Newton's laws of motion are three

physical laws

Scientific laws or laws of science are statements, based on reproducibility, repeated experiments or observations, that describe or prediction, predict a range of natural phenomena. The term ''law'' has diverse usage in many cases (approximate, a ...

that describe the relationship between the

motion

In physics, motion is when an object changes its position with respect to a reference point in a given time. Motion is mathematically described in terms of displacement, distance, velocity, acceleration, speed, and frame of reference to an o ...

of an object and the

force

In physics, a force is an influence that can cause an Physical object, object to change its velocity unless counterbalanced by other forces. In mechanics, force makes ideas like 'pushing' or 'pulling' mathematically precise. Because the Magnitu ...

s acting on it. These laws, which provide the basis for Newtonian mechanics, can be paraphrased as follows:

# A body remains at rest, or in motion at a constant speed in a straight line, unless it is acted upon by a force.

# At any instant of time, the net force on a body is equal to the body's

acceleration

In mechanics, acceleration is the Rate (mathematics), rate of change of the velocity of an object with respect to time. Acceleration is one of several components of kinematics, the study of motion. Accelerations are Euclidean vector, vector ...

multiplied by its mass or, equivalently, the rate at which the body's

momentum

In Newtonian mechanics, momentum (: momenta or momentums; more specifically linear momentum or translational momentum) is the product of the mass and velocity of an object. It is a vector quantity, possessing a magnitude and a direction. ...

is changing with time.

# If two bodies exert forces on each other, these forces have the same magnitude but opposite directions.

The three laws of motion were first stated by

Isaac Newton

Sir Isaac Newton () was an English polymath active as a mathematician, physicist, astronomer, alchemist, theologian, and author. Newton was a key figure in the Scientific Revolution and the Age of Enlightenment, Enlightenment that followed ...

in his ''

Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica

(English: ''The Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy''), often referred to as simply the (), is a book by Isaac Newton that expounds Newton's laws of motion and his law of universal gravitation. The ''Principia'' is written in Lati ...

'' (''Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy''), originally published in 1687. Newton used them to investigate and explain the motion of many physical objects and systems. In the time since Newton, new insights, especially around the concept of energy, built the field of

classical mechanics

Classical mechanics is a Theoretical physics, physical theory describing the motion of objects such as projectiles, parts of Machine (mechanical), machinery, spacecraft, planets, stars, and galaxies. The development of classical mechanics inv ...

on his foundations. Limitations to Newton's laws have also been discovered; new theories are necessary when objects move at very high speeds (

special relativity

In physics, the special theory of relativity, or special relativity for short, is a scientific theory of the relationship between Spacetime, space and time. In Albert Einstein's 1905 paper, Annus Mirabilis papers#Special relativity,

"On the Ele ...

), are very massive (

general relativity

General relativity, also known as the general theory of relativity, and as Einstein's theory of gravity, is the differential geometry, geometric theory of gravitation published by Albert Einstein in 1915 and is the current description of grav ...

), or are very small (

quantum mechanics

Quantum mechanics is the fundamental physical Scientific theory, theory that describes the behavior of matter and of light; its unusual characteristics typically occur at and below the scale of atoms. Reprinted, Addison-Wesley, 1989, It is ...

).

Prerequisites

Newton's laws are often stated in terms of ''point'' or ''particle'' masses, that is, bodies whose volume is negligible. This is a reasonable approximation for real bodies when the motion of internal parts can be neglected, and when the separation between bodies is much larger than the size of each. For instance, the Earth and the Sun can both be approximated as pointlike when considering the orbit of the former around the latter, but the Earth is not pointlike when considering activities on its surface.

The mathematical description of motion, or

kinematics

In physics, kinematics studies the geometrical aspects of motion of physical objects independent of forces that set them in motion. Constrained motion such as linked machine parts are also described as kinematics.

Kinematics is concerned with s ...

, is based on the idea of specifying positions using numerical coordinates. Movement is represented by these numbers changing over time: a body's trajectory is represented by a function that assigns to each value of a time variable the values of all the position coordinates. The simplest case is one-dimensional, that is, when a body is constrained to move only along a straight line. Its position can then be given by a single number, indicating where it is relative to some chosen reference point. For example, a body might be free to slide along a track that runs left to right, and so its location can be specified by its distance from a convenient zero point, or

origin, with negative numbers indicating positions to the left and positive numbers indicating positions to the right. If the body's location as a function of time is

, then its average velocity over the time interval from

to

is

Here, the Greek letter

(

delta

Delta commonly refers to:

* Delta (letter) (Δ or δ), the fourth letter of the Greek alphabet

* D (NATO phonetic alphabet: "Delta"), the fourth letter in the Latin alphabet

* River delta, at a river mouth

* Delta Air Lines, a major US carrier ...

) is used, per tradition, to mean "change in". A positive average velocity means that the position coordinate

increases over the interval in question, a negative average velocity indicates a net decrease over that interval, and an average velocity of zero means that the body ends the time interval in the same place as it began.

Calculus

Calculus is the mathematics, mathematical study of continuous change, in the same way that geometry is the study of shape, and algebra is the study of generalizations of arithmetic operations.

Originally called infinitesimal calculus or "the ...

gives the means to define an ''instantaneous'' velocity, a measure of a body's speed and direction of movement at a single moment of time, rather than over an interval. One notation for the instantaneous velocity is to replace

with the symbol

, for example,

This denotes that the instantaneous velocity is the

derivative

In mathematics, the derivative is a fundamental tool that quantifies the sensitivity to change of a function's output with respect to its input. The derivative of a function of a single variable at a chosen input value, when it exists, is t ...

of the position with respect to time. It can roughly be thought of as the ratio between an infinitesimally small change in position

to the infinitesimally small time interval

over which it occurs.

More carefully, the velocity and all other derivatives can be defined using the concept of a

limit.

A function

has a limit of

at a given input value

if the difference between

and

can be made arbitrarily small by choosing an input sufficiently close to

. One writes,

Instantaneous velocity can be defined as the limit of the average velocity as the time interval shrinks to zero:

''Acceleration'' is to velocity as velocity is to position: it is the derivative of the velocity with respect to time. Acceleration can likewise be defined as a limit:

Consequently, the acceleration is the ''second derivative'' of position,

often written

.

Position, when thought of as a displacement from an origin point, is a

vector

Vector most often refers to:

* Euclidean vector, a quantity with a magnitude and a direction

* Disease vector, an agent that carries and transmits an infectious pathogen into another living organism

Vector may also refer to:

Mathematics a ...

: a quantity with both magnitude and direction.

Velocity and acceleration are vector quantities as well. The mathematical tools of vector algebra provide the means to describe motion in two, three or more dimensions. Vectors are often denoted with an arrow, as in

, or in bold typeface, such as

. Often, vectors are represented visually as arrows, with the direction of the vector being the direction of the arrow, and the magnitude of the vector indicated by the length of the arrow. Numerically, a vector can be represented as a list; for example, a body's velocity vector might be

, indicating that it is moving at 3 metres per second along the horizontal axis and 4 metres per second along the vertical axis. The same motion described in a different

coordinate system

In geometry, a coordinate system is a system that uses one or more numbers, or coordinates, to uniquely determine and standardize the position of the points or other geometric elements on a manifold such as Euclidean space. The coordinates are ...

will be represented by different numbers, and vector algebra can be used to translate between these alternatives.

The study of mechanics is complicated by the fact that household words like ''energy'' are used with a technical meaning. Moreover, words which are synonymous in everyday speech are not so in physics: ''force'' is not the same as ''power'' or ''pressure'', for example, and ''mass'' has a different meaning than ''weight''.

The physics concept of ''force'' makes quantitative the everyday idea of a push or a pull. Forces in Newtonian mechanics are often due to strings and ropes, friction, muscle effort, gravity, and so forth. Like displacement, velocity, and acceleration, force is a vector quantity.

Laws

First law

Translated from Latin, Newton's first law reads,

:''Every object perseveres in its state of rest, or of uniform motion in a right line, unless it is compelled to change that state by forces impressed thereon.''

Newton's first law expresses the principle of

inertia

Inertia is the natural tendency of objects in motion to stay in motion and objects at rest to stay at rest, unless a force causes the velocity to change. It is one of the fundamental principles in classical physics, and described by Isaac Newto ...

: the natural behavior of a body is to move in a straight line at constant speed. A body's motion preserves the status quo, but external forces can perturb this.

The modern understanding of Newton's first law is that no

inertial observer

In classical physics and special relativity, an inertial frame of reference (also called an inertial space or a Galilean reference frame) is a frame of reference in which objects exhibit inertia: they remain at rest or in uniform motion relative ...

is privileged over any other. The concept of an inertial observer makes quantitative the everyday idea of feeling no effects of motion. For example, a person standing on the ground watching a train go past is an inertial observer. If the observer on the ground sees the train moving smoothly in a straight line at a constant speed, then a passenger sitting on the train will also be an inertial observer: the train passenger ''feels'' no motion. The principle expressed by Newton's first law is that there is no way to say which inertial observer is "really" moving and which is "really" standing still. One observer's state of rest is another observer's state of uniform motion in a straight line, and no experiment can deem either point of view to be correct or incorrect. There is no absolute standard of rest.

Newton himself believed that

absolute space and time

Absolute space and time is a concept in physics and philosophy about the properties of the universe. In physics, absolute space and time may be a preferred frame.

Early concept

A version of the concept of absolute space (in the sense of a prefe ...

existed, but that the only measures of space or time accessible to experiment are relative.

Second law

:''The change of motion of an object is proportional to the force impressed; and is made in the direction of the straight line in which the force is impressed.''

By "motion", Newton meant the quantity now called

momentum

In Newtonian mechanics, momentum (: momenta or momentums; more specifically linear momentum or translational momentum) is the product of the mass and velocity of an object. It is a vector quantity, possessing a magnitude and a direction. ...

, which depends upon the amount of matter contained in a body, the speed at which that body is moving, and the direction in which it is moving. In modern notation, the momentum of a body is the product of its mass and its velocity:

where all three quantities can change over time.

In common cases the mass

does not change with time and the derivative acts only upon the velocity. Then force equals the product of the mass and the time derivative of the velocity, which is the acceleration:

As the acceleration is the second derivative of position with respect to time, this can also be written

Newton's second law, in modern form, states that the time derivative of the momentum is the force:

When applied to

systems of variable mass, the equation above is only valid only for a fixed set of particles. Applying the derivative as in

can lead to incorrect results.

For example, the momentum of a water jet system must include the momentum of the ejected water:

The forces acting on a body

add as vectors, and so the total force on a body depends upon both the magnitudes and the directions of the individual forces.

When the net force on a body is equal to zero, then by Newton's second law, the body does not accelerate, and it is said to be in

mechanical equilibrium

In classical mechanics, a particle is in mechanical equilibrium if the net force on that particle is zero. By extension, a physical system made up of many parts is in mechanical equilibrium if the net force on each of its individual parts is ze ...

. A state of mechanical equilibrium is ''stable'' if, when the position of the body is changed slightly, the body remains near that equilibrium. Otherwise, the equilibrium is ''unstable.''

A common visual representation of forces acting in concert is the

free body diagram, which schematically portrays a body of interest and the forces applied to it by outside influences. For example, a free body diagram of a block sitting upon an

inclined plane

An inclined plane, also known as a ramp, is a flat supporting surface tilted at an angle from the vertical direction, with one end higher than the other, used as an aid for raising or lowering a load. The inclined plane is one of the six clas ...

can illustrate the combination of gravitational force,

"normal" force, friction, and string tension.

Newton's second law is sometimes presented as a ''definition'' of force, i.e., a force is that which exists when an inertial observer sees a body accelerating. This is sometimes regarded as a potential

tautology — acceleration implies force, force implies acceleration. However, Newton's second law not only merely defines the force by the acceleration: forces exist as separate from the acceleration produced by the force in a particular system. The same force that is identified as producing acceleration to an object can then be applied to any other object, and the resulting accelerations (coming from that same force) will always be inversely proportional to the mass of the object. What Newton's Second Law states is that all the effect of a force onto a system can be reduced to two pieces of information: the magnitude of the force, and it's direction, and then goes on to specify what the effect is.

Beyond that, an equation detailing the force might also be specified, like

Newton's law of universal gravitation

Newton's law of universal gravitation describes gravity as a force by stating that every particle attracts every other particle in the universe with a force that is Proportionality (mathematics)#Direct proportionality, proportional to the product ...

. By inserting such an expression for

into Newton's second law, an equation with predictive power can be written. Newton's second law has also been regarded as setting out a research program for physics, establishing that important goals of the subject are to identify the forces present in nature and to catalogue the constituents of matter.

However, forces can often be measured directly with no acceleration being involved, such as through

weighing scale

A scale or balance is a device used to measure weight or mass. These are also known as mass scales, weight scales, mass balances, massometers, and weight balances.

The traditional scale consists of two plates or bowls suspended at equal d ...

s. By postulating a physical object that can be directly measured independently from acceleration, Newton made a objective physical statement with the second law alone, the predictions of which can be verified even if no force law is given.

Third law

:''To every action, there is always opposed an equal reaction; or, the mutual actions of two bodies upon each other are always equal, and directed to contrary parts.''

In other words, if one body exerts a force on a second body, the second body is also exerting a force on the first body, of equal magnitude in the opposite direction. Overly brief paraphrases of the third law, like "action equals

reaction

Reaction may refer to a process or to a response to an action, event, or exposure.

Physics and chemistry

*Chemical reaction

*Nuclear reaction

*Reaction (physics), as defined by Newton's third law

* Chain reaction (disambiguation)

Biology and ...

" might have caused confusion among generations of students: the "action" and "reaction" apply to different bodies. For example, consider a book at rest on a table. The Earth's gravity pulls down upon the book. The "reaction" to that "action" is ''not'' the support force from the table holding up the book, but the gravitational pull of the book acting on the Earth.

Newton's third law relates to a more fundamental principle, the

conservation of momentum

In Newtonian mechanics, momentum (: momenta or momentums; more specifically linear momentum or translational momentum) is the product of the mass and velocity of an object. It is a vector quantity, possessing a magnitude and a direction. ...

. The latter remains true even in cases where Newton's statement does not, for instance when

force fields as well as material bodies carry momentum, and when momentum is defined properly, in

quantum mechanics

Quantum mechanics is the fundamental physical Scientific theory, theory that describes the behavior of matter and of light; its unusual characteristics typically occur at and below the scale of atoms. Reprinted, Addison-Wesley, 1989, It is ...

as well. In Newtonian mechanics, if two bodies have momenta

and

respectively, then the total momentum of the pair is

, and the rate of change of

is

By Newton's second law, the first term is the total force upon the first body, and the second term is the total force upon the second body. If the two bodies are isolated from outside influences, the only force upon the first body can be that from the second, and vice versa. By Newton's third law, these forces have equal magnitude but opposite direction, so they cancel when added, and

is constant. Alternatively, if

is known to be constant, it follows that the forces have equal magnitude and opposite direction.

Candidates for additional laws

Various sources have proposed elevating other ideas used in classical mechanics to the status of Newton's laws. For example, in Newtonian mechanics, the total mass of a body made by bringing together two smaller bodies is the sum of their individual masses.

Frank Wilczek

Frank Anthony Wilczek ( or ; born May 15, 1951) is an American theoretical physicist, mathematician and Nobel laureate. He is the Herman Feshbach Professor of Physics at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), Founding Director ...

has suggested calling attention to this assumption by designating it "Newton's Zeroth Law". Another candidate for a "zeroth law" is the fact that at any instant, a body reacts to the forces applied to it at that instant. Likewise, the idea that forces add like vectors (or in other words obey the

superposition principle

The superposition principle, also known as superposition property, states that, for all linear systems, the net response caused by two or more stimuli is the sum of the responses that would have been caused by each stimulus individually. So th ...

), and the idea that forces change the energy of a body, have both been described as a "fourth law".

Moreover, some texts organize the basic ideas of Newtonian mechanics into different postulates, other than the three laws as commonly phrased, with the goal of being more clear about what is empirically observed and what is true by definition.

Examples

The study of the behavior of massive bodies using Newton's laws is known as Newtonian mechanics. Some example problems in Newtonian mechanics are particularly noteworthy for conceptual or historical reasons.

Uniformly accelerated motion

If a body falls from rest near the surface of the Earth, then in the absence of air resistance, it will accelerate at a constant rate. This is known as

free fall

In classical mechanics, free fall is any motion of a physical object, body where gravity is the only force acting upon it.

A freely falling object may not necessarily be falling down in the vertical direction. If the common definition of the word ...

. The speed attained during free fall is proportional to the elapsed time, and the distance traveled is proportional to the square of the elapsed time. Importantly, the acceleration is the same for all bodies, independently of their mass. This follows from combining Newton's second law of motion with his

law of universal gravitation. The latter states that the magnitude of the gravitational force from the Earth upon the body is

where

is the mass of the falling body,

is the mass of the Earth,

is Newton's constant, and

is the distance from the center of the Earth to the body's location, which is very nearly the radius of the Earth. Setting this equal to

, the body's mass

cancels from both sides of the equation, leaving an acceleration that depends upon

,

, and

, and

can be taken to be constant. This particular value of acceleration is typically denoted

:

If the body is not released from rest but instead launched upwards and/or horizontally with nonzero velocity, then free fall becomes

projectile motion. When air resistance can be neglected, projectiles follow

parabola

In mathematics, a parabola is a plane curve which is Reflection symmetry, mirror-symmetrical and is approximately U-shaped. It fits several superficially different Mathematics, mathematical descriptions, which can all be proved to define exactl ...

-shaped trajectories, because gravity affects the body's vertical motion and not its horizontal. At the peak of the projectile's trajectory, its vertical velocity is zero, but its acceleration is

downwards, as it is at all times. Setting the wrong vector equal to zero is a common confusion among physics students.

Uniform circular motion

When a body is in uniform circular motion, the force on it changes the direction of its motion but not its speed. For a body moving in a circle of radius

at a constant speed

, its acceleration has a magnitude

and is directed toward the center of the circle. The force required to sustain this acceleration, called the

centripetal force

Centripetal force (from Latin ''centrum'', "center" and ''petere'', "to seek") is the force that makes a body follow a curved trajectory, path. The direction of the centripetal force is always orthogonality, orthogonal to the motion of the bod ...

, is therefore also directed toward the center of the circle and has magnitude

. Many

orbit

In celestial mechanics, an orbit (also known as orbital revolution) is the curved trajectory of an object such as the trajectory of a planet around a star, or of a natural satellite around a planet, or of an artificial satellite around an ...

s, such as that of the Moon around the Earth, can be approximated by uniform circular motion. In such cases, the centripetal force is gravity, and by Newton's law of universal gravitation has magnitude

, where

is the mass of the larger body being orbited. Therefore, the mass of a body can be calculated from observations of another body orbiting around it.

Newton's cannonball is a

thought experiment

A thought experiment is an imaginary scenario that is meant to elucidate or test an argument or theory. It is often an experiment that would be hard, impossible, or unethical to actually perform. It can also be an abstract hypothetical that is ...

that interpolates between projectile motion and uniform circular motion. A cannonball that is lobbed weakly off the edge of a tall cliff will hit the ground in the same amount of time as if it were dropped from rest, because the force of gravity only affects the cannonball's momentum in the downward direction, and its effect is not diminished by horizontal movement. If the cannonball is launched with a greater initial horizontal velocity, then it will travel farther before it hits the ground, but it will still hit the ground in the same amount of time. However, if the cannonball is launched with an even larger initial velocity, then the curvature of the Earth becomes significant: the ground itself will curve away from the falling cannonball. A very fast cannonball will fall away from the inertial straight-line trajectory at the same rate that the Earth curves away beneath it; in other words, it will be in orbit (imagining that it is not slowed by air resistance or obstacles).

Harmonic motion

Consider a body of mass

able to move along the

axis, and suppose an equilibrium point exists at the position

. That is, at

, the net force upon the body is the zero vector, and by Newton's second law, the body will not accelerate. If the force upon the body is proportional to the displacement from the equilibrium point, and directed to the equilibrium point, then the body will perform

simple harmonic motion. Writing the force as

, Newton's second law becomes

This differential equation has the solution

where the frequency

is equal to

, and the constants

and

can be calculated knowing, for example, the position and velocity the body has at a given time, like

.

One reason that the harmonic oscillator is a conceptually important example is that it is good approximation for many systems near a stable mechanical equilibrium. For example, a

pendulum

A pendulum is a device made of a weight suspended from a pivot so that it can swing freely. When a pendulum is displaced sideways from its resting, equilibrium position, it is subject to a restoring force due to gravity that will accelerate i ...

has a stable equilibrium in the vertical position: if motionless there, it will remain there, and if pushed slightly, it will swing back and forth. Neglecting air resistance and friction in the pivot, the force upon the pendulum is gravity, and Newton's second law becomes

where

is the length of the pendulum and

is its angle from the vertical. When the angle

is small, the

sine

In mathematics, sine and cosine are trigonometric functions of an angle. The sine and cosine of an acute angle are defined in the context of a right triangle: for the specified angle, its sine is the ratio of the length of the side opposite th ...

of

is nearly equal to

(see

small-angle approximation), and so this expression simplifies to the equation for a simple harmonic oscillator with frequency

.

A harmonic oscillator can be ''damped,'' often by friction or viscous drag, in which case energy bleeds out of the oscillator and the amplitude of the oscillations decreases over time. Also, a harmonic oscillator can be ''driven'' by an applied force, which can lead to the phenomenon of

resonance

Resonance is a phenomenon that occurs when an object or system is subjected to an external force or vibration whose frequency matches a resonant frequency (or resonance frequency) of the system, defined as a frequency that generates a maximu ...

.

Objects with variable mass

Newtonian physics treats matter as being neither created nor destroyed, though it may be rearranged. It can be the case that an object of interest gains or loses mass because matter is added to or removed from it. In such a situation, Newton's laws can be applied to the individual pieces of matter, keeping track of which pieces belong to the object of interest over time. For instance, if a rocket of mass

, moving at velocity

, ejects matter at a velocity

relative to the rocket, then

[

where is the net external force (e.g., a planet's gravitational pull).]

Fan and sail

The fan and sail example is a situation studied in discussions of Newton's third law.

The fan and sail example is a situation studied in discussions of Newton's third law.sailboat

A sailboat or sailing boat is a boat propelled partly or entirely by sails and is smaller than a sailing ship. Distinctions in what constitutes a sailing boat and ship vary by region and maritime culture.

Types

Although sailboat terminology ...

and blows on its sail. From the third law, one would reason that the force of the air pushing in one direction would cancel out the force done by the fan on the sail, leaving the entire apparatus stationary. However, because the system is not entirely enclosed, there are conditions in which the vessel will move; for example, if the sail is built in a manner that redirects the majority of the airflow back towards the fan, the net force will result in the vessel moving forward.

Work and energy

The concept of energy

Energy () is the physical quantity, quantitative physical property, property that is transferred to a physical body, body or to a physical system, recognizable in the performance of Work (thermodynamics), work and in the form of heat and l ...

was developed after Newton's time, but it has become an inseparable part of what is considered "Newtonian" physics. Energy can broadly be classified into kinetic, due to a body's motion, and potential

Potential generally refers to a currently unrealized ability. The term is used in a wide variety of fields, from physics to the social sciences to indicate things that are in a state where they are able to change in ways ranging from the simple r ...

, due to a body's position relative to others. Thermal energy

The term "thermal energy" is often used ambiguously in physics and engineering. It can denote several different physical concepts, including:

* Internal energy: The energy contained within a body of matter or radiation, excluding the potential en ...

, the energy carried by heat flow, is a type of kinetic energy not associated with the macroscopic motion of objects but instead with the movements of the atoms and molecules of which they are made. According to the work-energy theorem, when a force acts upon a body while that body moves along the line of the force, the force does ''work'' upon the body, and the amount of work done is equal to the change in the body's kinetic energy. In many cases of interest, the net work done by a force when a body moves in a closed loop — starting at a point, moving along some trajectory, and returning to the initial point — is zero. If this is the case, then the force can be written in terms of the gradient

In vector calculus, the gradient of a scalar-valued differentiable function f of several variables is the vector field (or vector-valued function) \nabla f whose value at a point p gives the direction and the rate of fastest increase. The g ...

of a function called a scalar potential

In mathematical physics, scalar potential describes the situation where the difference in the potential energies of an object in two different positions depends only on the positions, not upon the path taken by the object in traveling from one p ...

:conservation of energy

The law of conservation of energy states that the total energy of an isolated system remains constant; it is said to be Conservation law, ''conserved'' over time. In the case of a Closed system#In thermodynamics, closed system, the principle s ...

. Without friction to dissipate a body's energy into heat, the body's energy will trade between potential and (non-thermal) kinetic forms while the total amount remains constant. Any gain of kinetic energy, which occurs when the net force on the body accelerates it to a higher speed, must be accompanied by a loss of potential energy. So, the net force upon the body is determined by the manner in which the potential energy decreases.

Rigid-body motion and rotation

A rigid body is an object whose size is too large to neglect and which maintains the same shape over time. In Newtonian mechanics, the motion of a rigid body is often understood by separating it into movement of the body's center of mass

In physics, the center of mass of a distribution of mass in space (sometimes referred to as the barycenter or balance point) is the unique point at any given time where the weight function, weighted relative position (vector), position of the d ...

and movement around the center of mass.

Center of mass

Significant aspects of the motion of an extended body can be understood by imagining the mass of that body concentrated to a single point, known as the center of mass. The location of a body's center of mass depends upon how that body's material is distributed. For a collection of pointlike objects with masses at positions , the center of mass is located at where is the total mass of the collection. In the absence of a net external force, the center of mass moves at a constant speed in a straight line. This applies, for example, to a collision between two bodies. If the total external force is not zero, then the center of mass changes velocity as though it were a point body of mass . This follows from the fact that the internal forces within the collection, the forces that the objects exert upon each other, occur in balanced pairs by Newton's third law. In a system of two bodies with one much more massive than the other, the center of mass will approximately coincide with the location of the more massive body.

Significant aspects of the motion of an extended body can be understood by imagining the mass of that body concentrated to a single point, known as the center of mass. The location of a body's center of mass depends upon how that body's material is distributed. For a collection of pointlike objects with masses at positions , the center of mass is located at where is the total mass of the collection. In the absence of a net external force, the center of mass moves at a constant speed in a straight line. This applies, for example, to a collision between two bodies. If the total external force is not zero, then the center of mass changes velocity as though it were a point body of mass . This follows from the fact that the internal forces within the collection, the forces that the objects exert upon each other, occur in balanced pairs by Newton's third law. In a system of two bodies with one much more massive than the other, the center of mass will approximately coincide with the location of the more massive body.

Rotational analogues of Newton's laws

When Newton's laws are applied to rotating extended bodies, they lead to new quantities that are analogous to those invoked in the original laws. The analogue of mass is the moment of inertia

The moment of inertia, otherwise known as the mass moment of inertia, angular/rotational mass, second moment of mass, or most accurately, rotational inertia, of a rigid body is defined relatively to a rotational axis. It is the ratio between ...

, the counterpart of momentum is angular momentum

Angular momentum (sometimes called moment of momentum or rotational momentum) is the rotational analog of Momentum, linear momentum. It is an important physical quantity because it is a Conservation law, conserved quantity – the total ang ...

, and the counterpart of force is torque

In physics and mechanics, torque is the rotational analogue of linear force. It is also referred to as the moment of force (also abbreviated to moment). The symbol for torque is typically \boldsymbol\tau, the lowercase Greek letter ''tau''. Wh ...

.

Angular momentum is calculated with respect to a reference point. If the displacement vector from a reference point to a body is and the body has momentum , then the body's angular momentum with respect to that point is, using the vector cross product

In mathematics, the cross product or vector product (occasionally directed area product, to emphasize its geometric significance) is a binary operation on two vectors in a three-dimensional oriented Euclidean vector space (named here E), and ...

, Taking the time derivative of the angular momentum gives The first term vanishes because and point in the same direction. The remaining term is the torque, When the torque is zero, the angular momentum is constant, just as when the force is zero, the momentum is constant.

Multi-body gravitational system

Newton's law of universal gravitation states that any body attracts any other body along the straight line connecting them. The size of the attracting force is proportional to the product of their masses, and inversely proportional to the square of the distance between them. Finding the shape of the orbits that an inverse-square force law will produce is known as the

Newton's law of universal gravitation states that any body attracts any other body along the straight line connecting them. The size of the attracting force is proportional to the product of their masses, and inversely proportional to the square of the distance between them. Finding the shape of the orbits that an inverse-square force law will produce is known as the Kepler problem

In classical mechanics, the Kepler problem is a special case of the two-body problem, in which the two bodies interact by a central force that varies in strength as the inverse square of the distance between them. The force may be either attra ...

. The Kepler problem can be solved in multiple ways, including by demonstrating that the Laplace–Runge–Lenz vector

In classical mechanics, the Laplace–Runge–Lenz vector (LRL vector) is a vector (geometric), vector used chiefly to describe the shape and orientation of the orbit (celestial mechanics), orbit of one astronomical body around another, such as a ...

is constant, or by applying a duality transformation to a 2-dimensional harmonic oscillator. However it is solved, the result is that orbits will be conic section

A conic section, conic or a quadratic curve is a curve obtained from a cone's surface intersecting a plane. The three types of conic section are the hyperbola, the parabola, and the ellipse; the circle is a special case of the ellipse, tho ...

s, that is, ellipse

In mathematics, an ellipse is a plane curve surrounding two focus (geometry), focal points, such that for all points on the curve, the sum of the two distances to the focal points is a constant. It generalizes a circle, which is the special ty ...

s (including circles), parabola

In mathematics, a parabola is a plane curve which is Reflection symmetry, mirror-symmetrical and is approximately U-shaped. It fits several superficially different Mathematics, mathematical descriptions, which can all be proved to define exactl ...

s, or hyperbola

In mathematics, a hyperbola is a type of smooth function, smooth plane curve, curve lying in a plane, defined by its geometric properties or by equations for which it is the solution set. A hyperbola has two pieces, called connected component ( ...

s. The eccentricity

Eccentricity or eccentric may refer to:

* Eccentricity (behavior), odd behavior on the part of a person, as opposed to being "normal"

Mathematics, science and technology Mathematics

* Off-Centre (geometry), center, in geometry

* Eccentricity (g ...

of the orbit, and thus the type of conic section, is determined by the energy and the angular momentum of the orbiting body. Planets do not have sufficient energy to escape the Sun, and so their orbits are ellipses, to a good approximation; because the planets pull on one another, actual orbits are not exactly conic sections.

If a third mass is added, the Kepler problem becomes the three-body problem, which in general has no exact solution in closed form. That is, there is no way to start from the differential equations implied by Newton's laws and, after a finite sequence of standard mathematical operations, obtain equations that express the three bodies' motions over time.Numerical methods

Numerical analysis is the study of algorithms that use numerical approximation (as opposed to symbolic manipulations) for the problems of mathematical analysis (as distinguished from discrete mathematics). It is the study of numerical methods t ...

can be applied to obtain useful, albeit approximate, results for the three-body problem. The positions and velocities of the bodies can be stored in variables within a computer's memory; Newton's laws are used to calculate how the velocities will change over a short interval of time, and knowing the velocities, the changes of position over that time interval can be computed. This process is looped to calculate, approximately, the bodies' trajectories. Generally speaking, the shorter the time interval, the more accurate the approximation.

Chaos and unpredictability

Nonlinear dynamics

Newton's laws of motion allow the possibility of chaos.

Newton's laws of motion allow the possibility of chaos.double pendulum

In physics and mathematics, in the area of dynamical systems, a double pendulum, also known as a chaotic pendulum, is a pendulum with another pendulum attached to its end, forming a simple physical system that exhibits rich dynamical systems, dy ...

, dynamical billiards, and the Fermi–Pasta–Ulam–Tsingou problem.

Newton's laws can be applied to fluid

In physics, a fluid is a liquid, gas, or other material that may continuously motion, move and Deformation (physics), deform (''flow'') under an applied shear stress, or external force. They have zero shear modulus, or, in simpler terms, are M ...

s by considering a fluid as composed of infinitesimal pieces, each exerting forces upon neighboring pieces. The Euler momentum equation is an expression of Newton's second law adapted to fluid dynamics.density

Density (volumetric mass density or specific mass) is the ratio of a substance's mass to its volume. The symbol most often used for density is ''ρ'' (the lower case Greek letter rho), although the Latin letter ''D'' (or ''d'') can also be u ...

, and there is a net force upon it if the fluid pressure varies from one side of it to another. Accordingly, becomes

where is the density, is the pressure, and stands for an external influence like a gravitational pull. Incorporating the effect of viscosity

Viscosity is a measure of a fluid's rate-dependent drag (physics), resistance to a change in shape or to movement of its neighboring portions relative to one another. For liquids, it corresponds to the informal concept of ''thickness''; for e ...

turns the Euler equation into a Navier–Stokes equation:

where is the kinematic viscosity

Viscosity is a measure of a fluid's rate-dependent drag (physics), resistance to a change in shape or to movement of its neighboring portions relative to one another. For liquids, it corresponds to the informal concept of ''thickness''; for e ...

.

Singularities

It is mathematically possible for a collection of point masses, moving in accord with Newton's laws, to launch some of themselves away so forcefully that they fly off to infinity in a finite time. This unphysical behavior, known as a "noncollision singularity",Millennium Prize Problems

The Millennium Prize Problems are seven well-known complex mathematics, mathematical problems selected by the Clay Mathematics Institute in 2000. The Clay Institute has pledged a US $1 million prize for the first correct solution to each problem ...

.

Relation to other formulations of classical physics

Classical mechanics can be mathematically formulated in multiple different ways, other than the "Newtonian" description (which itself, of course, incorporates contributions from others both before and after Newton). The physical content of these different formulations is the same as the Newtonian, but they provide different insights and facilitate different types of calculations. For example, Lagrangian mechanics

In physics, Lagrangian mechanics is a formulation of classical mechanics founded on the d'Alembert principle of virtual work. It was introduced by the Italian-French mathematician and astronomer Joseph-Louis Lagrange in his presentation to the ...

helps make apparent the connection between symmetries and conservation laws, and it is useful when calculating the motion of constrained bodies, like a mass restricted to move along a curving track or on the surface of a sphere.Hamiltonian mechanics

In physics, Hamiltonian mechanics is a reformulation of Lagrangian mechanics that emerged in 1833. Introduced by Sir William Rowan Hamilton, Hamiltonian mechanics replaces (generalized) velocities \dot q^i used in Lagrangian mechanics with (gener ...

is convenient for statistical physics

In physics, statistical mechanics is a mathematical framework that applies statistical methods and probability theory to large assemblies of microscopic entities. Sometimes called statistical physics or statistical thermodynamics, its applicati ...

,perturbation theory

In mathematics and applied mathematics, perturbation theory comprises methods for finding an approximate solution to a problem, by starting from the exact solution of a related, simpler problem. A critical feature of the technique is a middle ...

.

Lagrangian

Lagrangian mechanics

In physics, Lagrangian mechanics is a formulation of classical mechanics founded on the d'Alembert principle of virtual work. It was introduced by the Italian-French mathematician and astronomer Joseph-Louis Lagrange in his presentation to the ...

differs from the Newtonian formulation by considering entire trajectories at once rather than predicting a body's motion at a single instant.Calculus of variations

The calculus of variations (or variational calculus) is a field of mathematical analysis that uses variations, which are small changes in Function (mathematics), functions

and functional (mathematics), functionals, to find maxima and minima of f ...

provides the mathematical tools for finding this path.partial derivative

In mathematics, a partial derivative of a function of several variables is its derivative with respect to one of those variables, with the others held constant (as opposed to the total derivative, in which all variables are allowed to vary). P ...

s of the Lagrangian gives

which is a restatement of Newton's second law. The left-hand side is the time derivative of the momentum, and the right-hand side is the force, represented in terms of the potential energy.Noether's theorem

Noether's theorem states that every continuous symmetry of the action of a physical system with conservative forces has a corresponding conservation law. This is the first of two theorems (see Noether's second theorem) published by the mat ...

, which relates symmetries and conservation laws. The conservation of momentum can be derived by applying Noether's theorem to a Lagrangian for a multi-particle system, and so, Newton's third law is a theorem rather than an assumption.

Hamiltonian

In

In Hamiltonian mechanics

In physics, Hamiltonian mechanics is a reformulation of Lagrangian mechanics that emerged in 1833. Introduced by Sir William Rowan Hamilton, Hamiltonian mechanics replaces (generalized) velocities \dot q^i used in Lagrangian mechanics with (gener ...

, the dynamics of a system are represented by a function called the Hamiltonian, which in many cases of interest is equal to the total energy of the system.

Hamilton–Jacobi

The Hamilton–Jacobi equation

In physics, the Hamilton–Jacobi equation, named after William Rowan Hamilton and Carl Gustav Jacob Jacobi, is an alternative formulation of classical mechanics, equivalent to other formulations such as Newton's laws of motion, Lagrangian mecha ...

provides yet another formulation of classical mechanics, one which makes it mathematically analogous to wave optics.gradient

In vector calculus, the gradient of a scalar-valued differentiable function f of several variables is the vector field (or vector-valued function) \nabla f whose value at a point p gives the direction and the rate of fastest increase. The g ...

of :

The Hamilton–Jacobi equation for a point mass is

The relation to Newton's laws can be seen by considering a point mass moving in a time-independent potential , in which case the Hamilton–Jacobi equation becomes

Taking the gradient of both sides, this becomes

Interchanging the order of the partial derivatives on the left-hand side, and using the power and chain rule

In calculus, the chain rule is a formula that expresses the derivative of the Function composition, composition of two differentiable functions and in terms of the derivatives of and . More precisely, if h=f\circ g is the function such that h ...

s on the first term on the right-hand side,

Gathering together the terms that depend upon the gradient of ,

This is another re-expression of Newton's second law. The expression in brackets is a ''total'' or ''material'' derivative as mentioned above, in which the first term indicates how the function being differentiated changes over time at a fixed location, and the second term captures how a moving particle will see different values of that function as it travels from place to place:

Relation to other physical theories

Thermodynamics and statistical physics

In

In statistical physics

In physics, statistical mechanics is a mathematical framework that applies statistical methods and probability theory to large assemblies of microscopic entities. Sometimes called statistical physics or statistical thermodynamics, its applicati ...

, the kinetic theory of gases

The kinetic theory of gases is a simple classical model of the thermodynamic behavior of gases. Its introduction allowed many principal concepts of thermodynamics to be established. It treats a gas as composed of numerous particles, too small ...

applies Newton's laws of motion to large numbers (typically on the order of the Avogadro number

The Avogadro constant, commonly denoted or , is an SI defining constant with an exact value of when expressed in reciprocal moles.

It defines the ratio of the number of constituent particles to the amount of substance in a sample, where th ...

) of particles. Kinetic theory can explain, for example, the pressure

Pressure (symbol: ''p'' or ''P'') is the force applied perpendicular to the surface of an object per unit area over which that force is distributed. Gauge pressure (also spelled ''gage'' pressure)The preferred spelling varies by country and eve ...

that a gas exerts upon the container holding it as the aggregate of many impacts of atoms, each imparting a tiny amount of momentum.Langevin equation

In physics, a Langevin equation (named after Paul Langevin) is a stochastic differential equation describing how a system evolves when subjected to a combination of deterministic and fluctuating ("random") forces. The dependent variables in a Lange ...

is a special case of Newton's second law, adapted for the case of describing a small object bombarded stochastically by even smaller ones.Brownian motion

Brownian motion is the random motion of particles suspended in a medium (a liquid or a gas). The traditional mathematical formulation of Brownian motion is that of the Wiener process, which is often called Brownian motion, even in mathematical ...

.

Electromagnetism

Newton's three laws can be applied to phenomena involving electricity

Electricity is the set of physical phenomena associated with the presence and motion of matter possessing an electric charge. Electricity is related to magnetism, both being part of the phenomenon of electromagnetism, as described by Maxwel ...

and magnetism

Magnetism is the class of physical attributes that occur through a magnetic field, which allows objects to attract or repel each other. Because both electric currents and magnetic moments of elementary particles give rise to a magnetic field, ...

, though subtleties and caveats exist.

Coulomb's law

Coulomb's inverse-square law, or simply Coulomb's law, is an experimental scientific law, law of physics that calculates the amount of force (physics), force between two electric charge, electrically charged particles at rest. This electric for ...

for the electric force between two stationary, electrically charged bodies has much the same mathematical form as Newton's law of universal gravitation: the force is proportional to the product of the charges, inversely proportional to the square of the distance between them, and directed along the straight line between them. The Coulomb force that a charge exerts upon a charge is equal in magnitude to the force that exerts upon , and it points in the exact opposite direction. Coulomb's law is thus consistent with Newton's third law.

Electromagnetism treats forces as produced by ''fields'' acting upon charges. The Lorentz force law provides an expression for the force upon a charged body that can be plugged into Newton's second law in order to calculate its acceleration. According to the Lorentz force law, a charged body in an electric field experiences a force in the direction of that field, a force proportional to its charge and to the strength of the electric field. In addition, a ''moving'' charged body in a magnetic field experiences a force that is also proportional to its charge, in a direction perpendicular to both the field and the body's direction of motion. Using the vector cross product

In mathematics, the cross product or vector product (occasionally directed area product, to emphasize its geometric significance) is a binary operation on two vectors in a three-dimensional oriented Euclidean vector space (named here E), and ...

,

If the electric field vanishes (), then the force will be perpendicular to the charge's motion, just as in the case of uniform circular motion studied above, and the charge will circle (or more generally move in a helix

A helix (; ) is a shape like a cylindrical coil spring or the thread of a machine screw. It is a type of smooth space curve with tangent lines at a constant angle to a fixed axis. Helices are important in biology, as the DNA molecule is for ...

) around the magnetic field lines at the cyclotron frequency .Mass spectrometry

Mass spectrometry (MS) is an analytical technique that is used to measure the mass-to-charge ratio of ions. The results are presented as a ''mass spectrum'', a plot of intensity as a function of the mass-to-charge ratio. Mass spectrometry is used ...

works by applying electric and/or magnetic fields to moving charges and measuring the resulting acceleration, which by the Lorentz force law yields the mass-to-charge ratio

The mass-to-charge ratio (''m''/''Q'') is a physical quantity Ratio, relating the ''mass'' (quantity of matter) and the ''electric charge'' of a given particle, expressed in Physical unit, units of kilograms per coulomb (kg/C). It is most widely ...

.

Collections of charged bodies do not always obey Newton's third law: there can be a change of one body's momentum without a compensatory change in the momentum of another. The discrepancy is accounted for by momentum carried by the electromagnetic field itself. The momentum per unit volume of the electromagnetic field is proportional to the Poynting vector

In physics, the Poynting vector (or Umov–Poynting vector) represents the directional energy flux (the energy transfer per unit area, per unit time) or '' power flow'' of an electromagnetic field. The SI unit of the Poynting vector is the wat ...

.speed of light

The speed of light in vacuum, commonly denoted , is a universal physical constant exactly equal to ). It is exact because, by international agreement, a metre is defined as the length of the path travelled by light in vacuum during a time i ...

and find it to be the value predicted by the Maxwell equations. In other words, light provides an absolute standard for speed, yet the principle of inertia holds that there should be no such standard. This tension is resolved in the theory of special relativity, which revises the notions of ''space'' and ''time'' in such a way that all inertial observers will agree upon the speed of light in vacuum.

Special relativity

In special relativity, the rule that Wilczek called "Newton's Zeroth Law" breaks down: the mass of a composite object is not merely the sum of the masses of the individual pieces.rest mass

The invariant mass, rest mass, intrinsic mass, proper mass, or in the case of bound systems simply mass, is the portion of the total mass of an object or system of objects that is independent of the overall motion of the system. More precisely, ...

and is the Lorentz factor

The Lorentz factor or Lorentz term (also known as the gamma factor) is a dimensionless quantity expressing how much the measurements of time, length, and other physical properties change for an object while it moves. The expression appears in sev ...

, which depends upon the body's speed. Alternatively, momentum and force can be represented as four-vector

In special relativity, a four-vector (or 4-vector, sometimes Lorentz vector) is an object with four components, which transform in a specific way under Lorentz transformations. Specifically, a four-vector is an element of a four-dimensional vect ...

s.

Newton's third law must be modified in special relativity. The third law refers to the forces between two bodies at the same moment in time, and a key feature of special relativity is that simultaneity is relative. Events that happen at the same time relative to one observer can happen at different times relative to another. So, in a given observer's frame of reference, action and reaction may not be exactly opposite, and the total momentum of interacting bodies may not be conserved. The conservation of momentum is restored by including the momentum stored in the field that describes the bodies' interaction.

Newtonian mechanics is a good approximation to special relativity when the speeds involved are small compared to that of light.

General relativity

General relativity

General relativity, also known as the general theory of relativity, and as Einstein's theory of gravity, is the differential geometry, geometric theory of gravitation published by Albert Einstein in 1915 and is the current description of grav ...

is a theory of gravity that advances beyond that of Newton. In general relativity, the gravitational force of Newtonian mechanics is reimagined as curvature of spacetime

In physics, spacetime, also called the space-time continuum, is a mathematical model that fuses the three dimensions of space and the one dimension of time into a single four-dimensional continuum. Spacetime diagrams are useful in visualiz ...

. A curved path like an orbit, attributed to a gravitational force in Newtonian mechanics, is not the result of a force deflecting a body from an ideal straight-line path, but rather the body's attempt to fall freely through a background that is itself curved by the presence of other masses. A remark by John Archibald Wheeler

John Archibald Wheeler (July 9, 1911April 13, 2008) was an American theoretical physicist. He was largely responsible for reviving interest in general relativity in the United States after World War II. Wheeler also worked with Niels Bohr to e ...

that has become proverbial among physicists summarizes the theory: "Spacetime tells matter how to move; matter tells spacetime how to curve."Einstein field equations

In the General relativity, general theory of relativity, the Einstein field equations (EFE; also known as Einstein's equations) relate the geometry of spacetime to the distribution of Matter#In general relativity and cosmology, matter within it. ...

, which require tensor calculus

In mathematics, a tensor is an algebraic object that describes a multilinear relationship between sets of algebraic objects associated with a vector space. Tensors may map between different objects such as vectors, scalars, and even other ...

to express.

Quantum mechanics

Quantum mechanics

Quantum mechanics is the fundamental physical Scientific theory, theory that describes the behavior of matter and of light; its unusual characteristics typically occur at and below the scale of atoms. Reprinted, Addison-Wesley, 1989, It is ...

is a theory of physics originally developed in order to understand microscopic phenomena: behavior at the scale of molecules, atoms or subatomic particles. Generally and loosely speaking, the smaller a system is, the more an adequate mathematical model will require understanding quantum effects. The conceptual underpinning of quantum physics is very different from that of classical physics. Instead of thinking about quantities like position, momentum, and energy as properties that an object ''has'', one considers what result might ''appear'' when a measurement

Measurement is the quantification of attributes of an object or event, which can be used to compare with other objects or events.

In other words, measurement is a process of determining how large or small a physical quantity is as compared to ...

of a chosen type is performed. Quantum mechanics allows the physicist to calculate the probability that a chosen measurement will elicit a particular result. The expectation value

In probability theory, the expected value (also called expectation, expectancy, expectation operator, mathematical expectation, mean, expectation value, or first moment) is a generalization of the weighted average. Informally, the expected va ...

for a measurement is the average of the possible results it might yield, weighted by their probabilities of occurrence.

The Ehrenfest theorem

The Ehrenfest theorem, named after Austrian theoretical physicist Paul Ehrenfest, relates the time derivative of the expectation values of the position and momentum operators ''x'' and ''p'' to the expectation value of the force F=-V'(x) on a m ...

provides a connection between quantum expectation values and Newton's second law, a connection that is necessarily inexact, as quantum physics is fundamentally different from classical. In quantum physics, position and momentum are represented by mathematical entities known as Hermitian operator

In mathematics, a self-adjoint operator on a complex vector space ''V'' with inner product \langle\cdot,\cdot\rangle is a linear map ''A'' (from ''V'' to itself) that is its own adjoint. That is, \langle Ax,y \rangle = \langle x,Ay \rangle for al ...

s, and the Born rule

The Born rule is a postulate of quantum mechanics that gives the probability that a measurement of a quantum system will yield a given result. In one commonly used application, it states that the probability density for finding a particle at a ...

is used to calculate the expectation values of a position measurement or a momentum measurement. These expectation values will generally change over time; that is, depending on the time at which (for example) a position measurement is performed, the probabilities for its different possible outcomes will vary. The Ehrenfest theorem says, roughly speaking, that the equations describing how these expectation values change over time have a form reminiscent of Newton's second law. However, the more pronounced quantum effects are in a given situation, the more difficult it is to derive meaningful conclusions from this resemblance.

History

The concepts invoked in Newton's laws of motion — mass, velocity, momentum, force — have predecessors in earlier work, and the content of Newtonian physics was further developed after Newton's time. Newton combined knowledge of celestial motions with the study of events on Earth and showed that one theory of mechanics could encompass both.

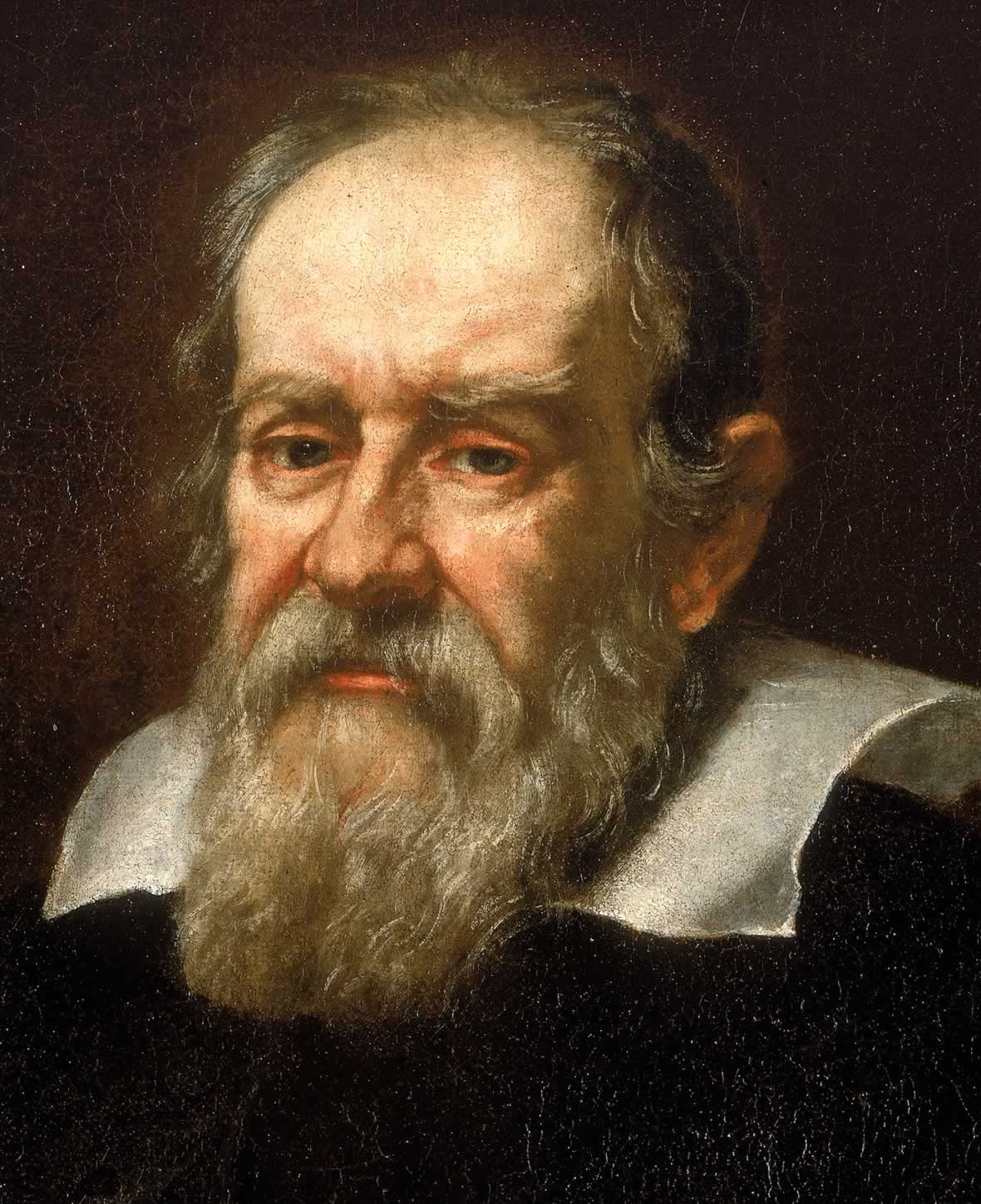

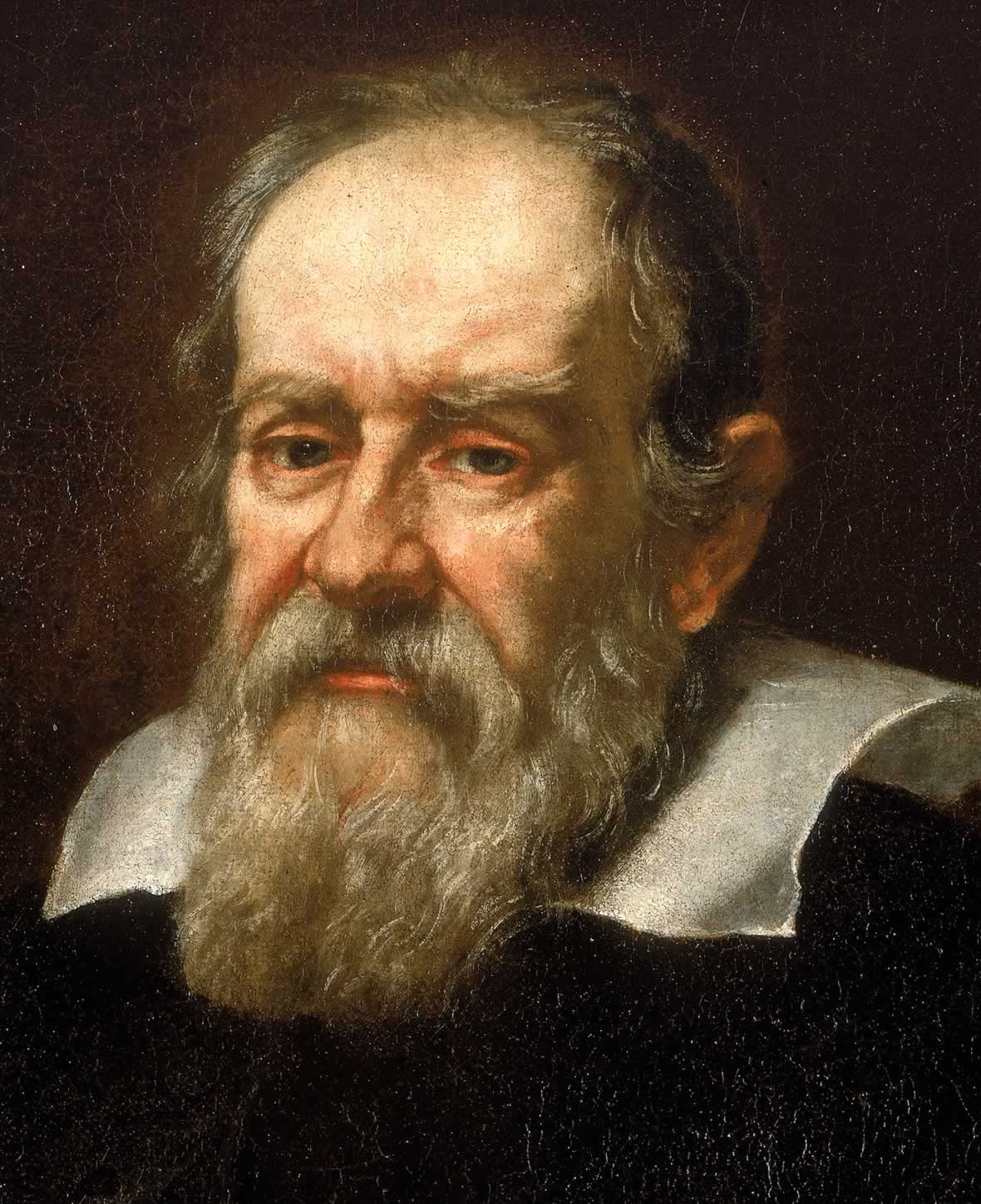

As noted by scholar I. Bernard Cohen, Newton's work was more than a mere synthesis of previous results, as he selected certain ideas and further transformed them, with each in a new form that was useful to him, while at the same time proving false of certain basic or fundamental principles of scientists such as Galileo Galilei

Galileo di Vincenzo Bonaiuti de' Galilei (15 February 1564 – 8 January 1642), commonly referred to as Galileo Galilei ( , , ) or mononymously as Galileo, was an Italian astronomer, physicist and engineer, sometimes described as a poly ...

, Johannes Kepler

Johannes Kepler (27 December 1571 – 15 November 1630) was a German astronomer, mathematician, astrologer, Natural philosophy, natural philosopher and writer on music. He is a key figure in the 17th-century Scientific Revolution, best know ...

, René Descartes

René Descartes ( , ; ; 31 March 1596 – 11 February 1650) was a French philosopher, scientist, and mathematician, widely considered a seminal figure in the emergence of modern philosophy and Modern science, science. Mathematics was paramou ...

, and Nicolaus Copernicus

Nicolaus Copernicus (19 February 1473 – 24 May 1543) was a Renaissance polymath who formulated a mathematical model, model of Celestial spheres#Renaissance, the universe that placed heliocentrism, the Sun rather than Earth at its cen ...

. He approached natural philosophy with mathematics in a completely novel way, in that instead of a preconceived natural philosophy, his style was to begin with a mathematical construct, and build on from there, comparing it to the real world to show that his system accurately accounted for it.

Antiquity and medieval background

Aristotle and "violent" motion

The subject of physics is often traced back to Aristotle

Aristotle (; 384–322 BC) was an Ancient Greek philosophy, Ancient Greek philosopher and polymath. His writings cover a broad range of subjects spanning the natural sciences, philosophy, linguistics, economics, politics, psychology, a ...

, but the history of the concepts involved is obscured by multiple factors. An exact correspondence between Aristotelian and modern concepts is not simple to establish: Aristotle did not clearly distinguish what we would call speed and force, used the same term for density

Density (volumetric mass density or specific mass) is the ratio of a substance's mass to its volume. The symbol most often used for density is ''ρ'' (the lower case Greek letter rho), although the Latin letter ''D'' (or ''d'') can also be u ...

and viscosity

Viscosity is a measure of a fluid's rate-dependent drag (physics), resistance to a change in shape or to movement of its neighboring portions relative to one another. For liquids, it corresponds to the informal concept of ''thickness''; for e ...

, and conceived of motion as always through a medium, rather than through space. In addition, some concepts often termed "Aristotelian" might better be attributed to his followers and commentators upon him. These commentators found that Aristotelian physics had difficulty explaining projectile motion. Aristotle divided motion into two types: "natural" and "violent". The "natural" motion of terrestrial solid matter was to fall downwards, whereas a "violent" motion could push a body sideways. Moreover, in Aristotelian physics, a "violent" motion requires an immediate cause; separated from the cause of its "violent" motion, a body would revert to its "natural" behavior. Yet, a javelin continues moving after it leaves the thrower's hand. Aristotle concluded that the air around the javelin must be imparted with the ability to move the javelin forward.

Philoponus and impetus

John Philoponus

John Philoponus ( Greek: ; , ''Ioánnis o Philóponos''; c. 490 – c. 570), also known as John the Grammarian or John of Alexandria, was a Coptic Miaphysite philologist, Aristotelian commentator and Christian theologian from Alexandria, Byza ...

, a Byzantine Greek

Medieval Greek (also known as Middle Greek, Byzantine Greek, or Romaic; Greek: ) is the stage of the Greek language between the end of classical antiquity in the 5th–6th centuries and the end of the Middle Ages, conventionally dated to the F ...

thinker active during the sixth century, found this absurd: the same medium, air, was somehow responsible both for sustaining motion and for impeding it. If Aristotle's idea were true, Philoponus said, armies would launch weapons by blowing upon them with bellows. Philoponus argued that setting a body into motion imparted a quality, impetus, that would be contained within the body itself. As long as its impetus was sustained, the body would continue to move. In the following centuries, versions of impetus theory were advanced by individuals including Nur ad-Din al-Bitruji, Avicenna

Ibn Sina ( – 22 June 1037), commonly known in the West as Avicenna ( ), was a preeminent philosopher and physician of the Muslim world, flourishing during the Islamic Golden Age, serving in the courts of various Iranian peoples, Iranian ...

, Abu'l-Barakāt al-Baghdādī, John Buridan, and Albert of Saxony. In retrospect, the idea of impetus can be seen as a forerunner of the modern concept of momentum. The intuition that objects move according to some kind of impetus persists in many students of introductory physics.

Inertia and the first law

The French philosopher René Descartes

René Descartes ( , ; ; 31 March 1596 – 11 February 1650) was a French philosopher, scientist, and mathematician, widely considered a seminal figure in the emergence of modern philosophy and Modern science, science. Mathematics was paramou ...

introduced the concept of inertia by way of his "laws of nature" in '' The World'' (''Traité du monde et de la lumière'') written 1629–33. However, ''The World'' purported a heliocentric

Heliocentrism (also known as the heliocentric model) is a Superseded theories in science#Astronomy and cosmology, superseded astronomical model in which the Earth and Solar System, planets orbit around the Sun at the center of the universe. His ...

worldview, and in 1633 this view had given rise a great conflict between Galileo Galilei

Galileo di Vincenzo Bonaiuti de' Galilei (15 February 1564 – 8 January 1642), commonly referred to as Galileo Galilei ( , , ) or mononymously as Galileo, was an Italian astronomer, physicist and engineer, sometimes described as a poly ...

and the Roman Catholic Inquisition. Descartes knew about this controversy and did not wish to get involved. ''The World'' was not published until 1664, ten years after his death. The modern concept of inertia is credited to Galileo. Based on his experiments, Galileo concluded that the "natural" behavior of a moving body was to keep moving, until something else interfered with it. In ''Two New Sciences'' (1638) Galileo wrote:Galileo recognized that in projectile motion, the Earth's gravity affects vertical but not horizontal motion. However, Galileo's idea of inertia was not exactly the one that would be codified into Newton's first law. Galileo thought that a body moving a long distance inertially would follow the curve of the Earth. This idea was corrected by Isaac Beeckman, Descartes, and

The modern concept of inertia is credited to Galileo. Based on his experiments, Galileo concluded that the "natural" behavior of a moving body was to keep moving, until something else interfered with it. In ''Two New Sciences'' (1638) Galileo wrote:Galileo recognized that in projectile motion, the Earth's gravity affects vertical but not horizontal motion. However, Galileo's idea of inertia was not exactly the one that would be codified into Newton's first law. Galileo thought that a body moving a long distance inertially would follow the curve of the Earth. This idea was corrected by Isaac Beeckman, Descartes, and Pierre Gassendi

Pierre Gassendi (; also Pierre Gassend, Petrus Gassendi, Petrus Gassendus; 22 January 1592 – 24 October 1655) was a French philosopher, Catholic priest, astronomer, and mathematician. While he held a church position in south-east France, he a ...

, who recognized that inertial motion should be motion in a straight line. Descartes published his laws of nature (laws of motion) with this correction in '' Principles of Philosophy'' (''Principia Philosophiae'') in 1644, with the heliocentric part toned down. According to American philosopher Richard J. Blackwell, Dutch scientist

According to American philosopher Richard J. Blackwell, Dutch scientist Christiaan Huygens

Christiaan Huygens, Halen, Lord of Zeelhem, ( , ; ; also spelled Huyghens; ; 14 April 1629 – 8 July 1695) was a Dutch mathematician, physicist, engineer, astronomer, and inventor who is regarded as a key figure in the Scientific Revolution ...

had worked out his own, concise version of the law in 1656.

Force and the second law

Christiaan Huygens, in his ''Horologium Oscillatorium

(English language, English: ''The Pendulum Clock: or Geometrical Demonstrations Concerning the Motion of Pendula as Applied to Clocks'') is a book published by Dutch mathematician and physicist Christiaan Huygens in 1673 and his major work on p ...

'' (1673), put forth the hypothesis that "By the action of gravity, whatever its sources, it happens that bodies are moved by a motion composed both of a uniform motion in one direction or another and of a motion downward due to gravity." Newton's second law generalized this hypothesis from gravity to all forces.

One important characteristic of Newtonian physics is that forces can act at a distance without requiring physical contact. For example, the Sun and the Earth pull on each other gravitationally, despite being separated by millions of kilometres. This contrasts with the idea, championed by Descartes among others, that the Sun's gravity held planets in orbit by swirling them in a vortex of transparent matter, '' aether''. Newton considered aetherial explanations of force but ultimately rejected them.

Momentum conservation and the third law

Johannes Kepler

Johannes Kepler (27 December 1571 – 15 November 1630) was a German astronomer, mathematician, astrologer, Natural philosophy, natural philosopher and writer on music. He is a key figure in the 17th-century Scientific Revolution, best know ...

suggested that gravitational attractions were reciprocal — that, for example, the Moon pulls on the Earth while the Earth pulls on the Moon — but he did not argue that such pairs are equal and opposite. In his '' Principles of Philosophy'' (1644), Descartes introduced the idea that during a collision between bodies, a "quantity of motion" remains unchanged. Descartes defined this quantity somewhat imprecisely by adding up the products of the speed and "size" of each body, where "size" for him incorporated both volume and surface area. Moreover, Descartes thought of the universe as a plenum, that is, filled with matter, so all motion required a body to displace a medium as it moved.

During the 1650s, Huygens studied collisions between hard spheres and deduced a principle that is now identified as the conservation of momentum. Christopher Wren

Sir Christopher Wren FRS (; – ) was an English architect, astronomer, mathematician and physicist who was one of the most highly acclaimed architects in the history of England. Known for his work in the English Baroque style, he was ac ...

would later deduce the same rules for elastic collisions that Huygens had, and John Wallis

John Wallis (; ; ) was an English clergyman and mathematician, who is given partial credit for the development of infinitesimal calculus.

Between 1643 and 1689 Wallis served as chief cryptographer for Parliament and, later, the royal court. ...

would apply momentum conservation to study inelastic collisions. Newton cited the work of Huygens, Wren, and Wallis to support the validity of his third law.

Newton arrived at his set of three laws incrementally. In a 1684 manuscript written to Huygens, he listed four laws: the principle of inertia, the change of motion by force, a statement about relative motion that would today be called Galilean invariance