Culture of Australia on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The culture of Australia is primarily a

The oldest surviving cultural traditions of Australia—and some of the oldest surviving cultural traditions on earth—are those of Australia's

The oldest surviving cultural traditions of Australia—and some of the oldest surviving cultural traditions on earth—are those of Australia's

/ref> Women became eligible to vote in South Australia in 1895. This was the first legislation in the world permitting women to stand for political office and, in 1897, Catherine Helen Spence, an Adelaidean, became the first female political candidate. Though constantly evolving, the key foundations for elected parliamentary government have maintained an historical continuity in Australia from the 1850s into the 21st century. During the colonial era, distinctive forms of Australian art, Some

Some

When the Australian colonies federated on 1 January 1901, an official competition for a design for an Australian flag was held. The design that was adopted contains the

When the Australian colonies federated on 1 January 1901, an official competition for a design for an Australian flag was held. The design that was adopted contains the

Although Australia has no official language, it is largely monolingual with English being the de facto

Although Australia has no official language, it is largely monolingual with English being the de facto

Comedy is an important part of the Australian identity. The "Australian sense of humour" is often characterised as dry, irreverent, self-deprecating and ironic, exemplified by the works of performing artists like Barry Humphries and Paul Hogan.Australian humour – australia.gov.au

Comedy is an important part of the Australian identity. The "Australian sense of humour" is often characterised as dry, irreverent, self-deprecating and ironic, exemplified by the works of performing artists like Barry Humphries and Paul Hogan.Australian humour – australia.gov.au

/ref> The convicts of the early colonial period helped establish anti-authoritarianism as a hallmark of Australian comedy. Influential in the establishment of stoic, dry wit as a characteristic of Australian humour were the bush balladeers of the 19th century, including

Western culture

image:Da Vinci Vitruve Luc Viatour.jpg, Leonardo da Vinci's ''Vitruvian Man''. Based on the correlations of ideal Body proportions, human proportions with geometry described by the ancient Roman architect Vitruvius in Book III of his treatise '' ...

, originally derived from Britain but also influenced by the unique geography of Australia and the cultural input of Aboriginal

Aborigine, aborigine or aboriginal may refer to:

*Aborigines (mythology), in Roman mythology

* Indigenous peoples, general term for ethnic groups who are the earliest known inhabitants of an area

*One of several groups of indigenous peoples, see ...

, Torres Strait Islander and other Australian people. The British colonisation of Australia began in 1788, and waves of multi-ethnic migration followed. Evidence of a significant Anglo-Celtic heritage includes the predominance of the English language

English is a West Germanic language of the Indo-European language family, with its earliest forms spoken by the inhabitants of early medieval England. It is named after the Angles, one of the ancient Germanic peoples that migrated to t ...

, the existence of a democratic system of government drawing upon the British traditions of Westminster

Westminster is an area of Central London, part of the wider City of Westminster.

The area, which extends from the River Thames to Oxford Street, has many visitor attractions and historic landmarks, including the Palace of Westminster, Buck ...

government, parliamentarianism and constitutional monarchy

A constitutional monarchy, parliamentary monarchy, or democratic monarchy is a form of monarchy in which the monarch exercises their authority in accordance with a constitution and is not alone in decision making. Constitutional monarchies di ...

, American constitutionalist and federalist

The term ''federalist'' describes several political beliefs around the world. It may also refer to the concept of parties, whose members or supporters called themselves ''Federalists''.

History Europe federation

In Europe, proponents of de ...

traditions, and Christianity

Christianity is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus of Nazareth

Jesus, likely from he, יֵשׁוּעַ, translit=Yēšūaʿ, label=Hebrew/Aramaic ( AD 30 or 33), also referred to as Jesu ...

as the dominant religion.

Aboriginal people are believed to have arrived as early as 60,000 years ago, and evidence of Aboriginal art

Indigenous Australian art includes art made by Aboriginal Australian and Torres Strait Islander peoples, including collaborations with others. It includes works in a wide range of media including painting on leaves, bark painting, wood carving ...

in Australia dates back at least 30,000 years. Several states and territories had their origins as penal colonies, with the first British convicts arriving at Sydney Cove

Sydney Cove ( Eora: ) is a bay on the southern shore of Sydney Harbour, one of several harbours in Port Jackson, on the coast of Sydney, New South Wales. Sydney Cove is a focal point for community celebrations, due to its central Sydney loca ...

in 1788. Stories of outlaws like the bushranger Ned Kelly have endured in Australian music, cinema and literature

Literature is any collection of written work, but it is also used more narrowly for writings specifically considered to be an art form, especially prose fiction, drama, and poetry. In recent centuries, the definition has expanded to inclu ...

. The Australian gold rushes from the 1850s brought wealth as well as new social tensions to Australia, including the miners' Eureka Stockade rebellion. The colonies established elected parliaments and rights for workers and women before most other Western nations.Geoffrey Blainey; A Very Short History of the World; Penguin Books; 2004;

Federation

A federation (also known as a federal state) is a political entity characterized by a union of partially self-governing provinces, states, or other regions under a central federal government (federalism). In a federation, the self-govern ...

in 1901 was the culmination of a growing sense of national identity that had developed over the latter half of the 19th century, as seen in the works of the Heidelberg School painters and writers like Banjo Paterson

Andrew Barton "Banjo" Paterson, (17 February 18645 February 1941) was an Australian bush poet, journalist and author. He wrote many ballads and poems about Australian life, focusing particularly on the rural and outback areas, including the d ...

, Henry Lawson

Henry Archibald Hertzberg Lawson (17 June 1867 – 2 September 1922) was an Australian writer and bush poet. Along with his contemporary Banjo Paterson, Lawson is among the best-known Australian poets and fiction writers of the colonial perio ...

and Dorothea Mackellar. The World Wars profoundly impacted Australia's national identity, with World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

introducing the ANZAC

The Australian and New Zealand Army Corps (ANZAC) was a First World War army corps of the Mediterranean Expeditionary Force. It was formed in Egypt in December 1914, and operated during the Gallipoli campaign. General William Birdwood comm ...

legend, and World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

seeing a reorientation from Britain to the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 U.S. state, states, a Washington, D.C., federal district, five ma ...

as the nation's foremost ally

An ally is a member of an alliance.

Ally may also refer to:

Place names

* Ally, Cantal, a commune in the Cantal department in south-central France

* Ally, County Tyrone, a townland in County Tyrone, Northern Ireland

* Ally, Haute-Loire, a com ...

. After the second war, 6.5 million migrants from 200 nations brought immense new diversity. Over time, the diverse food, lifestyle and cultural practices of immigrants have been absorbed into mainstream Australian culture.

Historical development of Australian culture

The oldest surviving cultural traditions of Australia—and some of the oldest surviving cultural traditions on earth—are those of Australia's

The oldest surviving cultural traditions of Australia—and some of the oldest surviving cultural traditions on earth—are those of Australia's Aboriginal

Aborigine, aborigine or aboriginal may refer to:

*Aborigines (mythology), in Roman mythology

* Indigenous peoples, general term for ethnic groups who are the earliest known inhabitants of an area

*One of several groups of indigenous peoples, see ...

and Torres Strait Islander peoples. Their ancestors have inhabited Australia for between 40,000 and 60,000 years, living a hunter-gatherer lifestyle. In 2006, the Indigenous population was estimated at 517,000 people, or 2.5 per cent of the total population. Most Aboriginal Australians have a belief system based on the Dreaming, or Dream time, which refers both to a time when ancestral spirits created land and culture, and to the knowledge and practices that define individual and community responsibilities and identity. Conflict and reconciliation between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians has been a source of much art and literature in Australia, and ancient Aboriginal art

Indigenous Australian art includes art made by Aboriginal Australian and Torres Strait Islander peoples, including collaborations with others. It includes works in a wide range of media including painting on leaves, bark painting, wood carving ...

istic styles and iconic inventions such as the boomerang, the didgeridoo and Indigenous Australian music have become symbols of modern Australia.

The arrival of the first British settlers at what is now Sydney in 1788 introduced Western civilisation to the Australian continent. Although Sydney was initially used by the British as a place of banishment for prisoners, the arrival of the British laid the foundations for Australia's democratic institutions and rule of law, and introduced the long traditions of English literature

English literature is literature written in the English language from United Kingdom, its crown dependencies, the Republic of Ireland, the United States, and the countries of the former British Empire. ''The Encyclopaedia Britannica'' defines E ...

, Western art and music, and Judeo-Christian ethics and religious outlook to a new continent.

The British Empire

The British Empire was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It began with the overseas possessions and trading post ...

expanded across the whole continent and established six colonies. The colonies were originally penal colonies, with the exception of Western Australia and South Australia

South Australia (commonly abbreviated as SA) is a state in the southern central part of Australia. It covers some of the most arid parts of the country. With a total land area of , it is the fourth-largest of Australia's states and territories ...

, which were established as a "free colony" with no convicts and a vision for a territory with political and religious freedoms, together with opportunities for wealth through business and pastoral investments. Though Western Australia became a penal colony after insufficient numbers of free settlers arrived. Adelaide, the capital of South Australia, grew from its status as a convict free region and experienced prosperity from the late nineteenth century.

Contact between the Indigenous Australians and the new settlers ranged from cordiality to violent conflict, but the diseases brought by Europeans were devastating to Aboriginal populations and culture. According to the historian Geoffrey Blainey, during the colonial period: "Smallpox, measles, influenza and other new diseases swept from one Aboriginal camp to another ... The main conqueror of Aborigines was to be disease and its ally, demoralization."

William Wentworth

William Charles Wentworth (August 179020 March 1872) was an Australian pastoralist, explorer, newspaper editor, lawyer, politician and author, who became one of the wealthiest and most powerful figures of early colonial New South Wales.

Throug ...

established Australia's first political party in 1835 to demand democratic government

Democracy (From grc, δημοκρατία, dēmokratía, ''dēmos'' 'people' and ''kratos'' 'rule') is a form of government in which the people have the authority to deliberate and decide legislation (" direct democracy"), or to choose g ...

for New South Wales. From the 1850s, the colonies set about writing constitutions which produced democratically advanced parliaments as Constitutional Monarchies

A constitutional monarchy, parliamentary monarchy, or democratic monarchy is a form of monarchy in which the monarch exercises their authority in accordance with a constitution and is not alone in decision making. Constitutional monarchies dif ...

with Queen Victoria

Victoria (Alexandrina Victoria; 24 May 1819 – 22 January 1901) was Queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland from 20 June 1837 until her death in 1901. Her reign of 63 years and 216 days was longer than that of any previ ...

as the head of state.

Women's suffrage in Australia

Women's suffrage in Australia was one of the early achievements of Australian democracy. Following the progressive establishment of male suffrage in the Australian colonies from the 1840s to the 1890s, an organised push for women's enfranchi ...

was achieved from the 1890s.AEC.gov.au/ref> Women became eligible to vote in South Australia in 1895. This was the first legislation in the world permitting women to stand for political office and, in 1897, Catherine Helen Spence, an Adelaidean, became the first female political candidate. Though constantly evolving, the key foundations for elected parliamentary government have maintained an historical continuity in Australia from the 1850s into the 21st century. During the colonial era, distinctive forms of Australian art,

music

Music is generally defined as the The arts, art of arranging sound to create some combination of Musical form, form, harmony, melody, rhythm or otherwise Musical expression, expressive content. Exact definition of music, definitions of mu ...

, language

Language is a structured system of communication. The structure of a language is its grammar and the free components are its vocabulary. Languages are the primary means by which humans communicate, and may be conveyed through a variety of ...

and literature

Literature is any collection of written work, but it is also used more narrowly for writings specifically considered to be an art form, especially prose fiction, drama, and poetry. In recent centuries, the definition has expanded to inclu ...

developed through movements like the Heidelberg school of painters and the work of bush balladeers like Henry Lawson

Henry Archibald Hertzberg Lawson (17 June 1867 – 2 September 1922) was an Australian writer and bush poet. Along with his contemporary Banjo Paterson, Lawson is among the best-known Australian poets and fiction writers of the colonial perio ...

and Banjo Paterson

Andrew Barton "Banjo" Paterson, (17 February 18645 February 1941) was an Australian bush poet, journalist and author. He wrote many ballads and poems about Australian life, focusing particularly on the rural and outback areas, including the d ...

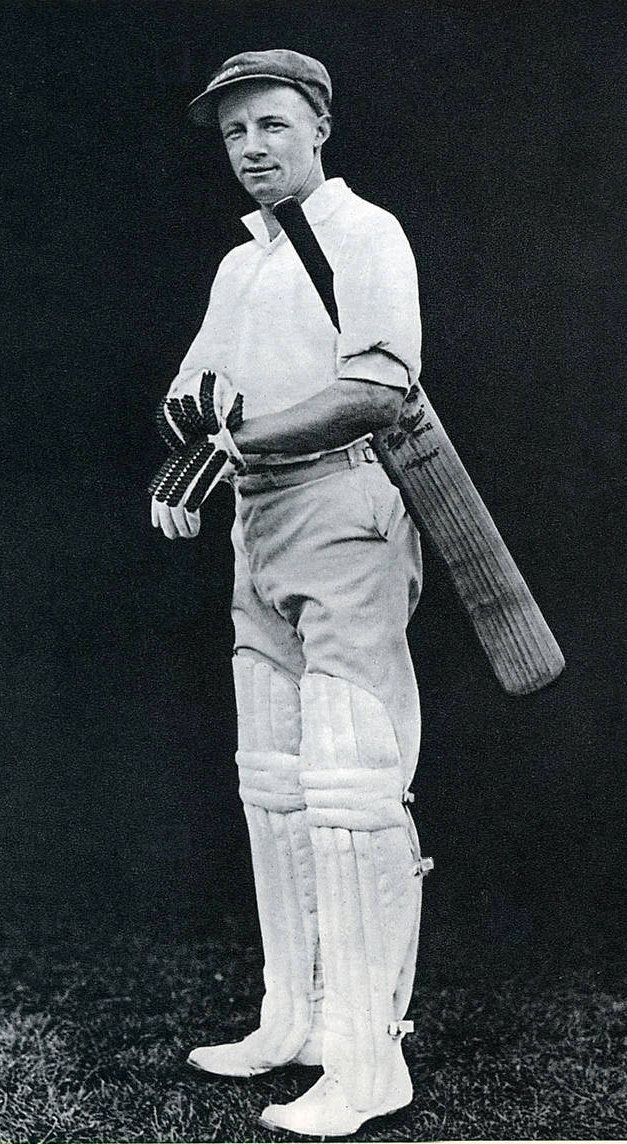

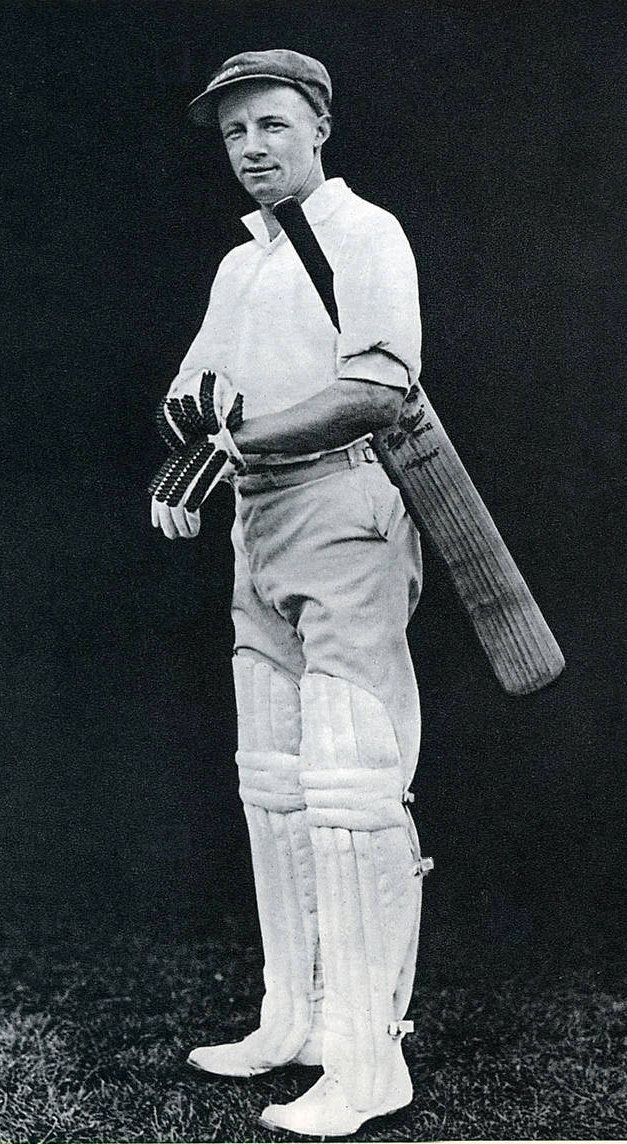

, whose poetry and prose did much to promote an egalitarian Australian outlook which placed a high value on the concept of " mateship". Games like cricket

Cricket is a bat-and-ball game played between two teams of eleven players on a field at the centre of which is a pitch with a wicket at each end, each comprising two bails balanced on three stumps. The batting side scores runs by st ...

and rugby were imported from Britain at this time and with a local variant of football, Australian Rules Football, became treasured cultural traditions.

The Commonwealth of Australia was founded in 1901, after a series of referendums conducted in the British colonies of Australasia

Australasia is a region that comprises Australia, New Zealand and some neighbouring islands in the Pacific Ocean. The term is used in a number of different contexts, including geopolitically, physiogeographically, philologically, and ecolo ...

. The Australian Constitution established a federal democracy and enshrined human rights

Human rights are moral principles or normsJames Nickel, with assistance from Thomas Pogge, M.B.E. Smith, and Leif Wenar, 13 December 2013, Stanford Encyclopedia of PhilosophyHuman Rights Retrieved 14 August 2014 for certain standards of hu ...

such as sections 41 (right to vote), 80 (right to trial by jury) and 116 (freedom of religion) as foundational principles of Australian law and included economic rights such as restricting the government to acquiring property only "on just terms". The Australian Labor Party

The Australian Labor Party (ALP), also simply known as Labor, is the major centre-left political party in Australia, one of two major parties in Australian politics, along with the centre-right Liberal Party of Australia. The party forms ...

was established in the 1890s and the Liberal Party of Australia

The Liberal Party of Australia is a centre-right political party in Australia, one of the two major parties in Australian politics, along with the centre-left Australian Labor Party. It was founded in 1944 as the successor to the United Aus ...

in 1944, both rising to be the dominant political parties and rivals of Australian politics, though various other parties have been and remain influential. Voting is compulsory in Australia and government is essentially formed by a group commanding a majority of seats in the Australian House of Representatives

The House of Representatives is the lower house of the bicameralism, bicameral Parliament of Australia, the upper house being the Australian Senate, Senate. Its composition and powers are established in Chapter I of the Constitution of Austra ...

selecting a leader who becomes Prime Minister

A prime minister, premier or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. Under those systems, a prime minister is ...

. Australia remains a constitutional monarchy

A constitutional monarchy, parliamentary monarchy, or democratic monarchy is a form of monarchy in which the monarch exercises their authority in accordance with a constitution and is not alone in decision making. Constitutional monarchies di ...

in which the largely ceremonial and procedural duties of the monarch are performed by a Governor General

Governor-general (plural ''governors-general''), or governor general (plural ''governors general''), is the title of an office-holder. In the context of governors-general and former British colonies, governors-general are appointed as viceroy ...

selected by the Australian government.

Australia fought at Britain's side from the outset of World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

and World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

and came under attack from the Empire of Japan during the latter conflict. These wars profoundly affected Australia's sense of nationhood and a proud military legend developed around the spirit of Australia's ANZAC

The Australian and New Zealand Army Corps (ANZAC) was a First World War army corps of the Mediterranean Expeditionary Force. It was formed in Egypt in December 1914, and operated during the Gallipoli campaign. General William Birdwood comm ...

troops, who came to symbolise the virtues of mateship, courage and endurance for the nation.

The Australian colonies had a period of extensive non-British European and Chinese immigration during the Australian gold rushes of the latter half of the 19th century, but following Federation in 1901, the Parliament instigated the White Australia Policy

The White Australia policy is a term encapsulating a set of historical policies that aimed to forbid people of non-European ethnic origin, especially Asians (primarily Chinese) and Pacific Islanders, from immigrating to Australia, starting ...

that gave preference to British migrants and ensured that Australia remained a predominantly Anglo-Celtic society until well into the 20th century. The post-World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

immigration program saw the policy relaxed then dismantled by successive governments, permitting large numbers of non-British Europeans, and later Asian and Middle Eastern migrants to arrive. The Menzies Government (1949-1966) Menzies Government may refer to:

*Menzies government (1939–1941)

*Menzies government (1949–1966) Menzies Government may refer to:

*Menzies government (1939–1941)

*Menzies government (1949–1966) Menzies Government may refer to:

* Menzies g ...

and Holt Government maintained the White Australia Policy but relaxed it, and then the legal barriers to multiracial immigration were dismantled during the 1970s, with the promotion of multiculturalism

The term multiculturalism has a range of meanings within the contexts of sociology, political philosophy, and colloquial use. In sociology and in everyday usage, it is a synonym for "Pluralism (political theory), ethnic pluralism", with the tw ...

by the Whitlam and Fraser Governments.

States and Territories of Australia

The states and territories are federated state, federated administrative divisions in Australia, ruled by regional governments that constitute the second level of governance between the Australian Government, federal government and local gov ...

retained discriminatory laws relating to voting rights for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people into the 1960s, at which point full legal equality was established. A 1967 referendum

The 1967 Australian referendum occurred on 27 May 1967 under the Holt Government. It contained three topics asked about in two questions, regarding the passage of two bills to alter the Australian Constitution.

The first question (''Constitution ...

to include all Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in the national electoral roll census was overwhelmingly approved by voters. In 1984, a group of Pintupi

The Pintupi are an Australian Aboriginal group who are part of the Western Desert cultural group and whose traditional land is in the area west of Lake Macdonald and Lake Mackay in Western Australia. These people moved (or were moved) into ...

people who were living a traditional hunter-gatherer desert-dwelling life were tracked down in the Gibson Desert and brought into a settlement. They are believed to have been the last uncontacted tribe.

While the British cultural influence remained strong into the 21st century, other influences became increasingly important. Australia's post-war period was marked by an influx of Europeans who broadened the nation's vision. The Hawaiian sport of surfing was adopted in Australia where a beach culture and the locally developed surf lifesaving movement was already burgeoning in the early 20th century. American pop culture and cinema were embraced in the 20th century, with country music and later rock and roll sweeping Australia, aided by the new technology of television and a host of American content. The 1956 Melbourne Olympics, the first to be broadcast to the world, announced a confident, prosperous post-war nation, and new cultural icons like Australian country music star Slim Dusty and dadaist Barry Humphries expressed a uniquely Australian identity.

Australia's contemporary immigration program has two components: a program for skilled and family migrants and a humanitarian program for refugees and asylum seekers. By 2010, the post-war immigration program had received more than 6.5 million migrants from every continent. The population tripled in the six decades to around 21 million in 2010, including people originating from 200 countries. More than 43 per cent of Australians were either born overseas or have one parent who was born overseas. The population is highly urbanised, with more than 75% of Australians living in urban centers, largely along the coast though there has been increased incentive to decentralise the population, concentrating it into developed regional or rural areas.

Contemporary Australia is a pluralistic society, rooted in liberal democratic traditions and espousing informality and egalitarianism as key societal values. While strongly influenced by Anglo-Celtic origins, the culture of Australia has also been shaped by multi-ethnic migration which has influenced all aspects of Australian life, including business, the arts, cuisine, sense of humor and sporting tastes.

Contemporary Australia is also a culture that is profoundly influenced by global movements of meaning and communication, including advertising culture. In turn, globalising corporations from Holden to Exxon have attempted to associate their brand with Australian cultural identity. This process intensified from the 1970s onwards. According to Paul James,

Symbols

When the Australian colonies federated on 1 January 1901, an official competition for a design for an Australian flag was held. The design that was adopted contains the

When the Australian colonies federated on 1 January 1901, an official competition for a design for an Australian flag was held. The design that was adopted contains the Union Flag

The Union Jack, or Union Flag, is the ''de facto'' national flag of the United Kingdom. Although no law has been passed making the Union Flag the official national flag of the United Kingdom, it has effectively become such through precedent. ...

in the left corner, symbolising Australia's historical links to the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the European mainland, continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotlan ...

, the stars of the Southern Cross on the right half of the flag indicating Australia's geographical location, and the seven-pointed Federation Star in the bottom left representing the six states and the territories of Australia. Other official flags include the Australian Aboriginal Flag, the Torres Strait Islander Flag

The Torres Strait Islander Flag is an official flag of Australia, and is the flag that represents Torres Strait Islander people. It was designed in 1992 by Bernard Namok. It won a local competition held by the Islands Coordinating Council, and ...

and the flags of the individual states and territories.

The Australian Coat of Arms was granted by King George V

George V (George Frederick Ernest Albert; 3 June 1865 – 20 January 1936) was King of the United Kingdom and the British Dominions, and Emperor of India, from 6 May 1910 until his death in 1936.

Born during the reign of his grandmother Q ...

in 1912 and consists of a shield containing the badges of the six states, within an ermine border. The crest above the shield and helmet is a seven-pointed gold star on a blue and gold wreath, representing the 6 states and the territories. The shield is supported by a red kangaroo and an emu

The emu () (''Dromaius novaehollandiae'') is the second-tallest living bird after its ratite relative the ostrich. It is endemic to Australia where it is the largest native bird and the only extant member of the genus '' Dromaius''. The ...

.

Green and gold were confirmed as Australia's national colours in 1984, though the colors had been adopted by many national sporting teams long before this. The Golden Wattle (''Acacia pycnantha'') was officially proclaimed as the national floral emblem in 1988.

Reflecting the country's status as a constitutional monarchy

A constitutional monarchy, parliamentary monarchy, or democratic monarchy is a form of monarchy in which the monarch exercises their authority in accordance with a constitution and is not alone in decision making. Constitutional monarchies di ...

, a number of royal symbols exist in Australia. These include symbols of the monarch of Australia, as well as the monarch's vice-regal representatives.

Despite the fact that the King of Australia is not resident in Australia, the Crown and royal institutions remain part of Australian life. Australian currency

The Australian dollar (sign: $; code: AUD) is the currency of Australia, including its external territories: Christmas Island, Cocos (Keeling) Islands, and Norfolk Island. It is officially used as currency by three independent Pacific Island s ...

, including all coins and the five-dollar note, bears an image of the late monarch, Queen Elizabeth II

Elizabeth II (Elizabeth Alexandra Mary; 21 April 1926 – 8 September 2022) was Queen of the United Kingdom and other Commonwealth realms from 6 February 1952 until her death in 2022. She was queen regnant of 32 sovereign states during ...

. Around 12% of public lands in Australia are referred to as Crown land

Crown land (sometimes spelled crownland), also known as royal domain, is a territorial area belonging to the monarch, who personifies the Crown. It is the equivalent of an entailed estate and passes with the monarchy, being inseparable from it ...

, including reserves set aside for environmental conservation as well as vacant land. There are many geographic places that have been named in honor of a reigning monarch, including the states of Queensland

)

, nickname = Sunshine State

, image_map = Queensland in Australia.svg

, map_caption = Location of Queensland in Australia

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name = Australia

, established_title = Before federation

, established_ ...

and Victoria, named after Queen Victoria

Victoria (Alexandrina Victoria; 24 May 1819 – 22 January 1901) was Queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland from 20 June 1837 until her death in 1901. Her reign of 63 years and 216 days was longer than that of any previ ...

, with numerous rivers, streets, squares, parks and buildings carrying the names of past or present members of the Royal Family. Through royal patronage there are many organisations in Australia that have been granted a ''Royal'' prefix. These organisations, including branches of the Australian Defence Force, often incorporate royal symbols into their imagery.

Language

Although Australia has no official language, it is largely monolingual with English being the de facto

Although Australia has no official language, it is largely monolingual with English being the de facto national language

A national language is a language (or language variant, e.g. dialect) that has some connection—de facto or de jure—with a nation. There is little consistency in the use of this term. One or more languages spoken as first languages in the te ...

. Australian English is a major variety of the language which is immediately distinguishable from British, American, and other national dialects by virtue of its unique accents, pronunciations, idioms and vocabulary, although its spelling more closely reflects British versions rather than American. According to the 2011 census, English is the only language spoken in the home for around 80% of the population. The next most common languages spoken at home are Mandarin (1.7%), Italian (1.5%), and Arabic (1.4%); almost all migrants speak some English. Australia has multiple sign languages, the most spoken known as Auslan, which in 2004 was the main language of about 6,500 deaf people, and Australian Irish Sign Language

Australian Irish Sign Language or AISL is a minority sign language in Australia. As a Francosign language, it is related to French Sign Language as opposed to Auslan which is a Banzsl language which is related to British Sign Language. AISL ...

with about 100 speakers.

It is believed that there were between 200 and 300 Australian Aboriginal languages at the time of first European contact, but only about 70 of these have survived and all but 20 are now endangered. An Indigenous language is the main language for 0.25% of the population.

Humour

Comedy is an important part of the Australian identity. The "Australian sense of humour" is often characterised as dry, irreverent, self-deprecating and ironic, exemplified by the works of performing artists like Barry Humphries and Paul Hogan.Australian humour – australia.gov.au

Comedy is an important part of the Australian identity. The "Australian sense of humour" is often characterised as dry, irreverent, self-deprecating and ironic, exemplified by the works of performing artists like Barry Humphries and Paul Hogan.Australian humour – australia.gov.au/ref> The convicts of the early colonial period helped establish anti-authoritarianism as a hallmark of Australian comedy. Influential in the establishment of stoic, dry wit as a characteristic of Australian humour were the bush balladeers of the 19th century, including

Henry Lawson

Henry Archibald Hertzberg Lawson (17 June 1867 – 2 September 1922) was an Australian writer and bush poet. Along with his contemporary Banjo Paterson, Lawson is among the best-known Australian poets and fiction writers of the colonial perio ...

, author of " The Loaded Dog". His contemporary, Banjo Paterson

Andrew Barton "Banjo" Paterson, (17 February 18645 February 1941) was an Australian bush poet, journalist and author. He wrote many ballads and poems about Australian life, focusing particularly on the rural and outback areas, including the d ...

, contributed a number of classic comic poems including ''The Man from Ironbark

"The Man From Ironbark" is a poem by Australian bush poet Banjo Paterson, Banjo Paterson (Andrew Barton Paterson). It is written in the iambic heptameter.

It was first published in ''The Bulletin (Australian periodical), The Bulletin'' on 17 Decem ...

'' and '' The Geebung Polo Club''. CJ Dennis wrote humor in the Australian vernacular – notably in '' The Songs of a Sentimental Bloke''. The '' Dad and Dave'' series about a farming family was an enduring hit of the early 20th century. The World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

ANZAC

The Australian and New Zealand Army Corps (ANZAC) was a First World War army corps of the Mediterranean Expeditionary Force. It was formed in Egypt in December 1914, and operated during the Gallipoli campaign. General William Birdwood comm ...

troops were said to often display irreverence in their relations with superior officers and dark humour in the face of battle.

Australian comedy has a strong tradition of self-mockery, from the outlandish Barry McKenzie ''expat-in-Europe'' ocker comedies of the 1970s, to the quirky outback characters of the '' "Crocodile" Dundee'' films of the 1980s, the suburban parody of Working Dog Productions' 1997 film '' The Castle'' and the dysfunctional suburban mother–daughter sitcom '' Kath & Kim''. In the 1970s, satirical talk-show host Norman Gunston (played by Garry McDonald), with his malapropisms, sweep-over hair and poorly shaven face, rose to great popularity by pioneering the satirical "ambush" interview technique and giving unique interpretations of pop songs. Roy and HG provide an affectionate but irreverent parody of Australia's obsession with sport.

The unique character and humour of Australian culture was defined in cartoons by immigrants, Emile Mercier and George Molnar

George Molnar ( hu, Molnár György) (25 April 1910, Nagyvárad – 16 November 1998, Sydney) was born in Nagyvárad, Austria-Hungary and came to Australia in 1939, where he practiced as a cartoonist and architecture lecturer.They're a Weird Mob'' (1957) by John O'Grady, which looks at Sydney through the eyes of an Italian immigrant. Post-war immigration has seen migrant humour flourish through the works of Vietnamese refugee

Anh Do

Anh Do (born 2 June 1977) is a Vietnamese-born Australian author, actor, comedian, and painter.

He has appeared on Australian TV shows such as ''Thank God You're Here'' and ''Good News Week'', and was runner-up on ''Dancing with the Stars'' in ...

, Egyptian-Australian stand-up comic Akmal Saleh and Greek-Australian actor Nick Giannopoulos.

Since the 1950s, the satirical character creations of Barry Humphries have included housewife "gigastar" Edna Everage and "Australian cultural attaché" Les Patterson, whose interests include boozing, chasing women and flatulence. For his delivery of dadaist and absurdist humor to millions, biographer Anne Pender described Humphries in 2010 as "the most significant comedian to emerge since Charlie Chaplin".

The vaudeville talents of Daryl Somers, Graham Kennedy, Don Lane and Bert Newton earned popular success during the early years of Australian television. The variety show '' Hey Hey It's Saturday'' screened for three decades. Among the best loved Australian sitcoms was '' Mother and Son'', about a divorcee who had moved back into the suburban home of his mother – but sketch comedy has been the stalwart of Australian television. '' The Comedy Company'', in the 1980s, featured the comic talents of Mary-Anne Fahey, Ian McFadyen, Mark Mitchell, Glenn Robbins, Kym Gyngell

Kym Gyngell (born 15 April 1952), sometimes also credited as Kim Gyngell, is an Australian comedian and film, television and stage actor. Gyngell won the Australian Film Institute Award for Best Actor in a Supporting Role in 1988 for his role as ...

and others. Growing out of Melbourne University and '' The D-Generation'' came '' The Late Show'' (1991–1993), starring the influential talents Santo Cilauro, Tom Gleisner, Jane Kennedy, Tony Martin, Mick Molloy

Michael Molloy (born 11 July 1966) is an Australian comedian, writer, producer, actor and television and radio presenter who has been active in radio, television, stand-up and film. He currently hosts '' The Front Bar'' on the Seven Network. ...

and Rob Sitch

Robert Ian Sitch (born 17 March 1962) is an Australian director, producer, screenwriter, actor and comedian.

Early life

Sitch was born in 1962, the son of Melbourne bus proprietor Charles (Charlie) Sitch. Sitch attended St Kevin's College and ...

(who later formed Working Dog Productions); and during the 1980s and 1990s '' Fast Forward'' ( Steve Vizard, Magda Szubanski, Marg Downey, Michael Veitch, Peter Moon and others) and its successor '' Full Frontal'', which launched the career of Eric Bana and featured Shaun Micallef

Shaun Patrick Micallef (; born 18 July 1962) is an Australian comedian, actor, writer and television presenter. He is currently the host of the satirical news comedy series ''Shaun Micallef's Mad as Hell'' on the ABC. He also hosted the game s ...

.

The perceptive wit of Clive James

Clive James (born Vivian Leopold James; 7 October 1939 – 24 November 2019) was an Australian critic, journalist, broadcaster, writer and lyricist who lived and worked in the United Kingdom from 1962 until his death in 2019.Andrew Denton has been popular in the talk-show interview style. Representatives of the "bawdy" strain of Australian comedy include Rodney Rude, Austen Tayshus and Chad Morgan. Rolf Harris helped defined a comic tradition in Australian music.

Cynical satire has had enduring popularity, with television series such as '' Frontline'', targeting the inner workings of "news and current affairs" TV journalism, ''

Founded in 1880, ''

Founded in 1880, ''

The Hollowmen

''The Hollowmen'' is an Australian television comedy series set in the offices of the Central Policy Unit, a fictional political advisory unit personally set up by the Prime Minister to help him get re-elected. Their brief is long-term vision; t ...

'' (2008), set in the office of the Prime Minister's political advisory (spin) department, and ''The Chaser's War on Everything

''The Chaser's War on Everything'' is an Australian television satirical comedy series broadcast on the Australian Broadcasting Corporation (ABC) television station ABC1. It has won an Australian Film Institute Award for Best Television Comedy S ...

'', which cynically examines domestic and international politics. Actor/writer Chris Lilley has produced a series of award-winning "mockumentary" style television series about Australian characters since 2005.

The annual Melbourne International Comedy Festival is one of the largest comedy festivals in the world, and a popular fixture on the city's cultural calendar.

Arts

The arts in Australia— film,music

Music is generally defined as the The arts, art of arranging sound to create some combination of Musical form, form, harmony, melody, rhythm or otherwise Musical expression, expressive content. Exact definition of music, definitions of mu ...

, painting

Painting is the practice of applying paint, pigment, color or other medium to a solid surface (called the "matrix" or "support"). The medium is commonly applied to the base with a brush, but other implements, such as knives, sponges, and ai ...

, theatre

Theatre or theater is a collaborative form of performing art that uses live performers, usually actors or actresses, to present the experience of a real or imagined event before a live audience in a specific place, often a stage. The perfor ...

, dance and crafts—have achieved international recognition. While much of Australia's cultural output has traditionally tended to fit with general trends and styles in Western arts, the arts as practised by Indigenous Australians

Indigenous Australians or Australian First Nations are people with familial heritage from, and membership in, the ethnic groups that lived in Australia before British colonisation. They consist of two distinct groups: the Aboriginal peoples o ...

represent a unique Australian cultural tradition, and Australia's landscape and history have contributed to some unique variations in the styles inherited by Australia's various migrant communities.

Literature

As the convict era passed—captured most famously in Marcus Clarke's '' For the Term of His Natural Life'' (1874), a seminal work of Tasmanian Gothic—the bush and Australian daily life assumed primacy as subjects. Charles Harpur, Henry Kendall and Adam Lindsay Gordon won fame in the mid-19th century for their lyric nature poems and patriotic verse. Gordon drew on Australian colloquy and idiom; Clarke assessed his work as "the beginnings of a national school of Australian poetry". First published in serial form in 1882, Rolf Boldrewood's '' Robbery Under Arms'' is regarded as the classic bushranging novel. Founded in 1880, ''

Founded in 1880, ''The Bulletin

Bulletin or The Bulletin may refer to:

Periodicals (newspapers, magazines, journals)

* Bulletin (online newspaper), a Swedish online newspaper

* ''The Bulletin'' (Australian periodical), an Australian magazine (1880–2008)

** Bulletin Debate, ...

'' did much to create the idea of an Australian national character—one of anti-authoritarianism, egalitarianism

Egalitarianism (), or equalitarianism, is a school of thought within political philosophy that builds from the concept of social equality, prioritizing it for all people. Egalitarian doctrines are generally characterized by the idea that all hu ...

, mateship and a concern for the " battler"—forged against the brutalities of the bush. This image was expressed within the works of its bush poets, the most famous of which are Henry Lawson

Henry Archibald Hertzberg Lawson (17 June 1867 – 2 September 1922) was an Australian writer and bush poet. Along with his contemporary Banjo Paterson, Lawson is among the best-known Australian poets and fiction writers of the colonial perio ...

, widely regarded as Australia's finest short-story writer, and Banjo Paterson

Andrew Barton "Banjo" Paterson, (17 February 18645 February 1941) was an Australian bush poet, journalist and author. He wrote many ballads and poems about Australian life, focusing particularly on the rural and outback areas, including the d ...

, author of classics such as "Clancy of the Overflow

"Clancy of the Overflow" is a poem by Banjo Paterson, first published in ''The Bulletin'', an Australian news magazine, on 21 December 1889. The poem is typical of Paterson, offering a romantic view of rural life, and is one of his best-known w ...

" (1889) and " The Man From Snowy River" (1890). In a literary debate about the nature of life in the bush, Lawson said Paterson was a romantic while Paterson attacked Lawson's pessimistic outlook. C. J. Dennis wrote humor in the Australian vernacular, notably in the verse novel '' The Songs of a Sentimental Bloke'' (1915), while Dorothy Mackellar

Isobel Marion Dorothea Mackellar, (1 July 1885 – 14 January 1968) was an Australian poet and fiction writer. Her poem '' My Country'' is widely known in Australia, especially its second stanza, which begins: "''I love a sunburnt countr ...

wrote the iconic patriotic poem " My Country" (1908) which rejected prevailing fondness for England's "green and shaded lanes" and declared: "I love a sunburned country". Early Australian children's literature

Children's literature or juvenile literature includes stories, books, magazines, and poems that are created for children. Modern children's literature is classified in two different ways: genre or the intended age of the reader.

Children's ...

was also embedded in the bush tradition; perennial favorites include Norman Lindsay's '' The Magic Pudding'' (1918), May Gibbs' '' Snugglepot and Cuddlepie'' (1918) and Dorothy Wall's '' Blinky Bill'' (1933).

Significant poets of the early 20th century include Kenneth Slessor, Mary Gilmore and Judith Wright. The nationalist Jindyworobak Movement arose in the 1930s and sought to develop a distinctive Australian poetry through the appropriation of Aboriginal languages and ideas. In contrast, the Angry Penguins, centered around Max Harris' journal of the same name, promoted international modernism

Modernism is both a philosophical and arts movement that arose from broad transformations in Western society during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The movement reflected a desire for the creation of new forms of art, philosophy, ...

. A backlash resulted in the Ern Malley affair of 1943, Australia's most famous literary hoax.

The legacy of Miles Franklin, renowned for her 1901 novel '' My Brilliant Career'', is the Miles Franklin Award, which is "presented each year to a novel which is of the highest literary merit and presents Australian life in any of its phases". Patrick White

Patrick Victor Martindale White (28 May 1912 – 30 September 1990) was a British-born Australian writer who published 12 novels, three short-story collections, and eight plays, from 1935 to 1987.

White's fiction employs humour, florid prose, ...

won the inaugural award for '' Voss'' in 1957; he went on to win the 1973 Nobel Prize in Literature

)

, image = Nobel Prize.png

, caption =

, awarded_for = Outstanding contributions in literature

, presenter = Swedish Academy

, holder = Annie Ernaux (2022)

, location = Stockholm, Sweden

, year = 1901 ...

. Peter Carey, Thomas Keneally and Richard Flanagan are recipients of the Booker Prize

The Booker Prize, formerly known as the Booker Prize for Fiction (1969–2001) and the Man Booker Prize (2002–2019), is a literary prize awarded each year for the best novel written in English and published in the United Kingdom or Ireland. ...

. Other acclaimed Australian authors include Colleen McCullough

Colleen Margaretta McCullough (; married name Robinson, previously Ion-Robinson; 1 June 193729 January 2015) was an Australian author known for her novels, her most well-known being '' The Thorn Birds'' and '' The Ladies of Missalonghi''.

Lif ...

, Nevil Shute

Nevil Shute Norway (17 January 189912 January 1960) was an English novelist and aeronautical engineer who spent his later years in Australia. He used his full name in his engineering career and Nevil Shute as his pen name, in order to protect ...

, Tim Winton, Ruth Park and Morris West. Helen Garner's 1977 novel '' Monkey Grip'' is widely considered one of Australia's first contemporary novels–she has since written both fiction and non-fiction work. Notable expatriate authors include the feminist Germaine Greer

Germaine Greer (; born 29 January 1939) is an Australian writer and public intellectual, regarded as one of the major voices of the radical feminist movement in the latter half of the 20th century.

Specializing in English and women's literatu ...

and humorist Clive James

Clive James (born Vivian Leopold James; 7 October 1939 – 24 November 2019) was an Australian critic, journalist, broadcaster, writer and lyricist who lived and worked in the United Kingdom from 1962 until his death in 2019.Les Murray and Bruce Dawe.

David Unaipon is known as the first Indigenous Australian author. Oodgeroo Noonuccal was the first

Hobart's Theatre Royal opened in 1837 and is Australia's oldest continuously operating theatre. Inaugurated in 1839, the Melbourne Athenaeum is one of Melbourne's oldest cultural institutions, and Adelaide's Queen's Theatre, established in 1841, is today the oldest purpose-built theatre on the mainland. The mid-19th-century gold rushes provided funds for the construction of grand theatres in the Victorian style, such as the Princess Theatre in Melbourne, established in 1854.

After Federation in 1901, theatre productions evidenced the new sense of national identity. '' On Our Selection'' (1912), based on the stories of Steele Rudd, portrays a pioneer farming family and became immensely popular. Sydney's grand Capitol Theatre opened in 1928 and after restoration remains one of the nation's finest auditoriums.

In 1955, '' Summer of the Seventeenth Doll'' by Ray Lawler portrayed resolutely Australian characters and went on to international acclaim. That same year, young Melbourne artist Barry Humphries performed as Edna Everage for the first time at Melbourne University's Union Theatre. His satirical stage creations, notably Dame Edna and Les Patterson, became Australian cultural icons. Humphries also achieved success in the US with tours on Broadway and has been honored in Australia and Britain.

Founded in Sydney 1958, the National Institute of Dramatic Art boasts famous alumni including Cate Blanchett, Mel Gibson and

Hobart's Theatre Royal opened in 1837 and is Australia's oldest continuously operating theatre. Inaugurated in 1839, the Melbourne Athenaeum is one of Melbourne's oldest cultural institutions, and Adelaide's Queen's Theatre, established in 1841, is today the oldest purpose-built theatre on the mainland. The mid-19th-century gold rushes provided funds for the construction of grand theatres in the Victorian style, such as the Princess Theatre in Melbourne, established in 1854.

After Federation in 1901, theatre productions evidenced the new sense of national identity. '' On Our Selection'' (1912), based on the stories of Steele Rudd, portrays a pioneer farming family and became immensely popular. Sydney's grand Capitol Theatre opened in 1928 and after restoration remains one of the nation's finest auditoriums.

In 1955, '' Summer of the Seventeenth Doll'' by Ray Lawler portrayed resolutely Australian characters and went on to international acclaim. That same year, young Melbourne artist Barry Humphries performed as Edna Everage for the first time at Melbourne University's Union Theatre. His satirical stage creations, notably Dame Edna and Les Patterson, became Australian cultural icons. Humphries also achieved success in the US with tours on Broadway and has been honored in Australia and Britain.

Founded in Sydney 1958, the National Institute of Dramatic Art boasts famous alumni including Cate Blanchett, Mel Gibson and

Australia has three architectural listings on

Australia has three architectural listings on

File:HydeParkBarracks.JPG, Hyde Park Barracks, Sydney

File:PortArthur main lowres.JPG, Convict architecture at Port Arthur, Tasmania

File:University of Sydney Main Quadrangle.jpg, The

Art Gallery of New South Wales. Retrieved 20 November 2012. while the Antipodeans and Brett Whiteley further explored the possibilities of figurative painting. Photographer Bill Henson, sculptor Ron Mueck, and "living art exhibit" Leigh Bowery are among Australia's best-known contemporary artists.

Australia's first dedicated film studio, the Limelight Department, was created by The Salvation Army in Melbourne in 1898, and is believed to be the world's first. The world's first feature-length film was the 1906 Australian production '' The Story of the Kelly Gang''. Tales of bushranging, gold mining, convict life and the colonial frontier dominated the silent film era of Australian cinema. Filmmakers such as

Australia's first dedicated film studio, the Limelight Department, was created by The Salvation Army in Melbourne in 1898, and is believed to be the world's first. The world's first feature-length film was the 1906 Australian production '' The Story of the Kelly Gang''. Tales of bushranging, gold mining, convict life and the colonial frontier dominated the silent film era of Australian cinema. Filmmakers such as  The 1990s saw a run of successful comedies including '' Muriel's Wedding'' and '' Strictly Ballroom'', which helped launch the careers of Toni Collette and Baz Luhrmann respectively. Australian humor features prominently in Australian film, with a strong tradition of self-mockery, from the '' Ozploitation'' style of the Barry McKenzie ''expat-in-Europe'' movies of the 1970s, to the Working Dog Productions' 1997 homage to suburbia '' The Castle'', starring Eric Bana in his debut film role. Comedies like the barn yard animation '' Babe'' (1995), directed by Chris Noonan;

The 1990s saw a run of successful comedies including '' Muriel's Wedding'' and '' Strictly Ballroom'', which helped launch the careers of Toni Collette and Baz Luhrmann respectively. Australian humor features prominently in Australian film, with a strong tradition of self-mockery, from the '' Ozploitation'' style of the Barry McKenzie ''expat-in-Europe'' movies of the 1970s, to the Working Dog Productions' 1997 homage to suburbia '' The Castle'', starring Eric Bana in his debut film role. Comedies like the barn yard animation '' Babe'' (1995), directed by Chris Noonan;

Music is an integral part of Aboriginal culture. The most famous feature of their music is the didgeridoo. This wooden instrument, used among the Aboriginal tribes of northern Australia, makes a distinctive droning sound and it has been adopted by a wide variety of non-Aboriginal performers.

Aboriginal musicians have turned their hand to Western popular musical forms, often to considerable commercial success. Pioneers include Lionel Rose and Jimmy Little, while notable contemporary examples include Archie Roach,

Music is an integral part of Aboriginal culture. The most famous feature of their music is the didgeridoo. This wooden instrument, used among the Aboriginal tribes of northern Australia, makes a distinctive droning sound and it has been adopted by a wide variety of non-Aboriginal performers.

Aboriginal musicians have turned their hand to Western popular musical forms, often to considerable commercial success. Pioneers include Lionel Rose and Jimmy Little, while notable contemporary examples include Archie Roach,

The

The

The earliest Western musical influences in Australia can be traced back to two distinct sources: the first free settlers who brought with them the European classical music tradition, and the large body of convicts and sailors, who brought the traditional folk music of England, Ireland, Scotland and Wales. The practicalities of building a colony mean that there is very little music extant from this early period, although some samples of music originating from Hobart and Sydney date back to the early-19th century.Oxford, A Dictionary of Australian Music, Edited by Warren Bebbington, Copyright 1998

The earliest Western musical influences in Australia can be traced back to two distinct sources: the first free settlers who brought with them the European classical music tradition, and the large body of convicts and sailors, who brought the traditional folk music of England, Ireland, Scotland and Wales. The practicalities of building a colony mean that there is very little music extant from this early period, although some samples of music originating from Hobart and Sydney date back to the early-19th century.Oxford, A Dictionary of Australian Music, Edited by Warren Bebbington, Copyright 1998

Experiments with television began in Australia in the 1930s and television was officially launched on 16 September 1956 in Sydney. Colour TV arrived in 1975. The Logie Awards are the major annual awards for Australian TV.

While US and British television is popular in Australia, locally produced content has had many successes. Successful local product has included ''

Experiments with television began in Australia in the 1930s and television was officially launched on 16 September 1956 in Sydney. Colour TV arrived in 1975. The Logie Awards are the major annual awards for Australian TV.

While US and British television is popular in Australia, locally produced content has had many successes. Successful local product has included '' While Australia has ubiquitous media coverage, the longest established part of that media is the

While Australia has ubiquitous media coverage, the longest established part of that media is the

Australia has no official state religion and the Australian Constitution prohibits the Commonwealth government from establishing a church or interfering with the

Australia has no official state religion and the Australian Constitution prohibits the Commonwealth government from establishing a church or interfering with the  Christianity has had an enduring impact on Australia. At the time of Federation in 1901, 97% of Australians professed to be Christians. The Anglican Church (formerly

Christianity has had an enduring impact on Australia. At the time of Federation in 1901, 97% of Australians professed to be Christians. The Anglican Church (formerly  The proportion of the total population who are Christian fell from 71% in 1996 to around 61.1% in 2011, while people affiliated with non-Christian religions increased from around 3.5% to 7.2% over the same period.

The proportion of the total population who are Christian fell from 71% in 1996 to around 61.1% in 2011, while people affiliated with non-Christian religions increased from around 3.5% to 7.2% over the same period.

/ref>

Australia's calendar of public holiday festivals begins with

Australia's calendar of public holiday festivals begins with

Contemporary Australian cuisine combines British and Indigenous origins with Mediterranean and Asian influences. Australia's abundant natural resources allow access to a large variety of quality meats, and to barbecue beef or lamb in the open air is considered a cherished national tradition. The great majority of Australians live close to the sea and Australian seafood restaurants have been listed among the world's best.

Bush tucker refers to a wide variety of plant and animal foods native to the Australian bush: bush fruits such as

Contemporary Australian cuisine combines British and Indigenous origins with Mediterranean and Asian influences. Australia's abundant natural resources allow access to a large variety of quality meats, and to barbecue beef or lamb in the open air is considered a cherished national tradition. The great majority of Australians live close to the sea and Australian seafood restaurants have been listed among the world's best.

Bush tucker refers to a wide variety of plant and animal foods native to the Australian bush: bush fruits such as  Early British settlers brought familiar meats and crops with them from Europe and these remain important in the Australian diet. The British settlers found some familiar game – such as

Early British settlers brought familiar meats and crops with them from Europe and these remain important in the Australian diet. The British settlers found some familiar game – such as

Australia's reputation as a nation of heavy drinkers goes back to the earliest days of colonial Sydney, when rum was used as currency and grain shortages followed the installation of the first stills. James Squires is considered to have founded Australia's first commercial brewery in 1798 and the Cascade Brewery in Hobart has been operating since 1832. Since the 1970s, Australian beers have become increasingly popular globally, with Foster's Lager being an iconic export. Foster's is not however the biggest seller on the local market, with alternatives including Carlton Draught and Victoria Bitter outselling it.

Billy tea was a staple drink of the Australian colonial period. It is typically boiled over a camp fire with a gum leaf added for flavoring.

The Australian wine industry is the world's fourth largest exporter of wine and contributes $5.5 billion per annum to the nation's economy. Wine is produced in every state, however, wine regions are mainly in the southern, cooler regions. Among the most famous wine districts are the Hunter Region and Barossa Valley and among the best known wine producers are Penfolds, Rosemount (wine), Rosemount Estate, Wynns Coonawarra Estate and Lindemans (wine), Lindemans. The Australian Penfolds Grange was the first wine from outside France or California to win the ''Wine Spectator'' award for Wine of the Year in 1995.

Australia's reputation as a nation of heavy drinkers goes back to the earliest days of colonial Sydney, when rum was used as currency and grain shortages followed the installation of the first stills. James Squires is considered to have founded Australia's first commercial brewery in 1798 and the Cascade Brewery in Hobart has been operating since 1832. Since the 1970s, Australian beers have become increasingly popular globally, with Foster's Lager being an iconic export. Foster's is not however the biggest seller on the local market, with alternatives including Carlton Draught and Victoria Bitter outselling it.

Billy tea was a staple drink of the Australian colonial period. It is typically boiled over a camp fire with a gum leaf added for flavoring.

The Australian wine industry is the world's fourth largest exporter of wine and contributes $5.5 billion per annum to the nation's economy. Wine is produced in every state, however, wine regions are mainly in the southern, cooler regions. Among the most famous wine districts are the Hunter Region and Barossa Valley and among the best known wine producers are Penfolds, Rosemount (wine), Rosemount Estate, Wynns Coonawarra Estate and Lindemans (wine), Lindemans. The Australian Penfolds Grange was the first wine from outside France or California to win the ''Wine Spectator'' award for Wine of the Year in 1995.

Australia has no official designated national dress, but iconic local styles include ''bushwear'' and ''surfwear''. The country's best-known fashion event is Australian Fashion Week, a twice yearly industry gathering showcasing seasonal collections from Australian and Asia Pacific Designers. Top Australian models include Elle Macpherson, Miranda Kerr and Jennifer Hawkins (Miss Universe 2004).

Major clothing brands associated with bushwear are the broad brimmed Akubra hats, Driza-Bone coats and RM Williams (company), RM Williams bushmen's outfitters (featuring in particular: moleskin trousers, riding boots and merino woolwear). Blundstone Footwear and Country Road (retailer), Country Road are also linked to this tradition. Made from the leaves of ''Livistona australis'', the cabbage tree hat was the first uniquely Australian headwear, dating back to the early 1800s, and was the hat of choice for colonial-born Australians. Traditionally worn by Jackaroo (trainee), jackaroos and swagman, swagmen in the blow-fly infested Australian outback, the cork hat is a type of headgear strongly associated with Australia, and comprises Cork (material), cork strung from the brim, to ward off insects.

World-famous Australian surfwear labels include Billabong (clothing), Billabong, Rip Curl, Mambo Graphics, Mambo and Quiksilver. Australian surfers popularised the ugg boot, a unisex sheepskin boot with fleece on the inside, a tanned outer surface and a synthetic sole. Worn by the working classes in Australia, the boot style emerged as a global fashion trend in the 2000s. Underwear and sleepwear brands include Bonds (clothing), Bonds, Berlei, Brett Blundy, Bras N Things and Peter Alexander (fashion designer), Peter Alexander.

The slouch hat was first worn by military forces in Australia in 1885, looped up on one side so that rifles could be held at the slope without damaging the brim. After federation, the slouch hat became standard Australian Army headgear in 1903 and since then it has developed into an important national symbol and is worn on ceremonial occasions by the Australian army.

Australia has no official designated national dress, but iconic local styles include ''bushwear'' and ''surfwear''. The country's best-known fashion event is Australian Fashion Week, a twice yearly industry gathering showcasing seasonal collections from Australian and Asia Pacific Designers. Top Australian models include Elle Macpherson, Miranda Kerr and Jennifer Hawkins (Miss Universe 2004).

Major clothing brands associated with bushwear are the broad brimmed Akubra hats, Driza-Bone coats and RM Williams (company), RM Williams bushmen's outfitters (featuring in particular: moleskin trousers, riding boots and merino woolwear). Blundstone Footwear and Country Road (retailer), Country Road are also linked to this tradition. Made from the leaves of ''Livistona australis'', the cabbage tree hat was the first uniquely Australian headwear, dating back to the early 1800s, and was the hat of choice for colonial-born Australians. Traditionally worn by Jackaroo (trainee), jackaroos and swagman, swagmen in the blow-fly infested Australian outback, the cork hat is a type of headgear strongly associated with Australia, and comprises Cork (material), cork strung from the brim, to ward off insects.

World-famous Australian surfwear labels include Billabong (clothing), Billabong, Rip Curl, Mambo Graphics, Mambo and Quiksilver. Australian surfers popularised the ugg boot, a unisex sheepskin boot with fleece on the inside, a tanned outer surface and a synthetic sole. Worn by the working classes in Australia, the boot style emerged as a global fashion trend in the 2000s. Underwear and sleepwear brands include Bonds (clothing), Bonds, Berlei, Brett Blundy, Bras N Things and Peter Alexander (fashion designer), Peter Alexander.

The slouch hat was first worn by military forces in Australia in 1885, looped up on one side so that rifles could be held at the slope without damaging the brim. After federation, the slouch hat became standard Australian Army headgear in 1903 and since then it has developed into an important national symbol and is worn on ceremonial occasions by the Australian army.

Australians generally have a relaxed attitude to what beachgoers wear, although this has not always been the case. At the start of the twentieth century a proposed ordinance in Sydney would have forced men to wear skirts over their "bathing costume" to be decent. This led to the 1907 Sydney bathing costume protests which resulted in the proposal being dropped. In 1961, Bondi Beach, Bondi inspector Aub Laidlaw, already known for kicking women off the beach for wearing bikinis, arrested several men wearing Swim Briefs, swim briefs charging them with indecency. The judge found the men not guilty because no pubic hair was exposed. As time went on Australians' attitudes to swimwear became much more relaxed. Over time swim briefs, better known locally as speedos or more recently as budgie smugglers, became an iconic swimwear for Australian males.

Australians generally have a relaxed attitude to what beachgoers wear, although this has not always been the case. At the start of the twentieth century a proposed ordinance in Sydney would have forced men to wear skirts over their "bathing costume" to be decent. This led to the 1907 Sydney bathing costume protests which resulted in the proposal being dropped. In 1961, Bondi Beach, Bondi inspector Aub Laidlaw, already known for kicking women off the beach for wearing bikinis, arrested several men wearing Swim Briefs, swim briefs charging them with indecency. The judge found the men not guilty because no pubic hair was exposed. As time went on Australians' attitudes to swimwear became much more relaxed. Over time swim briefs, better known locally as speedos or more recently as budgie smugglers, became an iconic swimwear for Australian males.

Cricket is Australia's most popular summer sport and has been played since colonial times. It is followed in all states and territories, unlike the football codes which vary in popularity between regions.

Cricket is Australia's most popular summer sport and has been played since colonial times. It is followed in all states and territories, unlike the football codes which vary in popularity between regions.

The first recorded cricket match in Australia took place in Sydney in 1803. Intercolonial cricket in Australia, Intercolonial contests started in 1851 and Sheffield Shield inter-state cricket continues to this day. In 1866–67, prominent cricketer and Australian rules football pioneer Tom Wills coached an Aboriginal cricket team, which later Australian Aboriginal cricket team in England in 1868, toured England in 1868 under the captaincy of Charles Lawrence (cricketer), Charles Lawrence. The 1876–77 season is notable for a match between a combined XI (cricket), XI from New South Wales and Victoria and a English cricket team in Australia and New Zealand in 1876–77, touring English team at the Melbourne Cricket Ground, which was later recognised as the first Test cricket, Test match. A famous victory on the Australian cricket team in England and the United States in 1882, 1882 tour of England resulted in the placement of a satirical obituary in an English newspaper saying that English cricket had "died", and the "body will be cremated and the ashes taken to Australia". The English media then dubbed the next English tour to Australia (English cricket team in Australia in 1882–83, 1882–83) as the quest to "regain the ashes". The tradition continues with the Ashes series, an icon of the sporting rivalry between the two countries.

Successful cricketers often become lasting celebrities in Australia. Sir Donald Bradman, who made his Test debut in the English cricket team in Australia in 1928–29, 1928–29 series against England, is regarded as the game's greatest batsman and a byword for sporting excellence. Other Australian cricketers who remain household names include Richie Benaud, Dennis Lillee and Shane Warne and others who pursued media careers after they retired from the game. Internationally, Australia has for most of the last century sat at or near the top of the cricketing world. In the 1970s, Australian media tycoon Kerry Packer founded World Series Cricket from which many international forms of the game have evolved.

Events on the cricket pitch have occasionally been elevated to diplomatic incidents in Australian history, such as the infamous Bodyline controversy of the 1930s, in which the English team bowled in a physically intimidating way leading to accusations of ''unsportsmanlike'' conduct.

The first recorded cricket match in Australia took place in Sydney in 1803. Intercolonial cricket in Australia, Intercolonial contests started in 1851 and Sheffield Shield inter-state cricket continues to this day. In 1866–67, prominent cricketer and Australian rules football pioneer Tom Wills coached an Aboriginal cricket team, which later Australian Aboriginal cricket team in England in 1868, toured England in 1868 under the captaincy of Charles Lawrence (cricketer), Charles Lawrence. The 1876–77 season is notable for a match between a combined XI (cricket), XI from New South Wales and Victoria and a English cricket team in Australia and New Zealand in 1876–77, touring English team at the Melbourne Cricket Ground, which was later recognised as the first Test cricket, Test match. A famous victory on the Australian cricket team in England and the United States in 1882, 1882 tour of England resulted in the placement of a satirical obituary in an English newspaper saying that English cricket had "died", and the "body will be cremated and the ashes taken to Australia". The English media then dubbed the next English tour to Australia (English cricket team in Australia in 1882–83, 1882–83) as the quest to "regain the ashes". The tradition continues with the Ashes series, an icon of the sporting rivalry between the two countries.

Successful cricketers often become lasting celebrities in Australia. Sir Donald Bradman, who made his Test debut in the English cricket team in Australia in 1928–29, 1928–29 series against England, is regarded as the game's greatest batsman and a byword for sporting excellence. Other Australian cricketers who remain household names include Richie Benaud, Dennis Lillee and Shane Warne and others who pursued media careers after they retired from the game. Internationally, Australia has for most of the last century sat at or near the top of the cricketing world. In the 1970s, Australian media tycoon Kerry Packer founded World Series Cricket from which many international forms of the game have evolved.

Events on the cricket pitch have occasionally been elevated to diplomatic incidents in Australian history, such as the infamous Bodyline controversy of the 1930s, in which the English team bowled in a physically intimidating way leading to accusations of ''unsportsmanlike'' conduct.

Australian rules football is the most highly attended spectator sport in Australia. Its core support lies in four of the six states: Victoria, South Australia, Western Australia and Tasmania. Originating in Melbourne in the late 1850s and codified in 1859, the sport is the world's oldest major football code. The national competition, the Australian Football League (AFL), History of the Australian Football League, evolved from the Victorian Football League in 1990, and has expanded to all states except Tasmania. The AFL Grand Final is traditionally played on the last Saturday of September at the Melbourne Cricket Ground, the sport's "spiritual home". Australian rules football culture has a strong set of rituals and traditions, such as kick-to-kick and wikt:barracking, barracking. International rules football is a hybrid sport of Australian football and Gaelic football devised to facilitate matches between Australia and Ireland.

Rugby union was first played in Australia in the 1860s and is followed predominately in Queensland, New South Wales and the Australian Capital Territory. The Australian national rugby union team, national team is known as the Wallabies. Despite having a relatively small player base, Australia has twice won the Rugby World Cup, in 1991 Rugby World Cup, 1991 and 1999 Rugby World Cup, 1999, and hosted the 2003 Rugby World Cup. Other notable competitions include the annual Bledisloe Cup, played against Australia's main rivals, the New Zealand All Blacks, and the Rugby Championship, involving South Africa national rugby union team, South Africa, New Zealand, and Argentina national rugby union team, Argentina. Provincial teams from Australia, South Africa and New Zealand compete in the annual Super Rugby competition. Rugby Test match (rugby union), test matches are also popular and have at times become highly politicised, such as when many Australians, including the Wallabies, demonstrated against the racially selected South African teams of the 1970s. Notable Australian rugby union players include Sir Edward Dunlop, Mark Ella and David Campese.