|

Modus (medieval Music)

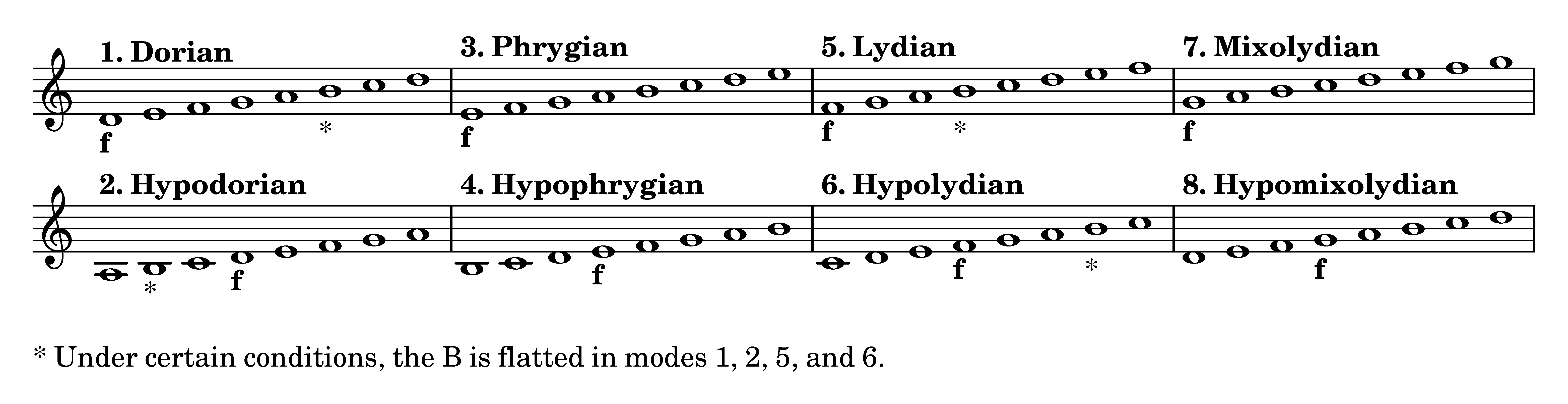

In medieval music theory, the Latin term modus (meaning "a measure", "standard of measurement", "quantity", "size", "length", or, rendered in English, mode) can be used in a variety of distinct senses. The most commonly used meaning today relates to the organisation of pitch in scales. Other meanings refer to the notation of rhythms. Modal scales In describing the tonality of early music, the term "mode" (or "tone") refers to any of eight sets of pitch intervals that may form a musical scale, representing the tonality of a piece and associated with characteristic melodic shapes (psalm tones) in Gregorian chant. Medieval modes (also called Gregorian mode or ''church modes'') were numbered, either from 1 to 8, or from 1 to 4 in pairs (authentic/ plagal), in which case they were usually named ''protus'' (first), ''deuterus'' (second), ''tertius'' (third), and ''tetrardus'' (fourth), but sometimes also named after the ancient Greek ''tonoi'' (with which, however, they are not ident ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Medieval Music Theory

Medieval music encompasses the sacred and secular music of Western Europe during the Middle Ages, from approximately the 6th to 15th centuries. It is the first and longest major era of Western classical music and followed by the Renaissance music; the two eras comprise what musicologists generally term as early music, preceding the common practice period. Following the traditional division of the Middle Ages, medieval music can be divided into Early (500–1150), High (1000–1300), and Late (1300–1400) medieval music. Medieval music includes liturgical music used for the church, and secular music, non-religious music; solely vocal music, such as Gregorian chant and choral music (music for a group of singers), solely instrumental music, and music that uses both voices and instruments (typically with the instruments accompanying the voices). Gregorian chant was sung by monks during Catholic Mass. The Mass is a reenactment of Christ's Last Supper, intended to provide a spi ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Hypolydian Mode

The Hypolydian mode, literally meaning "below Lydian", is the common name for the sixth of the eight church modes of medieval music theory. The name is taken from Ptolemy of Alexandria's term for one of his seven ''tonoi'', or transposition keys. This mode is the plagal counterpart of the authentic fifth mode. In medieval theory the Hypolydian mode was described either as (1) the diatonic octave species from C to the C an octave higher, divided at the final F (C–D–E–F + F–G–A–B–C) or (2) a mode with F as final and an ambitus from the C below the final to the D above it. The third above the final, A—corresponding to the reciting tone or "tenor" of the sixth psalm tone—was regarded as having an important melodic function in this mode. The sequence of intervals was therefore divided by the final into a lower tetrachord of tone-tone-semitone, and an upper pentachord of tone-tone-tone-semitone. However, from as early as the time of Hucbald Hucbald ( – 20 June ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Polyphony

Polyphony ( ) is a type of musical texture consisting of two or more simultaneous lines of independent melody, as opposed to a musical texture with just one voice, monophony, or a texture with one dominant melodic voice accompanied by chords, homophony. Within the context of the Western musical tradition, the term ''polyphony'' is usually used to refer to music of the late Middle Ages and Renaissance. Baroque forms such as fugue, which might be called polyphonic, are usually described instead as contrapuntal. Also, as opposed to the ''species'' terminology of counterpoint, polyphony was generally either "pitch-against-pitch" / "point-against-point" or "sustained-pitch" in one part with melismas of varying lengths in another. In all cases the conception was probably what Margaret Bent (1999) calls "dyadic counterpoint", with each part being written generally against one other part, with all parts modified if needed in the end. This point-against-point conception is opposed to " ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Pyrrhic

A pyrrhic (; el, πυρρίχιος ''pyrrichios'', from πυρρίχη ''pyrrichē'') is a metrical foot used in formal poetry. It consists of two unaccented, short syllables. It is also known as a dibrach. Poetic use in English Tennyson used pyrrhics and spondees quite frequently, for example, in '' In Memoriam'': When the blood creeps and the nerves prick. "When the" and "and the" in the second line may be considered as pyrrhics (also analyzable as ionic meter). Pyrrhics alone are not used to construct an entire poem due to the monotonous effect. Edgar Allan Poe observed that many experts rejected it from English metrics and concurred:The pyrrhic is rightfully dismissed. Its existence in either ancient or modern rhythm is purely chimerical, and the insisting on so perplexing a nonentity as a foot of two short syllables, affords, perhaps, the best evidence of the gross irrationality and subservience to authority which characterise our Prosody. War dance By extension, t ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Spondee

A spondee (Latin: ) is a metrical foot consisting of two long syllables, as determined by syllable weight in classical meters, or two stressed syllables in modern meters. The word comes from the Greek , , 'libation'. Spondees in Ancient Greek and Latin Libations Sometimes libations were accompanied by hymns in spondaic rhythm, as in the following hymn by the Greek poet Terpander (7th century BC), which consists of 20 long syllables: "Zeus, Beginning of all things, Leader of all things, Zeus, I make a libation to Thee this beginning of (my) hymns." In hexameter poetry However, in most Greek and Latin poetry, the spondee typically does not provide the basis for a metrical line in poetry. Instead, spondees are found as irregular feet in meter based on another type of foot. For example, the epics of Homer and Virgil are written in dactylic hexameter. This term suggests a line of six dactyls, but a spondee can be substituted in most positions. The first line of Virgil's ''Ae ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Anapest

An anapaest (; also spelled anapæst or anapest, also called antidactylus) is a metrical foot used in formal poetry. In classical quantitative meters it consists of two short syllables followed by a long one; in accentual stress meters it consists of two unstressed syllables followed by one stressed syllable. It may be seen as a reversed dactyl. This word comes from the Greek , ''anápaistos'', literally "struck back" and in a poetic context "a dactyl reversed". Because of its length and the fact that it ends with a stressed syllable and so allows for strong rhymes, anapaest can produce a very rolling verse, and allows for long lines with a great deal of internal complexity. Apart from their independent role, anapaests are sometimes used as substitutions in iambic verse. In strict iambic pentameter, anapaests are rare, but they are found with some frequency in freer versions of the iambic line, such as the verse of Shakespeare's last plays, or the lyric poetry of the 19th century ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Dactyl (poetry)

A dactyl (; el, δάκτυλος, ''dáktylos'', “finger”) is a foot in poetic meter. In quantitative verse, often used in Greek or Latin, a dactyl is a long syllable followed by two short syllables, as determined by syllable weight. The best-known use of dactylic verse is in the epics attributed to the Greek poet Homer, the Iliad and the Odyssey. In accentual verse, often used in English, a dactyl is a stressed syllable followed by two unstressed syllables—the opposite is the anapaest (two unstressed followed by a stressed syllable). An example of dactylic meter is the first line of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow's epic poem ''Evangeline'' (1847), which is in dactylic hexameter: :''This is the / forest prim- / eval. The / murmuring / pines and the / hemlocks, The first five feet of the line are dactyls; the sixth a trochee. Stephen Fry quotes Robert Browning's poem " The Lost Leader" as an example of the use of dactylic metre to great effect, creating verse with "great rhy ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Iamb (poetry)

An iamb () or iambus is a metrical foot used in various types of poetry. Originally the term referred to one of the feet of the quantitative meter of classical Greek prosody: a short syllable followed by a long syllable (as in () "beautiful (f.)"). This terminology was adopted in the description of accentual-syllabic verse in English, where it refers to a foot comprising an unstressed syllable followed by a stressed syllable (as in ''abóve''). Thus a Latin word like , because of its short-long rhythm, is considered by Latin scholars to be an iamb, but because it has a stress on the first syllable, in modern linguistics it is considered to be a trochee. Etymology R. S. P. Beekes has suggested that the grc, ἴαμβος ''iambos'' has a Pre-Greek origin. An old hypothesis is that the word is borrowed from Phrygian or Pelasgian, and literally means "Einschritt", i. e., "one-step", compare ''dithyramb'' and ''thriambus'', but H. S. Versnel rejects this etymology and sugg ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Trochee

In English poetic metre and modern linguistics, a trochee () is a metrical foot consisting of a stressed syllable followed by an unstressed one. But in Latin and Ancient Greek poetic metre, a trochee is a heavy syllable followed by a light one (also described as a long syllable followed by a short one). In this respect, a trochee is the reverse of an iamb. Thus the Latin word "there", because of its short-long rhythm, in Latin metrical studies is considered to be an iamb, but since it is stressed on the first syllable, in modern linguistics it is considered to be a trochee. The adjective form is ''trochaic''. The English word ''trochee'' is itself trochaic since it is composed of the stressed syllable followed by the unstressed syllable . Another name formerly used for a trochee was a choree (), or choreus. Etymology ''Trochee'' comes from French , adapted from Latin , originally from the Greek (), 'wheel', from the phrase (), literally 'running foot'; it is connected with ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Ternary Meter

Triple metre (or Am. triple meter, also known as triple time) is a musical metre characterized by a ''primary'' division of 3 beats to the bar, usually indicated by 3 (simple) or 9 (compound) in the upper figure of the time signature, with , , and being the most common examples. The upper figure being divisible by three does not of itself indicate triple metre; for example, a time signature of usually indicates compound duple metre, and similarly usually indicates compound quadruple metre. Shown below are a simple and a compound triple drum pattern. \new Staff \new Staff Stylistic differences In popular music, the metre is most often quadruple,Schroedl, Scott (2001). ''Play Drums Today!'', p. 42. Hal Leonard. . but this does not mean that triple metre does not appear. It features in a good amount of music by artists such as The Chipmunks, Louis Armstrong or Bob Dylan. In jazz, this and other more adventurous metres have become more common since Dave Brubeck's albu ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Notre-Dame School

The Notre-Dame school or the Notre-Dame school of polyphony refers to the group of composers working at or near the Notre-Dame Cathedral in Paris from about 1160 to 1250, along with the music they produced. The only composers whose names have come down to us from this time are Léonin and Pérotin. Both were mentioned by an anonymous English student, known as Anonymous IV, who was either working or studying at Notre-Dame later in the 13th century. In addition to naming the two composers as "the best composers of organum," and specifying that they compiled the big book of organum known as the ''Magnus Liber Organi'', he provides a few tantalizing bits of information on the music and the principles involved in its composition. Pérotin is the first composer of ''organum quadruplum''—four-voice polyphony—at least the first composer whose music has survived, since complete survivals of notated music from this time are scarce. Léonin, Pérotin and the other anonymous composer ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Foot (prosody)

The foot is the basic repeating rhythmic unit that forms part of a line of verse in most Indo-European traditions of poetry, including English accentual-syllabic verse and the quantitative meter of classical ancient Greek and Latin poetry. The unit is composed of syllables, and is usually two, three, or four syllables in length. The most common feet in English are the iamb, trochee, dactyl, and anapest. The foot might be compared to a bar, or a beat divided into pulse groups, in musical notation. The English word "foot" is a translation of the Latin term ''pes'', plural ''pedes'', which in turn is a translation of the Ancient Greek ποῦς, pl. πόδες. The Ancient Greek prosodists, who invented this terminology, specified that a foot must have both an arsis and a thesis, that is, a place where the foot was raised ("arsis") and where it was put down ("thesis") in beating time or in marching or dancing. The Greeks recognised three basic types of feet, the iambic (where the ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |