Burmese Buddhist on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The early history of Buddhism in Burma is hard to decipher.

The early history of Buddhism in Burma is hard to decipher.

The

The  The Burmese chronicles give a long list of monastic scholars (and their works) who worked during this era. Some important scholars of the Bagan era were Acariya Dhammasenapati, Aggavamsa Thera, Capata (Saddhammajotipala), Saddhammasiri, Vimalabuddhi, Aggapandita and Dhammadassi. Their work focused on the intricacies of Pali grammar as well as on Theravada Abhidhamma.

Another key figure of Bagan Buddhism was the Mon Buddhist monk Shin Uttarajīva. He was a leading religious leader during the reigns of

The Burmese chronicles give a long list of monastic scholars (and their works) who worked during this era. Some important scholars of the Bagan era were Acariya Dhammasenapati, Aggavamsa Thera, Capata (Saddhammajotipala), Saddhammasiri, Vimalabuddhi, Aggapandita and Dhammadassi. Their work focused on the intricacies of Pali grammar as well as on Theravada Abhidhamma.

Another key figure of Bagan Buddhism was the Mon Buddhist monk Shin Uttarajīva. He was a leading religious leader during the reigns of

This era saw the rise of various fragmented warring kingdoms (Burmese, Shan and Mon) all vying for power.

During this period, the western mainland remained divided between four main regional political-ethnic zones. In the Shan Realm, the

This era saw the rise of various fragmented warring kingdoms (Burmese, Shan and Mon) all vying for power.

During this period, the western mainland remained divided between four main regional political-ethnic zones. In the Shan Realm, the

Bayinnaung also promoted mass ordinations into the Sinhala Sangha at the

Bayinnaung also promoted mass ordinations into the Sinhala Sangha at the

In the mid-18th century, King

In the mid-18th century, King

On saints and wizards, Ideals of human perfection and power in contemporary Burmese Buddhism.

' Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Studies Volume 33 • Number 1–2 • 2010 (2011) pp. 453–488. Medawi was the first author of Burmese language vipassana meditation manuals (completing over thirty of these), focusing on the

Escaping Colonialism, Rescuing Religion

' (review of Alicia Turner’s ''Saving Buddhism''), Marginalia, LA Review of Books. Not only did Buddhism now lack state support, but many of the traditional jobs of the Burmese sangha, especially education, were being taken by secular institutions. The response to this perceived decline was a mass reform movement throughout the country which responded in different ways to the colonial situation. This included waves of Buddhist publishing, preaching, and the founding of hundreds of lay Buddhist organizations, as well as the promotion of vegetarianism, Buddhist education, moral and religious reform and the founding of schools. Lay persons, including working class individuals such as schoolteachers, and clerks, merchants were quite prominent in this Buddhist revival. They now assumed the responsibility of preserving the ''sasana'', one which had previously been taken by the king and royal elites. An important part of this revival movement was the widespread promotion of Buddhist doctrinal learning (especially of the Abhidhamma) coupled with the practice of meditation (among the monastic and lay communities).

An important part of this revival movement was the widespread promotion of Buddhist doctrinal learning (especially of the Abhidhamma) coupled with the practice of meditation (among the monastic and lay communities).

Since 1948 when the country gained its independence from

Since 1948 when the country gained its independence from

''Lay Buddhist Practice: The Shrine Room, Uposatha Day, Rains Residence'' (The Wheel No. 206/207).

Kandy, Sri Lanka:Buddhist Publication Society. Before a Buddha statue is used for veneration, it must be formally consecrated, in a ritual called '' buddhābhiseka'' or ''anay gaza tin'' (). This consecration, led by a Buddhist monk, including various offerings (candles, flowers, etc) and chanting of ''paritta'' and other verses such as ''aneka jāti saṃsāraṃ'' ("through the round of many births I roamed"), the 153rd verse of the

It is the most important duty of all Burmese parents to make sure their sons are admitted to the Buddhist ''

It is the most important duty of all Burmese parents to make sure their sons are admitted to the Buddhist ''

The

The

Buddhism in Myanmar-A Short History

Kandy, Sri Lanka: Buddhist Publication Society. * Charney, Michael W. (2006). ''Powerful Learning. Buddhist Literati and the Throne in Burma's Last Dynasty, 1752–1885''. Ann Arbor:

Description

* * Ferguson, J.P. & Mendelson, E.M. (1981). "Masters of the Buddhist Occult: The Burmese Weikzas". ''Contributions to Asian Studies'' 16, pp. 62–88. * * Hlaing, Maung Myint (August 1981). ''The Great Disciples of Buddha''. Zeyar Hlaing Literature House. pp. 66–68. * Matthews, Bruce "The Legacy of Tradition and Authority: Buddhism and the Nation in Myanmar", in: Ian Harris (ed.), ''Buddhism and Politics in Twentieth-Century Asia''. Continuum, London/New York 1999, pp. 26–53. * Pranke, Patrick (1995), "On Becoming a Buddhist Wizard," in

ed. Donald S. Lopez, Jr., Princeton: Princeton University Press,

Nibbana.com – Books and Articles by Myanmar Monks and Scholars for English-speaking Readers

BuddhaNet

G Appleton 1943

Saddhamma Foundation

Information about practising Buddhist meditation in Burma.

* ttp://www.timesonline.co.uk/tol/comment/faith/article3052917.ece Buddha's Irresistible Maroon ArmyDr Michael W Charney, SOAS, TIMESONLINE, 14 December 2007

MyanmarNet Myanmar Yadanar Dhamma Section

Dhamma Video Talks in English or Myanmar by Venerable Myanmar Monks {{DEFAULTSORT:Buddhism In Myanmar Religion in Myanmar

Buddhism

Buddhism ( , ), also known as Buddha Dharma and Dharmavinaya (), is an Indian religion or philosophical tradition based on teachings attributed to the Buddha. It originated in northern India as a -movement in the 5th century BCE, and gra ...

( my, ဗုဒ္ဓဘာသာ), specifically Theravāda Buddhism

''Theravāda'' () ( si, ථේරවාදය, my, ထေရဝါဒ, th, เถรวาท, km, ថេរវាទ, lo, ເຖຣະວາດ, pi, , ) is the most commonly accepted name of Buddhism's oldest existing school. The school' ...

( my, ထေရဝါဒဗုဒ္ဓဘာသာ), is the State religion

A state religion (also called religious state or official religion) is a religion or creed officially endorsed by a sovereign state. A state with an official religion (also known as confessional state), while not secular state, secular, is not n ...

of Myanmar

Myanmar, ; UK pronunciations: US pronunciations incl. . Note: Wikipedia's IPA conventions require indicating /r/ even in British English although only some British English speakers pronounce r at the end of syllables. As John C. Wells, Joh ...

since 1961, and practiced by nearly 90% of the population. It is the most religious Buddhist country in terms of the proportion of monks in the population and proportion of income spent on religion. Adherents are most likely found among the dominant Bamar people

The Bamar (, ; also known as the Burmans) are a Sino-Tibetan languages, Sino-Tibetan ethnic group native to Myanmar (formerly Burma) in Southeast Asia. With approximately 35 million people, the Bamar make up the largest ethnic group in Myanmar ...

, Shan, Rakhine, Mon, Karen

Karen may refer to:

* Karen (name), a given name and surname

* Karen (slang), a term and meme for a demanding woman displaying certain behaviors

People

* Karen people, an ethnic group in Myanmar and Thailand

** Karen languages or Karenic l ...

, and Chinese

Chinese can refer to:

* Something related to China

* Chinese people, people of Chinese nationality, citizenship, and/or ethnicity

**''Zhonghua minzu'', the supra-ethnic concept of the Chinese nation

** List of ethnic groups in China, people of ...

who are well integrated into Burmese society. Monks

A monk (, from el, μοναχός, ''monachos'', "single, solitary" via Latin ) is a person who practices religious asceticism by monastic living, either alone or with any number of other monks. A monk may be a person who decides to dedicat ...

, collectively known as the sangha

Sangha is a Sanskrit word used in many Indian languages, including Pali meaning "association", "assembly", "company" or "community"; Sangha is often used as a surname across these languages. It was historically used in a political context t ...

(community), are venerated members of Burmese society. Among many ethnic groups in Myanmar, including the Bamar and Shan, Theravada Buddhism is practiced in conjunction with the worship of nats, which are spirits who can intercede in worldly affairs.

Regarding the practice of Buddhism, two popular practices stand out: merit-making

Merit ( sa, puṇya, italic=yes, pi, puñña, italic=yes) is a concept considered fundamental to Buddhist ethics. It is a beneficial and protective force which accumulates as a result of good deeds, acts, or thoughts. Merit-making is important ...

and vipassanā meditation. There is also the less popular weizza

A weizza or weikza ( my, ဝိဇ္ဇာ, pi, vijjādhara) is an immortal, supernatural wizarding mystic in Buddhism in Burma associated with esoteric and occult practices such as recitation of spells, samatha, mysticism and alchemy. The goal ...

path. Merit-making is the most common path undertaken by Burmese Buddhists. This path involves the observance of the Five precepts

The Five precepts ( sa, pañcaśīla, italic=yes; pi, pañcasīla, italic=yes) or five rules of training ( sa, pañcaśikṣapada, italic=yes; pi, pañcasikkhapada, italic=yes) is the most important system of morality for Buddhist lay peo ...

and accumulation of good merit

Merit may refer to:

Religion

* Merit (Christianity)

* Merit (Buddhism)

* Punya (Hinduism)

* Imputed righteousness in Reformed Christianity

Companies and brands

* Merit (cigarette), a brand of cigarettes made by Altria

* Merit Energy Company, ...

through charity ( dana, often to monks) and good deeds to obtain a favorable rebirth

Rebirth may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media

Film

* ''Rebirth'' (2011 film), a 2011 Japanese drama film

* ''Rebirth'' (2016 film), a 2016 American thriller film

* ''Rebirth'', a documentary film produced by Project Rebirth

* ''The Re ...

. The meditation path, which has gained ground since the early 1900s, is a form of Buddhist meditation which is seen as leading to awakening and can involve intense meditation retreats. The weizza path is an esoteric system of occult practices (such as recitation of spells, samatha

''Samatha'' (Pāli; sa, शमथ ''śamatha''; ), "calm," "serenity," "tranquillity of awareness," and ''vipassanā'' (Pāli; Sanskrit ''vipaśyanā''), literally "special, super (''vi-''), seeing (''-passanā'')", are two qualities of the ...

and alchemy) believed to lead to life as a ''weizza'' ( my, ဝိဇ္ဇာ pi, vijjā), a semi-immortal and supernatural being who awaits the appearance of the future Buddha, Maitreya

Maitreya (Sanskrit: ) or Metteyya (Pali: ), also Maitreya Buddha or Metteyya Buddha, is regarded as the future Buddha of this world in Buddhist eschatology. As the 5th and final Buddha of the current kalpa, Maitreya's teachings will be aimed at ...

(Arimeitaya).

Pre-modern History

Buddhism in the Mon and Pyu states

The early history of Buddhism in Burma is hard to decipher.

The early history of Buddhism in Burma is hard to decipher. Pali

Pali () is a Middle Indo-Aryan liturgical language native to the Indian subcontinent. It is widely studied because it is the language of the Buddhist ''Pāli Canon'' or ''Tipiṭaka'' as well as the sacred language of ''Theravāda'' Buddhism ...

historical chronicles state that Ashoka

Ashoka (, ; also ''Asoka''; 304 – 232 BCE), popularly known as Ashoka the Great, was the third emperor of the Maurya Empire of Indian subcontinent during to 232 BCE. His empire covered a large part of the Indian subcontinent, ...

sent two bhikkhu

A ''bhikkhu'' (Pali: भिक्खु, Sanskrit: भिक्षु, ''bhikṣu'') is an ordained male in Buddhist monasticism. Male and female monastics ("nun", ''bhikkhunī'', Sanskrit ''bhikṣuṇī'') are members of the Sangha (Buddhist ...

s, Sona and Uttara, to ''Suvaṇṇabhūmi'' ("The Golden Land") around 228 BCE with other monks and sacred texts as part of his effort to spread Buddhism. The area has been recognized as being somewhere in ancient Southeast Asia

Southeast Asia, also spelled South East Asia and South-East Asia, and also known as Southeastern Asia, South-eastern Asia or SEA, is the geographical United Nations geoscheme for Asia#South-eastern Asia, south-eastern region of Asia, consistin ...

, possibly in Thaton

Thaton (; mnw, သဓီု ) is a town in Mon State, in southern Myanmar on the Tenasserim plains. Thaton lies along the National Highway 8 and is also connected by the National Road 85. It is 230 km south east of Yangon and 70 km ...

in lower Burma

Lower Myanmar ( my, အောက်မြန်မာပြည်, also called Lower Burma) is a geographic region of Myanmar and includes the low-lying Irrawaddy Delta (Ayeyarwady Region, Ayeyarwady, Bago Region, Bago and Yangon Regions), as we ...

or Nakon Pathom in Thailand

Thailand ( ), historically known as Siam () and officially the Kingdom of Thailand, is a country in Southeast Asia, located at the centre of the Indochinese Peninsula, spanning , with a population of almost 70 million. The country is bo ...

. However, this is uncertain.

An Andhra Ikshvaku

The Ikshvaku ( IAST: Ikṣvāku) dynasty ruled in the eastern Krishna River valley of India, from their capital at Vijayapuri (modern Nagarjunakonda in Andhra Pradesh) during approximately 3rd and 4th centuries CE. The Ikshvakus are also kn ...

inscription from about the 3rd century CE refers to the conversion of the Kiratas

The Kirāta ( sa, किरात) is a generic term in Sanskrit literature for people who had territory in the mountains, particularly in the Himalayas and Northeast India and who are believed to have been Sino-Tibetan in origin. The meaning o ...

(Cilatas) to Buddhism. These may have been the Mon-Khmer

The Austroasiatic languages , , are a large language family in Mainland Southeast Asia and South Asia. These languages are scattered throughout parts of Thailand, Laos, India, Myanmar, Malaysia, Bangladesh, Nepal, and southern China and are th ...

speaking peoples of ancient Arakan

Arakan ( or ) is a historic coastal region in Southeast Asia. Its borders faced the Bay of Bengal to its west, the Indian subcontinent to its north and Burma proper to its east. The Arakan Mountains isolated the region and made it accessi ...

and Lower Burma (i.e. the Pyu

Pyu, also spelled Phyu or Phyuu, United States National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency. is a town in Taungoo District, Bago Region in Myanmar. It is the administrative seat of Phyu Township

Pyu Township is a township in Taungoo District in the ...

states and Mon kingdoms). 3rd century Chinese texts speak of a "Kingdom of Liu-Yang," where people worshiped the Buddha, and there were "several thousand sramanas". This kingdom has been located in central Burma.

By the 4th century, most of Pyu had become predominantly Buddhist, though archaeological finds prove that their pre-Buddhist practices also remained firmly entrenched in the following centuries. According to the excavated texts, as well as the Chinese records, the predominant religion of the Pyu was Theravāda Buddhism

''Theravāda'' () ( si, ථේරවාදය, my, ထေရဝါဒ, th, เถรวาท, km, ថេរវាទ, lo, ເຖຣະວາດ, pi, , ) is the most commonly accepted name of Buddhism's oldest existing school. The school' ...

.Aung-Thwin 2005: 31–34Htin Aung 1967: 15–17

Peter Skilling concludes that there is firm epigraphical evidence for the dominant presence of Theravāda in the Pyu Kingdom of Sriksetra and the Mon kingdom of Dvaravati

The Dvaravati ( th, ทวารวดี ; ) was an ancient Mon kingdom from the 7th century to the 11th century that was located in the region now known as central Thailand. It was described by the Chinese pilgrim in the middle of the 7th ce ...

, "from about the 5th century CE onwards", though he adds that evidence shows that Mahāyāna

''Mahāyāna'' (; "Great Vehicle") is a term for a broad group of Buddhism, Buddhist traditions, Buddhist texts#Mahāyāna texts, texts, Buddhist philosophy, philosophies, and practices. Mahāyāna Buddhism developed in India (c. 1st century BC ...

was also present. The epigraphical evidence comes from Pali inscriptions which have been found in these areas. They use a variant of the South Indian Pallava script

The Pallava script or Pallava Grantha, is a Brahmic scripts, Brahmic script, named after the Pallava dynasty of South India, attested since the 4th century AD. As epigrapher Arlo Griffiths makes clear, however, the term is misleading as not all o ...

.Skilling, Peter. ''The Advent of Theravada Buddhism to Mainland South-east Asia'', Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Studies. Volume 20, Number 1, Summer 1997

Indeed, the oldest surviving Buddhist texts in the Pāli language come from Pyu city-state of Sri Ksetra. The text, which is dated from the mid 5th to mid 6th century, is written on solid gold plaques. The similarity of the script used in these plates with that of the Andhra

Andhra Pradesh (, abbr. AP) is a state in the south-eastern coastal region of India. It is the seventh-largest state by area covering an area of and tenth-most populous state with 49,386,799 inhabitants. It is bordered by Telangana to the ...

- Kuntala-Pallava

The Pallava dynasty existed from 275 CE to 897 CE, ruling a significant portion of the Deccan, also known as Tondaimandalam. The dynasty rose to prominence after the downfall of the Satavahana dynasty, with whom they had formerly served as fe ...

region indicates that Theravada in Burma first arrived from this part of South India.

According to Skilling the Pyu and Mon realms "were flourishing centres of Buddhist culture in their own right, on an equal footing with contemporary centres like Anuradhapura." These Mon-Pyu Buddhist traditions were the predominant form of Buddhism in Burma until the late 12th century when Shin Uttarajiva

The Venerable Shin Uttarajīva ( my, ရှင်ဥတ္တရဇီဝ ; died c. 5 October 1191) was Primate of Pagan Kingdom during the reigns of three kings Narathu, Naratheinkha and Narapatisithu from 1167 to 1191. The Theravada Budd ...

led the reform which imported the Sri Lankan Mahavihara

Mahavihara () is the Sanskrit and Pali term for a great vihara (centre of learning or Buddhist monastery) and is used to describe a monastic complex of viharas.

Mahaviharas of India

A range of monasteries grew up in ancient Magadha (modern Bihar ...

school to Burma.Harvey 1925: 55–56

From the 8th to the 12th centuries Indian Buddhist traditions increasingly spread to Southeast Asia via the Bay of Bengal

The Bay of Bengal is the northeastern part of the Indian Ocean, bounded on the west and northwest by India, on the north by Bangladesh, and on the east by Myanmar and the Andaman and Nicobar Islands of India. Its southern limit is a line between ...

trade network. Because of this, before the 12th century, the areas of Thailand, Myanmar, Laos, and Cambodia were influenced by the Buddhist traditions of India, some of which included the teachings of Mahāyāna Buddhism and the use of the Sanskrit language.Baruah, Bibhuti. ''Buddhist Sects and Sectarianism''. 2008. p. 131 In the 7th century, Yijing

The ''I Ching'' or ''Yi Jing'' (, ), usually translated ''Book of Changes'' or ''Classic of Changes'', is an ancient Chinese divination text that is among the oldest of the Chinese classics. Originally a divination manual in the Western Zho ...

noted in his travels that in Southeast Asia, all major sects of Indian Buddhism flourished.

Archaeological finds have also established the presence of Vajrayana

Vajrayāna ( sa, वज्रयान, "thunderbolt vehicle", "diamond vehicle", or "indestructible vehicle"), along with Mantrayāna, Guhyamantrayāna, Tantrayāna, Secret Mantra, Tantric Buddhism, and Esoteric Buddhism, are names referring t ...

, Mahayana

''Mahāyāna'' (; "Great Vehicle") is a term for a broad group of Buddhist traditions, texts, philosophies, and practices. Mahāyāna Buddhism developed in India (c. 1st century BCE onwards) and is considered one of the three main existing bra ...

and Hinduism

Hinduism () is an Indian religion or '' dharma'', a religious and universal order or way of life by which followers abide. As a religion, it is the world's third-largest, with over 1.2–1.35 billion followers, or 15–16% of the global p ...

in Burma. In Sri Ksetra, Pegu and other regions of ancient Burma, Brahmanical Hinduism was also a strong rival to Buddhism and was often in competition with it. This is attested in the Burmese historical chronicles. Prominent Mahayana figures such as Avalokiteśvara

In Buddhism, Avalokiteśvara (Sanskrit: अवलोकितेश्वर, IPA: ) is a bodhisattva who embodies the compassion of all Buddhas. He has 108 avatars, one notable avatar being Padmapāṇi (lotus bearer). He is variably depicted, ...

, Tara, Vaiśravaṇa

(Sanskrit: वैश्रवण) or (Pali; , , ja, 毘沙門天, Bishamonten, ko, 비사문천, Bisamuncheon, vi, Đa Văn Thiên Vương), is one of the Four Heavenly Kings, and is considered an important figure in Buddhism.

Names

The n ...

, and Hayagriva

Hayagriva, also spelled Hayagreeva ( sa, हयग्रीव IAST , ), is a Hindu deity, the horse-headed avatar of Vishnu. The purpose of this incarnation was to slay a danava also named Hayagriva (A descendant of Kashyapa and Danu), who ...

, were included in Pyu (and later Bagan) iconography. Brahmanical deities such as Brahma

Brahma ( sa, ब्रह्मा, Brahmā) is a Hindu god, referred to as "the Creator" within the Trimurti, the trinity of supreme divinity that includes Vishnu, and Shiva.Jan Gonda (1969)The Hindu Trinity Anthropos, Bd 63/64, H 1/2, pp. 21 ...

, Vishnu

Vishnu ( ; , ), also known as Narayana and Hari, is one of the principal deities of Hinduism. He is the supreme being within Vaishnavism, one of the major traditions within contemporary Hinduism.

Vishnu is known as "The Preserver" within t ...

, Shiva

Shiva (; sa, शिव, lit=The Auspicious One, Śiva ), also known as Mahadeva (; ɐɦaːd̪eːʋɐ, or Hara, is one of the principal deities of Hinduism. He is the Supreme Being in Shaivism, one of the major traditions within Hindu ...

, Garuda

Garuda (Sanskrit: ; Pāli: ; Vedic Sanskrit: गरुळ Garuḷa) is a Hindu demigod and divine creature mentioned in the Hindu, Buddhist and Jain faiths. He is primarily depicted as the mount (''vahana'') of the Hindu god Vishnu. Garuda is a ...

and Lakshmi

Lakshmi (; , sometimes spelled Laxmi, ), also known as Shri (, ), is one of the principal goddesses in Hinduism. She is the goddess of wealth, fortune, power, beauty, fertility and prosperity, and associated with ''Maya'' ("Illusion"). Alo ...

have been found, especially in Lower Burma.

Buddhism in the Bagan Kingdom

The

The Bamar people

The Bamar (, ; also known as the Burmans) are a Sino-Tibetan languages, Sino-Tibetan ethnic group native to Myanmar (formerly Burma) in Southeast Asia. With approximately 35 million people, the Bamar make up the largest ethnic group in Myanmar ...

(Burmese) also adopted Buddhism as they came into contact with the Pyu and Mon civilizations. Initially, Burmese Buddhism was dominated by an eclectic Buddhism called Ari Buddhism

Ari Buddhism or the Ari Gaing ( my, အရည်းဂိုဏ်း, ) is the name given to the religious practice common in Burma prior to Anawrahta's rise and the subsequent conversion of Bagan to Theravada Buddhism in the eleventh century. It ...

, which included Mahayana and Vajrayana elements as well animist practices like nat

Nat or NAT may refer to:

Computing

* Network address translation (NAT), in computer networking

Organizations

* National Actors Theatre, New York City, U.S.

* National AIDS trust, a British charity

* National Archives of Thailand

* National As ...

worship and influences from Brahmanism

The historical Vedic religion (also known as Vedicism, Vedism or ancient Hinduism and subsequently Brahmanism (also spelled as Brahminism)), constituted the religious ideas and practices among some Indo-Aryan peoples of northwest Indian Subco ...

.

The Bamar adoption of Buddhism accelerated in the 11th century during the reign of king Anawrahta

Anawrahta Minsaw ( my, အနော်ရထာ မင်းစော, ; 11 May 1014 – 11 April 1077) was the founder of the Pagan Empire. Considered the father of the Burmese nation, Anawrahta turned a small principality in the dry zone ...

(Pali: Aniruddha, 1044–1077) who transformed the Bagan Kingdom

The Kingdom of Pagan ( my, ပုဂံခေတ်, , ; also known as the Pagan Dynasty and the Pagan Empire; also the Bagan Dynasty or Bagan Empire) was the first Burmese kingdom to unify the regions that would later constitute modern-da ...

into a major power in the region through the conquest of the Irrawady river valley, which included the Mon city of Thaton

Thaton (; mnw, သဓီု ) is a town in Mon State, in southern Myanmar on the Tenasserim plains. Thaton lies along the National Highway 8 and is also connected by the National Road 85. It is 230 km south east of Yangon and 70 km ...

. During his reign, Mon Buddhist culture, architecture and writing came to be largely assimilated into the Bamar culture.

Though later historical chronicles (like the ''Sāsanavaṃsa

The or ''Thathanawin'' ( my, သာသနာဝင်, ) is a history of the Buddhist order in Burma, composed by the Burmese monk Paññāsāmi in 1861.Bischoff 1995Aung-Thwin 2005: 145 It is written in Pali prose, and based on earlier documen ...

'') state that Anawrahta conquered Thaton in order to obtain the Buddhist scriptures and that a "pure Theravada Buddhism" was established during his reign, it is likely that Theravada was known in Bagan before the 11th century. Furthermore, Bagan Theravāda was never truly "pure" as it included local animist rites, Naga

Naga or NAGA may refer to:

Mythology

* Nāga, a serpentine deity or race in Hindu, Buddhist and Jain traditions

* Naga Kingdom, in the epic ''Mahabharata''

* Phaya Naga, mythical creatures believed to live in the Laotian stretch of the Mekong Riv ...

worship and Brahmanical rites associated with Vishnu

Vishnu ( ; , ), also known as Narayana and Hari, is one of the principal deities of Hinduism. He is the supreme being within Vaishnavism, one of the major traditions within contemporary Hinduism.

Vishnu is known as "The Preserver" within t ...

officiated by Brahmin

Brahmin (; sa, ब्राह्मण, brāhmaṇa) is a varna as well as a caste within Hindu society. The Brahmins are designated as the priestly class as they serve as priests (purohit, pandit, or pujari) and religious teachers (guru ...

priests.

Anawrahta implemented a series of religious reforms throughout his kingdom, attempting to weaken the power of the Tantric Mahayana Ari monks (also called "Samanakuttakas") and their unorthodox ways.Coedès 1968: 149–150Niharranjan Ray (1946), p. 150 Burmese historical chronicles state that Anawrahta was converted by a Mon bhikkhu

A ''bhikkhu'' (Pali: भिक्खु, Sanskrit: भिक्षु, ''bhikṣu'') is an ordained male in Buddhist monasticism. Male and female monastics ("nun", ''bhikkhunī'', Sanskrit ''bhikṣuṇī'') are members of the Sangha (Buddhist ...

, Shin Arahan

, image =Shin Arahan.JPG

, caption = Statute of Shin Arahan in Ananda Temple

, birth name =

, alias =

, dharma_name = mnw, ဓမ္မဒဿဳ

, birth_date = c. 1034

, b ...

, to Theravāda Buddhism. The king may have been worried about the influence of the forest dwelling Ari Buddhist monks and sought a way to subvert their power. The Ari monks, who ate evening meals, drank liquor, and presided over animal sacrifices and sexual rites, were considered heretical by the more orthodox Theravāda circles of monks like Shin Arahan.Lieberman 2003: 115–116Htin Aung 1967: 32–37

Anawrahta banished many Ari priests who refused to conform and many of them fled to Popa Hill and the Shan Hills

The Shan Hills ( my, ရှမ်းရိုးမ; ''Shan Yoma''), also known as Shan Highland, is a vast mountainous zone that extends through Yunnan to Myanmar and Thailand. The whole region is made up of numerous mountain ranges separated ...

.Harvey 1925: 26–31 Anawrahta also invited Theravāda scholars from the Mon lands, Sri Lanka and India to Bagan. Their scholarship helped revitalize a more orthodox form of Theravāda Buddhism, with a focus on Pali learning and Abhidhamma philosophy.Htin Aung 1967: 36–37 Anawrahta is also known as a great temple builder. Some of his main achievements include the Shwezigon Pagoda

The Shwezigon Pagoda or Shwezigon Paya ( my-Mymr, ရွှေစည်းခုံဘုရား ) is a Buddhist stupa located in Nyaung-U, Myanmar. A prototype of Burmese stupas, it consists of a circular gold leaf-gilded stupa surrounded b ...

and the Shwesandaw Pagoda.

However, Anawrahta did not attempt to remove all non-Theravāda elements from his kingdom. Indeed, Anawrahta continued to support some Mahayana practices. He allowed and even promoted the worship of the traditional Burmese nat spirits and allowed their worship in Buddhist temples and pagodas, presumably as a way to attract and appease the population and gradually have them accept the new Buddhist religion.Harvey 1925: 33

Therefore, the spread and dominance of Theravāda in Burma was a gradual process taking centuries (and only really completed in around the 19th century). Hinduism, Ari Buddhism and nat worship remained influential forces in Burma at least until the 13th century, though the royal court generally favored Theravada. The Ari practices included the worship of Mahayana figures like Avalokiteśvara

In Buddhism, Avalokiteśvara (Sanskrit: अवलोकितेश्वर, IPA: ) is a bodhisattva who embodies the compassion of all Buddhas. He has 108 avatars, one notable avatar being Padmapāṇi (lotus bearer). He is variably depicted, ...

(''Lawka nat''), Tara and Manjushri. The worship of Brahmanical deities, especially Narayana

Narayana (Sanskrit: नारायण, IAST: ''Nārāyaṇa'') is one of the forms and names of Vishnu, who is in yogic slumber under the celestial waters, referring to the masculine principle. He is also known as Purushottama, and is co ...

, Vishnu, Ganesha

Ganesha ( sa, गणेश, ), also known as Ganapati, Vinayaka, and Pillaiyar, is one of the best-known and most worshipped deities in the Hindu pantheon and is the Supreme God in Ganapatya sect. His image is found throughout India. Hindu d ...

and Brahma

Brahma ( sa, ब्रह्मा, Brahmā) is a Hindu god, referred to as "the Creator" within the Trimurti, the trinity of supreme divinity that includes Vishnu, and Shiva.Jan Gonda (1969)The Hindu Trinity Anthropos, Bd 63/64, H 1/2, pp. 21 ...

, as well as the nats, also remained popular. These gods were worshiped in their own temples (such as Vaisnava Nathlaung Kyaung) as well as at Buddhist Temples.

Burmese Theravada did not ignore these practices, and in some cases incorporated them into the Theravada pantheon. Thus, the worship of Lokanatha was accepted in Burmese Theravada as well as the worship of a list of 37 Nats that were royally sanctioned. The influence of these various religions is still felt in folk Burmese Buddhism today, which contains several elements of nat worship, esotericism, Mahayana and Hinduism. The Weikza tradition is particularly influenced by these unorthodox elements.

It seems that Bagan Theravāda was mainly supported by elite city dwellers, with over 90 percent of religious gifts being given by royalty, aristocrats, military officers and temple artisans. Meanwhile, the peasants in the countryside tended to be more associated with the animistic nat based religion.

At its height, the Bagan Kingdom became an important center of Theravāda scholarship. According to Lieberman:At the great capital itself and some provincial centers, Buddhist temples supported an increasingly sophisticated Pali scholarship, part of an international tradition, which specialized in grammar and philosophical-psychological (''abhidhamma'') studies and which reportedly won the admiration of Sinhalese experts. Besides religious texts, Pagan’s monks read works in a variety of languages on prosody, phonology, grammar, astrology, alchemy, and medicine, and developed an independent school of legal studies. Most students, and probably the leading monks and nuns, came from aristocratic families.

The Burmese chronicles give a long list of monastic scholars (and their works) who worked during this era. Some important scholars of the Bagan era were Acariya Dhammasenapati, Aggavamsa Thera, Capata (Saddhammajotipala), Saddhammasiri, Vimalabuddhi, Aggapandita and Dhammadassi. Their work focused on the intricacies of Pali grammar as well as on Theravada Abhidhamma.

Another key figure of Bagan Buddhism was the Mon Buddhist monk Shin Uttarajīva. He was a leading religious leader during the reigns of

The Burmese chronicles give a long list of monastic scholars (and their works) who worked during this era. Some important scholars of the Bagan era were Acariya Dhammasenapati, Aggavamsa Thera, Capata (Saddhammajotipala), Saddhammasiri, Vimalabuddhi, Aggapandita and Dhammadassi. Their work focused on the intricacies of Pali grammar as well as on Theravada Abhidhamma.

Another key figure of Bagan Buddhism was the Mon Buddhist monk Shin Uttarajīva. He was a leading religious leader during the reigns of Narathu

, image = Dhammayangyi Temple at Bagan,Myanmar.jpg

, caption = Dhammayangyi Temple built by Narathu

, reign = 1167 – February 1171

, coronation =

, succession = King of Burma ...

(1167–1171), Naratheinkha

Naratheinkha ( my, နရသိင်္ခ, ; 1141–1174) was king of Pagan dynasty of Burma (Myanmar) from 1171 to 1174. He appointed his brother Narapati Sithu heir apparent and commander-in-chief. It was the first recorded instance in the ...

(1171–74) and Narapatisithu

Narapati Sithu ( my, နရပတိ စည်သူ, ; also Narapatisithu, Sithu II or Cansu II; 1138–1211) was king of Pagan dynasty of Burma (Myanmar) from 1174 to 1211. He is considered the last important king of Pagan. His peaceful and p ...

(1167–1191). Uttarajiva presided over the realignment of Burmese Buddhism

Buddhism ( my, ဗုဒ္ဓဘာသာ), specifically Theravāda Buddhism ( my, ထေရဝါဒဗုဒ္ဓဘာသာ), is the State religion of Myanmar since 1961, and practiced by nearly 90% of the population. It is the most re ...

with the Mahavihara school of Sri Lanka, moving away from the Conjeveram-Thaton

Thaton (; mnw, သဓီု ) is a town in Mon State, in southern Myanmar on the Tenasserim plains. Thaton lies along the National Highway 8 and is also connected by the National Road 85. It is 230 km south east of Yangon and 70 km ...

school of Shin Arahan

, image =Shin Arahan.JPG

, caption = Statute of Shin Arahan in Ananda Temple

, birth name =

, alias =

, dharma_name = mnw, ဓမ္မဒဿဳ

, birth_date = c. 1034

, b ...

.Hall 1960: 23 Even though the kings supported the reform and sent numerous monks to Sri Lanka to re-ordain, various Burmese monks of the old order (known as the Maramma Sangha) refused to ordain in the new Burmese Sri Lankan based order (the Sinhala Sangha), and this led to a schism. The schism lasted two centuries before the old order finally died out.

Later kings continued to support Theravada Buddhism and its mainly Mon scholarly elite. In the 13th century, the Bamar kings and elites built countless Buddhist stupas and temples, especially around the capital city of Bagan

Bagan (, ; formerly Pagan) is an ancient city and a UNESCO World Heritage Site in the Mandalay Region of Myanmar. From the 9th to 13th centuries, the city was the capital of the Bagan Kingdom, the first kingdom that unified the regions that wou ...

. These acts of generosity were a way to gain merit ('' puñña'') and to show that one had ''phun'' (glory, spiritual power). Bagan kings presented themselves as bodhisattvas, who saw themselves as responsible for the spiritual merit of their subjects. They also saw themselves as Dharma kings ( ''Dhammaraja'') who were protectors and promoters of the Buddhist religion. Bagan kings also promoted themselves as manifestations of the god Sakka.

The scale of state donations to Buddhist temples grew throughout the 13th century and many of these temples were also given arable land grants which were tax exempt as well as slaves

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

. Over time, this flow of wealth and agricultural capacity to the Buddhist temples put increasing economic strain on the kingdom.

To recover some of this wealth in an acceptable manner, kings often saw fit to "purify" or reform the Buddhist sangha

Sangha is a Sanskrit word used in many Indian languages, including Pali meaning "association", "assembly", "company" or "community"; Sangha is often used as a surname across these languages. It was historically used in a political context t ...

(monastic community). However in the 13th century, no Burmese kings were strong enough to manage and reform the increasingly rich and powerful sangha. The situation was also compounded by drier weather during the late 13th century and the 14th century (the Medieval Warm period

The Medieval Warm Period (MWP), also known as the Medieval Climate Optimum or the Medieval Climatic Anomaly, was a time of warm climate in the North Atlantic region that lasted from to . Proxy (climate), Climate proxy records show peak warmth oc ...

), which lowered crop yields.Lieberman (2003) p. 121 Because of this, the state was weak and divided. It was unable to resist the invasion of new enemies like the Mongols, Hanthawaddy and the Shans.

The invasions by neighboring Shan and Mon states as well as the Mongol invasions of Burma (13th century) brought the Bagan Empire

The Kingdom of Pagan ( my, ပုဂံခေတ်, , ; also known as the Pagan Dynasty and the Pagan Empire; also the Bagan Dynasty or Bagan Empire) was the first Burmese kingdom to unify the regions that would later constitute modern-da ...

to its end (the capital fell in 1287).

Era of Fragmentation (14th–16th centuries)

This era saw the rise of various fragmented warring kingdoms (Burmese, Shan and Mon) all vying for power.

During this period, the western mainland remained divided between four main regional political-ethnic zones. In the Shan Realm, the

This era saw the rise of various fragmented warring kingdoms (Burmese, Shan and Mon) all vying for power.

During this period, the western mainland remained divided between four main regional political-ethnic zones. In the Shan Realm, the Shan people

The Shan people ( shn, တႆး; , my, ရှမ်းလူမျိုး; ), also known as the Tai Long, or Tai Yai are a Tai ethnic group of Southeast Asia. The Shan are the biggest minority of Burma (Myanmar) and primarily live in th ...

established a loose confederation of valley kingdoms. The Shan kingdoms supported Theravada Buddhism in imitation of the Burmese elites, though the Buddhist institutions in the Shan realm never wielded political power as they did in the Burmese regions. In the 14th century, the Buddhist sangha continued to receive patronage from regional Shan kings like Thihathu

Thihathu ( my, သီဟသူ, ; 1265–1325) was a co-founder of the Myinsaing Kingdom, and the founder of the Pinya Kingdom in today's central Burma (Myanmar).Coedès 1968: 209 Thihathu was the youngest and most ambitious of the three brother ...

and scholarly activities continued under their reigns. Meanwhile, Arakan

Arakan ( or ) is a historic coastal region in Southeast Asia. Its borders faced the Bay of Bengal to its west, the Indian subcontinent to its north and Burma proper to its east. The Arakan Mountains isolated the region and made it accessi ...

was ruled by the kingdom of Mrauk-u, who also patronized Theravada Buddhism.

The main power in the Upper Burma

Upper Myanmar ( my, အထက်မြန်မာပြည်, also called Upper Burma) is a geographic region of Myanmar, traditionally encompassing Mandalay and its periphery (modern Mandalay, Sagaing, Magway Regions), or more broadly speak ...

region was the Kingdom of Ava

The Kingdom of Ava ( my, အင်းဝခေတ်, ) was the dominant kingdom that ruled upper Burma (Myanmar) from 1364 to 1555. Founded in 1365, the kingdom was the successor state to the petty kingdoms of Myinsaing, Pinya and Sagaing th ...

(founded in 1365), which was still the most populous region in the western mainland, despite all the sociopolitical disorder of the era. However, this kingdom was severely weakened economically (lacking coastal trade access), and continued to suffer from the Pagan era issue of tax free religious estates. The leaders of Buddhist institutions grew in power during this era, assuming administrative and even military offices. While most Ava kings supported the sangha, one infamous ruler, Thohanbwa

Thohanbwa ( my, သိုဟန်ဘွား, ; Shan: သိူဝ်ႁၢၼ်ၾႃ့; 1505 – May 1542) was king of Ava from 1527 to 1542. The eldest son of Sawlon of Mohnyin was a commander who actively participated in Monhyin's numer ...

is known as a king who pillaged and destroyed many monasteries and temples and massacred numerous monks.

In spite of the political weakness of the kingdom, Buddhist scholarship flourished during this time, with prominent scholars like Ariyavamsa, Silavamsa and Ratthasara composing numerous works. Ariyavamsa is known for his ''Manisaramañjusa'', a sub-commentary on the ''Abhidhammatthavibhavani,'' and his ''Manidipa,'' a commentary on the ''Atthasalini.'' He also wrote some works in Burmese, and thus was one of the first pioneers to write Buddhist works in that language.

In Lower Burma

Lower Myanmar ( my, အောက်မြန်မာပြည်, also called Lower Burma) is a geographic region of Myanmar and includes the low-lying Irrawaddy Delta (Ayeyarwady Region, Ayeyarwady, Bago Region, Bago and Yangon Regions), as we ...

the Mon people were dominant. The most powerful of the Mon kingdoms was Hanthawaddy (a.k.a. Ramaññadesa), founded by Wareru

Wareru ( mnw, ဝါရေဝ်ရောဝ်, my, ဝါရီရူး, ; also known as Wagaru; 20 March 1253 – 14 January 1307) was the founder of the Martaban Kingdom, located in present-day Myanmar (Burma). By using both diplomatic a ...

. He was a patron of Theravada Buddhism, and also led the compilation of the ''Wareru'' ''Dhammasattha'', an influential code of law patterned on Bagan customary law and influenced by Buddhism.

In spite of their support for Theravada Buddhism, many of the people in Burma during this era continued to practice animist and other non-Buddhist religious rites. Shan, Burmese and Mon elites often practiced animal sacrifice and worshiped nat spirits during this period. Meanwhile, the forest dwelling Ari monks continued to practice rites in which alcohol was imbibed and animals were sacrificed. However, there were also more orthodox Buddhist movements and tendencies in this era, such as a teetotal

Teetotalism is the practice or promotion of total personal abstinence from the psychoactive drug alcohol, specifically in alcoholic drinks. A person who practices (and possibly advocates) teetotalism is called a teetotaler or teetotaller, or is ...

movement which was influential from the 14th century onwards, as can be seen from surviving inscriptions of the era. By the 16th and 17th centuries, this movement seemed to have been successful in replacing the drinking of alcohol in public ceremonies with pickled tea.

The royalty also often promoted orthodoxy and Buddhist reform. The greatest of the Hanthawaddy kings, Dhammazedi

Dhammazedi ( my, ဓမ္မစေတီ, ; c. 1409–1492) was the 16th king of the Hanthawaddy Kingdom in Burma from 1471 to 1492. Considered one of the most enlightened rulers in Burmese history, by some accounts call him "the greatest" of al ...

(Dhammaceti), was a former Mon bhikkhu who ruled from 1471 to 1492. According to the Kalyani Inscriptions

The ''Kalyani Inscriptions'' ( my, ကလျာဏီကျောက်စာ), located in Bago, Burma (Myanmar), are the stone inscriptions erected by King Dhammazedi of Hanthawaddy Pegu between 1476 and 1479. Located at the Kalyani Ordinatio ...

, Dhammazedi carried out an extensive reform of the Buddhist sangha by sending thousands of Buddhist monks to Sri Lanka to receive ordination and training in the Mahavihara tradition. He also purified the sangha of undisciplined monks, such as monks who owned land or other forms of material wealth.

The invitation of Sinhalese monks and ordination lineages as a way to reform the sangha was also adopted in Mrauk-U, Ava, Toungoo, and Prome. These Sinhalese Theravada lineages spread throughout the mainland through the different trade routes, reaching the Shan realm, Thailand and Laos. They brought with them Theravada texts, rituals, lowland alphabets and calendars. These changes paved the way for the standardizing Theravada reforms of the first Taungoo dynasty in the mid-16th century.

Taungoo Buddhism (1510–1752)

In the 16th century, the BurmeseTaungoo dynasty

, conventional_long_name = Toungoo dynasty

, common_name = Taungoo dynasty

, era =

, status = Empire

, event_start = Independence from Ava

, year_start ...

unified all of Burma under energetic leaders like Tabinshwehti

Tabinshwehti ( my, တပင်ရွှေထီး, ; 16 April 1516 – 30 April 1550) was king of Burma (Myanmar) from 1530 to 1550, and the founder of the First Toungoo Empire. His military campaigns (1534–1549) created the largest kin ...

(r.1531–1550) and Bayinnaung

, image = File:Bayinnaung.JPG

, caption = Statue of Bayinnaung in front of the National Museum of Myanmar

, reign = 30 April 1550 – 10 October 1581

, coronation = 11 January 1551 at Toung ...

(r.1551–1581). Taungoo exploited the higher population of upper Burma along with European style firearms to create the largest empire in Southeast Asia.

Taungoo monarchs patronised the Mahavihara Theravada tradition (the Sinhala Sangha). During the First Toungoo Empire

The First Toungoo Empire ( my, တောင်ငူ ခေတ်, ; also known as the First Toungoo Dynasty, the Second Burmese Empire or simply the Toungoo Empire) was the dominant power in mainland Southeast Asia in the second half of the ...

, a reform movement led by the Taungoo kings took place, which attempted to standardize the Buddhism of Upper Burma and the Shan region in line with the Mahavihara tradition. These reforms were modeled after those of Dhammazedi.Harvey 1925: 172–173

Before the reform, the Buddhism of the Shan realm and Upper Burma was still heavily influenced by animism, Ari Buddhism and pre-Buddhist ritualism (which included animal and human sacrifice).Lieberman 2003: 135–136 Even in Lower Burma, where Theravada was more dominant, nat worship and Ari Buddhist practices also remained influential.

Bayinnaung attempted to bring the religious practice of his empire more in line with the orthodox Sri Lankan Mahavihara tradition (i.e. the Sinhala Sangha). Bayinnaung distributed copies of the Pali scriptures, promoted scholarship and built pagodas throughout his empire. One of the main temples built in his reign was the Mahazedi Pagoda at Pegu.

Bayinnaung also promoted mass ordinations into the Sinhala Sangha at the

Bayinnaung also promoted mass ordinations into the Sinhala Sangha at the Kalyani Ordination Hall

Kalyāṇī Ordination Hall (, pi, Kalyāṇī Sīmā) is a Buddhist ordination hall located in Bago, Myanmar. The ordination hall is a major pilgrimage site, and houses the Kalyani Inscriptions, a set of 10 sandstone pillars inscribed in Pali a ...

in the name of purifying the religion. He also prohibited all human and animal sacrifices throughout the kingdom. In particular, he forbade the Shan practice of killing the slaves and animals belonging to a ''saopha'' at his funeral.Htin Aung 1967: 117–118 He also sent Burmese Theravada monks to preach in the Shan realm. During his reign, there were great scholars such as Saddhammalamkara, Dhammabuddha and Ananda (known for his commentary on the ''Dhammasanghani's'' Abhidhammamatika).

Bayinnaung's reforms were continued by the monarchs of the Restored Toungoo Dynasty, who spent much of their efforts in religious projects. An important later king was Thalun

Thalun ( my, သာလွန်မင်း, ; 17 June 1584 – 27 August 1648) was the eighth king of Toungoo dynasty of Burma (Myanmar). During his 19-year reign, Thalun successfully rebuilt the war-torn country which had been under constant wa ...

(1584–1648), known for building a number of monasteries and chedis in Upper Burma and other acts of donation to the sangha. He also patronized various learned elders of his era, such as Tipitakalamkara, Ariyalamkara and Jambudhaja. Tipitakalamkara is the author of the ''Vinayalamkara'' and a commentary to the ''Atthasalini, while Jambhudhaja'' composed a commentary on the ''Vinayatthakatha.''

Thalun's successor Pindale

Pindale is a village in the Wundwin Township, Mandalay Division of central Myanmar.

See also

* Pindale Min

Pindale Min ( my, ပင်းတလဲမင်း, ; 23 March 1608 – 3 June 1661) was king of the Toungoo dynasty of Burma (Myanma ...

(1648–1661) also followed in his father's footsteps, building monasteries and patronizing Buddhist scholarship by figures such as Aggadhammalamkara, a great translator of various Abhidhamma works into Burmese (including the '' Patthana'' and the ''Dhammasangani''). His Taungoo successors also promoted learning and further construction projects for the sangha.

In the 17th and 18th centuries, Theravada practices became more regionally uniform, and the hill regions were drawn into closer contact with the basin.Lieberman 2003: 191–192 The consistent royal support of the Mahavihara Theravada tradition and the pacification of the Shan hill region led to the growth of rural monasteries ( ''kyaungs''), which became a near universal feature of Burmese village life.

The rural monasteries were the main center of education and by the 18th century the large majority of village males were learning to read and write in these monasteries. As literacy became more common (over 50 percent among males), the cost of transcribing and writing Buddhist texts decreased and they thus became more commonly available.

The 17th century saw a growth in the interest of Abhidhamma study and the translation of various classic works of Abhidhamma into the Burmese language, including the ''Atthasalini'' and the '' Abhidhammatthasangaha.'' This made the Abhidhamma more accessible to a much wider audience which probably included lay people''.''

At the same time, the Ari "Forest dweller" sect with their large landed estates virtually disappeared in this period due to various economic and political pressures.Lieberman 2003: 159 However, in spite of these changes and reforms, some animist and esoteric practices like nat worship and the Weikza remained popular throughout Burma.

During the reign of King Sanay (1673–1714), a great controversy swept the sangha over whether it was acceptable to wear the monk's robe so as to leave one shoulder exposed. This dispute would consume the sangha for almost a century.

Konbaung dynasty

In the mid-18th century, King

In the mid-18th century, King Alaungpaya

Alaungpaya ( my, အလောင်းဘုရား, ; also spelled Alaunghpaya or Alaung-Phra; 11 May 1760) was the founder of the Konbaung Dynasty of Burma (Myanmar). By the time of his death from illness during his campaign in Siam, this f ...

(1714–1760) established the Konbaung Dynasty

The Konbaung dynasty ( my, ကုန်းဘောင်ခေတ်, ), also known as Third Burmese Empire (တတိယမြန်မာနိုင်ငံတော်) and formerly known as the Alompra dynasty (အလောင်းဘ ...

(1752–1885) after a short period of rebellion and warfare.

His son, Bodawpaya

Bodawpaya ( my, ဘိုးတော်ဘုရား, ; th, ปดุง; 11 March 1745 – 5 June 1819) was the sixth king of the Konbaung dynasty of Burma. Born Maung Shwe Waing and later Badon Min, he was the fourth son of Alaungpaya, fo ...

(1745–1819), arbitrated the dispute concerning the correct way of wearing the monk robes by ruling in favour of covering both shoulders and the sangha was then unified under the Sudhammā Nikāya.Leider, Jacques P. ''Text, Lineage and Tradition in Burma. The Struggle for Norms and Religious Legitimacy Under King Bodawphaya (1782–1819).'' The Journal of Burma Studies Volume 9, 2004, pp. 82–129

Bodawpaya, a devout Buddhist, attempted to reform the sangha, aiming at a standard code of discipline and strict obedience to the scriptures. These reforms were known as the Sudhammā reforms. He appointed a council of sangharajas as leaders of the sangha, tasked with maintaining monastic discipline. He also appointed a sangha head (''sasanabaing''), Maung-daung Sayadaw, which was allowed to use the office and resources of the Royal Council to examine monks and defrock them if necessary. Various monks that did not meet the new standard were expelled from the sangha.

There were also monthly recitations of the vinaya in numerous cities throughout the realm. Regular examinations for monks were also organized, though this was a practice which had existed at least since the time of King Sinbyushin (1763–1776). If monks repeatedly failed their exams, they could be expelled from the sangha. Bodawpaya also made many donations to the Buddhist order, including regular food offerings, numerous copies of the Tipitaka and a wave of monastery and pagoda construction in the capital of Amarapura as well as the creation of animal sanctuaries (where hunting was prohibited). Bodawpaya also built numerous monasteries for learned Buddhist elders. One of the most learned scholars of this era was elder Ñāṇa, who wrote numerous works including commentaries on the ''Nettipakarana'', the ''Jatakatthakatha'' and the '' Digha Nikaya.''

Bodawpaya also sent many monks trained in vinaya to the provinces to enforce monastic standards and others were sent to preach the dharma in places “where the religion was not flourishing”.Leider, Jacques P. ''Text, Lineage and Tradition in Burma. The Struggle for Norms and Religious Legitimacy Under King Bodawphaya (1782–1819).'' The Journal of Burma Studies Volume 9, 2004, p. 87 Bodawpaya's policies also led to the persecution of the heretical Zoti (Joti/Zawti) sect, who rejected rebirth and believed in an omniscient creator nat who judged individuals after death for eternity. Under his auspices, the upasampada ordination was also re-introduced to Sri Lanka

Sri Lanka (, ; si, ශ්රී ලංකා, Śrī Laṅkā, translit-std=ISO (); ta, இலங்கை, Ilaṅkai, translit-std=ISO ()), formerly known as Ceylon and officially the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka, is an ...

where it established the Amarapura Nikaya

Amarapura ( my, အမရပူရ, MLCTS=a. ma. ra. pu ra., , ; also spelt as Ummerapoora) is a former capital of Myanmar, and now a township of Mandalay city. Amarapura is bounded by the Irrawaddy river in the west, Chanmyathazi Township in t ...

. Bodawpaya also attempted to regulate the ethics of the lay population. He banned liquor, opium, cannabis and the killing of animals in his capital. He also appealed to the lay population to keep the 5 precepts and the 8 precepts during the uposatha days.

According to Lieberman, the Konbaung crown was thoroughly involved in numerous different religious matters such as:

* appointing capital and provincial abbots,

* conducting regular monastic examinations,

* disseminating “purified” copies of the Tipitaka,

* sending missionaries to outlying provinces.

* issuing new explicitly Buddhist law codes

* outlawed liquor with severe punishment for recidivism

* harassing heretics and muslims

* forbidding of animal slaughter in the cities

*the promotion of an official pantheon of 37 nats

Konbaung era monastic and lay elites also launched a major reformation of Burmese intellectual life and monasticism, known as the Sudhamma Reformation. It led to, amongst other things, Burma's first proper state histories.Charney 2006: 96–107 It was during this era that the ''Thathana-wun-tha'' ( ''Sasanavamsa'', "Chronicle of the Buddhist religion") was written (1831).

Konbaung era monastics also wrote new commentaries on the canon. A key figure of this intellectual movement was the ascetic and sangharaja Ñāṇabhivamsa, who wrote commentaries on the Nettippakarana and other works as well as a sub-commentary on the Digha Nikaya. Furthermore, there was an increase in translations of Pali Buddhist works into the Burmese language. In the first half of the 19th century, almost the entire Sutta Pitaka became available in Burmese, and numerous commentaries continued to be composed on it. Buddhist texts also became much more widely available due to the growth of the use of modern printing methods.

During the Konbaung period, alcohol consumption became frowned upon at all social levels (though it of course continued in private). Ritualized public drinking was eventually replaced by the public drinking of pickled tea. The public slaughter and sale of meat (not fish) also ceased in the major towns. Government edicts were also passed against opium, opium derivatives, gambling, and prostitution as well as alcohol and hunting.

In the villages, rituals became more standardized, based on orthodox Theravada merit-making and monastics became objects of popular veneration. Popular culture also "became suffused with the Jatakas and Buddhist maxims." Indeed, Theravada Buddhism achieved an "unqualified superiority" in this era over the nat cults.

It was also during this period that the first vipassana meditation teachers began to popularize the widespread practice of Buddhist meditation. This included figures like the monks Waya-zawta and Medawi

Medawi ( pi, ; 1728–1816) was a Burmese Theravada Buddhist monk credited with being the first author of extant modern vipassanā manuals and thus may have been the first practitioner in the modern vipassana movement. Medawi's first manual date ...

(1728–1816). Waya-zawta flourished during the reign of Mahadhammayaza (1733–1752) and promised his followers could reach sotapanna through anagami levels of awakening under him.Pranke, Patrick. On saints and wizards, Ideals of human perfection and power in contemporary Burmese Buddhism.

' Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Studies Volume 33 • Number 1–2 • 2010 (2011) pp. 453–488. Medawi was the first author of Burmese language vipassana meditation manuals (completing over thirty of these), focusing on the

three marks of existence

In Buddhism, the three marks of existence are three characteristics (Pali: tilakkhaṇa; Sanskrit: त्रिलक्षण trilakṣaṇa) of all existence and beings, namely '' aniccā'' (impermanence), '' dukkha'' (commonly translated as "su ...

as they pertain to the five aggregates

(Sanskrit) or (Pāḷi) means "heaps, aggregates, collections, groupings". In Buddhism, it refers to the five aggregates of clinging (), the five material and mental factors that take part in the rise of craving and clinging. They are also ...

. Medawi promoted meditation as the way to prevent the decline of the Buddha's religion. He held that the Buddha's teaching was in decline only because people were not practicing it, and not, as others believed, because they lived in degenerate times.

Alongside of all the Theravada Buddhist activity, non-Buddhist rites and practices continued throughout the Konbaung era. These include the worship of ancestors, Hindu gods like Ganesha and Vishnu, and the Burmese nat spirits (which sometimes even included ceremonial sacrifices of living beings).

Modern era

Reign of Mindon Min (1853–1878)

KingMindon Min

Mindon Min ( my, မင်းတုန်းမင်း, ; 1808 – 1878), born Maung Lwin, was the penultimate King of Burma (Myanmar) from 1853 to 1878. He was one of the most popular and revered kings of Burma. Under his half brother King P ...

is a key figure in the modernization of Burmese Buddhism. He became king after Lower Burma

Lower Myanmar ( my, အောက်မြန်မာပြည်, also called Lower Burma) is a geographic region of Myanmar and includes the low-lying Irrawaddy Delta (Ayeyarwady Region, Ayeyarwady, Bago Region, Bago and Yangon Regions), as we ...

had been conquered by the British in 1852. Mindon spent most of his reign, which was generally peaceful, attempting to modernize his realm and reform the sangha.

After the Second Anglo-Burmese War concluded, many monks from Lower Burma had resettled in Mandalay, having fled there during the war. Mindon Min attempted to convince these bhikkhus to return to lower Burma so that they might continue to educate the people in Buddhism. Some of these monks did return.

However, many of the monks in lower Burma began to group together under certain local leaders who saw themselves as outside of royal control. One of these figures was Okpo Sayadaw, who taught that the sangha did not need the protection of a secular elite power as long as it strictly kept the monastic discipline. His movement also challenged the authority of the Thudhamma sect, and took new ordinations by themselves. His ideas also reached Upper Burma and gained popularity there.

Meanwhile, in Upper Burma, many monks were now moving out of the capital to Sagaing hills, seeking an environment that was stricter than the capital which they saw as promoting lavish lifestyles. At this time, the Sagaing hills area became a center for more strict monastic practice. One of monks who left for Sagaing was the Ngettwin Sayadaw. He was a popular figure, known for criticizing many traditional religious practices. Ngettwin Sayadaw, the 'Bird-cave Abbot' of Sagaing Hills, required his monks to practice vipassana meditation daily and keep a strict discipline. He also advised laypersons to meditate instead of give offerings to Buddha images (which he said were fruitless).Bischoff (1995), pp. 132–133. Another important figure of this period was Thingazar Sayadaw, who also stressed the importance of meditation practice and strict Vinaya.

Fearing that the Buddhist religion was in danger from colonialism and internal division, Mindon patronized and convened the Fifth Buddhist Council from 1868 to 1871. At this council, the Pali canon was recited and edited to a create a new edition and remove scribal transmission errors. When this was done, Mindon patronized the creation of a collection of 729 stone tablets inscribed with the new edition of the Pali canon. It remains the world's largest book. The tablets were then stored in 729 small pagodas at the Kuthodaw Pagoda complex.

Mindon's reign also saw the production of new scholarly works and translations of Pali texts. Ñeyyadhamma, the royal preceptor, wrote a sub-commentary to the Majjhima Nikaya (which had been translated into Burmese by his disciples). Paññasami (author of the ''Sasanavamsa'') also wrote numerous Pali works in this era, like the ''Silakatha'', and the ''Upayakatha''.

Another important Buddhist policy of Mindon was the establishment of animal sanctuaries, particularly outside Sagaing, at Maungdaung (near Alon), near the lower Chindwin ,

, image = Homalin aerial.jpg

, image_size =

, image_caption = The Chindwin at Homalin. The smaller, meandering Uyu River can be seen joining the Chindwin.

, map = Irrawaddyrivermap.jpg

, map_size =

, map_alt =

, map_caption ...

and around Meiktila lake

Lake Meiktila ( my, မိတ္ထီလာကန် ) is a lake located near Meiktila, Myanmar. It is long, averages half a mile across, and covers an area of . Mone-Dai dam supplies water to the lake. It is divided into two parts, north lake an ...

.

British rule

After Mindon’s death in 1877, his son Thibaw ascended the throne was weak and unable to prevent the British conquest of Upper Burma in 1886. This was an epoch making change, since the Buddhist sangha had now lost the support of the Burmese state for the first time in centuries. During the British administration of Lower and Upper Burma (from 1824 to 1948), government policies were generally secular which meant Buddhism and its institutions were not patronised or protected by the colonial government. Furthermore, monks who broke the vinaya now went unpunished by the government. The presence of Christian missionaries and missionary schools also became widespread. This resulted in tensions between the Buddhists, Christians and Europeans in Colonial Burma. As the authority and prestige of the sangha yielded to that of western educated colonial elites (and with the rise of western education in Burma), there was a general feeling among Burmese Buddhists during the colonial era that the Buddhist dispensation ( ''sasana'') was in decline and in danger of dying out.Kaloyanides, Alexandra (2015)Escaping Colonialism, Rescuing Religion

' (review of Alicia Turner’s ''Saving Buddhism''), Marginalia, LA Review of Books. Not only did Buddhism now lack state support, but many of the traditional jobs of the Burmese sangha, especially education, were being taken by secular institutions. The response to this perceived decline was a mass reform movement throughout the country which responded in different ways to the colonial situation. This included waves of Buddhist publishing, preaching, and the founding of hundreds of lay Buddhist organizations, as well as the promotion of vegetarianism, Buddhist education, moral and religious reform and the founding of schools. Lay persons, including working class individuals such as schoolteachers, and clerks, merchants were quite prominent in this Buddhist revival. They now assumed the responsibility of preserving the ''sasana'', one which had previously been taken by the king and royal elites.

An important part of this revival movement was the widespread promotion of Buddhist doctrinal learning (especially of the Abhidhamma) coupled with the practice of meditation (among the monastic and lay communities).

An important part of this revival movement was the widespread promotion of Buddhist doctrinal learning (especially of the Abhidhamma) coupled with the practice of meditation (among the monastic and lay communities). Ledi Sayadaw

Ledi Sayadaw U Ñaṇadhaja ( my, လယ်တီဆရာတော် ဦးဉာဏဓဇ, ; 1 December 1846 – 27 June 1923) was an influential Theravada Buddhist monk. He was recognized from a young age as being developed in both the theory ( ...

(1846–1923) became an influential figure of this "vipassana movement

The Vipassanā movement, also called (in the United States) the Insight Meditation Movement and American vipassana movement, refers to a branch of modern Burmese Theravāda Buddhism that promotes "bare insight" (''sukha-vipassana'') to attain ...

", which was seen as a way to safeguard and preserve Buddhism. He traveled widely teaching and preaching, and also founded numerous lay study and meditation groups. He also wrote voluminously. His output included meditation manuals and the ''Paramattha Sankhip,'' which was a Burmese verse translation of the ''Abhidhammatthasaṅgaha.'' According to Ledi, the study of this text and the practice of meditation allowed even laypersons to attain awakening "in this very life." His teachings were extremely influential for the later post-colonial spread of meditation by figures such as U Ba Khin

Sayagyi U Ba Khin ( my, ဘခင်, ; 6 March 1899 – 19 January 1971) was the first Accountant General of the Union of Burma. He was the founder of the International Meditation Centre in Yangon, Myanmar and is principally known as a leading ...

, S. N. Goenka

Satya Narayana Goenka (ISO 15919: ''Satyanārāyaṇ Goyankā''; ; 29 January 1924 – 29 September 2013) was an Indian teacher of Vipassanā meditation. Born in Burma to an Indian business family, he moved to India in 1969 and started tea ...

, and Mahasi Sayadaw

Mahāsī Sayādaw U Sobhana ( my, မဟာစည်ဆရာတော် ဦးသောဘန, ; 29 July 1904 – 14 August 1982) was a Burmese Theravada Buddhist monk and meditation master who had a significant impact on the teaching of vipa ...

.

According to Patrick Pranke, during the same period that the vipassana movement was growing, another alternative soteriological system called '' weikza-lam'' ("Path of esoteric knowledge") was also developing. The major goal of weikza path is not the attainment of arhatship, but the attainment of virtual immortality as a weikza ("wizard"). This system is one "whose methods and orientation fall largely outside the parameters of contemporary Theravāda orthodoxy."

A weikza-do (Pali: ''vijjā-dhara'') is a Buddhist wizard believed to have esoteric powers which he uses to defend the Buddhist dispensation and assist good people. The archetypal weikza include figures like Bo Min Gaung

Bo Min Gaung ( my, ဘိုးမင်းခေါင်) is a prominent 20th century weizza, or wizard, who lived in Myanmar near Mount Popa. He is associated with Dhammazedi, a prominent king of the Hanthawaddy Kingdom of ancient Myanmar in th ...

and Bo Bo Aung (though there is a diverse pantheon of weikzas). Weikzas are typically portrayed as a white clad layman who awaits the arrival of the future Buddha Metteya and extends his life through alchemy and magic.

During 19th and 20th century, numerous weikza-lam associations were founded, many of which believed in a millenarian myth which said that a righteous king called Setkya-min would defeat evil (along with Bo Bo Aung) and usher in a golden age in preparation for the arrival of Metteya. Other weikza followers do not subscribe to this unorthodox myth and simply wish to extend their lives so that they may live long enough to meet the next Buddha. While the practice of magic (for healing, immortality, magical protection and other ends) is a key element of weikza path, normative Buddhist practices like the five precepts and samatha

''Samatha'' (Pāli; sa, शमथ ''śamatha''; ), "calm," "serenity," "tranquillity of awareness," and ''vipassanā'' (Pāli; Sanskrit ''vipaśyanā''), literally "special, super (''vi-''), seeing (''-passanā'')", are two qualities of the ...

meditation are also important in weikza-lam.

During this time, there was also widespread opposition to the conversion efforts of Christian missionaries. One unique figure in this fight was the popular Irish Buddhist monk U Dhammaloka

U Dhammaloka ( my, ဦးဓမ္မလောက; c. 1856 – c. 1914) was an Irish-born migrant worker turned Buddhist monk, strong critic of Christian missionaries, and temperance campaigner who took an active role in the Asian Buddhist r ...

, who became a widely celebrated public preacher and polemicist against colonialism and Christian missionaries.

During the colonial period, the future of the Burmese nation was seen as closely tied to the future of the Buddhist dispensation. For the ethnic Burmese people, Burmese nationalism

Burmese may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to Myanmar, a country in Southeast Asia

* Burmese people

* Burmese language

* Burmese alphabet

* Burmese cuisine

* Burmese culture

Animals

* Burmese cat

* Burmese chicken

* Burmese (hor ...

was almost inseparable from their Buddhist identity. Indeed, a common slogan of the independence movement was "To be Burmese means to be Buddhist".

Therefore, many monks often participated in the nationalist struggle for independence, even though the majority of the senior monks leading the Burmese Sangha spoke out against monks participating in politics. They saw such activities as being contrary to the Vinaya rules. Likewise, many of the lay Buddhist organizations and its key organizers would also take part in the nationalist movement. One of the first and most influential of these nationalist Buddhist organizations was the Young Men’s Buddhist Association (YMBA), founded in 1906. They were the first organization to co-operate with politicized monks.

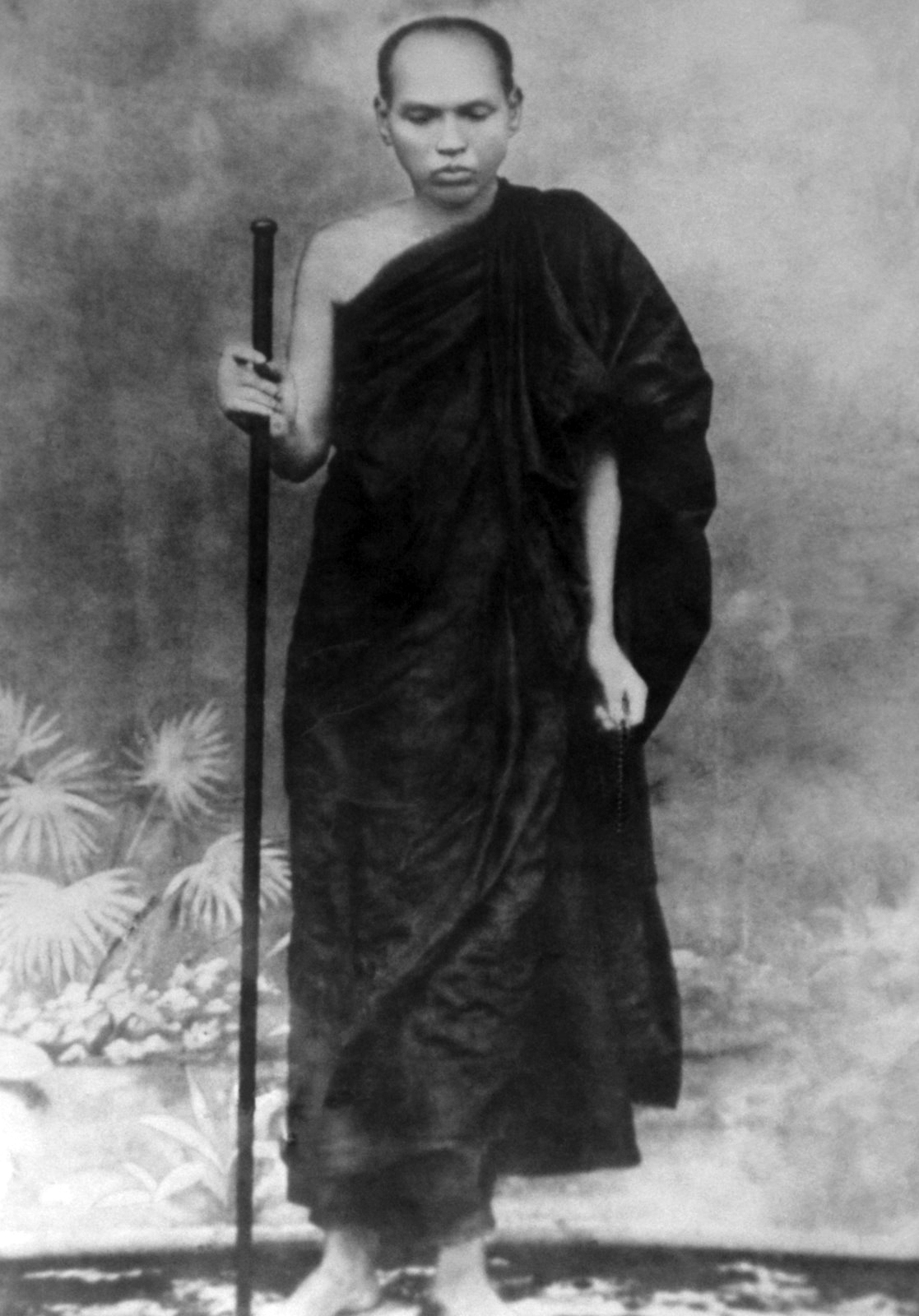

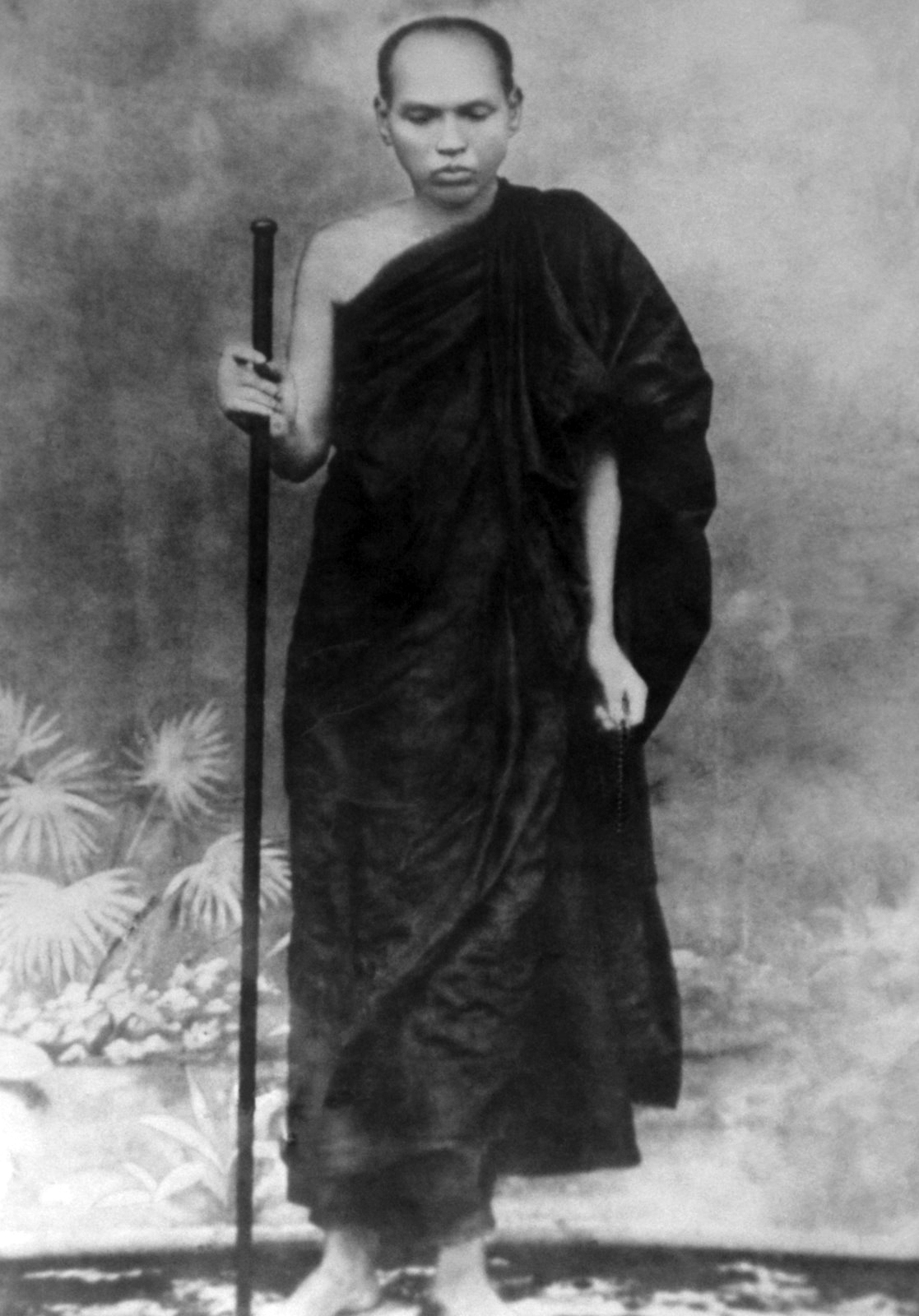

Politically involved monks included figures such as U Ottama

, image = Ven.Ottama.png

, caption =

, birth_name = Paw Tun Aung

, birth_date = 28 December 1879 1st waning of Pyatho 1241 ME

, birth_place = Rupa Village, Sittwe District, Arakan Division, British Burma

, death_date = 11th waning of Wag ...

, who argued that British rule was an obstacle to the practice of Buddhism and thus independence had to be gained, through violent means if necessary, though he also promoted Gandhian The followers of Mahatma Gandhi, the greatest figure of the Indian independence movement, are called Gandhians.

Gandhi's legacy includes a wide range of ideas ranging from his dream of ideal India (or ''Rama Rajya)'', economics, environmentalism, ...

tactics like boycotts and tax avoidance. In support of the use of violence, he quoted some Jatakas. He was arrested numerous times and died in jail, becoming a sort of martyr for the independence movement. However, Lehr points out that monastic political agitation "did not sit well with the population at large since this open participation in anti-colonial politics, or in social activism, was deemed to be a violation of the monastic rules."Lehr (2019), p. 170. The reputation of the activist monks was further damaged by the participation of a small group of monks in the anti-Indian Indo-Burmese riots of 1938.

Parliamentary era

Since 1948 when the country gained its independence from

Since 1948 when the country gained its independence from Great Britain

Great Britain is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean off the northwest coast of continental Europe. With an area of , it is the largest of the British Isles, the largest European island and the ninth-largest island in the world. It is ...

, both civil and military governments have supported Burmese Theravada Buddhism. The Ministry of Religious Affairs, created in 1948, was responsible for administering Buddhist affairs in Myanmar.

The first Burmese prime minister, U Nu

Nu ( my, ဦးနု; ; 25 May 1907 – 14 February 1995), commonly known as U Nu also known by the honorific name Thakin Nu, was a leading Burmese statesman and nationalist politician. He was the first Prime Minister of Burma under the pr ...

was influenced by socialist principles and was also a devout Buddhist who promoted a kind of Buddhist socialism

Buddhist socialism is a political ideology which advocates socialism based on the principles of Buddhism. Both Buddhism and socialism seek to provide an end to suffering by analyzing its conditions and removing its main causes through praxis. ...

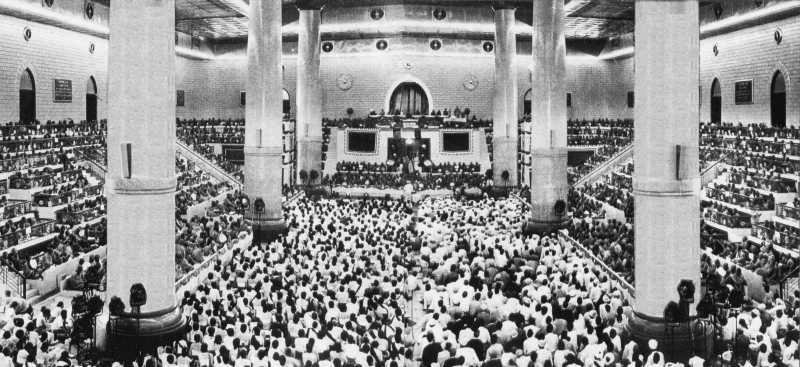

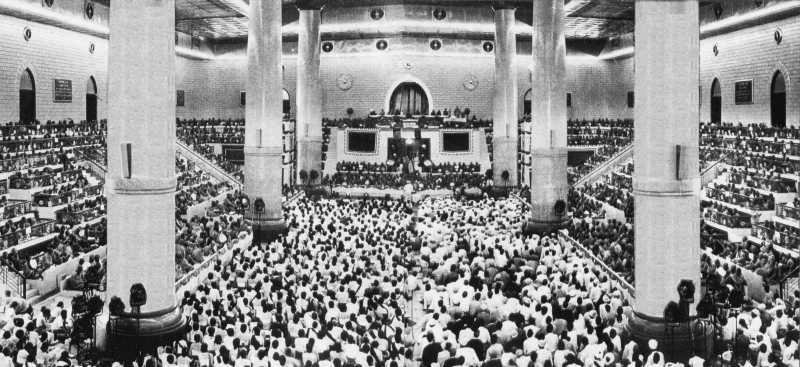

. In 1954, U Nu, convened the Sixth Buddhist Synod at the newly built Kaba Aye Pagoda

Kaba Aye Pagoda ( my, ကမ္ဘာအေးစေတီ; ; also spelt Gaba Aye Pagoda; lit. World Peace Pagoda), formally Thiri Mingala Gaba Aye Zedidaw, ), is a Buddhist pagoda located on Kaba Aye Road, Mayangon Township, Yangon, Myanma ...

and Maha Pasana Guha (Great Cave) in Rangoon

Yangon ( my, ရန်ကုန်; ; ), formerly spelled as Rangoon, is the capital of the Yangon Region and the largest city of Myanmar (also known as Burma). Yangon served as the capital of Myanmar until 2006, when the military government ...

(Yangon). It was attended by 2,500 monks, and established the International Institute for Advanced Buddhist studies, located on the premises of the Kaba Aye Pagoda. The main output of the council was the a new version of the Pali Canon, the "Sixth Council Tipitaka" (''Chaṭṭha Saṅgāyana Tipiṭaka'').

U Nu also led to make Buddhism as the State Religion

A state religion (also called religious state or official religion) is a religion or creed officially endorsed by a sovereign state. A state with an official religion (also known as confessional state), while not secular state, secular, is not n ...

. The Union Parliament

The Union Parliament ( my, ပြည်ထောင်စုလွှတ်တော်) was the bicameral legislature of the Union of Burma from 1948 to 1962, when it was disbanded by the Union Revolutionary Council. It consisted of an upper h ...

passed and the president Mahn Win Maung enacted the followings; the 1961 Act of the Third Amendment of the Constitution (that amended the 1947 Constitution to make Buddhism as State Religion) on 26 August 1961, and the State Religion Promotion and Support Act on 2 October 1961. U Nu also made the uposatha

The Uposatha ( sa, Upavasatha) is a Buddhist day of observance, in existence from the Buddha's time (600 BCE), and still being kept today by Buddhist practitioners. The Buddha taught that the Uposatha day is for "the cleansing of the defiled mind ...

days public holidays, required government schools to teach Buddhist students the Buddhist scriptures, banned cattle slaughter, and commuted some death sentences

Capital punishment, also known as the death penalty, is the state-sanctioned practice of deliberately killing a person as a punishment for an actual or supposed crime, usually following an authorized, rule-governed process to conclude that t ...

. While U Nu was overthrown as prime minister by Ne Win (who undid some of U Nu's religious policies) in 1962, he continued to travel and to teach Buddhism and remained an important Burmese spiritual leader and literary figure.

During the parliamentary era, Buddhism also became an ideological barrier against communism. Both U Nu and Burmese monk and philosopher U Kelatha argued that Buddhism had to counter the Marxist

Marxism is a Left-wing politics, left-wing to Far-left politics, far-left method of socioeconomic analysis that uses a Materialism, materialist interpretation of historical development, better known as historical materialism, to understand S ...