Musical system of ancient Greece on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The musical system of ancient Greece evolved over a period of more than 500 years from simple

The central three columns of the diagram show, first the modern note-names, then the two systems of symbols used in ancient Greece: the vocalic (favoured by singers) and instrumental (favoured by instrumentalists). The modern note-names are given in the

The central three columns of the diagram show, first the modern note-names, then the two systems of symbols used in ancient Greece: the vocalic (favoured by singers) and instrumental (favoured by instrumentalists). The modern note-names are given in the

Die Hymnen des Dionysius und Mesomedes: Text und Melodieen nach Handschriften und den alten Ausgaben bearbeitet von Dr. Friedrich Bellermann

'. Berlin: Albert Förstner. * Jan, Karl von (ed.) (1895). ''Musici scriptores graeci: Aristoteles, Euclides, Nicomachus, Bacchius, Gaudentius, Alypius et melodiarum veterum quidquid exstat''. Bibliotheca scriptorum graecorum et romanorum Teubneriana. Leipzig: B. G. Teubner. * * Mathiesen, Thomas J. (2001d). "Alypius lupios. ''

booklet on the modes of ancient Greece

with detailed examples of the construction of Aolus (reed pipe instruments) and monochord, which might help reconstruct the intervals and modes of the Greeks * Nikolaos Ioannidis musician, composer, has attempted t

from a combination of the ancient texts (to be performed) and his knowledge of Greek music. * A mid-19th century, 1902 edition, Henry S. Macran

''The Harmonics of Aristoxenus''

The Barbera translation cited above is more up to date. * Joe Monzo (2004)

Analysis of Aristoxenus

Full of interesting and insightful mathematical analysis. There are some original hypotheses outlined. *

Analysis of Archytas

something of a complement to the above Aristoxenus but, dealing with the earlier and arithmetically precise Archytas:. An incidental note. Erickson is keen to demonstrate that Archytas tuning system not only corresponds with Platos Harmonia, but also with the practice of musicians. Erickson mentions the ease of tuning with the Lyre. * Austrian Academy of Science

examples of instruments and compositionsEnsemble Kérylos

a music group led by scholar

scales

Scale or scales may refer to:

Mathematics

* Scale (descriptive set theory), an object defined on a set of points

* Scale (ratio), the ratio of a linear dimension of a model to the corresponding dimension of the original

* Scale factor, a number w ...

of tetrachord

In music theory, a tetrachord ( el, τετράχορδoν; lat, tetrachordum) is a series of four notes separated by three intervals. In traditional music theory, a tetrachord always spanned the interval of a perfect fourth, a 4:3 frequency pr ...

s, or divisions of the perfect fourth

A fourth is a musical interval encompassing four staff positions in the music notation of Western culture, and a perfect fourth () is the fourth spanning five semitones (half steps, or half tones). For example, the ascending interval from C to ...

, into several complex systems encompassing tetrachords and octaves, as well as octave scales divided into seven to thirteen intervals.

Any discussion of the music of ancient Greece

Music was almost universally present in ancient Greek society, from marriages, funerals, and religious ceremonies to theatre, folk music, and the ballad-like reciting of epic poetry. It thus played an integral role in the lives of ancient Gr ...

, theoretical, philosophical or aesthetic, is fraught with two problems: there are few examples of written music, and there are many, sometimes fragmentary, theoretical and philosophical accounts. The empirical research of scholars like Richard Crocker, C. André Barbera, and John Chalmers has made it possible to look at the ancient Greek systems as a whole without regard to the tastes of any one ancient theorist. The primary genera they examine are those of Pythagoras and the Pythagorean school

Pythagorean, meaning of or pertaining to the ancient Ionian mathematician, philosopher, and music theorist Pythagoras, may refer to:

Philosophy

* Pythagoreanism, the esoteric and metaphysical beliefs purported to have been held by Pythagoras

* ...

, Archytas

Archytas (; el, Ἀρχύτας; 435/410–360/350 BC) was an Ancient Greek philosopher, mathematician, music theorist, astronomer, statesman, and strategist. He was a scientist of the Pythagorean school and famous for being the reputed found ...

, Aristoxenos

Aristoxenus of Tarentum ( el, Ἀριστόξενος ὁ Ταραντῖνος; born 375, fl. 335 BC) was a Greek Peripatetic philosopher, and a pupil of Aristotle. Most of his writings, which dealt with philosophy, ethics and music, have been ...

, and Ptolemy

Claudius Ptolemy (; grc-gre, Πτολεμαῖος, ; la, Claudius Ptolemaeus; AD) was a mathematician, astronomer, astrologer, geographer, and music theorist, who wrote about a dozen scientific treatises, three of which were of importanc ...

(including his versions of the genera of Didymos and Eratosthenes

Eratosthenes of Cyrene (; grc-gre, Ἐρατοσθένης ; – ) was a Greek polymath: a mathematician, geographer, poet, astronomer, and music theorist. He was a man of learning, becoming the chief librarian at the Library of Alexandr ...

).

Overview of the first complete tone system

As an initial introduction to the principal names and divisions of the Ancient Greek tone system we will give a depiction of the "perfect system" or systema teleion, which was elaborated in its entirety by about the turn of the 5th to 4th centuryBCE

Common Era (CE) and Before the Common Era (BCE) are year notations for the Gregorian calendar (and its predecessor, the Julian calendar), the world's most widely used calendar era. Common Era and Before the Common Era are alternatives to the or ...

.

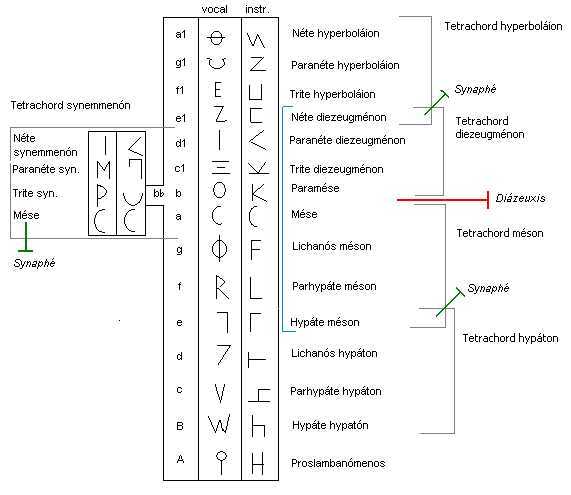

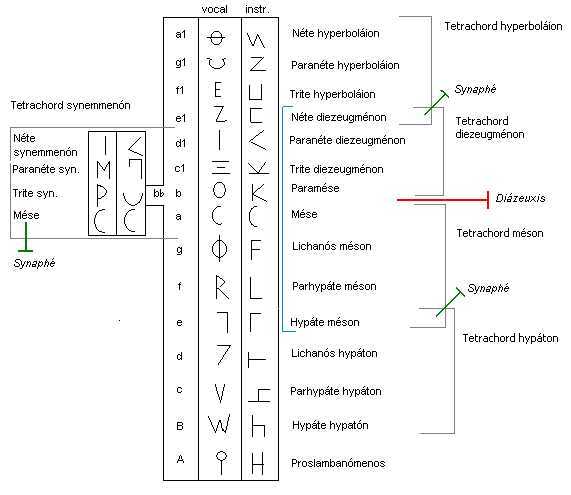

The following diagram reproduces information from Chalmer. It shows the common ancient ''harmoniai'', the ''tonoi'' in all ''genera'', and the system as a whole in one complete map.

The central three columns of the diagram show, first the modern note-names, then the two systems of symbols used in ancient Greece: the vocalic (favoured by singers) and instrumental (favoured by instrumentalists). The modern note-names are given in the

The central three columns of the diagram show, first the modern note-names, then the two systems of symbols used in ancient Greece: the vocalic (favoured by singers) and instrumental (favoured by instrumentalists). The modern note-names are given in the Helmholtz pitch notation

Helmholtz pitch notation is a system for naming musical notes of the Western chromatic scale. Fully described and normalized by the German scientist Hermann von Helmholtz, it uses a combination of upper and lower case letters (A to G), and th ...

, and the Greek note symbols are as given in the work of . Note that the pitches of the notes in modern notation are conventional, going back to the time of a publication by in 1840; in practice the pitches would have been somewhat lower.

The section spanned by a blue brace is the range of the central octave

In music, an octave ( la, octavus: eighth) or perfect octave (sometimes called the diapason) is the interval between one musical pitch and another with double its frequency. The octave relationship is a natural phenomenon that has been refer ...

. The range is approximately what we today depict as follows:

Note that Greek theorists conceived of scales as descending from higher pitch to lower (the opposite of modern practice).

The earliest Greek scales were tetrachord

In music theory, a tetrachord ( el, τετράχορδoν; lat, tetrachordum) is a series of four notes separated by three intervals. In traditional music theory, a tetrachord always spanned the interval of a perfect fourth, a 4:3 frequency pr ...

s, which were series of four descending tones, with the top and bottom tones being a fourth apart in modern terms. The sub-intervals of the tetrachord were unequal, with the largest intervals always at the top, and the smallest at the bottom. The 'characteristic interval' of a tetrachord is its largest one.

The Greater Perfect System (''systema teleion meizon'') was composed of four stacked tetrachords called (from lowest to highest) the ''Hypaton'', ''Meson'', ''Diezeugmenon'' and '' Hyperbolaion'' tetrachords. These are shown on the right hand side of the diagram. Octaves were composed from two stacked tetrachords connected by one common tone, the ''synaphe''.

At the position of the ''paramese'', the continuity of the system encounters a boundary (at b-flat, b). To retain the logic of the internal divisions of the tetrachords and avoid the ''Meson'' being forced into three whole tone steps (b–a–g–f), an interstitial note, the ''diazeuxis'' ('dividing'), was introduced between the ''paramese'' and ''mese''. This procedure gives its name to the tetrachord ''diezeugmenon'', which means the 'divided'.

To bridge the inconsistency of the ''diazeuxis'', the system allowed moving the ''nete'' one step up, permitting the construction of the ''Synemmenon'' ('conjunct') tetrachord – shown at the far left of the diagram.

The use of the ''Synemmenon'' tetrachord effected a modulation of the system, hence the name ''systema metabolon'', the modulating system, also called the Lesser Perfect System. This was considered apart, built of three stacked tetrachords — the ''Hypaton'', ''Meson'' and ''Synemmenon''. The first two of these are the same as the first two tetrachords of the Greater Perfect System, with a third tetrachord placed above the ''Meson''. When all these are considered together, with the ''Synemmenon'' tetrachord placed between the ''Meson'' and ''Diezeugmenon'' tetrachords, they make up the Immutable (or Unmodulating) System (systema ametabolon). The lowest tone does not belong to the system of tetrachords, as is reflected in its name, the ''Proslambanomenos'', the adjoined.

In sum, it is clear that the Ancient Greeks conceived of a unified system with the tetrachord as the basic structure, but the octave as the principle of unification.

Below we elaborate the mathematics that led to the logic of the system of tetrachords just described.

The Pythagoreans

After the discovery of the fundamental intervals (octave, fourth and fifth), the first systematic divisions of the octave we know of were those ofPythagoras

Pythagoras of Samos ( grc, Πυθαγόρας ὁ Σάμιος, Pythagóras ho Sámios, Pythagoras the Samian, or simply ; in Ionian Greek; ) was an ancient Ionian Greek philosopher and the eponymous founder of Pythagoreanism. His poli ...

to whom was often attributed the discovery that the frequency of a vibrating string is inversely proportional to its length. Pythagoras

Pythagoras of Samos ( grc, Πυθαγόρας ὁ Σάμιος, Pythagóras ho Sámios, Pythagoras the Samian, or simply ; in Ionian Greek; ) was an ancient Ionian Greek philosopher and the eponymous founder of Pythagoreanism. His poli ...

construed the intervals arithmetically, allowing for 1:1 = Unison, 2:1 = Octave, 3:2 = Fifth, 4:3 = Fourth. Pythagoras's scale consists of a stack of perfect fifths, the ratio 3:2 (see also Pythagorean Interval

In musical tuning theory, a Pythagorean interval is a musical interval with frequency ratio equal to a power of two divided by a power of three, or vice versa.Benson, Donald C. (2003). ''A Smoother Pebble: Mathematical Explorations'', p.56. . " ...

and Pythagorean Tuning

Pythagorean tuning is a system of musical tuning in which the frequency ratios of all intervals are based on the ratio 3:2.Bruce Benward and Marilyn Nadine Saker (2003). ''Music: In Theory and Practice'', seventh edition, 2 vols. (Boston: ...

).

The earliest such description of a scale is found in Philolaus fr. B6. Philolaus

Philolaus (; grc, Φιλόλαος, ''Philólaos''; ) was a Greek Pythagorean and pre-Socratic philosopher. He was born in a Greek colony in Italy and migrated to Greece. Philolaus has been called one of three most prominent figures in the Pyt ...

recognizes that, if we go up the interval of a fourth from any given note, and then up the interval of a fifth, the final note is an octave above the first note. Thus, the octave is made up of a fourth and a fifth. ... Philolaus's scale thus consisted of the following intervals: 9:8, 9:8, 256:243 hese three intervals take us up a fourth 9:8, 9:8, 9:8, 256:243 hese four intervals make up a fifth and complete the octave from our starting note This scale is known as the Pythagorean diatonic and is the scale that Plato

Plato ( ; grc-gre, Πλάτων ; 428/427 or 424/423 – 348/347 BC) was a Greek philosopher born in Athens during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. He founded the Platonist school of thought and the Academy, the first institution ...

adopted in the construction of the world soul in the ''Timaeus'' (36a-b).

The next notable Pythagorean theorist we know of is Archytas

Archytas (; el, Ἀρχύτας; 435/410–360/350 BC) was an Ancient Greek philosopher, mathematician, music theorist, astronomer, statesman, and strategist. He was a scientist of the Pythagorean school and famous for being the reputed found ...

, contemporary and friend of Plato, who explained the use of arithmetic, geometric and harmonic means in tuning musical instruments. Euclid

Euclid (; grc-gre, Εὐκλείδης; BC) was an ancient Greek mathematician active as a geometer and logician. Considered the "father of geometry", he is chiefly known for the '' Elements'' treatise, which established the foundations of ...

further developed Archytas's theory in his ''The Division of the Canon'' (''Katatomē kanonos'', the Latin ''Sectio Canonis''). He elaborated the acoustics with reference to the frequency of vibrations (or movements).

Archytas provided a rigorous proof that the basic musical intervals cannot be divided in half, or in other words, that there is no mean proportional between numbers in super-particular ratio (octave 2:1, fourth 4:3, fifth 3:2, 9:8).

Archytas was also the first ancient Greek theorist to provide ratios for all 3 genera

Genus ( plural genera ) is a taxonomic rank used in the biological classification of living and fossil organisms as well as viruses. In the hierarchy of biological classification, genus comes above species and below family. In binomial nomenclat ...

. The three genera of tetrachord

In music theory, a tetrachord ( el, τετράχορδoν; lat, tetrachordum) is a series of four notes separated by three intervals. In traditional music theory, a tetrachord always spanned the interval of a perfect fourth, a 4:3 frequency pr ...

s recognized by Archytas have the following ratios:

*The enharmonic – 5:4, 36:35, and 28:27

*The chromatic – 32:27, 243:224, and 28:27;

*The diatonic – 9:8, 8:7, and 28:27.

These three tunings appear to have corresponded to the actual musical practice of his day.

The genera

Genus ( plural genera ) is a taxonomic rank used in the biological classification of living and fossil organisms as well as viruses. In the hierarchy of biological classification, genus comes above species and below family. In binomial nomenclat ...

arose after the framing interval of the tetrachord was fixed, because the two internal notes (called ''lichanoi'' and ''parhypate'') still had variable tunings. Tetrachords were classified into genera depending on the position of the ''lichanos'' (thus the name ''lichanos'', which means "the indicator"). For instance a ''lichanos'' that is a minor third

In music theory, a minor third is a musical interval that encompasses three half steps, or semitones. Staff notation represents the minor third as encompassing three staff positions (see: interval number). The minor third is one of two com ...

from the bottom and a major second

In Western music theory, a major second (sometimes also called whole tone or a whole step) is a second spanning two semitones (). A second is a musical interval encompassing two adjacent staff positions (see Interval number for more de ...

from the top, defines the genus diatonic

Diatonic and chromatic are terms in music theory that are most often used to characterize scales, and are also applied to musical instruments, intervals, chords, notes, musical styles, and kinds of harmony. They are very often used as a ...

. The other two genera, chromatic

Diatonic and chromatic are terms in music theory that are most often used to characterize scales, and are also applied to musical instruments, intervals, chords, notes, musical styles, and kinds of harmony. They are very often used as a p ...

and enharmonic

In modern musical notation and tuning, an enharmonic equivalent is a note, interval, or key signature that is equivalent to some other note, interval, or key signature but "spelled", or named differently. The enharmonic spelling of a writte ...

, were defined in similar fashion.

More generally, three ''genera'' of seven octave ''species'' can be recognized, depending on the positioning of the interposed tones in the component tetrachord

In music theory, a tetrachord ( el, τετράχορδoν; lat, tetrachordum) is a series of four notes separated by three intervals. In traditional music theory, a tetrachord always spanned the interval of a perfect fourth, a 4:3 frequency pr ...

s:

*The diatonic genus is composed of tones and semitones,

*the chromatic genus is composed of semitones and a minor third,

*the enharmonic genus consists of a major third and two quarter-tones or diesis.

Within these basic forms, the intervals of the chromatic and diatonic genera were varied further by three and two "shades" (''chroai''), respectively .

The elaboration of tetrachords was also accompanied by penta- and hexachords. The joining of a tetrachord and a pentachord yields an octachord, i.e. the complete seven-tone scale plus a higher octave of the base note. However, this was also produced by joining two tetrachords, which were linked by means of an intermediary or shared note. The final evolution of the system did not end with the octave as such but with the ''Systema teleion'', a set of five tetrachords linked by conjunction and disjunction into arrays of tones spanning two octaves, as explained above.

The system of Aristoxenus

Having elaborated the ''Systema teleion'', we will now examine the most significant individual system, that ofAristoxenos

Aristoxenus of Tarentum ( el, Ἀριστόξενος ὁ Ταραντῖνος; born 375, fl. 335 BC) was a Greek Peripatetic philosopher, and a pupil of Aristotle. Most of his writings, which dealt with philosophy, ethics and music, have been ...

, which influenced much classification well into the Middle Ages.

Aristoxenus was a disciple of Aristotle

Aristotle (; grc-gre, Ἀριστοτέλης ''Aristotélēs'', ; 384–322 BC) was a Greek philosopher and polymath during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. Taught by Plato, he was the founder of the Peripatetic school of ...

who flourished in the 4th century BC. He introduced a radically different model for creating scales, and the nature of his scales deviated sharply from his predecessors. His system was based on seven "octave species

In the musical system of ancient Greece, an octave species (εἶδος τοῦ διὰ πασῶν, or σχῆμα τοῦ διὰ πασῶν) is a specific sequence of intervals within an octave. In '' Elementa harmonica'', Aristoxenus clas ...

" named after Greek regions and ethnicities – Dorian, Lydian, etc. This association of the ethnic names with the octave species appears to have preceded Aristoxenus, and the same system of names was revived in the Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) , from , with the same meanings. is a period in European history marking the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and covering the 15th and 16th centuries, characterized by an effort to revive and surpass ide ...

as names of musical modes

Mode ( la, modus meaning "manner, tune, measure, due measure, rhythm, melody") may refer to:

Arts and entertainment

* '' MO''D''E (magazine)'', a defunct U.S. women's fashion magazine

* ''Mode'' magazine, a fictional fashion magazine which is ...

according to the harmonic theory of that time, which was however quite different to that of the ancient Greeks. Thus the names Dorian, Lydian etc. should not be taken to imply a historical continuity between the systems.

In contrast to Archytas who distinguished his "genera" only by moving the ''lichanoi'', Aristoxenus varied both ''lichanoi'' and ''parhypate'' in considerable ranges. Instead of using discrete ratios to place the intervals in his scales, Aristoxenus used continuously variable quantities: as a result he obtained scales of thirteen notes to an octave, and considerably different qualities of consonance.

The octave species in the Aristoxenian tradition were:

* Mixolydian: ''hypate hypaton–paramese'' (b–b′)

* Lydian: ''parhypate hypaton–trite diezeugmenon'' (c′–c″)

* Phrygian: ''lichanos hypaton–paranete diezeugmenon'' (d′–d″)

* Dorian: ''hypate meson–nete diezeugmenon'' (e′–e″)

* Hypolydian: ''parhypate meson–trite hyperbolaion'' (f′–f″)

* Hypophrygian: ''lichanos meson–paranete hyperbolaion'' (g′–g″)

* Common, Locrian, or Hypodorian: ''mese–nete hyperbolaion'' or ''proslambanomenos–mese'' (a′–a″ or a–a′)

These names are derived from:

*an Ancient Greek subgroup (Dorians

The Dorians (; el, Δωριεῖς, ''Dōrieîs'', singular , ''Dōrieús'') were one of the four major ethnic groups into which the Hellenes (or Greeks) of Classical Greece divided themselves (along with the Aeolians, Achaeans, and Ioni ...

),

*a small region in central Greece (Locris

Locris (; el, label= Modern Greek, Λοκρίδα, Lokrída; grc, Λοκρίς, Lokrís) was a region of ancient Greece, the homeland of the Locrians, made up of three distinct districts.

Locrian tribe

The city of Locri in Calabria ( Italy) ...

),

*certain neighboring (non-Greek) peoples from Asia Minor

Anatolia, tr, Anadolu Yarımadası), and the Anatolian plateau, also known as Asia Minor, is a large peninsula in Western Asia and the westernmost protrusion of the Asian continent. It constitutes the major part of modern-day Turkey. The re ...

(Lydia

Lydia ( Lydian: 𐤮𐤱𐤠𐤭𐤣𐤠, ''Śfarda''; Aramaic: ''Lydia''; el, Λυδία, ''Lȳdíā''; tr, Lidya) was an Iron Age kingdom of western Asia Minor located generally east of ancient Ionia in the modern western Turkish pro ...

, Phrygia

In classical antiquity, Phrygia ( ; grc, Φρυγία, ''Phrygía'' ) was a kingdom in the west central part of Anatolia, in what is now Asian Turkey, centered on the Sangarios River. After its conquest, it became a region of the great empir ...

).

*The prefixes ''myxo'' and ''hypo'' were added to these to form associated scales above and below.

Aristoxenian ''tonoi''

The term ''tonos'' (pl. ''tonoi'') was used in four senses, for it could designate a note, an interval, a region of the voice, and a pitch. The ancient writerCleonides Cleonides ( el, Κλεονείδης) is the author of a Greek treatise on music theory titled Εἰσαγωγὴ ἁρμονική ''Eisagōgē harmonikē'' (Introduction to Harmonics). The date of the treatise, based on internal evidence, can be e ...

attributes thirteen ''tonoi'' to Aristoxenus, which represent a transposition of the tones of the Pythagorean system into a more uniform progressive scale over the range of an octave.

According to Cleonides, these transpositional ''tonoi'' were named analogously to the octave species, supplemented with new terms to raise the number of degrees from seven to thirteen. In fact, Aristoxenus criticized the application of these names by the earlier theorists, whom he called the "Harmonicists".

According to the interpretation of at least two modern authorities, in the Aristoxenian ''tonoi'' the Hypodorian is the lowest, and the Mixolydian is next-to-highest: the reverse of the case of the octave species. The nominal base pitches are as follows (in descending order, after Mathiesen; Solomon uses the octave between A and a instead):

The octave species in all genera

Based on the above, it can be seen that the Aristochene system of tones and octave species can be combined with the Pythagorean system of "genera" to produce a more complete system in which each octave species of thirteen tones (Dorian, Lydian, etc.) can be declined into a system of seven tones by selecting particular tones and semitones to form genera (Diatonic, Chromatic, and Enharmonic). The order of theoctave species

In the musical system of ancient Greece, an octave species (εἶδος τοῦ διὰ πασῶν, or σχῆμα τοῦ διὰ πασῶν) is a specific sequence of intervals within an octave. In '' Elementa harmonica'', Aristoxenus clas ...

names in the following table are the original Greek ones, followed by later alternatives (Greek and other). The species and notation are built around the template of the Dorian.

Diatonic

Chromatic

Enharmonic

The oldest ''harmoniai'' in three genera

In the notation above and below, the standard double-flat symbol is used to accommodate as far as possible the modern musical convention that demands every note in a scale to have a distinct, sequential letter; so interpret only as meaning the immediate prior letter in the alphabet. This is a complication unnecessary in Greek notation, which had distinct symbols for each half-flat, flat, or natural note. The superscript symbol after a letter indicates an approximately half-flattened version of the named note; the exact degree of flattening intended depending on which of several tunings was used. Hence a three-tone falling-pitch sequence d, d, d, with the second note, d, about -flat (aquarter-tone

A quarter tone is a pitch halfway between the usual notes of a chromatic scale or an interval about half as wide (aurally, or logarithmically) as a semitone, which itself is half a whole tone. Quarter tones divide the octave by 50 cents each, a ...

flat) from the first note, d, and the same d about -sharp (a quarter-tone sharp) from the following d.

The (d) listed first for the Dorian is the ''Proslambanómenos'', which was appended as it was, and falls outside of the linked-tetrachord scheme.

These tables are a depiction of Aristides Quintilianus Aristides Quintilianus (Greek: Ἀριστείδης Κοϊντιλιανός) was the Greek author of an ancient musical treatise, ''Perì musikês'' (Περὶ Μουσικῆς, i.e. ''On Music''; Latin: ''De Musica'')

According to Theodore Kar ...

's enharmonic ''harmoniai'', the diatonic of Henderson and Chalmers chromatic versions. Chalmers, from whom they originate, states:

The superficial resemblance of these octave species with the church modes

Mode ( la, modus meaning "manner, tune, measure, due measure, rhythm, melody") may refer to:

Arts and entertainment

* '' MO''D''E (magazine)'', a defunct U.S. women's fashion magazine

* ''Mode'' magazine, a fictional fashion magazine which is ...

is misleading: The conventional representation as a section (such as C D E F followed by D E F G) is incorrect. The species were re-tunings of the central octave such that the sequences of intervals (the cyclical modes divided by ratios defined by genus) corresponded to the notes of the Perfect Immutable System as depicted above.

Dorian

Phrygian

Lydian

Mixolydian

Syntonolydian

Ionian (Iastian)

Ptolemy and the Alexandrians

In marked contrast to his predecessors,Ptolemy

Claudius Ptolemy (; grc-gre, Πτολεμαῖος, ; la, Claudius Ptolemaeus; AD) was a mathematician, astronomer, astrologer, geographer, and music theorist, who wrote about a dozen scientific treatises, three of which were of importanc ...

's scales employed a division of the ''pyknon'' in the ratio of 1:2, melodic, in place of equal divisions. Ptolemy, in his ''Harmonics'', ii.3–11, construed the ''tonoi'' differently, presenting all seven octave species within a fixed octave, through chromatic inflection of the scale degrees (comparable to the modern conception of building all seven modal scales on a single tonic). In Ptolemy's system, therefore there are only seven ''tonoi''. Ptolemy preserved Archytas's tunings in his ''Harmonics'' as well as transmitting the tunings of Eratosthenes

Eratosthenes of Cyrene (; grc-gre, Ἐρατοσθένης ; – ) was a Greek polymath: a mathematician, geographer, poet, astronomer, and music theorist. He was a man of learning, becoming the chief librarian at the Library of Alexandr ...

and Didymos and providing his own ratios and scales.

''Harmoniai''

In music theory the Greek word ''harmonia'' can signify the enharmonic genus of tetrachord, the seven octave species, or a style of music associated with one of the ethnic types or the ''tonoi'' named by them. Particularly in the earliest surviving writings, ''harmonia'' is regarded not as a scale, but as the epitome of the stylised singing of a particular district or people or occupation. When the late 6th-century poet Lasus of Hermione referred to the Aeolian ''harmonia'', for example, he was more likely thinking of a melodic style characteristic of Greeks speaking the Aeolic dialect than of a scale pattern. In the ''Republic

A republic () is a " state in which power rests with the people or their representatives; specifically a state without a monarchy" and also a "government, or system of government, of such a state." Previously, especially in the 17th and 18th ...

'', Plato

Plato ( ; grc-gre, Πλάτων ; 428/427 or 424/423 – 348/347 BC) was a Greek philosopher born in Athens during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. He founded the Platonist school of thought and the Academy, the first institution ...

uses the term inclusively to encompass a particular type of scale, range and register, characteristic rhythmic pattern, textual subject, etc.

The philosophical writings of Plato and Aristotle

Aristotle (; grc-gre, Ἀριστοτέλης ''Aristotélēs'', ; 384–322 BC) was a Greek philosopher and polymath during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. Taught by Plato, he was the founder of the Peripatetic school of ...

(c. 350 BCE

Common Era (CE) and Before the Common Era (BCE) are year notations for the Gregorian calendar (and its predecessor, the Julian calendar), the world's most widely used calendar era. Common Era and Before the Common Era are alternatives to the or ...

) include sections that describe the effect of different ''harmoniai'' on mood and character formation (see below on ethos). For example, in the ''Republic'' (iii.10–11) Plato describes the music a person is exposed to as molding the person's character, which he discusses as particularly relevant for the proper education of the guardians of his ideal State. Aristotle in the ''Politics'' (viii:1340a:40–1340b:5):

Aristotle remarks further:

Ethos

The ancient Greeks have used the word ''ethos'' (ἔθος or ἦθος), in this context best rendered by "character" (in the sense of patterns of being and behaviour, but not necessarily with "moral" implications), to describe the ways music can convey, foster, and even generate emotional or mental states. Beyond this general description, there is no unified "Greek ethos theory" but "many different views, sometimes sharply opposed." Ethos is attributed to the ''tonoi'' or ''harmoniai'' or modes (for instance, Plato, in the ''Republic'' (iii: 398d–399a), attributes "virility" to the " Dorian," and "relaxedness" to the " Lydian" mode), instruments (especially theaulos

An ''aulos'' ( grc, αὐλός, plural , ''auloi'') or ''tibia'' (Latin) was an ancient Greek wind instrument, depicted often in art and also attested by archaeology.

Though ''aulos'' is often translated as "flute" or " double flute", it was u ...

and the cithara

The kithara (or Latinized cithara) ( el, κιθάρα, translit=kithāra, lat, cithara) was an ancient Greek musical instrument in the yoke lutes family. In modern Greek the word ''kithara'' has come to mean "guitar", a word which etymolog ...

, but also others), rhythms, and sometimes even the genus

Genus ( plural genera ) is a taxonomic rank used in the biological classification of living and fossil organisms as well as viruses. In the hierarchy of biological classification, genus comes above species and below family. In binomial nom ...

and individual tones. The most comprehensive treatment of musical ethos is provided by Aristides Quintilianus Aristides Quintilianus (Greek: Ἀριστείδης Κοϊντιλιανός) was the Greek author of an ancient musical treatise, ''Perì musikês'' (Περὶ Μουσικῆς, i.e. ''On Music''; Latin: ''De Musica'')

According to Theodore Kar ...

in his book ''On Music'', with the original conception of assigning ethos to the various musical parameters according to the general categories of male and female. Aristoxenus

Aristoxenus of Tarentum ( el, Ἀριστόξενος ὁ Ταραντῖνος; born 375, fl. 335 BC) was a Greek Peripatetic philosopher, and a pupil of Aristotle. Most of his writings, which dealt with philosophy, ethics and music, have been ...

was the first Greek theorist to point out that ethos does not only reside in the individual parameters but also in the musical piece as a whole (cited in Pseudo-Plutarch, ''De Musica'' 32: 1142d ff; see also Aristides Quintilianus 1.12). The Greeks were interested in musical ethos particularly in the context of education (so Plato in his ''Republic'' and Aristotle in his eighth book of his ''Politics''), with implications for the well-being of the State. Many other ancient authors refer to what we nowadays would call psychological effect of music and draw judgments for the appropriateness (or value) of particular musical features or styles, while others, in particular Philodemus

Philodemus of Gadara ( grc-gre, Φιλόδημος ὁ Γαδαρεύς, ''Philodēmos'', "love of the people"; c. 110 – prob. c. 40 or 35 BC) was an Arabic Epicurean philosopher and poet. He studied under Zeno of Sidon in Athens, before movin ...

(in his fragmentary work ''De musica'') and Sextus Empiricus

Sextus Empiricus ( grc-gre, Σέξτος Ἐμπειρικός, ; ) was a Greek Pyrrhonist philosopher and Empiric school physician. His philosophical works are the most complete surviving account of ancient Greek and Roman Pyrrhonism, and ...

(in his sixth book of his work ''Adversus mathematicos''), deny that music possesses any influence on the human person apart from generating pleasure. These different views anticipate in some way the modern debate in music philosophy whether music on its own or absolute music

Absolute music (sometimes abstract music) is music that is not explicitly 'about' anything; in contrast to program music, it is non- representational.M. C. Horowitz (ed.), ''New Dictionary of the History of Ideas'', , vol.1, p. 5 The idea of abs ...

, independent of text, is able to elicit emotions on the listener or musician.

Melos

Cleonides describes "melic" composition, "the employment of the materials subject to harmonic practice with due regard to the requirements of each of the subjects under consideration"—which, together with the scales, ''tonoi'', and ''harmoniai'' resemble elements found in medieval modal theory. According to Aristides Quintilianus (''On Music'', i.12), melic composition is subdivided into three classes: dithyrambic, nomic, and tragic. These parallel his three classes of rhythmic composition: systaltic, diastaltic and hesychastic. Each of these broad classes of melic composition may contain various subclasses, such as erotic, comic and panegyric, and any composition might be elevating (diastaltic), depressing (systaltic), or soothing (hesychastic). The classification of the ''requirements'' we have fromProclus

Proclus Lycius (; 8 February 412 – 17 April 485), called Proclus the Successor ( grc-gre, Πρόκλος ὁ Διάδοχος, ''Próklos ho Diádokhos''), was a Greek Neoplatonist philosopher, one of the last major classical philosophe ...

''Useful Knowledge'' as preserved by Photios

Photios I ( el, Φώτιος, ''Phōtios''; c. 810/820 – 6 February 893), also spelled PhotiusFr. Justin Taylor, essay "Canon Law in the Age of the Fathers" (published in Jordan Hite, T.O.R., & Daniel J. Ward, O.S.B., "Readings, Cases, Materia ...

:

* for the gods—hymn

A hymn is a type of song, and partially synonymous with devotional song, specifically written for the purpose of adoration or prayer, and typically addressed to a deity or deities, or to a prominent figure or personification. The word ''hymn ...

, prosodion

Prosodion (Greek: ) in ancient Greece was a processional song to the altar of a deity, mainly Apollo or Artemis, sung ritually before the Paean hymn. It is one of the earliest musical types used by the Greeks. The prosodion was accompanied by the ...

, paean

A paean () is a song or lyric poem expressing triumph or thanksgiving. In classical antiquity, it is usually performed by a chorus, but some examples seem intended for an individual voice ( monody). It comes from the Greek παιάν (also π� ...

, dithyramb

The dithyramb (; grc, διθύραμβος, ''dithyrambos'') was an ancient Greek hymn sung and danced in honor of Dionysus, the god of wine and fertility; the term was also used as an epithet of the god. Plato, in '' The Laws'', while discussing ...

, nomos, adonidia, iobakchos, and hyporcheme;

* for humans— encomion, epinikion, skolion

A skolion (from grc, σκόλιον) (pl. skolia), also scolion (pl. scolia), was a song sung by invited guests at banquets in ancient Greece. Often extolling the virtues of the gods or heroic men, skolia were improvised to suit the occasion and ...

, erotica

Erotica is literature or art that deals substantively with subject matter that is erotic, sexually stimulating or sexually arousing. Some critics regard pornography as a type of erotica, but many consider it to be different. Erotic art may use ...

, epithalamia, hymenaios

Hymen ( grc, Ὑμήν), Hymenaios or Hymenaeus, in Hellenistic religion, is a god of marriage ceremonies, inspiring feasts and song. Related to the god's name, a ''hymenaios'' is a genre of Greek lyric poetry sung during the procession of the ...

, sillos, threnos, and epikedeion;

* for the gods and humans—partheneion, daphnephorika, tripodephorika, oschophorika, and eutika

According to Mathiesen:

Unicode

Music symbols of ancient Greece were added to theUnicode

Unicode, formally The Unicode Standard,The formal version reference is is an information technology standard for the consistent encoding, representation, and handling of text expressed in most of the world's writing systems. The standard, ...

Standard in March 2005 with the release of version 4.1.

See also

*Alypius of Alexandria

Alypius of Alexandria ( grc-gre, Ἀλύπιος) was a Greek writer on music who flourished in the 4th century CE. Of his works, only a small fragment has been preserved, under the title of ''Introduction to Music'' ().

Works

The work of Alypius ...

* Delphic Hymns

* Seikilos epitaph

The Seikilos epitaph is the oldest surviving complete musical composition, including musical notation, from anywhere in the world. The epitaph has been variously dated, but seems to be either from the 1st or the 2nd century CE. The song, the melo ...

* Mesomedes

* Oxyrhynchus hymn

References

Sources * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *Further reading

* (1840).Die Hymnen des Dionysius und Mesomedes: Text und Melodieen nach Handschriften und den alten Ausgaben bearbeitet von Dr. Friedrich Bellermann

'. Berlin: Albert Förstner. * Jan, Karl von (ed.) (1895). ''Musici scriptores graeci: Aristoteles, Euclides, Nicomachus, Bacchius, Gaudentius, Alypius et melodiarum veterum quidquid exstat''. Bibliotheca scriptorum graecorum et romanorum Teubneriana. Leipzig: B. G. Teubner. * * Mathiesen, Thomas J. (2001d). "Alypius lupios. ''

The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians

''The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians'' is an encyclopedic dictionary of music and musicians. Along with the German-language '' Die Musik in Geschichte und Gegenwart'', it is one of the largest reference works on the history and t ...

'', second edition, edited by Stanley Sadie

Stanley John Sadie (; 30 October 1930 – 21 March 2005) was an influential and prolific British musicologist, music critic, and editor. He was editor of the sixth edition of the '' Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians'' (1980), which was pub ...

and John Tyrrell. London: Macmillan Publishers.

* Meibom, Marcus (ed.) (1652). ''Antiquae musicae auctores septem: Graece et latine'', 2 vols. Amsterdam: Apud Ludovicum Elzevirium. Facsimile reprint in Monuments of Music and Music Literature in Facsimile, Second Series: Music Literature 51. New York: Broude Bros., 1977. .

*

* Winnington-Ingram, Reginald P. (1954). "Greek Music (Ancient)". ''Grove's Dictionary of Music and Musicians

''The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians'' is an encyclopedic dictionary of music and musicians. Along with the German-language ''Die Musik in Geschichte und Gegenwart'', it is one of the largest reference works on the history and theo ...

'', fifth edition, edited by Eric Blom

Eric Walter Blom (20 August 188811 April 1959) was a Swiss-born British-naturalised music lexicographer, music critic and writer. He is best known as the editor of the 5th edition of '' Grove's Dictionary of Music and Musicians'' (1954).

Bio ...

. New York: St. Martin's Press.

External links

* Elsie Hamiltonbooklet on the modes of ancient Greece

with detailed examples of the construction of Aolus (reed pipe instruments) and monochord, which might help reconstruct the intervals and modes of the Greeks * Nikolaos Ioannidis musician, composer, has attempted t

from a combination of the ancient texts (to be performed) and his knowledge of Greek music. * A mid-19th century, 1902 edition, Henry S. Macran

''The Harmonics of Aristoxenus''

The Barbera translation cited above is more up to date. * Joe Monzo (2004)

Analysis of Aristoxenus

Full of interesting and insightful mathematical analysis. There are some original hypotheses outlined. *

Robert Erickson

Robert Erickson (March 7, 1917 – April 24, 1997) was an American composer.

Education

Erickson was born in Marquette, Michigan. He studied with Ernst Krenek from 1936 to 1947: "I had already studied—and abandoned—the twelve tone sys ...

, American composer and academicAnalysis of Archytas

something of a complement to the above Aristoxenus but, dealing with the earlier and arithmetically precise Archytas:. An incidental note. Erickson is keen to demonstrate that Archytas tuning system not only corresponds with Platos Harmonia, but also with the practice of musicians. Erickson mentions the ease of tuning with the Lyre. * Austrian Academy of Science

examples of instruments and compositions

a music group led by scholar

Annie Bélis

Annie Bélis (born 1951) is a French archaeologist, philologist, papyrologist and musician. She is a research director at the French CNRS, specialized in music from classical antiquity, Ancient Greece and Ancient Rome.

Career

A former student ...

, dedicated to the recreation of ancient Greek and Roman music and playing scores written on inscriptions and papyri.

{{DEFAULTSORT:Musical Mode

Ancient Greek music

Ancient Greek music theory

Melody types

Musical tuning