Derafš-e Kāvīān

/ref> The period of Sasanian rule is considered to be a high point in Iranian history and in many ways was the peak of ancient Iranian culture before the conquest by Arab Muslims under the

Name

Officially, the Empire was known as the Empire of Iranians ( Middle Persian: ''ērānšahr'',History

Origins and early history (205–310)

Conflicting accounts shroud the details of the fall of the Parthian Empire and subsequent rise of the Sassanian Empire in mystery. The Sassanian Empire was established in Estakhr by

Conflicting accounts shroud the details of the fall of the Parthian Empire and subsequent rise of the Sassanian Empire in mystery. The Sassanian Empire was established in Estakhr by  Once Ardashir was appointed '' shah'' (king), he moved his capital further to the south of Pars and founded Ardashir-Khwarrah (formerly ''Gur'', modern day Firuzabad). The city, well protected by high mountains and easily defensible due to the narrow passes that approached it, became the center of Ardashir's efforts to gain more power. It was surrounded by a high, circular wall, probably copied from that of Darabgerd. Ardashir's palace was on the north side of the city; remains of it are extant. After establishing his rule over Pars, Ardashir rapidly extended his territory, demanding fealty from the local princes of Fars, and gaining control over the neighbouring provinces of

Once Ardashir was appointed '' shah'' (king), he moved his capital further to the south of Pars and founded Ardashir-Khwarrah (formerly ''Gur'', modern day Firuzabad). The city, well protected by high mountains and easily defensible due to the narrow passes that approached it, became the center of Ardashir's efforts to gain more power. It was surrounded by a high, circular wall, probably copied from that of Darabgerd. Ardashir's palace was on the north side of the city; remains of it are extant. After establishing his rule over Pars, Ardashir rapidly extended his territory, demanding fealty from the local princes of Fars, and gaining control over the neighbouring provinces of  At that time the Arsacid dynasty was divided between supporters of

At that time the Arsacid dynasty was divided between supporters of  Ardashir I's son Shapur I continued the expansion of the empire, conquering

Ardashir I's son Shapur I continued the expansion of the empire, conquering  Shapur had intensive development plans. He ordered the construction of the first dam bridge in Iran and founded many cities, some settled in part by emigrants from the Roman territories, including Christians who could exercise their faith freely under Sassanid rule. Two cities, Bishapur and

Shapur had intensive development plans. He ordered the construction of the first dam bridge in Iran and founded many cities, some settled in part by emigrants from the Roman territories, including Christians who could exercise their faith freely under Sassanid rule. Two cities, Bishapur and  During the second encounter, Roman forces seized Narseh's camp, his treasury, his harem, and his wife. Galerius advanced into Media and Adiabene, winning successive victories, most prominently near Erzurum, and securing Nisibis ( Nusaybin, Turkey) before 1 October 298. He then advanced down the Tigris, taking Ctesiphon. Narseh had previously sent an ambassador to Galerius to plead for the return of his wives and children. Peace negotiations began in the spring of 299, with both Diocletian and Galerius presiding.

The conditions of the peace were heavy: Persia would give up territory to Rome, making the Tigris the boundary between the two empires. Further terms specified that Armenia was returned to Roman domination, with the fort of Ziatha as its border; Caucasian Iberia would pay allegiance to Rome under a Roman appointee; Nisibis, now under Roman rule, would become the sole conduit for trade between Persia and Rome; and Rome would exercise control over the five satrapies between the Tigris and Armenia:

During the second encounter, Roman forces seized Narseh's camp, his treasury, his harem, and his wife. Galerius advanced into Media and Adiabene, winning successive victories, most prominently near Erzurum, and securing Nisibis ( Nusaybin, Turkey) before 1 October 298. He then advanced down the Tigris, taking Ctesiphon. Narseh had previously sent an ambassador to Galerius to plead for the return of his wives and children. Peace negotiations began in the spring of 299, with both Diocletian and Galerius presiding.

The conditions of the peace were heavy: Persia would give up territory to Rome, making the Tigris the boundary between the two empires. Further terms specified that Armenia was returned to Roman domination, with the fort of Ziatha as its border; Caucasian Iberia would pay allegiance to Rome under a Roman appointee; Nisibis, now under Roman rule, would become the sole conduit for trade between Persia and Rome; and Rome would exercise control over the five satrapies between the Tigris and Armenia: First Golden Era (309–379)

Following Hormizd II's death, northern Arabs started to ravage and plunder the western cities of the empire, even attacking the province of Fars, the birthplace of the Sassanid kings. Meanwhile, Persian nobles killed Hormizd II's eldest son, blinded the second, and imprisoned the third (who later escaped into Roman territory). The throne was reserved for Shapur II, the unborn child of one of Hormizd II's wives who was crowned ''in utero'': the crown was placed upon his mother's stomach. During his youth the empire was controlled by his mother and the nobles. Upon his coming of age, Shapur II assumed power and quickly proved to be an active and effective ruler.

He first led his small but disciplined army south against the Arabs, whom he defeated, securing the southern areas of the empire. He then began his first campaign against the Romans in the west, where Persian forces won a series of battles but were unable to make territorial gains due to the failure of repeated sieges of the key frontier city of Nisibis, and Roman success in retaking the cities of Singara and Amida after they had previously fallen to the Persians.

These campaigns were halted by nomadic raids along the eastern borders of the empire, which threatened Transoxiana, a strategically critical area for control of the

Following Hormizd II's death, northern Arabs started to ravage and plunder the western cities of the empire, even attacking the province of Fars, the birthplace of the Sassanid kings. Meanwhile, Persian nobles killed Hormizd II's eldest son, blinded the second, and imprisoned the third (who later escaped into Roman territory). The throne was reserved for Shapur II, the unborn child of one of Hormizd II's wives who was crowned ''in utero'': the crown was placed upon his mother's stomach. During his youth the empire was controlled by his mother and the nobles. Upon his coming of age, Shapur II assumed power and quickly proved to be an active and effective ruler.

He first led his small but disciplined army south against the Arabs, whom he defeated, securing the southern areas of the empire. He then began his first campaign against the Romans in the west, where Persian forces won a series of battles but were unable to make territorial gains due to the failure of repeated sieges of the key frontier city of Nisibis, and Roman success in retaking the cities of Singara and Amida after they had previously fallen to the Persians.

These campaigns were halted by nomadic raids along the eastern borders of the empire, which threatened Transoxiana, a strategically critical area for control of the  From around 370, however, towards the end of the reign of Shapur II, the Sasanians lost the control of

From around 370, however, towards the end of the reign of Shapur II, the Sasanians lost the control of Intermediate Era (379–498)

From Shapur II's death until Kavad I's first coronation, there was a largely peaceful period with the Romans (by this time the Eastern Roman or Byzantine Empire) engaged in just two brief wars with the Sassanian Empire, the first in 421–422 and the second in 440. Throughout this era, Sasanian religious policy differed dramatically from king to king. Despite a series of weak leaders, the administrative system established during Shapur II's reign remained strong, and the empire continued to function effectively.

After Shapur II died in 379, the empire passed on to his half-brother

From Shapur II's death until Kavad I's first coronation, there was a largely peaceful period with the Romans (by this time the Eastern Roman or Byzantine Empire) engaged in just two brief wars with the Sassanian Empire, the first in 421–422 and the second in 440. Throughout this era, Sasanian religious policy differed dramatically from king to king. Despite a series of weak leaders, the administrative system established during Shapur II's reign remained strong, and the empire continued to function effectively.

After Shapur II died in 379, the empire passed on to his half-brother  Bahram V's son

Bahram V's son  At the beginning of the 5th century, the Hephthalites (White Huns), along with other nomadic groups, attacked Iran. At first Bahram V and Yazdegerd II inflicted decisive defeats against them and drove them back eastward. The Huns returned at the end of the 5th century and defeated Peroz I (457–484) in 483. Following this victory, the Huns invaded and plundered parts of eastern Iran continually for two years. They exacted heavy tribute for some years thereafter.

These attacks brought instability and chaos to the kingdom. Peroz tried again to drive out the Hephthalites, but on the way to

At the beginning of the 5th century, the Hephthalites (White Huns), along with other nomadic groups, attacked Iran. At first Bahram V and Yazdegerd II inflicted decisive defeats against them and drove them back eastward. The Huns returned at the end of the 5th century and defeated Peroz I (457–484) in 483. Following this victory, the Huns invaded and plundered parts of eastern Iran continually for two years. They exacted heavy tribute for some years thereafter.

These attacks brought instability and chaos to the kingdom. Peroz tried again to drive out the Hephthalites, but on the way to VI

Second Golden Era (498–622)

The second golden era began after the second reign of Kavad I. With the support of the

The second golden era began after the second reign of Kavad I. With the support of the  After the reign of Kavad I, his son

After the reign of Kavad I, his son  The new peace arrangement allowed the two empires to focus on military matters elsewhere: Khosrow focused on the Sassanid Empire's eastern frontier while Maurice restored Byzantine control of the Balkans. Circa 600, the Hephthalites had been raiding the Sassanid Empire as far as

The new peace arrangement allowed the two empires to focus on military matters elsewhere: Khosrow focused on the Sassanid Empire's eastern frontier while Maurice restored Byzantine control of the Balkans. Circa 600, the Hephthalites had been raiding the Sassanid Empire as far as Decline and fall (622–651)

While successful at its first stage (from 602 to 622), the campaign of Khosrau II had actually exhausted the Persian army and treasuries. In an effort to rebuild the national treasuries, Khosrau overtaxed the population. Thus, while his empire was on the verge of total defeat, In response, Khosrau, in coordination with Avar and Slavic forces, launched a siege on the Byzantine capital of Constantinople in 626. The Sassanids, led by Shahrbaraz, attacked the city on the eastern side of the

In response, Khosrau, in coordination with Avar and Slavic forces, launched a siege on the Byzantine capital of Constantinople in 626. The Sassanids, led by Shahrbaraz, attacked the city on the eastern side of the  The impact of Heraclius's victories, the devastation of the richest territories of the Sassanid Empire, and the humiliating destruction of high-profile targets such as Ganzak and Dastagerd fatally undermined Khosrau's prestige and his support among the Persian aristocracy. In early 628, he was overthrown and murdered by his son Kavadh II (628), who immediately brought an end to the war, agreeing to withdraw from all occupied territories. In 629, Heraclius restored the True Cross to Jerusalem in a majestic ceremony. Kavadh died within months, and chaos and civil war followed. Over a period of four years and five successive kings, the Sassanid Empire weakened considerably. The power of the central authority passed into the hands of the generals. It would take several years for a strong king to emerge from a series of coups, and the Sassanids never had time to recover fully.

The impact of Heraclius's victories, the devastation of the richest territories of the Sassanid Empire, and the humiliating destruction of high-profile targets such as Ganzak and Dastagerd fatally undermined Khosrau's prestige and his support among the Persian aristocracy. In early 628, he was overthrown and murdered by his son Kavadh II (628), who immediately brought an end to the war, agreeing to withdraw from all occupied territories. In 629, Heraclius restored the True Cross to Jerusalem in a majestic ceremony. Kavadh died within months, and chaos and civil war followed. Over a period of four years and five successive kings, the Sassanid Empire weakened considerably. The power of the central authority passed into the hands of the generals. It would take several years for a strong king to emerge from a series of coups, and the Sassanids never had time to recover fully.

In early 632, a grandson of Khosrau I, who had lived in hiding in Estakhr, Yazdegerd III, acceded to the throne. The same year, the first raiders from the Arab tribes, newly united by

In early 632, a grandson of Khosrau I, who had lived in hiding in Estakhr, Yazdegerd III, acceded to the throne. The same year, the first raiders from the Arab tribes, newly united by  In 637, a Muslim army under the Caliph

In 637, a Muslim army under the Caliph Descendants

It is believed that the following dynasties and noble families have ancestors among the Sassanian rulers: * The Dabuyid dynasty (642–760) descendant ofGovernment

The Sassanids established an empire roughly within the frontiers achieved by the Parthian Arsacids, with the capital at Ctesiphon in the Asoristan province. In administering this empire, Sassanid rulers took the title of ''shahanshah'' (King of Kings), becoming the central overlords and also assumed guardianship of the sacred fire, the symbol of the national religion. This symbol is explicit on Sassanid coins where the reigning monarch, with his crown and regalia of office, appears on the obverse, backed by the sacred fire, the symbol of the national religion, on the coin's reverse. Sassanid queens had the title ofSasanian military

The active army of the Sassanid Empire originated fromRole of priests

The relationship between priests and warriors was important, because the concept of Ērānshahr had been revived by the priests. Without this relationship, the Sassanid Empire would not have survived in its beginning stages. Because of this relationship between the warriors and the priests, religion and state were considered inseparable in the Zoroastrian religion. However, it is this same relationship that caused the weakening of the Empire, when each group tried to impose their power onto the other. Disagreements between the priests and the warriors led to fragmentation within the empire, which led to its downfall.Infantry

The

The Navy

TheCavalry

The cavalry used during the Sassanid Empire were two types of heavy cavalry units: Clibanarii and Cataphracts. The first cavalry force, composed of elite noblemen trained since youth for military service, was supported by light cavalry, infantry and archers. Mercenaries and tribal people of the empire, including the Turks, Kushans, Sarmatians, Khazars, Georgians, and Armenians were included in these first cavalry units. The second cavalry involved the use of the war elephants. In fact, it was their specialty to deploy elephants as cavalry support.

Unlike the Parthians, the Sassanids developed advanced siege engines. The development of siege weapons was a useful weapon during conflicts with Rome, in which success hinged upon the ability to seize cities and other fortified points; conversely, the Sassanids also developed a number of techniques for defending their own cities from attack. The Sassanid army was much like the preceding Parthian army, although some of the Sassanid's heavy cavalry were equipped with lances, while Parthian armies were heavily equipped with bows. The Roman historian Ammianus Marcellinus's description of Shapur II's clibanarii cavalry manifestly shows how heavily equipped it was, and how only a portion were spear equipped:

Horsemen in the Sassanid cavalry lacked a stirrup. Instead, they used a war saddle which had a cantle at the back and two guard clamps which curved across the top of the rider's thighs. This allowed the horsemen to stay in the saddle at all times during the battle, especially during violent encounters.

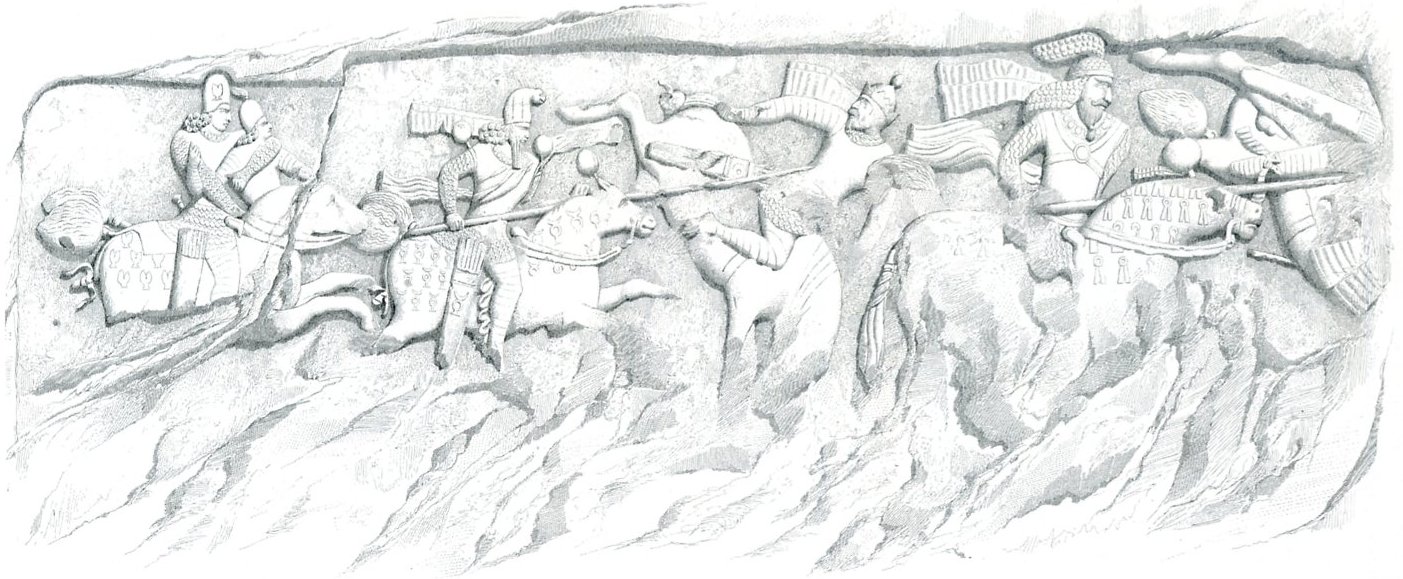

The Byzantine emperor Maurikios also emphasizes in his ''Strategikon'' that many of the Sassanid heavy cavalry did not carry spears, relying on their bows as their primary weapons. However the Taq-i Bustan reliefs and Al-Tabari's famed list of equipment required for dihqan knights which included the lance, provide a contrast. What is certain is that the horseman's paraphernalia was extensive.

The amount of money involved in maintaining a warrior of the Asawaran (Azatan) knightly caste required a small estate, and the Asawaran (Azatan) knightly caste received that from the throne, and in return, were the throne's most notable defenders in time of war.

The cavalry used during the Sassanid Empire were two types of heavy cavalry units: Clibanarii and Cataphracts. The first cavalry force, composed of elite noblemen trained since youth for military service, was supported by light cavalry, infantry and archers. Mercenaries and tribal people of the empire, including the Turks, Kushans, Sarmatians, Khazars, Georgians, and Armenians were included in these first cavalry units. The second cavalry involved the use of the war elephants. In fact, it was their specialty to deploy elephants as cavalry support.

Unlike the Parthians, the Sassanids developed advanced siege engines. The development of siege weapons was a useful weapon during conflicts with Rome, in which success hinged upon the ability to seize cities and other fortified points; conversely, the Sassanids also developed a number of techniques for defending their own cities from attack. The Sassanid army was much like the preceding Parthian army, although some of the Sassanid's heavy cavalry were equipped with lances, while Parthian armies were heavily equipped with bows. The Roman historian Ammianus Marcellinus's description of Shapur II's clibanarii cavalry manifestly shows how heavily equipped it was, and how only a portion were spear equipped:

Horsemen in the Sassanid cavalry lacked a stirrup. Instead, they used a war saddle which had a cantle at the back and two guard clamps which curved across the top of the rider's thighs. This allowed the horsemen to stay in the saddle at all times during the battle, especially during violent encounters.

The Byzantine emperor Maurikios also emphasizes in his ''Strategikon'' that many of the Sassanid heavy cavalry did not carry spears, relying on their bows as their primary weapons. However the Taq-i Bustan reliefs and Al-Tabari's famed list of equipment required for dihqan knights which included the lance, provide a contrast. What is certain is that the horseman's paraphernalia was extensive.

The amount of money involved in maintaining a warrior of the Asawaran (Azatan) knightly caste required a small estate, and the Asawaran (Azatan) knightly caste received that from the throne, and in return, were the throne's most notable defenders in time of war.

Relations with neighboring regimes

Frequent warfare with the Romans and to a lesser extent others

The Sassanids, like the Parthians, were in constant hostilities with the Roman Empire. The Sassanids, who succeeded the Parthians, were recognized as one of the leading world powers alongside its neighboring rival the Byzantine Empire, or Eastern Roman Empire, for a period of more than 400 years. Following the division of the Roman Empire in 395, the Byzantine Empire, with its capital at Constantinople, continued as Persia's principal western enemy, and main enemy in general. Hostilities between the two empires became more frequent. The Sassanids, similar to the Roman Empire, were in a constant state of conflict with neighboring kingdoms and nomadic hordes. Although the threat of nomadic incursions could never be fully resolved, the Sassanids generally dealt much more successfully with these matters than did the Romans, due to their policy of making coordinated campaigns against threatening nomads.

The last of the many and frequent wars with the Byzantines, the climactic

The Sassanids, like the Parthians, were in constant hostilities with the Roman Empire. The Sassanids, who succeeded the Parthians, were recognized as one of the leading world powers alongside its neighboring rival the Byzantine Empire, or Eastern Roman Empire, for a period of more than 400 years. Following the division of the Roman Empire in 395, the Byzantine Empire, with its capital at Constantinople, continued as Persia's principal western enemy, and main enemy in general. Hostilities between the two empires became more frequent. The Sassanids, similar to the Roman Empire, were in a constant state of conflict with neighboring kingdoms and nomadic hordes. Although the threat of nomadic incursions could never be fully resolved, the Sassanids generally dealt much more successfully with these matters than did the Romans, due to their policy of making coordinated campaigns against threatening nomads.

The last of the many and frequent wars with the Byzantines, the climactic  In the north, Khazars and the Western Turkic Khaganate frequently assaulted the northern provinces of the empire. They plundered Media in 634. Shortly thereafter, the Persian army defeated them and drove them out. The Sassanids built numerous fortifications in the Caucasus region to halt these attacks, such as the imposing fortifications built in Derbent (

In the north, Khazars and the Western Turkic Khaganate frequently assaulted the northern provinces of the empire. They plundered Media in 634. Shortly thereafter, the Persian army defeated them and drove them out. The Sassanids built numerous fortifications in the Caucasus region to halt these attacks, such as the imposing fortifications built in Derbent (War with Axum

In 522, before Khosrau's reign, a group of monophysite

In 522, before Khosrau's reign, a group of monophysite Relations with China

Like their predecessors the Parthians, the Sassanid Empire carried out active foreign relations with China, and ambassadors from Persia frequently traveled to China. Chinese documents report on sixteen Sassanid embassies to China from 455 to 555. Commercially, land and sea trade with China was important to both the Sassanid and Chinese Empires. Large numbers of Sassanid coins have been found in southern China, confirming maritime trade. On different occasions, Sassanid kings sent their most talented Persian musicians and dancers to the Chinese imperial court at Luoyang during the Jin and

On different occasions, Sassanid kings sent their most talented Persian musicians and dancers to the Chinese imperial court at Luoyang during the Jin and Relations with India

Following the conquest of Iran and neighboring regions, Shapur I extended his authority northwest of the Indian subcontinent. The previously autonomous

Following the conquest of Iran and neighboring regions, Shapur I extended his authority northwest of the Indian subcontinent. The previously autonomous Society

Urbanism and nomadism

In contrast to Parthian society, the Sassanids renewed emphasis on a

In contrast to Parthian society, the Sassanids renewed emphasis on a Shahanshah

The head of the Sasanian Empire was the '' shahanshah'' (king of kings), also simply known as the ''shah'' (king). His health and welfare was of high importance—accordingly, the phrase "May you be immortal" was used to reply to him. The Sasanian coins which appeared from the 6th-century and afterwards depict a moon and sun, which, in the words of the Iranian historian

The head of the Sasanian Empire was the '' shahanshah'' (king of kings), also simply known as the ''shah'' (king). His health and welfare was of high importance—accordingly, the phrase "May you be immortal" was used to reply to him. The Sasanian coins which appeared from the 6th-century and afterwards depict a moon and sun, which, in the words of the Iranian historian Class division

Sassanid society was immensely complex, with separate systems of social organization governing numerous different groups within the empire.Nicolle, p. 11 Historians believe society comprised fourSlavery

In general, mass slavery was never practiced by the Iranians, and in many cases the situation and lives of semi-slaves (prisoners of war) were, in fact, better than those of the commoner. In Persia, the term "slave" was also used for debtors who had to use some of their time to serve in a fire-temple. The most common slaves in the Sasanian Empire were the household servants, who worked in private estates and at the fire-temples. Usage of a woman slave in a home was common, and her master had outright control over her and could even produce children with her if he wanted to. Slaves also received wages and were able to have their own families whether they were female or male. Harming a slave was considered a crime, and not even the king himself was allowed to do it.K. D. Irani, Morris Silver, ''Social Justice in the Ancient World '', 224 pp., Greenwood Publishing Group, 1995, , (see p.87) The master of a slave was allowed to free the person when he wanted to, which, no matter what faith the slave believed in, was considered a good deed. A slave could also be freed if his/her master died.Culture

Education

There was a major school, called the Grand School, in the capital. In the beginning, only 50 students were allowed to study at the Grand School. In less than 100 years, enrollment at the Grand School was over 30,000 students.Society

On a lower level, Sasanian society was divided into Azatan (freemen). The Azatan formed a large low-aristocracy of low-level administrators, mostly living on small estates. The Azatan provided the cavalry backbone of the Sasanian army.The arts, science and literature

The Sasanian kings were patrons of letters and philosophy. Khosrau I had the works of Plato and Aristotle, translated into Pahlavi, taught at Gundishapur, and read them himself. During his reign, many historical annals were compiled, of which the sole survivor is the

The Sasanian kings were patrons of letters and philosophy. Khosrau I had the works of Plato and Aristotle, translated into Pahlavi, taught at Gundishapur, and read them himself. During his reign, many historical annals were compiled, of which the sole survivor is the Economy

Due to the majority of the inhabitants being of peasant stock, the Sasanian economy relied on farming and agriculture, Khuzestan and Iraq being the most important provinces for it. The Nahravan Canal is one of the greatest examples of Sasanian irrigation systems, and many of these things can still be found in Iran. The mountains of the Sasanian state were used for lumbering by the nomads of the region, and the centralized nature of the Sasanian state allowed it to impose taxes on the nomads and inhabitants of the mountains. During the reign of Khosrau I, further land was brought under centralized administration.Tafazzoli & Khromov, p. 48

Two trade routes were used during the Sasanian period: one in the north, the famous Silk Route, and one less prominent route on the southern Sasanian coast. The factories of

Due to the majority of the inhabitants being of peasant stock, the Sasanian economy relied on farming and agriculture, Khuzestan and Iraq being the most important provinces for it. The Nahravan Canal is one of the greatest examples of Sasanian irrigation systems, and many of these things can still be found in Iran. The mountains of the Sasanian state were used for lumbering by the nomads of the region, and the centralized nature of the Sasanian state allowed it to impose taxes on the nomads and inhabitants of the mountains. During the reign of Khosrau I, further land was brought under centralized administration.Tafazzoli & Khromov, p. 48

Two trade routes were used during the Sasanian period: one in the north, the famous Silk Route, and one less prominent route on the southern Sasanian coast. The factories of Industry and trade

Persian industry under the Sasanians developed from domestic to urban forms. Guilds were numerous. Good roads and bridges, well patrolled, enabled state post and merchant caravans to link Ctesiphon with all provinces; and harbors were built in the Persian Gulf to quicken trade with India. Sasanian merchants ranged far and wide and gradually ousted Romans from the lucrative Indian Ocean trade routes.Nicolle, p. 6 Recent archeological discovery has shown the interesting fact that Sasanians used special labels (commercial labels) on goods as a way of promoting their brands and distinguish between different qualities.

Khosrau I further extended the already vast trade network. The Sasanian state now tended toward monopolistic control of trade, with luxury goods assuming a far greater role in the trade than heretofore, and the great activity in building of ports, caravanserais, bridges and the like, was linked to trade and urbanization. The Persians dominated international trade, both in the Indian Ocean, Central Asia and South Russia, in the time of Khosrau, although competition with the Byzantines was at times intense. Sassanian settlements in Oman and Yemen testify to the importance of trade with India, but the silk trade with China was mainly in the hands of Sasanian vassals and the Iranian people, the Sogdians.

The main exports of the Sasanians were silk; woolen and golden textiles; carpets and rugs; hides; and leather and pearls from the Persian Gulf. There were also goods in transit from China (paper, silk) and India (spices), which Sasanian customs imposed taxes upon, and which were re-exported from the Empire to Europe.

It was also a time of increased metallurgical production, so Iran earned a reputation as the "armory of Asia". Most of the Sasanian mining centers were at the fringes of the Empire – in Armenia, the Caucasus and above all, Transoxania. The extraordinary mineral wealth of the

Persian industry under the Sasanians developed from domestic to urban forms. Guilds were numerous. Good roads and bridges, well patrolled, enabled state post and merchant caravans to link Ctesiphon with all provinces; and harbors were built in the Persian Gulf to quicken trade with India. Sasanian merchants ranged far and wide and gradually ousted Romans from the lucrative Indian Ocean trade routes.Nicolle, p. 6 Recent archeological discovery has shown the interesting fact that Sasanians used special labels (commercial labels) on goods as a way of promoting their brands and distinguish between different qualities.

Khosrau I further extended the already vast trade network. The Sasanian state now tended toward monopolistic control of trade, with luxury goods assuming a far greater role in the trade than heretofore, and the great activity in building of ports, caravanserais, bridges and the like, was linked to trade and urbanization. The Persians dominated international trade, both in the Indian Ocean, Central Asia and South Russia, in the time of Khosrau, although competition with the Byzantines was at times intense. Sassanian settlements in Oman and Yemen testify to the importance of trade with India, but the silk trade with China was mainly in the hands of Sasanian vassals and the Iranian people, the Sogdians.

The main exports of the Sasanians were silk; woolen and golden textiles; carpets and rugs; hides; and leather and pearls from the Persian Gulf. There were also goods in transit from China (paper, silk) and India (spices), which Sasanian customs imposed taxes upon, and which were re-exported from the Empire to Europe.

It was also a time of increased metallurgical production, so Iran earned a reputation as the "armory of Asia". Most of the Sasanian mining centers were at the fringes of the Empire – in Armenia, the Caucasus and above all, Transoxania. The extraordinary mineral wealth of the Religion

Zoroastrianism

Under Parthian rule, Zoroastrianism had fragmented into regional variations which also saw the rise of local cult-deities, some from Iranian religious tradition but others drawn from Greek tradition too. Greek paganism and religious ideas had spread and mixed with Zoroastrianism when Alexander the Great had conquered the

Under Parthian rule, Zoroastrianism had fragmented into regional variations which also saw the rise of local cult-deities, some from Iranian religious tradition but others drawn from Greek tradition too. Greek paganism and religious ideas had spread and mixed with Zoroastrianism when Alexander the Great had conquered the Tansar and his justification for Ardashir I's rebellion

From the very beginning of Sassanid rule in 224, an orthodoxInfluence of Kartir

Zoroastrian calendar reforms under the Sasanians

The Persians had long known of the Egyptian calendar, with its 365 days divided into 12 months. However, the traditional Zoroastrian calendar had 12 months of 30 days each. During the reign ofThree Great Fires

Reflecting the regional rivalry and bias the Sassanids are believed to have held against their

Reflecting the regional rivalry and bias the Sassanids are believed to have held against their Iconoclasm and the elevation of Persian over other Iranian languages

The early Sassanids ruled against the use of cult images in worship, and so statues and idols were removed from many temples and, where possible, sacred fires were installed instead. This policy extended even to the 'non-Iran' regions of the empire during some periods. Hormizd I allegedly destroyed statues erected for the dead in Armenia. However, only cult-statues were removed. The Sassanids continued to use images to represent the deities of Zoroastrianism, including that ofDevelopments in Zoroastrian literature and liturgy by the Sasanians

Some scholars of Zoroastrianism such as Mary Boyce have speculated that it is possible that the '' yasna'' service was lengthened during the Sassanid era "to increase its impressiveness". This appears to have been done by joining the Gathic '' Staota Yesnya'' with the '' haoma'' ceremony. Furthermore, it is believed that another longer service developed, known as the '' Visperad'', which derived from the extended yasna. This was developed for the celebration of the seven holy days of obligation (the '' Of great importance for Zoroastrianism was the creation of the Avestan alphabet by the Sassanids, which enabled the accurate rendering of the Avesta in written form (including in its original language/phonology) for the first time. The alphabet was based on the

Of great importance for Zoroastrianism was the creation of the Avestan alphabet by the Sassanids, which enabled the accurate rendering of the Avesta in written form (including in its original language/phonology) for the first time. The alphabet was based on the ''

Christianity

Christians in the Sasanian Empire belonged mainly to theOther religions

Some of the recent excavations have discovered the Buddhist,Language

Official languages

During the early Sasanian period, Middle Persian along with Koine Greek andRegional languages

Although Middle Persian was the native language of the Sasanians (who, however, were not originally fromLegacy and importance

The influence of the Sasanian Empire continued long after it fell. The empire, through the guidance of several able emperors prior to its fall, had achieved a Persian Culture, Persian renaissance that would become a driving force behind the Islamic world, civilization of the newly established religion ofIn Europe

Sasanian culture and military structure had a significant influence on Culture of ancient Rome, Roman civilization. The structure and character of the Roman army was affected by the methods of Persian warfare. In a modified form, the Roman Imperial autocracy imitated the royal ceremonies of the Sasanian court at Ctesiphon, and those in turn had an influence on the ceremonial traditions of the courts of medieval and modern Europe. The origin of the formalities of European diplomacy is attributed to the diplomatic relations between the Persian governments and the Roman Empire.

Sasanian culture and military structure had a significant influence on Culture of ancient Rome, Roman civilization. The structure and character of the Roman army was affected by the methods of Persian warfare. In a modified form, the Roman Imperial autocracy imitated the royal ceremonies of the Sasanian court at Ctesiphon, and those in turn had an influence on the ceremonial traditions of the courts of medieval and modern Europe. The origin of the formalities of European diplomacy is attributed to the diplomatic relations between the Persian governments and the Roman Empire.

In Jewish history

Important developments in Jewish history are associated with the Sassanian Empire. The Babylonian Talmud was composed between the third and sixth centuries in Sasanian Persia and major Jewish academies of learning were established in Sura (city), Sura and Pumbedita that became cornerstones of Talmudic Academies in Babylonia, Jewish scholarship. Several individuals of the Imperial family such as Ifra Hormizd the Queen mother of Shapur II and QueenIn India

The collapse of the Sasanian Empire led to Islam slowly replacing Zoroastrianism as the primary religion of Iran. A large number of Zoroastrians chose to emigrate to escape Islamic persecution. According to the ''Qissa-i Sanjan'', one group of those refugees landed in what is now Gujarat, India, where they were allowed greater freedom to observe their old customs and to preserve their faith. The descendants of those Zoroastrians would play a small but significant role in the development of India. Today there are over 70,000 Zoroastrians in India.

The Zoroastrians still use a variant of the religious calendar instituted under the Sasanians. That calendar still marks the number of years since the accession of Yazdegerd III, just as it did in 632.

The collapse of the Sasanian Empire led to Islam slowly replacing Zoroastrianism as the primary religion of Iran. A large number of Zoroastrians chose to emigrate to escape Islamic persecution. According to the ''Qissa-i Sanjan'', one group of those refugees landed in what is now Gujarat, India, where they were allowed greater freedom to observe their old customs and to preserve their faith. The descendants of those Zoroastrians would play a small but significant role in the development of India. Today there are over 70,000 Zoroastrians in India.

The Zoroastrians still use a variant of the religious calendar instituted under the Sasanians. That calendar still marks the number of years since the accession of Yazdegerd III, just as it did in 632.

Chronology

*224–241: Reign of

*224–241: Reign of Byzantine Empire received Amida (Mesopotamia), Amida for 1,000 pounds of gold. *526–532: War with the Byzantine Empire. Treaty of Eternal Peace (532), Eternal Peace: The Sasanian Empire keeps Iberia and the Byzantine Empire receives Lazica and Persarmenia;John W Barker, ''Justinian and the later Roman Empire'', 118. the Byzantine Empire pays tribute 11,000 lbs gold/year. *531–579: Reign of Khosrau I, "with the immortal soul" (Anushirvan). *541–562: War with the Byzantine Empire. *572–591: War with the Byzantine Empire. *580: The Sasanians under Hormizd IV abolish the monarchy of the Kingdom of Iberia (antiquity), Kingdom of Iberia. Direct control through Sasanian Iberia, Sasanian-appointed governors starts. *590: Rebellion of Bahram Chobin and other Sasanian nobles, Khosrau II overthrows Hormizd IV but loses the throne to Bahram Chobin. *591: Khosrau II regains the throne with help from the Byzantine Empire and cedes Persian Armenia and the western half of Iberia to the Byzantine Empire. *593: Attempted usurpation of Hormizd V *595–602: Rebellion of Vistahm *603–628: War with the Byzantine Empire. Persia occupies Byzantine Mesopotamia, Anatolia, Syria, Palestine, Egypt and the Transcaucasus, before being driven to withdraw to pre-war frontiers by Byzantine counter-offensive *610: Arabs defeat a Sasanian army at Battle of Thi Qar, Dhu-Qar *626: Unsuccessful siege of Constantinople by Avars, Persians, and Slavs. *627: Byzantine Emperor

See also

* List of Sasanian revolts and civil wars * List of Zoroastrian states and dynasties * Military of the Sasanian Empire * Romans in Persia * Sasanian art * Sasanian family tree * Sasanian music * Women in the Sasanian EmpireNotes

References

Bibliography

* G. Reza Garosi (2012): ''The Colossal Statue of Shapur I in the Context of Sasanian Sculptures''. Publisher: Persian Heritage Foundation, New York. * G. Reza Garosi (2009), ''Die Kolossal-Statue Šāpūrs I. im Kontext der sasanidischen Plastik''. Verlag Philipp von Zabern, Mainz, Germany. * * * * Börm, Henning (2008)"Das Königtum der Sasaniden – Strukturen und Probleme. Bemerkungen aus althistorischer Sicht."

''Klio'' 90, pp. 423ff. * Börm, Henning (2010)

"Herrscher und Eliten in der Spätantike."

In: Henning Börm, Josef Wiesehöfer (eds.): ''Commutatio et contentio. Studies in the Late Roman, Sasanian, and Early Islamic Near East''. Düsseldorf: Wellem, pp. 159ff. * Börm, Henning (2016).

A Threat or a Blessing? The Sasanians and the Roman Empire

. In: Carsten Binder, Henning Börm, Andreas Luther (eds.): ''Diwan. Studies in the History and Culture of the Ancient Near East and the Eastern Mediterranean''. Duisburg: Wellem, pp. 615ff. * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * Howard-Johnston, James: "The Sasanian's Strategic Dilemma". In: Henning Börm - Josef Wiesehöfer (eds.), ''Commutatio et contentio. Studies in the Late Roman, Sasanian, and Early Islamic Near East'', Wellem Verlag, Düsseldorf 2010, pp. 37–70. * * * * * * * * * * * Rawlinson, George, ''The Seven Great Monarchies of the Ancient Eastern World: The Seventh Monarchy: History of the Sassanian or New Persian Empire'', IndyPublish.com, 2005 [1884]. * Ali Akbar Sarfaraz, Sarfaraz, Ali Akbar, and Bahman Firuzmandi, ''Mad, Hakhamanishi, Ashkani, Sasani'', Marlik, 1996. * * * Parviz Marzban, ''Kholaseh Tarikhe Honar'', Elmiv Farhangi, 2001. * * * * * * * * * * * Stokvis A.M.H.J., Manuel d'Histoire, de Généalogie et de Chronologie de tous les Etats du Globe depuis les temps les plus reculés jusqu'à nos jours, Leiden, 1888–1893 (ré-édition en 1966 par B.M.Israel) * * * Wiesehöfer, Josef: ''The Late Sasanian Near East''. In: Chase Robinson (ed.), ''The New Cambridge History of Islam'' vol. 1. Cambridge 2010, pp. 98–152. * Yarshater, Ehsan: ''The Cambridge History of Iran'' vol. 3 p. 1 Cambridge 1983, pp. 568–592. * *

Further reading

* * Michael H. Dodgeon, Samuel N. C. Lieu. ''The Roman Eastern frontier and the Persian Wars (AD 226–363). Part 1''. Routledge. London, 1994 * * Labourt, J. ''Le Christianisme dans l'empire Perse, sous la Dynastie Sassanide (224–632).'' Paris: Librairie Victor Lecoffre, 1904. * * (Original from the Bavarian State Library) * (Original from the New York Public Library)External links

Sasanika: the History and Culture of Sasanians

* ''Sasanian rock reliefs'', Photos from Iran

.

entry in the Encyclopædia Iranica

The Sassanians

The Sassanians by Iraj Bashiri, University of Minnesota.

The Art of Sassanians, on Iran Chamber Society

ECAI.org ''The Near East in Late Antiquity: The Sasanian Empire''

Google Books on Roman Eastern Frontier (part 1)

A Review of Sassanid Images and Inscriptions, on Iran Chamber Society

Sassanid textile

''The continuation of Sassanid Art''

Ctesiphon; The capital of the Parthian and the Sassanid empires, on Iran Chamber Society

Islamic Conquest of Persia

Pirooz in China, By Frank Wong

The Sassanian Empire

BBC – BBC Radio 4, Radio 4 ''In Our Time (BBC Radio 4), In Our Time'' programme (available as .ram file)

The Sassanian Empire: Further Reading

History of Iran on Iran Chamber Society

Christianity in Ancient Iran: Aba & The Church in Persia, on Iran Chamber Society

iranchamber.com

{{authority control Sasanian Empire, Superpowers Ancient history of Iraq Medieval Iraq Ancient Anatolia States in medieval Anatolia History of Abkhazia History of Dagestan Ancient history of Georgia (country) Medieval Georgia (country) Ancient history of Afghanistan Ancient history of Pakistan History of Central Asia Ancient Syria History of the Levant Empires and kingdoms of Iran Ancient Armenia 6th century in Armenia 7th century in Armenia Ancient history of Azerbaijan 224 establishments 651 disestablishments Countries in ancient Africa Former empires States and territories established in the 220s