Pierre Boulez on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Pierre Louis Joseph Boulez (; 26 March 1925 – 5 January 2016) was a French composer, conductor and writer, and the founder of several musical institutions. He was one of the dominant figures of post-war

Pierre Louis Joseph Boulez (; 26 March 1925 – 5 January 2016) was a French composer, conductor and writer, and the founder of several musical institutions. He was one of the dominant figures of post-war

Around the same time he was introduced to Andrée Vaurabourg, wife of the composer

Around the same time he was introduced to Andrée Vaurabourg, wife of the composer

On 12 February 1946 the pianist Yvette Grimaud gave the first public performances of Boulez's music (''Douze Notations'' and ''Trois Psalmodies'') at the Concerts du Triptyque. Boulez earned money by giving mathematics lessons to his landlord's son. He also played the

On 12 February 1946 the pianist Yvette Grimaud gave the first public performances of Boulez's music (''Douze Notations'' and ''Trois Psalmodies'') at the Concerts du Triptyque. Boulez earned money by giving mathematics lessons to his landlord's son. He also played the

In 1954, with the financial backing of Barrault and Renaud, Boulez started a series of concerts at the Petit Marigny theatre. They became known as the Domaine musical. The concerts focused initially on three areas: pre-war classics still unfamiliar in Paris (such as Bartók and Webern), works by the new generation (Stockhausen, Nono) and neglected masters from the past (

In 1954, with the financial backing of Barrault and Renaud, Boulez started a series of concerts at the Petit Marigny theatre. They became known as the Domaine musical. The concerts focused initially on three areas: pre-war classics still unfamiliar in Paris (such as Bartók and Webern), works by the new generation (Stockhausen, Nono) and neglected masters from the past (

In 1970 Boulez was asked by President Pompidou to return to France and set up an institute specialising in musical research and creation at the arts complex—now known as the

In 1970 Boulez was asked by President Pompidou to return to France and set up an institute specialising in musical research and creation at the arts complex—now known as the

In 1992, Boulez gave up the directorship of IRCAM and was succeeded by Laurent Bayle.Barbedette, 223. He was composer in residence at that year's

In 1992, Boulez gave up the directorship of IRCAM and was succeeded by Laurent Bayle.Barbedette, 223. He was composer in residence at that year's

He remained active as a conductor over the next six years. In 2007 he was re-united with Chéreau for a production of Janáček's '' From the House of the Dead'' (Theater an der Wien, Amsterdam and Aix). In April of the same year, as part of the Festtage in Berlin, Boulez and

He remained active as a conductor over the next six years. In 2007 he was re-united with Chéreau for a production of Janáček's '' From the House of the Dead'' (Theater an der Wien, Amsterdam and Aix). In April of the same year, as part of the Festtage in Berlin, Boulez and

, 6 August 2013. Retrieved 6 January 2016. In late 2011, when he was already quite frail, he led the combined Ensemble Intercontemporain and Lucerne Festival Academy, with the soprano Barbara Hannigan, in a tour of six European cities of his own ''Pli selon pli''. His final appearance as a conductor was in Salzburg on 28 January 2012 with the

For the text of his next major work, ''

For the text of his next major work, ''

"The Magus"

. ''

Boulez read widely and identified

Boulez read widely and identified

Boulez also conducted in the opera house. His chosen repertoire was small and included no Italian opera. Apart from Wagner, he conducted only twentieth-century works. Of his work with Wieland Wagner on ''Wozzeck'' and ''Parsifal'', Boulez said: "I would willingly have hitched, if not my entire fate, then at least a part of it, to someone like him, for urdiscussions about music and productions were thrilling."

They planned other productions together, including ''

Boulez also conducted in the opera house. His chosen repertoire was small and included no Italian opera. Apart from Wagner, he conducted only twentieth-century works. Of his work with Wieland Wagner on ''Wozzeck'' and ''Parsifal'', Boulez said: "I would willingly have hitched, if not my entire fate, then at least a part of it, to someone like him, for urdiscussions about music and productions were thrilling."

They planned other productions together, including '' For the centenary ''Ring'' in Bayreuth, Boulez originally asked

For the centenary ''Ring'' in Bayreuth, Boulez originally asked

Between 1966 and 1989 he recorded for Columbia Records (later Sony Classical). Among the first projects were the Paris ''Wozzeck'' (with Walter Berry) and the Covent Garden ''Pelléas et Mélisande'' (with

Between 1966 and 1989 he recorded for Columbia Records (later Sony Classical). Among the first projects were the Paris ''Wozzeck'' (with Walter Berry) and the Covent Garden ''Pelléas et Mélisande'' (with

In October 2016, the large concert hall of the

In October 2016, the large concert hall of the

Boulez pages at Universal Edition

– publisher of most of his work, including audio extracts and a calendar of forthcoming performances.

BBC artist page

– includes interviews with, and about, Boulez and extracts from works. *

Audio recordings with Pierre Boulez

in the Online Archive of the

Composer's entry on IRCAM's database

{{DEFAULTSORT:Boulez, Pierre 20th-century classical composers 21st-century classical composers 1925 births 2016 deaths BBC Symphony Orchestra Collège de France faculty Commandeurs of the Ordre des Arts et des Lettres Composers for cello Composers for piano Composers for violin Conservatoire de Paris alumni Deutsche Grammophon artists French electronic musicians Edison Classical Music Awards Oeuvreprijs winners Ernst von Siemens Music Prize winners French male conductors (music) French classical composers French male classical composers French male writers French music theorists Glenn Gould Prize winners Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award winners Grand Crosses of the Order of Saint James of the Sword Honorary Commanders of the Order of the British Empire Honorary Members of the Royal Academy of Music Honorary Members of the Royal Philharmonic Society Ivor Novello Award winners Kyoto laureates in Arts and Philosophy LGBT classical composers LGBT classical musicians Members of the Academy of Arts, Berlin Members of the European Academy of Sciences and Arts Music directors of the New York Philharmonic Knights Commander of the Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany Ondists People from Montbrison, Loire Pupils of René Leibowitz Recipients of the Austrian Decoration for Science and Art Recipients of the Gold Medal for Merit to Culture – Gloria Artis Recipients of the Léonie Sonning Music Prize Recipients of the Pour le Mérite (civil class) Recipients of the Praemium Imperiale Royal Philharmonic Society Gold Medallists Twelve-tone and serial composers Wolf Prize in Arts laureates 20th-century French conductors (music) 20th-century French male musicians 20th-century French composers 21st-century French composers Members of the German Academy for Language and Literature

Pierre Louis Joseph Boulez (; 26 March 1925 – 5 January 2016) was a French composer, conductor and writer, and the founder of several musical institutions. He was one of the dominant figures of post-war

Pierre Louis Joseph Boulez (; 26 March 1925 – 5 January 2016) was a French composer, conductor and writer, and the founder of several musical institutions. He was one of the dominant figures of post-war Western classical music

Classical music generally refers to the art music of the Western world, considered to be distinct from Western folk music or popular music traditions. It is sometimes distinguished as Western classical music, as the term "classical music" ...

.

Born in Montbrison in the Loire department of France, the son of an engineer, Boulez studied at the Conservatoire de Paris

The Conservatoire de Paris (), also known as the Paris Conservatory, is a college of music and dance founded in 1795. Officially known as the Conservatoire National Supérieur de Musique et de Danse de Paris (CNSMDP), it is situated in the avenue ...

with Olivier Messiaen

Olivier Eugène Prosper Charles Messiaen (, ; ; 10 December 1908 – 27 April 1992) was a French composer, organist, and ornithologist who was one of the major composers of the 20th century. His music is rhythmically complex; harmonical ...

, and privately with Andrée Vaurabourg and René Leibowitz

René Leibowitz (; 17 February 1913 – 29 August 1972) was a Polish, later naturalised French, composer, conductor, music theorist and teacher. He was historically significant in promoting the music of the Second Viennese School in Paris after ...

. He began his professional career in the late 1940s as music director of the Renaud-Barrault theatre company in Paris. He was a leading figure in avant-garde music

Avant-garde music is music that is considered to be at the forefront of innovation in its field, with the term "avant-garde" implying a critique of existing aesthetic conventions, rejection of the status quo in favor of unique or original eleme ...

, playing an important role in the development of integral serialism (in the 1950s), controlled chance music (in the 1960s) and the electronic transformation of instrumental music in real time (from the 1970s onwards). His tendency to revise earlier compositions meant that his body of work was relatively small, but it included pieces regarded by many as landmarks of twentieth-century music, such as ''Le Marteau sans maître

''Le Marteau sans maître'' (; The Hammer without a Master) is a chamber cantata by French composer Pierre Boulez. The work, which received its premiere in 1955, sets surrealist poetry by René Char for contralto and six instrumentalists. It ...

'', ''Pli selon pli

''Pli selon pli'' (Fold by fold) is a piece of classical music by the French composer Pierre Boulez. It carries the subtitle ''Portrait de Mallarmé'' (Portrait of Mallarmé). It is scored for a solo soprano and orchestra and uses the texts of ...

'' and ''Répons

''Répons'' is a composition by French composer Pierre Boulez for a large chamber orchestra with six percussion soloists and live electronics. The six soloists play harp, cimbalom, vibraphone, glockenspiel/xylophone, and two pianos. It was premie ...

''. His uncompromising commitment to modernism and the trenchant, polemic

Polemic () is contentious rhetoric intended to support a specific position by forthright claims and to undermine the opposing position. The practice of such argumentation is called ''polemics'', which are seen in arguments on controversial topics ...

al tone in which he expressed his views on music led some to criticise him as a dogmatist.

Alongside his activities as a composer, Boulez was one of the most prominent conductors of his generation. In a career lasting more than sixty years, he was music director of the New York Philharmonic

The New York Philharmonic, officially the Philharmonic-Symphony Society of New York, Inc., globally known as New York Philharmonic Orchestra (NYPO) or New York Philharmonic-Symphony Orchestra, is a symphony orchestra based in New York City. It is ...

and the Ensemble intercontemporain

The Ensemble intercontemporain (EIC) is a French music ensemble, based in Paris, that is dedicated to contemporary music. Pierre Boulez founded the EIC in 1976 for this purpose, the first permanent organization of its type in the world.

Organi ...

, chief conductor of the BBC Symphony Orchestra

The BBC Symphony Orchestra (BBC SO) is a British orchestra based in London. Founded in 1930, it was the first permanent salaried orchestra in London, and is the only one of the city's five major symphony orchestras not to be self-governing. T ...

and principal guest conductor of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra

The Chicago Symphony Orchestra (CSO) was founded by Theodore Thomas in 1891. The ensemble makes its home at Orchestra Hall in Chicago and plays a summer season at the Ravinia Festival. The music director is Riccardo Muti, who began his tenu ...

and the Cleveland Orchestra

The Cleveland Orchestra, based in Cleveland, is one of the five American orchestras informally referred to as the " Big Five". Founded in 1918 by the pianist and impresario Adella Prentiss Hughes, the orchestra plays most of its concerts at Seve ...

. He made frequent appearances with many other orchestras, including the Vienna Philharmonic

The Vienna Philharmonic (VPO; german: Wiener Philharmoniker, links=no) is an orchestra that was founded in 1842 and is considered to be one of the finest in the world.

The Vienna Philharmonic is based at the Musikverein in Vienna, Austria. It ...

, the Berlin Philharmonic

The Berlin Philharmonic (german: Berliner Philharmoniker, links=no, italic=no) is a German orchestra based in Berlin. It is one of the most popular, acclaimed and well-respected orchestras in the world.

History

The Berlin Philharmonic was fo ...

and the London Symphony Orchestra

The London Symphony Orchestra (LSO) is a British symphony orchestra based in London. Founded in 1904, the LSO is the oldest of London's orchestras, symphony orchestras. The LSO was created by a group of players who left Henry Wood's Queen's ...

. He was known for his performances of the music of the first half of the twentieth century—including Debussy

(Achille) Claude Debussy (; 22 August 1862 – 25 March 1918) was a French composer. He is sometimes seen as the first Impressionism in music, Impressionist composer, although he vigorously rejected the term. He was among the most infl ...

and Ravel

Joseph Maurice Ravel (7 March 1875 – 28 December 1937) was a French composer, pianist and conductor. He is often associated with Impressionism along with his elder contemporary Claude Debussy, although both composers rejected the term. In ...

, Stravinsky

Igor Fyodorovich Stravinsky (6 April 1971) was a Russian composer, pianist and conductor, later of French (from 1934) and American (from 1945) citizenship. He is widely considered one of the most important and influential composers of the ...

and Bartók, and the Second Viennese School

The Second Viennese School (german: Zweite Wiener Schule, Neue Wiener Schule) was the group of composers that comprised Arnold Schoenberg and his pupils, particularly Alban Berg and Anton Webern, and close associates in early 20th-century Vienna ...

—as well as that of his contemporaries, such as Ligeti, Berio and Carter. His work in the opera house included the ''Jahrhundertring

The ''Jahrhundertring'' (''Centenary Ring'') was the production of Richard Wagner's ''Ring Cycle'', '' Der Ring des Nibelungen'', at the Bayreuth Festival in 1976, celebrating the centenary of both the festival and the first performance of the com ...

''—the production of Wagner

Wilhelm Richard Wagner ( ; ; 22 May 181313 February 1883) was a German composer, theatre director, polemicist, and conductor who is chiefly known for his operas (or, as some of his mature works were later known, "music dramas"). Unlike most op ...

's ''Ring'' cycle for the centenary of the Bayreuth Festival

The Bayreuth Festival (german: link=no, Bayreuther Festspiele) is a music festival held annually in Bayreuth, Germany, at which performances of operas by the 19th-century German composer Richard Wagner are presented. Wagner himself conceived ...

—and the world premiere of the three-act version of Alban Berg

Alban Maria Johannes Berg ( , ; 9 February 1885 – 24 December 1935) was an Austrian composer of the Second Viennese School. His compositional style combined Romantic lyricism with the twelve-tone technique. Although he left a relatively sm ...

's ''Lulu

Lulu may refer to:

Companies

* LuLu, an early automobile manufacturer

* Lulu.com, an online e-books and print self-publishing platform, distributor, and retailer

* Lulu Hypermarket, a retail chain in Asia

* Lululemon Athletica or simply Lulu, ...

''. His recorded legacy is extensive.

He founded several musical institutions: the Domaine musical, Institut de recherche et coordination acoustique/musique

An institute is an organisational body created for a certain purpose. They are often research organisations ( research institutes) created to do research on specific topics, or can also be a professional body.

In some countries, institutes ca ...

(IRCAM), Ensemble intercontemporain and Cité de la Musique

The Cité de la Musique ("City of Music"), also known as Philharmonie 2, is a group of institutions dedicated to music and situated in the Parc de la Villette, 19th arrondissement of Paris, France. It was designed with the nearby Conservatoire de ...

in Paris, and the Lucerne Festival Academy in Switzerland.

Biography

1925–1943: Childhood and school days

Pierre Boulez was born on 26 March 1925, in Montbrison, a small town in theLoire department

Loire (; ; frp, Lêre; oc, Léger or ''Leir'') is a landlocked department in the Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes region of France occupying the river Loire's upper reaches. Its prefecture is Saint-Étienne. It had a population of 765,634 in 2019.

of east-central France, to Léon and Marcelle (''née'' Calabre) Boulez. He was the third of four children: an older sister, Jeanne (1922–2018) and younger brother, Roger (b. 1936) were preceded by a first child, also called Pierre (b. 1920), who died in infancy. Léon (1891–1969), an engineer and technical director of a steel factory, is described by biographers as an authoritarian figure, but with a strong sense of fairness; Marcelle (1897–1985) as an outgoing, good-humoured woman, who deferred to her husband's strict Catholic beliefs, while not necessarily sharing them. The family prospered, moving in 1929 from the apartment above a pharmacy, where Boulez was born, to a comfortable detached house, where he spent most of his childhood.

From the age of seven Boulez went to school at the Institut Victor de Laprade, a Catholic seminary where the thirteen-hour school day was filled with study and prayer. By the age of eighteen he had repudiated Catholicism although later in life he described himself as an agnostic.

As a child, Boulez took piano lessons, played chamber music with local amateurs and sang in the school choir. After completing the first part of his baccalaureate a year early, he spent the academic year of 1940–41 at the Pensionnat St. Louis, a boarding school in nearby Saint-Étienne

Saint-Étienne (; frp, Sant-Etiève; oc, Sant Estève, ) is a city and the prefecture of the Loire department in eastern-central France, in the Massif Central, southwest of Lyon in the Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes region.

Saint-Étienne is the ...

. The following year he took classes in advanced mathematics at the Cours Sogno in Lyon (a school established by the Lazaristes) with a view to gaining admission to the École Polytechnique

École may refer to:

* an elementary school in the French educational stages normally followed by secondary education establishments (collège and lycée)

* École (river), a tributary of the Seine

The Seine ( , ) is a river in northern Franc ...

in Paris. His father hoped this would lead to a career in engineering. He was in Lyon

Lyon,, ; Occitan: ''Lion'', hist. ''Lionés'' also spelled in English as Lyons, is the third-largest city and second-largest metropolitan area of France. It is located at the confluence of the rivers Rhône and Saône, to the northwest of ...

when the Vichy government

Vichy France (french: Régime de Vichy; 10 July 1940 – 9 August 1944), officially the French State ('), was the fascist French state headed by Marshal Philippe Pétain during World War II. Officially independent, but with half of its terr ...

fell, the Germans took over and the city became a centre of the resistance.

In Lyon, Boulez first heard an orchestra, saw his first operas (''Boris Godunov

Borís Fyodorovich Godunóv (; russian: Борис Фёдорович Годунов; 1552 ) ruled the Tsardom of Russia as ''de facto'' regent from c. 1585 to 1598 and then as the first non-Rurikid tsar from 1598 to 1605. After the end of hi ...

'' and ''Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg

(; "The Master-Singers of Nuremberg"), WWV 96, is a music drama, or opera, in three acts, by Richard Wagner. It is the longest opera commonly performed, taking nearly four and a half hours, not counting two breaks between acts, and is traditi ...

'') and met the well-known soprano Ninon Vallin

Eugénie "Ninon" Vallin (8 September 1886 22 November 1961) was a French soprano who achieved considerable popularity in opera, operetta and classical song recitals during an international career that lasted for more than four decades.

Care ...

, who asked him to play for her. Impressed by his ability, she persuaded his father to allow him to apply to the Conservatoire de Lyon

A music school is an educational institution specialized in the study, training, and research of music. Such an institution can also be known as a school of music, music academy, music faculty, college of music, music department (of a larger ins ...

. He was rejected but was determined to pursue a career in music. The following year, with his sister's support in the face of opposition from his father, he studied the piano and harmony privately with Lionel de Pachmann (son of the pianist Vladimir). "Our parents were strong, but finally we were stronger than they", Boulez later said. In fact, when he moved to Paris in the autumn of 1943, hoping to enrol at the Conservatoire de Paris

The Conservatoire de Paris (), also known as the Paris Conservatory, is a college of music and dance founded in 1795. Officially known as the Conservatoire National Supérieur de Musique et de Danse de Paris (CNSMDP), it is situated in the avenue ...

, Léon accompanied him, helped him to find a room (in the 7th arrondissement) and subsidised him until he could earn a living.

1943–1946: Musical education

In October 1943, he auditioned unsuccessfully for the advanced piano class at the Conservatoire, but he was admitted in January 1944 to the preparatory harmony class of Georges Dandelot. He made such fast progress that, by May 1944, Dandelot described him as "the best of the class". Around the same time he was introduced to Andrée Vaurabourg, wife of the composer

Around the same time he was introduced to Andrée Vaurabourg, wife of the composer Arthur Honegger

Arthur Honegger (; 10 March 1892 – 27 November 1955) was a Swiss composer who was born in France and lived a large part of his life in Paris. A member of Les Six, his best known work is probably '' Antigone'', composed between 1924 and 1927 ...

. Between April 1944 and May 1946 he studied counterpoint privately with her. He greatly enjoyed working with her and she remembered him as an exceptional student, using his exercises as models until the end of her teaching career. In June 1944 he approached Olivier Messiaen

Olivier Eugène Prosper Charles Messiaen (, ; ; 10 December 1908 – 27 April 1992) was a French composer, organist, and ornithologist who was one of the major composers of the 20th century. His music is rhythmically complex; harmonical ...

, who wrote in his diary: 'Likes modern music. Wants to study harmony with me from now on.' Boulez began to attend the private seminars which Messiaen gave to selected students; in January 1945, he joined Messiaen's advanced harmony class at the Conservatoire.

Boulez moved to two small attic rooms in the Marais

Marais (, meaning "marsh") may refer to:

People

* Marais (given name)

* Marais (surname)

Other uses

* Le Marais, historic district of Paris

* Théâtre du Marais, the name of several theatres and theatrical troupes in Paris, France

* Marais ( ...

district of Paris, where he lived for the next thirteen years. In February 1945 he attended a private performance of Schoenberg's Wind Quintet

A wind quintet, also known as a woodwind quintet, is a group of five wind players (most commonly flute, oboe, clarinet, French horn and bassoon).

Unlike the string quartet (of 4 string instruments) with its homogeneous blend of sound color, the ...

, conducted by René Leibowitz

René Leibowitz (; 17 February 1913 – 29 August 1972) was a Polish, later naturalised French, composer, conductor, music theorist and teacher. He was historically significant in promoting the music of the Second Viennese School in Paris after ...

, the composer and follower of Schoenberg. Its strict use of twelve-tone technique

The twelve-tone technique—also known as dodecaphony, twelve-tone serialism, and (in British usage) twelve-note composition—is a method of musical composition first devised by Austrian composer Josef Matthias Hauer, who published his "law ...

was a revelation to him and he organised a group of fellow students to take private lessons with Leibowitz. It was here that he also discovered the music of Webern

Anton Friedrich Wilhelm von Webern (3 December 188315 September 1945), better known as Anton Webern (), was an Austrian composer and conductor whose music was among the most radical of its milieu in its sheer concision, even aphorism, and stea ...

. He eventually found Leibowitz's approach too doctrinaire and broke angrily with him in 1946 when Leibowitz tried to criticise one of his early works.

In June 1945, Boulez was one of four Conservatoire students awarded ''premier prix''. He was described in the examiner's report as "the most gifted—a composer". Although registered at the Conservatoire for the academic year 1945–46, he soon boycotted Simone Plé-Caussade

Simone-Marie Plé-Caussade (14 August 1897, Paris – 6 August 1986, Bagnères-de-Bigorre) was a French music pedagogue, composer and pianist. She wrote mainly works for solo piano and organ in addition to choral works, songs, chamber music, and ...

's counterpoint and fugue class, infuriated by what he described as her "lack of imagination", and organised a petition that Messiaen be given a full professorship in composition. Over the winter of 1945–46 he immersed himself in Balinese and Japanese music

In Japan, music includes a wide array of distinct genres, both traditional and modern. The word for "music" in Japanese is 音楽 (''ongaku''), combining the kanji 音 ''on'' (sound) with the kanji 楽 ''gaku'' (music, comfort). Japan is the wo ...

and African drumming

Sub-Saharan African music is characterised by a "strong rhythmic interest" that exhibits common characteristics in all regions of this vast territory, so that Arthur Morris Jones (1889–1980) has described the many local approaches as constit ...

at the Musée Guimet

The Guimet Museum (full name in french: Musée national des arts asiatiques-Guimet; MNAAG; ) is an art museum located at 6, place d'Iéna in the 16th arrondissement of Paris, France. Literally translated into English, its full name is the Nationa ...

and the Musée de l'Homme

The Musée de l'Homme (French, "Museum of Mankind" or "Museum of Humanity") is an anthropology museum in Paris, France. It was established in 1937 by Paul Rivet for the 1937 '' Exposition Internationale des Arts et Techniques dans la Vie Modern ...

in Paris: "I almost chose the career of an ethnomusicologist

Ethnomusicology is the study of music from the cultural and social aspects of the people who make it. It encompasses distinct theoretical and methodical approaches that emphasize cultural, social, material, cognitive, biological, and other dim ...

because I was so fascinated by that music. It gives a different feeling of time."

1946–1953: Early career in Paris

On 12 February 1946 the pianist Yvette Grimaud gave the first public performances of Boulez's music (''Douze Notations'' and ''Trois Psalmodies'') at the Concerts du Triptyque. Boulez earned money by giving mathematics lessons to his landlord's son. He also played the

On 12 February 1946 the pianist Yvette Grimaud gave the first public performances of Boulez's music (''Douze Notations'' and ''Trois Psalmodies'') at the Concerts du Triptyque. Boulez earned money by giving mathematics lessons to his landlord's son. He also played the ondes Martenot

The ondes Martenot ( ; , "Martenot waves") or ondes musicales ("musical waves") is an early electronic musical instrument. It is played with a keyboard or by moving a ring along a wire, creating "wavering" sounds similar to a theremin. A playe ...

(an early electronic instrument), improvising accompaniments to radio dramas and occasionally deputising in the pit orchestra of the Folies Bergère

The Folies Bergère () is a cabaret music hall, located in Paris, France. Located at 32 Rue Richer in the 9th Arrondissement, the Folies Bergère was built as an opera house by the architect Plumeret. It opened on 2 May 1869 as the Folies Trév ...

. In October 1946 the actor and director Jean-Louis Barrault

Jean-Louis Bernard Barrault (; 8 September 1910 – 22 January 1994) was a French actor, director and mime artist who worked on both screen and stage.

Biography

Barrault was born in Le Vésinet in France in 1910. His father was 'a Burgundi ...

engaged him to play the ondes for a production of ''Hamlet

''The Tragedy of Hamlet, Prince of Denmark'', often shortened to ''Hamlet'' (), is a tragedy written by William Shakespeare sometime between 1599 and 1601. It is Shakespeare's longest play, with 29,551 words. Set in Denmark, the play depi ...

'' for the new company he and his wife, Madeleine Renaud, had formed at the Théâtre Marigny

The Théâtre Marigny is a theatre in Paris, situated near the junction of the Champs-Élysées and the Avenue Marigny in the 8th arrondissement.

It was originally built to designs of the architect Charles Garnier for the display of a panoram ...

. Boulez was soon appointed music director of the Compagnie Renaud-Barrault, a post he held for nine years. He arranged and conducted incidental music, mostly by composers whose music he disliked (such as Milhaud and Tchaikovsky

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky , group=n ( ; 7 May 1840 – 6 November 1893) was a Russian composer of the Romantic period. He was the first Russian composer whose music would make a lasting impression internationally. He wrote some of the most pop ...

), but it gave him the chance to work with professional musicians, while leaving time to compose during the day.

His involvement with the company also broadened his horizons: in 1947 they toured to Belgium and Switzerland ("absolutely ''pays de cocagne

''Land of Milk and Honey'' () is a 1971 French documentary film directed by Pierre Étaix

Pierre Étaix (; 23 November 1928 – 14 October 2016) was a French clown, comedian and filmmaker. Étaix made a series of short- and feature-length films, ...

'', my first discovery of the big world"); in 1948 they took ''Hamlet'' to the second Edinburgh International Festival

The Edinburgh International Festival is an annual arts festival in Edinburgh, Scotland, spread over the final three weeks in August. Notable figures from the international world of music (especially classical music) and the performing arts are ...

; in 1951 they gave a season of plays in London, at the invitation of Laurence Olivier

Laurence Kerr Olivier, Baron Olivier (; 22 May 1907 – 11 July 1989) was an English actor and director who, along with his contemporaries Ralph Richardson and John Gielgud, was one of a trio of male actors who dominated the British stage o ...

; and between 1950 and 1957 there were three tours to South America and two to North America. Much of the music he wrote for the company was lost during the student occupation of the Théâtre de l'Odéon in 1968.

The period between 1947 and 1950 was one of intense compositional activity for Boulez. New works included the first two piano sonatas and initial versions of two cantatas on poems by René Char

René Émile Char (; 14 June 1907 – 19 February 1988) was a French poet and member of the French Resistance.

Biography

Char was born in L'Isle-sur-la-Sorgue in the Vaucluse department of France, the youngest of the four children of Emile ...

, ''Le Visage nuptial

''Le Visage nuptial'' (''The Nuptial Face'') is a secular cantata for soprano, contralto, choir of women and orchestra by Pierre Boulez. Originally composed in 1946–47 on a poem by René Char for two voices, two ondes Martenot, piano and per ...

'' and '' Le Soleil des eaux''. In October 1951 a substantial work for eighteen solo instruments, ''Polyphonie X

''Polyphonie X'' (1950–51) is a three- movement composition by Pierre Boulez for eighteen instruments divided into seven groups, with a duration of roughly fifteen minutes. Following the work's premiere, Boulez withdrew the score, stating that it ...

'', caused a scandal at its premiere at the Donaueschingen Festival

The Donaueschingen Festival (german: Donaueschinger Musiktage, links=no) is a festival for new music that takes place every October in the small town of Donaueschingen in south-western Germany. Founded in 1921, it is considered the oldest festiva ...

, some audience members disrupting the performance with hisses and whistles.

Around this time, Boulez met two composers who were to be important influences: John Cage and Karlheinz Stockhausen

Karlheinz Stockhausen (; 22 August 1928 – 5 December 2007) was a German composer, widely acknowledged by critics as one of the most important but also controversial composers of the 20th and early 21st centuries. He is known for his groundb ...

. His friendship with Cage began in 1949 when Cage was visiting Paris. Cage introduced Boulez to two publishers ( Heugel and Amphion) who agreed to take his recent pieces; Boulez helped to arrange a private performance of Cage's ''Sonatas and Interludes for Prepared Piano

''Sonatas and Interludes'' is a cycle of twenty pieces for prepared piano by American avant-garde composer John Cage (1912–1992). It was composed in 1946–48, shortly after Cage's introduction to Indian philosophy and the teachings of art his ...

''. When Cage returned to New York they began an intense, six-year correspondence about the future of music. In 1952 Stockhausen arrived in Paris to study with Messiaen.Barbedette, 214. Although Boulez knew no German and Stockhausen no French, the rapport between them was instant: "A friend translated ndwe gesticulated wildly ... We talked about music all the time—in a way I've never talked about it with anyone else."

Towards the end of 1951, a tour with the Renaud-Barrault company took him to New York for the first time, where he met Stravinsky and Varèse. He stayed at Cage's apartment but their friendship was already cooling as he could not accept Cage's increasing commitment to compositional procedures based on chance and he later broke off contact with him.

In July 1952, Boulez attended the International Summer Course for New Music in Darmstadt

Darmstadt () is a city in the States of Germany, state of Hesse in Germany, located in the southern part of the Frankfurt Rhine Main Area, Rhine-Main-Area (Frankfurt Metropolitan Region). Darmstadt has around 160,000 inhabitants, making it th ...

for the first time. As well as Stockhausen, Boulez was in contact there with other composers who would become significant figures in contemporary music, including Luciano Berio

Luciano Berio (24 October 1925 – 27 May 2003) was an Italian composer noted for his experimental work (in particular his 1968 composition ''Sinfonia'' and his series of virtuosic solo pieces titled '' Sequenza''), and for his pioneering wo ...

, Luigi Nono

Luigi Nono (; 29 January 1924 – 8 May 1990) was an Italian avant-garde composer of classical music.

Biography

Early years

Nono, born in Venice, was a member of a wealthy artistic family; his grandfather was a notable painter. Nono b ...

, Bruno Maderna

Bruno Maderna (21 April 1920 – 13 November 1973) was an Italian conductor and composer.

Life

Maderna was born Bruno Grossato in Venice but later decided to take the name of his mother, Caterina Carolina Maderna.Interview with Maderna‘s thr ...

, and Henri Pousseur

Henri Léon Marie-Thérèse Pousseur (23 June 1929 – 6 March 2009) was a Belgian classical composer, teacher, and music theorist.

Biography

Pousseur was born in Malmedy and studied at the Academies of Music in Liège and in Brussels from 1947 to ...

. Boulez quickly became one of the leaders of the post-war modernist movement in the arts. As the music critic Alex Ross observed: "at all times he seemed absolutely sure of what he was doing. Amid the confusion of postwar life, with so many truths discredited, his certitude was reassuring."

1954–1959: Le Domaine musical

In 1954, with the financial backing of Barrault and Renaud, Boulez started a series of concerts at the Petit Marigny theatre. They became known as the Domaine musical. The concerts focused initially on three areas: pre-war classics still unfamiliar in Paris (such as Bartók and Webern), works by the new generation (Stockhausen, Nono) and neglected masters from the past (

In 1954, with the financial backing of Barrault and Renaud, Boulez started a series of concerts at the Petit Marigny theatre. They became known as the Domaine musical. The concerts focused initially on three areas: pre-war classics still unfamiliar in Paris (such as Bartók and Webern), works by the new generation (Stockhausen, Nono) and neglected masters from the past (Machaut

Guillaume de Machaut (, ; also Machau and Machault; – April 1377) was a French composer and poet who was the central figure of the style in late medieval music. His dominance of the genre is such that modern musicologists use his death to ...

, Gesualdo)—although for practical reasons the last category fell away in subsequent seasons. Boulez proved an energetic and accomplished administrator and the concerts were an immediate success. They attracted musicians, painters and writers, as well as fashionable society, but they were so costly that Boulez had to turn to wealthy private patrons for support.

Key events in the Domaine's history included a Webern festival (1955), the European premiere of Stravinsky's ''Agon

Agon (Greek ) is a Greek term for a conflict, struggle or contest. This could be a contest in athletics, in chariot or horse racing, or in music or literature at a public festival in ancient Greece. Agon is the word-forming element in 'agony', ...

'' (1957) and first performances of Messiaen's '' Oiseaux exotiques'' (1955) and ''Sept Haïkaï'' (1963). The concerts moved to the Salle Gaveau

The Salle Gaveau, named after the French piano maker Gaveau, is a classical concert hall in Paris, located at 45-47 rue La Boétie, in the 8th arrondissement of Paris. It is particularly intended for chamber music.

Construction

The plans for th ...

(1956–1959) and then to the Théâtre de l'Odéon (1959–1968). Boulez remained director until 1967, when Gilbert Amy succeeded him.

On 18 June 1955, Hans Rosbaud

Hans Rosbaud (22 July 1895 – 29 December 1962) was an Austrian conductor, particularly associated with the music of the twentieth century.

Biography

Rosbaud was born in Graz. As children, he and his brother Paul Rosbaud performed with their ...

conducted the first performance of Boulez's best-known work, ''Le Marteau sans maître

''Le Marteau sans maître'' (; The Hammer without a Master) is a chamber cantata by French composer Pierre Boulez. The work, which received its premiere in 1955, sets surrealist poetry by René Char for contralto and six instrumentalists. It ...

'', at the ISCM Festival in Baden-Baden. A nine-movement cycle for alto voice and instrumental ensemble based on poems by René Char, it was an immediate, international success. William Glock

Sir William Frederick Glock, CBE (3 May 190828 June 2000) was a British music critic and musical administrator who was instrumental in introducing the Continental avant-garde, notably promoting the career of Pierre Boulez.

Biography

Glock was bo ...

wrote: "even at a first hearing, though difficult to take in, it was so utterly new in sound, texture and feeling that it seemed to possess a mythical quality like that of Schoenberg's ''Pierrot lunaire''." When Boulez conducted the work in Los Angeles in early 1957, Stravinsky—who described it as "one of the few significant works of the post-war period of exploration"—attended the performance. Boulez dined several times with the Stravinskys and (according to Robert Craft

Robert Lawson Craft (October 20, 1923 – November 10, 2015) was an American conductor and writer. He is best known for his intimate professional relationship with Igor Stravinsky, on which Craft drew in producing numerous recordings and books.

...

) "soon captivated the older composer with new musical ideas, and an extraordinary intelligence, quickness and humour". Relations soured somewhat the following year over the first Paris performance of Stravinsky's '' Threni'' for the Domaine musical. Poorly planned by Boulez and nervously conducted by Stravinsky, the performance broke down more than once.

In January 1958, the ''Improvisations sur Mallarmé (I et II)'' were premiered, forming the kernel of a piece which would grow over the next four years into a vast, five-movement "portrait of Mallarmé", ''Pli selon pli

''Pli selon pli'' (Fold by fold) is a piece of classical music by the French composer Pierre Boulez. It carries the subtitle ''Portrait de Mallarmé'' (Portrait of Mallarmé). It is scored for a solo soprano and orchestra and uses the texts of ...

''. It received its premiere in Donaueschingen in October 1962.

Around this time, Boulez's relations with Stockhausen grew increasingly tense as (according to the biographer Joan Peyser) he saw the younger man supplanting him as the leader of the avant-garde.

1959–1971: International conducting career

In 1959, Boulez left Paris forBaden-Baden

Baden-Baden () is a spa town in the state of Baden-Württemberg, south-western Germany, at the north-western border of the Black Forest mountain range on the small river Oos, ten kilometres (six miles) east of the Rhine, the border with France, ...

, where he had an arrangement with the South-West German Radio orchestra to work as composer-in-residence and to conduct some smaller concerts, as well as access to an electronic studio where he could work on a new piece (''Poésie pour pouvoir''). He moved into, and eventually bought, a large hillside villa, which was his main residence for the rest of his life.

During this period, he turned increasingly to conducting. His first engagement as an orchestral conductor had been in 1956, when he conducted the Venezuela Symphony Orchestra

The Venezuela Symphony Orchestra ( es, Orquesta Sinfónica de Venezuela) is an orchestra in Venezuela, founded in 1930. They perform at the Ríos Reyna concert-hall in the Teresa Carreño Cultural Complex.

See also

*Venezuelan music

Severa ...

while on tour with Barrault. In Cologne he conducted his own ''Le Visage nuptial'' in 1957 and—with Bruno Maderna and the composer—the first performances of Stockhausen's ''Gruppen

''Gruppen'' (german: Groups) for three orchestras (1955–57) is amongst the best-known compositions of German composer Karlheinz Stockhausen, and is Work Number 6 in the composer's catalog of works. ''Gruppen'' is "a landmark in 20th-century mu ...

'' in 1958. His breakthrough came in 1959 when he replaced the ailing Hans Rosbaud at short notice in demanding programmes of twentieth-century music at the Aix-en-Provence

Aix-en-Provence (, , ; oc, label=Provençal, Ais de Provença in classical norm, or in Mistralian norm, ; la, Aquae Sextiae), or simply Aix ( medieval Occitan: ''Aics''), is a city and commune in southern France, about north of Marseille. ...

and Donaueschingen Festivals. This led to debuts with the Amsterdam Concertgebouw, Bavarian Radio Symphony and Berlin Philharmonic Orchestras. In 1963 he conducted the Orchestre National de France

The Orchestre national de France (ONF; literal translation, ''National Orchestra of France'') is a French symphony orchestra based in Paris, founded in 1934. Placed under the administration of the French national radio (named Radio France since ...

in the 50th anniversary performance of Stravinsky's ''The Rite of Spring'' at the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées in Paris, where the piece had had its riotous premiere.

That same year, he conducted his first opera, Berg's ''Wozzeck

''Wozzeck'' () is the first opera by the Austrian composer Alban Berg. It was composed between 1914 and 1922 and first performed in 1925. The opera is based on the drama ''Woyzeck'', which the German playwright Georg Büchner left incomplete at h ...

'' at the Opéra National de Paris

The Paris Opera (, ) is the primary opera and ballet company of France. It was founded in 1669 by Louis XIV as the , and shortly thereafter was placed under the leadership of Jean-Baptiste Lully and officially renamed the , but continued to be k ...

, directed by Barrault. The conditions were exceptional, with thirty orchestral rehearsals instead of the usual three or four, the critical response was favourable and after the first performance the musicians rose to applaud him. He conducted ''Wozzeck'' again in April 1966 at the Frankfurt Opera in a new production by Wieland Wagner

Wieland Wagner (5 January 1917 – 17 October 1966) was a German opera director, grandson of Richard Wagner. As co-director of the Bayreuth Festival when it re-opened after World War II, he was noted for innovative new stagings of the operas, depa ...

.

Wieland Wagner had already invited Boulez to conduct Wagner's ''Parsifal

''Parsifal'' ( WWV 111) is an opera or a music drama in three acts by the German composer Richard Wagner and his last composition. Wagner's own libretto for the work is loosely based on the 13th-century Middle High German epic poem '' Parziv ...

'' at the Bayreuth Festival later in the season, and Boulez returned to conduct revivals in 1967, 1968 and 1970. He also conducted performances of Wagner's ''Tristan und Isolde

''Tristan und Isolde'' (''Tristan and Isolde''), WWV 90, is an opera in three acts by Richard Wagner to a German libretto by the composer, based largely on the 12th-century romance Tristan and Iseult by Gottfried von Strassburg. It was compos ...

'' with the Bayreuth company at the Osaka Festival in Japan in 1967, but the lack of adequate rehearsal made it an experience he later said he would rather forget. By contrast, his conducting of the new production (by Václav Kašlík) of Debussy's '' Pelléas et Mélisande'' at Covent Garden

Covent Garden is a district in London, on the eastern fringes of the West End, between St Martin's Lane and Drury Lane. It is associated with the former fruit-and-vegetable market in the central square, now a popular shopping and tourist sit ...

in 1969 was praised for its combination of "delicacy and sumptuousness".

In 1965, the Edinburgh International Festival

The Edinburgh International Festival is an annual arts festival in Edinburgh, Scotland, spread over the final three weeks in August. Notable figures from the international world of music (especially classical music) and the performing arts are ...

staged the first full-scale retrospective of Boulez as composer and conductor. In 1966, he proposed a reorganisation of French musical life to the then minister of culture, André Malraux

Georges André Malraux ( , ; 3 November 1901 – 23 November 1976) was a French novelist, art theorist, and minister of cultural affairs. Malraux's novel ''La Condition Humaine'' ( Man's Fate) (1933) won the Prix Goncourt. He was appointed by P ...

, but Malraux instead appointed the conservative Marcel Landowski

Marcel François Paul Landowski (18 February 1915 – 23 December 1999) was a French composer, biographer and arts administrator.

Biography

Born at Pont-l'Abbé, Finistère, Brittany, he was the son of French sculptor Paul Landowski and g ...

as head of music at the Ministry of Culture. Boulez expressed his fury in an article in the ''Nouvel Observateur'', announcing that he was "going on strike with regard to any aspect of official music in France."

The previous year, in March 1965, he had made his orchestral debut in the United States with the Cleveland Orchestra

The Cleveland Orchestra, based in Cleveland, is one of the five American orchestras informally referred to as the " Big Five". Founded in 1918 by the pianist and impresario Adella Prentiss Hughes, the orchestra plays most of its concerts at Seve ...

. He became its principal guest conductor in February 1969, a post he held until the end of 1971. After the death of George Szell

George Szell (; June 7, 1897 – July 30, 1970), originally György Széll, György Endre Szél, or Georg Szell, was a Hungarian-born American conductor and composer. He is widely considered one of the twentieth century's greatest condu ...

in July 1970, he took on the role of music advisor for two years, but the title was largely honorary, owing to his commitments in London and New York. In the 1968–69 season, he also made guest appearances in Boston, Chicago and Los Angeles.

Apart from ''Pli selon pli'', the only substantial new work to emerge in the first half of the 1960s was the final version of Book 2 of his ''Structures'' for two pianos. Midway through the decade, however, Boulez appeared to find his voice again and produced a number of new works, including ''Éclat'' (1965), a short and brilliant piece for small ensemble, which by 1970 had grown into a substantial half-hour work, ''Éclat/Multiples''.

1971–1977: London and New York

Boulez first conducted theBBC Symphony Orchestra

The BBC Symphony Orchestra (BBC SO) is a British orchestra based in London. Founded in 1930, it was the first permanent salaried orchestra in London, and is the only one of the city's five major symphony orchestras not to be self-governing. T ...

in February 1964, at Worthing

Worthing () is a seaside town in West Sussex, England, at the foot of the South Downs, west of Brighton, and east of Chichester. With a population of 111,400 and an area of , the borough is the second largest component of the Brighton and H ...

, accompanying Vladimir Ashkenazy

Vladimir Davidovich Ashkenazy (russian: Влади́мир Дави́дович Ашкена́зи, ''Vladimir Davidovich Ashkenazi''; born 6 July 1937) is an internationally recognized solo pianist, chamber music performer, and conductor. He i ...

in a Chopin piano concerto. Boulez recalled the experience: "It was terrible, I felt like a waiter who keeps dropping the plates."

His appearances with the orchestra over the next five years included his debuts at the Proms

The BBC Proms or Proms, formally named the Henry Wood Promenade Concerts Presented by the BBC, is an eight-week summer season of daily orchestral classical music concerts and other events held annually, predominantly in the Royal Albert Ha ...

and at Carnegie Hall (1965) and tours to Moscow and Leningrad, Berlin and Prague (1967). In January 1969 William Glock, controller of music at the BBC, announced his appointment as chief conductor.Glock, 139.

Two months later, Boulez conducted the New York Philharmonic for the first time. His performances so impressed both orchestra and management that he was offered the chief conductorship in succession to Leonard Bernstein

Leonard Bernstein ( ; August 25, 1918 – October 14, 1990) was an American conductor, composer, pianist, music educator, author, and humanitarian. Considered to be one of the most important conductors of his time, he was the first America ...

. Glock was dismayed and tried to persuade him that accepting the New York position would detract both from his work in London and his ability to compose but Boulez could not resist the opportunity (as Glock put it) "to reform the music-making of both these world cities" and in June the New York appointment was confirmed.

His tenure in New York lasted between 1971 and 1977 and was not an unqualified success. The dependence on a subscription audience limited his programming. He introduced more key works from the first half of the twentieth century and, with earlier repertoire, sought out less well-known pieces. In his first season, for example, he conducted Liszt's ''The Legend of Saint Elizabeth'' and ''Via Crucis''. Performances of new music were comparatively rare in the subscription series. The players admired his musicianship but came to regard him as dry and unemotional by comparison with Bernstein, although it was widely accepted that he improved the standard of playing.Heyworth (1986), 36. He returned on only three occasions to the orchestra in later years.

His time with the BBC Symphony Orchestra was altogether happier. With the resources of the BBC behind him, he could be bolder in his choice of repertoire. There were occasional forays into the nineteenth century, particularly at the Proms (Beethoven's ''Missa solemnis

{{Audio, De-Missa solemnis.ogg, Missa solemnis is Latin for Solemn Mass, and is a genre of musical settings of the Mass Ordinary, which are festively scored and render the Latin text extensively, opposed to the more modest Missa brevis. In Frenc ...

'' in 1972; the Brahms

Johannes Brahms (; 7 May 1833 – 3 April 1897) was a German composer, pianist, and conductor of the mid- Romantic period. Born in Hamburg into a Lutheran family, he spent much of his professional life in Vienna. He is sometimes grouped wit ...

'' German Requiem'' in 1973), but for the most part he worked intensively with the orchestra on the music of the twentieth century. He conducted works by the younger generation of British composers—such as Harrison Birtwistle

Sir Harrison Birtwistle (15 July 1934 – 18 April 2022) was an English composer of contemporary classical music best known for his operas, often based on mythological subjects. Among his many compositions, his better known works include '' T ...

and Peter Maxwell Davies

Sir Peter Maxwell Davies (8 September 1934 – 14 March 2016) was an English composer and conductor, who in 2004 was made Master of the Queen's Music.

As a student at both the University of Manchester and the Royal Manchester College of Mus ...

—but Britten

Edward Benjamin Britten, Baron Britten (22 November 1913 – 4 December 1976, aged 63) was an English composer, conductor, and pianist. He was a central figure of 20th-century British music, with a range of works including opera, other ...

and Tippett

Tippett is a surname. Notable people with the surname include:

* Andre Tippett (born 1959), American Hall of Fame footballer

*Clark Tippet (1954–1992), American dancer

*Dave Tippett (born 1961), ice hockey coach

* Keith Tippett (born 1947), Eng ...

were absent from his programmes. His relations with the musicians were generally excellent. He was chief conductor between 1971 and 1975, continuing as chief guest conductor until 1977. Thereafter he returned to the orchestra frequently until his last appearance at an all- Janáček Prom in August 2008.

In both cities, Boulez sought out venues where new music could be presented more informally: in New York he began a series of "Rug Concerts"—when the seats in Avery Fisher Hall

David Geffen Hall is a concert hall in New York City's Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts complex on Manhattan's Upper West Side. The 2,200-seat auditorium opened in 1962, and is the home of the New York Philharmonic.

The facility, designe ...

were taken out and the audience sat on the floor—and a contemporary music series called "Prospective Encounters" in Greenwich Village

Greenwich Village ( , , ) is a neighborhood on the west side of Lower Manhattan in New York City, bounded by 14th Street to the north, Broadway to the east, Houston Street to the south, and the Hudson River to the west. Greenwich Village ...

. In London he gave concerts at the Roundhouse, a former railway turntable shed which Peter Brook

Peter Stephen Paul Brook (21 March 1925 – 2 July 2022) was an English theatre and film director. He worked first in England, from 1945 at the Birmingham Repertory Theatre, from 1947 at the Royal Opera House, and from 1962 for the Royal Shak ...

had also used for radical theatre productions. His aim was "to create a feeling that we are all, audience, players and myself, taking part in an act of exploration".

During this period, the music of Ravel came to the forefront of his repertoire. Between 1969 and 1975, he recorded the orchestral works with the New York Philharmonic and the Cleveland Orchestra and in 1973 he made studio recordings for the BBC of the two one-act operas (L'enfant et les sortilèges

''L'enfant et les sortilèges: Fantaisie lyrique en deux parties'' (''The Child and the Spells: A Lyric Fantasy in Two Parts'') is an opera in one act, with music by Maurice Ravel to a libretto by Colette. It is Ravel's second opera, his first b ...

and L'heure espagnole

''L'heure espagnole'' is a French one-act opera from 1911, described as a ''comédie musicale'', with music by Maurice Ravel to a French libretto by Franc-Nohain, based on Franc-Nohain's 1904 play ('comédie-bouffe') of the same nameStoullig E. ' ...

).

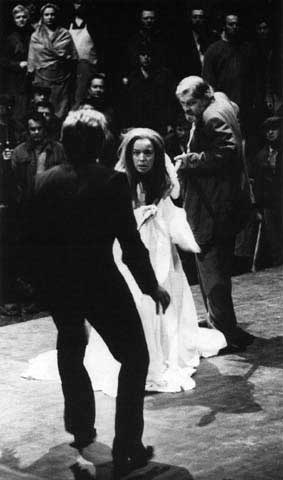

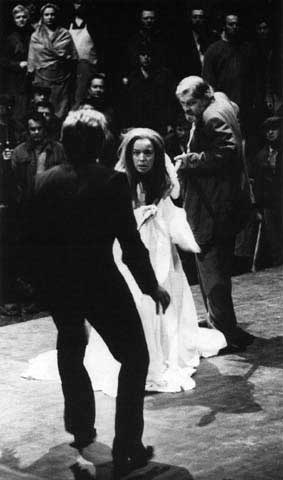

In 1972, Wolfgang Wagner

Wolfgang Wagner (30 August 191921 March 2010) was a German opera director. He is best known as the director (Festspielleiter) of the Bayreuth Festival, a position he initially assumed alongside his brother Wieland in 1951 until the latter's d ...

, who had succeeded his brother Wieland as director of the Bayreuth Festival, invited Boulez to conduct the 1976 centenary production of Wagner's ''Der Ring des Nibelungen

(''The Ring of the Nibelung''), WWV 86, is a cycle of four German-language epic music dramas composed by Richard Wagner. The works are based loosely on characters from Germanic heroic legend, namely Norse legendary sagas and the ''Nibelung ...

''. The director was Patrice Chéreau

Patrice Chéreau (; 2 November 1944 – 7 October 2013) was a French opera and theatre director, filmmaker, actor and producer. In France he is best known for his work for the theatre, internationally for his films '' La Reine Margot'' and ...

. Highly controversial in its first year, according to Barry Millington by the end of the run in 1980 "enthusiasm for the production vastly outweighed disapproval". It was televised around the world.

A small number of new works emerged during this period, of which perhaps the most important is ''Rituel in memoriam Bruno Maderna

''Rituel in memoriam Bruno Maderna'' (1974–75) is a composition for orchestra in eight groups by Pierre Boulez. Biographer Dominique Jameux wrote that the piece has "obvious audience appeal", and that it represented a desire to establish "immed ...

'' (1975).

1977–1992: IRCAM

In 1970 Boulez was asked by President Pompidou to return to France and set up an institute specialising in musical research and creation at the arts complex—now known as the

In 1970 Boulez was asked by President Pompidou to return to France and set up an institute specialising in musical research and creation at the arts complex—now known as the Centre Georges Pompidou

The Centre Pompidou (), more fully the Centre national d'art et de culture Georges-Pompidou ( en, National Georges Pompidou Centre of Art and Culture), also known as the Pompidou Centre in English, is a complex building in the Beaubourg area of ...

—which was planned for the Beaubourg district of Paris. The Institut de Recherche et Coordination Acoustique / Musique (IRCAM

IRCAM (French: ''Ircam, '', English: Institute for Research and Coordination in Acoustics/Music) is a French institute dedicated to the research of music and sound, especially in the fields of avant garde and electro-acoustical art music. It is ...

) opened in 1977.

Boulez’s model was the Bauhaus

The Staatliches Bauhaus (), commonly known as the Bauhaus (), was a German art school operational from 1919 to 1933 that combined crafts and the fine arts.Oxford Dictionary of Art and Artists (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 4th edn., 2 ...

, which had been a meeting place for artists and scientists of all disciplines. IRCAM's aims included research into acoustics, instrumental design and the use of computers in music. The original building was constructed underground, partly to isolate it acoustically (an above-ground extension was added later). The institution was criticised for absorbing too much state subsidy, Boulez for wielding too much power. At the same time he founded the Ensemble Intercontemporain

The Ensemble intercontemporain (EIC) is a French music ensemble, based in Paris, that is dedicated to contemporary music. Pierre Boulez founded the EIC in 1976 for this purpose, the first permanent organization of its type in the world.

Organi ...

, a virtuoso ensemble which specialised in twentieth-century music and the creation of new works.

In 1979, Boulez conducted the world premiere of the three-act version of Alban Berg's ''Lulu

Lulu may refer to:

Companies

* LuLu, an early automobile manufacturer

* Lulu.com, an online e-books and print self-publishing platform, distributor, and retailer

* Lulu Hypermarket, a retail chain in Asia

* Lululemon Athletica or simply Lulu, ...

'' at the Paris Opera

The Paris Opera (, ) is the primary opera and ballet company of France. It was founded in 1669 by Louis XIV as the , and shortly thereafter was placed under the leadership of Jean-Baptiste Lully and officially renamed the , but continued to be k ...

in Friedrich Cerha’s completion, and in Patrice Chéreau

Patrice Chéreau (; 2 November 1944 – 7 October 2013) was a French opera and theatre director, filmmaker, actor and producer. In France he is best known for his work for the theatre, internationally for his films '' La Reine Margot'' and ...

's production. Otherwise he scaled back his conducting commitments to concentrate on IRCAM. Most of his appearances during this period were with his own Ensemble intercontemporain—including tours to the United States (1986), Australia (1988), the Soviet Union (1990) and Canada (1991)—although he also renewed his links in the 1980s with the Los Angeles Philharmonic Orchestra.

By contrast, he composed significantly more during this period, producing a series of pieces which used the potential, developed at IRCAM, electronically to transform sound in real time. The first of these was ''Répons

''Répons'' is a composition by French composer Pierre Boulez for a large chamber orchestra with six percussion soloists and live electronics. The six soloists play harp, cimbalom, vibraphone, glockenspiel/xylophone, and two pianos. It was premie ...

'' (1981–1984), a 40-minute work for soloists, ensemble and electronics. He also radically reworked earlier pieces, including ''Notations I-IV'', a transcription and expansion of tiny piano pieces for large orchestra (1945–1980)Barbedette, 221. and his cantata on poems by René Char, ''Le Visage nuptial'' (1946–1989).Samuel (2002), 421—422.

In 1980, the five original directors of the IRCAM departments, including the composer Luciano Berio

Luciano Berio (24 October 1925 – 27 May 2003) was an Italian composer noted for his experimental work (in particular his 1968 composition ''Sinfonia'' and his series of virtuosic solo pieces titled '' Sequenza''), and for his pioneering wo ...

, resigned. Although Boulez declared these changes "very healthy", it clearly represented a crisis in his leadership.

Retrospectives of his music were mounted in Paris (Festival d'Automne, 1981), Baden-Baden (1985) and London (BBC, 1989).Samuel (2002), 419–20. From 1976 to 1995, he held the Chair in ''Invention, technique et langage en musique'' at the Collège de France

The Collège de France (), formerly known as the ''Collège Royal'' or as the ''Collège impérial'' founded in 1530 by François I, is a higher education and research establishment ('' grand établissement'') in France. It is located in Paris ...

. In 1988 he made a series of six programmes for French television, ''Boulez XXe siècle'', each of which focused on a specific aspect of contemporary music (rhythm, timbre, form etc.) He also bought a flat on the 30th floor of a building in the Front de Seine

Front de Seine is a development in the district of Beaugrenelle in Paris, France, located along the river Seine in the 15th arrondissement at the south of the Eiffel Tower. It is, with the 13th arrondissement, one of the few districts in the ...

district of Paris.Boulez (2017), 117 (note).

1992–2006: Return to conducting

In 1992, Boulez gave up the directorship of IRCAM and was succeeded by Laurent Bayle.Barbedette, 223. He was composer in residence at that year's

In 1992, Boulez gave up the directorship of IRCAM and was succeeded by Laurent Bayle.Barbedette, 223. He was composer in residence at that year's Salzburg Festival

The Salzburg Festival (german: Salzburger Festspiele) is a prominent festival of music and drama established in 1920. It is held each summer (for five weeks starting in late July) in the Austrian town of Salzburg, the birthplace of Wolfgang Ama ...

.

The previous year he began a series of annual residencies with the Cleveland Orchestra and the Chicago Symphony Orchestra. In 1995 he was named principal guest conductor in Chicago, only the third conductor to hold that position in the orchestra's history. He held the post until 2005, when he became conductor emeritus. His 70th birthday in 1995 was marked by a six-month retrospective tour with the London Symphony Orchestra, taking in Paris, Vienna, New York and Tokyo. In 2001 he conducted a major Bartók cycle with the Orchestre de Paris.

This period also marked a return to the opera house, including two productions with Peter Stein: Debussy's ''Pelléas et Mélisande'' (1992, Welsh National Opera

Welsh National Opera (WNO) ( cy, Opera Cenedlaethol Cymru) is an opera company based in Cardiff, Wales; it gave its first performances in 1946. It began as a mainly amateur body and transformed into an all-professional ensemble by 1973. In its ...

and Théâtre du Châtelet, Paris); and Schoenberg's ''Moses und Aron

''Moses und Aron'' (English: '' Moses and Aaron'') is a three-act opera by Arnold Schoenberg with the third act unfinished. The German libretto is by the composer after the Book of Exodus. Hungarian composer Zoltán Kocsis completed the last act ...

'' (1995, Dutch National Opera

The Dutch National Opera (DNO; formerly De Nederlandse Opera, now De Nationale Opera in Dutch) is a Dutch opera company based in Amsterdam, Netherlands. Its present home base is the Dutch National Opera & Ballet housed in the Stopera building, a ...

and Salzburg Festival

The Salzburg Festival (german: Salzburger Festspiele) is a prominent festival of music and drama established in 1920. It is held each summer (for five weeks starting in late July) in the Austrian town of Salzburg, the birthplace of Wolfgang Ama ...

). In 2004 and 2005 he returned to Bayreuth to conduct a controversial new production of ''Parsifal'' directed by Christoph Schlingensief

Christoph Maria Schlingensief (24 October 1960 – 21 August 2010) was a German theatre director, performance artist, and filmmaker. Starting as an independent underground filmmaker, Schlingensief later staged productions for theatres and festivals ...

.

The two most substantial compositions from this period are '' ...explosante-fixe...'' (1993), which had its origins in 1972 as a tribute to Stravinsky and which again used the electronic resources of IRCAM, and ''sur Incises

''Incises'' (1994/2001) and ''Sur Incises'' (1996/1998) are two related works of the French composer Pierre Boulez. The pitches of the row used in ''Incises'' and ''Sur Incises'' are based on the Sacher hexachord, the same as those used in the r ...

'' (1998), for which he was awarded the 2001 Grawemeyer Prize for composition.

He continued to work on institutional organisation. He co-founded the Cité de la Musique

The Cité de la Musique ("City of Music"), also known as Philharmonie 2, is a group of institutions dedicated to music and situated in the Parc de la Villette, 19th arrondissement of Paris, France. It was designed with the nearby Conservatoire de ...

, which opened in La Villette on the outskirts of Paris in 1995. Consisting of a modular concert hall, museum and mediatheque—with the Paris' Conservatoire on an adjacent site—it became the home to the Ensemble Intercontemporain

The Ensemble intercontemporain (EIC) is a French music ensemble, based in Paris, that is dedicated to contemporary music. Pierre Boulez founded the EIC in 1976 for this purpose, the first permanent organization of its type in the world.

Organi ...

and attracted a diverse audience. In 2004, he co-founded the Lucerne Festival Academy, an orchestral institute for young musicians, dedicated to music of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. For the next ten years he spent the last three weeks of summer working with young composers and conducting concerts with the Academy's orchestra.

2006–2016: Last years

Boulez's last major work was ''Dérive 2'' (2006), a 45-minute piece for eleven instruments. He left a number of compositional projects unfinished, including the remaining ''Notations'' for orchestra. He remained active as a conductor over the next six years. In 2007 he was re-united with Chéreau for a production of Janáček's '' From the House of the Dead'' (Theater an der Wien, Amsterdam and Aix). In April of the same year, as part of the Festtage in Berlin, Boulez and

He remained active as a conductor over the next six years. In 2007 he was re-united with Chéreau for a production of Janáček's '' From the House of the Dead'' (Theater an der Wien, Amsterdam and Aix). In April of the same year, as part of the Festtage in Berlin, Boulez and Daniel Barenboim

Daniel Barenboim (; in he, דניאל בארנבוים, born 15 November 1942) is an Argentine-born classical pianist and conductor based in Berlin. He has been since 1992 General Music Director of the Berlin State Opera and "Staatskapellmeist ...

gave a cycle of the Mahler

Gustav Mahler (; 7 July 1860 – 18 May 1911) was an Austro-Bohemian Romantic composer, and one of the leading conductors of his generation. As a composer he acted as a bridge between the 19th-century Austro-German tradition and the modernism o ...

symphonies with the Staatskapelle Berlin

The Staatskapelle Berlin () is a German orchestra and the resident orchestra of the Berlin State Opera, Unter den Linden. The orchestra is one of the oldest in the world. Until the fall of the German Empire in 1918 the orchestra's name was ''Kö ...

, which they repeated two years later at Carnegie Hall. In late 2007 the Orchestre de Paris and the Ensemble Intercontemporain presented a retrospective of Boulez's music and in 2008 the Louvre

The Louvre ( ), or the Louvre Museum ( ), is the world's most-visited museum, and an historic landmark in Paris, France. It is the home of some of the best-known works of art, including the ''Mona Lisa'' and the ''Venus de Milo''. A central l ...

mounted the exhibition ''Pierre Boulez, Œuvre: fragment''.

His appearances became more infrequent after an eye operation in 2010 left him with severely impaired sight. Other health problems included a shoulder injury resulting from a fall.WQXR Staff, "Pierre Boulez Breaks His Shoulder, Cancels in Lucerne", 6 August 2013. Retrieved 6 January 2016. In late 2011, when he was already quite frail, he led the combined Ensemble Intercontemporain and Lucerne Festival Academy, with the soprano Barbara Hannigan, in a tour of six European cities of his own ''Pli selon pli''. His final appearance as a conductor was in Salzburg on 28 January 2012 with the

Vienna Philharmonic

The Vienna Philharmonic (VPO; german: Wiener Philharmoniker, links=no) is an orchestra that was founded in 1842 and is considered to be one of the finest in the world.

The Vienna Philharmonic is based at the Musikverein in Vienna, Austria. It ...

Orchestra and Mitsuko Uchida

is a classical pianist and conductor, born in Japan and naturalised in Britain, particularly noted for her interpretations of Mozart and Schubert.

She has appeared with many notable orchestras, recorded a wide repertory with several labels, w ...

in a programme of Schoenberg (''Begleitmusik zu einer Lichtspielszene'' and the Piano Concerto), Mozart (Piano Concerto No.19 in F major K459) and Stravinsky (''Pulcinella Suite

''Pulcinella'' is a one-act ballet by Igor Stravinsky based on an 18th-century play, ''Quatre Polichinelles semblables'' ("Four identical Pulcinellas"). Pulcinella is a stock character originating from ''commedia dell'arte''.

The ballet premie ...

''). Thereafter he cancelled all conducting engagements.

Later in 2012, he worked with the Diotima Quartet, making final revisions to his only string quartet, ''Livre pour quatuor'', begun in 1948. In 2013 he oversaw the release on Deutsche Grammophon

Deutsche Grammophon (; DGG) is a German classical music record label that was the precursor of the corporation PolyGram. Headquartered in Berlin Friedrichshain, it is now part of Universal Music Group (UMG) since its merger with the UMG family o ...

of ''Pierre Boulez: Complete Works'', a 13-CD survey of all his authorised compositions. He remained Director of the Lucerne Festival Academy until 2014, but his health prevented him from taking part in the many celebrations held across the world for his 90th birthday in 2015. These included a multi-media exhibition at the Musée de la Musique in Paris, which focused in particular on the inspiration Boulez had drawn from literature and the visual arts.

Boulez died on 5 January 2016 at his home in Baden-Baden. He was buried on 13 January in Baden-Baden's main cemetery following a private funeral service at the town's Stiftskirche. At a memorial service the next day at the Church of Saint-Sulpice in Paris, eulogists included Daniel Barenboim

Daniel Barenboim (; in he, דניאל בארנבוים, born 15 November 1942) is an Argentine-born classical pianist and conductor based in Berlin. He has been since 1992 General Music Director of the Berlin State Opera and "Staatskapellmeist ...

, Renzo Piano

Renzo Piano (; born 14 September 1937) is an Italian architect. His notable buildings include the Centre Georges Pompidou in Paris (with Richard Rogers, 1977), The Shard in London (2012), the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York City ...

, and Laurent Bayle, then president of the Philharmonie de Paris

The Philharmonie de Paris () ( en, Paris Philharmonic) is a complex of concert halls in Paris, France. The buildings also house exhibition spaces and rehearsal rooms. The main buildings are all located in the Parc de la Villette at the northeaste ...

, whose large concert hall had been inaugurated the previous year, thanks in no small measure to Boulez's influence.

Compositions

Juvenilia and student works

Boulez's earliest surviving compositions date from his school days in 1942–43, mostly songs on texts by Baudelaire, Gautier andRilke

René Karl Wilhelm Johann Josef Maria Rilke (4 December 1875 – 29 December 1926), shortened to Rainer Maria Rilke (), was an Austrian poet and novelist. He has been acclaimed as an idiosyncratic and expressive poet, and is widely recog ...

. Gerald Bennett describes the pieces as "modest, delicate and rather anonymous mployinga certain number of standard elements of French salon music of the time—whole-tone scales, pentatonic scales and polytonality".

As a student at the Conservatoire Boulez composed a series of pieces influenced first by Honegger and Jolivet (''Prelude, Toccata and Scherzo'' and ''Nocturne'' for solo piano (1944–45)) and then by Messiaen (''Trois psalmodies'' for piano (1945) and a Quartet for four ondes Martenot (1945–46)). The encounter with Schoenberg—through his studies with Leibowitz—was the catalyst for his first piece of serial music, the ''Thème et variations'' for piano, left hand (1945). Peter O'Hagan describes it as "his boldest and most ambitious work to date".

''Douze notations'' and the work in progress

It is in the ''Douze notations'' for piano (December 1945) that Bennett first detects the influence of Webern. In the two months after the composition of the piano ''Notations'' Boulez attempted an (unperformed and unpublished) orchestration of eleven of the twelve short pieces. Over a decade later he re-used two of them in instrumental interludes in ''Improvisation I sur Mallarmé''. Then in the mid-1970s he embarked on a further, more radical transformation of the ''Notations'' into extended works for very large orchestra, a project which preoccupied him to the end of his life, nearly seventy years after the original composition. This is only the most extreme example of a lifelong tendency to revisit earlier works: "as long as my ideas have not exhausted every possibility of proliferation they stay in my mind." Robert Piencikowski characterises this in part as "an obsessional concern for perfection" and observes that with some pieces (such as ''Le Visage nuptial'') "one could speak of successive distinct versions, each one presenting a particular state of the musical material, without the successor invalidating the previous one or vice versa"—although he notes that Boulez almost invariably vetoed the performance of previous versions.First published works