Monocacy Boulevard on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Frederick is a city in and the

In 1748, Frederick County was formed by carving a section off of

In 1748, Frederick County was formed by carving a section off of

As the county seat for Western Maryland, Frederick not only was an important market town but also the seat of justice. Although Montgomery County and Washington County were split off from Frederick County in 1776, Frederick remained the seat of the smaller (though still large) county. Important lawyers who practiced in Frederick included

As the county seat for Western Maryland, Frederick not only was an important market town but also the seat of justice. Although Montgomery County and Washington County were split off from Frederick County in 1776, Frederick remained the seat of the smaller (though still large) county. Important lawyers who practiced in Frederick included  Frederick was also known during the nineteenth century for its religious pluralism, with one of its main thoroughfares, Church Street, hosting about a half dozen major churches. In 1793, All Saints Church hosted the first confirmation of an American citizen, by the newly consecrated Episcopal Bishop Thomas Claggett. That original colonial building was replaced in 1814 by a brick classical revival structure. It still stands today, although the principal worship space has become an even larger brick gothic church joining it at the back and facing Frederick's City Hall (so the parish remains the oldest Episcopal Church in western Maryland). The main Catholic church, dedicated to St. John the Evangelist, was built in 1800, then rebuilt in 1837 (across the street) one block north of Church Street on East Second Street, where it still stands along with a school and convent established by the

Frederick was also known during the nineteenth century for its religious pluralism, with one of its main thoroughfares, Church Street, hosting about a half dozen major churches. In 1793, All Saints Church hosted the first confirmation of an American citizen, by the newly consecrated Episcopal Bishop Thomas Claggett. That original colonial building was replaced in 1814 by a brick classical revival structure. It still stands today, although the principal worship space has become an even larger brick gothic church joining it at the back and facing Frederick's City Hall (so the parish remains the oldest Episcopal Church in western Maryland). The main Catholic church, dedicated to St. John the Evangelist, was built in 1800, then rebuilt in 1837 (across the street) one block north of Church Street on East Second Street, where it still stands along with a school and convent established by the

. ''

Frederick became Maryland's capital city briefly in 1861, as the legislature moved from Annapolis to vote on the secession question. President Lincoln arrested several members, and the assembly was unable to convene a quorum to vote on secession.

As a major crossroads, Frederick, like

Frederick became Maryland's capital city briefly in 1861, as the legislature moved from Annapolis to vote on the secession question. President Lincoln arrested several members, and the assembly was unable to convene a quorum to vote on secession.

As a major crossroads, Frederick, like  A legend related by

A legend related by

Frederick is well known for the "clustered spires" skyline of its historic downtown churches. These spires are depicted on the city's seal and many other city-affiliated logos and insignia. The phrase "clustered spires" is used as the name of several city locations such as Clustered Spires Cemetery and the city-operated Clustered Spires Golf Course.

Frederick is well known for the "clustered spires" skyline of its historic downtown churches. These spires are depicted on the city's seal and many other city-affiliated logos and insignia. The phrase "clustered spires" is used as the name of several city locations such as Clustered Spires Cemetery and the city-operated Clustered Spires Golf Course.

The scale of the older part of the city is dense, with streets and sidewalks suitable for pedestrians, and a variety of shops and restaurants, comprising what ''

The scale of the older part of the city is dense, with streets and sidewalks suitable for pedestrians, and a variety of shops and restaurants, comprising what ''

Chabad Lubavitch of Fredrick

, a

Print

Frederick's newspaper of record is the ''

Resolution 13-08

as a permanent standing committee called the Bicycle and Pedestrian Advisory Committee (BPAC). The BPAC advises City officials and staff on the sound development, management, and safe use of The City of Frederick's pedestrian and bicycle systems as they relate to infrastructure, accessibility, and promoting the benefits of these systems.

"Bobby Steggart"

''Frederick News Post'', May 14, 2010 *

Official city government website

{{Authority control 1745 establishments in Maryland Cities in Maryland Cities in Frederick County, Maryland County seats in Maryland Palatine German settlement in Maryland Pennsylvania German culture in Maryland Populated places established in 1745 Washington metropolitan area Monocacy River Cities in the Baltimore–Washington metropolitan area

county seat

A county seat is an administrative center, seat of government, or capital city of a county or civil parish. The term is in use in Canada, China, Hungary, Romania, Taiwan, and the United States. The equivalent term shire town is used in the US st ...

of Frederick County, Maryland

Frederick County is located in the northern part of the U.S. state of Maryland. At the 2020 U.S. Census, the population was 271,717. The county seat is Frederick.

Frederick County is included in the Washington-Arlington-Alexandria, DC-VA-MD-WV ...

. It is part of the Baltimore–Washington Metropolitan Area. Frederick has long been an important crossroads, located at the intersection of a major north–south Native American trail and east–west routes to the Chesapeake Bay

The Chesapeake Bay ( ) is the largest estuary in the United States. The Bay is located in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic region and is primarily separated from the Atlantic Ocean by the Delmarva Peninsula (including the parts: the ...

, both at Baltimore

Baltimore ( , locally: or ) is the List of municipalities in Maryland, most populous city in the U.S. state of Maryland, fourth most populous city in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic, and List of United States cities by popula ...

and what became Washington, D.C.

)

, image_skyline =

, image_caption = Clockwise from top left: the Washington Monument and Lincoln Memorial on the National Mall, United States Capitol, Logan Circle, Jefferson Memorial, White House, Adams Morgan, ...

and across the Appalachian mountains

The Appalachian Mountains, often called the Appalachians, (french: Appalaches), are a system of mountains in eastern to northeastern North America. The Appalachians first formed roughly 480 million years ago during the Ordovician Period. They ...

to the Ohio River

The Ohio River is a long river in the United States. It is located at the boundary of the Midwestern and Southern United States, flowing southwesterly from western Pennsylvania to its mouth on the Mississippi River at the southern tip of Illino ...

watershed. It is a part of the Washington-Arlington-Alexandria, DC-VA-MD-WV Metropolitan Statistical Area

The Washington metropolitan area, also commonly referred to as the National Capital Region, is the metropolitan area centered on Washington, D.C. The metropolitan area includes all of Washington, D.C. and parts of the states of Maryland, Virgin ...

, which is part of a greater Washington-Baltimore-Arlington, DC-MD-VA-WV-PA Combined Statistical Area. The city's population was 78,171 people as of the 2020 United States census

The United States census of 2020 was the twenty-fourth decennial United States census. Census Day, the reference day used for the census, was April 1, 2020. Other than a pilot study during the 2000 census, this was the first U.S. census to of ...

, making it the second-largest incorporated city in Maryland (behind Baltimore

Baltimore ( , locally: or ) is the List of municipalities in Maryland, most populous city in the U.S. state of Maryland, fourth most populous city in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic, and List of United States cities by popula ...

). Frederick is home to Frederick Municipal Airport (IATA

The International Air Transport Association (IATA ) is a trade association of the world's airlines founded in 1945. IATA has been described as a cartel since, in addition to setting technical standards for airlines, IATA also organized tariff ...

: FDK), which accommodates general aviation

General aviation (GA) is defined by the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) as all civil aviation aircraft operations with the exception of commercial air transport or aerial work, which is defined as specialized aviation services ...

, and Fort Detrick

Fort Detrick () is a United States Army Futures Command installation located in Frederick, Maryland. Historically, Fort Detrick was the center of the U.S. biological weapons program from 1943 to 1969. Since the discontinuation of that program, i ...

, a U.S. Army

The United States Army (USA) is the land service branch of the United States Armed Forces. It is one of the eight U.S. uniformed services, and is designated as the Army of the United States in the U.S. Constitution.Article II, section 2, cl ...

bioscience/communications research installation and Frederick county's largest employer.

History

Pre-Colonization

Located whereCatoctin Mountain

Catoctin Mountain, along with the geologically associated Bull Run Mountains, forms the easternmost mountain ridge of the Blue Ridge Mountains, which are in turn a part of the Appalachian Mountains range. The ridge runs northeast–southwest for ...

(the easternmost ridge of the Blue Ridge mountains

The Blue Ridge Mountains are a physiographic province of the larger Appalachian Mountains range. The mountain range is located in the Eastern United States, and extends 550 miles southwest from southern Pennsylvania through Maryland, West Virgin ...

) meets the rolling hills of the Piedmont region, the Frederick area became a crossroads even before European explorers and traders arrived. Native American hunters (possibly including the Susquehannock

The Susquehannock people, also called the Conestoga by some English settlers or Andastes were Iroquoian Native Americans who lived in areas adjacent to the Susquehanna River and its tributaries, ranging from its upper reaches in the southern p ...

s, the Algonquian-speaking Shawnee

The Shawnee are an Algonquian-speaking indigenous people of the Northeastern Woodlands. In the 17th century they lived in Pennsylvania, and in the 18th century they were in Pennsylvania, Ohio, Indiana and Illinois, with some bands in Kentucky a ...

, or the Seneca

Seneca may refer to:

People and language

* Seneca (name), a list of people with either the given name or surname

* Seneca people, one of the six Iroquois tribes of North America

** Seneca language, the language of the Seneca people

Places Extrat ...

or Tuscarora Tuscarora may refer to the following:

First nations and Native American people and culture

* Tuscarora people

**''Federal Power Commission v. Tuscarora Indian Nation'' (1960)

* Tuscarora language, an Iroquoian language of the Tuscarora people

* ...

or other members of the Iroquois Confederation

The Iroquois ( or ), officially the Haudenosaunee ( meaning "people of the longhouse"), are an Iroquoian-speaking confederacy of First Nations peoples in northeast North America/ Turtle Island. They were known during the colonial years to ...

) followed the Monocacy River

The Monocacy River () is a free-flowing left tributary to the Potomac River, which empties into the Atlantic Ocean via the Chesapeake Bay. The river is long,U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline data ...

from the Susquehanna River

The Susquehanna River (; Lenape: Siskëwahane) is a major river located in the Mid-Atlantic region of the United States, overlapping between the lower Northeast and the Upland South. At long, it is the longest river on the East Coast of the ...

watershed in Pennsylvania to the Potomac River

The Potomac River () drains the Mid-Atlantic United States, flowing from the Potomac Highlands into Chesapeake Bay. It is long,U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map. Retrieved Augus ...

watershed and the lands of the more agrarian and maritime Algonquian peoples

The Algonquian are one of the most populous and widespread North American native language groups. Historically, the peoples were prominent along the Atlantic Coast and into the interior along the Saint Lawrence River and around the Great Lakes. T ...

, particularly the Lenape

The Lenape (, , or Lenape , del, Lënapeyok) also called the Leni Lenape, Lenni Lenape and Delaware people, are an indigenous peoples of the Northeastern Woodlands, who live in the United States and Canada. Their historical territory includ ...

of the Delaware valley or the Piscataway Piscataway may refer to:

*Piscataway people, a Native American ethnic group native to the southern Mid-Atlantic States

*Piscataway language

*Piscataway, Maryland, an unincorporated community

*Piscataway, New Jersey, a township

*Piscataway Creek, Ma ...

and Powhatan

The Powhatan people (; also spelled Powatan) may refer to any of the indigenous Algonquian people that are traditionally from eastern Virginia. All of the Powhatan groups descend from the Powhatan Confederacy. In some instances, The Powhatan ...

of the lower Potomac watershed and Chesapeake Bay. This became known as the Monocacy Trail or even the Great Indian Warpath

The Great Indian Warpath (GIW)—also known as the Great Indian War and Trading Path, or the Seneca Trail—was that part of the network of trails in eastern North America developed and used by Native Americans which ran through the Great Appala ...

, with some travelers continuing southward through the "Great Appalachian Valley

The Great Appalachian Valley, also called The Great Valley or Great Valley Region, is one of the major landform features of eastern North America. It is a gigantic trough—a chain of valley lowlands—and the central feature of the Appalachian M ...

" (Shenandoah Valley

The Shenandoah Valley () is a geographic valley and cultural region of western Virginia and the Eastern Panhandle of West Virginia. The valley is bounded to the east by the Blue Ridge Mountains, to the west by the eastern front of the Ridge- ...

, etc.) to the western Piedmont

it, Piemontese

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 =

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographics1_title1 =

, demographics1_info1 =

, demographics1_title2 ...

in North Carolina

North Carolina () is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States. The state is the 28th largest and 9th-most populous of the United States. It is bordered by Virginia to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the east, Georgia and So ...

, or traveling down other watersheds in Virginia toward the Chesapeake Bay

The Chesapeake Bay ( ) is the largest estuary in the United States. The Bay is located in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic region and is primarily separated from the Atlantic Ocean by the Delmarva Peninsula (including the parts: the ...

, such as those of the Rappahannock, James

James is a common English language surname and given name:

*James (name), the typically masculine first name James

* James (surname), various people with the last name James

James or James City may also refer to:

People

* King James (disambiguat ...

and York Rivers.

Colonial era

The earliest European settlement was slightly north of Frederick in Monocacy, Maryland. Monocacy was founded before 1730 (when the Indian trail became a wagon road) and was abandoned before theAmerican Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was a major war of the American Revolution. Widely considered as the war that secured the independence of t ...

, likely due to the river's periodic flooding, hostilities predating the French and Indian War

The French and Indian War (1754–1763) was a theater of the Seven Years' War, which pitted the North American colonies of the British Empire against those of the French, each side being supported by various Native American tribes. At the ...

, or simply Frederick's better location with easier access to the Potomac River near its confluence with the Monocacy.

Daniel Dulany—a land speculator—laid out "Frederick Town" by 1745. Three years earlier, All Saints Church had been founded on a hilltop near a warehouse/trading post. Sources disagree as to which Frederick the town was named for, but the likeliest candidates are Frederick Calvert, 6th Baron Baltimore

Frederick Calvert, 6th Baron Baltimore (6 February 1731 – 4 September 1771), styled The Hon. Frederick Calvert until 1751, was an English nobleman and last in line of the Barons Baltimore. Although he exercised almost feudal power in the Pr ...

(one of the proprietors of Maryland), Frederick Louis, Prince of Wales

Frederick, Prince of Wales, (Frederick Louis, ; 31 January 170731 March 1751), was the eldest son and heir apparent of King George II of Great Britain. He grew estranged from his parents, King George and Caroline of Ansbach, Queen Caroline. Fr ...

, and Frederick the Great

Frederick II (german: Friedrich II.; 24 January 171217 August 1786) was King in Prussia from 1740 until 1772, and King of Prussia from 1772 until his death in 1786. His most significant accomplishments include his military successes in the Sil ...

, King of Prussia.

In 1748, Frederick County was formed by carving a section off of

In 1748, Frederick County was formed by carving a section off of Prince George's County

)

, demonym = Prince Georgian

, ZIP codes = 20607–20774

, area codes = 240, 301

, founded date = April 23

, founded year = 1696

, named for = Prince George of Denmark

, leader_title = Executive

, leader_name = Angela D. Alsobrook ...

. Frederick Town (now Frederick) was made the county seat of Frederick County. The county originally extended to the Appalachian mountains (areas further west being disputed between the colonies of Virginia and Pennsylvania until 1789). The current town's first house was built by a young German Reformed

The Evangelical and Reformed Church (E&R) was a Protestant Christian denomination in the United States. It was formed in 1934 by the merger of the Reformed Church in the United States (RCUS) with the Evangelical Synod of North America (ESNA). A m ...

schoolmaster from the Rhineland Palatinate named Johann Thomas Schley (died 1790), who led a party of immigrants (including his wife, Maria Von Winz) to the Maryland colony. The Palatinate settlers bought land from Dulany on the banks of Carroll Creek, and Schley's house stood at the northwest corner of Middle Alley and East Patrick Street into the 20th century. Schley's settlers also founded a German Reformed Church

Calvinism (also called the Reformed Tradition, Reformed Protestantism, Reformed Christianity, or simply Reformed) is a major branch of Protestantism that follows the theological tradition and forms of Christian practice set down by John Cal ...

(today known as Evangelical Reformed Church, and part of the UCC The initialism UCC may stand for:

Law

* Uniform civil code of India, referring to proposed Civil code in the legal system of India, which would apply equally to all irrespective of their religion

* Uniform Commercial Code, a 1952 uniform act to ...

). Probably the oldest house still standing in Frederick today is Schifferstadt

Schifferstadt ( pfl, Schiwwerschdadd, ''Schiffaschdad'', or ''Schiwwerschdadt'') is a town in the Rhein-Pfalz-Kreis, in Rhineland-Palatinate, Germany. If not including Ludwigshafen (the district free city that is the capital of Rhein-Pfalz-Kreis), ...

, built in 1756 by German settler Joseph Brunner and now the Schifferstadt Architectural Museum.

Schley's group was among the many Pennsylvania Dutch

The Pennsylvania Dutch ( Pennsylvania Dutch: ), also known as Pennsylvania Germans, are a cultural group formed by German immigrants who settled in Pennsylvania during the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries. They emigrated primarily from German-spe ...

(ethnic Germans) (as well as Scots-Irish and French and later Irish) who migrated south and westward in the late-18th century. Frederick was an important stop along the migration route that became known as the Great Wagon Road

Great may refer to: Descriptions or measurements

* Great, a relative measurement in physical space, see Size

* Greatness, being divine, majestic, superior, majestic, or transcendent

People

* List of people known as "the Great"

*Artel Great (born ...

, which came down from Gettysburg, Pennsylvania

Gettysburg (; non-locally ) is a borough and the county seat of Adams County in the U.S. state of Pennsylvania. The Battle of Gettysburg (1863) and President Abraham Lincoln's Gettysburg Address are named for this town.

Gettysburg is home to th ...

and Emmitsburg, Maryland

Emmitsburg is a town in Frederick County, Maryland, United States, south of the Mason-Dixon line separating Maryland from Pennsylvania. Founded in 1785, Emmitsburg is the home of Mount St. Mary's University. The town has two Catholic pilgrima ...

and continued south following the Great Appalachian Valley

The Great Appalachian Valley, also called The Great Valley or Great Valley Region, is one of the major landform features of eastern North America. It is a gigantic trough—a chain of valley lowlands—and the central feature of the Appalachian M ...

through Winchester

Winchester is a City status in the United Kingdom, cathedral city in Hampshire, England. The city lies at the heart of the wider City of Winchester, a local government Districts of England, district, at the western end of the South Downs Nation ...

and Roanoke, Virginia

Roanoke ( ) is an independent city in the U.S. state of Virginia. At the 2020 census, the population was 100,011, making it the 8th most populous city in the Commonwealth of Virginia and the largest city in Virginia west of Richmond. It is lo ...

. Another important route continued along the Potomac River from near Frederick, to Hagerstown, where it split. One branch crossed the Potomac River near Martinsburg, West Virginia

Martinsburg is a city in and the seat of Berkeley County, West Virginia, in the tip of the state's Eastern Panhandle region in the lower Shenandoah Valley. Its population was 18,835 in the 2021 census estimate, making it the largest city in the E ...

and continued down into the Shenandoah valley. The other continued west to Cumberland, Maryland

Cumberland is a U.S. city in and the county seat of Allegany County, Maryland

Maryland ( ) is a state in the Mid-Atlantic region of the United States. It shares borders with Virginia, West Virginia, and the District of Columbia to its s ...

and ultimately crossed the Appalachian Mountains

The Appalachian Mountains, often called the Appalachians, (french: Appalaches), are a system of mountains in eastern to northeastern North America. The Appalachians first formed roughly 480 million years ago during the Ordovician Period. They ...

into the watershed of the Ohio River

The Ohio River is a long river in the United States. It is located at the boundary of the Midwestern and Southern United States, flowing southwesterly from western Pennsylvania to its mouth on the Mississippi River at the southern tip of Illino ...

. Thus, British General Edward Braddock

Major-general (United Kingdom), Major-General Edward Braddock (January 1695 – 13 July 1755) was a British officer and commander-in-chief for the Thirteen Colonies during the start of the French and Indian War (1754–1763), the North American f ...

marched his troops (including the youthful George Washington

George Washington (February 22, 1732, 1799) was an American military officer, statesman, and Founding Father who served as the first president of the United States from 1789 to 1797. Appointed by the Continental Congress as commander of th ...

) west in 1755 through Frederick on the way to their fateful ambush near Fort Duquesne

Fort Duquesne (, ; originally called ''Fort Du Quesne'') was a fort established by the French in 1754, at the confluence of the Allegheny and Monongahela rivers. It was later taken over by the British, and later the Americans, and developed a ...

(later Fort Pitt, then Pittsburgh

Pittsburgh ( ) is a city in the Commonwealth (U.S. state), Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, United States, and the county seat of Allegheny County, Pennsylvania, Allegheny County. It is the most populous city in both Allegheny County and Wester ...

) during the French and Indian War

The French and Indian War (1754–1763) was a theater of the Seven Years' War, which pitted the North American colonies of the British Empire against those of the French, each side being supported by various Native American tribes. At the ...

. However, the British after the Proclamation of 1763

The Royal Proclamation of 1763 was issued by King George III on 7 October 1763. It followed the Treaty of Paris (1763), which formally ended the Seven Years' War and transferred French territory in North America to Great Britain. The Proclam ...

restricted that westward migration route until after the American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was a major war of the American Revolution. Widely considered as the war that secured the independence of t ...

. Other westward migrants continued south from Frederick to Roanoke along the Great Wagon Road, crossing the Appalachians into Kentucky

Kentucky ( , ), officially the Commonwealth of Kentucky, is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States and one of the states of the Upper South. It borders Illinois, Indiana, and Ohio to the north; West Virginia and Virginia to ...

and Tennessee

Tennessee ( , ), officially the State of Tennessee, is a landlocked state in the Southeastern region of the United States. Tennessee is the 36th-largest by area and the 15th-most populous of the 50 states. It is bordered by Kentucky to th ...

at the Cumberland Gap

The Cumberland Gap is a pass through the long ridge of the Cumberland Mountains, within the Appalachian Mountains, near the junction of the U.S. states of Kentucky, Virginia, and Tennessee. It is famous in American colonial history for its rol ...

near the Virginia/North Carolina border.

Other German settlers in Frederick were Evangelical Lutherans

Lutheranism is one of the largest branches of Protestantism, identifying primarily with the theology of Martin Luther, the 16th-century German monk and reformer whose efforts to reform the theology and practice of the Catholic Church launched th ...

, led by Rev. Henry Muhlenberg

Henry Melchior Muhlenberg (an anglicanization of Heinrich Melchior Mühlenberg) (September 6, 1711 – October 7, 1787), was a German Lutheran pastor sent to North America as a missionary, requested by Pennsylvania colonists.

Integral to the ...

. They moved their mission church from Monocacy to what became a large complex a few blocks further down Church Street from the Anglicans and the German Reformed Church. Methodist missionary Robert Strawbridge

Robert Strawbridge (born 1732 - died 1781) was a Methodist preacher born in Drumsna, County Leitrim, Ireland.

Early life and ancestral history

Information detailing the early life of Robert Strawbridge is somewhat limited. One article, Robe ...

, who accepted an invitation to preach at Frederick town in 1770, and Francis Asbury

Francis Asbury (August 20 or 21, 1745 – March 31, 1816) was one of the first two bishops of the Methodist Episcopal Church in the United States. During his 45 years in the colonies and the newly independent United States, he devoted his life to ...

, who arrived two years later, both helped found a congregation which became Calvary Methodist Church, worshipping in a log building from 1792 (although superseded by larger buildings in 1841, 1865, 1910 and 1930). Frederick also had a Catholic mission, to which Rev. Jean DuBois was assigned in 1792, which became St. John the Evangelist Church (built in 1800).

To control this crossroads during the American Revolution

The American Revolution was an ideological and political revolution that occurred in British America between 1765 and 1791. The Americans in the Thirteen Colonies formed independent states that defeated the British in the American Revolut ...

, the British garrisoned a German Hessian

A Hessian is an inhabitant of the German state of Hesse.

Hessian may also refer to:

Named from the toponym

*Hessian (soldier), eighteenth-century German regiments in service with the British Empire

**Hessian (boot), a style of boot

**Hessian f ...

regiment in the town;

Early 19th century

As the county seat for Western Maryland, Frederick not only was an important market town but also the seat of justice. Although Montgomery County and Washington County were split off from Frederick County in 1776, Frederick remained the seat of the smaller (though still large) county. Important lawyers who practiced in Frederick included

As the county seat for Western Maryland, Frederick not only was an important market town but also the seat of justice. Although Montgomery County and Washington County were split off from Frederick County in 1776, Frederick remained the seat of the smaller (though still large) county. Important lawyers who practiced in Frederick included John Hanson

John Hanson ( – November 15, 1783) was an American Founding Father, merchant, and politician from Maryland during the Revolutionary Era. In 1779, Hanson was elected as a delegate to the Continental Congress after serving in a variety of ...

, Francis Scott Key

Francis Scott Key (August 1, 1779January 11, 1843) was an American lawyer, author, and amateur poet from Frederick, Maryland, who wrote the lyrics for the American national anthem "The Star-Spangled Banner". Key observed the British bombardment ...

and Roger B. Taney

Roger Brooke Taney (; March 17, 1777 – October 12, 1864) was the fifth chief justice of the United States, holding that office from 1836 until his death in 1864. Although an opponent of slavery, believing it to be an evil practice, Taney belie ...

.

Frederick was also known during the nineteenth century for its religious pluralism, with one of its main thoroughfares, Church Street, hosting about a half dozen major churches. In 1793, All Saints Church hosted the first confirmation of an American citizen, by the newly consecrated Episcopal Bishop Thomas Claggett. That original colonial building was replaced in 1814 by a brick classical revival structure. It still stands today, although the principal worship space has become an even larger brick gothic church joining it at the back and facing Frederick's City Hall (so the parish remains the oldest Episcopal Church in western Maryland). The main Catholic church, dedicated to St. John the Evangelist, was built in 1800, then rebuilt in 1837 (across the street) one block north of Church Street on East Second Street, where it still stands along with a school and convent established by the

Frederick was also known during the nineteenth century for its religious pluralism, with one of its main thoroughfares, Church Street, hosting about a half dozen major churches. In 1793, All Saints Church hosted the first confirmation of an American citizen, by the newly consecrated Episcopal Bishop Thomas Claggett. That original colonial building was replaced in 1814 by a brick classical revival structure. It still stands today, although the principal worship space has become an even larger brick gothic church joining it at the back and facing Frederick's City Hall (so the parish remains the oldest Episcopal Church in western Maryland). The main Catholic church, dedicated to St. John the Evangelist, was built in 1800, then rebuilt in 1837 (across the street) one block north of Church Street on East Second Street, where it still stands along with a school and convent established by the Visitation Sisters

, image = Salesas-escut.gif

, size = 175px

, abbreviation = V.S.M.

, nickname = Visitandines

, motto =

, formation =

, founder = Saint Bishop Francis de ...

. The stone Evangelical Lutheran Church of 1752 was also rebuilt and enlarged in 1825, then replaced by the current twin-spired structure in 1852.

The oldest African-American church in the town is Asbury United Methodist Church, founded as the Old Hill Church, a mixed congregation in 1818. It became an African-American congregation in 1864, renamed Asbury Methodist Episcopal Church in 1870, and built its current building on All Saints Street in 1921.

Together, these churches dominated the town, set against the backdrop of the first ridge of the Appalachians, Catoctin Mountain

Catoctin Mountain, along with the geologically associated Bull Run Mountains, forms the easternmost mountain ridge of the Blue Ridge Mountains, which are in turn a part of the Appalachian Mountains range. The ridge runs northeast–southwest for ...

. The abolitionist poet John Greenleaf Whittier

John Greenleaf Whittier (December 17, 1807 – September 7, 1892) was an American Quaker poet and advocate of the abolition of slavery in the United States. Frequently listed as one of the fireside poets, he was influenced by the Scottish poet ...

later immortalized this view of Frederick in his poem to Barbara Fritchie

Barbara Fritchie (née Hauer; December 3, 1766 – December 18, 1862), also known as Barbara Frietchie, and sometimes spelled Frietschie, was a Unionist during the Civil War. She became part of American folklore in part from a popular poem ...

: "The clustered spires of Frederick stand / Green-walled by the hills of Maryland."

When U.S. President

The president of the United States (POTUS) is the head of state and head of government of the United States of America. The president directs the executive branch of the federal government and is the commander-in-chief of the United States ...

Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson (April 13, 1743 – July 4, 1826) was an American statesman, diplomat, lawyer, architect, philosopher, and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as the third president of the United States from 18 ...

commissioned the building of the National Road

The National Road (also known as the Cumberland Road) was the first major improved highway in the United States built by the Federal Government of the United States, federal government. Built between 1811 and 1837, the road connected the Pot ...

from Baltimore toward St. Louis

St. Louis () is the second-largest city in Missouri, United States. It sits near the confluence of the Mississippi and the Missouri Rivers. In 2020, the city proper had a population of 301,578, while the bi-state metropolitan area, which e ...

(eventually built to Vandalia, then the state capital of Illinois), the "National Pike" ran through Frederick along Patrick Street. (This later became U.S. Route 40.) Frederick's Jacob Engelbrecht corresponded with Jefferson in 1824 (receiving a transcribed psalm in return), and kept a diary from 1819-1878 which remains an important first-hand account of 19th century life from its viewpoint on the National Road. An important house remaining from this era is the Tyler Spite House, built in 1814 at 112 W. Church Street by a local doctor to prevent the city from extending Record Street south through his land to meet West Patrick Street.Williams, N. (April 2, 1990). "This Maryland House was built just for spite". ''Los Angeles Times

The ''Los Angeles Times'' (abbreviated as ''LA Times'') is a daily newspaper that started publishing in Los Angeles in 1881. Based in the LA-adjacent suburb of El Segundo since 2018, it is the sixth-largest newspaper by circulation in the Un ...

''."A Matter of Spite". ''

Frederick News-Post

''The Frederick News-Post'' is the local newspaper of Frederick County, Maryland. In addition to discussing local news, the newspaper addresses international, national, and regional news. The paper publishes six days a week.

History

On October ...

''.

Frederick also became one of the new nation's leading mining counties in the early 19th century. It exported gold, copper, limestone, marble, iron and other minerals. As early as the American Revolution, Catoctin Furnace near Thurmont became important for iron production. Other mining areas split off into Washington County, Maryland

Washington County is located in the western part of the U.S. state of Maryland. As of the 2020 census, the population was 154,705. Its county seat is Hagerstown. Washington County was the first county in the United States to be named for the ...

and Allegheny County, Maryland

Allegany County is located in the northwestern part of the U.S. state of Maryland. As of the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, the population was 68,106. Its county seat is Cumberland, Maryland, Cumberland. The name ''Allegany'' may come f ...

but continued to ship their ore through Frederick to Eastern cities and ports.

Frederick had easy access to the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal

The Chesapeake and Ohio Canal, abbreviated as the C&O Canal and occasionally called the "Grand Old Ditch," operated from 1831 until 1924 along the Potomac River between Washington, D.C. and Cumberland, Maryland. It replaced the Potomac Canal, wh ...

, which began operations in 1831 and continued hauling freight until 1924. Also in 1831, the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad

The Baltimore and Ohio Railroad was the first common carrier railroad and the oldest railroad in the United States, with its first section opening in 1830. Merchants from Baltimore, which had benefited to some extent from the construction of ...

(B&O) completed its Frederick Branch line from the Frederick (or Monocacy) Junction off the main Western Line from Baltimore to Harpers Ferry

Harpers Ferry is a historic town in Jefferson County, West Virginia. It is located in the lower Shenandoah Valley. The population was 285 at the 2020 census. Situated at the confluence of the Potomac and Shenandoah rivers, where the U.S. stat ...

, Cumberland

Cumberland ( ) is a historic county in the far North West England. It covers part of the Lake District as well as the north Pennines and Solway Firth coast. Cumberland had an administrative function from the 12th century until 1974. From 19 ...

, and the Ohio River

The Ohio River is a long river in the United States. It is located at the boundary of the Midwestern and Southern United States, flowing southwesterly from western Pennsylvania to its mouth on the Mississippi River at the southern tip of Illino ...

. The railroad reached Chicago

(''City in a Garden''); I Will

, image_map =

, map_caption = Interactive Map of Chicago

, coordinates =

, coordinates_footnotes =

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name ...

and St. Louis

St. Louis () is the second-largest city in Missouri, United States. It sits near the confluence of the Mississippi and the Missouri Rivers. In 2020, the city proper had a population of 301,578, while the bi-state metropolitan area, which e ...

by the 1850s.

Civil War

Frederick became Maryland's capital city briefly in 1861, as the legislature moved from Annapolis to vote on the secession question. President Lincoln arrested several members, and the assembly was unable to convene a quorum to vote on secession.

As a major crossroads, Frederick, like

Frederick became Maryland's capital city briefly in 1861, as the legislature moved from Annapolis to vote on the secession question. President Lincoln arrested several members, and the assembly was unable to convene a quorum to vote on secession.

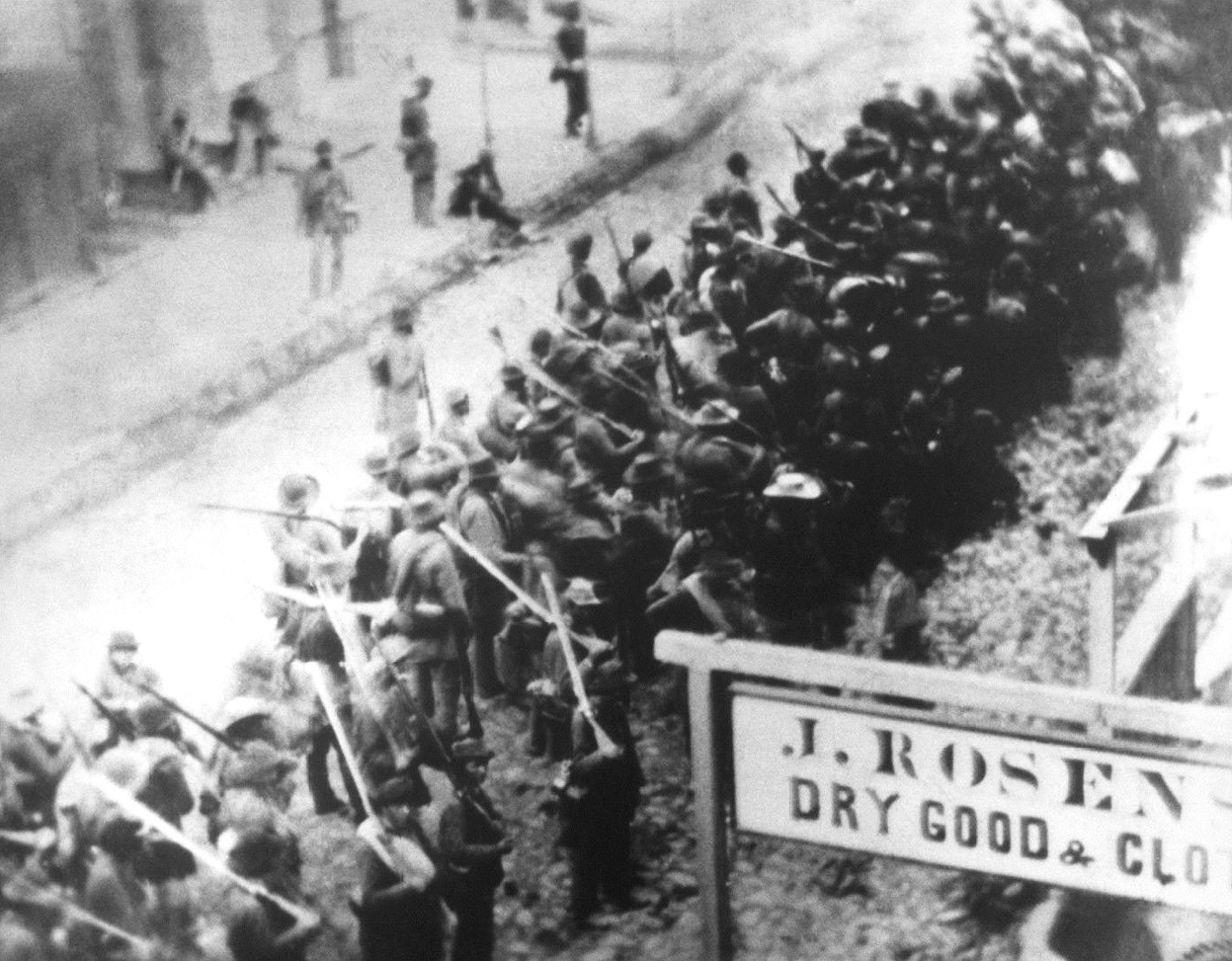

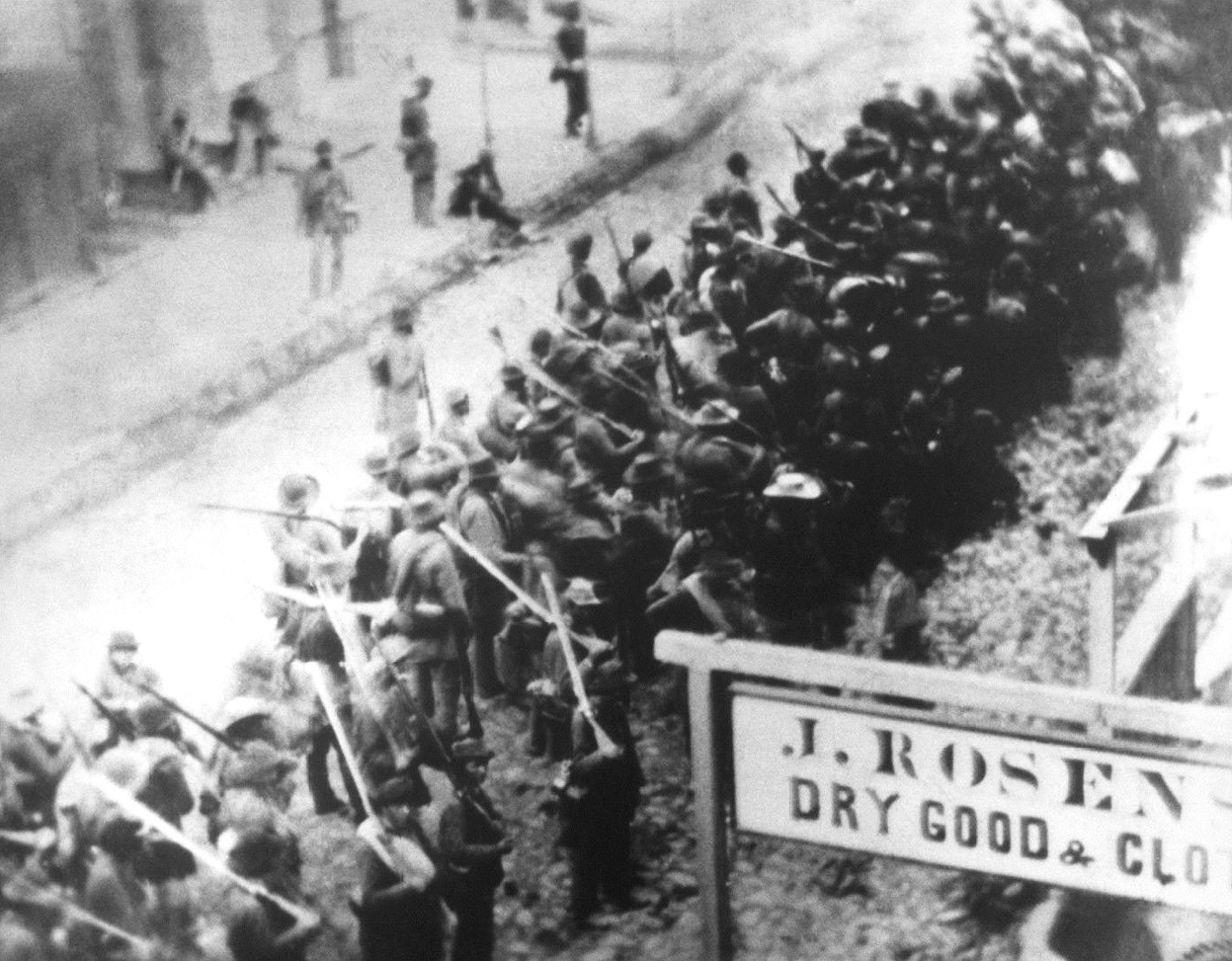

As a major crossroads, Frederick, like Winchester, Virginia

Winchester is the most north western independent city in the Commonwealth of Virginia. It is the county seat of Frederick County, although the two are separate jurisdictions. The Bureau of Economic Analysis combines the city of Winchester wit ...

, and Martinsburg, West Virginia

Martinsburg is a city in and the seat of Berkeley County, West Virginia, in the tip of the state's Eastern Panhandle region in the lower Shenandoah Valley. Its population was 18,835 in the 2021 census estimate, making it the largest city in the E ...

, saw considerable action during the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states th ...

. Slaves

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

also escaped from or through Frederick (since Maryland was still a "slave state" although it had not seceded) to join the Union forces, work against the Confederacy and seek freedom. During the Maryland campaigns, both Union

Union commonly refers to:

* Trade union, an organization of workers

* Union (set theory), in mathematics, a fundamental operation on sets

Union may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment

Music

* Union (band), an American rock group

** ''Un ...

and Confederate

Confederacy or confederate may refer to:

States or communities

* Confederate state or confederation, a union of sovereign groups or communities

* Confederate States of America, a confederation of secessionist American states that existed between 1 ...

troops marched through the city. Frederick also hosted several hospitals to nurse the wounded from those battles, as is related in the National Museum of Civil War Medicine

__NOTOC__

The National Museum of Civil War Medicine is a U.S. historic education institution located in Frederick, Maryland. Its focus involves the medical, surgical and nursing practices during the American Civil War (1861-1865).

History

The ...

on East Patrick Street.

A legend related by

A legend related by John Greenleaf Whittier

John Greenleaf Whittier (December 17, 1807 – September 7, 1892) was an American Quaker poet and advocate of the abolition of slavery in the United States. Frequently listed as one of the fireside poets, he was influenced by the Scottish poet ...

claimed that Frederick's Pennsylvania Dutch women (including Barbara Fritchie

Barbara Fritchie (née Hauer; December 3, 1766 – December 18, 1862), also known as Barbara Frietchie, and sometimes spelled Frietschie, was a Unionist during the Civil War. She became part of American folklore in part from a popular poem ...

who reportedly waved a flag) booed the Confederates in September 1862, as General Stonewall Jackson

Thomas Jonathan "Stonewall" Jackson (January 21, 1824 – May 10, 1863) was a Confederate general during the American Civil War, considered one of the best-known Confederate commanders, after Robert E. Lee. He played a prominent role in nearl ...

led his light infantry division through Frederick on his way to the battles of Crampton's, Fox's and Turner's Gaps on South Mountain and Antietam

The Battle of Antietam (), or Battle of Sharpsburg particularly in the Southern United States, was a battle of the American Civil War fought on September 17, 1862, between Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia and Union ...

near Sharpsburg. Union Major General Jesse L. Reno's IX Corps followed Jackson's men through the city a few days later on the way to the Battle of South Mountain

The Battle of South Mountain—known in several early Southern accounts as the Battle of Boonsboro Gap—was fought on September 14, 1862, as part of the Maryland campaign of the American Civil War. Three pitched battles were fought for posses ...

, where Reno died. The sites of the battles are due west of the city along the National Road

The National Road (also known as the Cumberland Road) was the first major improved highway in the United States built by the Federal Government of the United States, federal government. Built between 1811 and 1837, the road connected the Pot ...

, west of Burkittsville. Confederate troops under Jackson and Walker unsuccessfully attempted to halt the Federal army's westward advance into the Cumberland Valley

The Cumberland Valley is a northern constituent valley of the Great Appalachian Valley, within the Atlantic Seaboard watershed in Pennsylvania and Maryland. The Appalachian Trail crosses through the valley.

Geography

The valley is bound to th ...

and towards Sharpsburg. Gathland State Park

Gathland State Park is a public recreation area and historic preserve located on South Mountain near Burkittsville, Maryland, in the United States. The state park occupies the former estate of war correspondent George Alfred Townsend (1841-19 ...

has the War Correspondents' Memorial stone arch erected by reporter/editor George Alfred Townsend (1841–1914). The 1889 memorial commemorating Major General Reno and the Union soldiers of his IX Corps is on Reno Monument Road west of Middletown, just below the summit of Fox's Gap

Fox's Gap, also known as Fox Gap, is a wind gap in the South Mountain Range of the Blue Ridge Mountains, located in Frederick County and Washington County, Maryland. The gap is traversed by Reno Monument Road. The Appalachian Trail also cross ...

, as is a 1993 memorial to slain Confederate Brig. Gen. Samuel Garland Jr., and the North Carolina

North Carolina () is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States. The state is the 28th largest and 9th-most populous of the United States. It is bordered by Virginia to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the east, Georgia and So ...

troops who held the line.

President Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation thro ...

, on his way to visit Gen. George McClellan

George Brinton McClellan (December 3, 1826 – October 29, 1885) was an American soldier, Civil War Union general, civil engineer, railroad executive, and politician who served as the 24th governor of New Jersey. A graduate of West Point, McCl ...

after the Battle of South Mountain

The Battle of South Mountain—known in several early Southern accounts as the Battle of Boonsboro Gap—was fought on September 14, 1862, as part of the Maryland campaign of the American Civil War. Three pitched battles were fought for posses ...

and the Battle of Antietam

The Battle of Antietam (), or Battle of Sharpsburg particularly in the Southern United States, was a battle of the American Civil War fought on September 17, 1862, between Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia and Union G ...

, delivered a short speech at what was then the B. & O. Railroad depot at the current intersection of East All Saints and South Market Streets. A plaque commemorates the speech (at what is today the Frederick Community Action Agency, a Social Services office).

At the Prospect Hall mansion off Jefferson Street to Buckeystown Pike near what is now Butterfly Lane, in the early morning hours of June 28, 1863, a messenger arrived from President Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation thro ...

and General-in-Chief Henry Halleck

Henry Wager Halleck (January 16, 1815 – January 9, 1872) was a senior United States Army officer, scholar, and lawyer. A noted expert in military studies, he was known by a nickname that became derogatory: "Old Brains". He was an important par ...

, informing General George Meade

George Gordon Meade (December 31, 1815 – November 6, 1872) was a United States Army officer and civil engineer best known for decisively defeating Confederate States Army, Confederate Full General (CSA), General Robert E. Lee at the Battle ...

that he would be replacing General Joseph Hooker

Joseph Hooker (November 13, 1814 – October 31, 1879) was an American Civil War general for the Union, chiefly remembered for his decisive defeat by Confederate General Robert E. Lee at the Battle of Chancellorsville in 1863.

Hooker had serv ...

after the latter's disastrous performance at Chancellorsville in May. The Army of the Potomac

The Army of the Potomac was the principal Union Army in the Eastern Theater of the American Civil War. It was created in July 1861 shortly after the First Battle of Bull Run and was disbanded in June 1865 following the surrender of the Confedera ...

camped around the Prospect Hall property for the several days as skirmishers pursued Lee's Confederate Army of Northern Virginia

The Army of Northern Virginia was the primary military force of the Confederate States of America in the Eastern Theater of the American Civil War. It was also the primary command structure of the Department of Northern Virginia. It was most oft ...

prior to Gettysburg. A large granite rectangular monument made from one of the boulders at the "Devil's Den" in Gettysburg to the east along the driveway commemorates the midnight change-of-command.

In July 1864, in the third Southern invasion, Confederate troops led by Lieutenant General Jubal Early occupied Frederick and extorted $200,000 ($ in dollars) from citizens for not razing the city on their way to Washington D.C. Union troops under Major General Lew Wallace

Lewis Wallace (April 10, 1827February 15, 1905) was an American lawyer, Union general in the American Civil War, governor of the New Mexico Territory, politician, diplomat, and author from Indiana. Among his novels and biographies, Wallace is ...

fought a successful delaying action, in what became the last significant Confederate advance at the Battle of Monocacy

The Battle of Monocacy (also known as Monocacy Junction) was fought on July 9, 1864, about from Frederick, Maryland, as part of the Valley Campaigns of 1864 during the American Civil War. Confederate forces under Lt. Gen. Jubal A. Early def ...

, also known as the "Battle that saved Washington." The Monocacy National Battlefield

Monocacy National Battlefield is a unit of the National Park Service, the site of the Battle of Monocacy in the American Civil War fought on July 9, 1864. The battlefield straddles the Monocacy River southeast of the city of Frederick, Maryland. ...

lies just southeast of the city limits, along the Monocacy River

The Monocacy River () is a free-flowing left tributary to the Potomac River, which empties into the Atlantic Ocean via the Chesapeake Bay. The river is long,U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline data ...

at the B. & O. Railroad junction where two bridges cross the stream - an iron-truss bridge for the railroad and a covered wooden bridge for the Frederick-Urbana-Georgetown Pike, which was the site of the main battle of July 1864. Some skirmishing occurred further northeast of town at the stone-arched "Jug Bridge" where the National Road

The National Road (also known as the Cumberland Road) was the first major improved highway in the United States built by the Federal Government of the United States, federal government. Built between 1811 and 1837, the road connected the Pot ...

crossed the Monocacy; and an artillery bombardment occurred along the National Road west of town near Red Man's Hill and Prospect Hall mansion as the Union troops retreated eastward. Antietam National Battlefield

Antietam National Battlefield is a National Park Service-protected area along Antietam Creek in Sharpsburg, Washington County, northwestern Maryland. It commemorates the American Civil War Battle of Antietam that occurred on September 17, 1862. ...

and South Mountain State Battlefield Park which commemorates the 1862 battles are located 23 miles and 35 miles respectively to the west-northwest. While Gettysburg National Battlefield

The Gettysburg National Military Park protects and interprets the landscape of the 1863 Battle of Gettysburg during the American Civil War. Located in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, the park is managed by the National Park Service. The GNMP propert ...

of 1863 lies approximately to the north-northeast.

The reconstructed home of Barbara Fritchie

Barbara Fritchie (née Hauer; December 3, 1766 – December 18, 1862), also known as Barbara Frietchie, and sometimes spelled Frietschie, was a Unionist during the Civil War. She became part of American folklore in part from a popular poem ...

stands on West Patrick Street, just past Carroll Creek linear park. Fritchie, a significant figure in Maryland history in her own right, is buried in Frederick's Mount Olivet Cemetery. British Prime Minister Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 Winston Churchill in the Second World War, dur ...

quoted Whittier's poem to President Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (; ; January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), often referred to by his initials FDR, was an American politician and attorney who served as the 32nd president of the United States from 1933 until his death in 1945. As the ...

when they stopped here in 1941 on a car trip to the presidential retreat, then called "Shangra-La" (now "Camp David

Camp David is the country retreat for the president of the United States of America. It is located in the wooded hills of Catoctin Mountain Park, in Frederick County, Maryland, near the towns of Thurmont and Emmitsburg, about north-northwe ...

") within the Catoctin Mountains near Thurmont.

Late 19th century

AdmiralWinfield Scott Schley

Winfield Scott Schley (9 October 1839 – 2 October 1911) was a rear admiral in the United States Navy and the hero of the Battle of Santiago de Cuba during the Spanish–American War.

Biography

Early life

Born at "Richfields" (his father's far ...

(1839–1911) was born at "Richfields", the mansion home of his father. He became an important naval commander of the American fleet on board his flagship and heavy cruiser USS ''Baltimore'' along with Admiral William T. Sampson

William Thomas Sampson (February 9, 1840 – May 6, 1902) was a United States Navy rear admiral known for his victory in the Battle of Santiago de Cuba during the Spanish–American War.

Biography

He was born in Palmyra, New York, and entered ...

in the Battle of Santiago de Cuba

The Battle of Santiago de Cuba was a decisive naval engagement that occurred on July 3, 1898 between an American fleet, led by William T. Sampson and Winfield Scott Schley, against a Spanish fleet led by Pascual Cervera y Topete, which occurred ...

off the shores of the Spanish island colony of Cuba

Cuba ( , ), officially the Republic of Cuba ( es, República de Cuba, links=no ), is an island country comprising the island of Cuba, as well as Isla de la Juventud and several minor archipelagos. Cuba is located where the northern Caribbea ...

in the Spanish–American War

, partof = the Philippine Revolution, the decolonization of the Americas, and the Cuban War of Independence

, image = Collage infobox for Spanish-American War.jpg

, image_size = 300px

, caption = (clock ...

in 1898. Major Henry Schley's son, Dr. Fairfax Schley, was instrumental in setting up the Frederick County Agricultural Society and the Great Frederick Fair. Gilmer Schley served as Mayor from 1919 to 1922, and the Schleys remained one of the town's leading families into the late-20th century.

Nathaniel Wilson Schley, a prominent banker, and his wife Mary Margaret Schley helped organize and raise funds for the annual Great Frederick Fair, one of the two largest agricultural fairs in the State. Since the 1960s, the fair has featured many outstanding country-western singers and become a major music festival. Schley Avenue commemorates the family's role in the city's heritage.

The Frederick and Pennsylvania Line railroad ran from Frederick to the Pennsylvania–Maryland State line, a/k/a Mason–Dixon line

The Mason–Dixon line, also called the Mason and Dixon line or Mason's and Dixon's line, is a demarcation line separating four U.S. states, forming part of the borders of Pennsylvania, Maryland, Delaware, and West Virginia (part of Virginia ...

. Chartered in 1867, construction began in 1869 and the line opened October 8, 1872. However, it defaulted on its interest payments in 1874 and acquired by the Pennsylvania Railroad

The Pennsylvania Railroad (reporting mark PRR), legal name The Pennsylvania Railroad Company also known as the "Pennsy", was an American Class I railroad that was established in 1846 and headquartered in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. It was named ...

in 1875, which formed a new division to operate the rail line. In the spring of 1896, the Frederick and Pennsylvania Line railroad was liquidated in a judicial sale to the Pennsylvania Railroad for $150,000. The railroad survived through mergers and the Penn-Central bankruptcy. However, the State of Maryland acquired the Frederick and Pennsylvania Line in 1982. As of 2013, all but two miles () at the southern terminus at Frederick still exist, operated by either the Walkersville Southern, or the Maryland Midland Railway (MMID) railroads.

Jewish

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""The ...

pioneers Henry Lazarus and Levy Cohan settled in Frederick in the 1740s as merchants. Mostly German Jewish immigrants organized a community in the mid-19th century, creating the Frederick Hebrew Congregation in 1858. Later the congregation lapsed, but was reorganized in 1917 as a cooperative effort between the older settlers and more recently arrived Eastern European Jews under the name Beth Sholom Congregation.

In 1905, Rev. E. B. Hatcher started the First Baptist

Baptists form a major branch of Protestantism distinguished by baptizing professing Christian believers only (believer's baptism), and doing so by complete immersion. Baptist churches also generally subscribe to the doctrines of soul compete ...

Church of Frederick.

After the Civil War, the Maryland legislature established racially segregated public facilities by the end of the 19th century, re-imposing white supremacy. Black institutions were typically underfunded in the state, and it was not until 1921 that Frederick established a public high school for African Americans

African Americans (also referred to as Black Americans and Afro-Americans) are an ethnic group consisting of Americans with partial or total ancestry from sub-Saharan Africa. The term "African American" generally denotes descendants of ens ...

. First located at 170 West All Saints Street, it moved to 250 Madison Street, where it eventually was adapted as South Frederick Elementary

South is one of the cardinal directions or compass points. The direction is the opposite of north and is perpendicular to both east and west.

Etymology

The word ''south'' comes from Old English ''sūþ'', from earlier Proto-Germanic ''*sunþaz ...

. The building presently houses the Lincoln Elementary School. The Laboring Sons Memorial Grounds, a cemetery for free blacks, was founded in 1851.

Geography

Frederick is located in Frederick County in the northern part of the state of Maryland. The city has served as a major crossroads since colonial times. Today it is located at the junction ofInterstate 70

Interstate 70 (I-70) is a major east–west Interstate Highway System, Interstate Highway in the United States that runs from Interstate 15, I-15 near Cove Fort, Utah, to a park and ride lot just east of Interstate 695 (Maryland), I-695 in ...

, Interstate 270, U.S. Route 340

U.S. Route 340 (US 340) is a spur route of US 40, and runs from Greenville, Virginia to Frederick, Maryland. In Virginia, it runs north–south, parallel and east of US 11, from US 11 north of Greenville via Waynesboro, Grottoes, Elkton, ...

, U.S. Route 40, U.S. Route 40 Alternate

U.S. Route 40 has at least eight extant special routes.

Current routes WaKeeney business loop

U.S. Route 40 Business (US-40 Bus.) is a business route through WaKeeney, Kansas, that was recommended in 1979 as substitute for the formerly pro ...

and U.S. Route 15

U.S. Route 15 (US 15) is a -long United States highway, designated along South Carolina, North Carolina, Virginia, Maryland, Pennsylvania, and New York. The route is signed north–south, from U.S. Route 17 Alternate in Walterboro, South Caro ...

(which runs north–south). In relation to nearby cities, Frederick lies west of Baltimore

Baltimore ( , locally: or ) is the List of municipalities in Maryland, most populous city in the U.S. state of Maryland, fourth most populous city in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic, and List of United States cities by popula ...

, north and slightly west of Washington, D.C.

)

, image_skyline =

, image_caption = Clockwise from top left: the Washington Monument and Lincoln Memorial on the National Mall, United States Capitol, Logan Circle, Jefferson Memorial, White House, Adams Morgan, ...

, southeast of Hagerstown and southwest of Harrisburg, Pennsylvania

Harrisburg is the capital city of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, United States, and the county seat of Dauphin County. With a population of 50,135 as of the 2021 census, Harrisburg is the 9th largest city and 15th largest municipality in Pe ...

. The city's coordinates are 39°25'35" North, 77°25'13" West (39.426294, −77.420403).

According to the United States Census Bureau

The United States Census Bureau (USCB), officially the Bureau of the Census, is a principal agency of the U.S. Federal Statistical System, responsible for producing data about the American people and economy. The Census Bureau is part of the ...

, the city has a total area of , of which is land and is water. The city's area is predominantly land, with small areas of water being the Monocacy River

The Monocacy River () is a free-flowing left tributary to the Potomac River, which empties into the Atlantic Ocean via the Chesapeake Bay. The river is long,U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline data ...

, which runs to the east of the city, Carroll Creek (which runs through the city and causes periodic floods, such as that during the summer of 1972 and fall of 1976), as well as several neighborhood ponds and small city owned lakes, such as Culler Lake, a man-made small body of water in the downtown area.

Climate

The climate in this area is characterized by hot, humid summers and generally cool winters. It lies to the west of thefall line

A fall line (or fall zone) is the area where an upland region and a coastal plain meet and is typically prominent where rivers cross it, with resulting rapids or waterfalls. The uplands are relatively hard crystalline basement rock, and the coa ...

, which gives the city slightly lower temperatures compared to locales further east. According to the Köppen Climate Classification

The Köppen climate classification is one of the most widely used climate classification systems. It was first published by German-Russian climatologist Wladimir Köppen (1846–1940) in 1884, with several later modifications by Köppen, notabl ...

system, Frederick has a humid subtropical climate

A humid subtropical climate is a zone of climate characterized by hot and humid summers, and cool to mild winters. These climates normally lie on the southeast side of all continents (except Antarctica), generally between latitudes 25° and 40° ...

, abbreviated ''Cfa'' on climate maps.

Demographics

2010 census

As of the 2010 U.S.census

A census is the procedure of systematically acquiring, recording and calculating information about the members of a given population. This term is used mostly in connection with national population and housing censuses; other common censuses incl ...

, there were 65,239 people residing in Frederick city and roughly 27,000 households. The city's population grew by 23.6% in the ten years since the 2000 census, making it the fastest growing incorporated area in the state of Maryland with a population of over 50,000 for 2010.

2010 census data put the racial makeup of the city at 61% White

White is the lightest color and is achromatic (having no hue). It is the color of objects such as snow, chalk, and milk, and is the opposite of black. White objects fully reflect and scatter all the visible wavelengths of light. White on ...

, 18.6% Black

Black is a color which results from the absence or complete absorption of visible light. It is an achromatic color, without hue, like white and grey. It is often used symbolically or figuratively to represent darkness. Black and white have o ...

or African American

African Americans (also referred to as Black Americans and Afro-Americans) are an ethnic group consisting of Americans with partial or total ancestry from sub-Saharan Africa. The term "African American" generally denotes descendants of ens ...

, 0.2% Native American, 5.8% Asian American

Asian Americans are Americans of Asian ancestry (including naturalized Americans who are immigrants from specific regions in Asia and descendants of such immigrants). Although this term had historically been used for all the indigenous people ...

, and 14.4% Hispanic

The term ''Hispanic'' ( es, hispano) refers to people, Spanish culture, cultures, or countries related to Spain, the Spanish language, or Hispanidad.

The term commonly applies to countries with a cultural and historical link to Spain and to Vic ...

or Latino

Latino or Latinos most often refers to:

* Latino (demonym), a term used in the United States for people with cultural ties to Latin America

* Hispanic and Latino Americans in the United States

* The people or cultures of Latin America;

** Latin A ...

of any race. Roughly 4% of the city's population was of two or more races.

In regard to minority group growth, the 2010 census data show the city's Hispanic population at 9,402, a 271 percent increase compared with 2,533 in 2000, making Hispanics/Latinos the fastest growing race group in the city and in Frederick county (267 percent increase). Frederick city had 3,800 Asian residents in 2010, a 128 percent increase from the city's 1,664 Asian residents in 2000. The city's black or African-American population increased 56 percent, from 7,777 in 2000 to 12,144 in 2010.

For the roughly 27,000 households in the city, 30.6% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 41.7% were married couples living together, 12.8% had a female householder with no husband present, and 41% were non-families. Approximately 31% of all households were made up of individuals living alone and 8.1% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.46 and the average family size was 3.11.

2009 American Community Survey

As of 2009, 27.5% of the city's population was under the age of 19, 24.5% were between 20 and 34, 28.1% were between 35 and 54, 9.0% were between 55 and 64, and 10.5% were 65 years of age or older. The median age of a Frederick city resident for 2009 was 34 years. For adults aged 18 or older, the population was 48.6% male and 51.4% female. According to U.S. census data for 2009, the median annual income for a household in Frederick city was $64,833, and the median annual income for a family was $77,642. Males had a median annual income of $49,129 versus $41,986 for females. Theper capita income

Per capita income (PCI) or total income measures the average income earned per person in a given area (city, region, country, etc.) in a specified year. It is calculated by dividing the area's total income by its total population.

Per capita i ...

for the city was $31,123. Approximately 7.7% of the total population, 5.3% of families, and 5.2% of adults aged 65 and older were living below the poverty line

The poverty threshold, poverty limit, poverty line or breadline is the minimum level of income deemed adequate in a particular country. The poverty line is usually calculated by estimating the total cost of one year's worth of necessities for t ...

. The unemployment rate in the city for adults over the age of 18 was 5.1%.

In regard to educational attainment for individuals aged 25 or older as of 2009, 34% of the city's residents had a bachelor's or advanced professional degree, 29.6% had some college or an associate degree, 21.6% had a high school diploma or equivalency, 6.8% had between a 9th and 12th grade level of education, and 3.6% had an 8th grade or lower level of education.

The median value of a home in Frederick city as of 2009 was $303,900, with the bulk of owner-occupied homes valued at between $300,000 and $500,000. The median cost of a rental unit was $1,054 per month, with the bulk of rental units priced between $1,000 and $1,500 per month.

2009 census data indicated that roughly 89% of the workforce commuted to work by automobile, with an average commute time of approximately 30 minutes.

Government

City executive

In 2017, Democrat Michael O'Connor was elected mayor of Frederick. Previous mayors include: *Lawrence Brengle (1817) *Hy Kuhn (1818–1820) * George Baer Jr. (1820–1823) * John L. Harding (1823–1826) *George Kolb (1826–1829) * Thomas Carlton (1829–1835) *Daniel Kolb (1835–1838) *Michael Baltzell (1838–1841) *George Hoskins (1841–1847) *M. E. Bartgis (1847–1849) *James Bartgis (1849–1856) *Lewis Brunner (1856–1859) *W. G. Cole (1859–1865) *J. Engelbrecht (1865–1868) *Valerius Ebert (1868–1871) *Thomas M. Holbruner (1871–1874) *Lewis M. Moberly (1874–1883) *Hiram Bartgis (1883–1889) *Lewis H. Doll (1889–1890) *Lewis Brunner (1890–1892) *John E. Fleming (1892–1895) *Aquilla R. Yeakle (1895–1898) *William F. Chilton (1898–1901) *George Edward Smith (1901–1910) *John Edward Schell (1910–1913) *Lewis H. Fraley (1913–1919) *Gilmer Schley (1919–1922) *Lloyd C. Culler (1922–1931) *Elmer F. Munshower (1931–1934) *Lloyd C. Culler (1934–1943) *Hugh V. Gittinger (1943–1946) *Lloyd C. Culler (1946–1950) *Elmer F. Munshower (1950–1951) *Donald B. Rice (1951–1954) *John A. Derr (1954–1958) *Jacob R. Ramsburg (1958–1962) *E. Paul Magaha (1962–1966) *John A. Derr (1966–1970) *E. Paul Magaha (1970–1974) * Ronald N. Young (1974–1990) *Paul P. Gordon (1990–1994) *James S. Grimes (1994–2002) *Jennifer Dougherty

Jennifer P. Dougherty (born April 13, 1961) was elected Frederick, Maryland, Frederick, Maryland's first female mayor in 2001. Dougherty defeated 2-term incumbent Republican Mayor James S. Grimes.

Dougherty campaigned for re-election in 2005 ...

(2002–2005)

*W. Jeff Holtzinger (2005–2009)

*Randy McClement (2009–2017)

*Michael O'Connor (2017-)

Recent mayoral elections

Representative body

Frederick has a board of aldermen of six members (one of whom is the mayor) that serves as its legislative body. Elections are held every four years. Following the elections on November 2, 2021, Kelly Russell, Donna Kuzemchak, Derek Shackelford, Katie Nash, and Ben MacShane, all Democrats, were elected to the board. Democrat Michael O'Connor was re-elected mayor.Police

The city has its ownpolice department

The police are a constituted body of persons empowered by a state, with the aim to enforce the law, to ensure the safety, health and possessions of citizens, and to prevent crime and civil disorder. Their lawful powers include arrest and ...

.

Economy

Frederick's relative proximity to Washington, D.C., has always been an important factor in the development of its local economy, as well as the presence of Fort Detrick, its largest employer. Frederick is the home of Riverside Research Park, a large biomedical research park located on Frederick's east side. Tenants include the relocated main offices of theNational Cancer Institute

The National Cancer Institute (NCI) coordinates the United States National Cancer Program and is part of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), which is one of eleven agencies that are part of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. ...

's Frederick National Laboratory for Cancer Research

The Frederick National Laboratory for Cancer Research (FNLCR) is a United States federally funded research and development center (FFRDC) supported by the National Cancer Institute and managed by the private contractor Leidos Biomedical Research. ...

as well as Charles River Labs. As a result of continued and enhanced federal government

A federation (also known as a federal state) is a political entity characterized by a union of partially self-governing provinces, states, or other regions under a central federal government (federalism). In a federation, the self-governin ...

investment, the Frederick area will likely maintain a continued growth pattern over the next decade. Frederick has also been impacted by recent national trends centered on the gentrification of the downtown areas of cities across the nation (particularly in the northeast and mid-Atlantic), and to re-brand them as sites for cultural consumption.

The Frederick Historic District

The Frederick Historic District is a national historic district in Frederick, Maryland. The district encompasses the core of the city and contains a variety of residential, commercial, ecclesiastical, and industrial buildings dating from the la ...

in the city's downtown houses more than 200 retailers, restaurants and antique shops along Market, Patrick and East Streets. Restaurants feature a diverse array of cuisines, including Italian American, Thai, Vietnamese, and Cuban, as well as a number of regionally recognized dining establishments, such as The Tasting Room and Olde Towne Tavern.

In addition to retail and dining, downtown Frederick is home to 600 businesses and organizations totaling nearly 5,000 employees. A growing technology sector can be found in downtown's historic renovated spaces, as well as in new office buildings located along Carroll Creek Park.

Carroll Creek Park began as a flood control project in the late 1970s. It was an effort to reduce the risk to downtown Frederick from the 100-year floodplain and restore economic vitality to the historic commercial district. Today, more than $150 million in private investing is underway or planned in new construction, infill development or historic renovation in the park area.

The first phase of the park improvements, totaling nearly $11 million in construction, run from Court Street to just past Carroll Street. New elements to the park include brick pedestrian paths, water features, planters with shade trees and plantings, pedestrian bridges and a 350-seat amphitheater for outdoor performances.

A recreational and cultural resource, the park also serves as an economic development catalyst, with private investment along the creek functioning as a key component to the park's success. More than 400,000 sf of office space; 150,000 sf of commercial/retail space; nearly 300 residential units; and more than 2,000 parking spaces are planned or under construction.

On the first Saturday of every month, Frederick hosts an evening event in the downtown area called "First Saturday". Each Saturday has a theme, and activities are planned according to those themes in the downtown area (particularly around the Carroll Creek Promenade). The event spans a ten-block area of Frederick and takes place from 5 p.m. to 9 p.m. During the late spring, summer, and early fall months, this event draws particularly large crowds from neighboring cities and towns in Maryland, and nearby locations in the tri-state area (Virginia and Pennsylvania). The average number of attendees visiting downtown Frederick during first Saturday events is around 11,000, with higher numbers from May to October.

Top employers

According to the county'scomprehensive annual financial report