Sakhalin Island on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Sakhalin ( rus, Сахали́н, r=Sakhalín, p=səxɐˈlʲin; ja, 樺太 ''Karafuto''; zh, c=, p=Kùyèdǎo, s=库页岛, t=庫頁島;

Humans lived on Sakhalin in the

Humans lived on Sakhalin in the

The Manchu

The Manchu

The first European known to visit Sakhalin was Martin Gerritz de Vries, who mapped

The first European known to visit Sakhalin was Martin Gerritz de Vries, who mapped

On the basis of its belief that it was an extension of Hokkaido, both geographically and culturally, Japan again proclaimed sovereignty over the whole island (as well as the

On the basis of its belief that it was an extension of Hokkaido, both geographically and culturally, Japan again proclaimed sovereignty over the whole island (as well as the

Japanese forces invaded and occupied Sakhalin in the closing stages of the

Japanese forces invaded and occupied Sakhalin in the closing stages of the

On September 1, 1983,

On September 1, 1983,

– an article in the ''

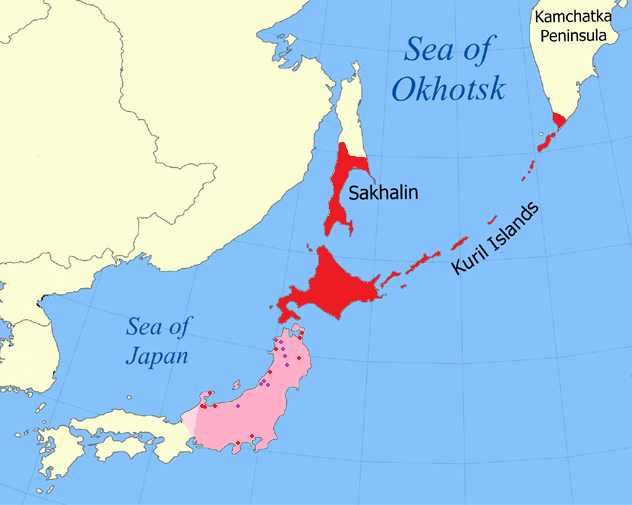

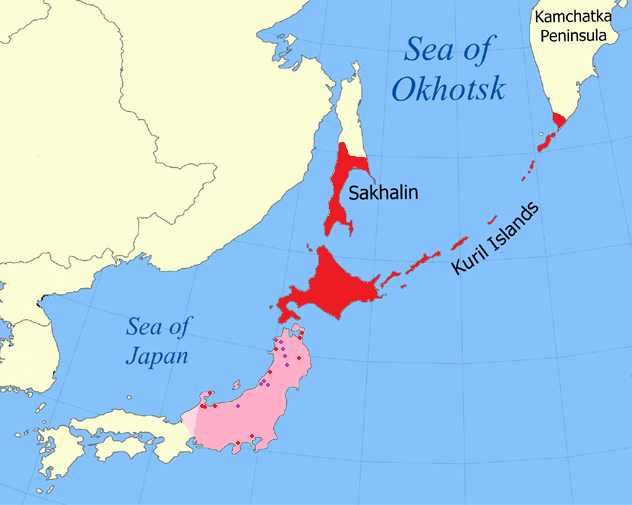

File:Sakhalin and her surroundings English ver.png, Sakhalin and its surroundings.

File:Кекуры Мыса Великан 3.jpg, Velikan Cape, Sakhalin

File:Хребет Жданко и бухта Тихая.jpg, Zhdanko Mountain Ridge

At the beginning of the 20th century, some 32,000 Russians (of whom over 22,000 were convicts) inhabited Sakhalin along with several thousand native inhabitants. In 2010, the island's population was recorded at 497,973, 83% of whom were ethnic

At the beginning of the 20th century, some 32,000 Russians (of whom over 22,000 were convicts) inhabited Sakhalin along with several thousand native inhabitants. In 2010, the island's population was recorded at 497,973, 83% of whom were ethnic

The whole of the island is covered with dense

The whole of the island is covered with dense

File:Sakhalin Train.jpg, A passenger train in

Sakhalin is a classic "

Sakhalin is a classic "

Map of the Sakhalin Hydrocarbon Region

– at Blackbourn Geoconsulting

TransGlobal Highway

– Proposed Sakhalin–Hokkaidō Friendship Tunnel

Maps of Ezo, Sakhalin and Kuril Islands

from 1854 {{Authority control Ainu geography Geography of Northeast Asia Islands of Sakhalin Oblast Islands of the Pacific Ocean Islands of the Russian Far East Islands of the Sea of Okhotsk Pacific Coast of Russia Physiographic provinces

Manchu

The Manchus (; ) are a Tungusic East Asian ethnic group native to Manchuria in Northeast Asia. They are an officially recognized ethnic minority in China and the people from whom Manchuria derives its name. The Later Jin (1616–1636) and ...

: ᠰᠠᡥᠠᠯᡳᠶᠠᠨ, ''Sahaliyan''; Orok: Бугата на̄, ''Bugata nā''; Nivkh

Nivkh or Amuric or Gilyak may refer to:

* Nivkh people

The Nivkh, or Gilyak (also Nivkhs or Nivkhi, or Gilyaks; ethnonym: Нивхгу, ''Nʼivxgu'' (Amur) or Ниғвңгун, ''Nʼiɣvŋgun'' (E. Sakhalin) "the people"), are an indigenous et ...

: Yh-mif) is the largest island of Russia. It is north of the Japanese archipelago

The Japanese archipelago (Japanese: 日本列島, ''Nihon rettō'') is a archipelago, group of 6,852 islands that form the country of Japan, as well as the Russian island of Sakhalin. It extends over from the Sea of Okhotsk in the northeast to t ...

, and is administered as part of the Sakhalin Oblast

Sakhalin Oblast ( rus, Сахали́нская о́бласть, r=Sakhalínskaya óblast', p=səxɐˈlʲinskəjə ˈobləsʲtʲ) is a federal subjects of Russia, federal subject of Russia (an oblast) comprising the island of Sakhalin and the K ...

. Sakhalin is situated in the Pacific Ocean, sandwiched between the Sea of Okhotsk

The Sea of Okhotsk ( rus, Охо́тское мо́ре, Ohótskoye móre ; ja, オホーツク海, Ohōtsuku-kai) is a marginal sea of the western Pacific Ocean. It is located between Russia's Kamchatka Peninsula on the east, the Kuril Islands ...

to the east and the Sea of Japan

The Sea of Japan is the marginal sea between the Japanese archipelago, Sakhalin, the Korean Peninsula, and the mainland of the Russian Far East. The Japanese archipelago separates the sea from the Pacific Ocean. Like the Mediterranean Sea, it h ...

to the west. It is located just off Khabarovsk Krai

Khabarovsk Krai ( rus, Хабаровский край, r=Khabarovsky kray, p=xɐˈbarəfskʲɪj kraj) is a federal subject (a krai) of Russia. It is geographically located in the Russian Far East and is a part of the Far Eastern Federal District ...

, and is north of Hokkaido

is Japan's second largest island and comprises the largest and northernmost prefecture, making up its own region. The Tsugaru Strait separates Hokkaidō from Honshu; the two islands are connected by the undersea railway Seikan Tunnel.

The la ...

in Japan. The island has a population of roughly 500,000, the majority of which are Russians. The indigenous peoples

Indigenous peoples are culturally distinct ethnic groups whose members are directly descended from the earliest known inhabitants of a particular geographic region and, to some extent, maintain the language and culture of those original people ...

of the island are the Ainu, Oroks

Oroks (''Ороки'' in Russian; self-designation: ''Ulta, Ulcha''), sometimes called Uilta, are a people in the Sakhalin Oblast (mainly the eastern part of the island) in Russia. The Orok language belongs to the Southern group of the Tungu ...

, and Nivkhs

The Nivkh, or Gilyak (also Nivkhs or Nivkhi, or Gilyaks; ethnonym: Нивхгу, ''Nʼivxgu'' (Amur) or Ниғвңгун, ''Nʼiɣvŋgun'' (E. Sakhalin) "the people"), are an indigenous ethnic group inhabiting the northern half of Sakhalin Islan ...

, who are now present in very small numbers.

The Island's name is derived from the Manchu

The Manchus (; ) are a Tungusic East Asian ethnic group native to Manchuria in Northeast Asia. They are an officially recognized ethnic minority in China and the people from whom Manchuria derives its name. The Later Jin (1616–1636) and ...

word ''Sahaliyan'' (ᠰᠠᡥᠠᠯᡳᠶᠠᠨ). Sakhalin was once part of China during the Qing dynasty

The Qing dynasty ( ), officially the Great Qing,, was a Manchu-led imperial dynasty of China and the last orthodox dynasty in Chinese history. It emerged from the Later Jin dynasty founded by the Jianzhou Jurchens, a Tungusic-speak ...

, although Chinese control was relaxed at times. Sakhalin was later claimed by both Russia and Japan over the course of the 19th and 20th centuries. These disputes sometimes involved military conflicts and divisions of the island between the two powers. In 1875, Japan ceded its claims to Russia in exchange for the northern Kuril Islands

The Kuril Islands or Kurile Islands (; rus, Кури́льские острова́, r=Kuril'skiye ostrova, p=kʊˈrʲilʲskʲɪjə ɐstrɐˈva; Japanese: or ) are a volcanic archipelago currently administered as part of Sakhalin Oblast in the ...

. In 1905, following the Russo-Japanese War

The Russo-Japanese War ( ja, 日露戦争, Nichiro sensō, Japanese-Russian War; russian: Ру́сско-япóнская войнá, Rússko-yapónskaya voyná) was fought between the Empire of Japan and the Russian Empire during 1904 and 1 ...

, the island was divided, with the south going to Japan. Russia has held all of the island since seizing the Japanese portion, as well as all the Kuril Islands, in the final days of World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

in 1945. Japan no longer claims any of Sakhalin, although it does still claim the southern Kuril Islands. Most Ainu on Sakhalin moved to Hokkaido, to the south across the La Pérouse Strait

La Pérouse Strait (russian: пролив Лаперуза), or Sōya Strait, is a strait dividing the southern part of the Russian island of Sakhalin from the northern part of the Japanese island of Hokkaidō, and connecting the Sea of Japan on t ...

, when the Japanese were displaced from the island in 1949.

Etymology

TheManchus

The Manchus (; ) are a Tungusic East Asian ethnic group native to Manchuria in Northeast Asia. They are an officially recognized ethnic minority in China and the people from whom Manchuria derives its name. The Later Jin (1616–1636) and Q ...

called it "Sahaliyan ula angga hada" (Island at the Mouth of the Black River) . ''Sahaliyan'', the word that has been borrowed in the form of "Sakhalin", means "black" in Manchu, ''ula'' means "river" and ''sahaliyan ula'' (, "Black River") is the proper Manchu name of the Amur River

The Amur (russian: река́ Аму́р, ), or Heilong Jiang (, "Black Dragon River", ), is the world's List of longest rivers, tenth longest river, forming the border between the Russian Far East and Northeast China, Northeastern China (Inne ...

.

The island was also called "Kuye Fiyaka". The word "Kuye" used by the Qing is "most probably related to ''kuyi'', the name given to the Sakhalin Ainu by their Nivkh and Nanai neighbors." When the Ainu migrated onto the mainland, the Chinese described a "strong Kui (or Kuwei, Kuwu, Kuye, Kugi, ''i.e.'' Ainu) presence in the area otherwise dominated by the Gilemi or Jilimi (Nivkh and other Amur peoples)." Related names were in widespread use in the region, for example the Kuril Ainu called themselves ''koushi''.

History

Early history

Humans lived on Sakhalin in the

Humans lived on Sakhalin in the Neolithic

The Neolithic period, or New Stone Age, is an Old World archaeological period and the final division of the Stone Age. It saw the Neolithic Revolution, a wide-ranging set of developments that appear to have arisen independently in several parts ...

Stone Age. Flint implements such as those found in Siberia

Siberia ( ; rus, Сибирь, r=Sibir', p=sʲɪˈbʲirʲ, a=Ru-Сибирь.ogg) is an extensive geographical region, constituting all of North Asia, from the Ural Mountains in the west to the Pacific Ocean in the east. It has been a part of ...

have been found at Dui and Kusunai in great numbers, as well as polished stone hatchets similar to European examples, primitive pottery with decorations like those of the Olonets

Olonets (russian: Оло́нец; krl, Anus, olo, Anuksenlinnu; fi, Aunus, Aunuksenkaupunki or Aunuksenlinna) is a town and the administrative center of Olonetsky District of the Republic of Karelia, Russia, located on the Olonka River to t ...

, and stone weights used with fishing nets. A later population familiar with bronze left traces in earthen walls and kitchen-midden

A midden (also kitchen midden or shell heap) is an old dump for domestic waste which may consist of animal bone, human excrement, botanical material, mollusc shells, potsherds, lithics (especially debitage), and other artifacts and ecofact ...

s on Aniva Bay

Aniva Bay (Russian: Залив Анива (''Zaliv Aniva''), Japanese: 亜庭湾, Aniwa Bay, or Aniva Gulf) is located at the southern end of Sakhalin Island, Russia, north of the island of Hokkaidō, Japan. The largest city on the bay is Kors ...

.

Indigenous people

Indigenous peoples are culturally distinct ethnic groups whose members are directly descended from the earliest known inhabitants of a particular geographic region and, to some extent, maintain the language and culture of those original people ...

of Sakhalin include the Ainu in the southern half, the Oroks

Oroks (''Ороки'' in Russian; self-designation: ''Ulta, Ulcha''), sometimes called Uilta, are a people in the Sakhalin Oblast (mainly the eastern part of the island) in Russia. The Orok language belongs to the Southern group of the Tungu ...

in the central region, and the Nivkhs

The Nivkh, or Gilyak (also Nivkhs or Nivkhi, or Gilyaks; ethnonym: Нивхгу, ''Nʼivxgu'' (Amur) or Ниғвңгун, ''Nʼiɣvŋgun'' (E. Sakhalin) "the people"), are an indigenous ethnic group inhabiting the northern half of Sakhalin Islan ...

in the north.

Yuan and Ming tributaries

After theMongols

The Mongols ( mn, Монголчууд, , , ; ; russian: Монголы) are an East Asian ethnic group native to Mongolia, Inner Mongolia in China and the Buryatia Republic of the Russian Federation. The Mongols are the principal membe ...

conquered the Jin dynasty (1234), they suffered raids by the Nivkh

Nivkh or Amuric or Gilyak may refer to:

* Nivkh people

The Nivkh, or Gilyak (also Nivkhs or Nivkhi, or Gilyaks; ethnonym: Нивхгу, ''Nʼivxgu'' (Amur) or Ниғвңгун, ''Nʼiɣvŋgun'' (E. Sakhalin) "the people"), are an indigenous et ...

and Udege people

Udege (russian: Удэгейцы; ude, удиэ or , or Udihe, Udekhe, and Udeghe correspondingly) are a native people of the Primorsky Krai and Khabarovsk Krai regions in Russia. They live along the tributaries of the Ussuri, Amur, Khunga ...

s. In response, the Mongols established an administration post at Nurgan (present-day Tyr, Russia

Tyr (russian: Тыр) is a settlement in Ulchsky District of Khabarovsk Krai, Russia, located on the right bank of the Amur River, near the mouth of the Amgun River, about upstream from Nikolayevsk-on-Amur.

Tyr has been known as a historical ...

) at the junction of the Amur

The Amur (russian: река́ Аму́р, ), or Heilong Jiang (, "Black Dragon River", ), is the world's List of longest rivers, tenth longest river, forming the border between the Russian Far East and Northeast China, Northeastern China (Inne ...

and Amgun

The Amgun () is a river in Khabarovsk Krai, Russia that flows northeast and joins the river Amur from the left, 146 km upstream from its outflow into sea. The length of the river is . The area of its basin is . The Amgun is formed by the co ...

rivers in 1263, and forced the submission of the two peoples.

From the Nivkh perspective, their surrender to the Mongols essentially established a military alliance against the Ainu who had invaded their lands. According to the ''History of Yuan

The ''History of Yuan'' (''Yuán Shǐ''), also known as the ''Yuanshi'', is one of the official Chinese historical works known as the ''Twenty-Four Histories'' of China. Commissioned by the court of the Ming dynasty, in accordance to political ...

'', a group of people known as the ''Guwei'' (, the Nivkh name for Ainu), from Sakhalin invaded and fought with the Jilimi (Nivkh people) every year. On 30 November 1264, the Mongols attacked the Ainu. The Ainu resisted Mongol rule and rebelled in 1284, but by 1308 had been subdued. They paid tribute to the Mongol Yuan dynasty

The Yuan dynasty (), officially the Great Yuan (; xng, , , literally "Great Yuan State"), was a Mongol-led imperial dynasty of China and a successor state to the Mongol Empire after its division. It was established by Kublai, the fifth ...

at posts in Wuliehe, Nanghar, and Boluohe.

The Chinese Ming dynasty

The Ming dynasty (), officially the Great Ming, was an Dynasties in Chinese history, imperial dynasty of China, ruling from 1368 to 1644 following the collapse of the Mongol Empire, Mongol-led Yuan dynasty. The Ming dynasty was the last ort ...

of 1368 to 1644 placed Sakhalin under its "system for subjugated peoples" (''ximin tizhi''). From 1409 to 1411 the Ming established an outpost called the Nurgan Regional Military Commission

The Nurgan Regional Military Commission () was a Chinese administrative seat established in Manchuria during the Ming dynasty, located on the banks of the Amur River, about 100 km from the sea, at Nurgan city (modern Tyr, Russia). Nurgan ...

near the ruins of Tyr on the Siberian mainland, which continued operating until the mid-1430s. There is some evidence that the Ming eunuch Admiral Yishiha

Yishiha (; also Išiqa or Isiha; Jurchen: ) ( fl. 1409–1451) was a Jurchen eunuch of the Ming dynasty of China. He served the Ming emperors who commissioned several expeditions down the Songhua and Amur Rivers during the period of Ming rule o ...

reached Sakhalin in 1413 during one of his expeditions to the lower Amur, and granted Ming titles to a local chieftain. Link is to partial text.

The Ming recruited headmen from Sakhalin for administrative posts such as commander (), assistant commander (), and "official charged with subjugation" (). In 1431 one such assistant commander, Alige, brought marten

A marten is a weasel-like mammal in the genus ''Martes'' within the subfamily Guloninae, in the family Mustelidae. They have bushy tails and large paws with partially retractile claws. The fur varies from yellowish to dark brown, depending on t ...

pelts as tribute to the Wuliehe post. In 1437 four other assistant commanders (Zhaluha, Sanchiha, Tuolingha, and Alingge) also presented tribute. According to the ''Ming Shilu

The ''Ming Shilu'' () contains the imperial annals of the emperors of the Ming dynasty (1368–1644). It is the single largest historical source for the dynasty. According to modern historians, it "plays an extremely important role in the histo ...

'', these posts, like the position of headman, were hereditary and passed down the patrilineal line. During these tributary missions, the headmen would bring their sons, who later inherited their titles. In return for tribute, the Ming awarded them with silk uniforms.

Nivkh

Nivkh or Amuric or Gilyak may refer to:

* Nivkh people

The Nivkh, or Gilyak (also Nivkhs or Nivkhi, or Gilyaks; ethnonym: Нивхгу, ''Nʼivxgu'' (Amur) or Ниғвңгун, ''Nʼiɣvŋgun'' (E. Sakhalin) "the people"), are an indigenous et ...

women in Sakhalin married Han Chinese Ming officials when the Ming took tribute from Sakhalin and the Amur river region.

Qing tributary

The Manchu

The Manchu Qing dynasty

The Qing dynasty ( ), officially the Great Qing,, was a Manchu-led imperial dynasty of China and the last orthodox dynasty in Chinese history. It emerged from the Later Jin dynasty founded by the Jianzhou Jurchens, a Tungusic-speak ...

which came to power in China in 1644 called Sakhalin "Kuyedao (Simplified Chinese

Simplification, Simplify, or Simplified may refer to:

Mathematics

Simplification is the process of replacing a mathematical expression by an equivalent one, that is simpler (usually shorter), for example

* Simplification of algebraic expressions, ...

: 库页岛, Kùyè dăo)" (the island of the Ainu) or "Kuye Fiyaka ( )". The Manchus

The Manchus (; ) are a Tungusic East Asian ethnic group native to Manchuria in Northeast Asia. They are an officially recognized ethnic minority in China and the people from whom Manchuria derives its name. The Later Jin (1616–1636) and Q ...

called it "Sagaliyan ula angga hada" (Island at the Mouth of the Black River). The Qing first asserted influence over Sakhalin after the 1689 Treaty of Nerchinsk

The Treaty of Nerchinsk () of 1689 was the first treaty between the Tsardom of Russia and the Qing dynasty of China. The Russians gave up the area north of the Amur River as far as the Stanovoy Range and kept the area between the Argun River ...

, which defined the Stanovoy Mountains

The Stanovoy Range (russian: Станово́й хребе́т, ''Stanovoy khrebet''; sah, Сир кура; ), is a mountain range located in the Sakha Republic and Amur Oblast, Far Eastern Federal District. It is also known as Sükebayatur a ...

as the border between the Qing and the Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended the Great Northern War. ...

s. In the following year the Qing sent forces to the Amur

The Amur (russian: река́ Аму́р, ), or Heilong Jiang (, "Black Dragon River", ), is the world's List of longest rivers, tenth longest river, forming the border between the Russian Far East and Northeast China, Northeastern China (Inne ...

estuary and demanded that the residents, including the Sakhalin Ainu, pay tribute. To enforce its influence, the Qing sent soldiers and mandarins across Sakhalin, reaching most parts of the island except the southern tip. The Qing imposed a fur-tribute system on the region's inhabitants.

The Qing dynasty established an office in Ningguta, situated midway along the Mudan River

The Mudan River (; IPA: ; ) is a river in Heilongjiang province in China. It is a right tributary of the Sunggari River.

Its modern Chinese name can be translated as the "Peony River". In the past it was also known as the Hurka or Hurha River ...

, to handle fur from the lower Amur and Sakhalin. Tribute was supposed to be brought to regional offices, but the lower Amur and Sakhalin were considered too remote, so the Qing sent officials directly to these regions every year to collect tribute and to present awards. In 1732, 6 ''hala'', 18 ''gasban'', and 148 households were registered as tribute bearers in Sakhalin. During the reign of the Qianlong Emperor

The Qianlong Emperor (25 September 17117 February 1799), also known by his temple name Emperor Gaozong of Qing, born Hongli, was the fifth Emperor of the Qing dynasty and the fourth Qing emperor to rule over China proper, reigning from 1735 t ...

(r. 1736–95), a trade post existed at Delen, upstream of Kiji Lake, according to Rinzo Mamiya. There were 500–600 people at the market during Mamiya's stay there.

Local native Sakhalin chiefs had their daughters taken as wives by Manchu officials as sanctioned by the Qing dynasty when the Qing exercised jurisdiction in Sakhalin and took tribute from them.

Japanese exploration and colonization

In 1635 Matsumae Kinhiro, the second daimyō ofMatsumae Domain

The was a Japanese clan that was confirmed in the possession of the area around Matsumae, Hokkaidō as a march fief in 1590 by Toyotomi Hideyoshi, and charged with defending it, and by extension the whole of Japan, from the Ainu "barbarians" ...

in Hokkaidō, sent Satō Kamoemon and Kakizaki Kuroudo on an expedition to Sakhalin. One of the Matsumae explorers, Kodō Shōzaemon, stayed in the island in the winter of 1636 and sailed along the east coast to Taraika (now Poronaysk

Poronaysk (russian: Порона́йск; ja, 敷香町 ''Shisuka-chō''; Ainu: ''Sistukari'' or ''Sisi Tukari'') is a town and the administrative center of Poronaysky District of Sakhalin Oblast, Russia, located on the Poronay River north of ...

) in the spring of 1637.

In an early colonization attempt, a Japanese settlement was established at Ōtomari on Sakhalin's southern end in 1679. Cartographers of the Matsumae clan

The was a Japanese clan that was confirmed in the possession of the area around Matsumae, Hokkaidō as a march fief in 1590 by Toyotomi Hideyoshi, and charged with defending it, and by extension the whole of Japan, from the Ainu "barbarians" ...

drew a map of the island and called it "Kita-Ezo" (Northern Ezo, Ezo

(also spelled Yezo or Yeso) is the Japanese term historically used to refer to the lands to the north of the Japanese island of Honshu. It included the northern Japanese island of Hokkaido, which changed its name from "Ezo" to "Hokkaidō" in 18 ...

being the old Japanese name for the islands north of Honshu

, historically called , is the largest and most populous island of Japan. It is located south of Hokkaidō across the Tsugaru Strait, north of Shikoku across the Inland Sea, and northeast of Kyūshū across the Kanmon Straits. The island separ ...

).

In the 1780s the influence of the Japanese Tokugawa Shogunate

The Tokugawa shogunate (, Japanese 徳川幕府 ''Tokugawa bakufu''), also known as the , was the military government of Japan during the Edo period from 1603 to 1868. Nussbaum, Louis-Frédéric. (2005)"''Tokugawa-jidai''"in ''Japan Encyclopedia ...

on the Ainu of southern Sakhalin increased significantly. By the beginning of the 19th century, the Japanese economic zone extended midway up the east coast, to Taraika. With the exception of the Nayoro Ainu located on the west coast in close proximity to China, most Ainu stopped paying tribute to the Qing dynasty. The Matsumae clan

The was a Japanese clan that was confirmed in the possession of the area around Matsumae, Hokkaidō as a march fief in 1590 by Toyotomi Hideyoshi, and charged with defending it, and by extension the whole of Japan, from the Ainu "barbarians" ...

was nominally in charge of Sakhalin, but they neither protected nor governed the Ainu there. Instead they extorted the Ainu for Chinese silk, which they sold in Honshu

, historically called , is the largest and most populous island of Japan. It is located south of Hokkaidō across the Tsugaru Strait, north of Shikoku across the Inland Sea, and northeast of Kyūshū across the Kanmon Straits. The island separ ...

as Matsumae's special product. To obtain Chinese silk, the Ainu fell into debt, owing much fur to the Santan (Ulch people

The Ulch people, also known as Ulch or Ulchi, (russian: ульчи, obsolete ольчи; Ulch: , nani) are an indigenous people of the Russian Far East, who speak a Tungusic language known as Ulch. Over 90% of Ulchis live in Ulchsky District ...

), who lived near the Qing office. The Ainu also sold the silk uniforms (''mangpao'', ''bufu'', and ''chaofu'') given to them by the Qing, which made up the majority of what the Japanese knew as ''nishiki'' and ''jittoku''. As dynastic uniforms, the silk was of considerably higher quality than that traded at Nagasaki

is the capital and the largest city of Nagasaki Prefecture on the island of Kyushu in Japan.

It became the sole port used for trade with the Portuguese and Dutch during the 16th through 19th centuries. The Hidden Christian Sites in the ...

, and enhanced Matsumae prestige as exotic items. Eventually the Tokugawa government, realizing that they could not depend on the Matsumae, took control of Sakhalin in 1807.

Japan proclaimed sovereignty over Sakhalin in 1807, and in 1809 Mamiya Rinzō

was a Japanese explorer of the late Edo period. He is best known for his exploration of Karafuto, now known as Sakhalin. He mapped areas of northeast Asia then unknown to Japanese.

Biography

Mamiya was born in 1775 in Tsukuba District, Hitach ...

claimed that it was an island.

The Santan Japanese traders seized Rishiri Ainu women when they were trading in Sakhalin to become their wives.

European exploration

The first European known to visit Sakhalin was Martin Gerritz de Vries, who mapped

The first European known to visit Sakhalin was Martin Gerritz de Vries, who mapped Cape Patience

Cape Patience (russian: Полуостров Терпения, ''Poluostrov Terpeniya'') is a peninsula protruding km of east-central Sakhalin Island into the Sea of Okhotsk. It forms the eastern boundary of the Gulf of Patience. The width of t ...

and Cape Aniva on the island's east coast in 1643. The Dutch

Dutch commonly refers to:

* Something of, from, or related to the Netherlands

* Dutch people ()

* Dutch language ()

Dutch may also refer to:

Places

* Dutch, West Virginia, a community in the United States

* Pennsylvania Dutch Country

People E ...

captain, however, was unaware that it was an island, and 17th-century maps usually showed these points (and often Hokkaido as well) as part of the mainland. As part of a nationwide Sino-French cartographic program, Jesuits

The Society of Jesus ( la, Societas Iesu; abbreviation: SJ), also known as the Jesuits (; la, Iesuitæ), is a religious order (Catholic), religious order of clerics regular of pontifical right for men in the Catholic Church headquartered in Rom ...

Jean-Baptiste Régis

Jean-Baptiste Régis (11 June 1663 or 29 January 1664 – 24 November 1738) was a French Jesuit missionary in imperial China.

Biography and works

He was born at Istres, in Provence, on 11 June 1663, or 29 January 1664; died in Beijing on 24 Novem ...

, Pierre Jartoux, and Xavier Ehrenbert Fridelli joined a Chinese team visiting the lower Amur

The Amur (russian: река́ Аму́р, ), or Heilong Jiang (, "Black Dragon River", ), is the world's List of longest rivers, tenth longest river, forming the border between the Russian Far East and Northeast China, Northeastern China (Inne ...

(known to them under its Manchu

The Manchus (; ) are a Tungusic East Asian ethnic group native to Manchuria in Northeast Asia. They are an officially recognized ethnic minority in China and the people from whom Manchuria derives its name. The Later Jin (1616–1636) and ...

name, Sahaliyan Ula, i.e. the "Black River"), in 1709, and learned of the existence of the nearby offshore island from the ''Ke tcheng'' natives of the lower Amur.

The Jesuits did not have a chance to visit the island, and the geographical information provided by the ''Ke tcheng'' people and Manchus who had been to the island was insufficient to allow them to identify it as the land visited by de Vries in 1643. As a result, many 17th-century maps showed a rather strangely shaped Sakhalin, which included only the northern half of the island (with Cape Patience), while Cape Aniva, discovered by de Vries, and the "Black Cape" (Cape Crillon) were thought to form part of the mainland.

Only with the 1787 expedition of Jean-François de La Pérouse

Jean-François is a French given name. Notable people bearing the given name include:

* Jean-François Carenco (born 1952), French politician

* Jean-François Champollion (1790–1832), French Egyptologist

* Jean-François Clervoy (born 1958), Fr ...

did the island began to resemble something of its true shape on European maps. Though unable to pass through its northern "bottleneck" due to contrary winds, La Perouse charted most of the Strait of Tartary

Strait of Tartary or Gulf of Tartary (russian: Татарский пролив; ; ja, 間宮海峡, Mamiya kaikyō, Mamiya Strait; ko, 타타르 해협) is a strait in the Pacific Ocean dividing the Russian island of Sakhalin from mainland Asia ...

, and islanders he encountered near today's Strait of Nevelskoy

The Nevelskoy Strait (russian: Пролив Невельско́го) is a strait within the Strait of Tartary located at the narrowest point between Sakhalin and the Asian mainland. The Nevelskoy Strait is administratively part of Russia on the b ...

told him that the island was called "Tchoka" (or at least that is how he recorded the name in French), and "Tchoka" appears on some maps thereafter.

19th century

Russo-Japanese rivalry

On the basis of its belief that it was an extension of Hokkaido, both geographically and culturally, Japan again proclaimed sovereignty over the whole island (as well as the

On the basis of its belief that it was an extension of Hokkaido, both geographically and culturally, Japan again proclaimed sovereignty over the whole island (as well as the Kuril Islands

The Kuril Islands or Kurile Islands (; rus, Кури́льские острова́, r=Kuril'skiye ostrova, p=kʊˈrʲilʲskʲɪjə ɐstrɐˈva; Japanese: or ) are a volcanic archipelago currently administered as part of Sakhalin Oblast in the ...

chain) in 1845, in the face of competing claims from Russia. In 1849, however, the Russian navigator Gennady Nevelskoy

Gennady Ivanovich Nevelskoy (; in Drakino, now in Soligalichsky District, Kostroma Oblast – in St. Petersburg) was a Russian navigator.

In 1848 Nevelskoy set out in command of what became the to the area of the present-day ...

recorded the existence and navigability of the strait later given his name, and Russian settlers began establishing coal mines, administration facilities, schools, and churches on the island. In 1853–54, Nikolay Rudanovsky

Nikolay Vasilyevich Rudanovsky (russian: Николай Васильевич Рудановский, 1819 — 1882) was a Russian marine officer and explorer, notable for leading several expeditions in 1853-54 to survey and to map the southern par ...

surveyed and mapped the island.

In 1855, Russia and Japan signed the Treaty of Shimoda

The Treaty of Shimoda (下田条約, ''Shimoda Jouyaku'') (formally Treaty of Commerce and Navigation between Japan and Russia 日露和親条約, ''Nichi-Ro Washin Jouyaku'') of February 7, 1855, was the first treaty between the Russian Empire, a ...

, which declared that nationals of both countries could inhabit the island: Russians in the north, and Japanese in the south, without a clearly defined boundary between. Russia also agreed to dismantle its military base at Ootomari. Following the Opium War

The First Opium War (), also known as the Opium War or the Anglo-Sino War was a series of military engagements fought between Britain and the Qing dynasty of China between 1839 and 1842. The immediate issue was the Chinese enforcement of the ...

, Russia forced China to sign the Treaty of Aigun

The Treaty of Aigun (Russian: Айгунский договор; ) was an 1858 treaty between the Russian Empire and the Qing dynasty that established much of the modern border between the Russian Far East and China by ceding much of Manchuria ( ...

(1858) and the Convention of Peking

The Convention of Peking or First Convention of Peking is an agreement comprising three distinct treaties concluded between the Qing dynasty of China and Great Britain, France, and the Russian Empire in 1860. In China, they are regarded as amon ...

(1860), under which China lost to Russia all claims to territories north of Heilongjiang

Heilongjiang () formerly romanized as Heilungkiang, is a province in northeast China. The standard one-character abbreviation for the province is (). It was formerly romanized as "Heilungkiang". It is the northernmost and easternmost province ...

(Amur

The Amur (russian: река́ Аму́р, ), or Heilong Jiang (, "Black Dragon River", ), is the world's List of longest rivers, tenth longest river, forming the border between the Russian Far East and Northeast China, Northeastern China (Inne ...

) and east of Ussuri

The Ussuri or Wusuli (russian: Уссури; ) is a river that runs through Khabarovsk and Primorsky Krais, Russia and the southeast region of Northeast China. It rises in the Sikhote-Alin mountain range, flowing north and forming part of the Si ...

.

In 1857 the Russians established a penal colony

A penal colony or exile colony is a settlement used to exile prisoners and separate them from the general population by placing them in a remote location, often an island or distant colonial territory. Although the term can be used to refer to ...

. The island remained under shared sovereignty until the signing of the 1875 Treaty of Saint Petersburg, in which Japan surrendered its claims in Sakhalin to Russia. In 1890 the distinguished author Anton Chekhov

Anton Pavlovich Chekhov (; 29 January 1860 Old Style date 17 January. – 15 July 1904 Old Style date 2 July.) was a Russian playwright and short-story writer who is considered to be one of the greatest writers of all time. His career ...

visited the penal colony on Sakhalin and published a memoir of his journey.

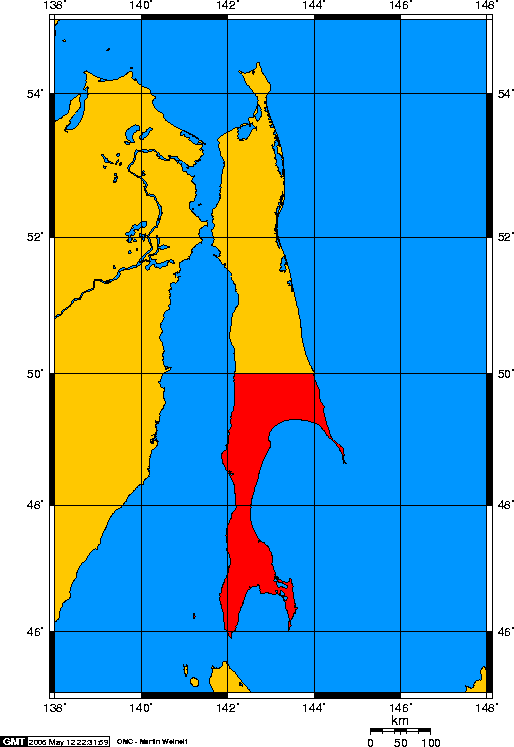

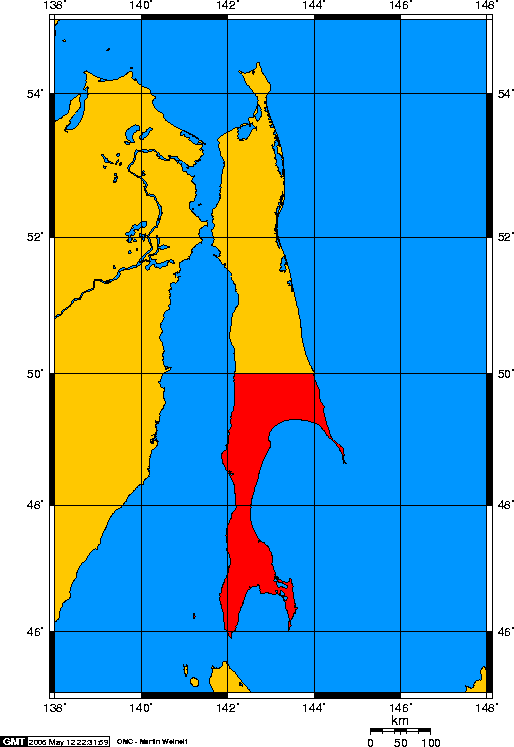

Division along 50th parallel

Japanese forces invaded and occupied Sakhalin in the closing stages of the

Japanese forces invaded and occupied Sakhalin in the closing stages of the Russo-Japanese War

The Russo-Japanese War ( ja, 日露戦争, Nichiro sensō, Japanese-Russian War; russian: Ру́сско-япóнская войнá, Rússko-yapónskaya voyná) was fought between the Empire of Japan and the Russian Empire during 1904 and 1 ...

. In accordance with the Treaty of Portsmouth

A treaty is a formal, legally binding written agreement between actors in international law. It is usually made by and between sovereign states, but can include international organizations, individuals, business entities, and other legal perso ...

of 1905, the southern part of the island below the 50th parallel north reverted to Japan, while Russia retained the northern three-fifths. In 1920, during the Siberian Intervention

The Siberian intervention or Siberian expedition of 1918–1922 was the dispatch of troops of the Entente powers to the Russian Maritime Provinces as part of a larger effort by the western powers, Japan, and China to support White Russian fo ...

, Japan again occupied the northern part of the island, returning it to the Soviet Union in 1925.

South Sakhalin was administered by Japan as Karafuto Prefecture

Karafuto Prefecture ( ja, 樺太庁, ''Karafuto-chō''; russian: Префектура Карафуто, Prefektura Karafuto), commonly known as South Sakhalin, was a prefecture of Japan located in Sakhalin from 1907 to 1949.

Karafuto became ter ...

(), with the capital at Toyohara (today's Yuzhno-Sakhalinsk

Yuzhno-Sakhalinsk ( rus, Ю́жно-Сахали́нск, a=Ru-Южно-Сахалинск.ogg, p=ˈjuʐnə səxɐˈlʲinsk, literally "South Sakhalin City") is a city on Sakhalin island, and the administrative center of Sakhalin Oblast, Russia. I ...

). A large number of migrants were brought in from Korea.

The northern, Russian, half of the island formed Sakhalin Oblast

Sakhalin Oblast ( rus, Сахали́нская о́бласть, r=Sakhalínskaya óblast', p=səxɐˈlʲinskəjə ˈobləsʲtʲ) is a federal subjects of Russia, federal subject of Russia (an oblast) comprising the island of Sakhalin and the K ...

, with the capital at Aleksandrovsk-Sakhalinsky.

Whaling

Between 1848 and 1902,American

American(s) may refer to:

* American, something of, from, or related to the United States of America, commonly known as the "United States" or "America"

** Americans, citizens and nationals of the United States of America

** American ancestry, pe ...

whaleship

A whaler or whaling ship is a specialized vessel, designed or adapted for whaling: the catching or processing of whales.

Terminology

The term ''whaler'' is mostly historic. A handful of nations continue with industrial whaling, and one, Japa ...

s hunted whale

Whales are a widely distributed and diverse group of fully aquatic placental marine mammals. As an informal and colloquial grouping, they correspond to large members of the infraorder Cetacea, i.e. all cetaceans apart from dolphins and ...

s off Sakhalin. They cruised for bowhead and gray whale

The gray whale (''Eschrichtius robustus''), also known as the grey whale,Britannica Micro.: v. IV, p. 693. gray back whale, Pacific gray whale, Korean gray whale, or California gray whale, is a baleen whale that migrates between feeding and bree ...

s to the north and right whale

Right whales are three species of large baleen whales of the genus ''Eubalaena'': the North Atlantic right whale (''E. glacialis''), the North Pacific right whale (''E. japonica'') and the Southern right whale (''E. australis''). They are clas ...

s to the east and south.

On June 7, 1855, the ship ''Jefferson'' (396 tons), of New London

New London may refer to:

Places United States

*New London, Alabama

*New London, Connecticut

*New London, Indiana

*New London, Iowa

*New London, Maryland

*New London, Minnesota

*New London, Missouri

*New London, New Hampshire, a New England town

** ...

, was wrecked on Cape Levenshtern, on the northeastern side of the island, during a fog. All hands were saved as well as 300 barrels of whale oil

Whale oil is oil obtained from the blubber of whales. Whale oil from the bowhead whale was sometimes known as train oil, which comes from the Dutch word ''traan'' ("tears, tear" or "drop").

Sperm oil, a special kind of oil obtained from the ...

.

Second World War

In August 1945, after repudiating theSoviet–Japanese Neutrality Pact

The , also known as the , was a non-aggression pact between the Soviet Union and the Empire of Japan signed on April 13, 1941, two years after the conclusion of the Soviet-Japanese Border War. The agreement meant that for most of World War II, ...

, the Soviet Union invaded southern Sakhalin, an action planned secretly at the Yalta Conference

The Yalta Conference (codenamed Argonaut), also known as the Crimea Conference, held 4–11 February 1945, was the World War II meeting of the heads of government of the United States, the United Kingdom, and the Soviet Union to discuss the post ...

. The Soviet attack started on August 11, 1945, a few days before the surrender of Japan. The Soviet 56th Rifle Corps, part of the 16th Army, consisting of the 79th Rifle Division

The 79th Motor Rifle Division was a motorized infantry division of the Soviet Army. It was converted from the 79th Rifle Division in 1957 and inherited the honorific "Sakhalin". The division was awarded the Order of the Red Banner. The 79th Rifle ...

, the 2nd Rifle Brigade, the 5th Rifle Brigade and the 214 Armored Brigade, attacked the Japanese 88th Infantry Division. Although the Soviet Red Army outnumbered the Japanese by three to one, they advanced only slowly due to strong Japanese resistance. It was not until the 113th Rifle Brigade and the 365th Independent Naval Infantry Rifle Battalion from Sovetskaya Gavan landed on Tōro, a seashore village of western Karafuto, on August 16 that the Soviets broke the Japanese defense line. Japanese resistance grew weaker after this landing. Actual fighting continued until August 21. From August 22 to August 23, most remaining Japanese units agreed to a ceasefire. The Soviets completed the conquest of Karafuto on August 25, 1945 by occupying the capital of Toyohara.

Of the approximately 400,000 people – mostly Japanese and Korean – who lived on South Sakhalin in 1944, about 100,000 were evacuated to Japan during the last days of the war. The remaining 300,000 stayed behind, some for several more years.

While the vast majority of Sakhalin Japanese and Koreans were gradually repatriated between 1946 and 1950, tens of thousands of Sakhalin Koreans

Sakhalin Koreans are Russian citizens and residents of Korean descent living on Sakhalin Island, who can trace their roots to the immigrants from the Gyeongsang and Jeolla provinces of Korea during the late 1930s and early 1940s, the latter ...

(and a number of their Japanese spouses) remained in the Soviet Union.

No final peace treaty has been signed and the status of four neighboring islands remains disputed

Controversy is a state of prolonged public dispute or debate, usually concerning a matter of conflicting opinion or point of view. The word was coined from the Latin ''controversia'', as a composite of ''controversus'' – "turned in an opposite d ...

. Japan renounced its claims of sovereignty over southern Sakhalin and the Kuril Islands in the Treaty of San Francisco

The , also called the , re-established peaceful relations between Japan and the Allied Powers on behalf of the United Nations by ending the legal state of war and providing for redress for hostile actions up to and including World War II. It w ...

(1951), but maintains that the four offshore islands of Hokkaido

is Japan's second largest island and comprises the largest and northernmost prefecture, making up its own region. The Tsugaru Strait separates Hokkaidō from Honshu; the two islands are connected by the undersea railway Seikan Tunnel.

The la ...

currently administered by Russia were not subject to this renunciation. Japan granted mutual exchange visas for Japanese and Ainu families divided by the change in status. Recently, economic and political cooperation has gradually improved between the two nations despite disagreements.

Recent history

On September 1, 1983,

On September 1, 1983, Korean Air Flight 007

Korean Air Lines Flight 007 (KE007/KAL007)The flight number KAL 007 was used by air traffic control, while the public flight booking system used KE 007 was a scheduled Korean Air Lines flight from New York City to Seoul via Anchorage, Alas ...

, a South Korean civilian airliner, flew over Sakhalin and was shot down by the Soviet Union, just west of Sakhalin Island, near the smaller Moneron Island

Moneron Island, (russian: Монерон, ja, 海馬島 Kaibato, ja, トド島 Todojima, Ainu: Todomoshiri) is a small island off Sakhalin Island. It is a part of the Russian Federation.

Description

Moneron has an area of about and a high ...

. The Soviet Union claimed it was a spy plane; however, commanders on the ground realized it was a commercial aircraft. All 269 passengers and crew died, including a U.S. Congressman, Larry McDonald

Lawrence Patton McDonald (April 1, 1935 – September 1, 1983) was an American politician and a member of the United States House of Representatives, representing Georgia's 7th congressional district as a Democrat from 1975 until he was killed ...

.

On 27 May 1995, the 7.0 Neftegorsk earthquake shook the former Russian settlement of Neftegorsk with a maximum Mercalli intensity

The Modified Mercalli intensity scale (MM, MMI, or MCS), developed from Giuseppe Mercalli's Mercalli intensity scale of 1902, is a seismic intensity scale used for measuring the intensity of shaking produced by an earthquake. It measures the eff ...

of IX (''Violent''). Total damage was $64.1–300 million, with 1,989 deaths and 750 injured. The settlement was not rebuilt.

Geography

Sakhalin is separated from the mainland by the narrow and shallowStrait of Tartary

Strait of Tartary or Gulf of Tartary (russian: Татарский пролив; ; ja, 間宮海峡, Mamiya kaikyō, Mamiya Strait; ko, 타타르 해협) is a strait in the Pacific Ocean dividing the Russian island of Sakhalin from mainland Asia ...

, which often freezes in winter in its narrower part, and from Hokkaido

is Japan's second largest island and comprises the largest and northernmost prefecture, making up its own region. The Tsugaru Strait separates Hokkaidō from Honshu; the two islands are connected by the undersea railway Seikan Tunnel.

The la ...

, Japan, by the Soya Strait or La Pérouse Strait

La Pérouse Strait (russian: пролив Лаперуза), or Sōya Strait, is a strait dividing the southern part of the Russian island of Sakhalin from the northern part of the Japanese island of Hokkaidō, and connecting the Sea of Japan on t ...

. Sakhalin is the largest island in Russia, being long, and wide, with an area of . It lies at similar latitudes to England, Wales and Ireland.

Its orography

Orography is the study of the topographic relief of mountains, and can more broadly include hills, and any part of a region's elevated terrain. Orography (also known as ''oreography'', ''orology'' or ''oreology'') falls within the broader discipl ...

and geological structure are imperfectly known. One theory is that Sakhalin arose from the Sakhalin Island Arc. Nearly two-thirds of Sakhalin are mountainous. Two parallel ranges of mountains traverse it from north to south, reaching . The Western Sakhalin Mountains peak in Mount Ichara, , while the Eastern Sakhalin Mountains's highest peak, Mount Lopatin , is also the island's highest mountain. Tym-Poronaiskaya Valley separates the two ranges. Susuanaisky and Tonino-Anivsky ranges traverse the island in the south, while the swampy Northern-Sakhalin plain occupies most of its north.Ivlev, A. M. Soils of Sakhalin. New Delhi: Indian National Scientific Documentation Centre, 1974. Pages 9–28.

Crystalline rocks crop out at several capes; Cretaceous

The Cretaceous ( ) is a geological period that lasted from about 145 to 66 million years ago (Mya). It is the third and final period of the Mesozoic Era, as well as the longest. At around 79 million years, it is the longest geological period of th ...

limestone

Limestone ( calcium carbonate ) is a type of carbonate sedimentary rock which is the main source of the material lime. It is composed mostly of the minerals calcite and aragonite, which are different crystal forms of . Limestone forms whe ...

s, containing an abundant and specific fauna of gigantic ammonite

Ammonoids are a group of extinct marine mollusc animals in the subclass Ammonoidea of the class Cephalopoda. These molluscs, commonly referred to as ammonites, are more closely related to living coleoids (i.e., octopuses, squid and cuttlefish) ...

s, occur at Dui on the west coast; and Tertiary

Tertiary ( ) is a widely used but obsolete term for the geologic period from 66 million to 2.6 million years ago.

The period began with the demise of the non-avian dinosaurs in the Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event, at the start ...

conglomerates, sandstone

Sandstone is a clastic sedimentary rock composed mainly of sand-sized (0.0625 to 2 mm) silicate grains. Sandstones comprise about 20–25% of all sedimentary rocks.

Most sandstone is composed of quartz or feldspar (both silicates) ...

s, marl

Marl is an earthy material rich in carbonate minerals, clays, and silt. When hardened into rock, this becomes marlstone. It is formed in marine or freshwater environments, often through the activities of algae.

Marl makes up the lower part o ...

s, and clay

Clay is a type of fine-grained natural soil material containing clay minerals (hydrous aluminium phyllosilicates, e.g. kaolin, Al2 Si2 O5( OH)4).

Clays develop plasticity when wet, due to a molecular film of water surrounding the clay par ...

s, folded by subsequent upheavals, are found in many parts of the island. The clays, which contain layers of good coal and abundant fossilized vegetation, show that during the Miocene period, Sakhalin formed part of a continent which comprised north Asia, Alaska, and Japan, and enjoyed a comparatively warm climate. The Pliocene

The Pliocene ( ; also Pleiocene) is the epoch in the geologic time scale that extends from 5.333 million to 2.58Arctic Ocean

The Arctic Ocean is the smallest and shallowest of the world's five major oceans. It spans an area of approximately and is known as the coldest of all the oceans. The International Hydrographic Organization (IHO) recognizes it as an ocean, a ...

s was probably broader than it is now.

Main rivers: The Tym, long and navigable by rafts and light boats for , flows north and northeast with numerous rapids and shallows, and enters the Sea of Okhotsk

The Sea of Okhotsk ( rus, Охо́тское мо́ре, Ohótskoye móre ; ja, オホーツク海, Ohōtsuku-kai) is a marginal sea of the western Pacific Ocean. It is located between Russia's Kamchatka Peninsula on the east, the Kuril Islands ...

.Тымь– an article in the ''

Great Soviet Encyclopedia

The ''Great Soviet Encyclopedia'' (GSE; ) is one of the largest Russian-language encyclopedias, published in the Soviet Union from 1926 to 1990. After 2002, the encyclopedia's data was partially included into the later ''Bolshaya rossiyskaya e ...

''. (In Russian, retrieved 21 June 2020.) The Poronay flows south-southeast to the Gulf of Patience

Gulf of Patience is a large body of water off the southeastern coast of Sakhalin, Russia.

Geography

The Gulf of Patience is located in the southern Sea of Okhotsk, between the main body of Sakhalin Island in the west and Cape Patience in the eas ...

or Shichiro Bay, on the southeastern coast. Three other small streams enter the wide semicircular Aniva Bay

Aniva Bay (Russian: Залив Анива (''Zaliv Aniva''), Japanese: 亜庭湾, Aniwa Bay, or Aniva Gulf) is located at the southern end of Sakhalin Island, Russia, north of the island of Hokkaidō, Japan. The largest city on the bay is Kors ...

or Higashifushimi Bay at the southern extremity of the island.

The northernmost point of Sakhalin is Cape of Elisabeth on the Schmidt Peninsula, while Cape Crillon

Cape Crillon (russian: Мыс Крильон, ja, 西能登呂岬 "Nishinotoro-misaki" (Cape Nishinotoro in Japanese), ) is the southernmost point of Sakhalin. The cape was named by Frenchman Jean-François de La Pérouse, who was the first Europe ...

is the southernmost point of the island.

Sakhalin has two smaller islands associated with it, Moneron Island

Moneron Island, (russian: Монерон, ja, 海馬島 Kaibato, ja, トド島 Todojima, Ainu: Todomoshiri) is a small island off Sakhalin Island. It is a part of the Russian Federation.

Description

Moneron has an area of about and a high ...

and Ush Island. Moneron, the only land mass in the Tatar strait, long and wide, is about west from the nearest coast of Sakhalin and from the port city of Nevelsk. Ush Island is an island off of the northern coast of Sakhalin.

Demographics

At the beginning of the 20th century, some 32,000 Russians (of whom over 22,000 were convicts) inhabited Sakhalin along with several thousand native inhabitants. In 2010, the island's population was recorded at 497,973, 83% of whom were ethnic

At the beginning of the 20th century, some 32,000 Russians (of whom over 22,000 were convicts) inhabited Sakhalin along with several thousand native inhabitants. In 2010, the island's population was recorded at 497,973, 83% of whom were ethnic Russians

, native_name_lang = ru

, image =

, caption =

, population =

, popplace =

118 million Russians in the Russian Federation (2002 ''Winkler Prins'' estimate)

, region1 =

, pop1 ...

, followed by about 30,000 Koreans

Koreans ( South Korean: , , North Korean: , ; see names of Korea) are an East Asian ethnic group native to the Korean Peninsula.

Koreans mainly live in the two Korean nation states: North Korea and South Korea (collectively and simply refe ...

(5.5%). Smaller minorities were the Ainu, Ukrainians

Ukrainians ( uk, Українці, Ukraintsi, ) are an East Slavs, East Slavic ethnic group native to Ukraine. They are the seventh-largest nation in Europe. The native language of the Ukrainians is Ukrainian language, Ukrainian. The majority ...

, Tatars

The Tatars ()Tatar

in the Collins English Dictionary is an umbrella term for different

, in the Collins English Dictionary is an umbrella term for different

Yakuts

The Yakuts, or the Sakha ( sah, саха, ; , ), are a Turkic ethnic group who mainly live in the Republic of Sakha in the Russian Federation, with some extending to the Amur, Magadan, Sakhalin regions, and the Taymyr and Evenk Districts ...

and Evenks

The Evenks (also spelled Ewenki or Evenki based on their endonym )Autonym: (); russian: Эвенки (); (); formerly known as Tungus or Tunguz; mn, Хамниган () or Aiwenji () are a Tungusic people of North Asia. In Russia, the Even ...

. The native inhabitants currently consist of some 2,000 Nivkhs

The Nivkh, or Gilyak (also Nivkhs or Nivkhi, or Gilyaks; ethnonym: Нивхгу, ''Nʼivxgu'' (Amur) or Ниғвңгун, ''Nʼiɣvŋgun'' (E. Sakhalin) "the people"), are an indigenous ethnic group inhabiting the northern half of Sakhalin Islan ...

and 750 Oroks

Oroks (''Ороки'' in Russian; self-designation: ''Ulta, Ulcha''), sometimes called Uilta, are a people in the Sakhalin Oblast (mainly the eastern part of the island) in Russia. The Orok language belongs to the Southern group of the Tungu ...

. The Nivkhs in the north support themselves by fishing and hunting. In 2008 there were 6,416 births and 7,572 deaths.

The administrative center of the oblast, Yuzhno-Sakhalinsk

Yuzhno-Sakhalinsk ( rus, Ю́жно-Сахали́нск, a=Ru-Южно-Сахалинск.ogg, p=ˈjuʐnə səxɐˈlʲinsk, literally "South Sakhalin City") is a city on Sakhalin island, and the administrative center of Sakhalin Oblast, Russia. I ...

, a city of about 175,000, has a large Korean minority, typically referred to as Sakhalin Koreans

Sakhalin Koreans are Russian citizens and residents of Korean descent living on Sakhalin Island, who can trace their roots to the immigrants from the Gyeongsang and Jeolla provinces of Korea during the late 1930s and early 1940s, the latter ...

, who were forcibly brought by the Japanese during World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

to work in the coal mines. Most of the population lives in the southern half of the island, centered mainly around Yuzhno-Sakhalinsk and two ports, Kholmsk

Kholmsk (russian: Холмск), known until 1946 as Maoka ( ja, 真岡), is a port town and the administrative center of Kholmsky District of Sakhalin Oblast, Russia. It is located on the southwest coast of the Sakhalin Island, on coast of the g ...

and Korsakov (population about 40,000 each).

The 400,000 Japanese

Japanese may refer to:

* Something from or related to Japan, an island country in East Asia

* Japanese language, spoken mainly in Japan

* Japanese people, the ethnic group that identifies with Japan through ancestry or culture

** Japanese diaspor ...

inhabitants of Sakhalin (including the Japanized indigenous Ainu) who had not already been evacuated during the war were deported following the invasion of the southern portion of the island by the Soviet Union in 1945 at the end of World War II.

Climate

The Sea of Okhotsk ensures that Sakhalin has a cold and humid climate, ranging fromhumid continental

A humid continental climate is a climatic region defined by Russo-German climatologist Wladimir Köppen in 1900, typified by four distinct seasons and large seasonal temperature differences, with warm to hot (and often humid) summers and freezing ...

(Köppen Köppen is a German surname. Notable people with the surname include:

* Bernd Köppen (born 1951), German pianist and composer

* Carl Köppen (1833-1907), German military advisor in Meiji era Japan

* Edlef Köppen (1893–1939), German author and ...

''Dfb'') in the south to subarctic

The subarctic zone is a region in the Northern Hemisphere immediately south of the true Arctic, north of humid continental regions and covering much of Alaska, Canada, Iceland, the north of Scandinavia, Siberia, and the Cairngorms. Generally, ...

(''Dfc'') in the centre and north. The maritime influence makes summers much cooler than in similar-latitude inland cities such as Harbin

Harbin (; mnc, , v=Halbin; ) is a sub-provincial city and the provincial capital and the largest city of Heilongjiang province, People's Republic of China, as well as the second largest city by urban population after Shenyang and largest ...

or Irkutsk

Irkutsk ( ; rus, Иркутск, p=ɪrˈkutsk; Buryat language, Buryat and mn, Эрхүү, ''Erhüü'', ) is the largest city and administrative center of Irkutsk Oblast, Russia. With a population of 617,473 as of the 2010 Census, Irkutsk is ...

, but makes the winters much snowier and a few degrees warmer than in interior East Asian cities at the same latitude. Summers are foggy with little sunshine.

Precipitation is heavy, owing to the strong onshore winds in summer and the high frequency of North Pacific storms affecting the island in the autumn. It ranges from around on the northwest coast to over in southern mountainous regions. In contrast to interior east Asia with its pronounced summer maximum, onshore winds ensure Sakhalin has year-round precipitation with a peak in the autumn.

Flora and fauna

The whole of the island is covered with dense

The whole of the island is covered with dense forest

A forest is an area of land dominated by trees. Hundreds of definitions of forest are used throughout the world, incorporating factors such as tree density, tree height, land use, legal standing, and ecological function. The United Nations' ...

s, mostly conifer

Conifers are a group of conifer cone, cone-bearing Spermatophyte, seed plants, a subset of gymnosperms. Scientifically, they make up the phylum, division Pinophyta (), also known as Coniferophyta () or Coniferae. The division contains a single ...

ous. The Yezo

(also spelled Yezo or Yeso) is the Japanese term historically used to refer to the lands to the north of the Japanese island of Honshu. It included the northern Japanese island of Hokkaido, which changed its name from "Ezo" to "Hokkaidō" in 18 ...

(or Yeddo) spruce (''Picea jezoensis''), the Sakhalin fir

''Abies sachalinensis'', the Sakhalin fir, is a species of conifer in the family Pinaceae. It is found in Sakhalin island and southern Kurils (Russia), and also in northern Hokkaido ( Japan).

The first discovery by a European was by Carl Fri ...

(''Abies sachalinensis'') and the Dahurian larch

''Larix gmelinii'', the Dahurian larch or Gmelin larch, is a species of larch native to eastern Siberia and adjacent northeastern Mongolia, northeastern China (Heilongjiang), South Korea and North Korea.

Description

''Larix gmelinii'' is a m ...

(''Larix gmelinii'') are the chief trees; on the upper parts of the mountains are the Siberian dwarf pine

''Pinus pumila'', commonly known as the Siberian dwarf pine, dwarf Siberian pine, dwarf stone pine, Japanese stone pine, or creeping pine, is a tree in the family Pinaceae native to northeastern Asia and the Japanese isles. It shares the common ...

(''Pinus pumila'') and the Kurile bamboo (''Sasa kurilensis''). Birch

A birch is a thin-leaved deciduous hardwood tree of the genus ''Betula'' (), in the family Betulaceae, which also includes alders, hazels, and hornbeams. It is closely related to the beech-oak family Fagaceae. The genus ''Betula'' contains 30 ...

es, both Siberian silver birch (''Betula platyphylla

''Betula platyphylla'', the Asian white birch or Japanese white birch, is a tree species in the family Betulaceae. It can be found in subarctic and temperate Asia in Japan, China, Korea, Mongolia, and Russian Far East and Siberia

Siberia ...

'') and Erman's birch

''Betula ermanii'', or Erman's birch, is a species of birch tree belonging to the family Betulaceae. It is an extremely variable species and can be found in Northeast China, Korea, Japan, and Russian Far East ( Kuril Islands, Sakhalin, Kamcha ...

(''B. ermanii''), poplar, elm

Elms are deciduous and semi-deciduous trees comprising the flowering plant genus ''Ulmus'' in the plant family Ulmaceae. They are distributed over most of the Northern Hemisphere, inhabiting the temperate and tropical-montane regions of North ...

, bird cherry

Bird cherry is a common name for the European plant '' Prunus padus''.

Bird cherry may also refer to:

* ''Prunus'' subg. ''Padus'', a group of species closely related to ''Prunus padus''

* ''Prunus avium'', the cultivated cherry, with the Latin e ...

(''Prunus padus''), Japanese yew (''Taxus cuspidata''), and several willow

Willows, also called sallows and osiers, from the genus ''Salix'', comprise around 400 speciesMabberley, D.J. 1997. The Plant Book, Cambridge University Press #2: Cambridge. of typically deciduous trees and shrubs, found primarily on moist s ...

s are mixed with the conifers; while farther south the maple

''Acer'' () is a genus of trees and shrubs commonly known as maples. The genus is placed in the family Sapindaceae.Stevens, P. F. (2001 onwards). Angiosperm Phylogeny Website. Version 9, June 2008 nd more or less continuously updated since http ...

, rowan

The rowans ( or ) or mountain-ashes are shrubs or trees in the genus ''Sorbus

''Sorbus'' is a genus of over 100 species of trees and shrubs in the rose family, Rosaceae. Species of ''Sorbus'' (''s.l.'') are commonly known as whitebeam, r ...

and oak

An oak is a tree or shrub in the genus ''Quercus'' (; Latin "oak tree") of the beech family, Fagaceae. There are approximately 500 extant species of oaks. The common name "oak" also appears in the names of species in related genera, notably ''L ...

, as also the Japanese ''Panax ricinifolium'', the Amur cork tree

''Phellodendron amurense'' is a species of tree in the family Rutaceae, commonly called the Amur cork tree. It is a major source of '' huáng bò'' ( or 黄 檗), one of the 50 fundamental herbs used in traditional Chinese medicine. The Ainu pe ...

(''Phellodendron amurense''), the spindle

Spindle may refer to:

Textiles and manufacturing

* Spindle (textiles), a straight spike to spin fibers into yarn

* Spindle (tool), a rotating axis of a machine tool

Biology

* Common spindle and other species of shrubs and trees in genus ''Euony ...

(''Euonymus macropterus'') and the vine ('' Vitis thunbergii'') make their appearance. The underwoods abound in berry-bearing plants (e.g. cloudberry

''Rubus chamaemorus'' is a species of flowering plant in the rose family Rosaceae, native to cool temperate regions, alpine and arctic tundra and boreal forest. This herbaceous perennial produces amber-colored edible fruit similar to the blackbe ...

, cranberry

Cranberries are a group of evergreen dwarf shrubs or trailing vines in the subgenus ''Oxycoccus'' of the genus ''Vaccinium''. In Britain, cranberry may refer to the native species ''Vaccinium oxycoccos'', while in North America, cranberry ...

, crowberry

''Empetrum nigrum'', crowberry, black crowberry, or, in western Alaska, blackberry, is a flowering plant species in the heather family Ericaceae with a near circumboreal distribution in the Northern Hemisphere. It is usually dioecious, but there ...

, red whortleberry

''Vaccinium vitis-idaea'', the lingonberry, partridgeberry, mountain cranberry or cowberry, is a small evergreen shrub in the heath family Ericaceae, that bears edible fruit. It is native to boreal forest and Arctic tundra throughout the Norther ...

), red-berried elder (''Sambucus racemosa

''Sambucus racemosa'' is a species of elderberry known by the common names red elderberry and red-berried elder.

Distribution and habitat

It is native to Europe, northern temperate Asia, and North America across Canada and the United States. It ...

''), wild raspberry

The raspberry is the edible fruit of a multitude of plant species in the genus ''Rubus'' of the rose family, most of which are in the subgenus '' Idaeobatus''. The name also applies to these plants themselves. Raspberries are perennial with w ...

, and spiraea

''Spiraea'' , sometimes spelled spirea in common names, and commonly known as meadowsweets or steeplebushes, is a genus of about 80 to 100 species

.

Bear

Bears are carnivoran mammals of the family Ursidae. They are classified as caniforms, or doglike carnivorans. Although only eight species of bears are extant, they are widespread, appearing in a wide variety of habitats throughout the Nor ...

s, fox

Foxes are small to medium-sized, omnivorous mammals belonging to several genera of the family Canidae. They have a flattened skull, upright, triangular ears, a pointed, slightly upturned snout, and a long bushy tail (or ''brush'').

Twelve sp ...

es, otter

Otters are carnivorous mammals in the subfamily Lutrinae. The 13 extant otter species are all semiaquatic, aquatic, or marine, with diets based on fish and invertebrates. Lutrinae is a branch of the Mustelidae family, which also includes wea ...

s, and sable

The sable (''Martes zibellina'') is a species of marten, a small omnivorous mammal primarily inhabiting the forest environments of Russia, from the Ural Mountains throughout Siberia, and northern Mongolia. Its habitat also borders eastern Kaza ...

s are numerous, as are reindeer

Reindeer (in North American English, known as caribou if wild and ''reindeer'' if domesticated) are deer in the genus ''Rangifer''. For the last few decades, reindeer were assigned to one species, ''Rangifer tarandus'', with about 10 subspe ...

in the north, and musk deer

Musk deer can refer to any one, or all seven, of the species that make up ''Moschus'', the only extant genus of the family Moschidae. Despite being commonly called deer, they are not true deer belonging to the family Cervidae, but rather their fa ...

, hare

Hares and jackrabbits are mammals belonging to the genus ''Lepus''. They are herbivores, and live solitarily or in pairs. They nest in slight depressions called forms, and their young are able to fend for themselves shortly after birth. The ge ...

s, squirrel

Squirrels are members of the family Sciuridae, a family that includes small or medium-size rodents. The squirrel family includes tree squirrels, ground squirrels (including chipmunks and prairie dogs, among others), and flying squirrels. Squ ...

s, rats, and mice

A mouse ( : mice) is a small rodent. Characteristically, mice are known to have a pointed snout, small rounded ears, a body-length scaly tail, and a high breeding rate. The best known mouse species is the common house mouse (''Mus musculus' ...

everywhere. The bird

Birds are a group of warm-blooded vertebrates constituting the class Aves (), characterised by feathers, toothless beaked jaws, the laying of hard-shelled eggs, a high metabolic rate, a four-chambered heart, and a strong yet lightweigh ...

population is mostly the common east Siberian, but there are some endemic

Endemism is the state of a species being found in a single defined geographic location, such as an island, state, nation, country or other defined zone; organisms that are indigenous to a place are not endemic to it if they are also found elsew ...

or near-endemic breeding species, notably the endangered

An endangered species is a species that is very likely to become extinct in the near future, either worldwide or in a particular political jurisdiction. Endangered species may be at risk due to factors such as habitat loss, poaching and inva ...

Nordmann's greenshank

Nordmann's greenshank (''Tringa guttifer'') or the spotted greenshank, is a wader in the large family Scolopacidae, the typical waders.

Description

The Nordmann's greenshank is a medium-sized sandpiper, at long, with a slightly upturned, bicol ...

(''Tringa guttifer'') and the Sakhalin leaf warbler (''Phylloscopus borealoides''). The rivers swarm with fish

Fish are aquatic, craniate, gill-bearing animals that lack limbs with digits. Included in this definition are the living hagfish, lampreys, and cartilaginous and bony fish as well as various extinct related groups. Approximately 95% of li ...

, especially species of salmon

Salmon () is the common name for several list of commercially important fish species, commercially important species of euryhaline ray-finned fish from the family (biology), family Salmonidae, which are native to tributary, tributaries of the ...

(''Oncorhynchus''). Numerous whale

Whales are a widely distributed and diverse group of fully aquatic placental marine mammals. As an informal and colloquial grouping, they correspond to large members of the infraorder Cetacea, i.e. all cetaceans apart from dolphins and ...

s visit the sea coast, including the critically endangered Western Pacific gray whale

The gray whale (''Eschrichtius robustus''), also known as the grey whale,Britannica Micro.: v. IV, p. 693. gray back whale, Pacific gray whale, Korean gray whale, or California gray whale, is a baleen whale that migrates between feeding and bree ...

, for which the coast of Sakhalin is the only known feeding ground. Other endangered whale species known to occur in this area are the North Pacific right whale

The North Pacific right whale (''Eubalaena japonica'') is a very large, thickset baleen whale species that is extremely rare and endangered.

The Northeast Pacific population, which summers in the southeastern Bering Sea and Gulf of Alaska, may ...

, the bowhead whale

The bowhead whale (''Balaena mysticetus'') is a species of baleen whale belonging to the family Balaenidae and the only living representative of the genus ''Balaena''. They are the only baleen whale endemic to the Arctic and subarctic waters, ...

, and the beluga whale

The beluga whale () (''Delphinapterus leucas'') is an Arctic and sub-Arctic cetacean. It is one of two members of the family Monodontidae, along with the narwhal, and the only member of the genus ''Delphinapterus''. It is also known as the whi ...

.

Transport

Sea

Transport, especially by sea, is an important segment of the economy. Nearly all the cargo arriving for Sakhalin (and theKuril Islands

The Kuril Islands or Kurile Islands (; rus, Кури́льские острова́, r=Kuril'skiye ostrova, p=kʊˈrʲilʲskʲɪjə ɐstrɐˈva; Japanese: or ) are a volcanic archipelago currently administered as part of Sakhalin Oblast in the ...

) is delivered by cargo boats, or by ferries, in railway wagons, through the Vanino-Kholmsk train ferry from the mainland port of Vanino to Kholmsk. The ports of Korsakov and Kholmsk are the largest and handle all kinds of goods, while coal

Coal is a combustible black or brownish-black sedimentary rock, formed as rock strata called coal seams. Coal is mostly carbon with variable amounts of other elements, chiefly hydrogen, sulfur, oxygen, and nitrogen.

Coal is formed when dea ...

and timber

Lumber is wood that has been processed into dimensional lumber, including beams and planks or boards, a stage in the process of wood production. Lumber is mainly used for construction framing, as well as finishing (floors, wall panels, wi ...

shipments often go through other ports. In 1999, a ferry service was opened between the ports of Korsakov and Wakkanai

' meaning "cold water river" is a city located in Sōya Subprefecture, Hokkaido, Japan. It is the capital of Sōya Subprefecture. It contains Japan's northernmost point, Cape Sōya, from which the Russian island of Sakhalin can be seen.

As of ...

, Japan, and operated through the autumn of 2015, when service was suspended.

For the 2016 summer season, this route will be served by a highspeed catamaran ferry from Singapore named Penguin 33. The ferry is owned by Penguin International Limited and operated by Sakhalin Shipping Company.

Sakhalin's main shipping company is Sakhalin Shipping Company, headquartered in Kholmsk on the island's west coast.

Rail

About 30% of all inland transport volume is carried by the island's railways, most of which are organized as theSakhalin Railway

Sakhalin Railway (russian: Сахалинская железная дорога) is one of the railway division under Far Eastern Railway that primarily serves in Sakhalin Island. Due to its island location, the railway becomes the second isolated ...

( Сахалинская железная дорога), which is one of the 17 territorial divisions of the Russian Railways

Russian Railways (russian: link=no, ОАО «Российские железные дороги» (ОАО «РЖД»), OAO Rossiyskie zheleznye dorogi (OAO RZhD)) is a Russian fully state-owned vertically integrated railway company, both manag ...

.

The Sakhalin Railway

Sakhalin Railway (russian: Сахалинская железная дорога) is one of the railway division under Far Eastern Railway that primarily serves in Sakhalin Island. Due to its island location, the railway becomes the second isolated ...

network extends from Nogliki

Nogliki (russian: Ноглики) is an urban locality (an urban-type settlement) and the administrative center of Nogliksky District of Sakhalin Oblast, Russia, located near the eastern coast of Sakhalin Island, about inland from the Sea of O ...

in the north to Korsakov in the south. Sakhalin's railway has a connection with the rest of Russia via a train ferry

A train ferry is a ship (ferry) designed to carry railway vehicles. Typically, one level of the ship is fitted with railway tracks, and the vessel has a door at the front and/or rear to give access to the wharves. In the United States, train f ...

operating between Vanino and Kholmsk

Kholmsk (russian: Холмск), known until 1946 as Maoka ( ja, 真岡), is a port town and the administrative center of Kholmsky District of Sakhalin Oblast, Russia. It is located on the southwest coast of the Sakhalin Island, on coast of the g ...

.

The process of converting the railways from the Japanese gauge to the Russian gauge began in 2004 and

was completed in 2019.

The original Japanese D51 steam locomotive

The is a type of 2-8-2 steam locomotive built by the Japanese Government Railways (JGR), the Japanese National Railways (JNR), and Kawasaki Heavy Industries Rolling Stock Company, Kisha Seizo, Hitachi, Nippon Sharyo, Mitsubishi, and Mitsubishi H ...

s were used by the Soviet Railways until 1979.

Besides the main network run by the Russian Railways, until December 2006 the local oil company (Sakhalinmorneftegaz) operated a corporate narrow-gauge line extending for from Nogliki further north to Okha ( Узкоколейная железная дорога Оха – Ноглики). During the last years of its service, it gradually deteriorated; the service was terminated in December 2006, and the line was dismantled in 2007–2008.

Nogliki

Nogliki (russian: Ноглики) is an urban locality (an urban-type settlement) and the administrative center of Nogliksky District of Sakhalin Oblast, Russia, located near the eastern coast of Sakhalin Island, about inland from the Sea of O ...

File:Japanese SL D51-22.jpg, A Japanese D51 steam locomotive

The is a type of 2-8-2 steam locomotive built by the Japanese Government Railways (JGR), the Japanese National Railways (JNR), and Kawasaki Heavy Industries Rolling Stock Company, Kisha Seizo, Hitachi, Nippon Sharyo, Mitsubishi, and Mitsubishi H ...

outside the Yuzhno-Sakhalinsk Railway Station

Air

Sakhalin is connected by regular flights toMoscow

Moscow ( , US chiefly ; rus, links=no, Москва, r=Moskva, p=mɐskˈva, a=Москва.ogg) is the capital and largest city of Russia. The city stands on the Moskva River in Central Russia, with a population estimated at 13.0 million ...

, Khabarovsk

Khabarovsk ( rus, Хабaровск, a=Хабаровск.ogg, r=Habárovsk, p=xɐˈbarəfsk) is the largest types of inhabited localities in Russia, city and the administrative centre of Khabarovsk Krai, Russia,Law #109 located from the China ...

, Vladivostok

Vladivostok ( rus, Владивосто́к, a=Владивосток.ogg, p=vɫədʲɪvɐˈstok) is the largest city and the administrative center of Primorsky Krai, Russia. The city is located around the Zolotoy Rog, Golden Horn Bay on the Sea ...

and other cities of Russia. Yuzhno-Sakhalinsk Airport