Bangladesh Air Force Personnel on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Bangladesh (}, ), officially the People's Republic of Bangladesh, is a country in

,

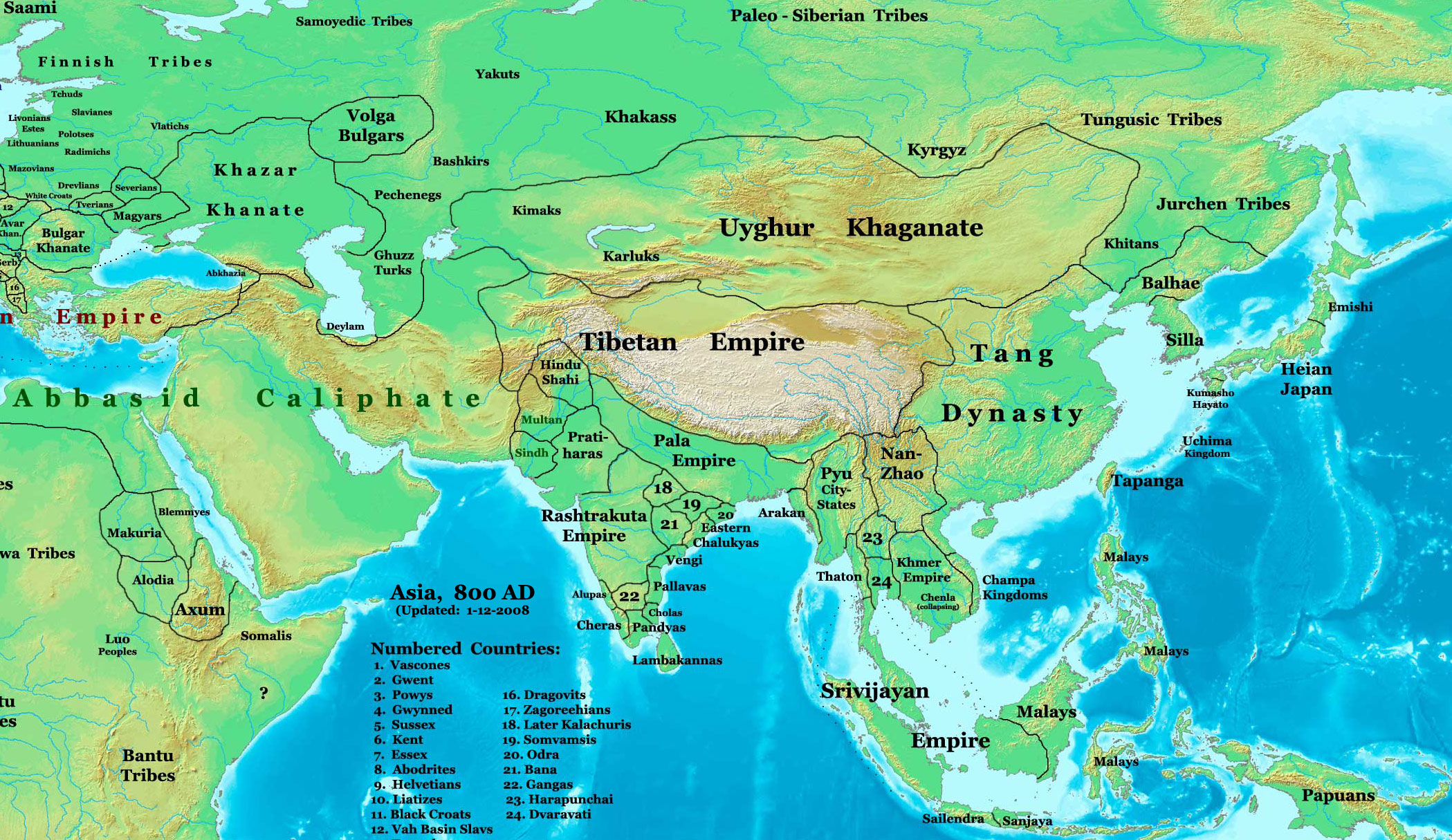

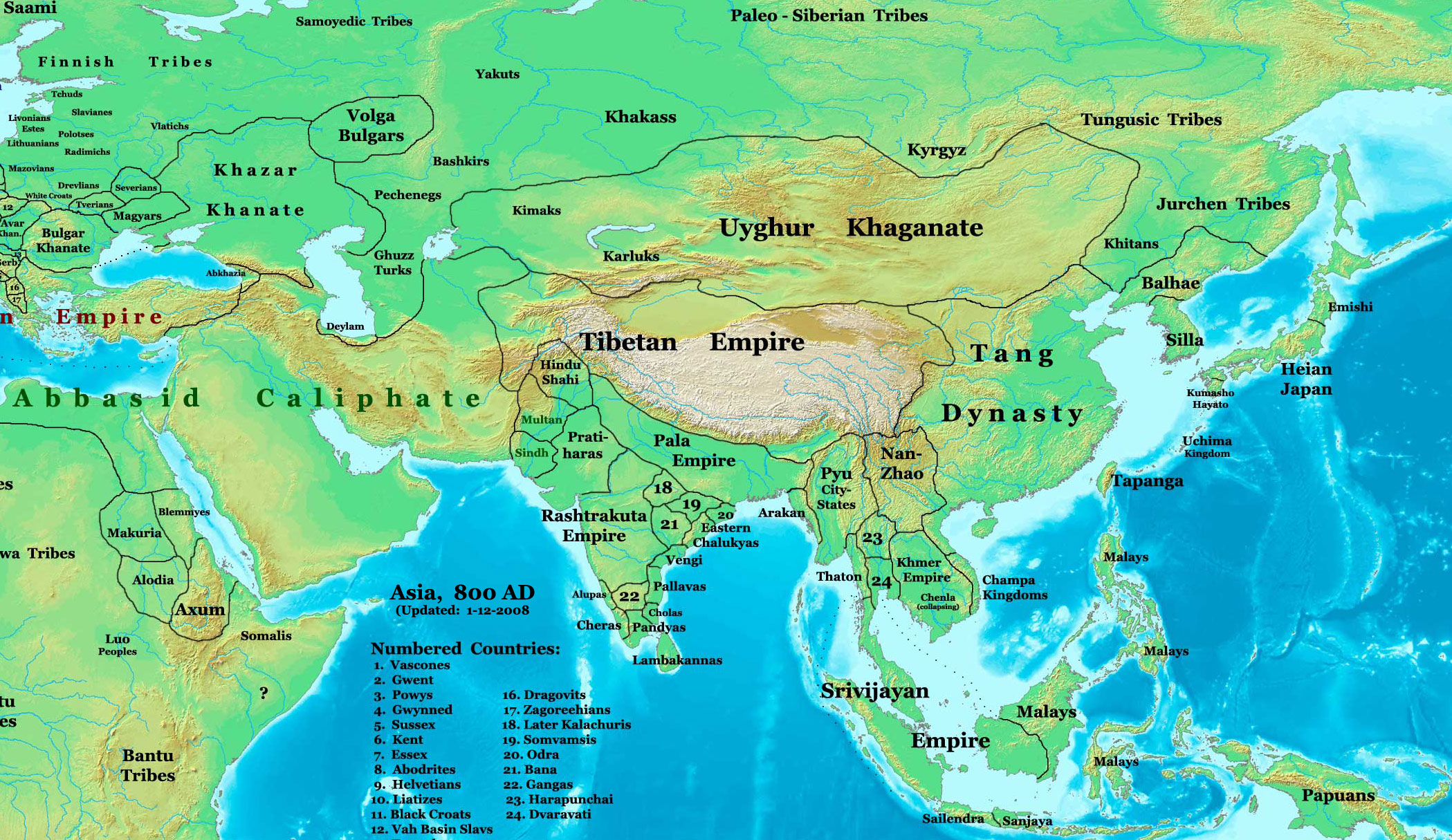

The early history of Islam in Bengal is divided into two phases. The first phase is the period of maritime trade with Arabia and Persia between the 8th and 12th centuries. The second phase covers centuries of Muslim dynastic rule after the Islamic conquest of Bengal. The writings of Al-Idrisi, Ibn Hawqal,

The early history of Islam in Bengal is divided into two phases. The first phase is the period of maritime trade with Arabia and Persia between the 8th and 12th centuries. The second phase covers centuries of Muslim dynastic rule after the Islamic conquest of Bengal. The writings of Al-Idrisi, Ibn Hawqal,

The

The

Empire, Mughal

, ''History of World Trade Since 1450'', edited by John J. McCusker, vol. 1, Macmillan Reference USA, 2006, pp. 237–240, ''World History in Context''. Retrieved 3 August 2017 The Bengal Subah, described as the ''Paradise of the Nations'', was the empire's wealthiest province, and a major global exporter,

''The Mughal Empire'', page 202

Development Centre Studies The World Economy Historical Statistics: Historical Statistics

', OECD Publishing, , pages 259–261 Eastern Bengal was a thriving

Two decades after

Two decades after  After the 1757

After the 1757

Bengals plunder gifted the British Industrial Revolution

'' The Financial Express'', 8 February 2010 Economic mismanagement, alongside drought and a smallpox epidemic, directly led to the Great Bengal famine of 1770, which is estimated to have caused the deaths of between 1 million and 10 million people. Several rebellions broke out during the early 19th century (including one led by Titumir), as Company rule had displaced the Muslim ruling class from power. A conservative Islamic cleric, Haji Shariatullah, sought to overthrow the British by propagating Islamic revivalism. Several towns in Bangladesh participated in the Although it won most seats in 1937, the Bengal Congress boycotted the legislature.

Although it won most seats in 1937, the Bengal Congress boycotted the legislature.

The

The

"Statistics of Democide: Genocide and Mass Murder Since 1900"

. Transaction Publishers, Rutgers University. , Chapter 8

Table 8.2 Pakistan Genocide in Bangladesh Estimates, Sources, and Calculations

Under international pressure, Pakistan released Rahman from imprisonment on 8 January 1972 and he was flown by the British Royal Air Force to a million-strong homecoming in Dacca. Remaining Indian troops were withdrawn by 12 March 1972, three months after the war ended. The cause of Bangladeshi self-determination was recognised around the world. By August 1972, the new state was recognised by 86 countries. Pakistan recognised Bangladesh in 1974 after pressure from most of the Muslim countries.

The constituent assembly adopted the constitution of Bangladesh on 4 November 1972, establishing a secular, multiparty parliamentary democracy. The new constitution included references to

The constituent assembly adopted the constitution of Bangladesh on 4 November 1972, establishing a secular, multiparty parliamentary democracy. The new constitution included references to

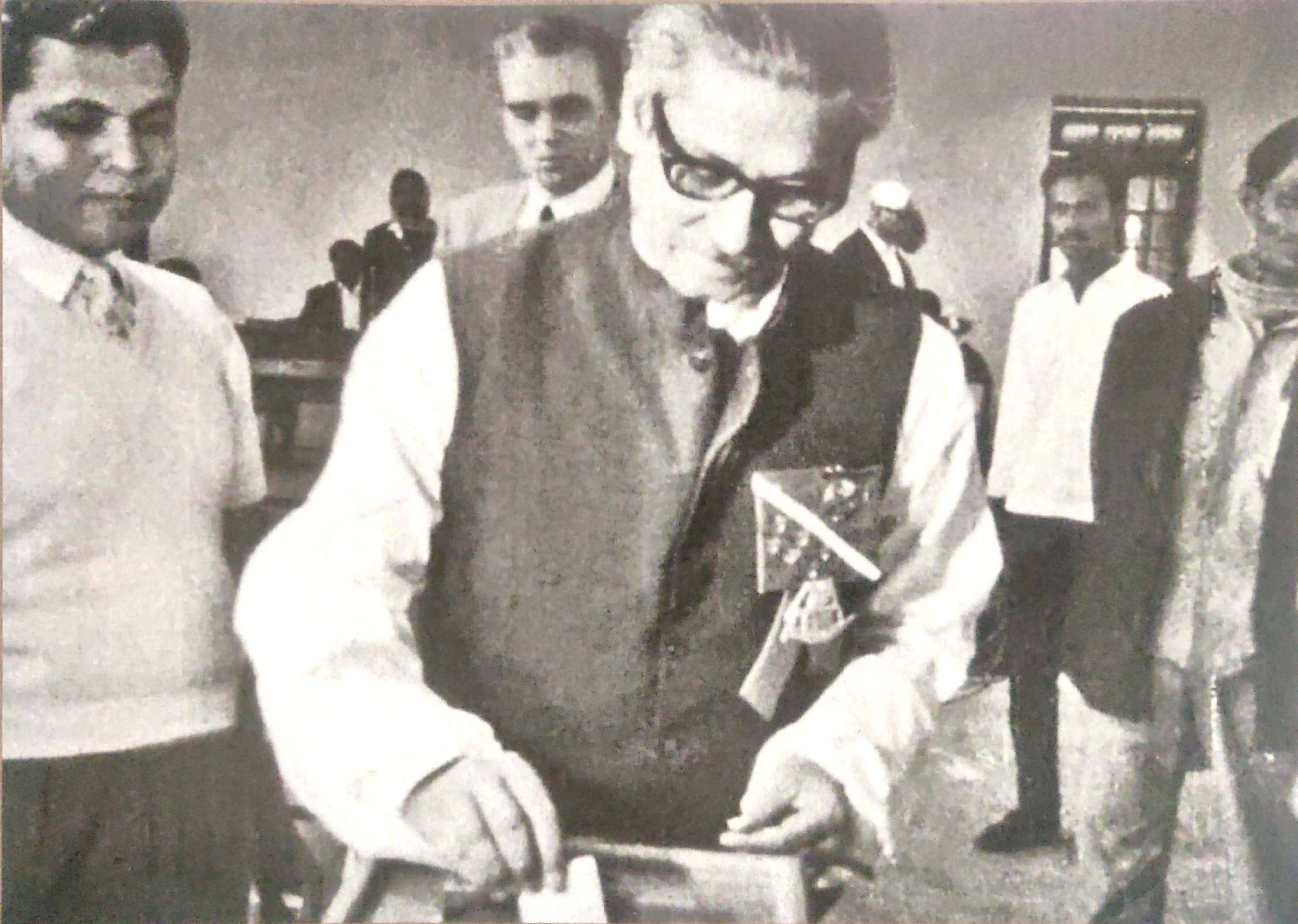

After the 1991 general election, the twelfth amendment to the constitution restored the parliamentary republic and Begum Khaleda Zia became Bangladesh's first female prime minister. Zia, a former first lady, led a BNP government from 1990 to 1996. In 1991, her finance minister, Saifur Rahman, began a major programme to liberalise the Bangladeshi economy.

In February 1996, a general election was held, which was boycotted by all opposition parties giving a 300 (of 300) seat victory for BNP. This election was deemed illegitimate, so a system of a

After the 1991 general election, the twelfth amendment to the constitution restored the parliamentary republic and Begum Khaleda Zia became Bangladesh's first female prime minister. Zia, a former first lady, led a BNP government from 1990 to 1996. In 1991, her finance minister, Saifur Rahman, began a major programme to liberalise the Bangladeshi economy.

In February 1996, a general election was held, which was boycotted by all opposition parties giving a 300 (of 300) seat victory for BNP. This election was deemed illegitimate, so a system of a

Bangladesh is a small, lush country in

Bangladesh is a small, lush country in

South Asia

South Asia is the southern subregion of Asia, which is defined in both geographical and ethno-cultural terms. The region consists of the countries of Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Maldives, Nepal, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka.;;;;;;;; ...

. It is the eighth-most populous country in the world, with a population exceeding 165 million people in an area of . Bangladesh is among the most densely populated countries in the world, and shares land borders with India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by area, the second-most populous country, and the most populous democracy in the world. Bounded by the Indian Ocean on the so ...

to the west, north, and east, and Myanmar

Myanmar, ; UK pronunciations: US pronunciations incl. . Note: Wikipedia's IPA conventions require indicating /r/ even in British English although only some British English speakers pronounce r at the end of syllables. As John C. Wells, Joh ...

to the southeast; to the south it has a coastline along the Bay of Bengal

The Bay of Bengal is the northeastern part of the Indian Ocean, bounded on the west and northwest by India, on the north by Bangladesh, and on the east by Myanmar and the Andaman and Nicobar Islands of India. Its southern limit is a line between ...

. It is narrowly separated from Bhutan

Bhutan (; dz, འབྲུག་ཡུལ་, Druk Yul ), officially the Kingdom of Bhutan,), is a landlocked country in South Asia. It is situated in the Eastern Himalayas, between China in the north and India in the south. A mountainous ...

and Nepal

Nepal (; ne, नेपाल ), formerly the Federal Democratic Republic of Nepal ( ne,

सङ्घीय लोकतान्त्रिक गणतन्त्र नेपाल ), is a landlocked country in South Asia. It is mai ...

by the Siliguri Corridor; and from China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's most populous country, with a population exceeding 1.4 billion, slightly ahead of India. China spans the equivalent of five time zones and ...

by the Indian state of Sikkim

Sikkim (; ) is a state in Northeastern India. It borders the Tibet Autonomous Region of China in the north and northeast, Bhutan in the east, Province No. 1 of Nepal in the west and West Bengal in the south. Sikkim is also close to the Siligur ...

in the north. Dhaka

Dhaka ( or ; bn, ঢাকা, Ḍhākā, ), formerly known as Dacca, is the capital and largest city of Bangladesh, as well as the world's largest Bengali-speaking city. It is the eighth largest and sixth most densely populated city ...

, the capital and largest city

The United Nations uses three definitions for what constitutes a city, as not all cities in all jurisdictions are classified using the same criteria. Cities may be defined as the cities proper, the extent of their urban area, or their metropo ...

, is the nation's political, financial and cultural centre. Chittagong

Chittagong ( /ˈtʃɪt əˌɡɒŋ/ ''chit-uh-gong''; ctg, চিটাং; bn, চিটাগং), officially Chattogram ( bn, চট্টগ্রাম), is the second-largest city in Bangladesh after Dhaka and third largest city in B ...

, the second-largest city, is the busiest port on the Bay of Bengal. The official language is Bengali

Bengali or Bengalee, or Bengalese may refer to:

*something of, from, or related to Bengal, a large region in South Asia

* Bengalis, an ethnic and linguistic group of the region

* Bengali language, the language they speak

** Bengali alphabet, the w ...

, one of the easternmost branches of the Indo-European language family

The Indo-European languages are a language family native to the overwhelming majority of Europe, the Iranian plateau, and the northern Indian subcontinent. Some European languages of this family, English, French, Portuguese, Russian, Dutch ...

.

Bangladesh forms the sovereign part of the historic and ethnolinguistic

Ethnolinguistics (sometimes called cultural linguistics) is an area of anthropological linguistics that studies the relationship between a language and the nonlinguistic cultural behavior of the people who speak that language.

__NOTOC__

Examples ...

region of Bengal

Bengal ( ; bn, বাংলা/বঙ্গ, translit=Bānglā/Bôngô, ) is a geopolitical, cultural and historical region in South Asia, specifically in the eastern part of the Indian subcontinent at the apex of the Bay of Bengal, predom ...

, which was divided during the Partition of India

The Partition of British India in 1947 was the Partition (politics), change of political borders and the division of other assets that accompanied the dissolution of the British Raj in South Asia and the creation of two independent dominions: ...

in 1947. The country has a Bengali Muslim majority. Ancient Bengal was an important cultural centre in the Indian subcontinent

The Indian subcontinent is a list of the physiographic regions of the world, physiographical region in United Nations geoscheme for Asia#Southern Asia, Southern Asia. It is situated on the Indian Plate, projecting southwards into the Indian O ...

as the home of the states of Vanga, Pundra

Pundravardhana or Pundra Kingdom ( sa, Puṇḍravardhana), was an ancient kingdom during the Iron Age period in India with a territory that included parts of present-day Rajshahi and Rangpur Divisions of Bangladesh as well as the West Dina ...

, Gangaridai, Gauda, Samatata, and Harikela

Harikela () was an ancient empire located in the eastern region of the Indian subcontinent. Originally, it was a neighboring independent and independent township of ancient East Bengal, which had a continuous existence of about 500 years. The st ...

. The Mauryan, Gupta

Gupta () is a common surname or last name of Indian origin. It is based on the Sanskrit word गोप्तृ ''goptṛ'', which means 'guardian' or 'protector'. According to historian R. C. Majumdar, the surname ''Gupta'' was adopted by se ...

, Pala Pala may refer to:

Places

Chad

*Pala, Chad, the capital of the region of Mayo-Kebbi Ouest

Estonia

* Pala, Kose Parish, village in Kose Parish, Harju County

* Pala, Kuusalu Parish, village in Kuusalu Parish, Harju County

*Pala, Järva County, vi ...

, Sena

Sena may refer to:

Places

* Sanandaj or Sena, city in northwestern Iran

* Sena (state constituency), represented in the Perlis State Legislative Assembly

* Sena, Dashtestan, village in Bushehr Province, Iran

* Sena, Huesca, municipality in Huesc ...

, Chandra

Chandra ( sa, चन्द्र, Candra, shining' or 'moon), also known as Soma ( sa, सोम), is the Hindu god of the Moon, and is associated with the night, plants and vegetation. He is one of the Navagraha (nine planets of Hinduism) and ...

and Deva

Deva may refer to:

Entertainment

* ''Deva'' (1989 film), a 1989 Kannada film

* ''Deva'' (1995 film), a 1995 Tamil film

* ''Deva'' (2002 film), a 2002 Bengali film

* Deva (2007 Telugu film)

* ''Deva'' (2017 film), a 2017 Marathi film

* Deva ...

dynasties were the last pre-Islamic rulers of Bengal. The Muslim conquest of Bengal began in 1204 when Bakhtiar Khalji overran northern Bengal and invaded Tibet. Becoming part of the Delhi Sultanate

The Delhi Sultanate was an Islamic empire based in Delhi that stretched over large parts of the Indian subcontinent for 320 years (1206–1526).

, three city-states emerged in the 14th century with much of eastern Bengal being ruled from Sonargaon. Sufi

Sufism ( ar, ''aṣ-ṣūfiyya''), also known as Tasawwuf ( ''at-taṣawwuf''), is a mystic body of religious practice, found mainly within Sunni Islam but also within Shia Islam, which is characterized by a focus on Islamic spirituality, ...

missionary leaders like Sultan Balkhi

Shah Sultan Balkhi ( bn, শাহ সুলতান বলখী, fa, ), also known by his sobriquet, Mahisawar ( bn, মাহিসওয়ার, fa, , Mâhi-Savâr, Fish-rider), was a 14th-century Muslim saint. His name is associated wi ...

, Shah Jalal and Shah Makhdum Rupos

‘Abd al-Quddūs Jalāl ad-Dīn ( ar, عبد القدوس جلال الدين), best known as Shah Makhdum ( bn, শাহ মখদুম), and also known as Rupos, was a Sufi Muslim figure in Bangladesh. He is associated with the spread of Is ...

helped in spreading Muslim rule. The region was unified into an independent, unitary Bengal Sultanate

The Sultanate of Bengal ( Middle Bengali: শাহী বাঙ্গালা ''Shahī Baṅgala'', Classical Persian: ''Saltanat-e-Bangālah'') was an empire based in Bengal for much of the 14th, 15th and 16th centuries. It was the dominan ...

. Under Mughal rule, eastern Bengal continued to prosper as the melting pot of Muslims in the eastern subcontinent and attracted traders from around the world. The Bengali elite were among the richest people in the world due to strong trade networks like the muslin trade which supplied textiles, such as 40% of Dutch imports from Asia.Om Prakash, "Empire, Mughal", History of World Trade Since 1450, edited by John J. McCusker, vol. 1, Macmillan Reference US, 2006, pp. 237–240, World History in Context. Retrieved 3 August 2017 Mughal Bengal became increasingly assertive and independent under the Nawabs of Bengal

The Nawab of Bengal ( bn, বাংলার নবাব) was the hereditary ruler of Bengal Subah in Mughal India. In the early 18th-century, the Nawab of Bengal was the ''de facto'' independent ruler of the three regions of Bengal, Bihar, ...

in the 18th century. In 1757, the betrayal of Mir Jafar

Sayyid Mīr Jaʿfar ʿAlī Khān Bahādur ( – 5 February 1765) was a military general who became the first dependent Nawab of Bengal of the British East India Company. His reign has been considered by many historians as the start of the expan ...

resulted in the defeat of Nawab Siraj-ud-Daulah to the British East India Company

The East India Company (EIC) was an English, and later British, joint-stock company founded in 1600 and dissolved in 1874. It was formed to trade in the Indian Ocean region, initially with the East Indies (the Indian subcontinent and Southea ...

and eventual British dominance across South Asia. The Bengal Presidency

The Bengal Presidency, officially the Presidency of Fort William and later Bengal Province, was a subdivision of the British Empire in India. At the height of its territorial jurisdiction, it covered large parts of what is now South Asia and ...

grew into the largest administrative unit in British India

The provinces of India, earlier presidencies of British India and still earlier, presidency towns, were the administrative divisions of British governance on the Indian subcontinent. Collectively, they have been called British India. In one ...

. The creation of Eastern Bengal and Assam in 1905 set a precedent for the emergence of Bangladesh. In 1940, the first Prime Minister of Bengal

The Prime Minister of Bengal was the head of government of Bengal Presidency, Bengal Province and the Leader of the House in the Bengal Legislative Assembly in British India. The position was dissolved upon the Partition of Bengal (1947), Partitio ...

supported the Lahore Resolution with the hope of creating a state in the eastern subcontinent. Prior to the partition of Bengal, the Prime Minister of Bengal proposed a Bengali sovereign state. A referendum

A referendum (plural: referendums or less commonly referenda) is a direct vote by the electorate on a proposal, law, or political issue. This is in contrast to an issue being voted on by a representative. This may result in the adoption of a ...

and the announcement of the Radcliffe Line established the present-day territorial boundary of Bangladesh.

In 1947, East Bengal

ur,

, common_name = East Bengal

, status = Province of the Dominion of Pakistan

, p1 = Bengal Presidency

, flag_p1 = Flag of British Bengal.svg

, s1 = East ...

became the most populous province in the Dominion of Pakistan

Between 14 August 1947 and 23 March 1956, Pakistan was an independent federal dominion in the Commonwealth of Nations, created by the passing of the Indian Independence Act 1947 by the British parliament, which also created the Dominion of I ...

. It was renamed as East Pakistan

East Pakistan was a Pakistani province established in 1955 by the One Unit Scheme, One Unit Policy, renaming the province as such from East Bengal, which, in modern times, is split between India and Bangladesh. Its land borders were with India ...

with Dhaka becoming the country's legislative capital. The Bengali Language Movement in 1952; the East Bengali legislative election, 1954

Legislative elections were held in East Bengal between 8 and 12 March 1954, the first since Pakistan became an independent country in 1947. The opposition United Front led by the Awami League and Krishak Sramik Party won a landslide victory with ...

; the 1958 Pakistani coup d'état

The 1958 Pakistani coup d'état began on October 7, when the first President of Pakistan Iskander Mirza abrogated the Constitution of Pakistan and declared martial law, and lasted until October 27, when Mirza himself was deposed by Gen. Ayub Kha ...

; the Six point movement of 1966; and the 1970 Pakistani general election

General elections were held in Pakistan on 7 December 1970 to elect members of the National Assembly. They were the first general elections since the independence of Pakistan and ultimately the only ones held prior to the independence of Bang ...

resulted in the rise of Bengali nationalism and pro-democracy movements in East Pakistan. The refusal of the Pakistani military junta to transfer power to the Awami League In Urdu language, Awami is the adjectival form for '' Awam'', the Urdu language word for common people.

The adjective appears in the following proper names:

*Awami Colony, a neighbourhood of Landhi Town in Karachi, Sindh, Pakistan

*Awami Front, wa ...

led by Sheikh Mujibur Rahman led to the Bangladesh Liberation War

The Bangladesh Liberation War ( bn, মুক্তিযুদ্ধ, , also known as the Bangladesh War of Independence, or simply the Liberation War in Bangladesh) was a revolution and War, armed conflict sparked by the rise of the Benga ...

in 1971, in which the Mukti Bahini

The Mukti Bahini ( bn, মুক্তিবাহিনী, translates as 'freedom fighters', or liberation army), also known as the Bangladesh Forces, was the guerrilla resistance movement consisting of the Bangladeshi military, paramilitary ...

aided by India waged a successful armed revolution

This is a list of revolutions, rebellions, insurrections, and uprisings.

BC

:

:

:

:

1–999 AD

1000–1499

1500–1699

* 1501–1504: The Knut Alvsson, Alvsson's Dano-Swedish War (1501–12), rebellion against King John, ...

. The conflict saw the 1971 Bangladesh genocide

The genocide in Bangladesh began on 25 March 1971 with the launch of Operation Searchlight, as the government of Pakistan, dominated by West Pakistan, began a military crackdown on East Pakistan (now Bangladesh) to suppress Bengali peopl ...

and the massacre of pro-independence Bengali civilians, including intellectuals

An intellectual is a person who engages in critical thinking

Critical thinking is the analysis of available facts, evidence, observations, and arguments to form a judgement. The subject is complex; several different definitions exist, ...

. The new state of Bangladesh became the first constitutionally secular state

A secular state is an idea pertaining to secularity, whereby a State (polity), state is or purports to be officially neutral in matters of religion, supporting neither religion nor irreligion. A secular state claims to treat all its citizens ...

in South Asia in 1972. Islam

Islam (; ar, ۘالِإسلَام, , ) is an Abrahamic religions, Abrahamic Monotheism#Islam, monotheistic religion centred primarily around the Quran, a religious text considered by Muslims to be the direct word of God in Islam, God (or ...

was declared the state religion in 1988. In 2010, the Bangladesh Supreme Court

The Supreme Court of Bangladesh ( bn, বাংলাদেশ সুপ্রীম কোর্ট) is the highest court of law in Bangladesh. It is composed of the High Court Division and the Appellate Division, and was created by Part VI C ...

reaffirmed secular principles in the constitution.

A middle power in the Indo-Pacific

The Indo-Pacific is a vast biogeographic region of Earth.

In a narrow sense, sometimes known as the Indo-West Pacific or Indo-Pacific Asia, it comprises the tropical waters of the Indian Ocean, the western and central Pacific Ocean, and the ...

, Bangladesh is the second largest economy in South Asia. It maintains the third-largest military

A military, also known collectively as armed forces, is a heavily armed, highly organized force primarily intended for warfare. It is typically authorized and maintained by a sovereign state, with its members identifiable by their distinct ...

in the region and is a major contributor to UN peacekeeping operations. The large Muslim

Muslims ( ar, المسلمون, , ) are people who adhere to Islam, a monotheistic religion belonging to the Abrahamic tradition. They consider the Quran, the foundational religious text of Islam, to be the verbatim word of the God of Abrah ...

population of Bangladesh makes it the third-largest Muslim-majority country. Bangladesh is a unitary

Unitary may refer to:

Mathematics

* Unitary divisor

* Unitary element

* Unitary group

* Unitary matrix

* Unitary morphism

* Unitary operator

* Unitary transformation

* Unitary representation

* Unitarity (physics)

* ''E''-unitary inverse semigroup ...

parliamentary

A parliamentary system, or parliamentarian democracy, is a system of democracy, democratic government, governance of a sovereign state, state (or subordinate entity) where the Executive (government), executive derives its democratic legitimacy ...

constitutional republic based on the Westminster system. Bengalis

Bengalis (singular Bengali bn, বাঙ্গালী/বাঙালি ), also rendered as Bangalee or the Bengali people, are an Indo-Aryan peoples, Indo-Aryan ethnolinguistic group originating from and culturally affiliated with the ...

make up 99% of the total population of Bangladesh. The country consists of eight divisions, 64 districts and 495 subdistricts. It hosts one of the largest refugee

A refugee, conventionally speaking, is a displaced person who has crossed national borders and who cannot or is unwilling to return home due to well-founded fear of persecution.

populations in the world due to the Rohingya genocide

The Rohingya genocide is a series of ongoing persecutions and killings of the Muslim Rohingya people by the Burmese military. The genocide has consisted of two phases to date: the first was a military crackdown that occurred from October 2016 ...

. Bangladesh faces many challenges, particularly effects of climate change

The effects of climate change impact the physical environment, ecosystems and human societies. The environmental effects of climate change are broad and far-reaching. They affect the water cycle, oceans, sea and land ice (glaciers), sea level ...

. Bangladesh has been a leader within the Climate Vulnerable Forum

The Climate Vulnerable Forum (CVF) is a global partnership of countries that are disproportionately affected by the consequences of climate change. The forum addresses the negative effects of climate change as a result of heightened socioeconomic ...

. It hosts the headquarters of BIMSTEC

The Bay of Bengal Initiative for Multi-Sectoral Technical and Economic Cooperation (BIMSTEC) is an international organisation of seven South Asian and Southeast Asian nations, housing 1.73 billion people and having a combined gross domestic pro ...

. It is a founding member of SAARC

The South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC) is the regional intergovernmental organization and geopolitical union of states in South Asia. Its member states are Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Maldives, Nepal, Pakistan, ...

, as well as a member of the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation and the Commonwealth of Nations

The Commonwealth of Nations, simply referred to as the Commonwealth, is a political association of 56 member states, the vast majority of which are former territories of the British Empire. The chief institutions of the organisation are the Co ...

.

Etymology

The etymology of ''Bangladesh'' ("Bengali Country") can be traced to the early 20th century, when Bengali patriotic songs, such as ''Namo Namo Namo Bangladesh Momo'' by Kazi Nazrul Islam and ''Aaji Bangladesher Hridoy'' byRabindranath Tagore

Rabindranath Tagore (; bn, রবীন্দ্রনাথ ঠাকুর; 7 May 1861 – 7 August 1941) was a Bengali polymath who worked as a poet, writer, playwright, composer, philosopher, social reformer and painter. He resh ...

, used the term. The term ''Bangladesh'' was often written as two words, ''Bangla Desh'', in the past. Starting in the 1950s, Bengali nationalists used the term in political rallies in East Pakistan

East Pakistan was a Pakistani province established in 1955 by the One Unit Scheme, One Unit Policy, renaming the province as such from East Bengal, which, in modern times, is split between India and Bangladesh. Its land borders were with India ...

. The term ''Bangla'' is a major name for both the Bengal

Bengal ( ; bn, বাংলা/বঙ্গ, translit=Bānglā/Bôngô, ) is a geopolitical, cultural and historical region in South Asia, specifically in the eastern part of the Indian subcontinent at the apex of the Bay of Bengal, predom ...

region and the Bengali language

Bengali ( ), generally known by its endonym Bangla (, ), is an Indo-Aryan languages, Indo-Aryan language native to the Bengal region of South Asia. It is the official, national, and most widely spoken language of Bangladesh and the second m ...

. The origins of the term ''Bangla'' are unclear, with theories pointing to a Bronze Age

The Bronze Age is a historic period, lasting approximately from 3300 BC to 1200 BC, characterized by the use of bronze, the presence of writing in some areas, and other early features of urban civilization. The Bronze Age is the second pri ...

proto-Dravidian

Proto-Dravidian is the linguistic reconstruction of the common ancestor of the Dravidian languages. It is thought to have differentiated into Proto-North Dravidian, Proto-Central Dravidian, and Proto-South Dravidian, although the date of diversi ...

tribe, the Austric word "Bonga" (Sun god), and the Iron Age Vanga Kingdom. The earliest known usage of the term is the Nesari plate in 805 AD. The term ''Vangaladesa'' is found in 11th-century South Indian records. The term gained official status during the Sultanate of Bengal in the 14th century. Shamsuddin Ilyas Shah

Haji Ilyas, better known as Shamsuddin Ilyas Shah ( bn, শামসুদ্দীন ইলিয়াস শাহ, fa, ), was the founder of the Sultanate of Bengal and its inaugural Ilyas Shahi dynasty which ruled the region for 150 year ...

proclaimed himself as the first "Shah

Shah (; fa, شاه, , ) is a royal title that was historically used by the leading figures of Iranian monarchies.Yarshater, EhsaPersia or Iran, Persian or Farsi, ''Iranian Studies'', vol. XXII no. 1 (1989) It was also used by a variety of ...

of Bangala" in 1342. The word ''Bangāl'' became the most common name for the region during the Islamic period. 16th-century historian Abu'l-Fazl ibn Mubarak

Abu'l-Fazl ibn Mubarak, also known as Abul sharma, Abu'l Fadl and Abu'l-Fadl 'Allami (14 January 1551 – 22 August 1602), was the grand vizier of the Mughal emperor Akbar, from his appointment in 1579 until his death in 1602. He was the au ...

mentions in his ''Ain-i-Akbari

The ''Ain-i-Akbari'' ( fa, ) or the "Administration of Akbar", is a 16th-century detailed document recording the administration of the Mughal Empire under Emperor Akbar, written by his court historian, Abu'l Fazl in the Persian language. It for ...

'' that the addition of the suffix ''"al"'' came from the fact that the ancient rajahs of the land raised mounds of earth 10 feet high and 20 in breadth in lowlands at the foot of the hills which were called "al". This is also mentioned in Ghulam Husain Salim

Ğulām Husayn "Salīm" Zaydpūrī was a historian who migrated to Bengal and was employed there as a postmaster to the English East India Company

The East India Company (EIC) was an English, and later British, joint-stock company founded ...

's Riyaz-us-Salatin

Riyaz-us-Salatin ( fa, ) is the first British-era historic book on the Muslim rule in Bengal that was published in Bengal in 1788. It was written by Ghulam Husain Salim Zaidpuri.

Content

The books starts with the arrival of Muhammad bin Bakhti ...

.RIYAZU-S-SALĀTĪN: A History of Bengal,

Ghulam Husain Salim

Ğulām Husayn "Salīm" Zaydpūrī was a historian who migrated to Bengal and was employed there as a postmaster to the English East India Company

The East India Company (EIC) was an English, and later British, joint-stock company founded ...

, The Asiatic Society, Calcutta, 1902. The Indo-Aryan suffix ''Desh'' is derived from the Sanskrit word ''deśha'', which means "land" or "country". Hence, the name ''Bangladesh'' means "Land of Bengal" or "Country of Bengal".

History

Ancient Bengal

Stone Age

The Stone Age was a broad prehistoric period during which stone was widely used to make tools with an edge, a point, or a percussion surface. The period lasted for roughly 3.4 million years, and ended between 4,000 BC and 2,000 BC, with t ...

tools found in Bangladesh indicate human habitation for over 20,000 years, and remnants of Copper Age

The Copper Age, also called the Chalcolithic (; from grc-gre, χαλκός ''khalkós'', "copper" and ''líthos'', "stone") or (A)eneolithic (from Latin '' aeneus'' "of copper"), is an archaeological period characterized by regular ...

settlements date back 4,000 years. Ancient Bengal was settled by Austroasiatic

The Austroasiatic languages , , are a large language family

A language family is a group of languages related through descent from a common ''ancestral language'' or ''parental language'', called the proto-language of that family. The te ...

s, Tibeto-Burmans, Dravidians

The Dravidian peoples, or Dravidians, are an ethnolinguistic and cultural group living in South Asia who predominantly speak any of the Dravidian languages. There are around 250 million native speakers of Dravidian languages. Dravidian spe ...

and Indo-Aryans in consecutive waves of migration. Archaeological evidence confirms that by the second millennium BCE, rice-cultivating communities inhabited the region. By the 11th century people lived in systemically aligned housing, buried their dead, and manufactured copper ornaments and black and red pottery. The Ganges

The Ganges ( ) (in India: Ganga ( ); in Bangladesh: Padma ( )). "The Ganges Basin, known in India as the Ganga and in Bangladesh as the Padma, is an international river to which India, Bangladesh, Nepal and China are the riparian states." is ...

, Brahmaputra

The Brahmaputra is a trans-boundary river which flows through Tibet, northeast India, and Bangladesh. It is also known as the Yarlung Tsangpo in Tibetan, the Siang/Dihang River in Arunachali, Luit in Assamese, and Jamuna River in Bangla. It ...

and Meghna rivers were natural arteries for communication and transportation, and estuaries on the Bay of Bengal permitted maritime trade. The early Iron Age

The Iron Age is the final epoch of the three-age division of the prehistory and protohistory of humanity. It was preceded by the Stone Age (Paleolithic, Mesolithic, Neolithic) and the Bronze Age (Chalcolithic). The concept has been mostly appl ...

saw the development of metal weaponry, coinage, agriculture and irrigation

Irrigation (also referred to as watering) is the practice of applying controlled amounts of water to land to help grow Crop, crops, Landscape plant, landscape plants, and Lawn, lawns. Irrigation has been a key aspect of agriculture for over 5,00 ...

. Major urban settlements formed during the late Iron Age, in the mid-first millennium BCE

The 1st millennium BC, also known as the last millennium BC, was the period of time lasting from the years 1000 BC to 1 BC (10th to 1st centuries BC; in astronomy: JD – ). It encompasses the Iron Age in the Old World and sees the transit ...

, when the Northern Black Polished Ware culture developed. In 1879, Alexander Cunningham

Major General Sir Alexander Cunningham (23 January 1814 – 28 November 1893) was a British Army engineer with the Bengal Engineer Group who later took an interest in the history and archaeology of India. In 1861, he was appointed to the newly ...

identified Mahasthangarh

Mahasthangarh ( bn, মহাস্থানগড়, ''Môhasthangôṛ'') is one of the earliest urban archaeological sites so far discovered in Bangladesh. The village Mahasthan in Shibganj upazila of Bogra District contains the remain ...

as the capital of the Pundra Kingdom mentioned in the ''Rigveda

The ''Rigveda'' or ''Rig Veda'' ( ', from ' "praise" and ' "knowledge") is an ancient Indian collection of Vedic Sanskrit hymns (''sūktas''). It is one of the four sacred canonical Hindu texts (''śruti'') known as the Vedas. Only one Sh ...

''. The oldest inscription in Bangladesh was found in Mahasthangarh and dates from the 3rd century BCE. It is written in the Brahmi script

Brahmi (; ; ISO: ''Brāhmī'') is a writing system of ancient South Asia. "Until the late nineteenth century, the script of the Aśokan (non-Kharosthi) inscriptions and its immediate derivatives was referred to by various names such as 'lath' o ...

.

Greek and Roman records of the ancient Gangaridai Kingdom, which (according to legend) deterred the invasion of Alexander the Great

Alexander III of Macedon ( grc, wikt:Ἀλέξανδρος, Ἀλέξανδρος, Alexandros; 20/21 July 356 BC – 10/11 June 323 BC), commonly known as Alexander the Great, was a king of the Ancient Greece, ancient Greek kingdom of Maced ...

, are linked to the fort city in Wari-Bateshwar

The Wari-Bateshwar (Bengali: উয়ারী-বটেশ্বর,''Uari-Bôṭeshshor'') ruins in Narsingdi, Dhaka Division, Bangladesh is one of the earliest urban archaeological sites in Bangladesh. Excavation in the site unearthed a ...

. The site is also identified with the prosperous trading centre of Souanagoura listed on Ptolemy's world map

The Ptolemy world map is a map of the world known to Greco-Roman societies in the 2nd century. It is based on the description contained in Ptolemy's book ''Geography'', written . Based on an inscription in several of the earliest surviving manusc ...

. Roman geographers noted a large seaport in southeastern Bengal, corresponding to the present-day Chittagong

Chittagong ( /ˈtʃɪt əˌɡɒŋ/ ''chit-uh-gong''; ctg, চিটাং; bn, চিটাগং), officially Chattogram ( bn, চট্টগ্রাম), is the second-largest city in Bangladesh after Dhaka and third largest city in B ...

region.

Ancient Buddhist

Buddhism ( , ), also known as Buddha Dharma and Dharmavinaya (), is an Indian religion or philosophical tradition based on teachings attributed to the Buddha. It originated in northern India as a -movement in the 5th century BCE, and ...

and Hindu

Hindus (; ) are people who religiously adhere to Hinduism.Jeffery D. Long (2007), A Vision for Hinduism, IB Tauris, , pages 35–37 Historically, the term has also been used as a geographical, cultural, and later religious identifier for ...

states which ruled Bangladesh included the Vanga, Samatata and Pundra kingdoms, the Mauryan and Gupta Empire

The Gupta Empire was an ancient Indian empire which existed from the early 4th century CE to late 6th century CE. At its zenith, from approximately 319 to 467 CE, it covered much of the Indian subcontinent. This period is considered as the Gol ...

s, the Varman dynasty

The Varman dynasty (350–650) was the first historical dynasty of the Kamarupa kingdom. It was established by Pushyavarman, a contemporary of Samudragupta. The earlier Varmans were subordinates of the Gupta Empire, but as the power of the Gup ...

, Shashanka

Shashanka (IAST: Śaśāṃka) was the first independent king of a unified polity in the Bengal region, called the Gauda Kingdom and is a major figure in Bengali history. He reigned in the 7th century, some historians place his rule between circ ...

's kingdom, the Khadga and Candra dynasties, the Pala Empire, the Sena dynasty, the Harikela

Harikela () was an ancient empire located in the eastern region of the Indian subcontinent. Originally, it was a neighboring independent and independent township of ancient East Bengal, which had a continuous existence of about 500 years. The st ...

kingdom and the Deva dynasty. These states had well-developed currencies, banking, shipping, architecture, and art, and the ancient universities of Bikrampur and Mainamati

Moinamoti (''Môynamoti'') is an isolated low, dimpled range of hills, dotted with more than 50 ancient Buddhist settlements dating between the 8th and 12th century CE. It was part of the ancient Tripura division of Bengal. It extends through the ...

hosted scholars and students from other parts of Asia. Xuanzang

Xuanzang (, ; 602–664), born Chen Hui / Chen Yi (), also known as Hiuen Tsang, was a 7th-century Chinese Buddhist monk, scholar, traveler, and translator. He is known for the epoch-making contributions to Chinese Buddhism, the travelogue of ...

of China was a noted scholar who resided at the Somapura Mahavihara

Somapura Mahavihara ( bn, সোমপুর মহাবিহার, Shompur Môhabihar) in Paharpur, Badalgachhi Upazila, Badalgachhi, Naogaon District, Naogaon, Bangladesh is among the best known Buddhist viharas or monasteries in the Indi ...

(the largest monastery in ancient India), and Atisa travelled from Bengal to Tibet

Tibet (; ''Böd''; ) is a region in East Asia, covering much of the Tibetan Plateau and spanning about . It is the traditional homeland of the Tibetan people. Also resident on the plateau are some other ethnic groups such as Monpa people, ...

to preach Buddhism. The earliest form of the Bengali language

Bengali ( ), generally known by its endonym Bangla (, ), is an Indo-Aryan languages, Indo-Aryan language native to the Bengal region of South Asia. It is the official, national, and most widely spoken language of Bangladesh and the second m ...

emerged during the eighth century. Seafarers in the Bay of Bengal

The Bay of Bengal is the northeastern part of the Indian Ocean, bounded on the west and northwest by India, on the north by Bangladesh, and on the east by Myanmar and the Andaman and Nicobar Islands of India. Its southern limit is a line between ...

where modern Bangladesh is now located, have also been sailing and trading with Southeast Asia

Southeast Asia, also spelled South East Asia and South-East Asia, and also known as Southeastern Asia, South-eastern Asia or SEA, is the geographical United Nations geoscheme for Asia#South-eastern Asia, south-eastern region of Asia, consistin ...

and exported Buddhist and Hindu cultures to the region since the early Christian era.

Islamic Bengal

The early history of Islam in Bengal is divided into two phases. The first phase is the period of maritime trade with Arabia and Persia between the 8th and 12th centuries. The second phase covers centuries of Muslim dynastic rule after the Islamic conquest of Bengal. The writings of Al-Idrisi, Ibn Hawqal,

The early history of Islam in Bengal is divided into two phases. The first phase is the period of maritime trade with Arabia and Persia between the 8th and 12th centuries. The second phase covers centuries of Muslim dynastic rule after the Islamic conquest of Bengal. The writings of Al-Idrisi, Ibn Hawqal, Al-Masudi

Al-Mas'udi ( ar, أَبُو ٱلْحَسَن عَلِيّ ٱبْن ٱلْحُسَيْن ٱبْن عَلِيّ ٱلْمَسْعُودِيّ, '; –956) was an Arab historian, geographer and traveler. He is sometimes referred to as the "Herodotus ...

, Ibn Khordadbeh

Abu'l-Qasim Ubaydallah ibn Abdallah ibn Khordadbeh ( ar, ابوالقاسم عبیدالله ابن خرداذبه; 820/825–913), commonly known as Ibn Khordadbeh (also spelled Ibn Khurradadhbih; ), was a high-ranking Persian bureaucrat and ...

and Sulaiman Sulaiman is an English transliteration of the Arabic name that means "peaceful" and corresponds to the Jewish name Hebrew: שְׁלֹמֹה, Shlomoh) and the English Solomon (/ˈsɒləmən/) . Solomon was the scriptural figure who was king of ...

record the maritime links between Arabia, Persia and Bengal. Muslim trade with Bengal flourished after the fall of the Sasanian Empire

The Sasanian () or Sassanid Empire, officially known as the Empire of Iranians (, ) and also referred to by historians as the Neo-Persian Empire, was the History of Iran, last Iranian empire before the early Muslim conquests of the 7th-8th cen ...

and the Arab takeover of Persian trade routes. Much of this trade occurred with southeastern Bengal in areas east of the Meghna River

The Meghna River ( bn, মেঘনা নদী) is one of the major rivers in Bangladesh, one of the three that form the Ganges Delta, the largest delta on earth, which fans out to the Bay of Bengal. A part of the Surma-Meghna River System, ...

. There is speculation regarding the presence of a Muslim community in Bangladesh as early as 690 CE; this is based on the discovery of one of South Asia's oldest mosques in northern Bangladesh. Bengal was possibly used as a transit route to China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's most populous country, with a population exceeding 1.4 billion, slightly ahead of India. China spans the equivalent of five time zones and ...

by the earliest Muslims. Abbasid

The Abbasid Caliphate ( or ; ar, الْخِلَافَةُ الْعَبَّاسِيَّة, ') was the third caliphate to succeed the Islamic prophet Muhammad. It was founded by a dynasty descended from Muhammad's uncle, Abbas ibn Abdul-Muttalib ...

coins have been discovered in the archaeological ruins of Paharpur and Mainamati

Moinamoti (''Môynamoti'') is an isolated low, dimpled range of hills, dotted with more than 50 ancient Buddhist settlements dating between the 8th and 12th century CE. It was part of the ancient Tripura division of Bengal. It extends through the ...

. A collection of Sasanian, Umayyad

The Umayyad Caliphate (661–750 CE; , ; ar, ٱلْخِلَافَة ٱلْأُمَوِيَّة, al-Khilāfah al-ʾUmawīyah) was the second of the four major caliphates established after the death of Muhammad. The caliphate was ruled by the ...

and Abbasid coins are preserved in the Bangladesh National Museum.

The Muslim conquest of Bengal began with the 1204 Ghurid

The Ghurid dynasty (also spelled Ghorids; fa, دودمان غوریان, translit=Dudmân-e Ğurīyân; self-designation: , ''Šansabānī'') was a Persianate dynasty and a clan of presumably eastern Iranian Tajik origin, which ruled from the ...

expeditions led by Muhammad bin Bakhtiyar Khalji

Ikhtiyār al-Dīn Muḥammad Bakhtiyār Khaljī, (Pashto :اختيار الدين محمد بختيار غلزۍ, fa, اختیارالدین محمد بختیار خلجی, bn, ইখতিয়ারউদ্দীন মুহম্মদ � ...

, who overran the Sena capital in Gauda and led the first Muslim army into Tibet. The conquest of Bengal was inscribed in gold coins of the Delhi Sultanate

The Delhi Sultanate was an Islamic empire based in Delhi that stretched over large parts of the Indian subcontinent for 320 years (1206–1526).

. Bengal was ruled by the Sultans of Delhi for a century under the Mamluk

Mamluk ( ar, مملوك, mamlūk (singular), , ''mamālīk'' (plural), translated as "one who is owned", meaning " slave", also transliterated as ''Mameluke'', ''mamluq'', ''mamluke'', ''mameluk'', ''mameluke'', ''mamaluke'', or ''marmeluke'') ...

, Balban, and Tughluq dynasties. In the 14th century, three city-states emerged in Bengal, including Sonargaon led by Fakhruddin Mubarak Shah, Satgaon

Saptagram (Bengali: সপ্তগ্রাম; colloquially called ''Satgaon'') was a major port, the chief city and sometimes capital of southern Bengal, in ancient and medieval times, the location presently being in the Hooghly district in t ...

led by Shamsuddin Ilyas Shah

Haji Ilyas, better known as Shamsuddin Ilyas Shah ( bn, শামসুদ্দীন ইলিয়াস শাহ, fa, ), was the founder of the Sultanate of Bengal and its inaugural Ilyas Shahi dynasty which ruled the region for 150 year ...

and Lakhnauti led by Alauddin Ali Shah. These city-states were led by former governors who declared independence from Delhi. The Moroccan traveler Ibn Battuta

Abu Abdullah Muhammad ibn Battutah (, ; 24 February 13041368/1369),; fully: ; Arabic: commonly known as Ibn Battuta, was a Berbers, Berber Maghrebi people, Maghrebi scholar and explorer who travelled extensively in the lands of Afro-Eurasia, ...

visited eastern Bengal during the reign of Fakhruddin Mubarak Shah. Ibn Battuta also visited the Sufi

Sufism ( ar, ''aṣ-ṣūfiyya''), also known as Tasawwuf ( ''at-taṣawwuf''), is a mystic body of religious practice, found mainly within Sunni Islam but also within Shia Islam, which is characterized by a focus on Islamic spirituality, ...

leader Shah Jalal in Sylhet

Sylhet ( bn, সিলেট) is a metropolitan city in northeastern Bangladesh. It is the administrative seat of the Sylhet Division. Located on the north bank of the Surma River at the eastern tip of Bengal, Sylhet has a subtropical climate an ...

. Sufis played an important role in spreading Islam in Bengal through both peaceful conversion and militarily overthrowing pre-Islamic rulers. In 1352, Shamsuddin Ilyas Shah united the three city-states into a single, unitary and independent Bengal Sultanate

The Sultanate of Bengal ( Middle Bengali: শাহী বাঙ্গালা ''Shahī Baṅgala'', Classical Persian: ''Saltanat-e-Bangālah'') was an empire based in Bengal for much of the 14th, 15th and 16th centuries. It was the dominan ...

. The new Sultan of Bengal led the first Muslim army into Nepal

Nepal (; ne, नेपाल ), formerly the Federal Democratic Republic of Nepal ( ne,

सङ्घीय लोकतान्त्रिक गणतन्त्र नेपाल ), is a landlocked country in South Asia. It is mai ...

and forced the Sultan of Delhi to retreat during an invasion. The army of Ilyas Shah reached as far as Varanasi

Varanasi (; ; also Banaras or Benares (; ), and Kashi.) is a city on the Ganges river in northern India that has a central place in the traditions of pilgrimage, death, and mourning in the Hindu world.

*

*

*

* The city has a syncretic t ...

in the northwest, Kathmandu

, pushpin_map = Nepal Bagmati Province#Nepal#Asia

, coordinates =

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name =

, subdivision_type1 = Province

, subdivision_name1 = Bagmati Prov ...

in the north, Kamarupa

Kamarupa (; also called Pragjyotisha or Pragjyotisha-Kamarupa), an early state during the Classical period on the Indian subcontinent, was (along with Davaka) the first historical kingdom of Assam.

Though Kamarupa prevailed from 350 to 11 ...

in the east and Orissa

Odisha (English: , ), formerly Orissa ( the official name until 2011), is an Indian state located in Eastern India. It is the 8th largest state by area, and the 11th largest by population. The state has the third largest population of Sch ...

in the south. Ilyas Shah raided many of these areas and returned to Bengal with treasures. During the reign of Sikandar Shah, Delhi recognised Bengal's independence. The Bengal Sultanate established a network of mint towns which acted as a provincial capitals where the Sultan's currency was minted. Bengal became the eastern frontier of the Islamic world, which stretched from Muslim Spain in the west to Bengal in the east. The Bengali language crystallized as an official court language during the Bengal Sultanate, with prominent writers like Nur Qutb Alam, Usman Serajuddin

ʿUthmān Sirāj ad-Dīn al-Bangālī ( ar, عثمان سراج الدين البنغالي; 1258-1357), known affectionately by followers as Akhi Siraj ( bn, আখি সিরাজ), was a 14th-century Bengali Muslim Islamic scholar, scholar. ...

, Alaul Haq

ʿAlā ul-Ḥaq wa ad-Dīn ʿUmar ibn As`ad al-Khālidī al-Bangālī ( ar, علاء الحق والدين عمر بن أسعد الخالدي البنغالي), commonly known as Alaul Haq ( bn, আলাউল হক) or reverentially by the sob ...

, Alaol, Shah Muhammad Sagir

Shah Muhammad Sagir ( bn, শাহ মুহম্মদ সগীর) was one of the earliest Bengali Muslim poets, if not the first.

Life

Shah Muhammad Sagir was a poet of the 14/15th century, during the reign of the Sultan of Bengal Ghiyasuddi ...

, Abdul Hakim

Abdul Hakim ( ar, عبد الحكيم, translit=ʻAbd al-Ḥakīm) is a Muslim male given name, and in modern usage, first name or surname. It is built from the Arabic words '' Abd'', ''al-'' and ''Hakim''. The name means "servant of the All-wise" ...

and Syed Sultan

Syed Sultan ( bn, সৈয়দ সুলতান) was a medieval Bengali Muslim writer and epic poet. He is best known for his magnum opus, the ''Nabibangsha'', which was one of the first translations of the Qisas Al-Anbiya into the Bengali la ...

; and the emergence of '' Dobhashi'' to write Muslim epics in Bengali literature.

The Bengal Sultanate was a melting pot of Muslim political, mercantile and military elites. Muslims from other parts of the world migrated to Bengal for military, bureaucratic and household services. Immigrants included Persians who were lawyers, teachers, clerics, and scholars; Turks from upper India who were originally recruited in Central Asia

Central Asia, also known as Middle Asia, is a subregion, region of Asia that stretches from the Caspian Sea in the west to western China and Mongolia in the east, and from Afghanistan and Iran in the south to Russia in the north. It includes t ...

; and Abyssinians who came via East Africa and arrived in the Bengali port of Chittagong. A highly commercialized and monetized economy evolved.

The two most prominent dynasties of the Bengal Sultanate were the Ilyas Shahi and Hussain Shahi dynasties. The reign of Sultan Ghiyasuddin Azam Shah

Ghiyasuddin A'zam Shah ( bn, গিয়াসউদ্দীন আজম শাহ, fa, ) was the third Sultan of Bengal and the Ilyas Shahi dynasty. He was one of the most prominent medieval Bengali sultans. He established diplomatic relatio ...

saw the opening of diplomatic relations with Ming China

The Ming dynasty (), officially the Great Ming, was an imperial dynasty of China, ruling from 1368 to 1644 following the collapse of the Mongol-led Yuan dynasty. The Ming dynasty was the last orthodox dynasty of China ruled by the Han peop ...

. Ghiyasuddin was also a friend of the Persian poet Hafez. The reign of the Sultan Jalaluddin Muhammad Shah

Jalaluddin Muhammad Shah ( bn, জালালউদ্দীন মুহম্মদ শাহ; born as Yadu or Jadu) was a 15th-century Sultan of Bengal and an important figure in medieval Bengali history. Born a Hindu to his aristocratic fat ...

saw the development of Bengali architecture

The architecture of Bengal, which comprises the modern country of Bangladesh and the Indian states of West Bengal, Tripura and Assam's Barak Valley, has a long and rich history, blending indigenous elements from the Indian subcontinent, with influ ...

. During the early 15th century, the Restoration of Min Saw Mon

The restoration of Min Saw Mon was a military campaign led by the Bengal Sultanate to help Min Saw Mon regain control of his Launggyet Dynasty. The campaign was successful. Min Saw Mon was restored to the Launggyet throne, and northern Arakan becam ...

in Arakan was aided by the army of the Bengal Sultanate. As a result, Arakan became a tributary state of Bengal. Even though Arakan later became independent, Bengali Muslim influence in Arakan persisted for 300 years due to the settlement of Bengali bureaucrats, poets, military personnel, farmers, artisans, and sailors. The kings of Arakan fashioned themselves after Bengali Sultans and adopted Muslim titles. During the reign of Sultan Alauddin Hussain Shah, the Bengal Sultanate dispatched a naval flotilla and an army of 24,000 soldiers led by Shah Ismail Ghazi

Shah Ismail Ghazi ( bn, শাহ ইসমাঈল গাজী) was a 15th-century Sufi Muslim preacher based in Bengal. He came to Bengal in the mid-fifteenth century during the reign of Rukunuddin Barbak Shah, settling in the country's capit ...

to conquer Assam

Assam (; ) is a state in northeastern India, south of the eastern Himalayas along the Brahmaputra and Barak River valleys. Assam covers an area of . The state is bordered by Bhutan and Arunachal Pradesh to the north; Nagaland and Manipur ...

.Majumdar, R.C. (ed.) (2006). ''The Delhi Sultanate'', Mumbai: Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan, pp.215–20 Bengali forces penetrated deep into the Brahmaputra Valley. Hussain Shah's forces also conquered Jajnagar in Orissa. In Tripura

Tripura (, Bengali: ) is a state in Northeast India. The third-smallest state in the country, it covers ; and the seventh-least populous state with a population of 36.71 lakh ( 3.67 million). It is bordered by Assam and Mizoram to the east a ...

, Bengal helped Ratna Manikya I

Ratna Manikya I (d. 1487), also known as Ratna Fa, was the Maharaja of Tripura from 1462 to the late 1480s. Though he had gained the throne by overthrowing his predecessor, Ratna's reign was notable for the peace and prosperity it had entailed in ...

to assume the throne. The Jaunpur Sultanate, Pratapgarh Kingdom

The Pratapgarh Kingdom ( bn, প্রতাপগড় রাজ্য) was a Medieval India, medieval state in the north-east of the Indian subcontinent. Composed of the present-day Indian district of Karimganj district, Karimganj, as well ...

and the island of Chandradwip

Chandradwip or Chandradvipa is a small region in Barisal District, Bangladesh. It was once the ancient and medieval name of Barishal.

History

The history of Chandradwip goes back to the Pre-Pala Period.

Chandradwip was successively ruled by the ...

also came under Bengali control. By 1500, Gaur became the fifth-most populous city in the world with a population of 200,000. The river port of Sonargaon was used as a base by the Sultans of Bengal during campaigns against Assam, Tripura and Arakan. The Sultans launched many naval raids from Sonargaon. João de Barros

João de Barros () (1496 – 20 October 1570), called the ''Portuguese Livy'', is one of the first great Portuguese historians, most famous for his ''Décadas da Ásia'' ("Decades of Asia"), a history of the Portuguese in India, Asia, and southea ...

described the seaport of Chittagong as "the most famous and wealthy city of the Kingdom of Bengal". Maritime trade linked Bengal with China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's most populous country, with a population exceeding 1.4 billion, slightly ahead of India. China spans the equivalent of five time zones and ...

, Malacca

Malacca ( ms, Melaka) is a state in Malaysia located in the southern region of the Malay Peninsula, next to the Strait of Malacca. Its capital is Malacca City, dubbed the Historic City, which has been listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site si ...

, Sumatra

Sumatra is one of the Sunda Islands of western Indonesia. It is the largest island that is fully within Indonesian territory, as well as the sixth-largest island in the world at 473,481 km2 (182,812 mi.2), not including adjacent i ...

, Brunei

Brunei ( , ), formally Brunei Darussalam ( ms, Negara Brunei Darussalam, Jawi alphabet, Jawi: , ), is a country located on the north coast of the island of Borneo in Southeast Asia. Apart from its South China Sea coast, it is completely sur ...

, Portuguese India

The State of India ( pt, Estado da Índia), also referred as the Portuguese State of India (''Estado Português da Índia'', EPI) or simply Portuguese India (), was a state of the Portuguese Empire founded six years after the discovery of a se ...

, East Africa

East Africa, Eastern Africa, or East of Africa, is the eastern subregion of the African continent. In the United Nations Statistics Division scheme of geographic regions, 10-11-(16*) territories make up Eastern Africa:

Due to the historical ...

, Arabia, Persia, Mesopotamia, Yemen

Yemen (; ar, ٱلْيَمَن, al-Yaman), officially the Republic of Yemen,, ) is a country in Western Asia. It is situated on the southern end of the Arabian Peninsula, and borders Saudi Arabia to the Saudi Arabia–Yemen border, north and ...

and the Maldives

Maldives (, ; dv, ދިވެހިރާއްޖެ, translit=Dhivehi Raajje, ), officially the Republic of Maldives ( dv, ދިވެހިރާއްޖޭގެ ޖުމްހޫރިއްޔާ, translit=Dhivehi Raajjeyge Jumhooriyyaa, label=none, ), is an archipelag ...

. Bengali ships were among the biggest vessels plying the Bay of Bengal

The Bay of Bengal is the northeastern part of the Indian Ocean, bounded on the west and northwest by India, on the north by Bangladesh, and on the east by Myanmar and the Andaman and Nicobar Islands of India. Its southern limit is a line between ...

, Indian Ocean

The Indian Ocean is the third-largest of the world's five oceanic divisions, covering or ~19.8% of the water on Earth's surface. It is bounded by Asia to the north, Africa to the west and Australia to the east. To the south it is bounded by th ...

and Pacific Ocean

The Pacific Ocean is the largest and deepest of Earth's five oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic Ocean in the north to the Southern Ocean (or, depending on definition, to Antarctica) in the south, and is bounded by the continen ...

. A royal vessel from Bengal accommodated three embassies from Bengal, Brunei and Sumatra while en route to China and was the only vessel capable of transporting three embassies. Many wealthy Bengali shipowners and merchants lived in Malacca. The Sultans permitted the opening of the Portuguese settlement in Chittagong

Chittagong, the second largest city and main port of Bangladesh, was home to a thriving trading post of the Portuguese Empire in the East in the 16th and 17th centuries. The Portuguese first arrived in Chittagong around 1528 and left in 1666 af ...

. The disintegration of the Bengal Sultanate began with the intervention of the Suri Empire

The Sur Empire ( ps, د سرو امپراتورۍ, dë sru amparāturəi; fa, امپراطوری سور, emperâturi sur) was an Afghan dynasty which ruled a large territory in the northern part of the Indian subcontinent for nearly 16 year ...

. Babur

Babur ( fa, , lit= tiger, translit= Bābur; ; 14 February 148326 December 1530), born Mīrzā Zahīr ud-Dīn Muhammad, was the founder of the Mughal Empire in the Indian subcontinent. He was a descendant of Timur and Genghis Khan through his ...

began invading Bengal after creating the Mughal Empire. The Bengal Sultanate collapsed with the overthrow of the Karrani dynasty during the reign of Akbar. However, the Bhati

Bhati is a clan of Rajputs

History

The Bhatis reportedly originated in Mathura through a common ancestor named Bhati, who was a descendant of Pradyumn. According to the seventeenth-century Nainsi ri Khyat, the Bhatis after losing Mathura ...

region of eastern Bengal continued to be ruled by aristocrats of the former Bengal Sultanate led by Isa Khan. They formed an independent federation called the Twelve Bhuiyans, with their capital in Sonargaon. They defeated the Mughals in several naval battles. The Bhuiyans ultimately succumbed to the Mughals after Musa Khan was defeated.

The

The Mughal Empire

The Mughal Empire was an early-modern empire that controlled much of South Asia between the 16th and 19th centuries. Quote: "Although the first two Timurid emperors and many of their noblemen were recent migrants to the subcontinent, the d ...

controlled Bengal by the 17th century. During the reign of Emperor Akbar

Abu'l-Fath Jalal-ud-din Muhammad Akbar (25 October 1542 – 27 October 1605), popularly known as Akbar the Great ( fa, ), and also as Akbar I (), was the third Mughal emperor, who reigned from 1556 to 1605. Akbar succeeded his father, Hum ...

, the Bengali agrarian calendar was reformed to facilitate tax collection. The Mughals established Dhaka as a fort city and commercial metropolis, and it was the capital of Bengal Subah for 75 years. In 1666, the Mughals expelled the Arakanese from Chittagong. Mughal Bengal attracted foreign traders for its muslin

Muslin () is a cotton fabric of plain weave. It is made in a wide range of weights from delicate sheers to coarse sheeting. It gets its name from the city of Mosul, Iraq, where it was first manufactured.

Muslin of uncommonly delicate handsp ...

and silk goods, and the Armenians

Armenians ( hy, հայեր, ''hayer'' ) are an ethnic group native to the Armenian highlands of Western Asia. Armenians constitute the main population of Armenia and the ''de facto'' independent Artsakh. There is a wide-ranging diaspora ...

were a notable merchant community. A Portuguese settlement in Chittagong

Chittagong, the second largest city and main port of Bangladesh, was home to a thriving trading post of the Portuguese Empire in the East in the 16th and 17th centuries. The Portuguese first arrived in Chittagong around 1528 and left in 1666 af ...

flourished in the southeast, and a Dutch settlement in Rajshahi existed in the north. Bengal accounted for 40% of overall Dutch imports from Asia; including more than 50% of textiles and around 80% of silks.Om Prakash

Om Prakash (born Om Prakash Chibber 19 December 1919 – 21 February 1998) was an Indian film actor. He was born in Jammu as Om Prakash Chibber and went on to become a well-known character actor of Bollywood. His most well-known movies are Nam ...

,Empire, Mughal

, ''History of World Trade Since 1450'', edited by John J. McCusker, vol. 1, Macmillan Reference USA, 2006, pp. 237–240, ''World History in Context''. Retrieved 3 August 2017 The Bengal Subah, described as the ''Paradise of the Nations'', was the empire's wealthiest province, and a major global exporter,

John F. Richards

John F. Richards (November 3, 1938 – August 23, 2007) was a historian of South Asia and in particular of the Mughal Empire. He was Professor of History at Duke University, North Carolina, and a recipient in 2007 of the Distinguished Contributio ...

(1995)''The Mughal Empire'', page 202

Cambridge University Press

Cambridge University Press is the university press of the University of Cambridge. Granted letters patent by Henry VIII of England, King Henry VIII in 1534, it is the oldest university press

A university press is an academic publishing hou ...

a notable centre of worldwide industries such as muslin

Muslin () is a cotton fabric of plain weave. It is made in a wide range of weights from delicate sheers to coarse sheeting. It gets its name from the city of Mosul, Iraq, where it was first manufactured.

Muslin of uncommonly delicate handsp ...

, cotton textiles, silk, and shipbuilding

Shipbuilding is the construction of ships and other floating vessels. It normally takes place in a specialized facility known as a shipyard. Shipbuilders, also called shipwrights, follow a specialized occupation that traces its roots to befor ...

. Its citizens also enjoyed one of the world's most superior living standards

Standard of living is the level of income, comforts and services available, generally applied to a society or location, rather than to an individual. Standard of living is relevant because it is considered to contribute to an individual's quality ...

.

During the 18th century, the Nawabs of Bengal

The Nawab of Bengal ( bn, বাংলার নবাব) was the hereditary ruler of Bengal Subah in Mughal India. In the early 18th-century, the Nawab of Bengal was the ''de facto'' independent ruler of the three regions of Bengal, Bihar, ...

became the region's ''de facto'' rulers. The ruler's title is popularly known as the ''Nawab of Bengal, Bihar, and Orissa'', given that the Bengali Nawab's realm encompassed much of the eastern subcontinent. The Nawabs forged alliances with European colonial companies, making the region relatively prosperous early in the century. Bengal accounted for 50% of the gross domestic product of the empire. The Bengali economy relied on textile manufacturing

Textile Manufacturing or Textile Engineering is a major industry. It is largely based on the conversion of fibre into yarn, then yarn into fabric. These are then dyed or printed, fabricated into cloth which is then converted into useful goods ...

, shipbuilding, saltpetre

Potassium nitrate is a chemical compound with the chemical formula . This alkali metal nitrate salt is also known as Indian saltpetre (large deposits of which were historically mined in India). It is an ionic salt of potassium ions K+ and nitra ...

production, craftsmanship, and agricultural produce. Bengal was a major hub for international trade – silk and cotton textiles from Bengal were worn in Europe, Japan, Indonesia, and Central Asia. Annual Bengali shipbuilding output was 223,250tons, compared to an output of 23,061tons in the nineteen colonies of North America. Bengali shipbuilding proved to be more advanced than European shipbuilding before the Industrial Revolution. The flush deck

Flush deck is a term in naval architecture. It can refer to any deck of a ship which is continuous from stem to stern.

History

The flush deck design originated with rice ships built in Bengal Subah, Mughal India (modern Bangladesh), resulting i ...

of Bengali rice ships was later replicated in European shipbuilding to replace the stepped deck design for ship hulls. Maddison, Angus (2003): Development Centre Studies The World Economy Historical Statistics: Historical Statistics

', OECD Publishing, , pages 259–261 Eastern Bengal was a thriving

melting pot

The melting pot is a monocultural metaphor for a heterogeneous society becoming more homogeneous, the different elements "melting together" with a common culture; an alternative being a homogeneous society becoming more heterogeneous throug ...

with strong trade and cultural networks. It was a relatively prosperous part of the subcontinent and the center of the Muslim population in the eastern subcontinent. The Muslims of eastern Bengal included people of diverse origins from different parts of the world.

The Bengali Muslim population was a product of conversion and religious evolution, and their pre-Islamic beliefs included elements of Buddhism and Hinduism. The construction of mosques, Islamic academies (madrasas) and Sufi monasteries (khanqah

A khanqah ( fa, خانقاه) or khangah ( fa, خانگاه; also transliterated as ''khankah'', ''khaneqa'', ''khanegah'' or ''khaneqah''; also Arabized ''hanegah'', ''hanikah'', ''hanekah'', ''khankan''), also known as a ribat (), is a buildin ...

s) facilitated conversion, and Islamic cosmology

Islamic cosmology is the cosmology of Islamic societies. It is mainly derived from the Qur'an, Hadith, Sunnah, and current Islamic as well as other pre-Islamic sources. The Qur'an itself mentions seven heavens.Qur'an 2:29

Metaphysical principl ...

played a significant role in developing Bengali Muslim society. Scholars have theorised that Bengalis were attracted to Islam by its egalitarian social order, which contrasted with the Hindu caste system. By the 15th century, Muslim poets were widely writing in the Bengali language. Syncretic cults, such as the Baul movement, emerged on the fringes of Bengali Muslim society. The Persianate culture was significant in Bengal, where cities like Sonargaon became the easternmost centres of Persian influence.

In 1756, nawab Siraj ud-Daulah sought to rein in the rising power of the British East India Company

The East India Company (EIC) was an English, and later British, joint-stock company founded in 1600 and dissolved in 1874. It was formed to trade in the Indian Ocean region, initially with the East Indies (the Indian subcontinent and Southea ...

by revoking their free trade rights and demanding the dismantling of their fortification in Calcutta. A military conflict ensued which culminated in the Battle of Plassey

The Battle of Plassey was a decisive victory of the British East India Company over the Nawab of Bengal and his French allies on 23 June 1757, under the leadership of Robert Clive. The victory was made possible by the defection of Mir Jafar, ...

on 22 June 1757. Robert Clive

Robert Clive, 1st Baron Clive, (29 September 1725 – 22 November 1774), also known as Clive of India, was the first British Governor of the Bengal Presidency. Clive has been widely credited for laying the foundation of the British ...

exploited rivalries within the nawab's family, bribing Mir Jafar

Sayyid Mīr Jaʿfar ʿAlī Khān Bahādur ( – 5 February 1765) was a military general who became the first dependent Nawab of Bengal of the British East India Company. His reign has been considered by many historians as the start of the expan ...

, the nawab's uncle and commander in chief, to ensure Siraj-ud-Daula's defeat. Clive rewarded Mir Jafar by making him nawab in place of Siraj-ud-Daula, but henceforth the position was a figurehead appointed and controlled by the company. After Plassey, the Mughal emperor ruled Bengal in name only. Effective power rested with the company. Historians often describe the battle as "the beginning of British colonial rule in South Asia". Historian Willem van Schendel describes it as "The beginning of empire" for Britain.

The Company replaced Mir Jafar with his son-in-law, Mir Kasim, in 1760. Mir Kasim challenged British control by allying with Mughal emperor Shah Alam II

Shah Alam II (; 25 June 1728 – 19 November 1806), also known by his birth name Ali Gohar (or Ali Gauhar), was the seventeenth Mughal Emperor and the son of Alamgir II. Shah Alam II became the emperor of a crumbling Mughal empire. His powe ...

and the Nawab of Awadh, Shuja ud-Daulah, but the company decisively defeated the three at the Battle of Buxar

The Battle of Buxar was fought between 22 and 23 October 1764, between the forces under the command of the British East India Company, led by Hector Munro, and the combined armies of Mir Qasim, Nawab of Bengal till 1764; the Nawab of Awadh, Sh ...

on 23 October 1764. The resulting treaty made the Mughal emperor a puppet of the British and gave the company the right to collect taxes (''diwani

Diwani is a calligraphic variety of Arabic script, a cursive style developed during the reign of the early Ottoman Turks (16th century - early 17th century). It reached its height of popularity under Süleyman I the Magnificent (1520–1566) ...

'') in Bengal, Bihar, and Orissa, giving them de facto control of the region. The Company used Bengal's tax revenue to conquer the rest of India. By 1857, the Company controlled over 60% of the subcontinent directly, and exercised indirect rule over the remainder.

Colonial period

Two decades after

Two decades after Vasco Da Gama

Vasco da Gama, 1st Count of Vidigueira (; ; c. 1460s – 24 December 1524), was a Portuguese explorer and the first European to reach India by sea.

His initial voyage to India by way of Cape of Good Hope (1497–1499) was the first to link E ...

's landing in Calicut

Kozhikode (), also known in English as Calicut, is a city along the Malabar Coast in the state of Kerala in India. It has a corporation limit population of 609,224 and a metropolitan population of more than 2 million, making it the second la ...

, the Bengal Sultanate permitted the Portuguese settlement in Chittagong to be established in 1528. It became the first European colonial enclave in Bengal. The Bengal Sultanate lost control of Chittagong in 1531 after Arakan declared independence and the established Kingdom of Mrauk U.

Portuguese ships from Goa and Malacca

Malacca ( ms, Melaka) is a state in Malaysia located in the southern region of the Malay Peninsula, next to the Strait of Malacca. Its capital is Malacca City, dubbed the Historic City, which has been listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site si ...

began frequenting the port city in the 16th century. The '' cartaz'' system was introduced and required all ships in the area to purchase naval trading licenses from the Portuguese settlement. Slave trade

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

and piracy flourished. The nearby island of Sandwip was conquered in 1602. In 1615, the Portuguese Navy defeated a joint Dutch East India Company

The United East India Company ( nl, Verenigde Oostindische Compagnie, the VOC) was a chartered company established on the 20th March 1602 by the States General of the Netherlands amalgamating existing companies into the first joint-stock ...

and Arakanese fleet near the coast of Chittagong.

The Bengal Sultan after 1534 allowed the Portuguese to create several settlements at Chitagoong, Satgaon, Hughli, Bandel, and Dhaka. In 1535, the Portuguese allied with the Bengal sultan and held the Teliagarhi pass from Patna

Patna (

), historically known as Pataliputra, is the capital and largest city of the state of Bihar in India. According to the United Nations, as of 2018, Patna had a population of 2.35 million, making it the 19th largest city in India. ...

helping to avoid the invasion by the Mughals. By then several of the products came from Patna and the Portuguese send in traders, establishing a factory there since 1580.

By the time the Portuguese assured military help against Sher Shah, the Mughals already had started to conquer the Sultanate of Ghiyasuddin Mahmud.

The region has been described as the "Paradise of Nations", and its inhabitants's living standards

Standard of living is the level of income, comforts and services available, generally applied to a society or location, rather than to an individual. Standard of living is relevant because it is considered to contribute to an individual's quality ...

and real wages

Real wages are wages adjusted for inflation, or, equivalently, wages in terms of the amount of goods and services that can be bought. This term is used in contrast to nominal wages or unadjusted wages.

Because it has been adjusted to account f ...

were among the highest in the world. It alone accounted for 40% of Dutch imports outside the Europe

Europe is a large peninsula conventionally considered a continent in its own right because of its great physical size and the weight of its history and traditions. Europe is also considered a Continent#Subcontinents, subcontinent of Eurasia ...

an continent. The eastern part of Bengal was globally prominent in industries such as textile manufacturing

Textile Manufacturing or Textile Engineering is a major industry. It is largely based on the conversion of fibre into yarn, then yarn into fabric. These are then dyed or printed, fabricated into cloth which is then converted into useful goods ...

and shipbuilding

Shipbuilding is the construction of ships and other floating vessels. It normally takes place in a specialized facility known as a shipyard. Shipbuilders, also called shipwrights, follow a specialized occupation that traces its roots to befor ...

, and it was a major exporter of silk

Silk is a natural protein fiber, some forms of which can be woven into textiles. The protein fiber of silk is composed mainly of fibroin and is produced by certain insect larvae to form cocoons. The best-known silk is obtained from the coc ...

and cotton

Cotton is a soft, fluffy staple fiber that grows in a boll, or protective case, around the seeds of the cotton plants of the genus ''Gossypium'' in the mallow family Malvaceae. The fiber is almost pure cellulose, and can contain minor perce ...

textile

Textile is an umbrella term that includes various fiber-based materials, including fibers, yarns, filaments, threads, different fabric types, etc. At first, the word "textiles" only referred to woven fabrics. However, weaving is not the ...

s, steel

Steel is an alloy made up of iron with added carbon to improve its strength and fracture resistance compared to other forms of iron. Many other elements may be present or added. Stainless steels that are corrosion- and oxidation-resistant ty ...

, saltpeter, and agricultural

Agriculture or farming is the practice of cultivating Plant, plants and livestock. Agriculture was the key development in the rise of Sedentism, sedentary human civilization, whereby farming of Domestication, domesticated species created food ...

and industrial produce in the world.

In 1666, the Mughal government of Bengal led by viceroy Shaista Khan moved to retake Chittagong from Portuguese and Arakanese control. The Anglo-Mughal War

The Anglo-Mughal War, also known as Child's War, was the first Anglo-Indian War on the Indian Subcontinent.

The English East India Company had been given a monopoly and numerous fortified bases on western and south-eastern coast of the Mughal ...

was witnessed in 1686.

After the 1757

After the 1757 Battle of Plassey