Gaelic Clothing And Fashion on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

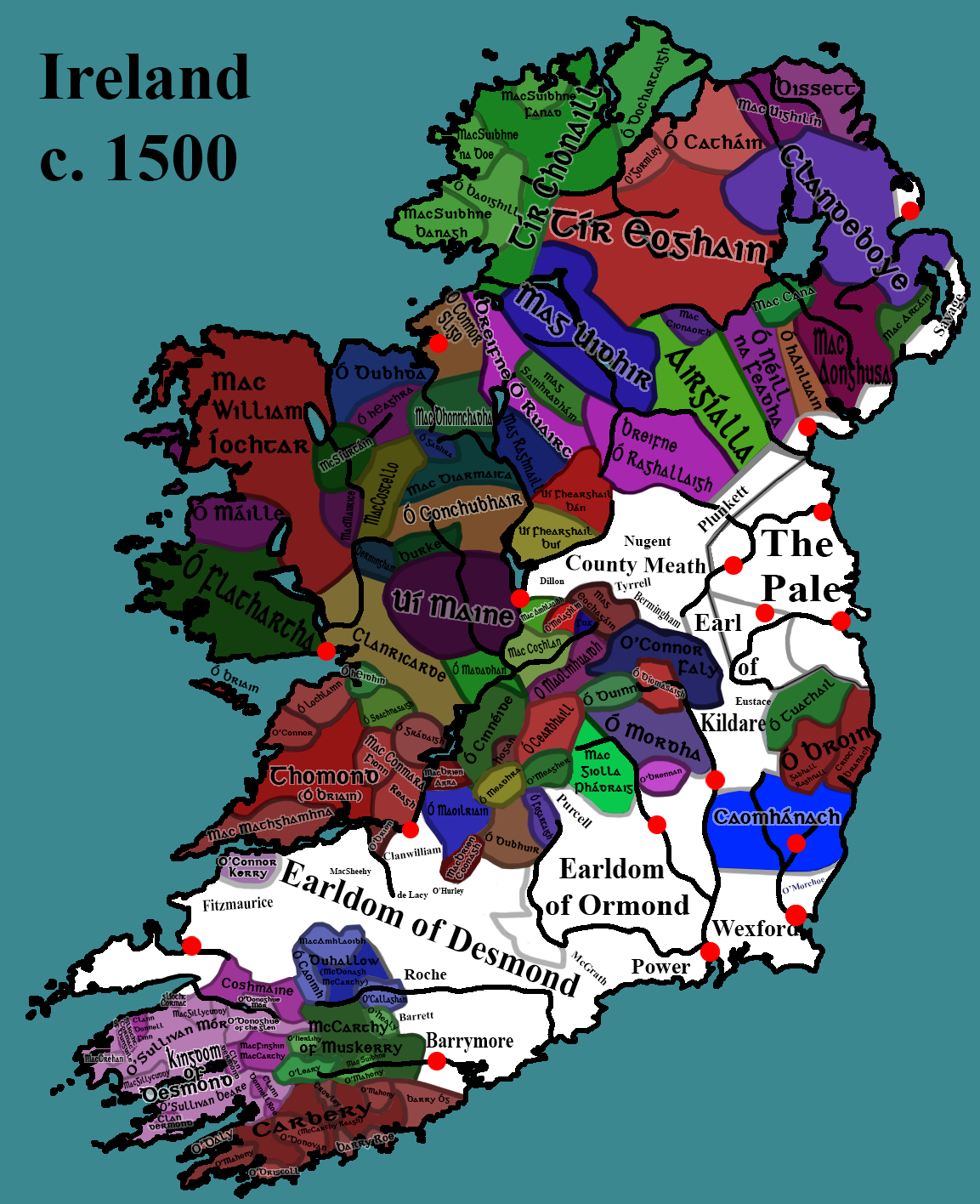

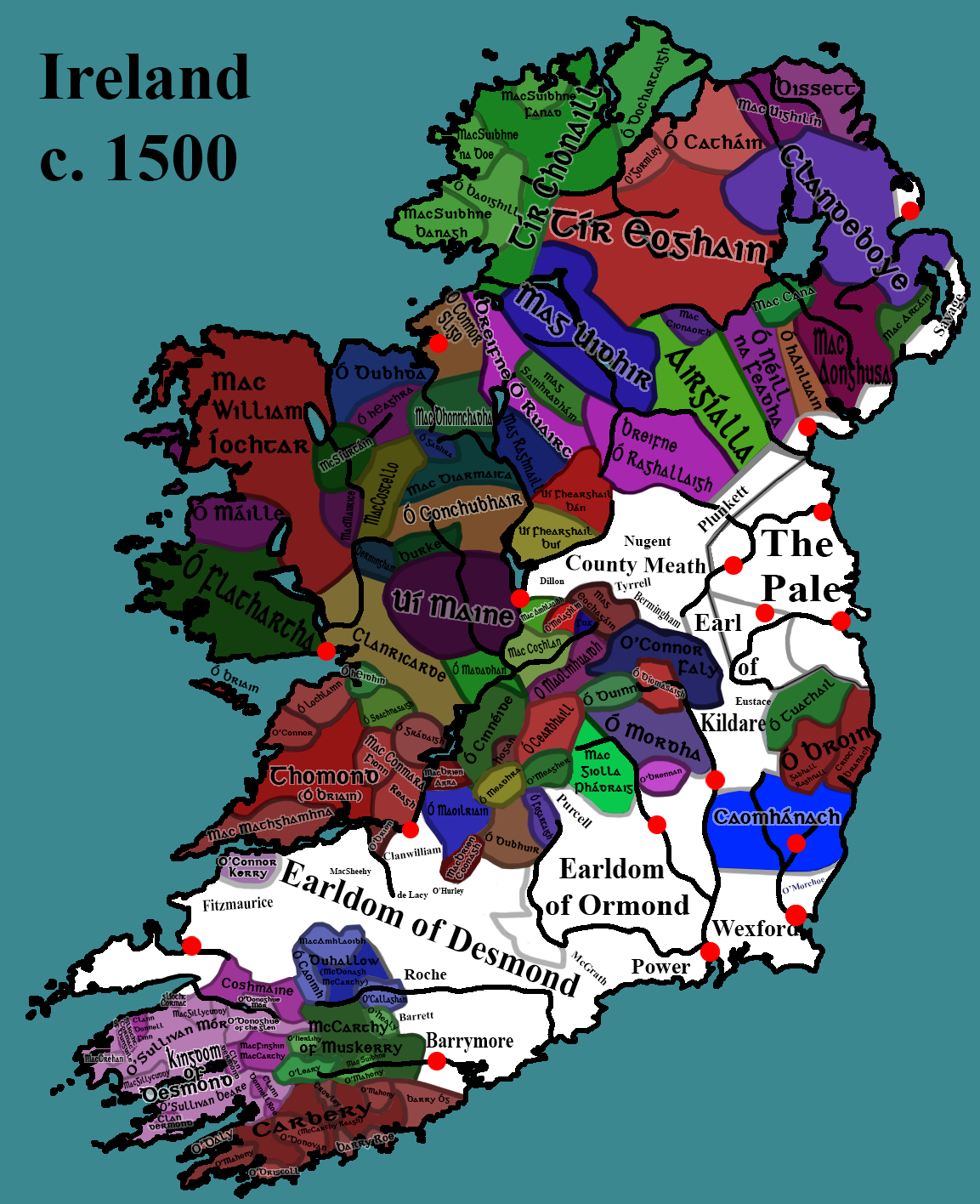

Gaelic Ireland ( ga, ├ēire Ghaelach) was the Gaelic political and social order, and associated culture, that existed in Ireland from the late prehistoric era until the early 17th century. It comprised the whole island before Anglo-Normans conquered parts of Ireland in the 1170s. Thereafter, it comprised that part of the country not under foreign dominion at a given time (i.e. the part beyond The Pale). For most of its history, Gaelic Ireland was a "patchwork" hierarchy of territories ruled by a hierarchy of kings or chiefs, who were chosen or elected through tanistry. Warfare between these territories was common. Occasionally, a powerful ruler was acknowledged as

Gaelic Ireland ( ga, ├ēire Ghaelach) was the Gaelic political and social order, and associated culture, that existed in Ireland from the late prehistoric era until the early 17th century. It comprised the whole island before Anglo-Normans conquered parts of Ireland in the 1170s. Thereafter, it comprised that part of the country not under foreign dominion at a given time (i.e. the part beyond The Pale). For most of its history, Gaelic Ireland was a "patchwork" hierarchy of territories ruled by a hierarchy of kings or chiefs, who were chosen or elected through tanistry. Warfare between these territories was common. Occasionally, a powerful ruler was acknowledged as

Gaelic law was originally passed down orally, but was written down in Old Irish during the period 600ŌĆō900 AD. This collection of oral and written laws is known as the ''F├®nechas'' or, in English, as the Brehon Law(s). The brehons (Old Irish: ''brithem'', plural ''brithemain'') were the

Gaelic law was originally passed down orally, but was written down in Old Irish during the period 600ŌĆō900 AD. This collection of oral and written laws is known as the ''F├®nechas'' or, in English, as the Brehon Law(s). The brehons (Old Irish: ''brithem'', plural ''brithemain'') were the

Ancient Irish culture was

Ancient Irish culture was

For most of the Gaelic period, dwellings and farm buildings were circular with conical thatched roofs (see roundhouse). Square and rectangle-shaped buildings gradually became more common, and by the 14th or 15th century they had replaced round buildings completely. In some areas, buildings were made mostly of stone. In others, they were built of timber, wattle and daub, or a mix of materials. Most ancient and early medieval stone buildings were of dry stone construction. Some buildings would have had glass windows. Among the wealthy, it was common for women to have their own 'apartment' called a ''grianan'' (anglicized "greenan") in the sunniest part of the homestead.

The dwellings of freemen and their families were often surrounded by a circular rampart called a "

For most of the Gaelic period, dwellings and farm buildings were circular with conical thatched roofs (see roundhouse). Square and rectangle-shaped buildings gradually became more common, and by the 14th or 15th century they had replaced round buildings completely. In some areas, buildings were made mostly of stone. In others, they were built of timber, wattle and daub, or a mix of materials. Most ancient and early medieval stone buildings were of dry stone construction. Some buildings would have had glass windows. Among the wealthy, it was common for women to have their own 'apartment' called a ''grianan'' (anglicized "greenan") in the sunniest part of the homestead.

The dwellings of freemen and their families were often surrounded by a circular rampart called a "

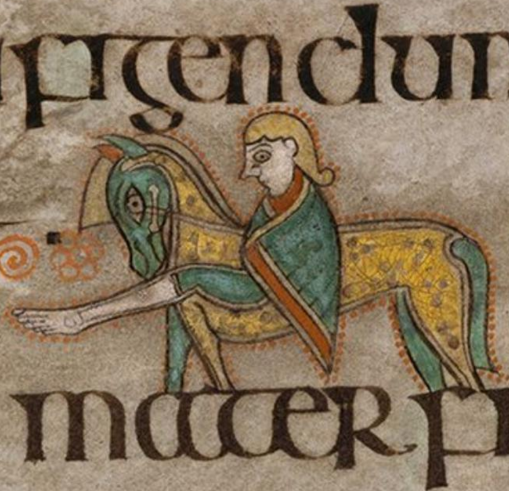

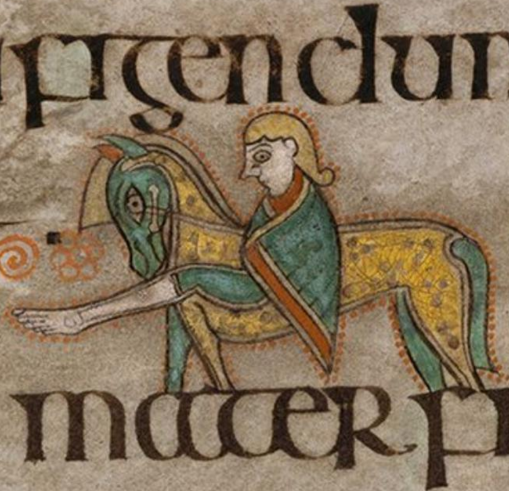

Throughout the Middle Ages, the common clothing amongst the Gaelic Irish consisted of a ''brat'' (a woollen semi circular cloak) worn over a ''l├®ine'' (a loose-fitting, long-sleeved tunic made of linen). For men the ''l├®ine'' reached to their ankles but was hitched up by means of a crios (pronounced 'kriss') which was a type of woven belt. The l├®ine was hitched up to knee level. Women wore the l├®ine at full length. Men sometimes wore tight-fitting trews (Gaelic tri├║bhas) but otherwise went bare-legged. The ''brat'' was simply thrown over both shoulders or sometimes over only one. Occasionally the brat was fastened with a ''dealg'' ( brooch), with men usually wearing the ''dealg'' at their shoulders and women at their chests. The ''ionar'' (a short, tight-fitting jacket) became popular later on. In '' Topographia Hibernica'', written during the 1180s,

Throughout the Middle Ages, the common clothing amongst the Gaelic Irish consisted of a ''brat'' (a woollen semi circular cloak) worn over a ''l├®ine'' (a loose-fitting, long-sleeved tunic made of linen). For men the ''l├®ine'' reached to their ankles but was hitched up by means of a crios (pronounced 'kriss') which was a type of woven belt. The l├®ine was hitched up to knee level. Women wore the l├®ine at full length. Men sometimes wore tight-fitting trews (Gaelic tri├║bhas) but otherwise went bare-legged. The ''brat'' was simply thrown over both shoulders or sometimes over only one. Occasionally the brat was fastened with a ''dealg'' ( brooch), with men usually wearing the ''dealg'' at their shoulders and women at their chests. The ''ionar'' (a short, tight-fitting jacket) became popular later on. In '' Topographia Hibernica'', written during the 1180s,

Warfare was common in Gaelic Ireland, as territories, kingdoms and

Warfare was common in Gaelic Ireland, as territories, kingdoms and

As mentioned before, Gaelic Ireland was split into many clann territories and kingdoms called '' t├║ath'' (plural: ''t├║atha''). Although there was no central government or parliament, a number of local, regional and national gatherings were held. These combined features of assemblies and

As mentioned before, Gaelic Ireland was split into many clann territories and kingdoms called '' t├║ath'' (plural: ''t├║atha''). Although there was no central government or parliament, a number of local, regional and national gatherings were held. These combined features of assemblies and

The prehistory of Ireland included a protohistorical period, when the literate cultures of Greece and Rome first began to take notice of the Irish, and a further proto-literate period of ogham epigraphy, before the early

The prehistory of Ireland included a protohistorical period, when the literate cultures of Greece and Rome first began to take notice of the Irish, and a further proto-literate period of ogham epigraphy, before the early

Gaelic Ireland of this era still consisted of the many semi-independent territories called ( t├║atha), and attempts were made by various factions to gain political control over the whole of the island. For the first two centuries of this period, this was mainly a rivalry between putative High Kings of Ireland from the

Gaelic Ireland of this era still consisted of the many semi-independent territories called ( t├║atha), and attempts were made by various factions to gain political control over the whole of the island. For the first two centuries of this period, this was mainly a rivalry between putative High Kings of Ireland from the

Ireland became Christianized between the 5th and 7th centuries. Pope Adrian IV, the only English pope, had already issued a Papal Bull in 1155 giving Henry II of England authority to

Ireland became Christianized between the 5th and 7th centuries. Pope Adrian IV, the only English pope, had already issued a Papal Bull in 1155 giving Henry II of England authority to

By 1261, the weakening of the Anglo-Norman Lordship had become manifest following a string of military defeats. In the chaotic situation, local Irish lords won back large amounts of land. The invasion by Edward Bruce in 1315ŌĆō18 at a time of great famine weakened the Norman economy. The

By 1261, the weakening of the Anglo-Norman Lordship had become manifest following a string of military defeats. In the chaotic situation, local Irish lords won back large amounts of land. The invasion by Edward Bruce in 1315ŌĆō18 at a time of great famine weakened the Norman economy. The

* Connacht. The

* Connacht. The  *

*

In 1603, with the Union of the Crowns, King James of Scotland also became

In 1603, with the Union of the Crowns, King James of Scotland also became

Gaelic Ireland ( ga, ├ēire Ghaelach) was the Gaelic political and social order, and associated culture, that existed in Ireland from the late prehistoric era until the early 17th century. It comprised the whole island before Anglo-Normans conquered parts of Ireland in the 1170s. Thereafter, it comprised that part of the country not under foreign dominion at a given time (i.e. the part beyond The Pale). For most of its history, Gaelic Ireland was a "patchwork" hierarchy of territories ruled by a hierarchy of kings or chiefs, who were chosen or elected through tanistry. Warfare between these territories was common. Occasionally, a powerful ruler was acknowledged as

Gaelic Ireland ( ga, ├ēire Ghaelach) was the Gaelic political and social order, and associated culture, that existed in Ireland from the late prehistoric era until the early 17th century. It comprised the whole island before Anglo-Normans conquered parts of Ireland in the 1170s. Thereafter, it comprised that part of the country not under foreign dominion at a given time (i.e. the part beyond The Pale). For most of its history, Gaelic Ireland was a "patchwork" hierarchy of territories ruled by a hierarchy of kings or chiefs, who were chosen or elected through tanistry. Warfare between these territories was common. Occasionally, a powerful ruler was acknowledged as High King of Ireland

High King of Ireland ( ga, Ardr├Ł na h├ēireann ) was a royal title in Gaelic Ireland held by those who had, or who are claimed to have had, lordship over all of Ireland. The title was held by historical kings and later sometimes assigned ana ...

. Society was made up of clans

A clan is a group of people united by actual or perceived kinship

and descent. Even if lineage details are unknown, clans may claim descent from founding member or apical ancestor. Clans, in indigenous societies, tend to be endogamous, meaning ...

and, like the rest of Europe, was structured hierarchically according to class. Throughout this period, the economy was mainly pastoral

A pastoral lifestyle is that of shepherds herding livestock around open areas of land according to seasons and the changing availability of water and pasture. It lends its name to a genre of literature, art, and music (pastorale) that depicts ...

and money was generally not used. A Gaelic Irish style of dress, music, dance

Dance is a performing art form consisting of sequences of movement, either improvised or purposefully selected. This movement has aesthetic and often symbolic value. Dance can be categorized and described by its choreography, by its repertoir ...

, sport and art can be identified, with Irish art later merging with Anglo-Saxon styles to create Insular art

Insular art, also known as Hiberno-Saxon art, was produced in the post-Roman era of Great Britain and Ireland. The term derives from ''insula'', the Latin term for "island"; in this period Britain and Ireland shared a largely common style dif ...

.

Gaelic Ireland was initially pagan

Paganism (from classical Latin ''p─üg─ünus'' "rural", "rustic", later "civilian") is a term first used in the fourth century by early Christians for people in the Roman Empire who practiced polytheism, or ethnic religions other than Judaism. ...

and had an oral culture maintained by traditional Gaelic storytellers/historians, the '' seanchaidhthe''. Writing, in the form of inscription in the ogham alphabet, began in the protohistoric period, perhaps as early as the 1st century. The conversion to Christianity

Conversion to Christianity is the religious conversion of a previously non-Christian person to Christianity. Different Christian denominations may perform various different kinds of rituals or ceremonies initiation into their community of believ ...

, beginning in the 5th century, accompanied the introduction of literature. In the Middle Ages, Irish mythology and Brehon law were recorded by Irish monks, albeit partly Christianized. Gaelic Irish monasteries were important centres of learning. Irish missionaries and scholars were influential in western Europe and helped to spread Christianity to much of Britain and parts of mainland Europe.

In the 9th century, Vikings began raiding and founding settlements along Ireland's coasts and waterways, which became its first large towns. Over time, these settlers were assimilated and became the Norse-Gaels. After the Norman invasion

The Norman Conquest (or the Conquest) was the 11th-century invasion and occupation of England by an army made up of thousands of Norman, Breton, Flemish, and French troops, all led by the Duke of Normandy, later styled William the Conq ...

of 1169ŌĆō71, large swathes of Ireland came under the control of Norman lords, leading to centuries of conflict with the native Irish. The King of England

The monarchy of the United Kingdom, commonly referred to as the British monarchy, is the constitutional form of government by which a hereditary sovereign reigns as the head of state of the United Kingdom, the Crown Dependencies (the Bailiw ...

claimed sovereignty over this territory ŌĆō the Lordship of Ireland ŌĆō and the island as a whole. However, the Gaelic system continued in areas outside Anglo-Norman control. The territory under English control gradually shrank to an area known as the Pale and, outside this, many Hiberno-Norman

From the 12th century onwards, a group of Normans invaded and settled in Gaelic Ireland. These settlers later became known as Norman Irish or Hiberno-Normans. They originated mainly among Cambro-Norman families in Wales and Anglo-Normans from ...

lords adopted Gaelic culture.

In 1542, the Lordship of Ireland became the Kingdom of Ireland

The Kingdom of Ireland ( ga, label=Classical Irish, an R├Łoghacht ├ēireann; ga, label=Modern Irish, an R├Łocht ├ēireann, ) was a monarchy on the island of Ireland that was a client state of England and then of Great Britain. It existed from ...

when Henry VIII of England was given the title of King of Ireland

King is the title given to a male monarch in a variety of contexts. The female equivalent is queen, which title is also given to the consort of a king.

*In the context of prehistory, antiquity and contemporary indigenous peoples, the tit ...

by the Parliament of Ireland. The English then began to extend their control over the island. By 1607, Ireland was fully under English control, bringing the old Gaelic political and social order to an end.

Culture and society

Gaelic culture and society was centred around the ''fine'' (explained below). Gaelic Ireland had a rich oral culture and appreciation of deeper and intellectual pursuits. '' Fil├Ł'' and '' draoithe'' (druids) were held in high regard during Pagan times and orally passed down the history and traditions of their people. Later, many of their spiritual and intellectual tasks were passed on to Christian monks, after said religion prevailed from the 5th century onwards. However, the ''fil├Ł'' continued to hold a high position. Poetry, music, storytelling, literature and other art forms were highly prized and cultivated in both pagan and Christian Gaelic Ireland. Hospitality, bonds of kinship and the fulfilment of social and ritual responsibilities were highly important. Like Britain, Gaelic Ireland consisted not of one single unified kingdom, but several. The main kingdoms were Ulaid (Ulster), Mide (Meath), Laigin (Leinster), Muma (Munster, consisting of Iarmuman, Tuadmumain and Desmumain), Connacht, Br├®ifne (Breffny), In Tuaiscert (The North), andAirg├Łalla

Airg├Łalla (Modern Irish: Oirialla, English: Oriel, Latin: ''Ergallia'') was a medieval Irish over-kingdom and the collective name for the confederation of tribes that formed it. The confederation consisted of nine minor kingdoms, all independe ...

(Oriel). Each of these overkingdoms were built upon lordships known as '' t├║atha'' (singular: ''t├║ath''). Law tracts from the early 700s describe a hierarchy of kings: kings of ''t├║ath'' subject to kings of several ''t├║atha'' who again were subject to the regional overkings. Already before the 8th century these overkingdoms had begun to replace the t├║atha as the basic sociopolitical unit.

Religion and mythology

Paganism

Before Christianization, the Gaelic Irish were polytheistic orpagan

Paganism (from classical Latin ''p─üg─ünus'' "rural", "rustic", later "civilian") is a term first used in the fourth century by early Christians for people in the Roman Empire who practiced polytheism, or ethnic religions other than Judaism. ...

. They had many gods and goddesses, which generally have parallels in the pantheons of other European nations. Two groups of supernatural beings who appear throughout Irish mythologyŌĆöthe Tuatha D├® Danann and FomoriansŌĆöare believed to represent the Gaelic pantheon. They were also animists, believing that all aspects of the natural world contained spirits, and that these spirits could be communicated with. Burial practicesŌĆöwhich included burying food, weapons, and ornaments with the deadŌĆösuggest a belief in life after death. Some have equated this afterlife with the Otherworld realms known as Magh Meall and T├Łr na n├ōg in Irish mythology. There were four main religious festivals each year, marking the traditional four divisions of the year ŌĆō Samhain, Imbolc, Bealtaine and Lughnasadh.

The mythology of Ireland was originally passed down orally

The word oral may refer to:

Relating to the mouth

* Relating to the mouth, the first portion of the alimentary canal that primarily receives food and liquid

**Oral administration of medicines

** Oral examination (also known as an oral exam or oral ...

, but much of it was eventually written down by Irish monks, who Christianized and modified it to an extent. This large body of work is often split into three overlapping cycles: the Mythological Cycle, the Ulster Cycle, and the Fenian Cycle. The first cycle is a pseudo-history that describes how Ireland, its people and its society came to be. The second cycle tells of the lives and deaths of Ulaidh heroes and villains such as C├║chulainn, Queen Medb and Conall Cernach. The third cycle tells of the exploits of Fionn mac Cumhaill and the Fianna. There are also a number of tales that do not fit into these cycles ŌĆō this includes the ''immrama

An immram (; plural immrama; ga, iomramh , 'voyage') is a class of Old Irish tales concerning a hero's sea journey to the Otherworld (see T├Łr na n├ōg and Mag Mell). Written in the Christian era and essentially Christian in aspect, they pr ...

'' and ''echtrai

An Echtra or Echtrae (pl. Echtrai), is a type of pre-Christian Old Irish literature about a hero's adventures in the Otherworld or with otherworldly beings.

Definition and etymology

In Irish literature ''Echtrae'' and ''Immram'' are tales of voy ...

'', which are tales of voyages to the ' Otherworld'.

Christianity

The introduction of Christianity to Ireland dates to sometime before the 5th century, with Palladius (later bishop of Ireland) sent by Pope Celestine I in the mid-5th century to preach "''ad Scotti in Christum''"M. De Paor ŌĆō L. De Paor, Early Christian Ireland, London, 1958, p. 27. or in other words to minister to theScoti

''Scoti'' or ''Scotti'' is a Latin name for the Gaels,Duffy, Se├Īn. ''Medieval Ireland: An Encyclopedia''. Routledge, 2005. p.698 first attested in the late 3rd century. At first it referred to all Gaels, whether in Ireland or Great Britain, but l ...

or Irish "believing in Christ". Early medieval traditions credit Saint Patrick

Saint Patrick ( la, Patricius; ga, P├Īdraig ; cy, Padrig) was a fifth-century Romano-British Christian missionary and bishop in Ireland. Known as the "Apostle of Ireland", he is the primary patron saint of Ireland, the other patron saints be ...

as being the first Primate of Ireland. Christianity would eventually supplant the existing pagan

Paganism (from classical Latin ''p─üg─ünus'' "rural", "rustic", later "civilian") is a term first used in the fourth century by early Christians for people in the Roman Empire who practiced polytheism, or ethnic religions other than Judaism. ...

traditions, with the prologue of the 9th century ''Martyrology of Tallaght

The ''Martyrology of Tallaght'', which is closely related to the '' F├®lire ├ōengusso'' or ''Martyrology of ├ōengus the Culdee'', is an eighth- or ninth-century martyrology, a list of saints and their feast days assembled by M├Īel Ruain and/o ...

'' (attributed to author ├ōengus of Tallaght) speaking of the last vestiges of paganism in Ireland.

Social and political structure

In Gaelic Ireland each person belonged to anagnatic

Patrilineality, also known as the male line, the spear side or agnatic kinship, is a common kinship system in which an individual's family membership derives from and is recorded through their father's lineage. It generally involves the inheritanc ...

kin-group known as a ''fine'' (plural: ''finte''). This was a large group of related people supposedly descended from one progenitor through male forebears. It was headed by a man whose office was known in Old Irish as a ''cenn fine'' or ''to├Łsech'' (plural: ''to├Łsig''). Nicholls suggests that they would be better thought of as akin to the modern-day corporation. Within each ''fine'', the family descended from a common great-grandparent was called a '' derbfine'' (modern form ''dearbhfhine''), lit. "close clan". The ''cland'' (modern form ''clann'') referred to the children of the nuclear family.

Succession

Succession is the act or process of following in order or sequence.

Governance and politics

*Order of succession, in politics, the ascension to power by one ruler, official, or monarch after the death, resignation, or removal from office of ...

to the kingship was through tanistry. When a man became king, a relative was elected to be his deputy or 'tanist' (Irish: ''t├Īnaiste'', plural ''tanaist├Ł''). When the king died, his tanist would automatically succeed him. The tanist had to share the same ''derbfine'' and he was elected by other members of the ''derbfine''. Tanistry meant that the kingship usually went to whichever relative was deemed to be the most fitting. Sometimes there would be more than one tanist at a time and they would succeed each other in order of seniority. Some Anglo-Norman lordships later adopted tanistry from the Irish.

Gaelic Ireland was divided into a hierarchy of territories ruled by a hierarchy of kings of chiefs. The smallest territory was the '' t├║ath'' (plural: ''t├║atha''), which was typically the territory of a single kin-group. It was ruled by a ''r├Ł t├║aithe'' (king of a ''t├║ath'') or ''to├Łsech t├║aithe'' (leader of a ''t├║ath''). Several ''t├║atha'' formed a ''m├│r t├║ath'' (overkingdom), which was ruled by a ''r├Ł m├│r t├║ath'' or ''ruir├Ł'' (overking). Several ''m├│r t├║atha'' formed a ''c├│iced'' (province), which was ruled by a ''r├Ł c├│icid'' or ''r├Ł ruirech'' (provincial king). In the early Middle Ages the ''t├║atha'' was the main political unit, but over time they were subsumed into bigger conglomerate territories and became much less important politically.

Gaelic society was structured hierarchically, with those further up the hierarchy generally having more privileges, wealth and power than those further down.

* The top social layer was the ''s├│ernemed'', which included kings, tanists, ''ceann finte'', '' fili'', clerics, and their immediate families. The roles of a ''fili'' included reciting traditional lore, eulogizing the king and satirizing injustices within the kingdom. Before the Christianization of Ireland, this group also included the druid

A druid was a member of the high-ranking class in ancient Celtic cultures. Druids were religious leaders as well as legal authorities, adjudicators, lorekeepers, medical professionals and political advisors. Druids left no written accounts. Whi ...

s (''dru├Ł'') and vates (''f├Īith'').

* Below that were the ''d├│ernemed'', which included professionals such as jurists (''brithem''), physicians, skilled craftsmen, skilled musicians, scholars, and so on. A master in a particular profession was known as an '' ollam'' (modern spelling: ''ollamh''). The various professionsŌĆöincluding law, poetry, medicine, history and genealogyŌĆöwere associated with particular families and the positions became hereditary. Since the poets, jurists and doctors depended on the patronage

Patronage is the support, encouragement, privilege, or financial aid that an organization or individual bestows on another. In the history of art, arts patronage refers to the support that kings, popes, and the wealthy have provided to artists su ...

of the ruling families, the end of the Gaelic order brought their demise.

* Below that were freemen who owned land and cattle (for example the ''b├│aire

B├│aire was a title given to a member of medieval and earlier Gaelic societies prior to the introductions of English law according to Early Irish law

Early Irish law, historically referred to as (English: Freeman-ism) or (English: Law of F ...

'').

* Below that were freemen who did not own land or cattle, or who owned very little.

* Below that were the unfree, which included serf

Serfdom was the status of many peasants under feudalism, specifically relating to manorialism, and similar systems. It was a condition of debt bondage and indentured servitude with similarities to and differences from slavery, which developed ...

s and slave

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slaveŌĆösomeone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

s. Slaves were typically criminals ( debt slaves) or prisoners of war. Slavery and serfdom was inherited, though slavery in Ireland had died out by 1200.

* The warrior bands known as '' fianna'' generally lived apart from society. A ''fian'' was typically composed of young men who had not yet come into their inheritance of land. A member of a ''fian'' was called a ''f├®nnid'' and the leader of a ''fian'' was a ''r├Łgf├®nnid''. Geoffrey Keating, in his 17th-century ''History of Ireland'', says that during the winter the ''fianna'' were quartered and fed by the nobility, during which time they would keep order on their behalf. But during the summer, from Bealtaine to Samhain, they were beholden to live by hunting for food and for hides to sell.

Although distinct, these ranks were not utterly exclusive caste

Caste is a form of social stratification characterised by endogamy, hereditary transmission of a style of life which often includes an occupation, ritual status in a hierarchy, and customary social interaction and exclusion based on cultura ...

s like those of India. It was possible to rise or sink from one rank to another. Rising upward could be achieved a number of ways, such as by gaining wealth, by gaining skill in some department, by qualifying for a learned profession, by showing conspicuous valour, or by performing some service to the community. An example of the latter is a person choosing to become a ''briugu'' (hospitaller). A ''briugu'' had to have his house open to any guests, which included feeding no matter how big the group. For the ''briugu'' to fulfill these duties, he was allowed more land and privileges, but this could be lost if he ever refused guests.

A freeman could further himself by becoming the client of one or more lords. The lord made his client a grant of property (i.e. livestock or land) and, in return, the client owed his lord yearly payments of food and fixed amounts of work. The clientship agreement could last until the lord's death. If the client died, his heirs would carry on the agreement. This system of clientship enabled social mobility as a client could increase his wealth until he could afford clients of his own, thus becoming a lord. Clientship was also practised between nobles, which established hierarchies of homage and political support.

Law

Gaelic law was originally passed down orally, but was written down in Old Irish during the period 600ŌĆō900 AD. This collection of oral and written laws is known as the ''F├®nechas'' or, in English, as the Brehon Law(s). The brehons (Old Irish: ''brithem'', plural ''brithemain'') were the

Gaelic law was originally passed down orally, but was written down in Old Irish during the period 600ŌĆō900 AD. This collection of oral and written laws is known as the ''F├®nechas'' or, in English, as the Brehon Law(s). The brehons (Old Irish: ''brithem'', plural ''brithemain'') were the jurist

A jurist is a person with expert knowledge of law; someone who analyses and comments on law. This person is usually a specialist legal scholar, mostly (but not always) with a formal qualification in law and often a legal practitioner. In the Uni ...

s in Gaelic Ireland. Becoming a brehon took many years of training and the office was, or became, largely hereditary. Most legal cases

A precedent is a principle or rule established in a previous legal case that is either binding on or persuasive for a court or other tribunal when deciding subsequent cases with similar issues or facts. Common law#Disambiguate civil law, Common- ...

were contested privately between opposing parties, with the brehons acting as arbitrators.

Offences against people and property were primarily settled by the offender paying compensation to the victims. Although any such offence required compensation, the law made a distinction between intentional and unintentional harm, and between murder and manslaughter

Manslaughter is a common law legal term for homicide considered by law as less culpable than murder. The distinction between murder and manslaughter is sometimes said to have first been made by the ancient Athenian lawmaker Draco in the 7th cen ...

. If an offender did not pay outright, his property was seized until he did so. Should the offender be unable to pay, his family would be responsible for doing so. Should the family be unable or unwilling to pay, responsibility would broaden to the wider kin-group. Hence, it has been argued that "the people were their own police". Acts of violence were generally settled by payment of compensation known as an '' ├®raic'' fine; the Gaelic equivalent of the Welsh '' galanas'' and the Germanic '' weregild''. If a free person was murdered, the ''├®raic'' was equal to 21 cows, regardless of the victim's rank in society. Each member of the murder victim's agnatic kin-group received a payment based on their closeness to the victim, their status, and so forth. There were separate payments for the kin-group of the victim's mother, and for the victim's foster-kin.

Execution seems to have been rare and carried out only as a last resort. If a murderer was unable or unwilling to pay ''├®raic'' and was handed to his victim's family, they might kill him if they wished should nobody intervene by paying the ''├®raic''. Habitual or particularly serious offenders might be expelled from the kin-group and its territory. Such people became outlaws (with no protection from the law) and anyone who sheltered him became liable for his crimes. If he still haunted the territory and continued his crimes there, he was proclaimed in a public assembly and after this anyone might lawfully kill him.

Each person had an honour-price, which varied depending on their rank in society. This honour-price was to be paid to them if their honour was violated by certain offences. Those of higher rank had a higher honour-price. However, an offence against the property of a poor man (who could ill afford it), was punished more harshly than a similar offence upon a wealthy man. The clergy were more harshly punished than the laity

In religious organizations, the laity () consists of all members who are not part of the clergy, usually including any non-ordained members of religious orders, e.g. a nun or a lay brother.

In both religious and wider secular usage, a layperson ...

. When a layman had paid his fine he would go through a probationary period and then regain his standing, but a clergyman could never regain his standing.

Some laws were pre-Christian in origin. These secular laws existed in parallel, and sometimes in conflict, with Church law. Although brehons usually dealt with legal cases, kings would have been able to deliver judgments also, but it is unclear how much they would have had to rely on brehons. Kings had their own brehons to deal with cases involving the king's own rights and to give him legal advice. Unlike other kingdoms in Europe, Gaelic kingsŌĆöby their own authorityŌĆöcould not enact new laws as they wished and could not be "above the law". They could, however, enact temporary emergency laws. It was mainly through these emergency powers that the Church attempted to change Gaelic law.

The law texts take great care to define social status, the rights and duties that went with that status, and the relationships between people. For example, ''ceann finte'' had to take responsibility for members of their ''fine'', acting as a surety

In finance, a surety , surety bond or guaranty involves a promise by one party to assume responsibility for the debt obligation of a borrower if that borrower defaults. Usually, a surety bond or surety is a promise by a surety or guarantor to pay ...

for some of their deeds and making sure debts were paid. He would also be responsible for unmarried women after the death of their fathers.

Marriage, women and children

Ancient Irish culture was

Ancient Irish culture was patriarchal

Patriarchy is a social system in which positions of Dominance hierarchy, dominance and Social privilege, privilege are primarily held by men. It is used, both as a technical Anthropology, anthropological term for families or clans controll ...

. The Brehon law excepted women from the ordinary course of the law so that, in general, every woman had to have a male guardian. However, women had some legal capacity. By the 8th century, the preferred form of marriage was one between social equals, under which a woman was technically legally dependent on her husband and had half his honor price, but could exercise considerable authority in regard to the transfer of property. Such women were called "women of joint dominion". Thus historian Patrick Weston Joyce could write that, relative to other European countries of the time, free women in Gaelic Ireland "held a good position" and their social and property rights were "in most respects, quite on a level with men".

Gaelic Irish society was also patrilineal, with land being primarily owned by men and inherited by the sons. Only when a man had no sons would his land pass to his daughters, and then only for their lifetimes. Upon their deaths, the land was redistributed among their father's male relations. Under Brehon law, rather than inheriting land, daughters had assigned to them a certain number of their father's cattle as their marriage-portion. It seems that, throughout the Middle Ages, the Gaelic Irish kept many of their marriage laws and traditions separate from those of the Church. Under Gaelic law, married women could hold property independent of their husbands, a link was maintained between married women and their own families, couples could easily divorce or separate, and men could have concubines (which could be lawfully bought). These laws differed from most of contemporary Europe and from Church law.

The lawful age of marriage was fifteen for girls and eighteen for boys, the respective ages at which fosterage ended. Upon marriage, the families of the bride and bridegroom were expected to contribute to the match. It was custom for the bridegroom and his family to pay a ''coibche'' (modern spelling: ''coibhche'') and the bride was allowed a share of it. If the marriage ended owing to a fault of the husband then the ''coibche'' was kept by the wife and her family, but if the fault lay with the wife then the ''coibche'' was to be returned. It was custom for the bride to receive a ''spr├®id'' (modern spelling: ''spr├®idh'') from her family (or foster family) upon marriage. This was to be returned if the marriage ended through divorce or the death of the husband. Later, the ''spr├®id'' seems to have been converted into a dowry. Women could seek divorce/separation as easily as men could and, when obtained on her behalf, she kept all the property she had brought her husband during their marriage. Trial marriages seem to have been popular among the rich and powerful, and thus it has been argued that cohabitation before marriage must have been acceptable. It also seems that the wife of a chieftain was entitled to some share of the chief's authority over his territory. This led to some Gaelic Irish wives wielding a great deal of political power.

Before the Norman invasion, it was common for priests and monks to have wives. This remained mostly unchanged after the Norman invasion, despite protests from bishops and archbishops. The authorities classed such women as priests' concubines and there is evidence that a formal contract of concubinage existed between priests and their women. However, unlike other concubines, they seem to have been treated just as wives were.

In Gaelic Ireland a kind of fosterage was common, whereby (for a certain length of time) children would be left in the care of others to strengthen family ties or political bonds. Foster parents were beholden to teach their foster children or to have them taught. Foster parents who had properly done their duties were entitled to be supported by their foster children in old age (if they were in need and had no children of their own). As with divorce, Gaelic law again differed from most of Europe and from Church law in giving legal standing to both "legitimate" and "illegitimate" children.

Settlements and architecture

For most of the Gaelic period, dwellings and farm buildings were circular with conical thatched roofs (see roundhouse). Square and rectangle-shaped buildings gradually became more common, and by the 14th or 15th century they had replaced round buildings completely. In some areas, buildings were made mostly of stone. In others, they were built of timber, wattle and daub, or a mix of materials. Most ancient and early medieval stone buildings were of dry stone construction. Some buildings would have had glass windows. Among the wealthy, it was common for women to have their own 'apartment' called a ''grianan'' (anglicized "greenan") in the sunniest part of the homestead.

The dwellings of freemen and their families were often surrounded by a circular rampart called a "

For most of the Gaelic period, dwellings and farm buildings were circular with conical thatched roofs (see roundhouse). Square and rectangle-shaped buildings gradually became more common, and by the 14th or 15th century they had replaced round buildings completely. In some areas, buildings were made mostly of stone. In others, they were built of timber, wattle and daub, or a mix of materials. Most ancient and early medieval stone buildings were of dry stone construction. Some buildings would have had glass windows. Among the wealthy, it was common for women to have their own 'apartment' called a ''grianan'' (anglicized "greenan") in the sunniest part of the homestead.

The dwellings of freemen and their families were often surrounded by a circular rampart called a "ringfort

Ringforts, ring forts or ring fortresses are circular fortified settlements that were mostly built during the Bronze Age up to about the year 1000. They are found in Northern Europe, especially in Ireland. There are also many in South Wales ...

". There are two main kinds of ringfort. The ''r├Īth'' is an earthen ringfort, averaging 30m diameter, with a dry outside ditch. The ''cathair'' or ''caiseal'' is a stone ringfort. The ringfort would typically have enclosed the family home, small farm buildings or workshops, and animal pens. Most date to the period 500ŌĆō1000 CE and there is evidence of large-scale ringfort desertion at the end of the first millennium. The remains of between 30,000 and 40,000 lasted into the 19th century to be mapped by Ordnance Survey Ireland

Ordnance Survey Ireland (OSI; ga, Suirbh├®ireacht Ordan├Īis ├ēireann) is the national mapping agency of Ireland. It was established on 4 March 2002 as a body corporate. It is the successor to the former Ordnance Survey of Ireland. It and the ...

. Another kind of native dwelling was the '' crann├│g'', which were roundhouses built on artificial islands in lakes.

There were very few nucleated settlements, but after the 5th century some monasteries became the heart of small "monastic towns". By the 10th century the Norse-Gaelic ports of Dublin, Wexford, Cork and Limerick had grown into substantial settlements, all ruled by Gaelic kings by 1052. In this era many of the Irish round towers were built.

In the fifty years before the Norman invasion

The Norman Conquest (or the Conquest) was the 11th-century invasion and occupation of England by an army made up of thousands of Norman, Breton, Flemish, and French troops, all led by the Duke of Normandy, later styled William the Conq ...

, the term "castle" ( sga, caist├®l/caisl├®n) appears in Gaelic writings, although there are few intact surviving examples of pre-Norman castles. After the invasion, the Normans built motte-and-bailey castles in the areas they occupied, some of which were converted from ringforts. By 1300 "some mottes, especially in frontier areas, had almost certainly been built by the Gaelic Irish in imitation". The Normans gradually replaced wooden motte-and-baileys with stone castles and tower houses. Tower houses are free-standing multi-storey stone towers usually surrounded by a wall (see bawn

A bawn is the defensive wall surrounding an Irish tower house. It is the anglicised version of the Irish word ''b├Ībh├║n'' (sometimes spelt ''badh├║n''), possibly meaning "cattle-stronghold" or "cattle-enclosure".See alternative traditional spe ...

) and ancillary buildings. Gaelic families had begun to build their own tower houses by the 15th century. As many as 7000 may have been built, but they were rare in areas with little Norman settlement or contact. They are concentrated in counties Limerick and Clare but are lacking in Ulster, except the area around Strangford Lough.

In Gaelic law, a 'sanctuary' called a ''maighin digona'' surrounded each person's dwelling. The ''maighin digona's'' size varied according to the owner's rank. In the case of a ''b├│aire

B├│aire was a title given to a member of medieval and earlier Gaelic societies prior to the introductions of English law according to Early Irish law

Early Irish law, historically referred to as (English: Freeman-ism) or (English: Law of F ...

'' it stretched as far as he, while sitting at his house, could cast a ''cnairsech'' (variously described as a spear or sledgehammer). The owner of a ''maighin digona'' could offer its protection to someone fleeing from pursuers, who would then have to bring that person to justice by lawful means.

Economy

Gaelic Ireland was involved in trade with Britain and mainland Europe from ancient times, and this trade increased over the centuries. Tacitus, for example, wrote in the 1st century that most of Ireland's harbours were known to the Romans through commerce. There are many passages in early Irish literature that mentionluxury goods

In economics, a luxury good (or upmarket good) is a good for which demand increases more than what is proportional as income rises, so that expenditures on the good become a greater proportion of overall spending. Luxury goods are in contrast to n ...

imported from foreign lands, and the fair

A fair (archaic: faire or fayre) is a gathering of people for a variety of entertainment or commercial activities. Fairs are typically temporary with scheduled times lasting from an afternoon to several weeks.

Types

Variations of fairs incl ...

of Carman in Leinster included a market of foreign traders. In the Middle Ages the main exports were textiles such as wool and linen

Linen () is a textile made from the fibers of the flax plant.

Linen is very strong, absorbent, and dries faster than cotton. Because of these properties, linen is comfortable to wear in hot weather and is valued for use in garments. It also ...

while the main imports were luxury items.

Money was seldom used in Gaelic society; instead, goods and services were usually exchanged for other goods and services ( barter). The economy was mainly a pastoral

A pastoral lifestyle is that of shepherds herding livestock around open areas of land according to seasons and the changing availability of water and pasture. It lends its name to a genre of literature, art, and music (pastorale) that depicts ...

one, based on livestock ( cows, sheep, pigs, goats, etc.) and their products. Cattle was "the main element in the Irish pastoral economy" and the main form of wealth, providing milk, butter, cheese

Cheese is a dairy product produced in wide ranges of flavors, textures, and forms by coagulation of the milk protein casein. It comprises proteins and fat from milk, usually the milk of cows, buffalo, goats, or sheep. During production, ...

, meat

Meat is animal flesh that is eaten as food. Humans have hunted, farmed, and scavenged animals for meat since prehistoric times. The establishment of settlements in the Neolithic Revolution allowed the domestication of animals such as chic ...

, fat, hides, and so forth. They were a "highly mobile form of wealth and economic resource which could be quickly and easily moved to a safer locality in time of war or trouble". The nobility owned great herds of cattle that had herdsmen and guards. Sheep, goats and pigs were also a valuable resource but had a lesser role in Irish pastoralism.

Horticulture was practised; the main crops being oats, wheat and barley, although flax

Flax, also known as common flax or linseed, is a flowering plant, ''Linum usitatissimum'', in the family Linaceae. It is cultivated as a food and fiber crop in regions of the world with temperate climates. Textiles made from flax are known in ...

was also grown for making linen.

Transhumance was also practised, whereby people moved with their livestock to higher pastures in summer and back to lower pastures in the cooler months. The summer pasture was called the ''buaile'' (anglicized as ''booley'') and it is noteworthy that the Irish word for ''boy'' (''buachaill'') originally meant a herdsman. Many moorland

Moorland or moor is a type of habitat found in upland areas in temperate grasslands, savannas, and shrublands and montane grasslands and shrublands biomes, characterised by low-growing vegetation on acidic soils. Moorland, nowadays, generally ...

areas were "shared as a common summer pasturage by the people of a whole parish or barony".

Transport

Gaelic Ireland was well furnished with roads and bridges. Bridges were typically wooden and in some places the roads were laid with wood and stone. There were five main roads leading from Tara: Sl├Łghe Asail,Sl├Łghe Chualann

(; modern spelling ) was a road in Early Christian Ireland running south across ("the Ford of Hurdles"; now Dublin city) entering the territory of Cualu or Cuala before going west of the Wicklow Mountains. The ancient name for Dublin was ' Bail ...

, Sl├Łghe D├Īla, Sl├Łghe M├│r and Sl├Łghe Midluachra.

Horses were one of the main means of long-distance transport. Although horseshoe

A horseshoe is a fabricated product designed to protect a horse hoof from wear. Shoes are attached on the palmar surface (ground side) of the hooves, usually nailed through the insensitive hoof wall that is anatomically akin to the human toen ...

s and reins were used, the Gaelic Irish did not use saddles, stirrup

A stirrup is a light frame or ring that holds the foot of a rider, attached to the saddle by a strap, often called a ''stirrup leather''. Stirrups are usually paired and are used to aid in mounting and as a support while using a riding animal ( ...

s or spurs. Every man was trained to spring from the ground on to the back of his horse (an ''ech-l├®im'' or "steed-leap") and they urged-on and guided their horses with a rod having a hooked goad at the end.

Two-wheeled and four-wheeled chariot

A chariot is a type of cart driven by a charioteer, usually using horses to provide rapid motive power. The oldest known chariots have been found in burials of the Sintashta culture in modern-day Chelyabinsk Oblast, Russia, dated to c. 2000&nbs ...

s (singular ''carbad'') were used in Ireland from ancient times, both in private life and in war. They were big enough for two people, made of wickerwork and wood, and often had decorated hoods. The wheels were spoked, shod all round with iron, and were from three to four and a half feet high. Chariots were generally drawn by horses or oxen, with horse-drawn chariots being more common among chiefs and military men. War chariots

A chariot is a type of cart driven by a charioteer, usually using horses to provide rapid motive power. The oldest known chariots have been found in burials of the Sintashta culture in modern-day Chelyabinsk Oblast, Russia, dated to c. 2000&nb ...

furnished with scythes and spikes, like those of the ancient Gauls and Britons, are mentioned in literature.

Boats used in Gaelic Ireland include canoes, currachs, sailboats and Irish galley

The Irish galley was a vessel in use in the West of Ireland down to the seventeenth century, and was propelled both by oars and sail. In fundamental respects it resembled the Scottish galley or Birlinn, bìrlinn, their mutual ancestor being the Vik ...

s. Ferryboats were used to cross wide rivers and are often mentioned in the Brehon Laws as subject to strict regulations. Sometimes they were owned by individuals and sometimes they were the common property of those living round the ferry. Large boats were used for trade with mainland Europe.

Dress

Throughout the Middle Ages, the common clothing amongst the Gaelic Irish consisted of a ''brat'' (a woollen semi circular cloak) worn over a ''l├®ine'' (a loose-fitting, long-sleeved tunic made of linen). For men the ''l├®ine'' reached to their ankles but was hitched up by means of a crios (pronounced 'kriss') which was a type of woven belt. The l├®ine was hitched up to knee level. Women wore the l├®ine at full length. Men sometimes wore tight-fitting trews (Gaelic tri├║bhas) but otherwise went bare-legged. The ''brat'' was simply thrown over both shoulders or sometimes over only one. Occasionally the brat was fastened with a ''dealg'' ( brooch), with men usually wearing the ''dealg'' at their shoulders and women at their chests. The ''ionar'' (a short, tight-fitting jacket) became popular later on. In '' Topographia Hibernica'', written during the 1180s,

Throughout the Middle Ages, the common clothing amongst the Gaelic Irish consisted of a ''brat'' (a woollen semi circular cloak) worn over a ''l├®ine'' (a loose-fitting, long-sleeved tunic made of linen). For men the ''l├®ine'' reached to their ankles but was hitched up by means of a crios (pronounced 'kriss') which was a type of woven belt. The l├®ine was hitched up to knee level. Women wore the l├®ine at full length. Men sometimes wore tight-fitting trews (Gaelic tri├║bhas) but otherwise went bare-legged. The ''brat'' was simply thrown over both shoulders or sometimes over only one. Occasionally the brat was fastened with a ''dealg'' ( brooch), with men usually wearing the ''dealg'' at their shoulders and women at their chests. The ''ionar'' (a short, tight-fitting jacket) became popular later on. In '' Topographia Hibernica'', written during the 1180s, Gerald de Barri

Gerald de Barri or Gerald of Barry, was a mediaeval Bishop of Cork.

Barry was appointed in 1359 and received possession of the temporalities on 2 February 1360. He was appointed again on 8 November 1362 and confirmed on 1 February 1365. He died o ...

wrote that the Irish commonly wore hoods at that time (perhaps forming part of the ''brat''), while Edmund Spenser

Edmund Spenser (; 1552/1553 ŌĆō 13 January 1599) was an English poet best known for ''The Faerie Queene'', an epic poem and fantastical allegory celebrating the Tudor dynasty and Elizabeth I. He is recognized as one of the premier craftsmen of ...

wrote in the 1580s that the ''brat'' was (in general) their main item of clothing. Gaelic clothing does not appear to have been influenced by outside styles.

Women invariably grew their hair long and, as in other European cultures, this custom was also common among the men. It is said that the Gaelic Irish took great pride in their long hairŌĆöfor example, a person could be forced to pay the heavy fine of two cows for shaving a man's head against his will. For women, very long hair was seen as a mark of beauty. Sometimes, wealthy men and women would braid their hair and fasten hollow golden balls to the braids. Another style that was popular among some medieval Gaelic men was the ''glib'' (short all over except for a long, thick lock of hair towards the front of the head). A band or ribbon around the forehead was the typical way of holding one's hair in place. For the wealthy, this band was often a thin and flexible band of burnished gold, silver or findruine. When the Anglo-Normans and the English colonized Ireland, hair length came to signify one's allegiance. Irishmen who cut their hair short were deemed to be forsaking their Irish heritage. Likewise, English colonists who grew their hair long at the back were deemed to be giving in to the Irish life.

Gaelic men typically wore a beard and mustache, and it was often seen as dishonourable for a Gaelic man to have no facial hair. Beard styles varied ŌĆō the long forked beard and the rectangular Mesopotamian-style beard were fashionable at times.

Warfare

Warfare was common in Gaelic Ireland, as territories, kingdoms and

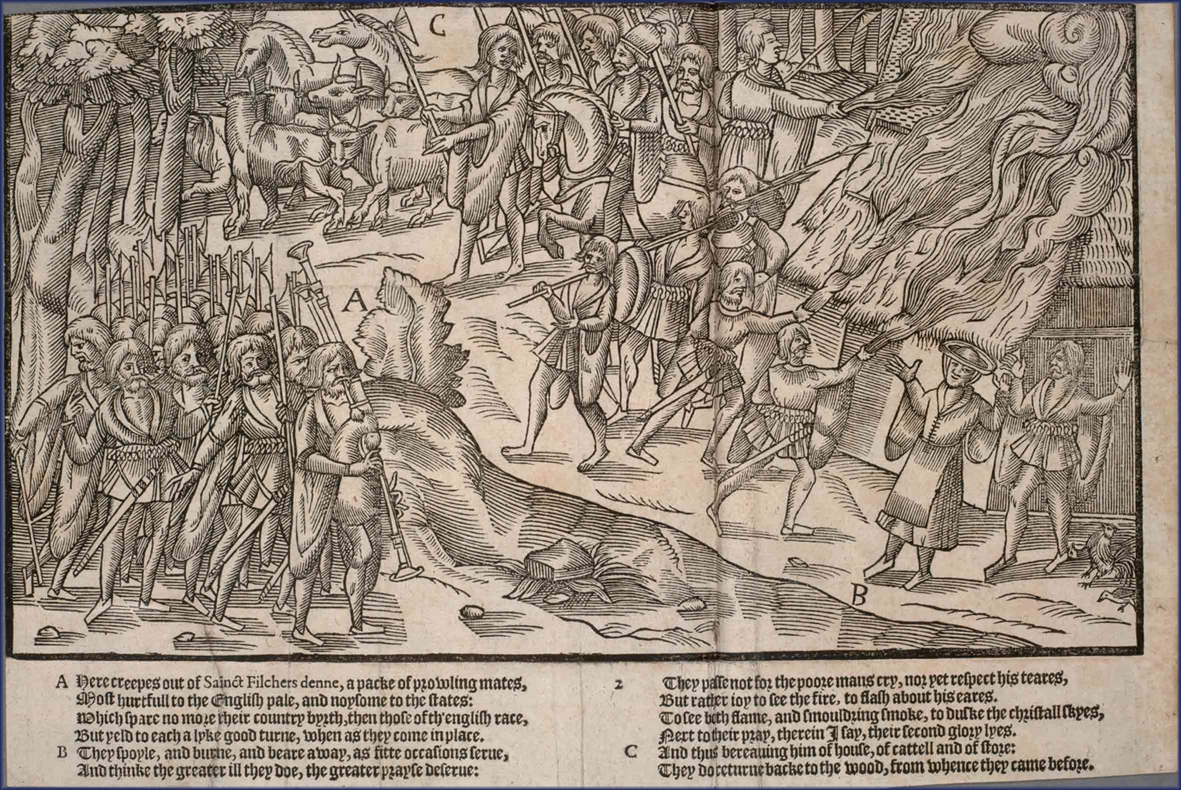

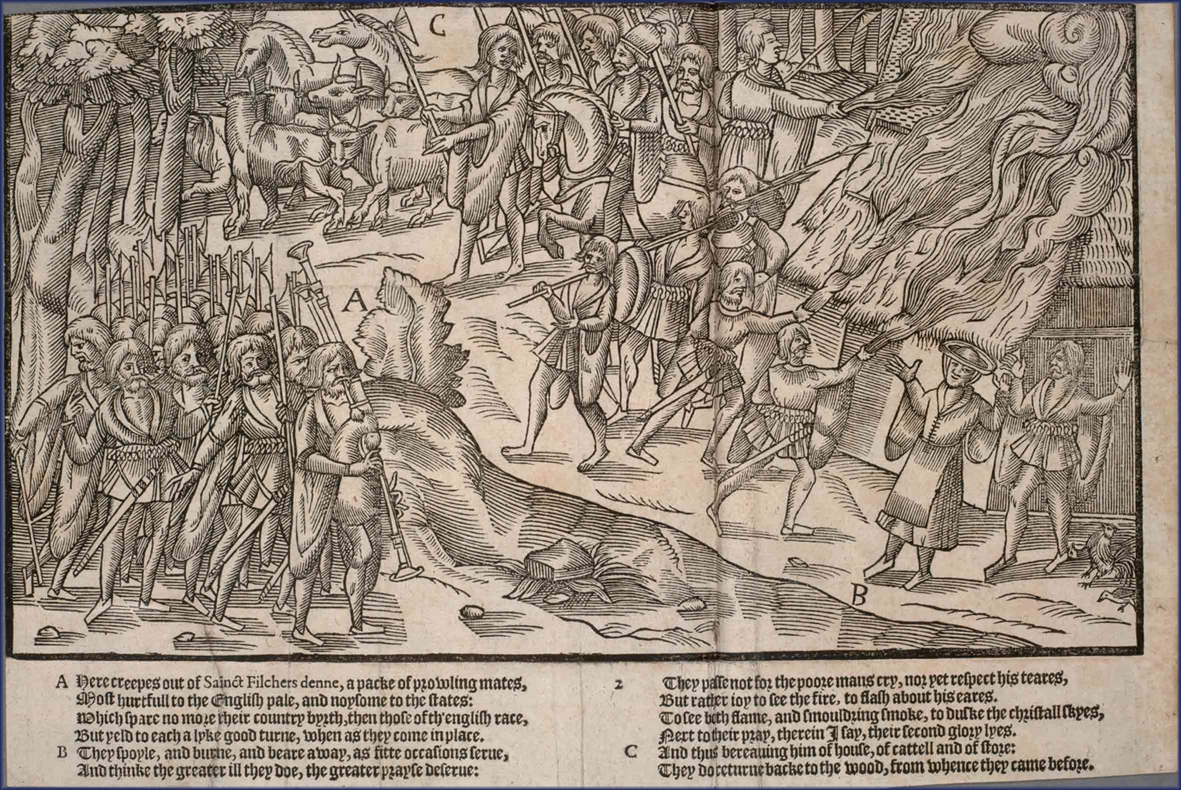

Warfare was common in Gaelic Ireland, as territories, kingdoms and clans

A clan is a group of people united by actual or perceived kinship

and descent. Even if lineage details are unknown, clans may claim descent from founding member or apical ancestor. Clans, in indigenous societies, tend to be endogamous, meaning ...

fought for supremacy against each other and later against the Vikings and Anglo-Normans.

Champion warfare is a common theme in Early Irish mythology, literature and culture. In the Middle Ages all able-bodied men, apart from the learned and the clergy, were eligible for military service on behalf of the king or chief

Chief may refer to:

Title or rank

Military and law enforcement

* Chief master sergeant, the ninth, and highest, enlisted rank in the U.S. Air Force and U.S. Space Force

* Chief of police, the head of a police department

* Chief of the boa ...

. Throughout the Middle Ages and for some time after, outsiders often wrote that the Irish style of warfare differed greatly from what they deemed to be the norm in Western Europe. The Gaelic Irish preferred hit-and-run raids (the ''crech''), which involved catching the enemy unaware. If this worked they would then seize any valuables (mainly livestock) and potentially valuable hostages, burn the crops, and escape. The cattle raid was a social institution and was called a '' T├Īin B├│'' in Gaelic literature. Although hit-and-run raiding was the preferred tactic in medieval times, there were also pitched battles. From at least the 11th century, kings maintained small permanent fighting forces known as ''lucht tighe'' "troops of the household", who were often given houses and land on the king's mensal land. These were well-trained and equipped professional soldiers made up of infantry and cavalry

Historically, cavalry (from the French word ''cavalerie'', itself derived from "cheval" meaning "horse") are soldiers or warriors who fight mounted on horseback. Cavalry were the most mobile of the combat arms, operating as light cavalry ...

. By the reign of Brian Boru, Irish kings were taking large armies on campaign

Campaign or The Campaign may refer to:

Types of campaigns

* Campaign, in agriculture, the period during which sugar beets are harvested and processed

* Advertising campaign, a series of advertisement messages that share a single idea and theme

* B ...

over long distances and using naval forces in tandem with land forces.

A typical medieval Irish army included light infantry

Light infantry refers to certain types of lightly equipped infantry throughout history. They have a more mobile or fluid function than other types of infantry, such as heavy infantry or line infantry. Historically, light infantry often fought ...

, heavy infantry and cavalry

Historically, cavalry (from the French word ''cavalerie'', itself derived from "cheval" meaning "horse") are soldiers or warriors who fight mounted on horseback. Cavalry were the most mobile of the combat arms, operating as light cavalry ...

. The bulk of the army was made up of light infantry called '' ceithern'' (anglicized 'kern'). The ceithern wandered Ireland offering their services for hire and usually wielded swords, skenes (a kind of long knife), short spears, bows and shields. The cavalry was usually made up of a king or chieftain and his close relatives. They usually rode without saddles but wore armour and iron helmets and wielded swords, skenes and long spears or lances. One kind of Irish cavalry was the hobelar. After the Norman invasion there emerged a kind of heavy infantry called '' gall├│glaigh'' (anglicized 'gallo lass'). They were originally Scottish mercenaries who appeared in the 13th century, but by the 15th century most large ''t├║atha'' had their own hereditary force of Irish ''gall├│glaigh''. Some Anglo-Norman lordships also began using ''gall├│glaigh'' in imitation of the Irish. They usually wore mail and iron helmets and wielded sparth axe

A polearm or pole weapon is a close combat weapon in which the main fighting part of the weapon is fitted to the end of a long shaft, typically of wood, thereby extending the user's effective range and striking power. Polearms are predominant ...

s, claymore

A claymore (; from gd, claidheamh- m├▓r, "great sword") is either the Scottish variant of the late medieval two-handed sword or the Scottish variant of the basket-hilted sword. The former is characterised as having a cross hilt of forward-sl ...

s, and sometimes spears or lances. The ''gall├│glaigh'' furnished the retreating plunderers with a "moving line of defence from which the horsemen could make short, sharp charges, and behind which they could retreat when pursued". As their armor made them less nimble, they were sometimes planted at strategic spots along the line of retreat. The kern, horsemen and ''gall├│glaigh'' had lightly armed servants to carry their weapons into battle.

Warriors were sometimes rallied into battle by blowing horns and warpipes. According to Gerald de Barri

Gerald de Barri or Gerald of Barry, was a mediaeval Bishop of Cork.

Barry was appointed in 1359 and received possession of the temporalities on 2 February 1360. He was appointed again on 8 November 1362 and confirmed on 1 February 1365. He died o ...

(in the 12th century), they did not wear armour

Armour (British English) or armor (American English; see spelling differences) is a covering used to protect an object, individual, or vehicle from physical injury or damage, especially direct contact weapons or projectiles during combat, or fr ...

, as they deemed it burdensome to wear and "brave and honourable" to fight without it. Instead, most ordinary soldiers fought semi-naked and carried only their weapons and a small round shield ŌĆö Spenser wrote that these shields were covered with leather and painted in bright colours. Kings and chiefs sometimes went into battle wearing helmets adorned with eagle feathers. For ordinary soldiers, their thick hair often served as a helmet, but they sometimes wore simple helmets made from animal hides.

Arts

Visual art

Artwork from Ireland's Gaelic period is found on pottery, jewellery, weapons, drinkware, tableware,stone carving

Stone carving is an activity where pieces of rough natural stone are shaped by the controlled removal of stone. Owing to the permanence of the material, stone work has survived which was created during our prehistory or past time.

Work carried ...

s and illuminated manuscript

An illuminated manuscript is a formally prepared document where the text is often supplemented with flourishes such as borders and miniature illustrations. Often used in the Roman Catholic Church for prayers, liturgical services and psalms, the ...

s. Irish art from about 300 BC incorporates patterns and styles which developed in west central Europe. By about AD 600, after the Christianization of Ireland had begun, a style melding Irish, Mediterranean and Germanic Anglo-Saxon

The Anglo-Saxons were a Cultural identity, cultural group who inhabited England in the Early Middle Ages. They traced their origins to settlers who came to Britain from mainland Europe in the 5th century. However, the ethnogenesis of the Anglo- ...

elements emerged, and was spread to Britain and mainland Europe by the Hiberno-Scottish mission. This is known as ''Insular art

Insular art, also known as Hiberno-Saxon art, was produced in the post-Roman era of Great Britain and Ireland. The term derives from ''insula'', the Latin term for "island"; in this period Britain and Ireland shared a largely common style dif ...

'' or ''Hiberno-Saxon'' art, which continued in some form in Ireland until the 12th century, although the Viking invasions ended its "Golden Age". Most surviving works of Insular art were either made by monks or made for monasteries, with the exception of brooches, which were likely made and used by both clergy and laity. Examples of Insular art from Ireland include the ''Book of Kells

The Book of Kells ( la, Codex Cenannensis; ga, Leabhar Cheanannais; Dublin, Trinity College Library, MS A. I. 8 sometimes known as the Book of Columba) is an illuminated manuscript Gospel book in Latin, containing the four Gospels of the New ...

'', Muiredach's High Cross, the Tara Brooch, the Ardagh Hoard the Derrynaflan Chalice

The Derrynaflan Chalice is an 8th- or 9th-century chalice that was found as part of the Derrynaflan Hoard of five liturgical vessels. The discovery was made on 17 February 1980 near Killenaule, County Tipperary in Ireland. According to art ...

, and the late Cross of Cong, which also uses Viking styles.

Literature

Music and dance

AlthoughGerald de Barri

Gerald de Barri or Gerald of Barry, was a mediaeval Bishop of Cork.

Barry was appointed in 1359 and received possession of the temporalities on 2 February 1360. He was appointed again on 8 November 1362 and confirmed on 1 February 1365. He died o ...

had an overtly negative view of the Irish, in '' Topographia Hibernica'' (1188) he conceded that they were more skilled at playing music than any other nation he had seen. He claimed that the two main instruments were the "harp

The harp is a stringed musical instrument that has a number of individual strings running at an angle to its soundboard; the strings are plucked with the fingers. Harps can be made and played in various ways, standing or sitting, and in orche ...

" and "tabor

Tabor may refer to:

Places

Czech Republic

* T├Ībor, a town in the South Bohemian Region

** T├Ībor District, the surrounding district

* T├Ībor, a village and part of Velk├® Heraltice in the Moravian-Silesian Region

Israel

* Mount Tabor, Galil ...

" (see also bodhr├Īn), that their music was fast and lively, and that their songs always began and ended with B-flat B-flat or B may refer to:

* B (musical note)

* B major

* B minor

B minor is a minor scale based on B, consisting of the pitches B, C, D, E, F, G, and A. Its key signature has two sharps. Its relative major is D major and its parallel ma ...

. In ''A History of Irish Music'' (1905), W. H. Grattan Flood

Chevalier William Henry Grattan Flood (baptised 1 November 1857 ŌĆō 6 August 1928) was a noted Irish author, composer, musicologist, and historian. As a writer and ecclesiastical composer, his personal contributions to Irish music produced endu ...

wrote that there were at least ten instruments in general use by the Gaelic Irish. These were the ''cruit'' (a small harp) and '' clairseach'' (a bigger harp with typically 30 strings), the ''timpan'' (a small string instrument

String instruments, stringed instruments, or chordophones are musical instruments that produce sound from vibrating strings when a performer plays or sounds the strings in some manner.

Musicians play some string instruments by plucking the ...

played with a bow or plectrum), the ''feadan'' (a fife

Fife (, ; gd, Fìobha, ; sco, Fife) is a council area, historic county, registration county and lieutenancy area of Scotland. It is situated between the Firth of Tay and the Firth of Forth, with inland boundaries with Perth and Kinross (i ...

), the ''buinne'' (an oboe or flute

The flute is a family of classical music instrument in the woodwind group. Like all woodwinds, flutes are aerophones, meaning they make sound by vibrating a column of air. However, unlike woodwind instruments with reeds, a flute is a reedless ...

), the ''guthbuinne'' (a bassoon

The bassoon is a woodwind instrument in the double reed family, which plays in the tenor and bass ranges. It is composed of six pieces, and is usually made of wood. It is known for its distinctive tone color, wide range, versatility, and virtuo ...

-type horn), the ''bennbuabhal'' and ''corn'' ( hornpipes), the ''cuislenna'' (bagpipes

Bagpipes are a woodwind instrument using enclosed reeds fed from a constant reservoir of air in the form of a bag. The Great Highland bagpipes are well known, but people have played bagpipes for centuries throughout large parts of Europe, No ...

ŌĆō see Great Irish Warpipes), the ''stoc'' and ''sturgan'' ( clarions or trumpets), and the ''cnamha'' ( castanets). He also mentions the fiddle

A fiddle is a bowed string musical instrument, most often a violin. It is a colloquial term for the violin, used by players in all genres, including classical music. Although in many cases violins and fiddles are essentially synonymous, th ...

as being used in the 8th century as compliment to Irish music.

Sport

Assemblies

As mentioned before, Gaelic Ireland was split into many clann territories and kingdoms called '' t├║ath'' (plural: ''t├║atha''). Although there was no central government or parliament, a number of local, regional and national gatherings were held. These combined features of assemblies and

As mentioned before, Gaelic Ireland was split into many clann territories and kingdoms called '' t├║ath'' (plural: ''t├║atha''). Although there was no central government or parliament, a number of local, regional and national gatherings were held. These combined features of assemblies and fair

A fair (archaic: faire or fayre) is a gathering of people for a variety of entertainment or commercial activities. Fairs are typically temporary with scheduled times lasting from an afternoon to several weeks.

Types

Variations of fairs incl ...

s.

In Ireland, the highest of these was the '' feis'' at Teamhair na R├Ł (Tara), which was held every third Samhain. This was a gathering of the leading men of the whole island ŌĆō kings

Kings or King's may refer to:

*Monarchs: The sovereign heads of states and/or nations, with the male being kings

*One of several works known as the "Book of Kings":

**The Books of Kings part of the Bible, divided into two parts

**The ''Shahnameh'' ...

, lords

Lords may refer to:

* The plural of Lord

Places

*Lords Creek, a stream in New Hanover County, North Carolina

* Lord's, English Cricket Ground and home of Marylebone Cricket Club and Middlesex County Cricket Club

People

*Traci Lords (born 1 ...

, chieftains, druid

A druid was a member of the high-ranking class in ancient Celtic cultures. Druids were religious leaders as well as legal authorities, adjudicators, lorekeepers, medical professionals and political advisors. Druids left no written accounts. Whi ...

s, judges etc. Below this was the ''├│enach

An aonach or ├│enach was an ancient Irish public national assembly called upon the death of a king, queen, or notable sage or warrior as part of ancestor worship practices. As well as the entertainment, the ├│enach was an occasion on which kings an ...

'' (modern spelling: ''aonach''). These were regional or provincial gatherings open to everyone. Examples include that held at Tailtin each Lughnasadh, and that held at Uisneach each Bealtaine. The main purpose of these gatherings was to promulgate and reaffirm the laws ŌĆō they were read aloud in public that they might not be forgotten, and any changes in them carefully explained to those present.

Each t├║ath or clann had two assemblies of its own. These were the ''cuirmtig'', which was open to all clann members, and the ''dal'' (a term later adopted for the Irish parliament ŌĆō see D├Īil ├ēireann

D├Īil ├ēireann ( , ; ) is the lower house, and principal chamber, of the Oireachtas (Irish legislature), which also includes the President of Ireland and Seanad ├ēireann (the upper house).Article 15.1.2┬║ of the Constitution of Ireland read ...

), which was open only to clann chiefs. Each clann had a further assembly called a ''tocomra'', in which the clann chief (''to├Łsech'', modern taoiseach) and his deputy/successor ('' t├Īnaiste'') were elected.

Notable Irish kings

* List of kings * List of High kingsHistory

Before 400

The prehistory of Ireland included a protohistorical period, when the literate cultures of Greece and Rome first began to take notice of the Irish, and a further proto-literate period of ogham epigraphy, before the early

The prehistory of Ireland included a protohistorical period, when the literate cultures of Greece and Rome first began to take notice of the Irish, and a further proto-literate period of ogham epigraphy, before the early historical period

Human history, also called world history, is the narrative of humanity's past. It is understood and studied through anthropology, archaeology, genetics, and linguistics. Since the invention of writing, human history has been studied through ...

began in the early 5th century.

During this period, the Gaels traded with the Roman Empire and also raided and colonized Britain during the end of Roman rule in Britain

The end of Roman rule in Britain was the transition from Roman Britain to post-Roman Britain. Roman rule ended in different parts of Britain at different times, and under different circumstances.

In 383, the usurper Magnus Maximus withdrew tr ...

. The Romans of this era called these Gaelic raiders ''Scoti

''Scoti'' or ''Scotti'' is a Latin name for the Gaels,Duffy, Se├Īn. ''Medieval Ireland: An Encyclopedia''. Routledge, 2005. p.698 first attested in the late 3rd century. At first it referred to all Gaels, whether in Ireland or Great Britain, but l ...

'' and their homeland '' Hibernia'' or '' Scotia''. ''Scoti'' was a Latin name that first referred to all the Gaels, whether in Ireland or Great Britain, but later came to refer only to the Gaels in northern Britain. As time went on, the Gaels began intensifying their raids and colonies in Roman Britain (c. 200ŌĆō500 AD).

For much of this period, the island of Ireland was divided into numerous clan territories and kingdoms (known as t├║atha).

400 to 800

The early medieval history of Ireland, often called Early Christian Ireland, spans the 5th to 8th centuries, from a gradual emergence out of the protohistoric period ( Ogham inscriptions in Primitive Irish, negative mentions inGreco-Roman

The Greco-Roman civilization (; also Greco-Roman culture; spelled Graeco-Roman in the Commonwealth), as understood by modern scholars and writers, includes the geographical regions and countries that culturallyŌĆöand so historicallyŌĆöwere di ...

ethnography) to the beginning of the Viking Age.

The introduction of Christianity to Ireland dates to sometime before the 5th century. With Palladius the eventual first Bishop of Ireland being sent during this period (mid-5th century) by Pope Celestine I to preach "''ad Scotti in Christum''" or in other words to minister to the Scoti

''Scoti'' or ''Scotti'' is a Latin name for the Gaels,Duffy, Se├Īn. ''Medieval Ireland: An Encyclopedia''. Routledge, 2005. p.698 first attested in the late 3rd century. At first it referred to all Gaels, whether in Ireland or Great Britain, but l ...

or Irish "believing in Christ". Early medieval traditions credit Saint Patrick

Saint Patrick ( la, Patricius; ga, P├Īdraig ; cy, Padrig) was a fifth-century Romano-British Christian missionary and bishop in Ireland. Known as the "Apostle of Ireland", he is the primary patron saint of Ireland, the other patron saints be ...

as being the first Primate of Ireland.

The Gaelic Kingdom of D├Īl Riata is said to have been founded in the 5th century by the legendary king┬Ā'' Fergus M├│r mac Eirc'' or Fergus M├│r in Argyll or "''the coast of the Gaels''" located in modern-day Scotland.┬ĀThe D├Īl Riata had a strong┬Ā seafaring┬Āculture and a large naval fleet.

From the 5th century on, clerics of Christianised Ireland such as Brigid of Kildare, Saint MacCul, Saint Moluag, Saint Caill├Łn

In religious belief, a saint is a person who is recognized as having an exceptional degree of holiness, likeness, or closeness to God. However, the use of the term ''saint'' depends on the context and denomination. In Catholic, Eastern Ortho ...

, Columbanus

Columbanus ( ga, Columb├Īn; 543 ŌĆō 21 November 615) was an Irish missionary notable for founding a number of monasteries after 590 in the Frankish and Lombard kingdoms, most notably Luxeuil Abbey in present-day France and Bobbio Abbey in pr ...

as well as the Twelve Apostles of Ireland: Saint Ciar├Īn of Saighir, Saint Ciar├Īn of Clonmacnoise, Saint Brendan of Birr, Saint Brendan of Clonfert, Saint Columba of Terryglass

Columba of Terryglass (Colum) (died 13 December 552) was the son of Ninnidh, a descendant of Crinthainn, King of Leinster. Columba was a disciple of St. Finnian of Clonard. He was one of the Twelve Apostles of Ireland.

Life

In his youth he lea ...

, Saint Columba, Saint Mobh├Ł, Saint Ruadh├Īn of Lorrha, Saint Sean├Īn, Saint Ninnidh

Ninnidh (alias Ninnidh the Pious, ga, Ninnidh leth derc, meaning one eyed Ninnidh, Nennius, Nennidhius, Ninnaid) was a 6th-century Ireland, Irish Christian saint. St. Ninnidh is regarded as one of the Twelve Apostles of Ireland. He is associate ...

, Saint Laisr├®n mac Nad Fro├Łch and Saint Canice were active in ministry in Ireland and as missionaries

A missionary is a member of a religious group which is sent into an area in order to promote its faith or provide services to people, such as education, literacy, social justice, health care, and economic development.Thomas Hale 'On Being a Mi ...

throughout Europe in Gaul, the Isle of Mann

)

, anthem = "O Land of Our Birth"

, image = Isle of Man by Sentinel-2.jpg

, image_map = Europe-Isle_of_Man.svg

, mapsize =

, map_alt = Location of the Isle of Man in Europe

, map_caption = Location of the Isle of Man (green)

in Europe ...

, in Scotland, in the Anglo-Saxon

The Anglo-Saxons were a Cultural identity, cultural group who inhabited England in the Early Middle Ages. They traced their origins to settlers who came to Britain from mainland Europe in the 5th century. However, the ethnogenesis of the Anglo- ...

Kingdoms of England and in the Frankish Empire thus spreading Gaelic cultural influence to Continental Europe

Continental Europe or mainland Europe is the contiguous continent of Europe, excluding its surrounding islands. It can also be referred to ambiguously as the European continent, ŌĆō which can conversely mean the whole of Europe ŌĆō and, by ...

and even as far away as Iceland.

By the 8th century, the King of the Picts, '' ├ōengus mac Fergusso'' or Angus I expanded the influence of his kingdom using conquest, subjugation and diplomacy over the Gaels of Dal Riata, the Britons of Strathclyde and the Anglo-Saxons of Northumbria.

During this period, in addition to kingdoms or t├║atha, the 5 main over-kingdoms begin to form. (Old Irish ''c├│iceda'', Modern Irish ''c├║ige''). These were Ulaid (in the north), Connacht (in the west), Laighin (in the southeast), Mumhan (in the south) and Mide (in the centre).

800 to 1169

The history of Ireland 800ŌĆō1169 covers the period in the history of Ireland from the first Viking raids to theNorman invasion

The Norman Conquest (or the Conquest) was the 11th-century invasion and occupation of England by an army made up of thousands of Norman, Breton, Flemish, and French troops, all led by the Duke of Normandy, later styled William the Conq ...

.

Beginning in 795, small bands of Vikings began plundering monastic settlements along the coast of Ireland. By 853, Viking leader Amla├Łb had become the first king of Dublin. He ruled along with his brothers ├Źmar and Auisle. His dynasty, the U├Ł ├Źmair ruled over the following decades. During this period there was regular warfare between the Vikings and the Irish, and between two separate groups of Norse