Francis Poulenc on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Two unrelated events in 1936 combined to inspire a reawakening of religious faith and a new depth of seriousness in Poulenc's music. His fellow composer Pierre-Octave Ferroud was killed in a car crash so violent that he was decapitated, and almost immediately afterwards, while on holiday, Poulenc visited the sanctuary of

Two unrelated events in 1936 combined to inspire a reawakening of religious faith and a new depth of seriousness in Poulenc's music. His fellow composer Pierre-Octave Ferroud was killed in a car crash so violent that he was decapitated, and almost immediately afterwards, while on holiday, Poulenc visited the sanctuary of

"The Sacred Music of Francis Poulenc: A Centennial Tribute"

''Sacred Music'', Volume 126, Number 2, Summer 1999, pp. 5–19 Poulenc's new compositions were not all in this serious vein; his incidental music to the play ''La Reine Margot'', starring

"Constructing the Monk: Francis Poulenc and the Post-War Context"

''Intersections'', Volume 32, Number 1, 2012, pp. 203–230 In 1936 Poulenc began giving frequent recitals with Bernac. At the

"Bernac, Pierre"

Grove Music Online, Oxford University Press, retrieved 5 October 2014 considered him one of the "three great meetings" of his professional career, the other two being Éluard and Landowska. In Johnson's words, "for twenty-five years Bernac was Poulenc's counsellor and conscience", and the composer relied on him for advice not only on song-writing, but on his operas and choral music. Throughout the decade, Poulenc was popular with British audiences; he established a fruitful relationship with the BBC in London, which broadcast many of his works. With Bernac, he made his first tour of Britain in 1938. His music was also popular in America, seen by many as "the quintessence of French wit, elegance and high spirits"."N.Y. Musical Tributes to Francis Poulenc", ''The Times'', 17 April 1963, p. 14 In the last years of the 1930s, Poulenc's compositions continued to vary between serious and light-hearted works. '' Quatre motets pour un temps de pénitence'' (Four Penitential Motets, 1938–39) and the song "Bleuet" (1939), an elegiac meditation on death, contrast with the song cycle '' Fiançailles pour rire'' (Light-Hearted Betrothal), which recaptures the spirit of ''Les biches'', in the opinion of Hell.Hell, pp. 60–61

For most of the war, Poulenc was in Paris, giving recitals with Bernac, concentrating on French songs. Under Nazi rule he was in a vulnerable position, as a known homosexual (Destouches narrowly avoided arrest and deportation), but in his music he made many gestures of defiance of the Germans. Fancourt, Daisy

For most of the war, Poulenc was in Paris, giving recitals with Bernac, concentrating on French songs. Under Nazi rule he was in a vulnerable position, as a known homosexual (Destouches narrowly avoided arrest and deportation), but in his music he made many gestures of defiance of the Germans. Fancourt, Daisy

"Les Six"

Music and the Holocaust, retrieved 6 October 2014 He set to music verses by poets prominent in the

"Making Music in Occupied Paris"

''The Musical Times'', Spring, 2006, pp. 23–50 He was a founder-member of the Front National (pour musique) which the Nazi authorities viewed with suspicion for its association with banned musicians such as Milhaud and Shortly after the war, Poulenc had a brief affair with a woman, Fréderique ("Freddy") Lebedeff, with whom he had a daughter, Marie-Ange, in 1946. The child was brought up without knowing who her father was (Poulenc was supposedly her "godfather") but he made generous provision for her, and she was the principal beneficiary of his will.

In the post-war period Poulenc crossed swords with composers of the younger generation who rejected Stravinsky's recent work and insisted that only the precepts of the Second Viennese School were valid. Poulenc defended Stravinsky and expressed incredulity that "in 1945 we are speaking as if the aesthetic of twelve tones is the only possible salvation for contemporary music". His view that Berg had taken serialism as far as it could go and that Schoenberg's music was now "desert, stone soup, ersatz music, or poetic vitamins" earned him the enmity of composers such as Pierre Boulez. Those disagreeing with Poulenc attempted to paint him as a relic of the pre-war era, frivolous and unprogressive. This led him to focus on his more serious works, and to try to persuade the French public to listen to them. In the US and Britain, with their strong choral traditions, his religious music was frequently performed, but performances in France were much rarer, so that the public and the critics were often unaware of his serious compositions.

In 1948 Poulenc made his first visit to the US, in a two-month concert tour with Bernac.Hell, p. 74 He returned there frequently until 1961, giving recitals with Bernac or Duval and as soloist in the world premiere of his Piano Concerto (1949), commissioned by the Boston Symphony Orchestra.

Shortly after the war, Poulenc had a brief affair with a woman, Fréderique ("Freddy") Lebedeff, with whom he had a daughter, Marie-Ange, in 1946. The child was brought up without knowing who her father was (Poulenc was supposedly her "godfather") but he made generous provision for her, and she was the principal beneficiary of his will.

In the post-war period Poulenc crossed swords with composers of the younger generation who rejected Stravinsky's recent work and insisted that only the precepts of the Second Viennese School were valid. Poulenc defended Stravinsky and expressed incredulity that "in 1945 we are speaking as if the aesthetic of twelve tones is the only possible salvation for contemporary music". His view that Berg had taken serialism as far as it could go and that Schoenberg's music was now "desert, stone soup, ersatz music, or poetic vitamins" earned him the enmity of composers such as Pierre Boulez. Those disagreeing with Poulenc attempted to paint him as a relic of the pre-war era, frivolous and unprogressive. This led him to focus on his more serious works, and to try to persuade the French public to listen to them. In the US and Britain, with their strong choral traditions, his religious music was frequently performed, but performances in France were much rarer, so that the public and the critics were often unaware of his serious compositions.

In 1948 Poulenc made his first visit to the US, in a two-month concert tour with Bernac.Hell, p. 74 He returned there frequently until 1961, giving recitals with Bernac or Duval and as soloist in the world premiere of his Piano Concerto (1949), commissioned by the Boston Symphony Orchestra.

In 1953, Poulenc was offered a commission by La Scala and the

In 1953, Poulenc was offered a commission by La Scala and the

Francis Poulenc: musicien français 1899–1963, retrieved 22 October 2014 Poulenc visited the US in 1960 and 1961. Among his works given during these trips were the American premiere of ''La Voix humaine'' at Carnegie Hall in New York, with Duval, and the world premiere of his Gloria, a large-scale work for soprano, four-part mixed chorus and orchestra, conducted in Boston by Charles Munch. In 1961 Poulenc published a book about Chabrier, a 187-page study of which a reviewer wrote in the 1980s, "he writes with love and insight of a composer whose views he shared on matters like the primacy of melody and the essential seriousness of humour." The works of Poulenc's last twelve months included '' Sept répons des ténèbres'' for voices and orchestra, the Clarinet Sonata and the Oboe Sonata. On 30 January 1963, at his flat opposite the

On 30 January 1963, at his flat opposite the

"Francis Poulenc (1899–1963) Piano Music, Volume 3"

Naxos Music Library, retrieved 22 October 2014 Poulenc's favoured Intermezzo was the last of three. Numbers one and two were composed in August 1934; the A flat followed in March 1943. The commentators Marina and Victor Ledin describe the work as "the embodiment of the word 'charming'. The music seems simply to roll off the pages, each sound following another in such an honest and natural way, with eloquence and unmistakable Frenchness."Ledin, Marina and Victor

"Francis Poulenc (1899–1963) Piano Music, Volume 1"

Naxos Music Library, retrieved 22 October 2014 The eight nocturnes were composed across nearly a decade (1929–38). Whether or not Poulenc originally conceived them as an integral set, he gave the eighth the title "To serve as Coda for the Cycle" (''Pour servir de Coda au Cycle''). Although they share their generic title with the nocturnes of

"Poulenc: The Complete Songs – review"

''The Guardian'', 17 October 2013 Johnson calls the cycle ''Tel Jour, Telle Nuit'' (1937) the composer's "watershed work", and Nichols regards it as "a masterpiece worthy to stand beside Fauré's '' La Bonne Chanson''". Clements finds in the Éluard settings a profundity "worlds away from the brittle, facetious surfaces of Poulenc's early orchestral and instrumental music". The first of the ''Deux poèmes de Louis Aragon'' (1943), titled simply "C", is described by Johnson as "a masterpiece known the world over; it is the most unusual, and perhaps the most moving, song about the ravages of war ever composed." In an overview of the songs in 1973, the musical scholar Yvonne Gouverné said, "With Poulenc, the melodic line matches the text so well that it seems in some way to complete it, thanks to the gift which the music has for penetrating the very essence of a given poem; nobody has better crafted a phrase than Poulenc, highlighting the colour of the words."Gouverné, Yvonne

"Francis Poulenc"

, Francis Poulenc: musicien français 1899–1963, retrieved 27 October 2014 Among the lighter pieces, one of the composer's most popular songs is a setting of '' Les Chemins de l'amour'' for

Poulenc turned to opera only in the latter half of his career. Having achieved fame by his early twenties, he was in his forties before attempting his first opera. He attributed this to the need for maturity before tackling the subjects he chose to set. In 1958 he told an interviewer, "When I was 24 I was able to write ''Les biches'' utit is obvious that unless a composer of 30 has the genius of a Mozart or the precociousness of Schubert he couldn't write ''The Carmelites'' – the problems are too profound." In Sams's view, all three of Poulenc's operas display a depth of feeling far distant from "the cynical stylist of the 1920s": '' Les Mamelles de Tirésias'' (1947), despite the riotous plot, is full of nostalgia and a sense of loss. In the two avowedly serious operas, ''

Poulenc turned to opera only in the latter half of his career. Having achieved fame by his early twenties, he was in his forties before attempting his first opera. He attributed this to the need for maturity before tackling the subjects he chose to set. In 1958 he told an interviewer, "When I was 24 I was able to write ''Les biches'' utit is obvious that unless a composer of 30 has the genius of a Mozart or the precociousness of Schubert he couldn't write ''The Carmelites'' – the problems are too profound." In Sams's view, all three of Poulenc's operas display a depth of feeling far distant from "the cynical stylist of the 1920s": '' Les Mamelles de Tirésias'' (1947), despite the riotous plot, is full of nostalgia and a sense of loss. In the two avowedly serious operas, ''

"Dialogues des Carmélites"

''The New Grove Dictionary of Opera'', Grove Music Online, Oxford Music Online, Oxford University Press, retrieved 22 October 2014 By the time of the last of the operas, ''La Voix humaine'', Poulenc felt able to give the soprano stretches of music with no orchestral accompaniment at all, though when the orchestra plays, Poulenc calls for the music to be "bathed in sensuality".

A 1984 discography of Poulenc's music lists recordings by more than 1,300 conductors, soloists and ensembles, including the conductors Leonard Bernstein, Charles Dutoit, Milhaud, Charles Munch,

A 1984 discography of Poulenc's music lists recordings by more than 1,300 conductors, soloists and ensembles, including the conductors Leonard Bernstein, Charles Dutoit, Milhaud, Charles Munch,

''The Musical Times'', March 1963, p. 205 Boulez did not take a reciprocal view, remarking in 2010, "There are always people who will take an easy intellectual path. Poulenc coming after ''The Rite of Spring, Sacre [du Printemps]''. It was not progress." Other composers have found more merit in Poulenc's work; Stravinsky wrote to him in 1931: "You are truly good, and that is what I find again and again in your music". In his last years Poulenc observed, "if people are still interested in my music in 50 years' time it will be for my ''Stabat Mater'' rather than the ''Mouvements perpétuels''." In a centenary tribute in ''The Times'' Gerald Larner commented that Poulenc's prediction was wrong, and that in 1999 the composer was widely celebrated for both sides of his musical character: "both the fervent Catholic and the naughty boy, for both the Gloria and Les Biches, both Les Dialogues des Carmélites and Les Mamelles de Tirésias." At around the same time the writer Jessica Duchen described Poulenc as "a fizzing, bubbling mass of Gallic energy who can move you to both laughter and tears within seconds. His language speaks clearly, directly and humanely to every generation."Duchen, Jessica

"Plucky chicken: Sensual, witty and unfairly dismissed as lightweight"

''The Guardian'', 1 January 1999

Francis Poulenc 1899–1963, the official website (French and English version)

Poulenc material

in the BBC Radio 3 archives * *

Guide to the Lambiotte Family/Francis Poulenc archive, 1920–1994

(Woodson Research Center, Fondren Library, Rice University, Houston, TX, USA) * {{DEFAULTSORT:Poulenc, Francis 1899 births 1963 deaths 20th-century classical composers 20th-century French male classical pianists Ballets Russes composers Burials at Père Lachaise Cemetery Catholic liturgical composers Classical piano duos Composers for piano French ballet composers French classical composers French composers of sacred music French male classical composers French military personnel of World War I French military personnel of World War II French opera composers French Roman Catholics Les Six LGBT classical composers LGBT classical musicians LGBT musicians from France LGBT Roman Catholics Male opera composers Musicians from Paris Neoclassical composers

Francis Jean Marcel Poulenc (; 7 January 189930 January 1963) was a French composer and pianist. His compositions include

Poulenc was born in the 8th arrondissement of Paris, the younger child and only son of Émile Poulenc and his wife, Jenny, ''née'' Royer. Émile Poulenc was a joint owner of

Poulenc was born in the 8th arrondissement of Paris, the younger child and only son of Émile Poulenc and his wife, Jenny, ''née'' Royer. Émile Poulenc was a joint owner of

"Poulenc, Francis"

Grove Music Online, Oxford Music Online, Oxford University Press, retrieved 24 August 2014 The critic Claude Rostand later described Poulenc as "half monk and half naughty boy". Poulenc grew up in a musical household; his mother was a capable pianist, with a wide repertoire ranging from classical to less elevated works that gave him a lifelong taste for what he called "adorable bad music".Hell, p. 2 He took piano lessons from the age of five; when he was eight he first heard the music of

" Poulenc, Francis"

''The New Grove Dictionary of Opera'', Grove Music Online, Oxford Music Online, Oxford University Press, retrieved 24 August 2014 Four of Poulenc's early works were premiered at the Salle Huyghens in the

As the decade progressed, Poulenc produced a range of compositions, from songs to chamber music and another ballet, ''

As the decade progressed, Poulenc produced a range of compositions, from songs to chamber music and another ballet, ''

in which songs

A song is a musical composition intended to be performed by the human voice. This is often done at distinct and fixed pitches (melodies) using patterns of sound and silence. Songs contain various forms, such as those including the repetition ...

, solo piano works, chamber music, choral pieces, operas, ballets, and orchestral concert music. Among the best-known are the piano suite '' Trois mouvements perpétuels'' (1919), the ballet ''Les biches

''Les biches'' () ("The Hinds" or "The Does", or "The Darlings") is a one-act ballet to music by Francis Poulenc, choreographed by Bronislava Nijinska and premiered by the Ballets Russes on 6 January 1924 at the Salle Garnier in Monte Carlo. Ni ...

'' (1923), the ''Concert champêtre

''Concert champêtre'' (, ''Pastoral Concerto''), FP 49, is a harpsichord concerto by Francis Poulenc, which also exists in a version for piano solo with very slight changes in the solo part.

It was written in 1927–28 for the harpsichordist ...

'' (1928) for harpsichord and orchestra, the Organ Concerto

An organ concerto is a piece of music, an instrumental concerto for a pipe organ soloist with an orchestra. The form first evolved in the 18th century, when composers including Antonio Vivaldi, George Frideric Handel and Johann Sebastian Bach w ...

(1938), the opera ''Dialogues des Carmélites

' (''Dialogues of the Carmelites''), FP 159, is an opera in three acts, divided into twelve scenes with linking orchestral interludes, with music and libretto by Francis Poulenc, completed in 1956. The composer's second opera, Poulenc wrote the ...

'' (1957), and the '' Gloria'' (1959) for soprano, choir, and orchestra.

As the only son of a prosperous manufacturer, Poulenc was expected to follow his father into the family firm, and he was not allowed to enrol at a music college. Largely self-educated musically, he studied with the pianist Ricardo Viñes

Ricardo Viñes y Roda (, ca, Ricard Viñes i Roda, ; 5 February 1875 – 29 April 1943) was a Spanish pianist. He gave the premieres of works by Ravel, Debussy, Satie, Falla and Albéniz. He was the piano teacher of the composer Francis Pou ...

, who became his mentor after the composer's parents died. Poulenc also made the acquaintance of Erik Satie, under whose tutelage he became one of a group of young composers known collectively as ''Les Six

"Les Six" () is a name given to a group of six composers, five of them French and one Swiss, who lived and worked in Montparnasse. The name, inspired by Mily Balakirev's '' The Five'', originates in two 1920 articles by critic Henri Collet in ' ...

''. In his early works Poulenc became known for his high spirits and irreverence. During the 1930s a much more serious side to his nature emerged, particularly in the religious music he composed from 1936 onwards, which he alternated with his more light-hearted works.

In addition to his work as a composer, Poulenc was an accomplished pianist. He was particularly celebrated for his performing partnerships with the baritone Pierre Bernac

Pierre Louis Bernac (né Bertin; 12 January 1899 – 17 October 1979) was a French singer, a baryton-martin, known as an interpreter of the French mélodie. He had a close artistic association with Francis Poulenc, with whom he performed i ...

(who also advised him in vocal writing) and the soprano Denise Duval

Denise Duval (23 October 192125 January 2016) was a French soprano, best known for her performances in the works of Francis Poulenc on stage and in recital. During an international career, Duval created the roles of Thérèse in '' Les mamelles de ...

. He toured in Europe and America with both of them, and made a number of recordings as a pianist. He was among the first composers to see the importance of the gramophone, and he recorded extensively from 1928 onwards.

In his later years, and for decades after his death, Poulenc had a reputation, particularly in his native country, as a humorous, lightweight composer, and his religious music was often overlooked. In the 21st century, more attention has been given to his serious works, with many new productions of ''Dialogues des Carmélites'' and ''La voix humaine

' (English: ''The Human Voice'') is a forty-minute, one-act opera for soprano and orchestra composed by Francis Poulenc in 1958. The work is based on the play of the same name by Jean Cocteau, who, along with French soprano Denise Duval, worked ...

'' worldwide, and numerous live and recorded performances of his songs and choral music.

Life

Early years

Poulenc Frères

Poulenc Frères (Poulenc Brothers) was a French chemical, pharmaceutical and photographic supplies company that had its origins in a Paris pharmacy founded in 1827.

From 1852 it began to manufacture (or package) photographic chemicals.

It took the ...

, a successful manufacturer of pharmaceuticals (later Rhône-Poulenc

Rhône-Poulenc () was a French chemical and pharmaceutical company founded in 1928. In 1999 it merged with Hoechst AG to form Aventis. As of 2015, the pharmaceutical operations of Rhône-Poulenc are part of Sanofi and the chemicals divisions a ...

). He was a member of a pious Roman Catholic family from Espalion

Espalion (; oc, Espaliu) is a commune in the Aveyron department in southern France.

Population

Sights

*Château de Calmont d'Olt

*The Pont-Vieux (Old Bridge) is part of the World Heritage Sites of the Routes of Santiago de Compostela in Fr ...

in the département

In the administrative divisions of France, the department (french: département, ) is one of the three levels of government under the national level (" territorial collectivities"), between the administrative regions and the communes. Ninety ...

of Aveyron

Aveyron (; oc, Avairon; ) is a department in the region of Occitania, Southern France. It was named after the river Aveyron. Its inhabitants are known as ''Aveyronnais'' (masculine) or ''Aveyronnaises'' (feminine) in French. The inhabitants ...

. Jenny Poulenc was from a Parisian family with wide artistic interests. In Poulenc's view, the two sides of his nature grew out of this background: a deep religious faith from his father's family and a worldly and artistic side from his mother's.Chimènes, Myriam and Roger Nichols"Poulenc, Francis"

Grove Music Online, Oxford Music Online, Oxford University Press, retrieved 24 August 2014 The critic Claude Rostand later described Poulenc as "half monk and half naughty boy". Poulenc grew up in a musical household; his mother was a capable pianist, with a wide repertoire ranging from classical to less elevated works that gave him a lifelong taste for what he called "adorable bad music".Hell, p. 2 He took piano lessons from the age of five; when he was eight he first heard the music of

Debussy

(Achille) Claude Debussy (; 22 August 1862 – 25 March 1918) was a French composer. He is sometimes seen as the first Impressionist composer, although he vigorously rejected the term. He was among the most influential composers of the ...

and was fascinated by the originality of the sound. Other composers whose works influenced his development were Schubert

Franz Peter Schubert (; 31 January 179719 November 1828) was an Austrian composer of the late Classical and early Romantic eras. Despite his short lifetime, Schubert left behind a vast ''oeuvre'', including more than 600 secular vocal wor ...

and Stravinsky: the former's ''Winterreise

''Winterreise'' (, ''Winter Journey'') is a song cycle for voice and piano by Franz Schubert ( D. 911, published as Op. 89 in 1828), a setting of 24 poems by German poet Wilhelm Müller. It is the second of Schubert's two song cycles on Müller' ...

'' and the latter's ''The Rite of Spring

, image = Roerich Rite of Spring.jpg

, image_size = 350px

, caption = Concept design for act 1, part of Nicholas Roerich's designs for Diaghilev's 1913 production of '

, composer = Igor Stravinsky

, based_on ...

'' made a deep impression on him. At his father's insistence, Poulenc followed a conventional school career, studying at the Lycée Condorcet

The Lycée Condorcet () is a school founded in 1803 in Paris, France, located at 8, rue du Havre, in the city's 9th arrondissement. It is one of the four oldest high schools in Paris and also one of the most prestigious. Since its inception, var ...

in Paris rather than at a music conservatory.

In 1916 a childhood friend, Raymonde Linossier (1897–1930), introduced Poulenc to Adrienne Monnier

Adrienne Monnier (26 April 1892 – 19 June 1955) was a French bookseller, writer, and publisher, and an influential figure in the modernist writing scene in Paris in the 1920s and 1930s.

Formative years

Monnier was born in Paris on 26 April 18 ...

's bookshop, the ''Maison des Amis des Livres''. There he met the ''avant-garde'' poets Guillaume Apollinaire

Guillaume Apollinaire) of the Wąż coat of arms. (; 26 August 1880 – 9 November 1918) was a French poet, playwright, short story writer, novelist, and art critic of Polish descent.

Apollinaire is considered one of the foremost poets of t ...

, Max Jacob

Max Jacob (; 12 July 1876 – 5 March 1944) was a French poet, painter, writer, and critic.

Life and career

After spending his childhood in Quimper, Brittany, he enrolled in the Paris Colonial School, which he left in 1897 for an artistic ca ...

, Paul Éluard

Paul Éluard (), born Eugène Émile Paul Grindel (; 14 December 1895 – 18 November 1952), was a French poet and one of the founders of the Surrealist movement.

In 1916, he chose the name Paul Éluard, a matronymic borrowed from his maternal ...

and Louis Aragon

Louis Aragon (, , 3 October 1897 – 24 December 1982) was a French poet who was one of the leading voices of the surrealist movement in France. He co-founded with André Breton and Philippe Soupault the surrealist review ''Littérature''. He ...

. He later set many of their poems to music. In the same year he became the pupil of pianist Ricardo Viñes

Ricardo Viñes y Roda (, ca, Ricard Viñes i Roda, ; 5 February 1875 – 29 April 1943) was a Spanish pianist. He gave the premieres of works by Ravel, Debussy, Satie, Falla and Albéniz. He was the piano teacher of the composer Francis Pou ...

. The biographer Henri Hell comments that Viñes's influence on his pupil was profound, both as to pianistic technique and the style of Poulenc's keyboard works. Poulenc later said of Viñes:

He was a most delightful man, a bizarre hidalgo with enormous moustachios, a flat-brimmed sombrero in the purest Spanish style, and button boots which he used to rap my shins when I didn't change the pedalling enough. ... I admired him madly, because, at this time, in 1914, he was the only virtuoso who played Debussy andWhen Poulenc was sixteen his mother died; his father died two years later. Viñes became more than a teacher: he was, in the words of Myriam Chimènes in the '' Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians'', the young man's "spiritual mentor". He encouraged his pupil to compose, and he later gave the premieres of three early Poulenc works. Through him Poulenc became friendly with two composers who helped shape his early development:Ravel Joseph Maurice Ravel (7 March 1875 – 28 December 1937) was a French composer, pianist and conductor. He is often associated with Impressionism along with his elder contemporary Claude Debussy, although both composers rejected the term. In .... That meeting with Viñes was paramount in my life: I owe him everything ... In reality it is to Viñes that I owe my fledgling efforts in music and everything I know about the piano.

Georges Auric

Georges Auric (; 15 February 1899 – 23 July 1983) was a French composer, born in Lodève, Hérault, France. He was considered one of ''Les Six'', a group of artists informally associated with Jean Cocteau and Erik Satie. Before he turned 20 he ...

and Erik Satie.

Auric, who was the same age as Poulenc, was an early developer musically; by the time the two met, Auric's music had already been performed at important Parisian concert venues. The two young composers shared a similar musical outlook and enthusiasms, and for the rest of Poulenc's life Auric was his most trusted friend and guide. Poulenc called him "my true brother in spirit". Satie, an eccentric figure, isolated from the mainstream French musical establishment, was a mentor to several rising young composers, including Auric, Louis Durey and Arthur Honegger

Arthur Honegger (; 10 March 1892 – 27 November 1955) was a Swiss composer who was born in France and lived a large part of his life in Paris. A member of Les Six, his best known work is probably ''Antigone'', composed between 1924 and 1927 t ...

. After initially dismissing Poulenc as a bourgeois amateur, he relented and admitted him to the circle of protégés, whom he called ''"Les Nouveaux Jeunes"''. Poulenc described Satie's influence on him as "immediate and wide, on both the spiritual and musical planes". Pianist Alfred Cortot commented that Poulenc's '' Trois mouvements perpétuels'' were "reflections of the ironical outlook of Satie adapted to the sensitive standards of the current intellectual circles".Hell, p. 4

First compositions and ''Les Six''

Poulenc made his début as a composer in 1917 with his '' Rapsodie nègre'', a ten-minute, five- movement piece for baritone and chamber group; it was dedicated to Satie and premiered at one of a series of concerts of new music run by the singer Jane Bathori. There was a fashion for African arts in Paris at the time, and Poulenc was delighted to run across some published verses purportedly Liberian, but full of Parisianboulevard

A boulevard is a type of broad avenue planted with rows of trees, or in parts of North America, any urban highway.

Boulevards were originally circumferential roads following the line of former city walls.

In American usage, boulevards may ...

slang. He used one of the poems in two sections of the rhapsody. The baritone engaged for the first performance lost his nerve on the platform, and the composer, though no singer, jumped in. This ''jeu d'esprit'' was the first of many examples of what Anglophone critics came to call "leg-Poulenc". Ravel was amused by the piece and commented on Poulenc's ability to invent his own folklore. Stravinsky was impressed enough to use his influence to secure Poulenc a contract with a publisher, a kindness that Poulenc never forgot.

In 1917 Poulenc got to know Ravel well enough to have serious discussions with him about music. He was dismayed by Ravel's judgments, which exalted composers whom Poulenc thought little of above those he greatly admired.Nichols, p. 117 He told Satie of this unhappy encounter; Satie replied with a dismissive epithet for Ravel who, he said, talked "a load of rubbish". For many years Poulenc was equivocal about Ravel's music, though always respecting him as a man. Ravel's modesty about his own music particularly appealed to Poulenc, who sought throughout his life to follow Ravel's example.Nichols, pp. 117–118

From January 1918 to January 1921 Poulenc was a conscript in the French army in the last months of the First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

and the immediate post-war period. Between July and October 1918 he served at the Franco-German front, after which he was given a series of auxiliary posts, ending as a typist at the Ministry of Aviation

The Ministry of Aviation was a department of the United Kingdom government established in 1959. Its responsibilities included the regulation of civil aviation and the supply of military aircraft, which it took on from the Ministry of Supply.

...

. His duties allowed him time for composition; the '' Trois mouvements perpétuels'' for piano and the Sonata for Piano Duet were written at the piano of the local elementary school at Saint-Martin-sur-le-Pré, and he completed his first song cycle

A song cycle (german: Liederkreis or Liederzyklus) is a group, or cycle (music), cycle, of individually complete Art song, songs designed to be performed in a sequence as a unit.Susan Youens, ''Grove online''

The songs are either for solo voice ...

, '' Le bestiaire'', setting poems by Apollinaire. The sonata did not create a deep public impression, but the song cycle made the composer's name known in France, and the ''Trois mouvements perpétuels'' rapidly became an international success.Hell, pp. 9–10 The exigencies of music-making in wartime taught Poulenc much about writing for whatever instruments were available; then, and later, some of his works were for unusual combinations of players."Francis Poulenc", ''The Guardian'', 31 January 1963, p. 7

At this stage in his career Poulenc was conscious of his lack of academic musical training; the critic and biographer Jeremy Sams

Jeremy Sams (born 12 January 1957) is a British theatre director, writer, translator, orchestrator, musical director, film composer, and lyricist.

Early life and education

Sams is the son of the late Shakespearean scholar and musicologist Eri ...

writes that it was the composer's good luck that the public mood was turning against late- romantic lushness in favour of the "freshness and insouciant charm" of his works, technically unsophisticated though they were.Sams, Jeremy" Poulenc, Francis"

''The New Grove Dictionary of Opera'', Grove Music Online, Oxford Music Online, Oxford University Press, retrieved 24 August 2014 Four of Poulenc's early works were premiered at the Salle Huyghens in the

Montparnasse

Montparnasse () is an area in the south of Paris, France, on the left bank of the river Seine, centred at the crossroads of the Boulevard du Montparnasse and the Rue de Rennes, between the Rue de Rennes and boulevard Raspail. Montparnasse has bee ...

area, where between 1917 and 1920 the cellist Félix Delgrange presented concerts of music by young composers. Among them were Auric, Durey, Honegger, Darius Milhaud

Darius Milhaud (; 4 September 1892 – 22 June 1974) was a French composer, conductor, and teacher. He was a member of Les Six—also known as ''The Group of Six''—and one of the most prolific composers of the 20th century. His compositions ...

and Germaine Tailleferre who, with Poulenc, became known collectively as ''"Les Six

"Les Six" () is a name given to a group of six composers, five of them French and one Swiss, who lived and worked in Montparnasse. The name, inspired by Mily Balakirev's '' The Five'', originates in two 1920 articles by critic Henri Collet in ' ...

"''. After one of their concerts, the critic Henri Collet

Henri Collet (; 5 November 1885 – 23 November 1951) was a French composer and music critic who lived in Paris.

Biography

Born in Paris, Collet first studied at the Conservatory of Music at Bordeaux before going to Madrid to study Spanish liter ...

published an article titled, "The Five Russians, the Six Frenchmen and Satie". According to Milhaud:

In completely arbitrary fashion Collet chose the names of six composers, Auric, Durey, Honegger, Poulenc, Tailleferre and myself, for no other reason than that we knew each other, that we were friends and were represented in the same programmes, but without the slightest concern for our different attitudes and our different natures. Auric and Poulenc followed the ideas ofCocteau, though similar in age to ''Les Six'', was something of a father-figure to the group. His literary style, "paradoxical and lapidary" in Hell's phrase, was anti-romantic, concise and irreverent. It greatly appealed to Poulenc, who made his first setting of Cocteau's words in 1919 and his last in 1961. When members of ''Les Six'' collaborated with each other, they contributed their own individual sections to the joint work. Their 1920 piano suite '' L'Album des Six'' consists of six separate and unrelated pieces. Their 1921 ballet '' Les mariés de la tour Eiffel'' contains three sections by Milhaud, two apiece by Auric, Poulenc and Tailleferre, one by Honegger and none by Durey, who was already distancing himself from the group. In the early 1920s Poulenc remained concerned at his lack of formal musical training. Satie was suspicious of music colleges, but Ravel advised Poulenc to take composition lessons; Milhaud suggested the composer and teacher Charles Koechlin.Hell, p. 21 Poulenc worked with him intermittently from 1921 to 1925.Cocteau Jean Maurice Eugène Clément Cocteau (, , ; 5 July 1889 – 11 October 1963) was a French poet, playwright, novelist, designer, filmmaker, visual artist and critic. He was one of the foremost creatives of the su ..., Honegger was a product of German Romanticism and my leanings were towards a Mediterranean lyrical art ... Collet's article made such a wide impression that the Groupe des Six had come into being.

1920s: increasing fame

From the early 1920s Poulenc was well received abroad, particularly in Britain, both as a performer and a composer. In 1921 Ernest Newman wrote in ''The Manchester Guardian

''The Guardian'' is a British daily newspaper. It was founded in 1821 as ''The Manchester Guardian'', and changed its name in 1959. Along with its sister papers ''The Observer'' and ''The Guardian Weekly'', ''The Guardian'' is part of the Gu ...

'', "I keep my eye on Francis Poulenc, a young man who has only just arrived at his twenties. He ought to develop into a farceur of the first order." Newman said that he had rarely heard anything so deliciously absurd as parts of Poulenc's song cycle ''Cocardes'', with its accompaniment played by the unorthodox combination of cornet, trombone, violin and percussion. In 1922 Poulenc and Milhaud travelled to Vienna to meet Alban Berg, Anton Webern

Anton Friedrich Wilhelm von Webern (3 December 188315 September 1945), better known as Anton Webern (), was an Austrian composer and conductor whose music was among the most radical of its milieu in its sheer concision, even aphorism, and stead ...

and Arnold Schönberg

Arnold Schoenberg or Schönberg (, ; ; 13 September 187413 July 1951) was an Austrian-American composer, music theorist, teacher, writer, and painter. He is widely considered one of the most influential composers of the 20th century. He was as ...

. Neither of the French composers was influenced by their Austrian colleagues' revolutionary twelve-tone

The twelve-tone technique—also known as dodecaphony, twelve-tone serialism, and (in British usage) twelve-note composition—is a method of musical composition first devised by Austrian composer Josef Matthias Hauer, who published his "law o ...

system, but they admired the three as its leading proponents. The following year Poulenc received a commission from Sergei Diaghilev

Sergei Pavlovich Diaghilev ( ; rus, Серге́й Па́влович Дя́гилев, , sʲɪˈrɡʲej ˈpavləvʲɪdʑ ˈdʲæɡʲɪlʲɪf; 19 August 1929), usually referred to outside Russia as Serge Diaghilev, was a Russian art critic, pa ...

for a full-length ballet score. He decided that the theme would be a modern version of the classical French ''fête galante

''Fête galante'' () (courtship party) is a category of painting specially created by the French Academy in 1717 to describe Antoine Watteau's (1684–1721) variations on the theme of the fête champêtre, which featured figures in ball dress o ...

''. This work, ''Les biches

''Les biches'' () ("The Hinds" or "The Does", or "The Darlings") is a one-act ballet to music by Francis Poulenc, choreographed by Bronislava Nijinska and premiered by the Ballets Russes on 6 January 1924 at the Salle Garnier in Monte Carlo. Ni ...

'', was an immediate success, first in Monte Carlo in January 1924 and then in Paris in May, under the direction of André Messager

André Charles Prosper Messager (; 30 December 1853 – 24 February 1929) was a French composer, organist, pianist and conductor. His compositions include eight ballets and thirty opéra comique, opéras comiques, opérettes and other stage wo ...

; it has remained one of Poulenc's best-known scores. Poulenc's new celebrity after the success of the ballet was the unexpected cause of his estrangement from Satie: among the new friends Poulenc made was Louis Laloy

Louis Laloy ( Gray, 18 February 1874 – Dole, 4 March 1944 ) was a French musicologist, writer and sinologist.

A Doctor of Letters (he spoke French, English, German, Italian, Latin, Russian, Greek and Chinese), he became an eminent musicologist ...

, a writer whom Satie regarded with implacable enmity.Schmidt (2001), p. 136 Auric, who had just enjoyed a similar triumph with a Diaghilev ballet, ''Les Fâcheux'', was also repudiated by Satie for becoming a friend of Laloy.

As the decade progressed, Poulenc produced a range of compositions, from songs to chamber music and another ballet, ''

As the decade progressed, Poulenc produced a range of compositions, from songs to chamber music and another ballet, ''Aubade

An aubade is a morning love song (as opposed to a serenade, intended for performance in the evening), or a song or poem about lovers separating at dawn. It has also been defined as "a song or instrumental composition concerning, accompanying, or ev ...

''. Hell suggests that Koechlin's influence occasionally inhibited Poulenc's natural simple style, and that Auric offered useful guidance to help him appear in his true colours. At a concert of music by the two friends in 1926, Poulenc's songs were sung for the first time by the baritone Pierre Bernac

Pierre Louis Bernac (né Bertin; 12 January 1899 – 17 October 1979) was a French singer, a baryton-martin, known as an interpreter of the French mélodie. He had a close artistic association with Francis Poulenc, with whom he performed i ...

, from whom, in Hell's phrase, "the name of Poulenc was soon to be inseparable." Another performer with whom the composer came to be closely associated was the harpsichordist Wanda Landowska

Wanda Aleksandra Landowska (5 July 1879 – 16 August 1959) was a Polish harpsichordist and pianist whose performances, teaching, writings and especially her many recordings played a large role in reviving the popularity of the harpsichord in ...

. He heard her as the soloist in Falla's '' El retablo de maese Pedro'' (1923), an early example of the use of a harpsichord in a modern work, and was immediately taken with the sound. At Landowska's request he wrote a concerto, the ''Concert champêtre

''Concert champêtre'' (, ''Pastoral Concerto''), FP 49, is a harpsichord concerto by Francis Poulenc, which also exists in a version for piano solo with very slight changes in the solo part.

It was written in 1927–28 for the harpsichordist ...

'', which she premiered in 1929 with the Orchestre Symphonique de Paris conducted by Pierre Monteux.

The biographer Richard D. E. Burton comments that, in the late 1920s, Poulenc might have seemed to be in an enviable position: professionally successful and independently well-off, having inherited a substantial fortune from his father.Burton, p. 37 He bought a large country house, , at Noizay

Noizay () is a commune in the Indre-et-Loire department in central France.

Population

See also

*Communes of the Indre-et-Loire department

The following is a list of the 272 communes of the Indre-et-Loire department of France.

The commune ...

, Indre-et-Loire, south-west of Paris, where he retreated to compose in peaceful surroundings. Yet he was troubled, struggling to come to terms with his sexuality, which was predominantly homosexual. His first serious affair was with the painter Richard Chanlaire, to whom he sent a copy of the ''Concert champêtre'' score inscribed:

Nevertheless, while this affair was in progress Poulenc proposed marriage to his friend Raymonde Linossier. As she was not only well aware of his homosexuality but was also romantically attached elsewhere, she refused him, and their relationship became strained. He suffered the first of many periods of depression, which affected his ability to compose, and he was devastated in January 1930 when Linossier died suddenly at the age of 32. On her death he wrote, "All my youth departs with her, all that part of my life that belonged only to her. I sob ... I am now twenty years older".Ivry, p. 74 His affair with Chanlaire petered out in 1931, though they remained lifelong friends.

1930s: new seriousness

At the start of the decade, Poulenc returned to writing songs, after a two-year break from doing so. His "Epitaphe", to a poem byMalherbe Malherbe may refer to:

People

* Malherbe (surname)

** François de Malherbe (1555-1628), French poet, reformer of French language

Places France

* La Haye-Malherbe, municipality of Eure (département), Eure

* Malherbe-sur-Ajon, new municipal ...

, was written in memory of Linossier, and is described by the pianist Graham Johnson as "a profound song in every sense". The following year Poulenc wrote three sets of songs, to words by Apollinaire and Max Jacob, some of which were serious in tone, and others reminiscent of his earlier light-hearted style, as were others of his works of the early 1930s. In 1932 his music was among the first to be broadcast on television, in a transmission by the BBC #REDIRECT BBC #REDIRECT BBC

Here i going to introduce about the best teacher of my life b BALAJI sir. He is the precious gift that I got befor 2yrs . How has helped and thought all the concept and made my success in the 10th board exam. ...

...Reginald Kell

Reginald Clifford Kell (8 June 19065 August 1981) was an English clarinettist. He was noted especially for his career as a soloist and chamber music player. He was the principal clarinettist in leading British orchestras, including the London P ...

and Gilbert Vinter

Gilbert Vinter (4 May 1909 – 10 October 1969) was an English conductor and composer, most celebrated for his compositions for brass bands.

Life

Vinter was born in Lincoln. As a youth, he was a chorister at Lincoln Cathedral, and eventually ...

played his Sonata for clarinet and bassoon

The ''Sonate pour clarinette et basson'' (Sonata for clarinet and bassoon), FP 32a, is a piece of chamber music composed by Francis Poulenc in 1922.

Composition

This sonata is the third work of chamber music of the composer after the sonata for ...

. At about this time Poulenc began a relationship with Raymond Destouches, a chauffeur; as with Chanlaire earlier, what began as a passionate affair changed into a deep and lasting friendship. Destouches, who married in the 1950s, remained close to Poulenc until the end of the composer's life.

Two unrelated events in 1936 combined to inspire a reawakening of religious faith and a new depth of seriousness in Poulenc's music. His fellow composer Pierre-Octave Ferroud was killed in a car crash so violent that he was decapitated, and almost immediately afterwards, while on holiday, Poulenc visited the sanctuary of

Two unrelated events in 1936 combined to inspire a reawakening of religious faith and a new depth of seriousness in Poulenc's music. His fellow composer Pierre-Octave Ferroud was killed in a car crash so violent that he was decapitated, and almost immediately afterwards, while on holiday, Poulenc visited the sanctuary of Rocamadour

Rocamadour (; ''Rocamador'' in Occitan) is a commune in the Lot department in Southwestern France. It lies in the former province of Quercy.

Rocamadour has attracted visitors for its setting in a gorge above a tributary of the River Dordogn ...

. He later explained:

A few days earlier I'd just heard of the tragic death of my colleague ... As I meditated on the fragility of our human frame, I was drawn once more to the life of the spirit. Rocamadour had the effect of restoring me to the faith of my childhood. This sanctuary, undoubtedly the oldest in France ... had everything to captivate me ... The same evening of this visit to Rocamadour, I began my ''Litanies à la Vierge noire'' for female voices and organ. In that work I tried to get across the atmosphere of "peasant devotion" that had struck me so forcibly in that lofty chapel.Other works that followed continued the composer's new-found seriousness, including many settings of Éluard's surrealist and humanist poems. In 1937 he composed his first major liturgical work, the

Mass

Mass is an intrinsic property of a body. It was traditionally believed to be related to the quantity of matter in a physical body, until the discovery of the atom and particle physics. It was found that different atoms and different eleme ...

in G major for soprano and mixed choir '' a cappella'', which has become the most frequently performed of all his sacred works.Thibodeau, Ralph"The Sacred Music of Francis Poulenc: A Centennial Tribute"

''Sacred Music'', Volume 126, Number 2, Summer 1999, pp. 5–19 Poulenc's new compositions were not all in this serious vein; his incidental music to the play ''La Reine Margot'', starring

Yvonne Printemps

Yvonne Printemps (; born Yvonne Wigniolle; 25 July 1894 – 19 January 1977) was a French singer and actress who achieved stardom on stage and screen in France and internationally.

Printemps went on the stage in Paris at the age of 12, and ...

, was pastiche 16th-century dance music, and became popular under the title '' Suite française''. Music critics generally continued to define Poulenc by his light-hearted works, and it was not until the 1950s that his serious side was widely recognised.Moore, Christopher"Constructing the Monk: Francis Poulenc and the Post-War Context"

''Intersections'', Volume 32, Number 1, 2012, pp. 203–230 In 1936 Poulenc began giving frequent recitals with Bernac. At the

École Normale

École may refer to:

* an elementary school in the French educational stages normally followed by secondary education establishments (collège and lycée)

* École (river), a tributary of the Seine flowing in région Île-de-France

* École, Savoi ...

in Paris they gave the premiere of Poulenc's '' Cinq poèmes de Paul Éluard''. They continued to perform together for more than twenty years, in Paris and internationally, until Bernac's retirement in 1959. Poulenc, who composed 90 songs for his collaborator, Blyth, Alan"Bernac, Pierre"

Grove Music Online, Oxford University Press, retrieved 5 October 2014 considered him one of the "three great meetings" of his professional career, the other two being Éluard and Landowska. In Johnson's words, "for twenty-five years Bernac was Poulenc's counsellor and conscience", and the composer relied on him for advice not only on song-writing, but on his operas and choral music. Throughout the decade, Poulenc was popular with British audiences; he established a fruitful relationship with the BBC in London, which broadcast many of his works. With Bernac, he made his first tour of Britain in 1938. His music was also popular in America, seen by many as "the quintessence of French wit, elegance and high spirits"."N.Y. Musical Tributes to Francis Poulenc", ''The Times'', 17 April 1963, p. 14 In the last years of the 1930s, Poulenc's compositions continued to vary between serious and light-hearted works. '' Quatre motets pour un temps de pénitence'' (Four Penitential Motets, 1938–39) and the song "Bleuet" (1939), an elegiac meditation on death, contrast with the song cycle '' Fiançailles pour rire'' (Light-Hearted Betrothal), which recaptures the spirit of ''Les biches'', in the opinion of Hell.Hell, pp. 60–61

1940s: war and post-war

Poulenc was briefly a soldier again during theSecond World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposi ...

; he was called up on 2 June 1940 and served in an anti-aircraft unit at Bordeaux

Bordeaux ( , ; Gascon oc, Bordèu ; eu, Bordele; it, Bordò; es, Burdeos) is a port city on the river Garonne in the Gironde department, Southwestern France. It is the capital of the Nouvelle-Aquitaine region, as well as the prefect ...

. After France surrendered to Germany, Poulenc was demobilised from the army on 18 July 1940. He spent the summer of that year with family and friends at Brive-la-Gaillarde in south-central France. In the early months of the war, he had composed little new music, instead re-orchestrating ''Les biches'' and reworking his 1932 Sextet

A sextet (or hexad) is a formation containing exactly six members. The former term is commonly associated with vocal ensembles (e.g. The King's Singers, Affabre Concinui) or musical instrument groups, but can be applied to any situation where six ...

for piano and winds. At Brive-la-Gaillarde he began three new works, and once back at his home in Noizay in October he started on a fourth. These were '' L'Histoire de Babar, le petit éléphant'' for piano and narrator, the Cello Sonata

A cello sonata is usually a sonata written for solo cello with piano accompaniment. The most famous Romantic-era cello sonatas are those written by Johannes Brahms and Ludwig van Beethoven. Some of the earliest cello sonatas were written in the 1 ...

, the ballet ''Les Animaux modèles

''Les Animaux modèles'', FP 111, is a ballet dating from 1940 to 1942 with music by Francis Poulenc. It was the third and final ballet that he composed and was staged at the Paris Opéra in 1942, with choreography by Serge Lifar, who also danced ...

'' and the song cycle '' Banalités''.

For most of the war, Poulenc was in Paris, giving recitals with Bernac, concentrating on French songs. Under Nazi rule he was in a vulnerable position, as a known homosexual (Destouches narrowly avoided arrest and deportation), but in his music he made many gestures of defiance of the Germans. Fancourt, Daisy

For most of the war, Poulenc was in Paris, giving recitals with Bernac, concentrating on French songs. Under Nazi rule he was in a vulnerable position, as a known homosexual (Destouches narrowly avoided arrest and deportation), but in his music he made many gestures of defiance of the Germans. Fancourt, Daisy"Les Six"

Music and the Holocaust, retrieved 6 October 2014 He set to music verses by poets prominent in the

French Resistance

The French Resistance (french: La Résistance) was a collection of organisations that fought the German occupation of France during World War II, Nazi occupation of France and the Collaborationism, collaborationist Vichy France, Vichy régim ...

, including Aragon and Éluard. In ''Les Animaux modèles'', premiered at the Opéra

This is a glossary list of opera genres, giving alternative names.

"Opera" is an Italian word (short for "opera in musica"); it was not at first ''commonly'' used in Italy (or in other countries) to refer to the genre of particular works. Most c ...

in 1942, he included the tune, repeated several times, of the anti-German song "Vous n'aurez pas l'Alsace et la Lorraine".Simeone Nigel"Making Music in Occupied Paris"

''The Musical Times'', Spring, 2006, pp. 23–50 He was a founder-member of the Front National (pour musique) which the Nazi authorities viewed with suspicion for its association with banned musicians such as Milhaud and

Paul Hindemith

Paul Hindemith (; 16 November 189528 December 1963) was a German composer, music theorist, teacher, violist and conductor. He founded the Amar Quartet in 1921, touring extensively in Europe. As a composer, he became a major advocate of the ' ...

. In 1943 he wrote a cantata for unaccompanied double choir intended for Belgium, ''Figure humaine

''Figure humaine'' (''Human Figure''), FP 120, by Francis Poulenc is a cantata for double mixed choir of 12 voices composed in 1943 on texts by Paul Éluard including " 'Liberté". Written during the Nazi occupation of France, it was premiered i ...

'', setting eight of Éluard's poems. The work, ending with "Liberté", could not be given in France while the Germans were in control; its first performance was broadcast from a BBC studio in London in March 1945, and it was not sung in Paris until 1947. The music critic of ''The Times

''The Times'' is a British daily national newspaper based in London. It began in 1785 under the title ''The Daily Universal Register'', adopting its current name on 1 January 1788. ''The Times'' and its sister paper '' The Sunday Times'' (f ...

'' later wrote that the work "is among the very finest choral works of our time and in itself removes Poulenc from the category of ''petit maître'' to which ignorance has generally been content to relegate him."

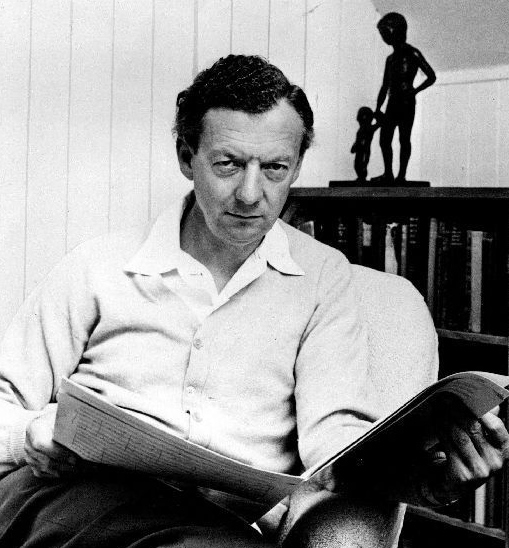

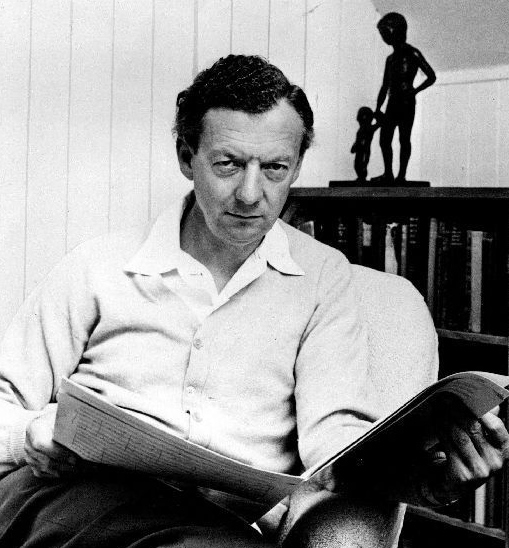

In January 1945, commissioned by the French government, Poulenc and Bernac flew from Paris to London, where they received an enthusiastic welcome. The London Philharmonic Orchestra gave a reception in the composer's honour; he and Benjamin Britten

Edward Benjamin Britten, Baron Britten (22 November 1913 – 4 December 1976, aged 63) was an English composer, conductor, and pianist. He was a central figure of 20th-century British music, with a range of works including opera, other ...

were the soloists in a performance of Poulenc's Double Piano Concerto at the Royal Albert Hall; with Bernac he gave recitals of French ''mélodie A ''mélodie'' () is a form of French art song, arising in the mid-19th century. It is comparable to the German ''Lied''. A ''chanson'', by contrast, is a folk or popular French song.

The literal meaning of the word in the French language is "melod ...

s'' and piano works at the Wigmore Hall

Wigmore Hall is a concert hall located at 36 Wigmore Street, London. Originally called Bechstein Hall, it specialises in performances of chamber music, early music, vocal music and song recitals. It is widely regarded as one of the world's leadi ...

and the National Gallery

The National Gallery is an art museum in Trafalgar Square in the City of Westminster, in Central London, England. Founded in 1824, it houses a collection of over 2,300 paintings dating from the mid-13th century to 1900. The current Director ...

, and recorded for the BBC. Bernac was overwhelmed by the public's response; when he and Poulenc stepped out on the Wigmore Hall stage, "the audience rose and my emotion was such that instead of beginning to sing, I began to weep." After their fortnight's stay, the two returned home on the first boat-train to leave London for Paris since May 1940.

In Paris, Poulenc completed his scores for ''L'Histoire de Babar, le petit éléphant'' and his first opera, '' Les mamelles de Tirésias'' (The Breasts of Tiresias

In Greek mythology, Tiresias (; grc, Τειρεσίας, Teiresías) was a blind prophet of Apollo in Thebes, famous for clairvoyance and for being transformed into a woman for seven years. He was the son of the shepherd Everes and the nym ...

), a short opéra bouffe

Opéra bouffe (, plural: ''opéras bouffes'') is a genre of late 19th-century French operetta, closely associated with Jacques Offenbach, who produced many of them at the Théâtre des Bouffes-Parisiens, inspiring the genre's name.

Opéras bouff ...

of about an hour's duration. The work is a setting of Apollinaire's play of the same name, staged in 1917. Sams describes the opera as "high-spirited topsy-turveydom" concealing "a deeper and sadder theme – the need to repopulate and rediscover a France ravaged by war".Sams, p. 282 It was premiered in June 1947 at the Opéra-Comique, and was a critical success, but did not prove popular with the public. The leading female role was taken by Denise Duval

Denise Duval (23 October 192125 January 2016) was a French soprano, best known for her performances in the works of Francis Poulenc on stage and in recital. During an international career, Duval created the roles of Thérèse in '' Les mamelles de ...

, who became the composer's favourite soprano, frequent recital partner and dedicatee of some of his music. He called her the nightingale who made him cry (''"Mon rossignol à larmes"'').

Shortly after the war, Poulenc had a brief affair with a woman, Fréderique ("Freddy") Lebedeff, with whom he had a daughter, Marie-Ange, in 1946. The child was brought up without knowing who her father was (Poulenc was supposedly her "godfather") but he made generous provision for her, and she was the principal beneficiary of his will.

In the post-war period Poulenc crossed swords with composers of the younger generation who rejected Stravinsky's recent work and insisted that only the precepts of the Second Viennese School were valid. Poulenc defended Stravinsky and expressed incredulity that "in 1945 we are speaking as if the aesthetic of twelve tones is the only possible salvation for contemporary music". His view that Berg had taken serialism as far as it could go and that Schoenberg's music was now "desert, stone soup, ersatz music, or poetic vitamins" earned him the enmity of composers such as Pierre Boulez. Those disagreeing with Poulenc attempted to paint him as a relic of the pre-war era, frivolous and unprogressive. This led him to focus on his more serious works, and to try to persuade the French public to listen to them. In the US and Britain, with their strong choral traditions, his religious music was frequently performed, but performances in France were much rarer, so that the public and the critics were often unaware of his serious compositions.

In 1948 Poulenc made his first visit to the US, in a two-month concert tour with Bernac.Hell, p. 74 He returned there frequently until 1961, giving recitals with Bernac or Duval and as soloist in the world premiere of his Piano Concerto (1949), commissioned by the Boston Symphony Orchestra.

Shortly after the war, Poulenc had a brief affair with a woman, Fréderique ("Freddy") Lebedeff, with whom he had a daughter, Marie-Ange, in 1946. The child was brought up without knowing who her father was (Poulenc was supposedly her "godfather") but he made generous provision for her, and she was the principal beneficiary of his will.

In the post-war period Poulenc crossed swords with composers of the younger generation who rejected Stravinsky's recent work and insisted that only the precepts of the Second Viennese School were valid. Poulenc defended Stravinsky and expressed incredulity that "in 1945 we are speaking as if the aesthetic of twelve tones is the only possible salvation for contemporary music". His view that Berg had taken serialism as far as it could go and that Schoenberg's music was now "desert, stone soup, ersatz music, or poetic vitamins" earned him the enmity of composers such as Pierre Boulez. Those disagreeing with Poulenc attempted to paint him as a relic of the pre-war era, frivolous and unprogressive. This led him to focus on his more serious works, and to try to persuade the French public to listen to them. In the US and Britain, with their strong choral traditions, his religious music was frequently performed, but performances in France were much rarer, so that the public and the critics were often unaware of his serious compositions.

In 1948 Poulenc made his first visit to the US, in a two-month concert tour with Bernac.Hell, p. 74 He returned there frequently until 1961, giving recitals with Bernac or Duval and as soloist in the world premiere of his Piano Concerto (1949), commissioned by the Boston Symphony Orchestra.

1950–63: ''The Carmelites'' and last years

Poulenc began the 1950s with a new partner in his private life, Lucien Roubert, a travelling salesman. Professionally Poulenc was productive, writing a seven-song cycle setting poems by Éluard, '' La Fraîcheur et le feu'' (1950), and the '' Stabat Mater'', in memory of the painter Christian Bérard, composed in 1950 and premiered the following year. In 1953, Poulenc was offered a commission by La Scala and the

In 1953, Poulenc was offered a commission by La Scala and the Milan

Milan ( , , Lombard: ; it, Milano ) is a city in northern Italy, capital of Lombardy, and the second-most populous city proper in Italy after Rome. The city proper has a population of about 1.4 million, while its metropolitan city h ...

ese publisher Casa Ricordi

Casa Ricordi is a publisher of primarily classical music and opera. Its classical repertoire represents one of the important sources in the world through its publishing of the work of the major 19th-century Italian composers such as Gioachino Ro ...

for a ballet. He considered the story of St Margaret of Cortona but found a dance version of her life impracticable. He preferred to write an opera on a religious theme; Ricordi suggested ''Dialogues des Carmélites'', an unfilmed screenplay by Georges Bernanos

Louis Émile Clément Georges Bernanos (; 20 February 1888 – 5 July 1948) was a French author, and a soldier in World War I. A Catholic with monarchist leanings, he was critical of elitist thought and was opposed to what he identified as defe ...

. The text, based on a short story by Gertrud von Le Fort

The Baroness Gertrud von Le Fort (full name ''Gertrud Auguste Lina Elsbeth Mathilde Petrea Freiin von Le Fort''; 11 October 1876 – 1 November 1971) was a German writer of novels, poems and essays.

Life

Le Fort was born in the city of Mind ...

, depicts the Martyrs of Compiègne

The Martyrs of Compiègne were the 16 members of the Carmel of Compiègne, France: 11 Discalced Carmelite nuns, three lay sisters, and two externs (or tertiaries). They were executed by the guillotine towards the end of the Reign of Terror, at ...

, nuns guillotined during the French Revolution for their religious beliefs. Poulenc found it "such a moving and noble work","Les Dialogues de Poulenc: The Composer on his Opera", ''The Times'', 26 February 1958, p. 3 ideal for his libretto, and he began composition in August 1953.

During the composition of the opera, Poulenc suffered two blows. He learned of a dispute between Bernanos's estate and the writer Emmet Lavery

Emmet Godfrey Lavery (November 8, 1902 – January 1, 1986) was an American playwright and screenwriter.

Born in Poughkeepsie, Lavery trained as a lawyer, before devoting his career to the theatre and to film. He wrote the English libretto for E ...

, who held the rights to theatrical adaptations of Le Fort's novel; this caused Poulenc to stop work on his opera. At about the same time Roubert became gravely ill. Intense worry pushed Poulenc into a nervous breakdown, and in November 1954 he was in a clinic at L'Haÿ-les-Roses

L'Haÿ-les-Roses () is a Communes of France, commune in the southern suburbs of Paris, France. It is located from the Kilometre Zero, centre of Paris. L'Haÿ-les-Roses is a ''Subprefectures in France, sous-préfecture'' of the Val-de-Marne ''Dépa ...

, outside Paris, heavily sedated. When he recovered, and the literary rights and royalty payments disputes with Lavery were settled, he resumed work on ''Dialogues des Carmélites

' (''Dialogues of the Carmelites''), FP 159, is an opera in three acts, divided into twelve scenes with linking orchestral interludes, with music and libretto by Francis Poulenc, completed in 1956. The composer's second opera, Poulenc wrote the ...

'' in between extensive touring with Bernac in England. As his personal wealth had declined since the 1920s he required the substantial income earned from his recitals.

While working on the opera, Poulenc composed little else; exceptions were two ''mélodies'', and a short orchestral movement, "Bucolique" in a collective work, ''Variations sur le nom de Marguerite Long

''Variations sur le nom de Marguerite Long'' (Variations on the name Marguerite Long) is a collaborative orchestral suite written by eight French composers in 1956, in honour of the pianist Marguerite Long.

It was first performed on 4 June 1956 by ...

'' (1954), to which his old friends from ''Les Six'' Auric and Milhaud also contributed. As Poulenc was writing the last pages of his opera in October 1955, Roubert died at the age of forty-seven. The composer wrote to a friend, "Lucien was delivered from his martyrdom ten days ago and the final copy of ''Les Carmélites'' was completed (take note) at the very moment my dear breathed his last."

The opera was first given in January 1957 at La Scala in Italian translation. Between then and the French premiere Poulenc introduced one of his most popular late works, the Flute Sonata, which he and Jean-Pierre Rampal

Jean-Pierre Louis Rampal (7 January 1922 – 20 May 2000) was a French flautist. He has been personally "credited with returning to the Western concert flute, flute the popularity as a solo classical instrument it had not held since the 18th ce ...

performed in June at the Strasbourg Music Festival. Three days later, on 21 June, came the Paris premiere of ''Dialogues des Carmélites'' at the Opéra. It was a tremendous success, to the composer's considerable relief. At around this time Poulenc began his last romantic relationship, with Louis Gautier, a former soldier; they remained partners to the end of Poulenc's life.

In 1958 Poulenc embarked on a collaboration with his old friend Cocteau, in an operatic version of the latter's 1930 monodrama

A monodrama is a theatrical or operatic piece played by a single actor or singer, usually portraying one character.

In opera

In opera, a monodrama was originally a melodrama with one role such as Jean-Jacques Rousseau's '' Pygmalion'', which w ...

''La Voix humaine

' (English: ''The Human Voice'') is a forty-minute, one-act opera for soprano and orchestra composed by Francis Poulenc in 1958. The work is based on the play of the same name by Jean Cocteau, who, along with French soprano Denise Duval, worked ...

''. The work was produced in February 1959 at the Opéra-Comique, under Cocteau's direction, with Duval as the tragic deserted woman speaking to her former lover by telephone. In May Poulenc's 60th birthday was marked, a few months late, by his last concert with Bernac before the latter's retirement from public performance."Biography"Francis Poulenc: musicien français 1899–1963, retrieved 22 October 2014 Poulenc visited the US in 1960 and 1961. Among his works given during these trips were the American premiere of ''La Voix humaine'' at Carnegie Hall in New York, with Duval, and the world premiere of his Gloria, a large-scale work for soprano, four-part mixed chorus and orchestra, conducted in Boston by Charles Munch. In 1961 Poulenc published a book about Chabrier, a 187-page study of which a reviewer wrote in the 1980s, "he writes with love and insight of a composer whose views he shared on matters like the primacy of melody and the essential seriousness of humour." The works of Poulenc's last twelve months included '' Sept répons des ténèbres'' for voices and orchestra, the Clarinet Sonata and the Oboe Sonata.

On 30 January 1963, at his flat opposite the

On 30 January 1963, at his flat opposite the Jardin du Luxembourg

The Jardin du Luxembourg (), known in English as the Luxembourg Garden, colloquially referred to as the Jardin du Sénat (Senate Garden), is located in the 6th arrondissement of Paris, France. Creation of the garden began in 1612 when Marie de' ...

, Poulenc suffered a fatal heart attack. His funeral was at the nearby church of Saint-Sulpice. In compliance with his wishes, none of his music was performed; Marcel Dupré

Marcel Jean-Jules Dupré () (3 May 1886 – 30 May 1971) was a French organist, composer, and pedagogue.

Biography

Born in Rouen into a wealthy musical family, Marcel Dupré was a child prodigy. His father Aimable Albert Dupré was titular o ...

played works by Bach

Johann Sebastian Bach (28 July 1750) was a German composer and musician of the late Baroque period. He is known for his orchestral music such as the ''Brandenburg Concertos''; instrumental compositions such as the Cello Suites; keyboard wor ...

on the grand organ of the church. Poulenc was buried at Père Lachaise Cemetery

Père Lachaise Cemetery (french: Cimetière du Père-Lachaise ; formerly , "East Cemetery") is the largest cemetery in Paris, France (). With more than 3.5 million visitors annually, it is the most visited necropolis in the world. Notable figure ...

, alongside his family.

Music

Poulenc's music is essentially diatonic. In Henri Hell's view, this is because the main feature of Poulenc's musical art is his melodic gift. In the words of Roger Nichols in the ''Grove'' dictionary, "For oulencthe most important element of all was melody and he found his way to a vast treasury of undiscovered tunes within an area that had, according to the most up-to-date musical maps, been surveyed, worked and exhausted." The commentator George Keck writes, "His melodies are simple, pleasing, easily remembered, and most often emotionally expressive."Keck, p. 18 Poulenc said that he was not inventive in his harmonic language. The composer Lennox Berkeley wrote of him, "All through his life, he was content to use conventional harmony, but his use of it was so individual, so immediately recognizable as his own, that it gave his music freshness and validity." Keck considers Poulenc's harmonic language "as beautiful, interesting and personal as his melodic writing ... clear, simple harmonies moving in obviously defined tonal areas with chromaticism that is rarely more than passing". Poulenc had no time for musical theories; in one of his many radio interviews he called for "a truce to composing by theory, doctrine, rule!" He was dismissive of what he saw as the dogmatism of latter-day adherents to dodecaphony, led byRené Leibowitz

René Leibowitz (; 17 February 1913 – 29 August 1972) was a Polish, later naturalised French, composer, conductor, music theorist and teacher. He was historically significant in promoting the music of the Second Viennese School in Paris after ...

, and greatly regretted that the adoption of a theoretical approach had affected the music of Olivier Messiaen, of whom he had earlier had high hopes. To Hell, almost all Poulenc's music is "directly or indirectly inspired by the purely melodic associations of the human voice". Poulenc was a painstaking craftsman, though a myth grew up – ''"la légende de facilité"'' – that his music came easily to him; he commented, "The myth is excusable, since I do everything to conceal my efforts."

The pianist Pascal Rogé commented in 1999 that both sides of Poulenc's musical nature were equally important: "You must accept him as a whole. If you take away either part, the serious or the non-serious, you destroy him. If one part is erased you get only a pale photocopy of what he really is."Larner, Gerald. "Maître with the light touch", ''The Times'', 6 January 1999, p. 30 Poulenc recognised the dichotomy, but in all his works he wanted music that was "healthy, clear and robust – music as frankly French as Stravinsky's is Slav". Landormy, Paul. 162

Orchestral and concertante

Poulenc's principal works for large orchestra comprise two ballets, a Sinfonietta and four keyboard concertos. The first of the ballets, ''Les biches

''Les biches'' () ("The Hinds" or "The Does", or "The Darlings") is a one-act ballet to music by Francis Poulenc, choreographed by Bronislava Nijinska and premiered by the Ballets Russes on 6 January 1924 at the Salle Garnier in Monte Carlo. Ni ...

'', was first performed in 1924 and remains one of his best-known works. Nichols writes in ''Grove'' that the clear and tuneful score has no deep, or even shallow, symbolism, a fact "accentuated by a tiny passage of mock- Wagnerian brass, complete with emotive minor 9ths". The first two of the four concertos are in Poulenc's light-hearted vein. The ''Concert champêtre

''Concert champêtre'' (, ''Pastoral Concerto''), FP 49, is a harpsichord concerto by Francis Poulenc, which also exists in a version for piano solo with very slight changes in the solo part.

It was written in 1927–28 for the harpsichordist ...

'' for harpsichord and orchestra (1927–28), evokes the countryside seen from a Parisian point of view: Nichols comments that the fanfares in the last movement bring to mind the bugles in the barracks of Vincennes

Vincennes (, ) is a commune in the Val-de-Marne department in the eastern suburbs of Paris, France. It is located from the centre of Paris. It is next to but does not include the Château de Vincennes and Bois de Vincennes, which are attache ...

in the Paris suburbs. The Concerto for two pianos and orchestra (1932) is similarly a work intended purely to entertain. It draws on a variety of stylistic sources: the first movement ends in a manner reminiscent of Balinese gamelan

Gamelan () ( jv, ꦒꦩꦼꦭꦤ꧀, su, ᮌᮙᮨᮜᮔ᮪, ban, ᬕᬫᭂᬮᬦ᭄) is the traditional ensemble music of the Javanese, Sundanese, and Balinese peoples of Indonesia, made up predominantly of percussive instruments. T ...

, and the slow movement begins in a Mozartian style, which Poulenc gradually fills out with his own characteristic personal touches. The Organ Concerto

An organ concerto is a piece of music, an instrumental concerto for a pipe organ soloist with an orchestra. The form first evolved in the 18th century, when composers including Antonio Vivaldi, George Frideric Handel and Johann Sebastian Bach w ...

(1938) is in a much more serious vein. Poulenc said that it was "on the outskirts" of his religious music, and there are passages that draw on the church music of Bach

Johann Sebastian Bach (28 July 1750) was a German composer and musician of the late Baroque period. He is known for his orchestral music such as the ''Brandenburg Concertos''; instrumental compositions such as the Cello Suites; keyboard wor ...

, though there are also interludes in breezy popular style. The second ballet score, ''Les Animaux modèles

''Les Animaux modèles'', FP 111, is a ballet dating from 1940 to 1942 with music by Francis Poulenc. It was the third and final ballet that he composed and was staged at the Paris Opéra in 1942, with choreography by Serge Lifar, who also danced ...