Geology of Tasmania on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The geology of

The geology of

On King Island now in Bass Strait, the oldest Tasmanian rocks are found. On the west side of King Island, there are

On King Island now in Bass Strait, the oldest Tasmanian rocks are found. On the west side of King Island, there are  In the Tyennan block, the Precambrian basement that forms the central core of Tasmania there are two formations. First, the Oonah Formation contains

In the Tyennan block, the Precambrian basement that forms the central core of Tasmania there are two formations. First, the Oonah Formation contains

"The Geology of Central Western Tasmania: Context for a Major Mineralised Province", in ''Journal of Undergraduate Science Engineering and Technology''

/ref> Phyllite near

''Time ŌĆō Space Diagram for Tasmania''

Mineral Resources Tasmania and AGSO 1998; an

synthesis

/ref> The Wurawina Supergroup formed in the Duck Creek Syncline amongst other places. This syncline is oriented eastŌĆōwest, located on the west coast south of the mouth of the

''Geological Survey Explanatory Report Geological Atlas 1:250,000 series sheet SK55/7 Port Davey''

1977 The Meredith Batholith contains biotite adamellite. It contains ten separate plutons. A

In the Permian, glacial conditions predominated with, icecaps on the land, and ice floating on the sea, as a result of which

In the Permian, glacial conditions predominated with, icecaps on the land, and ice floating on the sea, as a result of which  Siltstone with

Siltstone with

''Geological Survey Explanatory Report Geological Atlas 1:250,000 series sheet SK55/8 Hobart''

1979 and at Mount Ossa. These sandstones were laid down by east flowing rivers.

Continental conditions resulted in sandstone deposits, which represent the upper layers of the Parmeener Super Group. The lowest levels are a sparkling clean quartz sandstone free of coal. The uppermost parts have sandstone and beds of coal. Coal was mined at Newtown, Kaoota, Mount Lloyd,

Continental conditions resulted in sandstone deposits, which represent the upper layers of the Parmeener Super Group. The lowest levels are a sparkling clean quartz sandstone free of coal. The uppermost parts have sandstone and beds of coal. Coal was mined at Newtown, Kaoota, Mount Lloyd,

A major intrusion of dolerite occurred in the Jurassic. This was a widespread phenomena covering over one third of Tasmania, and possibly more in the past. This intrusion also affected

A major intrusion of dolerite occurred in the Jurassic. This was a widespread phenomena covering over one third of Tasmania, and possibly more in the past. This intrusion also affected

The Geology and Mineral Deposits of Tasmania: a summary

Tasmanian Geological Survey Bulletin 72, Mineral Resources Tasmania 2007 In Tasmania the rock is characteristic of many mountains with its columnar joining and dark blue grey colour. The composition is 40%

''Soil development on dolerite and its implications for landscape history in southeastern Tasmania''

Most of the intrusions are in the form of sills up to 500 m thick. Mostly the sills are in the Parmeener Super Group rocks. There are also stepped sills, inclined sheets, cones and some dykes. Closely adjacent country rocks were metamorphosed to

''Microcontinent formation around Australia''

in Geological Society of Australia Special Publication 22, 2001 page 400-405 This extension created a number of sedimentary basins:

Volcanic vents opened up . Lava flows of basalt up to 20 meters thick were formed. Some volcanoes were explosive with

Volcanic vents opened up . Lava flows of basalt up to 20 meters thick were formed. Some volcanoes were explosive with

In the

In the

''Exposure dating and glacial reconstruction at Mount Field, Tasmania, Australia, identifies MIS 3 and MIS 2 glacial advances and climatic variability''

in ''Journal of Quaternary Science'' Vol. 21(4) p363-376 2006. The ice cap on the Central Plateau was around 65 km in diameter. Its western limit was the

''Geological Survey Explanatory Report Geological Atlas 1:250,000 series sheet SK55/5 Queenstown''

1976 Several

Several unusual minerals are known from Tasmania:

Several unusual minerals are known from Tasmania:

Active seismic exploration reveals the nature of the deep crust. It shows that the Tyennan block plumbs the depth to the moho which is about 33 km underneath. The Tyennan Block slopes below the Adamsfield-Jubilee Element. Under the Tasmania Basin the block is stretched, with faults in to several large blocks that have tilted down. Above these the Adamsfield-Jubilee Element sediments have filled in the topography. Below the north east element the moho is 36 km deep with alternating seismically fast and slow rocks in the mid crust.

The Tyennan Block and the Rocky Cape Element have a boundary that dips at 30┬░ to the east to the base of the crust. The Dundas Element lies on top of this boundary. A shallower Moho occurs under the Rocky Cape Block at 26 to 28 km. A deep segment is found under the central north of the state, down to 34 km. Shallower moho depths also occur under southeast and southern Tasmania. A low seismic velocity zone occurs under the Tamar Fracture System. East of this zone is the Northeast Tasmania Block with higher seismic velocities. The high speed zone boundary meets the east coast near

Active seismic exploration reveals the nature of the deep crust. It shows that the Tyennan block plumbs the depth to the moho which is about 33 km underneath. The Tyennan Block slopes below the Adamsfield-Jubilee Element. Under the Tasmania Basin the block is stretched, with faults in to several large blocks that have tilted down. Above these the Adamsfield-Jubilee Element sediments have filled in the topography. Below the north east element the moho is 36 km deep with alternating seismically fast and slow rocks in the mid crust.

The Tyennan Block and the Rocky Cape Element have a boundary that dips at 30┬░ to the east to the base of the crust. The Dundas Element lies on top of this boundary. A shallower Moho occurs under the Rocky Cape Block at 26 to 28 km. A deep segment is found under the central north of the state, down to 34 km. Shallower moho depths also occur under southeast and southern Tasmania. A low seismic velocity zone occurs under the Tamar Fracture System. East of this zone is the Northeast Tasmania Block with higher seismic velocities. The high speed zone boundary meets the east coast near

''A mineralogical field guide for a Western Tasmania minerals and museums tour''

2001 Other unpaid people studied Tasmanian geology such as Paweł Edmund Strzelecki, Joseph Milligan who was a surgeon, R.M. Johnson,

''A Brief History of the Department of Mines ŌĆō 1882 to 2000''

2001 Tannatt William Edgeworth David, a geologist working out of Sydney, was a proponent of the idea of Permo-Carboniferous glaciations. He studied the evidence for past glaciations in Tasmania. Professor S. Warren Carey established the Department of Geology at the

Professor S. Warren Carey established the Department of Geology at the

Mineral Resources Tasmania: Online maps

Mineral Resources Tasmania

Geoscience Australia ŌĆō Tasmanian TASGO 3D model

{{Geology of Australia

The geology of

The geology of Tasmania

)

, nickname =

, image_map = Tasmania in Australia.svg

, map_caption = Location of Tasmania in AustraliaCoordinates:

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdi ...

is complex, with the world's biggest exposure of diabase, or dolerite. The rock record contains representatives of each period of the Neoproterozoic

The Neoproterozoic Era is the unit of geologic time from 1 billion to 538.8 million years ago.

It is the last era of the Precambrian Supereon and the Proterozoic Eon; it is subdivided into the Tonian, Cryogenian, and Ediacaran periods. It is prec ...

, Paleozoic

The Paleozoic (or Palaeozoic) Era is the earliest of three geologic eras of the Phanerozoic Eon.

The name ''Paleozoic'' ( ;) was coined by the British geologist Adam Sedgwick in 1838

by combining the Greek words ''palai├│s'' (, "old") and ...

, Mesozoic

The Mesozoic Era ( ), also called the Age of Reptiles, the Age of Conifers, and colloquially as the Age of the Dinosaurs is the second-to-last era of Earth's geological history, lasting from about , comprising the Triassic, Jurassic and Cretace ...

and Cenozoic

The Cenozoic ( ; ) is Earth's current geological era, representing the last 66million years of Earth's history. It is characterised by the dominance of mammals, birds and flowering plants, a cooling and drying climate, and the current configu ...

eras. It is one of the few southern hemisphere areas that were glaciated during the Pleistocene

The Pleistocene ( , often referred to as the ''Ice age'') is the geological Epoch (geology), epoch that lasted from about 2,580,000 to 11,700 years ago, spanning the Earth's most recent period of repeated glaciations. Before a change was fina ...

with glacial landforms in the higher parts. The west coast region hosts significant mineralisation and numerous active and historic mines.

Geological history

The earliest geological history is recorded in rocks from over . Older rocks fromwestern Tasmania

The West Coast of Tasmania is mainly isolated rough country, associated with wilderness, mining and tourism. It served as the location of an early convict settlement in the early history of Van Diemen's Land, and contrasts sharply with the mor ...

and King Island were strongly folded and metamorphosed into rocks such as quartzite

Quartzite is a hard, non- foliated metamorphic rock which was originally pure quartz sandstone.Essentials of Geology, 3rd Edition, Stephen Marshak, p 182 Sandstone is converted into quartzite through heating and pressure usually related to tec ...

. After this there are many signs of glaciation

A glacial period (alternatively glacial or glaciation) is an interval of time (thousands of years) within an ice age that is marked by colder temperatures and glacier advances. Interglacials, on the other hand, are periods of warmer climate bet ...

from the Cryogenian

The Cryogenian (from grc, ╬║ŽüŽŹ╬┐Žé, kr├Įos, meaning "cold" and , romanized: , meaning "birth") is a geologic period that lasted from . It forms the second geologic period of the Neoproterozoic Era, preceded by the Tonian Period and followed ...

, as well as the global warming

In common usage, climate change describes global warmingŌĆöthe ongoing increase in global average temperatureŌĆöand its effects on Earth's climate system. Climate change in a broader sense also includes previous long-term changes to ...

that occurred at the start of the Ediacaran

The Ediacaran Period ( ) is a geological period that spans 96 million years from the end of the Cryogenian Period 635 million years ago (Mya), to the beginning of the Cambrian Period 538.8 Mya. It marks the end of the Proterozoic Eon, and t ...

period. An orogeny

Orogeny is a mountain building process. An orogeny is an event that takes place at a convergent plate margin when plate motion compresses the margin. An '' orogenic belt'' or ''orogen'' develops as the compressed plate crumples and is uplifted ...

folded the older Precambrian

The Precambrian (or Pre-Cambrian, sometimes abbreviated pĻ×Æ, or Cryptozoic) is the earliest part of Earth's history, set before the current Phanerozoic Eon. The Precambrian is so named because it preceded the Cambrian, the first period of th ...

rocks. In the Cambrian

The Cambrian Period ( ; sometimes symbolized Ļ×Æ) was the first geological period of the Paleozoic Era, and of the Phanerozoic Eon. The Cambrian lasted 53.4 million years from the end of the preceding Ediacaran Period 538.8 million years ago ...

time the Tyennan block forming the south west

The points of the compass are a set of horizontal, radially arrayed compass directions (or azimuths) used in navigation and cartography. A compass rose is primarily composed of four cardinal directionsŌĆönorth, east, south, and westŌĆöeach sep ...

and central Tasmania, was pushed up and slightly over the land of north west Tasmania

North West Tasmania is one of the regions of Tasmania in Australia. The region comprises the whole of the north west, including the ''North West Coast'' and the northern reaches of the ''West Coast''. It is usually accepted as extending as f ...

, the Tyennan Orogeny. Then there were volcanic action and sediments from the Cambrian and Ordovician

The Ordovician ( ) is a geologic period and system, the second of six periods of the Paleozoic Era. The Ordovician spans 41.6 million years from the end of the Cambrian Period million years ago (Mya) to the start of the Silurian Period Mya.

T ...

. The large ore deposits were formed on the West Coast. The north east of Tasmania began to form as part of the Lachlan Orogen The Lachlan Fold Belt (LFB) or Lachlan Orogen is a geological subdivision of the east part of Australia. It is a zone of folded and faulted rocks of similar age. It dominates New South Wales and Victoria, also extending into Tasmania, the Austra ...

with turbidity flow

A turbidity current is most typically an underwater current of usually rapidly moving, sediment-laden water moving down a slope; although current research (2018) indicates that water-saturated sediment may be the primary actor in the process. T ...

s of mud and sand on to the ocean floor. In the Devonian the Tabberabberan Orogeny caused more folding, and intrusion of granite

Granite () is a coarse-grained ( phaneritic) intrusive igneous rock composed mostly of quartz, alkali feldspar, and plagioclase. It forms from magma with a high content of silica and alkali metal oxides that slowly cools and solidifies un ...

on the west and east coasts, and probably joined the east of Tasmania to the west.

In the Permian

The Permian ( ) is a geologic period and stratigraphic system which spans 47 million years from the end of the Carboniferous Period million years ago (Mya), to the beginning of the Triassic Period 251.9 Mya. It is the last period of the Paleo ...

period, conditions were again glacial and the Tasmania basin formed, with low sea levels in the Triassic

The Triassic ( ) is a geologic period and system which spans 50.6 million years from the end of the Permian Period 251.902 million years ago ( Mya), to the beginning of the Jurassic Period 201.36 Mya. The Triassic is the first and shortest per ...

. A giant intrusion of magma happened in the Jurassic

The Jurassic ( ) is a geologic period and stratigraphic system that spanned from the end of the Triassic Period million years ago (Mya) to the beginning of the Cretaceous Period, approximately Mya. The Jurassic constitutes the middle period of ...

forming diabase

Diabase (), also called dolerite () or microgabbro,

is a mafic, holocrystalline, subvolcanic rock equivalent to volcanic basalt or plutonic gabbro. Diabase dikes and sills are typically shallow intrusive bodies and often exhibit fine-grain ...

, or dolerite which gives many of the Tasmanian mountains their characteristic appearance. Continental breakup happened in the Cretaceous

The Cretaceous ( ) is a geological period that lasted from about 145 to 66 million years ago (Mya). It is the third and final period of the Mesozoic Era, as well as the longest. At around 79 million years, it is the longest geological period of ...

and Cenozoic

The Cenozoic ( ; ) is Earth's current geological era, representing the last 66million years of Earth's history. It is characterised by the dominance of mammals, birds and flowering plants, a cooling and drying climate, and the current configu ...

Periods, splitting off undersea plateaus, forming Bass Strait

Bass Strait () is a strait separating the island states and territories of Australia, state of Tasmania from the Australian mainland (more specifically the coast of Victoria (Australia), Victoria, with the exception of the land border across Bo ...

and ultimately breaking Tasmania away from Antarctica

Antarctica () is Earth's southernmost and least-populated continent. Situated almost entirely south of the Antarctic Circle and surrounded by the Southern Ocean, it contains the geographic South Pole. Antarctica is the fifth-largest cont ...

. In the Cenozoic, a couple of basins extended inland from Macquarie Harbour

Macquarie Harbour is a shallow fjord in the West Coast region of Tasmania, Australia. It is approximately , and has an average depth of , with deeper places up to . It is navigable by shallow-draft vessels. The main channel is kept clear by th ...

and the northern Midlands

The Midlands (also referred to as Central England) are a part of England that broadly correspond to the Kingdom of Mercia of the Early Middle Ages, bordered by Wales, Northern England and Southern England. The Midlands were important in the In ...

. The higher mountains were glaciated during the Pleistocene

The Pleistocene ( , often referred to as the ''Ice age'') is the geological Epoch (geology), epoch that lasted from about 2,580,000 to 11,700 years ago, spanning the Earth's most recent period of repeated glaciations. Before a change was fina ...

.

Precambrian

The oldest rocks in Tasmania from the Precambrian form several blocks. The blocks are King Island; Rocky Cape in the North West, Dundas Element in the mid west; Sheffield Element in the central north; Tyennan Element in the west central and south west; and the Adamsfield-Jubilee Element in the south central to south coast. The island's oldest rocks seem to have originated when that part of the island was attached to western North America. Analysis ofmonazite

Monazite is a primarily reddish-brown phosphate mineral that contains rare-earth elements. Due to variability in composition, monazite is considered a group of minerals. The most common species of the group is monazite-(Ce), that is, the ceriu ...

and zircon

Zircon () is a mineral belonging to the group of nesosilicates and is a source of the metal zirconium. Its chemical name is zirconium(IV) silicate, and its corresponding chemical formula is Zr SiO4. An empirical formula showing some of t ...

in rocks of the ancient Rocky Cape Group in north-west Tasmania found that they are between 1.45 billion and 1.33 billion years old. These minerals, strongly resemble those found in Montana

Montana () is a state in the Mountain West division of the Western United States. It is bordered by Idaho to the west, North Dakota and South Dakota to the east, Wyoming to the south, and the Canadian provinces of Alberta, British Columb ...

, Idaho

Idaho ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Pacific Northwest region of the Western United States. To the north, it shares a small portion of the CanadaŌĆōUnited States border with the province of British Columbia. It borders the states of Monta ...

and southern British Columbia

British Columbia (commonly abbreviated as BC) is the westernmost province of Canada, situated between the Pacific Ocean and the Rocky Mountains. It has a diverse geography, with rugged landscapes that include rocky coastlines, sandy beaches, for ...

. Fossils called ''Horodyskia

''Horodyskia'' is a fossilised organism found in rocks dated from to . Its shape has been described as a "string of beads" connected by a very fine thread. It is considered one of the oldest known eukaryotes.

Biology

Comparisons of differe ...

'' have also been found in both sites. Importantly, at more than 1 billion years old, the fossils are some of the oldest visible to the naked eye. Previous theories had suggested that Tasmania emerged from central Australia as the supercontinents broke apart, but the recent spectroscopic and radioactive dating evidence contradicts this.

Tasmania's geographic location during the Precambrian is still unclear, but it is clear that some of it was linked to an area of ancient North America. The rocks of Tasmania are much older than those of the east coast of Australia indicating a different geologic history. Alternative ideas for the location are presented below

Below may refer to:

*Earth

*Ground (disambiguation)

*Soil

*Floor

*Bottom (disambiguation)

*Less than

*Temperatures below freezing

*Hell or underworld

People with the surname

*Ernst von Below (1863ŌĆō1955), German World War I general

*Fred Below ( ...

.

On King Island now in Bass Strait, the oldest Tasmanian rocks are found. On the west side of King Island, there are

On King Island now in Bass Strait, the oldest Tasmanian rocks are found. On the west side of King Island, there are basalt

Basalt (; ) is an aphanitic (fine-grained) extrusive igneous rock formed from the rapid cooling of low-viscosity lava rich in magnesium and iron (mafic lava) exposed at or very near the surface of a rocky planet or moon. More than 90 ...

s that have been metamorphosed by amphibolite

Amphibolite () is a metamorphic rock that contains amphibole, especially hornblende and actinolite, as well as plagioclase feldspar, but with little or no quartz. It is typically dark-colored and dense, with a weakly foliated or schistose (flaky ...

grade metamorphism at . Sedimentary rocks such as feldspathic sandstone that have been altered to schist

Schist ( ) is a medium-grained metamorphic rock showing pronounced schistosity. This means that the rock is composed of mineral grains easily seen with a low-power hand lens, oriented in such a way that the rock is easily split into thin flakes ...

and quartzite. Detrital zircons have been dated to 1350, 1444, 1600, 1768 and 1900 Ma. A dolerite

Diabase (), also called dolerite () or microgabbro,

is a mafic, holocrystalline, subvolcanic rock equivalent to volcanic basalt or plutonic gabbro. Diabase dikes and sills are typically shallow intrusive bodies and often exhibit fine-grain ...

sill

Sill may refer to:

* Sill (dock), a weir at the low water mark retaining water within a dock

* Sill (geology), a subhorizontal sheet intrusion of molten or solidified magma

* Sill (geostatistics)

* Sill (river), a river in Austria

* Sill plate, ...

was intruded. Granite intruded in the Cryogenian. The granite contains inherited zircon

Zircon () is a mineral belonging to the group of nesosilicates and is a source of the metal zirconium. Its chemical name is zirconium(IV) silicate, and its corresponding chemical formula is Zr SiO4. An empirical formula showing some of t ...

s from . The Wickham deformation affected the earlier rocks by heating to 470 to 480 ┬░C at pressures below 300 MPa

MPA or mPa may refer to:

Academia

Academic degrees

* Master of Performing Arts

* Master of Professional Accountancy

* Master of Public Administration

* Master of Public Affairs

Schools

* Mesa Preparatory Academy

* Morgan Park Academy

* Mou ...

, and tight folding. This was followed later in the Neoproterozoic

The Neoproterozoic Era is the unit of geologic time from 1 billion to 538.8 million years ago.

It is the last era of the Precambrian Supereon and the Proterozoic Eon; it is subdivided into the Tonian, Cryogenian, and Ediacaran periods. It is prec ...

on the eastern side of the island with beds of diamictite

Diamictite (; from Ancient Greek ''╬┤╬╣╬▒'' (dia-): ''through'' and ''┬Ą╬Ą╬╣╬║ŽäŽīŽé'' (meikt├│s): ''mixed'') is a type of lithified sedimentary rock that consists of nonsorted to poorly sorted terrigenous sediment containing particles that r ...

, dolomite Dolomite may refer to:

*Dolomite (mineral), a carbonate mineral

*Dolomite (rock), also known as dolostone, a sedimentary carbonate rock

*Dolomite, Alabama, United States, an unincorporated community

*Dolomite, California, United States, an unincor ...

, mudstone

Mudstone, a type of mudrock, is a fine-grained sedimentary rock whose original constituents were clays or muds. Mudstone is distinguished from '' shale'' by its lack of fissility (parallel layering).Blatt, H., and R.J. Tracy, 1996, ''Petrology.' ...

, tholeiite

The tholeiitic magma series is one of two main magma series in subalkaline igneous rocks, the other being the calc-alkaline series. A magma series is a chemically distinct range of magma compositions that describes the evolution of a mafic magma ...

, and picrite

Picrite basalt or picrobasalt is a variety of high-magnesium olivine basalt that is very rich in the mineral olivine. It is dark with yellow-green olivine phenocrysts (20-50%) and black to dark brown pyroxene, mostly augite.

The olivine-rich p ...

interleaved with conglomerate

Conglomerate or conglomeration may refer to:

* Conglomerate (company)

* Conglomerate (geology)

* Conglomerate (mathematics)

In popular culture:

* The Conglomerate (American group), a production crew and musical group founded by Busta Rhymes

** ...

. Also dykes of augite

Augite is a common rock-forming pyroxene mineral with formula . The crystals are monoclinic and prismatic. Augite has two prominent cleavages, meeting at angles near 90 degrees.

Characteristics

Augite is a solid solution in the pyroxene group ...

syenite

Syenite is a coarse-grained intrusive igneous rock with a general composition similar to that of granite, but deficient in quartz, which, if present at all, occurs in relatively small concentrations (< 5%). Some syenites contain larger prop ...

, picrite and 580 Ma tholeiite dolerite were intruded. An interpretation is that deposits occurred in a tidal area, with a continental

Continental may refer to:

Places

* Continent, the major landmasses of Earth

* Continental, Arizona, a small community in Pima County, Arizona, US

* Continental, Ohio, a small town in Putnam County, US

Arts and entertainment

* ''Continental'' ( ...

rift

In geology, a rift is a linear zone where the lithosphere is being pulled apart and is an example of extensional tectonics.

Typical rift features are a central linear downfaulted depression, called a graben, or more commonly a half-grabe ...

allowing magma

Magma () is the molten or semi-molten natural material from which all igneous rocks are formed. Magma is found beneath the surface of the Earth, and evidence of magmatism has also been discovered on other terrestrial planets and some natura ...

from the mantle

A mantle is a piece of clothing, a type of cloak. Several other meanings are derived from that.

Mantle may refer to:

*Mantle (clothing), a cloak-like garment worn mainly by women as fashionable outerwear

**Mantle (vesture), an Eastern Orthodox ve ...

to intrude. These newer Proterozoic sediments were then tilted and faulted.

The latter tholeiite igneous rocks have a strong magnetic signature, and this can be detected from the rock underneath Bass Strait. The band of rocks is 35 km wide. It extends north northeast to Phillip Island, Victoria, and also south 40 km to just off the west coast of Tasmania stopping at the Braddon River Fault

In the Rocky Cape Block west of Wynyard and north of Granville Harbour, the Precambrian rocks consist of the Rocky Cape Group from the Stenian

The Stenian Period (, from grc, ŽāŽä╬Ą╬ĮŽīŽé, sten├│s, meaning "narrow") is the final geologic period in the Mesoproterozoic Era and lasted from Mya to Mya (million years ago). Instead of being based on stratigraphy, these dates are defined ...

period, with Cowrie Siltstone

Siltstone, also known as aleurolite, is a clastic sedimentary rock that is composed mostly of silt. It is a form of mudrock with a low clay mineral content, which can be distinguished from shale by its lack of fissility.Blatt ''et al.'' 1980, ...

, Detention Subgroup, Irby Siltstone, and Jacob Quartzite. The sequence covers most of the block and is over 5700 metres thick. Currents travelled either northwesterly or southeasterly. The metamorphic belt titled the Arthur Lineament forms the limits of the Rocky Cape Group to the south east. The Burnie Formation followed in the Tonian

The Tonian (from grc, ŽäŽī╬Į╬┐Žé, t├│nos, meaning "stretch") is the first geologic period of the Neoproterozoic Era. It lasted from to Mya (million years ago). Instead of being based on stratigraphy, these dates are defined by the ICS based o ...

period south east of the lineament with greywacke

Greywacke or graywacke (German ''grauwacke'', signifying a grey, earthy rock) is a variety of sandstone generally characterized by its hardness, dark color, and poorly sorted angular grains of quartz, feldspar, and small rock fragments or lit ...

and slaty mudstone, and also some basic pillow lava

Pillow lavas are lavas that contain characteristic pillow-shaped structures that are attributed to the extrusion of the lava underwater, or ''subaqueous extrusion''. Pillow lavas in volcanic rock are characterized by thick sequences of discont ...

s. The Oonah Formation has even more varieties of rock than the Burnie formation, also including conglomerate, quartz sandstone, dolomite and chert

Chert () is a hard, fine-grained sedimentary rock composed of microcrystalline or cryptocrystalline quartz, the mineral form of silicon dioxide (SiO2). Chert is characteristically of biological origin, but may also occur inorganically as a ...

. The Bowry Formation in the Cryogenian was intruded by granite (Bowry granitoids) . These have been metamorphosed to the blueschist

Blueschist (), also called glaucophane schist, is a metavolcanic rock that forms by the metamorphism of basalt and rocks with similar composition at high pressures and low temperatures (), approximately corresponding to a depth of . The blue ...

level. In the Smithton Synclinorium the Togari Group followed with conglomerate from the Sturtian

The Sturtian glaciation was a Snowball Earth glaciation, or perhaps multiple glaciations, during the Cryogenian Period when the Earth experienced repeated large-scale glaciations. The duration of the Sturtian glaciation has been variously defined, ...

and Marinoan glaciation

The Marinoan glaciation, sometimes also known as the Varanger glaciation, was a period of worldwide glaciation that lasted from approximately 650 to 632.3 ┬▒ 5.9 Ma (million years ago) during the Cryogenian period. This glaciation possibly cover ...

s and dolomite marking the end of Cryogenian and on into the Ediacaran and Cambrian. The Togari group contains greywacke, conglomerate, diamictite, mafic volcanic rocks, and quartz sandstone, and mudstone. The components of the Togari Group are called Forest Conglomerate and Quartzite, Black River Dolomite, Kanunnah subgroup (containing the lavas) and Smithton Dolomite. These rocks are important for determining the boundary between the Cryogenian and Ediacaran periods as they contain volcanics that can be dated and dolomites marking the end of glaciations and marking the period boundary.

Near Corinna

Corinna or Korinna ( grc, ╬ÜŽīŽü╬╣╬Į╬Į╬▒, Korinna) was an ancient Greek lyric poet from Tanagra in Boeotia. Although ancient sources portray her as a contemporary of Pindar (born ), not all modern scholars accept the accuracy of this tradition ...

the Ahrberg group is correlated with the Togari Group and the Success Creek Group. It contains the Donaldson Formation (a marine fan), Savage Dolomite which contains stromatolite

Stromatolites () or stromatoliths () are layered sedimentary formations ( microbialite) that are created mainly by photosynthetic microorganisms such as cyanobacteria, sulfate-reducing bacteria, and Pseudomonadota (formerly proteobacteria). T ...

s; Bernafai Volcanics containing albite

Albite is a plagioclase feldspar mineral. It is the sodium endmember of the plagioclase solid solution series. It represents a plagioclase with less than 10% anorthite content. The pure albite endmember has the formula . It is a tectosilicate ...

epidote

Epidote is a calcium aluminium iron sorosilicate mineral.

Description

Well developed crystals of epidote, Ca2Al2(Fe3+;Al)(SiO4)(Si2O7)O(OH), crystallizing in the monoclinic system, are of frequent occurrence: they are commonly prismatic in ...

actinolite

Actinolite is an amphibole silicate mineral with the chemical formula .

Etymology

The name ''actinolite'' is derived from the Greek word ''aktis'' (), meaning "beam" or "ray", because of the mineral's fibrous nature.

Mineralogy

Actinolite is ...

chlorite

The chlorite ion, or chlorine dioxide anion, is the halite with the chemical formula of . A chlorite (compound) is a compound that contains this group, with chlorine in the oxidation state of +3. Chlorites are also known as salts of chlorou ...

; Corinna Dolomite, and Tunnelrace Volcanics. Where the dolomite has been dissolved away over million of years it has left layers of very pure silica

Silicon dioxide, also known as silica, is an oxide of silicon with the chemical formula , most commonly found in nature as quartz and in various living organisms. In many parts of the world, silica is the major constituent of sand. Silica is ...

flour, an important mineral resource.

The Dundas Element lowest level starts with the Oonah Formation with greywacke, dolomite and basic volcanics. The Oonah Formation appeared between . It has three sections, Mount Bischoff Inlier

An inlier is an area of older rocks surrounded by younger rocks. Inliers are typically formed by the erosion of overlying younger rocks to reveal a limited exposure of the older underlying rocks. Faulting or folding may also contribute to the obser ...

, the Ramsay River Inlier and the Dundas Inlier. The Success Creek Group from the Cryogenian has diamictite, quartz sandstone (Dalcoath Formation), and mudstone. It includes the Renison Bell Formation named after the Renison Bell mine. The red rock member is hematite

Hematite (), also spelled as haematite, is a common iron oxide compound with the formula, Fe2O3 and is widely found in rocks and soils. Hematite crystals belong to the rhombohedral lattice system which is designated the alpha polymorph of . ...

stained chert. The sediments slumped while soft forming folds and breccia

Breccia () is a rock composed of large angular broken fragments of minerals or rocks cemented together by a fine-grained matrix.

The word has its origins in the Italian language, in which it means "rubble". A breccia may have a variety of ...

and m├®lange

In geology, a m├®lange is a large-scale breccia, a mappable body of rock characterized by a lack of continuous bedding and the inclusion of fragments of rock of all sizes, contained in a fine-grained deformed matrix. The m├®lange typically cons ...

. They were then capped with limestone

Limestone ( calcium carbonate ) is a type of carbonate sedimentary rock which is the main source of the material lime. It is composed mostly of the minerals calcite and aragonite, which are different crystal forms of . Limestone forms w ...

. The group is up to 1000 metres thick. The Crimson Creek Formation consists of greywacke with tholeiitic basalt. It is from 4000 to 5000 metres thick. This formation could be as late as the early Cambrian. The basalt is probably the same as mafic lavas of the Kanunnah Subgroup.

The Sheffield Element extends from Wynyard past Devonport and the Asbestos Range on the north coast and as far south east as Golden Valley. It contains structural elements called Dial Range Trough, Forth Massif, Fossey Mountains Trough. The oldest Precambrian rocks are the Ulverstone Metamorphic Complex and Forth Metamorphic Complex. This is assumed to be the same age as metamorphic rocks from the Tyennan Block, at from the Stenian

The Stenian Period (, from grc, ŽāŽä╬Ą╬ĮŽīŽé, sten├│s, meaning "narrow") is the final geologic period in the Mesoproterozoic Era and lasted from Mya to Mya (million years ago). Instead of being based on stratigraphy, these dates are defined ...

. This contains zircons predominantly dated , but also from 1710, 1851, the oldest being , and the youngest . The Burnie or Oonah Formation with Greywacke is possibly from the Tonian period, dated around . Slate from both the Burnie and Oonah formations is dated at . Both of these formations came from a shallow marine shelf. The Cooee Dolerite intruded the Burnie Formation at . Zircon grains in the Cooee Dolerite are from mostly .

The Barrington Chert is finely laminated and has flaggy bedding. It is found in the Dial Range and Fossey Mountain Troughs, up to 1 km thick. The Motton Spilite lies on top of the chert. It consists of pillow lava, massive lava flows, sediments made from volcanic fragments, and chert breccia. The basalt is an ocean floor type. The Badger Head Inlier consists of deformed Burnie Formation. The Andersons Creek Ultramafic Complex is west of Beaconsfield

Beaconsfield ( ) is a market town and civil parish within the unitary authority of Buckinghamshire, England, west-northwest of central London and south-southeast of Aylesbury. Three other towns are within : Gerrards Cross, Amersham and High W ...

and east of the inlier with serpentinite

Serpentinite is a rock composed predominantly of one or more serpentine group minerals, the name originating from the similarity of the texture of the rock to that of the skin of a snake. Serpentinite has been called ''serpentine'' or ''s ...

, pyroxenite

Pyroxenite is an ultramafic igneous rock consisting essentially of minerals of the pyroxene group, such as augite, diopside, hypersthene, bronzite or enstatite. Pyroxenites are classified into clinopyroxenites, orthopyroxenites, and the we ...

, gabbro

Gabbro () is a phaneritic (coarse-grained), mafic intrusive igneous rock formed from the slow cooling of magnesium-rich and iron-rich magma into a holocrystalline mass deep beneath the Earth's surface. Slow-cooling, coarse-grained gabbro is ...

and a sliver of oolitic chert introduced as a fault bounded block. To the west of the Badger Head Inlier is the Port Sorell Formation, a tectonic m├®lange of marine sediment

Marine sediment, or ocean sediment, or seafloor sediment, are deposits of insoluble particles that have accumulated on the seafloor. These particles have their origins in soil and rocks and have been transported from the land to the sea, mai ...

s and dolerite.

turbidite

A turbidite is the geologic deposit of a turbidity current, which is a type of amalgamation of fluidal and sediment gravity flow responsible for distributing vast amounts of clastic sediment into the deep ocean.

Sequencing

Turbidites wer ...

with quartz sandstone

Sandstone is a clastic sedimentary rock composed mainly of sand-sized (0.0625 to 2 mm) silicate grains. Sandstones comprise about 20–25% of all sedimentary rocks.

Most sandstone is composed of quartz or feldspar (both silicat ...

interbedded with siltstone deposited by gravity flows. This has been deformed with tight folds that have been overturned, and exhibits crenulation cleavage and brittle faulting. Zircons in the quartzite have peak numbers aged and . Secondly, the Scotchfire Metamorphic Complex contains quartzite deposited in the sea from windblown desert sands, schist

Schist ( ) is a medium-grained metamorphic rock showing pronounced schistosity. This means that the rock is composed of mineral grains easily seen with a low-power hand lens, oriented in such a way that the rock is easily split into thin flakes ...

and phyllite

Phyllite ( ) is a type of foliated metamorphic rock created from slate that is further metamorphosed so that very fine grained white mica achieves a preferred orientation.Stephen Marshak ''Essentials of Geology'', 3rd ed. It is primarily compo ...

possibly from a delta. Small quantities of dolomite and boulder conglomerate

Conglomerate or conglomeration may refer to:

* Conglomerate (company)

* Conglomerate (geology)

* Conglomerate (mathematics)

In popular culture:

* The Conglomerate (American group), a production crew and musical group founded by Busta Rhymes

** ...

are also included. The complex includes boudinage structure and ''en echelon'' veins

Veins are blood vessels in humans and most other animals that carry blood towards the heart. Most veins carry deoxygenated blood from the tissues back to the heart; exceptions are the pulmonary and umbilical veins, both of which carry oxygenated ...

.Kathryn Harris"The Geology of Central Western Tasmania: Context for a Major Mineralised Province", in ''Journal of Undergraduate Science Engineering and Technology''

/ref> Phyllite near

Strathgordon

Strathgordon is a rural locality in the local government area (LGA) of Derwent Valley in the South-east LGA region of Tasmania. The locality is about west of the town of New Norfolk. The 2016 census recorded a population of 15 for the state s ...

has been dated at . Metamorphism to greenschist facies

Greenschists are metamorphic rocks that formed under the lowest temperatures and pressures usually produced by regional metamorphism, typically and 2ŌĆō10 kilobars (). Greenschists commonly have an abundance of green minerals such as chlorite, ...

occurred at around 400 ┬░C and 300 MPa. The Franklin Metamorphic Complex is near Mount Franklin. At Raglan Range the rocks are a mixture of quartzite and knotted schist

Schist ( ) is a medium-grained metamorphic rock showing pronounced schistosity. This means that the rock is composed of mineral grains easily seen with a low-power hand lens, oriented in such a way that the rock is easily split into thin flakes ...

. Metamorphism in this area was higher grade with almandine

Almandine (), also known as almandite, is a species of mineral belonging to the garnet group. The name is a corruption of alabandicus, which is the name applied by Pliny the Elder to a stone found or worked at Alabanda, a town in Caria in Asi ...

garnet

Garnets () are a group of silicate minerals that have been used since the Bronze Age as gemstones and abrasives.

All species of garnets possess similar physical properties and crystal forms, but differ in chemical composition. The different ...

forming. The Collingwood area experienced the highest grade of metamorphism with garnet-mica schist, mica schist and garnet-mica-kyanite

Kyanite is a typically blue aluminosilicate mineral, found in aluminium-rich metamorphic pegmatites and sedimentary rock. It is the high pressure polymorph of andalusite and sillimanite, and the presence of kyanite in metamorphic rocks gener ...

gneiss

Gneiss ( ) is a common and widely distributed type of metamorphic rock. It is formed by high-temperature and high-pressure metamorphic processes acting on formations composed of igneous or sedimentary rocks. Gneiss forms at higher temperatures a ...

present, and enough heat to form veins of migmatite

Migmatite is a composite rock found in medium and high-grade metamorphic environments, commonly within Precambrian cratonic blocks. It consists of two or more constituents often layered repetitively: one layer is an older metamorphic rock th ...

. Eclogite

Eclogite () is a metamorphic rock containing garnet (almandine- pyrope) hosted in a matrix of sodium-rich pyroxene (omphacite). Accessory minerals include kyanite, rutile, quartz, lawsonite, coesite, amphibole, phengite, paragonite, ...

and garnet amphibolite are believed to be the remains of basalt. The eclogite has been heated to 700┬░ at 1520 MPa, a burial depth of perhaps 50 km. Metamorphism happened at the same time as the Cambrian ultramafic

Ultramafic rocks (also referred to as ultrabasic rocks, although the terms are not wholly equivalent) are igneous and meta-igneous rocks with a very low silica content (less than 45%), generally >18% MgO, high FeO, low potassium, and are composed ...

complexes were introduced.

In the Neoproterozoic in the Jane River basin, the very thick Jane River Dolomite appeared.

The Adamsfield Jubilee element is east of the Tyennan Block. It has a strip exposed on the surface that includes the Florentine Synclinorium, The Adamsfield District, the Jubilee Region, and down to the South Coast at Precipitous Bluff

Precipitous Bluff or ''PB'' is a mountain in the South West Wilderness of Tasmania located north east of New River lagoon.

Geology and Geography

It is visible from the South Coast Track and the Moonlight Ridge walk with a prominence of over ...

and Surprise Bay. It also underlies the Tasmania Basin across southeastern Tasmania, but not including the east coast. The subsurface structure has been studied from a few outliers, boreholes, xenolith

A xenolith ("foreign rock") is a rock fragment ( country rock) that becomes enveloped in a larger rock during the latter's development and solidification. In geology, the term ''xenolith'' is almost exclusively used to describe inclusions in ig ...

s, and gravity and magnetic surveys. The basement at 5 km deep is the same as the Tyennan metamorphic rocks (Scotchfire Metamorphic Complex). Its oldest exposed rocks are from the Clark Group, of pelitic rocks, some with stromatolite

Stromatolites () or stromatoliths () are layered sedimentary formations ( microbialite) that are created mainly by photosynthetic microorganisms such as cyanobacteria, sulfate-reducing bacteria, and Pseudomonadota (formerly proteobacteria). T ...

s, and evaporite

An evaporite () is a water- soluble sedimentary mineral deposit that results from concentration and crystallization by evaporation from an aqueous solution. There are two types of evaporite deposits: marine, which can also be described as ocean ...

s, and overlaid with orthoquartzite. The Weld River Group lies above, starting with 0.5 km thickness of conglomerate and sandstone, then up to 3 km of dolomite, interbedded with sandstone, mudstone and diamictite. Glacial dropstones are found in the interbedding, suggesting Cryogenian age, however ╬┤13C

In geochemistry, paleoclimatology, and paleoceanography ''╬┤''13C (pronounced "delta c thirteen") is an isotopic signature, a measure of the ratio of stable isotopes 13C : 12C, reported in parts per thousand (per mil, ŌĆ░). The measure is al ...

profiles suggest Ediacaran age instead. Gravity and magnetic studies indicate that this sort of dolomite (dense and non-magnetic) underlies Hobart and Bruny Island in a northŌĆōsouth strip, and also in a region west of Hobart.

The Cape Sorell Block is a region of metamorphosed sediments from the Mesoproterozoic

The Mesoproterozoic Era is a geologic era that occurred from . The Mesoproterozoic was the first era of Earth's history for which a fairly definitive geological record survives. Continents existed during the preceding era (the Paleoproterozoic), ...

, to the south of the west end of Macquarie Harbour. It is separated from Neoproterozoic

The Neoproterozoic Era is the unit of geologic time from 1 billion to 538.8 million years ago.

It is the last era of the Precambrian Supereon and the Proterozoic Eon; it is subdivided into the Tonian, Cryogenian, and Ediacaran periods. It is prec ...

rocks by a low angle thrust fault

A thrust fault is a break in the Earth's crust, across which older rocks are pushed above younger rocks.

Thrust geometry and nomenclature

Reverse faults

A thrust fault is a type of reverse fault that has a dip of 45 degrees or less.

If ...

. The Neoproterozoic rocks contain greywacke, mudstone and pillow lavas of the Lucas Creek Volcanics (matching the Crimson Creek Formation), mudstone, siltstone (matching the Success Creek Group) and dolomite (correlating with the Togari Group). South east of this is a metamorphosed belt of dolomite rich sediments correlated with the Oonah Formation. An ultramafic belt called Point Hibbs M├®lange reaches the coast near Point Hibbs. This has been complexly faulted with Cambrian, Ordovician

The Ordovician ( ) is a geologic period and system, the second of six periods of the Paleozoic Era. The Ordovician spans 41.6 million years from the end of the Cambrian Period million years ago (Mya) to the start of the Silurian Period Mya.

T ...

and Devonian

The Devonian ( ) is a geologic period and system of the Paleozoic era, spanning 60.3 million years from the end of the Silurian, million years ago (Mya), to the beginning of the Carboniferous, Mya. It is named after Devon, England, wh ...

sediments and limestone.

At the end of the Precambrian uplift there were several raised blocks forming land above the sea: the Tyennan Uplift in the central and south west Tasmania, the Rocky Cape uplift in the north west, and the Forth uplift, near Forth in the north. The far north west also had uplift as probably also did some region to the east. Basins formed were the Smithton Basin, Dial Range Basin, Fossey Mountain Basin and the Adamsfield Basin.

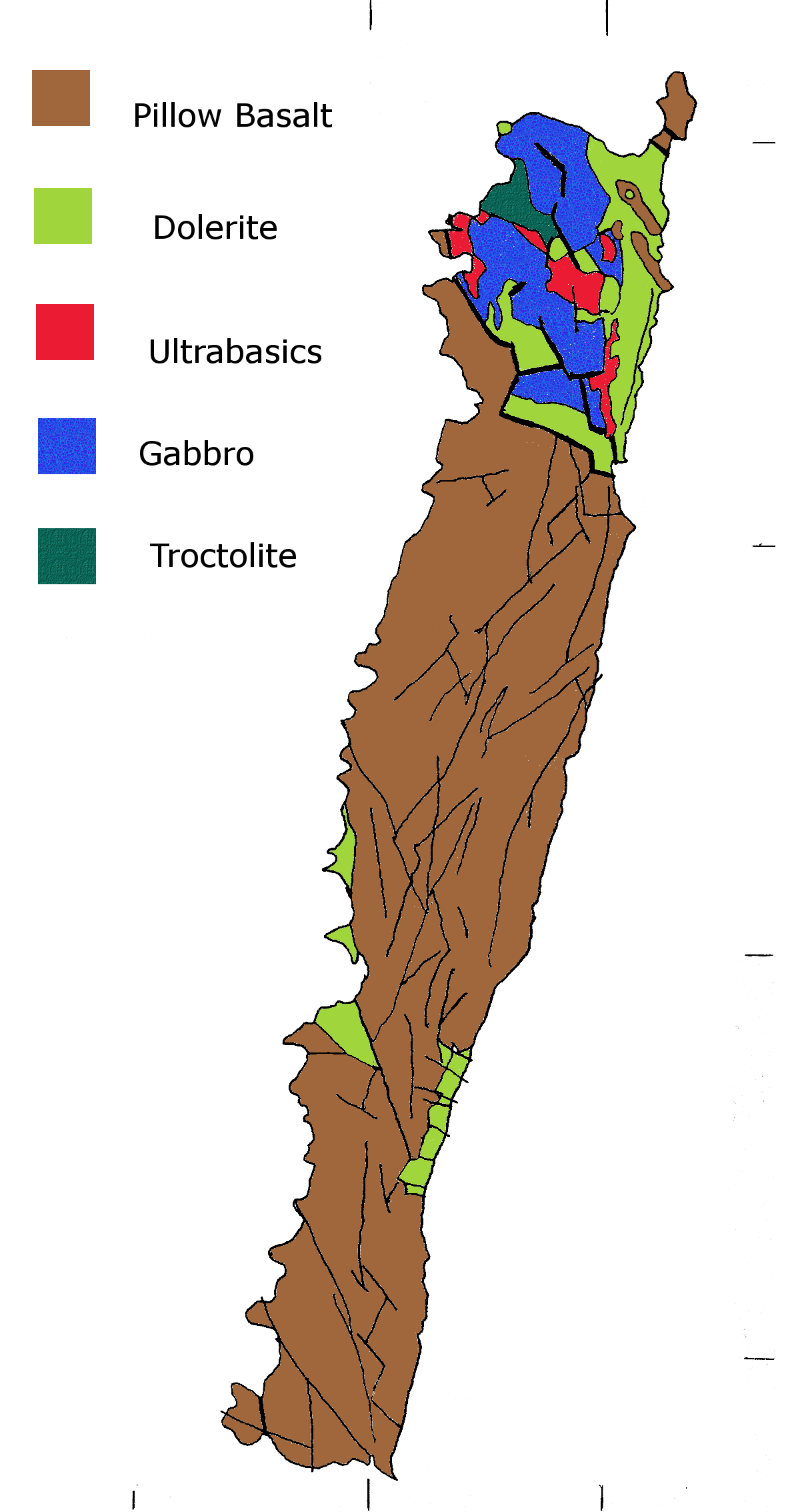

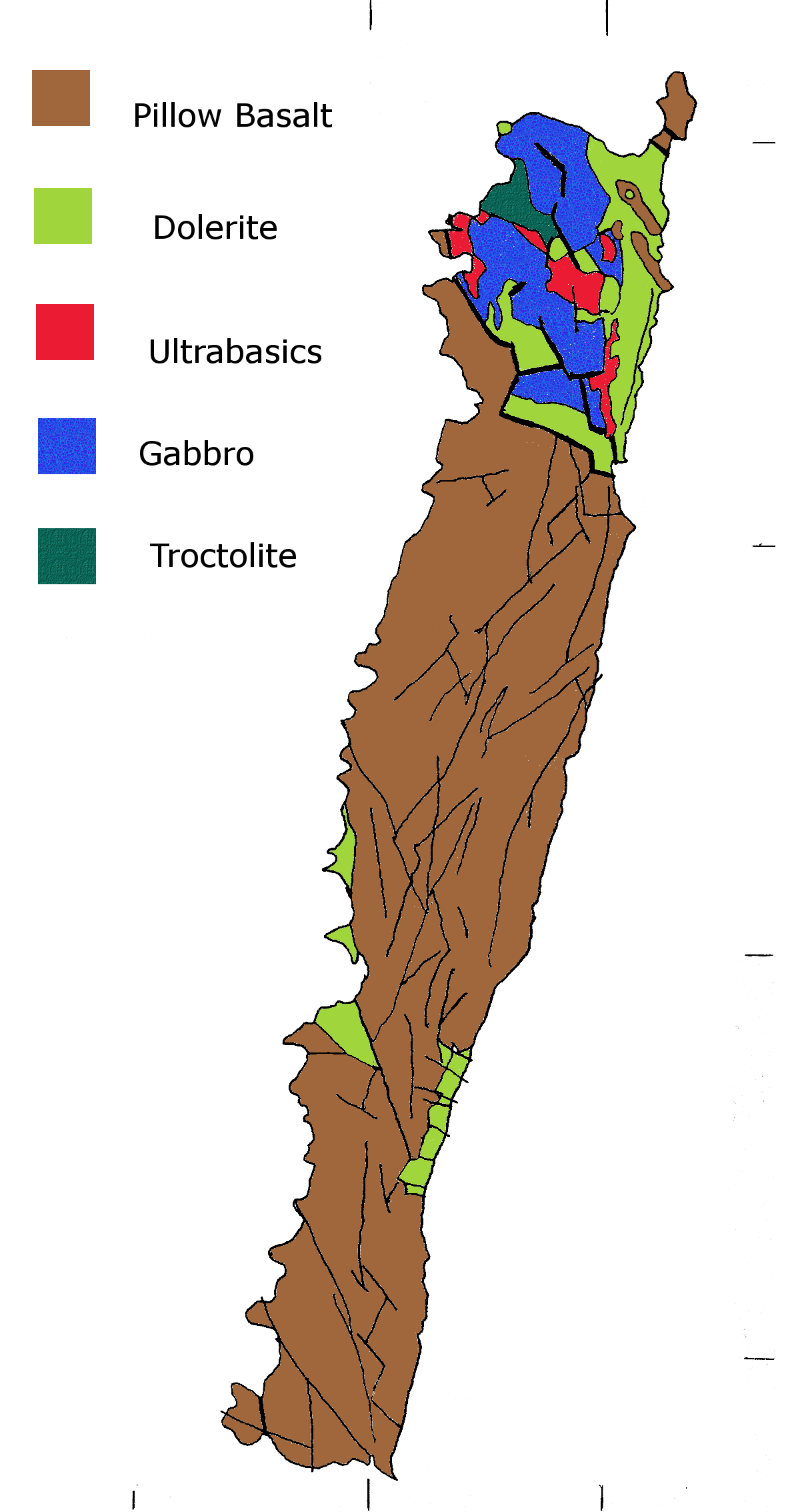

Early Cambrian

Next an oceanic arc collided with eastern Australia. This resulted in deep oceanic crust being thrust in a sheet over the top of the Precambrian rocks. This has left behind severalultramafic

Ultramafic rocks (also referred to as ultrabasic rocks, although the terms are not wholly equivalent) are igneous and meta-igneous rocks with a very low silica content (less than 45%), generally >18% MgO, high FeO, low potassium, and are composed ...

complexes bounded with faults from the older rocks. These take the form of layered pyroxenite

Pyroxenite is an ultramafic igneous rock consisting essentially of minerals of the pyroxene group, such as augite, diopside, hypersthene, bronzite or enstatite. Pyroxenites are classified into clinopyroxenites, orthopyroxenites, and the we ...

and dunite

Dunite (), also known as olivinite (not to be confused with the mineral olivenite), is an intrusive igneous rock of ultramafic composition and with phaneritic (coarse-grained) texture. The mineral assemblage is greater than 90% olivine, w ...

; layered dunite and harzburgite

Harzburgite, an ultramafic, igneous rock, is a variety of peridotite consisting mostly of the two minerals olivine and low-calcium (Ca) pyroxene (enstatite); it is named for occurrences in the Harz Mountains of Germany. It commonly contains a f ...

; and layered pyroxenite, peridotite

Peridotite ( ) is a dense, coarse-grained igneous rock consisting mostly of the silicate minerals olivine and pyroxene. Peridotite is ultramafic, as the rock contains less than 45% silica. It is high in magnesium (Mg2+), reflecting the high pr ...

and gabbro

Gabbro () is a phaneritic (coarse-grained), mafic intrusive igneous rock formed from the slow cooling of magnesium-rich and iron-rich magma into a holocrystalline mass deep beneath the Earth's surface. Slow-cooling, coarse-grained gabbro is ...

. The layering has developed sedimentary like structures including cross bedding. This has been serpentinised, with magnetite

Magnetite is a mineral and one of the main iron ores, with the chemical formula Fe2+Fe3+2O4. It is one of the oxides of iron, and is ferrimagnetic; it is attracted to a magnet and can be magnetized to become a permanent magnet itself. With ...

separating out. Several mineral deposits are associated such as osmiridium

Osmiridium and iridosmine are natural alloys of the elements osmium and iridium, with traces of other platinum-group metals.

Osmiridium has been defined as containing a higher proportion of iridium, with iridosmine containing more osmium. However ...

, and chromium

Chromium is a chemical element with the symbol Cr and atomic number 24. It is the first element in group 6. It is a steely-grey, lustrous, hard, and brittle transition metal.

Chromium metal is valued for its high corrosion resistance and hard ...

. The ultrabasic rocks are rich in orthopyroxene, which is unusual, usually clinopyroxene is found in such rocks. They were formed at high temperature but low pressure. The Heazlewood Ultramafic Complex solidified at . Other ultramafic occurrences include the Cape Sorell and Serpentine Hill Complexes.

As part of this collision, three exotic suites of basalt were tectonically introduced into the Dundas Block. Near Waratah

Waratah (''Telopea'') is an Australian-endemic genus of five species of large shrubs or small trees, native to the southeastern parts of Australia (New South Wales, Victoria, and Tasmania). The best-known species in this genus is ''Telopea speci ...

is a sub-alkaline basalt from an ocean floor, another is a high-magnesium andesite

Andesite () is a volcanic rock of intermediate composition. In a general sense, it is the intermediate type between silica-poor basalt and silica-rich rhyolite. It is fine-grained (aphanitic) to porphyritic in texture, and is composed predo ...

-basalt with chrome spinel

Spinel () is the magnesium/aluminium member of the larger spinel group of minerals. It has the formula in the cubic crystal system. Its name comes from the Latin word , which means ''spine'' in reference to its pointed crystals.

Properties

S ...

and clinoenstatite named boninitic rock after the Bonin Islands

The Bonin Islands, also known as the , are an archipelago of over 30 subtropical and tropical islands, some directly south of Tokyo, Japan and northwest of Guam. The name "Bonin Islands" comes from the Japanese word ''bunin'' (an archaic rea ...

. This magma produced the layered pyroxenite dunite in the ultramafic area. Thirdly there is a low titanium

Titanium is a chemical element with the symbol Ti and atomic number 22. Found in nature only as an oxide, it can be reduced to produce a lustrous transition metal with a silver color, low density, and high strength, resistant to corrosion i ...

basalt-andesite with extreme light rare-earth element

The rare-earth elements (REE), also called the rare-earth metals or (in context) rare-earth oxides or sometimes the lanthanides ( yttrium and scandium are usually included as rare earths), are a set of 17 nearly-indistinguishable lustrous silv ...

depletion that produced the layered pyroxenite-peridotite and associated gabbro cumulate

Cumulate rocks are igneous rocks formed by the accumulation of crystals from a magma either by settling or floating. Cumulate rocks are named according to their texture; cumulate texture is diagnostic of the conditions of formation of this group o ...

.

Two kinds of basalt from the Birchs InletŌĆōMainwaring River Volcanics, occur in a belt north from Veridian Point and west of the south end of Birchs Inlet

The Birchs Inlet, also spelt Birch's Inlet or Birches Inlet, is a narrow cove or coastal inlet on the south-western side of Macquarie Harbour on the west coast of Tasmania, Australia. The inlet is located within the Southwest National Park, par ...

.

In the Adamsfield area The Ragged Basin Complex is a broken up formation of chert, sandstone, red mudstone and mafic magma derived rocks. The sandstone is derived from metamorphic and volcanic fragments. Ultramafic rocks are serpentinised. They are not ophiolite

An ophiolite is a section of Earth's oceanic crust and the underlying upper mantle that has been uplifted and exposed above sea level and often emplaced onto continental crustal rocks.

The Greek word ßĮäŽå╬╣Žé, ''ophis'' (''snake'') is found ...

s, but instead are cumulates of heavy minerals in a shallow magma chamber. The densest mineral, osmiridium

Osmiridium and iridosmine are natural alloys of the elements osmium and iridium, with traces of other platinum-group metals.

Osmiridium has been defined as containing a higher proportion of iridium, with iridosmine containing more osmium. However ...

has been concentrated and mined at Adamsfield. These rocks are allochthon

upright=1.6, Schematic overview of a thrust system. The hanging wall block is (when it has reasonable proportions) called a nappe. If an erosional hole is created in the nappe that is called a window (geology)">window. A klippe is a solitary ou ...

ous, meaning that they were inserted into position by tectonic processes.

Cambrian

Mount Read Volcanics

TheMount Read Volcanics

The Mount Read Volcanics is a Cambrian volcanic belt that exists in Western Tasmania.

It is a complex belt due to folding, faulting and a range of tectonic events.

It is a productive mineralised belt that has profitable copper-silver and gold p ...

are a 250 km long belt that is 10 to 20 km wide attached to the western edge of the Tyennan Block or eastern side of the Dundas Element. The volcanics consist of underwater eruptions interbedded with sediment. A range of lava from basic through intermediate to acid are present along with intrusions and volcanic clastics such as breccia

Breccia () is a rock composed of large angular broken fragments of minerals or rocks cemented together by a fine-grained matrix.

The word has its origins in the Italian language, in which it means "rubble". A breccia may have a variety of ...

and pumice

Pumice (), called pumicite in its powdered or dust form, is a volcanic rock that consists of highly vesicular rough-textured volcanic glass, which may or may not contain crystals. It is typically light-colored. Scoria is another vesicular v ...

. The breccia includes pieces of andesite, dacite

Dacite () is a volcanic rock formed by rapid solidification of lava that is high in silica and low in alkali metal oxides. It has a fine-grained ( aphanitic) to porphyritic texture and is intermediate in composition between andesite and rhyo ...

and massive sulfide

Sulfide (British English also sulphide) is an inorganic anion of sulfur with the chemical formula S2ŌłÆ or a compound containing one or more S2ŌłÆ ions. Solutions of sulfide salts are corrosive. ''Sulfide'' also refers to chemical compounds la ...

. The massive sulfides were formed by hot spring

A hot spring, hydrothermal spring, or geothermal spring is a spring produced by the emergence of geothermally heated groundwater onto the surface of the Earth. The groundwater is heated either by shallow bodies of magma (molten rock) or by circ ...

s on the sea floor. These have become ore deposits for copper

Copper is a chemical element with the symbol Cu (from la, cuprum) and atomic number 29. It is a soft, malleable, and ductile metal with very high thermal and electrical conductivity. A freshly exposed surface of pure copper has a pink ...

, lead, zinc

Zinc is a chemical element with the symbol Zn and atomic number 30. Zinc is a slightly brittle metal at room temperature and has a shiny-greyish appearance when oxidation is removed. It is the first element in group 12 (IIB) of the periodi ...

and silver

Silver is a chemical element with the symbol Ag (from the Latin ', derived from the Proto-Indo-European ''hŌééerŪĄ'': "shiny" or "white") and atomic number 47. A soft, white, lustrous transition metal, it exhibits the highest electrical ...

. The volcanics extend south to Elliot Bay. The Noddy Creek Volcanics extend north of high Rocky Point to Macquarie Harbour

Macquarie Harbour is a shallow fjord in the West Coast region of Tasmania, Australia. It is approximately , and has an average depth of , with deeper places up to . It is navigable by shallow-draft vessels. The main channel is kept clear by th ...

with pyroxene and feldspar containing andesite as lava, breccia and intrusives.

The Sticht Range Beds form a sedimentary base sitting on the Tyennan Block metamorphic rocks. Parts of the volcanics were from , and the younger Tyndall Groups has a dating of . Fossils also indicate a late middle Cambrian age. Zircons in the volcanics have two age groups: matching the metamorphic rock in the Tyennan block; and without a satisfactory explanation.

In the Dial Range Trough the middle Cambrian saw the deposition of the Cateena Group of conglomerate (of purple mudstone pebbles), sandstone with feldspar, mudstone and greywacke and some felsic volcanics. The age is Florian to Undillan. This was followed by the Radfords Creek Group which has a base of a conglomerate of chert and basalt fragments. The age is Boomerangian to Late Mindyallan.

In the Adamsfield area the Trial Ridge Beds, Island Road Formation, and Boyd River Formation consists of conglomerate and greywacke. They contain fossils of agnostoids.

Cambrian granites

The Murchison Granite intruded east of the Mount Read Volcanics. It consists of dioritic granodiorite. Major mineral deposits were formed at Mount Lyell, Rosebery and Henty. Granite also intruded in the Cambrian at Low Rocky Point and Elliott Bay. The north west element was altered by the Tyennan Orogeny around . The Arthur Lineament was metamorphosed to phyllite, slate andschist

Schist ( ) is a medium-grained metamorphic rock showing pronounced schistosity. This means that the rock is composed of mineral grains easily seen with a low-power hand lens, oriented in such a way that the rock is easily split into thin flakes ...

ose quartzite, The Burnie and Oonah Formation were folded in various ways, and the Rocky Cape Group and the Smithton Synclinorium developed cleavage texture. The Tyennan Orogeny corresponds with the first phase of the Delamerian Orogeny in South Australia

South Australia (commonly abbreviated as SA) is a States and territories of Australia, state in the southern central part of Australia. It covers some of the most arid parts of the country. With a total land area of , it is the fourth-largest o ...

and the Ross Orogeny in North Victoria Land

Victoria Land is a region in eastern Antarctica which fronts the western side of the Ross Sea and the Ross Ice Shelf, extending southward from about 70┬░30'S to 78┬░00'S, and westward from the Ross Sea to the edge of the Antarctic Plateau. I ...

, Antarctica.

The Dove Granite intruded the Tyennan Block metamorphics with several small plugs in the north dated at .

Dundas Group

The Dundas group are Cambrian sedimentary beds that interfinger with the Mount Read Volcanics. They lieunconformably

An unconformity is a buried erosional or non-depositional surface separating two rock masses or strata of different ages, indicating that sediment deposition was not continuous. In general, the older layer was exposed to erosion for an interval ...

on the Precambrian basement. The kind of rock is sandstone, laminated mudstone and a pebble conglomerate in which the pebbles consist of quartzite, sandstone and green mudstone. The group was formed as a submarine fan. The conglomerate includes volcanic fragments where it borders the Mount Read Volcanics, indicating that it was deposited at the same time. The Huskisson Group is from the same time period.

In the Smithton Synclinorium the Scopus Formation is from the same period between Boomerangian and Idamean. The rocks are wacke

Greywacke or graywacke (German ''grauwacke'', signifying a grey, earthy rock) is a variety of sandstone generally characterized by its hardness, dark color, and poorly sorted angular grains of quartz, feldspar, and small rock fragments or ...

and mudstone in a submarine fan with currents flowing to the north. A channel is marked by conglomerate. Most of the material came from volcanics, but also included grit from the older Precambrian rocks.

The Fossey Mountains Trough contains Cambrian intermediate volcanics, and greywacke where trilobite fossils show the age as late Middle Cambrian. Boomerangian age fossils were found in Paradise

In religion, paradise is a place of exceptional happiness and delight. Paradisiacal notions are often laden with pastoral imagery, and may be cosmogonical or eschatological or both, often compared to the miseries of human civilization: in para ...

.

Ordovician

During theOrdovician

The Ordovician ( ) is a geologic period and system, the second of six periods of the Paleozoic Era. The Ordovician spans 41.6 million years from the end of the Cambrian Period million years ago (Mya) to the start of the Silurian Period Mya.

T ...

Tasmania was near the equator and was joined to Gondwana

Gondwana () was a large landmass, often referred to as a supercontinent, that formed during the late Neoproterozoic (about 550 million years ago) and began to break up during the Jurassic period (about 180 million years ago). The final sta ...

. The Tyennan Block was uplifted with the Great Lyell Scarp as an active fault

An active fault is a fault that is likely to become the source of another earthquake sometime in the future. Geologists commonly consider faults to be active if there has been movement observed or evidence of seismic activity during the last 10,0 ...

.

The Ordovician Wurawina supergroup comprises the Denison Group and the Gordon group. The Owen Conglomerate, part of the Denison group, lies conformably on the Dundas Group, but unconformably on the Mount Read Volcanics. The pebbles include quartz, quartzite, quartz sandstone, pale pink mudstone and chert, embedded in a matrix of sand. The Owen Group rocks are found on the West Coast Range

The West Coast Range is a mountain range located in the West Coast region of Tasmania, Australia.

The range lies to the west and north of the main parts of the Franklin-Gordon Wild Rivers National Park.

The range has had a significant nu ...

. The conglomerate was derived from the highlands of the uplifted Tyennan Block and is up to 1500 meters thick. The lowest section is the Jukes Conglomerate, with Lower Owen Conglomerate and Middle Owen Conglomerate above. Upper Owen Sandstone is found in Queenstown, it formed while the Great Lyell Fault was active, resulting in folding of the lower parts. The Pioneer Beds are the top layer, containing chert

Chert () is a hard, fine-grained sedimentary rock composed of microcrystalline or cryptocrystalline quartz, the mineral form of silicon dioxide (SiO2). Chert is characteristically of biological origin, but may also occur inorganically as a ...

and chromite

Chromite is a crystalline mineral composed primarily of iron(II) oxide and chromium(III) oxide compounds. It can be represented by the chemical formula of FeCr2O4. It is an oxide mineral belonging to the spinel group. The element magnesium can ...

. Correlated rocks also occur in a syncline south west of Birchs Inlet, around the upper part of the Wanderer River, and in the Dial Range Trough the equivalent unit is called the Duncan Conglomerate. The Duncan Conglomerate has pebbles mostly of chert, but also some of quartzite, hematite and lava. On the west side of the Dial Range trough at Penguin

Penguins (order Sphenisciformes , family Spheniscidae ) are a group of aquatic flightless birds. They live almost exclusively in the Southern Hemisphere: only one species, the Gal├Īpagos penguin, is found north of the Equator. Highly adap ...

the Beecraft Megabreccia sits on top of the Burnie Formation. It consists of blocks of chert up to 120 metres long, embedded in conglomerate. The Teatree Point Megabreccia is similar and about 150 metres thick. The Lobster Creek Volcanics is actually an intrusion of plagioclase pyroxene hornblende porphyry dated at .

Conglomerate and sandstone in the Fossey Mountains Trough is exposed in a band on Black Bluff Range, Mount Roland, and Gog Range. Another band runs through Saint Valentines Peak, Loyetea, Gunns Plains to the Dial Range

The Dial Range is a small mountain range in northwest Tasmania, south of the town of Penguin near the coast. It extends about north to south and 4-5 km west to east. It is bordered on the east and south by the Leven River, with the Gunns Plai ...

. On top of this is sandstone, a dolerite sill, and basalts altered to chlorite

The chlorite ion, or chlorine dioxide anion, is the halite with the chemical formula of . A chlorite (compound) is a compound that contains this group, with chlorine in the oxidation state of +3. Chlorites are also known as salts of chlorou ...

and hematite

Hematite (), also spelled as haematite, is a common iron oxide compound with the formula, Fe2O3 and is widely found in rocks and soils. Hematite crystals belong to the rhombohedral lattice system which is designated the alpha polymorph of . ...

. These units are called the Roland Conglomerate and Moina Sandstone and represent contrasting stratigraphic architecture to that observed in western Tasmania, a reflection of evolution of different rift depocentres.

The Gordon limestone belongs to the Gordon group. It is formed over western Tasmania

The West Coast of Tasmania is mainly isolated rough country, associated with wilderness, mining and tourism. It served as the location of an early convict settlement in the early history of Van Diemen's Land, and contrasts sharply with the mor ...

and is conformable on the Owen Conglomerate and lies unconformably over the Precambrian rocks north of Zeehan. The limestone occurs in the Dundas and Sheffield Elements and the Florentine Synclinorium. The conditions of its formation were in or near the intertidal zone. The time of its formation was between early Caradoc

Caradoc Vreichvras (; Modern cy, Caradog Freichfras, ) was a semi-legendary ancestor to the kings of Gwent. He may have lived during the 5th or 6th century. He is remembered in the Matter of Britain as a Knight of the Round Table, under the ...

and mid Ashgill

Ashgill is a village in South Lanarkshire, Scotland near Larkhall. It is part of the Dalserf parish. The village church dates back to 1889

The village has a shop

The local school was first in Scotland to have an automated bell, installed in 1 ...

. A type section is at Mole Creek

Mole Creek is a town in the upper Mersey Valley, in the central north of Tasmania, Australia. Mole Creek is well known for its honey and accounts for about 35 percent of Tasmania's honey production.

The locality is in the Meander Valley Coun ...

. The Flowery Gully Limestone near Beaconsfield started deposition at an earlier time Llanvirn or Llandeilo than the limestones further west.

In the central north of the Sheffield element is the Early Arenig age Caroline Creek Sandstone on a bed of chert conglomerate. The Cabbage Tree Formation is east of the Andersons Creek Ultramafic Complex, and is sandstone and conglomerate.

In North east Tasmania the Mathinna Group starts in the Ordovician with Stony Head Sandstone, a quartz sandstone formed in turbidity flows. Turquoise Bluff Slate formed from shale. Fossils are rare (mostly sparse graptolites), and ages hard to determine.D. B. Seymour and C. R. Calve''Time ŌĆō Space Diagram for Tasmania''

Mineral Resources Tasmania and AGSO 1998; an

synthesis

/ref> The Wurawina Supergroup formed in the Duck Creek Syncline amongst other places. This syncline is oriented eastŌĆōwest, located on the west coast south of the mouth of the

Pieman River

The Pieman River is a major perennial river located in the West Coast, Tasmania, west coast region of Tasmania, Australia.

Course and features

Formed by the confluence of the Mackintosh River and Murchison River (Tasmania), Murchison River, the ...

. It consists of conglomerate equivalent to Mount Zeehan Conglomerate, sandstone, siltstone, shale and micrite equivalent to the Gordon Group, and finally equivalents to the Eldon Group (to Devonian). The Wurawina Supergroup also occurs in the Adamsfield Element with the Denison Group consisting of Singing Creek Formation (of quartzawacke), Great Dome Sandstone, Reeds Conglomerate, Squirrel Creek Formation. Then above this the Gordon Group consists of Karmberg Limestone, Cashions Creek Limestone, Benjamin Limestone, and Arndell Sandstone all from shallow marine conditions. Limestones are also found at Lune River, Precipitous Bluff and produced in deeper water at Surprise Bay on the south Coast.

Silurian

The Mathinna Group continued in theSilurian

The Silurian ( ) is a geologic period and system spanning 24.6 million years from the end of the Ordovician Period, at million years ago ( Mya), to the beginning of the Devonian Period, Mya. The Silurian is the shortest period of the Paleoz ...

period with Bellingham Formation and Sidling Sandstone. In western Tasmania, after the Gordon Group came the Eldon Group consisting of Crotty Quartzite, Amber Slate, Keel Quartzite, Austral Creek Siltstone, Florence Quartzite and Bell Shale. The time of the Eldon group is between Aeronian

In the geologic timescale, the Aeronian is an age of the Llandovery Epoch of the Silurian Period of the Paleozoic Era of the Phanerozoic Eon that began 440.8 ┬▒ 1.2 Ma and ended 438.5 ┬▒ 1.1 Ma (million years ago). The Aeronian Age succeeds ...

and Pragian

The Pragian is one of three faunal stages in the Early Devonian Epoch. It lasted from 410.8 ┬▒ 2.8 million years ago to 407.6 ┬▒ 2.8 million years ago. It was preceded by the Lochkovian Stage and followed by the Emsian Stage. The most importan ...

, but with a depositional gap in the Ludlow

Ludlow () is a market town in Shropshire, England. The town is significant in the history of the Welsh Marches and in relation to Wales. It is located south of Shrewsbury and north of Hereford, on the A49 road which bypasses the town. The ...

and early Pridoli.

In the Adamsfield element is the Tiger Range Group with Gell Quartzite, Richea Siltstone, Currawong Quartzite and possibly McLeod Creek

Formation. Upper layers have been removed by erosion.

Devonian

In early to midDevonian

The Devonian ( ) is a geologic period and system of the Paleozoic era, spanning 60.3 million years from the end of the Silurian, million years ago (Mya), to the beginning of the Carboniferous, Mya. It is named after Devon, England, wh ...

the Tabberabban Orogeny compressed Tasmania in the eastŌĆōwest direction. Reverse faults were activated, and folding with axes running north west and north-north east were formed. Tight folds were formed with axes in the northŌĆōsouth direction at first. Later folding in the northwest to west-northwest direction was superimposed. Faulting relieved some stress and cleavage developed in the rocks. In the Fossey Mountains Trough, the intersecting folds have made dome

A dome () is an architectural element similar to the hollow upper half of a sphere. There is significant overlap with the term cupola, which may also refer to a dome or a structure on top of a dome. The precise definition of a dome has been a m ...

and basin shaped structures. Uplift and erosion occurred. A quartz-feldspar porphyry intruded the Timbs Group in the southern Arthur Lineament at .

In the north east of Tasmania the Mathinna Group received its last deposits in the form of turbidites in the Bellingham Formation and Sidling Sandstone containing more feldspar.

Granites were intruded in the east of Tasmania around . The St Marys Porphyrite is an ash flow

A pyroclastic flow (also known as a pyroclastic density current or a pyroclastic cloud) is a fast-moving current of hot gas and volcanic matter (collectively known as tephra) that flows along the ground away from a volcano at average speeds of bu ...

of dacite from . Three large batholith

A batholith () is a large mass of intrusive igneous rock (also called plutonic rock), larger than in area, that forms from cooled magma deep in Earth's crust. Batholiths are almost always made mostly of felsic or intermediate rock types, s ...

s are in the north east: Scottsdale, Eddystone and Blue Tier. Gravity measurements show that granite underlies most of north east Tasmania at depth. Its western edge is a shelf running from Noland Bay in the north to Great Oyster Bay on the east coast. Granite also underlies the east coast with outcrops on Freycinet Peninsula, Maria Island, and Tasman Peninsula and the Hyppolite Rocks. The eastern Bass Strait Islands also show large exposures of granite, including Flinders, Cape Barren, and Clarke Island. Even the Tasmanian islands in the far north of Bass Strait are composed of granite, including Rodondo Island, Moncoeur Island, Kent Group including Deal Island, and Judgement Rocks. Hogan Island and Curtis Island. These islands formed a land bridge in the last ice age and butt up against Wilsons Promontory

Wilsons Promontory, is a peninsula that forms the southernmost part of the Australian mainland, located in the state of Victoria.

South Point at is the southernmost tip of Wilsons Promontory and hence of mainland Australia. Located at nea ...

in Victoria

Victoria most commonly refers to:

* Victoria (Australia), a state of the Commonwealth of Australia

* Victoria, British Columbia, provincial capital of British Columbia, Canada

* Victoria (mythology), Roman goddess of Victory

* Victoria, Seychelle ...

. In the Blue Tier Granite, granodiorite

Granodiorite () is a coarse-grained ( phaneritic) intrusive igneous rock similar to granite, but containing more plagioclase feldspar than orthoclase feldspar.

The term banatite is sometimes used informally for various rocks ranging from gr ...

came first. Adamellite

Quartz monzonite is an intrusive, felsic, igneous rock that has an approximately equal proportion of orthoclase and plagioclase feldspars. It is typically a light colored phaneritic (coarse-grained) to porphyritic granitic rock. The plagiocl ...

intruded, named Mount Pearson Pluton and feeding the St Marys Porphyrite at . A second stage of adamellite came at and alkali-feldspar granite derived by fractional crystallisation followed at . Similar ages and sequences of types apply to the other batholiths. In the batholiths there are quartz-feldspar porphyry and dolerite dykes. S-type granite