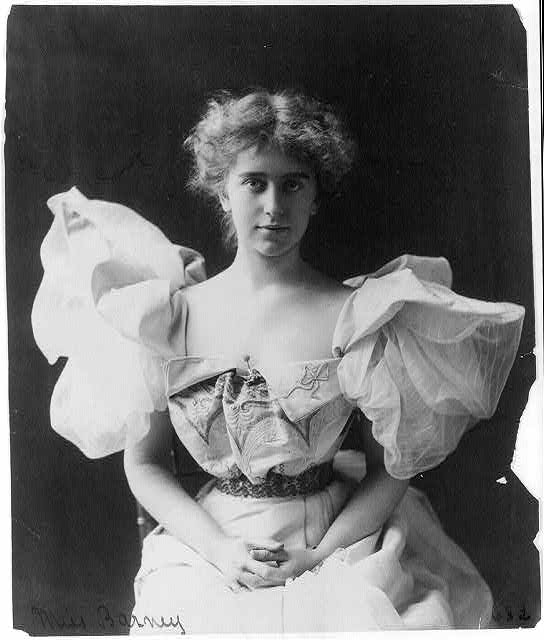

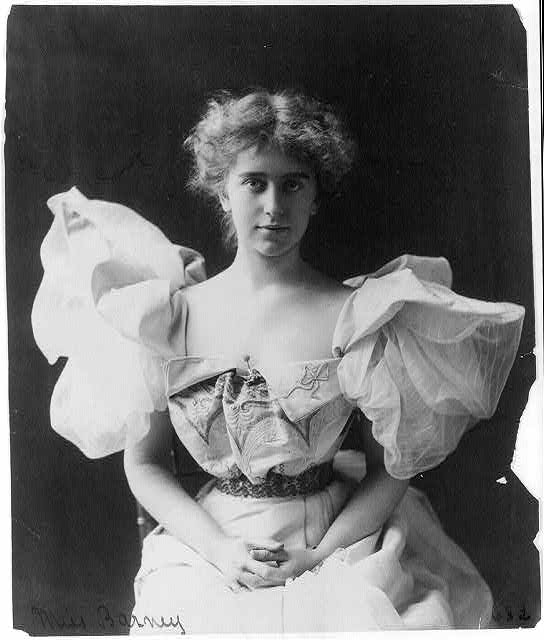

Natalie Barney on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Natalie Clifford Barney (October 31, 1876 – February 2, 1972) was an American writer who hosted a

Natalie Clifford Barney (October 31, 1876 – February 2, 1972) was an American writer who hosted a

Barney's earliest intimate relationship was with

Barney's earliest intimate relationship was with

Barney stood to inherit some family wealth held in trust if she either married or waited for her father's death. While courting de Pougy, Barney was engaged to Robert Cassat, a member of another wealthy railroad family. Barney was open with Cassat about her love of women and relationship with de Pougy. In the hopes of securing the Barney trust money, the three briefly considered a rushed wedding between Barney and Cassat and an adoption of de Pougy. When Cassat ended the engagement, Barney attempted unsuccessfully to persuade her father to give her the money anyway.

By the end of 1899, the two had broken up after quarreling repeatedly over Barney's desire to "rescue" de Pougy from her life as a courtesan. Despite the breakup, the two continued having liaisons for decades.

Their on-and-off affair became the subject of de Pougy's tell-all ''

Barney stood to inherit some family wealth held in trust if she either married or waited for her father's death. While courting de Pougy, Barney was engaged to Robert Cassat, a member of another wealthy railroad family. Barney was open with Cassat about her love of women and relationship with de Pougy. In the hopes of securing the Barney trust money, the three briefly considered a rushed wedding between Barney and Cassat and an adoption of de Pougy. When Cassat ended the engagement, Barney attempted unsuccessfully to persuade her father to give her the money anyway.

By the end of 1899, the two had broken up after quarreling repeatedly over Barney's desire to "rescue" de Pougy from her life as a courtesan. Despite the breakup, the two continued having liaisons for decades.

Their on-and-off affair became the subject of de Pougy's tell-all ''

''Je Me Souviens'' was published in 1910, after Vivien's death. That same year, Barney published ''Actes et Entr'actes'' (''Acts and Interludes''), a collection of short plays and poems. One of the plays was ''Équivoque'' (''Ambiguity''), a revisionist version of the legend of Sappho's death: instead of throwing herself off a cliff for the love of

''Je Me Souviens'' was published in 1910, after Vivien's death. That same year, Barney published ''Actes et Entr'actes'' (''Acts and Interludes''), a collection of short plays and poems. One of the plays was ''Équivoque'' (''Ambiguity''), a revisionist version of the legend of Sappho's death: instead of throwing herself off a cliff for the love of

For over 60 years, Barney hosted a literary

For over 60 years, Barney hosted a literary

Despite several of her lovers' objections, Barney practiced, and advocated,

Despite several of her lovers' objections, Barney practiced, and advocated,

Élisabeth de Gramont, the

Élisabeth de Gramont, the

Barney's support of Wilde included occasional permission to stay for a few weeks at Rue Jacob. Brooks' disapproval of the relationship increased over the years, aggravated by Wilde's presence in Barney's home. Wilde, the only of Barney's loves to share her enthusiastic rejection of monogamy, strove conscientiously but futilely for Brooks' favor. This culminated in Brooks' ultimatum, delivered in 1931, in which she described Wilde as a rat "gnawing at the very foundation of our friendship". Barney chose Brooks and separated from Wilde; Brooks later allowed Wilde to return and became less critical of Wilde's ways.

Like Vivien, Wilde was intensely self-destructive and struggled deeply with mental illness. She attempted suicide several times, and spent much of her life addicted to alcohol and heroin. Barney, a vocal opponent of drug use and alcoholism, financed

Barney's support of Wilde included occasional permission to stay for a few weeks at Rue Jacob. Brooks' disapproval of the relationship increased over the years, aggravated by Wilde's presence in Barney's home. Wilde, the only of Barney's loves to share her enthusiastic rejection of monogamy, strove conscientiously but futilely for Brooks' favor. This culminated in Brooks' ultimatum, delivered in 1931, in which she described Wilde as a rat "gnawing at the very foundation of our friendship". Barney chose Brooks and separated from Wilde; Brooks later allowed Wilde to return and became less critical of Wilde's ways.

Like Vivien, Wilde was intensely self-destructive and struggled deeply with mental illness. She attempted suicide several times, and spent much of her life addicted to alcohol and heroin. Barney, a vocal opponent of drug use and alcoholism, financed

The salon resumed in 1949 and continued to attract young writers for whom it was as much a piece of history as a place where literary reputations were made.

The salon resumed in 1949 and continued to attract young writers for whom it was as much a piece of history as a place where literary reputations were made.

Barney and the women in her social circle are the subject of Djuna Barnes's ''Ladies Almanack'' (1928), a ''roman à clef'' written in an archaic, Rabelaisian style, with Barnes's own illustrations in the style of Elizabethan woodcuts. She has the lead role as Dame Evangeline Musset, "who was in her Heart one Grand Red Cross for the Pursuance, the Relief and the Distraction, of such Girls as in their Hinder Parts, and their Fore Parts, and in whatsoever Parts did suffer them most, lament Cruelly". "[A] Pioneer and a Menace" in her youth, Dame Musset has reached "a witty and learned Fifty"; she rescues women in distress, dispenses wisdom, and upon her death is elevated to sainthood. Also appearing pseudonymously are de Gramont, Brooks, Dolly Wilde, Hall and her partner Una, Lady Troubridge, Janet Flanner and Solita Solano, and Mina Loy. The obscure language, inside jokes, and ambiguity of ''Ladies Almanack'' have kept critics arguing about whether it is an affectionate satire or a bitter attack, but Barney herself loved the book and reread it throughout her life.

On October 26, 2009, Barney was honored with a historical marker in her home town of Dayton, Ohio. The marker is the first in Ohio to note the sexual orientation of its honoree.

Barney's French novel, ''Amants féminins ou la troisième'', believed to have been written in 1926, was published in 2013. It was translated into English by Chelsea Ray and published in 2016 as ''Women Lovers or The Third Woman''.

Barney and the women in her social circle are the subject of Djuna Barnes's ''Ladies Almanack'' (1928), a ''roman à clef'' written in an archaic, Rabelaisian style, with Barnes's own illustrations in the style of Elizabethan woodcuts. She has the lead role as Dame Evangeline Musset, "who was in her Heart one Grand Red Cross for the Pursuance, the Relief and the Distraction, of such Girls as in their Hinder Parts, and their Fore Parts, and in whatsoever Parts did suffer them most, lament Cruelly". "[A] Pioneer and a Menace" in her youth, Dame Musset has reached "a witty and learned Fifty"; she rescues women in distress, dispenses wisdom, and upon her death is elevated to sainthood. Also appearing pseudonymously are de Gramont, Brooks, Dolly Wilde, Hall and her partner Una, Lady Troubridge, Janet Flanner and Solita Solano, and Mina Loy. The obscure language, inside jokes, and ambiguity of ''Ladies Almanack'' have kept critics arguing about whether it is an affectionate satire or a bitter attack, but Barney herself loved the book and reread it throughout her life.

On October 26, 2009, Barney was honored with a historical marker in her home town of Dayton, Ohio. The marker is the first in Ohio to note the sexual orientation of its honoree.

Barney's French novel, ''Amants féminins ou la troisième'', believed to have been written in 1926, was published in 2013. It was translated into English by Chelsea Ray and published in 2016 as ''Women Lovers or The Third Woman''.

The Temple of Friendship at ruevisconti.com

(French language, dozens of photos)

Djuna Barnes Papers

(102 linear ft.) are housed at the McKeldin Library at the University of Maryland

Romaine Brooks Papers, 1940–1968

(1.1 linear ft.) are housed at the Smithsonian Institution Archives of American Art

When Natalie Barney met Oscar Wilde

Letter from Natalie Clifford Barney to Liane de Pougy

(in French) * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Barney, Natalie 1876 births 1972 deaths 20th-century American novelists Activists from Ohio American expatriates in France American pacifists American people of Dutch descent American people of English descent American people of French descent American people of German-Jewish descent American poets in French American salon-holders American women dramatists and playwrights American women novelists American women poets Burials at Passy Cemetery American lesbian writers LGBT dramatists and playwrights LGBT memoirists LGBT people from Ohio American LGBT poets American LGBT novelists Novelists from Ohio Writers from Dayton, Ohio 20th-century American women Muses

Natalie Clifford Barney (October 31, 1876 – February 2, 1972) was an American writer who hosted a

Natalie Clifford Barney (October 31, 1876 – February 2, 1972) was an American writer who hosted a literary salon

A salon is a gathering of people held by an inspiring host. During the gathering they amuse one another and increase their knowledge through conversation. These gatherings often consciously followed Horace's definition of the aims of poetry, "ei ...

at her home in Paris that brought together French and international writers. She influenced other authors through her salon and also with her poetry, plays, and epigram

An epigram is a brief, interesting, memorable, and sometimes surprising or satirical statement. The word is derived from the Greek "inscription" from "to write on, to inscribe", and the literary device has been employed for over two mille ...

s, often thematically tied to her lesbianism and feminism

Feminism is a range of socio-political movements and ideologies that aim to define and establish the political, economic, personal, and social equality of the sexes. Feminism incorporates the position that society prioritizes the male po ...

.

Barney was born into a wealthy family. She was partly educated in France, and expressed a desire from a young age to live openly as a lesbian. She moved to France with her first romantic partner, Eva Palmer

Evelina "Eva" Palmer-Sikelianos ( el, Εύα Πάλμερ-Σικελιανού; January 9, 1874 – June 4, 1952) was an American woman notable for her study and promotion of Classical Greek culture, weaving, theater, choral dance and music. Palm ...

. Inspired by the work of Sappho

Sappho (; el, Σαπφώ ''Sapphō'' ; Aeolic Greek ''Psápphō''; c. 630 – c. 570 BC) was an Archaic Greek poet from Eresos or Mytilene on the island of Lesbos. Sappho is known for her lyric poetry, written to be sung while accompanied ...

, Barney began publishing love poems to women under her own name as early as 1900. Writing in both French and English, she supported feminism and pacifism

Pacifism is the opposition or resistance to war, militarism (including conscription and mandatory military service) or violence. Pacifists generally reject theories of Just War. The word ''pacifism'' was coined by the French peace campaig ...

. She opposed monogamy

Monogamy ( ) is a form of dyadic relationship in which an individual has only one partner during their lifetime. Alternately, only one partner at any one time ( serial monogamy) — as compared to the various forms of non-monogamy (e.g., polyg ...

and had many overlapping long and short-term relationships, including on-and-off romances with poet Renée Vivien

Renée Vivien (born Pauline Mary Tarn; 11 June 1877 – 18 November 1909) was a British poet who wrote in French, in the style of the Symbolistes and the Parnassiens. A high-profile lesbian in the Paris of the Belle Époque, she is notable for he ...

and courtesan Liane de Pougy

Liane de Pougy (born Anne-Marie Chassaigne, 2 July 1869 – 26 December 1950), was a Folies Bergère vedette and dancer renowned as one of Paris's most beautiful and notorious courtesans.

Early life and marriage

Anne-Marie Chassaigne was born ...

and longer relationships with writer Élisabeth de Gramont

Antoinette Corisande Élisabeth, Duchess of Clermont-Tonnerre (née de Gramont; 23 April 1875 – 6 December 1954) was a French writer of the early 20th century, best known for her long-term lesbian relationship with Natalie Clifford Barney ...

and painter Romaine Brooks

Romaine Brooks (born Beatrice Romaine Goddard; May 1, 1874 – December 7, 1970) was an American painter who worked mostly in Paris and Capri. She specialized in portraiture and used a subdued tonal palette keyed to the color gray. Brooks ignore ...

.

Barney hosted a salon at her home in Paris for more than 60 years, bringing together writers and artists from around the world, including many leading figures in French, American, and British literature. Attendees of various sexualities expressed themselves and mingled comfortably at the weekly gatherings. She worked to promote writing by women and hosted a "Women's Academy" (L'Académie des Femmes) in her salon as a response to the all-male French Academy

French (french: français(e), link=no) may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to France

** French language, which originated in France, and its various dialects and accents

** French people, a nation and ethnic group identified with France ...

. The salon closed for the duration of World War II while Barney lived in Italy with Brooks. She initially espoused some pro-fascist views, but supported the Allies by the end of the war. After the war, she returned to Paris, resumed the salon, and continued influencing or inspiring writers such as Truman Capote

Truman Garcia Capote ( ; born Truman Streckfus Persons; September 30, 1924 – August 25, 1984) was an American novelist, screenwriter, playwright and actor. Several of his short stories, novels, and plays have been praised as literary classics, ...

.

Barney had a wide literary influence. Remy de Gourmont

Remy de Gourmont (4 April 1858 – 27 September 1915) was a French symbolist poet, novelist, and influential critic. He was widely read in his era, and an important influence on Blaise Cendrars and Georges Bataille. The spelling ''Rémy'' de G ...

addressed public letters to her using the nickname ''l'Amazon'' (the Amazon), and Barney's association with both de Gourmont and the nickname lasted until her death. Her life and love affairs served as inspiration for many novels written by others, ranging from de Pougy's erotic French bestseller ''Idylle Saphique'' to Radclyffe Hall

Marguerite Antonia Radclyffe Hall (12 August 1880 – 7 October 1943) was an English poet and author, best known for the novel '' The Well of Loneliness'', a groundbreaking work in lesbian literature. In adulthood, Hall often went by the name ...

's ''The Well of Loneliness

''The Well of Loneliness'' is a lesbian novel by British author Radclyffe Hall that was first published in 1928 by Jonathan Cape. It follows the life of Stephen Gordon, an Englishwoman from an upper-class family whose " sexual inversion" (homo ...

'', the most famous lesbian novel of the twentieth century.

Early life

Barney was born in 1876 inDayton, Ohio

Dayton () is the sixth-largest city in the U.S. state of Ohio and the county seat of Montgomery County. A small part of the city extends into Greene County. The 2020 U.S. census estimate put the city population at 137,644, while Greater ...

, to Albert Clifford Barney and Alice Pike Barney

Alice Pike Barney (born Alice Pike; 1857–1931) was an American painter. She was active in Washington, D.C. and worked to make Washington into a center of the arts. Her two daughters were the writer and salon hostess Natalie Clifford Barney and ...

. Alice learned to love the arts from her father, who owned Pike's Opera House

Pike's Opera House, later renamed the Grand Opera House, was a theater in New York City on the northwest corner of 8th Avenue and 23rd Street, in the Chelsea neighborhood of Manhattan. It was constructed in 1868, at a cost of a million dolla ...

in Cincinnati, Ohio

Cincinnati ( ) is a city in the U.S. state of Ohio and the county seat of Hamilton County. Settled in 1788, the city is located at the northern side of the confluence of the Licking and Ohio rivers, the latter of which marks the state lin ...

. Albert Barney partially inherited his family's railroad car manufacturing company, Barney & Smith Car Works.

When Barney was five years old, she encountered Oscar Wilde

Oscar Fingal O'Flahertie Wills Wilde (16 October 185430 November 1900) was an Irish poet and playwright. After writing in different forms throughout the 1880s, he became one of the most popular playwrights in London in the early 1890s. He is ...

at a New York hotel. Wilde scooped her up as she ran past him fleeing a group of small boys and held her out of their reach. Then he sat her down on his knee and told her a story. The next day he joined Barney and her mother on the beach, and Wilde inspired Alice to pursue art seriously, which she did despite her husband's disapproval.

Like many girls of her time, Barney had a haphazard education. Her interest in the French language began with a governess

A governess is a largely obsolete term for a woman employed as a private tutor, who teaches and trains a child or children in their home. A governess often lives in the same residence as the children she is teaching. In contrast to a nanny, th ...

who read Jules Verne

Jules Gabriel Verne (;''Longman Pronunciation Dictionary''. ; 8 February 1828 – 24 March 1905) was a French novelist, poet, and playwright. His collaboration with the publisher Pierre-Jules Hetzel led to the creation of the ''Voyages extraord ...

stories aloud to her, so she would have to learn quickly to understand them. She and her younger sister Laura

Laura may refer to:

People

* Laura (given name)

* Laura, the British code name for the World War I Belgian spy Marthe Cnockaert

Places Australia

* Laura, Queensland, a town on the Cape York Peninsula

* Laura, South Australia

* Laura Bay, a bay on ...

attended Les Ruches, a French boarding school in Fontainebleau

Fontainebleau (; ) is a commune in the metropolitan area of Paris, France. It is located south-southeast of the centre of Paris. Fontainebleau is a sub-prefecture of the Seine-et-Marne department, and it is the seat of the ''arrondissement ...

, France, founded by feminist Marie Souvestre

Marie Souvestre (28 April 1830 – 30 March 1905) was an educator who sought to develop independent minds in young women. She founded a school in France and when she left the school with one of her teachers she founded Allenswood Academy in Lo ...

. As an adult, she spoke and wrote French fluently.

When she was ten, her family moved from Ohio to the Scott Circle

Scott Circle is an area in the northwest quadrant of Washington, D.C. that is centred on the junction of Massachusetts Avenue, Rhode Island Avenue, and 16th Street, N.W.

Originally a neighborhood recreational area, unlike Dupont Circle where poli ...

area of Washington D.C., spending summers at their large cottage in Bar Harbor, Maine

Bar Harbor is a resort town on Mount Desert Island in Hancock County, Maine

Maine () is a U.S. state, state in the New England and Northeastern United States, Northeastern regions of the United States. It borders New Hampshire to the wes ...

. As the rebellious and unconventional daughter of one of the wealthiest families in town, she was often mentioned in Washington newspapers. In her early twenties she made headlines by galloping through Bar Harbor while driving a second horse on a lead ahead of her, riding astride instead of sidesaddle

Sidesaddle riding is a form of equestrianism that uses a type of saddle which allows female riders to sit aside rather than astride an equine. Sitting aside dates back to antiquity and developed in European countries in the Middle Ages as a way ...

.

Barney later said she knew she was a lesbian by age twelve, and she was determined to "live openly, without hiding anything".

Early relationships

Eva Palmer

Barney's earliest intimate relationship was with

Barney's earliest intimate relationship was with Eva Palmer

Evelina "Eva" Palmer-Sikelianos ( el, Εύα Πάλμερ-Σικελιανού; January 9, 1874 – June 4, 1952) was an American woman notable for her study and promotion of Classical Greek culture, weaving, theater, choral dance and music. Palm ...

. They became acquainted during summer vacations in Bar Harbor, Maine, and began a sexual relationship during one such trip in 1893. Barney likened Palmer's appearance to that of a medieval virgin. The two remained close for several years. As young adults in Paris they shared an apartment at 4 rue Chalgrin and eventually took their own residences in Neuilly

Neuilly (, ) is a common place name in France, deriving from the male given name ''Nobilis'' or '' Novellius''. It may refer to:Adrian Room, ''Placenames of the World'' (2006), p. 265.

References

{{SIA ...

. Barney frequently solicited Palmer's help in her romantic pursuits of other women, including Pauline Tarn. Palmer ultimately left Barney's side for Greece and eventually married Angelos Sikelianos

Angelos Sikelianos ( el, Άγγελος Σικελιανός; 28 March 1884 – 19 June 1951) was a Greek lyric poet and playwright. His themes include Greek history, religious symbolism as well as universal harmony in poems such as ''The Moonstru ...

. Their relationship did not survive this turn of events: Barney took a dim view of Angelos and heated letters were exchanged. Later in their lives the friendship was repaired through correspondence and reunions in New York.

Liane de Pougy

In 1899, after seeing thecourtesan

Courtesan, in modern usage, is a euphemism for a "kept" mistress or prostitute, particularly one with wealthy, powerful, or influential clients. The term historically referred to a courtier, a person who attended the court of a monarch or other ...

Liane de Pougy

Liane de Pougy (born Anne-Marie Chassaigne, 2 July 1869 – 26 December 1950), was a Folies Bergère vedette and dancer renowned as one of Paris's most beautiful and notorious courtesans.

Early life and marriage

Anne-Marie Chassaigne was born ...

at a dance hall in Paris, Barney presented herself at de Pougy's residence in a page

Page most commonly refers to:

* Page (paper), one side of a leaf of paper, as in a book

Page, PAGE, pages, or paging may also refer to:

Roles

* Page (assistance occupation), a professional occupation

* Page (servant), traditionally a young ma ...

costume and announced she was a "page of love" sent by Sappho

Sappho (; el, Σαπφώ ''Sapphō'' ; Aeolic Greek ''Psápphō''; c. 630 – c. 570 BC) was an Archaic Greek poet from Eresos or Mytilene on the island of Lesbos. Sappho is known for her lyric poetry, written to be sung while accompanied ...

. Although de Pougy was one of the most famous women in France, constantly sought after by wealthy and titled men, Barney's audacity charmed her.

Barney stood to inherit some family wealth held in trust if she either married or waited for her father's death. While courting de Pougy, Barney was engaged to Robert Cassat, a member of another wealthy railroad family. Barney was open with Cassat about her love of women and relationship with de Pougy. In the hopes of securing the Barney trust money, the three briefly considered a rushed wedding between Barney and Cassat and an adoption of de Pougy. When Cassat ended the engagement, Barney attempted unsuccessfully to persuade her father to give her the money anyway.

By the end of 1899, the two had broken up after quarreling repeatedly over Barney's desire to "rescue" de Pougy from her life as a courtesan. Despite the breakup, the two continued having liaisons for decades.

Their on-and-off affair became the subject of de Pougy's tell-all ''

Barney stood to inherit some family wealth held in trust if she either married or waited for her father's death. While courting de Pougy, Barney was engaged to Robert Cassat, a member of another wealthy railroad family. Barney was open with Cassat about her love of women and relationship with de Pougy. In the hopes of securing the Barney trust money, the three briefly considered a rushed wedding between Barney and Cassat and an adoption of de Pougy. When Cassat ended the engagement, Barney attempted unsuccessfully to persuade her father to give her the money anyway.

By the end of 1899, the two had broken up after quarreling repeatedly over Barney's desire to "rescue" de Pougy from her life as a courtesan. Despite the breakup, the two continued having liaisons for decades.

Their on-and-off affair became the subject of de Pougy's tell-all ''roman à clef

''Roman à clef'' (, anglicised as ), French for ''novel with a key'', is a novel about real-life events that is overlaid with a façade of fiction. The fictitious names in the novel represent real people, and the "key" is the relationship b ...

'', ''Idylle Saphique'' (''Sapphic Idyll''). Published in 1901, the book and its sexually suggestive scenes became the talk of Paris, reprinted more than 70 times in its first year. Barney was soon well known as the model for one of the characters.

Barney herself contributed a chapter to ''Idylle Saphique'' in which she described reclining at de Pougy's feet in a screened box at the theater, watching Sarah Bernhardt's play ''Hamlet

''The Tragedy of Hamlet, Prince of Denmark'', often shortened to ''Hamlet'' (), is a tragedy written by William Shakespeare sometime between 1599 and 1601. It is Shakespeare's longest play, with 29,551 words. Set in Denmark, the play depi ...

''. During intermission, Barney (as "Flossie") compares Hamlet's plight with that of women: "What is there for women who feel the passion for action when pitiless Destiny holds them in chains? Destiny made us women at a time when the law of men is the only law that is recognized." She also wrote ''Lettres à une Connue'' (''Letters to a Woman I Have Known''), her own epistolary novel

An epistolary novel is a novel written as a series of letters. The term is often extended to cover novels that intersperse documents of other kinds with the letters, most commonly diary entries and newspaper clippings, and sometimes considered ...

about the affair. Although Barney failed to find a publisher for the book and later called it naïve and clumsy, it is notable for its discussion of homosexuality, which Barney regarded as natural and compared to albinism

Albinism is the congenital absence of melanin in an animal or plant resulting in white hair, feathers, scales and skin and pink or blue eyes. Individuals with the condition are referred to as albino.

Varied use and interpretation of the term ...

. "My queerness," she said, "is not a vice, is not deliberate, and harms no one."

Renée Vivien

In November 1899, Barney met the poet Pauline Tarn, better known by her pen nameRenée Vivien

Renée Vivien (born Pauline Mary Tarn; 11 June 1877 – 18 November 1909) was a British poet who wrote in French, in the style of the Symbolistes and the Parnassiens. A high-profile lesbian in the Paris of the Belle Époque, she is notable for he ...

. For Vivien it was love at first sight

Love at first sight is a personal experience as well as a common trope in literature: a person or character feels an instant, extreme, and ultimately long-lasting romantic attraction for a stranger upon first seeing that stranger. Described by p ...

, while Barney became fascinated with Vivien after hearing her recite one of her poems, which Barney described as "haunted by the desire for death". Their romantic relationship was also a creative exchange that inspired both of them to write. Barney provided a feminist theoretical framework which Vivien explored in her poetry. They adapted the imagery of the Symbolist poet

Symbolism was a late 19th-century art movement of French and Belgian origin in poetry and other arts seeking to represent absolute truths symbolically through language and metaphorical images, mainly as a reaction against naturalism and realism ...

s along with the conventions of courtly love

Courtly love ( oc, fin'amor ; french: amour courtois ) was a medieval European literary conception of love that emphasized nobility and chivalry. Medieval literature is filled with examples of knights setting out on adventures and performing vari ...

to describe love between women, also finding examples of heroic women in history and myth. Sappho was an especially important influence and they studied Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

so as to read the surviving fragments of her poetry in the original. Both wrote plays about her life.

Vivien saw Barney as a muse

In ancient Greek religion and mythology, the Muses ( grc, Μοῦσαι, Moûsai, el, Μούσες, Múses) are the inspirational goddesses of literature, science, and the arts. They were considered the source of the knowledge embodied in the ...

and as Barney put it, "she had found new inspiration through me, almost without knowing me". Barney felt Vivien had cast her as a '' femme fatale'' and that she wanted "to lose herself... entirely in suffering" for the sake of her art. Vivien also believed in monogamy

Monogamy ( ) is a form of dyadic relationship in which an individual has only one partner during their lifetime. Alternately, only one partner at any one time ( serial monogamy) — as compared to the various forms of non-monogamy (e.g., polyg ...

, which Barney was unwilling to agree to. While Barney was visiting her family in Washington, D.C. in 1901, Vivien stopped answering her letters. Barney tried to get her back for years, at one point persuading a friend, operatic mezzo-soprano Emma Calvé

Emma Calvé, born Rosa Emma Calvet (15 August 1858 – 6 January 1942) was a French operatic soprano.

Calvé was probably the most famous French female opera singer of the Belle Époque. Hers was an international career, and she sang regularl ...

, to sing under Vivien's window so she could throw a poem (wrapped around a bouquet of flowers) up to Vivien on her balcony. Both flowers and poem were intercepted and returned by a governess.

In 1904 she wrote ''Je Me Souviens'' (''I Remember''), an intensely personal prose poem about their relationship which was presented as a single handwritten copy to Vivien in an attempt to win her back. They reconciled and traveled together to Lesbos

Lesbos or Lesvos ( el, Λέσβος, Lésvos ) is a Greek island located in the northeastern Aegean Sea. It has an area of with approximately of coastline, making it the third largest island in Greece. It is separated from Asia Minor by the n ...

, where they lived happily together for a short time and discussed starting a school of poetry for women like the one which Sappho, according to tradition, had founded on Lesbos some 2,500 years before. However, Vivien soon got a letter from her lover Baroness Hélène van Zuylen

Baroness Hélène van Zuylen van Nijevelt van de Haar or Hélène de Zuylen de Nyevelt de Haar, née de Rothschild (21 August 1863 – 17 October 1947) was a French author and a member of the prominent Rothschild banking family. She collaborated ...

and went to Constantinople

la, Constantinopolis ota, قسطنطينيه

, alternate_name = Byzantion (earlier Greek name), Nova Roma ("New Rome"), Miklagard/Miklagarth ( Old Norse), Tsargrad ( Slavic), Qustantiniya (Arabic), Basileuousa ("Queen of Cities"), Megalopolis ( ...

thinking she would break up with her in person. Vivien planned to meet Barney in Paris afterward, but instead stayed with the Baroness. This time, the breakup was permanent.

Vivien's health declined rapidly after this. The author Colette

Sidonie-Gabrielle Colette (; 28 January 1873 – 3 August 1954), known mononymously as Colette, was a French author and woman of letters. She was also a mime, actress, and journalist. Colette is best known in the English-speaking world for her ...

, who herself had an affair with Barney in 1906, was Vivien's friend and neighbor. According to Colette, Vivien ate almost nothing and drank heavily, even rinsing her mouth with perfumed water to hide the smell. Colette's account has led some to call Vivien an anorexic

Anorexia nervosa, often referred to simply as anorexia, is an eating disorder characterized by underweight, low weight, Calorie restriction, food restriction, body image disturbance, fear of gaining weight, and an overpowering desire to be thi ...

, but this diagnosis did not yet exist at the time. Vivien was also addicted to the sedative chloral hydrate

Chloral hydrate is a geminal diol with the formula . It is a colorless solid. It has limited use as a sedative and hypnotic pharmaceutical drug. It is also a useful laboratory chemical reagent and precursor. It is derived from chloral (trich ...

. In 1908 she attempted suicide by overdosing on laudanum

Laudanum is a tincture of opium containing approximately 10% powdered opium by weight (the equivalent of 1% morphine). Laudanum is prepared by dissolving extracts from the opium poppy (''Papaver somniferum Linnaeus'') in alcohol (ethanol).

R ...

and died the following year. In a memoir written fifty years later, Barney said, "She could not be saved. Her life was a long suicide. Everything turned to dust and ashes in her hands."

In 1949, two years after the death of Hélène van Zuylen, Barney restored the Renée Vivien Prize

Renée (without the accent in non-French speaking countries) is a French/Latin feminine given name.

Renée is the female form of René, with the extra –e making it feminine according to French grammar. The name Renée is the French form of ...

with a financial grant under the authority of the ''Société des gens de lettres

Lactalis is a French multinational dairy products corporation, owned by the Besnier family and based in Laval, Mayenne, France. The company's former name was Besnier SA.

Lactalis is the largest dairy products group in the world, and is the sec ...

'' and took on the chairmanship of the jury in 1950.

Olive Custance

Barney purchased and read ''Opals'' in 1900, a debut collection of poems byOlive Custance

Olive Eleanor Custance (7 February 1874 – 12 February 1944), also known as Lady Alfred Douglas, was an English poet and wife of Lord Alfred Douglas. She was part of the aesthetic movement of the 1890s, and a contributor to ''The Yellow Boo ...

. Responding to the lesbian themes in the poetry, Barney began corresponding with Custance and exchanging poems. The two met in 1901 at Barney and Vivien's home in Paris, and they soon began a short romantic relationship. While Barney's infidelity aggravated Vivien, Custance was also pursuing a relationship with Lord Alfred Douglas

Lord Alfred Bruce Douglas (22 October 1870 – 20 March 1945), also known as Bosie Douglas, was an English poet and journalist, and a lover of Oscar Wilde. At Oxford he edited an undergraduate journal, ''The Spirit Lamp'', that carried a homoer ...

, who she would later marry.

Poetry and plays

In 1900, Barney published her first book, a collection of poems called '' Quelques Portraits-Sonnets de Femmes'' (''Some Portrait-Sonnets of Women''). The poems were written in traditional French verse and a formal, old-fashioned style since Barney did not care forfree verse

Free verse is an open form of poetry, which in its modern form arose through the French '' vers libre'' form. It does not use consistent meter patterns, rhyme, or any musical pattern. It thus tends to follow the rhythm of natural speech.

Defini ...

. ''Quelques Portraits'' has been described as "apprentice work", a classifier which betrays its historical significance. According to biographer Suzanne Rodriguez, the collection's publication meant that Barney became the first woman poet to openly write about the love of women since Sappho. Her mother contributed pastel illustrations of the poems' subjects, wholly unaware three of the four women who modelled for her were her daughter's lovers.

Reviews were generally positive and glossed over the lesbian theme of the poems, some even misrepresenting it. The ''Washington Mirror'' said Barney "writes odes to men's lips and eyes; not like a novice, either". However, a headline in a society gossip paper cried out "Sappho Sings in Washington" and this alerted her father, who bought and destroyed the publisher's remaining stock and printing plates.

To escape her father's sway Barney published her next book, ''Cinq Petits Dialogues Grecs'' (''Five Short Greek Dialogues'', 1901), under the pseudonym Tryphé

Tryphé (Greek: '' τρυφἠ'') – variously glossed as "softness",

"voluptuousness",

"magnificence"

and "extravagance", none fully adequate – is a concept that drew attention (and severe criticism) in Roman antiquity when it became a signif ...

. The name came from the works of Pierre Louÿs

Pierre Louÿs (; 10 December 1870 – 4 June 1925) was a French poet and writer, most renowned for lesbian and classical themes in some of his writings. He is known as a writer who sought to "express pagan sensuality with stylistic perfection" ...

, who helped edit and revise the manuscript

A manuscript (abbreviated MS for singular and MSS for plural) was, traditionally, any document written by hand – or, once practical typewriters became available, typewritten – as opposed to mechanically printed or reproduced ...

. Barney also dedicated the book to him. The first of the dialogues is set in ancient Greece and contains a long description of Sappho, who is "more faithful in her inconstancy than others in their fidelity". Another argues for paganism

Paganism (from classical Latin ''pāgānus'' "rural", "rustic", later "civilian") is a term first used in the fourth century by early Christians for people in the Roman Empire who practiced polytheism, or ethnic religions other than Judaism. ...

over Christianity. After the death of Barney's father in 1902, his approximately $9 million fortune ($ million in 2018) was left in trust with annual income to be split equally between Barney, her mother, and her sister. His death and the money freed her from any need to conceal the authorship of her books; she never used a pseudonym again. She considered scandal "the best way of getting rid of nuisances" (meaning heterosexual attention from young men).

''Je Me Souviens'' was published in 1910, after Vivien's death. That same year, Barney published ''Actes et Entr'actes'' (''Acts and Interludes''), a collection of short plays and poems. One of the plays was ''Équivoque'' (''Ambiguity''), a revisionist version of the legend of Sappho's death: instead of throwing herself off a cliff for the love of

''Je Me Souviens'' was published in 1910, after Vivien's death. That same year, Barney published ''Actes et Entr'actes'' (''Acts and Interludes''), a collection of short plays and poems. One of the plays was ''Équivoque'' (''Ambiguity''), a revisionist version of the legend of Sappho's death: instead of throwing herself off a cliff for the love of Phaon

In Greek mythology, Phaon (Ancient Greek: Φάων; ''gen''.: Φάωνος) was a mythical boatman of Mytilene in Lesbos. He was old and ugly when Aphrodite came to his boat. She put on the guise of a crone. Phaon ferried her over to Asia Minor a ...

the sailor, she does so out of grief that Phaon is marrying the woman she loves. The play incorporates quotations from Sappho's fragments, with Barney's own footnotes in Greek, and was performed with ancient Greek-inspired music and dance.

Barney did not take her poetry as seriously as Vivien did, saying "if I had one ambition it was to make my life itself into a poem". Her plays were only performed through amateur productions in her garden. According to Karla Jay

Karla Jay (born February 22, 1947) is a distinguished professor emerita at Pace University, where she taught English and directed the women's and gender studies program between 1974 and 2009. A pioneer in the field of lesbian and gay studies, she ...

, most of them lacked coherent plots and "would probably baffle even the most sympathetic audience". After 1910 she mostly wrote the epigram

An epigram is a brief, interesting, memorable, and sometimes surprising or satirical statement. The word is derived from the Greek "inscription" from "to write on, to inscribe", and the literary device has been employed for over two mille ...

s and memoirs, for which she is better known. Her last book of poetry was called ''Poems & Poemes: Autres Alliances'' and came out in 1920, bringing together romantic poetry in both French and English. Barney asked Ezra Pound

Ezra Weston Loomis Pound (30 October 1885 – 1 November 1972) was an expatriate American poet and critic, a major figure in the early modernist poetry movement, and a fascist collaborator in Italy during World War II. His works includ ...

to edit the poems, but ignored his detailed recommendations.

Salon

For over 60 years, Barney hosted a literary

For over 60 years, Barney hosted a literary salon

Salon may refer to:

Common meanings

* Beauty salon, a venue for cosmetic treatments

* French term for a drawing room, an architectural space in a home

* Salon (gathering), a meeting for learning or enjoyment

Arts and entertainment

* Salon ...

, first in Neuilly but mostly at her home at 20, Rue Jacob, in Paris. Her salon was a weekly, Friday gathering at which people met to socialize and discuss literature, art, music and any other topic of interest. Though she hosted some of the most prominent male writers of her time, Barney strove to shed light on female writers and their work.

In addition to its focus on women, Barney's salon was distinguished by its deliberately international character. She brought together expatriate

An expatriate (often shortened to expat) is a person who resides outside their native country. In common usage, the term often refers to educated professionals, skilled workers, or artists taking positions outside their home country, either ...

Modernists

Modernism is both a philosophical and arts movement that arose from broad transformations in Western society during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The movement reflected a desire for the creation of new forms of art, philosophy, an ...

with members of the French Academy

French (french: français(e), link=no) may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to France

** French language, which originated in France, and its various dialects and accents

** French people, a nation and ethnic group identified with France ...

. The salon Biographer Joan Schenkar described Barney's salon as "a place where lesbian assignations ''and'' appointments with academics could coexist in a kind of cheerful, cross-pollinating, cognitive dissonance". The range of sexualities welcomed at the salon was also uncommon in Paris, and Barney's openness with her own sexuality made her salon comfortable to homosexual or bisexual attendees.

In the 1900s Barney held early gatherings of the salon at her house in Neuilly. The entertainment included poetry readings and theatricals

''Theatricals'' is a book of two plays by Henry James published in 1894. The plays, ''Tenants'' and ''Disengaged'', had failed to be produced, so James put them out in book form with a rueful preface about his inability to get the plays onto the ...

(in which Colette sometimes performed). Mata Hari

Margaretha Geertruida MacLeod (née Zelle; 7 August 187615 October 1917), better known by the stage name Mata Hari (), was a Dutch exotic dancer and courtesan who was convicted of being a spy for Germany during World War I. She was executed ...

performed a dance once, riding into the garden naked as Lady Godiva

Lady Godiva (; died between 1066 and 1086), in Old English , was a late Anglo-Saxon noblewoman who is relatively well documented as the wife of Leofric, Earl of Mercia, and a patron of various churches and monasteries. Today, she is mainly re ...

on a white horse harnessed with turquoise

Turquoise is an opaque, blue-to-green mineral that is a hydrated phosphate of copper and aluminium, with the chemical formula . It is rare and valuable in finer grades and has been prized as a gemstone and ornamental stone for thousands of y ...

cloisonné

Cloisonné () is an ancient technique for decorating metalwork objects with colored material held in place or separated by metal strips or wire, normally of gold. In recent centuries, vitreous enamel has been used, but inlays of cut gemstone ...

. The play ''Equivoque'' may have led Barney to leave Neuilly in 1909. According to a contemporary newspaper article, her landlord objected to her holding an outdoor performance of a play about Sappho, which he felt "followed nature too closely". She canceled her lease and rented the pavilion

In architecture, ''pavilion'' has several meanings:

* It may be a subsidiary building that is either positioned separately or as an attachment to a main building. Often it is associated with pleasure. In palaces and traditional mansions of Asia ...

on Rue Jacob in Paris's Latin Quarter

The Latin Quarter of Paris (french: Quartier latin, ) is an area in the 5th and the 6th arrondissements of Paris. It is situated on the left bank of the Seine, around the Sorbonne.

Known for its student life, lively atmosphere, and bistros, ...

, and her salon was held there until the late 1960s. This was a small two-story house, separated on three sides from the main building on the street. Next to the pavilion was a large, overgrown garden with a Doric Doric may refer to:

* Doric, of or relating to the Dorians of ancient Greece

** Doric Greek, the dialects of the Dorians

* Doric order, a style of ancient Greek architecture

* Doric mode, a synonym of Dorian mode

* Doric dialect (Scotland)

* Doric ...

"Temple of Friendship" tucked into one corner. In this new location, the salon grew a more prim outward face, with poetry readings and conversation, perhaps because Barney had been told the pavilion's floors would not hold up to large dancing parties. Frequent guests during this period included poets Pierre Louÿs and Paul Claudel

Paul Claudel (; 6 August 1868 – 23 February 1955) was a French poet, dramatist and diplomat, and the younger brother of the sculptor Camille Claudel. He was most famous for his verse dramas, which often convey his devout Catholicism.

Early l ...

, diplomat Philippe Berthelot

Philippe Berthelot (October 9, 1866 – November 22, 1934) was an important French diplomat, son of Marcellin Berthelot and Sophie Berthelot. He was a republican (as opposed to monarchists and the far-right leagues at the time).

Born in Sèvr ...

and translator J. C. Mardrus

Joseph Charles Mardrus, otherwise known as "Jean-Charles Mardrus" (1868–1949), was a French physician, poet, and a noted translator. Today he is best known for his translation of the '' Thousand and One Nights'' from Arabic into French, which w ...

.

During World War I, the salon became a haven for those opposed to the war. Henri Barbusse

Henri Barbusse (; 17 May 1873 – 30 August 1935) was a French novelist and a member of the French Communist Party. He was a lifelong friend of Albert Einstein.

Life

The son of a French father and an English mother, Barbusse was born in Asnièr ...

gave a reading from his anti-war novel ''Under Fire

Under Fire may refer to:

Books

* ''Under Fire'' (Barbusse novel) (French: ''Le Feu''), a novel by Henri Barbusse

* ''Under Fire'' (Blackwood novel), by Grant Blackwood in Tom Clancy's Jack Ryan Jr. franchise series

* ''Under Fire'' (North book ...

'' and Barney hosted a Women's Congress for Peace. Other visitors to the salon during the war included Oscar Milosz

Oscar Vladislas de Lubicz Milosz ( lt, Oskaras Milašius; ) (28 May 1877 – 2 March 1939) was a French language poet, playwright, novelist, essayist and representative of Lithuania at the League of Nations.Czesław Miłosz, Cynthia L. Haven ...

, Auguste Rodin and poet Alan Seeger

Alan Seeger (22 June 1888 – 4 July 1916) was an American war poet who fought and died in World War I during the Battle of the Somme, serving in the French Foreign Legion. Seeger was the brother of Charles Seeger, a noted American pacifi ...

, who came while on leave from the French Foreign Legion

The French Foreign Legion (french: Légion étrangère) is a corps of the French Army which comprises several specialties: infantry, cavalry, engineers, airborne troops. It was created in 1831 to allow foreign nationals into the French Army ...

.

Ezra Pound was a close friend of Barney's and often visited. The two schemed together to subsidize Paul Valéry

Ambroise Paul Toussaint Jules Valéry (; 30 October 1871 – 20 July 1945) was a French poet, essayist, and philosopher. In addition to his poetry and fiction (drama and dialogues), his interests included aphorisms on art, history, letters, mu ...

and T. S. Eliot

Thomas Stearns Eliot (26 September 18884 January 1965) was a poet, essayist, publisher, playwright, literary critic and editor.Bush, Ronald. "T. S. Eliot's Life and Career", in John A Garraty and Mark C. Carnes (eds), ''American National Biogr ...

so they could quit their jobs and focus on writing, but Valéry found other patrons

Patronage is the support, encouragement, privilege, or financial aid that an organization or individual bestows on another. In the history of art, arts patronage refers to the support that kings, popes, and the wealthy have provided to artists su ...

and Eliot refused the grant

Grant or Grants may refer to:

Places

*Grant County (disambiguation)

Australia

* Grant, Queensland, a locality in the Barcaldine Region, Queensland, Australia

United Kingdom

* Castle Grant

United States

*Grant, Alabama

* Grant, Inyo County, ...

. Pound introduced Barney to avant-garde

The avant-garde (; In 'advance guard' or ' vanguard', literally 'fore-guard') is a person or work that is experimental, radical, or unorthodox with respect to art, culture, or society.John Picchione, The New Avant-garde in Italy: Theoretical ...

composer George Antheil

George Johann Carl Antheil (; July 8, 1900 – February 12, 1959) was an American avant-garde composer, pianist, author, and inventor whose modernist musical compositions explored the modern sounds – musical, industrial, and mechanical – of t ...

, and, while her own taste in music leaned towards the traditional, she hosted premieres of Antheil's ''Symphony for Five Instruments'' and ''First String Quartet''. It was also at Barney's salon that Pound met his longtime mistress, the violinist Olga Rudge

Olga Rudge (April 13, 1895 – March 15, 1996) was an American-born concert violinist, now mainly remembered as the long-time mistress of the poet Ezra Pound, by whom she had a daughter, Mary.

A gifted concert violinist of international re ...

.

In 1927 Barney started an ''Académie des Femmes'' (Women's Academy) to honor women writers. This was a response to the influential Académie Française

An academy (Attic Greek: Ἀκαδήμεια; Koine Greek Ἀκαδημία) is an institution of secondary education, secondary or tertiary education, tertiary higher education, higher learning (and generally also research or honorary membershi ...

(French Academy) which had been founded in the 17th century by Louis XIII

Louis XIII (; sometimes called the Just; 27 September 1601 – 14 May 1643) was King of France from 1610 until his death in 1643 and King of Navarre (as Louis II) from 1610 to 1620, when the crown of Navarre was merged with the French crown ...

and whose 40 members included no women at the time. Unlike the French Academy, Barney's was not a formal organization but rather a series of readings held as part of the regular Friday salons. Honorees included Colette, Gertrude Stein

Gertrude Stein (February 3, 1874 – July 27, 1946) was an American novelist, poet, playwright, and art collector. Born in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, in the Allegheny West (Pittsburgh), Allegheny West neighborhood and raised in Oakland, Calif ...

, Anna Wickham

Anna Wickham was the pseudonym of Edith Alice Mary Harper (1883 – 1947), an English/Australian poet who was a pioneer of modernist poetry, and one of the most important female poets writing during the first half of the twentieth century. She wa ...

, Rachilde

Rachilde was the pen name and preferred identity of novelist and playwright Marguerite Vallette-Eymery (11 February 1860 – 4 April 1953). Born near Périgueux, Dordogne, Aquitaine, France during the Second French Empire, Rachilde went on t ...

, Lucie Delarue-Mardrus, Mina Loy

Mina Loy (born Mina Gertrude Löwy; 27 December 1882 – 25 September 1966) was a British-born artist, writer, poet, playwright, novelist, painter, designer of lamps, and bohemian. She was one of the last of the first-generation modernists to ...

, Djuna Barnes

Djuna Barnes (, June 12, 1892 – June 18, 1982) was an American artist, illustrator, journalist, and writer who is perhaps best known for her novel ''Nightwood'' (1936), a cult classic of Lesbian literature, lesbian fiction and an important work ...

and posthumously, Renée Vivien. The academy's activities wound down after 1927.

Other visitors to the salon during the 1920s included French writers Jeanne Galzy

Jeanne Galzy (1883–1977), born Louise Jeanne Baraduc, was a French novelist and biographer from Montpellier. She was a long-time member of the jury for the Prix Femina. Largely forgotten today, she was known as a regional author, but also wro ...

, André Gide

André Paul Guillaume Gide (; 22 November 1869 – 19 February 1951) was a French author and winner of the Nobel Prize in Literature (in 1947). Gide's career ranged from its beginnings in the symbolist movement, to the advent of anticolonialism ...

, Anatole France

(; born , ; 16 April 1844 – 12 October 1924) was a French poet, journalist, and novelist with several best-sellers. Ironic and skeptical, he was considered in his day the ideal French man of letters. He was a member of the Académie Franç ...

, Max Jacob

Max Jacob (; 12 July 1876 – 5 March 1944) was a French poet, painter, writer, and critic.

Life and career

After spending his childhood in Quimper, Brittany, he enrolled in the Paris Colonial School, which he left in 1897 for an artistic ca ...

, Louis Aragon

Louis Aragon (, , 3 October 1897 – 24 December 1982) was a French poet who was one of the leading voices of the surrealist movement in France. He co-founded with André Breton and Philippe Soupault the surrealist review '' Littérature''. He w ...

and Jean Cocteau

Jean Maurice Eugène Clément Cocteau (, , ; 5 July 1889 – 11 October 1963) was a French poet, playwright, novelist, designer, filmmaker, visual artist and critic. He was one of the foremost creatives of the s ...

. English-language writers also visited, including Ford Madox Ford

Ford Madox Ford (né Joseph Leopold Ford Hermann Madox Hueffer ( ); 17 December 1873 – 26 June 1939) was an English novelist, poet, critic and editor whose journals '' The English Review'' and '' The Transatlantic Review'' were instrumental i ...

, W. Somerset Maugham

William Somerset Maugham ( ; 25 January 1874 – 16 December 1965) was an English writer, known for his plays, novels and short stories. Born in Paris, where he spent his first ten years, Maugham was schooled in England and went to a German un ...

, F. Scott Fitzgerald

Francis Scott Key Fitzgerald (September 24, 1896 – December 21, 1940) was an American novelist, essayist, and short story writer. He is best known for his novels depicting the flamboyance and excess of the Jazz Age—a term he popularize ...

, Sinclair Lewis

Harry Sinclair Lewis (February 7, 1885 – January 10, 1951) was an American writer and playwright. In 1930, he became the first writer from the United States (and the first from the Americas) to receive the Nobel Prize in Literature, which wa ...

, Sherwood Anderson

Sherwood Anderson (September 13, 1876 – March 8, 1941) was an American novelist and short story writer, known for subjective and self-revealing works. Self-educated, he rose to become a successful copywriter and business owner in Cleveland and ...

, Thornton Wilder

Thornton Niven Wilder (April 17, 1897 – December 7, 1975) was an American playwright and novelist. He won three Pulitzer Prizes — for the novel ''The Bridge of San Luis Rey'' and for the plays '' Our Town'' and '' The Skin of Our Teeth'' — ...

, T. S. Eliot and William Carlos Williams

William Carlos Williams (September 17, 1883 – March 4, 1963) was an American poet, writer, and physician closely associated with modernism and imagism.

In addition to his writing, Williams had a long career as a physician practicing both ped ...

. Barney also hosted German poet Rainer Maria Rilke

René Karl Wilhelm Johann Josef Maria Rilke (4 December 1875 – 29 December 1926), shortened to Rainer Maria Rilke (), was an Austrian poet and novelist. He has been acclaimed as an idiosyncratic and expressive poet, and is widely recog ...

, Bengali poet Rabindranath Tagore

Rabindranath Tagore (; bn, রবীন্দ্রনাথ ঠাকুর; 7 May 1861 – 7 August 1941) was a Bengali polymath who worked as a poet, writer, playwright, composer, philosopher, social reformer and painter. He resh ...

(the first Nobel laureate from Asia), Romanian aesthetician and diplomat Matila Ghyka

Prince Matila Costiescu Ghyka (; born ''Matila Costiescu''; 13 September 1881 – 14 July 1965), was a Romanian naval officer, novelist, mathematician, historian, philosopher, academic and diplomat. He did not return to Romania after World ...

, journalist Janet Flanner

Janet Flanner (March 13, 1892 – November 7, 1978) was an American writer and pioneering narrative journalist who served as the Paris correspondent of ''The New Yorker'' magazine from 1925 until she retired in 1975.Yagoda, Ben ''About T ...

(also known as Genêt, who set the ''New Yorker

New Yorker or ''variant'' primarily refers to:

* A resident of the State of New York

** Demographics of New York (state)

* A resident of New York City

** List of people from New York City

* ''The New Yorker'', a magazine founded in 1925

* '' The ...

'' style), journalist, activist and publisher Nancy Cunard

Nancy Clara Cunard (10 March 1896 – 17 March 1965) was a British writer, heiress and political activist. She was born into the British upper class, and devoted much of her life to fighting racism and fascism. She became a muse to some of the ...

, publishers Caresse and Harry Crosby

Harry Crosby (June 4, 1898 – December 10, 1929) was an American heir, World War I veteran, ''bon vivant'', poet, and publisher who for some epitomized the Lost Generation in American literature. He was the son of one of the richest banking fam ...

, publisher Blanche Knopf

Blanche Wolf Knopf (July 30, 1894 – June 4, 1966) was the president of Alfred A. Knopf, Inc., and wife of publisher Alfred A. Knopf Sr., with whom she established the firm in 1915. Blanche traveled the world seeking new authors and was especia ...

, art collector and patron Peggy Guggenheim

Marguerite "Peggy" Guggenheim ( ; August 26, 1898 – December 23, 1979) was an American art collector, bohemian and socialite. Born to the wealthy New York City Guggenheim family, she was the daughter of Benjamin Guggenheim, who went down with ...

, Sylvia Beach

Sylvia may refer to:

People

*Sylvia (given name)

*Sylvia (singer), American country music and country pop singer and songwriter

*Sylvia Robinson, American singer, record producer, and record label executive

*Sylvia Vrethammar, Swedish singer credi ...

(the bookstore owner who published James Joyce

James Augustine Aloysius Joyce (2 February 1882 – 13 January 1941) was an Irish novelist, poet, and literary critic. He contributed to the Modernism, modernist avant-garde movement and is regarded as one of the most influential and important ...

's '' Ulysses''), painters Tamara de Lempicka

Tamara Łempicka (born Tamara Rosalia Gurwik-Górska; 16 May 1898 – 18 March 1980), better known as Tamara de Lempicka, was a Polish painter who spent her working life in France and the United States. She is best known for her polished Art De ...

and Marie Laurencin

Marie Laurencin (31 October 1883 – 8 June 1956) was a French painter and printmaker. She became an important figure in the Parisian avant-garde as a member of the Cubists associated with the Section d'Or.

Biography

Laurencin was born in Paris, ...

and dancer Isadora Duncan

Angela Isadora Duncan (May 26, 1877 or May 27, 1878 – September 14, 1927) was an American dancer and choreographer, who was a pioneer of modern contemporary dance, who performed to great acclaim throughout Europe and the US. Born and raised in ...

.

For her 1929 book ''Aventures de l'Esprit'' (''Adventures of the Mind'') Barney drew a social diagram which crowded the names of over a hundred people who had attended the salon into a rough map of the house, garden and Temple of Friendship. The first half of the book had reminiscences of 13 male writers she had known or met over the years and the second half had a chapter for each member of her ''Académie des Femmes''.

In the late 1920s Radclyffe Hall

Marguerite Antonia Radclyffe Hall (12 August 1880 – 7 October 1943) was an English poet and author, best known for the novel '' The Well of Loneliness'', a groundbreaking work in lesbian literature. In adulthood, Hall often went by the name ...

drew a crowd reading her novel ''The Well of Loneliness

''The Well of Loneliness'' is a lesbian novel by British author Radclyffe Hall that was first published in 1928 by Jonathan Cape. It follows the life of Stephen Gordon, an Englishwoman from an upper-class family whose " sexual inversion" (homo ...

'', recently banned in the UK. A reading by poet Edna St. Vincent Millay

Edna St. Vincent Millay (February 22, 1892 – October 19, 1950) was an American lyrical poet and playwright. Millay was a renowned social figure and noted feminist in New York City during the Roaring Twenties and beyond. She wrote much of her ...

packed the salon in 1932. At another Friday salon in the 1930s Virgil Thomson

Virgil Thomson (November 25, 1896 – September 30, 1989) was an American composer and critic. He was instrumental in the development of the "American Sound" in classical music. He has been described as a modernist, a neoromantic, a neoclassi ...

sang from ''Four Saints in Three Acts

''Four Saints in Three Acts'' is an opera composed in 1928 by Virgil Thomson, setting a libretto written in 1927 by Gertrude Stein. It contains about 20 saints and is in at least four acts. It was groundbreaking in form, content, and for its all- ...

'', an opera based on a libretto by Stein.

Of the famous Modernist writers who spent time in Paris, Ernest Hemingway

Ernest Miller Hemingway (July 21, 1899 – July 2, 1961) was an American novelist, short-story writer, and journalist. His economical and understated style—which he termed the iceberg theory—had a strong influence on 20th-century fic ...

never made an appearance at the salon. James Joyce came once or twice but did not care for it. Marcel Proust

Valentin Louis Georges Eugène Marcel Proust (; ; 10 July 1871 – 18 November 1922) was a French novelist, critic, and essayist who wrote the monumental novel '' In Search of Lost Time'' (''À la recherche du temps perdu''; with the previous En ...

never attended a Friday but did come once to talk with Barney about lesbian culture whilst doing research for '' In Search of Lost Time'', though he ended up too nervous to bring up the subject.

Epigrams and novel

''Éparpillements'' (''Scatterings'', 1910) was Barney's first collection of ''pensées''—literally, thoughts. This literary form had been associated with salon culture in France since the 17th century, when the genre was perfected at the salon of Madame de Sablé. Barney's ''pensées'', like de Sablé's own ''Maximes'', were short, often one-lineepigrams

An epigram is a brief, interesting, memorable, and sometimes surprising or satirical statement. The word is derived from the Greek "inscription" from "to write on, to inscribe", and the literary device has been employed for over two millen ...

or ''bon mot

Many words in the English vocabulary are of French origin, most coming from the Anglo-Norman spoken by the upper classes in England for several hundred years after the Norman Conquest, before the language settled into what became Modern Engl ...

s'' such as "There are more evil ears than bad mouths" and "To be married is to be neither alone nor together."

Her literary career got a boost after she sent a copy of ''Éparpillements'' to Remy de Gourmont

Remy de Gourmont (4 April 1858 – 27 September 1915) was a French symbolist poet, novelist, and influential critic. He was widely read in his era, and an important influence on Blaise Cendrars and Georges Bataille. The spelling ''Rémy'' de G ...

, a French poet, literary critic, and philosopher who had become a recluse after contracting the disfiguring disease lupus vulgaris

Lupus vulgaris (also known as tuberculosis luposa) are painful cutaneous tuberculosis skin lesions with nodular appearance, most often on the face around the nose, eyelids, lips, cheeks, ears and neck. It is the most common '' Mycobacterium tuber ...

in his thirties. He was impressed enough to invite her to one of the Sunday gatherings at his home, at which he usually received only a small group of old friends. She was a rejuvenating influence in his life, coaxing him out for evening car rides, dinners at the Rue Jacob, a masked ball, even a short cruise on the Seine

The Seine ( , ) is a river in northern France. Its drainage basin is in the Paris Basin (a geological relative lowland) covering most of northern France. It rises at Source-Seine, northwest of Dijon in northeastern France in the Langres plate ...

. He turned some of their wide-ranging conversations into a series of letters that he published in the ''Mercure de France

The was originally a French gazette and literary magazine first published in the 17th century, but after several incarnations has evolved as a publisher, and is now part of the Éditions Gallimard publishing group.

The gazette was published f ...

'', addressing her as ''l'Amazone,'' a French word that can mean either ''horsewoman'' or ''Amazon

Amazon most often refers to:

* Amazons, a tribe of female warriors in Greek mythology

* Amazon rainforest, a rainforest covering most of the Amazon basin

* Amazon River, in South America

* Amazon (company), an American multinational technolog ...

''; the letters were later collected in book form. He died in 1915, but the nickname he gave her would stay with her all her life—even her tombstone identifies her as "the Amazon of Remy de Gourmont"—and his ''Letters to the Amazon'' left readers wanting to know more about the woman who had inspired them.

Barney obliged in 1920 with ''Pensées d'une Amazone'' (''Thoughts of an Amazon''), her most overtly political work. In the first section, "Sexual Adversity, War, and Feminism", she developed feminist and pacifist

Pacifism is the opposition or resistance to war, militarism (including conscription and mandatory military service) or violence. Pacifists generally reject theories of Just War. The word ''pacifism'' was coined by the French peace campaig ...

themes, describing war as an "involuntary and collective suicide ordained by man". In war, she said, men "father death as women mother life, with courage and without choice". The epigrammatic form makes it difficult to determine the details of Barney's views; ideas are presented only to be dropped, and some ''pensées'' seem to contradict others. Some critics interpret her as saying that the aggression that leads to war is visible in all male relationships. Karla Jay, however, argues that her philosophy was not that sweeping, and is better summed up by the epigram "Those who ''love'' war lack the love of an adequate sport—the art of living."

Another section of ''Pensées d'une Amazone'', "Misunderstanding, or Sappho's Lawsuit", gathered historical writings about homosexuality along with her own commentary. She also covered topics such as alcohol, friendship, old age, and literature, writing "Novels are longer than life" and "Romanticism is a childhood ailment; those who had it young are the most robust." A third volume, ''Nouvelles Pensées de l'Amazone'' (''New Thoughts of the Amazon''), appeared in 1939.

''The One Who is Legion, or A.D.'s After-Life'' (1930) was Barney's only book written entirely in English, as well as her only novel. Illustrated by Romaine Brooks

Romaine Brooks (born Beatrice Romaine Goddard; May 1, 1874 – December 7, 1970) was an American painter who worked mostly in Paris and Capri. She specialized in portraiture and used a subdued tonal palette keyed to the color gray. Brooks ignore ...

, it concerns a person who committed suicide, known only as A.D., who is brought back to life as a genderless, hermaphroditic

In reproductive biology, a hermaphrodite () is an organism that has both kinds of reproductive organs and can produce both gametes associated with male and female sexes.

Many taxonomic groups of animals (mostly invertebrates) do not have se ...

being and reads the book of their own life. This book-within-a-book, entitled ''The Love-Lives of A.D.'', is a collection of hymns, poems and epigrams, much like Barney's own other writings.

Major relationships

Despite several of her lovers' objections, Barney practiced, and advocated,

Despite several of her lovers' objections, Barney practiced, and advocated, non-monogamy

Non-monogamy (or nonmonogamy) is an umbrella term for every practice or philosophy of non-dyadic intimate relationship that does not strictly hew to the standards of monogamy, particularly that of having only one person with whom to exchange sex ...

. As early as 1901, in ''Cinq Petits Dialogues Grecs,'' she argued in favor of multiple relationships and against jealousy; in ''Éparpillements'' she wrote "One is unfaithful to those one loves in order that their charm does not become mere habit". While she could be quite jealous herself, she actively encouraged at least some of her lovers to be non-monogamous as well.

Due in part to Jean Chalon's early biography of her, published in English as ''Portrait of a Seductress'', Barney had become more widely known for her many relationships than for her writing or her salon. She once wrote out a list, divided into three categories: liaisons, demi-liaisons, and adventures. Colette was a demi-liaison, while the artist and furniture designer Eyre de Lanux

Eyre de Lanux ( ; born Elizabeth Eyre; March 20, 1894 – September 8, 1996) was an American artist, writer, and designer. De Lanux is best known for designing lacquered furniture and geometric patterned rugs, in the art deco style, in Par ...

, with whom she had an off-and-on affair for several years, was listed as an adventure. Among the liaisons—the relationships that she considered most important—were Custance, Vivien, Élisabeth de Gramont

Antoinette Corisande Élisabeth, Duchess of Clermont-Tonnerre (née de Gramont; 23 April 1875 – 6 December 1954) was a French writer of the early 20th century, best known for her long-term lesbian relationship with Natalie Clifford Barney ...

, Brooks, and Dolly Wilde

Dorothy Ierne Wilde, known as Dolly Wilde (11 July 1895 – 10 April 1941), was an English socialite, made famous by her family connections and her reputation as a witty conversationalist. Her charm and humour made her a popular guest at s ...

. Many of her affairs, like those with Colette and Lucie Delarue-Mardrus, evolved into lifelong friendships.

Élisabeth de Gramont

Élisabeth de Gramont, the

Élisabeth de Gramont, the Duchess

Duke is a male title either of a monarch ruling over a duchy, or of a member of royalty, or nobility. As rulers, dukes are ranked below emperors, kings, grand princes, grand dukes, and sovereign princes. As royalty or nobility, they are ran ...

of Clermont-Tonnerre, was a writer best known for her popular memoirs. A descendant of Henry IV of France

Henry IV (french: Henri IV; 13 December 1553 – 14 May 1610), also known by the epithets Good King Henry or Henry the Great, was King of Navarre (as Henry III) from 1572 and King of France from 1589 to 1610. He was the first monarc ...

, she had grown up among the aristocracy; when she was a child, according to Janet Flanner, "peasants on her farm ... begged her not to clean her shoes before entering their houses". Her father's ancestors had squandered their fortune and he married into the Rothschild family

The Rothschild family ( , ) is a wealthy Ashkenazi Jewish family originally from Frankfurt that rose to prominence with Mayer Amschel Rothschild (1744–1812), a court factor to the German Landgraves of Hesse-Kassel in the Free City of F ...

after her birth; she did not have any access to her step-mother's wealth. She looked back on this lost world of wealth and privilege with little regret, and became known as the "red duchess" for her support of socialism. Encouraged by her father to wed into security, she married Philibert de Clermont-Tonnere and had two daughters. He was violent and tyrannical.

The poet Lucie Delarue-Mardrus

Lucie Delarue-Mardrus (3 November 1874 in Honfleur – 26 April 1945 ) was a French journalist, poet, novelist, sculptor, historian and designer. She was a prolific writer, who produced more than 70 books in her lifetime.

In France, sh ...

introduced Barney and de Gramont in 1909 or 1910. The couple shared academic interests and attended Remy de Gourmont's salon together.

Barney wrote an unpublished novel inspired by their early relationship, ''L’Adultère ingénue'' (''The Adulterous Ingénue

The ''ingénue'' (, , ) is a stock character in literature, film and a role type in the theater, generally a girl or a young woman, who is endearingly innocent. ''Ingénue'' may also refer to a new young actress or one typecast in such rol ...

'').

De Gramont accepted Barney's nonmonogamy—perhaps reluctantly at first—and went out of her way to be gracious to her other lovers, always including Brooks when she invited Barney to vacation in the country.

Though the two conducted their affair clandestinely, de Gramont's husband found them out and attempted to stop them from seeing each other. He was unsuccessful, and he divorced de Gramont in 1920 after a period of separation. In 1918 she and Barney wrote up a marriage contract stating: "No one union shall be so strong as this union, nor another joining so tender—nor relationship so lasting". The relationship continued until de Gramont's death in 1954.

Romaine Brooks

Barney's longest relationship was with the American painter Romaine Brooks, whom she met around 1915. Brooks specialized inportrait

A portrait is a painting, photograph, sculpture, or other artistic representation of a person, in which the face and its expressions are predominant. The intent is to display the likeness, personality, and even the mood of the person. For this ...

ure and was noted for her somber palette of gray, black, and white. During the 1920s she painted portraits of several members of Barney's social circle, including de Gramont and Barney herself.

Brooks tolerated Barney's casual affairs well enough to tease her about them, and had a few of her own over the years, but could become jealous when a new love became serious. Usually she simply left town, but at one point she gave Barney an ultimatum to choose between her and Dolly Wilde—relenting once Barney had given in. At the same time, while Brooks was devoted to Barney, she did not want to live with her as a full-time couple; she disliked Paris, disdained Barney's friends, hated the constant socializing on which Barney thrived, and felt that she was fully herself only when alone. To accommodate Brooks's need for solitude they built a summer home consisting of two separate wings joined by a dining room, which they called ''Villa Trait d'Union'', the hyphenated villa. Brooks also spent much of the year in Italy or travelling elsewhere in Europe, away from Barney. Their relationship lasted for over fifty years.

Dolly Wilde