The swastika (卐 or 卍) is an ancient religious and cultural symbol, predominantly in various

Eurasia

Eurasia (, ) is the largest continental area on Earth, comprising all of Europe and Asia. Primarily in the Northern and Eastern Hemispheres, it spans from the British Isles and the Iberian Peninsula in the west to the Japanese archipelago a ...

n, as well as some

African

African or Africans may refer to:

* Anything from or pertaining to the continent of Africa:

** People who are native to Africa, descendants of natives of Africa, or individuals who trace their ancestry to indigenous inhabitants of Africa

*** Ethn ...

and

American

American(s) may refer to:

* American, something of, from, or related to the United States of America, commonly known as the "United States" or "America"

** Americans, citizens and nationals of the United States of America

** American ancestry, pe ...

cultures, now also widely recognized for its appropriation by the

Nazi Party

The Nazi Party, officially the National Socialist German Workers' Party (german: Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei or NSDAP), was a far-right politics, far-right political party in Germany active between 1920 and 1945 that crea ...

and by

neo-Nazi

Neo-Nazism comprises the post–World War II militant, social, and political movements that seek to revive and reinstate Nazism, Nazi ideology. Neo-Nazis employ their ideology to promote hatred and Supremacism#Racial, racial supremacy (ofte ...

s.

It continues to be used as a symbol of divinity and spirituality in

Indian religions

Indian religions, sometimes also termed Dharmic religions or Indic religions, are the religions that originated in the Indian subcontinent. These religions, which include Hinduism, Jainism, Buddhism, and Sikhism,Adams, C. J."Classification of ...

, including

Hinduism

Hinduism () is an Indian religion or '' dharma'', a religious and universal order or way of life by which followers abide. As a religion, it is the world's third-largest, with over 1.2–1.35 billion followers, or 15–16% of the global p ...

,

Buddhism

Buddhism ( , ), also known as Buddha Dharma and Dharmavinaya (), is an Indian religion or philosophical tradition based on teachings attributed to the Buddha. It originated in northern India as a -movement in the 5th century BCE, and gra ...

, and

Jainism

Jainism ( ), also known as Jain Dharma, is an Indian religions, Indian religion. Jainism traces its spiritual ideas and history through the succession of twenty-four tirthankaras (supreme preachers of ''Dharma''), with the first in the current ...

.

It generally takes the form of a

cross

A cross is a geometrical figure consisting of two intersecting lines or bars, usually perpendicular to each other. The lines usually run vertically and horizontally. A cross of oblique lines, in the shape of the Latin letter X, is termed a sa ...

, the arms of which are of equal length and perpendicular to the adjacent arms, each bent midway at a right angle.

The word ''swastika'' comes from sa,

स्वस्तिक, svastika, meaning "conducive to well-being".

In

Hinduism

Hinduism () is an Indian religion or '' dharma'', a religious and universal order or way of life by which followers abide. As a religion, it is the world's third-largest, with over 1.2–1.35 billion followers, or 15–16% of the global p ...

, the right-facing symbol (clockwise) () is called ', symbolizing ("sun"), prosperity and good luck, while the left-facing symbol (counter-clockwise) () is called ''sauwastika'', symbolising night or

tantric aspects of

Kali

Kali (; sa, काली, ), also referred to as Mahakali, Bhadrakali, and Kalika ( sa, कालिका), is a Hinduism, Hindu goddess who is considered to be the goddess of ultimate power, time, destruction and change in Shaktism. In t ...

.

In

Jain symbolism, it represents

Suparshvanatha

Suparshvanatha ( sa, सुपार्श्वनाथ ), also known as Suparśva, was the seventh Jain '' Tīrthankara'' of the present age ('' avasarpini''). He was born to King Pratistha and Queen ''Prithvi'' at Varanasi on 12 Jestha Sh ...

the seventh of 24

Tirthankara

In Jainism, a ''Tirthankara'' (Sanskrit: '; English: literally a 'ford-maker') is a saviour and spiritual teacher of the ''dharma'' (righteous path). The word ''tirthankara'' signifies the founder of a '' tirtha'', which is a fordable passag ...

s (

spiritual teacher

This is an index of religious honorifics from various religions.

Buddhism

Christianity

Eastern Orthodox

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints

Protestantism

Catholicism

Hinduism

Islam

Judaism ...

s and

saviours), while in

Buddhist symbolism

Buddhist symbolism is the use of symbols (Sanskrit: ''pratīka'') to represent certain aspects of the Buddha's Dharma (teaching). Early Buddhist symbols which remain important today include the Dharma wheel, the Indian lotus, the three jewels an ...

it represents the auspicious footprints of the

Buddha

Siddhartha Gautama, most commonly referred to as the Buddha, was a śramaṇa, wandering ascetic and religious teacher who lived in South Asia during the 6th or 5th century BCE and founded Buddhism.

According to Buddhist tradition, he was ...

.

In several major

Indo-European

The Indo-European languages are a language family native to the overwhelming majority of Europe, the Iranian plateau, and the northern Indian subcontinent. Some European languages of this family, English, French, Portuguese, Russian, Dutch ...

religions, the swastika symbolises lightning bolts, representing the

thunder god

Polytheistic peoples from many cultures have postulated a thunder god, the personification or source of the forces of thunder and lightning; a lightning god does not have a typical depiction, and will vary based on the culture. In Indo-European c ...

and the

king of the gods, such as

Indra

Indra (; Sanskrit: इन्द्र) is the king of the devas (god-like deities) and Svarga (heaven) in Hindu mythology. He is associated with the sky, lightning, weather, thunder, storms, rains, river flows, and war. volumes/ref> I ...

in

Vedic Hinduism,

Zeus

Zeus or , , ; grc, Δῐός, ''Diós'', label=Genitive case, genitive Aeolic Greek, Boeotian Aeolic and Doric Greek#Laconian, Laconian grc-dor, Δεύς, Deús ; grc, Δέος, ''Déos'', label=Genitive case, genitive el, Δίας, ''D� ...

in the

ancient Greek religion

Religious practices in ancient Greece encompassed a collection of beliefs, rituals, and mythology, in the form of both popular public religion and cult practices. The application of the modern concept of "religion" to ancient cultures has been ...

,

Jupiter

Jupiter is the fifth planet from the Sun and the List of Solar System objects by size, largest in the Solar System. It is a gas giant with a mass more than two and a half times that of all the other planets in the Solar System combined, but ...

in the

ancient Roman religion

Religion in ancient Rome consisted of varying imperial and provincial religious practices, which were followed both by the people of Rome as well as those who were brought under its rule.

The Romans thought of themselves as highly religious, ...

, and

Thor

Thor (; from non, Þórr ) is a prominent god in Germanic paganism. In Norse mythology, he is a hammer-wielding æsir, god associated with lightning, thunder, storms, sacred trees and groves in Germanic paganism and mythology, sacred groves ...

in the

ancient Germanic religion

Germanic paganism or Germanic religion refers to the traditional, culturally significant religion of the Germanic peoples. With a chronological range of at least one thousand years in an area covering Scandinavia, the British Isles, modern Germ ...

.

The symbol is found in the archeological remains of the

Indus Valley Civilisation

The Indus Valley Civilisation (IVC), also known as the Indus Civilisation was a Bronze Age civilisation in the northwestern regions of South Asia, lasting from 3300 BCE to 1300 BCE, and in its mature form 2600 BCE to 1900&n ...

and

Samarra

Samarra ( ar, سَامَرَّاء, ') is a city in Iraq. It stands on the east bank of the Tigris in the Saladin Governorate, north of Baghdad. The city of Samarra was founded by Abbasid Caliph Al-Mutasim for his Turkish professional army ...

, as well as in early

Byzantine

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantinopl ...

and

Christian artwork.

Used for the first time by far-right Romanian politician

A. C. Cuza

Alexandru C. Cuza (8 November 1857 – 3 November 1947), also known as A. C. Cuza, was a Romanian far-right politician and economist.

Early life

Born in Iași, Cuza attended secondary school in his native city and in Dresden, Saxony, Germany, ...

as a symbol of international antisemitism prior to World War I, it was a symbol of

auspiciousness and good luck for most of the

Western world

The Western world, also known as the West, primarily refers to the various nations and state (polity), states in the regions of Europe, North America, and Oceania. until the 1930s,

when the German Nazi Party adopted the swastika as an emblem of the

Aryan race

The Aryan race is an obsolete historical race concept that emerged in the late-19th century to describe people of Proto-Indo-European heritage as a racial grouping. The terminology derives from the historical usage of Aryan, used by modern I ...

. As a result of

World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

and

the Holocaust

The Holocaust, also known as the Shoah, was the genocide of European Jews during World War II. Between 1941 and 1945, Nazi Germany and its collaborators systematically murdered some six million Jews across German-occupied Europe; a ...

, in the West it continues to be strongly associated with

Nazism

Nazism ( ; german: Nazismus), the common name in English for National Socialism (german: Nationalsozialismus, ), is the far-right totalitarian political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in Na ...

,

antisemitism

Antisemitism (also spelled anti-semitism or anti-Semitism) is hostility to, prejudice towards, or discrimination against Jews. A person who holds such positions is called an antisemite. Antisemitism is considered to be a form of racism.

Antis ...

,

, or simply evil. As a consequence, its use in some countries, including Germany, is prohibited by law. However, the swastika remains a symbol of good luck and prosperity in Hindu, Buddhist and Jain countries such as Nepal, India, Thailand, Mongolia, Sri Lanka, China and Japan, and by some peoples, such as the

Navajo

The Navajo (; British English: Navaho; nv, Diné or ') are a Native American people of the Southwestern United States.

With more than 399,494 enrolled tribal members , the Navajo Nation is the largest federally recognized tribe in the United ...

people of the Southwest United States. It is also commonly used in Hindu marriage ceremonies and

Dipavali

Diwali (), Dewali, Divali, or Deepavali ( IAST: ''dīpāvalī''), also known as the Festival of Lights, related to Jain Diwali, Bandi Chhor Divas, Tihar, Swanti, Sohrai, and Bandna, is a religious celebration in Indian religions. It is ...

celebrations.

In various European languages, it is known as the ''

fylfot

The fylfot or fylfot cross ( ) and its mirror image, the gammadion are a type of swastika associated with medieval Anglo-Saxon culture. It is a cross with perpendicular extensions, usually at 90° or close angles, radiating in the same direc ...

'', ''gammadion'', ''tetraskelion'', or ''cross cramponnée'' (a term in Anglo-Norman

heraldry

Heraldry is a discipline relating to the design, display and study of armorial bearings (known as armory), as well as related disciplines, such as vexillology, together with the study of ceremony, rank and pedigree. Armory, the best-known branch ...

);

German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany (of or related to)

**Germania (historical use)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizens of Germany, see also German nationality law

**Ger ...

: ;

French

French (french: français(e), link=no) may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to France

** French language, which originated in France, and its various dialects and accents

** French people, a nation and ethnic group identified with Franc ...

: ;

Italian: ;

Latvian: ''

ugunskrusts

Ugunskrusts ( Latvian for 'Fire Cross'; other names — ''Cross of Fire'', '' Pērkonkrusts (Cross of Thunder (Thunder Cross))'', ''Cross of Perun (Cross of Perkūnas)'', ''Cross of Branches'', ''Cross of Laima'') is the swastika as a symbol ...

''. In

Mongolian it is called хас (''khas'') and mainly used in seals. In

Chinese

Chinese can refer to:

* Something related to China

* Chinese people, people of Chinese nationality, citizenship, and/or ethnicity

**''Zhonghua minzu'', the supra-ethnic concept of the Chinese nation

** List of ethnic groups in China, people of va ...

it is called 卍字 (''wànzì''), pronounced ''manji'' in

Japanese, ''manja'' (만자) in

Korean and ''vạn tự / chữ vạn'' in

Vietnamese.

Reverence for the swastika symbol in Asian cultures, in contrast to the stigma attached to it in the West, has led to misinterpretations and misunderstandings.

Etymology and nomenclature

The word ''swastika'' has been used in the

Indian subcontinent

The Indian subcontinent is a list of the physiographic regions of the world, physiographical region in United Nations geoscheme for Asia#Southern Asia, Southern Asia. It is situated on the Indian Plate, projecting southwards into the Indian O ...

since 500

BCE. The word was first recorded by the ancient linguist

Pāṇini

, era = ;;6th–5th century BCE

, region = Indian philosophy

, main_interests = Grammar, linguistics

, notable_works = ' (Sanskrit#Classical Sanskrit, Classical Sanskrit)

, influenced=

, notable_ideas=Descript ...

in his work ''

Ashtadhyayi''. It is alternatively spelled in contemporary texts as ''svastika'', and other spellings were occasionally used in the 19th and early 20th century, such as ''suastika''. It was derived from the

Sanskrit

Sanskrit (; attributively , ; nominally , , ) is a classical language belonging to the Indo-Aryan branch of the Indo-European languages. It arose in South Asia after its predecessor languages had diffused there from the northwest in the late ...

term (

Devanagari

Devanagari ( ; , , Sanskrit pronunciation: ), also called Nagari (),Kathleen Kuiper (2010), The Culture of India, New York: The Rosen Publishing Group, , page 83 is a left-to-right abugida (a type of segmental Writing systems#Segmental syste ...

), which transliterates to ' under the commonly used IAST transliteration system, but is pronounced closer to ''swastika'' when letters are used with their English values.

An important early use of the word swastika in a European text was in 1871 with the publications of

Heinrich Schliemann

Johann Ludwig Heinrich Julius Schliemann (; 6 January 1822 – 26 December 1890) was a German businessman and pioneer in the field of archaeology. He was an advocate of the historicity of places mentioned in the works of Homer and an archaeologi ...

, who discovered more than 1,800 ancient samples of the swastika symbol and its variants while digging the

Hisarlik

Hisarlik (Turkish: ''Hisarlık'', "Place of Fortresses"), often spelled Hissarlik, is the Turkish name for an ancient city located in what is known historically as Anatolia.A compound of the noun, hisar, "fortification," and the suffix -lik. The s ...

mound near the Aegean Sea coast for the history of Troy. Schliemann linked his findings to the Sanskrit .

The word ''swastika'' is derived from the Sanskrit root , which is composed of 'good, well' and 'is; it is; there is'.

The word occurs frequently in the

Vedas

upright=1.2, The Vedas are ancient Sanskrit texts of Hinduism. Above: A page from the '' Atharvaveda''.

The Vedas (, , ) are a large body of religious texts originating in ancient India. Composed in Vedic Sanskrit, the texts constitute the ...

as well as in classical literature, meaning "health, luck, success, prosperity", and it was commonly used as a greeting.

The final is a common suffix that could have multiple meanings. According to

Monier-Williams

Sir Monier Monier-Williams (; né Williams; 12 November 1819 – 11 April 1899) was a British scholar who was the second Boden Professor of Sanskrit at Oxford University, England. He studied, documented and taught Asian languages, especially S ...

, a majority of scholars consider it a

solar symbol.

The sign implies something fortunate, lucky, or auspicious, and it denotes auspiciousness or well-being.

The earliest known use of the word swastika is in

Panini's ''Ashtadhyayi'', which uses it to explain one of the Sanskrit grammar rules, in the context of a type of identifying mark on a cow's ear.

Most scholarship suggests that Panini lived in or before the 4th century BCE, possibly in 6th or 5th century BCE.

By the 19th century, the term ''swastika'' was adopted into the English lexicon, replacing ''gammadion'' from Greek . In 1878, Irish scholar

Charles Graves used ''swastika'' as the common English name for the symbol, after defining it as equivalent to the

French

French (french: français(e), link=no) may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to France

** French language, which originated in France, and its various dialects and accents

** French people, a nation and ethnic group identified with Franc ...

term ''croix gammée''a cross with arms shaped like the Greek letter

gamma

Gamma (uppercase , lowercase ; ''gámma'') is the third letter of the Greek alphabet. In the system of Greek numerals it has a value of 3. In Ancient Greek, the letter gamma represented a voiced velar stop . In Modern Greek, this letter re ...

(Γ). Shortly thereafter, British antiquarians

Edward Thomas and

Robert Sewell separately published their studies about the symbol, using ''swastika'' as the common English term.

The concept of a "reversed" swastika was probably first made among European scholars by

Eugène Burnouf

Eugène Burnouf (; April 8, 1801May 28, 1852) was a French scholar, an Indologist and orientalist. His notable works include a study of Sanskrit literature, translation of the Hindu text ''Bhagavata Purana'' and Buddhist text ''Lotus Sutra''. He ...

in 1852, and taken up by

Schliemann in ''Ilios'' (1880), based on a letter from

Max Müller

Friedrich Max Müller (; 6 December 1823 – 28 October 1900) was a German-born philologist and Orientalist, who lived and studied in Britain for most of his life. He was one of the founders of the western academic disciplines of Indian ...

that quotes Burnouf. The term ''sauwastika'' is used in the sense of "backwards swastika" by

Eugène Goblet d'Alviella (1894): "In India it

he ''gammadion''

He or HE may refer to:

Language

* He (pronoun), an English pronoun

* He (kana), the romanization of the Japanese kana へ

* He (letter), the fifth letter of many Semitic alphabets

* He (Cyrillic), a letter of the Cyrillic script called ''He'' in ...

bears the name of ''swastika'', when its arms are bent towards the right, and ''sauwastika'' when they are turned in the other direction."

Other names for the symbol include:

* ''tetragammadion'' (Greek: ) or ''cross gammadion'' ( la, crux gammata; French: ), as each arm resembles the Greek letter Γ ()

* ''hooked cross'' (German: ), ''angled cross'' (), or ''crooked cross'' ()

* ''cross cramponned'', ''cramponnée'', or ''cramponny'' in heraldry, as each arm resembles a

crampon or angle-iron (german: Winkelmaßkreuz)

* ''

fylfot

The fylfot or fylfot cross ( ) and its mirror image, the gammadion are a type of swastika associated with medieval Anglo-Saxon culture. It is a cross with perpendicular extensions, usually at 90° or close angles, radiating in the same direc ...

'', chiefly in heraldry and architecture

* ''tetraskelion'' (Greek: ), literally meaning 'four-legged', especially when composed of four conjoined legs (compare

triskelion/triskele reek:

* ''

ugunskrusts

Ugunskrusts ( Latvian for 'Fire Cross'; other names — ''Cross of Fire'', '' Pērkonkrusts (Cross of Thunder (Thunder Cross))'', ''Cross of Perun (Cross of Perkūnas)'', ''Cross of Branches'', ''Cross of Laima'') is the swastika as a symbol ...

'' (Latvian for "Fire Cross"; other namesCross of Fire, Pērkonkrusts (Cross of Thunder (Thunder Cross)), Cross of

Perun (Cross of

Perkūnas), Cross of Branches, Cross of

Laima)

* ''whirling logs'' (Navajo): can denote abundance, prosperity, healing, and luck

Appearance

All swastikas are bent crosses based on a

chiral symmetry, but they appear with different

geometric

Geometry (; ) is, with arithmetic, one of the oldest branches of mathematics. It is concerned with properties of space such as the distance, shape, size, and relative position of figures. A mathematician who works in the field of geometry is ca ...

details: as compact crosses with short legs, as crosses with large arms and as motifs in a pattern of unbroken lines. Chirality describes an absence of

reflective symmetry

In mathematics, reflection symmetry, line symmetry, mirror symmetry, or mirror-image symmetry is symmetry with respect to a reflection. That is, a figure which does not change upon undergoing a reflection has reflectional symmetry.

In 2D th ...

, with the existence of two versions that are

mirror image

A mirror image (in a plane mirror) is a reflected duplication of an object that appears almost identical, but is reversed in the direction perpendicular to the mirror surface. As an optical effect it results from reflection off from substances ...

s of each other. The mirror-image forms are typically described as left-facing or left-hand (卍) and right-facing or right-hand (卐).

The compact swastika can be seen as a chiral irregular

icosagon

In geometry, an icosagon or 20-gon is a twenty-sided polygon. The sum of any icosagon's interior angles is 3240 degrees.

Regular icosagon

The regular icosagon has Schläfli symbol , and can also be constructed as a truncated decagon, , or a t ...

(20-sided

polygon

In geometry, a polygon () is a plane figure that is described by a finite number of straight line segments connected to form a closed ''polygonal chain'' (or ''polygonal circuit''). The bounded plane region, the bounding circuit, or the two toge ...

) with fourfold (90°)

rotational symmetry

Rotational symmetry, also known as radial symmetry in geometry, is the property a shape has when it looks the same after some rotation by a partial turn. An object's degree of rotational symmetry is the number of distinct orientations in which i ...

. Such a swastika proportioned on a 5×5 square grid and with the broken portions of its legs shortened by one unit can

tile the plane by

translation

Translation is the communication of the Meaning (linguistic), meaning of a #Source and target languages, source-language text by means of an Dynamic and formal equivalence, equivalent #Source and target languages, target-language text. The ...

alone. The Nazi swastika used a 5×5 diagonal grid, but with the legs unshortened.

Written characters

The swastika was adopted as a standard character in

Chinese

Chinese can refer to:

* Something related to China

* Chinese people, people of Chinese nationality, citizenship, and/or ethnicity

**''Zhonghua minzu'', the supra-ethnic concept of the Chinese nation

** List of ethnic groups in China, people of va ...

, "" () and as such entered various other

East Asian languages, including

Chinese script

Chinese characters () are logograms developed for the writing of Chinese. In addition, they have been adapted to write other East Asian languages, and remain a key component of the Japanese writing system where they are known as ''kanji' ...

. In Japanese the symbol is called or .

The swastika is included in the

Unicode

Unicode, formally The Unicode Standard,The formal version reference is is an information technology Technical standard, standard for the consistent character encoding, encoding, representation, and handling of Character (computing), text expre ...

character sets of two languages. In the Chinese block it is U+534D

卍 (left-facing) and U+5350 for the swastika

卐 (right-facing); The latter has a mapping in the original

Big5

Big-5 or Big5 is a Chinese character encoding method used in Taiwan, Hong Kong, and Macau for traditional Chinese characters.

The People's Republic of China (PRC), which uses simplified Chinese characters, uses the GB 18030 character set inst ...

character set, but the former does not (although it is in Big5+). In Unicode 5.2, two swastika symbols and two swastikas were added to the

Tibetan block: swastika , , and swastikas , .

Meaning

European hypotheses of the swastika are often treated in conjunction with

cross symbol

A cross is a geometrical figure consisting of two intersecting lines or bars, usually perpendicular to each other. The lines usually run vertically and horizontally. A cross of oblique lines, in the shape of the Latin letter X, is termed a sa ...

s in general, such as the

sun cross of

Bronze Age religion. Beyond its certain presence in the "

proto-writing

Proto-writing consists of visible marks communicating limited information. Such systems emerged from earlier traditions of symbol systems in the early Neolithic, as early as the 7th millennium BC in Eastern Europe and China. They used ideograph ...

" symbol systems, such as the

Vinča script

Vinča ( sr-cyr, Винча, ) is a suburban settlement of Belgrade, Serbia. It is part of the municipality of Grocka. Vinča-Belo Brdo, an important archaeological site that gives its name to the Neolithic Vinča culture, is located in the vill ...

, which appeared during the

Neolithic

The Neolithic period, or New Stone Age, is an Old World archaeological period and the final division of the Stone Age. It saw the Neolithic Revolution, a wide-ranging set of developments that appear to have arisen independently in several parts ...

.

North pole

According to

René Guénon, the swastika represents the north pole, and the rotational movement around a centre or immutable axis (''

axis mundi

In astronomy, axis mundi is the Latin term for the axis of Earth between the celestial poles.

In a geocentric coordinate system, this is the axis of rotation of the celestial sphere.

Consequently, in ancient Greco-Roman astronomy, the '' ...

''), and only secondly it represents the

Sun as a reflected function of the north pole. As such it is a symbol of life, of the vivifying role of the supreme principle of the universe, the

absolute Absolute may refer to:

Companies

* Absolute Entertainment, a video game publisher

* Absolute Radio, (formerly Virgin Radio), independent national radio station in the UK

* Absolute Software Corporation, specializes in security and data risk manage ...

God, in relation to the cosmic order. It represents the activity (the Hellenic ''

Logos

''Logos'' (, ; grc, wikt:λόγος, λόγος, lógos, lit=word, discourse, or reason) is a term used in Western philosophy, psychology and rhetoric and refers to the appeal to reason that relies on logic or reason, inductive and deductive ...

'', the Hindu ''

Om'', the Chinese ''

Taiyi'', "Great One") of the principle of the universe in the formation of the world. According to Guénon, the swastika in its polar value has the same meaning of the

yin and yang

Yin and yang ( and ) is a Chinese philosophy, Chinese philosophical concept that describes opposite but interconnected forces. In Chinese cosmology, the universe creates itself out of a primary chaos of material energy, organized into the c ...

symbol of the Chinese tradition, and of other traditional symbols of the working of the universe, including the letters Γ (

gamma

Gamma (uppercase , lowercase ; ''gámma'') is the third letter of the Greek alphabet. In the system of Greek numerals it has a value of 3. In Ancient Greek, the letter gamma represented a voiced velar stop . In Modern Greek, this letter re ...

) and G, symbolising the

Great Architect of the Universe

The Great Architect of the Universe (also Grand Architect of the Universe, or Supreme Architect of the Universe), is a conception of God discussed by many Christian theologians and apologists. As a designation it is used within Freemasonry to re ...

of

Masonic thought.

According to the scholar Reza Assasi, the swastika represents the north

ecliptic north pole

An orbital pole is either point at the ends of an imaginary line segment that runs through the center of an orbit (of a revolving body like a planet, moon or satellite) and is perpendicular to the orbital plane. Projected onto the celestial sphe ...

centred in

ζ Draconis, with the constellation

Draco

Draco is the Latin word for serpent or dragon.

Draco or Drako may also refer to:

People

* Draco (lawgiver) (from Greek: Δράκων; 7th century BC), the first lawgiver of ancient Athens, Greece, from whom the term ''draconian'' is derived

* D ...

as one of its beams. He argues that this symbol was later attested as the four-horse chariot of

Mithra in ancient

Iran

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran, and also called Persia, is a country located in Western Asia. It is bordered by Iraq and Turkey to the west, by Azerbaijan and Armenia to the northwest, by the Caspian Sea and Turkmeni ...

ian culture. They believed the cosmos was pulled by four heavenly horses who revolved around a fixed centre in a clockwise direction. He suggests that this notion later flourished in Roman

Mithraism

Mithraism, also known as the Mithraic mysteries or the Cult of Mithras, was a Roman mystery religion centered on the god Mithras. Although inspired by Iranian worship of the Zoroastrian divinity (''yazata'') Mithra, the Roman Mithras is linke ...

, as the symbol appears in Mithraic iconography and astronomical representations.

According to the Russian archaeologist

Gennady Zdanovich

Gennadii Borisovich Zdanovich (Russian: Геннадий Борисович Зданович; 4 October 1938 – 19 November 2020) was a Russian archaeologist based at the historical site of Arkaim, Chelyabinsk, Russia.

Zdanovich led the excavat ...

, who studied some of the oldest examples of the symbol in

Sintashta culture, the swastika symbolises the universe, representing the spinning constellations of the

celestial north pole

The north and south celestial poles are the two points in the sky where Earth's axis of rotation, indefinitely extended, intersects the celestial sphere. The north and south celestial poles appear permanently directly overhead to observers at ...

centred in

α Ursae Minoris, specifically the

Little

Little is a synonym for small size and may refer to:

Arts and entertainment

* ''Little'' (album), 1990 debut album of Vic Chesnutt

* ''Little'' (film), 2019 American comedy film

*The Littles, a series of children's novels by American author John P ...

and

Big Dipper (or Chariots), or Ursa Minor and Ursa Major.

Gennady Zdanovich

Gennadii Borisovich Zdanovich (Russian: Геннадий Борисович Зданович; 4 October 1938 – 19 November 2020) was a Russian archaeologist based at the historical site of Arkaim, Chelyabinsk, Russia.

Zdanovich led the excavat ...

"О мировоззрении древних жителей «Страны Городов»"

''Русский след'', 26 June 2017. Likewise, according to René Guénon the swastika is drawn by visualising the Big Dipper/Great Bear in the four phases of revolution around the pole star.

Comet

In their 1985 book ''

Comet

A comet is an icy, small Solar System body that, when passing close to the Sun, warms and begins to release gases, a process that is called outgassing. This produces a visible atmosphere or coma, and sometimes also a tail. These phenomena ar ...

'',

Carl Sagan

Carl Edward Sagan (; ; November 9, 1934December 20, 1996) was an American astronomer, planetary scientist, cosmologist, astrophysicist, astrobiologist, author, and science communicator. His best known scientific contribution is research on ext ...

and

Ann Druyan

Ann Druyan ( ; born June 13, 1949) is an Emmy and Peabody Award-winning American documentary producer and director specializing in the communication of science. She co-wrote the 1980 PBS documentary series ''Cosmos'', hosted by Carl Sagan, w ...

argue that the appearance of a rotating

comet

A comet is an icy, small Solar System body that, when passing close to the Sun, warms and begins to release gases, a process that is called outgassing. This produces a visible atmosphere or coma, and sometimes also a tail. These phenomena ar ...

with a four-pronged tail as early as 2,000 years BCE could explain why the swastika is found in the cultures of both the

Old World

The "Old World" is a term for Afro-Eurasia that originated in Europe , after Europeans became aware of the existence of the Americas. It is used to contrast the continents of Africa, Europe, and Asia, which were previously thought of by the ...

and the . The

Han dynasty

The Han dynasty (, ; ) was an imperial dynasty of China (202 BC – 9 AD, 25–220 AD), established by Liu Bang (Emperor Gao) and ruled by the House of Liu. The dynasty was preceded by the short-lived Qin dynasty (221–207 BC) and a warr ...

''

Book of Silk'' (2nd century BCE) depicts such a comet with a swastika-like symbol.

Bob Kobres, in a 1992 paper, contends that the swastika-like comet on the Han-dynasty manuscript was labelled a "long tailed pheasant star" (''dixing'') because of its resemblance to a bird's foot or footprint.

Similar comparisons had been made by J.F. Hewitt in 1907, as well as a 1908 article in ''

Good Housekeeping''. Kobres goes on to suggest an association of mythological birds and comets also outside of China.

Four winds

In

Native American culture, particularly among the

Pima people

The Pima (or Akimel O'odham, also spelled Akimel Oʼotham, "River People," formerly known as ''Pima'') are a group of Native Americans living in an area consisting of what is now central and southern Arizona, as well as northwestern Mexico in ...

of

Arizona

Arizona ( ; nv, Hoozdo Hahoodzo ; ood, Alĭ ṣonak ) is a state in the Southwestern United States. It is the 6th largest and the 14th most populous of the 50 states. Its capital and largest city is Phoenix. Arizona is part of the Fou ...

, the swastika is a symbol of the four winds. Anthropologist

Frank Hamilton Cushing

Frank Hamilton Cushing (July 22, 1857 in North East Township, Erie County, Pennsylvania – April 10, 1900 in Washington, D.C.) was an American anthropologist and ethnologist. He made pioneering studies of the Zuni Indians of New Mexico by enter ...

noted that among the Pima the symbol of the four winds is made from a cross with the four curved arms (similar to a broken

sun cross), and concludes "the right-angle swastika is primarily a representation of the circle of the four wind gods standing at the head of their trails, or directions."

Prehistory

The earliest known swastika is from 10,000 BCEpart of "an intricate meander pattern of joined-up swastikas" found on a late

paleolithic

The Paleolithic or Palaeolithic (), also called the Old Stone Age (from Greek: παλαιός ''palaios'', "old" and λίθος ''lithos'', "stone"), is a period in human prehistory that is distinguished by the original development of stone too ...

figurine of a bird, carved from

mammoth

A mammoth is any species of the extinct elephantid genus ''Mammuthus'', one of the many genera that make up the order of trunked mammals called proboscideans. The various species of mammoth were commonly equipped with long, curved tusks and, ...

ivory, found in

Mezine

Mezine is a place within the modern country of Ukraine which has the most artifact finds of Paleolithic culture origin. The Epigravettian site is located on a bank of the Desna River in Novhorod-Siverskyi Raion of Chernihiv Oblast, northern Ukrain ...

,

Ukraine

Ukraine ( uk, Україна, Ukraïna, ) is a country in Eastern Europe. It is the second-largest European country after Russia, which it borders to the east and northeast. Ukraine covers approximately . Prior to the ongoing Russian inv ...

. It has been suggested that this swastika may be a stylised picture of a

stork

Storks are large, long-legged, long-necked wading birds with long, stout bills. They belong to the family called Ciconiidae, and make up the order Ciconiiformes . Ciconiiformes previously included a number of other families, such as herons an ...

in flight. As the carving was found near

phallic objects, this may also support the idea that the pattern was a fertility symbol.

In the mountains of Iran, there are swastikas or spinning wheels inscribed on stone walls, which are estimated to be more than 7,000 years old. One instance is in Khorashad,

Birjand

Birjand ( fa, بیرجند , also Romanized as Bīrjand and Birdjand) is the capital of the Iranian province of South Khorasan. The city is known for its saffron, barberry, jujube, and handmade carpet exports.

Birjand had a population of 187,0 ...

, on the holy wall

Lakh Mazar.

Mirror-image swastikas (clockwise and counter-clockwise) have been found on ceramic pottery in the

Devetashka cave

Devetàshka cave ( bg, Деветашката пещера) is a large karst cave around east of Letnitsa and northeast of Lovech, near the village of Devetaki on the east bank of the river Osam, in Bulgaria. The site has been continuously oc ...

,

Bulgaria

Bulgaria (; bg, България, Bǎlgariya), officially the Republic of Bulgaria,, ) is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the eastern flank of the Balkans, and is bordered by Romania to the north, Serbia and North Macedon ...

, dated to 6,000 BCE.

Some of the earliest archaeological evidence of the swastika in the

Indian subcontinent

The Indian subcontinent is a list of the physiographic regions of the world, physiographical region in United Nations geoscheme for Asia#Southern Asia, Southern Asia. It is situated on the Indian Plate, projecting southwards into the Indian O ...

can be dated to 3,000 BCE.

The investigators put forth the hypothesis that the swastika moved westward from the Indian subcontinent to

Finland

Finland ( fi, Suomi ; sv, Finland ), officially the Republic of Finland (; ), is a Nordic country in Northern Europe. It shares land borders with Sweden to the northwest, Norway to the north, and Russia to the east, with the Gulf of B ...

,

Scandinavia

Scandinavia; Sámi languages: /. ( ) is a subregion#Europe, subregion in Northern Europe, with strong historical, cultural, and linguistic ties between its constituent peoples. In English usage, ''Scandinavia'' most commonly refers to Denmark, ...

, the

Scottish Highlands

The Highlands ( sco, the Hielands; gd, a’ Ghàidhealtachd , 'the place of the Gaels') is a historical region of Scotland. Culturally, the Highlands and the Lowlands diverged from the Late Middle Ages into the modern period, when Lowland Sco ...

and other parts of

Europe

Europe is a large peninsula conventionally considered a continent in its own right because of its great physical size and the weight of its history and traditions. Europe is also considered a Continent#Subcontinents, subcontinent of Eurasia ...

. In

England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe b ...

, neolithic or Bronze Age stone carvings of the symbol have been found on

Ilkley Moor

Ilkley Moor is part of Rombalds Moor, the moorland between Ilkley and Keighley in West Yorkshire, England. The moor, which rises to 402 m (1,319 ft) above sea level, is well known as the inspiration for the Yorkshire "county anthem" ...

, such as the

Swastika Stone

The Swastika Stone is a stone adorned with a design that resembles a swastika, located on the Woodhouse Crag on the northern edge of Ilkley Moor in West Yorkshire, England. The design has a double outline with four curved arms and an attached ...

.

Swastikas have also been found on pottery in archaeological digs in Africa, in the area of

Kush

Kush or Cush may refer to:

Bible

* Cush (Bible), two people and one or more places in the Hebrew Bible

Places

* Kush (mountain), a mountain near Kalat, Pakistan Balochistan

* Kush (satrapy), a satrapy of the Achaemenid Empire

* Hindu Kush, a m ...

and on pottery at the

Jebel Barkal temples, in

Iron Age

The Iron Age is the final epoch of the three-age division of the prehistory and protohistory of humanity. It was preceded by the Stone Age (Paleolithic, Mesolithic, Neolithic) and the Bronze Age (Chalcolithic). The concept has been mostly appl ...

designs of the northern

Caucasus

The Caucasus () or Caucasia (), is a region between the Black Sea and the Caspian Sea, mainly comprising Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia, and parts of Southern Russia. The Caucasus Mountains, including the Greater Caucasus range, have historically ...

(

Koban culture

The Koban culture (c. 1100 to 400 BC) is a late Bronze Age and Iron Age culture of the northern and central Caucasus. It is preceded by the Colchian culture of the western Caucasus and the Kharachoi culture further east.

It is named after the v ...

), and in

Neolithic China

This is a list of Neolithic cultures of China that have been unearthed by archaeologists. They are sorted in chronological order from earliest to latest and are followed by a schematic visualization of these cultures.

It would seem that the defin ...

in the

Majiabang

The Majiabang culture, also named Ma-chia-pang culture, was a Chinese Neolithic culture that existed at the mouth of the Yangtze River, primarily around Lake Tai near Shanghai and north of Hangzhou Bay. The culture spread throughout southern Jiang ...

and

Majiayao cultures.

Other Iron Age attestations of the swastika can be associated with

Indo-European

The Indo-European languages are a language family native to the overwhelming majority of Europe, the Iranian plateau, and the northern Indian subcontinent. Some European languages of this family, English, French, Portuguese, Russian, Dutch ...

cultures such as the

Illyrians

The Illyrians ( grc, Ἰλλυριοί, ''Illyrioi''; la, Illyrii) were a group of Indo-European languages, Indo-European-speaking peoples who inhabited the western Balkan Peninsula in ancient times. They constituted one of the three main Paleo ...

,

Indo-Iranians,

Celt

The Celts (, see pronunciation for different usages) or Celtic peoples () are. "CELTS location: Greater Europe time period: Second millennium B.C.E. to present ancestry: Celtic a collection of Indo-European peoples. "The Celts, an ancient ...

s,

Greeks

The Greeks or Hellenes (; el, Έλληνες, ''Éllines'' ) are an ethnic group and nation indigenous to the Eastern Mediterranean and the Black Sea regions, namely Greece, Cyprus, Albania, Italy, Turkey, Egypt, and, to a lesser extent, oth ...

,

Germanic peoples

The Germanic peoples were historical groups of people that once occupied Central Europe and Scandinavia during antiquity and into the early Middle Ages. Since the 19th century, they have traditionally been defined by the use of ancient and ear ...

and

Slavs

Slavs are the largest European ethnolinguistic group. They speak the various Slavic languages, belonging to the larger Balto-Slavic branch of the Indo-European languages. Slavs are geographically distributed throughout northern Eurasia, main ...

. In

Sintashta culture's "

Country of Towns

In the archaeology of Russia, the Country of Towns (russian: Страна городов, ''strana gorodov'') is a tentative term for a territory in the southern Trans-Urals where a number of middle Bronze Age (~2,000 BC) fortified settlements of ...

", ancient

Indo-European

The Indo-European languages are a language family native to the overwhelming majority of Europe, the Iranian plateau, and the northern Indian subcontinent. Some European languages of this family, English, French, Portuguese, Russian, Dutch ...

settlements in southern

Russia

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a List of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and North Asia, Northern Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, largest country in the ...

, it has been found a great concentration of some of the oldest swastika patterns.

The swastika is also seen in

Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a transcontinental country spanning the northeast corner of Africa and southwest corner of Asia via a land bridge formed by the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediter ...

during the Coptic period. Textile number T.231-1923 held at the V&A Museum in London includes small swastikas in its design. This piece was found at Qau-el-Kebir, near

Asyut, and is dated between 300 and 600 CE.

The ''Tierwirbel'' (the German for "animal whorl" or "whirl of animals") is a characteristic motif in Bronze Age Central Asia, the

Eurasian Steppe

The Eurasian Steppe, also simply called the Great Steppe or the steppes, is the vast steppe ecoregion of Eurasia in the temperate grasslands, savannas and shrublands biome. It stretches through Hungary, Bulgaria, Romania, Moldova and Transnistri ...

, and later also in Iron Age

Scythian and

European

European, or Europeans, or Europeneans, may refer to:

In general

* ''European'', an adjective referring to something of, from, or related to Europe

** Ethnic groups in Europe

** Demographics of Europe

** European cuisine, the cuisines of Europe ...

(

Baltic

Baltic may refer to:

Peoples and languages

* Baltic languages, a subfamily of Indo-European languages, including Lithuanian, Latvian and extinct Old Prussian

*Balts (or Baltic peoples), ethnic groups speaking the Baltic languages and/or originati ...

and

Germanic) culture, showing rotational symmetric arrangement of an

animal motif, often four birds' heads. Even wider diffusion of this "Asiatic" theme has been proposed, to the Pacific and even North America (especially

Moundville).

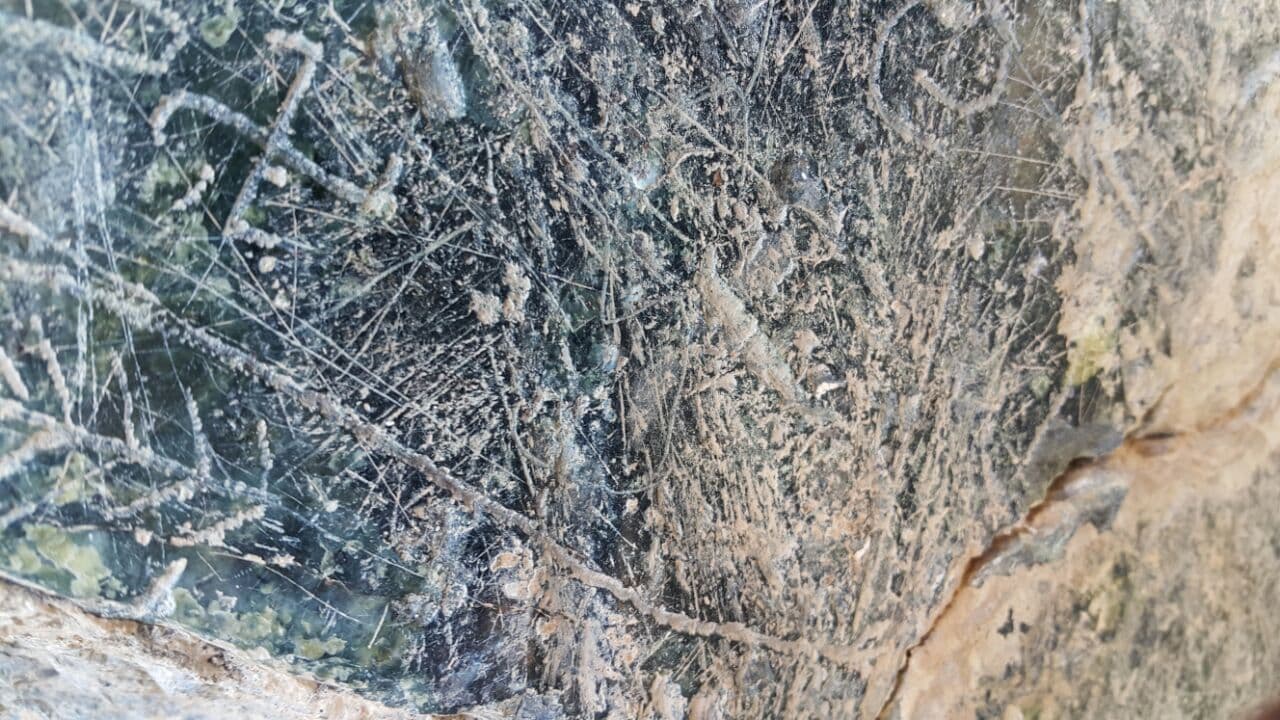

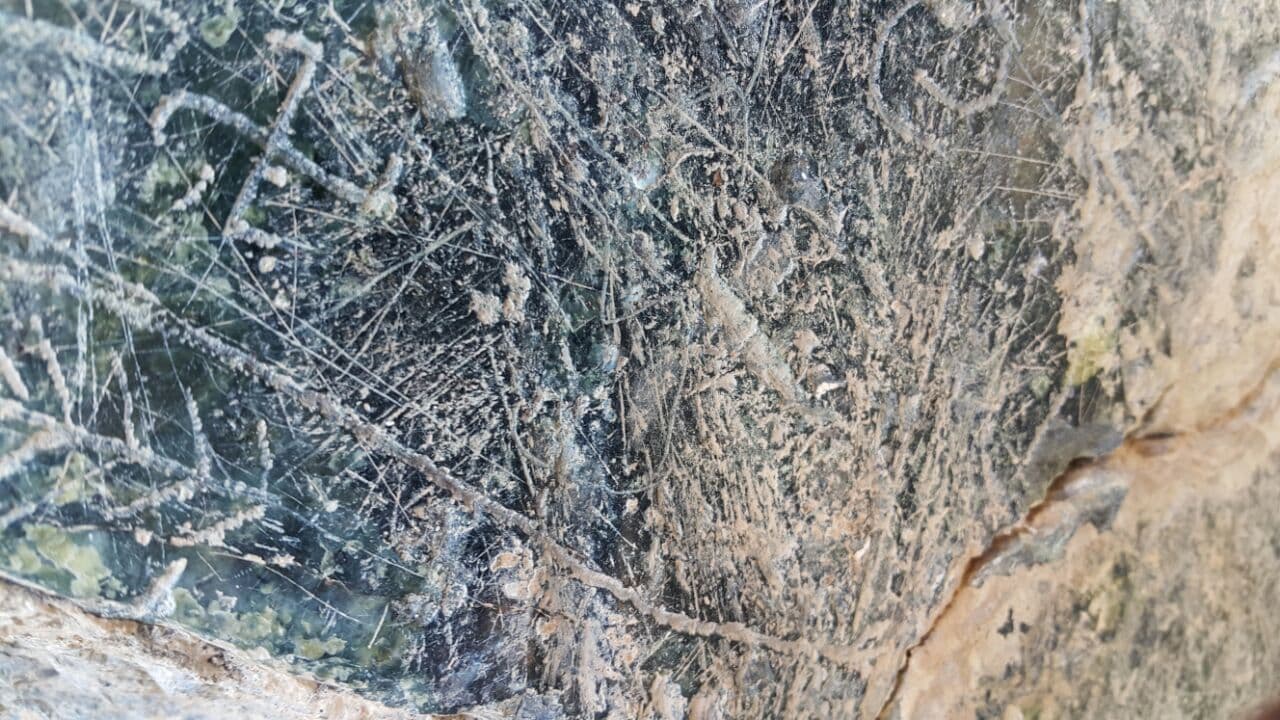

File:The petroglyph with swastikas, in Geghama mountains, Armenia.jpg, The petroglyph with swastikas, Gegham mountains

Gegham mountains (or Gegham Ridge, ISO 9985: Geġam), hy, Գեղամա լեռնաշղթա (''Geghama lernasheghta'') are a range of mountains in Armenia. The range is a tableland-type watershed basin of Sevan Lake from east, inflows of rivers ...

, Armenia

Armenia (), , group=pron officially the Republic of Armenia,, is a landlocked country in the Armenian Highlands of Western Asia.The UNbr>classification of world regions places Armenia in Western Asia; the CIA World Factbook , , and ''Ox ...

, circa 8,000 - 5,000 BCE

File:Samarra bowl.jpg, The Samarra

Samarra ( ar, سَامَرَّاء, ') is a city in Iraq. It stands on the east bank of the Tigris in the Saladin Governorate, north of Baghdad. The city of Samarra was founded by Abbasid Caliph Al-Mutasim for his Turkish professional army ...

bowl, from Iraq

Iraq,; ku, عێراق, translit=Êraq officially the Republic of Iraq, '; ku, کۆماری عێراق, translit=Komarî Êraq is a country in Western Asia. It is bordered by Turkey to Iraq–Turkey border, the north, Iran to Iran–Iraq ...

, circa 4,000 BCE, held at the Pergamonmuseum

The Pergamon Museum (; ) is a listed building on the Museum Island in the historic centre of Berlin. It was built from 1910 to 1930 by order of German Emperor Wilhelm II according to plans by Alfred Messel and Ludwig Hoffmann in Stripped Clas ...

, Berlin. The swastika in the centre of the design is a reconstruction.

File:IndusValleySeals swastikas.JPG, Swastika seals from Mohenjo-daro, Pakistan

Pakistan ( ur, ), officially the Islamic Republic of Pakistan ( ur, , label=none), is a country in South Asia. It is the world's List of countries and dependencies by population, fifth-most populous country, with a population of almost 24 ...

, of the Indus Valley civilisation

The Indus Valley Civilisation (IVC), also known as the Indus Civilisation was a Bronze Age civilisation in the northwestern regions of South Asia, lasting from 3300 BCE to 1300 BCE, and in its mature form 2600 BCE to 1900&n ...

, circa 2,100 - 1,750 BCE, preserved at the British Museum

The British Museum is a public museum dedicated to human history, art and culture located in the Bloomsbury area of London. Its permanent collection of eight million works is among the largest and most comprehensive in existence. It docum ...

File:Swastika iran.jpg, A swastika necklace excavated from Marlik

Marlik is an ancient site near Roudbar in Gilan, in northern Iran. Marlik, also known as ''Cheragh-Ali Tepe''D. Josiya Negahban Marlik is located in the valley of Gohar Rud (gem river), a tributary of Sepid Rud in Gilan Province in Northern Ira ...

, Gilan province, northern Iran

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran, and also called Persia, is a country located in Western Asia. It is bordered by Iraq and Turkey to the west, by Azerbaijan and Armenia to the northwest, by the Caspian Sea and Turkmeni ...

, circa 1,200 - 1,050 BCE

Historical use

In

Asia

Asia (, ) is one of the world's most notable geographical regions, which is either considered a continent in its own right or a subcontinent of Eurasia, which shares the continental landmass of Afro-Eurasia with Africa. Asia covers an area ...

, the swastika symbol first appears in the archaeological record around

3000 BCE in the Indus Valley Civilisation.

It also appears in the

Bronze

Bronze is an alloy consisting primarily of copper, commonly with about 12–12.5% tin and often with the addition of other metals (including aluminium, manganese, nickel, or zinc) and sometimes non-metals, such as phosphorus, or metalloids such ...

and

Iron Age

The Iron Age is the final epoch of the three-age division of the prehistory and protohistory of humanity. It was preceded by the Stone Age (Paleolithic, Mesolithic, Neolithic) and the Bronze Age (Chalcolithic). The concept has been mostly appl ...

cultures around the

Black Sea

The Black Sea is a marginal mediterranean sea of the Atlantic Ocean lying between Europe and Asia, east of the Balkans, south of the East European Plain, west of the Caucasus, and north of Anatolia. It is bounded by Bulgaria, Georgia, Roma ...

and the

Caspian Sea

The Caspian Sea is the world's largest inland body of water, often described as the world's largest lake or a full-fledged sea. An endorheic basin, it lies between Europe and Asia; east of the Caucasus, west of the broad steppe of Central Asia ...

. In all these cultures, the swastika symbol does not appear to occupy any marked position or significance, appearing as just one form of a series of similar symbols of varying complexity. In the

Zoroastrian

Zoroastrianism is an Iranian religion and one of the world's oldest organized faiths, based on the teachings of the Iranian-speaking prophet Zoroaster. It has a dualistic cosmology of good and evil within the framework of a monotheistic on ...

religion of

Persia

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran, and also called Persia, is a country located in Western Asia. It is bordered by Iraq and Turkey to the west, by Azerbaijan and Armenia to the northwest, by the Caspian Sea and Turkmeni ...

, the swastika was a symbol of the revolving sun, infinity, or continuing creation. It is one of the most common symbols on

Mesopotamia

Mesopotamia ''Mesopotamíā''; ar, بِلَاد ٱلرَّافِدَيْن or ; syc, ܐܪܡ ܢܗܪ̈ܝܢ, or , ) is a historical region of Western Asia situated within the Tigris–Euphrates river system, in the northern part of the F ...

n coins.

The icon has been of spiritual significance to Indian religions such as Hinduism, Buddhism and Jainism.

The swastika is a sacred symbol in the

Bön

''Bon'', also spelled Bön () and also known as Yungdrung Bon (, "eternal Bon"), is a Tibetan culture, Tibetan religious tradition with many similarities to Tibetan Buddhism and also many unique features.Samuel 2012, pp. 220-221. Bon initiall ...

religion, native to

Tibet

Tibet (; ''Böd''; ) is a region in East Asia, covering much of the Tibetan Plateau and spanning about . It is the traditional homeland of the Tibetan people. Also resident on the plateau are some other ethnic groups such as Monpa people, ...

.

South Asia

Hinduism

The swastika is an important Hindu symbol.

The swastika symbol is commonly used before entrances or on doorways of homes or temples, to mark the starting page of financial statements, and

mandala

A mandala ( sa, मण्डल, maṇḍala, circle, ) is a geometric configuration of symbols. In various spiritual traditions, mandalas may be employed for focusing attention of practitioners and adepts, as a spiritual guidance tool, for e ...

s constructed for rituals such as weddings or welcoming a newborn.

The swastika has a particular association with

Diwali

Diwali (), Dewali, Divali, or Deepavali ( IAST: ''dīpāvalī''), also known as the Festival of Lights, related to Jain Diwali, Bandi Chhor Divas, Tihar, Swanti, Sohrai, and Bandna, is a religious celebration in Indian religions. It is ...

, being drawn in ''

rangoli'' (coloured sand) or formed with

deepak

Deepak (दीपक) is a Hindi word meaning lamp, from the Sanskrit source word for light. The name Deepak symbolizes a bright future. In the twentieth century, it became very popular as a first name for male Hindus. Names like ''Deepa'' (male ...

lights on the floor outside Hindu houses and on wall hangings and other decorations.

In the diverse traditions within Hinduism, both the clockwise and counterclockwise swastika are found, with different meanings. The clockwise or right hand icon is called ''swastika'', while the counterclockwise or left hand icon is called ''sauwastika'' or ''sauvastika''.

The clockwise swastika is a solar symbol (

Surya

Surya (; sa, सूर्य, ) is the sun as well as the solar deity in Hinduism. He is traditionally one of the major five deities in the Smarta tradition, all of whom are considered as equivalent deities in the Panchayatana puja and a m ...

), suggesting the motion of the Sun in India (the northern hemisphere), where it appears to enter from the east, then ascend to the south at midday, exiting to the west.

The counterclockwise ''sauwastika'' is less used; it connotes the night, and in tantric traditions it is an icon for the goddess

Kali

Kali (; sa, काली, ), also referred to as Mahakali, Bhadrakali, and Kalika ( sa, कालिका), is a Hinduism, Hindu goddess who is considered to be the goddess of ultimate power, time, destruction and change in Shaktism. In t ...

, the terrifying form of

Devi

Devī (; Sanskrit: देवी) is the Sanskrit word for 'goddess'; the masculine form is ''deva''. ''Devi'' and ''deva'' mean 'heavenly, divine, anything of excellence', and are also gender-specific terms for a deity in Hinduism.

The conce ...

Durga

Durga ( sa, दुर्गा, ) is a major Hindu goddess, worshipped as a principal aspect of the mother goddess Mahadevi. She is associated with protection, strength, motherhood, destruction, and wars.

Durga's legend centres around co ...

.

The symbol also represents activity, karma, motion, wheel, and in some contexts the lotus.

According to Norman McClelland its symbolism for motion and the Sun may be from shared prehistoric cultural roots.

Jaipur 03-2016 38 Garh Ganesh Temple.jpg, A Hindu temple in Rajasthan

Rajasthan (; lit. 'Land of Kings') is a state in northern India. It covers or 10.4 per cent of India's total geographical area. It is the largest Indian state by area and the seventh largest by population. It is on India's northwestern si ...

, India

हनुमान जयन्ति.png, A swastika inside a temple

A Hindu Swastika at Goa Lawah Temple Bali Indonesia.jpg, The Balinese Hindu pura Goa Lawah

Pura Goa Lawah (Balinese "Bat Cave Temple") is a Balinese Hindu temple or a pura located in Klungkung, Bali, Indonesia. Pura Goa Lawah is often included among the ''Sad Kahyangan Jagad'', or the "six sanctuaries of the world", the six holiest pla ...

entrance

Bali 014 - Ubud - swastika.jpg, A Balinese Hindu shrine

Buddhism

In

Buddhism

Buddhism ( , ), also known as Buddha Dharma and Dharmavinaya (), is an Indian religion or philosophical tradition based on teachings attributed to the Buddha. It originated in northern India as a -movement in the 5th century BCE, and gra ...

, the swastika is considered to symbolise the auspicious footprints of the Buddha.

The left-facing sauwastika is often imprinted on the chest, feet or palms of

Buddha

Siddhartha Gautama, most commonly referred to as the Buddha, was a śramaṇa, wandering ascetic and religious teacher who lived in South Asia during the 6th or 5th century BCE and founded Buddhism.

According to Buddhist tradition, he was ...

images. It is an aniconic symbol for the Buddha in many parts of Asia and homologous with the

''dharma wheel''.

The shape symbolises eternal cycling, a theme found in the ''

samsara'' doctrine of Buddhism.

The swastika symbol is common in

esoteric tantric traditions of Buddhism, along with Hinduism, where it is found with

chakra

Chakras (, ; sa , text=चक्र , translit=cakra , translit-std=IAST , lit=wheel, circle; pi, cakka) are various focal points used in a variety of ancient meditation practices, collectively denominated as Tantra, or the esoteric or ...

theories and other meditative aids.

The clockwise symbol is more common, and contrasts with the counter clockwise version common in the Tibetan

Bon

''Bon'', also spelled Bön () and also known as Yungdrung Bon (, "eternal Bon"), is a Tibetan religious tradition with many similarities to Tibetan Buddhism and also many unique features.Samuel 2012, pp. 220-221. Bon initially developed in t ...

tradition and locally called ''yungdrung''.

Jainism

In

Jainism

Jainism ( ), also known as Jain Dharma, is an Indian religions, Indian religion. Jainism traces its spiritual ideas and history through the succession of twenty-four tirthankaras (supreme preachers of ''Dharma''), with the first in the current ...

, it is a symbol of the seventh ''

tīrthaṅkara'',

Suparśvanātha

Suparshvanatha ( sa, सुपार्श्वनाथ ), also known as Suparśva, was the seventh Jain '' Tīrthankara'' of the present age ('' avasarpini''). He was born to King Pratistha and Queen ''Prithvi'' at Varanasi on 12 Jestha Sh ...

.

In the

Śvētāmbara

The Śvētāmbara (; ''śvētapaṭa''; also spelled ''Shwethambara'', ''Svetambar'', ''Shvetambara'' or ''Swetambar'') is one of the two main branches of Jainism, the other being the ''Digambara''. Śvētāmbara means "white-clad", and refers ...

tradition, it is also one of the ''

aṣṭamaṅgala'' or eight auspicious symbols. All

Jain temples and holy books must contain the swastika and ceremonies typically begin and end with creating a swastika mark several times with rice around the altar. Jains use rice to make a swastika in front of statues and then put an offering on it, usually a ripe or dried fruit, a sweet ( hi, मिठाई ), or a coin or currency note. The four arms of the swastika symbolise the four places where a soul could be reborn in ''

samsara'', the cycle of birth and death''

svarga

Svarga (), also known as Indraloka and Svargaloka, is the celestial abode of the devas in Hinduism. Svarga is one of the seven higher lokas ( esoteric planes) in Hindu cosmology. Svarga is often translated as heaven, though it is regarded to b ...

'' "heaven", ''

naraka

Naraka ( sa, नरक) is the realm of hell in Indian religions. According to some schools of Hinduism, Sikhism, Jainism and Buddhism, ''Naraka'' is a place of torment. The word ''Neraka'' (modification of ''Naraka'') in Indonesian and Malaysia ...

'' "hell", ''manushya'' "humanity" or ''tiryancha'' "as flora or fauna"before the soul attains ''

moksha

''Moksha'' (; sa, मोक्ष, '), also called ''vimoksha'', ''vimukti'' and ''mukti'', is a term in Hinduism, Buddhism, Jainism and Sikhism for various forms of emancipation, enlightenment, liberation, and release. In its soteriology, ...

'' "salvation" as a ''

siddha

''Siddha'' (Sanskrit: '; "perfected one") is a term that is used widely in Indian religions and culture. It means "one who is accomplished." It refers to perfected masters who have achieved a high degree of physical as well as spiritual ...

'', having ended the cycle of birth and death and become

omniscient

Omniscience () is the capacity to know everything. In Hinduism, Sikhism and the Abrahamic religions, this is an attribute of God. In Jainism, omniscience is an attribute that any individual can eventually attain. In Buddhism, there are diffe ...

.

East Asia

The swastika is an auspicious symbol in China where it was introduced from India with

Buddhism

Buddhism ( , ), also known as Buddha Dharma and Dharmavinaya (), is an Indian religion or philosophical tradition based on teachings attributed to the Buddha. It originated in northern India as a -movement in the 5th century BCE, and gra ...

.

In 693, during the

Tang dynasty

The Tang dynasty (, ; zh, t= ), or Tang Empire, was an Dynasties in Chinese history, imperial dynasty of China that ruled from 618 to 907 AD, with an Zhou dynasty (690–705), interregnum between 690 and 705. It was preceded by the Sui dyn ...

, it was declared as "the source of all good fortune" and was called by

Wu Zetian

Wu Zetian (17 February 624 – 16 December 705), personal name Wu Zhao, was the ''de facto'' ruler of the Tang dynasty from 665 to 705, ruling first through others and then (from 690) in her own right. From 665 to 690, she was first empres ...

becoming a Chinese word.

The Chinese character for () is similar to the swastika in shape and can be appeared into two different variations:《》and 《》. As the Chinese character ( and/or ) is homonym for the Chinese word of "ten thousand" () and "infinity", as such the Chinese character is itself a symbol of immortality

and infinity.

It was also a representation of

longevity

The word " longevity" is sometimes used as a synonym for "life expectancy" in demography. However, the term ''longevity'' is sometimes meant to refer only to especially long-lived members of a population, whereas ''life expectancy'' is always d ...

.

The Chinese character could be used as a stand-alone《》or《》or as be used as pairs《 》in Chinese visual arts, decorative arts, and clothing due to its auspicious connotation.

Adding the character ( and/or ) to other auspicious Chinese symbols or patterns can multiply that wish by 10,000 times.

It can be combined with other Chinese characters, such as the Chinese character 《》for longevity where it is sometimes even integrated into the Chinese character to augment the menaning of longevity.

The paired swastika symbols ( and ) are included, at least since the

Liao Dynasty

The Liao dynasty (; Khitan: ''Mos Jælud''; ), also known as the Khitan Empire (Khitan: ''Mos diau-d kitai huldʒi gur''), officially the Great Liao (), was an imperial dynasty of China that existed between 916 and 1125, ruled by the Yelü ...

(907–1125 CE), as part of the

Chinese writing system and are

variant characters for 《萬》 or 《万》 (''wàn'' in Mandarin, 《만》(''man'') in Korean, Cantonese, and Japanese, ''vạn'' in Vietnamese) meaning "

myriad

A myriad (from Ancient Greek grc, μυριάς, translit=myrias, label=none) is technically the number 10,000 (ten thousand); in that sense, the term is used in English almost exclusively for literal translations from Greek, Latin or Sinospher ...

".

The character can also be stylized in the form of the , Chinese auspicious clouds.

File:Shou Swastika.svg, Chinese character integrated into one of the stylistic versions of the Chinese character

File:Robe, dragon, man's (AM 9838-33).jpg, Paired character wan on a dragon robe, Qing dynasty

Japan

When the Chinese writing system was introduced to Japan in the 8th century, the swastika was adopted into the Japanese language and culture. It is commonly referred as the ''manji'' (lit. "10,000-character"). Since the Middle Ages, it has been used as a ''

mon

Mon, MON or Mon. may refer to:

Places

* Mon State, a subdivision of Myanmar

* Mon, India, a town in Nagaland

* Mon district, Nagaland

* Mon, Raebareli, a village in Uttar Pradesh, India

* Mon, Switzerland, a village in the Canton of Grisons

* An ...

'' by various Japanese families such as

Tsugaru clan,

Hachisuka clan

The are descendants of Emperor Seiwa (850-880) of Japan and are a branch of the Ashikaga clan through the Shiba clan (Seiwa Genji).

History

Ashikaga Ieuji (13th century), son of Ashikaga Yasuuji, was the first to adopt the name Shiba. The Shiba ...

or around 60 clans that belong to

Tokugawa clan

The is a Japanese dynasty that was formerly a powerful ''daimyō'' family. They nominally descended from Emperor Seiwa (850–880) and were a branch of the Minamoto clan (Seiwa Genji) through the Matsudaira clan. The early history of this clan r ...

. On

Japanese maps

The earliest known term used for maps in Japan is believed to be ''kata'' (, roughly "form"), which was probably in use until roughly the 8th century. During the Nara period, the term ''zu'' () came into use, but the term most widely used and asso ...

, a swastika (left-facing and horizontal) is used to mark the location of a Buddhist temple. The right-facing swastika is often referred to as the or , and can also be called .

In

Chinese

Chinese can refer to:

* Something related to China

* Chinese people, people of Chinese nationality, citizenship, and/or ethnicity

**''Zhonghua minzu'', the supra-ethnic concept of the Chinese nation

** List of ethnic groups in China, people of va ...

and

Japanese art

Japanese art covers a wide range of art styles and media, including ancient pottery, sculpture, ink painting and calligraphy on silk and paper, ''ukiyo-e'' paintings and woodblock prints, ceramics, origami, and more recently manga and anime. It ...

, the swastika is often found as part of a repeating pattern. One common pattern, called ''sayagata'' in Japanese, comprises left- and right-facing swastikas joined by lines. As the negative space between the lines has a distinctive shape, the sayagata pattern is sometimes called the ''key fret'' motif in English.

Caucasus

In

Armenia

Armenia (), , group=pron officially the Republic of Armenia,, is a landlocked country in the Armenian Highlands of Western Asia.The UNbr>classification of world regions places Armenia in Western Asia; the CIA World Factbook , , and ''Ox ...

the swastika is called the "

arevakhach" and "kerkhach" ( hy, կեռխաչ)

and is the ancient symbol of eternity and eternal light (i.e. God). Swastikas in

Armenia

Armenia (), , group=pron officially the Republic of Armenia,, is a landlocked country in the Armenian Highlands of Western Asia.The UNbr>classification of world regions places Armenia in Western Asia; the CIA World Factbook , , and ''Ox ...

were found on petroglyphs from the copper age, predating the Bronze Age. During the Bronze Age it was depicted on

cauldrons, belts,

medallion

A medal or medallion is a small portable artistic object, a thin disc, normally of metal, carrying a design, usually on both sides. They typically have a commemorative purpose of some kind, and many are presented as awards. They may be int ...

s and other items. Among the oldest petroglyphs is the seventh letter of the Armenian alphabet: Է("E" which means "is" or "to be") depicted as a half-swastika.

Swastikas can also be seen on early Medieval churches and fortresses, including the principal tower in Armenia's historical capital city of

Ani

Ani ( hy, Անի; grc-gre, Ἄνιον, ''Ánion''; la, Abnicum; tr, Ani) is a ruined medieval Armenian city now situated in Turkey's province of Kars, next to the closed border with Armenia.

Between 961 and 1045, it was the capital of th ...

.

The same symbol can be found on

Armenian carpets, cross-stones (''

khachkar

A ''khachkar'', also known as a ''khatchkar'' or Armenian cross-stone ( hy, խաչքար, , խաչ xačʿ "cross" + քար kʿar "stone") is a carved, memorial stele bearing a cross, and often with additional motifs such as rosettes, in ...

'') and in medieval manuscripts, as well as on modern monuments as a

symbol of eternity.

Old

petroglyph

A petroglyph is an image created by removing part of a rock surface by incising, picking, carving, or abrading, as a form of rock art. Outside North America, scholars often use terms such as "carving", "engraving", or other descriptions ...

s of four-beam and other swastikas were recorded in

Dagestan

Dagestan ( ; rus, Дагеста́н, , dəɡʲɪˈstan, links=yes), officially the Republic of Dagestan (russian: Респу́блика Дагеста́н, Respúblika Dagestán, links=no), is a republic of Russia situated in the North C ...

, in particular, among the

Avars.

According to

Vakhushti of Kartli

Vakhushti ( ka, ვახუშტი, tr) (1696–1757) was a Georgian royal prince (''batonishvili''), geographer, historian and cartographer. His principal historical and geographic works, ''Description of the Kingdom of Georgia'' and the ''Geo ...

, the tribal banner of the

Avar khans

Avar(s) or AVAR may refer to:

Peoples and states

* Avars (Caucasus), a modern Northeast Caucasian-speaking people in the North Caucasus, Dagestan, Russia

**Avar language, the modern Northeast Caucasian language spoken by the Avars of the North C ...

depicted a wolf with a standard with a double-spiral swastika.

Petroglyphs with swastikas were depicted on medieval

Vainakh tower architecture

The Vainakh tower architecture ( inh, Вайнаьх Гlала архитектур), also called Nakh architecture, is a characteristic feature of ancient and medieval architecture of Chechnya and Ingushetia.

History

The oldest fortifications in ...

(see sketches by scholar Bruno Plaetschke from the 1920s).

Thus, a rectangular swastika was made in engraved form on the entrance of a residential tower in the settlement

Khimoy

Khimoy (russian: Химой, ce, ХӀима, ''Hima'') is a rural locality (a '' selo'') and the administrative center of Sharoysky Municipal District, the Chechen Republic, Russia. (The selo of Sharoy

Sharoy (russian: Шарой, ce, Ш� ...

,

Chechnya

Chechnya ( rus, Чечня́, Chechnyá, p=tɕɪtɕˈnʲa; ce, Нохчийчоь, Noxçiyçö), officially the Chechen Republic,; ce, Нохчийн Республика, Noxçiyn Respublika is a republic of Russia. It is situated in the ...

.

Khachkar

A ''khachkar'', also known as a ''khatchkar'' or Armenian cross-stone ( hy, խաչքար, , խաչ xačʿ "cross" + քար kʿar "stone") is a carved, memorial stele bearing a cross, and often with additional motifs such as rosettes, in ...

with swastikas and hexafoil

The hexafoil is a design with six-fold dihedral symmetry composed from six ''vesica piscis'' lenses arranged radially around a central point, often shown enclosed in a circumference of another six lenses. It is also sometimes known as a "daisy wh ...

s in Sanahin, Armenia

File:Символы_свастики_на_арке_средневековой_башни_в_Чечне.jpg, Swastika on the medieval tower arche in Khimoy

Khimoy (russian: Химой, ce, ХӀима, ''Hima'') is a rural locality (a '' selo'') and the administrative center of Sharoysky Municipal District, the Chechen Republic, Russia. (The selo of Sharoy

Sharoy (russian: Шарой, ce, Ш� ...

, Chechnya

Northern Europe

Germanic Iron Age

The swastika shape (also called a ''fylfot'') appears on various Germanic

Migration Period

The Migration Period was a period in European history marked by large-scale migrations that saw the fall of the Western Roman Empire and subsequent settlement of its former territories by various tribes, and the establishment of the post-Roman ...

and

Viking Age

The Viking Age () was the period during the Middle Ages when Norsemen known as Vikings undertook large-scale raiding, colonizing, conquest, and trading throughout Europe and reached North America. It followed the Migration Period and the Ger ...

artifacts, such as the 3rd-century

Værløse Fibula

The sequence ''alu'' () is found in numerous Elder Futhark runic inscriptions of Germanic Iron Age Scandinavia (and more rarely in early Anglo-Saxon England) between the 3rd and the 8th century. The word usually appears either alone (such as on t ...

from Zealand, Denmark, the

Gothic

Gothic or Gothics may refer to:

People and languages

*Goths or Gothic people, the ethnonym of a group of East Germanic tribes

**Gothic language, an extinct East Germanic language spoken by the Goths

**Crimean Gothic, the Gothic language spoken b ...

spearhead from

Brest-Litovsk

Brest ( be, Брэст / Берасьце, Bieraście, ; russian: Брест, ; uk, Берестя, Berestia; lt, Brasta; pl, Brześć; yi, בריסק, Brisk), formerly Brest-Litovsk (russian: Брест-Литовск, lit=Lithuanian Br ...

, today in

Belarus

Belarus,, , ; alternatively and formerly known as Byelorussia (from Russian ). officially the Republic of Belarus,; rus, Республика Беларусь, Respublika Belarus. is a landlocked country in Eastern Europe. It is bordered by R ...

, the 9th-century

Snoldelev Stone

The Snoldelev Stone, listed as DR 248 in the Rundata catalog, is a 9th-century runestone that was originally located at Snoldelev, Ramsø, Denmark.

Description

The Snoldelev Stone, which is 1.25 meters in height, is decorated with painted scratc ...

from

Ramsø Ramsø was a municipality (Danish '' kommune'') in the former Roskilde County on the island of Zealand (''Sjælland'') in east Denmark until January 1, 2007. The municipality covered an area of and had a total population in 2005 of 9,320. Its last ...

, Denmark, and numerous Migration Period

bracteates drawn left-facing or right-facing.

The

pagan

Paganism (from classical Latin ''pāgānus'' "rural", "rustic", later "civilian") is a term first used in the fourth century by early Christians for people in the Roman Empire who practiced polytheism, or ethnic religions other than Judaism. ...

Anglo-Saxon

The Anglo-Saxons were a Cultural identity, cultural group who inhabited England in the Early Middle Ages. They traced their origins to settlers who came to Britain from mainland Europe in the 5th century. However, the ethnogenesis of the Anglo- ...

ship burial

A ship burial or boat grave is a burial in which a ship or boat is used either as the tomb for the dead and the grave goods, or as a part of the grave goods itself. If the ship is very small, it is called a boat grave. This style of burial was pr ...

at

Sutton Hoo

Sutton Hoo is the site of two early medieval cemeteries dating from the 6th to 7th centuries near the English town of Woodbridge. Archaeologists have been excavating the area since 1938, when a previously undisturbed ship burial containing a ...