Asian Relations Conference on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Asian Relations Conference was an international conference that took place in

The Asian Relations Conference was an international conference that took place in

Tibet received the invitation through

Tibet received the invitation through

In 1947, the end of colonial rule in India was in sight. The partition of India would occur four and a half months later, and several communal riots broke out in March.

India fielded the largest delegation with 52 delegates and 6 observers. Guests invited by India included

In 1947, the end of colonial rule in India was in sight. The partition of India would occur four and a half months later, and several communal riots broke out in March.

India fielded the largest delegation with 52 delegates and 6 observers. Guests invited by India included

Palestine Jewish Delegation (10/0)

#

Palestine Jewish Delegation (10/0)

#

The Asian Relations Conference was an international conference that took place in

The Asian Relations Conference was an international conference that took place in New Delhi

New Delhi (, , ''Naī Dillī'') is the capital of India and a part of the National Capital Territory of Delhi (NCT). New Delhi is the seat of all three branches of the government of India, hosting the Rashtrapati Bhavan, Parliament Ho ...

from 23 March to 2 April, 1947. Organized by the Indian Council of World Affairs (ICWA), the Conference was hosted by Jawaharlal Nehru

Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru (; ; ; 14 November 1889 – 27 May 1964) was an Indian anti-colonial nationalist, secular humanist, social democrat—

*

*

*

* and author who was a central figure in India during the middle of the 20t ...

, then the Vice-President of the interim Viceroy's Executive Council The Viceroy's Executive Council was the cabinet of the government of British India headed by the Viceroy of India. It is also known as the Council of the Governor-General of India. It was transformed from an advisory council into a cabinet consistin ...

, and presided by Sarojini Naidu

Sarojini Naidu (''née'' Chattopadhyay; 13 February 1879 – 2 March 1949) was an Indian political activist, feminist and poet. A proponent of civil rights, women's emancipation, and anti-imperialistic ideas, she was an important person in Ind ...

. Its goal was to promote cultural, intellectual and social exchange between Asia

Asia (, ) is one of the world's most notable geographical regions, which is either considered a continent in its own right or a subcontinent of Eurasia, which shares the continental landmass of Afro-Eurasia with Africa. Asia covers an are ...

n countries.

Envisioned to be non-political, the Conference included almost all Asian countries, as well as several independence movements. These included nations and communities that were on opposing sides, which inevitably raised political questions. Though the conference achieved an immediate sense of solidarity among Asian nations and saw the establishment of the Asian Relations Organisation, suspicions of an Indian or Chinese hegemony held by the minor nations did not allow the organisation to be effective, nor the second Asian Relations Conference held in 1950 to be as successful as the first.

Conception and organisation

It is not known who first conceived the idea of the Asian conference. Though Nehru stated, in the opening speech of the conference, that "the idea of such a conference arose simultaneously in many minds and many countries of Asia", some observers at the conference attributed the conference to Nehru. As early as December 1945, Jawaharlal Nehru stated in an interview that an Asian conference could further promote cooperation between Asian countries. ReporterPhillips Talbot

William Phillips Talbot (June 7, 1915 – October 1, 2010) was a United States Ambassador to Greece (1965–69) and, at his death, member of the American Academy of Diplomacy, the Council of American Ambassadors and the Council on Foreign Re ...

stated that the conference was conceived by Nehru in 1946 as a response to the impact of the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposi ...

on Asia. In March of that year, Nehru had a meeting with Aung San

Aung San (, ; 13 February 191519 July 1947) was a Burmese politician, independence activist and revolutionary. He was instrumental in Myanmar's struggle for independence from British rule, but he was assassinated just six months before his goa ...

during his South East Asia tour. It was reported that the topic of an Asian Conference was discussed. In August, he credited the 1927 League against Imperialism

The League against Imperialism and Colonial Oppression (french: Ligue contre l'impérialisme et l'oppression coloniale; german: Liga gegen Kolonialgreuel und Unterdrückung) was a transnational anti-imperialist organization in the interwar period. ...

, which he attended, as his inspiration for an Asian conference. Another possible engineer of the conference was B. Shiva Rao

Benegal Shiva Rao (26 February 1891 – 15 December 1975) was an Indian journalist and politician. He was a member of the Constituent Assembly of India and an elected representative of the South Kanara constituency in the First Lok Sabha (later ...

, who was involved in the Indian Institute of International Affairs (IIIA) and the Indian Council of World Affairs (ICWA), and who attended Institute of Pacific Relations

The Institute of Pacific Relations (IPR) was an international NGO established in 1925 to provide a forum for discussion of problems and relations between nations of the Pacific Rim. The International Secretariat, the center of most IPR activity o ...

(IPR) and United Nations

The United Nations (UN) is an intergovernmental organization whose stated purposes are to maintain international peace and security, develop friendly relations among nations, achieve international cooperation, and be a centre for harmoniz ...

conferences. In September 1945, he proposed the idea of an Asian conference, parallel to that of the United Nation's, to the ICWA and Nehru.

The decision to organise the conference was formalized on 21 May, 1946 by the Executive Committee of the ICWA, The ICWA claimed to be "an unofficial and non-political body" which would "not express an opinion on any aspect of Indian or international affairs", though Nehru had stated that the conference "might develop a solidarity and strength which could lead to a real inter-Asian policy." The ICWA was a private organisation, freeing the conference from the influence of the Viceroy's Executive Council, though Nehru had sought backing from the government, only to be turned down by Minister of Finance Liaquat Ali Khan

Liaquat Ali Khan ( ur, ; 1 October 1895 – 16 October 1951), also referred to in Pakistan as ''Quaid-e-Millat'' () or ''Shaheed-e-Millat'' ( ur, lit=Martyr of the Nation, label=none, ), was a Pakistani statesman, lawyer, political theoris ...

who saw the conference as a chance for Nehru to amass personal glory. The cultural aspect of the conference was emphasized to avoid disapproval from the West. The format was modelled after the 1945 IPR Conference at Hot Springs, Virginia

Hot Springs is a census-designated place (CDP) in Bath County, Virginia, United States. The population as of the 2010 Census was 738. It is located about southwest of Warm Springs on U.S. Route 220.

Hot Springs has several historic resorts, f ...

, which was attended by the ICWA. In a speech on 22 August, 1946, Nehru stated in a speech that the conference "will help to promote good relations with neighbouring countries. It will help to pool ideas and experience with a view to raising living standards. It will strengthen cultural, social and economic ties among the peoples of Asia." The conference was envisioned by Nehru to be non-political, though this would prove difficult as the conference must balance the positions of various conflicting nations.

Active preparations began on 31 August, 1946, when the Organising Committee was established. Nehru was made President of the Committee, which included Sarojini Naidu

Sarojini Naidu (''née'' Chattopadhyay; 13 February 1879 – 2 March 1949) was an Indian political activist, feminist and poet. A proponent of civil rights, women's emancipation, and anti-imperialistic ideas, she was an important person in Ind ...

, Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan

Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan (; 5 September 1888 – 17 April 1975), natively Radhakrishnayya, was an Indian philosopher and statesman. He served as the 2nd President of India from 1962 to 1967. He also 1st Vice President of India from 1952 ...

, Abul Kalam Azad

Abul Kalam Ghulam Muhiyuddin Ahmed bin Khairuddin Al-Hussaini Azad (; 11 November 1888 – 22 February 1958) was an Indian independence activist, Islamic theologian, writer and a senior leader of the Indian National Congress. Following In ...

, Asaf Ali, Baldev Singh, Shanti Swaroop Bhatnagar

Sir Shanti Swaroop Bhatnagar OBE, FNI, FASc, FRS, FRIC, FInstP (21 February 1894 – 1 January 1955) was an Indian colloid chemist, academic and scientific administrator. The first director-general of the Council of Scientific and Indust ...

, G. D. Birla, Hannah Sen

Hannah Sen (1894–1957) was an Indian educator, politician, and feminist. She was a member of the first Indian Rajya Sabha (upper house of Parliament) from 1952 to 1957 and the president of the All India Women's Conference in 1951-52. She was a f ...

, Hansa Jivraj Mehta

Hansa Jivraj Mehta (3 July 1897 – 4 April 1995) was a reformist, social activist, educator, independence activist, feminist and writer from India.

Early life

Hansa Mehta was born in a Nagar Brahmin family on 3 July 1897. She was a daughter ...

, Kamaladevi Chattopadhyay

Kamaladevi Chattopadhyay (3 April 1903 – 29 October 1988) was an Indian social reformer and freedom activist. She was most remembered for her contribution to the Indian independence movement; for being the driving force behind the renaissanc ...

, Bidhan Chandra Roy

Bidhan Chandra Roy (1 July 1882 – 1 July 1962) was an Indian physician, educationist, and statesman who served as Chief Minister of West Bengal from 1948 until his death in 1962. Roy played a key role in the founding of several institutio ...

, Vijaya Lakshmi Pandit

Vijaya Lakshmi Pandit (''née'' Swarup Nehru; 18 August 1900 – 1 December 1990) was an Indian diplomat and politician who was the 6th Governor of Maharashtra from 1962 to 1964 and 8th President of the United Nations General Assembly from 19 ...

, Zakir Husain

Zakir Husain Khan (8 February 1897 – 3 May 1969) was an Indian educationist and politician who served as the third president of India from 13 May 1967 until his death on 3 May 1969.

Born in Hyderabad in a Afridi Pashtun family, Husain ...

and Ishtiaq Hussain Qureshi. Nehru joined the Interim Government of India

The Interim Government of India, also known as the Provisional Government of India, formed on 2 September 1946 from the newly elected Constituent Assembly of India, had the task of assisting the transition of British India to independence. It ...

in September, and it was thought inappropriate for him to be the President of the committee. Sarojini Naidu was elected the President in Nehru's place. Funding was largely acquired through public subscription, along with donation from businesses such as the Birlas and the Tata Group

The Tata Group () is an Indian multinational conglomerate headquartered in Mumbai. Established in 1868, it is India's largest conglomerate, with products and services in over 150 countries, and operations in 100 countries across six continents ...

. Several princely states ruler, including that of Baroda

Vadodara (), also known as Baroda, is the second largest city in the Indian state of Gujarat. It serves as the administrative headquarters of the Vadodara district and is situated on the banks of the Vishwamitri River, from the state capital ...

, Patiala

Patiala () is a city in southeastern Punjab, northwestern India. It is the fourth largest city in the state and is the administrative capital of Patiala district. Patiala is located around the '' Qila Mubarak'' (the 'Fortunate Castle') construct ...

and Jaipur

Jaipur (; Hindi: ''Jayapura''), formerly Jeypore, is the capital and largest city of the Indian state of Rajasthan. , the city had a population of 3.1 million, making it the tenth most populous city in the country. Jaipur is also known ...

, were personally persuaded by Naidu to provide cars, drivers, fuel and lodgings for delegates in their Delhi houses.

The conference raised concerns from the West of a possible Asian bloc, and Nehru had to affirm that the conference would not "be opposed in any way to America or the Soviet Union or any other power or group of powers."

The topics of discussions were originally to be settled by the various Asian countries, but owing to time constraints 8 topics, to be discussed in "Round Tables", were eventually decided by the ICWA:

# National Movements for Freedom

# Racial Problems

# Inter-Asian Migration

# Transition from Colonial to National Economy

# Agricultural Reconstruction and Industrial Development

# Labour Problems and Social Services

# Cultural Problems

# Status of Women and Women's Movement

"Defence and Security questions" was originally the first topic, but it was replaced by "National Movements for Freedom" to avoid controversial political issues at the conference.

Delegates invited

All Asian countries were invited, along withEgypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a transcontinental country spanning the northeast corner of Africa and southwest corner of Asia via a land bridge formed by the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Medit ...

who was thought to be closely aligned to the Middle East, and observers from the West. Nehru had also requested delegations to include "at least one woman delegate from your country who will be able to assist the Conference by presenting the women’s point of view on the various matters before the conference and, in particular, in the discussing of the status of women and women’s movements in Asia which is one of the main topics suggested for the agenda." In total, delegates from 28 countries and 8 institutions attended the Conference.

Japan was invited but did not attend, as foreign travel was prohibited by the Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers (SCAP). Nehru stated that he would not give representation of the Japanese to General Douglas MacArthur or the SCAP over the Japanese people themselves. For the attendees, while most delegates did not oppose the attendance of Japan as the conference was of a non-political nature, a delegate from the Philippines

The Philippines (; fil, Pilipinas, links=no), officially the Republic of the Philippines ( fil, Republika ng Pilipinas, links=no),

* bik, Republika kan Filipinas

* ceb, Republika sa Pilipinas

* cbk, República de Filipinas

* hil, Republ ...

objected to Japan's inclusion due to Japanese war crimes in the Philippines.

The All-India Muslim League

The All-India Muslim League (AIML) was a political party established in Dhaka in 1906 when a group of prominent Muslim politicians met the Viceroy of British India, Lord Minto, with the goal of securing Muslim interests on the Indian subcont ...

, which viewed itself as the sole representation of Muslims in India, declined the invitation to the conference. The ICWA was seen as closely aligned with the Indian National Congress

The Indian National Congress (INC), colloquially the Congress Party but often simply the Congress, is a political party in India with widespread roots. Founded in 1885, it was the first modern nationalist movement to emerge in the British E ...

and the Brahmin

Brahmin (; sa, ब्राह्मण, brāhmaṇa) is a varna as well as a caste within Hindu society. The Brahmins are designated as the priestly class as they serve as priests (purohit, pandit, or pujari) and religious teachers (gur ...

-dominated institution. In a statement, the League denounced the conference as "a thinly disguised attempt on the part of the Hindu Congress to boost itself politically as the prospective leader of the Asiatic peoples" and the "sole cultural representative of this vast sub-continent." The organisers, meanwhile, argued that "political problems, particularly of a controversial character or relating to the internal affairs of any participating countries are deliberately excluded from the agenda of the Conference." Syria, Lebanon

Lebanon ( , ar, لُبْنَان, translit=lubnān, ), officially the Republic of Lebanon () or the Lebanese Republic, is a country in Western Asia. It is located between Syria to Lebanon–Syria border, the north and east and Israel to Blue ...

and Yemen

Yemen (; ar, ٱلْيَمَن, al-Yaman), officially the Republic of Yemen,, ) is a country in Western Asia. It is situated on the southern end of the Arabian Peninsula, and borders Saudi Arabia to the Saudi Arabia–Yemen border, north and ...

did not participate in the conference due to this boycott.

Six Kenyan leaders, upon hearing news of a conference of colonised nations, wrote to Nehru asking for African representation in the conference. Nehru denied on the basis that it was an Asian conference, but invited Kenyan observers. Nehru also offered scholarships to Africans studying in India. In a private letter to Shafa’at Ahmad Khan, former Indian High Commissioner to South Africa, Nehru wrote that "this will indicate to Africa and to the world how much interested we are in the advance and progress of backward peoples."

Conference

The conference was held between 23 March and 2 April, 1947, lasting for 10 days. The President of the Organizing Committee of the Conference was Sarojini Naidu. Its opening and closing session were held publicly under a largepandal

A ''pandal'' in India and neighbouring countries, is a fabricated structure, either temporary or permanent, that is used at many places such as either outside a building or in an open area such as along a public road or in front of a house. This ca ...

in Purana Qila

Purana Qila () is one of the oldest forts in Delhi, India. Built by the second Mughal Emperor Humayun and Surid Sultan Sher Shah Suri, it is thought by many to be located on the site of the ancient city of Indraprastha. The fort formed the in ...

.

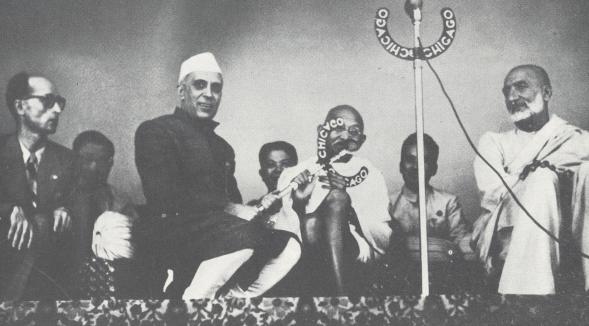

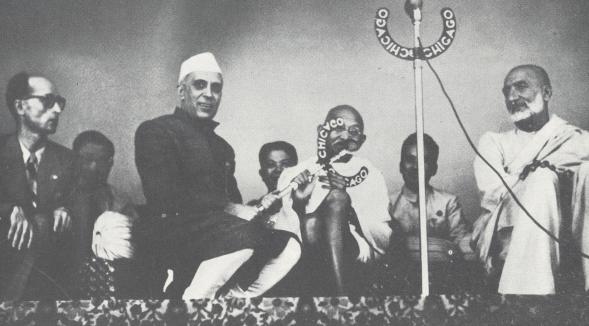

The opening session featured speeches by Naidu and Nehru. In his speech, Nehru reiterated that the conference "shall not discuss the internal politics of any country because that is rather beyond the scope of our present meeting", and that his intentions for the conference was that "some permanent Asian Institute for the study of common problems and to bring about closer relations will emerge" and "also perhaps a School of Asian Studies."

The official language of the conference was English, though Russian, French, Arabic, Persian, and Chinese interpreters were available. Some delegates, such as Tibet, brought their own interpreters. In one session, the idea of a new auxiliary language for Asia was discussed. Indian linguist Baburam Saxena denounced English and suggested Hindu, while the Soviet republics suggested Russian. There were some support for the use of Esperanto. Alfred Bonne, professor of psychology and member of the Jewish delegation, proposed a new language based on Esperanto. Ultimately, English prevailed as the international Asian language when the Georgian delegation, who did not speak English, agreed to its use.

China and Tibet

Tibet received the invitation through

Tibet received the invitation through Hugh Edward Richardson

Hugh Edward Richardson (22 December 1905 – 3 December 2000) was an Indian Civil Service officer, British diplomat and Tibetologist. His academic work focused on the history of the Tibetan empire, and in particular on epigraphy. He was am ...

, the Representative of British India in Lhasa, who advised the Tibetans that it would be a good opportunity to assert Tibet's ''de facto'' independence. The team of delegates, geshe

Geshe (Tib. ''dge bshes'', short for ''dge-ba'i bshes-gnyen'', "virtuous friend"; translation of Skt. ''kalyāņamitra'') or geshema is a Tibetan Buddhist academic degree for monks and nuns. The degree is emphasized primarily by the Gelug lineage, ...

s, interpreters and servants was led by Teiji Tsewang Rigzing Sampho and Khenchung Lobsang Wangyal of the Tibetan Foreign Office. The delegation brought along with them documents relating to the Indo-Tibetan borders, including the original copy of the Simla Convention

The Simla Convention, officially the Convention Between Great Britain, China, and Tibet,

, in hope of reclaiming the disputed North-East Frontier Tracts.

While the Republic of China enjoyed cordial relations with India, China viewed Tibet as their sovereign territory and protested Nehru's invitation to Tibet. Dai Jitao

Dai Jitao or Tai Chi-t'ao (; January 6, 1891 – February 21, 1949) was a Chinese journalist, an early Kuomintang member, and the first head of the Examination Yuan of the Republic of China. He is often referred to as Dai Chuanxian () or by his ...

, who was supposed to lead the delegation, declined to attend due to the Tibetan issue. K. P. S. Menon, India’s Agent-General in China, had to convince China that the conference was a cultural organization where no political conclusions could be drawn. He also agreed to call Tibetan delegates "representatives" instead. In a letter to Menon, Nehru wrote that he was "unable to understand Chinese attitude to Asian Conference when Conference Organisers have fully explained the position which is in no way injurious to Chinese interests. Non-official cultural conference cannot be expected to consider political niceties."

The Tibetan delegation heard about the Chinese opposition for the first time when they arrived at Calcutta

Kolkata (, or , ; also known as Calcutta , List of renamed places in India#West Bengal, the official name until 2001) is the Capital city, capital of the Indian States and union territories of India, state of West Bengal, on the eastern ba ...

. They sent their servants ahead to Delhi, to see if their invitation and accommodations were cancelled. The Indian Government assured that they were still invited. It was reported the journey from Lhasa

Lhasa (; Lhasa dialect: ; bo, text=ལྷ་ས, translation=Place of Gods) is the urban center of the prefecture-level Lhasa City and the administrative capital of Tibet Autonomous Region in Southwest China. The inner urban area of Lhas ...

to New Delhi took 21 days. Upon their arrival, they were urged by Nehru to keep the conference non-political and not to raise their border issue. The Tibetan delegates agreed not to be the first to raise the border issue, but would "not remain a silent spectator if the Chinese did."

During the conference, Chinese observer George Yeh

George Kung-chao Yeh (1904–1981), also known as Yeh Kung-chao, was a diplomat and politician of the Republic of China. Educated in the U.S. and the U.K., he graduated from Amherst College in 1925 and later Cambridge University. He taught En ...

protested to Nehru that the map on the stage showed Tibet as independent of China, and that the Chinese delegation would withdraw unless the map was corrected. According to one account, Yeh, a calligrapher and painter, was eventually allowed by Nehru to paint Tibet the same colour as China. Later, the Chinese Ambassador in India attempted to bribe the Tibetan delegations, promising to pursue the Tibetan border dispute and offered money, supposedly for the expenses related to the conference, though this was refused by the Tibetans. Eventually, Chiang Kai-shek sent a message to Chinese Embassy in Delhi, saying that he absolutely wanted the Tibetans to accept the money, which was once again refused by Teiji Sampho in a personal telegram. The conference also saw the first appearance of the flag of Tibet

Tibet is a region in East Asia covering much of the Tibetan Plateau that is currently administered by People's Republic of China as the Tibet Autonomous Region and claimed by the Republic of China as the Tibet Area and the Central Tibetan Adm ...

at an international gathering, but also the last international event Tibet participated in, before their annexation by China in 1950.

Outside of the dispute with China, the Tibetans was not high-profile participants of the conference, partly due to their isolation from international politics. Their main interest was religion, and they bought a message from the Dalai Lama

Dalai Lama (, ; ) is a title given by the Tibetan people to the foremost spiritual leader of the Gelug or "Yellow Hat" school of Tibetan Buddhism, the newest and most dominant of the four major schools of Tibetan Buddhism. The 14th and current D ...

.

On the other hand, China remained active in the discussions for "Racial Problems" and "Inter-Asian Migration." Chinese delegates were concerned about the legal status of Chinese immigrant populations in Southeast Asian. The Southeast Asian nations, including Ceylon, Burma, and Malaya, accused the Chinese and Indian immigrants to be "narrow minded" and "refused to assimilate", and called for the dual citizenship (and allegiance) issue of these immigrants to be resolved. Chinese delegate Wen Yuan-ning, who headed the discussions, called for equality of "persons of foreign origin who have settled in a country." The consensus reached was that equality for all citizens should be respected. At the closing session, George Yeh announced to the public that China would host the next session in 1949, though the second conference never materialized.

Other notable Chinese delegates included its leader Zheng Yanfen, Han Lih-wu, Yi Yun Chen and Tan Yun-Shan.

French Indochina and Vietnam

High Commissioner in IndochinaGeorges Thierry d'Argenlieu

Georges Thierry d'Argenlieu, in religion Father Louis of the Trinity, O.C.D. (7 August 1889 – 7 September 1964), was a Discalced Carmelite friar and priest, who was also a diplomat and French Navy officer and admiral; he became one of the m ...

initially did not wish to accept the invitations for French Indochina

French Indochina (previously spelled as French Indo-China),; vi, Đông Dương thuộc Pháp, , lit. 'East Ocean under French Control; km, ឥណ្ឌូចិនបារាំង, ; th, อินโดจีนฝรั่งเศส, ...

in fear of anti-French demonstration at the conference, but changed his mind to avoid representation given to the Viet Minh

The Việt Minh (; abbreviated from , chữ Nôm and Hán tự: ; french: Ligue pour l'indépendance du Viêt Nam, ) was a national independence coalition formed at Pác Bó by Hồ Chí Minh on 19 May 1941. Also known as the Việt Minh Fro ...

, Khmer Issarak

The Khmer Issarak ( km, ខ្មែរឥស្សរៈ, or 'Independent Khmer') was a "loosely structured" anti- French and anti-colonial independence movement. The movement has been labelled as “amorphous”. The Issarak was ...

or the Lao Issara

The Lao Issara ( lo, ລາວອິດສະລະ ) was an anti-French, nationalist movement formed on 12 October 1945 by Prince Phetsarath. This short-lived movement emerged after the Japanese defeat in World War II and became the government ...

. The delegations for French Indochina was handpicked by the French. Princess Pingpeang Yukanthor represented Cambodia

Cambodia (; also Kampuchea ; km, កម្ពុជា, UNGEGN: ), officially the Kingdom of Cambodia, is a country located in the southern portion of the Indochinese Peninsula in Southeast Asia, spanning an area of , bordered by Thailan ...

, Dang Ngoc Chan represented Cochinchina

Cochinchina or Cochin-China (, ; vi, Đàng Trong (17th century - 18th century, Việt Nam (1802-1831), Đại Nam (1831-1862), Nam Kỳ (1862-1945); km, កូសាំងស៊ីន, Kosăngsin; french: Cochinchine; ) is a historical exony ...

and Ouroth Souvarnavong represented Laos.

North Vietnam

North Vietnam, officially the Democratic Republic of Vietnam (DRV; vi, Việt Nam Dân chủ Cộng hòa), was a socialist state supported by the Soviet Union (USSR) and the People's Republic of China (PRC) in Southeast Asia that existed f ...

, on the other hand, was represented by Tran Van Luan (Deputy of the National Assembly

In politics, a national assembly is either a unicameral legislature, the lower house of a bicameral legislature, or both houses of a bicameral legislature together. In the English language it generally means "an assembly composed of the rep ...

), Tran Van Giau (Former President of the Viet Minh Resistance Committee in Cochinchina) and Mai Te Chau (Permanent delegate of the Viet Minh in New Delhi). The delegations reported that two squads of messengers were killed while smuggling credentials from Ho Chi Minh

(: ; born ; 19 May 1890 – 2 September 1969), commonly known as (' Uncle Hồ'), also known as ('President Hồ'), (' Old father of the people') and by other aliases, was a Vietnamese revolutionary and statesman. He served as P ...

’s headquarters in Bangkok, and arrived late at the conference. At the conference, the North Vietnamese denounced French imperialism and asked for help against the French. They made various requests to India, such as a formation of a "fighting federation", for India to recognize their government and intervene in the UN on their behalf. When they began reading a message from Ho Chi Minh, Nehru, despite his known sympathies to Ho, interrupted their speech. Nehru argued that he could only provide moral support to the Vietnamese, as any non-moral support would mean war with the French. Asian specialist Evelyn Colbert wrote that his decision was influenced by India's hope to enter negotiations over France's enclave in India with the French.

India

In 1947, the end of colonial rule in India was in sight. The partition of India would occur four and a half months later, and several communal riots broke out in March.

India fielded the largest delegation with 52 delegates and 6 observers. Guests invited by India included

In 1947, the end of colonial rule in India was in sight. The partition of India would occur four and a half months later, and several communal riots broke out in March.

India fielded the largest delegation with 52 delegates and 6 observers. Guests invited by India included Christoph von Fürer-Haimendorf

Christoph von Fürer-Haimendorf or Christopher von Fürer-Haimendorf FRAI (22 June 1909 – 11 June 1995) was an Austrian ethnologist and professor at the School of Oriental and African Studies at London. He spent forty years studying tr ...

. During the opening of the conference, Mahatma Gandhi

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi (; ; 2 October 1869 – 30 January 1948), popularly known as Mahatma Gandhi, was an Indian lawyer, anti-colonial nationalist Quote: "... marks Gandhi as a hybrid cosmopolitan figure who transformed ... anti- ...

was visiting villages in an attempt to quell riots and violence. Nehru, in his opening speech, noted that Gandhi was "engrossed in the service of the common man in India, and even this Conference could not drag him away from it." However, Gandhi was able to attend on 1–2 April after he was urgently summoned for a meeting with Mountbatten in Delhi. He addressed the communal riots in his closing speech, calling them "a shameful thing and it is an exhibition which I would like you not to carry to your respective countries but bury here."

During discussion for "National Movements for Freedom", India faced some criticism regarding the presence of Indian troops in the British colonial subjugation of Burma, Ceylon, Malaya and Indonesia. North Vietnam pointed out that French planes were still allowed to refuel in Indian bases. Nehru argued that only French hospital planes were allowed to be refueled in India, that his government had begun withdrawing troops from Indonesia and affirmed that "no Asian country should give any direct or indirect assistance to any colonial power in its attempts to keep any Asian country in subjection." When confronted about the issue of Indian immigrants and their dual citizenships in Southeast Asia, the Indian delegates showed "indifference" and implied that the immigrants' "right to return" could be revoked.

One goal of the conference, though denied by Nehru, was to propel India to be the leader of new Asia. In the opening speech, Nehru stated that "it is fitting that India should play her part in this new phase of Asian Development... She is the natural centre and focal point of the many forces at work in Asia."

Jewish delegation, Egypt and Arab League

Mandatory Palestine

Mandatory Palestine ( ar, فلسطين الانتدابية '; he, פָּלֶשְׂתִּינָה (א״י) ', where "E.Y." indicates ''’Eretz Yiśrā’ēl'', the Land of Israel) was a geopolitical entity established between 1920 and 1948 ...

was represented by the Jewish community

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""The ...

from the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. The delegation was led by Professor Hugo Bergmann, and notable delegates included David Hacohen

David Hacohen ( he, דוד הכהן, born 20 October 1898, died 19 February 1984) was an Israeli politician who served as a member of the Knesset between 1949 and 1953, and again from 1955 until 1969. He fought with the Ottoman Army in World War ...

. There was no representation for Palestinian Arabs

Palestinians ( ar, الفلسطينيون, ; he, פָלַסְטִינִים, ) or Palestinian people ( ar, الشعب الفلسطيني, label=none, ), also referred to as Palestinian Arabs ( ar, الفلسطينيين العرب, label=non ...

, though Egypt and observers from the Arab League would come to defend Palestinian interests and disputed some statements made by the Jewish delegation. The Egyptian team was led by one of its observers, Abdul Wahab Azzam Bey.

When Bergmann referred to Palestine as the holy land for his community, Karima El-Said of Egypt sought to respond. Nehru remarked that “we have tried to avoid, for obvious reasons, raising and discussing controversial issues at this Conference... but some reference was made... I think it only right that she should have a chance." In her response, El-Said stated that "we strongly object to any settlement in Palestine except for the Arabs... The Arabs must live in Palestine. Palestine cannot belong any more to its original inhabitants." The Jewish delegation's request to respond was refused by the chairman, and as a result they walked out of the conference, though they were later persuaded by Shanti Swaroop Bhatnagar

Sir Shanti Swaroop Bhatnagar OBE, FNI, FASc, FRS, FRIC, FInstP (21 February 1894 – 1 January 1955) was an Indian colloid chemist, academic and scientific administrator. The first director-general of the Council of Scientific and Indust ...

to return and shake hands with the Arab delegates. In the closing speech of that session, Nehru said the "question of Palestine itself will be settled in co-operation between them and not by any appeal to or reliance upon any outsider." The Arab League observer Takieddin el-Solh

Takieddin el-Solh (also Takieddin Solh, Takieddin as-Solh; ar, تقي الدين الصلح) (1908 – 27 November 1988) was a Lebanese politician who served as the Prime Minister of Lebanon from 1973 to 1974, and again briefly in 1980.

El- ...

followed with a speech rebutting the Jewish delegates. On the next day, the observer from Egypt Abdul Ahab Azzam issued a signed statement against the Jewish delegation. Mostafa Momen of Egypt also organised a press conference, where he denounced the inclusion of Jewish representatives from European nations representing Palestine.

Soviet republics

Soviet republics participating in the conference includedArmenia

Armenia (), , group=pron officially the Republic of Armenia,, is a landlocked country in the Armenian Highlands of Western Asia.The UNbr>classification of world regions places Armenia in Western Asia; the CIA World Factbook , , and ' ...

, Azerbaijan

Azerbaijan (, ; az, Azərbaycan ), officially the Republic of Azerbaijan, , also sometimes officially called the Azerbaijan Republic is a transcontinental country located at the boundary of Eastern Europe and Western Asia. It is a part of t ...

, Georgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the Caucasus region of Eurasia

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the Southeast United States

Georgia may also refer to:

Places

Historical states and entities

* Related to the ...

, Kazakhstan

Kazakhstan, officially the Republic of Kazakhstan, is a transcontinental country located mainly in Central Asia and partly in Eastern Europe. It borders Russia to the north and west, China to the east, Kyrgyzstan to the southeast, Uzbeki ...

and Uzbekistan

Uzbekistan (, ; uz, Ozbekiston, italic=yes / , ; russian: Узбекистан), officially the Republic of Uzbekistan ( uz, Ozbekiston Respublikasi, italic=yes / ; russian: Республика Узбекистан), is a doubly landlocked co ...

, who sent separate delegates. Kirghizia and Turkmenistan

Turkmenistan ( or ; tk, Türkmenistan / Түркменистан, ) is a country located in Central Asia, bordered by Kazakhstan to the northwest, Uzbekistan to the north, east and northeast, Afghanistan to the southeast, Iran to the sout ...

arrived late, landing in Delhi one day after the closing plenary. They praised the Soviet system, and tried to demonstrate how it had helped them overcome the many problems faced by the countries in the conference. They claimed that "no strikes occurred in the Soviet Union... because industry belongs to society as a whole." Kazakhstan promoted her democratic and agricultural reforms, and together with Uzbekistan reported their achievements in education after it was made free and compulsory. The Georgian delegation was led by Victor Kupradze, who headed one session of the Round Table for "Cultural Problems." The country promoted her scientific and culture progress since the Russian Revolution in 1917.

US observers commented that "upon request they gladly told of the achievements of their respective governments but their complacency precluded any admission of even the existence of such problems as were plaguing other countries of Asia" and, according to diplomat G. H. Jansen, "in consequence, the report is full of flattering references to the Soviet republics."

Other nations

Afghanistan

The delegation fromAfghanistan

Afghanistan, officially the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan,; prs, امارت اسلامی افغانستان is a landlocked country located at the crossroads of Central Asia and South Asia. Referred to as the Heart of Asia, it is bordere ...

was led by Dr. Abdul Majid Khan, President of the Kabul University

Kabul University (KU; prs, دانشگاه کابل, translit= Dāneshgāh-e-Kābul; ps, د کابل پوهنتون, translit=Da Kābul Pohantūn) is one of the major and oldest institutions of higher education in Afghanistan. It is in the 3rd ...

, who headed one session of the Round Table for "Cultural Problems".

Bhutan

Bhutan

Bhutan (; dz, འབྲུག་ཡུལ་, Druk Yul ), officially the Kingdom of Bhutan,), is a landlocked country in South Asia. It is situated in the Eastern Himalayas, between China in the north and India in the south. A mountainou ...

sent two observers, Jigme Palden Dorji and Rani C. Dorji, but no delegates.

Burma

Burma

Myanmar, ; UK pronunciations: US pronunciations incl. . Note: Wikipedia's IPA conventions require indicating /r/ even in British English although only some British English speakers pronounce r at the end of syllables. As John Wells explai ...

was, at the time of the conference, undergoing the 1947 Burmese general election, and Aung San

Aung San (, ; 13 February 191519 July 1947) was a Burmese politician, independence activist and revolutionary. He was instrumental in Myanmar's struggle for independence from British rule, but he was assassinated just six months before his goa ...

did not attend due to his campaign. The Burmese delegation was led by Justice Kyaw Myint of the Rangoon High Court. Notable delegates included Htin Aung

Htin Aung ( my, ထင်အောင် ; also Maung Htin Aung; 18 May 1909 – 10 May 1978) was a writer and scholar of Burmese culture and history. Educated at Oxford and Cambridge, Htin Aung wrote several books on Burmese history and culture ...

, Hla Myint

Hla Myint ( my, လှမြင့် ; 1920 – 9 March 2017) was a Burmese economist noted as one of the pioneers of development economics as well as for his contributions to welfare economics. He stressed, long before it became popular, the i ...

, Thein Han

Thein Han ( my, သိန်းဟန်, ; 1910–1986) was a major Yangon painter of the post-World War II era who produced a number of memorable works and who had an abiding influence on the evolution of the more conservative painting styles in ...

, Tha Hla, Ba Lwin, M. A. Rashid

M. A. Rashid (January 16, 1919 – November 6, 1981) was a Bangladeshi educator. He served as the 1st Vice-chancellor of Bangladesh University of Engineering and Technology during 1962–1970. He was awarded Independence Day Award in 1982 by the ...

and Mya Sein, while notable observers included Thakin Mya and Chan Htoon.

The Burmese resistance to British was discussed, with the Philippines proposing "a policy of peaceful resistance" for the country, which Daw Saw Inn rejected as "the Burmese are a nation of fighters." The Burmese delegation, along with Ceylon and Malaya, also raised the issue of Chinese and Indian immigrants in their countries.

Ceylon

The Ceylon delegation was led by S. W. R. D. Bandaranaike, who also headed the Round Table for Transition from Colonial to National Economy. Notable delegates included C. W. W. Kannangara,Justin Samarasekera

Justin Samarasekera (21 May 1916— 19 October 2003) was a Sri Lankan architect. He is considered to be one of the founding fathers of the architectural profession in Sri Lanka and a pioneer of architectural education in the country.

Early l ...

, Cissy Cooray and E. M. V. Naganathan, while notable observers included George E. de Silva, Anil de Silva and E. W. Kannangara. Bandaranaike proposed the formation of an Asian economic bloc, though it was opposed by Southeast Asian nations such as Indonesia, Malaya and Vietnam, who cautioned against a repeat of Japanese Asianism. The Ceylonese delegation, along with Burma and Malaya, also raised the issue of Chinese and Indian immigrants in their countries.

Indonesia

Indonesia had recently gained recognition from Netherlands, and negotiated for trade and diplomatic relations during the conference. The Indonesian delegation was led by Dr. Abu Hanifa. Other notable delegates included Siauw Giok Tjhan andAli Sastroamidjojo

Ali Sastroamidjojo ( EYD: Ali Sastroamijoyo; 21 May 1903 – 13 March 1975) was an Indonesian politician and diplomat who served as prime minister of Indonesia from 1953 until 1955 and again from 1956 until 1957. He also served as the Indo ...

, and observers included Agus Salim and Mochtar Lubis

Mochtar Lubis (; 7 March 1922 – 2 July 2004) was an Indonesian Batak journalist and novelist who co-founded ''Indonesia Raya'' and monthly literary magazine "Horison". His novel ''Senja di Jakarta'' (''Twilight in Jakarta'' in English) ...

. Prime Minister of Indonesia Sutan Sjahrir missed the opening session as he was signing an agreement with the Dutch, but was later brought in an Indian plane chartered for him by Nehru’s government that allowed him to arrive in time for the closing ceremony.

Iran

TheIran

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran, and also called Persia, is a country located in Western Asia. It is bordered by Iraq and Turkey to the west, by Azerbaijan and Armenia to the northwest, by the Caspian Sea and Turkmeni ...

delegation was led by Gholam Hossein Sadighi

Gholam Hossein Sadighi ( fa, غلامحسین صدیقی; 3 December 1905 – 28 April 1991) was an Iranian politician and Minister of Interior in the government of Prime Minister Mohammad Mossadegh in 1953. After a CIA-backed coup d'etat ...

. Notable delegates included Mehdi Bayani

Mehdi Bayani ( fa, مهدی بیانی; 1906 – February 6, 1968) was the founder and the first head of the National Library of Iran, specialist in Persian manuscripts and calligraphy, writer, researcher, and professor at the University o ...

and Safiyeh Firous, who headed one session of the Round Table for "Status of Women and Women's Movement". Ali-Asghar Hekmat

Hekmat-e Shirazi حکمت شیرازی or Mirza Ali-Asghar Khan Hekmat-e Shirazi (16 June 1892 – 25 August 1980) was an Iranian politician, diplomat and author who served as the Iranian Minister of Foreign Affairs, Minister of Justice, and M ...

served as one of the three observers.

Korea

Korea was represented by delegates from theRepublic of Korea

South Korea, officially the Republic of Korea (ROK), is a country in East Asia, constituting the southern part of the Korean Peninsula and sharing a land border with North Korea. Its western border is formed by the Yellow Sea, while its ea ...

(South Korea). It had recently been independent from Japanese rule. The delegation, missing a flight in Shanghai, arrived on the last day, and was led by Dr. Lark Geoon Paik of the Chosun Christian University. During the discussion for "National Movements for Freedom", Korean delegates raised the issue regarding its occupation by Allied forces. They stated that, despite the promises of freedom and independence by the Cairo Declaration, "what the Koreans got was Allied occupation and

a division of the country into two."

Malaya

The Malayan Union delegation was led by Dr. Burhanuddin and included John Thivy,Abdullah CD

Cik Dat bin Anjang Abdullah, commonly known as Abdullah CD (born 2 October 1923), is a former Malaysian politician who served as chairman and General Secretary of the Communist Party of Malaya (CPM).

Biography

Abdullah was born on 2 October 1 ...

, E. E. C. Thuraisingham, P. P. Narayanan, S. A. Ganapathy and Philip Hoalim, who headed the Round Table for "National Movements for Freedom". Thivy proposed the idea of a "neutrality bloc" that will not provide manpower or resources to colonial powers, though this was not adopted. The Malay delegation, along with Ceylon and Burma, also raised the issue of Chinese and Indian immigrants in their countries.

Mongolia

TheMongolian People's Republic

The Mongolian People's Republic ( mn, Бүгд Найрамдах Монгол Ард Улс, БНМАУ; , ''BNMAU''; ) was a socialist state which existed from 1924 to 1992, located in the historical region of Outer Mongolia in East Asia. It w ...

had recently broken free from China. The delegation took a detour to Moscow to pick up Russian interpreter, who was to be their only contact with the other delegates. They arrived on the last day of the conference, and was led by Lubsan Vandan of the Committee of Sciences.

Nepal

Nepal

Nepal (; ne, :ne:नेपाल, नेपाल ), formerly the Federal Democratic Republic of Nepal ( ne,

सङ्घीय लोकतान्त्रिक गणतन्त्र नेपाल ), is a landlocked country in S ...

sent 5 delegates. Its leader, Major-General Bijaya Shumshere Jung Bahadur Rana, headed the discussions for "Agricultural Reconstruction and Industrial Development". Another notable Nepalese delegate was Surya Prasad Upadhyaya.

Philippines

The Philippines

The Philippines (; fil, Pilipinas, links=no), officially the Republic of the Philippines ( fil, Republika ng Pilipinas, links=no),

* bik, Republika kan Filipinas

* ceb, Republika sa Pilipinas

* cbk, República de Filipinas

* hil, Republ ...

, which had recently become independent, sent a delegation led by Anastacio de Castro. De Castro denounced American imperialism during the conference. Other delegates included Paz Policarpio Mendez, who headed one session of Round Table for "Status of Women and Women's Movement".

Siam

The 2-memberSiam

Thailand ( ), historically known as Siam () and officially the Kingdom of Thailand, is a country in Southeast Asia, located at the centre of the Indochinese Peninsula, spanning , with a population of almost 70 million. The country is bo ...

ese delegation was led by Phraya Anuman Rajadhon

Phya Anuman Rajadhon ( th, พระยาอนุมานราชธน; , also spelled ''Phaya Anuman Rajadhon'' or ''Phrayā Anuman Rajadhon''; December 14, 1888 – July 12, 1969), was one of modern Thailand's most remarkable scholars. He ...

, who headed one session of Round Table for "Cultural Problems", along with Sukich Nimmanheminda

Sukich Nimmanheminda ( th, สุกิจ นิมมานเหมินท์, 25 November 1906 – 2 February 1976) was a Thai scholar, educator, politician and diplomat. He was a professor at Chulalongkorn University and served as its secre ...

.

Turkey

Turkey

Turkey ( tr, Türkiye ), officially the Republic of Türkiye ( tr, Türkiye Cumhuriyeti, links=no ), is a transcontinental country located mainly on the Anatolian Peninsula in Western Asia, with a small portion on the Balkan Peninsula in ...

only sent one observer, H. Kocaman, who was the Turkish Vice-Consul in India.

Observers

The Arab League,United Nations

The United Nations (UN) is an intergovernmental organization whose stated purposes are to maintain international peace and security, develop friendly relations among nations, achieve international cooperation, and be a centre for harmoniz ...

, Australia, the United Kingdom, the United States and the Soviet Union sent observers.

The Arab League observer was Takieddin el-Solh

Takieddin el-Solh (also Takieddin Solh, Takieddin as-Solh; ar, تقي الدين الصلح) (1908 – 27 November 1988) was a Lebanese politician who served as the Prime Minister of Lebanon from 1973 to 1974, and again briefly in 1980.

El- ...

, and the United Nations observer was Kamal Kumar of the United Nations Information Centre

United Nations Information Centres (UNIC) is an organization which was established in 1946. Its headquarters is situated at New York, USA, and it currently works worldwide in 63 countries. These centres are managed by the United Nations to exchan ...

in New Delhi.

Australia sent Gerald Parker of the Australian Institute of International Affairs

The Australian Institute of International Affairs (AIIA) is an Australian research institute and think tank which focuses on International relations. It publishes the ''Australian Journal of International Affairs''. It is one of the oldest act ...

and John McCallum

John McCallum (born 9 April 1950) is a Canadian politician, economist, diplomat and former university professor. A former Liberal Member of Parliament ( MP), McCallum was the Canadian Ambassador to China from 2017 to 2019. He was asked for ...

of the Australian Institute of Political Science as observers. According to McCallum, Australia "adhered strictly to listener."

The United Kingdom observers included V. K. Krishna Menon of the India Institute, along with W. W. Russell and Nicholas Mansergh of the Royal Institute of International Affairs

Royal may refer to:

People

* Royal (name), a list of people with either the surname or given name

* A member of a royal family

Places United States

* Royal, Arkansas, an unincorporated community

* Royal, Illinois, a village

* Royal, Iowa, a ci ...

. The United States sent observers from the Institute of Pacific Relations

The Institute of Pacific Relations (IPR) was an international NGO established in 1925 to provide a forum for discussion of problems and relations between nations of the Pacific Rim. The International Secretariat, the center of most IPR activity o ...

, which included Virginia Thompson, Richard Adloff and Phillips Talbot

William Phillips Talbot (June 7, 1915 – October 1, 2010) was a United States Ambassador to Greece (1965–69) and, at his death, member of the American Academy of Diplomacy, the Council of American Ambassadors and the Council on Foreign Re ...

.

The Soviet Union sent observers from the Institute of Pacific Relations, which included E. M. Zhukov and T. P. Plyshevski. One delegate, writing about the Soviet observers, stated that “it is hard to get to know them. They have come here and seem interested in discussions. But, except for cultural topics, they regularly tell us they have already solved all problems that are facing the rest of us and conversation stops there.”

Result

The Asian Relations Organization (ARO) was established as a result of the conference. A provisional council of 30 members elected Nehru its president.B. Shiva Rao

Benegal Shiva Rao (26 February 1891 – 15 December 1975) was an Indian journalist and politician. He was a member of the Constituent Assembly of India and an elected representative of the South Kanara constituency in the First Lok Sabha (later ...

and Han Lih-wu of China were made the ARO's general secretaries. The following goals were laid out:

# To promote the study and understanding of Asian problems and relations in their Asian and world aspects

# To foster friendly relations and co-operation among the peoples of Asia and between them and the rest of the world

# To further the progress and well-being of the peoples of Asia

Most nations were not enthusiastic about the ARO, as they feared that it would allow India or China to exert influence over them. This led to the delegates of some Southeast Asian nations to visit Aung San in Rangoon immediately after the conference to discuss the formation of a Southeast Asian organisation. The ARO was closed in 1955 as there was "little work for the Organisation", and merged back into the ICWA.

At the closing session, Nehru announced that "an academic institute should be set up in the capital of each Asian country with a view to studying the history and culture of Asia," though this plan never came into being.

The second Asian Relations Conference was to be held in Nanking

Nanjing (; , Mandarin pronunciation: ), alternately romanized as Nanking, is the capital of Jiangsu province of the People's Republic of China. It is a sub-provincial city, a megacity, and the second largest city in the East China region. T ...

, China in April, 1949. As the Chinese Civil War

The Chinese Civil War was fought between the Kuomintang-led government of the Republic of China and forces of the Chinese Communist Party, continuing intermittently since 1 August 1927 until 7 December 1949 with a Communist victory on m ...

intensified in 1948, the Philippines offered to host the conference instead. The second conference was held in Baguio

Baguio ( ,

), officially the City of Baguio ( ilo, Siudad ti Baguio; fil, Lungsod ng Baguio), is a 1st class highly urbanized city in the Cordillera Administrative Region, Philippines. It is known as the "Summer Capital of the Philippines", ...

, Philippines in May 1950, though participation was limited to India, Pakistan, Ceylon, Thailand, New Zealand, Australia and the Philippines. Nehru, attempting to keep the conference non-political, dismissed the idea of a proposed Asian Regional Organisation and military cooperation between the Philippines and Australia.

Western reactions focused on Asia's future role on the world stage, in particular that of India and China. A British observer wrote that "even though the Conference may not decisively influence the course of events in Asia, it was the outward and visible sign of Asia’s new importance in world affairs." Western observers also criticized what they saw as India’s imperial ambitions displayed during the conference.

List of Participants

The official list of participants names 231 people who were distributed among the following countries (number of delegates / number of observers): #Afghanistan

Afghanistan, officially the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan,; prs, امارت اسلامی افغانستان is a landlocked country located at the crossroads of Central Asia and South Asia. Referred to as the Heart of Asia, it is bordere ...

(5/2)

# Armenia

Armenia (), , group=pron officially the Republic of Armenia,, is a landlocked country in the Armenian Highlands of Western Asia.The UNbr>classification of world regions places Armenia in Western Asia; the CIA World Factbook , , and ' ...

(2/0)

# Azerbaijan

Azerbaijan (, ; az, Azərbaycan ), officially the Republic of Azerbaijan, , also sometimes officially called the Azerbaijan Republic is a transcontinental country located at the boundary of Eastern Europe and Western Asia. It is a part of t ...

(2/0)

# Bhutan

Bhutan (; dz, འབྲུག་ཡུལ་, Druk Yul ), officially the Kingdom of Bhutan,), is a landlocked country in South Asia. It is situated in the Eastern Himalayas, between China in the north and India in the south. A mountainou ...

(0/2)

# Burma

Myanmar, ; UK pronunciations: US pronunciations incl. . Note: Wikipedia's IPA conventions require indicating /r/ even in British English although only some British English speakers pronounce r at the end of syllables. As John Wells explai ...

(15/4)

# Cambodia

Cambodia (; also Kampuchea ; km, កម្ពុជា, UNGEGN: ), officially the Kingdom of Cambodia, is a country located in the southern portion of the Indochinese Peninsula in Southeast Asia, spanning an area of , bordered by Thailan ...

, Cochin China

Cochinchina or Cochin-China (, ; vi, Đàng Trong (17th century - 18th century, Việt Nam (1802-1831), Đại Nam (1831-1862), Nam Kỳ (1862-1945); km, កូសាំងស៊ីន, Kosăngsin; french: Cochinchine; ) is a historical exon ...

and Laos (3/0)

# Ceylon (13/5)

# China (8/1)

# Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a transcontinental country spanning the northeast corner of Africa and southwest corner of Asia via a land bridge formed by the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Medit ...

(3/2)

# Georgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the Caucasus region of Eurasia

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the Southeast United States

Georgia may also refer to:

Places

Historical states and entities

* Related to the ...

(2/0)

# India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by area, the second-most populous country, and the most populous democracy in the world. Bounded by the Indian Ocean on the so ...

(49/6)

# Indonesia

Indonesia, officially the Republic of Indonesia, is a country in Southeast Asia and Oceania between the Indian and Pacific oceans. It consists of over 17,000 islands, including Sumatra, Java, Sulawesi, and parts of Borneo and New Guine ...

(15/6)

# Iran

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran, and also called Persia, is a country located in Western Asia. It is bordered by Iraq and Turkey to the west, by Azerbaijan and Armenia to the northwest, by the Caspian Sea and Turkmeni ...

(3/3)

# Kazakhstan

Kazakhstan, officially the Republic of Kazakhstan, is a transcontinental country located mainly in Central Asia and partly in Eastern Europe. It borders Russia to the north and west, China to the east, Kyrgyzstan to the southeast, Uzbeki ...

(2/0)

# Kirghizia (1/0)

# Korea

Korea ( ko, 한국, or , ) is a peninsular region in East Asia. Since 1945, it has been divided at or near the 38th parallel, with North Korea (Democratic People's Republic of Korea) comprising its northern half and South Korea (Republic o ...

(3/0)

# Malaya (14/0)

# Mongolia

Mongolia; Mongolian script: , , ; lit. "Mongol Nation" or "State of Mongolia" () is a landlocked country in East Asia, bordered by Russia to the north and China to the south. It covers an area of , with a population of just 3.3 million, ...

(2/1)

# Nepal

Nepal (; ne, :ne:नेपाल, नेपाल ), formerly the Federal Democratic Republic of Nepal ( ne,

सङ्घीय लोकतान्त्रिक गणतन्त्र नेपाल ), is a landlocked country in S ...

(5/3)

# The Philippines

The Philippines (; fil, Pilipinas, links=no), officially the Republic of the Philippines ( fil, Republika ng Pilipinas, links=no),

* bik, Republika kan Filipinas

* ceb, Republika sa Pilipinas

* cbk, República de Filipinas

* hil, Republ ...

(6/0)

# Siam

Thailand ( ), historically known as Siam () and officially the Kingdom of Thailand, is a country in Southeast Asia, located at the centre of the Indochinese Peninsula, spanning , with a population of almost 70 million. The country is bo ...

(2/2)

# Tajikistan

Tajikistan (, ; tg, Тоҷикистон, Tojikiston; russian: Таджикистан, Tadzhikistan), officially the Republic of Tajikistan ( tg, Ҷумҳурии Тоҷикистон, Jumhurii Tojikiston), is a landlocked country in Centr ...

(2/0)

# Tibet

Tibet (; ''Böd''; ) is a region in East Asia, covering much of the Tibetan Plateau and spanning about . It is the traditional homeland of the Tibetan people. Also resident on the plateau are some other ethnic groups such as Monpa, Taman ...

(4/0)

# Turkey

Turkey ( tr, Türkiye ), officially the Republic of Türkiye ( tr, Türkiye Cumhuriyeti, links=no ), is a transcontinental country located mainly on the Anatolian Peninsula in Western Asia, with a small portion on the Balkan Peninsula in ...

(0/1)

# Turkmenistan

Turkmenistan ( or ; tk, Türkmenistan / Түркменистан, ) is a country located in Central Asia, bordered by Kazakhstan to the northwest, Uzbekistan to the north, east and northeast, Afghanistan to the southeast, Iran to the sout ...

(1/0)

# Uzbekistan

Uzbekistan (, ; uz, Ozbekiston, italic=yes / , ; russian: Узбекистан), officially the Republic of Uzbekistan ( uz, Ozbekiston Respublikasi, italic=yes / ; russian: Республика Узбекистан), is a doubly landlocked co ...

(2/0)

# Vietnam

Vietnam or Viet Nam ( vi, Việt Nam, ), officially the Socialist Republic of Vietnam,., group="n" is a country in Southeast Asia, at the eastern edge of mainland Southeast Asia, with an area of and population of 96 million, making i ...

(3/0)

The following states and organizations sent observers only:

* Australia (0/2)

* Arab League (0/1)

* United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the European mainland, continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotlan ...

(0/3)

* Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, ...

(0/2)

* United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territori ...

(0/3)

* United Nations

The United Nations (UN) is an intergovernmental organization whose stated purposes are to maintain international peace and security, develop friendly relations among nations, achieve international cooperation, and be a centre for harmoniz ...

(0/1)

See also

*Congress of the Peoples of the East

The Congress of the Peoples of the East () was a multinational conference held in September 1920 by the Communist International in Baku, Azerbaijan (then the capital of Soviet Azerbaijan). The congress was attended by nearly 1,900 delegates from a ...

*Pan-Asianism

Satellite photograph of Asia in orthographic projection.

Pan-Asianism (''also known as Asianism or Greater Asianism'') is an ideology aimed at creating a political and economic unity among Asian peoples. Various theories and movements of Pan-Asi ...

*Asian–African Conference

The first large-scale Asian–African or Afro–Asian Conference ( id, Konferensi Asia–Afrika)—also known as the Bandung Conference—was a meeting of Asian and African states, most of which were newly independent, which took place on 18–2 ...

Citations

References

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * {{Cold War 1947 in India 20th-century diplomatic conferences Diplomatic conferences in India Politics of Asia 1947 conferences 1947 in international relations India–Tibet relations India–Vietnam relations India–Taiwan relations China–India relations Taiwan–Tibet relations China–Tibet relations France–Vietnam relations