 1919 in international relations 1920 in international relations 1919 conferences 1920 conferences Georges Clemenceau Presidency of Woodrow Wilson

World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

, in which the victorious Allies

An alliance is a relationship among people, groups, or states that have joined together for mutual benefit or to achieve some common purpose, whether or not explicit agreement has been worked out among them. Members of an alliance are called ...

set the peace terms for the defeated Central Powers

The Central Powers, also known as the Central Empires,german: Mittelmächte; hu, Központi hatalmak; tr, İttifak Devletleri / ; bg, Централни сили, translit=Tsentralni sili was one of the two main coalitions that fought in ...

. Dominated by the leaders of Britain, France, the United States and Italy, the conference resulted in five treaties that rearranged the maps of Europe and parts of Asia, Africa and the Pacific Islands, and also imposed financial penalties. Germany, Austria-Hungary, Turkey and the other losing nations were not given a voice in the deliberations; this later gave rise to political resentments that lasted for decades. The arrangements made by this conference are considered one of the great watersheds of 20th-century geopolitical history.

The conference involved diplomats from 32 countries and nationalities. Its major decisions were the creation of the League of Nations

The League of Nations (french: link=no, Société des Nations ) was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference that ...

and the five peace treaties with the defeated states. Main arrangements agreed upon in the treaties were, among others, the transition of German and Ottoman overseas possessions as " mandates" from the hands of these countries chiefly into the hands of Britain and France; the imposition of reparations upon Germany; and the drawing of new national boundaries, sometimes involving plebiscites

A referendum (plural: referendums or less commonly referenda) is a direct vote by the electorate on a proposal, law, or political issue. This is in contrast to an issue being voted on by a representative. This may result in the adoption of a ...

, to reflect ethnic boundaries more closely.

US President Woodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson (December 28, 1856February 3, 1924) was an American politician and academic who served as the 28th president of the United States from 1913 to 1921. A member of the Democratic Party, Wilson served as the president of ...

in 1917 commissioned a group of about 150 academics to research topics likely to arise in diplomatic talks on the European stage, and to develop a set of principles to be used for the peace negotiations

A peace treaty is an agreement between two or more hostile parties, usually countries or governments, which formally ends a state of war between the parties. It is different from an armistice, which is an agreement to stop hostilities; a surre ...

in order to end World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

. The results of this research were summarized in the so called Fourteen Points

U.S. President Woodrow Wilson

The Fourteen Points was a statement of principles for peace that was to be used for peace negotiations in order to end World War I. The principles were outlined in a January 8, 1918 speech on war aims and peace terms ...

document that became the basis for the terms of the German surrender during the conference, as it had earlier been the basis of the German government's negotiations in the Armistice of 11 November 1918

The Armistice of 11 November 1918 was the armistice signed at Le Francport near Compiègne that ended fighting on land, sea, and air in World War I between the Entente and their last remaining opponent, Germany. Previous armistices ...

.

The main result of the conference was the Treaty of Versailles

The Treaty of Versailles (french: Traité de Versailles; german: Versailler Vertrag, ) was the most important of the peace treaties of World War I. It ended the state of war between Germany and the Allied Powers. It was signed on 28 June ...

with Germany; Article 231 of that treaty placed the whole guilt for the war on "the aggression of Germany and her allies". That provision proved very humiliating for German leaders, armies and citizens alike, and set the stage for the expensive reparations that Germany was intended to pay (only a small portion of which had been delivered when it stopped paying after 1931). The five great powers at that time, France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

, Britain

Britain most often refers to:

* The United Kingdom, a sovereign state in Europe comprising the island of Great Britain, the north-eastern part of the island of Ireland and many smaller islands

* Great Britain, the largest island in the United King ...

, Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical re ...

, Japan

Japan ( ja, 日本, or , and formally , ''Nihonkoku'') is an island country in East Asia. It is situated in the northwest Pacific Ocean, and is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan, while extending from the Sea of Okhotsk in the north ...

and the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territorie ...

, controlled the Conference. The " Big Four" leaders were French Prime Minister

The prime minister of France (french: link=no, Premier ministre français), officially the prime minister of the French Republic, is the head of government of the French Republic and the leader of the Council of Ministers.

The prime minister i ...

Georges Clemenceau

Georges Benjamin Clemenceau (, also , ; 28 September 1841 – 24 November 1929) was a French statesman who served as Prime Minister of France from 1906 to 1909 and again from 1917 until 1920. A key figure of the Independent Radicals, he was a ...

, British Prime Minister

The prime minister of the United Kingdom is the head of government of the United Kingdom. The prime minister advises the sovereign on the exercise of much of the royal prerogative, chairs the Cabinet and selects its ministers. As moder ...

David Lloyd George

David Lloyd George, 1st Earl Lloyd-George of Dwyfor, (17 January 1863 – 26 March 1945) was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1916 to 1922. He was a Liberal Party politician from Wales, known for leading the United Kingdom during t ...

, US President

The president of the United States (POTUS) is the head of state and head of government of the United States of America. The president directs the executive branch of the federal government and is the commander-in-chief of the United Stat ...

Woodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson (December 28, 1856February 3, 1924) was an American politician and academic who served as the 28th president of the United States from 1913 to 1921. A member of the Democratic Party, Wilson served as the president of ...

, and Italian Prime Minister

The Prime Minister of Italy, officially the President of the Council of Ministers ( it, link=no, Presidente del Consiglio dei Ministri), is the head of government of the Italian Republic. The office of president of the Council of Ministers is ...

Vittorio Emanuele Orlando

Vittorio Emanuele Orlando (19 May 1860 – 1 December 1952) was an Italian statesman, who served as the Prime Minister of Italy from October 1917 to June 1919. Orlando is best known for representing Italy in the 1919 Paris Peace Conference with h ...

. Together with teams of diplomats and jurists

A jurist is a person with expert knowledge of law; someone who analyses and comments on law. This person is usually a specialist legal scholar, mostly (but not always) with a formal qualification in law and often a legal practitioner. In the U ...

, they met informally 145 times and agreed upon all major decisions before they were ratified.Rene Albrecht-Carrie, ''Diplomatic History of Europe Since the Congress of Vienna'' (1958) p. 363

The conference began on 18 January 1919. With respect to its end, Professor Michael Neiberg

Michael Scott Neiberg is an American historian, who specializes in 20th-century military history.

Career

Neiberg serves as the inaugural Chair of War Studies in the Department of National Security and Strategy at the United States Army War Coll ...

noted, "Although the senior statesmen stopped working personally on the conference in June 1919, the formal peace process did not really end until July 1923, when the Treaty of Lausanne

The Treaty of Lausanne (french: Traité de Lausanne) was a peace treaty negotiated during the Lausanne Conference of 1922–23 and signed in the Palais de Rumine, Lausanne, Switzerland, on 24 July 1923. The treaty officially settled the conflic ...

was signed." The entire process is often referred to as the "Versailles Conference", although only the signing of the first treaty took place in the historic palace; the negotiations occurred at the Quai d'Orsay

The Quai d'Orsay ( , ) is a quay in the 7th arrondissement of Paris. It is part of the left bank of the Seine opposite the Place de la Concorde. The Quai becomes the Quai Anatole-France east of the Palais Bourbon, and the Quai Branly west of t ...

in Paris.

Overview and direct results

The Conference formally opened on 18 January 1919 at the Quai d’Orsay in Paris.Erik Goldstein ''The First World War Peace Settlements, 1919–1925'' p. 49 Routledge (2013) This date was symbolic, as it was the anniversary of the proclamation ofWilliam I

William I; ang, WillelmI (Bates ''William the Conqueror'' p. 33– 9 September 1087), usually known as William the Conqueror and sometimes William the Bastard, was the first Norman king of England, reigning from 1066 until his death in 1087 ...

as German Emperor

The German Emperor (german: Deutscher Kaiser, ) was the official title of the head of state and hereditary ruler of the German Empire. A specifically chosen term, it was introduced with the 1 January 1871 constitution and lasted until the offi ...

in 1871, in the Hall of Mirrors

The Hall of Mirrors (french: Grande Galerie, Galerie des Glaces, Galerie de Louis XIV) is a grand Baroque style gallery and one of the most emblematic rooms in the royal Palace of Versailles near Paris, France. The grandiose ensemble of the hal ...

at the Palace of Versailles

The Palace of Versailles ( ; french: Château de Versailles ) is a former royal residence built by King Louis XIV located in Versailles, Yvelines, Versailles, about west of Paris, France. The palace is owned by the French Republic and since 19 ...

, shortly before the end of the Siege of Paris – a day itself imbued with significance in its turn in Germany as the anniversary of the establishment of the Kingdom of Prussia

The Kingdom of Prussia (german: Königreich Preußen, ) was a German kingdom that constituted the state of Prussia between 1701 and 1918.Marriott, J. A. R., and Charles Grant Robertson. ''The Evolution of Prussia, the Making of an Empire''. Re ...

in 1701.

The Delegates from 27 nations (delegates representing 5 nationalities were for the most part ignored) were assigned to 52 commissions, which held 1,646 sessions to prepare reports, with the help of many experts, on topics ranging from prisoners of war to undersea cables, to international aviation, to responsibility for the war. Key recommendations were folded into the Treaty of Versailles

The Treaty of Versailles (french: Traité de Versailles; german: Versailler Vertrag, ) was the most important of the peace treaties of World War I. It ended the state of war between Germany and the Allied Powers. It was signed on 28 June ...

with Germany, which had 15 chapters and 440 clauses, as well as treaties for the other defeated nations.

The five major powers (France, Britain, Italy, the U.S., and Japan) controlled the Conference. Amongst the "Big Five", in practice Japan only sent a former prime minister and played a small role; and the " Big Four" leaders dominated the conference.

The four met together informally 145 times and made all the major decisions, which in turn were ratified by other attendees. The open meetings of all the delegations approved the decisions made by the Big Four. The conference came to an end on 21 January 1920 with the inaugural General Assembly of the League of Nations

The League of Nations (french: link=no, Société des Nations ) was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference that ...

.

Five major peace treaties were prepared at the Paris Peace Conference (with, in parentheses, the affected countries):

* the Treaty of Versailles

The Treaty of Versailles (french: Traité de Versailles; german: Versailler Vertrag, ) was the most important of the peace treaties of World War I. It ended the state of war between Germany and the Allied Powers. It was signed on 28 June ...

, 28 June 1919 (Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwe ...

)

* the Treaty of Saint-Germain

A treaty is a formal, legally binding written agreement between actors in international law. It is usually made by and between sovereign states, but can include international organizations, individuals, business entities, and other legal pers ...

, 10 September 1919 (Austria

Austria, , bar, Östareich officially the Republic of Austria, is a country in the southern part of Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine states, one of which is the capital, Vienna, the most populous ...

)

* the Treaty of Neuilly

The Treaty of Neuilly-sur-Seine (french: Traité de Neuilly-sur-Seine) required Bulgaria to cede various territories, after Bulgaria had been one of the Central Powers defeated in World War I. The treaty was signed on 27 November 1919 at Neuilly ...

, 27 November 1919 (Bulgaria

Bulgaria (; bg, България, Bǎlgariya), officially the Republic of Bulgaria,, ) is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the eastern flank of the Balkans, and is bordered by Romania to the north, Serbia and North Macedon ...

)

* the Treaty of Trianon

The Treaty of Trianon (french: Traité de Trianon, hu, Trianoni békeszerződés, it, Trattato del Trianon) was prepared at the Paris Peace Conference (1919–1920), Paris Peace Conference and was signed in the Grand Trianon château in ...

, 4 June 1920 (Hungary

Hungary ( hu, Magyarország ) is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Spanning of the Carpathian Basin, it is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine to the northeast, Romania to the east and southeast, Serbia to the south, Croatia a ...

)

* the Treaty of Sèvres

The Treaty of Sèvres (french: Traité de Sèvres) was a 1920 treaty signed between the Allies of World War I and the Ottoman Empire. The treaty ceded large parts of Ottoman territory to France, the United Kingdom, Greece and Italy, as well ...

, 10 August 1920; subsequently revised by the Treaty of Lausanne

The Treaty of Lausanne (french: Traité de Lausanne) was a peace treaty negotiated during the Lausanne Conference of 1922–23 and signed in the Palais de Rumine, Lausanne, Switzerland, on 24 July 1923. The treaty officially settled the conflic ...

, 24 July 1923 (Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

/Republic of Turkey

Turkey ( tr, Türkiye ), officially the Republic of Türkiye ( tr, Türkiye Cumhuriyeti, links=no ), is a list of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country located mainly on the Anatolia, Anatolian Peninsula in Western Asia, with ...

).

The major decisions were the establishment of the League of Nations

The League of Nations (french: link=no, Société des Nations ) was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference that ...

; the five peace treaties with defeated enemies; the awarding of German and Ottoman overseas possessions as "mandates", chiefly to members of the British Empire and to France; reparations imposed on Germany; and the drawing of new national boundaries (sometimes with plebiscites) to better reflect the forces of nationalism. The main result was the Treaty of Versailles

The Treaty of Versailles (french: Traité de Versailles; german: Versailler Vertrag, ) was the most important of the peace treaties of World War I. It ended the state of war between Germany and the Allied Powers. It was signed on 28 June ...

, with Germany, which in section 231 laid the guilt for the war on "the aggression of Germany and her allies". This provision proved humiliating for Germany and set the stage for very high reparations Germany was supposed to pay (it paid only a small portion before reparations ended in 1931).According to British historian AJP Taylor the treaty seemed to Germans "wicked, unfair" and "dictation, a slave treaty" but one which they would repudiate at some stage if it "did not fall to pieces of its own absurdity."

As the conference's decisions were enacted unilaterally and largely on the whims of the Big Four, Paris

Paris () is the capital and most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), making it the 30th most densely populated city in the world in 2020. S ...

was effectively the center of a world government

World government is the concept of a single political authority with jurisdiction over all humanity. It is conceived in a variety of forms, from tyrannical to democratic, which reflects its wide array of proponents and detractors.

A world gove ...

during the conference, which deliberated over and implemented the sweeping changes to the political geography

Political geography is concerned with the study of both the spatially uneven outcomes of political processes and the ways in which political processes are themselves affected by spatial structures. Conventionally, for the purposes of analysis, po ...

of Europe

Europe is a large peninsula conventionally considered a continent in its own right because of its great physical size and the weight of its history and traditions. Europe is also considered a Continent#Subcontinents, subcontinent of Eurasia ...

. Most famously, the Treaty of Versailles itself weakened the German military

The ''Bundeswehr'' (, meaning literally: ''Federal Defence'') is the armed forces of the Federal Republic of Germany. The ''Bundeswehr'' is divided into a military part (armed forces or ''Streitkräfte'') and a civil part, the military part con ...

and placed full blame for the war and costly reparations on Germany's shoulders, and the later humiliation and resentment in Germany is often sometimes considered by historians to be one of the direct causes of Nazi Party

The Nazi Party, officially the National Socialist German Workers' Party (german: Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei or NSDAP), was a far-right politics, far-right political party in Germany active between 1920 and 1945 that crea ...

's electoral successes and one of the indirect causes of World War II. The League of Nations proved controversial in the United States since critics said it subverted the powers of the US Congress

The United States Congress is the legislature of the federal government of the United States. It is bicameral, composed of a lower body, the House of Representatives, and an upper body, the Senate. It meets in the U.S. Capitol in Washin ...

to declare war; the US Senate

The United States Senate is the upper chamber of the United States Congress, with the House of Representatives being the lower chamber. Together they compose the national bicameral legislature of the United States.

The composition and powe ...

did not ratify any of the peace treaties and so the United States never joined the League. Instead, the 1921–1923 Harding administration

Warren G. Harding's tenure as the 29th president of the United States lasted from March 4, 1921 until his death on August 2, 1923. Harding presided over the country in the aftermath of World War I. A Republican from Ohio, Harding held office du ...

concluded new treaties with Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwe ...

, Austria

Austria, , bar, Östareich officially the Republic of Austria, is a country in the southern part of Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine states, one of which is the capital, Vienna, the most populous ...

, and Hungary

Hungary ( hu, Magyarország ) is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Spanning of the Carpathian Basin, it is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine to the northeast, Romania to the east and southeast, Serbia to the south, Croatia a ...

. The German Weimar Republic

The Weimar Republic (german: link=no, Weimarer Republik ), officially named the German Reich, was the government of Germany from 1918 to 1933, during which it was a constitutional federal republic for the first time in history; hence it is al ...

was not invited to attend the conference at Versailles. Representatives of White Russia

White Russia, White Russian, or Russian White may refer to:

White Russia

*White Ruthenia, a historical reference for a territory in the eastern part of present-day Belarus

* An archaic literal translation for Belarus/Byelorussia/Belorussia

* Rus ...

but not Communist Russia were at the conference. Numerous other nations sent delegations to appeal for various unsuccessful additions to the treaties, and parties lobbied for causes ranging from independence for the countries of the South Caucasus

The South Caucasus, also known as Transcaucasia or the Transcaucasus, is a geographical region on the border of Eastern Europe and Western Asia, straddling the southern Caucasus Mountains. The South Caucasus roughly corresponds to modern Arme ...

to Japan's unsuccessful proposal for racial equality

Racial equality is a situation in which people of all races and ethnicities are treated in an egalitarian/equal manner. Racial equality occurs when institutions give individuals legal, moral, and political rights. In present-day Western society, ...

to the other great powers.

Mandates

A central issue of the conference was the disposition of the overseas colonies of Germany (Austria-Hungary did not have major colonies, and the Ottoman Empire was a separate issue). The British dominions wanted their reward for their sacrifice. Australia wantedNew Guinea

New Guinea (; Hiri Motu

Hiri Motu, also known as Police Motu, Pidgin Motu, or just Hiri, is a language of Papua New Guinea, which is spoken in surrounding areas of Port Moresby (Capital of Papua New Guinea).

It is a simplified version of ...

, New Zealand wanted Samoa

Samoa, officially the Independent State of Samoa; sm, Sāmoa, and until 1997 known as Western Samoa, is a Polynesian island country consisting of two main islands (Savai'i and Upolu); two smaller, inhabited islands (Manono Island, Manono an ...

, and South Africa wanted South West Africa

South West Africa ( af, Suidwes-Afrika; german: Südwestafrika; nl, Zuidwest-Afrika) was a territory under South African administration from 1915 to 1990, after which it became modern-day Namibia. It bordered Angola (Portuguese colony before 1 ...

. Wilson wanted the League to administer all German colonies until they were ready for independence. Lloyd George realized he needed to support his dominions and so he proposed a compromise: there be three types of mandates. Mandates for the Turkish provinces were one category and would be divided up between Britain and France.

The second category, of New Guinea, Samoa, and South West Africa, were located so close to responsible supervisors that the mandates could hardly be given to anyone except Australia, New Zealand, and South Africa. Finally, the African colonies would need the careful supervision as "Class B" mandates, which could be provided only by experienced colonial powers: Britain, France, and Belgium although Italy and Portugal received small amounts of territory. Wilson and the others finally went along with the solution. The dominions received " Class C Mandates" to the colonies that they wanted. Japan obtained mandates over German possessions north of the

The second category, of New Guinea, Samoa, and South West Africa, were located so close to responsible supervisors that the mandates could hardly be given to anyone except Australia, New Zealand, and South Africa. Finally, the African colonies would need the careful supervision as "Class B" mandates, which could be provided only by experienced colonial powers: Britain, France, and Belgium although Italy and Portugal received small amounts of territory. Wilson and the others finally went along with the solution. The dominions received " Class C Mandates" to the colonies that they wanted. Japan obtained mandates over German possessions north of the Equator

The equator is a circle of latitude, about in circumference, that divides Earth into the Northern and Southern hemispheres. It is an imaginary line located at 0 degrees latitude, halfway between the North and South poles. The term can als ...

.

Wilson wanted no mandates for the United States, but his main advisor, Colonel House

Edward Mandell House (July 26, 1858 – March 28, 1938) was an American diplomat, and an adviser to President Woodrow Wilson. He was known as Colonel House, although his rank was honorary and he had performed no military service. He was a highl ...

, was deeply involved in awarding the others. Wilson was especially offended by Australian demands and had some memorable clashes with Hughes (the Australian Prime Minister), this the most famous:

:

British approach

The maintenance of the unity, territories, and interests of the British Empire was an overarching concern for the British delegates to the conference, but they entered the conference with more specific goals with this order of priority:

* Ensuring the security of France

* Removing the threat of the

The maintenance of the unity, territories, and interests of the British Empire was an overarching concern for the British delegates to the conference, but they entered the conference with more specific goals with this order of priority:

* Ensuring the security of France

* Removing the threat of the German High Seas Fleet

The High Seas Fleet (''Hochseeflotte'') was the battle fleet of the German Empire, German German Imperial Navy, Imperial Navy and saw action during the World War I, First World War. The formation was created in February 1907, when the Home Fleet ...

* Settling territorial contentions

* Supporting the League of Nations

The Racial Equality Proposal put forth by the Japanese did not directly conflict with any core British interest, but as the conference progressed, its full implications on immigration to the British dominions

The term ''Dominion'' is used to refer to one of several self-governing nations of the British Empire.

"Dominion status" was first accorded to Canada, Australia, New Zealand, Newfoundland, South Africa, and the Irish Free State at the 19 ...

, with Australia

Australia, officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a Sovereign state, sovereign country comprising the mainland of the Australia (continent), Australian continent, the island of Tasmania, and numerous List of islands of Australia, sma ...

taking particular exception, became a major point of contention within the delegation.

Ultimately, the British delegation did not treat that proposal as a fundamental aim of the conference; they were willing to sacrifice the Racial Equality Proposal to placate the Australian delegation and thus help to satisfy their own overarching aim of preserving the unity of the British empire.

Britain had reluctantly consented to the attendance of separate delegations from British dominions, but the British managed to rebuff attempts by the envoys of the newly proclaimed Irish Republic

The Irish Republic ( ga, Poblacht na hÉireann or ) was an unrecognised revolutionary state that declared its independence from the United Kingdom in January 1919. The Republic claimed jurisdiction over the whole island of Ireland, but by ...

to put a case to the conference for Irish self-determination

The right of a people to self-determination is a cardinal principle in modern international law (commonly regarded as a ''jus cogens'' rule), binding, as such, on the United Nations as authoritative interpretation of the Charter's norms. It stat ...

, diplomatic recognition, and membership in the proposed League of Nations. The Irish envoys' final "Demand for Recognition" in a letter to Clemenceau, the conference chairman, was not answered. Britain had been planning to renege on the Government of Ireland Act 1914

The Government of Ireland Act 1914 (4 & 5 Geo. 5 c. 90), also known as the Home Rule Act, and before enactment as the Third Home Rule Bill, was an Act passed by the Parliament of the United Kingdom intended to provide home rule (self-governm ...

and instead to replace it with a new Government of Ireland Bill which would partition Ireland into two Irish Home Rule

The Irish Home Rule movement was a movement that campaigned for Devolution, self-government (or "home rule") for Ireland within the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. It was the dominant political movement of Irish nationalism from 1 ...

states (which eventually was passed as the Government of Ireland Act 1920). The planned two states would both be within the United Kingdom and so neither would have dominion status.

David Lloyd George commented that he did "not do badly" at the peace conference "considering I was seated between Jesus Christ

Jesus, likely from he, יֵשׁוּעַ, translit=Yēšūaʿ, label=Hebrew/Aramaic ( AD 30 or 33), also referred to as Jesus Christ or Jesus of Nazareth (among other names and titles), was a first-century Jewish preacher and religious ...

and Napoleon

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader who ...

." This was a reference to the great idealism of Wilson, who desired merely to punish Germany, and the stark realism of Clemenceau, who was determined to see Germany effectively destroyed.

Dominion representation

The dominion governments were not originally given separate invitations to the conference, and had been expected to send representatives as part of the British delegation.

Convinced that Canada had become a nation on the battlefields of Europe, Prime Minister

The dominion governments were not originally given separate invitations to the conference, and had been expected to send representatives as part of the British delegation.

Convinced that Canada had become a nation on the battlefields of Europe, Prime Minister Sir Robert Borden

Sir Robert Laird Borden (June 26, 1854 – June 10, 1937) was a Canadian lawyer and politician who served as the eighth prime minister of Canada from 1911 to 1920. He is best known for his leadership of Canada during World War I.

Borden ...

demanded that it have a separate seat at the conference. That was initially opposed not only by Britain but also by the United States, which saw any Dominion delegation as an extra British vote. Borden responded by pointing out that since Canada had lost nearly 60,000 men, a far larger proportion of its men than the 50,000 American men lost, it had at least the right to the representation of a "minor" power. Lloyd George eventually relented, and persuaded the reluctant Americans to accept the presence of delegations from Canada, India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by area, the second-most populous country, and the most populous democracy in the world. Bounded by the Indian Ocean on the so ...

, Australia, Newfoundland

Newfoundland and Labrador (; french: Terre-Neuve-et-Labrador; frequently abbreviated as NL) is the easternmost province of Canada, in the country's Atlantic region. The province comprises the island of Newfoundland and the continental region ...

, New Zealand, and South Africa, and that those countries receive their own seats in the League of Nations.

Canada, despite its huge losses in the war, did not ask for either reparations or mandates.

The Australian delegation, led by Australian Prime Minister Billy Hughes

William Morris Hughes (25 September 1862 – 28 October 1952) was an Australian politician who served as the seventh prime minister of Australia, in office from 1915 to 1923. He is best known for leading the country during World War I, but ...

fought greatly for its demands: reparations, the annexation of German New Guinea

German New Guinea (german: Deutsch-Neu-Guinea) consisted of the northeastern part of the island of New Guinea and several nearby island groups and was the first part of the German colonial empire. The mainland part of the territory, called , ...

, and the rejection of the Racial Equality Proposal. He said that he had no objection to the proposal if it was stated in unambiguous terms that it did not confer any right to enter Australia. He was concerned by the increasing power of Japan. Within months of the declaration of war in 1914, Japan, Australia, and New Zealand had seized all of Germany's possessions in the Far East

The ''Far East'' was a European term to refer to the geographical regions that includes East and Southeast Asia as well as the Russian Far East to a lesser extent. South Asia is sometimes also included for economic and cultural reasons.

The ter ...

and the Pacific Ocean

The Pacific Ocean is the largest and deepest of Earth's five oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic Ocean in the north to the Southern Ocean (or, depending on definition, to Antarctica) in the south, and is bounded by the continen ...

. The British had given their blessing for Japan to occupy German possessions, but Hughes was alarmed by that policy.

French approach

French Prime Minister

French Prime Minister Georges Clemenceau

Georges Benjamin Clemenceau (, also , ; 28 September 1841 – 24 November 1929) was a French statesman who served as Prime Minister of France from 1906 to 1909 and again from 1917 until 1920. A key figure of the Independent Radicals, he was a ...

controlled his delegation, and his chief goal was to weaken Germany militarily, strategically, and economically. Having personally witnessed two German attacks on French soil in the last 40 years, he was adamant for Germany not to be permitted to attack France again. Particularly, Clemenceau sought an American and British joint guarantee of French security in the event of another German attack.

Clemenceau also expressed skepticism and frustration with Wilson's Fourteen Points

U.S. President Woodrow Wilson

The Fourteen Points was a statement of principles for peace that was to be used for peace negotiations in order to end World War I. The principles were outlined in a January 8, 1918 speech on war aims and peace terms ...

and complained: "Mr. Wilson bores me with his fourteen points. Why, God Almighty has only ten!" Wilson gained some favour by signing a mutual defense treaty with France, but he did not present it to his country's government for ratification and so it never took effect.

Another possible French policy was to seek a rapprochement

In international relations, a rapprochement, which comes from the French word ''rapprocher'' ("to bring together"), is a re-establishment of cordial relations between two countries. This may be done due to a mutual enemy, as was the case with Germ ...

with Germany. In May 1919 the diplomat René Massigli

René Massigli (; 22 March 1888 – 3 February 1988) was a French diplomat who played a leading role as a senior official at the Quai d'Orsay and was regarded as one of the leading French experts on Germany, which he greatly distrusted.

Early ca ...

was sent on several secret missions to Berlin

Berlin ( , ) is the capital and largest city of Germany by both area and population. Its 3.7 million inhabitants make it the European Union's most populous city, according to population within city limits. One of Germany's sixteen constitue ...

. During his visits, he offered, on behalf of his government, to revise the territorial and economic clauses of the upcoming peace treaty. Massigli spoke of the desirability of "practical, verbal discussions" between French and German officials that would lead to a "Franco-German collaboration." Furthermore, Massigli told the Germans that the French thought of the "Anglo-Saxon powers" (the United States and the British Empire) as the major threat to France in the post-war world. He argued that both France and Germany had a joint interest in opposing "Anglo-Saxon domination" of the world, and he warned that the "deepening of opposition" between the French and the Germans "would lead to the ruin of both countries, to the advantage of the Anglo-Saxon powers."Trachtenberg (1979), p. 43.

The Germans rejected Massigli's offers because they believed that the intention was to trick them into accepting the Treaty of Versailles unchanged; also, the German Foreign Minister, Count Ulrich von Brockdorff-Rantzau

Ulrich Karl Christian Graf von Brockdorff-Rantzau (29 May 1869 – 8 September 1928) was a German diplomat who became the first Foreign Minister of the Weimar Republic. In that capacity, he led the German delegation at the Paris Peace Conference ...

, thought that the United States was more likely to reduce the severity of the penalties than France was. (Lloyd George was the one who eventually pushed for better terms for Germany.)

Italian approach

In 1914, Italy remained neutral despite the Triple Alliance with Germany and Austria-Hungary. In 1915, it joined the Allies to gain the territories promised by the

In 1914, Italy remained neutral despite the Triple Alliance with Germany and Austria-Hungary. In 1915, it joined the Allies to gain the territories promised by the Triple Entente

The Triple Entente (from French '' entente'' meaning "friendship, understanding, agreement") describes the informal understanding between the Russian Empire, the French Third Republic, and the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland as well a ...

in the secret Treaty of London: Trentino

Trentino ( lld, Trentin), officially the Autonomous Province of Trento, is an autonomous province of Italy, in the country's far north. The Trentino and South Tyrol constitute the region of Trentino-Alto Adige/Südtirol, an autonomous region ...

, the Tyrol

Tyrol (; historically the Tyrole; de-AT, Tirol ; it, Tirolo) is a historical region in the Alps - in Northern Italy and western Austria. The area was historically the core of the County of Tyrol, part of the Holy Roman Empire, Austrian Emp ...

as far as Brenner, Trieste

Trieste ( , ; sl, Trst ; german: Triest ) is a city and seaport in northeastern Italy. It is the capital city, and largest city, of the autonomous region of Friuli Venezia Giulia, one of two autonomous regions which are not subdivided into provi ...

, Istria

Istria ( ; Croatian language, Croatian and Slovene language, Slovene: ; ist, Eîstria; Istro-Romanian language, Istro-Romanian, Italian language, Italian and Venetian language, Venetian: ; formerly in Latin and in Ancient Greek) is the larges ...

, most of the Dalmatian Coast

Dalmatia (; hr, Dalmacija ; it, Dalmazia; see #Name, names in other languages) is one of the four historical region, historical regions of Croatia, alongside Croatia proper, Slavonia, and Istria. Dalmatia is a narrow belt of the east shore of ...

(except Fiume

Rijeka ( , , ; also known as Fiume hu, Fiume, it, Fiume ; local Chakavian: ''Reka''; german: Sankt Veit am Flaum; sl, Reka) is the principal seaport and the third-largest city in Croatia (after Zagreb and Split). It is located in Primor ...

), Valona, a protectorate over Albania, Antalya

Antalya () is the List of largest cities and towns in Turkey, fifth-most populous city in Turkey as well as the capital of Antalya Province. Located on Anatolia's southwest coast bordered by the Taurus Mountains, Antalya is the largest Turkish cit ...

(in Turkey), and possibly colonies in Africa.

Italian Prime Minister Vittorio Emanuele Orlando

Vittorio Emanuele Orlando (19 May 1860 – 1 December 1952) was an Italian statesman, who served as the Prime Minister of Italy from October 1917 to June 1919. Orlando is best known for representing Italy in the 1919 Paris Peace Conference with h ...

tried to obtain full implementation of the Treaty of London, as agreed by France and Britain before the war. He had popular support because of the loss of 700,000 soldiers and a budget deficit of 12,000,000,000 Italian lire

The lira (; plural lire) was the currency of Italy between 1861 and 2002. It was first introduced by the Napoleonic Kingdom of Italy in 1807 at par with the French franc, and was subsequently adopted by the different states that would eventually f ...

during the war made both the government and people feel entitled to all of those territories and even others not mentioned in the Treaty of London, particularly Fiume, which many Italians believed should be annexed to Italy because of the city's Italian population.

Orlando, unable to speak English, conducted negotiations jointly with his Foreign Minister Sidney Sonnino

Sidney Costantino, Baron Sonnino (11 March 1847 – 24 November 1922) was an Italian statesman, 19th prime minister of Italy and twice served briefly as one, in 1906 and again from 1909 to 1910. In 1901, he founded a new major newspaper, '' Il Gio ...

, a Protestant

Protestantism is a Christian denomination, branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Reformation, Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century agai ...

of British origins who spoke the language. Together, they worked primarily to secure the partition of the Habsburg monarchy

The Habsburg monarchy (german: Habsburgermonarchie, ), also known as the Danubian monarchy (german: Donaumonarchie, ), or Habsburg Empire (german: Habsburgerreich, ), was the collection of empires, kingdoms, duchies, counties and other polities ...

. At the conference, Italy gained Istria

Istria ( ; Croatian language, Croatian and Slovene language, Slovene: ; ist, Eîstria; Istro-Romanian language, Istro-Romanian, Italian language, Italian and Venetian language, Venetian: ; formerly in Latin and in Ancient Greek) is the larges ...

, Trieste

Trieste ( , ; sl, Trst ; german: Triest ) is a city and seaport in northeastern Italy. It is the capital city, and largest city, of the autonomous region of Friuli Venezia Giulia, one of two autonomous regions which are not subdivided into provi ...

, Trentino

Trentino ( lld, Trentin), officially the Autonomous Province of Trento, is an autonomous province of Italy, in the country's far north. The Trentino and South Tyrol constitute the region of Trentino-Alto Adige/Südtirol, an autonomous region ...

, and South Tyrol

it, Provincia Autonoma di Bolzano – Alto Adige lld, Provinzia Autonoma de Balsan/Bulsan – Südtirol

, settlement_type = Autonomous province

, image_skyline =

, image_alt ...

. Most of Dalmatia

Dalmatia (; hr, Dalmacija ; it, Dalmazia; see #Name, names in other languages) is one of the four historical region, historical regions of Croatia, alongside Croatia proper, Slavonia, and Istria. Dalmatia is a narrow belt of the east shore of ...

, however, was given to the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes, and Fiume remained disputed territory, causing a nationalist outrage. Orlando obtained other results, such as the permanent membership of Italy in the League of Nations

The League of Nations (french: link=no, Société des Nations ) was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference that ...

and the promise by the Allies to transfer British Jubaland and the French Aozou strip

The Aouzou Strip (; ar, قطاع أوزو, Qiṭāʿ Awzū, french: Bande d'Aozou) is a strip of land in northern Chad that lies along the border with Libya, extending south to a depth of about 100 kilometers into Chad's Borkou, Ennedi Ouest ...

to Italian colonies. Protectorates over Albania and Antalya were also recognized, but nationalists considered the war to be a mutilated victory

Mutilated victory ( Italian: ''vittoria mutilata'') is a term coined by Gabriele D’Annunzio at the end of World War I, used to describe the dissatisfaction of Italian nationalists concerning territorial rewards in favor of the Kingdom of Italy a ...

, and Orlando was ultimately forced to abandon the conference and to resign. Francesco Saverio Nitti

Francesco Saverio Vincenzo de Paolo Nitti (19 July 1868 – 20 February 1953) was an Italian economist and political figure. A Radical, he served as Prime Minister of Italy between 1919 and 1920.

According to the ''Catholic Encyclopedia'' (" ...

took his place and signed the treaties.

There was a general disappointment in Italy, which the nationalists and fascists used to build the idea that Italy was betrayed by the Allies and refused what had been promised. That was a cause for the general rise of Italian fascism. Orlando refused to see the war as a mutilated victory and replied to nationalists calling for a greater expansion, "Italy today is a great state... on par with the great historic and contemporary states. This is, for me, our main and principal expansion."

Japanese approach

Japan sent a large delegation, headed by the former Prime Minister, Marquis

Japan sent a large delegation, headed by the former Prime Minister, Marquis Saionji Kinmochi

Prince was a Japanese politician and statesman who served as Prime Minister of Japan from 1906 to 1908 and from 1911 to 1912. He was elevated from marquis to prince in 1920. As the last surviving member of Japan's ''genrō,'' he was the most i ...

. It was originally one of the "big five" but relinquished that role because of its slight interest in European affairs. Instead, it focused on two demands: the inclusion of its Racial Equality Proposal

The was an amendment to the Treaty of Versailles that was considered at the 1919 Paris Peace Conference. Proposed by Japan, it was never intended to have any universal implications, but one was attached to it anyway, which caused its controversy. ...

in the League's Covenant and Japanese territorial claims with respect to former German colonies: Shantung

Shandong ( , ; ; alternately romanized as Shantung) is a coastal province of the People's Republic of China and is part of the East China region.

Shandong has played a major role in Chinese history since the beginning of Chinese civilizati ...

(including Kiaochow

The Jiaozhou Bay (; german: Kiautschou Bucht, ) is a bay located in the prefecture-level city of Qingdao (Tsingtau), China.

The bay has historically been romanized as Kiaochow, Kiauchau or Kiao-Chau in English and Kiautschou in German.

Geo ...

) and the Pacific islands north of the Equator (the Marshall Islands

The Marshall Islands ( mh, Ṃajeḷ), officially the Republic of the Marshall Islands ( mh, Aolepān Aorōkin Ṃajeḷ),'' () is an independent island country and microstate near the Equator in the Pacific Ocean, slightly west of the Internati ...

, Micronesia

Micronesia (, ) is a subregion of Oceania, consisting of about 2,000 small islands in the western Pacific Ocean. It has a close shared cultural history with three other island regions: the Philippines to the west, Polynesia to the east, and ...

, the Mariana Islands

The Mariana Islands (; also the Marianas; in Chamorro: ''Manislan Mariånas'') are a crescent-shaped archipelago comprising the summits of fifteen longitudinally oriented, mostly dormant volcanic mountains in the northwestern Pacific Ocean, betw ...

, and the Carolines). The former Foreign Minister Baron Makino Nobuaki

Count was a Japanese politician and imperial court official. As Lord Keeper of the Privy Seal of Japan, Makino served as Emperor Hirohito’s chief counselor on the monarch’s position in Japanese society and policymaking. In this capacity, he ...

was ''de facto'' chief, and Saionji's role was symbolic and limited because of his history of ill-health. The Japanese delegation became unhappy after it had received only half of the rights of Germany, and it then walked out of the conference.

Racial equality proposal

During the negotiations, the leader of the Japanese delegation, Saionji Kinmochi, proposed the inclusion of a " racial equality clause" in theCovenant of the League of Nations

The Covenant of the League of Nations was the charter of the League of Nations. It was signed on 28 June 1919 as Part I of the Treaty of Versailles, and became effective together with the rest of the Treaty on 10 January 1920.

Creation

Early d ...

on 13 February as an amendment to Article 21.:

The equality of nations being a basic principle of the League of Nations, the High Contracting Parties agree to accord as soon as possible to all alien nationals of states, members of the League, equal and just treatment in every respect making no distinction, either in law or in fact, on account of their race or nationality.The clause quickly proved problematic to both the American and British delegations. Though the proposal itself was compatible with Britain's stance of nominal equality for all

British subject

The term "British subject" has several different meanings depending on the time period. Before 1949, it referred to almost all subjects of the British Empire (including the United Kingdom, Dominions, and colonies, but excluding protectorates ...

s as a principle for maintaining imperial unity, there were significant deviations in the stated interests of its dominion

The term ''Dominion'' is used to refer to one of several self-governing nations of the British Empire.

"Dominion status" was first accorded to Canada, Australia, New Zealand, Newfoundland, South Africa, and the Irish Free State at the 1926 ...

s, notably Australia

Australia, officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a Sovereign state, sovereign country comprising the mainland of the Australia (continent), Australian continent, the island of Tasmania, and numerous List of islands of Australia, sma ...

and South Africa

South Africa, officially the Republic of South Africa (RSA), is the southernmost country in Africa. It is bounded to the south by of coastline that stretch along the South Atlantic and Indian Oceans; to the north by the neighbouring countri ...

. Though both dominions could not vote on the decision individually, they were strongly opposed to the clause and pressured Britain to do likewise. Ultimately, the British delegation succumbed to imperial pressure and abstained from voting for the clause. Meanwhile, though Wilson was indifferent to the clause, there was fierce resistance to it from the American public, and he ruled as Conference chairman that a unanimous vote was required for the Japanese proposal to pass. Ultimately, on the day of the vote, only 11 of the 17 delegates voted in favor of the proposal. The defeat of the proposal influenced Japan's turn from co-operation with the Western world

The Western world, also known as the West, primarily refers to the various nations and state (polity), states in the regions of Europe, North America, and Oceania.

into more nationalist and militarist policies and approaches.

Territorial claims

The Japanese claim to Shantung faced strong challenges from the Chinese patriotic student group. In 1914, at the outset of the war, Japan had seized the territory that had been granted to Germany in 1897 and also seized the German islands in the Pacific north of the equator. In 1917, Japan had made secret agreements with Britain, France, and Italy to guarantee their annexation of these territories. With Britain, there was an agreement to support British annexation of thePacific Islands

Collectively called the Pacific Islands, the islands in the Pacific Ocean are further categorized into three major island groups: Melanesia, Micronesia, and Polynesia. Depending on the context, the term ''Pacific Islands'' may refer to one of se ...

south of the Equator

The equator is a circle of latitude, about in circumference, that divides Earth into the Northern and Southern hemispheres. It is an imaginary line located at 0 degrees latitude, halfway between the North and South poles. The term can als ...

. Despite a generally pro-Chinese view by the American delegation, Article 156 of the Treaty of Versailles transferred German concessions in the Jiaozhou Bay

The Jiaozhou Bay (; german: Kiautschou Bucht, ) is a bay located in the prefecture-level city of Qingdao (Tsingtau), China.

The bay has historically been romanized as Kiaochow, Kiauchau or Kiao-Chau in English and Kiautschou in German.

Geogra ...

, China, to Japan rather than returning sovereign authority to China. The leader of the Chinese delegation, Lu Zhengxiang, demanded a reservation be inserted before he would sign the treaty. After the reservation was denied, the treaty was signed by all the delegations except that of China. Chinese outrage over that provision led to demonstrations known as the May Fourth Movement

The May Fourth Movement was a Chinese anti-imperialist, cultural, and political movement which grew out of student protests in Beijing on May 4, 1919. Students gathered in front of Tiananmen (The Gate of Heavenly Peace) to protest the Chinese ...

. The Pacific Islands north of the equator became a class C mandate, administered by Japan.

American approach

Until Wilson's arrival in Europe in December 1918, no sitting American president had ever visited the continent. Wilson's 1918

Until Wilson's arrival in Europe in December 1918, no sitting American president had ever visited the continent. Wilson's 1918 Fourteen Points

U.S. President Woodrow Wilson

The Fourteen Points was a statement of principles for peace that was to be used for peace negotiations in order to end World War I. The principles were outlined in a January 8, 1918 speech on war aims and peace terms ...

had helped win many hearts and minds as the war ended, not only in America but all over Europe, including Germany, as well as its allies in and the former subjects of the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

.

Wilson's diplomacy and his Fourteen Points had essentially established the conditions for the armistices that had brought an end to World War I. Wilson felt it to be his duty and obligation to the people of the world to be a prominent figure at the peace negotiations. High hopes and expectations were placed on him to deliver what he had promised for the postwar era. In doing so, Wilson ultimately began to lead the foreign policy of the United States towards interventionism, a move that has been strongly resisted in some United States circles ever since.

Once Wilson arrived, however, he found "rivalries, and conflicting claims previously submerged." He worked mostly at trying to influence both the French, led by Georges Clemenceau

Georges Benjamin Clemenceau (, also , ; 28 September 1841 – 24 November 1929) was a French statesman who served as Prime Minister of France from 1906 to 1909 and again from 1917 until 1920. A key figure of the Independent Radicals, he was a ...

, and the British, led by David Lloyd George

David Lloyd George, 1st Earl Lloyd-George of Dwyfor, (17 January 1863 – 26 March 1945) was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1916 to 1922. He was a Liberal Party politician from Wales, known for leading the United Kingdom during t ...

, in their treatment of Germany and its allies in Europe and the former Ottoman Empire in the Middle East

The Middle East ( ar, الشرق الأوسط, ISO 233: ) is a geopolitical region commonly encompassing Arabian Peninsula, Arabia (including the Arabian Peninsula and Bahrain), Anatolia, Asia Minor (Asian part of Turkey except Hatay Pro ...

. Wilson's attempts to gain acceptance of his Fourteen Points ultimately failed; France and Britain each refused to adopt specific points as well as certain core principles.

Several of the Fourteen Points conflicted with the desires of European powers. The United States did not consider it fair or warranted that Article 231 of the Treaty of Versailles declared Germany solely responsible for the war. (The United States did not sign peace treaties with the Central Powers until 1921 under President Warren Harding

Warren Gamaliel Harding (November 2, 1865 – August 2, 1923) was the 29th president of the United States, serving from 1921 until his death in 1923. A member of the Republican Party, he was one of the most popular sitting U.S. presidents. A ...

, when separate documents were signed with Germany, Austria, and Hungary respectively.)

In the Middle East, negotiations were complicated by competing aims and claims, and the new mandate system. The United States expressed a hope to establish a more liberal and diplomatic world as stated in the Fourteen Points, in which democracy, sovereignty, liberty and self-determination

The right of a people to self-determination is a cardinal principle in modern international law (commonly regarded as a ''jus cogens'' rule), binding, as such, on the United Nations as authoritative interpretation of the Charter's norms. It stat ...

would be respected. France and Britain, on the other hand, already controlled empires through which they wielded power over their subjects around the world, and aspired to maintain and expand their colonial power rather than relinquish it.

In light of the previously-secret Sykes–Picot Agreement

The Sykes–Picot Agreement () was a 1916 secret treaty between the United Kingdom and France, with assent from the Russian Empire and the Kingdom of Italy, to define their mutually agreed Sphere of influence, spheres of influence and control in a ...

and following the adoption of the mandate system on the Arab provinces of the former Ottoman Empire, the conference heard statements from competing Zionists and Arabs. Wilson then recommended an international commission of inquiry to ascertain the wishes of the local inhabitants. The idea, first accepted by Great Britain and France, was later rejected, but became the purely-American King–Crane Commission which toured all Syria and Palestine during the summer of 1919 taking statements and sampling opinion. Its report, presented to Wilson, was kept secret from the public until ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid ...

'' broke the story in December 1922. A pro-Zionist joint resolution on Palestine was passed by the United States Congress in September 1922.

France and Britain tried to appease Wilson by consenting to the establishment of his League of Nations

The League of Nations (french: link=no, Société des Nations ) was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference that ...

. However, because isolationist sentiment in the United States was strong, and because some of the articles in the League Charter conflicted with the US Constitution

The Constitution of the United States is the supreme law of the United States of America. It superseded the Articles of Confederation, the nation's first constitution, in 1789. Originally comprising seven articles, it delineates the nation ...

, the United States never ratified the Treaty of Versailles

The Treaty of Versailles (french: Traité de Versailles; german: Versailler Vertrag, ) was the most important of the peace treaties of World War I. It ended the state of war between Germany and the Allied Powers. It was signed on 28 June ...

or joined the League that Wilson had helped to create to further peace by diplomacy, rather than war, and the conditions that can breed peace.

Greek approach

Greek Prime Minister Eleftherios Venizelos took part in the conference as Greece's chief representative. Wilson was said to have placed Venizelos first for personal ability among all delegates in Paris. Venizelos proposed Greek expansion inThrace

Thrace (; el, Θράκη, Thráki; bg, Тракия, Trakiya; tr, Trakya) or Thrake is a geographical and historical region in Southeast Europe, now split among Bulgaria, Greece, and Turkey, which is bounded by the Balkan Mountains to t ...

and Asia Minor

Anatolia, tr, Anadolu Yarımadası), and the Anatolian plateau, also known as Asia Minor, is a large peninsula in Western Asia and the westernmost protrusion of the Asian continent. It constitutes the major part of modern-day Turkey. The re ...

, which had been part of the defeated Kingdom of Bulgaria

The Tsardom of Bulgaria ( bg, Царство България, translit=Tsarstvo Balgariya), also referred to as the Third Bulgarian Tsardom ( bg, Трето Българско Царство, translit=Treto Balgarsko Tsarstvo, links=no), someti ...

and the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

; Northern Epirus

sq, Epiri i Veriut rup, Epiru di Nsusu

, type = Part of the wider historic region of Epirus

, image_blank_emblem =

, blank_emblem_type =

, image_map = Epirus across Greece Albania4.svg

, map_caption ...

, Imvros

Imbros or İmroz Adası, officially Gökçeada (lit. ''Heavenly Island'') since 29 July 1970,Alexis Alexandris, "The Identity Issue of The Minorities in Greece And Turkey", in Hirschon, Renée (ed.), ''Crossing the Aegean: An Appraisal of the 1 ...

; and Tenedos

Tenedos (, ''Tenedhos'', ), or Bozcaada in Turkish, is an island of Turkey in the northeastern part of the Aegean Sea. Administratively, the island constitutes the Bozcaada district of Çanakkale Province. With an area of it is the third l ...

for the realization of the ''Megali Idea

The Megali Idea ( el, Μεγάλη Ιδέα, Megáli Idéa, Great Idea) is a nationalist and irredentist concept that expresses the goal of reviving the Byzantine Empire, by establishing a Greek state, which would include the large Greek popu ...

''. He also reached the Venizelos-Tittoni agreement with the Italians on the cession of the Dodecanese

The Dodecanese (, ; el, Δωδεκάνησα, ''Dodekánisa'' , ) are a group of 15 larger plus 150 smaller Greek islands in the southeastern Aegean Sea and Eastern Mediterranean, off the coast of Turkey's Anatolia, of which 26 are inhabited. ...

(apart from Rhodes) to Greece. For the Pontic Greeks

The Pontic Greeks ( pnt, Ρωμαίοι, Ρωμίοι, tr, Pontus Rumları or , el, Πόντιοι, or , , ka, პონტოელი ბერძნები, ), also Pontian Greeks or simply Pontians, are an ethnically Greek group in ...

, he proposed a common Pontic-Armenian state.

As a liberal politician, Venizelos was a strong supporter of the Fourteen Points and the League of Nations.

Chinese approach

The Chinese delegation was led by Lu Zhengxiang, who was accompanied byWellington Koo

Koo Vi Kyuin (; January 29, 1888 – November 14, 1985), better known as V. K. Wellington Koo, was a statesman of the Republic of China. He was one of Republic of China's representatives at the Paris Peace Conference of 1919.

Wellington Koo ...

and Cao Rulin

Cao Rulin (; January 23, 1877 – August 1966, Midland, Michigan, United States) was Vice-Minister of Foreign Affairs of the Beiyang Government, and an important member of the pro-Japanese movement in the early 20th century. He was a Shanghai ...

. Koo demanded Germany's concessions on Shandong

Shandong ( , ; ; alternately romanized as Shantung) is a coastal province of the People's Republic of China and is part of the East China region.

Shandong has played a major role in Chinese history since the beginning of Chinese civilizati ...

be returned to China. He also called for an end to imperialist institutions such as extraterritoriality

In international law, extraterritoriality is the state of being exempted from the jurisdiction of local law, usually as the result of diplomatic negotiations.

Historically, this primarily applied to individuals, as jurisdiction was usually cla ...

, legation

A legation was a diplomatic representative office of lower rank than an embassy. Where an embassy was headed by an ambassador, a legation was headed by a Envoy Extraordinary and Minister Plenipotentiary, minister. Ambassadors diplomatic rank, out ...

guards, and foreign leaseholds. Despite American support and the ostensible spirit of self-determination

The right of a people to self-determination is a cardinal principle in modern international law (commonly regarded as a ''jus cogens'' rule), binding, as such, on the United Nations as authoritative interpretation of the Charter's norms. It stat ...

, the Western powers refused his claims but instead transferred the German concessions to Japan. That sparked widespread student protests in China on 4 May, later known as the May Fourth Movement