Clive James (born Vivian Leopold James; 7 October 1939 – 24 November 2019) was an Australian critic, journalist, broadcaster, writer and lyricist who lived and worked in the United Kingdom from 1962 until his death in 2019.pop music

Pop music is a genre of popular music that originated in its modern form during the mid-1950s in the United States and the United Kingdom. The terms ''popular music'' and ''pop music'' are often used interchangeably, although the former describ ...

. Vocalists of the famous big bands moved on to being marketed and performing as solo pop singers; these included Frank Sinatra, Peggy Lee

Norma Deloris Egstrom (May 26, 1920 – January 21, 2002), known professionally as Peggy Lee, was an American jazz and popular music singer, songwriter, composer, and actress, over a career spanning seven decades. From her beginning as a vocalis ...

, Dick Haymes

Richard Benjamin Haymes (September 13, 1918 – March 28, 1980) was an Argentinian singer and actor. He was one of the most popular male vocalists of the 1940s and early 1950s. He was the older brother of Bob Haymes, an actor, television host, ...

, and Doris Day

Doris Day (born Doris Mary Kappelhoff; April 3, 1922 – May 13, 2019) was an American actress, singer, and activist. She began her career as a big band singer in 1939, achieving commercial success in 1945 with two No. 1 recordings, " Sent ...

.Big Joe Turner

Joseph Vernon "Big Joe" Turner Jr. (May 18, 1911 – November 24, 1985) was an American singer from Kansas City, Missouri. According to songwriter Doc Pomus, "Rock and roll would have never happened without him." His greatest fame was due t ...

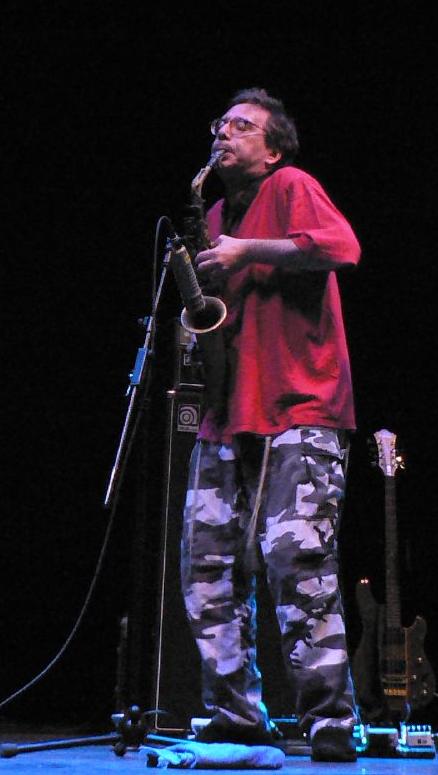

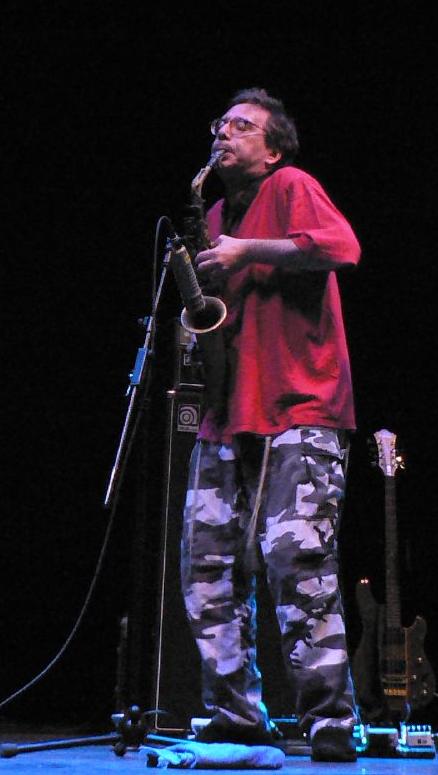

and saxophonist Louis Jordan

Louis Thomas Jordan (July 8, 1908 – February 4, 1975) was an American saxophonist, multi-instrumentalist, songwriter and bandleader who was popular from the late 1930s to the early 1950s. Known as " the King of the Jukebox", he earned his high ...

, who were discouraged by bebop's increasing complexity, pursued more lucrative endeavors in rhythm and blues, jump blues

Jump blues is an up-tempo style of blues, usually played by small groups and featuring horn instruments. It was popular in the 1940s and was a precursor of rhythm and blues and rock and roll. Appreciation of jump blues was renewed in the 1990s a ...

, and eventually rock and roll

Rock and roll (often written as rock & roll, rock 'n' roll, or rock 'n roll) is a genre of popular music that evolved in the United States during the late 1940s and early 1950s. It originated from African-American music such as jazz, rhythm an ...

.

Bebop

In the early 1940s, bebop-style performers began to shift jazz from danceable popular music toward a more challenging "musician's music". The most influential bebop musicians included saxophonist Charlie Parker, pianists Bud Powell

Earl Rudolph "Bud" Powell (September 27, 1924 – July 31, 1966) was an American jazz pianist and composer. Along with Charlie Parker, Thelonious Monk, Kenny Clarke and Dizzy Gillespie, Powell was a leading figure in the development of mod ...

and Thelonious Monk

Thelonious Sphere Monk (, October 10, 1917 – February 17, 1982) was an American jazz pianist and composer. He had a unique improvisational style and made numerous contributions to the standard jazz repertoire, including " 'Round Midnight", ...

, trumpeters Dizzy Gillespie and Clifford Brown, and drummer Max Roach

Maxwell Lemuel Roach (January 10, 1924 – August 16, 2007) was an American jazz drummer and composer. A pioneer of bebop, he worked in many other styles of music, and is generally considered one of the most important drummers in history. He wo ...

. Divorcing itself from dance music, bebop established itself more as an art form, thus lessening its potential popular and commercial appeal.

Composer Gunther Schuller

Gunther Alexander Schuller (November 22, 1925June 21, 2015) was an American composer, conductor, horn player, author, historian, educator, publisher, and jazz musician.

Biography and works

Early years

Schuller was born in Queens, New York City ...

wrote: "In 1943 I heard the great Earl Hines band which had Bird in it and all those other great musicians. They were playing all the flatted fifth chords and all the modern harmonies and substitutions and Dizzy Gillespie runs in the trumpet section work. Two years later I read that that was 'bop' and the beginning of modern jazz ... but the band never made recordings."

Dizzy Gillespie wrote: "People talk about the Hines band being 'the incubator of bop' and the leading exponents of that music ended up in the Hines band. But people also have the erroneous impression that the music was new. It was not. The music evolved from what went before. It was the same basic music. The difference was in how you got from here to here to here...naturally each age has got its own shit."

Since bebop was meant to be listened to, not danced to, it could use faster tempos. Drumming shifted to a more elusive and explosive style, in which the ride cymbal was used to keep time while the snare and bass drum were used for accents. This led to a highly syncopated music with a linear rhythmic complexity.[Floyd, Samuel A., Jr. (1995). ''The Power of Black Music: Interpreting its history from Africa to the United States''. New York: Oxford University Press.]

Bebop musicians employed several harmonic devices which were not previously typical in jazz, engaging in a more abstracted form of chord-based improvisation. Bebop scales are traditional scales with an added chromatic passing note; bebop also uses "passing" chords, substitute chord

In music theory, chord substitution is the technique of using a chord in place of another in a progression of chords, or a chord progression. Much of the European classical repertoire and the vast majority of blues, jazz and rock music songs a ...

s, and altered chord

An altered chord is a chord that replaces one or more notes from the diatonic scale with a neighboring pitch from the chromatic scale. By the broadest definition, any chord with a non-diatonic chord tone is an altered chord. The simplest examp ...

s. New forms of chromaticism

Chromaticism is a compositional technique interspersing the primary diatonic pitches and chords with other pitches of the chromatic scale. In simple terms, within each octave, diatonic music uses only seven different notes, rather than the ...

and dissonance were introduced into jazz, and the dissonant tritone

In music theory, the tritone is defined as a musical interval composed of three adjacent whole tones (six semitones). For instance, the interval from F up to the B above it (in short, F–B) is a tritone as it can be decomposed into the three ad ...

(or "flatted fifth") interval became the "most important interval of bebop" Chord progressions for bebop tunes were often taken directly from popular swing-era tunes and reused with a new and more complex melody and/or reharmonized with more complex chord progressions to form new compositions, a practice which was already well-established in earlier jazz, but came to be central to the bebop style. Bebop made use of several relatively common chord progressions, such as blues (at base, I–IV–V, but often infused with ii–V motion) and "rhythm changes" (I–VI–ii–V) – the chords to the 1930s pop standard "I Got Rhythm

"I Got Rhythm" is a piece composed by George Gershwin with lyrics by Ira Gershwin and published in 1930, which became a jazz standard. Its chord progression, known as the " rhythm changes", is the foundation for many other popular jazz tunes suc ...

". Late bop also moved towards extended forms that represented a departure from pop and show tunes.

The harmonic development in bebop is often traced back to a moment experienced by Charlie Parker while performing "Cherokee" at Clark Monroe's Uptown House, New York, in early 1942. "I'd been getting bored with the stereotyped changes that were being used...and I kept thinking there's bound to be something else. I could hear it sometimes. I couldn't play it...I was working over 'Cherokee,' and, as I did, I found that by using the higher intervals of a chord as a melody line and backing them with appropriately related changes, I could play the thing I'd been hearing. It came alive."Gerhard Kubik

Gerhard Kubik (born 10 December 1934) is an Austrian music ethnologist from Vienna. He studied ethnology, musicology and African languages at the University of Vienna. He published his doctoral dissertation in 1971 and achieved habilitation in 1 ...

postulates that harmonic development in bebop sprang from blues and African-related tonal sensibilities rather than 20th-century Western classical music. "Auditory inclinations were the African legacy in arker'slife, reconfirmed by the experience of the blues tonal system, a sound world at odds with the Western diatonic chord categories. Bebop musicians eliminated Western-style functional harmony in their music while retaining the strong central tonality of the blues as a basis for drawing upon various African matrices."While for an outside observer, the harmonic innovations in bebop would appear to be inspired by experiences in Western "serious" music, from Claude Debussy

(Achille) Claude Debussy (; 22 August 1862 – 25 March 1918) was a French composer. He is sometimes seen as the first Impressionism in music, Impressionist composer, although he vigorously rejected the term. He was among the most infl ...

to Arnold Schoenberg

Arnold Schoenberg or Schönberg (, ; ; 13 September 187413 July 1951) was an Austrian-American composer, music theorist, teacher, writer, and painter. He is widely considered one of the most influential composers of the 20th century. He was as ...

, such a scheme cannot be sustained by the evidence from a cognitive approach. Claude Debussy did have some influence on jazz, for example, on Bix Beiderbecke's piano playing. And it is also true that Duke Ellington adopted and reinterpreted some harmonic devices in European contemporary music. West Coast jazz would run into such debts as would several forms of cool jazz, but bebop has hardly any such debts in the sense of direct borrowings. On the contrary, ideologically, bebop was a strong statement of rejection of any kind of eclecticism, propelled by a desire to activate something deeply buried in self. Bebop then revived tonal-harmonic ideas transmitted through the blues and reconstructed and expanded others in a basically non-Western harmonic approach. The ultimate significance of all this is that the experiments in jazz during the 1940s brought back to African-American music

African-American music is an umbrella term covering a diverse range of music and musical genres largely developed by African Americans and their culture. Their origins are in musical forms that first came to be due to the condition of slaver ...

several structural principles and techniques rooted in African traditions.

These divergences from the jazz mainstream of the time met a divided, sometimes hostile response among fans and musicians, especially swing players who bristled at the new harmonic sounds. To hostile critics, bebop seemed filled with "racing, nervous phrases". But despite the friction, by the 1950s bebop had become an accepted part of the jazz vocabulary.

Afro-Cuban jazz (cu-bop)

Machito and Mario Bauza

The general consensus among musicians and musicologists is that the first original jazz piece to be overtly based in clave was "Tanga" (1943), composed by Cuban-born Mario Bauza and recorded by Machito and his Afro-Cubans in New York City. "Tanga" began as a spontaneous descarga

A descarga (literally ''discharge'' in Spanish) is an improvised jam session consisting of variations on Cuban music themes, primarily son montuno, but also guajira, bolero, guaracha and rumba. The genre is strongly influenced by jazz and it ...

(Cuban jam session), with jazz solos superimposed on top.

This was the birth of Afro-Cuban jazz

Afro-Cuban jazz is the earliest form of Latin jazz. It mixes Afro-Cuban clave-based rhythms with jazz harmonies and techniques of improvisation. Afro-Cuban music has deep roots in African ritual and rhythm.{{cite web, Cuba: Son and Afro-Cuban ...

. The use of clave brought the African ''timeline'', or ''key pattern

Key pattern is the generic term for an interlocking Geometry, geometric motif made from straight lines or bars that intersect to form Rectilinear polygon, rectilinear spiral shapes. According to Allen and Anderson, the negative space between the li ...

'', into jazz. Music organized around key patterns convey a two-celled (binary) structure, which is a complex level of African cross-rhythm. Within the context of jazz, however, harmony is the primary referent, not rhythm. The harmonic progression can begin on either side of clave, and the harmonic "one" is always understood to be "one". If the progression begins on the "three-side" of clave, it is said to be in ''3–2 clave'' (shown below). If the progression begins on the "two-side", it is in ''2–3 clave''.

:

\new RhythmicStaff

Dizzy Gillespie and Chano Pozo

Mario Bauzá introduced bebop innovator Dizzy Gillespie to Cuban conga drummer and composer Chano Pozo. Gillespie and Pozo's brief collaboration produced some of the most enduring Afro-Cuban jazz standards. " Manteca" (1947) is the first jazz standard to be rhythmically based on clave. According to Gillespie, Pozo composed the layered, contrapuntal

Mario Bauzá introduced bebop innovator Dizzy Gillespie to Cuban conga drummer and composer Chano Pozo. Gillespie and Pozo's brief collaboration produced some of the most enduring Afro-Cuban jazz standards. " Manteca" (1947) is the first jazz standard to be rhythmically based on clave. According to Gillespie, Pozo composed the layered, contrapuntal guajeo

A guajeo (Anglicized pronunciation: ''wa-hey-yo'') is a typical Cuban ostinato melody, most often consisting of arpeggiated chords in syncopated patterns. Some musicians only use the term ''guajeo'' for ostinato patterns played specifically by ...

s (Afro-Cuban ostinato

In music, an ostinato (; derived from Italian word for ''stubborn'', compare English ''obstinate'') is a motif or phrase that persistently repeats in the same musical voice, frequently in the same pitch. Well-known ostinato-based pieces include ...

s) of the A section and the introduction, while Gillespie wrote the bridge. Gillespie recounted: "If I'd let it go like hanowanted it, it would have been strictly Afro-Cuban all the way. There wouldn't have been a bridge. I thought I was writing an eight-bar bridge, but ... I had to keep going and ended up writing a sixteen-bar bridge." The bridge gave "Manteca" a typical jazz harmonic structure, setting the piece apart from Bauza's modal "Tanga" of a few years earlier.

Gillespie's collaboration with Pozo brought specific African-based rhythms into bebop. While pushing the boundaries of harmonic improvisation, ''cu-bop'' also drew from African rhythm. Jazz arrangements with a Latin A section and a swung B section, with all choruses swung during solos, became common practice with many Latin tunes of the jazz standard repertoire. This approach can be heard on pre-1980 recordings of "Manteca", "A Night in Tunisia

"A Night in Tunisia" is a musical composition written by Dizzy Gillespie around 1940–42, while Gillespie was playing with the Benny Carter band. It has become a jazz standard. It is also known as "Interlude", and with lyrics by Raymond Leveen ...

", "Tin Tin Deo", and " On Green Dolphin Street".

African cross-rhythm

Cuban percussionist Mongo Santamaria first recorded his composition " Afro Blue" in 1959.

"Afro Blue" was the first jazz standard built upon a typical African three-against-two (3:2) cross-rhythm, or

Cuban percussionist Mongo Santamaria first recorded his composition " Afro Blue" in 1959.

"Afro Blue" was the first jazz standard built upon a typical African three-against-two (3:2) cross-rhythm, or hemiola

In music, hemiola (also hemiolia) is the ratio 3:2. The equivalent Latin term is sesquialtera. In rhythm, ''hemiola'' refers to three beats of equal value in the time normally occupied by two beats. In pitch, ''hemiola'' refers to the interval of ...

. The piece begins with the bass repeatedly playing 6 cross-beats per each measure of , or 6 cross-beats per 4 main beats—6:4 (two cells of 3:2).

The following example shows the original ostinato

In music, an ostinato (; derived from Italian word for ''stubborn'', compare English ''obstinate'') is a motif or phrase that persistently repeats in the same musical voice, frequently in the same pitch. Well-known ostinato-based pieces include ...

"Afro Blue" bass line. The cross noteheads indicate the main beats (not bass notes).

:

\new Staff <<

\new voice \relative c

\new voice \relative c

>>

When John Coltrane

John William Coltrane (September 23, 1926 – July 17, 1967) was an American jazz saxophonist, bandleader and composer. He is among the most influential and acclaimed figures in the history of jazz and 20th-century music.

Born and rai ...

covered "Afro Blue" in 1963, he inverted the metric hierarchy, interpreting the tune as a jazz waltz with duple cross-beats superimposed (2:3). Originally a B pentatonic

A pentatonic scale is a musical scale with five notes per octave, in contrast to the heptatonic scale, which has seven notes per octave (such as the major scale and minor scale).

Pentatonic scales were developed independently by many anci ...

blues, Coltrane expanded the harmonic structure of "Afro Blue".

Perhaps the most respected Afro-cuban jazz

Afro-Cuban jazz is the earliest form of Latin jazz. It mixes Afro-Cuban clave-based rhythms with jazz harmonies and techniques of improvisation. Afro-Cuban music has deep roots in African ritual and rhythm.{{cite web, Cuba: Son and Afro-Cuban ...

combo of the late 1950s was vibraphonist Cal Tjader

Callen Radcliffe Tjader Jr. ( ; July 16, 1925 – May 5, 1982) was an American Latin Jazz musician, known as the most successful non-Latino Latin musician. He explored other jazz idioms, even as he continued to perform music of Afro-Jazz, ...

's band. Tjader had Mongo Santamaria, Armando Peraza

Armando Peraza (May 30, 1924 – April 14, 2014) was a Latin jazz percussionist and a member of the rock band Santana. Peraza played congas, bongos, and timbales.

Biography

Early life

Born in Lawton Batista, Havana, Cuba in 1924 (although the ...

, and Willie Bobo

William Correa (February 28, 1934 – September 15, 1983), better known by his stage name Willie Bobo,Biography ''AllMusic'' was an American Latin jazz percussionist of Puerto Rican descent. Bobo rejected the stereotypical expectations of Lati ...

on his early recording dates.

Dixieland revival

In the late 1940s, there was a revival of Dixieland

Dixieland jazz, also referred to as traditional jazz, hot jazz, or simply Dixieland, is a style of jazz based on the music that developed in New Orleans at the start of the 20th century. The 1917 recordings by the Original Dixieland Jass Band ...

, harking back to the contrapuntal New Orleans style. This was driven in large part by record company reissues of jazz classics by the Oliver, Morton, and Armstrong bands of the 1930s. There were two types of musicians involved in the revival: the first group was made up of those who had begun their careers playing in the traditional style and were returning to it (or continuing what they had been playing all along), such as Bob Crosby's Bobcats, Max Kaminsky, Eddie Condon

Albert Edwin Condon (November 16, 1905 – August 4, 1973) was an American jazz banjoist, guitarist, and bandleader. A leading figure in Chicago jazz, he also played piano and sang.

Early years

Condon was born in Goodland, Indiana, the son of ...

, and Wild Bill Davison.Conrad Janis

Conrad Janis (February 11, 1928 – March 1, 2022) was a jazz trombonist and actor who starred in film and television during the Golden Age Era in the 1950s and 1960s. He played the role of Mindy McConnell's father, Frederick, on television's ' ...

, and Ward Kimball

Ward Walrath Kimball (March 4, 1914 – July 8, 2002) was an American animator employed by Walt Disney Animation Studios. He was part of Walt Disney's main team of animators, known collectively as Disney's Nine Old Men. His films have been honored ...

and his Firehouse Five Plus Two Jazz Band. By the late 1940s, Louis Armstrong's Allstars band became a leading ensemble. Through the 1950s and 1960s, Dixieland was one of the most commercially popular jazz styles in the US, Europe, and Japan, although critics paid little attention to it.

Hard bop

Hard bop is an extension of bebop (or "bop") music that incorporates influences from blues, rhythm and blues, and gospel, especially in saxophone and piano playing. Hard bop was developed in the mid-1950s, coalescing in 1953 and 1954; it developed partly in response to the vogue for cool jazz in the early 1950s and paralleled the rise of rhythm and blues. It has been described as "funky" and can be considered a relative of

Hard bop is an extension of bebop (or "bop") music that incorporates influences from blues, rhythm and blues, and gospel, especially in saxophone and piano playing. Hard bop was developed in the mid-1950s, coalescing in 1953 and 1954; it developed partly in response to the vogue for cool jazz in the early 1950s and paralleled the rise of rhythm and blues. It has been described as "funky" and can be considered a relative of soul jazz

Soul jazz or funky jazz is a subgenre of jazz that incorporates strong influences from hard bop, blues, soul, gospel and rhythm and blues. Soul jazz is often characterized by organ trios featuring the Hammond organ and small combos including t ...

.Newport Jazz Festival

The Newport Jazz Festival is an annual American multi-day jazz music festival held every summer in Newport, Rhode Island. Elaine Lorillard established the festival in 1954, and she and husband Louis Lorillard financed it for many years. They hi ...

introduced the style to the jazz world. Further leaders of hard bop's development included the Clifford Brown/Max Roach Quintet, Art Blakey's Jazz Messengers, the Horace Silver Quintet, and trumpeters Lee Morgan

Edward Lee Morgan (July 10, 1938 – February 19, 1972) was an American jazz trumpeter and composer.

One of the key hard bop musicians of the 1960s, Morgan came to prominence in his late teens, recording on John Coltrane's '' Blue Train'' ...

and Freddie Hubbard

Frederick Dewayne Hubbard (April 7, 1938 – December 29, 2008) was an American jazz trumpeter. He played bebop, hard bop, and post-bop styles from the early 1960s onwards. His unmistakable and influential tone contributed to new perspectives f ...

. The late 1950s to early 1960s saw hard boppers form their own bands as a new generation of blues- and bebop-influenced musicians entered the jazz world, from pianists Wynton Kelly

Wynton Charles Kelly (December 2, 1931 – April 12, 1971) was an American jazz pianist and composer. He is known for his lively, blues-based playing and as one of the finest accompanists in jazz. He began playing professionally at the age of ...

and Tommy Flanagan

Thomas Lee Flanagan (March 16, 1930 – November 16, 2001) was an American jazz pianist and composer. He grew up in Detroit, initially influenced by such pianists as Art Tatum, Teddy Wilson, and Nat King Cole, and then by bebop musicians. ...

Joe Henderson

Joe Henderson (April 24, 1937 – June 30, 2001) was an American jazz tenor saxophonist. In a career spanning more than four decades, Henderson played with many of the leading American players of his day and recorded for several prominent l ...

and Hank Mobley

Henry "Hank" Mobley (July 7, 1930 – May 30, 1986) was an American hard bop and soul jazz tenor saxophonist and composer. Mobley was described by Leonard Feather as the "middleweight champion of the tenor saxophone", a metaphor used to des ...

. Coltrane, Johnny Griffin

John Arnold Griffin III (April 24, 1928 – July 25, 2008) was an American jazz tenor saxophonist. Nicknamed "the Little Giant" for his short stature and forceful playing, Griffin's career began in the mid-1940s and continued until the month of ...

, Mobley, and Morgan all participated on the album '' A Blowin' Session'' (1957), considered by Al Campbell to have been one of the high points of the hard bop era.

Hard bop was prevalent within jazz for about a decade spanning from 1955 to 1965,neo-bop

Neo-bop (also called neotraditionalist) refers to a style of jazz that gained popularity in the 1980s among musicians who found greater aesthetic affinity for acoustically based, swinging, melodic forms of jazz than for free jazz and jazz fusion th ...

.

Modal jazz

Modal jazz is a development which began in the later 1950s which takes the mode, or musical scale, as the basis of musical structure and improvisation. Previously, a solo was meant to fit into a given chord progression

In a musical composition, a chord progression or harmonic progression (informally chord changes, used as a plural) is a succession of chords. Chord progressions are the foundation of harmony in Western musical tradition from the common practice ...

, but with modal jazz, the soloist creates a melody using one (or a small number of) modes. The emphasis is thus shifted from harmony to melody: "Historically, this caused a seismic shift among jazz musicians, away from thinking vertically (the chord), and towards a more horizontal approach (the scale)", explained pianist Mark Levine

Mark Andrew LeVine is an American historian, musician, writer, and professor. He is a professor of history at the University of California, Irvine.

Education

LeVine received his B.A. in comparative religion and biblical studies from Hunter ...

.

The modal theory stems from a work by George Russell. Miles Davis introduced the concept to the greater jazz world with ''Kind of Blue

''Kind of Blue'' is a studio album by American jazz trumpeter, composer, and bandleader Miles Davis. It was recorded on March 2 and April 22, 1959, at Columbia's 30th Street Studio in New York City, and released on August 17 of that year by C ...

'' (1959), an exploration of the possibilities of modal jazz which would become the best selling jazz album of all time. In contrast to Davis' earlier work with hard bop and its complex chord progression and improvisation, ''Kind of Blue'' was composed as a series of modal sketches in which the musicians were given scales that defined the parameters of their improvisation and style.

"I didn't write out the music for ''Kind of Blue'', but brought in sketches for what everybody was supposed to play because I wanted a lot of spontaneity," recalled Davis. The track "So What" has only two chords: D-7 and E-7.

Other innovators in this style include Jackie McLean

John Lenwood "Jackie" McLean (May 17, 1931 – March 31, 2006) was an American jazz alto saxophonist, composer, bandleader, and educator, and is one of the few musicians to be elected to the ''DownBeat'' Hall of Fame in the year of their dea ...

, and two of the musicians who had also played on ''Kind of Blue'': John Coltrane and Bill Evans.

Free jazz

Free jazz, and the related form of

Free jazz, and the related form of avant-garde jazz

Avant-garde jazz (also known as avant-jazz and experimental jazz) is a style of music and improvisation that combines avant-garde art music and composition with jazz. It originated in the early 1950s and developed through to the late 1960s. Orig ...

, broke through into an open space of "free tonality" in which meter, beat, and formal symmetry all disappeared, and a range of world music from India, Africa, and Arabia were melded into an intense, even religiously ecstatic or orgiastic style of playing. While loosely inspired by bebop, free jazz tunes gave players much more latitude; the loose harmony and tempo was deemed controversial when this approach was first developed. The bassist Charles Mingus

Charles Mingus Jr. (April 22, 1922 – January 5, 1979) was an American jazz upright bassist, pianist, composer, bandleader, and author. A major proponent of collective improvisation, he is considered to be one of the greatest jazz musicians an ...

is also frequently associated with the avant-garde in jazz, although his compositions draw from myriad styles and genres.

The first major stirrings came in the 1950s with the early work of Ornette Coleman

Randolph Denard Ornette Coleman (March 9, 1930 – June 11, 2015) was an American jazz saxophonist, violinist, trumpeter, and composer known as a principal founder of the free jazz genre, a term derived from his 1960 album '' Free Jazz: A Col ...

(whose 1960 album '' Free Jazz: A Collective Improvisation'' coined the term) and Cecil Taylor

Cecil Percival Taylor (March 25, 1929April 5, 2018) was an American pianist and poet.

Taylor was classically trained and was one of the pioneers of free jazz. His music is characterized by an energetic, physical approach, resulting in complex ...

. In the 1960s, exponents included Albert Ayler, Gato Barbieri

Leandro "Gato" Barbieri (November 28, 1932 – April 2, 2016) was an Argentine jazz tenor saxophonist who rose to fame during the free jazz movement in the 1960s and is known for his Latin jazz recordings of the 1970s. His nickname, Gato, is Spa ...

, Carla Bley

Carla Bley (born Lovella May Borg; May 11, 1936) is an American jazz composer, pianist, organist and bandleader. An important figure in the free jazz movement of the 1960s, she is perhaps best known for her jazz opera '' Escalator over the Hill'' ...

, Don Cherry

Donald Stewart Cherry (born February 5, 1934) is a Canadian former ice hockey player, coach, and television commentator. Cherry played one game in the National Hockey League (NHL) with the Boston Bruins, and later coached the team for five se ...

, Larry Coryell

Larry Coryell (born Lorenz Albert Van DeLinder III; April 2, 1943 – February 19, 2017) was an American jazz guitarist.

Early life

Larry Coryell was born in Galveston, Texas, United States. He never knew his biological father, a musician. He w ...

, John Coltrane

John William Coltrane (September 23, 1926 – July 17, 1967) was an American jazz saxophonist, bandleader and composer. He is among the most influential and acclaimed figures in the history of jazz and 20th-century music.

Born and rai ...

, Bill Dixon, Jimmy Giuffre

James Peter Giuffre (, ; April 26, 1921 – April 24, 2008) was an American jazz clarinetist, saxophonist, composer, and arranger. He is known for developing forms of jazz which allowed for free interplay between the musicians, anticipating f ...

, Steve Lacy Steve Lacy may refer to:

Music

* Steve Lacy (saxophonist) (1934–2004), American jazz saxophonist and composer

* Steve Lacy (singer) (born 1998), American musician

Other occupations

*Steve Lacy (coach) (1908–2000), American college sports coach ...

, Michael Mantler

Michael Mantler (born August 10, 1943) is an Austrian avant-garde jazz trumpeter and composer of contemporary music.

Career: United States

Mantler was born in Vienna, Austria. In the early 1960s, he was a student at the Academy of Music and V ...

, Sun Ra

Le Sony'r Ra (born Herman Poole Blount, May 22, 1914 – May 30, 1993), better known as Sun Ra, was an American jazz composer, bandleader, piano and synthesizer player, and poet known for his experimental music, "cosmic" philosophy, prolific ou ...

, Roswell Rudd

Roswell Hopkins Rudd Jr. (November 17, 1935 – December 21, 2017) was an American jazz trombonist and composer.

Although skilled in a variety of genres of jazz (including Dixieland, which he performed while in college), and other genres of musi ...

, Pharoah Sanders

Pharoah Sanders (born Ferrell Lee Sanders; October 13, 1940 – September 24, 2022) was an American jazz saxophonist. Known for his overblowing, harmonic, and multiphonic techniques on the saxophone, as well as his use of " sheets of sound", S ...

, and John Tchicai. In developing his late style, Coltrane was especially influenced by the dissonance of Ayler's trio with bassist Gary Peacock and drummer Sunny Murray, a rhythm section honed with Cecil Taylor

Cecil Percival Taylor (March 25, 1929April 5, 2018) was an American pianist and poet.

Taylor was classically trained and was one of the pioneers of free jazz. His music is characterized by an energetic, physical approach, resulting in complex ...

as leader. In November 1961, Coltrane played a gig at the Village Vanguard, which resulted in the classic ''Chasin' the 'Trane'', which ''DownBeat'' magazine panned as "anti-jazz". On his 1961 tour of France, he was booed, but persevered, signing with the new Impulse! Records

Impulse! Records (occasionally styled as "¡mpulse! Records" and "¡!") is an American jazz record company and label established by Creed Taylor in 1960. John Coltrane was among Impulse!'s earliest signings. Thanks to consistent sales and positi ...

in 1960 and turning it into "the house that Trane built", while championing many younger free jazz musicians, notably Archie Shepp

Archie Shepp (born May 24, 1937) is an American jazz saxophonist, educator and playwright who since the 1960s has played a central part in the development of avant-garde jazz.

Biography Early life

Shepp was born in Fort Lauderdale, Florida, but ...

, who often played with trumpeter Bill Dixon, who organized the 4-day " October Revolution in Jazz" in Manhattan in 1964, the first free jazz festival.

A series of recordings with the Classic Quartet in the first half of 1965 show Coltrane's playing becoming increasingly abstract, with greater incorporation of devices like multiphonics

A multiphonic is an extended technique on a monophonic musical instrument (one that generally produces only one note at a time) in which several notes are produced at once. This includes wind, reed, and brass instruments, as well as the human voic ...

, utilization of overtones, and playing in the altissimo

Altissimo (Italian for ''very high'') is the uppermost register on woodwind instruments. For clarinets, which overblow on odd harmonics, the altissimo notes are those based on the fifth, seventh, and higher harmonics. For other woodwinds, the a ...

register, as well as a mutated return to Coltrane's sheets of sound. In the studio, he all but abandoned his soprano to concentrate on the tenor saxophone. In addition, the quartet responded to the leader by playing with increasing freedom. The group's evolution can be traced through the recordings ''The John Coltrane Quartet Plays

'' The John Coltrane Quartet Plays'' (full title ''The John Coltrane Quartet Plays Chim Chim Cheree, Song of Praise, Nature Boy, Brazilia'') is an album by jazz musician John Coltrane, recorded in February and May 1965, shortly after the release of ...

'', '' Living Space'' and '' Transition'' (both June 1965), '' New Thing at Newport'' (July 1965), '' Sun Ship'' (August 1965), and '' First Meditations'' (September 1965).

In June 1965, Coltrane and 10 other musicians recorded '' Ascension'', a 40-minute-long piece without breaks that included adventurous solos by young avant-garde musicians as well as Coltrane, and was controversial primarily for the collective improvisation sections that separated the solos. Dave Liebman

David Liebman (born September 4, 1946) is an American saxophonist, flautist and jazz educator. He is known for his innovative lines and use of atonality. He was a frequent collaborator with pianist Richie Beirach.

In June 2010, he received ...

later called it "the torch that lit the free jazz thing". After recording with the quartet over the next few months, Coltrane invited Pharoah Sanders to join the band in September 1965. While Coltrane used over-blowing frequently as an emotional exclamation-point, Sanders would opt to overblow his entire solo, resulting in a constant screaming and screeching in the altissimo range of the instrument.

Free jazz in Europe

Free jazz was played in Europe in part because musicians such as Ayler, Taylor,

Free jazz was played in Europe in part because musicians such as Ayler, Taylor, Steve Lacy Steve Lacy may refer to:

Music

* Steve Lacy (saxophonist) (1934–2004), American jazz saxophonist and composer

* Steve Lacy (singer) (born 1998), American musician

Other occupations

*Steve Lacy (coach) (1908–2000), American college sports coach ...

, and Eric Dolphy

Eric Allan Dolphy Jr. (June 20, 1928 – June 29, 1964) was an American jazz alto saxophonist, bass clarinetist and flautist. On a few occasions, he also played the clarinet and piccolo. Dolphy was one of several multi-instrumentalists to ...

spent extended periods of time there, and European musicians such as Michael Mantler

Michael Mantler (born August 10, 1943) is an Austrian avant-garde jazz trumpeter and composer of contemporary music.

Career: United States

Mantler was born in Vienna, Austria. In the early 1960s, he was a student at the Academy of Music and V ...

and John Tchicai traveled to the U.S. to experience American music firsthand. European contemporary jazz was shaped by Peter Brötzmann, John Surman, Krzysztof Komeda, Zbigniew Namysłowski, Tomasz Stanko, Lars Gullin, Joe Harriott, Albert Mangelsdorff, Kenny Wheeler, Graham Collier, Michael Garrick and Mike Westbrook. They were eager to develop approaches to music that reflected their heritage.

Since the 1960s, creative centers of jazz in Europe have developed, such as the creative jazz scene in Amsterdam. Following the work of drummer Han Bennink and pianist Misha Mengelberg, musicians started to explore by improvising collectively until a form (melody, rhythm, a famous song) is found Jazz critic Kevin Whitehead documented the free jazz scene in Amsterdam and some of its main exponents such as the ICP (Instant Composers Pool) orchestra in his book ''New Dutch Swing''. Since the 1990s Keith Jarrett has defended free jazz from criticism. British writer Stuart Nicholson has argued European contemporary jazz has an identity different from American jazz and follows a different trajectory.

Latin jazz

Latin jazz is jazz that employs Latin American rhythms and is generally understood to have a more specific meaning than simply jazz from Latin America. A more precise term might be ''Afro-Latin jazz'', as the jazz subgenre typically employs rhythms that either have a direct analog in Africa or exhibit an African rhythmic influence beyond what is ordinarily heard in other jazz. The two main categories of Latin jazz are Afro-Cuban jazz

Afro-Cuban jazz is the earliest form of Latin jazz. It mixes Afro-Cuban clave-based rhythms with jazz harmonies and techniques of improvisation. Afro-Cuban music has deep roots in African ritual and rhythm.{{cite web, Cuba: Son and Afro-Cuban ...

and Brazilian jazz.

In the 1960s and 1970s, many jazz musicians had only a basic understanding of Cuban and Brazilian music, and jazz compositions which used Cuban or Brazilian elements were often referred to as "Latin tunes", with no distinction between a Cuban son montuno and a Brazilian bossa nova. Even as late as 2000, in Mark Gridley's ''Jazz Styles: History and Analysis'', a bossa nova bass line is referred to as a "Latin bass figure". It was not uncommon during the 1960s and 1970s to hear a conga playing a Cuban tumbao while the drumset and bass played a Brazilian bossa nova pattern. Many jazz standards such as "Manteca", "On Green Dolphin Street" and "Song for My Father" have a "Latin" A section and a swung B section. Typically, the band would only play an even-eighth "Latin" feel in the A section of the head and swing throughout all of the solos. Latin jazz specialists like Cal Tjader

Callen Radcliffe Tjader Jr. ( ; July 16, 1925 – May 5, 1982) was an American Latin Jazz musician, known as the most successful non-Latino Latin musician. He explored other jazz idioms, even as he continued to perform music of Afro-Jazz, ...

tended to be the exception. For example, on a 1959 live Tjader recording of "A Night in Tunisia", pianist Vince Guaraldi soloed through the entire form over an authentic mambo (music), mambo.

Afro-Cuban jazz renaissance

For most of its history, Afro-Cuban jazz had been a matter of superimposing jazz phrasing over Cuban rhythms. But by the end of the 1970s, a new generation of New York City musicians had emerged who were fluent in both salsa (music), salsa dance music and jazz, leading to a new level of integration of jazz and Cuban rhythms. This era of creativity and vitality is best represented by the Gonzalez brothers Jerry (congas and trumpet) and Andy (bass). During 1974–1976, they were members of one of Eddie Palmieri's most experimental salsa groups: salsa was the medium, but Palmieri was stretching the form in new ways. He incorporated parallel fourths, with McCoy Tyner-type vamps. The innovations of Palmieri, the Gonzalez brothers and others led to an Afro-Cuban jazz renaissance in New York City.

This occurred in parallel with developments in Cuba The first Cuban band of this new wave was Irakere. Their "Chékere-son" (1976) introduced a style of "Cubanized" bebop-flavored horn lines that departed from the more angular guajeo-based lines which were typical of Cuban popular music and Latin jazz up until that time. It was based on Charlie Parker's composition "Billie's Bounce", jumbled together in a way that fused clave and bebop horn lines. In spite of the ambivalence of some band members towards Irakere's Afro-Cuban folkloric / jazz fusion, their experiments forever changed Cuban jazz: their innovations are still heard in the high level of harmonic and rhythmic complexity in Cuban jazz and in the jazzy and complex contemporary form of popular dance music known as timba.

Afro-Brazilian jazz

Brazilian jazz, such as bossa nova, is derived from samba, with influences from jazz and other 20th-century classical and popular music styles. Bossa is generally moderately paced, with melodies sung in Portuguese or English, whilst the related jazz-samba is an adaptation of street samba into jazz.

The bossa nova style was pioneered by Brazilians João Gilberto and Antônio Carlos Jobim and was made popular by Elizete Cardoso's recording of "Chega de Saudade" on the ''Canção do Amor Demais'' LP. Gilberto's initial releases, and the 1959 film ''Black Orpheus'', achieved significant popularity in Latin America; this spread to North America via visiting American jazz musicians. The resulting recordings by Charlie Byrd and Stan Getz cemented bossa nova's popularity and led to a worldwide boom, with 1963's ''Getz/Gilberto'', numerous recordings by famous jazz performers such as

Brazilian jazz, such as bossa nova, is derived from samba, with influences from jazz and other 20th-century classical and popular music styles. Bossa is generally moderately paced, with melodies sung in Portuguese or English, whilst the related jazz-samba is an adaptation of street samba into jazz.

The bossa nova style was pioneered by Brazilians João Gilberto and Antônio Carlos Jobim and was made popular by Elizete Cardoso's recording of "Chega de Saudade" on the ''Canção do Amor Demais'' LP. Gilberto's initial releases, and the 1959 film ''Black Orpheus'', achieved significant popularity in Latin America; this spread to North America via visiting American jazz musicians. The resulting recordings by Charlie Byrd and Stan Getz cemented bossa nova's popularity and led to a worldwide boom, with 1963's ''Getz/Gilberto'', numerous recordings by famous jazz performers such as Ella Fitzgerald

Ella Jane Fitzgerald (April 25, 1917June 15, 1996) was an American jazz singer, sometimes referred to as the "First Lady of Song", "Queen of Jazz", and "Lady Ella". She was noted for her purity of tone, impeccable diction, phrasing, timing, i ...

and Frank Sinatra, and the eventual entrenchment of the bossa nova style as a lasting influence in world music.

Brazilian percussionists such as Airto Moreira and Naná Vasconcelos also influenced jazz internationally by introducing Afro-Brazilian folkloric instruments and rhythms into a wide variety of jazz styles, thus attracting a greater audience to them.

While bossa nova has been labeled as jazz by music critics, namely those from outside of Brazil, it has been rejected by many prominent bossa nova musicians such as Jobim, who once said "Bossa nova is not Brazilian jazz."

African-inspired

Rhythm

The first jazz standard

Jazz standards are musical compositions that are an important part of the musical repertoire of jazz musicians, in that they are widely known, performed, and recorded by jazz musicians, and widely known by listeners. There is no definitive l ...

composed by a non-Latino to use an overt African cross-rhythm was Wayne Shorter's "Footprints (composition), Footprints" (1967). On the version recorded on ''Miles Smiles'' by Miles Davis, the bass switches to a tresillo figure at 2:20. "Footprints" is not, however, a Latin jazz tune: African rhythmic structures are accessed directly by Ron Carter (bass) and Tony Williams (drummer), Tony Williams (drums) via the rhythmic sensibilities of swing

Swing or swinging may refer to:

Apparatus

* Swing (seat), a hanging seat that swings back and forth

* Pendulum, an object that swings

* Russian swing, a swing-like circus apparatus

* Sex swing, a type of harness for sexual intercourse

* Swing rid ...

. Throughout the piece, the four beats, whether sounded or not, are maintained as the temporal referent. The following example shows the and forms of the bass line. The slashed noteheads indicate the main beat music, beats (not bass notes), where one ordinarily taps their foot to "keep time".

:

Pentatonic scales

The use of pentatonic scales was another trend associated with Africa. The use of pentatonic scales in Africa probably goes back thousands of years.

McCoy Tyner perfected the use of the pentatonic scale in his solos, and also used parallel fifths and fourths, which are common harmonies in West Africa.

The minor pentatonic scale is often used in blues improvisation, and like a blues scale, a minor pentatonic scale can be played over all of the chords in a blues. The following pentatonic lick was played over blues changes by Joe Henderson

Joe Henderson (April 24, 1937 – June 30, 2001) was an American jazz tenor saxophonist. In a career spanning more than four decades, Henderson played with many of the leading American players of his day and recorded for several prominent l ...

on Horace Silver's "African Queen" (1965).

Jazz pianist, theorist, and educator Mark Levine

Mark Andrew LeVine is an American historian, musician, writer, and professor. He is a professor of history at the University of California, Irvine.

Education

LeVine received his B.A. in comparative religion and biblical studies from Hunter ...

refers to the scale generated by beginning on the fifth step of a pentatonic scale as the ''V pentatonic scale''.

Levine points out that the V pentatonic scale works for all three chords of the standard II–V–I jazz progression. This is a very common progression, used in pieces such as Miles Davis' "Tune Up". The following example shows the V pentatonic scale over a II–V–I progression.

Accordingly, John Coltrane's "Giant Steps" (1960), with its 26 chords per 16 bars, can be played using only three pentatonic scales. Coltrane studied Nicolas Slonimsky's ''Thesaurus of Scales and Melodic Patterns'', which contains material that is virtually identical to portions of "Giant Steps". The harmonic complexity of "Giant Steps" is on the level of the most advanced 20th-century art music. Superimposing the pentatonic scale over "Giant Steps" is not merely a matter of harmonic simplification, but also a sort of "Africanizing" of the piece, which provides an alternate approach for soloing. Mark Levine observes that when mixed in with more conventional "playing the changes", pentatonic scales provide "structure and a feeling of increased space".

Sacred and liturgical jazz

As noted above, jazz has incorporated from its inception aspects of African-American sacred music including spirituals and hymns. Secular jazz musicians often performed renditions of spirituals and hymns as part of their repertoire or isolated compositions such as "Come Sunday", part of "Black and Beige Suite" by Duke Ellington

Edward Kennedy "Duke" Ellington (April 29, 1899 – May 24, 1974) was an American jazz pianist, composer, and leader of his eponymous jazz orchestra from 1923 through the rest of his life. Born and raised in Washington, D.C., Ellington was ba ...

. Later many other jazz artists borrowed from black gospel music. However, it was only after World War II that a few jazz musicians began to compose and perform extended works intended for religious settings and/or as religious expression. Since the 1950s, sacred and liturgical music has been performed and recorded by many prominent jazz composers and musicians. The "Abyssinian Mass" by Wynton Marsalis

Wynton Learson Marsalis (born October 18, 1961) is an American trumpeter, composer, teacher, and artistic director of Jazz at Lincoln Center. He has promoted classical and jazz music, often to young audiences. Marsalis has won nine Grammy Awar ...

(Blueengine Records, 2016) is a recent example.

Relatively little has been written about sacred and liturgical jazz. In a 2013 doctoral dissertation, Angelo Versace examined the development of sacred jazz in the 1950s using disciplines of musicology and history. He noted that the traditions of black gospel music and jazz were combined in the 1950s to produce a new genre, "sacred jazz".Duke Ellington

Edward Kennedy "Duke" Ellington (April 29, 1899 – May 24, 1974) was an American jazz pianist, composer, and leader of his eponymous jazz orchestra from 1923 through the rest of his life. Born and raised in Washington, D.C., Ellington was ba ...

. Prior to his death in 1974 in response to contacts from Grace Cathedral in San Francisco, Duke Ellington

Edward Kennedy "Duke" Ellington (April 29, 1899 – May 24, 1974) was an American jazz pianist, composer, and leader of his eponymous jazz orchestra from 1923 through the rest of his life. Born and raised in Washington, D.C., Ellington was ba ...

wrote three Sacred Concerts: 1965 – A Concert of Sacred Music; 1968 – Second Sacred Concert; 1973 – Third Sacred Concert.

The most prominent form of sacred and liturgical jazz is the jazz mass. Although most often performed in a concert setting rather than church worship setting, this form has many examples. An eminent example of composers of the jazz mass was Mary Lou Williams. Williams converted to Catholicism in 1957, and proceeded to compose three masses in the jazz idiom. One was composed in 1968 to honor the Assassination of Martin Luther King Jr., recently assassinated Martin Luther King Jr. and the third was commissioned by a pontifical commission. It was performed once in 1975 in St Patrick's Cathedral in New York City. However the Catholic Church has not embraced jazz as appropriate for worship. In 1966 Joe Masters recorded "Jazz Mass" for Columbia Records. A jazz ensemble was joined by soloists and choir using the English text of the Roman Catholic Mass. Other examples include "Jazz Mass in Concert" by Lalo Schiffrin (Aleph Records, 1998, UPC 0651702632725) and "Jazz Mass" by Vince Guaraldi (Fantasy Records, 1965). In England, classical composer Will Todd recorded his "Jazz Missa Brevis" with a jazz ensemble, soloists and the St Martin's Voices on a 2018 Signum Records release, "Passion Music/Jazz Missa Brevis" also released as "Mass in Blue", and jazz organist James Taylor composed "The Rochester Mass" (Cherry Red Records, 2015). In 2013, Versace put forth bassist Ike Sturm and New York composer Deanna Witkowski as contemporary exemplars of sacred and liturgical jazz.

Jazz fusion

In the late 1960s and early 1970s, the hybrid form of jazz-rock fusion was developed by combining jazz improvisation with rock rhythms, electric instruments and the highly amplified stage sound of rock musicians such as Jimi Hendrix and Frank Zappa. Jazz fusion often uses mixed meters, odd time signatures, syncopation, complex chords, and harmonies.

According to AllMusic:

In the late 1960s and early 1970s, the hybrid form of jazz-rock fusion was developed by combining jazz improvisation with rock rhythms, electric instruments and the highly amplified stage sound of rock musicians such as Jimi Hendrix and Frank Zappa. Jazz fusion often uses mixed meters, odd time signatures, syncopation, complex chords, and harmonies.

According to AllMusic:

... until around 1967, the worlds of jazz and rock were nearly completely separate. [However, ...] as rock became more creative and its musicianship improved, and as some in the jazz world became bored with hard bop

Hard bop is a subgenre of jazz that is an extension of bebop (or "bop") music. Journalists and record companies began using the term in the mid-1950s to describe a new current within jazz that incorporated influences from rhythm and blues, gosp ...

and did not want to play strictly free jazz, avant-garde music, the two different idioms began to trade ideas and occasionally combine forces.

Miles Davis' new directions

In 1969, Davis fully embraced the electric instrument approach to jazz with ''In a Silent Way'', which can be considered his first fusion album. Composed of two side-long suites edited heavily by producer Teo Macero, this quiet, static album would be equally influential to the development of ambient music.

As Davis recalls:

The music I was really listening to in 1968 was James Brown, the great guitar player Jimi Hendrix, and a new group who had just come out with a hit record, "Dance to the Music (Sly and the Family Stone album), Dance to the Music", Sly and the Family Stone ... I wanted to make it more like rock. When we recorded ''In a Silent Way'' I just threw out all the chord sheets and told everyone to play off of that.

Two contributors to ''In a Silent Way'' also joined organist Larry Young (musician), Larry Young to create one of the early acclaimed fusion albums: Emergency! (album), ''Emergency!'' (1969) by The Tony Williams Lifetime.

Psychedelic-jazz

=Weather Report

=

Weather Report's self-titled electronic and psychedelic ''Weather Report (1971 album), Weather Report'' debut album caused a sensation in the jazz world on its arrival in 1971, thanks to the pedigree of the group's members (including percussionist Airto Moreira), and their unorthodox approach to music. The album featured a softer sound than would be the case in later years (predominantly using acoustic bass with Shorter exclusively playing soprano saxophone, and with no synthesizers involved), but is still considered a classic of early fusion. It built on the avant-garde experiments which Joe Zawinul and Shorter had pioneered with Miles Davis on ''Bitches Brew'', including an avoidance of head-and-chorus composition in favor of continuous rhythm and movement – but took the music further. To emphasize the group's rejection of standard methodology, the album opened with the inscrutable avant-garde atmospheric piece "Milky Way", which featured by Shorter's extremely muted saxophone inducing vibrations in Zawinul's piano strings while the latter pedaled the instrument. ''DownBeat'' described the album as "music beyond category", and awarded it Album of the Year in the magazine's polls that year.

Weather Report's subsequent releases were creative funk-jazz works.

Jazz-rock

Although some jazz purists protested against the blend of jazz and rock, many jazz innovators crossed over from the contemporary hard bop scene into fusion. As well as the electric instruments of rock (such as electric guitar, electric bass, electric piano and synthesizer keyboards), fusion also used the powerful amplification, Distortion (music), "fuzz" pedals, wah-wah pedals and other effects that were used by 1970s-era rock bands. Notable performers of jazz fusion included Miles Davis, Eddie Harris, keyboardists Joe Zawinul, Chick Corea, and Herbie Hancock, vibraphonist Gary Burton, drummer Tony Williams (drummer), violinist Jean-Luc Ponty, guitarists Larry Coryell

Larry Coryell (born Lorenz Albert Van DeLinder III; April 2, 1943 – February 19, 2017) was an American jazz guitarist.

Early life

Larry Coryell was born in Galveston, Texas, United States. He never knew his biological father, a musician. He w ...

, Al Di Meola, John McLaughlin (musician), John McLaughlin, Ryo Kawasaki, and Frank Zappa, saxophonist Wayne Shorter and bassists Jaco Pastorius and Stanley Clarke. Jazz fusion was also popular in Japan, where the band Casiopea released more than thirty fusion albums.

According to jazz writer Stuart Nicholson, "just as free jazz appeared on the verge of creating a whole new musical language in the 1960s ... jazz-rock briefly suggested the promise of doing the same" with albums such as Williams' ''Emergency! (album), Emergency!'' (1970) and Davis' ''Agharta (album), Agharta'' (1975), which Nicholson said "suggested the potential of evolving into something that might eventually define itself as a wholly independent genre quite apart from the sound and conventions of anything that had gone before." This development was stifled by commercialism, Nicholson said, as the genre "mutated into a peculiar species of jazz-inflected pop music that eventually took up residence on FM radio" at the end of the 1970s.

Jazz-funk

By the mid-1970s, the sound known as jazz-funk had developed, characterized by a strong beat (music), back beat (Groove (music), groove), electrified sounds and, often, the presence of electronic analog synthesizers. Jazz-funk also draws influences from traditional African music, Afro-Cuban rhythms and Jamaican reggae, notably Kingston bandleader Sonny Bradshaw. Another feature is the shift of emphasis from improvisation to composition: arrangements, melody and overall writing became important. The integration of funk, soul music, soul, and Rhythm and blues, R&B music into jazz resulted in the creation of a genre whose spectrum is wide and ranges from strong Musical improvisation#Jazz improvisation, jazz improvisation to soul, funk or disco with jazz arrangements, jazz riffs and jazz solos, and sometimes soul vocals.

Traditionalism in the 1980s

The 1980s saw something of a reaction against the fusion and free jazz that had dominated the 1970s. Trumpeter

The 1980s saw something of a reaction against the fusion and free jazz that had dominated the 1970s. Trumpeter Wynton Marsalis

Wynton Learson Marsalis (born October 18, 1961) is an American trumpeter, composer, teacher, and artistic director of Jazz at Lincoln Center. He has promoted classical and jazz music, often to young audiences. Marsalis has won nine Grammy Awar ...

emerged early in the decade, and strove to create music within what he believed was the tradition, rejecting both fusion and free jazz and creating extensions of the small and large forms initially pioneered by artists such as Louis Armstrong and Duke Ellington

Edward Kennedy "Duke" Ellington (April 29, 1899 – May 24, 1974) was an American jazz pianist, composer, and leader of his eponymous jazz orchestra from 1923 through the rest of his life. Born and raised in Washington, D.C., Ellington was ba ...

, as well as the hard bop of the 1950s. It is debatable whether Marsalis' critical and commercial success was a cause or a symptom of the reaction against Fusion and Free Jazz and the resurgence of interest in the kind of jazz pioneered in the 1960s (particularly modal jazz and post-bop); nonetheless there were many other manifestations of a resurgence of traditionalism, even if fusion and free jazz were by no means abandoned and continued to develop and evolve.

For example, several musicians who had been prominent in the fusion genre during the 1970s began to record acoustic jazz once more, including Chick Corea and Herbie Hancock. Other musicians who had experimented with electronic instruments in the previous decade had abandoned them by the 1980s; for example, Bill Evans, Joe Henderson

Joe Henderson (April 24, 1937 – June 30, 2001) was an American jazz tenor saxophonist. In a career spanning more than four decades, Henderson played with many of the leading American players of his day and recorded for several prominent l ...

, and Stan Getz

Stanley Getz (February 2, 1927 – June 6, 1991) was an American jazz saxophonist. Playing primarily the tenor saxophone, Getz was known as "The Sound" because of his warm, lyrical tone, with his prime influence being the wispy, mellow timbre o ...

. Even the 1980s music of Miles Davis, although certainly still fusion, adopted a far more accessible and recognizably jazz-oriented approach than his abstract work of the mid-1970s, such as a return to a theme-and-solos approach.

The emergence of young jazz talent beginning to perform in older, established musicians' groups further impacted the resurgence of traditionalism in the jazz community. In the 1970s, the groups of Betty Carter

Betty Carter (born Lillie Mae Jones; May 16, 1929 – September 26, 1998) was an American jazz singer known for her improvisational technique, scatting and other complex musical abilities that demonstrated her vocal talent and imaginative int ...

and The Jazz Messengers, Art Blakey and the Jazz Messengers retained their conservative jazz approaches in the midst of fusion and jazz-rock, and in addition to difficulty booking their acts, struggled to find younger generations of personnel to authentically play traditional styles such as hard bop

Hard bop is a subgenre of jazz that is an extension of bebop (or "bop") music. Journalists and record companies began using the term in the mid-1950s to describe a new current within jazz that incorporated influences from rhythm and blues, gosp ...

and bebop

Bebop or bop is a style of jazz developed in the early-to-mid-1940s in the United States. The style features compositions characterized by a fast tempo, complex chord progressions with rapid chord changes and numerous changes of key, instrum ...

. In the late 1970s, however, a resurgence of younger jazz players in Blakey's band began to occur. This movement included musicians such as Valery Ponomarev and Bobby Watson, Dennis Irwin and James Williams (musician), James Williams.

In the 1980s, in addition to Wynton Marsalis, Wynton and Branford Marsalis, the emergence of pianists in the Jazz Messengers such as Donald Brown (musician), Donald Brown, Mulgrew Miller, and later, Benny Green, bassists such as Charles Fambrough, Lonnie Plaxico (and later, Peter Washington and Essiet Essiet) horn players such as Bill Pierce (saxophonist), Bill Pierce, Donald Harrison and later Javon Jackson and Terence Blanchard emerged as talented jazz musicians, all of whom made significant contributions in the 1990s and 2000s.

The young Jazz Messengers' contemporaries, including Roy Hargrove, Marcus Roberts, Wallace Roney and Mark Whitfield were also influenced by Wynton Marsalis

Wynton Learson Marsalis (born October 18, 1961) is an American trumpeter, composer, teacher, and artistic director of Jazz at Lincoln Center. He has promoted classical and jazz music, often to young audiences. Marsalis has won nine Grammy Awar ...

's emphasis toward jazz tradition. These younger rising stars rejected avant-garde approaches and instead championed the acoustic jazz sound of Charlie Parker, Thelonious Monk

Thelonious Sphere Monk (, October 10, 1917 – February 17, 1982) was an American jazz pianist and composer. He had a unique improvisational style and made numerous contributions to the standard jazz repertoire, including " 'Round Midnight", ...

and early recordings of the first Miles Davis quintet. This group of "Young Lions" sought to reaffirm jazz as a high art tradition comparable to the discipline of classical music.Betty Carter

Betty Carter (born Lillie Mae Jones; May 16, 1929 – September 26, 1998) was an American jazz singer known for her improvisational technique, scatting and other complex musical abilities that demonstrated her vocal talent and imaginative int ...

's rotation of young musicians in her group foreshadowed many of New York's preeminent traditional jazz players later in their careers. Among these musicians were Jazz Messenger alumni Benny Green (pianist), Benny Green, Branford Marsalis and Ralph Peterson Jr., as well as Kenny Washington (musician), Kenny Washington, Lewis Nash, Curtis Lundy, Cyrus Chestnut, Mark Shim, Craig Handy, Greg Hutchinson and Marc Cary, Taurus Mateen and Geri Allen.

Out of the Blue (American band), O.T.B. ensemble included a rotation of young jazz musicians such as Kenny Garrett, Steve Wilson (jazz musician), Steve Wilson, Kenny Davis (musician), Kenny Davis, Renee Rosnes, Ralph Peterson Jr., Billy Drummond, and Robert Hurst (musician), Robert Hurst.the very leaders of the avant garde started to signal a retreat from the core principles of free jazz. Anthony Braxton began recording standards over familiar chord changes. Cecil Taylor

Cecil Percival Taylor (March 25, 1929April 5, 2018) was an American pianist and poet.

Taylor was classically trained and was one of the pioneers of free jazz. His music is characterized by an energetic, physical approach, resulting in complex ...

played duets in concert with Mary Lou Williams, and let her set out structured harmonies and familiar jazz vocabulary under his blistering keyboard attack. And the next generation of progressive players would be even more accommodating, moving inside and outside the changes without thinking twice. Musicians such as David Murray or Don Pullen may have felt the call of free-form jazz, but they never forgot all the other ways one could play African-American music for fun and profit.

Pianist Keith Jarrett—whose bands of the 1970s had played only original compositions with prominent free jazz elements—established his so-called 'Standards Trio' in 1983, which, although also occasionally exploring collective improvisation, has primarily performed and recorded jazz standards. Chick Corea similarly began exploring jazz standards in the 1980s, having neglected them for the 1970s.

In 1987, the United States House of Representatives and Senate passed a bill proposed by Democratic Representative John Conyers Jr. to define jazz as a unique form of American music, stating "jazz is hereby designated as a rare and valuable national American treasure to which we should devote our attention, support and resources to make certain it is preserved, understood and promulgated." It passed in the House on September 23, 1987, and in the Senate on November 4, 1987.[HR-57 Cente]

HR-57 Center for the Preservation of Jazz and Blues, with the six-point mandate.

Smooth jazz

In the early 1980s, a commercial form of jazz fusion called "pop fusion" or "smooth jazz" became successful, garnering significant radio airplay in "quiet storm" time slots at radio stations in urban markets across the U.S. This helped to establish or bolster the careers of vocalists including Al Jarreau, Anita Baker, Chaka Khan, and Sade Adu, Sade, as well as saxophonists including Grover Washington Jr., Kenny G, Kirk Whalum, Boney James, and David Sanborn. In general, smooth jazz is downtempo (the most widely played tracks are of 90–105 beats per minute), and has a lead melody-playing instrument (saxophone, especially soprano and tenor, and legato electric guitar are popular).

In his ''Newsweek'' article "The Problem With Jazz Criticism", Stanley Crouch considers Miles Davis' playing of fusion to be a turning point that led to smooth jazz. Critic Aaron J. West has countered the often negative perceptions of smooth jazz, stating:

In the early 1980s, a commercial form of jazz fusion called "pop fusion" or "smooth jazz" became successful, garnering significant radio airplay in "quiet storm" time slots at radio stations in urban markets across the U.S. This helped to establish or bolster the careers of vocalists including Al Jarreau, Anita Baker, Chaka Khan, and Sade Adu, Sade, as well as saxophonists including Grover Washington Jr., Kenny G, Kirk Whalum, Boney James, and David Sanborn. In general, smooth jazz is downtempo (the most widely played tracks are of 90–105 beats per minute), and has a lead melody-playing instrument (saxophone, especially soprano and tenor, and legato electric guitar are popular).

In his ''Newsweek'' article "The Problem With Jazz Criticism", Stanley Crouch considers Miles Davis' playing of fusion to be a turning point that led to smooth jazz. Critic Aaron J. West has countered the often negative perceptions of smooth jazz, stating:

I challenge the prevalent marginalization and malignment of smooth jazz in the standard jazz narrative. Furthermore, I question the assumption that smooth jazz is an unfortunate and unwelcomed evolutionary outcome of the jazz-fusion era. Instead, I argue that smooth jazz is a long-lived musical style that merits multi-disciplinary analyses of its origins, critical dialogues, performance practice, and reception.

Acid jazz, nu jazz, and jazz rap

Acid jazz developed in the UK in the 1980s and 1990s, influenced by jazz-funk and electronic music, electronic dance music. Acid jazz often contains various types of electronic composition (sometimes including Sampling (music), sampling or live DJ cutting and scratching), but it is just as likely to be played live by musicians, who often showcase jazz interpretation as part of their performance. Richard S. Ginell of AllMusic considers Roy Ayers "one of the prophets of acid jazz".

Punk jazz and jazzcore

The relaxation of orthodoxy which was concurrent with post-punk in London and New York City led to a new appreciation of jazz. In London, the Pop Group began to mix free jazz and dub reggae into their brand of punk rock. In New York, No Wave took direct inspiration from both free jazz and punk. Examples of this style include Lydia Lunch's ''Queen of Siam'',

The relaxation of orthodoxy which was concurrent with post-punk in London and New York City led to a new appreciation of jazz. In London, the Pop Group began to mix free jazz and dub reggae into their brand of punk rock. In New York, No Wave took direct inspiration from both free jazz and punk. Examples of this style include Lydia Lunch's ''Queen of Siam'',[Bangs, Lester. "Free Jazz / Punk Rock". ''Musician Magazine'', 1979]

Access date: July 20, 2008. Gray, the work of James Chance and the Contortions (who mixed Soul music, Soul with free jazz and punk rock, punk)[ and the Lounge Lizards][ (the first group to call themselves "punk jazz").

John Zorn took note of the emphasis on speed and dissonance that was becoming prevalent in punk rock, and incorporated this into free jazz with the release of the ''Spy vs Spy (album), Spy vs. Spy'' album in 1986, a collection of ]Ornette Coleman

Randolph Denard Ornette Coleman (March 9, 1930 – June 11, 2015) was an American jazz saxophonist, violinist, trumpeter, and composer known as a principal founder of the free jazz genre, a term derived from his 1960 album '' Free Jazz: A Col ...

tunes done in the contemporary thrashcore style. In the same year, Sonny Sharrock, Peter Brötzmann, Bill Laswell, and Ronald Shannon Jackson recorded the first album under the name Last Exit (free jazz band), Last Exit, a similarly aggressive blend of thrash and free jazz. These developments are the origins of ''jazzcore'', the fusion of free jazz with hardcore punk.

M-Base

The M-Base movement started in the 1980s, when a loose collective of young African-American musicians in New York which included Steve Coleman, Greg Osby, and Gary Thomas (musician), Gary Thomas developed a complex but grooving sound.

In the 1990s, most M-Base participants turned to more conventional music, but Coleman, the most active participant, continued developing his music in accordance with the M-Base concept.

The M-Base movement started in the 1980s, when a loose collective of young African-American musicians in New York which included Steve Coleman, Greg Osby, and Gary Thomas (musician), Gary Thomas developed a complex but grooving sound.

In the 1990s, most M-Base participants turned to more conventional music, but Coleman, the most active participant, continued developing his music in accordance with the M-Base concept.

1990s–present

Since the 1990s, jazz has been characterized by a pluralism in which no one style dominates, but rather a wide range of styles and genres are popular. Individual performers often play in a variety of styles, sometimes in the same performance. Pianist Brad Mehldau and The Bad Plus have explored contemporary rock music within the context of the traditional jazz acoustic piano trio, recording instrumental jazz versions of songs by rock musicians. The Bad Plus have also incorporated elements of free jazz into their music. A firm avant-garde or free jazz stance has been maintained by some players, such as saxophonists Greg Osby and Charles Gayle, while others, such as James Carter (musician), James Carter, have incorporated free jazz elements into a more traditional framework.

Harry Connick Jr. began his career playing stride piano and the Dixieland jazz of his home, New Orleans, beginning with his first recording when he was 10 years old.Wynton Marsalis

Wynton Learson Marsalis (born October 18, 1961) is an American trumpeter, composer, teacher, and artistic director of Jazz at Lincoln Center. He has promoted classical and jazz music, often to young audiences. Marsalis has won nine Grammy Awar ...

and other experts reviewing the entire history of American jazz to that time. It received some criticism, however, for its failure to reflect the many distinctive non-American traditions and styles in jazz that had developed, and its limited representation of US developments in the last quarter of the 20th century.

The mid-2010s saw an increasing influence of R&B, hip-hop, and pop music on jazz. In 2015, Kendrick Lamar released his third studio album, ''To Pimp a Butterfly''. The album heavily featured prominent contemporary jazz artists such as Thundercat (musician), Thundercat

See also

* Jazz (Henri Matisse)

* Jazz piano

* Jazz royalty

* Victorian Jazz Archive

* Hogan Jazz Archive

* International Jazz Day

* Bibliography of jazz

* Timeline of jazz education

* List of certified jazz recordings

* List of jazz festivals

* List of jazz genres

* List of jazz musicians

* List of jazz standards

* List of jazz venues

* List of jazz venues in the United States

Notes

References

* .

*

* Includes a 120-page interview with Hines plus many photos.

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

* New printing 1986.

*

* Also: Jazz (miniseries), ''Jazz'' (2001 miniseries).

Further reading

*

* Ian Carr, Carr, Ian. ''Music Outside: Contemporary Jazz in Britain.'' 2nd edition. London: Northway.

*

* Downbeat (2009). ''The Great Jazz Interviews'': Frank Alkyer & Ed Enright (eds). Hal Leonard Books.

* Gridley, Mark C. 2004. ''Concise Guide to Jazz'', fourth edition. Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Pearson/Prentice Hall.

* Nairn, Charlie. 1975. ''Earl 'Fatha' Hines'': 1 hour 'solo' documentary made in "Blues Alley" Jazz Club, Washington DC, for ATV, England, 1975: produced/directed by Charlie Nairn: original 16mm film plus out-takes of additional tunes from that film archived in British Film Institute Library at bfi.org.uk and itvstudios.com: DVD copies with Jean Gray Hargrove Music Library [who hold The Earl Hines Collection/Archive], University of California, Berkeley: also University of Chicago, Hogan Jazz Archive Tulane University New Orleans and Louis Armstrong House Museum Libraries.

* Schuller, Gunther. 1991. ''The Swing Era: The Development of Jazz, 1930–1945''. Oxford University Press.

External links

Jazz at the Smithsonian Museum

Alabama Jazz Hall of Fame website

RedHotJazz.com

Jazz at Lincoln Center

American Jazz Museum

website

{{Authority control

Jazz,

African-American cultural history

African-American music

American styles of music

Jazz terminology

Musical improvisation

Popular music

Radio formats

Traditional music

The origin of the word ''

The origin of the word '' Female jazz performers and composers have contributed to jazz throughout its history. Although

Female jazz performers and composers have contributed to jazz throughout its history. Although

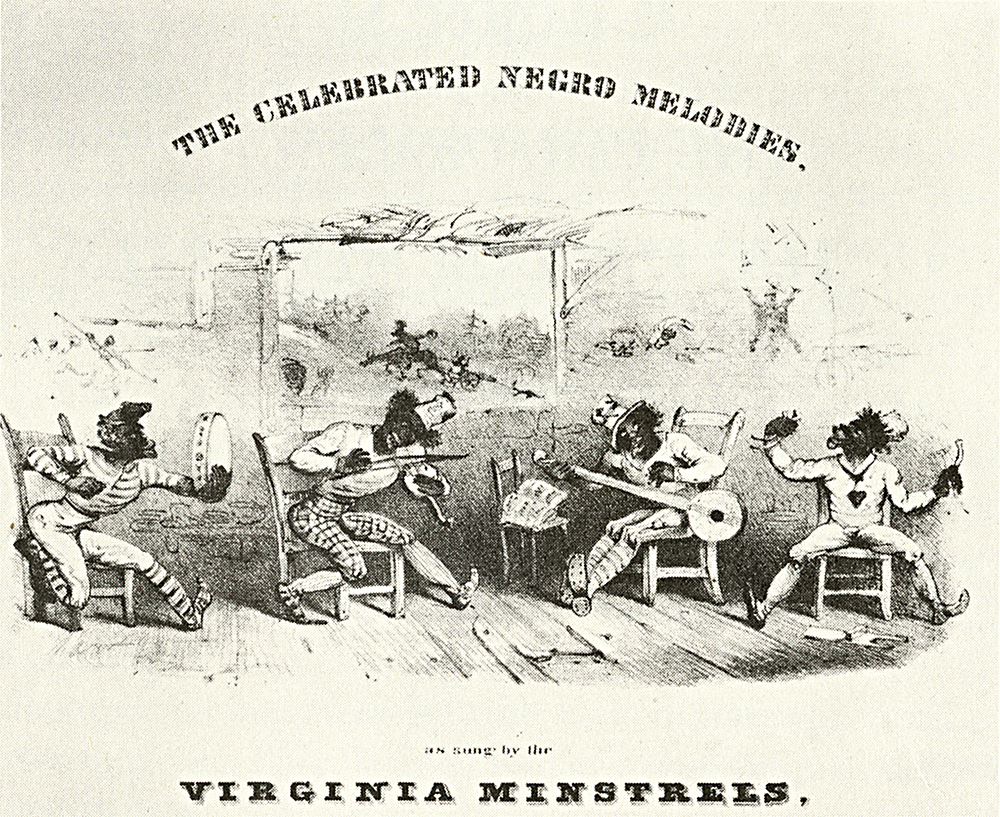

By the 18th century, slaves in the New Orleans area gathered socially at a special market, in an area which later became known as Congo Square, famous for its African dances.

By 1866, the

By the 18th century, slaves in the New Orleans area gathered socially at a special market, in an area which later became known as Congo Square, famous for its African dances.

By 1866, the  During the early 19th century an increasing number of black musicians learned to play European instruments, particularly the violin, which they used to parody European dance music in their own

During the early 19th century an increasing number of black musicians learned to play European instruments, particularly the violin, which they used to parody European dance music in their own  The abolition of