Sappho Lesvou F.C. on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Sappho (; el, Σαπφώ ''Sapphō'' ;

Sappho (; el, Σαπφώ ''Sapphō'' ;

Sappho was said to have three brothers: Erigyius, Larichus, and Charaxus. According to

Sappho was said to have three brothers: Erigyius, Larichus, and Charaxus. According to

Sappho probably wrote around 10,000 lines of poetry; today, only about 650 survive. She is best known for her

Sappho probably wrote around 10,000 lines of poetry; today, only about 650 survive. She is best known for her

In antiquity, Sappho's poetry was highly admired, and several ancient sources refer to her as the "tenth Muse". The earliest surviving poem to do so is a third-century BC epigram by

In antiquity, Sappho's poetry was highly admired, and several ancient sources refer to her as the "tenth Muse". The earliest surviving poem to do so is a third-century BC epigram by

By the medieval period, Sappho's works had been lost, though she was still quoted in later authors. Her work became more accessible in the sixteenth century through printed editions of those authors who had quoted her. In 1508

By the medieval period, Sappho's works had been lost, though she was still quoted in later authors. Her work became more accessible in the sixteenth century through printed editions of those authors who had quoted her. In 1508  It was not long after the rediscovery of Sappho that her sexuality once again became the focus of critical attention. In the early seventeenth century,

It was not long after the rediscovery of Sappho that her sexuality once again became the focus of critical attention. In the early seventeenth century,

The Digital Sappho

Commentaries on Sappho's fragments

William Annis.

Fragments of Sappho

translated by Gregory Nagy and Julia Dubnoff

Sappho

Sappho

BBC Radio 4, ''Great Lives''. * *

Ancient Greek literature recitations

hosted by the Society for the Oral Reading of Greek and Latin Literature. Including a recording of Sappho 1 by Stephen Daitz. {{Authority control 7th-century BC births 7th-century BC women poets 7th-century BC Greek people 7th-century BC poets 6th-century BC Greek people 6th-century BC poets 6th-century BC women writers Aeolic Greek poets Ancient Eresians Ancient Greek erotic poets Nine Lyric Poets Poets from ancient Lesbos Greek women composers Ancient Greek women poets Ancient Mytileneans 7th-century BC Greek women 6th-century BC Greek women Ancient LGBT people

Sappho (; el, Σαπφώ ''Sapphō'' ;

Sappho (; el, Σαπφώ ''Sapphō'' ; Aeolic Greek

In linguistics, Aeolic Greek (), also known as Aeolian (), Lesbian or Lesbic dialect, is the set of dialects of Ancient Greek spoken mainly in Boeotia; in Thessaly; in the Aegean island of Lesbos; and in the Greek colonies of Aeolis in Anatolia ...

''Psápphō''; c. 630 – c. 570 BC) was an Archaic Greek

Archaic Greece was the period in Greek history lasting from circa 800 BC to the second Persian invasion of Greece in 480 BC, following the Greek Dark Ages and succeeded by the Classical period. In the archaic period, Greeks settled across the M ...

poet from Eresos

Eresos (; el, Ερεσός; grc, Ἔρεσος) and its twin beach village Skala Eresou are located in the southwest part of the Greek island of Lesbos. They are villages visited by considerable numbers of tourists. From 1999 until 2010, Ereso ...

or Mytilene

Mytilene (; el, Μυτιλήνη, Mytilíni ; tr, Midilli) is the capital of the Greek island of Lesbos, and its port. It is also the capital and administrative center of the North Aegean Region, and hosts the headquarters of the University of ...

on the island of Lesbos

Lesbos or Lesvos ( el, Λέσβος, Lésvos ) is a Greek island located in the northeastern Aegean Sea. It has an area of with approximately of coastline, making it the third largest island in Greece. It is separated from Anatolia, Asia Minor ...

. Sappho is known for her lyric poetry

Modern lyric poetry is a formal type of poetry which expresses personal emotions or feelings, typically spoken in the first person.

It is not equivalent to song lyrics, though song lyrics are often in the lyric mode, and it is also ''not'' equi ...

, written to be sung while accompanied by music. In ancient times, Sappho was widely regarded as one of the greatest lyric poets and was given names such as the "Tenth Muse" and "The Poetess". Most of Sappho's poetry is now lost, and what is extant has mostly survived in fragmentary form; only the "Ode to Aphrodite

The Ode to Aphrodite (or Sappho fragment 1) is a lyric poem by the archaic Greek poet Sappho, who wrote in the late seventh and early sixth centuries BCE, in which the speaker calls on the help of Aphrodite in the pursuit of a beloved. The poem ...

" is certainly complete. As well as lyric poetry, ancient commentators claimed that Sappho wrote elegiac and iambic poetry. Three epigrams attributed to Sappho are extant, but these are actually Hellenistic

In Classical antiquity, the Hellenistic period covers the time in Mediterranean history after Classical Greece, between the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC and the emergence of the Roman Empire, as signified by the Battle of Actium in ...

imitations of Sappho's style.

Little is known of Sappho's life. She was from a wealthy family from Lesbos, though her parents' names are uncertain. Ancient sources say that she had three brothers; Charaxos (Χάραξος), Larichos (Λάριχος) and Eurygios (Εὐρύγιος). Two of them, Charaxos and Larichos, are also mentioned in the Brothers Poem

The Brothers Poem or Brothers Song is a series of lines of verse attributed to the Archaic Greece, archaic Greek poet Sappho ( – ), which had been lost since antiquity until being rediscovered in 2014. Most of its text, apart from its opening ...

discovered in 2014. She was exiled to Sicily around 600 BC, and may have continued to work until around 570 BC. According to legend, she killed herself by leaping from the Leucadian cliffs due to her love for the ferryman Phaon

In Greek mythology, Phaon (Ancient Greek: Φάων; ''gen''.: Φάωνος) was a mythical boatman of Mytilene in Lesbos

Lesbos or Lesvos ( el, Λέσβος, Lésvos ) is a Greek island located in the northeastern Aegean Sea. It has an area of ...

.

Sappho was a prolific poet, probably composing around 10,000 lines. Her poetry was well-known and greatly admired through much of antiquity, and she was among the canon of Nine Lyric Poets

The Nine Lyric or Melic Poets were a canonical group of ancient Greek poets esteemed by the scholars of Hellenistic Alexandria as worthy of critical study. In the Palatine Anthology it is said that they established lyric song.

They were:

*Alcman o ...

most highly esteemed by scholars of Hellenistic

In Classical antiquity, the Hellenistic period covers the time in Mediterranean history after Classical Greece, between the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC and the emergence of the Roman Empire, as signified by the Battle of Actium in ...

Alexandria. Sappho's poetry is still considered extraordinary and her works continue to influence other writers. Beyond her poetry, she is well known as a symbol of love and desire between women, with the English words '' sapphic'' and ''lesbian

A lesbian is a Homosexuality, homosexual woman.Zimmerman, p. 453. The word is also used for women in relation to their sexual identity or sexual behavior, regardless of sexual orientation, or as an adjective to characterize or associate n ...

'' deriving from her name and that of her home island respectively.

Ancient sources

Modern knowledge of Sappho comes both from what can be inferred from her own poetry, and from mentions of her in other ancient texts. Sappho's own poetry is the only contemporary source for her life. The earliest surviving biography of Sappho dates to the late second or early third century AD, approximately eight centuries after Sappho's own life; the next is the ''Suda'', a Byzantine-era encyclopedia. Other sources which mention details of Sappho's life were written much closer to her own era, beginning in the fifth century BC. The information about Sappho's life recorded in ancient sources was derived from statements in her own poetry which ancient authors assumed were biographical, along with local traditions. Some of the ancient traditions about Sappho, such as those about her sexuality and appearance, may derive from comedy. Until the nineteenth century, ancient sources about archaic poets' lives were largely accepted uncritically. In the nineteenth century classicists began to be more sceptical of these traditions, and instead tried to derive biographical information from their surviving poetry. In the latter half of the twentieth century, scholars became increasingly sceptical of Greek lyric poetry as a source of autobiographical information. Some scholars, such asMary Lefkowitz

Mary R. Lefkowitz (born April 30, 1935) is an American scholar of Classics. She is the Professor Emerita of Classical Studies at Wellesley College in Wellesley, Massachusetts, where she previously worked from 1959 to 2005. She has published ten b ...

, argued that almost nothing can be known about the lives of early Greek poets such as Sappho; most scholars believe that ancient testimonies about poets' lives contain some truth but must be treated with caution.

Life

Little is known about Sappho's life for certain. She was from the island of Lesbos and lived at the end of the seventh and beginning of the sixth centuries BC. This is the date given by most ancient sources, who considered her a contemporary of Alcaeus andPittacus

Pittacus (; grc-gre, Πιττακός; 640 – 568 BC) was an ancient Mytilenean military general and one of the Seven Sages of Greece.

Biography

Pittacus was a native of Mytilene and son of Hyrradius. He became a Mytilenaean general who, with ...

. She therefore may have been born in the third quarter of the seventh century – Franco Ferrari infers a date of around 650 or 640 BC; David Campbell suggests around or before 630 BC. Gregory Hutchinson suggests she was active until around 570 BC.

Tradition names her mother as Cleïs. This may derive from a now-lost poem or record, though ancient scholars may simply have guessed this name, assuming that Sappho's daughter Cleïs was named after her. Sappho's father's name is less certain. Ten names are known for Sappho's father from ancient sources; this proliferation of possible names suggests that he was not explicitly named in any of Sappho's poetry. The earliest and most commonly attested name for Sappho's father is Scamandronymus. In Ovid's ''Heroides

The ''Heroides'' (''The Heroines''), or ''Epistulae Heroidum'' (''Letters of Heroines''), is a collection of fifteen epistolary

Epistolary means "in the form of a letter or letters", and may refer to:

* Epistolary ( la, epistolarium), a Christi ...

'', Sappho's father died when she was seven. He is not mentioned in any of her surviving works, but Campbell suggests that this detail may have been based on a now-lost poem. Sappho's own name is found in numerous variant spellings; the form that appears in her own extant poetry is Psappho (Ψάπφω).

Sappho was said to have three brothers: Erigyius, Larichus, and Charaxus. According to

Sappho was said to have three brothers: Erigyius, Larichus, and Charaxus. According to Athenaeus

Athenaeus of Naucratis (; grc, Ἀθήναιος ὁ Nαυκρατίτης or Nαυκράτιος, ''Athēnaios Naukratitēs'' or ''Naukratios''; la, Athenaeus Naucratita) was a Greek rhetorician and grammarian, flourishing about the end of th ...

, she often praised Larichus for pouring wine in the town hall of Mytilene, an office held by boys of the best families. This indication that Sappho was born into an aristocratic family is consistent with the sometimes rarefied environments that her verses record. One ancient tradition tells of a relation between Charaxus and the Egyptian courtesan Rhodopis

"Rhodopis" ( grc-gre, Ῥοδῶπις ) is an ancient tale about a Greek slave girl who marries the king of Egypt. The story was first recorded by the Greek historian Strabo in the late first century BC or early first century AD and is considere ...

. Herodotus, the oldest source of the story, reports that Charaxus ransomed Rhodopis for a large sum and that Sappho wrote a poem rebuking him for this. The names of two of the brothers, Charaxus and Larichus, are mentioned in the Brothers Poem

The Brothers Poem or Brothers Song is a series of lines of verse attributed to the Archaic Greece, archaic Greek poet Sappho ( – ), which had been lost since antiquity until being rediscovered in 2014. Most of its text, apart from its opening ...

, discovered in 2014; the final brother, Erigyius, is mentioned in three ancient sources but nowhere in the extant works of Sappho.

She may have had a daughter named Cleïs, who is referred to in two fragments. Not all scholars accept that Cleïs was Sappho's daughter. Fragment 132 describes Cleïs as "παῖς" (''pais''), which, as well as meaning "child", can also refer to the "youthful beloved in a male homosexual liaison". It has been suggested that Cleïs was one of Sappho's younger lovers, rather than her daughter, though Judith Hallett argues that the language used in fragment 132 suggests that Sappho was referring to Cleïs as her daughter.

According to the Suda

The ''Suda'' or ''Souda'' (; grc-x-medieval, Σοῦδα, Soûda; la, Suidae Lexicon) is a large 10th-century Byzantine encyclopedia of the ancient Mediterranean world, formerly attributed to an author called Soudas (Σούδας) or Souidas ...

, Sappho was married to Kerkylas of Andros

Andros ( el, Άνδρος, ) is the northernmost island of the Greek Cyclades archipelago, about southeast of Euboea, and about north of Tinos. It is nearly long, and its greatest breadth is . It is for the most part mountainous, with many fr ...

. This name appears to have been invented by a comic poet: the name "Kerkylas" () appears to be a diminutive of the word (), a possible meaning of which is "penis", and is not otherwise attested as a name, while "Andros", as well as being the name of a Greek island, is a form of the Greek word (), which means "man". Thus, the name may be a joke. An English equivalent would be that Sappho was married to "Dick-Allcock from the Isle of Man".

One tradition said that Sappho was exiled from Lesbos around 600 BC. The Parian Chronicle

The Parian Chronicle or Parian Marble ( la, Marmor Parium, Mar. Par.) is a Greek chronology, covering the years from 1582 BC to 299 BC, inscribed on a stele. Found on the island of Paros in two sections, and sold in Smyrna in the early 17 ...

records Sappho going into exile in Sicily some time between 604 and 595, perhaps coinciding with Pittacus

Pittacus (; grc-gre, Πιττακός; 640 – 568 BC) was an ancient Mytilenean military general and one of the Seven Sages of Greece.

Biography

Pittacus was a native of Mytilene and son of Hyrradius. He became a Mytilenaean general who, with ...

taking power in 597. This may have been as a result of her family's involvement with the conflicts between political elites on Lesbos in this period, the same reason for the exile of Sappho's contemporary Alcaeus from Mytilene around the same time.

A tradition going back at least to Menander

Menander (; grc-gre, Μένανδρος ''Menandros''; c. 342/41 – c. 290 BC) was a Greek dramatist and the best-known representative of Athenian New Comedy. He wrote 108 comedies and took the prize at the Lenaia festival eight times. His rec ...

(Fr. 258 K) suggested that Sappho killed herself by jumping off the Leucadian cliffs for love of Phaon

In Greek mythology, Phaon (Ancient Greek: Φάων; ''gen''.: Φάωνος) was a mythical boatman of Mytilene in Lesbos

Lesbos or Lesvos ( el, Λέσβος, Lésvos ) is a Greek island located in the northeastern Aegean Sea. It has an area of ...

, a ferryman. This is regarded as ahistorical by modern scholars, perhaps invented by the comic poets or originating from a misreading of a first-person reference in a non-biographical poem. The legend may have resulted in part from a desire to assert Sappho as heterosexual.

Works

Sappho probably wrote around 10,000 lines of poetry; today, only about 650 survive. She is best known for her

Sappho probably wrote around 10,000 lines of poetry; today, only about 650 survive. She is best known for her lyric poetry

Modern lyric poetry is a formal type of poetry which expresses personal emotions or feelings, typically spoken in the first person.

It is not equivalent to song lyrics, though song lyrics are often in the lyric mode, and it is also ''not'' equi ...

, written to be accompanied by music. The Suda also attributes to Sappho epigrams

An epigram is a brief, interesting, memorable, and sometimes surprising or satirical statement. The word is derived from the Greek "inscription" from "to write on, to inscribe", and the literary device has been employed for over two millen ...

, elegiacs The adjective ''elegiac'' has two possible meanings. First, it can refer to something of, relating to, or involving, an elegy or something that expresses similar mournfulness or sorrow. Second, it can refer more specifically to poetry composed in ...

, and iambics; three of these epigrams are extant, but are in fact later Hellenistic poems inspired by Sappho. The iambic and elegiac poems attributed to her in the Suda may also be later imitations. Ancient authors claim that Sappho primarily wrote love poetry, and the indirect transmission of Sappho's work supports this notion. However, the papyrus tradition suggests that this may not have been the case: a series of papyri published in 2014 contains fragments of ten consecutive poems from Book I of the Alexandrian edition of Sappho, of which only two are certainly love poems, while at least three and possibly four are primarily concerned with family.

Ancient editions

Sappho's poetry was probably first written down on Lesbos, either in her lifetime or shortly afterwards, initially probably in the form of a score for performers of her work. In the fifth century BC, Athenian book publishers probably began to produce copies of Lesbian lyric poetry, some including explanatory material and glosses as well as the poems themselves. Some time in the second or third century, Alexandrian scholars produced a critical edition of Sappho's poetry. There may have been more than one Alexandrian edition –John J. Winkler

John Jack Winkler (11 August 1943, in St. Louis – 26 April 1990, in Stanford, California) was an American philologist and Benedictine monk.

Winkler studied classical studies at Saint Louis University from 1960 to 1963 and then went to England, ...

argues for two, one edited by Aristophanes of Byzantium

__NOTOC__

Aristophanes of Byzantium ( grc-gre, Ἀριστοφάνης ὁ Βυζάντιος ; BC) was a Hellenistic Greek scholar, critic and grammarian, particularly renowned for his work in Homeric scholarship, but also for work on other ...

and another by his pupil Aristarchus of Samothrace

Aristarchus of Samothrace ( grc-gre, Ἀρίσταρχος ὁ Σαμόθραξ ''Aristarchos o Samothrax''; c. 220 – c. 143 BC) was an ancient Greek grammarian, noted as the most influential of all scholars of Homeric poetry. He was the h ...

. This is not certain – ancient sources tell us that Aristarchus' edition of Alcaeus replaced the edition by Aristophanes, but are silent on whether Sappho's work also went through multiple editions.

The Alexandrian edition of Sappho's poetry was based on the existing Athenian collections, and was divided into at least eight books, though the exact number is uncertain. Many modern scholars have followed Denys Page, who conjectured a ninth book in the standard edition; Yatromanolakis doubts this, noting that though ancient sources refer to an eighth book of Sappho's poetry, none mention a ninth. The Alexandrian edition of Sappho probably grouped her poems by their metre: ancient sources tell us that each of the first three books contained poems in a single specific metre. Ancient editions of Sappho, possibly starting with the Alexandrian edition, seem to have ordered the poems in at least the first book of Sappho's poetry – which contained works composed in Sapphic stanza

The Sapphic stanza, named after Sappho, is an Aeolic verse form of four lines. Originally composed in quantitative verse and unrhymed, since the Middle Ages imitations of the form typically feature rhyme and accentual prosody. It is "the longest ...

s – alphabetically.

Even after the publication of the standard Alexandrian edition, Sappho's poetry continued to circulate in other poetry collections. For instance, the Cologne Papyrus on which the Tithonus poem

The Tithonus poem, also known as the old age poem or (with fragments of another poem by Sappho discovered at the same time) the New Sappho, is a poem by the archaic Greek poet Sappho. It is part of fragment 58 in Eva-Maria Voigt's edition of ...

is preserved was part of a Hellenistic anthology of poetry, which contained poetry arranged by theme, rather than by metre and incipit, as it was in the Alexandrian edition.

Surviving poetry

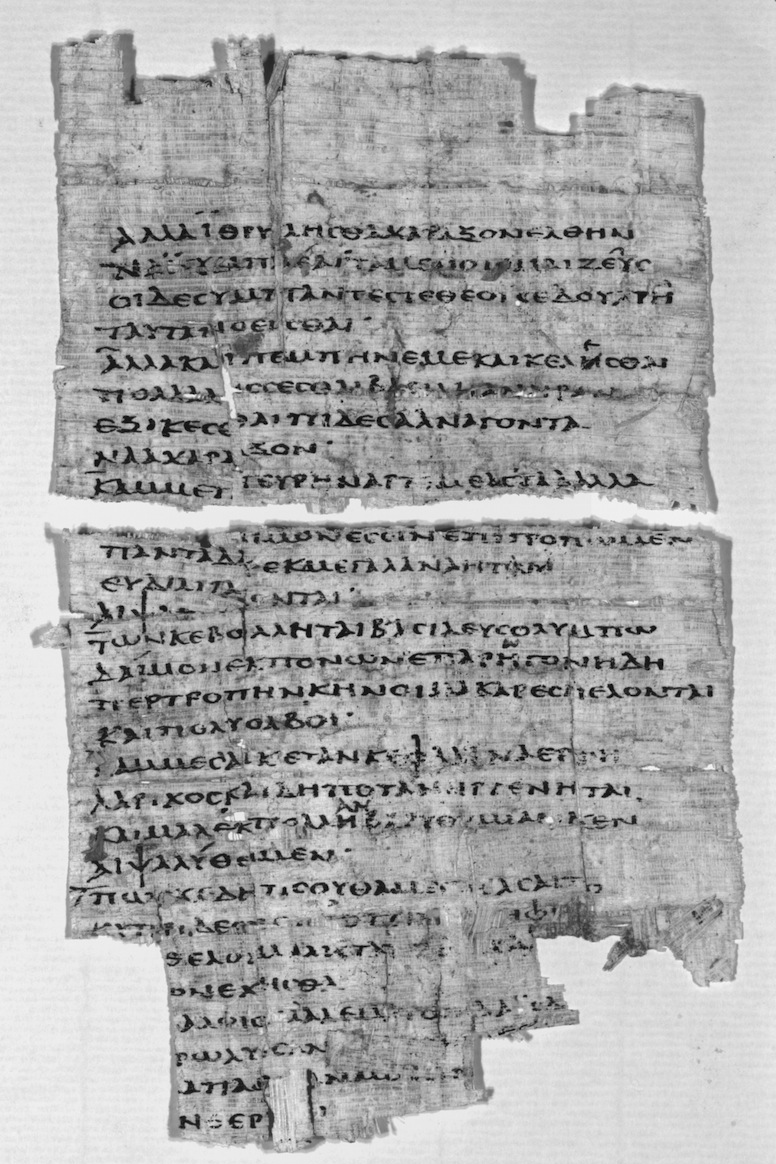

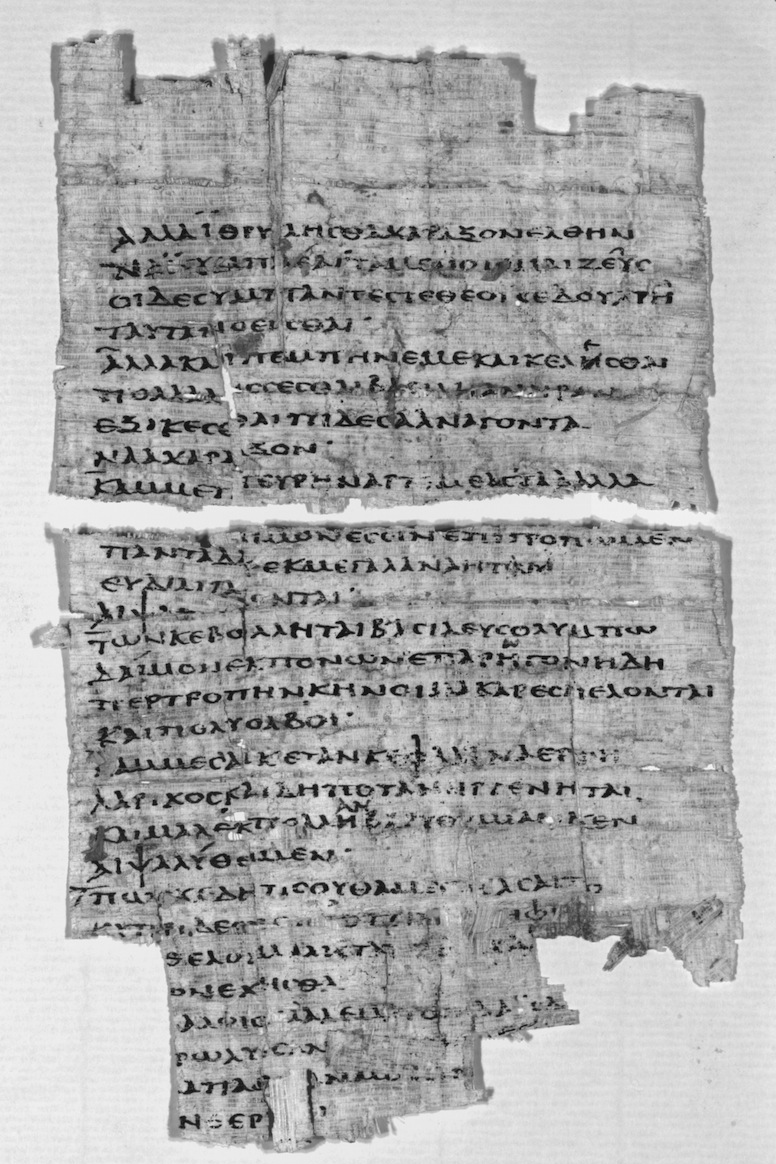

The earliest surviving manuscripts of Sappho, including the potsherd on which fragment 2 is preserved, date to the third century BC, and thus might predate the Alexandrian edition. The latest surviving copies of Sappho's poems transmitted directly from ancient times are written on parchmentcodex

The codex (plural codices ) was the historical ancestor of the modern book. Instead of being composed of sheets of paper, it used sheets of vellum, papyrus, or other materials. The term ''codex'' is often used for ancient manuscript books, with ...

pages from the sixth and seventh centuries AD, and were surely reproduced from ancient papyri now lost. Manuscript copies of Sappho's works may have survived a few centuries longer, but around the 9th century her poetry appears to have disappeared, and by the twelfth century, John Tzetzes

John Tzetzes ( grc-gre, Ἰωάννης Τζέτζης, Iōánnēs Tzétzēs; c. 1110, Constantinople – 1180, Constantinople) was a Byzantine poet and grammarian who is known to have lived at Constantinople in the 12th century.

He was able to p ...

could write that "the passage of time has destroyed Sappho and her works".

According to legend, Sappho's poetry was lost because the church disapproved of her morals. These legends appear to have originated in the Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) , from , with the same meanings. is a period in European history marking the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and covering the 15th and 16th centuries, characterized by an effort to revive and surpass ideas ...

– around 1550, Jerome Cardan

Gerolamo Cardano (; also Girolamo or Geronimo; french: link=no, Jérôme Cardan; la, Hieronymus Cardanus; 24 September 1501– 21 September 1576) was an Italian polymath, whose interests and proficiencies ranged through those of mathematician, ...

wrote that Gregory Nazianzen

Gregory of Nazianzus ( el, Γρηγόριος ὁ Ναζιανζηνός, ''Grēgorios ho Nazianzēnos''; ''Liturgy of the Hours'' Volume I, Proper of Saints, 2 January. – 25 January 390,), also known as Gregory the Theologian or Gregory N ...

had Sappho's work publicly destroyed, and at the end of the sixteenth century Joseph Justus Scaliger

Joseph Justus Scaliger (; 5 August 1540 – 21 January 1609) was a French Calvinist religious leader and scholar, known for expanding the notion of classical history from Greek and Ancient Roman history to include Persian, Babylonian, Jewish an ...

claimed that Sappho's works were burned in Rome and Constantinople in 1073 on the orders of Pope Gregory VII

Pope Gregory VII ( la, Gregorius VII; 1015 – 25 May 1085), born Hildebrand of Sovana ( it, Ildebrando di Soana), was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 22 April 1073 to his death in 1085. He is venerated as a saint ...

.

In reality, Sappho's work was probably lost as the demand for it was insufficiently great for it to be copied onto parchment when codices superseded papyrus scrolls as the predominant form of book. A contributing factor to the loss of Sappho's poems may have been her Aeolic dialect

In linguistics, Aeolic Greek (), also known as Aeolian (), Lesbian or Lesbic dialect, is the set of dialects of Ancient Greek spoken mainly in Boeotia; in Thessaly; in the Aegean island of Lesbos; and in the Greek colonies of Aeolis in Anatolia ...

, considered provincial in a period where the Attic dialect

Attic Greek is the Greek dialect of the ancient region of Attica, including the ''polis'' of Athens. Often called classical Greek, it was the prestige dialect of the Greek world for centuries and remains the standard form of the language that is ...

was seen as the true classical Greek, and had become the standard for literary compositions. Consequently, many readers found Sappho's dialect difficult to understand: in the second century AD, the Roman author Apuleius

Apuleius (; also called Lucius Apuleius Madaurensis; c. 124 – after 170) was a Numidian Latin-language prose writer, Platonist philosopher and rhetorician. He lived in the Roman province of Numidia, in the Berber city of Madauros, modern-day ...

specifically remarks on its "strangeness", and several commentaries on the subject demonstrate the difficulties that readers had with it. This was part of a more general decline in interest in the archaic poets; indeed, the surviving papyri suggest that Sappho's poetry survived longer than that of her contemporaries such as Alcaeus.

Only approximately 650 lines of Sappho's poetry still survive, of which just one poem – the "Ode to Aphrodite" – is complete, and more than half of the original lines survive in around ten more fragments. Many of the surviving fragments of Sappho contain only a single word – for example, fragment 169A is simply a word meaning "wedding gifts", and survives as part of a dictionary of rare words. The two major sources of surviving fragments of Sappho are quotations in other ancient works, from a whole poem to as little as a single word, and fragments of papyrus, many of which were discovered at Oxyrhynchus

Oxyrhynchus (; grc-gre, Ὀξύρρυγχος, Oxýrrhynchos, sharp-nosed; ancient Egyptian ''Pr-Medjed''; cop, or , ''Pemdje''; ar, البهنسا, ''Al-Bahnasa'') is a city in Middle Egypt located about 160 km south-southwest of Cairo ...

in Egypt. Other fragments survive on other materials, including parchment and potsherds. The oldest surviving fragment of Sappho currently known is the Cologne papyrus which contains the Tithonus poem, dating to the third century BC.

Until the last quarter of the nineteenth century, only the ancient quotations of Sappho survived. In 1879, the first new discovery of a fragment of Sappho was made at Fayum

Faiyum ( ar, الفيوم ' , borrowed from cop, ̀Ⲫⲓⲟⲙ or Ⲫⲓⲱⲙ ' from egy, pꜣ ym "the Sea, Lake") is a city in Middle Egypt. Located southwest of Cairo, in the Faiyum Oasis, it is the capital of the modern Faiyum ...

. By the end of the nineteenth century, Grenfell and Hunt

Hunting is the human practice of seeking, pursuing, capturing, or killing wildlife or feral animals. The most common reasons for humans to hunt are to harvest food (i.e. meat) and useful animal products (fur/ hide, bone/tusks, horn/antler, e ...

had begun to excavate an ancient rubbish dump at Oxyrhynchus, leading to the discoveries of many previously unknown fragments of Sappho. Fragments of Sappho continue to be rediscovered. Most recently, major discoveries in 2004 (the "Tithonus poem" and a new, previously unknown fragment) and 2014 (fragments of nine poems: five already known but with new readings, four, including the "Brothers Poem

The Brothers Poem or Brothers Song is a series of lines of verse attributed to the Archaic Greece, archaic Greek poet Sappho ( – ), which had been lost since antiquity until being rediscovered in 2014. Most of its text, apart from its opening ...

", not previously known) have been reported in the media around the world.

Style

Sappho worked within a well-developed tradition of Lesbian poetry, which had evolved its own poetic diction, metres, and conventions. Prior to Sappho and her contemporary Alcaeus, Lesbos was associated with poetry and music through the mythicalOrpheus

Orpheus (; Ancient Greek: Ὀρφεύς, classical pronunciation: ; french: Orphée) is a Thracian bard, legendary musician and prophet in ancient Greek religion. He was also a renowned poet and, according to the legend, travelled with Jaso ...

and Arion

Arion (; grc-gre, Ἀρίων; fl. c. 700 BC) was a kitharode in ancient Greece, a Dionysiac poet credited with inventing the dithyramb. The islanders of Lesbos claimed him as their native son, but Arion found a patron in Periander, tyrant ...

, and the seventh-century BC poet Terpander

Terpander ( grc-gre, Τέρπανδρος ''Terpandros''), of Antissa in Lesbos, was a Greek poet and citharede who lived about the first half of the 7th century BC. He was the father of Greek music and through it, of lyric poetry, although his o ...

. The Lesbian metrical tradition in which Sappho composed her poetry was distinct from that of the rest of Greece as its lines always contained a fixed number of syllables – in contrast to other traditions which allowed for the substitution of two short syllables for one long or vice versa.

Sappho was one of the first Greek poets to adopt the "lyric 'I'" – to write poetry adopting the viewpoint of a specific person, in contrast to the earlier epic poets Homer

Homer (; grc, Ὅμηρος , ''Hómēros'') (born ) was a Greek poet who is credited as the author of the ''Iliad'' and the ''Odyssey'', two epic poems that are foundational works of ancient Greek literature. Homer is considered one of the ...

and Hesiod

Hesiod (; grc-gre, Ἡσίοδος ''Hēsíodos'') was an ancient Greek poet generally thought to have been active between 750 and 650 BC, around the same time as Homer. He is generally regarded by western authors as 'the first written poet i ...

, who present themselves more as "conduits of divine inspiration". Her poetry explores individual identity and personal emotions – desire, jealousy, and love; it also adopts and reinterprets the existing imagery of epic poetry in exploring these themes. It seems to have been composed for a variety of occasions both public and private, and probably encompassed both solo and choral

A choir ( ; also known as a chorale or chorus) is a musical ensemble of singers. Choral music, in turn, is the music written specifically for such an ensemble to perform. Choirs may perform music from the classical music repertoire, which ...

works. Along with the love poetry for which she is best known, her surviving works include poetry focused on the family, epic-influenced narrative, wedding songs, cult hymns, and invective.

Sappho's poetry is known for its clear language and simple thoughts, sharply-drawn images, and use of direct quotation which brings a sense of immediacy. Unexpected word-play is a characteristic feature of her style. An example is from fragment 96: "now she stands out among Lydian women as after sunset the rose-fingered moon exceeds all stars", a variation of the Homeric epithet A characteristic of Homer's style is the use of epithets, as in "rosy-fingered" Dawn or "swift-footed" Achilles. Epithets are used because of the constraints of the dactylic hexameter (i.e., it is convenient to have a stockpile of metrically fitting ...

"rosy-fingered Dawn". Sappho's poetry often uses hyperbole

Hyperbole (; adj. hyperbolic ) is the use of exaggeration as a rhetorical device or figure of speech. In rhetoric, it is also sometimes known as auxesis (literally 'growth'). In poetry and oratory, it emphasizes, evokes strong feelings, and ...

, according to ancient critics "because of its charm". An example is found in fragment 111, where Sappho writes that "The groom approaches like Ares ..Much bigger than a big man".

Leslie Kurke Leslie V. Kurke (born 1959) is a Goldman School of Public Policy, Richard and Rhoda Goldman Distinguished Professor, Professor of Classics and Comparative Literature at University of California, Berkeley.

She graduated from Bryn Mawr College with a ...

groups Sappho with those archaic Greek poets from what has been called the "élite" ideological tradition, which valued luxury (''habrosyne'') and high birth. These elite poets tended to identify themselves with the worlds of Greek myths, gods, and heroes, as well as the wealthy East, especially Lydia

Lydia (Lydian language, Lydian: 𐤮𐤱𐤠𐤭𐤣𐤠, ''Śfarda''; Aramaic: ''Lydia''; el, Λυδία, ''Lȳdíā''; tr, Lidya) was an Iron Age Monarchy, kingdom of western Asia Minor located generally east of ancient Ionia in the mod ...

. Thus in fragment 2 Sappho has Aphrodite "pour into golden cups nectar lavishly mingled with joys", while in the Tithonus poem she explicitly states that "I love the finer things 'habrosyne''. According to Page DuBois, the language, as well as the content, of Sappho's poetry evokes an aristocratic sphere. She contrasts Sappho's "flowery, ..adorned" style with the "austere, decorous, restrained" style embodied in the works of later classical authors such as Sophocles

Sophocles (; grc, Σοφοκλῆς, , Sophoklễs; 497/6 – winter 406/5 BC)Sommerstein (2002), p. 41. is one of three ancient Greek tragedians, at least one of whose plays has survived in full. His first plays were written later than, or co ...

, Demosthenes

Demosthenes (; el, Δημοσθένης, translit=Dēmosthénēs; ; 384 – 12 October 322 BC) was a Greek statesman and orator in ancient Athens. His orations constitute a significant expression of contemporary Athenian intellectual prow ...

, and Pindar

Pindar (; grc-gre, Πίνδαρος , ; la, Pindarus; ) was an Ancient Greek lyric poet from Thebes. Of the canonical nine lyric poets of ancient Greece, his work is the best preserved. Quintilian wrote, "Of the nine lyric poets, Pindar is ...

.

Music

Sappho's poetry was written to be sung but its musical content is largely uncertain. As it is unlikely that any system ofmusical notation

Music notation or musical notation is any system used to visually represent aurally perceived music played with instruments or sung by the human voice through the use of written, printed, or otherwise-produced symbols, including notation fo ...

existed in Ancient Greece before the fifth century, the original music that would have accompanied Sappho's songs probably did not survive until the classical period, and no ancient musical scores to accompany Sappho's poetry survive. Sappho was said to have written in the mixolydian mode

Mixolydian mode may refer to one of three things: the name applied to one of the ancient Greek ''harmoniai'' or ''tonoi'', based on a particular octave species or scale; one of the medieval church modes; or a modern musical mode or diatonic scal ...

, which was considered sorrowful; it was commonly used in Greek tragedy

Greek tragedy is a form of theatre from Ancient Greece and Greek inhabited Anatolia. It reached its most significant form in Athens in the 5th century BC, the works of which are sometimes called Attic tragedy.

Greek tragedy is widely believed t ...

, and Aristoxenus

Aristoxenus of Tarentum ( el, Ἀριστόξενος ὁ Ταραντῖνος; born 375, fl. 335 BC) was a Greek Peripatetic philosopher, and a pupil of Aristotle. Most of his writings, which dealt with philosophy, ethics and music, have been ...

believed that the tragedians learned it from Sappho. Aristoxenus attributed Sappho the invention of this mode, but this remains a dubious claim. The classicist Stefan Hagel speculated that perhaps instead Sappho first popularized the association between mixolydian and mournfulness. While there are no attestations that she used other mode

Mode ( la, modus meaning "manner, tune, measure, due measure, rhythm, melody") may refer to:

Arts and entertainment

* '' MO''D''E (magazine)'', a defunct U.S. women's fashion magazine

* ''Mode'' magazine, a fictional fashion magazine which is ...

s, she presumably varied them depending on the poem's character. When originally sung, each syllable of the her text likely corresponded to one note as the use of lengthy melisma

Melisma ( grc-gre, μέλισμα, , ; from grc, , melos, song, melody, label=none, plural: ''melismata'') is the singing of a single syllable of text while moving between several different notes in succession. Music sung in this style is referr ...

s developed in the later classical period.

Sappho chiefly wrote for two formats: solo singers and choirs. With Alcaeus, she pioneered a new style of sung monody

In music, monody refers to a solo vocal style distinguished by having a single melodic line and instrumental accompaniment. Although such music is found in various cultures throughout history, the term is specifically applied to Italian song of ...

(single-line melody) that departed from the multi-part choral style which largely defined earlier Greek music. This style afforded her more opportunities to individualize the content of her poems; the historian Plutarch

Plutarch (; grc-gre, Πλούταρχος, ''Ploútarchos''; ; – after AD 119) was a Greek Middle Platonist philosopher, historian, biographer, essayist, and priest at the Temple of Apollo in Delphi. He is known primarily for his ''P ...

noted that she "speaks words mingled truly with fire, and through her songs, she draws up the heat of her heart". Some scholars theorize that the Tithonus Poem was among her works meant for a solo singer. Only fragments of Sappho's choral works are extant, and of these, slightly more of her epithalamia

An epithalamium (; Latin form of Greek ἐπιθαλάμιον ''epithalamion'' from ἐπί ''epi'' "upon," and θάλαμος ''thalamos'' nuptial chamber) is a poem written specifically for the bride on the way to her marital chamber. This form ...

wedding songs survive. The later compositions were probably meant for antiphonal

An antiphonary or antiphonal is one of the liturgical books intended for use (i.e. in the liturgical choir), and originally characterized, as its name implies, by the assignment to it principally of the antiphons used in various parts of the L ...

performance between either a male and female choir or a soloist and choir.

In Sappho's time, sung poetry was accompanied by musical instrument

A musical instrument is a device created or adapted to make musical sounds. In principle, any object that produces sound can be considered a musical instrument—it is through purpose that the object becomes a musical instrument. A person who pl ...

s, which usually doubled the voice in unison

In music, unison is two or more musical parts that sound either the same pitch or pitches separated by intervals of one or more octaves, usually at the same time. ''Rhythmic unison'' is another term for homorhythm.

Definition

Unison or per ...

or played homophonically an octave

In music, an octave ( la, octavus: eighth) or perfect octave (sometimes called the diapason) is the interval between one musical pitch and another with double its frequency. The octave relationship is a natural phenomenon that has been refer ...

higher or lower. Her poems mention numerous instruments, including the pēktis, a harp of Lydian origin, and lyre

The lyre () is a stringed musical instrument that is classified by Hornbostel–Sachs as a member of the lute-family of instruments. In organology, a lyre is considered a yoke lute, since it is a lute in which the strings are attached to a yoke ...

. Sappho is most closely associated with the barbitos

The barbiton, or barbitos ( Gr: βάρβιτον or βάρβιτος; Lat. ''barbitus''), is an ancient stringed instrument related to the lyre known from Greek and Roman classics.

The Greek instrument was a bass version of the kithara, and ...

, a lyre-like string instrument which was deep in pitch. Euphorion of Chalcis

Euphorion of Chalcis ( el, Εὐφορίων ὁ Χαλκιδεύς) was a Greek poet and grammarian, born at Chalcis in Euboea about 275 BC.

Euphorion spent much of his life in Athens, where he amassed great wealth. After studying philosophy w ...

reports that she referred to it in her poetry, and a well-known 5th century vase by either the Dokimasia Painter

The Dokimasia Painter (active between 480 and 460 BC at Athens) was a Greek vase-painter of the Attic red-figure style. His actual name is unknown and his conventional name is derived from his name-vase, showing the inspection of horses at the D ...

or Brygos Painter

The Brygos Painter was an ancient Greek Attic red-figure vase painter of the Late Archaic period. Together with Onesimos, Douris and Makron, he is among the most important cup painters of his time. He was active in the first third of the 5th ...

includes Sappho and Alcaeus with barbitoi. Sappho mentions the aulos

An ''aulos'' ( grc, αὐλός, plural , ''auloi'') or ''tibia'' (Latin) was an ancient Greek wind instrument, depicted often in art and also attested by archaeology.

Though ''aulos'' is often translated as "flute" or "double flute", it was usu ...

, a wind instrument with two pipes, in fragment 44 as accompanying the song of the Trojan women at Hector

In Greek mythology, Hector (; grc, Ἕκτωρ, Hektōr, label=none, ) is a character in Homer's Iliad. He was a Trojan prince and the greatest warrior for Troy during the Trojan War. Hector led the Trojans and their allies in the defense o ...

and Andromache

In Greek mythology, Andromache (; grc, Ἀνδρομάχη, ) was the wife of Hector, daughter of Eetion, and sister to Podes. She was born and raised in the city of Cilician Thebe, over which her father ruled. The name means 'man battler' or ...

's wedding, but not as accompanying her own poetry. Later Greek commentators wrongly believed that she had invented the plectrum

A plectrum is a small flat tool used for plucking or strumming of a stringed instrument. For hand-held instruments such as guitars and mandolins, the plectrum is often called a pick and is held as a separate tool in the player's hand. In harpsic ...

.

Sexuality

The common term ''lesbian'' is an allusion to Sappho, originating from the name of the island ofLesbos

Lesbos or Lesvos ( el, Λέσβος, Lésvos ) is a Greek island located in the northeastern Aegean Sea. It has an area of with approximately of coastline, making it the third largest island in Greece. It is separated from Anatolia, Asia Minor ...

, where she was born. However, she has not always been considered so. In classical Athenian comedy (from the Old Comedy

Old Comedy (''archaia'') is the first period of the ancient Greek comedy, according to the canonical division by the Alexandrian grammarians.Mastromarco (1994) p.12 The most important Old Comic playwright is Aristophanes – whose works, with thei ...

of the fifth century to Menander in the late fourth and early third centuries BC), Sappho was caricatured as a promiscuous heterosexual woman, and it is not until the Hellenistic period that the first sources which explicitly discuss Sappho's homoeroticism are preserved. The earliest of these is a fragmentary biography written on papyrus in the late third or early second century BC, which states that Sappho was "accused by some of being irregular in her ways and a woman-lover". Denys Page comments that the phrase "by some" implies that even the full corpus of Sappho's poetry did not provide conclusive evidence of whether she described herself as having sex with women. These ancient authors do not appear to have believed that Sappho did, in fact, have sexual relationships with other women, and as late as the tenth century the Suda records that Sappho was "slanderously accused" of having sexual relationships with her "female pupils".

Among modern scholars, Sappho's sexuality is still debated – André Lardinois has described it as the "Great Sappho Question". Early translators of Sappho sometimes heterosexualised her poetry. Ambrose Philips

Ambrose Philips (167418 June 1749) was an English poet and politician. He feuded with other poets of his time, resulting in Henry Carey bestowing the nickname "Namby-Pamby" upon him, which came to mean affected, weak, and maudlin speech or verse. ...

' 1711 translation of the Ode to Aphrodite

The Ode to Aphrodite (or Sappho fragment 1) is a lyric poem by the archaic Greek poet Sappho, who wrote in the late seventh and early sixth centuries BCE, in which the speaker calls on the help of Aphrodite in the pursuit of a beloved. The poem ...

portrayed the object of Sappho's desire as male, a reading that was followed by virtually every other translator of the poem until the twentieth century, while in 1781 Alessandro Verri interpreted fragment 31 as being about Sappho's love for Phaon. Friedrich Gottlieb Welcker

Friedrich Gottlieb Welcker (4 November 1784 – 17 December 1868) was a German classical philologist and archaeologist.

Biography

Welcker was born at Grünberg, Hesse-Darmstadt. Having studied classical philology at the University of Giessen ...

argued that Sappho's feelings for other women were "entirely idealistic and non-sensual", while Karl Otfried Müller

Karl Otfried Müller ( la, Carolus Mullerus; 28 August 1797 – 1 August 1840) was a German scholar and Philodorian, or admirer of ancient Sparta, who introduced the modern study of Greek mythology.

Biography

He was born at Brieg (modern Brze ...

wrote that fragment 31 described "nothing but a friendly affection": Glenn Most comments that "one wonders what language Sappho would have used to describe her feelings if they had been ones of sexual excitement", if this theory were correct. By 1970, it would be argued that the same poem contained "proof positive of appho'slesbianism".

Today, it is generally accepted that Sappho's poetry portrays homoerotic feelings: as Sandra Boehringer puts it, her works "clearly celebrate eros between women". Toward the end of the twentieth century, though, some scholars began to reject the question of whether or not Sappho was a lesbian – Glenn Most wrote that Sappho herself "would have had no idea what people mean when they call her nowadays a homosexual", André Lardinois stated that it is "nonsensical" to ask whether Sappho was a lesbian, and Page duBois calls the question a "particularly obfuscating debate".

One of the major focuses of scholars studying Sappho has been to attempt to determine the cultural context in which Sappho's poems were composed and performed. Various cultural contexts and social roles played by Sappho have been suggested, including teacher, cult-leader, and poet performing for a circle of female friends. However, the performance contexts of many of Sappho's fragments are not easy to determine, and for many more than one possible context is conceivable.

One longstanding suggestion of a social role for Sappho is that of "Sappho as schoolmistress". At the beginning of the twentieth century, the German classicist Ulrich von Wilamowitz-Moellendorff

Enno Friedrich Wichard Ulrich von Wilamowitz-Moellendorff (22 December 1848 – 25 September 1931) was a German classical philologist. Wilamowitz, as he is known in scholarly circles, was a renowned authority on Ancient Greece and its literature ...

posited that Sappho was a sort of schoolteacher, to "explain away Sappho's passion for her 'girls and defend her from accusations of homosexuality. The view continues to be influential, both among scholars and the general public, though more recently the idea has been criticised by historians as anachronistic and has been rejected by several prominent classicists as unjustified by the evidence. In 1959, Denys Page, for example, stated that Sappho's extant fragments portray "the loves and jealousies, the pleasures and pains, of Sappho and her companions"; and he adds, "We have found, and shall find, no trace of any formal or official or professional relationship between them... no trace of Sappho the principal of an academy." David A. Campbell in 1967 judged that Sappho may have "presided over a literary coterie", but that "evidence for a formal appointment as priestess or teacher is hard to find". None of Sappho's own poetry mentions her teaching, and the earliest source to support the idea of Sappho as a teacher comes from Ovid, six centuries after Sappho's lifetime. Despite these problems, many newer interpretations of Sappho's social role are still based on this idea. In these interpretations, Sappho was involved in the ritual education of girls, for instance as a trainer of choruses of girls.

Even if Sappho did compose songs for training choruses of young girls, not all of her poems can be interpreted in this light, and despite scholars' best attempts to find one, Yatromanolakis argues that there is no single performance context to which all of Sappho's poems can be attributed. Parker argues that Sappho should be considered as part of a group of female friends for whom she would have performed, just as her contemporary Alcaeus is. Some of her poetry appears to have been composed for identifiable formal occasions, but many of her songs are about – and possibly were to be performed at – banquets.

Legacy

Ancient reputation

In antiquity, Sappho's poetry was highly admired, and several ancient sources refer to her as the "tenth Muse". The earliest surviving poem to do so is a third-century BC epigram by

In antiquity, Sappho's poetry was highly admired, and several ancient sources refer to her as the "tenth Muse". The earliest surviving poem to do so is a third-century BC epigram by Dioscorides

Pedanius Dioscorides ( grc-gre, Πεδάνιος Διοσκουρίδης, ; 40–90 AD), “the father of pharmacognosy”, was a Greek physician, pharmacologist, botanist, and author of ''De materia medica'' (, On Medical Material) —a 5-vol ...

, but poems are preserved in the ''Greek Anthology'' by Antipater of Sidon and attributed to Plato on the same theme. She was sometimes referred to as "The Poetess", just as Homer was "The Poet". The scholars of Alexandria included her in the canon of nine lyric poets. According to Aelian, the Athenian lawmaker and poet Solon

Solon ( grc-gre, Σόλων; BC) was an Athenian statesman, constitutional lawmaker and poet. He is remembered particularly for his efforts to legislate against political, economic and moral decline in Archaic Athens.Aristotle ''Politics'' ...

asked to be taught a song by Sappho "so that I may learn it and then die". This story may well be apocryphal, especially as Ammianus Marcellinus tells a similar story about Socrates and a song of Stesichorus

Stesichorus (; grc-gre, Στησίχορος, ''Stēsichoros''; c. 630 – 555 BC) was a Greek lyric poet native of today's Calabria (Southern Italy). He is best known for telling epic stories in lyric metres, and for some ancient traditions abou ...

, but it is indicative of how highly Sappho's poetry was considered in the ancient world.

Sappho's poetry also influenced other ancient authors. In Greek, the Hellenistic poet Nossis

Nossis ( grc-gre, Νοσσίς) was a Hellenistic Greek poet from Epizephyrian Locris in today's Calabria (Southern Italy). She seems to have been active in the early third century BC, as she wrote an epitaph for the Hellenistic dramatist Rhinthon ...

was described by Marilyn B. Skinner as an imitator of Sappho, and Kathryn Gutzwiller argues that Nossis explicitly positioned herself as an inheritor of Sappho's position as a woman poet. Beyond poetry, Plato cites Sappho in his '' Phaedrus'', and Socrates

Socrates (; ; –399 BC) was a Greek philosopher from Athens who is credited as the founder of Western philosophy and among the first moral philosophers of the ethical tradition of thought. An enigmatic figure, Socrates authored no te ...

' second speech on love in that dialogue appears to echo Sappho's descriptions of the physical effects of desire in fragment 31. In the first century BC, Catullus

Gaius Valerius Catullus (; 84 - 54 BCE), often referred to simply as Catullus (, ), was a Latin poet of the late Roman Republic who wrote chiefly in the neoteric style of poetry, focusing on personal life rather than classical heroes. His s ...

established the themes and metres of Sappho's poetry as a part of Latin literature, adopting the Sapphic stanza, believed in antiquity to have been invented by Sappho, giving his lover in his poetry the name "Lesbia

Lesbia was the literary pseudonym used by the Roman poet Gaius Valerius Catullus ( 82–52 BC) to refer to his lover. Lesbia is traditionally identified with Clodia, the wife of Quintus Caecilius Metellus Celer and sister of Publius Clodius Pulc ...

" in reference to Sappho, and adapting and translating Sappho's 31st fragment in his poem 51.

Other ancient poets wrote about Sappho's life. She was a popular character in ancient Athenian comedy, and at least six separate comedies called ''Sappho'' are known. The earliest known ancient comedy to take Sappho as its main subject was the early-fifth or late-fourth century BC ''Sappho'' by Ameipsias

Ameipsias ( grc, , fl. late 5th century BC) of Athens was an Ancient Greek comic poet, a contemporary of Aristophanes, whom he twice bested in the dramatic contests. His ''Konnos'' () gained a second prize at the City Dionysia in 423, when Aristo ...

, though nothing is known of it apart from its name. As these comedies survive only in fragments, it is uncertain exactly how they portrayed Sappho, but she was likely characterised as a promiscuous woman. In Diphilos' play, she was the lover of the poets Anacreon

Anacreon (; grc-gre, Ἀνακρέων ὁ Τήϊος; BC) was a Greek lyric poet, notable for his drinking songs and erotic poems. Later Greeks included him in the canonical list of Nine Lyric Poets. Anacreon wrote all of his poetry in the ...

and Hipponax. Sappho was also a favourite subject in the visual arts. She was the most commonly depicted poet on sixth and fifth-century Attic red-figure vase paintings – though unlike male poets such as Anacreon and Alcaeus, in the four surviving vases in which she is identified by an inscription she is never shown singing. She was also shown on coins from Mytilene and Lesbos from the first to third centuries AD, and reportedly depicted in a sculpture by Silanion

Silanion ( grc-gre, Σιλανίων, ''gen.'' Σιλανίωνος) was the best-known of the Greek portrait-sculptors working during the fourth century BC. Pliny gives his ''floruit'' as the 113th Olympiad, that is, around 328–325 BCE (''Na ...

at Syracuse, statues in Pergamon and Constantinople, and a painting by the Hellenistic artist Leon.

From the fourth century BC, ancient works portray Sappho as a tragic heroine, driven to suicide by her unrequited love for Phaon. A fragment of a play by Menander says that Sappho threw herself off of the cliff at Leucas out of her love for him. Ovid's ''Heroides'' 15 is written as a letter from Sappho to Phaon, and when it was first rediscovered in the 15th century was thought to be a translation of an authentic letter of Sappho's. Sappho's suicide was also depicted in classical art, for instance on a first-century BC basilica in Rome near the Porta Maggiore

The Porta Maggiore ("Larger Gate"), or Porta Prenestina, is one of the eastern gates in the ancient but well-preserved 3rd-century Aurelian Walls of Rome. Through the gate ran two ancient roads: the Via Praenestina and the Via Labicana. The Via P ...

.

While Sappho's poetry was admired in the ancient world, her character was not always so well considered. In the Roman period, critics found her lustful and perhaps even homosexual. Horace

Quintus Horatius Flaccus (; 8 December 65 – 27 November 8 BC), known in the English-speaking world as Horace (), was the leading Roman lyric poet during the time of Augustus (also known as Octavian). The rhetorician Quintilian regarded his ' ...

called her "mascula Sappho" in his ''Epistles'', which the later Porphyrio

''Porphyrio'' is the swamphen or swamp hen bird genus in the rail family. It includes some smaller species which are usually called "purple gallinules", and which are sometimes separated as genus ''Porphyrula'' or united with the gallinules pro ...

commented was "either because she is famous for her poetry, in which men more often excel, or because she is maligned for having been a tribad". By the third century AD, the difference between Sappho's literary reputation as a poet and her moral reputation as a woman had become so significant that the suggestion that there were in fact two Sapphos began to develop. In his ''Historical Miscellanies'', Aelian wrote that there was "another Sappho, a courtesan, not a poetess".Aelian, ''Historical Miscellanies'' 12.19 = T 4

Modern reception

By the medieval period, Sappho's works had been lost, though she was still quoted in later authors. Her work became more accessible in the sixteenth century through printed editions of those authors who had quoted her. In 1508

By the medieval period, Sappho's works had been lost, though she was still quoted in later authors. Her work became more accessible in the sixteenth century through printed editions of those authors who had quoted her. In 1508 Aldus Manutius

Aldus Pius Manutius (; it, Aldo Pio Manuzio; 6 February 1515) was an Italian printer and humanist who founded the Aldine Press. Manutius devoted the later part of his life to publishing and disseminating rare texts. His interest in and preserv ...

printed an edition of Dionysius of Halicarnassus

Dionysius of Halicarnassus ( grc, Διονύσιος Ἀλεξάνδρου Ἁλικαρνασσεύς,

; – after 7 BC) was a Greek historian and teacher of rhetoric, who flourished during the reign of Emperor Augustus. His literary sty ...

, which contained Sappho 1, the "Ode to Aphrodite", and the first printed edition of Longinus' ''On the Sublime'', complete with his quotation of Sappho 31, appeared in 1554. In 1566, the French printer Robert Estienne produced an edition of the Greek lyric poets which contained around 40 fragments attributed to Sappho.

In 1652, the first English translation of a poem by Sappho was published, in John Hall John Hall may refer to:

Academics

* John Hall (NYU President) (fl. c. 1890), American academic

* John A. Hall (born 1949), sociology professor at McGill University, Montreal

* John F. Hall (born 1951), professor of classics at Brigham Young Unive ...

's translation of ''On the Sublime''. In 1681 Anne Le Fèvre

Anne Le Fèvre Dacier (1647 – 17 August 1720), better known during her lifetime as Madame Dacier, was a French scholar, translator, commentator and editor of the classics, including the ''Iliad'' and the ''Odyssey''. She sought to champion ...

's French edition of Sappho made her work even more widely known. Theodor Bergk

Theodor Bergk (22 May 181220 July 1881) was a German philologist, an authority on classical Greek poetry.

Biography

He was born in Leipzig as the son of Johann Adam Bergk. After studying at the University of Leipzig, where he profited by the inst ...

's 1854 edition became the standard edition of Sappho in the second half of the 19th century; in the first part of the 20th, the papyrus discoveries of new poems by Sappho led to editions and translations by Edwin Marion Cox

The name Edwin means "rich friend". It comes from the Old English elements "ead" (rich, blessed) and "ƿine" (friend). The original Anglo-Saxon form is Eadƿine, which is also found for Anglo-Saxon figures.

People

* Edwin of Northumbria (died ...

and John Maxwell Edmonds

John Maxwell Edmonds (21 January 1875 – 18 March 1958) was an English classicist, poet and dramatist and the author of several celebrated martial epitaphs.

Biography

Edmonds was born in Stroud, Gloucestershire on 21 January 1875. His father ...

, and culminated in the 1955 publication of Edgar Lobel

Edgar Lobel (24 December 1888 – 7 July 1982) was a Romanian-British classicist and papyrologist who is best known for his four decades overseeing the publication of the literary texts among the Oxyrhynchus Papyri and for his edition of Sappho a ...

's and Denys Page

Sir Denys Lionel Page (11 May 19086 July 1978) was a British classicist and textual critic who served as the 34th Regius Professor of Greek at the University of Cambridge and the 35th Master of Jesus College, Cambridge. He is best known for h ...

's ''Poetarum Lesbiorum Fragmenta''.

Like the ancients, modern critics have tended to consider Sappho's poetry "extraordinary". As early as the 9th century, Sappho was referred to as a talented woman poet, and in works such as Boccaccio

Giovanni Boccaccio (, , ; 16 June 1313 – 21 December 1375) was an Italian people, Italian writer, poet, correspondent of Petrarch, and an important Renaissance humanism, Renaissance humanist. Born in the town of Certaldo, he became so we ...

's '' De Claris Mulieribus'' and Christine de Pisan

Christine de Pizan or Pisan (), born Cristina da Pizzano (September 1364 – c. 1430), was an Italian poet and court writer for King Charles VI of France and several French dukes.

Christine de Pizan served as a court writer in medieval France ...

's ''Book of the City of Ladies

''The Book of the City of Ladies'' or ''Le Livre de la Cité des Dames'' (finished by 1405), is perhaps Christine de Pizan's most famous literary work, and it is her second work of lengthy prose. Pizan uses the vernacular French language to comp ...

'' she gained a reputation as a learned lady. Even after Sappho's works had been lost, the Sapphic stanza continued to be used in medieval lyric poetry, and with the rediscovery of her work in the Renaissance, she began to increasingly influence European poetry. In the 16th century, members of La Pléiade

La Pléiade () was a group of 16th-century French Renaissance poets whose principal members were Pierre de Ronsard, Joachim du Bellay and Jean-Antoine de Baïf. The name was a reference to another literary group, the original Alexandrian Pleiad ...

, a circle of French poets, were influenced by her to experiment with Sapphic stanzas and with writing love-poetry with a first-person female voice. Early modern and modern composers have also been inspired by Sappho; notable compositions based on her life or works include operas such as ''Sappho'' (1794) by Jean-Paul-Égide Martini

Jean-Paul-Égide Martini, also known as Jean-Paul-Gilles Martini (31 August 1741 – 14 February 1816;) was a French composer of German birth during the classical period. He is best known today for the vocal romance "Plaisir d'amour," on w ...

, ''Sappho

Sappho (; el, Σαπφώ ''Sapphō'' ; Aeolic Greek ''Psápphō''; c. 630 – c. 570 BC) was an Archaic Greek poet from Eresos or Mytilene on the island of Lesbos. Sappho is known for her Greek lyric, lyric poetry, written to be sung while ...

'' (1897) by Jules Massenet

Jules Émile Frédéric Massenet (; 12 May 1842 – 13 August 1912) was a French composer of the Romantic era best known for his operas, of which he wrote more than thirty. The two most frequently staged are '' Manon'' (1884) and ''Werther' ...

, ''Sappho'' (1963) by Peggy Glanville-Hicks

Peggy Winsome Glanville-Hicks (29 December 191225 June 1990) was an Australian composer and music critic.

Biography

Peggy Glanville Hicks, born in Melbourne, first studied composition with Fritz Hart at the Albert Street Conservatorium in Me ...

; the percussion piece '' Psappha'' (1975) and orchestral work '' Aïs'' (1980) by Iannis Xenakis

Giannis Klearchou Xenakis (also spelled for professional purposes as Yannis or Iannis Xenakis; el, Γιάννης "Ιωάννης" Κλέαρχου Ξενάκης, ; 29 May 1922 – 4 February 2001) was a Romanian-born Greek-French avant-garde ...

; and the composition ''Charaxos, Eos and Tithonos'' (2014) by Theodore Antoniou

Theodore Antoniou ( el, Θεόδωρος Αντωνίου, ''Theódoros Andoníou''; February 10, 1935 – December 26, 2018), was a Greek composer and conductor. His works vary from operas and choral works to chamber music, from film and theatre m ...

.

From the Romantic era

Romanticism (also known as the Romantic movement or Romantic era) was an artistic, literary, musical, and intellectual movement that originated in Europe towards the end of the 18th century, and in most areas was at its peak in the approximate ...

, Sappho's work – especially her "Ode to Aphrodite" – has been a key influence of conceptions of what lyric poetry should be. Such influential poets as Alfred Lord Tennyson

Alfred Tennyson, 1st Baron Tennyson (6 August 1809 – 6 October 1892) was an English poet. He was the Poet Laureate during much of Queen Victoria's reign. In 1829, Tennyson was awarded the Chancellor's Gold Medal at Cambridge for one of his ...

in the nineteenth century, and A. E. Housman

Alfred Edward Housman (; 26 March 1859 – 30 April 1936) was an English classical scholar and poet. After an initially poor performance while at university, he took employment as a clerk in London and established his academic reputation by pub ...

in the twentieth, have been influenced by her poetry. Tennyson based poems including "Eleanore" and "Fatima" on Sappho's fragment 31, while three of Housman's works are adaptations of the Midnight poem

The midnight poem is a fragment of Greek lyric poetry preserved by Hephaestion. It is possibly by the archaic Greek poet Sappho, and is fragment 168 B in Eva-Maria Voigt's edition of her works. It is also sometimes known as PMG fr. adesp. 97 ...

, long thought to be by Sappho though the authorship is now disputed. At the beginning of the twentieth century, the Imagists

Imagism was a movement in early-20th-century Anglo-American poetry that favored precision of imagery

Imagery is visual symbolism, or figurative language that evokes a mental image or other kinds of sense impressions, especially in a literar ...

– especially Ezra Pound

Ezra Weston Loomis Pound (30 October 1885 – 1 November 1972) was an expatriate American poet and critic, a major figure in the early modernist poetry movement, and a Fascism, fascist collaborator in Italy during World War II. His works ...

, H. D.

Hilda Doolittle (September 10, 1886 – September 27, 1961) was an American modernist poet, novelist, and memoirist who wrote under the name H.D. throughout her life. Her career began in 1911 after she moved to London and co-founded the ...

, and Richard Aldington

Richard Aldington (8 July 1892 – 27 July 1962), born Edward Godfree Aldington, was an English writer and poet, and an early associate of the Imagist movement. He was married to the poet Hilda Doolittle (H. D.) from 1911 to 1938. His 50-year w ...

– were influenced by Sappho's fragments; a number of Pound's poems in his early collection ''Lustra'' were adaptations of Sapphic poems, while H. D.'s poetry was frequently Sapphic in "style, theme or content", and in some cases, such as "Fragment 40" more specifically invoke Sappho's writing.

It was not long after the rediscovery of Sappho that her sexuality once again became the focus of critical attention. In the early seventeenth century,

It was not long after the rediscovery of Sappho that her sexuality once again became the focus of critical attention. In the early seventeenth century, John Donne

John Donne ( ; 22 January 1572 – 31 March 1631) was an English poet, scholar, soldier and secretary born into a recusant family, who later became a clergy, cleric in the Church of England. Under royal patronage, he was made Dean of St Paul's ...

wrote "Sapho to Philaenis", returning to the idea of Sappho as a hypersexual lover of women. The modern debate on Sappho's sexuality began in the 19th century, with Welcker publishing, in 1816, an article defending Sappho from charges of prostitution and lesbianism, arguing that she was chaste – a position which would later be taken up by Wilamowitz at the end of the 19th and Henry Thornton Wharton at the beginning of the 20th centuries. In the nineteenth century Sappho was co-opted by the Decadent Movement

The Decadent movement (Fr. ''décadence'', “decay”) was a late-19th-century artistic and literary movement, centered in Western Europe, that followed an aesthetic ideology of excess and artificiality.

The Decadent movement first flourished ...

as a lesbian "daughter of de Sade", by Charles Baudelaire

Charles Pierre Baudelaire (, ; ; 9 April 1821 – 31 August 1867) was a French poetry, French poet who also produced notable work as an essayist and art critic. His poems exhibit mastery in the handling of rhyme and rhythm, contain an exoticis ...

in France and later Algernon Charles Swinburne

Algernon Charles Swinburne (5 April 1837 – 10 April 1909) was an English poet, playwright, novelist, and critic. He wrote several novels and collections of poetry such as ''Poems and Ballads'', and contributed to the famous Eleventh Edition ...

in England. By the late 19th century, lesbian writers such as Michael Field and Amy Levy

Amy Judith Levy (10 November 1861 – 9 September 1889) was an English essayist, poet, and novelist best remembered for her literary gifts; her experience as the second Jewish woman at Cambridge University, and as the first Jewish student at N ...

became interested in Sappho for her sexuality, and by the turn of the twentieth century she was a sort of "patron saint of lesbians".

From the beginning of the 19th century, women poets such as Felicia Hemans

Felicia Dorothea Hemans (25 September 1793 – 16 May 1835) was an English poet (who identified as Welsh by adoption). Two of her opening lines, "The boy stood on the burning deck" and "The stately homes of England", have acquired classic statu ...

(''The Last Song of Sappho'') and Letitia Elizabeth Landon

Letitia Elizabeth Landon (14 August 1802 – 15 October 1838) was an English poet and novelist, better known by her initials L.E.L.

The writings of Landon are transitional between Romanticism and the Victorian Age. Her first major breakthrough ...

(''Sketch the First. Sappho'', and in ''Ideal Likenesses'') took Sappho as one of their progenitors. Sappho also began to be regarded as a role model for campaigners for women's rights, beginning with works such as Caroline Norton

Caroline Elizabeth Sarah Norton, Lady Stirling-Maxwell (22 March 1808 – 15 June 1877) was an active English social reformer and author.Perkin, pp. 26–28. She left her husband in 1836, who sued her close friend Lord Melbourne, then the Whig ...

's ''The Picture of Sappho''. Later in that century, she would become a model for the so-called New Woman

The New Woman was a feminist ideal that emerged in the late 19th century and had a profound influence well into the 20th century. In 1894, Irish writer Sarah Grand (1854–1943) used the term "new woman" in an influential article, to refer to ...

– independent and educated women who desired social and sexual autonomy – and by the 1960s, the feminist Sappho was – along with the hypersexual, often but not exclusively lesbian Sappho – one of the two most important cultural perceptions of Sappho.

The discoveries of new poems by Sappho in 2004 and 2014 excited both scholarly and media attention. The announcement of the Tithonus poem was the subject of international news coverage, and was described by Marilyn Skinner as "the '' trouvaille'' of a lifetime".

See also

*Ancient Greek literature

Ancient Greek literature is literature written in the Ancient Greek language from the earliest texts until the time of the Byzantine Empire. The earliest surviving works of ancient Greek literature, dating back to the early Archaic period, are ...

* Papyrus Oxyrhynchus 7

Papyrus Oxyrhynchus 7 (P. Oxy. 7) is a papyrus found at Oxyrhynchus in Egypt. It was discovered by Bernard Pyne Grenfell and Arthur Surridge Hunt in 1897, and published in 1898. It dates to the third century AD. The papyrus is now in the Brit ...

– papyrus preserving Sappho fr. 5

* Papyrus Oxyrhynchus 1231

Papyrus Oxyrhynchus 1231 (P. Oxy. 1231 or P. Oxy. X 1231) is a papyrus discovered at Oxyrhynchus in Egypt, first published in 1914 by Bernard Pyne Grenfell and Arthur Surridge Hunt. The papyrus preserves fragments of the second half of Book I o ...

– papyrus preserving Sappho fr. 15–30

* Lesbian poetry

A lesbian is a Homosexuality, homosexual woman.Zimmerman, p. 453. The word is also used for women in relation to their sexual identity or sexual behavior, regardless of sexual orientation, or as an adjective to characterize or associate n ...

Notes

References

Works cited

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *Further reading

* * * * * * * * * * * * *External links

The Digital Sappho

Commentaries on Sappho's fragments

William Annis.

Fragments of Sappho

translated by Gregory Nagy and Julia Dubnoff

Sappho

BBC Radio 4

BBC Radio 4 is a British national radio station owned and operated by the BBC that replaced the BBC Home Service in 1967. It broadcasts a wide variety of spoken-word programmes, including news, drama, comedy, science and history from the BBC' ...

, ''In Our Time''.

Sappho

BBC Radio 4, ''Great Lives''. * *

Ancient Greek literature recitations

hosted by the Society for the Oral Reading of Greek and Latin Literature. Including a recording of Sappho 1 by Stephen Daitz. {{Authority control 7th-century BC births 7th-century BC women poets 7th-century BC Greek people 7th-century BC poets 6th-century BC Greek people 6th-century BC poets 6th-century BC women writers Aeolic Greek poets Ancient Eresians Ancient Greek erotic poets Nine Lyric Poets Poets from ancient Lesbos Greek women composers Ancient Greek women poets Ancient Mytileneans 7th-century BC Greek women 6th-century BC Greek women Ancient LGBT people