, mottoeng =

The Lord is my light

, established =

, endowment =

£6.1 billion (including colleges) (2019)

, budget = £2.145 billion (2019–20)

, chancellor =

The Lord Patten of Barnes

, vice_chancellor =

Louise Richardson

, students = 24,515 (2019)

, undergrad = 11,955

, postgrad = 12,010

, other = 541 (2017)

, city =

Oxford

, country = England

, coordinates =

, campus_type =

University town

, athletics_affiliations =

Blue (university sport)

A blue is an award of sporting colours earned by athletes at some universities and schools for competition at the highest level. The awarding of blues began at Oxford and Cambridge universities in England. They are now awarded at a number of other ...

, logo_size = 250px

, website =

, logo = University of Oxford.svg

, colours =

Oxford Blue

, faculty = 6,995 (2020)

, academic_affiliations = ,

The University of Oxford is a

collegiate research university in

Oxford, England. There is evidence of teaching as early as 1096,

making it the oldest university in the

English-speaking world and the

world's second-oldest university in continuous operation.

It grew rapidly from 1167 when

Henry II banned English students from attending the

University of Paris.

After disputes between students and Oxford townsfolk in 1209, some academics fled north-east to

Cambridge where they established what became the

University of Cambridge.

The two English

ancient universities share many common features and are jointly referred to as ''

Oxbridge

Oxbridge is a portmanteau of Oxford and Cambridge, the two oldest, wealthiest, and most famous universities in the United Kingdom. The term is used to refer to them collectively, in contrast to other British universities, and more broadly to de ...

''. Both are ranked among the most prestigious universities in the world.

The university is made up of

thirty-nine semi-autonomous constituent colleges, five

permanent private halls, and a range of academic departments which are organised into four

divisions. All the colleges are self-governing institutions within the university, each controlling its own membership and with its own internal structure and activities. All students are members of a college.

It does not have a main campus, and its buildings and facilities are scattered throughout the city centre.

Undergraduate teaching at Oxford consists of lectures, small-group

tutorials at the colleges and halls, seminars, laboratory work and occasionally further tutorials provided by the central university faculties and departments.

Postgraduate teaching is provided predominantly centrally.

Oxford operates the world's oldest

university museum

A university museum is a repository of collections run by a university, typically founded to aid teaching and research within the institution of higher learning. The Ashmolean Museum at the University of Oxford in England is an early example, ori ...

, as well as the largest

university press in the world and the largest academic library system nationwide.

In the fiscal year ending 31 July 2019, the university had a total income of £2.45 billion, of which £624.8 million was from research grants and contracts.

Oxford has educated a wide range of notable alumni, including 30

prime ministers of the United Kingdom and many heads of state and government around the world.

73 Nobel Prize laureates, 4 Fields Medalists, and 6 Turing Award winners have studied, worked, or held visiting fellowships at the University of Oxford, while its alumni have won 160

Olympic medals.

Oxford is the home of numerous scholarships, including the

Rhodes Scholarship

The Rhodes Scholarship is an international postgraduate award for students to study at the University of Oxford, in the United Kingdom.

Established in 1902, it is the oldest graduate scholarship in the world. It is considered among the world' ...

, one of the oldest international graduate scholarship programmes.

History

Founding

The University of Oxford's foundation date is unknown.

It is known that teaching at Oxford existed in some form as early as 1096, but it is unclear when the university came into being.

The scholar

Theobald of Étampes

Theobald of Étampes ( la, Theobaldus Stampensis; french: Thibaud or Thibault d'Étampes; born before 1080, died after 1120) was a medieval schoolmaster and theologian hostile to priestly celibacy. He is the first scholar known to have lectured a ...

lectured at Oxford in the early 1100s.

It grew quickly from 1167 when English students returned from the

University of Paris.

The historian

Gerald of Wales lectured to such scholars in 1188, and the first known foreign scholar,

Emo of Friesland, arrived in 1190. The head of the university had the title of

chancellor

Chancellor ( la, cancellarius) is a title of various official positions in the governments of many nations. The original chancellors were the of Roman courts of justice—ushers, who sat at the or lattice work screens of a basilica or law cou ...

from at least 1201, and the masters were recognised as a ''universitas'' or corporation in 1231.

The university was granted a royal charter in 1248 during the reign of King

Henry III.

After disputes between students and Oxford townsfolk in 1209, some academics fled from the violence to

Cambridge, later forming the

University of Cambridge.

The students associated together on the basis of geographical origins, into two '

nations', representing the North (''northerners'' or ''Boreales'', who included the

English people from north of the

River Trent and the

Scots

Scots usually refers to something of, from, or related to Scotland, including:

* Scots language, a language of the West Germanic language family native to Scotland

* Scots people, a nation and ethnic group native to Scotland

* Scoti, a Latin na ...

) and the South (''southerners'' or ''Australes'', who included English people from south of the Trent, the Irish and the

Welsh

Welsh may refer to:

Related to Wales

* Welsh, referring or related to Wales

* Welsh language, a Brittonic Celtic language spoken in Wales

* Welsh people

People

* Welsh (surname)

* Sometimes used as a synonym for the ancient Britons (Celtic peopl ...

).

In later centuries, geographical origins continued to influence many students' affiliations when membership of a

college or

hall

In architecture, a hall is a relatively large space enclosed by a roof and walls. In the Iron Age and early Middle Ages in northern Europe, a mead hall was where a lord and his retainers ate and also slept. Later in the Middle Ages, the gr ...

became customary in Oxford. In addition, members of many

religious order

A religious order is a lineage of communities and organizations of people who live in some way set apart from society in accordance with their specific religious devotion, usually characterized by the principles of its founder's religious practi ...

s, including

Dominicans,

Franciscans,

Carmelites and

Augustinians

Augustinians are members of Christian religious orders that follow the Rule of Saint Augustine, written in about 400 AD by Augustine of Hippo. There are two distinct types of Augustinians in Catholic religious orders dating back to the 12th–13 ...

, settled in Oxford in the mid-13th century, gained influence and maintained houses or halls for students.

[Christopher Brooke, Roger Highfield. Oxford and Cambridge.] At about the same time, private benefactors established colleges as self-contained scholarly communities. Among the earliest such founders were

William of Durham

William of Durham (died 1249) is said to have founded University College, Oxford, England.[Univers ...](_blank)

, who in 1249 endowed

University College,

and

John Balliol, father of a future

King of Scots;

Balliol College bears his name.

Another founder,

Walter de Merton, a

Lord Chancellor of England and afterwards

Bishop of Rochester

The Bishop of Rochester is the ordinary of the Church of England's Diocese of Rochester in the Province of Canterbury.

The town of Rochester has the bishop's seat, at the Cathedral Church of Christ and the Blessed Virgin Mary, which was foun ...

, devised a series of regulations for college life;

Merton College

Merton College (in full: The House or College of Scholars of Merton in the University of Oxford) is one of the constituent colleges of the University of Oxford in England. Its foundation can be traced back to the 1260s when Walter de Merton, ch ...

thereby became the model for such establishments at Oxford, as well as at the University of Cambridge. Thereafter, an increasing number of students lived in colleges rather than in halls and religious houses.

In 1333–1334, an attempt by some dissatisfied Oxford scholars to found a new

university at Stamford, Lincolnshire, was blocked by the universities of Oxford and Cambridge petitioning King

Edward III

Edward III (13 November 1312 – 21 June 1377), also known as Edward of Windsor before his accession, was King of England and Lord of Ireland from January 1327 until his death in 1377. He is noted for his military success and for restoring r ...

. Thereafter, until the 1820s, no new universities were allowed to be founded in England, even in London; thus, Oxford and Cambridge had a duopoly, which was unusual in large western European countries.

Renaissance period

The new learning of the

Renaissance greatly influenced Oxford from the late 15th century onwards. Among university scholars of the period were

William Grocyn, who contributed to the revival of

Greek language studies, and

John Colet, the noted

biblical scholar

Biblical studies is the academic application of a set of diverse disciplines to the study of the Bible (the Old Testament and New Testament).''Introduction to Biblical Studies, Second Edition'' by Steve Moyise (Oct 27, 2004) pages 11–12 Fo ...

.

With the

English Reformation

The English Reformation took place in 16th-century England when the Church of England broke away from the authority of the pope and the Catholic Church. These events were part of the wider European Protestant Reformation, a religious and poli ...

and the breaking of communion with the

Roman Catholic Church,

recusant scholars from Oxford fled to continental Europe, settling especially at the

University of Douai. The method of teaching at Oxford was transformed from the medieval

scholastic method

Scholasticism was a medieval school of philosophy that employed a Organon, critical organic method of philosophical analysis predicated upon the Aristotelianism, Aristotelian categories (Aristotle), 10 Categories. Christian scholasticism eme ...

to Renaissance education, although institutions associated with the university suffered losses of land and revenues. As a centre of learning and scholarship, Oxford's reputation declined in the

Age of Enlightenment; enrolments fell and teaching was neglected.

In 1636,

William Laud, the chancellor and

Archbishop of Canterbury

The archbishop of Canterbury is the senior bishop and a principal leader of the Church of England, the ceremonial head of the worldwide Anglican Communion and the diocesan bishop of the Diocese of Canterbury. The current archbishop is Justi ...

, codified the university's statutes. These, to a large extent, remained its governing regulations until the mid-19th century. Laud was also responsible for the granting of a charter securing privileges for the

University Press, and he made significant contributions to the

Bodleian Library

The Bodleian Library () is the main research library of the University of Oxford, and is one of the oldest libraries in Europe. It derives its name from its founder, Sir Thomas Bodley. With over 13 million printed items, it is the second- ...

, the main library of the university. From the beginnings of the

Church of England as the

established church

A state religion (also called religious state or official religion) is a religion or creed officially endorsed by a sovereign state. A state with an official religion (also known as confessional state), while not secular, is not necessarily a t ...

until 1866, membership of the church was a requirement to receive the BA degree from the university and "

dissenters" were only permitted to receive the MA in 1871.

The university was a centre of the

Royalist party during the

English Civil War (1642–1649), while the town favoured the opposing

Parliamentarian cause. From the mid-18th century onwards, however, the university took little part in political conflicts.

Wadham College, founded in 1610, was the undergraduate college of

Sir Christopher Wren. Wren was part of a brilliant group of experimental scientists at Oxford in the 1650s, the

Oxford Philosophical Club, which included

Robert Boyle and

Robert Hooke

Robert Hooke FRS (; 18 July 16353 March 1703) was an English polymath active as a scientist, natural philosopher and architect, who is credited to be one of two scientists to discover microorganisms in 1665 using a compound microscope that ...

. This group held regular meetings at Wadham under the guidance of the college's Warden,

John Wilkins, and the group formed the nucleus that went on to found the

Royal Society.

Modern period

Students

Before reforms in the early 19th century, the curriculum at Oxford was notoriously narrow and impractical.

Sir Spencer Walpole, a historian of contemporary Britain and a senior government official, had not attended any university. He said, "Few medical men, few solicitors, few persons intended for commerce or trade, ever dreamed of passing through a university career." He quoted the Oxford University Commissioners in 1852 stating: "The education imparted at Oxford was not such as to conduce to the advancement in life of many persons, except those intended for the ministry." Nevertheless, Walpole argued:

Out of the students who matriculated in 1840, 65% were sons of professionals (34% were Anglican ministers). After graduation, 87% became professionals (59% as Anglican clergy). Out of the students who matriculated in 1870, 59% were sons of professionals (25% were Anglican ministers). After graduation, 87% became professionals (42% as Anglican clergy).

M. C. Curthoys and H. S. Jones argue that the rise of organised sport was one of the most remarkable and distinctive features of the history of the universities of Oxford and Cambridge in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. It was carried over from the athleticism prevalent at the public schools such as

Eton,

Winchester

Winchester is a City status in the United Kingdom, cathedral city in Hampshire, England. The city lies at the heart of the wider City of Winchester, a local government Districts of England, district, at the western end of the South Downs Nation ...

,

Shrewsbury

Shrewsbury ( , also ) is a market town, civil parish, and the county town of Shropshire, England, on the River Severn, north-west of London; at the 2021 census, it had a population of 76,782. The town's name can be pronounced as either 'Sh ...

, and

Harrow

Harrow may refer to:

Places

* Harrow, Victoria, Australia

* Harrow, Ontario, Canada

* The Harrow, County Wexford, a village in Ireland

* London Borough of Harrow, England

** Harrow, London, a town in London

** Harrow (UK Parliament constituency)

...

.

All students, regardless of their chosen area of study, were required to spend (at least) their first year preparing for a first-year examination that was heavily focused on

classical languages. Science students found this particularly burdensome and supported a separate science degree with

Greek language study removed from their required courses. This concept of a Bachelor of Science had been adopted at other European universities (

London University had implemented it in 1860) but an 1880 proposal at Oxford to replace the classical requirement with a modern language (like German or French) was unsuccessful. After considerable internal wrangling over the structure of the arts curriculum, in 1886 the "natural science preliminary" was recognized as a qualifying part of the first year examination.

At the start of 1914, the university housed about 3,000 undergraduates and about 100 postgraduate students. During the First World War, many undergraduates and fellows joined the armed forces. By 1918 virtually all fellows were in uniform, and the student population in residence was reduced to 12 per cent of the pre-war total.

The

University Roll of Service records that, in total, 14,792 members of the university served in the war, with 2,716 (18.36%) killed. Not all the members of the university who served in the Great War were on the Allied side; there is a remarkable memorial to members of New College who served in the German armed forces, bearing the inscription, 'In memory of the men of this college who coming from a foreign land entered into the inheritance of this place and returning fought and died for their country in the war 1914–1918'. During the war years the university buildings became hospitals, cadet schools and military training camps.

Reforms

Two parliamentary commissions in 1852 issued recommendations for Oxford and Cambridge.

Archibald Campbell Tait, former headmaster of Rugby School, was a key member of the Oxford Commission; he wanted Oxford to follow the German and Scottish model in which the professorship was paramount. The commission's report envisioned a centralised university run predominantly by professors and faculties, with a much stronger emphasis on research. The professional staff should be strengthened and better paid. For students, restrictions on entry should be dropped, and more opportunities given to poorer families. It called for an enlargement of the curriculum, with honours to be awarded in many new fields. Undergraduate scholarships should be open to all Britons. Graduate fellowships should be opened up to all members of the university. It recommended that fellows be released from an obligation for ordination. Students were to be allowed to save money by boarding in the city, instead of in a college.

The system of separate

honour schools for different subjects began in 1802, with Mathematics and

Literae Humaniores.

Schools of "Natural Sciences" and "Law, and Modern History" were added in 1853.

By 1872, the last of these had split into "Jurisprudence" and "Modern History". Theology became the sixth honour school. In addition to these B.A. Honours degrees, the postgraduate

Bachelor of Civil Law (B.C.L.) was, and still is, offered.

The mid-19th century saw the impact of the

Oxford Movement

The Oxford Movement was a movement of high church members of the Church of England which began in the 1830s and eventually developed into Anglo-Catholicism. The movement, whose original devotees were mostly associated with the University of O ...

(1833–1845), led among others by the future Cardinal

John Henry Newman. The influence of the reformed model of German universities reached Oxford via key scholars such as

Edward Bouverie Pusey,

Benjamin Jowett and

Max Müller.

Administrative reforms during the 19th century included the replacement of oral examinations with written entrance tests, greater tolerance for

religious dissent, and the establishment of four women's colleges. Privy Council decisions in the 20th century (e.g. the abolition of compulsory daily worship, dissociation of the Regius Professorship of Hebrew from clerical status, diversion of colleges' theological bequests to other purposes) loosened the link with traditional belief and practice. Furthermore, although the university's emphasis had historically been on classical knowledge, its curriculum expanded during the 19th century to include scientific and medical studies. Knowledge of

Ancient Greek was required for admission until 1920, and Latin until 1960.

The University of Oxford began to award doctorates for research in the first third of the 20th century. The first Oxford DPhil in mathematics was awarded in 1921.

The mid-20th century saw many distinguished continental scholars, displaced by

Nazism and communism, relocating to Oxford.

The list of distinguished scholars at the University of Oxford is long and includes many who have made major contributions to politics, the sciences, medicine, and literature. As of October 2022, 73 Nobel laureates and more than 50 world leaders have been affiliated with the University of Oxford.

Women's education

The university passed a statute in 1875 allowing examinations for women at roughly undergraduate level;

for a brief period in the early 1900s, this allowed the "

steamboat ladies" to receive ''

ad eundem'' degrees from the

University of Dublin

The University of Dublin ( ga, Ollscoil Átha Cliath), corporately designated the Chancellor, Doctors and Masters of the University of Dublin, is a university located in Dublin, Ireland. It is the degree-awarding body for Trinity College Dubl ...

. In June 1878, the ''

Association for the Education of Women

The Association for the Education of Women or Association for Promoting the Higher Education of Women in Oxford (AEW) was formed in 1878 to promote the education of women at the University of Oxford. It provided lectures and tutorials for stu ...

'' (AEW) was formed, aiming for the eventual creation of a college for women in Oxford. Some of the more prominent members of the association were

George Granville Bradley,

T. H. Green

Thomas Hill Green (7 April 183626 March 1882), known as T. H. Green, was an English philosopher, political radical and temperance reformer, and a member of the British idealism movement. Like all the British idealists, Green was influ ...

and

Edward Stuart Talbot. Talbot insisted on a specifically

Anglican

Anglicanism is a Western Christian tradition that has developed from the practices, liturgy, and identity of the Church of England following the English Reformation, in the context of the Protestant Reformation in Europe. It is one of th ...

institution, which was unacceptable to most of the other members. The two parties eventually split, and Talbot's group founded

Lady Margaret Hall

Lady Margaret Hall (LMH) is one of the constituent colleges of the University of Oxford in England, located on the banks of the River Cherwell at Norham Gardens in north Oxford and adjacent to the University Parks. The college is more formall ...

in 1878, while T. H. Green founded the non-denominational

Somerville College in 1879. Lady Margaret Hall and Somerville opened their doors to their first 21 students (12 from Somerville, 9 from Lady Margaret Hall) in 1879, who attended lectures in rooms above an Oxford baker's shop.

There were also 25 women students living at home or with friends in 1879, a group which evolved into the Society of Oxford Home-Students and in 1952 into

St Anne's College.

These first three societies for women were followed by

St Hugh's (1886) and

St Hilda's (1893). All of these colleges later became coeducational, starting with

Lady Margaret Hall

Lady Margaret Hall (LMH) is one of the constituent colleges of the University of Oxford in England, located on the banks of the River Cherwell at Norham Gardens in north Oxford and adjacent to the University Parks. The college is more formall ...

and

St Anne's in 1979, and finishing with

St Hilda's, which began to accept male students in 2008. In the early 20th century, Oxford and Cambridge were widely perceived to be bastions of

male privilege, however the integration of women into Oxford moved forward during the First World War. In 1916 women were admitted as medical students on a par with men, and in 1917 the university accepted financial responsibility for women's examinations.

On 7 October 1920 women became eligible for admission as full members of the university and were given the right to take degrees. In 1927 the university's dons created a quota that limited the number of female students to a quarter that of men, a ruling which was not abolished until 1957.

However, during this period Oxford colleges were

single sex, so the number of women was also limited by the capacity of the women's colleges to admit students. It was not until 1959 that the women's colleges were given full collegiate status.

In 1974,

Brasenose

Brasenose College (BNC) is one of the constituent colleges of the University of Oxford in the United Kingdom. It began as Brasenose Hall in the 13th century, before being founded as a college in 1509. The library and chapel were added in the mi ...

,

Jesus,

Wadham,

Hertford

Hertford ( ) is the county town of Hertfordshire, England, and is also a civil parish in the East Hertfordshire district of the county. The parish had a population of 26,783 at the 2011 census.

The town grew around a ford on the River Lea, ne ...

and

St Catherine's became the first previously all-male colleges to admit women.

The majority of men's colleges accepted their first female students in 1979,

with

Christ Church following in 1980, and

Oriel becoming the last men's college to admit women in 1985. Most of Oxford's graduate colleges were founded as coeducational establishments in the 20th century, with the exception of St Antony's, which was founded as a men's college in 1950 and began to accept women only in 1962. By 1988, 40% of undergraduates at Oxford were female; in 2016, 45% of the student population, and 47% of undergraduate students, were female.

In June 2017, Oxford announced that starting the following academic year, history students may choose to sit a take-home exam in some courses, with the intention that this will equalise rates of firsts awarded to women and men at Oxford. That same summer, maths and computer science tests were extended by 15 minutes, in a bid to see if female student scores would improve.

The detective novel ''

Gaudy Night'' by

Dorothy L. Sayers, herself one of the first women to gain an academic degree from Oxford, is largely set in the all-female

Shrewsbury College, Oxford (based on Sayers' own

Somerville College), and the issue of women's education is central to its plot. Social historian and Somerville College alumna

Jane Robinson's book ''Bluestockings: A Remarkable History of the First Women to Fight for an Education'' gives a very detailed and immersive account of this history.

Buildings and sites

Map

Main sites

The university is a "city university" in that it does not have a main campus; instead, colleges, departments, accommodation, and other facilities are scattered throughout the city centre. The

Science Area

The Oxford University Science Area in Oxford, England, is where most of the science departments at the University of Oxford are located.

Overview

The main part of the Science Area is located to the south of the University Parks and to the nort ...

, in which most science departments are located, is the area that bears closest resemblance to a campus. The ten-acre (4-hectare)

Radcliffe Observatory Quarter

The Radcliffe Observatory Quarter (ROQ) is a major University of Oxford development project in Oxford, England, in the estate of the old Radcliffe Infirmary hospital.

The site, covering 10 acres (3.7 hectares) is in central north Oxford. It is b ...

in the northwest of the city is currently under development. However, the larger colleges' sites are of similar size to these areas.

Iconic university buildings include the

Radcliffe Camera, the

Sheldonian Theatre used for music concerts, lectures, and university ceremonies, and the

Examination Schools, where examinations and some lectures take place. The

University Church of St Mary the Virgin was used for university ceremonies before the construction of the Sheldonian.

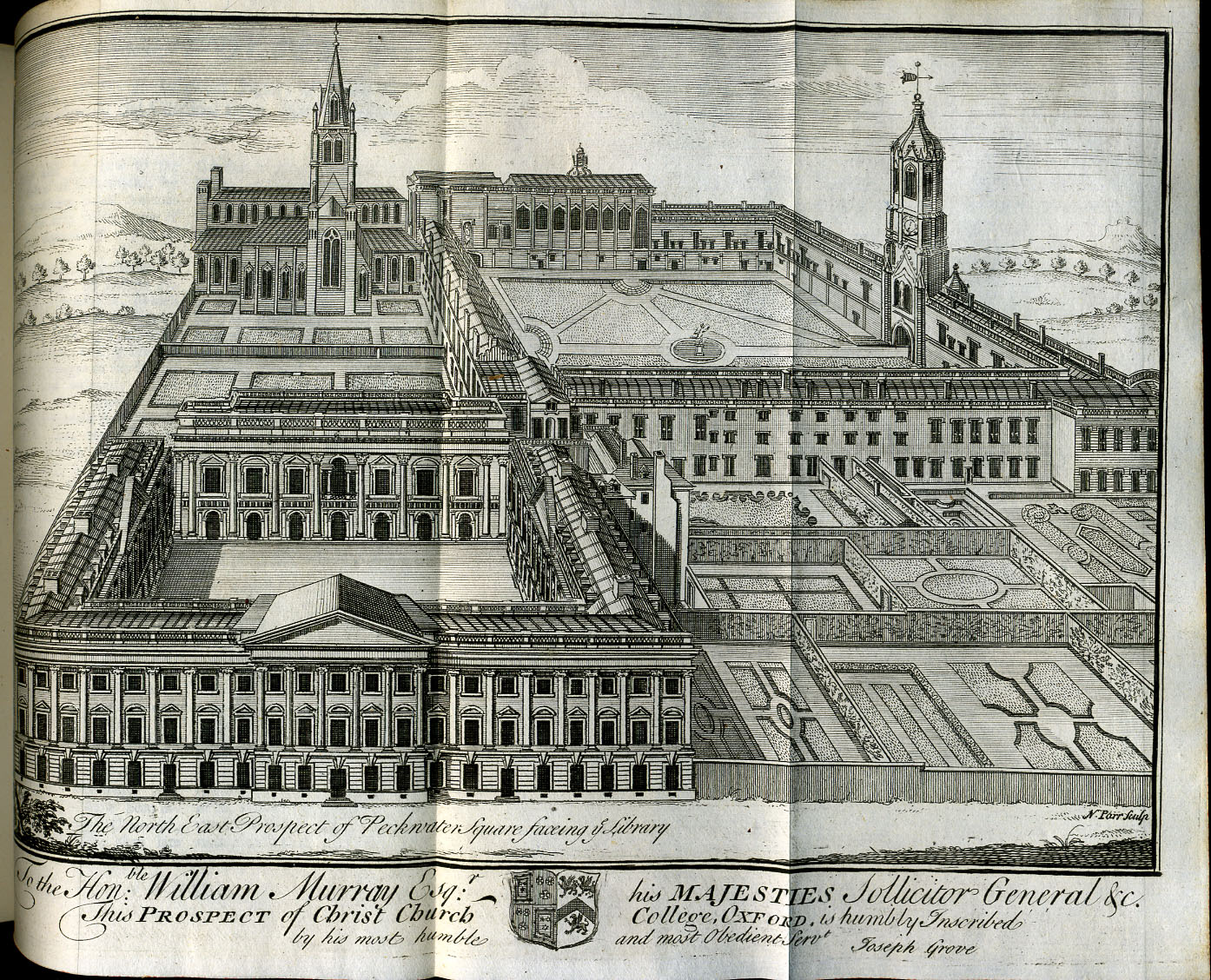

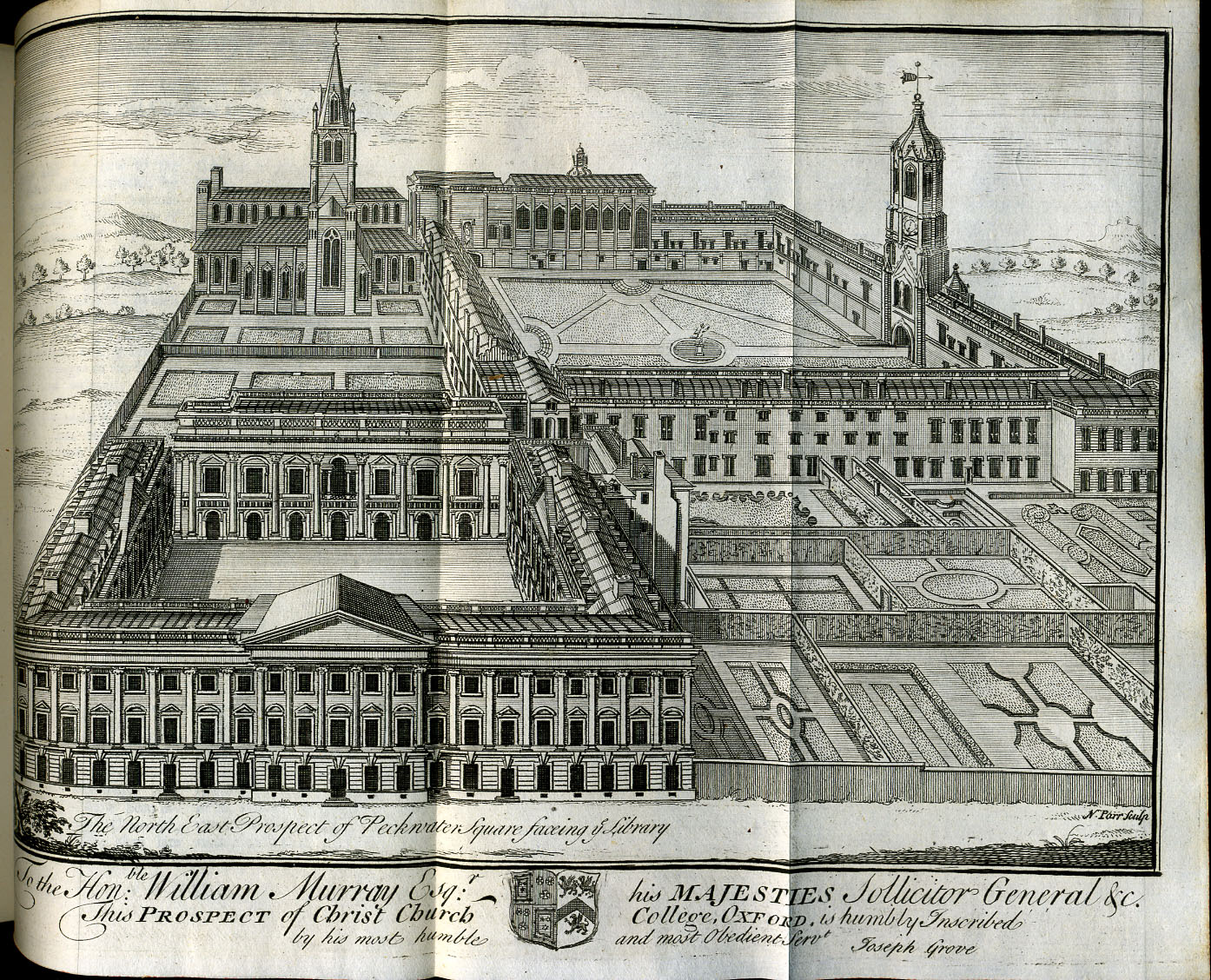

Christ Church Cathedral uniquely serves as both a college chapel and as a cathedral.

In 2012–2013, the university built the controversial one-hectare (400 m × 25 m)

Castle Mill

Castle Mill is a graduate housing complex of the University of Oxford in Oxford, England.

Overview

Castle Mill is located north of Oxford railway station along Roger Dudman Way, just to the west of the railway tracks and the Oxford Down Ca ...

development of 4–5-storey blocks of student flats overlooking

Cripley Meadow and the historic

Port Meadow, blocking views of the spires in the city centre. The development has been likened to building a "skyscraper beside

Stonehenge

Stonehenge is a prehistoric monument on Salisbury Plain in Wiltshire, England, west of Amesbury. It consists of an outer ring of vertical sarsen standing stones, each around high, wide, and weighing around 25 tons, topped by connectin ...

".

Parks

The

University Parks are a 70-acre (28 ha) parkland area in the northeast of the city, near

Keble College,

Somerville College and

Lady Margaret Hall

Lady Margaret Hall (LMH) is one of the constituent colleges of the University of Oxford in England, located on the banks of the River Cherwell at Norham Gardens in north Oxford and adjacent to the University Parks. The college is more formall ...

. It is open to the public during daylight hours. As well as providing gardens and exotic plants, the Parks contains numerous sports fields, used for official and unofficial fixtures, and also contains sites of special interest including the Genetic Garden, an experimental garden to elucidate and investigate evolutionary processes.

The

Botanic Garden on the

High Street is the oldest

botanic garden in the UK. It contains over 8,000 different plant species on . It is one of the most diverse yet compact major collections of plants in the world and includes representatives of over 90% of the higher plant families. The

Harcourt Arboretum is a site six miles (10 km) south of the city that includes native woodland and of meadow. The

Wytham Woods

Wytham Woods are a biological Site of Special Scientific Interest north-west of Oxford in Oxfordshire. It is a Nature Conservation Review site.

Habitats in this site, which formerly belonged to Abingdon Abbey, include ancient woodland and limes ...

are owned by the university and used for research in

zoology and

climate change.

There are also various collegiate-owned open spaces open to the public, including

Bagley Wood

Bagley Wood is a wood in the parish of Kennington between Oxford and Abingdon in Oxfordshire, England (in Berkshire until 1974). It is traversed from north to south by the A34 road, which was rerouted through the wood in 1972.

History

Bagley W ...

and most notably

Christ Church Meadow.

Organisation

As a

collegiate university, Oxford is structured as a federation, comprising over forty self-governing

colleges

A college (Latin: ''collegium'') is an educational institution or a constituent part of one. A college may be a degree-awarding tertiary educational institution, a part of a collegiate or federal university, an institution offerin ...

and

halls, along with a central administration headed by the

Vice-Chancellor.

Academic departments are located centrally within the structure of the federation; they are not affiliated with any particular college. Departments provide facilities for teaching and research, determine the syllabi and guidelines for the teaching of students, perform research, and deliver lectures and seminars.

Colleges arrange the tutorial teaching for their undergraduates, and the members of an academic department are spread around many colleges. Though certain colleges do have subject alignments (e.g.,

Nuffield College

Nuffield College () is one of the constituent colleges of the University of Oxford in England. It is a graduate college and specialises in the social sciences, particularly economics, politics and sociology. Nuffield is one of Oxford's newer co ...

as a centre for the social sciences), these are exceptions, and most colleges will have a broad mix of academics and students from a diverse range of subjects. Facilities such as libraries are provided on all these levels: by the central university (the

Bodleian), by the departments (individual departmental libraries, such as the English Faculty Library), and by colleges (each of which maintains a multi-discipline library for the use of its members).

Central governance

The university's formal head is the

Chancellor

Chancellor ( la, cancellarius) is a title of various official positions in the governments of many nations. The original chancellors were the of Roman courts of justice—ushers, who sat at the or lattice work screens of a basilica or law cou ...

, currently

Lord Patten of Barnes

Christopher Francis Patten, Baron Patten of Barnes, (; born 12 May 1944) is a British politician who was the 28th and last Governor of Hong Kong from 1992 to 1997 and Chairman of the Conservative Party from 1990 to 1992. He was made a life pe ...

, though as at most British universities, the Chancellor is a titular figure and is not involved with the day-to-day running of the university. The Chancellor is elected by the members of

Convocation

A convocation (from the Latin ''wikt:convocare, convocare'' meaning "to call/come together", a translation of the Ancient Greek, Greek wikt:ἐκκλησία, ἐκκλησία ''ekklēsia'') is a group of people formally assembled for a speci ...

, a body comprising all graduates of the university, and holds office until death.

The

Vice-Chancellor, currently

Louise Richardson,

is the ''de facto'' head of the university. Five pro-vice-chancellors have specific responsibilities for education; research; planning and resources; development and external affairs; and personnel and equal opportunities. The University Council is the executive policy-forming body, which consists of the vice-chancellor as well as heads of departments and other members elected by

Congregation, in addition to observers from the

students' union

A students' union, also known by many other names, is a student organization present in many colleges, universities, and high schools. In higher education, the students' union is often accorded its own building on the campus, dedicated to social, ...

. Congregation, the "parliament of the dons", comprises over 3,700 members of the university's academic and administrative staff, and has ultimate responsibility for legislative matters: it discusses and pronounces on policies proposed by the University Council.

Two university

proctors, elected annually on a rotating basis from two of the colleges, are the internal ombudsmen who make sure that the university and its members adhere to its statutes. This role incorporates student discipline and complaints, as well as oversight of the university's proceedings. The university's professors are collectively referred to as the

Statutory Professors of the University of Oxford. They are particularly influential in the running of the university's graduate programmes. Examples of statutory professors are the

Chichele Professorships and the

Drummond Professor of Political Economy

The Drummond Professorship of Political Economy at All Souls College, Oxford has been held by a number of distinguished individuals, including three Nobel laureates. The professorship is named after and was founded by Henry Drummond.

List of ...

. The various academic faculties, departments, and institutes are organised into four

divisions, each with its own head and elected board. They are the Humanities Division; the Social Sciences Division; the Mathematical, Physical and Life Sciences Division; and the Medical Sciences Division.

The University of Oxford is a "public university" in the sense that it receives some public money from the government, but it is a "private university" in the sense that it is entirely self-governing and, in theory, could choose to become entirely private by rejecting public funds.

Colleges

To be a member of the university, all students, and most academic staff, must also be a member of a college or hall. There are thirty-nine

colleges of the University of Oxford and five

permanent private halls (PPHs), each controlling its membership and with its own internal structure and activities.

Not all colleges offer all courses, but they generally cover a broad range of subjects.

The colleges are:

The permanent private halls were founded by different Christian denominations. One difference between a college and a PPH is that whereas colleges are governed by the

fellows Fellows may refer to Fellow, in plural form.

Fellows or Fellowes may also refer to:

Places

* Fellows, California, USA

* Fellows, Wisconsin, ghost town, USA

Other uses

* Fellows Auctioneers, established in 1876.

*Fellowes, Inc., manufacturer of wo ...

of the college, the governance of a PPH resides, at least in part, with the corresponding Christian denomination. The five current PPHs are:

The PPHs and colleges join as the Conference of Colleges, which represents the common concerns of the several

colleges

A college (Latin: ''collegium'') is an educational institution or a constituent part of one. A college may be a degree-awarding tertiary educational institution, a part of a collegiate or federal university, an institution offerin ...

of the university, to discuss matters of shared interest and to act collectively when necessary, such as in dealings with the central university. The Conference of Colleges was established as a recommendation of the

Franks Commission in 1965.

Teaching members of the colleges (i.e. fellows and tutors) are collectively and familiarly known as

dons, although the term is rarely used by the university itself. In addition to residential and dining facilities, the colleges provide social, cultural, and recreational activities for their members. Colleges have responsibility for admitting undergraduates and organising their tuition; for graduates, this responsibility falls upon the departments. There is no common title for the heads of colleges: the titles used include Warden, Provost, Principal, President, Rector, Master and Dean.

Finances

In 2017–18, the university had an income of £2,237m; key sources were research grants (£579.1m) and academic fees (£332.5m).

The colleges had a total income of £492.9m.

While the university has a larger annual income and operating budget, the colleges have a larger aggregate endowment: over £4.9bn compared to the university's £1.2bn.

The central University's endowment, along with some of the colleges', is managed by the university's wholly-owned endowment management office, Oxford University Endowment Management, formed in 2007. The university used to maintain substantial investments in fossil fuel companies. However, in April 2020, the university committed to divest from direct investments in fossil fuel companies and to require indirect investments in fossil fuel companies be subjected to the Oxford Martin Principles.

The total assets of the colleges of £6.3 billion also exceed total university assets of £4.1 billion.

The college figure does not reflect all the assets held by the colleges as their accounts do not include the cost or value of many of their main sites or heritage assets such as works of art or libraries.

The university was one of the first in the UK to raise money through a major public fundraising campaign, the

Campaign for Oxford

The Campaign for the University of Oxford, or simply Campaign for Oxford, is a fundraising appeal for the University of Oxford, started in 1988.

It is the biggest fundraising campaign for Higher Education in Europe and one of the largest u ...

. The current campaign, its second, was launched in May 2008 and is entitled "Oxford Thinking – The Campaign for the University of Oxford". This is looking to support three areas: academic posts and programmes, student support, and buildings and infrastructure; having passed its original target of £1.25 billion in March 2012, the target was raised to £3 billion.

The campaign had raised a total of £2.8 billion by July 2018.

Funding criticisms

The university has faced criticism for some of its sources of donations and funding. In 2017, attention was drawn to historical donations including All Souls College receiving £10,000 from slave trader

Christopher Codrington in 1710, and Oriel College having receiving taken £100,000 from the will of the imperialist

Cecil Rhodes

Cecil John Rhodes (5 July 1853 – 26 March 1902) was a British mining magnate and politician in southern Africa who served as Prime Minister of the Cape Colony from 1890 to 1896.

An ardent believer in British imperialism, Rhodes and his Br ...

in 1902. In 1996 a donation of £20 million was received from

Wafic Saïd

Wafic Rida Saïd ( ar, وفيق رضا سعيد) (born 21 December 1939) is a Syrian- Saudi-Canadian financier, businessman, and philanthropist, who has resided for many years in Monaco.David Pallister, 'The man of substance in the shadows', ''T ...

who was involved in the

Al-Yammah arms deal, and taking £150 million from the US billionaire businessman

Stephen A. Schwarzman

Stephen Allen Schwarzman (born February 14, 1947) is an American billionaire businessman. He is the chairman and CEO of The Blackstone Group, a global private equity firm he established in 1985 with Peter G. Peterson, former chairman and CEO of ...

in 2019. The university has defended its decisions saying it "takes legal, ethical and reputational issues into consideration."

The university has also faced criticism, as noted above, over its decision to accept donations from fossil fuel companies having received £21.8 million from the fossil fuel industry between 2010 and 2015 and £18.8 million between 2015 and 2020.

The university accepted £6 million from The Alexander Mosley Charitable Trust in 2021. Former racing driver

Max Mosley claims to have set up the trust "to house the fortune he inherited" from his father,

Oswald Mosley who was founder of two far right groups

Union Movement and the

British Union of Fascists

The British Union of Fascists (BUF) was a British fascist political party formed in 1932 by Oswald Mosley. Mosley changed its name to the British Union of Fascists and National Socialists in 1936 and, in 1937, to the British Union. In 1939, fo ...

.

Affiliations

Oxford is a member of the

Russell Group of research-led

British universities, the

G5, the

League of European Research Universities, and the

International Alliance of Research Universities. It is also a core member of the

Europaeum and forms part of the "

golden triangle" of highly research intensive and elite English universities.

Academic profile

Admission

In common with most British universities, prospective students apply through the

UCAS application system, but prospective applicants for the University of Oxford, along with those for medicine, dentistry, and

University of Cambridge applicants, must observe an earlier deadline of 15 October. The

Sutton Trust maintains that Oxford University and Cambridge University recruit disproportionately from 8 schools which accounted for 1,310 Oxbridge places during three years, contrasted with 1,220 from 2,900 other schools.

To allow a more personalised judgement of students, who might otherwise apply for both, undergraduate applicants are not permitted to apply to both Oxford and Cambridge in the same year. The only exceptions are applicants for

organ scholarships and those applying to read for a second undergraduate degree.

Oxford has the lowest offer rate of all Russell Group universities.

Most applicants choose to apply to one of the individual colleges, which work with each other to ensure that the best students gain a place somewhere at the university regardless of their college preferences. Shortlisting is based on achieved and predicted exam results, school references, and, in some subjects, written admission tests or candidate-submitted written work. Approximately 60% of applicants are shortlisted, although this varies by subject. If a large number of shortlisted applicants for a subject choose one college, then students who named that college may be reallocated randomly to under-subscribed colleges for the subject. The colleges then invite shortlisted candidates for interview, where they are provided with food and accommodation for around three days in December. Most applicants will be individually interviewed by academics at more than one college. Students from outside Europe can be interviewed remotely, for example, over the Internet.

Offers are sent out in early January, with each offer usually being from a specific college. One in four successful candidates receives an offer from a college that they did not apply to. Some courses may make "open offers" to some candidates, who are not assigned to a particular college until

A Level results day in August.

The university has come under criticism for the number of students it accepts from private schools; for instance,

Laura Spence's rejection from the university in 2000 led to widespread debate. In 2016, the University of Oxford gave 59% of offers to UK students to students from state schools, while about 93% of all UK pupils and 86% of post-16 UK pupils are educated in state schools.

However, 64% of UK applicants were from state schools and the university notes that state school students apply disproportionately to oversubscribed subjects. The proportion of students coming from state schools has been increasing. From 2015 to 2019, the state proportion of total UK students admitted each year was: 55.6%, 58.0%, 58.2%, 60.5% and 62.3%.

Oxford University spends over £6 million per year on outreach programs to encourage applicants from underrepresented demographics.

In 2018 the university's annual admissions report revealed that eight of Oxford's colleges had accepted fewer than three black applicants in the past three years.

Labour MP

David Lammy

David Lindon Lammy (born 19 July 1972) is an English politician serving as Shadow Secretary of State for Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Affairs since 2021. A member of the Labour Party, he has been Member of Parliament (MP) for Tottenh ...

said, "This is social apartheid and it is utterly unrepresentative of life in modern Britain." In 2020, Oxford had increased its proportion of Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic (BAME) students to record levels.

The number of BAME undergraduates accepted to the university in 2020 rose to 684 students, or 23.6% of the UK intake, up from 558 or 22% in 2019; the number of Black students was 106 (3.7% of the intake), up from 80 students (3.2%).

UCAS data also showed that Oxford is more likely than comparable institutions to make offers to ethnic minority and socially disadvantaged pupils.

Teaching and degrees

Undergraduate teaching is centred on the tutorial, where 1–4 students spend an hour with an academic discussing their week's work, usually an essay (humanities, most social sciences, some mathematical, physical, and life sciences) or problem sheet (most mathematical, physical, and life sciences, and some social sciences). The university itself is responsible for conducting examinations and conferring degrees. Undergraduate teaching takes place during three eight-week academic terms:

Michaelmas,

Hilary and

Trinity. (These are officially known as 'Full Term': 'Term' is a lengthier period with little practical significance.) Internally, the weeks in a term begin on Sundays, and are referred to numerically, with the initial week known as "first week", the last as "eighth week" and with the numbering extended to refer to weeks before and after term (for example "noughth week" precedes term). Undergraduates must be in residence from Thursday of 0th week. These teaching terms are shorter than those of most other British universities, and their total duration amounts to less than half the year. However, undergraduates are also expected to do some academic work during the three holidays (known as the Christmas, Easter, and Long Vacations).

Research degrees at the master's and doctoral level are conferred in all subjects studied at graduate level at the university.

Scholarships and financial support

There are many opportunities for students at Oxford to receive financial help during their studies. The Oxford Opportunity Bursaries, introduced in 2006, are university-wide means-based bursaries available to any British undergraduate, with a total possible grant of £10,235 over a 3-year degree. In addition, individual colleges also offer bursaries and funds to help their students. For graduate study, there are many scholarships attached to the university, available to students from all sorts of backgrounds, from

Rhodes Scholarship

The Rhodes Scholarship is an international postgraduate award for students to study at the University of Oxford, in the United Kingdom.

Established in 1902, it is the oldest graduate scholarship in the world. It is considered among the world' ...

s to the relatively new Weidenfeld Scholarships. Oxford also offers the

Clarendon Scholarship

The Clarendon Fund Scholarship is a scholarship at the University of Oxford. All Oxford University applicants to degree bearing graduate courses are automatically considered for the Clarendon Scholarship.

Established in 2000 and launched in 200 ...

which is open to graduate applicants of all nationalities. The Clarendon Scholarship is principally funded by

Oxford University Press in association with colleges and other partnership awards. In 2016, Oxford University announced that it is to run its first free online economics course as part of a "

massive open online course" (Mooc) scheme, in partnership with a US online university network. The course available is called 'From Poverty to Prosperity: Understanding Economic Development'.

Students successful in early examinations are rewarded by their colleges with scholarships and

exhibitions, normally the result of a long-standing endowment, although since the introduction of tuition fees the amounts of money available are purely nominal. Scholars, and exhibitioners in some colleges, are entitled to wear a more voluminous undergraduate gown; "commoners" (originally those who had to pay for their "commons", or food and lodging) are restricted to a short, sleeveless garment. The term "scholar" in relation to Oxford therefore has a specific meaning as well as the more general meaning of someone of outstanding academic ability. In previous times, there were "noblemen commoners" and "gentlemen commoners", but these ranks were abolished in the 19th century. "Closed" scholarships, available only to candidates who fitted specific conditions such as coming from specific schools, were abolished in the 1970s and 1980s.

Libraries

The university maintains the largest university library system in the UK,

and, with over 11 million volumes housed on of shelving, the Bodleian group is the second-largest library in the UK, after the

British Library. The Bodleian is a

legal deposit library, which means that it is entitled to request a free copy of every book published in the UK. As such, its collection is growing at a rate of over three miles (five kilometres) of shelving every year.

The buildings referred to as the university's main research library,

The Bodleian

The Bodleian Library () is the main research library of the University of Oxford, and is one of the oldest libraries in Europe. It derives its name from its founder, Sir Thomas Bodley. With over 13 million printed items, it is the secon ...

, consist of the original Bodleian Library in the Old Schools Quadrangle, founded by

Sir Thomas Bodley

Sir Thomas Bodley (2 March 1545 – 28 January 1613) was an English diplomat and scholar who founded the Bodleian Library in Oxford.

Origins

Thomas Bodley was born on 2 March 1545, in the second-to-last year of the reign of King Henry VIII, ...

in 1598 and opened in 1602, the

Radcliffe Camera, the

Clarendon Building, and the

Weston Library. A tunnel underneath

Broad Street connects these buildings, with the Gladstone Link, which opened to readers in 2011, connecting the Old Bodleian and Radcliffe Camera.

The

Bodleian Libraries

The Bodleian Libraries are a collection of 28 libraries that serve the University of Oxford in England, including the Bodleian Library itself, as well as many other (but not all) central and faculty libraries. As of the 2016–17 year, the librari ...

group was formed in 2000, bringing the Bodleian Library and some of the subject libraries together.

It now comprises 28

libraries, a number of which have been created by bringing previously separate collections together, including the

Sackler Library,

Law Library,

Social Science Library and

Radcliffe Science Library

The Radcliffe Science Library (RSL) is the main teaching and research science library at the University of Oxford in Oxford, England. Being officially part of the Bodleian Libraries, the library holds the Legal Deposit material for the sciences a ...

.

Another major product of this collaboration has been a joint integrated library system,

OLIS

OLiS (Oficjalna Lista Sprzedaży; en, Official Sales Chart) is the official chart of the highest selling music albums in Poland. The chart exists since 23 October 2000 and is provided by Polish Society of the Phonographic Industry, ZPAV.

This is ...

(Oxford Libraries Information System), and its public interface, SOLO (Search Oxford Libraries Online), which provides an electronic catalogue covering all member libraries, as well as the libraries of individual colleges and other faculty libraries, which are not members of the group but do share cataloguing information.

A new book depository opened in

South Marston,

Swindon

Swindon () is a town and unitary authority with Borough status in the United Kingdom, borough status in Wiltshire, England. As of the 2021 Census, the population of Swindon was 201,669, making it the largest town in the county. The Swindon un ...

in October 2010, and recent building projects include the remodelling of the New Bodleian building, which was renamed the Weston Library when it reopened in 2015.

The renovation is designed to better showcase the library's various treasures (which include a Shakespeare

First Folio and a

Gutenberg Bible) as well as temporary exhibitions.

The Bodleian engaged in a mass-digitisation project with Google in 2004. Notable electronic resources hosted by the Bodleian Group include the ''Electronic Enlightenment Project'', which was awarded the 2010 Digital Prize by the

British Society for Eighteenth-Century Studies.

Museums

Oxford maintains a number of museums and galleries, open for free to the public. The

Ashmolean Museum

The Ashmolean Museum of Art and Archaeology () on Beaumont Street, Oxford, England, is Britain's first public museum. Its first building was erected in 1678–1683 to house the cabinet of curiosities that Elias Ashmole gave to the University of ...

, founded in 1683, is the oldest museum in the UK, and the oldest university museum in the world. It holds significant collections of art and archaeology, including works by

Michelangelo

Michelangelo di Lodovico Buonarroti Simoni (; 6 March 1475 – 18 February 1564), known as Michelangelo (), was an Italian sculptor, painter, architect, and poet of the High Renaissance. Born in the Republic of Florence, his work was insp ...

,

Leonardo da Vinci,

Turner, and

Picasso

Pablo Ruiz Picasso (25 October 1881 – 8 April 1973) was a Spanish painter, sculptor, printmaker, ceramicist and Scenic design, theatre designer who spent most of his adult life in France. One of the most influential artists of the 20th ce ...

, as well as treasures such as the

Scorpion Macehead, the

Parian Marble and the

Alfred Jewel

The Alfred Jewel is a piece of Anglo-Saxon goldsmithing work made of enamel and quartz enclosed in gold. It was discovered in 1693, in North Petherton, Somerset, England and is now one of the most popular exhibits at the Ashmolean Museum in Ox ...

. It also contains "

The Messiah

In Abrahamic religions, a messiah or messias (; ,

; ,

; ) is a saviour or liberator of a group of people. The concepts of ''mashiach'', messianism, and of a Messianic Age originated in Judaism, and in the Hebrew Bible, in which a ''mashiach'' ...

", a pristine Stradivarius violin, regarded by some as one of the finest examples in existence.

The

University Museum of Natural History holds the university's zoological, entomological and geological specimens. It is housed in a large neo-Gothic building on

Parks Road, in the university's

Science Area

The Oxford University Science Area in Oxford, England, is where most of the science departments at the University of Oxford are located.

Overview

The main part of the Science Area is located to the south of the University Parks and to the nort ...

. Among its collection are the skeletons of a ''

Tyrannosaurus rex'' and ''

Triceratops'', and the most complete remains of a

dodo found anywhere in the world. It also hosts the

Simonyi Professorship of the Public Understanding of Science, currently held by

Marcus du Sautoy.

Adjoining the Museum of Natural History is the

Pitt Rivers Museum, founded in 1884, which displays the university's archaeological and anthropological collections, currently holding over 500,000 items. It recently built a new research annexe; its staff have been involved with the teaching of anthropology at Oxford since its foundation, when as part of his donation General

Augustus Pitt Rivers stipulated that the university establish a lectureship in anthropology.

The

Museum of the History of Science is housed on Broad Street in the world's oldest-surviving purpose-built museum building. It contains 15,000 artefacts, from antiquity to the 20th century, representing almost all aspects of the

history of science

The history of science covers the development of science from ancient times to the present. It encompasses all three major branches of science: natural, social, and formal.

Science's earliest roots can be traced to Ancient Egypt and Meso ...

. In the Faculty of Music on

St Aldate's

St Aldate's () is a street in central Oxford, England, named after Saint Aldate, but formerly known as Fish Street.

The street runs south from the generally acknowledged centre of Oxford at Carfax. The Town Hall, which includes the Museum o ...

is the

Bate Collection of Musical Instruments, a collection mostly of instruments from Western classical music, from the medieval period onwards.

Christ Church Picture Gallery holds a collection of over 200

old master paintings.

Publishing

The Oxford University Press is the world's second oldest and currently the largest

university press by the number of publications.

More than 6,000 new books are published annually, including many reference, professional, and academic works (such as the ''

Oxford English Dictionary'', the ''

Concise Oxford English Dictionary

The ''Concise Oxford English Dictionary'' (officially titled ''The Concise Oxford Dictionary'' until 2002, and widely abbreviated ''COD'' or ''COED'') is probably the best-known of the 'smaller' Oxford dictionaries. The latest edition contains ...

'', the ''

Oxford World's Classics'', the ''

Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'', and the ''

Concise Dictionary of National Biography

''The Concise Dictionary of National Biography: From Earliest Times to 1985'' is a dictionary of biographies of people from the United Kingdom. It was published in three volumes by Oxford University Press in 1992.. The dictionary provides summa ...

'').

Rankings and reputation

Oxford is regularly ranked within the top five universities in the world and is currently ranked first in the world in the ''

Times Higher Education World University Rankings'', as well as the

Forbes's World University Rankings. It held the number one position in the ''Times Good University Guide'' for eleven consecutive years, and the

medical school

A medical school is a tertiary educational institution, or part of such an institution, that teaches medicine, and awards a professional degree for physicians. Such medical degrees include the Bachelor of Medicine, Bachelor of Surgery (MBBS, M ...

has also maintained first place in the "Clinical, Pre-Clinical & Health" table of the ''Times Higher Education (THE) World University Rankings'' for the past seven consecutive years. In 2021, it ranked sixth among the universities around the world by

SCImago Institutions Rankings. The ''THE'' has also recognised Oxford as one of the world's "six super brands" on its ''World Reputation Rankings'', along with

Berkeley,

Cambridge,

Harvard

Harvard University is a private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Founded in 1636 as Harvard College and named for its first benefactor, the Puritan clergyman John Harvard, it is the oldest institution of higher le ...

,

MIT, and

Stanford

Stanford University, officially Leland Stanford Junior University, is a private research university in Stanford, California. The campus occupies , among the largest in the United States, and enrolls over 17,000 students. Stanford is considere ...

. The university is fifth worldwide on the ''

US News'' ranking. Its

Saïd Business School came 13th in the world in ''Financial Times'' ''Global MBA Ranking''.

Oxford was ranked 13th in the world in 2022 by the Nature Index, which measures the largest contributors to papers published in 82 leading journals.

It is ranked fifth best university worldwide and first in Britain for forming

CEOs according to the

''Professional Ranking World Universities'', and first in the UK for the quality of its graduates as chosen by the recruiters of the UK's major companies.

In the 2018

Complete University Guide, all 38 subjects offered by Oxford rank within the top 10 nationally meaning Oxford was one of only two multi-faculty universities (along with

Cambridge) in the UK to have 100% of their subjects in the top 10. Computer Science, Medicine, Philosophy, Politics and Psychology were ranked first in the UK by the guide.

According to the QS World University Rankings by Subject, the University of Oxford also ranks as number one in the world for four Humanities disciplines: English Language and Literature,

Modern Languages,

Geography, and History. It also ranks second globally for Anthropology, Archaeology, Law, Medicine, Politics & International Studies, and Psychology.

Student life

Traditions

Academic dress

Academic dress is a traditional form of clothing for academic settings, mainly tertiary (and sometimes secondary) education, worn mainly by those who have obtained a university degree (or similar), or hold a status that entitles them to assum ...

is required for examinations, matriculation, disciplinary hearings, and when visiting university officers. A referendum held among the Oxford student body in 2015 showed 76% against making it voluntary in examinations – 8,671 students voted, with the 40.2% turnout the highest ever for a UK student union referendum. This was widely interpreted by students as being a vote not so much on making

subfusc voluntary, but rather, in effect, on abolishing it by default, in that if a minority of people came to exams without subfusc, the rest would soon follow. In July 2012 the regulations regarding academic dress were modified to be more inclusive to

transgender people.

Other traditions and customs vary by college. For example, some colleges have

formal hall

Formal hall or formal meal is a meal held at some of the oldest universities in the United Kingdom and the Republic of Ireland (as well as some other Commonwealth countries) at which students usually dress in formal attire and often gowns to d ...

six times a week, but in others this only happens occasionally, or even not at all. At most colleges these formal meals require gowns to be worn, and a Latin grace is said.

''Balls'' are major events held by colleges; the largest, held triennially in ninth week of Trinity Term, are called

commemoration ball

A Commemoration ball is a formal ball held by one of the colleges of the University of Oxford in the 9th week of Trinity Term, the week after the end of the last Full Term of the academic year, which is known as "Commemoration Week". Commemorati ...

s; the dress code is usually

white tie. Many other colleges hold smaller events during the year that they call summer balls or parties. These are usually held on an annual or irregular basis, and are usually

black tie

Black tie is a semi-formal Western dress code for evening events, originating in British and American conventions for attire in the 19th century. In British English, the dress code is often referred to synecdochically by its principal element fo ...

.

Punting is a common summer leisure activity.

There are several more or less quirky traditions peculiar to individual colleges, for example the

All Souls Mallard song.

Clubs and societies

Sport is played between college teams, in tournaments known as

cuppers (the term is also used for some non-sporting competitions). In addition to these there are higher standard

university wide groups. Significant focus is given to annual

varsity

Varsity may refer to:

*University, an institution of higher (or tertiary) education and research which awards academic degrees in various academic disciplines

Places

*Varsity, Calgary, a neighbourhood in Calgary, Alberta, Canada

* Varsity Lakes ...

matches played against Cambridge, the most famous of which is

The Boat Race, watched by a TV audience of between five and ten million viewers. This outside interest reflects the importance of rowing to many of those within the university. Much attention is given to the termly intercollegiate rowing regattas: Christ Church Regatta,

Torpids, and

Summer Eights. A

blue is an award given to those who compete at the university team level in certain sports. As well as traditional sports, there are teams for activities such as

Octopush and

quidditch.

There are two weekly student newspapers: the independent ''

Cherwell'' and OUSU's ''

The Oxford Student''. Other publications include the

''Isis'' magazine, the satirical ''

Oxymoron

An oxymoron (usual plural oxymorons, more rarely oxymora) is a figure of speech that juxtaposes concepts with opposing meanings within a word or phrase that creates an ostensible self-contradiction. An oxymoron can be used as a rhetorical devi ...

'', the graduate ''

Oxonian Review'', the ''Oxford Political Review'', and the online only newspaper ''The Oxford Blue''. The

student radio station is

Oxide Radio. Most colleges have chapel choirs. Music, drama, and other arts societies exist both at the collegiate level and as university-wide groups, such as the

Oxford University Dramatic Society and the

Oxford Revue. Unlike most other collegiate societies, musical ensembles actively encourage players from other colleges.

Most academic areas have student societies of some form which are open to students studying all courses, for example the

Scientific Society. There are groups for almost all faiths, political parties, countries, and cultures.

The

Oxford Union (not to be confused with the

Oxford University Student Union) hosts weekly debates and high-profile speakers. There have historically been elite invitation-only societies such as the

Bullingdon Club

The Bullingdon Club is a private all-male dining club for Oxford University students. It is known for its wealthy members, grand banquets, and bad behaviour, including vandalism of restaurants and students' rooms. The club is known to select it ...

.

Student union and common rooms

The

Oxford University Student Union, formerly better known by its acronym OUSU and now rebranded as Oxford SU,

exists to represent students in the university's decision-making, to act as the voice for students in the national higher education policy debate, and to provide direct services to the student body. Reflecting the collegiate nature of the University of Oxford itself, OUSU is both an association of Oxford's more than 21,000 individual students and a federation of the affiliated college common rooms, and other affiliated organisations that represent subsets of the undergraduate and graduate students. The OUSU Executive Committee includes six full-time salaried sabbatical officers, who generally serve in the year following completion of their Final Examinations.

The importance of collegiate life is such that for many students their college JCR (Junior Common Room, for undergraduates) or MCR (Middle Common Room, for graduates) is seen as more important than OUSU. JCRs and MCRs each have a committee, with a president and other elected students representing their peers to college authorities. Additionally, they organise events and often have significant budgets to spend as they wish (money coming from their colleges and sometimes other sources such as student-run bars). (It is worth noting that JCR and MCR are terms that are used to refer to rooms for use by members, as well as the student bodies.) Not all colleges use this JCR/MCR structure, for example

Wadham College's entire student population is represented by a combined Students' Union and purely graduate colleges have different arrangements.

Notable alumni

Throughout its history, a sizeable number of Oxford alumni, known as Oxonians, have become notable in many varied fields, both academic and otherwise. A total of 70 Nobel prize-winners have studied or taught at Oxford, with prizes won in all six categories.

More information on notable members of the university can be found in the

individual college articles. An individual may be associated with two or more colleges, as an undergraduate, postgraduate and/or member of staff.

Politics

Thirty British

prime ministers have attended Oxford, including

William Gladstone

William Ewart Gladstone ( ; 29 December 1809 – 19 May 1898) was a British statesman and Liberal politician. In a career lasting over 60 years, he served for 12 years as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, spread over four non-conse ...

,

H. H. Asquith,

Clement Attlee

Clement Richard Attlee, 1st Earl Attlee, (3 January 18838 October 1967) was a British politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1945 to 1951 and Leader of the Labour Party from 1935 to 1955. He was Deputy Prime Mini ...

,

Harold Macmillan

Maurice Harold Macmillan, 1st Earl of Stockton, (10 February 1894 – 29 December 1986) was a British Conservative statesman and politician who was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1957 to 1963. Caricatured as "Supermac", he ...

,

Edward Heath,

Harold Wilson

James Harold Wilson, Baron Wilson of Rievaulx, (11 March 1916 – 24 May 1995) was a British politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from October 1964 to June 1970, and again from March 1974 to April 1976. He ...

,

Margaret Thatcher,

Tony Blair,

David Cameron

David William Donald Cameron (born 9 October 1966) is a British former politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 2010 to 2016 and Leader of the Conservative Party from 2005 to 2016. He previously served as Leader o ...

,

Theresa May,

Boris Johnson,

Liz Truss and

Rishi Sunak

Rishi Sunak (; born 12 May 1980) is a British politician who has served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom and Leader of the Conservative Party (UK), Leader of the Conservative Party since October 2022. He previously held two Cabinet of ...

. Of all the post-war prime ministers, only

Gordon Brown was educated at a university other than Oxford (the

University of Edinburgh), while

Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 Winston Churchill in the Second World War, dur ...

,

James Callaghan

Leonard James Callaghan, Baron Callaghan of Cardiff, ( ; 27 March 191226 March 2005), commonly known as Jim Callaghan, was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1976 to 1979 and Leader of the Labour Party from 1976 to 1980. Callaghan is ...

and

John Major

Sir John Major (born 29 March 1943) is a British former politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom and Leader of the Conservative Party (UK), Leader of the Conservative Party from 1990 to 1997, and as Member of Parliament ...

never attended a university.

Over 100 Oxford alumni were elected to the

House of Commons in 2010.

This includes former

Leader of the Opposition

The Leader of the Opposition is a title traditionally held by the leader of the largest political party not in government, typical in countries utilizing the parliamentary system form of government. The leader of the opposition is typically se ...

,

Ed Miliband, and numerous members of the cabinet and

shadow cabinet. Additionally, over 140 Oxonians sit in the

House of Lords.

At least 30 other international leaders have been educated at Oxford.

This number includes

Harald V of Norway,

Abdullah II of Jordan

Abdullah II bin Al-Hussein ( ar, عبدالله الثاني بن الحسين , translit=ʿAbd Allāh aṯ-ṯānī ibn al-Ḥusayn; born 30 January 1962) is King of Jordan, having ascended the throne on 7 February 1999. He is a member of t ...

,

, five

Prime Ministers of Australia (

John Gorton,

Malcolm Fraser,

Bob Hawke

Robert James Lee Hawke (9 December 1929 – 16 May 2019) was an Australian politician and union organiser who served as the 23rd prime minister of Australia from 1983 to 1991, holding office as the leader of the Australian Labor Party (A ...

,

Tony Abbott, and

Malcolm Turnbull), Six

Prime Ministers of Pakistan (

Liaquat Ali Khan,

Huseyn Shaheed Suhrawardy, Sir

Feroz Khan Noon,

Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto,

Benazir Bhutto

Benazir Bhutto ( ur, بینظیر بُھٹو; sd, بينظير ڀُٽو; Urdu ; 21 June 1953 – 27 December 2007) was a Pakistani politician who served as the 11th and 13th prime minister of Pakistan from 1988 to 1990 and again from 1993 t ...

and

Imran Khan),

two

Prime Ministers of Canada (

Lester B. Pearson and

John Turner),

two

Prime Ministers of India (

Manmohan Singh

Manmohan Singh (; born 26 September 1932) is an Indian politician, economist and statesman who served as the 13th prime minister of India from 2004 to 2014. He is also the third longest-serving prime minister after Jawaharlal Nehru and Indir ...

and

Indira Gandhi

Indira Priyadarshini Gandhi (; Given name, ''née'' Nehru; 19 November 1917 – 31 October 1984) was an Indian politician and a central figure of the Indian National Congress. She was elected as third prime minister of India in 1966 ...

, though the latter did not finish her degree),

(

S. W. R. D. Bandaranaike),

Norman Washington Manley of Jamaica,

Haitham bin Tariq Al Said (Sultan of

Oman)

Eric Williams (Prime Minister of Trinidad and Tobago),

Pedro Pablo Kuczynski (former President of Peru),

Abhisit Vejjajiva (former Prime Minister of Thailand), and

Bill Clinton (the first President of the United States to have attended Oxford; he attended as a

Rhodes Scholar

The Rhodes Scholarship is an international postgraduate award for students to study at the University of Oxford, in the United Kingdom.

Established in 1902, it is the oldest graduate scholarship in the world. It is considered among the world' ...

).

(Deputy Prime Minister of

Zimbabwe), was a

Rhodes Scholar

The Rhodes Scholarship is an international postgraduate award for students to study at the University of Oxford, in the United Kingdom.

Established in 1902, it is the oldest graduate scholarship in the world. It is considered among the world' ...

in 1991.