Wilhelm Richard Wagner ( ; ; 22 May 181313 February 1883) was a German composer, theatre director,

polemic

Polemic () is contentious rhetoric intended to support a specific position by forthright claims and to undermine the opposing position. The practice of such argumentation is called ''polemics'', which are seen in arguments on controversial topic ...

ist, and conductor who is chiefly known for his operas (or, as some of his mature works were later known, "music dramas"). Unlike most opera composers, Wagner wrote both the

libretto

A libretto (Italian for "booklet") is the text used in, or intended for, an extended musical work such as an opera, operetta, masque, oratorio, cantata or musical. The term ''libretto'' is also sometimes used to refer to the text of major li ...

and the music for each of his stage works. Initially establishing his reputation as a composer of works in the romantic vein of

Carl Maria von Weber

Carl Maria Friedrich Ernst von Weber (18 or 19 November 17865 June 1826) was a German composer, conductor, virtuoso pianist, guitarist, and critic who was one of the first significant composers of the Romantic era. Best known for his operas, ...

and

Giacomo Meyerbeer

Giacomo Meyerbeer (born Jakob Liebmann Beer; 5 September 1791 – 2 May 1864) was a German opera composer, "the most frequently performed opera composer during the nineteenth century, linking Mozart and Wagner". With his 1831 opera '' Robert le ...

, Wagner revolutionised opera through his concept of the ''

Gesamtkunstwerk

A ''Gesamtkunstwerk'' (, literally 'total artwork', translated as 'total work of art', 'ideal work of art', 'universal artwork', 'synthesis of the arts', 'comprehensive artwork', or 'all-embracing art form') is a work of art that makes use of al ...

'' ("total work of art"), by which he sought to synthesise the poetic, visual, musical and dramatic arts, with music subsidiary to drama. He described this vision in a series of essays published between 1849 and 1852. Wagner realised these ideas most fully in the first half of the four-opera cycle ''

Der Ring des Nibelungen

(''The Ring of the Nibelung''), WWV 86, is a cycle of four German-language epic music dramas composed by Richard Wagner. The works are based loosely on characters from Germanic heroic legend, namely Norse legendary sagas and the '' Nibe ...

'' (''The Ring of the

Nibelung'').

His compositions, particularly those of his later period, are notable for their complex

textures, rich

harmonies

In music, harmony is the process by which individual sounds are joined together or composed into whole units or compositions. Often, the term harmony refers to simultaneously occurring frequencies, pitches ( tones, notes), or chords. Howev ...

and

orchestration

Orchestration is the study or practice of writing music for an orchestra (or, more loosely, for any musical ensemble, such as a concert band) or of adapting music composed for another medium for an orchestra. Also called "instrumentation", orch ...

, and the elaborate use of

leitmotif

A leitmotif or leitmotiv () is a "short, recurring musical phrase" associated with a particular person, place, or idea. It is closely related to the musical concepts of ''idée fixe'' or ''motto-theme''. The spelling ''leitmotif'' is an anglic ...

s—musical phrases associated with individual characters, places, ideas, or plot elements. His advances in musical language, such as extreme

chromaticism

Chromaticism is a compositional technique interspersing the primary diatonic pitches and chords with other pitches of the chromatic scale. In simple terms, within each octave, diatonic music uses only seven different notes, rather than the tw ...

and quickly shifting

tonal centres, greatly influenced the development of classical music. His ''

Tristan und Isolde

''Tristan und Isolde'' (''Tristan and Isolde''), WWV 90, is an opera in three acts by Richard Wagner to a German libretto by the composer, based largely on the 12th-century romance Tristan and Iseult by Gottfried von Strassburg. It was comp ...

'' is sometimes described as marking the start of

modern music.

Wagner had his own opera house built, the

Bayreuth Festspielhaus

The ''Bayreuth Festspielhaus'' or Bayreuth Festival Theatre (german: link=no, Bayreuther Festspielhaus, ) is an opera house north of Bayreuth, Germany, built by the 19th-century German composer Richard Wagner and dedicated solely to the performa ...

, which embodied many novel design features. The ''Ring'' and ''

Parsifal

''Parsifal'' ( WWV 111) is an opera or a music drama in three acts by the German composer Richard Wagner and his last composition. Wagner's own libretto for the work is loosely based on the 13th-century Middle High German epic poem ''Parzival ...

'' were premiered here and his

most important stage works continue to be performed at the annual

Bayreuth Festival

The Bayreuth Festival (german: link=no, Bayreuther Festspiele) is a music festival held annually in Bayreuth, Germany, at which performances of operas by the 19th-century German composer Richard Wagner are presented. Wagner himself conceived ...

, run by his descendants. His thoughts on the relative contributions of music and drama in opera were to change again, and he reintroduced some traditional forms into his last few stage works, including ''

Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg

(; "The Master-Singers of Nuremberg"), WWV 96, is a music drama, or opera, in three acts, by Richard Wagner. It is the longest opera commonly performed, taking nearly four and a half hours, not counting two breaks between acts, and is tradit ...

'' (''The Mastersingers of Nuremberg'').

Until his final years, Wagner's life was characterised by political exile, turbulent love affairs, poverty and repeated flight from his creditors. His controversial writings on music, drama and politics have attracted extensive comment – particularly, since the late 20th century, where they express

antisemitic

Antisemitism (also spelled anti-semitism or anti-Semitism) is hostility to, prejudice towards, or discrimination against Jews. A person who holds such positions is called an antisemite. Antisemitism is considered to be a form of racism.

Ant ...

sentiments. The effect of his ideas can be traced in many of the arts throughout the 20th century; his influence spread beyond composition into conducting, philosophy, literature, the visual arts and theatre.

Biography

Early years

Richard Wagner was born to an

ethnic German family in

Leipzig

Leipzig ( , ; Upper Saxon: ) is the most populous city in the German state of Saxony. Leipzig's population of 605,407 inhabitants (1.1 million in the larger urban zone) as of 2021 places the city as Germany's eighth most populous, as ...

, who lived at No 3, the

Brühl (''The House of the Red and White Lions'') in the

Jewish quarter on 22 May 1813. He was baptized at

St. Thomas Church. He was the ninth child of Carl Friedrich Wagner, who was a clerk in the Leipzig police service, and his wife, Johanna Rosine (née Paetz), the daughter of a baker. Wagner's father Carl died of

typhoid fever

Typhoid fever, also known as typhoid, is a disease caused by '' Salmonella'' serotype Typhi bacteria. Symptoms vary from mild to severe, and usually begin six to 30 days after exposure. Often there is a gradual onset of a high fever over severa ...

six months after Richard's birth. Afterwards, his mother Johanna lived with Carl's friend, the actor and playwright

Ludwig Geyer

Ludwig Heinrich Christian Geyer (21 January 1779 – 30 September 1821) was a German actor, playwright, and painter.

Life and career

Born in Eisleben, he was the stepfather of composer Richard Wagner, whose biological father had died some six ...

. In August 1814 Johanna and Geyer probably married—although no documentation of this has been found in the Leipzig church registers. She and her family moved to Geyer's residence in

Dresden

Dresden (, ; Upper Saxon: ''Dräsdn''; wen, label= Upper Sorbian, Drježdźany) is the capital city of the German state of Saxony and its second most populous city, after Leipzig. It is the 12th most populous city of Germany, the fourth ...

. Until he was fourteen, Wagner was known as Wilhelm Richard Geyer. He almost certainly thought that Geyer was his biological father.

Geyer's love of the theatre came to be shared by his stepson, and Wagner took part in his performances. In his autobiography

''Mein Leben'' Wagner recalled once playing the part of an angel. In late 1820, Wagner was enrolled at Pastor Wetzel's school at Possendorf, near Dresden, where he received some piano instruction from his Latin teacher. He struggled to play a proper

scale at the keyboard and preferred playing theatre overtures

by ear. Following Geyer's death in 1821, Richard was sent to the

Kreuzschule

The ''Kreuzschule'' (German for "School of the Cross") in Dresden (also known by its Latin name, ''schola crucis'') is the oldest surviving school in Dresden and one of the oldest in Germany. As early as 1300, a schoolmaster (''Cunradus puerorum r ...

, the boarding school of the

Dresdner Kreuzchor, at the expense of Geyer's brother. At the age of nine he was hugely impressed by the

Gothic

Gothic or Gothics may refer to:

People and languages

*Goths or Gothic people, the ethnonym of a group of East Germanic tribes

**Gothic language, an extinct East Germanic language spoken by the Goths

**Crimean Gothic, the Gothic language spoken b ...

elements of

Carl Maria von Weber

Carl Maria Friedrich Ernst von Weber (18 or 19 November 17865 June 1826) was a German composer, conductor, virtuoso pianist, guitarist, and critic who was one of the first significant composers of the Romantic era. Best known for his operas, ...

's opera ''

Der Freischütz

' ( J. 277, Op. 77 ''The Marksman'' or ''The Freeshooter'') is a German opera with spoken dialogue in three acts by Carl Maria von Weber with a libretto by Friedrich Kind, based on a story by Johann August Apel and Friedrich Laun from their 1810 ...

,'' which he saw Weber conduct. At this period Wagner entertained ambitions as a playwright. His first creative effort, listed in the ''

Wagner-Werk-Verzeichnis'' (the standard listing of Wagner's works) as WWV 1, was a tragedy called ''

Leubald.'' Begun when he was in school in 1826, the play was strongly influenced by

Shakespeare

William Shakespeare ( 26 April 1564 – 23 April 1616) was an English playwright, poet and actor. He is widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England's nation ...

and

Goethe

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (28 August 1749 – 22 March 1832) was a German poet, playwright, novelist, scientist, statesman, theatre director, and critic. His works include plays, poetry, literature, and aesthetic criticism, as well as tr ...

. Wagner was determined to set it to music and persuaded his family to allow him music lessons.

By 1827, the family had returned to Leipzig. Wagner's first lessons in

harmony

In music, harmony is the process by which individual sounds are joined together or composed into whole units or compositions. Often, the term harmony refers to simultaneously occurring frequencies, pitches ( tones, notes), or chords. Howeve ...

were taken during 1828–1831 with Christian Gottlieb Müller. In January 1828 he first heard

Beethoven

Ludwig van Beethoven (baptised 17 December 177026 March 1827) was a German composer and pianist. Beethoven remains one of the most admired composers in the history of Western music; his works rank amongst the most performed of the classic ...

's

7th Symphony and then, in March, the same composer's

9th Symphony (both at the

Gewandhaus

Gewandhaus is a concert hall in Leipzig, the home of the Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra. Today's hall is the third to bear this name; like the second, it is noted for its fine acoustics.

History

The first Gewandhaus (''Altes Gewandhaus'')

The f ...

). Beethoven became a major inspiration, and Wagner wrote a piano transcription of the 9th Symphony. He was also greatly impressed by a performance of

Mozart

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (27 January 17565 December 1791), baptised as Joannes Chrysostomus Wolfgangus Theophilus Mozart, was a prolific and influential composer of the Classical period. Despite his short life, his rapid pace of composition r ...

's ''

Requiem

A Requiem or Requiem Mass, also known as Mass for the dead ( la, Missa pro defunctis) or Mass of the dead ( la, Missa defunctorum), is a Mass of the Catholic Church offered for the repose of the soul or souls of one or more deceased persons, ...

.'' Wagner's early

piano sonata

A piano sonata is a sonata written for a solo piano. Piano sonatas are usually written in three or four movements, although some piano sonatas have been written with a single movement ( Scarlatti, Liszt, Scriabin, Medtner, Berg), others with ...

s and his first attempts at orchestral

overture

Overture (from French language, French ''ouverture'', "opening") in music was originally the instrumental introduction to a ballet, opera, or oratorio in the 17th century. During the early Romantic era, composers such as Ludwig van Beethoven, Be ...

s date from this period.

In 1829 he saw a performance by

dramatic soprano

A dramatic soprano is a type of operatic soprano with a powerful, rich, emotive voice that can sing over, or cut through, a full orchestra. Thicker vocal folds in dramatic voices usually (but not always) mean less agility than lighter voices but a ...

Wilhelmine Schröder-Devrient, and she became his ideal of the fusion of drama and music in opera. In ''Mein Leben'', Wagner wrote, "When I look back across my entire life I find no event to place beside this in the impression it produced on me," and claimed that the "profoundly human and ecstatic performance of this incomparable artist" kindled in him an "almost demonic fire."

In 1831, Wagner enrolled at the

Leipzig University

Leipzig University (german: Universität Leipzig), in Leipzig in Saxony, Germany, is one of the world's oldest universities and the second-oldest university (by consecutive years of existence) in Germany. The university was founded on 2 December ...

, where he became a member of the Saxon

student fraternity

Fraternities and sororities are social organizations at colleges and universities in North America.

Generally, membership in a fraternity or sorority is obtained as an undergraduate student, but continues thereafter for life. Some accept gradua ...

. He took composition lessons with the

Thomaskantor

(Cantor at St. Thomas) is the common name for the musical director of the , now an internationally known boys' choir founded in Leipzig in 1212. The official historic title of the Thomaskantor in Latin, ', describes the two functions of cantor ...

Theodor Weinlig. Weinlig was so impressed with Wagner's musical ability that he refused any payment for his lessons. He arranged for his pupil's Piano Sonata in B-flat major (which was consequently dedicated to him) to be published as Wagner's Op. 1. A year later, Wagner composed his

Symphony in C major, a Beethovenesque work performed in Prague in 1832 and at the Leipzig Gewandhaus in 1833. He then began to work on an opera, ''

Die Hochzeit

''Die Hochzeit'' (''The Wedding'', WWV 31) is an unfinished opera by Richard Wagner which predates his completed works in the genre. Wagner completed the libretto, then started composing the music in the second half of 1832 when he was just ninete ...

'' (''The Wedding''), which he never completed.

Early career and marriage (1833–1842)

In 1833, Wagner's brother Albert managed to obtain for him a position as choirmaster at the theatre in

Würzburg

Würzburg (; Main-Franconian: ) is a city in the region of Franconia in the north of the German state of Bavaria. Würzburg is the administrative seat of the ''Regierungsbezirk'' Lower Franconia. It spans the banks of the Main River.

Würzburg ...

. In the same year, at the age of 20, Wagner composed his first complete opera, ''

Die Feen'' (''The Fairies''). This work, which imitated the style of Weber, went unproduced until half a century later, when it was premiered in

Munich

Munich ( ; german: München ; bar, Minga ) is the capital and most populous city of the German state of Bavaria. With a population of 1,558,395 inhabitants as of 31 July 2020, it is the third-largest city in Germany, after Berlin and ...

shortly after the composer's death in 1883.

Having returned to Leipzig in 1834, Wagner held a brief appointment as musical director at the opera house in

Magdeburg

Magdeburg (; nds, label=Low Saxon, Meideborg ) is the capital and second-largest city of the German state Saxony-Anhalt. The city is situated at the Elbe river.

Otto I, the first Holy Roman Emperor and founder of the Archdiocese of Magdebu ...

during which he wrote ''

Das Liebesverbot'' (''The Ban on Love''), based on Shakespeare's ''

Measure for Measure

''Measure for Measure'' is a play by William Shakespeare, believed to have been written in 1603 or 1604 and first performed in 1604, according to available records. It was published in the '' First Folio'' of 1623.

The play's plot features its ...

''. This was staged at Magdeburg in 1836 but closed before the second performance; this, together with the financial collapse of the theatre company employing him, left the composer in bankruptcy. Wagner had fallen for one of the leading ladies at Magdeburg, the actress

Christine Wilhelmine "Minna" Planer and after the disaster of ''Das Liebesverbot'' he followed her to

Königsberg

Königsberg (, ) was the historic Prussian city that is now Kaliningrad, Russia. Königsberg was founded in 1255 on the site of the ancient Old Prussian settlement ''Twangste'' by the Teutonic Knights during the Northern Crusades, and was ...

, where she helped him to get an engagement at the theatre. The two married in

Tragheim Church

Tragheim Church, 1930

Tragheim Church (german: Tragheimer Kirche) was a Protestant church in the Tragheim quarter of Königsberg, Germany.

History

At the beginning of the 17th century the Lutheran residents of Tragheim attended Löbenicht Ch ...

on 24 November 1836. In May 1837, Minna left Wagner for another man, and this was but only the first débâcle of a tempestuous marriage. In June 1837, Wagner moved to

Riga

Riga (; lv, Rīga , liv, Rīgõ) is the capital and largest city of Latvia and is home to 605,802 inhabitants which is a third of Latvia's population. The city lies on the Gulf of Riga at the mouth of the Daugava river where it meets the ...

(then in the

Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended the Great Northern War ...

), where he became music director of the local opera; having in this capacity engaged Minna's sister Amalie (also a singer) for the theatre, he presently resumed relations with Minna during 1838.

By 1839, the couple had amassed such large debts that they fled Riga on the run from creditors. Debts would plague Wagner for most of his life. Initially they took a stormy sea passage to London, from which Wagner drew the inspiration for his opera ''

Der fliegende Holländer

' (''The Flying Dutchman''), WWV 63, is a German-language opera, with libretto and music by Richard Wagner. The central theme is redemption through love. Wagner conducted the premiere at the Königliches Hoftheater Dresden in 1843.

Wagner cla ...

'' (''The Flying Dutchman''), with a plot based on a sketch by

Heinrich Heine

Christian Johann Heinrich Heine (; born Harry Heine; 13 December 1797 – 17 February 1856) was a German poet, writer and literary critic. He is best known outside Germany for his early lyric poetry, which was set to music in the form of '' Lied ...

. The Wagners settled in Paris in September 1839 and stayed there until 1842. Wagner made a scant living by writing articles and short novelettes such as ''A pilgrimage to Beethoven'', which sketched his growing concept of "music drama", and ''An end in Paris'', where he depicts his own miseries as a German musician in the French metropolis. He also provided arrangements of operas by other composers, largely on behalf of the

Schlesinger Schlesinger is a German surname (in part also Jewish) meaning "Silesian" from the older regional term ''Schlesinger''; someone from ''Schlesing'' (Silesia); in modern Standard German (or Hochdeutsch) a '' Schlesier'' is someone from '' Schlesien'' ...

publishing house. During this stay he completed his third and fourth operas ''

Rienzi

' (''Rienzi, the last of the tribunes''; WWV 49) is an early opera by Richard Wagner in five acts, with the libretto written by the composer after Edward Bulwer-Lytton's novel of the same name (1835). The title is commonly shortened to ''Ri ...

'' and ''Der fliegende Holländer''.

Dresden (1842–1849)

Wagner had completed ''Rienzi'' in 1840. With the strong support of

Giacomo Meyerbeer

Giacomo Meyerbeer (born Jakob Liebmann Beer; 5 September 1791 – 2 May 1864) was a German opera composer, "the most frequently performed opera composer during the nineteenth century, linking Mozart and Wagner". With his 1831 opera '' Robert le ...

, it was accepted for performance by the Dresden

Court Theatre (''Hofoper'') in the

Kingdom of Saxony

The Kingdom of Saxony (german: Königreich Sachsen), lasting from 1806 to 1918, was an independent member of a number of historical confederacies in Napoleonic through post-Napoleonic Germany. The kingdom was formed from the Electorate of Sax ...

and in 1842, Wagner moved to Dresden. His relief at returning to Germany was recorded in his "

Autobiographic Sketch" of 1842, where he wrote that, en route from Paris, "For the first time I saw the

Rhine

), Surselva, Graubünden, Switzerland

, source1_coordinates=

, source1_elevation =

, source2 = Rein Posteriur/Hinterrhein

, source2_location = Paradies Glacier, Graubünden, Switzerland

, source2_coordinates=

, source ...

—with hot tears in my eyes, I, poor artist, swore eternal fidelity to my German fatherland." ''Rienzi'' was staged to considerable acclaim on 20 October.

Wagner lived in Dresden for the next six years, eventually being appointed the Royal Saxon Court Conductor. During this period, he staged there ''Der fliegende Holländer'' (2 January 1843) and

''Tannhäuser'' (19 October 1845), the first two of his three middle-period operas. Wagner also mixed with artistic circles in Dresden, including the composer

Ferdinand Hiller

Ferdinand (von) Hiller (24 October 1811 – 11 May 1885) was a German composer, conductor, pianist, writer and music director.

Biography

Ferdinand Hiller was born to a wealthy Jewish family in Frankfurt am Main, where his father Justus (orig ...

and the architect

Gottfried Semper

Gottfried Semper (; 29 November 1803 – 15 May 1879) was a German architect, art critic, and professor of architecture who designed and built the Semper Opera House in Dresden between 1838 and 1841. In 1849 he took part in the May Uprising i ...

.

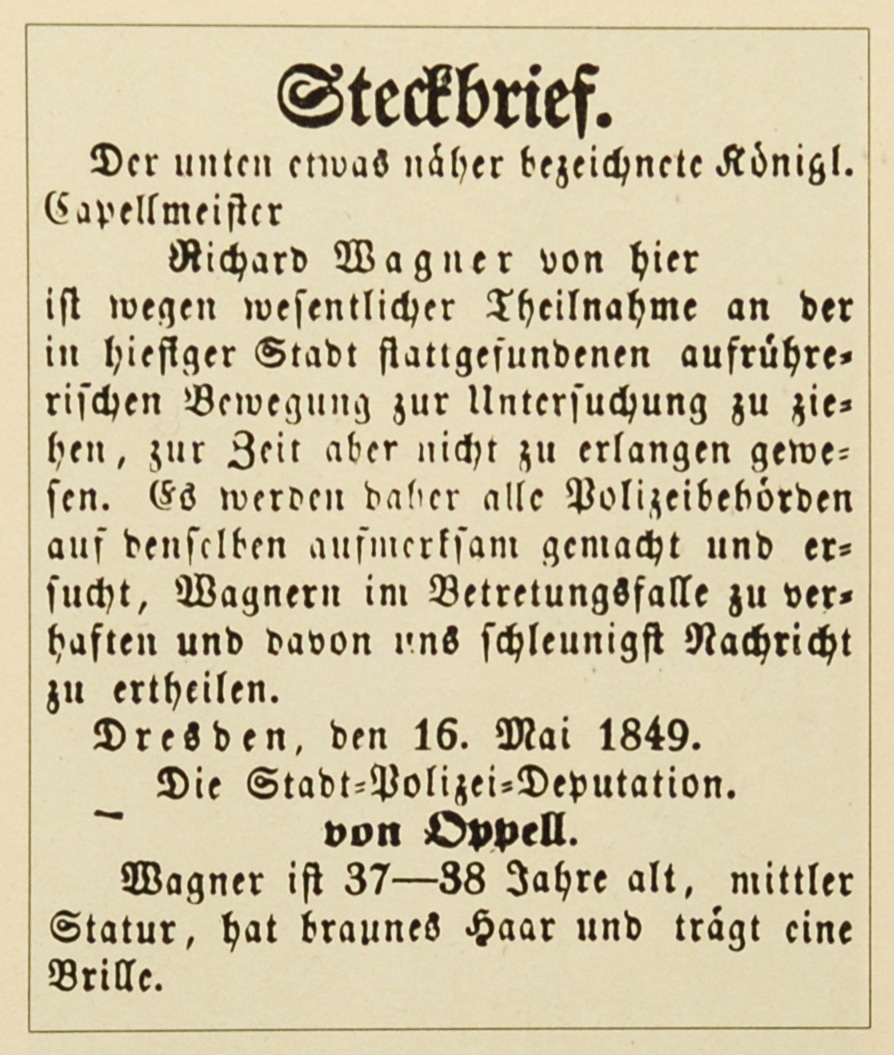

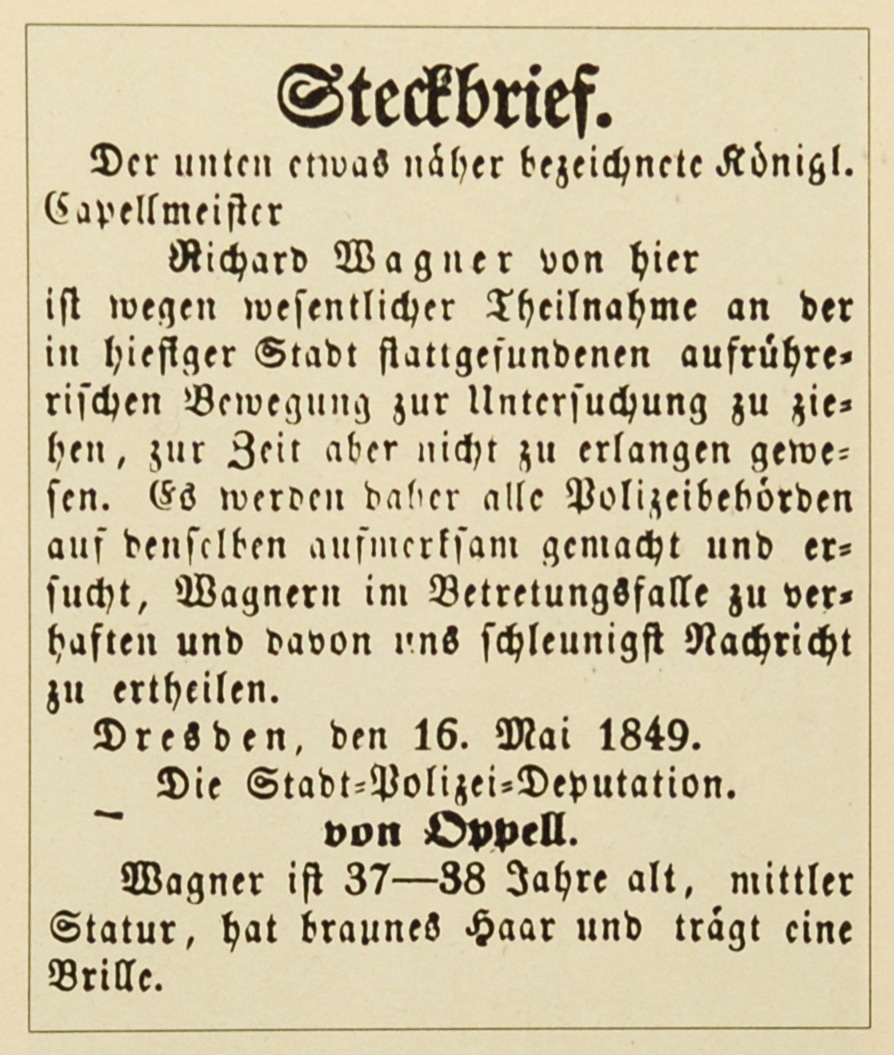

Wagner's involvement in

left-wing politics

Left-wing politics describes the range of political ideologies that support and seek to achieve social equality and egalitarianism, often in opposition to social hierarchy. Left-wing politics typically involve a concern for those in ...

abruptly ended his welcome in Dresden. Wagner was active among

socialist

Socialism is a left-wing economic philosophy and movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to private ownership. As a term, it describes the ...

German nationalists there, regularly receiving such guests as the conductor and radical editor

August Röckel and the Russian

anarchist

Anarchism is a political philosophy and movement that is skeptical of all justifications for authority and seeks to abolish the institutions it claims maintain unnecessary coercion and hierarchy, typically including, though not necessar ...

Mikhail Bakunin

Mikhail Alexandrovich Bakunin (; 1814–1876) was a Russian revolutionary anarchist, socialist and founder of collectivist anarchism. He is considered among the most influential figures of anarchism and a major founder of the revolutionary s ...

. He was also influenced by the ideas of

Pierre-Joseph Proudhon

Pierre-Joseph Proudhon (, , ; 15 January 1809, Besançon – 19 January 1865, Paris) was a French socialist,Landauer, Carl; Landauer, Hilde Stein; Valkenier, Elizabeth Kridl (1979) 959 "The Three Anticapitalistic Movements". ''European Socia ...

and

Ludwig Feuerbach

Ludwig Andreas von Feuerbach (; 28 July 1804 – 13 September 1872) was a German anthropologist and philosopher, best known for his book '' The Essence of Christianity'', which provided a critique of Christianity that strongly influenced gene ...

. Widespread discontent came to a head in 1849, when the unsuccessful

May Uprising in Dresden broke out, in which Wagner played a

minor supporting role. Warrants were issued for the revolutionaries' arrest. Wagner had to flee, first visiting Paris and then settling in

Zürich

, neighboring_municipalities = Adliswil, Dübendorf, Fällanden, Kilchberg, Maur, Oberengstringen, Opfikon, Regensdorf, Rümlang, Schlieren, Stallikon, Uitikon, Urdorf, Wallisellen, Zollikon

, twintowns = Kunming, San Francisco

Z ...

where he at first took refuge with a friend,

Alexander Müller.

In exile: Switzerland (1849–1858)

Wagner was to spend the next twelve years in exile from Germany. He had completed ''

Lohengrin'', the last of his middle-period operas, before the Dresden uprising, and now wrote desperately to his friend

Franz Liszt

Franz Liszt, in modern usage ''Liszt Ferenc'' . Liszt's Hungarian passport spelled his given name as "Ferencz". An orthographic reform of the Hungarian language in 1922 (which was 36 years after Liszt's death) changed the letter "cz" to simpl ...

to have it staged in his absence. Liszt conducted the premiere in

Weimar

Weimar is a city in the state of Thuringia, Germany. It is located in Central Germany between Erfurt in the west and Jena in the east, approximately southwest of Leipzig, north of Nuremberg and west of Dresden. Together with the neighbouri ...

in August 1850.

Nevertheless, Wagner was in grim personal straits, isolated from the German musical world and without any regular income. In 1850, Julie, the wife of his friend Karl Ritter, began to pay him a small pension which she maintained until 1859. With help from her friend Jessie Laussot, this was to have been augmented to an annual sum of 3,000

Thaler

A thaler (; also taler, from german: Taler) is one of the large silver coins minted in the states and territories of the Holy Roman Empire and the Habsburg monarchy during the Early Modern period. A ''thaler'' size silver coin has a diameter o ...

s per year, but the plan was abandoned when Wagner began an affair with Mme. Laussot. Wagner even plotted an elopement with her in 1850, which her husband prevented. Meanwhile, Wagner's wife Minna, who had disliked the operas he had written after ''Rienzi'', was falling into a deepening

depression. Wagner fell victim to ill-health, according to

Ernest Newman

Ernest Newman (30 November 1868 – 7 July 1959) was an English music critic and musicologist. ''Grove's Dictionary of Music and Musicians'' describes him as "the most celebrated British music critic in the first half of the 20th century." His ...

"largely a matter of overwrought nerves", which made it difficult for him to continue writing.

Wagner's primary published output during his first years in Zürich was a set of essays. In "

The Artwork of the Future" (1849), he described a vision of opera as ''

Gesamtkunstwerk

A ''Gesamtkunstwerk'' (, literally 'total artwork', translated as 'total work of art', 'ideal work of art', 'universal artwork', 'synthesis of the arts', 'comprehensive artwork', or 'all-embracing art form') is a work of art that makes use of al ...

'' ("total work of art"), in which the various arts such as music, song, dance, poetry, visual arts and stagecraft were unified. "

Judaism in Music

"Das Judenthum in der Musik" ( German for "Jewishness in Music", but normally translated ''Judaism in Music''; spelled after its first publications, according to modern German spelling practice, as ‘Judentum’) is an essay by Richard Wagner whi ...

" (1850) was the first of Wagner's writings to feature

antisemitic

Antisemitism (also spelled anti-semitism or anti-Semitism) is hostility to, prejudice towards, or discrimination against Jews. A person who holds such positions is called an antisemite. Antisemitism is considered to be a form of racism.

Ant ...

views. In this polemic Wagner argued, frequently using traditional antisemitic abuse, that Jews had no connection to the German spirit, and were thus capable of producing only shallow and artificial music. According to him, they composed music to achieve popularity and, thereby, financial success, as opposed to creating genuine works of art.

In "

Opera and Drama" (1851), Wagner described the

aesthetics

Aesthetics, or esthetics, is a branch of philosophy that deals with the nature of beauty and taste, as well as the philosophy of art (its own area of philosophy that comes out of aesthetics). It examines aesthetic values, often expressed t ...

of drama that he was using to create the ''Ring'' operas. Before leaving Dresden, Wagner had drafted a scenario that eventually became the four-opera cycle ''

Der Ring des Nibelungen

(''The Ring of the Nibelung''), WWV 86, is a cycle of four German-language epic music dramas composed by Richard Wagner. The works are based loosely on characters from Germanic heroic legend, namely Norse legendary sagas and the '' Nibe ...

''. He initially

wrote the libretto for a single opera, ''Siegfrieds Tod'' (''Siegfried's Death''), in 1848. After arriving in Zürich, he expanded the story with the opera ''Der junge Siegfried'' (''Young Siegfried''), which explored the

hero's background. He completed the text of the cycle by writing the libretti for ''

Die Walküre

(; ''The Valkyrie''), WWV 86B, is the second of the four music dramas that constitute Richard Wagner's ''Der Ring des Nibelungen'' (English: ''The Ring of the Nibelung''). It was performed, as a single opera, at the National Theatre Munich on ...

'' (''The

Valkyrie

In Norse mythology, a valkyrie ("chooser of the slain") is one of a host of female figures who guide souls of the dead to the god Odin's hall Valhalla. There, the deceased warriors become (Old Norse "single (or once) fighters"Orchard (1997: ...

'') and ''

Das Rheingold

''Das Rheingold'' (; ''The Rhinegold''), WWV 86A, is the first of the four music dramas that constitute Richard Wagner's '' Der Ring des Nibelungen'' (English: ''The Ring of the Nibelung''). It was performed, as a single opera, at the National ...

'' (''The Rhine Gold'') and revising the other libretti to agree with his new concept, completing them in 1852. The concept of opera expressed in "Opera and Drama" and in other essays effectively renounced the operas he had previously written, up to and including ''Lohengrin.'' Partly in an attempt to explain his change of views, Wagner published in 1851 the autobiographical "

A Communication to My Friends". This contained his first public announcement of what was to become the ''Ring'' cycle:

I shall never write an ''Opera'' more. As I have no wish to invent an arbitrary title for my works, I will call them Dramas ...

I propose to produce my myth in three complete dramas, preceded by a lengthy Prelude (Vorspiel). ...

At a specially-appointed Festival, I propose, some future time, to produce those three Dramas with their Prelude, ''in the course of three days and a fore-evening'' mphasis in original

Wagner began composing the music for ''Das Rheingold'' between November 1853 and September 1854, following it immediately with ''Die Walküre'' (written between June 1854 and March 1856). He began work on the third ''Ring'' opera, which he now called simply ''

Siegfried,'' probably in September 1856, but by June 1857 he had completed only the first two acts. He decided to put the work aside to concentrate on a new idea: ''

Tristan und Isolde

''Tristan und Isolde'' (''Tristan and Isolde''), WWV 90, is an opera in three acts by Richard Wagner to a German libretto by the composer, based largely on the 12th-century romance Tristan and Iseult by Gottfried von Strassburg. It was comp ...

,'' based on the

Arthurian love story ''

Tristan and Iseult

Tristan and Iseult, also known as Tristan and Isolde and other names, is a medieval chivalric romance told in numerous variations since the 12th century. Based on a Celtic legend and possibly other sources, the tale is a tragedy about the illic ...

.''

One source of inspiration for ''Tristan und Isolde'' was the philosophy of

Arthur Schopenhauer

Arthur Schopenhauer ( , ; 22 February 1788 – 21 September 1860) was a German philosopher. He is best known for his 1818 work ''The World as Will and Representation'' (expanded in 1844), which characterizes the phenomenal world as the prod ...

, notably his ''

The World as Will and Representation

''The World as Will and Representation'' (''WWR''; german: Die Welt als Wille und Vorstellung, ''WWV''), sometimes translated as ''The World as Will and Idea'', is the central work of the German philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer. The first edition ...

,'' to which Wagner had been introduced in 1854 by his poet friend

Georg Herwegh

Georg Friedrich Rudolph Theodor Herwegh (31 May 1817 – 7 April 1875) was a German poet,Herwegh, Georg, The Columbia Encyclopedia (2008) who is considered part of the Young Germany movement.

Biography

He was born in Stuttgart on 31 May 1817, ...

. Wagner later called this the most important event of his life. His personal circumstances certainly made him an easy convert to what he understood to be Schopenhauer's philosophy, a deeply pessimistic view of the human condition. He remained an adherent of Schopenhauer for the rest of his life.

One of Schopenhauer's doctrines was that music held a supreme role in the arts as a direct expression of the world's essence, namely, blind, impulsive will. This doctrine contradicted Wagner's view, expressed in "Opera and Drama", that the music in opera had to be subservient to the drama. Wagner scholars have argued that Schopenhauer's influence caused Wagner to assign a more commanding role to music in his later operas, including the latter half of the ''Ring'' cycle, which he had yet to compose. Aspects of Schopenhauerian doctrine found their way into Wagner's subsequent libretti.

A second source of inspiration was Wagner's infatuation with the poet-writer

Mathilde Wesendonck

Agnes Mathilde Wesendonck (née Luckemeyer; 23 December 182831 August 1902) was a German poet and author. The words of five of her verses were the basis of Richard Wagner's '' Wesendonck Lieder''; the composer was infatuated with her, and his ...

, the wife of the silk merchant Otto Wesendonck. Wagner met the Wesendoncks, who were both great admirers of his music, in Zürich in 1852. From May 1853 onwards Wesendonck made several loans to Wagner to finance his household expenses in Zürich, and in 1857 placed a cottage on his estate at Wagner's disposal, which became known as the ''Asyl'' ("asylum" or "place of rest"). During this period, Wagner's growing passion for his patron's wife inspired him to put aside work on the ''Ring'' cycle (which was not resumed for the next twelve years) and begin work on ''Tristan''. While planning the opera, Wagner composed the ''

Wesendonck Lieder,'' five songs for voice and piano, setting poems by Mathilde. Two of these settings are explicitly subtitled by Wagner as "studies for ''Tristan und Isolde''".

Among the conducting engagements that Wagner undertook for revenue during this period, he gave several concerts in 1855 with the

Philharmonic Society of London

The Royal Philharmonic Society (RPS) is a British music society, formed in 1813. Its original purpose was to promote performances of instrumental music in London. Many composers and performers have taken part in its concerts. It is now a me ...

, including one before

Queen Victoria

Victoria (Alexandrina Victoria; 24 May 1819 – 22 January 1901) was Queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland from 20 June 1837 until her death in 1901. Her reign of 63 years and 216 days was longer than that of any previ ...

. The Queen enjoyed his ''Tannhäuser'' overture and spoke with Wagner after the concert, writing of him in her diary that he was "short, very quiet, wears spectacles & has a very finely-developed forehead, a hooked nose & projecting chin."

In exile: Venice and Paris (1858–1862)

Wagner's uneasy affair with Mathilde collapsed in 1858, when Minna intercepted a letter to Mathilde from him. After the resulting confrontation with Minna, Wagner left Zürich alone, bound for

Venice

Venice ( ; it, Venezia ; vec, Venesia or ) is a city in northeastern Italy and the capital of the Veneto Regions of Italy, region. It is built on a group of 118 small islands that are separated by canals and linked by over 400 ...

, where he rented an apartment in the

Palazzo Giustinian, while Minna returned to Germany. Wagner's attitude to Minna had changed; the editor of his correspondence with her, John Burk, has said that she was to him "an invalid, to be treated with kindness and consideration, but, except at a distance,

asa menace to his peace of mind." Wagner continued his correspondence with Mathilde and his friendship with her husband Otto, who maintained his financial support of the composer. In an 1859 letter to Mathilde, Wagner wrote, half-satirically, of ''Tristan'': "Child! This Tristan is turning into something ''terrible''. This final act!!!—I fear the opera will be banned ... only mediocre performances can save me! Perfectly good ones will be bound to drive people mad."

In November 1859, Wagner once again moved to Paris to oversee production of a new revision of ''Tannhäuser'', staged thanks to the efforts of Princess

Pauline von Metternich

Pauline Clémentine Marie Walburga, Princess of Metternich-Winneburg zu Beilstein (''née'' Countess Pauline Sándor de Szlavnicza; 25 February 1836 – 28 September 1921) was a famous Austrian socialite, mainly active in Vienna and Paris. Known ...

, whose husband was the Austrian ambassador in Paris. The performances of the Paris ''Tannhäuser'' in 1861 were

a notable fiasco. This was partly a consequence of the conservative tastes of the

Jockey Club

The Jockey Club is the largest commercial horse racing organisation in the United Kingdom. It owns 15 of Britain's famous racecourses, including Aintree, Cheltenham, Epsom Downs and both the Rowley Mile and July Course in Newmarket, a ...

, which organised demonstrations in the theatre to protest at the presentation of the ballet feature in act 1 (instead of its traditional location in the second act); but the opportunity was also exploited by those who wanted to use the occasion as a veiled political protest against the pro-Austrian policies of

Napoleon III

Napoleon III (Charles Louis Napoléon Bonaparte; 20 April 18089 January 1873) was the first President of France (as Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte) from 1848 to 1852 and the last monarch of France as Emperor of the French from 1852 to 1870. A neph ...

. It was during this visit that Wagner met the French poet

Charles Baudelaire

Charles Pierre Baudelaire (, ; ; 9 April 1821 – 31 August 1867) was a French poet who also produced notable work as an essayist and art critic. His poems exhibit mastery in the handling of rhyme and rhythm, contain an exoticism inherited fr ...

, who wrote an appreciative brochure, "". The opera was withdrawn after the third performance and Wagner left Paris soon after. He had sought a reconciliation with Minna during this Paris visit, and although she joined him there, the reunion was not successful and they again parted from each other when Wagner left.

Return and resurgence (1862–1871)

The political ban that had been placed on Wagner in Germany after he had fled Dresden was fully lifted in 1862. The composer settled in

Biebrich, on the Rhine near Wiesbaden in

Hesse

Hesse (, , ) or Hessia (, ; german: Hessen ), officially the State of Hessen (german: links=no, Land Hessen), is a state in Germany. Its capital city is Wiesbaden, and the largest urban area is Frankfurt. Two other major historic cities are ...

. Here Minna visited him for the last time: they parted irrevocably, though Wagner continued to give financial support to her while she lived in Dresden until her death in 1866.

In Biebrich, Wagner at last began work on ''Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg'', his only mature comedy. Wagner wrote a first draft of the libretto in 1845, and he had resolved to develop it during a visit he had made to Venice with the Wesendoncks in 1860, where he was inspired by

Titian

Tiziano Vecelli or Vecellio (; 27 August 1576), known in English as Titian ( ), was an Italians, Italian (Republic of Venice, Venetian) painter of the Renaissance, considered the most important member of the 16th-century Venetian school (art), ...

's painting ''

The Assumption of the Virgin''. Throughout this period (1861–1864) Wagner sought to have ''Tristan und Isolde'' produced in Vienna. Despite many rehearsals, the opera remained unperformed, and gained a reputation as being "impossible" to sing, which added to Wagner's financial problems.

Wagner's fortunes took a dramatic upturn in 1864, when

King Ludwig II succeeded to the throne of

Bavaria

Bavaria ( ; ), officially the Free State of Bavaria (german: Freistaat Bayern, link=no ), is a state in the south-east of Germany. With an area of , Bavaria is the largest German state by land area, comprising roughly a fifth of the total l ...

at the age of 18. The young king, an ardent admirer of Wagner's operas, had the composer brought to Munich. The King, who was homosexual, expressed in his correspondence a passionate personal adoration for the composer, and Wagner in his responses had no scruples about feigning reciprocal feelings. Ludwig settled Wagner's considerable debts, and proposed to stage ''Tristan'', ''Die Meistersinger'', the ''Ring'', and the other operas Wagner planned. Wagner also began to dictate his autobiography, ''Mein Leben'', at the King's request. Wagner noted that his rescue by Ludwig coincided with news of the death of his earlier mentor (but later supposed enemy) Giacomo Meyerbeer, and regretted that "this operatic master, who had done me so much harm, should not have lived to see this day."

After grave difficulties in rehearsal, ''Tristan und Isolde'' premiered at the

National Theatre Munich

The National Theatre (german: link=no, Nationaltheater) on Max-Joseph-Platz in Munich, Germany, is a historic opera house, home of the Bavarian State Opera, Bavarian State Orchestra and the Bavarian State Ballet.

Building

First theatre ...

on 10 June 1865, the first Wagner opera premiere in almost 15 years. (The premiere had been scheduled for 15 May, but was delayed by bailiffs acting for Wagner's creditors, and also because the Isolde,

Malvina Schnorr von Carolsfeld, was hoarse and needed time to recover.) The conductor of this premiere was

Hans von Bülow

Freiherr Hans Guido von Bülow (8 January 1830 – 12 February 1894) was a German conductor, virtuoso pianist, and composer of the Romantic era. As one of the most distinguished conductors of the 19th century, his activity was critical for es ...

, whose wife,

Cosima, had given birth in April that year to a daughter, named Isolde, a child not of Bülow but of Wagner.

Cosima was 24 years younger than Wagner and was herself illegitimate, the daughter of the Countess

Marie d'Agoult

Marie Cathérine Sophie, Comtesse d'Agoult (née de Flavigny; 31 December 18055 March 1876), was a Franco-German romantic author and historian, known also by her pen name, Daniel Stern.

Life

Marie was born in Frankfurt am Main, Germany, with th ...

, who had left her husband for

Franz Liszt

Franz Liszt, in modern usage ''Liszt Ferenc'' . Liszt's Hungarian passport spelled his given name as "Ferencz". An orthographic reform of the Hungarian language in 1922 (which was 36 years after Liszt's death) changed the letter "cz" to simpl ...

. Liszt initially disapproved of his daughter's involvement with Wagner, though nevertheless, the two men were friends. The indiscreet affair scandalised Munich, and Wagner also fell into disfavour with many leading members of the court, who were suspicious of his influence on the King. In December 1865, Ludwig was finally forced to ask the composer to leave Munich. He apparently also toyed with the idea of abdicating to follow his hero into exile, but Wagner quickly dissuaded him.

Ludwig installed Wagner at the

Villa Tribschen, beside Switzerland's

Lake Lucerne

__NOTOC__

Lake Lucerne (german: Vierwaldstättersee, literally "Lake of the four forested settlements" (in English usually translated as ''forest cantons''), french: lac des Quatre-Cantons, it, lago dei Quattro Cantoni) is a lake in central S ...

. ''Die Meistersinger'' was completed at Tribschen in 1867, and premiered in Munich on 21 June the following year. At Ludwig's insistence, "special previews" of the first two works of the ''Ring'', ''Das Rheingold'' and ''Die Walküre'', were performed at Munich in 1869 and 1870, but Wagner retained his dream, first expressed in "A Communication to My Friends", to present the first complete cycle at a special festival with a new, dedicated,

opera house

An opera house is a theatre building used for performances of opera. It usually includes a stage, an orchestra pit, audience seating, and backstage facilities for costumes and building sets.

While some venues are constructed specifically fo ...

.

Minna had died of a heart attack on 25 January 1866 in Dresden. Wagner did not attend the funeral. Following Minna's death Cosima wrote to Hans von Bülow several times asking him to grant her a divorce, but Bülow refused to concede this. He consented only after she had two more children with Wagner; another daughter, named Eva, after the heroine of ''Meistersinger'', and a son

Siegfried, named for the hero of the ''Ring''. The divorce was finally sanctioned, after delays in the legal process, by a Berlin court on 18 July 1870. Richard and Cosima's wedding took place on 25 August 1870. On Christmas Day of that year, Wagner arranged a surprise performance (its premiere) of the ''

Siegfried Idyll

The ', WWV 103, by Richard Wagner is a symphonic poem for chamber orchestra.

Background

Wagner composed the ''Siegfried Idyll'' as a birthday present to his second wife, Cosima, after the birth of their son Siegfried in 1869. It was first per ...

'' for Cosima's birthday. The marriage to Cosima lasted to the end of Wagner's life.

Wagner, settled into his new-found domesticity, turned his energies towards completing the ''Ring'' cycle. He had not abandoned polemics: he republished his 1850 pamphlet "Judaism in Music", originally issued under a pseudonym, under his own name in 1869. He extended the introduction, and wrote a lengthy additional final section. The publication led to several public protests at early performances of ''Die Meistersinger'' in Vienna and Mannheim.

Bayreuth (1871–1876)

In 1871, Wagner decided to move to

Bayreuth

Bayreuth (, ; bar, Bareid) is a town in northern Bavaria, Germany, on the Red Main river in a valley between the Franconian Jura and the Fichtelgebirge Mountains. The town's roots date back to 1194. In the 21st century, it is the capital o ...

, which was to be the location of his new opera house. The town council donated a large plot of land—the "Green Hill"—as a site for the theatre. The Wagners moved to the town the following year, and the foundation stone for the

Bayreuth Festspielhaus

The ''Bayreuth Festspielhaus'' or Bayreuth Festival Theatre (german: link=no, Bayreuther Festspielhaus, ) is an opera house north of Bayreuth, Germany, built by the 19th-century German composer Richard Wagner and dedicated solely to the performa ...

("Festival Theatre") was laid. Wagner initially announced the first Bayreuth Festival, at which for the first time the ''Ring'' cycle would be presented complete, for 1873, but since Ludwig had declined to finance the project, the start of building was delayed and the proposed date for the festival was deferred. To raise funds for the construction, "

Wagner societies" were formed in several cities, and Wagner began touring Germany conducting concerts. By the spring of 1873, only a third of the required funds had been raised; further pleas to Ludwig were initially ignored, but early in 1874, with the project on the verge of collapse, the King relented and provided a loan. The full building programme included the family home, "

Wahnfried

Wahnfried was the name given by Richard Wagner to his villa in Bayreuth. The name is a German compound of (delusion, madness) and (peace, freedom).

Financed by King Ludwig II of Bavaria, the house was constructed from 1872 to 1874 under Bayreu ...

", into which Wagner, with Cosima and the children, moved from their temporary accommodation on 18 April 1874. The theatre was completed in 1875, and the festival scheduled for the following year. Commenting on the struggle to finish the building, Wagner remarked to Cosima: "Each stone is red with my blood and yours".

For the design of the Festspielhaus, Wagner appropriated some of the ideas of his former colleague, Gottfried Semper, which he had previously solicited for a proposed new opera house at Munich. Wagner was responsible for several theatrical innovations at Bayreuth; these include darkening the auditorium during performances, and placing the orchestra in a pit out of view of the audience.

The Festspielhaus finally opened on 13 August 1876 with ''Das Rheingold'', at last taking its place as the first evening of the complete ''Ring'' cycle; the 1876

Bayreuth Festival

The Bayreuth Festival (german: link=no, Bayreuther Festspiele) is a music festival held annually in Bayreuth, Germany, at which performances of operas by the 19th-century German composer Richard Wagner are presented. Wagner himself conceived ...

therefore saw the premiere of the complete cycle, performed as a sequence as the composer had intended. The 1876 Festival consisted of three full ''Ring'' cycles (under the baton of

Hans Richter). At the end, critical reactions ranged between that of the Norwegian composer

Edvard Grieg

Edvard Hagerup Grieg ( , ; 15 June 18434 September 1907) was a Norwegian composer and pianist. He is widely considered one of the foremost Romantic era composers, and his music is part of the standard classical repertoire worldwide. His use of ...

, who thought the work "divinely composed", and that of the French newspaper ''

Le Figaro

''Le Figaro'' () is a French daily morning newspaper founded in 1826. It is headquartered on Boulevard Haussmann in the 9th arrondissement of Paris. The oldest national newspaper in France, ''Le Figaro'' is one of three French newspapers of r ...

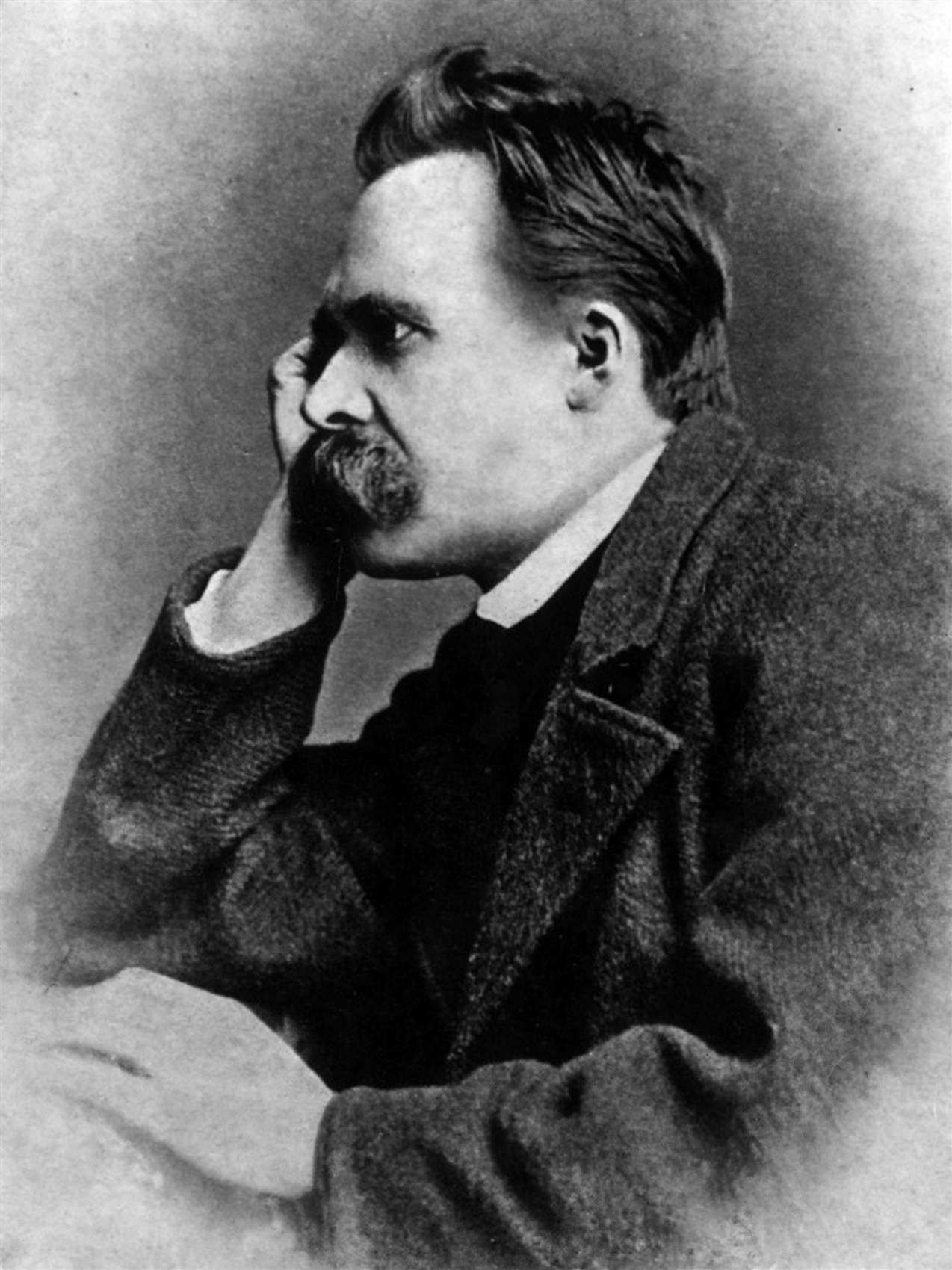

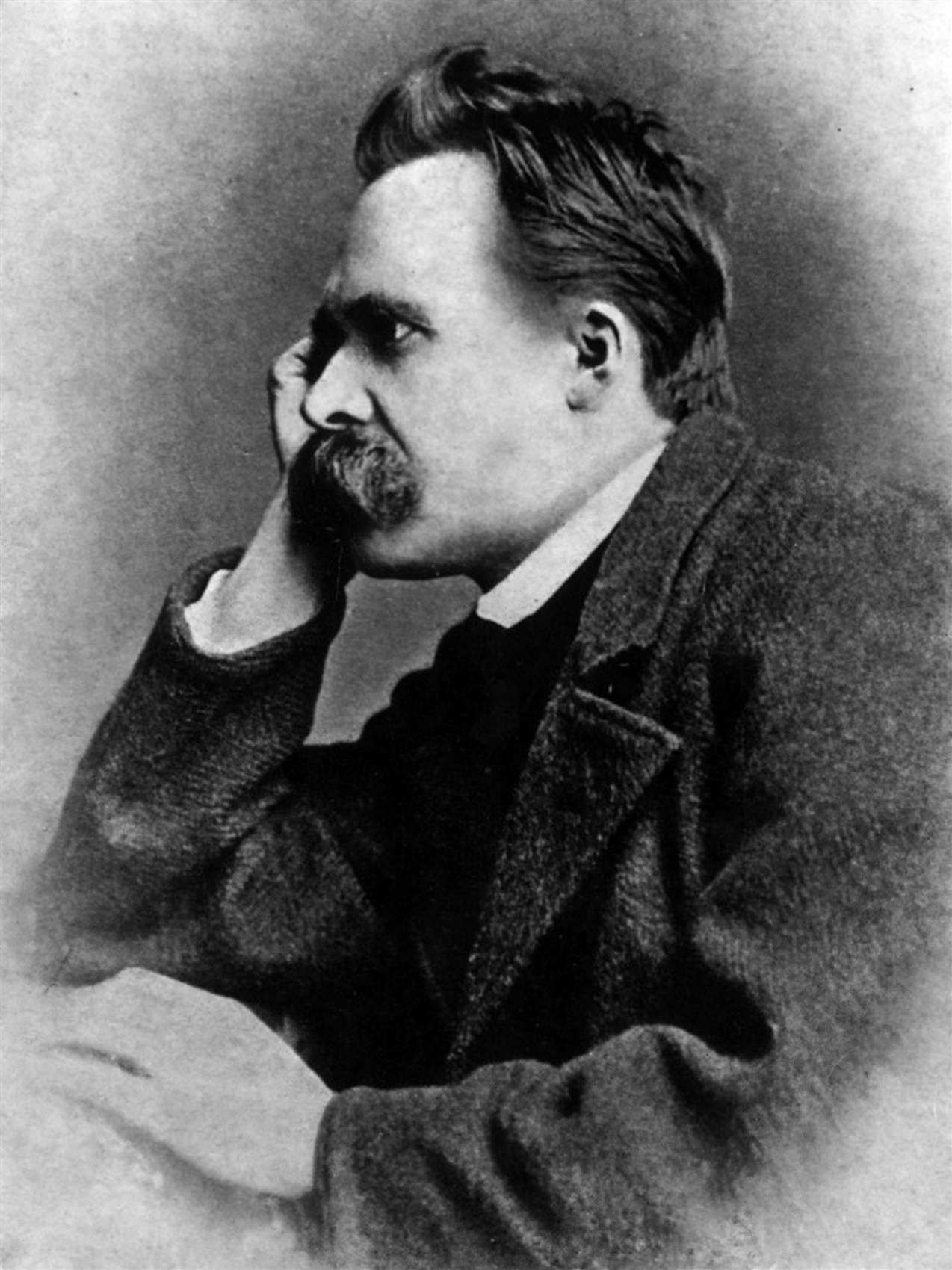

'', which called the music "the dream of a lunatic". The disillusioned included Wagner's friend and disciple

Friedrich Nietzsche

Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche (; or ; 15 October 1844 – 25 August 1900) was a German philosopher, prose poet, cultural critic, philologist, and composer whose work has exerted a profound influence on contemporary philosophy. He began his ...

, who, having published his eulogistic essay "Richard Wagner in Bayreuth" before the festival as part of his ''

Untimely Meditations'', was bitterly disappointed by what he saw as Wagner's pandering to increasingly exclusivist German nationalism; his breach with Wagner began at this time. The festival firmly established Wagner as an artist of European, and indeed world, importance: attendees included

Kaiser Wilhelm I, the Emperor

Pedro II of Brazil

Dom PedroII (2 December 1825 – 5 December 1891), nicknamed "the Magnanimous" ( pt, O Magnânimo), was the second and last monarch of the Empire of Brazil, reigning for over 58 years. He was born in Rio de Janeiro, the seventh child of Emp ...

,

Anton Bruckner

Josef Anton Bruckner (; 4 September 182411 October 1896) was an Austrian composer, organist, and music theorist best known for his symphonies, masses, Te Deum and motets. The first are considered emblematic of the final stage of Austro-Ger ...

,

Camille Saint-Saëns

Charles-Camille Saint-Saëns (; 9 October 183516 December 1921) was a French composer, organist, conductor and pianist of the Romantic music, Romantic era. His best-known works include Introduction and Rondo Capriccioso (1863), the Piano C ...

and

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky , group=n ( ; 7 May 1840 – 6 November 1893) was a Russian composer of the Romantic period. He was the first Russian composer whose music would make a lasting impression internationally. He wrote some of the most popu ...

.

Wagner was far from satisfied with the Festival; Cosima recorded that months later, his attitude towards the productions was "Never again, never again!" Moreover, the festival finished with a deficit of about 150,000 marks. The expenses of Bayreuth and of Wahnfried meant that Wagner still sought further sources of income by conducting or taking on commissions such as the ''Centennial March'' for America, for which he received $5000.

Last years (1876–1883)

Following the first Bayreuth Festival, Wagner began work on ''

Parsifal

''Parsifal'' ( WWV 111) is an opera or a music drama in three acts by the German composer Richard Wagner and his last composition. Wagner's own libretto for the work is loosely based on the 13th-century Middle High German epic poem ''Parzival ...

'', his final opera. The composition took four years, much of which Wagner spent in Italy for health reasons. From 1876 to 1878 Wagner also embarked on the last of his documented emotional liaisons, this time with

Judith Gautier, whom he had met at the 1876 Festival. Wagner was also much troubled by problems of financing ''Parsifal'', and by the prospect of the work being performed by other theatres than Bayreuth. He was once again assisted by the liberality of King Ludwig, but was still forced by his personal financial situation in 1877 to sell the rights of several of his unpublished works (including the ''Siegfried Idyll'') to the publisher

Schott.

Wagner wrote several articles in his later years, often on political topics, and often

reactionary

In political science, a reactionary or a reactionist is a person who holds political views that favor a return to the '' status quo ante'', the previous political state of society, which that person believes possessed positive characteristics abs ...

in tone, repudiating some of his earlier, more liberal, views. These include "Religion and Art" (1880) and "Heroism and Christianity" (1881), which were printed in the journal ''

Bayreuther Blätter

''Bayreuther Blätter'' (''Bayreuth pages'') was a monthly journal founded in by Richard Wagner 1878 and edited by Hans von Wolzogen until his death in 1938. It was written primarily for visitors to the Bayreuth Festival.

The newsletter carried ...

'', published by his supporter

Hans von Wolzogen. Wagner's sudden interest in Christianity at this period, which infuses ''Parsifal'', was contemporary with his increasing alignment with

German nationalism

German nationalism () is an ideological notion that promotes the unity of Germans and German-speakers into one unified nation state. German nationalism also emphasizes and takes pride in the patriotism and national identity of Germans as one n ...

, and required on his part, and the part of his associates, "the rewriting of some recent Wagnerian history", so as to represent, for example, the ''Ring'' as a work reflecting Christian ideals. Many of these later articles, including "What is German?" (1878, but based on a draft written in the 1860s), repeated Wagner's antisemitic preoccupations.

Wagner completed ''Parsifal'' in January 1882, and a second Bayreuth Festival was held for the new opera, which premiered on 26 May. Wagner was by this time extremely ill, having suffered a series of increasingly severe

angina

Angina, also known as angina pectoris, is chest pain or pressure, usually caused by insufficient blood flow to the heart muscle (myocardium). It is most commonly a symptom of coronary artery disease.

Angina is typically the result of obstr ...

attacks. During the sixteenth and final performance of ''Parsifal'' on 29 August, he entered the pit unseen during act 3, took the baton from conductor

Hermann Levi, and led the performance to its conclusion.

After the festival, the Wagner family journeyed to Venice for the winter. Wagner died of a heart attack at the age of 69 on 13 February 1883 at

Ca' Vendramin Calergi, a 16th-century

palazzo

A palace is a grand residence, especially a royal residence, or the home of a head of state or some other high-ranking dignitary, such as a bishop or archbishop. The word is derived from the Latin name palātium, for Palatine Hill in Rome which ...

on the

Grand Canal. The legend that the attack was prompted by argument with Cosima over Wagner's supposedly amorous interest in the singer

Carrie Pringle

Carrie Pringle (Caroline Mary Isabelle Pringle; 19 March 1859 – 12 November 1930) was an Austrian-born British soprano singer. She performed the role of one of the Flowermaidens in the 1882 premiere of Richard Wagner's ''Parsifal'' at the Bayr ...

, who had been a Flower-maiden in ''Parsifal'' at Bayreuth, is without credible evidence. After a funerary

gondola

The gondola (, ; vec, góndoła ) is a traditional, flat-bottomed Venetian rowing boat, well suited to the conditions of the Venetian lagoon. It is typically propelled by a gondolier, who uses a rowing oar, which is not fastened to the hull, ...

bore Wagner's remains over the Grand Canal, his body was taken to Germany where it was buried in the garden of the Villa Wahnfried in Bayreuth.

Works

Wagner's musical output is listed by the ''Wagner-Werk-Verzeichnis'' (WWV) as comprising 113 works, including fragments and projects. The first complete scholarly edition of his musical works in print was commenced in 1970 under the aegis of the

Bavarian Academy of Fine Arts and the

Akademie der Wissenschaften und der Literatur of

Mainz

Mainz () is the capital and largest city of Rhineland-Palatinate, Germany.

Mainz is on the left bank of the Rhine, opposite to the place that the Main joins the Rhine. Downstream of the confluence, the Rhine flows to the north-west, with Ma ...

, and is presently under the editorship of

Egon Voss. It will consist of 21 volumes (57 books) of music and 10 volumes (13 books) of relevant documents and texts. As at October 2017, three volumes remain to be published. The publisher is

Schott Music

Schott Music () is one of the oldest German music publishers. It is also one of the largest music publishing houses in Europe, and is the second oldest music publisher after Breitkopf & Härtel. The company headquarters of Schott Music were fo ...

.

Operas

Wagner's operatic works are his primary artistic legacy. Unlike most opera composers, who generally left the task of writing the

libretto

A libretto (Italian for "booklet") is the text used in, or intended for, an extended musical work such as an opera, operetta, masque, oratorio, cantata or musical. The term ''libretto'' is also sometimes used to refer to the text of major li ...

(the text and lyrics) to others, Wagner wrote his own libretti, which he referred to as "poems".

From 1849 onwards, he urged a new concept of opera often referred to as "music drama" (although he later rejected this term), in which all musical, poetic and dramatic elements were to be fused together—the ''

Gesamtkunstwerk

A ''Gesamtkunstwerk'' (, literally 'total artwork', translated as 'total work of art', 'ideal work of art', 'universal artwork', 'synthesis of the arts', 'comprehensive artwork', or 'all-embracing art form') is a work of art that makes use of al ...

''. Wagner developed a compositional style in which the importance of the orchestra is equal to that of the singers. The orchestra's dramatic role in the later operas includes the use of

leitmotif

A leitmotif or leitmotiv () is a "short, recurring musical phrase" associated with a particular person, place, or idea. It is closely related to the musical concepts of ''idée fixe'' or ''motto-theme''. The spelling ''leitmotif'' is an anglic ...

s, musical phrases that can be interpreted as announcing specific characters, locales, and plot elements; their complex interweaving and evolution illuminates the progression of the drama. These operas are still, despite Wagner's reservations, referred to by many writers as "music dramas".

Early works (to 1842)

Wagner's earliest attempts at opera were often uncompleted. Abandoned works include

a pastoral opera based on

Goethe

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (28 August 1749 – 22 March 1832) was a German poet, playwright, novelist, scientist, statesman, theatre director, and critic. His works include plays, poetry, literature, and aesthetic criticism, as well as tr ...

's ''Die Laune des Verliebten'' (''The Infatuated Lover's Caprice''), written at the age of 17, ''

Die Hochzeit

''Die Hochzeit'' (''The Wedding'', WWV 31) is an unfinished opera by Richard Wagner which predates his completed works in the genre. Wagner completed the libretto, then started composing the music in the second half of 1832 when he was just ninete ...

'' (''The Wedding''), on which Wagner worked in 1832, and the

singspiel

A Singspiel (; plural: ; ) is a form of German-language music drama, now regarded as a genre of opera. It is characterized by spoken dialogue, which is alternated with ensembles, songs, ballads, and aria

In music, an aria ( Italian: ; plur ...

''

Männerlist größer als Frauenlist

''Männerlist größer als Frauenlist oder Die glückliche Bärenfamilie'' (''Men Are More Cunning Than Women, or The Happy Bear Family''; WWV 48) is an unfinished Singspiel by Richard Wagner, written between 1837 and 1838.

''Männerlist'' was W ...

'' (''Men are More Cunning than Women'', 1837–1838). ''

Die Feen'' (''The Fairies'', 1833) was not performed in the composer's lifetime and ''

Das Liebesverbot'' (''The Ban on Love'', 1836) was withdrawn after its first performance. ''

Rienzi

' (''Rienzi, the last of the tribunes''; WWV 49) is an early opera by Richard Wagner in five acts, with the libretto written by the composer after Edward Bulwer-Lytton's novel of the same name (1835). The title is commonly shortened to ''Ri ...

'' (1842) was Wagner's first opera to be successfully staged. The compositional style of these early works was conventional—the relatively more sophisticated ''Rienzi'' showing the clear influence of

Grand Opera

Grand opera is a genre of 19th-century opera generally in four or five acts, characterized by large-scale casts and orchestras, and (in their original productions) lavish and spectacular design and stage effects, normally with plots based on o ...

''à la'' Spontini and Meyerbeer—and did not exhibit the innovations that would mark Wagner's place in musical history. Later in life, Wagner said that he did not consider these works to be part of his

''oeuvre''; and they have been performed only rarely in the last hundred years, although the overture to ''Rienzi'' is an occasional concert-hall piece. ''Die Feen'', ''Das Liebesverbot'', and ''Rienzi'' were performed at both Leipzig and Bayreuth in 2013 to mark the composer's bicentenary.

"Romantic operas" (1843–1851)

Wagner's middle stage output began with ''

Der fliegende Holländer

' (''The Flying Dutchman''), WWV 63, is a German-language opera, with libretto and music by Richard Wagner. The central theme is redemption through love. Wagner conducted the premiere at the Königliches Hoftheater Dresden in 1843.

Wagner cla ...

'' (''The Flying Dutchman'', 1843), followed by ''

Tannhäuser

Tannhäuser (; gmh, Tanhûser), often stylized, "The Tannhäuser," was a German Minnesinger and traveling poet. Historically, his biography, including the dates he lived, is obscure beyond the poetry, which suggests he lived between 1245 and ...

'' (1845) and ''

Lohengrin'' (1850). These three operas are sometimes referred to as Wagner's "romantic operas". They reinforced the reputation, among the public in Germany and beyond, that Wagner had begun to establish with ''Rienzi''. Although distancing himself from the style of these operas from 1849 onwards, he nevertheless reworked both ''Der fliegende Holländer'' and ''Tannhäuser'' on several occasions. These three operas are considered to represent a significant developmental stage in Wagner's musical and operatic maturity as regards thematic handling, portrayal of emotions and orchestration. They are the earliest works included in the

Bayreuth canon

The Bayreuth canon consists of those operas by the German composer Richard Wagner (1813–1883) that have been performed at the Bayreuth Festival. The festival, which is dedicated to the staging of these works, was founded by Wagner in 1876 in the ...

, the mature operas that Cosima staged at the Bayreuth Festival after Wagner's death in accordance with his wishes. All three (including the differing versions of ''Der fliegende Holländer'' and ''Tannhäuser'') continue to be regularly performed throughout the world, and have been frequently recorded. They were also the operas by which his fame spread during his lifetime.

"Music dramas" (1851–1882)

= Starting the ''Ring''

=

Wagner's late dramas are considered his masterpieces. ''Der Ring des Nibelungen'', commonly referred to as the ''Ring'' or "''Ring'' cycle", is a set of four operas based loosely on figures and elements of

Germanic mythology

Germanic mythology consists of the body of myths native to the Germanic peoples, including Norse mythology, Anglo-Saxon mythology, and Continental Germanic mythology. It was a key element of Germanic paganism.

Origins

As the Germanic lang ...

—particularly from the later

Norse mythology

Norse, Nordic, or Scandinavian mythology is the body of myths belonging to the North Germanic peoples, stemming from Old Norse religion and continuing after the Christianization of Scandinavia, and into the Nordic folklore of the modern per ...

—notably the

Old Norse

Old Norse, Old Nordic, or Old Scandinavian, is a stage of development of North Germanic dialects before their final divergence into separate Nordic languages. Old Norse was spoken by inhabitants of Scandinavia and their overseas settlement ...

''

Poetic Edda

The ''Poetic Edda'' is the modern name for an untitled collection of Old Norse anonymous narrative poems, which is distinct from the ''Prose Edda'' written by Snorri Sturluson. Several versions exist, all primarily of text from the Icelandic med ...

'' and ''

Volsunga Saga'', and the

Middle High German

Middle High German (MHG; german: Mittelhochdeutsch (Mhd.)) is the term for the form of German spoken in the High Middle Ages. It is conventionally dated between 1050 and 1350, developing from Old High German and into Early New High German. Hig ...

''

Nibelungenlied

The ( gmh, Der Nibelunge liet or ), translated as ''The Song of the Nibelungs'', is an epic poem written around 1200 in Middle High German. Its anonymous poet was likely from the region of Passau. The is based on an oral tradition of Germani ...

''. Wagner specifically developed the libretti for these operas according to his interpretation of ''

Stabreim'', highly alliterative rhyming verse-pairs used in old Germanic poetry. They were also influenced by Wagner's concepts of

ancient Greek

Ancient Greek includes the forms of the Greek language used in ancient Greece and the ancient world from around 1500 BC to 300 BC. It is often roughly divided into the following periods: Mycenaean Greek (), Dark Ages (), the Archaic pe ...

drama, in which

tetralogies

A tetralogy (from Greek τετρα- ''tetra-'', "four" and -λογία ''-logia'', "discourse") is a compound work that is made up of four distinct works. The name comes from the Attic theater, in which a tetralogy was a group of three tragedies f ...

were a component of

Athenian festivals

The festival calendar of Classical Athens involved the staging of many festivals each year. This includes festivals held in honor of Athena, Dionysus, Apollo, Artemis, Demeter, Persephone, Hermes, and Herakles. Other Athenian festivals were b ...

, and which he had amply discussed in his essay "

Oper und Drama Oper may refer to:

;Technology

* Operator (disambiguation)

** IRC operator

*Outstanding Physical Education Preparation, a website for PE preparation

;Opera

* Deutsche Oper Berlin, Oper Leipzig, Komische Oper Berlin, Alte Oper

* Romantische Oper, g ...

".

The first two components of the ''Ring'' cycle were ''

Das Rheingold

''Das Rheingold'' (; ''The Rhinegold''), WWV 86A, is the first of the four music dramas that constitute Richard Wagner's '' Der Ring des Nibelungen'' (English: ''The Ring of the Nibelung''). It was performed, as a single opera, at the National ...

'' (''The Rhinegold''), which was completed in 1854, and ''

Die Walküre

(; ''The Valkyrie''), WWV 86B, is the second of the four music dramas that constitute Richard Wagner's ''Der Ring des Nibelungen'' (English: ''The Ring of the Nibelung''). It was performed, as a single opera, at the National Theatre Munich on ...

'' (''The

Valkyrie

In Norse mythology, a valkyrie ("chooser of the slain") is one of a host of female figures who guide souls of the dead to the god Odin's hall Valhalla. There, the deceased warriors become (Old Norse "single (or once) fighters"Orchard (1997: ...

''), which was finished in 1856. In ''Das Rheingold'', with its "relentlessly talky 'realism'

ndthe absence of lyrical '

numbers, Wagner came very close to the musical ideals of his 1849–1851 essays. ''Die Walküre'', which contains what is virtually a traditional

aria

In music, an aria ( Italian: ; plural: ''arie'' , or ''arias'' in common usage, diminutive form arietta , plural ariette, or in English simply air) is a self-contained piece for one voice, with or without instrumental or orchestral accompa ...

(Siegmund's ''Winterstürme'' in the first act), and the quasi-

choral

A choir ( ; also known as a chorale or chorus) is a musical ensemble of singers. Choral music, in turn, is the music written specifically for such an ensemble to perform. Choirs may perform music from the classical music repertoire, which s ...

appearance of the Valkyries themselves, shows more "operatic" traits, but has been assessed by Barry Millington as "the music drama that most satisfactorily embodies the theoretical principles of 'Oper und Drama'... A thoroughgoing synthesis of poetry and music is achieved without any notable sacrifice in musical expression."

= ''Tristan und Isolde'' and ''Die Meistersinger''

=

While composing the opera ''

Siegfried'', the third part of the ''Ring'' cycle, Wagner interrupted work on it and between 1857 and 1864 wrote the tragic love story ''

Tristan und Isolde

''Tristan und Isolde'' (''Tristan and Isolde''), WWV 90, is an opera in three acts by Richard Wagner to a German libretto by the composer, based largely on the 12th-century romance Tristan and Iseult by Gottfried von Strassburg. It was comp ...

'' and his only mature comedy ''

Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg

(; "The Master-Singers of Nuremberg"), WWV 96, is a music drama, or opera, in three acts, by Richard Wagner. It is the longest opera commonly performed, taking nearly four and a half hours, not counting two breaks between acts, and is tradit ...

'' (''The Mastersingers of Nuremberg''), two works that are also part of the regular operatic canon.

''Tristan'' is often granted a special place in musical history; many see it as the beginning of the move away from conventional

harmony

In music, harmony is the process by which individual sounds are joined together or composed into whole units or compositions. Often, the term harmony refers to simultaneously occurring frequencies, pitches ( tones, notes), or chords. Howeve ...

and

tonality

Tonality is the arrangement of pitches and/or chords of a musical work in a hierarchy of perceived relations, stabilities, attractions and directionality. In this hierarchy, the single pitch or triadic chord with the greatest stability is ca ...

and consider that it lays the groundwork for the direction of classical music in the 20th century. Wagner felt that his musico-dramatical theories were most perfectly realised in this work with its use of "the art of transition" between dramatic elements and the balance achieved between vocal and orchestral lines. Completed in 1859, the work was given its first performance in Munich, conducted by Bülow, in June 1865.

''Die Meistersinger'' was originally conceived by Wagner in 1845 as a sort of comic pendant to ''Tannhäuser''. Like ''Tristan'', it was premiered in Munich under the baton of Bülow, on 21 June 1868, and became an immediate success. Millington describes ''Meistersinger'' as "a rich, perceptive music drama widely admired for its warm humanity", but its strong German

nationalist

Nationalism is an idea and movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the state. As a movement, nationalism tends to promote the interests of a particular nation (as in a group of people), Smith, Anthony. ''Nationalism: Th ...

overtones have led some to cite it as an example of Wagner's reactionary politics and antisemitism.

= Completing the ''Ring''

=

When Wagner returned to writing the music for the last act of ''Siegfried'' and for ''

Götterdämmerung

' (; ''Twilight of the Gods''), WWV 86D, is the last in Richard Wagner's cycle of four music dramas titled (''The Ring of the Nibelung'', or ''The Ring Cycle'' or ''The Ring'' for short). It received its premiere at the on 17 August 1876, as ...

'' (''Twilight of the Gods''), as the final part of the ''Ring'', his style had changed once more to something more recognisable as "operatic" than the aural world of ''Rheingold'' and ''Walküre'', though it was still thoroughly stamped with his own originality as a composer and suffused with leitmotifs. This was in part because the libretti of the four ''Ring'' operas had been written in reverse order, so that the book for ''Götterdämmerung'' was conceived more "traditionally" than that of ''Rheingold''; still, the self-imposed strictures of the ''Gesamtkunstwerk'' had become relaxed. The differences also result from Wagner's development as a composer during the period in which he wrote ''Tristan'', ''Meistersinger'' and the Paris version of ''Tannhäuser''. From act 3 of ''Siegfried'' onwards, the ''Ring'' becomes more

chromatic

Diatonic and chromatic are terms in music theory that are most often used to characterize scales, and are also applied to musical instruments, intervals, chords, notes, musical styles, and kinds of harmony. They are very often used as a p ...

melodically, more complex harmonically and more developmental in its treatment of leitmotifs.

Wagner took 26 years from writing the first draft of a libretto in 1848 until he completed ''Götterdämmerung'' in 1874. The ''Ring'' takes about 15 hours to perform and is the only undertaking of such size to be regularly presented on the world's stages.

= ''Parsifal''

=

Wagner's final opera, ''

Parsifal

''Parsifal'' ( WWV 111) is an opera or a music drama in three acts by the German composer Richard Wagner and his last composition. Wagner's own libretto for the work is loosely based on the 13th-century Middle High German epic poem ''Parzival ...

'' (1882), which was his only work written especially for his Bayreuth Festspielhaus and which is described in the score as a "''Bühnenweihfestspiel''" ("festival play for the consecration of the stage"), has a storyline suggested by elements of the legend of the

Holy Grail