A Turing machine is a

mathematical model of computation describing an

abstract machine

In computer science, an abstract machine is a theoretical model that allows for a detailed and precise analysis of how a computer system functions. It is similar to a mathematical function in that it receives inputs and produces outputs based on p ...

that manipulates symbols on a strip of tape according to a table of rules. Despite the model's simplicity, it is capable of implementing any

computer algorithm

In mathematics and computer science, an algorithm () is a finite sequence of Rigour#Mathematics, mathematically rigorous instructions, typically used to solve a class of specific Computational problem, problems or to perform a computation. Algo ...

.

The machine operates on an infinite memory tape divided into

discrete

Discrete may refer to:

*Discrete particle or quantum in physics, for example in quantum theory

* Discrete device, an electronic component with just one circuit element, either passive or active, other than an integrated circuit

* Discrete group, ...

cells, each of which can hold a single symbol drawn from a

finite set

In mathematics, particularly set theory, a finite set is a set that has a finite number of elements. Informally, a finite set is a set which one could in principle count and finish counting. For example,

is a finite set with five elements. Th ...

of symbols called the

alphabet

An alphabet is a standard set of letter (alphabet), letters written to represent particular sounds in a spoken language. Specifically, letters largely correspond to phonemes as the smallest sound segments that can distinguish one word from a ...

of the machine. It has a "head" that, at any point in the machine's operation, is positioned over one of these cells, and a "state" selected from a finite set of states. At each step of its operation, the head reads the symbol in its cell. Then, based on the symbol and the machine's own present state, the machine writes a symbol into the same cell, and moves the head one step to the left or the right, or halts the computation. The choice of which replacement symbol to write, which direction to move the head, and whether to halt is based on a finite table that specifies what to do for each combination of the current state and the symbol that is read.

As with a real computer program, it is possible for a Turing machine to go into an

infinite loop

In computer programming, an infinite loop (or endless loop) is a sequence of instructions that, as written, will continue endlessly, unless an external intervention occurs, such as turning off power via a switch or pulling a plug. It may be inte ...

which will never halt.

The Turing machine was invented in 1936 by

Alan Turing

Alan Mathison Turing (; 23 June 1912 – 7 June 1954) was an English mathematician, computer scientist, logician, cryptanalyst, philosopher and theoretical biologist. He was highly influential in the development of theoretical computer ...

,

who called it an "a-machine" (automatic machine). It was Turing's doctoral advisor,

Alonzo Church

Alonzo Church (June 14, 1903 – August 11, 1995) was an American computer scientist, mathematician, logician, and philosopher who made major contributions to mathematical logic and the foundations of theoretical computer science. He is bes ...

, who later coined the term "Turing machine" in a review.

[see note in forward to The Collected Works of Alonzo Church ()] With this model, Turing was able to answer two questions in the negative:

* Does a machine exist that can determine whether any arbitrary machine on its tape is "circular" (e.g., freezes, or fails to continue its computational task)?

* Does a machine exist that can determine whether any arbitrary machine on its tape ever prints a given symbol?

[Turing 1936 in ''The Undecidable'' 1965:132-134; Turing's definition of "circular" is found on page 119.]

Thus by providing a mathematical description of a very simple device capable of arbitrary computations, he was able to prove properties of computation in general—and in particular, the

uncomputability of the ''

Entscheidungsproblem

In mathematics and computer science, the ; ) is a challenge posed by David Hilbert and Wilhelm Ackermann in 1928. It asks for an algorithm that considers an inputted statement and answers "yes" or "no" according to whether it is universally valid ...

'', or 'decision problem' (whether every mathematical statement is provable or disprovable).

[Turing 1936 in ''The Undecidable'' 1965:145]

Turing machines proved the existence of fundamental limitations on the power of mechanical computation.

While they can express arbitrary computations, their minimalist design makes them too slow for computation in practice: real-world

computer

A computer is a machine that can be Computer programming, programmed to automatically Execution (computing), carry out sequences of arithmetic or logical operations (''computation''). Modern digital electronic computers can perform generic set ...

s are based on different designs that, unlike Turing machines, use

random-access memory

Random-access memory (RAM; ) is a form of Computer memory, electronic computer memory that can be read and changed in any order, typically used to store working Data (computing), data and machine code. A random-access memory device allows ...

.

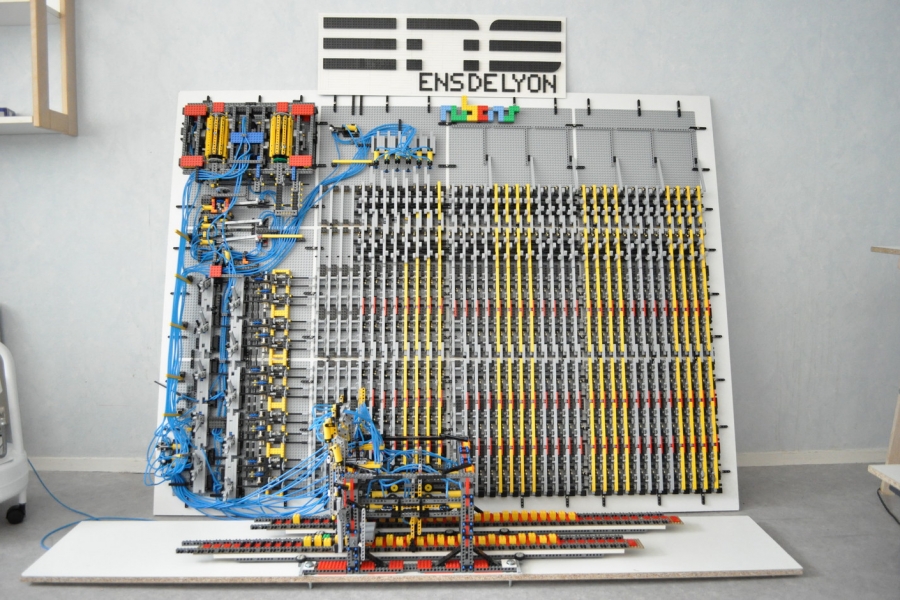

Turing completeness

In computability theory, a system of data-manipulation rules (such as a model of computation, a computer's instruction set, a programming language, or a cellular automaton) is said to be Turing-complete or computationally universal if it can b ...

is the ability for a

computational model

A computational model uses computer programs to simulate and study complex systems using an algorithmic or mechanistic approach and is widely used in a diverse range of fields spanning from physics, engineering, chemistry and biology to economics ...

or a system of instructions to simulate a Turing machine. A programming language that is Turing complete is theoretically capable of expressing all tasks accomplishable by computers; nearly all programming languages are Turing complete if the limitations of finite memory are ignored.

Overview

A Turing machine is an idealised model of a

central processing unit

A central processing unit (CPU), also called a central processor, main processor, or just processor, is the primary Processor (computing), processor in a given computer. Its electronic circuitry executes Instruction (computing), instructions ...

(CPU) that controls all data manipulation done by a computer, with the canonical machine using sequential memory to store data. Typically, the sequential memory is represented as a tape of infinite length on which the machine can perform read and write operations.

In the context of

formal language

In logic, mathematics, computer science, and linguistics, a formal language is a set of strings whose symbols are taken from a set called "alphabet".

The alphabet of a formal language consists of symbols that concatenate into strings (also c ...

theory, a Turing machine (

automaton

An automaton (; : automata or automatons) is a relatively self-operating machine, or control mechanism designed to automatically follow a sequence of operations, or respond to predetermined instructions. Some automata, such as bellstrikers i ...

) is capable of

enumerating some arbitrary subset of valid strings of an

alphabet

An alphabet is a standard set of letter (alphabet), letters written to represent particular sounds in a spoken language. Specifically, letters largely correspond to phonemes as the smallest sound segments that can distinguish one word from a ...

. A set of strings which can be enumerated in this manner is called a

recursively enumerable language

In mathematics, logic and computer science, a formal language is called recursively enumerable (also recognizable, partially decidable, semidecidable, Turing-acceptable or Turing-recognizable) if it is a recursively enumerable subset in the set o ...

. The Turing machine can equivalently be defined as a model that recognises valid input strings, rather than enumerating output strings.

Given a Turing machine ''M'' and an arbitrary string ''s'', it is generally not possible to decide whether ''M'' will eventually produce ''s''. This is due to the fact that the

halting problem

In computability theory (computer science), computability theory, the halting problem is the problem of determining, from a description of an arbitrary computer program and an input, whether the program will finish running, or continue to run for ...

is unsolvable, which has major implications for the theoretical limits of computing.

The Turing machine is capable of processing an

unrestricted grammar

In automata theory, the class of unrestricted grammars (also called semi-Thue, type-0 or phrase structure grammars) is the most general class of grammars in the Chomsky hierarchy. No restrictions are made on the productions of an unrestricted gramm ...

, which further implies that it is capable of robustly evaluating

first-order logic

First-order logic, also called predicate logic, predicate calculus, or quantificational logic, is a collection of formal systems used in mathematics, philosophy, linguistics, and computer science. First-order logic uses quantified variables over ...

in an infinite number of ways. This is famously demonstrated through

lambda calculus

In mathematical logic, the lambda calculus (also written as ''λ''-calculus) is a formal system for expressing computability, computation based on function Abstraction (computer science), abstraction and function application, application using var ...

.

A Turing machine that is able to simulate any other Turing machine is called a

universal Turing machine

In computer science, a universal Turing machine (UTM) is a Turing machine capable of computing any computable sequence, as described by Alan Turing in his seminal paper "On Computable Numbers, with an Application to the Entscheidungsproblem". Co ...

(UTM, or simply a universal machine). Another mathematical formalism,

lambda calculus

In mathematical logic, the lambda calculus (also written as ''λ''-calculus) is a formal system for expressing computability, computation based on function Abstraction (computer science), abstraction and function application, application using var ...

, with a similar "universal" nature was introduced by

Alonzo Church

Alonzo Church (June 14, 1903 – August 11, 1995) was an American computer scientist, mathematician, logician, and philosopher who made major contributions to mathematical logic and the foundations of theoretical computer science. He is bes ...

. Church's work intertwined with Turing's to form the basis for the

Church–Turing thesis

In Computability theory (computation), computability theory, the Church–Turing thesis (also known as computability thesis, the Turing–Church thesis, the Church–Turing conjecture, Church's thesis, Church's conjecture, and Turing's thesis) ...

. This thesis states that Turing machines, lambda calculus, and other similar formalisms of

computation

A computation is any type of arithmetic or non-arithmetic calculation that is well-defined. Common examples of computation are mathematical equation solving and the execution of computer algorithms.

Mechanical or electronic devices (or, hist ...

do indeed capture the informal notion of

effective method

In metalogic, mathematical logic, and computability theory, an effective method or effective procedure is a finite-time, deterministic procedure for solving a problem from a specific class. An effective method is sometimes also called a mechani ...

s in

logic

Logic is the study of correct reasoning. It includes both formal and informal logic. Formal logic is the study of deductively valid inferences or logical truths. It examines how conclusions follow from premises based on the structure o ...

and

mathematics

Mathematics is a field of study that discovers and organizes methods, Mathematical theory, theories and theorems that are developed and Mathematical proof, proved for the needs of empirical sciences and mathematics itself. There are many ar ...

and thus provide a model through which one can reason about an

algorithm

In mathematics and computer science, an algorithm () is a finite sequence of Rigour#Mathematics, mathematically rigorous instructions, typically used to solve a class of specific Computational problem, problems or to perform a computation. Algo ...

or "mechanical procedure" in a mathematically precise way without being tied to any particular formalism. Studying the

abstract properties of Turing machines has yielded many insights into

computer science

Computer science is the study of computation, information, and automation. Computer science spans Theoretical computer science, theoretical disciplines (such as algorithms, theory of computation, and information theory) to Applied science, ...

,

computability theory

Computability theory, also known as recursion theory, is a branch of mathematical logic, computer science, and the theory of computation that originated in the 1930s with the study of computable functions and Turing degrees. The field has since ex ...

, and

complexity theory.

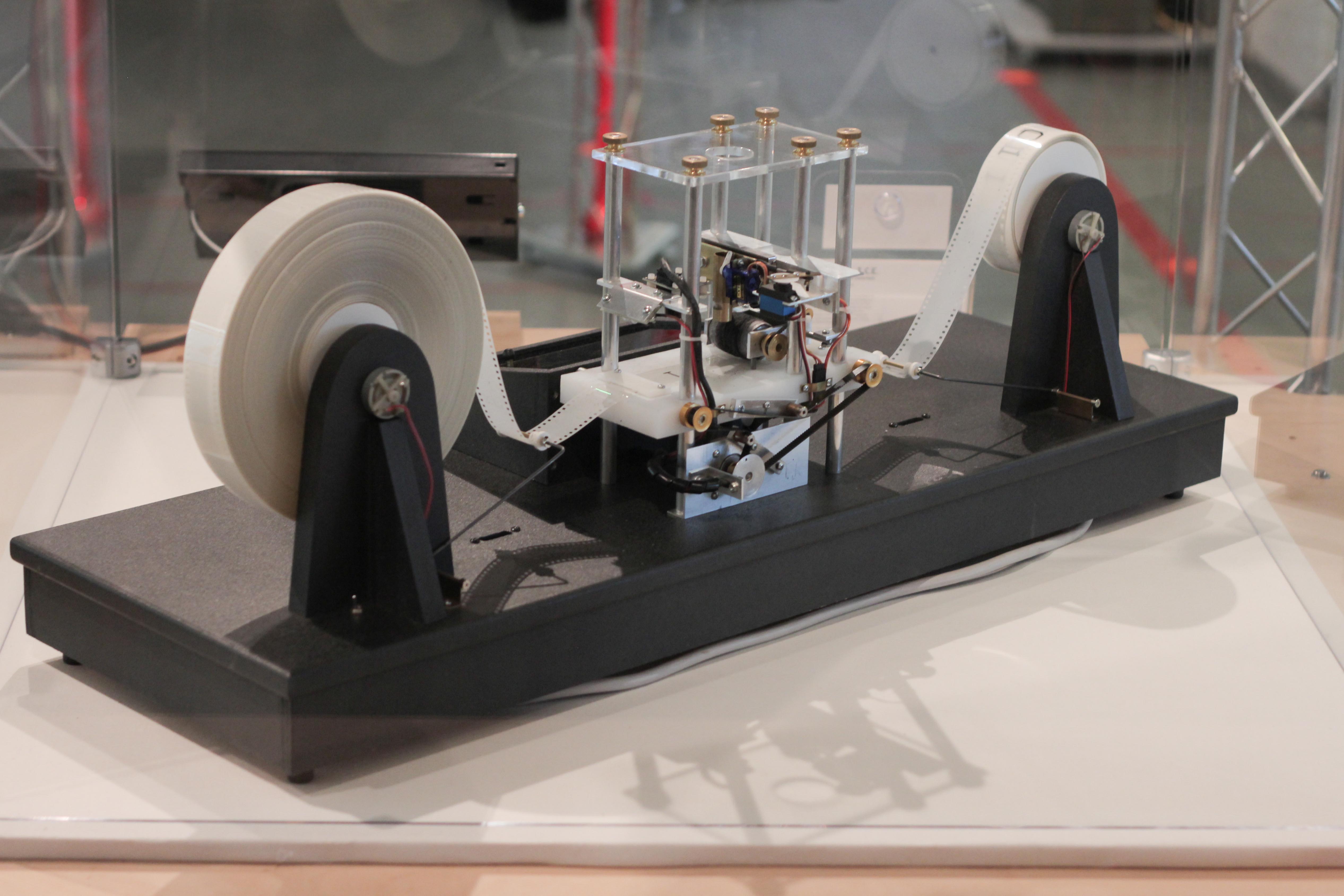

Physical description

In his 1948 essay, "Intelligent Machinery", Turing wrote that his machine consists of:

Description

The Turing machine mathematically models a machine that mechanically operates on a tape. On this tape are symbols, which the machine can read and write, one at a time, using a tape head. Operation is fully determined by a finite set of elementary instructions such as "in state 42, if the symbol seen is 0, write a 1; if the symbol seen is 1, change into state 17; in state 17, if the symbol seen is 0, write a 1 and change to state 6;" etc. In the original article ("

", see also

references below), Turing imagines not a mechanism, but a person whom he calls the "computer", who executes these deterministic mechanical rules slavishly (or as Turing puts it, "in a desultory manner").

More explicitly, a Turing machine consists of:

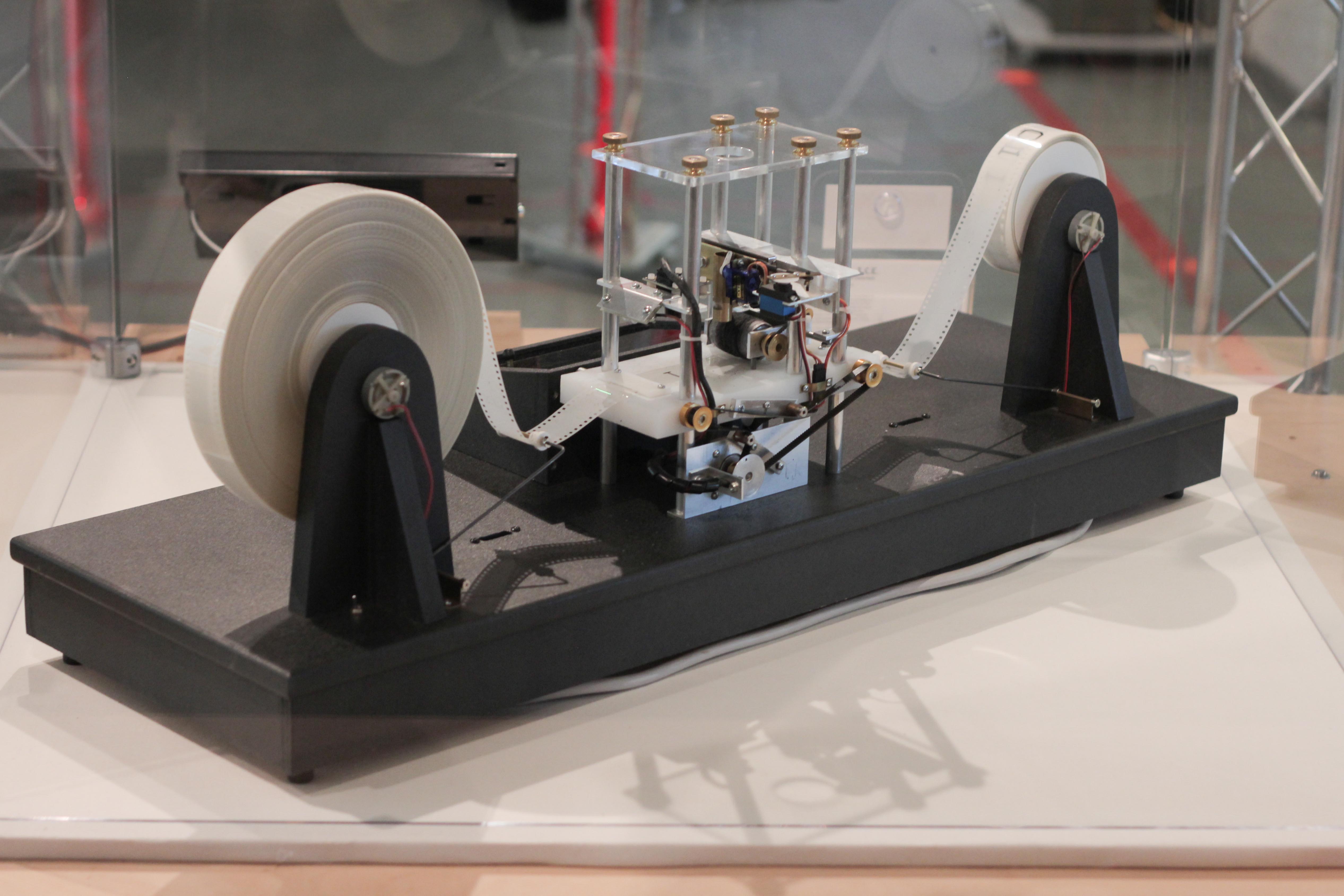

* A ''tape'' divided into cells, one next to the other. Each cell contains a symbol from some finite alphabet. The alphabet contains a special blank symbol (here written as '0') and one or more other symbols. The tape is assumed to be arbitrarily extendable to the left and to the right, so that the Turing machine is always supplied with as much tape as it needs for its computation. Cells that have not been written before are assumed to be filled with the blank symbol. In some models the tape has a left end marked with a special symbol; the tape extends or is indefinitely extensible to the right.

* A ''head'' that can read and write symbols on the tape and move the tape left and right one (and only one) cell at a time. In some models the head moves and the tape is stationary.

* A ''state register'' that stores the state of the Turing machine, one of finitely many. Among these is the special ''start state'' with which the state register is initialised. These states, writes Turing, replace the "state of mind" a person performing computations would ordinarily be in.

* A finite ''table'' of instructions that, given the ''state''(q

i) the machine is currently in ''and'' the ''symbol''(a

j) it is reading on the tape (the symbol currently under the head), tells the machine to do the following ''in sequence'' (for the 5-

tuple

In mathematics, a tuple is a finite sequence or ''ordered list'' of numbers or, more generally, mathematical objects, which are called the ''elements'' of the tuple. An -tuple is a tuple of elements, where is a non-negative integer. There is o ...

models):

# Either erase or write a symbol (replacing a

j with a

j1).

# Move the head (which is described by d

k and can have values: 'L' for one step left ''or'' 'R' for one step right ''or'' 'N' for staying in the same place).

# Assume the same or a ''new state'' as prescribed (go to state q

i1).

In the 4-tuple models, erasing or writing a symbol (a

j1) and moving the head left or right (d

k) are specified as separate instructions. The table tells the machine to (ia) erase or write a symbol ''or'' (ib) move the head left or right, ''and then'' (ii) assume the same or a new state as prescribed, but not both actions (ia) and (ib) in the same instruction. In some models, if there is no entry in the table for the current combination of symbol and state, then the machine will halt; other models require all entries to be filled.

Every part of the machine (i.e. its state, symbol-collections, and used tape at any given time) and its actions (such as printing, erasing and tape motion) is ''finite'', ''discrete'' and ''distinguishable''; it is the unlimited amount of tape and runtime that gives it an unbounded amount of

storage space.

Formal definition

Following , a (one-tape) Turing machine can be formally defined as a 7-

tuple

In mathematics, a tuple is a finite sequence or ''ordered list'' of numbers or, more generally, mathematical objects, which are called the ''elements'' of the tuple. An -tuple is a tuple of elements, where is a non-negative integer. There is o ...

where

*

is a finite, non-empty set of ''tape alphabet symbols'';

*

is the ''blank symbol'' (the only symbol allowed to occur on the tape infinitely often at any step during the computation);

*

is the set of ''input symbols'', that is, the set of symbols allowed to appear in the initial tape contents;

*

is a finite, non-empty set of ''states'';

*

is the ''initial state'';

*

is the set of ''final states'' or ''accepting states''. The initial tape contents is said to be ''accepted'' by

if it eventually halts in a state from

.

*

is a

partial function

In mathematics, a partial function from a set to a set is a function from a subset of (possibly the whole itself) to . The subset , that is, the '' domain'' of viewed as a function, is called the domain of definition or natural domain ...

called the ''transition function'', where L is left shift, R is right shift. If

is not defined on the current state and the current tape symbol, then the machine halts; intuitively, the transition function specifies the next state transited from the current state, which symbol to overwrite the current symbol pointed by the head, and the next head movement.

A variant allows "no shift", say N, as a third element of the set of directions

.

The 7-tuple for the 3-state

busy beaver

In theoretical computer science, the busy beaver game aims to find a terminating Computer program, program of a given size that (depending on definition) either produces the most output possible, or runs for the longest number of steps. Since an ...

looks like this (see more about this busy beaver at

Turing machine examples):

*

(states);

*

(tape alphabet symbols);

*

(blank symbol);

*

(input symbols);

*

(initial state);

*

(final states);

*

see state-table below (transition function).

Initially all tape cells are marked with

.

Additional details required to visualise or implement Turing machines

In the words of van Emde Boas (1990), p. 6: "The set-theoretical object

is formal seven-tuple description similar to the aboveprovides only partial information on how the machine will behave and what its computations will look like."

For instance,

* There will need to be many decisions on what the symbols actually look like, and a failproof way of reading and writing symbols indefinitely.

* The shift left and shift right operations may shift the tape head across the tape, but when actually building a Turing machine it is more practical to make the tape slide back and forth under the head instead.

* The tape can be finite, and automatically extended with blanks as needed (which is closest to the mathematical definition), but it is more common to think of it as stretching infinitely at one or both ends and being pre-filled with blanks except on the explicitly given finite fragment the tape head is on (this is, of course, not implementable in practice). The tape ''cannot'' be fixed in length, since that would not correspond to the given definition and would seriously limit the range of computations the machine can perform to those of a

linear bounded automaton

In computer science, a linear bounded automaton (plural linear bounded automata, abbreviated LBA) is a restricted form of Turing machine.

Operation

A linear bounded automaton is a Turing machine that satisfies the following three conditions:

* ...

if the tape was proportional to the input size, or

finite-state machine

A finite-state machine (FSM) or finite-state automaton (FSA, plural: ''automata''), finite automaton, or simply a state machine, is a mathematical model of computation. It is an abstract machine that can be in exactly one of a finite number o ...

if it was strictly fixed-length.

Alternative definitions

Definitions in literature sometimes differ slightly, to make arguments or proofs easier or clearer, but this is always done in such a way that the resulting machine has the same computational power. For example, the set could be changed from

to

, where ''N'' ("None" or "No-operation") would allow the machine to stay on the same tape cell instead of moving left or right. This would not increase the machine's computational power.

The most common convention represents each "Turing instruction" in a "Turing table" by one of nine 5-tuples, per the convention of Turing/Davis (Turing (1936) in ''The Undecidable'', p. 126–127 and Davis (2000) p. 152):

: (definition 1): (q

i, S

j, S

k/E/N, L/R/N, q

m)

:: ( current state q

i , symbol scanned S

j , print symbol S

k/erase E/none N , move_tape_one_square left L/right R/none N , new state q

m )

Other authors (Minsky (1967) p. 119, Hopcroft and Ullman (1979) p. 158, Stone (1972) p. 9) adopt a different convention, with new state q

m listed immediately after the scanned symbol S

j:

: (definition 2): (q

i, S

j, q

m, S

k/E/N, L/R/N)

:: ( current state q

i , symbol scanned S

j , new state q

m , print symbol S

k/erase E/none N , move_tape_one_square left L/right R/none N )

For the remainder of this article "definition 1" (the Turing/Davis convention) will be used.

In the following table, Turing's original model allowed only the first three lines that he called N1, N2, N3 (cf. Turing in ''The Undecidable'', p. 126). He allowed for erasure of the "scanned square" by naming a 0th symbol S

0 = "erase" or "blank", etc. However, he did not allow for non-printing, so every instruction-line includes "print symbol S

k" or "erase" (cf. footnote 12 in Post (1947), ''The Undecidable'', p. 300). The abbreviations are Turing's (''The Undecidable'', p. 119). Subsequent to Turing's original paper in 1936–1937, machine-models have allowed all nine possible types of five-tuples:

Any Turing table (list of instructions) can be constructed from the above nine 5-tuples. For technical reasons, the three non-printing or "N" instructions (4, 5, 6) can usually be dispensed with. For examples see

Turing machine examples.

Less frequently the use of 4-tuples are encountered: these represent a further atomization of the Turing instructions (cf. Post (1947), Boolos & Jeffrey (1974, 1999), Davis-Sigal-Weyuker (1994)); also see more at

Post–Turing machine

A Post machine or Post–Turing machineRajendra Kumar, ''Theory of Automata'', Tata McGraw-Hill Education, 2010, p. 343. is a "program formulation" of a type of Turing machine, comprising a variant of Emil Post's Turing-equivalent model of comput ...

.

The "state"

The word "state" used in context of Turing machines can be a source of confusion, as it can mean two things. Most commentators after Turing have used "state" to mean the name/designator of the current instruction to be performed—i.e. the contents of the state register. But Turing (1936) made a strong distinction between a record of what he called the machine's "m-configuration", and the machine's (or person's) "state of progress" through the computation—the current state of the total system. What Turing called "the state formula" includes both the current instruction and ''all'' the symbols on the tape:

Earlier in his paper Turing carried this even further: he gives an example where he placed a symbol of the current "m-configuration"—the instruction's label—beneath the scanned square, together with all the symbols on the tape (''The Undecidable'', p. 121); this he calls "the ''complete configuration''" (''The Undecidable'', p. 118). To print the "complete configuration" on one line, he places the state-label/m-configuration to the ''left'' of the scanned symbol.

A variant of this is seen in Kleene (1952) where

Kleene

Stephen Cole Kleene ( ; January 5, 1909 – January 25, 1994) was an American mathematician. One of the students of Alonzo Church, Kleene, along with Rózsa Péter, Alan Turing, Emil Post, and others, is best known as a founder of the branch of ...

shows how to write the

Gödel number of a machine's "situation": he places the "m-configuration" symbol q

4 over the scanned square in roughly the center of the 6 non-blank squares on the tape (see the Turing-tape figure in this article) and puts it to the ''right'' of the scanned square. But Kleene refers to "q

4" itself as "the machine state" (Kleene, p. 374–375). Hopcroft and Ullman call this composite the "instantaneous description" and follow the Turing convention of putting the "current state" (instruction-label, m-configuration) to the ''left'' of the scanned symbol (p. 149), that is, the instantaneous description is the composite of non-blank symbols to the left, state of the machine, the current symbol scanned by the head, and the non-blank symbols to the right.

''Example: total state of 3-state 2-symbol busy beaver after 3 "moves"'' (taken from example "run" in the figure below):

:: 1A1

This means: after three moves the tape has ... 000110000 ... on it, the head is scanning the right-most 1, and the state is ''A''. Blanks (in this case represented by "0"s) can be part of the total state as shown here: ''B''01; the tape has a single 1 on it, but the head is scanning the 0 ("blank") to its left and the state is ''B''.

"State" in the context of Turing machines should be clarified as to which is being described: the current instruction, or the list of symbols on the tape together with the current instruction, or the list of symbols on the tape together with the current instruction placed to the left of the scanned symbol or to the right of the scanned symbol.

Turing's biographer Andrew Hodges (1983: 107) has noted and discussed this confusion.

"State" diagrams

To the right: the above table as expressed as a "state transition" diagram.

Usually large tables are better left as tables (Booth, p. 74). They are more readily simulated by computer in tabular form (Booth, p. 74). However, certain concepts—e.g. machines with "reset" states and machines with repeating patterns (cf. Hill and Peterson p. 244ff)—can be more readily seen when viewed as a drawing.

Whether a drawing represents an improvement on its table must be decided by the reader for the particular context.

The reader should again be cautioned that such diagrams represent a snapshot of their table frozen in time, ''not'' the course ("trajectory") of a computation ''through'' time and space. While every time the busy beaver machine "runs" it will always follow the same state-trajectory, this is not true for the "copy" machine that can be provided with variable input "parameters".

The diagram "progress of the computation" shows the three-state busy beaver's "state" (instruction) progress through its computation from start to finish. On the far right is the Turing "complete configuration" (Kleene "situation", Hopcroft–Ullman "instantaneous description") at each step. If the machine were to be stopped and cleared to blank both the "state register" and entire tape, these "configurations" could be used to rekindle a computation anywhere in its progress (cf. Turing (1936) ''The Undecidable'', pp. 139–140).

Equivalent models

Many machines that might be thought to have more computational capability than a simple universal Turing machine can be shown to have no more power (Hopcroft and Ullman p. 159, cf. Minsky (1967)). They might compute faster, perhaps, or use less memory, or their instruction set might be smaller, but they cannot compute more powerfully (i.e. more mathematical functions). (The

Church–Turing thesis

In Computability theory (computation), computability theory, the Church–Turing thesis (also known as computability thesis, the Turing–Church thesis, the Church–Turing conjecture, Church's thesis, Church's conjecture, and Turing's thesis) ...

''hypothesises'' this to be true for any kind of machine: that anything that can be "computed" can be computed by some Turing machine.)

A Turing machine is equivalent to a single-stack

pushdown automaton

In the theory of computation, a branch of theoretical computer science, a pushdown automaton (PDA) is

a type of automaton that employs a stack.

Pushdown automata are used in theories about what can be computed by machines. They are more capab ...

(PDA) that has been made more flexible and concise by relaxing the

last-in-first-out (LIFO) requirement of its stack. In addition, a Turing machine is also equivalent to a two-stack PDA with standard LIFO semantics, by using one stack to model the tape left of the head and the other stack for the tape to the right.

At the other extreme, some very simple models turn out to be

Turing-equivalent Turing equivalence may refer to:

* As related to Turing completeness, Turing equivalence means having computational power equivalent to a universal Turing machine

* Turing degree

In computer science and mathematical logic the Turing degree (named ...

, i.e. to have the same computational power as the Turing machine model.

Common equivalent models are the

multi-tape Turing machine,

multi-track Turing machine, machines with input and output, and the

''non-deterministic'' Turing machine (NDTM) as opposed to the ''deterministic'' Turing machine (DTM) for which the action table has at most one entry for each combination of symbol and state.

Read-only, right-moving Turing machines are equivalent to

DFAs (as well as

NFAs by conversion using the

NFA to DFA conversion

In the theory of computation and automata theory, the powerset construction or subset construction is a standard method for converting a nondeterministic finite automaton (NFA) into a deterministic finite automaton (DFA) which recognizes the same f ...

algorithm).

For practical and didactic intentions, the equivalent

register machine

In mathematical logic and theoretical computer science, a register machine is a generic class of abstract machines, analogous to a Turing machine and thus Turing complete. Unlike a Turing machine that uses a tape and head, a register machine u ...

can be used as a usual

assembly programming language

A programming language is a system of notation for writing computer programs.

Programming languages are described in terms of their Syntax (programming languages), syntax (form) and semantics (computer science), semantics (meaning), usually def ...

.

A relevant question is whether or not the computation model represented by concrete programming languages is Turing equivalent. While the computation of a real computer is based on finite states and thus not capable to simulate a Turing machine, programming languages themselves do not necessarily have this limitation. Kirner et al., 2009 have shown that among the general-purpose programming languages some are Turing complete while others are not. For example,

ANSI C

ANSI C, ISO C, and Standard C are successive standards for the C programming language published by the American National Standards Institute (ANSI) and ISO/IEC JTC 1/SC 22/WG 14 of the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) and the ...

is not Turing complete, as all instantiations of ANSI C (different instantiations are possible as the standard deliberately leaves certain behaviour undefined for legacy reasons) imply a finite-space memory. This is because the size of memory reference data types, called ''pointers'', is accessible inside the language. However, other programming languages like

Pascal do not have this feature, which allows them to be Turing complete in principle.

It is just Turing complete in principle, as

memory allocation

Memory management (also dynamic memory management, dynamic storage allocation, or dynamic memory allocation) is a form of resource management applied to computer memory. The essential requirement of memory management is to provide ways to dynam ...

in a programming language is allowed to fail, which means the programming language can be Turing complete when ignoring failed memory allocations, but the compiled programs executable on a real computer cannot.

Choice c-machines, oracle o-machines

Early in his paper (1936) Turing makes a distinction between an "automatic machine"—its "motion ... completely determined by the configuration" and a "choice machine":

Turing (1936) does not elaborate further except in a footnote in which he describes how to use an a-machine to "find all the provable formulae of the

ilbertcalculus" rather than use a choice machine. He "suppose

that the choices are always between two possibilities 0 and 1. Each proof will then be determined by a sequence of choices i

1, i

2, ..., i

n (i

1 = 0 or 1, i

2 = 0 or 1, ..., i

n = 0 or 1), and hence the number 2

n + i

12

n-1 + i

22

n-2 + ... +i

n completely determines the proof. The automatic machine carries out successively proof 1, proof 2, proof 3, ..." (Footnote ‡, ''The Undecidable'', p. 138)

This is indeed the technique by which a deterministic (i.e., a-) Turing machine can be used to mimic the action of a

nondeterministic Turing machine

In theoretical computer science, a nondeterministic Turing machine (NTM) is a theoretical model of computation whose governing rules specify more than one possible action when in some given situations. That is, an NTM's next state is ''not'' comp ...

; Turing solved the matter in a footnote and appears to dismiss it from further consideration.

An

oracle machine

In complexity theory and computability theory, an oracle machine is an abstract machine used to study decision problems. It can be visualized as a black box, called an oracle, which is able to solve certain problems in a single operation. The ...

or o-machine is a Turing a-machine that pauses its computation at state "o" while, to complete its calculation, it "awaits the decision" of "the oracle"—an entity unspecified by Turing "apart from saying that it cannot be a machine" (Turing (1939), ''The Undecidable'', p. 166–168).

Universal Turing machines

As Turing wrote in ''The Undecidable'', p. 128 (italics added):

This finding is now taken for granted, but at the time (1936) it was considered astonishing. The model of computation that Turing called his "universal machine"—"U" for short—is considered by some (cf. Davis (2000)) to have been the fundamental theoretical breakthrough that led to the notion of the

stored-program computer

A stored-program computer is a computer that stores program instructions in electronically, electromagnetically, or optically accessible memory. This contrasts with systems that stored the program instructions with plugboards or similar mechani ...

.

In terms of

computational complexity

In computer science, the computational complexity or simply complexity of an algorithm is the amount of resources required to run it. Particular focus is given to computation time (generally measured by the number of needed elementary operations ...

, a multi-tape universal Turing machine need only be slower by

logarithm

In mathematics, the logarithm of a number is the exponent by which another fixed value, the base, must be raised to produce that number. For example, the logarithm of to base is , because is to the rd power: . More generally, if , the ...

ic factor compared to the machines it simulates. This result was obtained in 1966 by F. C. Hennie and

R. E. Stearns. (Arora and Barak, 2009, theorem 1.9)

Comparison with real machines

Turing machines are more powerful than some other kinds of automata, such as

finite-state machine

A finite-state machine (FSM) or finite-state automaton (FSA, plural: ''automata''), finite automaton, or simply a state machine, is a mathematical model of computation. It is an abstract machine that can be in exactly one of a finite number o ...

s and

pushdown automata

In the theory of computation, a branch of theoretical computer science, a pushdown automaton (PDA) is

a type of automaton that employs a stack.

Pushdown automata are used in theories about what can be computed by machines. They are more capab ...

. According to the

Church–Turing thesis

In Computability theory (computation), computability theory, the Church–Turing thesis (also known as computability thesis, the Turing–Church thesis, the Church–Turing conjecture, Church's thesis, Church's conjecture, and Turing's thesis) ...

, they are as powerful as real machines, and are able to execute any operation that a real program can. What is neglected in this statement is that, because a real machine can only have a finite number of ''configurations'', it is nothing but a finite-state machine, whereas a Turing machine has an unlimited amount of storage space available for its computations.

There are a number of ways to explain why Turing machines are useful models of real computers:

* Anything a real computer can compute, a Turing machine can also compute. For example: "A Turing machine can simulate any type of subroutine found in programming languages, including recursive procedures and any of the known parameter-passing mechanisms" (Hopcroft and Ullman p. 157). A large enough FSA can also model any real computer, disregarding IO. Thus, a statement about the limitations of Turing machines will also apply to real computers.

* The difference lies only with the ability of a Turing machine to manipulate an unbounded amount of data. However, given a finite amount of time, a Turing machine (like a real machine) can only manipulate a finite amount of data.

* Like a Turing machine, a real machine can have its storage space enlarged as needed, by acquiring more disks or other storage media.

* Descriptions of real machine programs using simpler abstract models are often much more complex than descriptions using Turing machines. For example, a Turing machine describing an algorithm may have a few hundred states, while the equivalent deterministic finite automaton (DFA) on a given real machine has quadrillions. This makes the DFA representation infeasible to analyze.

* Turing machines describe algorithms independent of how much memory they use. There is a limit to the memory possessed by any current machine, but this limit can rise arbitrarily in time. Turing machines allow us to make statements about algorithms which will (theoretically) hold forever, regardless of advances in ''conventional'' computing machine architecture.

* Algorithms running on Turing-equivalent abstract machines can have arbitrary-precision data types available and never have to deal with unexpected conditions (including, but not limited to, running

out of memory

Out of memory (OOM) is an often undesired state of computer operation where no additional memory can be allocated for use by programs or the operating system. Such a system will be unable to load any additional programs, and since many programs ...

).

Limitations

Computational complexity theory

A limitation of Turing machines is that they do not model the strengths of a particular arrangement well. For instance, modern stored-program computers are actually instances of a more specific form of

abstract machine

In computer science, an abstract machine is a theoretical model that allows for a detailed and precise analysis of how a computer system functions. It is similar to a mathematical function in that it receives inputs and produces outputs based on p ...

known as the

random-access stored-program machine or RASP machine model. Like the universal Turing machine, the RASP stores its "program" in "memory" external to its finite-state machine's "instructions". Unlike the universal Turing machine, the RASP has an infinite number of distinguishable, numbered but unbounded "registers"—memory "cells" that can contain any integer (cf. Elgot and Robinson (1964), Hartmanis (1971), and in particular Cook-Rechow (1973); references at

random-access machine

In computer science, random-access machine (RAM or RA-machine) is a model of computation that describes an abstract machine in the general class of register machines. The RA-machine is very similar to the counter machine but with the added capab ...

). The RASP's finite-state machine is equipped with the capability for indirect addressing (e.g., the contents of one register can be used as an address to specify another register); thus the RASP's "program" can address any register in the register-sequence. The upshot of this distinction is that there are computational optimizations that can be performed based on the memory indices, which are not possible in a general Turing machine; thus when Turing machines are used as the basis for bounding running times, a "false lower bound" can be proven on certain algorithms' running times (due to the false simplifying assumption of a Turing machine). An example of this is

binary search

In computer science, binary search, also known as half-interval search, logarithmic search, or binary chop, is a search algorithm that finds the position of a target value within a sorted array. Binary search compares the target value to the m ...

, an algorithm that can be shown to perform more quickly when using the RASP model of computation rather than the Turing machine model.

Interaction

In the early days of computing, computer use was typically limited to

batch processing

Computerized batch processing is a method of running software programs called jobs in batches automatically. While users are required to submit the jobs, no other interaction by the user is required to process the batch. Batches may automatically ...

, i.e., non-interactive tasks, each producing output data from given input data. Computability theory, which studies computability of functions from inputs to outputs, and for which Turing machines were invented, reflects this practice.

Since the 1970s,

interactive

Across the many fields concerned with interactivity, including information science, computer science, human-computer interaction, communication, and industrial design, there is little agreement over the meaning of the term "interactivity", but mo ...

use of computers became much more common. In principle, it is possible to model this by having an external agent read from the tape and write to it at the same time as a Turing machine, but this rarely matches how interaction actually happens; therefore, when describing interactivity, alternatives such as

I/O automata are usually preferred.

Comparison with the arithmetic model of computation

The

arithmetic model of computation

In computing, especially computational geometry, a real RAM (random-access machine) is a mathematical model of a computer that can compute with exact real numbers instead of the binary fixed-point or floating-point numbers used by most actual co ...

differs from the Turing model in two aspects:

* In the arithmetic model, every real number requires a single memory cell, whereas in the Turing model the storage size of a real number depends on the number of bits required to represent it.

* In the arithmetic model, every basic arithmetic operation on real numbers (addition, subtraction, multiplication and division) can be done in a single step, whereas in the Turing model the run-time of each arithmetic operation depends on the length of the operands.

Some algorithms run in polynomial time in one model but not in the other one. For example:

* The

Euclidean algorithm

In mathematics, the Euclidean algorithm,Some widely used textbooks, such as I. N. Herstein's ''Topics in Algebra'' and Serge Lang's ''Algebra'', use the term "Euclidean algorithm" to refer to Euclidean division or Euclid's algorithm, is a ...

runs in polynomial time in the Turing model, but not in the arithmetic model.

* The algorithm that reads ''n'' numbers and then computes

by

repeated squaring

In mathematics and computer programming, exponentiating by squaring is a general method for fast computation of large positive integer powers of a number, or more generally of an element of a semigroup, like a polynomial or a square matrix. Some ...

runs in polynomial time in the Arithmetic model, but not in the Turing model. This is because the number of bits required to represent the outcome is exponential in the input size.

However, if an algorithm runs in polynomial time in the arithmetic model, and in addition, the binary length of all involved numbers is polynomial in the length of the input, then it is always polynomial-time in the Turing model. Such an algorithm is said to run in

strongly polynomial time.

History

Historical background: computational machinery

Robin Gandy

Robin Oliver Gandy (22 September 1919 – 20 November 1995) was a British mathematician and logician. He was a friend, student, and associate of Alan Turing, having been supervised by Turing during his PhD at the University of Cambridge, where ...

(1919–1995)—a student of Alan Turing (1912–1954), and his lifelong friend—traces the lineage of the notion of "calculating machine" back to

Charles Babbage

Charles Babbage (; 26 December 1791 – 18 October 1871) was an English polymath. A mathematician, philosopher, inventor and mechanical engineer, Babbage originated the concept of a digital programmable computer.

Babbage is considered ...

(circa 1834) and actually proposes "Babbage's Thesis":

Gandy's analysis of Babbage's

analytical engine describes the following five operations (cf. p. 52–53):

# The arithmetic functions +, −, ×, where − indicates "proper" subtraction: if .

# Any sequence of operations is an operation.

# Iteration of an operation (repeating n times an operation P).

# Conditional iteration (repeating n times an operation P conditional on the "success" of test T).

# Conditional transfer (i.e., conditional "

goto").

Gandy states that "the functions which can be calculated by (1), (2), and (4) are precisely those which are

Turing computable." (p. 53). He cites other proposals for "universal calculating machines" including those of

Percy Ludgate

Percy Edwin Ludgate (2 August 1883 – 16 October 1922) was an Ireland, Irish amateur scientist who designed the second analytical engine (general-purpose Turing-complete computer) in history.

Life

Ludgate was born on 2 August 1883 in Skibb ...

(1909),

Leonardo Torres Quevedo

Leonardo Torres Quevedo (; 28 December 1852 – 18 December 1936) was a Spanish civil engineer, mathematician and inventor, known for his numerous engineering innovations, including Aerial tramway, aerial trams, airships, catamarans, and remote ...

(1914),

[L. Torres Quevedo. ''Ensayos sobre Automática – Su definicion. Extension teórica de sus aplicaciones,'' Revista de la Academia de Ciencias Exacta, Revista 12, pp. 391–418, 1914.][Torres Quevedo. L. (1915)]

"Essais sur l'Automatique - Sa définition. Etendue théorique de ses applications"

''Revue Génerale des Sciences Pures et Appliquées'', vol. 2, pp. 601–611. Maurice d'Ocagne (1922),

Louis Couffignal (1933),

Vannevar Bush

Vannevar Bush ( ; March 11, 1890 – June 28, 1974) was an American engineer, inventor and science administrator, who during World War II, World War II headed the U.S. Office of Scientific Research and Development (OSRD), through which almo ...

(1936),

Howard Aiken

Howard Hathaway Aiken (March 8, 1900 – March 14, 1973) was an American physicist and a list of pioneers in computer science, pioneer in computing. He was the original conceptual designer behind IBM's Harvard Mark I, the United States' first C ...

(1937). However:

The Entscheidungsproblem (the "decision problem"): Hilbert's tenth question of 1900

With regard to

Hilbert's problems

Hilbert's problems are 23 problems in mathematics published by German mathematician David Hilbert in 1900. They were all unsolved at the time, and several proved to be very influential for 20th-century mathematics. Hilbert presented ten of the pr ...

posed by the famous mathematician

David Hilbert

David Hilbert (; ; 23 January 1862 – 14 February 1943) was a German mathematician and philosopher of mathematics and one of the most influential mathematicians of his time.

Hilbert discovered and developed a broad range of fundamental idea ...

in 1900, an aspect of

problem #10 had been floating about for almost 30 years before it was framed precisely. Hilbert's original expression for No. 10 is as follows:

By 1922, this notion of "

Entscheidungsproblem

In mathematics and computer science, the ; ) is a challenge posed by David Hilbert and Wilhelm Ackermann in 1928. It asks for an algorithm that considers an inputted statement and answers "yes" or "no" according to whether it is universally valid ...

" had developed a bit, and

H. Behmann stated that

By the 1928 international congress of mathematicians, Hilbert "made his questions quite precise. First, was mathematics ''

complete

Complete may refer to:

Logic

* Completeness (logic)

* Completeness of a theory, the property of a theory that every formula in the theory's language or its negation is provable

Mathematics

* The completeness of the real numbers, which implies t ...

'' ... Second, was mathematics ''

consistent

In deductive logic, a consistent theory is one that does not lead to a logical contradiction. A theory T is consistent if there is no formula \varphi such that both \varphi and its negation \lnot\varphi are elements of the set of consequences ...

'' ... And thirdly, was mathematics ''

decidable''?" (Hodges p. 91, Hawking p. 1121). The first two questions were answered in 1930 by

Kurt Gödel

Kurt Friedrich Gödel ( ; ; April 28, 1906 – January 14, 1978) was a logician, mathematician, and philosopher. Considered along with Aristotle and Gottlob Frege to be one of the most significant logicians in history, Gödel profoundly ...

at the very same meeting where Hilbert delivered his retirement speech (much to the chagrin of Hilbert); the third—the Entscheidungsproblem—had to wait until the mid-1930s.

The problem was that an answer first required a precise definition of "definite general applicable prescription", which Princeton professor

Alonzo Church

Alonzo Church (June 14, 1903 – August 11, 1995) was an American computer scientist, mathematician, logician, and philosopher who made major contributions to mathematical logic and the foundations of theoretical computer science. He is bes ...

would come to call "

effective calculability

In metalogic, mathematical logic, and computability theory, an effective method or effective procedure is a finite-time, deterministic procedure for solving a problem from a specific class. An effective method is sometimes also called a mechanic ...

", and in 1928 no such definition existed. But over the next 6–7 years

Emil Post

Emil Leon Post (; February 11, 1897 – April 21, 1954) was an American mathematician and logician. He is best known for his work in the field that eventually became known as computability theory.

Life

Post was born in Augustów, Suwałki Govern ...

developed his definition of a worker moving from room to room writing and erasing marks per a list of instructions (Post 1936), as did Church and his two students

Stephen Kleene

Stephen Cole Kleene ( ; January 5, 1909 – January 25, 1994) was an American mathematician. One of the students of Alonzo Church, Kleene, along with Rózsa Péter, Alan Turing, Emil Post, and others, is best known as a founder of the branch of ...

and

J. B. Rosser by use of Church's lambda-calculus and Gödel's

recursion theory

Computability theory, also known as recursion theory, is a branch of mathematical logic, computer science, and the theory of computation that originated in the 1930s with the study of computable functions and Turing degrees. The field has since ex ...

(1934). Church's paper (published 15 April 1936) showed that the Entscheidungsproblem was indeed "undecidable"

[The narrower question posed in ]Hilbert's tenth problem

Hilbert's tenth problem is the tenth on the list of mathematical problems that the German mathematician David Hilbert posed in 1900. It is the challenge to provide a general algorithm that, for any given Diophantine equation (a polynomial equatio ...

, about Diophantine equation ''Diophantine'' means pertaining to the ancient Greek mathematician Diophantus. A number of concepts bear this name:

*Diophantine approximation

In number theory, the study of Diophantine approximation deals with the approximation of real n ...

s, remains unresolved until 1970, when the relationship between recursively enumerable set

In computability theory, a set ''S'' of natural numbers is called computably enumerable (c.e.), recursively enumerable (r.e.), semidecidable, partially decidable, listable, provable or Turing-recognizable if:

*There is an algorithm such that the ...

s and Diophantine set

In mathematics, a Diophantine equation is an equation of the form ''P''(''x''1, ..., ''x'j'', ''y''1, ..., ''y'k'') = 0 (usually abbreviated ''P''(', ') = 0) where ''P''(', ') is a polynomial with integer coefficients, where ''x''1, ..., ''x' ...

s is finally laid bare. and beat Turing to the punch by almost a year (Turing's paper submitted 28 May 1936, published January 1937). In the meantime, Emil Post submitted a brief paper in the fall of 1936, so Turing at least had priority over Post. While Church refereed Turing's paper, Turing had time to study Church's paper and add an Appendix where he sketched a proof that Church's lambda-calculus and his machines would compute the same functions.

And Post had only proposed a definition of

calculability and criticised Church's "definition", but had proved nothing.

Alan Turing's a-machine

In the spring of 1935, Turing as a young Master's student at

King's College, Cambridge

King's College, formally The King's College of Our Lady and Saint Nicholas in Cambridge, is a List of colleges of the University of Cambridge, constituent college of the University of Cambridge. The college lies beside the River Cam and faces ...

, took on the challenge; he had been stimulated by the lectures of the logician

M. H. A. Newman "and learned from them of Gödel's work and the Entscheidungsproblem ... Newman used the word 'mechanical' ... In his obituary of Turing 1955 Newman writes:

Gandy states that:

While Gandy believed that Newman's statement above is "misleading", this opinion is not shared by all. Turing had a lifelong interest in machines: "Alan had dreamt of inventing typewriters as a boy;

is motherMrs. Turing had a typewriter; and he could well have begun by asking himself what was meant by calling a typewriter 'mechanical'" (Hodges p. 96). While at Princeton pursuing his PhD, Turing built a Boolean-logic multiplier (see below). His PhD thesis, titled "

Systems of Logic Based on Ordinals", contains the following definition of "a computable function":

Alan Turing invented the "a-machine" (automatic machine) in 1936.

[ Turing submitted his paper on 31 May 1936 to the London Mathematical Society for its ''Proceedings'' (cf. Hodges 1983:112), but it was published in early 1937 and offprints were available in February 1937 (cf. Hodges 1983:129) It was Turing's doctoral advisor, ]Alonzo Church

Alonzo Church (June 14, 1903 – August 11, 1995) was an American computer scientist, mathematician, logician, and philosopher who made major contributions to mathematical logic and the foundations of theoretical computer science. He is bes ...

, who later coined the term "Turing machine" in a review.Entscheidungsproblem

In mathematics and computer science, the ; ) is a challenge posed by David Hilbert and Wilhelm Ackermann in 1928. It asks for an algorithm that considers an inputted statement and answers "yes" or "no" according to whether it is universally valid ...

'' ('decision problem').Automatic Computing Engine

The Automatic Computing Engine (ACE) was a British early Electronic storage, electronic Serial computer, serial stored-program computer design by Alan Turing. Turing completed the ambitious design in late 1945, having had experience in the yea ...

), " uring'sACE proposal was effectively self-contained, and its roots lay not in the EDVAC

EDVAC (Electronic Discrete Variable Automatic Computer) was one of the earliest electronic computers. It was built by Moore School of Electrical Engineering at the University of Pennsylvania. Along with ORDVAC, it was a successor to the ENIAC. ...

he USA's initiative but in his own universal machine" (Hodges p. 318). Arguments still continue concerning the origin and nature of what has been named by Kleene (1952) Turing's Thesis. But what Turing ''did prove'' with his computational-machine model appears in his paper "" (1937):

Turing's example (his second proof): If one is to ask for a general procedure to tell us: "Does this machine ever print 0", the question is "undecidable".

1937–1970: The "digital computer", the birth of "computer science"

In 1937, while at Princeton working on his PhD thesis, Turing built a digital (Boolean-logic) multiplier from scratch, making his own electromechanical relays

A relay

Electromechanical relay schematic showing a control coil, four pairs of normally open and one pair of normally closed contacts

An automotive-style miniature relay with the dust cover taken off

A relay is an electrically operated switc ...

(Hodges p. 138). "Alan's task was to embody the logical design of a Turing machine in a network of relay-operated switches ..." (Hodges p. 138). While Turing might have been just initially curious and experimenting, quite-earnest work in the same direction was going in Germany (Konrad Zuse

Konrad Ernst Otto Zuse (; ; 22 June 1910 – 18 December 1995) was a German civil engineer, List of pioneers in computer science, pioneering computer scientist, inventor and businessman. His greatest achievement was the world's first programm ...

(1938)), and in the United States (Howard Aiken

Howard Hathaway Aiken (March 8, 1900 – March 14, 1973) was an American physicist and a list of pioneers in computer science, pioneer in computing. He was the original conceptual designer behind IBM's Harvard Mark I, the United States' first C ...

) and George Stibitz

George Robert Stibitz (April 30, 1904 – January 31, 1995) was an American researcher at Bell Labs who is internationally recognized as one of the fathers of the modern digital computer. He was known for his work in the 1930s and 1940s on the r ...

(1937); the fruits of their labors were used by both the Axis and Allied militaries in World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

(cf. Hodges p. 298–299). In the early to mid-1950s Hao Wang and Marvin Minsky

Marvin Lee Minsky (August 9, 1927 – January 24, 2016) was an American cognitive scientist, cognitive and computer scientist concerned largely with research in artificial intelligence (AI). He co-founded the Massachusetts Institute of Technology ...

reduced the Turing machine to a simpler form (a precursor to the Post–Turing machine

A Post machine or Post–Turing machineRajendra Kumar, ''Theory of Automata'', Tata McGraw-Hill Education, 2010, p. 343. is a "program formulation" of a type of Turing machine, comprising a variant of Emil Post's Turing-equivalent model of comput ...

of Martin Davis); simultaneously European researchers were reducing the new-fangled electronic computer

A computer is a machine that can be programmed to automatically carry out sequences of arithmetic or logical operations (''computation''). Modern digital electronic computers can perform generic sets of operations known as ''programs'', wh ...

to a computer-like theoretical object equivalent to what was now being called a "Turing machine". In the late 1950s and early 1960s, the coincidentally parallel developments of Melzak and Lambek (1961), Minsky (1961), and Shepherdson and Sturgis (1961) carried the European work further and reduced the Turing machine to a more friendly, computer-like abstract model called the counter machine

A counter machine or counter automaton is an abstract machine used in a formal logic and theoretical computer science to model computation. It is the most primitive of the four types of register machines. A counter machine comprises a set of on ...

; Elgot and Robinson (1964), Hartmanis (1971), Cook and Reckhow (1973) carried this work even further with the register machine

In mathematical logic and theoretical computer science, a register machine is a generic class of abstract machines, analogous to a Turing machine and thus Turing complete. Unlike a Turing machine that uses a tape and head, a register machine u ...

and random-access machine

In computer science, random-access machine (RAM or RA-machine) is a model of computation that describes an abstract machine in the general class of register machines. The RA-machine is very similar to the counter machine but with the added capab ...

models—but basically all are just multi-tape Turing machines with an arithmetic-like instruction set.

1970–present: as a model of computation

Today, the counter, register and random-access machines and their sire the Turing machine continue to be the models of choice for theorists investigating questions in the theory of computation

In theoretical computer science and mathematics, the theory of computation is the branch that deals with what problems can be solved on a model of computation, using an algorithm, how efficiently they can be solved or to what degree (e.g., app ...

. In particular, computational complexity theory

In theoretical computer science and mathematics, computational complexity theory focuses on classifying computational problems according to their resource usage, and explores the relationships between these classifications. A computational problem ...

makes use of the Turing machine:

See also

* Arithmetical hierarchy

In mathematical logic, the arithmetical hierarchy, arithmetic hierarchy or Kleene–Mostowski hierarchy (after mathematicians Stephen Cole Kleene and Andrzej Mostowski) classifies certain sets based on the complexity of formulas that define th ...

* Bekenstein bound, showing the impossibility of infinite-tape Turing machines of finite size and bounded energy

* BlooP and FlooP

* Chaitin's constant

In the computer science subfield of algorithmic information theory, a Chaitin constant (Chaitin omega number) or halting probability is a real number that, informally speaking, represents the probability that a randomly constructed program will ...

or Omega (computer science) for information relating to the halting problem

* Chinese room

The Chinese room argument holds that a computer executing a program cannot have a mind, understanding, or consciousness, regardless of how intelligently or human-like the program may make the computer behave. The argument was presented in a 19 ...

* Conway's Game of Life

The Game of Life, also known as Conway's Game of Life or simply Life, is a cellular automaton devised by the British mathematician John Horton Conway in 1970. It is a zero-player game, meaning that its evolution is determined by its initial ...

, a Turing-complete cellular automaton

* Digital infinity

Digital infinity is a technical term in theoretical linguistics. Alternative formulations are "discrete infinity" and "the infinite use of finite means". The idea is that all human languages follow a simple logical principle, according to which a l ...

* ''The Emperor's New Mind

''The Emperor's New Mind: Concerning Computers, Minds and The Laws of Physics'' is a 1989 book by the mathematical physicist Roger Penrose.

Penrose argues that human consciousness is non-algorithmic, and thus is not capable of being modeled by ...

''

* Enumerator (in theoretical computer science)

* Genetix

* '' Gödel, Escher, Bach: An Eternal Golden Braid'', a famous book that discusses, among other topics, the Church–Turing thesis

* Halting problem

In computability theory (computer science), computability theory, the halting problem is the problem of determining, from a description of an arbitrary computer program and an input, whether the program will finish running, or continue to run for ...

, for more references

* Harvard architecture

The Harvard architecture is a computer architecture with separate computer storage, storage and signal pathways for Machine code, instructions and data. It is often contrasted with the von Neumann architecture, where program instructions and d ...

* Imperative programming

In computer science, imperative programming is a programming paradigm of software that uses Statement (computer science), statements that change a program's state (computer science), state. In much the same way that the imperative mood in natural ...

* Langton's ant and Turmites, simple two-dimensional analogues of the Turing machine

* List of things named after Alan Turing

* Modified Harvard architecture

A modified Harvard architecture is a variation of the Harvard computer architecture that, unlike the pure Harvard architecture, allows memory that contains instructions to be accessed as data. Most modern computers that are documented as Harvar ...

* Quantum Turing machine

A quantum Turing machine (QTM) or universal quantum computer is an abstract machine used to model the effects of a quantum computer. It provides a simple model that captures all of the power of quantum computation—that is, any quantum algorith ...

* Claude Shannon

Claude Elwood Shannon (April 30, 1916 – February 24, 2001) was an American mathematician, electrical engineer, computer scientist, cryptographer and inventor known as the "father of information theory" and the man who laid the foundations of th ...

, another leading thinker in information theory

* Turing machine examples

* Turing tarpit

A Turing tarpit (or Turing tar-pit) is any programming language or computer interface that allows for flexibility in function but is difficult to learn and use because it offers little or no support for common tasks. The phrase was coined in 198 ...

, any computing system or language that, despite being Turing complete, is generally considered useless for practical computing

* Unorganised machine, for Turing's very early ideas on neural networks

* Von Neumann architecture

The von Neumann architecture—also known as the von Neumann model or Princeton architecture—is a computer architecture based on the '' First Draft of a Report on the EDVAC'', written by John von Neumann in 1945, describing designs discus ...

Notes

References

Primary literature, reprints, and compilations

* B. Jack Copeland

Brian Jack Copeland (born 1950) is Professor of Philosophy at the University of Canterbury, Christchurch, New Zealand, and author of books on the computing pioneer Alan Turing.

Education

Copeland was educated at the University of Oxford, obt ...

ed. (2004), ''The Essential Turing: Seminal Writings in Computing, Logic, Philosophy, Artificial Intelligence, and Artificial Life plus The Secrets of Enigma,'' Clarendon Press (Oxford University Press), Oxford UK, . Contains the Turing papers plus a draft letter to Emil Post

Emil Leon Post (; February 11, 1897 – April 21, 1954) was an American mathematician and logician. He is best known for his work in the field that eventually became known as computability theory.

Life

Post was born in Augustów, Suwałki Govern ...

re his criticism of "Turing's convention", and Donald W. Davies' ''Corrections to Turing's Universal Computing Machine''

* Martin Davis (ed.) (1965), ''The Undecidable'', Raven Press, Hewlett, NY.

* Emil Post (1936), "Finite Combinatory Processes—Formulation 1", ''Journal of Symbolic Logic'', 1, 103–105, 1936. Reprinted in ''The Undecidable'', pp. 289ff.

* Emil Post (1947), "Recursive Unsolvability of a Problem of Thue", ''Journal of Symbolic Logic'', vol. 12, pp. 1–11. Reprinted in ''The Undecidable'', pp. 293ff. In the Appendix of this paper Post comments on and gives corrections to Turing's paper of 1936–1937. In particular see the footnotes 11 with corrections to the universal computing machine coding and footnote 14 with comments on Turing's first and second proofs.

*

* Reprinted in ''The Undecidable'', pp. 115–154.

* Alan Turing, 1948, "Intelligent Machinery." Reprinted in "Cybernetics: Key Papers." Ed. C.R. Evans and A.D.J. Robertson. Baltimore: University Park Press, 1968. p. 31. Reprinted in

* F. C. Hennie and R. E. Stearns. ''Two-tape simulation of multitape Turing machines''. JACM, 13(4):533–546, 1966.

Computability theory

*

* Some parts have been significantly rewritten by Burgess. Presentation of Turing machines in context of Lambek "abacus machines" (cf. Register machine

In mathematical logic and theoretical computer science, a register machine is a generic class of abstract machines, analogous to a Turing machine and thus Turing complete. Unlike a Turing machine that uses a tape and head, a register machine u ...

) and recursive functions, showing their equivalence.

* Taylor L. Booth (1967), ''Sequential Machines and Automata Theory'', John Wiley and Sons, Inc., New York. Graduate level engineering text; ranges over a wide variety of topics, Chapter IX ''Turing Machines'' includes some recursion theory.

* . On pages 12–20 he gives examples of 5-tuple tables for Addition, The Successor Function, Subtraction (x ≥ y), Proper Subtraction (0 if x < y), The Identity Function and various identity functions, and Multiplication.

*

* . On pages 90–103 Hennie discusses the UTM with examples and flow-charts, but no actual 'code'.

* Centered around the issues of machine-interpretation of "languages", NP-completeness, etc.

*

* Stephen Kleene

Stephen Cole Kleene ( ; January 5, 1909 – January 25, 1994) was an American mathematician. One of the students of Alonzo Church, Kleene, along with Rózsa Péter, Alan Turing, Emil Post, and others, is best known as a founder of the branch of ...

(1952), ''Introduction to Metamathematics'', North–Holland Publishing Company, Amsterdam Netherlands, 10th impression (with corrections of 6th reprint 1971). Graduate level text; most of Chapter XIII ''Computable functions'' is on Turing machine proofs of computability of recursive functions, etc.

* . With reference to the role of Turing machines in the development of computation (both hardware and software) see 1.4.5 ''History and Bibliography'' pp. 225ff and 2.6 ''History and Bibliography''pp. 456ff.

* Zohar Manna, 1974, '' Mathematical Theory of Computation''. Reprinted, Dover, 2003.

* Marvin Minsky

Marvin Lee Minsky (August 9, 1927 – January 24, 2016) was an American cognitive scientist, cognitive and computer scientist concerned largely with research in artificial intelligence (AI). He co-founded the Massachusetts Institute of Technology ...

, ''Computation: Finite and Infinite Machines'', Prentice–Hall, Inc., N.J., 1967. See Chapter 8, Section 8.2 "Unsolvability of the Halting Problem."

* Chapter 2: Turing machines, pp. 19–56.

* Hartley Rogers, Jr.

Hartley Rogers Jr. (July 6, 1926 – July 17, 2015) was an American mathematician who worked in computability theory, and was a professor in the MIT Mathematics Department, Mathematics Department of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Biogr ...

, ''Theory of Recursive Functions and Effective Computability'', The MIT Press, Cambridge MA, paperback edition 1987, original McGraw-Hill edition 1967, (pbk.)

* Chapter 3: The Church–Turing Thesis, pp. 125–149.

*

* Peter van Emde Boas 1990, ''Machine Models and Simulations'', pp. 3–66, in Jan van Leeuwen

Jan van Leeuwen (born 17 December 1946 in Waddinxveen) is a Dutch computer scientist and emeritus professor of computer science at the Department of Information and Computing Sciences at Utrecht University. , ed., ''Handbook of Theoretical Computer Science, Volume A: Algorithms and Complexity'', The MIT Press/Elsevier, lace? (Volume A). QA76.H279 1990.

Church's thesis

*

*

Small Turing machines

* Rogozhin, Yurii, 1998,

A Universal Turing Machine with 22 States and 2 Symbols

, ''Romanian Journal of Information Science and Technology'', 1(3), 259–265, 1998. (surveys known results about small universal Turing machines)

* Stephen Wolfram

Stephen Wolfram ( ; born 29 August 1959) is a British-American computer scientist, physicist, and businessman. He is known for his work in computer algebra and theoretical physics. In 2012, he was named a fellow of the American Mathematical So ...

, 2002

''A New Kind of Science''

Wolfram Media,

* Brunfiel, Geoff

''Nature'', October 24. 2007.

* Jim Giles (2007)

New Scientist, October 24, 2007.

* Alex Smith

Universality of Wolfram's 2, 3 Turing Machine

Submission for the Wolfram 2, 3 Turing Machine Research Prize.

* Vaughan Pratt, 2007,

, FOM email list. October 29, 2007.

* Martin Davis, 2007,

, an

FOM email list. October 26–27, 2007.

* Alasdair Urquhart, 2007

, FOM email list. October 26, 2007.

* Hector Zenil (Wolfram Research), 2007

, FOM email list. October 29, 2007.

* Todd Rowland, 2007,

Confusion on FOM

, Wolfram Science message board, October 30, 2007.

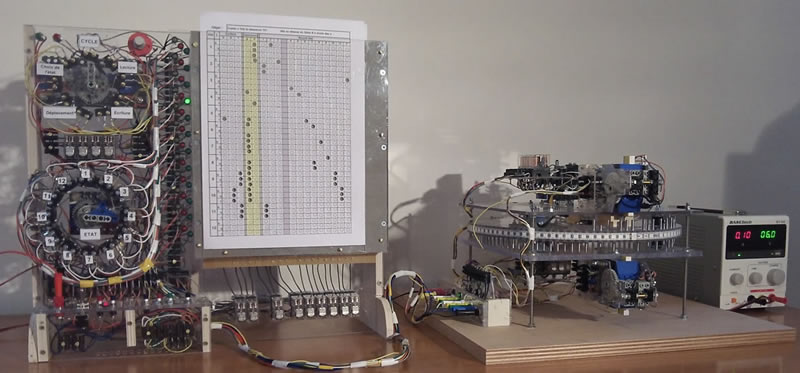

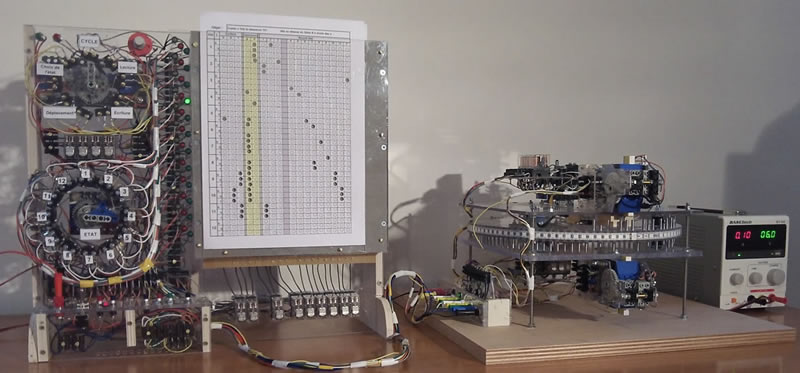

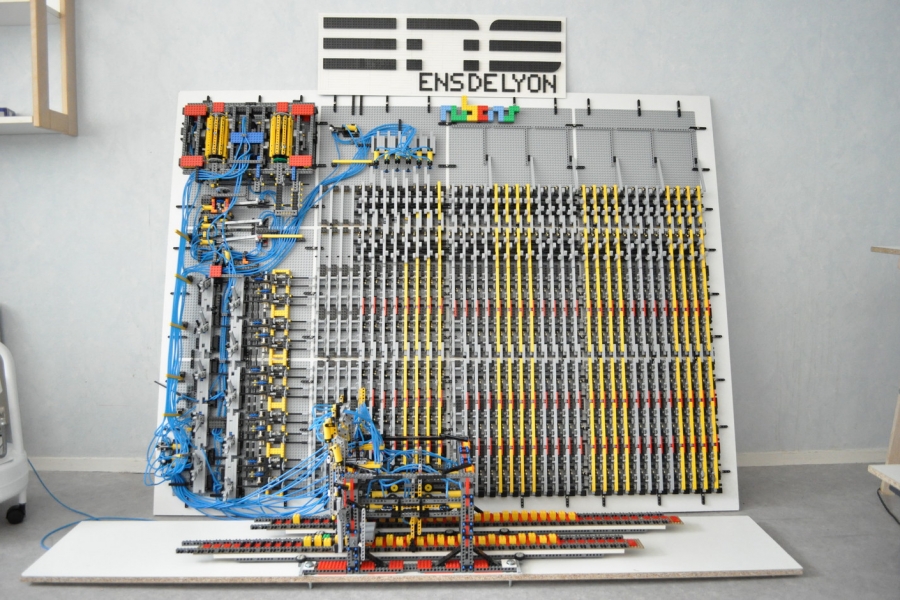

* Olivier and Marc RAYNAUD, 2014

A programmable prototype to achieve Turing machines

" LIMOS Laboratory of Blaise Pascal University (Clermont-Ferrand in France).

Other

*

* Robin Gandy

Robin Oliver Gandy (22 September 1919 – 20 November 1995) was a British mathematician and logician. He was a friend, student, and associate of Alan Turing, having been supervised by Turing during his PhD at the University of Cambridge, where ...

, "The Confluence of Ideas in 1936", pp. 51–102 in Rolf Herken, see below.

* Stephen Hawking

Stephen William Hawking (8January 194214March 2018) was an English theoretical physics, theoretical physicist, cosmologist, and author who was director of research at the Centre for Theoretical Cosmology at the University of Cambridge. Between ...

(editor), 2005, ''God Created the Integers: The Mathematical Breakthroughs that Changed History'', Running Press, Philadelphia, . Includes Turing's 1936–1937 paper, with brief commentary and biography of Turing as written by Hawking.

*

* Andrew Hodges

Andrew Philip Hodges ( ; born 1949) is a British mathematician, author and emeritus senior research fellow at Wadham College, Oxford.

Education

Hodges was born in London in 1949 and educated at Birkbeck, University of London, where he was award ...

, '' Alan Turing: The Enigma'', Simon and Schuster

Simon & Schuster LLC (, ) is an American publishing house owned by Kohlberg Kravis Roberts since 2023. It was founded in New York City in 1924, by Richard L. Simon and M. Lincoln Schuster. Along with Penguin Random House, Hachette Book Group US ...

, New York. Cf. Chapter "The Spirit of Truth" for a history leading to, and a discussion of, his proof.

*

* Roger Penrose

Sir Roger Penrose (born 8 August 1931) is an English mathematician, mathematical physicist, Philosophy of science, philosopher of science and Nobel Prize in Physics, Nobel Laureate in Physics. He is Emeritus Rouse Ball Professor of Mathematics i ...

, ''The Emperor's New Mind: Concerning Computers, Minds, and the Laws of Physics'', Oxford University Press