In the oldest texts of

Buddhism, ''dhyāna'' () or ''jhāna'' () is a component of the training of the mind (''

bhavana''), commonly translated as

meditation, to withdraw the mind from the automatic responses to sense-impressions, "burn up" the

defilements, and leading to a "state of perfect

equanimity

Equanimity (Latin: ''æquanimitas'', having an even mind; ''aequus'' even; ''animus'' mind/soul) is a state of inner peace, psychological stability and composure which is undisturbed by experience of or exposure to emotions, pain, or other phenom ...

and awareness (''

upekkhā-

sati-

parisuddhi'')." ''Dhyāna'' may have been the core practice of

pre-sectarian Buddhism, in combination with several related practices which together lead to perfected mindfulness and detachment.

In the later commentarial tradition, which has survived in present-day

Theravāda, ''dhyāna'' is equated with "concentration", a state of one-pointed absorption in which there is a diminished awareness of the surroundings. In the contemporary Theravāda-based

Vipassana movement, this absorbed state of mind is regarded as unnecessary and even non-beneficial for the

first stage of awakening, which has to be reached by mindfulness of the body and ''vipassanā'' (insight into impermanence). Since the 1980s, scholars and practitioners have started to question these positions, arguing for a more comprehensive and integrated understanding and approach, based on the oldest descriptions of ''dhyāna'' in the ''

suttas''.

In Buddhist traditions of ''

Chán

Chan (; of ), from Sanskrit '' dhyāna'' (meaning "meditation" or "meditative state"), is a Chinese school of Mahāyāna Buddhism. It developed in China from the 6th century CE onwards, becoming especially popular during the Tang and So ...

'' and ''

Zen'' (the names of which are, respectively, the Chinese and Japanese pronunciations of ''dhyāna''), as in Theravada and Tiantai,

anapanasati

Ānāpānasati (Pali; Sanskrit ''ānāpānasmṛti''), meaning "mindfulness of breathing" ("sati" means mindfulness; "ānāpāna" refers to inhalation and exhalation), paying attention to the breath. It is the quintessential form of Buddhist me ...

(mindfulness of breathing), which is transmitted in the Buddhist tradition as a means to develop dhyana, is a central practice. In the Chan/Zen-tradition this practice is ultimately based on

Sarvastivāda meditation techniques transmitted since the beginning of the

Common Era.

Etymology

''Dhyāna'', Pali ''jhana'', from Proto-Indo-European root ''*√dheie-'', "to see, to look", "to show".

[Jayarava, ''Nāmapada: a guide to names in the Triratna Buddhist Order''] which in the earliest layer of text of the

Vedas refers to "imaginative vision" and associated with goddess

Saraswati with powers of knowledge, wisdom and poetic eloquence.

[Jan Gonda (1963), The Vision of Vedic Poets, Walter de Gruyter, , pages 289-301] This term developed into the variant ''√dhyā'', "to contemplate, meditate, think",[William Mahony (1997), The Artful Universe: An Introduction to the Vedic Religious Imagination, State University of New York Press, , pages 171-177, 222]

According to Buddhaghosa

Buddhaghosa was a 5th-century Indian Theravada Buddhist commentator, translator and philosopher. He worked in the Great Monastery (''Mahāvihāra'') at Anurādhapura, Sri Lanka and saw himself as being part of the Vibhajjavāda school and in t ...

(5th century CE Theravāda exegete), the term ''jhāna'' (Skt. ''dhyāna'') is derived from the verb ''jhayati'', "to think or meditate", while the verb ''jhapeti'', "to burn up", explicates its function, namely burning up opposing states, burning up or destroying "the mental defilements preventing ..the development of serenity and insight."

The ''jhāna/dhyana''-stages

The Pāḷi canon describes four progressive states of ''jhāna'' called ''rūpa jhāna'' ("form ''jhāna''"), and four additional meditative attainments called ''arūpa'' ("without form").

Integrated set of practices

Meditation and contemplation form an integrated set of practices with several other practices, which are fully realized with the onset of ''dhyāna''. As described in the Noble Eightfold Path, right view leads to leaving the household life and becoming a wandering monk. ''Sīla'' (morality) comprises the rules for right conduct. Right effort

The Noble Eightfold Path (Pali: ; Sanskrit: ) is an early summary of the path of Buddhist practices leading to liberation from samsara, the painful cycle of rebirth, in the form of nirvana.

The Eightfold Path consists of eight practices: ri ...

, or the four right efforts, which already contains elements of ''dhyana'', aim to prevent the arising of unwholesome states, and to generate wholesome states. This includes ''indriya samvara'' (sense restraint), controlling the response to sensual perceptions, not giving in to lust and aversion but simply noticing the objects of perception as they appear. Right effort and mindfulness

Mindfulness is the practice of purposely bringing one's attention to the present-moment experience without evaluation, a skill one develops through meditation or other training. Mindfulness derives from ''sati'', a significant element of Hind ...

("to remember to observe"), notably mindfulness of breathing, calm the mind-body complex, releasing unwholesome states and habitual patterns, and encouraging the development of wholesome states and non-automatic responses. By following these cumulative steps and practices, the mind becomes set, almost naturally, for the equanimity of ''dhyāna'', reinforcing the development of wholesome states, which in return further reinforces equanimity and mindfulness.

The ''rūpa jhāna''s

The ''arūpa āyatana''s

Grouped into the ''jhāna''-scheme are four meditative states referred to in the early texts as ''arūpa-āyatana''s. These are also referred to in commentarial literature as ''arūpa-jhāna''s ("formless" or "immaterial" ''jhānas''), corresponding to the ''arūpa-loka'' (translated as the "formless realm" or the "formless dimensions"), to be distinguished from the first four ''jhānas'' (''rūpa jhāna''s). In the Buddhist canonical texts, the word "''jhāna''" is never explicitly used to denote them; they are instead referred to as ''āyatana

''Āyatana'' (Pāli; Sanskrit: आयतन) is a Buddhist term that has been translated as "sense base", "sense-media" or "sense sphere". In Buddhism, there are six ''internal'' sense bases (Pali: ''ajjhattikāni āyatanāni''; also known as ...

''. However, they are sometimes mentioned in sequence after the first four ''jhāna''s (other texts, e.g. MN 121, treat them as a distinct set of attainments) and thus came to be treated by later exegetes as ''jhāna''s. The formless ''jhāna''s are related to, or derived from, yogic meditation, while the ''jhāna''s proper are related to the cultivation of the mind. The state of complete dwelling in emptiness is reached when the eighth ''jhāna'' is transcended.

The four ''arūpa-āyatana''s/''arūpa-jhāna''s are:

* Fifth ''jhāna'': infinite space (Pāḷi ''ākāsānañcāyatana'', Skt. ''ākāśānantyāyatana'')

* Sixth ''jhāna'': infinite consciousness (Pāḷi ''viññāṇañcāyatana'', Skt. ''vijñānānantyāyatana'')

* Seventh ''jhāna'': infinite nothingness (Pāḷi ''ākiñcaññāyatana'', Skt. ''ākiṃcanyāyatana'')

* Eighth ''jhāna'': neither perception nor non-perception (Pāḷi ''nevasaññānāsaññāyatana'', Skt. ''naivasaṃjñānāsaṃjñāyatana'')

Although the "Dimension of Nothingness" and the "Dimension of Neither Perception nor Non-Perception" are included in the list of nine ''jhāna''s taught by the Buddha (see section on ''nirodha-samāpatti'' below), they are not included in the Noble Eightfold Path. Noble Truth number eight is ''sammā samādhi'' (Right Concentration), and only the first four ''jhāna''s are considered "Right Concentration". If he takes a disciple through all the ''jhāna''s, the emphasis is on the "Cessation of Feelings and Perceptions" rather than stopping short at the "Dimension of Neither Perception nor Non-Perception".

''Nirodha-samāpatti''

Beyond the dimension of neither perception nor non-perception lies a state called ''nirodha samāpatti'', the "cessation of perception, feelings and consciousness".[Majjhima NIkaya 111]

''Anuppada Sutta''

/ref>

Only in commentarial and scholarly literature, this is sometimes called the "ninth ''jhāna''".[Steven Sutcliffe, ''Religion: Empirical Studies.'' Ashgate Publishing, Ltd., 2004, page 135.] Another name for this state is ''saññāvedayitanirodha'' ("cessation of perception and feeling"). According to Buddhaghosa's ''Visuddhimagga'' (XXIII, 18), it is characterized by the temporary suppression of consciousness and its concomitant mental factors, so the contemplative reaches a state unconscious (''acittaka'') for a week at most. In the ''nirodha'' remain unically some elementary physiological process designated, in the ''Mahāvedalla-sutta'', by the terms ''āyu'' and ''usmā''.

Broader dhyana-practices

While ''dhyana'' typically refers to the four ''jhanas/dhyanas'', the term also refers to a set of practives which seem to go back to a very early stage of the Buddhist tradition. These practices are the contemplation on the body-parts and their repulsiveness (''patikulamanasikara

Paṭik(k)ūlamanasikāra is a Pāli term that is generally translated as "reflections on repulsiveness". It refers to a traditional Buddhist meditation whereby thirty-one parts of the body are contemplated in a variety of ways. In addition to ...

''); contemplation on the elements of which the body is composed; contemplation on the stages of decay of a dead body; and mindfulness of breathing (''anapanasati

Ānāpānasati (Pali; Sanskrit ''ānāpānasmṛti''), meaning "mindfulness of breathing" ("sati" means mindfulness; "ānāpāna" refers to inhalation and exhalation), paying attention to the breath. It is the quintessential form of Buddhist me ...

''). These practices are described in the '' Satipatthana Sutta'' of the Pali canon and the equivalent texts of the Chinese '' agamas'', in which they are interwoven with the factors of the four ''dhyanas'' or the seven factors of awakening ('' bojjhanga''). This set of practices was also transmitted via the ''Dhyana sutras

Dhyana may refer to:

Meditative practices in Indian religions

* Dhyana in Buddhism (Pāli: ''jhāna'')

* Dhyana in Hinduism

* Jain Dhyāna, see Jain meditation

Jain meditation (''dhyāna'') has been the central practice of spirituality in ...

'', which are based on the Sarvastivada-tradition, forming the basis of the Chan/Zen-tradition.

Early Buddhism

The Buddhist tradition has incorporated two traditions regarding the use of ''jhāna''. There is a tradition that stresses attaining insight ('' vipassanā'') as the means to awakening (''bodhi

The English term enlightenment is the Western translation of various Buddhist terms, most notably bodhi and vimutti. The abstract noun ''bodhi'' (; Sanskrit: बोधि; Pali: ''bodhi''), means the knowledge or wisdom, or awakened intellect ...

'', ''prajñā'', ''kenshō'') and liberation

Liberation or liberate may refer to:

Film and television

* ''Liberation'' (film series), a 1970–1971 series about the Great Patriotic War

* "Liberation" (''The Flash''), a TV episode

* "Liberation" (''K-9''), an episode

Gaming

* '' Liberati ...

(''vimutti'', ''nibbāna''). But the Buddhist tradition has also incorporated the yogic tradition, as reflected in the use of ''jhāna'' as a concentrative practice, which is rejected in other ''sūtra''s as not resulting in the final result of liberation. One solution to this contradiction is the conjunctive use of ''vipassanā'' and '' samatha''.

Origins of the ''jhana/dhyana''-stages

Textual accounts

The '' Mahasaccaka Sutta'', ''Majjhima Nikaya'' 36, narrates the story of the Buddha's awakening. According to this story, he learned two kinds of meditation from two teachers, Uddaka Rāmaputta and Āḷāra Kālāma. These forms of meditation did not lead to liberation, and he then underwent harsh ascetic practices, with which he eventually also became disillusioned. The Buddha then recalled a meditative state he entered by chance as a child:

Originally, the practice of ''dhyāna'' itself may have constituted the core liberating practice of early Buddhism, since in this state all "pleasure and pain" had waned. According to Vetter,

Possible Buddhist transformation of yogic practices

The time of the Buddha saw the rise of the śramaṇa movement, ascetic practitioners with a body of shared teachings and practices. The strict delineation of this movement into Jainism, Buddhism and brahmanical/Upanishadic traditions is a later development. According to Crangle, the development of meditative practices in ancient India was a complex interplay between Vedic and non-Vedic traditions. According to Bronkhorst, the four ''rūpa jhāna'' may be an original contribution of the Buddha to the religious practices of ancient India, forming an alternative to the ascetic practices of the Jains and similar śramaṇa traditions, while the ''arūpa āyatanas'' were incorporated from non-Buddhist ascetic traditions.

Kalupahana argues that the Buddha "reverted to the meditational practices" he had learned from Āḷāra Kālāma and Uddaka Rāmaputta, "directed at the appeasement of mind rather than the development of insight." Moving beyond these initial practices, reflection gave him the essential insight into conditioning, and learned him how to appease his "dispostional tendencies", without either being dominated by them, nor completely annihilating them.

Wynne argues that the attainment of the formless meditative absorption was incorporated from Brahmanical practices, and have Brahmnanical cosmogenies as their doctrinal background. Wynne therefore concludes that these practices were borrowed from a Brahminic source, namely Uddaka Rāmaputta and Āḷāra Kālāma. Yet, the Buddha rejected their goals, as they were not liberating, and discovered his own path to awakening, which "consisted of the adaptation of the old yogic techniques to the practice of mindfulness and attainment of insight." Thus "radically transform d application of yogic practices was conceptualized in the scheme of the four ''jhāna''s.

Yet, according to Bronkhorst, the Buddha's teachings developed primarily in response to Jain teachings, not Brahmanical teachings,and the account of the Buddha practicing under Uddaka Rāmaputta and Āḷāra Kālāma is entirely fictitious, and meant to flesh out the mentioning of those names in the post-enlightenment narrative in Majjhima Nikaya 36.[Vishvapani (rev.) (1997). Review: Origin of Buddhist Meditation. Retrieved 2011-2-17 from "Western Buddhist Review" at http://www.westernbuddhistreview.com/vol5/the-origin-of-buddhist-meditation.html.]

Five possibilities regarding ''jhāna'' and liberation

A stock phrase in the canon states that one develops the four rupa dhyanas and then attains liberating insight. While the texts often refer to comprehending the four noble truths as constituting this "liberating insight", Schmithausen notes that the four noble truths as constituting "liberating insight" (here referring to '' paññā'') is a later addition to texts such as Majjhima Nikaya 36.

Schmithausen discerns three possible roads to liberation as described in the suttas, to which Vetter adds a fourth possibility, while the attainment of ''nirodha-samāpatti'' may constitute a fifth possibility:

# Mastering the four ''jhāna''s, whereafter "liberating insight" is attained;

# Mastering the four ''jhāna''s and the four ''arūpa''s, whereafter "liberating insight" is attained;

# Liberating insight itself suffices;

# The four ''jhāna''s themselves constituted the core liberating practice of early Buddhism, c.q. the Buddha;

# Liberation is attained in ''nirodha-samāpatti''.[Peter Harvey, ''An Introduction to Buddhism.'' Cambridge University Press, 1990, page 252.]

''Rūpa jhāna'' followed by liberating insight

According to the Theravada-tradition, the meditator uses the ''jhāna'' state to bring the mind to rest, and to strengthen and sharpen the mind, in order to investigate the true nature of phenomena (''dhamma'') and to gain insight into impermanence, suffering and not-self. According to the Theravada-tradition, the arahant is aware that the ''jhānas'' are ultimately unsatisfactory, realizing that the meditative attainments are also anicca, impermanent.[Nathan Katz, ''Buddhist Images of Human Perfection: The Arahant of the Sutta Piṭaka Compared with the Bodhisattva and the Mahāsiddha.'' Motilal Banarsidass, 1990, page 78.]

In the ''Mahasaccaka Sutta'' (''Majjhima Nikaya'' 36), which narrates the story of the Buddha's awakening, ''dhyāna'' is followed by insight into the four noble truths. The mention of the four noble truths as constituting "liberating insight" is probably a later addition. Vetter notes that such insight is not possible in a state of ''dhyāna'', when interpreted as concentration, since discursive thinking is eliminated in such a state. He also notes that the emphasis on "liberating insight" developed only after the four noble truths were introduced as an expression of what this "liberating insight" constituted. In time, other expressions took over this function, such as pratītyasamutpāda

''Pratītyasamutpāda'' (Sanskrit: प्रतीत्यसमुत्पाद, Pāli: ''paṭiccasamuppāda''), commonly translated as dependent origination, or dependent arising, is a key doctrine in Buddhism shared by all schools of ...

and the emptiness of the self.

''Rūpa jhāna'' and the ''arūpa''s, followed by liberating insight

This scheme is rejected by scholars as a later development, since the ''arūpas'' are akin to non-Buddhist practices, and rejected elsewhere in the canon.

Insight alone suffices

The emphasis on "liberating insight" alone seems to be a later development, in response to developments in Indian religious thought, which saw "liberating insight" as essential to liberation. This may also have been due to an over-literal interpretation by later scholastics of the terminology used by the Buddha, and to the problems involved with the practice of ''dhyana'', and the need to develop an easier method.

Contemporary scholars have discerned a broader application of ''jhāna'' in historical Buddhist practice. According to Alexander Wynne, the ultimate aim of ''dhyāna'' was the attainment of insight, and the application of the meditative state to the practice of mindfulness. According to Frauwallner, mindfulness was a means to prevent the arising of craving, which resulted simply from contact between the senses and their objects. According to Frauwallner, this may have been the Buddha's original idea. According to Wynne, this stress on mindfulness may have led to the intellectualism which favoured insight over the practice of ''dhyāna''.

''Jhāna'' itself is liberating

Both Schmithausen and Bronkhorst note that the attainment of insight, which is a cognitive activity, cannot be possible in a state wherein all cognitive activity has ceased. According to Vetter, the practice of ''Rupa Jhāna'' itself may have constituted the core practice of early Buddhism, with practices such as sila and mindfulness aiding its development. It is the "middle way" between self-mortification, ascribed by Bronkhorst to Jainism, and indulgence in sensual pleasure. Vetter emphasizes that dhyana is a form of non-sensual happiness. The eightfold path can be seen as a path of preparation which leads to the practice of samadhi.

Liberation in nirodha-samāpatti

According to some texts, after progressing through the eight ''jhānas'' ''and'' the stage of ''nirodha-samāpatti'', a person is liberated.

Theravada

The five hindrances

In the commentarial tradition, the development of ''jhāna'' is described as the development of five mental factors

Mental factors ( sa, चैतसिक, caitasika or ''chitta samskara'' ; pi, cetasika; Tibetan: སེམས་བྱུང ''sems byung''), in Buddhism, are identified within the teachings of the Abhidhamma (Buddhist psychology). They are d ...

(Sanskrit: ''caitasika''; Pali: ''cetasika'') that counteract the five hindrances:

# '' vitakka'' ("applied thought") counteracts sloth and torpor (lethargy and drowsiness)

# '' vicāra'' ("sustained thought") counteracts doubt (uncertainty)

# '' pīti'' (rapture) counteracts ill-will (malice)

# ''sukha

''Sukha'' (Pali and ) means happiness, pleasure, ease, joy or bliss. Among the early scriptures, 'sukha' is set up as a contrast to 'preya' (प्रेय) meaning a transient pleasure, whereas the pleasure of 'sukha' has an authentic state h ...

'' (non-sensual pleasure) counteracts restlessness-worry (excitation and anxiety)

# '' ekaggata'' (one-pointedness) counteracts sensory desire

''Jhana'' as concentration

Buddhagosa's ''Visuddhimagga'' considers ''jhana'' to be an exercise in concentration-meditation. His views, together with the ''Satipatthana Sutta'', inspired the development, in the 19th and 20th century, of new meditation techniques which gained a great popularity among lay audiences in the second half of the 20th century.

''Samadhi''

According to Henepola Gunaratana

Bhante Henepola Gunaratana is a Sri Lankan Theravada Buddhist monk. He is affectionately known as Bhante G. Bhante Gunaratana is currently the abbot of the Bhavana Society, a monastery and meditation retreat center that he founded in High Vi ...

, the term "jhana" is closely connected with "samadhi", which is generally rendered as "concentration". The word "samadhi" is almost interchangeable with the word "samatha", serenity.[Henepola Gunaratana, ''The Jhanas in Theravada Buddhist Meditation''](_blank)

/ref> According to Gunaratana, in the widest sense the word samadhi is being used for the practices which lead to the development of serenity. In this sense, samadhi and jhana are close in meaning. Nevertheless, they are not exactly identical, since "certain differences in their suggested and contextual meanings prevent unqualified identification of the two terms." Samadhi signifies only one mental factor, namely one-pointedness, while the word "jhana" encompasses the whole state of consciousness, "or at least the whole group of mental factors individuating that meditative state as a jhana."

Development and application of concentration

According to the Pāli canon commentary, access/neighbourhood concentration (''upacāra-samādhi'') is a stage of meditation that the meditator reaches before entering into ''jhāna''. The overcoming of the five hindrances mark the entry into access concentration. Access concentration is not mentioned in the discourses of the Buddha, but there are several ''suttas'' where a person gains insight into the ''Dhamma'' on hearing a teaching from the Buddha.

According to Tse-fu Kuan, at the state of ''access concentration'', some meditators may experience vivid mental imagery, which is similar to a vivid dream. They are as vivid as if seen by the eye, but in this case the meditator is fully aware and conscious that they are seeing mental images. According to Tse-fu Kuan, this is discussed in the early texts, and expanded upon in Theravāda commentaries.

According to Venerable Sujivo, as the concentration becomes stronger, the feelings of breathing and of having a physical body will completely disappear, leaving only pure awareness. At this stage inexperienced meditators may become afraid, thinking that they are going to die if they continue the concentration, because the feeling of breathing and the feeling of having a physical body has completely disappeared. They should not be so afraid and should continue their concentration in order to reach "full concentration" (''jhāna'').

A meditator should first master the lower ''jhānas'', before they can go into the higher ''jhānas''. According to Nathan Katz, the early suttas state that "the most exquisite of recluses" is able to attain any of the ''jhānas'' and abide in them without difficulty.nibbana

Nirvana (Sanskrit: निर्वाण, '; Pali: ') is "blowing out" or "quenching" of the activities of the worldly mind and its related suffering. Nirvana is the goal of the Hinayana and Theravada Buddhist paths, and marks the soteriologica ...

''.

According to the later Theravāda commentorial tradition as outlined by Buddhagoṣa in his ''Visuddhimagga

The ''Visuddhimagga'' (Pali; English: ''The Path of Purification''), is the 'great treatise' on Buddhist practice and Theravāda Abhidhamma written by Buddhaghosa approximately in the 5th century in Sri Lanka. It is a manual condensing and syst ...

'', after coming out of the state of ''jhāna'' the meditator will be in the state of post-''jhāna'' access concentration. In this state the investigation and analysis of the true nature of phenomena begins, which leads to insight into the characteristics of impermanence, suffering and not-self arises.

Criticism

While the ''jhānas'' are often understood as deepening states of concentration, due to its description as such in the ''Abhidhamma'', and the ''Visuddhimagga'', since the 1980s both academic scholars and contemporary Theravādins have started to question this understanding, raising questions about the interpretation of the ''jhanas'' as being states of absorption which are not necessary for the attainment of liberation. While groundbreaking research on this topic has been done by Bareau, Schmithausen, Stuart-Fox, Bucknell, Vetter, Bronkhorst, and Wynne, Theravada practitioners have also scrutinized and criticised the ''samatha''-''vipassana'' distinction. Reassessments of the description of ''jhana'' in the suttas consider ''jhana'' and ''vipassana'' to be an integrated practice, leading to a "tranquil and equanimous awareness of whatever arises in the field of experience."

Scholarly criticism

While the commentarial tradition regards ''vitarka'' and ''vicara'' as initial and sustained concentration on a meditation object, Roderick S. Bucknell notes that ''vitarka'' and ''vicara'' may refer to "probably nothing other than the normal process of discursive thought, the familiar but usually unnoticed stream of mental imagery and verbalization." Bucknell further notes that " ese conclusions conflict with the widespread conception of the first ''jhāna'' as a state of deep concentration."

According to Stuart-Fox, the Abhidhamma separated ''vitarka'' from ''vicara'', and ''ekaggata'' (one-pointedness) was added to the description of the first ''dhyāna'' to give an equal number of five hindrances and five antidotes. The commentarial tradition regards the qualities of the first ''dhyāna'' to be antidotes to the five hindrances, and ''ekaggata'' may have been added to the first ''dhyāna'' to give exactly five antidotes for the five hindrances. Stuart-Fox further notes that ''vitarka'', being discursive thought, will do very little as an antidote for sloth and torpor, reflecting the inconsistencies which were introduced by the scholastics.

Vetter, Gombrich and Wynne note that the first and second ''jhana'' represent the onset of ''dhyāna'' due to withdrawal and right effort

The Noble Eightfold Path (Pali: ; Sanskrit: ) is an early summary of the path of Buddhist practices leading to liberation from samsara, the painful cycle of rebirth, in the form of nirvana.

The Eightfold Path consists of eight practices: ri ...

''c.q.'' the four right efforts, followed by concentration, whereas the third and fourth ''jhāna'' combine concentration with mindfulness. Polak, elaborating on Vetter, notes that the onset of the first ''dhyāna'' is described as a quite natural process, due to the preceding efforts to restrain the senses and the nurturing of wholesome states. Regarding ''samādhi'' as the eighth step of the Noble Eightfold Path, Vetter notes that ''samādhi'' consists of the four stages of ''dhyāna'' meditation, but

According to Richard Gombrich, the sequence of the four ''rūpa jhāna''s describes two different cognitive states: "I know this is controversial, but it seems to me that the third and fourth jhanas are thus quite unlike the second." Gombrich and Wynne note that, while the second ''jhāna'' denotes a state of absorption, in the third and fourth ''jhāna'' one comes out of this absorption, being mindfully aware of objects while being indifferent to them. According to Gombrich, "the later tradition has falsified the jhana by classifying them as the quintessence of the concentrated, calming kind of meditation, ignoring the other—and indeed higher—element. According to Lusthaus, "mindfulness in he fourth dhyana

He or HE may refer to:

Language

* He (pronoun), an English pronoun

* He (kana), the romanization of the Japanese kana へ

* He (letter), the fifth letter of many Semitic alphabets

* He (Cyrillic), a letter of the Cyrillic script called ''He'' in ...

is an alert, relaxed awareness detached from positive and negative conditioning."

Gethin, followed by Polak and Arbel, further notes that there is a "definite affinity" between the four ''jhāna''s and the '' bojjhaṅgā'', the seven factors of awakening. According to Gethin, the early Buddhist texts have "a broadly consistent vision" regarding meditation practice. Various practices lead to the development of the factors of awakening, which are not only the means to, but also the constituents of, awakening. According to Gethin, ''satipaṭṭhāna'' and ''ānāpānasati'' are related to a formula that summarizes the Buddhist path to awakening as "abandoning the hindrances, establishing ..mindfulness, and developing the seven factors of awakening." This results in a "heightened awareness", "overcoming distracting and disturbing emotions", which are not particular elements of the path to awakening, but rather common disturbing and distracting emotions. Gethin further states that "the exegetical literature is essentially true to the vision of meditation presented in the Nikayas," applying the "perfect mindfulness, stillness and lucidity" of the ''jhanas'' to the contemplation of "reality", of the way things really are, as temporary and ever-changing. It is in this sense that "the ''jhana'' state has the transcendent, transforming quality of awakening."

Alexander Wynne states that the ''dhyāna''-scheme is poorly understood. According to Wynne, words expressing the inculcation of awareness, such as ''sati'', ''sampajāno'', and ''upekkhā'', are mistranslated or understood as particular factors of meditative states, whereas they refer to a particular way of perceiving the sense objects:

'' Upekkhā'', equanimity, which is perfected in the fourth ''dhyāna'', is one of the four '' Brahmā-vihāra''. While the commentarial tradition downplayed the importance of the ''Brahmā-vihāra'', Gombrich notes that the Buddhist usage of the term ''Brahmā-vihāra'' originally referred to an awakened state of mind, and a concrete attitude toward other beings which was equal to "living with Brahman" here and now. The later tradition took those descriptions too literally, linking them to cosmology and understanding them as "living with Brahman" by rebirth in the Brahmā-world. According to Gombrich, "the Buddha taught that kindness—what Christians tend to call love—was a way to salvation.

Contemporary Theravada reassessment - the "Jhana wars"

While Theravada-meditation was introduced to the west as ''vipassana''-meditation, which rejected the usefulness of ''jhana'', there is a growing interest among western ''vipassana''-practitioners in ''jhana''. The nature and practice of ''jhana'' is a topic of debate and contention among western convert Theravadins, to the extent that the disputes have even been called "the Jhana wars."

=Criticism of ''Visudhimagga''

=

The ''Visuddhimagga'', and the "pioneering popularizing work of Daniel Goleman", has been influential in the (mis)understanding of ''dhyana'' being a form of concentration-meditation. The ''Visuddhimagga'' is centered around '' kasina''-meditation, a form of concentration-meditation in which the mind is focused on a (mental) object.[Bhikkhu Thanissaro]

''Concentration and Discernment''

/ref> According to Thanissaro Bhikkhu, " e text then tries to fit all other meditation methods into the mold of kasina practice, so that they too give rise to countersigns, but even by its own admission, breath meditation does not fit well into the mold."Bhante Henepola Gunaratana

Bhante Henepola Gunaratana is a Sri Lankan Theravada Buddhist monk. He is affectionately known as Bhante G. Bhante Gunaratana is currently the abbot of the Bhavana Society, a monastery and meditation retreat center that he founded in High Vi ...

also notes that what "the suttas say is not the same as what the Visuddhimagga says ..they are actually different," leading to a divergence between a raditionalscholarly understanding and a practical understanding based on meditative experience. Gunaratana further notes that Buddhaghosa invented several key meditation terms which are not to be found in the suttas, such as "''parikamma samadhi'' (preparatory concentration), ''upacara samadhi'' (access concentration), ''appanasamadhi'' (absorption concentration)." Gunaratana also notes that Buddhaghosa's emphasis on ''kasina''-meditation is not to be found in the suttas, where ''dhyana'' is always combined with mindfulness.

According to scholar Tilman Vetter, ''dhyana'' as a preparation of discriminating insight must have been different from the ''dhyana''-practice introduced by the Buddha, using kasina-exercises to produce a "more artificially produced dhyana", resulting in the cessation of apperceptions and feelings. Shankman notes that kasina-exercises are propagated in Buddhaghosa

Buddhaghosa was a 5th-century Indian Theravada Buddhist commentator, translator and philosopher. He worked in the Great Monastery (''Mahāvihāra'') at Anurādhapura, Sri Lanka and saw himself as being part of the Vibhajjavāda school and in t ...

's ''Visuddhimagga

The ''Visuddhimagga'' (Pali; English: ''The Path of Purification''), is the 'great treatise' on Buddhist practice and Theravāda Abhidhamma written by Buddhaghosa approximately in the 5th century in Sri Lanka. It is a manual condensing and syst ...

'', which is considered the authoritative commentary on meditation practice in the Theravada tradition, but differs from the Pali canon in its description of ''jhana''. While the suttas connect ''samadhi'' to mindfulness and awareness of the body, for Buddhaghosa ''jhana'' is a purely mental exercise, in which one-pointed concentration leads to a narrowing of attention.

=''Jhana'' as integrated practice

=

Several western teachers (Thanissaro Bhikkhu, Leigh Brasington, Richard Shankman) make a distinction between "sutta-oriented" ''jhana'' and "''Visuddhimagga''-oriented" ''jhana,'' dubbed "minimalists" and "maximalists" by Kenneth Rose.

Ṭhānissaro Bhikkhu

Ṭhānissaro Bhikkhu (also known as Ajahn Geoff; born ) is an American Buddhist monk. Belonging to the Thai Forest Tradition, for 10 years he studied under the forest master Ajahn Fuang Jotiko (himself a student of Ajahn Lee). Since 1993 he ha ...

, a western teacher in the Thai Forest Tradition

The Kammaṭṭhāna Forest Tradition of Thailand (from pi, kammaṭṭhāna meaning Kammaṭṭhāna, "place of work"), commonly known in the West as the Thai Forest Tradition, is a Parampara, lineage of Theravada Buddhist monasticism.

The ...

, has repeatedly argued that the Pali Canon and the ''Visuddhimagga'' give different descriptions of the jhanas, regarding the ''Visuddhimagga''-description to be incorrect. According to Ṭhānissaro Bhikkhu warns against the development of strong states of concentration. Arbel describes the fourth ''jhāna'' as "non-reactive and lucid awareness", not as a state of deep concentration.

According to Richard Shankman, the ''sutta'' descriptions of ''jhāna'' practice explain that the meditator does not emerge from ''jhāna'' to practice ''vipassana'' but rather the work of insight is done whilst in ''jhāna'' itself. In particular the meditator is instructed to "enter and remain in the fourth ''jhāna''" before commencing the work of insight in order to uproot the mental defilements.[Richard Shankman, ''The Experience of Samadhi – an in depth Exploration of Buddhist Meditation'', Shambala publications 2008]

Keren Arbel has conducted extensive research on the ''jhanas'' and the contemporary criticisms of the commentarial interpretation. Based on this research, and her own experience as a senior meditation-teacher, she gives a reconstructed account of the original meaning of the ''dhyanas''. She argues that ''jhana'' is an integrated practice, describing the fourth ''jhana'' as "non-reactive and lucid awareness", not as a state of deep concentration. According to Arbel, it develops "a mind which is not conditioned by habitual reaction-patterns of likes and dislikes ..a profoundly wise relation to experience, not tainted by any kind of wrong perception and mental reactivity rooted in craving (''tanha'').

According to Kenneth Rose, the ''Visuddhimagga''-oriented "maximalist" approach is a return to ancient Indian "mainstream practices", in which physical and mental immobility was thought to lead to liberation from ''samsara'' and rebirth. This approach was rejected by the Buddha, turning to a gentler approach which results in ''upekkha'' and ''sati'', equanimous awareness of experience.

In Mahāyāna traditions

Mahāyāna Buddhism includes numerous schools of practice. Each draw upon various Buddhist sūtras, philosophical treatises, and commentaries, and each has its own emphasis, mode of expression, and philosophical outlook. Accordingly, each school has its own meditation methods for the purpose of developing samādhi and prajñā, with the goal of ultimately attaining enlightenment.

Mahāyāna Buddhism includes numerous schools of practice. Each draw upon various Buddhist sūtras, philosophical treatises, and commentaries, and each has its own emphasis, mode of expression, and philosophical outlook. Accordingly, each school has its own meditation methods for the purpose of developing samādhi and prajñā, with the goal of ultimately attaining enlightenment.

Preservation of ''dhyana'' as open awareness

Both Polak and Arbel suggest that the traditions of Dzogchen

Dzogchen (, "Great Perfection" or "Great Completion"), also known as ''atiyoga'' ( utmost yoga), is a tradition of teachings in Indo-Tibetan Buddhism and Yungdrung Bon aimed at discovering and continuing in the ultimate ground of existence. ...

, Mahamudra and Chan

Chan may refer to:

Places

*Chan (commune), Cambodia

*Chan Lake, by Chan Lake Territorial Park in Northwest Territories, Canada

People

*Chan (surname), romanization of various Chinese surnames (including 陳, 曾, 詹, 戰, and 田)

*Chan Caldwel ...

preserve or resemble ''dhyana'' as an open awareness of body and mind, thus transcending the dichotomy between '' vipassana'' and '' samatha''.

Chan Buddhism

Anapanasati and dhyāna are a central aspect of Buddhist practice in Chan, necessary for progress on the path and "true entry into the Dharma".

Origins

In China, the word ''dhyāna'' was originally transliterated with and shortened to just in common usage. The word and the practice of meditation entered into Chinese through the translations of An Shigao (fl. c. 148–180 CE), and Kumārajīva (334–413 CE), who translated Dhyāna sutras

The Dhyāna sutras ( ''chan jing'') (Japanese 禅経 ''zen-gyo'') or "meditation summaries" () or also known as The Zen Sutras are a group of early Buddhist meditation texts which are mostly based on the Yogacara meditation teachings of the Sarvās ...

, which were influential early meditation texts mostly based on the Yogacara meditation teachings of the Sarvāstivāda school of Kashmir

Kashmir () is the northernmost geographical region of the Indian subcontinent. Until the mid-19th century, the term "Kashmir" denoted only the Kashmir Valley between the Great Himalayas and the Pir Panjal Range. Today, the term encompas ...

circa 1st–4th centuries CE.[Deleanu, Florin (1992)]

Mindfulness of Breathing in the Dhyāna Sūtras

Transactions of the International Conference of Orientalists in Japan (TICOJ) 37, 42–57. The word ''chán'' became the designation for Chan Buddhism

Chan (; of ), from Sanskrit '' dhyāna'' (meaning "meditation" or "meditative state"), is a Chinese school of Mahāyāna Buddhism. It developed in China from the 6th century CE onwards, becoming especially popular during the Tang and So ...

( Korean Seon, Vietnamese Thiền

Vietnamese may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to Vietnam, a country in Southeast Asia

** A citizen of Vietnam. See Demographics of Vietnam.

* Vietnamese people, or Kinh people, a Southeast Asian ethnic group native to Vietnam

** Over ...

, Japanese Zen

:''See also Zen for an overview of Zen, Chan Buddhism for the Chinese origins, and Sōtō, Rinzai school, Rinzai and Ōbaku for the three main schools of Zen in Japan''

Japanese Zen refers to the Japanese forms of Zen, Zen Buddhism, an orig ...

).

In Chinese Buddhism, following the ''Ur-text'' of the Satipatthana Sutra and the ''dhyana sutras'', ''dhyāna'' refers to various kinds of meditation techniques and their preparatory practices, which are necessary to practice ''dhyana''. The five main types of meditation in the ''Dhyana sutras'' are anapanasati

Ānāpānasati (Pali; Sanskrit ''ānāpānasmṛti''), meaning "mindfulness of breathing" ("sati" means mindfulness; "ānāpāna" refers to inhalation and exhalation), paying attention to the breath. It is the quintessential form of Buddhist me ...

(mindfulness of breathing); paṭikūlamanasikāra meditation, mindfulness of the impurities of the body; loving-kindness maitrī meditation; the contemplation on the twelve links of pratītyasamutpāda

''Pratītyasamutpāda'' (Sanskrit: प्रतीत्यसमुत्पाद, Pāli: ''paṭiccasamuppāda''), commonly translated as dependent origination, or dependent arising, is a key doctrine in Buddhism shared by all schools of ...

; and the contemplation on the Buddha's thirty-two Characteristics.[Ven. Dr. Yuanci]

A Study of the Meditation Methods in the DESM and Other Early Chinese Texts

, The Buddhist Academy of China.

Downplaying the body-recollections (but maintaining the awareness of imminent death), the early Chan-tradition developed the notions or practices of ''wu nian'' ("no thought, no "fixation on thought, such as one's own views, experiences, and knowledge") and ''fēi sīliàng'' (, Japanese: ''hishiryō'', "nonthinking"); and ''kanxin'' ("observing the mind") and ''shou-i pu i'' (, "maintaining the one without wavering") turning the attention from the objects of experience, to the nature of mind, the perceiving subject itself, which is equated with Buddha-nature

Buddha-nature refers to several related Mahayana Buddhist terms, including '' tathata'' ("suchness") but most notably ''tathāgatagarbha'' and ''buddhadhātu''. ''Tathāgatagarbha'' means "the womb" or "embryo" (''garbha'') of the "thus-gone ...

.

Mindfulness

=Observing the breath

=

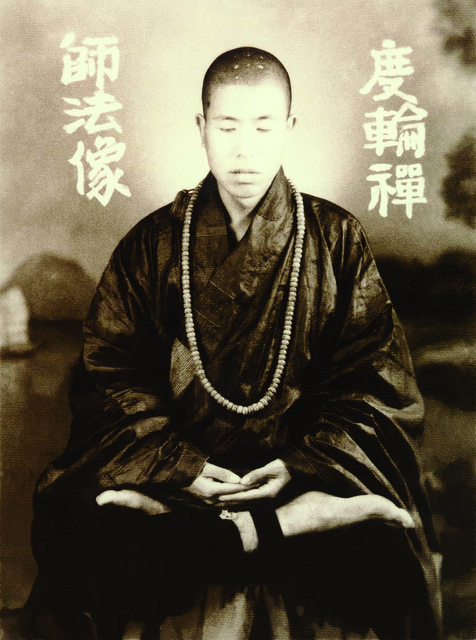

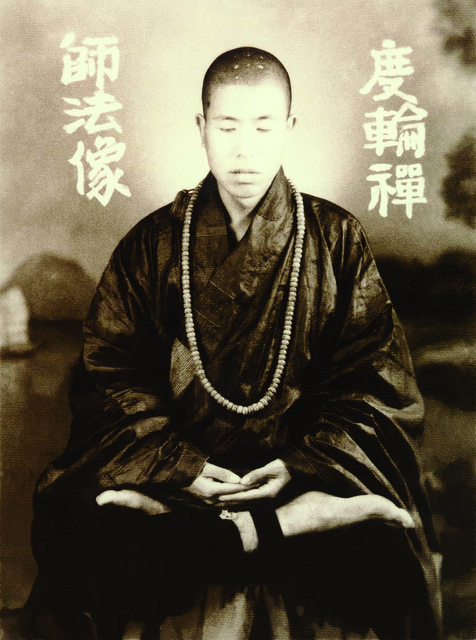

During sitting meditation, practitioners usually assume a position such as the

During sitting meditation, practitioners usually assume a position such as the lotus position

Lotus position or Padmasana ( sa, पद्मासन, translit=padmāsana) is a cross-legged sitting meditation pose from ancient India, in which each foot is placed on the opposite thigh. It is an ancient asana in yoga, predating hatha ...

, half-lotus, Burmese, or yoga postures, using the dhyāna mudrā

A mudra (; sa, मुद्रा, , "seal", "mark", or "gesture"; ,) is a symbolic or ritual gesture or pose in Hinduism, Jainism and Buddhism. While some mudras involve the entire body, most are performed with the hands and fingers.

As wel ...

. To regulate the mind, awareness is directed towards counting or watching the breath or by bringing that awareness to the energy center below the navel (see also ānāpānasati

Ānāpānasati (Pali; Sanskrit ''ānāpānasmṛti''), meaning "mindfulness of breathing" ("sati" means mindfulness; "ānāpāna" refers to inhalation and exhalation), paying attention to the breath. It is the quintessential form of Buddhist ...

).

=Observing the mind

=

In the Sōtō school of Zen, meditation with no objects, anchors, or content, is the primary form of practice. The meditator strives to be aware of the stream of thoughts, allowing them to arise and pass away without interference. Considerable textual, philosophical, and phenomenological justification of this practice can be found throughout Dōgen's ''Shōbōgenzō'', as for example in the "Principles of Zazen"

Insight

=Pointing to the nature of the mind

=

According to Charles Luk, in the earliest traditions of Chán, there was no fixed method or formula for teaching meditation, and all instructions were simply heuristic methods, to point to the true nature of the mind, also known as ''Buddha-nature

Buddha-nature refers to several related Mahayana Buddhist terms, including '' tathata'' ("suchness") but most notably ''tathāgatagarbha'' and ''buddhadhātu''. ''Tathāgatagarbha'' means "the womb" or "embryo" (''garbha'') of the "thus-gone ...

''.[Luk, Charles. ''The Secrets of Chinese Meditation.'' 1964. p. 44] A traditional formula of this is, "Chán points directly to the human mind, to enable people to see their true nature and become buddhas."

=Kōan practice

=

At the beginning of the

At the beginning of the Sòng dynasty

The Song dynasty (; ; 960–1279) was an imperial dynasty of China that began in 960 and lasted until 1279. The dynasty was founded by Emperor Taizu of Song following his usurpation of the throne of the Later Zhou. The Song conquered the rest ...

, practice with the kōan method became popular, whereas others practiced "silent illumination". This became the source of some differences in practice between the Línjì and Cáodòng school

Caodong school () is a Chinese Chan Buddhist sect and one of the Five Houses of Chán.

Etymology

The key figure in the Caodong school was founder Dongshan Liangjie (807-869, 洞山良价 or Jpn. Tozan Ryokai). Some attribute the name "Cáodòng" ...

s.

A kōan, literally "public case", is a story or dialogue, describing an interaction between a Zen master and a student. These anecdotes give a demonstration of the master's insight. Koans emphasize the non-conceptional insight that the Buddhist teachings are pointing to. Koans can be used to provoke the "great doubt", and test a student's progress in Zen practice.

Kōan-inquiry may be practiced during zazen (sitting meditation), kinhin

Walking meditation, sometimes known as kinhin (Chinese: 經行; Pinyin: ''jīngxíng''; Romaji: ''kinhin'' or ''kyōgyō''; Korean: ''gyeonghyaeng''; Vietnamese: ''kinh hành''), is a practice within several forms of Buddhism that involve movemen ...

(walking meditation), and throughout all the activities of daily life. Kōan practice is particularly emphasized by the Japanese Rinzai school

The Rinzai school ( ja, , Rinzai-shū, zh, t=臨濟宗, s=临济宗, p=Línjì zōng) is one of three sects of Zen in Japanese Buddhism (along with Sōtō and Ōbaku). The Chinese Linji school of Chan was first transmitted to Japan by Myōan E ...

, but it also occurs in other schools or branches of Zen depending on the teaching line.

The Zen student's mastery of a given kōan is presented to the teacher in a private interview (referred to in Japanese as ''dokusan'' (独参), ''daisan'' (代参), or ''sanzen'' (参禅)). While there is no unique answer to a kōan, practitioners are expected to demonstrate their understanding of the kōan and of Zen through their responses. The teacher may approve or disapprove of the answer and guide the student in the right direction. The interaction with a Zen teacher is central in Zen, but makes Zen practice also vulnerable to misunderstanding and exploitation.

Vajrayāna

B. Alan Wallace

Bruce Alan Wallace (born 1950) is an American author and expert on Tibetan Buddhism. His books discuss Eastern and Western scientific, philosophical, and contemplative modes of inquiry, often focusing on the relationships between science and Buddh ...

holds that modern Tibetan Buddhism lacks emphasis on achieving levels of concentration higher than access concentration.[B. Alan Wallace, ''The Bridge of Quiescence: Experiencing Tibetan Buddhist Meditation.'' Carus Publishing Company, 1998, pages 215–216.] According to Wallace, one possible explanation for this situation is that virtually all Tibetan Buddhist meditators seek to become enlightened through the use of tantric practices. These require the presence of sense desire and passion in one's consciousness, but ''jhāna'' effectively inhibits these phenomena.

Related concepts in Indian religions

Dhyana is an important ancient practice mentioned in the Vedic and post-Vedic literature of Hinduism, as well as early texts of Jainism.[ Dhyana in Buddhism influenced these practices as well as was influenced by them, likely in its origins and its later development.]

Parallels with Patanjali's Ashtanga Yoga

There are parallels with the fourth to eighth stages of Patanjali's Ashtanga Yoga, as mentioned in his classical work, '' Yoga Sutras of Patanjali'', which were compiled around 400 CE by, taking materials about yoga from older traditions.

Patanjali discerns ''bahiranga'' (external) aspects of yoga namely, yama, niyama, asana

An asana is a body posture, originally and still a general term for a sitting meditation pose,Verse 46, chapter II, "Patanjali Yoga sutras" by Swami Prabhavananda, published by the Sri Ramakrishna Math p. 111 and later extended in hatha yoga ...

, pranayama, and the ''antaranga'' (internal) yoga. Having actualized the ''pratyahara'' stage, a practitioner is able to effectively engage into the practice of Samyama. At the stage of ''pratyahara'', the consciousness of the individual is internalized in order that the sensations from the senses

A sense is a biological system used by an organism for sensation, the process of gathering information about the world through the detection of stimuli. (For example, in the human body, the brain which is part of the central nervous system rec ...

of taste, touch, sight, hearing and smell don't reach their respective centers in the brain and takes the '' sadhaka'' (practitioner) to next stages of Yoga, namely Dharana (concentration), Dhyana

Dhyana may refer to:

Meditative practices in Indian religions

* Dhyana in Buddhism (Pāli: ''jhāna'')

* Dhyana in Hinduism

* Jain Dhyāna, see Jain meditation

Other

*''Dhyana'', a work by British composer John Tavener (1944-2013)

* ''Dhyana'' ...

(meditation), and Samadhi (mystical absorption), being the aim of all Yogic practices.

The Eight Limbs of the yoga sutras show Samadhi as one of its limbs. The ''Eight limbs of the Yoga Sutra'' was influenced by Buddhism. Vyasa's Yogabhashya, the commentary to the Yogasutras, and Vacaspati Misra's subcommentary state directly that the samadhi techniques are directly borrowed from the Buddhists' Jhana, with the addition of the mystical and divine interpretations of mental absorption. The Yoga Sutra, especially the fourth segment of Kaivalya Pada, contains several polemical verses critical of Buddhism, particularly the Vijñānavāda school of Vasubandhu.

The suttas show that during the time of the Buddha, Nigantha Nataputta, the Jain leader, did not even believe that it is possible to enter a state where the thoughts and examination stop.[Bodhi, Bhikkhu (trans.) (2000). ''The Connected Discourses of the Buddha: A New Translation of the Samyutta Nikaya.'' Boston: Wisdom Publications. .]

See also

* Research on meditation

The psychological and physiological effects of meditation have been studied. In recent years, studies of meditation have increasingly involved the use of modern instruments, such as fMRI and EEG, which are able to observe brain physiology and n ...

* Altered state of consciousness

* Jñāna

Notes

References

Sources

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

Further reading

;Scholarly (philological/historical)

* Analayo

Bhikkhu Anālayo is a bhikkhu (Buddhist monk), scholar, and meditation teacher. He was born in Germany in 1962, and went forth in 1995 in Sri Lanka. He is best known for his comparative studies of Early Buddhist Texts as preserved by the variou ...

(2017)

''Early Buddhist Meditation Studies''

(defence of traditional Theravada position)

*

*

* Polak (2011), ''Reexamining Jhana''

*

*

;Re-assessment of ''jhana'' in Theravada

* Arbel, Keren (2017)

''Early Buddhist Meditation''

Taylor & Francis

*

* Shankman, Richard (2008), ''The Experience of Samadhi''

External links

; From Sutta Pitaka

descriptions and similes from the Pali Canon's Anguttara Nikaya and Dhammapada

The Dhammapada (Pāli; sa, धर्मपद, Dharmapada) is a collection of sayings of the Buddha in verse form and one of the most widely read and best known Buddhist scriptures. The original version of the Dhammapada is in the Khuddaka ...

, by John T. Bullitt.

; Theravādin Buddhist perspective

* Henepola Gunaratana

Bhante Henepola Gunaratana is a Sri Lankan Theravada Buddhist monk. He is affectionately known as Bhante G. Bhante Gunaratana is currently the abbot of the Bhavana Society, a monastery and meditation retreat center that he founded in High Vi ...

,

Jhanas in Theravada Buddhist Meditation

'

* Ajahn Brahmavamso

Phra Visuddhisamvarathera ( th, พระวิสุทธิสังวรเถร), known as Ajahn Brahmavaṃso, or simply Ajahn Brahm (born Peter Betts on 7 August 1951), is a British-born Theravada Buddhist monk. Currently, Ajahn Brah ...

Travelogue to the four Jhanas

* Ajahn Brahmavamso

* Thanissaro Bhikkhu

''Jhana not by the numbers''

* Bhante Vimalaramsi Mahāthera

Dhamma-Talks on the Anupada-Sutta. This provides a highly detailed account of the progression through the jhānas.

''Sutta-style jhanas: a western phenomenon?''

Dhamma Wheel

;Mahayana

* Nagarjuna

;Others

* Leigh Breighton

''Jhana Wars!''

Simple, Suttas

*O'Brien, Barbara.

Jhanas or Dhyanas: A Progression of Buddhist Meditation

" ''Learn Religions'', 28 Sept. 2018.

{{DEFAULTSORT:Dhyana in Buddhism

Buddhist meditation

Zen Buddhist philosophical concepts

Mindfulness (Buddhism)

Sanskrit words and phrases

In the oldest texts of Buddhism, ''dhyāna'' () or ''jhāna'' () is a component of the training of the mind ('' bhavana''), commonly translated as meditation, to withdraw the mind from the automatic responses to sense-impressions, "burn up" the defilements, and leading to a "state of perfect

In the oldest texts of Buddhism, ''dhyāna'' () or ''jhāna'' () is a component of the training of the mind ('' bhavana''), commonly translated as meditation, to withdraw the mind from the automatic responses to sense-impressions, "burn up" the defilements, and leading to a "state of perfect

During sitting meditation, practitioners usually assume a position such as the

During sitting meditation, practitioners usually assume a position such as the