A steamboat is a boat that is

propelled primarily by

steam power

A steam engine is a heat engine that performs mechanical work using steam as its working fluid. The steam engine uses the force produced by steam pressure to push a piston back and forth inside a cylinder. This pushing force can be trans ...

, typically driving propellers or

paddlewheel

A paddle wheel is a form of waterwheel or impeller in which a number of paddles are set around the periphery of the wheel. It has several uses, of which some are:

* Very low-lift water pumping, such as flooding paddy fields at no more than about ...

s. Steamboats sometimes use the

prefix designation SS, S.S. or S/S (for 'Screw Steamer') or PS (for 'Paddle Steamer'); however, these designations are most often used for

steamship

A steamship, often referred to as a steamer, is a type of steam-powered vessel, typically ocean-faring and seaworthy, that is propelled by one or more steam engines that typically move (turn) propellers or paddlewheels. The first steamships ...

s.

The term ''steamboat'' is used to refer to smaller, insular, steam-powered boats working on lakes and rivers, particularly

riverboat

A riverboat is a watercraft designed for inland navigation on lakes, rivers, and artificial waterways. They are generally equipped and outfitted as work boats in one of the carrying trades, for freight or people transport, including luxury un ...

s. As using steam became more reliable, steam power became applied to larger, ocean-going vessels.

Background

Limitations of the Newcomen steam engine

Early steamboat designs used

Newcomen steam engines. These engines were large, heavy, and produced little power, which resulted in an unfavorable power-to-weight ratio. The Newcomen engine also produced a reciprocating or rocking motion because it was designed for pumping. The piston stroke was caused by a water jet in the steam-filled cylinder, which condensed the steam, creating a vacuum, which in turn caused atmospheric pressure to drive the piston downward. The piston relied on the weight of the rod connecting to the underground pump to return the piston to the top of the cylinder. The heavy weight of the Newcomen engine required a structurally strong boat, and the reciprocating motion of the engine beam required a complicated mechanism to produce propulsion.

Rotary motion engines

James Watt

James Watt (; 30 January 1736 (19 January 1736 OS) – 25 August 1819) was a Scottish inventor, mechanical engineer, and chemist who improved on Thomas Newcomen's 1712 Newcomen steam engine with his Watt steam engine in 1776, which was fun ...

's design improvements increased the efficiency of the steam engine, improving the power-to-weight ratio, and created an engine capable of rotary motion by using a double-acting cylinder which injected steam at each end of the piston stroke to move the piston back and forth. The rotary steam engine simplified the mechanism required to turn a paddle wheel to propel a boat. Despite the improved efficiency and rotary motion, the power-to-weight ratio of

Boulton and Watt

Boulton & Watt was an early British engineering and manufacturing firm in the business of designing and making marine and stationary steam engines. Founded in the English West Midlands around Birmingham in 1775 as a partnership between the Engli ...

steam engine was still low.

High-pressure steam engines

The high-pressure steam engine was the development that made the steamboat practical. It had a high power-to-weight ratio and was fuel efficient. High pressure engines were made possible by improvements in the design of boilers and engine components so that they could withstand internal pressure, although boiler explosions were common due to lack of instrumentation like pressure gauges.

Attempts at making high-pressure engines had to wait until the expiration of the

Boulton and Watt

Boulton & Watt was an early British engineering and manufacturing firm in the business of designing and making marine and stationary steam engines. Founded in the English West Midlands around Birmingham in 1775 as a partnership between the Engli ...

patent in 1800. Shortly thereafter high-pressure engines by

Richard Trevithick

Richard Trevithick (13 April 1771 – 22 April 1833) was a British inventor and mining engineer. The son of a mining captain, and born in the mining heartland of Cornwall, Trevithick was immersed in mining and engineering from an early age. He w ...

and

Oliver Evans

Oliver Evans (September 13, 1755 – April 15, 1819) was an American inventor, engineer and businessman born in rural Delaware and later rooted commercially in Philadelphia. He was one of the first Americans building steam engines and an advoca ...

were introduced.

Compound or multiple expansion steam engines

The

compound steam engine

A compound steam engine unit is a type of steam engine where steam is expanded in two or more stages.

A typical arrangement for a compound engine is that the steam is first expanded in a high-pressure ''(HP)'' cylinder, then having given up he ...

became widespread in the late 19th century. Compounding uses exhaust steam from a high pressure cylinder to a lower pressure cylinder and greatly improves efficiency. With compound engines it was possible for trans ocean steamers to carry less coal than freight.

Compound steam engine powered ships enabled a great increase in international trade.

Steam turbines

The most efficient steam engine used for

marine propulsion

Marine propulsion is the mechanism or system used to generate thrust to move a watercraft through water. While paddles and sails are still used on some smaller boats, most modern ships are propelled by mechanical systems consisting of an electr ...

is the

steam turbine

A steam turbine is a machine that extracts thermal energy from pressurized steam and uses it to do mechanical work on a rotating output shaft. Its modern manifestation was invented by Charles Parsons in 1884. Fabrication of a modern steam turbin ...

. It was developed near the end of the 19th century and was used throughout the 20th century.

History

Early designs

An apocryphal story from 1851 attributes the earliest steamboat to

Denis Papin

Denis Papin FRS (; 22 August 1647 – 26 August 1713) was a French physicist, mathematician and inventor, best known for his pioneering invention of the steam digester, the forerunner of the pressure cooker and of the steam engine.

Early lif ...

for a boat he built in 1705. Papin was an early innovator in steam power and the inventor of the

steam digester

The steam digester or bone digester (also known as Papin’s digester) is a high-pressure cooker invented by French physicist Denis Papin in 1679. It is a device for extracting fats from bones in a high-pressure steam environment, which also rend ...

, the first

pressure cooker

Pressure cooking is the process of cooking food under high pressure steam and water or a water-based cooking liquid, in a sealed vessel known as a ''pressure cooker''. High pressure limits boiling, and creates higher cooking temperatures which c ...

, which played an important role in

James Watt

James Watt (; 30 January 1736 (19 January 1736 OS) – 25 August 1819) was a Scottish inventor, mechanical engineer, and chemist who improved on Thomas Newcomen's 1712 Newcomen steam engine with his Watt steam engine in 1776, which was fun ...

's steam experiments. However, Papin's boat was not steam-powered but powered by hand-cranked paddles.

A steamboat was described and patented by English physician John Allen in 1729. In 1736,

Jonathan Hulls

Jonathan Hulls or Hull (baptised 1699 – 1758) was an English inventor, a pioneer of steam navigation. Traditionally, he was recognised as the first person to make practical experiments with steam to propel a vessel; but evidence to substantiate ...

was granted a patent in England for a

Newcomen engine-powered steamboat (using a pulley instead of a beam, and a pawl and ratchet to obtain rotary motion), but it was the improvement in steam engines by

James Watt

James Watt (; 30 January 1736 (19 January 1736 OS) – 25 August 1819) was a Scottish inventor, mechanical engineer, and chemist who improved on Thomas Newcomen's 1712 Newcomen steam engine with his Watt steam engine in 1776, which was fun ...

that made the concept feasible.

William Henry of Lancaster,

Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania (; ( Pennsylvania Dutch: )), officially the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, is a state spanning the Mid-Atlantic, Northeastern, Appalachian, and Great Lakes regions of the United States. It borders Delaware to its southeast, ...

, having learned of Watt's engine on a visit to England, made his own engine, and put it in a boat. The boat sank, and while Henry made an improved model, he did not appear to have much success, though he may have inspired others.

[ Jordan, 1910, pp. 49–50]

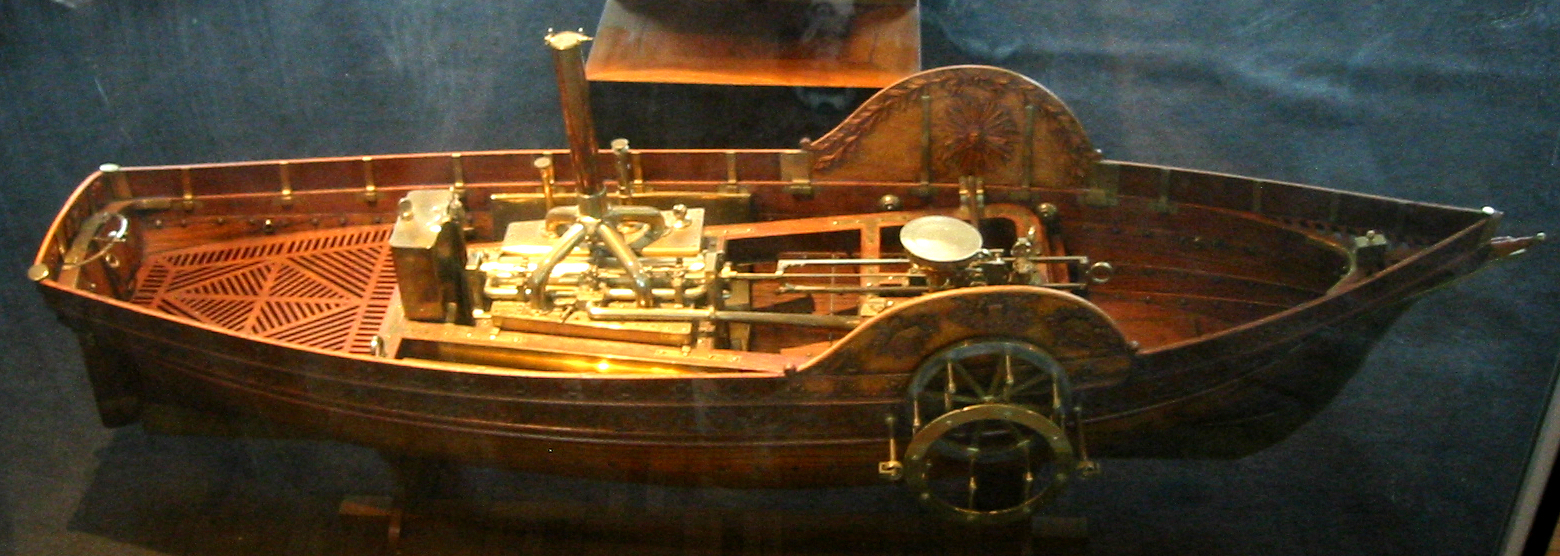

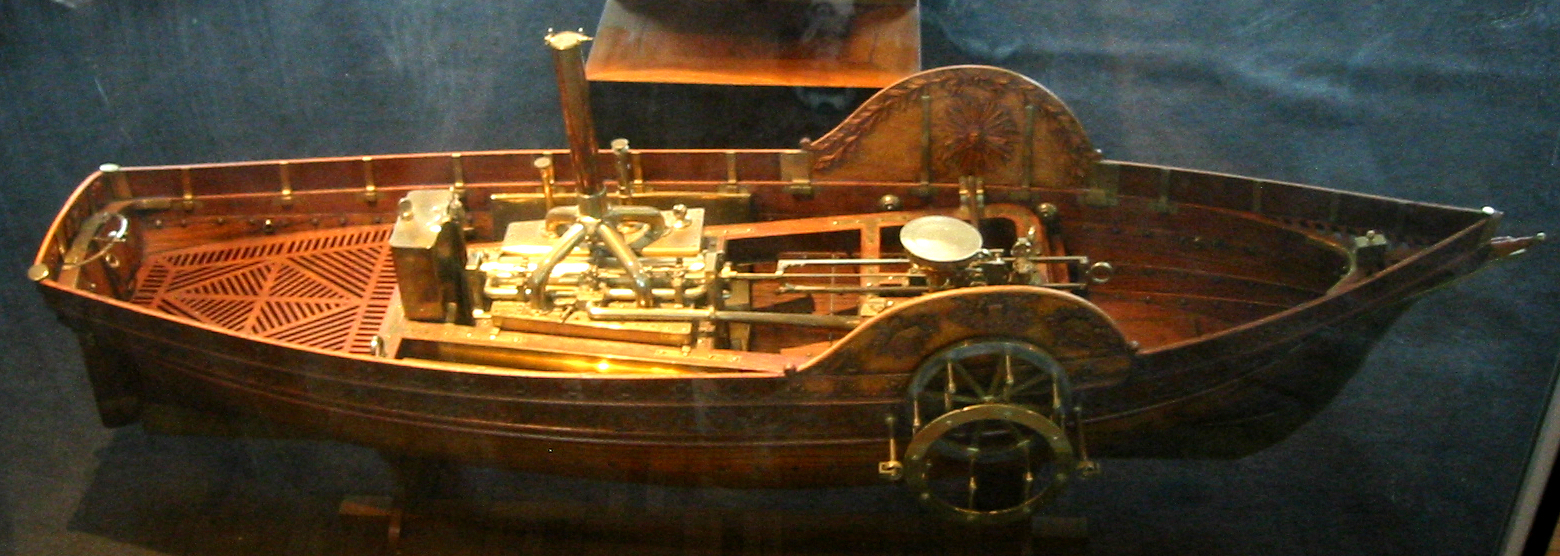

The first steam-powered ship ''

Pyroscaphe

''Pyroscaphe'' was an early experimental steamship built by Marquis de Jouffroy d'Abbans in 1783. The first demonstration took place on 15 July 1783 on the river Saône in France. After the first demonstration, it was said that the hull had open ...

'' was a paddle steamer powered by a

Newcomen steam engine

The atmospheric engine was invented by Thomas Newcomen in 1712, and is often referred to as the Newcomen fire engine (see below) or simply as a Newcomen engine. The engine was operated by condensing steam drawn into the cylinder, thereby creati ...

; it was built in France in 1783 by Marquis

Claude de Jouffroy Claude may refer to:

__NOTOC__ People and fictional characters

* Claude (given name), a list of people and fictional characters

* Claude (surname), a list of people

* Claude Lorrain (c. 1600–1682), French landscape painter, draughtsman and etcher ...

and his colleagues as an improvement of an earlier attempt, the 1776 ''Palmipède''. At its first demonstration on 15 July 1783, ''Pyroscaphe'' travelled upstream on the river

Saône

The Saône ( , ; frp, Sona; lat, Arar) is a river in eastern France. It is a right tributary of the Rhône, rising at Vioménil in the Vosges department and joining the Rhône in Lyon, at the southern end of the Presqu'île.

The name deri ...

for some fifteen minutes before the engine failed. Presumably this was easily repaired as the boat is said to have made several such journeys. Following this, De Jouffroy attempted to get the government interested in his work, but for political reasons was instructed that he would have to build another version on the Seine in Paris. De Jouffroy did not have the funds for this, and, following the events of the French revolution, work on the project was discontinued after he left the country.

Similar boats were made in 1785 by

John Fitch in

Philadelphia

Philadelphia, often called Philly, is the largest city in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, the sixth-largest city in the U.S., the second-largest city in both the Northeast megalopolis and Mid-Atlantic regions after New York City. Sinc ...

and

William Symington

William Symington (1764–1831) was a Scottish engineer and inventor, and the builder of the first practical steamboat, the Charlotte Dundas.

Early life

Symington was born in Leadhills, South Lanarkshire, Scotland, to a family he described as ...

in

Dumfries

Dumfries ( ; sco, Dumfries; from gd, Dùn Phris ) is a market town and former royal burgh within the Dumfries and Galloway council area of Scotland. It is located near the mouth of the River Nith into the Solway Firth about by road from the ...

, Scotland. Fitch successfully trialled his boat in 1787, and in 1788, he began operating a regular commercial service along the

Delaware River

The Delaware River is a major river in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic region of the United States. From the meeting of its branches in Hancock (village), New York, Hancock, New York, the river flows for along the borders of N ...

between Philadelphia and Burlington, New Jersey, carrying as many as 30 passengers. This boat could typically make and travelled more than during its short length of service. The Fitch steamboat was not a commercial success, as this travel route was adequately covered by relatively good wagon roads. The following year, a second boat made excursions, and in 1790, a third boat ran a series of trials on the

Delaware River

The Delaware River is a major river in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic region of the United States. From the meeting of its branches in Hancock (village), New York, Hancock, New York, the river flows for along the borders of N ...

before patent disputes dissuaded Fitch from continuing.

[

Meanwhile, ]Patrick Miller of Dalswinton

Patrick Miller of Dalswinton, just north of Dumfries (1731–1815) was a Scottish banker, shareholder in the Carron Company engineering works and inventor. Miller is buried in a tomb against the southern wall of Greyfriars Kirkyard in Edinbur ...

, near Dumfries

Dumfries ( ; sco, Dumfries; from gd, Dùn Phris ) is a market town and former royal burgh within the Dumfries and Galloway council area of Scotland. It is located near the mouth of the River Nith into the Solway Firth about by road from the ...

, Scotland

Scotland (, ) is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. Covering the northern third of the island of Great Britain, mainland Scotland has a border with England to the southeast and is otherwise surrounded by the Atlantic Ocean to the ...

, had developed double-hulled boats propelled by manually cranked paddle wheels placed between the hulls, even attempting to interest various European governments in a giant warship version, long. Miller sent King Gustav III

Gustav III (29 March 1792), also called ''Gustavus III'', was King of Sweden from 1771 until his assassination in 1792. He was the eldest son of Adolf Frederick of Sweden and Queen Louisa Ulrika of Prussia.

Gustav was a vocal opponent of what ...

of Sweden an actual small-scale version, long, called ''Experiment''. Miller then engaged engineer William Symington

William Symington (1764–1831) was a Scottish engineer and inventor, and the builder of the first practical steamboat, the Charlotte Dundas.

Early life

Symington was born in Leadhills, South Lanarkshire, Scotland, to a family he described as ...

to build his patent steam engine that drove a stern-mounted paddle wheel in a boat in 1785. The boat was successfully tried out on Dalswinton Loch in 1788 and was followed by a larger steamboat the next year. Miller then abandoned the project.

19th century

The failed project of Patrick Miller caught the attention of Lord Dundas, Governor of the

The failed project of Patrick Miller caught the attention of Lord Dundas, Governor of the Forth and Clyde Canal

The Forth and Clyde Canal is a canal opened in 1790, crossing central Scotland; it provided a route for the seagoing vessels of the day between the Firth of Forth and the Firth of Clyde at the narrowest part of the Scottish Lowlands. This allo ...

Company, and at a meeting with the canal company's directors on 5 June 1800, they approved his proposals for the use of ''"a model of a boat by Captain Schank to be worked by a steam engine by Mr Symington"'' on the canal.

The boat was built by Alexander Hart at Grangemouth

Grangemouth ( sco, Grangemooth; gd, Inbhir Ghrainnse, ) is a town in the Falkirk council area, Scotland. Historically part of the county of Stirlingshire, the town lies in the Forth Valley, on the banks of the Firth of Forth, east of Falkirk ...

to Symington's design with a vertical cylinder engine and crosshead transmitting power to a crank driving the paddlewheels. Trials on the River Carron in June 1801 were successful and included towing sloop

A sloop is a sailboat with a single mast typically having only one headsail in front of the mast and one mainsail aft of (behind) the mast. Such an arrangement is called a fore-and-aft rig, and can be rigged as a Bermuda rig with triangular sa ...

s from the river Forth

The River Forth is a major river in central Scotland, long, which drains into the North Sea on the east coast of the country. Its drainage basin covers much of Stirlingshire in Scotland's Central Belt. The Gaelic name for the upper reach of th ...

up the Carron and thence along the Forth and Clyde Canal

The Forth and Clyde Canal is a canal opened in 1790, crossing central Scotland; it provided a route for the seagoing vessels of the day between the Firth of Forth and the Firth of Clyde at the narrowest part of the Scottish Lowlands. This allo ...

.

In 1801, Symington patented a horizontal steam engine directly linked to a crank. He got support from Lord Dundas to build a second steamboat, which became famous as the ''Charlotte Dundas

''Charlotte Dundas'' is regarded as the world's second successful steamboat, the first towing steamboat and the boat that demonstrated the practicality of steam power for ships.Fry, p. 27.

Early experiments

Development of experimental steam engi ...

'', named in honour of Lord Dundas's daughter. Symington designed a new hull around his powerful horizontal engine, with the crank driving a large paddle wheel in a central upstand in the hull, aimed at avoiding damage to the canal banks.

The new boat was 56 ft (17.1 m) long, 18 ft (5.5 m) wide and 8 ft (2.4 m) depth, with a wooden hull. The boat was built by John Allan and the engine by the Carron Company

The Carron Company was an ironworks established in 1759 on the banks of the River Carron near Falkirk, in Stirlingshire, Scotland. After initial problems, the company was at the forefront of the Industrial Revolution in the United Kingdom. ...

.

The first sailing was on the canal in Glasgow

Glasgow ( ; sco, Glesca or ; gd, Glaschu ) is the most populous city in Scotland and the fourth-most populous city in the United Kingdom, as well as being the 27th largest city by population in Europe. In 2020, it had an estimated popul ...

on 4 January 1803, with Lord Dundas and a few of his relatives and friends on board. The crowd were pleased with what they saw, but Symington wanted to make improvements and another more ambitious trial was made on 28 March. On this occasion, the ''Charlotte Dundas'' towed two 70 ton barges 30 km (almost 20 miles) along the Forth and Clyde Canal

The Forth and Clyde Canal is a canal opened in 1790, crossing central Scotland; it provided a route for the seagoing vessels of the day between the Firth of Forth and the Firth of Clyde at the narrowest part of the Scottish Lowlands. This allo ...

to Glasgow

Glasgow ( ; sco, Glesca or ; gd, Glaschu ) is the most populous city in Scotland and the fourth-most populous city in the United Kingdom, as well as being the 27th largest city by population in Europe. In 2020, it had an estimated popul ...

, and despite "a strong breeze right ahead" that stopped all other canal boats it took only nine and a quarter hours, giving an average speed of about 3 km/h (2 mph). The ''Charlotte Dundas'' was the first practical steamboat, in that it demonstrated the practicality of steam power for ships, and was the first to be followed by continuous development of steamboats.

The American,

The American, Robert Fulton

Robert Fulton (November 14, 1765 – February 24, 1815) was an American engineer and inventor who is widely credited with developing the world's first commercially successful steamboat, the (also known as ''Clermont''). In 1807, that steamboat ...

, was present at the trials of the ''Charlotte Dundas'' and was intrigued by the potential of the steamboat. While working in France, he corresponded with and was helped by the Scottish engineer Henry Bell, who may have given him the first model of his working steamboat. He designed his own steamboat, which sailed along the River Seine

)

, mouth_location = Le Havre/Honfleur

, mouth_coordinates =

, mouth_elevation =

, progression =

, river_system = Seine basin

, basin_size =

, tributaries_left = Yonne, Loing, Eure, Risle

, tributarie ...

in 1803.

He later obtained a Boulton and Watt

Boulton & Watt was an early British engineering and manufacturing firm in the business of designing and making marine and stationary steam engines. Founded in the English West Midlands around Birmingham in 1775 as a partnership between the Engli ...

steam engine, shipped to America, where his first proper steamship was built in 1807, ''North River Steamboat

The ''North River Steamboat'' or ''North River'', colloquially known as the ''Clermont'', is widely regarded as the world's first vessel to demonstrate the viability of using steam propulsion for commercial water transportation. Built in 1807, ...

'' (later known as ''Clermont''), which carried passengers between New York City and Albany, New York

Albany ( ) is the capital of the U.S. state of New York, also the seat and largest city of Albany County. Albany is on the west bank of the Hudson River, about south of its confluence with the Mohawk River, and about north of New York City ...

. ''Clermont'' was able to make the trip in 32 hours. The steamboat was powered by a Boulton and Watt

Boulton & Watt was an early British engineering and manufacturing firm in the business of designing and making marine and stationary steam engines. Founded in the English West Midlands around Birmingham in 1775 as a partnership between the Engli ...

engine and was capable of long-distance travel. It was the first commercially successful steamboat, transporting passengers along the Hudson River

The Hudson River is a river that flows from north to south primarily through eastern New York. It originates in the Adirondack Mountains of Upstate New York and flows southward through the Hudson Valley to the New York Harbor between N ...

.

In 1807 Robert L. Stevens began operation of the ''Phoenix

Phoenix most often refers to:

* Phoenix (mythology), a legendary bird from ancient Greek folklore

* Phoenix, Arizona, a city in the United States

Phoenix may also refer to:

Mythology

Greek mythological figures

* Phoenix (son of Amyntor), a ...

'', which used a high-pressure engine in combination with a low-pressure condensing engine. The first steamboats powered only by high pressure were the ''Aetna'' and ''Pennsylvania'', designed and built by Oliver Evans

Oliver Evans (September 13, 1755 – April 15, 1819) was an American inventor, engineer and businessman born in rural Delaware and later rooted commercially in Philadelphia. He was one of the first Americans building steam engines and an advoca ...

.

In October 1811 a ship designed by John Stevens, ''Little Juliana'', would operate as the first steam-powered ferry between Hoboken

Hoboken ( ; Unami: ') is a city in Hudson County in the U.S. state of New Jersey. As of the 2020 U.S. census, the city's population was 60,417. The Census Bureau's Population Estimates Program calculated that the city's population was 58,69 ...

and New York City. Stevens' ship was engineered as a twin-screw-driven steamboat in juxtaposition to ''Clermont''s Boulton and Watt engine.River Clyde

The River Clyde ( gd, Abhainn Chluaidh, , sco, Clyde Watter, or ) is a river that flows into the Firth of Clyde in Scotland. It is the ninth-longest river in the United Kingdom, and the third-longest in Scotland. It runs through the major cit ...

in Scotland.Naples

Naples (; it, Napoli ; nap, Napule ), from grc, Νεάπολις, Neápolis, lit=new city. is the regional capital of Campania and the third-largest city of Italy, after Rome and Milan, with a population of 909,048 within the city's adminis ...

, where it had been built.

Ocean-going

The first sea-going steamboat was Richard Wright's first steamboat "Experiment", an ex-French

The first sea-going steamboat was Richard Wright's first steamboat "Experiment", an ex-French lugger

A lugger is a sailing vessel defined by its rig, using the lug sail on all of its one or several masts. They were widely used as working craft, particularly off the coasts of France, England, Ireland and Scotland. Luggers varied extensively i ...

; she steamed from Leeds

Leeds () is a city and the administrative centre of the City of Leeds district in West Yorkshire, England. It is built around the River Aire and is in the eastern foothills of the Pennines. It is also the third-largest settlement (by populati ...

to Yarmouth

Yarmouth may refer to:

Places Canada

*Yarmouth County, Nova Scotia

**Yarmouth, Nova Scotia

**Municipality of the District of Yarmouth

**Yarmouth (provincial electoral district)

**Yarmouth (electoral district)

* Yarmouth Township, Ontario

*New ...

, arriving Yarmouth 19 July 1813. "Tug", the first tugboat, was launched by the Woods Brothers, Port Glasgow, on 5 November 1817; in the summer of 1818 she was the first steamboat to travel round the North of Scotland to the East Coast.

Steamships required carrying fuel (coal) at the expense of the regular payload. For this reason for some time sailships remained more economically viable for long voyages. However, as the steam engine technology improved, more power could be generated by the same quantity of fuel and longer distances could be traveled. A steamship built in 1855 required about 40% of its available cargo space to store enough coal to cross the Atlantic, but by the 1860s, transatlantic steamship services became cost-effective and steamships began to dominate these routes. By the 1870s, particularly in conjunction with the opening of the Suez Canal

The Suez Canal ( arz, قَنَاةُ ٱلسُّوَيْسِ, ') is an artificial sea-level waterway in Egypt, connecting the Mediterranean Sea to the Red Sea through the Isthmus of Suez and dividing Africa and Asia. The long canal is a popular ...

in 1869, South Asia became economically accessible for steamships from Europe. By the 1890s, the steamship technology so improved that steamships became economically viable even on long-distance voyages such as linking Great Britain with its Pacific Asian colonies, such as Singapore

Singapore (), officially the Republic of Singapore, is a sovereign island country and city-state in maritime Southeast Asia. It lies about one degree of latitude () north of the equator, off the southern tip of the Malay Peninsula, borde ...

and Hong Kong

Hong Kong ( (US) or (UK); , ), officially the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region of the People's Republic of China ( abbr. Hong Kong SAR or HKSAR), is a city and special administrative region of China on the eastern Pearl River Delt ...

. This resulted in the downfall of sailing.

Use by country

United States

Origins

The era of the steamboat in the United States began in Philadelphia

Philadelphia, often called Philly, is the largest city in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, the sixth-largest city in the U.S., the second-largest city in both the Northeast megalopolis and Mid-Atlantic regions after New York City. Sinc ...

in 1787 when John Fitch (1743–1798) made the first successful trial of a 45-foot (14-meter) steamboat on the Delaware River

The Delaware River is a major river in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic region of the United States. From the meeting of its branches in Hancock (village), New York, Hancock, New York, the river flows for along the borders of N ...

on 22 August 1787, in the presence of members of the United States Constitutional Convention

The Constitutional Convention took place in Philadelphia from May 25 to September 17, 1787. Although the convention was intended to revise the league of states and first system of government under the Articles of Confederation, the intention fr ...

. Fitch later (1790) built a larger vessel that carried passengers and freight between Philadelphia and Burlington, New Jersey

Burlington is a city in Burlington County, in the U.S. state of New Jersey. It is a suburb of Philadelphia. As of the 2020 United States census, the city's population was 9,743.

Burlington was first incorporated on October 24, 1693, and was r ...

on the Delaware. His steamboat was not a financial success and was shut down after a few months service, however this marks the first use of marine steam propulsion in scheduled regular passenger transport service.

Oliver Evans

Oliver Evans (September 13, 1755 – April 15, 1819) was an American inventor, engineer and businessman born in rural Delaware and later rooted commercially in Philadelphia. He was one of the first Americans building steam engines and an advoca ...

(1755–1819) was a Philadelphia

Philadelphia, often called Philly, is the largest city in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, the sixth-largest city in the U.S., the second-largest city in both the Northeast megalopolis and Mid-Atlantic regions after New York City. Sinc ...

n inventor born in Newport, Delaware

Newport is a town in New Castle County, Delaware, United States. It is on the Christina River. It is best known for being the home of colonial inventor Oliver Evans. The population was 1,055 at the 2010 census. Four limited access highways, I-95 ...

, to a family of Welsh

Welsh may refer to:

Related to Wales

* Welsh, referring or related to Wales

* Welsh language, a Brittonic Celtic language spoken in Wales

* Welsh people

People

* Welsh (surname)

* Sometimes used as a synonym for the ancient Britons (Celtic peop ...

settlers. He designed an improved high-pressure steam engine

A steam engine is a heat engine that performs mechanical work using steam as its working fluid. The steam engine uses the force produced by steam pressure to push a piston back and forth inside a cylinder. This pushing force can be trans ...

in 1801 but did not build itpower-to-weight ratio

Power-to-weight ratio (PWR, also called specific power, or power-to-mass ratio) is a calculation commonly applied to engines and mobile power sources to enable the comparison of one unit or design to another. Power-to-weight ratio is a measuremen ...

, making it practical to apply it in locomotives and steamboats. Evans became so depressed with the poor protection that the US patent law gave inventors that he eventually took all his engineering drawings and invention ideas and destroyed them to prevent his children wasting their time in court fighting patent infringements.

Robert Fulton

Robert Fulton (November 14, 1765 – February 24, 1815) was an American engineer and inventor who is widely credited with developing the world's first commercially successful steamboat, the (also known as ''Clermont''). In 1807, that steamboat ...

constructed a steamboat to ply a route between New York City and Albany, New York

Albany ( ) is the capital of the U.S. state of New York, also the seat and largest city of Albany County. Albany is on the west bank of the Hudson River, about south of its confluence with the Mohawk River, and about north of New York City ...

on the Hudson River

The Hudson River is a river that flows from north to south primarily through eastern New York. It originates in the Adirondack Mountains of Upstate New York and flows southward through the Hudson Valley to the New York Harbor between N ...

. He successfully obtained a monopoly on Hudson River traffic after terminating a prior 1797 agreement with John Stevens, who owned extensive land on the Hudson River in New Jersey. The former agreement had partitioned northern Hudson River traffic to Livingston and southern to Stevens, agreeing to use ships designed by Stevens for both operations.Pittsburgh

Pittsburgh ( ) is a city in the Commonwealth (U.S. state), Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, United States, and the county seat of Allegheny County, Pennsylvania, Allegheny County. It is the most populous city in both Allegheny County and Wester ...

to steam down the Ohio River

The Ohio River is a long river in the United States. It is located at the boundary of the Midwestern and Southern United States, flowing southwesterly from western Pennsylvania to its mouth on the Mississippi River at the southern tip of Illino ...

to the Mississippi

Mississippi () is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States, bordered to the north by Tennessee; to the east by Alabama; to the south by the Gulf of Mexico; to the southwest by Louisiana; and to the northwest by Arkansas. Miss ...

and on to New Orleans. In 1817 a consortium in Sackets Harbor, New York

Sackets Harbor (earlier spelled Sacketts Harbor) is a village in Jefferson County, New York, United States, on Lake Ontario. The population was 1,450 at the 2010 census. The village was named after land developer and owner Augustus Sackett, who ...

, funded the construction of the first US steamboat, ''Ontario'', to run on Lake Ontario

Lake Ontario is one of the five Great Lakes of North America. It is bounded on the north, west, and southwest by the Canadian province of Ontario, and on the south and east by the U.S. state of New York. The Canada–United States border sp ...

and the Great Lakes, beginning the growth of lake commercial and passenger traffic. In his book '' Life on the Mississippi'', river pilot

A maritime pilot, marine pilot, harbor pilot, port pilot, ship pilot, or simply pilot, is a mariner who maneuvers ships through dangerous or congested waters, such as harbors or river mouths. Maritime pilots are regarded as skilled professional ...

and author Mark Twain

Samuel Langhorne Clemens (November 30, 1835 – April 21, 1910), known by his pen name Mark Twain, was an American writer, humorist, entrepreneur, publisher, and lecturer. He was praised as the "greatest humorist the United States has p ...

described much of the operation of such vessels.

Types of ships

By 1849 the shipping industry was in transition from sail-powered boats to steam-powered boats and from wood construction to an ever-increasing metal construction. There were basically three different types of ships being used: standard sailing ship

A sailing ship is a sea-going vessel that uses sails mounted on masts to harness the power of wind and propel the vessel. There is a variety of sail plans that propel sailing ships, employing square-rigged or fore-and-aft sails. Some ships c ...

s of several different types, clipper

A clipper was a type of mid-19th-century merchant sailing vessel, designed for speed. Clippers were generally narrow for their length, small by later 19th century standards, could carry limited bulk freight, and had a large total sail area. "C ...

s, and paddle steamer

A paddle steamer is a steamship or steamboat powered by a steam engine that drives paddle wheels to propel the craft through the water. In antiquity, paddle wheelers followed the development of poles, oars and sails, where the first uses wer ...

s with paddles mounted on the side or rear. River steamboats typically used rear-mounted paddles and had flat bottoms and shallow hulls designed to carry large loads on generally smooth and occasionally shallow rivers. Ocean-going paddle steamers typically used side-wheeled paddles and used narrower, deeper hulls designed to travel in the often stormy weather encountered at sea. The ship hull design was often based on the clipper ship design with extra bracing to support the loads and strains imposed by the paddle wheels when they encountered rough water.

The first paddle-steamer to make a long ocean voyage was the 320-ton , built in 1819 expressly for packet ship

Packet boats were medium-sized boats designed for domestic mail, passenger, and freight transportation in European countries and in North American rivers and canals, some of them steam driven. They were used extensively during the 18th and 19th ...

mail and passenger service to and from Liverpool

Liverpool is a city and metropolitan borough in Merseyside, England. With a population of in 2019, it is the 10th largest English district by population and its metropolitan area is the fifth largest in the United Kingdom, with a popul ...

, England. On 22 May 1819, the watch on the ''Savannah'' sighted Ireland after 23 days at sea. The Allaire Iron Works

The Allaire Iron Works was a leading 19th-century American marine engineering company based in New York City. Founded in 1816 by engineer and philanthropist James P. Allaire, the Allaire Works was one of the world's first companies dedicated to the ...

of New York supplied ''Savannah's'''s engine cylinder, while the rest of the engine components and running gear were manufactured by the Speedwell Ironworks

Speedwell Ironworks was an ironworks in Speedwell Village, on Speedwell Avenue (part of U.S. Route 202), just north of downtown Morristown, in Morris County, New Jersey, United States. At this site Alfred Vail and Samuel Morse first demonstrate ...

of New Jersey

New Jersey is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Northeastern regions of the United States. It is bordered on the north and east by the state of New York; on the east, southeast, and south by the Atlantic Ocean; on the west by the Delaware ...

. The low-pressure engine was of the inclined direct-acting type, with a single cylinder and a stroke. ''Savannah'''s engine and machinery were unusually large for their time. The ship's wrought-iron

Wrought iron is an iron alloy with a very low carbon content (less than 0.08%) in contrast to that of cast iron (2.1% to 4%). It is a semi-fused mass of iron with fibrous slag inclusions (up to 2% by weight), which give it a wood-like "grain" t ...

paddlewheel

A paddle wheel is a form of waterwheel or impeller in which a number of paddles are set around the periphery of the wheel. It has several uses, of which some are:

* Very low-lift water pumping, such as flooding paddy fields at no more than about ...

s were 16 feet in diameter with eight buckets per wheel. For fuel, the vessel carried of coal and of wood.[Smithsonian, p. 618]

The SS ''Savannah'' was too small to carry much fuel, and the engine was intended only for use in calm weather and to get in and out of harbors. Under favorable winds the sails alone were able to provide a speed of at least four knots. The ''Savannah'' was judged not a commercial success, and its engine was removed and it was converted back to a regular sailing ship. By 1848 steamboats built by both United States and British shipbuilders were already in use for mail and passenger service across the Atlantic Ocean—a journey.

Since paddle steamers typically required from of coal per day to keep their engines running, they were more expensive to run. Initially, nearly all seagoing steamboats were equipped with mast and sails to supplement the

Since paddle steamers typically required from of coal per day to keep their engines running, they were more expensive to run. Initially, nearly all seagoing steamboats were equipped with mast and sails to supplement the steam engine

A steam engine is a heat engine that performs mechanical work using steam as its working fluid. The steam engine uses the force produced by steam pressure to push a piston back and forth inside a cylinder. This pushing force can be trans ...

power and provide power for occasions when the steam engine needed repair or maintenance. These steamships typically concentrated on high value cargo, mail and passengers and only had moderate cargo capabilities because of their required loads of coal. The typical paddle wheel steamship was powered by a coal burning engine that required firemen to shovel the coal to the burners.

By 1849 the screw propeller

A propeller (colloquially often called a screw if on a ship or an airscrew if on an aircraft) is a device with a rotating hub and radiating blades that are set at a pitch to form a helical spiral which, when rotated, exerts linear thrust upon ...

had been invented and was slowly being introduced as iron increasingly was used in ship construction and the stress introduced by propellers could be compensated for. As the 1800s progressed the timber and lumber needed to make wooden ships got ever more expensive, and the iron plate needed for iron ship construction got much cheaper as the massive iron works at Merthyr Tydfil

Merthyr Tydfil (; cy, Merthyr Tudful ) is the main town in Merthyr Tydfil County Borough, Wales, administered by Merthyr Tydfil County Borough Council. It is about north of Cardiff. Often called just Merthyr, it is said to be named after Tydf ...

, Wales, for example, got ever more efficient. The propeller put a lot of stress on the rear of the ships and would not see widespread use till the conversion from wood boats to iron boats was complete—well underway by 1860. By the 1840s the ocean-going steam ship industry was well established as the Cunard Line

Cunard () is a British shipping and cruise line based at Carnival House at Southampton, England, operated by Carnival UK and owned by Carnival Corporation & plc. Since 2011, Cunard and its three ships have been registered in Hamilton, Berm ...

and others demonstrated.

The last sailing frigate of the US Navy, , had been launched in 1855.

West Coast

In the mid-1840s the acquisition of Oregon and California opened up the West Coast to American steamboat traffic. Starting in 1848 Congress subsidized the Pacific Mail Steamship Company

The Pacific Mail Steamship Company was founded April 18, 1848, as a joint stock company under the laws of the State of New York by a group of New York City merchants. Incorporators included William H. Aspinwall, Edwin Bartlett (American consul ...

with $199,999 to set up regular packet ship

Packet boats were medium-sized boats designed for domestic mail, passenger, and freight transportation in European countries and in North American rivers and canals, some of them steam driven. They were used extensively during the 18th and 19th ...

, mail, passenger, and cargo routes in the Pacific Ocean. This regular scheduled route went from Panama City

Panama City ( es, Ciudad de Panamá, links=no; ), also known as Panama (or Panamá in Spanish), is the capital and largest city of Panama. It has an urban population of 880,691, with over 1.5 million in its metropolitan area. The city is locat ...

, Nicaragua and Mexico to and from San Francisco

San Francisco (; Spanish language, Spanish for "Francis of Assisi, Saint Francis"), officially the City and County of San Francisco, is the commercial, financial, and cultural center of Northern California. The city proper is the List of Ca ...

and Oregon

Oregon () is a U.S. state, state in the Pacific Northwest region of the Western United States. The Columbia River delineates much of Oregon's northern boundary with Washington (state), Washington, while the Snake River delineates much of it ...

. Panama City was the Pacific terminus of the Isthmus of Panama

The Isthmus of Panama ( es, Istmo de Panamá), also historically known as the Isthmus of Darien (), is the narrow strip of land that lies between the Caribbean Sea and the Pacific Ocean, linking North and South America. It contains the country ...

trail across Panama. The Atlantic Ocean mail contract from East Coast cities and New Orleans to and from the Chagres River in Panama was won by the United States Mail Steamship Company

The United States Mail Steamship Company – also called the United States Mail Line, or the U.S. Mail Line – was a passenger steamship line formed in 1920 by the United States Shipping Board (USSB) to run the USSB's fleet of ex-German ocean l ...

whose first paddle wheel

A paddle wheel is a form of waterwheel or impeller in which a number of paddles are set around the periphery of the wheel. It has several uses, of which some are:

* Very low-lift water pumping, such as flooding paddy fields at no more than about ...

steamship, the SS Falcon (1848) was dispatched on 1 December 1848 to the Caribbean (Atlantic) terminus of the Isthmus of Panama

The Isthmus of Panama ( es, Istmo de Panamá), also historically known as the Isthmus of Darien (), is the narrow strip of land that lies between the Caribbean Sea and the Pacific Ocean, linking North and South America. It contains the country ...

trail—the Chagres River.

The SS ''California'' (1848), the first Pacific Mail Steamship Company

The Pacific Mail Steamship Company was founded April 18, 1848, as a joint stock company under the laws of the State of New York by a group of New York City merchants. Incorporators included William H. Aspinwall, Edwin Bartlett (American consul ...

paddle wheel

A paddle wheel is a form of waterwheel or impeller in which a number of paddles are set around the periphery of the wheel. It has several uses, of which some are:

* Very low-lift water pumping, such as flooding paddy fields at no more than about ...

steamship, left New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the List of United States cities by population, most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the L ...

on 6 October 1848 with only a partial load of her about 60 saloon (about $300 fare) and 150 steerage (about $150 fare) passenger capacity. Only a few were going all the way to California. Her crew numbered about 36 men. She left New York well before confirmed word of the California Gold Rush

The California Gold Rush (1848–1855) was a gold rush that began on January 24, 1848, when gold was found by James W. Marshall at Sutter's Mill in Coloma, California. The news of gold brought approximately 300,000 people to California fro ...

had reached the East Coast. Once the California Gold Rush

The California Gold Rush (1848–1855) was a gold rush that began on January 24, 1848, when gold was found by James W. Marshall at Sutter's Mill in Coloma, California. The news of gold brought approximately 300,000 people to California fro ...

was confirmed by President James Polk

James is a common English language surname and given name:

*James (name), the typically masculine first name James

* James (surname), various people with the last name James

James or James City may also refer to:

People

* King James (disambiguat ...

in his State of the Union address

The State of the Union Address (sometimes abbreviated to SOTU) is an annual message delivered by the president of the United States to a joint session of the United States Congress near the beginning of each calendar year on the current conditio ...

on 5 December 1848 people started rushing to Panama City to catch the SS California. The picked up more passengers in Valparaiso, Chile and Panama City

Panama City ( es, Ciudad de Panamá, links=no; ), also known as Panama (or Panamá in Spanish), is the capital and largest city of Panama. It has an urban population of 880,691, with over 1.5 million in its metropolitan area. The city is locat ...

, Panama and showed up in San Francisco, loaded with about 400 passengers—twice the passengers it had been designed for—on 28 February 1849. She had left behind about another 400–600 potential passengers still looking for passage from Panama City. The ''SS California ''had made the trip from Panama and Mexico after steaming around Cape Horn

Cape Horn ( es, Cabo de Hornos, ) is the southernmost headland of the Tierra del Fuego archipelago of southern Chile, and is located on the small Hornos Island. Although not the most southerly point of South America (which are the Diego Ramírez ...

from New York—see SS ''California'' (1848).

The trips by paddle wheel steamship to Panama and Nicaragua from New York, Philadelphia, Boston, via New Orleans and Havana were about long and took about two weeks. Trips across the Isthmus of Panama

The Isthmus of Panama ( es, Istmo de Panamá), also historically known as the Isthmus of Darien (), is the narrow strip of land that lies between the Caribbean Sea and the Pacific Ocean, linking North and South America. It contains the country ...

or Nicaragua typically took about one week by native canoe

A canoe is a lightweight narrow water vessel, typically pointed at both ends and open on top, propelled by one or more seated or kneeling paddlers facing the direction of travel and using a single-bladed paddle.

In British English, the term ...

and mule

The mule is a domestic equine hybrid between a donkey and a horse. It is the offspring of a male donkey (a jack) and a female horse (a mare). The horse and the donkey are different species, with different numbers of chromosomes; of the two pos ...

back. The trip to or from San Francisco to Panama City could be done by paddle wheel

A paddle wheel is a form of waterwheel or impeller in which a number of paddles are set around the periphery of the wheel. It has several uses, of which some are:

* Very low-lift water pumping, such as flooding paddy fields at no more than about ...

steamer in about three weeks. In addition to this travel time via the Panama route typically had a two- to four-week waiting period to find a ship going from Panama City, Panama

Panama City ( es, Ciudad de Panamá, links=no; ), also known as Panama (or Panamá in Spanish), is the capital and largest city of Panama. It has an urban population of 880,691, with over 1.5 million in its metropolitan area. The city is locat ...

to San Francisco before 1850. It was 1850 before enough paddle wheel steamers were available in the Atlantic and Pacific routes to establish regularly scheduled journeys.

Other steamships soon followed, and by late 1849, paddle wheel steamships like the SS ''McKim'' (1848) were carrying miners and their supplies the trip from San Francisco up the extensive Sacramento–San Joaquin River Delta

The Sacramento–San Joaquin River Delta, or California Delta, is an expansive inland river delta and estuary in Northern California. The Delta is formed at the western edge of the Central Valley by the confluence of the Sacramento and San ...

to Stockton, California

Stockton is a city in and the county seat of San Joaquin County, California, San Joaquin County in the Central Valley (California), Central Valley of the U.S. state of California. Stockton was founded by Carlos Maria Weber in 1849 after he acquir ...

, Marysville, California

Marysville is a city and the county seat of Yuba County, California, located in the Gold Country region of Northern California. As of the 2010 United States Census, the population was 12,072, reflecting a decrease of 196 from the 12,268 counted ...

, Sacramento

)

, image_map = Sacramento County California Incorporated and Unincorporated areas Sacramento Highlighted.svg

, mapsize = 250x200px

, map_caption = Location within Sacramento ...

, etc. to get about closer to the gold fields. Steam-powered tugboat

A tugboat or tug is a marine vessel that manoeuvres other vessels by pushing or pulling them, with direct contact or a tow line. These boats typically tug ships in circumstances where they cannot or should not move under their own power, su ...

s and towboat

A pusher, pusher craft, pusher boat, pusher tug, or towboat, is a boat designed for pushing barges or car floats. In the United States, the industries that use these vessels refer to them as towboats. These vessels are characterized by a squar ...

s started working in the San Francisco Bay soon after this to expedite shipping in and out of the bay.

As the passenger, mail and high value freight business to and from California boomed more and more paddle steamers were brought into service—eleven by the Pacific Mail Steamship Company alone. The trip to and from California via Panama and paddle wheeled steamers could be done, if there were no waits for shipping, in about 40 days—over 100 days less than by wagon or 160 days less than a trip around Cape Horn

Cape Horn ( es, Cabo de Hornos, ) is the southernmost headland of the Tierra del Fuego archipelago of southern Chile, and is located on the small Hornos Island. Although not the most southerly point of South America (which are the Diego Ramírez ...

. About 20–30% of the California Argonauts are thought to have returned to their homes, mostly on the East Coast of the United States via Panama—the fastest way home. Many returned to California after settling their business in the East with their wives, family and/or sweethearts. Most used the Panama or Nicaragua route till 1855 when the completion of the Panama Railroad

The Panama Canal Railway ( es, Ferrocarril de Panamá) is a railway line linking the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean in Central America. The route stretches across the Isthmus of Panama from Colón (Atlantic) to Balboa (Pacific, near P ...

made the Panama Route much easier, faster and more reliable. Between 1849 and 1869 when the first transcontinental railroad

North America's first transcontinental railroad (known originally as the "Pacific Railroad" and later as the " Overland Route") was a continuous railroad line constructed between 1863 and 1869 that connected the existing eastern U.S. rail netwo ...

was completed across the United States about 800,000 travelers had used the Panama route. Most of the roughly $50,000,000 of gold found each year in California were shipped East via the Panama route on paddle steamers, mule trains and canoes and later the Panama Railroad

The Panama Canal Railway ( es, Ferrocarril de Panamá) is a railway line linking the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean in Central America. The route stretches across the Isthmus of Panama from Colón (Atlantic) to Balboa (Pacific, near P ...

across Panama. After 1855 when the Panama Railroad was completed the Panama Route was by far the quickest and easiest way to get to or from California from the East Coast of the U.S. or Europe. Most California bound merchandise still used the slower but cheaper Cape Horn

Cape Horn ( es, Cabo de Hornos, ) is the southernmost headland of the Tierra del Fuego archipelago of southern Chile, and is located on the small Hornos Island. Although not the most southerly point of South America (which are the Diego Ramírez ...

sailing ship

A sailing ship is a sea-going vessel that uses sails mounted on masts to harness the power of wind and propel the vessel. There is a variety of sail plans that propel sailing ships, employing square-rigged or fore-and-aft sails. Some ships c ...

route. The sinking of the paddle steamer

A paddle steamer is a steamship or steamboat powered by a steam engine that drives paddle wheels to propel the craft through the water. In antiquity, paddle wheelers followed the development of poles, oars and sails, where the first uses wer ...

(the ''Ship of Gold'') in a hurricane on 12 September 1857 and the loss of about $2 million in California gold indirectly led to the Panic of 1857

The Panic of 1857 was a financial panic in the United States caused by the declining international economy and over-expansion of the domestic economy. Because of the invention of the telegraph by Samuel F. Morse in 1844, the Panic of 1857 was ...

.

Steamboat traffic including passenger and freight business grew exponentially in the decades before the Civil War. So too did the economic and human losses inflicted by snags, shoals, boiler explosions, and human error.

Civil War

During the

During the US Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states th ...

the Battle of Hampton Roads

The Battle of Hampton Roads, also referred to as the Battle of the ''Monitor'' and ''Virginia'' (rebuilt and renamed from the USS ''Merrimack'') or the Battle of Ironclads, was a naval battle during the American Civil War.

It was fought over t ...

, often referred to as either the Battle of the ''Monitor

Monitor or monitor may refer to:

Places

* Monitor, Alberta

* Monitor, Indiana, town in the United States

* Monitor, Kentucky

* Monitor, Oregon, unincorporated community in the United States

* Monitor, Washington

* Monitor, Logan County, West Vir ...

'' and ''Merrimack'' or the ''Battle of Ironclads'', was fought over two days with steam-powered ironclad warships

An ironclad is a steam-propelled warship protected by iron or steel armor plates, constructed from 1859 to the early 1890s. The ironclad was developed as a result of the vulnerability of wooden warships to explosive or incendiary shells. Th ...

, 8–9 March 1862. The battle occurred in Hampton Roads

Hampton Roads is the name of both a body of water in the United States that serves as a wide channel for the James River, James, Nansemond River, Nansemond and Elizabeth River (Virginia), Elizabeth rivers between Old Point Comfort and Sewell's ...

, a roadstead

A roadstead (or ''roads'' – the earlier form) is a body of water sheltered from rip currents, spring tides, or ocean swell where ships can lie reasonably safely at anchor without dragging or snatching.United States Army technical manual, TM 5- ...

in Virginia where the Elizabeth

Elizabeth or Elisabeth may refer to:

People

* Elizabeth (given name), a female given name (including people with that name)

* Elizabeth (biblical figure), mother of John the Baptist

Ships

* HMS ''Elizabeth'', several ships

* ''Elisabeth'' (sch ...

and Nansemond River

The Nansemond River is a U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map accessed April 1, 2011 tributary of the James River in Virginia in the United States. Virginian colonists named the river ...

s meet the James River

The James River is a river in the U.S. state of Virginia that begins in the Appalachian Mountains and flows U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map , accessed April 1, 2011 to Chesapea ...

just before it enters Chesapeake Bay

The Chesapeake Bay ( ) is the largest estuary in the United States. The Bay is located in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic region and is primarily separated from the Atlantic Ocean by the Delmarva Peninsula (including the parts: the ...

adjacent to the city of Norfolk

Norfolk () is a ceremonial and non-metropolitan county in East Anglia in England. It borders Lincolnshire to the north-west, Cambridgeshire to the west and south-west, and Suffolk to the south. Its northern and eastern boundaries are the No ...

. The battle was a part of the effort of the Confederate States of America

The Confederate States of America (CSA), commonly referred to as the Confederate States or the Confederacy was an unrecognized breakaway republic in the Southern United States that existed from February 8, 1861, to May 9, 1865. The Confeder ...

to break the Union Naval blockade, which had cut off Virginia from all international trade.Battle of Vicksburg

The siege of Vicksburg (May 18 – July 4, 1863) was the final major military action in the Vicksburg campaign of the American Civil War. In a series of maneuvers, Union Maj. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant and his Army of the Tennessee crossed the Missis ...

involved monitors

Monitor or monitor may refer to:

Places

* Monitor, Alberta

* Monitor, Indiana, town in the United States

* Monitor, Kentucky

* Monitor, Oregon, unincorporated community in the United States

* Monitor, Washington

* Monitor, Logan County, West Vir ...

and ironclad riverboats. The USS ''Cairo'' is a survivor of the Vicksburg battle. Trade on the river was suspended for two years because of a Confederate's Mississippi blockade before the union victory at Vicksburg reopened the river on 4 July 1863. The triumph of Eads ironclads, and Farragut's seizure of New Orleans, secured the river for the Union North.

Although Union forces gained control of Mississippi River tributaries, travel there was still subject to interdiction by the Confederates. The Ambush of the steamboat J. R. Williams

The ambush of the steamboat ''J.R. Williams'' was a military engagement during the American Civil War. It took place on June 15, 1864, on the Arkansas River in the Choctaw Nation (Indian Territory) which became encompassed by the State of Oklaho ...

, which was carrying supplies from Fort Smith to Fort Gibson

Fort Gibson is a historic military site next to the modern city of Fort Gibson, in Muskogee County Oklahoma. It guarded the American frontier in Indian Territory from 1824 to 1888. When it was constructed, the fort was farther west than any othe ...

along the Arkansas River on 16 July 1863 demonstrated this. The steamboat was destroyed, the cargo was lost, and the tiny Union escort was run off. The loss did not affect the Union war effort, however.

The worst of all steamboat accidents occurred at the end of the Civil War in April 1865, when the steamboat '' Sultana'', carrying an over-capacity load of returning Union soldiers recently freed from a Confederate prison camp, blew up, causing more than 1,700 deaths.

Mississippi and Missouri river traffic

For most of the 19th century and part of the early 20th century, trade on the Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the second-longest river and chief river of the second-largest drainage system in North America, second only to the Hudson Bay drainage system. From its traditional source of Lake Itasca in northern Minnesota, it f ...

was dominated by paddle-wheel steamboats. Their use generated rapid development of economies of port cities; the exploitation of agricultural and commodity products, which could be more easily transported to markets; and prosperity along the major rivers. Their success led to penetration deep into the continent, where ''Anson Northup

''Anson Northup'' (possibly ''Anson Northrup'') was a sternwheel riverboat named for her captain who was the first to navigate the Red River of the North from Fort Abercrombie, Dakota Territory, to Fort Garry, Rupert's Land, departing 6 June a ...

'' in 1859 became first steamer to cross the Canada–US border on the Red River. They would also be involved in major political events, as when Louis Riel

Louis Riel (; ; 22 October 1844 – 16 November 1885) was a Canadian politician, a founder of the province of Manitoba, and a political leader of the Métis people. He led two resistance movements against the Government of Canada and its first ...

seized ''International

International is an adjective (also used as a noun) meaning "between nations".

International may also refer to:

Music Albums

* ''International'' (Kevin Michael album), 2011

* ''International'' (New Order album), 2002

* ''International'' (The T ...

'' at Fort Garry

Fort Garry, also known as Upper Fort Garry, was a Hudson's Bay Company trading post at the confluence of the Red and Assiniboine rivers in what is now downtown Winnipeg. It was established in 1822 on or near the site of the North West Company's ...

, or Gabriel Dumont was engaged by '' Northcote'' at Batoche. Steamboats were held in such high esteem that they could become state symbols; the Steamboat ''Iowa'' (1838) is incorporated in the Seal of Iowa

The Great Seal of the State of Iowa was created in 1847 (one year after Iowa became a U.S. state) and depicts a citizen soldier standing in a wheat field surrounded by symbols including farming, mining, and transportation with the Mississippi Riv ...

because it represented speed, power, and progress.

At the same time, the expanding steamboat traffic had severe adverse environmental effects, in the Middle Mississippi Valley especially, between St. Louis and the river's confluence with the

At the same time, the expanding steamboat traffic had severe adverse environmental effects, in the Middle Mississippi Valley especially, between St. Louis and the river's confluence with the Ohio

Ohio () is a state in the Midwestern region of the United States. Of the fifty U.S. states, it is the 34th-largest by area, and with a population of nearly 11.8 million, is the seventh-most populous and tenth-most densely populated. The sta ...

. The steamboats consumed much wood for fuel, and the river floodplain and banks became deforested. This led to instability in the banks, addition of silt to the water, making the river both shallower and hence wider and causing unpredictable, lateral movement of the river channel across the wide, ten-mile floodplain, endangering navigation. Boats designated as snagpullers to keep the channels free had crews that sometimes cut remaining large trees or more back from the banks, exacerbating the problems. In the 19th century, the flooding of the Mississippi became a more severe problem than when the floodplain was filled with trees and brush.

Most steamboats were destroyed by boiler explosions or fires—and many sank in the river, with some of those buried in silt as the river changed course. From 1811 to 1899, 156 steamboats were lost to snags or rocks between St. Louis and the Ohio River. Another 411 were damaged by fire, explosions or ice during that period. One of the few surviving Mississippi sternwheelers from this period, ''

Most steamboats were destroyed by boiler explosions or fires—and many sank in the river, with some of those buried in silt as the river changed course. From 1811 to 1899, 156 steamboats were lost to snags or rocks between St. Louis and the Ohio River. Another 411 were damaged by fire, explosions or ice during that period. One of the few surviving Mississippi sternwheelers from this period, ''Julius C. Wilkie

The gens Julia (''gēns Iūlia'', ) was one of the most prominent patrician families in ancient Rome. Members of the gens attained the highest dignities of the state in the earliest times of the Republic. The first of the family to obtain the ...

'', was operated as a museum ship

A museum ship, also called a memorial ship, is a ship that has been preserved and converted into a museum open to the public for educational or memorial purposes. Some are also used for training and recruitment purposes, mostly for the small numb ...

at Winona, Minnesota

Winona is a city in and the county seat of Winona County, in the state of Minnesota. Located in bluff country on the Mississippi River, its most noticeable physical landmark is Sugar Loaf. The city is named after legendary figure Winona, who ...

, until its destruction in a fire in 1981. The replacement, built ''in situ'', was not a steamboat. The replica was scrapped in 2008.

From 1844 through 1857, luxurious palace steamer

Palace steamers were luxurious steamships that carried passengers and cargo around the North American Great Lakes

The Great Lakes, also called the Great Lakes of North America, are a series of large interconnected freshwater lakes in the ...

s carried passengers and cargo around the North American Great Lakes. Great Lakes passenger steamers

The history of commercial passenger shipping on the Great Lakes is long but uneven. It reached its zenith between the mid-19th century and the 1950s. As early as 1844, palace steamers carried passengers and cargo around the Great Lakes. By 1900, ...

reached their zenith during the century from 1850 to 1950. The is the last of the once-numerous passenger-carrying steam-powered car ferries operating on the Great Lakes. A unique style of bulk carrier

A bulk carrier or bulker is a merchant ship specially designed to transport unpackaged bulk cargo — such as grains, coal, ore, steel coils, and cement — in its cargo holds. Since the first specialized bulk carrier was built in 1852, econom ...

known as the lake freighter

Lake freighters, or lakers, are bulk carrier vessels that operate on the Great Lakes of North America. These vessels are traditionally called boats, although classified as ships.

Since the late 19th century, lakers have carried bulk cargoes of m ...

was developed on the Great Lakes. The ''St. Marys Challenger'', launched in 1906, is the oldest operating steamship in the United States. She runs a Skinner Marine Unaflow 4-cylinder reciprocating steam engine as her power plant.

Women started to become steamboat captains in the late 19th century. The first woman to earn her steamboat master's license was Mary Millicent Miller

Mary Millicent Miller ( ''née'' Mary Millicent Garretson; 1846 – October 30, 1894) was an American steamboat master who was the first American woman to acquire a steamboat master's license.

Biography

Miller was born in 1846 in Portland, Kentu ...

, in 1884. In 1888, Callie Leach French

Callie M. Leach French ("Aunt Callie" 1861–1935) was an American steamboat captain and pilot. For much of her career as a captain, she worked with her husband, towing showboats along the Ohio, Monogahela and Mississippi Rivers. She played the ca ...

earned her first class license.

=Steamboats in rivers on the west side of the Mississippi River

=

Steamboats also operated on the Red River to Shreveport

Shreveport ( ) is a city in the U.S. state of Louisiana. It is the third most populous city in Louisiana after New Orleans and Baton Rouge, Louisiana, Baton Rouge, respectively. The Shreveport–Bossier City metropolitan area, with a population o ...

, Louisiana.

In April 1815, Captain Henry Miller Shreve was the first person to bring a steamboat, the Enterprise, up the Red River.

By 1839 after Captain Henry Miller Shreve

Henry Miller Shreve (October 21, 1785 – March 6, 1851) was the American inventor and steamboat captain who opened the Mississippi, Ohio, and Red rivers to steamboat navigation. Shreveport, Louisiana, is named in his honor.

Shreve was also instru ...

broke the Great Raft

The Great Raft was a gigantic log jam or series of "rafts" that clogged the Red and Atchafalaya rivers and was unique in North America in terms of its scale.

Origin

The Great Raft probably began forming in the 12th century. It grew from its up ...

log jam had been 160 miles long on the river.

In the late 1830s, the steamboats in rivers on the west side of the Mississippi River were a long, wide, shallow draft vessel, lightly built with an engine on the deck. These newer steamboats could sail in just 20 inches of water. Contemporaries claimed that they could "run with a lot of heavy dew".

Walking the steamboat over sandbars or away from reefs

Walking the boat was a way of lifting the bow of a steamboat like on crutches, getting up and down a sandbank with poles, blocks, and strong rigging, and using paddlewheels to lift and move the ship through successive steps, on the helm. Moving of a boat from a sandbar was by its own action known as "walking the boat" and "grass-hoppering". Two long, strong poles were pushed forward from the bow on either side of the boat into the sandbar at a high degree of angle. Near the end of each pole, a block was secured with a strong rope or clamp that passed through pulleys that lowered through a pair of similar blocks attached to the deck near the bow. The end of each line went to a winch which, when turned, was taut and, with its weight on the stringers, slightly raised the bow of the boat. Activation of the forward paddlewheels and placement of the poles caused the bow of the boat to raise and move the boat forward perhaps a few feet. It was laborious and dangerous work for the crew, even with a Steam donkey

A steam donkey or donkey engine is a steam engine, steam-powered winch once widely used in logging, mining, Shipping industry, maritime, and other industrial applications.

Steam powered donkeys were commonly found on large metal-hulled multi-m ...

driven capstan winch.

Double-tripping

Double-tripping means making two voyages by leaving a cargo of a steamboat ashore to lighten boats load during times of extremely low water or when ice impedes progress. The boat had to return (and therefore make a second trip) to retrieve the cargo.

Piston Rings, Steel replaced cotton seals, 1854

1854: John Ramsbottom publishes a report on his use of oversized split steel piston rings which maintain a seal by outward spring tension on the cylinder wall. This improved efficiency by allowing much better sealing (compared to earlier cotton seals) which allowed significantly higher system pressures before "blow-by" is experienced.

Allen Steam Engine at 3 to 5 times higher speeds, 1862

1862: The Allen steam engine (later called Porter-Allen) is exhibited at the London Exhibition. It is precision engineered and balanced allowing it to operate at from three to five times the speed of other stationary engines. The short stroke and high speed minimize condensation in the cylinder, significantly improving efficiency. The high speed allows direct coupling or the use of reduced sized pulleys and belting.

Boilers, Water Tubes, Not Explosive, 1867

Triple Expansion Steam Engine, 1881

Steam Turbine, 1884

20th century

The ''Belle of Louisville

''Belle of Louisville'' is a steamboat owned and operated by the city of Louisville, Kentucky, and moored at its downtown wharf next to the Riverfront Plaza/Belvedere during its annual operational period. The steamboat claims itself the "most wid ...

'' is the oldest operating steamboat in the United States, and the oldest operating Mississippi River-style steamboat in the world. She was laid down as ''Idlewild'' in 1914, and is currently located in Louisville, Kentucky.

Five major commercial steamboats currently operate on the inland waterways of the United States. The only remaining overnight cruising steamboat is the 432-passenger ''American Queen

''American Queen'' is said to be the largest river steamboat ever built. The ship was built in 1995 and is a six-deck recreation of a classic Mississippi riverboat, built by McDermott Shipyard for the ''Delta Queen'' Steamboat Company. Although ...

'', which operates week-long cruises on the Mississippi, Ohio, Cumberland and Tennessee Rivers 11 months out of the year. The others are day boats: they are the steamers ''Chautauqua Belle

The steamer ''Chautauqua Belle'' is an authentic Mississippi River-style sternwheel steamboat owned and operated by U.S. Steam Lines Ltd, operating on Chautauqua Lake in Western New York.

History

Originally financed and built by Captain James W ...

'' at Chautauqua Lake, New York, '' Minne Ha-Ha'' at Lake George, New York, operating on Lake George; the ''Belle of Louisville

''Belle of Louisville'' is a steamboat owned and operated by the city of Louisville, Kentucky, and moored at its downtown wharf next to the Riverfront Plaza/Belvedere during its annual operational period. The steamboat claims itself the "most wid ...

'' in Louisville, Kentucky

Louisville ( , , ) is the largest city in the Commonwealth of Kentucky and the 28th most-populous city in the United States. Louisville is the historical seat and, since 2003, the nominal seat of Jefferson County, on the Indiana border ...

, operating on the Ohio River; and the ''Natchez Natchez may refer to:

Places

* Natchez, Alabama, United States

* Natchez, Indiana, United States

* Natchez, Louisiana, United States

* Natchez, Mississippi, a city in southwestern Mississippi, United States

* Grand Village of the Natchez, a site o ...

'' in New Orleans, Louisiana, operating on the Mississippi River. For modern craft operated on rivers, see the Riverboat

A riverboat is a watercraft designed for inland navigation on lakes, rivers, and artificial waterways. They are generally equipped and outfitted as work boats in one of the carrying trades, for freight or people transport, including luxury un ...

article.

Canada

In Canada, the city of Terrace

Terrace may refer to:

Landforms and construction

* Fluvial terrace, a natural, flat surface that borders and lies above the floodplain of a stream or river

* Terrace, a street suffix

* Terrace, the portion of a lot between the public sidewalk a ...

, British Columbia, celebrates "Riverboat Days" each summer. Built on the banks of the Skeena River

The Skeena River is the second-longest river entirely within British Columbia, Canada (after the Fraser River). Since ancient times, the Skeena has been an important transportation artery, particularly for the Tsimshian and the Gitxsan—whose n ...

, the city depended on the steamboat for transportation and trade into the 20th century. The first steamer to enter the Skeena was ''Union'' in 1864. In 1866 ''Mumford'' attempted to ascend the river, but it was only able to reach the Kitsumkalum River. It was not until 1891 Hudson's Bay Company

The Hudson's Bay Company (HBC; french: Compagnie de la Baie d'Hudson) is a Canadian retail business group. A fur trading business for much of its existence, HBC now owns and operates retail stores in Canada. The company's namesake business div ...

sternwheeler ''Caledonia'' successfully negotiated Kitselas Canyon

Kitselas Canyon, also Kitsalas Canyon is a stretch of the Skeena River in northwestern British Columbia, Canada, between the community of Usk and the Tsimshian community of Kitselas. It was a major obstacle to steamboat travel on the Skeena Ri ...

and reached Hazelton. A number of other steamers were built around the turn of the 20th century, in part due to the growing fish industry