Tudor music on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Early music of Britain and Ireland, from the earliest recorded times until the beginnings of the

Early music of Britain and Ireland, from the earliest recorded times until the beginnings of the

In the early Middle Ages, ecclesiastical music was dominated by

In the early Middle Ages, ecclesiastical music was dominated by

From the mid-15th century we begin to have relatively large numbers of works that have survived from English composers in documents such as the early 15th century

From the mid-15th century we begin to have relatively large numbers of works that have survived from English composers in documents such as the early 15th century

Ireland, Scotland, and Wales shared a tradition of

Ireland, Scotland, and Wales shared a tradition of

The impact of

The impact of

During this period, music printing (technically more complex than the printing of written text) was adopted from continental practice. Around 1520

During this period, music printing (technically more complex than the printing of written text) was adopted from continental practice. Around 1520

The English Madrigal School was the brief but intense flowering of the musical

The English Madrigal School was the brief but intense flowering of the musical

Campion was also a composer of court masques, an elaborate performance involving music and dancing, singing and acting, within a complex

Campion was also a composer of court masques, an elaborate performance involving music and dancing, singing and acting, within a complex

James VI, king of Scotland from 1567, was a major patron of the arts in general. He made statutory provision to reform and promote the teaching of music. He rebuilt the Chapel Royal at Stirling in 1594 and the choir was used for state occasions like the baptism of his son Henry.P. Le Huray, ''Music and the Reformation in England, 1549–1660'' (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1978), pp. 83–5. He followed the tradition of employing lutenists for his private entertainment, as did other members of his family.T. Carter and J. Butt, ''The Cambridge History of Seventeenth-Century Music'' (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005), pp. 280, 300, 433 and 541. When he went south to take the throne of England in 1603 as James I, he removed one of the major sources of patronage in Scotland. The Scottish Chapel Royal was now used only for occasional state visits, beginning to fall into disrepair, and from now on the court in Westminster would be the only major source of royal musical patronage. When Charles I returned in 1633 to be crowned he brought many musicians from the English Chapel Royal for the service. Both James and his son Charles I, king from 1625, continued the Elizabethan patronage of

James VI, king of Scotland from 1567, was a major patron of the arts in general. He made statutory provision to reform and promote the teaching of music. He rebuilt the Chapel Royal at Stirling in 1594 and the choir was used for state occasions like the baptism of his son Henry.P. Le Huray, ''Music and the Reformation in England, 1549–1660'' (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1978), pp. 83–5. He followed the tradition of employing lutenists for his private entertainment, as did other members of his family.T. Carter and J. Butt, ''The Cambridge History of Seventeenth-Century Music'' (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005), pp. 280, 300, 433 and 541. When he went south to take the throne of England in 1603 as James I, he removed one of the major sources of patronage in Scotland. The Scottish Chapel Royal was now used only for occasional state visits, beginning to fall into disrepair, and from now on the court in Westminster would be the only major source of royal musical patronage. When Charles I returned in 1633 to be crowned he brought many musicians from the English Chapel Royal for the service. Both James and his son Charles I, king from 1625, continued the Elizabethan patronage of

The period between the ascendancy of Parliament in London in 1642, to the Restoration of the monarchy in 1660, radically changed the pattern of British music. The loss of the court removed the major source of patronage, the theatres were closed in London in 1642 and certain forms of music, particularly those associated with traditional events or the liturgical calendar (like

The period between the ascendancy of Parliament in London in 1642, to the Restoration of the monarchy in 1660, radically changed the pattern of British music. The loss of the court removed the major source of patronage, the theatres were closed in London in 1642 and certain forms of music, particularly those associated with traditional events or the liturgical calendar (like

Early music of Britain and Ireland, from the earliest recorded times until the beginnings of the

Early music of Britain and Ireland, from the earliest recorded times until the beginnings of the Baroque

The Baroque (, ; ) is a style of architecture, music, dance, painting, sculpture, poetry, and other arts that flourished in Europe from the early 17th century until the 1750s. In the territories of the Spanish and Portuguese empires including ...

in the 17th century, was a diverse and rich culture, including sacred and secular music and ranging from the popular to the elite. Each of the major nations of England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe ...

, Ireland

Ireland ( ; ga, Éire ; Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean, in north-western Europe. It is separated from Great Britain to its east by the North Channel, the Irish Sea, and St George's Channel. Ireland is the s ...

, Scotland

Scotland (, ) is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. Covering the northern third of the island of Great Britain, mainland Scotland has a border with England to the southeast and is otherwise surrounded by the Atlantic Ocean to ...

, and Wales

Wales ( cy, Cymru ) is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is bordered by England to the east, the Irish Sea to the north and west, the Celtic Sea to the south west and the Bristol Channel to the south. It had a population in ...

retained unique forms of music and of instrumentation, but British music was highly influenced by continental developments, while British composers made an important contribution to many of the major movements in early music in Europe, including the polyphony

Polyphony ( ) is a type of musical texture consisting of two or more simultaneous lines of independent melody, as opposed to a musical texture with just one voice, monophony, or a texture with one dominant melodic voice accompanied by chords, ...

of the Ars Nova and laid some of the foundations of later national and international classical music. Musicians from the British Isles also developed some distinctive forms of music, including Celtic chant

Celtic chant is the liturgical plainchant repertory of the Celtic rite of the Catholic Church performed in Britain, Ireland and Brittany. It is related to, but distinct from the Gregorian chant of the Sarum use of the Roman rite which officially ...

, the Contenance Angloise, the rota

Rota or ROTA may refer to:

Places

* Rota (island), in the Marianas archipelago

* Rota (volcano), in Nicaragua

* Rota, Andalusia, a town in Andalusia, Spain

* Naval Station Rota, Spain

People

* Rota (surname), a surname (including a list of peop ...

, polyphonic votive antiphon

An antiphon ( Greek ἀντίφωνον, ἀντί "opposite" and φωνή "voice") is a short chant in Christian ritual, sung as a refrain. The texts of antiphons are the Psalms. Their form was favored by St Ambrose and they feature prominentl ...

s, and the carol in the medieval era and English madrigal

A madrigal is a form of secular vocal music most typical of the Renaissance (15th–16th c.) and early Baroque (1600–1750) periods, although revisited by some later European composers. The polyphonic madrigal is unaccompanied, and the number ...

s, lute ayres, and masques in the Renaissance era, which would lead to the development of English language opera

The history of opera in the English language commences in the 17th century.

Earliest examples

In England, one of opera's antecedents in the 16th century was an afterpiece which came at the end of a play; often scandalous and consisting in the mai ...

at the height of the Baroque in the 18th century.

Medieval music to 1450

Surviving sources indicate that there was a rich and varied musical soundscape in medieval Britain.R. McKitterick, C. T. Allmand, T. Reuter, D. Abulafia, P. Fouracre, J. Simon, C. Riley-Smith, M. Jones, eds, ''The New Cambridge Medieval History: C. 1415- C. 1500'' (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995), pp. 319–25. Historians usually distinguish between ecclesiastical music, designed for use in church, or in religious ceremonies, and secular music for use from royal and baronial courts, celebrations of some religious events, to public and private entertainments of the people. Our understanding of this music is limited by a lack of written sources for much of what was an oral culture.Church music

In the early Middle Ages, ecclesiastical music was dominated by

In the early Middle Ages, ecclesiastical music was dominated by monophonic

Monaural or monophonic sound reproduction (often shortened to mono) is sound intended to be heard as if it were emanating from one position. This contrasts with stereophonic sound or ''stereo'', which uses two separate audio channels to reproduc ...

plainchant

Plainsong or plainchant (calque from the French ''plain-chant''; la, cantus planus) is a body of chants used in the liturgies of the Western Church. When referring to the term plainsong, it is those sacred pieces that are composed in Latin text ...

. The separate development of British Christianity from the direct influence of Rome until the 8th century, with its flourishing monastic culture, led to the development of a distinct form of liturgical

Liturgy is the customary public ritual of worship performed by a religious group. ''Liturgy'' can also be used to refer specifically to public worship by Christians. As a religious phenomenon, liturgy represents a communal response to and partic ...

Celtic chant

Celtic chant is the liturgical plainchant repertory of the Celtic rite of the Catholic Church performed in Britain, Ireland and Brittany. It is related to, but distinct from the Gregorian chant of the Sarum use of the Roman rite which officially ...

.D. O. Croinin, ed., ''Prehistoric and Early Ireland: Prehistoric and Early Ireland'', vol I (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005), p. 798. Although no notations of this music survive, later sources suggest distinctive melodic patterns. This was superseded, as elsewhere in Europe, from the 11th century by Gregorian chant

Gregorian chant is the central tradition of Western plainchant, a form of monophonic, unaccompanied sacred song in Latin (and occasionally Greek) of the Roman Catholic Church. Gregorian chant developed mainly in western and central Europe dur ...

. The version of this chant linked to the liturgy as used in the Diocese of Salisbury

The Diocese of Salisbury is a Church of England diocese in the south of England, within the ecclesiastical Province of Canterbury. The diocese covers most of Dorset (excepting the deaneries of Bournemouth and Christchurch, which fall within the ...

, the Sarum Use

The Use of Sarum (or Use of Salisbury, also known as the Sarum Rite) is the Latin liturgical rite developed at Salisbury Cathedral and used from the late eleventh century until the English Reformation. It is largely identical to the Roman rite ...

, first recorded from the 13th century, became dominant in England. This Sarum Chant became the model for English composers until it was supplanted at the Reformation

The Reformation (alternatively named the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation) was a major movement within Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the Catholic Church and in ...

in the mid-16th century, influencing settings for masses, hymns

A hymn is a type of song, and partially synonymous with devotional song, specifically written for the purpose of adoration or prayer, and typically addressed to a deity or deities, or to a prominent figure or personification. The word ''hymn'' ...

and Magnificats. Scottish music was highly influenced by continental developments, with figures like thirteenth-century musical theorist Simon Tailler who studied in Paris, before returning to Scotland where he introduced several reforms of church music.K. Elliott and F. Rimmer, ''A History of Scottish Music'' (London: British Broadcasting Corporation, 1973), pp. 8–12. Scottish collections of music like the thirteenth-century 'Wolfenbüttel 677', which is associated with St Andrews

St Andrews ( la, S. Andrea(s); sco, Saunt Aundraes; gd, Cill Rìmhinn) is a town on the east coast of Fife in Scotland, southeast of Dundee and northeast of Edinburgh. St Andrews had a recorded population of 16,800 , making it Fife's fourt ...

, contain mostly French compositions, but with some distinctive local styles. The first notations of Welsh music that survive are from the 14th century, including matins

Matins (also Mattins) is a canonical hour in Christian liturgy, originally sung during the darkness of early morning.

The earliest use of the term was in reference to the canonical hour, also called the vigil, which was originally celebrated ...

, lauds

Lauds is a canonical hour of the Divine office. In the Roman Rite Liturgy of the Hours it is one of the major hours, usually held after Matins, in the early morning hours.

Name

The name is derived from the three last psalms of the psalter (148 ...

and vespers

Vespers is a service of evening prayer, one of the canonical hours in Eastern Orthodox, Oriental Orthodox, Catholic (both Latin and Eastern), Lutheran, and Anglican liturgies. The word for this fixed prayer time comes from the Latin , mea ...

for St David's Day

Saint David's Day ( cy, Dydd Gŵyl Dewi Sant or ; ), or the Feast of Saint David, is the feast day of Saint David, the patron saint of Wales, and falls on 1 March, the date of Saint David's death in 589 AD. The feast has been regularly celebr ...

.J. T. Koch, ''Celtic Culture: A Historical Encyclopedia'' (Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO, 2006), p. 1765.

Ars nova

In the 14th century, the EnglishFranciscan

, image = FrancescoCoA PioM.svg

, image_size = 200px

, caption = A cross, Christ's arm and Saint Francis's arm, a universal symbol of the Franciscans

, abbreviation = OFM

, predecessor =

, ...

friar Simon Tunsted, usually credited with the authorship of ''Quatuor Principalia Musicae'': a treatise on musical composition, is believed to have been one of the theorists who influenced the ' ars nova', a movement which developed in France and then Italy, replacing the restrictive styles of Gregorian plainchant with complex polyphony

Polyphony ( ) is a type of musical texture consisting of two or more simultaneous lines of independent melody, as opposed to a musical texture with just one voice, monophony, or a texture with one dominant melodic voice accompanied by chords, ...

. The tradition was well established in England by the 15th century and was widely used in religious, and what became, purely educational establishments, including Eton College

Eton College () is a Public school (United Kingdom), public school in Eton, Berkshire, England. It was founded in 1440 by Henry VI of England, Henry VI under the name ''Kynge's College of Our Ladye of Eton besyde Windesore'',Nevill, p. 3 ff. i ...

, and the colleges that became the Universities of Oxford

Oxford () is a city in England. It is the county town and only city of Oxfordshire. In 2020, its population was estimated at 151,584. It is north-west of London, south-east of Birmingham and north-east of Bristol. The city is home to the ...

and Cambridge

Cambridge ( ) is a university city and the county town in Cambridgeshire, England. It is located on the River Cam approximately north of London. As of the 2021 United Kingdom census, the population of Cambridge was 145,700. Cambridge bec ...

. The motet

In Western classical music, a motet is mainly a vocal musical composition, of highly diverse form and style, from high medieval music to the present. The motet was one of the pre-eminent polyphonic forms of Renaissance music. According to Ma ...

' Sub Arturo plebs' attributed to Johannes Alanus and dated to the mid or late 14th century, includes a list of Latinised names of musicians from the English court that shows the flourishing of court music, the importance of royal patronage in this era and the growing influence of the ''ars nova''. Included in the list is J. de Alto Bosco, who has been identified with the composer and theorist John Hanboys, author of ''Summa super musicam continuam et discretam'', a work that discusses the origins of musical notation and mensuration from the 13th century and proposed several new methods for recording music.

Contenance Angloise

From the mid-15th century we begin to have relatively large numbers of works that have survived from English composers in documents such as the early 15th century

From the mid-15th century we begin to have relatively large numbers of works that have survived from English composers in documents such as the early 15th century Old Hall Manuscript

The Old Hall Manuscript (British Library, Add MS 57950) is the largest, most complete, and most significant source of English sacred music of the late 14th and early 15th centuries, and as such represents the best source for late Medieval English ...

. Probably the first, and one of the best represented is Leonel Power

Leonel Power (also spelled ''Lionel, Lyonel, Leonellus, Leonelle''; ''Polbero''; 1370 to 1385 – 5 June 1445) was an English composer of the late Medieval and early Renaissance music. Along with John Dunstaple, he was a dominant figure of 15th ...

(c. 1380–1445), who was probably the choir master of Christ Church, Canterbury and enjoyed noble patronage from Thomas of Lancaster, 1st Duke of Clarence

Thomas of Lancaster, Duke of Clarence (autumn 1387 – 22 March 1421) was a medieval English prince and soldier, the second son of Henry IV of England, brother of Henry V, and heir to the throne in the event of his brother's death. He acted ...

and John of Lancaster, 1st Duke of Bedford

John of Lancaster, Duke of Bedford KG (20 June 138914 September 1435) was a medieval English prince, general and statesman who commanded England's armies in France during a critical phase of the Hundred Years' War. Bedford was the third son of ...

(1389–1435). John Dunstaple

John Dunstaple (or Dunstable, – 24 December 1453) was an English composer whose music helped inaugurate the transition from the medieval to the Renaissance periods. The central proponent of the ''Contenance angloise'' style (), Dunstaple w ...

(or Dunstable) was the most celebrated composer of the 'Contenance Angloise' (English manner), a distinctive style of polyphony that used full, rich harmonies based on the third and sixth, which was highly influential in the fashionable Burgundian court of Philip the Good

Philip III (french: Philippe le Bon; nl, Filips de Goede; 31 July 1396 – 15 June 1467) was Duke of Burgundy from 1419 until his death. He was a member of a cadet line of the Valois dynasty, to which all 15th-century kings of France belonge ...

.R. H. Fritze and W. B. Robison, ''Historical Dictionary of Late Medieval England, 1272–1485'' (Santa Barbara, CA: Greenwood, 2002), p. 363. Nearly all his manuscript music in England was lost during the Dissolution of the Monasteries (1536-1540), but some of his works have been reconstructed from copies found in continental Europe, particularly in Italy. The existence of these copies is testament to his widespread fame within Europe. He may have been the first composer to provide liturgical music

Liturgical music originated as a part of religious ceremony, and includes a number of traditions, both ancient and modern. Liturgical music is well known as a part of Catholic Mass, the Anglican Holy Communion service (or Eucharist) and Evensong ...

with an instrumental accompaniment. Royal interest in music is suggested by the works attributed to Roy Henry

Roy Henry ("King" Henry) () was an English composer, almost certainly the pseudonym of an English King: probably Henry V, but also possibly Henry IV. His music, two compositions in all, appears in a position of prominence in the Old Hall Manusc ...

in the Old Hall Manuscript, suspected to be Henry IV or Henry V Henry V may refer to:

People

* Henry V, Duke of Bavaria (died 1026)

* Henry V, Holy Roman Emperor (1081/86–1125)

* Henry V, Duke of Carinthia (died 1161)

* Henry V, Count Palatine of the Rhine (c. 1173–1227)

* Henry V, Count of Luxembourg (121 ...

. This tradition was continued by figures such as Walter Frye (c. 1420–1475), whose masses were recorded and highly influential in France and the Netherlands.J. Caldwell, ''The Oxford History of English Music'' (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998), pp. 151–2. Similarly, John Hothby

John Hothby (''Otteby'', ''Hocby'', ''Octobi'', ''Ottobi'', 1410–1487), also known by his Latinised names Johannes Ottobi or Johannes de Londonis, was an English Renaissance music theorist and composer who travelled widely in Europe and gain ...

(c. 1410–1487), an English Carmelite

, image =

, caption = Coat of arms of the Carmelites

, abbreviation = OCarm

, formation = Late 12th century

, founder = Early hermits of Mount Carmel

, founding_location = Mount Ca ...

monk, who travelled widely and, although leaving little composed music, wrote several theoretical treatises, including ''La Calliopea legale'', and is credited with introducing innovations to the medieval pitch system.T. Dumitrescu, ''The Early Tudor Court and International Musical Relations'' (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2007), pp. 63 and 197–9. The Scottish king James I James I may refer to:

People

*James I of Aragon (1208–1276)

*James I of Sicily or James II of Aragon (1267–1327)

*James I, Count of La Marche (1319–1362), Count of Ponthieu

*James I, Count of Urgell (1321–1347)

*James I of Cyprus (1334–13 ...

was in captivity in England from 1406 to 1423, where he earned a reputation as a poet and composer and may have been responsible for taking English and continental styles and musicians back to the Scottish court on his release.

Secular music

Ireland, Scotland, and Wales shared a tradition of

Ireland, Scotland, and Wales shared a tradition of bards

In Celtic cultures, a bard is a professional story teller, verse-maker, music composer, oral historian and genealogist, employed by a patron (such as a monarch or chieftain) to commemorate one or more of the patron's ancestors and to praise ...

, who acted as musicians, but also as poets, story tellers, historians, genealogists, and lawyers, relying on an oral tradition that stretched back generations. Often accompanying themselves on the harp

The harp is a stringed musical instrument that has a number of individual strings running at an angle to its soundboard; the strings are plucked with the fingers. Harps can be made and played in various ways, standing or sitting, and in orc ...

, they can also be seen in records of the Scottish courts throughout the medieval period. We also know from the work of Gerald of Wales

Gerald of Wales ( la, Giraldus Cambrensis; cy, Gerallt Gymro; french: Gerald de Barri; ) was a Cambro-Norman priest and historian. As a royal clerk to the king and two archbishops, he travelled widely and wrote extensively. He studied and taugh ...

that at least from the 12th century, group singing was a major part of the social life of ordinary people in Wales. From the 11th century particularly important in English secular music were minstrels, sometimes attached to a wealthy household, noble, or royal court, but probably more often moving from place to place and occasion to occasion in pursuit of payment. Many appear to have composed their own works, and can be seen as the first secular composers, and some crossed international boundaries, transferring songs and styles of music. Because literacy, and musical notation in particular, were preserves of the clergy in this period the survival of secular music is much more limited than for church music. Nevertheless, some were noted, occasionally by clergymen who had an interest in secular music. England in particular produced three distinctive secular musical forms in this period: the rota, the polyphonic votive antiphon, and the carol.

Rotas

A rota is a form of round, known to have been used from the 13th century in England. The earliest surviving piece of composed music in the British Isles, and perhaps the oldest recorded folk song in Europe, is a rota: a setting of ' Sumer Is Icumen In' ('Summer is a-coming in') from the mid-13th century, possibly written byW. de Wycombe

W. de Wycombe (Wicumbe, and perhaps Whichbury) (late 13th century) was an England, English composer and copyist of the Medieval music, Medieval era. He was precentor of the priory of Leominster in Herefordshire. It is possible that he was the comp ...

, precentor of the priory of Leominster

Leominster ( ) is a market town in Herefordshire, England, at the confluence of the River Lugg and its tributary the River Kenwater. The town is north of Hereford and south of Ludlow in Shropshire. With a population of 11,700, Leominster i ...

in Herefordshire, and set for six parts. Although few are recorded, the use of rotas seems to have been widespread in England and it has been suggested that the English talent for polyphony may have its origins in this form of music.

Votive Antiphons

Polyphonic votive antiphons emerged in England in the 14th century as a setting of a text honouring theVirgin Mary

Mary; arc, ܡܪܝܡ, translit=Mariam; ar, مريم, translit=Maryam; grc, Μαρία, translit=María; la, Maria; cop, Ⲙⲁⲣⲓⲁ, translit=Maria was a first-century Jewish woman of Nazareth, the wife of Joseph and the mother of ...

, but separate from the mass

Mass is an intrinsic property of a body. It was traditionally believed to be related to the quantity of matter in a physical body, until the discovery of the atom and particle physics. It was found that different atoms and different ele ...

and office

An office is a space where an organization's employees perform administrative work in order to support and realize objects and goals of the organization. The word "office" may also denote a position within an organization with specific ...

, often after compline

Compline ( ), also known as Complin, Night Prayer, or the Prayers at the End of the Day, is the final prayer service (or office) of the day in the Christian tradition of canonical hours, which are prayed at fixed prayer times.

The English ...

. Towards the end of the 15th century they began to be written by English composers as expanded settings for as many as nine parts with increasing complexity and vocal range. The largest collection of such antiphons is in the late 15th century Eton choirbook.H. Benham, ''John Taverner: His Life and Music'' (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2003), pp. 48–9.

Carols

Carols developed in the 14th century as simple songs with a verse and refrain structure. Carols were usually connected with a religious festival, particularly Christmas. They were derived from a form ofcircle dance

Circle dance, or chain dance, is a style of social dance done in a circle, semicircle or a curved line to musical accompaniment, such as rhythm instruments and singing, and is a type of dance where anyone can join in without the need of par ...

accompanied by singers, which was popular from the mid-12th century. From the 14th century they were used as processional songs, particularly at Advent, Easter, and Christmas, and to accompany religious mystery plays

Mystery plays and miracle plays (they are distinguished as two different forms although the terms are often used interchangeably) are among the earliest formally developed plays in medieval Europe. Medieval mystery plays focused on the represe ...

. Because the tradition of carols continued into the modern era, we know more of their structure and variety than most other secular forms of medieval music.

Renaissance c. 1450–c. 1660

The impact of

The impact of Renaissance humanism

Renaissance humanism was a revival in the study of classical antiquity, at first in Italy and then spreading across Western Europe in the 14th, 15th, and 16th centuries. During the period, the term ''humanist'' ( it, umanista) referred to teache ...

on music can be seen in England the late 15th century under Edward IV

Edward IV (28 April 1442 – 9 April 1483) was King of England from 4 March 1461 to 3 October 1470, then again from 11 April 1471 until his death in 1483. He was a central figure in the Wars of the Roses, a series of civil wars in Englan ...

(r. 1461–1483) and Henry VII (r. 1485–1509). Although the influence of English music on the continent declined from the mid-15th century as the Burgundian School

The Burgundian School was a group of composers active in the 15th century in what is now northern and eastern France, Belgium, and the Netherlands, centered on the court of the Dukes of Burgundy. The school inaugurated the music of Burgundy.

T ...

became the dominant force in the West, English music continued to flourish with the first composers being awarded doctorates at Oxford and Cambridge, including Thomas Santriste, who was provost of King's College, Cambridge

King's College is a constituent college of the University of Cambridge. Formally The King's College of Our Lady and Saint Nicholas in Cambridge, the college lies beside the River Cam and faces out onto King's Parade in the centre of the cit ...

, and Henry Abyngdon

Henry Abyngdon, Abingdon or Abington (c. 1418 – 1 September 1497) was an English ecclesiastic and musician, perhaps the first to receive a university degree in music.

Biography

He may have been connected with the village of Abington in Cambridg ...

, who was Master of Music at Worcester Cathedral

Worcester Cathedral is an Anglican cathedral in Worcester, in Worcestershire, England, situated on a bank overlooking the River Severn. It is the seat of the Bishop of Worcester. Its official name is the Cathedral Church of Christ and the Bless ...

and from 1465–83 Master of the King's Music. Edward IV

Edward IV (28 April 1442 – 9 April 1483) was King of England from 4 March 1461 to 3 October 1470, then again from 11 April 1471 until his death in 1483. He was a central figure in the Wars of the Roses, a series of civil wars in Englan ...

chartered and patronised the first guild

A guild ( ) is an association of artisans and merchants who oversee the practice of their craft/trade in a particular area. The earliest types of guild formed as organizations of tradesmen belonging to a professional association. They sometim ...

of musicians in London in 1472, a pattern copied in other major towns cities as musicians formed guilds or waites, creating local monopolies with greater organisation, but arguably ending the role of the itinerant minstrel. There were increasing numbers of foreign musicians, particularly those from France and the Netherlands, at the court, becoming a majority of those known to have been employed by the death of Henry VII. His mother, Lady Margaret Beaufort

Lady Margaret Beaufort (usually pronounced: or ; 31 May 1441/43 – 29 June 1509) was a major figure in the Wars of the Roses of the late fifteenth century, and mother of King Henry VII of England, the first Tudor monarch.

A descendant o ...

, was the major sponsor of music during his reign, commissioning several settings for new liturgical feasts and ordinary of the mass. The result was a very elaborate style which balanced the many parts of the setting and prefigured Renaissance developments elsewhere.R. Bray, 'England i, 1485–1600' in J. Haar, ''European Music, 1520–1640'' (Woodbridge: Boydell, 2006), pp. 490–502. Similar developments can be seen in Scotland. In the late 15th century a series of Scottish musicians trained in the Netherlands before returning home, including John Broune, Thomas Inglis and John Fety, the last of whom became master of the song school in Aberdeen and then Edinburgh, introducing the new five-fingered organ playing technique.J. Wormald, ''Court, Kirk, and Community: Scotland, 1470–1625'' (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1991), pp. 58 and 118. In 1501 James IV

James IV (17 March 1473 – 9 September 1513) was King of Scotland from 11 June 1488 until his death at the Battle of Flodden in 1513. He inherited the throne at the age of fifteen on the death of his father, James III, at the Battle of Sauch ...

refounded the Chapel Royal within Stirling Castle

Stirling Castle, located in Stirling, is one of the largest and most important castles in Scotland, both historically and architecturally. The castle sits atop Castle Hill, an intrusive crag, which forms part of the Stirling Sill geological ...

, with a new and enlarged choir, it became the focus of Scottish liturgical music. Burgundian and English influences came north with Henry VII's daughter Margaret Tudor

Margaret Tudor (28 November 1489 – 18 October 1541) was Queen of Scotland from 1503 until 1513 by marriage to King James IV. She then served as regent of Scotland during her son's minority, and successfully fought to extend her regency. Ma ...

, who married James IV in 1503.M. Gosman, A. A. MacDonald, A. J. Vanderjagt and A. Vanderjagt, ''Princes and princely culture, 1450–1650'' (Brill, 2003), p. 163. In Wales, as elsewhere, the local nobility were increasingly Anglicised and the bardic tradition started to decline, resulting in the first Eisteddfod

In Welsh culture, an ''eisteddfod'' is an institution and festival with several ranked competitions, including in poetry and music.

The term ''eisteddfod'', which is formed from the Welsh morphemes: , meaning 'sit', and , meaning 'be', means, ac ...

s being held from 1527, in an attempt to preserve the tradition. In this period it seems that most Welsh composers tended to cross the border and seek employment in the English royal and noble households, including John Lloyd (c. 1475–1523) who was employed in the household of the Edward Stafford, 3rd Duke of Buckingham

Edward Stafford, 3rd Duke of Buckingham (3 February 1478 – 17 May 1521) was an English nobleman. He was the son of Henry Stafford, 2nd Duke of Buckingham, and Katherine Woodville, and nephew of Elizabeth Woodville and King Edward IV. Thu ...

and became a Gentleman of the Chapel Royal from 1509 and Robert Jones (fl.c.1520–35) who also became a gentleman of the Chapel Royal.

Henry VIII and James V

Henry VIII

Henry VIII (28 June 149128 January 1547) was King of England from 22 April 1509 until his death in 1547. Henry is best known for his six marriages, and for his efforts to have his first marriage (to Catherine of Aragon) annulled. His disa ...

and James V

James V (10 April 1512 – 14 December 1542) was King of Scotland from 9 September 1513 until his death in 1542. He was crowned on 21 September 1513 at the age of seventeen months. James was the son of King James IV and Margaret Tudor, and du ...

were both enthusiastic patrons of music. Henry (1491–1547) played various instruments, of which he had a large collection, including, at his death, seventy eight recorder

Recorder or The Recorder may refer to:

Newspapers

* ''Indianapolis Recorder'', a weekly newspaper

* ''The Recorder'' (Massachusetts newspaper), a daily newspaper published in Greenfield, Massachusetts, US

* ''The Recorder'' (Port Pirie), a news ...

s. He is sometimes credited with compositions, including the part-song ' Pastime with Good Company'. In the early part of his reign and his marriage to Catherine of Aragon

Catherine of Aragon (also spelt as Katherine, ; 16 December 1485 – 7 January 1536) was Queen of England as the first wife of King Henry VIII from their marriage on 11 June 1509 until their annulment on 23 May 1533. She was previously ...

secular court music focused around an emphasis on courtly love

Courtly love ( oc, fin'amor ; french: amour courtois ) was a medieval European literary conception of love that emphasized nobility and chivalry. Medieval literature is filled with examples of knights setting out on adventures and performing var ...

, probably acquired from the Burgundian court, result in compositions like William Cornysh

William Cornysh the Younger (also spelled Cornyshe or Cornish) (1465 – October 1523) was an English composer, dramatist, actor, and poet.

Life

In his only surviving poem, which was written in Fleet Prison, he claims that he has been conv ...

's (1465–1515) 'Yow and I and Amyas'. Among the most eminent musicians of Henry VIII's reign was John Taverner (1490–1545), organist of the College

A college (Latin: ''collegium'') is an educational institution or a constituent part of one. A college may be a degree-awarding tertiary educational institution, a part of a collegiate or federal university, an institution offerin ...

founded at Oxford

Oxford () is a city in England. It is the county town and only city of Oxfordshire. In 2020, its population was estimated at 151,584. It is north-west of London, south-east of Birmingham and north-east of Bristol. The city is home to the ...

by Thomas Wolsey

Thomas Wolsey ( – 29 November 1530) was an English statesman and Catholic bishop. When Henry VIII became King of England in 1509, Wolsey became the king's Lord High Almoner, almoner. Wolsey's affairs prospered and by 1514 he had become the ...

from 1526–1530. His principal works include masses, magnificats and motets, of which the most famous is 'Dum Transisset Sabbatum'. Thomas Tallis

Thomas Tallis (23 November 1585; also Tallys or Talles) was an English composer of High Renaissance music. His compositions are primarily vocal, and he occupies a primary place in anthologies of English choral music. Tallis is considered one o ...

(c. 1505–85) took polyphonic composition to new heights with works like his 'Spem in alium

''Spem in alium'' (Latin for "Hope in any other") is a 40-part Renaissance motet by Thomas Tallis, composed in c. 1570 for eight choirs of five voices each. It is considered by some critics to be the greatest piece of English early music. H. B. ...

', a motet

In Western classical music, a motet is mainly a vocal musical composition, of highly diverse form and style, from high medieval music to the present. The motet was one of the pre-eminent polyphonic forms of Renaissance music. According to Ma ...

for forty independent voices. In Scotland James V (1512–42) had a similar interest in music. A talented lute player he introduced French chansons and consorts of viols to his court and was patron to composers such as David Peebles

David Peebles ables(d. 1579?) was a Scottish composer of religious music.

Biography

Little is known of his life but the majority of his work dates to between 1530 and 1576. He is known to have been a canon at the Augustinian Priory of St Andre ...

(c. 1510–1579?).

Reformation

The Reformation naturally had a profound impact on the religious music of Britain. The loss of many abbeys, collegiate churches and religious orders intensified a process by which humanism had made careers writing church music decline in importance compared with employment in the royal and noble households. Many composers also responded to the liturgical changes brought about by the Reformation. From the 1540s during theReformation in England

The English Reformation took place in 16th-century England when the Church of England broke away from the authority of the pope and the Catholic Church. These events were part of the wider European Protestant Reformation, a religious and po ...

sacred music was being set to English language texts along with Latin. The legacy of Tallis includes the harmonised versions of the plainsong

Plainsong or plainchant (calque from the French ''plain-chant''; la, cantus planus) is a body of chants used in the liturgies of the Western Church. When referring to the term plainsong, it is those sacred pieces that are composed in Latin text ...

responses of the English church service that are still in use by the Church of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the established Christian church in England and the mother church of the international Anglican Communion. It traces its history to the Christian church recorded as existing in the Roman province of Brit ...

.R. M. Wilson, ''Anglican Chant and Chanting in England, Scotland, and America, 1660 to 1820'' (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1996), pp. 146–7 and 196–7. The Lutheranism

Lutheranism is one of the largest branches of Protestantism, identifying primarily with the theology of Martin Luther, the 16th-century German monk and Protestant Reformers, reformer whose efforts to reform the theology and practice of the Cathol ...

that influenced the early Scottish Reformation

The Scottish Reformation was the process by which Kingdom of Scotland, Scotland broke with the Pope, Papacy and developed a predominantly Calvinist national Church of Scotland, Kirk (church), which was strongly Presbyterianism, Presbyterian in ...

attempted to accommodate Catholic musical traditions into worship, drawing on Latin hymns and vernacular songs. The most important product of this tradition in Scotland was ''The Gude and Godlie Ballatis'', which were spiritual satires on popular ballads composed by the brothers James, John

John is a common English name and surname:

* John (given name)

* John (surname)

John may also refer to:

New Testament

Works

* Gospel of John, a title often shortened to John

* First Epistle of John, often shortened to 1 John

* Secon ...

and Robert Wedderburn. Never adopted by the kirk, they nevertheless remained popular and were reprinted from the 1540s to the 1620s. Later the Calvinism that came to dominate the Scottish Reformation was much more hostile to Catholic musical tradition and popular music, placing an emphasis on what was biblical, which meant the Psalms

The Book of Psalms ( or ; he, תְּהִלִּים, , lit. "praises"), also known as the Psalms, or the Psalter, is the first book of the ("Writings"), the third section of the Tanakh, and a book of the Old Testament. The title is derived ...

. The Scottish psalter

Decisions concerning the conduct of public worship in the Church of Scotland are entirely at the discretion of the parish minister. As a result, a wide variety of musical resources are used. However, at various times in its history, the General A ...

of 1564 was commissioned by the Assembly of the Church. It drew on the work of French musician Clément Marot

Clément Marot (23 November 1496 – 12 September 1544) was a French Renaissance poet.

Biography

Youth

Marot was born at Cahors, the capital of the province of Quercy, some time during the winter of 1496–1497. His father, Jean Marot (c.& ...

, Calvin's contributions to the Strasbourg psalter

A psalter is a volume containing the Book of Psalms, often with other devotional material bound in as well, such as a liturgical calendar and litany of the Saints. Until the emergence of the book of hours in the Late Middle Ages, psalters w ...

of 1539 and English writers, particularly the 1561 edition of the psalter produced by William Whittingham

William Whittingham (c. 1524–1579) was an English Puritan, a Marian exile, and a translator of the Geneva Bible. He was well connected to the circles around John Knox, Bullinger, and Calvin, and firmly resisted the continuance of the English li ...

for the English congregation in Geneva. The intention was to produce individual tunes for each psalm, but of 150 psalms, 105 had proper tunes and in the seventeenth century, common tunes, which could be used for psalms with the same metre, became more common. The need for simplicity for whole congregations that would now all sing these psalms, unlike the trained choirs who had sung the many parts of polyphonic hymns, necessitated simplicity and most church compositions were confined to homophonic

In music, homophony (;, Greek: ὁμόφωνος, ''homóphōnos'', from ὁμός, ''homós'', "same" and φωνή, ''phōnē'', "sound, tone") is a texture in which a primary part is supported by one or more additional strands that flesh ...

settings.A. Thomas, ''The Renaissance'', in T. M. Devine and J. Wormald, ''The Oxford Handbook of Modern Scottish History'' (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012), , p. 198. There is some evidence that polyphony survived and it was incorporated into editions of the psalter from 1625, but usually with the congregation singing the melody and trained singers the contra-tenor, treble and bass parts.J. Wormald, ''Court, Kirk, and Community: Scotland, 1470-1625'' (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1991), , pp. 187-90.

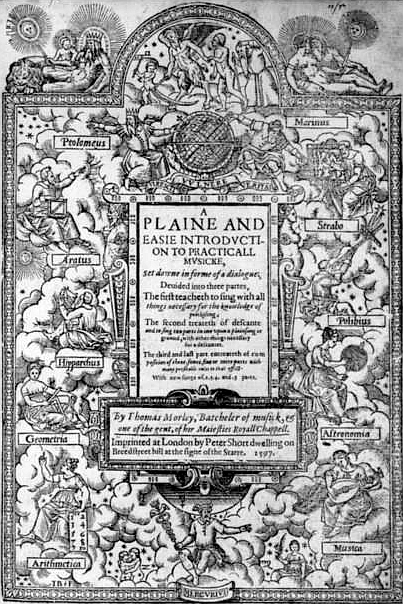

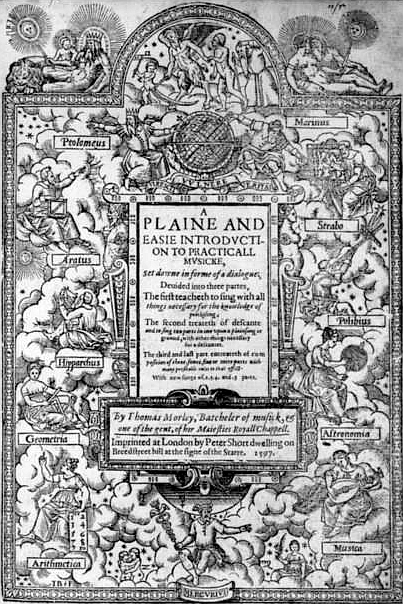

Music publication

During this period, music printing (technically more complex than the printing of written text) was adopted from continental practice. Around 1520

During this period, music printing (technically more complex than the printing of written text) was adopted from continental practice. Around 1520 John Rastell

John Rastell (or Rastall) (c. 1475 – 1536) was an English printer, author, member of parliament, and barrister.

Life

Born in Coventry, he is vaguely reported by Anthony à Wood to have been "educated for a time in grammaticals and philosophi ...

initiated the single-impression method for printing music, in which the staff lines, words, and notes were all part of a single piece of type, making it much easier to produce, although not necessarily clearer. Elizabeth I

Elizabeth I (7 September 153324 March 1603) was Queen of England and Ireland from 17 November 1558 until her death in 1603. Elizabeth was the last of the five House of Tudor monarchs and is sometimes referred to as the "Virgin Queen".

Eli ...

granted the monopoly of music publishing to Tallis and his pupil William Byrd

William Byrd (; 4 July 1623) was an English composer of late Renaissance music. Considered among the greatest composers of the Renaissance, he had a profound influence on composers both from his native England and those on the continent. He ...

which ensured that their works were widely distributed and have survived in various editions, but arguably limited the potential for music publishing in Britain.J. P. Wainright, 'England ii, 1603–1642' in J. Haar, ed., ''European Music, 1520–1640'' (Woodbridge: Boydell, 2006), pp. 509–21.

Mary, Queen of Scots and Elizabeth I

James V's daughter,Mary, Queen of Scots

Mary, Queen of Scots (8 December 1542 – 8 February 1587), also known as Mary Stuart or Mary I of Scotland, was Queen of Scotland from 14 December 1542 until her forced abdication in 1567.

The only surviving legitimate child of James V of S ...

, also played the lute, virginals

The virginals (or virginal) is a keyboard instrument of the harpsichord family. It was popular in Europe during the late Renaissance and early Baroque periods.

Description

A virginal is a smaller and simpler rectangular or polygonal form of ha ...

and (unlike her father) was a fine singer.A. Frazer, ''Mary Queen of Scots'' (London: Book Club Associates, 1969), pp. 206–7. She was brought up in the French court and brought many influences from there when she returned to rule Scotland from 1561, employing lutenists and viol players in her household. Mary's position as a Catholic gave a new lease of life to the choir of the Scottish Chapel Royal in her reign, but the destruction of Scottish church organs meant that instrumentation to accompany the mass had to employ bands of musicians with trumpets, drums, fifes, bagpipes and tabors. In England her cousin Elizabeth I

Elizabeth I (7 September 153324 March 1603) was Queen of England and Ireland from 17 November 1558 until her death in 1603. Elizabeth was the last of the five House of Tudor monarchs and is sometimes referred to as the "Virgin Queen".

Eli ...

was also trained in music. She played the lute, virginals, sang, danced, and even claimed to have composed dance music. She was major patron for English musicians composers (particularly in the Chapel Royal

The Chapel Royal is an establishment in the Royal Household serving the spiritual needs of the sovereign and the British Royal Family. Historically it was a body of priests and singers that travelled with the monarch. The term is now also appl ...

) while in her royal household she employed numerous foreign musicians in her consorts of viols, flutes, recorders, and sackbuts and shawms. Byrd emerged as the leading composer of the Elizabethan court, writing sacred and secular polyphony, viol

The viol (), viola da gamba (), or informally gamba, is any one of a family of bowed, fretted, and stringed instruments with hollow wooden bodies and pegboxes where the tension on the strings can be increased or decreased to adjust the pitc ...

, keyboard

Keyboard may refer to:

Text input

* Keyboard, part of a typewriter

* Computer keyboard

** Keyboard layout, the software control of computer keyboards and their mapping

** Keyboard technology, computer keyboard hardware and firmware

Music

* Mu ...

and consort music

A consort of instruments was a phrase used in England during the 16th and 17th centuries to indicate an instrumental ensemble. These could be of the same or a variety of instruments. Consort music enjoyed considerable popularity at court and in ho ...

, reflecting the growth in the range of instruments and forms of music available in Tudor and Stuart Britain

The Stuart period of British history lasted from 1603 to 1714 during the dynasty of the House of Stuart. The period ended with the death of Queen Anne and the accession of King George I from the German House of Hanover.

The period was plagu ...

. The outstanding Scottish composer of the era was Robert Carver (c.1485–c.1570) whose works included the nineteen-part motet 'O Bone Jesu'.

English Madrigal School

The English Madrigal School was the brief but intense flowering of the musical

The English Madrigal School was the brief but intense flowering of the musical madrigal

A madrigal is a form of secular vocal music most typical of the Renaissance (15th–16th c.) and early Baroque (1600–1750) periods, although revisited by some later European composers. The polyphonic madrigal is unaccompanied, and the number ...

in England, mostly from 1588 to 1627. Based on the Italian musical form and patronised by Elizabeth I

Elizabeth I (7 September 153324 March 1603) was Queen of England and Ireland from 17 November 1558 until her death in 1603. Elizabeth was the last of the five House of Tudor monarchs and is sometimes referred to as the "Virgin Queen".

Eli ...

after the highly popular ''Musica transalpina'' by Nicholas Yonge in 1588. English madrigals were a cappella

''A cappella'' (, also , ; ) music is a performance by a singer or a singing group without instrumental accompaniment, or a piece intended to be performed in this way. The term ''a cappella'' was originally intended to differentiate between Ren ...

, predominantly light in style, and generally began as either copies or direct translations of Italian

Italian(s) may refer to:

* Anything of, from, or related to the people of Italy over the centuries

** Italians, an ethnic group or simply a citizen of the Italian Republic or Italian Kingdom

** Italian language, a Romance language

*** Regional Ita ...

models, mostly set for three to six verses. The most influential composers of madrigals in England whose work has survived were Thomas Morley

Thomas Morley (1557 – early October 1602) was an English composer, theorist, singer and organist of the Renaissance. He was one of the foremost members of the English Madrigal School. Referring to the strong Italian influence on the Engl ...

, Thomas Weelkes

Thomas Weelkes (baptised 25 October 1576 – 30 November 1623) was an English composer and organist. He became organist of Winchester College in 1598, moving to Chichester Cathedral. His works are chiefly vocal, and include madrigals, anth ...

and John Wilbye

John Wilbye (baptized 7 March 1574September 1638) was an English madrigal composer.

Early life and education

The son of a tanner, he was born at Brome, Suffolk, England. (Brome is near Diss.)

Career

Wilbye received the patronage of the Cornwa ...

. One of the more notable compilations of English madrigals was ''The Triumphs of Oriana

''The Triumphs of Oriana'' is a book of English madrigals, compiled and published in 1601 by Thomas Morley, which first edition has 25 pieces by 23 composers (Thomas Morley and Ellis Gibbons have two madrigals). It was said to have been made to ...

'', a collection of madrigals compiled by Thomas Morley and devoted to Elizabeth I.S. Lord and D. Brinkman, ''Music from the Age of Shakespeare: a Cultural History'' (Santa Barbara, CA: Greenwood, 2003), pp. 41–2 and 522. Madrigals continued to be composed in England through the 1620s, but stopped in the early 1630s as they began to seem obsolete as new forms of music began to emerge from the continent.G. J. Buelow, ''History of Baroque Music: Music in the Seventeenth and First Half of the Eighteenth Centuries'' (Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 2004), pp. 26, 306, 309 and 327–8.

Lute ayres

Also emerging from the Elizabethan court were ayres, solo songs, occasionally with more (usually three) parts, accompanied on alute

A lute ( or ) is any plucked string instrument with a neck and a deep round back enclosing a hollow cavity, usually with a sound hole or opening in the body. It may be either fretted or unfretted.

More specifically, the term "lute" can ref ...

. Their popularity began with the publication of John Dowland

John Dowland (c. 1563 – buried 20 February 1626) was an English Renaissance composer, lutenist, and singer. He is best known today for his melancholy songs such as "Come, heavy sleep", " Come again", "Flow my tears", " I saw my Lady weepe", ...

's (1563–1626) ''First Booke of Songs or Ayres'' (1597). Dowland had travelled extensively in Europe and probably based his ayres on the Italian monody and French air de cour

The ''air de cour'' was a popular type of secular vocal music in France in the late Renaissance and early Baroque period, from about 1570 until around 1650. From approximately 1610 to 1635, during the reign of Louis XIII, this was the predominant ...

. His most famous ayres include " Come again", "Flow, my tears

"Flow, my tears" (originally en-emodeng, Flow my teares fall from your springs, italic=no) is a lute song (specifically, an "ayre") by the accomplished lutenist and composer John Dowland (1563–1626). Originally composed as an instrumental under ...

", " I saw my Lady weepe" and " In darkness let me dwell". The genre was further developed by Thomas Campion

Thomas Campion (sometimes spelled Campian; 12 February 1567 – 1 March 1620) was an English composer, poet, and physician. He was born in London, educated at Cambridge, studied law in Gray's inn. He wrote over a hundred lute songs, masques ...

(1567–1620), whose ''Books of Airs'' (1601) (co-written with Philip Rosseter) containing over one hundred lute song

The term lute song is given to a music style from the late 16th century to early 17th century, late Renaissance to early Baroque, that was predominantly in England and France. Lute songs were generally in strophic form or verse repeating with a h ...

s and which was reprinted four times in the 1610s. Although this printing boom died out in the 1620s ayres continued to be written and performed and were often incorporated into court masques.

Consort music

Consorts of instruments developed in the Tudor period in England as either 'whole' consorts, that is, all instruments of the same family (for example, a set ofviol

The viol (), viola da gamba (), or informally gamba, is any one of a family of bowed, fretted, and stringed instruments with hollow wooden bodies and pegboxes where the tension on the strings can be increased or decreased to adjust the pitc ...

s played together) and a 'mixed' or 'broken' consort, consisting of instruments from various families (for example viol

The viol (), viola da gamba (), or informally gamba, is any one of a family of bowed, fretted, and stringed instruments with hollow wooden bodies and pegboxes where the tension on the strings can be increased or decreased to adjust the pitc ...

s and lute

A lute ( or ) is any plucked string instrument with a neck and a deep round back enclosing a hollow cavity, usually with a sound hole or opening in the body. It may be either fretted or unfretted.

More specifically, the term "lute" can ref ...

). Major forms of music composed for consorts included: fantasias, In Nomine

In Nomine is a title given to a large number of pieces of English polyphonic, predominantly instrumental music, first composed during the 16th century.

History

This "most conspicuous single form in the early development of English consort mus ...

s, variations

Variation or Variations may refer to:

Science and mathematics

* Variation (astronomy), any perturbation of the mean motion or orbit of a planet or satellite, particularly of the moon

* Genetic variation, the difference in DNA among individua ...

, dances, and fantasia-suites. Many of the major composers of the 16th and 17th centuries produced work for consorts, including William Byrd, Giovanni Coperario, Orlando Gibbons

Orlando Gibbons ( bapt. 25 December 1583 – 5 June 1625) was an English composer and keyboard player who was one of the last masters of the English Virginalist School and English Madrigal School. The best known member of a musical fam ...

, John Jenkins and Henry Purcell

Henry Purcell (, rare: September 1659 – 21 November 1695) was an English composer.

Purcell's style of Baroque music was uniquely English, although it incorporated Italian and French elements. Generally considered among the greatest E ...

.

Masques

Campion was also a composer of court masques, an elaborate performance involving music and dancing, singing and acting, within a complex

Campion was also a composer of court masques, an elaborate performance involving music and dancing, singing and acting, within a complex stage design

Scenic design (also known as scenography, stage design, or set design) is the creation of theatrical, as well as film or television scenery. Scenic designers come from a variety of artistic backgrounds, but in recent years, are mostly trai ...

, in which the architectural framing and costumes might be designed by a renowned architect, such as Inigo Jones

Inigo Jones (; 15 July 1573 – 21 June 1652) was the first significant architect in England and Wales in the early modern period, and the first to employ Vitruvian rules of proportion and symmetry in his buildings.

As the most notable archit ...

, to present a deferential allegory flattering to a noble or royal patron. These developed out of the medieval tradition of guising in the early Tudor period and became increasingly complex under Elizabeth I, James VI and I

James VI and I (James Charles Stuart; 19 June 1566 – 27 March 1625) was King of Scotland as James VI from 24 July 1567 and King of England and Ireland as James I from the union of the Scottish and English crowns on 24 March 1603 until ...

and Charles I Charles I may refer to:

Kings and emperors

* Charlemagne (742–814), numbered Charles I in the lists of Holy Roman Emperors and French kings

* Charles I of Anjou (1226–1285), also king of Albania, Jerusalem, Naples and Sicily

* Charles I of ...

. Professional actors and musicians were hired for the speaking and singing parts. Shakespeare

William Shakespeare ( 26 April 1564 – 23 April 1616) was an English playwright, poet and actor. He is widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England's nation ...

included masque like sections in many of his plays and Ben Jonson

Benjamin "Ben" Jonson (c. 11 June 1572 – c. 16 August 1637) was an English playwright and poet. Jonson's artistry exerted a lasting influence upon English poetry and stage comedy. He popularised the comedy of humours; he is best known for t ...

is known to have written them. Often, the masquers who did not speak or sing were courtiers: James I's Queen Consort, Anne of Denmark

Anne of Denmark (; 12 December 1574 – 2 March 1619) was the wife of King James VI and I; as such, she was Queen of Scotland from their marriage on 20 August 1589 and Queen of England and Ireland from the union of the Scottish and Eng ...

, frequently danced with her ladies in masques between 1603 and 1611, and Charles I Charles I may refer to:

Kings and emperors

* Charlemagne (742–814), numbered Charles I in the lists of Holy Roman Emperors and French kings

* Charles I of Anjou (1226–1285), also king of Albania, Jerusalem, Naples and Sicily

* Charles I of ...

performed in the masques at his court. The masque largely ended with the closure of the theatres and the exile of the court under the Commonwealth

A commonwealth is a traditional English term for a political community founded for the common good. Historically, it has been synonymous with "republic". The noun "commonwealth", meaning "public welfare, general good or advantage", dates from the ...

.

Music in the theatre

Performances of Elizabethan and Jacobean plays frequently included the use of music, with performances on organs, lutes, viols and pipes for up to an hour before the actual performance, and texts indicates that they were used during the plays. Plays, perhaps particularly the heavier histories and tragedies, were frequently broken up with a short musical play, perhaps derived from the Italianintermezzo

In music, an intermezzo (, , plural form: intermezzi), in the most general sense, is a composition which fits between other musical or dramatic entities, such as acts of a play or movements of a larger musical work. In music history, the term ha ...

, with music, jokes and dancing, known as a 'jigg' and from which the jig dance derives its name. After the closure of the London theatres in 1642 these tendencies developed into sung plays that are recognisable as English Opera's, the first usually being thought of as William Davenant

Sir William Davenant (baptised 3 March 1606 – 7 April 1668), also spelled D'Avenant, was an English poet and playwright. Along with Thomas Killigrew, Davenant was one of the rare figures in English Renaissance theatre whose career spanned b ...

's (1606–68) ''The Siege of Rhodes

''The Siege of Rhodes'' is an opera written to a text by the impresario William Davenant. The score is by five composers, the vocal music by Henry Lawes, Matthew Locke, and Captain Henry Cooke, and the instrumental music by Charles Coleman and G ...

'' (1656), originally given in a private performance. The development of native English opera had to wait for the Restoration of the monarchy in 1660 and the patronage of Charles II.

James VI and I and Charles I 1567–1642

James VI, king of Scotland from 1567, was a major patron of the arts in general. He made statutory provision to reform and promote the teaching of music. He rebuilt the Chapel Royal at Stirling in 1594 and the choir was used for state occasions like the baptism of his son Henry.P. Le Huray, ''Music and the Reformation in England, 1549–1660'' (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1978), pp. 83–5. He followed the tradition of employing lutenists for his private entertainment, as did other members of his family.T. Carter and J. Butt, ''The Cambridge History of Seventeenth-Century Music'' (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005), pp. 280, 300, 433 and 541. When he went south to take the throne of England in 1603 as James I, he removed one of the major sources of patronage in Scotland. The Scottish Chapel Royal was now used only for occasional state visits, beginning to fall into disrepair, and from now on the court in Westminster would be the only major source of royal musical patronage. When Charles I returned in 1633 to be crowned he brought many musicians from the English Chapel Royal for the service. Both James and his son Charles I, king from 1625, continued the Elizabethan patronage of

James VI, king of Scotland from 1567, was a major patron of the arts in general. He made statutory provision to reform and promote the teaching of music. He rebuilt the Chapel Royal at Stirling in 1594 and the choir was used for state occasions like the baptism of his son Henry.P. Le Huray, ''Music and the Reformation in England, 1549–1660'' (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1978), pp. 83–5. He followed the tradition of employing lutenists for his private entertainment, as did other members of his family.T. Carter and J. Butt, ''The Cambridge History of Seventeenth-Century Music'' (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005), pp. 280, 300, 433 and 541. When he went south to take the throne of England in 1603 as James I, he removed one of the major sources of patronage in Scotland. The Scottish Chapel Royal was now used only for occasional state visits, beginning to fall into disrepair, and from now on the court in Westminster would be the only major source of royal musical patronage. When Charles I returned in 1633 to be crowned he brought many musicians from the English Chapel Royal for the service. Both James and his son Charles I, king from 1625, continued the Elizabethan patronage of church music

Church music is Christian music written for performance in church, or any musical setting of ecclesiastical liturgy, or music set to words expressing propositions of a sacred nature, such as a hymn.

History

Early Christian music

The ...

, where the focus remained on settings of Anglican services and anthems, employing the long lived Bryd and then following in his footsteps composers such as Orlando Gibbons

Orlando Gibbons ( bapt. 25 December 1583 – 5 June 1625) was an English composer and keyboard player who was one of the last masters of the English Virginalist School and English Madrigal School. The best known member of a musical fam ...

(1583–1625) and Thomas Tomkins

Thomas Tomkins (1572 – 9 June 1656) was a Welsh-born composer of the late Tudor and early Stuart period. In addition to being one of the prominent members of the English Madrigal School, he was a skilled composer of keyboard and consort m ...

(1572–1656). The emphasis on the liturgical content of services under Charles I, associated with Archbishop William Laud

William Laud (; 7 October 1573 – 10 January 1645) was a bishop in the Church of England. Appointed Archbishop of Canterbury by Charles I in 1633, Laud was a key advocate of Charles I's religious reforms, he was arrested by Parliament in 1640 ...

, meant a need for fuller musical accompaniment. In 1626 the musical establishment of the royal household was sufficient to necessitate the creation of a new office of 'Master of the King's Music' and probably the most important composer of the reign was William Lawes (1602–45), who produced fantasia suites, consort music for harp, viols and organ and music for individual instruments, including lutes. This establishment was disrupted by the outbreak of civil war

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government polici ...

in England in 1642, but a smaller musical establishment was kept at the King's alternative capital at Oxford

Oxford () is a city in England. It is the county town and only city of Oxfordshire. In 2020, its population was estimated at 151,584. It is north-west of London, south-east of Birmingham and north-east of Bristol. The city is home to the ...

for the duration of the conflict.

Civil War and Commonwealth 1642–60

The period between the ascendancy of Parliament in London in 1642, to the Restoration of the monarchy in 1660, radically changed the pattern of British music. The loss of the court removed the major source of patronage, the theatres were closed in London in 1642 and certain forms of music, particularly those associated with traditional events or the liturgical calendar (like

The period between the ascendancy of Parliament in London in 1642, to the Restoration of the monarchy in 1660, radically changed the pattern of British music. The loss of the court removed the major source of patronage, the theatres were closed in London in 1642 and certain forms of music, particularly those associated with traditional events or the liturgical calendar (like morris dancing

Morris dancing is a form of English folk dance. It is based on rhythmic stepping and the execution of choreographed figures by a group of dancers, usually wearing bell pads on their shins. Implements such as sticks, swords and handkerchiefs may ...

and carols), and certain forms of church music, including collegiate choirs

A choir ( ; also known as a chorale or chorus) is a musical ensemble of singers. Choral music, in turn, is the music written specifically for such an ensemble to perform. Choirs may perform music from the classical music repertoire, which sp ...

and organs, were discouraged or abolished where parliament was able to enforce its authority.D. C. Price, ''Patrons and Musicians of the English Renaissance'' (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1981), p. 154. There was, however, no Puritan

The Puritans were English Protestants in the 16th and 17th centuries who sought to purify the Church of England of Roman Catholic practices, maintaining that the Church of England had not been fully reformed and should become more Protestant. ...

ban on secular

Secularity, also the secular or secularness (from Latin ''saeculum'', "worldly" or "of a generation"), is the state of being unrelated or neutral in regards to religion. Anything that does not have an explicit reference to religion, either negativ ...

music and Cromwell

Oliver Cromwell (25 April 15993 September 1658) was an English politician and military officer who is widely regarded as one of the most important statesmen in English history. He came to prominence during the 1639 to 1651 Wars of the Three Ki ...

had the organ from Magdalen College, Oxford

Magdalen College (, ) is a constituent college of the University of Oxford. It was founded in 1458 by William of Waynflete. Today, it is the fourth wealthiest college, with a financial endowment of £332.1 million as of 2019 and one of the ...

set up at Hampton Court Palace

Hampton Court Palace is a Grade I listed royal palace in the London Borough of Richmond upon Thames, southwest and upstream of central London on the River Thames. The building of the palace began in 1514 for Cardinal Thomas Wolsey, the chie ...

and employed an organist and other musicians. Musical entertainment was provided at official receptions, and at the wedding of Cromwell's daughter. Since the opportunities for large scale composition and public performance were limited, music under the Protectorate became a largely private matter and flourished in domestic settings, particularly in the larger private houses. The consort of viol

The viol (), viola da gamba (), or informally gamba, is any one of a family of bowed, fretted, and stringed instruments with hollow wooden bodies and pegboxes where the tension on the strings can be increased or decreased to adjust the pitc ...

s enjoyed a resurgence in popularity and leading composers of new pieces were John Jenkins and Matthew Locke Matthew Locke may refer to:

* Matthew Locke (administrator) (fl. 1660–1683), English Secretary at War from 1666 to 1683

* Matthew Locke (composer) (c. 1621–1677), English Baroque composer and music theorist

* Matthew Locke (soldier) (1974–2 ...

.D. D. Boyden, ''The History of Violin Playing from Its Origins to 1761: and its Relationship to the Violin and Violin Music'' (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1990), p. 233. Christopher Simpson's work, ''The Division Violist'', first published in 1659, was for many years the leading manual on playing the viol and on the art of extemporising "divisions to a ground

Ground may refer to:

Geology

* Land, the surface of the Earth not covered by water

* Soil, a mixture of clay, sand and organic matter present on the surface of the Earth

Electricity

* Ground (electricity), the reference point in an electrical c ...

", in Britain and continental Europe and is still used as a reference by early music

Early music generally comprises Medieval music (500–1400) and Renaissance music (1400–1600), but can also include Baroque music (1600–1750). Originating in Europe, early music is a broad musical era for the beginning of Western classi ...

revivalists.

See also

*Classical music of the United Kingdom

Classical music of the United Kingdom is taken in this article to mean classical music in the sense elsewhere defined, of formally composed and written music of chamber, concert and church type as distinct from popular, traditional, or folk music ...

*Chronological list of Scottish classical composers

The following is a chronological list of classical music composers living and working in Scotland, or originating from Scotland.

Renaissance

Baroque

Classical era

Romantic

Modern/Contemporary

See also

* Classical music of the United K ...

*Music of the United Kingdom

Throughout the history of the British Isles, the United Kingdom has been a major music producer, drawing inspiration from Church Music.

Traditional folk music, using instruments of England, Scotland, Northern Ireland, and Wales. Each of the ...

*Early music

Early music generally comprises Medieval music (500–1400) and Renaissance music (1400–1600), but can also include Baroque music (1600–1750). Originating in Europe, early music is a broad musical era for the beginning of Western classi ...

* Mary Remnant

Notes

{{Music of the United Kingdom Early music British music history History of the British Isles