rhetoric on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Rhetoric is the art of persuasion. It is one of the three ancient arts of discourse ( trivium) along with

Scholars have debated the scope of rhetoric since ancient times. Although some have limited rhetoric to the specific realm of political discourse, to many modern scholars it encompasses every aspect of culture. Contemporary studies of rhetoric address a much more diverse range of domains than was the case in ancient times. While classical rhetoric trained speakers to be effective persuaders in public forums and in institutions such as courtrooms and assemblies, contemporary rhetoric investigates human discourse writ large. Rhetoricians have studied the discourses of a wide variety of domains, including the natural and social sciences, fine art, religion, journalism, digital media, fiction, history, cartography, and architecture, along with the more traditional domains of politics and the law.

Because the ancient Greeks valued public political participation, rhetoric emerged as an important curriculum for those desiring to influence politics. Rhetoric is still associated with its political origins. However, even the original instructors of Western speech—the Sophists—disputed this limited view of rhetoric. According to Sophists like Gorgias, a successful rhetorician could speak convincingly on a topic in any field, regardless of his experience in that field. This suggested rhetoric could be a means of communicating any expertise, not just politics. In his '' Encomium to Helen'', Gorgias even applied rhetoric to fiction by seeking, for his amusement, to prove the blamelessness of the mythical

Scholars have debated the scope of rhetoric since ancient times. Although some have limited rhetoric to the specific realm of political discourse, to many modern scholars it encompasses every aspect of culture. Contemporary studies of rhetoric address a much more diverse range of domains than was the case in ancient times. While classical rhetoric trained speakers to be effective persuaders in public forums and in institutions such as courtrooms and assemblies, contemporary rhetoric investigates human discourse writ large. Rhetoricians have studied the discourses of a wide variety of domains, including the natural and social sciences, fine art, religion, journalism, digital media, fiction, history, cartography, and architecture, along with the more traditional domains of politics and the law.

Because the ancient Greeks valued public political participation, rhetoric emerged as an important curriculum for those desiring to influence politics. Rhetoric is still associated with its political origins. However, even the original instructors of Western speech—the Sophists—disputed this limited view of rhetoric. According to Sophists like Gorgias, a successful rhetorician could speak convincingly on a topic in any field, regardless of his experience in that field. This suggested rhetoric could be a means of communicating any expertise, not just politics. In his '' Encomium to Helen'', Gorgias even applied rhetoric to fiction by seeking, for his amusement, to prove the blamelessness of the mythical

Aristotle: Rhetoric is an antistrophes to dialectic. "Let rhetoric e defined asan ability ynamis in each articularcase, to see the available means of persuasion." "Rhetoric is a counterpart of dialectic" — an art of practical civic reasoning, applied to deliberative, judicial, and "display" speeches in political assemblies, lawcourts, and other public gatherings.

Aristotle: Rhetoric is an antistrophes to dialectic. "Let rhetoric e defined asan ability ynamis in each articularcase, to see the available means of persuasion." "Rhetoric is a counterpart of dialectic" — an art of practical civic reasoning, applied to deliberative, judicial, and "display" speeches in political assemblies, lawcourts, and other public gatherings.

For the Romans, oration became an important part of public life.

For the Romans, oration became an important part of public life.

One influential figure in the rebirth of interest in classical rhetoric was Erasmus (–1536). His 1512 work, ''De Duplici Copia Verborum et Rerum'' (also known as '' Copia: Foundations of the Abundant Style''), was widely published (it went through more than 150 editions throughout Europe) and became one of the basic school texts on the subject. Its treatment of rhetoric is less comprehensive than the classic works of antiquity, but provides a traditional treatment of (matter and form). Its first book treats the subject of , showing the student how to use schemes and tropes; the second book covers . Much of the emphasis is on abundance of variation ( means "plenty" or "abundance", as in copious or cornucopia), so both books focus on ways to introduce the maximum amount of variety into discourse. For instance, in one section of the ''De Copia'', Erasmus presents two hundred variations of the sentence "Always, as long as I live, I shall remember you" ("") Another of his works, the extremely popular '' The Praise of Folly'', also had considerable influence on the teaching of rhetoric in the later 16th century. Its orations in favour of qualities such as madness spawned a type of exercise popular in Elizabethan grammar schools, later called adoxography, which required pupils to compose passages in praise of useless things.

Juan Luis Vives (1492–1540) also helped shape the study of rhetoric in England. A Spaniard, he was appointed in 1523 to the Lectureship of Rhetoric at Oxford by Cardinal Wolsey, and was entrusted by Henry VIII to be one of the tutors of Mary. Vives fell into disfavor when Henry VIII divorced Catherine of Aragon and left England in 1528. His best-known work was a book on education, ', published in 1531, and his writings on rhetoric included ' (1533), ' (1533), and a treatise on letter writing, ' (1536).

It is likely that many well-known English writers were exposed to the works of Erasmus and Vives (as well as those of the Classical rhetoricians) in their schooling, which was conducted in Latin (not English), often included some study of Greek, and placed considerable emphasis on rhetoric.

The mid-16th century saw the rise of vernacular rhetorics—those written in English rather than in the Classical languages. Adoption of works in English was slow, however, due to the strong scholastic orientation toward Latin and Greek. Leonard Cox's ''The Art or Crafte of Rhetoryke'' (; second edition published in 1532) is the earliest text on rhetorics in English; it was, for the most part, a translation of the work of Philipp Melanchthon. Thomas Wilson's ' (1553) presents a traditional treatment of rhetoric, for instance, the standard five canons of rhetoric. Other notable works included Angel Day's ' (1586, 1592), George Puttenham's ' (1589), and Richard Rainholde's ' (1563).

During this same period, a movement began that would change the organization of the school curriculum in Protestant and especially Puritan circles and that led to rhetoric losing its central place. A French scholar, Petrus Ramus (1515–1572), dissatisfied with what he saw as the overly broad and redundant organization of the trivium, proposed a new curriculum. In his scheme of things, the five components of rhetoric no longer lived under the common heading of rhetoric. Instead, invention and disposition were determined to fall exclusively under the heading of dialectic, while style, delivery, and memory were all that remained for rhetoric. Ramus was martyred during the French Wars of Religion. His teachings, seen as inimical to Catholicism, were short-lived in France but found a fertile ground in the Netherlands, Germany, and England.

One of Ramus' French followers, Audomarus Talaeus (Omer Talon) published his rhetoric, ''Institutiones Oratoriae'', in 1544. This work emphasized style, and became so popular that it was mentioned in John Brinsley's (1612) ''; '' as being the "". Many other Ramist rhetorics followed in the next half-century, and by the 17th century, their approach became the primary method of teaching rhetoric in Protestant and especially Puritan circles. John Milton (1608–1674) wrote a textbook in logic or dialectic in Latin based on Ramus' work.

Ramism could not exert any influence on the established Catholic schools and universities, which remained loyal to Scholasticism, or on the new Catholic schools and universities founded by members of the

One influential figure in the rebirth of interest in classical rhetoric was Erasmus (–1536). His 1512 work, ''De Duplici Copia Verborum et Rerum'' (also known as '' Copia: Foundations of the Abundant Style''), was widely published (it went through more than 150 editions throughout Europe) and became one of the basic school texts on the subject. Its treatment of rhetoric is less comprehensive than the classic works of antiquity, but provides a traditional treatment of (matter and form). Its first book treats the subject of , showing the student how to use schemes and tropes; the second book covers . Much of the emphasis is on abundance of variation ( means "plenty" or "abundance", as in copious or cornucopia), so both books focus on ways to introduce the maximum amount of variety into discourse. For instance, in one section of the ''De Copia'', Erasmus presents two hundred variations of the sentence "Always, as long as I live, I shall remember you" ("") Another of his works, the extremely popular '' The Praise of Folly'', also had considerable influence on the teaching of rhetoric in the later 16th century. Its orations in favour of qualities such as madness spawned a type of exercise popular in Elizabethan grammar schools, later called adoxography, which required pupils to compose passages in praise of useless things.

Juan Luis Vives (1492–1540) also helped shape the study of rhetoric in England. A Spaniard, he was appointed in 1523 to the Lectureship of Rhetoric at Oxford by Cardinal Wolsey, and was entrusted by Henry VIII to be one of the tutors of Mary. Vives fell into disfavor when Henry VIII divorced Catherine of Aragon and left England in 1528. His best-known work was a book on education, ', published in 1531, and his writings on rhetoric included ' (1533), ' (1533), and a treatise on letter writing, ' (1536).

It is likely that many well-known English writers were exposed to the works of Erasmus and Vives (as well as those of the Classical rhetoricians) in their schooling, which was conducted in Latin (not English), often included some study of Greek, and placed considerable emphasis on rhetoric.

The mid-16th century saw the rise of vernacular rhetorics—those written in English rather than in the Classical languages. Adoption of works in English was slow, however, due to the strong scholastic orientation toward Latin and Greek. Leonard Cox's ''The Art or Crafte of Rhetoryke'' (; second edition published in 1532) is the earliest text on rhetorics in English; it was, for the most part, a translation of the work of Philipp Melanchthon. Thomas Wilson's ' (1553) presents a traditional treatment of rhetoric, for instance, the standard five canons of rhetoric. Other notable works included Angel Day's ' (1586, 1592), George Puttenham's ' (1589), and Richard Rainholde's ' (1563).

During this same period, a movement began that would change the organization of the school curriculum in Protestant and especially Puritan circles and that led to rhetoric losing its central place. A French scholar, Petrus Ramus (1515–1572), dissatisfied with what he saw as the overly broad and redundant organization of the trivium, proposed a new curriculum. In his scheme of things, the five components of rhetoric no longer lived under the common heading of rhetoric. Instead, invention and disposition were determined to fall exclusively under the heading of dialectic, while style, delivery, and memory were all that remained for rhetoric. Ramus was martyred during the French Wars of Religion. His teachings, seen as inimical to Catholicism, were short-lived in France but found a fertile ground in the Netherlands, Germany, and England.

One of Ramus' French followers, Audomarus Talaeus (Omer Talon) published his rhetoric, ''Institutiones Oratoriae'', in 1544. This work emphasized style, and became so popular that it was mentioned in John Brinsley's (1612) ''; '' as being the "". Many other Ramist rhetorics followed in the next half-century, and by the 17th century, their approach became the primary method of teaching rhetoric in Protestant and especially Puritan circles. John Milton (1608–1674) wrote a textbook in logic or dialectic in Latin based on Ramus' work.

Ramism could not exert any influence on the established Catholic schools and universities, which remained loyal to Scholasticism, or on the new Catholic schools and universities founded by members of the

Argumentation and Advocacy

' *

College Composition and Communication

' *

College English

' *

Enculturation

' *

Harlot

' *

Kairos

' *

Peitho

' *

Present Tense

' *

Relevant Rhetoric

' *

Rhetoric Review

' *

Rhetoric Society Quarterly (RSQ)

' *

XChanges

'

grammar

In linguistics, grammar is the set of rules for how a natural language is structured, as demonstrated by its speakers or writers. Grammar rules may concern the use of clauses, phrases, and words. The term may also refer to the study of such rul ...

and logic

Logic is the study of correct reasoning. It includes both formal and informal logic. Formal logic is the study of deductively valid inferences or logical truths. It examines how conclusions follow from premises based on the structure o ...

/ dialectic. As an academic discipline

An academic discipline or academic field is a subdivision of knowledge that is taught and researched at the college or university level. Disciplines are defined (in part) and recognized by the academic journals in which research is published, a ...

within the humanities

Humanities are academic disciplines that study aspects of human society and culture, including Philosophy, certain fundamental questions asked by humans. During the Renaissance, the term "humanities" referred to the study of classical literature a ...

, rhetoric aims to study the techniques that speakers or writers use to inform, persuade, and motivate their audience

An audience is a group of people who participate in a show or encounter a work of art, literature (in which they are called "readers"), theatre, music (in which they are called "listeners"), video games (in which they are called "players"), or ...

s. Rhetoric also provides heuristics for understanding, discovering, and developing argument

An argument is a series of sentences, statements, or propositions some of which are called premises and one is the conclusion. The purpose of an argument is to give reasons for one's conclusion via justification, explanation, and/or persu ...

s for particular situations.

Aristotle

Aristotle (; 384–322 BC) was an Ancient Greek philosophy, Ancient Greek philosopher and polymath. His writings cover a broad range of subjects spanning the natural sciences, philosophy, linguistics, economics, politics, psychology, a ...

defined rhetoric as "the faculty of observing in any given case the available means of persuasion", and since mastery of the art was necessary for victory in a case at law, for passage of proposals in the assembly, or for fame as a speaker in civic ceremonies, he called it "a combination of the science of logic and of the ethical branch of politics". Aristotle also identified three persuasive audience appeals: logos, pathos, and ethos. The five canons of rhetoric

Rhetoric is the art of persuasion. It is one of the three ancient arts of discourse ( trivium) along with grammar and logic/ dialectic. As an academic discipline within the humanities, rhetoric aims to study the techniques that speakers or w ...

, or phases of developing a persuasive speech, were first codified in classical Rome: invention, arrangement, style, memory

Memory is the faculty of the mind by which data or information is encoded, stored, and retrieved when needed. It is the retention of information over time for the purpose of influencing future action. If past events could not be remembe ...

, and delivery.

From Ancient Greece

Ancient Greece () was a northeastern Mediterranean civilization, existing from the Greek Dark Ages of the 12th–9th centuries BC to the end of classical antiquity (), that comprised a loose collection of culturally and linguistically r ...

to the late 19th century, rhetoric played a central role in Western education and Islamic education in training orators, lawyer

A lawyer is a person who is qualified to offer advice about the law, draft legal documents, or represent individuals in legal matters.

The exact nature of a lawyer's work varies depending on the legal jurisdiction and the legal system, as w ...

s, counsellors, historian

A historian is a person who studies and writes about the past and is regarded as an authority on it. Historians are concerned with the continuous, methodical narrative and research of past events as relating to the human species; as well as the ...

s, statesmen, and poet

A poet is a person who studies and creates poetry. Poets may describe themselves as such or be described as such by others. A poet may simply be the creator (thought, thinker, songwriter, writer, or author) who creates (composes) poems (oral t ...

s.

Uses

Scope

Scholars have debated the scope of rhetoric since ancient times. Although some have limited rhetoric to the specific realm of political discourse, to many modern scholars it encompasses every aspect of culture. Contemporary studies of rhetoric address a much more diverse range of domains than was the case in ancient times. While classical rhetoric trained speakers to be effective persuaders in public forums and in institutions such as courtrooms and assemblies, contemporary rhetoric investigates human discourse writ large. Rhetoricians have studied the discourses of a wide variety of domains, including the natural and social sciences, fine art, religion, journalism, digital media, fiction, history, cartography, and architecture, along with the more traditional domains of politics and the law.

Because the ancient Greeks valued public political participation, rhetoric emerged as an important curriculum for those desiring to influence politics. Rhetoric is still associated with its political origins. However, even the original instructors of Western speech—the Sophists—disputed this limited view of rhetoric. According to Sophists like Gorgias, a successful rhetorician could speak convincingly on a topic in any field, regardless of his experience in that field. This suggested rhetoric could be a means of communicating any expertise, not just politics. In his '' Encomium to Helen'', Gorgias even applied rhetoric to fiction by seeking, for his amusement, to prove the blamelessness of the mythical

Scholars have debated the scope of rhetoric since ancient times. Although some have limited rhetoric to the specific realm of political discourse, to many modern scholars it encompasses every aspect of culture. Contemporary studies of rhetoric address a much more diverse range of domains than was the case in ancient times. While classical rhetoric trained speakers to be effective persuaders in public forums and in institutions such as courtrooms and assemblies, contemporary rhetoric investigates human discourse writ large. Rhetoricians have studied the discourses of a wide variety of domains, including the natural and social sciences, fine art, religion, journalism, digital media, fiction, history, cartography, and architecture, along with the more traditional domains of politics and the law.

Because the ancient Greeks valued public political participation, rhetoric emerged as an important curriculum for those desiring to influence politics. Rhetoric is still associated with its political origins. However, even the original instructors of Western speech—the Sophists—disputed this limited view of rhetoric. According to Sophists like Gorgias, a successful rhetorician could speak convincingly on a topic in any field, regardless of his experience in that field. This suggested rhetoric could be a means of communicating any expertise, not just politics. In his '' Encomium to Helen'', Gorgias even applied rhetoric to fiction by seeking, for his amusement, to prove the blamelessness of the mythical Helen of Troy

Helen (), also known as Helen of Troy, or Helen of Sparta, and in Latin as Helena, was a figure in Greek mythology said to have been the most beautiful woman in the world. She was believed to have been the daughter of Zeus and Leda (mythology), ...

in starting the Trojan War.

Plato

Plato ( ; Greek language, Greek: , ; born BC, died 348/347 BC) was an ancient Greek philosopher of the Classical Greece, Classical period who is considered a foundational thinker in Western philosophy and an innovator of the writte ...

defined the scope of rhetoric by discarding any connotation of religious ritual or magical incantation, simply taking the term in its literal sense, which means "leading the soul" through words. He criticized the Sophists for using rhetoric to deceive rather than to discover truth. In '' Gorgias'', one of his Socratic Dialogues, Plato defines rhetoric as the persuasion of ignorant masses within the courts and assemblies. Rhetoric, in Plato's opinion, is merely a form of flattery and functions similarly to culinary arts, which mask the undesirability of unhealthy food by making it taste good. Plato considered any speech of lengthy prose

Prose is language that follows the natural flow or rhythm of speech, ordinary grammatical structures, or, in writing, typical conventions and formatting. Thus, prose ranges from informal speaking to formal academic writing. Prose differs most n ...

aimed at flattery as within the scope of rhetoric. Some scholars, however, contest the idea that Plato despised rhetoric and instead view his dialogues as a dramatization of complex rhetorical principles. Socrates explained the relationship between rhetoric in flattery when he maintained that a rhetorician who teaches anyone how to persuade people in an assembly to do what he wants, without knowledge of what is just or unjust, engages in a kind of flattery (''kolakeia'') that constitutes an image (''eidolon'') of a part of the art of politics.

Aristotle both redeemed rhetoric from Plato and narrowed its focus by defining three genres of rhetoric— deliberative, forensic or judicial, and epideictic. Yet, even as he provided order to existing rhetorical theories, Aristotle generalized the definition of rhetoric to be the ability to identify the appropriate means of persuasion in a given situation based upon the art of rhetoric (''technê''). This made rhetoric applicable to all fields, not just politics. Aristotle viewed the enthymeme based upon logic

Logic is the study of correct reasoning. It includes both formal and informal logic. Formal logic is the study of deductively valid inferences or logical truths. It examines how conclusions follow from premises based on the structure o ...

(especially, based upon the syllogism) as the basis of rhetoric.

Aristotle also outlined generic constraints that focused the rhetorical art squarely within the domain of public political practice. He restricted rhetoric to the domain of the contingent or probable: those matters that admit multiple legitimate opinions or arguments.

Since the time of Aristotle, logic has changed. For example, modal logic has undergone a major development that also modifies rhetoric.

The contemporary neo-Aristotelian and neo-Sophistic positions on rhetoric mirror the division between the Sophists and Aristotle. Neo-Aristotelians generally study rhetoric as political discourse, while the neo-Sophistic view contends that rhetoric cannot be so limited. Rhetorical scholar Michael Leff characterizes the conflict between these positions as viewing rhetoric as a "thing contained" versus a "container". The neo-Aristotelian view threatens the study of rhetoric by restraining it to such a limited field, ignoring many critical applications of rhetorical theory, criticism, and practice. Simultaneously, the neo-Sophists threaten to expand rhetoric beyond a point of coherent theoretical value.

In more recent years, people studying rhetoric have tended to enlarge its object domain beyond speech. Kenneth Burke asserted humans use rhetoric to resolve conflicts by identifying shared characteristics and interests in symbols. People engage in identification, either to assign themselves or another to a group. This definition of rhetoric as identification broadens the scope from strategic and overt political persuasion to the more implicit tactics of identification found in an immense range of sources. Burke focused on the interplay of identification and division, maintaining that identification compensates for an original division by preventing a strict separation between objects, people, and spaces. This is achieved by assigning to them common properties through linguistic symbols.

Among the many scholars who have since pursued Burke's line of thought, James Boyd White sees rhetoric as a broader domain of social experience in his notion of constitutive rhetoric

Constitutive rhetoric is a theory of discourse devised by James Boyd White about the capacity of language or symbols to create a collective identity for an audience, especially by means of condensation symbols, literature, and narratives. Suc ...

. Influenced by theories of social construction, White argues that culture is "reconstituted" through language. Just as language influences people, people influence language. Language is socially constructed, and depends on the meanings people attach to it. Because language is not rigid and changes depending on the situation, the very usage of language is rhetorical. An author, White would say, is always trying to construct a new world and persuading his or her readers to share that world within the text.

People engage in rhetoric any time they speak or produce meaning. Even in the field of science

Science is a systematic discipline that builds and organises knowledge in the form of testable hypotheses and predictions about the universe. Modern science is typically divided into twoor threemajor branches: the natural sciences, which stu ...

, via practices which were once viewed as being merely the objective testing and reporting of knowledge, scientists persuade their audience to accept their findings by sufficiently demonstrating that their study or experiment was conducted reliably and resulted in sufficient evidence to support their conclusions.

The vast scope of rhetoric is difficult to define. Political discourse remains the paradigmatic example for studying and theorizing specific techniques and conceptions of persuasion or rhetoric.

As a civic art

Throughout European History, rhetoric meant persuasion in public and political settings such as assemblies and courts. Because of its associations with democratic institutions, rhetoric is commonly said to flourish in open and democratic societies with rights of free speech, free assembly, and political enfranchisement for some portion of the population. Those who classify rhetoric as a civic art believe that rhetoric has the power to shape communities, form the character of citizens, and greatly affect civic life. Rhetoric was viewed as a civic art by several of the ancient philosophers. Aristotle and Isocrates were two of the first to see rhetoric in this light. In '' Antidosis'', Isocrates states, "We have come together and founded cities and made laws and invented arts; and, generally speaking, there is no institution devised by man which the power of speech has not helped us to establish." With this statement he argues that rhetoric is a fundamental part of civic life in every society and that it has been necessary in the foundation of all aspects of society. He further argues in '' Against the Sophists'' that rhetoric, although it cannot be taught to just anyone, is capable of shaping the character of man. He writes, "I do think that the study of political discourse can help more than any other thing to stimulate and form such qualities of character." Aristotle, writing several years after Isocrates, supported many of his arguments and argued for rhetoric as a civic art. In the words of Aristotle, in the ''Rhetoric'', rhetoric is "...the faculty of observing in any given case the available means of persuasion". According to Aristotle, this art of persuasion could be used in public settings in three different ways: "A member of the assembly decides about future events, a juryman about past events: while those who merely decide on the orator's skill are observers. From this it follows that there are three divisions of oratory—(1) political, (2) forensic, and (3) the ceremonial oratory of display". Eugene Garver, in his critique of Aristotle's ''Rhetoric'', confirms that Aristotle viewed rhetoric as a civic art. Garver writes, "''Rhetoric'' articulates a civic art of rhetoric, combining the almost incompatible properties of and appropriateness to citizens." Each of Aristotle's divisions plays a role in civic life and can be used in a different way to affect the . Because rhetoric is a public art capable of shaping opinion, some of the ancients, includingPlato

Plato ( ; Greek language, Greek: , ; born BC, died 348/347 BC) was an ancient Greek philosopher of the Classical Greece, Classical period who is considered a foundational thinker in Western philosophy and an innovator of the writte ...

found fault in it. They claimed that while it could be used to improve civic life, it could be used just as easily to deceive or manipulate. The masses were incapable of analyzing or deciding anything on their own and would therefore be swayed by the most persuasive speeches. Thus, civic life could be controlled by whoever could deliver the best speech. Plato explores the problematic moral status of rhetoric twice: in ''Gorgias'' and in ''The Phaedrus'', a dialogue best-known for its commentary on love.

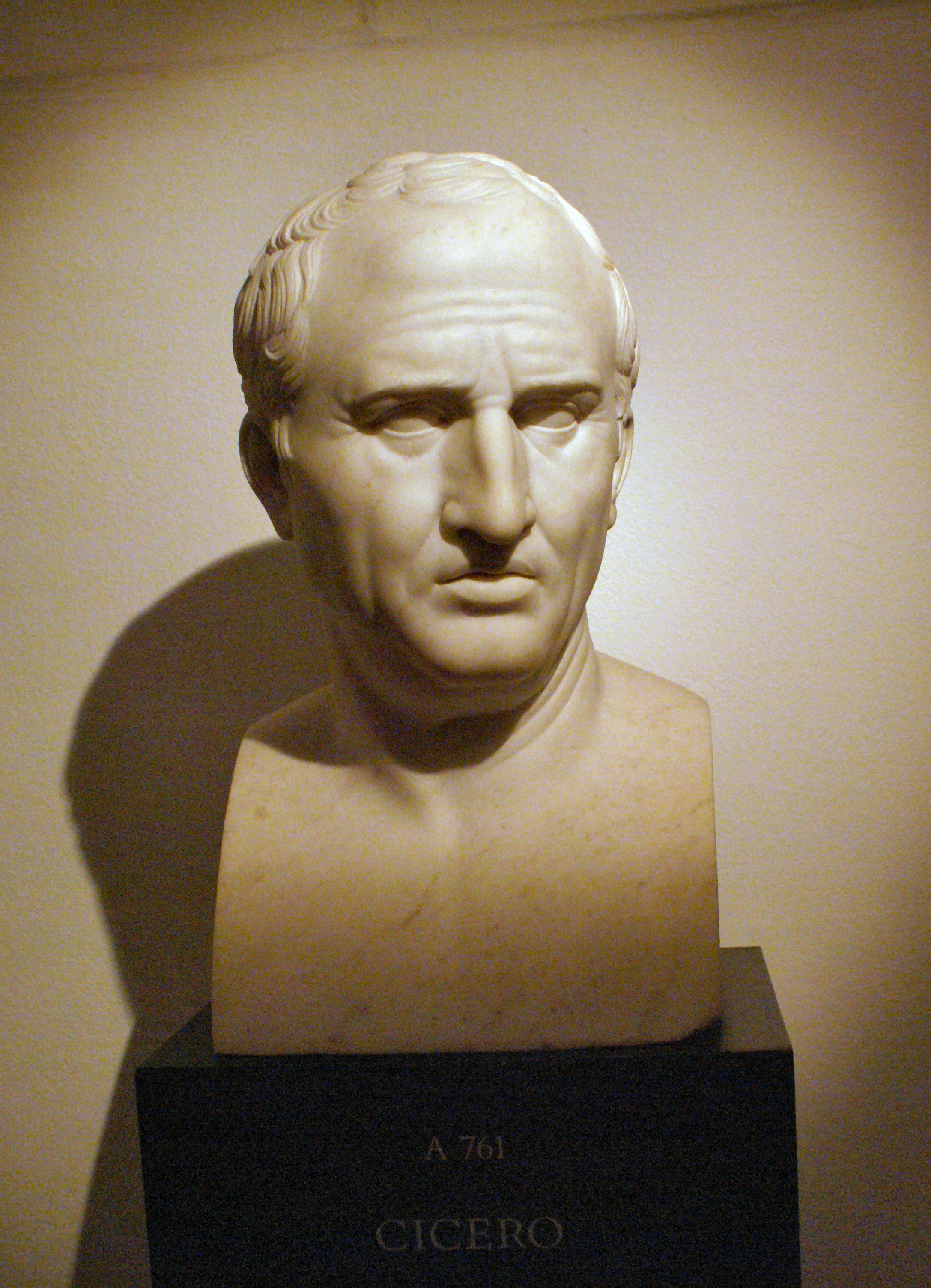

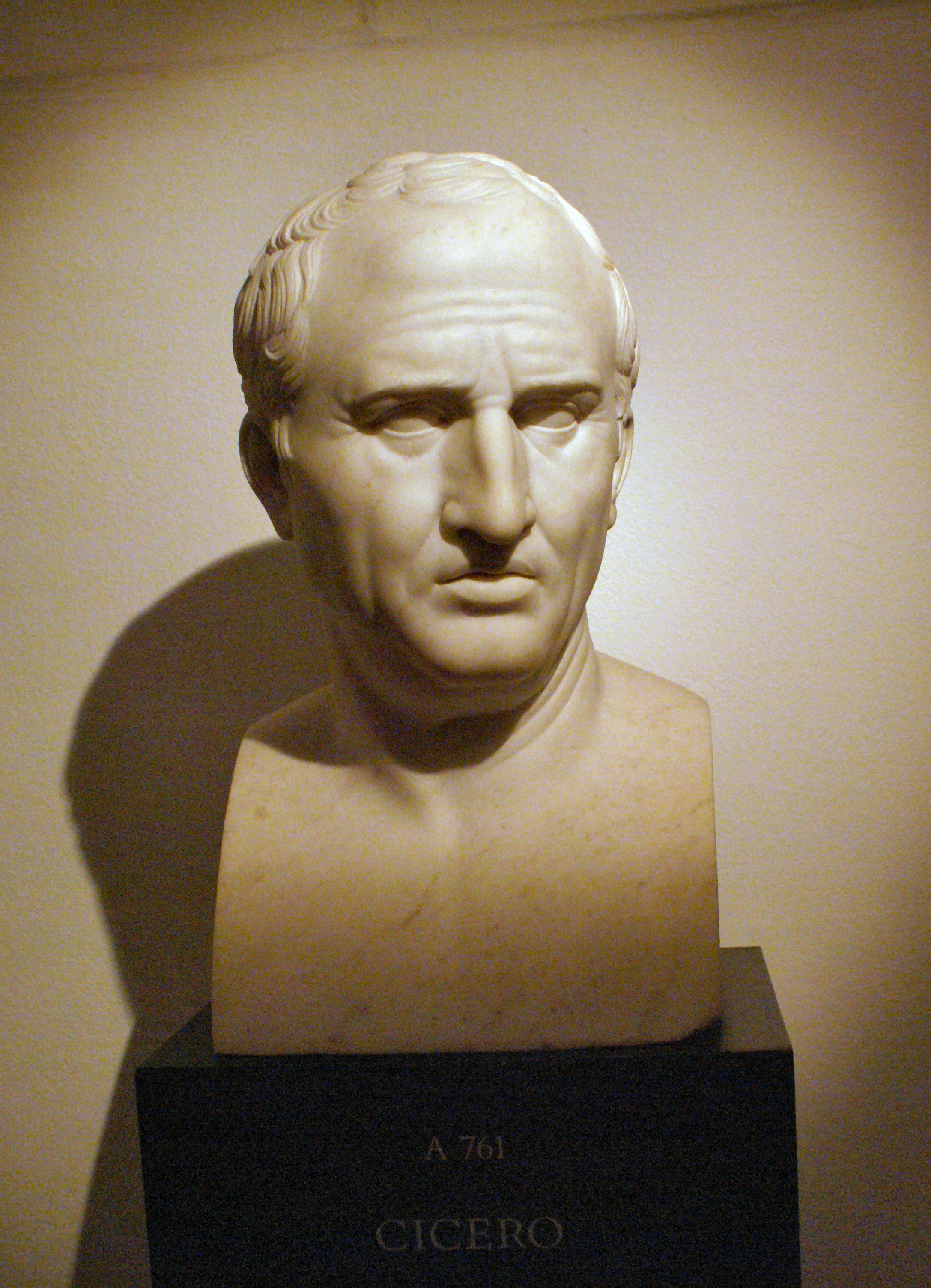

More trusting in the power of rhetoric to support a republic, the Roman orator Cicero

Marcus Tullius Cicero ( ; ; 3 January 106 BC – 7 December 43 BC) was a Roman statesman, lawyer, scholar, philosopher, orator, writer and Academic skeptic, who tried to uphold optimate principles during the political crises tha ...

argued that art required something more than eloquence. A good orator needed also to be a good person, enlightened on a variety of civic topics. In '' De Oratore'', modeled on Plato's dialogues, Cicero emphasized that effective rhetoric comes from a combination of wisdom (sapientia) and eloquence (eloquentia).Keith, William M. The Rhetorical Tradition: The Origins of Rhetoric, pp. 5–8. According to Cicero, the ideal orator must demonstrate not only stylistic skill but also moral integrity and broad learning, thus uniting theory and practice for the betterment of the state. Influenced by Aristotelian ideas, Cicero advanced the tradition by systematizing the five canons of rhetoric—inventio (invention), dispositio (arrangement), elocutio (style), memoria (memory), and pronuntiatio (delivery)—which he saw as key to crafting persuasive discourse.Crowley, Sharon, and Debra Hawhee. Ancient Rhetorics for Contemporary Students. In this view, a well-trained orator, who draws from philosophy, law, and other disciplines, is best able to address civic and ethical challenges, thus underscoring Cicero's vision of rhetoric as both an intellectual and ethical pursuit.

Modern works continue to support the claims of the ancients that rhetoric is an art capable of influencing civic life. In ''Political Style'', Robert Hariman claims that "questions of freedom, equality, and justice often are raised and addressed through performances ranging from debates to demonstrations without loss of moral content". James Boyd White argues that rhetoric is capable not only of addressing issues of political interest but that it can influence culture as a whole. In his book, ''When Words Lose Their Meaning'', he argues that words of persuasion and identification define community and civic life. He states that words produce "the methods by which culture is maintained, criticized, and transformed".

Rhetoric remains relevant as a civic art. In speeches, as well as in non-verbal forms, rhetoric continues to be used as a tool to influence communities from local to national levels.

As a political tool

Political parties employ "manipulative rhetoric" to advance their party-line goals and lobbyist agendas. They use it to portray themselves as champions of compassion, freedom, and culture, all while implementing policies that appear to contradict these claims. It serves as a form of political propaganda, presented to sway and maintain public opinion in their favor, and garner a positive image, potentially at the expense of suppressing dissent or criticism. An example of this is the government's actions in freezing bank accounts and regulating internet speech, ostensibly to protect the vulnerable and preserve freedom of expression, despite contradicting values and rights. Going back to the fifth century BCE, the term rhetoric originated in Ancient Greece. During this period, a new government (democracy) had been formed and as speech was the main method of information, an effective communication strategy was needed. Sophists, a group of intellectuals from Sicily, taught the ancient Greeks the art of persuasive speech in order to be able to navigate themselves in the court and senate. This new technique was then used as an effective method of speech in political speeches and throughout government. Consequently people began to fear that persuasive speech would overpower truth. However, Aristotle argued that speech can be used to classify, study, and interpret speeches and as a useful skill. Aristotle believed that this technique was an art, and that persuasive speech could have truth and logic embedded within it. In the end, rhetoric speech still remained popular and was used by many scholars and philosophers.Lundberg, C. O., & Keith, W. M. (2018). The essential guide to rhetoric. Bedford/St. Martin's. As a course of study

The study of rhetoric trains students to speak and/or write effectively, and to critically understand and analyze discourse. It is concerned with how people use symbols, especially language, to reach agreement that permits coordinated effort. Rhetoric as a course of study has evolved since its ancient beginnings, and has adapted to the particular exigencies of various times, venues, and applications ranging from architecture to literature. Although the curriculum has transformed in a number of ways, it has generally emphasized the study of principles and rules of composition as a means for moving audiences. Rhetoric began as a civic art in Ancient Greece where students were trained to develop tactics of oratorical persuasion, especially in legal disputes. Rhetoric originated in a school ofpre-Socratic

Pre-Socratic philosophy, also known as early Greek philosophy, is ancient Greek philosophy before Socrates. Pre-Socratic philosophers were mostly interested in cosmology, the beginning and the substance of the universe, but the inquiries of the ...

philosophers known as the Sophists . Demosthenes and Lysias emerged as major orators during this period, and Isocrates and Gorgias as prominent teachers. Modern teachings continue to reference these rhetoricians and their work in discussions of classical rhetoric and persuasion.

Rhetoric was taught in universities during the Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the 5th to the late 15th centuries, similarly to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire and ...

as one of the three original liberal arts or trivium (along with logic

Logic is the study of correct reasoning. It includes both formal and informal logic. Formal logic is the study of deductively valid inferences or logical truths. It examines how conclusions follow from premises based on the structure o ...

and grammar

In linguistics, grammar is the set of rules for how a natural language is structured, as demonstrated by its speakers or writers. Grammar rules may concern the use of clauses, phrases, and words. The term may also refer to the study of such rul ...

). During the medieval period, political rhetoric declined as republican oratory died out and the emperors of Rome garnered increasing authority. With the rise of European monarchs, rhetoric shifted into courtly and religious applications. Augustine exerted strong influence on Christian rhetoric in the Middle Ages, advocating the use of rhetoric to lead audiences to truth and understanding, especially in the church. The study of liberal arts, he believed, contributed to rhetorical study: "In the case of a keen and ardent nature, fine words will come more readily through reading and hearing the eloquent than by pursuing the rules of rhetoric." Poetry and letter writing became central to rhetorical study during the Middle Ages. After the fall of the Roman republic, poetry became a tool for rhetorical training since there were fewer opportunities for political speech. Letter writing was the primary way business was conducted both in state and church, so it became an important aspect of rhetorical education.

Rhetorical education became more restrained as style and substance separated in 16th-century France, and attention turned to the scientific method. Influential scholars like Peter Ramus argued that the processes of invention and arrangement should be elevated to the domain of philosophy, while rhetorical instruction should be chiefly concerned with the use of figures and other forms of the ornamentation of language. Scholars such as Francis Bacon

Francis Bacon, 1st Viscount St Alban (; 22 January 1561 – 9 April 1626) was an English philosopher and statesman who served as Attorney General and Lord Chancellor of England under King James I. Bacon argued for the importance of nat ...

developed the study of "scientific rhetoric" which rejected the elaborate style characteristic of classical oration. This plain language carried over to John Locke

John Locke (; 29 August 1632 (Old Style and New Style dates, O.S.) – 28 October 1704 (Old Style and New Style dates, O.S.)) was an English philosopher and physician, widely regarded as one of the most influential of the Enlightenment thi ...

's teaching, which emphasized concrete knowledge and steered away from ornamentation in speech, further alienating rhetorical instruction—which was identified wholly with such ornamentation—from the pursuit of knowledge.

In the 18th century, rhetoric assumed a more social role, leading to the creation of new education systems (predominantly in England): " Elocution schools" in which girls and women analyzed classic literature, most notably the works of William Shakespeare

William Shakespeare ( 23 April 1564 – 23 April 1616) was an English playwright, poet and actor. He is widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England's nation ...

, and discussed pronunciation tactics.

The study of rhetoric underwent a revival with the rise of democratic institutions during the late 18th and early 19th centuries. Hugh Blair was a key early leader of this movement. In his most famous work, ''Lectures on Rhetoric and Belles Lettres'', he advocates rhetorical study for common citizens as a resource for social success. Many American colleges and secondary schools used Blair's text throughout the 19th century to train students of rhetoric.

Political rhetoric also underwent renewal in the wake of the U.S. and French revolutions. The rhetorical studies of ancient Greece and Rome were resurrected as speakers and teachers looked to Cicero

Marcus Tullius Cicero ( ; ; 3 January 106 BC – 7 December 43 BC) was a Roman statesman, lawyer, scholar, philosopher, orator, writer and Academic skeptic, who tried to uphold optimate principles during the political crises tha ...

and others to inspire defenses of the new republics. Leading rhetorical theorists included John Quincy Adams of Harvard

Harvard University is a private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts, United States. Founded in 1636 and named for its first benefactor, the Puritan clergyman John Harvard, it is the oldest institution of higher lear ...

, who advocated the democratic advancement of rhetorical art. Harvard's founding of the Boylston Professorship of Rhetoric and Oratory sparked the growth of the study of rhetoric in colleges across the United States. Harvard's rhetoric program drew inspiration from literary sources to guide organization and style, and studies the rhetoric used in political communication to illustrate how political figures persuade audiences. William G. Allen became the first American college professor of rhetoric, at New-York Central College, 1850–1853.

Debate clubs and lyceums also developed as forums in which common citizens could hear speakers and sharpen debate skills. The American lyceum in particular was seen as both an educational and social institution, featuring group discussions and guest lecturers. These programs cultivated democratic values and promoted active participation in political analysis.

Throughout the 20th century, rhetoric developed as a concentrated field of study, with the establishment of rhetorical courses in high schools and universities. Courses such as public speaking

Public speaking, is the practice of delivering speeches to a live audience. Throughout history, public speaking has held significant cultural, religious, and political importance, emphasizing the necessity of effective rhetorical skills. It all ...

and speech analysis apply fundamental Greek theories (such as the modes of persuasion: , , and ) and trace rhetorical development through history. Rhetoric earned a more esteemed reputation as a field of study with the emergence of Communication Studies departments and of Rhetoric and Composition programs within English departments in universities, and in conjunction with the linguistic turn in Western philosophy

Western philosophy refers to the Philosophy, philosophical thought, traditions and works of the Western world. Historically, the term refers to the philosophical thinking of Western culture, beginning with the ancient Greek philosophy of the Pre ...

. Rhetorical study has broadened in scope, and is especially used by the fields of marketing, politics, and literature.

Another area of rhetoric is the study of cultural rhetorics, which is the communication that occurs between cultures and the study of the way members of a culture communicate with each other. These ideas can then be studied and understood by other cultures, in order to bridge gaps in modes of communication and help different cultures communicate effectively with each other. James Zappen defines cultural rhetorics as the idea that rhetoric is concerned with negotiation and listening, not persuasion, which differs from ancient definitions. Some ancient rhetoric was disparaged because its persuasive techniques could be used to teach falsehoods. Communication as studied in cultural rhetorics is focused on listening and negotiation, and has little to do with persuasion.

Canons

Rhetorical education focused on five canons. The serve as a guide to creating persuasive messages and arguments: ; '' inventio'' (invention) : the process that leads to the development and refinement of an argument. ; '' dispositio'' (disposition, or arrangement) : used to determine how an argument should be organized for greatest effect, usually beginning with the '' exordium'' ; '' elocutio'' (style) : determining how to present the arguments ; '' memoria'' (memory) : the process of learning and memorizing the speech and persuasive messages ; ''pronuntiatio

Pronuntiatio was the discipline of delivering speeches in Western classical rhetoric. It is one of the five canons of classical rhetoric (the others being inventio, dispositio, elocutio, and memoria) that concern the crafting and delivery of ...

'' (presentation) and '' actio'' (delivery) : the gestures, pronunciation, tone, and pace used when presenting the persuasive arguments—the Grand Style.

Memory

Memory is the faculty of the mind by which data or information is encoded, stored, and retrieved when needed. It is the retention of information over time for the purpose of influencing future action. If past events could not be remembe ...

was added much later to the original four canons.

Music

During theRenaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) is a Periodization, period of history and a European cultural movement covering the 15th and 16th centuries. It marked the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and was characterized by an effort to revive and sur ...

rhetoric enjoyed a resurgence, and as a result nearly every author who wrote about music before the Romantic era discussed rhetoric. Joachim Burmeister wrote in 1601, "there is only little difference between music and the nature of oration". Christoph Bernhard in the latter half of the century said "...until the art of music has attained such a height in our own day, that it may indeed be compared to a rhetoric, in view of the multitude of figures".

Knowledge

Epistemology

Epistemology is the branch of philosophy that examines the nature, origin, and limits of knowledge. Also called "the theory of knowledge", it explores different types of knowledge, such as propositional knowledge about facts, practical knowle ...

and rhetoric have been compared to one another for decades, but the specifications of their similarities have gone undefined. Since scholar Robert L. Scott stated that, "rhetoric is epistemic," rhetoricians and philosophers alike have struggled to concretely define the expanse of implications these words hold. Those who have identified this inconsistency maintain the idea that Scott's relation is important, but requires further study.

The root of the issue lies in the ambiguous use of the term rhetoric itself, as well as the epistemological terms knowledge

Knowledge is an Declarative knowledge, awareness of facts, a Knowledge by acquaintance, familiarity with individuals and situations, or a Procedural knowledge, practical skill. Knowledge of facts, also called propositional knowledge, is oft ...

, certainty, and truth

Truth or verity is the Property (philosophy), property of being in accord with fact or reality.Merriam-Webster's Online Dictionarytruth, 2005 In everyday language, it is typically ascribed to things that aim to represent reality or otherwise cor ...

. Though counterintuitive and vague, Scott's claims are accepted by some academics, but are then used to draw different conclusions. Sonja K. Foss, for example, takes on the view that, "rhetoric creates knowledge," whereas James Herrick writes that rhetoric assists in people's ability to form belief

A belief is a subjective Attitude (psychology), attitude that something is truth, true or a State of affairs (philosophy), state of affairs is the case. A subjective attitude is a mental state of having some Life stance, stance, take, or opinion ...

s, which are defined as knowledge

Knowledge is an Declarative knowledge, awareness of facts, a Knowledge by acquaintance, familiarity with individuals and situations, or a Procedural knowledge, practical skill. Knowledge of facts, also called propositional knowledge, is oft ...

once they become widespread in a community.

It is unclear whether Scott holds that certainty is an inherent part of establishing knowledge

Knowledge is an Declarative knowledge, awareness of facts, a Knowledge by acquaintance, familiarity with individuals and situations, or a Procedural knowledge, practical skill. Knowledge of facts, also called propositional knowledge, is oft ...

, his references to the term abstract. He is not the only one, as the debate's persistence in philosophical circles long predates his addition of rhetoric. There is an overwhelming majority that does support the concept of certainty as a requirement for knowledge

Knowledge is an Declarative knowledge, awareness of facts, a Knowledge by acquaintance, familiarity with individuals and situations, or a Procedural knowledge, practical skill. Knowledge of facts, also called propositional knowledge, is oft ...

, but it is at the definition of certainty where parties begin to diverge. One definition maintains that certainty is subjective and feeling-based, the other that it is a byproduct of justification.

The more commonly accepted definition of rhetoric claims it is synonymous with persuasion. For rhetorical purposes, this definition, like many others, is too broad. The same issue presents itself with definitions that are too narrow. Rhetoricians in support of the epistemic view of rhetoric have yet to agree in this regard.

Philosophical teachings refer to knowledge

Knowledge is an Declarative knowledge, awareness of facts, a Knowledge by acquaintance, familiarity with individuals and situations, or a Procedural knowledge, practical skill. Knowledge of facts, also called propositional knowledge, is oft ...

as a justified true belief. However, the Gettier Problem explores the room for fallacy in this concept. Therefore, the Gettier Problem impedes the effectivity of the argument of Richard A. Cherwitz and James A. Hikins, who employ the justified true belief standpoint in their argument for rhetoric as epistemic. Celeste Condit Railsback takes a different approach, drawing from Ray E. McKerrow's system of belief

A belief is a subjective Attitude (psychology), attitude that something is truth, true or a State of affairs (philosophy), state of affairs is the case. A subjective attitude is a mental state of having some Life stance, stance, take, or opinion ...

based on validity rather than certainty.

William D. Harpine refers to the issue of unclear definitions that occurs in the theories of "rhetoric is epistemic" in his 2004 article "What Do You Mean, Rhetoric Is Epistemic?". In it, he focuses on uncovering the most appropriate definitions for the terms "rhetoric", "knowledge", and "certainty". According to Harpine, certainty is either objective or subjective. Although both Scotts and Cherwitz and Hikins theories deal with some form of certainty, Harpine believes that knowledge is not required to be neither objectively nor subjectively certain. In terms of "rhetoric", Harpine argues that the definition of rhetoric as "the art of persuasion" is the best choice in the context of this theoretical approach of rhetoric as epistemic. Harpine then proceeds to present two methods of approaching the idea of rhetoric as epistemic based on the definitions presented. One centers on Alston's view that one's beliefs are justified if formed by one's normal doxastic while the other focuses on the causal theory of knowledge. Both approaches manage to avoid Gettier's problems and do not rely on unclear conceptions of certainty.

In the discussion of rhetoric and epistemology

Epistemology is the branch of philosophy that examines the nature, origin, and limits of knowledge. Also called "the theory of knowledge", it explores different types of knowledge, such as propositional knowledge about facts, practical knowle ...

, comes the question of ethics

Ethics is the philosophy, philosophical study of Morality, moral phenomena. Also called moral philosophy, it investigates Normativity, normative questions about what people ought to do or which behavior is morally right. Its main branches inclu ...

. Is it ethical

Ethics is the philosophical study of moral phenomena. Also called moral philosophy, it investigates normative questions about what people ought to do or which behavior is morally right. Its main branches include normative ethics, applied e ...

for rhetoric to present itself in the branch of knowledge

Knowledge is an Declarative knowledge, awareness of facts, a Knowledge by acquaintance, familiarity with individuals and situations, or a Procedural knowledge, practical skill. Knowledge of facts, also called propositional knowledge, is oft ...

? Scott rears this question, addressing the issue, not with ambiguity in the definitions of other terms, but against subjectivity regarding certainty. Ultimately, according to Thomas O. Sloane, rhetoric and epistemology

Epistemology is the branch of philosophy that examines the nature, origin, and limits of knowledge. Also called "the theory of knowledge", it explores different types of knowledge, such as propositional knowledge about facts, practical knowle ...

exist as counterparts, working towards the same purpose of establishing knowledge

Knowledge is an Declarative knowledge, awareness of facts, a Knowledge by acquaintance, familiarity with individuals and situations, or a Procedural knowledge, practical skill. Knowledge of facts, also called propositional knowledge, is oft ...

, with the common enemy of subjective certainty.

History and development

Rhetoric is a persuasive speech that holds people to a common purpose and therefore facilitates collective action. During the fifth century BCE, Athens had become active in metropolis and people all over there. During this time the Greek city state had been experimenting with a new form of government—democracy, ''demos'', "the people". Political and cultural identity had been tied to the city area—the citizens of Athens formed institutions to the red processes: are the Senate, jury trials, and forms of public discussions, but people needed to learn how to navigate these new institutions. With no forms of passing on the information, other than word of mouth the Athenians needed an effective strategy to inform the people. A group of wandering Sicilians, later known as the Sophists, began teaching the Athenians persuasive speech, with the goal of navigating the courts and senate. The sophists became speech teachers known as ''Sophia;'' Greek for "wisdom" and root for philosophy, or "''love of wisdom"''—the sophists came to be common term for someone who sold wisdom for money. Although there is no clear understanding why the Sicilians engaged to educating the Athenians persuasive speech. It is known that the Athenians did, indeed rely on persuasive speech, more during public speak, and four new political processes, also increasing the sophists trainings leading too many victories for legal cases, public debate, and even a simple persuasive speech. This ultimately led to concerns rising on falsehood over truth, with highly trained, persuasive speakers, knowingly, misinforming. Rhetoric has its origins inMesopotamia

Mesopotamia is a historical region of West Asia situated within the Tigris–Euphrates river system, in the northern part of the Fertile Crescent. Today, Mesopotamia is known as present-day Iraq and forms the eastern geographic boundary of ...

. Some of the earliest examples of rhetoric can be found in the Akkadian writings of the princess and priestess Enheduanna (). As the first named author in history, Enheduanna's writing exhibits numerous rhetorical features that would later become canon in Ancient Greece. Enheduanna's "The Exaltation of Inanna", includes an exordium, argument

An argument is a series of sentences, statements, or propositions some of which are called premises and one is the conclusion. The purpose of an argument is to give reasons for one's conclusion via justification, explanation, and/or persu ...

, and peroration, as well as elements of , , and , and repetition and metonymy

Metonymy () is a figure of speech in which a concept is referred to by the name of something associated with that thing or concept. For example, the word " suit" may refer to a person from groups commonly wearing business attire, such as sales ...

. She is also known for describing her process of invention in "The Exaltation of Inanna", moving between first- and third-person address to relate her composing process in collaboration with the goddess Inanna, reflecting a mystical enthymeme in drawing upon a Cosmic audience.

Later examples of early rhetoric can be found in the Neo-Assyrian Empire

The Neo-Assyrian Empire was the fourth and penultimate stage of ancient Assyrian history. Beginning with the accession of Adad-nirari II in 911 BC, the Neo-Assyrian Empire grew to dominate the ancient Near East and parts of South Caucasus, Nort ...

during the time of Sennacherib

Sennacherib ( or , meaning "Sin (mythology), Sîn has replaced the brothers") was the king of the Neo-Assyrian Empire from 705BC until his assassination in 681BC. The second king of the Sargonid dynasty, Sennacherib is one of the most famous A ...

().

In ancient Egypt

Ancient Egypt () was a cradle of civilization concentrated along the lower reaches of the Nile River in Northeast Africa. It emerged from prehistoric Egypt around 3150BC (according to conventional Egyptian chronology), when Upper and Lower E ...

, rhetoric had existed since at least the Middle Kingdom period (). The five canons of eloquence in ancient Egyptian rhetoric were silence, timing, restraint, fluency, and truthfulness. The Egyptians

Egyptians (, ; , ; ) are an ethnic group native to the Nile, Nile Valley in Egypt. Egyptian identity is closely tied to Geography of Egypt, geography. The population is concentrated in the Nile Valley, a small strip of cultivable land stretchi ...

held eloquent speaking in high esteem. Egyptian rules of rhetoric specified that "knowing when not to speak is essential, and very respected, rhetorical knowledge", making rhetoric a "balance between eloquence and wise silence". They also emphasized "adherence to social behaviors that support a conservative status quo" and they held that "skilled speech should support, not question, society".

In ancient China

The history of China spans several millennia across a wide geographical area. Each region now considered part of the Chinese world has experienced periods of unity, fracture, prosperity, and strife. Chinese civilization first emerged in the Y ...

, rhetoric dates back to the Chinese philosopher, Confucius

Confucius (; pinyin: ; ; ), born Kong Qiu (), was a Chinese philosopher of the Spring and Autumn period who is traditionally considered the paragon of Chinese sages. Much of the shared cultural heritage of the Sinosphere originates in the phil ...

(). The tradition of Confucianism

Confucianism, also known as Ruism or Ru classicism, is a system of thought and behavior originating in ancient China, and is variously described as a tradition, philosophy, Religious Confucianism, religion, theory of government, or way of li ...

emphasized the use of eloquence in speaking.

The use of rhetoric can also be found in the ancient Biblical tradition.

Ancient Greece

In Europe, organized thought about public speaking began inancient Greece

Ancient Greece () was a northeastern Mediterranean civilization, existing from the Greek Dark Ages of the 12th–9th centuries BC to the end of classical antiquity (), that comprised a loose collection of culturally and linguistically r ...

.

In ancient Greece

Ancient Greece () was a northeastern Mediterranean civilization, existing from the Greek Dark Ages of the 12th–9th centuries BC to the end of classical antiquity (), that comprised a loose collection of culturally and linguistically r ...

, the earliest mention of oratorical skill occurs in Homer

Homer (; , ; possibly born ) was an Ancient Greece, Ancient Greek poet who is credited as the author of the ''Iliad'' and the ''Odyssey'', two epic poems that are foundational works of ancient Greek literature. Despite doubts about his autho ...

's ''Iliad

The ''Iliad'' (; , ; ) is one of two major Ancient Greek epic poems attributed to Homer. It is one of the oldest extant works of literature still widely read by modern audiences. As with the ''Odyssey'', the poem is divided into 24 books and ...

'', in which heroes like Achilles

In Greek mythology, Achilles ( ) or Achilleus () was a hero of the Trojan War who was known as being the greatest of all the Greek warriors. The central character in Homer's ''Iliad'', he was the son of the Nereids, Nereid Thetis and Peleus, ...

, Hector, and Odysseus were honored for their ability to advise and exhort their peers and followers (the or army) to wise and appropriate action. With the rise of the democratic , speaking skill was adapted to the needs of the public and political life of cities in ancient Greece. Greek citizens used oratory to make political and judicial decisions, and to develop and disseminate philosophical ideas. For modern students, it can be difficult to remember that the wide use and availability of written texts is a phenomenon that was just coming into vogue in Classical Greece. In Classical times, many of the great thinkers and political leaders performed their works before an audience, usually in the context of a competition or contest for fame, political influence, and cultural capital. In fact, many of them are known only through the texts that their students, followers, or detractors wrote down. was the Greek term for "orator": A was a citizen who regularly addressed juries and political assemblies and who was thus understood to have gained some knowledge about public speaking in the process, though in general facility with language was often referred to as , "skill with arguments" or "verbal artistry".

Possibly the first study about the power of language may be attributed to the philosopher Empedocles (d. ), whose theories on human knowledge would provide a basis for many future rhetoricians. The first written manual is attributed to Corax and his pupil Tisias. Their work, as well as that of many of the early rhetoricians, grew out of the courts of law; Tisias, for example, is believed to have written judicial speeches that others delivered in the courts.

Rhetoric evolved as an important art, one that provided the orator with the forms, means, and strategies for persuading an audience of the correctness of the orator's arguments. Today the term ''rhetoric'' can be used at times to refer only to the form of argumentation, often with the pejorative connotation that rhetoric is a means of obscuring the truth. Classical philosopher

Philosophy ('love of wisdom' in Ancient Greek) is a systematic study of general and fundamental questions concerning topics like existence, reason, knowledge, Value (ethics and social sciences), value, mind, and language. It is a rational an ...

s believed quite the contrary: the skilled use of rhetoric was essential to the discovery of truths, because it provided the means of ordering and clarifying arguments.

Sophists

Teaching in oratory was popularized in by itinerant teachers known as sophists, the best known of whom were Protagoras (), Gorgias (), and Isocrates (). Aspasia of Miletus is believed to be one of the first women to engage in private and public rhetorical activities as a Sophist. The Sophists were a disparate group who travelled from city to city, teaching in public places to attract students and offer them an education. Their central focus was on , or what we might broadly refer to as discourse, its functions and powers. They defined parts of speech, analyzed poetry, parsed close synonyms, invented argumentation strategies, and debated the nature of reality. They claimed to make their students better, or, in other words, to teach virtue. They thus claimed that human excellence was not an accident of fate or a prerogative of noble birth, but an art or "" that could be taught and learned. They were thus among the first humanists. Several Sophists also questioned received wisdom about the gods and the Greek culture, which they believed was taken for granted by Greeks of their time, making these Sophists among the first agnostics. For example, some argued that cultural practices were a function of convention or rather than blood or birth or . They argued further that the morality or immorality of any action could not be judged outside of the cultural context within which it occurred. The well-known phrase, "Man is the measure of all things" arises from this belief. One of the Sophists' most famous, and infamous, doctrines has to do with probability and counter arguments. They taught that every argument could be countered with an opposing argument, that an argument's effectiveness derived from how "likely" it appeared to the audience (its probability of seeming true), and that any probability argument could be countered with an inverted probability argument. Thus, if it seemed likely that a strong, poor man were guilty of robbing a rich, weak man, the strong poor man could argue, on the contrary, that this very likelihood (that he would be a suspect) makes it unlikely that he committed the crime, since he would most likely be apprehended for the crime. They also taught and were known for their ability to make the weaker (or worse) argument the stronger (or better). Aristophanes famously parodies the clever inversions that sophists were known for in his play '' The Clouds''. The word "sophistry" developed negative connotations in ancient Greece that continue today, but in ancient Greece, Sophists were popular and well-paid professionals, respected for their abilities and also criticized for their excesses. According to William Keith and Christian Lundberg, as the Greek society shifted towards more democratic values, the Sophists were responsible for teaching the newly democratic Greek society the importance of persuasive speech and strategic communication for its new governmental institutions.Isocrates

Isocrates (), like the Sophists, taught public speaking as a means of human improvement, but he worked to distinguish himself from the Sophists, whom he saw as claiming far more than they could deliver. He suggested that while an art of virtue or excellence did exist, it was only one piece, and the least, in a process of self-improvement that relied much more on honing one's talent, desire, constant practice, and the imitation of good models. Isocrates believed that practice in speaking publicly about noble themes and important questions would improve the character of both speaker and audience while also offering the best service to a city. Isocrates was an outspoken champion of rhetoric as a mode of civic engagement. He thus wrote his speeches as "models" for his students to imitate in the same way that poets might imitate Homer or Hesiod, seeking to inspire in them a desire to attain fame through civic leadership. His was the first permanent school inAthens

Athens ( ) is the Capital city, capital and List of cities and towns in Greece, largest city of Greece. A significant coastal urban area in the Mediterranean, Athens is also the capital of the Attica (region), Attica region and is the southe ...

and it is likely that Plato's Academy and Aristotle's Lyceum were founded in part as a response to Isocrates. Though he left no handbooks, his speeches (''" Antidosis"'' and ''" Against the Sophists"'' are most relevant to students of rhetoric) became models of oratory and keys to his entire educational program. He was one of the canonical " Ten Attic Orators". He influenced Cicero

Marcus Tullius Cicero ( ; ; 3 January 106 BC – 7 December 43 BC) was a Roman statesman, lawyer, scholar, philosopher, orator, writer and Academic skeptic, who tried to uphold optimate principles during the political crises tha ...

and Quintilian

Marcus Fabius Quintilianus (; 35 – 100 AD) was a Roman educator and rhetorician born in Hispania, widely referred to in medieval schools of rhetoric and in Renaissance writing. In English translation, he is usually referred to as Quin ...

, and through them, the entire educational system of the west.

Plato

Plato

Plato ( ; Greek language, Greek: , ; born BC, died 348/347 BC) was an ancient Greek philosopher of the Classical Greece, Classical period who is considered a foundational thinker in Western philosophy and an innovator of the writte ...

() outlined the differences between true and false rhetoric in a number of dialogues—particularly the '' Gorgias'' and '' Phaedrus'', dialogues in which Plato disputes the sophistic notion that the art of persuasion (the Sophists' art, which he calls "rhetoric"), can exist independent of the art of dialectic. Plato claims that since Sophists appeal only to what seems probable, they are not advancing their students and audiences, but simply flattering them with what they want to hear. While Plato's condemnation of rhetoric is clear in the ''Gorgias'', in the ''Phaedrus'' he suggests the possibility of a true art wherein rhetoric is based upon the knowledge produced by dialectic. He relies on a dialectically informed rhetoric to appeal to the main character, Phaedrus, to take up philosophy. Thus Plato's rhetoric is actually dialectic (or philosophy) "turned" toward those who are not yet philosophers and are thus unready to pursue dialectic directly. Plato's animosity against rhetoric, and against the Sophists, derives not only from their inflated claims to teach virtue and their reliance on appearances, but from the fact that his teacher, Socrates, was sentenced to death after Sophists' efforts.

Some scholars, however, see Plato not as an opponent of rhetoric but rather as a nuanced rhetorical theorist who dramatized rhetorical practice in his dialogues and imagined rhetoric as more than just oratory.

Aristotle

Aristotle: Rhetoric is an antistrophes to dialectic. "Let rhetoric e defined asan ability ynamis in each articularcase, to see the available means of persuasion." "Rhetoric is a counterpart of dialectic" — an art of practical civic reasoning, applied to deliberative, judicial, and "display" speeches in political assemblies, lawcourts, and other public gatherings.

Aristotle: Rhetoric is an antistrophes to dialectic. "Let rhetoric e defined asan ability ynamis in each articularcase, to see the available means of persuasion." "Rhetoric is a counterpart of dialectic" — an art of practical civic reasoning, applied to deliberative, judicial, and "display" speeches in political assemblies, lawcourts, and other public gatherings.

Aristotle

Aristotle (; 384–322 BC) was an Ancient Greek philosophy, Ancient Greek philosopher and polymath. His writings cover a broad range of subjects spanning the natural sciences, philosophy, linguistics, economics, politics, psychology, a ...

() was a student of Plato who set forth an extended treatise on rhetoric that still repays careful study today. In the first sentence of '' The Art of Rhetoric'', Aristotle says that "rhetoric is the of dialectic". As the "" of a Greek ode responds to and is patterned after the structure of the "" (they form two sections of the whole and are sung by two parts of the chorus), so the art of rhetoric follows and is structurally patterned after the art of dialectic because both are arts of discourse production. While dialectical methods are necessary to find truth in theoretical matters, rhetorical methods are required in practical matters such as adjudicating somebody's guilt or innocence when charged in a court of law, or adjudicating a prudent course of action to be taken in a deliberative assembly.

For Plato and Aristotle, dialectic involves persuasion, so when Aristotle says that rhetoric is the of dialectic, he means that rhetoric as he uses the term has a domain or scope of application that is parallel to, but different from, the domain or scope of application of dialectic. Claude Pavur explains that " e Greek prefix 'anti' does not merely designate opposition, but it can also mean 'in place of'".

Aristotle's treatise on rhetoric systematically describes civic rhetoric as a human art or skill (). It is more of than it is an interpretive theory with a rhetorical tradition. Aristotle's art of rhetoric emphasizes persuasion as the purpose of rhetoric. His definition of rhetoric as "the faculty of observing in any given case the available means of persuasion", essentially a mode of discovery, limits the art to the inventional process; Aristotle emphasizes the logical aspect of this process. A speaker supports the probability of a message by logical, ethical, and emotional proofs.

Aristotle identifies three steps or "offices" of rhetoric—invention, arrangement, and style—and three different types of rhetorical proof:

; : Aristotle's theory of character and how the character and credibility of a speaker can influence an audience to consider him/her to be believable—there being three qualities that contribute to a credible ethos: perceived intelligence, virtuous character, and goodwill

; : the use of emotional appeals to alter the audience's judgment through metaphor, amplification, storytelling, or presenting the topic in a way that evokes strong emotions in the audience

; : the use of reasoning, either inductive or deductive, to construct an argument

Aristotle emphasized '' enthymematic reasoning'' as central to the process of rhetorical invention, though later rhetorical theorists placed much less emphasis on it. An "enthymeme" follows the form of a syllogism, however it excludes either the major or minor premise. An enthymeme is persuasive because the audience provides the missing premise. Because the audience participates in providing the missing premise, they are more likely to be persuaded by the message.

Aristotle identified three different types or genres of civic rhetoric:

; Forensic (also known as judicial) : concerned with determining the truth or falseness of events that took place in the past and issues of guilt—for example, in a courtroom

; Deliberative (also known as political) : concerned with determining whether or not particular actions should or should not be taken in the future—for example, making laws

; Epideictic (also known as ceremonial) : concerned with praise and blame, values, right and wrong, demonstrating beauty and skill in the present—for example, a eulogy or a wedding toast

Another Aristotelian doctrine was the idea of topics (also referred to as common topics or commonplaces). Though the term had a wide range of application (as a memory technique or compositional exercise, for example) it most often referred to the "seats of argument"—the list of categories of thought or modes of reasoning—that a speaker could use to generate arguments or proofs. The topics were thus a heuristic or inventional tool designed to help speakers categorize and thus better retain and apply frequently used types of argument. For example, since we often see effects as "like" their causes, one way to invent an argument (about a future effect) is by discussing the cause (which it will be "like"). This and other rhetorical topics derive from Aristotle's belief that there are certain predictable ways in which humans (particularly non-specialists) draw conclusions from premises. Based upon and adapted from his dialectical Topics, the rhetorical topics became a central feature of later rhetorical theorizing, most famously in Cicero's work of that name.

India

'' India's Struggle for Independence'' offers a vivid description of the culture that sprang up around the newspaper in village India of the early 1870s: This reading and discussion was the focal point of origin of the modern Indian rhetorical movement. Much before this, ancients such as Kautilya, Birbal, and the like indulged in a great deal of discussion and persuasion. Keith Lloyd argued that much of the recital of theVedas

FIle:Atharva-Veda samhita page 471 illustration.png, upright=1.2, The Vedas are ancient Sanskrit texts of Hinduism. Above: A page from the ''Atharvaveda''.

The Vedas ( or ; ), sometimes collectively called the Veda, are a large body of relig ...

can be likened to the recital of ancient Greek poetry. Lloyd proposed including the '' Nyāya Sūtras'' in the field of rhetorical studies, exploring its methods within their historical context, comparing its approach to the traditional logical syllogism, and relating it to modern perspectives of Stephen Toulmin, Kenneth Burke, and Chaim Perelman.

is a Sanskrit word which means "just" or "right" and refers to "the science of right and wrong reasoning".

is also a Sanskrit word which means string or thread. Here sutra refers to a collection of aphorism in the form of a manual. Each sutra is a short rule usually consisted of one or two sentences. An example of a sutra is: "Reality is truth, and what is true is so, irrespective of whether we know it is, or are aware of that truth." The ''Nyāya Sūtras'' is an ancient Indian Sanskrit text composed by Aksapada Gautama. It is the foundational text of the Nyaya school of Hindu philosophy. It is estimated that the text was composed between and . The text may have been composed by more than one author, over a period of time. Radhakrishan and Moore placed its origin in the "though some of the contents of the Nyaya Sutra are certainly a post-Christian era". The ancient school of Nyaya extended over a period of one thousand years, beginning with Gautama about and ending with Vatsyayana about .

Nyaya provides insight into Indian rhetoric. Nyaya presents an argumentative approach with which a rhetor can decide about any argument. In addition, it proposes an approach to thinking about cultural tradition which is different from Western rhetoric. Whereas Toulmin emphasizes the situational dimension of argumentative genre as the fundamental component of any rhetorical logic; Nyaya views this situational rhetoric .

Some of India's famous rhetors include Kabir Das, Rahim Das, Chanakya

Chanakya (ISO 15919, ISO: ', चाणक्य, ), according to legendary narratives preserved in various traditions dating from the 4th to 11th century CE, was a Brahmin who assisted the first Mauryan emperor Chandragupta Maurya, Chandragup ...

, and Chandragupt Maurya.

Rome

Cicero

For the Romans, oration became an important part of public life.