Portsmouth UK Local Election 2014 Map (v2) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Portsmouth ( ) is a

Although Portsmouth was not mentioned in the 1086

Although Portsmouth was not mentioned in the 1086

In 1623,

In 1623,

A major

A major

On 1 October 1916, Portsmouth was bombed by a

On 1 October 1916, Portsmouth was bombed by a

Portsmouth was affected by the decline of the British Empire in the second half of the 20th century. Shipbuilding jobs fell from 46 percent of the workforce in 1951 to 14 per cent in 1966, drastically reducing manpower in the dockyard. The city council attempted to create new work; an industrial estate was built in Fratton in 1948, and others were built at Paulsgrove and Farlington during the 1950s and 1960s. Although traditional industries such as brewing and corset manufacturing disappeared during this time, electrical engineering became a major employer. Despite the cutbacks in traditional sectors, Portsmouth remained attractive to industry.

Portsmouth was affected by the decline of the British Empire in the second half of the 20th century. Shipbuilding jobs fell from 46 percent of the workforce in 1951 to 14 per cent in 1966, drastically reducing manpower in the dockyard. The city council attempted to create new work; an industrial estate was built in Fratton in 1948, and others were built at Paulsgrove and Farlington during the 1950s and 1960s. Although traditional industries such as brewing and corset manufacturing disappeared during this time, electrical engineering became a major employer. Despite the cutbacks in traditional sectors, Portsmouth remained attractive to industry.

South of Portsmouth are

South of Portsmouth are

Portsmouth is the only city in the

Portsmouth is the only city in the

The city is administered by

The city is administered by

Ten per cent of Portsmouth's workforce is employed at Portsmouth Naval Dockyard, which is linked to the city's biggest industry, defence; the headquarters of

Ten per cent of Portsmouth's workforce is employed at Portsmouth Naval Dockyard, which is linked to the city's biggest industry, defence; the headquarters of  Development of Gunwharf Quays continued until 2007, when the No.1 Gunwharf Quays residential tower was completed. The development of the former Brickwoods Brewery site included the construction of the 22-storey Admiralty Quarter Tower, the tallest in a complex of primarily low-rise residential buildings. Number One Portsmouth, a proposed 25-storey tower opposite Portsmouth & Southsea station, was announced at the end of October 2008. In August 2009, internal demolition of the existing building had begun. A high-rise student dormitory, nicknamed "The Blade", has begun construction on the site of the

Development of Gunwharf Quays continued until 2007, when the No.1 Gunwharf Quays residential tower was completed. The development of the former Brickwoods Brewery site included the construction of the 22-storey Admiralty Quarter Tower, the tallest in a complex of primarily low-rise residential buildings. Number One Portsmouth, a proposed 25-storey tower opposite Portsmouth & Southsea station, was announced at the end of October 2008. In August 2009, internal demolition of the existing building had begun. A high-rise student dormitory, nicknamed "The Blade", has begun construction on the site of the  Portsmouth's two Queen Elizabeth-class aircraft carriers, and , were ordered by defence secretary

Portsmouth's two Queen Elizabeth-class aircraft carriers, and , were ordered by defence secretary

Portsmouth is the hometown of Fanny Price, the main character of

Portsmouth is the hometown of Fanny Price, the main character of

port

A port is a maritime facility comprising one or more wharves or loading areas, where ships load and discharge cargo and passengers. Although usually situated on a sea coast or estuary, ports can also be found far inland, such as H ...

and city

A city is a human settlement of notable size.Goodall, B. (1987) ''The Penguin Dictionary of Human Geography''. London: Penguin.Kuper, A. and Kuper, J., eds (1996) ''The Social Science Encyclopedia''. 2nd edition. London: Routledge. It can be def ...

in the ceremonial county of Hampshire

Hampshire (, ; abbreviated to Hants) is a ceremonial and non-metropolitan county in western South East England on the coast of the English Channel. Home to two major English cities on its south coast, Southampton and Portsmouth, Hampshire ...

in southern England. The city of Portsmouth has been a unitary authority

A unitary authority is a local authority responsible for all local government functions within its area or performing additional functions that elsewhere are usually performed by a higher level of sub-national government or the national governmen ...

since 1 April 1997 and is administered by Portsmouth City Council

Portsmouth City Council is the local authority of the city of Portsmouth, Hampshire, England. It is a unitary authority, having the powers of a non-metropolitan county and district council combined. It provides a full range of local government s ...

.

Portsmouth is the most densely populated city in the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the European mainland, continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotlan ...

, with a population last recorded at 208,100. Portsmouth is located south-west of London

London is the capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary dow ...

and south-east of Southampton. Portsmouth is mostly located on Portsea Island

Portsea Island is a flat and low-lying natural island in area, just off the southern coast of Hampshire in England. Portsea Island contains the majority of the city of Portsmouth.

Portsea Island has the third-largest population of all th ...

; the only English city not on the mainland of Great Britain

Great Britain is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean off the northwest coast of continental Europe. With an area of , it is the largest of the British Isles, the largest European island and the ninth-largest island in the world. It i ...

. Portsea Island has the third highest population in the British Isles

The British Isles are a group of islands in the North Atlantic Ocean off the north-western coast of continental Europe, consisting of the islands of Great Britain, Ireland, the Isle of Man, the Inner and Outer Hebrides, the Northern Isles, ...

after the islands of Great Britain

Great Britain is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean off the northwest coast of continental Europe. With an area of , it is the largest of the British Isles, the largest European island and the ninth-largest island in the world. It i ...

and Ireland

Ireland ( ; ga, Éire ; Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean, in Northwestern Europe, north-western Europe. It is separated from Great Britain to its east by the North Channel (Grea ...

. Portsmouth also forms part of the regional South Hampshire conurbation, which includes the city of Southampton

Southampton () is a port city in the ceremonial county of Hampshire in southern England. It is located approximately south-west of London and west of Portsmouth. The city forms part of the South Hampshire built-up area, which also covers Po ...

and the boroughs of Eastleigh

Eastleigh is a town in Hampshire, England, between Southampton and Winchester. It is the largest town and the administrative seat of the Borough of Eastleigh, with a population of 24,011 at the 2011 census.

The town lies on the River Itchen, ...

, Fareham, Gosport, Havant

Havant ( ) is a town in the south-east corner of Hampshire, England between Portsmouth and Chichester. Its borough (population: 125,000) comprises the town (45,826) and its suburbs including the resort of Hayling Island as well as Rowland's Cast ...

and Waterlooville.

Portsmouth is one of the world's best known ports, its history can be traced to Roman times and has been a significant Royal Navy dockyard and base for centuries. Portsmouth was first established as a town with a royal charter on 2 May 1194. Portsmouth was England's first line of defence during an attempted French invasion in 1545 at the Battle of the Solent, famously notable for the sinking of the carrack ''Mary Rose

The ''Mary Rose'' (launched 1511) is a carrack-type warship of the English Tudor navy of King Henry VIII. She served for 33 years in several wars against France, Scotland, and Brittany. After being substantially rebuilt in 1536, she saw her ...

'' and witnessed by King Henry VIII of England from Southsea Castle. Portsmouth has the world's oldest dry dock, ''"The Great Stone Dock"''; originally built in 1698, rebuilt in 1769 and presently known as "No.5 Dock". The world's first mass production line

A production line is a set of sequential operations established in a factory where components are assembled to make a finished article or where materials are put through a refining process to produce an end-product that is suitable for onward c ...

was established at the naval base's Block Mills which produced pulley blocks for the Royal Navy fleet. By the early-19th century, Portsmouth was the most heavily fortified city in the world, and was considered "the world's greatest naval port" at the height of the British Empire

The British Empire was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It began with the overseas possessions and trading posts e ...

throughout ''Pax Britannica

''Pax Britannica'' (Latin for "British Peace", modelled after '' Pax Romana'') was the period of relative peace between the great powers during which the British Empire became the global hegemonic power and adopted the role of a " global pol ...

''. By 1859, a ring of defensive land and sea forts, known as the Palmerston Forts

The Palmerston Forts are a group of forts and associated structures around the coasts of the United Kingdom and Ireland.

The forts were built during the Victorian period on the recommendations of the 1860 Royal Commission on the Defence of the ...

had been built around Portsmouth in anticipation of an invasion from continental Europe.

In the 20th century, Portsmouth achieved city status City status is a symbolic and legal designation given by a national or subnational government. A municipality may receive city status because it already has the qualities of a city, or because it has some special purpose.

Historically, city status ...

on 21 April 1926. During the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposi ...

, the city was a pivotal embarkation point for the D-Day landings

The Normandy landings were the landing operations and associated airborne operations on Tuesday, 6 June 1944 of the Allied invasion of Normandy in Operation Overlord during World War II. Codenamed Operation Neptune and often referred to as ...

and was bombed extensively in the Portsmouth Blitz

Portsmouth is an island port city situated on Portsea Island in the county of Hampshire, England. Its history has been influenced by its association with the sea, and its proximity to London, and mainland Europe.

Roman

Portus Adurni which l ...

, which resulted in the deaths of 930 people. In 1982, a large Royal Navy task force departed from Portsmouth for the Falklands War. Her Majesty's Yacht ''Britannia'' was formerly based in Portsmouth and oversaw the transfer of Hong Kong in 1997, after which, Britannia was retired from royal service, decommissioned and relocated to Leith

Leith (; gd, Lìte) is a port area in the north of the city of Edinburgh, Scotland, founded at the mouth of the Water of Leith. In 2021, it was ranked by ''Time Out'' as one of the top five neighbourhoods to live in the world.

The earliest ...

as a museum ship.

HMNB Portsmouth is an operational Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against ...

base and is home to two-thirds of the UK's surface fleet. The base has long been nicknamed Pompey, a nickname it shares with the wider city of Portsmouth and Portsmouth Football Club

Portsmouth Football Club is a professional football club based in Portsmouth, Hampshire, England, which compete in . They are also known as ''Pompey'', a local nickname used by both HMNB Portsmouth and the city of Portsmouth; the ''Pompey'' nick ...

. The naval base also contains the National Museum of the Royal Navy and Portsmouth Historic Dockyard; which has a collection of historic warships, including the ''Mary Rose

The ''Mary Rose'' (launched 1511) is a carrack-type warship of the English Tudor navy of King Henry VIII. She served for 33 years in several wars against France, Scotland, and Brittany. After being substantially rebuilt in 1536, she saw her ...

'', Lord Nelson

Vice-Admiral Horatio Nelson, 1st Viscount Nelson, 1st Duke of Bronte (29 September 1758 – 21 October 1805) was a British flag officer in the Royal Navy. His inspirational leadership, grasp of strategy, and unconventional tactics brought a ...

's flagship, (the world's oldest naval ship still in commission), and , the Royal Navy's first ironclad warship

An ironclad is a steam-propelled warship protected by iron or steel armor plates, constructed from 1859 to the early 1890s. The ironclad was developed as a result of the vulnerability of wooden warships to explosive or incendiary shells. Th ...

.

The former shore establishment has been redeveloped into a large retail outlet destination known as Gunwharf Quays

Gunwharf Quays is a shopping centre located in the Portsea area of the city of Portsmouth in England. It was constructed in the early 21st century on the site of what had once been HM Gunwharf, Portsmouth. This was one of several such facilitie ...

which opened in 2001. Portsmouth is among the few British cities with two cathedrals: the Anglican Cathedral of St Thomas and the Roman Catholic

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

*Rome, the capital city of Italy

*Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*'' Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a lette ...

Cathedral of St John the Evangelist. The waterfront and Portsmouth Harbour

Portsmouth Harbour is a biological Site of Special Scientific Interest between Portsmouth and Gosport in Hampshire. It is a Ramsar site and a Special Protection Area.

It is a large natural harbour in Hampshire, England. Geographically it i ...

are dominated by the Spinnaker Tower

The Spinnaker Tower is a landmark observation tower in Portsmouth, England. It is the centrepiece of the redevelopment of Portsmouth Harbour, which was supported by a National Lottery grant. The tower's design was chosen by Portsmouth reside ...

, one of the United Kingdom's tallest structures at .

Southsea

Southsea is a seaside resort and a geographic area of Portsmouth, Portsea Island in England. Southsea is located 1.8 miles (2.8 km) to the south of Portsmouth's inner city-centre. Southsea is not a separate town as all of Portsea Island's s ...

is Portsmouth's seaside resort

A seaside resort is a resort town, town, village, or hotel that serves as a Resort, vacation resort and is located on a coast. Sometimes the concept includes an aspect of official accreditation based on the satisfaction of certain requirements, suc ...

, which was named after Southsea Castle. Southsea has two piers; Clarence Pier

Clarence Pier is an amusement pier in Portsmouth

Portsmouth ( ) is a port and city in the ceremonial county of Hampshire in southern England. The city of Portsmouth has been a unitary authority since 1 April 1997 and is administered b ...

amusement park and South Parade Pier

The South Parade Pier is a pier in Portsmouth, England. It is one of two piers in the city, the other being Clarence Pier. The pier once had a long hall down its centre which housed a seating area and a small restaurant. The outside of the hall ...

. The world's only regular hovercraft service operates from Southsea Hoverport

Southsea Hoverport is adjacent to Clarence Pier in the Southsea area of Portsmouth in southern England. From here frequent hovercraft services leave for Ryde on the Isle of Wight. The journey time is quicker than the conventional boats that sail ...

to Ryde

Ryde is an English seaside town and civil parish on the north-east coast of the Isle of Wight. The built-up area had a population of 23,999 according to the 2011 Census and an estimate of 24,847 in 2019. Its growth as a seaside resort came af ...

on the Isle of Wight

The Isle of Wight ( ) is a county in the English Channel, off the coast of Hampshire, from which it is separated by the Solent. It is the largest and second-most populous island of England. Referred to as 'The Island' by residents, the Isle of ...

. Southsea Common is a large open-air public recreation space which serves as a venue for a wide variety of annual events.

Portsmouth F.C. is the city's professional association football

Association football, more commonly known as football or soccer, is a team sport played between two teams of 11 players who primarily use their feet to propel the ball around a rectangular field called a pitch. The objective of the game is ...

club and play their home games at Fratton Park

Fratton Park is a football ground in Portsmouth, England, which is the home of Portsmouth F.C. Fratton Park remains as the only home football ground in Portsmouth FC's entire history.

The early Fratton Park was designed by local architect A ...

. The city has several mainline railway stations that connect to London Victoria

Victoria station, also known as London Victoria, is a central London railway terminus and connected London Underground station in Victoria, in the City of Westminster, managed by Network Rail. Named after the nearby Victoria Street (not the Q ...

and London Waterloo

Waterloo station (), also known as London Waterloo, is a central London terminus on the National Rail network in the United Kingdom, in the Waterloo area of the London Borough of Lambeth. It is connected to a London Underground station of ...

amongst other lines in southern England. Portsmouth International Port

Also known as Portsmouth Port or Portsmouth Continental Ferry Port, Portsmouth International Port is a cruise, ferry and cargo terminal located in the city of Portsmouth on the south coast of England.

History

Portsmouth investigated three l ...

is a commercial cruise ship and ferry port for international destinations. The port is the second busiest in the United Kingdom after Dover

Dover () is a town and major ferry port in Kent, South East England. It faces France across the Strait of Dover, the narrowest part of the English Channel at from Cap Gris Nez in France. It lies south-east of Canterbury and east of Maidstone ...

, handling around three million passengers a year. The city formerly had its own airport, Portsmouth Airport, until its closure in 1973. The University of Portsmouth

The University of Portsmouth is a public university in Portsmouth, England. It is one of only four universities in the South East England, South East of England rated as Gold in the Government's Teaching Excellence Framework. With approximately 28 ...

enrols 23,000 students and is ranked among the world's best modern universities.

Portsmouth is the birthplace of notable people such as author Charles Dickens

Charles John Huffam Dickens (; 7 February 1812 – 9 June 1870) was an English writer and social critic. He created some of the world's best-known fictional characters and is regarded by many as the greatest novelist of the Victorian e ...

, engineer Isambard Kingdom Brunel

Isambard Kingdom Brunel (; 9 April 1806 – 15 September 1859) was a British civil engineer who is considered "one of the most ingenious and prolific figures in engineering history," "one of the 19th-century engineering giants," and "one ...

, former Prime Minister James Callaghan

Leonard James Callaghan, Baron Callaghan of Cardiff, ( ; 27 March 191226 March 2005), commonly known as Jim Callaghan, was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1976 to 1979 and Leader of the Labour Party from 1976 to 1980. Callaghan is ...

, actor Peter Sellers

Peter Sellers (born Richard Henry Sellers; 8 September 1925 – 24 July 1980) was an English actor and comedian. He first came to prominence performing in the BBC Radio comedy series ''The Goon Show'', featured on a number of hit comic songs ...

and author-journalist Christopher Hitchens

Christopher Eric Hitchens (13 April 1949 – 15 December 2011) was a British-American author and journalist who wrote or edited over 30 books (including five essay collections) on culture, politics, and literature. Born and educated in England, ...

.

History

Early history

TheRomans

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

*Rome, the capital city of Italy

* Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*''Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a lette ...

built Portus Adurni

Portus Adurni was a Roman fort in the Roman province of Britannia situated at the north end of Portsmouth Harbour. It was part of the Saxon Shore, and is the best-preserved Roman fort north of the Alps. Around an eighth of the fort has been exca ...

, a fort

A fortification is a military construction or building designed for the defense of territories in warfare, and is also used to establish rule in a region during peacetime. The term is derived from Latin ''fortis'' ("strong") and ''facere'' ...

, at nearby Portchester

Portchester is a locality and suburb northwest of Portsmouth, England. It is part of the borough of Fareham in Hampshire. Once a small village, Portchester is now a busy part of the expanding conurbation between Portsmouth and Southampton o ...

in the late third century. The city's Old English

Old English (, ), or Anglo-Saxon, is the earliest recorded form of the English language, spoken in England and southern and eastern Scotland in the early Middle Ages. It was brought to Great Britain by Anglo-Saxon settlement of Britain, Anglo ...

Anglo-Saxon name, "Portesmuða", is derived from ''port'' (a haven) and ''muða'' (the mouth of a large river or estuary). In the ''Anglo-Saxon Chronicle

The ''Anglo-Saxon Chronicle'' is a collection of annals in Old English, chronicling the history of the Anglo-Saxons. The original manuscript of the ''Chronicle'' was created late in the 9th century, probably in Wessex, during the reign of Alf ...

'', a warrior named Port and his two sons killed a noble Briton in Portsmouth in 501. Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 Winston Churchill in the Second World War, dur ...

, in ''A History of the English-Speaking Peoples

''A History of the English-Speaking Peoples'' is a four-volume history of Britain and its former colonies and possessions throughout the world, written by Winston Churchill, covering the period from Caesar's invasions of Britain (55 BC) to the en ...

'', wrote that Port was a pirate who founded Portsmouth in 501.

England's southern coast was vulnerable to Danish Viking invasions during the eighth and ninth centuries, and was conquered by Danish pirates in 787. In 838, during the reign of Æthelwulf, King of Wessex

Æthelwulf (; Old English for "Noble Wolf"; died 13 January 858) was King of Wessex from 839 to 858. In 825 his father, King Ecgberht, defeated King Beornwulf of Mercia, ending a long Mercian dominance over Anglo-Saxon England south of the H ...

, a Danish fleet landed between Portsmouth and Southampton and plundered the region. Æthelwulf sent Wulfherd and the governor of Dorset

Dorset ( ; archaically: Dorsetshire , ) is a county in South West England on the English Channel coast. The ceremonial county comprises the unitary authority areas of Bournemouth, Christchurch and Poole and Dorset (unitary authority), Dors ...

shire to confront the Danes at Portsmouth, where most of their ships were docked. Although the Danes were driven off, Wulfherd was killed. The Danes returned in 1001 and pillaged Portsmouth and the surrounding area, threatening the English with extinction. They were massacred by the English survivors the following year; rebuilding began, although the town experienced further attacks until 1066

1066 (Roman numerals, MLXVI) was a common year starting on Sunday of the Julian calendar.

Events

Worldwide

* March 20 – Halley's Comet reaches perihelion. Its appearance is subsequently recorded in the Bayeux Tapestry.

Asia

* ''un ...

.

Norman to Tudor

Although Portsmouth was not mentioned in the 1086

Although Portsmouth was not mentioned in the 1086 Domesday Book

Domesday Book () – the Middle English spelling of "Doomsday Book" – is a manuscript record of the "Great Survey" of much of England and parts of Wales completed in 1086 by order of King William I, known as William the Conqueror. The manusc ...

, ''Bocheland'' ( Buckland), ''Copenore'' (Copnor

Copnor is an area of Portsmouth, England, located on the eastern side of Portsea Island. The population of Copnor Ward at the 2011 Census was 13,608. As Copenore, it was one of the three villages listed as being on Portsea Island in the Domesda ...

), and ''Frodentone'' (Fratton

Fratton is a residential and formerly industrial area of Portsmouth in Hampshire, England. Victorian style terraced houses are dominant in the area, typical of most residential areas of Portsmouth. Fratton has many discount shops and "greasy spoo ...

) were. According to some sources, it was founded in 1180 by the Anglo-Norman merchant Jean de Gisors

Jean de Gisors (1133–1220) was a Norman lord of the fortress of Gisors in Normandy, where meetings were traditionally convened between English and French kings. It was here, in 1188, a squabble occurred that involved the cutting of an elm.

Ini ...

.

King Henry II died in 1189; his son, Richard I

Richard I (8 September 1157 – 6 April 1199) was King of England from 1189 until his death in 1199. He also ruled as Duke of Normandy, Aquitaine and Gascony, Lord of Cyprus, and Count of Poitiers, Anjou, Maine, and Nantes, and was overl ...

(who had spent most of his life in France), arrived in Portsmouth en route to his coronation in London. When Richard returned from captivity in Austria

Austria, , bar, Östareich officially the Republic of Austria, is a country in the southern part of Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine states, one of which is the capital, Vienna, the most populous ...

in May 1194, he summoned an army and a fleet of 100 ships to the port. Richard gave Portsmouth market-town status with a royal charter on 2 May, authorising an annual fifteen-day free-market fair, weekly markets and a local court to deal with minor matters, and exempted its inhabitants from an £18 annual tax. He granted the town the coat of arms of Isaac Komnenos of Cyprus

Isaac Doukas Komnenos (or Ducas Comnenus, c. 1155 – 1195/1196) was a claimant to the Byzantine Empire and the ruler of Cyprus from 1184 to 1191. Contemporary sources commonly refer to him as the emperor of Cyprus. He lost the island to King ...

, whom he had defeated during the Third Crusade

The Third Crusade (1189–1192) was an attempt by three European monarchs of Western Christianity (Philip II of France, Richard I of England and Frederick I, Holy Roman Emperor) to reconquer the Holy Land following the capture of Jerusalem by ...

in 1191: "a crescent of gold on a shade of azure, with a blazing star of eight points", reflecting significant involvement of local soldiers, sailors, and vessels in the holy war. The 1194 royal charter's 800th anniversary was celebrated in 1994 with ceremonies at the city museum.

King John reaffirmed RichardI's rights and privileges, and established a permanent naval base. The first docks were begun by William of Wrotham in 1212, and John summoned his earls, barons, and military advisers to plan an invasion of Normandy

Normandy (; french: link=no, Normandie ; nrf, Normaundie, Nouormandie ; from Old French , plural of ''Normant'', originally from the word for "northman" in several Scandinavian languages) is a geographical and cultural region in Northwestern ...

. In 1229, declaring war against France, HenryIII assembled a force described by historian Lake Allen as "one of the finest armies that had ever been raised in England". The invasion stalled, and returned from France in October 1231. HenryIII summoned troops to invade Guienne

Guyenne or Guienne (, ; oc, Guiana ) was an old French province which corresponded roughly to the Roman province of '' Aquitania Secunda'' and the archdiocese of Bordeaux.

The name "Guyenne" comes from ''Aguyenne'', a popular transformation o ...

in 1242, and EdwardI sent supplies for his army in France in 1295. Commercial interests had grown by the following century, and its exports included wool, corn, grain, and livestock.

Edward II

Edward II (25 April 1284 – 21 September 1327), also called Edward of Caernarfon, was King of England and Lord of Ireland from 1307 until he was deposed in January 1327. The fourth son of Edward I, Edward became the heir apparent to t ...

ordered all ports on the south coast to assemble their largest vessels at Portsmouth to carry soldiers and horses to the Duchy of Aquitaine

The Duchy of Aquitaine ( oc, Ducat d'Aquitània, ; french: Duché d'Aquitaine, ) was a historical fiefdom in western, central, and southern areas of present-day France to the south of the river Loire, although its extent, as well as its name, fluc ...

in 1324 to strengthen defences. A French fleet commanded by David II of Scotland

David II (5 March 1324 – 22 February 1371) was King of Scots from 1329 until his death in 1371. Upon the death of his father, Robert the Bruce, David succeeded to the throne at the age of five, and was crowned at Scone in November 1331, becom ...

attacked in the English Channel

The English Channel, "The Sleeve"; nrf, la Maunche, "The Sleeve" (Cotentinais) or ( Jèrriais), (Guernésiais), "The Channel"; br, Mor Breizh, "Sea of Brittany"; cy, Môr Udd, "Lord's Sea"; kw, Mor Bretannek, "British Sea"; nl, Het Kana ...

, ransacked the Isle of Wight

The Isle of Wight ( ) is a county in the English Channel, off the coast of Hampshire, from which it is separated by the Solent. It is the largest and second-most populous island of England. Referred to as 'The Island' by residents, the Isle of ...

and threatened the town. EdwardIII instructed all maritime towns to build vessels and raise troops to rendezvous at Portsmouth. Two years later, a French fleet led by Nicholas Béhuchet

Nicholas is a male given name and a surname.

The Eastern Orthodox Church, the Roman Catholic Church, and the Anglicanism, Anglican Churches celebrate Saint Nicholas every year on December 6, which is the name day for "Nicholas". In Greece, the n ...

raided Portsmouth and destroyed most of the town; only the stone-built church and hospital survived. After the raid, EdwardIII exempted the town from national taxes to aid its reconstruction. In 1377, shortly after Edward died, the French landed in Portsmouth. Although the town was plundered and burnt, its inhabitants drove the French off to raid towns in the West Country

The West Country (occasionally Westcountry) is a loosely defined area of South West England, usually taken to include all, some, or parts of the counties of Cornwall, Devon, Dorset, Somerset, Bristol, and, less commonly, Wiltshire, Gloucesters ...

.

Henry V Henry V may refer to:

People

* Henry V, Duke of Bavaria (died 1026)

* Henry V, Holy Roman Emperor (1081/86–1125)

* Henry V, Duke of Carinthia (died 1161)

* Henry V, Count Palatine of the Rhine (c. 1173–1227)

* Henry V, Count of Luxembourg (121 ...

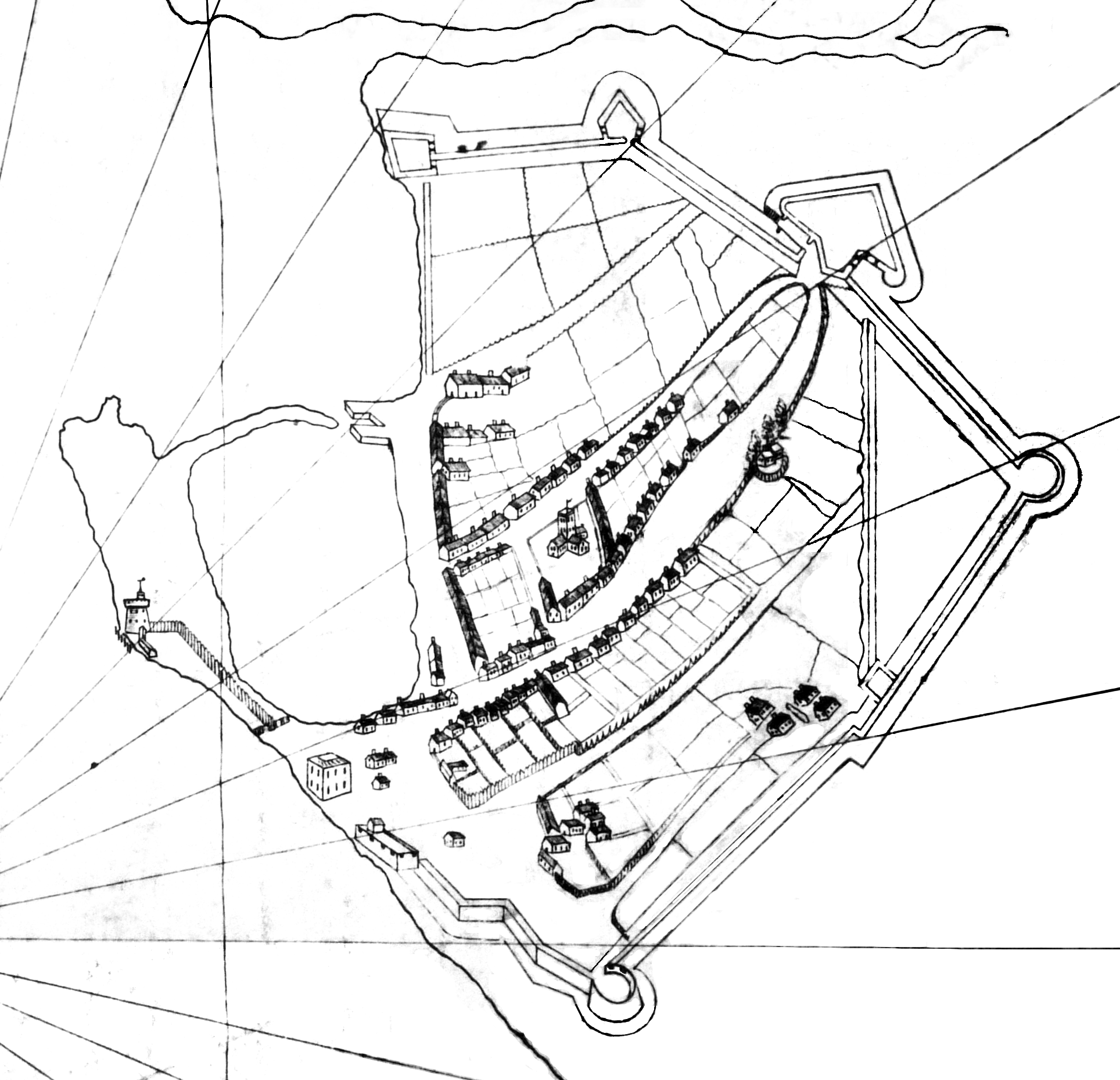

built Portsmouth's first permanent fortifications

A fortification is a military construction or building designed for the defense of territories in warfare, and is also used to establish rule in a region during peacetime. The term is derived from Latin ''fortis'' ("strong") and ''facere'' ...

. In 1416, a number of French ships blockaded the town (which housed ships which were set to invade Normandy); Henry gathered a fleet at Southampton, and invaded the Norman coast in August of that year. Recognising the town's growing importance, he ordered a wooden Round Tower

A fortified tower (also defensive tower or castle tower or, in context, just tower) is one of the defensive structures used in fortifications, such as castles, along with curtain walls. Castle towers can have a variety of different shapes and fu ...

to be built at the mouth of the harbour; it was completed in 1426. Henry VII rebuilt the fortifications with stone, assisted Robert Brygandine and Sir Reginald Bray

Sir Reginald Bray (c. 1440 – 5 August 1503) was an English administrator and statesman. He was the Chancellor of the Duchy and County Palatine of Lancaster under Henry VII, briefly Treasurer of the Exchequer, and one of the most influent ...

in the construction of the world's first dry dock, and raised the Square Tower

The Square Tower is one of the oldest parts of the fortifications of Portsmouth, England. It is a Grade I listed building.

History

A tower was built in 1494 as part of the fortifications and served as a home to the Governor of Portsmouth.

I ...

in 1494. He made Portsmouth a Royal Dockyard, England's only dockyard considered "national". Although King Alfred

Alfred the Great (alt. Ælfred 848/849 – 26 October 899) was King of the West Saxons from 871 to 886, and King of the Anglo-Saxons from 886 until his death in 899. He was the youngest son of King Æthelwulf and his first wife Osburh, who bot ...

may have used Portsmouth to build ships as early as the ninth century, the first warship recorded as constructed in the town was the ''Sweepstake'' (built in 1497).

Henry VIII

Henry VIII (28 June 149128 January 1547) was King of England from 22 April 1509 until his death in 1547. Henry is best known for his six marriages, and for his efforts to have his first marriage (to Catherine of Aragon) annulled. His disa ...

built Southsea Castle, financed by the Dissolution of the Monasteries, in 1539 in anticipation of a French invasion. He also invested heavily in the town's dockyard, expanding it to . Around this time, a Tudor defensive boom

A boom or a chain (also boom defence, harbour chain, river chain, chain boom, boom chain or variants) is an obstacle strung across a navigable stretch of water to control or block navigation.

In modern times they usually have civil uses, such as ...

stretched from the Round Tower to Fort Blockhouse in Gosport to protect Portsmouth Harbour.

From Southsea Castle, Henry witnessed his flagship ''Mary Rose'' sink in action against the French fleet in the 1545 Battle of the Solent with the loss of about 500 lives. Some historians believe that the ''Mary Rose'' turned too quickly and submerged her open gun ports; according to others, it sank due to poor design. Portsmouth's fortifications were improved by successive monarchs. The town experienced an outbreak of plague

Plague or The Plague may refer to:

Agriculture, fauna, and medicine

*Plague (disease), a disease caused by ''Yersinia pestis''

* An epidemic of infectious disease (medical or agricultural)

* A pandemic caused by such a disease

* A swarm of pes ...

in 1563, which killed about 300 of its 2,000 inhabitants.

Stuart to Georgian

In 1623,

In 1623, Charles I Charles I may refer to:

Kings and emperors

* Charlemagne (742–814), numbered Charles I in the lists of Holy Roman Emperors and French kings

* Charles I of Anjou (1226–1285), also king of Albania, Jerusalem, Naples and Sicily

* Charles I of ...

(then Prince of Wales) returned to Portsmouth from France and Spain. His unpopular military adviser, George Villiers, 1st Duke of Buckingham

George Villiers, 1st Duke of Buckingham, 28 August 1592 – 23 August 1628), was an English courtier, statesman, and patron of the arts. He was a favourite and possibly also a lover of King James I of England. Buckingham remained at the ...

, was stabbed to death in an Old Portsmouth

Old Portsmouth is a district of the city of Portsmouth. It is the area covered by the original medieval town of Portsmouth as planned by Jean de Gisors. It is situated in the south west corner of Portsea Island.

The area contains many historic bu ...

pub by war veteran John Felton five years later. Felton never attempted to escape, and was caught walking the streets when soldiers confronted him; he said, "I know that he is dead, for I had the force of forty men when I struck the blow". Felton was hanged, and his body chained to a gibbet

A gibbet is any instrument of public execution (including guillotine, decapitation, executioner's block, Impalement, impalement stake, gallows, hanging gallows, or related Scaffold (execution site), scaffold). Gibbeting is the use of a gallows- ...

on Southsea Common as a warning to others. The murder took place in the Greyhound public house on High Street, which is now Buckingham House and has a commemorative plaque.

Most residents (including the mayor) supported the parliamentarians during the English Civil War

The English Civil War (1642–1651) was a series of civil wars and political machinations between Parliamentarians (" Roundheads") and Royalists led by Charles I ("Cavaliers"), mainly over the manner of England's governance and issues of re ...

, although military governor Colonel Goring

Colonel (abbreviated as Col., Col or COL) is a senior military Officer (armed forces), officer rank used in many countries. It is also used in some police forces and paramilitary organizations.

In the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries, a colonel wa ...

supported the royalists

A royalist supports a particular monarch as head of state for a particular kingdom, or of a particular dynastic claim. In the abstract, this position is royalism. It is distinct from monarchism, which advocates a monarchical system of governm ...

. The town, a base of the parliamentarian navy, was blockaded from the sea. Parliamentarian troops were sent to besiege it, and the guns of Southsea Castle were fired at the town's royalist garrison. Parliamentarians in Gosport joined the assault, damaging St Thomas's Church. On 5 September 1642, the remaining royalists in the garrison at the Square Tower were forced to surrender after Goring threatened to blow it up; he and his garrison were allowed safe passage.

Under the Commonwealth of England

The Commonwealth was the political structure during the period from 1649 to 1660 when England and Wales, later along with Ireland and Scotland, were governed as a republic after the end of the Second English Civil War and the trial and execut ...

, Robert Blake Robert Blake may refer to:

Sportspeople

* Bob Blake (American football) (1885–1962), American football player

* Robbie Blake (born 1976), English footballer

* Bob Blake (ice hockey) (1914–2008), American ice hockey player

* Rob Blake (born 19 ...

used the harbour as his base during the First Anglo-Dutch War

The First Anglo-Dutch War, or simply the First Dutch War, ( nl, Eerste Engelse (zee-)oorlog, "First English (Sea) War"; 1652–1654) was a conflict fought entirely at sea between the navies of the Commonwealth of England and the Dutch Republic, ...

in 1652 and the Anglo-Spanish War. He died within sight of the town, returning from Cádiz

Cádiz (, , ) is a city and port in southwestern Spain. It is the capital of the Province of Cádiz, one of eight that make up the autonomous community of Andalusia.

Cádiz, one of the oldest continuously inhabited cities in Western Europe, ...

. After the end of the Civil War

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies ...

, Portsmouth was among the first towns to declare CharlesII king and began to prosper. The first ship built in over 100 years, , was launched in 1650; twelve ships were built between 1650 and 1660. After the Restoration

Restoration is the act of restoring something to its original state and may refer to:

* Conservation and restoration of cultural heritage

** Audio restoration

** Film restoration

** Image restoration

** Textile restoration

* Restoration ecology

...

, CharlesII married Catherine of Braganza

Catherine of Braganza ( pt, Catarina de Bragança; 25 November 1638 – 31 December 1705) was List of English royal consorts, Queen of England, List of Scottish royal consorts, Scotland and Ireland during her marriage to Charles II of England, ...

at the Royal Garrison Church. During the late 17th century, Portsmouth continued to grow; a new wharf was constructed in 1663 for military use, and a mast pond was dug in 1665. In 1684, a list of ships docked in Portsmouth was evidence of its increasing national importance. Between 1667 and 1685, the town's fortifications were rebuilt; new walls were constructed with bastion

A bastion or bulwark is a structure projecting outward from the curtain wall of a fortification, most commonly angular in shape and positioned at the corners of the fort. The fully developed bastion consists of two faces and two flanks, with fi ...

s and two moats were dug, making Portsmouth one of the world's most heavily fortified places.

In 1759, General James Wolfe

James Wolfe (2 January 1727 – 13 September 1759) was a British Army officer known for his training reforms and, as a Major-general (United Kingdom), major general, remembered chiefly for his victory in 1759 over the Kingdom of France, French ...

sailed to capture Quebec

Quebec ( ; )According to the Canadian government, ''Québec'' (with the acute accent) is the official name in Canadian French and ''Quebec'' (without the accent) is the province's official name in Canadian English is one of the thirtee ...

; the expedition, although successful, cost him his life. His body was brought back to Portsmouth in November, and received high naval and military honours. Two years later, on 30 May 1775, Captain James Cook

James Cook (7 November 1728 Old Style date: 27 October – 14 February 1779) was a British explorer, navigator, cartographer, and captain in the British Royal Navy, famous for his three voyages between 1768 and 1779 in the Pacific Ocean an ...

arrived on after circumnavigating the globe. The 11-ship First Fleet

The First Fleet was a fleet of 11 ships that brought the first European and African settlers to Australia. It was made up of two Royal Navy vessels, three store ships and six convict transports. On 13 May 1787 the fleet under the command ...

left on 13 May 1787 to establish the first European colony in Australia

Australia, officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a Sovereign state, sovereign country comprising the mainland of the Australia (continent), Australian continent, the island of Tasmania, and numerous List of islands of Australia, sma ...

, the beginning of prisoner transportation; Captain William Bligh

Vice-Admiral William Bligh (9 September 1754 – 7 December 1817) was an officer of the Royal Navy and a colonial administrator. The mutiny on the HMS ''Bounty'' occurred in 1789 when the ship was under his command; after being set adrift i ...

of also sailed from the harbour that year. After the 28 April 1789 mutiny on the ''Bounty'', was dispatched from Portsmouth to bring the mutineers back for trial. The court-martial

A court-martial or court martial (plural ''courts-martial'' or ''courts martial'', as "martial" is a postpositive adjective) is a military court or a trial conducted in such a court. A court-martial is empowered to determine the guilt of memb ...

opened on 12 September 1792 aboard in Portsmouth Harbour; of the ten remaining men, three were sentenced to death. In 1789, a chapel was erected in Prince George's Street and was dedicated to St John by the Bishop of Winchester. Around this time, a bill

Bill(s) may refer to:

Common meanings

* Banknote, paper cash (especially in the United States)

* Bill (law), a proposed law put before a legislature

* Invoice, commercial document issued by a seller to a buyer

* Bill, a bird or animal's beak

Plac ...

was passed in the House of Commons on the creation of a canal to link Portsmouth to Chichester; however, the project was abandoned.

The city's nickname, Pompey, is thought to have derived from the log entry of Portsmouth Point

Portsmouth Point, or "Spice Island", is part of Old Portsmouth in Portsmouth, Hampshire, on the southern coast of England. The name Spice Island comes from the area's seedy reputation, as it was known as the "Spice of Life". Men were easily found ...

(contracted "Po'm.P." – ''Ports''m''outh ''P.''oint) as ships entered the harbour; navigational charts use the contraction. According to one historian, the name may have been brought back from a group of Portsmouth-based sailors who visited Pompey's Pillar in Alexandria

Alexandria ( or ; ar, ٱلْإِسْكَنْدَرِيَّةُ ; grc-gre, Αλεξάνδρεια, Alexándria) is the second largest city in Egypt, and the largest city on the Mediterranean coast. Founded in by Alexander the Great, Alexandria ...

, Egypt, around 1781. Another theory is that it is named after the harbour's guardship, , a 74-gun French ship of the line

A ship of the line was a type of naval warship constructed during the Age of Sail from the 17th century to the mid-19th century. The ship of the line was designed for the naval tactic known as the line of battle, which depended on the two colu ...

captured in 1793.

Portsmouth's coat of arms is attested in the early 19th century as "azure a crescent or, surmounted by an estoile of eight points of the last." Its design is apparently based on 18th-century mayoral seals. A connection of the coat of arms with the Great Seal of Richard I (which had a separate star and crescent) dates to the 20th century.

Industrial Revolution to Edwardian

Marc Isambard Brunel

Sir Marc Isambard Brunel (, ; 25 April 1769 – 12 December 1849) was a French-British engineer who is most famous for the work he did in Britain. He constructed the Thames Tunnel and was the father of Isambard Kingdom Brunel.

Born in Franc ...

established the world's first mass-production line at Portsmouth Block Mills

The Portsmouth Block Mills form part of the Portsmouth Dockyard at Portsmouth, Hampshire, England, and were built during the Napoleonic Wars to supply the British Royal Navy with pulley blocks. They started the age of mass-production using all- ...

, making pulley

A pulley is a wheel on an axle or shaft that is designed to support movement and change of direction of a taut cable or belt, or transfer of power between the shaft and cable or belt. In the case of a pulley supported by a frame or shell that ...

blocks for rigging

Rigging comprises the system of ropes, cables and chains, which support a sailing ship or sail boat's masts—''standing rigging'', including shrouds and stays—and which adjust the position of the vessel's sails and spars to which they are ...

on the navy's ships. The first machines were installed in January 1803, and the final set (for large blocks) in March 1805. In 1808, the mills produced 130,000 blocks. By the turn of the 19th century, Portsmouth was the largest industrial site in the world; it had a workforce of 8,000, and an annual budget of £570,000.

In 1805, Admiral Nelson

Vice-Admiral Horatio Nelson, 1st Viscount Nelson, 1st Duke of Bronte (29 September 1758 – 21 October 1805) was a British flag officer in the Royal Navy. His inspirational leadership, grasp of strategy, and unconventional tactics brought abo ...

left Portsmouth to command the fleet which defeated France and Spain at the Battle of Trafalgar

The Battle of Trafalgar (21 October 1805) was a naval engagement between the British Royal Navy and the combined fleets of the French and Spanish Navies during the War of the Third Coalition (August–December 1805) of the Napoleonic Wars (180 ...

. The Royal Navy's reliance on Portsmouth led to its becoming the most fortified city in the world. The Royal Navy's West Africa Squadron

The West Africa Squadron, also known as the Preventative Squadron, was a squadron of the British Royal Navy whose goal was to suppress the Atlantic slave trade by patrolling the coast of West Africa. Formed in 1808 after the British Parliame ...

, tasked with halting the slave trade, began operating out of Portsmouth in 1808. A network of forts, known as the Palmerston Forts

The Palmerston Forts are a group of forts and associated structures around the coasts of the United Kingdom and Ireland.

The forts were built during the Victorian period on the recommendations of the 1860 Royal Commission on the Defence of the ...

, was built around the town as part of a programme led by Prime Minister Lord Palmerston

Henry John Temple, 3rd Viscount Palmerston, (20 October 1784 – 18 October 1865) was a British statesman who was twice Prime Minister of the United Kingdom in the mid-19th century. Palmerston dominated British foreign policy during the period ...

to defend British military bases from an inland attack following an Anglo-French war scare in 1859. The forts were nicknamed "Palmerston's Follies" because their armaments were pointed inland and not out to sea.

In April 1811, the Portsea Island Company constructed the first piped-water supply to upper- and middle-class houses. It supplied water to about 4,500 of Portsmouth's 14,000 houses, generating an income of £5,000 a year. HMS ''Victory''s active career ended in 1812, when she was moored in Portsmouth Harbour and used as a depot ship

A depot ship is an auxiliary ship used as a mobile or fixed base for submarines, destroyers, minesweepers, fast attack craft, landing craft, or other small ships with similarly limited space for maintenance equipment and crew dining, berthing an ...

. The town of Gosport contributed £75 a year to the ship's maintenance. In 1818, John Pounds

John Pounds (17 June 1766 – 1 January 1839) was a teacher and altruist born in Portsmouth, and the man most responsible for the creation of the concept of Ragged schools. After Pounds' death, Thomas Guthrie (often credited with the creation of ...

began teaching working-class children in the country's first ragged school

Ragged schools were charitable organisations dedicated to the free education of destitute children in 19th century Britain. The schools were developed in working-class districts. Ragged schools were intended for society's most destitute children ...

. The Portsea Improvement Commissioners installed gas street lighting throughout Portsmouth in 1820, followed by Old Portsmouth three years later.

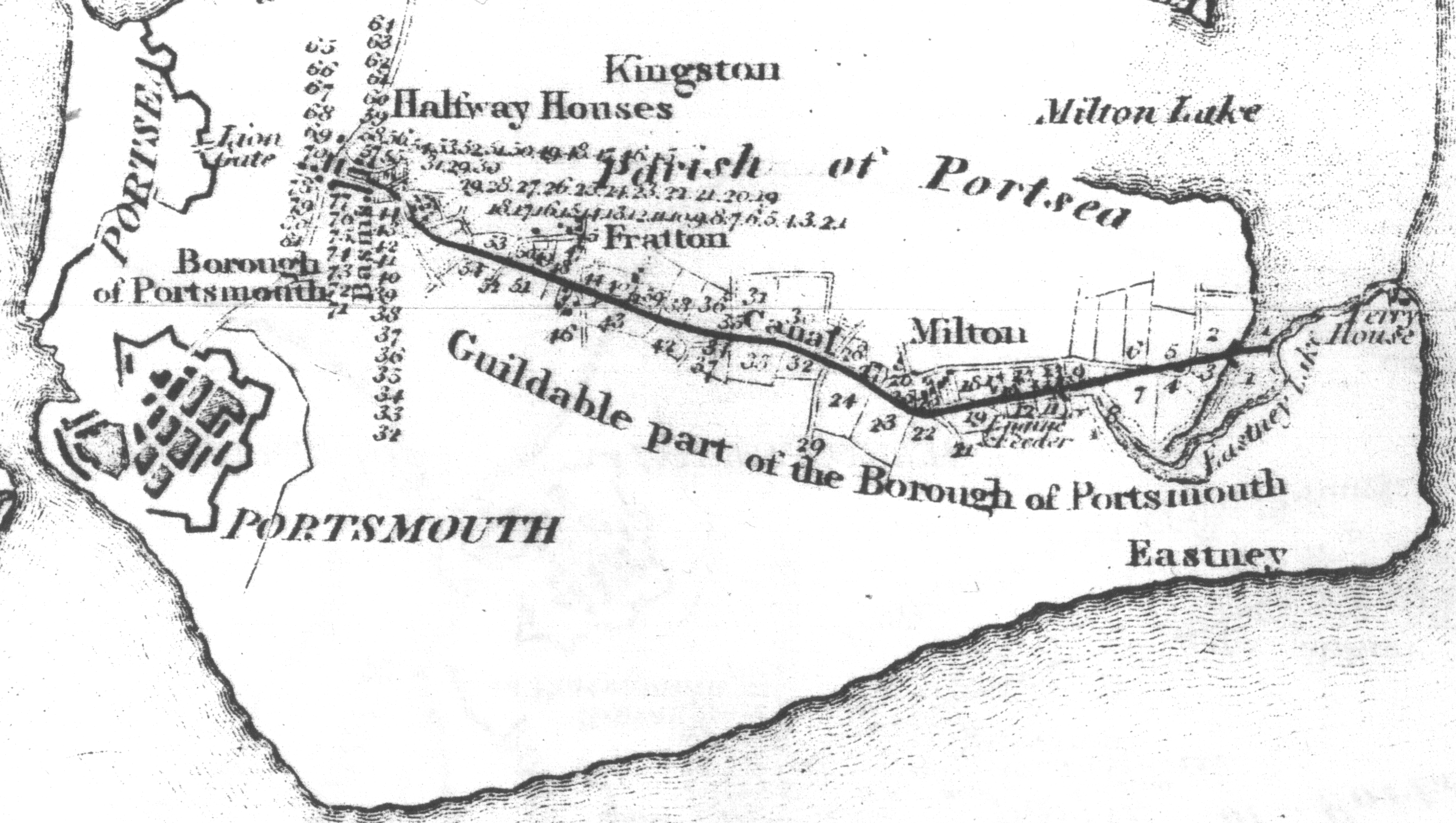

During the 19th century, Portsmouth expanded across Portsea Island. Buckland was merged into the town by the 1860s, and Fratton

Fratton is a residential and formerly industrial area of Portsmouth in Hampshire, England. Victorian style terraced houses are dominant in the area, typical of most residential areas of Portsmouth. Fratton has many discount shops and "greasy spoo ...

and Stamshaw were incorporated by the next decade. Between 1865 and 1870, the council built sewers after more than 800 people died in a cholera

Cholera is an infection of the small intestine by some strains of the bacterium ''Vibrio cholerae''. Symptoms may range from none, to mild, to severe. The classic symptom is large amounts of watery diarrhea that lasts a few days. Vomiting and ...

epidemic; according to a by-law

A by-law (bye-law, by(e)law, by(e) law), or as it is most commonly known in the United States bylaws, is a set of rules or law established by an organization or community so as to regulate itself, as allowed or provided for by some higher authorit ...

, any house within of a sewer had to be connected to it. By 1871 the population had risen to 100,000, and the national census listed Portsmouth's population as 113,569. A working-class suburb was constructed in the 1870s, when about 1,820 houses were built, and it became Somerstown. Despite public-health improvements, 514 people died in an 1872 smallpox

Smallpox was an infectious disease caused by variola virus (often called smallpox virus) which belongs to the genus Orthopoxvirus. The last naturally occurring case was diagnosed in October 1977, and the World Health Organization (WHO) c ...

epidemic. On 21 December of that year, the ''Challenger'' expedition embarked on a circumnavigation of the globe for scientific research.

When the British Empire

The British Empire was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It began with the overseas possessions and trading posts e ...

was at its height of power, covering a quarter of Earth's total land area and 458 million people at the turn of the 20th century, Portsmouth was considered "the world's greatest naval port". In 1900, Portsmouth Dockyard employed 8,000 people– a figure which increased to 23,000 during the First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

. The whole of Portsea Island came united under the control of Portsmouth borough council in 1904.

1913 terrorist attack

A major

A major terrorist

Terrorism, in its broadest sense, is the use of criminal violence to provoke a state of terror or fear, mostly with the intention to achieve political or religious aims. The term is used in this regard primarily to refer to intentional violen ...

incident occurred in the city in 1913, which led to the deaths of two men. During the suffragette bombing and arson campaign

Suffragettes in Great Britain and Ireland orchestrated a bombing and arson campaign between the years 1912 and 1914. The campaign was instigated by the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU), and was a part of their wider campaign for women's ...

of 1912–1914, militant

The English word ''militant'' is both an adjective and a noun, and it is generally used to mean vigorously active, combative and/or aggressive, especially in support of a cause, as in "militant reformers". It comes from the 15th century Latin " ...

suffragettes

A suffragette was a member of an activist women's organisation in the early 20th century who, under the banner "Votes for Women", fought for the right to vote in public elections in the United Kingdom. The term refers in particular to members ...

of the Women's Social and Political Union

The Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU) was a women-only political movement and leading militant organisation campaigning for women's suffrage in the United Kingdom from 1903 to 1918. Known from 1906 as the suffragettes, its membership and ...

carried out a series of politically motivated bombing and arson attacks nationwide as part of their campaign for women's suffrage

Women's suffrage is the right of women to vote in elections. Beginning in the start of the 18th century, some people sought to change voting laws to allow women to vote. Liberal political parties would go on to grant women the right to vot ...

. In one of the more serious suffragette attacks, a fire was purposely started at Portsmouth dockyard

His Majesty's Naval Base, Portsmouth (HMNB Portsmouth) is one of three operating bases in the United Kingdom for the Royal Navy (the others being HMNB Clyde and HMNB Devonport). Portsmouth Naval Base is part of the city of Portsmouth; it is l ...

on 20 December 1913, in which two sailors were killed after it spread through the industrial area. The fire spread rapidly as there were many old wooden buildings in the area, including the historic semaphore tower which dated back to the eighteenth century, which was completely destroyed. The damage to the dockyard area cost the city £200,000 in damages, equivalent to £23,600,000 today. In the midst of the firestorm, a battleship, , had to be towed to safety to avoid the flames. The two victims were a pensioner and a signalman.

The attack was notable enough to be reported on in the press in the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territorie ...

, with the ''New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid d ...

'' reporting on the disaster two days after with the headline "Big Portsmouth Fire Loss". The report also disclosed that at a previous police raid on a suffragette headquarters, "papers were discovered disclosing a plan to fire the yard".

First and Second World Wars

On 1 October 1916, Portsmouth was bombed by a

On 1 October 1916, Portsmouth was bombed by a Zeppelin

A Zeppelin is a type of rigid airship named after the German inventor Count Ferdinand von Zeppelin () who pioneered rigid airship development at the beginning of the 20th century. Zeppelin's notions were first formulated in 1874Eckener 1938, pp ...

airship. Although the Oberste Heeresleitung

The ''Oberste Heeresleitung'' (, Supreme Army Command or OHL) was the highest echelon of command of the army (''Heer'') of the German Empire. In the latter part of World War I, the Third OHL assumed dictatorial powers and became the ''de facto'' ...

(German Supreme Army Command) said that the town was "lavishly bombarded with good results", there were no reports of bombs dropped in the area. According to another source, the bombs were mistakenly dropped into the harbour rather than the dockyard. About 1,200 ships were refitted in the dockyard during the war, making it one of the empire's most strategic ports at the time.

Portsmouth's boundaries were extended onto the mainland of Great Britain

Great Britain is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean off the northwest coast of continental Europe. With an area of , it is the largest of the British Isles, the largest European island and the ninth-largest island in the world. It i ...

between 1920 and 1932 by incorporating Paulsgrove

Paulsgrove is an area of northern Portsmouth, Hampshire, England. Initially a small independent hamlet for many centuries, it was admitted to the city limits in 1920 and grew rapidly after the end of the Second World War.

History

Paulsgrove exi ...

, Wymering, Cosham

Cosham ( or ) is a northern suburb of Portsmouth lying within the city boundary but off Portsea Island. It is mentioned in the Domesday Book of 1086 along with Drayton and Wymering (mainland) and Bocheland ( Buckland), Frodington (Fratton) and C ...

, Drayton and Farlington into Portsmouth. Portsmouth was granted city status City status is a symbolic and legal designation given by a national or subnational government. A municipality may receive city status because it already has the qualities of a city, or because it has some special purpose.

Historically, city status ...

in 1926 after a long campaign by the borough council. The application was made on the grounds that it was the "first naval port of the kingdom". In 1929, the city council added the motto

A motto (derived from the Latin , 'mutter', by way of Italian , 'word' or 'sentence') is a sentence or phrase expressing a belief or purpose, or the general motivation or intention of an individual, family, social group, or organisation. Mot ...

"Heaven's Light Our Guide" to the medieval coat of arms. Except for the celestial objects in the arms, the motto was that of the Star of India and referred to the troopships bound for British India

The provinces of India, earlier presidencies of British India and still earlier, presidency towns, were the administrative divisions of British governance on the Indian subcontinent. Collectively, they have been called British India. In one ...

which left from the port. The crest and supporter

In heraldry, supporters, sometimes referred to as ''attendants'', are figures or objects usually placed on either side of the shield and depicted holding it up.

Early forms of supporters are found in medieval seals. However, unlike the coro ...

s are based on those of the royal arms, but altered to show the city's maritime connections: the lions and unicorn have fish tails, and a naval crown and a representation of the Tudor defensive boom which stretched across Portsmouth Harbour are around the unicorn.

During the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposi ...

, the city (particularly the port) was bombed extensively by the Luftwaffe

The ''Luftwaffe'' () was the aerial-warfare branch of the German ''Wehrmacht'' before and during World War II. Germany's military air arms during World War I, the ''Luftstreitkräfte'' of the Imperial Army and the '' Marine-Fliegerabtei ...

in the Portsmouth Blitz.

Portsmouth experienced 67 air raids between July 1940 and May 1944, which destroyed 6,625 houses and severely damaged 6,549. The air raids caused 930 deaths and wounded almost 3,000 people, many in the dockyard and military establishments. On the night of the city's heaviest raid (10 January 1941), the Luftwaffe dropped 140 tonnes of high-explosive bombs which killed 171 people and left 3,000 homeless. Many of the city's houses were damaged, and areas of Landport

Landport is a district located on Portsea Island and is considered the city centre of modern-day Portsmouth, England. The district is centred around Commercial Road and encompasses the Guildhall, Civic Centre, Portsmouth and Southsea Statio ...

and Old Portsmouth destroyed; the future site of Gunwharf Quays

Gunwharf Quays is a shopping centre located in the Portsea area of the city of Portsmouth in England. It was constructed in the early 21st century on the site of what had once been HM Gunwharf, Portsmouth. This was one of several such facilitie ...

was razed to the ground. The Guildhall

A guildhall, also known as a "guild hall" or "guild house", is a historical building originally used for tax collecting by municipalities or merchants in Great Britain and the Low Countries. These buildings commonly become town halls and in som ...

was hit by an incendiary bomb which burnt out the interior and destroyed its inner walls, although the civic plate was retrieved unharmed from the vault under the front steps. After the raid, Portsmouth mayor Denis Daley wrote for the ''Evening News'':

Portsmouth Harbour was a vital military embarkation point for the 6 June 1944 D-Day landings. Southwick House

Southwick House is a Grade II listed 19th-century manor house of the Southwick Estate in Hampshire, England, about north of Portsmouth. It is home to the Defence School of Policing and Guarding, and related military police capabilities.

History ...

, just north of the city, was the headquarters of Supreme Allied Commander Dwight D. Eisenhower

Dwight David "Ike" Eisenhower (born David Dwight Eisenhower; ; October 14, 1890 – March 28, 1969) was an American military officer and statesman who served as the 34th president of the United States from 1953 to 1961. During World War II, ...

. A V-1 flying bomb

The V-1 flying bomb (german: Vergeltungswaffe 1 "Vengeance Weapon 1") was an early cruise missile. Its official Ministry of Aviation (Nazi Germany), Reich Aviation Ministry () designation was Fi 103. It was also known to the Allies as the buz ...

hit Newcomen Road on 15 July 1944, killing 15 people.

1945 to present

Much of the city's housing stock was damaged during the war. The wreckage was cleared in an attempt to improve housing quality after the war; before permanent accommodations could be built, Portsmouth City Council built prefabs for those who had lost their homes. More than 700 prefab houses were constructed between 1945 and 1947, some over bomb sites. The first permanent houses were built away from the city centre, in new developments such asPaulsgrove

Paulsgrove is an area of northern Portsmouth, Hampshire, England. Initially a small independent hamlet for many centuries, it was admitted to the city limits in 1920 and grew rapidly after the end of the Second World War.

History

Paulsgrove exi ...

and Leigh Park

Leigh Park is a large suburb (population 27,500) of Havant, in Hampshire, England. It currently forms the bulk or whole of four electoral wards: Battins, Bondfields, Barncroft and Warren Park (generally referred to as 'The Warren').

Staunton C ...

; construction of council estates in Paulsgrove was completed in 1953. The first Leigh Park housing estates were completed in 1949, although construction in the area continued until 1974. Builders still occasionally find unexploded bombs, such as on the site of the destroyed Hippodrome Theatre in 1984. Despite efforts by the city council to build new housing, a 1955 survey indicated that 7,000 houses in Portsmouth were unfit for human habitation. A controversial decision was made to replace a section of the central city, including Landport, Somerstown and Buckland, with council housing during the 1960s and early 1970s. The success of the project and the quality of its housing are debatable.

Portsmouth was affected by the decline of the British Empire in the second half of the 20th century. Shipbuilding jobs fell from 46 percent of the workforce in 1951 to 14 per cent in 1966, drastically reducing manpower in the dockyard. The city council attempted to create new work; an industrial estate was built in Fratton in 1948, and others were built at Paulsgrove and Farlington during the 1950s and 1960s. Although traditional industries such as brewing and corset manufacturing disappeared during this time, electrical engineering became a major employer. Despite the cutbacks in traditional sectors, Portsmouth remained attractive to industry.

Portsmouth was affected by the decline of the British Empire in the second half of the 20th century. Shipbuilding jobs fell from 46 percent of the workforce in 1951 to 14 per cent in 1966, drastically reducing manpower in the dockyard. The city council attempted to create new work; an industrial estate was built in Fratton in 1948, and others were built at Paulsgrove and Farlington during the 1950s and 1960s. Although traditional industries such as brewing and corset manufacturing disappeared during this time, electrical engineering became a major employer. Despite the cutbacks in traditional sectors, Portsmouth remained attractive to industry. Zurich Insurance Group

Zurich Insurance Group Ltd is a Swiss insurance company, headquartered in Zürich, and the country's largest insurer. As of 2021, the group is the world's 112th largest public company according to ''Forbes'' Global 2000s list, and in 2011 it ran ...

moved their UK headquarters to the city in 1968, and IBM relocated their European headquarters in 1979. Portsmouth's population had dropped from about 200,000 to 177,142 by the end of the 1960s. Defence Secretary John Nott

Sir John William Frederic Nott (born 1 February 1932) is a former British Conservative Party politician. He was a senior politician of the late 1970s and early 1980s, playing a prominent role as Secretary of State for Defence during the 1982 in ...

decided in the early 1980s that of the four home dockyards, Portsmouth and Chatham

Chatham may refer to:

Places and jurisdictions Canada

* Chatham Islands (British Columbia)

* Chatham Sound, British Columbia

* Chatham, New Brunswick, a former town, now a neighbourhood of Miramichi

* Chatham (electoral district), New Brunswic ...

would be closed. The city council won a concession, however, and the dockyard was downgraded instead to a naval base.

On 2 April 1982, Argentine forces invaded two British territories in the South Atlantic: the Falkland Islands

The Falkland Islands (; es, Islas Malvinas, link=no ) is an archipelago in the South Atlantic Ocean on the Patagonian Shelf. The principal islands are about east of South America's southern Patagonian coast and about from Cape Dubouzet ...

and South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands

)

, anthem = "God Save the King"

, song_type =

, song =

, image_map = South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands in United Kingdom.svg

, map_caption = Location of South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands in the southern Atlantic Oce ...

. The British government's response was to dispatch a naval task force, and the aircraft carriers and sailed from Portsmouth for the South Atlantic on 5 April. The successful outcome of the war reaffirmed Portsmouth's significance as a naval port and its importance to the defence of British interests. In January 1997, Her Majesty's Yacht ''Britannia'' embarked from the city on her final voyage to oversee the handover of Hong Kong; for many, this marked the end of the empire. She was decommissioned on 11 December of that year at Portsmouth Naval Base in the presence of the queen, the Duke of Edinburgh

Duke of Edinburgh, named after the city of Edinburgh in Scotland, was a substantive title that has been created three times since 1726 for members of the British royal family. It does not include any territorial landholdings and does not produc ...

, and twelve senior members of the royal family.

Redevelopment of the naval shore establishment began in 2001 as a complex of retail outlets, clubs, pubs, and a shopping centre known as Gunwharf Quays. Construction of the Spinnaker Tower

The Spinnaker Tower is a landmark observation tower in Portsmouth, England. It is the centrepiece of the redevelopment of Portsmouth Harbour, which was supported by a National Lottery grant. The tower's design was chosen by Portsmouth reside ...

, sponsored by the National Lottery, began at Gunwharf Quays in 2003. The Tricorn Centre

The Tricorn Centre was a shopping, nightclub and car park complex in Portsmouth, Hampshire, England. It was designed in the Brutalist style by Owen Luder and Rodney Gordon and took its name from the site's shape which from the air resembled ...

, called "the ugliest building in the UK" by the BBC, was demolished in late 2004 after years of debate over the expense of demolition and whether it was worth preserving as an example of 1960s brutalist architecture

Brutalist architecture is an architectural style that emerged during the 1950s in the United Kingdom, among the reconstruction projects of the post-war era. Brutalist buildings are characterised by minimalist constructions that showcase the ba ...

. Designed by Owen Luder as part of a project to "revitalise" Portsmouth in the 1960s, it consisted of a shopping centre, market, nightclubs, and a multistorey car park

A multistorey car park (British and Singapore English) or parking garage (American English), also called a multistory, parking building, parking structure, parkade (mainly Canadian), parking ramp, parking deck or indoor parking, is a build ...

. Portsmouth celebrated the 200th anniversary of the Battle of Trafalgar

The Battle of Trafalgar (21 October 1805) was a naval engagement between the British Royal Navy and the combined fleets of the French and Spanish Navies during the War of the Third Coalition (August–December 1805) of the Napoleonic Wars (180 ...

in 2005, with Queen Elizabeth II

Elizabeth II (Elizabeth Alexandra Mary; 21 April 1926 – 8 September 2022) was Queen of the United Kingdom and other Commonwealth realms from 6 February 1952 until her death in 2022. She was queen regnant of 32 sovereign states during ...

present at a fleet review

A fleet review or naval review is an event where a gathering of ships from a particular navy is paraded and reviewed by an incumbent head of state and/or other official civilian and military dignitaries. A number of national navies continue to ...

and a mock battle. The naval base is home to two-thirds of Britain's surface fleet.

Geography

Portsmouth is by road from central London, west ofBrighton

Brighton () is a seaside resort and one of the two main areas of the City of Brighton and Hove in the county of East Sussex, England. It is located south of London.

Archaeological evidence of settlement in the area dates back to the Bronze A ...

, and east of Southampton

Southampton () is a port city in the ceremonial county of Hampshire in southern England. It is located approximately south-west of London and west of Portsmouth. The city forms part of the South Hampshire built-up area, which also covers Po ...

. It is located primarily on Portsea Island

Portsea Island is a flat and low-lying natural island in area, just off the southern coast of Hampshire in England. Portsea Island contains the majority of the city of Portsmouth.

Portsea Island has the third-largest population of all th ...

and is the United Kingdom's only island city, although the city has expanded to the mainland. Gosport is a borough to the west. Portsea Island is separated from the mainland by Portsbridge Creek

Portsbridge Creek, also known as Portcreek, Portsea Creek, Canal Creek and Ports Creek, is a tidal waterway just off the southern coast of England that runs between Portsea Island and the mainland from Langstone Harbour to Tipner Lake. Through ...

, which is crossed by three road bridges (the M275 motorway

The M275 is a long, dual three-lane motorway in Hampshire, southern England. It is the principal road route for entering and leaving Portsmouth. It continues as the A3 into Portsmouth, and meets the M27 at its northern terminus. From the mo ...

, the A3 road

The A3, known as the Portsmouth Road or London Road in sections, is a major road connecting the City of London and Portsmouth passing close to Kingston upon Thames, Guildford, Haslemere and Petersfield. For much of its length, it is classified ...

, and the A2030 road

The A2030 is a road in Hampshire. The road starts off at junction 5 of the A3(M), near the village of Bedhampton. The road then runs west along the base of Portsdown Hill, following the old route of the A27 into Portsmouth until it reaches th ...

), a railway bridge, and two footbridges. Portsea Island, part of the Hampshire Basin

The Hampshire Basin is a geological basin of Palaeogene age in southern England, underlying parts of Hampshire, the Isle of Wight, Dorset, and Sussex. Like the London Basin to the northeast, it is filled with sands and clays of Paleocene and yo ...

, is low-lying; most of the island is less than above sea level

Height above mean sea level is a measure of the vertical distance (height, elevation or altitude) of a location in reference to a historic mean sea level taken as a vertical datum. In geodesy, it is formalized as ''orthometric heights''.

The comb ...

. The island's highest natural elevation is the Kingston Cross road junction, at above ordinary spring tide.

Old Portsmouth

Old Portsmouth is a district of the city of Portsmouth. It is the area covered by the original medieval town of Portsmouth as planned by Jean de Gisors. It is situated in the south west corner of Portsea Island.

The area contains many historic bu ...

, the original town, is in the south-west part of the island and includes Portsmouth Point

Portsmouth Point, or "Spice Island", is part of Old Portsmouth in Portsmouth, Hampshire, on the southern coast of England. The name Spice Island comes from the area's seedy reputation, as it was known as the "Spice of Life". Men were easily found ...