Norwich School (educational Institution) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Norwich School (formally King Edward VI Grammar School, Norwich) is a selective English

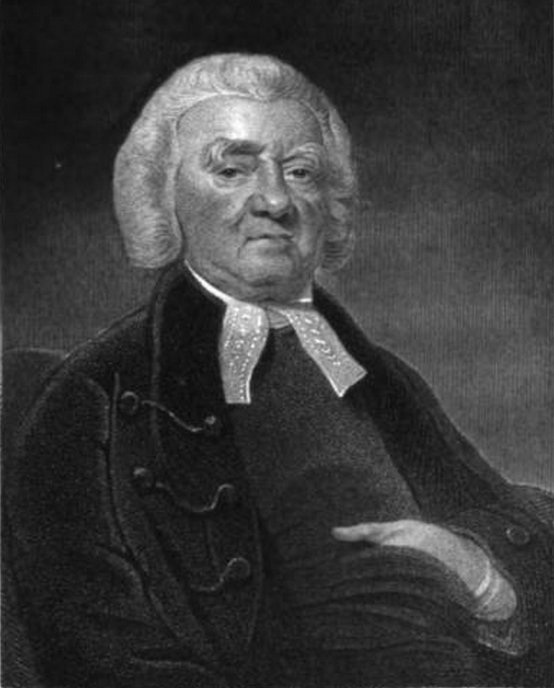

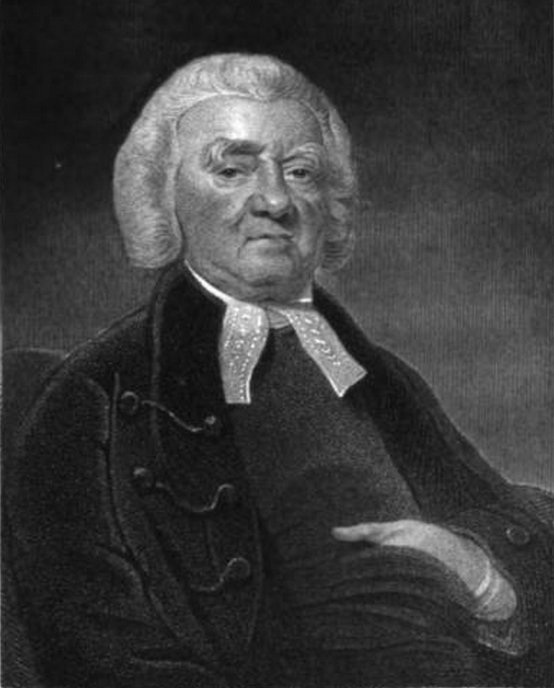

The system of education remained largely unchanged until the late 18th century. Samuel Parr, master from 1778 to 1785 was noted for his use of corporal punishment, commonplace at the time. One pupil remarked:

The system of education remained largely unchanged until the late 18th century. Samuel Parr, master from 1778 to 1785 was noted for his use of corporal punishment, commonplace at the time. One pupil remarked:

St Ethelbert's Gate is one of the entrances to the south section of the Close. The room above the gateway was originally a chapel dedicated to Saint Ethelbert the King and came to be used by the school in 1944. It was used as an art room before its conversion into the Barbirolli music practice room, named after Lady Barbirolli, under Philip Stibbe's headship (1975–1984), a project financed by the Dyers.. A scheduled monument, the gateway was built in 1316 by the citizens of Norwich as penance for a riot in 1272 which damaged many of the priory buildings. It was substantially restored in 1815 by William Wilkins, an Old Norvicensian, and underwent further renovations in 1964 which saw the stonework and carvings replaced under the supervision of Sir Bernard Feilden. Art historian Veronica Sekules describes the St Ethelbert's Gate as it was in the 14th century as "a highly decorative building presenting a façade rich in images, which the cathedral otherwise lacked. In a sense it would have operated as a principal façade and, in as far as one can glean from the remaining images, it communicated a strong message designating the gate as the opening to hallowed ground beyond."

St Ethelbert's Gate is one of the entrances to the south section of the Close. The room above the gateway was originally a chapel dedicated to Saint Ethelbert the King and came to be used by the school in 1944. It was used as an art room before its conversion into the Barbirolli music practice room, named after Lady Barbirolli, under Philip Stibbe's headship (1975–1984), a project financed by the Dyers.. A scheduled monument, the gateway was built in 1316 by the citizens of Norwich as penance for a riot in 1272 which damaged many of the priory buildings. It was substantially restored in 1815 by William Wilkins, an Old Norvicensian, and underwent further renovations in 1964 which saw the stonework and carvings replaced under the supervision of Sir Bernard Feilden. Art historian Veronica Sekules describes the St Ethelbert's Gate as it was in the 14th century as "a highly decorative building presenting a façade rich in images, which the cathedral otherwise lacked. In a sense it would have operated as a principal façade and, in as far as one can glean from the remaining images, it communicated a strong message designating the gate as the opening to hallowed ground beyond."

School House, 70 The Close, was formerly part of the Carnary college but now contains classrooms and school offices. While much of the building dates to around 1830, extensive 14th and 15th century features remain such as the stone entrance archway. The building, which is Grade I listed, adjoins the Erpingham Gate and is three storeys high and has eight

School House, 70 The Close, was formerly part of the Carnary college but now contains classrooms and school offices. While much of the building dates to around 1830, extensive 14th and 15th century features remain such as the stone entrance archway. The building, which is Grade I listed, adjoins the Erpingham Gate and is three storeys high and has eight

Norwich School website

Old Norvicensian website

Profile

on the Independent Schools Council website {{Good article Educational institutions established in the 11th century Member schools of the Headmasters' and Headmistresses' Conference Schools in Norwich, Norwich School Organisations based in England with royal patronage Independent schools in Norfolk Church of England independent schools in the Diocese of Norwich 11th-century establishments in England English Gothic architecture in Norfolk Grade I listed educational buildings Grade I listed buildings in Norfolk Scheduled monuments in Norfolk Schools with a royal charter Choir schools in England 1547 establishments in England King Edward VI Schools

independent

Independent or Independents may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media Artist groups

* Independents (artist group), a group of modernist painters based in the New Hope, Pennsylvania, area of the United States during the early 1930s

* Independe ...

day school in the close of Norwich Cathedral

Norwich Cathedral is an Anglican cathedral in Norwich, Norfolk, dedicated to the Holy and Undivided Trinity. It is the cathedral church for the Church of England Diocese of Norwich and is one of the Norwich 12 heritage sites.

The cathedra ...

, Norwich

Norwich () is a cathedral city and district of Norfolk, England, of which it is the county town. Norwich is by the River Wensum, about north-east of London, north of Ipswich and east of Peterborough. As the seat of the Episcopal see, See of ...

. Among the oldest schools in the United Kingdom, it has a traceable history to 1096 as an episcopal grammar school

A grammar school is one of several different types of school in the history of education in the United Kingdom and other English-speaking countries, originally a school teaching Latin, but more recently an academically oriented secondary school ...

established by Herbert de Losinga

Herbert de Losinga (died 22 July 1119) was the first Bishop of Norwich. He founded Norwich Cathedral in 1096 when he was Bishop of Thetford.

Life

Losinga was born in Exmes, near Argentan, Normandy, the son of Robert de LosingaDoubleday and Page ...

, first Bishop of Norwich

The Bishop of Norwich is the ordinary of the Church of England Diocese of Norwich in the Province of Canterbury. The diocese covers most of the county of Norfolk and part of Suffolk. The bishop of Norwich is Graham Usher.

The see is in t ...

. In the 16th century the school came under the control of the city of Norwich and moved to Blackfriars' Hall following a successful petition to Henry VIII

Henry VIII (28 June 149128 January 1547) was King of England from 22 April 1509 until his death in 1547. Henry is best known for his six marriages, and for his efforts to have his first marriage (to Catherine of Aragon) annulled. His disa ...

. The school was refounded in 1547 in a royal charter

A royal charter is a formal grant issued by a monarch under royal prerogative as letters patent. Historically, they have been used to promulgate public laws, the most famous example being the English Magna Carta (great charter) of 1215, b ...

granted by Edward VI

Edward VI (12 October 1537 – 6 July 1553) was King of England and Ireland from 28 January 1547 until his death in 1553. He was crowned on 20 February 1547 at the age of nine. Edward was the son of Henry VIII and Jane Seymour and the first E ...

and moved to its current site beside the cathedral in 1551. In the 19th century it became independent of the city and its classical curriculum was broadened in response to the declining demand for classical education following the Industrial Revolution

The Industrial Revolution was the transition to new manufacturing processes in Great Britain, continental Europe, and the United States, that occurred during the period from around 1760 to about 1820–1840. This transition included going f ...

.

Early statutes declared the school was to instruct 90 sons of Norwich citizens, though it has since grown to a total enrolment of approximately 1,020 pupils. For most of its history it was a boys' school, before becoming co-educational in the sixth form

In the education systems of England, Northern Ireland, Wales, Jamaica, Trinidad and Tobago and some other Commonwealth countries, sixth form represents the final two years of secondary education, ages 16 to 18. Pupils typically prepare for ...

in 1994 and in every year group in 2010. The school is divided into the Senior School, which has around 850 pupils aged from 11 to 18 across eight houses, and the Lower School, which was established in 1946 and has around 250 pupils aged from 4 to 11. The school educates the choristers of the cathedral, with which the school has a close relationship and which is used for morning assemblies and events throughout the academic year. In league tables of British schools it is consistently ranked first in Norfolk and Suffolk and amongst the highest in the United Kingdom.

Former pupils are referred to as Old Norvicensians or ONs. The school has maintained a strong academic tradition and has educated a number of notable figures including Lord Nelson

Vice-Admiral Horatio Nelson, 1st Viscount Nelson, 1st Duke of Bronte (29 September 1758 – 21 October 1805) was a British flag officer in the Royal Navy. His inspirational leadership, grasp of strategy, and unconventional tactics brought a ...

, Sir Edward Coke

''Sir'' is a formal honorific address in English for men, derived from Sire in the High Middle Ages. Both are derived from the old French "Sieur" (Lord), brought to England by the French-speaking Normans, and which now exist in French only as ...

and 18 Fellows of the Royal Society

Fellowship of the Royal Society (FRS, ForMemRS and HonFRS) is an award granted by the judges of the Royal Society of London to individuals who have made a "substantial contribution to the improvement of natural knowledge, including mathemati ...

among many others. Several members of the Norwich School

Norwich School (formally King Edward VI Grammar School, Norwich) is a selective English independent day school in the close of Norwich Cathedral, Norwich. Among the oldest schools in the United Kingdom, it has a traceable history to 1096 as a ...

of painters, the first provincial art movement

An art movement is a tendency or style in art with a specific common philosophy or goal, followed by a group of artists during a specific period of time, (usually a few months, years or decades) or, at least, with the heyday of the movement defin ...

in England, were educated at the school and the movement's founder, John Crome

John Crome (22 December 176822 April 1821), once known as Old Crome to distinguish him from his artist son John Berney Crome, was an English landscape painter of the Romantic era, one of the principal artists and founding members of the Norw ...

, also taught at the school.. It is a founding member of the Headmasters' and Headmistresses' Conference

The Headmasters' and Headmistresses' Conference (HMC) is an association of the head teachers of 361 independent schools (both boarding schools and day schools), some traditionally described as public schools. 298 Members are based in the Un ...

(HMC), a member of the Choir Schools' Association

The Choir Schools' Association is a United Kingdom, U.K. organisation that provides support to choir schools and choristers, and promotes singing, in particular of music for Christian worship in the cathedral tradition. It represents 44 choir scho ...

and has a historical connection with the Worshipful Company of Dyers

The Worshipful Company of Dyers is one of the Livery Companies of the City of London. The Dyers' Guild existed in the twelfth century; it received a Royal Charter in 1471. It originated as a trade association for members of the dyeing industr ...

, one of the Livery Companies of the City of London

The City of London is a city, ceremonial county and local government district that contains the historic centre and constitutes, alongside Canary Wharf, the primary central business district (CBD) of London. It constituted most of London f ...

.

History

Establishment and early history

Norwich School traces its origins to the founding of an episcopalgrammar school

A grammar school is one of several different types of school in the history of education in the United Kingdom and other English-speaking countries, originally a school teaching Latin, but more recently an academically oriented secondary school ...

in 1096 by Herbert de Losinga

Herbert de Losinga (died 22 July 1119) was the first Bishop of Norwich. He founded Norwich Cathedral in 1096 when he was Bishop of Thetford.

Life

Losinga was born in Exmes, near Argentan, Normandy, the son of Robert de LosingaDoubleday and Page ...

, first Bishop of Norwich

The Bishop of Norwich is the ordinary of the Church of England Diocese of Norwich in the Province of Canterbury. The diocese covers most of the county of Norfolk and part of Suffolk. The bishop of Norwich is Graham Usher.

The see is in t ...

. The continuity of the current Norwich School with the 1096 school would make it one of the oldest surviving schools in the United Kingdom... The newly established school occupied a site on "Holmstrete" in the parish of St Matthew between the close of Norwich Cathedral

Norwich Cathedral is an Anglican cathedral in Norwich, Norfolk, dedicated to the Holy and Undivided Trinity. It is the cathedral church for the Church of England Diocese of Norwich and is one of the Norwich 12 heritage sites.

The cathedra ...

and the River Wensum.. Until the English Reformation

The English Reformation took place in 16th-century England when the Church of England broke away from the authority of the pope and the Catholic Church. These events were part of the wider European Protestant Reformation, a religious and poli ...

the bishop would appoint the headteacher (termed Head Master by the school), though on several occasions this role had been fulfilled by the Archbishop of Canterbury

The archbishop of Canterbury is the senior bishop and a principal leader of the Church of England, the ceremonial head of the worldwide Anglican Communion and the diocesan bishop of the Diocese of Canterbury. The current archbishop is Just ...

. The earliest known headteacher is Vincent of Scarning, who is mentioned in 1240 regarding a financial dispute with a school in Rudham.

In 1538, the school was separated from its cathedral foundation and placed under the control of the mayor, sheriffs, and commonalty of the city of Norwich following a successful petition to Henry VIII

Henry VIII (28 June 149128 January 1547) was King of England from 22 April 1509 until his death in 1547. Henry is best known for his six marriages, and for his efforts to have his first marriage (to Catherine of Aragon) annulled. His disa ...

for the possession of Blackfriars' Hall, a Dominican friary

A monastery is a building or complex of buildings comprising the domestic quarters and workplaces of monastics, monks or nuns, whether living in communities or alone (hermits). A monastery generally includes a place reserved for prayer whic ...

which was surrendered to the Crown in the Dissolution of the Monasteries. Two prominent citizens of the city, Augustine Steward

Augustine Steward (1491 – 1571), of Norwich, Norfolk, was an English politician.

Family

Augustine Steward was born and baptised in the parish of St. George’s Tombland, Norwich, the son of Jeffrey Steward (d.1504), an Alderman of Norwich an ...

and Edward Rede, after consulting Thomas Howard, 3rd Duke of Norfolk

Thomas Howard, 3rd Duke of Norfolk, (1473 – 25 August 1554) was a prominent English politician and nobleman of the Tudor era. He was an uncle of two of the wives of King Henry VIII, Anne Boleyn and Catherine Howard, both of whom were beheade ...

, promised on the city's behalf "to fynd a perpetual free-schole therein for the good erudicion and education of yought in lernyng and vertue".. Following repairs, the school moved to the former friary in 1541, occupying part of the south-west cloister

A cloister (from Latin ''claustrum'', "enclosure") is a covered walk, open gallery, or open arcade running along the walls of buildings and forming a quadrangle or garth. The attachment of a cloister to a cathedral or church, commonly against ...

, where it educated 20 boys under a master and a sub-master.

16th and 17th centuries

The school was refounded as King Edward VI Grammar School in aroyal charter

A royal charter is a formal grant issued by a monarch under royal prerogative as letters patent. Historically, they have been used to promulgate public laws, the most famous example being the English Magna Carta (great charter) of 1215, b ...

granted by Edward VI

Edward VI (12 October 1537 – 6 July 1553) was King of England and Ireland from 28 January 1547 until his death in 1553. He was crowned on 20 February 1547 at the age of nine. Edward was the son of Henry VIII and Jane Seymour and the first E ...

dated 7 May 1547.

Issued four months into the king's accession, the charter expressly implemented an arrangement designed by Henry VIII and was confirmed by Edward Seymour, Lord Protector

Lord Protector (plural: ''Lords Protector'') was a title that has been used in British constitutional law for the head of state. It was also a particular title for the British heads of state in respect to the established church. It was sometimes ...

... Unusually for a cathedral city

Cathedral city is a city status in the United Kingdom.

Cathedral city may also refer to:

* Cathedral City, California, a city in Southern California, United States

* Cathedral City Cheddar, a brand of Cheddar cheese

* Cathedral City High Scho ...

Norwich did not receive a cathedral school following the Reformation, but an endowed city grammar school.. Norwich Cathedral was the first of the eight cathedral priories to surrender to the Crown, formally being re-established as a secular cathedral with a dean and chapter on 2 May 1538. Consequently, negotiations over the refoundation charter were between the city, rather than the cathedral, and the Crown. Known as the Great Hospital Charter, it granted the city possession of St Giles' hospital, also called the Great Hospital, and merged the school with it in the hope of achieving an integrated system of education and poor relief. These plans were never realised, however, as the Great Hospital was partially stripped for building materials and later sacked during Kett's Rebellion

Kett's Rebellion was a revolt in Norfolk, England during the reign of Edward VI, largely in response to the enclosure of land. It began at Wymondham on 8 July 1549 with a group of rebels destroying fences that had been put up by wealthy landowners ...

in 1549. The school temporarily occupied St Luke's House, a building north-west of the cathedral.

In 1550 the city purchased the former chantry

A chantry is an ecclesiastical term that may have either of two related meanings:

# a chantry service, a Christian liturgy of prayers for the dead, which historically was an obiit, or

# a chantry chapel, a building on private land, or an area i ...

chapel and college of St John the Evangelist beside the cathedral for the use of the grammar school out of the £200 each year at their disposal in a licence in mortmain

Mortmain () is the perpetual, inalienable ownership of real estate by a corporation or legal institution; the term is usually used in the context of its prohibition. Historically, the land owner usually would be the religious office of a church ...

to purchase and add to the revenues of the Great Hospital.. Founded in 1316 by John Salmon, Bishop of Norwich, the chapel, in addition to its role as a chantry dedicated to the souls of Salmon's parents and the predecessors and successors of the Bishops of Norwich had also been used as a charnel house

A charnel house is a vault or building where human skeletal remains are stored. They are often built near churches for depositing bones that are unearthed while digging graves. The term can also be used more generally as a description of a pl ...

and contained the Wodehouse chantry, founded by Henry V Henry V may refer to:

People

* Henry V, Duke of Bavaria (died 1026)

* Henry V, Holy Roman Emperor (1081/86–1125)

* Henry V, Duke of Carinthia (died 1161)

* Henry V, Count Palatine of the Rhine (c. 1173–1227)

* Henry V, Count of Luxembourg (121 ...

at the request of John Wodehous, a veteran of the Battle of Agincourt

The Battle of Agincourt ( ; french: Azincourt ) was an English victory in the Hundred Years' War. It took place on 25 October 1415 ( Saint Crispin's Day) near Azincourt, in northern France. The unexpected English victory against the numeric ...

.. The school moved to the site in the summer of 1551, where it has remained ever since. The chapel was used as the main schoolroom while the other buildings were used to provide a library and accommodation for the master and boarding

Boarding may refer to:

*Boarding, used in the sense of "room and board", i.e. lodging and meals as in a:

** Boarding house

**Boarding school

*Boarding (horses) (also known as a livery yard, livery stable, or boarding stable), is a stable where ho ...

pupils. The arrangement continued until the 19th century, and today the building is used as the school chapel.

A master and "usher" (deputy headteacher) were to be appointed by the city out of the revenues assigned to them, who were required to have a good knowledge of classical languages, namely Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through ...

and Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

. Additionally, the master was required to be a university graduate, of "sound religion", and not to take on additional work. The salary of the usher was £6. 13s. 4d. and the master a "handsome" sum of £10, which by 1636 had risen to £50. The 1566 statutes declared the school was to provide Greek and Latin instruction for 90 sons of Norwich citizens free of expense and up to ten fee-paying pupils.. By the 19th century the city was observed to generally leave room for as many boarders and other day scholars to sufficiently remunerate the teachers. Admission was limited to boys thought to benefit from the education offered, and the school was highly selective as a result. The education was based on erudition, the eventual goal being that by the age of 18 the pupils would have learned "to vary one sentence diversely, to make a verse exactly, to endight an epistle eloquently and learnedly, to declaim of a theme simple, and last of all to attain some competent knowledge of the Greek tongue". Pupils were taught rhetoric based on the ''Rhetorica ad Herennium

The ''Rhetorica ad Herennium'' (''Rhetoric for Herennius''), formerly attributed to Cicero or Cornificius, but in fact of unknown authorship, sometimes ascribed to an unnamed doctor, is the oldest surviving Latin book on rhetoric, dating from the ...

'', and Greek centred around the works of Homer

Homer (; grc, Ὅμηρος , ''Hómēros'') (born ) was a Greek poet who is credited as the author of the ''Iliad'' and the ''Odyssey'', two epic poems that are foundational works of ancient Greek literature. Homer is considered one of the ...

and Virgil

Publius Vergilius Maro (; traditional dates 15 October 7021 September 19 BC), usually called Virgil or Vergil ( ) in English, was an ancient Roman poet of the Augustan period. He composed three of the most famous poems in Latin literature: th ...

. In addition to classical literature, etiquette was taught as both were deemed fundamental to a good education. Edward Coke

Edward is an English given name. It is derived from the Anglo-Saxon name ''Ēadweard'', composed of the elements '' ēad'' "wealth, fortune; prosperous" and '' weard'' "guardian, protector”.

History

The name Edward was very popular in Anglo-Sax ...

studied at the school at the age of eight from 1560 until 1567, where he is said to have been taught to value the "forcefulness of freedom of speech", something he later applied as a judge.

As part of the annual Guild Day procession of the inauguration of the new mayor of Norwich it was tradition for the head boy to deliver a short speech in Latin from the school porch "commending justice and obedyence" to the mayor and corporation.. Afterwards the orator would attend the guild dinner, historically riding in the procession on a white horse, but in later years taken in the mayor's carriage. When Elizabeth I

Elizabeth I (7 September 153324 March 1603) was Queen of England and Ireland from 17 November 1558 until her death in 1603. Elizabeth was the last of the five House of Tudor monarchs and is sometimes referred to as the "Virgin Queen".

Eli ...

visited Norwich on a separate occasion in 1578 the master at the time, Stephen Limbert, is said to have delivered an oration, which "so pleased Her Majesty that she said it had been the best she had heard, and gave him her hand to kiss, and afterwards sent back to enquire his name.". The encounter has been said to characterise the public image of Elizabeth I as a monarch who indulged her subjects with goodwill and has been used for the interpretation of the character of Theseus in Shakespeare

William Shakespeare ( 26 April 1564 – 23 April 1616) was an English playwright, poet and actor. He is widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England's nation ...

's ''A Midsummer Night's Dream

''A Midsummer Night's Dream'' is a comedy written by William Shakespeare 1595 or 1596. The play is set in Athens, and consists of several subplots that revolve around the marriage of Theseus and Hippolyta. One subplot involves a conflict a ...

''.

18th and 19th centuries

The system of education remained largely unchanged until the late 18th century. Samuel Parr, master from 1778 to 1785 was noted for his use of corporal punishment, commonplace at the time. One pupil remarked:

The system of education remained largely unchanged until the late 18th century. Samuel Parr, master from 1778 to 1785 was noted for his use of corporal punishment, commonplace at the time. One pupil remarked:

Parr's fame for severity spread a sort of panic through the city, especially among the mothers, who would sometimes interpose a remonstrance, which occasioned a ludicrous scene, but seldom availed the culprit, while the wiser were willing to leave their boys in his hands.Richard Twining, the tea merchant, however, was advised by his brother John to send his eldest son to Norwich, writing of Parr, "I have been told that he flogs too much, but I doubt those from whom I have heard it think ''any'' use of punishment too much". Parr's daily teaching was interrupted at midday when he sent a boy to the pastry-cook's across the road for a pie, which he ate by the schoolroom fire. On the resignation of his headship in 1785, historian Warren Derry comments, "an object of terror was gone, but the glory of the place had gone with it"..

John Crome

John Crome (22 December 176822 April 1821), once known as Old Crome to distinguish him from his artist son John Berney Crome, was an English landscape painter of the Romantic era, one of the principal artists and founding members of the Norw ...

, the landscape painter and founder of the Norwich School of painters

The Norwich School of painters was the first provincial art movement established in Britain, active in the early 19th century. Artists of the school were inspired by the natural environment of the Norfolk landscape and owed some influence to the wo ...

, became a drawing master at the school at the beginning of the 19th century, a position he held for many years. The Norwich School of painters was the first provincial art movement in England, and Crome has been described as one of the most prominent British landscape painters alongside Constable

A constable is a person holding a particular office, most commonly in criminal law enforcement. The office of constable can vary significantly in different jurisdictions. A constable is commonly the rank of an officer within the police. Other peop ...

and Gainsborough. Several notable artists of the movement were educated at the school including John Sell Cotman

John Sell Cotman (16 May 1782 – 24 July 1842) was an English marine and landscape painter, etcher, illustrator, author and a leading member of the Norwich School of painters.

Born in Norwich, the son of a silk merchant and lace dealer, C ...

, James Stark, George Vincent, John Berney Crome

John Berney (or Barney) Crome (1 December 1794 – 15 September 1842) was an English landscape and marine painter associated with the Norwich School of painters. He is sometimes known by the nickname 'Young Crome' to distinguish him from hi ...

, and Edward Thomas Daniell

Edward Thomas Daniell (6 June 180424 September 1842) was an English artist known for his etchings and the landscape paintings he made during an expedition to the Middle East, including Lycia, part of modern-day Turkey. He is associated with the ...

. Frederick Sandys

Anthony Frederick Augustus Sandys (born Antonio Frederic Augustus Sands; 1 May 1829 – 25 June 1904), usually known as Frederick Sandys, was a British painter, illustrator, and draughtsman, associated with the Pre-Raphaelites. He was also assoc ...

, the "Norwich Pre-Raphaelite

The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood (later known as the Pre-Raphaelites) was a group of English painters, poets, and art critics, founded in 1848 by William Holman Hunt, John Everett Millais, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, William Michael Rossetti, Jam ...

", who also attended the school, had his roots in the movement. Some staff, such as Dr. Samuel Forster, were associated with the movement; Forster was headteacher when John Sell Cotman attended the school. Forster became vice president of the Norwich Society of Artists, the society established in 1803 for artists of the movement. Charles Hodgson who taught mathematics and art, and his son David who taught art, were also supporters of Crome.

The number of pupils fluctuated significantly at the beginning of the 19th century, with usual numbers between 100 and 150 pupils, but falling to eight pupils in 1811 and 30 in 1859.. Under the headship of the classical scholar Edward Valpy

Edward Valpy (1764–1832) was an English cleric, classical scholar and schoolteacher.

Life

Valpy, the fourth son of Richard Valpy of St. John's, Jersey, by his wife Catherine, daughter of John Chevalier, was born at Reading. He was educated at Tr ...

(1810–1829) pupil numbers increased and the school enjoyed a prosperous period, though its development was hindered by its charter whose trustees preferred to spend most of the £7,000 a year income on the Great Hospital, leaving £300 for the school. Valpy published a popular textbook on Latin style, ''Elegantiae Latinae'' (1803), which went through ten editions in his lifetime and ''The Greek Testament, with English notes, selected and original'' (1815) in three volumes. In 1837, in the wake of the Municipal Reform Act

The Municipal Corporations Act 1835 (5 & 6 Will 4 c 76), sometimes known as the Municipal Reform Act, was an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom that reformed local government in the incorporated boroughs of England and Wales. The legi ...

the patronage of the governors went to twenty-one independent trustees appointed by the Lord Chancellor

The lord chancellor, formally the lord high chancellor of Great Britain, is the highest-ranking traditional minister among the Great Officers of State in Scotland and England in the United Kingdom, nominally outranking the prime minister. Th ...

, separating the governance of the school from the city corporation.. As a result of a later 1858 court case ''Attorney-General v. Hudson'' the school became independent of the Great Hospital, gaining an endowment of its own and a Board of Governors

A board of directors (commonly referred simply as the board) is an executive committee that jointly supervises the activities of an organization, which can be either a for-profit or a nonprofit organization such as a business, nonprofit organi ...

to administer it. The original objects of the school to provide education for poor boys was abolished and replaced with boarding fees of £60 a year for sons of laymen, £45 for sons of clergymen, and 12 guinea

Guinea ( ),, fuf, 𞤘𞤭𞤲𞤫, italic=no, Gine, wo, Gine, nqo, ߖߌ߬ߣߍ߫, bm, Gine officially the Republic of Guinea (french: République de Guinée), is a coastal country in West Africa. It borders the Atlantic Ocean to the we ...

s a year for day pupils.. A separate school was established to provide training for boys to enter industry and trade called the King Edward VI Middle School or Commercial School. Opened in 1862 and located in the cloisters of Blackfriars' it had 200 pupils and charged a tuition fee of four guineas a year.

By the mid-19th century the school failed to cater to the requirements of the new urban middle class due to its predominant focus on classical education and was perceived by the city's large Nonconformist community as too exclusively Anglican

Anglicanism is a Western Christian tradition that has developed from the practices, liturgy, and identity of the Church of England following the English Reformation, in the context of the Protestant Reformation in Europe. It is one of t ...

. The school, however, underwent dramatic reform under Augustus Jessopp

Augustus Jessopp (20 December 1823 – 12 February 1914) was an English cleric and writer. He spent periods of time as a schoolmaster and then later as a clergyman in Norfolk, England. He wrote regular articles for '' The Nineteenth Century'', ...

, one of the great Victorian reforming headteachers, whose headship lasted from 1859 to 1879. Influenced by Thomas Arnold

Thomas Arnold (13 June 1795 – 12 June 1842) was an English educator and historian. He was an early supporter of the Broad Church Anglican movement. As headmaster of Rugby School from 1828 to 1841, he introduced several reforms that were wide ...

's reforms at Rugby

Rugby may refer to:

Sport

* Rugby football in many forms:

** Rugby league: 13 players per side

*** Masters Rugby League

*** Mod league

*** Rugby league nines

*** Rugby league sevens

*** Touch (sport)

*** Wheelchair rugby league

** Rugby union: 1 ...

and the new Victorian public schools, the school was remodelled into a public school.. The curriculum was broadened to include non-classical subjects such as mathematics, drawing, German and French, as part of a trend seen in several schools including Marlborough College

( 1 Corinthians 3:6: God gives the increase)

, established =

, type = Public SchoolIndependent day and boarding

, religion = Church of England

, president = Nicholas Holtam

, head_label = Master

, head = Louis ...

, Rossall

Rossall is a settlement in Lancashire, England and a suburb of the market town of Fleetwood. It is situated on a coastal plain called The Fylde. Blackpool Tramway runs through Rossall, with two stations: Rossall School on Broadway and Rossall ...

, Wellington

Wellington ( mi, Te Whanganui-a-Tara or ) is the capital city of New Zealand. It is located at the south-western tip of the North Island, between Cook Strait and the Remutaka Range. Wellington is the second-largest city in New Zealand by ...

, Clifton

Clifton may refer to:

People

* Clifton (surname)

* Clifton (given name)

Places

Australia

*Clifton, Queensland, a town

** Shire of Clifton

*Clifton, New South Wales, a suburb of Wollongong

* Clifton, Western Australia

Canada

* Clifton, Nova Sc ...

and Richmond

Richmond most often refers to:

* Richmond, Virginia, the capital of Virginia, United States

* Richmond, London, a part of London

* Richmond, North Yorkshire, a town in England

* Richmond, British Columbia, a city in Canada

* Richmond, Californi ...

to establish modern departments where pupils would be allowed to omit learning Greek and follow a non-classical curriculum to fulfill the increasing demand for a "high" but less classical education. A strict moral code was instilled, the chapel becoming the focal point of school life, a prefect

Prefect (from the Latin ''praefectus'', substantive adjectival form of ''praeficere'': "put in front", meaning in charge) is a magisterial title of varying definition, but essentially refers to the leader of an administrative area.

A prefect's ...

orial system was implemented to encourage leadership and responsibility, and there was a greater focus on sport which was thought to foster team spirit and individual initiative, reflecting the prevailing belief in muscular Christianity

Muscular Christianity is a philosophical movement that originated in England in the mid-19th century, characterized by a belief in patriotic duty, discipline, self-sacrifice, masculinity, and the moral and physical beauty of athleticism.

The mov ...

among educationalists.

The Schools Inquiry Commission (1864–1868), which examined endowed grammar schools under the chairmanship of Lord Taunton, reported that the school "gives the highest education in the county of Norfolk

Norfolk () is a ceremonial and non-metropolitan county in East Anglia in England. It borders Lincolnshire to the north-west, Cambridgeshire to the west and south-west, and Suffolk to the south. Its northern and eastern boundaries are the Nor ...

" and sent on average twice as many boys to university as all the other endowed schools in Norfolk each year.. The commissioners also praised the Commercial School, despite it facing competition from similar schools: "the extent of its usefulness and the soundness of its practical teaching, is second to none". These reforms were accompanied by building expansion, such as the completion in 1860 of the Gothic Revival

Gothic Revival (also referred to as Victorian Gothic, neo-Gothic, or Gothick) is an architectural movement that began in the late 1740s in England. The movement gained momentum and expanded in the first half of the 19th century, as increasingly ...

north wing of School House which contained a large dormitory for boarding pupils. By 1872 there were 127 pupils, 91 of whom were boarders who were drawn from all over the south-east of England. At the first meeting of the Headmasters' Conference

The Headmasters' and Headmistresses' Conference (HMC) is an association of the head teachers of 361 independent schools (both boarding schools and day schools), some traditionally described as public schools. 298 Members are based in the Uni ...

in 1869 Jessopp represented Norwich School as one of the original thirteen members. Although successful his efforts were hindered by the effects of agricultural depression as four-fifths of endowment income came from land, and the school ultimately thrived as a city day school.

20th century to present

Extensive building development was completed in 1908, which included converting the chapel back to religious use, a redesigned School Lodge and a block of six classrooms designed byEdward Boardman

Edward Boardman (1833–1910) was a Norwich born architect. He succeeded John Brown as the most successful Norwich architect in the second half of the 19th century.Board of Education

A board of education, school committee or school board is the board of directors or board of trustees of a school, local school district or an equivalent institution.

The elected council determines the educational policy in a small regional ar ...

in return for offering 10 percent of its intake to places funded by central government. The First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

saw the establishment of an Officers Training Corps

The Officers' Training Corps (OTC), more fully called the University Officers' Training Corps (UOTC), are military leadership training units operated by the British Army. Their focus is to develop the leadership abilities of their members whilst ...

company associated with the Norfolk Regiment

The Royal Norfolk Regiment was a line infantry regiment of the British Army until 1959. Its predecessor regiment was raised in 1685 as Henry Cornwall's Regiment of Foot. In 1751, it was numbered like most other British Army regiments and named ...

, which disbanded in 1918.. Pupil numbers grew steadily to 277 in 1930 and there was further modernisation of the curriculum. During the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposi ...

several buildings were destroyed in the Baedeker raids on Norwich, while School End House was commandeered by the Auxiliary Territorial Service

The Auxiliary Territorial Service (ATS; often pronounced as an acronym) was the women's branch of the British Army during the Second World War. It was formed on 9 September 1938, initially as a women's voluntary service, and existed until 1 Februa ...

and the Bishop's Palace was used by the American Red Cross

The American Red Cross (ARC), also known as the American National Red Cross, is a non-profit humanitarian organization that provides emergency assistance, disaster relief, and disaster preparedness education in the United States. It is the des ...

. Inhumations were reportedly disturbed in 1939 when air-raid shelters were being dug on the current site of the playground, previously the old cathedral cemetery. In total, 102 pupils who attended the school died in the two world wars.

Post-war reconstruction was assisted by the Dean and Chapter who leased further buildings in the Close and the Worshipful Company of Dyers

The Worshipful Company of Dyers is one of the Livery Companies of the City of London. The Dyers' Guild existed in the twelfth century; it received a Royal Charter in 1471. It originated as a trade association for members of the dyeing industr ...

, one of the Livery Companies of the City of London

The City of London is a city, ceremonial county and local government district that contains the historic centre and constitutes, alongside Canary Wharf, the primary central business district (CBD) of London. It constituted most of London f ...

, through HH Judge Norman Daynes, an ON and Prime Warden of the Company. Though functional the new buildings had little aesthetic value; according to Pevsner they "spoil the North West part of the precinct beyond hope of redemption".. The Dyers' continue to be a major benefactor of the school. Following the Education Act 1944

The Education Act 1944 (7 and 8 Geo 6 c. 31) made major changes in the provision and governance of secondary schools in England and Wales. It is also known as the "Butler Act" after the President of the Board of Education, R. A. Butler. Historians ...

the school became a direct grant grammar school

A direct grant grammar school was a type of selective secondary school in the United Kingdom that existed between 1945 and 1976. One quarter of the places in these schools were directly funded by central government, while the remainder attracted ...

, increasing the number of free places to one quarter of its intake, however reverted to full independence when the scheme was phased out in 1975. A preparatory school called the Lower School was established in 1946, rebuilt in 1971 by architects Feilden and Mawson, and has undergone several extensions since. The 1950s saw a closer relationship with the Dean and Chapter following the merger of the choir school and the lease of the Bishop's Palace..

Boarding was phased out in 1989 and the buildings used for boarding, School House and the Bishop's Palace, were converted into teaching space. Girls were admitted to the sixth form

In the education systems of England, Northern Ireland, Wales, Jamaica, Trinidad and Tobago and some other Commonwealth countries, sixth form represents the final two years of secondary education, ages 16 to 18. Pupils typically prepare for ...

for the first time in 1994, ending nearly 900 years of single-sex education. In 1999 the Daynes Sports Centre opened and the former gymnasium was converted into the Blake Drama Studio and two further laboratories. The same year the artists Cornford & Cross were commissioned by the Norwich Gallery to produce a series of sculptures beside the River Wensum. One of the works, ''Jerusalem'', was installed on the school playing fields until July 2002. Part of the installation was later donated to the art department. In 2008 new science laboratories opened on St Faiths Lane in the south section of the Close. The facilities include a seismometer

A seismometer is an instrument that responds to ground noises and shaking such as caused by earthquakes, volcanic eruptions, and explosions. They are usually combined with a timing device and a recording device to form a seismograph. The outpu ...

which is part of the British Geological Survey

The British Geological Survey (BGS) is a partly publicly funded body which aims to advance geoscientific knowledge of the United Kingdom landmass and its continental shelf by means of systematic surveying, monitoring and research.

The BGS hea ...

's schools network. That same year, the school began to admit girls below the sixth form for the first time, initially as young as age eleven. The next year, 2009, all school-age girls were eligible for admission. An eighth house called Seagrim, named after distinguished ONs Derek

Derek is a masculine given name. It is the English language short form of '' Diederik'', the Low Franconian form of the name Theodoric. Theodoric is an old Germanic name with an original meaning of "people-ruler".

Common variants of the name ar ...

and Hugh Seagrim, was created in 2009. In 2011 the first female head of school

A head master, head instructor, bureaucrat, headmistress, head, chancellor, principal or school director (sometimes another title is used) is the staff member of a school with the greatest responsibility for the management of the school. In som ...

in the school's history was chosen. In late 2013 work began to extend the Lower School. The extension of the Lower School was completed in 2018 when 4 changing rooms and a shower block had been converted into classrooms for roughly 60 pupils from Reception to Year 3. This has allowed pupils to enter the school at the age of 4 instead of 7.

There are currently plans to build a new Refectory

A refectory (also frater, frater house, fratery) is a dining room, especially in monasteries, boarding schools and academic institutions. One of the places the term is most often used today is in graduate seminaries. The name derives from the Lat ...

in the Senior School site to provide space for the evergrowing number of pupils at the school. There are plans in place for the old refectory (only meant to have been temporary when built) to be demolished and classrooms built in its place.

Location and buildings

The school is principally located within the 44 acre (17.81 ha) cathedral close of Norwich Cathedral, known as "the Close", though over time has expanded beyond the precinct boundaries. In addition to the site next to the cathedral the Senior School uses buildings spread throughout the Close for teaching, many of which arelisted building

In the United Kingdom, a listed building or listed structure is one that has been placed on one of the four statutory lists maintained by Historic England in England, Historic Environment Scotland in Scotland, in Wales, and the Northern I ...

s of historic interest, and several are scheduled monument

In the United Kingdom, a scheduled monument is a nationally important archaeological site or historic building, given protection against unauthorised change.

The various pieces of legislation that legally protect heritage assets from damage and ...

s of national importance. The Lower School is located in the Lower Close between the east end of the cathedral and the River Wensum.

Chapel

The school chapel, located next to the Erpingham Gate and the west door of the cathedral in what was the west part of the cathedral cemetery, was originally thechantry

A chantry is an ecclesiastical term that may have either of two related meanings:

# a chantry service, a Christian liturgy of prayers for the dead, which historically was an obiit, or

# a chantry chapel, a building on private land, or an area i ...

chapel and college of St John the Evangelist built in 1316 by John Salmon, Bishop of Norwich, who specified that;

... in this chapel we ordain that there shall be for ever four priests, and we decree that they shall celebrate for our souls and for the souls of our father and mother, Solomon and Amice, and for the souls of our predecessors and successors the Bishops of Norwich ... The said priests, however, in the buildings built by us next the Chapel for their use, shall dwell and remain eating and drinking together and living in common.Alternatively known as the Carnary chapel and college, the complex was originally formed of separate buildings which were later joined together. The entrance porch to the chapel was added between 1446 and 1472 during the episcopate of Walter Lyhart, Bishop of Norwich. The

crypt

A crypt (from Latin '' crypta'' " vault") is a stone chamber beneath the floor of a church or other building. It typically contains coffins, sarcophagi, or religious relics.

Originally, crypts were typically found below the main apse of a c ...

beneath the chapel was used as a charnel house

A charnel house is a vault or building where human skeletal remains are stored. They are often built near churches for depositing bones that are unearthed while digging graves. The term can also be used more generally as a description of a pl ...

administered by the sacristan

A sacristan is an officer charged with care of the sacristy, the church, and their contents.

In ancient times, many duties of the sacrist were performed by the doorkeepers ( ostiarii), and later by the treasurers and mansionarii. The Decreta ...

of the cathedral which stored the bones of people buried in the churches of the city to await resurrection, and the ocular windows of the chapel would allow visitors to view the charnel remains. From 1421 to 1476 the crypt was also the location of the Wodehous chantry, established by Henry V Henry V may refer to:

People

* Henry V, Duke of Bavaria (died 1026)

* Henry V, Holy Roman Emperor (1081/86–1125)

* Henry V, Duke of Carinthia (died 1161)

* Henry V, Count Palatine of the Rhine (c. 1173–1227)

* Henry V, Count of Luxembourg (121 ...

at the request of John Wodehous, a veteran of the Battle of Agincourt

The Battle of Agincourt ( ; french: Azincourt ) was an English victory in the Hundred Years' War. It took place on 25 October 1415 ( Saint Crispin's Day) near Azincourt, in northern France. The unexpected English victory against the numeric ...

. The college was dissolved in 1547 during the English Reformation

The English Reformation took place in 16th-century England when the Church of England broke away from the authority of the pope and the Catholic Church. These events were part of the wider European Protestant Reformation, a religious and poli ...

by the Abolition of Chantries Act before being purchased by the city in 1550, and used by the school shortly after. Until the 19th century the chapel was used as the main classroom, though it was not until 1908 the chapel returned to the role of religious assembly and 1940 when it was consecrated for use as a church, due to the cost of refurbishment.

The chapel is constructed from stone with a plain tiled roof and comprises four bays above a four bay twin-aisled undercroft

An undercroft is traditionally a cellar or storage room, often brick-lined and vaulted, and used for storage in buildings since medieval times. In modern usage, an undercroft is generally a ground (street-level) area which is relatively open ...

. The windows originally contained the names and arms of benefactors who contributed to the renovation of the chapel after its purchase by the city and the imperial crown of Edward VI, but by the 19th century many had been lost. Blomefield

Rev. Francis Blomefield (23 July 170516 January 1752), FSA, Rector of Fersfield in Norfolk, was an English antiquarian who wrote a county history of Norfolk: ''An Essay Towards a Topographical History of the County of Norfolk''. It includes ...

's ''History of the County of Norfolk'', compiled in the 18th century, identifies the coat of arms of the Drapers, Grocers, and St George's arms; with the family arms of the Palmers, Symbarbs and the Ruggs. Following renovations carried out in 1937–40 six windows contain stained glass panels mainly depicting shields. Among those that can be seen today are the coat of arms of the Worshipful Company of Dyers, and a shield carrying the Latin motto which literally translates to "Fame is equal to the toil". The motto, which comes from the '' Satires'' of Horace

Quintus Horatius Flaccus (; 8 December 65 – 27 November 8 BC), known in the English-speaking world as Horace (), was the leading Roman lyric poet during the time of Augustus (also known as Octavian). The rhetorician Quintilian regarded his ' ...

, has been taken out of context as in the poem Horace explains that fame never corresponds to the effort one has made. The art historian Eric Fernie

Eric Campbell Fernie (born 9 June 1939, Edinburgh) is a Scottish art historian.

Education

Fernie was educated at the University of the Witwatersrand (BA Hons Fine Arts) and the University of London (Academic Diploma).‘FERNIE, Prof. Eric Campb ...

suggests the style of the chapel is firmly within the palatial tradition of two-storey chapels along with the Palatine Chapel, Aachen, La Sainte-Chapelle and the Royal Chapel of St Stephen. In contrast archaeologist Roberta Gilchrist suggests that the design was influenced by the "visual culture of medieval death", its architecture holding additional iconographic meaning connected to its use for storage of charnel. The old charnel house is a scheduled monument and the chapel above is a Grade I listed building.

Erpingham Gate and St Ethelbert's Gate

The Erpingham Gate is the primary entrance to the north section of the Close, directly opposite the west door of the cathedral. It was commissioned bySir Thomas Erpingham

Sir Thomas Erpingham (27 June 1428) was an English soldier and administrator who loyally served three generations of the House of Lancaster, including Henry IV and Henry V, and whose military career spanned four decades. After the Lancastrian ...

, a commander in the Battle of Agincourt

The Battle of Agincourt ( ; french: Azincourt ) was an English victory in the Hundred Years' War. It took place on 25 October 1415 ( Saint Crispin's Day) near Azincourt, in northern France. The unexpected English victory against the numeric ...

and was constructed between 1416 and 1425. The top of the arch contains a canopied niche which is thought originally to have been dedicated to the Five Holy Wounds

In Catholic tradition, the Five Holy Wounds, also known as the Five Sacred Wounds or the Five Precious Wounds, are the five piercing wounds that Jesus Christ suffered during his crucifixion. The wounds have been the focus of particular devotions, ...

of Christ, flanked by the Four Evangelists and with the Holy Trinity

The Christian doctrine of the Trinity (, from 'threefold') is the central dogma concerning the nature of God in most Christian churches, which defines one God existing in three coequal, coeternal, consubstantial divine persons: God th ...

above, but was replaced in the 18th century with a kneeling statue of Erpingham wearing armour and surcoat with a collar of Esses and the Order of the Garter

The Most Noble Order of the Garter is an order of chivalry founded by Edward III of England in 1348. It is the most senior order of knighthood in the British honours system, outranked in precedence only by the Victoria Cross and the Georg ...

below his left knee. The rest of the gateway is decorated with the coat of arms of Erpingham and members of his family, together with his motto ''yenk'' (think) on small scrolls. It has been restored several times: first in the 18th century, then by E. W. Tristram in 1938 and again by Feilden and Mawson in 1989. It is a scheduled monument and adjoins School House and the Music School, which occupy 70 and 71 The Close respectively.

St Ethelbert's Gate is one of the entrances to the south section of the Close. The room above the gateway was originally a chapel dedicated to Saint Ethelbert the King and came to be used by the school in 1944. It was used as an art room before its conversion into the Barbirolli music practice room, named after Lady Barbirolli, under Philip Stibbe's headship (1975–1984), a project financed by the Dyers.. A scheduled monument, the gateway was built in 1316 by the citizens of Norwich as penance for a riot in 1272 which damaged many of the priory buildings. It was substantially restored in 1815 by William Wilkins, an Old Norvicensian, and underwent further renovations in 1964 which saw the stonework and carvings replaced under the supervision of Sir Bernard Feilden. Art historian Veronica Sekules describes the St Ethelbert's Gate as it was in the 14th century as "a highly decorative building presenting a façade rich in images, which the cathedral otherwise lacked. In a sense it would have operated as a principal façade and, in as far as one can glean from the remaining images, it communicated a strong message designating the gate as the opening to hallowed ground beyond."

St Ethelbert's Gate is one of the entrances to the south section of the Close. The room above the gateway was originally a chapel dedicated to Saint Ethelbert the King and came to be used by the school in 1944. It was used as an art room before its conversion into the Barbirolli music practice room, named after Lady Barbirolli, under Philip Stibbe's headship (1975–1984), a project financed by the Dyers.. A scheduled monument, the gateway was built in 1316 by the citizens of Norwich as penance for a riot in 1272 which damaged many of the priory buildings. It was substantially restored in 1815 by William Wilkins, an Old Norvicensian, and underwent further renovations in 1964 which saw the stonework and carvings replaced under the supervision of Sir Bernard Feilden. Art historian Veronica Sekules describes the St Ethelbert's Gate as it was in the 14th century as "a highly decorative building presenting a façade rich in images, which the cathedral otherwise lacked. In a sense it would have operated as a principal façade and, in as far as one can glean from the remaining images, it communicated a strong message designating the gate as the opening to hallowed ground beyond."

Nelson's statue

The Grade II listed statue ofLord Nelson

Vice-Admiral Horatio Nelson, 1st Viscount Nelson, 1st Duke of Bronte (29 September 1758 – 21 October 1805) was a British flag officer in the Royal Navy. His inspirational leadership, grasp of strategy, and unconventional tactics brought a ...

, an Old Norvicensian, was sculpted by Thomas Milnes in 1847. Milnes was later asked to model the lions for the base of Nelson's Column

Nelson's Column is a monument in Trafalgar Square in the City of Westminster, Central London, built to commemorate Vice-Admiral Horatio Nelson's decisive victory at the Battle of Trafalgar over the combined French and Spanish navies, during whic ...

in Trafalgar Square

Trafalgar Square ( ) is a public square in the City of Westminster, Central London, laid out in the early 19th century around the area formerly known as Charing Cross. At its centre is a high column bearing a statue of Admiral Nelson comm ...

, but the commission was eventually given to Sir Edwin Landseer

Sir Edwin Henry Landseer (7 March 1802 – 1 October 1873) was an English painter and sculptor, well known for his paintings of animals – particularly horses, dogs, and stags. However, his best-known works are the lion sculptures at the bas ...

. Nelson is depicted in vice admiral full-dress uniform, with epaulette

Epaulette (; also spelled epaulet) is a type of ornamental shoulder piece or decoration used as insignia of rank by armed forces and other organizations. Flexible metal epaulettes (usually made from brass) are referred to as ''shoulder scales' ...

s and three stars on the cuff, resting a telescope on a cannon with a hawser

Hawser () is a nautical term for a thick cable or rope used in mooring or towing a ship.

A hawser passes through a hawsehole, also known as a cat hole, located on the hawse. The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language, third editi ...

at his feet. He lost most of his right arm in 1797, shown by his empty right sleeve which is pinned to his uniform to support the cloak which falls from his left shoulder. The octagonal granite plinth is inscribed with "Nelson". It was originally located outside the Norwich Guildhall but was relocated to its current site next to the school in the Upper Close in 1856 at the suggestion of the sculptor Richard Westmacott the Younger.

Other buildings

School House, 70 The Close, was formerly part of the Carnary college but now contains classrooms and school offices. While much of the building dates to around 1830, extensive 14th and 15th century features remain such as the stone entrance archway. The building, which is Grade I listed, adjoins the Erpingham Gate and is three storeys high and has eight

School House, 70 The Close, was formerly part of the Carnary college but now contains classrooms and school offices. While much of the building dates to around 1830, extensive 14th and 15th century features remain such as the stone entrance archway. The building, which is Grade I listed, adjoins the Erpingham Gate and is three storeys high and has eight bays

A bay is a recessed, coastal body of water that directly connects to a larger main body of water, such as an ocean, a lake, or another bay. A large bay is usually called a gulf, sea, sound, or bight. A cove is a small, circular bay with a na ...

. School End House, 69 The Close, is a 17th-century timber-framed

Timber framing (german: Holzfachwerk) and "post-and-beam" construction are traditional methods of building with heavy timbers, creating structures using squared-off and carefully fitted and joined timbers with joints secured by large woode ...

house built against the east end of the school chapel. Formerly a home, the Grade I listed building is now the senior common room for staff and a school office. The entrance is pilaster

In classical architecture, a pilaster is an architectural element used to give the appearance of a supporting column and to articulate an extent of wall, with only an ornamental function. It consists of a flat surface raised from the main wal ...

ed and is surrounded by lion-mask roundel

A roundel is a circular disc used as a symbol. The term is used in heraldry, but also commonly used to refer to a type of national insignia used on military aircraft, generally circular in shape and usually comprising concentric rings of dif ...

s. The Music School, 71 The Close, was built in 1626–28 as a home for the prebendaries of the cathedral, funded by the chapter. Typical of the period, the Grade II* listed building was constructed from flint-rubble, brick, and reused materials from monastic buildings in the Close. It replaced an earlier house and incorporates the remains of a medieval free-standing bell tower

A bell tower is a tower that contains one or more bells, or that is designed to hold bells even if it has none. Such a tower commonly serves as part of a Christian church, and will contain church bells, but there are also many secular bell tow ...

originating in the 12th or 13th century, rebuilt around 1300 and largely demolished by 1580.

The Bishop's Palace was built on the site of the former Anglo-Saxon

The Anglo-Saxons were a cultural group who inhabited England in the Early Middle Ages. They traced their origins to settlers who came to Britain from mainland Europe in the 5th century. However, the ethnogenesis of the Anglo-Saxons happened wit ...

parish church

A parish church (or parochial church) in Christianity is the church which acts as the religious centre of a parish. In many parts of the world, especially in rural areas, the parish church may play a significant role in community activities, ...

of Holy Trinity. The primary wing was completed during Bishop de Losinga's episcopate (1091–1119).. Bishops Suffield (1244–1257) and Salmon (1298–1325) developed the palace and its grounds substantially. Under Bishop Salmon the palace underwent ambitious expansion, possibly prompted by damage from the riot of 1272 and his personal success of being elected as Lord Chancellor to Edward III

Edward III (13 November 1312 – 21 June 1377), also known as Edward of Windsor before his accession, was King of England and Lord of Ireland from January 1327 until his death in 1377. He is noted for his military success and for restoring r ...

in 1319.. The main feature of the original palace was a three-storey fortified tower which was directly connected to the cathedral, drawing upon the precedent of Carolingian

The Carolingian dynasty (; known variously as the Carlovingians, Carolingus, Carolings, Karolinger or Karlings) was a Frankish noble family named after Charlemagne, grandson of mayor Charles Martel and a descendant of the Arnulfing and Pippi ...

imperial palaces. In c. 1858 the building underwent major restoration under the supervision of Ewan Christian

Ewan Christian (1814–1895) was a British architect. He is most frequently noted for the restorations of Southwell Minster and Carlisle Cathedral, and the design of the National Portrait Gallery. He was Architect to the Ecclesiastical Commiss ...

.. The building came to be used by the school in 1958. Today the building contains classrooms where mathematics and geography are taught, the junior common room (for sixth form pupils) and libraries in the former parlour and undercroft.

The former private chapel of Edward Reynolds

Edward Reynolds (November 1599 – 28 July 1676) was a bishop of Norwich in the Church of England and an author.Cyclopaedia of Biblical, Theological, and Ecclesiastical Literature. Prepared by the Rev. John M'Clintock, D.D., and James Strong, ...

, Bishop of Norwich, was built in 1662 almost entirely at his own expense. It replaced an earlier chapel which had been severely damaged by a mob during Bishop Hall's episcopate (1641–1656). Constructed from stone with a plain tile roof, it annexes the Bishop's Palace. There is a coat of arms above the doorway but it is badly weathered. The Grade II* listed building was previously used by the dean and chapter for the storage of records and came to be used as a library by the school under S. M. Andrews' headship (1967–75) following renovations funded by the Dyers.

Organisation and administration

The school is divided into the Lower School, a preparatory feeder school which has around 250 pupils from ages 4 to 11, and the Senior School which has around 850 pupils aged from 12 to 18. Like many other independent schools the school has its own distinctive names for year groups called "forms". The school's academic year is divided into threeterm

Term may refer to:

* Terminology, or term, a noun or compound word used in a specific context, in particular:

**Technical term, part of the specialized vocabulary of a particular field, specifically:

***Scientific terminology, terms used by scient ...

s: ''Michaelmas

Michaelmas ( ; also known as the Feast of Saints Michael, Gabriel, and Raphael, the Feast of the Archangels, or the Feast of Saint Michael and All Angels) is a Christian festival observed in some Western liturgical calendars on 29 September, a ...

'' term, from early September to mid-December; ''Lent

Lent ( la, Quadragesima, 'Fortieth') is a solemn religious moveable feast#Lent, observance in the liturgical calendar commemorating the 40 days Jesus spent fasting in the desert and enduring Temptation of Jesus, temptation by Satan, according ...

'' term, from early January to mid-March; and ''Trinity

The Christian doctrine of the Trinity (, from 'threefold') is the central dogma concerning the nature of God in most Christian churches, which defines one God existing in three coequal, coeternal, consubstantial divine persons: God th ...

'' term, from mid-April to early July. In the middle of each term there is a week-long half-term holiday. The pupils receive an extra week of holiday in the three major holidays between terms, compared to most state school

State schools (in England, Wales, Australia and New Zealand) or public schools ( Scottish English and North American English) are generally primary or secondary schools that educate all students without charge. They are funded in whole or in ...

s of England. The school is a registered charity. The school's charitable work includes financial and practical support of the Diskit Monastery

Diskit Monastery also known as Deskit Gompa or Diskit Gompa is the oldest and largest Buddhist monastery (gompa) in Diskit, in the Nubra Valley in the Leh district of Ladakh, India.

It belongs to the Gelugpa (Yellow Hat) sect of Tibetan Buddh ...

and the GTC Monastic School in Ladakh

Ladakh () is a region administered by India as a union territory which constitutes a part of the larger Kashmir region and has been the subject of dispute between India, Pakistan, and China since 1947. (subscription required) Quote: "Jammu a ...

, India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, seventh-largest country by area, the List of countries and dependencies by population, second-most populous ...

, a primary school and health centre in Zambia

Zambia (), officially the Republic of Zambia, is a landlocked country at the crossroads of Central, Southern and East Africa, although it is typically referred to as being in Southern Africa at its most central point. Its neighbours are t ...

and a community centre in Boulogne Sur Mer, Argentina

Argentina (), officially the Argentine Republic ( es, link=no, República Argentina), is a country in the southern half of South America. Argentina covers an area of , making it the List of South American countries by area, second-largest ...

.

The headmaster is a member of the Headmasters' and Headmistresses' Conference and is responsible to the governors for the whole school from 4 to 18, though is primarily based in the Senior School. Housemasters are managed by the principal deputy head, who is accountable to the headteacher for the pastoral care and discipline of the school, as well as for much of the rest of the school's non-academic activity. The governors form the Board of Governors, also known as the Council of Management, which meets each term and is headed by a chairman. Past chairmen have included Donald Dalrymple ON, physician and Liberal MP for Bath (1868–73), J. J. Colman, head of the Colman's

Colman's is an English manufacturer of mustard and other sauces, formerly based and produced for 160 years at Carrow, in Norwich, Norfolk. Owned by Unilever since 1995, Colman's is one of the oldest existing food brands, famous for a limited ra ...

mustard company and Liberal MP for Norwich (1890–1898), Augustus Jessopp (1900–1903), James Stuart, founder of the University Extension Movement and Rector of the University of St Andrews (1903–1913), E. E. Blyth, first Lord Mayor of Norwich (1913–1934), David Cranage

David Herbert Somerset Cranage (10 October 1866 – 22 October 1957) was an Anglican Dean.

Born on 10 October 1866, the son of Dr Joseph Edward Cranage of Old Hall, Wellington, Shropshire, he was educated at King's College, Cambridge. Ordained i ...

, Dean of Norwich (1934–1945), and General Manager of Norwich Union

Norwich Union was the name of insurance company Aviva's British arm before June 2009. It was originally established in 1797. It was listed on the London Stock Exchange and was once a constituent of the FTSE 100 Index.

On 29 April 2008, Aviva ...

E. F. Williamson (1945–1954). The current chairman is P. J. E. Smith. Several governor positions are appointed by organisations closely connected to the school. The dean and chapter of Norwich Cathedral appoint one governor, and the Worshipful Company of Dyers appoint three. The school's historical connection with the Dyers, one of the Livery Companies of the City of London, dates back to 1947 when HH Judge Norman Daynes, an Old Norvicensian, was the Prime Warden of the Company. The charitable trust of the Company continues to be a major benefactor of the school through the funding of building expansion and bursaries. The school is also a member of the Choir Schools' Association

The Choir Schools' Association is a United Kingdom, U.K. organisation that provides support to choir schools and choristers, and promotes singing, in particular of music for Christian worship in the cathedral tradition. It represents 44 choir scho ...

and the Lower School is a member of the Independent Association of Prep Schools.

The school is selective; admission is based on assessments in English, mathematics and reasoning, an academic reference from the applicant's current school and an interview. The main entry point to enter the Lower School is at age 4 (Reception), age 7 (Year 3

Year 3 is an educational year group in schools in many countries including England, Wales, Australia, New Zealand and Malaysia. It is usually the third year of compulsory education and incorporates students aged between six to seven however some ...

), and ages 11 (Year 7

Year 7 is an educational year group in schools in many countries including England, Wales, Australia and New Zealand. It is the seventh full year (or eighth in Australia) of compulsory education and is roughly equivalent to grade 6 in the United ...

), 13 ( Year 9) and 16 to enter the Senior School. There are academic, music and other scholarships which reduce school fees by up to one-fifth, as well as means-tested bursaries

A bursary is a monetary award made by any educational institution or funding authority to individuals or groups. It is usually awarded to enable a student to attend school, university or college when they might not be able to, otherwise. Some a ...

up to the entirety of school fees. In addition, the charitable trust of the Dyers' provide a bursary to cover half the school fees of one pupil in each academic year. Cathedral choristers also receive bursaries which cover half of school fees through the Norwich Cathedral Choir Endowment Fund.. The fees for the 2013/2014 academic year for the Lower School were £11,997 per annum (£3,999 per term), and £13,167 per annum (£4,389 per term) for the Senior School. However, the fees for the 2018/2019 academic year are £11,493 per annum for Pre-prep, £15,441 per annum for Years 3-6 and £16,941 per annum for pupils in the Senior School The school also charges fees for lunches and entries for public examinations.

School life

Norwich Cathedral is used by the school on weekdays for morning assemblies and events throughout the academic year. The choristers of the cathedral are also educated at the school. The school has a Christian ethos, and emphasisesChristian values Christian values historically refers to values derived from the teachings of Jesus Christ. The term has various applications and meanings, and specific definitions can vary widely between denominations, geographical locations and different schools ...

such as love and compassion as underpinning its activities. ''Tatler

''Tatler'' is a British magazine published by Condé Nast Publications focusing on fashion and lifestyle, as well as coverage of high society and politics. It is targeted towards the British upper-middle class and upper class, and those interes ...

'' describes the school as "fantastically unstuffy". Former headteacher, Chris Brown, in an interview as chairman of the HMC in 2001 commented that the school does not fit the stereotype of a public school but is better described as an "independent grammar" because of the school's philanthropy and outreach in the community. Richard Harries, author of one of the school's histories argues that due to the evolution of the school it does not fit either public or grammar school stereotypes and that it is most properly described as an independent school among "the distinguished group of City independent schools", such as City of London School

, established =

, closed =

, type = Public school Boys' independent day school

, president =

, head_label = Headmaster

, head = Alan Bird

, chair_label = Chair of Governors

, chair = Ian Seaton

, founder = John Carpenter

, special ...

and Manchester Grammar School