Charles Santley on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

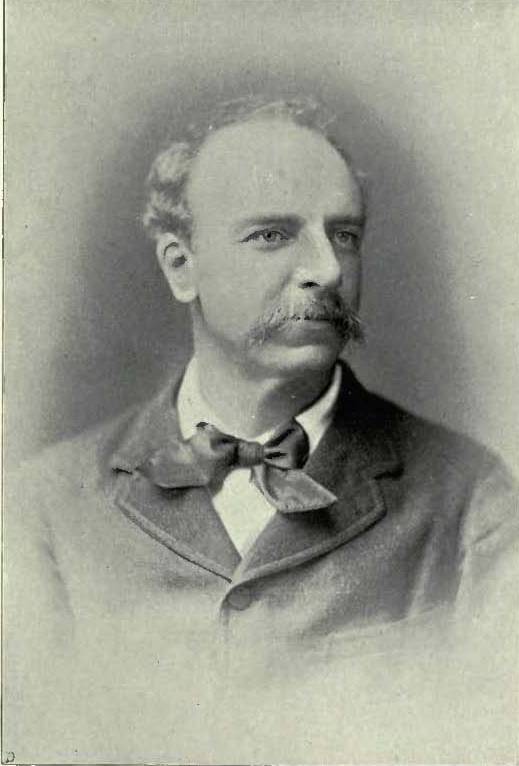

Sir Charles Santley (28 February 1834 – 22 September 1922) was an English

Sir Charles Santley (28 February 1834 – 22 September 1922) was an English

Santley was the elder son of William Santley, a journeyman bookbinder,C. Santley, ''Student and Singer: The Reminiscences of Charles Santley'' 3rd Edition (Edward Arnold, London 1892), p.6. organist and music teacher of

Santley was the elder son of William Santley, a journeyman bookbinder,C. Santley, ''Student and Singer: The Reminiscences of Charles Santley'' 3rd Edition (Edward Arnold, London 1892), p.6. organist and music teacher of

"Santley, Sir Charles (1834–1922)"

''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'', Oxford University Press, 2004, accessed 28 April 2011 His voice began to break before he was fourteen. Following musical lessons from his father (who insisted upon his singing tenor), he passed the examination for admission to the second tenors of the

Mapleson won Santley back for his own Italian opera company, and in the 1862–63 season at Majesty's, he performed in ''

Mapleson won Santley back for his own Italian opera company, and in the 1862–63 season at Majesty's, he performed in ''

After the festival season, Santley toured in Mapleson's company during the autumn (with Italo Gardoni as lead tenor), appearing in ''Faust'', ''Oberon'' and ''Mireille'', In November 1864 he set off for

After the festival season, Santley toured in Mapleson's company during the autumn (with Italo Gardoni as lead tenor), appearing in ''Faust'', ''Oberon'' and ''Mireille'', In November 1864 he set off for

The concert tour itself was not a financial success. Santley therefore entered into an agreement with

The concert tour itself was not a financial success. Santley therefore entered into an agreement with

Santley gave recitals at the Monday Popular Concerts, and appeared with the

Santley gave recitals at the Monday Popular Concerts, and appeared with the  In January 1894 he was with

In January 1894 he was with

Sir Charles Santley (28 February 1834 – 22 September 1922) was an English

Sir Charles Santley (28 February 1834 – 22 September 1922) was an English opera

Opera is a form of theatre in which music is a fundamental component and dramatic roles are taken by singers. Such a "work" (the literal translation of the Italian word "opera") is typically a collaboration between a composer and a librett ...

and oratorio

An oratorio () is a large musical composition for orchestra, choir, and soloists. Like most operas, an oratorio includes the use of a choir, soloists, an instrumental ensemble, various distinguishable characters, and arias. However, opera is mus ...

singer with a ''bravura''From the Italian verb ''bravare'', to show off. A florid, ostentatious style or a passage of music requiring technical skill technique who became the most eminent English baritone

A baritone is a type of classical male singing voice whose vocal range lies between the bass and the tenor voice-types. The term originates from the Greek (), meaning "heavy sounding". Composers typically write music for this voice in the r ...

and male concert singer of the Victorian era

In the history of the United Kingdom and the British Empire, the Victorian era was the period of Queen Victoria's reign, from 20 June 1837 until her death on 22 January 1901. The era followed the Georgian period and preceded the Edwardia ...

. His has been called 'the longest, most distinguished and most versatile vocal career which history records.'

Santley appeared in many major opera and oratorio productions in Great Britain and North America, giving numerous recitals as well. Having made his debut in Italy in 1857 after undertaking vocal studies in that country, he elected to base himself in England for the remainder of his life, apart from occasional trips overseas. One of the highlights of his stage career occurred in 1870 when he led the cast in the first Wagner

Wilhelm Richard Wagner ( ; ; 22 May 181313 February 1883) was a German composer, theatre director, polemicist, and conductor who is chiefly known for his operas (or, as some of his mature works were later known, "music dramas"). Unlike most op ...

opera to be performed in London, ''The Flying Dutchman

The ''Flying Dutchman'' ( nl, De Vliegende Hollander) is a legendary ghost ship, allegedly never able to make port, but doomed to sail the seven seas forever. The myth is likely to have originated from the 17th-century Golden Age of the Dut ...

'', at the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane

The Theatre Royal, Drury Lane, commonly known as Drury Lane, is a West End theatre and Grade I listed building in Covent Garden, London, England. The building faces Catherine Street (earlier named Bridges or Brydges Street) and backs onto Dr ...

. Santley retired from opera during the 1870s in order to concentrate on the lucrative concert circuit.

Santley also wrote books on vocal technique and two sets of memoirs.

Early training

Santley was the elder son of William Santley, a journeyman bookbinder,C. Santley, ''Student and Singer: The Reminiscences of Charles Santley'' 3rd Edition (Edward Arnold, London 1892), p.6. organist and music teacher of

Santley was the elder son of William Santley, a journeyman bookbinder,C. Santley, ''Student and Singer: The Reminiscences of Charles Santley'' 3rd Edition (Edward Arnold, London 1892), p.6. organist and music teacher of Liverpool

Liverpool is a city and metropolitan borough in Merseyside, England. With a population of in 2019, it is the 10th largest English district by population and its metropolitan area is the fifth largest in the United Kingdom, with a popul ...

in northern England. He had a brother and two sisters, one of whom named Catherine should not be confused with the actor-manager Kate Santley

Evangeline Estelle Gazina (c. 1837Culme, John ''Footlight Notes'', No. 361, 14 August 2004, accessed 7 September 2012; an"Kate Santley by Sarony Cabinet Card" ''Remains to Be Seen'', accessed 7 September 2012 – 18 January 1923), better known u ...

. He was educated at the Liverpool Institute High School, and as a boy sang alto in the choir of a local Unitarian church.John Warrack

John Hamilton Warrack (born 1928, in London) is an English music critic, writer on music, and oboist.

Warrack is the son of Scottish conductor and composer Guy Warrack. He was educated at Winchester College (1941-6) and then at the Royal College ...

"Santley, Sir Charles (1834–1922)"

''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'', Oxford University Press, 2004, accessed 28 April 2011 His voice began to break before he was fourteen. Following musical lessons from his father (who insisted upon his singing tenor), he passed the examination for admission to the second tenors of the

Liverpool Philharmonic Society

Royal Liverpool Philharmonic is a music organisation based in Liverpool, England, that manages a professional symphony orchestra, a concert venue, and extensive programmes of learning through music. Its orchestra, the Royal Liverpool Philharmon ...

on his fifteenth birthday, and in the same year took part in the concerts at the opening of the Philharmonic Hall. It was not until he reached the age of seventeen to eighteen that he rebelled against his father's decree and dropped into the bass clef, and was pronounced to be a bass. Santley was apprenticed to the provision trade. He enlisted, however, as a violinist in the Festival Choral Society and the Società Armonica, and as a chorus member, with his father and sister, he sang in a performance of Haydn

Franz Joseph Haydn ( , ; 31 March 173231 May 1809) was an Austrian composer of the Classical period. He was instrumental in the development of chamber music such as the string quartet and piano trio. His contributions to musical form have led ...

's '' The Creation'' at the Collegiate Institution, Liverpool, in which Jenny Lind was a soloist. Soon afterwards he was in a hand-picked choir for Handel

George Frideric (or Frederick) Handel (; baptised , ; 23 February 1685 – 14 April 1759) was a German-British Baroque composer well known for his operas, oratorios, anthems, concerti grossi, and organ concertos. Handel received his training i ...

's ''Messiah

In Abrahamic religions, a messiah or messias (; ,

; ,

; ) is a saviour or liberator of a group of people. The concepts of ''mashiach'', messianism, and of a Messianic Age originated in Judaism, and in the Hebrew Bible, in which a ''mashiach'' ...

'', where the tenor Sims Reeves

John Sims Reeves (21 October 1821 – 25 October 1900) was an English operatic, oratorio and ballad tenor vocalist during the mid-Victorian era.

Reeves began his singing career in 1838 but continued his vocal studies until 1847. He soon establ ...

headed the soloists, at the Eisteddfod

In Welsh culture, an ''eisteddfod'' is an institution and festival with several ranked competitions, including in poetry and music.

The term ''eisteddfod'', which is formed from the Welsh morphemes: , meaning 'sit', and , meaning 'be', means, a ...

at Rhuddlan Castle

Rhuddlan Castle ( cy, Castell Rhuddlan; ) is a castle located in Rhuddlan, Denbighshire, Wales. It was erected by Edward I in 1277, following the First Welsh War.

Much of the work was overseen by master mason James of Saint George. Rhudd ...

, and was in the chorus for ''Elijah

Elijah ( ; he, אֵלִיָּהוּ, ʾĒlīyyāhū, meaning "My God is Yahweh/YHWH"; Greek form: Elias, ''Elías''; syr, ܐܸܠܝܼܵܐ, ''Elyāe''; Arabic: إلياس or إليا, ''Ilyās'' or ''Ilyā''. ) was, according to the Books of ...

'' and Rossini

Gioachino Antonio Rossini (29 February 1792 – 13 November 1868) was an Italian composer who gained fame for his 39 operas, although he also wrote many songs, some chamber music and piano pieces, and some sacred music. He set new standards f ...

's '' Stabat Mater'' under Julius Benedict

Sir Julius Benedict (27 November 1804 – 5 June 1885) was a German-born composer and conductor, resident in England for most of his career.

Life and music

Benedict was born in Stuttgart, the son of a Jewish banker, and in 1820 learnt compo ...

at the Liverpool Festival. He heard Pauline Viardot

Pauline Viardot (; 18 July 1821 – 18 May 1910) was a nineteenth-century French mezzo-soprano, pedagogue and composer of Spanish descent.

Born Michelle Ferdinande Pauline García, her name appears in various forms. When it is not simply "Pauli ...

, Luigi Lablache

Luigi Lablache (6 December 1794 – 23 January 1858) was an Italian opera singer of French and Irish ancestry. He was most noted for his comic performances, possessing a powerful and agile bass voice, a wide range, and adroit acting skills: Lepo ...

and Mario

is a character created by Japanese video game designer Shigeru Miyamoto. He is the title character of the ''Mario'' franchise and the mascot of Japanese video game company Nintendo. Mario has appeared in over 200 video games since his creat ...

there. While acting as accompanist to his sister at St. Anne's Catholic Church, Edge Hill, Liverpool

Liverpool is a city and metropolitan borough in Merseyside, England. With a population of in 2019, it is the 10th largest English district by population and its metropolitan area is the fifth largest in the United Kingdom, with a popul ...

, he sang 'Et incarnatus est' from Haydn

Franz Joseph Haydn ( , ; 31 March 173231 May 1809) was an Austrian composer of the Classical period. He was instrumental in the development of chamber music such as the string quartet and piano trio. His contributions to musical form have led ...

's ''Second Mass'', reading from the same score as Julius Stockhausen

The gens Julia (''gēns Iūlia'', ) was one of the most prominent patrician (ancient Rome), patrician families in ancient Rome. Members of the gens attained the highest dignities of the state in the earliest times of the Roman Republic, Republic ...

, as a trial, and obtained a place as bass soloist, modelling himself upon the style of the Austrian bass Josef Staudigl

Josef Staudigl (the elder) (b. Wöllersdorf, 14 April 1807; d. Vienna, 28 March 1861) was an Austrian bass singer.

Life

Staudigl attended the school in Wiener Neustadt and, from 1825, was a novice in the Benedictine monastery of Stift Melk ...

(1807–1861), and of the German bass Karl Formes

Karl Johann Franz Formes (b. Mülheim am Rhein, 7 August 1815; d. San Francisco, 15 December 1889), also called Charles John Formes, was a German bass opera and oratorio singer who had a long international career especially in Germany, London and ...

(1815–1889) (whom he heard as Sarastro in London).

In 1855, Santley went to Italy to study as a singer, with advice from Sims Reeves to visit Lamperti in Milan

Milan ( , , Lombard: ; it, Milano ) is a city in northern Italy, capital of Lombardy, and the second-most populous city proper in Italy after Rome. The city proper has a population of about 1.4 million, while its metropolitan city h ...

. However he chose to study under Gaetano Nava

Gaetano (anglicized ''Cajetan'') is an Italian masculine given name. It is also used as a surname. It is derived from the Latin ''Caietanus'', meaning "from ''Caieta''" (the modern Gaeta). The given name has been in use in Italy since medieval p ...

, who became his lifelong friend. Nava taught him buffo

''Opera buffa'' (; "comic opera", plural: ''opere buffe'') is a genre of opera. It was first used as an informal description of Italian comic operas variously classified by their authors as ''commedia in musica'', ''commedia per musica'', ''dramm ...

roles in Rossini's ''La Cenerentola

' (''Cinderella, or Goodness Triumphant'') is an operatic ''dramma giocoso'' in two acts by Gioachino Rossini. The libretto was written by Jacopo Ferretti, based on the libretti written by Charles-Guillaume Étienne for the opera '' Cendrillon'' ...

'', ''L'italiana in Algeri

''L'italiana in Algeri'' (; ''The Italian Girl in Algiers'') is an operatic ''dramma giocoso'' in two acts by Gioachino Rossini to an Italian libretto by Angelo Anelli, based on his earlier text set by Luigi Mosca. It premiered at the Teatro San ...

'' and ''Il Turco in Italia

''Il turco in Italia'' (English: ''The Turk in Italy'') is an opera buffa in two acts by Gioachino Rossini. The Italian-language libretto was written by Felice Romani. It was a re-working of a libretto by Caterino Mazzolà set as an opera (w ...

'', and in Mercadante's operas, laying the basis of sound vocal technique as a baritone. He also taught him Italian speech. Santley studied duets from Bellini's '' Zaira'' and Rossini

Gioachino Antonio Rossini (29 February 1792 – 13 November 1868) was an Italian composer who gained fame for his 39 operas, although he also wrote many songs, some chamber music and piano pieces, and some sacred music. He set new standards f ...

's ''Semiramide

''Semiramide'' () is an opera in two acts by Gioachino Rossini.

The libretto by Gaetano Rossi is based on Voltaire's tragedy ''Semiramis'', which in turn was based on the legend of Semiramis of Assyria. The opera was first performed at La Fenice ...

'' and '' The Siege of Corinth''. He was a frequent guest at concerts and conversaziones of the Marani family. At the theatres he heard Antonio Giuglini

Antonio Giuglini (16 or 17 January 1825 – 12 October 1865) was an Italian operatic tenor. During the last eight years of his life, before he developed signs of mental instability, he earned renown as one of the leading stars of the operatic ...

, Scheggi, Marini and Enrico Delle Sedie

Enrico Augusto Delle Sedie (17 June 1824 – 28 November 1907) was an Italian operatic baritone who sang extensively in Europe, performing the bel canto repertoire and in works by Verdi.

Early life

He was born in Livorno and studied with Cesario ...

, and saw Ristori in ''Maria Stuarda

''Maria Stuarda'' (Mary Stuart) is a tragic opera (''tragedia lirica''), in two acts, by Gaetano Donizetti, to a libretto by Giuseppe Bardari, based on Andrea Maffei's translation of Friedrich Schiller's 1800 play '' Maria Stuart''.

The opera i ...

'', attending La Scala

La Scala (, , ; abbreviation in Italian of the official name ) is a famous opera house in Milan, Italy. The theatre was inaugurated on 3 August 1778 and was originally known as the ' (New Royal-Ducal Theatre alla Scala). The premiere performan ...

, Milan, and the Carcano Theatre. He made his stage debut on 1 January 1857 in Pavia

Pavia (, , , ; la, Ticinum; Medieval Latin: ) is a town and comune of south-western Lombardy in northern Italy, south of Milan on the lower Ticino river near its confluence with the Po. It has a population of c. 73,086. The city was the capit ...

as Dr Grenvill in ''La traviata

''La traviata'' (; ''The Fallen Woman'') is an opera in three acts by Giuseppe Verdi set to an Italian libretto by Francesco Maria Piave. It is based on ''La Dame aux camélias'' (1852), a play by Alexandre Dumas ''fils'' adapted from his own 18 ...

'' (later in the same run singing Germont ''père''), and Don Silva in ''Ernani

''Ernani'' is an operatic ''dramma lirico'' in four acts by Giuseppe Verdi to an Italian libretto by Francesco Maria Piave, based on the 1830 play ''Hernani (drama), Hernani'' by Victor Hugo.

Verdi was commissioned by the Teatro La Fenice in V ...

''. Other minor engagements followed, After a thin summer, however, Henry Fothergill Chorley

Henry Fothergill Chorley (15 December 1808 – 16 February 1872) was an English literary, art and music critic, writer and editor. He was also an author of novels, drama, poetry and lyrics.

Chorley was a prolific and important music and litera ...

visited and urged his return to England.

Oratorio, 1857–1872

In 1857 Santley returned to London, and made his first appearance (16 November) forJohn Hullah

John Pyke Hullah (27 June 1812 – 21 February 1884) was an English composer and teacher of music, whose promotion of vocal training is associated with the singing-class movement.

Life and career

Hullah was born at Worcester. He was a pupil ...

in the role of Adam in Haydn

Franz Joseph Haydn ( , ; 31 March 173231 May 1809) was an Austrian composer of the Classical period. He was instrumental in the development of chamber music such as the string quartet and piano trio. His contributions to musical form have led ...

's ''Creation

Creation may refer to:

Religion

*''Creatio ex nihilo'', the concept that matter was created by God out of nothing

* Creation myth, a religious story of the origin of the world and how people first came to inhabit it

* Creationism, the belief tha ...

'': it is related that he broke down in the duet ''Graceful Consort'' owing to nerves, but the audience burst into applause for him and bade him continue. Manuel García, who heard him, offered training which Santley accepted gratefully. There were a few concerts at the Crystal Palace

Crystal Palace may refer to:

Places Canada

* Crystal Palace Complex (Dieppe), a former amusement park now a shopping complex in Dieppe, New Brunswick

* Crystal Palace Barracks, London, Ontario

* Crystal Palace (Montreal), an exhibition building ...

and elsewhere, under Chorley's guidance, and at a Chorley party he met Gertrude Kemble, who became his wife a year later. Through her he was introduced to the salon of Henry Greville, at whose musical parties he joined company with Mario

is a character created by Japanese video game designer Shigeru Miyamoto. He is the title character of the ''Mario'' franchise and the mascot of Japanese video game company Nintendo. Mario has appeared in over 200 video games since his creat ...

, Giulia Grisi

Giulia Grisi (22 May 1811 – 29 November 1869) was an Italian opera singer. She performed widely in Europe, the United States and South America and was among the leading sopranos of the 19th century.Chisholm 1911, p. ?

Her second husband was Gio ...

, Italo Gardoni

Italo Gardoni (12 March 1821 – 26 March 1882) was a leading operatic tenore di grazia singer from Italy who enjoyed a major international career during the middle decades of the 19th century. Along with Giovanni Mario, Gaetano Fraschini, Enric ...

, Ciro Pinsuti

Ciro Pinsuti (9 May 1829 – 10 March 1888) was an Anglo-Italian composer. Educated in music for a career as a pianist, he studied composition under Rossini. From 1848 he made his home in England, where he became a teacher of singing, and in ...

and others.

After an audition with Michael Costa, he sang in Mendelssohn

Jakob Ludwig Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy (3 February 18094 November 1847), born and widely known as Felix Mendelssohn, was a German composer, pianist, organist and conductor of the early Romantic music, Romantic period. Mendelssohn's compositi ...

's ''St. Paul

Paul; grc, Παῦλος, translit=Paulos; cop, ⲡⲁⲩⲗⲟⲥ; hbo, פאולוס השליח (previously called Saul of Tarsus;; ar, بولس الطرسوسي; grc, Σαῦλος Ταρσεύς, Saũlos Tarseús; tr, Tarsuslu Pavlus; ...

'' in Manchester under Charles Hallé

Sir Charles Hallé (born Karl Halle; 11 April 181925 October 1895) was an Anglo-German pianist and conductor, and founder of The Hallé orchestra in 1858.

Life

Hallé was born Karl Halle on 11 April 1819 in Hagen, Westphalia. After settling ...

, and in March 1858 he first sang Mendelssohn's ''Elijah'' (at Exeter Hall, Liverpool), of which he became a leading interpreter for over 50 years. From the first, he was given firm encouragement by Sims Reeves and Clara Novello

Clara Anastasia Novello (10 June 1818 – 12 March 1908) was an acclaimed soprano, the fourth daughter of Vincent Novello, a musician and music publisher, and his wife, Mary Sabilla Hehl. Her acclaimed soprano and pure style made her one o ...

, and by Mario and Grisi, with whom he sang on various occasions. At the inauguration of the original Leeds Festival

The Reading and Leeds Festivals are a pair of annual music festivals that take place in Reading and Leeds in England. The events take place simultaneously on the Friday, Saturday and Sunday of the August bank holiday weekend. The Reading Festiv ...

of autumn 1858 he was the star performer (with Willoughby Weiss) in Rossini

Gioachino Antonio Rossini (29 February 1792 – 13 November 1868) was an Italian composer who gained fame for his 39 operas, although he also wrote many songs, some chamber music and piano pieces, and some sacred music. He set new standards f ...

's ''Stabat Mater'' . In the autumn of 1859 he was singing items from ''St Paul'', ''Judas Maccabaeus

Judah Maccabee (or Judas Maccabeus, also spelled Machabeus, or Maccabæus, Hebrew: יהודה המכבי, ''Yehudah HaMakabi'') was a Jewish priest (''kohen'') and a son of the priest Mattathias. He led the Maccabean Revolt against the Seleu ...

'' and ''Messiah

In Abrahamic religions, a messiah or messias (; ,

; ,

; ) is a saviour or liberator of a group of people. The concepts of ''mashiach'', messianism, and of a Messianic Age originated in Judaism, and in the Hebrew Bible, in which a ''mashiach'' ...

'' at the Bradford

Bradford is a city and the administrative centre of the City of Bradford district in West Yorkshire, England. The city is in the Pennines' eastern foothills on the banks of the Bradford Beck. Bradford had a population of 349,561 at the 2011 ...

Festival, shortly before embarking on his initial operatic season.

In 1861 he sang ''Elijah'' in his first appearance at the Birmingham Triennial Music Festival

The Birmingham Triennial Musical Festival, in Birmingham, England, founded in 1784, was the longest-running classical music festival of its kind. It last took place in 1912.

History

The first music festival, over three days in September 1768 ...

. In July of the following year, at St James's Hall

St. James's Hall was a concert hall in London that opened on 25 March 1858, designed by architect and artist Owen Jones, who had decorated the interior of the Crystal Palace. It was situated between the Quadrant in Regent Street and Piccadilly, ...

Piccadilly, he appeared in the Philharmonic Society's 50th Jubilee Concert, singing an item from Hummel's ''Mathilde of Guise'', and ''With Joy the Impatient Husbandman'' from Haydn

Franz Joseph Haydn ( , ; 31 March 173231 May 1809) was an Austrian composer of the Classical period. He was instrumental in the development of chamber music such as the string quartet and piano trio. His contributions to musical form have led ...

's ''The Seasons''. On that occasion he shared a platform (though in separate performance) with Jenny Lind, the pianist Lucy Anderson

Lucy Anderson (bap. 18 February 1795 – 24 December 1878) was the most eminent of the English pianists of the early Victorian era. She is mentioned in the same breath as English pianists of the calibre of William Sterndale Bennett.

She ...

(her last public appearance), Thérèse Tietjens

Thérèse Carolina Johanne Alexandra Tietjens (17 July 1831, Hamburg3 October 1877, London) was a leading opera and oratorio soprano. She made her career chiefly in London during the 1860s and 1870s, but her sequence of musical triumphs in th ...

, and Alfredo Piatti the cellist, under the direction of William Sterndale Bennett

Sir William Sterndale Bennett (13 April 18161 February 1875) was an English composer, pianist, conductor and music educator. At the age of ten Bennett was admitted to the London Royal Academy of Music (RAM), where he remained for ten years. B ...

. Bennett had just drilled a new orchestra to a level of high efficiency, creating a sensation before a huge audience. In 1862 Santley appeared at the Handel

George Frideric (or Frederick) Handel (; baptised , ; 23 February 1685 – 14 April 1759) was a German-British Baroque composer well known for his operas, oratorios, anthems, concerti grossi, and organ concertos. Handel received his training i ...

Festival at the Crystal Palace

Crystal Palace may refer to:

Places Canada

* Crystal Palace Complex (Dieppe), a former amusement park now a shopping complex in Dieppe, New Brunswick

* Crystal Palace Barracks, London, Ontario

* Crystal Palace (Montreal), an exhibition building ...

.

The year 1863 saw his first appearance at the Worcester

Worcester may refer to:

Places United Kingdom

* Worcester, England, a city and the county town of Worcestershire in England

** Worcester (UK Parliament constituency), an area represented by a Member of Parliament

* Worcester Park, London, Engla ...

and Norwich

Norwich () is a cathedral city and district of Norfolk, England, of which it is the county town. Norwich is by the River Wensum, about north-east of London, north of Ipswich and east of Peterborough. As the seat of the See of Norwich, with ...

festivals: at Worcester he sang in Schachner's new work ''Israel's return from Babylon'', and at Norwich he introduced Julius Benedict

Sir Julius Benedict (27 November 1804 – 5 June 1885) was a German-born composer and conductor, resident in England for most of his career.

Life and music

Benedict was born in Stuttgart, the son of a Jewish banker, and in 1820 learnt compo ...

's ''Richard Coeur de Lion'', a great success. In April 1864 he sang in Handel's ''Messiah'', and in a miscellaneous concert, at Stratford-upon-Avon

Stratford-upon-Avon (), commonly known as just Stratford, is a market town and civil parish in the Stratford-on-Avon district, in the county of Warwickshire, in the West Midlands region of England. It is situated on the River Avon, north-we ...

for the Shakespeare

William Shakespeare ( 26 April 1564 – 23 April 1616) was an English playwright, poet and actor. He is widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England's nation ...

centenary festival. At the Hereford

Hereford () is a cathedral city, civil parish and the county town of Herefordshire, England. It lies on the River Wye, approximately east of the border with Wales, south-west of Worcester and north-west of Gloucester. With a population ...

Festival he sang the second part of ''The Creation'', an English version of Rossini's ''Stabat Mater'' and Benedict's ''Richard''. At the Birmingham festival of 1864 was given Michael Costa's new work ''Naaman'', where (as Elisha) he sang opposite Sims Reeves and the young Adelina Patti

Adelina Patti (19 February 184327 September 1919) was an Italian 19th-century opera singer, earning huge fees at the height of her career in the music capitals of Europe and America. She first sang in public as a child in 1851, and gave her la ...

(then making her first appearance in oratorio). Santley also appeared there in ''Messiah'' and Arthur Sullivan

Sir Arthur Seymour Sullivan (13 May 1842 – 22 November 1900) was an English composer. He is best known for 14 comic opera, operatic Gilbert and Sullivan, collaborations with the dramatist W. S. Gilbert, including ''H.M.S. Pinaf ...

's ''The Masque at Kenilworth

''Kenilworth, A Masque of the Days of Queen Elizabeth'' (commonly referred to as "The Masque at Kenilworth"), is a cantata with music by Arthur Sullivan and words by Henry Fothergill Chorley (with an extended Shakespeare quotation) that premier ...

''.

The autumn of 1865 witnessed his debut appearance at the Gloucester

Gloucester ( ) is a cathedral city and the county town of Gloucestershire in the South West of England. Gloucester lies on the River Severn, between the Cotswolds to the east and the Forest of Dean to the west, east of Monmouth and east ...

Festival, where he sang ''Elijah'', the first part of ''St. Paul

Paul; grc, Παῦλος, translit=Paulos; cop, ⲡⲁⲩⲗⲟⲥ; hbo, פאולוס השליח (previously called Saul of Tarsus;; ar, بولس الطرسوسي; grc, Σαῦλος Ταρσεύς, Saũlos Tarseús; tr, Tarsuslu Pavlus; ...

'', part of ''Messiah'', and Mendelssohn's ''First Walpurgis Night''. In 1866 he was at Worcester Festival, and then at Norwich, where Costa's ''Naaman'' was given again, in the presence of the Prince and Princess of Wales, and Benedict's new cantata '' St. Cecilia'' (libretto by Chorley) was introduced. At Hereford in 1867 the main event for Santley was singing with the famous soprano Jenny Lind for the first time, in the oratorio ''Ruth'' by Otto Goldschmidt

Otto Moritz David Goldschmidt (21 August 1829 – 24 February 1907) was a German composer, conductor and pianist, known for his piano concertos and other piano pieces. He married the "Swedish Nightingale", soprano Jenny Lind.

Life

Goldschmidt w ...

. There, and at Birmingham festival, Willoughby Weiss took most of the sacred bass or baritone roles. Santley sang bass arias from the ''Messiah'', Gounod's ''Mass'', Benedict's ''St. Cecilia'' and J. F. Barnett's ''The Ancient Mariner''.

Returning to the Birmingham Festival in 1867 he was a soloist in the premiere of the Sacred Cantata The Woman of Samaria by William Sterndale Bennett

Sir William Sterndale Bennett (13 April 18161 February 1875) was an English composer, pianist, conductor and music educator. At the age of ten Bennett was admitted to the London Royal Academy of Music (RAM), where he remained for ten years. B ...

, conducted by the composer.

At the Handel Festival in June 1868 he sang the ''Messiah'' solos, and on the selection day, 'O voi dell'Erebo' from ''La Resurrezione'' and 'O ruddier than the cherry' from '' Acis and Galatea''. He also sang 'The Lord is a Man of War' with Signor Foli

Allan James Foley (7 August 1837 – 10 October 1899), distinguished 19th century Irish bass opera singer, was born at Cahir, Tipperary. In accordance with the prevailing preference for Italian artists, he changed the spelling (but not the ...

. At Hereford he sang Dr Wesley's anthem ''The Wilderness'', and under Dr Wesley, ''Elijah'', with Louisa Pyne

Louisa Bodda-Pyne (30 April 1828 – 20 March 1904) was an England, English soprano and opera company manager.

Biography

Life and career

Born into a theatrical family as Louisa Fanny Pyne, she was the youngest daughter of the alto George Griggs ...

. In 1869 a Rossini festival took place at the Crystal Palace, with a chorus and orchestra of about 3,000, in which he sang in the ''Stabat Mater'', and appeared in the scene of the 'Blessing of the Banners' from '' The Siege of Corinth''. In mid-May he sang in the first performance in England of Rossini's ''Petite Messe Solennelle

Gioachino Rossini's ''Petite messe solennelle'' (Little solemn mass) was written in 1863, possibly at the request of Count Alexis Pillet-Will for his wife Louise to whom it is dedicated. The composer, who had retired from composing operas more ...

'', with the dramatic soprano Thérèse Tietjens, Pietro Mongini and the mezzo-soprano Sofia Scalchi

Sofia Scalchi (November 29, 1850 – August 22, 1922) was an Italian operatic contralto who could also sing in the mezzo-soprano range. Her career was international, and she appeared at leading theatres in both Europe and America.

Singing ...

. It was also performed that year at the Worcester and Norwich festivals. At Worcester, Reeves, Santley, Trebelli and Tietjens gave the first performance of Sullivan's '' The Prodigal Son'', under the composer's baton. At Norwich there was also Hugo Pierson's oratorio ''Hezekiah.''

At the close of the 1868–69 season of the Philharmonic Society of London

The Royal Philharmonic Society (RPS) is a British music society, formed in 1813. Its original purpose was to promote performances of instrumental music in London. Many composers and performers have taken part in its concerts. It is now a memb ...

Santley, Tietjens and Nilsson took part in the final supernumerary concert, held at St James's Hall

St. James's Hall was a concert hall in London that opened on 25 March 1858, designed by architect and artist Owen Jones, who had decorated the interior of the Crystal Palace. It was situated between the Quadrant in Regent Street and Piccadilly, ...

for the first time before the Society moved there permanently in the next season. These three singers were among the original ten recipients to be awarded the Society's gold medal at its first presentation in 1871.

In early 1870, as his departure from the theatre was approaching, Santley sang at concerts in London and at Exeter Hall. Then, under the management of George Wood, he made a six-week concert tour of the provinces. The touring company included Clarice Sinico, the violinist August Wilhelmj

__NOTOC__

August Emil Daniel Ferdinand Wilhelmj ( ; 21 September 184522 January 1908) was a German violinist and teacher.

Wilhelmj was born in Usingen and was considered a child prodigy; when Henriette Sontag heard him in 1852 at seven years o ...

and the pianist Arabella Goddard

Arabella Goddard (12 January 18366 April 1922) was an English pianist.

She was born and died in France. Her parents, Thomas Goddard, an heir to a Salisbury cutlery firm, and Arabella née Ingles, were part of an English community of expatriat ...

(later joined by Ernst Pauer). Santley's concert singing reached a high point of acclaim during his subsequent United States and Canadian tour of 1871–72. In such songs as "To Anthea", "Simon the Cellarer" and the "Maid of Athens", he was viewed as being unapproachable, and his oratorio

An oratorio () is a large musical composition for orchestra, choir, and soloists. Like most operas, an oratorio includes the use of a choir, soloists, an instrumental ensemble, various distinguishable characters, and arias. However, opera is mus ...

singing was praised for perpetuating the finest traditions of the art form. In 1872, he took part in a joint recital with Pauline Rita at St James's Hall

St. James's Hall was a concert hall in London that opened on 25 March 1858, designed by architect and artist Owen Jones, who had decorated the interior of the Crystal Palace. It was situated between the Quadrant in Regent Street and Piccadilly, ...

, London.

Operatic career 1857–1876

The early years

In the first years after his return to England, Santley used often to sing buffo duets (for example 'Che l'antipatica vostra figura' from Ricci's ''Chiara di Rosemberg'') withGiorgio Ronconi

Giorgio Ronconi (6 August 1810 – 8 January 1890) was an Italian operatic baritone celebrated for his brilliant acting and compelling stage presence. In 1842, he created the title-role in Giuseppe Verdi's ''Nabucco'' at La Scala, Milan.

Personal ...

and Giovanni Belletti

Giovanni Battista Belletti (17 February 1813 – 27 December 1890)"Belletti, Giovanni Battista"< ...

, at parties held by the influential critic H. F. Chorley. In 1859 he made his debut at Covent Garden

Covent Garden is a district in London, on the eastern fringes of the West End, between St Martin's Lane and Drury Lane. It is associated with the former fruit-and-vegetable market in the central square, now a popular shopping and tourist si ...

as Hoel in Meyerbeer

Giacomo Meyerbeer (born Jakob Liebmann Beer; 5 September 1791 – 2 May 1864) was a German opera composer, "the most frequently performed opera composer during the nineteenth century, linking Mozart and Wagner". With his 1831 opera ''Robert le d ...

's opera ''Dinorah''. In the same season he sang in the English ''Il trovatore

''Il trovatore'' ('The Troubadour') is an opera in four acts by Giuseppe Verdi to an Italian libretto largely written by Salvadore Cammarano, based on the play ''El trovador'' (1836) by Antonio García Gutiérrez. It was García Gutiérrez's mos ...

'' (Di Luna), ''The Rose of Castille

''The Rose of Castille'' (or ''Castile'') is an opera in three acts, with music by Michael William Balfe to an English-language libretto by Augustus Glossop Harris and Edmund Falconer, after the libretto by Adolphe d'Ennery and Clairville (alias ...

'', ''Satanella'', ''La sonnambula

''La sonnambula'' (''The Sleepwalker'') is an opera semiseria in two acts, with music in the '' bel canto'' tradition by Vincenzo Bellini set to an Italian libretto by Felice Romani, based on a scenario for a ''ballet-pantomime'' written by Eug ...

'', and as Rhineberg in Wallace

Wallace may refer to:

People

* Clan Wallace in Scotland

* Wallace (given name)

* Wallace (surname)

* Wallace (footballer, born 1986), full name Wallace Fernando Pereira, Brazilian football left-back

* Wallace (footballer, born 1987), full name ...

's ''Lurline'', with William Harrison and Louisa Pyne

Louisa Bodda-Pyne (30 April 1828 – 20 March 1904) was an England, English soprano and opera company manager.

Biography

Life and career

Born into a theatrical family as Louisa Fanny Pyne, she was the youngest daughter of the alto George Griggs ...

. Wallace transcribed the latter role (originally for bass) to suit his higher register, and composed the character's part in the final act expressly for him. ''Dinorah'' also received a royal command performance before Queen Victoria and Prince Albert. He was also able to fit in performances of Gluck

Christoph Willibald (Ritter von) Gluck (; 2 July 1714 – 15 November 1787) was a composer of Italian and French opera in the early classical period (music), classical period. Born in the Upper Palatinate and raised in Bohemia, both part of the ...

's ''Iphigénie en Tauride

''Iphigénie en Tauride'' (, ''Iphigenia in Tauris'') is a 1779 opera by Christoph Willibald Gluck in four acts. It was his fifth opera for the French stage. The libretto was written by Nicolas-François Guillard.

With ''Iphigénie,'' Gluck took ...

'' in Manchester, with Sims Reeves

John Sims Reeves (21 October 1821 – 25 October 1900) was an English operatic, oratorio and ballad tenor vocalist during the mid-Victorian era.

Reeves began his singing career in 1838 but continued his vocal studies until 1847. He soon establ ...

and Catherine Hayes, for Charles Hallé. These were twice repeated at the residence of Lord Ward in Park Lane

Park Lane is a dual carriageway road in the City of Westminster in Central London. It is part of the London Inner Ring Road and runs from Hyde Park Corner in the south to Marble Arch in the north. It separates Hyde Park to the west from May ...

, London.

Santley appeared in English opera for Mapleson at Her Majesty's Theatre

Her Majesty's Theatre is a West End theatre situated on Haymarket, London, Haymarket in the City of Westminster, London. The present building was designed by Charles J. Phipps and was constructed in 1897 for actor-manager Herbert Beerbohm Tree, ...

in the 1860–61 season. Mapleson mounted a new opera, George Alexander Macfarren

Sir George Alexander Macfarren (2 March 181331 October 1887) was an English composer and musicologist.

Life

George Alexander Macfarren was born in London on 2 March 1813 to George Macfarren, a dancing-master, dramatic author and journalist, wh ...

's ''Robin Hood'', featuring a cast led by Sims Reeves and stage-debutante Helen Lemmens-Sherrington

Helen Lemmens-Sherrington (4 October 1834 – 9 May 1906) was an English concert and operatic soprano prominent from the 1850s to the 1880s. Born in northern England, she spent much of her childhood and later life in Belgium, where she studied at ...

, under the direction of Charles Hallé

Sir Charles Hallé (born Karl Halle; 11 April 181925 October 1895) was an Anglo-German pianist and conductor, and founder of The Hallé orchestra in 1858.

Life

Hallé was born Karl Halle on 11 April 1819 in Hagen, Westphalia. After settling ...

. In the same season Santley sang (for Pyne and Harrison) ''Fra Diavolo

Fra Diavolo (lit. Brother Devil; 7 April 1771–11 November 1806), is the popular name given to Michele Pezza, a famous guerrilla leader who resisted the French occupation of Naples, proving an "inspirational practitioner of popular insurrect ...

'', ''La Reine Topaze'', ''The Bohemian Girl

''The Bohemian Girl'' is an Irish Romantic opera composed by Michael William Balfe with a libretto by Alfred Bunn. The plot is loosely based on a Miguel de Cervantes' tale, ''La Gitanilla''.

The best-known aria from the piece is " I Dreamt I Dwe ...

'' (with Mme Parepa), ''Il trovatore'' and Wallace's ''The Amber Witch'', which later transferred to Drury Lane

Drury Lane is a street on the eastern boundary of the Covent Garden area of London, running between Aldwych and High Holborn. The northern part is in the borough of Camden and the southern part in the City of Westminster.

Notable landmarks ...

. He was announced to sing in Verdi

Giuseppe Fortunino Francesco Verdi (; 9 or 10 October 1813 – 27 January 1901) was an Italian composer best known for his operas. He was born near Busseto to a provincial family of moderate means, receiving a musical education with the h ...

's ''Macbeth

''Macbeth'' (, full title ''The Tragedie of Macbeth'') is a tragedy by William Shakespeare. It is thought to have been first performed in 1606. It dramatises the damaging physical and psychological effects of political ambition on those w ...

'' with Giulia Grisi in 1861, but the promotion collapsed.

For the season of 1861–62, Santley returned to Covent Garden, opening in Howard Glover's ''Ruy Blas'' (as Don Sallust, Harrison as Ruy Blas), then in a re-cast version of ''Robin Hood'', and finally in Balfe's '' The Puritan's Daughter''. He also created the role of 'Danny Man' in Julius Benedict

Sir Julius Benedict (27 November 1804 – 5 June 1885) was a German-born composer and conductor, resident in England for most of his career.

Life and music

Benedict was born in Stuttgart, the son of a Jewish banker, and in 1820 learnt compo ...

's ''The Lily of Killarney

''The Lily of Killarney'' is an opera in three acts by Julius Benedict. The libretto, by John Oxenford and Dion Boucicault, is based on Boucicault's own play ''The Colleen Bawn''. The opera received its premiere at Covent Garden Theatre, Londo ...

'', which was performed nightly for five or six weeks. Worn out by this busy season, Santley decided to turn his attention to Italian opera, and, armed with a letter from Michael Costa, paid a visit to Rossini

Gioachino Antonio Rossini (29 February 1792 – 13 November 1868) was an Italian composer who gained fame for his 39 operas, although he also wrote many songs, some chamber music and piano pieces, and some sacred music. He set new standards f ...

in Paris. This meeting proved disappointing; but he made an Italian début at Covent Garden in 1862 when he sang the role of di Luna in ''Il trovatore'' for three nights at Covent Garden, 'in place of Graziani, to oblige Mr. Gye': that was with the English soprano Fanny Gordosa, Constance Nantier-Didiée, the Italian dramatic tenor Enrico Tamberlik

Enrico Tamberlik (16 March 1820 – 13 March 1889) was an Italian tenor who sang to great acclaim at Europe and America's leading opera venues. He excelled in the heroic roles of the Italian and French repertories and was renowned for his po ...

and the Franco-Italian bass-baritone Joseph Tagliafico. Santley's performances were received rapturously by the Covent Garden audience.

Mapleson's Italian Opera

Mapleson won Santley back for his own Italian opera company, and in the 1862–63 season at Majesty's, he performed in ''

Mapleson won Santley back for his own Italian opera company, and in the 1862–63 season at Majesty's, he performed in ''Il trovatore

''Il trovatore'' ('The Troubadour') is an opera in four acts by Giuseppe Verdi to an Italian libretto largely written by Salvadore Cammarano, based on the play ''El trovador'' (1836) by Antonio García Gutiérrez. It was García Gutiérrez's mos ...

'' (as Di Luna), ''The Marriage of Figaro

''The Marriage of Figaro'' ( it, Le nozze di Figaro, links=no, ), K. 492, is a ''commedia per musica'' (opera buffa) in four acts composed in 1786 by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, with an Italian libretto written by Lorenzo Da Ponte. It premie ...

'' (as Almaviva) and ''Les Huguenots

() is an opera by Giacomo Meyerbeer and is one of the most popular and spectacular examples of grand opera. In five acts, to a libretto

A libretto (Italian for "booklet") is the text used in, or intended for, an extended musical work suc ...

'' (as de Nevers). He returned to Covent Garden for the English Opera, however, appearing in ''the Lily of Killarney

''The Lily of Killarney'' is an opera in three acts by Julius Benedict. The libretto, by John Oxenford and Dion Boucicault, is based on Boucicault's own play ''The Colleen Bawn''. The opera received its premiere at Covent Garden Theatre, Londo ...

'', ''Dinorah

''Dinorah'', originally ''Le pardon de Ploërmel'' (''The Pardon of Ploërmel''), is an 1859 French opéra comique in three acts with music by Giacomo Meyerbeer and a libretto by Jules Barbier and Michel Carré. The story takes place near the rura ...

'', and Balfe's ''The Armourer of Nantes

''The Armourer of Nantes'' is an opera in three acts, with music by Michael William Balfe and libretto by J. V. Bridgman. The opera is based on Victor Hugo's 1833 play ''Marie Tudor'' and set in Nantes, France, in 1498. The opera was first produce ...

''. In defence of his decision to move to Italian opera, Santley notes that since 1859-60 he had been singing about 110 opera performances per season, in addition to fulfilling concurrent concert engagements.

With Mapleson's Italian Opera he joined some of the 19th century's most celebrated singers, including Thérèse Tietjens

Thérèse Carolina Johanne Alexandra Tietjens (17 July 1831, Hamburg3 October 1877, London) was a leading opera and oratorio soprano. She made her career chiefly in London during the 1860s and 1870s, but her sequence of musical triumphs in th ...

, Marietta Alboni

Maria Anna Marzia (called Marietta) Alboni (6 March 1826 – 23 June 1894) was a renowned Italian contralto opera singer. She is considered "one of the greatest contraltos in operatic history".

Biography

Alboni was born at Città di Castello, i ...

, Antonio Giuglini

Antonio Giuglini (16 or 17 January 1825 – 12 October 1865) was an Italian operatic tenor. During the last eight years of his life, before he developed signs of mental instability, he earned renown as one of the leading stars of the operatic ...

and Zelia Trebelli. Once the 1862–63 season was over, Santley paid a visit to Paris and saw Mme Carvalho perform in Gounod

Charles-François Gounod (; ; 17 June 181818 October 1893), usually known as Charles Gounod, was a French composer. He wrote twelve operas, of which the most popular has always been ''Faust (opera), Faust'' (1859); his ''Roméo et Juliette'' (18 ...

's ''Faust

Faust is the protagonist of a classic German legend based on the historical Johann Georg Faust ( 1480–1540).

The erudite Faust is highly successful yet dissatisfied with his life, which leads him to make a pact with the Devil at a crossroads ...

'', which Mapleson had obtained for the 1863 season in London. In the new season (begun with ''Il trovatore''), Carvalho and Santley appeared together in the premiere of Schira's '' Niccolo de' Lapi'', Santley creating the title-role. He also played the elder Germont in ''La traviata''.

The first performance of ''Faust'' in England followed. It was given in a problematic English translation by Henry Fothergill Chorley

Henry Fothergill Chorley (15 December 1808 – 16 February 1872) was an English literary, art and music critic, writer and editor. He was also an author of novels, drama, poetry and lyrics.

Chorley was a prolific and important music and litera ...

, which nevertheless remained the standard translation until well into the 20th century. Santley appeared as Valentine. The other cast members were Tietjens (as Marguerite), Trebelli (Siebel), Antonio Giuglini

Antonio Giuglini (16 or 17 January 1825 – 12 October 1865) was an Italian operatic tenor. During the last eight years of his life, before he developed signs of mental instability, he earned renown as one of the leading stars of the operatic ...

(Faust) and Edouard Gassier (Mephisto). In July 1863 the company performed Weber's ''Oberon

Oberon () is a king of the fairies in medieval and Renaissance literature. He is best known as a character in William Shakespeare's play ''A Midsummer Night's Dream'', in which he is King of the Fairies and spouse of Titania, Queen of the Fair ...

'' with Reeves, Tietjens, Alboni and Alessandro Bettini. Santley appeared as Scherasmin. In the autumn, after the Worcester and Norwich festivals, Santley joined the Mapleson company's annual tour, beginning in Dublin. Sims Reeves had joined the company to perform the roles of Edgardo, Huon and Faust (with Tietjens and Trebelli as his partners).

After hearing Santley's Valentine, Gounod composed the aria ''Even bravest heart'' expressly for him to an original English text by Chorley (now, ironically, better known in French translation as ''Avant de quitter'' or in Italian as ''Dio possente'') and this was introduced in London in January 1864 at the opening of the spring session. Also appearing in this production were Reeves, Lemmens-Sherrington and Salvatore Marchesi (the latter as Mephisto). Late in the run, however, Santley took on the role of Mephisto, in an 'abominable red costume'. ''Faust'' was later produced with Tietjens, Gardoni, Trebelli, and Signor Junca, with Santley resuming his place. In the same season he appeared in the English premiere of Nicolai's ''Die Lustigen Weiber von Windsor

''The Merry Wives of Windsor'' (German: ''Die lustigen Weiber von Windsor'') is an opera in three acts by Otto Nicolai to a German libretto by Salomon Hermann Mosenthal based on the play ''The Merry Wives of Windsor'' by William Shakespeare.

The ...

'' and in Gounod's ''Mireille

Mireille () is a French given name, derived from the Provençal Occitan name ''Mirèio'' (or ''Mirèlha'' in the classical norm of Occitan, ). It could be related to the Occitan verb ''mirar'' "to look, to admire" or to the given names ''Miriam'' ...

'' (with Giuglini and Tietjens). He appeared, too, as Plunkett in ''Martha

Martha (Hebrew: מָרְתָא) is a biblical figure described in the Gospels of Luke and John. Together with her siblings Lazarus and Mary of Bethany, she is described as living in the village of Bethany near Jerusalem. She was witness to ...

'', as the Duke in ''Lucrezia Borgia

Lucrezia Borgia (; ca-valencia, Lucrècia Borja, links=no ; 18 April 1480 – 24 June 1519) was a Spanish-Italian noblewoman of the House of Borgia who was the daughter of Pope Alexander VI and Vannozza dei Cattanei. She reigned as the Govern ...

'', and as the Minister in ''Fidelio

''Fidelio'' (; ), originally titled ' (''Leonore, or The Triumph of Marital Love''), Op. 72, is Ludwig van Beethoven's only opera. The German libretto was originally prepared by Joseph Sonnleithner from the French of Jean-Nicolas Bouilly, with ...

''.

The company in transition

After the festival season, Santley toured in Mapleson's company during the autumn (with Italo Gardoni as lead tenor), appearing in ''Faust'', ''Oberon'' and ''Mireille'', In November 1864 he set off for

After the festival season, Santley toured in Mapleson's company during the autumn (with Italo Gardoni as lead tenor), appearing in ''Faust'', ''Oberon'' and ''Mireille'', In November 1864 he set off for Barcelona

Barcelona ( , , ) is a city on the coast of northeastern Spain. It is the capital and largest city of the autonomous community of Catalonia, as well as the second most populous municipality of Spain. With a population of 1.6 million within ci ...

, where he was booked for a three-month season at the Liceu

The Gran Teatre del Liceu (, English: Great Theatre of the Lyceum), known as ''El Liceu'', is an opera house in Barcelona, Catalonia, Spain. Located in La Rambla, it is the oldest running theatre in Barcelona.

Founded in 1837 at another loca ...

. His Di Luna was warmly received, and he followed with his first ''Rigoletto

''Rigoletto'' is an opera in three acts by Giuseppe Verdi. The Italian libretto was written by Francesco Maria Piave based on the 1832 play ''Le roi s'amuse'' by Victor Hugo. Despite serious initial problems with the Austrian censors who had cont ...

'', and ''La traviata''. He also played Enrico in ''Lucia'', Obertal in ''Le Prophète

''Le prophète'' (''The Prophet'') is a grand opera in five acts by Giacomo Meyerbeer, which was premiered in Paris on 16 April 1849. The French-language libretto was by Eugène Scribe and Émile Deschamps, after passages from the ''Essay on the ...

'', and Renato in ''Un ballo in maschera

''Un ballo in maschera'' ''(A Masked Ball)'' is an 1859 opera in three acts by Giuseppe Verdi. The text, by Antonio Somma, was based on Eugène Scribe's libretto for Daniel Auber's 1833 five act opera, '' Gustave III, ou Le bal masqué''.

The ...

''. He arrived back in Britain to join Mapleson's spring tour at Dublin, on the same day stepping in at Tietjens's insistence to save a failing production of ''Lucrezia Borgia''. During this tour he also performed Carlo Quinto in ''Ernani'' for the first time and sang at the Theatre Royal at Liverpool, the fulfilment of a childhood ambition.

In the spring of 1865, Giuglini left the company, and the Croatian diva Ilma de Murska

''Ilma'' is a genus of skipper (butterfly), skippers in the family Hesperiidae.

ReferencesNatural History Museum Lepidoptera genus database

Hesperiinae Hesperiidae genera {{Hesperiinae-stub ...

joined it, appearing in ''Lucia di Lammermoor''. Santley took on three new roles: Papageno in Mozart's ''Hesperiinae Hesperiidae genera {{Hesperiinae-stub ...

Magic Flute

''The Magic Flute'' (German: , ), K. 620, is an opera in two acts by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart to a German libretto by Emanuel Schikaneder. The work is in the form of a '' Singspiel'', a popular form during the time it was written that inc ...

'', Creonte in Cherubini's ''Médée

''Médée'' is a dramatic tragedy in five acts written in alexandrine verse by Pierre Corneille in 1635.

Summary

The heroine of the play is the sorceress Médée. After Médée gives Jason twin boys, Jason leaves her for Creusa. Médée ...

'' and Pizarro in Beethoven's ''Fidelio'' (opposite Tietjens). In September there was a short touring season, in which he played Don Giovanni

''Don Giovanni'' (; K. 527; Vienna (1788) title: , literally ''The Rake Punished, or Don Giovanni'') is an opera in two acts with music by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart to an Italian libretto by Lorenzo Da Ponte. Its subject is a centuries-old Spanis ...

(with Mario

is a character created by Japanese video game designer Shigeru Miyamoto. He is the title character of the ''Mario'' franchise and the mascot of Japanese video game company Nintendo. Mario has appeared in over 200 video games since his creat ...

) for the first time, at Manchester. He also sang Caspar in ''Der Freischütz

' ( J. 277, Op. 77 ''The Marksman'' or ''The Freeshooter'') is a German opera with spoken dialogue in three acts by Carl Maria von Weber with a libretto by Friedrich Kind, based on a story by Johann August Apel and Friedrich Laun from their 181 ...

'' in London in October. Santley then went on to appear in a season at La Scala, Milan, where ''Il trovatore'' was staged for his debut there as de Luna (he alone of all the cast was not hooted by the audience), as well as Nicolai's ''Il Templario

''Il templario'' is an Italian-language opera by the German composer Otto Nicolai from a libretto written by based on Walter Scott's 1819 novel ''Ivanhoe''.

It has been noted that Nicolai's work for the opera stage, which followed the successfu ...

'' (in which he sang the role of Brian the Templar). Returning to London in March 1866, Santley appeared in the spring season with Tietjens, Gardoni and Gassier in ''Iphigénie en Tauride''. He also sang in ''Dinorah'' (with de Murska and Gardoni) and ''Ernani'' (with Tietjens, Tasca and Gassier). During the autumn, he performed as Leporello in ''Don Giovanni'' at Her Majesty's.

The year 1867 brought the engagement of Sweden's Christine Nilsson

Christina Nilsson, Countess de Casa Miranda, also called Christine Nilsson (20 August 1843 – 22 November 1921) was a Swedish dramatic coloratura soprano. Possessed of a pure and brilliant voice of first three then two and a half octaves tr ...

, and Santley appeared with her in ''La traviata'' and ''I Lombardi''. ''La forza del destino'' was also given, along with ''Don Giovanni'', ''Dinorah'', ''Fidelio'', ''Oberon'', ''Medea'', ''Der Freischütz'' and ''Les Huguenots''. After the autumn tour with Alessandro Bettini in ''Les Huguenots'', the November session opened with ''Faust'', followed by ''La traviata'' and ''Martha'', and ''Linda di Chamounix'', in which Santley first sang the part of Antonio. ''Don Giovanni'', with Clara Louise Kellogg

Clara Louise Kellogg (July 9, 1842 – May 13, 1916) was an American operatic soprano.

Biography

Clara Louise Kellogg was born in Sumterville, South Carolina, the daughter of Jane Elizabeth (Crosby) and George Kellogg. She received her music ...

as Zerlina and Santley as Leporello, proved to be the final operatic performance of that season: Santley had been due to play Pizarro, when the news came to him, while he was appearing in concert in Brighton

Brighton () is a seaside resort and one of the two main areas of the City of Brighton and Hove in the county of East Sussex, England. It is located south of London.

Archaeological evidence of settlement in the area dates back to the Bronze A ...

, that Her Majesty's Theatre

Her Majesty's Theatre is a West End theatre situated on Haymarket, London, Haymarket in the City of Westminster, London. The present building was designed by Charles J. Phipps and was constructed in 1897 for actor-manager Herbert Beerbohm Tree, ...

had been burnt to the ground. Santley had sung the last notes ever to be heard in that theatre.

After the fire

The company presented a fresh season, commencing in March 1868 at Drury Lane. In it, Santley sang Fernando in ''La Gazza Ladra

''La gazza ladra'' (, ''The Thieving Magpie'') is a ''melodramma'' or opera semiseria in two acts by Gioachino Rossini, with a libretto by Giovanni Gherardini based on ''La pie voleuse'' by Théodore Baudouin d'Aubigny and Louis-Charles Caigni ...

'' with Kellogg, Trebelli, Bettini and Foli Foli is both a surname and a given name. Notable people with the name include:

*Signor Foli (1837–1899), 19th century Irish bass opera singer

*Tim Foli (born 1950), American former professional baseball player

*Foli Adade (born 1991), Ghanaian pr ...

, and the title role in ''Rigoletto'' with Kellogg and the prominent tenor Gaetano Fraschini. Also produced at Drury Lane that season were ''Les Huguenots'', ''Le nozze di Figaro'', ''La Figlia del Reggimento'' and ''Faust'' (with Nilsson as Marguerite). At Nilsson's benefit concert, Santley played the final scene of '' I Due Foscari'', and his Doge was compared favourably to Ronconi's.

In July Santley appeared in ''Le Nozze'' at the Crystal Palace. The London autumn season was held at Covent Garden, with Santley's old hero Karl Formes joining the tour cast. The American soprano Minnie Hauk

Minnie Hauk in a cabinet card photograph, ca. 1880

Amalia Mignon Hauck "Minnie" Hauk (November 16, 1851 – February 6, 1929) was an American operatic first dramatic soprano than mezzo-soprano.

Early life

She was born in New York City on Novemb ...

also appeared (in ''La Sonnambula''). During the ensuing tour, Santley sang Tom Tug in Charles Dibdin

Charles Dibdin (before 4 March 1745 – 25 July 1814) was an English composer, musician, dramatist, novelist, singer and actor. With over 600 songs to his name, for many of which he wrote both the lyrics and the music and performed them himself, ...

's ''The Waterman

''The'' () is a grammatical article in English, denoting persons or things already mentioned, under discussion, implied or otherwise presumed familiar to listeners, readers, or speakers. It is the definite article in English. ''The'' is the m ...

'' for the first time, at Leeds

Leeds () is a city and the administrative centre of the City of Leeds district in West Yorkshire, England. It is built around the River Aire and is in the eastern foothills of the Pennines. It is also the third-largest settlement (by populati ...

. The next season, he sang it twice more in Leeds, and once each in Sheffield

Sheffield is a city status in the United Kingdom, city in South Yorkshire, England, whose name derives from the River Sheaf which runs through it. The city serves as the administrative centre of the City of Sheffield. It is Historic counties o ...

and Bradford

Bradford is a city and the administrative centre of the City of Bradford district in West Yorkshire, England. The city is in the Pennines' eastern foothills on the banks of the Bradford Beck. Bradford had a population of 349,561 at the 2011 ...

. The airs from ''The Waterman'' 'The jolly young waterman' and 'Then farewell, my trim-built wherry' were sung by Santley to acclaim.

Her Majesty's remained closed, and in 1869 Mapleson was drawn into a merger with the Royal Italian Opera. With the merged company, Santley performed in ''Rigoletto'' with Vanzini, Scalchi, Mongini and Foli, in ''Norma'' and ''Fidelio'', in ''Linda di Chamounix'' with di Murska and in ''Il trovatore''. ''La Gazza Ladra'' was also staged with Santley appearing opposite Trebelli, Bettini and Patti. Santley led the cast, with Nilsson as his Ophelia, in the London premiere of ''Hamlet

''The Tragedy of Hamlet, Prince of Denmark'', often shortened to ''Hamlet'' (), is a tragedy written by William Shakespeare sometime between 1599 and 1601. It is Shakespeare's longest play, with 29,551 words. Set in Denmark, the play depicts ...

'' by Ambroise Thomas

Charles Louis Ambroise Thomas (; 5 August 1811 – 12 February 1896) was a French composer and teacher, best known for his operas '' Mignon'' (1866) and ''Hamlet'' (1868).

Born into a musical family, Thomas was a student at the Conservatoire de ...

. He enjoyed the role, which was sung in Italian, apart from the 'Brindisi'. He also played Hoel in ''Dinorah'' opposite Patti, and although a planned partnership with her in ''L'Etoile du Nord'' did not occur, they did perform ''Rigoletto'' together for Patti's benefit. Santley's ''Hamlet'' was repeated in the autumn, with de Murska replacing Nilsson, and with Karl Formes as the ghost.

Early in 1870 the company made an operatic tour of Scotland

Scotland (, ) is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. Covering the northern third of the island of Great Britain, mainland Scotland has a border with England to the southeast and is otherwise surrounded by the Atlantic Ocean to the ...

, during which Santley sang Don Giovanni. At Drury Lane, in the following Italian season managed by George Wood, Santley sang The Dutchman in ''The Flying Dutchman

The ''Flying Dutchman'' ( nl, De Vliegende Hollander) is a legendary ghost ship, allegedly never able to make port, but doomed to sail the seven seas forever. The myth is likely to have originated from the 17th-century Golden Age of the Dut ...

'' (in Italian, as ''L'Ollandese Dannato''), opposite di Murska, and with Signor Foli as Daland. This was the first presentation of a Wagner opera in London. It took place in July 1870. But several other promised productions either did not occur ''(Macbeth

''Macbeth'' (, full title ''The Tragedie of Macbeth'') is a tragedy by William Shakespeare. It is thought to have been first performed in 1606. It dramatises the damaging physical and psychological effects of political ambition on those w ...

'', Cherubini's ''Les Deux Journees'', Rossini's ''Tancredi

''Tancredi'' is a ''melodramma eroico'' ('' opera seria'' or heroic opera) in two acts by composer Gioachino Rossini and librettist Gaetano Rossi (who was also to write ''Semiramide'' ten years later), based on Voltaire's play ''Tancrède'' (176 ...

'') or the baritone role in them was given to another artist. (Lothario in Thomas' ''Mignon

''Mignon'' is an 1866 ''opéra comique'' (or opera in its second version) in three acts by Ambroise Thomas. The original French libretto was by Jules Barbier and Michel Carré, based on Goethe's 1795-96 novel '' Wilhelm Meisters Lehrjahre''. The ...

'', for example, was assigned not to Santley but to the French baritone Jean-Baptiste Faure

Jean-Baptiste Faure () (15 January 1830 – 9 November 1914) was a French operatic baritone and art collector who also composed several classical songs.

Singing career

Faure was born in Moulins. A choirboy in his youth, he entered the Pari ...

).

Attempt to found an English lyric theatre

Rather than accept another season with the joint company, Santley decided to establish a new English Opera enterprise at the Gaiety Theatre, working with the theatre's music director and conductor,Meyer Lutz

Wilhelm Meyer Lutz (19 May 1829 – 31 January 1903) was a German-born British composer and conductor who is best known for light music, musical theatre and Victorian burlesque, burlesques of well-known works.

Emigrating to the UK at the age of ...

. In autumn 1870 he launched a successful nine-week run at the Gaiety with Hérold's ''Zampa

''Zampa'','' ou La fiancée de marbre'' (''Zampa, or the Marble Bride'') is an opéra comique in three acts by French composer Ferdinand Hérold, with a libretto by Mélesville.

The overture to the opera is one of Hérold's most famous works an ...

''. He refused to sing ''Don Giovanni'' but he did stage ''Fra Diavolo'' (with himself in title role), and, in the lead-up to Christmas, ''The Waterman''. Performances of ''Fra Diavolo'' continued through February 1871, while Lortzing

Gustav Albert Lortzing (23 October 1801 – 21 January 1851) was a German composer, librettist, actor and singer. He is considered to be the main representative of the German ''Spieloper'', a form similar to the French ''opéra comique'', which ...

's ''Czar und Zimmerman'' (as ''Peter the Shipwright'') was staged for Easter. This production proved a success but Santley could not persuade the Gaiety's manager, John Hollingshead

John Hollingshead (9 September 1827 – 9 October 1904) was an English theatrical impresario, journalist and writer during the latter half of the 19th century. After a journalism career, Hollingshead managed the Alhambra Theatre and was later th ...

, to produce Auber's ''Le Cheval de bronze'' as a follow-up. Feeling that his long-cherished project of an English lyric theatre could never be accomplished, he decided to turn his back on the stage altogether. Instead, in 1872–1873, he set out on a concert tour of in the United States and Canada.

With Carl Rosa's company

The concert tour itself was not a financial success. Santley therefore entered into an agreement with

The concert tour itself was not a financial success. Santley therefore entered into an agreement with Carl Rosa

Carl August Nicholas Rosa (22 March 184230 April 1889) was a German-born musical impresario best remembered for founding an English opera company known as the Carl Rosa Opera Company. He started his company in 1869 together with his wife, Euphro ...

to join his Italian season in New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the List of United States cities by population, most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the L ...

in March 1872; but he joined them first for the English season to play ''Zampa'' and ''Fra Diavolo'', at Baltimore

Baltimore ( , locally: or ) is the List of municipalities in Maryland, most populous city in the U.S. state of Maryland, fourth most populous city in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic, and List of United States cities by popula ...

, Philadelphia

Philadelphia, often called Philly, is the largest city in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, the sixth-largest city in the U.S., the second-largest city in both the Northeast megalopolis and Mid-Atlantic regions after New York City. Sinc ...

, Newark

Newark most commonly refers to:

* Newark, New Jersey, city in the United States

* Newark Liberty International Airport, New Jersey; a major air hub in the New York metropolitan area

Newark may also refer to:

Places Canada

* Niagara-on-the ...

and elsewhere. He played Valentin in ''Faust'' at Philadelphia. In the Italian season, from mid-March to the end of April, he was with Mme Parepa-Rosa, Adelaide Phillips and the tenor Theodore Wachtel (1823–1893), and with Karl Formes, who sang Marcel in ''Les Huguenots'' with Santley (Saint-Bris), at the Academy of Music in New York under Adolph Neuendorff

Adolf Heinrich Anton Magnus Neuendorff (June 13, 1843 − December 4, 1897), also known as Adolph Neuendorff, was a German American composer, violinist, pianist and conductor, stage director, and theater manager.

Life Early years

Born in Hamb ...

. Santley was also particularly proud to have sung once in that season with his friend and idol, Giorgio Ronconi, who was Leporello to Santley's Don Giovanni. The company also played ''Il trovatore'', ''Rigoletto'', ''Lucrezia Borgia'', ''Martha'' and ''Guglielmo Tell

''William Tell'' (french: Guillaume Tell, link=no; it, Guglielmo Tell, link=no) is a French-language opera in four acts by Italian composer Gioachino Rossini to a libretto by Victor-Joseph Étienne de Jouy and L. F. Bis, based on Friedrich S ...

''. The houses and receipts were enormous, and they sailed to England well pleased in early May 1872.

In 1873 Carl Rosa invited Santley to appear as Telramund in a planned English ''Lohengrin

Lohengrin () is a character in German Arthurian literature. The son of Parzival (Percival), he is a knight of the Holy Grail sent in a boat pulled by swans to rescue a maiden who can never ask his identity. His story, which first appears in Wolf ...

'' at Drury Lane. Santley accepted, but the project failed with the untimely death of Mme Parepa-Rosa. (''Lohengrin'' was not heard in London until 1875). Santley's wish to play Wolfram in ''Tannhäuser

Tannhäuser (; gmh, Tanhûser), often stylized, "The Tannhäuser," was a German Minnesinger and traveling poet. Historically, his biography, including the dates he lived, is obscure beyond the poetry, which suggests he lived between 1245 and ...

'' also remained unrealised. He disliked the prominence of the Wagnerian orchestra and regretted the innovation which saw orchestral players being relegated to a pit beneath the opera stage.

However, in 1875 Carl Rosa tempted him back to the stage for a season at the Princess's Theatre, London, in which he played in ''Le nozze di Figaro'', ''Il trovatore'', '' The Siege of Rochelle'' (as Michel), Cherubini's '' The Water Carrier'' (Mikelì) and '' The Porter of Havre'' (Martin). In Figaro he was cast as Almaviva, but was transferred to the role of Figaro, singing with Sig. Campobello (Almaviva), Aynsley Cook

Aynsley is both a given name and a surname. Notable people with the name include:

* Aynsley Dunbar, English drummer

* Aynsley Lister, English blues-rock guitarist/singer and songwriter

* Cecil Aynsley, 20th century Australian rugby league footba ...

(Bartolo), Charles Lyall (Basilio), Ostava Torriani (Contessa), Rose Hersee

Rose Hersee (13 December 1845 – 26 November 1924) was an English operatic soprano. She was a founder-member of the Carl Rosa Opera Company and later formed and performed in the Rose Hersee Opera Company.

Biography

Hersee was the daughter of Hen ...

(Susanna), Josephine York (Cherubino) and Mrs Aynsley Cook (Marcellina). This received a special performance for the Prince and Princess of Wales. There was a provincial tour in the autumn.

In autumn 1876 at the Lyceum Theatre, again with Carl Rosa, Santley revived his ''Flying Dutchman'', this time in English, with Ostava Torriani as Senta. Between the London season and the provincial tour which followed they performed it 50 times. Among the cities visited were Edinburgh (four performances) and Glasgow (two performances).

In the same season they undertook a work new to him, Nicolo's ''Joconde

Joconde is the central database created in 1975 and now available online, maintained by the French Ministry of Culture, for objects in the collections of the main French public and private museums listed as ''Musées de France'', according to ...

'', and he played ''Zampa'' and ''The Porter of Havre'' again. The final work was a new opera with a role (Claude Melnotte) written especially for him, the '' Pauline'' of F. H. Cowen: the work was not successful. The tour took them to Dublin, Sheffield, Hanley and Birmingham

Birmingham ( ) is a city and metropolitan borough in the metropolitan county of West Midlands in England. It is the second-largest city in the United Kingdom with a population of 1.145 million in the city proper, 2.92 million in the West ...

. That, apart from two appearances as Sir Harry in ''The School for Scandal

''The School for Scandal'' is a comedy of manners written by Richard Brinsley Sheridan. It was first performed in London at Drury Lane Theatre on 8 May 1777.

Plot

Act I

Scene I: Lady Sneerwell, a wealthy young widow, and her hireling Sna ...

'' at Drury Lane benefits, and his eventual farewell appearance at Covent Garden in 1911,Eaglefield-Hull 1924, 435. was the end of his stage career.

Later years

Santley gave recitals at the Monday Popular Concerts, and appeared with the

Santley gave recitals at the Monday Popular Concerts, and appeared with the Joachim

Joachim (; ''Yəhōyāqīm'', "he whom Yahweh has set up"; ; ) was, according to Christian tradition, the husband of Saint Anne and the father of Mary, the mother of Jesus. The story of Joachim and Anne first appears in the Biblical apocryphal ...

String Quartet and Mme Clara Schumann

Clara Josephine Schumann (; née Wieck; 13 September 1819 – 20 May 1896) was a German pianist, composer, and piano teacher. Regarded as one of the most distinguished pianists of the Romantic era, she exerted her influence over the course of a ...

. He settled down to concert and oratorio work in England. He converted to Roman Catholicism in 1880, and in 1887 Pope Leo XIII

Pope Leo XIII ( it, Leone XIII; born Vincenzo Gioacchino Raffaele Luigi Pecci; 2 March 1810 – 20 July 1903) was the head of the Catholic Church from 20 February 1878 to his death in July 1903. Living until the age of 93, he was the second-old ...

created him a Knight Commander of St Gregory the Great. He married twice, first (in 1858) to Gertrude Kemble (granddaughter of Charles Kemble

Charles Kemble (25 November 1775 – 12 November 1854) was a Welsh-born English actor of a prominent theatre family.

Life

Charles Kemble was one of 13 siblings and the youngest son of English Roman Catholic theatre manager/actor Roger Kemble ...

), who before her marriage had a professional career as a soprano singer. Their daughter Edith also became a concert singer. Gertrude died in 1882. The couple had five children. Santley's second wife was Elizabeth Mary Rose-Innes.