LGBT Rights In Spain on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT) rights in Spain have undergone several significant changes over the last decades to become some of the most advanced in the world. As of the 2020s,

In 1822, the Kingdom of Spain's first penal code was adopted and same-sex sexual intercourse was legalised. In 1928, under the dictatorship of

In 1822, the Kingdom of Spain's first penal code was adopted and same-sex sexual intercourse was legalised. In 1928, under the dictatorship of

In 1994, the ''Ley de Arrendamientos Urbanos'' was passed, giving same-sex couples some recognition rights. Registries for same-sex couples were created in all of Spain's 17 autonomous communities:

In 1994, the ''Ley de Arrendamientos Urbanos'' was passed, giving same-sex couples some recognition rights. Registries for same-sex couples were created in all of Spain's 17 autonomous communities:

Spanish law prohibits discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation, gender identity, HIV status, and "any other personal or social condition or circumstance.” in employment and provision of goods and services. A comprehensive anti-discrimination bill, called the Zerolo Law, was passed by the

Spanish law prohibits discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation, gender identity, HIV status, and "any other personal or social condition or circumstance.” in employment and provision of goods and services. A comprehensive anti-discrimination bill, called the Zerolo Law, was passed by the

In November 2006, the Zapatero Government passed a law that allows

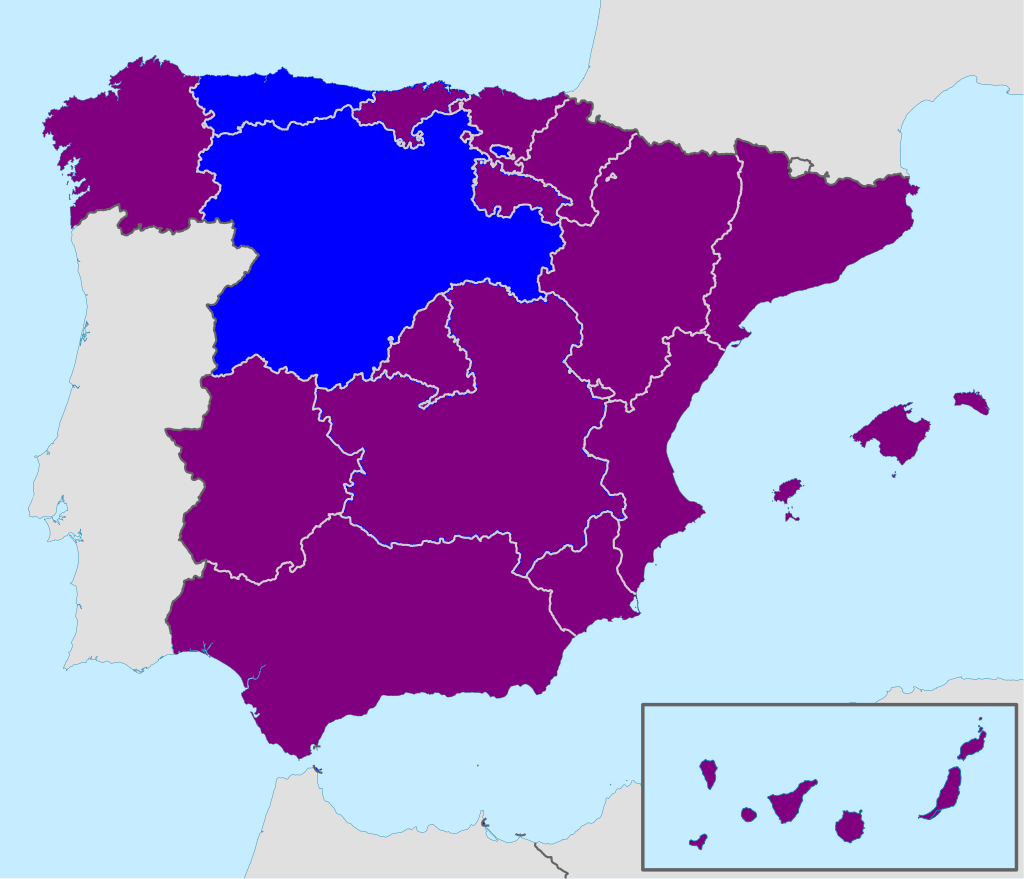

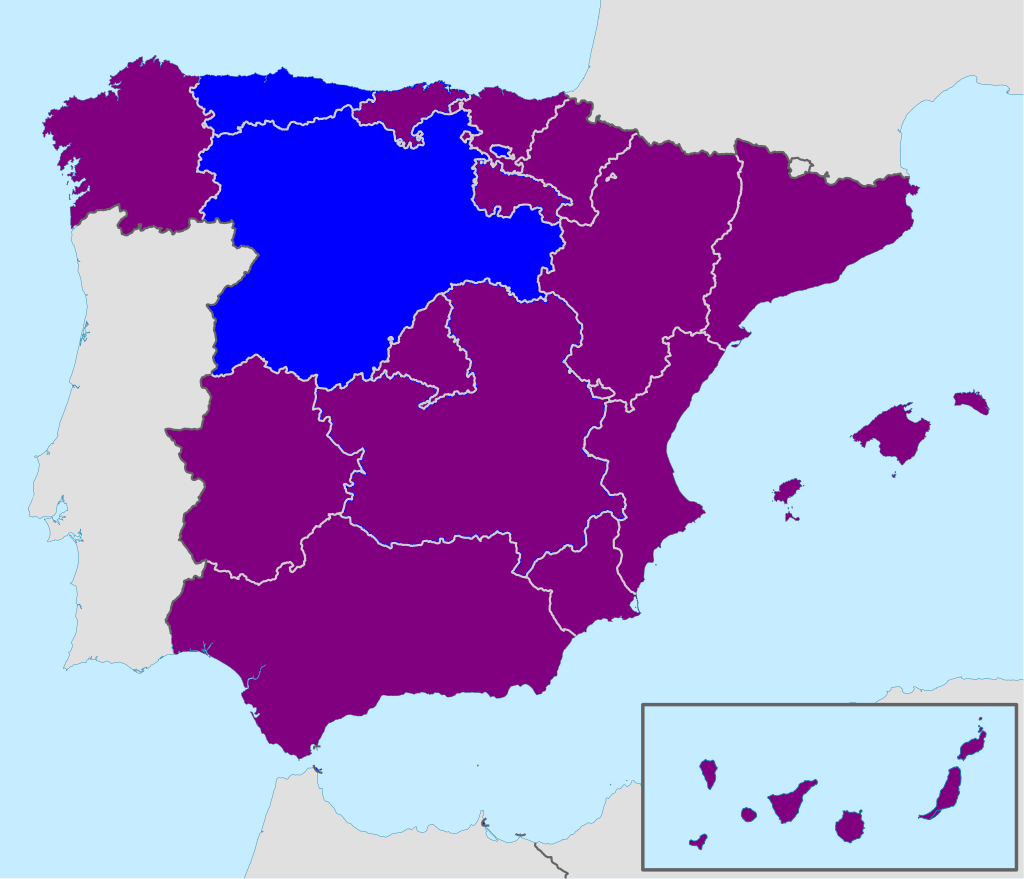

In November 2006, the Zapatero Government passed a law that allows  Many of Spain's autonomous communities have their own laws which allow trans people to change their legal gender identity. Catalonia (since 2014), Andalucía (since 2014), Valencia (since 2014), Extremadura (since 2015), Balearic Islands (since 2016), Madrid (since 2016), Murcia (since 2016), Navarre (since 2017), Aragón (since 2018), Basque Country (since 2019), Cantabria (since 2020), Canary Islands (since 2021), La Rioja (since 2022), and Castilla-La Mancha (since 2022) allow trans people to self-declare their gender identity. In Galicia, a gender change requires a medical diagnosis.

Many of Spain's autonomous communities have their own laws which allow trans people to change their legal gender identity. Catalonia (since 2014), Andalucía (since 2014), Valencia (since 2014), Extremadura (since 2015), Balearic Islands (since 2016), Madrid (since 2016), Murcia (since 2016), Navarre (since 2017), Aragón (since 2018), Basque Country (since 2019), Cantabria (since 2020), Canary Islands (since 2021), La Rioja (since 2022), and Castilla-La Mancha (since 2022) allow trans people to self-declare their gender identity. In Galicia, a gender change requires a medical diagnosis.

The autonomous

The autonomous

/ref> In January 2019,

The first gay organisation in Spain was the Spanish Homosexual Liberation Movement (MELH, '' Movimiento Español de Liberación Homosexual'', '' Moviment Espanyol d'Alliberament Homosexual''), which was founded in 1970 in

The first gay organisation in Spain was the Spanish Homosexual Liberation Movement (MELH, '' Movimiento Español de Liberación Homosexual'', '' Moviment Espanyol d'Alliberament Homosexual''), which was founded in 1970 in

Fiona Govan, Madrid; 4 March 2013; ''

At the beginning of the 20th century, Spanish authors, like

At the beginning of the 20th century, Spanish authors, like

Early representation of homosexuality in Spanish cinema was difficult due to censorship by the Franco regime. The first movie that shows any kind of homosexuality, very discreetly, was ''Diferente'', a musical from 1961, directed by Luis María Delgado. Up to 1977, if homosexuals appeared at all, it was to ridicule them as the "funny effeminate faggot".

During the Spanish transition to democracy, the first films appeared where homosexuality was not portrayed in a negative way. Examples are ''

Early representation of homosexuality in Spanish cinema was difficult due to censorship by the Franco regime. The first movie that shows any kind of homosexuality, very discreetly, was ''Diferente'', a musical from 1961, directed by Luis María Delgado. Up to 1977, if homosexuals appeared at all, it was to ridicule them as the "funny effeminate faggot".

During the Spanish transition to democracy, the first films appeared where homosexuality was not portrayed in a negative way. Examples are ''

During Franco's dictatorship, musicians seldom made any reference to homosexuality in their songs or in public speeches. An exception was the '' copla'' singer Miguel de Molina, openly homosexual and against Franco. De Molina fled to

During Franco's dictatorship, musicians seldom made any reference to homosexuality in their songs or in public speeches. An exception was the '' copla'' singer Miguel de Molina, openly homosexual and against Franco. De Molina fled to

Several openly gay politicians have served in public office in Spain. One of the most prominent gay politicians is Jerónimo Saavedra, who served as

Several openly gay politicians have served in public office in Spain. One of the most prominent gay politicians is Jerónimo Saavedra, who served as

Sports is traditionally a difficult area for LGBT visibility. Recently though, there have been professional sportswomen and sportsmen who have come out. These include

Sports is traditionally a difficult area for LGBT visibility. Recently though, there have been professional sportswomen and sportsmen who have come out. These include

Spain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = '' Plus ultra'' ( Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem = (English: "Royal March")

, ...

is considered one of the most culturally liberal and LGBT-friendly countries in the world.

Among ancient Romans

In modern historiography, ancient Rome refers to Roman civilisation from the founding of the city of Rome in the 8th century BC to the collapse of the Western Roman Empire in the 5th century AD. It encompasses the Roman Kingdom (753–509 B ...

in Spain, sexual interaction between men was viewed as commonplace and marriages between men occurred during the early Roman Empire, but a law against homosexuality was promulgated by Christian emperors Constantius II

Constantius II (Latin: ''Flavius Julius Constantius''; grc-gre, Κωνστάντιος; 7 August 317 – 3 November 361) was Roman emperor from 337 to 361. His reign saw constant warfare on the borders against the Sasanian Empire and Germanic ...

and Constans

Flavius Julius Constans ( 323 – 350), sometimes called Constans I, was Roman emperor from 337 to 350. He held the imperial rank of ''caesar'' from 333, and was the youngest son of Constantine the Great.

After his father's death, he was made ...

, and Roman moral norms underwent significant changes leading up to the 4th century. Laws against sodomy were later established during the legislative period. They were first repealed from the Spanish Code in 1822, but changed again along with societal attitudes towards homosexuality during the Spanish Civil War

The Spanish Civil War ( es, Guerra Civil Española)) or The Revolution ( es, La Revolución, link=no) among Nationalists, the Fourth Carlist War ( es, Cuarta Guerra Carlista, link=no) among Carlism, Carlists, and The Rebellion ( es, La Rebeli ...

and Francisco Franco

Francisco Franco Bahamonde (; 4 December 1892 – 20 November 1975) was a Spanish general who led the Nationalist forces in overthrowing the Second Spanish Republic during the Spanish Civil War and thereafter ruled over Spain from 19 ...

's regime

In politics, a regime (also "régime") is the form of government or the set of rules, cultural or social norms, etc. that regulate the operation of a government or institution and its interactions with society. According to Yale professor Juan J ...

.

Throughout the late-20th century, the rights of the LGBT

' is an initialism that stands for lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender. In use since the 1990s, the initialism, as well as some of its common variants, functions as an umbrella term for sexuality and gender identity.

The LGBT term i ...

community received more awareness and same-sex sexual activity became legal once again in 1979 with an equal age of consent

The age of consent is the age at which a person is considered to be legally competent to consent to sexual acts. Consequently, an adult who engages in sexual activity with a person younger than the age of consent is unable to legally cla ...

to heterosexual intercourse. After recognising unregistered cohabitation

Unregistered cohabitation is a legal status (sometimes ''de facto'') given to same-sex or opposite-sex couples in certain jurisdictions. They may be similar to common-law marriages.

More specifically, unregistered cohabitation may refer to:

* ...

between same-sex couples countrywide and registered partnerships in certain cities and communities since 1994 and 1997, Spain legalised both same-sex marriage

Same-sex marriage, also known as gay marriage, is the marriage of two people of the same sex or gender. marriage between same-sex couples is legally performed and recognized in 33 countries, with the most recent being Mexico, constituting ...

and adoption rights for same-sex couples in 2005. Transgender individuals can change their legal gender without the need for sex reassignment surgery

Gender-affirming surgery (GAS) is a surgical procedure, or series of procedures, that alters a transgender or transsexual person's physical appearance and sexual characteristics to resemble those associated with their identified gender, and al ...

or sterilisation. Discrimination in employment regarding sexual orientation

Sexual orientation is an enduring pattern of romantic or sexual attraction (or a combination of these) to persons of the opposite sex or gender, the same sex or gender, or to both sexes or more than one gender. These attractions are generally ...

has been banned nationwide since 1995. A broader law prohibiting discrimination based on sexual orientation and gender identity in employment and provision of goods and services nationwide was passed in 2022. LGBT people are allowed to serve in the military and MSMs can donate blood since 2005.

Spain has been recognised as one of the most culturally liberal and LGBT-friendly countries in the world and LGBT culture

LGBT culture is a culture shared by lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer individuals. It is sometimes referred to as queer culture (indicating people who are queer), while the term gay culture may be used to mean "LGBT culture" or ...

has had a significant role in Spanish literature

Spanish literature generally refers to literature ( Spanish poetry, prose, and drama) written in the Spanish language within the territory that presently constitutes the Kingdom of Spain. Its development coincides and frequently intersects wit ...

, music

Music is generally defined as the The arts, art of arranging sound to create some combination of Musical form, form, harmony, melody, rhythm or otherwise Musical expression, expressive content. Exact definition of music, definitions of mu ...

, cinema and other forms of entertainment as well as social issues and politics. Public opinion on homosexuality is noted by pollsters as being overwhelmingly positive, with a study conducted by the Pew Research Center in 2013 indicating that more than 88 percent of Spanish citizens accepted homosexuality, making it the most LGBT-friendly of the 39 countries polled. LGBT visibility has also increased in several layers of society such as the Guardia Civil

The Civil Guard ( es, Guardia Civil, link=no; ) is the oldest law enforcement agency in Spain and is one of two national police forces. As a national gendarmerie force, it is military in nature and is responsible for civil policing under the a ...

, army, judicial, and clergy. However, in other areas such as sports, the LGBT community remains marginalised. Spanish film directors such as Pedro Almodóvar

Pedro Almodóvar Caballero (; (often known simply as Almodóvar) born 25 September 1949) is a Spanish filmmaker. His films are marked by melodrama, irreverent humour, bold colour, glossy décor, quotations from popular culture, and complex narra ...

have increased awareness regarding LGBT tolerance in Spain among international audiences. In 2007, Madrid

Madrid ( , ) is the capital and most populous city of Spain. The city has almost 3.4 million inhabitants and a metropolitan area population of approximately 6.7 million. It is the second-largest city in the European Union (EU), an ...

hosted the annual Europride celebration and hosted WorldPride in 2017. The cities of Barcelona

Barcelona ( , , ) is a city on the coast of northeastern Spain. It is the capital and largest city of the autonomous community of Catalonia, as well as the second most populous municipality of Spain. With a population of 1.6 million within ...

and Madrid

Madrid ( , ) is the capital and most populous city of Spain. The city has almost 3.4 million inhabitants and a metropolitan area population of approximately 6.7 million. It is the second-largest city in the European Union (EU), an ...

also have a reputation as two of the most LGBT-friendly cities in the world. Gran Canaria

Gran Canaria (, ; ), also Grand Canary Island, is the third-largest and second-most-populous island of the Canary Islands, an archipelago off the Atlantic coast of Northwest Africa which is part of Spain. the island had a population of that co ...

is also known worldwide as an LGBT tourist destination.

LGBT history in Spain

Roman Empire

The Romans brought, as with other aspects of their culture, their sexual morality to Spain. Romans were open-minded about their relationships, and sexuality among men was commonplace. Among the Romans, bisexuality seems to have been perceived as the ideal.Edward Gibbon

Edward Gibbon (; 8 May 173716 January 1794) was an English historian, writer, and member of parliament. His most important work, '' The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire'', published in six volumes between 1776 and 1788, is ...

mentions, of the first fifteen emperors, "Claudius was the only one whose taste in love was entirely correct" – the implication being that he was the only one not to take men or boys as lovers. Gibbon based this on Suetonius' factual statement that "He had a great passion for women, but had no interest in men." Suetonius and the other ancient authors actually used this against Claudius. They accused him of being dominated by these same women and wives, of being uxorious, and of being a womaniser

Womanizer may refer to:

* "Womanizer" (term), a promiscuous heterosexual man

* "Womanizer" (song), a 2008 song by Britney Spears

* "Womanizer", a 1977 song by Blood, Sweat & Tears from '' Brand New Day''

* ''Womanizer'', a 2004 album by Absolute ...

.

Marriages between men occurred during the early Roman Empire. These marriages were condemned by law in the Theodosian Code

The ''Codex Theodosianus'' (Eng. Theodosian Code) was a compilation of the laws of the Roman Empire under the Christian emperors since 312. A commission was established by Emperor Theodosius II and his co-emperor Valentinian III on 26 March 429 a ...

of Christian emperors Constantius and Constans on 16 December 342. Martial

Marcus Valerius Martialis (known in English as Martial ; March, between 38 and 41 AD – between 102 and 104 AD) was a Roman poet from Hispania (modern Spain) best known for his twelve books of ''Epigrams'', published in Rome between AD 86 an ...

, a first-century poet, born and educated in Bílbilis (now Calatayud

Calatayud (; 2014 pop. 20,658) is a municipality in the Province of Zaragoza, within Aragón, Spain, lying on the river Jalón, in the midst of the Sistema Ibérico mountain range. It is the second-largest town in the province after the capital, ...

in Aragon, Spain), but spent most of his life in Rome, attests to same-sex marriages between men during the early Roman Empire. He also characterised Roman life in epigram

An epigram is a brief, interesting, memorable, and sometimes surprising or satirical statement. The word is derived from the Greek "inscription" from "to write on, to inscribe", and the literary device has been employed for over two mille ...

s and poems. In a fictitious first person, he talks about anal and vaginal penetration, and about receiving fellatio

Fellatio (also known as fellation, and in slang as blowjob, BJ, giving head, or sucking off) is an oral sex act involving a person stimulating the penis of another person by using the mouth, throat, or both. Oral stimulation of the scrotum may ...

from both men and women. He also attests to adult men who played passive roles with other men. He describes, for example, the case of an older man who played the passive role and let a younger slave occupy the active role.

The first recorded marriage between two men occurred during the reign of Emperor Nero

Nero Claudius Caesar Augustus Germanicus ( ; born Lucius Domitius Ahenobarbus; 15 December AD 37 – 9 June AD 68), was the fifth Roman emperor and final emperor of the Julio-Claudian dynasty, reigning from AD 54 unt ...

, who is reported to have married two other men on different occasions. Roman Emperor Elagabalus

Marcus Aurelius Antoninus (born Sextus Varius Avitus Bassianus, 204 – 11/12 March 222), better known by his nickname "Elagabalus" (, ), was Roman emperor from 218 to 222, while he was still a teenager. His short reign was conspicuous for s ...

is also reported to have done the same. Emperors who were universally praised and lauded by the Romans such as Hadrian

Hadrian (; la, Caesar Trâiānus Hadriānus ; 24 January 76 – 10 July 138) was Roman emperor from 117 to 138. He was born in Italica (close to modern Santiponce in Spain), a Roman '' municipium'' founded by Italic settlers in Hispan ...

and Trajan

Trajan ( ; la, Caesar Nerva Traianus; 18 September 539/11 August 117) was Roman emperor from 98 to 117. Officially declared ''optimus princeps'' ("best ruler") by the senate, Trajan is remembered as a successful soldier-emperor who presid ...

openly had male lovers, although it is not recorded whether or not they ever married their lovers. Hadrian's lover, Antinuous

Antinous, also called Antinoös, (; grc-gre, Ἀντίνοος; 27 November – before 30 October 130) was a Greek youth from Bithynia and a favourite and probable lover of the Roman emperor Hadrian. Following his premature death before his ...

, received deification upon his death and numerous statues exist of him today, more than any other non-imperial person.

Among the conservative upper Senatorial classes, status was more important than the person in any sexual relationship. Thus, Roman citizens could penetrate non-citizen males, plebeian (or low class) males, male slaves, boys, eunuch

A eunuch ( ) is a male who has been castration, castrated. Throughout history, castration often served a specific social function.

The earliest records for intentional castration to produce eunuchs are from the Sumerian city of Lagash in the 2n ...

s and male prostitutes just as easily as young female slaves, concubines and female prostitutes. However, no upper class citizen would allow himself to be penetrated by another man, regardless of age or status. He would have to play the active role in any sexual relationship with a man. There was a strict distinction between an active homosexual (who would have sex with men and women) and a passive homosexual (who was regarded as servile and effeminate). This morality was in fact used against Julius Caesar, whose allegedly passive sexual interactions with the King of Bithynia

Bithynia (; Koine Greek: , ''Bithynía'') was an ancient region, kingdom and Roman province in the northwest of Asia Minor (present-day Turkey), adjoining the Sea of Marmara, the Bosporus, and the Black Sea. It bordered Mysia to the sout ...

, Nicomedes, were commented everywhere in Rome. However, many people in the upper classes ignored such negative ideas about playing a passive role, as is proved by the actions of the Roman emperors Nero

Nero Claudius Caesar Augustus Germanicus ( ; born Lucius Domitius Ahenobarbus; 15 December AD 37 – 9 June AD 68), was the fifth Roman emperor and final emperor of the Julio-Claudian dynasty, reigning from AD 54 unt ...

and Elagabalus

Marcus Aurelius Antoninus (born Sextus Varius Avitus Bassianus, 204 – 11/12 March 222), better known by his nickname "Elagabalus" (, ), was Roman emperor from 218 to 222, while he was still a teenager. His short reign was conspicuous for s ...

.

In contrast to the Greeks, evidence for homosexual relationships between men of the same age exists for the Romans. These sources are diverse and include such things as the Roman novel ''Satyricon

The ''Satyricon'', ''Satyricon'' ''liber'' (''The Book of Satyrlike Adventures''), or ''Satyrica'', is a Latin work of fiction believed to have been written by Gaius Petronius, though the manuscript tradition identifies the author as Titus Petr ...

'', graffiti and paintings found at Pompeii as well as inscriptions left on tombs and papyri found in Egypt. Generally speaking, however, a kind of pederasty

Pederasty or paederasty ( or ) is a sexual relationship between an adult man and a pubescent or adolescent boy. The term ''pederasty'' is primarily used to refer to historical practices of certain cultures, particularly ancient Greece and an ...

(not unlike the one that can be found among the Greeks) was dominant in Rome. It is important to note, though, that even among heterosexual relationships, men tended to marry women much younger than themselves, usually in their early teens.

Lesbianism was also known, in two forms. Feminine women would have sex with adolescent girls: a kind of female pederasty, and masculine women followed male pursuits, including fighting, hunting and relationships with other women.

The first law against same-sex marriage was promulgated by the Christian emperors Constantius II

Constantius II (Latin: ''Flavius Julius Constantius''; grc-gre, Κωνστάντιος; 7 August 317 – 3 November 361) was Roman emperor from 337 to 361. His reign saw constant warfare on the borders against the Sasanian Empire and Germanic ...

and Constans

Flavius Julius Constans ( 323 – 350), sometimes called Constans I, was Roman emperor from 337 to 350. He held the imperial rank of ''caesar'' from 333, and was the youngest son of Constantine the Great.

After his father's death, he was made ...

. Nevertheless, the Christian emperors continued to collect taxes on male prostitutes until the reign of Anastasius (491–581). In the year 390, Christian emperors Valentinian II

Valentinian II ( la, Valentinianus; 37115 May 392) was a Roman emperor in the western part of the Roman empire between AD 375 and 392. He was at first junior co-ruler of his brother, was then sidelined by a usurper, and only after 388 sole rule ...

, Theodosius I

Theodosius I ( grc-gre, Θεοδόσιος ; 11 January 347 – 17 January 395), also called Theodosius the Great, was Roman emperor from 379 to 395. During his reign, he succeeded in a crucial war against the Goths, as well as in two ...

and Arcadius

Arcadius ( grc-gre, Ἀρκάδιος ; 377 – 1 May 408) was Roman emperor from 383 to 408. He was the eldest son of the ''Augustus'' Theodosius I () and his first wife Aelia Flaccilla, and the brother of Honorius (). Arcadius ruled the e ...

declared homosexual sex to be illegal and those who were guilty of it were condemned to be burned alive in front of the public. Christian Emperor Justinian I

Justinian I (; la, Iustinianus, ; grc-gre, Ἰουστινιανός ; 48214 November 565), also known as Justinian the Great, was the Byzantine emperor from 527 to 565.

His reign is marked by the ambitious but only partly realized ''renovat ...

(527–565) made homosexuals a scapegoat for problems such as "famines, earthquakes, and pestilences".

As a result of this, Roman morality changed by the 4th century. For example, Ammianus Marcellinus

Ammianus Marcellinus (occasionally anglicised as Ammian) (born , died 400) was a Roman soldier and historian who wrote the penultimate major historical account surviving from antiquity (preceding Procopius). His work, known as the ''Res Gestae' ...

harshly condemned the sexual behaviour of the Taifali, a tribe located between the Carpathian Mountains and the Black Sea

The Black Sea is a marginal mediterranean sea of the Atlantic Ocean lying between Europe and Asia, east of the Balkans, south of the East European Plain, west of the Caucasus, and north of Anatolia. It is bounded by Bulgaria, Georgia, ...

which practiced the Greek-style pederasty. In 342, emperors Constans and Constantius II introduced a law to punish passive homosexuality (possibly by castration), to which later in 390 Theodosius I would add death by fire to all passive homosexuals that worked in brothel

A brothel, bordello, ranch, or whorehouse is a place where people engage in sexual activity with prostitutes. However, for legal or cultural reasons, establishments often describe themselves as massage parlors, bars, strip clubs, body rub p ...

s. In 438, this law was expanded to include all passive homosexuals, in 533 Justinian punished any homosexual act with castration and death by fire, and in 559 this law became even more strict.

Three reasons have been given for this change of attitude. Procopius

Procopius of Caesarea ( grc-gre, Προκόπιος ὁ Καισαρεύς ''Prokópios ho Kaisareús''; la, Procopius Caesariensis; – after 565) was a prominent late antique Greek scholar from Caesarea Maritima. Accompanying the Roman ge ...

, historian at Justinian's court, considered that behind the laws were political motivations, as they allowed Justinian to destroy his enemies and confiscate their properties, and were hardly efficient stopping homosexuality between ordinary citizens. The second reason, and perhaps the more important one, was the rising influence of Christianity in the Roman society, including the Christian paradigm about sex serving solely for reproduction purposes. Colin Spencer, in his book ''Homosexuality: A History'', suggests the possibility that a certain sense of self-preservation in the Roman society after suffering some epidemic such as the Black fever increased the reproductive pressure in individuals. This phenomenon would be combined with the rising influence of Stoicism

Stoicism is a school of Hellenistic philosophy founded by Zeno of Citium in Athens in the early 3rd century BCE. It is a philosophy of personal virtue ethics informed by its system of logic and its views on the natural world, asserting that ...

in the Empire.

Until the year 313, there was no common doctrine about homosexuality in Christianity, but it is the mistaken belief that Paul had already condemned it as ''contra natura'', though he had no exegetical reason for doing so:

Eventually, the Church Fathers created a literary ''corpus'' in which homosexuality and sex were condemned most energetically, fighting against a common practice in that epoch's society. On the other hand, homosexuality was identified with heresy, not only because of the pagan traditions, but also due to the rites of some gnostic sects or Manichaeism

Manichaeism (;

in New Persian ; ) is a former major religionR. van den Broek, Wouter J. Hanegraaff ''Gnosis and Hermeticism from Antiquity to Modern Times''SUNY Press, 1998 p. 37 founded in the 3rd century AD by the Parthian prophet Mani ( ...

, which, according to Augustine of Hippo

Augustine of Hippo ( , ; la, Aurelius Augustinus Hipponensis; 13 November 354 – 28 August 430), also known as Saint Augustine, was a theologian and philosopher of Berber origin and the bishop of Hippo Regius in Numidia, Roman North A ...

, practised homosexual rites.

Kingdom of the Visigoths (418–718)

TheGermanic peoples

The Germanic peoples were historical groups of people that once occupied Central Europe and Scandinavia during antiquity and into the early Middle Ages. Since the 19th century, they have traditionally been defined by the use of ancient and ear ...

had little tolerance for both passive homosexuality and women, whom they considered on the same level as "imbeciles" and slaves, and glorified the warrior camaraderie between men. However, there are reports in Scandinavian countries of feminine and transvestite pastors, and the Nordic gods, the Æsir

The Æsir (Old Norse: ) are the gods of the principal pantheon in Norse religion. They include Odin, Frigg, Höðr, Thor, and Baldr. The second Norse pantheon is the Vanir. In Norse mythology, the two pantheons wage war against each oth ...

, including Thor

Thor (; from non, Þórr ) is a prominent god in Germanic paganism. In Norse mythology, he is a hammer-wielding god associated with lightning, thunder, storms, sacred groves and trees, strength, the protection of humankind, hallowing ...

and Odin, obtained arcane recognition drinking semen.

In the Early Middle Ages

The Early Middle Ages (or early medieval period), sometimes controversially referred to as the Dark Ages, is typically regarded by historians as lasting from the late 5th or early 6th century to the 10th century. They marked the start of the M ...

, attitudes toward homosexuality remained constant. There are known cases of homosexual behaviour which did not receive punishment, even if they were not accepted. For example, King Clovis I on his baptism day confessed to having relationships with other men; or Alcuin

Alcuin of York (; la, Flaccus Albinus Alcuinus; 735 – 19 May 804) – also called Ealhwine, Alhwin, or Alchoin – was a scholar, clergyman, poet, and teacher from York, Northumbria. He was born around 735 and became the student o ...

, an Anglo-Saxon poet whose verses and letters contain homoerotism.

One of the first legal corpus that considered male homosexuality a crime in Europe was the '' Liber Iudiciorum'' (or ''Lex Visigothorum''). The Visigoth law included in that code (L. 3,5,6) punished sodomy

Sodomy () or buggery (British English) is generally anal or oral sex between people, or sexual activity between a person and a non-human animal ( bestiality), but it may also mean any non-procreative sexual activity. Originally, the term ''so ...

with banishment

Exile is primarily penal expulsion from one's native country, and secondarily expatriation or prolonged absence from one's homeland under either the compulsion of circumstance or the rigors of some high purpose. Usually persons and peoples suf ...

and castration. Within the term "castration" were included all ''sexual crimes'' considered ''unnatural'', such as male homosexuality, anal sex

Anal sex or anal intercourse is generally the insertion and thrusting of the erect penis into a person's anus, or anus and rectum, for sexual pleasure.Sepages 270–271for anal sex information, anpage 118for information about the clitoris. O ...

(heterosexual and homosexual) and zoophilia

Zoophilia is a paraphilia involving a sexual fixation on non-human animals. Bestiality is cross-species sexual activity between humans and non-human animals. The terms are often used interchangeably, but some researchers make a distinction ...

. Lesbianism was considered sodomy only if it included phallic aids.

It was King Chindasuinth

Chindasuinth (also spelled Chindaswinth, Chindaswind, Chindasuinto, Chindasvindo, or Khindaswinth ( Latin: Chintasvintus, Cindasvintus; 563 – 30 September 653) was Visigothic King of Hispania, from 642 until his death in 653. He succeeded Tu ...

(642–653) who dictated that the punishment for homosexuality should be castration. Such a harsh measure was unheard of in Visigoth laws, except for the cases of Jews practising circumcision

Circumcision is a procedure that removes the foreskin from the human penis. In the most common form of the operation, the foreskin is extended with forceps, then a circumcision device may be placed, after which the foreskin is excised. Topic ...

. After being castrated, the culprit was given to the care of the local bishop, who would then banish him. If he was married, the marriage was declared void, the dowry

A dowry is a payment, such as property or money, paid by the bride's family to the groom or his family at the time of marriage. Dowry contrasts with the related concepts of bride price and dower. While bride price or bride service is a payment ...

was returned to the woman and any possessions distributed among his heirs.

Islamic Spain (718–1492)

The Muslims who invaded and successfully conquered the peninsula in the early 8th century had a noticeably more open attitude to homosexuality than their Visigothic predecessors. In the book ''Medieval Iberia: An Encyclopedia'', Daniel Eisenberg describes homosexuality as "a key symbolic issue throughout the Middle Ages in Iberia", stating that in al-Andalus, homosexual pleasures were indulged in by the intellectual and political elite. There is significant evidence for this. Rulers, such asAbd-ar-Rahman III

ʿAbd al-Rahmān ibn Muḥammad ibn ʿAbd Allāh ibn Muḥammad ibn ʿAbd al-Raḥmān ibn al-Ḥakam al-Rabdī ibn Hishām ibn ʿAbd al-Raḥmān al-Dākhil () or ʿAbd al-Rahmān III (890 - 961), was the Umayyad Emir of Córdoba from 912 to 9 ...

, Al-Hakam II

Al-Hakam II, also known as Abū al-ʿĀṣ al-Mustanṣir bi-Llāh al-Hakam b. ʿAbd al-Raḥmān (; January 13, 915 – October 16, 976), was the Caliph of Córdoba. He was the second ''Umayyad'' Caliph of Córdoba in Al-Andalus, and son of Ab ...

, Hisham II

Hisham II or Abu'l-Walid Hisham II al-Mu'ayyad bi-llah (, Abū'l-Walīd Hishām al-Muʾayyad bi-ʾllāh) (son of Al-Hakam II and Subh of Cordoba) was the third Umayyad Caliph of Spain, in Al-Andalus from 976 to 1009, and 1010–13.

Reign

In ...

, and Al Mu'tamid ibn Abbad

Al-Mu'tamid Muhammad ibn Abbad al-Lakhmi ( ar, المعتمد محمد ابن عباد بن اسماعيل اللخمي; reigned c. 1069–1091, lived 1040–1095), also known as Abbad III, was the third and last ruler of the Taifa of Se ...

, openly kept male harems, to the point that, to ensure an offspring, a girl had to be disguised as a boy to seduce Al-Hakam II. It was said that male prostitutes charged higher fees and had a higher class of clientele than did their female counterparts. Evidence can also be found in the repeated criticisms of Christians and especially the abundant poetry of homosexual nature. References to both pederasty and love between adult males have been found. Although homosexual practices were never officially condoned, prohibitions against them were rarely enforced, and usually there was not even a pretense of doing so. Sexual activity between men was not seen as a form of identity. Very little is known about lesbian sexual activity during this period.

Kingdom of Spain (1492–1812)

By 1492, the last Islamic kingdom in the Iberian Peninsula, theEmirate of Granada

)

, common_languages = Official language: Classical ArabicOther languages: Andalusi Arabic, Mozarabic, Berber, Ladino

, capital = Granada

, religion = Majority religion: Sunni IslamMinority religions:Roma ...

, was invaded and conquered by the Crown of Castile and the Crown of Aragon

The Crown of Aragon ( , ) an, Corona d'Aragón ; ca, Corona d'Aragó, , , ; es, Corona de Aragón ; la, Corona Aragonum . was a composite monarchy ruled by one king, originated by the dynastic union of the Kingdom of Aragon and the County of ...

. This marked the Christian unification of the Iberian peninsula and the return of Catholic morality. By the early sixteenth century, royal codes decreed death by burning for sodomy

Sodomy () or buggery (British English) is generally anal or oral sex between people, or sexual activity between a person and a non-human animal ( bestiality), but it may also mean any non-procreative sexual activity. Originally, the term ''so ...

and was punished by civil authorities. It fell under the jurisdiction of the Inquisition only in the territories of Aragon, when, in 1524, Clement VII

Pope Clement VII ( la, Clemens VII; it, Clemente VII; born Giulio de' Medici; 26 May 1478 – 25 September 1534) was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 19 November 1523 to his death on 25 September 1534. Deemed "the ...

, in a papal brief, granted jurisdiction over sodomy to the Inquisition of Aragon, whether or not it was related to heresy

Heresy is any belief or theory that is strongly at variance with established beliefs or customs, in particular the accepted beliefs of a church or religious organization. The term is usually used in reference to violations of important religi ...

. In Castile, cases of sodomy were not adjudicated, unless related to heresy

Heresy is any belief or theory that is strongly at variance with established beliefs or customs, in particular the accepted beliefs of a church or religious organization. The term is usually used in reference to violations of important religi ...

. The tribunal of Zaragoza

Zaragoza, also known in English as Saragossa,''Encyclopædia Britannica'"Zaragoza (conventional Saragossa)" is the capital city of the Zaragoza Province and of the autonomous community of Aragon, Spain. It lies by the Ebro river and its tribut ...

distinguished itself for its severity in judging these offences: between 1571 and 1579 more than 100 men accused of sodomy

Sodomy () or buggery (British English) is generally anal or oral sex between people, or sexual activity between a person and a non-human animal ( bestiality), but it may also mean any non-procreative sexual activity. Originally, the term ''so ...

were prosecuted and at least 36 were executed; in total, between 1570 and 1630 there were 534 trials and 102 executions. This does not include, however, those normally executed by the secular authorities.

First French Empire

In 1812, Barcelona wasannexed

Annexation (Latin ''ad'', to, and ''nexus'', joining), in international law, is the forcible acquisition of one state's territory by another state, usually following military occupation of the territory. It is generally held to be an illegal act ...

into the First French Empire

The First French Empire, officially the French Republic, then the French Empire (; Latin: ) after 1809, also known as Napoleonic France, was the empire ruled by Napoleon Bonaparte, who established French hegemony over much of continental ...

and incorporated into the First French Empire

The First French Empire, officially the French Republic, then the French Empire (; Latin: ) after 1809, also known as Napoleonic France, was the empire ruled by Napoleon Bonaparte, who established French hegemony over much of continental ...

as part of the department Montserrat (later ''Bouches-de-l'Èbre–Montserrat''), where it remained until it was returned to Spain in 1814. During that time same-sex sexual intercourse was legal in Barcelona.

Kingdom of Spain (1814–1931)

In 1822, the Kingdom of Spain's first penal code was adopted and same-sex sexual intercourse was legalised. In 1928, under the dictatorship of

In 1822, the Kingdom of Spain's first penal code was adopted and same-sex sexual intercourse was legalised. In 1928, under the dictatorship of Miguel Primo de Rivera

Miguel Primo de Rivera y Orbaneja, 2nd Marquess of Estella (8 January 1870 – 16 March 1930), was a dictator, aristocrat, and military officer who served as Prime Minister of Spain from 1923 to 1930 during Spain's Restoration era. He deep ...

, the offense of "habitual homosexual acts" was recriminalised in Spain.

Second Spanish Republic

In 1932, same-sex sexual intercourse was again legalised inSpain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = '' Plus ultra'' ( Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem = (English: "Royal March")

, ...

.Francoist Spain

At the start of theSpanish Civil War

The Spanish Civil War ( es, Guerra Civil Española)) or The Revolution ( es, La Revolución, link=no) among Nationalists, the Fourth Carlist War ( es, Cuarta Guerra Carlista, link=no) among Carlism, Carlists, and The Rebellion ( es, La Rebeli ...

in 1936, the gay poet Federico García Lorca

Federico del Sagrado Corazón de Jesús García Lorca (5 June 1898 – 19 August 1936), known as Federico García Lorca ( ), was a Spanish poet, playwright, and theatre director. García Lorca achieved international recognition as an emblemat ...

was executed by Nationalist forces. Between 1936 and 1939, right-wing, Catholic forces led by General Francisco Franco

Francisco Franco Bahamonde (; 4 December 1892 – 20 November 1975) was a Spanish general who led the Nationalist forces in overthrowing the Second Spanish Republic during the Spanish Civil War and thereafter ruled over Spain from 193 ...

took over Spain, and Franco was dictator of the country until his death in 1975. Legal reforms in 1944 and 1963 punished same-sex sexual intercourse as "scandalous public behavior". In 1954, vagrancy laws were modified to declare that homosexuals are "a danger", equating homosexuality with proxenetism ( procuring). The text of the law declared that the measures "are not proper punishments, but mere security measures, set with a doubly preventive end, with the purpose of collective guarantee and the aspiration of correcting those subjects fallen to the lowest levels of morality. This law is not intended to punish, but to correct and reform". However, the way the law was applied was clearly punitive and arbitrary: police would often use the vagrancy laws against suspected political dissenters, using homosexuality (actual or perceived) as a way to go around the judicial guarantees.

However, in other cases, the harassment of gay, bisexual and transgender people was clearly directed at their sexual mores, and homosexuals (mostly men) were sent to special prisons called ''galerías de invertidos'' ("galleries of inverts"). Thousands of homosexual men and women were jailed, put in camps, or locked up in mental institutions under Franco's dictatorship, which lasted for 36 years until his death in 1975. The year Franco died, his regime began to give way to the current constitutional democracy, but in the early 1970s gay prisoners were overlooked by political activism in favour of more "traditional" political dissenters. Some gay activists deplored the fact that reparations were not made until 2008.

However, in the 1960s, a clandestine gay scene began to emerge in Barcelona

Barcelona ( , , ) is a city on the coast of northeastern Spain. It is the capital and largest city of the autonomous community of Catalonia, as well as the second most populous municipality of Spain. With a population of 1.6 million within ...

, and in the countercultural centers of Ibiza and Sitges

Sitges (, , ) is a town about 35 kilometres southwest of Barcelona, in Spain, renowned worldwide for its Film Festival, Carnival, and LGBT Culture. Located between the Garraf Massif and the Mediterranean Sea, it is known for its beaches, nightspot ...

(a town in the province of Barcelona, Catalonia

Catalonia (; ca, Catalunya ; Aranese Occitan: ''Catalonha'' ; es, Cataluña ) is an autonomous community of Spain, designated as a '' nationality'' by its Statute of Autonomy.

Most of the territory (except the Val d'Aran) lies on the no ...

, that remains a highly popular gay tourist destination). In the late 1960s and the 1970s, a body of gay literature emerged in Catalan

Catalan may refer to:

Catalonia

From, or related to Catalonia:

* Catalan language, a Romance language

* Catalans, an ethnic group formed by the people from, or with origins in, Northern or southern Catalonia

Places

* 13178 Catalan, asteroid ...

. Attitudes in greater Spain began to change with the return to democracy after Franco's death through a cultural movement known as La Movida Madrileña. This movement, along with growth of the gay rights movement

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) movements are social movements that advocate for LGBT people in society. Some focus on equal rights, such as the ongoing movement for same-sex marriage, while others focus on liberation, as in the ...

in the rest of Europe and the Western world, was a large factor in making Spain today one of Europe's most socially tolerant places.

In 1970, Spanish law provided for a three-year prison sentence for those accused of same-sex sexual intercourse.

Kingdom of Spain (1975–present)

Same-sex sexual intercourse was again legalised in Spain in 1979, and is its status today. In December 2001, the Spanish Parliament pledged to wipe clean the criminal records of thousands of gay and bisexual men and women who were jailed during Franco's regime. The decision meant that sentences for homosexuality and bisexuality were taken off police files. Further reparations were made in 2008.Law regarding same-sex sexual activity

Same-sex sexual acts were lawful in Spain from 1822 to 1954, with the exception of the offence of "unusual or outrageous indecent acts with same-sex persons" between the years 1928 and 1932. However, some homosexuals were arrested in the days of the Second Spanish Republic under the ''Ley de Vagos y Maleantes'' ("Vagrants and Common Delinquents Law"). Homosexual acts were made unlawful duringFrancisco Franco

Francisco Franco Bahamonde (; 4 December 1892 – 20 November 1975) was a Spanish general who led the Nationalist forces in overthrowing the Second Spanish Republic during the Spanish Civil War and thereafter ruled over Spain from 19 ...

's time in power, first by an amendment to the aforementioned law in 1954, and later by the ''Ley de Peligrosidad y Rehabilitación Social'' ("Law on Danger and Social Rehabilitation") in 1970. In 1979, the Adolfo Suárez

Adolfo Suárez González, 1st Duke of Suárez (; 25 September 1932 – 23 March 2014) was a Spanish lawyer and politician. Suárez was Spain's first democratically elected prime minister since the Second Spanish Republic and a key figure in th ...

Government reversed the prohibition of homosexual acts.

A new penal code was introduced in Spain in 1995 which specified an age of consent

The age of consent is the age at which a person is considered to be legally competent to consent to sexual acts. Consequently, an adult who engages in sexual activity with a person younger than the age of consent is unable to legally cla ...

of 12 for all sexual acts, but this was raised to 13 in 1999 and to 16 in 2015.

Recognition of same-sex relationships

In 1994, the ''Ley de Arrendamientos Urbanos'' was passed, giving same-sex couples some recognition rights. Registries for same-sex couples were created in all of Spain's 17 autonomous communities:

In 1994, the ''Ley de Arrendamientos Urbanos'' was passed, giving same-sex couples some recognition rights. Registries for same-sex couples were created in all of Spain's 17 autonomous communities: Catalonia

Catalonia (; ca, Catalunya ; Aranese Occitan: ''Catalonha'' ; es, Cataluña ) is an autonomous community of Spain, designated as a '' nationality'' by its Statute of Autonomy.

Most of the territory (except the Val d'Aran) lies on the no ...

(1998), Aragon

Aragon ( , ; Spanish and an, Aragón ; ca, Aragó ) is an autonomous community in Spain, coextensive with the medieval Kingdom of Aragon. In northeastern Spain, the Aragonese autonomous community comprises three provinces (from north to so ...

(1999), Navarre

Navarre (; es, Navarra ; eu, Nafarroa ), officially the Chartered Community of Navarre ( es, Comunidad Foral de Navarra, links=no ; eu, Nafarroako Foru Komunitatea, links=no ), is a foral autonomous community and province in northern Spain, ...

(2000), Castile-La Mancha (2000), Valencia

Valencia ( va, València) is the capital of the autonomous community of Valencia and the third-most populated municipality in Spain, with 791,413 inhabitants. It is also the capital of the province of the same name. The wider urban area al ...

(2001), the Balearic Islands (2001), Madrid

Madrid ( , ) is the capital and most populous city of Spain. The city has almost 3.4 million inhabitants and a metropolitan area population of approximately 6.7 million. It is the second-largest city in the European Union (EU), an ...

(2001), Asturias

Asturias (, ; ast, Asturies ), officially the Principality of Asturias ( es, Principado de Asturias; ast, Principáu d'Asturies; Galician-Asturian: ''Principao d'Asturias''), is an autonomous community in northwest Spain.

It is coextensi ...

(2002), Andalusia

Andalusia (, ; es, Andalucía ) is the southernmost autonomous community in Peninsular Spain. It is the most populous and the second-largest autonomous community in the country. It is officially recognised as a "historical nationality". The ...

(2002), Castile and León (2002), Extremadura

Extremadura (; ext, Estremaúra; pt, Estremadura; Fala: ''Extremaúra'') is an autonomous community of Spain. Its capital city is Mérida, and its largest city is Badajoz. Located in the central-western part of the Iberian Peninsula, ...

(2003), the Basque Country

Basque Country may refer to:

* Basque Country (autonomous community), as used in Spain ( es, País Vasco, link=no), also called , an Autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community of Spain (shown in pink on the map)

* French Basque Country o ...

(2003), the Canary Islands

The Canary Islands (; es, Canarias, ), also known informally as the Canaries, are a Spanish autonomous community and archipelago in the Atlantic Ocean, in Macaronesia. At their closest point to the African mainland, they are west of Mo ...

(2003), Cantabria

Cantabria (, also , , Cantabrian: ) is an autonomous community in northern Spain with Santander as its capital city. It is called a ''comunidad histórica'', a historic community, in its current Statute of Autonomy. It is bordered on the ea ...

(2005), Galicia

Galicia may refer to:

Geographic regions

* Galicia (Spain), a region and autonomous community of northwestern Spain

** Gallaecia, a Roman province

** The post-Roman Kingdom of the Suebi, also called the Kingdom of Gallaecia

** The medieval King ...

(2008), La Rioja

La Rioja () is an autonomous community and province in Spain, in the north of the Iberian Peninsula. Its capital is Logroño. Other cities and towns in the province include Calahorra, Arnedo, Alfaro, Haro, Santo Domingo de la Calzada, a ...

(2010) and Murcia

Murcia (, , ) is a city in south-eastern Spain, the Capital (political), capital and most populous city of the autonomous community of the Region of Murcia, and the List of municipalities of Spain, seventh largest city in the country. It has a ...

(2018), and in both autonomous cities; Ceuta

Ceuta (, , ; ar, سَبْتَة, Sabtah) is a Spanish autonomous city on the north coast of Africa.

Bordered by Morocco, it lies along the boundary between the Mediterranean Sea and the Atlantic Ocean. It is one of several Spanish territo ...

(1998) and Melilla

Melilla ( , ; ; rif, Mřič ; ar, مليلية ) is an autonomous city of Spain located in north Africa. It lies on the eastern side of the Cape Three Forks, bordering Morocco and facing the Mediterranean Sea. It has an area of . It was ...

(2008). These registries grant unmarried couples some benefits, but the effect is mainly symbolic.

Same-sex marriage

Same-sex marriage, also known as gay marriage, is the marriage of two people of the same sex or gender. marriage between same-sex couples is legally performed and recognized in 33 countries, with the most recent being Mexico, constituting ...

and adoption were legalised by the Cortes Generales

The Cortes Generales (; en, Spanish Parliament, lit=General Courts) are the bicameral legislative chambers of Spain, consisting of the Congress of Deputies (the lower house), and the Senate (the upper house).

The Congress of Deputies meet ...

under the administration of Socialist

Socialism is a left-wing economic philosophy and movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to private ownership. As a term, it describes the ...

Prime Minister José Luis Rodríguez Zapatero

José Luis Rodríguez Zapatero (; born 4 August 1960) is a Spanish politician and member of the Spanish Socialist Workers' Party (PSOE). He was the Prime Minister of Spain being elected for two terms, in the 2004 and 2008 general electi ...

in 2005, making Spain the third country in the world to do so.

Soon after the same-sex marriage bill became law, a member of the Guardia Civil, a military-police force, married his lifelong partner, prompting the organisation to allow same-sex partners to cohabitate in the barracks, the first police force in Europe to accommodate a same-sex partner in a military installation.

Adoption and parenting

Adoption by same-sex couples

Same-sex adoption is the adoption of children by same-sex couples. It may take the form of a joint adoption by the couple, or of the adoption by one partner of the other's biological child ( stepchild adoption).

Joint adoption by same-sex cou ...

has been legal nationwide in Spain since July 2005. Some of Spain's autonomous communities had already legalised such adoptions beforehand, notably Navarre

Navarre (; es, Navarra ; eu, Nafarroa ), officially the Chartered Community of Navarre ( es, Comunidad Foral de Navarra, links=no ; eu, Nafarroako Foru Komunitatea, links=no ), is a foral autonomous community and province in northern Spain, ...

in 2000, the Basque Country

Basque Country may refer to:

* Basque Country (autonomous community), as used in Spain ( es, País Vasco, link=no), also called , an Autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community of Spain (shown in pink on the map)

* French Basque Country o ...

in 2003, Aragon

Aragon ( , ; Spanish and an, Aragón ; ca, Aragó ) is an autonomous community in Spain, coextensive with the medieval Kingdom of Aragon. In northeastern Spain, the Aragonese autonomous community comprises three provinces (from north to so ...

in 2004, Catalonia

Catalonia (; ca, Catalunya ; Aranese Occitan: ''Catalonha'' ; es, Cataluña ) is an autonomous community of Spain, designated as a '' nationality'' by its Statute of Autonomy.

Most of the territory (except the Val d'Aran) lies on the no ...

in 2005 and Cantabria

Cantabria (, also , , Cantabrian: ) is an autonomous community in northern Spain with Santander as its capital city. It is called a ''comunidad histórica'', a historic community, in its current Statute of Autonomy. It is bordered on the ea ...

in 2005. Furthermore, in Asturias

Asturias (, ; ast, Asturies ), officially the Principality of Asturias ( es, Principado de Asturias; ast, Principáu d'Asturies; Galician-Asturian: ''Principao d'Asturias''), is an autonomous community in northwest Spain.

It is coextensi ...

, Andalusia and Extremadura

Extremadura (; ext, Estremaúra; pt, Estremadura; Fala: ''Extremaúra'') is an autonomous community of Spain. Its capital city is Mérida, and its largest city is Badajoz. Located in the central-western part of the Iberian Peninsula, ...

, same-sex couples could jointly begin procedures to temporarily or permanently take children in care.

Since 2015, married lesbian couples can register both their names on their child(ren)'s certificates. This does not apply to cohabiting couples or couples in de facto unions, where the non-biological mother must normally go through an adoption process to be legally recognized as the child's mother.

Lesbian couples and single women may access in vitro fertilisation

In vitro fertilisation (IVF) is a process of fertilisation where an egg is combined with sperm in vitro ("in glass"). The process involves monitoring and stimulating an individual's ovulatory process, removing an ovum or ova (egg or eggs) f ...

(IVF) and assisted reproductive treatments. Prior to 2019, this was mostly in the private sector, where such treatments were much more expensive (around 7,500 euro

The euro (symbol: €; code: EUR) is the official currency of 19 out of the member states of the European Union (EU). This group of states is known as the eurozone or, officially, the euro area, and includes about 340 million citizens . ...

s for IVF). In 2018, following reports that Spain had one of the lowest birth rates in Europe (with reportedly more deaths than births in 2017), measures extending free reproductive treatments for lesbians and single women to public hospitals were announced. The measures took effect in January 2019. Surrogacy

Surrogacy is an arrangement, often supported by a legal agreement, whereby a woman agrees to delivery/labour for another person or people, who will become the child's parent(s) after birth. People may seek a surrogacy arrangement when pregnan ...

is prohibited in Spain regardless of sexual orientation, though surrogacy arrangements undertaken overseas are usually recognized.

In November 2021, an executive order

In the United States, an executive order is a directive by the president of the United States that manages operations of the federal government. The legal or constitutional basis for executive orders has multiple sources. Article Two of ...

was signed to allow free IVF treatment for single women and women in same-sex relationships throughout Spain. A bill has been formally introduced to implement the decision permanently.

Discrimination protections

Spanish law prohibits discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation, gender identity, HIV status, and "any other personal or social condition or circumstance.” in employment and provision of goods and services. A comprehensive anti-discrimination bill, called the Zerolo Law, was passed by the

Spanish law prohibits discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation, gender identity, HIV status, and "any other personal or social condition or circumstance.” in employment and provision of goods and services. A comprehensive anti-discrimination bill, called the Zerolo Law, was passed by the Cortes Generales

The Cortes Generales (; en, Spanish Parliament, lit=General Courts) are the bicameral legislative chambers of Spain, consisting of the Congress of Deputies (the lower house), and the Senate (the upper house).

The Congress of Deputies meet ...

on 30 June 2022.

Prior to the Zerolo law, employment discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation

Sexual orientation is an enduring pattern of romantic or sexual attraction (or a combination of these) to persons of the opposite sex or gender, the same sex or gender, or to both sexes or more than one gender. These attractions are generally ...

had been illegal in the country since 1995 but employment discrimination on the basis of gender identity was not banned nationwide. The first autonomous community to ban such discrimination was Navarre

Navarre (; es, Navarra ; eu, Nafarroa ), officially the Chartered Community of Navarre ( es, Comunidad Foral de Navarra, links=no ; eu, Nafarroako Foru Komunitatea, links=no ), is a foral autonomous community and province in northern Spain, ...

in 2009. The Basque Country

Basque Country may refer to:

* Basque Country (autonomous community), as used in Spain ( es, País Vasco, link=no), also called , an Autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community of Spain (shown in pink on the map)

* French Basque Country o ...

followed suit in 2012, Andalusia

Andalusia (, ; es, Andalucía ) is the southernmost autonomous community in Peninsular Spain. It is the most populous and the second-largest autonomous community in the country. It is officially recognised as a "historical nationality". The ...

, the Canary Islands

The Canary Islands (; es, Canarias, ), also known informally as the Canaries, are a Spanish autonomous community and archipelago in the Atlantic Ocean, in Macaronesia. At their closest point to the African mainland, they are west of Mo ...

, Catalonia

Catalonia (; ca, Catalunya ; Aranese Occitan: ''Catalonha'' ; es, Cataluña ) is an autonomous community of Spain, designated as a '' nationality'' by its Statute of Autonomy.

Most of the territory (except the Val d'Aran) lies on the no ...

, and Galicia

Galicia may refer to:

Geographic regions

* Galicia (Spain), a region and autonomous community of northwestern Spain

** Gallaecia, a Roman province

** The post-Roman Kingdom of the Suebi, also called the Kingdom of Gallaecia

** The medieval King ...

in 2014, Extremadura

Extremadura (; ext, Estremaúra; pt, Estremadura; Fala: ''Extremaúra'') is an autonomous community of Spain. Its capital city is Mérida, and its largest city is Badajoz. Located in the central-western part of the Iberian Peninsula, ...

in 2015, Madrid

Madrid ( , ) is the capital and most populous city of Spain. The city has almost 3.4 million inhabitants and a metropolitan area population of approximately 6.7 million. It is the second-largest city in the European Union (EU), an ...

, Murcia

Murcia (, , ) is a city in south-eastern Spain, the Capital (political), capital and most populous city of the autonomous community of the Region of Murcia, and the List of municipalities of Spain, seventh largest city in the country. It has a ...

, and the Balearic Islands in 2016, Valencia

Valencia ( va, València) is the capital of the autonomous community of Valencia and the third-most populated municipality in Spain, with 791,413 inhabitants. It is also the capital of the province of the same name. The wider urban area al ...

in April 2017, and Aragon

Aragon ( , ; Spanish and an, Aragón ; ca, Aragó ) is an autonomous community in Spain, coextensive with the medieval Kingdom of Aragon. In northeastern Spain, the Aragonese autonomous community comprises three provinces (from north to so ...

in January 2019., Cantabria

Cantabria (, also , , Cantabrian: ) is an autonomous community in northern Spain with Santander as its capital city. It is called a ''comunidad histórica'', a historic community, in its current Statute of Autonomy. It is bordered on the ea ...

in November 2020 La Rioja

La Rioja () is an autonomous community and province in Spain, in the north of the Iberian Peninsula. Its capital is Logroño. Other cities and towns in the province include Calahorra, Arnedo, Alfaro, Haro, Santo Domingo de la Calzada, a ...

in February 2022 and Castilla-La Mancha in May 2022.

Article 4(2) of the ''Workers' Statute'' ( es, link=no, Estatuto de los trabajadores); gl, Estatuto dos traballadores; eu, Langileen Estatutua; ast, Estatutu de los trabayadores reads as follows:

Discrimination in the provisions of goods and services based on sexual orientation and gender identity was not banned nationwide either. The aforementioned autonomous communities all ban such discrimination within their anti-discrimination laws. Discrimination in health services and education based on sexual orientation and gender identity has been banned in Spain since 2011 and 2013, respectively.

Ten autonomous communities also ban discrimination based on sex characteristics, thereby protecting intersex

Intersex people are individuals born with any of several sex characteristics including chromosome patterns, gonads, or genitals that, according to the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, "do not fit typical b ...

people from discrimination. These autonomous communities are Galicia (2014), Catalonia (2014), Extremadura (2015), the Balearic Islands (2016), Madrid (2016), Murcia (2016), Valencia (2017), Navarre (2017), Andalusia (2018), and Aragon (2019).

Bias-motivated speech and violence

Hate speech on the basis of both sexual orientation and gender identity has been banned since 1995. Additionally, under the country's hate crime law, crimes motivated by the victim's sexual orientation or gender identity, amongst other categories, result in additional legal penalties. TheSecretary of State for Security

The Secretary of State for Security (SES) of Spain is the second-highest-ranking official in the Ministry of the Interior.

The SES is appointed by the Monarch with the advise of the Minister of the Interior. The Secretariat of State for Security ...

reported that instances of violence against LGBT people decreased 4% in 2018. This contrasted with figures from other sources. The ''Observatorio Madrileño'' reported a 7% increase in anti-LGBT violence in Madrid, while the Observatory Against Homophobia of Catalonia () reported a 30% increase in the first few months of 2019.

Since January 2019, teachers and students in Madrid are obliged to report cases of bullying, including against LGBT students.

Military service

Lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender people may serve openly in the Spanish Armed Forces.Transgender and intersex rights

In November 2006, the Zapatero Government passed a law that allows

In November 2006, the Zapatero Government passed a law that allows transgender

A transgender (often abbreviated as trans) person is someone whose gender identity or gender expression does not correspond with their sex assigned at birth. Many transgender people experience dysphoria, which they seek to alleviate through ...

people to register under their preferred sex in public documents such as birth certificates, identity cards and passports without undergoing prior surgical change. However a professional diagnosis is still required. The law came into effect on 17 March 2007. In July 2019, the Constitutional Court of Spain declared that prohibiting transgender minors from accessing legal gender changes is unconstitutional. The court ruled that transgender minors who are "mature enough" may register their new sex on their identity cards, and struck down the article of the 2007 legislation that limited this possibility only to those over 18. The first minor to change his legal gender did so in December 2019.

A new bill was approved in June 2022 by the Spanish government that would grant permission for people above 16 to change their gender without restrictions, and for people between 12 and 16 under certain conditions.Teenagers between 14 and 16 could do so by requesting approval from their parents (or from a judge if they cannot agree); teenagers between 12 and 14 would require judicial authorisation. The bill was promoted by the left-wing Unidas Podemos

Unidas Podemos (), formerly called Unidos Podemos () and also known in English as United We Can, is a democratic socialist electoral alliance formed by Podemos, United Left, and other left-wing to far-left parties in May to contest the 2016 Sp ...

party, but its approval was initially delayed because the Spanish Socialist Workers' Party

The Spanish Socialist Workers' Party ( es, Partido Socialista Obrero Español ; PSOE ) is a social-democraticThe PSOE is described as a social-democratic party by numerous sources:

*

*

*

* political party in Spain. The PSOE has been in go ...

opposed, questioning the bill's treatment of transgender teenagers and expressing concerns that it may cause gender inequality. The dispute was resolved when Carmen Calvo, the then Vice President of the government, left the Executive. Lawmakers have yet to approve the bill.

Intersex

Intersex people are individuals born with any of several sex characteristics including chromosome patterns, gonads, or genitals that, according to the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, "do not fit typical b ...

infants in Spain may undergo medical interventions to have their sex characteristics altered. Human rights groups consider these surgeries unnecessary and, they argue, should only be performed if the applicant consents to the operation (i.e. has reached the age of 18). Andalusia

Andalusia (, ; es, Andalucía ) is the southernmost autonomous community in Peninsular Spain. It is the most populous and the second-largest autonomous community in the country. It is officially recognised as a "historical nationality". The ...

, Aragon

Aragon ( , ; Spanish and an, Aragón ; ca, Aragó ) is an autonomous community in Spain, coextensive with the medieval Kingdom of Aragon. In northeastern Spain, the Aragonese autonomous community comprises three provinces (from north to so ...

, the Balearic Islands, Extremadura

Extremadura (; ext, Estremaúra; pt, Estremadura; Fala: ''Extremaúra'') is an autonomous community of Spain. Its capital city is Mérida, and its largest city is Badajoz. Located in the central-western part of the Iberian Peninsula, ...

, Madrid

Madrid ( , ) is the capital and most populous city of Spain. The city has almost 3.4 million inhabitants and a metropolitan area population of approximately 6.7 million. It is the second-largest city in the European Union (EU), an ...

, Murcia

Murcia (, , ) is a city in south-eastern Spain, the Capital (political), capital and most populous city of the autonomous community of the Region of Murcia, and the List of municipalities of Spain, seventh largest city in the country. It has a ...

, Navarre

Navarre (; es, Navarra ; eu, Nafarroa ), officially the Chartered Community of Navarre ( es, Comunidad Foral de Navarra, links=no ; eu, Nafarroako Foru Komunitatea, links=no ), is a foral autonomous community and province in northern Spain, ...

, and Valencia

Valencia ( va, València) is the capital of the autonomous community of Valencia and the third-most populated municipality in Spain, with 791,413 inhabitants. It is also the capital of the province of the same name. The wider urban area al ...

ban the use of medical interventions on intersex children.

In April 2019, the Catalan Department of Labor, Social Affairs and Families announced that official documents in Catalonia would include the option "non-binary" alongside male and female.

Self-identification national bill

In December 2022, by a vote of 188-150 passed a bill within theSpanish Congress of Deputies

The Congress of Deputies ( es, link=no, Congreso de los Diputados, italic=unset) is the lower house of the Cortes Generales, Spain's legislative branch. The Congress meets in the Palace of the Parliament () in Madrid.

It has 350 members ele ...

to allow transgender individuals "self-identification" on birth certificates at a national level. The bill is awaiting a vote within the Spain Senate

The Senate ( es, Senado) is the upper house of the Cortes Generales, which along with the Congress of Deputies – the lower chamber – comprises the Parliament of the Kingdom of Spain. The Senate meets in the Palace of the Senate in Madrid.

T ...

.

Blood donation

Gay and bisexual men are allowed to donate blood in Spain. For anyone regardless of sexual orientation, the deferral period is six months following the last sexual encounter.Conversion therapy

community of Madrid

The Community of Madrid (; es, Comunidad de Madrid ) is one of the seventeen autonomous communities of Spain. It is located in the centre of the Iberian Peninsula, and of the Central Plateau (''Meseta Central''). Its capital and largest mun ...

approved a conversion therapy

Conversion therapy is the pseudoscientific practice of attempting to change an individual's sexual orientation, gender identity, or gender expression to align with heterosexual and cisgender norms. In contrast to evidence-based medicine and cli ...

ban in July 2016. The ban went into effect on 1 January 2017, and applies to medical, psychiatric, psychological and religious groups. In August 2016, an LGBT advocacy group brought charges under the new law against a Madrid woman who offered conversion therapy. In September 2019, the woman was fined 20,000 euro

The euro (symbol: €; code: EUR) is the official currency of 19 out of the member states of the European Union (EU). This group of states is known as the eurozone or, officially, the euro area, and includes about 340 million citizens . ...

s.

Murcia

Murcia (, , ) is a city in south-eastern Spain, the Capital (political), capital and most populous city of the autonomous community of the Region of Murcia, and the List of municipalities of Spain, seventh largest city in the country. It has a ...

approved a conversion therapy ban in May 2016, which came into effect on 1 June 2016. Unlike the other bans, the Murcia ban only applies to health professional

A health professional, healthcare professional, or healthcare worker (sometimes abbreviated HCW) is a provider of health care treatment and advice based on formal training and experience. The field includes those who work as a nurse, physician (suc ...

s.

Valencia

Valencia ( va, València) is the capital of the autonomous community of Valencia and the third-most populated municipality in Spain, with 791,413 inhabitants. It is also the capital of the province of the same name. The wider urban area al ...

banned the use of conversion therapies in April 2017. Andalusia

Andalusia (, ; es, Andalucía ) is the southernmost autonomous community in Peninsular Spain. It is the most populous and the second-largest autonomous community in the country. It is officially recognised as a "historical nationality". The ...

followed suit in December 2017, with the law coming into force on 4 February 2018.Ley 8/2017, de 28 de diciembre, para garantizar los derechos, la igualdad de trato y no discriminación de las personas LGTBI y sus familiares en Andalucía/ref> In January 2019,

Aragon

Aragon ( , ; Spanish and an, Aragón ; ca, Aragó ) is an autonomous community in Spain, coextensive with the medieval Kingdom of Aragon. In northeastern Spain, the Aragonese autonomous community comprises three provinces (from north to so ...

made it an offense to promote and/or perform conversion therapy.

In April 2019, the Government of the Community of Madrid announced it was investigating the Roman Catholic Diocese of Alcalá de Henares for violating conversion therapy laws. This followed reports that a journalist named Ángel Villascusa posed as a gay man and attended a counselling service provided by the diocese. Villascusa alleged the bishop was running illegal conversion therapy sessions. The bishop was defended by the Catholic Church in Spain

, native_name_lang =

, image = Sevilla Cathedral - Southeast.jpg

, imagewidth = 300px

, alt =

, caption = Cathedral of Saint Mary of the See in Seville

, abbreviation =

, type ...

. Minister of Health, Consumer Affairs and Social Welfare María Luisa Carcedo

María Luisa Carcedo Roces (born 30 August 1953) is a Spanish doctor, politician and former senator who belongs to the Spanish Socialist Workers' Party (PSOE). From 2018 to 2020, she served as minister of Health, Consumer Affairs and Social Welf ...

called for a nationwide ban on conversion therapy

Conversion therapy is the pseudoscientific practice of attempting to change an individual's sexual orientation, gender identity, or gender expression to align with heterosexual and cisgender norms. In contrast to evidence-based medicine and cli ...

. She said, "they he Churchare breaking the law therefore, in the first instance, these courses have to be completely abolished. I thought that, in Spain, accepting the various sexual orientations was assumed in all areas, but unfortunately we see that there are still pockets where people are told what their sexual orientation should be".

LGBT rights movement in Spain

The first gay organisation in Spain was the Spanish Homosexual Liberation Movement (MELH, '' Movimiento Español de Liberación Homosexual'', '' Moviment Espanyol d'Alliberament Homosexual''), which was founded in 1970 in

The first gay organisation in Spain was the Spanish Homosexual Liberation Movement (MELH, '' Movimiento Español de Liberación Homosexual'', '' Moviment Espanyol d'Alliberament Homosexual''), which was founded in 1970 in Barcelona

Barcelona ( , , ) is a city on the coast of northeastern Spain. It is the capital and largest city of the autonomous community of Catalonia, as well as the second most populous municipality of Spain. With a population of 1.6 million within ...

. The group also established centers in Madrid

Madrid ( , ) is the capital and most populous city of Spain. The city has almost 3.4 million inhabitants and a metropolitan area population of approximately 6.7 million. It is the second-largest city in the European Union (EU), an ...

and Bilbao

)

, motto =

, image_map =

, mapsize = 275 px

, map_caption = Interactive map outlining Bilbao

, pushpin_map = Spain Basque Country#Spain#Europe

, pushpin_map_caption ...