Amazigh Rap on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Berbers, or the Berber peoples, also known as Amazigh or Imazighen, are a diverse grouping of distinct

The

The

Human fossils excavated at the Ifri n'Amr ou Moussa site in Morocco have been

Human fossils excavated at the Ifri n'Amr ou Moussa site in Morocco have been

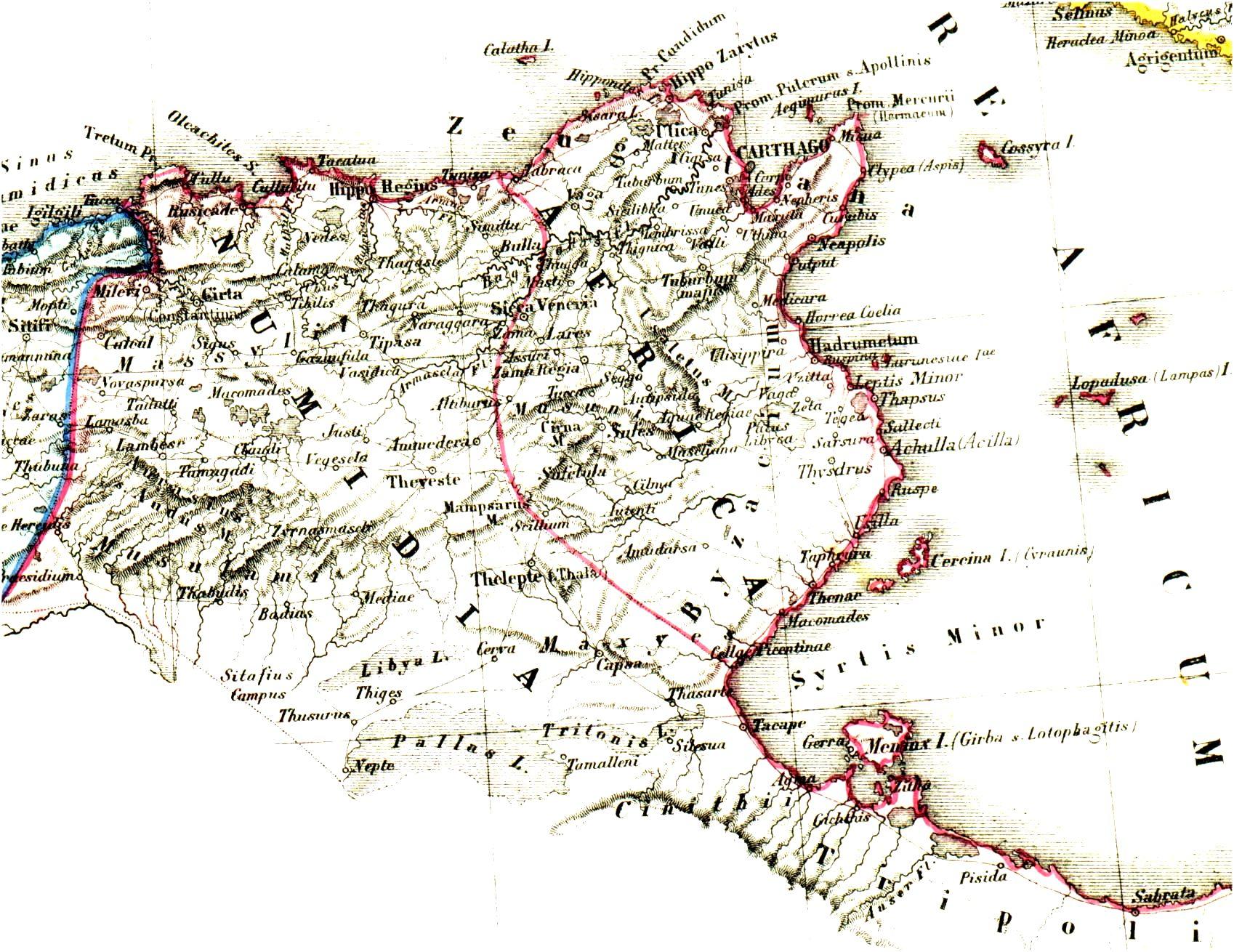

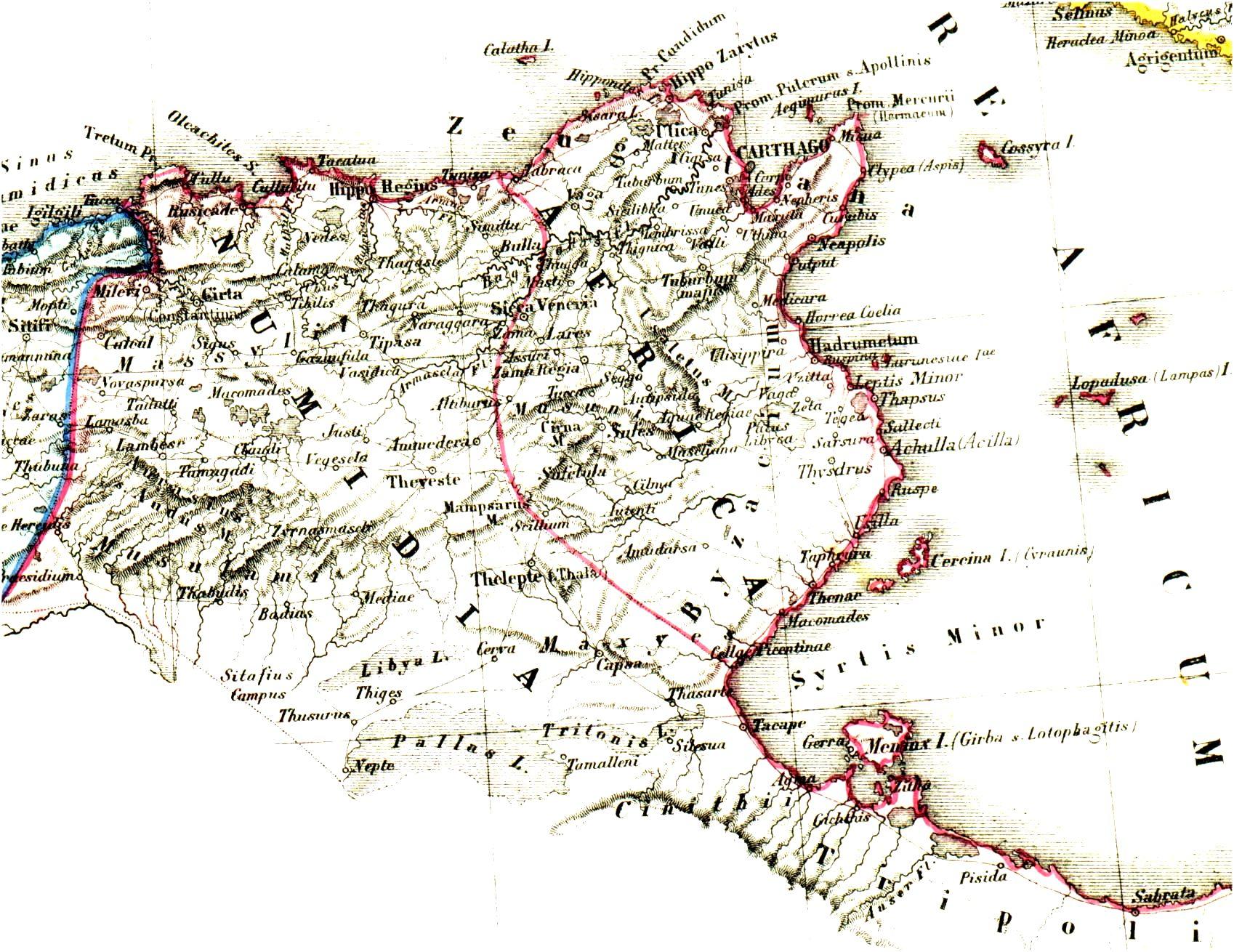

In fact, for a time their numerical and military superiority (the best horse riders of that time) enabled some Berber kingdoms to impose a tribute on Carthage, a condition that continued into the 5th century BC. Also, due to the Berbero-Libyan Meshwesh dynasty's rule of Egypt (945–715 BC), the Berbers near Carthage commanded significant respect (yet probably appearing more rustic than the elegant Libyan pharaohs on the Nile). Correspondingly, in early Carthage, careful attention was given to securing the most favourable treaties with the Berber chieftains, "which included intermarriage between them and the Punic aristocracy". In this regard, perhaps the legend about

In fact, for a time their numerical and military superiority (the best horse riders of that time) enabled some Berber kingdoms to impose a tribute on Carthage, a condition that continued into the 5th century BC. Also, due to the Berbero-Libyan Meshwesh dynasty's rule of Egypt (945–715 BC), the Berbers near Carthage commanded significant respect (yet probably appearing more rustic than the elegant Libyan pharaohs on the Nile). Correspondingly, in early Carthage, careful attention was given to securing the most favourable treaties with the Berber chieftains, "which included intermarriage between them and the Punic aristocracy". In this regard, perhaps the legend about  Yet in times of stress at Carthage, when a foreign force might be pushing against the city-state, some Berbers would see it as an opportunity to advance their interests, given their otherwise low status in Punic society. Thus, when the Greeks under

Yet in times of stress at Carthage, when a foreign force might be pushing against the city-state, some Berbers would see it as an opportunity to advance their interests, given their otherwise low status in Punic society. Thus, when the Greeks under  The Berbers gain historicity gradually during the

The Berbers gain historicity gradually during the

BBC World Service , The Story of Africa some perhaps

Numidia (20246 BC) was an ancient Berber kingdom in modern Algeria and part of Tunisia. It later alternated between being a

Numidia (20246 BC) was an ancient Berber kingdom in modern Algeria and part of Tunisia. It later alternated between being a

According to historians of the Middle Ages, the Berbers were divided into two branches, Butr and Baranis (known also as Botr and Barnès), descended from Mazigh ancestors, who were themselves divided into tribes and subtribes. Each region of the Maghreb contained several fully independent tribes (e.g.,

According to historians of the Middle Ages, the Berbers were divided into two branches, Butr and Baranis (known also as Botr and Barnès), descended from Mazigh ancestors, who were themselves divided into tribes and subtribes. Each region of the Maghreb contained several fully independent tribes (e.g.,  Before the eleventh century, most of Northwest Africa had become a Berber-speaking

Before the eleventh century, most of Northwest Africa had become a Berber-speaking

Just to the west of Aghlabid lands, Abd ar Rahman ibn Rustam ruled most of the central Maghreb from

Just to the west of Aghlabid lands, Abd ar Rahman ibn Rustam ruled most of the central Maghreb from

The Muslims who invaded the

The Muslims who invaded the

New waves of Berber settlers arrived in al-Andalus in the 10th century, brought as mercenaries by Abd ar-Rahman III, who proclaimed himself caliph in 929, to help him in his campaigns to restore Umayyad authority in areas that had overthrown it during the reigns of the previous emirs. These new Berbers "lacked any familiarity with the pattern of relationships" that had existed in al-Andalus in the 700s and 800s; thus they were not involved in the same web of traditional conflicts and loyalties as the previously already existing Berber garrisons.

New frontier settlements were built for the new Berber mercenaries. Written sources state that some of the mercenaries were placed in Calatrava, which was refortified. Another Berber settlement called , west of Toledo, is not mentioned in the historical sources, but has been excavated archaeologically. It was a fortified town, had walls, and a separate fortress or alcazar. Two cemeteries have also been discovered. The town was established in the 900s as a frontier town for Berbers, probably of the Nafza tribe. It was abandoned soon after the Castilian occupation of Toledo in 1085. The Berber inhabitants took all their possessions with them.

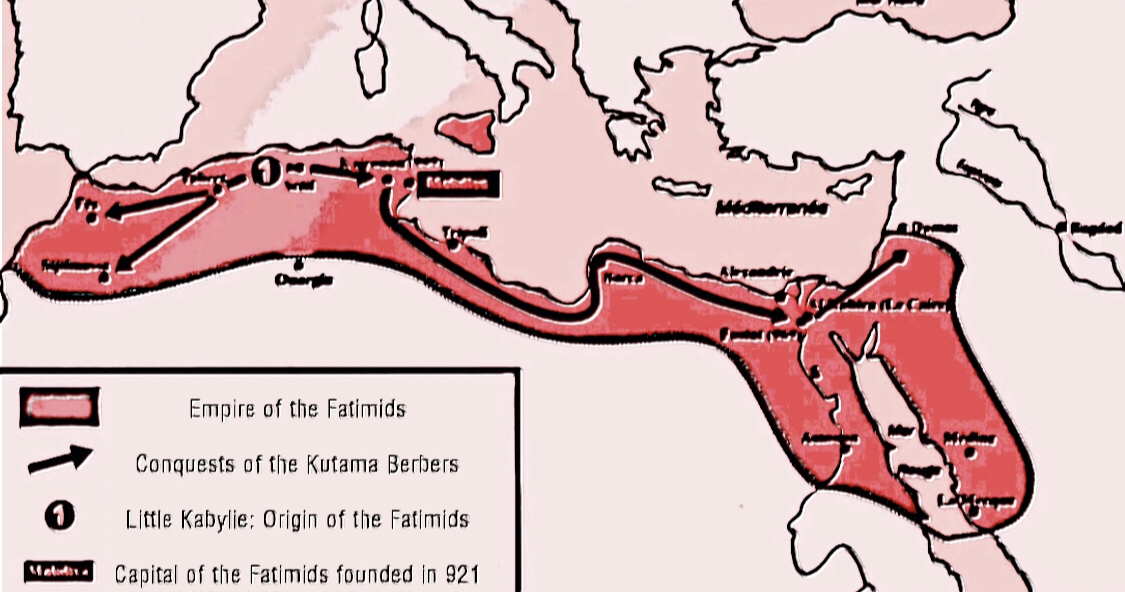

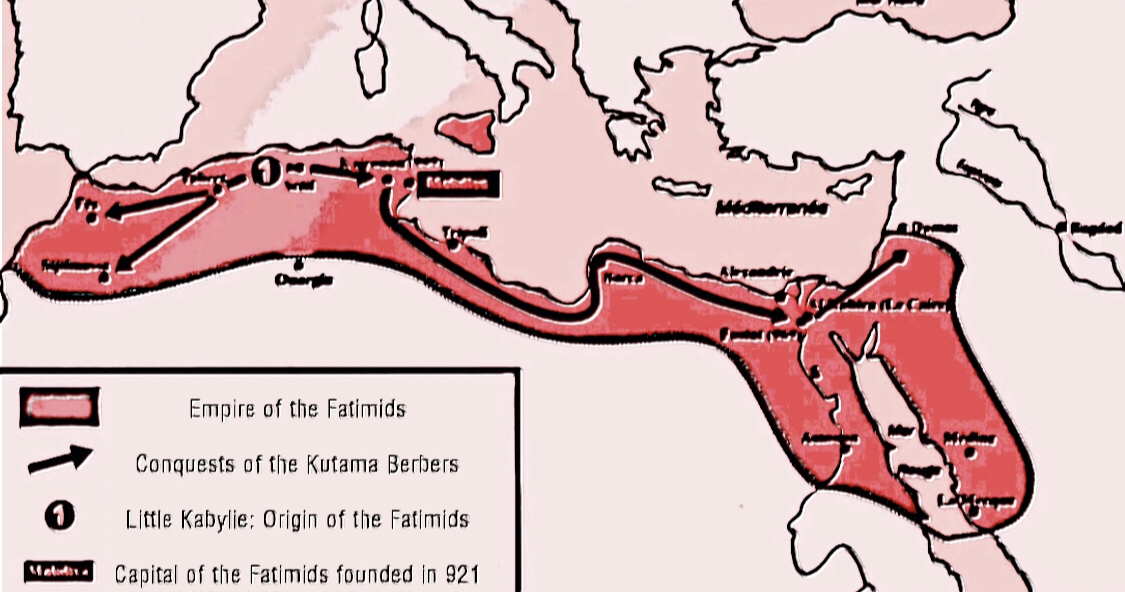

In the 900s, the Umayyad caliphate faced a challenge from the Fatimids in North Africa. The Fatimid Caliphate of the 10th century was established by the Kutama Berbers. After taking the city of Kairouan and overthrowing the Aghlabids in 909, the Mahdi Ubayd Allah was installed by the Kutama as Imam and Caliph, which posed a direct challenge to the Umayyad's own claim. The Fatimids gained overlordship over the Idrisids, then launched a conquest of the Maghreb. To counter the threat, the Umayyads crossed the strait to take Ceuta in 931, and actively formed alliances with Berber confederacies, such as the Zenata and the Awraba. Rather than fighting each other directly, the Fatimids and Umayyads competed for Berber allegiances. In turn, this provided a motivation for the further conversion of Berbers to Islam, many of the Berbers, particularly farther south, away from the Mediterranean, being still Christian and pagan. In turn, this would contribute to the establishment of the Almoravid dynasty and Almohad Caliphate, which would have a major impact on al-Andalus and contribute to the end of the Umayyad caliphate.

New waves of Berber settlers arrived in al-Andalus in the 10th century, brought as mercenaries by Abd ar-Rahman III, who proclaimed himself caliph in 929, to help him in his campaigns to restore Umayyad authority in areas that had overthrown it during the reigns of the previous emirs. These new Berbers "lacked any familiarity with the pattern of relationships" that had existed in al-Andalus in the 700s and 800s; thus they were not involved in the same web of traditional conflicts and loyalties as the previously already existing Berber garrisons.

New frontier settlements were built for the new Berber mercenaries. Written sources state that some of the mercenaries were placed in Calatrava, which was refortified. Another Berber settlement called , west of Toledo, is not mentioned in the historical sources, but has been excavated archaeologically. It was a fortified town, had walls, and a separate fortress or alcazar. Two cemeteries have also been discovered. The town was established in the 900s as a frontier town for Berbers, probably of the Nafza tribe. It was abandoned soon after the Castilian occupation of Toledo in 1085. The Berber inhabitants took all their possessions with them.

In the 900s, the Umayyad caliphate faced a challenge from the Fatimids in North Africa. The Fatimid Caliphate of the 10th century was established by the Kutama Berbers. After taking the city of Kairouan and overthrowing the Aghlabids in 909, the Mahdi Ubayd Allah was installed by the Kutama as Imam and Caliph, which posed a direct challenge to the Umayyad's own claim. The Fatimids gained overlordship over the Idrisids, then launched a conquest of the Maghreb. To counter the threat, the Umayyads crossed the strait to take Ceuta in 931, and actively formed alliances with Berber confederacies, such as the Zenata and the Awraba. Rather than fighting each other directly, the Fatimids and Umayyads competed for Berber allegiances. In turn, this provided a motivation for the further conversion of Berbers to Islam, many of the Berbers, particularly farther south, away from the Mediterranean, being still Christian and pagan. In turn, this would contribute to the establishment of the Almoravid dynasty and Almohad Caliphate, which would have a major impact on al-Andalus and contribute to the end of the Umayyad caliphate.

With the help of his new mercenary forces, Abd ar-Rahman launched a series of attacks on parts of the Iberian peninsula that had fallen away from Umayyad allegiance. In the 920s he campaigned against the areas that rebelled under Umar ibn Hafsun and refused to submit until the 920s. He conquered Mérida in 928–929, Ceuta in 931, and Toledo in 932. In 934 he began a campaign in the north against Ramiro II of Leon and Muhammad ibn Hashim al-Tujibi, the governor of Zaragoza. According to

With the help of his new mercenary forces, Abd ar-Rahman launched a series of attacks on parts of the Iberian peninsula that had fallen away from Umayyad allegiance. In the 920s he campaigned against the areas that rebelled under Umar ibn Hafsun and refused to submit until the 920s. He conquered Mérida in 928–929, Ceuta in 931, and Toledo in 932. In 934 he began a campaign in the north against Ramiro II of Leon and Muhammad ibn Hashim al-Tujibi, the governor of Zaragoza. According to

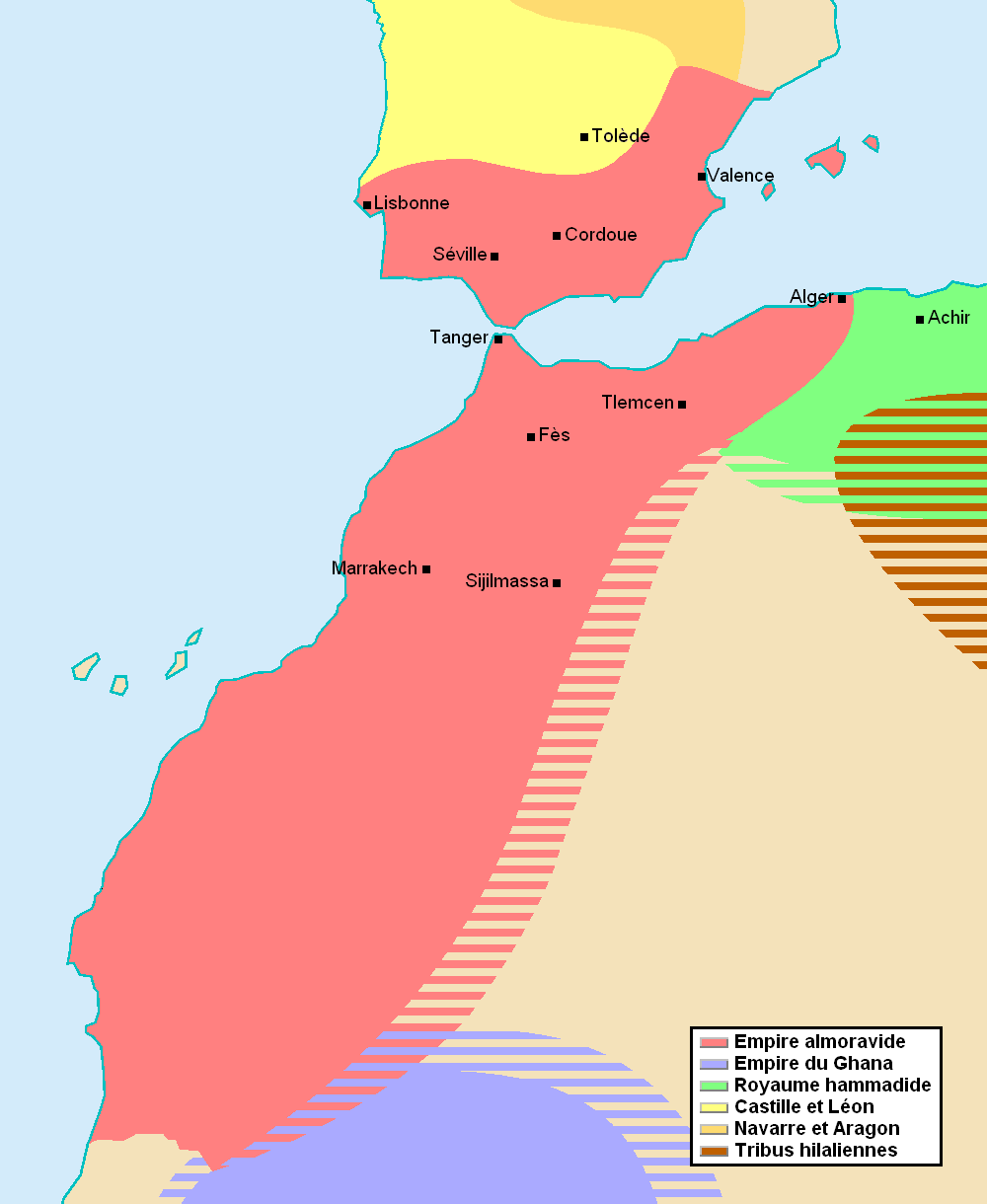

During the taifa period, the Almoravid empire developed in northwest Africa, whose core was formed by the

During the taifa period, the Almoravid empire developed in northwest Africa, whose core was formed by the

The Kabylians were independent of outside control during the period of

The Kabylians were independent of outside control during the period of

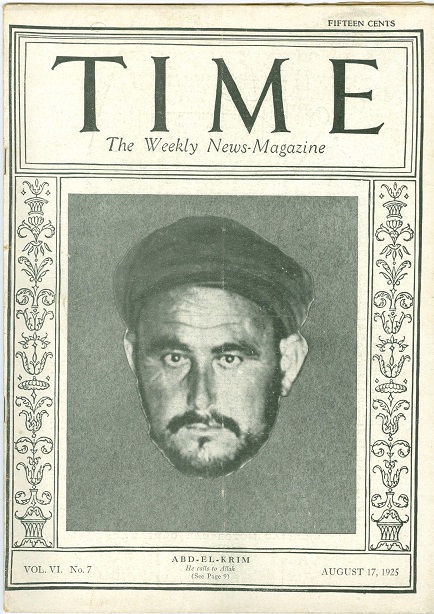

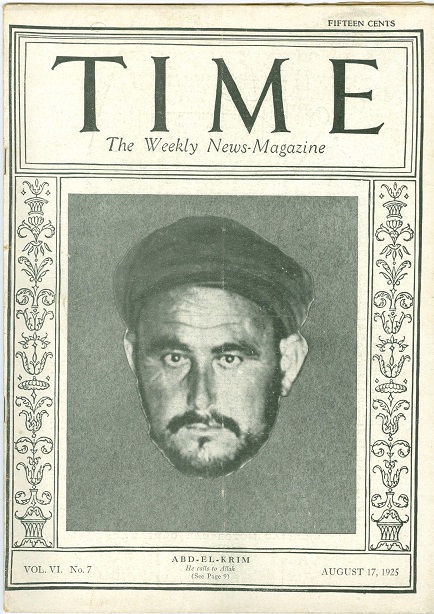

Volume 4, publié par M. Th. Houtsma, Page 600 The Kingdom of Ait Abbas was a Berber state of North Africa, controlling Lesser Kabylie and its surroundings from the sixteenth century to the nineteenth century. It is referred to in the Spanish historiography as ; sometimes more commonly referred to by its ruling family, the Mokrani, in Berber ( ). Its capital was the In 1912, Morocco was divided into French and Spanish zones. The Rif Berbers rebelled, led by

In 1912, Morocco was divided into French and Spanish zones. The Rif Berbers rebelled, led by  The Black Spring was a series of violent disturbances and political demonstrations by Kabyle activists in the Kabylie region of Algeria in 2001. In the

The Black Spring was a series of violent disturbances and political demonstrations by Kabyle activists in the Kabylie region of Algeria in 2001. In the

Prominent Berber ethnic groups include the Kabyles—from

Prominent Berber ethnic groups include the Kabyles—from

According to a 2004 estimate, there were about 2.2 million Berber immigrants in Europe, especially the Riffians in Belgium, the Netherlands, and France; and Algerians of Kabyles and Chaouis heritage in France.

According to a 2004 estimate, there were about 2.2 million Berber immigrants in Europe, especially the Riffians in Belgium, the Netherlands, and France; and Algerians of Kabyles and Chaouis heritage in France.

The Berber languages form a branch of the Afroasiatic language family, a large family that also includes Semitic languages like Arabic and the Ancient Egyptian language. Most Berbers speak

The Berber languages form a branch of the Afroasiatic language family, a large family that also includes Semitic languages like Arabic and the Ancient Egyptian language. Most Berbers speak

The Berber identity encompasses language, religion, and ethnicity, and is rooted in the entire history and geography of North Africa. Berbers are not an entirely homogeneous ethnicity, and they include a range of societies, ancestries, and lifestyles. The unifying forces for the Berber people may be their shared language or a collective identification with Berber heritage and history.

As a legacy of the spread of Islam, the Berbers are now mostly Sunni Islam, Sunni Muslim. However, the Mozabite people, Mozabite Berbers of the M'zab, M'zab Valley in the town of Ghardaïa in Algeria and some Libyan Berbers in the Nafusa Mountains and Zuwara are primarily adherents of

The Berber identity encompasses language, religion, and ethnicity, and is rooted in the entire history and geography of North Africa. Berbers are not an entirely homogeneous ethnicity, and they include a range of societies, ancestries, and lifestyles. The unifying forces for the Berber people may be their shared language or a collective identification with Berber heritage and history.

As a legacy of the spread of Islam, the Berbers are now mostly Sunni Islam, Sunni Muslim. However, the Mozabite people, Mozabite Berbers of the M'zab, M'zab Valley in the town of Ghardaïa in Algeria and some Libyan Berbers in the Nafusa Mountains and Zuwara are primarily adherents of

ethnic group

An ethnicity or ethnic group is a group of people with shared attributes, which they collectively believe to have, and long-term endogamy. Ethnicities share attributes like language, culture, common sets of ancestry, traditions, society, re ...

s indigenous to North Africa

North Africa (sometimes Northern Africa) is a region encompassing the northern portion of the African continent. There is no singularly accepted scope for the region. However, it is sometimes defined as stretching from the Atlantic shores of t ...

who predate the arrival of Arabs in the Maghreb. Their main connections are identified by their usage of Berber languages

The Berber languages, also known as the Amazigh languages or Tamazight, are a branch of the Afroasiatic language family. They comprise a group of closely related but mostly mutually unintelligible languages spoken by Berbers, Berber communities, ...

, most of them mutually unintelligible, which are part of the Afroasiatic language family

The Afroasiatic languages (also known as Afro-Asiatic, Afrasian, Hamito-Semitic, or Semito-Hamitic) are a language family (or "phylum") of about 400 languages spoken predominantly in West Asia, North Africa, the Horn of Africa, and parts of the ...

.

They are indigenous

Indigenous may refer to:

*Indigenous peoples

*Indigenous (ecology)

In biogeography, a native species is indigenous to a given region or ecosystem if its presence in that region is the result of only local natural evolution (though often populari ...

to the Maghreb

The Maghreb (; ), also known as the Arab Maghreb () and Northwest Africa, is the western part of the Arab world. The region comprises western and central North Africa, including Algeria, Libya, Mauritania, Morocco, and Tunisia. The Maghreb al ...

region of North Africa, where they live in scattered communities across parts of Morocco

Morocco, officially the Kingdom of Morocco, is a country in the Maghreb region of North Africa. It has coastlines on the Mediterranean Sea to the north and the Atlantic Ocean to the west, and has land borders with Algeria to Algeria–Morocc ...

, Algeria

Algeria, officially the People's Democratic Republic of Algeria, is a country in the Maghreb region of North Africa. It is bordered to Algeria–Tunisia border, the northeast by Tunisia; to Algeria–Libya border, the east by Libya; to Alger ...

, Libya

Libya, officially the State of Libya, is a country in the Maghreb region of North Africa. It borders the Mediterranean Sea to the north, Egypt to Egypt–Libya border, the east, Sudan to Libya–Sudan border, the southeast, Chad to Chad–L ...

, and to a lesser extent Tunisia

Tunisia, officially the Republic of Tunisia, is a country in the Maghreb region of North Africa. It is bordered by Algeria to the west and southwest, Libya to the southeast, and the Mediterranean Sea to the north and east. Tunisia also shares m ...

, Mauritania

Mauritania, officially the Islamic Republic of Mauritania, is a sovereign country in Maghreb, Northwest Africa. It is bordered by the Atlantic Ocean to the west, Western Sahara to Mauritania–Western Sahara border, the north and northwest, ...

, northern Mali

Mali, officially the Republic of Mali, is a landlocked country in West Africa. It is the List of African countries by area, eighth-largest country in Africa, with an area of over . The country is bordered to the north by Algeria, to the east b ...

and northern Niger

Niger, officially the Republic of the Niger, is a landlocked country in West Africa. It is a unitary state Geography of Niger#Political geography, bordered by Libya to the Libya–Niger border, north-east, Chad to the Chad–Niger border, east ...

. Smaller Berber communities are also found in Burkina Faso

Burkina Faso is a landlocked country in West Africa, bordered by Mali to the northwest, Niger to the northeast, Benin to the southeast, Togo and Ghana to the south, and Ivory Coast to the southwest. It covers an area of 274,223 km2 (105,87 ...

and Egypt

Egypt ( , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a country spanning the Northeast Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to northe ...

's Siwa Oasis

The Siwa Oasis ( ) is an urban oasis in Egypt. It is situated between the Qattara Depression and the Great Sand Sea in the Western Desert (Egypt), Western Desert, east of the Egypt–Libya border and from the Egyptian capital city of Cairo. I ...

.

Descended from Stone Age tribes of North Africa, accounts of the Imazighen were first mentioned in Ancient Egyptian writings. From about 2000 BC, Berber languages

The Berber languages, also known as the Amazigh languages or Tamazight, are a branch of the Afroasiatic language family. They comprise a group of closely related but mostly mutually unintelligible languages spoken by Berbers, Berber communities, ...

spread westward from the Nile Valley

The Nile (also known as the Nile River or River Nile) is a major north-flowing river in northeastern Africa. It flows into the Mediterranean Sea. The Nile is the longest river in Africa. It has historically been considered the longest river i ...

across the northern Sahara

The Sahara (, ) is a desert spanning across North Africa. With an area of , it is the largest hot desert in the world and the list of deserts by area, third-largest desert overall, smaller only than the deserts of Antarctica and the northern Ar ...

into the Maghreb. A series of Berber peoples such as the Mauri

Mauri (from which derives the English term "Moors") was the Latin designation for the Berber population of Mauretania, located in the west side of North Africa on the shores of the Mediterranean Sea, Mauretania Tingitana and Mauretania Caesarien ...

, Masaesyli

The Masaesyli were a Berber tribe of western Numidia (central and western Algeria) and the main antagonists of the Massylii in eastern Numidia.

During the Second Punic War the Masaesyli initially supported the Roman Republic and were led by Sy ...

, Massyli

The Massylii or Maesulians ( Neo-Punic: , ) were a Berber federation in eastern Numidia (central and eastern Algeria), which was formed by an amalgamation of smaller tribes during the 4th century BC.Nigel Bagnall, The Punic Wars, p. 270. They were ...

, Musulamii, Gaetuli

Gaetuli was the Romanised name of an ancient Berber tribe inhabiting ''Getulia''. The latter district covered the large desert region south of the Atlas Mountains, bordering the Sahara. Other documents place Gaetulia in pre-Roman times along the M ...

, and Garamantes

The Garamantes (; ) were ancient peoples, who may have descended from Berbers, Berber tribes, Toubous, Toubou tribes, and Saharan Pastoral period, pastoralists that settled in the Fezzan region by at least 1000 BC and established a civilization t ...

gave rise to Berber kingdoms, such as Numidia

Numidia was the ancient kingdom of the Numidians in northwest Africa, initially comprising the territory that now makes up Algeria, but later expanding across what is today known as Tunisia and Libya. The polity was originally divided between ...

and Mauretania

Mauretania (; ) is the Latin name for a region in the ancient Maghreb. It extended from central present-day Algeria to the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, encompassing northern present-day Morocco, and from the Mediterranean Sea, Mediterranean in the ...

. Other kingdoms appeared in late antiquity, such as Altava

Altava was an ancient Romano-Berber city in present-day Algeria. It served as the capital of the ancient Berber Kingdom of Altava. During the French presence, the town was called ''Lamoriciere''. It was situated in the modern Ouled Mimoun near Tl ...

, Aurès

Aurès () is a natural region located in the mountainous area of the Aurès Mountains, Aurès range, in eastern Algeria. The region includes the provinces of Algeria, Algerian provinces of Batna Province, Batna, Tebessa Province, Tebessa, Consta ...

, Ouarsenis

The Ouarsenis or Ouanchariss (Berber language: ⵡⴰⵔⵙⵏⵉⵙ, ''Warsnis'' (meaning "nothing higher") ''Adrar en Warsnis'', ) is a mountain range and inhabited region in northwestern Algeria.

Geography

The range is located at about 80 ...

, and Hodna

The Hodna () is a natural region of Algeria located between the Tell and Saharan Atlas ranges at the eastern end of the '' Hautes Plaines''. It is a vast depression lying in the northeastern section of M'Sila Province and the western end of Bat ...

. Berber kingdoms were eventually suppressed by the Arab conquests of the 7th and 8th centuries AD. This started a process of cultural and linguistic assimilation known as Arabization

Arabization or Arabicization () is a sociology, sociological process of cultural change in which a non-Arab society becomes Arabs, Arab, meaning it either directly adopts or becomes strongly influenced by the Arabic, Arabic language, Arab cultu ...

, which influenced the Berber population. Arabization involved the spread of Arabic language

Arabic (, , or , ) is a Central Semitic languages, Central Semitic language of the Afroasiatic languages, Afroasiatic language family spoken primarily in the Arab world. The International Organization for Standardization (ISO) assigns lang ...

and Arab culture

Arab culture is the culture of the Arabs, from the Atlantic Ocean in the west to the Arabian Sea in the east, in a region of the Middle East and North Africa known as the Arab world. The various religions the Arabs have adopted throughout Histor ...

among the Berbers, leading to the adoption of Arabic as the primary language and conversion to Islam

Islam is an Abrahamic religions, Abrahamic monotheistic religion based on the Quran, and the teachings of Muhammad. Adherents of Islam are called Muslims, who are estimated to number Islam by country, 2 billion worldwide and are the world ...

. Notably, the Arab migrations to the Maghreb

The Arab migrations to the Maghreb involved successive waves of Human migration, migration and Settler, settlement by Arabs, Arab people in the Maghreb region of Africa, encompassing modern-day Algeria, Libya, Morocco and Tunisia. The process to ...

from the 7th century to the 17th century accelerated this process. Berber tribes remained powerful political forces and founded new ruling dynasties in the 10th and 11th centuries, such as the Zirids

The Zirid dynasty (), Banu Ziri (), was a Sanhaja Berber dynasty from what is now Algeria which ruled the central Maghreb from 972 to 1014 and Ifriqiya (eastern Maghreb) from 972 to 1148.

Descendants of Ziri ibn Manad, a military leader of th ...

, Hammadids, various Zenata

The Zenata (; ) are a group of Berber tribes, historically one of the largest Berber confederations along with the Sanhaja and Masmuda. Their lifestyle was either nomadic or semi-nomadic.

Society

The 14th-century historiographer Ibn Khaldun repo ...

principalities in the western Maghreb, and several Taifa

The taifas (from ''ṭā'ifa'', plural ''ṭawā'if'', meaning "party, band, faction") were the independent Muslim principalities and kingdoms of the Iberian Peninsula (modern Portugal and Spain), referred to by Muslims as al-Andalus, that em ...

kingdoms in al-Andalus

Al-Andalus () was the Muslim-ruled area of the Iberian Peninsula. The name refers to the different Muslim states that controlled these territories at various times between 711 and 1492. At its greatest geographical extent, it occupied most o ...

, and empires of the Almoravids

The Almoravid dynasty () was a Berber Muslim dynasty centered in the territory of present-day Morocco. It established an empire that stretched over the western Maghreb and Al-Andalus, starting in the 1050s and lasting until its fall to the Almo ...

and Almohads

The Almohad Caliphate (; or or from ) or Almohad Empire was a North African Berber Muslim empire founded in the 12th century. At its height, it controlled much of the Iberian Peninsula (Al-Andalus) and North Africa (the Maghreb).

The Almohad ...

. Their Berber successors – the Marinids, the Zayyanids, and the Hafsids

The Hafsid dynasty ( ) was a Sunni Muslim dynasty of Berber descentC. Magbaily Fyle, ''Introduction to the History of African Civilization: Precolonial Africa'', (University Press of America, 1999), 84. that ruled Ifriqiya (modern day Tunisia, w ...

– continued to rule until the 16th century. From the 16th century onward, the process continued in the absence of Berber dynasties; in Morocco, they were replaced by Arabs claiming descent from the Islamic prophet Muhammad.

Berbers are divided into several diverse ethnic groups and Berber languages, such as Kabyles, Chaouis and Rifians

Riffians or Rifians (, singular: ; ) are a Berber ethnic group originally from the Rif region of northeastern Morocco (includes the autonomous city of Spain, Melilla). Communities of Riffian immigrants are also found in southern Spain, Netherland ...

. Historically, Berbers across the region did not see themselves as a single cultural or linguistic unit, nor was there a greater "Berber community", due to their differing cultures. They also did not refer to themselves as Berbers/Amazigh but had their own terms to refer to their own groups and communities. They started being referred to collectively as Berbers after the Arab conquests of the 7th century and this distinction was revived by French colonial

French colonial architecture includes several styles of architecture used by the French during colonization. French colonial architecture has a long history, beginning in North America in 1604 and being most active in the Western Hemisphere (Car ...

administrators in the 19th century. Today, the term "Berber" is viewed as pejorative by many who prefer the term "Amazigh". Since the late 20th century, a trans-national movement ''–'' known as Berberism

Berberism is a Berber ethnonationalist movement, that started mainly in Kabylia (Algeria) and Morocco during the French colonial era with the Kabyle myth and was largely driven by colonial capitalism and France's divide and conquer policy. ...

or the Berber Culture Movement ''–'' has emerged among various parts of the Berber populations of North Africa to promote a collective Amazigh ethnic identity

An ethnicity or ethnic group is a group of people with shared attributes, which they collectively believe to have, and long-term endogamy. Ethnicities share attributes like language, culture, common sets of ancestry, traditions, society, rel ...

and to militate for greater linguistic rights and cultural recognition.

Names and etymology

The indigenous populations of theMaghreb

The Maghreb (; ), also known as the Arab Maghreb () and Northwest Africa, is the western part of the Arab world. The region comprises western and central North Africa, including Algeria, Libya, Mauritania, Morocco, and Tunisia. The Maghreb al ...

region of North Africa

North Africa (sometimes Northern Africa) is a region encompassing the northern portion of the African continent. There is no singularly accepted scope for the region. However, it is sometimes defined as stretching from the Atlantic shores of t ...

are collectively known as Berbers or Amazigh in English.

Tribal titles such as ''Barabara'' and ''Beraberata'' appear in Egyptian inscriptions of 1700 and 1300 BC, and the Berbers were probably intimately related with the Egyptians in very early times. Thus the true ethnic name may have become confused with ''Barbari'', the designation used by classical conquerors.

The plural form Imazighen is sometimes also used in English. While Berber is more widely known among English-speakers, its usage is a subject of debate, due to its historical background as an exonym

An endonym (also known as autonym ) is a common, name for a group of people, individual person, geographical place, language, or dialect, meaning that it is used inside a particular group or linguistic community to identify or designate them ...

and present equivalence with the Arabic

Arabic (, , or , ) is a Central Semitic languages, Central Semitic language of the Afroasiatic languages, Afroasiatic language family spoken primarily in the Arab world. The International Organization for Standardization (ISO) assigns lang ...

word for "barbarian

A barbarian is a person or tribe of people that is perceived to be primitive, savage and warlike. Many cultures have referred to other cultures as barbarians, sometimes out of misunderstanding and sometimes out of prejudice.

A "barbarian" may ...

". Historically, Berbers did not refer to themselves as Berbers/Amazigh but had their own terms to refer to themselves. For example, the Kabyle use the term "Leqbayel" to refer to their own people, while the Chaoui identified as "Ishawiyen", instead of Berber/Amazigh.

Stéphane Gsell proposed the translation "noble/free" for the term Amazigh based on Leo Africanus

Johannes Leo Africanus (born al-Ḥasan ibn Muḥammad ibn Aḥmad al-Wazzān al-Zayyātī al-Fasī, ; – ) was an Andalusi diplomat and author who is best known for his 1526 book '' Cosmographia et geographia de Affrica'', later publish ...

's translation of "awal amazigh" as "noble language" referring to the Berber languages

The Berber languages, also known as the Amazigh languages or Tamazight, are a branch of the Afroasiatic language family. They comprise a group of closely related but mostly mutually unintelligible languages spoken by Berbers, Berber communities, ...

; this definition remains disputed and is largely seen as an undue extrapolation. The term Amazigh also has a cognate

In historical linguistics, cognates or lexical cognates are sets of words that have been inherited in direct descent from an etymological ancestor in a common parent language.

Because language change can have radical effects on both the s ...

in the Tuareg

The Tuareg people (; also spelled Twareg or Touareg; endonym, depending on variety: ''Imuhaɣ'', ''Imušaɣ'', ''Imašeɣăn'' or ''Imajeɣăn'') are a large Berber ethnic group, traditionally nomadic pastoralists, who principally inhabit th ...

''"Amajegh"'', meaning noble. "Mazigh" was used as a tribal surname in Roman

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

*Rome, the capital city of Italy

*Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of Roman civilization

*Epistle to the Romans, shortened to Romans, a letter w ...

Mauretania Caesariensis

Mauretania Caesariensis (Latin for "Caesarea, Numidia, Caesarean Mauretania") was a Roman province located in present-day Algeria. The full name refers to its capital Caesarea, Numidia, Caesarea Mauretaniae (modern Cherchell).

The province had ...

.

Abraham Isaac Laredo proposes that the term Amazigh could be derived from "Mezeg", which is the name of Dedan of Sheba

Sheba, or Saba, was an ancient South Arabian kingdoms in pre-Islamic Arabia, South Arabian kingdom that existed in Yemen (region), Yemen from to . Its inhabitants were the Sabaeans, who, as a people, were indissociable from the kingdom itself f ...

in the Targum

A targum (, ''interpretation'', ''translation'', ''version''; plural: targumim) was an originally spoken translation of the Hebrew Bible (also called the ) that a professional translator ( ''mǝṯurgǝmān'') would give in the common language o ...

.

The medieval Arab historian Ibn Khaldun

Ibn Khaldun (27 May 1332 – 17 March 1406, 732–808 Hijri year, AH) was an Arabs, Arab Islamic scholar, historian, philosopher and sociologist. He is widely acknowledged to be one of the greatest social scientists of the Middle Ages, and cons ...

says the Berbers were descendants of Barbar, the son of Tamalla, son of Mazigh, son of Canaan

CanaanThe current scholarly edition of the Septuagint, Greek Old Testament spells the word without any accents, cf. Septuaginta : id est Vetus Testamentum graece iuxta LXX interprets. 2. ed. / recogn. et emendavit Robert Hanhart. Stuttgart : D ...

, son of Ham

Ham is pork from a leg cut that has been preserved by wet or dry curing, with or without smoking."Bacon: Bacon and Ham Curing" in '' Chambers's Encyclopædia''. London: George Newnes, 1961, Vol. 2, p. 39. As a processed meat, the term '' ...

, son of Noah

Noah (; , also Noach) appears as the last of the Antediluvian Patriarchs (Bible), patriarchs in the traditions of Abrahamic religions. His story appears in the Hebrew Bible (Book of Genesis, chapters 5–9), the Quran and Baháʼí literature, ...

.

The Numidian

Numidia was the ancient kingdom of the Numidians in northwest Africa, initially comprising the territory that now makes up Algeria, but later expanding across what is today known as Tunisia and Libya. The polity was originally divided between ...

, Mauri

Mauri (from which derives the English term "Moors") was the Latin designation for the Berber population of Mauretania, located in the west side of North Africa on the shores of the Mediterranean Sea, Mauretania Tingitana and Mauretania Caesarien ...

and Libu

The Libu (; also transcribed Rebu, Libo, Lebu, Lbou, Libou) were an Ancient Libyan tribe of Berber origin, from which the name ''Libya'' derives.

Early history

Their tribal origin in Ancient Libya is first attested in Egyptian language texts ...

populations of antiquity are typically understood by contemporary writers to have referred to approximately the same population as modern Berbers.

History

The areas of North Africa that have retained the Berber language and traditions best have been, in general, Algeria, Libya, Morocco and Tunisia. Much of Berber culture is still celebrated among the cultural elite in Morocco and Algeria, especially inKabylia

Kabylia or Kabylie (; in Kabyle: Tamurt n leqbayel; in Tifinagh: ⵜⴰⵎⵓⵔⵜ ⵏ ⵍⴻⵇⴱⴰⵢⴻⵍ; ), meaning "Land of the Tribes" is a mountainous coastal region in northern Algeria and the homeland of the Kabyle people. It is ...

, the Aurès

Aurès () is a natural region located in the mountainous area of the Aurès Mountains, Aurès range, in eastern Algeria. The region includes the provinces of Algeria, Algerian provinces of Batna Province, Batna, Tebessa Province, Tebessa, Consta ...

and the Atlas Mountains

The Atlas Mountains are a mountain range in the Maghreb in North Africa. They separate the Sahara Desert from the Mediterranean Sea and the Atlantic Ocean; the name "Atlantic" is derived from the mountain range, which stretches around through M ...

. The Kabyles were one of the few peoples in North Africa who remained independent during successive rule by the Carthaginians

The Punic people, usually known as the Carthaginians (and sometimes as Western Phoenicians), were a Semitic people, Semitic people who Phoenician settlement of North Africa, migrated from Phoenicia to the Western Mediterranean during the Iron ...

, Romans, Byzantines, Vandals

The Vandals were a Germanic people who were first reported in the written records as inhabitants of what is now Poland, during the period of the Roman Empire. Much later, in the fifth century, a group of Vandals led by kings established Vand ...

, and the Ottoman Turks

The Ottoman Turks () were a Turkic peoples, Turkic ethnic group in Anatolia. Originally from Central Asia, they migrated to Anatolia in the 13th century and founded the Ottoman Empire, in which they remained socio-politically dominant for the e ...

. Even after the Arab

Arabs (, , ; , , ) are an ethnic group mainly inhabiting the Arab world in West Asia and North Africa. A significant Arab diaspora is present in various parts of the world.

Arabs have been in the Fertile Crescent for thousands of years ...

conquest of North Africa, the Kabyle people still maintained possession of their mountains.

Prehistory

The

The Maghreb

The Maghreb (; ), also known as the Arab Maghreb () and Northwest Africa, is the western part of the Arab world. The region comprises western and central North Africa, including Algeria, Libya, Mauritania, Morocco, and Tunisia. The Maghreb al ...

region in northwestern Africa is believed to have been inhabited by Berbers from at least 10,000 BC. Cave paintings

In archaeology, cave paintings are a type of parietal art (which category also includes petroglyphs, or engravings), found on the wall or ceilings of caves. The term usually implies prehistoric origin. These paintings were often created by ''Hom ...

, which have been dated to twelve millennia before present, have been found in the Tassili n'Ajjer

Tassili n'Ajjer (Berber: ''Tassili n Ajjer'', ; "Plateau of rivers") is a mountain range in the Sahara desert, located in south-eastern Algeria. It holds one of the most important groupings of prehistoric cave art in the world, and covers an ar ...

region of southeastern Algeria. Other rock art

In archaeology, rock arts are human-made markings placed on natural surfaces, typically vertical stone surfaces. A high proportion of surviving historic and prehistoric rock art is found in caves or partly enclosed rock shelters; this type al ...

has been discovered at Tadrart Acacus

The Acacus Mountains or Tadrart Akakus ( / ALA-LC: ''Tadrārt Akākūs'') form a mountain range in the desert of the Ghat District in western Libya, part of the Sahara. They are situated east of the city of Ghat, Libya, and stretch north from th ...

in the Libyan desert. A Neolithic

The Neolithic or New Stone Age (from Ancient Greek, Greek 'new' and 'stone') is an archaeological period, the final division of the Stone Age in Mesopotamia, Asia, Europe and Africa (c. 10,000 BCE to c. 2,000 BCE). It saw the Neolithic Revo ...

society, marked by domestication

Domestication is a multi-generational Mutualism (biology), mutualistic relationship in which an animal species, such as humans or leafcutter ants, takes over control and care of another species, such as sheep or fungi, to obtain from them a st ...

and subsistence agriculture

Subsistence agriculture occurs when farmers grow crops on smallholdings to meet the needs of themselves and their families. Subsistence agriculturalists target farm output for survival and for mostly local requirements. Planting decisions occu ...

and richly depicted in the Tassili n'Ajjer paintings, developed and predominated in the Saharan and Mediterranean region (the Maghreb) of northern Africa between 6000 and 2000 BC (until the classical period).

Prehistoric Tifinagh

Tifinagh ( Tuareg Berber language: ; Neo-Tifinagh: ; Berber Latin alphabet: ; ) is a script used to write the Berber languages. Tifinagh is descended from the ancient Libyco-Berber alphabet. The traditional Tifinagh, sometimes called Tuareg Tifi ...

inscriptions were found in the Oran

Oran () is a major coastal city located in the northwest of Algeria. It is considered the second most important city of Algeria, after the capital, Algiers, because of its population and commercial, industrial and cultural importance. It is w ...

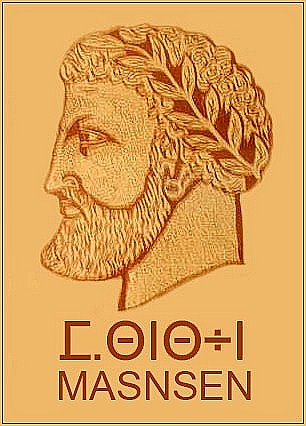

region. During the pre-Roman era, several successive independent states (Massylii) existed before King Masinissa

Masinissa (''c.'' 238 BC – 148 BC), also spelled Massinissa, Massena and Massan, was an ancient Numidian king best known for leading a federation of Massylii Berber tribes during the Second Punic War (218–201 BC), ultimately uniting the ...

unified the people of Numidia

Numidia was the ancient kingdom of the Numidians in northwest Africa, initially comprising the territory that now makes up Algeria, but later expanding across what is today known as Tunisia and Libya. The polity was originally divided between ...

.Histoire de l'émigration kabyle en France au XXe siècle: réalités culturelles ... De Karina Slimani-Direche

Mythology

According to the Roman historianGaius Sallustius Crispus

Gaius Sallustius Crispus, usually anglicised as Sallust (, ; –35 BC), was a historian and politician of the Roman Republic from a plebeian family. Probably born at Amiternum in the country of the Sabines, Sallust became a partisan of Julius C ...

, the original people of North Africa are the Gaetulians and the Libyans, they were the prehistoric peoples that crossed to Africa from the Iberian Peninsula

The Iberian Peninsula ( ), also known as Iberia, is a peninsula in south-western Europe. Mostly separated from the rest of the European landmass by the Pyrenees, it includes the territories of peninsular Spain and Continental Portugal, comprisin ...

, then much later, Hercules

Hercules (, ) is the Roman equivalent of the Greek divine hero Heracles, son of Jupiter and the mortal Alcmena. In classical mythology, Hercules is famous for his strength and for his numerous far-ranging adventures.

The Romans adapted the Gr ...

and his army crossed from Iberia to North Africa where his army intermarried with the local populace and settled the region permanently, the Medes of his army that married the Libyans formed the Maur people, while the other part of his Army formed the Nomadas or as they are today known as the Numidians

The Numidians were the Berber population of Numidia (present-day Algeria). The Numidians were originally a semi-nomadic people, they migrated frequently as nomads usually do, but during certain seasons of the year, they would return to the same ...

which later on united all of Berber tribes of North Africa under the rule of Massinissa

Masinissa (''c.'' 238 BC – 148 BC), also spelled Massinissa, Massena and Massan, was an ancient Numidian king best known for leading a federation of Massylii Berber tribes during the Second Punic War (218–201 BC), ultimately uniting th ...

.

Other sources

According to the '' Al-Fiḥrist'', the Barber (i.e. Berbers) comprised one of seven principal races in Africa. The medieval Tunisian scholarIbn Khaldun

Ibn Khaldun (27 May 1332 – 17 March 1406, 732–808 Hijri year, AH) was an Arabs, Arab Islamic scholar, historian, philosopher and sociologist. He is widely acknowledged to be one of the greatest social scientists of the Middle Ages, and cons ...

(1332–1406), recounting the oral traditions prevalent in his day, sets down two popular opinions as to the origin of the Berbers: according to one opinion, they are descended from Canaan, son of Ham, and have for ancestors Berber, son of Temla, son of Mazîgh, son of Canaan, son of Ham, a son of Noah; alternatively, Abou-Bekr Mohammed es-Souli (947 AD) held that they are descended from Berber, the son of Keloudjm (Casluhim

The Casluhim or Casluhites () were an ancient Egyptian people mentioned in the Bible and related literature.

Biblical accounts

According to the Book of Genesis () and the Books of Chronicles (), the Casluhim were descendants of Mizraim (Egypt) so ...

), the son of Mesraim, the son of Ham.

Scientific

As of about 5000 BC, the populations of North Africa were descended primarily from theIberomaurusian

The Iberomaurusian is a backed bladelet lithic industry found near the coasts of Morocco, Algeria, and Tunisia. It is also known from a single major site in Libya, the Haua Fteah, where the industry is known as the Eastern Oranian.The "Weste ...

and Capsian cultures, with a more recent intrusion being associated with the Neolithic Revolution

The Neolithic Revolution, also known as the First Agricultural Revolution, was the wide-scale transition of many human cultures during the Neolithic period in Afro-Eurasia from a lifestyle of hunter-gatherer, hunting and gathering to one of a ...

. The proto-Berber tribes evolved from these prehistoric communities during the late Bronze

Bronze is an alloy consisting primarily of copper, commonly with about 12–12.5% tin and often with the addition of other metals (including aluminium, manganese, nickel, or zinc) and sometimes non-metals (such as phosphorus) or metalloid ...

- and early Iron

Iron is a chemical element; it has symbol Fe () and atomic number 26. It is a metal that belongs to the first transition series and group 8 of the periodic table. It is, by mass, the most common element on Earth, forming much of Earth's o ...

ages.

Uniparental DNA analysis has established ties between Berbers and other Afroasiatic speakers in Africa. Most of these populations belong to the E1b1b

E-M215 or E1b1b, formerly known as E3b, is a major human Y-chromosome DNA haplogroup. E-M215 has two basal branches, E-M35 and E-M281. E-M35 is primarily distributed in North Africa and the Horn of Africa, and occurs at moderate frequencies in ...

paternal haplogroup, with Berber speakers having among the highest frequencies of this lineage.

Additionally, genomic analysis found that Berber and other Maghreb communities have a high frequency of an ancestral component that originated in the Near East. This Maghrebi element peaks among Tunisian Berbers. This ancestry is related to the Coptic/Ethio-Somali component, which diverged from these and other West Eurasian-affiliated components before the Holocene

The Holocene () is the current geologic time scale, geological epoch, beginning approximately 11,700 years ago. It follows the Last Glacial Period, which concluded with the Holocene glacial retreat. The Holocene and the preceding Pleistocene to ...

.;

In 2013, Iberomaurusian skeletons from the prehistoric sites of Taforalt

Taforalt, or Grotte des Pigeons, is a cave in the province of Berkane, Aït Iznasen region, Morocco, possibly the oldest cemetery in North Africa. It contained at least 34 Iberomaurusian adolescent and adult human skeletons, as well as young ...

and Afalou in the Maghreb were also analyzed for ancient DNA

Ancient DNA (aDNA) is DNA isolated from ancient sources (typically Biological specimen, specimens, but also environmental DNA). Due to degradation processes (including Crosslinking of DNA, cross-linking, deamination and DNA fragmentation, fragme ...

. All of the specimens belonged to maternal clades associated with either North Africa or the northern and southern Mediterranean littoral

The littoral zone, also called litoral or nearshore, is the part of a sea, lake, or river that is close to the shore. In coastal ecology, the littoral zone includes the intertidal zone extending from the high water mark (which is rarely i ...

, indicating gene flow between these areas since the Epipaleolithic

In archaeology, the Epipalaeolithic or Epipaleolithic (sometimes Epi-paleolithic etc.) is a period occurring between the Upper Paleolithic and Neolithic during the Stone Age. Mesolithic also falls between these two periods, and the two are someti ...

. The ancient Taforalt individuals carried the mtDNA haplogroup

A haplotype is a group of alleles in an organism that are inherited together from a single parent, and a haplogroup (haploid from the , ''haploûs'', "onefold, simple" and ) is a group of similar haplotypes that share a common ancestor with a sing ...

s U6, H, JT, and V, which points to population continuity in the region dating from the Iberomaurusian period.

radiocarbon dated

Radiocarbon dating (also referred to as carbon dating or carbon-14 dating) is a method for determining the age of an object containing organic material by using the properties of radiocarbon, a radioactive isotope of carbon.

The method was de ...

to the Early Neolithic period, BC. Ancient DNA analysis of these specimens indicates that they carried paternal haplotypes related to the E1b1b1b1a (E-M81) subclade and the maternal haplogroups U6a and M1, all of which are frequent among present-day communities in the Maghreb. These ancient individuals also bore an autochthonous

Autochthon, autochthons or autochthonous may refer to:

Nature

* Autochthon (geology), a sediment or rock that can be found at its site of formation or deposition

* Autochthon (nature), or landrace, an indigenous animal or plant

* Autochthonou ...

Maghrebi genomic component that peaks among modern Berbers, indicating that they were ancestral to populations in the area. Additionally, fossils excavated at the Kelif el Boroud site near Rabat

Rabat (, also , ; ) is the Capital (political), capital city of Morocco and the List of cities in Morocco, country's seventh-largest city with an urban population of approximately 580,000 (2014) and a metropolitan population of over 1.2 million. ...

were found to carry the broadly-distributed paternal haplogroup T-M184 as well as the maternal haplogroups K1, T2 and X2, the latter of which were common mtDNA lineages in Neolithic Europe

Europe is a continent located entirely in the Northern Hemisphere and mostly in the Eastern Hemisphere. It is bordered by the Arctic Ocean to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the west, the Mediterranean Sea to the south, and Asia to the east ...

and Anatolia

Anatolia (), also known as Asia Minor, is a peninsula in West Asia that makes up the majority of the land area of Turkey. It is the westernmost protrusion of Asia and is geographically bounded by the Mediterranean Sea to the south, the Aegean ...

. These ancient individuals likewise bore the Berber-associated Maghrebi genomic component. This altogether indicates that the late-Neolithic Kehf el Baroud inhabitants were ancestral to contemporary populations in the area, but also likely experienced gene flow from Europe

Europe is a continent located entirely in the Northern Hemisphere and mostly in the Eastern Hemisphere. It is bordered by the Arctic Ocean to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the west, the Mediterranean Sea to the south, and Asia to the east ...

.

The late-Neolithic Kehf el Baroud inhabitants were modelled as being of about 50% local North African ancestry and 50% Early European Farmer

Early European Farmers (EEF) were a group of the Anatolian Neolithic Farmers (ANF) who brought agriculture to Europe and Northwest Africa. The Anatolian Neolithic Farmers were an ancestral component, first identified in farmers from Anatolia (als ...

(EEF) ancestry. It was suggested that EEF ancestry had entered North Africa through Cardial Ware

Cardium pottery or Cardial ware is a Neolithic decorative style that gets its name from the imprinting of the clay with the heart-shaped shell of the '' Corculum cardissa'', a member of the cockle family Cardiidae. These forms of pottery are ...

colonists from Iberia sometime between 5000 and 3000 BC. They were found to be closely related to the Guanches

The Guanche were the Indigenous peoples, indigenous inhabitants of the Spain, Spanish Canary Islands, located in the Atlantic Ocean some to the west of modern Morocco and the North African coast. The islanders spoke the Guanche language, which i ...

of the Canary Islands

The Canary Islands (; ) or Canaries are an archipelago in the Atlantic Ocean and the southernmost Autonomous communities of Spain, Autonomous Community of Spain. They are located in the northwest of Africa, with the closest point to the cont ...

. The authors of the study suggested that the Berbers of Morocco carried a substantial amount of EEF ancestry before the establishment of Roman colonies in Berber Africa.

Antiquity

The great tribes of Berbers in classical antiquity (when they were often known as ancient Libyans) were said to be three (roughly, from west to east): the Mauri, theNumidians

The Numidians were the Berber population of Numidia (present-day Algeria). The Numidians were originally a semi-nomadic people, they migrated frequently as nomads usually do, but during certain seasons of the year, they would return to the same ...

near Carthage

Carthage was an ancient city in Northern Africa, on the eastern side of the Lake of Tunis in what is now Tunisia. Carthage was one of the most important trading hubs of the Ancient Mediterranean and one of the most affluent cities of the classic ...

, and the Gaetuli

Gaetuli was the Romanised name of an ancient Berber tribe inhabiting ''Getulia''. The latter district covered the large desert region south of the Atlas Mountains, bordering the Sahara. Other documents place Gaetulia in pre-Roman times along the M ...

ans. The Mauri inhabited the far west (ancient Mauretania

Mauretania (; ) is the Latin name for a region in the ancient Maghreb. It extended from central present-day Algeria to the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, encompassing northern present-day Morocco, and from the Mediterranean Sea, Mediterranean in the ...

, now Morocco and central Algeria). The Numidians occupied the regions between the Mauri and the city-state of Carthage. Both the Mauri and the Numidians had significant sedentary

Sedentary lifestyle is a lifestyle type, in which one is physically inactive and does little or no physical movement and/or exercise. A person living a sedentary lifestyle is often sitting or lying down while engaged in an activity like soc ...

populations living in villages, and their peoples both tilled the land and tended herds. The Gaetulians lived to the near south, on the northern margins of the Sahara

The Sahara (, ) is a desert spanning across North Africa. With an area of , it is the largest hot desert in the world and the list of deserts by area, third-largest desert overall, smaller only than the deserts of Antarctica and the northern Ar ...

, and were less settled, with predominantly pastoral

The pastoral genre of literature, art, or music depicts an idealised form of the shepherd's lifestyle – herding livestock around open areas of land according to the seasons and the changing availability of water and pasture. The target au ...

elements.

For their part, the Phoenicia

Phoenicians were an Ancient Semitic-speaking peoples, ancient Semitic group of people who lived in the Phoenician city-states along a coastal strip in the Levant region of the eastern Mediterranean, primarily modern Lebanon and the Syria, Syrian ...

ns (Semitic-speaking

The Semitic languages are a branch of the Afroasiatic language family. They include Arabic,

Amharic, Tigrinya, Aramaic, Hebrew, Maltese, Modern South Arabian languages and numerous other ancient and modern languages. They are spoken by more t ...

Canaan

CanaanThe current scholarly edition of the Septuagint, Greek Old Testament spells the word without any accents, cf. Septuaginta : id est Vetus Testamentum graece iuxta LXX interprets. 2. ed. / recogn. et emendavit Robert Hanhart. Stuttgart : D ...

ites) came from perhaps the most advanced multicultural sphere then existing, the western coast of the Fertile Crescent

The Fertile Crescent () is a crescent-shaped region in the Middle East, spanning modern-day Iraq, Israel, Jordan, Lebanon, Palestine, and Syria, together with northern Kuwait, south-eastern Turkey, and western Iran. Some authors also include ...

region of West Asia

West Asia (also called Western Asia or Southwest Asia) is the westernmost region of Asia. As defined by most academics, UN bodies and other institutions, the subregion consists of Anatolia, the Arabian Peninsula, Iran, Mesopotamia, the Armenian ...

. Accordingly, the material culture of Phoenicia was likely more functional and efficient, and their knowledge more advanced, than that of the early Berbers. Hence, the interactions between Berbers and Phoenicians were often asymmetrical. The Phoenicians worked to keep their cultural cohesion and ethnic solidarity, and continuously refreshed their close connection with Tyre, the mother city.

The earliest Phoenician coastal outposts were probably meant merely to resupply and service ships bound for the lucrative metals trade with the Iberians, and perhaps at first regarded trade with the Berbers as unprofitable. However, the Phoenicians eventually established strategic colonial cities in many Berber areas, including sites outside of present-day Tunisia, such as the settlements at Oea

Oea (; ) was an ancient city in present-day Tripoli, Libya. It was founded by the Phoenicians in the 7th century BC and later became a Roman–Berber colony. As part of the Roman Africa Nova province, Oea and surrounding Tripolitania wer ...

, Leptis Magna

Leptis or Lepcis Magna, also known by #Names, other names in classical antiquity, antiquity, was a prominent city of the Carthaginian Empire and Roman Libya at the mouth of the Wadi Lebda in the Mediterranean.

Established as a Punic people, Puni ...

, Sabratha

Sabratha (; also ''Sabratah'', ''Siburata''), in the Zawiya DistrictVolubilis

Volubilis (; ; ) is a partly excavated Berber-Roman city in Morocco, situated near the city of Meknes, that may have been the capital of the Kingdom of Mauretania, at least from the time of King Juba II. Before Volubilis, the capital of the kin ...

, Chellah

The Chellah or Shalla ( or ; ), is a medieval fortified Muslim necropolis and ancient archeological site in Rabat, Morocco, located on the south (left) side of the Bou Regreg estuary. The earliest evidence of the site's occupation suggests that th ...

, and Mogador

Essaouira ( ; ), known until the 1960s as Mogador (, or ), is a port city in the western Morocco, Moroccan region of Marrakesh-Safi, on the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic coast. It has 77,966 inhabitants as of 2014.

The foundation of the city of Essao ...

(now in Morocco). As in Tunisia, these centres were trading hubs, and later offered support for resource development, such as processing olive oil

Olive oil is a vegetable oil obtained by pressing whole olives (the fruit of ''Olea europaea'', a traditional Tree fruit, tree crop of the Mediterranean Basin) and extracting the oil.

It is commonly used in cooking for frying foods, as a cond ...

at Volubilis and Tyrian purple

Tyrian purple ( ''porphúra''; ), also known as royal purple, imperial purple, or imperial dye, is a reddish-purple natural dye. The name Tyrian refers to Tyre, Lebanon, once Phoenicia. It is secreted by several species of predatory sea snails ...

dye at Mogador. For their part, most Berbers maintained their independence as farmers or semi-pastorals, although, due to the example of Carthage, their organized politics increased in scope and sophistication.

Dido

Dido ( ; , ), also known as Elissa ( , ), was the legendary founder and first queen of the Phoenician city-state of Carthage (located in Tunisia), in 814 BC.

In most accounts, she was the queen of the Phoenician city-state of Tyre (located ...

, the foundress of Carthage, as related by Trogus is apposite. Her refusal to wed the Mauritani chieftain Hiarbus might be indicative of the complexity of the politics involved.

Eventually, the Phoenician trading stations would evolve into permanent settlements, and later into small towns, which would presumably require a wide variety of goods as well as sources of food, which could be satisfied through trade with the Berbers. Yet, here too, the Phoenicians probably would be drawn into organizing and directing such local trade, and also into managing agricultural production. In the 5th century BC, Carthage expanded its territory, acquiring Cape Bon

Cape Bon ("Good Cape"), also known as Res et-Teib (), Shrīk Peninsula, or Watan el Kibli, is a peninsula in far northeastern Tunisia. Cape Bon is also the name of the northernmost point on the peninsula, also known as Res ed-Der, and known in ant ...

and the fertile Wadi Majardah, later establishing control over productive farmlands for several hundred kilometres. Appropriation of such wealth in land by the Phoenicians would surely provoke some resistance from the Berbers; although in warfare, too, the technical training, social organization, and weaponry of the Phoenicians would seem to work against the tribal Berbers. This social-cultural interaction in early Carthage has been summarily described:

For a period, the Berbers were in constant revolt, and in 396 there was a great uprising.

Yet the Berbers lacked cohesion; and although 200,000 strong at one point, they succumbed to hunger, their leaders were offered bribes, and "they gradually broke up and returned to their homes". Thereafter, "a series of revolts took place among the Libyans erbersfrom the fourth century onwards".

The Berbers had become involuntary 'hosts' to the settlers from the east, and were obliged to accept the dominance of Carthage for centuries. Nonetheless, therein they persisted largely unassimilated, as a separate, submerged entity, as a culture of mostly passive urban and rural poor within the civil structures created by Punic rule. In addition, and most importantly, the Berber peoples also formed quasi-independent satellite societies along the steppe

In physical geography, a steppe () is an ecoregion characterized by grassland plains without closed forests except near rivers and lakes.

Steppe biomes may include:

* the montane grasslands and shrublands biome

* the tropical and subtropica ...

s of the frontier and beyond, where a minority continued as free 'tribal republics'. While benefiting from Punic material culture and political-military institutions, these peripheral Berbers (also called Libyans)—while maintaining their own identity, culture, and traditions—continued to develop their own agricultural skills and village societies, while living with the newcomers from the east in an asymmetric symbiosis.

As the centuries passed, a society of Punic people of Phoenician descent but born in Africa, called emerged there. This term later came to be applied also to Berbers acculturated to urban Phoenician culture. Yet the whole notion of a Berber apprenticeship to the Punic civilization has been called an exaggeration sustained by a point of view fundamentally foreign to the Berbers. A population of mixed ancestry, Berber and Punic, evolved there, and there would develop recognized niches in which Berbers had proven their utility. For example, the Punic state began to field Berber–Numidian cavalry under their commanders on a regular basis. The Berbers eventually were required to provide soldiers (at first "unlikely" paid "except in booty"), which by the fourth century BC became "the largest single element in the Carthaginian army".

Yet in times of stress at Carthage, when a foreign force might be pushing against the city-state, some Berbers would see it as an opportunity to advance their interests, given their otherwise low status in Punic society. Thus, when the Greeks under

Yet in times of stress at Carthage, when a foreign force might be pushing against the city-state, some Berbers would see it as an opportunity to advance their interests, given their otherwise low status in Punic society. Thus, when the Greeks under Agathocles

Agathocles ( Greek: ) is a Greek name. The most famous person called Agathocles was Agathocles of Syracuse, the tyrant of Syracuse. The name is derived from and .

Other people named Agathocles include:

*Agathocles, a sophist, teacher of Damon

...

(361–289 BC) of Sicily landed at Cape Bon and threatened Carthage (in 310 BC), there were Berbers, under Ailymas, who went over to the invading Greeks. During the long Second Punic War

The Second Punic War (218 to 201 BC) was the second of Punic Wars, three wars fought between Ancient Carthage, Carthage and Roman Republic, Rome, the two main powers of the western Mediterranean Basin, Mediterranean in the 3rd century BC. For ...

(218–201 BC) with Rome (see below), the Berber King Masinissa ( BC) joined with the invading Roman general Scipio, resulting in the war-ending defeat of Carthage at Zama, despite the presence of their renowned general Hannibal; on the other hand, the Berber King Syphax

Syphax (, ''Sýphax''; , ) was a king of the Masaesyli tribe of western Numidia (present-day Algeria) during the last quarter of the 3rd century BC. His story is told in Livy's ''Ab Urbe Condita'' (written c. 27–25 BC).

(d. 202 BC) had supported Carthage. The Romans, too, read these cues, so that they cultivated their Berber alliances and, subsequently, favored the Berbers who advanced their interests following the Roman victory.

Carthage was faulted by her ancient rivals for the "harsh treatment of her subjects" as well as for "greed and cruelty". Her Libyan Berber sharecroppers, for example, were required to pay half of their crops as tribute to the city-state during the emergency of the First Punic War

The First Punic War (264–241 BC) was the first of three wars fought between Rome and Carthage, the two main powers of the western Mediterranean in the early 3rd century BC. For 23 years, in the longest continuous conflict and grea ...

. The normal exaction taken by Carthage was likely "an extremely burdensome" one-quarter. Carthage once famously attempted to reduce the number of its Libyan and foreign soldiers, leading to the Mercenary War

The Mercenary War, also known as the Truceless War, was a mutiny by troops that were employed by Ancient Carthage, Carthage at the end of the First Punic War (264241 BC), supported by uprisings of African settlements revolting against C ...

(240–237 BC). The city-state also seemed to reward those leaders known to deal ruthlessly with its subject peoples, hence the frequent Berber insurrections. Moderns fault Carthage for failure "to bind her subjects to herself, as Rome did er Italians, yet Rome and the Italians held far more in common perhaps than did Carthage and the Berbers. Nonetheless, a modern criticism is that the Carthaginians "did themselves a disservice" by failing to promote the common, shared quality of "life in a properly organized city" that inspires loyalty, particularly with regard to the Berbers. Again, the tribute demanded by Carthage was onerous.R. Bosworth Smith

Reginald Bosworth Smith (1839–1908) was an English academic, schoolmaster, man of letters and author.

Background and early life

Born on 28 June 1839 at West Stafford rectory, Dorset, he was the second son in the large family of Reginald Southwel ...

, ''Carthage and the Carthaginians'' (London: Longmans, Green 1878, 1908) at 45–46

e most ruinous tribute was imposed and exacted with unsparing rigour from the subject native states, and no slight one either from the cognate Phoenician states. ... Hence arose that universal disaffection, or rather that deadly hatred, on the part of her foreign subjects, and even of the Phoenician dependencies, toward Carthage, on which every invader of Africa could safely count as his surest support. ... This was the fundamental, the ineradicable weakness of the Carthaginian Empire ...The Punic relationship with the majority of the Berbers continued throughout the life of Carthage. The unequal development of material culture and social organization perhaps fated the relationship to be an uneasy one. A long-term cause of Punic instability, there was no melding of the peoples. It remained a source of stress and a point of weakness for Carthage. Yet there were degrees of convergence on several particulars, discoveries of mutual advantage, occasions of friendship, and family.

The Berbers gain historicity gradually during the

The Berbers gain historicity gradually during the Roman era

In modern historiography, ancient Rome is the Roman people, Roman civilisation from the founding of Rome, founding of the Italian city of Rome in the 8th century BC to the Fall of the Western Roman Empire, collapse of the Western Roman Em ...

. Byzantine authors mention the (Amazigh) as tribal people raiding the monasteries of Cyrenaica

Cyrenaica ( ) or Kyrenaika (, , after the city of Cyrene), is the eastern region of Libya. Cyrenaica includes all of the eastern part of Libya between the 16th and 25th meridians east, including the Kufra District. The coastal region, als ...

. Garamantia was a notable Berber kingdom that flourished in the Fezzan

Fezzan ( , ; ; ; ) is the southwestern region of modern Libya. It is largely desert, but broken by mountains, uplands, and dry river valleys (wadis) in the north, where oases enable ancient towns and villages to survive deep in the otherwise in ...

area of modern-day Libya in the Sahara desert between 400 BC and 600 AD.

Roman-era Cyrenaica became a center of early Christianity

Early Christianity, otherwise called the Early Church or Paleo-Christianity, describes the History of Christianity, historical era of the Christianity, Christian religion up to the First Council of Nicaea in 325. Spread of Christianity, Christian ...

. Some pre-Islamic Berbers were Christians

A Christian () is a person who follows or adheres to Christianity, a monotheistic Abrahamic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus Christ. Christians form the largest religious community in the world. The words '' Christ'' and ''C ...

(there is a strong correlation between adherence to the Donatist

Donatism was a schism from the Catholic Church in the Archdiocese of Carthage from the fourth to the sixth centuries. Donatists argued that Christian clergy must be faultless for their ministry to be effective and their prayers and sacraments to ...

doctrine and being a Berber, ascribed to the doctrine matching their culture, as well as their being alienated from the dominant Roman culture of the Catholic church),"The Berbers"BBC World Service , The Story of Africa some perhaps

Jewish

Jews (, , ), or the Jewish people, are an ethnoreligious group and nation, originating from the Israelites of History of ancient Israel and Judah, ancient Israel and Judah. They also traditionally adhere to Judaism. Jewish ethnicity, rel ...

, and some adhered to their traditional polytheist religion. The Roman-era authors Apuleius

Apuleius ( ), also called Lucius Apuleius Madaurensis (c. 124 – after 170), was a Numidians, Numidian Latin-language prose writer, Platonist philosopher and rhetorician. He was born in the Roman Empire, Roman Numidia (Roman province), province ...

and St. Augustine

Augustine of Hippo ( , ; ; 13 November 354 – 28 August 430) was a theologian and philosopher of Berber origin and the bishop of Hippo Regius in Numidia, Roman North Africa. His writings deeply influenced the development of Western philosop ...

were born in Numidia, as were three pope

The pope is the bishop of Rome and the Head of the Church#Catholic Church, visible head of the worldwide Catholic Church. He is also known as the supreme pontiff, Roman pontiff, or sovereign pontiff. From the 8th century until 1870, the po ...

s, one of whom, Pope Victor I

Pope Victor I (died 199) was a Roman African prelate of the Catholic Church who served as the Bishop of Rome in the late second century. The dates of his tenure are uncertain, but one source states he became pope in 189 and gives the year of h ...

, served during the reign of Roman emperor Septimius Severus

Lucius Septimius Severus (; ; 11 April 145 – 4 February 211) was Roman emperor from 193 to 211. He was born in Leptis Magna (present-day Al-Khums, Libya) in the Roman province of Africa. As a young man he advanced through cursus honorum, the ...

, who was a North African of Roman/Punic ancestry (perhaps with some Berber blood).

Numidia

Numidia (20246 BC) was an ancient Berber kingdom in modern Algeria and part of Tunisia. It later alternated between being a

Numidia (20246 BC) was an ancient Berber kingdom in modern Algeria and part of Tunisia. It later alternated between being a Roman province

The Roman provinces (, pl. ) were the administrative regions of Ancient Rome outside Roman Italy that were controlled by the Romans under the Roman Republic and later the Roman Empire. Each province was ruled by a Roman appointed as Roman g ...

and being a Roman client state

A client state in the context of international relations is a State (polity), state that is economically, politically, and militarily subordinated to a more powerful controlling state. Alternative terms for a ''client state'' are satellite state, ...

. The kingdom was located on the eastern border of modern Algeria, bordered by the Roman province of Mauretania (in modern Algeria and Morocco) to the west, the Roman province of Africa

Africa was a Roman province on the northern coast of the continent of Africa. It was established in 146 BC, following the Roman Republic's conquest of Carthage in the Third Punic War. It roughly comprised the territory of present-day Tunisi ...

(modern Tunisia) to the east, the Mediterranean to the north, and the Sahara Desert to the south. Its people were the Numidians.

The name was first applied by Polybius

Polybius (; , ; ) was a Greek historian of the middle Hellenistic period. He is noted for his work , a universal history documenting the rise of Rome in the Mediterranean in the third and second centuries BC. It covered the period of 264–146 ...

and other historians during the third century BC to indicate the territory west of Carthage, including the entire north of Algeria as far as the river Mulucha ( Muluya), about west of Oran. The Numidians were conceived of as two great groups: the Massylii in eastern Numidia, and the Masaesyli in the west. During the first part of the Second Punic War, the eastern Massylii, under King Gala

Gala may refer to:

Music

* ''Gala'' (album), a 1990 album by the English alternative rock band Lush

* Gala (singer), Italian singer and songwriter

*'' Gala – The Collection'', a 2016 album by Sarah Brightman

* GALA Choruses, an association of ...

, were allied with Carthage, while the western Masaesyli, under King Syphax, were allied with Rome.

In 206 BC, the new king of the Massylii, Masinissa, allied himself with Rome, and Syphax, of the Masaesyli, switched his allegiance to the Carthaginian side. At the end of the war, the victorious Romans gave all of Numidia to Masinissa. At the time of his death in 148 BC, Masinissa's territory extended from Mauretania to the boundary of Carthaginian territory, and southeast as far as Cyrenaica, so that Numidia entirely surrounded Carthage except towards the sea.

Masinissa was succeeded by his son Micipsa

Micipsa ( Numidian: ''Mikiwsan''; , ; died BC) was the eldest legitimate son of Masinissa, the King of Numidia, a Berber kingdom in North Africa. Micipsa became the King of Numidia in 148 BC.

Early life

In 151 BC, Masinissa sent Micipsa and his ...

. When Micipsa died in 118 BC, he was succeeded jointly by his two sons Hiempsal I

Hiempsal I (died c. 117 BC), son of Micipsa and grandson of Masinissa, was a king of Numidia in the late 2nd century BC.

Micipsa, on his deathbed, left his two sons, Adherbal and Hiempsal, together with his cousin, Jugurtha, joint heirs of his ...

and Adherbal and Masinissa's illegitimate grandson, Jugurtha

Jugurtha or Jugurthen (c. 160 – 104 BC) was a king of Numidia, the ancient kingdom of the Numidians in northwest Africa. When the Numidian king Micipsa, who had adopted Jugurtha, died in 118 BC, Micipsa's two sons, Hiempsal and Adherbal ...

, of Berber origin, who was very popular among the Numidians. Hiempsal and Jugurtha quarreled immediately after the death of Micipsa. Jugurtha had Hiempsal killed, which led to open war with Adherbal.

After Jugurtha defeated him in open battle, Adherbal fled to Rome for help. The Roman officials, allegedly due to bribes but perhaps more likely out of a desire to quickly end conflict in a profitable client kingdom, sought to settle the quarrel by dividing Numidia into two parts. Jugurtha was assigned the western half. However, soon after, conflict broke out again, leading to the Jugurthine War

The Jugurthine War (; 112–106 BC) was an armed conflict between the Roman Republic and King Jugurtha of Numidia, a kingdom on the north African coast approximating to modern Algeria. Jugurtha was the nephew and adopted son of Micipsa, ki ...

between Rome and Numidia.

Mauretania

In antiquity, Mauretania (3rd century BC44 BC) was an ancient Mauri Berber kingdom in modern Morocco and part of Algeria. It became a client state of theRoman empire

The Roman Empire ruled the Mediterranean and much of Europe, Western Asia and North Africa. The Roman people, Romans conquered most of this during the Roman Republic, Republic, and it was ruled by emperors following Octavian's assumption of ...

in 33 BC, after the death of king Bocchus II

Bocchus II was a king of Mauretania in the 1st century BC. He was the son of Mastanesosus, who died in 49 BC, upon which Bocchus inherited the throne.

Biography

He was the son of Mastanesosus, king of Mauretania. His father was identified fro ...

, then a full Roman province in AD 40, after the death of its last king, Ptolemy of Mauretania

Ptolemy of Mauretania (, ''Ptolemaîos''; ; 13 9BC–AD40) was the last Roman client king and ruler of Mauretania for Rome. He was the son of Juba II, the king of Numidia and a member of the Berber Massyles tribe, as well as a descendant of th ...

, a member of the Ptolemaic dynasty

The Ptolemaic dynasty (; , ''Ptolemaioi''), also known as the Lagid dynasty (, ''Lagidai''; after Ptolemy I's father, Lagus), was a Macedonian Greek royal house which ruled the Ptolemaic Kingdom in Ancient Egypt during the Hellenistic period. ...

.

Middle Ages

Sanhaja