Modes (music) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

In

Tonaries, lists of chant titles grouped by mode, appear in western sources around the turn of the 9th century. The influence of developments in Byzantium, from Jerusalem and Damascus, for instance the works of Saints

Tonaries, lists of chant titles grouped by mode, appear in western sources around the turn of the 9th century. The influence of developments in Byzantium, from Jerusalem and Damascus, for instance the works of Saints  According to Carolingian theorists the eight church modes, or

According to Carolingian theorists the eight church modes, or  After the reciting tone, every mode is distinguished by scale degrees called "mediant" and "participant". The mediant is named from its position between the final and reciting tone. In the authentic modes it is the third of the scale, unless that note should happen to be B, in which case C substitutes for it. In the plagal modes, its position is somewhat irregular. The participant is an auxiliary note, generally adjacent to the mediant in authentic modes and, in the plagal forms, coincident with the reciting tone of the corresponding authentic mode (some modes have a second participant).

Only one accidental is used commonly in

After the reciting tone, every mode is distinguished by scale degrees called "mediant" and "participant". The mediant is named from its position between the final and reciting tone. In the authentic modes it is the third of the scale, unless that note should happen to be B, in which case C substitutes for it. In the plagal modes, its position is somewhat irregular. The participant is an auxiliary note, generally adjacent to the mediant in authentic modes and, in the plagal forms, coincident with the reciting tone of the corresponding authentic mode (some modes have a second participant).

Only one accidental is used commonly in

Although the names of the modern modes are Greek and some have names used in ancient Greek theory for some of the ''harmoniai'', the names of the modern modes are conventional and do not refer to the sequences of intervals found even in the diatonic genus of the Greek

Although the names of the modern modes are Greek and some have names used in ancient Greek theory for some of the ''harmoniai'', the names of the modern modes are conventional and do not refer to the sequences of intervals found even in the diatonic genus of the Greek

Divisions of the Tetrachord / Peri ton tou tetrakhordou katatomon / Sectiones tetrachordi: A Prolegomenon to the Construction of Musical Scales

', edited by Larry Polansky and Carter Scholz, foreword by Lou Harrison. Hanover, New Hampshire: Frog Peak Music. . * Fellerer, Karl Gustav (1982). "Kirchenmusikalische Reformbestrebungen um 1800". ''Analecta Musicologica: Veröffentlichungen der Musikgeschichtlichen Abteilung des Deutschen Historischen Instituts in Rom'' 21:393–408. * Grout, Donald, Claude V. Palisca, and

''Apollo's Lyre: Greek Music and Music Theory in Antiquity and the Middle Ages''

Publications of the Center for the History of Music Theory and Literature 2. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. . *McAlpine, Fiona (2004). "Beginnings and Endings: Defining the Mode in a Medieval Chant". ''Studia Musicologica Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae'' 45, nos. 1 & 2 (17th International Congress of the International Musicological Society IMS Study Group Cantus Planus): 165–177. * (1997). "Mode et système. Conceptions ancienne et moderne de la modalité". ''Musurgia'' 4, no. 3:67–80. * Meeùs, Nicolas (2000). "Fonctions modales et qualités systémiques". ''Musicae Scientiae, Forum de discussion'' 1:55–63. * Meier, Bernhard (1974). ''Die Tonarten der klassischen Vokalpolyphonie: nach den Quellen dargestellt''. Utrecht. * Meier, Bernhard (1988). ''The Modes of Classical Vocal Polyphony: Described According to the Sources,'' translated from the German by Ellen S. Beebe, with revisions by the author. New York: Broude Brothers. * Meier, Bernhard (1992). ''Alte Tonarten: dargestellt an der Instrumentalmusik des 16. und 17. Jahrhunderts.'' Kassel * Miller, Ron (1996). ''Modal Jazz Composition and Harmony'', Vol. 1. Rottenburg, Germany: Advance Music. * Ordoulidis, Nikos. (2011).

The Greek Popular Modes

. ''British Postgraduate Musicology'' 11 (December). (Online journal, accessed 24 December 2011) * Pfaff, Maurus (1974). "Die Regensburger Kirchenmusikschule und der cantus gregorianus im 19. und 20. Jahrhundert". ''Gloria Deo-pax hominibus. Festschrift zum hundertjährigen Bestehen der Kirchenmusikschule Regensburg'', Schriftenreihe des Allgemeinen Cäcilien-Verbandes für die Länder der Deutschen Sprache 9, edited by

Beyond Medici: The Struggle for Progress in Chant

. ''Sacred Music'' 135, no. 2 (Summer): 26–44. * Scharnagl, August (1994). " Carl Proske (1794–1861)". In ''Musica divina: Ausstellung zum 400. Todesjahr von Giovanni Pierluigi Palestrina und Orlando di Lasso und zum 200. Geburtsjahr von Carl Proske. Ausstellung in der Bischöflichen Zentralbibliothek Regensburg, 4. November 1994 bis 3. Februar 1995'', Bischöfliches Zentralarchiv und Bischöfliche Zentralbibliothek Regensburg: Kataloge und Schriften, no. 11, edited by Paul Mai, 12–52. Regensburg: Schnell und Steiner, 1994. * Schnorr, Klemens (2004). "El cambio de la edición oficial del canto gregoriano de la editorial Pustet/Ratisbona a la de Solesmes en la época del Motu proprio". In ''El Motu proprio de San Pío X y la Música (1903–2003). Barcelona, 2003'', edited by Mariano Lambea, introduction by María Rosario Álvarez Martínez and José Sierra Pérez. ''Revista de musicología'' 27, no. 1 (June) 197–209. * Street, Donald (1976). "The Modes of Limited Transposition". ''

All modes mapped out in all positions for 6, 7 and 8 string guitarThe use of guitar modes in jazz music

John Chalmers

Eric Friedlander MD

An interactive demonstration of many scales and modes

an approach to the original singing of the Homeric epics and early Greek epic and lyrical poetry by Ioannidis Nikolaos *

Ἀριστοξενου ἁρμονικα στοιχεια: The Harmonics of Aristoxenus

', edited with translation notes introduction and index of words by Henry S. Macran. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1902. * Monzo, Joe. 2004.

The Measurement of Aristoxenus's Divisions of the Tetrachord

{{DEFAULTSORT:Musical Mode Melody types Ancient Greek music theory Catholic music

music theory

Music theory is the study of the practices and possibilities of music. ''The Oxford Companion to Music'' describes three interrelated uses of the term "music theory". The first is the "rudiments", that are needed to understand music notation (ke ...

, the term mode or ''modus'' is used in a number of distinct senses, depending on context.

Its most common use may be described as a type of musical scale

In music theory, a scale is any set of musical notes ordered by fundamental frequency or pitch. A scale ordered by increasing pitch is an ascending scale, and a scale ordered by decreasing pitch is a descending scale.

Often, especially in the ...

coupled with a set of characteristic melodic and harmonic behaviors. It is applied to major and minor

In Western music, the adjectives major and minor may describe a chord, scale, or key. As such, composition, movement, section, or phrase may be referred to by its key, including whether that key is major or minor.

Intervals

Some intervals ma ...

keys as well as the seven diatonic mode

In music theory, a diatonic scale is any heptatonic scale that includes five whole steps (whole tones) and two half steps (semitones) in each octave, in which the two half steps are separated from each other by either two or three whole steps, ...

s (including the former as Ionian and Aeolian) which are defined by their starting note or tonic. (Olivier Messiaen

Olivier Eugène Prosper Charles Messiaen (, ; ; 10 December 1908 – 27 April 1992) was a French composer, organist, and ornithologist who was one of the major composers of the 20th century. His music is rhythmically complex; harmonically ...

's modes of limited transposition Modes of limited transposition are musical modes or scales that fulfill specific criteria relating to their symmetry and the repetition of their interval groups. These scales may be transposed to all twelve notes of the chromatic scale, but at leas ...

are strictly a scale type.) Related to the diatonic modes are the eight church modes or Gregorian modes, in which authentic and plagal forms of scales are distinguished by ambitus

In ancient Roman law, ''ambitus'' was a crime of political corruption, mainly a candidate's attempt to influence the outcome (or direction) of an election through bribery or other forms of soft power. The Latin word ''ambitus'' is the origin ...

and tenor

A tenor is a type of classical music, classical male singing human voice, voice whose vocal range lies between the countertenor and baritone voice types. It is the highest male chest voice type. The tenor's vocal range extends up to C5. The lo ...

or reciting tone

In chant, a reciting tone (also called a recitation tone) can refer to either a repeated musical pitch or to the entire melodic formula for which that pitch is a structural note. In Gregorian chant, the first is also called tenor, dominant or tuba ...

. Although both diatonic and gregorian modes borrow terminology from ancient Greece

Ancient Greece ( el, Ἑλλάς, Hellás) was a northeastern Mediterranean civilization, existing from the Greek Dark Ages of the 12th–9th centuries BC to the end of classical antiquity ( AD 600), that comprised a loose collection of cult ...

, the Greek ''tonoi'' do not otherwise resemble their mediaeval/modern counterparts.

In the Middle Ages the term modus was used to describe both intervals and rhythm. Modal rhythm

In medieval music, the rhythmic modes were set patterns of long and short durations (or rhythms). The value of each note is not determined by the form of the written note (as is the case with more recent European musical notation), but rather by ...

was an essential feature of the modal notation system of the Notre-Dame school

The Notre-Dame school or the Notre-Dame school of polyphony refers to the group of composers working at or near the Notre-Dame Cathedral in Paris from about 1160 to 1250, along with the music they produced.

The only composers whose names hav ...

at the turn of the 12th century. In the mensural notation

Mensural notation is the musical notation system used for European vocal polyphonic music from the later part of the 13th century until about 1600. The term "mensural" refers to the ability of this system to describe precisely measured rhythm ...

that emerged later, modus specifies the subdivision of the ''longa''.

Outside of Western classical music

Classical music generally refers to the art music of the Western world, considered to be distinct from Western folk music or popular music traditions. It is sometimes distinguished as Western classical music, as the term "classical music" also ...

, "mode" is sometimes used to embrace similar concepts such as ''Octoechos

Oktōēchos (here transcribed "Octoechos"; Greek: ;The feminine form exists as well, but means the book octoechos. from ὀκτώ "eight" and ἦχος "sound, mode" called echos; Slavonic: Осмогласие, ''Osmoglasie'' from о́см� ...

'', ''maqam

MAQAM is a US-based production company specializing in Arabic and Middle Eastern media. The company was established by a small group of Arabic music and culture lovers, later becoming a division of 3B Media Inc. "MAQAM" is an Arabic word meaning a ...

'', ''pathet

Pathet ( jv, ꦥꦛꦼꦠ꧀, translit=Pathet, also patet) is an organizing concept in central Javanese gamelan music in Indonesia. It is a system of tonal hierarchies in which some notes are emphasized more than others. The word means '"to da ...

'' etc. (see #Analogues in different musical traditions below).

Mode as a general concept

Regarding the concept of mode as applied to pitch relationships generally,Harold S. Powers

Harold Stone Powers (August 5, 1928 – March 15, 2007) was an American musicologist, ethnomusicologist, and music theorist.

Career

Born in New York City on August 5, 1928, he earned his B.Mus. in piano from Syracuse University in 1950 and an M ...

proposed that "mode" has "a twofold sense", denoting either a "particularized scale" or a "generalized tune", or both. "If one thinks of scale and tune as representing the poles of a continuum of melodic predetermination, then most of the area between can be designated one way or the other as being in the domain of mode".

In 1792, Sir Willam Jones applied the term "mode" to the music of "the Persians

The Persians are an Iranian ethnic group who comprise over half of the population of Iran. They share a common cultural system and are native speakers of the Persian language as well as of the languages that are closely related to Persian.

...

and the Hindoos". As early as 1271, Amerus applied the concept to ''cantilenis organicis'', i.e. most probably polyphony. It is still heavily used with regard to Western polyphony

Polyphony ( ) is a type of musical texture consisting of two or more simultaneous lines of independent melody, as opposed to a musical texture with just one voice, monophony, or a texture with one dominant melodic voice accompanied by chords, h ...

before the onset of the common practice period

In European art music, the common-practice period is the era of the tonal system. Most of its features persisted from the mid- Baroque period through the Classical and Romantic periods, roughly from 1650 to 1900. There was much stylistic evoluti ...

, as for example "modale Mehrstimmigkeit" by Carl Dahlhaus

Carl Dahlhaus (10 June 1928 – 13 March 1989) was a German musicologist who was among the leading postwar musicologists of the mid to late 20th-century. A prolific scholar, he had broad interests though his research focused on 19th- and 20th- ...

or "Tonarten" of the 16th and 17th centuries found by Bernhard Meier.

The word encompasses several additional meanings. Authors from the 9th century until the early 18th century (e.g., Guido of Arezzo

Guido of Arezzo ( it, Guido d'Arezzo; – after 1033) was an Italian music theorist and pedagogue of High medieval music. A Benedictine monk, he is regarded as the inventor—or by some, developer—of the modern staff notation that had a ma ...

) sometimes employed the Latin ''modus'' for interval, or for qualities of individual notes. In the theory of late-medieval mensural

Mensural notation is the musical notation system used for European vocal polyphonic music from the later part of the 13th century until about 1600. The term "mensural" refers to the ability of this system to describe precisely measured rhythmi ...

polyphony (e.g., Franco of Cologne

Franco of Cologne (; also Franco of Paris) was a German music theorist and possibly a composer. He was one of the most influential theorists of the Late Middle Ages, and was the first to propose an idea which was to transform musical notation per ...

), ''modus'' is a rhythmic relationship between long and short values or a pattern made from them; in mensural music most often theorists applied it to division of longa into 3 or 2 breves.

Modes and scales

Amusical scale

In music theory, a scale is any set of musical notes ordered by fundamental frequency or pitch. A scale ordered by increasing pitch is an ascending scale, and a scale ordered by decreasing pitch is a descending scale.

Often, especially in the ...

is a series of pitches in a distinct order.

The concept of "mode" in Western music theory has three successive stages: in Gregorian chant

Gregorian chant is the central tradition of Western plainchant, a form of monophonic, unaccompanied sacred song in Latin (and occasionally Greek) of the Roman Catholic Church. Gregorian chant developed mainly in western and central Europe durin ...

theory, in Renaissance polyphonic theory, and in tonal harmonic music of the common practice period. In all three contexts, "mode" incorporates the idea of the diatonic scale

In music theory, a diatonic scale is any heptatonic scale that includes five whole steps (whole tones) and two half steps (semitones) in each octave, in which the two half steps are separated from each other by either two or three whole steps, ...

, but differs from it by also involving an element of melody type

Melody type or type-melody is a set of melodic formulas, figures, and patterns.

Term and typical meanings

"Melody type" is a fundamental notion for understanding a nature of Western and non-Western musical modes, according to Harold Powers' ...

. This concerns particular repertories of short musical figures

Figure may refer to:

General

*A shape, drawing, depiction, or geometric configuration

*Figure (wood), wood appearance

*Figure (music), distinguished from musical motif

*Noise figure, in telecommunication

*Dance figure, an elementary dance patter ...

or groups of tones within a certain scale so that, depending on the point of view, mode takes on the meaning of either a "particularized scale" or a "generalized tune". Modern musicological

Musicology (from Greek μουσική ''mousikē'' 'music' and -λογια ''-logia'', 'domain of study') is the scholarly analysis and research-based study of music. Musicology departments traditionally belong to the humanities, although some mu ...

practice has extended the concept of mode to earlier musical systems, such as those of Ancient Greek music

Music was almost universally present in ancient Greek society, from marriages, funerals, and religious ceremonies to theatre, folk music, and the ballad-like reciting of epic poetry. It thus played an integral role in the lives of ancient Greek ...

, Jewish cantillation

Cantillation is the ritual chanting of prayers and responses. It often specifically refers to Jewish Hebrew cantillation. Cantillation sometimes refers to diacritics used in texts that are to be chanted in liturgy.

Cantillation includes:

* Chant

...

, and the Byzantine

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantinopl ...

system of '' octoechoi'', as well as to other non-Western types of music.

By the early 19th century, the word "mode" had taken on an additional meaning, in reference to the difference between major and minor keys, specified as "major mode

The major scale (or Ionian mode) is one of the most commonly used musical scales, especially in Western music. It is one of the diatonic scales. Like many musical scales, it is made up of seven notes: the eighth duplicates the first at double ...

" and "minor mode

In music theory, the minor scale is three scale patterns – the natural minor scale (or Aeolian mode), the harmonic minor scale, and the melodic minor scale (ascending or descending) – rather than just two as with the major scale, which also ...

". At the same time, composers were beginning to conceive "modality" as something outside of the major/minor system that could be used to evoke religious feelings or to suggest folk-music

Folk music is a music genre that includes traditional folk music and the contemporary genre that evolved from the former during the 20th-century folk revival. Some types of folk music may be called world music. Traditional folk music has be ...

idioms.

Greek modes

Early Greek treatises describe three interrelated concepts that are related to the later, medieval idea of "mode": (1)scales

Scale or scales may refer to:

Mathematics

* Scale (descriptive set theory), an object defined on a set of points

* Scale (ratio), the ratio of a linear dimension of a model to the corresponding dimension of the original

* Scale factor, a number w ...

(or "systems"), (2) ''tonos'' – pl. ''tonoi'' – (the more usual term used in medieval theory for what later came to be called "mode"), and (3) ''harmonia'' (harmony) – pl. ''harmoniai'' – this third term subsuming the corresponding ''tonoi'' but not necessarily the converse.

Greek scales

The Greek scales in the Aristoxenian tradition were: *Mixolydian

Mixolydian mode may refer to one of three things: the name applied to one of the ancient Greek ''harmoniai'' or ''tonoi'', based on a particular octave species or scale; one of the medieval church modes; or a modern musical mode or diatonic scal ...

: ''hypate hypaton–paramese'' (b–b′)

* Lydian: ''parhypate hypaton–trite diezeugmenon'' (c′–c″)

* Phrygian: ''lichanos hypaton–paranete diezeugmenon'' (d′–d″)

* Dorian: ''hypate meson–nete diezeugmenon'' (e′–e″)

* Hypolydian: ''parhypate meson–trite hyperbolaion'' (f′–f″)

* Hypophrygian: ''lichanos meson–paranete hyperbolaion'' (g′–g″)

* Common, Locrian, or Hypodorian: ''mese–nete hyperbolaion'' or ''proslambnomenos–mese'' (a′–a″ or a–a′)

These names are derived from an ancient Greek subgroup (Dorians

The Dorians (; el, Δωριεῖς, ''Dōrieîs'', singular , ''Dōrieús'') were one of the four major ethnic groups into which the Hellenes (or Greeks) of Classical Greece divided themselves (along with the Aeolians, Achaeans, and Ionians) ...

), a small region in central Greece (Locris

Locris (; el, label=Modern Greek, Λοκρίδα, Lokrída; grc, Λοκρίς, Lokrís) was a region of ancient Greece, the homeland of the Locrians, made up of three distinct districts.

Locrian tribe

The city of Locri in Calabria (Italy), ...

), and certain neighboring peoples (non-Greek but related to them) from Asia Minor

Anatolia, tr, Anadolu Yarımadası), and the Anatolian plateau, also known as Asia Minor, is a large peninsula in Western Asia and the westernmost protrusion of the Asian continent. It constitutes the major part of modern-day Turkey. The re ...

(Lydia

Lydia (Lydian language, Lydian: 𐤮𐤱𐤠𐤭𐤣𐤠, ''Śfarda''; Aramaic: ''Lydia''; el, Λυδία, ''Lȳdíā''; tr, Lidya) was an Iron Age Monarchy, kingdom of western Asia Minor located generally east of ancient Ionia in the mod ...

, Phrygia

In classical antiquity, Phrygia ( ; grc, Φρυγία, ''Phrygía'' ) was a kingdom in the west central part of Anatolia, in what is now Asian Turkey, centered on the Sangarios River. After its conquest, it became a region of the great empires ...

). The association of these ethnic names with the octave species

In the musical system of ancient Greece, an octave species (εἶδος τοῦ διὰ πασῶν, or σχῆμα τοῦ διὰ πασῶν) is a specific sequence of intervals within an octave. In '' Elementa harmonica'', Aristoxenus classi ...

appears to precede Aristoxenus

Aristoxenus of Tarentum ( el, Ἀριστόξενος ὁ Ταραντῖνος; born 375, fl. 335 BC) was a Greek Peripatetic philosopher, and a pupil of Aristotle. Most of his writings, which dealt with philosophy, ethics and music, have been ...

, who criticized their application to the ''tonoi'' by the earlier theorists whom he called the "Harmonicists." According to Bélis (2001), he felt that their diagrams, which exhibit 28 consecutive dieses, were "... devoid of any musical reality since more than two quarter-tones are never heard in succession."

Depending on the positioning (spacing) of the interposed tones in the tetrachord

In music theory, a tetrachord ( el, τετράχορδoν; lat, tetrachordum) is a series of four notes separated by three intervals. In traditional music theory, a tetrachord always spanned the interval of a perfect fourth, a 4:3 frequency propo ...

s, three ''genera'' of the seven octave species can be recognized. The diatonic genus (composed of tones and semitones), the chromatic genus (semitones and a minor third), and the enharmonic genus

In the musical system of ancient Greece, genus (Greek: γένος 'genos'' pl. γένη 'genē'' Latin: ''genus'', pl. ''genera'' "type, kind") is a term used to describe certain classes of intonations of the two movable notes within a tetrach ...

(with a major third and two quarter tone

A quarter tone is a pitch halfway between the usual notes of a chromatic scale or an interval about half as wide (aurally, or logarithmically) as a semitone, which itself is half a whole tone. Quarter tones divide the octave by 50 cents each, a ...

s or dieses). The framing interval of the perfect fourth is fixed, while the two internal pitches are movable. Within the basic forms, the intervals of the chromatic and diatonic genera were varied further by three and two "shades" (''chroai''), respectively.

In contrast to the medieval modal system, these scales and their related ''tonoi'' and ''harmoniai'' appear to have had no hierarchical relationships amongst the notes that could establish contrasting points of tension and rest, although the ''mese'' ("middle note") may have had some sort of gravitational function.

''Tonoi''

The term ''tonos'' (pl. ''tonoi'') was used in four senses: "as note, interval, region of the voice, and pitch. We use it of the region of the voice whenever we speak of Dorian, or Phrygian, or Lydian, or any of the other tones".Cleonides Cleonides ( el, Κλεονείδης) is the author of a Greek treatise on music theory titled Εἰσαγωγὴ ἁρμονική ''Eisagōgē harmonikē'' (Introduction to Harmonics). The date of the treatise, based on internal evidence, can be e ...

attributes thirteen ''tonoi'' to Aristoxenus, which represent a progressive transposition of the entire system (or scale) by semitone over the range of an octave between the Hypodorian and the Hypermixolydian. According to Cleonides, Aristoxenus's transpositional ''tonoi'' were named analogously to the octave species, supplemented with new terms to raise the number of degrees from seven to thirteen. However, according to the interpretation of at least three modern authorities, in these transpositional ''tonoi'' the Hypodorian is the lowest, and the Mixolydian next-to-highest – the reverse of the case of the octave species, with nominal base pitches as follows (descending order):

* F: Hypermixolydian (or Hyperphrygian)

* E: High Mixolydian or Hyperiastian

* E: Low Mixolydian or Hyperdorian

* D: Lydian

* C: Low Lydian or Aeolian

* C: Phrygian

* B: Low Phrygian or Iastian

* B: Dorian

* A: Hypolydian

* G: Low Hypolydian or Hypoaelion

* G: Hypophrygian

* F: Low Hypophrygian or Hypoiastian

* F: Hypodorian

Ptolemy

Claudius Ptolemy (; grc-gre, Πτολεμαῖος, ; la, Claudius Ptolemaeus; AD) was a mathematician, astronomer, astrologer, geographer, and music theorist, who wrote about a dozen scientific treatises, three of which were of importanc ...

, in his ''Harmonics'', ii.3–11, construed the ''tonoi'' differently, presenting all seven octave species within a fixed octave, through chromatic inflection of the scale degrees (comparable to the modern conception of building all seven modal scales on a single tonic). In Ptolemy's system, therefore there are only seven ''tonoi''. Pythagoras

Pythagoras of Samos ( grc, Πυθαγόρας ὁ Σάμιος, Pythagóras ho Sámios, Pythagoras the Samos, Samian, or simply ; in Ionian Greek; ) was an ancient Ionians, Ionian Ancient Greek philosophy, Greek philosopher and the eponymou ...

also construed the intervals arithmetically (if somewhat more rigorously, initially allowing for 1:1 = Unison, 2:1 = Octave, 3:2 = Fifth, 4:3 = Fourth and 5:4 = Major Third within the octave). In their diatonic genus, these ''tonoi'' and corresponding ''harmoniai'' correspond with the intervals of the familiar modern major and minor scales. See Pythagorean tuning

Pythagorean tuning is a system of musical tuning in which the frequency ratios of all intervals are based on the ratio 3:2.Bruce Benward and Marilyn Nadine Saker (2003). ''Music: In Theory and Practice'', seventh edition, 2 vols. (Boston: Mc ...

and Pythagorean interval

In musical tuning theory, a Pythagorean interval is a musical interval with frequency ratio equal to a power of two divided by a power of three, or vice versa.Benson, Donald C. (2003). ''A Smoother Pebble: Mathematical Explorations'', p.56. . ...

.

''Harmoniai''

In music theory the Greek word ''harmonia'' can signify the enharmonic genus oftetrachord

In music theory, a tetrachord ( el, τετράχορδoν; lat, tetrachordum) is a series of four notes separated by three intervals. In traditional music theory, a tetrachord always spanned the interval of a perfect fourth, a 4:3 frequency propo ...

, the seven octave species, or a style of music associated with one of the ethnic types or the ''tonoi'' named by them.

Particularly in the earliest surviving writings, ''harmonia'' is regarded not as a scale, but as the epitome of the stylised singing of a particular district or people or occupation. When the late-6th-century poet Lasus of Hermione

Lasus of Hermione ( el, Λάσος ὁ Ἑρμιονεύς) was a Greek lyric poet of the 6th century BC from the city of Hermione in the Argolid. He is known to have been active at Athens under the reign of the Peisistratids. Pseudo-Plutarch's ...

referred to the Aeolian ''harmonia'', for example, he was more likely thinking of a melodic style characteristic of Greeks speaking the Aeolic dialect

In linguistics, Aeolic Greek (), also known as Aeolian (), Lesbian or Lesbic dialect, is the set of dialects of Ancient Greek spoken mainly in Boeotia; in Thessaly; in the Aegean island of Lesbos; and in the Greek colonies of Aeolis in Anatolia ...

than of a scale pattern. By the late 5th century BC, these regional types are being described in terms of differences in what is called ''harmonia'' – a word with several senses, but here referring to the pattern of intervals between the notes sounded by the strings of a lyra

Lyra (; Latin for lyre, from Greek ''λύρα'') is a small constellation. It is one of the 48 listed by the 2nd century astronomer Ptolemy, and is one of the modern 88 constellations recognized by the International Astronomical Union. Lyra was ...

or a kithara.

However, there is no reason to suppose that, at this time, these tuning patterns stood in any straightforward and organised relations to one another. It was only around the year 400 that attempts were made by a group of theorists known as the harmonicists to bring these ''harmoniai'' into a single system and to express them as orderly transformations of a single structure. Eratocles was the most prominent of the harmonicists, though his ideas are known only at second hand, through Aristoxenus, from whom we learn they represented the ''harmoniai'' as cyclic reorderings of a given series of intervals within the octave, producing seven octave species

In the musical system of ancient Greece, an octave species (εἶδος τοῦ διὰ πασῶν, or σχῆμα τοῦ διὰ πασῶν) is a specific sequence of intervals within an octave. In '' Elementa harmonica'', Aristoxenus classi ...

. We also learn that Eratocles confined his descriptions to the enharmonic genus.

In the ''Republic

A republic () is a "state in which power rests with the people or their representatives; specifically a state without a monarchy" and also a "government, or system of government, of such a state." Previously, especially in the 17th and 18th c ...

'', Plato

Plato ( ; grc-gre, Πλάτων ; 428/427 or 424/423 – 348/347 BC) was a Greek philosopher born in Athens during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. He founded the Platonist school of thought and the Academy, the first institution ...

uses the term inclusively to encompass a particular type of scale, range and register, characteristic rhythmic pattern, textual subject, etc. He held that playing music in a particular ''harmonia'' would incline one towards specific behaviors associated with it, and suggested that soldiers should listen to music in Dorian or Phrygian ''harmoniai'' to help make them stronger but avoid music in Lydian, Mixolydian or Ionian ''harmoniai'', for fear of being softened. Plato believed that a change in the musical modes of the state would cause a wide-scale social revolution.

The philosophical writings of Plato and Aristotle

Aristotle (; grc-gre, Ἀριστοτέλης ''Aristotélēs'', ; 384–322 BC) was a Greek philosopher and polymath during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. Taught by Plato, he was the founder of the Peripatetic school of phil ...

(c. 350 BC) include sections that describe the effect of different ''harmoniai'' on mood and character formation. For example, Aristotle stated in his ''Politics

Politics (from , ) is the set of activities that are associated with making decisions in groups, or other forms of power relations among individuals, such as the distribution of resources or status. The branch of social science that studies ...

'':

Aristotle continues by describing the effects of rhythm, and concludes about the combined effect of rhythm and ''harmonia'' (viii:1340b:10–13):

The word ''ethos

Ethos ( or ) is a Greek word meaning "character" that is used to describe the guiding beliefs or ideals that characterize a community, nation, or ideology; and the balance between caution, and passion. The Greeks also used this word to refer to ...

'' (ἦθος) in this context means "moral character", and Greek ethos theory concerns the ways that music can convey, foster, and even generate ethical states.

''Melos''

Some treatises also describe "melic" composition (μελοποιΐα), "the employment of the materials subject to harmonic practice with due regard to the requirements of each of the subjects under consideration" – which, together with the scales, ''tonoi'', and ''harmoniai'' resemble elements found in medieval modal theory. According toAristides Quintilianus Aristides Quintilianus (Greek: Ἀριστείδης Κοϊντιλιανός) was the Greek author of an ancient musical treatise, ''Perì musikês'' (Περὶ Μουσικῆς, i.e. ''On Music''; Latin: ''De Musica'')

According to Theodore Kar ...

, melic composition is subdivided into three classes: dithyrambic, nomic, and tragic. These parallel his three classes of rhythmic composition: systaltic, diastaltic and hesychastic. Each of these broad classes of melic composition may contain various subclasses, such as erotic, comic and panegyric, and any composition might be elevating (diastaltic), depressing (systaltic), or soothing (hesychastic).

According to Thomas J. Mathiesen, music as a performing art was called ''melos'', which in its perfect form (μέλος τέλειον) comprised not only the melody and the text (including its elements of rhythm and diction) but also stylized dance movement. Melic and rhythmic composition (respectively, μελοποιΐα and ῥυθμοποιΐα) were the processes of selecting and applying the various components of melos and rhythm to create a complete work. According to Aristides Quintilianus:

Western Church

Tonaries, lists of chant titles grouped by mode, appear in western sources around the turn of the 9th century. The influence of developments in Byzantium, from Jerusalem and Damascus, for instance the works of Saints

Tonaries, lists of chant titles grouped by mode, appear in western sources around the turn of the 9th century. The influence of developments in Byzantium, from Jerusalem and Damascus, for instance the works of Saints John of Damascus

John of Damascus ( ar, يوحنا الدمشقي, Yūḥanna ad-Dimashqī; gr, Ἰωάννης ὁ Δαμασκηνός, Ioánnēs ho Damaskēnós, ; la, Ioannes Damascenus) or John Damascene was a Christian monk, priest, hymnographer, and a ...

(d. 749) and Cosmas of Maiouma, are still not fully understood. The eight-fold division of the Latin modal system, in a four-by-two matrix, was certainly of Eastern provenance, originating probably in Syria or even in Jerusalem, and was transmitted from Byzantine sources to Carolingian practice and theory during the 8th century. However, the earlier Greek model for the Carolingian system was probably ordered like the later Byzantine '' oktōēchos'', that is, with the four principal (authentic

Authenticity or authentic may refer to:

* Authentication, the act of confirming the truth of an attribute

Arts and entertainment

* Authenticity in art, ways in which a work of art or an artistic performance may be considered authentic

Music

* A ...

) modes first, then the four plagals, whereas the Latin modes were always grouped the other way, with the authentics and plagals paired.

The 6th-century scholar Boethius

Anicius Manlius Severinus Boethius, commonly known as Boethius (; Latin: ''Boetius''; 480 – 524 AD), was a Roman senator, consul, ''magister officiorum'', historian, and philosopher of the Early Middle Ages. He was a central figure in the tr ...

had translated Greek music theory treatises by Nicomachus

Nicomachus of Gerasa ( grc-gre, Νικόμαχος; c. 60 – c. 120 AD) was an important ancient mathematician and music theorist, best known for his works ''Introduction to Arithmetic'' and ''Manual of Harmonics'' in Greek. He was born in ...

and Ptolemy

Claudius Ptolemy (; grc-gre, Πτολεμαῖος, ; la, Claudius Ptolemaeus; AD) was a mathematician, astronomer, astrologer, geographer, and music theorist, who wrote about a dozen scientific treatises, three of which were of importanc ...

into Latin. Later authors created confusion by applying mode as described by Boethius to explain plainchant

Plainsong or plainchant (calque from the French ''plain-chant''; la, cantus planus) is a body of chants used in the liturgies of the Western Church. When referring to the term plainsong, it is those sacred pieces that are composed in Latin text. ...

modes, which were a wholly different system. In his ''De institutione musica'', book 4 chapter 15, Boethius, like his Hellenistic sources, twice used the term ''harmonia'' to describe what would likely correspond to the later notion of "mode", but also used the word "modus" – probably translating the Greek word τρόπος (''tropos''), which he also rendered as Latin ''tropus'' – in connection with the system of transpositions required to produce seven diatonic octave species, so the term was simply a means of describing transposition and had nothing to do with the church modes

A Gregorian mode (or church mode) is one of the eight systems of pitch organization used in Gregorian chant.

History

The name of Pope Gregory I was attached to the variety of chant that was to become the dominant variety in medieval western and ...

.

Later, 9th-century theorists applied Boethius's terms ''tropus'' and ''modus'' (along with "tonus") to the system of church modes. The treatise ''De Musica'' (or ''De harmonica institutione'') of Hucbald

Hucbald ( – 20 June 930; also Hucbaldus or Hubaldus) was a Benedictine monk active as a music theorist, poet, composer, teacher, and hagiographer. He was long associated with Saint-Amand Abbey, so is often known as Hucbald of St Amand. Deeply i ...

synthesized the three previously disparate strands of modal theory: chant theory, the Byzantine ''oktōēchos'' and Boethius's account of Hellenistic theory. The late-9th- and early 10th-century compilation known as the ''Alia musica'' imposed the seven octave transpositions, known as ''tropus'' and described by Boethius, onto the eight church modes, but its compilator also mentions the Greek (Byzantine) echoi translated by the Latin term ''sonus''. Thus, the names of the modes became associated with the eight church tones and their modal formulas – but this medieval interpretation does not fit the concept of the ancient Greek harmonics treatises. The modern understanding of mode does not reflect that it is made of different concepts that do not all fit.

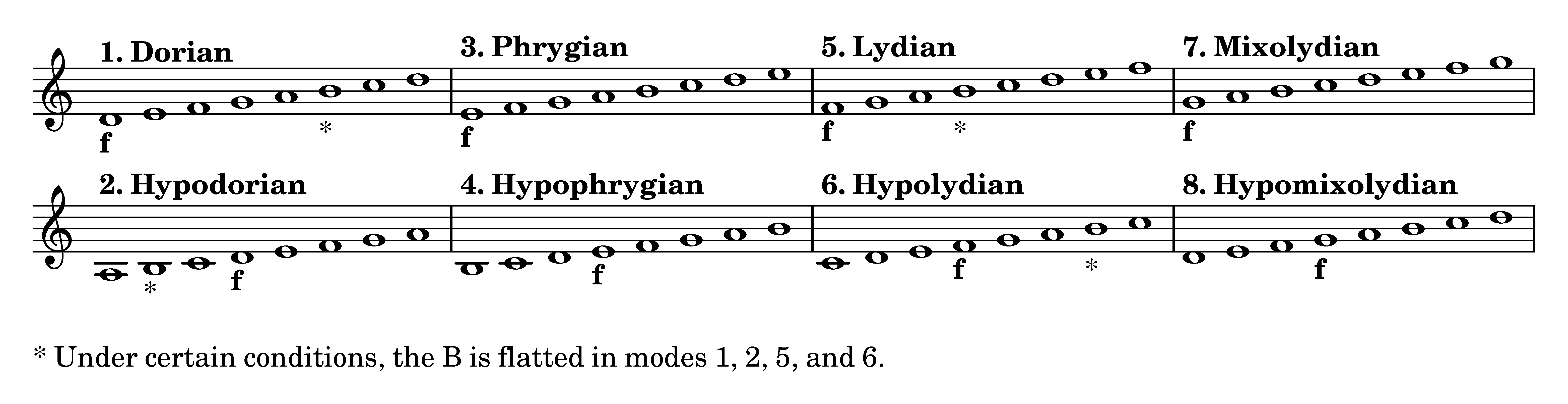

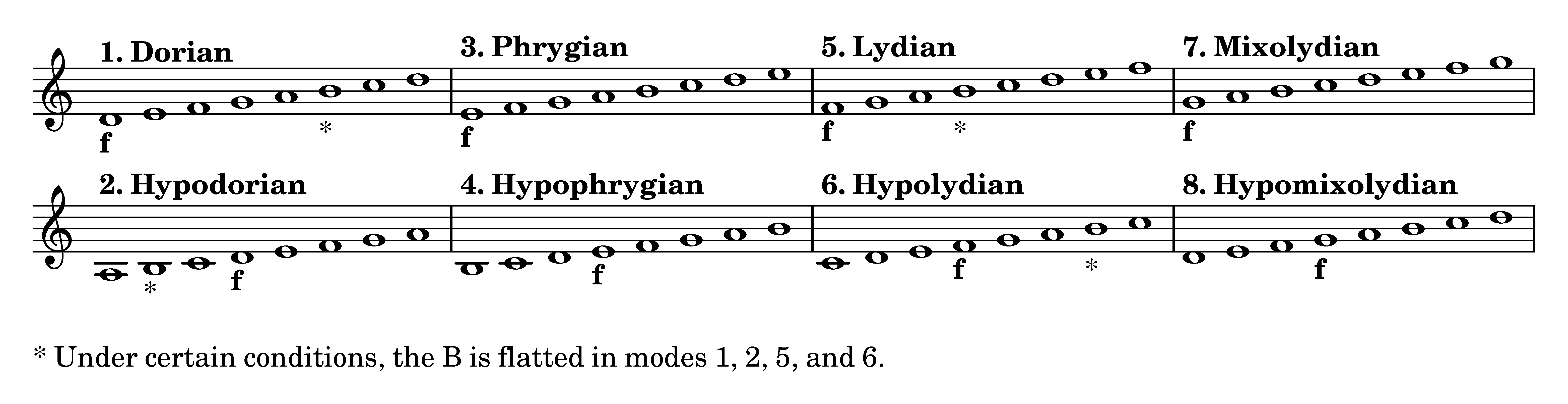

According to Carolingian theorists the eight church modes, or

According to Carolingian theorists the eight church modes, or Gregorian mode

A Gregorian mode (or church mode) is one of the eight systems of pitch organization used in Gregorian chant.

History

The name of Pope Gregory I was attached to the variety of chant that was to become the dominant variety in medieval western and ...

s, can be divided into four pairs, where each pair shares the "final

Final, Finals or The Final may refer to:

*Final (competition), the last or championship round of a sporting competition, match, game, or other contest which decides a winner for an event

** Another term for playoffs, describing a sequence of cont ...

" note and the four notes above the final, but they have different intervals concerning the species of the fifth. If the octave is completed by adding three notes above the fifth, the mode is termed ''authentic'', but if the octave is completed by adding three notes below, it is called ''plagal'' (from Greek πλάγιος, "oblique, sideways"). Otherwise explained: if the melody moves mostly above the final, with an occasional cadence to the sub-final, the mode is authentic. Plagal modes shift range and also explore the fourth below the final as well as the fifth above. In both cases, the strict ambitus

In ancient Roman law, ''ambitus'' was a crime of political corruption, mainly a candidate's attempt to influence the outcome (or direction) of an election through bribery or other forms of soft power. The Latin word ''ambitus'' is the origin ...

of the mode is one octave. A melody that remains confined to the mode's ambitus is called "perfect"; if it falls short of it, "imperfect"; if it exceeds it, "superfluous"; and a melody that combines the ambituses of both the plagal and authentic is said to be in a "mixed mode".

Although the earlier (Greek) model for the Carolingian system was probably ordered like the Byzantine ''oktōēchos'', with the four authentic modes first, followed by the four plagals, the earliest extant sources for the Latin system are organized in four pairs of authentic and plagal modes sharing the same final: protus authentic/plagal, deuterus authentic/plagal, tritus authentic/plagal, and tetrardus authentic/plagal.

Each mode has, in addition to its final, a "reciting tone

In chant, a reciting tone (also called a recitation tone) can refer to either a repeated musical pitch or to the entire melodic formula for which that pitch is a structural note. In Gregorian chant, the first is also called tenor, dominant or tuba ...

", sometimes called the "dominant". It is also sometimes called the "tenor", from Latin ''tenere'' "to hold", meaning the tone around which the melody principally centres. The reciting tones of all authentic modes began a fifth above the final, with those of the plagal modes a third

Third or 3rd may refer to:

Numbers

* 3rd, the ordinal form of the cardinal number 3

* , a fraction of one third

* Second#Sexagesimal divisions of calendar time and day, 1⁄60 of a ''second'', or 1⁄3600 of a ''minute''

Places

* 3rd Street (d ...

above. However, the reciting tones of modes 3, 4, and 8 rose one step

Step(s) or STEP may refer to:

Common meanings

* Stairs#Step, Steps, making a staircase

* Walking

* Dance move

* Military step, or march

** Marching

Arts Films and television

* Steps (TV series), ''Steps'' (TV series), Hong Kong

* Step (film), ' ...

during the 10th and 11th centuries with 3 and 8 moving from B to C (half step

A semitone, also called a half step or a half tone, is the smallest musical interval commonly used in Western tonal music, and it is considered the most dissonant when sounded harmonically.

It is defined as the interval between two adjacent no ...

) and that of 4 moving from G to A (whole step

In Western music theory, a major second (sometimes also called whole tone or a whole step) is a second spanning two semitones (). A second is a musical interval encompassing two adjacent staff positions (see Interval number for more de ...

).

After the reciting tone, every mode is distinguished by scale degrees called "mediant" and "participant". The mediant is named from its position between the final and reciting tone. In the authentic modes it is the third of the scale, unless that note should happen to be B, in which case C substitutes for it. In the plagal modes, its position is somewhat irregular. The participant is an auxiliary note, generally adjacent to the mediant in authentic modes and, in the plagal forms, coincident with the reciting tone of the corresponding authentic mode (some modes have a second participant).

Only one accidental is used commonly in

After the reciting tone, every mode is distinguished by scale degrees called "mediant" and "participant". The mediant is named from its position between the final and reciting tone. In the authentic modes it is the third of the scale, unless that note should happen to be B, in which case C substitutes for it. In the plagal modes, its position is somewhat irregular. The participant is an auxiliary note, generally adjacent to the mediant in authentic modes and, in the plagal forms, coincident with the reciting tone of the corresponding authentic mode (some modes have a second participant).

Only one accidental is used commonly in Gregorian chant

Gregorian chant is the central tradition of Western plainchant, a form of monophonic, unaccompanied sacred song in Latin (and occasionally Greek) of the Roman Catholic Church. Gregorian chant developed mainly in western and central Europe durin ...

– B may be lowered by a half-step to B. This usually (but not always) occurs in modes V and VI, as well as in the upper tetrachord

In music theory, a tetrachord ( el, τετράχορδoν; lat, tetrachordum) is a series of four notes separated by three intervals. In traditional music theory, a tetrachord always spanned the interval of a perfect fourth, a 4:3 frequency propo ...

of IV, and is optional in other modes except III, VII and VIII.

In 1547, the Swiss theorist Henricus Glareanus published the ''Dodecachordon'', in which he solidified the concept of the church modes, and added four additional modes: the Aeolian (mode 9), Hypoaeolian

The Hypoaeolian mode, literally meaning "below Aeolian", is the name assigned by Henricus Glareanus in his ''Dodecachordon'' (1547) to the musical plagal mode on A, which uses the diatonic octave species from E to the E an octave above, divided ...

(mode 10), Ionian (mode 11), and Hypoionian (mode 12). A little later in the century, the Italian Gioseffo Zarlino

Gioseffo Zarlino (31 January or 22 March 1517 – 4 February 1590) was an Italian music theorist and composer of the Renaissance. He made a large contribution to the theory of counterpoint as well as to musical tuning.

Life and career

Zarlin ...

at first adopted Glarean's system in 1558, but later (1571 and 1573) revised the numbering and naming conventions in a manner he deemed more logical, resulting in the widespread promulgation of two conflicting systems.

Zarlino's system reassigned the six pairs of authentic–plagal mode numbers to finals in the order of the natural hexachord, C–D–E–F–G–A, and transferred the Greek names as well, so that modes 1 through 8 now became C-authentic to F-plagal, and were now called by the names Dorian to Hypomixolydian. The pair of G modes were numbered 9 and 10 and were named Ionian and Hypoionian, while the pair of A modes retained both the numbers and names (11, Aeolian, and 12 Hypoaeolian) of Glarean's system. While Zarlino's system became popular in France, Italian composers preferred Glarean's scheme because it retained the traditional eight modes, while expanding them. Luzzasco Luzzaschi

Luzzasco Luzzaschi (c. 1545 – 10 September 1607) was an Italian composer, organist, and teacher of the late Renaissance. He was born and died in Ferrara, and despite evidence of travels to Rome it is assumed that Luzzaschi spent the majority o ...

was an exception in Italy, in that he used Zarlino's new system.

In the late-18th and 19th centuries, some chant reformers (notably the editors of the Mechlin

Mechelen (; french: Malines ; traditional English name: MechlinMechelen has been known in English as ''Mechlin'', from where the adjective ''Mechlinian'' is derived. This name may still be used, especially in a traditional or historical contex ...

, Pustet

Friedrich Pustet GmbH & Co. KG is a German publishing firm, located in Regensburg.

The original home of the Pustets was the Republic of Venice, where the name Bustetto is common. Probably in the seventeenth century, the founder of the Ratisbon l ...

-Ratisbon (Regensburg

Regensburg or is a city in eastern Bavaria, at the confluence of the Danube, Naab and Regen rivers. It is capital of the Upper Palatinate subregion of the state in the south of Germany. With more than 150,000 inhabitants, Regensburg is the f ...

), and Rheims

Reims ( , , ; also spelled Rheims in English) is the most populous city in the French department of Marne, and the 12th most populous city in France. The city lies northeast of Paris on the Vesle river, a tributary of the Aisne.

Founded by ...

-Cambrai

Cambrai (, ; pcd, Kimbré; nl, Kamerijk), formerly Cambray and historically in English Camerick or Camericke, is a city in the Nord (French department), Nord Departments of France, department and in the Hauts-de-France Regions of France, regio ...

Office-Books, collectively referred to as the Cecilian Movement

The Cecilian Movement for church music reform began in Germany in the second half of the 1800s as a reaction to the liberalization of the Enlightenment.

The Cecilian Movement received great impetus from Regensburg, where Franz Xaver Haberl had a ...

) renumbered the modes once again, this time retaining the original eight mode numbers and Glareanus's modes 9 and 10, but assigning numbers 11 and 12 to the modes on the final B, which they named Locrian and Hypolocrian (even while rejecting their use in chant). The Ionian and Hypoionian modes (on C) become in this system modes 13 and 14.

Given the confusion between ancient, medieval, and modern terminology, "today it is more consistent and practical to use the traditional designation of the modes with numbers one to eight", using Roman numeral

Roman numerals are a numeral system that originated in ancient Rome and remained the usual way of writing numbers throughout Europe well into the Late Middle Ages. Numbers are written with combinations of letters from the Latin alphabet, eac ...

(I–VIII), rather than using the pseudo-Greek naming system. Medieval terms, first used in Carolingian treatises, later in Aquitanian tonaries, are still used by scholars today: the Greek ordinals ("first", "second", etc.) transliterated into the Latin alphabet protus (πρῶτος), deuterus (δεύτερος), tritus (τρίτος), and tetrardus (τέταρτος). In practice they can be specified as authentic or as plagal like "protus authentus / plagalis".

Use

A mode indicated a primary pitch (a final), the organization of pitches in relation to the final, the suggested range, themelodic formula

Melody type or type-melody is a set of melodic formulas, figures, and patterns.

Term and typical meanings

"Melody type" is a fundamental notion for understanding a nature of Western and non-Western musical modes, according to Harold Powers' ...

s associated with different modes, the location and importance of cadence

In Western musical theory, a cadence (Latin ''cadentia'', "a falling") is the end of a phrase in which the melody or harmony creates a sense of full or partial resolution, especially in music of the 16th century onwards.Don Michael Randel (1999) ...

s, and the affect (i.e., emotional effect/character). Liane Curtis writes that "Modes should not be equated with scales: principles of melodic organization, placement of cadences, and emotional affect are essential parts of modal content" in Medieval and Renaissance music.

Dahlhaus lists "three factors that form the respective starting points for the modal theories of Aurelian of Réôme

Aurelian of Réôme (Aurelianus Reomensis) (fl. c. 840 – 850) was a Frankish writer and music theorist. He is the author of the ''Musica disciplina'', the earliest extant treatise on music from medieval Europe.

Life

Next to nothing is k ...

, Hermannus Contractus

Blessed Hermann of Reichenau (18 July 1013– 24 September 1054), also known by other names, was an 11th-century Benedictine monk and scholar. He composed works on history, music theory, mathematics, and astronomy, as well as many hymn ...

, and Guido of Arezzo

Guido of Arezzo ( it, Guido d'Arezzo; – after 1033) was an Italian music theorist and pedagogue of High medieval music. A Benedictine monk, he is regarded as the inventor—or by some, developer—of the modern staff notation that had a ma ...

":

* the relation of modal formulas to the comprehensive system of tonal relationships embodied in the diatonic scale

* the partitioning of the octave into a modal framework

* the function of the modal final as a relational center.

The oldest medieval treatise regarding modes is ''Musica disciplina'' by Aurelian of Réôme

Aurelian of Réôme (Aurelianus Reomensis) (fl. c. 840 – 850) was a Frankish writer and music theorist. He is the author of the ''Musica disciplina'', the earliest extant treatise on music from medieval Europe.

Life

Next to nothing is k ...

(dating from around 850) while Hermannus Contractus was the first to define modes as partitionings of the octave. However, the earliest Western source using the system of eight modes is the Tonary of St Riquier, dated between about 795 and 800.

Various interpretations of the "character" imparted by the different modes have been suggested. Three such interpretations, from Guido of Arezzo

Guido of Arezzo ( it, Guido d'Arezzo; – after 1033) was an Italian music theorist and pedagogue of High medieval music. A Benedictine monk, he is regarded as the inventor—or by some, developer—of the modern staff notation that had a ma ...

(995–1050), Adam of Fulda (1445–1505), and Juan de Espinosa Medrano (1632–1688), follow:

Modern modes

Modern Western modes use the same set of notes as themajor scale

The major scale (or Ionian mode) is one of the most commonly used musical scales, especially in Western music. It is one of the diatonic scales. Like many musical scales, it is made up of seven notes: the eighth duplicates the first at double i ...

, in the same order, but starting from one of its seven degrees in turn as a tonic, and so present a different sequence of whole and half step

A semitone, also called a half step or a half tone, is the smallest musical interval commonly used in Western tonal music, and it is considered the most dissonant when sounded harmonically.

It is defined as the interval between two adjacent no ...

s. With the interval sequence of the major scale being W–W–H–W–W–W–H, where "W" means a whole tone (whole step) and "H" means a semitone (half step), it is thus possible to generate the following modes:

For the sake of simplicity, the examples shown above are formed by natural note

In music theory, a natural (♮) is an accidental which cancels previous accidentals and represents the unaltered pitch of a note. A note is natural when it is neither flat () nor sharp () (nor double-flat nor double-sharp ) (nor triple-fla ...

s (also called "white notes", as they can be played using the white keys of a piano keyboard

A musical keyboard is the set of adjacent depressible levers or keys on a musical instrument. Keyboards typically contain keys for playing the twelve notes of the Western musical scale, with a combination of larger, longer keys and smaller, sh ...

). However, any transposition of each of these scales is a valid example of the corresponding mode. In other words, transposition preserves mode.

Although the names of the modern modes are Greek and some have names used in ancient Greek theory for some of the ''harmoniai'', the names of the modern modes are conventional and do not refer to the sequences of intervals found even in the diatonic genus of the Greek

Although the names of the modern modes are Greek and some have names used in ancient Greek theory for some of the ''harmoniai'', the names of the modern modes are conventional and do not refer to the sequences of intervals found even in the diatonic genus of the Greek octave species

In the musical system of ancient Greece, an octave species (εἶδος τοῦ διὰ πασῶν, or σχῆμα τοῦ διὰ πασῶν) is a specific sequence of intervals within an octave. In '' Elementa harmonica'', Aristoxenus classi ...

sharing the same name.

Analysis

Each mode has characteristic intervals and chords that give it its distinctive sound. The following is an analysis of each of the seven modern modes. The examples are provided in a key signature with no sharps or flats (scales composed ofnatural note

In music theory, a natural (♮) is an accidental which cancels previous accidentals and represents the unaltered pitch of a note. A note is natural when it is neither flat () nor sharp () (nor double-flat nor double-sharp ) (nor triple-fla ...

s).

Ionian (I)

TheIonian mode

Ionian mode is a musical mode or, in modern usage, a diatonic scale also called the major scale.

It is the name assigned by Heinrich Glarean in 1547 to his new authentic mode on C (mode 11 in his numbering scheme), which uses the diatonic octav ...

is the modern major scale

The major scale (or Ionian mode) is one of the most commonly used musical scales, especially in Western music. It is one of the diatonic scales. Like many musical scales, it is made up of seven notes: the eighth duplicates the first at double i ...

. The example composed of natural notes begins on C, and is also known as the C-major

C major (or the key of C) is a major scale based on C, consisting of the pitches C, D, E, F, G, A, and B. C major is one of the most common keys used in music. Its key signature has no flats or sharps. Its relative minor is A minor and i ...

scale:

*Tonic triad: C major

*Tonic seventh chord

A seventh chord is a chord consisting of a triad plus a note forming an interval of a seventh above the chord's root. When not otherwise specified, a "seventh chord" usually means a dominant seventh chord: a major triad together with a minor ...

: CM7

*Dominant triad: G (in modern tonal thinking, the fifth or dominant scale degree

In music theory, the scale degree is the position of a particular note on a scale relative to the tonic, the first and main note of the scale from which each octave is assumed to begin. Degrees are useful for indicating the size of intervals and ...

, which in this case is G, is the next-most important chord root after the tonic)

*Seventh chord on the dominant: G7 (a dominant seventh chord

In music theory, a dominant seventh chord, or major minor seventh chord, is a seventh chord, usually built on the fifth degree of the major scale, and composed of a root, major third, perfect fifth, and minor seventh. Thus it is a major triad tog ...

, so-called because of its position in this – and only this – modal scale)

Dorian (II)

TheDorian mode

Dorian mode or Doric mode can refer to three very different but interrelated subjects: one of the Ancient Greek ''harmoniai'' (characteristic melodic behaviour, or the scale structure associated with it); one of the medieval musical modes; or—mos ...

is the second mode. The example composed of natural notes begins on D:

The Dorian mode is very similar to the modern natural minor scale

In music theory, the minor scale is three scale patterns – the natural minor scale (or Aeolian mode), the harmonic minor scale, and the melodic minor scale (ascending or descending) – rather than just two as with the major scale, which also ...

(see Aeolian mode below). The only difference with respect to the natural minor scale is in the sixth scale degree

In music theory, the scale degree is the position of a particular note on a scale relative to the tonic, the first and main note of the scale from which each octave is assumed to begin. Degrees are useful for indicating the size of intervals and ...

, which is a major sixth (M6) above the tonic, rather than a minor sixth (m6).

*Tonic triad: Dm

*Tonic seventh chord: Dm7

*Dominant triad: Am

*Seventh chord on the dominant: Am7 (a minor seventh chord

In music, a minor seventh chord is a seventh chord composed of a root note, together with a minor third, a perfect fifth, and a minor seventh (1, 3, 5, 7).

For example, the minor seventh chord built on C, commonly written as C–7, h ...

)

Phrygian (III)

ThePhrygian mode

The Phrygian mode (pronounced ) can refer to three different musical modes: the ancient Greek ''tonos'' or ''harmonia,'' sometimes called Phrygian, formed on a particular set of octave species or scales; the Medieval Phrygian mode, and the modern ...

is the third mode. The example composed of natural notes starts on E:

The Phrygian mode is very similar to the modern natural minor scale

In music theory, the minor scale is three scale patterns – the natural minor scale (or Aeolian mode), the harmonic minor scale, and the melodic minor scale (ascending or descending) – rather than just two as with the major scale, which also ...

(see Aeolian mode below). The only difference with respect to the natural minor scale is in the second scale degree

In music theory, the scale degree is the position of a particular note on a scale relative to the tonic, the first and main note of the scale from which each octave is assumed to begin. Degrees are useful for indicating the size of intervals and ...

, which is a minor second (m2) above the tonic, rather than a major second (M2).

*Tonic triad: Em

*Tonic seventh chord: Em7

*Dominant triad: Bdim

*Seventh chord on the dominant: Bø7 (a half-diminished seventh chord

In music theory, the half-diminished seventh chord (also known as a half-diminished chord or a minor seventh flat five chord) is a seventh chord composed of a root note, together with a minor third, a diminished fifth, and a minor seventh (1, ...

)

Lydian (IV)

TheLydian mode

The modern Lydian mode is a seven-tone musical scale formed from a rising pattern of pitches comprising three whole tones, a semitone, two more whole tones, and a final semitone.

:

Because of the importance of the major scale in modern music ...

is the fourth mode. The example composed of natural notes starts on F:

The single tone that differentiates this scale from the major scale

The major scale (or Ionian mode) is one of the most commonly used musical scales, especially in Western music. It is one of the diatonic scales. Like many musical scales, it is made up of seven notes: the eighth duplicates the first at double i ...

(Ionian mode) is its fourth degree

Degree may refer to:

As a unit of measurement

* Degree (angle), a unit of angle measurement

** Degree of geographical latitude

** Degree of geographical longitude

* Degree symbol (°), a notation used in science, engineering, and mathematics

...

, which is an augmented fourth (A4) above the tonic (F), rather than a perfect fourth (P4).

*Tonic triad: F

*Tonic seventh chord: FM7

*Dominant triad: C

*Seventh chord on the dominant: CM7 (a major seventh chord

In music, a major seventh chord is a seventh chord in which the third is a major third above the root and the seventh is a major seventh above the root. The major seventh chord, sometimes also called a ''Delta chord'', can be written as maj7, M7, , ...

)

Mixolydian (V)

TheMixolydian mode

Mixolydian mode may refer to one of three things: the name applied to one of the ancient Greek ''harmoniai'' or ''tonoi'', based on a particular octave species or scale; one of the medieval church modes; or a modern musical mode or diatonic scal ...

is the fifth mode. The example composed of natural notes begins on G:

The single tone that differentiates this scale from the major scale (Ionian mode) is its seventh degree, which is a minor seventh (m7) above the tonic (G), rather than a major seventh (M7). Therefore, the seventh scale degree becomes a subtonic

In music, the subtonic is the degree of a musical scale which is a whole step below the tonic note. In a major key, it is a lowered, or flattened, seventh scale degree (). It appears as the seventh scale degree in the natural minor and descendin ...

to the tonic because it is now a whole tone lower than the tonic, in contrast to the seventh degree in the major scale, which is a semitone tone lower than the tonic (leading-tone

In music theory, a leading-tone (also called a subsemitone, and a leading-note in the UK) is a note or pitch which resolves or "leads" to a note one semitone higher or lower, being a lower and upper leading-tone, respectively. Typically, ''the ...

).

*Tonic triad: G

*Tonic seventh chord: G7 (the dominant seventh chord in this mode is the seventh chord built on the tonic degree)

*Dominant triad: Dm

*Seventh chord on the dominant: Dm7 (a minor seventh chord)

Aeolian (VI)

TheAeolian mode

The Aeolian mode is a musical mode or, in modern usage, a diatonic scale also called the natural minor scale. On the white piano keys, it is the scale that starts with A. Its ascending interval form consists of a ''key note, whole step, half step ...

is the sixth mode. It is also called the natural minor scale

In music theory, the minor scale is three scale patterns – the natural minor scale (or Aeolian mode), the harmonic minor scale, and the melodic minor scale (ascending or descending) – rather than just two as with the major scale, which also ...

. The example composed of natural notes begins on A, and is also known as the A natural-minor scale:

*Tonic triad: Am

*Tonic seventh chord: Am7

*Dominant triad: Em

*Seventh chord on the dominant: Em7 (a minor seventh chord)

Locrian (VII)

TheLocrian mode The Locrian mode is the seventh mode of the major scale. It is either a musical mode or simply a diatonic scale. On the piano, it is the scale that starts with B and only uses the white keys from there. Its ascending form consists of the key note, ...

is the seventh mode. The example composed of natural notes begins on B:

The distinctive scale degree

In music theory, the scale degree is the position of a particular note on a scale relative to the tonic, the first and main note of the scale from which each octave is assumed to begin. Degrees are useful for indicating the size of intervals and ...

here is the diminished fifth (d5). This makes the tonic triad diminished, so this mode is the only one in which the chords built on the tonic and dominant scale degrees have their roots separated by a diminished, rather than perfect, fifth. Similarly the tonic seventh chord is half-diminished.

*Tonic triad: Bdim or B°

*Tonic seventh chord: Bm75 or Bø7

*Dominant triad: F

*Seventh chord on the dominant: FM7 (a major seventh chord)

Summary

The modes can be arranged in the following sequence, which follows thecircle of fifths

In music theory, the circle of fifths is a way of organizing the 12 chromatic pitches as a sequence of perfect fifths. (This is strictly true in the standard 12-tone equal temperament system — using a different system requires one interval ...

. In this sequence, each mode has one more lowered interval relative to the tonic than the mode preceding it. Thus, taking Lydian as reference, Ionian (major) has a lowered fourth; Mixolydian, a lowered fourth and seventh; Dorian, a lowered fourth, seventh, and third; Aeolian (natural minor), a lowered fourth, seventh, third, and sixth; Phrygian, a lowered fourth, seventh, third, sixth, and second; and Locrian, a lowered fourth, seventh, third, sixth, second, and fifth. Put another way, the augmented fourth of the Lydian mode has been reduced to a perfect fourth in Ionian, the major seventh in Ionian to a minor seventh in Mixolydian, etc.

The first three modes are sometimes called major, the next three minor, and the last one diminished (Locrian), according to the quality of their tonic triads. The Locrian mode is traditionally considered theoretical rather than practical because the triad built on the first scale degree is diminished. Because diminished triad

In music theory, a diminished triad (also known as the minor flatted fifth) is a triad consisting of two minor thirds above the root. It is a minor triad with a lowered ( flattened) fifth. When using chord symbols, it may be indicated by the s ...

s are not consonant they do not lend themselves to cadential endings and cannot be tonicized according to traditional practice.

* The Ionian mode corresponds to the major scale. Scales in the Lydian mode are major scales with an augmented fourth

Augment or augmentation may refer to:

Language

*Augment (Indo-European), a syllable added to the beginning of the word in certain Indo-European languages

*Augment (Bantu languages), a morpheme that is prefixed to the noun class prefix of nouns i ...

. The Mixolydian mode corresponds to the major scale with a minor seventh

In music theory, a minor seventh is one of two musical intervals that span seven staff positions. It is ''minor'' because it is the smaller of the two sevenths, spanning ten semitones. The major seventh spans eleven. For example, the interval f ...

.

* The Aeolian mode is identical to the natural minor scale

In music theory, the minor scale is three scale patterns – the natural minor scale (or Aeolian mode), the harmonic minor scale, and the melodic minor scale (ascending or descending) – rather than just two as with the major scale, which also ...

. The Dorian mode corresponds to the natural minor scale with a major sixth

In music from Western culture, a sixth is a musical interval encompassing six note letter names or staff positions (see Interval number for more details), and the major sixth is one of two commonly occurring sixths. It is qualified as ''major ...

. The Phrygian mode corresponds to the natural minor scale with a minor second

A semitone, also called a half step or a half tone, is the smallest musical interval commonly used in Western tonal music, and it is considered the most dissonant when sounded harmonically.

It is defined as the interval between two adjacent no ...

.

* The Locrian is neither a major nor a minor mode because, although its third scale degree is minor, the fifth degree is diminished instead of perfect. For this reason it is sometimes called a "diminished" scale, though in jazz theory this term is also applied to the octatonic scale

An octatonic scale is any eight-note musical scale. However, the term most often refers to the symmetric scale composed of alternating whole and half steps, as shown at right. In classical theory (in contrast to jazz theory), this symmetrical ...

. This interval is enharmonic

In modern musical notation and tuning, an enharmonic equivalent is a note, interval, or key signature that is equivalent to some other note, interval, or key signature but "spelled", or named differently. The enharmonic spelling of a written n ...

ally equivalent to the augmented fourth found between scale degrees 1 and 4 in the Lydian mode and is also referred to as the tritone

In music theory, the tritone is defined as a musical interval composed of three adjacent whole tones (six semitones). For instance, the interval from F up to the B above it (in short, F–B) is a tritone as it can be decomposed into the three a ...

.

Use

Use and conception of modes or modality today is different from that in early music. As Jim Samson explains, "Clearly any comparison of medieval and modern modality would recognize that the latter takes place against a background of some three centuries of harmonic tonality, permitting, and in the 19th century requiring, a dialogue between modal and diatonic procedure". Indeed, when 19th-century composers revived the modes, they rendered them more strictly than Renaissance composers had, to make their qualities distinct from the prevailing major-minor system. Renaissance composers routinely sharped leading tones at cadences and lowered the fourth in the Lydian mode. The Ionian, or Iastian, mode is another name for themajor scale

The major scale (or Ionian mode) is one of the most commonly used musical scales, especially in Western music. It is one of the diatonic scales. Like many musical scales, it is made up of seven notes: the eighth duplicates the first at double i ...

used in much Western music. The Aeolian forms the base of the most common Western minor scale; in modern practice the Aeolian mode is differentiated from the minor by using only the seven notes of the Aeolian mode. By contrast, minor mode compositions of the common practice period

In European art music, the common-practice period is the era of the tonal system. Most of its features persisted from the mid- Baroque period through the Classical and Romantic periods, roughly from 1650 to 1900. There was much stylistic evoluti ...

frequently raise the seventh scale degree by a semitone to strengthen the cadences

In Western musical theory, a cadence (Latin ''cadentia'', "a falling") is the end of a phrase in which the melody or harmony creates a sense of full or partial resolution, especially in music of the 16th century onwards.Don Michael Randel (1999) ...

, and in conjunction also raise the sixth scale degree by a semitone to avoid the awkward interval of an augmented second. This is particularly true of vocal music.

Traditional folk music provides countless examples of modal melodies. For example, Irish traditional music

Irish traditional music (also known as Irish trad, Irish folk music, and other variants) is a genre of folk music that developed in Ireland.

In ''A History of Irish Music'' (1905), W. H. Grattan Flood wrote that, in Gaelic Ireland, there w ...

makes extensive usage not only of the major mode, but also the Mixolydian, Dorian, and Aeolian modes. Much Flamenco

Flamenco (), in its strictest sense, is an art form based on the various folkloric music traditions of southern Spain, developed within the gitano subculture of the region of Andalusia, and also having historical presence in Extremadura and ...

music is in the Phrygian mode, though frequently with the third and seventh degrees raised by a semitone.

Zoltán Kodály

Zoltán Kodály (; hu, Kodály Zoltán, ; 16 December 1882 – 6 March 1967) was a Hungarian composer, ethnomusicologist, pedagogue, linguist, and philosopher. He is well known internationally as the creator of the Kodály method of music ed ...

, Gustav Holst

Gustav Theodore Holst (born Gustavus Theodore von Holst; 21 September 1874 – 25 May 1934) was an English composer, arranger and teacher. Best known for his orchestral suite ''The Planets'', he composed many other works across a range ...

, and Manuel de Falla

Manuel de Falla y Matheu (, 23 November 187614 November 1946) was an Andalusian Spanish composer and pianist. Along with Isaac Albéniz, Francisco Tárrega, and Enrique Granados, he was one of Spain's most important musicians of the first hal ...

use modal elements as modifications of a diatonic

Diatonic and chromatic are terms in music theory that are most often used to characterize Scale (music), scales, and are also applied to musical instruments, Interval (music), intervals, Chord (music), chords, Musical note, notes, musical sty ...

background, while modality replaces diatonic tonality

Tonality is the arrangement of pitches and/or chords of a musical work in a hierarchy of perceived relations, stabilities, attractions and directionality. In this hierarchy, the single pitch or triadic chord with the greatest stability is call ...

in the music of Claude Debussy

(Achille) Claude Debussy (; 22 August 1862 – 25 March 1918) was a French composer. He is sometimes seen as the first Impressionist composer, although he vigorously rejected the term. He was among the most influential composers of the ...

and Béla Bartók

Béla Viktor János Bartók (; ; 25 March 1881 – 26 September 1945) was a Hungarian composer, pianist, and ethnomusicologist. He is considered one of the most important composers of the 20th century; he and Franz Liszt are regarded as H ...

.

Other types

While the term "mode" is still most commonly understood to refer to Ionian, Dorian, Phrygian, Lydian, Mixolydian, Aeolian, or Locrian modes, in modern music theory the word is often applied to scales other than the diatonic. This is seen, for example, inmelodic minor

In music theory, the minor scale is three scale patterns – the natural minor scale (or Aeolian mode), the harmonic minor scale, and the melodic minor scale (ascending or descending) – rather than just two as with the major scale, which al ...

scale harmony, which is based on the seven rotations of the ascending melodic minor scale, yielding some interesting scales as shown below. The "chord" row lists tetrads

Tetrad ('group of 4') or tetrade may refer to:

* Tetrad (area), an area 2 km x 2 km square

* Tetrad (astronomy), four total lunar eclipses within two years

* Tetrad (chromosomal formation)

* Tetrad (general relativity), or frame field

** Tetrad fo ...

that can be built from the pitches in the given mode (in jazz notation, the symbol Δ is for a major seventh

In music from Western culture, a seventh is a musical interval encompassing seven staff positions (see Interval number for more details), and the major seventh is one of two commonly occurring sevenths. It is qualified as ''major'' because it i ...

).