Louis Bl%C3%A9riot on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Louis Charles Joseph Blériot ( , also , ; 1 July 1872 – 1 August 1936) was a French

The Blériot IV was damaged in a taxiing accident at Bagatelle on 12 November 1906. The disappointment of the failure of his aircraft was compounded by the success of Alberto Santos Dumont later that day, when he managed to fly his 14-bis a distance of , winning the Aéro Club de France prize for the first flight of over 100 metres. This also took place at Bagatelle, and was witnessed by Blériot. The partnership with Voisin was dissolved and Blériot established his own business, Recherches Aéronautiques Louis Blériot, where he started creating his own aircraft, experimenting with various configurationsSanger 2008, pp. 92–93. and eventually creating the world's first successful powered monoplane.

The first of these, the canard configuration Blériot V, was first tried on 21 March 1907, when Blériot limited his experiments to ground runs, which resulted in damage to the undercarriage. Two further ground trials, also damaging the aircraft, were undertaken, followed by another attempt on 5 April. The flight was only of around 6 m (20 ft), after which he cut his engine and landed, slightly damaging the undercarriage. More trials followed, the last on 19 April when, travelling at a speed of around 50 km/h (30 mph), the aircraft left the ground, Blériot over-responded when the nose began to rise, and the machine hit the ground nose-first, and somersaulted. The aircraft was largely destroyed, but Blériot was, by great good fortune, unhurt. The engine of the aircraft was immediately behind his seat, and he was very lucky not to have been crushed by it.

This was followed by the Blériot VI, a tandem wing design, first tested on 7 July, when the aircraft failed to lift off. Blériot then enlarged the wings slightly, and on 11 July a short successful flight of around 25–30 metres (84–100 ft) was made, reaching an altitude of around 2 m (7 ft). This was Blériot's first truly successful flight. Further successful flights took place that month, and by 25 July he had managed a flight of 150 m (490 ft). On 6 August he managed to reach an altitude of 12 m (39 ft), but one of the blades of the propeller worked loose, resulting in a heavy landing which damaged the aircraft. He then fitted a 50 hp (37 kW) V-16 Antoinette engine. Tests on 17 September showed a startling improvement in performance: the aircraft quickly reached an altitude of 25 m (82 ft), when the engine suddenly cut out and the aircraft went into a spiralling nosedive. In desperation Blériot climbed out of his seat and threw himself towards the tail. The aircraft partially pulled out of the dive, and came to earth in a more or less horizontal attitude. His only injuries were some minor cuts on the face, caused by fragments of glass from his broken goggles. After this crash Blériot abandoned the aircraft, concentrating on his next machine.

This, the

The Blériot IV was damaged in a taxiing accident at Bagatelle on 12 November 1906. The disappointment of the failure of his aircraft was compounded by the success of Alberto Santos Dumont later that day, when he managed to fly his 14-bis a distance of , winning the Aéro Club de France prize for the first flight of over 100 metres. This also took place at Bagatelle, and was witnessed by Blériot. The partnership with Voisin was dissolved and Blériot established his own business, Recherches Aéronautiques Louis Blériot, where he started creating his own aircraft, experimenting with various configurationsSanger 2008, pp. 92–93. and eventually creating the world's first successful powered monoplane.

The first of these, the canard configuration Blériot V, was first tried on 21 March 1907, when Blériot limited his experiments to ground runs, which resulted in damage to the undercarriage. Two further ground trials, also damaging the aircraft, were undertaken, followed by another attempt on 5 April. The flight was only of around 6 m (20 ft), after which he cut his engine and landed, slightly damaging the undercarriage. More trials followed, the last on 19 April when, travelling at a speed of around 50 km/h (30 mph), the aircraft left the ground, Blériot over-responded when the nose began to rise, and the machine hit the ground nose-first, and somersaulted. The aircraft was largely destroyed, but Blériot was, by great good fortune, unhurt. The engine of the aircraft was immediately behind his seat, and he was very lucky not to have been crushed by it.

This was followed by the Blériot VI, a tandem wing design, first tested on 7 July, when the aircraft failed to lift off. Blériot then enlarged the wings slightly, and on 11 July a short successful flight of around 25–30 metres (84–100 ft) was made, reaching an altitude of around 2 m (7 ft). This was Blériot's first truly successful flight. Further successful flights took place that month, and by 25 July he had managed a flight of 150 m (490 ft). On 6 August he managed to reach an altitude of 12 m (39 ft), but one of the blades of the propeller worked loose, resulting in a heavy landing which damaged the aircraft. He then fitted a 50 hp (37 kW) V-16 Antoinette engine. Tests on 17 September showed a startling improvement in performance: the aircraft quickly reached an altitude of 25 m (82 ft), when the engine suddenly cut out and the aircraft went into a spiralling nosedive. In desperation Blériot climbed out of his seat and threw himself towards the tail. The aircraft partially pulled out of the dive, and came to earth in a more or less horizontal attitude. His only injuries were some minor cuts on the face, caused by fragments of glass from his broken goggles. After this crash Blériot abandoned the aircraft, concentrating on his next machine.

This, the  Three of his aircraft were displayed at the first Paris Aero Salon, held at the end of December: the

Three of his aircraft were displayed at the first Paris Aero Salon, held at the end of December: the

The ''Daily Mail'' prize was first announced in October 1908, with a prize of £500 being offered for a flight made before the end of the year. When 1908 passed with no serious attempt being made, the offer was renewed for the year of 1909, with the prize money doubled to £1,000. Like some of the other prizes offered, it was widely seen as nothing more than a way to gain cheap publicity for the paper: the Paris newspaper '' Le Matin'' commenting that there was no chance of the prize being won.

The English Channel had been crossed many times by balloon, beginning with

The ''Daily Mail'' prize was first announced in October 1908, with a prize of £500 being offered for a flight made before the end of the year. When 1908 passed with no serious attempt being made, the offer was renewed for the year of 1909, with the prize money doubled to £1,000. Like some of the other prizes offered, it was widely seen as nothing more than a way to gain cheap publicity for the paper: the Paris newspaper '' Le Matin'' commenting that there was no chance of the prize being won.

The English Channel had been crossed many times by balloon, beginning with

"100 Years Later, Celebrating a Historic Flight in Europe."

''

Before

Before

photo and caption,

"Rivendell Blériot."

''cyclofiend.com,'' 2009. Retrieved: 24 April 2012. *A propeller moonlet in the rings of Saturn was nicknamed Bleriot by imaging scientists. *The pianist and compose

Giuseppe Sanalitro

paid homage to Louis Blériot with the concept album for solo pian

Au-delà

(2021). *In the Academy Award-Winning 1933 movie '' Cavalcade'', Edward Marryot and Edith Harris, while on the beach proclaiming their love for each other, witness the historic flight by Louis Blériot over the English Channel. *In the ITV series

US Centennial of Flight Commission: Louis Blériot

* ttps://www.pbs.org/wgbh/nova/bleriot/ "A Daring Flight"- homepage of the '' NOVA'' TV episode *

Louis Blériot Memorial Behind Dover Castle UK

Louis Blériot and wife at House of Commons, after Channel crossing

(by

View footage of Blériot's flight in 1909

"Seadromes! Says Blériot," ''Popular Mechanics'', October 1935, one of the last interviews given by Blériot before his death.Bleriot

(center), in 1927, with

aviator

An aircraft pilot or aviator is a person who controls the flight of an aircraft by operating its directional flight controls. Some other aircrew members, such as navigators or flight engineers, are also considered aviators, because they a ...

, inventor

An invention is a unique or novel device, method, composition, idea or process. An invention may be an improvement upon a machine, product, or process for increasing efficiency or lowering cost. It may also be an entirely new concept. If an ...

, and engineer

Engineers, as practitioners of engineering, are professionals who Invention, invent, design, analyze, build and test machines, complex systems, structures, gadgets and materials to fulfill functional objectives and requirements while considerin ...

. He developed the first practical headlamp for cars and established a profitable business manufacturing them, using much of the money he made to finance his attempts to build a successful aircraft. Blériot was the first to use the combination of hand-operated joystick and foot-operated rudder control as used to the present day to operate the aircraft control surfaces. Blériot was also the first to make a working, powered, piloted monoplane

A monoplane is a fixed-wing aircraft configuration with a single mainplane, in contrast to a biplane or other types of multiplanes, which have multiple planes.

A monoplane has inherently the highest efficiency and lowest drag of any wing con ...

.Gibbs-Smith 1953, p. 239 In 1909 he became world-famous for making the first airplane flight across the English Channel, winning the prize of £1,000 offered by the ''Daily Mail

The ''Daily Mail'' is a British daily middle-market tabloid newspaper and news websitePeter Wilb"Paul Dacre of the Daily Mail: The man who hates liberal Britain", ''New Statesman'', 19 December 2013 (online version: 2 January 2014) publish ...

'' newspaper. He was the founder of Blériot Aéronautique, a successful aircraft manufacturing company.

Early years

Born at No.17h rue de l'Arbre à Poires (now rue Sadi-Carnot) inCambrai

Cambrai (, ; pcd, Kimbré; nl, Kamerijk), formerly Cambray and historically in English Camerick or Camericke, is a city in the Nord department and in the Hauts-de-France region of France on the Scheldt river, which is known locally as the ...

, Louis was the first of five children born to Clémence and Charles Blériot. In 1882, aged 10, Blériot was sent as a boarder to the Institut Notre Dame in Cambrai, where he frequently won class prizes, including one for engineering drawing. When he was 15, he moved on to the Lycée at Amiens

Amiens (English: or ; ; pcd, Anmien, or ) is a city and commune in northern France, located north of Paris and south-west of Lille. It is the capital of the Somme department in the region of Hauts-de-France. In 2021, the population of ...

, where he lived with an aunt. After passing the exams for his baccalaureate in science and German, he determined to try to enter the prestigious École Centrale

The Ecoles Centrales Group is an alliance, consisting of following grandes écoles of engineering:

* CentraleSupélec (formed by merger of École Centrale Paris and Supélec) established in 2015

* École centrale de Lille established in 1854

* � ...

in Paris. Entrance was by a demanding exam for which special tuition was necessary: consequently Blériot spent a year at the Collège Sainte-Barbe in Paris

Paris () is the capital and most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), making it the 30th most densely populated city in the world in 2020. Si ...

. He passed the exam, placing 74th among the 243 successful candidates, and doing especially well in the tests of engineering drawing ability. After three years of demanding study at the École Centrale, Blériot graduated 113th of 203 in his graduating class. He then embarked on a term of compulsory military service, and spent a year as a sub-lieutenant in the 24th Artillery Regiment, stationed in Tarbes

Tarbes (; Gascon: ''Tarba'') is a commune in the Hautes-Pyrénées department in the Occitanie region of southwestern France. It is the capital of Bigorre and of the Hautes-Pyrénées. It has been a commune since 1790. It was known as ''Turba'' ...

in the Pyrenees

The Pyrenees (; es, Pirineos ; french: Pyrénées ; ca, Pirineu ; eu, Pirinioak ; oc, Pirenèus ; an, Pirineus) is a mountain range straddling the border of France and Spain. It extends nearly from its union with the Cantabrian Mountains to ...

.

He later got a job with Baguès, an electrical engineering company in Paris. He left the company after developing the world's first practical headlamp for automobiles, using a compact integral acetylene

Acetylene ( systematic name: ethyne) is the chemical compound with the formula and structure . It is a hydrocarbon and the simplest alkyne. This colorless gas is widely used as a fuel and a chemical building block. It is unstable in its pure ...

generator. In 1897, Blériot opened a showroom for headlamps at 41 rue de Richlieu in Paris. The business was successful, and soon he was supplying his lamps to both Renault

Groupe Renault ( , , , also known as the Renault Group in English; legally Renault S.A.) is a French multinational automobile manufacturer established in 1899. The company produces a range of cars and vans, and in the past has manufactured ...

and Panhard-Levassor, two of the foremost automobile manufacturers of the day.

In October 1900 Blériot was lunching in his usual restaurant near his showroom when his eye was caught by a young woman dining with her parents. That evening, he told his mother "I saw a young woman today. I will marry her, or I will marry no one." A bribe to a waiter secured details of her identity; she was Alice Védères, the daughter of a retired army officer. Blériot set about courting her with the same determination that he later brought to his aviation experiments, and on 21 February 1901 the couple were married.

Early aviation experiments

Blériot had become interested in aviation while at the Ecole Centrale, but his serious experimentation was probably sparked by seeingClément Ader

Clément Ader (2 April 1841 – 3 May 1925) was a French inventor and engineer who was born near Toulouse in Muret, Haute-Garonne, and died in Toulouse. He is remembered primarily for his pioneering work in aviation. In 1870 he was also one of ...

's Avion III at the 1900 Exposition Universelle. By then his headlamp business was doing well enough for Blériot to be able to devote both time and money to experimentation. His first experiments were with a series of ornithopters, which were unsuccessful. In April 1905, Blériot met Gabriel Voisin, who was then employed by Ernest Archdeacon

Ernest Archdeacon (23 March 1863 – 3 January 1950) was a French lawyer and aviation pioneer before the First World War. He made his first balloon flight at the age of 20. He commissioned a copy of the 1902 Wright No. 3 glider but ha ...

to assist with his experimental gliders.

Blériot was a spectator at Voisin's first trials of the floatplane glider he had built on 8 June 1905. Cine photography was among Blériot's hobbies, and the film footage of this flight was shot by him. The success of these trials prompted him to commission a similar machine from Voisin, the Blériot II Blériot may refer to:

* Louis Blériot, a French aviation pioneer

* Blériot Aéronautique, an aircraft manufacturer founded by Louis Blériot

* Blériot-Whippet

The Blériot-Whippet was a British 4 wheeled cyclecar made from 1920 to 1927 by th ...

glider. On 18 July an attempt to fly this aircraft was made, ending in a crash in which Voisin nearly drowned, but this did not deter Blériot. Indeed, he suggested that Voisin should stop working for Archdeacon and enter into partnership with him. Voisin accepted the proposal, and the two men established the ''Ateliers d' Aviation Edouard Surcouf, Blériot et Voisin''. Active between 1905 and 1906, the company built two unsuccessful powered aircraft, the Blériot III and the Blériot IV, which was largely a rebuild of its predecessor. Both these aircraft were powered with the lightweight Antoinette engines being developed by Léon Levavasseur. Blériot became a shareholder in the company, and in May 1906, joined the board of directors.

The Blériot IV was damaged in a taxiing accident at Bagatelle on 12 November 1906. The disappointment of the failure of his aircraft was compounded by the success of Alberto Santos Dumont later that day, when he managed to fly his 14-bis a distance of , winning the Aéro Club de France prize for the first flight of over 100 metres. This also took place at Bagatelle, and was witnessed by Blériot. The partnership with Voisin was dissolved and Blériot established his own business, Recherches Aéronautiques Louis Blériot, where he started creating his own aircraft, experimenting with various configurationsSanger 2008, pp. 92–93. and eventually creating the world's first successful powered monoplane.

The first of these, the canard configuration Blériot V, was first tried on 21 March 1907, when Blériot limited his experiments to ground runs, which resulted in damage to the undercarriage. Two further ground trials, also damaging the aircraft, were undertaken, followed by another attempt on 5 April. The flight was only of around 6 m (20 ft), after which he cut his engine and landed, slightly damaging the undercarriage. More trials followed, the last on 19 April when, travelling at a speed of around 50 km/h (30 mph), the aircraft left the ground, Blériot over-responded when the nose began to rise, and the machine hit the ground nose-first, and somersaulted. The aircraft was largely destroyed, but Blériot was, by great good fortune, unhurt. The engine of the aircraft was immediately behind his seat, and he was very lucky not to have been crushed by it.

This was followed by the Blériot VI, a tandem wing design, first tested on 7 July, when the aircraft failed to lift off. Blériot then enlarged the wings slightly, and on 11 July a short successful flight of around 25–30 metres (84–100 ft) was made, reaching an altitude of around 2 m (7 ft). This was Blériot's first truly successful flight. Further successful flights took place that month, and by 25 July he had managed a flight of 150 m (490 ft). On 6 August he managed to reach an altitude of 12 m (39 ft), but one of the blades of the propeller worked loose, resulting in a heavy landing which damaged the aircraft. He then fitted a 50 hp (37 kW) V-16 Antoinette engine. Tests on 17 September showed a startling improvement in performance: the aircraft quickly reached an altitude of 25 m (82 ft), when the engine suddenly cut out and the aircraft went into a spiralling nosedive. In desperation Blériot climbed out of his seat and threw himself towards the tail. The aircraft partially pulled out of the dive, and came to earth in a more or less horizontal attitude. His only injuries were some minor cuts on the face, caused by fragments of glass from his broken goggles. After this crash Blériot abandoned the aircraft, concentrating on his next machine.

This, the

The Blériot IV was damaged in a taxiing accident at Bagatelle on 12 November 1906. The disappointment of the failure of his aircraft was compounded by the success of Alberto Santos Dumont later that day, when he managed to fly his 14-bis a distance of , winning the Aéro Club de France prize for the first flight of over 100 metres. This also took place at Bagatelle, and was witnessed by Blériot. The partnership with Voisin was dissolved and Blériot established his own business, Recherches Aéronautiques Louis Blériot, where he started creating his own aircraft, experimenting with various configurationsSanger 2008, pp. 92–93. and eventually creating the world's first successful powered monoplane.

The first of these, the canard configuration Blériot V, was first tried on 21 March 1907, when Blériot limited his experiments to ground runs, which resulted in damage to the undercarriage. Two further ground trials, also damaging the aircraft, were undertaken, followed by another attempt on 5 April. The flight was only of around 6 m (20 ft), after which he cut his engine and landed, slightly damaging the undercarriage. More trials followed, the last on 19 April when, travelling at a speed of around 50 km/h (30 mph), the aircraft left the ground, Blériot over-responded when the nose began to rise, and the machine hit the ground nose-first, and somersaulted. The aircraft was largely destroyed, but Blériot was, by great good fortune, unhurt. The engine of the aircraft was immediately behind his seat, and he was very lucky not to have been crushed by it.

This was followed by the Blériot VI, a tandem wing design, first tested on 7 July, when the aircraft failed to lift off. Blériot then enlarged the wings slightly, and on 11 July a short successful flight of around 25–30 metres (84–100 ft) was made, reaching an altitude of around 2 m (7 ft). This was Blériot's first truly successful flight. Further successful flights took place that month, and by 25 July he had managed a flight of 150 m (490 ft). On 6 August he managed to reach an altitude of 12 m (39 ft), but one of the blades of the propeller worked loose, resulting in a heavy landing which damaged the aircraft. He then fitted a 50 hp (37 kW) V-16 Antoinette engine. Tests on 17 September showed a startling improvement in performance: the aircraft quickly reached an altitude of 25 m (82 ft), when the engine suddenly cut out and the aircraft went into a spiralling nosedive. In desperation Blériot climbed out of his seat and threw himself towards the tail. The aircraft partially pulled out of the dive, and came to earth in a more or less horizontal attitude. His only injuries were some minor cuts on the face, caused by fragments of glass from his broken goggles. After this crash Blériot abandoned the aircraft, concentrating on his next machine.

This, the Blériot VII

The Blériot VII was an early French aeroplane built by Louis Blériot.

Design and development

Following the success with the tandem wing configuration of the Blériot VI, he continued this line of development. The rear wing of his new design ...

, was a monoplane with tail surfaces arranged in what has become, apart from its use of differential elevators movement for lateral control, the modern conventional layout. This aircraft, which first flew on 16 November 1907, has been recognised as the first successful monoplane. On 6 December Blériot managed two flights of over 500 metres, including a successful U-turn. This was the most impressive achievement to date of any of the French pioneer aviators, causing Patrick Alexander to write to Major Baden Baden-Powell, president of the Royal Aeronautical Society, "I got back from Paris last night. I think Blériot with his new machine is leading the way". Two more successful flights were made on 18 December, but the undercarriage collapsed after the second flight; the aircraft overturned and was wrecked.

Blériot's next aircraft, the Blériot VIII

The Blériot VIII was a French pioneer era aeroplane built by Louis Blériot, significant for its adoption of both a configuration and a control system that were to set a standard for decades to come.

Design and development

The previous year, B ...

was shown to the press in February 1908. Although it was the first to use of a successful combination of hand/arm-operated joystick and foot-operated rudder control, this was a failure in its first form. After modifications, it proved successful, and on 31 October 1908 he succeeded in making a cross-country flight, making a round trip from Toury to Arteny and back, a total distance of . This was not the first cross-country flight by a narrow margin, since Henri Farman had flown from Bouy to Rheims the preceding day. Four days later, the aircraft was destroyed in a taxiing accident.

Three of his aircraft were displayed at the first Paris Aero Salon, held at the end of December: the

Three of his aircraft were displayed at the first Paris Aero Salon, held at the end of December: the Blériot IX __NOTOC__

The Blériot IX was an unsuccessful early French aeroplane built by Louis Blériot. Encouraged by the ever-increasing altitude, distance, and duration of flights with the Blériot VIII in 1908, he built a new machine along the same gen ...

monoplane; the Blériot X __NOTOC__

The Blériot X was an unfinished early French aeroplane by Louis Blériot. Its design was quite unlike anything else he had built and was modelled closely on the successful aircraft of the Wright brothers: a pusher biplane with elevat ...

, a three-seat pusher biplane; and the Blériot XI, which went on to be his most successful model. The first two of the designs, which used Antoinette engines, never flew, possibly because at this time, Blériot severed his connection with the Antoinette company because the company had begun to design and construct aircraft as well as engines, presenting Blériot with a conflict of interests. The Type XI was initially powered by a REP engine and was first flown with this engine on 18 January 1909, but although the aircraft flew well, after a very short time in the air, the engine began to overheat, leading Blériot to get in touch with Alessandro Anzani, who had developed a successful motorcycle engine and had subsequently entered the aero-engine market. Importantly, Anzani was associated with Lucien Chauvière, who had designed a sophisticated laminated walnut propeller. The combination of a reliable engine and an efficient propeller contributed greatly to the success of the Type XI.

This was shortly followed by the Blériot XII, a high-wing two-seater monoplane first flown on 21 May, and for a while Blériot concentrated on flying this machine, flying it with a passenger on 2 July, and on 12 July making the world's first flight with two passengers, one of whom was Santos Dumont. A few days later the crankshaft

A crankshaft is a mechanical component used in a piston engine to convert the reciprocating motion into rotational motion. The crankshaft is a rotating shaft containing one or more crankpins, that are driven by the pistons via the connecti ...

of the E.N.V. engine broke, and Blériot resumed trials of the Type XI. On 25 June he made a flight lasting 15 minutes and 30 seconds, his longest to date, and the following day increased this personal record to over 36 minutes. At the end of July he took part in an aviation meet at Douai, where he made a flight lasting over 47 minutes in the Type XII on 3 July: the following day he flew the Type XI for 50 minutes at another meet at Juvisy, and on 13 July, he made a cross-country flight of from Etampes to Orléans

Orléans (;"Orleans"

(US) and asbestos Asbestos () is a naturally occurring fibrous silicate mineral. There are six types, all of which are composed of long and thin fibrous crystals, each fibre being composed of many microscopic "fibrils" that can be released into the atmosphere b ...

insulation worked loose from the exhaust pipe after 15 minutes in the air. After half an hour, one of his shoes had been burnt through and he was in considerable pain, but nevertheless continued his flight until engine failure ended the flight. Blériot suffered third-degree burns, and his injuries took over two months to heal.

On 16 June 1909, Blériot and Voisin were jointly awarded the Prix Osiris, awarded by the (US) and asbestos Asbestos () is a naturally occurring fibrous silicate mineral. There are six types, all of which are composed of long and thin fibrous crystals, each fibre being composed of many microscopic "fibrils" that can be released into the atmosphere b ...

Institut de France

The (; ) is a French learned society, grouping five , including the Académie Française. It was established in 1795 at the direction of the National Convention. Located on the Quai de Conti in the 6th arrondissement of Paris, the institut ...

every three years to the Frenchman who had made the greatest contribution to science. Three days later, on 19 July, he informed the ''Daily Mail

The ''Daily Mail'' is a British daily middle-market tabloid newspaper and news websitePeter Wilb"Paul Dacre of the Daily Mail: The man who hates liberal Britain", ''New Statesman'', 19 December 2013 (online version: 2 January 2014) publish ...

'' of his intention to make an attempt to win the thousand-pound prize offered by the paper for a successful crossing of the English Channel

The English Channel, "The Sleeve"; nrf, la Maunche, "The Sleeve" ( Cotentinais) or ( Jèrriais), ( Guernésiais), "The Channel"; br, Mor Breizh, "Sea of Brittany"; cy, Môr Udd, "Lord's Sea"; kw, Mor Bretannek, "British Sea"; nl, Het Ka ...

in a heavier-than-air aircraft.

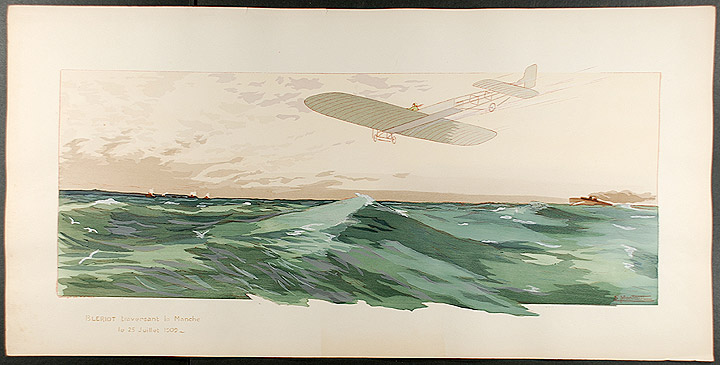

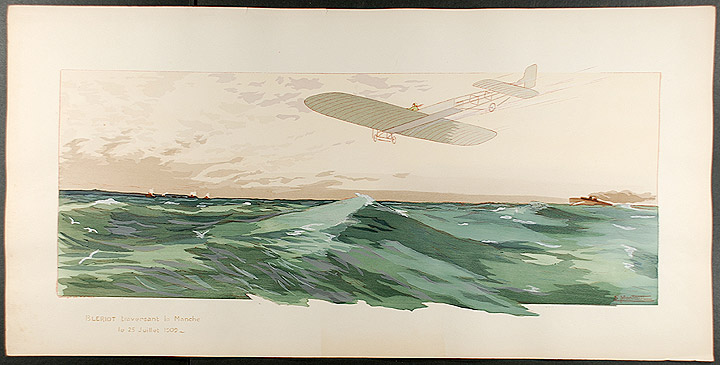

1909 Channel crossing

The ''Daily Mail'' prize was first announced in October 1908, with a prize of £500 being offered for a flight made before the end of the year. When 1908 passed with no serious attempt being made, the offer was renewed for the year of 1909, with the prize money doubled to £1,000. Like some of the other prizes offered, it was widely seen as nothing more than a way to gain cheap publicity for the paper: the Paris newspaper '' Le Matin'' commenting that there was no chance of the prize being won.

The English Channel had been crossed many times by balloon, beginning with

The ''Daily Mail'' prize was first announced in October 1908, with a prize of £500 being offered for a flight made before the end of the year. When 1908 passed with no serious attempt being made, the offer was renewed for the year of 1909, with the prize money doubled to £1,000. Like some of the other prizes offered, it was widely seen as nothing more than a way to gain cheap publicity for the paper: the Paris newspaper '' Le Matin'' commenting that there was no chance of the prize being won.

The English Channel had been crossed many times by balloon, beginning with Jean-Pierre Blanchard

Jean-Pierre rançoisBlanchard (4 July 1753 – 7 March 1809) was a French inventor, best known as a pioneer of gas balloon flight, who distinguished himself in the conquest of the air in a balloon, in particular the first crossing of the Engli ...

and John Jeffries

John Jeffries (5 February 1744 – 16 September 1819) was an American physician, scientist, and military surgeon with the British Army in Nova Scotia and New York during the American Revolution. He is best known for accompanying French invent ...

's crossing in 1785.Gibbs-Smith 1953, pp. 96–97."Balloon Intelligence." '' Daily Universal Register,''Issue 8, January 1785, p. 2.

Blériot, who intended to fly across the Channel in his Type XI monoplane, had three rivals for the prize, the most serious being Hubert Latham

Arthur Charles Hubert Latham (10 January 1883 – 25 June 1912) was a French aviation pioneer. He was the first person to attempt to cross the English Channel in an aeroplane. Due to engine failure during his first of two attempts to cross ...

, a French national of English extraction flying an Antoinette IV

The Antoinette IV was an early French monoplane.

Design and development

The Antoinette IV was a high-wing aircraft with a fuselage of extremely narrow triangular cross-section and a cruciform tail. Power was provided by a V8 engine of Léon Le ...

monoplane. He was favoured by both the United Kingdom and France to win. The others were Charles de Lambert, a Russian aristocrat with French ancestry, and one of Wilbur Wright's pupils, and Arthur Seymour, an Englishman who reputedly owned a Voisin biplane. De Lambert got as far as establishing a base at Wissant

Wissant (; from nl, Witzand, lang, “white sand”) is a seaside commune in the Pas-de-Calais department in the Hauts-de-France region of France.

Geography

Wissant is a fishing port and farming village located approximately north of Boulogn ...

, near Calais, but Seymour did nothing beyond submitting his entry to the ''Daily Mail''. Lord Northcliffe, who had befriended Wilbur Wright during his sensational 1908 public demonstrations in France, had offered the prize hoping that Wilbur would win. Wilbur wanted to make an attempt and cabled brother Orville in the USA. Orville, then recuperating from serious injuries sustained in a crash, replied telling him not to make the Channel attempt until he could come to France and assist. Also Wilbur had already amassed a fortune in prize money for altitude and duration flights and had secured sales contracts for the Wright Flyer with the French, Italians, British and Germans; his tour in Europe was essentially complete by the summer of 1909. Both brothers saw the Channel reward of only a thousand pounds as insignificant considering the dangers of the flight.

Latham arrived in Calais

Calais ( , , traditionally , ) is a port city in the Pas-de-Calais department, of which it is a subprefecture. Although Calais is by far the largest city in Pas-de-Calais, the department's prefecture is its third-largest city of Arras. Th ...

in early July, and set up his base at Sangatte in the semi-derelict buildings which had been constructed for a 1881 attempt to dig a tunnel under the Channel. The event was the subject of great public interest; it was reported that there were 10,000 visitors at Calais and a similar crowd at Dover

Dover () is a town and major ferry port in Kent, South East England. It faces France across the Strait of Dover, the narrowest part of the English Channel at from Cap Gris Nez in France. It lies south-east of Canterbury and east of Maids ...

. The Marconi Company

The Marconi Company was a British telecommunications and engineering company that did business under that name from 1963 to 1987. Its roots were in the Wireless Telegraph & Signal Company founded by Italian inventor Guglielmo Marconi in 189 ...

set up a special radio link for the occasion, with one station on Cap Blanc Nez at Sangatte and the other on the roof of the Lord Warden Hotel in Dover. The crowds were in for a wait: the weather was windy, and Latham did not make an attempt until 19 July, but from his destination his aircraft developed engine trouble and was forced to make the world's first landing of an aircraft on the sea. Latham was rescued by the French destroyer '' Harpon'' and taken back to France,Walsh 2007, pp. 93-97. where he was met by the news that Blériot had entered the competition. Blériot, accompanied by two mechanics and his friend Alfred Leblanc

Alfred Leblanc (13 April 1869 – 22 November 1921) was a pioneer French aviator.

Biography

He was born on 13 April 1869 in Paris. In 1888, he became the technical director of the Victor Bidault metal foundry. A keen sportsman, he was an ener ...

, arrived in Calais on Wednesday 21 July and set up their base at a farm near the beach at Les Baraques, between Calais and Sangatte. The following day a replacement aircraft for Latham was delivered from the Antoinette factory. The wind was too strong for an attempted crossing on Friday and Saturday, but on Saturday evening it began to drop, raising hopes in both camps.

Leblanc went to bed at around midnight but was too keyed up to sleep well; at two o'clock, he was up, and judging that the weather was ideal woke Blériot who, unusually, was pessimistic and had to be persuaded to eat breakfast. His spirits revived, however, and by half past three, his wife Alice had boarded the destroyer ''Escopette'', which was to escort the flight.

At 4:15 am, 25 July, watched by an excited crowd, Blériot made a short trial flight in his Type XI, and then, on a signal that the sun had risen (the competition rules required a flight between sunrise and sunset), he took off at 4:41 to attempt the crossing. Flying at approximately and an altitude

Altitude or height (also sometimes known as depth) is a distance measurement, usually in the vertical or "up" direction, between a reference datum and a point or object. The exact definition and reference datum varies according to the context ...

of about 250 ft (76 m), he set off across the Channel. Not having a compass

A compass is a device that shows the cardinal directions used for navigation and geographic orientation. It commonly consists of a magnetized needle or other element, such as a compass card or compass rose, which can pivot to align itself with ...

, Blériot took his course from the ''Escopette'', which was heading for Dover, but he soon overtook the ship. The visibility deteriorated, and he later said, "for more than 10 minutes I was alone, isolated, lost in the midst of the immense sea, and I did not see anything on the horizon or a single ship".Clark, Nicola"100 Years Later, Celebrating a Historic Flight in Europe."

''

The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid ...

,'' 24 July 2009. Retrieved: 25 July 2009. The grey line of the English coast, however, came into sight on his left; the wind had increased, and had blown him to the east of his intended course. Altering course, he followed the line of the coast about a mile offshore until he spotted Charles Fontaine, the correspondent from '' Le Matin'' waving a large Tricolour

A tricolour () or tricolor () is a type of flag or banner design with a triband design which originated in the 16th century as a symbol of republicanism, liberty, or revolution. The flags of France, Italy, Romania, Mexico, and Ireland were ...

as a signal. Unlike Latham, Blériot had not visited Dover to find a suitable spot to land, and the choice had been made by Fontaine, who had selected a patch of gently sloping land called Northfall Meadow, close to Dover Castle

Dover Castle is a medieval castle in Dover, Kent, England and is Grade I listed. It was founded in the 11th century and has been described as the "Key to England" due to its defensive significance throughout history. Some sources say it is th ...

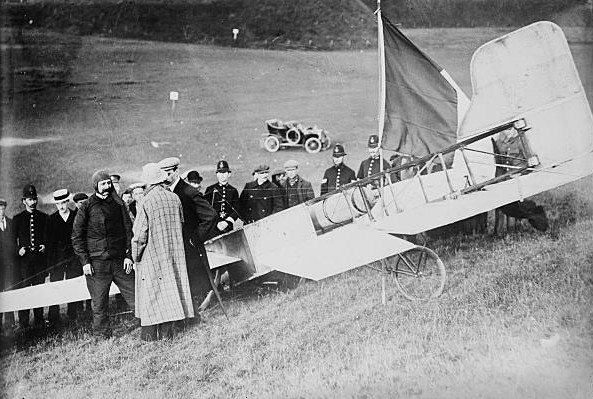

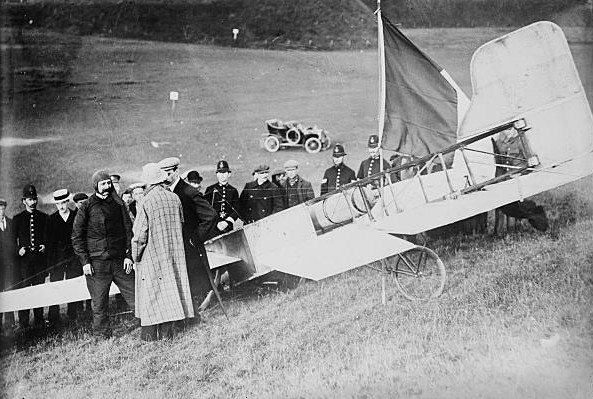

, on top of the cliffs. Once over land, Blériot circled twice to lose height, and cut his engine at an altitude of about , making a heavy "pancake" landing due to the gusty wind conditions; the undercarriage was damaged and one blade of the propeller was shattered, but Blériot was unhurt. The flight had taken 36 minutes and 30 seconds.

News of his departure had been sent by radio to Dover, but it was generally expected that he would attempt to land on the beach to the west of the town. The ''Daily Mail'' correspondent, realising that Blériot had landed near the castle, set off at speed in a motor car and took Blériot to the harbour, where he was reunited with his wife. The couple, surrounded by a cheering crowd and photographers, were then taken to the Lord Warden Hotel at the foot of the Admiralty Pier; Blériot had become a celebrity.

The ''Blériot Memorial'', the outline of the aircraft laid out in granite setts in the turf (funded by oil manufacturer Alexander Duckham), marks his landing spot above the cliffs near Dover Castle

Dover Castle is a medieval castle in Dover, Kent, England and is Grade I listed. It was founded in the 11th century and has been described as the "Key to England" due to its defensive significance throughout history. Some sources say it is th ...

. .

The aircraft which was used in the crossing is now preserved in the Musée des Arts et Métiers in Paris.

Later life

Blériot's success brought about an immediate transformation of the status of ''Recherches Aéronautiques Louis Blériot.'' By the time of the Channel flight, he had spent at least 780,000 francs on his aviation experiments. (To put this figure into context, one of Blériot's skilled mechanics was paid 250 francs a month.) Now this investment began to pay off: orders for copies of the Type XI quickly came, and by the end of the year, orders for over 100 aircraft had been received, each selling for 10,000 francs. At the end of August, Blériot was one of the flyers at the Grande Semaine d'Aviation held at Reims, where he was narrowly beaten by Glenn Curtiss in the first Gordon Bennett Trophy. Blériot did, however, succeed in winning the prize for the fastest lap of the circuit, establishing a new world speed record for aircraft. Blériot followed his flights at Reims with appearances at other aviation meetings inBrescia

Brescia (, locally ; lmo, link=no, label= Lombard, Brèsa ; lat, Brixia; vec, Bressa) is a city and '' comune'' in the region of Lombardy, Northern Italy. It is situated at the foot of the Alps, a few kilometers from the lakes Garda and Iseo ...

, Budapest

Budapest (, ; ) is the capital and most populous city of Hungary. It is the ninth-largest city in the European Union by population within city limits and the second-largest city on the Danube river; the city has an estimated population o ...

, Bucharest

Bucharest ( , ; ro, București ) is the capital and largest city of Romania, as well as its cultural, industrial, and financial centre. It is located in the southeast of the country, on the banks of the Dâmbovița River, less than north o ...

in 1909 (making the first airplane flights in both Hungary

Hungary ( hu, Magyarország ) is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Spanning of the Carpathian Basin, it is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine to the northeast, Romania to the east and southeast, Serbia to the south, Cr ...

and Romania

Romania ( ; ro, România ) is a country located at the crossroads of Central Europe, Central, Eastern Europe, Eastern, and Southeast Europe, Southeastern Europe. It borders Bulgaria to the south, Ukraine to the north, Hungary to the west, S ...

). Up to this time he had had great good luck in walking away from accidents that had destroyed the aircraft, but his luck deserted him in December 1909 at an aviation meeting in Istanbul

)

, postal_code_type = Postal code

, postal_code = 34000 to 34990

, area_code = +90 212 (European side) +90 216 (Asian side)

, registration_plate = 34

, blank_name_sec2 = GeoTLD

, blank_i ...

. Flying in gusty conditions to placate an impatient and restive crowd, he crashed on top of a house, breaking several ribs and suffering internal injuries: he was hospitalized for three weeks.

Between 1909 and the outbreak of World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

in 1914, Blériot produced about 900 aircraft, most of them variations of the Type XI model. Blériot monoplanes and Voisin-type biplanes, with the latter's Farman derivatives dominated the pre-war aviation market. There were concerns about the safety of monoplanes in general, both in France and the UK. The French government grounded all monoplanes in the French Army from February 1912 after accidents to four Blériots, but lifted it after trials in May supported Blériot's analysis of the problem and led to a strengthening of the landing wires. The brief but influential ban on the use of monoplanes by the Military Wing (though not the Naval Wing) in the UK was triggered by accidents to other manufacturer's aircraft; Blériots were not involved.

Along with five other European aircraft builders, from 1910, Blériot was involved in a five-year legal struggle with the Wright Brothers over the latter's wing warping patents. The Wrights' claim was dismissed in the French and the German courts.

From 1913 or earlier, Blériot's aviation activities were handled by Blériot Aéronautique, based at Suresnes, which continued to design and produce aircraft up to the nationalisation of most of the French aircraft industry in 1937, when it was absorbed into SNCASO.

In 1913, a consortium led by Blériot bought the Société pour les Appareils Deperdussin aircraft manufacturer and he became the president of the company in 1914. He renamed it the Société Pour L'Aviation et ses Dérivés (SPAD); this company produced World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

fighter aircraft such as the SPAD S.XIII.

Before

Before World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

, Blériot had opened British flying schools at Brooklands

Brooklands was a motor racing circuit and aerodrome built near Weybridge in Surrey, England, United Kingdom. It opened in 1907 and was the world's first purpose-built 'banked' motor racing circuit as well as one of Britain's first airfields ...

, in Surrey

Surrey () is a ceremonial county, ceremonial and non-metropolitan county, non-metropolitan counties of England, county in South East England, bordering Greater London to the south west. Surrey has a large rural area, and several significant ur ...

and at Hendon

Hendon is an urban area in the Borough of Barnet, North-West London northwest of Charing Cross. Hendon was an ancient manor and parish in the county of Middlesex and a former borough, the Municipal Borough of Hendon; it has been part of Gre ...

Aerodrome

An aerodrome (Commonwealth English) or airdrome (American English) is a location from which aircraft flight operations take place, regardless of whether they involve air cargo, passengers, or neither, and regardless of whether it is for publi ...

. Realising that a British company would have more chance to sell his models to the British government, in 1915, he set up the Blériot Manufacturing Aircraft Company Ltd. The hoped for orders did not follow, as the Blériot design was seen as outdated. Following an unresolved conflict over control of the company, it was wound up on 24 July 1916. Even before the closure of this company Blériot was planning a new venture in the UK. Initially named Blériot and SPAD Ltd and based in Addlestone, it became the Air Navigation and Engineering Company

Air Navigation and Engineering Company Limited was a British aircraft manufacturer from its formation in 1919 to 1927.

History

The company was formed in 1919 when the Blériot & SPAD Manufacturing Company Limited was renamed. The company was ...

(ANEC) in May 1918. ANEC survived in a difficult aviation climate until late 1926, producing Blériot-Whippet cars, the Blériot 500cc motorcycle, as well as several light aircraft.

In 1927, Blériot, long retired from flying, was present to welcome Charles Lindbergh

Charles Augustus Lindbergh (February 4, 1902 – August 26, 1974) was an American aviator, military officer, author, inventor, and activist. On May 20–21, 1927, Lindbergh made the first nonstop flight from New York City to Paris, a distance o ...

when he landed at Le Bourget field completing his transatlantic flight. The two men, separated in age by 30 years, had each made history by crossing significant bodies of water, and shared a photo opportunity in Paris."Lindbergh in Paris with Bleriot Photograph,"photo and caption,

Wisconsin Historical Society

The Wisconsin Historical Society (officially the State Historical Society of Wisconsin) is simultaneously a state agency and a private membership organization whose purpose is to maintain, promote and spread knowledge relating to the history of N ...

, retrieved September 13, 2021

In 1934, Blériot visited Newark Airport

Newark Liberty International Airport , originally Newark Metropolitan Airport and later Newark International Airport, is an international airport straddling the boundary between the cities of Newark in Essex County and Elizabeth in Union Co ...

in New Jersey

New Jersey is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Northeastern regions of the United States. It is bordered on the north and east by the state of New York; on the east, southeast, and south by the Atlantic Ocean; on the west by the Delawa ...

and predicted commercial overseas flights by 1938.

Death

Blériot remained active in the aviation business until his death on 1 August 1936 inParis

Paris () is the capital and most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), making it the 30th most densely populated city in the world in 2020. Si ...

due to a heart attack

A myocardial infarction (MI), commonly known as a heart attack, occurs when blood flow decreases or stops to the coronary artery of the heart, causing damage to the heart muscle. The most common symptom is chest pain or discomfort which ma ...

. After a funeral with full military honours at Les Invalides

The Hôtel des Invalides ( en, "house of invalids"), commonly called Les Invalides (), is a complex of buildings in the 7th arrondissement of Paris, France, containing museums and monuments, all relating to the military history of France, ...

he was buried in the Cimetière des Gonards

The Cimetière des Gonards is the largest cemetery in Versailles on the outskirts of Paris. It began operations in 1879. The cemetery covers an area of and contains more than 12,000 graves.

Description

This is a rurally landscaped cemetery, t ...

in Versailles

The Palace of Versailles ( ; french: Château de Versailles ) is a former royal residence built by King Louis XIV located in Versailles, about west of Paris, France. The palace is owned by the French Republic and since 1995 has been managed, ...

.

Legacy

In 1930, Blériot himself instituted the ''Blériot Trophy'', a one-time award which would be awarded to the first aircrew to sustain an average speed of over 2,000 kilometers per hour (1,242.742 miles per hour) over one half of an hour, an extremely ambitious and prophetic target in an era when the fastest aircraft were just breaking the 200 mph mark. The award was finally presented slightly more than three decades later by Alice Védères Blériot, widow of Louis Blériot, atParis, France

Paris () is the capital and most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), making it the 30th most densely populated city in the world in 2020. Si ...

, 27 May 1961, to the crew of the United States Air Force

The United States Air Force (USAF) is the air service branch of the United States Armed Forces, and is one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. Originally created on 1 August 1907, as a part of the United States Army Si ...

Convair B-58A jet bomber, AF serial number 59-2451, '' Firefly'', crewed by Aircraft Commander

Commander (commonly abbreviated as Cmdr.) is a common naval officer rank. Commander is also used as a rank or title in other formal organizations, including several police forces. In several countries this naval rank is termed frigate captain.

...

Major

Major ( commandant in certain jurisdictions) is a military rank of commissioned officer status, with corresponding ranks existing in many military forces throughout the world. When used unhyphenated and in conjunction with no other indicato ...

Elmer E. Murphy, Navigator

A navigator is the person on board a ship or aircraft responsible for its navigation.Grierson, MikeAviation History—Demise of the Flight Navigator FrancoFlyers.org website, October 14, 2008. Retrieved August 31, 2014. The navigator's prima ...

Major Eugene Moses, and Defensive Systems Officer First Lieutenant

First lieutenant is a commissioned officer military rank in many armed forces; in some forces, it is an appointment.

The rank of lieutenant has different meanings in different military formations, but in most forces it is sub-divided into a ...

David F. Dickerson who on 10 May 1961, sustained an average speed of 2,095 kmph (1,302.07 mph) over 30 minutes and 43 seconds, covering a ground track of 1,077.3 kilometers (669.4 miles). This same crew and aircraft went on to set a number of other speed records before being lost in an accident shortly after takeoff from Paris, not long after setting yet another speed record, winning the Harmon Trophy for a record-setting flight between New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the List of United States cities by population, most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the L ...

and Paris, France

Paris () is the capital and most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), making it the 30th most densely populated city in the world in 2020. Si ...

. This flight was 3,626.46 miles in 3 hours, 19 minutes, 58 seconds, for an average of 1,089.36 mph. The Blériot Trophy winning crew took over the aircraft for the return flight, but were all killed when the pilot lost control shortly after takeoff from the Paris Air Show during some attempted impromptu aerobatics.

The Blériot Trophy is a statuette

A figurine (a diminutive form of the word ''figure'') or statuette is a small, three-dimensional sculpture that represents a human, deity or animal, or, in practice, a pair or small group of them. Figurines have been made in many media, with c ...

in the classical style sculpted of polished white and black marble

Marble is a metamorphic rock composed of recrystallized carbonate minerals, most commonly calcite or dolomite. Marble is typically not foliated (layered), although there are exceptions. In geology, the term ''marble'' refers to metamorphose ...

stone, depicting a nude male figure of black marble emerging from stylized white marble clouds resembling female forms. It is now on permanent display at the McDermott Library of the United States Air Force Academy

The United States Air Force Academy (USAFA) is a United States service academy in El Paso County, Colorado, immediately north of Colorado Springs. It educates cadets for service in the officer corps of the United States Air Force and U ...

, Colorado Springs, Colorado

Colorado (, other variants) is a state in the Mountain West subregion of the Western United States. It encompasses most of the Southern Rocky Mountains, as well as the northeastern portion of the Colorado Plateau and the western edge of the ...

, USA.

In 1936 the Fédération Aéronautique Internationale established the " Louis Blériot medal" in his honor. The medal may be awarded up to three times a year to record setters in speed, altitude and distance categories in light aircraft, and is still being awarded.

In 1967 Blériot was inducted into the International Air & Space Hall of Fame.

On 25 July 2009, the centenary of the original Channel crossing, Frenchman Edmond Salis took off from Blériot Beach in a replica of Bleriot's aircraft. He landed successfully in Kent at the Duke of York's Royal Military School.

In popular culture

*In 2002 British train companyVirgin CrossCountry

Virgin CrossCountry was a train operating company in the United Kingdom operating the InterCity CrossCountry passenger franchise from January 1997 until November 2007. Virgin CrossCountry operated some of the longest direct rail services in t ...

named Class 221

The British Rail Class 221 ''Super Voyager'' is a class of tilting diesel-electric multiple unit express passenger trains built in Bruges, Belgium, by Bombardier Transportation in 2001/02.

The Class 221 are similar to the Class 220 ''Voy ...

221101 ''Louis Blériot''.

*In 2006 Rivendell Bicycle Works introduced a bicycle model named the "Blériot 650B" as a tribute to Blériot. It features his portrait on the seat tube.Edgar, Jim"Rivendell Blériot."

''cyclofiend.com,'' 2009. Retrieved: 24 April 2012. *A propeller moonlet in the rings of Saturn was nicknamed Bleriot by imaging scientists. *The pianist and compose

Giuseppe Sanalitro

paid homage to Louis Blériot with the concept album for solo pian

Au-delà

(2021). *In the Academy Award-Winning 1933 movie '' Cavalcade'', Edward Marryot and Edith Harris, while on the beach proclaiming their love for each other, witness the historic flight by Louis Blériot over the English Channel. *In the ITV series

Mr Selfridge

''Mr Selfridge'' is a British period drama television series about Harry Gordon Selfridge and his department store, Selfridge & Co, in London, set from 1908 to 1928. It was co-produced by ITV Studios and Masterpiece/WGBH for broadcast on ITV ...

in Season 1 Episode 2 Louis Blériot makes a personal appearance as a promotion for Selfridge's department store along with the plane he used to make the historic English Channel flight.

*In the 2022 song ''Icarus or Blériot'' by Brian Eno

Brian Peter George St John le Baptiste de la Salle Eno (; born Brian Peter George Eno, 15 May 1948) is a British musician, composer, record producer and visual artist best known for his contributions to ambient music and work in rock, pop a ...

.

See also

* Blériot Aéronautique * Early flying machines *List of firsts in aviation

This is a list of firsts in aviation. For a comprehensive list of women's records, see Women in aviation.

First person to fly

The first flight (including gliding) by a person is unknown. Several have been suggested.

* In 559 A.D., several pr ...

References

Notes

Citations

Bibliography

* Elliot, B.A. ''Blériot: Herald of an Age''. Stroud< UK: Tempus, 2000. . * Gibbs-Smith, C.H. ''A History of Flying''. London: Batsford, 1953. * Grey, C.G. ''Jane's All the World's Aircraft 1938''. London: David & Charles, 1972. . * Jane, F. T. ''Jane's All the World's Aircraft 1913''. Newton Abbot, UK: David & Charles, 1969. * Mackersey, Ian. ''The Wright Brothers: The Remarkable Story of the Aviation Pioneers who Changed the World''. London: Little, Brown, 2003. . * Sanger, R. ''Blériot in Britain''. Tonbridge, Kent, UK: Air Britain (Historians) Ltd., 2008. . * Taylor, M. J. ''Jane's Encyclopedia of Aviation''. New York: Portland House, 1989. . * Walsh, Barbara. ''Forgotten Aviator, Hubert Latham: A High-flying Gentleman.'' Stroud, UK: The History Press, 2007. .External links

US Centennial of Flight Commission: Louis Blériot

* ttps://www.pbs.org/wgbh/nova/bleriot/ "A Daring Flight"- homepage of the '' NOVA'' TV episode *

Louis Blériot Memorial Behind Dover Castle UK

Louis Blériot and wife at House of Commons, after Channel crossing

(by

John Benjamin Stone

Sir John Benjamin Stone (9 February 1838 – 2 July 1914) was a British Conservative politician and photographer.

Life and career

Stone was born in Duddeston, Birmingham the son of a manager at a local glass works. The business passed into th ...

)

View footage of Blériot's flight in 1909

"Seadromes! Says Blériot," ''Popular Mechanics'', October 1935, one of the last interviews given by Blériot before his death.

(center), in 1927, with

Charles Lindbergh

Charles Augustus Lindbergh (February 4, 1902 – August 26, 1974) was an American aviator, military officer, author, inventor, and activist. On May 20–21, 1927, Lindbergh made the first nonstop flight from New York City to Paris, a distance o ...

and Myron T. Herrick

*

{{DEFAULTSORT:Bleriot, Louis

1872 births

1936 deaths

People from Cambrai

École Centrale Paris alumni

Aviation history of France

Aviation pioneers

Members of the Early Birds of Aviation

French aerospace engineers

Commandeurs of the Légion d'honneur

French aviation record holders

Burials at the Cimetière des Gonards