Megalosaurus on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''Megalosaurus'' (meaning "great lizard", from

In 1699,

In 1699,

Lithophylacii Britannici Ichnographia, sive lapidium aliorumque fossilium Britannicorum singulari figura insignium

'. Gleditsch and Weidmann:London. Later studies found that the theropod tooth, known as specimen 1328 (

The earliest discoveries of dinosaurs: the records re-examined

''Proceedings of the Geologists' Association'' 113:185–197. OU 1328 has since been lost and it was not confidently assigned to ''Megalosaurus'' until the tooth was re-described by Delair & Sarjeant (2002). OU 1328 was collected near Caswell, near

''Megalosaurus'' may have been the first non

''Megalosaurus'' may have been the first non

During the last part of the eighteenth century, the number of fossils in British collections quickly increased. According to an hypothesis published by

During the last part of the eighteenth century, the number of fossils in British collections quickly increased. According to an hypothesis published by  By 1824, the material available to Buckland consisted of specimen OUM J13505, a piece of a right lower jaw with a single erupted tooth; OUM J13577, a posterior dorsal

By 1824, the material available to Buckland consisted of specimen OUM J13505, a piece of a right lower jaw with a single erupted tooth; OUM J13577, a posterior dorsal

The first reconstruction was given by Buckland himself. He considered ''Megalosaurus'' to be a quadruped. He thought it was an "amphibian", i.e. an animal capable of both swimming in the sea and walking on land. Generally, in his mind ''Megalosaurus'' resembled a gigantic lizard, but Buckland already understood from the form of the thighbone head that the legs were not so much sprawling as held rather upright. In the original description of 1824, Buckland repeated Cuvier's size estimate that ''Megalosaurus'' would have been forty feet long with the weight of a seven foot tall elephant. However, this had been based on the remains present at Oxford. Buckland had also been hurried into naming his new reptile by a visit he had made to the fossil collection of Mantell, who during the lecture announced to have acquired a fossil thighbone of enormous magnitude, twice as long as that just described. Today, this is known to have belonged to ''

The first reconstruction was given by Buckland himself. He considered ''Megalosaurus'' to be a quadruped. He thought it was an "amphibian", i.e. an animal capable of both swimming in the sea and walking on land. Generally, in his mind ''Megalosaurus'' resembled a gigantic lizard, but Buckland already understood from the form of the thighbone head that the legs were not so much sprawling as held rather upright. In the original description of 1824, Buckland repeated Cuvier's size estimate that ''Megalosaurus'' would have been forty feet long with the weight of a seven foot tall elephant. However, this had been based on the remains present at Oxford. Buckland had also been hurried into naming his new reptile by a visit he had made to the fossil collection of Mantell, who during the lecture announced to have acquired a fossil thighbone of enormous magnitude, twice as long as that just described. Today, this is known to have belonged to '' Around 1840, it became fashionable in England to espouse the concept of the

Around 1840, it became fashionable in England to espouse the concept of the  In 1852,

In 1852,

The quarries at

The quarries at  Apart from the finds in the

Apart from the finds in the

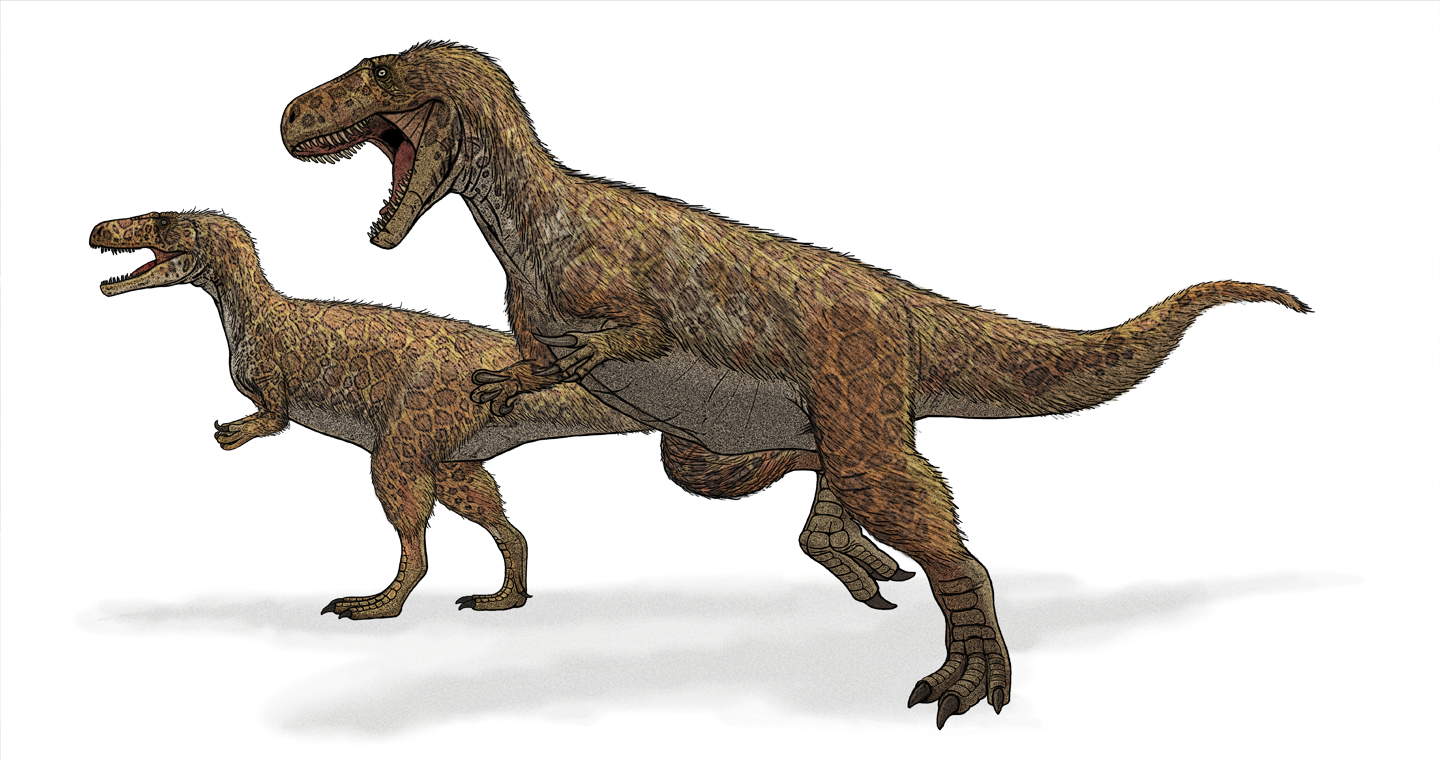

Since the first finds, many other ''Megalosaurus'' bones have been recovered; however, no complete skeleton has yet been found. Therefore, the details of its physical appearance cannot be certain. However, a full

Since the first finds, many other ''Megalosaurus'' bones have been recovered; however, no complete skeleton has yet been found. Therefore, the details of its physical appearance cannot be certain. However, a full

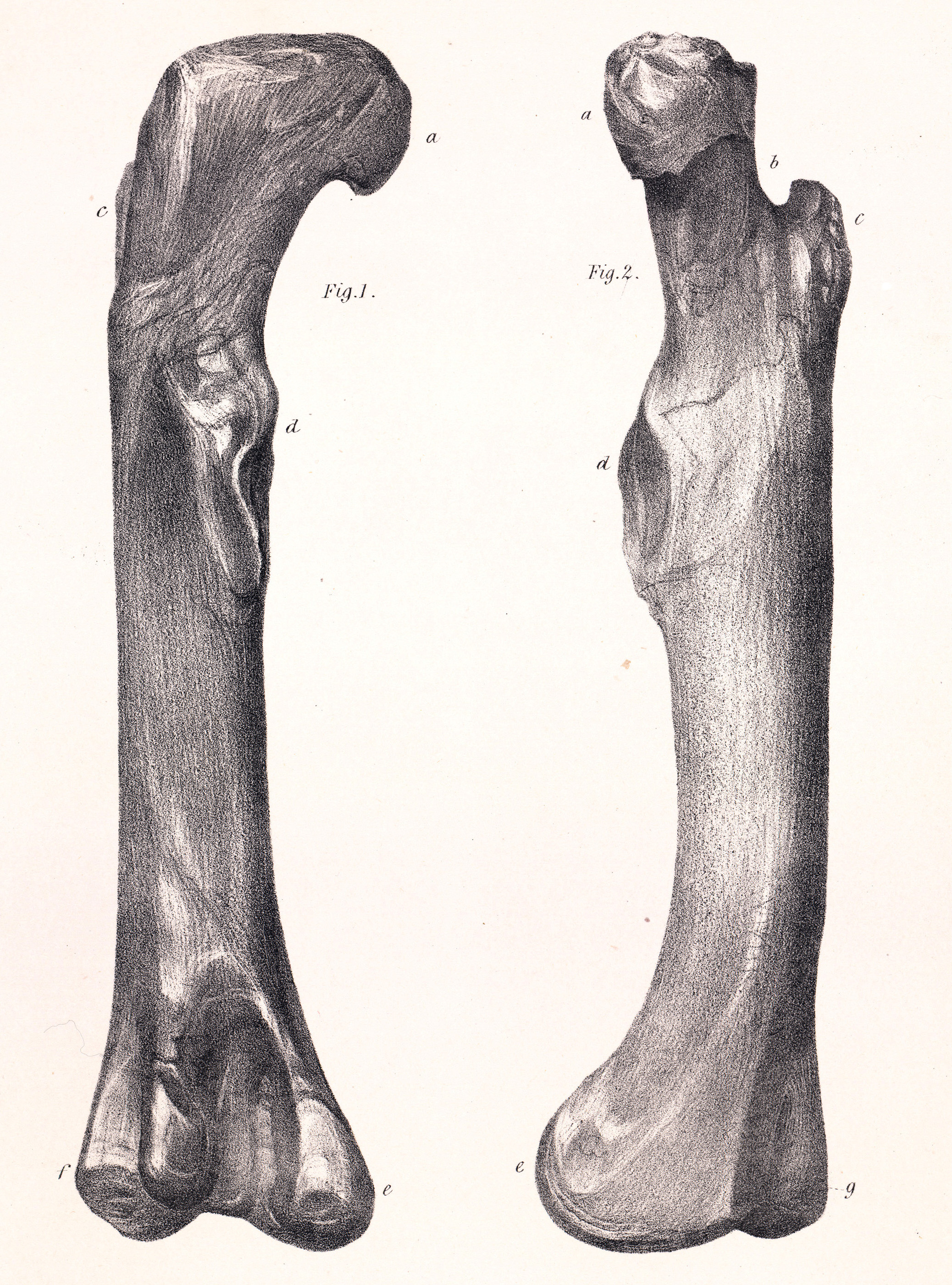

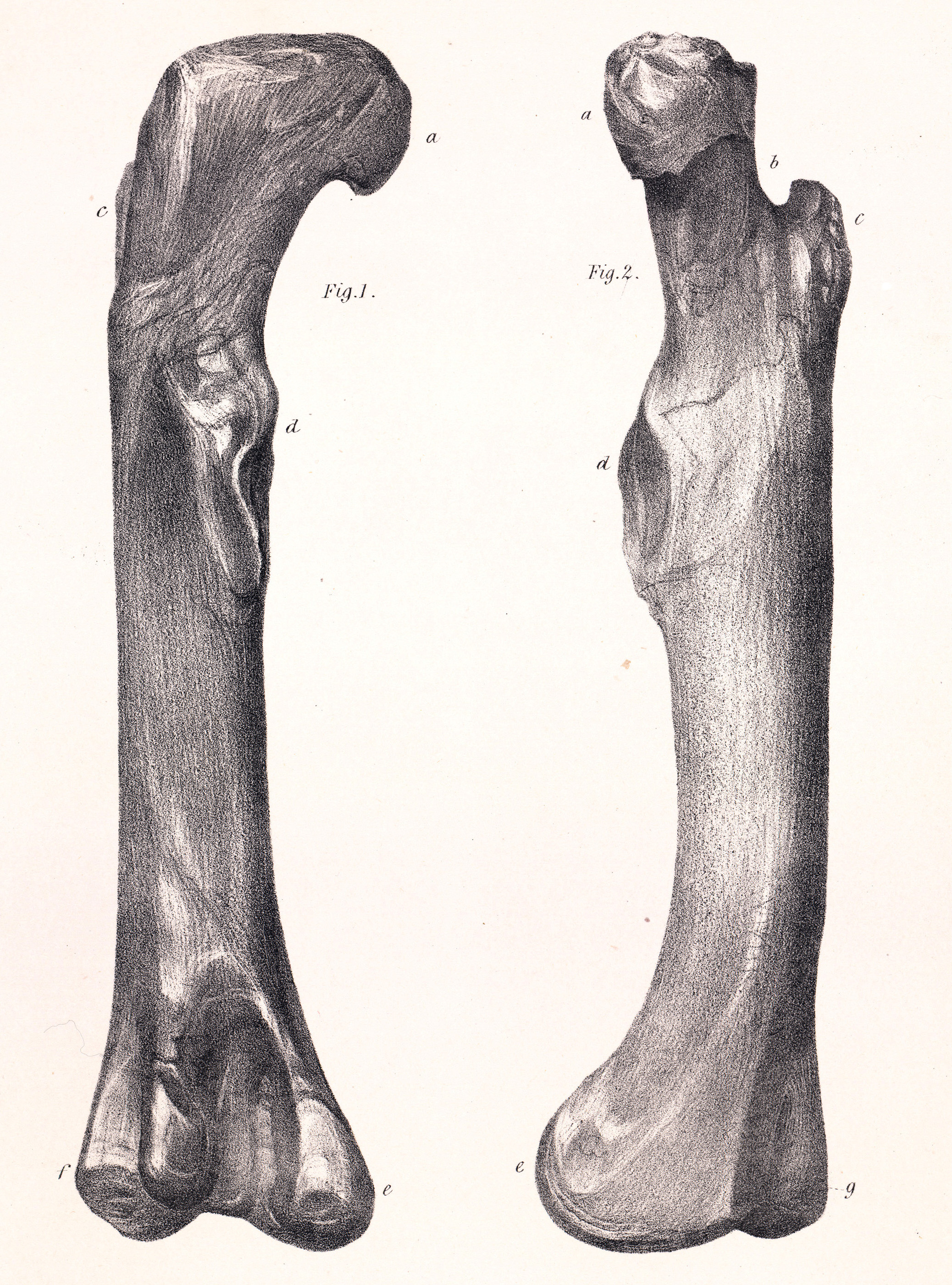

Traditionally, most texts, following Owen's estimate of 1841, give a body length of thirty feet or nine metres for ''Megalosaurus''. The lack of an articulated dorsal vertebral series makes it difficult to determine an exact size. David Bruce Norman in 1984 thought ''Megalosaurus'' was seven to eight metres long. Gregory S. Paul in 1988 estimated the weight tentatively at 1.1 tonnes, given a thighbone seventy-six centimetres long. The trend in the early twenty-first century to limit the material to the lectotype inspired even lower estimates, disregarding outliers of uncertain identity. Paul in 2010 estimated the size of ''Megalosaurus'' at in length and . However, the same year Benson claimed that ''Megalosaurus'', though medium-sized, was still among the largest of Middle Jurassic theropods. Specimen BMNH 31806, a thighbone 803 millimetres long, would indicate a body weight of 943 kilogrammes, using the extrapolation method of J.F. Anderson — which method, optimised for mammals, tends to underestimate theropod masses by at least a third. Furthermore, thighbone specimen OUM J13561 has a length of about eighty-six centimetres.

Traditionally, most texts, following Owen's estimate of 1841, give a body length of thirty feet or nine metres for ''Megalosaurus''. The lack of an articulated dorsal vertebral series makes it difficult to determine an exact size. David Bruce Norman in 1984 thought ''Megalosaurus'' was seven to eight metres long. Gregory S. Paul in 1988 estimated the weight tentatively at 1.1 tonnes, given a thighbone seventy-six centimetres long. The trend in the early twenty-first century to limit the material to the lectotype inspired even lower estimates, disregarding outliers of uncertain identity. Paul in 2010 estimated the size of ''Megalosaurus'' at in length and . However, the same year Benson claimed that ''Megalosaurus'', though medium-sized, was still among the largest of Middle Jurassic theropods. Specimen BMNH 31806, a thighbone 803 millimetres long, would indicate a body weight of 943 kilogrammes, using the extrapolation method of J.F. Anderson — which method, optimised for mammals, tends to underestimate theropod masses by at least a third. Furthermore, thighbone specimen OUM J13561 has a length of about eighty-six centimetres. In general, ''Megalosaurus'' had the typical build of a large theropod. It was bipedal, the horizontal torso being balanced by a long horizontal tail. The hindlimbs were long and strong with three forward-facing weight-bearing toes, the forelimbs relatively short but exceptionally robust and probably carrying three digits. Being a

In general, ''Megalosaurus'' had the typical build of a large theropod. It was bipedal, the horizontal torso being balanced by a long horizontal tail. The hindlimbs were long and strong with three forward-facing weight-bearing toes, the forelimbs relatively short but exceptionally robust and probably carrying three digits. Being a

The skull of ''Megalosaurus'' is poorly known. The discovered skull elements are generally rather large in relation to the rest of the material. This can either be coincidental or indicate that ''Megalosaurus'' had an uncommonly large head. The

The skull of ''Megalosaurus'' is poorly known. The discovered skull elements are generally rather large in relation to the rest of the material. This can either be coincidental or indicate that ''Megalosaurus'' had an uncommonly large head. The  The lower jaw is rather robust. It is also straight in top view, without much expansion at the jaw tip, suggesting the lower jaws as a pair, the

The lower jaw is rather robust. It is also straight in top view, without much expansion at the jaw tip, suggesting the lower jaws as a pair, the

Although the exact numbers are unknown, the

Although the exact numbers are unknown, the

The shoulderblade or

The shoulderblade or  In the pelvis, the ilium is long and low, with a convex upper profile. Its front blade is triangular and rather short; at the front end there is a small drooping point, separated by a notch from the pubic peduncle. The rear blade is roughly rectangular. The outer side of the ilium is concave, serving as an attachment surface for the '' Musculus iliofemoralis'', the main thigh muscle. Above the hip joint, on this surface a low vertical ridge is present with conspicuous vertical grooves. The bottom of the rear blade is excavated by a narrow but deep trough forming a bony shelf for the attachment of the ''

In the pelvis, the ilium is long and low, with a convex upper profile. Its front blade is triangular and rather short; at the front end there is a small drooping point, separated by a notch from the pubic peduncle. The rear blade is roughly rectangular. The outer side of the ilium is concave, serving as an attachment surface for the '' Musculus iliofemoralis'', the main thigh muscle. Above the hip joint, on this surface a low vertical ridge is present with conspicuous vertical grooves. The bottom of the rear blade is excavated by a narrow but deep trough forming a bony shelf for the attachment of the '' The thighbone is straight in front view. Seen from the same direction its head is perpendicular to the shaft, seen from above it is orientated 20° to the front. The

The thighbone is straight in front view. Seen from the same direction its head is perpendicular to the shaft, seen from above it is orientated 20° to the front. The

For decades after its discovery, ''Megalosaurus'' was seen by researchers as the definitive or typical large carnivorous dinosaur. As a result, it began to function as a "wastebasket taxon", and many large or small carnivorous dinosaurs from Europe and elsewhere were assigned to the genus. This slowly changed during the 20th century, when it became common to restrict the genus to fossils found in the middle Jurassic of England. Further restriction occurred in the late 20th and early 21st centuries, researchers such as

For decades after its discovery, ''Megalosaurus'' was seen by researchers as the definitive or typical large carnivorous dinosaur. As a result, it began to function as a "wastebasket taxon", and many large or small carnivorous dinosaurs from Europe and elsewhere were assigned to the genus. This slowly changed during the 20th century, when it became common to restrict the genus to fossils found in the middle Jurassic of England. Further restriction occurred in the late 20th and early 21st centuries, researchers such as

Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

, ', meaning 'big', 'tall' or 'great' and , ', meaning 'lizard') is an extinct genus

Genus ( plural genera ) is a taxonomic rank used in the biological classification of extant taxon, living and fossil organisms as well as Virus classification#ICTV classification, viruses. In the hierarchy of biological classification, genus com ...

of large carnivorous theropod

Theropoda (; ), whose members are known as theropods, is a dinosaur clade that is characterized by hollow bones and three toes and claws on each limb. Theropods are generally classed as a group of saurischian dinosaurs. They were ancestrally c ...

dinosaur

Dinosaurs are a diverse group of reptiles of the clade Dinosauria. They first appeared during the Triassic period, between 243 and 233.23 million years ago (mya), although the exact origin and timing of the evolution of dinosaurs is t ...

s of the Middle Jurassic

The Jurassic ( ) is a Geological period, geologic period and System (stratigraphy), stratigraphic system that spanned from the end of the Triassic Period million years ago (Mya) to the beginning of the Cretaceous Period, approximately Mya. The J ...

period

Period may refer to:

Common uses

* Era, a length or span of time

* Full stop (or period), a punctuation mark

Arts, entertainment, and media

* Period (music), a concept in musical composition

* Periodic sentence (or rhetorical period), a concept ...

(Bathonian

In the geologic timescale the Bathonian is an age and stage of the Middle Jurassic. It lasted from approximately 168.3 Ma to around 166.1 Ma (million years ago). The Bathonian Age succeeds the Bajocian Age and precedes the Callovian Age.

Strat ...

stage, 166 million years ago) of Southern England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe b ...

. Although fossils from other areas have been assigned to the genus, the only certain remains of ''Megalosaurus'' come from Oxfordshire

Oxfordshire is a ceremonial and non-metropolitan county in the north west of South East England. It is a mainly rural county, with its largest settlement being the city of Oxford. The county is a centre of research and development, primarily ...

and date to the late Middle Jurassic

The Middle Jurassic is the second epoch of the Jurassic Period. It lasted from about 174.1 to 163.5 million years ago. Fossils of land-dwelling animals, such as dinosaurs, from the Middle Jurassic are relatively rare, but geological formations co ...

.

''Megalosaurus'' was, in 1824, the first genus of non-avian dinosaur to be validly named. The type species

In zoological nomenclature, a type species (''species typica'') is the species name with which the name of a genus or subgenus is considered to be permanently taxonomically associated, i.e., the species that contains the biological type specimen ...

is ''Megalosaurus bucklandii'', named in 1827. In 1842, ''Megalosaurus'' was one of three genera on which Richard Owen

Sir Richard Owen (20 July 1804 – 18 December 1892) was an English biologist, comparative anatomist and paleontologist. Owen is generally considered to have been an outstanding naturalist with a remarkable gift for interpreting fossils.

Owe ...

based his Dinosauria. On Owen's directions a model was made as one of the Crystal Palace Dinosaurs

The Crystal Palace Dinosaurs are a series of sculptures of dinosaurs and other extinct animals, incorrect by modern standards, in the London borough of Bromley's Crystal Palace Park. Commissioned in 1852 to accompany the Crystal Palace after i ...

, which greatly increased the public interest for prehistoric reptiles. Over fifty other species would eventually be classified under the genus; at first, this was because so few types of dinosaur had been identified, but the practice continued even into the 20th century after many other dinosaurs had been discovered. Today it is understood that none of these additional species were directly related to ''M. bucklandii'', which is the only true ''Megalosaurus'' species. Because a complete skeleton of it has never been found, much is still unclear about its build.

The first naturalists who investigated ''Megalosaurus'' mistook it for a gigantic lizard of length. In 1842, Owen concluded that it was no longer than , standing on upright legs. He still thought it was a quadruped, though. Modern scientists, by comparing ''Megalosaurus'' with its direct relatives in the Megalosauridae

Megalosauridae is a monophyletic family of carnivorous theropod dinosaurs within the group Megalosauroidea. Appearing in the Middle Jurassic, megalosaurids were among the first major radiation of large theropod dinosaurs. They were a relatively ...

, were able to obtain a more accurate picture. ''Megalosaurus'' was about long, weighing about . It was bipedal, walking on stout hindlimbs, its horizontal torso balanced by a horizontal tail. Its forelimbs were short, though very robust. ''Megalosaurus'' had a rather large head, equipped with long curved teeth. It was generally a robust and heavily muscled animal.

Discovery and naming

Edward Lhuyd's tooth (specimen OU 1328)

In 1699,

In 1699, Edward Lhuyd

Edward Lhuyd FRS (; occasionally written Llwyd in line with modern Welsh orthography, 1660 – 30 June 1709) was a Welsh naturalist, botanist, linguist, geographer and antiquary. He is also named in a Latinate form as Eduardus Luidius.

Life

...

described what he believed to have been a fish

Fish are aquatic, craniate, gill-bearing animals that lack limbs with digits. Included in this definition are the living hagfish, lampreys, and cartilaginous and bony fish as well as various extinct related groups. Approximately 95% of li ...

tooth (called ''Plectronites''), later believed to be part of a belemnite

Belemnitida (or the belemnite) is an extinct order of squid-like cephalopods that existed from the Late Triassic to Late Cretaceous. Unlike squid, belemnites had an internal skeleton that made up the cone. The parts are, from the arms-most to ...

, that was illustrated alongside the holotype tooth

A tooth ( : teeth) is a hard, calcified structure found in the jaws (or mouths) of many vertebrates and used to break down food. Some animals, particularly carnivores and omnivores, also use teeth to help with capturing or wounding prey, tear ...

of the sauropod

Sauropoda (), whose members are known as sauropods (; from '' sauro-'' + '' -pod'', 'lizard-footed'), is a clade of saurischian ('lizard-hipped') dinosaurs. Sauropods had very long necks, long tails, small heads (relative to the rest of their bo ...

"Rutellum

This list of informally named dinosaurs is a listing of dinosaurs (excluding Aves; birds and their extinct relatives) that have never been given formally published scientific names. This list only includes names that were not properly published ...

impicatum" and another tooth, from a theropod

Theropoda (; ), whose members are known as theropods, is a dinosaur clade that is characterized by hollow bones and three toes and claws on each limb. Theropods are generally classed as a group of saurischian dinosaurs. They were ancestrally c ...

, in 1699.Lhuyd, E. (1699). Lithophylacii Britannici Ichnographia, sive lapidium aliorumque fossilium Britannicorum singulari figura insignium

'. Gleditsch and Weidmann:London. Later studies found that the theropod tooth, known as specimen 1328 (

University of Oxford

, mottoeng = The Lord is my light

, established =

, endowment = £6.1 billion (including colleges) (2019)

, budget = £2.145 billion (2019–20)

, chancellor ...

coll. #1328; lost?) almost certainly was a tooth crown that belonged to an unknown species of ''Megalosaurus''.Delair, J.B., and Sarjeant, W.A.S. (2002)The earliest discoveries of dinosaurs: the records re-examined

''Proceedings of the Geologists' Association'' 113:185–197. OU 1328 has since been lost and it was not confidently assigned to ''Megalosaurus'' until the tooth was re-described by Delair & Sarjeant (2002). OU 1328 was collected near Caswell, near

Witney

Witney is a market town on the River Windrush in West Oxfordshire in the county of Oxfordshire, England. It is west of Oxford. The place-name "Witney" is derived from the Old English for "Witta's island". The earliest known record of it is as ...

, Oxfordshire

Oxfordshire is a ceremonial and non-metropolitan county in the north west of South East England. It is a mainly rural county, with its largest settlement being the city of Oxford. The county is a centre of research and development, primarily ...

sometime during the 17th century and became the third dinosaur fossil to ever be illustrated,Gunther, R.T. (1945). ''Early Science in Oxford: Life and Letters of Edward Lhuyd'', volume 14. Author:Oxford. after "Scrotum humanum" in 1677 and "Rutellum impicatum" in 1699.

"Scrotum humanum"

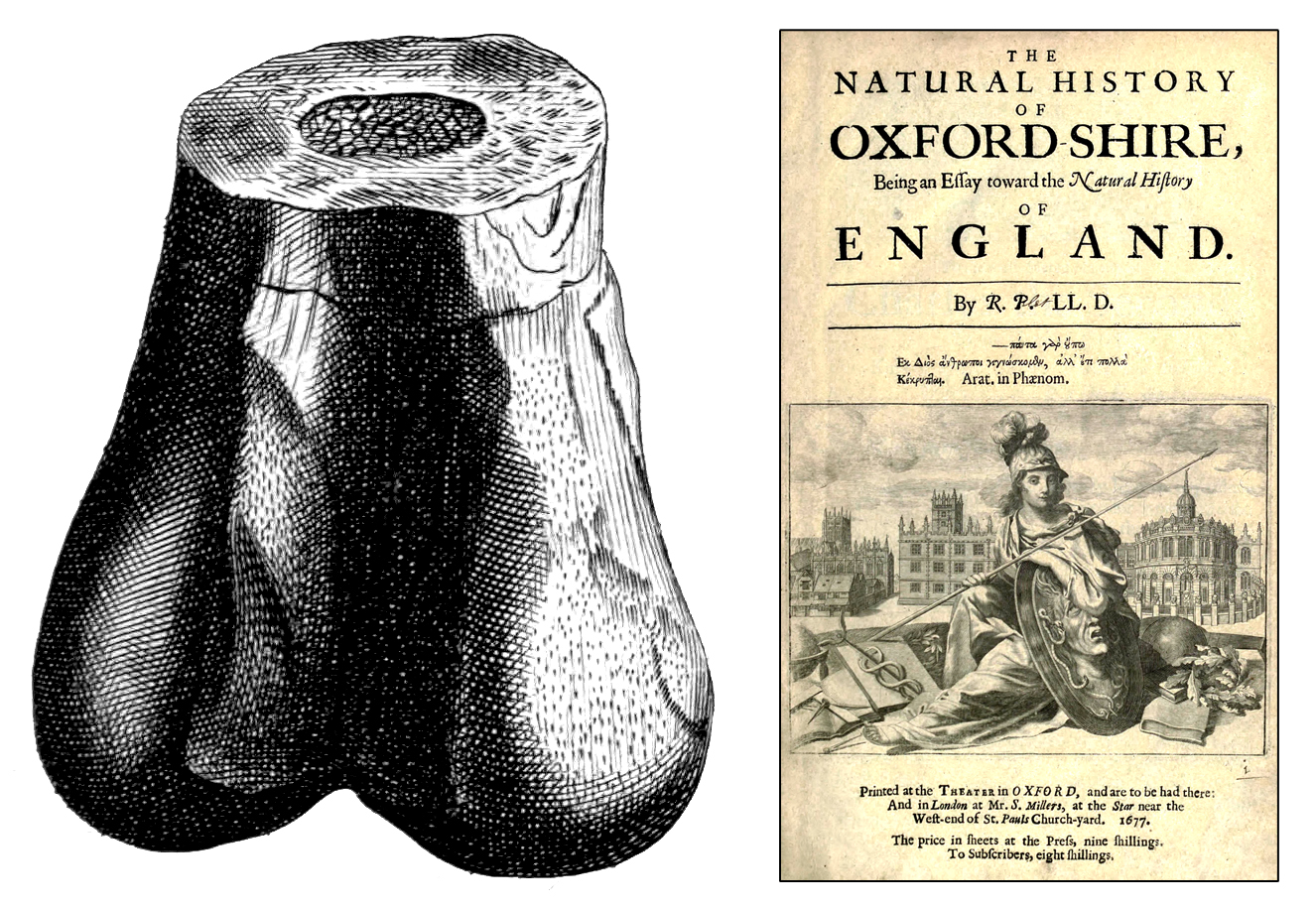

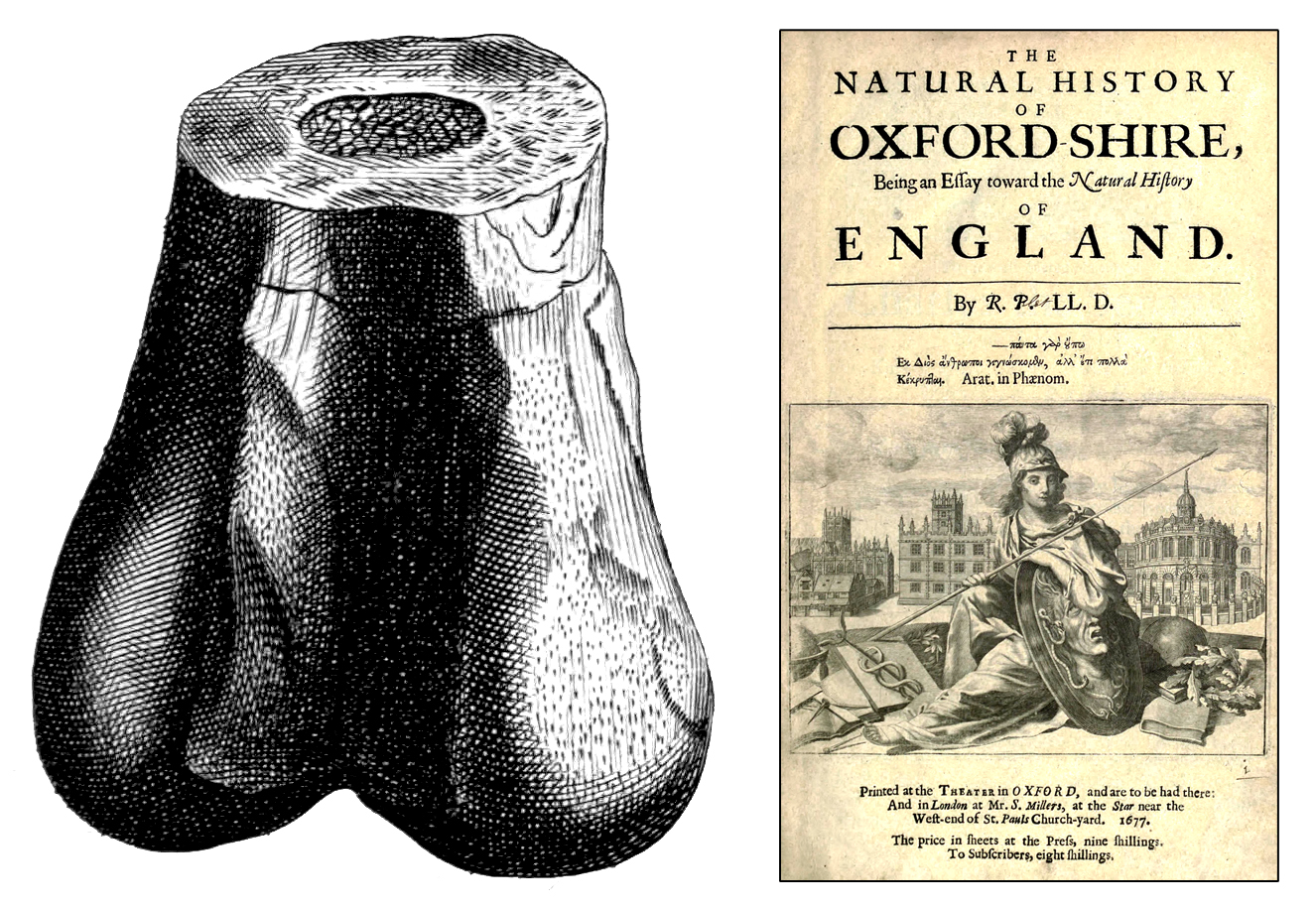

''Megalosaurus'' may have been the first non

''Megalosaurus'' may have been the first non avian

Avian may refer to:

*Birds or Aves, winged animals

*Avian (given name) (russian: Авиа́н, link=no), a male forename

Aviation

*Avro Avian, a series of light aircraft made by Avro in the 1920s and 1930s

*Avian Limited, a hang glider manufacture ...

dinosaur

Dinosaurs are a diverse group of reptiles of the clade Dinosauria. They first appeared during the Triassic period, between 243 and 233.23 million years ago (mya), although the exact origin and timing of the evolution of dinosaurs is t ...

to be described in the scientific literature. The earliest possible fossil of the genus, from the Taynton Limestone Formation

The Taynton LimestoneWeishampel, David B; et al. (2004). "Dinosaur distribution (Middle Jurassic, Europe)." In: Weishampel, David B.; Dodson, Peter; and Osmólska, Halszka (eds.): The Dinosauria, 2nd, Berkeley: University of California Press. Pp. 5 ...

, was the lower part of a femur

The femur (; ), or thigh bone, is the proximal bone of the hindlimb in tetrapod vertebrates. The head of the femur articulates with the acetabulum in the pelvic bone forming the hip joint, while the distal part of the femur articulates with ...

, discovered in the 17th century. It was originally described by Robert Plot as a thighbone of a Roman

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

*Rome, the capital city of Italy

*Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*''Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a letter ...

war elephant

A war elephant was an elephant that was trained and guided by humans for combat. The war elephant's main use was to charge the enemy, break their ranks and instill terror and fear. Elephantry is a term for specific military units using elephant ...

, and then as a biblical giant. Part of a bone was recovered from the Taynton Limestone Formation of Stonesfield

Stonesfield is a village and civil parish about north of Witney in Oxfordshire, and about 10 miles (17 km) north-west of Oxford. The village is on the crest of an escarpment. The parish extends mostly north and north-east of the village, ...

limestone quarry, Oxfordshire

Oxfordshire is a ceremonial and non-metropolitan county in the north west of South East England. It is a mainly rural county, with its largest settlement being the city of Oxford. The county is a centre of research and development, primarily ...

in 1676. Sir Thomas Pennyson gave the fragment to Robert Plot

Robert Plot (13 December 1640 – 30 April 1696) was an English naturalist, first Professor of Chemistry at the University of Oxford, and the first keeper of the Ashmolean Museum.

Early life and education

Born in Borden, Kent to parents Robe ...

, Professor of Chemistry at the University of Oxford

, mottoeng = The Lord is my light

, established =

, endowment = £6.1 billion (including colleges) (2019)

, budget = £2.145 billion (2019–20)

, chancellor ...

and first curator of the Ashmolean Museum

The Ashmolean Museum of Art and Archaeology () on Beaumont Street, Oxford, England, is Britain's first public museum. Its first building was erected in 1678–1683 to house the cabinet of curiosities that Elias Ashmole gave to the University of ...

, who published a description and illustration in his ''Natural History of Oxfordshire'' in 1676. It was the first illustration of a dinosaur bone published. Plot correctly identified the bone as the lower extremity of the thighbone

The femur (; ), or thigh bone, is the proximal bone of the hindlimb in tetrapod vertebrates. The head of the femur articulates with the acetabulum in the pelvic bone forming the hip joint, while the distal part of the femur articulates with ...

or femur

The femur (; ), or thigh bone, is the proximal bone of the hindlimb in tetrapod vertebrates. The head of the femur articulates with the acetabulum in the pelvic bone forming the hip joint, while the distal part of the femur articulates with ...

of a large animal and he recognized that it was too large to belong to any species known to be living in England. He therefore at first concluded it to be the thighbone of a Roman war elephant

A war elephant was an elephant that was trained and guided by humans for combat. The war elephant's main use was to charge the enemy, break their ranks and instill terror and fear. Elephantry is a term for specific military units using elephant ...

and later that of a giant human, such as those mentioned in the Bible. The bone has since been lost, but the illustration is detailed enough that some have since identified it as that of ''Megalosaurus''.

It has also been argued that this possible ''Megalosaurus'' bone was given the very first species name

In taxonomy, binomial nomenclature ("two-term naming system"), also called nomenclature ("two-name naming system") or binary nomenclature, is a formal system of naming species of living things by giving each a name composed of two parts, bot ...

ever applied to an extinct dinosaur. Plot's engraving of the Cornwell bone was again used in a book by Richard Brookes

Richard Brookes (fl. 1721 – 1763) was an English physician and author of compilations and translations on medicine, surgery, natural history, and geography, most of which went through several editions.

Life

He was at one time a rural practit ...

in 1763. Brookes, in a caption, called it "Scrotum

The scrotum or scrotal sac is an anatomical male reproductive structure located at the base of the penis that consists of a suspended dual-chambered sac of skin and smooth muscle. It is present in most terrestrial male mammals. The scrotum cont ...

humanum," apparently comparing its appearance to a pair of "human testicle

A testicle or testis (plural testes) is the male reproductive gland or gonad in all bilaterians, including humans. It is homologous to the female ovary. The functions of the testes are to produce both sperm and androgens, primarily testostero ...

s". However, it is possible that the attribution of this name stemmed from illustrator error, not Richard Brookes. In 1970, paleontologist Lambert Beverly Halstead pointed out that the similarity of ''Scrotum humanum'' to a modern species name, a so-called Linnaean " binomen" that has two parts, was not a coincidence. Linnaeus

Carl Linnaeus (; 23 May 1707 – 10 January 1778), also known after his ennoblement in 1761 as Carl von Linné Blunt (2004), p. 171. (), was a Swedish botanist, zoologist, taxonomist, and physician who formalised binomial nomenclature, the ...

, the founder of modern taxonomy

Taxonomy is the practice and science of categorization or classification.

A taxonomy (or taxonomical classification) is a scheme of classification, especially a hierarchical classification, in which things are organized into groups or types. ...

, had in the eighteenth century not merely devised a system for naming living creatures, but also for classifying geological objects. The book by Brookes was all about applying this latter system to curious stones found in England. According to Halstead, Brookes thus had deliberately used binomial nomenclature

In taxonomy, binomial nomenclature ("two-term naming system"), also called nomenclature ("two-name naming system") or binary nomenclature, is a formal system of naming species of living things by giving each a name composed of two parts, bot ...

, and had in fact indicated the possible type specimen

In biology, a type is a particular wiktionary:en:specimen, specimen (or in some cases a group of specimens) of an organism to which the scientific name of that organism is formally attached. In other words, a type is an example that serves to a ...

of a new biological genus. According to the rules of the International Code of Zoological Nomenclature

The International Code of Zoological Nomenclature (ICZN) is a widely accepted convention in zoology that rules the formal scientific naming of organisms treated as animals. It is also informally known as the ICZN Code, for its publisher, the ...

(ICZN), the name ''Scrotum humanum'' in principle had priority over ''Megalosaurus'' because it was published first. That Brookes understood that the stone did not actually represent a pair of petrified testicles was irrelevant. Merely the fact that the name had not been used in subsequent literature meant that it could be removed from competition for priority, because the ICZN states that if a name has never been considered valid after 1899, it can be made a ''nomen oblitum

In zoological nomenclature, a ''nomen oblitum'' (plural: ''nomina oblita''; Latin for "forgotten name") is a disused scientific name which has been declared to be obsolete (figuratively 'forgotten') in favour of another 'protected' name.

In its p ...

'', an invalid "forgotten name".

In 1993, after the death of Halstead, his friend William A.S. Sarjeant submitted a petition to the International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature

The International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature (ICZN) is an organization dedicated to "achieving stability and sense in the scientific naming of animals". Founded in 1895, it currently comprises 26 commissioners from 20 countries.

Orga ...

to formally suppress the name ''Scrotum'' in favour of ''Megalosaurus''. He wrote that the supposed junior synonym ''Megalosaurus bucklandii'' should be made a conserved name

A conserved name or ''nomen conservandum'' (plural ''nomina conservanda'', abbreviated as ''nom. cons.'') is a scientific name that has specific nomenclatural protection. That is, the name is retained, even though it violates one or more rules whic ...

to ensure its priority. However, the Executive Secretary of the ICZN at the time, Philip K. Tubbs, did not consider the petition to be admissible, concluding that the term "Scrotum humanum", published merely as a label for an illustration, did not constitute the valid creation of a new name, and stated that there was no evidence it was ever intended as such. Furthermore, the partial femur was too incomplete to definitely be referred to ''Megalosaurus'' and not a different, contemporary theropod.

Buckland's research

During the last part of the eighteenth century, the number of fossils in British collections quickly increased. According to an hypothesis published by

During the last part of the eighteenth century, the number of fossils in British collections quickly increased. According to an hypothesis published by science historian

The history of science and technology (HST) is a field of history that examines the understanding of the natural world (science) and the ability to manipulate it (technology) at different points in time. This academic discipline also studies the c ...

Robert Gunther

Robert William Theodore Gunther (23 August 1869 – 9 March 1940) was a historian of science, zoologist, and founder of the Museum of the History of Science, Oxford.

Gunther's father, Albert Günther, was Keeper of Zoology at the British Museu ...

in 1925, among them was a partial lower jaw of ''Megalosaurus''. It was discovered about underground in a Stonesfield Slate mine during the early 1790s and was acquired in October 1797 by Christopher Pegge

Sir Christopher Pegge M.D. (1765–1822) was an English physician.

Life

The son of Samuel Pegge the younger, by his first wife, he was born in London. He entered Christ Church, Oxford, as a commoner on 18 April 1782, and graduated B.A. on 23 F ...

for 10s.6d. and added to the collection of the Anatomy School of Christ Church College, Oxford.

In the early nineteenth century, more discoveries were made. In 1815, John Kidd reported the find of bones of giant tetrapods, again at the Stonesfield

Stonesfield is a village and civil parish about north of Witney in Oxfordshire, and about 10 miles (17 km) north-west of Oxford. The village is on the crest of an escarpment. The parish extends mostly north and north-east of the village, ...

quarry. The layers there are currently considered part of the Taynton Limestone Formation, dating to the mid-Bathonian

In the geologic timescale the Bathonian is an age and stage of the Middle Jurassic. It lasted from approximately 168.3 Ma to around 166.1 Ma (million years ago). The Bathonian Age succeeds the Bajocian Age and precedes the Callovian Age.

Strat ...

stage of the Jurassic

The Jurassic ( ) is a Geological period, geologic period and System (stratigraphy), stratigraphic system that spanned from the end of the Triassic Period million years ago (Mya) to the beginning of the Cretaceous Period, approximately Mya. The J ...

Period. The bones were apparently acquired by William Buckland

William Buckland Doctor of Divinity, DD, Royal Society, FRS (12 March 1784 – 14 August 1856) was an English theologian who became Dean of Westminster. He was also a geologist and paleontology, palaeontologist.

Buckland wrote the first full ...

, Professor of Geology at the University of Oxford and dean of Christ Church. Buckland also studied a lower jaw, according to Gunther the one bought by Pegge. Buckland did not know to what animal the bones belonged but, in 1818, after the Napoleonic Wars

The Napoleonic Wars (1803–1815) were a series of major global conflicts pitting the French Empire and its allies, led by Napoleon I, against a fluctuating array of European states formed into various coalitions. It produced a period of Fren ...

, the French comparative anatomist Georges Cuvier

Jean Léopold Nicolas Frédéric, Baron Cuvier (; 23 August 1769 – 13 May 1832), known as Georges Cuvier, was a French natural history, naturalist and zoology, zoologist, sometimes referred to as the "founding father of paleontology". Cuvier ...

visited Buckland in Oxford and realised that they were those of a giant lizard

Lizards are a widespread group of squamate reptiles, with over 7,000 species, ranging across all continents except Antarctica, as well as most oceanic island chains. The group is paraphyletic since it excludes the snakes and Amphisbaenia alt ...

-like creature. Buckland further studied the remains with his friend William Conybeare who in 1821 referred to them as the "Huge Lizard". In 1822 Buckland and Conybeare, in a joint article to be included in Cuvier's ''Ossemens'', intended to provide scientific names for both gigantic lizard-like creatures known at the time: the remains found near Maastricht

Maastricht ( , , ; li, Mestreech ; french: Maestricht ; es, Mastrique ) is a city and a municipality in the southeastern Netherlands. It is the capital and largest city of the province of Limburg. Maastricht is located on both sides of the ...

would be named ''Mosasaurus

''Mosasaurus'' (; "lizard of the Meuse River") is the type genus (defining example) of the mosasaurs, an extinct group of aquatic squamate reptiles. It lived from about 82 to 66 million years ago during the Campanian and Maastrichtian stages o ...

'' – then seen as a land-dwelling animal – while for the British lizard Conybeare had devised the name ''Megalosaurus'', from the Greek μέγας, ''megas'', "large". That year a publication failed to occur, but the physician James Parkinson

James Parkinson (11 April 175521 December 1824) was an English surgeon, apothecary, geologist, palaeontologist and political activist. He is best known for his 1817 work ''An Essay on the Shaking Palsy'', in which he was the first to describe ...

already in 1822 announced the name ''Megalosaurus'', illustrating one of the teeth and revealing the creature was forty feet long and eight feet high. It is generally considered the name in 1822 was still a ''nomen nudum

In taxonomy, a ''nomen nudum'' ('naked name'; plural ''nomina nuda'') is a designation which looks exactly like a scientific name of an organism, and may have originally been intended to be one, but it has not been published with an adequate descr ...

'' ("naked name"). Buckland, urged on by an impatient Cuvier, continued to work on the subject during 1823, letting his later wife Mary Morland provide drawings of the bones, that were to be the basis of illustrating lithographies. Finally, on 20 February 1824, during the same meeting of the Geological Society of London

The Geological Society of London, known commonly as the Geological Society, is a learned society based in the United Kingdom. It is the oldest national geological society in the world and the largest in Europe with more than 12,000 Fellows.

Fe ...

in which Conybeare described a very complete specimen of ''Plesiosaurus

''Plesiosaurus'' (Greek: ' ('), near to + ' ('), lizard) is a genus of extinct, large marine sauropterygian reptile that lived during the Early Jurassic. It is known by nearly complete skeletons from the Lias Group, Lias of England. It is disting ...

'', Buckland formally announced ''Megalosaurus''. The descriptions of the bones in the ''Transactions of the Geological Society'', in 1824, constitute a valid publication of the name. ''Megalosaurus'' was the first non-avian dinosaur genus named; the first of which the remains had with certainty been scientifically described was '' Streptospondylus'', in 1808 by Cuvier.

vertebra

The spinal column, a defining synapomorphy shared by nearly all vertebrates,Hagfish are believed to have secondarily lost their spinal column is a moderately flexible series of vertebrae (singular vertebra), each constituting a characteristic ...

; OUM J13579, an anterior caudal vertebra; OUM J13576, a sacrum

The sacrum (plural: ''sacra'' or ''sacrums''), in human anatomy, is a large, triangular bone at the base of the spine that forms by the fusing of the sacral vertebrae (S1S5) between ages 18 and 30.

The sacrum situates at the upper, back part ...

of five sacral vertebrae; OUM J13585, a cervical rib; OUM J13580, a rib; OUM J29881, an ilium of the pelvis

The pelvis (plural pelves or pelvises) is the lower part of the trunk, between the abdomen and the thighs (sometimes also called pelvic region), together with its embedded skeleton (sometimes also called bony pelvis, or pelvic skeleton).

The ...

, OUM J13563, a piece of the pubic bone

In vertebrates, the pubic region ( la, pubis) is the most forward-facing ( ventral and anterior) of the three main regions making up the coxal bone. The left and right pubic regions are each made up of three sections, a superior ramus, inferior ...

; OUM J13565, a part of the ischium

The ischium () form ...

; OUM J13561, a thighbone and OUM J13572, the lower part of a second metatarsal

The metatarsal bones, or metatarsus, are a group of five long bones in the foot, located between the tarsal bones of the hind- and mid-foot and the phalanges of the toes. Lacking individual names, the metatarsal bones are numbered from the med ...

. As he himself was aware, these did not all belong to the same individual; only the sacrum was articulated. Because they represented several individuals, the described fossils formed a syntype

In biological nomenclature, a syntype is any one of two or more biological types that is listed in a description of a taxon where no holotype was designated. Precise definitions of this and related terms for types have been established as part of ...

series. By modern standards, from these a single specimen has to be selected to serve as the type specimen on which the name is based. In 1990, Ralph Molnar

Ralph E. Molnar is a paleontologist who had been Curator of Mammals at the Queensland Museum and more recently associated with the Museum of Northern Arizona. He is also a research associate at the Texas natural Science Centre. He co-authored descr ...

chose the famous dentary

In anatomy, the mandible, lower jaw or jawbone is the largest, strongest and lowest bone in the human facial skeleton. It forms the lower jaw and holds the lower tooth, teeth in place. The mandible sits beneath the maxilla. It is the only movabl ...

(front part of the lower jaw), OUM J13505, as such a lectotype

In biology, a type is a particular specimen (or in some cases a group of specimens) of an organism to which the scientific name of that organism is formally attached. In other words, a type is an example that serves to anchor or centralizes the ...

.Molnar, R.E.; Seriozha M.K. & Dong Z. (1990). "Carnosauria" In: Because he was unaccustomed to the deep dinosaurian pelvis, much taller than with typical reptiles, Buckland misidentified several bones, interpreting the pubic bone as a fibula

The fibula or calf bone is a leg bone on the lateral side of the tibia, to which it is connected above and below. It is the smaller of the two bones and, in proportion to its length, the most slender of all the long bones. Its upper extremity is ...

and mistaking the ischium for a clavicle

The clavicle, or collarbone, is a slender, S-shaped long bone approximately 6 inches (15 cm) long that serves as a strut between the shoulder blade and the sternum (breastbone). There are two clavicles, one on the left and one on the rig ...

. Buckland identified the organism as being a giant animal belonging to the Sauria

Sauria is the clade containing the most recent common ancestor of archosaurs (such as crocodilians, dinosaurs, etc.) and lepidosaurs ( lizards and kin), and all its descendants. Since most molecular phylogenies recover turtles as more closely re ...

– the Lizards, at the time seen as including the crocodiles – and he placed it in the new genus ''Megalosaurus'', repeating an estimate by Cuvier that the largest pieces he described, indicated an animal twelve metres long in life.

Etymology

Buckland had not provided a specific name, as was not uncommon in the early nineteenth century, when the genus was still seen as the more essential concept. In 1826, Ferdinand von Ritgen gave this dinosaur a complete binomial, ''Megalosaurus conybeari'', which however was not much used by later authors and is now considered a ''nomen oblitum''. A year later, in 1827,Gideon Mantell

Gideon Algernon Mantell MRCS FRS (3 February 1790 – 10 November 1852) was a British obstetrician, geologist and palaeontologist. His attempts to reconstruct the structure and life of ''Iguanodon'' began the scientific study of dinosaurs: in ...

included ''Megalosaurus'' in his geological survey of southeastern England, and assigned the species its current valid binomial name, ''Megalosaurus bucklandii''. Until recently, the form ''Megalosaurus bucklandi'' was often used, a variant first published in 1832 by Christian Erich Hermann von Meyer

Christian Erich Hermann von Meyer (3 September 1801 – 2 April 1869), known as Hermann von Meyer, was a German palaeontologist. He was awarded the 1858 Wollaston medal by the Geological Society of London.

Life

He was born at Frankfurt am Ma ...

– and sometimes erroneously ascribed to von Ritgen – but the more original ''M. bucklandii'' has priority.

Early reconstructions

The first reconstruction was given by Buckland himself. He considered ''Megalosaurus'' to be a quadruped. He thought it was an "amphibian", i.e. an animal capable of both swimming in the sea and walking on land. Generally, in his mind ''Megalosaurus'' resembled a gigantic lizard, but Buckland already understood from the form of the thighbone head that the legs were not so much sprawling as held rather upright. In the original description of 1824, Buckland repeated Cuvier's size estimate that ''Megalosaurus'' would have been forty feet long with the weight of a seven foot tall elephant. However, this had been based on the remains present at Oxford. Buckland had also been hurried into naming his new reptile by a visit he had made to the fossil collection of Mantell, who during the lecture announced to have acquired a fossil thighbone of enormous magnitude, twice as long as that just described. Today, this is known to have belonged to ''

The first reconstruction was given by Buckland himself. He considered ''Megalosaurus'' to be a quadruped. He thought it was an "amphibian", i.e. an animal capable of both swimming in the sea and walking on land. Generally, in his mind ''Megalosaurus'' resembled a gigantic lizard, but Buckland already understood from the form of the thighbone head that the legs were not so much sprawling as held rather upright. In the original description of 1824, Buckland repeated Cuvier's size estimate that ''Megalosaurus'' would have been forty feet long with the weight of a seven foot tall elephant. However, this had been based on the remains present at Oxford. Buckland had also been hurried into naming his new reptile by a visit he had made to the fossil collection of Mantell, who during the lecture announced to have acquired a fossil thighbone of enormous magnitude, twice as long as that just described. Today, this is known to have belonged to ''Iguanodon

''Iguanodon'' ( ; meaning 'iguana-tooth'), named in 1825, is a genus of iguanodontian dinosaur. While many species have been classified in the genus ''Iguanodon'', dating from the late Jurassic Period to the early Cretaceous Period of Asia, Eu ...

'', or at least some iguanodontid

Iguanodontidae is a family of iguanodontians belonging to Styracosterna, a derived clade within Ankylopollexia.

Characterized by their elongated maxillae, they were herbivorous and typically large in size. This family exhibited locomotive dynam ...

, but at the time both men assumed this bone belonged to ''Megalosaurus'' also. Even taking into account the effects of allometry

Allometry is the study of the relationship of body size to shape, anatomy, physiology and finally behaviour, first outlined by Otto Snell in 1892, by D'Arcy Thompson in 1917 in ''On Growth and Form'' and by Julian Huxley in 1932.

Overview

Allom ...

, heavier animals having relatively stouter bones, Buckland was forced in the printed version of his lecture to estimate the maximum length of ''Megalosaurus'' at sixty to seventy feet. The existence of ''Megalosaurus'' posed some problems for Christian orthodoxy

Orthodoxy (from Greek: ) is adherence to correct or accepted creeds, especially in religion.

Orthodoxy within Christianity refers to acceptance of the doctrines defined by various creeds and ecumenical councils in Antiquity, but different Churc ...

, which typically held that suffering and death had only come into the world through Original Sin

Original sin is the Christian doctrine that holds that humans, through the fact of birth, inherit a tainted nature in need of regeneration and a proclivity to sinful conduct. The biblical basis for the belief is generally found in Genesis 3 (t ...

, which seemed irreconcilable with the presence of a gigantic devouring reptile during a pre-Adamitic phase of history. Buckland rejected the usual solution, that such carnivores would originally have been peaceful vegetarians, as infantile and claimed in one of the ''Bridgewater Treatises

The Bridgewater Treatises (1833–36) are a series of eight works that were written by leading scientific figures appointed by the President of the Royal Society in fulfilment of a bequest of £8000, made by Francis Henry Egerton, 8th Earl of Bridg ...

'' that ''Megalosaurus'' had played a beneficial role in creation by ending the lives of old and ill animals, "to diminish the aggregate amount of animal suffering".

Around 1840, it became fashionable in England to espouse the concept of the

Around 1840, it became fashionable in England to espouse the concept of the transmutation of species

Transmutation of species and transformism are unproven 18th and 19th-century evolutionary ideas about the change of one species into another that preceded Charles Darwin's theory of natural selection. The French ''Transformisme'' was a term used ...

as part of a general progressive development through time, as expressed in the work of Robert Chambers. In reaction, on 2 August 1841 Richard Owen

Sir Richard Owen (20 July 1804 – 18 December 1892) was an English biologist, comparative anatomist and paleontologist. Owen is generally considered to have been an outstanding naturalist with a remarkable gift for interpreting fossils.

Owe ...

during a lecture to the British Association for the Advancement of Science

The British Science Association (BSA) is a charity and learned society founded in 1831 to aid in the promotion and development of science. Until 2009 it was known as the British Association for the Advancement of Science (BA). The current Chie ...

claimed that certain prehistoric reptilian groups had already attained the organisational level of present mammals, implying there had been no progress. Owen presented three examples of such higher level reptiles: ''Iguanodon

''Iguanodon'' ( ; meaning 'iguana-tooth'), named in 1825, is a genus of iguanodontian dinosaur. While many species have been classified in the genus ''Iguanodon'', dating from the late Jurassic Period to the early Cretaceous Period of Asia, Eu ...

'', ''Hylaeosaurus

''Hylaeosaurus'' ( ; Greek: / "belonging to the forest" and / "lizard") is a herbivorous ankylosaurian dinosaur that lived about 136 million years ago, in the late Valanginian stage of the early Cretaceous period of England. It was found in ...

'' and ''Megalosaurus''. For these, the "lizard model" was entirely abandoned: they would have had an upright stance and a high metabolism. This also meant that earlier size estimates had been exaggerated. By simply adding the known length of the vertebrae, instead of extrapolating from a lizard, Owen arrived at a total body length for ''Megalosaurus'' of thirty feet. In the printed version of the lecture published in 1842, Owen united the three reptiles into a separate group: the Dinosauria. ''Megalosaurus'' was thus one of the three original dinosaurs.

In 1852,

In 1852, Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins

Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins (8 February 1807 – 27 January 1894) was an English sculptor and natural history artist renowned for his work on the life-size models of dinosaurs in the Crystal Palace Park in south London. The models, accurately ...

was commissioned to build a life-sized concrete model of ''Megalosaurus'' for the exhibition of prehistoric animals at the Crystal Palace Park in Sydenham, where it remains to this day. Hawkins worked under the direction of Owen and the statue reflected Owen's ideas that ''Megalosaurus'' would have been a mammal-like quadruped. The sculpture in Crystal Palace Park shows a conspicuous hump on the shoulders and it has been suggested this was inspired by a set of high vertebral spines acquired by Owen in the early 1850s. Today, they are seen as a separate genus '' Becklespinax'', but Owen referred them to ''Megalosaurus''. The models at the exhibition created a general public awareness for the first time, at least in England, that ancient reptiles had existed.

The presumption that carnivorous dinosaurs, like ''Megalosaurus'', were quadrupeds was first challenged by the find of ''Compsognathus

''Compsognathus'' (; Ancient Greek, Greek ''kompsos''/κομψός; "elegant", "refined" or "dainty", and ''gnathos''/γνάθος; "jaw") is a genus of small, bipedalism, bipedal, carnivore, carnivorous theropoda, theropod dinosaur. Members o ...

'' in 1859. That, however, was a very small animal, the significance of which for gigantic forms could be denied. In 1870, near Oxford, the type specimen of ''Eustreptospondylus

''Eustreptospondylus'' ( ; meaning "true ''Streptospondylus''") is a genus of megalosaurid Theropoda, theropod dinosaur, from the Oxfordian stage of the Late Jurassic period (some time between 163 and 154 million years ago) in southern Eng ...

'' was discovered – the first reasonably intact skeleton of a large theropod. It was clearly bipedal. Shortly afterwards, John Phillips created the first public display of a theropod skeleton in Oxford, arranging the known ''Megalosaurus'' bones, held by recesses in cardboard sheets, in a more or less natural position. During the 1870s, North America

North America is a continent in the Northern Hemisphere and almost entirely within the Western Hemisphere. It is bordered to the north by the Arctic Ocean, to the east by the Atlantic Ocean, to the southeast by South America and the Car ...

n discoveries of large theropods, like ''Allosaurus'', confirmed that they were bipedal. The Oxford University Museum of Natural History

The Oxford University Museum of Natural History, sometimes known simply as the Oxford University Museum or OUMNH, is a museum displaying many of the University of Oxford's natural history specimens, located on Parks Road in Oxford, England. It a ...

display contains most of the specimens from the original description by Buckland.

Later finds of ''Megalosaurus bucklandii''

Stonesfield

Stonesfield is a village and civil parish about north of Witney in Oxfordshire, and about 10 miles (17 km) north-west of Oxford. The village is on the crest of an escarpment. The parish extends mostly north and north-east of the village, ...

, which were worked until 1911, continued to produce ''Megalosaurus bucklandii'' fossils, mostly single bones from the pelvis

The pelvis (plural pelves or pelvises) is the lower part of the trunk, between the abdomen and the thighs (sometimes also called pelvic region), together with its embedded skeleton (sometimes also called bony pelvis, or pelvic skeleton).

The ...

and hindlimb

A hindlimb or back limb is one of the paired articulated appendages (limbs) attached on the caudal ( posterior) end of a terrestrial tetrapod vertebrate's torso.http://www.merriam-webster.com/medical/hind%20limb, Merriam Webster Dictionary-Hindl ...

s. Vertebrae and skull bones are rare. In 2010, Roger Benson

Roger is a given name, usually masculine, and a surname. The given name is derived from the Old French personal names ' and '. These names are of Germanic origin, derived from the elements ', ''χrōþi'' ("fame", "renown", "honour") and ', ' ( ...

counted a total of 103 specimens from the Stonesfield Slate, from a minimum of seven individuals. It has been contentious whether this material represents just a single taxon

In biology, a taxon (back-formation from ''taxonomy''; plural taxa) is a group of one or more populations of an organism or organisms seen by taxonomists to form a unit. Although neither is required, a taxon is usually known by a particular nam ...

. In 2004, Julia Day and Paul Barrett

Paul Franklyn "Legs" Barrett (14 December 1940 – 20 January 2019) was a UK agent and manager of 1950s style Rock and Roll artistes, an author and previously a singer, songwriter and film actor. Barrett is the discoverer, mentor and first ma ...

claimed that there were two morphotype

In biology, polymorphism is the occurrence of two or more clearly different morphs or forms, also referred to as alternative ''phenotypes'', in the population of a species. To be classified as such, morphs must occupy the same habitat at the s ...

s present, based on small differences in the thighbones. In 2008 Benson favoured this idea, but in 2010 concluded the differences were illusory. A maxilla fragment, specimen OUM J13506, was, in 1869 assigned, by Thomas Huxley

Thomas Henry Huxley (4 May 1825 – 29 June 1895) was an English biologist and anthropologist specialising in comparative anatomy. He has become known as "Darwin's Bulldog" for his advocacy of Charles Darwin's theory of evolution.

The stor ...

, to ''M. bucklandii''. In 1992 Robert Thomas Bakker claimed it represented a member of the Sinraptoridae; in 2007, Darren Naish

Darren William Naish is a British vertebrate palaeontologist, author and science communicator.

As a researcher, he is best known for his work describing and reevaluating dinosaurs and other Mesozoic reptiles, including '' Eotyrannus'', '' Xenop ...

thought it was a separate species belonging to the Abelisauroidea

Abelisauroidea is typically regarded as a Cretaceous group, though the earliest abelisauridae remains are known from the Middle Jurassic of Argentina (classified as the species Eoabelisaurus mefi) and possibly Madagascar (fragmentary remains of ...

. In 2010, Benson pointed out that the fragment was basically indistinguishable from other known ''M. bucklandii'' maxillae, to which it had in fact not been compared by the other authors.

Apart from the finds in the

Apart from the finds in the Taynton Limestone Formation

The Taynton LimestoneWeishampel, David B; et al. (2004). "Dinosaur distribution (Middle Jurassic, Europe)." In: Weishampel, David B.; Dodson, Peter; and Osmólska, Halszka (eds.): The Dinosauria, 2nd, Berkeley: University of California Press. Pp. 5 ...

, in 1939 Sidney Hugh Reynolds referred remains to ''Megalosaurus'' that had been found in the older Chipping Norton Limestone Formation dating from the early Bathonian

In the geologic timescale the Bathonian is an age and stage of the Middle Jurassic. It lasted from approximately 168.3 Ma to around 166.1 Ma (million years ago). The Bathonian Age succeeds the Bajocian Age and precedes the Callovian Age.

Strat ...

, about thirty single teeth and bones. Though the age disparity makes it problematic to assume an identity with ''Megalosaurus bucklandii'', in 2009 Benson could not establish any relevant anatomical differences with ''M. bucklandii'' among the remains found at one site, the New Park Quarry, and therefore affirmed the reference to that species. However, in another site, the Oakham Quarry, the material contained one bone, an ilium, that was clearly dissimilar.

Sometimes trace fossil

A trace fossil, also known as an ichnofossil (; from el, ἴχνος ''ikhnos'' "trace, track"), is a fossil record of biological activity but not the preserved remains of the plant or animal itself. Trace fossils contrast with body fossils, ...

s have been referred to ''Megalosaurus'' or to the ichnogenus

An ichnotaxon (plural ichnotaxa) is "a taxon based on the fossilized work of an organism", i.e. the non-human equivalent of an artifact. ''Ichnotaxa'' comes from the Greek ίχνος, ''ichnos'' meaning ''track'' and ταξις, ''taxis'' meaning ...

''Megalosauripus

''Megalosauripus'' is an ichnogenus that has been attributed to dinosaurs.Lockley, Martin G.; Meyer, Christian A.; dos Santos, Vanda Faria. (December 1998).Megalosauripus and the problematic concept of Megalosaur footprints. ''GAIA''. 15: 313–3 ...

''. In 1997, a famous group of fossilised footprints (ichnite

A fossil track or ichnite (Greek "''ιχνιον''" (''ichnion'') – a track, trace or footstep) is a fossilized footprint. This is a type of trace fossil. A fossil trackway is a sequence of fossil tracks left by a single organism. Over the year ...

s) was found in a limestone quarry at Ardley, twenty kilometres northeast of Oxford

Oxford () is a city in England. It is the county town and only city of Oxfordshire. In 2020, its population was estimated at 151,584. It is north-west of London, south-east of Birmingham and north-east of Bristol. The city is home to the ...

. They were thought to have been made by ''Megalosaurus'' and possibly also some left by ''Cetiosaurus

''Cetiosaurus'' () meaning 'whale lizard', from the Greek '/ meaning 'sea monster' (later, 'whale') and '/ meaning 'lizard', is a genus of herbivorous sauropod dinosaur from the Middle Jurassic Period, living about 168 million years ago in what ...

''. There are replicas of some of these footprints, set across the lawn of the Oxford University Museum of Natural History

The Oxford University Museum of Natural History, sometimes known simply as the Oxford University Museum or OUMNH, is a museum displaying many of the University of Oxford's natural history specimens, located on Parks Road in Oxford, England. It a ...

. One track was of a theropod accelerating from walking to running. According to Benson, such referrals are unprovable, as the tracks show no traits unique to ''Megalosaurus''. Certainly they should be limited to finds that are of the same age as ''Megalosaurus bucklandii''.

Finds from sites outside England, especially in France, have in the nineteenth and twentieth century been referred to ''M. bucklandii''. In 2010 Benson considered these as either clearly different or too fragmentary to establish an identity.

Description

Since the first finds, many other ''Megalosaurus'' bones have been recovered; however, no complete skeleton has yet been found. Therefore, the details of its physical appearance cannot be certain. However, a full

Since the first finds, many other ''Megalosaurus'' bones have been recovered; however, no complete skeleton has yet been found. Therefore, the details of its physical appearance cannot be certain. However, a full osteology

Osteology () is the scientific study of bones, practised by osteologists. A subdiscipline of anatomy, anthropology, and paleontology, osteology is the detailed study of the structure of bones, skeletal elements, teeth, microbone morphology, funct ...

of all known material was published in 2010 by Benson.

Size and general build

carnivore

A carnivore , or meat-eater (Latin, ''caro'', genitive ''carnis'', meaning meat or "flesh" and ''vorare'' meaning "to devour"), is an animal or plant whose food and energy requirements derive from animal tissues (mainly muscle, fat and other sof ...

, its large elongated head bore long dagger-like teeth to slice the flesh of its prey. The skeleton of ''Megalosaurus'' is highly ossified, indicating a robust and muscular animal, though the lower leg was not as heavily built as that of ''Torvosaurus'', a close relative.

Skull and lower jaws

The skull of ''Megalosaurus'' is poorly known. The discovered skull elements are generally rather large in relation to the rest of the material. This can either be coincidental or indicate that ''Megalosaurus'' had an uncommonly large head. The

The skull of ''Megalosaurus'' is poorly known. The discovered skull elements are generally rather large in relation to the rest of the material. This can either be coincidental or indicate that ''Megalosaurus'' had an uncommonly large head. The praemaxilla

The premaxilla (or praemaxilla) is one of a pair of small cranial bones at the very tip of the upper jaw of many animals, usually, but not always, bearing teeth. In humans, they are fused with the maxilla. The "premaxilla" of therian mammal has ...

is not known, making it impossible to determine whether the snout profile was curved or rectangular. A rather stubby snout is suggested by the fact that the front branch of the maxilla

The maxilla (plural: ''maxillae'' ) in vertebrates is the upper fixed (not fixed in Neopterygii) bone of the jaw formed from the fusion of two maxillary bones. In humans, the upper jaw includes the hard palate in the front of the mouth. The t ...

was short. In the depression around the antorbital fenestra

An antorbital fenestra (plural: fenestrae) is an opening in the skull that is in front of the eye sockets. This skull character is largely associated with archosauriforms, first appearing during the Triassic Period. Among extant archosaurs, bird ...

to the front, a smaller non-piercing hollowing can be seen that is probably homologous to the ''fenestra maxillaris''. The maxilla bears thirteen teeth. The teeth are relatively large, with a crown length up to seven centimetres. The teeth are supported from behind by tall, triangular, unfused interdental plates. The cutting edges bear eighteen to twenty ''denticula'' per centimetre. The tooth formula is probably 4, 13–14/13–14. The jugal bone

The jugal is a skull bone found in most reptiles, amphibians and birds. In mammals, the jugal is often called the malar or zygomatic. It is connected to the quadratojugal and maxilla, as well as other bones, which may vary by species.

Anato ...

is pneumatised, pierced by a large foramen from the direction of the antorbital fenestra. It was probably hollowed out by an outgrowth of an air sac

Air sacs are spaces within an organism where there is the constant presence of air. Among modern animals, birds possess the most air sacs (9–11), with their extinct dinosaurian relatives showing a great increase in the pneumatization (presence ...

in the nasal bone

The nasal bones are two small oblong bones, varying in size and form in different individuals; they are placed side by side at the middle and upper part of the face and by their junction, form the bridge of the upper one third of the nose.

Eac ...

. Such a level of pneumatisation of the jugal is not known from other megalosaurids and might represent a separate autapomorphy

In phylogenetics, an autapomorphy is a distinctive feature, known as a derived trait, that is unique to a given taxon. That is, it is found only in one taxon, but not found in any others or outgroup taxa, not even those most closely related to ...

.

The lower jaw is rather robust. It is also straight in top view, without much expansion at the jaw tip, suggesting the lower jaws as a pair, the

The lower jaw is rather robust. It is also straight in top view, without much expansion at the jaw tip, suggesting the lower jaws as a pair, the mandibula

In anatomy, the mandible, lower jaw or jawbone is the largest, strongest and lowest bone in the human facial skeleton. It forms the lower jaw and holds the lower teeth in place. The mandible sits beneath the maxilla. It is the only movable bone ...

, were narrow. Several traits in 2008 identified as autapomorphies, later transpired to have been the result of damage. However, a unique combination of traits is present in the wide longitudinal groove on the outer side (shared with ''Torvosaurus''), the small third dentary tooth and a vascular channel, below the row of interdental plates, that only is closed from the fifth tooth position onwards. The number of dentary teeth was probably thirteen or fourteen, though the preserved damaged specimens show at most eleven tooth sockets. The interdental plates have smooth inner sides, whereas those of the maxilla are vertically grooved; the same combination is shown by ''Piatnitzkysaurus

''Piatnitzkysaurus'' ( meaning "Piatnitzky's lizard") is a genus of megalosauroid theropod dinosaur that lived approximately 179 to 177 million years ago during the lower part of the Jurassic Period in what is now Argentina. ''Piatnitzkysaurus'' ...

''. The surangular

The suprangular or surangular is a jaw bone found in most land vertebrates, except mammals. Usually in the back of the jaw, on the upper edge, it is connected to all other jaw bones: dentary, angular, splenial and articular

The articular bone i ...

has no bony shelf, or even ridge, on its outer side. There is laterally an oval opening present in front of the jaw joint, a ''foramen surangulare posterior'', but a second ''foramen surangulare anterior'' to the front of it is lacking.

Vertebral column

Although the exact numbers are unknown, the

Although the exact numbers are unknown, the vertebral column

The vertebral column, also known as the backbone or spine, is part of the axial skeleton. The vertebral column is the defining characteristic of a vertebrate in which the notochord (a flexible rod of uniform composition) found in all chordata, ...

of ''Megalosaurus'' was probably divided into ten neck vertebrae, thirteen dorsal vertebrae, five sacral vertebrae and fifty to sixty tail vertebrae, as is common for basal Tetanurae

Tetanurae (/ˌtɛtəˈnjuːriː/ or "stiff tails") is a clade that includes most theropod dinosaurs, including megalosauroids, allosauroids, tyrannosauroids, ornithomimosaurs, compsognathids and maniraptorans (including birds). Tetanurans ar ...

.

The Stonesfield Slate material contains no neck vertebrae; but a single broken anterior cervical vertebra is known from the New Park Quarry, specimen BMNH R9674. The breakage reveals large internal air chambers. The vertebra is also otherwise heavily pneumatised, with large pleurocoels

Skeletal pneumaticity is the presence of air spaces within bones. It is generally produced during development by excavation of bone by pneumatic diverticula (air sacs) from an air-filled space, such as the lungs or nasal cavity. Pneumatization is h ...

, pneumatic excavations, on its sides. The rear facet of the centrum is strongly concave. The neck ribs are short. The front dorsal vertebrae are slightly opisthocoelous, with convex front centrum facets and concave rear centrum facets. They are also deeply keeled, with the ridge on the underside representing about 50% of the total centrum height. The front dorsals perhaps have a pleurocoel above the diapophysis, the lower rib joint process. The rear dorsal vertebrae, according to Benson, are not pneumatised. They are slightly amphicoelous, with hollow centrum facets. They have secondary joint processes, forming a hyposphene The hyposphene-hypantrum articulation is an accessory joint found in the vertebrae of several fossil reptiles of the group Archosauromorpha. It consists of a process on the backside of the vertebrae, the hyposphene, that fits in a depression in the ...

–hypantrum The hyposphene-hypantrum articulation is an accessory joint found in the vertebrae of several fossil reptiles of the group Archosauromorpha. It consists of a process on the backside of the vertebrae, the hyposphene, that fits in a depression in the ...

complex, the hyposphene having a triangular transverse cross-section. The height of the dorsal spines of the rear dorsals is unknown, but a high spine on a tail vertebra of the New Park Quarry material, specimen BMNH R9677, suggests the presence of a crest on the hip area. The spines of the five vertebrae of the sacrum form a supraneural plate, fused at the top. The undersides of the sacral vertebrae are rounded but the second sacral is keeled; normally it is the third or fourth sacral having a ridge. The sacral vertebrae seem not to be pneumatised but have excavations at their sides. The tail vertebrae are slightly amphicoelous, with hollow centrum facets on both the front and rear side. They have excavations at their sides and a longitudinal groove on the underside. The neural spines of the tail basis are transversely thin and tall, representing more than half of the total vertebral height.

Appendicular skeleton

The shoulderblade or

The shoulderblade or scapula

The scapula (plural scapulae or scapulas), also known as the shoulder blade, is the bone that connects the humerus (upper arm bone) with the clavicle (collar bone). Like their connected bones, the scapulae are paired, with each scapula on eithe ...

is short and wide, its length about 6.8 times the minimum width; this is a rare and basal trait within Tetanurae. Its top curves slightly to the rear in side view. On the lower outer side of the blade a broad ridge is present, running from just below the shoulder joint to about midlength where it gradually merges with the blade surface. The middle front edge over about 30% of its length is thinned forming a slightly protruding crest. The scapula constitutes about half of the shoulder joint, which is oriented obliquely sideways and to below. The coracoid

A coracoid (from Greek κόραξ, ''koraks'', raven) is a paired bone which is part of the shoulder assembly in all vertebrates except therian mammals (marsupials and placentals). In therian mammals (including humans), a coracoid process is prese ...

is in all known specimens fused with the scapula into a scapulocoracoid The scapulocoracoid is the unit of the pectoral girdle that contains the coracoid and scapula.

The coracoid itself is a beak-shaped bone that is commonly found in most vertebrates with a few exceptions.

The scapula is commonly known as the ''shoulde ...

, lacking a visible suture. The coracoid as such is an oval bone plate, with its longest side attached to the scapula. It is pierced by a large oval foramen

In anatomy and osteology, a foramen (;Entry "foramen"

in

but the usual boss for the attachment of the upper arm muscles is lacking.

The in

humerus

The humerus (; ) is a long bone in the arm that runs from the shoulder to the elbow. It connects the scapula and the two bones of the lower arm, the radius and ulna, and consists of three sections. The humeral upper extremity consists of a roun ...

is very robust with strongly expanded upper and lower ends. Humerus specimen OUMNH J.13575 has a length of 388 millimetres. Its shaft circumference equals about half of the total humerus length. The humerus head continues to the front and the rear into large bosses, together forming a massive bone plate. On the front outer side of the shaft a large triangular deltopectoral crest Deltopectoral may refer to;

* Clavipectoral triangle, also known as the deltopectoral triangle

* Deltopectoral groove

* Deltopectoral lymph nodes

One or two deltopectoral lymph nodes (or infraclavicular nodes) are found beside the cephalic vein, b ...

is present, the attachment for the '' Musculus pectoralis major'' and the '' Musculus deltoideus''. It covers about the upper half of the shaft length, its apex positioned rather low. The ulna

The ulna (''pl''. ulnae or ulnas) is a long bone found in the forearm that stretches from the elbow to the smallest finger, and when in anatomical position, is found on the medial side of the forearm. That is, the ulna is on the same side of t ...

is extremely robust, for its absolute size more heavily built than with any other known member of the Tetanurae. The only known specimen, BMNH 36585, has a length of 232 millimetres and a minimal shaft circumference of 142 millimetres. The ulna is straight in front view and has a large olecranon

The olecranon (, ), is a large, thick, curved bony eminence of the ulna, a long bone in the forearm that projects behind the elbow. It forms the most pointed portion of the elbow and is opposite to the cubital fossa or elbow pit. The olecranon ...

, the attachment process for the '' Musculus triceps brachii''. Radius

In classical geometry, a radius ( : radii) of a circle or sphere is any of the line segments from its center to its perimeter, and in more modern usage, it is also their length. The name comes from the latin ''radius'', meaning ray but also the ...

, wrist and hand are unknown.

In the pelvis, the ilium is long and low, with a convex upper profile. Its front blade is triangular and rather short; at the front end there is a small drooping point, separated by a notch from the pubic peduncle. The rear blade is roughly rectangular. The outer side of the ilium is concave, serving as an attachment surface for the '' Musculus iliofemoralis'', the main thigh muscle. Above the hip joint, on this surface a low vertical ridge is present with conspicuous vertical grooves. The bottom of the rear blade is excavated by a narrow but deep trough forming a bony shelf for the attachment of the ''

In the pelvis, the ilium is long and low, with a convex upper profile. Its front blade is triangular and rather short; at the front end there is a small drooping point, separated by a notch from the pubic peduncle. The rear blade is roughly rectangular. The outer side of the ilium is concave, serving as an attachment surface for the '' Musculus iliofemoralis'', the main thigh muscle. Above the hip joint, on this surface a low vertical ridge is present with conspicuous vertical grooves. The bottom of the rear blade is excavated by a narrow but deep trough forming a bony shelf for the attachment of the ''Musculus caudofemoralis brevis

Musculus may refer to:

* Andreas Musculus (1514–1581), German Lutheran theologian

*Heinrich Musculus (b. 1868), Swedish-Norwegian businessperson

*Wolfgang Musculus

Wolfgang Musculus, born "Müslin" or "Mauslein", (10 September 1497 – 30 Augus ...

''. The outer side of the rear blade does not match the inner side, which thus can be seen as a separate "medial blade" that in side view is visible in two places: in the corner between outer side and the ischial peduncle and as a small surface behind the extreme rear tip of the outer side of the rear blade. The pubic bone is straight. The pubic bones of both pelvis halves are connected via narrow bony skirts that originated at a rather high position on the rear side and continued downwards to a point low on the front side of the shaft. The ischium is S-shaped in side view, showing at the transition point between the two curvatures a rough boss on the outer side. On the front edge of the ischial shaft an obturator process is present in the form of a low ridge, at its top separated from the shaft by a notch. To below, this ridge continues into an exceptionally thick bony skirt at the inner rear side of the shaft, covering over half of its length. Towards the end of the shaft, this skirt gradually merges with it. The shaft eventually ends in a sizeable "foot" with a convex lower profile.

The thighbone is straight in front view. Seen from the same direction its head is perpendicular to the shaft, seen from above it is orientated 20° to the front. The

The thighbone is straight in front view. Seen from the same direction its head is perpendicular to the shaft, seen from above it is orientated 20° to the front. The greater trochanter

The greater trochanter of the femur is a large, irregular, quadrilateral eminence and a part of the skeletal system.

It is directed lateral and medially and slightly posterior. In the adult it is about 2–4 cm lower than the femoral head.Stan ...

is relatively wide and separated from the robust lesser trochanter

The lesser trochanter is a conical posteromedial bony projection of the femoral shaft. it serves as the principal insertion site of the iliopsoas muscle.

Structure

The lesser trochanter is a conical posteromedial projection of the shaft of the fe ...

in front of it, by a fissure. At the front base of the lesser trochanter a low accessory trochanter is present. At the lower end of the thighbone a distinct front, extensor, groove separates the condyle