USS Hancock (CV-19) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

USS ''Hancock'' (CV/CVA-19) was one of 24 s built during

The following afternoon, ''Hancock'' sailed for a rendezvous point west of the Marianas where units of Vice Admiral Mitscher's

The following afternoon, ''Hancock'' sailed for a rendezvous point west of the Marianas where units of Vice Admiral Mitscher's  ''Hancock'' returned to Ulithi on 27 November and departed from that island with her task group to maintain air patrol over enemy airfields on Luzon to prevent ''kamikazes'' from attacking amphibious vessels of the landing force in

''Hancock'' returned to Ulithi on 27 November and departed from that island with her task group to maintain air patrol over enemy airfields on Luzon to prevent ''kamikazes'' from attacking amphibious vessels of the landing force in

An enemy convoy north of Camranh Bay, Back in Japanese waters, ''Hancock'' joined other carriers in strikes against Kyūshū airfields, southwestern Honshū and shipping in the Inland Sea of Japan on 18 March. ''Hancock'' was refueling the destroyer on 20 March when ''kamikazes'' attacked the task force. One plane dove for the two ships but was disintegrated by gunfire when about overhead. Fragments of the plane hit ''Hancock''s deck while its engine and bomb crashed the

Back in Japanese waters, ''Hancock'' joined other carriers in strikes against Kyūshū airfields, southwestern Honshū and shipping in the Inland Sea of Japan on 18 March. ''Hancock'' was refueling the destroyer on 20 March when ''kamikazes'' attacked the task force. One plane dove for the two ships but was disintegrated by gunfire when about overhead. Fragments of the plane hit ''Hancock''s deck while its engine and bomb crashed the  ''Hancock'' was detached from her task group on 9 April and steamed to Pearl Harbor for repairs. She sailed back into action 13 June and attacked

''Hancock'' was detached from her task group on 9 April and steamed to Pearl Harbor for repairs. She sailed back into action 13 June and attacked

''Hancock'' commenced the SCB-27C conversion and modernization to an

''Hancock'' commenced the SCB-27C conversion and modernization to an  ''Hancock'' returned to San Francisco in March 1961, then entered the

''Hancock'' returned to San Francisco in March 1961, then entered the

''Hancock'' reached Japan on 19 November and soon was on patrol at Yankee Station in the Gulf of Tonkin. She remained active in Vietnamese waters until heading for home early in the spring of 1965. November found the carrier steaming back to the war zone. She was on patrol off Vietnam on 16 December; and, but for brief respites at Hong Kong, the Philippines, or Japan, ''Hancock'' remained on station launching her planes for strikes at enemy positions ashore until returning to Alameda on 1 August 1966. Her outstanding record during this combat tour won her the

''Hancock'' reached Japan on 19 November and soon was on patrol at Yankee Station in the Gulf of Tonkin. She remained active in Vietnamese waters until heading for home early in the spring of 1965. November found the carrier steaming back to the war zone. She was on patrol off Vietnam on 16 December; and, but for brief respites at Hong Kong, the Philippines, or Japan, ''Hancock'' remained on station launching her planes for strikes at enemy positions ashore until returning to Alameda on 1 August 1966. Her outstanding record during this combat tour won her the  Aircraft from ''Hancock'', along with those from and , joined with other planes for air strikes against North Vietnamese missile and antiaircraft sites south of the 19th parallel in response to attacks on unarmed U.S. reconnaissance aircraft on 21–22 November 1970 (Operation Freedom Bait). ''Hancock'' alternated with ''Ranger'' and on Yankee Station until 10 May 1971, when she was relieved by .

Aircraft from ''Hancock'', along with those from and , joined with other planes for air strikes against North Vietnamese missile and antiaircraft sites south of the 19th parallel in response to attacks on unarmed U.S. reconnaissance aircraft on 21–22 November 1970 (Operation Freedom Bait). ''Hancock'' alternated with ''Ranger'' and on Yankee Station until 10 May 1971, when she was relieved by .

Hancock, along with , was back on Yankee Station by 30 March 1972 when North Vietnam invaded South Vietnam. In response to the invasion, Naval aircraft from ''Hancock'' and other carriers flew tactical sorties during Operation Freedom Train against military and logistics targets in the southern part of North Vietnam. By the end of April, the strikes covered more areas in North Vietnam throughout the area below 20°25′ N. From 25 to 30 April 1972, aircraft from ''Hancock''s VA-55, VA-164, VF-211 and VA-212 struck enemy-held territory around Kontum and

Hancock, along with , was back on Yankee Station by 30 March 1972 when North Vietnam invaded South Vietnam. In response to the invasion, Naval aircraft from ''Hancock'' and other carriers flew tactical sorties during Operation Freedom Train against military and logistics targets in the southern part of North Vietnam. By the end of April, the strikes covered more areas in North Vietnam throughout the area below 20°25′ N. From 25 to 30 April 1972, aircraft from ''Hancock''s VA-55, VA-164, VF-211 and VA-212 struck enemy-held territory around Kontum and

File:USS Hancock (CV-19) underway at sea, circa in 1944.jpg, ''Hancock'' in dazzle camouflage 1944

File:Moving rockets aboard USS Hancock (CV-19), October 1944.jpg, Moving rockets aboard ''Hancock'' on 12 October 1944

File:USS Hancock (CVA-19) in San Francisco Bay in September 1957 (2).jpg, ''Hancock'' in

US Navy Legacy - USS ''Hancock'' (CV-19)

from Dictionary of American Fighting Ships and United States Naval Aviation, 1910–1995.

{{DEFAULTSORT:Hancock (CV-19) Essex-class aircraft carriers Ships built in Quincy, Massachusetts 1944 ships World War II aircraft carriers of the United States Cold War aircraft carriers of the United States Vietnam War aircraft carriers of the United States Ships named for Founding Fathers of the United States

World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

for the United States Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the maritime service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. It is the largest and most powerful navy in the world, with the estimated tonnage ...

. The ship was the fourth US Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the maritime service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. It is the largest and most powerful navy in the world, with the estimated tonnage ...

ship to bear the name and was named for Founding Father

The following list of national founding figures is a record, by country, of people who were credited with establishing a state. National founders are typically those who played an influential role in setting up the systems of governance, (i.e. ...

John Hancock

John Hancock ( – October 8, 1793) was an American Founding Father, merchant, statesman, and prominent Patriot of the American Revolution. He served as president of the Second Continental Congress and was the first and third Governor of ...

, president of the Second Continental Congress

The Second Continental Congress was a late-18th-century meeting of delegates from the Thirteen Colonies that united in support of the American Revolutionary War. The Congress was creating a new country it first named " United Colonies" and in ...

and first governor of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts

Massachusetts (Massachusett language, Massachusett: ''Muhsachuweesut assachusett writing systems, məhswatʃəwiːsət'' English: , ), officially the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, is the most populous U.S. state, state in the New England ...

.There is some controversy regarding the naming of fleet carriers after famous Americans. Some suggest that the carrier was named for the frigate ''Hancock'' of the Continental Navy and that no US fleet carrier was named directly for a person before . The other examples are was named for Benjamin Franklin, and was the fifth ship to bear the name, and was named for Peyton Randolph, President of the First Continental Congress. ''Hancock'' was commissioned in April 1944 and served in several campaigns in the Pacific Theater of Operations, earning four battle star

A service star is a miniature bronze or silver five-pointed star inch (4.8 mm) in diameter that is authorized to be worn by members of the eight uniformed services of the United States on medals and ribbons to denote an additional award or se ...

s. Decommissioned shortly after the end of the war, she was modernized and recommissioned in the early 1950s as an attack carrier (CVA). In her second career, she operated exclusively in the Pacific, playing a prominent role in the Vietnam War

The Vietnam War (also known by #Names, other names) was a conflict in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia from 1 November 1955 to the fall of Saigon on 30 April 1975. It was the second of the Indochina Wars and was officially fought between North Vie ...

, for which she earned a Navy Unit Commendation

The Navy Unit Commendation (NUC) is a United States Navy unit award that was established by order of the Secretary of the Navy James Forrestal on 18 December 1944.

History

Navy and U.S. Marine Corps commands may recommend any Navy or Marine Cor ...

. She was the first US Navy carrier to have steam catapults

An aircraft catapult is a device used to allow aircraft to take off from a very limited amount of space, such as the deck of a vessel, but can also be installed on land-based runways in rare cases. It is now most commonly used on aircraft carrier ...

installed. She was decommissioned in early 1976 and sold for scrap later that year.

Construction and commissioning

The ship waslaid down

Laying the keel or laying down is the formal recognition of the start of a ship's construction. It is often marked with a ceremony attended by dignitaries from the shipbuilding company and the ultimate owners of the ship.

Keel laying is one ...

as ''Ticonderoga'' on 26 January 1943 by Bethlehem Steel Co., Quincy, Massachusetts

Quincy ( ) is a coastal U.S. city in Norfolk County, Massachusetts, United States. It is the largest city in the county and a part of Metropolitan Boston as one of Boston's immediate southern suburbs. Its population in 2020 was 101,636, making ...

. She was renamed ''Hancock'' 1 May 1943 in response to an offer from the John Hancock Life Insurance Company to conduct a special bond drive to raise money for the ship if that name was used. (The shipyard at Quincy was in the company's home state.) CV-14 laid down as ''Hancock'' and under construction at the same time in Newport News, Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States, between the East Coast of the United States, Atlantic Coast and the Appalachian Mountains. The geography an ...

, took the name ''Ticonderoga'' instead.

The company's bond drive raised enough money to both build the ship and operate her for the first year. The ship was launched 24 January 1944 by Mrs. Juanita Gabriel-Ramsey, the wife of Rear Admiral DeWitt Clinton Ramsey, Chief of the Bureau of Aeronautics

The Bureau of Aeronautics (BuAer) was the U.S. Navy's material-support organization for naval aviation from 1921 to 1959. The bureau had "cognizance" (''i.e.'', responsibility) for the design, procurement, and support of naval aircraft and relat ...

. ''Hancock'' was commissioned 15 April 1944, with Captain

Captain is a title, an appellative for the commanding officer of a military unit; the supreme leader of a navy ship, merchant ship, aeroplane, spacecraft, or other vessel; or the commander of a port, fire or police department, election precinct, e ...

Fred C. Dickey in command.

Service history

World War II

After fitting out in theBoston Navy Yard

The Boston Navy Yard, originally called the Charlestown Navy Yard and later Boston Naval Shipyard, was one of the oldest shipbuilding facilities in the United States Navy. It was established in 1801 as part of the recent establishment of t ...

and shake-down training off Trinidad

Trinidad is the larger and more populous of the two major islands of Trinidad and Tobago. The island lies off the northeastern coast of Venezuela and sits on the continental shelf of South America. It is often referred to as the southernmos ...

and Venezuela

Venezuela (; ), officially the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela ( es, link=no, República Bolivariana de Venezuela), is a country on the northern coast of South America, consisting of a continental landmass and many islands and islets in ...

, ''Hancock'' returned to Boston for alterations on 9 July 1944. She departed Boston on 31 July en route to Pearl Harbor

Pearl Harbor is an American lagoon harbor on the island of Oahu, Hawaii, west of Honolulu. It was often visited by the Naval fleet of the United States, before it was acquired from the Hawaiian Kingdom by the U.S. with the signing of the ...

via the Panama Canal

The Panama Canal ( es, Canal de Panamá, link=no) is an artificial waterway in Panama that connects the Atlantic Ocean with the Pacific Ocean and divides North and South America. The canal cuts across the Isthmus of Panama and is a Channel ( ...

and San Diego

San Diego ( , ; ) is a city on the Pacific Ocean coast of Southern California located immediately adjacent to the Mexico–United States border. With a 2020 population of 1,386,932, it is the eighth most populous city in the United States ...

, and from there sailed on 24 September to join Admiral W. F. Halsey's 3rd Fleet at Ulithi

Ulithi ( yap, Wulthiy, , or ) is an atoll in the Caroline Islands of the western Pacific Ocean, about east of Yap.

Overview

Ulithi consists of 40 islets totaling , surrounding a lagoon about long and up to wide—at one of the largest ...

on 5 October. She was assigned to Rear Admiral Gerald F. Bogan's Carrier Task Group 38.2

The Fast Carrier Task Force (TF 38 when assigned to United States Third Fleet, Third Fleet, TF 58 when assigned to United States Fifth Fleet, Fifth Fleet), was the main striking force of the United States Navy in the Pacific War from January 194 ...

(TG 38.2).

The following afternoon, ''Hancock'' sailed for a rendezvous point west of the Marianas where units of Vice Admiral Mitscher's

The following afternoon, ''Hancock'' sailed for a rendezvous point west of the Marianas where units of Vice Admiral Mitscher's Fast Carrier Task Force

The Fast Carrier Task Force (TF 38 when assigned to Third Fleet, TF 58 when assigned to Fifth Fleet), was the main striking force of the United States Navy in the Pacific War from January 1944 through the end of the war in August 1945. The tas ...

38 (TF 38) were to raid Japanese air and sea bases in the Ryūkyūs

The , also known as the or the , are a chain of Japanese islands that stretch southwest from Kyushu to Taiwan: the Ōsumi, Tokara, Amami, Okinawa, and Sakishima Islands (further divided into the Miyako and Yaeyama Islands), with Yonag ...

, Formosa

Taiwan, officially the Republic of China (ROC), is an island country located in East Asia. The main island of Taiwan, formerly known in the Western political circles, press and literature as Formosa, makes up 99% of the land area of the territori ...

,Formosa was the name of the main the island of Taiwan in western literature until the 20th century. and the Philippines

The Philippines (; fil, Pilipinas, links=no), officially the Republic of the Philippines ( fil, Republika ng Pilipinas, links=no),

* bik, Republika kan Filipinas

* ceb, Republika sa Pilipinas

* cbk, República de Filipinas

* hil, Republ ...

, to paralyze Japanese air power during General MacArthur's invasion of Leyte

Leyte ( ) is an island in the Visayas group of islands in the Philippines. It is eighth-largest and sixth-most populous island in the Philippines, with a total population of 2,626,970 as of 2020 census.

Since the accessibility of land has be ...

.

The armada arrived off the Ryukyu Islands on 10 October 1944, with ''Hancock''submarine tender

A submarine tender is a type of depot ship that supplies and supports submarines.

Development

Submarines are small compared to most oceangoing vessels, and generally do not have the ability to carry large amounts of food, fuel, torpedoes, and ...

, 12 torpedo boat

A torpedo boat is a relatively small and fast naval ship designed to carry torpedoes into battle. The first designs were steam-powered craft dedicated to ramming enemy ships with explosive spar torpedoes. Later evolutions launched variants of s ...

s, 2 midget submarine

A midget submarine (also called a mini submarine) is any submarine under 150 tons, typically operated by a crew of one or two but sometimes up to six or nine, with little or no on-board living accommodation. They normally work with mother ships, ...

s, four cargo ships, and a number of sampan

A sampan is a relatively flat-bottomed Chinese and Malay wooden boat. Some sampans include a small shelter on board and may be used as a permanent habitation on inland waters. The design closely resembles Western hard chine boats like ...

s.

Formosan air base

An air base (sometimes referred to as a military air base, military airfield, military airport, air station, naval air station, air force station, or air force base) is an aerodrome used as a military base by a military force for the operatio ...

s were targeted on 12 October. ''Hancock''s pilots downed six Japanese planes and destroyed nine more on the ground. She also reported one cargo ship definitely sunk, three probably destroyed, and several others damaged.

As they repelled an enemy air raid that evening, ''Hancock''s gunners accounted for a Japanese plane during seven hours of uninterrupted general quarters. The following morning her planes resumed their assault, knocking out ammunition dump

An ammunition dump, ammunition supply point (ASP), ammunition handling area (AHA) or ammunition depot is a military storage facility for live ammunition and explosives.

The storage of live ammunition and explosives is inherently hazardous. Th ...

s, hangar

A hangar is a building or structure designed to hold aircraft or spacecraft. Hangars are built of metal, wood, or concrete. The word ''hangar'' comes from Middle French ''hanghart'' ("enclosure near a house"), of Germanic origin, from Frankish ...

s, barracks

Barracks are usually a group of long buildings built to house military personnel or laborers. The English word originates from the 17th century via French and Italian from an old Spanish word "barraca" ("soldier's tent"), but today barracks are ...

, and industrial plants ashore and damaging an enemy transport. As Japanese planes again attacked the Americans during their second night off Formosa, ''Hancock''s antiaircraft fire brought down another raider which crashed about off her flight deck.

As the American ships withdrew a heavy force of Japanese aircraft approached American naval power. One dropped a bomb off ''Hancock''s port bow a few seconds before being hit by the carrier's guns and crashing into the sea. Another bomb penetrated a gun platform but exploded harmlessly in the water. The task force was thereafter unmolested as they sailed toward the Philippines to support the landings at Leyte.

On 18 October, she launched planes against airfields and shipping at Laoag

Laoag, officially the City of Laoag ( ilo, Siudad ti Laoag; fil, Lungsod ng Laoag), is a 1st class component city and capital of the province of Ilocos Norte, Philippines. According to the 2020 census, it has a population of 111,651 people.

...

, Aparri, and Camiguin Island in Northern Luzon

Luzon (; ) is the largest and most populous island in the Philippines. Located in the northern portion of the Philippines archipelago, it is the economic and political center of the nation, being home to the country's capital city, Manila, ...

. Her planes struck the islands of Cebu

Cebu (; ceb, Sugbo), officially the Province of Cebu ( ceb, Lalawigan sa Sugbo; tl, Lalawigan ng Cebu; hil, Kapuroan sang Sugbo), is a province of the Philippines located in the Central Visayas region, and consists of a main island and ...

, Panay

Panay is the sixth-largest and fourth-most populous island in the Philippines, with a total land area of and has a total population of 4,542,926 as of 2020 census. Panay comprises 4.4 percent of the entire population of the country. The City o ...

, Negros, and Masbate

Masbate, officially the Province of Masbate ( Masbateño: ''Probinsya san Masbate''; tl, Lalawigan ng Masbate), is an island province in the Philippines located near the midsection of the nation's archipelago. Its provincial capital is Masbate ...

, pounding enemy airfields and shipping. The next day, she retired toward Ulithi with Vice Admiral John S. McCain, Sr.

John Sidney "Slew" McCain (August 9, 1884 – September 6, 1945) was a U.S. Navy admiral and the patriarch of the McCain military family. McCain held several command assignments during the Pacific campaign of World War II. He was a pioneer of a ...

's TG 38.1.

She received orders on 23 October to turn back to the area off Samar

Samar ( ) is the third-largest and seventh-most populous island in the Philippines, with a total population of 1,909,537 as of the 2020 census. It is located in the eastern Visayas, which are in the central Philippines. The island is divided in ...

to assist in the search for units of the Japanese fleet reportedly closing Leyte to challenge the American fleet, and to destroy amphibious forces which were struggling to take the island from Japan. ''Hancock'' did not reach Samar in time to assist the escort carriers and destroyers of " Taffy 3" during the main action of the Battle off Samar, but her planes did manage to attack the fleeing Japanese Center Force

Japanese may refer to:

* Something from or related to Japan, an island country in East Asia

* Japanese language, spoken mainly in Japan

* Japanese people, the ethnic group that identifies with Japan through ancestry or culture

** Japanese dias ...

as it passed through the San Bernardino Strait

The San Bernardino Strait ( fil, Kipot ng San Bernardino) is a strait in the Philippines, connecting the Samar Sea with the Philippine Sea. It separates the Bicol Peninsula of Luzon island from the island of Samar in the south.

History

During ...

. ''Hancock'' then rejoined Rear Admiral Bogan's Task Group with which she struck airfields and shipping in the vicinity of Manila

Manila ( , ; fil, Maynila, ), officially the City of Manila ( fil, Lungsod ng Maynila, ), is the capital city, capital of the Philippines, and its second-most populous city. It is Cities of the Philippines#Independent cities, highly urbanize ...

on 29 October 1944. During operations through 19 November, her planes gave direct support to advancing Army troops and attacked Japanese shipping over a area. She became flagship

A flagship is a vessel used by the commanding officer of a group of naval ships, characteristically a flag officer entitled by custom to fly a distinguishing flag. Used more loosely, it is the lead ship in a fleet of vessels, typically the f ...

of the Fast Carrier Task Force

The Fast Carrier Task Force (TF 38 when assigned to Third Fleet, TF 58 when assigned to Fifth Fleet), was the main striking force of the United States Navy in the Pacific War from January 1944 through the end of the war in August 1945. The tas ...

(TF 38) on 17 November 1944 when Admiral McCain came on board.

Unfavorable weather prevented operations until 25 November, when a ''kamikaze'' roared toward ''Hancock'', diving out of the sun. Antiaircraft

Anti-aircraft warfare, counter-air or air defence forces is the battlespace response to aerial warfare, defined by NATO as "all measures designed to nullify or reduce the effectiveness of hostile air action".AAP-6 It includes surface based ...

fire destroyed the plane some above the ship, but a section of its fuselage landed amidships, and a part of the wing hit the flight deck and burst into flames. The blaze was quickly extinguished without serious damage.

''Hancock'' returned to Ulithi on 27 November and departed from that island with her task group to maintain air patrol over enemy airfields on Luzon to prevent ''kamikazes'' from attacking amphibious vessels of the landing force in

''Hancock'' returned to Ulithi on 27 November and departed from that island with her task group to maintain air patrol over enemy airfields on Luzon to prevent ''kamikazes'' from attacking amphibious vessels of the landing force in Mindoro

Mindoro is the seventh largest and eighth-most populous island in the Philippines. With a total land area of 10,571 km2 ( 4,082 sq.mi ) and has a population of 1,408,454 as of 2020 census. It is located off the southwestern coast of Luz ...

. The first strikes were launched on 14 December against Clark

Clark is an English language surname, ultimately derived from the Latin with historical links to England, Scotland, and Ireland ''clericus'' meaning "scribe", "secretary" or a scholar within a religious order, referring to someone who was educat ...

and Angeles City

, anthem = Himno ning Angeles (Angeles Hymn)

, subdivision_type3 = District

, subdivision_name3 =

, established_title = Settled

, established_date = 1796

, established_title1 = Charter ...

Airfields as well as enemy ground targets on Salvador Island. The next day her planes struck installations at Masinloc, San Fernando, and Cabanatuan, while fighter patrols kept the Japanese airmen down. Her planes also attacked shipping in Manila Bay

Manila Bay ( fil, Look ng Maynila) is a natural harbor that serves the Port of Manila (on Luzon), in the Philippines. Strategically located around the capital city of the Philippines, Manila Bay facilitated commerce and trade between the Phi ...

.

''Hancock'' encountered Typhoon Cobra on 17 December 1944, in waves which broke over her flight deck

The flight deck of an aircraft carrier is the surface from which its aircraft take off and land, essentially a miniature airfield at sea. On smaller naval ships which do not have aviation as a primary mission, the landing area for helicopt ...

, some above her waterline

The waterline is the line where the hull of a ship meets the surface of the water. Specifically, it is also the name of a special marking, also known as an international load line, Plimsoll line and water line (positioned amidships), that ind ...

. She put into Ulithi 24 December and got underway six days later to attack airfields and shipping around the South China Sea

The South China Sea is a marginal sea of the Western Pacific Ocean. It is bounded in the north by the shores of South China (hence the name), in the west by the Indochinese Peninsula, in the east by the islands of Taiwan and northwestern Phil ...

. Her planes struck at Luzon airfields on 7–8 January 1945 and turned their attention back to Formosa on 9 January, hitting airfields and the Toko Seaplane StatioAn enemy convoy north of Camranh Bay,

Indochina

Mainland Southeast Asia, also known as the Indochinese Peninsula or Indochina, is the continental portion of Southeast Asia. It lies east of the Indian subcontinent and south of Mainland China and is bordered by the Indian Ocean to the west an ...

was the next target, with two ships sunk and 11 damaged. That afternoon ''Hancock'' launched strikes against airfields at Saigon

, population_density_km2 = 4,292

, population_density_metro_km2 = 697.2

, population_demonym = Saigonese

, blank_name = GRP (Nominal)

, blank_info = 2019

, blank1_name = – Total

, blank1_ ...

and shipping on the northeastern bulge of French Indochina

French Indochina (previously spelled as French Indo-China),; vi, Đông Dương thuộc Pháp, , lit. 'East Ocean under French Control; km, ឥណ្ឌូចិនបារាំង, ; th, อินโดจีนฝรั่งเศส, ...

. Strikes by the fast and mobile carrier force continued through 16 January, hitting Hainan Island

Hainan (, ; ) is the smallest and southernmost province of the People's Republic of China (PRC), consisting of various islands in the South China Sea. , the largest and most populous island in China,The island of Taiwan, which is slight ...

in the Gulf of Tonkin

The Gulf of Tonkin is a gulf at the northwestern portion of the South China Sea, located off the coasts of Tonkin ( northern Vietnam) and South China. It has a total surface area of . It is defined in the west and northwest by the northe ...

, the Pescadores Islands

The Penghu (, Hokkien POJ: ''Phîⁿ-ô͘'' or ''Phêⁿ-ô͘'' ) or Pescadores Islands are an archipelago of 90 islands and islets in the Taiwan Strait, located approximately west from the main island of Taiwan, covering an area ...

, and shipping in the harbor of Hong Kong. Raids against Formosa were resumed on 20 January. The next afternoon one of her planes returning from a sortie

A sortie (from the French word meaning ''exit'' or from Latin root ''surgere'' meaning to "rise up") is a deployment or dispatch of one military unit, be it an aircraft, ship, or troops, from a strongpoint. The term originated in siege warf ...

made a normal landing, taxied to a point abreast of the island, and disintegrated in a blinding explosion which killed 50 men and injured 75 others. Again outstanding work quickly brought the fires under control in time to land other planes which were still aloft. She returned to formation and launched strikes against Okinawa the next morning.

''Hancock'' reached Ulithi on 25 January, where Admiral McCain left the ship and relinquished command of the 5th Fleet. She sortied with the ships of her task group on 10 February and launched strikes against airfields in the vicinity of Tokyo on 16 February. On that day, her air group, Air Group 80, downed 71 enemy planes and accounted for 12 more the next. Her planes hit the enemy naval base

A naval base, navy base, or military port is a military base, where warships and naval ships are docked when they have no mission at sea or need to restock. Ships may also undergo repairs. Some naval bases are temporary homes to aircraft that us ...

s at Chichi Jima

, native_name_link =

, image_caption = Map of Chichijima, Anijima and Otoutojima

, image_size =

, pushpin_map = Japan complete

, pushpin_label = Chichijima

, pushpin_label_position =

, pushpin_map_alt =

, ...

and Haha Jima on 19 February, as part of a raid to isolate Iwo Jima

Iwo Jima (, also ), known in Japan as , is one of the Japanese Volcano Islands and lies south of the Bonin Islands. Together with other islands, they form the Ogasawara Archipelago. The highest point of Iwo Jima is Mount Suribachi at high. ...

from air and sea support during American landing. ''Hancock'' took station off this island to provide tactical support through 22 February, hitting enemy airfields and strafing Japanese troops ashore.

Returning to waters off the enemy home islands, ''Hancock'' launched her planes against targets on northern Honshū

, historically called , is the largest and most populous island of Japan. It is located south of Hokkaidō across the Tsugaru Strait, north of Shikoku across the Inland Sea, and northeast of Kyūshū across the Kanmon Straits. The island ...

, making a diversionary raid on the Nansei-shoto

The , also known as the or the , are a chain of Japanese islands that stretch southwest from Kyushu to Taiwan: the Ōsumi, Tokara, Amami, Okinawa, and Sakishima Islands (further divided into the Miyako and Yaeyama Islands), with Yonagun ...

islands on 1 March before returning to Ulithi on 4 March 1945.

Back in Japanese waters, ''Hancock'' joined other carriers in strikes against Kyūshū airfields, southwestern Honshū and shipping in the Inland Sea of Japan on 18 March. ''Hancock'' was refueling the destroyer on 20 March when ''kamikazes'' attacked the task force. One plane dove for the two ships but was disintegrated by gunfire when about overhead. Fragments of the plane hit ''Hancock''s deck while its engine and bomb crashed the

Back in Japanese waters, ''Hancock'' joined other carriers in strikes against Kyūshū airfields, southwestern Honshū and shipping in the Inland Sea of Japan on 18 March. ''Hancock'' was refueling the destroyer on 20 March when ''kamikazes'' attacked the task force. One plane dove for the two ships but was disintegrated by gunfire when about overhead. Fragments of the plane hit ''Hancock''s deck while its engine and bomb crashed the fantail

Fantails are small insectivorous songbirds of the genus ''Rhipidura'' in the family Rhipiduridae, native to Australasia, Southeast Asia and the Indian subcontinent. Most of the species are about long, specialist aerial feeders, and named as ...

of the destroyer. ''Hancock''s gunners shot down another plane as it neared the release point of its bombing run on the carrier.

''Hancock'' was reassigned to Carrier TG 58.3

The Fast Carrier Task Force (TF 38 when assigned to United States Third Fleet, Third Fleet, TF 58 when assigned to United States Fifth Fleet, Fifth Fleet), was the main striking force of the United States Navy in the Pacific War from January 194 ...

with which she struck the Nansei-shoto islands from 23 to 27 March and Minami Daito Island Minami ( kanji 南, hiragana みなみ) is a Japanese word meaning "south".

Places

Japan

There are several Minami wards in Japan, most of them appropriately in the south part of a city:

* Minami, Tokushima, a village in Tokushima Prefect ...

and Kyūshū at the end of the month.

When the 10th Army landed on the western coast of Okinawa on 1 April, ''Hancock'' was on hand to provide close air support

In military tactics, close air support (CAS) is defined as air action such as air strikes by fixed or rotary-winged aircraft against hostile targets near friendly forces and require detailed integration of each air mission with fire and movemen ...

. A ''kamikaze'' cartwheeled across her flight deck on 7 April and crashed into a group of planes while its bomb hit the port catapult

A catapult is a ballistic device used to launch a projectile a great distance without the aid of gunpowder or other propellants – particularly various types of ancient and medieval siege engines. A catapult uses the sudden release of store ...

to cause a tremendous explosion. Although 62 men were killed and 71 wounded, heroic efforts doused the fires within half an hour enabling her to be back in action before an hour had passed.

''Hancock'' was detached from her task group on 9 April and steamed to Pearl Harbor for repairs. She sailed back into action 13 June and attacked

''Hancock'' was detached from her task group on 9 April and steamed to Pearl Harbor for repairs. She sailed back into action 13 June and attacked Wake Island

Wake Island ( mh, Ānen Kio, translation=island of the Sida fallax, kio flower; also known as Wake Atoll) is a coral atoll in the western Pacific Ocean in the northeastern area of the Micronesia subregion, east of Guam, west of Honolulu, sou ...

on 20 June en route to the Philippines. ''Hancock'' sailed from San Pedro Bay with the other carriers on 1 July and attacked Tokyo airfields on 10 July. She continued to operate in Japanese waters until she received confirmation of Japan's capitulation on 15 August 1945 when she recalled her planes from their deadly missions before they reached their targets. However planes of her photo division were attacked by seven enemy aircraft over Sagami Wan. Three were shot down and a fourth escaped in a trail of smoke. Later that afternoon planes of ''Hancock''s air patrol shot down a Japanese torpedo plane as it dived on a British task force. Her planes flew missions over Japan in search of prison camps, dropping supplies and medicine, on 25 August. Information collected during these flights led to landings under command of Commodore R. W. Simpson which brought doctors and supplies to all Allied prisoner of war

A prisoner of war (POW) is a person who is held captive by a belligerent power during or immediately after an armed conflict. The earliest recorded usage of the phrase "prisoner of war" dates back to 1610.

Belligerents hold prisoners of ...

encampments.

When the formal surrender of the Japanese government was signed on board battleship , ''Hancock''s planes flew overhead. The carrier entered Tokyo Bay

is a bay located in the southern Kantō region of Japan, and spans the coasts of Tokyo, Kanagawa Prefecture, and Chiba Prefecture. Tokyo Bay is connected to the Pacific Ocean by the Uraga Channel. The Tokyo Bay region is both the most populous ...

on 10 September 1945 and sailed on 30 September embarking 1,500 passengers at Okinawa for transportation to San Pedro, California

San Pedro ( ; Spanish: "St. Peter") is a neighborhood within the City of Los Angeles, California. Formerly a separate city, it consolidated with Los Angeles in 1909. The Port of Los Angeles, a major international seaport, is partially located wi ...

, where she arrived on 21 October. ''Hancock'' was fitted out for Operation Magic Carpet

Operation Magic Carpet was the post- World War II operation by the War Shipping Administration to repatriate over eight million American military personnel from the European, Pacific, and Asian theaters. Hundreds of Liberty ships, Victory s ...

duty at San Pedro and sailed for Seeadler Harbor, Manus

Manus may refer to:

* Manus (anatomy), the zoological term for the distal portion of the forelimb of an animal (including the human hand)

* ''Manus'' marriage, a type of marriage during Roman times

Relating to locations around New Guinea

* Man ...

, Admiralty Islands

The Admiralty Islands are an archipelago group of 18 islands in the Bismarck Archipelago, to the north of New Guinea in the South Pacific Ocean. These are also sometimes called the Manus Islands, after the largest island.

These rainforest-co ...

on 2 November. On her return voyage, she carried 4,000 passengers who were debarked at San Diego on 4 December. A week later ''Hancock'' departed for her second ''Magic Carpet'' voyage, embarking 3,773 passengers at Manila for return to Alameda, California

Alameda ( ; ; Spanish for " tree-lined path") is a city in Alameda County, California, located in the East Bay region of the Bay Area. The city is primarily located on Alameda Island, but also spans Bay Farm Island and Coast Guard Island, as we ...

, on 20 January 1946. She embarked Air Group 7

The atmosphere of Earth is the layer of gases, known collectively as air, retained by Gravity of Earth, Earth's gravity that surrounds the planet and forms its planetary atmosphere. The atmosphere of Earth protects life on Earth by creating Atmo ...

at San Diego on 18 February for air operations off the coast of California. She sailed from San Diego on 11 March to embark men of two air groups and aircraft at Pearl Harbor for transportation to Saipan

Saipan ( ch, Sa’ipan, cal, Seipél, formerly in es, Saipán, and in ja, 彩帆島, Saipan-tō) is the largest island of the Northern Mariana Islands, a commonwealth of the United States in the western Pacific Ocean. According to 2020 est ...

, arriving on 1 April. After receiving two other air groups on board at Saipan, she loaded a cargo of aircraft at Guam

Guam (; ch, Guåhan ) is an organized, unincorporated territory of the United States in the Micronesia subregion of the western Pacific Ocean. It is the westernmost point and territory of the United States (reckoned from the geographic ce ...

and steamed by way of Pearl Harbor to Alameda, arriving on 23 April. She then steamed to Seattle, Washington

Seattle ( ) is a port, seaport city on the West Coast of the United States. It is the county seat, seat of King County, Washington, King County, Washington (state), Washington. With a 2020 population of 737,015, it is the largest city in bo ...

, on 29 April to await inactivation. The ship was decommissioned and entered the reserve fleet

A reserve fleet is a collection of naval vessels of all types that are fully equipped for service but are not currently needed; they are partially or fully decommissioned. A reserve fleet is informally said to be "in mothballs" or "mothballed"; ...

at Bremerton, Washington

Bremerton is a city in Kitsap County, Washington. The population was 37,729 at the 2010 census and an estimated 41,405 in 2019, making it the largest city on the Kitsap Peninsula. Bremerton is home to Puget Sound Naval Shipyard and the Bremerto ...

.

Pacific Fleet

''Hancock'' commenced the SCB-27C conversion and modernization to an

''Hancock'' commenced the SCB-27C conversion and modernization to an attack aircraft carrier

An aircraft carrier is a warship that serves as a seagoing airbase, equipped with a full-length flight deck and facilities for carrying, arming, deploying, and recovering aircraft. Typically, it is the capital ship of a fleet, as it allows ...

in Puget Sound

Puget Sound ( ) is a sound of the Pacific Northwest, an inlet of the Pacific Ocean, and part of the Salish Sea. It is located along the northwestern coast of the U.S. state of Washington. It is a complex estuarine system of interconnected m ...

15 December 1951 and was reclassified CVA-19 on 1 October 1952. She recommissioned on 15 February 1954, Captain W. S. Butts in command. She was the first carrier of the United States Fleet with steam catapults capable of launching high-performance jets. The modernization cost $60 million ($ today). She was off San Diego on 7 May 1954 for operations along the coast of California that included 17 June launching of the first aircraft to take off a United States carrier by means of a steam catapult. After a year of operations along the Pacific coast that included testing of Sparrow I and Regulus missile

The SSM-N-8A Regulus or the Regulus I was a United States Navy-developed ship-and-submarine-launched, nuclear-capable turbojet-powered second generation cruise missile, deployed from 1955 to 1964. Its development was an outgrowth of U.S. Navy ...

s and Cutlass

A cutlass is a short, broad sabre or slashing sword, with a straight or slightly curved blade sharpened on the cutting edge, and a hilt often featuring a solid cupped or basket-shaped guard. It was a common naval weapon during the early Age ...

jet aircraft, she sailed on 10 August 1955 for 7th Fleet

The Seventh Fleet is a numbered fleet of the United States Navy. It is headquartered at U.S. Fleet Activities Yokosuka, in Yokosuka, Kanagawa Prefecture, Japan. It is part of the United States Pacific Fleet. At present, it is the largest o ...

operations ranging from the shores of Japan to the Philippines and Okinawa.

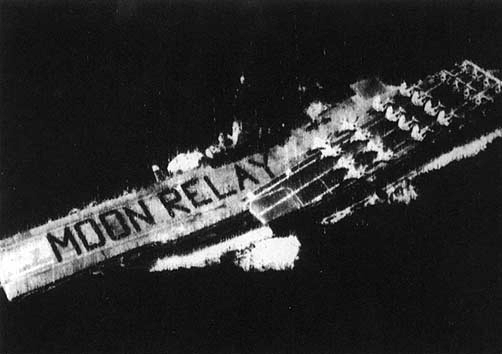

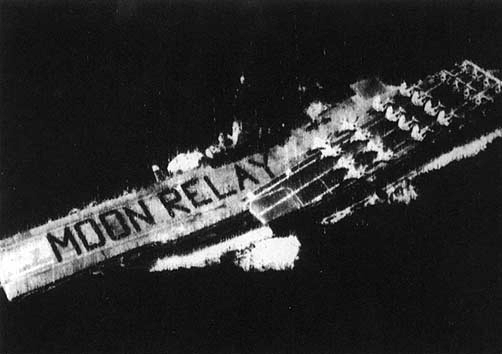

She returned to San Diego on 15 March 1956 and decommissioned on 13 April for her SCB-125 conversion that included the installation of an angled flight deck. ''Hancock'' recommissioned on 15 November 1956 for training out of San Diego until 6 April 1957, when she again sailed for Hawaii and the Far East. She returned to San Diego on 18 September 1957 and again departed for Japan on 15 February 1958. She was a unit of powerful carrier task groups taking station off Taiwan when the Nationalist Chinese islands of Quemoy and Matsu were threatened with Communist invasion in August 1958. The carrier returned to San Francisco on 2 October for overhaul in the San Francisco Naval Shipyard, followed by rigorous at-sea training out of San Francisco. On 1 August 1959, she sailed to reinforce the 7th Fleet as troubles in Laos demanded the watchful presence of powerful American forces in water off southeast Asia. She returned to San Francisco on 18 January 1960 and put to sea early in February to participate in the Communication Moon Relay project, a new demonstration of communications by reflecting ultra-high frequency waves off the moon

The Moon is Earth's only natural satellite. It is the fifth largest satellite in the Solar System and the largest and most massive relative to its parent planet, with a diameter about one-quarter that of Earth (comparable to the width ...

. She again departed in August to steam with the 7th Fleet in waters off Laos until lessening of tension in that area permitted operations ranging from Japan to the Philippines.

''Hancock'' returned to San Francisco in March 1961, then entered the

''Hancock'' returned to San Francisco in March 1961, then entered the Puget Sound Naval Shipyard

Puget Sound Naval Shipyard, officially Puget Sound Naval Shipyard and Intermediate Maintenance Facility (PSNS & IMF), is a United States Navy shipyard covering 179 acres (0.7 km2) on Puget Sound at Bremerton, Washington in uninterrupted u ...

for an overhaul

Overhaul may refer to:

*The process of overhauling, see

** Maintenance, repair, and overhaul

** Refueling and overhaul (eg. nuclear-powered ships)

**Time between overhaul

*Overhaul (firefighting), the process of searching for hidden fire extensio ...

that gave her new electronics gear and many other improvements. She again set sail for Far Eastern waters on 2 February 1962, patrolling in the South China Sea as crisis and strife mounted both in Laos and in South Vietnam. She again appeared off Quemoy and Matsu in June to stem a threatened Communist invasion there, then trained along the coast of Japan and in waters reaching to Okinawa. She returned to San Francisco on 7 October, made a brief cruise to the coast of Hawaii while qualifying pilots then again sailed on 7 June 1963 for the Far East.

''Hancock'' joined in combined defense exercises along the coast of South Korea

South Korea, officially the Republic of Korea (ROK), is a country in East Asia, constituting the southern part of the Korea, Korean Peninsula and sharing a Korean Demilitarized Zone, land border with North Korea. Its western border is formed ...

, then deployed off the coast of South Vietnam after the coup which resulted in the death of President Diem. She entered the Hunter's Point Naval Shipyard

The Hunters Point Naval Shipyard was a United States Navy shipyard in San Francisco, California, located on of waterfront at Hunters Point in the southeast corner of the city.

Originally, Hunters Point was a commercial shipyard established i ...

on 16 January 1964 for modernization that included installation of a new ordnance system, hull repairs, and aluminum decking for her flight deck. She celebrated her 20th birthday on 2 June while visiting San Diego. The carrier made a training cruise to Hawaii, then departed Alameda on 21 October for another tour of duty with the 7th Fleet in the Far East.

Vietnam War

''Hancock'' reached Japan on 19 November and soon was on patrol at Yankee Station in the Gulf of Tonkin. She remained active in Vietnamese waters until heading for home early in the spring of 1965. November found the carrier steaming back to the war zone. She was on patrol off Vietnam on 16 December; and, but for brief respites at Hong Kong, the Philippines, or Japan, ''Hancock'' remained on station launching her planes for strikes at enemy positions ashore until returning to Alameda on 1 August 1966. Her outstanding record during this combat tour won her the

''Hancock'' reached Japan on 19 November and soon was on patrol at Yankee Station in the Gulf of Tonkin. She remained active in Vietnamese waters until heading for home early in the spring of 1965. November found the carrier steaming back to the war zone. She was on patrol off Vietnam on 16 December; and, but for brief respites at Hong Kong, the Philippines, or Japan, ''Hancock'' remained on station launching her planes for strikes at enemy positions ashore until returning to Alameda on 1 August 1966. Her outstanding record during this combat tour won her the Navy Unit Commendation

The Navy Unit Commendation (NUC) is a United States Navy unit award that was established by order of the Secretary of the Navy James Forrestal on 18 December 1944.

History

Navy and U.S. Marine Corps commands may recommend any Navy or Marine Cor ...

.

Following operations off the West Coast, ''Hancock'' returned to Vietnam early in 1967 and resumed her strikes against Communist positions. After fighting during most of the first half of 1967, she returned to Alameda on 22 July and promptly began preparations for returning to battle.

In the summer of 1969, she was back in Alameda preparing for yet another deployment to southeast Asia. In July, while in pre-deployment night landing exercises, an F-8 came in too low and crashed into the round-down splitting the aircraft into two pieces which hurtled down the deck and erupted in a massive fuel-fed fire. While there were no deaths, damage to the flight deck was extensive, resulting in a frenetic 24 × 7 repair effort to be ready by the deployment date.

Aircraft from ''Hancock'', along with those from and , joined with other planes for air strikes against North Vietnamese missile and antiaircraft sites south of the 19th parallel in response to attacks on unarmed U.S. reconnaissance aircraft on 21–22 November 1970 (Operation Freedom Bait). ''Hancock'' alternated with ''Ranger'' and on Yankee Station until 10 May 1971, when she was relieved by .

Aircraft from ''Hancock'', along with those from and , joined with other planes for air strikes against North Vietnamese missile and antiaircraft sites south of the 19th parallel in response to attacks on unarmed U.S. reconnaissance aircraft on 21–22 November 1970 (Operation Freedom Bait). ''Hancock'' alternated with ''Ranger'' and on Yankee Station until 10 May 1971, when she was relieved by .

Hancock, along with , was back on Yankee Station by 30 March 1972 when North Vietnam invaded South Vietnam. In response to the invasion, Naval aircraft from ''Hancock'' and other carriers flew tactical sorties during Operation Freedom Train against military and logistics targets in the southern part of North Vietnam. By the end of April, the strikes covered more areas in North Vietnam throughout the area below 20°25′ N. From 25 to 30 April 1972, aircraft from ''Hancock''s VA-55, VA-164, VF-211 and VA-212 struck enemy-held territory around Kontum and

Hancock, along with , was back on Yankee Station by 30 March 1972 when North Vietnam invaded South Vietnam. In response to the invasion, Naval aircraft from ''Hancock'' and other carriers flew tactical sorties during Operation Freedom Train against military and logistics targets in the southern part of North Vietnam. By the end of April, the strikes covered more areas in North Vietnam throughout the area below 20°25′ N. From 25 to 30 April 1972, aircraft from ''Hancock''s VA-55, VA-164, VF-211 and VA-212 struck enemy-held territory around Kontum and Pleiku

Pleiku is a city in central Vietnam, located in the Central Highlands region. It is the capital of the Gia Lai Province. Many years ago, it was inhabited primarily by the Bahnar and Jarai ethnic groups, sometimes known as the Montagnards or D ...

.

On 17 March 1975 ''Hancock'' was ordered to offload her air wing. On arrival at Subic Bay, she offloaded CAG 21. On 26 March, Marine Heavy Lift Helicopter Squadron HMH-463

Marine Heavy Helicopter Squadron 463 (HMH-463) was a United States Marine Corps helicopter squadron consisting of CH-53E Super Stallion transport helicopters. The squadron, also known as "Pegasus", was last based at Marine Corps Air Station Kaneo ...

comprising 25 CH-53, CH-46, AH-1J and UH-1E helicopters embarked on ''Hancock'' and then proceeded to Subic Bay

Subic Bay is a bay on the west coast of the island of Luzon in the Philippines, about northwest of Manila Bay. An extension of the South China Sea, its shores were formerly the site of a major United States Navy facility, U.S. Naval Base Sub ...

to offload the other half of CAG 21. After taking on more helicopters at Subic Bay, ''Hancock'' was temporarily assigned to Amphibious Ready Group Bravo, standing by off Vung Tau, South Vietnam, but on 11 April she joined Amphibious Ready Group Alpha

Expeditionary Strike Group SEVEN/Task Force 76 (Amphibious Force U.S. SEVENTH Fleet) is a United States Navy task force. It is part of the United States Seventh Fleet and the USN's only permanently forward-deployed expeditionary strike grou ...

in the Gulf of Thailand. ''Hancock'' then took part in Operation Eagle Pull, the evacuation of Phnom Penh on 12 April 1975 and Operation Frequent Wind

Operation Frequent Wind was the final phase in the evacuation of American civilians and "at-risk" Vietnamese from Saigon, South Vietnam, before the takeover of the city by the North Vietnamese People's Army of Vietnam (PAVN) in the Fall of S ...

, the evacuation of Saigon on 29–30 April 1975. From 12 to 14 May, she was alerted, although not utilized, for the recovery of SS ''Mayagüez'', a US merchantman with 39 crew, seized in international waters on 12 May by the Communist Khmer Rouge

The Khmer Rouge (; ; km, ខ្មែរក្រហម, ; ) is the name that was popularly given to members of the Communist Party of Kampuchea (CPK) and by extension to the regime through which the CPK ruled Cambodia between 1975 and 197 ...

.

Decommissioning

''Hancock'' was decommissioned on 30 January 1976. She was stricken from the Navy list the following day,But theNaval Vessel Register

The ''Naval Vessel Register'' (NVR) is the official inventory of ships and service craft in custody of or titled by the United States Navy. It contains information on ships and service craft that make up the official inventory of the Navy from t ...

says a month earlier; and sold for scrap by the Defense Reutilization and Marketing Service DLA Disposition Services (formerly known as the Defense Reutilization and Marketing Service) is part of the United States Defense Logistics Agency. Headquartered at the Hart–Dole–Inouye Federal Center in Battle Creek, Michigan, the organizatio ...

(DRMS) on 1 September 1976. By January 1977, ex-''Hancock'' was being scrapped in Los Angeles harbor and artifacts were being sold to former crew members and the general public, including items ranging from portholes to the anchor chain. The Associated Press noted that some of the scrap metal from the World War II-serving aircraft carrier would ironically be sold to Japan to manufacture automobiles.

Awards

''Hancock'' was awarded theNavy Unit Commendation

The Navy Unit Commendation (NUC) is a United States Navy unit award that was established by order of the Secretary of the Navy James Forrestal on 18 December 1944.

History

Navy and U.S. Marine Corps commands may recommend any Navy or Marine Cor ...

and received four battle star

A service star is a miniature bronze or silver five-pointed star inch (4.8 mm) in diameter that is authorized to be worn by members of the eight uniformed services of the United States on medals and ribbons to denote an additional award or se ...

s on the Asiatic–Pacific Campaign Medal for service in World War II. She also earned 13 battle stars for service in Vietnam.

According to the US Navy Unit Awards website, ''Hancock'' and her crew received the following awards, in approximately chronological order:

* Navy Unit Commendation

The Navy Unit Commendation (NUC) is a United States Navy unit award that was established by order of the Secretary of the Navy James Forrestal on 18 December 1944.

History

Navy and U.S. Marine Corps commands may recommend any Navy or Marine Cor ...

for seven different time periods in World War II

* Armed Forces Expeditionary Medal

The Armed Forces Expeditionary Medal (AFEM) is a military award of the United States Armed Forces, which was first created in 1961 by Executive Order of President John Kennedy. The medal is awarded to members of the U.S. Armed Forces who, after ...

for Taiwan Straits from 26 August 1958 to 7 September 1958

* Armed Forces Expeditionary Medal

The Armed Forces Expeditionary Medal (AFEM) is a military award of the United States Armed Forces, which was first created in 1961 by Executive Order of President John Kennedy. The medal is awarded to members of the U.S. Armed Forces who, after ...

for Quemoy- Matsu from 14 September 1959 to 17 September 1959

* Armed Forces Expeditionary Medal

The Armed Forces Expeditionary Medal (AFEM) is a military award of the United States Armed Forces, which was first created in 1961 by Executive Order of President John Kennedy. The medal is awarded to members of the U.S. Armed Forces who, after ...

for Vietnam for five time periods that fell between 1 July 58 and 3 July 65

* Armed Forces Expeditionary Medal

The Armed Forces Expeditionary Medal (AFEM) is a military award of the United States Armed Forces, which was first created in 1961 by Executive Order of President John Kennedy. The medal is awarded to members of the U.S. Armed Forces who, after ...

for Korea for four time periods between 1 October 66 and 3 June 74

* Navy Unit Commendation

The Navy Unit Commendation (NUC) is a United States Navy unit award that was established by order of the Secretary of the Navy James Forrestal on 18 December 1944.

History

Navy and U.S. Marine Corps commands may recommend any Navy or Marine Cor ...

for service 6 December 1965 to 25 July 1966

* Navy Unit Commendation

The Navy Unit Commendation (NUC) is a United States Navy unit award that was established by order of the Secretary of the Navy James Forrestal on 18 December 1944.

History

Navy and U.S. Marine Corps commands may recommend any Navy or Marine Cor ...

for service 1 August 1968 to 22 February 1969

* Meritorious Unit Commendation

The Meritorious Unit Commendation (MUC; pronounced ''muck'') is a mid-level unit award of the United States Armed Forces. The U.S. Army awards units the Army MUC for exceptionally meritorious conduct in performance of outstanding achievement or ...

for service from 21 August 1969 to 31 March 1970

* Meritorious Unit Commendation

The Meritorious Unit Commendation (MUC; pronounced ''muck'') is a mid-level unit award of the United States Armed Forces. The U.S. Army awards units the Army MUC for exceptionally meritorious conduct in performance of outstanding achievement or ...

for service from 20 November 1970 to 7 May 1971

* Navy Unit Commendation

The Navy Unit Commendation (NUC) is a United States Navy unit award that was established by order of the Secretary of the Navy James Forrestal on 18 December 1944.

History

Navy and U.S. Marine Corps commands may recommend any Navy or Marine Cor ...

for service from 8 February 1972 to 14 September 1972

* Vietnam Service Medal

The Vietnam Service Medal is a military award of the United States Armed Forces established on 8 July 1965 by order of President Lyndon B. Johnson. The medal is awarded to recognize service during the Vietnam War by all members of the U.S. Ar ...

and Republic of Vietnam Meritorious Unit Citation for numerous time periods during the Vietnam war

* Operation Eagle Pull - 12 April 1975

** Armed Forces Expeditionary Medal

The Armed Forces Expeditionary Medal (AFEM) is a military award of the United States Armed Forces, which was first created in 1961 by Executive Order of President John Kennedy. The medal is awarded to members of the U.S. Armed Forces who, after ...

** Humanitarian Service Medal

The Humanitarian Service Medal (HSM) is a military service medal of the United States Armed Forces which was created on January 19, 1977 by President Gerald Ford under . The medal may be awarded to members of the United States military (includ ...

** Meritorious Unit Commendation

The Meritorious Unit Commendation (MUC; pronounced ''muck'') is a mid-level unit award of the United States Armed Forces. The U.S. Army awards units the Army MUC for exceptionally meritorious conduct in performance of outstanding achievement or ...

* Operation Frequent Wind

Operation Frequent Wind was the final phase in the evacuation of American civilians and "at-risk" Vietnamese from Saigon, South Vietnam, before the takeover of the city by the North Vietnamese People's Army of Vietnam (PAVN) in the Fall of S ...

- 29 to 30 April 1975

** Armed Forces Expeditionary Medal

The Armed Forces Expeditionary Medal (AFEM) is a military award of the United States Armed Forces, which was first created in 1961 by Executive Order of President John Kennedy. The medal is awarded to members of the U.S. Armed Forces who, after ...

** Humanitarian Service Medal

The Humanitarian Service Medal (HSM) is a military service medal of the United States Armed Forces which was created on January 19, 1977 by President Gerald Ford under . The medal may be awarded to members of the United States military (includ ...

** Navy Unit Commendation

The Navy Unit Commendation (NUC) is a United States Navy unit award that was established by order of the Secretary of the Navy James Forrestal on 18 December 1944.

History

Navy and U.S. Marine Corps commands may recommend any Navy or Marine Cor ...

Hancock was also awarded:

* American Campaign Medal

The American Campaign Medal is a military award of the United States Armed Forces which was first created on November 6, 1942, by issued by President Franklin D. Roosevelt. The medal was intended to recognize those military members who had perf ...

* World War II Victory Medal

The World War II Victory Medal is a service medal of the United States military which was established by an Act of Congress on 6 July 1945 (Public Law 135, 79th Congress) and promulgated by Section V, War Department Bulletin 12, 1945.

The Wo ...

* Navy Occupation Medal

* National Defense Service Medal

The National Defense Service Medal (NDSM) is a service award of the United States Armed Forces established by President Dwight D. Eisenhower in 1953. It is awarded to every member of the US Armed Forces who has served during any one of four ...

(2nd)

* Sea Service Ribbon

Gallery

San Francisco Bay

San Francisco Bay is a large tidal estuary in the United States, U.S. state of California, and gives its name to the San Francisco Bay Area. It is dominated by the big cities of San Francisco, San Jose, California, San Jose, and Oakland, Ca ...

in September 1957

File:5in gun firing on USS Hancock (CVA-19) in 1957.jpg, ''Hancock''Popular culture

On 3 April 1956,Elvis Presley

Elvis Aaron Presley (January 8, 1935 – August 16, 1977), or simply Elvis, was an American singer and actor. Dubbed the "Honorific nicknames in popular music, King of Rock and Roll", he is regarded as Cultural impact of Elvis Presley, one ...

appeared on ''The Milton Berle Show

''Texaco Star Theater'' was an American comedy-variety show, broadcast on radio from 1938 to 1949 and telecast from 1948 to 1956. It was one of the first successful examples of American television broadcasting, remembered as the show that gave M ...

'', shot onboard ''Hancock'' in San Diego, California

San Diego ( , ; ) is a city on the Pacific Ocean coast of Southern California located immediately adjacent to the Mexico–United States border. With a 2020 population of 1,386,932, it is the List of United States cities by population, eigh ...

. According to TRENDEX, the precursor of Nielsen, the show was seen live by 18 million TV viewers.

Notes

References

* *External links

US Navy Legacy - USS ''Hancock'' (CV-19)

from Dictionary of American Fighting Ships and United States Naval Aviation, 1910–1995.

{{DEFAULTSORT:Hancock (CV-19) Essex-class aircraft carriers Ships built in Quincy, Massachusetts 1944 ships World War II aircraft carriers of the United States Cold War aircraft carriers of the United States Vietnam War aircraft carriers of the United States Ships named for Founding Fathers of the United States