Cro-Magnons on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Early European modern humans (EEMH), or Cro-Magnons, were the first early modern humans (''Homo sapiens'') to settle in Europe, migrating from

Early European modern humans (EEMH), or Cro-Magnons, were the first early modern humans (''Homo sapiens'') to settle in Europe, migrating from

When early modern humans (''Homo sapiens'') migrated onto the European continent, they interacted with the indigenous Neanderthals (''H. neanderthalensis'') which had already inhabited Europe for hundreds of thousands of years. In 2019, Greek palaeoanthropologist Katerina Harvati and colleagues argued that two 210,000 year old skulls from

When early modern humans (''Homo sapiens'') migrated onto the European continent, they interacted with the indigenous Neanderthals (''H. neanderthalensis'') which had already inhabited Europe for hundreds of thousands of years. In 2019, Greek palaeoanthropologist Katerina Harvati and colleagues argued that two 210,000 year old skulls from

For 28 modern human specimens from 190 to 25 thousand years ago, average brain volume was estimated to have been about , and for 13 EEMH about . In comparison, present-day humans average , which is notably smaller. This is because the EEMH brain, though within the variation for present-day humans, exhibits longer average

For 28 modern human specimens from 190 to 25 thousand years ago, average brain volume was estimated to have been about , and for 13 EEMH about . In comparison, present-day humans average , which is notably smaller. This is because the EEMH brain, though within the variation for present-day humans, exhibits longer average

PDF

/ref> In regard to art, the Magdalenian produced some of the most intricate Palaeolithic pieces, and they even elaborately decorated normal, everyday objects.

As opposed to the patriarchy prominent in historical societies, the idea of a prehistoric predominance of either

As opposed to the patriarchy prominent in historical societies, the idea of a prehistoric predominance of either

The Upper Palaeolithic is characterised by evidence of expansive trade routes and the great distances at which communities could maintain interactions. The early Upper Palaeolithic is especially known for highly mobile lifestyles, with Gravettian groups (at least those analysed in Italy and Moravia, Ukraine) often sourcing some raw materials upwards of . However, it is debated if this represents

The Upper Palaeolithic is characterised by evidence of expansive trade routes and the great distances at which communities could maintain interactions. The early Upper Palaeolithic is especially known for highly mobile lifestyles, with Gravettian groups (at least those analysed in Italy and Moravia, Ukraine) often sourcing some raw materials upwards of . However, it is debated if this represents

EEMH cave sites quite often feature distinct spatial organisation, with certain areas specifically designated for specific activities, such as hearth areas, kitchens, butchering grounds, sleeping grounds, and trash pile. It is difficult to tell if all material from a site was deposited at about the same time, or if the site was used multiple times. EEMH are thought to have been quite mobile, indicated by the great lengths of trade routes, and such a lifestyle was likely supported by the constructions of temporary shelters in open environments, such as huts. Evidence of huts is typically associated with a hearth.

Magdalenian peoples, especially, are thought to have been highly migratory, following herds while repopulating Europe, and several cave and open-air sites indicate the area was abandoned and revisited regularly. The 19,000 year old Peyre Blanque site, France, and at least the area around it may have been revisited for thousands of years. In the Magdalenian, stone lined rectangular areas typically were interpreted as having been the foundations or flooring of huts. At Magdalenian Pincevent, France, small, circular dwellings were speculated to have existed based on the spacing of stone tools and bones; these sometimes featured an indoor hearth, work area, or sleeping space (but not all at the same time). A 23,000 year old hut from the Israeli

EEMH cave sites quite often feature distinct spatial organisation, with certain areas specifically designated for specific activities, such as hearth areas, kitchens, butchering grounds, sleeping grounds, and trash pile. It is difficult to tell if all material from a site was deposited at about the same time, or if the site was used multiple times. EEMH are thought to have been quite mobile, indicated by the great lengths of trade routes, and such a lifestyle was likely supported by the constructions of temporary shelters in open environments, such as huts. Evidence of huts is typically associated with a hearth.

Magdalenian peoples, especially, are thought to have been highly migratory, following herds while repopulating Europe, and several cave and open-air sites indicate the area was abandoned and revisited regularly. The 19,000 year old Peyre Blanque site, France, and at least the area around it may have been revisited for thousands of years. In the Magdalenian, stone lined rectangular areas typically were interpreted as having been the foundations or flooring of huts. At Magdalenian Pincevent, France, small, circular dwellings were speculated to have existed based on the spacing of stone tools and bones; these sometimes featured an indoor hearth, work area, or sleeping space (but not all at the same time). A 23,000 year old hut from the Israeli  Over 70 dwellings constructed by EEMH out of mammoth bones have been identified, primarily from the Russian Plain, possibly semi-permanent hunting camps. They seem to have built

Over 70 dwellings constructed by EEMH out of mammoth bones have been identified, primarily from the Russian Plain, possibly semi-permanent hunting camps. They seem to have built

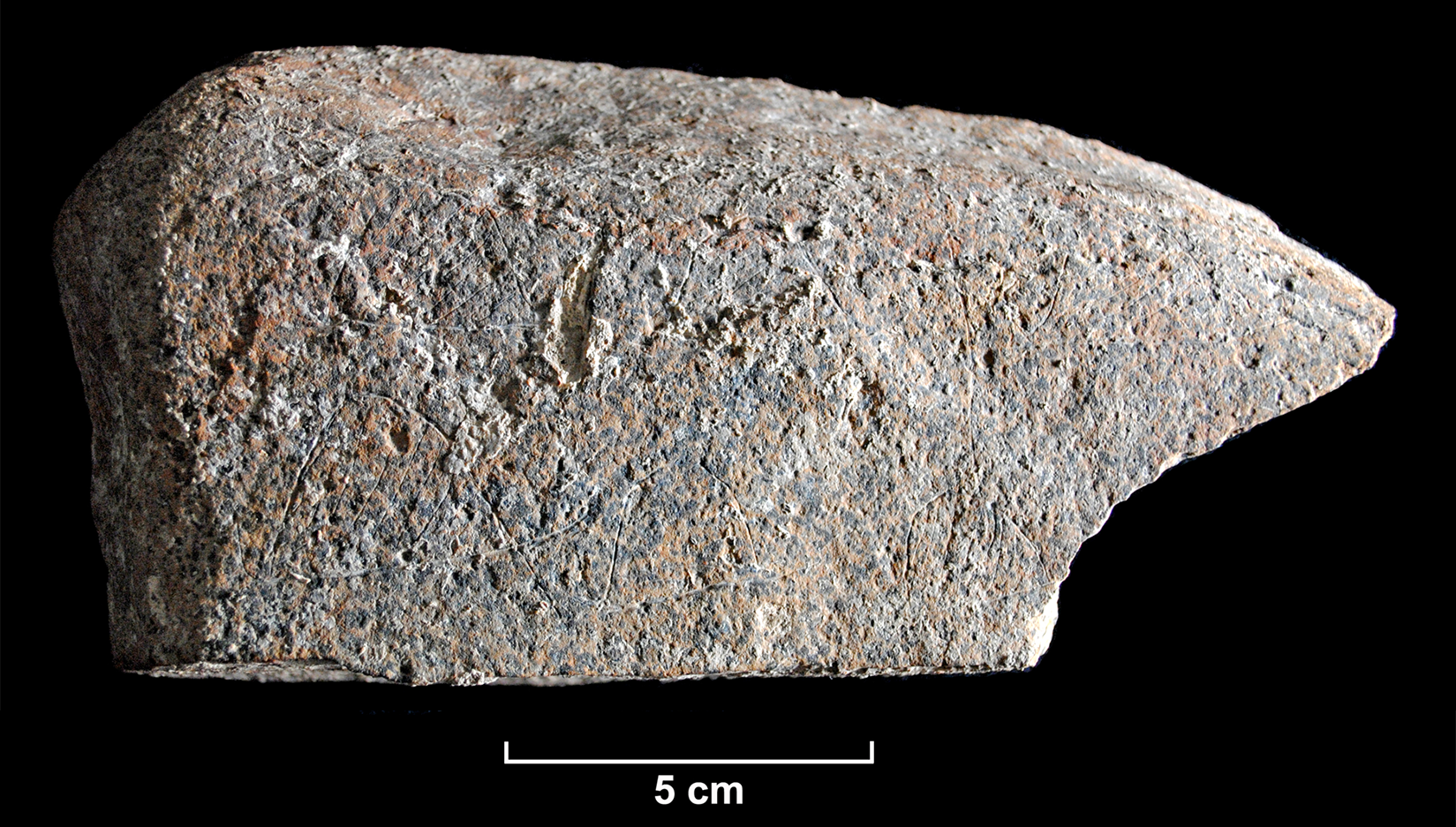

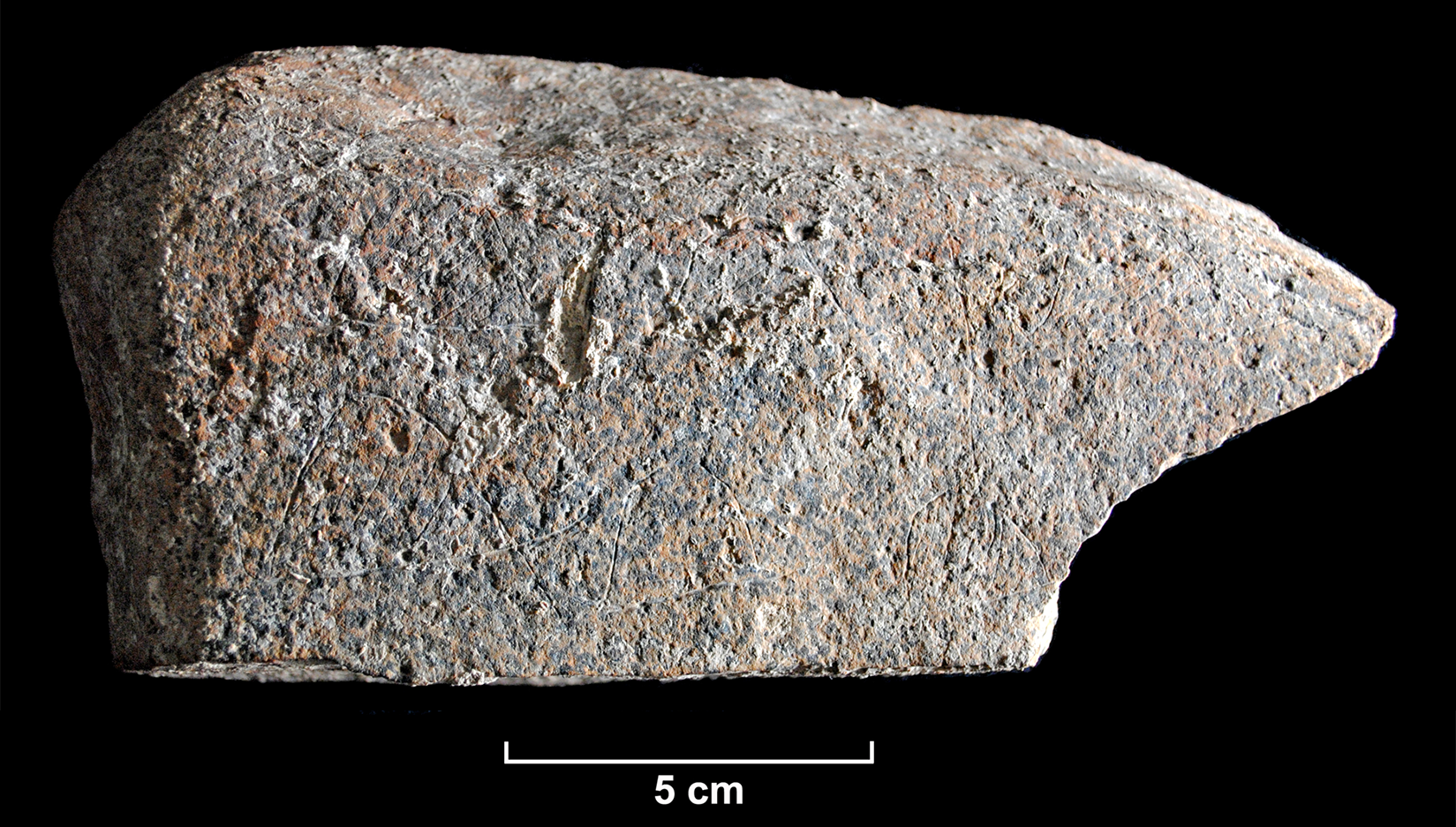

EEMH are commonly associated with large pieces of pigments ("crayons"), namely made of red ochre. For EEMH, it is typically assumed that ochre was used for some symbolic purposes, most notably for cosmetics such as body paint. This is because ochre in some sites had to be imported from incredibly long distances, and it is also associated with burials. It is unclear why they specifically chose red ochre instead of other colours. In terms of colour psychology, popular hypotheses include the putative " female cosmetic coalitions" hypothesis and the " red dress effect". It is also possible that ochre was chosen for its utility, such as an ingredient for adhesives, hide tanning agent, insect repellent, sunscreen, medicinal properties, dietary supplement, or as a soft hammer. EEMH appear to have been using grinding and crushing tools to process ochre before applying it to the skin.

In 1962, French archaeologists Saint-Just and Marthe Péquart identified bi-pointed needles in the Magdalenian

EEMH are commonly associated with large pieces of pigments ("crayons"), namely made of red ochre. For EEMH, it is typically assumed that ochre was used for some symbolic purposes, most notably for cosmetics such as body paint. This is because ochre in some sites had to be imported from incredibly long distances, and it is also associated with burials. It is unclear why they specifically chose red ochre instead of other colours. In terms of colour psychology, popular hypotheses include the putative " female cosmetic coalitions" hypothesis and the " red dress effect". It is also possible that ochre was chosen for its utility, such as an ingredient for adhesives, hide tanning agent, insect repellent, sunscreen, medicinal properties, dietary supplement, or as a soft hammer. EEMH appear to have been using grinding and crushing tools to process ochre before applying it to the skin.

In 1962, French archaeologists Saint-Just and Marthe Péquart identified bi-pointed needles in the Magdalenian

/ref> The emergence of textiles in the European archaeological record also coincides with the proliferation of the

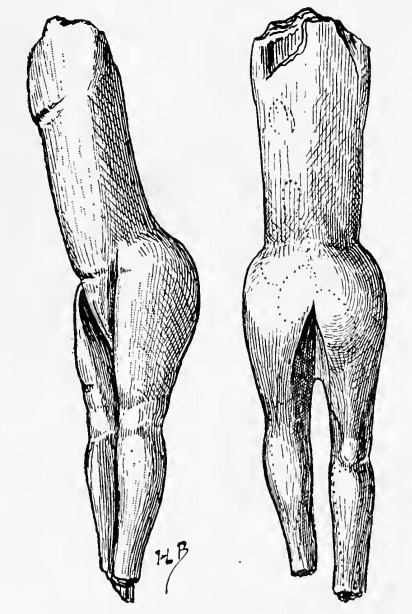

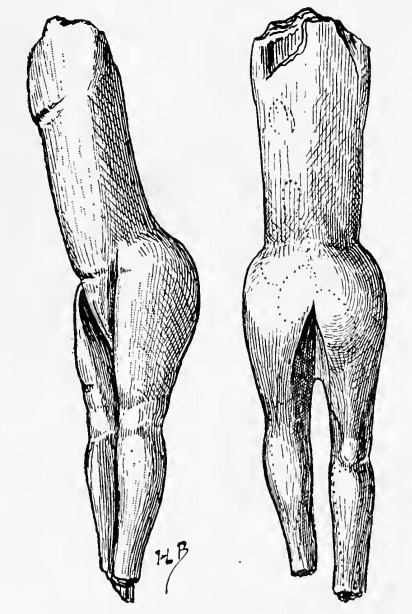

EEMH are known to have created

EEMH are known to have created  It is speculated that a few EEMH artefacts represent

It is speculated that a few EEMH artefacts represent

The "

The "

Early European modern humans (EEMH), or Cro-Magnons, were the first early modern humans (''Homo sapiens'') to settle in Europe, migrating from

Early European modern humans (EEMH), or Cro-Magnons, were the first early modern humans (''Homo sapiens'') to settle in Europe, migrating from Western Asia

Western Asia, West Asia, or Southwest Asia, is the westernmost subregion of the larger geographical region of Asia, as defined by some academics, UN bodies and other institutions. It is almost entirely a part of the Middle East, and includes Ana ...

, continuously occupying the continent possibly from as early as 56,800 years ago. They interacted and interbred with the indigenous Neanderthal

Neanderthals (, also ''Homo neanderthalensis'' and erroneously ''Homo sapiens neanderthalensis''), also written as Neandertals, are an extinct species or subspecies of archaic humans who lived in Eurasia until about 40,000 years ago. While the ...

s (''H. neanderthalensis'') of Europe and Western Asia, who went extinct 40,000 to 35,000 years ago; and from 37,000 years ago onwards all EEMH descended from a single founder population which contributes ancestry to present-day Europeans. Early European modern humans (EEMH) produced Upper Palaeolithic

The Upper Paleolithic (or Upper Palaeolithic) is the third and last subdivision of the Paleolithic or Old Stone Age. Very broadly, it dates to between 50,000 and 12,000 years ago (the beginning of the Holocene), according to some theories coin ...

cultures, the first major one being the Aurignacian, which was succeeded by the Gravettian

The Gravettian was an archaeological industry of the European Upper Paleolithic that succeeded the Aurignacian circa 33,000 years BP. It is archaeologically the last European culture many consider unified, and had mostly disappeared by ...

by 30,000 years ago. The Gravettian split into the Epi-Gravettian in the east and Solutrean

The Solutrean industry is a relatively advanced flint tool-making style of the Upper Paleolithic of the Final Gravettian, from around 22,000 to 17,000 BP. Solutrean sites have been found in modern-day France, Spain and Portugal.

Details

...

in the west, due to major climate degradation during the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM), peaking 21,000 years ago. As Europe warmed, the Solutrean evolved into the Magdalenian by 20,000 years ago, and these peoples recolonised Europe. The Magdalenian and Epi-Gravettian gave way to Mesolithic cultures as big game animals were dying out and the Last Glacial Period drew to a close.

EEMH were anatomically similar to present-day Europeans, but were more robust

Robustness is the property of being strong and healthy in constitution. When it is transposed into a system, it refers to the ability of tolerating perturbations that might affect the system’s functional body. In the same line ''robustness'' ca ...

, having broader faces, more prominent brow ridges, and bigger teeth. The earliest EEMH specimens also exhibit features that are reminiscent of those found in Neanderthals, as well as modern day African, European and aboriginal Australian populations. The first EEMH would have had darker skin; natural selection

Natural selection is the differential survival and reproduction of individuals due to differences in phenotype. It is a key mechanism of evolution, the change in the heritable traits characteristic of a population over generations. Cha ...

for lighter skin would not begin until 30,000 years ago. Before the LGM (Last Glacial Maximum), EEMH had overall low population density, tall stature similar to post-industrial humans, expansive trade routes stretching as long as , and hunted big game animals. EEMH had much higher populations than the Neanderthals, possibly due to higher fertility rates; life expectancy for both species was typically under 40 years. Following the LGM, population density increased as communities travelled less frequently (though for longer distances), and the need to feed so many more people in tandem with the increasing scarcity of big game caused them to rely more heavily on small or aquatic game, and more frequently participate in game drive system

The game drive system is a hunting strategy in which game are herded into confined or dangerous places where they can be more easily killed. It can also be used for animal capture as well as for hunting, such as for capturing mustangs. The use of ...

s and slaughter whole herds at a time. The EEMH arsenal included spears, spear-thrower

A spear-thrower, spear-throwing lever or ''atlatl'' (pronounced or ; Nahuatl ''ahtlatl'' ) is a tool that uses leverage to achieve greater velocity in dart or javelin-throwing, and includes a bearing surface which allows the user to store ene ...

s, harpoon

A harpoon is a long spear-like instrument and tool used in fishing, whaling, sealing, and other marine hunting to catch and injure large fish or marine mammals such as seals and whales. It accomplishes this task by impaling the target animal ...

s, and possibly throwing stick

The throwing stick or throwing club is a wooden rod with either a pointed tip or a spearhead attached to one end, intended for use as a weapon. A throwing stick can be either straight or roughly boomerang-shaped, and is much shorter than the j ...

s and Palaeolithic dog

The Paleolithic dog was a Late Pleistocene canine. They were directly associated with human hunting camps in Europe over 30,000 years ago and it is proposed that these were domesticated. They are further proposed to be either a proto-dog and the ...

s. EEMH likely commonly constructed temporary huts while moving around, and Gravettian peoples notably made large huts on the East European Plain

The East European Plain (also called the Russian Plain, "Extending from eastern Poland through the entire European Russia to the Ural Mountaina, the ''East European Plain'' encompasses all of the Baltic states and Belarus, nearly all of Ukraine, an ...

out of mammoth bones.

EEMH are well renowned for creating a diverse array of artistic works, including cave paintings, Venus figurine

A Venus figurine is any Upper Palaeolithic statuette portraying a woman, usually carved in the round.Fagan, Brian M., Beck, Charlotte, "Venus Figurines", ''The Oxford Companion to Archaeology'', 1996, Oxford University Press, pp. 740–741 Most ...

s, perforated baton

Perforated baton, bâton de commandement or bâton percé are names given by archaeologists to a type of particular prehistoric artifact from Prehistoric Europe, whose function remains debated. The name ''bâtons de commandement'' ("batons of ...

s, animal figurines, and geometric patterns. They may have decorated their bodies with ochre crayons and perhaps tattoos, scarification

Scarification involves scratching, etching, burning/branding, or superficially cutting designs, pictures, or words into the skin as a permanent body modification or body art. The body modification can take roughly 6–12 months to heal. In the ...

, and piercings. The exact symbolism of these works remains enigmatic, but EEMH are generally (though not universally) thought to have practiced shamanism, in which cave art — specifically of those depicting human/animal hybrids — played a central part. They also wore decorative beads, and plant-fibre clothes dyed with various plant-based dyes, which were possibly used as status symbols. For music, they produced bone flutes and whistles, and possibly also bullroarer

The bullroarer, ''rhombus'', or ''turndun'', is an ancient ritual musical instrument and a device historically used for communicating over great distances. It consists of a piece of wood attached to a string, which when swung in a large circle ...

s, rasps, drums, idiophone

An idiophone is any musical instrument that creates sound primarily by the vibration of the instrument itself, without the use of air flow (as with aerophones), strings (chordophones), membranes (membranophones) or electricity ( electroph ...

s, and other instruments. They buried their dead, though possibly only people which had achieved or were born into high status received burial.

Remains of Palaeolithic cultures have been known for centuries, but they were initially interpreted in a creationist

Creationism is the religious belief that nature, and aspects such as the universe, Earth, life, and humans, originated with supernatural acts of divine creation. Gunn 2004, p. 9, "The ''Concise Oxford Dictionary'' says that creationism is 'th ...

model, wherein they represented antediluvian

The antediluvian (alternatively pre-diluvian or pre-flood) period is the time period chronicled in the Bible between the fall of man and the Genesis flood narrative in biblical cosmology. The term was coined by Thomas Browne. The narrative takes ...

peoples which were wiped out by the Great Flood

A flood myth or a deluge myth is a myth in which a great flood, usually sent by a deity or deities, destroys civilization, often in an act of divine retribution. Parallels are often drawn between the flood waters of these myths and the primaeval ...

. Following the conception and popularisation of evolution

Evolution is change in the heritable characteristics of biological populations over successive generations. These characteristics are the expressions of genes, which are passed on from parent to offspring during reproduction. Variation ...

in the mid-to-late 19th century, EEMH became the subject of much scientific racism

Scientific racism, sometimes termed biological racism, is the pseudoscience, pseudoscientific belief that empirical evidence exists to support or justify racism (racial discrimination), racial inferiority, or racial superiority.. "Few tragedies ...

, with early race theories allying with Nordicism

Nordicism is an ideology of racism which views the historical race concept of the "Nordic race" as an endangered and superior racial group. Some notable and seminal Nordicist works include Madison Grant's book ''The Passing of the Great Race ...

and Pan-Germanism. Such historical race concepts

The concept of race as a categorization of anatomically modern humans (''Homo sapiens'') has an extensive history in Europe and the Americas. The contemporary word ''race'' itself is modern; historically it was used in the sense of "nation, eth ...

were overturned by the mid-20th century. During the first wave feminism

First-wave feminism was a period of feminist activity and thought that occurred during the 19th and early 20th century throughout the Western world. It focused on legal issues, primarily on securing women's right to vote. The term is often used s ...

movement, the Venus figurines were notably interpreted as evidence of some matriarchal religion

A matriarchal religion is a religion that focuses on a goddess or goddesses. The term is most often used to refer to theories of prehistoric matriarchal religions that were proposed by scholars such as Johann Jakob Bachofen, Jane Ellen Harrison, ...

, though such claims had mostly died down in academia by the 1970s.

Chronology

Apidima Cave

The Apidima Cave (, ''Spilaio Apidima'') is a complex of five caves four small caves located on the western shore of Mani Peninsula in Southern Greece. A systematic investigation of the cave has yielded Neanderthal and ''Homo sapiens'' fossils f ...

, Greece, represent modern humans rather than Neanderthals — indicating these populations have an unexpectedly deep history — but this was disputed in 2020 by French paleoanthropologist and colleagues. About 60,000 years ago, marine isotope stage

Marine isotope stages (MIS), marine oxygen-isotope stages, or oxygen isotope stages (OIS), are alternating warm and cool periods in the Earth's paleoclimate, deduced from oxygen isotope data reflecting changes in temperature derived from data f ...

3 began, characterised by volatile climatic patterns and sudden retreat and recolonisation events of forestland in way of open steppeland.

The earliest indication of Upper Palaeolithic

The Upper Paleolithic (or Upper Palaeolithic) is the third and last subdivision of the Paleolithic or Old Stone Age. Very broadly, it dates to between 50,000 and 12,000 years ago (the beginning of the Holocene), according to some theories coin ...

modern human migration into Europe is a series of modern human teeth with Neronian industry stone tools found at Grotte Mandrin Cave, Malataverne in France, dated in 2022 to between 56,800 and 51,700 years ago. The Neronian is one of the many industries associated with modern humans classed as transitional between the Middle and Upper Palaeolithic. Beyond this there is the Balkan Bohunician industry beginning 48,000 years ago, likely deriving from the Levantine Emiran

Emiran culture was a culture that existed in the Levant (Lebanon, Palestine , Syria, Jordan, Israel , and Arabia between the Middle Paleolithic and the Upper Paleolithic periods. It is the oldest known of the Upper Paleolithic cultures and r ...

industry, and the next oldest fossils date to roughly 45–43 thousand years ago in Bulgaria, Italy, and Britain. It is unclear, while migrating westward, if they followed the Danube

The Danube ( ; ) is a river that was once a long-standing frontier of the Roman Empire and today connects 10 European countries, running through their territories or being a border. Originating in Germany, the Danube flows southeast for , p ...

or went along the Mediterranean coast. About 45 to 44 thousand years ago, the Proto-Aurignacian culture, the first widely-recognised European Upper Palaeolithic culture, spread out across Europe, probably descending from the Near Eastern Ahmarian

The Ahmarian culture was a Paleolithic archeological industry in Levant dated at 46,000–42,000 BP and thought to be related to Levantine Emiran and younger European Aurignacian cultures.

The word “Ahmarian” was adopted from the archaeol ...

culture. After 40,000 years ago with the onset of Heinrich event

A Heinrich event is a natural phenomenon in which large groups of icebergs break off from glaciers and traverse the North Atlantic. First described by marine geologist Hartmut Heinrich (Heinrich, H., 1988), they occurred during five of the last ...

4 (a period of extreme seasonality), the Aurignacian proper evolved perhaps in South-Central Europe, and rapidly replaced other cultures across the continent. This wave of modern humans replaced Neanderthals and their Mousterian

The Mousterian (or Mode III) is an archaeological industry of stone tools, associated primarily with the Neanderthals in Europe, and to the earliest anatomically modern humans in North Africa and West Asia. The Mousterian largely defines the l ...

culture. In the Danube Valley, the Aurignacian features sites few and far between, compared to later traditions, until 35,000 years ago. From here, the "Typical Aurignacian" becomes quite prevalent, and extends until 29,000 years ago.

The Aurignacian was gradually replaced by the Gravettian

The Gravettian was an archaeological industry of the European Upper Paleolithic that succeeded the Aurignacian circa 33,000 years BP. It is archaeologically the last European culture many consider unified, and had mostly disappeared by ...

culture, but it is unclear when the Aurignacian went extinct because it is poorly defined. "Aurignacoid" or "Epi-Aurignacian" tools are identified as late as 18 to 15 thousand years ago. It is also unclear where the Gravettian originated from as it diverges strongly from the Aurignician (and therefore may not have descended from it). Nonetheless, genetic evidence indicates not all Aurignacian bloodlines went extinct. Hypotheses for Gravettian genesis include evolution: in Central Europe from the Szeletian

The Szeleta Culture is a transitional archaeological culture between the Middle Paleolithic and the Upper Palaeolithic, found in Austria, Moravia, northern Hungary, and southern Poland. It is dated 41,000 to 37,000 years before the present ( ...

(which developed from the Bohunician) which existed 41 to 37 thousand years ago; or from the Ahmarian or similar cultures from the Near East or the Caucasus which existed before 40,000 years ago. It is further debated where the earliest occurrence is identified, with the former hypothesis arguing for Germany about 37,500 years ago, and the latter III rockshelter in Crimea about 38 to 36 thousand years ago. In either case, the appearance of the Gravettian coincides with a significant temperature drop. Also around 37,000 years ago, the founder population of all later early European modern humans (EEMH) existed, and Europe would remain in genetic isolation from the rest of the world for the next 23,000 years.

Around 29,000 years ago, marine isotope stage 2 began and cooling intensified. This peaked about 21,000 years ago during the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM) when Scandinavia

Scandinavia; Sámi languages: /. ( ) is a subregion in Northern Europe, with strong historical, cultural, and linguistic ties between its constituent peoples. In English usage, ''Scandinavia'' most commonly refers to Denmark, Norway, and Swe ...

, the Baltic region, and the British Isles

The British Isles are a group of islands in the North Atlantic Ocean off the north-western coast of continental Europe, consisting of the islands of Great Britain, Ireland, the Isle of Man, the Inner and Outer Hebrides, the Northern Isles, ...

were covered in glaciers, and winter sea ice reached the French seaboard. The Alps

The Alps () ; german: Alpen ; it, Alpi ; rm, Alps ; sl, Alpe . are the highest and most extensive mountain range system that lies entirely in Europe, stretching approximately across seven Alpine countries (from west to east): France, Swi ...

were also covered in glaciers, and most of Europe was polar desert, with mammoth steppe

During the Last Glacial Maximum, the mammoth steppe, also known as steppe-tundra, was the Earth's most extensive biome. It spanned from Spain eastward across Eurasia to Canada and from the arctic islands southward to China. The mammoth steppe ...

and forest steppe

A forest steppe is a temperate-climate ecotone and habitat type composed of grassland interspersed with areas of woodland or forest.

Locations

Forest steppe primarily occurs in a belt of forest steppes across northern Eurasia from the eastern ...

dominating the Mediterranean coast. Consequently, large swathes of Europe were uninhabitable, and two distinct cultures emerged with unique technologies to adapt to the new environment: the Solutrean

The Solutrean industry is a relatively advanced flint tool-making style of the Upper Paleolithic of the Final Gravettian, from around 22,000 to 17,000 BP. Solutrean sites have been found in modern-day France, Spain and Portugal.

Details

...

in Southwestern Europe which invented brand new technologies, and the Epi-Gravettian from Italy to the East European Plain

The East European Plain (also called the Russian Plain, "Extending from eastern Poland through the entire European Russia to the Ural Mountaina, the ''East European Plain'' encompasses all of the Baltic states and Belarus, nearly all of Ukraine, an ...

which adapted the previous Gravettian technologies. Solutrean peoples inhabited the permafrost zone, whereas Epi-Gravettian peoples appear to have stuck to less harsh, seasonally frozen areas. Relatively few sites are known through this time. The glaciers began retreating about 20,000 years ago, and the Solutrean evolved into the Magdalenian, which would recolonise Western and Central Europe over the next couple thousand years. Starting during the Older Dryas

The Older Dryas was a stadial (cold) period between the Bølling and Allerød interstadials (warmer phases), about 14,000 years Before Present, towards the end of the Pleistocene. Its date is not well defined, with estimates varying by 400 years ...

roughly 14,000 years ago, Final Magdalenian traditions appear, namely the Azilian

The Azilian is a Mesolithic industry of the Franco-Cantabrian region of northern Spain and Southern France. It dates approximately 10,000–12,500 years ago. Diagnostic artifacts from the culture include projectile points (microliths with ro ...

, Hamburgian, and Creswellian. During the Bølling–Allerød warming, Near Eastern genes began showing up in the indigenous Europeans, indicating the end of Europe's genetic isolation. Possibly due to the continual reduction of European big game, the Magdalenian and Epi-Gravettian were completely replaced by the Mesolithic by the beginning of the Holocene.

Europe was completely re-peopled during the Holocene climatic optimum from 9 to 5 thousand years ago. Mesolithic Western Hunter-Gatherer

In archaeogenetics, the term Western Hunter-Gatherer (WHG), West European Hunter-Gatherer or Western European Hunter-Gatherer names a distinct ancestral component of modern Europeans, representing descent from a population of Mesolithic hunter-gat ...

s (WHG) contributed significantly to the present-day European genome, alongside Ancient North Eurasian

In archaeogenetics, the term Ancient North Eurasian (generally abbreviated as ANE) is the name given to an ancestral component that represents a lineage ancestral to the people of the Mal'ta–Buret' culture and populations closely related to th ...

s (ANE) which descended from the Siberian Mal'ta–Buret' culture

The Mal'ta–Buret' culture is an archaeological culture of 24,000 to 15,000 BP / 22'050 to 13'050 BC in the Upper Paleolithic on the upper Angara River in the area west of Lake Baikal in the Irkutsk Oblast, Siberia, Russian Federation. The ...

and Caucasus Hunter-Gatherers (CHG). Most present-day Europeans have a 40–60% WHG ratio, and the 8,000 year old Mesolithic Loschbour man

The Loschbour man (also Loschbur man) is a skeleton of ''Homo sapiens'' from the European Mesolithic discovered in 1935 in Mullerthal, in the commune of Waldbillig, Luxembourg.

History

The skeleton, nearly complete, was discovered on 7 Octob ...

seems to have had a similar genetic makeup. Near Eastern Neolithic

The Neolithic period, or New Stone Age, is an Old World archaeological period and the final division of the Stone Age. It saw the Neolithic Revolution, a wide-ranging set of developments that appear to have arisen independently in several p ...

farmers which split from the European hunter-gatherers about 40,000 years ago started to spread out across Europe by 8,000 years ago, ushering in the Neolithic

The Neolithic period, or New Stone Age, is an Old World archaeological period and the final division of the Stone Age. It saw the Neolithic Revolution, a wide-ranging set of developments that appear to have arisen independently in several p ...

with Early European Farmers

Early European Farmers (EEF), First European Farmers (FEF), Neolithic European Farmers, Ancient Aegean Farmers, or Anatolian Neolithic Farmers (ANF) are names used to describe a distinct group of early Neolithic farmers who brought agriculture to E ...

(EEF). EEF contribute about 30% of ancestry to present-day Baltic populations, and up to 90% in present-day Mediterranean populations. The latter may have inherited WHG ancestry via EEF introgression. The Eastern Hunter-Gatherers

In archaeogenetics, the term Eastern Hunter-Gatherer (EHG), sometimes East European Hunter-Gatherer, or Eastern European Hunter-Gatherer is the name given to a distinct ancestral component that represents descent from Mesolithic hunter-gatherers ...

(EHG) population identified around the steppes of the Ural

Ural may refer to:

*Ural (region), in Russia and Kazakhstan

*Ural Mountains, in Russia and Kazakhstan

*Ural (river), in Russia and Kazakhstan

* Ual (tool), a mortar tool used by the Bodo people of India

*Ural Federal District, in Russia

*Ural econ ...

s also dispersed, and the Scandinavian Hunter-Gatherer

In archaeogenetics, the term Scandinavian Hunter-Gatherer (SHG) is the name given to a distinct ancestral component that represents descent from Mesolithic hunter-gatherers of Scandinavia. Genetic studies suggest that the SHGs were a mix of Weste ...

s appear to be a mix of WHG and EHG. Around 4,500 years ago, the immigration of the Yamnaya

The Yamnaya culture or the Yamna culture (russian: Ямная культура, ua, Ямна культура lit. 'culture of pits'), also known as the Pit Grave culture or Ochre Grave culture, was a late Copper Age to early Bronze Age archa ...

and Corded Ware

The Corded Ware culture comprises a broad archaeological horizon of Europe between ca. 3000 BC – 2350 BC, thus from the late Neolithic, through the Chalcolithic, Copper Age, and ending in the early Bronze Age. Corded Ware culture en ...

cultures from the eastern steppes brought the Bronze Age

The Bronze Age is a historic period, lasting approximately from 3300 BC to 1200 BC, characterized by the use of bronze, the presence of writing in some areas, and other early features of urban civilization. The Bronze Age is the second prin ...

, the Proto-Indo-European language

Proto-Indo-European (PIE) is the reconstructed common ancestor of the Indo-European language family. Its proposed features have been derived by linguistic reconstruction from documented Indo-European languages. No direct record of Proto-Indo-E ...

, and more or less the present-day genetic makeup of Europeans.

Classification

EEMH have historically been referred to as "Cro-Magnons" in scientific literature until around the 1990s when the term "anatomically modern humans" became more popular. The name "Cro-Magnon" comes from the 5 skeletons discovered by French palaeontologistLouis Lartet

Louis Lartet (1840 – 1899) was a French geologist and paleontologist. He discovered the original Cro-Magnon 1, Cro-Magnon skeletons.

Louis Lartet was born in Castelnau-Magnoac, in Seissan in the ''département in France, département'' ...

in 1868 at the Cro-Magnon rock shelter

Cro-Magnon (, ; french: Abri de Cro-Magnon )French ''abri'' means "rock shelter", ''crô'' means "hole" in Occitan (standard French ''creux''), and ''Magnon'' is the surname of the land owner at the time. is an Aurignacian (Upper Paleolithic) si ...

, Les Eyzies

Les Eyzies (; oc, Las Aisiás) is a commune in the Dordogne department in Nouvelle-Aquitaine in southwestern France. It was established on 1 January 2019 by merger of the former communes of Les Eyzies-de-Tayac-Sireuil (the seat), Manaurie and ...

, Dordogne

Dordogne ( , or ; ; oc, Dordonha ) is a large rural department in Southwestern France, with its prefecture in Périgueux. Located in the Nouvelle-Aquitaine region roughly half-way between the Loire Valley and the Pyrenees, it is name ...

, France, after the area was accidentally discovered while clearing land for a railway station. Fossils and artefacts from the Palaeolithic had actually been known for decades, but these were interpreted in a creationist

Creationism is the religious belief that nature, and aspects such as the universe, Earth, life, and humans, originated with supernatural acts of divine creation. Gunn 2004, p. 9, "The ''Concise Oxford Dictionary'' says that creationism is 'th ...

model (as the concept of evolution

Evolution is change in the heritable characteristics of biological populations over successive generations. These characteristics are the expressions of genes, which are passed on from parent to offspring during reproduction. Variation ...

had not yet been conceived). For example, the Aurignacian Red Lady of Paviland

The Red Lady of Paviland is an Upper Paleolithic partial skeleton of a male dyed in red ochre and buried in Wales 33,000 BP. The bones were discovered in 1823 by William Buckland in an archaeological dig at Goat's Hole Cave (Paviland cave) – ...

(a young man) from South Wales was described by geologist Reverend William Buckland

William Buckland DD, FRS (12 March 1784 – 14 August 1856) was an English theologian who became Dean of Westminster. He was also a geologist and palaeontologist.

Buckland wrote the first full account of a fossil dinosaur, which he named ' ...

in 1822 as a citizen of Roman Britain

Roman Britain was the period in classical antiquity when large parts of the island of Great Britain were under occupation by the Roman Empire. The occupation lasted from AD 43 to AD 410. During that time, the territory conquered wa ...

. Subsequent authors contended the skeleton was either evidence of antediluvian

The antediluvian (alternatively pre-diluvian or pre-flood) period is the time period chronicled in the Bible between the fall of man and the Genesis flood narrative in biblical cosmology. The term was coined by Thomas Browne. The narrative takes ...

(before the Great Flood

A flood myth or a deluge myth is a myth in which a great flood, usually sent by a deity or deities, destroys civilization, often in an act of divine retribution. Parallels are often drawn between the flood waters of these myths and the primaeval ...

) people in Britain, or was swept far from the inhabited lands farther south by the powerful floodwaters. Buckland assumed the specimen was a woman because he was adorned with jewellery (shells, ivory rods and rings, and a wolf-bone skewer), and Buckland also stated (possibly in jest) the jewellery was evidence of witchcraft

Witchcraft traditionally means the use of magic or supernatural powers to harm others. A practitioner is a witch. In medieval and early modern Europe, where the term originated, accused witches were usually women who were believed to have ...

. Around this time, the uniformitarianism

Uniformitarianism, also known as the Doctrine of Uniformity or the Uniformitarian Principle, is the assumption that the same natural laws and processes that operate in our present-day scientific observations have always operated in the universe in ...

movement was gaining traction, headed principally by Charles Lyell, arguing that fossil materials well predated the biblical chronology

The chronology of the Bible is an elaborate system of lifespans, 'generations', and other means by which the Masoretic Hebrew Bible (the text of the Bible most commonly in use today) measures the passage of events from the creation to around 164 ...

.

Following Charles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin ( ; 12 February 1809 – 19 April 1882) was an English naturalist, geologist, and biologist, widely known for his contributions to evolutionary biology. His proposition that all species of life have descended ...

's 1859 ''On the Origin of Species

''On the Origin of Species'' (or, more completely, ''On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, or the Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life''),The book's full original title was ''On the Origin of Species by Me ...

'', racial anthropologists and raciologists began splitting off putative subspecies and sub-races of present-day humans based on unreliable and pseudoscientific metrics gathered from anthropometry

Anthropometry () refers to the measurement of the human individual. An early tool of physical anthropology, it has been used for identification, for the purposes of understanding human physical variation, in paleoanthropology and in various at ...

, physiognomy

Physiognomy (from the Greek , , meaning "nature", and , meaning "judge" or "interpreter") is the practice of assessing a person's character or personality from their outer appearance—especially the face. The term can also refer to the genera ...

, and phrenology continuing into the 20th century. This was a continuation of Carl Linnaeus

Carl Linnaeus (; 23 May 1707 – 10 January 1778), also known after his Nobility#Ennoblement, ennoblement in 1761 as Carl von Linné#Blunt, Blunt (2004), p. 171. (), was a Swedish botanist, zoologist, taxonomist, and physician who formalise ...

' 1735 '' Systema Naturae'', where he invented the modern classification system, in doing so classifying humans as ''Homo sapiens'' with several putative subspecies classifications for different races based on racist behavioural definitions (in accord with historical race concepts

The concept of race as a categorization of anatomically modern humans (''Homo sapiens'') has an extensive history in Europe and the Americas. The contemporary word ''race'' itself is modern; historically it was used in the sense of "nation, eth ...

): "''H. s. europaeus''" (European descent, governed by laws), "''H. s. afer''" (African descent, impulse), "''H. s. asiaticus''" (Asian descent, opinions), and "''H. s. americanus''" (Native American descent, customs). The racial classification system was quickly extended to fossil specimens, including both EEMH and the Neanderthals, after the true extent of their antiquity was recognised. In 1869, Lartet had proposed the subspecies classification "''H. s. fossilis''" for the Cro-Magnon remains. Other supposed subraces of the 'Cro-Magnon race' included (among many others): "''H. pre-aethiopicus''" for a skull from Dordogne which had "Ethiopic affinities"; "''H. predmosti''" or "''H. predmostensis''" for a series of skulls from Brno, Czech Republic, purportedly transitional between Neanderthals and EEMH; ''H. mentonensis'' for a skull from Menton

Menton (; , written ''Menton'' in classical norm or ''Mentan'' in Mistralian norm; it, Mentone ) is a commune in the Alpes-Maritimes department in the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur region on the French Riviera, close to the Italian border.

Me ...

, France; "''H. grimaldensis''" for Grimaldi man and other skeletons near Grimaldi, Monaco; and "''H. aurignacensis''" or "''H. a. hauseri''" for the Combe-Capelle skull.

These 'fossil races', alongside Ernst Haeckel's idea of there being backwards races which require further evolution (social darwinism

Social Darwinism refers to various theories and societal practices that purport to apply biological concepts of natural selection and survival of the fittest to sociology, economics and politics, and which were largely defined by scholars in We ...

), popularised the view in European thought that the civilised white man had descended from primitive, low browed ape ancestors through a series of savage races. Prominent brow-ridges were classified as an ape-like trait, and consequently Neanderthals (as well as Aboriginal Australians

Aboriginal Australians are the various Indigenous peoples of the Australian mainland and many of its islands, such as Tasmania, Fraser Island, Hinchinbrook Island, the Tiwi Islands, and Groote Eylandt, but excluding the Torres Strait Isl ...

) were considered a lowly race. These European fossils were considered to have been the ancestors to specifically living European races. Among the earliest attempts to classify EEMH was done by racial anthropologists Joseph Deniker

Joseph Deniker (russian: Иосиф Егорович Деникер, ''Yosif Yegorovich Deniker''; 6 March 1852, in Astrakhan – 18 March 1918, in Paris) was a Russian and French naturalist and anthropologist, known primarily for his attempts t ...

and William Z. Ripley

William Zebina Ripley (October 13, 1867 – August 16, 1941) was an American economist, lecturer at Columbia University, professor of economics at MIT, professor of political economy at Harvard University, and racial anthropologist. Ripley was fa ...

in 1900, who characterised them as tall and intelligent proto- Aryans, superior to other races, who descended from Scandinavia and Germany. Further race theories revolved around progressively lighter, blonder, and superior races (subspecies) evolving in Central Europe and spreading out in waves to replace their darker ancestors, culminating in the "Nordic race

The Nordic race was a racial concept which originated in 19th century anthropology. It was considered a race or one of the putative sub-races into which some late-19th to mid-20th century anthropologists divided the Caucasian race, claiming tha ...

". These aligned well with Nordicism

Nordicism is an ideology of racism which views the historical race concept of the "Nordic race" as an endangered and superior racial group. Some notable and seminal Nordicist works include Madison Grant's book ''The Passing of the Great Race ...

and Pan-Germanism (that is, Aryan supremacy), which gained popularity just before World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

, and was notably used by the Nazi

Nazism ( ; german: Nazismus), the common name in English for National Socialism (german: Nationalsozialismus, ), is the far-right totalitarian political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in ...

s to justify the conquest of Europe and the supremacy of the German people in World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposing ...

. Stature was among the characteristics used to distinguish these sub-races, so taller EEMH such as specimens from the French Cro-Magnon, Paviland, and Grimaldi sites were classified as ancestral to the "Nordic race", and smaller ones such as Combe-Capelle and Chancelade man

Chancelade man (the Chancelade cranium) is an ancient Anatomically modern humans, anatomically modern human fossil of a male found in Chancelade in France in 1888. The skeleton was that of a rather short man, who stood a mere tall.

Due to morpho ...

(also from France) were considered the forerunners of either the "Mediterranean race

The Mediterranean race (also Mediterranid race) was a historical race concepts, historical race concept that was a sub-race of the Caucasian race as categorised by anthropology, anthropologists in the late 19th to mid-20th centuries. According to ...

" or " Eskimoids". The Venus figurine

A Venus figurine is any Upper Palaeolithic statuette portraying a woman, usually carved in the round.Fagan, Brian M., Beck, Charlotte, "Venus Figurines", ''The Oxford Companion to Archaeology'', 1996, Oxford University Press, pp. 740–741 Most ...

s — sculptures of pregnant women with exaggerated breasts and thighs — were used as evidence of the presence of the " Negroid race" in Palaeolithic Europe, because they were interpreted as having been based on real women with steatopygia (a condition which causes thicker thighs, common in the women of the San people

The San peoples (also Saan), or Bushmen, are members of various Khoe, Tuu, or Kxʼa-speaking indigenous hunter-gatherer cultures that are the first cultures of Southern Africa, and whose territories span Botswana, Namibia, Angola, Zambia ...

of Southern Africa) and the hairdos of some are supposedly similar to those seen in Ancient Egypt. By the 1940s, the positivism movement — which fought to remove political and cultural bias from science and had begun about a century earlier — had gained popular support in European anthropology. Due to this movement and raciology's associations with Nazism, raciology fell out of practice.

Demographics

The beginning of the Upper Palaeolithic is thought to have been characterised by a major population increase in Europe, with the human population of Western Europe possibly increasing by a factor of 10 in the Neanderthal/modern human transition. The archaeological record indicates that the overwhelming majority of Palaeolithic people (both Neanderthals and modern humans) died before reaching the age of 40, with few elderly individuals recorded. It is possible the population boom was caused by a significant increase in fertility rates. A 2005 study estimated the population of Upper Palaeolithic Europe by calculating the total geographic area which was inhabited based on the archaeological record; averaged the population density ofChipewyan

The Chipewyan ( , also called ''Denésoliné'' or ''Dënesųłı̨né'' or ''Dënë Sųłınë́'', meaning "the original/real people") are a Dene Indigenous Canadian people of the Athabaskan language family, whose ancestors are identified ...

, Hän

The Hän, Han or Hwëch'in / Han Hwech’in (meaning "People of the River, i.e. Yukon River", in English also Hankutchin) are a First Nations people of Canada and an Alaska Native Athabaskan people of the United States; they are part of the At ...

, Hill people

Hill people, also referred to as mountain people, is a general term for people who live in the hills and mountains.

This includes all rugged land above and all land (including plateaus) above elevation.

The climate is generally harsh, with s ...

, and Naskapi

The Naskapi (Nascapi, Naskapee, Nascapee) are an Indigenous people of the Subarctic native to the historical country St'aschinuw (ᒋᑦ ᐊᔅᒋᓄᐤ, meaning 'our nclusiveland'), which is located in northern Quebec and Labrador, neighb ...

Native Americans which live in cold climates and applied to this to EEMH; and assumed that population density continually increased with time calculated by the change in the number of total sites per time period. The study calculated that: from 40 to 30 thousand years ago the population was roughly 1,700–28,400 (average 4,400); from 30 to 22 thousand years ago roughly 1,900–30,600 (average 4,800); from 22 to 16.5 thousand years ago roughly 2,300–37,700 (average 5,900); and 16.5–11.5 thousand years ago roughly 11,300–72,600 (average 28,700).

Following the LGM, EEMH are thought to have been much less mobile and featured a higher population density, indicated by seemingly shorter trade routes as well as symptoms of nutritional stress.

Biology

Physical attributes

For 28 modern human specimens from 190 to 25 thousand years ago, average brain volume was estimated to have been about , and for 13 EEMH about . In comparison, present-day humans average , which is notably smaller. This is because the EEMH brain, though within the variation for present-day humans, exhibits longer average

For 28 modern human specimens from 190 to 25 thousand years ago, average brain volume was estimated to have been about , and for 13 EEMH about . In comparison, present-day humans average , which is notably smaller. This is because the EEMH brain, though within the variation for present-day humans, exhibits longer average frontal lobe

The frontal lobe is the largest of the four major lobes of the brain in mammals, and is located at the front of each cerebral hemisphere (in front of the parietal lobe and the temporal lobe). It is parted from the parietal lobe by a groove be ...

length and taller occipital lobe

The occipital lobe is one of the four major lobes of the cerebral cortex in the brain of mammals. The name derives from its position at the back of the head, from the Latin ''ob'', "behind", and ''caput'', "head".

The occipital lobe is the vi ...

height. The parietal lobe

The parietal lobe is one of the four major lobes of the cerebral cortex in the brain of mammals. The parietal lobe is positioned above the temporal lobe and behind the frontal lobe and central sulcus.

The parietal lobe integrates sensory informa ...

s, however, are shorter in EEMH. It is unclear if this could equate to any functional differences between present-day and early modern humans.

EEMH are physically similar to present-day humans, with a globular braincase, completely flat face, gracile brow ridge, and defined chin. However, the bones of EEMH are somewhat thicker and more robust

Robustness is the property of being strong and healthy in constitution. When it is transposed into a system, it refers to the ability of tolerating perturbations that might affect the system’s functional body. In the same line ''robustness'' ca ...

. The earliest EEMH display features that are reminiscent of those seen in Neanderthals, as well as features observed in modern day African, European, and aboriginal Australian populations. Aurignacians featured a higher proportion of traits somewhat reminiscent of Neanderthals, such as (though not limited to) a slightly flattened skullcap and consequent occipital bun

The occipital bone () is a cranial dermal bone and the main bone of the occiput (back and lower part of the skull). It is trapezoidal in shape and curved on itself like a shallow dish. The occipital bone overlies the occipital lobes of the cereb ...

protruding from the back of the skull (the latter could be quite defined). Their frequency significantly diminished in Gravettians, and in 2007, palaeoanthropologist Erik Trinkaus concluded these were remnants of Neanderthal introgression which were eventually bred out of the gene pool in his review of the relevant morphology.

In early Upper Palaeolithic Western Europe, 20 men and 10 women were estimated to have averaged and , respectively. This is similar to post-industrial modern Northern Europeans. In contrast, in a sample of 21 and 15 late Upper Palaeolithic Western European men and women, the averages were and , similar to pre-industrial modern humans. It is unclear why earlier EEMH were taller, especially considering that cold-climate creatures are short-limbed and thus short-statured to better retain body heat. This has variously been explained as: retention of a hypothetically tall ancestral condition; higher-quality diet and nutrition due to the hunting of megafauna which later became uncommon or extinct; functional adaptation to increase stride length and movement efficiency while running during a hunt; increasing territorialism among later EEMH reducing gene flow between communities and increasing inbreeding

Inbreeding is the production of offspring from the mating or breeding of individuals or organisms that are closely related genetically. By analogy, the term is used in human reproduction, but more commonly refers to the genetic disorders and o ...

rate; or statistical bias due to small sample size or because taller people were more likely to achieve higher status in a group before the LGM and thus were more likely to be buried and preserved.

Prior to genetic analysis, it was generally assumed that EEMH, like present-day Europeans, were light skinned as an adaptation to better generate vitamin D

Vitamin D is a group of fat-soluble secosteroids responsible for increasing intestinal absorption of calcium, magnesium, and phosphate, and many other biological effects. In humans, the most important compounds in this group are vitamin D3 (c ...

from the less luminous sun farther north. However, of the 3 predominant genes responsible for lighter skin in present-day Europeans — KITLG, SLC24A5

SLC may refer to:

Places

* Salt Lake City, Utah

* Salt Lake City International Airport, IATA Airport Code

Education

* Sarah Lawrence College, NY

* School Leaving Certificate (Nepal)

* St. Lawrence College, Ontario, Canada

* Small Learning Com ...

, and SLC45A2 — the latter two, as well as the TYRP1

Tyrosinase-related protein 1, also known as TYRP1, is an intermembrane enzyme which in humans is encoded by the ''TYRP1'' gene.

Function

Tyrp1 is a melanocyte-specific gene product involved in melanin synthesis within melanosomes. Most Tyrp1 p ...

gene associated with lighter hair and eye colour, experienced positive selection as late as 19 to 11 thousand years ago during the Mesolithic transition. The variation of the gene which is associated with blue eye

Eye color is a polygenic phenotypic character determined by two distinct factors: the pigmentation of the eye's iris and the frequency-dependence of the scattering of light by the turbid medium in the stroma of the iris.

In humans, the pi ...

s in present-day humans, OCA2

P protein, also known as melanocyte-specific transporter protein or pink-eyed dilution protein homolog, is a protein that in humans is encoded by the oculocutaneous albinism II (''OCA2'') gene. The P protein is believed to be an integral membrane ...

, seems to have descended from a common ancestor about 10–6 thousand years ago somewhere in Northern Europe. Such a late timing was potentially caused by overall low population and/or low cross-continental movement required for such an adaptive shift in skin, hair, and eye colouration. However, KITLG experienced positive selection in EEMH (as well as East Asians) beginning approximately 30,000 years ago.

Genetics

While anatomically modern humans have been present outside of Africa during some isolated time intervals potentially as early as 250,000 years ago, present-day non-Africans descend from theout of Africa

''Out of Africa'' is a memoir by the Danish author Karen Blixen. The book, first published in 1937, recounts events of the seventeen years when Blixen made her home in Kenya, then called British East Africa. The book is a lyrical meditation on ...

expansion which occurred around 65–55 thousand years ago. This movement was an offshoot of the rapid expansion within East Africa associated with mtDNA haplogroup L3. Mitochondrial DNA analysis places EEMH as the sister group to Upper Palaeolithic East Asian groups (" Proto-Mongoloid"), divergence occurring roughly 50,000 years ago.

Initial genomic studies on the earliest EEMH in 2014, namely on the 37,000-year-old Kostenki-14 individual, identified 3 major lineages which are also present in present-day Europeans: one related to all later EEMH; a " Basal Eurasian" lineage which split from the common ancestor of present-day Europeans and East Asians before they split from each other; and another related to a 24,000-year-old individual from the Siberian Mal'ta–Buret' culture (near Lake Baikal). Contrary to this, Fu et al. (2016), evaluating much earlier European specimens, including Ust'-Ishim and Oase-1 from 45,000 years ago, found no evidence of a "Basal Eurasian" component to the genome, nor did they find evidence of Mal'ta–Buret' introgression when looking at a wider range of EEMH from the entire Upper Palaeolithic. The study instead concluded that such a genetic makeup in present-day Europeans stemmed from Near Eastern and Siberian introgression occurring predominantly in the Neolithic and the Bronze Age (though beginning by 14,000 years ago), but all EEMH specimens including and following Kostenki-14 contributed to the present-day European genome and were more closely related to present-day Europeans than East Asians. Earlier EEMH (10 tested in total), on the other hand, did not seem to be ancestral to any present-day population, nor did they form any cohesive group in and of themselves, each representing either completely distinct genetic lineages, admixture between major lineages, or have highly divergent ancestry. Because of these, the study also concluded that, beginning roughly 37,000 years ago, EEMH descended from a single founder population and were reproductively isolated from the rest of the world. The study reported that an Aurignacian individual from Grottes de Goyet, Belgium, has more genetic affinities to the Magdalenian inhabitants of Cueva de El Mirón, Spain, than to more or less contemporaneous Eastern European Gravettians.

Haplogroup

A haplotype is a group of alleles in an organism that are inherited together from a single parent, and a haplogroup (haploid from the el, ἁπλοῦς, ''haploûs'', "onefold, simple" and en, group) is a group of similar haplotypes that share ...

s identified in EEMH are the patrilineal (from father to son) Y-DNA haplogroups IJ, C1, and K2a; and matrilineal (from mother to child) mt-DNA haplogroup N, R, and U. Y-haplogroup IJ descended from Southwest Asia. Haplogroup I emerged about 35 to 30 thousand years ago, either in Europe or West Asia. Mt-haplogroup U5 arose in Europe just prior to the LGM, between 35 and 25 thousand years ago. The 14,000 year old Villabruna 1 skeleton from Ripari Villabruna

Ripari Villabruna is a small rock shelter in northern Italy with mesolithic burial remains. It contains several Cro-Magnon burials, with bodies and grave goods dated to 14,000 years BP. The site has added greatly to the understanding of the neol ...

, Italy, is the oldest identified bearer of Y-haplogroup R1b (R1b1a-L754* (xL389,V88)) found in Europe, likely brought in from eastern introgression. The Azilian " Bichon man" skeleton from the Swiss Jura

Swiss may refer to:

* the adjectival form of Switzerland

* Swiss people

Places

* Swiss, Missouri

* Swiss, North Carolina

*Swiss, West Virginia

* Swiss, Wisconsin

Other uses

*Swiss-system tournament, in various games and sports

*Swiss Internatio ...

was found to be associated with the WHG lineage. He was a bearer of Y-DNA haplogroup I2a and mtDNA haplogroup U5b1h.

Genetic evidence suggests early modern humans interbred with Neanderthals. Genes in the present-day genome are estimated to have entered about 65 to 47 thousand years ago, most likely in West Asia soon after modern humans left Africa. In 2015, the 40,000 year old modern human Oase 1 was found to have had 6–9% ( point estimate 7.3%) Neanderthal DNA, indicating a Neanderthal ancestor up to four to six generations earlier, but this hybrid Romanian population does not appear to have made a substantial contribution to the genomes of later Europeans. Therefore, it is possible that interbreeding was common between Neanderthals and EEMH which did not contribute to the present-day genome. The percentage of Neanderthal genes gradually decreased with time, which could indicate they were maladaptive and were selected out of the gene pool.

Valini et al. 2022 found that Europe was populated by three distinct lineages, the earliest inhabitants (represented by Zlaty Kun ~50kya) split from the common Eurasian lineage before the divergence of Western and Eastern Eurasians, but after the divergence of the hypothetical Basal-Eurasians. This earliest sample did not cluster with any modern human population, including Africans, and died out without leaving ancestry to modern peoples. The second wave (represented by Bacho Kiro

Bacho Kiro ( bg, Бачо Киро) (7 July 1835 – 28 May 1876) was the nickname of Kiro Petrov Zanev (Киро Петров Занев), a Bulgarian teacher, man of letters and revolutionary who took an active part in the April Uprising.

Bach ...

~45kya) appeared to be more closely related to modern East Asians

East Asian people (East Asians) are the people from East Asia, which consists of China, Taiwan, Japan, Mongolia, North Korea, and South Korea. The total population of all countries within this region is estimated to be 1.677 billion and 21% of t ...

and Australasians compared to Europeans, suggesting that this lineage split initially after the formation of Eastern Eurasians, and migrated instead northwestwards into Europe. This lineage similarly did not contribute ancestry to later populations, and was replaced by a West-Eurasian lineage (~40kya), which expanded into Europe and Siberia

Siberia ( ; rus, Сибирь, r=Sibir', p=sʲɪˈbʲirʲ, a=Ru-Сибирь.ogg) is an extensive region, geographical region, constituting all of North Asia, from the Ural Mountains in the west to the Pacific Ocean in the east. It has been a ...

. Proper Aurignacian people (40-26kya) were still part of a large Western Eurasian "meta-population", related to Paleolithic Siberian and Western Asian populations. Earlier samples (such as the Bacho Kiro sample) were relatively closer to East Asians and Australasians, although distinct from them.

Culture

There is a notable technological complexification coinciding with the replacement of Neanderthals with EEMH in the archaeological record, and so the terms "Middle Palaeolithic" and "Upper Palaeolithic" were created to distinguish between these two time periods. Largely based on Western European archaeology, the transition was dubbed the "Upper Palaeolithic Revolution," (extended to be a worldwide phenomenon) and the idea of " behavioural modernity" became associated with this event and early modern cultures. It is largely agreed that the Upper Palaeolithic seems to feature a higher rate of technological and cultural evolution than the Middle Palaeolithic, but it is debated if behavioural modernity was truly an abrupt development or was a slow progression initiating far earlier than the Upper Paleolithic, especially when considering the non-European archaeological record. Behaviourly modern practices include: the production ofmicrolith

A microlith is a small stone tool usually made of flint or chert and typically a centimetre or so in length and half a centimetre wide. They were made by humans from around 35,000 to 3,000 years ago, across Europe, Africa, Asia and Australia. Th ...

s, the common use of bone and antler, the common use of grinding and pounding tools, high quality evidence of body decoration and figurine production, long-distance trade networks, and improved hunting technology.Bar-Yosef, O & Zilhão, J (eds) 2002: Towards a definition of the Aurignacian. Proceedings of the Symposium held in Lisbon, Portugal, June 25–30. ''Trabalhos de Arqueologia'' no 45. 381 pp/ref> In regard to art, the Magdalenian produced some of the most intricate Palaeolithic pieces, and they even elaborately decorated normal, everyday objects.

Hunting and gathering

Historically,ethnographic

Ethnography (from Greek ''ethnos'' "folk, people, nation" and ''grapho'' "I write") is a branch of anthropology and the systematic study of individual cultures. Ethnography explores cultural phenomena from the point of view of the subject ...

studies on hunter-gatherer subsistence strategies have long placed emphasis on sexual division of labour and most especially the hunting of big game by men. This culminated in the 1966 book '' Man the Hunter'', which focuses almost entirely on the importance of male contributions of food to the group. As this was published during the second-wave feminism movement, this was quickly met with backlash from many female anthropologists. Among these was Australian archaeologist Betty Meehan

Betty Francis Meehan (born 1933) is an Australian archaeologist and anthropologist who has worked extensively with Aboriginal people in Arnhem Land, Northern Territory.

Early life and education

Meehan was born and grew up in Bourke, New South W ...

in her 1974 article ''Woman the Gatherer'', who argued that women play a vital role in these communities by gathering more reliable food plants and small game, as big game hunting has a low success rate. The concept of "Woman the Gatherer" has since gained significant support.

It has typically been assumed that EEMH closely studied prey habits in order to maximise return depending on the season. For example, large mammals (including red deer

The red deer (''Cervus elaphus'') is one of the largest deer species. A male red deer is called a stag or hart, and a female is called a hind. The red deer inhabits most of Europe, the Caucasus Mountains region, Anatolia, Iran, and parts of we ...

, horse

The horse (''Equus ferus caballus'') is a domesticated, one-toed, hoofed mammal. It belongs to the taxonomic family Equidae and is one of two extant subspecies of ''Equus ferus''. The horse has evolved over the past 45 to 55 million yea ...

s, and ibex

An ibex (plural ibex, ibexes or ibices) is any of several species of wild goat (genus ''Capra''), distinguished by the male's large recurved horns, which are transversely ridged in front. Ibex are found in Eurasia, North Africa and East Africa ...

) congregate seasonally, and reindeer

Reindeer (in North American English, known as caribou if wild and ''reindeer'' if domesticated) are deer in the genus ''Rangifer''. For the last few decades, reindeer were assigned to one species, ''Rangifer tarandus'', with about 10 sub ...

were possibly seasonally plagued by insects rendering fur sometimes unsuitable for hideworking. There is much evidence that EEMH, especially in Western Europe following the LGM, corralled large prey animals into natural confined spaces (such as against a cliff wall, a cul-de-sac, or a water body) in order to efficiently slaughter whole herds of animals (game drive system

The game drive system is a hunting strategy in which game are herded into confined or dangerous places where they can be more easily killed. It can also be used for animal capture as well as for hunting, such as for capturing mustangs. The use of ...

). They seem to have scheduled mass kills to coincide with migration patterns, in particular for red deer, horses, reindeer, bison, aurochs, and ibex, and occasionally woolly mammoth

The woolly mammoth (''Mammuthus primigenius'') is an extinct species of mammoth that lived during the Pleistocene until its extinction in the Holocene epoch. It was one of the last in a line of mammoth species, beginning with '' Mammuthus s ...

s. There are also multiple examples of consumption of seasonally abundant fish, becoming more prevalent in the mid-Upper-Palaeolithic. Nonetheless, Magdalenian peoples appear to have had a greater dependence on small animals, aquatic resources, and plants than predecessors, probably due to the relative scarcity of European big game following the LGM (Quaternary extinction event

The Quaternary period (from 2.588 ± 0.005 million years ago to the present) has seen the extinctions of numerous predominantly megafaunal species, which have resulted in a collapse in faunal density and diversity and the extinction of key ecolog ...

). Post-LGM peoples tend to have a higher rate of nutrient deficiency related ailments, including a reduction in height, which indicates these bands (probably due to decreased habitable territory) had to consume a much broader and less desirable food range to survive. The popularisation of game drive systems may have been an extension of increasing food return. In particularly southwestern France, EEMH depended heavily upon reindeer, and so it is hypothesised that these communities followed the herds, with occupation of the Perigord and the Pyrenees

The Pyrenees (; es, Pirineos ; french: Pyrénées ; ca, Pirineu ; eu, Pirinioak ; oc, Pirenèus ; an, Pirineus) is a mountain range straddling the border of France and Spain. It extends nearly from its union with the Cantabrian Mountains to ...

only occurring in the summer. Epi-Gravettian communities, in contrast, generally focused on hunting one species of large game, most commonly horse or bison. It is possible that human activity, in addition to the rapid retreat of favourable steppeland, inhibited recolonisation of most of Europe by megafauna following the LGM (such as mammoths, woolly rhinoceros

The woolly rhinoceros (''Coelodonta antiquitatis'') is an extinct species of rhinoceros that was common throughout Europe and Asia during the Pleistocene epoch and survived until the end of the last glacial period. The woolly rhinoceros was a me ...

es, Irish elk

The Irish elk (''Megaloceros giganteus''), also called the giant deer or Irish deer, is an extinct species of deer in the genus '' Megaloceros'' and is one of the largest deer that ever lived. Its range extended across Eurasia during the Pleist ...

, and cave lions), in part contributing to their final extinction which occurred by the beginning of or well into the Holocene depending on the species.

For weapons, EEMH crafted spearpoints using predominantly bone and antler, possibly because these materials were readily abundant. Compared to stone, these materials are compressive, making them fairly shatterproof. These were then hafted onto a shaft to be used as javelins. It is possible that Aurignacian craftsmen further hafted bone barbs onto the spearheads, but firm evidence of such technology is recorded earliest 23,500 years ago, and does not become more common until the Mesolithic. Aurignacian craftsmen produced lozenge

Lozenge or losange may refer to:

* Lozenge (shape), a type of rhombus

*Throat lozenge, a tablet intended to be dissolved slowly in the mouth to suppress throat ailments

*Lozenge (heraldry), a diamond-shaped object that can be placed on the field of ...

-shaped (diamond-like) spearheads. By 30,000 years ago, spearheads were manufactured with a more rounded-off base, and by 28,000 years ago spindle-shaped heads were introduced. During the Gravettian, spearheads with a bevelled base were being produced. By the beginning of the LGM, the spear-thrower

A spear-thrower, spear-throwing lever or ''atlatl'' (pronounced or ; Nahuatl ''ahtlatl'' ) is a tool that uses leverage to achieve greater velocity in dart or javelin-throwing, and includes a bearing surface which allows the user to store ene ...

was invented in Europe, which can increase the force and accuracy of the projectile. A possible boomerang

A boomerang () is a thrown tool, typically constructed with aerofoil sections and designed to spin about an axis perpendicular to the direction of its flight. A returning boomerang is designed to return to the thrower, while a non-returning ...

made of mammoth tusk was identified in Poland (though it may have been unable to return to the thrower), and dating to 23,000 years ago, it would be the oldest known boomerang. Stone spearheads with leaf- and shouldered-points become more prevalent in the Solutrean. Both large and small spearheads were produced in great quantity, and the smaller ones may have been attached to projectile darts

Darts or dart-throwing is a competitive sport in which two or more players bare-handedly throw small sharp-pointed missiles known as darts at a round target known as a dartboard.

Points can be scored by hitting specific marked areas of the bo ...

. Archery was possibly invented in the Solutrean, though less ambiguous bow technology is first reported in the Mesolithic. Bone technology was revitalised in the Magdalanian, and long-range technology as well as harpoon

A harpoon is a long spear-like instrument and tool used in fishing, whaling, sealing, and other marine hunting to catch and injure large fish or marine mammals such as seals and whales. It accomplishes this task by impaling the target animal ...

s become much more prevalent. Some harpoon fragments are speculated to have been leister

A leister is a type of spear used for spearfishing.

Leisters are three-pronged with backward-facing barbs, historically often built using materials such as bone and ivory, with tools such as the saw-knife. In many cases it could be disassembled ...

s or trident

A trident is a three- pronged spear. It is used for spear fishing and historically as a polearm.

The trident is the weapon of Poseidon, or Neptune, the God of the Sea in classical mythology. The trident may occasionally be held by other mari ...

s, and true harpoons are commonly found along seasonal salmon

Salmon () is the common name for several commercially important species of euryhaline ray-finned fish from the family Salmonidae, which are native to tributaries of the North Atlantic (genus ''Salmo'') and North Pacific (genus '' Oncorhy ...

migration routes.

Society

Social system

As opposed to the patriarchy prominent in historical societies, the idea of a prehistoric predominance of either

As opposed to the patriarchy prominent in historical societies, the idea of a prehistoric predominance of either matriarchy

Matriarchy is a social system in which women hold the primary power positions in roles of authority. In a broader sense it can also extend to moral authority, social privilege and control of property.

While those definitions apply in general ...

or matrifocal

A matrifocal family structure is one where mothers head families and fathers play a less important role in the home and in bringing up children.

Definition

The concept of the matrifocal family was introduced to the study of Caribbean societie ...

families (centred on motherhood) was first supposed in 1861 by legal scholar Johann Jakob Bachofen

Johann Jakob Bachofen (22 December 1815 – 25 November 1887) was a Swiss antiquarian, jurist, philologist, anthropologist, and professor for Roman law at the University of Basel from 1841 to 1845.

Bachofen is most often connected with h ...

. The earliest models of this believed that monogamy

Monogamy ( ) is a form of dyadic relationship in which an individual has only one partner during their lifetime. Alternately, only one partner at any one time (serial monogamy) — as compared to the various forms of non-monogamy (e.g., polyg ...

was not widely practiced in ancient times — thus, the paternal line was resultantly more difficult to keep track of than the maternal — resulting in a matrilineal

Matrilineality is the tracing of kinship through the female line. It may also correlate with a social system in which each person is identified with their matriline – their mother's lineage – and which can involve the inheritance ...

(and matriarchal) society. Matriarchs were then conquered by patriarchs at the dawn of civilisation. The switch from matriarchy to patriarchy and the hypothetical adoption of monogamy was seen as a leap forward. However, when the first Palaeolithic representations of humans were discovered, the so-called Venus figurines — which typically feature pronounced breasts, buttocks, and vulvas (areas generally sexualised in present-day Western Culture) — they were initially interpreted as pornographic in nature. The first Venus discovered was named the " Vénus impudique" ("immodest Venus") by the discoverer Paul Hurault, 8th Marquis de Vibraye, because it lacked clothes and had a prominent vulva. The name "Venus