Carbon Capture (other) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Carbon () is a chemical element with the

The

The

The

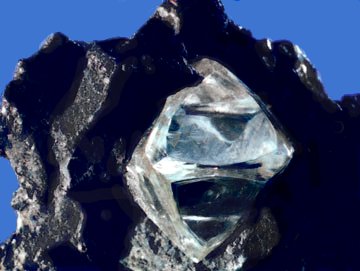

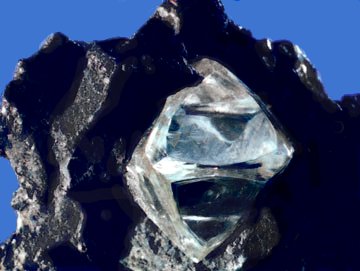

The  At very high pressures, carbon forms the more compact allotrope, diamond, having nearly twice the density of graphite. Here, each atom is bonded

At very high pressures, carbon forms the more compact allotrope, diamond, having nearly twice the density of graphite. Here, each atom is bonded  Of the other discovered allotropes,

Of the other discovered allotropes,

Carbon is the fourth most abundant chemical element in the observable universe by mass after hydrogen, helium, and oxygen. Carbon is abundant in the Sun,

Carbon is the fourth most abundant chemical element in the observable universe by mass after hydrogen, helium, and oxygen. Carbon is abundant in the Sun,

greatly upgraded database

for tracking polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in the universe. More than 20% of the carbon in the universe may be associated with PAHs, complex compounds of carbon and hydrogen without oxygen. These compounds figure in the PAH world hypothesis where they are hypothesized to have a role in abiogenesis and formation of life. PAHs seem to have been formed "a couple of billion years" after the

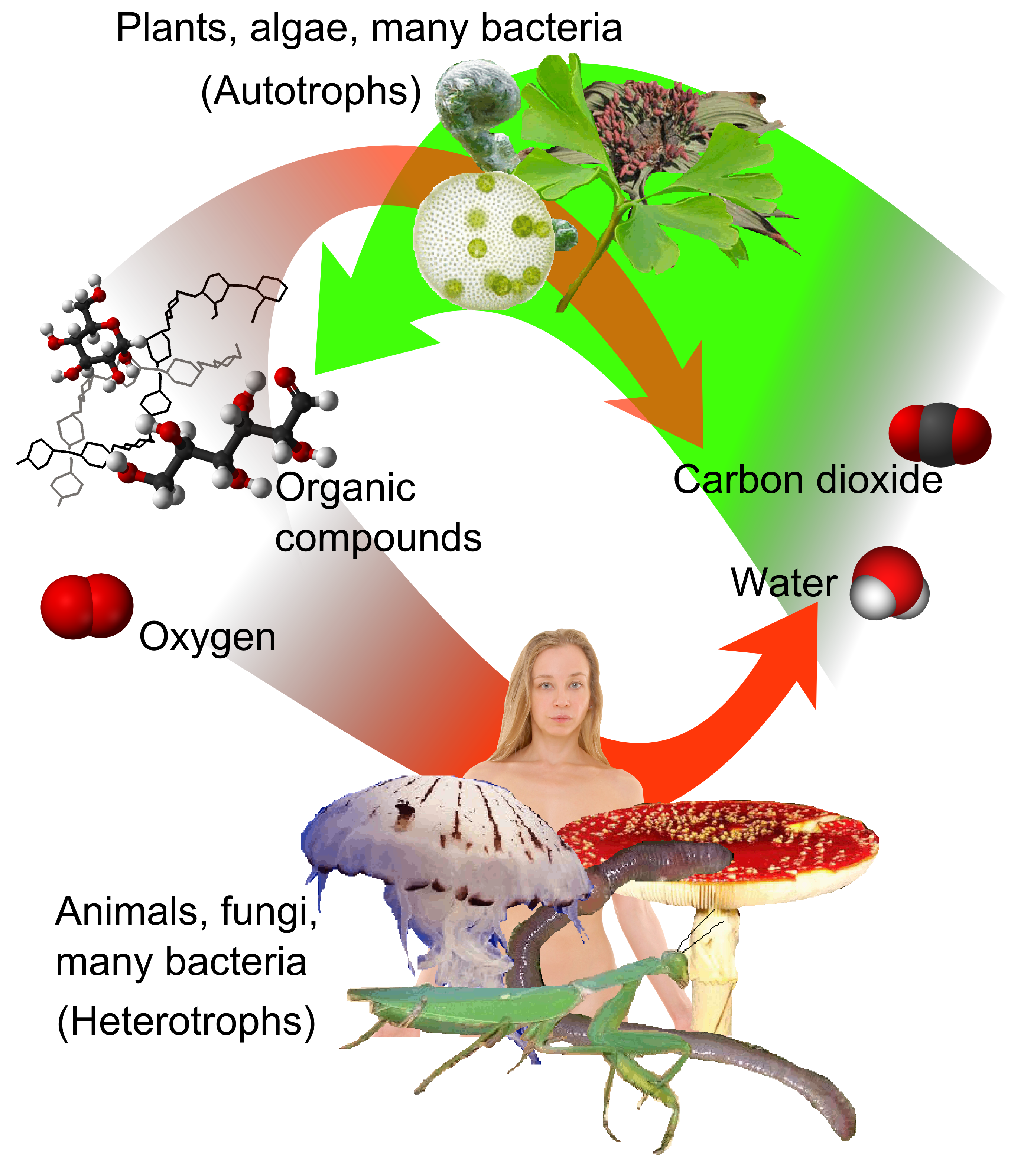

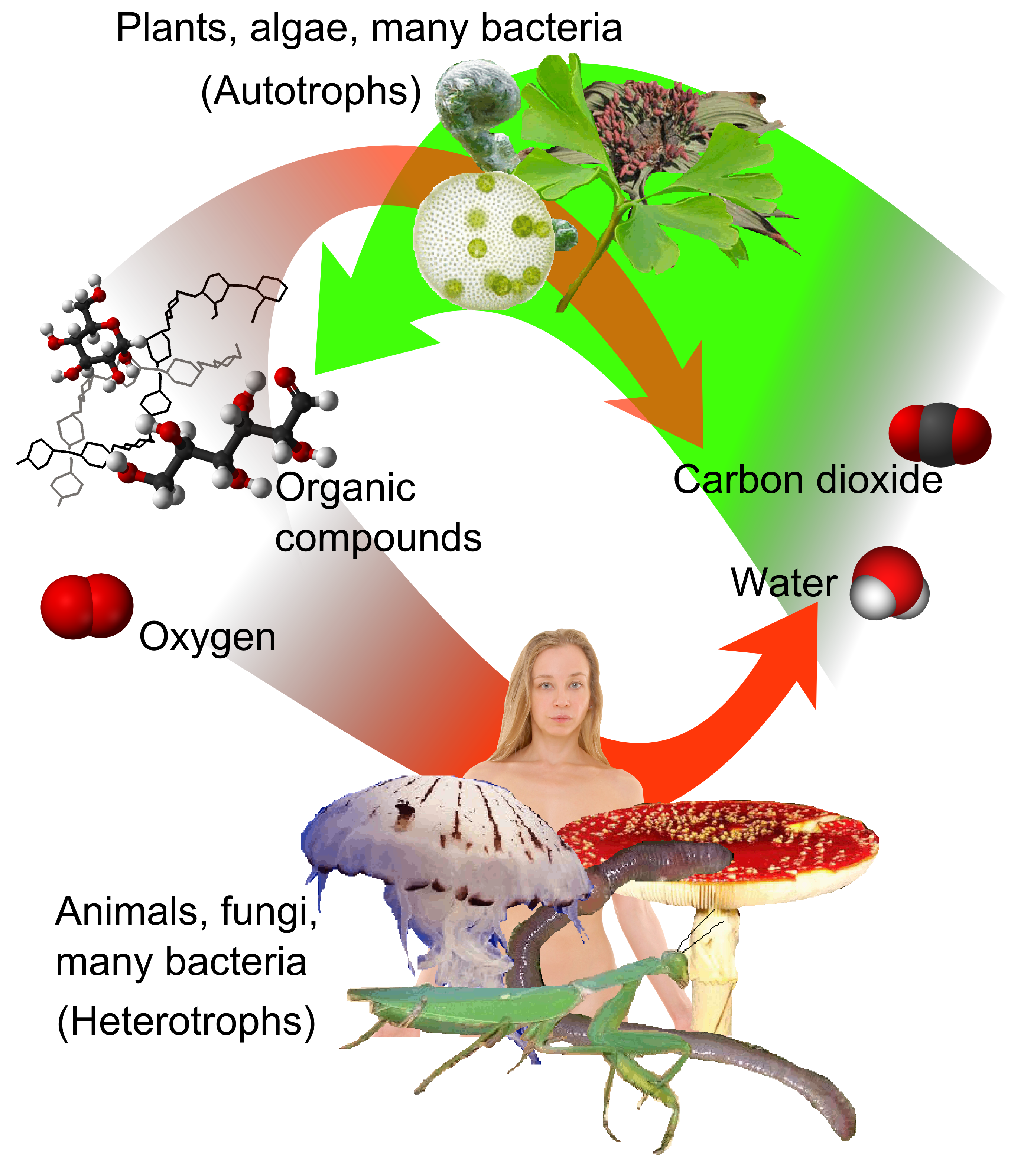

Under terrestrial conditions, conversion of one element to another is very rare. Therefore, the amount of carbon on Earth is effectively constant. Thus, processes that use carbon must obtain it from somewhere and dispose of it somewhere else. The paths of carbon in the environment form the carbon cycle. For example,

Under terrestrial conditions, conversion of one element to another is very rare. Therefore, the amount of carbon on Earth is effectively constant. Thus, processes that use carbon must obtain it from somewhere and dispose of it somewhere else. The paths of carbon in the environment form the carbon cycle. For example,

Carbon can form very long chains of interconnecting carbon–carbon bonds, a property that is called

Carbon can form very long chains of interconnecting carbon–carbon bonds, a property that is called

It is important to note that in the cases above, each of the bonds to carbon contain less than two formal electron pairs. Thus, the formal electron count of these species does not exceed an octet. This makes them hypercoordinate but not hypervalent. Even in cases of alleged 10-C-5 species (that is, a carbon with five ligands and a formal electron count of ten), as reported by Akiba and co-workers, electronic structure calculations conclude that the electron population around carbon is still less than eight, as is true for other compounds featuring four-electron

It is important to note that in the cases above, each of the bonds to carbon contain less than two formal electron pairs. Thus, the formal electron count of these species does not exceed an octet. This makes them hypercoordinate but not hypervalent. Even in cases of alleged 10-C-5 species (that is, a carbon with five ligands and a formal electron count of ten), as reported by Akiba and co-workers, electronic structure calculations conclude that the electron population around carbon is still less than eight, as is true for other compounds featuring four-electron

The English name ''carbon'' comes from the Latin ''carbo'' for coal and charcoal, whence also comes the

The English name ''carbon'' comes from the Latin ''carbo'' for coal and charcoal, whence also comes the  In 1722,

In 1722,

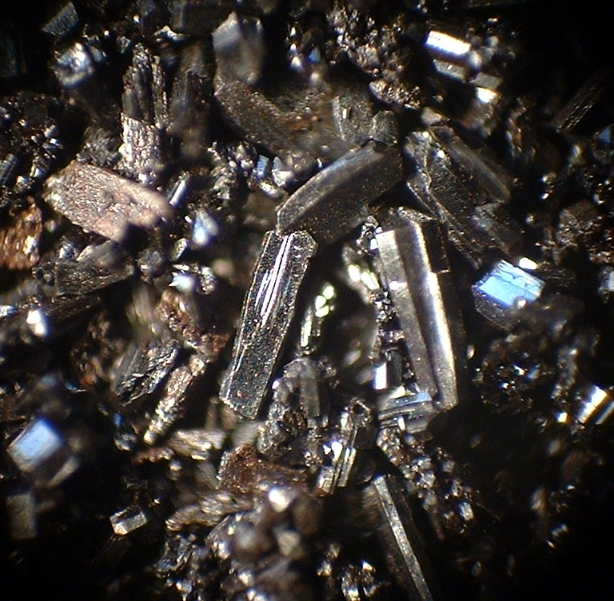

and Graphite: Mineral Commodity Summaries 2011 There are three types of natural graphite—amorphous, flake or crystalline flake, and vein or lump. Amorphous graphite is the lowest quality and most abundant. Contrary to science, in industry "amorphous" refers to very small crystal size rather than complete lack of crystal structure. Amorphous is used for lower value graphite products and is the lowest priced graphite. Large amorphous graphite deposits are found in China, Europe, Mexico and the United States. Flake graphite is less common and of higher quality than amorphous; it occurs as separate plates that crystallized in metamorphic rock. Flake graphite can be four times the price of amorphous. Good quality flakes can be processed into

The diamond supply chain is controlled by a limited number of powerful businesses, and is also highly concentrated in a small number of locations around the world (see figure).

Only a very small fraction of the diamond ore consists of actual diamonds. The ore is crushed, during which care has to be taken in order to prevent larger diamonds from being destroyed in this process and subsequently the particles are sorted by density. Today, diamonds are located in the diamond-rich density fraction with the help of X-ray fluorescence, after which the final sorting steps are done by hand. Before the use of X-rays became commonplace, the separation was done with grease belts; diamonds have a stronger tendency to stick to grease than the other minerals in the ore.

Historically diamonds were known to be found only in alluvial deposits in southern India. discussion on alluvial diamonds in India and elsewhere as well as earliest finds India led the world in diamond production from the time of their discovery in approximately the 9th century BC Ball was a Geologist in British service. Chapter I, Page 1 to the mid-18th century AD, but the commercial potential of these sources had been exhausted by the late 18th century and at that time India was eclipsed by Brazil where the first non-Indian diamonds were found in 1725.

Diamond production of primary deposits (kimberlites and lamproites) only started in the 1870s after the discovery of the diamond fields in South Africa. Production has increased over time and an accumulated total of over 4.5 billion carats have been mined since that date. Most commercially viable diamond deposits were in Russia, Botswana,

The diamond supply chain is controlled by a limited number of powerful businesses, and is also highly concentrated in a small number of locations around the world (see figure).

Only a very small fraction of the diamond ore consists of actual diamonds. The ore is crushed, during which care has to be taken in order to prevent larger diamonds from being destroyed in this process and subsequently the particles are sorted by density. Today, diamonds are located in the diamond-rich density fraction with the help of X-ray fluorescence, after which the final sorting steps are done by hand. Before the use of X-rays became commonplace, the separation was done with grease belts; diamonds have a stronger tendency to stick to grease than the other minerals in the ore.

Historically diamonds were known to be found only in alluvial deposits in southern India. discussion on alluvial diamonds in India and elsewhere as well as earliest finds India led the world in diamond production from the time of their discovery in approximately the 9th century BC Ball was a Geologist in British service. Chapter I, Page 1 to the mid-18th century AD, but the commercial potential of these sources had been exhausted by the late 18th century and at that time India was eclipsed by Brazil where the first non-Indian diamonds were found in 1725.

Diamond production of primary deposits (kimberlites and lamproites) only started in the 1870s after the discovery of the diamond fields in South Africa. Production has increased over time and an accumulated total of over 4.5 billion carats have been mined since that date. Most commercially viable diamond deposits were in Russia, Botswana,

Carbon is essential to all known living systems, and without it life as we know it could not exist (see

Carbon is essential to all known living systems, and without it life as we know it could not exist (see

Pure carbon has extremely low toxicity to humans and can be handled safely in the form of graphite or charcoal. It is resistant to dissolution or chemical attack, even in the acidic contents of the digestive tract. Consequently, once it enters into the body's tissues it is likely to remain there indefinitely. Carbon black was probably one of the first pigments to be used for tattooing, and Ötzi the Iceman was found to have carbon tattoos that survived during his life and for 5200 years after his death. Inhalation of coal dust or soot (carbon black) in large quantities can be dangerous, irritating lung tissues and causing the congestive

Pure carbon has extremely low toxicity to humans and can be handled safely in the form of graphite or charcoal. It is resistant to dissolution or chemical attack, even in the acidic contents of the digestive tract. Consequently, once it enters into the body's tissues it is likely to remain there indefinitely. Carbon black was probably one of the first pigments to be used for tattooing, and Ötzi the Iceman was found to have carbon tattoos that survived during his life and for 5200 years after his death. Inhalation of coal dust or soot (carbon black) in large quantities can be dangerous, irritating lung tissues and causing the congestive

Carbon

at '' The Periodic Table of Videos'' (University of Nottingham)

Carbon on Britannica

Carbon—Super Stuff. Animation with sound and interactive 3D-models.

{{good article Chemical elements Allotropes of carbon Reactive nonmetals Polyatomic nonmetals Native element minerals Reducing agents Chemical elements with hexagonal planar structure

symbol

A symbol is a mark, sign, or word that indicates, signifies, or is understood as representing an idea, object, or relationship. Symbols allow people to go beyond what is known or seen by creating linkages between otherwise very different conc ...

C and atomic number 6. It is nonmetal

In chemistry, a nonmetal is a chemical element that generally lacks a predominance of metallic properties; they range from colorless gases (like hydrogen) to shiny solids (like carbon, as graphite). The electrons in nonmetals behave differentl ...

lic and tetravalent—its atom making four electrons available to form covalent chemical bonds. It belongs to group 14 of the periodic table

The periodic table, also known as the periodic table of the (chemical) elements, is a rows and columns arrangement of the chemical elements. It is widely used in chemistry, physics, and other sciences, and is generally seen as an icon of ch ...

. Carbon makes up only about 0.025 percent of Earth's crust. Three isotopes occur naturally, C and C being stable, while C is a radionuclide

A radionuclide (radioactive nuclide, radioisotope or radioactive isotope) is a nuclide that has excess nuclear energy, making it unstable. This excess energy can be used in one of three ways: emitted from the nucleus as gamma radiation; transfer ...

, decaying with a half-life of about 5,730 years.

Carbon is one of the few elements known since antiquity.

Carbon is the 15th most abundant element in the Earth's crust, and the fourth most abundant element in the universe by mass after hydrogen, helium, and oxygen. Carbon's abundance, its unique diversity of organic compounds, and its unusual ability to form polymers at the temperatures commonly encountered on Earth, enables this element to serve as a common element of all known life. It is the second most abundant element in the human body

The human body is the structure of a Human, human being. It is composed of many different types of Cell (biology), cells that together create Tissue (biology), tissues and subsequently organ systems. They ensure homeostasis and the life, viabi ...

by mass (about 18.5%) after oxygen.

The atoms of carbon can bond together in diverse ways, resulting in various allotropes of carbon

Carbon is capable of forming many allotropy, allotropes (structurally different forms of the same element) due to its Valence (chemistry), valency. Well-known forms of carbon include diamond and graphite. In recent decades, many more allotrope ...

. Well-known allotropes include graphite, diamond, amorphous carbon and fullerenes. The physical properties

A physical property is any property that is measurable, whose value describes a state of a physical system. The changes in the physical properties of a system can be used to describe its changes between momentary states. Physical properties are o ...

of carbon vary widely with the allotropic form. For example, graphite is opaque

Opacity or opaque may refer to:

* Impediments to (especially, visible) light:

** Opacities, absorption coefficients

** Opacity (optics), property or degree of blocking the transmission of light

* Metaphors derived from literal optics:

** In lingui ...

and black while diamond is highly transparent. Graphite is soft enough to form a streak on paper (hence its name, from the Greek verb "γράφειν" which means "to write"), while diamond is the hardest naturally occurring material known. Graphite is a good electrical conductor while diamond has a low electrical conductivity

Electrical resistivity (also called specific electrical resistance or volume resistivity) is a fundamental property of a material that measures how strongly it resists electric current. A low resistivity indicates a material that readily allow ...

. Under normal conditions, diamond, carbon nanotube

A scanning tunneling microscopy image of a single-walled carbon nanotube

Rotating single-walled zigzag carbon nanotube

A carbon nanotube (CNT) is a tube made of carbon with diameters typically measured in nanometers.

''Single-wall carbon na ...

s, and graphene have the highest thermal conductivities of all known materials. All carbon allotropes are solids under normal conditions, with graphite being the most thermodynamically stable

In chemistry, chemical stability is the thermodynamic stability of a chemical system.

Thermodynamic stability occurs when a system is in its lowest energy state, or in chemical equilibrium with its environment. This may be a dynamic equilibriu ...

form at standard temperature and pressure. They are chemically resistant and require high temperature to react even with oxygen.

The most common oxidation state of carbon in inorganic compound

In chemistry, an inorganic compound is typically a chemical compound that lacks carbon–hydrogen bonds, that is, a compound that is not an organic compound. The study of inorganic compounds is a subfield of chemistry known as '' inorganic chemist ...

s is +4, while +2 is found in carbon monoxide and transition metal carbonyl complexes. The largest sources of inorganic carbon are limestones, dolomite Dolomite may refer to:

*Dolomite (mineral), a carbonate mineral

*Dolomite (rock), also known as dolostone, a sedimentary carbonate rock

*Dolomite, Alabama, United States, an unincorporated community

*Dolomite, California, United States, an unincor ...

s and carbon dioxide, but significant quantities occur in organic deposits of coal, peat, oil, and methane clathrate

Methane clathrate (CH4·5.75H2O) or (8CH4·46H2O), also called methane hydrate, hydromethane, methane ice, fire ice, natural gas hydrate, or gas hydrate, is a solid clathrate compound (more specifically, a clathrate hydrate) in which a large amou ...

s. Carbon forms a vast number of compounds, with almost ten million compounds described to date,

and yet that number is but a fraction of the number of theoretically possible compounds under standard conditions.

Characteristics

allotropes of carbon

Carbon is capable of forming many allotropy, allotropes (structurally different forms of the same element) due to its Valence (chemistry), valency. Well-known forms of carbon include diamond and graphite. In recent decades, many more allotrope ...

include graphite, one of the softest known substances, and diamond, the hardest naturally occurring substance. It bonds readily with other small atoms, including other carbon atoms, and is capable of forming multiple stable covalent bonds with suitable multivalent atoms. Carbon is known to form almost ten million compounds, a large majority of all chemical compounds. Carbon also has the highest sublimation

Sublimation or sublimate may refer to:

* ''Sublimation'' (album), by Canvas Solaris, 2004

* Sublimation (phase transition), directly from the solid to the gas phase

* Sublimation (psychology), a mature type of defense mechanism

* Sublimate of mer ...

point of all elements. At atmospheric pressure it has no melting point, as its triple point is at and , so it sublimes at about .

Graphite is much more reactive than diamond at standard conditions, despite being more thermodynamically stable, as its delocalised pi system is much more vulnerable to attack. For example, graphite can be oxidised by hot concentrated nitric acid at standard conditions to mellitic acid, C6(CO2H)6, which preserves the hexagonal units of graphite while breaking up the larger structure.Greenwood and Earnshaw, pp. 289–292.

Carbon sublimes in a carbon arc, which has a temperature of about 5800 K (5,530 °C or 9,980 °F). Thus, irrespective of its allotropic form, carbon remains solid at higher temperatures than the highest-melting-point metals such as tungsten or rhenium. Although thermodynamically prone to oxidation, carbon resists oxidation more effectively than elements such as iron and copper, which are weaker reducing agents at room temperature.

Carbon is the sixth element, with a ground-state electron configuration

In atomic physics and quantum chemistry, the electron configuration is the distribution of electrons of an atom or molecule (or other physical structure) in atomic or molecular orbitals. For example, the electron configuration of the neon atom ...

of 1s22s22p2, of which the four outer electrons are valence electrons. Its first four ionisation energies, 1086.5, 2352.6, 4620.5 and 6222.7 kJ/mol, are much higher than those of the heavier group-14 elements. The electronegativity of carbon is 2.5, significantly higher than the heavier group-14 elements (1.8–1.9), but close to most of the nearby nonmetals, as well as some of the second- and third-row transition metals. Carbon's covalent radii are normally taken as 77.2 pm (C−C), 66.7 pm (C=C) and 60.3 pm (C≡C), although these may vary depending on coordination number and what the carbon is bonded to. In general, covalent radius decreases with lower coordination number and higher bond order.Greenwood and Earnshaw, pp. 276–8.

Carbon-based compounds form the basis of all known life on Earth, and the carbon–nitrogen cycle provides some of the energy produced by the Sun and other star

A star is an astronomical object comprising a luminous spheroid of plasma (physics), plasma held together by its gravity. The List of nearest stars and brown dwarfs, nearest star to Earth is the Sun. Many other stars are visible to the naked ...

s. Although it forms an extraordinary variety of compounds, most forms of carbon are comparatively unreactive under normal conditions. At standard temperature and pressure, it resists all but the strongest oxidizers. It does not react with sulfuric acid

Sulfuric acid (American spelling and the preferred IUPAC name) or sulphuric acid ( Commonwealth spelling), known in antiquity as oil of vitriol, is a mineral acid composed of the elements sulfur, oxygen and hydrogen, with the molecular formu ...

, hydrochloric acid, chlorine or any alkalis

In chemistry, an alkali (; from ar, القلوي, al-qaly, lit=ashes of the saltwort) is a basic, ionic salt of an alkali metal or an alkaline earth metal. An alkali can also be defined as a base that dissolves in water. A solution of a so ...

. At elevated temperatures, carbon reacts with oxygen to form carbon oxides

In chemistry, an oxocarbon or oxide of carbon is a chemical compound consisting only of carbon and oxygen. The simplest and most common oxocarbons are carbon monoxide (CO) and carbon dioxide (). Many other stable (practically if not thermodynamica ...

and will rob oxygen from metal oxides to leave the elemental metal. This exothermic reaction is used in the iron and steel industry to smelt

Smelt may refer to:

* Smelting, chemical process

* The common name of various fish:

** Smelt (fish), a family of small fish, Osmeridae

** Australian smelt in the family Retropinnidae and species ''Retropinna semoni''

** Big-scale sand smelt ''At ...

iron and to control the carbon content of steel

Steel is an alloy made up of iron with added carbon to improve its strength and fracture resistance compared to other forms of iron. Many other elements may be present or added. Stainless steels that are corrosion- and oxidation-resistant ty ...

:

: + 4 C + 2 → 3 Fe + 4 .

Carbon reacts with sulfur

Sulfur (or sulphur in British English) is a chemical element with the symbol S and atomic number 16. It is abundant, multivalent and nonmetallic. Under normal conditions, sulfur atoms form cyclic octatomic molecules with a chemical formula ...

to form carbon disulfide, and it reacts with steam in the coal-gas reaction used in coal gasification Coal gasification is the process of producing syngas—a mixture consisting primarily of carbon monoxide (CO), hydrogen (H2), carbon dioxide (CO2), methane (CH4), and water vapour (H2O)—from coal and water, air and/or oxygen.

Historically, coal ...

:

:C + HO → CO + H.

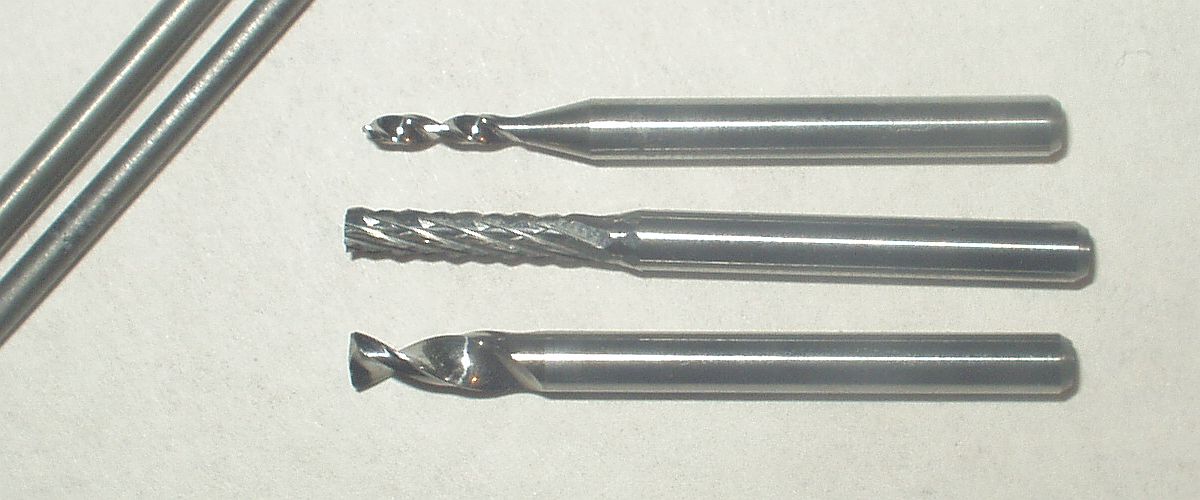

Carbon combines with some metals at high temperatures to form metallic carbides, such as the iron carbide cementite in steel and tungsten carbide, widely used as an abrasive and for making hard tips for cutting tools.

The system of carbon allotropes spans a range of extremes:

Allotropes

Atomic carbon

Atomic carbon, systematically named carbon and λ0-methane, also called monocarbon, is a colourless gaseous inorganic chemical with the chemical formula C (also written . It is kinetically unstable at ambient temperature and pressure, being remo ...

is a very short-lived species and, therefore, carbon is stabilized in various multi-atomic structures with diverse molecular configurations called allotropes. The three relatively well-known allotropes of carbon are amorphous carbon, graphite, and diamond. Once considered exotic, fullerenes are nowadays commonly synthesized and used in research; they include buckyball

Buckminsterfullerene is a type of fullerene with the formula C60. It has a cage-like fused-ring structure (truncated icosahedron) made of twenty hexagons and twelve pentagons, and resembles a soccer ball. Each of its 60 carbon atoms is bonded t ...

s,

carbon nanotube

A scanning tunneling microscopy image of a single-walled carbon nanotube

Rotating single-walled zigzag carbon nanotube

A carbon nanotube (CNT) is a tube made of carbon with diameters typically measured in nanometers.

''Single-wall carbon na ...

s,

carbon nanobuds and nanofibers. Several other exotic allotropes have also been discovered, such as lonsdaleite,

glassy carbon, carbon nanofoam Carbon nanofoam is an allotrope of carbon discovered in 1997 by Andrei V. Rode and co-workers at the Australian National University in Canberra. It consists of a cluster-assembly of carbon atoms strung together in a loose three-dimensional web. The ...

and linear acetylenic carbon (carbyne).

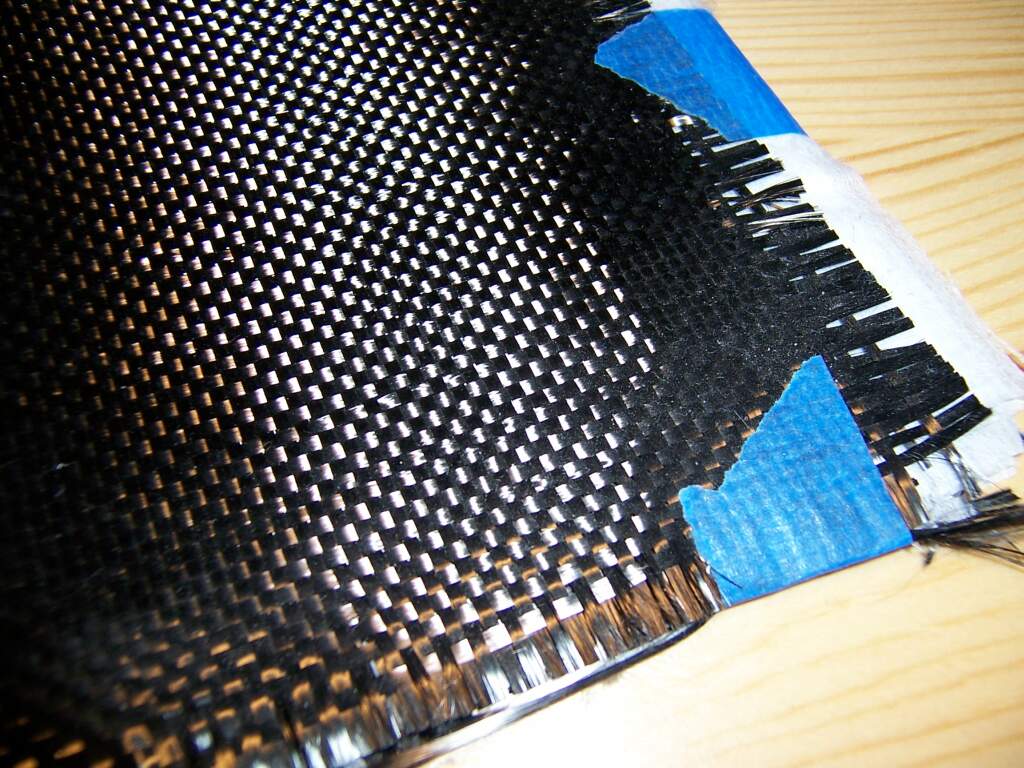

Graphene is a two-dimensional sheet of carbon with the atoms arranged in a hexagonal lattice. As of 2009, graphene appears to be the strongest material ever tested.

*

The process of separating it from graphite will require some further technological development before it is economical for industrial processes.

If successful, graphene could be used in the construction of a space elevator. It could also be used to safely store hydrogen for use in a hydrogen based engine in cars.

The

The amorphous

In condensed matter physics and materials science, an amorphous solid (or non-crystalline solid, glassy solid) is a solid that lacks the long-range order that is characteristic of a crystal.

Etymology

The term comes from the Greek ''a'' ("wi ...

form is an assortment of carbon atoms in a non-crystalline, irregular, glassy state, not held in a crystalline macrostructure. It is present as a powder, and is the main constituent of substances such as charcoal

Charcoal is a lightweight black carbon residue produced by strongly heating wood (or other animal and plant materials) in minimal oxygen to remove all water and volatile constituents. In the traditional version of this pyrolysis process, cal ...

, lampblack ( soot) and activated carbon

Activated carbon, also called activated charcoal, is a form of carbon commonly used to filter contaminants from water and air, among many other uses. It is processed (activated) to have small, low-volume pores that increase the surface area avail ...

. At normal pressures, carbon takes the form of graphite, in which each atom is bonded trigonally to three others in a plane composed of fused hexagonal rings, just like those in aromatic hydrocarbons. The resulting network is 2-dimensional, and the resulting flat sheets are stacked and loosely bonded through weak van der Waals forces. This gives graphite its softness and its cleaving properties (the sheets slip easily past one another). Because of the delocalization of one of the outer electrons of each atom to form a π-cloud, graphite conducts electricity, but only in the plane of each covalently bonded sheet. This results in a lower bulk electrical conductivity

Electrical resistivity (also called specific electrical resistance or volume resistivity) is a fundamental property of a material that measures how strongly it resists electric current. A low resistivity indicates a material that readily allow ...

for carbon than for most metals. The delocalization also accounts for the energetic stability of graphite over diamond at room temperature.

tetrahedrally

In a tetrahedral molecular geometry, a central atom is located at the center with four substituents that are located at the corners of a tetrahedron. The bond angles are cos−1(−) = 109.4712206...° ≈ 109.5° when all four substituents are ...

to four others, forming a 3-dimensional network of puckered six-membered rings of atoms. Diamond has the same cubic structure as silicon and germanium

Germanium is a chemical element with the symbol Ge and atomic number 32. It is lustrous, hard-brittle, grayish-white and similar in appearance to silicon. It is a metalloid in the carbon group that is chemically similar to its group neighbors s ...

, and because of the strength of the carbon-carbon bonds, it is the hardest naturally occurring substance measured by resistance to scratching. Contrary to the popular belief that ''"diamonds are forever"'', they are thermodynamically unstable (Δf''G''°(diamond, 298 K) = 2.9 kJ/mol) under normal conditions (298 K, 105 Pa) and should theoretically transform into graphite.

But due to a high activation energy barrier, the transition into graphite is so slow at normal temperature that it is unnoticeable. However, at very high temperatures diamond will turn into graphite, and diamonds can burn up in a house fire. The bottom left corner of the phase diagram for carbon has not been scrutinized experimentally. Although a computational study employing density functional theory methods reached the conclusion that as and , diamond becomes more stable than graphite by approximately 1.1 kJ/mol, more recent and definitive experimental and computational studies show that graphite is more stable than diamond for , without applied pressure, by 2.7 kJ/mol at ''T'' = 0 K and 3.2 kJ/mol at ''T'' = 298.15 K. Under some conditions, carbon crystallizes as lonsdaleite, a hexagonal crystal lattice with all atoms covalently bonded and properties similar to those of diamond.

Fullerenes are a synthetic crystalline formation with a graphite-like structure, but in place of flat hexagonal cells only, some of the cells of which fullerenes are formed may be pentagons, nonplanar hexagons, or even heptagons of carbon atoms. The sheets are thus warped into spheres, ellipses, or cylinders. The properties of fullerenes (split into buckyballs, buckytubes, and nanobuds) have not yet been fully analyzed and represent an intense area of research in nanomaterials. The names ''fullerene'' and ''buckyball'' are given after Richard Buckminster Fuller, popularizer of geodesic domes, which resemble the structure of fullerenes. The buckyballs are fairly large molecules formed completely of carbon bonded trigonally, forming spheroids (the best-known and simplest is the soccerball-shaped C buckminsterfullerene). Carbon nanotubes (buckytubes) are structurally similar to buckyballs, except that each atom is bonded trigonally in a curved sheet that forms a hollow cylinder. Nanobuds were first reported in 2007 and are hybrid buckytube/buckyball materials (buckyballs are covalently bonded to the outer wall of a nanotube) that combine the properties of both in a single structure.

Of the other discovered allotropes,

Of the other discovered allotropes, carbon nanofoam Carbon nanofoam is an allotrope of carbon discovered in 1997 by Andrei V. Rode and co-workers at the Australian National University in Canberra. It consists of a cluster-assembly of carbon atoms strung together in a loose three-dimensional web. The ...

is a ferromagnetic

Ferromagnetism is a property of certain materials (such as iron) which results in a large observed magnetic permeability, and in many cases a large magnetic coercivity allowing the material to form a permanent magnet. Ferromagnetic materials ...

allotrope discovered in 1997. It consists of a low-density cluster-assembly of carbon atoms strung together in a loose three-dimensional web, in which the atoms are bonded trigonally in six- and seven-membered rings. It is among the lightest known solids, with a density of about 2 kg/m. Similarly, glassy carbon contains a high proportion of closed porosity, but contrary to normal graphite, the graphitic layers are not stacked like pages in a book, but have a more random arrangement. Linear acetylenic carbon has the chemical structure −(C:::C)''n''−. Carbon in this modification is linear with ''sp'' orbital hybridization, and is a polymer with alternating single and triple bonds. This carbyne is of considerable interest to nanotechnology

Nanotechnology, also shortened to nanotech, is the use of matter on an atomic, molecular, and supramolecular scale for industrial purposes. The earliest, widespread description of nanotechnology referred to the particular technological goal o ...

as its Young's modulus is 40 times that of the hardest known material – diamond.

In 2015, a team at the North Carolina State University

North Carolina State University (NC State) is a public land-grant research university in Raleigh, North Carolina. Founded in 1887 and part of the University of North Carolina system, it is the largest university in the Carolinas. The universit ...

announced the development of another allotrope they have dubbed Q-carbon Amorphous carbon is free, reactive carbon that has no crystalline structure. Amorphous carbon materials may be stabilized by terminating dangling-π bonds with hydrogen. As with other amorphous solids, some short-range order can be observed. Amorph ...

, created by a high energy low duration laser pulse on amorphous carbon dust. Q-carbon is reported to exhibit ferromagnetism, fluorescence, and a hardness superior to diamonds.

In the vapor phase, some of the carbon is in the form of dicarbon

Diatomic carbon (systematically named dicarbon and 1λ2,2λ2-ethene), is a green, gaseous inorganic chemical with the chemical formula C=C (also written 2or C2). It is kinetically unstable at ambient temperature and pressure, being removed throug ...

(). When excited, this gas glows green.

Occurrence

Carbon is the fourth most abundant chemical element in the observable universe by mass after hydrogen, helium, and oxygen. Carbon is abundant in the Sun,

Carbon is the fourth most abundant chemical element in the observable universe by mass after hydrogen, helium, and oxygen. Carbon is abundant in the Sun, star

A star is an astronomical object comprising a luminous spheroid of plasma (physics), plasma held together by its gravity. The List of nearest stars and brown dwarfs, nearest star to Earth is the Sun. Many other stars are visible to the naked ...

s, comets, and in the atmospheres

The standard atmosphere (symbol: atm) is a unit of pressure defined as Pa. It is sometimes used as a ''reference pressure'' or ''standard pressure''. It is approximately equal to Earth's average atmospheric pressure at sea level.

History

The s ...

of most planets. Some meteorite

A meteorite is a solid piece of debris from an object, such as a comet, asteroid, or meteoroid, that originates in outer space and survives its passage through the atmosphere to reach the surface of a planet or Natural satellite, moon. When the ...

s contain microscopic diamonds that were formed when the Solar System was still a protoplanetary disk.

Microscopic diamonds may also be formed by the intense pressure and high temperature at the sites of meteorite impacts.

In 2014 NASA announced greatly upgraded database

for tracking polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in the universe. More than 20% of the carbon in the universe may be associated with PAHs, complex compounds of carbon and hydrogen without oxygen. These compounds figure in the PAH world hypothesis where they are hypothesized to have a role in abiogenesis and formation of life. PAHs seem to have been formed "a couple of billion years" after the

Big Bang

The Big Bang event is a physical theory that describes how the universe expanded from an initial state of high density and temperature. Various cosmological models of the Big Bang explain the evolution of the observable universe from the ...

, are widespread throughout the universe, and are associated with new stars and exoplanets.

It has been estimated that the solid earth as a whole contains 730 ppm of carbon, with 2000 ppm in the core and 120 ppm in the combined mantle and crust. Since the mass of the earth is , this would imply 4360 million gigatonnes of carbon. This is much more than the amount of carbon in the oceans or atmosphere (below).

In combination with oxygen in carbon dioxide, carbon is found in the Earth's atmosphere (approximately 900 gigatonnes of carbon — each ppm corresponds to 2.13 Gt) and dissolved in all water bodies (approximately 36,000 gigatonnes of carbon). Carbon in the biosphere has been estimated at 550 gigatonnes but with a large uncertainty, due mostly to a huge uncertainty in the amount of terrestrial deep subsurface bacteria. Hydrocarbons (such as coal, petroleum, and natural gas) contain carbon as well. Coal "reserves" (not "resources") amount to around 900 gigatonnes with perhaps 18,000 Gt of resources. Oil reserves are around 150 gigatonnes. Proven sources of natural gas are about (containing about 105 gigatonnes of carbon), but studies estimate another of "unconventional" deposits such as shale gas, representing about 540 gigatonnes of carbon.

Carbon is also found in methane hydrates

Methane clathrate (CH4·5.75H2O) or (8CH4·46H2O), also called methane hydrate, hydromethane, methane ice, fire ice, natural gas hydrate, or gas hydrate, is a solid clathrate compound (more specifically, a clathrate hydrate) in which a large amou ...

in polar regions and under the seas. Various estimates put this carbon between 500, 2500 Gt, or 3,000 Gt.

In the past, quantities of hydrocarbons were greater. According to one source, in the period from 1751 to 2008 about 347 gigatonnes of carbon were released as carbon dioxide to the atmosphere from burning of fossil fuels. Another source puts the amount added to the atmosphere for the period since 1750 at 879 Gt, and the total going to the atmosphere, sea, and land (such as peat bogs) at almost 2,000 Gt.

Carbon is a constituent (about 12% by mass) of the very large masses of carbonate rock ( limestone, dolomite Dolomite may refer to:

*Dolomite (mineral), a carbonate mineral

*Dolomite (rock), also known as dolostone, a sedimentary carbonate rock

*Dolomite, Alabama, United States, an unincorporated community

*Dolomite, California, United States, an unincor ...

, marble and so on). Coal is very rich in carbon (anthracite

Anthracite, also known as hard coal, and black coal, is a hard, compact variety of coal that has a submetallic luster. It has the highest carbon content, the fewest impurities, and the highest energy density of all types of coal and is the hig ...

contains 92–98%) and is the largest commercial source of mineral carbon, accounting for 4,000 gigatonnes or 80% of fossil fuel

A fossil fuel is a hydrocarbon-containing material formed naturally in the Earth's crust from the remains of dead plants and animals that is extracted and burned as a fuel. The main fossil fuels are coal, oil, and natural gas. Fossil fuels m ...

.

As for individual carbon allotropes, graphite is found in large quantities in the United States (mostly in New York

New York most commonly refers to:

* New York City, the most populous city in the United States, located in the state of New York

* New York (state), a state in the northeastern United States

New York may also refer to:

Film and television

* '' ...

and Texas), Russia, Mexico, Greenland, and India. Natural diamonds occur in the rock kimberlite, found in ancient volcanic "necks", or "pipes". Most diamond deposits are in Africa, notably in South Africa, Namibia, Botswana, the Republic of the Congo

The Republic of the Congo (french: République du Congo, ln, Republíki ya Kongó), also known as Congo-Brazzaville, the Congo Republic or simply either Congo or the Congo, is a country located in the western coast of Central Africa to the w ...

, and Sierra Leone. Diamond deposits have also been found in Arkansas, Canada, the Russian Arctic, Brazil, and in Northern and Western Australia

Australia, officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a Sovereign state, sovereign country comprising the mainland of the Australia (continent), Australian continent, the island of Tasmania, and numerous List of islands of Australia, sma ...

. Diamonds are now also being recovered from the ocean floor off the Cape of Good Hope

The Cape of Good Hope ( af, Kaap die Goeie Hoop ) ;''Kaap'' in isolation: pt, Cabo da Boa Esperança is a rocky headland on the Atlantic coast of the Cape Peninsula in South Africa.

A common misconception is that the Cape of Good Hope is t ...

. Diamonds are found naturally, but about 30% of all industrial diamonds used in the U.S. are now manufactured.

Carbon-14 is formed in upper layers of the troposphere and the stratosphere at altitudes of 9–15 km by a reaction that is precipitated by cosmic rays. Thermal neutrons are produced that collide with the nuclei of nitrogen-14, forming carbon-14 and a proton. As such, of atmospheric carbon dioxide contains carbon-14.

Carbon-rich asteroids are relatively preponderant in the outer parts of the asteroid belt in the Solar System. These asteroids have not yet been directly sampled by scientists. The asteroids can be used in hypothetical space-based carbon mining, which may be possible in the future, but is currently technologically impossible.

Isotopes

Isotopes of carbon areatomic nuclei

The atomic nucleus is the small, dense region consisting of protons and neutrons at the center of an atom, discovered in 1911 by Ernest Rutherford based on the 1909 Geiger–Marsden gold foil experiment. After the discovery of the neutron ...

that contain six proton

A proton is a stable subatomic particle, symbol , H+, or 1H+ with a positive electric charge of +1 ''e'' elementary charge. Its mass is slightly less than that of a neutron and 1,836 times the mass of an electron (the proton–electron mass ...

s plus a number of neutrons (varying from 2 to 16). Carbon has two stable, naturally occurring isotopes. The isotope carbon-12

Carbon-12 (12C) is the most abundant of the two stable isotopes of carbon (carbon-13 being the other), amounting to 98.93% of element carbon on Earth; its abundance is due to the triple-alpha process by which it is created in stars. Carbon-12 i ...

(C) forms 98.93% of the carbon on Earth, while carbon-13 (C) forms the remaining 1.07%. The concentration of C is further increased in biological materials because biochemical reactions discriminate against C. In 1961, the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) adopted the isotope carbon-12

Carbon-12 (12C) is the most abundant of the two stable isotopes of carbon (carbon-13 being the other), amounting to 98.93% of element carbon on Earth; its abundance is due to the triple-alpha process by which it is created in stars. Carbon-12 i ...

as the basis for atomic weights. Identification of carbon in nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) experiments is done with the isotope C.

Carbon-14

Carbon-14, C-14, or radiocarbon, is a radioactive isotope of carbon with an atomic nucleus containing 6 protons and 8 neutrons. Its presence in organic materials is the basis of the radiocarbon dating method pioneered by Willard Libby and coll ...

(C) is a naturally occurring radioisotope, created in the upper atmosphere (lower stratosphere

The stratosphere () is the second layer of the atmosphere of the Earth, located above the troposphere and below the mesosphere. The stratosphere is an atmospheric layer composed of stratified temperature layers, with the warm layers of air ...

and upper troposphere) by interaction of nitrogen with cosmic rays. It is found in trace amounts on Earth of 1 part per trillion

''Trillion'' is a number with two distinct definitions:

* 1,000,000,000,000, i.e. one million million, or (ten to the twelfth power), as defined on the short scale. This is now the meaning in both American and British English.

* 1,000,000,000,0 ...

(0.0000000001%) or more, mostly confined to the atmosphere and superficial deposits, particularly of peat and other organic materials. This isotope decays by 0.158 MeV β emission. Because of its relatively short half-life of 5730 years, C is virtually absent in ancient rocks. The amount of C in the atmosphere

An atmosphere () is a layer of gas or layers of gases that envelop a planet, and is held in place by the gravity of the planetary body. A planet retains an atmosphere when the gravity is great and the temperature of the atmosphere is low. A s ...

and in living organisms is almost constant, but decreases predictably in their bodies after death. This principle is used in radiocarbon dating

Radiocarbon dating (also referred to as carbon dating or carbon-14 dating) is a method for determining the age of an object containing organic material by using the properties of radiocarbon, a radioactive isotope of carbon.

The method was dev ...

, invented in 1949, which has been used extensively to determine the age of carbonaceous materials with ages up to about 40,000 years.

There are 15 known isotopes of carbon and the shortest-lived of these is C which decays through proton emission and alpha decay and has a half-life of 1.98739 × 10 s. The exotic C exhibits a nuclear halo, which means its radius is appreciably larger than would be expected if the nucleus

Nucleus ( : nuclei) is a Latin word for the seed inside a fruit. It most often refers to:

*Atomic nucleus, the very dense central region of an atom

*Cell nucleus, a central organelle of a eukaryotic cell, containing most of the cell's DNA

Nucle ...

were a sphere of constant density.

Formation in stars

Formation of the carbon atomic nucleus occurs within a giant or supergiant star through the triple-alpha process. This requires a nearly simultaneous collision of three alpha particles ( helium nuclei), as the products of further nuclear fusion reactions of helium with hydrogen or another helium nucleus producelithium-5

Naturally occurring lithium (3Li) is composed of two stable isotopes, lithium-6 and lithium-7, with the latter being far more abundant on Earth. Both of the natural isotopes have an unexpectedly low nuclear binding energy per nucleon ( for lit ...

and beryllium-8 respectively, both of which are highly unstable and decay almost instantly back into smaller nuclei. The triple-alpha process happens in conditions of temperatures over 100 megakelvins and helium concentration that the rapid expansion and cooling of the early universe prohibited, and therefore no significant carbon was created during the Big Bang

The Big Bang event is a physical theory that describes how the universe expanded from an initial state of high density and temperature. Various cosmological models of the Big Bang explain the evolution of the observable universe from the ...

.

According to current physical cosmology theory, carbon is formed in the interiors of stars on the horizontal branch

The horizontal branch (HB) is a stage of stellar evolution that immediately follows the red-giant branch in stars whose masses are similar to the Sun's. Horizontal-branch stars are powered by helium fusion in the core (via the triple-alpha process) ...

.

When massive stars die as supernova, the carbon is scattered into space as dust. This dust becomes component material for the formation of the next-generation star systems with accreted planets. The Solar System is one such star system with an abundance of carbon, enabling the existence of life as we know it.

The CNO cycle is an additional hydrogen fusion mechanism that powers stars, wherein carbon operates as a catalyst.

Rotational transitions of various isotopic forms of carbon monoxide (for example, CO, CO, and CO) are detectable in the submillimeter

Submillimetre astronomy or submillimeter astronomy (see spelling differences) is the branch of observational astronomy that is conducted at submillimetre wavelengths (i.e., terahertz radiation) of the electromagnetic spectrum. Astronomers plac ...

wavelength range, and are used in the study of newly forming stars in molecular clouds.

Carbon cycle

photosynthetic

Photosynthesis is a process used by plants and other organisms to convert light energy into chemical energy that, through cellular respiration, can later be released to fuel the organism's activities. Some of this chemical energy is stored in c ...

plants draw carbon dioxide from the atmosphere (or seawater) and build it into biomass, as in the Calvin cycle

The Calvin cycle, light-independent reactions, bio synthetic phase, dark reactions, or photosynthetic carbon reduction (PCR) cycle of photosynthesis is a series of chemical reactions that convert carbon dioxide and hydrogen-carrier compounds into ...

, a process of carbon fixation

Biological carbon fixation or сarbon assimilation is the process by which inorganic carbon (particularly in the form of carbon dioxide) is converted to organic compounds by living organisms. The compounds are then used to store energy and as ...

. Some of this biomass is eaten by animals, while some carbon is exhaled by animals as carbon dioxide. The carbon cycle is considerably more complicated than this short loop; for example, some carbon dioxide is dissolved in the oceans; if bacteria do not consume it, dead plant or animal matter may become petroleum or coal, which releases carbon when burned.

Compounds

Organic compounds

Carbon can form very long chains of interconnecting carbon–carbon bonds, a property that is called

Carbon can form very long chains of interconnecting carbon–carbon bonds, a property that is called catenation

In chemistry, catenation is the bonding of atoms of the same element into a series, called a ''chain''. A chain or a ring shape may be ''open'' if its ends are not bonded to each other (an open-chain compound), or ''closed'' if they are bonded ...

. Carbon-carbon bonds are strong and stable. Through catenation, carbon forms a countless number of compounds. A tally of unique compounds shows that more contain carbon than do not.

A similar claim can be made for hydrogen because most organic compounds contain hydrogen chemically bonded to carbon or another common element like oxygen or nitrogen.

The simplest form of an organic molecule is the hydrocarbon—a large family of organic molecules that are composed of hydrogen atoms bonded to a chain of carbon atoms. A hydrocarbon backbone can be substituted by other atoms, known as heteroatoms. Common heteroatoms that appear in organic compounds include oxygen, nitrogen, sulfur, phosphorus, and the nonradioactive halogens, as well as the metals lithium and magnesium. Organic compounds containing bonds to metal are known as organometallic compounds (''see below''). Certain groupings of atoms, often including heteroatoms, recur in large numbers of organic compounds. These collections, known as ''functional groups'', confer common reactivity patterns and allow for the systematic study and categorization of organic compounds. Chain length, shape and functional groups all affect the properties of organic molecules.

In most stable compounds of carbon (and nearly all stable ''organic'' compounds), carbon obeys the octet rule and is ''tetravalent'', meaning that a carbon atom forms a total of four covalent bonds (which may include double and triple bonds). Exceptions include a small number of stabilized ''carbocations'' (three bonds, positive charge), ''radicals'' (three bonds, neutral), ''carbanions'' (three bonds, negative charge) and ''carbenes'' (two bonds, neutral), although these species are much more likely to be encountered as unstable, reactive intermediates.

Carbon occurs in all known organic

Organic may refer to:

* Organic, of or relating to an organism, a living entity

* Organic, of or relating to an anatomical organ

Chemistry

* Organic matter, matter that has come from a once-living organism, is capable of decay or is the product ...

life and is the basis of organic chemistry. When united with hydrogen, it forms various hydrocarbons that are important to industry as refrigerant

A refrigerant is a working fluid used in the heat pump and refrigeration cycle, refrigeration cycle of air conditioning systems and heat pumps where in most cases they undergo a repeated phase transition from a liquid to a gas and back again. Ref ...

s, lubricant

A lubricant (sometimes shortened to lube) is a substance that helps to reduce friction between surfaces in mutual contact, which ultimately reduces the heat generated when the surfaces move. It may also have the function of transmitting forces, t ...

s, solvents, as chemical feedstock for the manufacture of plastics and petrochemicals, and as fossil fuel

A fossil fuel is a hydrocarbon-containing material formed naturally in the Earth's crust from the remains of dead plants and animals that is extracted and burned as a fuel. The main fossil fuels are coal, oil, and natural gas. Fossil fuels m ...

s.

When combined with oxygen and hydrogen, carbon can form many groups of important biological compounds including sugar

Sugar is the generic name for sweet-tasting, soluble carbohydrates, many of which are used in food. Simple sugars, also called monosaccharides, include glucose, fructose, and galactose. Compound sugars, also called disaccharides or double ...

s, lignans, chitin

Chitin ( C8 H13 O5 N)n ( ) is a long-chain polymer of ''N''-acetylglucosamine, an amide derivative of glucose. Chitin is probably the second most abundant polysaccharide in nature (behind only cellulose); an estimated 1 billion tons of chit ...

s, alcohol

Alcohol most commonly refers to:

* Alcohol (chemistry), an organic compound in which a hydroxyl group is bound to a carbon atom

* Alcohol (drug), an intoxicant found in alcoholic drinks

Alcohol may also refer to:

Chemicals

* Ethanol, one of sev ...

s, fats, and aromatic esters, carotenoid

Carotenoids (), also called tetraterpenoids, are yellow, orange, and red organic compound, organic pigments that are produced by plants and algae, as well as several bacteria, and Fungus, fungi. Carotenoids give the characteristic color to pumpki ...

s and terpenes. With nitrogen it forms alkaloids, and with the addition of sulfur also it forms antibiotic

An antibiotic is a type of antimicrobial substance active against bacteria. It is the most important type of antibacterial agent for fighting bacterial infections, and antibiotic medications are widely used in the treatment and prevention of ...

s, amino acids, and rubber products. With the addition of phosphorus to these other elements, it forms DNA and RNA

Ribonucleic acid (RNA) is a polymeric molecule essential in various biological roles in coding, decoding, regulation and expression of genes. RNA and deoxyribonucleic acid ( DNA) are nucleic acids. Along with lipids, proteins, and carbohydra ...

, the chemical-code carriers of life, and adenosine triphosphate (ATP), the most important energy-transfer molecule in all living cells.

Inorganic compounds

Commonly carbon-containing compounds which are associated with minerals or which do not contain bonds to the other carbon atoms, halogens, or hydrogen, are treated separately from classical organic compounds; the definition is not rigid, and the classification of some compounds can vary from author to author (see reference articles above). Among these are the simple oxides of carbon. The most prominent oxide is carbon dioxide (). This was once the principal constituent of the paleoatmosphere, but is a minor component of the Earth's atmosphere today. Dissolved in water, it forms carbonic acid (), but as most compounds with multiple single-bonded oxygens on a single carbon it is unstable. Through this intermediate, though, resonance-stabilized carbonate ions are produced. Some important minerals are carbonates, notablycalcite

Calcite is a Carbonate minerals, carbonate mineral and the most stable Polymorphism (materials science), polymorph of calcium carbonate (CaCO3). It is a very common mineral, particularly as a component of limestone. Calcite defines hardness 3 on ...

. Carbon disulfide () is similar. Nevertheless, due to its physical properties and its association with organic synthesis, carbon disulfide is sometimes classified as an ''organic'' solvent.

The other common oxide is carbon monoxide (CO). It is formed by incomplete combustion, and is a colorless, odorless gas. The molecules each contain a triple bond and are fairly polar

Polar may refer to:

Geography

Polar may refer to:

* Geographical pole, either of two fixed points on the surface of a rotating body or planet, at 90 degrees from the equator, based on the axis around which a body rotates

* Polar climate, the c ...

, resulting in a tendency to bind permanently to hemoglobin molecules, displacing oxygen, which has a lower binding affinity. Cyanide

Cyanide is a naturally occurring, rapidly acting, toxic chemical that can exist in many different forms.

In chemistry, a cyanide () is a chemical compound that contains a functional group. This group, known as the cyano group, consists of a ...

(CN), has a similar structure, but behaves much like a halide

In chemistry, a halide (rarely halogenide) is a binary chemical compound, of which one part is a halogen atom and the other part is an element or radical that is less electronegative (or more electropositive) than the halogen, to make a fluor ...

ion ( pseudohalogen). For example, it can form the nitride cyanogen molecule ((CN)), similar to diatomic halides. Likewise, the heavier analog of cyanide, cyaphide (CP), is also considered inorganic, though most simple derivatives are highly unstable. Other uncommon oxides are carbon suboxide

Carbon suboxide, or tricarbon dioxide, is an organic, oxygen-containing chemical compound with formula and structure . Its four cumulative double bonds make it a cumulene. It is one of the stable members of the series of linear oxocarbons , whi ...

(), the unstable dicarbon monoxide

Dicarbon monoxide (C2O) is a molecule that contains two carbon atoms and one oxygen atom. It is a linear molecule that, because of its simplicity, is of interest in a variety of areas. It is, however, so extremely reactive that it is not encounte ...

(CO), carbon trioxide (CO), cyclopentanepentone

Cyclopentanepentone, also known as leuconic acid, is a hypothetical organic compound with formula C5O5, the fivefold ketone of cyclopentane. It would be an oxide of carbon (an oxocarbon), indeed a pentamer of carbon monoxide.

As of 2000, the co ...

(CO),

cyclohexanehexone

Cyclohexanehexone, also known as hexaketocyclohexane and triquinoyl, is an organic compound with formula , the sixfold ketone of cyclohexane. It is an oxide of carbon (an oxocarbon), a hexamer of carbon monoxide.

The compound is expected to be ...

(CO), and mellitic anhydride (CO). However, mellitic anhydride is the triple acyl anhydride of mellitic acid; moreover, it contains a benzene ring. Thus, many chemists consider it to be organic.

With reactive metals, such as tungsten, carbon forms either carbides (C) or acetylides () to form alloys with high melting points. These anions are also associated with methane and acetylene

Acetylene (systematic name: ethyne) is the chemical compound with the formula and structure . It is a hydrocarbon and the simplest alkyne. This colorless gas is widely used as a fuel and a chemical building block. It is unstable in its pure ...

, both very weak acid

In computer science, ACID ( atomicity, consistency, isolation, durability) is a set of properties of database transactions intended to guarantee data validity despite errors, power failures, and other mishaps. In the context of databases, a sequ ...

s. With an electronegativity of 2.5, carbon prefers to form covalent bond

A covalent bond is a chemical bond that involves the sharing of electrons to form electron pairs between atoms. These electron pairs are known as shared pairs or bonding pairs. The stable balance of attractive and repulsive forces between atoms ...

s. A few carbides are covalent lattices, like carborundum

Silicon carbide (SiC), also known as carborundum (), is a hard chemical compound containing silicon and carbon. A semiconductor, it occurs in nature as the extremely rare mineral moissanite, but has been mass-produced as a powder and crystal sin ...

(SiC), which resembles diamond. Nevertheless, even the most polar and salt-like of carbides are not completely ionic compounds.Greenwood and Earnshaw, pp. 297–301

Organometallic compounds

Organometallic compounds by definition contain at least one carbon-metal covalent bond. A wide range of such compounds exist; major classes include simple alkyl-metal compounds (for example, tetraethyllead), η-alkene compounds (for example, Zeise's salt), and η-allyl compounds (for example, allylpalladium chloride dimer); metallocenes containing cyclopentadienyl ligands (for example,ferrocene

Ferrocene is an organometallic compound with the formula . The molecule is a complex consisting of two cyclopentadienyl rings bound to a central iron atom. It is an orange solid with a camphor-like odor, that sublimes above room temperature, a ...

); and transition metal carbene complexes. Many metal carbonyls and metal cyanides exist (for example, tetracarbonylnickel and potassium ferricyanide); some workers consider metal carbonyl and cyanide complexes without other carbon ligands to be purely inorganic, and not organometallic. However, most organometallic chemists consider metal complexes with any carbon ligand, even 'inorganic carbon' (e.g., carbonyls, cyanides, and certain types of carbides and acetylides) to be organometallic in nature. Metal complexes containing organic ligands without a carbon-metal covalent bond (e.g., metal carboxylates) are termed ''metalorganic'' compounds.

While carbon is understood to strongly prefer formation of four covalent bonds, other exotic bonding schemes are also known. Carborane

Carboranes are electron-delocalized (non-classically bonded) clusters composed of boron, carbon and hydrogen atoms.Grimes, R. N., ''Carboranes 3rd Ed.'', Elsevier, Amsterdam and New York (2016), . Like many of the related boron hydrides, these cl ...

s are highly stable dodecahedral derivatives of the 12H12sup>2- unit, with one BH replaced with a CH+. Thus, the carbon is bonded to five boron atoms and one hydrogen atom. The cation PhPAu)Ccontains an octahedral carbon bound to six phosphine-gold fragments. This phenomenon has been attributed to the aurophilicity of the gold ligands, which provide additional stabilization of an otherwise labile species. In nature, the iron-molybdenum cofactor ( FeMoco) responsible for microbial nitrogen fixation likewise has an octahedral carbon center (formally a carbide, C(-IV)) bonded to six iron atoms. In 2016, it was confirmed that, in line with earlier theoretical predictions, the hexamethylbenzene dication contains a carbon atom with six bonds. More specifically, the dication could be described structurally by the formulation eC(η5-C5Me5)sup>2+, making it an "organic metallocene" in which a MeC3+ fragment is bonded to a η5-C5Me5− fragment through all five of the carbons of the ring.

It is important to note that in the cases above, each of the bonds to carbon contain less than two formal electron pairs. Thus, the formal electron count of these species does not exceed an octet. This makes them hypercoordinate but not hypervalent. Even in cases of alleged 10-C-5 species (that is, a carbon with five ligands and a formal electron count of ten), as reported by Akiba and co-workers, electronic structure calculations conclude that the electron population around carbon is still less than eight, as is true for other compounds featuring four-electron

It is important to note that in the cases above, each of the bonds to carbon contain less than two formal electron pairs. Thus, the formal electron count of these species does not exceed an octet. This makes them hypercoordinate but not hypervalent. Even in cases of alleged 10-C-5 species (that is, a carbon with five ligands and a formal electron count of ten), as reported by Akiba and co-workers, electronic structure calculations conclude that the electron population around carbon is still less than eight, as is true for other compounds featuring four-electron three-center bond In chemistry, there are two types of three-center bonds:

*Three-center two-electron bond, found in electron-deficient compounds such as boranes

*Three-center four-electron bond

The 3-center 4-electron (3c–4e) bond is a model used to explain bond ...

ing.

History and etymology

The English name ''carbon'' comes from the Latin ''carbo'' for coal and charcoal, whence also comes the

The English name ''carbon'' comes from the Latin ''carbo'' for coal and charcoal, whence also comes the French

French (french: français(e), link=no) may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to France

** French language, which originated in France, and its various dialects and accents

** French people, a nation and ethnic group identified with Franc ...

''charbon'', meaning charcoal. In German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany (of or related to)

**Germania (historical use)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizens of Germany, see also German nationality law

**Ger ...

, Dutch and Danish

Danish may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to the country of Denmark

People

* A national or citizen of Denmark, also called a "Dane," see Demographics of Denmark

* Culture of Denmark

* Danish people or Danes, people with a Danish ance ...

, the names for carbon are ''Kohlenstoff'', ''koolstof'' and ''kulstof'' respectively, all literally meaning coal-substance.

Carbon was discovered in prehistory and was known in the forms of soot and charcoal

Charcoal is a lightweight black carbon residue produced by strongly heating wood (or other animal and plant materials) in minimal oxygen to remove all water and volatile constituents. In the traditional version of this pyrolysis process, cal ...

to the earliest human civilizations. Diamonds were known probably as early as 2500 BCE in China, while carbon in the form of charcoal

Charcoal is a lightweight black carbon residue produced by strongly heating wood (or other animal and plant materials) in minimal oxygen to remove all water and volatile constituents. In the traditional version of this pyrolysis process, cal ...

was made around Roman times by the same chemistry as it is today, by heating wood in a pyramid covered with clay to exclude air.

In 1722,

In 1722, René Antoine Ferchault de Réaumur

René Antoine Ferchault de Réaumur (; 28 February 1683, La Rochelle – 17 October 1757, Saint-Julien-du-Terroux) was a French entomologist and writer who contributed to many different fields, especially the study of insects. He introduced t ...

demonstrated that iron was transformed into steel through the absorption of some substance, now known to be carbon. In 1772, Antoine Lavoisier showed that diamonds are a form of carbon; when he burned samples of charcoal and diamond and found that neither produced any water and that both released the same amount of carbon dioxide per gram.

In 1779, Carl Wilhelm Scheele showed that graphite, which had been thought of as a form of lead, was instead identical with charcoal but with a small admixture of iron, and that it gave "aerial acid" (his name for carbon dioxide) when oxidized with nitric acid.

In 1786, the French scientists Claude Louis Berthollet, Gaspard Monge and C. A. Vandermonde confirmed that graphite was mostly carbon by oxidizing it in oxygen in much the same way Lavoisier had done with diamond. Some iron again was left, which the French scientists thought was necessary to the graphite structure. In their publication they proposed the name ''carbone'' (Latin ''carbonum'') for the element in graphite which was given off as a gas upon burning graphite. Antoine Lavoisier then listed carbon as an element in his 1789 textbook.

A new allotrope

Allotropy or allotropism () is the property of some chemical elements to exist in two or more different forms, in the same physical state, known as allotropes of the elements. Allotropes are different structural modifications of an element: the ...

of carbon, fullerene, that was discovered in 1985 includes nanostructured forms such as buckyball

Buckminsterfullerene is a type of fullerene with the formula C60. It has a cage-like fused-ring structure (truncated icosahedron) made of twenty hexagons and twelve pentagons, and resembles a soccer ball. Each of its 60 carbon atoms is bonded t ...

s and nanotubes.

Their discoverers – Robert Curl, Harold Kroto and Richard Smalley

Richard Errett Smalley (June 6, 1943 – October 28, 2005) was an American chemist who was the Gene and Norman Hackerman Professor of Chemistry, Physics, and Astronomy at Rice University. In 1996, along with Robert Curl, also a professor of ch ...

– received the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1996. The resulting renewed interest in new forms led to the discovery of further exotic allotropes, including glassy carbon, and the realization that " amorphous carbon" is not strictly amorphous

In condensed matter physics and materials science, an amorphous solid (or non-crystalline solid, glassy solid) is a solid that lacks the long-range order that is characteristic of a crystal.

Etymology

The term comes from the Greek ''a'' ("wi ...

.

Production

Graphite

Commercially viable natural deposits of graphite occur in many parts of the world, but the most important sources economically are inChina

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's most populous country, with a population exceeding 1.4 billion, slightly ahead of India. China spans the equivalent of five time zones and ...

, India, Brazil and North Korea. Graphite deposits are of metamorphic origin, found in association with quartz, mica

Micas ( ) are a group of silicate minerals whose outstanding physical characteristic is that individual mica crystals can easily be split into extremely thin elastic plates. This characteristic is described as perfect basal cleavage. Mica is ...

and feldspars in schists, gneisses and metamorphosed sandstones and limestone as lenses

A lens is a transmissive optical device which focuses or disperses a light beam by means of refraction. A simple lens consists of a single piece of transparent material, while a compound lens consists of several simple lenses (''elements''), ...

or veins

Veins are blood vessels in humans and most other animals that carry blood towards the heart. Most veins carry deoxygenated blood from the tissues back to the heart; exceptions are the pulmonary and umbilical veins, both of which carry oxygenated b ...

, sometimes of a metre or more in thickness. Deposits of graphite in Borrowdale, Cumberland

Cumberland ( ) is a historic county in the far North West England. It covers part of the Lake District as well as the north Pennines and Solway Firth coast. Cumberland had an administrative function from the 12th century until 1974. From 19 ...

, England were at first of sufficient size and purity that, until the 19th century, pencils were made by sawing blocks of natural graphite into strips before encasing the strips in wood. Today, smaller deposits of graphite are obtained by crushing the parent rock and floating the lighter graphite out on water.USGS Minerals Yearbook: Graphite, 2009and Graphite: Mineral Commodity Summaries 2011 There are three types of natural graphite—amorphous, flake or crystalline flake, and vein or lump. Amorphous graphite is the lowest quality and most abundant. Contrary to science, in industry "amorphous" refers to very small crystal size rather than complete lack of crystal structure. Amorphous is used for lower value graphite products and is the lowest priced graphite. Large amorphous graphite deposits are found in China, Europe, Mexico and the United States. Flake graphite is less common and of higher quality than amorphous; it occurs as separate plates that crystallized in metamorphic rock. Flake graphite can be four times the price of amorphous. Good quality flakes can be processed into

expandable graphite Expandable graphite (also known as exfoliated graphite) is produced from the naturally occurring mineral graphite. The layered structure of graphite allows molecules to be intercalated in between the graphite layers. Through incorporation of acids, ...

for many uses, such as flame retardants. The foremost deposits are found in Austria, Brazil, Canada, China, Germany and Madagascar. Vein or lump graphite is the rarest, most valuable, and highest quality type of natural graphite. It occurs in veins along intrusive contacts in solid lumps, and it is only commercially mined in Sri Lanka.

According to the USGS, world production of natural graphite was 1.1 million tonnes in 2010, to which China contributed 800,000 t, India 130,000 t, Brazil 76,000 t, North Korea 30,000 t and Canada 25,000 t. No natural graphite was reported mined in the United States, but 118,000 t of synthetic graphite with an estimated value of $998 million was produced in 2009.

Diamond

The diamond supply chain is controlled by a limited number of powerful businesses, and is also highly concentrated in a small number of locations around the world (see figure).

Only a very small fraction of the diamond ore consists of actual diamonds. The ore is crushed, during which care has to be taken in order to prevent larger diamonds from being destroyed in this process and subsequently the particles are sorted by density. Today, diamonds are located in the diamond-rich density fraction with the help of X-ray fluorescence, after which the final sorting steps are done by hand. Before the use of X-rays became commonplace, the separation was done with grease belts; diamonds have a stronger tendency to stick to grease than the other minerals in the ore.

Historically diamonds were known to be found only in alluvial deposits in southern India. discussion on alluvial diamonds in India and elsewhere as well as earliest finds India led the world in diamond production from the time of their discovery in approximately the 9th century BC Ball was a Geologist in British service. Chapter I, Page 1 to the mid-18th century AD, but the commercial potential of these sources had been exhausted by the late 18th century and at that time India was eclipsed by Brazil where the first non-Indian diamonds were found in 1725.

Diamond production of primary deposits (kimberlites and lamproites) only started in the 1870s after the discovery of the diamond fields in South Africa. Production has increased over time and an accumulated total of over 4.5 billion carats have been mined since that date. Most commercially viable diamond deposits were in Russia, Botswana,

The diamond supply chain is controlled by a limited number of powerful businesses, and is also highly concentrated in a small number of locations around the world (see figure).

Only a very small fraction of the diamond ore consists of actual diamonds. The ore is crushed, during which care has to be taken in order to prevent larger diamonds from being destroyed in this process and subsequently the particles are sorted by density. Today, diamonds are located in the diamond-rich density fraction with the help of X-ray fluorescence, after which the final sorting steps are done by hand. Before the use of X-rays became commonplace, the separation was done with grease belts; diamonds have a stronger tendency to stick to grease than the other minerals in the ore.

Historically diamonds were known to be found only in alluvial deposits in southern India. discussion on alluvial diamonds in India and elsewhere as well as earliest finds India led the world in diamond production from the time of their discovery in approximately the 9th century BC Ball was a Geologist in British service. Chapter I, Page 1 to the mid-18th century AD, but the commercial potential of these sources had been exhausted by the late 18th century and at that time India was eclipsed by Brazil where the first non-Indian diamonds were found in 1725.

Diamond production of primary deposits (kimberlites and lamproites) only started in the 1870s after the discovery of the diamond fields in South Africa. Production has increased over time and an accumulated total of over 4.5 billion carats have been mined since that date. Most commercially viable diamond deposits were in Russia, Botswana, Australia

Australia, officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a Sovereign state, sovereign country comprising the mainland of the Australia (continent), Australian continent, the island of Tasmania, and numerous List of islands of Australia, sma ...

and the Democratic Republic of Congo. By 2005, Russia produced almost one-fifth of the global diamond output (mostly in Yakutia territory; for example, Mir pipe and Udachnaya pipe

The Udachnaya pipe (russian: тру́бка Уда́чная, literally ''lucky pipe'') is a diamond deposit in the Daldyn- Alakit kimberlite field in Sakha Republic, Russia. It is an open-pit mine, and is located just outside the Arctic c ...

) but the Argyle mine

Argyle is an archaic spelling of Argyll, a county in western Scotland. Argyle may refer to:

Places Australia

* Argyle, Victoria

* Argyle County, New South Wales

**Electoral district of Argyle, a former electoral district for the Legislative ...

in Australia became the single largest source, producing 14 million carats in 2018. New finds, the Canadian mines at Diavik and Ekati, are expected to become even more valuable owing to their production of gem quality stones.

In the United States, diamonds have been found in Arkansas, Colorado and Montana. In 2004, a startling discovery of a microscopic diamond in the United States led to the January 2008 bulk-sampling of kimberlite pipes

Volcanic pipes or volcanic conduits are subterranean geological structures formed by the violent, supersonic eruption of deep-origin volcanoes. They are considered to be a type of ''diatreme''. Volcanic pipes are composed of a deep, narrow cone o ...

in a remote part of Montana.

Applications

Carbon is essential to all known living systems, and without it life as we know it could not exist (see

Carbon is essential to all known living systems, and without it life as we know it could not exist (see alternative biochemistry

Hypothetical types of biochemistry are forms of biochemistry agreed to be scientifically viable but not proven to exist at this time. The kinds of life, living organisms currently known on Earth all use carbon compounds for basic structural and m ...

). The major economic use of carbon other than food and wood is in the form of hydrocarbons, most notably the fossil fuel

A fossil fuel is a hydrocarbon-containing material formed naturally in the Earth's crust from the remains of dead plants and animals that is extracted and burned as a fuel. The main fossil fuels are coal, oil, and natural gas. Fossil fuels m ...

methane gas and crude oil

Petroleum, also known as crude oil, or simply oil, is a naturally occurring yellowish-black liquid mixture of mainly hydrocarbons, and is found in geological formations. The name ''petroleum'' covers both naturally occurring unprocessed crude ...

(petroleum). Crude oil

Petroleum, also known as crude oil, or simply oil, is a naturally occurring yellowish-black liquid mixture of mainly hydrocarbons, and is found in geological formations. The name ''petroleum'' covers both naturally occurring unprocessed crude ...

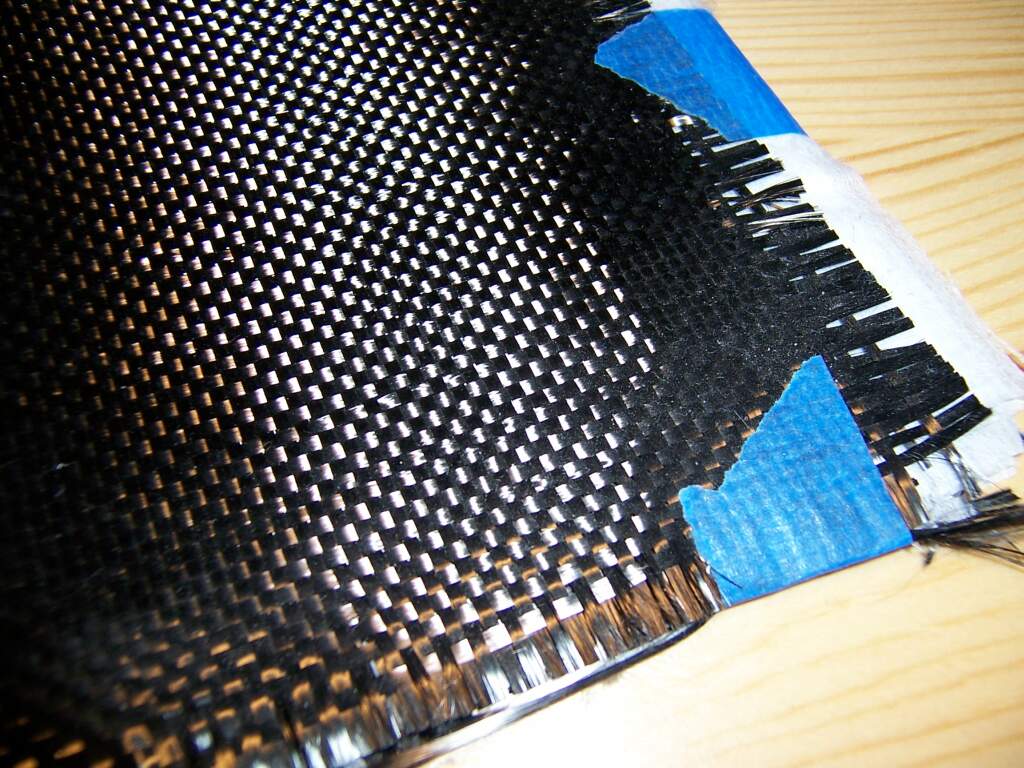

is distilled