Bivalvia () or bivalves, in previous centuries referred to as the Lamellibranchiata and Pelecypoda, is a

class

Class, Classes, or The Class may refer to:

Common uses not otherwise categorized

* Class (biology), a taxonomic rank

* Class (knowledge representation), a collection of individuals or objects

* Class (philosophy), an analytical concept used d ...

of

aquatic mollusc

Mollusca is a phylum of protostome, protostomic invertebrate animals, whose members are known as molluscs or mollusks (). Around 76,000 extant taxon, extant species of molluscs are recognized, making it the second-largest animal phylum ...

s (marine and freshwater) that have laterally compressed soft bodies enclosed by a calcified

exoskeleton

An exoskeleton () . is a skeleton that is on the exterior of an animal in the form of hardened integument, which both supports the body's shape and protects the internal organs, in contrast to an internal endoskeleton (e.g. human skeleton, that ...

consisting of a hinged pair of half-

shell

Shell may refer to:

Architecture and design

* Shell (structure), a thin structure

** Concrete shell, a thin shell of concrete, usually with no interior columns or exterior buttresses

Science Biology

* Seashell, a hard outer layer of a marine ani ...

s known as

valve

A valve is a device or natural object that regulates, directs or controls the flow of a fluid (gases, liquids, fluidized solids, or Slurry, slurries) by opening, closing, or partially obstructing various passageways. Valves are technically Pip ...

s. As a group, bivalves have no

head

A head is the part of an organism which usually includes the ears, brain, forehead, cheeks, chin, eyes, nose, and mouth, each of which aid in various sensory functions such as sight, hearing, smell, and taste. Some very simple ani ...

and lack some typical molluscan organs such as the

radula

The radula (; : radulae or radulas) is an anatomical structure used by mollusks for feeding, sometimes compared to a tongue. It is a minutely toothed, chitinous ribbon, which is typically used for scraping or cutting food before the food enters ...

and the

odontophore. Their

gill

A gill () is a respiration organ, respiratory organ that many aquatic ecosystem, aquatic organisms use to extract dissolved oxygen from water and to excrete carbon dioxide. The gills of some species, such as hermit crabs, have adapted to allow r ...

s have evolved into

ctenidia, specialised organs for feeding and breathing.

Common bivalves include

clam

Clam is a common name for several kinds of bivalve mollusc. The word is often applied only to those that are deemed edible and live as infauna, spending most of their lives halfway buried in the sand of the sea floor or riverbeds. Clams h ...

s,

oyster

Oyster is the common name for a number of different families of salt-water bivalve molluscs that live in marine or brackish habitats. In some species, the valves are highly calcified, and many are somewhat irregular in shape. Many, but no ...

s,

cockles,

mussel

Mussel () is the common name used for members of several families of bivalve molluscs, from saltwater and Freshwater bivalve, freshwater habitats. These groups have in common a shell whose outline is elongated and asymmetrical compared with other ...

s,

scallops, and numerous other

families that live in saltwater, as well as a number of families that live in freshwater. Majority of the class are

benthic

The benthic zone is the ecological region at the lowest level of a body of water such as an ocean, lake, or stream, including the sediment surface and some sub-surface layers. The name comes from the Ancient Greek word (), meaning "the depths". ...

filter feeder

Filter feeders are aquatic animals that acquire nutrients by feeding on organic matters, food particles or smaller organisms (bacteria, microalgae and zooplanktons) suspended in water, typically by having the water pass over or through a s ...

s that bury themselves in sediment, where they are relatively safe from

predation

Predation is a biological interaction in which one organism, the predator, kills and eats another organism, its prey. It is one of a family of common List of feeding behaviours, feeding behaviours that includes parasitism and micropredation ...

. Others lie on the sea floor or attach themselves to rocks or other hard surfaces. Some bivalves, such as scallops and

file shells, can

swim.

Shipworms bore into wood, clay, or stone and live inside these substances.

The

shell

Shell may refer to:

Architecture and design

* Shell (structure), a thin structure

** Concrete shell, a thin shell of concrete, usually with no interior columns or exterior buttresses

Science Biology

* Seashell, a hard outer layer of a marine ani ...

of a bivalve is composed of

calcium carbonate

Calcium carbonate is a chemical compound with the chemical formula . It is a common substance found in Rock (geology), rocks as the minerals calcite and aragonite, most notably in chalk and limestone, eggshells, gastropod shells, shellfish skel ...

, and consists of two, usually similar, parts called

valves. These valves are for feeding and for disposal of waste. These are joined together along one edge (the

hinge line) by a flexible

ligament

A ligament is a type of fibrous connective tissue in the body that connects bones to other bones. It also connects flight feathers to bones, in dinosaurs and birds. All 30,000 species of amniotes (land animals with internal bones) have liga ...

that, usually in conjunction with interlocking "teeth" on each of the valves, forms the

hinge

A hinge is a mechanical bearing that connects two solid objects, typically allowing only a limited angle of rotation between them. Two objects connected by an ideal hinge rotate relative to each other about a fixed axis of rotation, with all ...

. This arrangement allows the shell to be opened and closed without the two halves detaching. The shell is typically

bilaterally symmetrical, with the hinge lying in the

sagittal plane

The sagittal plane (; also known as the longitudinal plane) is an anatomical plane that divides the body into right and left sections. It is perpendicular to the transverse and coronal planes. The plane may be in the center of the body and divi ...

. Adult shell sizes of bivalves vary from fractions of a millimetre to over a metre in length, but the majority of species do not exceed 10 cm (4 in).

Bivalves have long been a part of the diet of coastal and

riparian

A riparian zone or riparian area is the interface between land and a river or stream. In some regions, the terms riparian woodland, riparian forest, riparian buffer zone, riparian corridor, and riparian strip are used to characterize a ripar ...

human populations. Oysters were

cultured in ponds by the Romans, and

mariculture has more recently become an important source of bivalves for food. Modern knowledge of molluscan reproductive cycles has led to the development of hatcheries and new culture techniques. A better understanding of the potential

hazards of eating raw or undercooked

shellfish

Shellfish, in colloquial and fisheries usage, are exoskeleton-bearing Aquatic animal, aquatic invertebrates used as Human food, food, including various species of Mollusca, molluscs, crustaceans, and echinoderms. Although most kinds of shellfish ...

has led to improved storage and processing.

Pearl oysters (the common name of two very different families in salt water and fresh water) are the most common source of natural

pearl

A pearl is a hard, glistening object produced within the soft tissue (specifically the mantle (mollusc), mantle) of a living Exoskeleton, shelled mollusk or another animal, such as fossil conulariids. Just like the shell of a mollusk, a pear ...

s. The shells of bivalves are used in craftwork, and the manufacture of jewellery and buttons. Bivalves have also been used in the biocontrol of pollution.

Bivalves appear in the

fossil record

A fossil (from Classical Latin , ) is any preserved remains, impression, or trace of any once-living thing from a past geological age. Examples include bones, shells, exoskeletons, stone imprints of animals or microbes, objects preserved ...

first in the early

Cambrian

The Cambrian ( ) is the first geological period of the Paleozoic Era, and the Phanerozoic Eon. The Cambrian lasted 51.95 million years from the end of the preceding Ediacaran period 538.8 Ma (million years ago) to the beginning of the Ordov ...

more than 500 million years ago. The total number of known living

species

A species () is often defined as the largest group of organisms in which any two individuals of the appropriate sexes or mating types can produce fertile offspring, typically by sexual reproduction. It is the basic unit of Taxonomy (biology), ...

is about 9,200. These species are placed within 1,260 genera and 106 families. Marine bivalves (including

brackish water

Brackish water, sometimes termed brack water, is water occurring in a natural environment that has more salinity than freshwater, but not as much as seawater. It may result from mixing seawater (salt water) and fresh water together, as in estuary ...

and

estuarine species) represent about 8,000 species, combined in four subclasses and 99 families with 1,100 genera. The largest

recent marine families are the

Veneridae

The Veneridae or venerids, common name: Venus (mythology), Venus clams, are a very large family of minute to large, saltwater clams, marine bivalve molluscs. Over 500 living species of venerid bivalves are known, most of which are edible, and m ...

, with more than 680 species and the

Tellinidae and

Lucinidae, each with over 500 species. The freshwater bivalves include seven families, the largest of which are the

Unionidae

The Unionidae are a Family (biology), family of freshwater mussels, the largest in the order Unionida, the bivalve molluscs sometimes known as river mussels, or simply as unionids.

The range of distribution for this family is world-wide. It is a ...

, with about 700 species.

Etymology

The

taxonomic term Bivalvia was first used by

Linnaeus

Carl Linnaeus (23 May 1707 – 10 January 1778), also known after ennoblement in 1761 as Carl von Linné,#Blunt, Blunt (2004), p. 171. was a Swedish biologist and physician who formalised binomial nomenclature, the modern system of naming o ...

in the

10th edition of his ''

Systema Naturae

' (originally in Latin written ' with the Orthographic ligature, ligature æ) is one of the major works of the Sweden, Swedish botanist, zoologist and physician Carl Linnaeus (1707–1778) and introduced the Linnaean taxonomy. Although the syste ...

'' in 1758 to refer to animals having shells composed of two

valves. More recently, the class was known as Pelecypoda, meaning "

axe

An axe (; sometimes spelled ax in American English; American and British English spelling differences#Miscellaneous spelling differences, see spelling differences) is an implement that has been used for thousands of years to shape, split, a ...

-foot" (based on the shape of the foot of the animal when extended).

The name "bivalve" is derived from the

Latin

Latin ( or ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally spoken by the Latins (Italic tribe), Latins in Latium (now known as Lazio), the lower Tiber area aroun ...

, meaning 'two', and , meaning 'leaves of a door'.

("Leaf" is an older word for the main, movable part of a door. We normally consider this the door itself.) Paired shells have evolved independently several times among animals that are not bivalves; other animals with paired valves include certain

gastropod

Gastropods (), commonly known as slugs and snails, belong to a large Taxonomy (biology), taxonomic class of invertebrates within the phylum Mollusca called Gastropoda ().

This class comprises snails and slugs from saltwater, freshwater, and fro ...

s (small

sea snail

Sea snails are slow-moving marine (ocean), marine gastropod Mollusca, molluscs, usually with visible external shells, such as whelk or abalone. They share the Taxonomic classification, taxonomic class Gastropoda with slugs, which are distinguishe ...

s in the family

Juliidae), members of the phylum

Brachiopoda and the minute crustaceans known as

ostracods and

conchostracans.

Anatomy

Bivalves have

bilaterally symmetrical and laterally flattened bodies, with a blade-shaped foot, vestigial head and no

radula

The radula (; : radulae or radulas) is an anatomical structure used by mollusks for feeding, sometimes compared to a tongue. It is a minutely toothed, chitinous ribbon, which is typically used for scraping or cutting food before the food enters ...

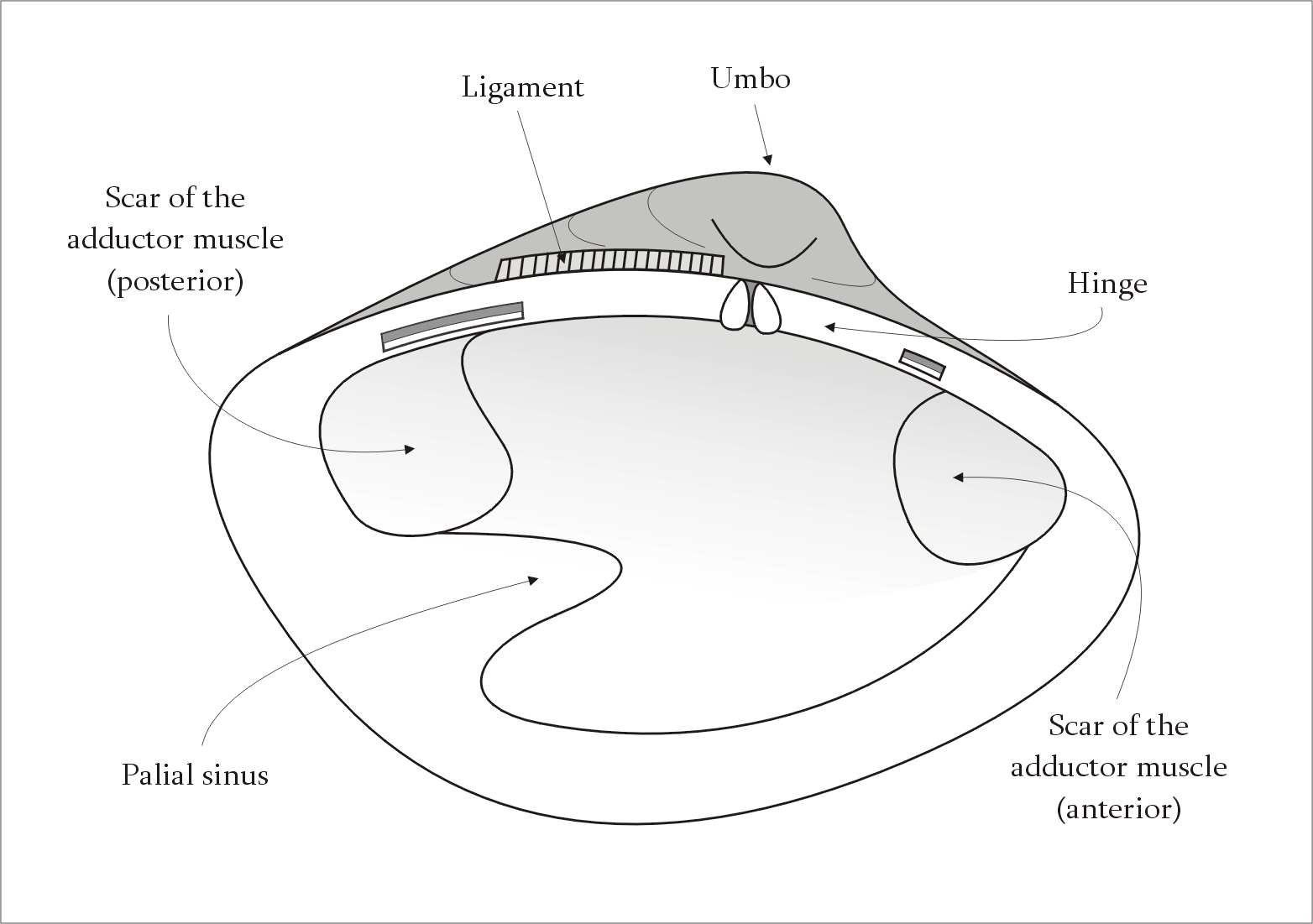

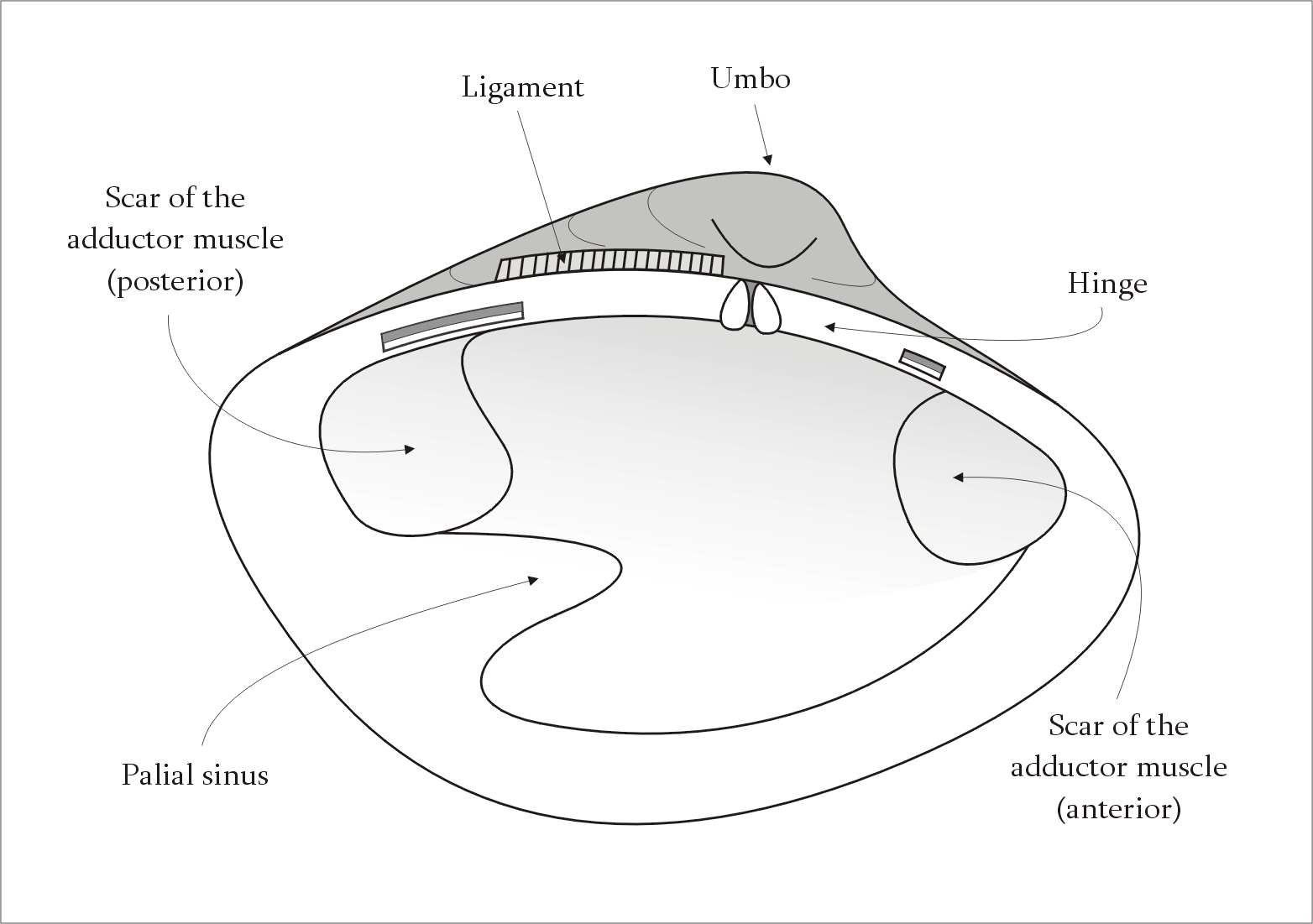

. At the dorsal or back region of the shell is the hinge point or line, which contain the

umbo and

beak

The beak, bill, or rostrum is an external anatomical structure found mostly in birds, but also in turtles, non-avian dinosaurs and a few mammals. A beak is used for pecking, grasping, and holding (in probing for food, eating, manipulating and ...

and the lower, curved margin is the ventral or underside region. The anterior or front of the shell is where the

byssus

A byssus () is a bundle of filaments secreted by many species of bivalve mollusc that function to attach the mollusc to a solid surface. Species from several families of clams have a byssus, including pen shells ( Pinnidae), true mussels (Mytili ...

(when present) and foot are located, and the posterior of the shell is where the siphons are located. With the hinge uppermost and with the anterior edge of the animal towards the viewer's left, the valve facing the viewer is the left valve and the opposing valve the right.

Many bivalves such as clams, which appear upright, are evolutionarily lying on their side.

Mantle and shell

The shell is composed of two

calcareous

Calcareous () is an adjective meaning "mostly or partly composed of calcium carbonate", in other words, containing lime (mineral), lime or being chalky. The term is used in a wide variety of Science, scientific disciplines.

In zoology

''Calcare ...

valves held together by a ligament. The valves are made of either

calcite

Calcite is a Carbonate minerals, carbonate mineral and the most stable Polymorphism (materials science), polymorph of calcium carbonate (CaCO3). It is a very common mineral, particularly as a component of limestone. Calcite defines hardness 3 on ...

, as is the case in oysters, or both calcite and

aragonite

Aragonite is a carbonate mineral and one of the three most common naturally occurring crystal forms of calcium carbonate (), the others being calcite and vaterite. It is formed by biological and physical processes, including precipitation fr ...

. Sometimes, the aragonite forms an inner,

nacreous layer, as is the case in the order

Pteriida. In other

taxa

In biology, a taxon (back-formation from ''taxonomy''; : taxa) is a group of one or more populations of an organism or organisms seen by taxonomists to form a unit. Although neither is required, a taxon is usually known by a particular name and ...

, alternate layers of calcite and aragonite are laid down.

The ligament and byssus, if calcified, are composed of aragonite.

The outermost layer of the shell is the

periostracum, a thin layer composed of horny

conchiolin. The periostracum is secreted by the outer mantle and is easily abraded. The outer surface of the valves is often sculpted, with clams often having concentric striations, scallops having radial ribs and oysters a latticework of irregular markings.

In all molluscs, the

mantle forms a thin

membrane

A membrane is a selective barrier; it allows some things to pass through but stops others. Such things may be molecules, ions, or other small particles. Membranes can be generally classified into synthetic membranes and biological membranes. Bi ...

that covers the animal's body and extends out from it in flaps or lobes. In bivalves, the mantle lobes secrete the valves, and the mantle crest secretes the whole hinge mechanism consisting of

ligament

A ligament is a type of fibrous connective tissue in the body that connects bones to other bones. It also connects flight feathers to bones, in dinosaurs and birds. All 30,000 species of amniotes (land animals with internal bones) have liga ...

, byssus threads (where present), and

teeth

A tooth (: teeth) is a hard, calcified structure found in the jaws (or mouths) of many vertebrates and used to break down food. Some animals, particularly carnivores and omnivores, also use teeth to help with capturing or wounding prey, tear ...

.

The posterior mantle edge may have two elongated extensions known as

siphons, through one of which water is inhaled, and the other expelled. The siphons retract into a cavity, known as the

pallial sinus.

The shell grows larger when more material is secreted by the mantle edge, and the valves themselves thicken as more material is secreted from the general mantle surface. Calcareous matter comes from both its diet and the surrounding seawater. Concentric rings on the exterior of a valve are commonly used to age bivalves. For some groups, a more precise method for determining the age of a shell is by cutting a cross section through it and examining the incremental growth bands.

The

shipworms, in the family

Teredinidae have greatly elongated bodies, but their shell valves are much reduced and restricted to the anterior end of the body, where they function as scraping organs that permit the animal to dig tunnels through wood.

Muscles and ligaments

The main muscular system in bivalves is the

posterior and anterior adductor muscles. These muscles connect the two valves and contract to close the shell. The valves are also joined dorsally by the hinge

ligament

A ligament is a type of fibrous connective tissue in the body that connects bones to other bones. It also connects flight feathers to bones, in dinosaurs and birds. All 30,000 species of amniotes (land animals with internal bones) have liga ...

, which is an extension of the periostracum. The ligament is responsible for opening the shell, and works against the adductor muscles when the animal opens and closes. Retractor muscles connect the mantle to the edge of the shell, along a line known as the

pallial line.

[ These muscles pull the mantle though the valves.][

In sedentary or recumbent bivalves that lie on one valve, such as the oysters and scallops, the anterior adductor muscle has been lost and the posterior muscle is positioned centrally. In species that can swim by flapping their valves, a single, central adductor muscle occurs. These muscles are composed of two types of muscle fibres, striated muscle bundles for fast actions and smooth muscle bundles for maintaining a steady pull. Paired pedal protractor and retractor muscles operate the animal's foot.]

Nervous system

The sedentary habits of the bivalves have meant that in general the nervous system

In biology, the nervous system is the complex system, highly complex part of an animal that coordinates its behavior, actions and sense, sensory information by transmitting action potential, signals to and from different parts of its body. Th ...

is less complex than in most other molluscs. The animals have no brain

The brain is an organ (biology), organ that serves as the center of the nervous system in all vertebrate and most invertebrate animals. It consists of nervous tissue and is typically located in the head (cephalization), usually near organs for ...

; the nervous system consists of a nerve network and a series of paired ganglia

A ganglion (: ganglia) is a group of neuron cell bodies in the peripheral nervous system. In the somatic nervous system, this includes dorsal root ganglia and trigeminal ganglia among a few others. In the autonomic nervous system, there a ...

. In all but the most primitive bivalves, two cerebropleural ganglia are on either side of the oesophagus

The esophagus (American English), oesophagus (British English), or œsophagus ( archaic spelling) ( see spelling difference) all ; : ((o)e)(œ)sophagi or ((o)e)(œ)sophaguses), colloquially known also as the food pipe, food tube, or gullet, ...

. The cerebral ganglia control the sensory organs, while the pleural ganglia supply nerves to the mantle cavity. The pedal ganglia, which control the foot, are at its base, and the visceral ganglia, which can be quite large in swimming bivalves, are under the posterior adductor muscle. These ganglia are both connected to the cerebropleural ganglia by nerve fibres. Bivalves with long siphons may also have siphonal ganglia to control them.[

]

Senses

The sensory organs of bivalves are largely located on the posterior mantle margins. The organs are usually mechanoreceptor

A mechanoreceptor, also called mechanoceptor, is a sensory receptor that responds to mechanical pressure or distortion. Mechanoreceptors are located on sensory neurons that convert mechanical pressure into action potential, electrical signals tha ...

s or chemoreceptor

A chemoreceptor, also known as chemosensor, is a specialized sensory receptor which transduces a chemical substance ( endogenous or induced) to generate a biological signal. This signal may be in the form of an action potential, if the chemorece ...

s, in some cases located on short tentacle

In zoology, a tentacle is a flexible, mobile, and elongated organ present in some species of animals, most of them invertebrates. In animal anatomy, tentacles usually occur in one or more pairs. Anatomically, the tentacles of animals work main ...

s. The osphradium is a patch of sensory cells located below the posterior adductor muscle that may serve to taste the water or measure its turbidity. Statocyst

The statocyst is a balance sensory receptor present in some aquatic invertebrates, including bivalves, cnidarians, ctenophorans, echinoderms, cephalopods, crustaceans, and gastropods, A similar structure is also found in '' Xenoturbella''. T ...

s within the organism help the bivalve to sense and correct its orientation.lens

A lens is a transmissive optical device that focuses or disperses a light beam by means of refraction. A simple lens consists of a single piece of transparent material, while a compound lens consists of several simple lenses (''elements'') ...

.retina

The retina (; or retinas) is the innermost, photosensitivity, light-sensitive layer of tissue (biology), tissue of the eye of most vertebrates and some Mollusca, molluscs. The optics of the eye create a focus (optics), focused two-dimensional ...

, and a concave mirror. All bivalves have light-sensitive cells that can detect a shadow falling over the animal.

Circulation and respiration

Bivalves have an open

Bivalves have an open circulatory system

In vertebrates, the circulatory system is a system of organs that includes the heart, blood vessels, and blood which is circulated throughout the body. It includes the cardiovascular system, or vascular system, that consists of the heart ...

that bathes the organs in blood ( hemolymph). The heart

The heart is a muscular Organ (biology), organ found in humans and other animals. This organ pumps blood through the blood vessels. The heart and blood vessels together make the circulatory system. The pumped blood carries oxygen and nutrie ...

has three chambers: two auricles receiving blood from the gills, and a single ventricle. The ventricle is muscular and pumps hemolymph into the aorta

The aorta ( ; : aortas or aortae) is the main and largest artery in the human body, originating from the Ventricle (heart), left ventricle of the heart, branching upwards immediately after, and extending down to the abdomen, where it splits at ...

, and then to the rest of the body. Some bivalves have a single aorta, but most also have a second, usually smaller, aorta serving the hind parts of the animal. The hemolymph usually lacks any respiratory pigment. In the carnivorous genus '' Poromya'', the hemolymph has red amoebocyte

An amebocyte or amoebocyte () is a motile cell (moving like an amoeba) in the bodies of invertebrates including cnidaria, echinoderms, mollusca, molluscs, tunicates, sponges, and some chelicerata, chelicerates.

Moving by pseudopodia, amebocytes c ...

s containing a haemoglobin pigment.gas exchange

Gas exchange is the physical process by which gases move passively by diffusion across a surface. For example, this surface might be the air/water interface of a water body, the surface of a gas bubble in a liquid, a gas-permeable membrane, or a b ...

. The respiratory demands of bivalves are low, due to their relative inactivity. Some freshwater species, when exposed to the air, can gape the shell slightly and gas exchange can take place. Oysters, including the Pacific oyster

The Pacific oyster, Japanese oyster, or Miyagi oyster (''Magallana gigas'') is an oyster native to the Pacific coast of Asia. It has become an introduced species in North America, Australia, Europe, and New Zealand.

Etymology

The genus ''Magal ...

(''Magallana gigas''), are recognized as having varying metabolic responses to environmental stress, with changes in respiration rate being frequently observed.

Digestive system

Modes of feeding

Most bivalves are filter feeder

Filter feeders are aquatic animals that acquire nutrients by feeding on organic matters, food particles or smaller organisms (bacteria, microalgae and zooplanktons) suspended in water, typically by having the water pass over or through a s ...

s, using their gills to capture particulate food such as phytoplankton

Phytoplankton () are the autotrophic (self-feeding) components of the plankton community and a key part of ocean and freshwater Aquatic ecosystem, ecosystems. The name comes from the Greek language, Greek words (), meaning 'plant', and (), mea ...

from the water. Protobranchs feed in a different way, scraping detritus from the seabed, and this may be the original mode of feeding used by all bivalves before the gills became adapted for filter feeding. These primitive bivalves hold on to the bottom with a pair of tentacles at the edge of the mouth, each of which has a single palp, or flap. The tentacles are covered in mucus

Mucus (, ) is a slippery aqueous secretion produced by, and covering, mucous membranes. It is typically produced from cells found in mucous glands, although it may also originate from mixed glands, which contain both Serous fluid, serous and muc ...

, which traps the food, and cilia, which transport the particles back to the palps. These then sort the particles, rejecting those that are unsuitable or too large to digest, and conveying others to the mouth.[

In more advanced bivalves, water is drawn into the shell from the posterior ]ventral

Standard anatomical terms of location are used to describe unambiguously the anatomy of humans and other animals. The terms, typically derived from Latin or Greek roots, describe something in its standard anatomical position. This position prov ...

surface of the animal, passes upwards through the gills, and doubles back to be expelled just above the intake. There may be two elongated, retractable siphons reaching up to the seabed, one each for the inhalant and exhalant streams of water. The gills of filter-feeding bivalves are known as ctenidia and have become highly modified to increase their ability to capture food. For example, the cilia

The cilium (: cilia; ; in Medieval Latin and in anatomy, ''cilium'') is a short hair-like membrane protrusion from many types of eukaryotic cell. (Cilia are absent in bacteria and archaea.) The cilium has the shape of a slender threadlike proj ...

on the gills, which originally served to remove unwanted sediment, have become adapted to capture food particles, and transport them in a steady stream of mucus to the mouth. The filaments of the gills are also much longer than those in more primitive bivalves, and are folded over to create a groove through which food can be transported. The structure of the gills varies considerably, and can serve as a useful means for classifying bivalves into groups.carnivorous

A carnivore , or meat-eater (Latin, ''caro'', genitive ''carnis'', meaning meat or "flesh" and ''vorare'' meaning "to devour"), is an animal or plant whose nutrition and energy requirements are met by consumption of animal tissues (mainly mu ...

, eating much larger prey

Predation is a biological interaction in which one organism, the predator, kills and eats another organism, its prey. It is one of a family of common feeding behaviours that includes parasitism and micropredation (which usually do not ki ...

than the tiny microalgae consumed by other bivalves. Muscles draw water in through the inhalant siphon which is modified into a cowl-shaped organ, sucking in prey. The siphon can be retracted quickly and inverted, bringing the prey within reach of the mouth. The gut is modified so that large food particles can be digested.endosymbiotic

An endosymbiont or endobiont is an organism that lives within the body or cells of another organism. Typically the two organisms are in a mutualistic relationship. Examples are nitrogen-fixing bacteria (called rhizobia), which live in the root ...

, being found only in the oesophagus of sea cucumbers. It has mantle folds that completely surround its small valves. When the sea cucumber sucks in sediment, the bivalve allows the water to pass over its gills and extracts fine organic particles. To prevent itself from being swept away, it attaches itself with byssal threads to the host's throat. The sea cucumber is unharmed.

Digestive tract

The digestive tract of typical bivalves consists of an oesophagus

The esophagus (American English), oesophagus (British English), or œsophagus ( archaic spelling) ( see spelling difference) all ; : ((o)e)(œ)sophagi or ((o)e)(œ)sophaguses), colloquially known also as the food pipe, food tube, or gullet, ...

, stomach

The stomach is a muscular, hollow organ in the upper gastrointestinal tract of Human, humans and many other animals, including several invertebrates. The Ancient Greek name for the stomach is ''gaster'' which is used as ''gastric'' in medical t ...

, and intestine

The gastrointestinal tract (GI tract, digestive tract, alimentary canal) is the tract or passageway of the digestive system that leads from the mouth to the anus. The tract is the largest of the body's systems, after the cardiovascular system. T ...

. Protobranch stomachs have a mere sac attached to them while filter-feeding bivalves have elongated rod of solidified mucus referred to as the " crystalline style" projected into the stomach from an associated sac. Cilia in the sac cause the style to rotate, winding in a stream of food-containing mucus from the mouth, and churning the stomach contents. This constant motion propels food particles into a sorting region at the rear of the stomach, which distributes smaller particles into the digestive glands, and heavier particles into the intestine. Waste material is consolidated in the rectum and voided as pellets into the exhalent water stream through an anal pore. Feeding and digestion are synchronized with diurnal and tidal cycles.

Carnivorous bivalves generally have reduced crystalline styles and the stomach has thick, muscular walls, extensive cuticular linings and diminished sorting areas and gastric chamber sections.

Excretory system

The excretory organs of bivalves are a pair of nephridia

The nephridium (: nephridia) is an invertebrate organ, found in pairs and performing a function similar to the vertebrate kidneys (which originated from the chordate nephridia). Nephridia remove metabolic wastes from an animal's body. Nephridia co ...

. Each of these consists of a long, looped, glandular tube, which opens into the pericardium

The pericardium (: pericardia), also called pericardial sac, is a double-walled sac containing the heart and the roots of the great vessels. It has two layers, an outer layer made of strong inelastic connective tissue (fibrous pericardium), ...

, and a bladder

The bladder () is a hollow organ in humans and other vertebrates that stores urine from the kidneys. In placental mammals, urine enters the bladder via the ureters and exits via the urethra during urination. In humans, the bladder is a distens ...

to store urine. They also have pericardial glands either line the auricles of the heart or attach to the pericardium, and serve as extra filtration organs. Metabolic waste is voided from the bladders through a nephridiopore near the front of the upper part of the mantle cavity and excreted.

Reproduction and development

The sexes are usually separate in bivalves but some hermaphroditism is known. The gonad

A gonad, sex gland, or reproductive gland is a Heterocrine gland, mixed gland and sex organ that produces the gametes and sex hormones of an organism. Female reproductive cells are egg cells, and male reproductive cells are sperm. The male gon ...

s either open into the nephridia or through a separate pore into a chamber over the gills.Spawning

Spawn is the Egg cell, eggs and Spermatozoa, sperm released or deposited into water by aquatic animals. As a verb, ''to spawn'' refers to the process of freely releasing eggs and sperm into a body of water (fresh or marine); the physical act is ...

may take place continually or be triggered by environmental factors such as day length, water temperature, or the presence of sperm in the water. Some species are "dribble spawners", releasing gametes during protracted period that can extend for weeks. Others are mass spawners and release their gametes in batches or all at once.

Fertilization is usually external. Typically, a short stage lasts a few hours or days before the eggs hatch into trochophore

A trochophore () is a type of free-swimming planktonic marine larva with several bands of cilia.

By moving their cilia rapidly, they make a water eddy to control their movement, and to bring their food closer in order to capture it more easily.

...

larvae. These later develop into veliger

A veliger is the planktonic larva of many kinds of sea snails and freshwater snails, as well as most bivalve molluscs (clams) and tusk shells.

Description

The veliger is the characteristic larva of the gastropod, bivalve and scaphopod taxono ...

larvae which settle on the seabed and undergo metamorphosis

Metamorphosis is a biological process by which an animal physically develops including birth transformation or hatching, involving a conspicuous and relatively abrupt change in the animal's body structure through cell growth and different ...

into adults.diatom

A diatom (Neo-Latin ''diatoma'') is any member of a large group comprising several Genus, genera of algae, specifically microalgae, found in the oceans, waterways and soils of the world. Living diatoms make up a significant portion of Earth's B ...

s or other phytoplankton. In temperate

In geography, the temperate climates of Earth occur in the middle latitudes (approximately 23.5° to 66.5° N/S of the Equator), which span between the tropics and the polar regions of Earth. These zones generally have wider temperature ran ...

regions, about 25% of species are lecithotrophic, depending on nutrients stored in the yolk of the egg where the main energy source is lipid

Lipids are a broad group of organic compounds which include fats, waxes, sterols, fat-soluble vitamins (such as vitamins A, D, E and K), monoglycerides, diglycerides, phospholipids, and others. The functions of lipids include storing ...

s. The longer the period is before the larva first feeds, the larger the egg and yolk need to be. The reproductive cost of producing these energy-rich eggs is high and they are usually smaller in number. For example, the Baltic tellin ('' Macoma balthica'') produces few, high-energy eggs. The larvae hatching out of these rely on the energy reserves and do not feed. After about four days, they become D-stage larvae, when they first develop hinged, D-shaped valves. These larvae have a relatively small dispersal potential before settling out. The common mussel (''Mytilus edulis

The blue mussel (''Mytilus edulis''), also known as the common mussel, is a medium-sized edible marine (ocean), marine bivalve mollusc in the family (biology), family Mytilidae, the only extant family in the order (biology), order Mytilida, known ...

'') produces 10 times as many eggs that hatch into larvae and soon need to feed to survive and grow. They can disperse more widely as they remain planktonic for a much longer time.

Freshwater bivalves have different lifecycle. Sperm is drawn into a female's gills with the inhalant water and internal fertilization takes place. The eggs hatch into glochidia larvae that develop within the female's shell. Later they are released and attach themselves parasitically to the gills or fins of a fish host. After several weeks they drop off their host, undergo metamorphosis and develop into adults on the substrate.Unionidae

The Unionidae are a Family (biology), family of freshwater mussels, the largest in the order Unionida, the bivalve molluscs sometimes known as river mussels, or simply as unionids.

The range of distribution for this family is world-wide. It is a ...

, commonly known as pocketbook mussels, have evolved an unusual reproductive strategy. The female's mantle protrudes from the shell and develops into an imitation small fish, complete with fish-like markings and false eyes. This decoy moves in the current and attracts the attention of real fish. Some fish see the decoy as prey, while others see a conspecific

Biological specificity is the tendency of a characteristic such as a behavior or a biochemical variation to occur in a particular species.

Biochemist Linus Pauling stated that "Biological specificity is the set of characteristics of living organism ...

. They approach for a closer look and the mussel releases huge numbers of larvae from its gills, dousing the inquisitive fish with its tiny, parasitic young. These glochidia larvae are drawn into the fish's gills, where they attach and trigger a tissue response that forms a small cyst around each larva. The larvae then feed by breaking down and digesting the tissue of the fish within the cysts. After a few weeks they release themselves from the cysts and fall to the stream bed as juvenile molluscs.

Comparison with brachiopods

Brachiopod

Brachiopods (), phylum (biology), phylum Brachiopoda, are a phylum of animals that have hard "valves" (shells) on the upper and lower surfaces, unlike the left and right arrangement in bivalve molluscs. Brachiopod valves are hinged at the rear e ...

s are shelled marine organisms that superficially resemble bivalves in that they are of similar size and have a hinged shell in two parts. However, brachiopods evolved from a very different ancestral line, and the resemblance to bivalves only arose because they occupy similar ecological niche

In ecology, a niche is the match of a species to a specific environmental condition.

Three variants of ecological niche are described by

It describes how an organism or population responds to the distribution of Resource (biology), resources an ...

s. The differences between the two groups are due to their separate ancestral origins. Different initial structures have been adapted to solve the same problems, a case of convergent evolution

Convergent evolution is the independent evolution of similar features in species of different periods or epochs in time. Convergent evolution creates analogous structures that have similar form or function but were not present in the last comm ...

. In modern times, brachiopods are not as common as bivalves.

Both groups have a shell consisting of two valves, but the organization of the shell is quite different in the two groups. In brachiopods, the two valves are positioned on the dorsal and ventral surfaces of the body, while in bivalves, the valves are on the left and right sides of the body, and are, in most cases, mirror images of one other. Brachiopods have a lophophore, a coiled, rigid cartilaginous internal apparatus adapted for filter feeding, a feature shared with two other major groups of marine invertebrates, the bryozoa

Bryozoa (also known as the Polyzoa, Ectoprocta or commonly as moss animals) are a phylum of simple, aquatic animal, aquatic invertebrate animals, nearly all living in sedentary Colony (biology), colonies. Typically about long, they have a spe ...

ns and the phoronids. Some brachiopod shells are made of calcium phosphate but most are calcium carbonate

Calcium carbonate is a chemical compound with the chemical formula . It is a common substance found in Rock (geology), rocks as the minerals calcite and aragonite, most notably in chalk and limestone, eggshells, gastropod shells, shellfish skel ...

in the form of the biomineral calcite

Calcite is a Carbonate minerals, carbonate mineral and the most stable Polymorphism (materials science), polymorph of calcium carbonate (CaCO3). It is a very common mineral, particularly as a component of limestone. Calcite defines hardness 3 on ...

, whereas bivalve shells are always composed entirely of calcium carbonate, often in the form of the biomineral aragonite

Aragonite is a carbonate mineral and one of the three most common naturally occurring crystal forms of calcium carbonate (), the others being calcite and vaterite. It is formed by biological and physical processes, including precipitation fr ...

.

Evolutionary history

The Cambrian explosion took place around 540 to 520 million years ago (Mya). In this geologically brief period, most major animal phyla

Phyla, the plural of ''phylum'', may refer to:

* Phylum, a biological taxon between Kingdom and Class

* by analogy, in linguistics, a large division of possibly related languages, or a major language family which is not subordinate to another

Phy ...

diverged including some of the first creatures with mineralized skeletons. Brachiopods and bivalves made their appearance at this time, and left their fossilized remains behind in the rocks.Devonian

The Devonian ( ) is a period (geology), geologic period and system (stratigraphy), system of the Paleozoic era (geology), era during the Phanerozoic eon (geology), eon, spanning 60.3 million years from the end of the preceding Silurian per ...

and Carboniferous

The Carboniferous ( ) is a Geologic time scale, geologic period and System (stratigraphy), system of the Paleozoic era (geology), era that spans 60 million years, from the end of the Devonian Period Ma (million years ago) to the beginning of the ...

periods, siphons first appeared, which, with the newly developed muscular foot, allowed the animals to bury themselves deep in the sediment.Paleozoic

The Paleozoic ( , , ; or Palaeozoic) Era is the first of three Era (geology), geological eras of the Phanerozoic Eon. Beginning 538.8 million years ago (Ma), it succeeds the Neoproterozoic (the last era of the Proterozoic Eon) and ends 251.9 Ma a ...

, around 400 Mya, the brachiopods were among the most abundant filter feeders in the ocean, and over 12,000 fossil species are recognized. By the Permian–Triassic extinction event

The Permian–Triassic extinction event (also known as the P–T extinction event, the Late Permian extinction event, the Latest Permian extinction event, the End-Permian extinction event, and colloquially as the Great Dying,) was an extinction ...

250 Mya, bivalves were undergoing a huge radiation

In physics, radiation is the emission or transmission of energy in the form of waves or particles through space or a material medium. This includes:

* ''electromagnetic radiation'' consisting of photons, such as radio waves, microwaves, infr ...

of diversity. The bivalves were hard hit by this event, but re-established themselves and thrived during the Triassic

The Triassic ( ; sometimes symbolized 🝈) is a geologic period and system which spans 50.5 million years from the end of the Permian Period 251.902 million years ago ( Mya), to the beginning of the Jurassic Period 201.4 Mya. The Triassic is t ...

period that followed. In contrast, the brachiopods lost 95% of their species diversity.buoyancy

Buoyancy (), or upthrust, is the force exerted by a fluid opposing the weight of a partially or fully immersed object (which may be also be a parcel of fluid). In a column of fluid, pressure increases with depth as a result of the weight of t ...

in soft sediments by developing spines on the shell, gaining the ability to swim, and in a few cases, adopting predatory habits.extinction event

An extinction event (also known as a mass extinction or biotic crisis) is a widespread and rapid decrease in the biodiversity on Earth. Such an event is identified by a sharp fall in the diversity and abundance of multicellular organisms. It occ ...

s.

Diversity of extant bivalves

The adult maximum size of living

Living or The Living may refer to:

Common meanings

*Life, a condition that distinguishes organisms from inorganic objects and dead organisms

** Living species, one that is not extinct

*Personal life, the course of an individual human's life

* ...

species of bivalve ranges from in '' Condylonucula maya'', a nut clam, to a length of in '' Kuphus polythalamia'', an elongated, burrowing shipworm. However, the species generally regarded as the largest living bivalve is the giant clam '' Tridacna gigas'', which can grow to a length of and a weight of more than 200 kg (441 lb). The largest known extinct

Extinction is the termination of an organism by the death of its Endling, last member. A taxon may become Functional extinction, functionally extinct before the death of its last member if it loses the capacity to Reproduction, reproduce and ...

bivalve is a species of ''Platyceramus

''Platyceramus'' was a genus of Cretaceous bivalve molluscs belonging to the extinct inoceramid lineage. It is sometimes classified as a subgenus of ''Inoceramus''.

Size

The largest and best known species is ''P. platinus''. Individuals of this ...

'' whose fossils measure up to in length.

In his 2010 treatise, ''Compendium of Bivalves'', Markus Huber gives the total number of living bivalve species as about 9,200 combined in 106 families. Huber states that the number of 20,000 living species, often encountered in literature, could not be verified and presents the following table to illustrate the known diversity:

Distribution

The bivalves are a highly successful class of invertebrates found in aquatic habitats throughout the world. Most are infaunal and live buried in sediment on the seabed, or in the sediment in freshwater habitats. A large number of bivalve species are found in the intertidal and sublittoral zones of the oceans. A sandy sea beach may superficially appear to be devoid of life, but often a very large number of bivalves and other invertebrates are living beneath the surface of the sand. On a large beach in

The bivalves are a highly successful class of invertebrates found in aquatic habitats throughout the world. Most are infaunal and live buried in sediment on the seabed, or in the sediment in freshwater habitats. A large number of bivalve species are found in the intertidal and sublittoral zones of the oceans. A sandy sea beach may superficially appear to be devoid of life, but often a very large number of bivalves and other invertebrates are living beneath the surface of the sand. On a large beach in South Wales

South Wales ( ) is a Regions of Wales, loosely defined region of Wales bordered by England to the east and mid Wales to the north. Generally considered to include the Historic counties of Wales, historic counties of Glamorgan and Monmouthshire ( ...

, careful sampling produced an estimate of 1.44 million cockles ('' Cerastoderma edule'') per acre of beach.hydrogen sulphide

Hydrogen sulfide is a chemical compound with the formula . It is a colorless chalcogen-hydride gas, and is toxic, corrosive, and flammable. Trace amounts in ambient atmosphere have a characteristic foul odor of rotten eggs. Swedish chemist Ca ...

, and the molluscs absorb nutrients synthesized by these bacteria. Some species are found in the hadal zone, like Vesicomya sergeevi, which occurs at depths of 7600–9530 meters. The saddle oyster, '' Enigmonia aenigmatica'', is a marine species that could be considered amphibious. It lives above the high tide mark in the tropical Indo-Pacific on the underside of mangrove

A mangrove is a shrub or tree that grows mainly in coastal saline water, saline or brackish water. Mangroves grow in an equatorial climate, typically along coastlines and tidal rivers. They have particular adaptations to take in extra oxygen a ...

leaves, on mangrove branches, and on sea walls in the splash zone.

Some freshwater bivalves have very restricted ranges. For example, the Ouachita creekshell mussel, '' Villosa arkansasensis'', is known only from the streams of the Ouachita Mountains

The Ouachita Mountains (), simply referred to as the Ouachitas, are a mountain range in western Arkansas and southeastern Oklahoma. They are formed by a thick succession of highly deformed Paleozoic strata constituting the Ouachita Fold and Thru ...

in Arkansas and Oklahoma, and like several other freshwater mussel species from the southeastern US, it is in danger of extinction. In contrast, a few species of freshwater bivalves, including the golden mussel (''Limnoperna fortunei

''Limnoperna fortunei'', the golden mussel, is a medium-sized Fresh water, freshwater Bivalvia, bivalve mollusc of the Family (biology), family Mytilidae. The native range of the species is China, but it has accidentally been introduced to South ...

''), are dramatically increasing their ranges. The golden mussel has spread from Southeast Asia to Argentina, where it has become an invasive species

An invasive species is an introduced species that harms its new environment. Invasive species adversely affect habitats and bioregions, causing ecological, environmental, and/or economic damage. The term can also be used for native spec ...

. Another well-travelled freshwater bivalve, the zebra mussel ('' Dreissena polymorpha'') originated in southeastern Russia, and has been accidentally introduced to inland waterways in North America and Europe, where the species damages water installations and disrupts local ecosystem

An ecosystem (or ecological system) is a system formed by Organism, organisms in interaction with their Biophysical environment, environment. The Biotic material, biotic and abiotic components are linked together through nutrient cycles and en ...

s.

Behaviour

Most bivalves adopt a sedentary or even sessile lifestyle, often spending their whole lives in the area in which they first settled as juveniles. The majority of bivalves are infaunal, living under the seabed, buried in soft substrates such as sand, silt, mud, gravel, or coral fragments. Many of these live in the

Most bivalves adopt a sedentary or even sessile lifestyle, often spending their whole lives in the area in which they first settled as juveniles. The majority of bivalves are infaunal, living under the seabed, buried in soft substrates such as sand, silt, mud, gravel, or coral fragments. Many of these live in the intertidal zone

The intertidal zone or foreshore is the area above water level at low tide and underwater at high tide; in other words, it is the part of the littoral zone within the tidal range. This area can include several types of habitats with various ...

where the sediment remains damp even when the tide is out. When buried in the sediment, burrowing bivalves are protected from the pounding of waves, desiccation, and overheating during low tide, and variations in salinity caused by rainwater. They are also out of the reach of many predators.mussel

Mussel () is the common name used for members of several families of bivalve molluscs, from saltwater and Freshwater bivalve, freshwater habitats. These groups have in common a shell whose outline is elongated and asymmetrical compared with other ...

s, attach themselves to hard surfaces using tough byssus

A byssus () is a bundle of filaments secreted by many species of bivalve mollusc that function to attach the mollusc to a solid surface. Species from several families of clams have a byssus, including pen shells ( Pinnidae), true mussels (Mytili ...

threads made of collagen

Collagen () is the main structural protein in the extracellular matrix of the connective tissues of many animals. It is the most abundant protein in mammals, making up 25% to 35% of protein content. Amino acids are bound together to form a trip ...

and elastin

Elastin is a protein encoded by the ''ELN'' gene in humans and several other animals. Elastin is a key component in the extracellular matrix of gnathostomes (jawed vertebrates). It is highly Elasticity (physics), elastic and present in connective ...

proteins. Some species, including the true oysters, the jewel boxes, the jingle shells, the thorny oysters and the kitten's paws, cement themselves to stones, rock or larger dead shells.neritic zone

The neritic zone (or sublittoral zone) is the relatively shallow part of the ocean above the drop-off of the continental shelf, approximately in depth.

From the point of view of marine biology it forms a relatively stable and well-illuminate ...

and, like most bivalves, are filter feeders.

Predators and defence

The thick shell and rounded shape of bivalves make them awkward for potential predators to tackle. Nevertheless, a number of different creatures include them in their diet. Many species of demersal fish feed on them including the common carp (''Cyprinus carpio''), which is being used in the upper Mississippi River to try to control the invasive zebra mussel (''Dreissena polymorpha''). Birds such as the Eurasian oystercatcher (''Haematopus ostralegus'') have specially adapted beaks which can pry open their shells. The herring gull (''Larus argentatus'') sometimes drops heavy shells onto rocks in order to crack them open. Sea otter

The sea otter (''Enhydra lutris'') is a marine mammal native to the coasts of the northern and eastern Pacific Ocean, North Pacific Ocean. Adult sea otters typically weigh between , making them the heaviest members of ...

s feed on a variety of bivalve species and have been observed to use stones balanced on their chests as anvils on which to crack open the shells. The Pacific walrus (''Odobenus rosmarus divergens'') is one of the main predators feeding on bivalves in Arctic waters. Shellfish have formed part of the human diet since prehistoric times, a fact evidenced by the remains of mollusc shells found in ancient middens. Examinations of these deposits in Peru has provided a means of dating long past El Niño events because of the disruption these caused to bivalve shell growth.radula

The radula (; : radulae or radulas) is an anatomical structure used by mollusks for feeding, sometimes compared to a tongue. It is a minutely toothed, chitinous ribbon, which is typically used for scraping or cutting food before the food enters ...

assisted by a shell-dissolving secretion. The dog whelk then inserts its extendible proboscis and sucks out the body contents of the victim, which is typically a blue mussel.

Razor shells can dig themselves into the sand with great speed to escape predation. When a Pacific razor clam (''Siliqua patula'') is laid on the surface of the beach, it can bury itself completely in seven seconds and the Atlantic jackknife clam, ''Ensis directus'', can do the same within fifteen seconds. Scallops and file clams can swim by opening and closing their valves rapidly; water is ejected on either side of the hinge area and they move with the flapping valves in front.siphon

A siphon (; also spelled syphon) is any of a wide variety of devices that involve the flow of liquids through tubes. In a narrower sense, the word refers particularly to a tube in an inverted "U" shape, which causes a liquid to flow upward, abo ...

s, they can be retracted back into the safety of the shell. If the siphons inadvertently get attacked by a predator, in some cases, they snap off. The animal can regenerate them later, a process that starts when the cells close to the damaged site become activated and remodel the tissue back to its pre-existing form and size. In some other cases, it does not snap off. If the siphon is exposed, it is the key for a predatory fish to obtain the entire body. This tactic has been observed against bivalves with an infaunal lifestyle.

Mariculture

Oysters

Oyster is the common name for a number of different families of Seawater, salt-water bivalve molluscs that live in Marine (ocean), marine or Brackish water, brackish habitats. In some species, the valves are highly Calcification, calcified, a ...

, mussels

Mussel () is the common name used for members of several families of bivalve molluscs, from saltwater and freshwater habitats. These groups have in common a shell whose outline is elongated and asymmetrical compared with other edible clams, whic ...

, clams, scallops and other bivalve species are grown with food materials that occur naturally in their culture environment in the sea and lagoons.carp

The term carp (: carp) is a generic common name for numerous species of freshwater fish from the family (biology), family Cyprinidae, a very large clade of ray-finned fish mostly native to Eurasia. While carp are prized game fish, quarries and a ...

s.dredging

Dredging is the excavation of material from a water environment. Possible reasons for dredging include improving existing water features; reshaping land and water features to alter drainage, navigability, and commercial use; constructing d ...

. Survival rates are low at about 5%.Pacific oyster

The Pacific oyster, Japanese oyster, or Miyagi oyster (''Magallana gigas'') is an oyster native to the Pacific coast of Asia. It has become an introduced species in North America, Australia, Europe, and New Zealand.

Etymology

The genus ''Magal ...

(''Crassostrea gigas'') is cultivated by similar methods but in larger volumes and in many more regions of the world. This oyster originated in Japan where it has been cultivated for many centuries.microalgae

Microalgae or microphytes are microscopic scale, microscopic algae invisible to the naked eye. They are phytoplankton typically found in freshwater and marine life, marine systems, living in both the water column and sediment. They are unicellul ...

and diatoms and grow fast. At metamorphosis the juveniles may be allowed to settle on PVC sheets or pipes, or crushed shell. In some cases, they continue their development in "upwelling culture" in large tanks of moving water rather than being allowed to settle on the bottom. They then may be transferred to transitional, nursery beds before being moved to their final rearing quarters. Culture there takes place on the bottom, in plastic trays, in mesh bags, on rafts or on long lines, either in shallow water or in the intertidal zone. The oysters are ready for harvesting in 18 to 30 months depending on the size required.

Use as food

Bivalves have been an important source of food for humans at least since Roman times and empty shells found in middens at archaeological sites are evidence of earlier consumption.

Bivalves have been an important source of food for humans at least since Roman times and empty shells found in middens at archaeological sites are evidence of earlier consumption.Oyster

Oyster is the common name for a number of different families of salt-water bivalve molluscs that live in marine or brackish habitats. In some species, the valves are highly calcified, and many are somewhat irregular in shape. Many, but no ...

s, scallops, clam

Clam is a common name for several kinds of bivalve mollusc. The word is often applied only to those that are deemed edible and live as infauna, spending most of their lives halfway buried in the sand of the sea floor or riverbeds. Clams h ...

s, ark clams, mussel

Mussel () is the common name used for members of several families of bivalve molluscs, from saltwater and Freshwater bivalve, freshwater habitats. These groups have in common a shell whose outline is elongated and asymmetrical compared with other ...

s and cockles are the most commonly consumed kinds of bivalve, and are eaten cooked or raw. In 1950, the year in which the Food and Agriculture Organization

The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations; . (FAO) is a specialized agency of the United Nations that leads international efforts to defeat hunger and improve nutrition and food security. Its Latin motto, , translates ...

(FAO) started making such information available, world trade in bivalve molluscs was 1,007,419 tons.dinoflagellate

The Dinoflagellates (), also called Dinophytes, are a monophyletic group of single-celled eukaryotes constituting the phylum Dinoflagellata and are usually considered protists. Dinoflagellates are mostly marine plankton, but they are also commo ...

s. These microalgae are not associated with sewage but occur unpredictably as algal bloom

An algal bloom or algae bloom is a rapid increase or accumulation in the population of algae in fresh water or marine water systems. It is often recognized by the discoloration in the water from the algae's pigments. The term ''algae'' encompass ...

s. Large areas of a sea or lake may change colour as a result of the proliferation of millions of single-cell algae, and this condition is known as a red tide.

Viral and bacterial infections

In 1816 in France, a physician, J. P. A. Pasquier, described an outbreak of typhoid

Typhoid fever, also known simply as typhoid, is a disease caused by ''Salmonella enterica'' serotype Typhi bacteria, also called ''Salmonella'' Typhi. Symptoms vary from mild to severe, and usually begin six to 30 days after exposure. Often ther ...

linked to the consumption of raw oysters. The first report of this kind in the United States was in Connecticut

Connecticut ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It borders Rhode Island to the east, Massachusetts to the north, New York (state), New York to the west, and Long Island Sound to the south. ...

in 1894. As sewage treatment programmes became more prevalent in the late 19th century, more outbreaks took place. This may have been because sewage was released through outlets into the sea providing more food for bivalves in estuaries and coastal habitats. A causal link between the bivalves and the illness was not easy to demonstrate because the illness might come on days or even weeks after the ingestion of the contaminated shellfish. One viral pathogen is the '' Norwalk'' virus. This is resistant to treatment with chlorine-containing chemicals and may be present in the marine environment even when coliform bacteria have been killed by the treatment of sewage.Shanghai

Shanghai, Shanghainese: , Standard Chinese pronunciation: is a direct-administered municipality and the most populous urban area in China. The city is located on the Chinese shoreline on the southern estuary of the Yangtze River, with the ...

area of China. An estimated 290,000 people were infected and there were 47 deaths. In the United States and the European Union, since the early 1990s regulations have been in place that are designed to prevent shellfish from contaminated waters entering restaurants.

Paralytic shellfish poisoning

Paralytic shellfish poisoning (PSP) is primarily caused by the consumption of bivalves that have accumulated toxins by feeding on toxic dinoflagellates, single-celled protists found naturally in the sea and inland waters. Saxitoxin is the most virulent of these. In mild cases, PSP causes tingling, numbness, sickness and diarrhoea. In more severe cases, the muscles of the chest wall may be affected leading to paralysis and even death. In 1937, researchers in California

California () is a U.S. state, state in the Western United States that lies on the West Coast of the United States, Pacific Coast. It borders Oregon to the north, Nevada and Arizona to the east, and shares Mexico–United States border, an ...

established the connection between blooms of these phytoplankton and PSP.μg

In the metric system, a microgram or microgramme is a Physical unit, unit of mass equal to one millionth () of a gram. The unit symbol is μg according to the International System of Units (SI); the recommended symbol in the United States and Uni ...

/g of saxitoxin equivalent in shellfish meat.

Amnesic shellfish poisoning

Amnesic shellfish poisoning (ASP) was first reported in eastern Canada in 1987. It is caused by the substance domoic acid

Domoic acid (DA) is a kainic acid-type neurotoxin that causes amnesic shellfish poisoning (ASP). It is produced by algae and accumulates in shellfish, sardines, and anchovies. When sea lions, otters, cetaceans, humans, and other predators eat cont ...

found in certain diatoms of the genus '' Pseudo-nitzschia''. Bivalves can become toxic when they filter these microalgae out of the water. Domoic acid is a low-molecular weight amino acid

Amino acids are organic compounds that contain both amino and carboxylic acid functional groups. Although over 500 amino acids exist in nature, by far the most important are the 22 α-amino acids incorporated into proteins. Only these 22 a ...

that is able to destroy brain cells causing memory loss, gastroenteritis

Gastroenteritis, also known as infectious diarrhea, is an inflammation of the Human gastrointestinal tract, gastrointestinal tract including the stomach and intestine. Symptoms may include diarrhea, vomiting, and abdominal pain. Fever, lack of ...

, long-term neurological problems or death. In an outbreak in the western United States in 1993, finfish were also implicated as vectors, and seabirds and mammals suffered neurological symptoms.

Ecosystem services

Ecosystem services

Ecosystem services are the various benefits that humans derive from Ecosystem, ecosystems. The interconnected Biotic_material, living and Abiotic, non-living components of the natural environment offer benefits such as pollination of crops, clean ...

provided by marine bivalves in relation to nutrient extraction from the coastal environment have gained increased attention to mitigate adverse effects of excess nutrient loading from human activities, such as agriculture and sewage discharge. These activities damage coastal ecosystems and require action from local, regional, and national environmental management. Marine bivalves filter particles like phytoplankton

Phytoplankton () are the autotrophic (self-feeding) components of the plankton community and a key part of ocean and freshwater Aquatic ecosystem, ecosystems. The name comes from the Greek language, Greek words (), meaning 'plant', and (), mea ...

, thereby transforming particulate organic matter into bivalve tissue or larger faecal pellets that are transferred to the benthos. Nutrient extraction from the coastal environment takes place through two different pathways: (i) harvest/removal of the bivalves – thereby returning nutrients back to land; or (ii) through increased denitrification

Denitrification is a microbially facilitated process where nitrate (NO3−) is reduced and ultimately produces molecular nitrogen (N2) through a series of intermediate gaseous nitrogen oxide products. Facultative anaerobic bacteria perform denitr ...

in proximity to dense bivalve aggregations, leading to loss of nitrogen to the atmosphere. Active use of marine bivalves for nutrient extraction may include a number of secondary effects on the ecosystem, such as filtration of particulate material. This leads to partial transformation of particulate-bound nutrients into dissolved nutrients via bivalve excretion or enhanced mineralization of faecal material.heavy metals

upright=1.2, Crystals of lead.html" ;"title="osmium, a heavy metal nearly twice as dense as lead">osmium, a heavy metal nearly twice as dense as lead

Heavy metals is a controversial and ambiguous term for metallic elements with relatively h ...

and persistent organic pollutants in their tissues. This is because they ingest the chemicals as they feed but their enzyme systems are not capable of metabolising them and as a result, the levels build up. This may be a health hazard for the molluscs themselves, and is one for humans who eat them. It also has certain advantages in that bivalves can be used in monitoring the presence and quantity of pollutants in their environment.

There are limitations to the use of bivalves as bioindicators. The level of pollutants found in the tissues varies with species, age, size, time of year and other factors. The quantities of pollutants in the water may vary and the molluscs may reflect past rather than present values. In a study near

There are limitations to the use of bivalves as bioindicators. The level of pollutants found in the tissues varies with species, age, size, time of year and other factors. The quantities of pollutants in the water may vary and the molluscs may reflect past rather than present values. In a study near Vladivostok

Vladivostok ( ; , ) is the largest city and the administrative center of Primorsky Krai and the capital of the Far Eastern Federal District of Russia. It is located around the Zolotoy Rog, Golden Horn Bay on the Sea of Japan, covering an area o ...

it was found that the level of pollutants in the bivalve tissues did not always reflect the high levels in the surrounding sediment in such places as harbours. The reason for this was thought to be that the bivalves in these locations did not need to filter so much water as elsewhere because of the water's high nutritional content.Persian Gulf

The Persian Gulf, sometimes called the Arabian Gulf, is a Mediterranean seas, mediterranean sea in West Asia. The body of water is an extension of the Arabian Sea and the larger Indian Ocean located between Iran and the Arabian Peninsula.Un ...

, the Atlantic pearl-oyster ('' Pinctada radiata'') is considered to be a useful bioindicator of heavy metals.

Crushed shells, available as a by-product of the seafood canning industry, can be used to remove pollutants from water. It has been found that, as long as the water is maintained at an alkaline pH, crushed shells will remove cadmium, lead and other heavy metals from contaminated waters by swapping the calcium in their constituent aragonite for the heavy metal, and retaining these pollutants in a solid form. The rock oyster ('' Saccostrea cucullata'') has been shown to reduce the levels of copper

Copper is a chemical element; it has symbol Cu (from Latin ) and atomic number 29. It is a soft, malleable, and ductile metal with very high thermal and electrical conductivity. A freshly exposed surface of pure copper has a pinkish-orang ...

and cadmium in contaminated waters in the Persian Gulf. The live animals acted as biofilters, selectively removing these metals, and the dead shells also had the ability to reduce their concentration.

Other uses

Conchology

Conchology, from Ancient Greek κόγχος (''kónkhos''), meaning "cockle (bivalve), cockle", and -logy from λόγος (''lógos''), meaning "study", is the study of mollusc shells. Conchology is one aspect of malacology, the study of mollus ...

is the scientific study of mollusc shells, but the term conchologist is also sometimes used to describe a collector of shells. Many people pick up shells on the beach or purchase them and display them in their homes. There are many private and public collections of mollusc shells, but the largest one in the world is at the Smithsonian Institution

The Smithsonian Institution ( ), or simply the Smithsonian, is a group of museums, Education center, education and Research institute, research centers, created by the Federal government of the United States, U.S. government "for the increase a ...

, which houses in excess of 20 million specimens.

Shells are used decoratively in many ways. They can be pressed into concrete or plaster to make decorative paths, steps or walls and can be used to embellish picture frames, mirrors or other craft items. They can be stacked up and glued together to make ornaments. They can be pierced and threaded onto necklaces or made into other forms of jewellery. Shells have had various uses in the past as body decorations, utensils, scrapers and cutting implements. Carefully cut and shaped shell tools dating back 32,000 years have been found in a cave in Indonesia. In this region, shell technology may have been developed in preference to the use of stone or bone implements, perhaps because of the scarcity of suitable rock materials.

The

Shells are used decoratively in many ways. They can be pressed into concrete or plaster to make decorative paths, steps or walls and can be used to embellish picture frames, mirrors or other craft items. They can be stacked up and glued together to make ornaments. They can be pierced and threaded onto necklaces or made into other forms of jewellery. Shells have had various uses in the past as body decorations, utensils, scrapers and cutting implements. Carefully cut and shaped shell tools dating back 32,000 years have been found in a cave in Indonesia. In this region, shell technology may have been developed in preference to the use of stone or bone implements, perhaps because of the scarcity of suitable rock materials.

The indigenous peoples of the Americas

In the Americas, Indigenous peoples comprise the two continents' pre-Columbian inhabitants, as well as the ethnic groups that identify with them in the 15th century, as well as the ethnic groups that identify with the pre-Columbian population of ...

living near the east coast used pieces of shell as wampum. The channeled whelk (''Busycotypus canaliculatus'') and the quahog (''Mercenaria mercenaria'') were used to make white and purple traditional patterns. The shells were cut, rolled, polished and drilled before being strung together and woven into belts. These were used for personal, social and ceremonial purposes and also, at a later date, for currency. The Winnebago Tribe from Wisconsin had numerous uses for freshwater mussels including using them as spoons, cups, ladles and utensils. They notched them to provide knives, graters and saws. They carved them into fish hooks and lures. They incorporated powdered shell into clay to temper their pottery vessels. They used them as scrapers for removing flesh from hides and for separating the scalps of their victims. They used shells as scoops for gouging out fired logs when building canoes and they drilled holes in them and fitted wooden handles for tilling the ground.

Button

A button is a fastener that joins two pieces of fabric together by slipping through a loop or by sliding through a buttonhole.

In modern clothing and fashion design, buttons are commonly made of plastic but also may be made of metal, wood, or ...

s have traditionally been made from a variety of freshwater and marine shells.Mohenjo-daro

Mohenjo-daro (; , ; ) is an archaeological site in Larkana District, Sindh, Pakistan. Built 2500 BCE, it was one of the largest settlements of the ancient Indus Valley Civilisation, and one of the world's earliest major city, cities, contemp ...

in the Indus Valley.

Sea silk is a fine fabric woven from the byssus

A byssus () is a bundle of filaments secreted by many species of bivalve mollusc that function to attach the mollusc to a solid surface. Species from several families of clams have a byssus, including pen shells ( Pinnidae), true mussels (Mytili ...

threads of bivalves, particularly the pen shell ('' Pinna nobilis''). It used to be produced in the Mediterranean region where these shells are endemic

Endemism is the state of a species being found only in a single defined geographic location, such as an island, state, nation, country or other defined zone; organisms that are indigenous to a place are not endemic to it if they are also foun ...

. It was an expensive fabric and overfishing

Overfishing is the removal of a species of fish (i.e. fishing) from a body of water at a rate greater than that the species can replenish its population naturally (i.e. the overexploitation of the fishery's existing Fish stocks, fish stock), resu ...

has much reduced populations of the pen shell.

Crushed shells are added as a calcareous supplement to the diet of laying poultry. Oyster shell and cockle shell are often used for this purpose and are obtained as a by-product from other industries.

Pearls and mother-of-pearl