Matilda of England on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Empress Matilda ( 7 February 110210 September 1167), also known as the Empress Maude, was one of the claimants to the English throne during the civil war known as

In late 1108 or early 1109, King

In late 1108 or early 1109, King

In 1120, the English political landscape had changed dramatically after the '' White Ship'' disaster. Around three hundred passengers – including Matilda's brother William Adelin and many other senior nobles – embarked one night on the ''White Ship'' to travel from

In 1120, the English political landscape had changed dramatically after the '' White Ship'' disaster. Around three hundred passengers – including Matilda's brother William Adelin and many other senior nobles – embarked one night on the ''White Ship'' to travel from

Matilda returned to Normandy in 1125 and spent about a year at the royal court, where her father was still hoping that his second marriage would generate a son. If this failed to happen, Matilda was Henry's preferred choice, and he declared that she was to be his rightful successor if he should not have another legitimate son. The Anglo-Norman barons were gathered together at Westminster on Christmas 1126, where they swore in January to recognise Matilda and any future legitimate heir she might have.

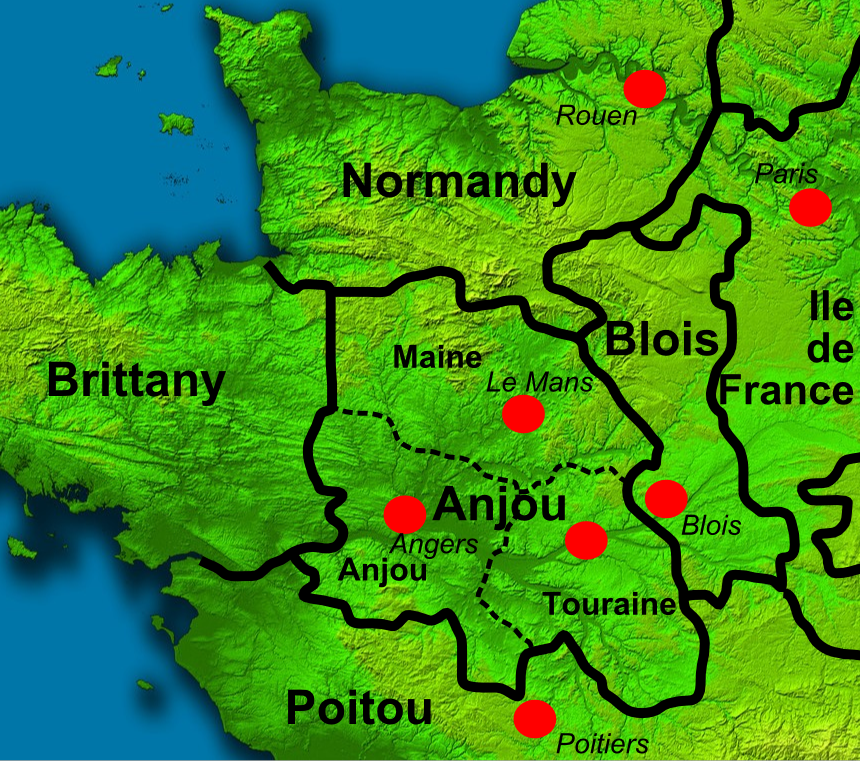

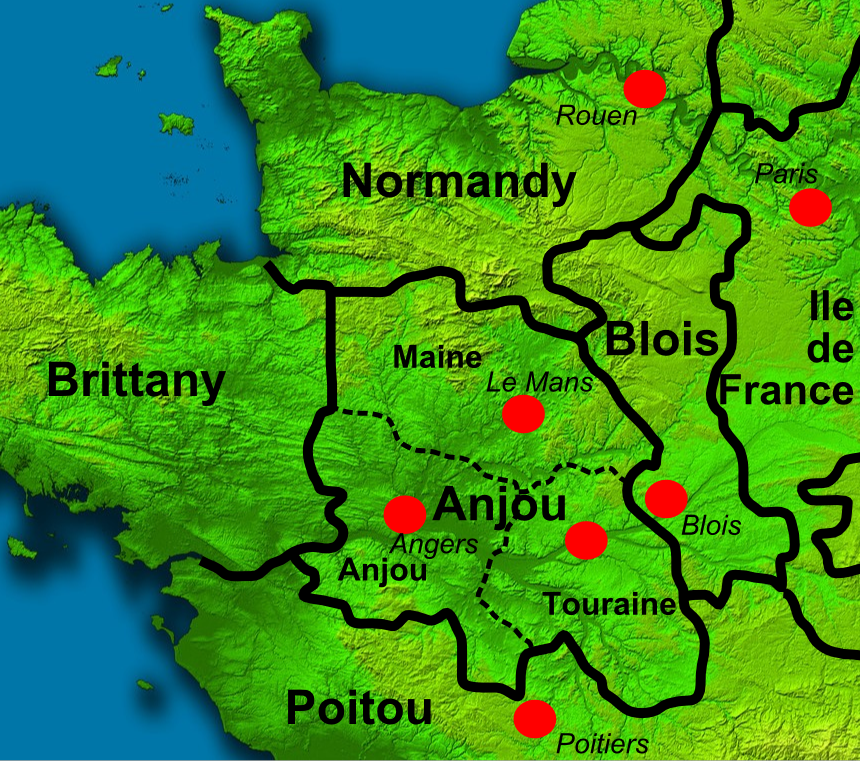

Henry began to formally look for a new husband for Matilda in early 1127 and received various offers from princes within the Empire. His preference was to use Matilda's marriage to secure the southern borders of Normandy by marrying her to Geoffrey, the eldest son of Count

Matilda returned to Normandy in 1125 and spent about a year at the royal court, where her father was still hoping that his second marriage would generate a son. If this failed to happen, Matilda was Henry's preferred choice, and he declared that she was to be his rightful successor if he should not have another legitimate son. The Anglo-Norman barons were gathered together at Westminster on Christmas 1126, where they swore in January to recognise Matilda and any future legitimate heir she might have.

Henry began to formally look for a new husband for Matilda in early 1127 and received various offers from princes within the Empire. His preference was to use Matilda's marriage to secure the southern borders of Normandy by marrying her to Geoffrey, the eldest son of Count

When news began to spread of Henry I's death, Matilda and Geoffrey were in Anjou, supporting the rebels in their campaign against the royal army, which included a number of Matilda's supporters such as Robert of Gloucester. Many of these barons had taken an oath to stay in Normandy until the late king was properly buried, which prevented them from returning to England. Nonetheless, Geoffrey and Matilda took the opportunity to march into southern Normandy and seize a number of key castles around

When news began to spread of Henry I's death, Matilda and Geoffrey were in Anjou, supporting the rebels in their campaign against the royal army, which included a number of Matilda's supporters such as Robert of Gloucester. Many of these barons had taken an oath to stay in Normandy until the late king was properly buried, which prevented them from returning to England. Nonetheless, Geoffrey and Matilda took the opportunity to march into southern Normandy and seize a number of key castles around

Matilda's half-brother, Robert of Gloucester, was one of the most powerful Anglo-Norman barons, controlling estates in Normandy as well as the

Matilda's half-brother, Robert of Gloucester, was one of the most powerful Anglo-Norman barons, controlling estates in Normandy as well as the

Empress Matilda's invasion finally began at the end of the summer of 1139. Baldwin de Redvers crossed over from Normandy to Wareham in August in an initial attempt to capture a port to receive Matilda's invading army, but Stephen's forces forced him to retreat into the south-west. The following month, the Empress was invited by her stepmother, Queen Adeliza, to land at

Empress Matilda's invasion finally began at the end of the summer of 1139. Baldwin de Redvers crossed over from Normandy to Wareham in August in an initial attempt to capture a port to receive Matilda's invading army, but Stephen's forces forced him to retreat into the south-west. The following month, the Empress was invited by her stepmother, Queen Adeliza, to land at

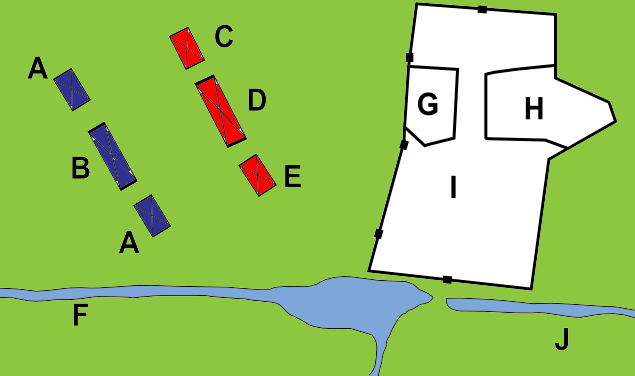

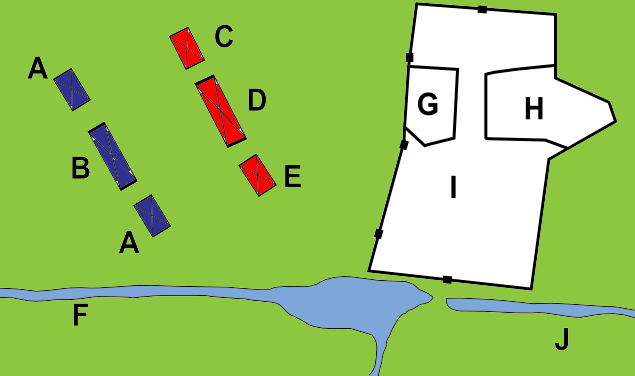

Matilda's fortunes changed dramatically for the better at the start of 1141. Ranulf of Chester, a powerful northern magnate, had fallen out with the King over the winter and Stephen had placed his castle in Lincoln under siege. In response, Robert of Gloucester and Ranulf advanced on Stephen's position with a larger force, resulting in the Battle of Lincoln on 2 February 1141. The King commanded the centre of his army, with Alan of Brittany on his right and William of Aumale on his left. Robert and Ranulf's forces had a superiority in cavalry and Stephen dismounted many of his own knights to form a solid infantry block. After an initial success in which William's forces destroyed the Angevins' Welsh infantry, the battle went well for Matilda's forces. Robert and Ranulf's cavalry encircled Stephen's centre, and the King found himself surrounded by the Angevin army. After much fighting, Robert's soldiers finally overwhelmed Stephen and he was taken away from the field in custody.

Matilda received Stephen in person at her court in Gloucester, before having him moved to

Matilda's fortunes changed dramatically for the better at the start of 1141. Ranulf of Chester, a powerful northern magnate, had fallen out with the King over the winter and Stephen had placed his castle in Lincoln under siege. In response, Robert of Gloucester and Ranulf advanced on Stephen's position with a larger force, resulting in the Battle of Lincoln on 2 February 1141. The King commanded the centre of his army, with Alan of Brittany on his right and William of Aumale on his left. Robert and Ranulf's forces had a superiority in cavalry and Stephen dismounted many of his own knights to form a solid infantry block. After an initial success in which William's forces destroyed the Angevins' Welsh infantry, the battle went well for Matilda's forces. Robert and Ranulf's cavalry encircled Stephen's centre, and the King found himself surrounded by the Angevin army. After much fighting, Robert's soldiers finally overwhelmed Stephen and he was taken away from the field in custody.

Matilda received Stephen in person at her court in Gloucester, before having him moved to

Matilda's position was transformed by her defeat at the Rout of Winchester. Her alliance with Henry of Blois proved short-lived and they soon fell out over political patronage and ecclesiastical policy; the Bishop transferred his support back to Stephen's cause. In response, in July Matilda and Robert of Gloucester besieged Henry of Blois in his episcopal castle at Winchester, using the royal castle in the city as the base for their operations. Stephen's wife, Queen Matilda, had kept his cause alive in the south-east of England, and the Queen, backed by her lieutenant

Matilda's position was transformed by her defeat at the Rout of Winchester. Her alliance with Henry of Blois proved short-lived and they soon fell out over political patronage and ecclesiastical policy; the Bishop transferred his support back to Stephen's cause. In response, in July Matilda and Robert of Gloucester besieged Henry of Blois in his episcopal castle at Winchester, using the royal castle in the city as the base for their operations. Stephen's wife, Queen Matilda, had kept his cause alive in the south-east of England, and the Queen, backed by her lieutenant

In the aftermath of the retreat from Winchester, Matilda rebuilt her court at

In the aftermath of the retreat from Winchester, Matilda rebuilt her court at

The character of the conflict in England gradually began to shift; by the late 1140s, the major fighting in the war was over, giving way to an intractable stalemate, with only the occasional outbreak of fresh fighting. Several of Matilda's key supporters died: in 1147 Robert of Gloucester died peacefully, and Brian Fitz Count gradually withdrew from public life, probably eventually joining a monastery; by 1151 he was dead. Many of Matilda's other followers joined the

The character of the conflict in England gradually began to shift; by the late 1140s, the major fighting in the war was over, giving way to an intractable stalemate, with only the occasional outbreak of fresh fighting. Several of Matilda's key supporters died: in 1147 Robert of Gloucester died peacefully, and Brian Fitz Count gradually withdrew from public life, probably eventually joining a monastery; by 1151 he was dead. Many of Matilda's other followers joined the

Matilda spent the rest of her life in Normandy, often acting as Henry's representative and presiding over the government of the Duchy. Early on, Matilda and her son issued charters in England and Normandy in their joint names, dealing with the various land claims that had arisen during the wars. Particularly in the initial years of his reign, the King drew on her for advice on policy matters. Matilda was involved in attempts to mediate between Henry and his Chancellor

Matilda spent the rest of her life in Normandy, often acting as Henry's representative and presiding over the government of the Duchy. Early on, Matilda and her son issued charters in England and Normandy in their joint names, dealing with the various land claims that had arisen during the wars. Particularly in the initial years of his reign, the King drew on her for advice on policy matters. Matilda was involved in attempts to mediate between Henry and his Chancellor

In the Holy Roman Empire, the young Matilda's court included knights, chaplains and ladies-in-waiting, although, unlike some queens of the period, she did not have her own personal chancellor to run her household, instead using the imperial chancellor. When acting as regent in Italy, she found the local rulers were prepared to accept a female ruler. Her Italian administration included the Italian chancellor, backed by experienced administrators. She was not called upon to make any major decisions, instead dealing with smaller matters and acting as the symbolic representative of her absent husband, meeting with and helping to negotiate with magnates and clergy.

The Anglo-Saxon queens of England had exercised considerable formal power, but this tradition had diminished under the Normans: at most their queens ruled temporarily as regents on their husbands' behalf when they were away travelling, rather than in their own right. On her return from Germany to Normandy and Anjou, Matilda styled herself as empress and the daughter of King Henry. As an , her status was elevated in medieval social and political thought above all men in England and France. On arrival in England, her charters' seal displayed the inscription . Matilda's enthroned portrait on her circular seal distinguished her from elite English contemporaries, both women – whose seals were usually oval with standing portraits – and men, whose seals were usually equestrian portraits. The seal did not depict her on horseback, however, as a male ruler would have been.; During the civil war for England, her status was uncertain; these unique distinctions were intended to overawe her subjects. Matilda also remained , a status that emphasised her claim to the crown was hereditary and derived from her male kin, being the only legitimate offspring of King Henry and Queen Matilda. It further advertised her mixed Anglo-Saxon and Norman descent and her claim as her royal father's sole heir in a century in which feudal tenancies were increasingly passed on by heredity and

In the Holy Roman Empire, the young Matilda's court included knights, chaplains and ladies-in-waiting, although, unlike some queens of the period, she did not have her own personal chancellor to run her household, instead using the imperial chancellor. When acting as regent in Italy, she found the local rulers were prepared to accept a female ruler. Her Italian administration included the Italian chancellor, backed by experienced administrators. She was not called upon to make any major decisions, instead dealing with smaller matters and acting as the symbolic representative of her absent husband, meeting with and helping to negotiate with magnates and clergy.

The Anglo-Saxon queens of England had exercised considerable formal power, but this tradition had diminished under the Normans: at most their queens ruled temporarily as regents on their husbands' behalf when they were away travelling, rather than in their own right. On her return from Germany to Normandy and Anjou, Matilda styled herself as empress and the daughter of King Henry. As an , her status was elevated in medieval social and political thought above all men in England and France. On arrival in England, her charters' seal displayed the inscription . Matilda's enthroned portrait on her circular seal distinguished her from elite English contemporaries, both women – whose seals were usually oval with standing portraits – and men, whose seals were usually equestrian portraits. The seal did not depict her on horseback, however, as a male ruler would have been.; During the civil war for England, her status was uncertain; these unique distinctions were intended to overawe her subjects. Matilda also remained , a status that emphasised her claim to the crown was hereditary and derived from her male kin, being the only legitimate offspring of King Henry and Queen Matilda. It further advertised her mixed Anglo-Saxon and Norman descent and her claim as her royal father's sole heir in a century in which feudal tenancies were increasingly passed on by heredity and

It is unclear how strong Matilda's personal piety was, although contemporaries praised her lifelong preference to be buried at the monastic site of Bec rather than the grander but more worldly Rouen, and believed her to have substantial, underlying religious beliefs. Like other members of the Anglo-Norman nobility, she bestowed considerable patronage on the Church. Early on in her life, she preferred the well-established

It is unclear how strong Matilda's personal piety was, although contemporaries praised her lifelong preference to be buried at the monastic site of Bec rather than the grander but more worldly Rouen, and believed her to have substantial, underlying religious beliefs. Like other members of the Anglo-Norman nobility, she bestowed considerable patronage on the Church. Early on in her life, she preferred the well-established

Contemporary chroniclers in England, France, Germany and Italy documented many aspects of Matilda's life, although the only biography of her, apparently written by Arnulf of Lisieux, has been lost. The chroniclers took a range of perspectives on her. In Germany, the chroniclers praised Matilda extensively and her reputation as the "good Matilda" remained positive. During the years of the Anarchy, works such as the ''Gesta Stephani'' took a much more negative tone, praising Stephen and condemning Matilda. Once Henry II assumed the throne, the tone of the chroniclers towards Matilda became more positive. Legends spread in the years after Matilda's death, including the suggestion that her first husband, Henry, had not died but had in fact secretly become a

Contemporary chroniclers in England, France, Germany and Italy documented many aspects of Matilda's life, although the only biography of her, apparently written by Arnulf of Lisieux, has been lost. The chroniclers took a range of perspectives on her. In Germany, the chroniclers praised Matilda extensively and her reputation as the "good Matilda" remained positive. During the years of the Anarchy, works such as the ''Gesta Stephani'' took a much more negative tone, praising Stephen and condemning Matilda. Once Henry II assumed the throne, the tone of the chroniclers towards Matilda became more positive. Legends spread in the years after Matilda's death, including the suggestion that her first husband, Henry, had not died but had in fact secretly become a

Review of Catherine Hanley's biography

{{DEFAULTSORT:Matilda, Empress 1102 births 1167 deaths 12th-century women rulers 12th-century English monarchs 12th-century Norman women Anglo-Normans Burials at Rouen Cathedral Countesses of Anjou Countesses of Maine Duchesses of Normandy English people of French descent English people of Scottish descent English princesses Holy Roman Empresses House of Normandy People from Sutton Courtenay People of The Anarchy Queens regnant of England Anglo-Norman women 12th-century English women 12th-century French women 12th-century French people 12th-century German women 12th-century women of the Holy Roman Empire Daughters of kings Remarried royal consorts Children of Henry I of England Royal reburials

the Anarchy

The Anarchy was a civil war in England and Normandy between 1138 and 1153, which resulted in a widespread breakdown in law and order. The conflict was a war of succession precipitated by the accidental death of William Adelin, the only legi ...

. The daughter of King Henry I of England

Henry I (c. 1068 – 1 December 1135), also known as Henry Beauclerc, was King of England from 1100 to his death in 1135. He was the fourth son of William the Conqueror and was educated in Latin and the liberal arts. On William's death in ...

, she moved to Germany as a child when she married the future Holy Roman Emperor Henry V

Henry V (german: Heinrich V.; probably 11 August 1081 or 1086 – 23 May 1125, in Utrecht) was King of Germany (from 1099 to 1125) and Holy Roman Emperor (from 1111 to 1125), as the fourth and last ruler of the Salian dynasty. He was made co-r ...

. She travelled with her husband to Italy in 1116, was controversially crowned in St Peter's Basilica

The Papal Basilica of Saint Peter in the Vatican ( it, Basilica Papale di San Pietro in Vaticano), or simply Saint Peter's Basilica ( la, Basilica Sancti Petri), is a Church (building), church built in the Renaissance architecture, Renaissanc ...

, and acted as the imperial regent

A regent (from Latin : ruling, governing) is a person appointed to govern a state '' pro tempore'' (Latin: 'for the time being') because the monarch is a minor, absent, incapacitated or unable to discharge the powers and duties of the monarchy ...

in Italy. Matilda and Henry V had no children, and when he died in 1125, the imperial crown was claimed by his rival Lothair of Supplinburg

Lothair III, sometimes numbered Lothair II and also known as Lothair of Supplinburg (1075 – 4 December 1137), was Holy Roman Emperor from 1133 until his death. He was appointed Duke of Saxony in 1106 and elected King of Germany in 1125 before ...

.

Matilda's younger and only full brother, William Adelin, died in the '' White Ship'' disaster of 1120, leaving Matilda's father and realm facing a potential succession crisis. On Emperor Henry V's death, Matilda was recalled to Normandy

Normandy (; french: link=no, Normandie ; nrf, Normaundie, Nouormandie ; from Old French , plural of ''Normant'', originally from the word for "northman" in several Scandinavian languages) is a geographical and cultural region in Northwestern ...

by her father, who arranged for her to marry Geoffrey of Anjou

Geoffrey V (24 August 1113 – 7 September 1151), called the Handsome, the Fair (french: link=no, le Bel) or Plantagenet, was the count of Anjou, Touraine and Maine by inheritance from 1129, and also Duke of Normandy by conquest from 1144. His ...

to form an alliance to protect his southern borders. Henry I had no further legitimate children and nominated Matilda as his heir, making his court swear an oath

Traditionally an oath (from Anglo-Saxon ', also called plight) is either a statement of fact or a promise taken by a sacrality as a sign of verity. A common legal substitute for those who conscientiously object to making sacred oaths is to g ...

of loyalty to her and her successors, but the decision was not popular in the Anglo-Norman Anglo-Norman may refer to:

*Anglo-Normans, the medieval ruling class in England following the Norman conquest of 1066

*Anglo-Norman language

**Anglo-Norman literature

*Anglo-Norman England, or Norman England, the period in English history from 1066 ...

court. Henry died in 1135, but Matilda and Geoffrey faced opposition from Anglo-Norman barons. The throne was instead taken by Matilda's cousin Stephen of Blois, who enjoyed the backing of the English Church

The Church of England (C of E) is the established Christian church in England and the mother church of the international Anglican Communion. It traces its history to the Christian church recorded as existing in the Roman province of Britain ...

. Stephen took steps to solidify his new regime but faced threats both from neighbouring powers and from opponents within his kingdom.

In 1139, Matilda crossed to England to take the kingdom by force, supported by her half-brother Robert of Gloucester and her uncle King David I of Scotland, while her husband, Geoffrey, focused on conquering Normandy. Matilda's forces captured Stephen at the Battle of Lincoln in 1141, but the Empress's attempt to be crowned at Westminster

Westminster is an area of Central London, part of the wider City of Westminster.

The area, which extends from the River Thames to Oxford Street, has many visitor attractions and historic landmarks, including the Palace of Westminster, B ...

collapsed in the face of bitter opposition from the London crowds. As a result of this retreat, Matilda was never formally declared Queen of England, and was instead titled "Lady of the English" (). Robert was captured following the Rout of Winchester in 1141, and Matilda agreed to exchange him for Stephen. Matilda became trapped in Oxford Castle

Oxford Castle is a large, partly ruined medieval castle on the western side of central Oxford in Oxfordshire, England. Most of the original moated, wooden motte and bailey castle was replaced in stone in the late 12th or early 13th century and ...

by Stephen's forces that winter, and to avoid capture was forced to escape at night across the frozen River Isis

"The Isis" () is an alternative name for the River Thames, used from its source in the Cotswolds until it is joined by the Thame at Dorchester in Oxfordshire. It derives from the ancient name for the Thames, ''Tamesis'', which in the Middle ...

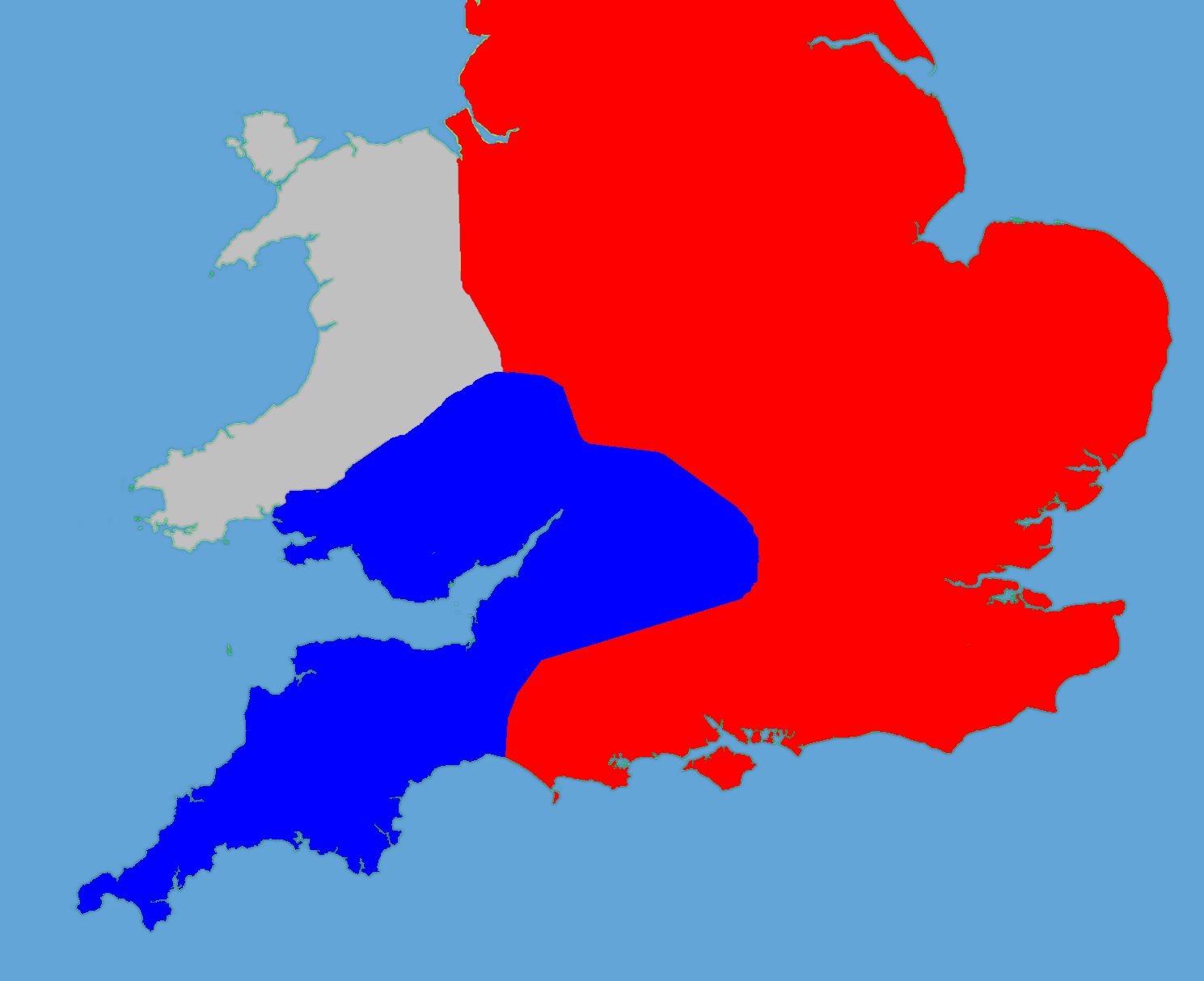

to Abingdon, reputedly wearing white as camouflage in the snow. The war degenerated into a stalemate, with Matilda controlling much of the south-west of England, and Stephen the south-east and the Midlands. Large parts of the rest of the country were in the hands of local, independent barons.

Matilda returned to Normandy, now in the hands of her husband, in 1148, leaving her eldest son to continue the campaign in England; he eventually succeeded to the throne as Henry II in 1154, forming the Angevin Empire

The Angevin Empire (; french: Empire Plantagenêt) describes the possessions of the House of Plantagenet during the 12th and 13th centuries, when they ruled over an area covering roughly half of France, all of England, and parts of Ireland and W ...

. She settled her court near Rouen

Rouen (, ; or ) is a city on the River Seine in northern France. It is the prefecture of the region of Normandy and the department of Seine-Maritime. Formerly one of the largest and most prosperous cities of medieval Europe, the population ...

and for the rest of her life concerned herself with the administration of Normandy, acting on her son's behalf when necessary. Particularly in the early years of her son's reign, she provided political advice and attempted to mediate during the Becket controversy. She worked extensively with the Church, founding Cistercian

The Cistercians, () officially the Order of Cistercians ( la, (Sacer) Ordo Cisterciensis, abbreviated as OCist or SOCist), are a Catholic religious order of monks and nuns that branched off from the Benedictines and follow the Rule of Saint B ...

monasteries, and was known for her piety. She was buried under the high altar at Bec Abbey

Bec Abbey, formally the Abbey of Our Lady of Bec (french: Abbaye Notre-Dame du Bec), is a Benedictine monastic foundation in the Eure ''département'', in the Bec valley midway between the cities of Rouen and Bernay. It is located in Le Bec Hel ...

after her death in 1167.

Early life

Matilda was born toHenry I Henry I may refer to:

876–1366

* Henry I the Fowler, King of Germany (876–936)

* Henry I, Duke of Bavaria (died 955)

* Henry I of Austria, Margrave of Austria (died 1018)

* Henry I of France (1008–1060)

* Henry I the Long, Margrave of the N ...

, King of England and Duke of Normandy

In the Middle Ages, the duke of Normandy was the ruler of the Duchy of Normandy in north-western France. The duchy arose out of a grant of land to the Viking leader Rollo by the French king Charles III in 911. In 924 and again in 933, Normand ...

, and his first wife, Matilda of Scotland, possibly around 7 February 1102 at Sutton Courtenay

Sutton Courtenay is a village and civil parish on the River Thames south of Abingdon-on-Thames and northwest of Didcot. Historically part of Berkshire, it has been administered as part of Oxfordshire since the 1974 boundary changes. The ...

, in Berkshire. Henry was the youngest son of William the Conqueror

William I; ang, WillelmI (Bates ''William the Conqueror'' p. 33– 9 September 1087), usually known as William the Conqueror and sometimes William the Bastard, was the first Norman king of England, reigning from 1066 until his death in 10 ...

, who had invaded England in 1066, creating an empire stretching into Wales. The invasion had created an Anglo-Norman Anglo-Norman may refer to:

*Anglo-Normans, the medieval ruling class in England following the Norman conquest of 1066

*Anglo-Norman language

**Anglo-Norman literature

*Anglo-Norman England, or Norman England, the period in English history from 1066 ...

elite, many with estates spread across both sides of the English Channel

The English Channel, "The Sleeve"; nrf, la Maunche, "The Sleeve" ( Cotentinais) or ( Jèrriais), ( Guernésiais), "The Channel"; br, Mor Breizh, "Sea of Brittany"; cy, Môr Udd, "Lord's Sea"; kw, Mor Bretannek, "British Sea"; nl, Het Ka ...

. These barons typically had close links to the kingdom of France

The Kingdom of France ( fro, Reaume de France; frm, Royaulme de France; french: link=yes, Royaume de France) is the historiographical name or umbrella term given to various political entities of France in the medieval and early modern period. ...

, which was then a loose collection of counties and smaller polities, under only the minimal control of the king. Her mother Matilda was the daughter of King Malcolm III of Scotland, a member of the West Saxon royal family, and a descendant of Alfred the Great

Alfred the Great (alt. Ælfred 848/849 – 26 October 899) was King of the West Saxons from 871 to 886, and King of the Anglo-Saxons from 886 until his death in 899. He was the youngest son of King Æthelwulf and his first wife Osburh, who bo ...

. For Henry, marrying Matilda of Scotland had given his reign increased legitimacy, and for her it had been an opportunity for high status and power in England.

Matilda had a younger, legitimate brother, William Adelin, and her father's relationships with numerous mistresses resulted in around 22 illegitimate siblings. Little is known about Matilda's earliest life, but she probably stayed with her mother, was taught to read, and was educated in religious morals. Among the nobles at her mother's court were her uncle David

David (; , "beloved one") (traditional spelling), , ''Dāwūd''; grc-koi, Δαυΐδ, Dauíd; la, Davidus, David; gez , ዳዊት, ''Dawit''; xcl, Դաւիթ, ''Dawitʿ''; cu, Давíдъ, ''Davidŭ''; possibly meaning "beloved one". w ...

, later the king of Scotland, and aspiring nobles such as her half-brother Robert of Gloucester, her cousin Stephen of Blois and Brian Fitz Count. In 1108 Henry left Matilda and her brother in the care of Anselm, the archbishop of Canterbury

The archbishop of Canterbury is the senior bishop and a principal leader of the Church of England, the ceremonial head of the worldwide Anglican Communion and the diocesan bishop of the Diocese of Canterbury. The current archbishop is Just ...

, while he travelled to Normandy; Anselm was a favoured cleric of Matilda's mother. There is no detailed description of Matilda's appearance; contemporaries described Matilda as being very beautiful, but this may have simply reflected the conventional practice among the chroniclers.

Holy Roman Empire

Marriage and coronation

In late 1108 or early 1109, King

In late 1108 or early 1109, King Henry V of Germany

Henry V (german: Heinrich V.; probably 11 August 1081 or 1086 – 23 May 1125, in Utrecht) was King of Germany (from 1099 to 1125) and Holy Roman Emperor (from 1111 to 1125), as the fourth and last ruler of the Salian dynasty. He was made co-ru ...

sent envoys to Normandy proposing that Matilda marry him, and wrote separately to her mother on the same matter. The match was attractive to the English king: his daughter would be marrying into one of the most prestigious dynasties in Europe, reaffirming his own, slightly questionable, status as the youngest son of a new royal house, and gaining him an ally in dealing with France. In return, Henry V would receive a dowry of 10,000 marks

Marks may refer to:

Business

* Mark's, a Canadian retail chain

* Marks & Spencer, a British retail chain

* Collective trade marks, trademarks owned by an organisation for the benefit of its members

* Marks & Co, the inspiration for the novel ...

, which he needed to fund an expedition to Rome for his coronation as the Holy Roman emperor. The final details of the deal were negotiated at Westminster

Westminster is an area of Central London, part of the wider City of Westminster.

The area, which extends from the River Thames to Oxford Street, has many visitor attractions and historic landmarks, including the Palace of Westminster, Bu ...

in June 1109 and, as a result of her changing status, Matilda attended a royal council for the first time that October. She left England in February 1110 to make her way to Germany.

The couple met at Liège

Liège ( , , ; wa, Lîdje ; nl, Luik ; german: Lüttich ) is a major city and municipality of Wallonia and the capital of the Belgian province of Liège.

The city is situated in the valley of the Meuse, in the east of Belgium, not far from b ...

before travelling to Utrecht

Utrecht ( , , ) is the List of cities in the Netherlands by province, fourth-largest city and a List of municipalities of the Netherlands, municipality of the Netherlands, capital and most populous city of the Provinces of the Netherlands, pro ...

where, on 10 April, they became officially betrothed. On 25 July Matilda was crowned German queen

German queen (german: Deutsche Königin) is the informal title used when referring to the wife of the king of the Kingdom of Germany. The official titles of the wives of German kings were Queen of the Germans and later Queen of the Romans ( la, ...

in a ceremony at Mainz

Mainz () is the capital and largest city of Rhineland-Palatinate, Germany.

Mainz is on the left bank of the Rhine, opposite to the place that the Main (river), Main joins the Rhine. Downstream of the confluence, the Rhine flows to the north-we ...

. There was a considerable age gap between the couple, as Matilda was only eight years old while Henry was 24. After the betrothal she was placed into the custody of Bruno

Bruno may refer to:

People and fictional characters

*Bruno (name), including lists of people and fictional characters with either the given name or surname

* Bruno, Duke of Saxony (died 880)

* Bruno the Great (925–965), Archbishop of Cologne, ...

, the archbishop of Trier

The Diocese of Trier, in English historically also known as ''Treves'' (IPA "tɾivz") from French ''Trèves'', is a Latin Church ecclesiastical territory or diocese of the Catholic church in Germany.Worms Worms may refer to:

*Worm, an invertebrate animal with a tube-like body and no limbs

Places

*Worms, Germany, a city

**Worms (electoral district)

*Worms, Nebraska, U.S.

*Worms im Veltlintal, the German name for Bormio, Italy

Arts and entertainme ...

amid extravagant celebrations. Matilda now entered public life in Germany, complete with her own household.

Political conflict broke out across the Empire shortly after the marriage, triggered when Henry arrested his chancellor, Archbishop Adalbert of Mainz

Adalbert I von Saarbrücken (died June 23, 1137) was Archbishop-Elector of Mainz from 1111 until his death. He played a key role in opposing Henry V, Holy Roman Emperor, during the Investiture Controversy, and secured the election of Lothair III ...

, and various other German princes. Rebellions followed, accompanied by opposition from within the Church, which played an important part in administering the Empire, and this led to the formal excommunication of the Emperor by Pope Paschal II

Pope Paschal II ( la, Paschalis II; 1050 1055 – 21 January 1118), born Ranierius, was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 13 August 1099 to his death in 1118. A monk of the Abbey of Cluny, he was cre ...

. Henry and Matilda marched over the Alps

The Alps () ; german: Alpen ; it, Alpi ; rm, Alps ; sl, Alpe . are the highest and most extensive mountain range system that lies entirely in Europe, stretching approximately across seven Alpine countries (from west to east): France, Sw ...

into Italy in early 1116, intent on settling matters permanently with the Pope. Matilda was now playing a full part in the imperial government, sponsoring royal grants, dealing with petitioners and taking part in ceremonial occasions. The rest of the year was spent establishing control of northern Italy, and in early 1117 the pair advanced on Rome itself.

Paschal fled when Henry and Matilda arrived with their army, and in his absence the papal envoy Maurice Bourdin

Gregory VIII (died 1137), born Mauritius Burdinus (''Maurice Bourdin''), was antipope from 10 March 1118 until 22 April 1121.

Biography

He was born in the Limousin, part of Occitania, France. He was educated at Cluny, at Limoges, and in Castile ...

, later antipope

An antipope ( la, antipapa) is a person who makes a significant and substantial attempt to occupy the position of Bishop of Rome and leader of the Catholic Church in opposition to the legitimately elected pope. At times between the 3rd and mid- ...

under the name Gregory VIII, crowned the pair at St Peter's Basilica

The Papal Basilica of Saint Peter in the Vatican ( it, Basilica Papale di San Pietro in Vaticano), or simply Saint Peter's Basilica ( la, Basilica Sancti Petri), is a church built in the Renaissance style located in Vatican City, the papal en ...

, probably that Easter and certainly (again) at Pentecost

Pentecost (also called Whit Sunday, Whitsunday or Whitsun) is a Christianity, Christian holiday which takes place on the 50th day (the seventh Sunday) after Easter Sunday. It commemorates the descent of the Holy Spirit upon the Apostles in the Ne ...

. Matilda used these ceremonies to claim the title of the empress of the Holy Roman Empire. The Empire was governed by monarchs who, like Henry V, had been elected by the major nobles to become the king. These kings typically hoped to be subsequently crowned by the pope as emperors, but this could not be guaranteed. Henry V had coerced Paschal II into crowning him in 1111, but Matilda's own status was less clear. As a result of her marriage she was clearly the legitimate queen of the Romans, a title that she used thereafter on her seal and charters, but it was uncertain if she had a legitimate claim to the title of empress. After his imperial coronation in 1111, Henry continued to call himself king and emperor of the Romans interchangeably.

Both Bourdin's status and the ceremonies themselves were deeply ambiguous. Strictly speaking, the ceremonies were not imperial coronations but instead were formal "crown-wearing" occasions, among the few times in the year when the rulers would wear their crowns in court.; ; Bourdin had also been excommunicated

Excommunication is an institutional act of religious censure used to end or at least regulate the communion of a member of a congregation with other members of the religious institution who are in normal communion with each other. The purpose ...

by the time he conducted the second ceremony, and he was later deposed and imprisoned for life by Pope Callixtus II

Pope Callixtus II or Callistus II ( – 13 December 1124), born Guy of Burgundy, was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 1 February 1119 to his death in 1124. His pontificate was shaped by the Investiture Controversy, ...

. Nonetheless, Matilda maintained that she had been officially crowned as the empress in Rome. Her use of the title became widely accepted. Matilda consistently used the title empress from 1117 until her death; chanceries and chroniclers alike conceded her the honorific, seemingly without question.

Widowhood

In 1118, Henry returned north over the Alps into Germany to suppress fresh rebellions, leaving Matilda as hisregent

A regent (from Latin : ruling, governing) is a person appointed to govern a state '' pro tempore'' (Latin: 'for the time being') because the monarch is a minor, absent, incapacitated or unable to discharge the powers and duties of the monarchy ...

to govern Italy. There are few records of her rule over the next two years, but she probably gained considerable practical experience of government. In 1119, she returned north to meet Henry in Lotharingia

Lotharingia ( la, regnum Lotharii regnum Lothariense Lotharingia; french: Lotharingie; german: Reich des Lothar Lotharingien Mittelreich; nl, Lotharingen) was a short-lived medieval successor kingdom of the Carolingian Empire. As a more durable ...

. Her husband was occupied in finding a compromise with the Pope, who had excommunicated him. In 1122, Henry and probably Matilda were at the Council of Worms. The council settled the long-running dispute with the Church when Henry gave up his rights to invest bishops with their episcopal regalia. Matilda attempted to visit her father in England that year, but the journey was blocked by Count Charles I of Flanders, whose territory she would have needed to pass through. Historian Marjorie Chibnall

Marjorie McCallum Chibnall (27 September 1915 – 23 June 2012) was an English historian, medievalist and Latin translator. She edited the ''Historia Ecclesiastica'' by Orderic Vitalis, with whom she shared the same birthplace of Atcham in Shr ...

argues Matilda had intended to discuss the inheritance of the English crown on this journey.

Matilda and Henry remained childless, but neither party was considered to be infertile and contemporary chroniclers blamed their situation on the Emperor and his sins against the Church. In early 1122, the couple travelled down the Rhine

), Surselva, Graubünden, Switzerland

, source1_coordinates=

, source1_elevation =

, source2 = Rein Posteriur/Hinterrhein

, source2_location = Paradies Glacier, Graubünden, Switzerland

, source2_coordinates=

, so ...

together as Henry continued to suppress the ongoing political unrest, but by now he was suffering from cancer. He died on 23 May 1125 in Utrecht, leaving Matilda in the protection of their nephew Frederick Frederick may refer to:

People

* Frederick (given name), the name

Nobility

Anhalt-Harzgerode

*Frederick, Prince of Anhalt-Harzgerode (1613–1670)

Austria

* Frederick I, Duke of Austria (Babenberg), Duke of Austria from 1195 to 1198

* Frederick ...

, the heir to his estates, and in possession of the imperial insignia. It is unclear what instructions he gave her about the future of the Empire, which faced another leadership election. Archbishop Adalbert subsequently convinced Matilda that she should give him the insignia, and led the electoral process which appointed Lothair of Supplinburg

Lothair III, sometimes numbered Lothair II and also known as Lothair of Supplinburg (1075 – 4 December 1137), was Holy Roman Emperor from 1133 until his death. He was appointed Duke of Saxony in 1106 and elected King of Germany in 1125 before ...

, a former enemy of Henry, as the new king.

Now aged 23, Matilda had only limited options as to how she might spend the rest of her life. Being childless, she could not exercise a role as an imperial regent, which left her with the choice of either becoming a nun

A nun is a woman who vows to dedicate her life to religious service, typically living under vows of poverty, chastity, and obedience in the enclosure of a monastery or convent.''The Oxford English Dictionary'', vol. X, page 599. The term is o ...

or remarrying. Some offers of marriage started to arrive from German princes, but she chose to return to Normandy. She does not appear to have expected to return to Germany, as she gave up her estates within the Empire and departed with her personal collection of jewels, her own imperial regalia, two of Henry's crowns, and the valuable relic of the Hand of St James the Apostle

The Hand of Saint James the Apostle is a holy relic brought to England by Empress Matilda in the 12th century. In 1539 at the Dissolution of the Monasteries, English monks hid the hand in an iron chest in the walls of Reading Abbey. It was dug ...

.

Succession crisis

In 1120, the English political landscape had changed dramatically after the '' White Ship'' disaster. Around three hundred passengers – including Matilda's brother William Adelin and many other senior nobles – embarked one night on the ''White Ship'' to travel from

In 1120, the English political landscape had changed dramatically after the '' White Ship'' disaster. Around three hundred passengers – including Matilda's brother William Adelin and many other senior nobles – embarked one night on the ''White Ship'' to travel from Barfleur

Barfleur () is a commune and fishing village in Manche, Normandy, northwestern France.

History

During the Middle Ages, Barfleur was one of the chief ports of embarkation for England.

* 1066: A large medallion fixed to a rock in the harbour ...

in Normandy across to England. The vessel foundered just outside the harbour, possibly as a result of overcrowding or excessive drinking by the ship's master and crew, and all but two of the passengers died. William Adelin was among the casualties.

With William dead, the succession to the English throne was thrown into doubt. Rules of succession were uncertain in western Europe at the time; in some parts of France, male primogeniture

Primogeniture ( ) is the right, by law or custom, of the firstborn legitimate child to inherit the parent's entire or main estate in preference to shared inheritance among all or some children, any illegitimate child or any collateral relativ ...

was becoming more popular, in which the eldest son would inherit a title. It was also traditional for the king of France to crown his successor while he was still alive, making the intended line of succession relatively clear. This was not the case in England, where the best a noble could do was to identify what Professor Eleanor Searle has termed a pool of legitimate heirs, leaving them to challenge and dispute the inheritance after his death. The problem was further complicated by the sequence of unstable Anglo-Norman successions over the previous sixty years. William the Conqueror had invaded England, his sons William Rufus

William II ( xno, Williame; – 2 August 1100) was King of England from 26 September 1087 until his death in 1100, with powers over Normandy and influence in Scotland. He was less successful in extending control into Wales. The third so ...

and Robert Curthose

Robert Curthose, or Robert II of Normandy ( 1051 – 3 February 1134, french: Robert Courteheuse / Robert II de Normandie), was the eldest son of William the Conqueror and succeeded his father as Duke of Normandy in 1087, reigning until 1106. ...

had fought a war between them to establish their inheritance, and Henry had only acquired control of Normandy by force. There had been no peaceful, uncontested successions.

Initially, Henry put his hopes in fathering another son. William and Matilda's mother—Matilda of Scotland—had died in 1118, and so Henry took a new wife, Adeliza of Louvain

Adeliza of Louvain, sometimes known in England as Adelicia of Louvain, also called Adela and Aleidis; (c. 1103 – March/April 1151) was Queen of England from 1121 to 1135, as the second wife of King Henry I. She was the daughter of Godfrey I, ...

. Henry and Adeliza did not conceive any children, and the future of the dynasty appeared at risk. Henry may have begun to look among his nephews for a possible heir. He may have considered his sister Adela

Adela may refer to:

* ''Adela'', a 1933 Romanian novel by Garabet Ibrăileanu

* ''Adela'' (1985 film), a 1985 Romanian film directed by Mircea Veroiu

* ''Adela'' (2000 film), a 2000 Argentine thriller film directed and written by Eduardo Mign ...

's son Stephen of Blois as a possible option and, perhaps in preparation for this, he arranged a beneficial marriage for Stephen to Empress Matilda's wealthy maternal cousin Countess Matilda I of Boulogne

Matilda (c.1105 – 3 May 1152) was Countess of Boulogne in her own right from 1125 and Queen of England from the accession of her husband, Stephen, in 1136 until her death in 1152. She supported Stephen in his struggle for the English throne ...

. Count Theobald IV of Blois Theobald is a Germanic dithematic name, composed from the elements '' theod-'' "people" and ''bald'' "bold". The name arrived in England with the Normans.

The name occurs in many spelling variations, including Theudebald, Diepold, Theobalt, Tybal ...

, another nephew and close ally, possibly also felt that he was in favour with Henry. William Clito

William Clito (25 October 110228 July 1128) was a member of the House of Normandy who ruled the County of Flanders from 1127 until his death and unsuccessfully claimed the Duchy of Normandy. As the son of Robert Curthose, the eldest son of William ...

, the only son of Robert Curthose, was King Louis VI of France

Louis VI (late 1081 – 1 August 1137), called the Fat (french: link=no, le Gros) or the Fighter (french: link=no, le Batailleur), was King of the Franks from 1108 to 1137.

Chronicles called him "King of Saint-Denis". Louis was the first member ...

's preferred choice, but William was in open rebellion against Henry and was therefore unsuitable. Henry might have also considered his own illegitimate son, Robert of Gloucester, as a possible candidate, but English tradition and custom would have looked unfavourably on this. Henry's plans shifted when Empress Matilda's husband, Emperor Henry, died in 1125.

Return to Normandy

Marriage to Geoffrey of Anjou

Matilda returned to Normandy in 1125 and spent about a year at the royal court, where her father was still hoping that his second marriage would generate a son. If this failed to happen, Matilda was Henry's preferred choice, and he declared that she was to be his rightful successor if he should not have another legitimate son. The Anglo-Norman barons were gathered together at Westminster on Christmas 1126, where they swore in January to recognise Matilda and any future legitimate heir she might have.

Henry began to formally look for a new husband for Matilda in early 1127 and received various offers from princes within the Empire. His preference was to use Matilda's marriage to secure the southern borders of Normandy by marrying her to Geoffrey, the eldest son of Count

Matilda returned to Normandy in 1125 and spent about a year at the royal court, where her father was still hoping that his second marriage would generate a son. If this failed to happen, Matilda was Henry's preferred choice, and he declared that she was to be his rightful successor if he should not have another legitimate son. The Anglo-Norman barons were gathered together at Westminster on Christmas 1126, where they swore in January to recognise Matilda and any future legitimate heir she might have.

Henry began to formally look for a new husband for Matilda in early 1127 and received various offers from princes within the Empire. His preference was to use Matilda's marriage to secure the southern borders of Normandy by marrying her to Geoffrey, the eldest son of Count Fulk V of Anjou

Fulk ( la, Fulco, french: Foulque or ''Foulques''; c. 1089/1092 – 13 November 1143), also known as Fulk the Younger, was the count of Anjou (as Fulk V) from 1109 to 1129 and the king of Jerusalem with his wife from 1131 to his death. During t ...

. Henry's control of Normandy had faced numerous challenges since he had conquered it in 1106, and the latest threat came from his nephew William Clito, the new count of Flanders, who enjoyed the support of the French king. It was essential to Henry that he not face a threat from the south as well as the east of Normandy. William Adelin had married Fulk's daughter Matilda

Matilda or Mathilda may refer to:

Animals

* Matilda (chicken) (1990–2006), World's Oldest Living Chicken record holder

* Matilda (horse) (1824–1846), British Thoroughbred racehorse

* Matilda, a dog of the professional wrestling tag-team The ...

, which would have cemented an alliance between Henry and Anjou, but the ''White Ship'' disaster put an end to this. Henry and Fulk argued over the fate of the marriage dowry, and this had encouraged Fulk to turn to support William Clito instead. Henry's solution was now to negotiate the marriage of Matilda to Geoffrey, recreating the former alliance.

Matilda appears to have been unimpressed by the prospect of marrying Geoffrey of Anjou. She felt that marrying the son of a count diminished her imperial status and was probably also unhappy about marrying someone so much younger than she was; Matilda was 25 and Geoffrey was 13. Hildebert

Hildebert (c. 105518 December 1133) was a French ecclesiastic, hagiographer and theologian. From 1096–97 he was bishop of Le Mans, then from 1125 until his death archbishop of Tours. Sometimes called Hildebert of Lavardin, his name may also be s ...

, the Archbishop of Tours

The Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Tours (Latin: ''Archidioecesis Turonensis''; French: ''Archidiocèse de Tours'') is an archdiocese of the Latin Rite of the Roman Catholic Church in France. The archdiocese has roots that go back to the 3rd cent ...

, eventually intervened to persuade her to go along with the engagement. Matilda finally agreed, and she travelled to Rouen in May 1127 with Robert of Gloucester and Brian Fitz Count where she was formally betrothed to Geoffrey. Over the course of the next year, Fulk decided to depart for Jerusalem, where he hoped to become king, leaving his possessions to Geoffrey. Henry knighted his future son-in-law, and Matilda and Geoffrey were married a week later on 17 June 1128 in Le Mans

Le Mans (, ) is a city in northwestern France on the Sarthe River where it meets the Huisne. Traditionally the capital of the province of Maine, it is now the capital of the Sarthe department and the seat of the Roman Catholic diocese of Le Man ...

by the bishops of Le Mans

Le Mans (, ) is a city in northwestern France on the Sarthe River where it meets the Huisne. Traditionally the capital of the province of Maine, it is now the capital of the Sarthe department and the seat of the Roman Catholic diocese of Le Man ...

and Séez. Fulk finally left Anjou for Jerusalem in 1129, declaring Geoffrey the count of Anjou and Maine.

Disputes

The marriage proved difficult, as the couple did not particularly like each other.; There was a further dispute over Matilda's dowry; she was granted various castles in Normandy by Henry, but it was not specified when the couple would actually take possession of them.; It is also unknown whether Henry intended Geoffrey to have any future claim on England or Normandy, and he was probably keeping Geoffrey's status deliberately uncertain. Soon after the marriage, Matilda left Geoffrey and returned to Normandy. Henry appears to have blamed Geoffrey for the separation, but the couple were finally reconciled in 1131. Henry summoned Matilda from Normandy, and she arrived in England that August. It was decided that Matilda would return to Geoffrey at a meeting of the King's great council in September. The council also gave another collective oath of allegiance to recognise her as Henry's heir. Matilda gave birth to her first son in March 1133 at Le Mans, the future Henry II. Henry I was delighted by the news and came to see her at Rouen. At Pentecost 1134, their second son Geoffrey was born in Rouen, but the childbirth was extremely difficult and Matilda appeared close to death. She made arrangements for her will and argued with her father about where she should be buried. Matilda preferredBec Abbey

Bec Abbey, formally the Abbey of Our Lady of Bec (french: Abbaye Notre-Dame du Bec), is a Benedictine monastic foundation in the Eure ''département'', in the Bec valley midway between the cities of Rouen and Bernay. It is located in Le Bec Hel ...

, but Henry wanted her to be interred at Rouen Cathedral

Rouen Cathedral (french: Cathédrale primatiale Notre-Dame de l'Assomption de Rouen) is a Roman Catholic church in Rouen, Normandy, France. It is the see of the Archbishop of Rouen, Primate of Normandy. It is famous for its three towers, each in ...

. Matilda recovered, and Henry was overjoyed by the birth of his second grandson, possibly insisting on another round of oaths from his nobility.

From then on, relations became increasingly strained between Matilda and Henry. Matilda and Geoffrey suspected that they lacked genuine support in England for their claim to the throne, and proposed in 1135 that the King should hand over the royal castles in Normandy to Matilda and should insist that the Norman nobility immediately swear allegiance to her. This would have given the couple a much more powerful position after Henry's death, but the King angrily refused, probably out of a concern that Geoffrey would try to seize power in Normandy while he was still alive. A fresh rebellion broke out in southern Normandy, and Geoffrey and Matilda intervened militarily on behalf of the rebels.

In the middle of this confrontation, Henry unexpectedly fell ill and died near Lyons-la-Forêt

Lyons-la-Forêt () is a commune of the Eure department, Normandy, in northwest France. Lyons-la-Forêt has distinctive historical geography, and architecture, and contemporary culture, as a consequence of the Forest of Lyons, and its bocage, and of ...

. It is uncertain what, if anything, Henry said about the succession before his death. Contemporary chronicler accounts were coloured by subsequent events. Sources favourable to Matilda suggested that Henry had reaffirmed his intent to grant all his lands to his daughter, while hostile chroniclers argued that Henry had renounced his former plans and had apologised for having forced the barons to swear an oath of allegiance to her.

Road to war

When news began to spread of Henry I's death, Matilda and Geoffrey were in Anjou, supporting the rebels in their campaign against the royal army, which included a number of Matilda's supporters such as Robert of Gloucester. Many of these barons had taken an oath to stay in Normandy until the late king was properly buried, which prevented them from returning to England. Nonetheless, Geoffrey and Matilda took the opportunity to march into southern Normandy and seize a number of key castles around

When news began to spread of Henry I's death, Matilda and Geoffrey were in Anjou, supporting the rebels in their campaign against the royal army, which included a number of Matilda's supporters such as Robert of Gloucester. Many of these barons had taken an oath to stay in Normandy until the late king was properly buried, which prevented them from returning to England. Nonetheless, Geoffrey and Matilda took the opportunity to march into southern Normandy and seize a number of key castles around Argentan

Argentan () is a commune and the seat of two cantons and of an arrondissement in the Orne department in northwestern France.

Argentan is located NE of Rennes, ENE of the Mont Saint-Michel, SE of Cherbourg, SSE of Caen, SW of Rouen and N ...

that had formed Matilda's disputed dowry. They then stopped, unable to advance further, pillaging the countryside and facing increased resistance from the Norman nobility and a rebellion in Anjou itself. Matilda was by now also pregnant with her third son, William

William is a male given name of Germanic origin.Hanks, Hardcastle and Hodges, ''Oxford Dictionary of First Names'', Oxford University Press, 2nd edition, , p. 276. It became very popular in the English language after the Norman conquest of Engl ...

; opinions vary among historians as to what extent this affected her military plans.; ;

Meanwhile, news of Henry's death had reached Stephen of Blois, conveniently placed in Boulogne, and he left for England, accompanied by his military household. Robert of Gloucester had garrisoned the ports of Dover and Canterbury and some accounts suggest that they refused Stephen access when he first arrived. Nonetheless Stephen reached the edge of London by 8 December and over the next week he began to seize power in England. The crowds in London proclaimed Stephen the new monarch, believing that he would grant the city new rights and privileges in return, and his brother, Henry of Blois

Henry of Blois ( c. 1096 8 August 1171), often known as Henry of Winchester, was Abbot of Glastonbury Abbey from 1126, and Bishop of Winchester from 1129 to his death. He was a younger son of Stephen Henry, Count of Blois by Adela of Normandy, da ...

, the bishop of Winchester

The Bishop of Winchester is the diocesan bishop of the Diocese of Winchester in the Church of England. The bishop's seat (''cathedra'') is at Winchester Cathedral in Hampshire. The Bishop of Winchester has always held ''ex officio'' (except dur ...

, delivered the support of the Church to Stephen. Stephen had sworn to support Matilda in 1127, but Henry convincingly argued that the late King had been wrong to insist that his court take the oath, and suggested that the King had changed his mind on his deathbed. Stephen's coronation was held at Westminster Abbey on 22 December.

Following the news that Stephen was gathering support in England, the Norman nobility had gathered at Le Neubourg

Le Neubourg is a commune in Eure, Normandy, France. The composer and organist Roger Boucher (1885–1918) was born in Le Neubourg.

History

In the 11th century the manor of Le Neubourg was a subsidiary holding of Roger de Beaumont (d.1094), a pri ...

to discuss declaring his elder brother Theobald Theobald is a Germanic dithematic name, composed from the elements '' theod-'' "people" and ''bald'' "bold". The name arrived in England with the Normans.

The name occurs in many spelling variations, including Theudebald, Diepold, Theobalt, Tybal ...

king. The Normans argued that the count, as the eldest grandson of William the Conqueror, had the most valid claim over the kingdom and the Duchy, and was certainly preferable to Matilda. Their discussions were interrupted by the sudden news from England that Stephen's coronation was to occur the next day. Theobald's support immediately ebbed away, as the barons were not prepared to support the division of England and Normandy by opposing Stephen.

Matilda gave birth to her third son William on 22 July 1136 at Argentan, and she then operated out of the border region for the next three years, establishing her household knights on estates around the area. Matilda may have asked Ulger

Ulger (''Ulgerius''; died 1149) was the Bishop of Angers from 1125. Like his predecessor, Rainald de Martigné (died 1123), he consolidated the Gregorian reform in his diocese.

Ulger was a student of Marbod and the latter's successor as archdeac ...

, the bishop of Angers

The Roman Catholic Diocese of Angers ( Latin: ''Dioecesis Andegavensis''; French: ''Diocèse d'Angers'') is a diocese of the Latin Rite of the Roman Catholic Church in France. The episcopal see is located in Angers Cathedral in the city of A ...

, to garner support for her claim with Pope Innocent II

Pope Innocent II ( la, Innocentius II; died 24 September 1143), born Gregorio Papareschi, was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 14 February 1130 to his death in 1143. His election as pope was controversial and the fi ...

in Rome, but if she did, Ulger was unsuccessful. Geoffrey invaded Normandy in early 1136 and, after a temporary truce, invaded again later the same year, raiding and burning estates rather than trying to hold the territory. Stephen returned to the Duchy in 1137, where he met with Louis VI and Theobald to agree to an informal alliance against Geoffrey and Matilda, to counter the growing Angevin

Angevin or House of Anjou may refer to:

*County of Anjou or Duchy of Anjou, a historical county, and later Duchy, in France

**Angevin (language), the traditional langue d'oïl spoken in Anjou

**Counts and Dukes of Anjou

* House of Ingelger, a Frank ...

power in the region. Stephen formed an army to retake Matilda's Argentan castles, but frictions between his Flemish mercenary forces and the local Norman barons resulted in a battle between the two-halves of his army. The Norman forces then deserted the King, forcing Stephen to give up his campaign. Stephen agreed to another truce with Geoffrey, promising to pay him 2,000 marks a year in exchange for peace along the Norman borders.

In England, Stephen's reign started off well, with lavish gatherings of the royal court that saw the King give out grants of land and favours to his supporters. Stephen received the support of Pope Innocent II

Pope Innocent II ( la, Innocentius II; died 24 September 1143), born Gregorio Papareschi, was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 14 February 1130 to his death in 1143. His election as pope was controversial and the fi ...

, thanks in part to the testimony of Louis VI and Theobald. Troubles rapidly began to emerge. Matilda's uncle, David I of Scotland, invaded the north of England on the news of Henry's death, taking Carlisle

Carlisle ( , ; from xcb, Caer Luel) is a city that lies within the Northern England, Northern English county of Cumbria, south of the Anglo-Scottish border, Scottish border at the confluence of the rivers River Eden, Cumbria, Eden, River C ...

, Newcastle Newcastle usually refers to:

*Newcastle upon Tyne, a city and metropolitan borough in Tyne and Wear, England

*Newcastle-under-Lyme, a town in Staffordshire, England

*Newcastle, New South Wales, a metropolitan area in Australia, named after Newcastle ...

and other key strongholds. Stephen rapidly marched north with an army and met David at Durham Durham most commonly refers to:

*Durham, England, a cathedral city and the county town of County Durham

*County Durham, an English county

* Durham County, North Carolina, a county in North Carolina, United States

*Durham, North Carolina, a city in N ...

, where a temporary compromise was agreed. South Wales rose in rebellion, and by 1137 Stephen was forced to abandon attempts to suppress the revolt. Stephen put down two revolts in the south-west led by Baldwin de Redvers

Baldwin de Redvers, 1st Earl of Devon (died 4 June 1155), feudal baron of Plympton in Devon, was the son of Richard de Redvers and his wife Adeline Peverel.

He was one of the first to rebel against King Stephen, and was the only first rank magnat ...

and Robert of Bampton; Baldwin was released after his capture and travelled to Normandy, where he became a vocal critic of the King.

Revolt

Matilda's half-brother, Robert of Gloucester, was one of the most powerful Anglo-Norman barons, controlling estates in Normandy as well as the

Matilda's half-brother, Robert of Gloucester, was one of the most powerful Anglo-Norman barons, controlling estates in Normandy as well as the Earldom of Gloucester

The title of Earl of Gloucester was created several times in the Peerage of England. A fictional earl is also a character in William Shakespeare's play ''King Lear.''

Earls of Gloucester, 1st Creation (1121)

*Robert, 1st Earl of Gloucester (1100 ...

. In 1138, he rebelled against Stephen, starting the descent into civil war in England. Robert renounced his fealty to the King and declared his support for Matilda, which triggered a major regional rebellion in Kent

Kent is a county in South East England and one of the home counties. It borders Greater London to the north-west, Surrey to the west and East Sussex to the south-west, and Essex to the north across the estuary of the River Thames; it faces ...

and across the south-west of England, although he himself remained in Normandy. Matilda had not been particularly active in asserting her claims to the throne since 1135 and in many ways it was Robert who took the initiative in declaring war in 1138. In France, Geoffrey took advantage of the situation by re-invading Normandy. David of Scotland also invaded the north of England once again, announcing that he was supporting the claim of Matilda to the throne, pushing south into Yorkshire

Yorkshire ( ; abbreviated Yorks), formally known as the County of York, is a Historic counties of England, historic county in northern England and by far the largest in the United Kingdom. Because of its large area in comparison with other Eng ...

.

Stephen responded quickly to the revolts and invasions, paying most attention to England rather than to Normandy. His wife Matilda was sent to Kent with ships and resources from Boulogne, with the task of retaking the key port of Dover

Dover () is a town and major ferry port in Kent, South East England. It faces France across the Strait of Dover, the narrowest part of the English Channel at from Cap Gris Nez in France. It lies south-east of Canterbury and east of Maidstone ...

, under Robert's control. A small number of Stephen's household knights were sent north to help the fight against the Scots, where David's forces were defeated later that year at the Battle of the Standard. Despite this victory, however, David still occupied most of the north. Stephen himself went west in an attempt to regain control of Gloucestershire

Gloucestershire ( abbreviated Glos) is a county in South West England. The county comprises part of the Cotswold Hills, part of the flat fertile valley of the River Severn and the entire Forest of Dean.

The county town is the city of Gl ...

, first striking north into the Welsh Marches

The Welsh Marches ( cy, Y Mers) is an imprecisely defined area along the border between England and Wales in the United Kingdom. The precise meaning of the term has varied at different periods.

The English term Welsh March (in Medieval Latin ...

, taking Hereford

Hereford () is a cathedral city, civil parish and the county town of Herefordshire, England. It lies on the River Wye, approximately east of the border with Wales, south-west of Worcester and north-west of Gloucester. With a population ...

and Shrewsbury

Shrewsbury ( , also ) is a market town, civil parish, and the county town of Shropshire, England, on the River Severn, north-west of London; at the 2021 census, it had a population of 76,782. The town's name can be pronounced as either 'Sh ...

, before heading south to Bath. The town of Bristol

Bristol () is a city, ceremonial county and unitary authority in England. Situated on the River Avon, it is bordered by the ceremonial counties of Gloucestershire to the north and Somerset to the south. Bristol is the most populous city in ...

itself proved too strong for him, and Stephen contented himself with raiding and pillaging the surrounding area. The rebels appear to have expected Robert to intervene with support, but he remained in Normandy throughout the year, trying to persuade the Empress Matilda to invade England herself. Dover finally surrendered to the Queen's forces later in the year.

By 1139, an invasion of England by Robert and Matilda appeared imminent. Geoffrey and Matilda had secured much of Normandy and, together with Robert, spent the beginning of the year mobilising forces for a cross-Channel expedition. Matilda also appealed to the papacy at the start of the year; her representative, Bishop Ulger, put forward her legal claim to the English throne on the grounds of her hereditary right and the oaths sworn by the barons. Arnulf of Lisieux

Arnulf of Lisieux (1104/1109 – 31 August 1184) was a medieval French bishop who figured prominently as a conservative figure during the Renaissance of the 12th century, built the Cathedral of Lisieux, which introduced Gothic architecture to No ...

led Stephen's case, arguing that because Matilda's mother had really been a nun, her claim to the throne was illegitimate. The Pope declined to reverse his earlier support for Stephen, but from Matilda's perspective the case usefully established that Stephen's claim was disputed.

Civil War

Initial moves

Arundel

Arundel ( ) is a market town and civil parish in the Arun District of the South Downs, West Sussex, England.

The much-conserved town has a medieval castle and Roman Catholic cathedral. Arundel has a museum and comes second behind much large ...

instead, and on 30 September Robert of Gloucester and Matilda arrived in England with a force of 140 knights. Matilda stayed at Arundel Castle

Arundel Castle is a restored and remodelled medieval castle in Arundel, West Sussex, England. It was established during the reign of Edward the Confessor and completed by Roger de Montgomery. The castle was damaged in the English Civil War a ...

, while Robert marched north-west to Wallingford and Bristol, hoping to raise support for the rebellion and to link up with Miles of Gloucester

Miles FitzWalter of Gloucester, 1st Earl of Hereford (died 24 December 1143) (''alias'' Miles of GloucesterSanders, I.J. English Baronies: A Study of their Origin and Descent 1086-1327, Oxford, 1960, p.7) was a great magnate based in the west of ...

, who took the opportunity to renounce his fealty to the King and declare for Matilda.

Stephen responded by promptly moving south, besieging Arundel and trapping Matilda inside the castle. Stephen then agreed to a truce proposed by his brother, Henry of Blois; the full details of the agreement are not known, but the results were that Matilda and her household of knights were released from the siege and escorted to the south-west of England, where they were reunited with Robert of Gloucester. The reasons for Matilda's release remain unclear. Stephen may have thought it was in his own best interests to release the Empress and concentrate instead on attacking Robert, seeing Robert, rather than Matilda, as his main opponent at this point in the conflict. Arundel Castle was also considered almost impregnable, and Stephen may have been worried that he risked tying down his army in the south whilst Robert roamed freely in the west. Another theory is that Stephen released Matilda out of a sense of chivalry

Chivalry, or the chivalric code, is an informal and varying code of conduct developed in Europe between 1170 and 1220. It was associated with the medieval Christianity, Christian institution of knighthood; knights' and gentlemen's behaviours we ...

; Stephen had a generous, courteous personality and women were not normally expected to be targeted in Anglo-Norman warfare.

After staying for a period in Robert's stronghold of Bristol, Matilda established her court in nearby Gloucester, still safely in the south-west but far enough away for her to remain independent of her half-brother. Although there had been only a few new defections to her cause, Matilda still controlled a compact block of territory stretching out from Gloucester and Bristol south into Wiltshire

Wiltshire (; abbreviated Wilts) is a historic and ceremonial county in South West England with an area of . It is landlocked and borders the counties of Dorset to the southwest, Somerset to the west, Hampshire to the southeast, Gloucestershire ...

, west into the Welsh Marches and east through the Thames Valley

The Thames Valley is an informally-defined sub-region of South East England, centred on the River Thames west of London, with Oxford as a major centre. Its boundaries vary with context. The area is a major tourist destination and economic hub, ...

as far as Oxford and Wallingford, threatening London. Her influence extended down into Devon and Cornwall, and north through Herefordshire

Herefordshire () is a county in the West Midlands of England, governed by Herefordshire Council. It is bordered by Shropshire to the north, Worcestershire to the east, Gloucestershire to the south-east, and the Welsh counties of Monmouthshire ...

, but her authority in these areas remained limited.

She faced a counterattack from Stephen, who started by attacking Wallingford Castle

Wallingford Castle was a major medieval castle situated in Wallingford in the English county of Oxfordshire (historically Berkshire), adjacent to the River Thames. Established in the 11th century as a motte-and-bailey design within an Anglo-Sa ...

which controlled the Thames corridor; it was held by Brian Fitz Count and Stephen found it too well defended. Stephen continued into Wiltshire to attack Trowbridge

Trowbridge ( ) is the county town of Wiltshire, England, on the River Biss in the west of the county. It is near the border with Somerset and lies southeast of Bath, 31 miles (49 km) southwest of Swindon and 20 miles (32 km) southe ...

, taking the castles of South Cerney

South Cerney is a village and civil parish in the Cotswold district of Gloucestershire, 3 miles south of Cirencester and close to the border with Wiltshire. It had a population of 3,074 according to the 2001 census, increasing to 3,464 at the ...

and Malmesbury

Malmesbury () is a town and civil parish in north Wiltshire, England, which lies approximately west of Swindon, northeast of Bristol, and north of Chippenham. The older part of the town is on a hilltop which is almost surrounded by the up ...

en route. In response, Miles marched east, attacking Stephen's rearguard forces at Wallingford and threatening an advance on London. Stephen was forced to give up his western campaign, returning east to stabilise the situation and protect his capital.

At the start of 1140, Nigel

Nigel ( ) is an English language, English masculine given name.

The English ''Nigel'' is commonly found in records dating from the Middle Ages; however, it was not used much before being revived by 19th-century antiquarians. For instance, Walte ...

, the Bishop of Ely, joined Matilda's faction. Hoping to seize East Anglia

East Anglia is an area in the East of England, often defined as including the counties of Norfolk, Suffolk and Cambridgeshire. The name derives from the Anglo-Saxon kingdom of the East Angles, a people whose name originated in Anglia, in ...

, he established his base of operations in the Isle of Ely

The Isle of Ely () is a historic region around the city of Ely in Cambridgeshire, England. Between 1889 and 1965, it formed an administrative county.

Etymology

Its name has been said to mean "island of eels", a reference to the creatures that ...

, then surrounded by protective fen

A fen is a type of peat-accumulating wetland fed by mineral-rich ground or surface water. It is one of the main types of wetlands along with marshes, swamps, and bogs. Bogs and fens, both peat-forming ecosystems, are also known as mires. T ...

land. Nigel faced a rapid response from Stephen, who made a surprise attack on the isle, forcing the Bishop to flee to Gloucester. Robert of Gloucester's men retook some of the territory that Stephen had taken in his 1139 campaign. In an effort to negotiate a truce, Henry of Blois held a peace conference at Bath, at which Matilda was represented by Robert. The conference collapsed after Henry and the clergy insisted that they should set the terms of any peace deal, which Stephen's representatives found unacceptable.

Battle of Lincoln

Matilda's fortunes changed dramatically for the better at the start of 1141. Ranulf of Chester, a powerful northern magnate, had fallen out with the King over the winter and Stephen had placed his castle in Lincoln under siege. In response, Robert of Gloucester and Ranulf advanced on Stephen's position with a larger force, resulting in the Battle of Lincoln on 2 February 1141. The King commanded the centre of his army, with Alan of Brittany on his right and William of Aumale on his left. Robert and Ranulf's forces had a superiority in cavalry and Stephen dismounted many of his own knights to form a solid infantry block. After an initial success in which William's forces destroyed the Angevins' Welsh infantry, the battle went well for Matilda's forces. Robert and Ranulf's cavalry encircled Stephen's centre, and the King found himself surrounded by the Angevin army. After much fighting, Robert's soldiers finally overwhelmed Stephen and he was taken away from the field in custody.

Matilda received Stephen in person at her court in Gloucester, before having him moved to