Al-Andalus Exiles on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Al-Andalus

translit. ; an, al-Andalus; ast, al-Ándalus; eu, al-Andalus; ber, ⴰⵏⴷⴰⵍⵓⵙ, label=

Berber

Berber or Berbers may refer to:

Ethnic group

* Berbers, an ethnic group native to Northern Africa

* Berber languages, a family of Afro-Asiatic languages

Places

* Berber, Sudan, a town on the Nile

People with the surname

* Ady Berber (1913–196 ...

, translit=Andalus; ca, al-Àndalus; gl, al-Andalus; oc, Al Andalús; pt, al-Ândalus; es, al-Ándalus () was the

Muslim

Muslims ( ar, المسلمون, , ) are people who adhere to Islam, a monotheistic religion belonging to the Abrahamic tradition. They consider the Quran, the foundational religious text of Islam, to be the verbatim word of the God of Abrah ...

-ruled area of the

Iberian Peninsula

The Iberian Peninsula (),

**

* Aragonese and Occitan: ''Peninsula Iberica''

**

**

* french: Péninsule Ibérique

* mwl, Península Eibérica

* eu, Iberiar penintsula also known as Iberia, is a peninsula in southwestern Europe, defi ...

. The term is used by modern historians for the former

Islamic states

An Islamic state is a state that has a form of government based on Islamic law (sharia). As a term, it has been used to describe various historical polities and theories of governance in the Islamic world. As a translation of the Arabic term ...

in modern Spain and Portugal.

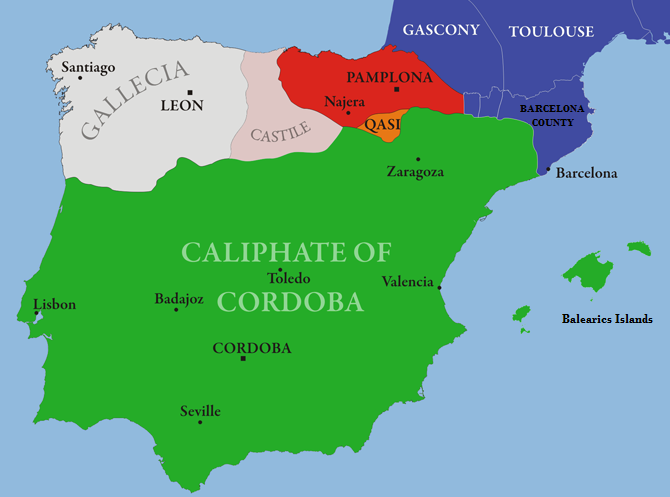

At its greatest geographical extent, it occupied most of the peninsula

and a part of present-day southern France,

Septimania

Septimania (french: Septimanie ; oc, Septimània ) is a historical region in modern-day Southern France. It referred to the western part of the Roman province of Gallia Narbonensis that passed to the control of the Visigoths in 462, when Septima ...

(8th century). For nearly a hundred years, from the 9th century to the 10th, al-Andalus extended its presence from

Fraxinetum

Fraxinetum or Fraxinet ( ar, فرخشنيط, translit=Farakhshanīt or , from Latin ''fraxinus'': "ash tree", ''fraxinetum'': "ash forest") was the site of a Muslim fortress in Provence between about 887 and 972. It is identified with modern ...

into the Alps with a series of organized raids and chronic banditry. The name describes the different Arab

[ and Muslim]Reconquista

The ' (Spanish, Portuguese and Galician for "reconquest") is a historiographical construction describing the 781-year period in the history of the Iberian Peninsula between the Umayyad conquest of Hispania in 711 and the fall of the Nasrid ...

progressed,["Para los autores árabes medievales, el término Al-Andalus designa la totalidad de las zonas conquistadas – siquiera temporalmente – por tropas arabo-musulmanas en territorios actualmente pertenecientes a Portugal, España y Francia" ("For medieval Arab authors, Al-Andalus designated all the conquered areas – even temporarily – by Arab-Muslim troops in territories now belonging to Spain, Portugal and France"), José Ángel García de Cortázar, ''V Semana de Estudios Medievales: Nájera, 1 al 5 de agosto de 1994'', Gobierno de La Rioja, Instituto de Estudios Riojanos, 1995, p. 52.]Emirate of Granada

The Emirate of Granada ( ar, إمارة غرﻧﺎﻃﺔ, Imārat Ġarnāṭah), also known as the Nasrid Kingdom of Granada ( es, Reino Nazarí de Granada), was an Emirate, Islamic realm in southern Iberia during the Late Middle Ages. It was the ...

.

Following the Umayyad conquest of the Christian Visigothic kingdom of Hispania, al-Andalus, then at its greatest extent, was divided into five administrative units, corresponding roughly to modern Andalusia

Andalusia (, ; es, Andalucía ) is the southernmost Autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community in Peninsular Spain. It is the most populous and the second-largest autonomous community in the country. It is officially recognised as a ...

; Castile and León; Navarre

Navarre (; es, Navarra ; eu, Nafarroa ), officially the Chartered Community of Navarre ( es, Comunidad Foral de Navarra, links=no ; eu, Nafarroako Foru Komunitatea, links=no ), is a foral autonomous community and province in northern Spain, ...

, Aragon

Aragon ( , ; Spanish and an, Aragón ; ca, Aragó ) is an autonomous community in Spain, coextensive with the medieval Kingdom of Aragon. In northeastern Spain, the Aragonese autonomous community comprises three provinces (from north to sou ...

, Catalonia

Catalonia (; ca, Catalunya ; Aranese Occitan: ''Catalonha'' ; es, Cataluña ) is an autonomous community of Spain, designated as a ''nationality'' by its Statute of Autonomy.

Most of the territory (except the Val d'Aran) lies on the north ...

; Portugal

Portugal, officially the Portuguese Republic ( pt, República Portuguesa, links=yes ), is a country whose mainland is located on the Iberian Peninsula of Southwestern Europe, and whose territory also includes the Atlantic archipelagos of ...

and Galicia; and the Languedoc-Roussillon

Languedoc-Roussillon (; oc, Lengadòc-Rosselhon ; ca, Llenguadoc-Rosselló) is a former administrative region of France. On 1 January 2016, it joined with the region of Midi-Pyrénées to become Occitania. It comprised five departments, and ...

area of Occitanie Occitanie may refer to:

*Occitania, a region in southern France called ''Occitanie'' in French

*Occitania (administrative region)

Occitania ( ; french: Occitanie ; oc, Occitània ; ca, Occitània ) is the southernmost administrative region of ...

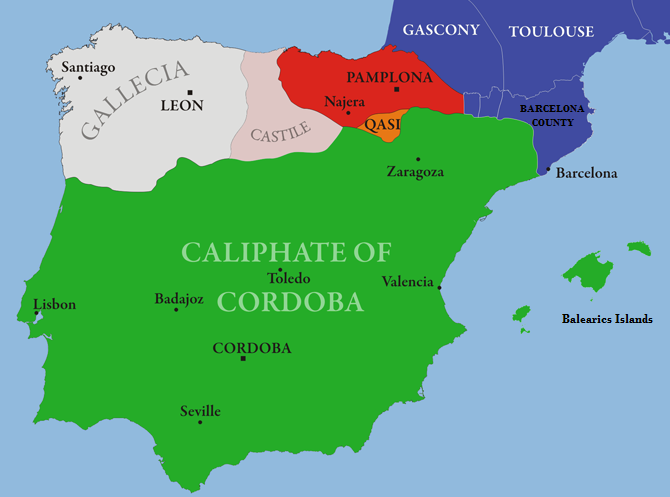

. As a political domain, it successively constituted a province of the Umayyad Caliphate

The Umayyad Caliphate (661–750 CE; , ; ar, ٱلْخِلَافَة ٱلْأُمَوِيَّة, al-Khilāfah al-ʾUmawīyah) was the second of the four major caliphates established after the death of Muhammad. The caliphate was ruled by th ...

, initiated by the Caliph al-Walid I

Al-Walid ibn Abd al-Malik ibn Marwan ( ar, الوليد بن عبد الملك بن مروان, al-Walīd ibn ʿAbd al-Malik ibn Marwān; ), commonly known as al-Walid I ( ar, الوليد الأول), was the sixth Umayyad Caliphate, Umayyad ca ...

(711–750); the Emirate of Córdoba

The Emirate of Córdoba ( ar, إمارة قرطبة, ) was a medieval Islamic kingdom in the Iberian Peninsula. Its founding in the mid-eighth century would mark the beginning of seven hundred years of Muslim rule in what is now Spain and Port ...

(c. 750–929); the Caliphate of Córdoba

The Caliphate of Córdoba ( ar, خلافة قرطبة; transliterated ''Khilāfat Qurṭuba''), also known as the Cordoban Caliphate was an Islamic state ruled by the Umayyad dynasty from 929 to 1031. Its territory comprised Iberia and parts o ...

(929–1031); the Caliphate of Córdoba's ''taifa

The ''taifas'' (singular ''taifa'', from ar, طائفة ''ṭā'ifa'', plural طوائف ''ṭawā'if'', a party, band or faction) were the independent Muslim principalities and kingdoms of the Iberian Peninsula (modern Portugal and Spain), re ...

'' (successor) kingdoms (1009–1110); the Sanhaja

The Sanhaja ( ber, Aẓnag, pl. Iẓnagen, and also Aẓnaj, pl. Iẓnajen; ar, صنهاجة, ''Ṣanhaja'' or زناگة ''Znaga'') were once one of the largest Berber tribal confederations, along with the Zanata and Masmuda confederations. Ma ...

Amazigh Almoravid Empire

The Almoravid dynasty ( ar, المرابطون, translit=Al-Murābiṭūn, lit=those from the ribats) was an imperial Berber Muslim dynasty centered in the territory of present-day Morocco. It established an empire in the 11th century that st ...

(1085–1145); the second taifa period (1140–1203); the Masmuda

The Masmuda ( ar, المصمودة, Berber: ⵉⵎⵙⵎⵓⴷⵏ) is a Berber tribal confederation of Morocco and one of the largest in the Maghreb, along with the Zanata and the Sanhaja. They were composed of several sub-tribes: Berghouatas, ...

Amazigh Almohad Caliphate

The Almohad Caliphate (; ar, خِلَافَةُ ٱلْمُوَحِّدِينَ or or from ar, ٱلْمُوَحِّدُونَ, translit=al-Muwaḥḥidūn, lit=those who profess the Tawhid, unity of God) was a North African Berbers, Berber M ...

(1147–1238); the third taifa period (1232–1287); and ultimately the Nasrid Emirate of Granada (1238–1492).

Under the Caliphate of Córdoba, al-Andalus was a centre of learning, and the city of Córdoba, the second largest in Europe, became one of the leading cultural and economic centres throughout the Mediterranean Basin

In biogeography, the Mediterranean Basin (; also known as the Mediterranean Region or sometimes Mediterranea) is the region of lands around the Mediterranean Sea that have mostly a Mediterranean climate, with mild to cool, rainy winters and w ...

, Europe, and the Islamic world. Achievements that advanced Islamic and Western science came from al-Andalus, including major advances in trigonometry ( Geber), astronomy ( Arzachel), surgery ( Abulcasis Al Zahrawi), pharmacology (Avenzoar

Abū Marwān ‘Abd al-Malik ibn Zuhr ( ar, أبو مروان عبد الملك بن زهر), traditionally known by his Latinized name Avenzoar (; 1094–1162), was an Arab physician, surgeon, and poet. He was born at Seville in medieval An ...

),agronomy

Agronomy is the science and technology of producing and using plants by agriculture for food, fuel, fiber, chemicals, recreation, or land conservation. Agronomy has come to include research of plant genetics, plant physiology, meteorology, and ...

(Ibn Bassal

Ibn Bassal ( ar, ابن بصال) was an 11th-century Andalusian Arab botanist and agronomist in Toledo and Seville, Spain who wrote about horticulture and arboriculture. He is best known for his book on agronomy, the ''Dīwān al-filāha'' (An ...

and Abū l-Khayr al-Ishbīlī

The Arab Agricultural Revolution was the transformation in agriculture from the 8th to the 13th century in the Islamic region of the Old World. The agronomic literature of the time, with major books by Ibn Bassal and Abū l-Khayr al-Ishbīlī, d ...

). Al-Andalus became a major educational center for Europe and the lands around the Mediterranean Sea as well as a conduit for cultural and scientific exchange between the Islamic and Christian worlds.jizya

Jizya ( ar, جِزْيَة / ) is a per capita yearly taxation historically levied in the form of financial charge on dhimmis, that is, permanent Kafir, non-Muslim subjects of a state governed by Sharia, Islamic law. The jizya tax has been unde ...

, to the state, which in return, provided internal autonomy in practicing their religion, and offered the same level of protections by the Muslim rulers. The jizya was not only a tax, however, but also a symbolic expression of subordination, according to orientalist Bernard Lewis.

For much of its history, al-Andalus existed in conflict with Christian kingdoms to the north. After the fall of the Umayyad caliphate, al-Andalus was fragmented into minor states and principalities. Attacks from the Christians intensified, led by the Castilians under Alfonso VI

Alphons (Latinized ''Alphonsus'', ''Adelphonsus'', or ''Adefonsus'') is a male given name recorded from the 8th century (Alfonso I of Asturias, r. 739–757) in the Christian successor states of the Visigothic kingdom in the Iberian peninsula. ...

. The Almoravid empire intervened and repelled the Christian attacks on the region, deposing the weak Andalusi Muslim princes, and included al-Andalus under direct Berber

Berber or Berbers may refer to:

Ethnic group

* Berbers, an ethnic group native to Northern Africa

* Berber languages, a family of Afro-Asiatic languages

Places

* Berber, Sudan, a town on the Nile

People with the surname

* Ady Berber (1913–196 ...

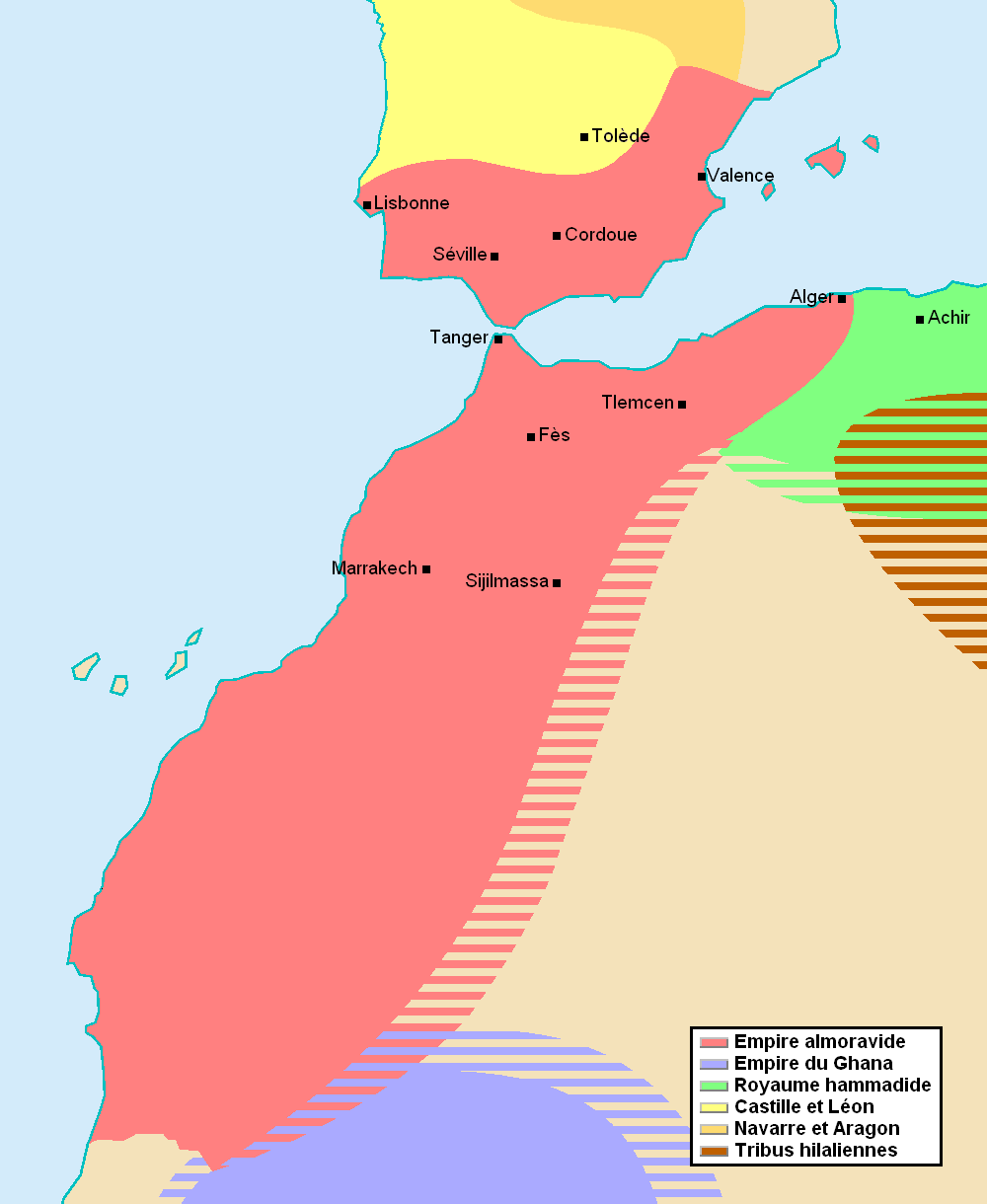

rule. In the next century and a half, al-Andalus became a province of the Berber Muslim empires of the Almoravids

The Almoravid dynasty ( ar, المرابطون, translit=Al-Murābiṭūn, lit=those from the ribats) was an imperial Berber Muslim dynasty centered in the territory of present-day Morocco. It established an empire in the 11th century that ...

and Almohads

The Almohad Caliphate (; ar, خِلَافَةُ ٱلْمُوَحِّدِينَ or or from ar, ٱلْمُوَحِّدُونَ, translit=al-Muwaḥḥidūn, lit=those who profess the unity of God) was a North African Berber Muslim empire fo ...

, both based in Marrakesh

Marrakesh or Marrakech ( or ; ar, مراكش, murrākuš, ; ber, ⵎⵕⵕⴰⴽⵛ, translit=mṛṛakc}) is the fourth largest city in the Kingdom of Morocco. It is one of the four Imperial cities of Morocco and is the capital of the Marrakes ...

.

Ultimately, the Christian kingdoms in the north of the Iberian Peninsula overpowered the Muslim states to the south. In 1085, Alfonso VI

Alphons (Latinized ''Alphonsus'', ''Adelphonsus'', or ''Adefonsus'') is a male given name recorded from the 8th century (Alfonso I of Asturias, r. 739–757) in the Christian successor states of the Visigothic kingdom in the Iberian peninsula. ...

captured Toledo, starting a gradual decline of Muslim power. With the fall of Córdoba in 1236, most of the south quickly fell under Christian rule, and the Emirate of Granada became a tributary state of the Kingdom of Castile

The Kingdom of Castile (; es, Reino de Castilla, la, Regnum Castellae) was a large and powerful state on the Iberian Peninsula during the Middle Ages. Its name comes from the host of castles constructed in the region. It began in the 9th centu ...

two years later. In 1249, the Portuguese Reconquista culminated with the conquest of the Algarve

The Algarve (, , ; from ) is the southernmost NUTS II region of continental Portugal. It has an area of with 467,495 permanent inhabitants and incorporates 16 municipalities ( ''concelhos'' or ''municípios'' in Portuguese).

The region has it ...

by Afonso III

Afonso III (; rare English alternatives: ''Alphonzo'' or ''Alphonse''), or ''Affonso'' (Archaic Portuguese), ''Alfonso'' or ''Alphonso'' (Portuguese-Galician) or ''Alphonsus'' (Latin), the Boulonnais ( Port. ''o Bolonhês''), King of Portugal ( ...

, leaving Granada as the last Muslim state on the Iberian Peninsula. Finally, on January 2, 1492, Emir Muhammad XII

Abu Abdallah Muhammad XII ( ar, أبو عبد الله محمد الثاني عشر, Abū ʿAbdi-llāh Muḥammad ath-thānī ʿashar) (c. 1460–1533), known in Europe as Boabdil (a Spanish rendering of the name ''Abu Abdallah''), was the ...

surrendered the Emirate of Granada to Queen Isabella I of Castile

Isabella I ( es, Isabel I; 22 April 1451 – 26 November 1504), also called Isabella the Catholic (Spanish: ''la Católica''), was Queen of Castile from 1474 until her death in 1504, as well as List of Aragonese royal consorts, Queen consort ...

, completing the Christian Reconquista of the peninsula.

Name

The toponym ''al-Andalus'' is first attested by inscriptions on coins minted in 716 by the new Muslim government of Iberia.dinars

The dinar () is the principal currency unit in several countries near the Mediterranean Sea, and its historical use is even more widespread.

The modern dinar's historical antecedents are the gold dinar and the silver dirham, the main coin of ...

'', were inscribed in both Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power of the ...

and Arabic

Arabic (, ' ; , ' or ) is a Semitic languages, Semitic language spoken primarily across the Arab world.Semitic languages: an international handbook / edited by Stefan Weninger; in collaboration with Geoffrey Khan, Michael P. Streck, Janet C ...

.Vandals

The Vandals were a Germanic peoples, Germanic people who first inhabited what is now southern Poland. They established Vandal Kingdom, Vandal kingdoms on the Iberian Peninsula, Mediterranean islands, and North Africa in the fifth century.

The ...

'' (''vándalos'' in Spanish); however, proposals since the 1980s have challenged this tradition. In 1986, Joaquín Vallvé proposed that "''al-Andalus''" was a corruption of the name ''Atlantis

Atlantis ( grc, Ἀτλαντὶς νῆσος, , island of Atlas (mythology), Atlas) is a fictional island mentioned in an allegory on the hubris of nations in Plato's works ''Timaeus (dialogue), Timaeus'' and ''Critias (dialogue), Critias'' ...

''.

History

Province of the Umayyad Caliphate

During the caliphate of the Umayyad Caliph

During the caliphate of the Umayyad Caliph Al-Walid I

Al-Walid ibn Abd al-Malik ibn Marwan ( ar, الوليد بن عبد الملك بن مروان, al-Walīd ibn ʿAbd al-Malik ibn Marwān; ), commonly known as al-Walid I ( ar, الوليد الأول), was the sixth Umayyad Caliphate, Umayyad ca ...

, the Moorish

The term Moor, derived from the ancient Mauri, is an exonym first used by Christian Europeans to designate the Muslim inhabitants of the Maghreb, the Iberian Peninsula, Sicily and Malta during the Middle Ages.

Moors are not a distinct or se ...

commander Tariq ibn-Ziyad

Ṭāriq ibn Ziyād ( ar, طارق بن زياد), also known simply as Tarik in English, was a Berber commander who served the Umayyad Caliphate and initiated the Muslim Umayyad conquest of Visigothic Hispania (present-day Spain and Portugal) ...

led an army of 7,000 that landed at Gibraltar

)

, anthem = " God Save the King"

, song = " Gibraltar Anthem"

, image_map = Gibraltar location in Europe.svg

, map_alt = Location of Gibraltar in Europe

, map_caption = United Kingdom shown in pale green

, mapsize =

, image_map2 = Gib ...

on April 30, 711, ostensibly to intervene in a Visigothic

The Visigoths (; la, Visigothi, Wisigothi, Vesi, Visi, Wesi, Wisi) were an early Germanic people who, along with the Ostrogoths, constituted the two major political entities of the Goths within the Roman Empire in late antiquity, or what is kno ...

civil war. After a decisive victory over King Roderic

Roderic (also spelled Ruderic, Roderik, Roderich, or Roderick; Spanish and pt, Rodrigo, ar, translit=Ludharīq, لذريق; died 711) was the Visigothic king in Hispania between 710 and 711. He is well-known as "the last king of the Goths". He ...

at the Battle of Guadalete

The Battle of Guadalete was the first major battle of the Umayyad conquest of Hispania, fought in 711 at an unidentified location in what is now southern Spain between the Christian Visigoths under their king, Roderic, and the invading forces of t ...

on July 19, 711, Tariq ibn-Ziyad, joined by Arab governor Musa ibn Nusayr

Musa ibn Nusayr ( ar, موسى بن نصير ''Mūsá bin Nuṣayr''; 640 – c. 716) served as a Umayyad governor and an Arab general under the Umayyad caliph Al-Walid I. He ruled over the Muslim provinces of North Africa (Ifriqiya), and direct ...

of Ifriqiya

Ifriqiya ( '), also known as al-Maghrib al-Adna ( ar, المغرب الأدنى), was a medieval historical region comprising today's Tunisia and eastern Algeria, and Tripolitania (today's western Libya). It included all of what had previously ...

, brought most of the Visigothic Kingdom

The Visigothic Kingdom, officially the Kingdom of the Goths ( la, Regnum Gothorum), was a kingdom that occupied what is now southwestern France and the Iberian Peninsula from the 5th to the 8th centuries. One of the Germanic peoples, Germanic su ...

under Muslim rule in a seven-year campaign. They crossed the Pyrenees

The Pyrenees (; es, Pirineos ; french: Pyrénées ; ca, Pirineu ; eu, Pirinioak ; oc, Pirenèus ; an, Pirineus) is a mountain range straddling the border of France and Spain. It extends nearly from its union with the Cantabrian Mountains to C ...

and occupied Visigothic Septimania

Septimania (french: Septimanie ; oc, Septimània ) is a historical region in modern-day Southern France. It referred to the western part of the Roman province of Gallia Narbonensis that passed to the control of the Visigoths in 462, when Septima ...

in southern France.

Most of the Iberian peninsula became part of the expanding Umayyad Empire

The Umayyad Caliphate (661–750 CE; , ; ar, ٱلْخِلَافَة ٱلْأُمَوِيَّة, al-Khilāfah al-ʾUmawīyah) was the second of the four major caliphates established after the death of Muhammad. The caliphate was ruled by the ...

, under the name of ''al-Andalus''. It was organized as a province subordinate to Ifriqiya

Ifriqiya ( '), also known as al-Maghrib al-Adna ( ar, المغرب الأدنى), was a medieval historical region comprising today's Tunisia and eastern Algeria, and Tripolitania (today's western Libya). It included all of what had previously ...

, so, for the first few decades, the governors of al-Andalus were appointed by the emir of Kairouan

Kairouan (, ), also spelled El Qayrawān or Kairwan ( ar, ٱلْقَيْرَوَان, al-Qayrawān , aeb, script=Latn, Qeirwān ), is the capital of the Kairouan Governorate in Tunisia and a UNESCO World Heritage Site. The city was founded by th ...

, rather than the Caliph in Damascus

)), is an adjective which means "spacious".

, motto =

, image_flag = Flag of Damascus.svg

, image_seal = Emblem of Damascus.svg

, seal_type = Seal

, map_caption =

, ...

. The regional capital was set at Córdoba, and the first influx of Muslim settlers was widely distributed.

The small army Tariq led in the initial conquest consisted mostly of Berbers, while Musa's largely Arab force of over 12,000 soldiers was accompanied by a group of ''mawālī'' (Arabic, موالي), that is, non-Arab Muslims, who were clients of the Arabs. The Berber soldiers accompanying Tariq were garrisoned in the centre and the north of the peninsula, as well as in the Pyrenees,Berber

Berber or Berbers may refer to:

Ethnic group

* Berbers, an ethnic group native to Northern Africa

* Berber languages, a family of Afro-Asiatic languages

Places

* Berber, Sudan, a town on the Nile

People with the surname

* Ady Berber (1913–196 ...

colonists who followed settled in all parts of the country north, east, south and west.Kingdom of Asturias

The Kingdom of Asturias ( la, Asturum Regnum; ast, Reinu d'Asturies) was a kingdom in the Iberian Peninsula founded by the Visigothic nobleman Pelagius. It was the first Christian political entity established after the Umayyad conquest of V ...

.

In the 720s, the al-Andalus governors launched several ''sa'ifa'' raids into

In the 720s, the al-Andalus governors launched several ''sa'ifa'' raids into Aquitaine

Aquitaine ( , , ; oc, Aquitània ; eu, Akitania; Poitevin-Saintongeais: ''Aguiéne''), archaic Guyenne or Guienne ( oc, Guiana), is a historical region of southwestern France and a former administrative region of the country. Since 1 January ...

but were severely defeated by Duke Odo the Great

Odo the Great (also called ''Eudes'' or ''Eudo'') (died 735–740), was the Duke of Aquitaine by 700. His territory included Vasconia in the south-west of Gaul and the Duchy of Aquitaine (at that point located north-east of the river Garonne), a r ...

of Aquitaine at the Battle of Toulouse (721)

The Battle of Toulouse (721) was a victory of an Aquitanian Christian army led by Duke Odo of Aquitaine over an Umayyad Muslim army besieging the city of Toulouse, and led by the governor of Al-Andalus, Al-Samh ibn Malik al-Khawlani. The vict ...

. However, after crushing Odo's Berber ally Uthman ibn Naissa

Uthman ibn Naissa () better known as Munuza, was a Berber governor depicted in different contradictory chronicles during the Umayyad conquest of Hispania.

Munuza in Asturias

One account says that he was the governor of Gijón (or possibly León) ...

on the eastern Pyrenees, Abdul Rahman Al Ghafiqi

Abd al-Rahman ibn Abd Allah Al-Ghafiqi ( ar, عبدالرحمن بن عبداللّه الغافقي, ʿAbd al-Raḥmān ibn ʿAbd Allāh al-Ghāfiqī; died 732), was an Arab Umayyad commander of Andalusian Muslims. He unsuccessfully led into ...

led an expedition north across the western Pyrenees and defeated the Aquitanian duke, who in turn appealed to the Frankish

Frankish may refer to:

* Franks, a Germanic tribe and their culture

** Frankish language or its modern descendants, Franconian languages

* Francia, a post-Roman state in France and Germany

* East Francia, the successor state to Francia in Germany ...

leader Charles Martel

Charles Martel ( – 22 October 741) was a Frankish political and military leader who, as Duke and Prince of the Franks and Mayor of the Palace, was the de facto ruler of Francia from 718 until his death. He was a son of the Frankish statesma ...

for assistance, offering to place himself under Carolingian sovereignty. At the Battle of Poitiers

The Battle of Poitiers was fought on 19September 1356 between a French army commanded by King JohnII and an Anglo- Gascon force under Edward, the Black Prince, during the Hundred Years' War. It took place in western France, south of Poi ...

in 732, the al-Andalus raiding army was defeated by Charles Martel. In 734, the Andalusi launched raids to the east, capturing Avignon

Avignon (, ; ; oc, Avinhon, label=Provençal dialect, Provençal or , ; la, Avenio) is the Prefectures in France, prefecture of the Vaucluse Departments of France, department in the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur Regions of France, region of So ...

and Arles

Arles (, , ; oc, label= Provençal, Arle ; Classical la, Arelate) is a coastal city and commune in the South of France, a subprefecture in the Bouches-du-Rhône department of the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur region, in the former province of ...

and overran much of Provence

Provence (, , , , ; oc, Provença or ''Prouvènço'' , ) is a geographical region and historical province of southeastern France, which extends from the left bank of the lower Rhône to the west to the Italian border to the east; it is bor ...

. In 737, they traveled up the Rhône

The Rhône ( , ; wae, Rotten ; frp, Rôno ; oc, Ròse ) is a major river in France and Switzerland, rising in the Alps and flowing west and south through Lake Geneva and southeastern France before discharging into the Mediterranean Sea. At Ar ...

valley, reaching as far north as Burgundy

Burgundy (; french: link=no, Bourgogne ) is a historical territory and former administrative region and province of east-central France. The province was once home to the Dukes of Burgundy from the early 11th until the late 15th century. The c ...

. Charles Martel of the Franks, with the assistance of Liutprand of the Lombards

The Lombards () or Langobards ( la, Langobardi) were a Germanic people who ruled most of the Italian Peninsula from 568 to 774.

The medieval Lombard historian Paul the Deacon wrote in the ''History of the Lombards'' (written between 787 and ...

, invaded Burgundy and Provence and expelled the raiders by 739.

Relations between Arabs and Berbers in al-Andalus had been tense in the years after the conquest. Berbers, heavily outnumbering the Arabs in the province, had done the bulk of the fighting, and were assigned the harsher duties (e.g., garrisoning the more troubled areas). Although some Arab governors had cultivated their Berber lieutenants, others had grievously mistreated them. Mutinies by Berber soldiers were frequent; e.g., in 729, the Berber commander Munnus had revolted and managed to carve out a rebel state in

Relations between Arabs and Berbers in al-Andalus had been tense in the years after the conquest. Berbers, heavily outnumbering the Arabs in the province, had done the bulk of the fighting, and were assigned the harsher duties (e.g., garrisoning the more troubled areas). Although some Arab governors had cultivated their Berber lieutenants, others had grievously mistreated them. Mutinies by Berber soldiers were frequent; e.g., in 729, the Berber commander Munnus had revolted and managed to carve out a rebel state in Cerdanya

Cerdanya () or often La Cerdanya ( la, Ceretani or ''Ceritania''; french: Cerdagne; es, Cerdaña), is a natural comarca and historical region of the eastern Pyrenees divided between France and Spain. Historically it was one of the counties ...

for a while.

In 740, a Berber Revolt

The Berber Revolt of 740–743 AD (122–125 AH in the Islamic calendar) took place during the reign of the Umayyad Caliph Hisham ibn Abd al-Malik and marked the first successful secession from the Arab caliphate (ruled from Damascus). Fired up b ...

erupted in the Maghreb

The Maghreb (; ar, الْمَغْرِب, al-Maghrib, lit=the west), also known as the Arab Maghreb ( ar, المغرب العربي) and Northwest Africa, is the western part of North Africa and the Arab world. The region includes Algeria, ...

(North Africa). To put down the rebellion, the Umayyad Caliph Hisham

Hisham ibn Abd al-Malik ( ar, هشام بن عبد الملك, Hishām ibn ʿAbd al-Malik; 691 – 6 February 743) was the tenth Umayyad caliph, ruling from 724 until his death in 743.

Early life

Hisham was born in Damascus, the administrat ...

dispatched a large Arab army, composed of regiments (''Jund

Under the early Caliphates, a ''jund'' ( ar, جند; plural ''ajnad'', اجناد) was a military division, which became applied to Arab military colonies in the conquered lands and, most notably, to the provinces into which Greater Syria (the L ...

s'') of Bilad Ash-Sham

Bilad al-Sham ( ar, بِلَاد الشَّام, Bilād al-Shām), often referred to as Islamic Syria or simply Syria in English-language sources, was a province of the Rashidun, Umayyad, Abbasid, and Fatimid caliphates. It roughly correspon ...

, to North Africa. But the great Umayyad army was crushed by the Berber rebels at the Battle of Bagdoura

The Battle of Bagdoura (or Baqdura) was a decisive confrontation in the Berber Revolt in late 741 CE. It was a follow-up to the Battle of the Nobles the previous year, and resulted in a major Berber victory over the Arabs by the Sebou River (nea ...

(in Morocco). Heartened by the victories of their North African brethren, the Berbers of al-Andalus quickly raised their own revolt. Berber garrisons in the north of the Iberian Peninsula mutinied, deposed their Arab commanders, and organized a large rebel army to march against the strongholds of Toledo, Cordoba, and Algeciras.

In 741, Balj b. Bishr led a detachment of some 10,000 Arab troops across the straits

A strait is an oceanic landform connecting two seas or two other large areas of water. The surface water generally flows at the same elevation on both sides and through the strait in either direction. Most commonly, it is a narrow ocean channe ...

.Granada

Granada (,, DIN 31635, DIN: ; grc, Ἐλιβύργη, Elibýrgē; la, Illiberis or . ) is the capital city of the province of Granada, in the autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community of Andalusia, Spain. Granada is located at the fo ...

), the Jordan jund in Rayyu (Málaga

Málaga (, ) is a municipality of Spain, capital of the Province of Málaga, in the autonomous community of Andalusia. With a population of 578,460 in 2020, it is the second-most populous city in Andalusia after Seville and the sixth most pop ...

and Archidona

Archidona is a town and municipality in the province of Málaga, part of the autonomous community of Andalusia in southern Spain. It is the center of the comarca of Nororiental de Málaga and the head of the judicial district that bears its name ...

), the Jund Filastin in Medina-Sidonia

Medina Sidonia is a city and municipality in the province of Cádiz in the autonomous community of Andalusia, southern Spain. Considered by some to be the oldest city in Europe, it is used as a military defence location because of its elevation. ...

and Jerez

Jerez de la Frontera (), or simply Jerez (), is a Spanish city and municipality in the province of Cádiz in the autonomous community of Andalusia, in southwestern Spain, located midway between the Atlantic Ocean and the Cádiz Mountains. , the ...

, the Emesa (Hims) jund in Seville

Seville (; es, Sevilla, ) is the capital and largest city of the Spanish autonomous community of Andalusia and the province of Seville. It is situated on the lower reaches of the River Guadalquivir, in the southwest of the Iberian Peninsula ...

and Niebla, and the Qinnasrin jund in Jaén. The Egypt jund was divided between Beja (Alentejo

Alentejo ( , ) is a geographical, historical, and cultural region of south–central and southern Portugal. In Portuguese, its name means "beyond () the Tagus river" (''Tejo'').

Alentejo includes the regions of Alto Alentejo and Baixo Alent ...

) in the west and Tudmir (Murcia

Murcia (, , ) is a city in south-eastern Spain, the capital and most populous city of the autonomous community of the Region of Murcia, and the seventh largest city in the country. It has a population of 460,349 inhabitants in 2021 (about one ...

) in the east. The arrival of the Syrians substantially increased the Arab element in the Iberian peninsula and helped strengthen the Muslim hold on the south. However, at the same time, unwilling to be governed, the Syrian ''junds'' carried on an existence of autonomous feudal anarchy, severely destabilizing the authority of the governor of al-Andalus.

A second significant consequence of the revolt was the expansion of the Kingdom of the Asturias

The Kingdom of Asturias ( la, Asturum Regnum; ast, Reinu d'Asturies) was a kingdom in the Iberian Peninsula founded by the Visigothic nobleman Pelagius. It was the first Christian political entity established after the Umayyad conquest of V ...

, hitherto confined to enclaves in the Cantabrian highlands. After the rebellious Berber garrisons evacuated the northern frontier fortresses, the Christian king Alfonso I of Asturias

Alfonso I of Asturias, called the Catholic (''el Católico''), (c. 693 – 757) was the third King of Asturias, reigning from 739 to his death in 757. His reign saw an extension of the Christian domain of Asturias, reconquering Galicia and Le ...

set about immediately seizing the empty forts for himself, quickly adding the northwestern provinces of Galicia and León to his fledgling kingdom. The Asturians evacuated the Christian populations from the towns and villages of the Galician-Leonese lowlands, creating an empty buffer zone in the Douro River

The Douro (, , ; es, Duero ; la, Durius) is the highest-flow river of the Iberian Peninsula. It rises near Duruelo de la Sierra in Soria Province, central Spain, meanders south briefly then flows generally west through the north-west part of ...

valley (the "Desert of the Duero

A desert is a barren area of landscape where little precipitation occurs and, consequently, living conditions are hostile for plant and animal life. The lack of vegetation exposes the unprotected surface of the ground to denudation. About on ...

"). This newly emptied frontier remained roughly in place for the next few centuries as the boundary between the Christian north and the Islamic south. Between this frontier and its heartland in the south, the al-Andalus state had three large march territories (''thughur''): the Lower March

The Lower March ( ar, الثغر الأدنى, ''al-Ṯaḡr al-ʾAdnā''; ) was a march of al-Andalus. It included territory that is now in Portugal.

As a borderland territory, it was home to the so-called ''muwalladun'' or indigenous converts a ...

(capital initially at Mérida, later Badajoz

Badajoz (; formerly written ''Badajos'' in English) is the capital of the Province of Badajoz in the autonomous community of Extremadura, Spain. It is situated close to the Portuguese border, on the left bank of the river Guadiana. The population ...

), the Middle March (centered at Toledo), and the Upper March

The Upper March (in ar, الثغر الأعلى, ''aṯ-Tagr al-A'la''; in Spanish: ''Marca Superior'') was an administrative and military division in northeast Al-Andalus, roughly corresponding to the Ebro valley and adjacent Mediterranean coa ...

(centered at Zaragoza

Zaragoza, also known in English as Saragossa,''Encyclopædia Britannica'"Zaragoza (conventional Saragossa)" is the capital city of the Zaragoza Province and of the autonomous community of Aragon, Spain. It lies by the Ebro river and its tributari ...

).

These disturbances and disorders also allowed the Franks, now under the leadership of Pepin the Short

the Short (french: Pépin le Bref; – 24 September 768), also called the Younger (german: Pippin der Jüngere), was King of the Franks from 751 until his death in 768. He was the first Carolingian to become king.

The younger was the son of ...

, to invade the strategic strip of Septimania

Septimania (french: Septimanie ; oc, Septimània ) is a historical region in modern-day Southern France. It referred to the western part of the Roman province of Gallia Narbonensis that passed to the control of the Visigoths in 462, when Septima ...

in 752, hoping to deprive al-Andalus of an easy launching pad for raids into Francia

Francia, also called the Kingdom of the Franks ( la, Regnum Francorum), Frankish Kingdom, Frankland or Frankish Empire ( la, Imperium Francorum), was the largest post-Roman barbarian kingdom in Western Europe. It was ruled by the Franks dur ...

. After a lengthy siege, the last Arab stronghold, the citadel of Narbonne

Narbonne (, also , ; oc, Narbona ; la, Narbo ; Late Latin:) is a commune in France, commune in Southern France in the Occitania (administrative region), Occitanie Regions of France, region. It lies from Paris in the Aude Departments of Franc ...

, finally fell to the Franks in 759. Al-Andalus was sealed off at the Pyrenees.

The third consequence of the Berber revolt was the collapse of the authority of the Damascus

)), is an adjective which means "spacious".

, motto =

, image_flag = Flag of Damascus.svg

, image_seal = Emblem of Damascus.svg

, seal_type = Seal

, map_caption =

, ...

Caliphate over the western provinces. With the Umayyad Caliphs distracted by the challenge of the Abbasid

The Abbasid Caliphate ( or ; ar, الْخِلَافَةُ الْعَبَّاسِيَّة, ') was the third caliphate to succeed the Islamic prophet Muhammad. It was founded by a dynasty descended from Muhammad's uncle, Abbas ibn Abdul-Muttalib ...

s in the east, the western provinces of the Maghreb and al-Andalus spun out of their control. From around 745, the Fihrids

The Fihrids (), also known as Banu Fihr (), were an Arab family and clan, prominent in North Africa and Al-Andalus in the 8th century.

The Fihrids were from the Arabian clan of Banu Fihr, part of the Quraysh, the tribe of the Prophet. Probably th ...

, an illustrious local Arab clan descended from Oqba ibn Nafi al-Fihri, seized power in the western provinces and ruled them almost as a private family empire of their own Abd al-Rahman ibn Habib al-Fihri

ʿAbd al-Raḥmān ibn Ḥabīb al-Fihrī () (died 755) was an Arab noble of the Fihrid family, and ruler of Ifriqiya (North Africa) from 745 through 755 AD.

Background

Abd al-Rahman ibn Habib was a great-grandson of Oqba ibn Nafi al-Fihri (Mu ...

in Ifriqiya and Yūsuf al-Fihri in al-Andalus. The Fihrids welcomed the fall of the Umayyads in the east, in 750, and sought to reach an understanding with the Abbasids, hoping they might be allowed to continue their autonomous existence. But when the Abbasids rejected the offer and demanded submission, the Fihrids declared independence and, probably out of spite, invited the deposed remnants of the Umayyad clan to take refuge in their dominions. It was a fateful decision that they soon regretted, for the Umayyads, the sons and grandsons of caliphs, had a more legitimate claim to rule than the Fihrids themselves. Rebellious-minded local lords, disenchanted with the autocratic rule of the Fihrids, conspired with the arriving Umayyad exiles.

Umayyad Emirate of Córdoba

Establishment

In 755, the exiled Umayyad prince Abd al-Rahman I (also called ''al-Dākhil'', the 'Immigrant') arrived on the coast of Spain.

In 755, the exiled Umayyad prince Abd al-Rahman I (also called ''al-Dākhil'', the 'Immigrant') arrived on the coast of Spain.Almuñécar

Almuñécar () is a Spanish city and municipality located in the southwestern part of the comarca of the Costa Granadina, in the province of Granada. It is located on the shores of the Mediterranean sea and borders the Granadin municipalities of O ...

.Málaga

Málaga (, ) is a municipality of Spain, capital of the Province of Málaga, in the autonomous community of Andalusia. With a population of 578,460 in 2020, it is the second-most populous city in Andalusia after Seville and the sixth most pop ...

and then Seville

Seville (; es, Sevilla, ) is the capital and largest city of the Spanish autonomous community of Andalusia and the province of Seville. It is situated on the lower reaches of the River Guadalquivir, in the southwest of the Iberian Peninsula ...

, finally besieging the capital of al-Andalus, Córdoba. Abd al-Rahman's army was exhausted after their conquest, meanwhile Governor Yūsuf al-Fihri had returned from quashing another rebellion with his army. The siege of Córdoba began, and noticing the starving state of Abd al-Rahman's army, al-Fihri began throwing lavish feasts every day as the siege went on, to tempt Abd al Rahman's supporters to defect to his side. However, Abd al-Rahman persisted, even rejecting a truce that would have allowed Abd al-Rahman to marry al-Fihri's daughter. After decisively defeating Yūsuf al-Fihri's army, Abd al-Rahman was able to conquer Córdoba, where he proclaimed himself emir in 756.

Rule

Abd al Rahman's rule was stable in the years after his conquest – he built major public works, most famously the Mosque of Córdoba, and helped urbanize the emirate while defending it from invaders, including the quashing of numerous rebellions, and decisively repelling the invasion by Charlemagne

Charlemagne ( , ) or Charles the Great ( la, Carolus Magnus; german: Karl der Große; 2 April 747 – 28 January 814), a member of the Carolingian dynasty, was King of the Franks from 768, King of the Lombards from 774, and the first Holy ...

(which would later inspire the epic, Chanson de Roland

''The Song of Roland'' (french: La Chanson de Roland) is an 11th-century ''chanson de geste'' based on the Frankish military leader Roland at the Battle of Roncevaux Pass in 778 AD, during the reign of the Carolingian king Charlemagne. It is ...

). By far the most important of these invasions was the attempted reconquest by the Abbasid Caliphate

The Abbasid Caliphate ( or ; ar, الْخِلَافَةُ الْعَبَّاسِيَّة, ') was the third caliphate to succeed the Islamic prophet Muhammad. It was founded by a dynasty descended from Muhammad's uncle, Abbas ibn Abdul-Muttalib ...

. In 763 Caliph Al-Mansur

Abū Jaʿfar ʿAbd Allāh ibn Muḥammad al-Manṣūr (; ar, أبو جعفر عبد الله بن محمد المنصور; 95 AH – 158 AH/714 CE – 6 October 775 CE) usually known simply as by his laqab Al-Manṣūr (المنصور) w ...

of the Abbasids installed al-Ala ibn-Mugith as governor of Africa (whose title gave him dominion over the province of al-Andalus). He planned to invade and destroy the Emirate of Córdoba, so in response Abd al Rahman fortified himself within the fortress of Carmona

Carmona may refer to:

Places Angola

* the former name of the town of Uíge

Costa Rica

* Carmona District, Nandayure, a district in Guanacaste Province

India

* Carmona, Goa, a village located in the Salcette district of South Goa, India

...

with a tenth as many soldiers as al-Ala ibn-Mugith]. After a long siege, it appeared that Abd al Rahman would be defeated, but in a last stand Abd al Rahman with his outnumbered forces opened the gates of the fortress and charged at the resting Abbasid army, and decisively defeated them. After being sent the embalmed head of al-Ala ibn-Mugith], it is said Al Mansur exclaimed "Praise be to God who has put the sea between me and this devil!".Al-Hakam I

Abu al-As al-Hakam ibn Hisham ibn Abd al-Rahman () was Umayyad Emir of Cordoba from 796 until 822 in Al-Andalus ( Moorish Iberia).

Biography

Al-Hakam was the second son of his father, his older brother having died at an early age. When he came ...

. The next few decades were relatively uneventful, with only occasional minor rebellions, and saw the rise of the emirate. In 822 Al Hakam died and was succeeded by Abd al-Rahman II

Abd ar-Rahman II () (792–852) was the fourth ''Umayyad'' Emir of Córdoba in al-Andalus from 822 until his death. A vigorous and effective frontier warrior, he was also well known as a patron of the arts.

Abd ar-Rahman was born in Toledo, the ...

, the first great emir of Córdoba. He rose to power with no opposition and sought to reform the emirate. He quickly reorganized the bureaucracy to be more efficient and built many mosques across the emirate. During his reign science and art flourished, as many scholars fled the Abbasid caliphate due to the disastrous Fourth Fitna

The Fourth Fitna or Great Abbasid Civil War resulted from the conflict between the brothers al-Amin and al-Ma'mun over the succession to the throne of the Abbasid Caliphate. Their father, Caliph Harun al-Rashid, had named al-Amin as the first suc ...

. The scholar Abbas ibn Firnas

Abu al-Qasim Abbas ibn Firnas ibn Wirdas al-Takurini ( ar, أبو القاسم عباس بن فرناس بن ورداس التاكرني; c. 809/810 – 887 A.D.), also known as Abbas ibn Firnas ( ar, عباس ابن فرناس), Latinized Armen ...

made an attempt to flee, though accounts vary on his success. In 852 Abd al Rahman II died, leaving behind him a powerful and well-established state that had become one of the most powerful in the Mediterranean.Muhammad I of Córdoba

Muhammad I (822–886) () was the ''Umayyad'' emir of Córdoba from 852 to 886 in the Al-Andalus (Moorish Iberia).

Biography

Muhammad was born in Córdoba. His reign was marked by several revolts and separatist movements of the Muwallad (Musl ...

, who according to legend had to wear women's clothing to sneak into the imperial palace and be crowned, since he was not the heir apparent. His reign marked a decline in the emirate, which was ended by Abd al-Rahman III

ʿAbd al-Rahmān ibn Muḥammad ibn ʿAbd Allāh ibn Muḥammad ibn ʿAbd al-Raḥmān ibn al-Ḥakam al-Rabdī ibn Hishām ibn ʿAbd al-Raḥmān al-Dākhil () or ʿAbd al-Rahmān III (890 - 961), was the Umayyad Emir of Córdoba from 912 to 92 ...

. His reign was marked by multiple rebellions, which were dealt with poorly and weakened the emirate, most disastrously following the rebellion of Umar ibn Hafsun

Umar ibn Hafsun ibn Ja'far ibn Salim ( ar, عمر بن حَفْصُون بن جَعْفَ بن سالم) (c. 850 – 917), known in Spanish history as Omar ben Hafsun, was a 9th-century political and military leader ...

. When Muhammad died, he was succeeded by emir Abdullah ibn Muhammad al-Umawi

Abdullah may refer to:

* Abdullah (name), a list of people with the given name or surname

* Abdullah, Kargı, Turkey, a village

* ''Abdullah'' (film), a 1980 Bollywood film directed by Sanjay Khan

* '' Abdullah: The Final Witness'', a 2015 Pakis ...

whose power barely reached outside of the city of Córdoba. As Ibn Hafsun ravaged the south, Abdullah did almost nothing, and slowly became more and more isolated, barely speaking to anyone. Abdullah purged his administration of his brothers, which lessened the bureaucracy's loyalty towards him. Around this time several local Arab lords began to revolt, including one Kurayb ibn Khaldun, who was able to conquer Seville. Some loyalists tried to quell the rebellion, but without proper material support, their efforts were in vain.

He declared that the next emir would be his grandson Abd al-Rahman III

ʿAbd al-Rahmān ibn Muḥammad ibn ʿAbd Allāh ibn Muḥammad ibn ʿAbd al-Raḥmān ibn al-Ḥakam al-Rabdī ibn Hishām ibn ʿAbd al-Raḥmān al-Dākhil () or ʿAbd al-Rahmān III (890 - 961), was the Umayyad Emir of Córdoba from 912 to 92 ...

, ignoring the claims of his four living children. Abdullah died in 912, and the throne passed to Abd al Rahman III. Through force of arms and diplomacy, he put down the rebellions that had disrupted his father's reign, obliterating Ibn Hafsun and hunting down his sons. After this he led several sieges against the Christians, sacking the city of Pamplona

Pamplona (; eu, Iruña or ), historically also known as Pampeluna in English, is the capital city of the Chartered Community of Navarre, in Spain. It is also the third-largest city in the greater Basque cultural region.

Lying at near above ...

, and restoring some prestige to the emirate. Meanwhile, across the sea the Fatimids

The Fatimid Caliphate was an Isma'ilism, Ismaili Shia Islam, Shi'a caliphate extant from the tenth to the twelfth centuries AD. Spanning a large area of North Africa, it ranged from the Atlantic Ocean in the west to the Red Sea in the ea ...

had risen up in force, ousted the Abbasid government in North Africa, and declared themselves a caliphate. Inspired by this action, Abd al Rahman joined the rebellion and declared himself caliph in 929.

Umayyad Caliphate of Córdoba

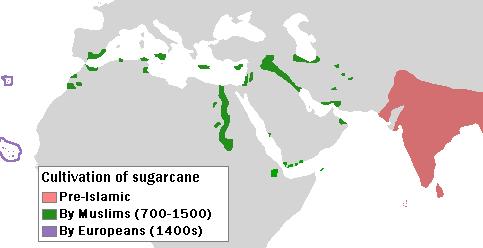

The period of the Caliphate is seen as the

The period of the Caliphate is seen as the golden age

The term Golden Age comes from Greek mythology, particularly the ''Works and Days'' of Hesiod, and is part of the description of temporal decline of the state of peoples through five Ages of Man, Ages, Gold being the first and the one during ...

of al-Andalus. Crops produced using irrigation, along with food imported from the Middle East, provided the area around Córdoba and some other ''Andalusī'' cities with an agricultural economic sector that was the most advanced in Europe by far, sparking the Arab Agricultural Revolution

The Arab Agricultural Revolution was the transformation in agriculture from the 8th to the 13th century in the Islamic region of the Old World. The agronomic literature of the time, with major books by Ibn Bassal and Abū l-Khayr al-Ishbīlī, ...

.Constantinople

la, Constantinopolis ota, قسطنطينيه

, alternate_name = Byzantion (earlier Greek name), Nova Roma ("New Rome"), Miklagard/Miklagarth (Old Norse), Tsargrad ( Slavic), Qustantiniya (Arabic), Basileuousa ("Queen of Cities"), Megalopolis (" ...

as the largest and most prosperous city in Europe.[Chandler, Tertius. ''Four Thousand Years of Urban Growth: An Historical Census'' (1987), St. David's University Press]

etext.org

). . Within the Islamic world, Córdoba was one of the leading cultural centres. The work of its most important philosophers and scientists (notably Abulcasis

Abū al-Qāsim Khalaf ibn al-'Abbās al-Zahrāwī al-Ansari ( ar, أبو القاسم خلف بن العباس الزهراوي; 936–1013), popularly known as al-Zahrawi (), Latinised as Albucasis (from Arabic ''Abū al-Qāsim''), was ...

and Averroes

Ibn Rushd ( ar, ; full name in ; 14 April 112611 December 1198), often Latinized as Averroes ( ), was an

Andalusian polymath and jurist who wrote about many subjects, including philosophy, theology, medicine, astronomy, physics, psycholog ...

) had a major influence on the intellectual life of medieval Europe.

Muslims and non-Muslims often came from abroad to study at the famous libraries and universities of al-Andalus, mainly after the reconquest of Toledo in 1085 and the establishment of translation institutions such as the Toledo School of Translators

The Toledo School of Translators ( es, Escuela de Traductores de Toledo) is the group of scholars who worked together in the city of Toledo during the 12th and 13th centuries, to translate many of the Judeo-Islamic philosophies and scientific w ...

. The most noted of those was Michael Scot

Michael Scot (Latin: Michael Scotus; 1175 – ) was a Scottish mathematician and scholar in the Middle Ages. He was educated at Oxford and Paris, and worked in Bologna and Toledo, where he learned Arabic. His patron was Frederick II of the H ...

(c. 1175 to c. 1235), who took the works of Ibn Rushd

Ibn Rushd ( ar, ; full name in ; 14 April 112611 December 1198), often Latinized as Averroes ( ), was an

Andalusian polymath and jurist who wrote about many subjects, including philosophy, theology, medicine, astronomy, physics, psychology, ...

("Averroes") and Ibn Sina

Ibn Sina ( fa, ابن سینا; 980 – June 1037 CE), commonly known in the West as Avicenna (), was a Persian polymath who is regarded as one of the most significant physicians, astronomers, philosophers, and writers of the Islamic G ...

("Avicenna") to Italy. This transmission of ideas significantly affected the formation of the European Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) , from , with the same meanings. is a period in European history marking the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and covering the 15th and 16th centuries, characterized by an effort to revive and surpass ideas ...

.[Perry, Marvin; Myrna Chase, Margaret C. Jacob, James R. Jacob]

''Western Civilization: Ideas, Politics, and Society''

(2008), 903 pages, pp. 261–262.

The Caliphate of Cordoba also had extensive trade with other parts of the Mediterranean, including Christian parts. Trade goods included luxury items (silk, ceramics, gold), essential foodstuffs (grain, olive oil, wine), and containers (such as ceramics for storing perishables). In the tenth century, Amalfitans were already trading Ifriqiya

Ifriqiya ( '), also known as al-Maghrib al-Adna ( ar, المغرب الأدنى), was a medieval historical region comprising today's Tunisia and eastern Algeria, and Tripolitania (today's western Libya). It included all of what had previously ...

n and Byzantine

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantinopl ...

silks in Umayyad Cordoba.Fatimid Egypt

The Fatimid Caliphate was an Ismaili Shi'a caliphate extant from the tenth to the twelfth centuries AD. Spanning a large area of North Africa, it ranged from the Atlantic Ocean in the west to the Red Sea in the east. The Fatimids, a d ...

was also a supplier of luxury goods, including elephant tusks, and raw or carved crystals. The Fatimids were traditionally thought to be the only supplier of such goods but were also valuable connections to Ghana

Ghana (; tw, Gaana, ee, Gana), officially the Republic of Ghana, is a country in West Africa. It abuts the Gulf of Guinea and the Atlantic Ocean to the south, sharing borders with Ivory Coast in the west, Burkina Faso in the north, and To ...

. Control over these trade routes was a cause of conflict between Umayyads and Fatimids.

''Taifas'' period

The Caliphate of Córdoba effectively collapsed during a ruinous civil war between 1009 and 1013, although it was not finally abolished until 1031 when ''al-Andalus'' broke up into a number of mostly independent mini-states and principalities called ''

The Caliphate of Córdoba effectively collapsed during a ruinous civil war between 1009 and 1013, although it was not finally abolished until 1031 when ''al-Andalus'' broke up into a number of mostly independent mini-states and principalities called ''taifa

The ''taifas'' (singular ''taifa'', from ar, طائفة ''ṭā'ifa'', plural طوائف ''ṭawā'if'', a party, band or faction) were the independent Muslim principalities and kingdoms of the Iberian Peninsula (modern Portugal and Spain), re ...

s''. In 1013, invading Berbers sacked Córdoba, massacring its inhabitants, pillaging the city, and burning the palace complex to the ground. The largest of the taifas to emerge were Badajoz

Badajoz (; formerly written ''Badajos'' in English) is the capital of the Province of Badajoz in the autonomous community of Extremadura, Spain. It is situated close to the Portuguese border, on the left bank of the river Guadiana. The population ...

(''Batalyaws''), Toledo (''Ṭulayṭulah''), Zaragoza

Zaragoza, also known in English as Saragossa,''Encyclopædia Britannica'"Zaragoza (conventional Saragossa)" is the capital city of the Zaragoza Province and of the autonomous community of Aragon, Spain. It lies by the Ebro river and its tributari ...

(''Saraqusta''), and Granada

Granada (,, DIN 31635, DIN: ; grc, Ἐλιβύργη, Elibýrgē; la, Illiberis or . ) is the capital city of the province of Granada, in the autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community of Andalusia, Spain. Granada is located at the fo ...

(''Ġarnāṭah''). After 1031, the ''taifas'' were generally too weak to defend themselves against repeated raids and demands for tribute from the Christian states to the north and west, which were known to the Muslims as "the Galician nations", and which had spread from their initial strongholds in Galicia, Asturias

Asturias (, ; ast, Asturies ), officially the Principality of Asturias ( es, Principado de Asturias; ast, Principáu d'Asturies; Galician-Asturian: ''Principao d'Asturias''), is an autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community in nor ...

, Cantabria

Cantabria (, also , , Cantabrian: ) is an autonomous community in northern Spain with Santander as its capital city. It is called a ''comunidad histórica'', a historic community, in its current Statute of Autonomy. It is bordered on the east ...

, the Basque country, and the Carolingian

The Carolingian dynasty (; known variously as the Carlovingians, Carolingus, Carolings, Karolinger or Karlings) was a Frankish noble family named after Charlemagne, grandson of mayor Charles Martel and a descendant of the Arnulfing and Pippin ...

''Marca Hispanica

The Hispanic March or Spanish March ( es, Marca Hispánica, ca, Marca Hispànica, Aragonese and oc, Marca Hispanica, eu, Hispaniako Marka, french: Marche d'Espagne), was a military buffer zone beyond the former province of Septimania, esta ...

'' to become the Kingdoms of Navarre

Navarre (; es, Navarra ; eu, Nafarroa ), officially the Chartered Community of Navarre ( es, Comunidad Foral de Navarra, links=no ; eu, Nafarroako Foru Komunitatea, links=no ), is a foral autonomous community and province in northern Spain, ...

, León, Portugal

Portugal, officially the Portuguese Republic ( pt, República Portuguesa, links=yes ), is a country whose mainland is located on the Iberian Peninsula of Southwestern Europe, and whose territory also includes the Atlantic archipelagos of ...

, Castile and Aragon

Aragon ( , ; Spanish and an, Aragón ; ca, Aragó ) is an autonomous community in Spain, coextensive with the medieval Kingdom of Aragon. In northeastern Spain, the Aragonese autonomous community comprises three provinces (from north to sou ...

, and the County of Barcelona

The County of Barcelona ( la, Comitatus Barcinonensis, ca, Comtat de Barcelona) was originally a frontier region under the rule of the Carolingian dynasty. In the 10th century, the Counts of Barcelona became progressively independent, heredi ...

. Eventually raids turned into conquests, and in response the ''Taifa'' kings were forced to request help from the Almoravid

The Almoravid dynasty ( ar, المرابطون, translit=Al-Murābiṭūn, lit=those from the ribats) was an imperial Berber Muslim dynasty centered in the territory of present-day Morocco. It established an empire in the 11th century that s ...

s, Muslim Berber rulers of the Maghreb

The Maghreb (; ar, الْمَغْرِب, al-Maghrib, lit=the west), also known as the Arab Maghreb ( ar, المغرب العربي) and Northwest Africa, is the western part of North Africa and the Arab world. The region includes Algeria, ...

. Their desperate maneuver would eventually fall to their disadvantage, however, as the Almoravids they had summoned from the south went on to conquer and annex all the ''Taifa'' kingdoms.

During the eleventh century several centers of power existed among the taifas, and the political situation shifted rapidly. Before the rise of the Almoravids from the south or the Christians from the north, the Abbadid

The Abbadid dynasty or Abbadids ( ar, بنو عباد, Banū ʿAbbādi) was an Arab Muslim dynasty which arose in al-Andalus on the downfall of the Caliphate of Cordoba (756–1031). After the collapse, there were multiple small Muslim states ca ...

-ruled Taifa of Seville

The Taifa of Seville ( ''Ta'ifat-u Ishbiliyyah'') was an Arab kingdom which was ruled by the Abbadid dynasty. It was established in 1023 and lasted until 1091, in what is today southern Spain and Portugal. It gained independence from the Calipha ...

succeeded in conquering a dozen lesser kingdoms, becoming the most powerful and renowned of the taifas, such that it could have laid claim to be the true heir to the Caliphate of Cordoba. The taifas were vulnerable and divided but had immense wealth. During its prominence the Taifa of Seville produced technically complex lusterware

Lustreware or lusterware (respectively the spellings for British English and American English) is a type of pottery or porcelain with a metallic glaze that gives the effect of iridescence. It is produced by metallic oxides in an overglaze finish, ...

and exerted significant influence on ceramic production across al-Andalus.

Almoravids, Almohads, and Marinids

In 1086 the

In 1086 the Almoravid

The Almoravid dynasty ( ar, المرابطون, translit=Al-Murābiṭūn, lit=those from the ribats) was an imperial Berber Muslim dynasty centered in the territory of present-day Morocco. It established an empire in the 11th century that s ...

ruler of Morocco, Yusuf ibn Tashfin

Yusuf ibn Tashfin, also Tashafin, Teshufin, ( ar, يوسف بن تاشفين ناصر الدين بن تالاكاكين الصنهاجي , Yūsuf ibn Tāshfīn Naṣr al-Dīn ibn Tālākakīn al-Ṣanhājī ; reigned c. 1061 – 1106) was l ...

, was invited by the Muslim princes in Iberia to defend them against Alfonso VI

Alphons (Latinized ''Alphonsus'', ''Adelphonsus'', or ''Adefonsus'') is a male given name recorded from the 8th century (Alfonso I of Asturias, r. 739–757) in the Christian successor states of the Visigothic kingdom in the Iberian peninsula. ...

, King of Castile and León. In that year, Tashfin crossed the straits to Algeciras

Algeciras ( , ) is a municipality of Spain belonging to the province of Cádiz, Andalusia. Located in the southern end of the Iberian Peninsula, near the Strait of Gibraltar, it is the largest city on the Bay of Gibraltar ( es, Bahía de Algeci ...

and inflicted a severe defeat on the Christians at the Battle of Sagrajas

The Battle of Sagrajas (23 October 1086), also called Zalaca or Zallaqa ( ar, معركة الزلاقة, translit=Maʿrakat az-Zallāqa), was a battle between the Almoravid army led by their King Yusuf ibn Tashfin and an army led by the Ca ...

. By 1094, ibn Tashfin had removed all Muslim princes in Iberia and had annexed their states, except for the one at Zaragoza

Zaragoza, also known in English as Saragossa,''Encyclopædia Britannica'"Zaragoza (conventional Saragossa)" is the capital city of the Zaragoza Province and of the autonomous community of Aragon, Spain. It lies by the Ebro river and its tributari ...

. He also regained Valencia

Valencia ( va, València) is the capital of the Autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community of Valencian Community, Valencia and the Municipalities of Spain, third-most populated municipality in Spain, with 791,413 inhabitants. It is ...

from the Christians. The city-kingdom had been conquered and ruled by El Cid

Rodrigo Díaz de Vivar (c. 1043 – 10 July 1099) was a Castilian knight and warlord in medieval Spain. Fighting with both Christian and Muslim armies during his lifetime, he earned the Arabic honorific ''al-sīd'', which would evolve into El ...

at the end of its second taifa

The ''taifas'' (singular ''taifa'', from ar, طائفة ''ṭā'ifa'', plural طوائف ''ṭawā'if'', a party, band or faction) were the independent Muslim principalities and kingdoms of the Iberian Peninsula (modern Portugal and Spain), re ...

period. The Almoravid dynasty made its capital in Marrakesh

Marrakesh or Marrakech ( or ; ar, مراكش, murrākuš, ; ber, ⵎⵕⵕⴰⴽⵛ, translit=mṛṛakc}) is the fourth largest city in the Kingdom of Morocco. It is one of the four Imperial cities of Morocco and is the capital of the Marrakes ...

, from which it ruled its domains in al-Andalus.Ibn Khaldun

Ibn Khaldun (; ar, أبو زيد عبد الرحمن بن محمد بن خلدون الحضرمي, ; 27 May 1332 – 17 March 1406, 732-808 AH) was an Arab

The Historical Muhammad', Irving M. Zeitlin, (Polity Press, 2007), p. 21; "It is, of ...

's asabiyyah

'Asabiyyah or 'asabiyya ( ar, عصبيّة, 'group feeling' or 'social cohesion') is a concept of social solidarity with an emphasis on unity, group consciousness, and a sense of shared purpose and social cohesion, originally used in the context ...

paradigm.

The Almoravids were succeeded by the

The Almoravids were succeeded by the Almohad

The Almohad Caliphate (; ar, خِلَافَةُ ٱلْمُوَحِّدِينَ or or from ar, ٱلْمُوَحِّدُونَ, translit=al-Muwaḥḥidūn, lit=those who profess the Tawhid, unity of God) was a North African Berbers, Berber M ...

s, another Berber dynasty, after the victory of Abu Yusuf Ya'qub al-Mansur

Abū Yūsuf Yaʿqūb ibn Yūsuf ibn Abd al-Muʾmin al-Manṣūr (; c. 1160 – 23 January 1199 Marrakesh), commonly known as Yaqub al-Mansur () or Moulay Yacoub (), was the third Almohad Caliph. Succeeding his father, al-Mansur reigned from 118 ...

over the Castilian Alfonso VIII

Alfonso VIII (11 November 11555 October 1214), called the Noble (''El Noble'') or the one of Las Navas (''el de las Navas''), was King of Castile from 1158 to his death and King of Toledo. After having suffered a great defeat with his own army at ...

at the Battle of Alarcos

Battle of Alarcos (July 18, 1195), was a battle between the Almohads led by Abu Yusuf Ya'qub al-Mansur and King Alfonso VIII of Castile.''Medieval Iberia: an encyclopedia'', 42. It resulted in the defeat of the Castilian forces and their subs ...

in 1195. In 1212, a coalition of Christian kings under the leadership of the Castilian Alfonso VIII defeated the Almohads at the Battle of Las Navas de Tolosa

The Battle of Las Navas de Tolosa, known in Islamic history as the Battle of Al-Uqab ( ar, معركة العقاب), took place on 16 July 1212 and was an important turning point in the ''Reconquista'' and the medieval history of Spain. The Christ ...

. The Almohads continued to rule Al-Andalus for another decade, though with much reduced power and prestige. The civil wars following the death of Abu Ya'qub Yusuf II rapidly led to the re-establishment of taifas. The taifas, newly independent but now weakened, were quickly conquered by Portugal, Castile, and Aragon. After the fall of Murcia

Murcia (, , ) is a city in south-eastern Spain, the capital and most populous city of the autonomous community of the Region of Murcia, and the seventh largest city in the country. It has a population of 460,349 inhabitants in 2021 (about one ...

(1243) and the Algarve

The Algarve (, , ; from ) is the southernmost NUTS II region of continental Portugal. It has an area of with 467,495 permanent inhabitants and incorporates 16 municipalities ( ''concelhos'' or ''municípios'' in Portuguese).

The region has it ...

(1249), only the Emirate of Granada

The Emirate of Granada ( ar, إمارة غرﻧﺎﻃﺔ, Imārat Ġarnāṭah), also known as the Nasrid Kingdom of Granada ( es, Reino Nazarí de Granada), was an Emirate, Islamic realm in southern Iberia during the Late Middle Ages. It was the ...

remained as a Muslim state in Iberia, tributary of Castile until 1492. Most of its tribute was paid in gold that was carried to Iberia from present-day Mali

Mali (; ), officially the Republic of Mali,, , ff, 𞤈𞤫𞤲𞥆𞤣𞤢𞥄𞤲𞤣𞤭 𞤃𞤢𞥄𞤤𞤭, Renndaandi Maali, italics=no, ar, جمهورية مالي, Jumhūriyyāt Mālī is a landlocked country in West Africa. Mali ...

and Burkina Faso

Burkina Faso (, ; , ff, 𞤄𞤵𞤪𞤳𞤭𞤲𞤢 𞤊𞤢𞤧𞤮, italic=no) is a landlocked country in West Africa with an area of , bordered by Mali to the northwest, Niger to the northeast, Benin to the southeast, Togo and Ghana to the ...

through the merchant routes of the Sahara

, photo = Sahara real color.jpg

, photo_caption = The Sahara taken by Apollo 17 astronauts, 1972

, map =

, map_image =

, location =

, country =

, country1 =

, ...

.

The last Muslim threat to the Christian kingdoms was the rise of the Marinids

The Marinid Sultanate was a Berber Muslim empire from the mid-13th to the 15th century which controlled present-day Morocco and, intermittently, other parts of North Africa (Algeria and Tunisia) and of the southern Iberian Peninsula (Spain) ar ...

in Morocco during the 14th century. They took Granada into their sphere of influence and occupied some of its cities, like Algeciras

Algeciras ( , ) is a municipality of Spain belonging to the province of Cádiz, Andalusia. Located in the southern end of the Iberian Peninsula, near the Strait of Gibraltar, it is the largest city on the Bay of Gibraltar ( es, Bahía de Algeci ...

. However, they were unable to take Tarifa

Tarifa (, Arabic: طريفة) is a Spanish municipality in the province of Cádiz, Andalusia. Located at the southernmost end of the Iberian Peninsula, it is primarily known as one of the world's most popular destinations for windsports. Tarifa ...

, which held out until the arrival of the Castilian Army led by Alfonso XI

Alfonso XI (13 August 131126 March 1350), called the Avenger (''el Justiciero''), was King of Castile and León. He was the son of Ferdinand IV of Castile and his wife Constance of Portugal. Upon his father's death in 1312, several disputes en ...

. The Castilian king, with the help of Afonso IV of Portugal

Afonso IVEnglish: ''Alphonzo'' or ''Alphonse'', or ''Affonso'' (Archaic Portuguese), ''Alfonso'' or ''Alphonso'' (Portuguese-Galician) or ''Alphonsus'' (Latin). (; 8 February 129128 May 1357), called the Brave ( pt, o Bravo, links=no), was King ...

and Peter IV of Aragon

Peter IV, ; an, Pero, ; es, Pedro, . In Catalan, he may also be nicknamed ''el del punyalet'': "he of the little dagger". (Catalan: ''Pere IV''; 5 September 1319 – 6 January 1387), called the Ceremonious (Catalan: ''el Cerimoniós''), w ...

, decisively defeated the Marinids at the Battle of Río Salado

The Battle of Río Salado also known as the Battle of Tarifa (30 October 1340) was a battle of the armies of King Afonso IV of Portugal and King Alfonso XI of Castile against those of Sultan Abu al-Hasan 'Ali of the Marinid dynasty and Yusuf I ...

in 1340 and took Algeciras in 1344. Gibraltar

)

, anthem = " God Save the King"

, song = " Gibraltar Anthem"

, image_map = Gibraltar location in Europe.svg

, map_alt = Location of Gibraltar in Europe

, map_caption = United Kingdom shown in pale green

, mapsize =

, image_map2 = Gib ...

, then under Granadian rule, was besieged in 1349–50. Alfonso XI and most of his army perished by the Black Death

The Black Death (also known as the Pestilence, the Great Mortality or the Plague) was a bubonic plague pandemic occurring in Western Eurasia and North Africa from 1346 to 1353. It is the most fatal pandemic recorded in human history, causi ...

. His successor, Peter of Castile

Peter ( es, Pedro; 30 August 133423 March 1369), called the Cruel () or the Just (), was King of Castile and León from 1350 to 1369. Peter was the last ruler of the main branch of the House of Ivrea. He was excommunicated by Pope Urban V for ...

, made peace with the Muslims and turned his attention to Christian lands, starting a period of almost 150 years of rebellions and wars between the Christian states that secured the survival of Granada.

Emirate of Granada, its fall, and aftermath

From the mid 13th to the late 15th century, the only remaining domain of al-Andalus was the Emirate of Granada, the last Muslim stronghold in the Iberian Peninsula. The emirate was established by Muhammad ibn al-Ahmar in 1230 and was ruled by the

From the mid 13th to the late 15th century, the only remaining domain of al-Andalus was the Emirate of Granada, the last Muslim stronghold in the Iberian Peninsula. The emirate was established by Muhammad ibn al-Ahmar in 1230 and was ruled by the Nasrid dynasty

The Nasrid dynasty ( ar, بنو نصر ''banū Naṣr'' or ''banū al-Aḥmar''; Spanish: ''Nazarí'') was the last Muslim dynasty in the Iberian Peninsula, ruling the Emirate of Granada from 1230 until 1492. Its members claimed to be of Arab ...

, the longest reigning dynasty in the history of al-Andalus. Although surrounded by Castilian lands, the emirate was wealthy through being tightly integrated in Mediterranean trade networks and enjoyed a period of considerable cultural and economic prosperity.Sierra Nevada

The Sierra Nevada () is a mountain range in the Western United States, between the Central Valley of California and the Great Basin. The vast majority of the range lies in the state of California, although the Carson Range spur lies primarily ...

as a natural barrier, helped to prolong Nasrid rule and allowed the emirate to prosper as a regional entrepôt

An ''entrepôt'' (; ) or transshipment port is a port, city, or trading post where merchandise may be imported, stored, or traded, usually to be exported again. Such cities often sprang up and such ports and trading posts often developed into co ...

with the Maghreb

The Maghreb (; ar, الْمَغْرِب, al-Maghrib, lit=the west), also known as the Arab Maghreb ( ar, المغرب العربي) and Northwest Africa, is the western part of North Africa and the Arab world. The region includes Algeria, ...

and the rest of Africa. The city of Granada also served as a refuge for Muslims fleeing during the Reconquista

The ' (Spanish, Portuguese and Galician for "reconquest") is a historiographical construction describing the 781-year period in the history of the Iberian Peninsula between the Umayyad conquest of Hispania in 711 and the fall of the Nasrid ...

, accepting numerous Muslims expelled from Christian controlled areas, doubling the size of the city and even becoming one of the largest in Europe throughout the 15th century in terms of population. In 1469, the marriage of Ferdinand of Aragon and

In 1469, the marriage of Ferdinand of Aragon and Isabella of Castile

Isabella I ( es, Isabel I; 22 April 1451 – 26 November 1504), also called Isabella the Catholic (Spanish: ''la Católica''), was Queen of Castile from 1474 until her death in 1504, as well as Queen consort of Aragon from 1479 until 1504 by ...

signaled the launch of the final assault on the emirate. The King and Queen convinced Pope Sixtus IV

Pope Sixtus IV ( it, Sisto IV: 21 July 1414 – 12 August 1484), born Francesco della Rovere, was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 9 August 1471 to his death in August 1484. His accomplishments as pope include ...

to declare their war a crusade. The Catholic Monarchs

The Catholic Monarchs were Queen Isabella I of Castile and King Ferdinand II of Aragon, whose marriage and joint rule marked the ''de facto'' unification of Spain. They were both from the House of Trastámara and were second cousins, being bot ...

crushed one center of resistance after another until finally on January 2, 1492, after a long siege, the emirate's last sultan Muhammad XII

Abu Abdallah Muhammad XII ( ar, أبو عبد الله محمد الثاني عشر, Abū ʿAbdi-llāh Muḥammad ath-thānī ʿashar) (c. 1460–1533), known in Europe as Boabdil (a Spanish rendering of the name ''Abu Abdallah''), was the ...

surrendered the city and the fortress palace, the renowned Alhambra

The Alhambra (, ; ar, الْحَمْرَاء, Al-Ḥamrāʾ, , ) is a palace and fortress complex located in Granada, Andalusia, Spain. It is one of the most famous monuments of Islamic architecture and one of the best-preserved palaces of the ...

(see Fall of Granada

The Granada War ( es, Guerra de Granada) was a series of military campaigns between 1482 and 1491 during the reign of the Catholic Monarchs, Isabella I of Castile and Ferdinand II of Aragon, against the Nasrid dynasty's Emirate of Granada. It e ...

).

By this time Muslims in Castile numbered half a million. After the fall, "100,000 had died or been enslaved, 200,000 emigrated, and 200,000 remained as the residual population. Many of the Muslim elite, including Muhammad XII

Abu Abdallah Muhammad XII ( ar, أبو عبد الله محمد الثاني عشر, Abū ʿAbdi-llāh Muḥammad ath-thānī ʿashar) (c. 1460–1533), known in Europe as Boabdil (a Spanish rendering of the name ''Abu Abdallah''), was the ...

, who had been given the area of the Alpujarras

The Alpujarra (, Arabic: ''al-bussarat'') is a natural and historical region in Andalusia, Spain, on the south slopes of the Sierra Nevada and the adjacent valley. The average elevation is above sea level. It extends over two provinces, ...

mountains as a principality, found life under Christian rule intolerable and passed over into North Africa." Under the conditions of the Capitulations of 1492, the Muslims in Granada were to be allowed to continue to practice their religion.

Mass

Mass forced conversions

Forced conversion is the adoption of a different religion or the adoption of irreligion under duress. Someone who has been forced to convert to a different religion or irreligion may continue, covertly, to adhere to the beliefs and practices which ...

of Muslims in 1499 led to a revolt

Rebellion, uprising, or insurrection is a refusal of obedience or order. It refers to the open resistance against the orders of an established authority.

A rebellion originates from a sentiment of indignation and disapproval of a situation and ...

that spread to Alpujarras and the mountains of Ronda

Ronda () is a town in the Spanish province of Málaga. It is located about west of the city of Málaga, within the autonomous community of Andalusia. Its population is about 35,000. Ronda is known for its cliff-side location and a deep chasm ...

; after this uprising the capitulations were revoked.Aragon