Sicilian People on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Sicilians or the Sicilian people are a

Technological and cultural change among the last Hunter-Gatherers of the Maghreb: the Capsian (10,000 B.P. to 6000 B.P.)

''Journal of World Prehistory'' 18(1): 57-105. Another archaeological site, originally identified by

Romance

Romance (from Vulgar Latin , "in the Roman language", i.e., "Latin") may refer to:

Common meanings

* Romance (love), emotional attraction towards another person and the courtship behaviors undertaken to express the feelings

* Romance languages, ...

speaking people

A person (plural, : people) is a being that has certain capacities or attributes such as reason, morality, consciousness or self-consciousness, and being a part of a culturally established form of social relations such as kinship, ownership of pr ...

who are indigenous

Indigenous may refer to:

*Indigenous peoples

*Indigenous (ecology), presence in a region as the result of only natural processes, with no human intervention

*Indigenous (band), an American blues-rock band

*Indigenous (horse), a Hong Kong racehorse ...

to the island of Sicily

(man) it, Siciliana (woman)

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 = Ethnicity

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographi ...

, the largest island in the Mediterranean Sea

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa, and on the ea ...

, as well as the largest and most populous of the autonomous regions

An autonomous administrative division (also referred to as an autonomous area, entity, unit, region, subdivision, or territory) is a subnational administrative division or internal territory of a sovereign state that has a degree of autonomy— ...

of Italy.

Origin and influences

The Sicilian people are indigenous to the island of Sicily, which was first populated beginning in thePaleolithic

The Paleolithic or Palaeolithic (), also called the Old Stone Age (from Greek: παλαιός ''palaios'', "old" and λίθος ''lithos'', "stone"), is a period in human prehistory that is distinguished by the original development of stone too ...

and Neolithic

The Neolithic period, or New Stone Age, is an Old World archaeological period and the final division of the Stone Age. It saw the Neolithic Revolution, a wide-ranging set of developments that appear to have arisen independently in several parts ...

periods. According to the famous Italian Historian Carlo Denina, the origin of the first inhabitants of Sicily is no less obscure than that of the first Italians, however, there is no doubt that a large part of these early individuals traveled to Sicily from Southern Italy

Southern Italy ( it, Sud Italia or ) also known as ''Meridione'' or ''Mezzogiorno'' (), is a macroregion of the Italian Republic consisting of its southern half.

The term ''Mezzogiorno'' today refers to regions that are associated with the peop ...

, others from the Islands of Greece

Greece has many islands, with estimates ranging from somewhere around 1,200 to 6,000, depending on the minimum size to take into account. The number of inhabited islands is variously cited as between 166 and 227.

The largest Greek island by a ...

, the coasts of West Asia

Western Asia, West Asia, or Southwest Asia, is the westernmost subregion of the larger geographical region of Asia, as defined by some academics, UN bodies and other institutions. It is almost entirely a part of the Middle East, and includes Ana ...

, Iberia

The Iberian Peninsula (),

**

* Aragonese and Occitan: ''Peninsula Iberica''

**

**

* french: Péninsule Ibérique

* mwl, Península Eibérica

* eu, Iberiar penintsula also known as Iberia, is a peninsula in southwestern Europe, defi ...

and West Europe

Western Europe is the western region of Europe. The region's countries and territories vary depending on context.

The concept of "the West" appeared in Europe in juxtaposition to "the East" and originally applied to the ancient Mediterranean ...

.

Prehistory

The aboriginal inhabitants of Sicily, long absorbed into the population, were tribes known to the ancient Greek writers as theElymians

The Elymians ( grc-gre, Ἔλυμοι, ''Élymoi''; Latin: ''Elymi'') were an ancient tribal people who inhabited the western part of Sicily during the Bronze Age and Classical antiquity.

Origins

According to Hellanicus of Lesbos, the Elymians ...

, the Sicanians, and the Sicels

The Sicels (; la, Siculi; grc, Σικελοί ''Sikeloi'') were an Italic tribe who inhabited eastern Sicily during the Iron Age. Their neighbours to the west were the Sicani. The Sicels gave Sicily the name it has held since antiquity, bu ...

, the latter being an Indo-European

The Indo-European languages are a language family native to the overwhelming majority of Europe, the Iranian plateau, and the northern Indian subcontinent. Some European languages of this family, English, French, Portuguese, Russian, Dutc ...

-speaking people of possible Italic affiliation, who migrated from the Italian mainland (likely from the Amalfi Coast

The Amalfi Coast ( it, Costiera amalfitana) is a stretch of coastline in southern Italy overlooking the Tyrrhenian Sea and the Gulf of Salerno. It is located south of the Sorrentine Peninsula and north of the Cilentan Coast.

Celebrated worldwide ...

or Calabria

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 =

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographics1_title1 =

, demographics1_info1 =

, demographics1_title2 ...

via the Strait of Messina

The Strait of Messina ( it, Stretto di Messina, Sicilian: Strittu di Missina) is a narrow strait between the eastern tip of Sicily (Punta del Faro) and the western tip of Calabria ( Punta Pezzo) in Southern Italy. It connects the Tyrrhenian Se ...

) during the second millennium BC, after whom the island was named. The Elymian tribes have been speculated to be a Indo-European

The Indo-European languages are a language family native to the overwhelming majority of Europe, the Iranian plateau, and the northern Indian subcontinent. Some European languages of this family, English, French, Portuguese, Russian, Dutc ...

people who migrated to Sicily from either Central Anatolia

The Central Anatolia Region ( tr, İç Anadolu Bölgesi) is a geographical region of Turkey. The largest city in the region is Ankara. Other big cities are Konya, Kayseri, Eskişehir, Sivas, and Aksaray.

Located in Central Turkey, it is borde ...

, Southern-Coastal Anatolia, Calabria, or one of the Aegean Islands, or perhaps were a collection of native migratory maritime-based tribes from all previously mentioned regions, and formed a common "Elymian" tribal identity/basis after settling down in Sicily. When the Elymians migrated to Sicily is unknown, however scholars of antiquity considered them to be the second oldest inhabitants, while the Sicanians, thought to be the oldest inhabitants of Sicily by scholars of antiquity, were speculated to also be a pre-Indo-European tribe, who migrated via boat

A boat is a watercraft of a large range of types and sizes, but generally smaller than a ship, which is distinguished by its larger size, shape, cargo or passenger capacity, or its ability to carry boats.

Small boats are typically found on inl ...

from the Xúquer river basin in Castellón, Cuenca, Valencia

Valencia ( va, València) is the capital of the Autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community of Valencian Community, Valencia and the Municipalities of Spain, third-most populated municipality in Spain, with 791,413 inhabitants. It is ...

and Alicante

Alicante ( ca-valencia, Alacant) is a city and municipality in the Valencian Community, Spain. It is the capital of the province of Alicante and a historic Mediterranean port. The population of the city was 337,482 , the second-largest in t ...

. Before the Sicanians lived in the easternmost part of the Iberian peninsula. The name 'Sicanus' has been asserted to have a possible link to the modern river known in Valencian

Valencian () or Valencian language () is the official, historical and traditional name used in the Valencian Community (Spain), and unofficially in the El Carche comarca in Murcia (Spain), to refer to the Romance language also known as Catal ...

as the Xúquer and in Castilian as the Júcar. The Beaker was introduced in Sicily from Sardinia and spread mainly in the north-west and south-west of the island. In the northwest and in the Palermo kept almost intact its cultural and social characteristics, while in the south-west there was a strong integration with local cultures. The only known single bell-shaped glass in eastern Sicily was found in Syracuse.The basic study is Joshua Whatmough in R.S. Conway, J. Whatmough and S.E. Johnson, ''The Prae-Italic Dialects of Italy'' (London 1933) vol. 2:431-500; a more recent study is A. Zamponi, "Il Siculo" in A.L. Prosdocimi, ed., ''Popoli e civiltà dell'Italia antica'', vol. 6 "Lingue e dialetti" (1978949-1012.)

All three tribes lived both a sedentary

Sedentary lifestyle is a lifestyle type, in which one is physically inactive and does little or no physical movement and or exercise. A person living a sedentary lifestyle is often sitting or lying down while engaged in an activity like soci ...

pastoral

A pastoral lifestyle is that of shepherds herding livestock around open areas of land according to seasons and the changing availability of water and pasture. It lends its name to a genre of literature, art, and music (pastorale) that depicts ...

and orchard farming lifestyle, and a semi-nomadic

A nomad is a member of a community without fixed habitation who regularly moves to and from the same areas. Such groups include hunter-gatherers, pastoral nomads (owning livestock), tinkers and trader nomads. In the twentieth century, the popu ...

fishing

Fishing is the activity of trying to catch fish. Fish are often caught as wildlife from the natural environment, but may also be caught from stocked bodies of water such as ponds, canals, park wetlands and reservoirs. Fishing techniques inclu ...

, transhumance

Transhumance is a type of pastoralism or nomadism, a seasonal movement of livestock between fixed summer and winter pastures. In montane regions (''vertical transhumance''), it implies movement between higher pastures in summer and lower vall ...

and mixed farming lifestyle. Prior to the Neolithic Revolution

The Neolithic Revolution, or the (First) Agricultural Revolution, was the wide-scale transition of many human cultures during the Neolithic period from a lifestyle of hunting and gathering to one of agriculture and settlement, making an incre ...

, Paleolithic Sicilians would have lived a hunter-gatherer

A traditional hunter-gatherer or forager is a human living an ancestrally derived lifestyle in which most or all food is obtained by foraging, that is, by gathering food from local sources, especially edible wild plants but also insects, fungi, ...

lifestyle, just like most human cultures before the Neolithic. The river Salsu was the territorial boundary between the Sicels and Sicanians. They wore basic clothing made of wool

Wool is the textile fibre obtained from sheep and other mammals, especially goats, rabbits, and camelids. The term may also refer to inorganic materials, such as mineral wool and glass wool, that have properties similar to animal wool.

As ...

, plant fibre

Fiber crops are field crops grown for their fibers, which are traditionally used to make paper, cloth, or rope.

Fiber crops are characterized by having a large concentration of cellulose, which is what gives them their strength. The fibers may b ...

, papyrus

Papyrus ( ) is a material similar to thick paper that was used in ancient times as a writing surface. It was made from the pith of the papyrus plant, '' Cyperus papyrus'', a wetland sedge. ''Papyrus'' (plural: ''papyri'') can also refer to a ...

, esparto grass

Esparto, halfah grass, or esparto grass is a fiber produced from two species of perennial grasses of north Africa, Spain and Portugal. It is used for crafts, such as cords, basketry, and espadrilles. '' Stipa tenacissima'' and '' Lygeum spart ...

, animal skins

A hide or skin is an animal skin treated for human use.

The word "hide" is related to the German word "Haut" which means skin. The industry defines hides as "skins" of large animals ''e.g''. cow, buffalo; while skins refer to "skins" of smaller an ...

, palm leaves

The Arecaceae is a family of perennial flowering plants in the monocot order Arecales. Their growth form can be climbers, shrubs, tree-like and stemless plants, all commonly known as palms. Those having a tree-like form are called palm trees. ...

, leather

Leather is a strong, flexible and durable material obtained from the tanning, or chemical treatment, of animal skins and hides to prevent decay. The most common leathers come from cattle, sheep, goats, equine animals, buffalo, pigs and hogs, ...

and fur

Fur is a thick growth of hair that covers the skin of mammals. It consists of a combination of oily guard hair on top and thick underfur beneath. The guard hair keeps moisture from reaching the skin; the underfur acts as an insulating blanket t ...

, and created everyday tools

A tool is an object that can extend an individual's ability to modify features of the surrounding environment or help them accomplish a particular task. Although many animals use simple tools, only human beings, whose use of stone tools dates ba ...

, as well as weapons

A weapon, arm or armament is any implement or device that can be used to deter, threaten, inflict physical damage, harm, or kill. Weapons are used to increase the efficacy and efficiency of activities such as hunting, crime, law enforcement, s ...

, using metal forging, woodworking

Woodworking is the skill of making items from wood, and includes cabinet making (cabinetry and furniture), wood carving, woodworking joints, joinery, carpentry, and woodturning.

History

Along with Rock (geology), stone, clay and animal parts, ...

and pottery

Pottery is the process and the products of forming vessels and other objects with clay and other ceramic materials, which are fired at high temperatures to give them a hard and durable form. Major types include earthenware, stoneware and por ...

. They typically lived in a nuclear family

A nuclear family, elementary family, cereal-packet family or conjugal family is a family group consisting of parents and their children (one or more), typically living in one home residence. It is in contrast to a single-parent family, the larger ...

unit, with some extended family

An extended family is a family that extends beyond the nuclear family of parents and their children to include aunts, uncles, grandparents, cousins or other relatives, all living nearby or in the same household. Particular forms include the stem ...

members as well, usually within a drystone hut, a neolithic long house

The Neolithic long house was a long, narrow timber dwelling built by the first farmers in Europe beginning at least as early as the period 5000 to 6000 BC. They first appeared in central Europe in connection with the early Neolithic cultures suc ...

or a simple hut

A hut is a small dwelling, which may be constructed of various local materials. Huts are a type of vernacular architecture because they are built of readily available materials such as wood, snow, ice, stone, grass, palm leaves, branches, hid ...

made of mud, stones, wood, palm leaves or grass. Their main methods of transportation were horseback, donkeys and chariots. Evidence of pet wildcats

The wildcat is a species complex comprising two small wild cat species: the European wildcat (''Felis silvestris'') and the African wildcat (''F. lybica''). The European wildcat inhabits forests in Europe, Anatolia and the Caucasus, while the ...

, cirneco dogs and children's toys have been discovered in archaeological digs, especially in cemetery tombs. Their diet was a typical Mediterranean diet

The Mediterranean diet is a diet inspired by the eating habits of people who live near the Mediterranean Sea. When initially formulated in the 1960s, it drew on the cuisines of Greece, Italy, France and Spain. In decades since, it has also incor ...

, including unique food varieties such as Gaglioppo

Gaglioppo is a red wine grape that is grown in southern Italy, primarily around Calabria. The vine performs well in drought conditions but is susceptible to Uncinula necator, oidium and peronospora. The grape produces wine that is full-bodied, ...

, Acitana

Acitana is a red Italian wine grape variety that is grown in northeast Sicily where it is often blended with Nerello Cappuccio and Nerello Mascalese around the village of Messina though Acitana is officially not a permitted variety for wines label ...

and Diamante citron

The Diamante citron (''Citrus medica'' var. ''vulgaris'' or cv. ''diamante'' − it, cedro di diamante, he, אתרוג קלבריה or גינובה) is a variety of citron named after the town of Diamante, located in the province of Cosenza, C ...

, while in modern times the Calabrian Salami, which is also produced in Sicily, and sometimes used to make spicy 'Nduja spreadable paste/sauce, is a popular type of salami sold in Brazil

Brazil ( pt, Brasil; ), officially the Federative Republic of Brazil (Portuguese: ), is the largest country in both South America and Latin America. At and with over 217 million people, Brazil is the world's fifth-largest country by area ...

and the Anglosphere

The Anglosphere is a group of English-speaking world, English-speaking nations that share historical and cultural ties with England, and which today maintain close political, diplomatic and military co-operation. While the nations included in d ...

. All 3 tribes also specialised in building megalith

A megalith is a large stone that has been used to construct a prehistoric structure or monument, either alone or together with other stones. There are over 35,000 in Europe alone, located widely from Sweden to the Mediterranean sea.

The ...

ic single-chambered dolmen tombs, a tradition which dates back to the Neolithic. "An important archaeological site, located in Southeast Sicily, is the Necropolis of Pantalica

The Necropolis of Pantalica is a collection of cemeteries with rock-cut chamber tombs in southeast Sicily, Italy. Dating from the 13th to the 7th centuries BC, there was thought to be over 5,000 tombs, although the most recent estimate suggests a ...

, a collection of cemeteries with rock-cut chamber tombs. Dating

Dating is a stage of romantic relationships in which two individuals engage in an activity together, most often with the intention of evaluating each other's suitability as a partner in a future intimate relationship. It falls into the categor ...

from the 13th to the 7th centuries BC., recent estimates suggest a figure of just under 4,000 tombs. They extend around the flanks of a large promontory located at the junction of the Anapo river with its tributary, the Calcinara

The Calcinara is a river in southeastern Sicily in Italy. It flows into the Anapo near the archaeological site of Pantalica

The Necropolis of Pantalica is a collection of cemeteries with rock-cut chamber tombs in southeast Sicily, Italy. Dating ...

, about 23 km (14 mi) northwest of Syracuse. Together with the city of Syracuse, Pantalica was listed as a UNESCO

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization is a specialized agency of the United Nations (UN) aimed at promoting world peace and security through international cooperation in education, arts, sciences and culture. It ...

World Heritage Site in 2005. The site was mainly excavated between 1895 and 1910 by the Italian archeologist, Paolo Orsi

Paolo Orsi (Rovereto, October 17, 1859 – November 8, 1935) was an Italian archaeologist and classicist.

Life

Orsi was born in Rovereto, then part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire and now in the province of Trento in Italy. After studying at a g ...

, although most of the tombs had already been looted long before his time. Items found within the tombs of Pantalica, some now on display at the Archaeology Museum in Syracuse, were the characteristic red-burnished pottery vessels, and metal objects, including weaponry (small knives and daggers) and clothing, such as bronze fibulae (brooches) and rings, which were placed with the deceased in the tombs. Most of the tombs contained between one to seven individuals of all ages and both sexes. Many tombs were evidently re-opened periodically for more burials. The average human life span at this time was probably around 30 years of age, although the size of the prehistoric population is hard to estimate from the available data, but might have been around 1000 people."

Nuragic ceramic remains, (from Sardinia

Sardinia ( ; it, Sardegna, label=Italian, Corsican and Tabarchino ; sc, Sardigna , sdc, Sardhigna; french: Sardaigne; sdn, Saldigna; ca, Sardenya, label=Algherese and Catalan) is the second-largest island in the Mediterranean Sea, after ...

), carbon dated to the 13th century BC, have been found in Lipari

Lipari (; scn, Lìpari) is the largest of the Aeolian Islands in the Tyrrhenian Sea off the northern coast of Sicily, southern Italy; it is also the name of the island's main town and ''comune'', which is administratively part of the Metropo ...

. The prehistoric Thapsos culture

The Thapsos Culture is defined as the civilization in ancient Sicily attested by archaeological findings of a large village located in the peninsula of Magnisi, between Augusta and Syracuse, that the Greeks called Thapsos.

I believe I have demo ...

, associated with the Sicani, shows noticeable influences from Mycenaean Greece

Mycenaean Greece (or the Mycenaean civilization) was the last phase of the Bronze Age

The Bronze Age is a historic period, lasting approximately from 3300 BC to 1200 BC, characterized by the use of bronze, the presence of writing in ...

.''Pantalica e i suoi monumenti'' di Paolo Orsi The type of burial found in the necropolis

A necropolis (plural necropolises, necropoles, necropoleis, necropoli) is a large, designed cemetery with elaborate tomb monuments. The name stems from the Ancient Greek ''nekropolis'', literally meaning "city of the dead".

The term usually im ...

of the Thapsos culture, is characterized by large rock-cut chamber tombs, and often of ''tholos-type'' that some scholars believe to be of Mycenaean derivation, while others believe it to be the traditional shape of the hut. The housing are made up of mostly circular huts bounded by stone walls, mainly in small numbers. Some huts have rectangular shape, particularly the roof. The economy was based on farming, herding, hunting and fishing. There are numerous evidences of trading networks, in particular of bronze vessels and weapons of Mycenaean and Nuragic (Sardinian) production. There were close trading relationships/networks established with the ''Milazzo Culture'' of the Aeolian Islands

The Aeolian Islands ( ; it, Isole Eolie ; scn, Ìsuli Eoli), sometimes referred to as the Lipari Islands or Lipari group ( , ) after their largest island, are a volcanic archipelago in the Tyrrhenian Sea north of Sicily, said to be named after ...

, and with the Apennine culture

The Apennine culture is a technology complex in central and southern Italy from the Italian Middle Bronze Age (15th–14th centuries BC). In the mid-20th century the Apennine was divided into Proto-, Early, Middle and Late , but now archaeolo ...

of mainland southern Italy. In Sicily's earlier prehistory

Prehistory, also known as pre-literary history, is the period of human history between the use of the first stone tools by hominins 3.3 million years ago and the beginning of recorded history with the invention of writing systems. The use of ...

, there is also evidence of trade with the Capsian

The Capsian culture was a Mesolithic and Neolithic culture centered in the Maghreb that lasted from about 8,000 to 2,700 BC. It was named after the town of Gafsa in Tunisia, which was known as Capsa in Roman times.

Capsian industry was concentr ...

and Iberomaurusian

The Iberomaurusian is a backed bladelet lithic industry found near the coasts of Morocco, Algeria, and Tunisia. It is also known from a single major site in Libya, the Haua Fteah, where the industry is locally known as the Eastern Oranian.The " ...

mesolithic

The Mesolithic (Greek: μέσος, ''mesos'' 'middle' + λίθος, ''lithos'' 'stone') or Middle Stone Age is the Old World archaeological period between the Upper Paleolithic and the Neolithic. The term Epipaleolithic is often used synonymous ...

cultures from Tunisia

)

, image_map = Tunisia location (orthographic projection).svg

, map_caption = Location of Tunisia in northern Africa

, image_map2 =

, capital = Tunis

, largest_city = capital

, ...

, with some lithic stone sites attested in certain parts of the island.2005 D. Lubell. Continuité et changement dans l'Epipaléolithique du Maghreb. In, M. Sahnouni (ed.) ''Le Paléolithique en Afrique: l’histoire la plus longue'', pp. 205-226. Paris: Guides de la Préhistoire Mondiale, Éditions Artcom’/Errance.2004 N. RahmaniTechnological and cultural change among the last Hunter-Gatherers of the Maghreb: the Capsian (10,000 B.P. to 6000 B.P.)

''Journal of World Prehistory'' 18(1): 57-105. Another archaeological site, originally identified by

Paolo Orsi

Paolo Orsi (Rovereto, October 17, 1859 – November 8, 1935) was an Italian archaeologist and classicist.

Life

Orsi was born in Rovereto, then part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire and now in the province of Trento in Italy. After studying at a g ...

on the basis of a particular ceramic style, is the Castelluccio culture which dates back to the Ancient Bronze Age (2000 B.C. approximately), and is seen as sort of a "prehistoric proto-civilization", located between Noto

Noto ( scn, Notu; la, Netum) is a city and in the Province of Syracuse, Sicily, Italy. It is southwest of the city of Syracuse at the foot of the Iblean Mountains. It lends its name to the surrounding area Val di Noto. In 2002 Noto and i ...

and Siracusa. The discovery of a prehistoric village in Castelluccio di Noto, next to the remains of prehistoric circular huts, led to finds of Ceramic

A ceramic is any of the various hard, brittle, heat-resistant and corrosion-resistant materials made by shaping and then firing an inorganic, nonmetallic material, such as clay, at a high temperature. Common examples are earthenware, porcelain ...

glass

Glass is a non-crystalline, often transparent, amorphous solid that has widespread practical, technological, and decorative use in, for example, window panes, tableware, and optics. Glass is most often formed by rapid cooling (quenching) of ...

decorated with brown lines on a yellow-reddish background, and tri-color with the use of white. The weapons used in the days of Castelluccio culture were green stone and basalt

Basalt (; ) is an aphanite, aphanitic (fine-grained) extrusive igneous rock formed from the rapid cooling of low-viscosity lava rich in magnesium and iron (mafic lava) exposed at or very near the planetary surface, surface of a terrestrial ...

axes and, in the most recent settlements, bronze axes, and frequently carved bones, considered idols similar to those of Malta

Malta ( , , ), officially the Republic of Malta ( mt, Repubblika ta' Malta ), is an island country in the Mediterranean Sea. It consists of an archipelago, between Italy and Libya, and is often considered a part of Southern Europe. It lies ...

, and of Troy II and III. Burials were made in rounded tombs carved into the rock, with doors with relief carving of spiral symbols and motifs that evoke the sexual act. The Castelluccio culture is dated to a period between 2200 BC and 1800 BC, although some believe it to be contemporary to the Middle-Late Helladic period

Helladic chronology is a relative dating system used in archaeology and art history. It complements the Minoan chronology scheme devised by Sir Arthur Evans for the categorisation of Bronze Age artefacts from the Minoan civilization within a h ...

(1800/1400 BC)." "Sites related to the Castelluccio culture were present in the villages of south-east Sicily, including Monte Casale

Monte Casale is a mountainous elevation on Sicily in Italy, reaching 910m above sea level, which (with the neighbouring Monte Lauro) formed part of the oldest volcanic formation of the Hyblaean Mountains. Their peaks form the boundary between t ...

, Cava/Quarry d'Ispica, Pachino

Pachino (; scn, Pachinu ) is a town and ''comune'' in the Province of Syracuse, Sicily (Italy). The name derives from the Latin word ''bacchus,'' which is the Roman god of wine, and the word ''vinum'', which means wine in Latin; originally the ...

, Niscemi

Niscemi is a little town and ''comune'' in the province of Caltanissetta, Sicily, Italy. It has a population of 27,558. It is located not far from Gela and Caltagirone and 90 km from Catania.

Etymology

The name Niscemi is derived from the ...

, Cava/Quarry Lazzaro, near Noto

Noto ( scn, Notu; la, Netum) is a city and in the Province of Syracuse, Sicily, Italy. It is southwest of the city of Syracuse at the foot of the Iblean Mountains. It lends its name to the surrounding area Val di Noto. In 2002 Noto and i ...

, of Rosolini

Rosolini ( scn, Rusalini) is a '' comune'' (municipality) in the Province of Syracuse,

Sicily, southern Italy. It is about southeast of Palermo and about southwest of Syracuse. Rosolini was a town in feudal times, and was a settlement in ...

, in the rocky Byzantine district of coastal Santa Febronia in Palagonia

Palagonia ( Sicilian: ''Palagunìa'', Latin: ''Palica'') is a ''comune'' (municipality) in the Metropolitan City of Catania in the Italian region Sicily, located about southeast of Palermo and about southwest of Catania. Palagonia borders the ...

, in Cuddaru d' Crastu (Tornabé-Mercato d'Arrigo) near Pietraperzia

Pietraperzia ( Sicilian: ''Petrapirzia'') is a ''comune'' in the province of Enna, in Sicilian region of southern Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. I ...

, where there are remains of a fortress partly carved in stone, and - with different ceramic forms - also near Agrigento

Agrigento (; scn, Girgenti or ; grc, Ἀκράγας, translit=Akrágas; la, Agrigentum or ; ar, كركنت, Kirkant, or ''Jirjant'') is a city on the southern coast of Sicily, Italy and capital of the province of Agrigento. It was one of ...

in Monte Grande

Monte Grande is a city which forms part of the urban agglomeration of Greater Buenos Aires. It is the administrative seat of Esteban Echeverría Partido in Buenos Aires Province, Argentina.

It was founded on April 3, 1889, by a company named ''Soc ...

. The discovery of a cup of 'Etna type' in the area of Comiso

Comiso ( scn, U Còmisu), is a comune of the Province of Ragusa, Sicily, southern Italy. As of 2017, its population was 29,857.

History

In the past Comiso has been incorrectly identified with the ancient Greek colony of Casmene.

Under the Byza ...

, among local ceramic objects led to the discovery of commercial trades with the Castelluccio sites of Paternò

Paternò ( scn, Patennò) is a southern Italian town and ''comune'' of the Metropolitan City of Catania, Sicily. With a population (2016) of 48,009, it is the third municipality of the province after Catania and Acireale.

Geography

Paternò ...

, Adrano

Adrano (, scn, Ddirnò), ancient '' Adranon'', is a town and in the Metropolitan City of Catania on the east coast of Sicily.

It is situated around northwest of Catania, which was also the capital of the province to which Adrano belonged, n ...

and Biancavilla

Biancavilla () is a town and '' comune'' in the Metropolitan City of Catania, Sicily, southern Italy. It is located between the towns of Adrano and S. Maria di Licodia, northwest of Catania. The town was founded and historically inhabited by t ...

, whose graves differ in making due to the hard basaltic terrain and also for the utilization of the lava cave

A lava cave is any cave formed in volcanic rock, though it typically means caves formed by volcanic processes, which are more properly termed volcanic caves. Sea caves, and other sorts of erosional and crevice caves, may be formed in volcanic roc ...

s as chamber tombs. In the area around Ragusa Ragusa is the historical name of Dubrovnik. It may also refer to:

Places Croatia

* the Republic of Ragusa (or Republic of Dubrovnik), the maritime city-state of Ragusa

* Cavtat (historically ' in Italian), a town in Dubrovnik-Neretva County, Cro ...

, there have been found evidences of mining among the ancient residents of Castelluccio; tunnels excavated by the use of basalt bats allowed the extraction and production of highly sought flint

Flint, occasionally flintstone, is a sedimentary cryptocrystalline form of the mineral quartz, categorized as the variety of chert that occurs in chalk or marly limestone. Flint was widely used historically to make stone tools and start fir ...

s. Some dolmens

A dolmen () or portal tomb is a type of single-chamber megalithic tomb, usually consisting of two or more upright megaliths supporting a large flat horizontal capstone or "table". Most date from the early Neolithic (40003000 BCE) and were somet ...

, dated back to this same period, with sole funeral function, are found in different parts of Sicily and attributable to a people not belonging to the Castelluccio Culture."

The Sicelian polytheistic

Polytheism is the belief in multiple deities, which are usually assembled into a pantheon of gods and goddesses, along with their own religious sects and rituals. Polytheism is a type of theism. Within theism, it contrasts with monotheism, the ...

worship of the ancient and native chthonic

The word chthonic (), or chthonian, is derived from the Ancient Greek word ''χθών, "khthon"'', meaning earth or soil. It translates more directly from χθόνιος or "in, under, or beneath the earth" which can be differentiated from Γῆ ...

, animistic

Animism (from Latin: ' meaning 'breath, spirit, life') is the belief that objects, places, and creatures all possess a distinct spiritual essence. Potentially, animism perceives all things—animals, plants, rocks, rivers, weather systems, hum ...

-cult deities associated with geysers known as the Palici

The Palici ( Ancient Greek: , romanized: ), or Palaci, were a pair of indigenous Sicilian chthonic deities in Roman mythology, and to a lesser extent in Greek mythology. They are mentioned in Ovid's ''Metamorphoses'' V, 406, and in Virgil's ''Aen ...

, as well as the worship of the volcano-fire god by the name of Adranos, were also worshiped throughout Sicily by the Elymians and Sicanians. Their (Palici) centre of worship was originally based on three small lakes that emitted sulphur

Sulfur (or sulphur in British English) is a chemical element with the symbol S and atomic number 16. It is abundant, multivalent and nonmetallic. Under normal conditions, sulfur atoms form cyclic octatomic molecules with a chemical formula ...

ous vapors in the Palagonia

Palagonia ( Sicilian: ''Palagunìa'', Latin: ''Palica'') is a ''comune'' (municipality) in the Metropolitan City of Catania in the Italian region Sicily, located about southeast of Palermo and about southwest of Catania. Palagonia borders the ...

n plains, and as a result these twin brothers were associated with geysers and the underworld

The underworld, also known as the netherworld or hell, is the supernatural world of the dead in various religious traditions and myths, located below the world of the living. Chthonic is the technical adjective for things of the underwor ...

. There was also a shrine to the Palici in Palacia, where people could subject themselves or others to tests of reliability through divine judgement; passing meant that an oath could be trusted. The mythological lineage of the Palici is uncertain. According to Macrobius

Macrobius Ambrosius Theodosius, usually referred to as Macrobius (fl. AD 400), was a Roman provincial who lived during the early fifth century, during late antiquity, the period of time corresponding to the Later Roman Empire, and when Latin was ...

, the nymph Thalia

Thalia, Thalía, Thaleia or Thalian may refer to:

People

* Thalia (given name), including a list of people with the name

* Thalía (born 1971), Mexican singer and actress

Mythological and fictional characters

* Thalia (Grace), one of the three ...

gave birth to the divine twins while living underneath the Earth. They were most likely either the sons of the native fire god Adranos, or, as Polish historian "Krzysztof Tomasz Witczak" suggests, the Palici may derive from the old Proto-Indo-European

Proto-Indo-European (PIE) is the reconstructed common ancestor of the Indo-European language family. Its proposed features have been derived by linguistic reconstruction from documented Indo-European languages. No direct record of Proto-Indo-E ...

mytheme of the divine twins

The Divine Twins are youthful horsemen, either gods or demigods, who serve as rescuers and healers in Proto-Indo-European mythology.

Like other Proto-Indo-European divinities, the Divine Twins are not directly attested by archaeological or writt ...

. Mount Etna

Mount Etna, or simply Etna ( it, Etna or ; scn, Muncibbeḍḍu or ; la, Aetna; grc, Αἴτνα and ), is an active stratovolcano on the east coast of Sicily, Italy, in the Metropolitan City of Catania, between the cities of Messina a ...

is named after the mythological Sicilian nymph

A nymph ( grc, νύμφη, nýmphē, el, script=Latn, nímfi, label=Modern Greek; , ) in ancient Greek folklore is a minor female nature deity. Different from Greek goddesses, nymphs are generally regarded as personifications of nature, are ty ...

called Aetna

Aetna Inc. () is an American managed health care company that sells traditional and consumer directed health care insurance and related services, such as medical, pharmaceutical, dental, behavioral health, long-term care, and disability plans, ...

, who might have been the possible mother to the Palici twins. Mount Etna was also believed to have been the region where Zeus

Zeus or , , ; grc, Δῐός, ''Diós'', label=Genitive case, genitive Aeolic Greek, Boeotian Aeolic and Doric Greek#Laconian, Laconian grc-dor, Δεύς, Deús ; grc, Δέος, ''Déos'', label=Genitive case, genitive el, Δίας, ''D� ...

buried the Serpentine giant Typhon

Typhon (; grc, Τυφῶν, Typhôn, ), also Typhoeus (; grc, Τυφωεύς, Typhōeús, label=none), Typhaon ( grc, Τυφάων, Typháōn, label=none) or Typhos ( grc, Τυφώς, Typhṓs, label=none), was a monstrous serpentine giant an ...

, and the humanoid giant Enceladus

Enceladus is the sixth-largest moon of Saturn (19th largest in the Solar System). It is about in diameter, about a tenth of that of Saturn's largest moon, Titan. Enceladus is mostly covered by fresh, clean ice, making it one of the most refle ...

in classical mythology. The Cyclopes

In Greek mythology and later Roman mythology, the Cyclopes ( ; el, Κύκλωπες, ''Kýklōpes'', "Circle-eyes" or "Round-eyes"; singular Cyclops ; , ''Kýklōps'') are giant one-eyed creatures. Three groups of Cyclopes can be distinguish ...

, giant one eyed humanoid creatures in classical Greco-Roman mythology, known as the maker of Zeus' thunderbolts, were traditionally associated with Sicily and the Aeolian Islands

The Aeolian Islands ( ; it, Isole Eolie ; scn, Ìsuli Eoli), sometimes referred to as the Lipari Islands or Lipari group ( , ) after their largest island, are a volcanic archipelago in the Tyrrhenian Sea north of Sicily, said to be named after ...

. The Cyclopes were said to have been assistants to the Greek blacksmith God Hephaestus

Hephaestus (; eight spellings; grc-gre, Ἥφαιστος, Hḗphaistos) is the Greek god of blacksmiths, metalworking, carpenters, craftsmen, artisans, sculptors, metallurgy, fire (compare, however, with Hestia), and volcanoes.Walter Burk ...

, at his forge in Sicily, underneath Mount Etna, or perhaps on one of the nearby Aeolian Islands. The Aeolian Islands, off the coast of Northwestern Sicily, were themselves named after the mythological king and "keeper of the heavy winds" known as Aeolus

In Greek mythology, Aeolus or Aiolos (; grc, Αἴολος , ) is a name shared by three mythical characters. These three personages are often difficult to tell apart, and even the ancient mythographers appear to have been perplexed about which A ...

. In his ''Hymn to Artemis

In ancient Greek mythology and religion, Artemis (; grc-gre, Ἄρτεμις) is the goddess of the hunt, the wilderness, wild animals, nature, vegetation, childbirth, care of children, and chastity. She was heavily identified wit ...

'', Cyrene poet Callimachus

Callimachus (; ) was an ancient Greek poet, scholar and librarian who was active in Alexandria during the 3rd century BC. A representative of Ancient Greek literature of the Hellenistic period, he wrote over 800 literary works in a wide variety ...

states that the Cyclopes on the Aeolian island of Lipari

Lipari (; scn, Lìpari) is the largest of the Aeolian Islands in the Tyrrhenian Sea off the northern coast of Sicily, southern Italy; it is also the name of the island's main town and ''comune'', which is administratively part of the Metropo ...

, working "at the anvils of Hephaestus

Hephaestus (; eight spellings; grc-gre, Ἥφαιστος, Hḗphaistos) is the Greek god of blacksmiths, metalworking, carpenters, craftsmen, artisans, sculptors, metallurgy, fire (compare, however, with Hestia), and volcanoes.Walter Burk ...

", make the bows and arrows used by Apollo

Apollo, grc, Ἀπόλλωνος, Apóllōnos, label=genitive , ; , grc-dor, Ἀπέλλων, Apéllōn, ; grc, Ἀπείλων, Apeílōn, label=Arcadocypriot Greek, ; grc-aeo, Ἄπλουν, Áploun, la, Apollō, la, Apollinis, label= ...

and Artemis

In ancient Greek mythology and religion, Artemis (; grc-gre, Ἄρτεμις) is the goddess of the hunt, the wilderness, wild animals, nature, vegetation, childbirth, care of children, and chastity. She was heavily identified wit ...

. The Hesiod

Hesiod (; grc-gre, Ἡσίοδος ''Hēsíodos'') was an ancient Greek poet generally thought to have been active between 750 and 650 BC, around the same time as Homer. He is generally regarded by western authors as 'the first written poet i ...

ic Latin poet Ovid

Pūblius Ovidius Nāsō (; 20 March 43 BC – 17/18 AD), known in English as Ovid ( ), was a Roman poet who lived during the reign of Augustus. He was a contemporary of the older Virgil and Horace, with whom he is often ranked as one of the th ...

names three Cyclopes "Brontes, Steropes and Acmonides" working as forge

A forge is a type of hearth used for heating metals, or the workplace (smithy) where such a hearth is located. The forge is used by the smith to heat a piece of metal to a temperature at which it becomes easier to shape by forging, or to th ...

rs inside Sicilian caves.

Besides Demeter

In ancient Greek religion and mythology, Demeter (; Attic: ''Dēmḗtēr'' ; Doric: ''Dāmā́tēr'') is the Olympian goddess of the harvest and agriculture, presiding over crops, grains, food, and the fertility of the earth. Although s ...

(the Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

goddess of agriculture

Agriculture or farming is the practice of cultivating plants and livestock. Agriculture was the key development in the rise of sedentary human civilization, whereby farming of domesticated species created food surpluses that enabled people to ...

and law

Law is a set of rules that are created and are enforceable by social or governmental institutions to regulate behavior,Robertson, ''Crimes against humanity'', 90. with its precise definition a matter of longstanding debate. It has been vario ...

), and Persephone

In ancient Greek mythology and religion, Persephone ( ; gr, Περσεφόνη, Persephónē), also called Kore or Cora ( ; gr, Κόρη, Kórē, the maiden), is the daughter of Zeus and Demeter. She became the queen of the underworld after ...

(the Greek personified

Personification occurs when a thing or abstraction is represented as a person, in literature or art, as a type of anthropomorphic metaphor. The type of personification discussed here excludes passing literary effects such as "Shadows hold their ...

goddess of vegetation

Vegetation is an assemblage of plant species and the ground cover they provide. It is a general term, without specific reference to particular taxa, life forms, structure, spatial extent, or any other specific botanical or geographic character ...

), The Phoenicia

Phoenicia () was an ancient thalassocratic civilization originating in the Levant region of the eastern Mediterranean, primarily located in modern Lebanon. The territory of the Phoenician city-states extended and shrank throughout their histor ...

n bull god Moloch

Moloch (; ''Mōleḵ'' or הַמֹּלֶךְ ''hamMōleḵ''; grc, Μόλοχ, la, Moloch; also Molech or Molek) is a name or a term which appears in the Hebrew Bible several times, primarily in the book of Leviticus. The Bible strongly co ...

(a significant deity also mentioned in the Hebrew Bible

The Hebrew Bible or Tanakh (;"Tanach"

''Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary''. Hebrew: ''Tān ...

), the Phoenician ''Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary''. Hebrew: ''Tān ...

moon goddess

A lunar deity or moon deity is a deity who represents the Moon, or an aspect of it. These deities can have a variety of functions and traditions depending upon the culture, but they are often related. Lunar deities and Moon worship can be found ...

of fertility

Fertility is the capability to produce offspring through reproduction following the onset of sexual maturity. The fertility rate is the average number of children born by a female during her lifetime and is quantified demographically. Fertili ...

and prosperity

Prosperity is the flourishing, thriving, good fortune and successful social status. Prosperity often produces profuse wealth including other factors which can be profusely wealthy in all degrees, such as happiness and health.

Competing notion ...

Astarte

Astarte (; , ) is the Hellenized form of the Ancient Near Eastern goddess Ashtart or Athtart (Northwest Semitic), a deity closely related to Ishtar (East Semitic), who was worshipped from the Bronze Age through classical antiquity. The name i ...

(with her Roman

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

*Rome, the capital city of Italy

*Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*''Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a letter ...

equivalent being Venus

Venus is the second planet from the Sun. It is sometimes called Earth's "sister" or "twin" planet as it is almost as large and has a similar composition. As an interior planet to Earth, Venus (like Mercury) appears in Earth's sky never fa ...

), the Punic

The Punic people, or western Phoenicians, were a Semitic people in the Western Mediterranean who migrated from Tyre, Phoenicia to North Africa during the Early Iron Age. In modern scholarship, the term ''Punic'' – the Latin equivalent of t ...

goddess Tanit

Tanit ( Punic: 𐤕𐤍𐤕 ''Tīnīt'') was a Punic goddess. She was the chief deity of Carthage alongside her consort Baal-Hamon.

Tanit is also called Tinnit. The name appears to have originated in Carthage (modern day Tunisia), though it doe ...

, and the weather

Weather is the state of the atmosphere, describing for example the degree to which it is hot or cold, wet or dry, calm or stormy, clear or cloudy. On Earth, most weather phenomena occur in the lowest layer of the planet's atmosphere, the ...

& war god

War is an intense armed conflict between states, governments, societies, or paramilitary groups such as mercenaries, insurgents, and militias. It is generally characterized by extreme violence, destruction, and mortality, using regul ...

Baal

Baal (), or Baal,; phn, , baʿl; hbo, , baʿal, ). ( ''baʿal'') was a title and honorific meaning "owner", "lord" in the Northwest Semitic languages spoken in the Levant during Ancient Near East, antiquity. From its use among people, it cam ...

(which later evolved into the Carthaginian The term Carthaginian ( la, Carthaginiensis ) usually refers to a citizen of Ancient Carthage.

It can also refer to:

* Carthaginian (ship), a three-masted schooner built in 1921

* Insurgent privateers; nineteenth-century South American privateers, ...

god Baal Hammon), as well as the Carthaginian chief god Baal Hammon, also had centres of cultic-worship throughout Sicily. The river Anapo

The Anapo ( Sicilian: ''Ànapu'') is a river in Sicily whose ancient Greek name is similar to the word for "swallowed up" LSJ sv. ἀναπίνω; ἀνάποσις and at many points on its course it runs underground. The Greek myth of Anapos is a ...

was viewed as the personification of the water god Anapos

Anapos was a water god of eastern Sicily in Greek mythology. When he opposed the rape of Persephone along with the nymph Cyane, Hades turned them into a river (the river Anapo in southern Sicily

(man) it, Siciliana (woman)

, population_ ...

in Greek-Sicilian mythology. The Elymians inhabited the western parts of Sicily, while the Sicanians inhabited the central parts, and the Sicels inhabited the eastern

Eastern may refer to:

Transportation

*China Eastern Airlines, a current Chinese airline based in Shanghai

*Eastern Air, former name of Zambia Skyways

*Eastern Air Lines, a defunct American airline that operated from 1926 to 1991

*Eastern Air Li ...

parts.

Ancient history

From the 11th century BC,Phoenicians

Phoenicia () was an ancient Semitic-speaking peoples, ancient thalassocracy, thalassocratic civilization originating in the Levant region of the eastern Mediterranean, primarily located in modern Lebanon. The territory of the Phoenician city-st ...

began to settle in western Sicily, having already started colonies on the nearby parts of North Africa

North Africa, or Northern Africa is a region encompassing the northern portion of the African continent. There is no singularly accepted scope for the region, and it is sometimes defined as stretching from the Atlantic shores of Mauritania in ...

and Malta

Malta ( , , ), officially the Republic of Malta ( mt, Repubblika ta' Malta ), is an island country in the Mediterranean Sea. It consists of an archipelago, between Italy and Libya, and is often considered a part of Southern Europe. It lies ...

. Sicily was later colonized and heavily settled by Greeks

The Greeks or Hellenes (; el, Έλληνες, ''Éllines'' ) are an ethnic group and nation indigenous to the Eastern Mediterranean and the Black Sea regions, namely Greece, Cyprus, Albania, Italy, Turkey, Egypt, and, to a lesser extent, oth ...

, beginning in the 8th century BC. Initially, this was restricted to the eastern

Eastern may refer to:

Transportation

*China Eastern Airlines, a current Chinese airline based in Shanghai

*Eastern Air, former name of Zambia Skyways

*Eastern Air Lines, a defunct American airline that operated from 1926 to 1991

*Eastern Air Li ...

and southern parts of the island. As the Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

and Phoenician communities grew more populous and more powerful, the Sicels and Sicanians were pushed further into the centre of the island. The independent Phoenician colonial settlements were eventually absorbed by Carthage

Carthage was the capital city of Ancient Carthage, on the eastern side of the Lake of Tunis in what is now Tunisia. Carthage was one of the most important trading hubs of the Ancient Mediterranean and one of the most affluent cities of the classi ...

during the 6th Century BC. By the 3rd century BC, Syracuse was the most populous Greek city state in the world. Sicilian politics was intertwined with politics in Greece

Greece,, or , romanized: ', officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the southern tip of the Balkans, and is located at the crossroads of Europe, Asia, and Africa. Greece shares land borders with ...

itself, leading Athens

Athens ( ; el, Αθήνα, Athína ; grc, Ἀθῆναι, Athênai (pl.) ) is both the capital and largest city of Greece. With a population close to four million, it is also the seventh largest city in the European Union. Athens dominates ...

, for example, to mount the disastrous Sicilian Expedition

The Sicilian Expedition was an Athenian military expedition to Sicily, which took place from 415–413 BC during the Peloponnesian War between Athens on one side and Sparta, Syracuse and Corinth on the other. The expedition ended in a devas ...

against Syracuse in 415-413 BC during the Peloponnesian War

The Peloponnesian War (431–404 BC) was an ancient Greek war fought between Athens and Sparta and their respective allies for the hegemony of the Greek world. The war remained undecided for a long time until the decisive intervention of th ...

, which ended up severely affecting a defeated Athens, both politically and economically, in the following years to come. Another battle which Syracuse took part in, this time under the Tyrant Hiero I of Syracuse

Hieron I ( el, Ἱέρων Α΄; usually Latinized Hiero) was the son of Deinomenes, the brother of Gelon and tyrant of Syracuse in Sicily from 478 to 467 BC. In succeeding Gelon, he conspired against a third brother, Polyzelos.

Life

During hi ...

, was the Battle of Cumae

The Battle of Cumae is the name given to at least two battles between Cumae and the Etruscans:

* In 524 BC an invading army of Umbrians, Daunians, Etruscans, and others were defeated by the Greeks of Cumae.

* The naval battle in 474 BC was bet ...

, where the combined navies

A navy, naval force, or maritime force is the branch of a nation's armed forces principally designated for naval and amphibious warfare; namely, lake-borne, riverine, littoral, or ocean-borne combat operations and related functions. It includ ...

of Syracuse and Cumae

Cumae ( grc, Κύμη, (Kumē) or or ; it, Cuma) was the first ancient Greek colony on the mainland of Italy, founded by settlers from Euboea in the 8th century BC and soon becoming one of the strongest colonies. It later became a rich Ro ...

defeated an Etruscan force, resulting in significant territorial loses for the Etruscans. The constant warfare between Ancient Carthage

Carthage () was a settlement in modern Tunisia that later became a city-state and then an empire. Founded by the Phoenicians in the ninth century BC, Carthage reached its height in the fourth century BC as one of the largest metropolises in t ...

and the Greek city-states

''Polis'' (, ; grc-gre, πόλις, ), plural ''poleis'' (, , ), literally means "city" in Greek. In Ancient Greece, it originally referred to an administrative and religious city center, as distinct from the rest of the city. Later, it also ...

eventually opened the door to an emerging third power

Third Power was an American psychedelic hard rock band from Detroit, Michigan, who released one album in 1970.

The group was formed in 1969, and became a prominent local club band before signing to Vanguard Records.Messanan Crisis, caused by Mamertine

In the 11th century, the mainland southern Italian powers were hiring Norman conquest of southern Italy, Norman mercenaries, who were Christians, Christian descendants of the Vikings; it was the Normans under Roger I of Sicily, Roger I (of the Hauteville dynasty) who conquered Sicily from the Muslims Battle of Cerami, over a period of thirty years until finally controlling the entire island by 1091 as the County of Sicily. In 1130, Roger II of Sicily, Roger II founded the Norman Kingdom of Sicily as an independent state with its own Sicilian Parliament, Parliament, language, schooling, army and currency, while the Sicilian culture evolved distinct traditions, clothing, linguistic changes, Sicilian cuisine, cuisine and customs not found in mainland Italy. A great number of families from Kingdom of Italy (Holy Roman Empire), northern Italy began settling in Sicily during this time, with some of their descendants forming distinct communities that survive to the present day, such as the Lombards of Sicily. Other migrants arrived from County of Apulia and Calabria, southern Italy, as well as Duchy of Normandy, Normandy County of Provence, southern France, England and other part of North Europe.

The Siculo-Norman rule of the Hauteville dynasty continued until 1198, when Frederick I of Sicily, Frederick II of Sicily, the son of a Siculo-Norman queen and a Hohenstaufen dynasty, Swabian-German emperor ascended the throne. In fact, it was during the reign of this Hohenstaufen king Frederick II, Holy Roman Emperor, Frederick II, that the poetic form known as a sonnet was invented by Giacomo da Lentini, the head Poet, Teacher and Notary of the Sicilian School, Sicilian School for Poetry. Frederick II was also responsible for the Muslim settlement of Lucera. His descendants governed Sicily until the Papal States, Papacy invited a Capetian dynasty, French prince to take the throne, which led to a decade-and-a-half of Kingdom of France, French rule under Charles I of Sicily; he was later deposed in the War of the Sicilian Vespers against County of Anjou, French rule, which put the daughter of Manfred of Sicily - Constance of Sicily, Queen of Aragon, Constance II and her husband Peter III of Aragon, a member of the House of Barcelona, on the throne. Their House of Barcelona, descendants ruled the Kingdom of Sicily until 1401. Following the Compromise of Caspe in 1412 the Sicilian throne passed to the Iberian Peninsula, Iberian monarchs from Crown of Aragon, Aragon and Crown of Castile, Castile.

In the 11th century, the mainland southern Italian powers were hiring Norman conquest of southern Italy, Norman mercenaries, who were Christians, Christian descendants of the Vikings; it was the Normans under Roger I of Sicily, Roger I (of the Hauteville dynasty) who conquered Sicily from the Muslims Battle of Cerami, over a period of thirty years until finally controlling the entire island by 1091 as the County of Sicily. In 1130, Roger II of Sicily, Roger II founded the Norman Kingdom of Sicily as an independent state with its own Sicilian Parliament, Parliament, language, schooling, army and currency, while the Sicilian culture evolved distinct traditions, clothing, linguistic changes, Sicilian cuisine, cuisine and customs not found in mainland Italy. A great number of families from Kingdom of Italy (Holy Roman Empire), northern Italy began settling in Sicily during this time, with some of their descendants forming distinct communities that survive to the present day, such as the Lombards of Sicily. Other migrants arrived from County of Apulia and Calabria, southern Italy, as well as Duchy of Normandy, Normandy County of Provence, southern France, England and other part of North Europe.

The Siculo-Norman rule of the Hauteville dynasty continued until 1198, when Frederick I of Sicily, Frederick II of Sicily, the son of a Siculo-Norman queen and a Hohenstaufen dynasty, Swabian-German emperor ascended the throne. In fact, it was during the reign of this Hohenstaufen king Frederick II, Holy Roman Emperor, Frederick II, that the poetic form known as a sonnet was invented by Giacomo da Lentini, the head Poet, Teacher and Notary of the Sicilian School, Sicilian School for Poetry. Frederick II was also responsible for the Muslim settlement of Lucera. His descendants governed Sicily until the Papal States, Papacy invited a Capetian dynasty, French prince to take the throne, which led to a decade-and-a-half of Kingdom of France, French rule under Charles I of Sicily; he was later deposed in the War of the Sicilian Vespers against County of Anjou, French rule, which put the daughter of Manfred of Sicily - Constance of Sicily, Queen of Aragon, Constance II and her husband Peter III of Aragon, a member of the House of Barcelona, on the throne. Their House of Barcelona, descendants ruled the Kingdom of Sicily until 1401. Following the Compromise of Caspe in 1412 the Sicilian throne passed to the Iberian Peninsula, Iberian monarchs from Crown of Aragon, Aragon and Crown of Castile, Castile.

Sicily has experienced the presence of a number of different cultures and ethnicities in its vast history, including the aboriginal peoples of differing Ethnolinguistic group, ethnolinguistic origins (

Sicily has experienced the presence of a number of different cultures and ethnicities in its vast history, including the aboriginal peoples of differing Ethnolinguistic group, ethnolinguistic origins (

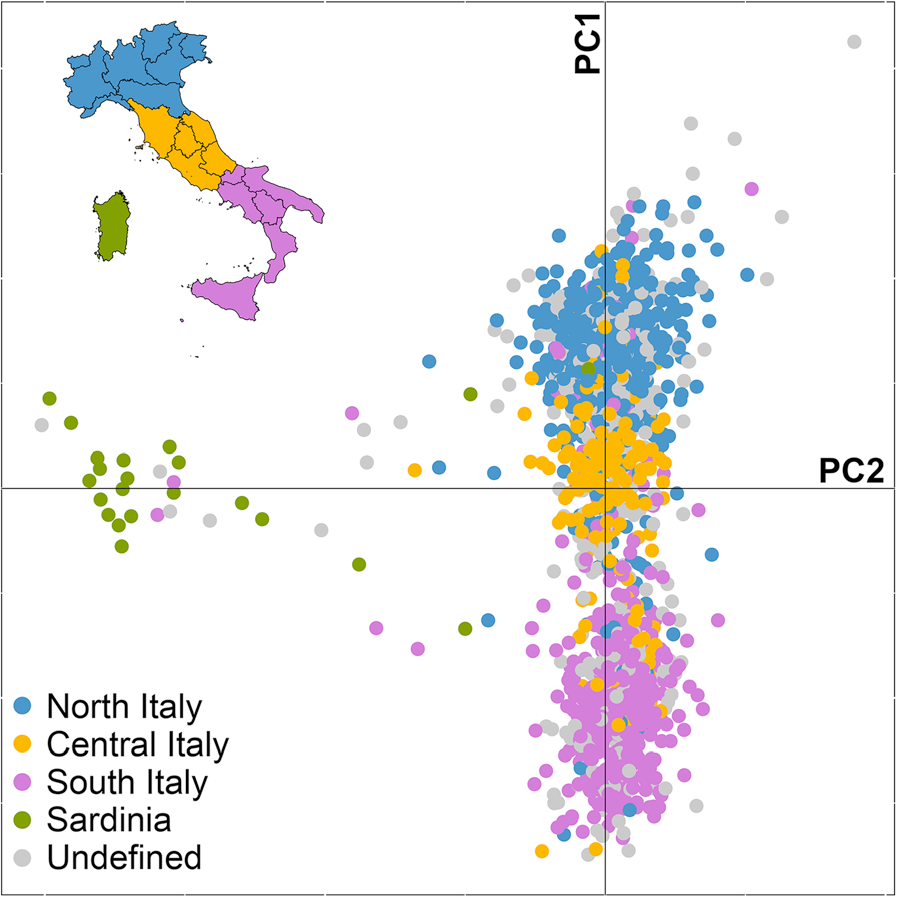

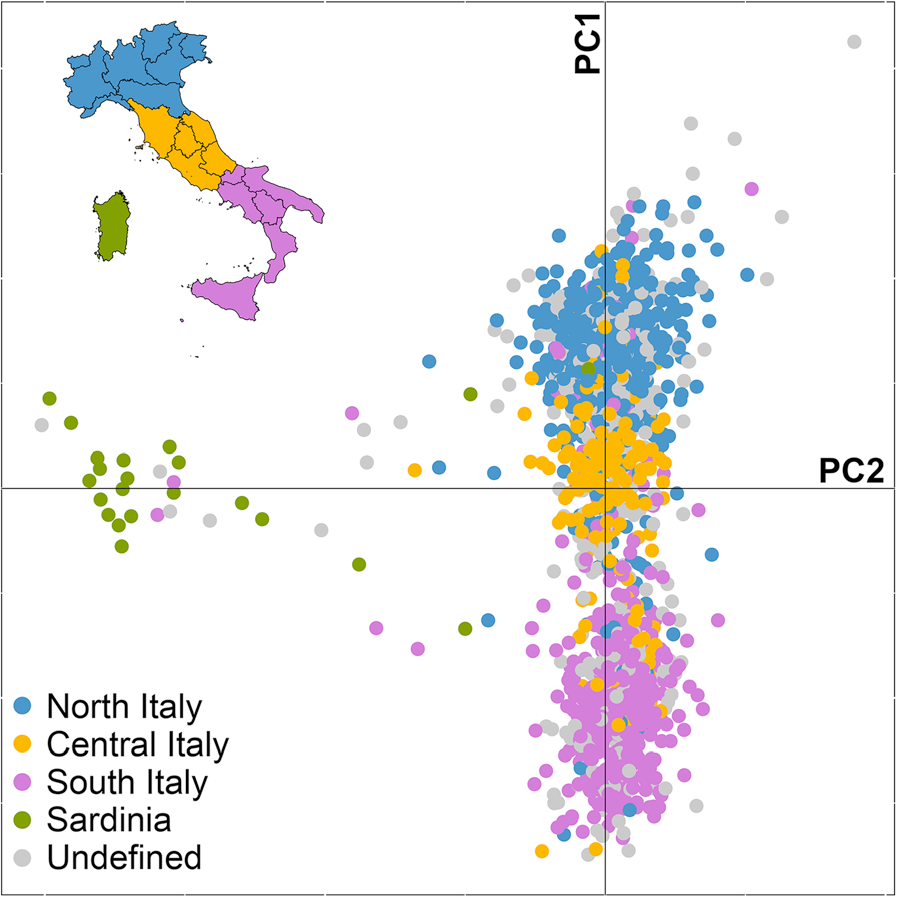

Several studies involving Genome-wide association study, whole genome analysis of mainland Italians and Sicilians have found that samples from Northern Italy,

Several studies involving Genome-wide association study, whole genome analysis of mainland Italians and Sicilians have found that samples from Northern Italy,

Today in Sicily most people are bilingual and speak both Italian and Sicilian language, Sicilian, a distinct and historical Romance languages, Romance language. Many Sicilian language, Sicilian words are of

Today in Sicily most people are bilingual and speak both Italian and Sicilian language, Sicilian, a distinct and historical Romance languages, Romance language. Many Sicilian language, Sicilian words are of

* The Arbëreshë people settled in Southern Italy in the 15th to 18th centuries in several waves of migrations. They are the descendants of mostly Tosk Albanian refugees of Christian faith who fled to Italy after the Albanian conquest and subsequent Islamisation by the Ottoman Empire, Ottoman Turks in the Balkans. They speak their own variant of the Arbëresh language. There are three identified Arbëreshë communities in the province of Palermo, which have maintained unchanged, with different aspects together, the ethnic, linguistic and religious origins. The areas are: Contessa Entellina, Piana degli Albanesi and Santa Cristina Gela; while the varieties of Piana and Santa Cristina Gela are similar enough to be entirely mutually intelligible, the variety of Contessa Entellina is not entirely intelligible. The largest centre is Piana degli Albanesi which, besides being the hub of Eparchy of Piana degli Albanesi, religious and socio-cultural communities, has guarded and defended their peculiarities intact over time. There are two other communities with a strong historical and linguistic heritage.

* The community of the Griko people, Greeks of Messina (or Siculo-Greeks) speaks modern Greek with some elements of the Ancient Greek, ancient Greek language spoken in the island, and Calabrian Greek. The Greek community was reconstituted in 2003 with the name of ''"Comunità Hellenica dello Stretto"'' (Hellenic Community of the Strait).

* The Arbëreshë people settled in Southern Italy in the 15th to 18th centuries in several waves of migrations. They are the descendants of mostly Tosk Albanian refugees of Christian faith who fled to Italy after the Albanian conquest and subsequent Islamisation by the Ottoman Empire, Ottoman Turks in the Balkans. They speak their own variant of the Arbëresh language. There are three identified Arbëreshë communities in the province of Palermo, which have maintained unchanged, with different aspects together, the ethnic, linguistic and religious origins. The areas are: Contessa Entellina, Piana degli Albanesi and Santa Cristina Gela; while the varieties of Piana and Santa Cristina Gela are similar enough to be entirely mutually intelligible, the variety of Contessa Entellina is not entirely intelligible. The largest centre is Piana degli Albanesi which, besides being the hub of Eparchy of Piana degli Albanesi, religious and socio-cultural communities, has guarded and defended their peculiarities intact over time. There are two other communities with a strong historical and linguistic heritage.

* The community of the Griko people, Greeks of Messina (or Siculo-Greeks) speaks modern Greek with some elements of the Ancient Greek, ancient Greek language spoken in the island, and Calabrian Greek. The Greek community was reconstituted in 2003 with the name of ''"Comunità Hellenica dello Stretto"'' (Hellenic Community of the Strait).

Historically, Sicily has been home to many religions, including Islam, Native religions, Judaism, Classical antiquity, Classical Paganism, Punic religion, Carthaginian religions, and Eastern Orthodox Church, Byzantine Orthodoxy, the coexistence of which has been historically seen as an ideal example of religious multiculturalism. Most Sicilians today are baptized as Catholic. Catholicism and Liturgical Latinization, Latinization in Sicily originated from the islands Norman occupiers and forced conversion continued under the Spanish invaders, where the majority of Sicily's population were forced to convert from their former religions. Despite the historical push for Catholicism in Sicily, a minority of other religious communities thrive in Sicily.

Sicilian Catholics

For Catholics in Sicily, the Hodegetria, Virgin Hodegetria is the patroness of Sicily. The Sicilian people are also known for their deep devotion to some Sicilian female saints: the martyrs Agatha of Sicily, Agatha and Saint Lucy, Lucy, who are the patron saints of Catania and Syracuse respectively, and the hermit Saint Rosalia, patroness of Palermo. Sicilian people have significantly contributed to the history of many religions. There have been four Sicilian Popes (Pope Agatho, Agatho, Pope Leo II, Leo II, Pope Sergius I, Sergius I, and Pope Stephen III, Stephen III) and a Sicilian Ecumenical Patriarch of Constantinople (Methodios I of Constantinople, Methodios I). Sicily is also mentioned in the New Testament in the ''Acts of the Apostles'', 28:11-13, in which Saint Paul briefly visits Sicily for three days before leaving the Island. It is believed he was the first Christian to ever set foot in Sicily.

Sicilian Muslims

During the Emirate of Sicily, period of Muslim rule, many Sicilians converted to Islam. Many Islamic scholars were born on the island, including Al-Maziri, a prominent jurist of the Maliki school of Sunni Islamic Law. Under the rule of Frederick II, Holy Roman Emperor, Frederick II, all Muslims were expelled from the Island following a rebellion of local Saracens who wished to keep their local independence in Western Sicily but were not allowed to due to Pope Gregory IX's demands. Any remaining Muslim was eventually expelled by the Spanish inquisition.

In more recent years, many immigrants from predominantly Muslim countries like Pakistan, Albania, Bangladesh, Morocco,

Historically, Sicily has been home to many religions, including Islam, Native religions, Judaism, Classical antiquity, Classical Paganism, Punic religion, Carthaginian religions, and Eastern Orthodox Church, Byzantine Orthodoxy, the coexistence of which has been historically seen as an ideal example of religious multiculturalism. Most Sicilians today are baptized as Catholic. Catholicism and Liturgical Latinization, Latinization in Sicily originated from the islands Norman occupiers and forced conversion continued under the Spanish invaders, where the majority of Sicily's population were forced to convert from their former religions. Despite the historical push for Catholicism in Sicily, a minority of other religious communities thrive in Sicily.

Sicilian Catholics

For Catholics in Sicily, the Hodegetria, Virgin Hodegetria is the patroness of Sicily. The Sicilian people are also known for their deep devotion to some Sicilian female saints: the martyrs Agatha of Sicily, Agatha and Saint Lucy, Lucy, who are the patron saints of Catania and Syracuse respectively, and the hermit Saint Rosalia, patroness of Palermo. Sicilian people have significantly contributed to the history of many religions. There have been four Sicilian Popes (Pope Agatho, Agatho, Pope Leo II, Leo II, Pope Sergius I, Sergius I, and Pope Stephen III, Stephen III) and a Sicilian Ecumenical Patriarch of Constantinople (Methodios I of Constantinople, Methodios I). Sicily is also mentioned in the New Testament in the ''Acts of the Apostles'', 28:11-13, in which Saint Paul briefly visits Sicily for three days before leaving the Island. It is believed he was the first Christian to ever set foot in Sicily.

Sicilian Muslims

During the Emirate of Sicily, period of Muslim rule, many Sicilians converted to Islam. Many Islamic scholars were born on the island, including Al-Maziri, a prominent jurist of the Maliki school of Sunni Islamic Law. Under the rule of Frederick II, Holy Roman Emperor, Frederick II, all Muslims were expelled from the Island following a rebellion of local Saracens who wished to keep their local independence in Western Sicily but were not allowed to due to Pope Gregory IX's demands. Any remaining Muslim was eventually expelled by the Spanish inquisition.

In more recent years, many immigrants from predominantly Muslim countries like Pakistan, Albania, Bangladesh, Morocco,

File:Bruno, Giuseppe (1836-1904) - Ragazzo siciliano - Da Artnet.jpg, Sicilian youth in traditional attire, 1890s

File:Crupi, Giovanni (1849-1925) - n. 0630 - Carretto siciliano - Ackland art museum.jpg, Sicilian cart, 1899

File:Sicilian monk (39322503152).jpg, A Sicilian monk

File:Bruno, Giuseppe (1836-1904) - n. 017 - Vecchio popolano - ebay.jpg, Old man from Sicily, 1890s

mercenaries

A mercenary, sometimes also known as a soldier of fortune or hired gun, is a private individual, particularly a soldier, that joins a military conflict for personal profit, is otherwise an outsider to the conflict, and is not a member of any o ...

from Campania

Campania (, also , , , ) is an administrative Regions of Italy, region of Italy; most of it is in the south-western portion of the Italian peninsula (with the Tyrrhenian Sea to its west), but it also includes the small Phlegraean Islands and the i ...

, when the city-states of Messina

Messina (, also , ) is a harbour city and the capital of the Italian Metropolitan City of Messina. It is the third largest city on the island of Sicily, and the 13th largest city in Italy, with a population of more than 219,000 inhabitants in ...

( Carthaginian-owned) and Syracuse ( Dorian-owned) were being constantly raided and pillaged by Mamertines

The Mamertines ( la, Mamertini, "sons of Mars", el, Μαμερτῖνοι) were mercenaries of Italian origin who had been hired from their home in Campania by Agathocles (361–289 BC), Tyrant of Syracuse and self-proclaimed King of Sicily. ...

, during the period (282-240 BC) when Central, Western and Northeast Sicily were put under Carthaginian rule, motivated the intervention of the Roman Republic

The Roman Republic ( la, Res publica Romana ) was a form of government of Rome and the era of the classical Roman civilization when it was run through public representation of the Roman people. Beginning with the overthrow of the Roman Kin ...

into Sicilian affairs, and led to the First Punic War

The First Punic War (264–241 BC) was the first of three wars fought between Rome and Carthage, the two main powers of the western Mediterranean in the early 3rd century BC. For 23 years, in the longest continuous conflict and grea ...

between Rome

, established_title = Founded

, established_date = 753 BC

, founder = King Romulus (legendary)

, image_map = Map of comune of Rome (metropolitan city of Capital Rome, region Lazio, Italy).svg

, map_caption ...

and Carthage

Carthage was the capital city of Ancient Carthage, on the eastern side of the Lake of Tunis in what is now Tunisia. Carthage was one of the most important trading hubs of the Ancient Mediterranean and one of the most affluent cities of the classi ...

. By the end of the war

War is an intense armed conflict between states, governments, societies, or paramilitary groups such as mercenaries, insurgents, and militias. It is generally characterized by extreme violence, destruction, and mortality, using regular o ...

in 242 BC, and with the death of Hiero II

Hiero II ( el, Ἱέρων Β΄; c. 308 BC – 215 BC) was the Greek tyrant of Syracuse from 275 to 215 BC, and the illegitimate son of a Syracusan noble, Hierocles, who claimed descent from Gelon. He was a former general of Pyrrhus of Epirus a ...

, all of Sicily except Syracuse was in Roman hands, becoming Rome's first province outside of the Italian peninsula. For the next 600 years, Sicily would be a province of the Roman Republic and later Empire

An empire is a "political unit" made up of several territories and peoples, "usually created by conquest, and divided between a dominant center and subordinate peripheries". The center of the empire (sometimes referred to as the metropole) ex ...

. Prior to Roman rule, there were three native Elymian

The Elymians ( grc-gre, Ἔλυμοι, ''Élymoi''; Latin: ''Elymi'') were an ancient tribal people who inhabited the western part of Sicily during the Bronze Age and Classical antiquity.

Origins

According to Hellanicus of Lesbos, the Elymians ...

towns by the names of Segesta

Segesta ( grc-gre, Ἔγεστα, ''Egesta'', or , ''Ségesta'', or , ''Aígesta''; scn, Siggésta) was one of the major cities of the Elymians, one of the three indigenous peoples of Sicily. The other major cities of the Elymians were Eryx a ...

, Eryx

Eryx is a French short-range portable semi-automatic command to line of sight (SACLOS) based wire-guided anti-tank missile (ATGM) manufactured by MBDA France and by MKEK under licence. The weapon can also be used against larger bunkers and smal ...

and Entella, as well as several Siculian

Siculian (or Sicel) is an extinct Indo-European language spoken in central and eastern Sicily by the Sicels. It is attested in less than thirty inscriptions from the late 6th century to 4th century BCE, and in around twenty-five glosses from ancie ...

towns called Agyrion, Kale Akte (founded by the Sicel leader Ducetius

Ducetius ( grc, Δουκέτιος) (died 440 BCE) was a Hellenized leader of the Sicels and founder of a united Sicilian state and numerous cities.LiviusDucetius of Sicily Retrieved on 25 April 2006. It is thought he may have been born around th ...

), Enna

Enna ( or ; grc, Ἔννα; la, Henna, less frequently ), known from the Middle Ages until 1926 as Castrogiovanni ( scn, Castrugiuvanni ), is a city and located roughly at the center of Sicily, southern Italy, in the province of Enna, towering ...

and Pantalica

The Necropolis of Pantalica is a collection of cemeteries with rock-cut chamber tombs in southeast Sicily, Italy. Dating from the 13th to the 7th centuries BC, there was thought to be over 5,000 tombs, although the most recent estimate suggests a ...

, and one Sicani

The Sicani (Ancient Greek Σῐκᾱνοί ''Sikānoí'') or Sicanians were one of three ancient peoples of Sicily present at the time of Phoenician and Greek colonization. The Sicani dwelt east of the Elymians and west of the Sicels, having, ac ...

an town known as Thapsos

Thapsos ( el, Θάψος) was a prehistoric village in Sicily of the middle Bronze Age. It was found by the Italian archaeologist Paolo Orsi on the small peninsula of Magnisi, near Priolo Gargallo. In its vicinity was born the Thapsos culture ...

. (Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

: Θάψος)

Sometime after Carthage conquered most of Sicily except for the Southeast which was still controlled by Syracuse, Pyrrhus of Epirus

Pyrrhus (; grc-gre, Πύρρος ; 319/318–272 BC) was a Greek king and statesman of the Hellenistic period.Plutarch. ''Parallel Lives'',Pyrrhus... He was king of the Greek tribe of Molossians, of the royal Aeacid house, and later he becam ...

, the Molossian

The Molossians () were a group of ancient Greek tribes which inhabited the region of Epirus in classical antiquity. Together with the Chaonians and the Thesprotians, they formed the main tribal groupings of the northwestern Greek group. On thei ...

king of Epirus

sq, Epiri rup, Epiru

, native_name_lang =

, settlement_type = Historical region