The

evolution

Evolution is change in the heritable characteristics of biological populations over successive generations. These characteristics are the expressions of genes, which are passed on from parent to offspring during reproduction. Variation ...

of

mammals

Mammals () are a group of vertebrate animals constituting the class Mammalia (), characterized by the presence of mammary glands which in females produce milk for feeding (nursing) their young, a neocortex (a region of the brain), fur o ...

has passed through many stages since the first appearance of their

synapsid

Synapsids + (, 'arch') > () "having a fused arch"; synonymous with ''theropsids'' (Greek, "beast-face") are one of the two major groups of animals that evolved from basal amniotes, the other being the sauropsids, the group that includes reptil ...

ancestors in the

Pennsylvanian sub-period of the late

Carboniferous

The Carboniferous ( ) is a geologic period and system of the Paleozoic that spans 60 million years from the end of the Devonian Period million years ago ( Mya), to the beginning of the Permian Period, million years ago. The name ''Carboniferou ...

period. By the mid-

Triassic

The Triassic ( ) is a geologic period and system which spans 50.6 million years from the end of the Permian Period 251.902 million years ago ( Mya), to the beginning of the Jurassic Period 201.36 Mya. The Triassic is the first and shortest per ...

, there were many synapsid species that looked like mammals. The lineage leading to today's mammals split up in the

Jurassic

The Jurassic ( ) is a geologic period and stratigraphic system that spanned from the end of the Triassic Period million years ago (Mya) to the beginning of the Cretaceous Period, approximately Mya. The Jurassic constitutes the middle period of ...

; synapsids from this period include ''

Dryolestes'', more closely related to extant

placental

Placental mammals (infraclass Placentalia ) are one of the three extant subdivisions of the class Mammalia, the other two being Monotremata and Marsupialia. Placentalia contains the vast majority of extant mammals, which are partly distinguishe ...

s and

marsupial

Marsupials are any members of the mammalian infraclass Marsupialia. All extant marsupials are endemic to Australasia, Wallacea and the Americas. A distinctive characteristic common to most of these species is that the young are carried in ...

s than to

monotreme

Monotremes () are prototherian mammals of the order Monotremata. They are one of the three groups of living mammals, along with placentals ( Eutheria), and marsupials (Metatheria). Monotremes are typified by structural differences in their brai ...

s, as well as ''

Ambondro'', more closely related to monotremes. Later on, the

eutheria

Eutheria (; from Greek , 'good, right' and , 'beast'; ) is the clade consisting of all therian mammals that are more closely related to placentals than to marsupials.

Eutherians are distinguished from noneutherians by various phenotypic tra ...

n and

metatheria

Metatheria is a mammalian clade that includes all mammals more closely related to marsupials than to placentals. First proposed by Thomas Henry Huxley in 1880, it is a more inclusive group than the marsupials; it contains all marsupials as w ...

n lineages separated; the metatherians are the animals more closely related to the marsupials, while the eutherians are those more closely related to the placentals. Since ''

Juramaia'', the earliest known eutherian, lived 160 million years ago in the Jurassic, this divergence must have occurred in the same period.

After the

Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event

The Cretaceous–Paleogene (K–Pg) extinction event (also known as the Cretaceous–Tertiary extinction) was a sudden mass extinction of three-quarters of the plant and animal species on Earth, approximately 66 million years ago. With the ...

wiped out the non-avian dinosaurs (

birds

Birds are a group of warm-blooded vertebrates constituting the class Aves (), characterised by feathers, toothless beaked jaws, the laying of hard-shelled eggs, a high metabolic rate, a four-chambered heart, and a strong yet lightweigh ...

being the only surviving dinosaurs) and several mammalian groups, placental and marsupial mammals diversified into many new forms and ecological niches throughout the

Paleogene

The Paleogene ( ; also spelled Palaeogene or Palæogene; informally Lower Tertiary or Early Tertiary) is a geologic period and system that spans 43 million years from the end of the Cretaceous Period million years ago ( Mya) to the beginning o ...

and

Neogene

The Neogene ( ), informally Upper Tertiary or Late Tertiary, is a geologic period and system that spans 20.45 million years from the end of the Paleogene Period million years ago ( Mya) to the beginning of the present Quaternary Period Mya. ...

, by the end of which all modern

orders

Order, ORDER or Orders may refer to:

* Categorization, the process in which ideas and objects are recognized, differentiated, and understood

* Heterarchy, a system of organization wherein the elements have the potential to be ranked a number of ...

had appeared.

The synapsid lineage became distinct from the

sauropsid

Sauropsida ("lizard faces") is a clade of amniotes, broadly equivalent to the class Reptilia. Sauropsida is the sister taxon to Synapsida, the other clade of amniotes which includes mammals as its only modern representatives. Although early syn ...

lineage in the late Carboniferous period, between 320 and 315 million years ago.

The only living synapsids are mammals, while the sauropsids gave rise to the

dinosaurs

Dinosaurs are a diverse group of reptiles of the clade Dinosauria. They first appeared during the Triassic period, between 243 and 233.23 million years ago (mya), although the exact origin and timing of the evolution of dinosaurs is the ...

, and today's reptiles and birds along with all the extinct amniotes more closely related to them than to mammals.

Primitive synapsids were traditionally called

mammal-like reptiles

Pelycosaur ( ) is an older term for basal or primitive Late Paleozoic synapsids, excluding the therapsids and their descendants. Previously, the term ''mammal-like reptile'' had been used, and pelycosaur was considered an order, but this is ...

or

pelycosaur

Pelycosaur ( ) is an older term for basal or primitive Late Paleozoic synapsids, excluding the therapsids and their descendants. Previously, the term ''mammal-like reptile'' had been used, and pelycosaur was considered an order, but this is ...

s, but both are now seen as outdated and disfavored

paraphyletic

In taxonomy, a group is paraphyletic if it consists of the group's last common ancestor and most of its descendants, excluding a few monophyletic subgroups. The group is said to be paraphyletic ''with respect to'' the excluded subgroups. In ...

terms, since they were not reptiles, nor part of reptile lineage. The modern term for these is stem mammals, and sometimes protomammals or paramammals.

Throughout the

Permian

The Permian ( ) is a geologic period and stratigraphic system which spans 47 million years from the end of the Carboniferous Period million years ago (Mya), to the beginning of the Triassic Period 251.9 Mya. It is the last period of the Paleo ...

period, the synapsids included the dominant

carnivore

A carnivore , or meat-eater (Latin, ''caro'', genitive ''carnis'', meaning meat or "flesh" and ''vorare'' meaning "to devour"), is an animal or plant whose food and energy requirements derive from animal tissues (mainly muscle, fat and other s ...

s and several important

herbivore

A herbivore is an animal anatomically and physiologically adapted to eating plant material, for example foliage or marine algae, for the main component of its diet. As a result of their plant diet, herbivorous animals typically have mouthpar ...

s. In the subsequent Triassic period, however, a previously obscure group of sauropsids, the

archosaur

Archosauria () is a clade of diapsids, with birds and crocodilians as the only living representatives. Archosaurs are broadly classified as reptiles, in the cladistic sense of the term which includes birds. Extinct archosaurs include non-avia ...

s, became the dominant vertebrates. The

mammaliaforms appeared during this period; their superior sense of smell, backed up by a large brain, facilitated entry into nocturnal niches with less exposure to archosaur predation. The nocturnal lifestyle may have contributed greatly to the development of mammalian traits such as

endothermy

An endotherm (from Greek ἔνδον ''endon'' "within" and θέρμη ''thermē'' "heat") is an organism that maintains its body at a metabolically favorable temperature, largely by the use of heat released by its internal bodily functions inste ...

and

hair

Hair is a protein filament that grows from follicles found in the dermis. Hair is one of the defining characteristics of mammals.

The human body, apart from areas of glabrous skin, is covered in follicles which produce thick terminal and fi ...

. Later in the

Mesozoic

The Mesozoic Era ( ), also called the Age of Reptiles, the Age of Conifers, and colloquially as the Age of the Dinosaurs is the second-to-last era of Earth's geological history, lasting from about , comprising the Triassic, Jurassic and Cretace ...

, after

theropod dinosaurs

Theropoda (; ), whose members are known as theropods, is a dinosaur clade that is characterized by hollow bones and three toes and claws on each limb. Theropods are generally classed as a group of saurischian dinosaurs. They were ancestrally c ...

replaced

rauisuchians as the dominant carnivores, mammals spread into other

ecological niche

In ecology, a niche is the match of a species to a specific environmental condition.

Three variants of ecological niche are described by

It describes how an organism or population responds to the distribution of resources and competitors (for ...

s. For example, some became

aquatic, some were

gliders, and some even

fed on juvenile dinosaurs.

Most of the evidence consists of

fossils

A fossil (from Classical Latin , ) is any preserved remains, impression, or trace of any once-living thing from a past geological age. Examples include bones, shells, exoskeletons, stone imprints of animals or microbes, objects preserved ...

. For many years, fossils of Mesozoic mammals and their immediate ancestors were very rare and fragmentary; but, since the mid-1990s, there have been many important new finds, especially in China. The relatively new techniques of

molecular phylogenetics

Molecular phylogenetics () is the branch of phylogeny that analyzes genetic, hereditary molecular differences, predominantly in DNA sequences, to gain information on an organism's evolutionary relationships. From these analyses, it is possible to ...

have also shed light on some aspects of mammalian evolution by estimating the timing of important divergence points for modern species. When used carefully, these techniques often, but not always, agree with the fossil record.

Although

mammary glands are a signature feature of modern mammals, little is known about the evolution of

lactation

Lactation describes the secretion of milk from the mammary glands and the period of time that a mother lactates to feed her young. The process naturally occurs with all sexually mature female mammals, although it may predate mammals. The proces ...

as these soft tissues are not often preserved in the fossil record. Most research concerning the evolution of mammals centers on the shapes of the teeth, the hardest parts of the

tetrapod

Tetrapods (; ) are four-limbed vertebrate animals constituting the superclass Tetrapoda (). It includes extant and extinct amphibians, sauropsids ( reptiles, including dinosaurs and therefore birds) and synapsids ( pelycosaurs, extinct t ...

body. Other important research characteristics include the evolution of the

middle ear bones, erect limb posture, a bony secondary

palate

The palate () is the roof of the mouth in humans and other mammals. It separates the oral cavity from the nasal cavity.

A similar structure is found in crocodilians, but in most other tetrapods, the oral and nasal cavities are not truly sepa ...

,

fur

Fur is a thick growth of hair that covers the skin of mammals. It consists of a combination of oily guard hair on top and thick underfur beneath. The guard hair keeps moisture from reaching the skin; the underfur acts as an insulating blanket t ...

, hair, and

warm-blooded

Warm-blooded is an informal term referring to animal species which can maintain a body temperature higher than their environment. In particular, homeothermic species maintain a stable body temperature by regulating metabolic processes. The onl ...

ness.

Definition of "mammal"

While living mammal species can be identified by the presence of milk-producing

mammary gland

A mammary gland is an exocrine gland in humans and other mammals that produces milk to feed young offspring. Mammals get their name from the Latin word ''mamma'', "breast". The mammary glands are arranged in organs such as the breasts in primat ...

s in the females, other features are required when classifying

fossils

A fossil (from Classical Latin , ) is any preserved remains, impression, or trace of any once-living thing from a past geological age. Examples include bones, shells, exoskeletons, stone imprints of animals or microbes, objects preserved ...

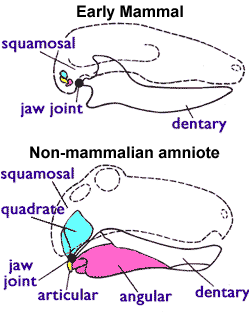

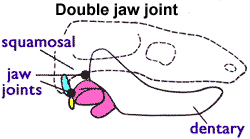

, because mammary glands and other soft-tissue features are not visible in fossils.

One such feature available for

paleontology

Paleontology (), also spelled palaeontology or palæontology, is the scientific study of life that existed prior to, and sometimes including, the start of the Holocene epoch (roughly 11,700 years before present). It includes the study of fossi ...

, shared by all living mammals (including

monotremes

Monotremes () are prototherian mammals of the order Monotremata. They are one of the three groups of living mammals, along with placentals (Eutheria), and marsupials ( Metatheria). Monotremes are typified by structural differences in their br ...

), but not present in any of the early

Triassic

The Triassic ( ) is a geologic period and system which spans 50.6 million years from the end of the Permian Period 251.902 million years ago ( Mya), to the beginning of the Jurassic Period 201.36 Mya. The Triassic is the first and shortest per ...

therapsid

Therapsida is a major group of eupelycosaurian synapsids that includes mammals, their ancestors and relatives. Many of the traits today seen as unique to mammals had their origin within early therapsids, including limbs that were oriented more ...

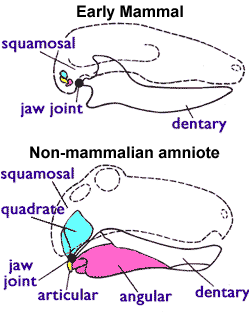

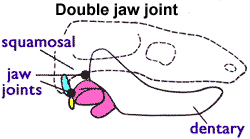

s, is shown in Figure 1 (on the right), namely: mammals use

two bones

2 (two) is a number, numeral and digit. It is the natural number following 1 and preceding 3. It is the smallest and only even prime number. Because it forms the basis of a duality, it has religious and spiritual significance in many cultur ...

for hearing that all other

amniotes

Amniotes are a clade of tetrapod vertebrates that comprises sauropsids (including all reptiles and birds, and extinct parareptiles and non-avian dinosaurs) and synapsids (including pelycosaurs and therapsids such as mammals). They are distingu ...

use for eating. The earliest amniotes had a jaw joint composed of the

articular

The articular bone is part of the lower jaw of most vertebrates, including most jawed fish, amphibians, birds and various kinds of reptiles, as well as ancestral mammals.

Anatomy

In most vertebrates, the articular bone is connected to two oth ...

(a small bone at the back of the lower jaw) and the

quadrate (a small bone at the back of the upper jaw). All non-mammalian

tetrapod

Tetrapods (; ) are four-limbed vertebrate animals constituting the superclass Tetrapoda (). It includes extant and extinct amphibians, sauropsids ( reptiles, including dinosaurs and therefore birds) and synapsids ( pelycosaurs, extinct t ...

s use this system including

amphibian

Amphibians are tetrapod, four-limbed and ectothermic vertebrates of the Class (biology), class Amphibia. All living amphibians belong to the group Lissamphibia. They inhabit a wide variety of habitats, with most species living within terres ...

s,

turtle

Turtles are an order of reptiles known as Testudines, characterized by a special shell developed mainly from their ribs. Modern turtles are divided into two major groups, the Pleurodira (side necked turtles) and Cryptodira (hidden necked tu ...

s,

lizard

Lizards are a widespread group of squamate reptiles, with over 7,000 species, ranging across all continents except Antarctica, as well as most oceanic island chains. The group is paraphyletic since it excludes the snakes and Amphisbaenia alt ...

s,

snake

Snakes are elongated, Limbless vertebrate, limbless, carnivore, carnivorous reptiles of the suborder Serpentes . Like all other Squamata, squamates, snakes are ectothermic, amniote vertebrates covered in overlapping Scale (zoology), scales. Ma ...

s,

crocodilia

Crocodilia (or Crocodylia, both ) is an order of mostly large, predatory, semiaquatic reptiles, known as crocodilians. They first appeared 95 million years ago in the Late Cretaceous period ( Cenomanian stage) and are the closest living ...

ns,

dinosaur

Dinosaurs are a diverse group of reptiles of the clade Dinosauria. They first appeared during the Triassic period, between 243 and 233.23 million years ago (mya), although the exact origin and timing of the evolution of dinosaurs is t ...

s (including the

birds

Birds are a group of warm-blooded vertebrates constituting the class Aves (), characterised by feathers, toothless beaked jaws, the laying of hard-shelled eggs, a high metabolic rate, a four-chambered heart, and a strong yet lightweigh ...

),

ichthyosaur

Ichthyosaurs (Ancient Greek for "fish lizard" – and ) are large extinct marine reptiles. Ichthyosaurs belong to the order known as Ichthyosauria or Ichthyopterygia ('fish flippers' – a designation introduced by Sir Richard Owen in 1842, altho ...

s,

pterosaur

Pterosaurs (; from Greek ''pteron'' and ''sauros'', meaning "wing lizard") is an extinct clade of flying reptiles in the order, Pterosauria. They existed during most of the Mesozoic: from the Late Triassic to the end of the Cretaceous (228 to ...

s and therapsids. But mammals have a different jaw joint, composed only of the

dentary

In anatomy, the mandible, lower jaw or jawbone is the largest, strongest and lowest bone in the human facial skeleton. It forms the lower jaw and holds the lower tooth, teeth in place. The mandible sits beneath the maxilla. It is the only movabl ...

(the lower jaw bone, which carries the teeth) and the

squamosal The squamosal is a skull bone found in most reptiles, amphibians, and birds. In fishes, it is also called the pterotic bone.

In most tetrapods, the squamosal and quadratojugal bones form the cheek series of the skull. The bone forms an ancestral co ...

(another small skull bone). In the Jurassic, their quadrate and articular bones evolved into the

incus

The ''incus'' (plural incudes) or anvil is a bone in the middle ear. The anvil-shaped small bone is one of three ossicles in the middle ear. The ''incus'' receives vibrations from the ''malleus'', to which it is connected laterally, and transmit ...

and

malleus

The malleus, or hammer, is a hammer-shaped small bone or ossicle of the middle ear. It connects with the incus, and is attached to the inner surface of the eardrum. The word is Latin for 'hammer' or 'mallet'. It transmits the sound vibrations fro ...

bones in the

middle ear

The middle ear is the portion of the ear medial to the eardrum, and distal to the oval window of the cochlea (of the inner ear).

The mammalian middle ear contains three ossicles, which transfer the vibrations of the eardrum into waves in the ...

.

[Mammalia: Overview – Palaeos](_blank)

Mammals also have a double

occipital condyle

The occipital condyles are undersurface protuberances of the occipital bone in vertebrates, which function in articulation with the superior facets of the atlas vertebra.

The condyles are oval or reniform (kidney-shaped) in shape, and their anteri ...

; they have two knobs at the base of the skull that fit into the topmost neck vertebra, while other tetrapods have a single occipital condyle.

In a 1981 article, Kenneth A. Kermack and his co-authors argued for drawing the line between mammals and earlier synapsids at the point where the mammalian pattern of

molar occlusion

Occlusion may refer to:

Health and fitness

* Occlusion (dentistry), the manner in which the upper and lower teeth come together when the mouth is closed

* Occlusion miliaria, a skin condition

* Occlusive dressing, an air- and water-tight trauma ...

was being acquired and the dentary-squamosal joint had appeared. The criterion chosen, they noted, is merely a matter of convenience; their choice was based on the fact that "the lower jaw is the most likely skeletal element of a Mesozoic mammal to be preserved."

Today, most paleontologists consider that animals are mammals if they satisfy this criterion.

[

]

The ancestry of mammals

Amniotes

The first fully terrestrial vertebrate

Vertebrates () comprise all animal taxa within the subphylum Vertebrata () ( chordates with backbones), including all mammals, birds, reptiles, amphibians, and fish. Vertebrates represent the overwhelming majority of the phylum Chordata, ...

s were amniotes

Amniotes are a clade of tetrapod vertebrates that comprises sauropsids (including all reptiles and birds, and extinct parareptiles and non-avian dinosaurs) and synapsids (including pelycosaurs and therapsids such as mammals). They are distingu ...

— their eggs had internal membranes that allowed the developing embryo

An embryo is an initial stage of development of a multicellular organism. In organisms that reproduce sexually, embryonic development is the part of the life cycle that begins just after fertilization of the female egg cell by the male spe ...

to breathe but kept water in. This allowed amniotes to lay eggs on dry land, while amphibians generally need to lay their eggs in water (a few amphibians, such as the common Suriname toad

The common Surinam toad or star-fingered toad (''Pipa pipa'') is an purely aquatic species of frog in the family ''Pipidae'' with a widespread distribution in South America. The species is known for incubating its eggs in honeycombed chambers in ...

, have evolved

Evolution is change in the heritable characteristics of biological populations over successive generations. These characteristics are the expressions of genes, which are passed on from parent to offspring during reproduction. Variation ...

other ways of getting around this limitation). The first amniotes apparently arose in the middle Carboniferous

The Carboniferous ( ) is a geologic period and system of the Paleozoic that spans 60 million years from the end of the Devonian Period million years ago ( Mya), to the beginning of the Permian Period, million years ago. The name ''Carboniferou ...

from the ancestral reptiliomorph

Reptiliomorpha (meaning reptile-shaped; in PhyloCode known as ''Pan-Amniota'') is a clade containing the amniotes and those tetrapods that share a more recent common ancestor with amniotes than with living amphibians ( lissamphibians). It was de ...

s.[ Carroll R.L. (1991): The origin of reptiles. In: Schultze H.-P., Trueb L., (ed) ''Origins of the higher groups of tetrapods — controversy and consensus''. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, pp 331-353.]

Within a few million years, two important amniote lineages became distinct: synapsid

Synapsids + (, 'arch') > () "having a fused arch"; synonymous with ''theropsids'' (Greek, "beast-face") are one of the two major groups of animals that evolved from basal amniotes, the other being the sauropsids, the group that includes reptil ...

s, from which mammals are descended, and sauropsid

Sauropsida ("lizard faces") is a clade of amniotes, broadly equivalent to the class Reptilia. Sauropsida is the sister taxon to Synapsida, the other clade of amniotes which includes mammals as its only modern representatives. Although early syn ...

s, from which lizard

Lizards are a widespread group of squamate reptiles, with over 7,000 species, ranging across all continents except Antarctica, as well as most oceanic island chains. The group is paraphyletic since it excludes the snakes and Amphisbaenia alt ...

s, snakes, turtles/tortoises, crocodilians, dinosaurs, and birds are descended.[ The earliest known fossils of synapsids and sauropsids (such as '']Archaeothyris

''Archaeothyris'' is an extinct genus of ophiacodontid synapsid that lived during the Late Carboniferous and is known from Nova Scotia. Dated to 306 million years ago, ''Archaeothyris'', along with a more poorly known synapsid called '' Echinerpe ...

'' and ''Hylonomus

''Hylonomus'' (; ''hylo-'' "forest" + ''nomos'' "dweller") is an extinct genus of reptile that lived 312 million years ago during the Late Carboniferous period.

It is the earliest unquestionable reptile (''Westlothiana'' is older, but in fact it ...

'', respectively) date from about 320 to 315 million years ago. The times of origin are difficult to know, because vertebrate fossils from the late Carboniferous are very rare, and therefore the actual first occurrences of each of these types of animal might have been considerably earlier than the first fossil.

Synapsids

Synapsid

Synapsids + (, 'arch') > () "having a fused arch"; synonymous with ''theropsids'' (Greek, "beast-face") are one of the two major groups of animals that evolved from basal amniotes, the other being the sauropsids, the group that includes reptil ...

skulls are identified by the distinctive pattern of the holes behind each eye, which served the following purposes:

*made the skull lighter without sacrificing strength.

*saved energy by using less bone.

*probably provided attachment points for jaw muscles. Having attachment points further away from the jaw made it possible for the muscles to be longer and therefore to exert a strong pull over a wide range of jaw movement without being stretched or contracted beyond their optimum range.

A number of creatures often - and incorrectly - believed to be dinosaur

Dinosaurs are a diverse group of reptiles of the clade Dinosauria. They first appeared during the Triassic period, between 243 and 233.23 million years ago (mya), although the exact origin and timing of the evolution of dinosaurs is t ...

s, hence part of the reptile lineage and sauropsids, were in fact synapsids. This includes the well-known dimetrodon

''Dimetrodon'' ( or ,) meaning "two measures of teeth,” is an extinct genus of non-mammalian synapsid that lived during the Cisuralian (Early Permian), around 295–272 million years ago (Mya). It is a member of the family Sphenacodontid ...

.

Terms used for discussing non-mammalian synapsids

When referring to the ancestors and close relatives of mammals, paleontologists also use the following terms of convenience:

* Pelycosaur

Pelycosaur ( ) is an older term for basal or primitive Late Paleozoic synapsids, excluding the therapsids and their descendants. Previously, the term ''mammal-like reptile'' had been used, and pelycosaur was considered an order, but this is no ...

s — all synapsids, and all of their descendants, except for therapsid

Therapsida is a major group of eupelycosaurian synapsids that includes mammals, their ancestors and relatives. Many of the traits today seen as unique to mammals had their origin within early therapsids, including limbs that were oriented more ...

s - the eventual ancestor of mammals. The pelycosaurs included the largest land vertebrates of the Early Permian 01 or '01 may refer to:

* The year 2001, or any year ending with 01

* The month of January

* 1 (number)

Music

* '01 (Richard Müller album), 01'' (Richard Müller album), 2001

* 01 (Son of Dave album), ''01'' (Son of Dave album), 2000

* 01 (Urban ...

, such as the 6 m (20 ft) long '' Cotylorhynchus hancocki''. Among the other large pelycosaurs were '' Dimetrodon grandis'' and '' Edaphosaurus cruciger''.

* Stem mammals (sometimes called protomammals or paramammals, and previously incorrectly called mammal-like reptiles) — all synapsids, and all of their descendants, except for mammals themselves.paraphyletic

In taxonomy, a group is paraphyletic if it consists of the group's last common ancestor and most of its descendants, excluding a few monophyletic subgroups. The group is said to be paraphyletic ''with respect to'' the excluded subgroups. In ...

terms (and in the latter case also based on incorrect historical belief that mammals evolved from reptiles rather than in parallel to them), and for that reason are disfavored and outdated terms rarely used in modern literature.

Therapsids

Therapsid

Therapsida is a major group of eupelycosaurian synapsids that includes mammals, their ancestors and relatives. Many of the traits today seen as unique to mammals had their origin within early therapsids, including limbs that were oriented more ...

s descended from sphenacodonts, a primitive synapsid, in the middle Permian

The Guadalupian is the second and middle series/epoch of the Permian. The Guadalupian was preceded by the Cisuralian and followed by the Lopingian. It is named after the Guadalupe Mountains of New Mexico and Texas, and dates between 272.95 ± 0. ...

, and took over from them as the dominant land vertebrates. They differ from earlier synapsids in several features of the skull and jaws, including larger temporal fenestrae

The skull is a bone protective cavity for the brain. The skull is composed of four types of bone i.e., cranial bones, facial bones, ear ossicles and hyoid bone. However two parts are more prominent: the cranium and the mandible. In humans, the ...

and incisor

Incisors (from Latin ''incidere'', "to cut") are the front teeth present in most mammals. They are located in the premaxilla above and on the mandible below. Humans have a total of eight (two on each side, top and bottom). Opossums have 18, whe ...

s that are equal in size.cynodont

The cynodonts () (clade Cynodontia) are a clade of eutheriodont therapsids that first appeared in the Late Permian (approximately 260 mya), and extensively diversified after the Permian–Triassic extinction event. Cynodonts had a wide variety ...

s in the late Permian, some of which had begun to resemble early mammals:palate

The palate () is the roof of the mouth in humans and other mammals. It separates the oral cavity from the nasal cavity.

A similar structure is found in crocodilians, but in most other tetrapods, the oral and nasal cavities are not truly sepa ...

. Most books and articles interpret this as a prerequisite for the evolution of mammals' high metabolic rate

Metabolism (, from el, μεταβολή ''metabolē'', "change") is the set of life-sustaining chemical reactions in organisms. The three main functions of metabolism are: the conversion of the energy in food to energy available to run cell ...

, because it enabled these animals to eat and breathe at the same time. But some scientists point out that some modern ectotherm

An ectotherm (from the Greek () "outside" and () "heat") is an organism in which internal physiological sources of heat are of relatively small or of quite negligible importance in controlling body temperature.Davenport, John. Animal Life a ...

s use a fleshy secondary palate to separate the mouth from the airway, and that a ''bony'' palate provides a surface on which the tongue can manipulate food, facilitating chewing rather than breathing.dentary

In anatomy, the mandible, lower jaw or jawbone is the largest, strongest and lowest bone in the human facial skeleton. It forms the lower jaw and holds the lower tooth, teeth in place. The mandible sits beneath the maxilla. It is the only movabl ...

gradually becomes the main bone of the lower jaw.

*progress towards an erect limb posture, which would increase the animals' stamina by avoiding Carrier's constraint

Carrier's constraint is the observation that air-breathing vertebrates which have two lungs and flex their bodies sideways during locomotion find it very difficult to move and breathe at the same time, because the sideways flexing expands one lung ...

. But this process was erratic and very slow — for example: all herbivorous therapsids retained sprawling limbs (some late forms may have had semi-erect hind limbs); Permian carnivorous therapsids had sprawling forelimbs, and some late Permian ones also had semi-sprawling hindlimbs. In fact, modern monotreme

Monotremes () are prototherian mammals of the order Monotremata. They are one of the three groups of living mammals, along with placentals ( Eutheria), and marsupials (Metatheria). Monotremes are typified by structural differences in their brai ...

s still have semi-sprawling forelimbs.

Therapsid family tree

(Simplified from Palaeos.com.[ Only those that are most relevant to the evolution of mammals are described below.)

Only the dicynodonts, therocephalians, and cynodonts survived into the Triassic.

]

Biarmosuchia

The Biarmosuchia

Biarmosuchians are an extinct clade of non-mammalian synapsids from the Permian. They are the most basal group of the therapsids. All of them were moderately-sized, lightly-built carnivores, intermediate in form between basal sphenacodont "pelyc ...

were the most primitive and pelycosaur-like of the therapsids.

Dinocephalians

Dinocephalia

Dinocephalians (terrible heads) are a clade of large-bodied early therapsids that flourished in the Early and Middle Permian between 279.5 and 260 million years ago (Ma), but became extinct during the Capitanian mass extinction event. Dinoceph ...

ns ("terrible heads") included both carnivores and herbivores. They were large; ''Anteosaurus

''Anteosaurus'' (meaning "Antaeus reptile") is an extinct genus of large carnivorous dinocephalian synapsid. It lived at the end of the Guadalupian (= Middle Permian) during the Capitanian stage, about 265 to 260 million years ago in what is now ...

'' was up to 6 m (20 ft) long. Some of the carnivores had semi-erect hindlimbs, but all dinocephalians had sprawling forelimbs. In many ways they were very primitive therapsids; for example, they had no secondary palate and their jaws were rather "reptilian".

Anomodonts

The

The anomodonts

Anomodontia is an extinct group of non-mammalian therapsids from the Permian and Triassic periods. By far the most speciose group are the dicynodonts, a clade of beaked, tusked herbivores.Chinsamy-Turan, A. (2011) ''Forerunners of Mammals: R ...

("anomalous teeth") were among the most successful of the herbivorous therapsids — one sub-group, the dicynodont

Dicynodontia is an extinct clade of anomodonts, an extinct type of non-mammalian therapsid. Dicynodonts were herbivorous animals with a pair of tusks, hence their name, which means 'two dog tooth'. Members of the group possessed a horny, typicall ...

s, survived almost to the end of the Triassic. But anomodonts were very different from modern herbivorous mammals, as their only teeth were a pair of fangs in the upper jaw and it is generally agreed that they had beaks like those of birds or ceratopsian

Ceratopsia or Ceratopia ( or ; Greek: "horned faces") is a group of herbivorous, beaked dinosaurs that thrived in what are now North America, Europe, and Asia, during the Cretaceous Period, although ancestral forms lived earlier, in the Jurassic. ...

s.

Theriodonts

The theriodonts ("beast teeth") and their descendants had jaw joints in which the articular

The articular bone is part of the lower jaw of most vertebrates, including most jawed fish, amphibians, birds and various kinds of reptiles, as well as ancestral mammals.

Anatomy

In most vertebrates, the articular bone is connected to two oth ...

bone of the lower jaw tightly gripped the very small quadrate bone

The quadrate bone is a skull bone in most tetrapods, including amphibians, sauropsids (reptiles, birds), and early synapsids.

In most tetrapods, the quadrate bone connects to the quadratojugal and squamosal bones in the skull, and forms upper ...

of the skull. This allowed a much wider gape and allowed one group, the carnivorous gorgonopsia

Gorgonopsia (from the Greek Gorgon, a mythological beast, and 'aspect') is an extinct clade of sabre-toothed therapsids from the Middle to Upper Permian roughly 265 to 252 million years ago. They are characterised by a long and narrow skull, a ...

ns ("gorgon faces"), to develop "sabre teeth". However, the jaw hinge of the theriodont had a longer term significance — the much reduced size of the quadrate bone was an important step in the development of the mammalian jaw joint and middle ear.

The gorgonopsians still had some primitive features: no bony secondary palate (other bones in the right places perform the same functions); sprawling forelimbs; hindlimbs that could operate in both sprawling and erect postures. The therocephalia

Therocephalia is an extinct suborder of eutheriodont therapsids (mammals and their close relatives) from the Permian and Triassic. The therocephalians ("beast-heads") are named after their large skulls, which, along with the structure of their ...

ns ("beast heads"), which appear to have arisen at about the same time as the gorgonopsians, had additional mammal-like features, e.g. their finger and toe bones had the same number of phalanges (segments) as in early mammals (and the same number that primates

Primates are a diverse order of mammals. They are divided into the strepsirrhines, which include the lemurs, galagos, and lorisids, and the haplorhines, which include the tarsiers and the simians (monkeys and apes, the latter including huma ...

have, including humans).

Cynodonts

The

The cynodonts

The cynodonts () (clade Cynodontia) are a clade of eutheriodont therapsids that first appeared in the Late Permian (approximately 260 mya), and extensively diversified after the Permian–Triassic extinction event. Cynodonts had a wide variety ...

, a theriodont group that also arose in the late Permian

The Permian ( ) is a geologic period and stratigraphic system which spans 47 million years from the end of the Carboniferous Period million years ago (Mya), to the beginning of the Triassic Period 251.9 Mya. It is the last period of the Paleo ...

, include the ancestors of all mammals. Cynodonts' mammal-like features include further reduction in the number of bones in the lower jaw, a secondary bony palate, cheek teeth with a complex pattern in the crowns, and a brain which filled the endocranial cavity.flash flood

A flash flood is a rapid flooding of low-lying areas: washes, rivers, dry lakes and depressions. It may be caused by heavy rain associated with a severe thunderstorm, hurricane, or tropical storm, or by meltwater from ice or snow flowing o ...

. The extensive shared burrows indicate that these animals were capable of complex social behaviors.

Their primitive synapsid and therapsid ancestors were very large (between ) but cynodonts gradually decreased in size (to ) even before the Permian-Triassic extinction event, probably due to competition with other therapsids. After the extinction event, the probainognathian cynodont group rapidly decreased in size (to 4 in–1.5 ft (10–50 cm)) due to new competition with archosaurs

Archosauria () is a clade of diapsids, with birds and crocodilians as the only living representatives. Archosaurs are broadly classified as reptiles, in the cladistic sense of the term which includes birds. Extinct archosaurs include non-avi ...

and transitioned to nocturnality

Nocturnality is an animal behavior characterized by being active during the night and sleeping during the day. The common adjective is "nocturnal", versus diurnal meaning the opposite.

Nocturnal creatures generally have highly developed sens ...

, evolving nocturnal features, pulmonary alveoli

A pulmonary alveolus (plural: alveoli, from Latin ''alveolus'', "little cavity"), also known as an air sac or air space, is one of millions of hollow, distensible cup-shaped cavities in the lungs where oxygen is exchanged for carbon dioxide. A ...

, bronchioles

The bronchioles or bronchioli (pronounced ''bron-kee-oh-lee'') are the smaller branches of the bronchial airways in the lower respiratory tract. They include the terminal bronchioles, and finally the respiratory bronchioles that mark the start o ...

and a developed diaphragm for a larger surface area for breathing, enucleated erythrocytes

Red blood cells (RBCs), also referred to as red cells, red blood corpuscles (in humans or other animals not having nucleus in red blood cells), haematids, erythroid cells or erythrocytes (from Greek ''erythros'' for "red" and ''kytos'' for "holl ...

, a large intestine

The large intestine, also known as the large bowel, is the last part of the gastrointestinal tract and of the digestive system in tetrapods. Water is absorbed here and the remaining waste material is stored in the rectum as feces before being r ...

which bears a true colon after the cecum

The cecum or caecum is a pouch within the peritoneum that is considered to be the beginning of the large intestine. It is typically located on the right side of the body (the same side of the body as the appendix (anatomy), appendix, to which i ...

, endothermy

An endotherm (from Greek ἔνδον ''endon'' "within" and θέρμη ''thermē'' "heat") is an organism that maintains its body at a metabolically favorable temperature, largely by the use of heat released by its internal bodily functions inste ...

, a hairy, glandular and thermoregulatory skin (which releases sebum

A sebaceous gland is a microscopic exocrine gland in the skin that opens into a hair follicle to secrete an oily or waxy matter, called sebum, which lubricates the hair and skin of mammals. In humans, sebaceous glands occur in the greatest nu ...

and sweat

Perspiration, also known as sweating, is the production of fluids secreted by the sweat glands in the skin of mammals.

Two types of sweat glands can be found in humans: eccrine glands and apocrine glands. The eccrine sweat glands are distribut ...

), and a 4-chambered heart

The heart is a muscular organ in most animals. This organ pumps blood through the blood vessels of the circulatory system. The pumped blood carries oxygen and nutrients to the body, while carrying metabolic waste such as carbon dioxide t ...

to maintain their high metabolism, larger brains, and fully upright hindlimb (forelimbs remained semi sprawling, and became like that only later, in therians

Theria (; Greek: , wild beast) is a subclass of mammals amongst the Theriiformes. Theria includes the eutherians (including the placental mammals) and the metatherians (including the marsupials) but excludes the egg-laying monotremes.

C ...

). Some skin glands may have evolved into mammary glands in females for fulfilling the metabolic demands of their offspring (which increased 10 times). Many skeletal changes occurred also: the dentary

In anatomy, the mandible, lower jaw or jawbone is the largest, strongest and lowest bone in the human facial skeleton. It forms the lower jaw and holds the lower tooth, teeth in place. The mandible sits beneath the maxilla. It is the only movabl ...

bone became stronger and held differentiated teeth, the pair of nasal openings in the skull became fused. These evolutionary changes lead to the first mammals

Mammals () are a group of vertebrate animals constituting the class Mammalia (), characterized by the presence of mammary glands which in females produce milk for feeding (nursing) their young, a neocortex (a region of the brain), fur o ...

(size around ). They also adapted to a burrowing

An Eastern chipmunk at the entrance of its burrow

A burrow is a hole or tunnel excavated into the ground by an animal to construct a space suitable for habitation or temporary refuge, or as a byproduct of locomotion. Burrows provide a form of sh ...

lifestyle, losing their big tail-based leg muscles which allowed dinosaurs to become bipedal, and explains why bipedal mammals are so rare.

Triassic takeover

The catastrophic mass extinction at the end of the Permian, around 252 million years ago, killed off about 70 percent of terrestrial

Terrestrial refers to things related to land or the planet Earth.

Terrestrial may also refer to:

* Terrestrial animal, an animal that lives on land opposed to living in water, or sometimes an animal that lives on or near the ground, as opposed to ...

vertebrate

Vertebrates () comprise all animal taxa within the subphylum Vertebrata () ( chordates with backbones), including all mammals, birds, reptiles, amphibians, and fish. Vertebrates represent the overwhelming majority of the phylum Chordata, ...

species and the majority of land plants.

As a result,ecosystems

An ecosystem (or ecological system) consists of all the organisms and the physical environment with which they interact. These biotic and abiotic components are linked together through nutrient cycles and energy flows. Energy enters the syste ...

and food chains

A food chain is a linear network of links in a food web starting from producer organisms (such as grass or algae which produce their own food via photosynthesis) and ending at an apex predator species (like grizzly bears or killer whales), de ...

collapsed, and the establishment of new stable ecosystems took about 30 million years. With the disappearance of the gorgonopsians, which were dominant predators in the late Permian,archosaur

Archosauria () is a clade of diapsids, with birds and crocodilians as the only living representatives. Archosaurs are broadly classified as reptiles, in the cladistic sense of the term which includes birds. Extinct archosaurs include non-avia ...

s, which includes the ancestors of crocodilians and dinosaurs.

The archosaurs quickly became the dominant carnivores,nitrogenous waste

Metabolic wastes or excrements are substances left over from metabolic processes (such as cellular respiration) which cannot be used by the organism (they are surplus or toxic), and must therefore be excreted. This includes nitrogen compounds, ...

in a uric acid

Uric acid is a heterocyclic compound of carbon, nitrogen, oxygen, and hydrogen with the formula C5H4N4O3. It forms ions and salts known as urates and acid urates, such as ammonium acid urate. Uric acid is a product of the metabolic breakdown of ...

paste containing little water, while the cynodonts probably excreted most such waste in a solution of urea

Urea, also known as carbamide, is an organic compound with chemical formula . This amide has two amino groups (–) joined by a carbonyl functional group (–C(=O)–). It is thus the simplest amide of carbamic acid.

Urea serves an important r ...

, as mammals do today; considerable water is required to keep urea dissolved.

However, this theory has been questioned, since it implies synapsids were necessarily less advantaged in water retention, that synapsid decline coincides with climate changes or archosaur diversity (neither of which has been tested) and the fact that desert-dwelling mammals are as well adapted in this department as archosaurs, and some cynodonts like ''Trucidocynodon

''Trucidocynodon'' is an extinct genus of ecteniniid cynodonts from Upper Triassic of Brazil. It contains a single species, ''Trucidocynodon riograndensis''. Fossils of ''Trucidocynodon'' were discovered in Santa Maria Formation outcrops in Pal ...

'' were large-sized predators.

The Triassic takeover was probably a vital factor in the evolution of the mammals. Two groups stemming from the early cynodonts were successful in niches that had minimal competition from the archosaurs: the tritylodonts

Tritylodontidae ("three-knob teeth", named after the shape of their cheek teeth) is an extinct family of small to medium-sized, highly specialized mammal-like cynodonts, bearing several mammalian traits like erect limbs, endothermy and details o ...

, which were herbivore

A herbivore is an animal anatomically and physiologically adapted to eating plant material, for example foliage or marine algae, for the main component of its diet. As a result of their plant diet, herbivorous animals typically have mouthpar ...

s, and the mammals, most of which were small nocturnal insectivore

A robber fly eating a hoverfly

An insectivore is a carnivorous animal or plant that eats insects. An alternative term is entomophage, which can also refer to the human practice of eating insects.

The first vertebrate insectivores wer ...

s (although some, like ''Sinoconodon

''Sinoconodon'' is an extinct genus of mammaliamorphs that appears in the fossil record of the Lufeng Formation of China in the Sinemurian stage of the Early Jurassic period, about 193 million years ago. While sharing many plesiomorphic tra ...

'', were carnivores that fed on vertebrate prey, while still others were herbivores or omnivore

An omnivore () is an animal that has the ability to eat and survive on both plant and animal matter. Obtaining energy and nutrients from plant and animal matter, omnivores digest carbohydrates, protein, fat, and fiber, and metabolize the nutr ...

s). As a result:

*The therapsid trend towards differentiated teeth with precise occlusion

Occlusion may refer to:

Health and fitness

* Occlusion (dentistry), the manner in which the upper and lower teeth come together when the mouth is closed

* Occlusion miliaria, a skin condition

* Occlusive dressing, an air- and water-tight trauma ...

accelerated, because of the need to hold captured arthropod

Arthropods (, (gen. ποδός)) are invertebrate animals with an exoskeleton, a Segmentation (biology), segmented body, and paired jointed appendages. Arthropods form the phylum Arthropoda. They are distinguished by their jointed limbs and Arth ...

s and crush their exoskeleton

An exoskeleton (from Greek ''éxō'' "outer" and ''skeletós'' "skeleton") is an external skeleton that supports and protects an animal's body, in contrast to an internal skeleton (endoskeleton) in for example, a human. In usage, some of the ...

s.

*As the body length of the mammals' ancestors fell below 10.5 cm (4 inches), advances in thermal insulation

Thermal insulation is the reduction of heat transfer (i.e., the transfer of thermal energy between objects of differing temperature) between objects in thermal contact or in range of radiative influence. Thermal insulation can be achieved with s ...

and temperature regulation

Thermoregulation is the ability of an organism to keep its body temperature within certain boundaries, even when the surrounding temperature is very different. A thermoconforming organism, by contrast, simply adopts the surrounding temperature ...

would have become necessary for nocturnal life.monotremes

Monotremes () are prototherian mammals of the order Monotremata. They are one of the three groups of living mammals, along with placentals (Eutheria), and marsupials ( Metatheria). Monotremes are typified by structural differences in their br ...

and therians

Theria (; Greek: , wild beast) is a subclass of mammals amongst the Theriiformes. Theria includes the eutherians (including the placental mammals) and the metatherians (including the marsupials) but excludes the egg-laying monotremes.

C ...

).

**The increase in the size of the olfactory lobes of the brain increased brain weight as a percentage of total body weight. Brain tissue requires a disproportionate amount of energy. The need for more food to support the enlarged brains increased the pressures for improvements in insulation, temperature regulation and feeding.

*Probably as a side-effect of the nocturnal life, mammals lost two of the four cone opsins

Animal opsins are G-protein-coupled receptors and a group of proteins made light-sensitive via a chromophore, typically retinal. When bound to retinal, opsins become Retinylidene proteins, but are usually still called opsins regardless. Most p ...

, photoreceptors in the retina

The retina (from la, rete "net") is the innermost, light-sensitive layer of tissue of the eye of most vertebrates and some molluscs. The optics of the eye create a focused two-dimensional image of the visual world on the retina, which then ...

, present in the eyes of the earliest amniotes. Paradoxically, this might have improved their ability to discriminate colors in dim light.

This retreat to a nocturnal role is called a nocturnal bottleneck, and is thought to explain many of the features of mammals.

From cynodonts to crown mammals

Fossil record

Mesozoic synapsids that had evolved to the point of having a jaw joint composed of the dentary and squamosal bones are preserved in few good fossils, mainly because they were mostly smaller than rats:

*They were largely restricted to environments that are less likely to provide good fossils

A fossil (from Classical Latin , ) is any preserved remains, impression, or trace of any once-living thing from a past geological age. Examples include bones, shells, exoskeletons, stone imprints of animals or microbes, objects preserved ...

. Floodplains

A floodplain or flood plain or bottomlands is an area of land adjacent to a river which stretches from the banks of its channel to the base of the enclosing valley walls, and which experiences flooding during periods of high discharge.Goudi ...

as the best terrestrial environments for fossilization provide few mammal fossils, because they are dominated by medium to large animals, and the mammals could not compete with archosaurs

Archosauria () is a clade of diapsids, with birds and crocodilians as the only living representatives. Archosaurs are broadly classified as reptiles, in the cladistic sense of the term which includes birds. Extinct archosaurs include non-avi ...

in the medium to large size range.

*Their delicate bones were vulnerable to being destroyed before they could be fossilized — by scavengers (including fungi

A fungus ( : fungi or funguses) is any member of the group of eukaryotic organisms that includes microorganisms such as yeasts and molds, as well as the more familiar mushrooms. These organisms are classified as a kingdom, separately from ...

and bacteria

Bacteria (; singular: bacterium) are ubiquitous, mostly free-living organisms often consisting of one biological cell. They constitute a large domain of prokaryotic microorganisms. Typically a few micrometres in length, bacteria were among ...

) and by being trodden on.

*Small fossils are harder to spot and more vulnerable to being destroyed by weathering and other natural stresses before they are discovered.

In the past years, however, the number of Mesozoic fossil mammals has increased decisively; only 116 genera were known in 1979, for example, but about 310 in 2007, with an increase in quality such that "at least 18 Mesozoic mammals are represented by nearly complete skeletons".

Mammals or mammaliaforms

Some writers restrict the term "mammal" to the crown group

In phylogenetics, the crown group or crown assemblage is a collection of species composed of the living representatives of the collection, the most recent common ancestor of the collection, and all descendants of the most recent common ancestor. ...

mammals, the group consisting of the most recent common ancestor of the monotremes

Monotremes () are prototherian mammals of the order Monotremata. They are one of the three groups of living mammals, along with placentals (Eutheria), and marsupials ( Metatheria). Monotremes are typified by structural differences in their br ...

, marsupials, and placentals

Placental mammals (infraclass Placentalia ) are one of the three extant subdivisions of the class Mammalia, the other two being Monotremata and Marsupialia. Placentalia contains the vast majority of extant mammals, which are partly distinguishe ...

, together with all the descendants of that ancestor. In an influential 1988 paper, Timothy Rowe advocated this restriction, arguing that "ancestry... provides the only means of properly defining taxa" and, in particular, that the divergence of the monotremes from the animals more closely related to marsupials and placentals "is of central interest to any study of Mammalia as a whole." To accommodate some related taxa falling outside the crown group, he defined the Mammaliaformes

Mammaliaformes ("mammalian forms") is a clade that contains the crown group mammals and their closest Extinction, extinct relatives; the group adaptive radiation, radiated from earlier probainognathian cynodonts. It is defined as the clade origin ...

as comprising "the last common ancestor of Morganucodontidae and Mammalia s he had defined the latter termand all its descendants." Besides Morganucodontidae, the newly defined taxon includes Docodonta and Kuehneotheriidae. Though haramiyids have been referred to the mammals since the 1860s, Rowe excluded them from the Mammaliaformes as falling outside his definition, putting them in a larger clade, the Mammaliamorpha

Mammaliamorpha is a clade of cynodonts. It contains the clades Tritylodontidae and Mammaliaformes, as well as a few genera that do not belong to either of these groups. The family Tritheledontidae has also been placed in Mammaliamorpha by some ph ...

.

Some writers have adopted this terminology noting, to avoid misunderstanding, that they have done so. Most paleontologists, however, still think that animals with the dentary-squamosal jaw joint and the sort of molars characteristic of modern mammals should formally be members of Mammalia.

Family tree – cynodonts to crown group mammals

(based o

Cynodontia:Dendrogram – Palaeos

Morganucodontidae

The Morganucodon

''Morganucodon'' (" Glamorgan tooth") is an early mammaliaform genus that lived from the Late Triassic to the Middle Jurassic. It first appeared about 205 million years ago. Unlike many other early mammaliaforms, ''Morganucodon'' is well represe ...

tidae first appeared in the late Triassic, about 205 million years ago. They are an excellent example of transitional fossils, since they have both the dentary-squamosal and articular-quadrate jaw joints. They were also one of the first discovered and most thoroughly studied of the mammaliaforms outside of the crown-group

In phylogenetics, the crown group or crown assemblage is a collection of species composed of the living representatives of the collection, the most recent common ancestor of the collection, and all descendants of the most recent common ancestor. ...

mammals, since an unusually large number of morganucodont fossils have been found.

Docodonts

Docodonts

Docodonta is an order of extinct mammaliaforms that lived during the Mesozoic, from the Middle Jurassic to Early Cretaceous. They are distinguished from other early mammaliaforms by their relatively complex molar teeth, from which the order ge ...

, among the most common Jurassic mammaliaforms, are noted for the sophistication of their molars. They are thought to have had general semi-aquatic tendencies, with the fish-eating '' Castorocauda'' ("beaver tail"), which lived in the mid-Jurassic

The Jurassic ( ) is a geologic period and stratigraphic system that spanned from the end of the Triassic Period million years ago (Mya) to the beginning of the Cretaceous Period, approximately Mya. The Jurassic constitutes the middle period of ...

about 164M years ago and was first discovered in 2004 and described in 2006, being the most well-understood example. ''Castorocauda'' was not a crown group mammal, but it is extremely important in the study of the evolution of mammals because the first find was an almost complete skeleton (a real luxury in paleontology) and it breaks the "small nocturnal insectivore" stereotype:[ See also the news item at ]

*It was noticeably larger than most Mesozoic mammaliaform fossils — about from its nose to the tip of its tail, and may have weighed .

*It provides the earliest absolutely certain evidence of hair and fur. Previously the earliest was ''Eomaia

''Eomaia'' ("dawn mother") is a genus of extinct fossil mammals containing the single species ''Eomaia scansoria'', discovered in rocks that were found in the Yixian Formation, Liaoning Province, China, and dated to the Barremian Age of the Lower ...

'', a crown group mammal from about 125M years ago.

*It had aquatic adaptations including flattened tail bones and remnants of soft tissue between the toes of the back feet, suggesting that they were webbed. Previously the earliest known semi-aquatic mammaliaforms were from the Eocene

The Eocene ( ) Epoch is a geological epoch (geology), epoch that lasted from about 56 to 33.9 million years ago (mya). It is the second epoch of the Paleogene Period (geology), Period in the modern Cenozoic Era (geology), Era. The name ''Eocene' ...

, about 110M years later.

*''Castorocaudas powerful forelimbs look adapted for digging. This feature and the spurs on its ankles make it resemble the platypus

The platypus (''Ornithorhynchus anatinus''), sometimes referred to as the duck-billed platypus, is a semiaquatic, egg-laying mammal Endemic (ecology), endemic to Eastern states of Australia, eastern Australia, including Tasmania. The platypu ...

, which also swims and digs.

*Its teeth look adapted for eating fish: the first two molars had cusps in a straight row, which made them more suitable for gripping and slicing than for grinding; and these molars are curved backwards, to help in grasping slippery prey.

''Hadrocodium''

The family tree above shows '' Hadrocodium'' as an "aunt" of crown mammals. This mammaliaform, dated about 195M years ago in the very early Jurassic, exhibits some important features:

*The jaw joint consists only of the squamosal and dentary bones, and the jaw contains no smaller bones to the rear of the dentary, unlike the therapsid design.

*In therapsids

Therapsida is a major group of eupelycosaurian synapsids that includes mammals, their ancestors and relatives. Many of the traits today seen as unique to mammals had their origin within early therapsids, including limbs that were oriented mor ...

and early mammaliaforms the eardrum

In the anatomy of humans and various other tetrapods, the eardrum, also called the tympanic membrane or myringa, is a thin, cone-shaped membrane that separates the external ear

The outer ear, external ear, or auris externa is the extern ...

may have stretched over a trough at the rear of the lower jaw. But ''Hadrocodium'' had no such trough, which suggests its ear was part of the cranium

The skull is a bone protective cavity for the brain. The skull is composed of four types of bone i.e., cranial bones, facial bones, ear ossicles and hyoid bone. However two parts are more prominent: the cranium and the mandible. In humans, the ...

, as it is in crown-group mammals — and hence that the former articular

The articular bone is part of the lower jaw of most vertebrates, including most jawed fish, amphibians, birds and various kinds of reptiles, as well as ancestral mammals.

Anatomy

In most vertebrates, the articular bone is connected to two oth ...

and quadrate had migrated to the middle ear and become the malleus

The malleus, or hammer, is a hammer-shaped small bone or ossicle of the middle ear. It connects with the incus, and is attached to the inner surface of the eardrum. The word is Latin for 'hammer' or 'mallet'. It transmits the sound vibrations fro ...

and incus

The ''incus'' (plural incudes) or anvil is a bone in the middle ear. The anvil-shaped small bone is one of three ossicles in the middle ear. The ''incus'' receives vibrations from the ''malleus'', to which it is connected laterally, and transmit ...

. On the other hand, the dentary has a "bay" at the rear that mammals lack. This suggests that ''Hadrocodium's'' dentary bone retained the same shape that it would have had if the articular and quadrate had remained part of the jaw joint, and therefore that ''Hadrocodium'' or a very close ancestor may have been the first to have a fully mammalian middle ear.

*Therapsids and earlier mammaliaforms had their jaw joints very far back in the skull, partly because the ear was at the rear end of the jaw but also had to be close to the brain. This arrangement limited the size of the braincase, because it forced the jaw muscles to run round and over it. ''Hadrocodium's'' braincase and jaws were no longer bound to each other by the need to support the ear, and its jaw joint was further forward. In its descendants or those of animals with a similar arrangement, the brain case was free to expand without being constrained by the jaw and the jaw was free to change without being constrained by the need to keep the ear near the brain — in other words it now became possible for mammaliaforms both to develop large brains and to adapt their jaws and teeth in ways that were purely specialized for eating.

Earliest crown mammals

The crown group

In phylogenetics, the crown group or crown assemblage is a collection of species composed of the living representatives of the collection, the most recent common ancestor of the collection, and all descendants of the most recent common ancestor. ...

mammals, sometimes called 'true mammals', are the extant

Extant is the opposite of the word extinct. It may refer to:

* Extant hereditary titles

* Extant literature, surviving literature, such as ''Beowulf'', the oldest extant manuscript written in English

* Extant taxon, a taxon which is not extinct, ...

mammals and their relatives back to their last common ancestor. Since this group has living members, DNA analysis can be applied in an attempt to explain the evolution of features that do not appear in fossils. This endeavor often involves molecular phylogenetics

Molecular phylogenetics () is the branch of phylogeny that analyzes genetic, hereditary molecular differences, predominantly in DNA sequences, to gain information on an organism's evolutionary relationships. From these analyses, it is possible to ...

, a technique that has become popular since the mid-1980s.

Family tree of early crown mammals

Cladogram after Z.-X Luo.

Color vision

Early amniotes had four opsin

Animal opsins are G-protein-coupled receptors and a group of proteins made light-sensitive via a chromophore, typically retinal. When bound to retinal, opsins become Retinylidene proteins, but are usually still called opsins regardless. Most pro ...

s in the cones of their retinas to use for distinguishing colours: one sensitive to red, one to green, and two corresponding to different shades of blue.cetacea

Cetacea (; , ) is an infraorder of aquatic mammals that includes whales, dolphins, and porpoises. Key characteristics are their fully aquatic lifestyle, streamlined body shape, often large size and exclusively carnivorous diet. They propel them ...

ns, which later lost the other blue opsin as well). Some placentals and marsupials, including higher primates, subsequently evolved green-sensitive opsins; like early crown mammals, therefore, their vision is trichromatic

Trichromacy or trichromatism is the possessing of three independent channels for conveying color information, derived from the three different types of cone cells in the eye. Organisms with trichromacy are called trichromats.

The normal expl ...

.

Australosphenida and Ausktribosphenidae

Ausktribosphenidae

Ausktribosphenidae is an extinct family of australosphenidan mammals from the Early Cretaceous of Australia and mid Cretaceous of South America.

Classification and taxonomy

Ausktribosphenidae is closely related to monotremes and hence the two f ...

is a group name that has been given to some rather puzzling finds that:tribosphenic molar

The molars or molar teeth are large, flat teeth at the back of the mouth. They are more developed in mammals. They are used primarily to grind food during chewing. The name ''molar'' derives from Latin, ''molaris dens'', meaning "millstone to ...

s, a type of tooth that is otherwise known only in placentals and marsupials.Cretaceous

The Cretaceous ( ) is a geological period that lasted from about 145 to 66 million years ago (Mya). It is the third and final period of the Mesozoic Era, as well as the longest. At around 79 million years, it is the longest geological period of th ...

deposits in Australia — but Australia was connected only to Antarctica, and placentals originated in the Northern Hemisphere and were confined to it until continental drift

Continental drift is the hypothesis that the Earth's continents have moved over geologic time relative to each other, thus appearing to have "drifted" across the ocean bed. The idea of continental drift has been subsumed into the science of pla ...

formed land connections from North America to South America, from Asia to Africa and from Asia to India (the late Cretaceous ma

here

shows how the southern continents are separated).

*are represented only by teeth and jaw fragments, which is not very helpful.

Australosphenida

The Australosphenida are a clade of mammals, containing mammals with tribosphenic molars, known from the Jurassic to Mid-Cretaceous of Gondwana. They are thought to have acquired their tribosphenic molars independently from those of Tribosphenida ...

is a group that has been defined in order to include the Ausktribosphenidae and monotremes

Monotremes () are prototherian mammals of the order Monotremata. They are one of the three groups of living mammals, along with placentals (Eutheria), and marsupials ( Metatheria). Monotremes are typified by structural differences in their br ...

. ''Asfaltomylos'' (mid- to late Jurassic, from Patagonia

Patagonia () refers to a geographical region that encompasses the southern end of South America, governed by Argentina and Chile. The region comprises the southern section of the Andes Mountains with lakes, fjords, temperate rainforests, and gl ...

) has been interpreted as a basal australosphenid (animal that has features shared with both Ausktribosphenidae and monotremes; lacks features that are peculiar to Ausktribosphenidae or monotremes; also lacks features that are absent in Ausktribosphenidae and monotremes) and as showing that australosphenids were widespread throughout Gondwanaland

Gondwana () was a large landmass, often referred to as a supercontinent, that formed during the late Neoproterozoic (about 550 million years ago) and began to break up during the Jurassic period (about 180 million years ago). The final stages ...

(the old Southern Hemisphere super-continent).Teinolophos

''Teinolophos'' is a prehistoric species of monotreme, or egg-laying mammal, from the Teinolophidae. It is known from four specimens, each consisting of a partial lower jawbone collected from the Wonthaggi Formation at Flat Rocks, Victoria, Aus ...

'', which lived somewhere between 121 and 112.5 million years ago, suggests that it was a "crown group" (advanced and relatively specialised) monotreme. This was taken as evidence that the basal (most primitive) monotremes must have appeared considerably earlier, but this has been disputed (see the following section). The study also indicated that some alleged Australosphenids were also "crown group" monotremes (e.g. ''Steropodon

''Steropodon'' is a genus of prehistoric monotreme, or egg-laying mammal. It contains a single species, ''Steropodon galmani'', that lived about 105 to 93.3 million years ago (mya) in the Early to Late Cretaceous period. It is one of the oldest m ...

'') and that other alleged Australosphenids (e.g. ''Ausktribosphenos'', ''Bishops'', ''Ambondro'', ''Asfaltomylos'') are more closely related to and possibly members of the Therian mammals (group that includes marsupials and placentals, see below).

Monotremes

''Teinolophos

''Teinolophos'' is a prehistoric species of monotreme, or egg-laying mammal, from the Teinolophidae. It is known from four specimens, each consisting of a partial lower jawbone collected from the Wonthaggi Formation at Flat Rocks, Victoria, Aus ...

'', from Australia, is the earliest known monotreme. A 2007 study (published 2008) suggests that it was not a basal (primitive, ancestral) monotreme but a full-fledged platypus

The platypus (''Ornithorhynchus anatinus''), sometimes referred to as the duck-billed platypus, is a semiaquatic, egg-laying mammal Endemic (ecology), endemic to Eastern states of Australia, eastern Australia, including Tasmania. The platypu ...

, and therefore that the platypus and echidna

Echidnas (), sometimes known as spiny anteaters, are quill-covered monotremes (egg-laying mammals) belonging to the family Tachyglossidae . The four extant species of echidnas and the platypus are the only living mammals that lay eggs and the ...

lineages diverged considerably earlier.water opossum

The water opossum (''Chironectes minimus''), also locally known as the yapok (), is a marsupial of the family Didelphidae.* It is the only living member of its genus, ''Chironectes''. This semiaquatic creature is found in and near freshwater ...

and the lutrine opossum; however, they both live in South America and thus don't come into contact with monotremes). Genetic evidence has determined that echidnas diverged from the platypus lineage as recently as 19-48M, when they made their transition from semi-aquatic to terrestrial lifestyle.cynodont

The cynodonts () (clade Cynodontia) are a clade of eutheriodont therapsids that first appeared in the Late Permian (approximately 260 mya), and extensively diversified after the Permian–Triassic extinction event. Cynodonts had a wide variety ...

ancestors:

*like lizards and birds, they use the same orifice to urinate, defecate and reproduce ("monotreme" means "one hole").

*they lay eggs

Humans and human ancestors have scavenged and eaten animal eggs for millions of years. Humans in Southeast Asia had domesticated chickens and harvested their eggs for food by 1,500 BCE. The most widely consumed eggs are those of fowl, especial ...

that are leathery and uncalcified, like those of lizards, turtles and crocodilians.

Unlike other mammals, female monotremes do not have nipples

The nipple is a raised region of tissue on the surface of the breast from which, in females, milk leaves the breast through the lactiferous ducts to feed an infant. The milk can flow through the nipple passively or it can be ejected by smooth m ...

and feed their young by "sweating" milk from patches on their bellies.

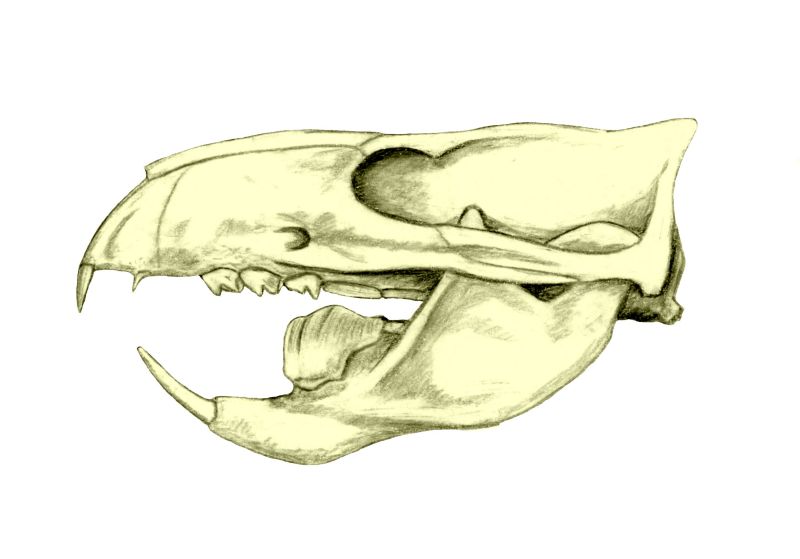

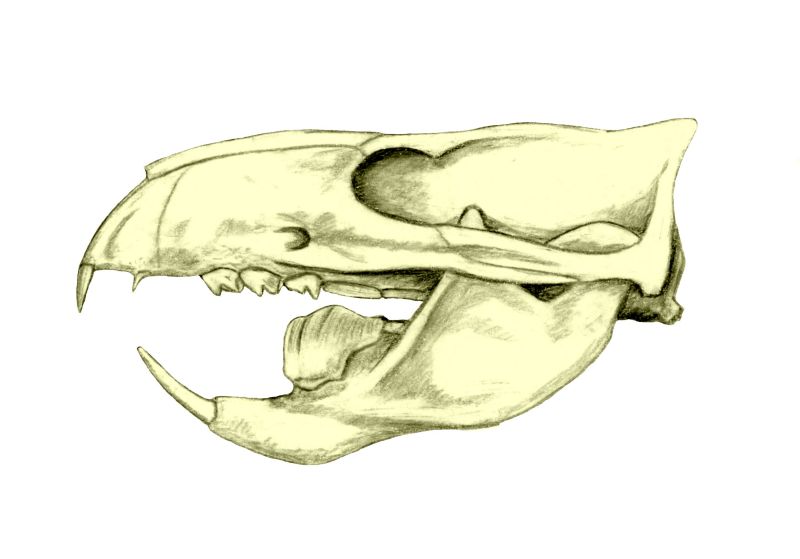

These features are not visible in fossils, and the main characteristics from paleontologists' point of view are:[

*a slender ]dentary

In anatomy, the mandible, lower jaw or jawbone is the largest, strongest and lowest bone in the human facial skeleton. It forms the lower jaw and holds the lower tooth, teeth in place. The mandible sits beneath the maxilla. It is the only movabl ...

bone in which the coronoid process is small or non-existent.

*the external opening of the ear lies at the posterior base of the jaw.

*the jugal

The jugal is a skull bone found in most reptiles, amphibians and birds. In mammals, the jugal is often called the malar or zygomatic. It is connected to the quadratojugal and maxilla, as well as other bones, which may vary by species.

Anatomy ...

bone is small or non-existent.

*a primitive pectoral girdle

The shoulder girdle or pectoral girdle is the set of bones in the appendicular skeleton which connects to the arm on each side. In humans it consists of the clavicle and scapula; in those species with three bones in the shoulder, it consists of t ...

with strong ventral

Standard anatomical terms of location are used to unambiguously describe the anatomy of animals, including humans. The terms, typically derived from Latin or Greek language, Greek roots, describe something in its standard anatomical position. Th ...

elements: coracoid

A coracoid (from Greek κόραξ, ''koraks'', raven) is a paired bone which is part of the shoulder assembly in all vertebrates except therian mammals (marsupials and placentals). In therian mammals (including humans), a coracoid process is prese ...

s, clavicles

The clavicle, or collarbone, is a slender, S-shaped long bone approximately 6 inches (15 cm) long that serves as a strut between the shoulder blade and the sternum (breastbone). There are two clavicles, one on the left and one on the right ...

and interclavicle