Hanford Engineer Works on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Hanford Engineer Works was a

The Hanford Engineer Works was a

On 23 September 1942,

On 23 September 1942,

Carpenter expressed reservations about the initial plan to build the reactors at Oak Ridge, due to the proximity of

Carpenter expressed reservations about the initial plan to build the reactors at Oak Ridge, due to the proximity of  They looked at sites in the vicinity of

They looked at sites in the vicinity of

The Manhattan District's Real Estate Branch divided the land into five areas. Area A, at the center of the site would be the location of the project facilities. This land would be acquired outright, and for safety and security reasons all non-project personnel would be removed. Area B was the area surrounding Area A, which comprised a safety zone; this land would be leased, with the occupants subject to eviction at short notice. Area C was earmarked for the workers' village and would be leased or purchased. Area D was earmarked for production plants and would be purchased. Finally there were two parcels of land designed as Area E, which would be acquired only if necessary. In all, 4,218 tracts totaling were to be acquired, making it one of the largest land acquisition projects in American history.

Most of the land (some 88 percent) was

The Manhattan District's Real Estate Branch divided the land into five areas. Area A, at the center of the site would be the location of the project facilities. This land would be acquired outright, and for safety and security reasons all non-project personnel would be removed. Area B was the area surrounding Area A, which comprised a safety zone; this land would be leased, with the occupants subject to eviction at short notice. Area C was earmarked for the workers' village and would be leased or purchased. Area D was earmarked for production plants and would be purchased. Finally there were two parcels of land designed as Area E, which would be acquired only if necessary. In all, 4,218 tracts totaling were to be acquired, making it one of the largest land acquisition projects in American history.

Most of the land (some 88 percent) was  Since construction plans had not yet been drawn up, and work on the site could not immediately commence, Groves saw no harm in postponing the taking of the physical possession of properties under cultivation to allow farmers to harvest the crops they had already planted. This reduced the hardship on the farmers, and avoided the wasting of food at a time when the nation was facing food shortages and the federal government was urging citizens to plant

Since construction plans had not yet been drawn up, and work on the site could not immediately commence, Groves saw no harm in postponing the taking of the physical possession of properties under cultivation to allow farmers to harvest the crops they had already planted. This reduced the hardship on the farmers, and avoided the wasting of food at a time when the nation was facing food shortages and the federal government was urging citizens to plant  From October 1943 until April 1944, the rate of settlements dropped to an average of seven per month. Groves became concerned that public attention generated by the trials and the inspection of tracts by juries where construction was now commencing might jeopardize project security. He arranged with Norman M. Littell, the assistant attorney general in charge of the Lands Division at the Justice Department, for additional flexibility in making adjustments to valuations to facilitate out of court settlement, and for the establishment of a second court and additional judges. Air conditioning was installed in the courtroom in Yakima to permit cases to be heard during the summer months.

Littell became convinced that the root of the problem was faulty appraisals, and on 13 October 1944, he appeared at the court in Yakima and asked Schwellenbach to put all condemnation trials on hold until the Justice Department could carry out reappraisals of the more than 700 tracts still awaiting settlement. The Under Secretary of War,

From October 1943 until April 1944, the rate of settlements dropped to an average of seven per month. Groves became concerned that public attention generated by the trials and the inspection of tracts by juries where construction was now commencing might jeopardize project security. He arranged with Norman M. Littell, the assistant attorney general in charge of the Lands Division at the Justice Department, for additional flexibility in making adjustments to valuations to facilitate out of court settlement, and for the establishment of a second court and additional judges. Air conditioning was installed in the courtroom in Yakima to permit cases to be heard during the summer months.

Littell became convinced that the root of the problem was faulty appraisals, and on 13 October 1944, he appeared at the court in Yakima and asked Schwellenbach to put all condemnation trials on hold until the Justice Department could carry out reappraisals of the more than 700 tracts still awaiting settlement. The Under Secretary of War,

Matthias and Church met in Wilmington on 2 March 1943, and drew up an outline of the layout of the Hanford Engineer Works. Normally for a development in such an isolated area, employees would be accommodated on site, but in this case for security and safety reasons it was desirable to house them at least away. Even the construction workforce could not be housed on site, because some plant operation would have to be carried out during startup testing. The Army and DuPont engineers decided to create two communities: a temporary constructions camp and a more substantial operating village. Rather than create temporary construction camps at each building site, there would be one large camp servicing all the sites.

Construction was expedited by locating them on the sites of existing villages, where they could take advantage of the buildings, roads and utility infrastructure already in place. The DuPont and Hanford Engineer Works engineers decided to locate the temporary construction camp on the site of the village of Hanford, which had a population of about 125. It was from the nearest process area site, which was considered to be sufficiently distant at startup. It was served by the Connell-Yakima state highway the Pasco- White Bluffs road, and a branch line of the

Matthias and Church met in Wilmington on 2 March 1943, and drew up an outline of the layout of the Hanford Engineer Works. Normally for a development in such an isolated area, employees would be accommodated on site, but in this case for security and safety reasons it was desirable to house them at least away. Even the construction workforce could not be housed on site, because some plant operation would have to be carried out during startup testing. The Army and DuPont engineers decided to create two communities: a temporary constructions camp and a more substantial operating village. Rather than create temporary construction camps at each building site, there would be one large camp servicing all the sites.

Construction was expedited by locating them on the sites of existing villages, where they could take advantage of the buildings, roads and utility infrastructure already in place. The DuPont and Hanford Engineer Works engineers decided to locate the temporary construction camp on the site of the village of Hanford, which had a population of about 125. It was from the nearest process area site, which was considered to be sufficiently distant at startup. It was served by the Connell-Yakima state highway the Pasco- White Bluffs road, and a branch line of the  As construction of the facilities got under way, Groves released construction workers working on barracks by purchasing hutments. These were simple, prefabricated

As construction of the facilities got under way, Groves released construction workers working on barracks by purchasing hutments. These were simple, prefabricated  There was also an airport with a

There was also an airport with a

Richland was chosen as the site for the operating village. The project engineers also considered

Richland was chosen as the site for the operating village. The project engineers also considered  Pehrson accepted the need for speed and efficiency, but his vision of a model late-20th century community differed from that of Groves. Groves was, for example, opposed to the stores having

Pehrson accepted the need for speed and efficiency, but his vision of a model late-20th century community differed from that of Groves. Groves was, for example, opposed to the stores having  Some 1,800 prefabricated houses were added to the plan. The company responsible for their manufacture, Prefabricated Engineering, did not have the equipment to transport them to Richland from its plant in

Some 1,800 prefabricated houses were added to the plan. The company responsible for their manufacture, Prefabricated Engineering, did not have the equipment to transport them to Richland from its plant in

The Manhattan District and DuPont set about recruiting a sizeable construction workforce with the help of the

The Manhattan District and DuPont set about recruiting a sizeable construction workforce with the help of the  Recruiting workers was one problem; keeping them was another. Turnover was a serious problem. Groves was sufficiently concerned to mandate

Recruiting workers was one problem; keeping them was another. Turnover was a serious problem. Groves was sufficiently concerned to mandate  Another source of labor was prisoners. The Manhattan District arranged with

Another source of labor was prisoners. The Manhattan District arranged with

The December 1942 layout of the Hanford Engineer Works provided for three reactors and two separation units, with the option to add another three reactors and a third separation unit. The three reactors were to be located near the Columbia River in the vicinity of White Bluffs in three areas designated 100-B, 100-D and 100-F. Each was located from any other installation. Three separation areas, 200 W, 200 N and 200 E were to the south. Two separation units were situated at 200-W, with about between them, and one at 200-E. There was one other production site, 300, which was located north of Richland.

The December 1942 layout of the Hanford Engineer Works provided for three reactors and two separation units, with the option to add another three reactors and a third separation unit. The three reactors were to be located near the Columbia River in the vicinity of White Bluffs in three areas designated 100-B, 100-D and 100-F. Each was located from any other installation. Three separation areas, 200 W, 200 N and 200 E were to the south. Two separation units were situated at 200-W, with about between them, and one at 200-E. There was one other production site, 300, which was located north of Richland.

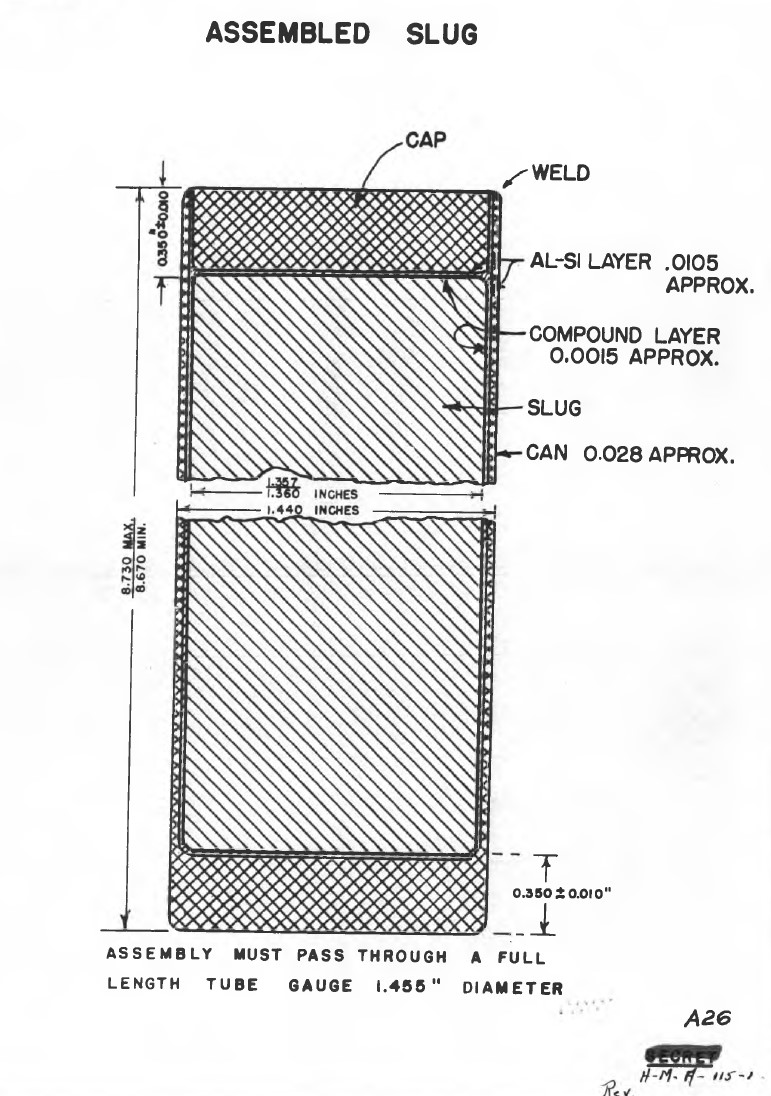

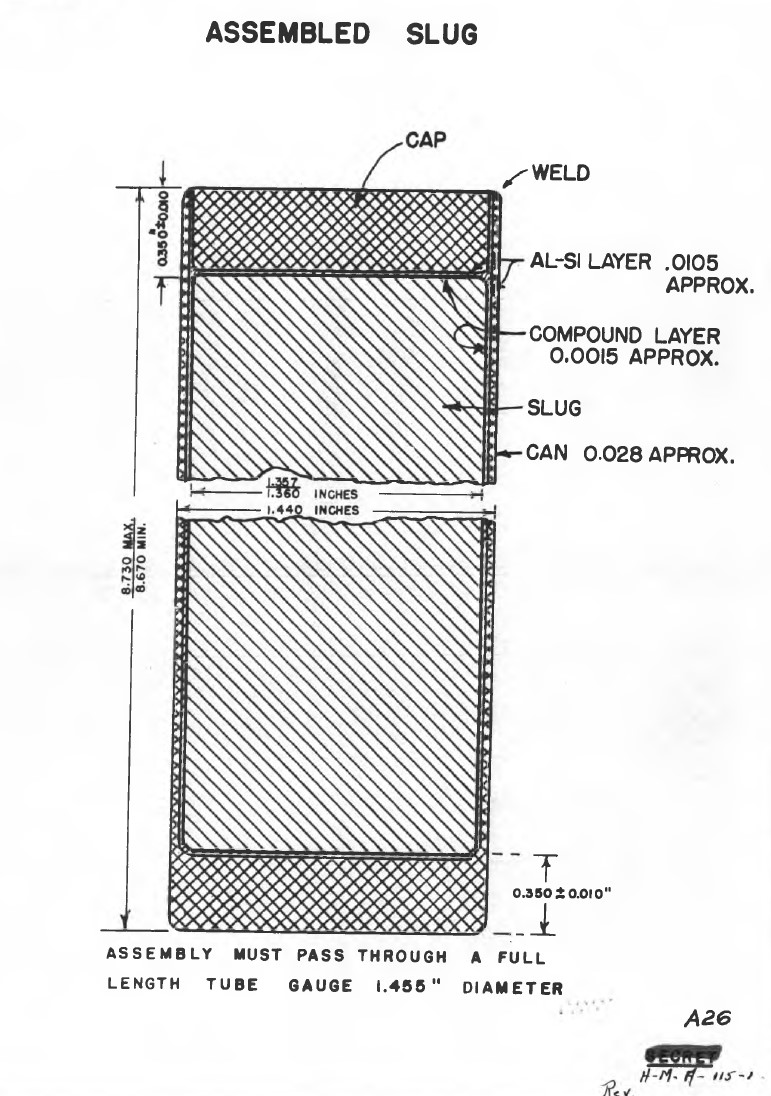

Uranium arrived at the Hanford Engineer Works in the form of

Uranium arrived at the Hanford Engineer Works in the form of

Construction work on the reactors could not commence until Wilmington released the plans, which did not occur until 4 October 1943, but the engineers were aware that they were to be water cooled and run at 250 MW. Construction therefore commenced on the

Construction work on the reactors could not commence until Wilmington released the plans, which did not occur until 4 October 1943, but the engineers were aware that they were to be water cooled and run at 250 MW. Construction therefore commenced on the  On 1 February 1944, with the thick concrete floor of the reactor building poured, workmen began assembling the reactor itself. The workmen set cast-iron blocks that would form the thermal shield, and the 726 laminated steel and

On 1 February 1944, with the thick concrete floor of the reactor building poured, workmen began assembling the reactor itself. The workmen set cast-iron blocks that would form the thermal shield, and the 726 laminated steel and  Then came the graphite. This arrived from the manufacturer in long blocks with a square cross section. Based on experience with the X-10 Graphite Reactor at the Clinton Engineer Works, the blocks were finished on site. An assembly-line process was used for this. Each block was carefully cleaned and numbered. Precision and cleanliness were emphasized; the workmen wore special uniforms and placed the graphite blocks with gloved hands. Each layer was vacuumed to remove dirt and dust. The last block was laid on 11 June, and the top shield was installed. The result was a mass of graphite across, high and from front to back. The reactors contained no moving parts; the only sounds were those of the pumps.

Compton, Fermi, Greenewalt, Matthias, Williams and personnel from Wilmington and the Metallurgical Laboratory were on hand for the startup of B Reactor on 13 September 1944. That day the Operations Department accepted responsibility for the 100-B area from the Construction Department, including some minor work that was unfinished. Fermi inserted the first slug at 17:43. A chain reaction commenced with no cooling water in the reactor (dry critical) at 02:30 on 15 September with 400 tubes loaded. With water flowing through the pipes, wet critical was achieved at 17:30 on 18 September, with 834 tubes loaded. Production operations commenced in low power mode at 22:48 on 26 September. The power was increased to 9 megawatts, but after an hour the operators noticed that power had started dropping off and by 18:30 on 27 September the reactor had shut down completely. The following morning the reactor suddenly started up, but it shut down again when the power level was raised.

The possibility that there was coolant leak or a contaminant in the water was investigated, but no evidence was found. Suspicion then fell on there being an unknown

Then came the graphite. This arrived from the manufacturer in long blocks with a square cross section. Based on experience with the X-10 Graphite Reactor at the Clinton Engineer Works, the blocks were finished on site. An assembly-line process was used for this. Each block was carefully cleaned and numbered. Precision and cleanliness were emphasized; the workmen wore special uniforms and placed the graphite blocks with gloved hands. Each layer was vacuumed to remove dirt and dust. The last block was laid on 11 June, and the top shield was installed. The result was a mass of graphite across, high and from front to back. The reactors contained no moving parts; the only sounds were those of the pumps.

Compton, Fermi, Greenewalt, Matthias, Williams and personnel from Wilmington and the Metallurgical Laboratory were on hand for the startup of B Reactor on 13 September 1944. That day the Operations Department accepted responsibility for the 100-B area from the Construction Department, including some minor work that was unfinished. Fermi inserted the first slug at 17:43. A chain reaction commenced with no cooling water in the reactor (dry critical) at 02:30 on 15 September with 400 tubes loaded. With water flowing through the pipes, wet critical was achieved at 17:30 on 18 September, with 834 tubes loaded. Production operations commenced in low power mode at 22:48 on 26 September. The power was increased to 9 megawatts, but after an hour the operators noticed that power had started dropping off and by 18:30 on 27 September the reactor had shut down completely. The following morning the reactor suddenly started up, but it shut down again when the power level was raised.

The possibility that there was coolant leak or a contaminant in the water was investigated, but no evidence was found. Suspicion then fell on there being an unknown

Priority for construction was accorded to facilities in the 300 and 100 areas, as they would be required first, and there was insufficient skilled labor to work on all the areas simultaneously. Little work was done on the 200 areas until January 1944. Although construction commenced on 26 June 1943, the work at 200-W was only three percent complete by the end of the year. The construction of the separation building, 221-T, was also affected by delays in delivery of critical equipment such as stainless steel pipe and the 10-ton crane. There were also some late design changes. The pace picked up in mid-1944, and 100-W was completed in December. Ground was broken in the 100-E area on 2 August 1943, but work was only six percent complete at the end of April 1944. It was completed in February 1945. Ground was broken at 200-N on 17 November 1943, and was completed in November 1944. T plant began processing irradiated slugs on 26 December 1944; B Plant followed on 13 April 1945. U plant never did, and was used as a training facility.

The quantity of plutonium in each canned slug was dependent on the time spent in the reactor, the position in the reactor, and the power level of the reactor. The history of each of the 70,000 slugs in each reactor was recorded and tracked with an automatic index card machine. Tubes could be selectively discharged. Discharge was effected simultaneously with recharging: as new slugs were inserted into the tube, the irradiated ones fell out the discharge side onto a

Priority for construction was accorded to facilities in the 300 and 100 areas, as they would be required first, and there was insufficient skilled labor to work on all the areas simultaneously. Little work was done on the 200 areas until January 1944. Although construction commenced on 26 June 1943, the work at 200-W was only three percent complete by the end of the year. The construction of the separation building, 221-T, was also affected by delays in delivery of critical equipment such as stainless steel pipe and the 10-ton crane. There were also some late design changes. The pace picked up in mid-1944, and 100-W was completed in December. Ground was broken in the 100-E area on 2 August 1943, but work was only six percent complete at the end of April 1944. It was completed in February 1945. Ground was broken at 200-N on 17 November 1943, and was completed in November 1944. T plant began processing irradiated slugs on 26 December 1944; B Plant followed on 13 April 1945. U plant never did, and was used as a training facility.

The quantity of plutonium in each canned slug was dependent on the time spent in the reactor, the position in the reactor, and the power level of the reactor. The history of each of the 70,000 slugs in each reactor was recorded and tracked with an automatic index card machine. Tubes could be selectively discharged. Discharge was effected simultaneously with recharging: as new slugs were inserted into the tube, the irradiated ones fell out the discharge side onto a  The separation buildings were massive windowless concrete structures, long, high and wide, with concrete walls thick. Inside, the buildings were canyons and galleries. The galleries contained piping and equipment. The canyons were divided into 22 sections in T plant and 20 in B plant. Each section contained two concrete cells. Sections were long, except for sections 1, 2 and 20, which were long. Most of the cells were square and deep, and were separated from each other by thick concrete blocks. Items could be moved about with a long

The separation buildings were massive windowless concrete structures, long, high and wide, with concrete walls thick. Inside, the buildings were canyons and galleries. The galleries contained piping and equipment. The canyons were divided into 22 sections in T plant and 20 in B plant. Each section contained two concrete cells. Sections were long, except for sections 1, 2 and 20, which were long. Most of the cells were square and deep, and were separated from each other by thick concrete blocks. Items could be moved about with a long  A series of chemical processing steps separated the plutonium from the remaining uranium and the fission waste products. The slugs were dumped into a dissolver, covered with

A series of chemical processing steps separated the plutonium from the remaining uranium and the fission waste products. The slugs were dumped into a dissolver, covered with

Throughout the war, the Manhattan Project maintained a top secret classification. Until news arrived of the

Throughout the war, the Manhattan Project maintained a top secret classification. Until news arrived of the

Dear Anne: a letter telling you all about "Life in Hanford"

A 1944 pamphlet that explains the steps to be taken by new employees upon their arrival.

Here's Hanford

A 1944 pamphlet that provides new employees with a detailed map and lists all the amenities to be found in the Hanford area.

Hanford

A 1945 pictorial record that documents construction of the Hanford Engineer Works.

Hanford Trailer City and Environment. Public domain photos selected from the Hanford Declassified Project.Building a Town. Public domain photos selected from the Hanford Declassified Project.

{{Coord, 46, 38, 51, N, 119, 35, 55, W, display=title, region:US_type:landmark History of Washington (state) History of the Manhattan Project Manhattan Project sites 1943 establishments in Washington (state)

The Hanford Engineer Works was a

The Hanford Engineer Works was a nuclear

Nuclear may refer to:

Physics

Relating to the nucleus of the atom:

* Nuclear engineering

*Nuclear physics

*Nuclear power

*Nuclear reactor

*Nuclear weapon

*Nuclear medicine

*Radiation therapy

*Nuclear warfare

Mathematics

*Nuclear space

*Nuclear ...

production complex established by the United States federal government

The federal government of the United States (U.S. federal government or U.S. government) is the Federation#Federal governments, national government of the United States, a federal republic located primarily in North America, composed of 50 ...

in 1943 as part of the Manhattan Project

The Manhattan Project was a research and development undertaking during World War II that produced the first nuclear weapons. It was led by the United States with the support of the United Kingdom and Canada. From 1942 to 1946, the project w ...

during World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

. The site, located at the Hanford Site

The Hanford Site is a decommissioned nuclear production complex operated by the United States federal government on the Columbia River in Benton County in the U.S. state of Washington. The site has been known by many names, including SiteW a ...

on the Columbia River

The Columbia River (Upper Chinook: ' or '; Sahaptin: ''Nch’i-Wàna'' or ''Nchi wana''; Sinixt dialect'' '') is the largest river in the Pacific Northwest region of North America. The river rises in the Rocky Mountains of British Columbia, C ...

in Benton County, Washington

Washington commonly refers to:

* Washington (state), United States

* Washington, D.C., the capital of the United States

** A metonym for the federal government of the United States

** Washington metropolitan area, the metropolitan area centered o ...

, was home to the B Reactor

The B Reactor at the Hanford Site, near Richland, Washington, was the first large-scale nuclear reactor ever built. The project was a key part of the Manhattan Project, the United States nuclear weapons development program during World War II. I ...

, the first full-scale plutonium

Plutonium is a radioactive chemical element with the symbol Pu and atomic number 94. It is an actinide metal of silvery-gray appearance that tarnishes when exposed to air, and forms a dull coating when oxidized. The element normally exhibi ...

production reactor. Plutonium manufactured at the site was used in the first atomic bomb

A nuclear weapon is an explosive device that derives its destructive force from nuclear reactions, either fission (fission bomb) or a combination of fission and fusion reactions (thermonuclear bomb), producing a nuclear explosion. Both bomb ...

in the Trinity test

Trinity was the code name of the first detonation of a nuclear weapon. It was conducted by the United States Army at 5:29 a.m. on July 16, 1945, as part of the Manhattan Project. The test was conducted in the Jornada del Muerto desert ab ...

, and in the Fat Man

"Fat Man" (also known as Mark III) is the codename for the type of nuclear bomb the United States detonated over the Japanese city of Nagasaki on 9 August 1945. It was the second of the only two nuclear weapons ever used in warfare, the fir ...

bomb that was used in the atomic bombing of Nagasaki in August 1945. It was commanded by Colonel

Colonel (abbreviated as Col., Col or COL) is a senior military officer rank used in many countries. It is also used in some police forces and paramilitary organizations.

In the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries, a colonel was typically in charge of ...

Franklin T. Matthias

Franklin Thompson Matthias (13 March 1908 – 3 December 1993) was an American civil engineer who directed the construction of the Hanford nuclear site, a key facility of the Manhattan Project during World War II.

A graduate of the University o ...

until January 1946, and then by Colonel Frederick J. Clarke.

Plutonium was a rare element that had only recently been isolated in the laboratory, but it was theorized that it could be produced by the irradiation of uranium

Uranium is a chemical element with the symbol U and atomic number 92. It is a silvery-grey metal in the actinide series of the periodic table. A uranium atom has 92 protons and 92 electrons, of which 6 are valence electrons. Uranium is weak ...

in a nuclear reactor

A nuclear reactor is a device used to initiate and control a fission nuclear chain reaction or nuclear fusion reactions. Nuclear reactors are used at nuclear power plants for electricity generation and in nuclear marine propulsion. Heat from nu ...

and used in an atomic bomb. The director of the Manhattan Project, Brigadier General

Brigadier general or Brigade general is a military rank used in many countries. It is the lowest ranking general officer in some countries. The rank is usually above a colonel, and below a major general or divisional general. When appointed ...

Leslie R. Groves Jr.

Lieutenant general (United States), Lieutenant General Leslie Richard Groves Jr. (17 August 1896 – 13 July 1970) was a United States Army Corps of Engineers Officer (armed forces), officer who oversaw the construction of the Pentagon and di ...

, engaged DuPont

DuPont de Nemours, Inc., commonly shortened to DuPont, is an American multinational chemical company first formed in 1802 by French-American chemist and industrialist Éleuthère Irénée du Pont de Nemours. The company played a major role in ...

to be the prime contractor for the design, construction and operation of the plutonium production complex. DuPont recommended that it be located far away from densely populated areas, and a site, codenamed Site W, was chosen on the Columbia River

The Columbia River (Upper Chinook: ' or '; Sahaptin: ''Nch’i-Wàna'' or ''Nchi wana''; Sinixt dialect'' '') is the largest river in the Pacific Northwest region of North America. The river rises in the Rocky Mountains of British Columbia, C ...

in the US state of Washington

Washington commonly refers to:

* Washington (state), United States

* Washington, D.C., the capital of the United States

** A metonym for the federal government of the United States

** Washington metropolitan area, the metropolitan area centered o ...

. The federal government acquired the land under its war powers authority and relocated some 1,500 nearby residents. The acquisition of 4,218 tracts of land totaling was one of the largest in US history. Disputes arose with farmers over the value of the land and compensation for crops that had already been planted. Where schedules allowed, the Army allowed the crops to be harvested. The land acquisition process dragged on and was not completed before the end of the Manhattan Project in December 1946.

Construction commenced in March 1943 and immediately launched a massive and technically challenging construction project. Most of the construction workforce, which reached a peak of nearly 45,000 in June 1944, lived in a temporary construction camp near the old Hanford townsite. Administrators, engineers and operating personnel lived in the government town established at Richland, which had a wartime peak population of 17,000. The Hanford Engineer Works erected 554 buildings, including three nuclear reactors (B, D and F). The reactors were graphite

Graphite () is a crystalline form of the element carbon. It consists of stacked layers of graphene. Graphite occurs naturally and is the most stable form of carbon under standard conditions. Synthetic and natural graphite are consumed on large ...

moderated

Moderation is the process of eliminating or lessening extremes. It is used to ensure normality throughout the medium on which it is being conducted. Common uses of moderation include:

*Ensuring consistency and accuracy in the marking of stud ...

and water cooled, and operated at 250 megawatts. They were penetrated horizontally by 2,004 tubes. Natural uranium sealed in aluminum cans (known as "slugs") was fed into them. Cooling water drawn from the Columbia River was pumped through the tubes at the rate of .

B Reactor went critical

Critical or Critically may refer to:

*Critical, or critical but stable, medical states

**Critical, or intensive care medicine

*Critical juncture, a discontinuous change studied in the social sciences.

*Critical Software, a company specializing in ...

in September 1944 and after overcoming neutron poisoning produced its first plutonium in November. Irradiated fuel slugs were transported by rail to two huge long, remotely operated chemical separation plants (T and B) away where plutonium was extracted from the irradiated slugs using the bismuth-phosphate process. Radioactive wastes from the chemical separations process were stored in underground tanks. The first batch of plutonium was processed in the T plant between December 1944 and February 1945 and was delivered to the Manhattan Project's Los Alamos Laboratory

The Los Alamos Laboratory, also known as Project Y, was a secret laboratory established by the Manhattan Project and operated by the University of California during World War II. Its mission was to design and build the first atomic bombs. Ro ...

. The identical D and F reactors came online in December 1944 and February 1945, respectively. The site suffered an outage on 10 March 1945 when a Japanese balloon bomb struck a high-tension power line. The Hanford Engineer Works built of roads, of railway, and four electrical substations. More than of concrete and of structural steel went into its construction. The total cost up to December 1946 was over $348million (equivalent to $billion in ).

Contractor selection

DuringWorld War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

, the S-1 Section

The S-1 Executive Committee laid the groundwork for the Manhattan Project by initiating and coordinating the early research efforts in the United States, and liaising with the Tube Alloys Project in Britain.

In the wake of the discovery of nucle ...

of the federal Office of Scientific Research and Development

The Office of Scientific Research and Development (OSRD) was an agency of the United States federal government created to coordinate scientific research for military purposes during World War II. Arrangements were made for its creation during May 1 ...

(OSRD) sponsored a research project on plutonium

Plutonium is a radioactive chemical element with the symbol Pu and atomic number 94. It is an actinide metal of silvery-gray appearance that tarnishes when exposed to air, and forms a dull coating when oxidized. The element normally exhibi ...

. Research was conducted by scientists at Columbia University

Columbia University (also known as Columbia, and officially as Columbia University in the City of New York) is a private research university in New York City. Established in 1754 as King's College on the grounds of Trinity Church in Manhatt ...

, Princeton University

Princeton University is a private university, private research university in Princeton, New Jersey. Founded in 1746 in Elizabeth, New Jersey, Elizabeth as the College of New Jersey, Princeton is the List of Colonial Colleges, fourth-oldest ins ...

, the University of Chicago

The University of Chicago (UChicago, Chicago, U of C, or UChi) is a private research university in Chicago, Illinois. Its main campus is located in Chicago's Hyde Park neighborhood. The University of Chicago is consistently ranked among the b ...

and the University of California at Berkeley

The University of California, Berkeley (UC Berkeley, Berkeley, Cal, or California) is a public land-grant research university in Berkeley, California. Established in 1868 as the University of California, it is the state's first land-grant univ ...

. Plutonium was a rare element that had only recently been synthesized in laboratories. It was theorized that plutonium was fissile

In nuclear engineering, fissile material is material capable of sustaining a nuclear fission chain reaction. By definition, fissile material can sustain a chain reaction with neutrons of thermal energy. The predominant neutron energy may be typ ...

and could be used in an atomic bomb

A nuclear weapon is an explosive device that derives its destructive force from nuclear reactions, either fission (fission bomb) or a combination of fission and fusion reactions (thermonuclear bomb), producing a nuclear explosion. Both bomb ...

. The United States government was concerned that Germany was developing a nuclear weapons program. The Metallurgical Laboratory

The Metallurgical Laboratory (or Met Lab) was a scientific laboratory at the University of Chicago that was established in February 1942 to study and use the newly discovered chemical element plutonium. It researched plutonium's chemistry and m ...

physicists in Chicago worked on designing nuclear reactor

A nuclear reactor is a device used to initiate and control a fission nuclear chain reaction or nuclear fusion reactions. Nuclear reactors are used at nuclear power plants for electricity generation and in nuclear marine propulsion. Heat from nu ...

s ("piles") that could irradiate uranium

Uranium is a chemical element with the symbol U and atomic number 92. It is a silvery-grey metal in the actinide series of the periodic table. A uranium atom has 92 protons and 92 electrons, of which 6 are valence electrons. Uranium is weak ...

and transmute it into plutonium. Meanwhile chemists investigated ways to chemically separate plutonium from uranium. The plutonium program became known as the X-10 project.

On 23 September 1942,

On 23 September 1942, Brigadier General

Brigadier general or Brigade general is a military rank used in many countries. It is the lowest ranking general officer in some countries. The rank is usually above a colonel, and below a major general or divisional general. When appointed ...

Leslie R. Groves Jr.

Lieutenant general (United States), Lieutenant General Leslie Richard Groves Jr. (17 August 1896 – 13 July 1970) was a United States Army Corps of Engineers Officer (armed forces), officer who oversaw the construction of the Pentagon and di ...

became the director of the Manhattan Project

The Manhattan Project was a research and development undertaking during World War II that produced the first nuclear weapons. It was led by the United States with the support of the United Kingdom and Canada. From 1942 to 1946, the project w ...

, as it came to be known. Stone & Webster

Stone & Webster was an American engineering services company based in Stoughton, Massachusetts. It was founded as an electrical testing lab and consulting firm by electrical engineers Charles A. Stone and Edwin S. Webster in 1889. In the early ...

had been engaged to carry out the construction program at the Clinton Engineer Works

The Clinton Engineer Works (CEW) was the production installation of the Manhattan Project that during World War II produced the enriched uranium used in the 1945 bombing of Hiroshima, as well as the first examples of reactor-produced plutoni ...

in Oak Ridge, Tennessee

Oak Ridge is a city in Anderson and Roane counties in the eastern part of the U.S. state of Tennessee, about west of downtown Knoxville. Oak Ridge's population was 31,402 at the 2020 census. It is part of the Knoxville Metropolitan Area. Oak ...

, but Groves appreciated that the task of designing, building and operating the Manhattan Project's facilities would be beyond the resources of a single firm. At the same time, he wanted to keep the number of major contractors down for security reasons. Groves was attracted to DuPont

DuPont de Nemours, Inc., commonly shortened to DuPont, is an American multinational chemical company first formed in 1802 by French-American chemist and industrialist Éleuthère Irénée du Pont de Nemours. The company played a major role in ...

, a firm he had worked with in the past on the construction of plants to produce explosives. Unlike most American firms, DuPont designed, built and operated its own plants. It had the experience and the expertise to be the prime contractor for all aspects of the plutonium production complex. This would have the added benefit of not requiring the Manhattan District to coordinate the plutonium project, thereby reducing Groves's own workload.

Groves arranged a meeting with Willis F. Harrington and Charles Stine from DuPont on 31 October and briefed them on the Manhattan Project. He arranged for a party of DuPont chemists and engineers, including Stine, Elmer Bolton

Elmer Keiser Bolton (June 23, 1886 – July 30, 1968) was an American chemist and research director for DuPont, notable for his role in developing neoprene and directing the research that led to the discovery of nylon.

Personal life

Bolton wa ...

, Roger Williams, Thomas H. Chilton and Crawford Greenewalt

Crawford Hallock Greenewalt (August 16, 1902 – September 28, 1993) was an American chemical engineer who served as president of the DuPont Company from 1948 to 1962 and as board chairman from 1962 to 1967.

Early life

Crawford Hallock Green ...

, to visit the Metallurgical Laboratory in Chicago on 4 November. On 10 November, Groves, Colonel Kenneth Nichols

Major General Kenneth David Nichols CBE (13 November 1907 – 21 February 2000), also known by Nick, was an officer in the United States Army, and a civil engineer who worked on the secret Manhattan Project, which developed the atomic bomb dur ...

(the deputy chief engineer of the Manhattan District), Arthur H. Compton

Arthur Holly Compton (September 10, 1892 – March 15, 1962) was an American physicist who won the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1927 for his 1923 discovery of the Compton effect, which demonstrated the particle nature of electromagnetic radia ...

(the director of the Metallurgical Laboratory) and Norman Hilberry

Norman Hilberry (March 11, 1899 – March 28, 1986) was an American physicist, best known as the director of the Argonne National Laboratory from 1956 to 1961. In December 1942 he was the man who stood ready with an axe to cut the scram line duri ...

(Compton's deputy) went to DuPont's corporate headquarters in Wilmington, Delaware

Wilmington ( Lenape: ''Paxahakink /'' ''Pakehakink)'' is the largest city in the U.S. state of Delaware. The city was built on the site of Fort Christina, the first Swedish settlement in North America. It lies at the confluence of the Christina ...

, where they met with the company's executive committee. Groves gave the President of DuPont, Walter S. Carpenter Jr.

Walter Samuel Carpenter Jr. (January 8, 1888 – February 2, 1976) was an American corporate executive from Wilmington, Delaware, who oversaw the DuPont company's involvement in the Manhattan Project to produce an atomic bomb for use during Wo ...

, assurances the President of the United States

The president of the United States (POTUS) is the head of state and head of government of the United States of America. The president directs the executive branch of the federal government and is the commander-in-chief of the United Stat ...

, Franklin Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (; ; January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), often referred to by his initials FDR, was an American politician and attorney who served as the 32nd president of the United States from 1933 until his death in 1945. As the ...

, the Secretary of War

The secretary of war was a member of the U.S. president's Cabinet, beginning with George Washington's administration. A similar position, called either "Secretary at War" or "Secretary of War", had been appointed to serve the Congress of the ...

, Henry L. Stimson

Henry Lewis Stimson (September 21, 1867 – October 20, 1950) was an American statesman, lawyer, and Republican Party politician. Over his long career, he emerged as a leading figure in U.S. foreign policy by serving in both Republican and D ...

, and the Chief of Staff of the United States Army

The chief of staff of the Army (CSA) is a statutory position in the United States Army held by a general officer. As the highest-ranking officer assigned to serve in the Department of the Army, the chief is the principal military advisor and a ...

, General

A general officer is an Officer (armed forces), officer of highest military ranks, high rank in the army, armies, and in some nations' air forces, space forces, and marines or naval infantry.

In some usages the term "general officer" refers t ...

George C. Marshall

George Catlett Marshall Jr. (December 31, 1880 – October 16, 1959) was an American army officer and statesman. He rose through the United States Army to become Chief of Staff of the United States Army, Chief of Staff of the US Army under Pre ...

, regarded the Manhattan Project as being of the greatest importance to the war effort.

To avoid being labeled as merchants of death

Merchants of death was an epithet used in the U.S. in the 1930s to attack industries and banks that had supplied and funded World War I (then called the Great War).

Origin

The term originated in 1932 as the title of an article about an arms d ...

, as DuPont had been after World War I, the executive committee insisted that it should receive no payment. For legal reasons, a Cost Plus Fixed Fee

A cost-plus contract, also termed a cost plus contract, is a contract such that a contractor is paid for all of its allowed expenses, ''plus'' additional payment to allow for a profit.Vannevar Bush

Vannevar Bush ( ; March 11, 1890 – June 28, 1974) was an American engineer, inventor and science administrator, who during World War II headed the U.S. Office of Scientific Research and Development (OSRD), through which almost all wartime ...

took a letter to Roosevelt noting that the government was assuming all responsibility for the hazards involved in the project, and Roosevelt initialed it.

Site selection

Carpenter expressed reservations about the initial plan to build the reactors at Oak Ridge, due to the proximity of

Carpenter expressed reservations about the initial plan to build the reactors at Oak Ridge, due to the proximity of Knoxville

Knoxville is a city in and the county seat of Knox County in the U.S. state of Tennessee. As of the 2020 United States census, Knoxville's population was 190,740, making it the largest city in the East Tennessee Grand Division and the state's ...

, which was just away. This was in stark contrast to the attitude of the physicists at the Metallurgical Laboratory; Eugene Wigner

Eugene Paul "E. P." Wigner ( hu, Wigner Jenő Pál, ; November 17, 1902 – January 1, 1995) was a Hungarian-American theoretical physicist who also contributed to mathematical physics. He received the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1963 "for his con ...

famously claimed that the reactors could be built on the Potomac River

The Potomac River () drains the Mid-Atlantic United States, flowing from the Potomac Highlands into Chesapeake Bay. It is long,U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map. Retrieved Augus ...

. A catastrophic accident might result in loss of life and severe health effects. Groves was concerned that even a less deadly accident might disrupt vital war production, particularly of aluminum, and force the evacuation of the Manhattan Project's isotope separation

Isotope separation is the process of concentrating specific isotopes of a chemical element by removing other isotopes. The use of the nuclides produced is varied. The largest variety is used in research (e.g. in chemistry where atoms of "marker" n ...

plants. But spreading the facilities at Oak Ridge out more would require the purchase of more land. Moreover, the number of reactors that needed to be built was still uncertain; for planning purpose it was intended to build six reactors and four chemical separation plants.

The ideal site was described by eight criteria:

#A clean and abundant water supply (at least )

#A large electric power supply (about 100,000 KW)

#A "hazardous manufacturing area" of at least

#Space for laboratory facilities at least from the nearest reactor or separations plant

#The employees' village no less than upwind of the plant

#No towns of more than a thousand people closer than from the hazardous rectangle

#No main highway, railway, or employee village closer than from the hazardous rectangle

#Ground that could bear heavy loads.

The most important of these criteria was the availability of electric power. The needs of war industries had created power shortages in many parts of the country, and using the Tennessee Valley Authority

The Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) is a federally owned electric utility corporation in the United States. TVA's service area covers all of Tennessee, portions of Alabama, Mississippi, and Kentucky, and small areas of Georgia, North Carolina ...

was ruled out because the Clinton Engineer Works was expected to use up all of its surplus power. This led to consideration of alternative sites in the Pacific Northwest and Southwest, where there was surplus electrical power. Between 18 and 31 December 1942, just twelve days after the Metallurgical Laboratory team led by Enrico Fermi

Enrico Fermi (; 29 September 1901 – 28 November 1954) was an Italian (later naturalized American) physicist and the creator of the world's first nuclear reactor, the Chicago Pile-1. He has been called the "architect of the nuclear age" and ...

started up Chicago Pile-1

Chicago Pile-1 (CP-1) was the world's first artificial nuclear reactor. On 2 December 1942, the first human-made self-sustaining nuclear chain reaction was initiated in CP-1, during an experiment led by Enrico Fermi. The secret development of t ...

, the first nuclear reactor, a three-man survey party consisting of Lieutenant Colonel

Lieutenant colonel ( , ) is a rank of commissioned officers in the armies, most marine forces and some air forces of the world, above a major and below a colonel. Several police forces in the United States use the rank of lieutenant colone ...

Franklin T. Matthias

Franklin Thompson Matthias (13 March 1908 – 3 December 1993) was an American civil engineer who directed the construction of the Hanford nuclear site, a key facility of the Manhattan Project during World War II.

A graduate of the University o ...

and DuPont engineers A. E. S. Hall and Gilbert P. Church inspected the most promising potential sites.

They looked at sites in the vicinity of

They looked at sites in the vicinity of Coeur d'Alene, Idaho

Coeur d'Alene ( ; french: Cœur d'Alène, lit=Heart of an stitching awl, Awl ) is a city and the county seat of Kootenai County, Idaho, United States. It is the largest city in North Idaho and the principal city of the Coeur d'Alene Metropolita ...

, Hanford and Mansfield, Washington, the Deschutes and John Day River

The John Day River is a tributary of the Columbia River, approximately long, in northeastern Oregon in the United States. It is known as the Mah-Hah River by the Cayuse people, the original inhabitants of the region. Undammed along its entire ...

Valleys in Oregon

Oregon () is a U.S. state, state in the Pacific Northwest region of the Western United States. The Columbia River delineates much of Oregon's northern boundary with Washington (state), Washington, while the Snake River delineates much of it ...

and Pit River

The Pit River is a major river draining from northeastern California into the state's Central Valley. The Pit, the Klamath and the Columbia are the only three rivers in the U.S. that cross the Cascade Range.

The longest tributary of the Sacr ...

in California, and Blythe The name Blythe ( or ) derives from Old English ''bliþe'' ("joyous, kind, cheerful, pleasant"; modern ''blithe''), and further back from Proto-Germanic ''*blithiz'' ("gentle, kind").

People

* Blythe (given name), including a list of people named ...

and Needles on the Colorado River

The Colorado River ( es, Río Colorado) is one of the principal rivers (along with the Rio Grande) in the Southwestern United States and northern Mexico. The river drains an expansive, arid drainage basin, watershed that encompasses parts of ...

in California

California is a U.S. state, state in the Western United States, located along the West Coast of the United States, Pacific Coast. With nearly 39.2million residents across a total area of approximately , it is the List of states and territori ...

. They wrote up their report on the plane back to Washington, DC. On 1 January 1943, Matthias called Groves from Portland, Oregon

Portland (, ) is a port city in the Pacific Northwest and the largest city in the U.S. state of Oregon. Situated at the confluence of the Willamette and Columbia rivers, Portland is the county seat of Multnomah County, the most populous co ...

, and reported that the Hanford site was "far more favorable in virtually all respects than any other". The survey party noted an abundance of aggregate, which could be used to make concrete, and that the ground appeared firm enough to hold the weight of massive structures, an assessment that would be confirmed by Army and United States Geological Survey

The United States Geological Survey (USGS), formerly simply known as the Geological Survey, is a scientific agency of the United States government. The scientists of the USGS study the landscape of the United States, its natural resources, ...

engineers. The survey party was particularly impressed by the presence of a high-voltage power line from Grand Coulee Dam

Grand Coulee Dam is a concrete gravity dam on the Columbia River in the U.S. state of Washington, built to produce hydroelectric power and provide irrigation water. Constructed between 1933 and 1942, Grand Coulee originally had two powerh ...

to Bonneville Dam

Bonneville Lock and Dam consists of several run-of-the-river dam structures that together complete a span of the Columbia River between the U.S. states of Oregon and Washington at River Mile 146.1. The dam is located east of Portland, Oregon, ...

that ran through the site, with an electrical substation

A substation is a part of an electrical generation, transmission, and distribution system. Substations transform voltage from high to low, or the reverse, or perform any of several other important functions. Between the generating station and ...

on its edge. Groves visited the site on 16 January 1943, and approved the selection. It was officially designated the Hanford Engineer Works, and the site codenamed " Site W".

Matthias had worked with Groves on their previous project, the construction of the Pentagon

The Pentagon is the headquarters building of the United States Department of Defense. It was constructed on an accelerated schedule during World War II. As a symbol of the U.S. military, the phrase ''The Pentagon'' is often used as a metony ...

. Groves intended for Matthias to become his deputy, but on the advice of the chief engineer of the Manhattan District, Colonel

Colonel (abbreviated as Col., Col or COL) is a senior military officer rank used in many countries. It is also used in some police forces and paramilitary organizations.

In the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries, a colonel was typically in charge of ...

James C. Marshall

Brigadier General James Creel Marshall (15 October 1897 – 19 July 1977) was a United States Army Corps of Engineers officer who was initially in charge of the Manhattan Project to build an atomic bomb during World War II.

A member of the Ju ...

, Matthias became the Hanford Site area engineer. Gilbert Church became the field project manager of DuPont's construction team. Part of the reason for sending them together on the survey party was to verify that they could get along with each other. As area engineer, Matthias had an unusual degree of autonomy. Hanford's isolated location meant that communications were limited, so day-to-day reporting back to Manhattan District headquarters in Oak Ridge was impractical. The project enjoyed an AAA rating, which meant that it had the War Production Board

The War Production Board (WPB) was an agency of the United States government that supervised war production during World War II. President Franklin D. Roosevelt established it in January 1942, with Executive Order 9024. The WPB replaced the Sup ...

's highest priority for procurement of raw materials and supplies.

DuPont created a TNX division within E. B. Yancey's explosives department under Roger Williams. Williams divided TNX into two subdivisions: a Technical Division headed by Greenewalt that worked with the Metallurgical Laboratory on design, and a Manufacturing Division under R. Monte Evans to supervise plant operations. Construction was the responsibility of DuPont's Engineering Department, whose head, E. G. Ackart, assigned responsibility for the plutonium project to his deputy Granville M. Read. Eventually, 90 percent of DuPont's engineering personnel and resources were devoted to the Manhattan Project.

Land acquisition

Stimson authorized the acquisition of the land on 8 February 1943. A Manhattan District project office opened inProsser, Washington

Prosser () is a city in and the county seat of Benton County, Washington, United States. Situated along the Yakima River, it had a population of 5,714 at the 2010 census.

History

Prosser was long home to Native Americans who lived and fished a ...

, on 22 February, and the Washington Title Insurance Company opened an office there to furnish title

A title is one or more words used before or after a person's name, in certain contexts. It may signify either generation, an official position, or a professional or academic qualification. In some languages, titles may be inserted between the f ...

certificates. Federal Judge Lewis B. Schwellenbach issued an order of possession under the Second War Powers Act the following day, and the first tract was acquired on 10 March.

The Manhattan District's Real Estate Branch divided the land into five areas. Area A, at the center of the site would be the location of the project facilities. This land would be acquired outright, and for safety and security reasons all non-project personnel would be removed. Area B was the area surrounding Area A, which comprised a safety zone; this land would be leased, with the occupants subject to eviction at short notice. Area C was earmarked for the workers' village and would be leased or purchased. Area D was earmarked for production plants and would be purchased. Finally there were two parcels of land designed as Area E, which would be acquired only if necessary. In all, 4,218 tracts totaling were to be acquired, making it one of the largest land acquisition projects in American history.

Most of the land (some 88 percent) was

The Manhattan District's Real Estate Branch divided the land into five areas. Area A, at the center of the site would be the location of the project facilities. This land would be acquired outright, and for safety and security reasons all non-project personnel would be removed. Area B was the area surrounding Area A, which comprised a safety zone; this land would be leased, with the occupants subject to eviction at short notice. Area C was earmarked for the workers' village and would be leased or purchased. Area D was earmarked for production plants and would be purchased. Finally there were two parcels of land designed as Area E, which would be acquired only if necessary. In all, 4,218 tracts totaling were to be acquired, making it one of the largest land acquisition projects in American history.

Most of the land (some 88 percent) was sagebrush

Sagebrush is the common name of several woody and herbaceous species of plants in the genus ''Artemisia''. The best known sagebrush is the shrub ''Artemisia tridentata''. Sagebrushes are native to the North American west.

Following is an alph ...

, where eighteen to twenty thousand sheep grazed. About 11 percent was farmland, although not all was under cultivation. Farmers felt that they should be compensated for the value of the crops they had planted as well as for the land itself. Most of the appraiser

An appraiser (from Latin ''appretiare'', "to value"), is a person that develops an opinion of the market value or other value of a product, most notably real estate.

The current definition of "appraiser" according to the Uniform Standards of Pro ...

s from the Federal Land Bank

The Farm Credit System (FCS) in the United States is a nationwide network of borrower-owned lending institutions and specialized service organizations. The Farm Credit System provides more than $304 billion in loans, leases, and related services t ...

were based in Seattle, Washington

Seattle ( ) is a port, seaport city on the West Coast of the United States. It is the county seat, seat of King County, Washington, King County, Washington (state), Washington. With a 2020 population of 737,015, it is the largest city in bo ...

, or Portland, Oregon

Portland (, ) is a port city in the Pacific Northwest and the largest city in the U.S. state of Oregon. Situated at the confluence of the Willamette and Columbia rivers, Portland is the county seat of Multnomah County, the most populous co ...

, and were unfamiliar with farming under irrigation. They found that the farms were small, mostly in area, and the farm buildings used a lot of salvaged timber and scrap; lumber was scarce in the desert. The fruit trees were much shorter than they were accustomed to; short trees used less water, were easier to pick, and withstood the wind better. Crops like asparagus

Asparagus, or garden asparagus, folk name sparrow grass, scientific name ''Asparagus officinalis'', is a perennial flowering plant species in the genus ''Asparagus''. Its young shoots are used as a spring vegetable.

It was once classified in ...

and mint

MiNT is Now TOS (MiNT) is a free software alternative operating system kernel for the Atari ST system and its successors. It is a multi-tasking alternative to TOS and MagiC. Together with the free system components fVDI device drivers, XaA ...

were unfamiliar to them, and because they visited in winter, many fields looked fallow, and the farmers themselves were sometimes absent for the season, often working in the shipyards in Seattle

Seattle ( ) is a seaport city on the West Coast of the United States. It is the seat of King County, Washington. With a 2020 population of 737,015, it is the largest city in both the state of Washington and the Pacific Northwest regio ...

. Some had been drafted into the Army and had left for the duration of the war but did not consider their land to be abandoned. There had not been many land sales in the area for comparison, and prices were poor during the Great Depression

The Great Depression (19291939) was an economic shock that impacted most countries across the world. It was a period of economic depression that became evident after a major fall in stock prices in the United States. The economic contagio ...

. Appraisals tended to be quite low.

Since construction plans had not yet been drawn up, and work on the site could not immediately commence, Groves saw no harm in postponing the taking of the physical possession of properties under cultivation to allow farmers to harvest the crops they had already planted. This reduced the hardship on the farmers, and avoided the wasting of food at a time when the nation was facing food shortages and the federal government was urging citizens to plant

Since construction plans had not yet been drawn up, and work on the site could not immediately commence, Groves saw no harm in postponing the taking of the physical possession of properties under cultivation to allow farmers to harvest the crops they had already planted. This reduced the hardship on the farmers, and avoided the wasting of food at a time when the nation was facing food shortages and the federal government was urging citizens to plant victory garden

Victory gardens, also called war gardens or food gardens for defense, were vegetable, fruit, and herb gardens planted at private residences and public parks in the United States, United Kingdom, Canada, Australia and Germany during World War I ...

s. Harvest dates ranged from 1 April to 15 June for asparagus, 20 June to 15 August for apples, apricots, peaches and pears, 1 to 15 September for mint, and 1 October for grape

A grape is a fruit, botanically a berry, of the deciduous woody vines of the flowering plant genus ''Vitis''. Grapes are a non- climacteric type of fruit, generally occurring in clusters.

The cultivation of grapes began perhaps 8,000 years ago, ...

s, so some farmers remained on their land longer than others. When the residents became a security hazard to the project, an order was issued on 5 July expelling them with two days' notice. Seven landowners refused to go, and Matthias had to arrange with the court for their eviction

Eviction is the removal of a tenant from rental property by the landlord. In some jurisdictions it may also involve the removal of persons from premises that were foreclosed by a mortgagee (often, the prior owners who defaulted on a mortgage ...

.

The harvest in the summer and fall of 1943 was exceptionally bountiful, and prices were high due to the war. This greatly increased the land prices that the government had to pay. It also promoted exaggerated ideas about the value of the land, leading to litigation. A particular problem was the irrigation districts: there were concerns about whether their assets would cover their debts, and the farmers had to pay off their share from the sale of their property. An appraisal on 7 August found that the bonds were adequately covered but until then many farmers refused to deal with the War Department. The irrigation districts provided a nucleus for organized opposition to the land acquisition project, and hired the law firm of Moulton & Powell to represent them and the veil of secrecy shrouding the Manhattan Project inevitably led to rumors about its activities. The biggest grievance was slow payment. On 18 June 1943, Matthias noted that only nineteen checks had been delivered for the two thousand transactions that had been completed.

Discontent over the acquisition was apparent in letters from Hanford site residents to the War and Justice Department

A justice ministry, ministry of justice, or department of justice is a ministry or other government agency in charge of the administration of justice. The ministry or department is often headed by a minister of justice (minister for justice in a ...

s. Bush briefed Roosevelt on the acquisition but the Truman Committee began making inquiries. On 15 June, the committee sent letters to Carpenter and Julius H. Amberg, Stimson's special assistant, seeking an explanation of the factors governing the choice of the location, the estimated cost of the project, and the need for the acquisition of so much land. At a cabinet

Cabinet or The Cabinet may refer to:

Furniture

* Cabinetry, a box-shaped piece of furniture with doors and/or drawers

* Display cabinet, a piece of furniture with one or more transparent glass sheets or transparent polycarbonate sheets

* Filing ...

meeting on 17 June, Roosevelt asked Stimson whether the Manhattan Project would consider moving plutonium production to another site. That afternoon Groves reassured Stimson that there was no other site "where the work could be done so well". Stimson then went to see the chairman of the committee, Senator Harry S. Truman

Harry S. Truman (May 8, 1884December 26, 1972) was the 33rd president of the United States, serving from 1945 to 1953. A leader of the Democratic Party, he previously served as the 34th vice president from January to April 1945 under Franklin ...

, who agreed to remove the Hanford site from the committee's investigations on the grounds of national security.

Between March and October 1943, settlements averaged 108 per month. The first condemnation trial began on 7 October. Trial juries were largely drawn from Yakima

Yakima ( or ) is a city in and the county seat of Yakima County, Washington, and the state's 11th-largest city by population. As of the 2020 census, the city had a total population of 96,968 and a metropolitan population of 256,728. The uninco ...

, where land productivity and prices were much greater, and they distrusted the Federal Land Bank appraisers. Under the usual procedure in Washington state, the juries visited the tracts under adjudication, and the appearance at the site of workers with DuPont identification badges generated rumors that the project had no military value and that government was using its power of eminent domain

Eminent domain (United States, Philippines), land acquisition (India, Malaysia, Singapore), compulsory purchase/acquisition (Australia, New Zealand, Ireland, United Kingdom), resumption (Hong Kong, Uganda), resumption/compulsory acquisition (Austr ...

for the benefit of private enterprise. The juries were sympathetic to the claims of the landowners and the payments awarded were well in excess of the government appraisals.

From October 1943 until April 1944, the rate of settlements dropped to an average of seven per month. Groves became concerned that public attention generated by the trials and the inspection of tracts by juries where construction was now commencing might jeopardize project security. He arranged with Norman M. Littell, the assistant attorney general in charge of the Lands Division at the Justice Department, for additional flexibility in making adjustments to valuations to facilitate out of court settlement, and for the establishment of a second court and additional judges. Air conditioning was installed in the courtroom in Yakima to permit cases to be heard during the summer months.

Littell became convinced that the root of the problem was faulty appraisals, and on 13 October 1944, he appeared at the court in Yakima and asked Schwellenbach to put all condemnation trials on hold until the Justice Department could carry out reappraisals of the more than 700 tracts still awaiting settlement. The Under Secretary of War,

From October 1943 until April 1944, the rate of settlements dropped to an average of seven per month. Groves became concerned that public attention generated by the trials and the inspection of tracts by juries where construction was now commencing might jeopardize project security. He arranged with Norman M. Littell, the assistant attorney general in charge of the Lands Division at the Justice Department, for additional flexibility in making adjustments to valuations to facilitate out of court settlement, and for the establishment of a second court and additional judges. Air conditioning was installed in the courtroom in Yakima to permit cases to be heard during the summer months.

Littell became convinced that the root of the problem was faulty appraisals, and on 13 October 1944, he appeared at the court in Yakima and asked Schwellenbach to put all condemnation trials on hold until the Justice Department could carry out reappraisals of the more than 700 tracts still awaiting settlement. The Under Secretary of War, Robert P. Patterson

Robert Porter Patterson Sr. (February 12, 1891 – January 22, 1952) was an American judge who served as United States Under Secretary of War, Under Secretary of War under President Franklin D. Roosevelt and US Secretary of War, U.S. Secretary of ...

sent a strongly worded letter to Attorney General

In most common law jurisdictions, the attorney general or attorney-general (sometimes abbreviated AG or Atty.-Gen) is the main legal advisor to the government. The plural is attorneys general.

In some jurisdictions, attorneys general also have exec ...

Francis Biddle

Francis Beverley Biddle (May 9, 1886 – October 4, 1968) was an American lawyer and judge who was the United States Attorney General during World War II. He also served as the primary American judge during the postwar Nuremberg Trials as well a ...

. This brought to a head a long-standing dispute between Biddle and Littell over the administration of the Lands Division, and Biddle asked for Littell's resignation. When this was not forthcoming, he had Roosevelt remove Littell from office on 26 November. When the Manhattan Project ended on 31 December 1946, there were still 237 tracts remaining to be settled. In all, was spent on land acquisition, including deposited for future awards, and $30,000 allocated for estimated future deficiencies.

About 1,500 residents of Hanford, White Bluffs, and nearby settlements were relocated, as well as the Wanapum

The Wanapum tribe of Native Americans formerly lived along the Columbia River from above Priest Rapids down to the mouth of the Snake River in what is now the US state of Washington. About 60 Wanapum still live near the present day site of Pri ...

people, Confederated Tribes and Bands of the Yakima Nation

The Yakama Indian Reservation (spelled Yakima until 1994) is a Native American reservation in Washington state of the federally recognized tribe known as the Confederated Tribes and Bands of the Yakama Nation. The tribe is made up of Klikitat ...

, Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation

The Umatilla Indian Reservation is an Indian reservation in the Pacific Northwest of the United States. It was created by The Treaty of June 9, 1855 between the United States and members of the Walla, Cayuse, and Umatilla tribes. It lies in nort ...

, and the Nez Perce

The Nez Percé (; autonym in Nez Perce language: , meaning "we, the people") are an Indigenous people of the Plateau who are presumed to have lived on the Columbia River Plateau in the Pacific Northwest region for at least 11,500 years.Ames, K ...

Tribe. Native Americans were accustomed to fishing in the Columbia River near White Bluffs for two or three weeks in October. The fish they caught was dried and provided food for the winter. They rejected offers of an annual cash payment, and a deal was struck with Chief Johnny Buck allowing Buck and his two assistants to issue passes to fish at the site. This authority was revoked in 1944 for security reasons. Matthias gave assurances to the Native Americans that their graves would be treated with respect, but it would be 15 years before the Wanapum people were allowed access to mark the cemeteries. In 1997, elders were permitted to bring children and young adults onto the site once a year to learn about their sacred site

Sacred space, sacred ground, sacred place, sacred temple, holy ground, or holy place refers to a location which is deemed to be sacred or hallowed. The sacredness of a natural feature may accrue through tradition or be granted through a bless ...

s.

Township

Hanford

Matthias and Church met in Wilmington on 2 March 1943, and drew up an outline of the layout of the Hanford Engineer Works. Normally for a development in such an isolated area, employees would be accommodated on site, but in this case for security and safety reasons it was desirable to house them at least away. Even the construction workforce could not be housed on site, because some plant operation would have to be carried out during startup testing. The Army and DuPont engineers decided to create two communities: a temporary constructions camp and a more substantial operating village. Rather than create temporary construction camps at each building site, there would be one large camp servicing all the sites.

Construction was expedited by locating them on the sites of existing villages, where they could take advantage of the buildings, roads and utility infrastructure already in place. The DuPont and Hanford Engineer Works engineers decided to locate the temporary construction camp on the site of the village of Hanford, which had a population of about 125. It was from the nearest process area site, which was considered to be sufficiently distant at startup. It was served by the Connell-Yakima state highway the Pasco- White Bluffs road, and a branch line of the

Matthias and Church met in Wilmington on 2 March 1943, and drew up an outline of the layout of the Hanford Engineer Works. Normally for a development in such an isolated area, employees would be accommodated on site, but in this case for security and safety reasons it was desirable to house them at least away. Even the construction workforce could not be housed on site, because some plant operation would have to be carried out during startup testing. The Army and DuPont engineers decided to create two communities: a temporary constructions camp and a more substantial operating village. Rather than create temporary construction camps at each building site, there would be one large camp servicing all the sites.

Construction was expedited by locating them on the sites of existing villages, where they could take advantage of the buildings, roads and utility infrastructure already in place. The DuPont and Hanford Engineer Works engineers decided to locate the temporary construction camp on the site of the village of Hanford, which had a population of about 125. It was from the nearest process area site, which was considered to be sufficiently distant at startup. It was served by the Connell-Yakima state highway the Pasco- White Bluffs road, and a branch line of the Chicago, Milwaukee, St. Paul and Pacific Railroad

The Chicago, Milwaukee, St. Paul and Pacific Railroad (CMStP&P), often referred to as the "Milwaukee Road" , was a Class I railroad that operated in the Midwest and Northwest of the United States from 1847 until 1986.

The company experience ...

. Electricity was available from the Pacific Power and Light Company substation, and water from local wells. Community facilities included stores, two fruit packing warehouses, a stock yard, a combined grade and high school, and a church. Groves inspected the site in March 1943.

Since DuPont and the Metallurgical Laboratory had yet to make much progress on the design of the reactors or the processing plants, it was not known how many construction workers would be required to build them. Town planning proceeded on the assumption that construction would require 25,000 to 28,000 workers, half of whom would live in the camp, but DuPont designed the camp to permit expansion. This proved to be wise; nearly twice that number of workers would ultimately be required, and the capacity of surrounding communities to absorb workers was limited. Three types of accommodation were provided in the camp: barracks, hutments and trailer parking. The first workers to arrive lived in 125 US Army pyramidal tents with wooden floors and sides while they erected the first barracks. Two types of barracks were erected: two-wing barracks for women and four-wing barracks for men. White and non-white people had separate barracks. Barracks construction commenced on 6 April 1943 and eventually 195 barracks were erected, the last of which were completed on 27 May 1944. There were 110 for white men, 21 for black men, 57 for white women and seven for black women. Not all were used for accommodation, and one white-women wing was turned over to the Women's Army Corps

The Women's Army Corps (WAC) was the women's branch of the United States Army. It was created as an Auxiliaries, auxiliary unit, the Women's Army Auxiliary Corps (WAAC) on 15 May 1942 and converted to an active duty status in the Army of the U ...

. The barracks could hold 29,216 workers.

As construction of the facilities got under way, Groves released construction workers working on barracks by purchasing hutments. These were simple, prefabricated

As construction of the facilities got under way, Groves released construction workers working on barracks by purchasing hutments. These were simple, prefabricated plywood

Plywood is a material manufactured from thin layers or "plies" of wood veneer that are glued together with adjacent layers having their wood grain rotated up to 90 degrees to one another. It is an engineered wood from the family of manufactured ...

and Celotex