Pherecydes of Syros on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Pherecydes of Syros (; ; fl. 6th century BCE) was an

Pherycydes is seen as a transitional figure between the mythological cosmogonies of

Pherycydes is seen as a transitional figure between the mythological cosmogonies of

Pherecydes of Syros

by Giannis Stamatellos

Fragments and Life of Pherecydes

at demonax.info

* ttp://www.maicar.com/GML/SevenSages.html The Seven Sages of Greece at Greek Mythology Link {{DEFAULTSORT:Pherecydes Of Syros Cosmogony People from Syros Presocratic philosophers Religious cosmologies Seven Sages of Greece 6th-century BC Greek philosophers

Ancient Greek

Ancient Greek (, ; ) includes the forms of the Greek language used in ancient Greece and the classical antiquity, ancient world from around 1500 BC to 300 BC. It is often roughly divided into the following periods: Mycenaean Greek (), Greek ...

mythographer and proto-philosopher

Philosophy ('love of wisdom' in Ancient Greek) is a systematic study of general and fundamental questions concerning topics like existence, reason, knowledge, Value (ethics and social sciences), value, mind, and language. It is a rational an ...

from the island of Syros

Syros ( ), also known as Siros or Syra, is a Greece, Greek island in the Cyclades, in the Aegean Sea. It is south-east of Athens. The area of the island is and at the 2021 census it had 21,124 inhabitants.

The largest towns are Ermoupoli, Ano S ...

. Little is known about his life and death. Some ancient testimonies counted Pherecydes among the Seven Sages of Greece

The Seven Sages or Seven Wise Men was the title given to seven philosophers, statesmen, and law-givers of the 7th–6th centuries BCE who were renowned for their wisdom

Wisdom, also known as sapience, is the ability to apply knowledge, ...

, although he is generally believed to have lived in the generation after them. Others claim he may have been a teacher of Pythagoras

Pythagoras of Samos (; BC) was an ancient Ionian Greek philosopher, polymath, and the eponymous founder of Pythagoreanism. His political and religious teachings were well known in Magna Graecia and influenced the philosophies of P ...

, a student of Pittacus, or a well-traveled autodidact

Autodidacticism (also autodidactism) or self-education (also self-learning, self-study and self-teaching) is the practice of education without the guidance of schoolmasters (i.e., teachers, professors, institutions).

Overview

Autodi ...

who had studied secret Phoenician books.

Pherecydes wrote a book on cosmogony

Cosmogony is any model concerning the origin of the cosmos or the universe.

Overview

Scientific theories

In astronomy, cosmogony is the study of the origin of particular astrophysical objects or systems, and is most commonly used in ref ...

, known as the "Pentemychos" or "Heptamychos". He was considered the first writer to communicate philosophical ideas in prose

Prose is language that follows the natural flow or rhythm of speech, ordinary grammatical structures, or, in writing, typical conventions and formatting. Thus, prose ranges from informal speaking to formal academic writing. Prose differs most n ...

as opposed to verse. However, other than a few short fragments preserved in quotations from other ancient philosophers and a long fragment discovered on an Egyptian papyrus, his work is lost. However, it survived into the Hellenistic period

In classical antiquity, the Hellenistic period covers the time in Greek history after Classical Greece, between the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC and the death of Cleopatra VII in 30 BC, which was followed by the ascendancy of the R ...

and a significant amount of its content can be conjectured indirectly through ancient testimonies. His cosmogony was derived from three divine principles: ''Zas'' (Life

Life, also known as biota, refers to matter that has biological processes, such as Cell signaling, signaling and self-sustaining processes. It is defined descriptively by the capacity for homeostasis, Structure#Biological, organisation, met ...

), '' Cthonie'' (Earth

Earth is the third planet from the Sun and the only astronomical object known to Planetary habitability, harbor life. This is enabled by Earth being an ocean world, the only one in the Solar System sustaining liquid surface water. Almost all ...

), and ''Chronos'' (Time

Time is the continuous progression of existence that occurs in an apparently irreversible process, irreversible succession from the past, through the present, and into the future. It is a component quantity of various measurements used to sequ ...

). In the narrative, Chronos creates the Classical elements

The classical elements typically refer to earth, water, air, fire, and (later) aether which were proposed to explain the nature and complexity of all matter in terms of simpler substances. Ancient cultures in Greece, Angola, Tibet, India, ...

and other gods in cavities within the earth. Later, Zas defeats the dragon Ophion

In some versions of Greek mythology, Ophion (; "serpent"; ''gen''.: Ὀφίωνος), also called Ophioneus ({{lang, grc, Ὀφιονεύς) ruled the world with Eurynome before the two of them were cast down by Cronus and Rhea.

Mythology

Pher ...

in a battle for supremacy and throws him in Oceanus

In Greek mythology, Oceanus ( ; , also , , or ) was a Titans, Titan son of Uranus (mythology), Uranus and Gaia, the husband of his sister the Titan Tethys (mythology), Tethys, and the father of the River gods (Greek mythology), river gods ...

. Zas marries Chthoniê, who then becomes the recognizable Earth ( Gê) with forests and mountains. Chronos retires from the world as creator, and Zas succeeds him as ruler and assigns all beings their place.

Pherecydes' cosmogony forms a bridge between the mythological thought of Hesiod

Hesiod ( or ; ''Hēsíodos''; ) was an ancient Greece, Greek poet generally thought to have been active between 750 and 650 BC, around the same time as Homer.M. L. West, ''Hesiod: Theogony'', Oxford University Press (1966), p. 40.Jasper Gr ...

and pre-Socratic

Pre-Socratic philosophy, also known as early Greek philosophy, is ancient Greek philosophy before Socrates. Pre-Socratic philosophers were mostly interested in cosmology, the beginning and the substance of the universe, but the inquiries of the ...

Greek philosophy

Ancient Greek philosophy arose in the 6th century BC. Philosophy was used to make sense of the world using reason. It dealt with a wide variety of subjects, including astronomy, epistemology, mathematics, political philosophy, ethics, metaphysic ...

; Aristotle

Aristotle (; 384–322 BC) was an Ancient Greek philosophy, Ancient Greek philosopher and polymath. His writings cover a broad range of subjects spanning the natural sciences, philosophy, linguistics, economics, politics, psychology, a ...

considered him one of the earliest thinkers to abandon traditional mythology in order to arrive at a systematic explanation of the world, although Plutarch

Plutarch (; , ''Ploútarchos'', ; – 120s) was a Greek Middle Platonist philosopher, historian, biographer, essayist, and priest at the Temple of Apollo (Delphi), Temple of Apollo in Delphi. He is known primarily for his ''Parallel Lives'', ...

, as well as many other writers, still gave him the title of '' theologus,'' as opposed to the later '' physiologoi'' of the Ionian school. Later hellenistic doxographers also considered him as one of the first thinkers to introduce a doctrine of the transmigration of souls to the Ancient Greek religion

Religious practices in ancient Greece encompassed a collection of beliefs, rituals, and Greek mythology, mythology, in the form of both popular public religion and Cult (religious practice), cult practices. The application of the modern concept ...

, which influenced the metempsychosis

In philosophy and theology, metempsychosis () is the transmigration of the soul, especially its reincarnation after death. The term is derived from ancient Greek philosophy, and has been recontextualized by modern philosophers such as Arthur Sc ...

of Pythagoreanism

Pythagoreanism originated in the 6th century BC, based on and around the teachings and beliefs held by Pythagoras and his followers, the Pythagoreans. Pythagoras established the first Pythagorean community in the Ancient Greece, ancient Greek co ...

, and the theogonies of Orphism

Orphism is the name given to a set of religious beliefs and practices originating in the ancient Greek and Hellenistic world, associated with literature ascribed to the mythical poet Orpheus, who descended into the Greek underworld and returned ...

. Various legends and miracles were ascribed to him, many of which tie him to the development of Pythagoreanism

Pythagoreanism originated in the 6th century BC, based on and around the teachings and beliefs held by Pythagoras and his followers, the Pythagoreans. Pythagoras established the first Pythagorean community in the Ancient Greece, ancient Greek co ...

or Orphism

Orphism is the name given to a set of religious beliefs and practices originating in the ancient Greek and Hellenistic world, associated with literature ascribed to the mythical poet Orpheus, who descended into the Greek underworld and returned ...

.

Life

Although it is relatively certain the Pherecydes was a native of the island ofSyros

Syros ( ), also known as Siros or Syra, is a Greece, Greek island in the Cyclades, in the Aegean Sea. It is south-east of Athens. The area of the island is and at the 2021 census it had 21,124 inhabitants.

The largest towns are Ermoupoli, Ano S ...

, and that he lived in the 6th century BCE, almost nothing else is known about his life. There is even some discrepancy in the ancient sources of his life as to when exactly he lived within the 6th century. The Suda

The ''Suda'' or ''Souda'' (; ; ) is a large 10th-century Byzantine Empire, Byzantine encyclopedia of the History of the Mediterranean region, ancient Mediterranean world, formerly attributed to an author called Soudas () or Souidas (). It is an ...

places his date of birth during the reign of King Alyattes

Alyattes ( Lydian language: ; ; reigned c. 635 – c. 585 BC), sometimes described as Alyattes I, was the fourth king of the Mermnad dynasty in Lydia, the son of Sadyattes, grandson of Ardys, and great-grandson of Gyges. He died after a r ...

in Lydia

Lydia (; ) was an Iron Age Monarchy, kingdom situated in western Anatolia, in modern-day Turkey. Later, it became an important province of the Achaemenid Empire and then the Roman Empire. Its capital was Sardis.

At some point before 800 BC, ...

(c. 605-560 BCE), which would place him as a contemporary of the Seven Sages of Greece

The Seven Sages or Seven Wise Men was the title given to seven philosophers, statesmen, and law-givers of the 7th–6th centuries BCE who were renowned for their wisdom

Wisdom, also known as sapience, is the ability to apply knowledge, ...

, among whose number he was occasionally included. Alternatively, Apollodorus

Apollodorus ( Greek: Ἀπολλόδωρος ''Apollodoros'') was a popular name in ancient Greece. It is the masculine gender of a noun compounded from Apollo, the deity, and doron, "gift"; that is, "Gift of Apollo." It may refer to:

:''Note: A ...

, places his floruit

''Floruit'' ( ; usually abbreviated fl. or occasionally flor.; from Latin for 'flourished') denotes a date or period during which a person was known to have been alive or active. In English, the unabbreviated word may also be used as a noun indic ...

several decades later, in the 59th Olympiad

An olympiad (, ''Olympiás'') is a period of four years, particularly those associated with the Ancient Olympic Games, ancient and Olympic Games, modern Olympic Games.

Although the ancient Olympics were established during Archaic Greece, Greece ...

(544–541 BCE), a generation later. Assuming that Pherecydes was born in this later generation, younger than the philosopher Thales

Thales of Miletus ( ; ; ) was an Ancient Greek philosophy, Ancient Greek Pre-Socratic philosophy, pre-Socratic Philosophy, philosopher from Miletus in Ionia, Asia Minor. Thales was one of the Seven Sages of Greece, Seven Sages, founding figure ...

(624-545 BC) and thus an older contemporary of Anaximander

Anaximander ( ; ''Anaximandros''; ) was a Pre-Socratic philosophy, pre-Socratic Ancient Greek philosophy, Greek philosopher who lived in Miletus,"Anaximander" in ''Chambers's Encyclopædia''. London: George Newnes Ltd, George Newnes, 1961, Vol. ...

, he would also be approximately the correct age for the Pythagorean

Pythagorean, meaning of or pertaining to the ancient Ionian mathematician, philosopher, and music theorist Pythagoras, may refer to:

Philosophy

* Pythagoreanism, the esoteric and metaphysical beliefs purported to have been held by Pythagoras

* Ne ...

tradition in which he is regarded as a teacher of Pythagoras. Most of the other biographical information is probably fiction, and the ambiguity and contradictions in the surviving testimonies suggest that any reliable biographical data that may have existed was no longer available in the Hellenistic period. The identity of Pherecydes was also unclear in ancient times because there were two authors of that name who both wrote about mythology: Pherecydes of Syros and Pherecydes of Athens

Pherecydes of Athens () (fl. c. 465 BC) was a Greek mythographer who wrote an ancient work in ten books, now lost, variously titled "Historiai" (''Ἱστορίαι'') or "Genealogicai" (''Γενελογίαι''). He is one of the authors (= '' FG ...

(fl. 5th century BC

The 5th century BC started the first day of 500 BC and ended the last day of 401 BC.

This century saw the establishment of Pataliputra as a capital of the Magadha (Mahajanapada), Magadha Empire. This city would later become the ruling capital o ...

).

According to a forged letter attributed to Thales, Pherecydes never traveled but according to other sources he traveled throughout the Greek cultural area, to Delphi

Delphi (; ), in legend previously called Pytho (Πυθώ), was an ancient sacred precinct and the seat of Pythia, the major oracle who was consulted about important decisions throughout the ancient Classical antiquity, classical world. The A ...

, the Peloponnese

The Peloponnese ( ), Peloponnesus ( ; , ) or Morea (; ) is a peninsula and geographic region in Southern Greece, and the southernmost region of the Balkans. It is connected to the central part of the country by the Isthmus of Corinth land bridg ...

, Ephesus

Ephesus (; ; ; may ultimately derive from ) was an Ancient Greece, ancient Greek city on the coast of Ionia, in present-day Selçuk in İzmir Province, Turkey. It was built in the 10th century BC on the site of Apasa, the former Arzawan capital ...

and Samos

Samos (, also ; , ) is a Greek island in the eastern Aegean Sea, south of Chios, north of Patmos and the Dodecanese archipelago, and off the coast of western Turkey, from which it is separated by the Mycale Strait. It is also a separate reg ...

. According to Josephus

Flavius Josephus (; , ; ), born Yosef ben Mattityahu (), was a Roman–Jewish historian and military leader. Best known for writing '' The Jewish War'', he was born in Jerusalem—then part of the Roman province of Judea—to a father of pr ...

and Byzantine

The Byzantine Empire, also known as the Eastern Roman Empire, was the continuation of the Roman Empire centred on Constantinople during late antiquity and the Middle Ages. Having survived the events that caused the fall of the Western Roman E ...

writers, Pherecydes also made a journey to Egypt

Egypt ( , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a country spanning the Northeast Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to northe ...

. Such a journey, however, is a common tale that is also part of other biographies of philosophers. A sun-dial (''heliotropion''), supposedly made by Pherecydes, was said by Diogenes Laërtius

Diogenes Laërtius ( ; , ; ) was a biographer of the Greek philosophers. Little is definitively known about his life, but his surviving book ''Lives and Opinions of Eminent Philosophers'' is a principal source for the history of ancient Greek ph ...

to be "preserved on the island of Syros." Several miraculous deeds were also attributed to Pherecydes; such as that he accurately predicted an earthquake on Syros after drinking from a well, or that he predicted the sinking of a ship that he saw along the coast of Syros, which then proceeded to sink. In Messene

Messene (Greek language, Greek: Μεσσήνη 𐀕𐀼𐀙 ''Messini''), officially Ancient Messene, is a local community within the regional unit (''perifereiaki enotita'') of Messenia in the region (''perifereia'') of Peloponnese (region), P ...

he allegedly warned his friend Perilaus that the city would be conquered. Finally, Hercules

Hercules (, ) is the Roman equivalent of the Greek divine hero Heracles, son of Jupiter and the mortal Alcmena. In classical mythology, Hercules is famous for his strength and for his numerous far-ranging adventures.

The Romans adapted the Gr ...

was said to have visited him in a dream and told him to tell the Spartans

Sparta was a prominent city-state in Laconia in ancient Greece. In antiquity, the city-state was known as Lacedaemon (), while the name Sparta referred to its main settlement in the valley of Evrotas river in Laconia, in southeastern P ...

not to value silver or gold, and that same night Heracles is said to have told the king of Sparta in his sleep to listen to Pherecydes. Many of those miracles however, were also attributed to other legendary philosophers such as Pythagoras or Epimenides

Epimenides of Knossos (or Epimenides of Crete) (; ) was a semi-mythical 7th- or 6th-century BC Greek seer and philosopher-poet, from Knossos or Phaistos.

Life

While tending his father's sheep, Epimenides is said to have fallen asleep for fifty ...

.

There are many conflicting legends that purport to be an account of the death of Pherecydes. According to one story, Pherecydes was killed and skinned as a sacrifice by the Spartans, and their king kept the skin out of respect for Pherecydes' wisdom. However, the same story was also told about Epimenides. Other accounts have the philosopher perishing in a battle between the Ephesians

The Epistle to the Ephesians is the tenth book of the New Testament.

Traditionally believed to have been written by the Apostle Paul around AD 62 during his imprisonment in Rome, the Epistle to the Ephesians closely resembles Colossians ...

and Magnesians, or throwing himself from Mount Corycus in Delphi, or succumbing to typhoid fever

Typhoid fever, also known simply as typhoid, is a disease caused by '' Salmonella enterica'' serotype Typhi bacteria, also called ''Salmonella'' Typhi. Symptoms vary from mild to severe, and usually begin six to 30 days after exposure. Often th ...

. According to Aelianus typhoid fever was a punishment for his wickedness . The latter story was already known to Aristotle and may have arisen from the idea that wise men did not care about physical care. Other stories connect Pherecydes' death to Pythagoras. However, the historicity of all this is debatable.

Influences

Pherecydes was designated as 'wise' (''sophos''), but onlyServius Servius may refer to:

* Servius (praenomen), a personal name during the Roman Republic

* Servius the Grammarian (fl. 4th/5th century), Roman Latin grammarian

* Servius Asinius Celer (died AD 46), Roman senator

* Servius Cornelius Cethegus, Roma ...

calls him a philosopher (''philosophus''). Aristotle places him between theologian

Theology is the study of religious belief from a religious perspective, with a focus on the nature of divinity. It is taught as an academic discipline, typically in universities and seminaries. It occupies itself with the unique content of ...

s and philosophers, because he no longer expressed himself completely mythical in his research. No consistent teacher of Pherecydes was known by name in late antiquity

Late antiquity marks the period that comes after the end of classical antiquity and stretches into the onset of the Early Middle Ages. Late antiquity as a period was popularized by Peter Brown (historian), Peter Brown in 1971, and this periodiza ...

; according to the doxographer

Doxography ( – "an opinion", "a point of view" + – "to write", "to describe") is a term used especially for the works of classical historians, describing the points of view of past philosophers and scientists. The term was coined by ...

Diogenes Laërtius

Diogenes Laërtius ( ; , ; ) was a biographer of the Greek philosophers. Little is definitively known about his life, but his surviving book ''Lives and Opinions of Eminent Philosophers'' is a principal source for the history of ancient Greek ph ...

Pherecydes was taught by Pittacus, but according to the ''Suda

The ''Suda'' or ''Souda'' (; ; ) is a large 10th-century Byzantine Empire, Byzantine encyclopedia of the History of the Mediterranean region, ancient Mediterranean world, formerly attributed to an author called Soudas () or Souidas (). It is an ...

'' he taught himself after he got his hands on 'the secret books of the Phoenicians

Phoenicians were an ancient Semitic group of people who lived in the Phoenician city-states along a coastal strip in the Levant region of the eastern Mediterranean, primarily modern Lebanon and the Syrian coast. They developed a maritime civi ...

'.

Although this latter claim is almost certainly fictitious, it may be based on the similarity between Pherecydes' ideas and Eastern religious motifs. For example, in his book he describes an important battle in the earliest times between Kronos and Ophion

In some versions of Greek mythology, Ophion (; "serpent"; ''gen''.: Ὀφίωνος), also called Ophioneus ({{lang, grc, Ὀφιονεύς) ruled the world with Eurynome before the two of them were cast down by Cronus and Rhea.

Mythology

Pher ...

, and this motif occurs in the Middle East

The Middle East (term originally coined in English language) is a geopolitical region encompassing the Arabian Peninsula, the Levant, Turkey, Egypt, Iran, and Iraq.

The term came into widespread usage by the United Kingdom and western Eur ...

. His father was named Babys, a name that presumably originated from southern Anatolia

Anatolia (), also known as Asia Minor, is a peninsula in West Asia that makes up the majority of the land area of Turkey. It is the westernmost protrusion of Asia and is geographically bounded by the Mediterranean Sea to the south, the Aegean ...

, based on linguistic evidence. Eternal time as god is also Middle Eastern. In addition, Pherecydes has been associated with Zoroastrianism

Zoroastrianism ( ), also called Mazdayasnā () or Beh-dīn (), is an Iranian religions, Iranian religion centred on the Avesta and the teachings of Zoroaster, Zarathushtra Spitama, who is more commonly referred to by the Greek translation, ...

. Isidore the Gnostic claimed that Pherecydes based his allegorical work on a 'prophecy of Ham'. Ham, as referred to here, may be Zoroaster

Zarathushtra Spitama, more commonly known as Zoroaster or Zarathustra, was an Iranian peoples, Iranian religious reformer who challenged the tenets of the contemporary Ancient Iranian religion, becoming the spiritual founder of Zoroastrianism ...

, who was quite well known in the Greek world of late antiquity. Isidore may have concluded this because the Zoroastrian literature available to him was influenced by Hellenization

Hellenization or Hellenification is the adoption of Greek culture, religion, language, and identity by non-Greeks. In the ancient period, colonisation often led to the Hellenisation of indigenous people in the Hellenistic period, many of the ...

, or because Pherecydes' work influenced it. There is also a short fragment in which Pherecydes talks about ambrosia

In the ancient Greek mythology, Greek myths, ambrosia (, ) is the food or drink of the Greek gods, and is often depicted as conferring longevity or immortality upon whoever consumed it. It was brought to the gods in Mount Olympus, Olympus by do ...

of the moon, the potion of the gods. This representation has parallels in the Samaveda

The ''Samaveda'' (, , from '' सामन्'', "song" and ''वेद'', "knowledge"), is the Veda of melodies and chants. It is an ancient Vedic Sanskrit text, and is one of the sacred scriptures in Hinduism. One of the four Vedas, it is a l ...

, where there the moon is a vessel from which the gods drink soma (god drink) and is important in the reincarnation theory as guardian of heaven.

Writings

Pherecydes wrote a cosmogony (explanatory model for the origin of the universe) that contained a theogony, an explanatory model for the gods and their properties. This work broke with the mythological and theological tradition and shows Eastern influences. Pherecydes, along withAnaximander

Anaximander ( ; ''Anaximandros''; ) was a Pre-Socratic philosophy, pre-Socratic Ancient Greek philosophy, Greek philosopher who lived in Miletus,"Anaximander" in ''Chambers's Encyclopædia''. London: George Newnes Ltd, George Newnes, 1961, Vol. ...

and Anaximenes, has long been regarded as one of the first Greek writers to compose his work in prose rather than hexameter verse. Martin Litchfield West

Martin Litchfield West, (23 September 1937 – 13 July 2015) was a British philologist and classical scholar. In recognition of his contribution to scholarship, he was appointed to the Order of Merit in 2014.

West wrote on ancient Greek music ...

notes that the subject matter that all of three of these authors wrote on, the nature of the universe and how it came to be, had been written in verse prior to these authors. West speculates based on the word choice that early logographers used ("words I have heard" instead of "I have read") that the original intent of a book written in prose was essentially a "write-up" of a lecture that a person interest in topics such as cosmology

Cosmology () is a branch of physics and metaphysics dealing with the nature of the universe, the cosmos. The term ''cosmology'' was first used in English in 1656 in Thomas Blount's ''Glossographia'', with the meaning of "a speaking of the wo ...

gave as a speech or public discourse. The book was known variously under the titles such as ''Seven niches'' ('' Heptamychos'', Ἑπτάμυχος), "Five niches" (Pentemychos, Πεντέμυχος), and ''Mixing of the Gods'' (''Theokrasia'', Θεοκρασία).

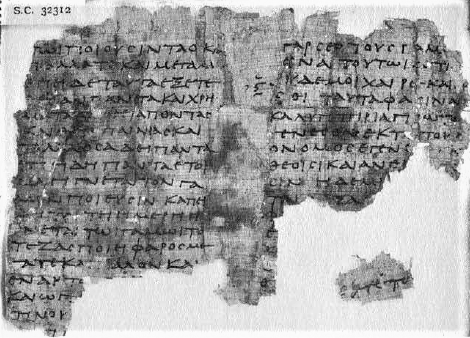

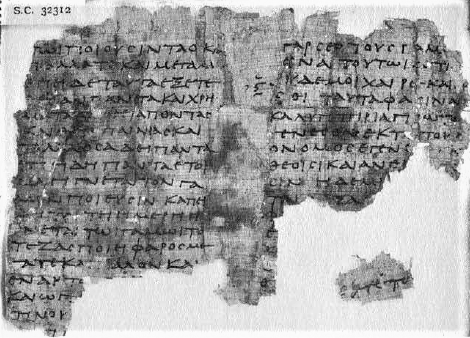

In this work, Pherecydes taught his philosophy through the medium of mythic representations. Although it is lost, it was extant in the Hellenistic period

In classical antiquity, the Hellenistic period covers the time in Greek history after Classical Greece, between the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC and the death of Cleopatra VII in 30 BC, which was followed by the ascendancy of the R ...

, and the fragments and testimony that survive from works that describe it are enough to reconstruct a basic outline. The opening sentence is given by Diogenes Laertius, and two fragments in the middle of the text have also been preserved in fragments from a 3rd century Egyptian papyrus discovered by Bernard Pyne Grenfell and Arthur Surridge Hunt, which was identified thanks to a comment by Clement of Alexandria

Titus Flavius Clemens, also known as Clement of Alexandria (; – ), was a Christian theology, Christian theologian and philosopher who taught at the Catechetical School of Alexandria. Among his pupils were Origen and Alexander of Jerusalem. A ...

about the contents of Pherecydes' book: 'Pherecydes of Syros says: "Zas made a great and beautiful robe, and made the earth and Ogenus on it, and the palace of Ogenus".'

Theogony

Pherecydes developed a unique, syncretistic theogony with a new beginning stage, in which Zas, Chronos, and Chthoniê were the first gods to exist all along. He was probably the first to do this. There is no creation out of nothing (''creatio ex nihilo

(Latin, 'creation out of nothing') is the doctrine that matter is not eternal but had to be created by some divine creative act. It is a theistic answer to the question of how the universe came to exist. It is in contrast to ''creatio ex mate ...

''). The cosmogony

Cosmogony is any model concerning the origin of the cosmos or the universe.

Overview

Scientific theories

In astronomy, cosmogony is the study of the origin of particular astrophysical objects or systems, and is most commonly used in ref ...

is justified through etymology, a new understanding of the deity Kronos as Chronos and the insertion of a creator god (demiurge

In the Platonic, Neopythagorean, Middle Platonic, and Neoplatonic schools of philosophy, the Demiurge () is an artisan-like figure responsible for fashioning and maintaining the physical universe. Various sects of Gnostics adopted the term '' ...

). Also, Pherecydes combined Greek mythology

Greek mythology is the body of myths originally told by the Ancient Greece, ancient Greeks, and a genre of ancient Greek folklore, today absorbed alongside Roman mythology into the broader designation of classical mythology. These stories conc ...

with non-Greek myths and religions. According to Aristotle, he was innovative in his approach, because he broke with the theological

Theology is the study of religious belief from a religious perspective, with a focus on the nature of divinity. It is taught as an academic discipline, typically in universities and seminaries. It occupies itself with the unique content of an ...

tradition and combined mythology with philosophy. Pherecydes' creation story therefore had to be more rational and concrete than Hesiod's ''Theogony

The ''Theogony'' () is a poem by Hesiod (8th–7th century BC) describing the origins and genealogy, genealogies of the Greek gods, composed . It is written in the Homeric Greek, epic dialect of Ancient Greek and contains 1,022 lines. It is one ...

''. He wrote that first Chaos came to be (''genetos'') without explanation, while Zas, Chronos and Chthoniê existed eternally (''êsan aeí''). The adoption of an eternal principle (''arche

In philosophy and science, a first principle is a basic proposition or assumption that cannot be deduced from any other proposition or assumption. First principles in philosophy are from first cause attitudes and taught by Aristotelians, and nuan ...

'') for the cosmos

The cosmos (, ; ) is an alternative name for the universe or its nature or order. Usage of the word ''cosmos'' implies viewing the universe as a complex and orderly system or entity.

The cosmos is studied in cosmologya broad discipline covering ...

was characteristic of Pre-Socratic

Pre-Socratic philosophy, also known as early Greek philosophy, is ancient Greek philosophy before Socrates. Pre-Socratic philosophers were mostly interested in cosmology, the beginning and the substance of the universe, but the inquiries of the ...

thinkers.

The sequence of Pherecydes' creation myth is as follows. First, there are the eternal gods Zas (Zeus), Chthoniê (Gaia) and Chronos (Kronos). Then Chronos creates elements in niches in the earth with his seed, from which other gods arise. This is followed by the three-day wedding of Zas and Chthonie. On the third day Zas makes the robe of the world, which he hangs from a winged oak and then presents as a wedding gift to Chthonie, and wraps around her. The "winged oak" in this cosmology has no precedent in Greek tradition. The stories are different but not mutually exclusive, because much is lacking in the fragments, but it seems clear that creation is hindered by chaotic forces. Before the world is ordered, a cosmic battle takes place, with Cronus as the head of one side and Ophion as the leader of the other. Ophion then attacks Kronos, who defeats him and throws him in Ogenos. Sometime after his battle with Ophion, Kronos is succeeded by Zas. This is implied by the fact that Zas/Zeus is ultimately the one who assigns the gods their domain in the world. For example, the Harpies

In Greek and Roman mythology, a harpy (plural harpies, , ; ) is a half-human and half-bird mythical creature, often believed to be a personification of storm winds. They feature in Homeric poems.

Descriptions

Harpies were generally depicted ...

are assigned to guard Tartarus

In Greek mythology, Tartarus (; ) is the deep abyss that is used as a dungeon of torment and suffering for the wicked and as the prison for the Titans. Tartarus is the place where, according to Plato's '' Gorgias'' (), souls are judged after ...

The fact that Kronos disappears into the background is due to his great magnificence. The argument for this is that Aristotle conceives Pherecydes as a semi-philosopher in that he connects the philosophical Good and Beautiful with the first, prevailing principle (''arche'') of the theologians, and eternity, according to Aristotle, is connected with the good. The three primordial gods are eternal, equal and wholly responsible for the world order.

Etymology

Pherecydes was interested inetymology

Etymology ( ) is the study of the origin and evolution of words—including their constituent units of sound and meaning—across time. In the 21st century a subfield within linguistics, etymology has become a more rigorously scientific study. ...

and word associations. Like Thales, he associated chaos

Chaos or CHAOS may refer to:

Science, technology, and astronomy

* '' Chaos: Making a New Science'', a 1987 book by James Gleick

* Chaos (company), a Bulgarian rendering and simulation software company

* ''Chaos'' (genus), a genus of amoebae

* ...

with the primordial elemental water, presumably because he associates the word 'chaos' with the verb 'cheesthai', 'to flow out', and because chaos is an undefined, disorderly state. By that approach he adapted god names, although Pherecydes probably saw his gods as traditional deities. He mentioned Rhea for example Rhê, presumably by association with ''rhein'' '(out)streams'. The common names were in the 6th century BC. already traditional. In addition, the names are not a Greek dialect. The reason for deviant forms is to make them resemble other words and to construct an original form.

*Zas resembles ''Zeus''. One explanation is association with the prefix ''za''- 'very', as in ''zatheos'' 'very divine'. An alternative is that the Sky deity

The sky often has important religious significance. Many polytheistic religions have deities associated with the sky.

The daytime sky deities are typically distinct from the nighttime ones. Stith Thompson's ''Motif-Index of Folk-Literature'' ...

is thus connected with the Earth Goddess

Earth is the third planet from the Sun and the only astronomical object known to Planetary habitability, harbor life. This is enabled by Earth being an ocean world, the only one in the Solar System sustaining liquid surface water. Almost all ...

''Gê''. Namely, the Cypriot form is ''Zã''. A third interpretation is based on the genitive form ''Zantos''. Pherecydes' father Babys came from Cilicia

Cilicia () is a geographical region in southern Anatolia, extending inland from the northeastern coasts of the Mediterranean Sea. Cilicia has a population ranging over six million, concentrated mostly at the Cilician plain (). The region inclu ...

, where the Luwian

Luwian (), sometimes known as Luvian or Luish, is an ancient language, or group of languages, within the Anatolian branch of the Indo-European language family. The ethnonym Luwian comes from ''Luwiya'' (also spelled ''Luwia'' or ''Luvia'') – ...

god Šanta was known as Sandes and Sandon. The Hittites

The Hittites () were an Anatolian peoples, Anatolian Proto-Indo-Europeans, Indo-European people who formed one of the first major civilizations of the Bronze Age in West Asia. Possibly originating from beyond the Black Sea, they settled in mo ...

identified it as the sky god, and the Greeks as Zeus or Heracles. Based on Zeus and Sandon with their associations, Pherecydes constructed a basic form with ''Zas''-''Zantos''. Zas (Zeus) is comparable with the Orphic Eros

Eros (, ; ) is the Greek god of love and sex. The Romans referred to him as Cupid or Amor. In the earliest account, he is a primordial god, while in later accounts he is the child of Aphrodite.

He is usually presented as a handsome young ma ...

in function, as a personification of masculine sexual creativity. According to Proclus

Proclus Lycius (; 8 February 412 – 17 April 485), called Proclus the Successor (, ''Próklos ho Diádokhos''), was a Greek Neoplatonist philosopher, one of the last major classical philosophers of late antiquity. He set forth one of th ...

, "Pherecydes used to say that Zeus changed into Eros when about to create, for the reason that, having created the world from opposites, he led it into agreement and peace and sowed sameness in all things, and unity that interpenetrates the universe".

*Chronos as time, the creator god, was unusual and is probably Eastern in origin. Phoenician myths and Zoroastrianism have a deified Time ( Zurvan) that also creates without a partner with its seed, but leaves the concrete design of the physical world to another god. The semen (seeds) of Chronos which can probably be considered as a ''watery chaos'' was placed in the recesses and composed numerous other offspring of gods. This is described in a fragment preserved in Damascius

Damascius (; ; 462 – after 538), known as "the last of the Athenian Neoplatonists", was the last scholarch of the neoplatonic Athenian school. He was one of the neoplatonic philosophers who left Athens after laws confirmed by emperor Jus ...

' ''On First Principles''. In later Greek poetry, Chronos (also called Aiōn) appears as personification

Personification is the representation of a thing or abstraction as a person, often as an embodiment or incarnation. In the arts, many things are commonly personified, including: places, especially cities, National personification, countries, an ...

. Some Pherecydes fragments say ''Kronos'', not ''Chronos''. The association between the two figures is not traditional but may be correct. According to Hermias and Probus, Pherecydes did connect Chronos with Kronos, perhaps on etymological grounds. After him Pindar

Pindar (; ; ; ) was an Greek lyric, Ancient Greek lyric poet from Thebes, Greece, Thebes. Of the Western canon, canonical nine lyric poets of ancient Greece, his work is the best preserved. Quintilian wrote, "Of the nine lyric poets, Pindar i ...

and Hellenistic orphism did this too.

*Chthoniê comes from ''chthôn'' 'earth' and ''chthonios'' 'in/under the earth'. It concerns the invisible part of the dark, primitive earth mass. ''Gê'', on the other hand, refers to the visible, differentiated Earth's surface

Earth is the third planet from the Sun and the only astronomical object known to Planetary habitability, harbor life. This is enabled by Earth being an ocean world, the only one in the Solar System sustaining liquid surface water. Almost all ...

. Chthoniê's role is related to myths about Cybele

Cybele ( ; Phrygian: ''Matar Kubileya, Kubeleya'' "Kubeleya Mother", perhaps "Mountain Mother"; Lydian: ''Kuvava''; ''Kybélē'', ''Kybēbē'', ''Kybelis'') is an Anatolian mother goddess; she may have a possible forerunner in the earliest ...

in western Anatolia. Herodotus

Herodotus (; BC) was a Greek historian and geographer from the Greek city of Halicarnassus (now Bodrum, Turkey), under Persian control in the 5th century BC, and a later citizen of Thurii in modern Calabria, Italy. He wrote the '' Histori ...

uses ''chthoniai theai'' as a name for Demeter

In ancient Greek religion and Greek mythology, mythology, Demeter (; Attic Greek, Attic: ''Dēmḗtēr'' ; Doric Greek, Doric: ''Dāmā́tēr'') is the Twelve Olympians, Olympian goddess of the harvest and agriculture, presiding over cro ...

( mother earth) and her daughter Persephone

In ancient Greek mythology and Ancient Greek religion, religion, Persephone ( ; , classical pronunciation: ), also called Kore ( ; ) or Cora, is the daughter of Zeus and Demeter. She became the queen of the Greek underworld, underworld afte ...

. Pherecydes probably regarded Chthoniê as 'mother of the gods'. Hesiod

Hesiod ( or ; ''Hēsíodos''; ) was an ancient Greece, Greek poet generally thought to have been active between 750 and 650 BC, around the same time as Homer.M. L. West, ''Hesiod: Theogony'', Oxford University Press (1966), p. 40.Jasper Gr ...

described Tartaros as being "in a recess (''muchos'') of broad-wayed earth". Hermann S. Schibli thinks the five ''muchoi'' were actually harboured within Chthonie, or at least were so initially when Chronos disposed his seed in the five "nooks". A close relationship is thought to exist between these recesses and Chthonie.

*Ogenos, Okeanos/Oceanus. This non-Greek name is explained by the Akkadian ''uginna''(circle) because Oceanus encircles the earth, or with the Aramaic

Aramaic (; ) is a Northwest Semitic language that originated in the ancient region of Syria and quickly spread to Mesopotamia, the southern Levant, Sinai, southeastern Anatolia, and Eastern Arabia, where it has been continually written a ...

''ôganâ'' 'basin' or ''ôgen'' 'edge/band/edging'. This Eastern influence has been suggested by assuming that Pherecydes knew of a world map

A world map is a map of most or all of the surface of Earth. World maps, because of their scale, must deal with the problem of projection. Maps rendered in two dimensions by necessity distort the display of the three-dimensional surface of t ...

such as the Babylonian world map Babylonian may refer to:

* Babylon, a Semitic Akkadian city/state of ancient Mesopotamia founded in 1894 BC

* Babylonia, an ancient Akkadian-speaking Semitic nation-state and cultural region based in central-southern Mesopotamia (present-day Iraq)

...

. Finally, the non-traditional Greek "abodes of Ogenos" ("Ogenou dómata") are parts of the earth covering Chthoniê, and resemble the regions beyond the ocean on the Babylonian map.

Cosmogony

The sequence of Pherecydes' cosmogony begins with the eternal gods Zas (Zeus), Chthoniê (Gê) and Chronos (Kronos), who "always existed." The first creation is an act of ordering in the cosmos through niches and division of the world. That creation coincides with the dichotomy of eternity-temporality and being-becoming. Chronos must step out of eternity to create, and creation means becoming. Later onPlato

Plato ( ; Greek language, Greek: , ; born BC, died 348/347 BC) was an ancient Greek philosopher of the Classical Greece, Classical period who is considered a foundational thinker in Western philosophy and an innovator of the writte ...

also used the distinction between eternal being and temporal genesis. This is opposed to the older cosmogony

Cosmogony is any model concerning the origin of the cosmos or the universe.

Overview

Scientific theories

In astronomy, cosmogony is the study of the origin of particular astrophysical objects or systems, and is most commonly used in ref ...

of Hesiod

Hesiod ( or ; ''Hēsíodos''; ) was an ancient Greece, Greek poet generally thought to have been active between 750 and 650 BC, around the same time as Homer.M. L. West, ''Hesiod: Theogony'', Oxford University Press (1966), p. 40.Jasper Gr ...

(8th–7th century BCE) where the initial state of the universe is Chaos, a dark void considered as a divine primordial condition and the creation is ''ex nihilo

(Latin, 'creation out of nothing') is the doctrine that matter is not eternal but had to be created by some divine creative act. It is a theistic answer to the question of how the universe came to exist. It is in contrast to ''creatio ex mate ...

'' (out of nothing).

The titles ''Penta''-/''Heptamychos'' and ''Theokrasia'' of the work indicate that niches (''mychoi'') and mixing are an important part of the creation story. Pherecydes first identified five niches (''mychoi''). If there were five niches in the story, they correspond to the five parts ('' moirai'') of the cosmos: the sea, underworld and heaven (the homer

Homer (; , ; possibly born ) was an Ancient Greece, Ancient Greek poet who is credited as the author of the ''Iliad'' and the ''Odyssey'', two epic poems that are foundational works of ancient Greek literature. Despite doubts about his autho ...

ic three-part division), plus the earth and Mount Olympus

Mount Olympus (, , ) is an extensive massif near the Thermaic Gulf of the Aegean Sea, located on the border between Thessaly and Macedonia (Greece), Macedonia, between the regional units of Larissa (regional unit), Larissa and Pieria (regional ...

. Therefore Damascius calls the five niches 'five worlds' and the ''Suda'' mentions the alternative title ''Pentamychos''. Once Chronos fills them to create the worlds, they turn into the five cosmic regions ("moirai") Uranus

Uranus is the seventh planet from the Sun. It is a gaseous cyan-coloured ice giant. Most of the planet is made of water, ammonia, and methane in a Supercritical fluid, supercritical phase of matter, which astronomy calls "ice" or Volatile ( ...

("heaven"), Tartarus, Chaos, Ether

In organic chemistry, ethers are a class of compounds that contain an ether group, a single oxygen atom bonded to two separate carbon atoms, each part of an organyl group (e.g., alkyl or aryl). They have the general formula , where R and R� ...

/Aer (“sky”) and Nyx (“night”). According to Porphyry, there were all kinds of caves and gates in the world. In classical antiquity

Classical antiquity, also known as the classical era, classical period, classical age, or simply antiquity, is the period of cultural History of Europe, European history between the 8th century BC and the 5th century AD comprising the inter ...

caves were associated with sexuality and birth. However, the niches here are not stone caves in mountains, because the world has yet to be shaped. They are cavities in the still primitive, undifferentiated mass of the Earth. At an early stage, Chronos creates with his seed the three elements fire, air (''pneuma'') and water. The Earth element already existed with Chthoniê. Warmth, humidity and 'airiness' were according to Ancient Greek medicine

Ancient Greek medicine was a compilation of theories and practices that were constantly expanding through new ideologies and trials. The Greek term for medicine was ''iatrikē'' (). Many components were considered in Ancient Greece, ancient Greek ...

three properties of seed, and through those principles the embryo developed. The first three concepts are traditional and appear in the Pherecydes fragments (eg fragment DK 7 B4 below). Poets like Probus and Hermias, equated Pherecydes' Zas with Aether because since Zeus is the Greek sky god

The sky often has important religious significance. Many polytheism, polytheistic religions have deity, deities associated with the sky.

The daytime sky deities are typically distinct from the nighttime ones. Stith Thompson's ''Motif-Index o ...

, he would have had Aether as his domain. The title ''Heptamychos'' in the ''Suda'' is explained by including Gê and Ogenos (hepta = seven). Pherecydes writes that Tartarus lies below the earth ("gê"), so that gê is therefore considered a separate region that could be seen.

Fire, air and water are placed in the niches by Chronos and mixed (''krasis''). Mixing elements in five niches only makes sense if those mixtures are in different proportions. Contrary to later philosophy of Anaxagoras

Anaxagoras (; , ''Anaxagóras'', 'lord of the assembly'; ) was a Pre-Socratic Greek philosopher. Born in Clazomenae at a time when Asia Minor was under the control of the Persian Empire, Anaxagoras came to Athens. In later life he was charged ...

, the world is not created from the mixtures, but a second generation of gods (''theokrasia)'', including Ophion. The formed gods derive their characteristics from the dominant element in each mixture and possibly associate them with the five regions. The elements may also be a later, stoic

Stoic may refer to:

* An adherent of Stoicism

Stoicism is a school of Hellenistic philosophy that flourished in ancient Greece and Rome. The Stoics believed that the universe operated according to reason, ''i.e.'' by a God which is immersed i ...

reinterpretation of the text, as the elements, especially air/pneuma, appear anachronistic and fit within Aristotelian and Stoic physiology

Physiology (; ) is the science, scientific study of function (biology), functions and mechanism (biology), mechanisms in a life, living system. As a branches of science, subdiscipline of biology, physiology focuses on how organisms, organ syst ...

. That means Chronos' seed will go straight into the niches. This representation is possible, because in a scholium at the ''Iliad

The ''Iliad'' (; , ; ) is one of two major Ancient Greek epic poems attributed to Homer. It is one of the oldest extant works of literature still widely read by modern audiences. As with the ''Odyssey'', the poem is divided into 24 books and ...

'', for example, it says that Chronos smeared two eggs with his seed and gave it to Hera. She had to keep the eggs underground (''kata gês'') so that Typhon

Typhon (; , ), also Typhoeus (; ), Typhaon () or Typhos (), was a monstrous serpentine giant and one of the deadliest creatures in Greek mythology. According to Hesiod, Typhon was the son of Gaia and Tartarus. However, one source has Typhon as t ...

was born, the enemy of Zeus. Typhon is a parallel of Pherecydes' serpent god Ophion.

Marriage between Zas and Chthoniê

It is quite possible that in the course of the theogony the primeval trio changed into the traditional Zeus, Kronos and Hera. Such changes have Orphic parallels: Rhea is Demeter after she becomes Zeus' mother, and Phanes simultaneously becomes Zeus andEros

Eros (, ; ) is the Greek god of love and sex. The Romans referred to him as Cupid or Amor. In the earliest account, he is a primordial god, while in later accounts he is the child of Aphrodite.

He is usually presented as a handsome young ma ...

. In Pherecydes, Chthoniê becomes Gê through marriage, after which she becomes the protector of the marriage, and that was traditionally the domain of Hera. Hera is also associated with the earth in some sources.

The marriage of the gods is a union (''hieros gamos

''Hieros gamos'', (from and 'marriage') or hierogamy (, 'holy marriage') is a sacred marriage that takes place between gods, especially when enacted in a symbolic ritual where human participants represent the deities.

The notion of ''hieros ...

'') where Zas makes a robe (''pharos'') depicting Gaia and Ogenos. This is an allegory for the acts of creation (''mellonta dêmiourgein''). Zas is a demiurge

In the Platonic, Neopythagorean, Middle Platonic, and Neoplatonic schools of philosophy, the Demiurge () is an artisan-like figure responsible for fashioning and maintaining the physical universe. Various sects of Gnostics adopted the term '' ...

and creates by turning into Eros. The robe is a covering, namely of Chthoniê, the earth's mass, thus taking as its domain the varied surface of the earth and the encircling ocean. Marriage is also etiological

Etiology (; alternatively spelled aetiology or ætiology) is the study of causation or origination. The word is derived from the Greek word ''()'', meaning "giving a reason for" (). More completely, etiology is the study of the causes, origin ...

, because it explains the origin of the ritual unveiling of the bride (''anakalypteria''). The cloth makes Chthoniê vivid and alive. She is the base matter, but Gê is the form of it.

The robe hangs on a winged oak. This passage is unique and has several interpretations. The robust oak was traditionally dedicated to Zeus and presumably indicates the solid structure and foundation of the earth. The roots and branches support the earth's surface. Below is Tartarus, and above it, according to Hesiod, grow "the ''roots'' of the earth and the barren sea". Pherecydes followed this archaic representation. The wings refer to the broad spreading branches of the oak. Over this hangs the cloth, which as the earth's surface is thus both smooth and varied in shape. The robe as a mythical image for the earth's surface also appears in some Orphic texts. In the ''Homeric Hymn to Demeter'', Persephone

In ancient Greek mythology and Ancient Greek religion, religion, Persephone ( ; , classical pronunciation: ), also called Kore ( ; ) or Cora, is the daughter of Zeus and Demeter. She became the queen of the Greek underworld, underworld afte ...

is weaving a rich robe representing the cosmos when she is carried off by Hades

Hades (; , , later ), in the ancient Greek religion and Greek mythology, mythology, is the god of the dead and the king of the Greek underworld, underworld, with which his name became synonymous. Hades was the eldest son of Cronus and Rhea ...

to the underworld.Finally, the proverb 'The face of the earth is the garment of Persephone' is in the style of early Pythagoreans, who had sayings like 'tears of Zeus' for rain and 'The sea is the tear of Kronos'.

The mythical images of the tree as an earthly structure and a robe as a gift at marriage have Greek cultic counterparts. In Plataeae, for example, the Daedala festival was celebrated, in which an oak was cut down to make a statue of a girl dressed as a bride. Zeus gave Persephone

In ancient Greek mythology and Ancient Greek religion, religion, Persephone ( ; , classical pronunciation: ), also called Kore ( ; ) or Cora, is the daughter of Zeus and Demeter. She became the queen of the Greek underworld, underworld afte ...

Sicily

Sicily (Italian language, Italian and ), officially the Sicilian Region (), is an island in the central Mediterranean Sea, south of the Italian Peninsula in continental Europe and is one of the 20 regions of Italy, regions of Italy. With 4. ...

or Thebes, while Cadmus

In Greek mythology, Cadmus (; ) was the legendary Phoenician founder of Boeotian Thebes, Greece, Thebes. He was, alongside Perseus and Bellerophon, the greatest hero and slayer of monsters before the days of Heracles. Commonly stated to be a ...

gave a robe to Harmonia

In Greek mythology, Harmonia (; /Ancient Greek phonology, harmoˈnia/, "harmony", "agreement") is the goddess of harmony and concord. Her Greek opposite is Eris (mythology), Eris and her Roman mythology, Roman counterpart is Concordia (mythol ...

. Still, the images may be oriental in origin. There are Mesopotamian

Mesopotamia is a historical region of West Asia situated within the Tigris–Euphrates river system, in the northern part of the Fertile Crescent. Today, Mesopotamia is known as present-day Iraq and forms the eastern geographic boundary o ...

parallels of the palace with a complex of spaces reserved for the bride and groom is built. There are also myths such as the one in which Anu takes heaven as his portion, whereupon Enlil

Enlil, later known as Elil and Ellil, is an List of Mesopotamian deities, ancient Mesopotamian god associated with wind, air, earth, and storms. He is first attested as the chief deity of the Sumerian pantheon, but he was later worshipped by t ...

takes the earth and gives it as a dowry to Ereshkigal

In Mesopotamian mythology, Ereshkigal (Sumerian language, Sumerian: 𒀭𒊩𒌆𒆠𒃲 REŠ.KI.GAL, lit. "Queen of the Great Earth") was the goddess of Kur, the land of the dead or underworld in Sumerian religion, Sumerian mythology. In la ...

, 'mistress of the great deep' (''chthoniê'').

Theomachy

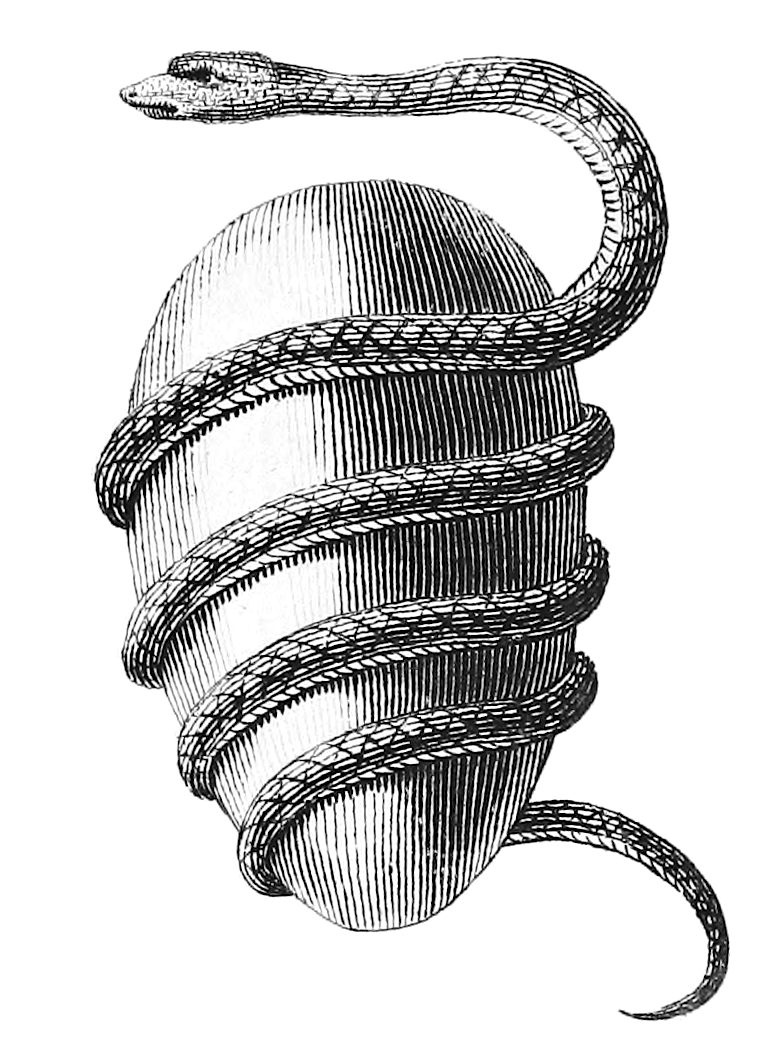

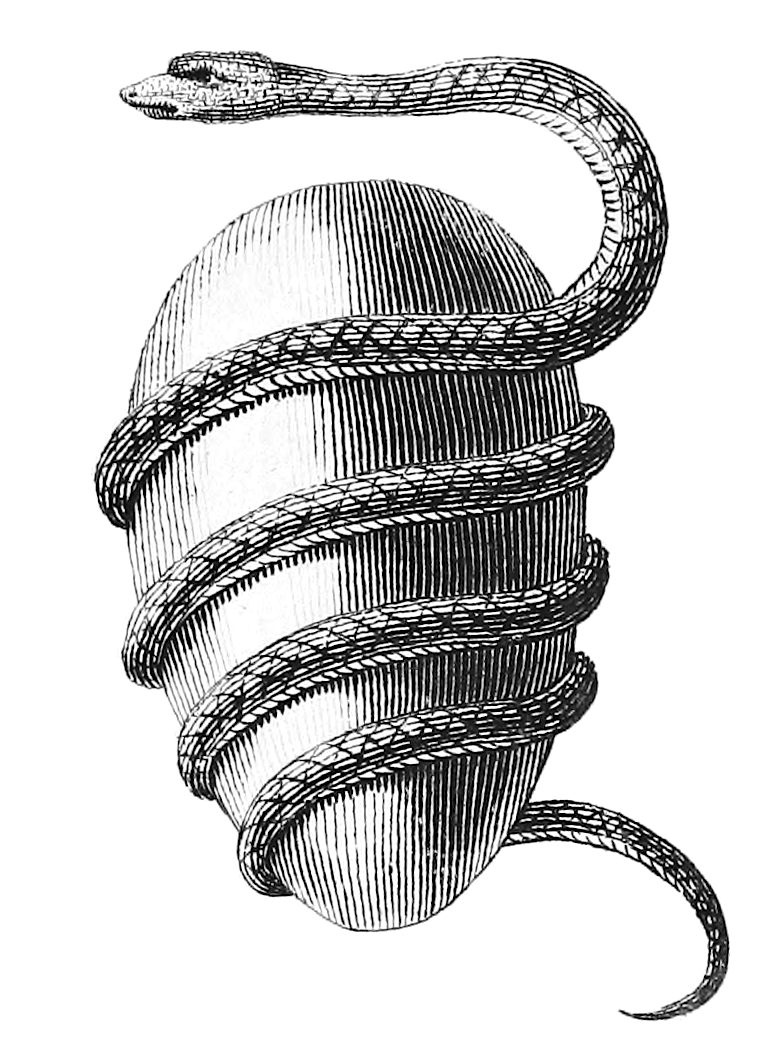

Pherecydes described a battle between Kronos and Ophion similar to that of Zeus andTyphon

Typhon (; , ), also Typhoeus (; ), Typhaon () or Typhos (), was a monstrous serpentine giant and one of the deadliest creatures in Greek mythology. According to Hesiod, Typhon was the son of Gaia and Tartarus. However, one source has Typhon as t ...

in Hesiod's older "Theogony". The stake of the battle is cosmic supremacy and is reminiscent of the Titanomachy

In Greek mythology, the Titanomachy (; ) was a ten-year war fought in ancient Thessaly, consisting of most of the Titans (the older generation of gods, based on Mount Othrys) fighting against the Twelve Olympians, Olympians (the younger generati ...

and Gigantomachy of traditional theogony, in which the successive conflicts between gods are described with the current world order as a result. In Pherecydes' cosmogony, however, no initial chaos or tyranny is overcome, followed by the establishment of a new order. The creative gods are eternal and co-equal. Their order is temporarily threatened by Ophion, but that threat becomes a (re)affirmation of the divine order, with Kronos as the first king. The battle is also etiological, for it explained the myths about ancient sea monsters in both Greece and Asia Minor

Anatolia (), also known as Asia Minor, is a peninsula in West Asia that makes up the majority of the land area of Turkey. It is the westernmost protrusion of Asia and is geographically bounded by the Mediterranean Sea to the south, the Aegean ...

and the Middle East

The Middle East (term originally coined in English language) is a geopolitical region encompassing the Arabian Peninsula, the Levant, Turkey, Egypt, Iran, and Iraq.

The term came into widespread usage by the United Kingdom and western Eur ...

. The battle is described by Celsus

Celsus (; , ''Kélsos''; ) was a 2nd-century Greek philosopher and opponent of early Christianity. His literary work '' The True Word'' (also ''Account'', ''Doctrine'' or ''Discourse''; Greek: )Hoffmann p.29 survives exclusively via quotati ...

:

'Pherecydes told the myth that an army was lined up against army, and he mentioned Kronos as leader of one, Ophion of the other, and he related their challenges and struggles, and that they agreed that the one who fell into Ogenos was the loser, while those who cast them out and conquered should possess the sky'.Chronos has become Kronos here. Presumably, as a prominent second creator, Zas also participates in the battle, after which he becomes Zeus. Ophion did not exist from the beginning but was born and had progeny of his own ( ''Ophionidai''). He is serpentine, because his name is derived from ''ophis'' 'snake'. Traditionally, Gaia (Gê) was regarded as the mother of Typhon, and Chthoniê/Gê may be the mother of Ophion here. Ophion may also have been produced on her own in Tartarus, the cave under the earth. Typhon also originated in a cave. Otherwise the father may be Chronos, because his seed is the niches of the earth. Ophion and its brood are often depicted as ruling the birthing cosmos for some time before falling from power. The chaotic forces are eternal and cannot be destroyed; instead they are thrown out from the ordered world and locked away in Tartaros in a kind of "appointment of the spheres", in which the victor (Zeus-Cronus) takes possession of the sky and of space and time. Cronus (or Zeus in the more popularly known version) orders the offspring out from the cosmos to Tartaros. There they are kept behind locked gates, fashioned in iron and bronze. We are told about chaotic beings put into the pentemychos, and we are told that the Darkness has an offspring that is cast into the recesses of Tartaros. No surviving fragment makes the connection, but it is possible that the prison-house in Tartaros and the pentemychos are ways of referring to the essentially same thing. According to

Celsus

Celsus (; , ''Kélsos''; ) was a 2nd-century Greek philosopher and opponent of early Christianity. His literary work '' The True Word'' (also ''Account'', ''Doctrine'' or ''Discourse''; Greek: )Hoffmann p.29 survives exclusively via quotati ...

, Pherecydes said that: "Below that portion is the portion of Tartaros; the daughters of Boreas (the north wind), the Harpies and Thuella (Storm), guard it; there Zeus banished any of the gods whenever one behaves with insolence." Thus the identity between Zeus' prison-house and the pentemychos seems likely. Judging from some ancient fragments Ophion is thrown into Oceanus

In Greek mythology, Oceanus ( ; , also , , or ) was a Titans, Titan son of Uranus (mythology), Uranus and Gaia, the husband of his sister the Titan Tethys (mythology), Tethys, and the father of the River gods (Greek mythology), river gods ...

, not into Tartaros. Exactly what entities or forces that were locked away in Pherecydes’ story cannot be known for sure. There may have been five principal figures. Ophion and Typhon are one and the same, and Eurynome

Eurynomê (; Ancient Greek: Εὐρυνόμη, from , ''eurys'', "broad" and , ''nomos'', "pasture" or "law") is a name that refers to the following characters in Greek mythology:

* Eurynome, pre-Olympian queen and wife of Ophion

* Eurynome (Oce ...

fought on the side of Ophion against Cronus. Chthonie is a principal "thing" of the underworld, but whether she is to be counted as one of the five or the five "sum-total" is an open question. Apart from these it is known that Ophion-Typhon mated with Echidna

Echidnas (), sometimes known as spiny anteaters, are quill-covered monotremes (egg-laying mammals) belonging to the Family (biology), family Tachyglossidae , living in Australia and New Guinea. The four Extant taxon, extant species of echidnas ...

, and that Echidna herself was somehow mysteriously "produced" by Callirhoe. If Pherecydes counted five principal entities in association the pentemychos doctrine, then Ophion, Eurynome, Echidna, Calirrhoe and Chthonie are the main contenders.

Legacy

Pherycydes is seen as a transitional figure between the mythological cosmogonies of

Pherycydes is seen as a transitional figure between the mythological cosmogonies of Hesiod

Hesiod ( or ; ''Hēsíodos''; ) was an ancient Greece, Greek poet generally thought to have been active between 750 and 650 BC, around the same time as Homer.M. L. West, ''Hesiod: Theogony'', Oxford University Press (1966), p. 40.Jasper Gr ...

and the first pre-Socratic philosophers. Aristotle wrote in his ''Metaphysics

Metaphysics is the branch of philosophy that examines the basic structure of reality. It is traditionally seen as the study of mind-independent features of the world, but some theorists view it as an inquiry into the conceptual framework of ...

'' that Pherecydes was partially a mythological writer and Plutarch, in his ''Parallel Lives

*

Culture of ancient Greece

Culture of ancient Rome

Ancient Greek biographical works

Ethics literature

History books about ancient Rome

Cultural depictions of Gaius Marius

Cultural depictions of Mark Antony

Cultural depictions of Cicero

...

'', instead wrote of him being a theologian. Pherecydes contributed to pre-Socratic philosophy of nature by denying that nothing comes from nothing and describing the mixture of three elements. Mixture (''krasis'') plays a role in later cosmologies, such as that of Anaxagoras

Anaxagoras (; , ''Anaxagóras'', 'lord of the assembly'; ) was a Pre-Socratic Greek philosopher. Born in Clazomenae at a time when Asia Minor was under the control of the Persian Empire, Anaxagoras came to Athens. In later life he was charged ...

, Plato

Plato ( ; Greek language, Greek: , ; born BC, died 348/347 BC) was an ancient Greek philosopher of the Classical Greece, Classical period who is considered a foundational thinker in Western philosophy and an innovator of the writte ...

('' Timaeus'') and in the Orphic poem ''Krater'' attributed to the Pythagorean philosopher Zopyrus of Tarentum.

Pythagoreanism

Out of all of the philosophers who were historical predecessors of Pythagoras, Pherycydes was the philosopher most often linked with him as one of his teachers. Not many prose treatises existed in the 6th century, Pythagoras may have learned of Pherecydes' work and adopted the idea of reincarnation. In Pythagoras' youth, when he still lived onSamos

Samos (, also ; , ) is a Greek island in the eastern Aegean Sea, south of Chios, north of Patmos and the Dodecanese archipelago, and off the coast of western Turkey, from which it is separated by the Mycale Strait. It is also a separate reg ...

, he is said to have visited Pherecydes on Delos

Delos (; ; ''Dêlos'', ''Dâlos''), is a small Greek island near Mykonos, close to the centre of the Cyclades archipelago. Though only in area, it is one of the most important mythological, historical, and archaeological sites in Greece. ...

and later buried him. An early variant of this story places this event later in Pythagoras' life when he lived in Croton. His visit to the sick Pherecydes was used to explain his absence during Cylon's rebellion in that city. These stories may have evolved from the story that Pythagoras was a student of Pherecydes. According to Apollonius, Pythagoras imitated Pherecydes in his 'miracles'. The historicity of the connection between the two has been debated, however, because their philosophies are otherwise unrelated, and because Pythagoras has been attributed all kinds of teachers over time. The confusion among later authors about the attribution of the miracles can perhaps be traced back to the poem of Ion of Chios

Ion of Chios (; ; c. 490/480 – c. 420 BC) was a Greek writer, dramatist, lyric poet and philosopher. He was a contemporary of Aeschylus, Euripides and Sophocles. Of his many plays and poems only a few titles and fragments have survived. He also ...

. Aristotle nevertheless stated in the 4th century BC

The 4th century BC started the first day of 400 BC and ended the last day of 301 BC. It is considered part of the Classical antiquity, Classical era, Epoch (reference date), epoch, or historical period.

This century marked the height of Classi ...

that both were friends, and the story already about their friendship certainly dates back to the 5th century BC

The 5th century BC started the first day of 500 BC and ended the last day of 401 BC.

This century saw the establishment of Pataliputra as a capital of the Magadha (Mahajanapada), Magadha Empire. This city would later become the ruling capital o ...

. It is believed that both philosophers once met.

Pherecydes' book was thought to have contained a mystical esoteric teaching, treated allegorically. A comparatively large number of sources say Pherecydes was the first to teach the Pythagorean

Pythagorean, meaning of or pertaining to the ancient Ionian mathematician, philosopher, and music theorist Pythagoras, may refer to:

Philosophy

* Pythagoreanism, the esoteric and metaphysical beliefs purported to have been held by Pythagoras

* Ne ...

doctrine of metempsychosis

In philosophy and theology, metempsychosis () is the transmigration of the soul, especially its reincarnation after death. The term is derived from ancient Greek philosophy, and has been recontextualized by modern philosophers such as Arthur Sc ...

, the transmigration of human souls. Both Cicero

Marcus Tullius Cicero ( ; ; 3 January 106 BC – 7 December 43 BC) was a Roman statesman, lawyer, scholar, philosopher, orator, writer and Academic skeptic, who tried to uphold optimate principles during the political crises tha ...

and Augustine

Augustine of Hippo ( , ; ; 13 November 354 – 28 August 430) was a theologian and philosopher of Berber origin and the bishop of Hippo Regius in Numidia, Roman North Africa. His writings deeply influenced the development of Western philosop ...

thought of him having given the first teaching of the "immortality of the soul". The Christian

A Christian () is a person who follows or adheres to Christianity, a Monotheism, monotheistic Abrahamic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus in Christianity, Jesus Christ. Christians form the largest religious community in the wo ...

Apponius mentioned Pherecydes' belief in metempsychosis in his argument against murder and executions because a good life is rewarded and a bad life is punished in the afterlife. The Middle Platonist Numenius, like Apponius, referred to the idea that the soul enters the body through the seed, and mentions a river in Pherecydes' representation of the underworld. The Neoplatonist Porphyry added 'corners, pits, caves, doors and gates' through which souls travel. Finally, the orator Themistius

Themistius ( ; 317 – c. 388 AD), nicknamed Euphrades (, "''eloquent''"), was a statesman, rhetorician and philosopher. He flourished in the reigns of Constantius II, Julian, Jovian, Valens, Gratian and Theodosius I, and he enjoyed the favo ...

reported that Pherecydes, like Pythagoras, considered killing a great sin. This suggests that impure deeds in a next life or after death must be expiated. Pherecydes may have regarded the soul as at least an immortal part of the sky or aether. That he was the first to teach such a thing is doubtful, but Schibli concludes that Pherecydes like "included in his book Pentemychos"at least a rudimentary treatment of the immortality of the soul, its wanderings in the underworld, and the reasons for the soul’s incarnations".

Similarities with other cosmogonies

The theogony of Pherecydes also shows similarities with Orphic theogonies such as the ''Orphic Hymns

The ''Orphic Hymns'' are a collection of eighty-seven ancient Greek hymns addressed to various deities, which were attributed in antiquity to the mythical poet Orpheus. They were composed in Asia Minor (located in modern-day Turkey), most likel ...

''. Both feature primordial serpents, the weaving of a cosmic robe and eternal Time as god who creates with his own seed by masturbation. Such Orphic aspects also appear in Epimenides' ''Theogony''. Pherecydes probably influenced the early Orphics, or possibly an earlier sect of Orphic practitioners influenced him. The battle between Kronos and Ophion also influenced the ''Bibliotheca'' of pseudo-Apollodorus, who drew on several previous theogonies, such as those of Hesiod and the Orphic religion. The story was also a source for the ''Argonautica

The ''Argonautica'' () is a Greek literature, Greek epic poem written by Apollonius of Rhodes, Apollonius Rhodius in the 3rd century BC. The only entirely surviving Hellenistic civilization, Hellenistic epic (though Aetia (Callimachus), Callim ...

'' by Apollonius of Rhodes

Apollonius of Rhodes ( ''Apollṓnios Rhódios''; ; fl. first half of 3rd century BC) was an ancient Greek literature, ancient Greek author, best known for the ''Argonautica'', an epic poem about Jason and the Argonauts and their quest for the Go ...

, in which Orpheus

In Greek mythology, Orpheus (; , classical pronunciation: ) was a Thracians, Thracian bard, legendary musician and prophet. He was also a renowned Ancient Greek poetry, poet and, according to legend, travelled with Jason and the Argonauts in se ...

sings about Ophion and Eurynome

Eurynomê (; Ancient Greek: Εὐρυνόμη, from , ''eurys'', "broad" and , ''nomos'', "pasture" or "law") is a name that refers to the following characters in Greek mythology:

* Eurynome, pre-Olympian queen and wife of Ophion

* Eurynome (Oce ...

who were overthrown by Kronos and Rhea. The association of Kronos with Chronos by the Greeks can probably also be traced back to Pherecydes. There are also many significant parallels between Pherecydes's cosmogony, Orphic theogonies, and the preserved accounts of Zoroastrian, Phoenician and Vedic cosmogonies. According to West, these myths have a common source that originates in the Levant

The Levant ( ) is the subregion that borders the Eastern Mediterranean, Eastern Mediterranean sea to the west, and forms the core of West Asia and the political term, Middle East, ''Middle East''. In its narrowest sense, which is in use toda ...

. The basic form is as follows. In the beginning there is no heaven and no earth, but a limitless abyss of water, shrouded in deep darkness. This condition has existed for centuries. Then the hermaphrodite and eternal Time makes love to itself. Thus he produces an egg. From that egg appears a radiant creator god, who made it heaven and earth.

Notes

Primary

Secondary

References

Ancient Testimony

In the Diels-Kranz numbering for testimony and fragments ofPre-Socratic philosophy

Pre-Socratic philosophy, also known as early Greek philosophy, is ancient Greek philosophy before Socrates. Pre-Socratic philosophers were mostly interested in cosmology, the beginning and the substance of the universe, but the inquiries of the ...

, Pherecydes of Syros is catalogued as number 7. The most recent edition of this catalogue is

*.

Biography

*A1. *A1a. *A2. *A2a. *A3. *A4. *A5. *A6. *A7. *A7a. *A8. *A9. *A10. *A11. *A12.Fragments

*B1. *B1a. *B2. *B3. *B4. *B5. *B6. *B7. *B8. *B9. *B10. *B11. *B12. *B13. *B13a.Secondary sources

* * * 'The Authors Named Pherecydes'. In: ''Mnemosyne'', volume 52, 1, pp. 1–15. * * * * * * * * *Further reading

* ''Orpheus and Greek Religion. A Study of the Orphic Movement.” Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1993 (1952). *External links

Pherecydes of Syros

by Giannis Stamatellos

Fragments and Life of Pherecydes

at demonax.info

* ttp://www.maicar.com/GML/SevenSages.html The Seven Sages of Greece at Greek Mythology Link {{DEFAULTSORT:Pherecydes Of Syros Cosmogony People from Syros Presocratic philosophers Religious cosmologies Seven Sages of Greece 6th-century BC Greek philosophers