Mohammed Al-Shamisi on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Muhammad ( ar, مُحَمَّد; 570 – 8 June 632 CE) was an

The name ''Muhammad'' () means "praiseworthy" in Arabic. It appears four times in the Quran. The Quran also addresses Muhammad in the second person by various appellations;

The name ''Muhammad'' () means "praiseworthy" in Arabic. It appears four times in the Quran. The Quran also addresses Muhammad in the second person by various appellations;

The

The

The Arabian Peninsula was, and still is, largely arid with volcanic soil, making agriculture difficult except near oases or springs. Towns and cities dotted the landscape, two of the most prominent being

The Arabian Peninsula was, and still is, largely arid with volcanic soil, making agriculture difficult except near oases or springs. Towns and cities dotted the landscape, two of the most prominent being

Muhammad's father,

Muhammad's father,

According to Muslim tradition, Muhammad's wife

According to Muslim tradition, Muhammad's wife

Muhammad's wife Khadijah and uncle Abu Talib both died in 619, the year thus being known as the "

Muhammad's wife Khadijah and uncle Abu Talib both died in 619, the year thus being known as the "

With the help of the exiled

With the help of the exiled

Negotiations commenced with emissaries traveling to and from Mecca. While these continued, rumors spread that one of the Muslim negotiators, Uthman bin al-Affan, had been killed by the Quraysh. Muhammad called upon the pilgrims to make a pledge not to flee (or to stick with Muhammad, whatever decision he made) if the situation descended into war with Mecca. This pledge became known as the "Pledge of Acceptance" or the " Pledge under the Tree". News of Uthman's safety allowed for negotiations to continue, and a treaty scheduled to last ten years was eventually signed between the Muslims and Quraysh. The main points of the treaty included: cessation of hostilities, the deferral of Muhammad's pilgrimage to the following year, and agreement to send back any Meccan who emigrated to Medina without permission from their protector.

Many Muslims were not satisfied with the treaty. However, the Quranic sura "

Negotiations commenced with emissaries traveling to and from Mecca. While these continued, rumors spread that one of the Muslim negotiators, Uthman bin al-Affan, had been killed by the Quraysh. Muhammad called upon the pilgrims to make a pledge not to flee (or to stick with Muhammad, whatever decision he made) if the situation descended into war with Mecca. This pledge became known as the "Pledge of Acceptance" or the " Pledge under the Tree". News of Uthman's safety allowed for negotiations to continue, and a treaty scheduled to last ten years was eventually signed between the Muslims and Quraysh. The main points of the treaty included: cessation of hostilities, the deferral of Muhammad's pilgrimage to the following year, and agreement to send back any Meccan who emigrated to Medina without permission from their protector.

Many Muslims were not satisfied with the treaty. However, the Quranic sura "

The truce of Hudaybiyyah was enforced for two years.Lings (1987), p. 291. The tribe of

The truce of Hudaybiyyah was enforced for two years.Lings (1987), p. 291. The tribe of

chapter 48

referencing Sirah by

Following the conquest of Mecca, Muhammad was alarmed by a military threat from the confederate tribes of

Following the conquest of Mecca, Muhammad was alarmed by a military threat from the confederate tribes of

In 632, at the end of the tenth year after migration to Medina, Muhammad completed his first true Islamic pilgrimage, setting precedent for the annual Great Pilgrimage, known as '' Hajj''. On the 9th of

In 632, at the end of the tenth year after migration to Medina, Muhammad completed his first true Islamic pilgrimage, setting precedent for the annual Great Pilgrimage, known as '' Hajj''. On the 9th of

, p. 3. Lewis Lord of U.S. News & World Report. 7 April 2008. With his head resting on Aisha's lap, he asked her to dispose of his last worldly goods (seven coins), then spoke his final words: According to the ''

Muhammad united several of the

Muhammad united several of the

(1998)

Historians generally agree that Islamic social changes in areas such as

In

In

Muhammad's life is traditionally defined into two periods: pre-hijra (emigration) in Mecca (from 570 to 622), and post-hijra in Medina (from 622 until 632). Muhammad is said to have had thirteen wives in total (although two have ambiguous accounts, Rayhana bint Zayd and

Muhammad's life is traditionally defined into two periods: pre-hijra (emigration) in Mecca (from 570 to 622), and post-hijra in Medina (from 622 until 632). Muhammad is said to have had thirteen wives in total (although two have ambiguous accounts, Rayhana bint Zayd and

Muslim tradition credits Muhammad with several miracles or supernatural events.A.J. Wensinck, ''Muʿd̲j̲iza'',

Muslim tradition credits Muhammad with several miracles or supernatural events.A.J. Wensinck, ''Muʿd̲j̲iza'',  The

The

After the

After the

Arab

The Arabs (singular: Arab; singular ar, عَرَبِيٌّ, DIN 31635: , , plural ar, عَرَب, DIN 31635, DIN 31635: , Arabic pronunciation: ), also known as the Arab people, are an ethnic group mainly inhabiting the Arab world in Wester ...

religious, social, and political leader and the founder of Islam. According to Islamic doctrine, he was a prophet

In religion, a prophet or prophetess is an individual who is regarded as being in contact with a divine being and is said to speak on behalf of that being, serving as an intermediary with humanity by delivering messages or teachings from the s ...

divinely inspired

Divine inspiration is the concept of a supernatural force, typically a deity, causing a person or people to experience a creative desire. It has been a commonly reported aspect of many religions, for thousands of years. Divine inspiration is often ...

to preach and confirm the monotheistic

Monotheism is the belief that there is only one deity, an all-supreme being that is universally referred to as God. Cross, F.L.; Livingstone, E.A., eds. (1974). "Monotheism". The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church (2 ed.). Oxford: Oxfor ...

teachings of Adam

Adam; el, Ἀδάμ, Adám; la, Adam is the name given in Genesis 1-5 to the first human. Beyond its use as the name of the first man, ''adam'' is also used in the Bible as a pronoun, individually as "a human" and in a collective sense as " ...

, Abraham

Abraham, ; ar, , , name=, group= (originally Abram) is the common Hebrews, Hebrew patriarch of the Abrahamic religions, including Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. In Judaism, he is the founding father of the Covenant (biblical), special ...

, Moses, Jesus

Jesus, likely from he, יֵשׁוּעַ, translit=Yēšūaʿ, label=Hebrew/Aramaic ( AD 30 or 33), also referred to as Jesus Christ or Jesus of Nazareth (among other names and titles), was a first-century Jewish preacher and religiou ...

, and other prophets

In religion, a prophet or prophetess is an individual who is regarded as being in contact with a divine being and is said to speak on behalf of that being, serving as an intermediary with humanity by delivering messages or teachings from the s ...

. He is believed to be the Seal of the Prophets

Seal of the Prophets ( ar, خاتم النبيين, translit=khātam an-nabīyīn or khātim an-nabīyīn; or ar, خاتم الأنبياء, translit=khātam al-anbiyā’ or khātim al-anbiyā), is a title used in the Qur'an and by Muslims ...

within Islam. Muhammad united Arabia

The Arabian Peninsula, (; ar, شِبْهُ الْجَزِيرَةِ الْعَرَبِيَّة, , "Arabian Peninsula" or , , "Island of the Arabs") or Arabia, is a peninsula of Western Asia, situated northeast of Africa on the Arabian Plate. ...

into a single Muslim polity

A polity is an identifiable political entity – a group of people with a collective identity, who are organized by some form of institutionalized social relations, and have a capacity to mobilize resources. A polity can be any other group of p ...

, with the Quran

The Quran (, ; Standard Arabic: , Quranic Arabic: , , 'the recitation'), also romanized Qur'an or Koran, is the central religious text of Islam, believed by Muslims to be a revelation from God. It is organized in 114 chapters (pl.: , sing.: ...

as well as his teachings and practices forming the basis of Islamic religious belief.

Muhammad was born approximately 570CE in Mecca

Mecca (; officially Makkah al-Mukarramah, commonly shortened to Makkah ()) is a city and administrative center of the Mecca Province of Saudi Arabia, and the holiest city in Islam. It is inland from Jeddah on the Red Sea, in a narrow val ...

. He was the son of Abdullah ibn Abd al-Muttalib

Abdullah may refer to:

* Abdullah (name), a list of people with the given name or surname

* Abdullah, Kargı, Turkey, a village

* ''Abdullah'' (film), a 1980 Bollywood film directed by Sanjay Khan

* '' Abdullah: The Final Witness'', a 2015 Pak ...

and Amina bint Wahb

Aminah bint Wahb ( ar, آمِنَة ٱبْنَت وَهْب, ', ), was a woman of the clan of Banu Zuhrah in the tribe of Quraysh, and the mother of the Islamic prophet Muhammad.

Early life and marriage

Aminah was born to Wahb ibn Abd Manaf a ...

. His father Abdullah was the son of Quraysh

The Quraysh ( ar, قُرَيْشٌ) were a grouping of Arab clans that historically inhabited and controlled the city of Mecca and its Kaaba. The Islamic prophet Muhammad was born into the Hashim clan of the tribe. Despite this, many of the Q ...

tribal leader Abd al-Muttalib ibn Hashim

Shayba ibn Hāshim ( ar, شَيْبَة بْن هَاشِم; 497–578), better known as ʿAbd al-Muṭṭalib, ( ar, عَبْد ٱلْمُطَّلِب , lit=Servant of Muttalib) was the fourth chief of the Quraysh tribal confederation. He was ...

, and he died a few months before Muhammad's birth. His mother Amina died when he was six, leaving Muhammad an orphan. He was raised under the care of his grandfather, Abd al-Muttalib, and paternal uncle, Abu Talib Abu Taleb or Abu Talib may refer to:

* Abu Talib ibn ‘Abd al-Muttalib (549-619), Arab leader and head of the Banu Hashim clan

* Abu Talib al-Makki (died 996), Arab scholar, jurist and mystic

* Abu Taleb Rostam (997–1029), Buyid amir of Ray, Ir ...

. In later years, he would periodically seclude himself in a mountain cave named Hira Hira may refer to:

Places

* Cave of Hira, a cave associated with Muhammad

*Al-Hirah, an ancient Arab city in Iraq

** Battle of Hira, 633AD, between the Sassanians and the Rashidun Caliphate

* Hira Mountains, Japan

* Hira, New Zealand, settlement ...

for several nights of prayer. When he was 40, Muhammad reported being visited by Gabriel

In Abrahamic religions (Judaism, Christianity and Islam), Gabriel (); Greek: grc, Γαβριήλ, translit=Gabriḗl, label=none; Latin: ''Gabriel''; Coptic: cop, Ⲅⲁⲃⲣⲓⲏⲗ, translit=Gabriêl, label=none; Amharic: am, ገብ� ...

in the cave and receiving his first revelation from God. In 613, Muhammad started preaching

A sermon is a religious discourse or oration by a preacher, usually a member of clergy. Sermons address a scriptural, theological, or moral topic, usually expounding on a type of belief, law, or behavior within both past and present contexts. E ...

these revelations publicly,Muhammad Mustafa Al-A'zami

Muhammad Mustafa Al-A'zami (1930 – 20 December 2017) was an Indian-born Saudi Arabian contemporary hadith scholar best known for his critical investigation of the theories of fellow Islamic scholars Ignác Goldziher, David Margoliouth, and Jo ...

(2003), ''The History of The Qur'anic Text: From Revelation to Compilation: A Comparative Study with the Old and New Testaments'', pp. 26–27. UK Islamic Academy. . proclaiming that " God is One", that complete "submission" (''islām

Islam (; ar, ۘالِإسلَام, , ) is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion centred primarily around the Quran, a religious text considered by Muslims to be the direct word of God (or ''Allah'') as it was revealed to Muhammad, the ...

'') to God is the right way of life (''dīn

Dīn ( ar, دين, Dīn, also anglicized as Deen) is an Arabic word with three general senses: judgment, custom, and religion. It is used by both Muslims and Arab Christians.

In Islamic terminology, the word refers to the way of life Muslims ...

''), and that he was a prophet and messenger of God, similar to the other prophets in Islam

Prophets in Islam ( ar, الأنبياء في الإسلام, translit=al-ʾAnbiyāʾ fī al-ʾIslām) are individuals in Islam who are believed to spread God's message on Earth and to serve as models of ideal human behaviour. Some prophets a ...

.

Muhammad's followers were initially few in number, and experienced hostility from Meccan polytheists for 13 years. To escape ongoing persecution, he sent some of his followers to Abyssinia

The Ethiopian Empire (), also formerly known by the exonym Abyssinia, or just simply known as Ethiopia (; Amharic and Tigrinya: ኢትዮጵያ , , Oromo: Itoophiyaa, Somali: Itoobiya, Afar: ''Itiyoophiyaa''), was an empire that historical ...

in 615, before he and his followers migrated from Mecca to Medina

Medina,, ', "the radiant city"; or , ', (), "the city" officially Al Madinah Al Munawwarah (, , Turkish: Medine-i Münevvere) and also commonly simplified as Madīnah or Madinah (, ), is the second-holiest city in Islam, and the capital of the ...

(then known as Yathrib) later in 622. This event, the ''Hijra

Hijra, Hijrah, Hegira, Hejira, Hijrat or Hijri may refer to:

Islam

* Hijrah (often written as ''Hejira'' in older texts), the migration of Muhammad from Mecca to Medina in 622 CE

* Migration to Abyssinia or First Hegira, of Muhammad's followers ...

'', marks the beginning of the Islamic calendar

The Hijri calendar ( ar, ٱلتَّقْوِيم ٱلْهِجْرِيّ, translit=al-taqwīm al-hijrī), also known in English as the Muslim calendar and Islamic calendar, is a lunar calendar consisting of 12 lunar months in a year of 354 ...

, also known as the Hijri Calendar. In Medina, Muhammad united the tribes under the Constitution of Medina. In December 629, after eight years of intermittent fighting with Meccan tribes, Muhammad gathered an army of 10,000 Muslim converts and marched on the city of Mecca. The conquest went largely uncontested and Muhammad seized the city with little bloodshed. In 632, a few months after returning from the Farewell Pilgrimage

The Farewell Pilgrimage ( ar, حِجَّة ٱلْوَدَاع, Ḥijjatu Al-Wadāʿ) refers to the one Hajj pilgrimage that Muhammad performed in the Islamic year 10 AH, following the Conquest of Mecca. Muslims believe that verse 22:27 of the Qur ...

, he fell ill and died. By the time of his death, most of the Arabian Peninsula had converted to Islam

Religious conversion is the adoption of a set of beliefs identified with one particular religious denomination to the exclusion of others. Thus "religious conversion" would describe the abandoning of adherence to one denomination and affiliatin ...

.

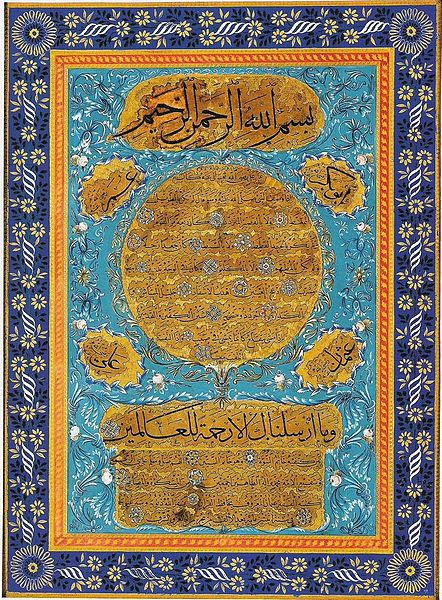

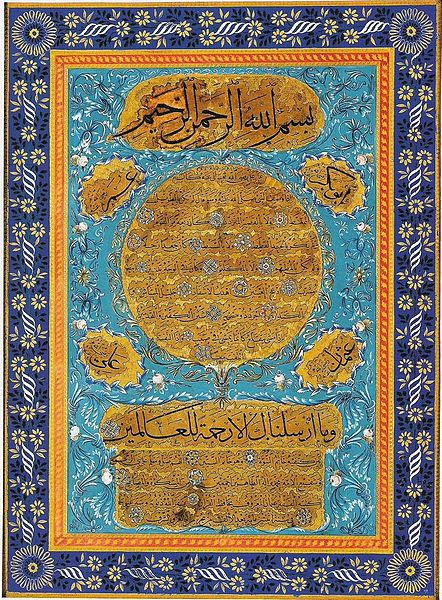

The revelations (each known as '' Ayah —'' literally, "Sign f God

F, or f, is the sixth letter in the Latin alphabet, used in the modern English alphabet, the alphabets of other western European languages and others worldwide. Its name in English is ''ef'' (pronounced ), and the plural is ''efs''.

His ...

) that Muhammad reported receiving until his death form the verses of the Quran, regarded by Muslims as the verbatim "Word of God" on which the religion is based. Besides the Quran, Muhammad's teachings and practices (''sunnah

In Islam, , also spelled ( ar, سنة), are the traditions and practices of the Islamic prophet Muhammad that constitute a model for Muslims to follow. The sunnah is what all the Muslims of Muhammad's time evidently saw and followed and pass ...

''), found in the Hadith

Ḥadīth ( or ; ar, حديث, , , , , , , literally "talk" or "discourse") or Athar ( ar, أثر, , literally "remnant"/"effect") refers to what the majority of Muslims believe to be a record of the words, actions, and the silent approval ...

and '' sira'' (biography) literature, are also upheld and used as sources

Source may refer to:

Research

* Historical document

* Historical source

* Source (intelligence) or sub source, typically a confidential provider of non open-source intelligence

* Source (journalism), a person, publication, publishing institute ...

of Islamic law (see Sharia).

Names and appellations

prophet

In religion, a prophet or prophetess is an individual who is regarded as being in contact with a divine being and is said to speak on behalf of that being, serving as an intermediary with humanity by delivering messages or teachings from the s ...

, messenger

''MESSENGER'' was a NASA robotic space probe that orbited the planet Mercury between 2011 and 2015, studying Mercury's chemical composition, geology, and magnetic field. The name is a backronym for "Mercury Surface, Space Environment, Geoch ...

, servant of God (abd''), announcer (''bashir''), witness (''shahid

''Shaheed'' ( , , ; pa, ਸ਼ਹੀਦ) denotes a martyr in Islam. The word is used frequently in the Quran in the generic sense of "witness" but only once in the sense of "martyr" (i.e. one who dies for his faith); ...

''), bearer of good tidings (''mubashshir''), warner (''nathir''), reminder (''mudhakkir''), one who calls nto God('' dā'ī''), light personified (''noor''), and the light-giving lamp (''siraj munir'').

Sources of biographical information

Quran

The

The Quran

The Quran (, ; Standard Arabic: , Quranic Arabic: , , 'the recitation'), also romanized Qur'an or Koran, is the central religious text of Islam, believed by Muslims to be a revelation from God. It is organized in 114 chapters (pl.: , sing.: ...

is the central religious text

Religious texts, including scripture, are texts which various religions consider to be of central importance to their religious tradition. They differ from literature by being a compilation or discussion of beliefs, mythologies, ritual prac ...

of Islam. Muslims believe it represents the words of God

In monotheistic thought, God is usually viewed as the supreme being, creator, and principal object of faith. Swinburne, R.G. "God" in Honderich, Ted. (ed)''The Oxford Companion to Philosophy'', Oxford University Press, 1995. God is typically ...

revealed by the archangel Gabriel

In Abrahamic religions (Judaism, Christianity and Islam), Gabriel (); Greek: grc, Γαβριήλ, translit=Gabriḗl, label=none; Latin: ''Gabriel''; Coptic: cop, Ⲅⲁⲃⲣⲓⲏⲗ, translit=Gabriêl, label=none; Amharic: am, ገብ� ...

to Muhammad.''Living Religions: An Encyclopaedia of the World's Faiths'', Mary Pat Fisher, 1997, p. 338, I.B. Tauris Publishers. The Quran, however, provides minimal assistance for Muhammad's chronological biography; most Quranic verses do not provide significant historical context.

Early biographies

Important sources regarding Muhammad's life may be found in the historic works by writers of the 2nd and 3rd centuries of the Muslim era (AH – 8th and 9th century CE). These include traditional Muslim biographies of Muhammad, which provide additional information about Muhammad's life.Reeves (2003), pp. 6–7. The earliest written ''sira'' (biographies of Muhammad and quotes attributed to him) isIbn Ishaq

Muḥammad ibn Isḥāq ibn Yasār ibn Khiyār (; according to some sources, ibn Khabbār, or Kūmān, or Kūtān, ar, محمد بن إسحاق بن يسار بن خيار, or simply ibn Isḥaq, , meaning "the son of Isaac"; died 767) was an 8 ...

's '' Life of God's Messenger'' written c. 767 CE (150 AH). Although the original work was lost, this sira survives as extensive excerpts in works by Ibn Hisham

Abū Muḥammad ʿAbd al-Malik ibn Hishām ibn Ayyūb al-Ḥimyarī al-Muʿāfirī al-Baṣrī ( ar, أبو محمد عبدالملك بن هشام ابن أيوب الحميري المعافري البصري; died 7 May 833), or Ibn Hisham, e ...

and to a lesser extent by Al-Tabari

( ar, أبو جعفر محمد بن جرير بن يزيد الطبري), more commonly known as al-Ṭabarī (), was a Muslim historian and scholar from Amol, Tabaristan. Among the most prominent figures of the Islamic Golden Age, al-Tabari ...

.S.A. Nigosian (2004), p. 6. However, Ibn Hisham wrote in the preface to his biography of Muhammad that he omitted matters from Ibn Ishaq's biography that "would distress certain people". Another early history source is the history of Muhammad's campaigns by al-Waqidi

Abu `Abdullah Muhammad Ibn ‘Omar Ibn Waqid al-Aslami (Arabic ) (c. 130 – 207 AH; c. 747 – 823 AD) was a historian commonly referred to as al-Waqidi (Arabic: ). His surname is derived from his grandfather's name Waqid and thus he became fa ...

(death 207 AH), and the work of Waqidi's secretary Ibn Sa'd al-Baghdadi

Abū ‘Abd Allāh Muḥammad ibn Sa‘d ibn Manī‘ al-Baṣrī al-Hāshimī or simply Ibn Sa'd ( ar, ابن سعد) and nicknamed ''Scribe of Waqidi'' (''Katib al-Waqidi''), was a scholar and Arabian biographer. Ibn Sa'd was born in 784/785 ...

(death 230 AH).

Many scholars accept these early biographies as authentic, though their accuracy is unascertainable. Recent studies have led scholars to distinguish between traditions touching legal matters and purely historical events. In the legal group, traditions could have been subject to invention while historic events, aside from exceptional cases, may have been only subject to "tendential shaping".

Hadith

Other important sources include thehadith

Ḥadīth ( or ; ar, حديث, , , , , , , literally "talk" or "discourse") or Athar ( ar, أثر, , literally "remnant"/"effect") refers to what the majority of Muslims believe to be a record of the words, actions, and the silent approval ...

collections, accounts of verbal and physical teachings and traditions attributed to Muhammad. Hadiths were compiled several generations after his death by Muslims including Muhammad al-Bukhari

Muhammad ( ar, مُحَمَّد; 570 – 8 June 632 CE) was an Arab religious, social, and political leader and the founder of Islam. According to Islamic doctrine, he was a prophet divinely inspired to preach and confirm the mono ...

, Muslim ibn al-Hajjaj

Abū al-Ḥusayn ‘Asākir ad-Dīn Muslim ibn al-Ḥajjāj ibn Muslim ibn Ward ibn Kawshādh Banu Qushayr, al-Qushayrī an-Naysābūrī ( ar, أبو الحسين عساكر الدين مسلم بن الحجاج بن مسلم بن وَرْد ب� ...

, Muhammad ibn Isa at-Tirmidhi

Abū ʿĪsā Muḥammad ibn ʿĪsā as-Sulamī aḍ-Ḍarīr al-Būghī at-Tirmidhī ( ar, أبو عيسى محمد بن عيسى السلمي الضرير البوغي الترمذي; fa, , ''Termezī''; 824 – 9 October 892 CE / 209 - 2 ...

, Abd ar-Rahman al-Nasai, Abu Dawood

Abū Dāwūd (Dā’ūd) Sulaymān ibn al-Ash‘ath ibn Isḥāq al-Azdī al-Sijistānī ( ar, أبو داود سليمان بن الأشعث الأزدي السجستاني), commonly known simply as Abū Dāwūd al-Sijistānī, was a scholar o ...

, Ibn Majah

Abū ʿAbd Allāh Muḥammad ibn Yazīd Ibn Mājah al-Rabʿī al-Qazwīnī ( ar, ابو عبد الله محمد بن يزيد بن ماجه الربعي القزويني; (b. 209/824, d. 273/887) commonly known as Ibn Mājah, was a medieval sch ...

, Malik ibn Anas

Malik ibn Anas ( ar, مَالِك بن أَنَس, 711–795 CE / 93–179 AH), whose full name is Mālik bin Anas bin Mālik bin Abī ʿĀmir bin ʿAmr bin Al-Ḥārith bin Ghaymān bin Khuthayn bin ʿAmr bin Al-Ḥārith al-Aṣbaḥī ...

, al-Daraqutni

Abu Hasan Ali ibn Umar ibn Ahmad ibn Mahdi al-Daraqutni (, 918 CE — 995 CE) was a 10th-century ''muhaddith'' best known for compiling the hadith collection '' Sunan al-Daraqutni''. He was celebrated later by Sunni hadith scholars such as the ...

.Lewis (1993), pp. 33–34.

Some Western academics cautiously view the hadith collections as accurate historical sources. Scholars such as Madelung Madelung is a German surname. It is also the name of multiple terms in mathematics and science based on people named Madelung.

People

* Erwin Madelung (1881–1972), German physicist

* Georg Hans Madelung (1889–1972), German aeronautical engineer ...

do not reject the narrations which have been compiled in later periods, but judge them in the context of history and on the basis of their compatibility with the events and figures. Muslim scholars on the other hand typically place a greater emphasis on the hadith literature instead of the biographical literature, since hadiths maintain a traditional chain of transmission (isnad

Hadith studies ( ar, علم الحديث ''ʻilm al-ḥadīth'' "science of hadith", also science of hadith, or science of hadith criticism or hadith criticism)

consists of several religious scholarly disciplines used by Muslim scholars in th ...

); the lack of such a chain for the biographical literature makes it unverifiable in their eyes.

Pre-Islamic Arabia

The Arabian Peninsula was, and still is, largely arid with volcanic soil, making agriculture difficult except near oases or springs. Towns and cities dotted the landscape, two of the most prominent being

The Arabian Peninsula was, and still is, largely arid with volcanic soil, making agriculture difficult except near oases or springs. Towns and cities dotted the landscape, two of the most prominent being Mecca

Mecca (; officially Makkah al-Mukarramah, commonly shortened to Makkah ()) is a city and administrative center of the Mecca Province of Saudi Arabia, and the holiest city in Islam. It is inland from Jeddah on the Red Sea, in a narrow val ...

and Medina

Medina,, ', "the radiant city"; or , ', (), "the city" officially Al Madinah Al Munawwarah (, , Turkish: Medine-i Münevvere) and also commonly simplified as Madīnah or Madinah (, ), is the second-holiest city in Islam, and the capital of the ...

. Medina was a large flourishing agricultural settlement, while Mecca was an important financial center for many surrounding tribes. Communal life was essential for survival in the desert conditions, supporting indigenous tribes against the harsh environment and lifestyle. Tribal affiliation, whether based on kinship or alliances, was an important source of social cohesion. Indigenous Arabs were either nomad

A nomad is a member of a community without fixed habitation who regularly moves to and from the same areas. Such groups include hunter-gatherers, pastoral nomads (owning livestock), tinkers and trader nomads. In the twentieth century, the po ...

ic or sedentary

Sedentary lifestyle is a lifestyle type, in which one is physically inactive and does little or no physical movement and or exercise. A person living a sedentary lifestyle is often sitting or lying down while engaged in an activity like soci ...

. Nomadic groups constantly traveled seeking water and pasture for their flocks, while the sedentary settled and focused on trade and agriculture. Nomadic survival also depended on raiding caravans or oases; nomads did not view this as a crime.Loyal Rue, ''Religion Is Not about God: How Spiritual Traditions Nurture Our Biological'', 2005, p. 224.

In pre-Islamic Arabia, gods or goddesses were viewed as protectors of individual tribes, their spirits associated with sacred trees, stones

In geology, rock (or stone) is any naturally occurring solid mass or aggregate of minerals or mineraloid matter. It is categorized by the minerals included, its chemical composition, and the way in which it is formed. Rocks form the Earth's ...

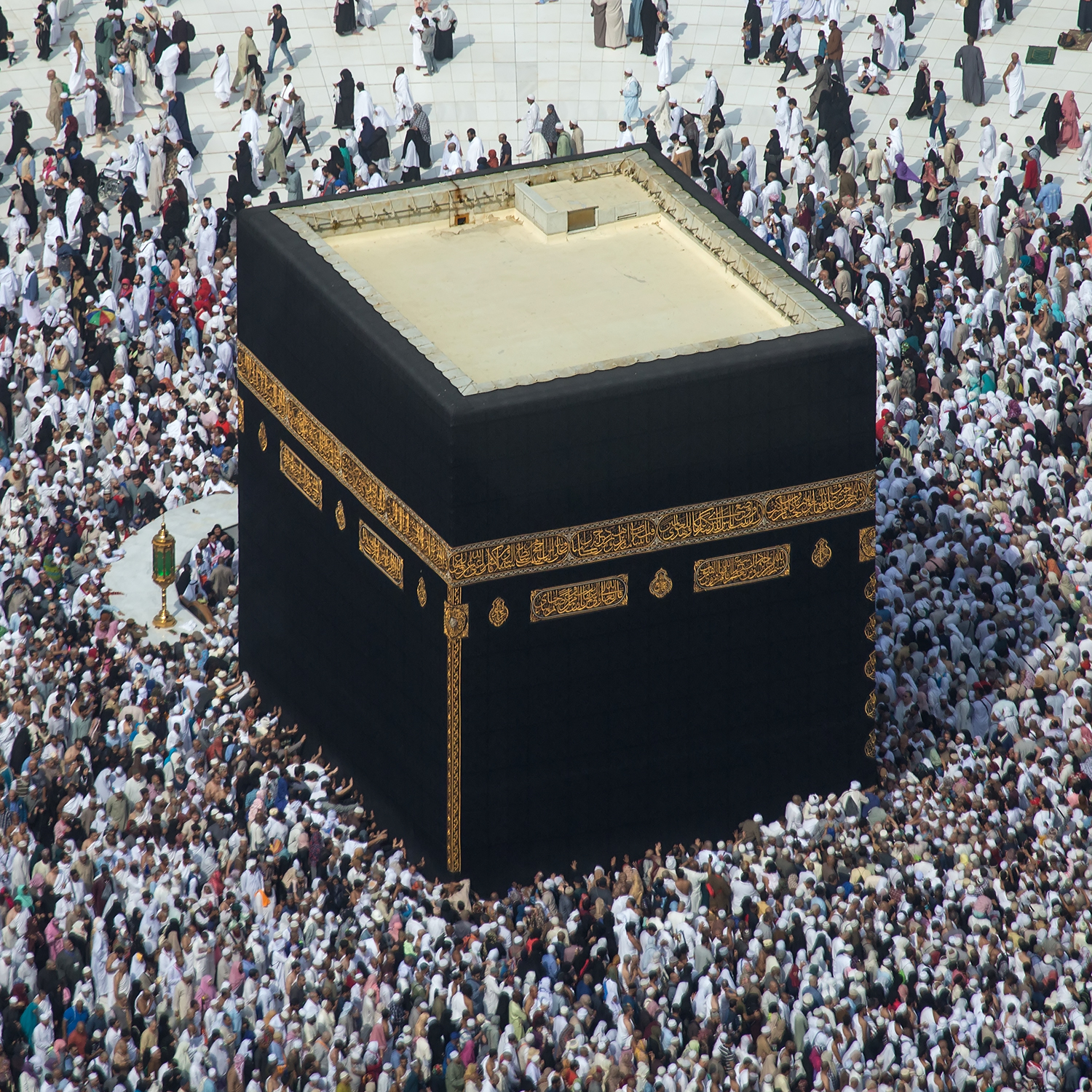

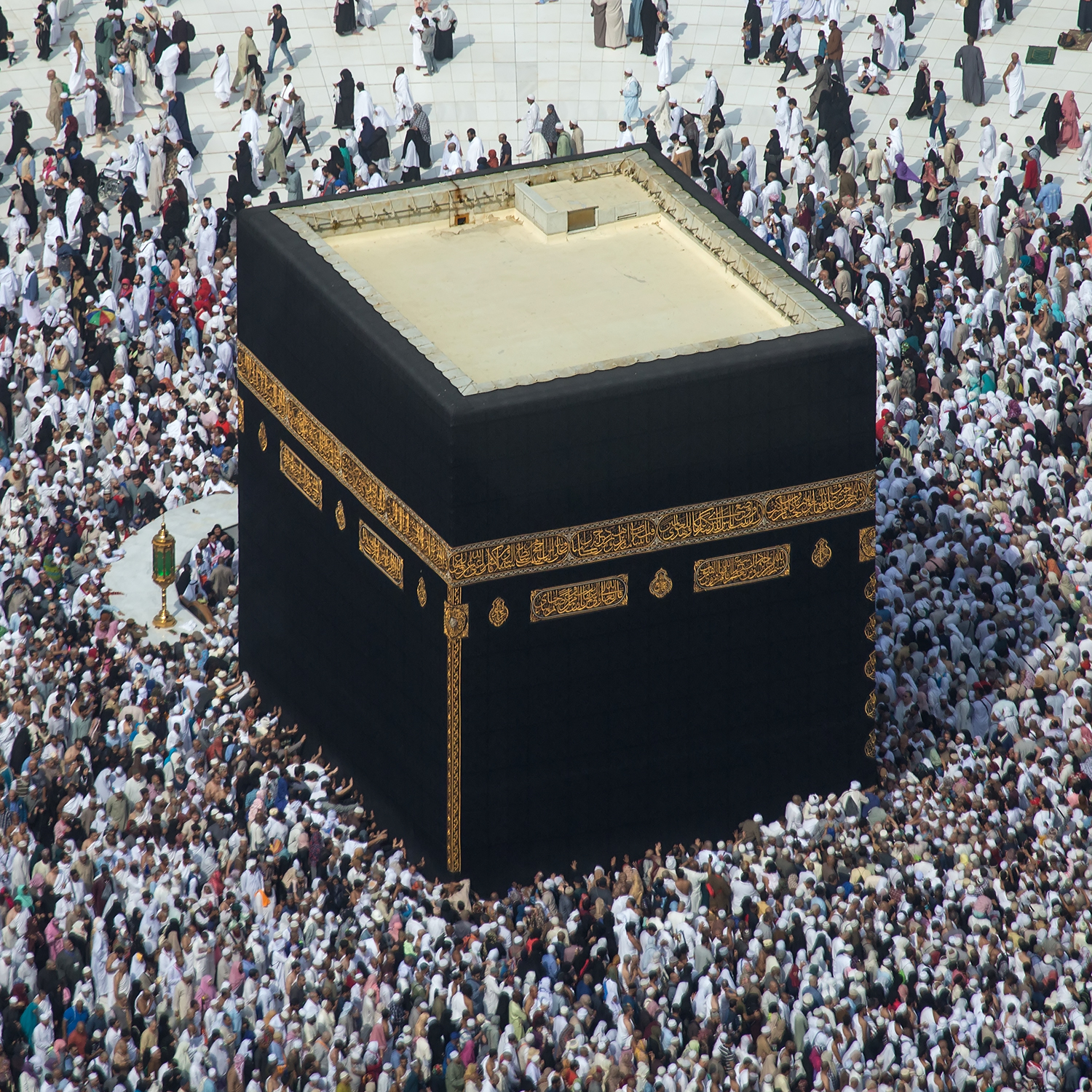

, springs and wells. As well as being the site of an annual pilgrimage, the Kaaba

The Kaaba (, ), also spelled Ka'bah or Kabah, sometimes referred to as al-Kaʿbah al-Musharrafah ( ar, ٱلْكَعْبَة ٱلْمُشَرَّفَة, lit=Honored Ka'bah, links=no, translit=al-Kaʿbah al-Musharrafah), is a building at the c ...

shrine in Mecca housed 360 idols of tribal patron deities. Three goddesses were worshipped, in some places as daughters of Allah: Allāt

Al-Lat ( ar, اللات, translit=Al-Lāt, ), also spelled Allat, Allatu and Alilat, is a pre-Islamic Arabian goddess worshipped under various associations throughout the entire Arabian Peninsula, including Mecca where she was worshipped along ...

, Manāt

( ar, مناة pausa, or Old Arabic manawat; also transliterated as ') was a pre-Islamic Arabian goddess worshiped in the Arabian Peninsula before the rise of Islam and the Islamic prophet Muhammad in the 7th century. She was among M ...

and al-'Uzzá. Monotheistic communities existed in Arabia, including Christians and Jews

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""T ...

. Hanif

In Islam, a ( ar, حنيف, ḥanīf; plural: , ), meaning "renunciate", is someone who maintains the pure monotheism of the patriarch Abraham. More specifically, in Islamic thought, renunciates were the people who, during the pre-Islamic peri ...

s – native pre-Islamic Arabs who "professed a rigid monotheism" – are also sometimes listed alongside Jews and Christians in pre-Islamic Arabia, although scholars dispute their historicity

Historicity is the historical actuality of persons and events, meaning the quality of being part of history instead of being a historical myth, legend, or fiction. The historicity of a claim about the past is its factual status. Historicity deno ...

. According to Muslim tradition, Muhammad himself was a Hanif and one of the descendants of Ishmael

Ishmael ''Ismaḗl''; Classical/Qur'anic Arabic: إِسْمَٰعِيْل; Modern Standard Arabic: إِسْمَاعِيْل ''ʾIsmāʿīl''; la, Ismael was the first son of Abraham, the common patriarch of the Abrahamic religions; and is cons ...

, son of Abraham

Abraham, ; ar, , , name=, group= (originally Abram) is the common Hebrews, Hebrew patriarch of the Abrahamic religions, including Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. In Judaism, he is the founding father of the Covenant (biblical), special ...

, although no known evidence exists for a historical Abraham or Ishmael, and the links are based solely on tradition instead of historical records.

The second half of the sixth century was a period of political disorder in Arabia and communication routes were no longer secure. Religious divisions were an important cause of the crisis. Judaism

Judaism ( he, ''Yahăḏūṯ'') is an Abrahamic, monotheistic, and ethnic religion comprising the collective religious, cultural, and legal tradition and civilization of the Jewish people. It has its roots as an organized religion in the ...

became the dominant religion in Yemen

Yemen (; ar, ٱلْيَمَن, al-Yaman), officially the Republic of Yemen,, ) is a country in Western Asia. It is situated on the southern end of the Arabian Peninsula, and borders Saudi Arabia to the north and Oman to the northeast an ...

while Christianity took root in the Persian Gulf

The Persian Gulf ( fa, خلیج فارس, translit=xalij-e fârs, lit=Gulf of Fars, ), sometimes called the ( ar, اَلْخَلِيْجُ ٱلْعَرَبِيُّ, Al-Khalīj al-ˁArabī), is a mediterranean sea in Western Asia. The bo ...

area. In line with broader trends of the ancient world, the region witnessed a decline in the practice of polytheistic cults and a growing interest in a more spiritual form of religion. While many were reluctant to convert to a foreign faith, those faiths provided intellectual and spiritual reference points.

During the early years of Muhammad's life, the Quraysh

The Quraysh ( ar, قُرَيْشٌ) were a grouping of Arab clans that historically inhabited and controlled the city of Mecca and its Kaaba. The Islamic prophet Muhammad was born into the Hashim clan of the tribe. Despite this, many of the Q ...

tribe to which he belonged became a dominant force in western Arabia. They formed the cult association of ''hums'', which tied members of many tribes in western Arabia to the Kaaba

The Kaaba (, ), also spelled Ka'bah or Kabah, sometimes referred to as al-Kaʿbah al-Musharrafah ( ar, ٱلْكَعْبَة ٱلْمُشَرَّفَة, lit=Honored Ka'bah, links=no, translit=al-Kaʿbah al-Musharrafah), is a building at the c ...

and reinforced the prestige of the Meccan sanctuary. To counter the effects of anarchy, Quraysh upheld the institution of sacred months during which all violence was forbidden, and it was possible to participate in pilgrimages and fairs without danger. Thus, although the association of ''hums'' was primarily religious, it also had important economic consequences for the city.

Life

Childhood and early life

Abu al-Qasim Muhammad ibn Abdullah ibn Abd al-Muttalib ibn HashimMuhammadEncyclopedia Britannica

An encyclopedia (American English) or encyclopædia (British English) is a reference work or compendium providing summaries of knowledge either general or special to a particular field or discipline. Encyclopedias are divided into articles ...

. Retrieved 15 February 2017. was born in Mecca about the year 570 and his birthday is believed to be in the month of Rabi' al-awwal. He belonged to the Banu Hashim

)

, type = Qurayshi Arab clan

, image =

, alt =

, caption =

, nisba = al-Hashimi

, location = Mecca, Hejaz Middle East, North Africa, Horn of Africa

, descended = Hashim ibn Abd Manaf

, parent_tribe = Qur ...

clan, part of the Quraysh tribe

The Quraysh ( ar, قُرَيْشٌ) were a grouping of Arab clans that historically inhabited and controlled the city of Mecca and its Kaaba. The Islamic prophet Muhammad was born into the Hashim clan of the tribe. Despite this, many of the ...

, which was one of Mecca

Mecca (; officially Makkah al-Mukarramah, commonly shortened to Makkah ()) is a city and administrative center of the Mecca Province of Saudi Arabia, and the holiest city in Islam. It is inland from Jeddah on the Red Sea, in a narrow val ...

's prominent families, although it appears less prosperous during Muhammad's early lifetime. Tradition places the year of Muhammad's birth as corresponding with the Year of the Elephant

The ʿām al-fīl ( ar, عام الفيل, Year of the Elephant) is the name in Islamic history for the year approximately equating to 570–571 CE. According to Islamic resources, it was in this year that Muhammad was born.Hajjah Adil, Amina, " ...

, which is named after the failed destruction of Mecca that year by the Abraha

Abraha ( Ge’ez: አብርሃ) (also spelled Abreha, died after CE 570;Stuart Munro-Hay (2003) "Abraha" in Siegbert Uhlig (ed.) ''Encyclopaedia Aethiopica: A-C''. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag. r. 525–at least 553S. C. Munro-Hay (1991) ''Aksum ...

, Yemen's king, who supplemented his army with elephants.

Alternatively some 20th century scholars have suggested different years, such as 568 or 569.

Abdullah

Abdullah may refer to:

* Abdullah (name), a list of people with the given name or surname

* Abdullah, Kargı, Turkey, a village

* ''Abdullah'' (film), a 1980 Bollywood film directed by Sanjay Khan

* '' Abdullah: The Final Witness'', a 2015 Pakis ...

, died almost six months before he was born. According to Islamic tradition, soon after birth he was sent to live with a Bedouin family in the desert, as desert life was considered healthier for infants; some western scholars reject this tradition's historicity. Muhammad stayed with his foster-mother, Halimah bint Abi Dhuayb

Halimah al-Sa'diyah ( ar, حليمة السعدية), was the foster-mother of the Islamic prophet Muhammad. Halimah and her husband were from the tribe of Sa'd b. Bakr, a subdivision of Hawazin (a large North Arabian tribe or group of tribes).

...

, and her husband until he was two years old. At the age of six, Muhammad lost his biological mother Amina

Aminatu (also Amina; died 1610) was a Hausa Muslim historical figure in the city-state Zazzau (now city of Zaria in Kaduna State), in what is now in the north-west region of Nigeria. She might have ruled in the mid-sixteenth century. A controve ...

to illness and became an orphan. For the next two years, until he was eight years old, Muhammad was under the guardianship of his paternal grandfather Abd al-Muttalib

Shayba ibn Hāshim ( ar, شَيْبَة بْن هَاشِم; 497–578), better known as ʿAbd al-Muṭṭalib, ( ar, عَبْد ٱلْمُطَّلِب , lit=Servant of Muttalib) was the fourth chief of the Quraysh tribal confederation. He was ...

, of the Banu Hashim clan until his death. He then came under the care of his uncle Abu Talib Abu Taleb or Abu Talib may refer to:

* Abu Talib ibn ‘Abd al-Muttalib (549-619), Arab leader and head of the Banu Hashim clan

* Abu Talib al-Makki (died 996), Arab scholar, jurist and mystic

* Abu Taleb Rostam (997–1029), Buyid amir of Ray, Ir ...

, the new leader of the Banu Hashim. According to Islamic historian William Montgomery Watt

William Montgomery Watt (14 March 1909 – 24 October 2006) was a Scottish Orientalist, historian, academic and Anglican priest. From 1964 to 1979, he was Professor of Arabic and Islamic studies at the University of Edinburgh.

Watt was one of ...

there was a general disregard by guardians in taking care of weaker members of the tribes in Mecca during the 6th century, "Muhammad's guardians saw that he did not starve to death, but it was hard for them to do more for him, especially as the fortunes of the clan of Hashim seem to have been declining at that time."

In his teens, Muhammad accompanied his uncle on Syrian trading journeys to gain experience in commercial trade. Islamic tradition states that when Muhammad was either nine or twelve while accompanying the Meccans' caravan to Syria, he met a Christian monk or hermit named Bahira

Bahira ( ar, بَحِيرَىٰ, syc, ܒܚܝܪܐ) was an Assyrian, likely Nestorian monk from the tribe of Abd al-Qays who, according to Islamic religion, foretold to the adolescent Muhammad his future as a prophet.Abel, A.Baḥīrā. ''Encycl ...

who is said to have foreseen Muhammad's career as a prophet of God.

Little is known of Muhammad during his later youth as available information is fragmented, making it difficult to separate history from legend. It is known that he became a merchant and "was involved in trade between the Indian Ocean

The Indian Ocean is the third-largest of the world's five oceanic divisions, covering or ~19.8% of the water on Earth's surface. It is bounded by Asia to the north, Africa to the west and Australia to the east. To the south it is bounded by ...

and the Mediterranean Sea

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa, and on the ...

."''Berkshire Encyclopedia of World History'' (2005), v. 3, p. 1025. Due to his upright character he acquired the nickname "al-Amin

Abu Musa Muhammad ibn Harun al-Rashid ( ar, أبو موسى محمد بن هارون الرشيد, Abū Mūsā Muḥammad ibn Hārūn al-Rashīd; April 787 – 24/25 September 813), better known by his laqab of Al-Amin ( ar, الأمين, al-Amī ...

" (Arabic: الامين), meaning "faithful, trustworthy" and "al-Sadiq" meaning "truthful" and was sought out as an impartial arbitrator. His reputation attracted a proposal in 595 from Khadijah

Khadija, Khadeeja or Khadijah ( ar, خديجة, Khadīja) is an Arabic feminine given name, the name of Khadija bint Khuwaylid, first wife of the Islamic prophet Muhammad. In 1995, it was one of the three most popular Arabic feminine names in th ...

, a successful businesswoman. Muhammad consented to the marriage, which by all accounts was a happy one.

Several years later, according to a narration collected by historian Ibn Ishaq

Muḥammad ibn Isḥāq ibn Yasār ibn Khiyār (; according to some sources, ibn Khabbār, or Kūmān, or Kūtān, ar, محمد بن إسحاق بن يسار بن خيار, or simply ibn Isḥaq, , meaning "the son of Isaac"; died 767) was an 8 ...

, Muhammad was involved with a well-known story about setting the Black Stone

The Black Stone ( ar, ٱلْحَجَرُ ٱلْأَسْوَد, ', 'Black Stone') is a rock set into the eastern corner of the Kaaba, the ancient building in the center of the Grand Mosque in Mecca, Saudi Arabia. It is revered by Muslims as an ...

in place in the wall of the Kaaba in 605 CE. The Black Stone, a sacred object, was removed during renovations to the Kaaba. The Meccan leaders could not agree which clan should return the Black Stone to its place. They decided to ask the next man who came through the gate to make that decision; that man was the 35-year-old Muhammad. This event happened five years before the first revelation by Gabriel to him. He asked for a cloth and laid the Black Stone in its center. The clan leaders held the corners of the cloth and together carried the Black Stone to the right spot, then Muhammad laid the stone, satisfying the honor of all.

Beginnings of the Quran

Muhammad began to pray alone in a cave named

Hira Hira may refer to:

Places

* Cave of Hira, a cave associated with Muhammad

*Al-Hirah, an ancient Arab city in Iraq

** Battle of Hira, 633AD, between the Sassanians and the Rashidun Caliphate

* Hira Mountains, Japan

* Hira, New Zealand, settlement ...

on Mount Jabal al-Nour, near Mecca for several weeks every year. Islamic tradition holds that during one of his visits to that cave, in the year 610 the angel Gabriel

In Abrahamic religions (Judaism, Christianity and Islam), Gabriel (); Greek: grc, Γαβριήλ, translit=Gabriḗl, label=none; Latin: ''Gabriel''; Coptic: cop, Ⲅⲁⲃⲣⲓⲏⲗ, translit=Gabriêl, label=none; Amharic: am, ገብ� ...

appeared to him and commanded Muhammad to recite verses that would be included in the Quran. Consensus exists that the first Quranic words revealed were the beginning of Quran 96:1.

Muhammad was deeply distressed upon receiving his first revelations. After returning home, Muhammad was consoled and reassured by Khadijah and her Christian cousin, Waraqah ibn Nawfal

Waraqah ibn Nawfal ibn Asad ibn Abd-al-Uzza ibn Qusayy Al-Qurashi (Arabic ) was the paternal first cousin of Khadija bint Khuwaylid, the first wife of the Islamic prophet Muhammad. He was considered to be a hanif, who practised the pure form ...

.Esposito (2010), p. 8. He also feared that others would dismiss his claims as being possessed. Shi'a tradition states Muhammad was not surprised or frightened at Gabriel's appearance; rather he welcomed the angel, as if he was expected. The initial revelation was followed by a three-year pause (a period known as ''fatra'') during which Muhammad felt depressed and further gave himself to prayers and spiritual practice

A spiritual practice or spiritual discipline (often including spiritual exercises) is the regular or full-time performance of actions and activities undertaken for the purpose of inducing spiritual experiences and cultivating spiritual developme ...

s. When the revelations resumed he was reassured and commanded to begin preaching: "Thy Guardian-Lord hath not forsaken thee, nor is He displeased."

Sahih Bukhari

Sahih al-Bukhari ( ar, صحيح البخاري, translit=Ṣaḥīḥ al-Bukhārī), group=note is a ''hadith'' collection and a book of ''sunnah'' compiled by the Persian scholar Muḥammad ibn Ismā‘īl al-Bukhārī (810–870) around 846. Al ...

narrates Muhammad describing his revelations as "sometimes it is (revealed) like the ringing of a bell". Aisha

Aisha ( ar, , translit=ʿĀʾisha bint Abī Bakr; , also , ; ) was Muhammad's third and youngest wife. In Islamic writings, her name is thus often prefixed by the title "Mother of the Believers" ( ar, links=no, , ʾumm al- muʾminīn), referr ...

reported, "I saw the Prophet being inspired Divinely on a very cold day and noticed the sweat dropping from his forehead (as the Inspiration was over)". According to Welch these descriptions may be considered genuine, since they are unlikely to have been forged by later Muslims. Muhammad was confident that he could distinguish his own thoughts from these messages. According to the Quran, one of the main roles of Muhammad is to warn the unbelievers of their eschatological

Eschatology (; ) concerns expectations of the end of the present age, human history, or of the world itself. The end of the world or end times is predicted by several world religions (both Abrahamic and non-Abrahamic), which teach that negat ...

punishment ( Quran 38:70, Quran 6:19). Occasionally the Quran did not explicitly refer to Judgment day but provided examples from the history of extinct communities and warns Muhammad's contemporaries of similar calamities.Uri Rubin, ''Muhammad'', Encyclopedia of the Qur'an

An encyclopedia (American English) or encyclopædia (British English) is a reference work or compendium providing summaries of knowledge either general or special to a particular field or discipline. Encyclopedias are divided into articles ...

. Muhammad did not only warn those who rejected God's revelation, but also dispensed good news for those who abandoned evil, listening to the divine words and serving God. Muhammad's mission also involves preaching monotheism: The Quran commands Muhammad to proclaim and praise the name of his Lord and instructs him not to worship idols or associate other deities with God.

The key themes of the early Quranic verses included the responsibility of man towards his creator; the resurrection of the dead, God's final judgment followed by vivid descriptions of the tortures in Hell and pleasures in Paradise, and the signs of God in all aspects of life. Religious duties required of the believers at this time were few: belief in God, asking for forgiveness of sins, offering frequent prayers, assisting others particularly those in need, rejecting cheating and the love of wealth (considered to be significant in the commercial life of Mecca), being chaste and not committing female

Female (symbol: ♀) is the sex of an organism that produces the large non-motile ova (egg cells), the type of gamete (sex cell) that fuses with the male gamete during sexual reproduction.

A female has larger gametes than a male. Females a ...

infanticide

Infanticide (or infant homicide) is the intentional killing of infants or offspring. Infanticide was a widespread practice throughout human history that was mainly used to dispose of unwanted children, its main purpose is the prevention of resou ...

.

Opposition

According to Muslim tradition, Muhammad's wife

According to Muslim tradition, Muhammad's wife Khadija

Khadija, Khadeeja or Khadijah ( ar, خديجة, Khadīja) is an Arabic feminine given name, the name of Khadija bint Khuwaylid, first wife of the Islamic prophet Muhammad. In 1995, it was one of the three most popular Arabic feminine names in t ...

was the first to believe he was a prophet. She was followed by Muhammad's ten-year-old cousin Ali ibn Abi Talib

ʿAlī ibn Abī Ṭālib ( ar, عَلِيّ بْن أَبِي طَالِب; 600 – 661 CE) was the last of four Rightly Guided Caliphs to rule Islam (r. 656 – 661) immediately after the death of Muhammad, and he was the first Shia Imam ...

, close friend Abu Bakr

Abu Bakr Abdallah ibn Uthman Abi Quhafa (; – 23 August 634) was the senior companion and was, through his daughter Aisha, a father-in-law of the Islamic prophet Muhammad, as well as the first caliph of Islam. He is known with the honori ...

, and adopted son Zaid

Zaid (also transliterated as Zayd, ar, زيد) is an Arabic given name and surname.

Zaid

*Zaid Abbas Jordanian basketball player

*Zaid Abdul-Aziz (born 1946), American basketball player

*Zaid Al-Harb (1887–1972), Kuwaiti poet

*Zaid al-Rifai ...

. Around 613, Muhammad began to preach to the public. Most Meccans ignored and mocked him, though a few became his followers. There were three main groups of early converts to Islam: younger brothers and sons of great merchants; people who had fallen out of the first rank in their tribe or failed to attain it; and the weak, mostly unprotected foreigners.Watt, ''The Cambridge History of Islam'' (1977), p. 36.

According to Ibn Saad, opposition in Mecca started when Muhammad delivered verses that condemned idol worship and the polytheism practiced by the Meccan forefathers. However, the Quranic exegesis maintains that it began as Muhammad started public preaching.Uri Rubin'', Quraysh'', Encyclopaedia of the Qur'an

An encyclopedia (American English) or encyclopædia (British English) is a reference work or compendium providing summaries of knowledge either general or special to a particular field or discipline. Encyclopedias are divided into articles ...

. As his followers increased, Muhammad became a threat to the local tribes and rulers of the city, whose wealth rested upon the Kaaba, the focal point of Meccan religious life that Muhammad threatened to overthrow. Muhammad's denunciation of the Meccan traditional religion was especially offensive to his own tribe, the Quraysh

The Quraysh ( ar, قُرَيْشٌ) were a grouping of Arab clans that historically inhabited and controlled the city of Mecca and its Kaaba. The Islamic prophet Muhammad was born into the Hashim clan of the tribe. Despite this, many of the Q ...

, as they were the guardians of the Kaaba. Powerful merchants attempted to convince Muhammad to abandon his preaching; he was offered admission to the inner circle of merchants, as well as an advantageous marriage. He refused both of these offers.

Tradition records at great length the persecution and ill-treatment towards Muhammad and his followers. Sumayyah bint Khayyat

Sumayyah bint Khabbāṭ ( ar, سُمَيَّة ٱبْنَت خَبَّاط) or Sumayyah bint Khayyāṭ (; c. 550 – 615 CE / 72 BH – 7 BH), was the mother of Ammar ibn Yasir and first member of the ''Ummah'' (Community) of the Islamic pro ...

, a slave of a prominent Meccan leader Abu Jahl

ʿAmr ibn Hishām al-Makhzūmī ( ar, عمرو بن هشام المخزومي), (570 – 13 March 624), also known as Abu Jahl (lit. 'Father of Ignorance'), was one of the Meccan polytheist pagan leaders from the Quraysh known for his opposition ...

, is famous as the first martyr of Islam; killed with a spear by her master when she refused to give up her faith. Bilal __NOTOC__

Bilal may refer to:

People

* Bilal (name) (a list of people with the name)

* Bilal ibn Rabah, a companion of Muhammad

* Bilal (American singer)

* Bilal (Lebanese singer)

Places

*Bilal Colony, a neighbourhood of Korangi Town in Karachi, ...

, another Muslim slave, was tortured by Umayyah ibn Khalaf

Umayya ibn Khalaf () (died 13 March 624) was an Arab slave master and the chieftain of the Banu Jumah of the Quraysh in the seventh century. He was one of the chief opponents against the Muslims led by Muhammad. Umayya is best known as the mast ...

who placed a heavy rock on his chest to force his conversion.

In 615, some of Muhammad's followers emigrated

Emigration is the act of leaving a resident country or place of residence with the intent to settle elsewhere (to permanently leave a country). Conversely, immigration describes the movement of people into one country from another (to permanentl ...

to the Ethiopian Kingdom of Aksum and founded a small colony under the protection of the Christian Ethiopian emperor Aṣḥama ibn Abjar. Ibn Sa'ad mentions two separate migrations. According to him, most of the Muslims returned to Mecca prior to Hijra

Hijra, Hijrah, Hegira, Hejira, Hijrat or Hijri may refer to:

Islam

* Hijrah (often written as ''Hejira'' in older texts), the migration of Muhammad from Mecca to Medina in 622 CE

* Migration to Abyssinia or First Hegira, of Muhammad's followers ...

, while a second group rejoined them in Medina. Ibn Hisham

Abū Muḥammad ʿAbd al-Malik ibn Hishām ibn Ayyūb al-Ḥimyarī al-Muʿāfirī al-Baṣrī ( ar, أبو محمد عبدالملك بن هشام ابن أيوب الحميري المعافري البصري; died 7 May 833), or Ibn Hisham, e ...

and Tabari

( ar, أبو جعفر محمد بن جرير بن يزيد الطبري), more commonly known as al-Ṭabarī (), was a Muslim historian and scholar from Amol, Tabaristan. Among the most prominent figures of the Islamic Golden Age, al-Tabari i ...

, however, only talk about one migration to Ethiopia. These accounts agree that Meccan persecution played a major role in Muhammad's decision to suggest that a number of his followers seek refuge among the Christians in Abyssinia. According to the famous letter of ʿUrwa preserved in al-Tabari, the majority of Muslims returned to their native town as Islam gained strength and as high ranking Meccans, such as Umar

ʿUmar ibn al-Khaṭṭāb ( ar, عمر بن الخطاب, also spelled Omar, ) was the second Rashidun caliph, ruling from August 634 until his assassination in 644. He succeeded Abu Bakr () as the second caliph of the Rashidun Caliphat ...

and Hamzah

Hamza ( ar, همزة ') () is a letter in the Arabic alphabet, representing the glottal stop . Hamza is not one of the 28 "full" letters and owes its existence to historical inconsistencies in the standard writing system. It is derived from ...

, converted.

However, there is a completely different story on the reason why the Muslims returned from Ethiopia to Mecca. According to this account—initially mentioned by Al-Waqidi

Abu `Abdullah Muhammad Ibn ‘Omar Ibn Waqid al-Aslami (Arabic ) (c. 130 – 207 AH; c. 747 – 823 AD) was a historian commonly referred to as al-Waqidi (Arabic: ). His surname is derived from his grandfather's name Waqid and thus he became fa ...

then rehashed by Ibn Sa'ad and Tabari

( ar, أبو جعفر محمد بن جرير بن يزيد الطبري), more commonly known as al-Ṭabarī (), was a Muslim historian and scholar from Amol, Tabaristan. Among the most prominent figures of the Islamic Golden Age, al-Tabari i ...

, but not by Ibn Hisham

Abū Muḥammad ʿAbd al-Malik ibn Hishām ibn Ayyūb al-Ḥimyarī al-Muʿāfirī al-Baṣrī ( ar, أبو محمد عبدالملك بن هشام ابن أيوب الحميري المعافري البصري; died 7 May 833), or Ibn Hisham, e ...

and not by Ibn Ishaq

Muḥammad ibn Isḥāq ibn Yasār ibn Khiyār (; according to some sources, ibn Khabbār, or Kūmān, or Kūtān, ar, محمد بن إسحاق بن يسار بن خيار, or simply ibn Isḥaq, , meaning "the son of Isaac"; died 767) was an 8 ...

. Muhammad, desperately hoping for an accommodation with his tribe, pronounced a verse acknowledging the existence of three Meccan goddesses considered to be the daughters of Allah. Muhammad retracted the verses the next day at the behest of Gabriel, claiming that the verses were whispered by the devil himself. Instead, a ridicule of these gods was offered. This episode, known as "The Story of the Cranes," is also known as "Satanic Verses

The Satanic Verses are words of "satanic suggestion" which the Islamic prophet Muhammad is alleged to have mistaken for divine revelation. The verses praise the three pagan Meccan goddesses: al-Lāt, al-'Uzzá, and Manāt and can be read in e ...

". According to the story, this led to a general reconciliation between Muhammad and the Meccans, and the Abyssinia Muslims began to return home. When they arrived Gabriel had informed Muhammad that the two verses were not part of the revelation, but had been inserted by Satan. Notable scholars at the time argued against the historic authenticity of these verses and the story itself on various grounds. Al-Waqidi was severely criticized by Islamic scholars such as Malik ibn Anas

Malik ibn Anas ( ar, مَالِك بن أَنَس, 711–795 CE / 93–179 AH), whose full name is Mālik bin Anas bin Mālik bin Abī ʿĀmir bin ʿAmr bin Al-Ḥārith bin Ghaymān bin Khuthayn bin ʿAmr bin Al-Ḥārith al-Aṣbaḥī ...

, al-Shafi'i

Abū ʿAbdillāh Muḥammad ibn Idrīs al-Shāfiʿī ( ar, أَبُو عَبْدِ ٱللهِ مُحَمَّدُ بْنُ إِدْرِيسَ ٱلشَّافِعِيُّ, 767–19 January 820 CE) was an Arab Muslim theologian, writer, and schol ...

, Ahmad ibn Hanbal

Ahmad ibn Hanbal al-Dhuhli ( ar, أَحْمَد بْن حَنْبَل الذهلي, translit=Aḥmad ibn Ḥanbal al-Dhuhlī; November 780 – 2 August 855 CE/164–241 AH), was a Muslim jurist, theologian, ascetic, hadith traditionist, and ...

, Al-Nasa'i

Al-Nasāʾī (214 – 303 AH; 829 – 915 CE), full name Abū ʿAbd al-Raḥmān Aḥmad ibn Shuʿayb ibn ʿAlī ibn Sīnān al-Nasāʾī, (variant: Abu Abdel-rahman Ahmed ibn Shua'ib ibn Ali ibn Sinan ibn Bahr ibn Dinar Al-Khurasani ...

, al-Bukhari, Abu Dawood

Abū Dāwūd (Dā’ūd) Sulaymān ibn al-Ash‘ath ibn Isḥāq al-Azdī al-Sijistānī ( ar, أبو داود سليمان بن الأشعث الأزدي السجستاني), commonly known simply as Abū Dāwūd al-Sijistānī, was a scholar o ...

, Al-Nawawi

Abū Zakariyyā Yaḥyā ibn Sharaf al-Nawawī ( ar, أبو زكريا يحيى بن شرف النووي; (631A.H-676A.H) (October 1230–21 December 1277), popularly known as al-Nawawī or Imam Nawawī, was a Sunni Shafi'ite jurist and ...

and others as a liar and forger. Later, the incident received some acceptance among certain groups, though strong objections to it continued onwards past the tenth century. The objections continued until rejection of these verses and the story itself eventually became the only acceptable orthodox Muslim position.

In 616 (or 617), the leaders of Makhzum

The Banu Makhzum () was one of the wealthy clans of the Quraysh. They are regarded as being among the three most powerful and influential clans in Mecca before the advent of Islam, the other two being the Banu Hashim (the tribe of the Islamic prop ...

and Banu Abd-Shams

Banu Abd Shams () refers to a clan within the Meccan tribe of Quraysh.

Ancestry

The clan names itself after Abd Shams ibn Abd Manaf, the son of Abd Manaf ibn Qusai and brother of Hashim ibn 'Abd Manaf, who was the great-grandfather of the Islami ...

, two important Quraysh clans, declared a public boycott against Banu Hashim, their commercial rival, to pressure it into withdrawing its protection of Muhammad. The boycott lasted three years but eventually collapsed as it failed in its objective. During this time, Muhammad was able to preach only during the holy pilgrimage months in which all hostilities between Arabs were suspended.

Isra and Mi'raj

Islamic tradition states that in 620, Muhammad experienced the ''Isra and Mi'raj

The Israʾ and Miʿraj ( ar, الإسراء والمعراج, ') are the two parts of a Night Journey that, according to Islam, the Islamic prophet Muhammad (570–632) took during a single night around the year 621 (1 BH – 0 BH). Wit ...

'', a miraculous night-long journey said to have occurred with the angel Gabriel

In Abrahamic religions (Judaism, Christianity and Islam), Gabriel (); Greek: grc, Γαβριήλ, translit=Gabriḗl, label=none; Latin: ''Gabriel''; Coptic: cop, Ⲅⲁⲃⲣⲓⲏⲗ, translit=Gabriêl, label=none; Amharic: am, ገብ� ...

. At the journey's beginning, the ''Isra'', he is said to have traveled from Mecca

Mecca (; officially Makkah al-Mukarramah, commonly shortened to Makkah ()) is a city and administrative center of the Mecca Province of Saudi Arabia, and the holiest city in Islam. It is inland from Jeddah on the Red Sea, in a narrow val ...

on a winged steed to "the farthest mosque." Later, during the ''Mi'raj'', Muhammad is said to have toured heaven

Heaven or the heavens, is a common religious cosmological or transcendent supernatural place where beings such as deities, angels, souls, saints, or venerated ancestors are said to originate, be enthroned, or reside. According to the bel ...

and hell, and spoke with earlier prophets, such as Abraham

Abraham, ; ar, , , name=, group= (originally Abram) is the common Hebrews, Hebrew patriarch of the Abrahamic religions, including Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. In Judaism, he is the founding father of the Covenant (biblical), special ...

, Moses, and Jesus

Jesus, likely from he, יֵשׁוּעַ, translit=Yēšūaʿ, label=Hebrew/Aramaic ( AD 30 or 33), also referred to as Jesus Christ or Jesus of Nazareth (among other names and titles), was a first-century Jewish preacher and religiou ...

. Ibn Ishaq

Muḥammad ibn Isḥāq ibn Yasār ibn Khiyār (; according to some sources, ibn Khabbār, or Kūmān, or Kūtān, ar, محمد بن إسحاق بن يسار بن خيار, or simply ibn Isḥaq, , meaning "the son of Isaac"; died 767) was an 8 ...

, author of the first biography of Muhammad, presents the event as a spiritual experience; later historians, such as Al-Tabari

( ar, أبو جعفر محمد بن جرير بن يزيد الطبري), more commonly known as al-Ṭabarī (), was a Muslim historian and scholar from Amol, Tabaristan. Among the most prominent figures of the Islamic Golden Age, al-Tabari ...

and Ibn Kathir, present it as a physical journey.

Some western scholars hold that the Isra and Mi'raj journey traveled through the heavens from the sacred enclosure at Mecca to the celestial ''al-Baytu l-Maʿmur'' (heavenly prototype of the Kaaba); later traditions indicate Muhammad's journey as having been from Mecca to Jerusalem.

Last years before Hijra

Muhammad's wife Khadijah and uncle Abu Talib both died in 619, the year thus being known as the "

Muhammad's wife Khadijah and uncle Abu Talib both died in 619, the year thus being known as the "Year of Sorrow

In the Islamic tradition, the Year of Sorrow ( ar, عام الحزن, ‘Ām al-Ḥuzn, also translated Year of Sadness) is the Hijri year in which Muhammad's wife Khadijah and his uncle and protector Abu Talib died. The year approximately coinc ...

". With the death of Abu Talib, leadership of the Banu Hashim clan passed to Abu Lahab

Abu or ABU may refer to:

Places

* Abu (volcano), a volcano on the island of Honshū in Japan

* Abu, Yamaguchi, a town in Japan

* Ahmadu Bello University, a university located in Zaria, Nigeria

* Atlantic Baptist University, a Christian universit ...

, a tenacious enemy of Muhammad. Soon afterward, Abu Lahab withdrew the clan's protection over Muhammad. This placed Muhammad in danger; the withdrawal of clan protection implied that blood revenge for his killing would not be exacted. Muhammad then visited Ta'if, another important city in Arabia, and tried to find a protector, but his effort failed and further brought him into physical danger. Muhammad was forced to return to Mecca. A Meccan man named Mut'im ibn Adi (and the protection of the tribe of Banu Nawfal

)

, type = Qurayshi / Adnanite Arab Tribe

, image =

, alt =

, caption = Banner of Banu Taym

, nisba = Al-Nawfal ()

, location = Western Arabian Peninsula, especially in Mecca (present-day Saudi Arabia)

, descen ...

) made it possible for him to safely re-enter his native city.

Many people visited Mecca on business or as pilgrims to the Kaaba

The Kaaba (, ), also spelled Ka'bah or Kabah, sometimes referred to as al-Kaʿbah al-Musharrafah ( ar, ٱلْكَعْبَة ٱلْمُشَرَّفَة, lit=Honored Ka'bah, links=no, translit=al-Kaʿbah al-Musharrafah), is a building at the c ...

. Muhammad took this opportunity to look for a new home for himself and his followers. After several unsuccessful negotiations, he found hope with some men from Yathrib (later called Medina). The Arab population of Yathrib were familiar with monotheism and were prepared for the appearance of a prophet because a Jewish community existed there. They also hoped, by the means of Muhammad and the new faith, to gain supremacy over Mecca; the Yathrib were jealous of its importance as the place of pilgrimage. Converts to Islam came from nearly all Arab tribes in Medina; by June of the subsequent year, seventy-five Muslims came to Mecca for pilgrimage and to meet Muhammad. Meeting him secretly by night, the group made what is known as the "'' Second Pledge of al-'Aqaba''", or, in Orientalists' view, the "''Pledge of War''". Following the pledges at Aqabah, Muhammad encouraged his followers to emigrate

Emigration is the act of leaving a resident country or place of residence with the intent to settle elsewhere (to permanently leave a country). Conversely, immigration describes the movement of people into one country from another (to permanentl ...

to Yathrib

Medina,, ', "the radiant city"; or , ', (), "the city" officially Al Madinah Al Munawwarah (, , Turkish: Medine-i Münevvere) and also commonly simplified as Madīnah or Madinah (, ), is the second-holiest city in Islam, and the capital of the ...

. As with the migration to Abyssinia

The migration to Abyssinia ( ar, الهجرة إلى الحبشة, translit=al-hijra ʾilā al-habaša), also known as the First Hijra ( ar, الهجرة الأولى, translit=al-hijrat al'uwlaa, label=none), was an episode in the early histor ...

, the Quraysh attempted to stop the emigration. However, almost all Muslims managed to leave.

Hijra

The Hijra is the migration of Muhammad and his followers from Mecca to Medina in 622 CE. In June 622, warned of a plot to assassinate him, Muhammad secretly slipped out of Mecca and moved his followers to Medina,Muhammad Mustafa Al-A'zami

Muhammad Mustafa Al-A'zami (1930 – 20 December 2017) was an Indian-born Saudi Arabian contemporary hadith scholar best known for his critical investigation of the theories of fellow Islamic scholars Ignác Goldziher, David Margoliouth, and Jo ...

(2003), ''The History of The Qur'anic Text: From Revelation to Compilation: A Comparative Study with the Old and New Testaments'', pp. 30–31. UK Islamic Academy. . north of Mecca.Muhammad Mustafa Al-A'zami

Muhammad Mustafa Al-A'zami (1930 – 20 December 2017) was an Indian-born Saudi Arabian contemporary hadith scholar best known for his critical investigation of the theories of fellow Islamic scholars Ignác Goldziher, David Margoliouth, and Jo ...

(2003), ''The History of The Qur'anic Text: From Revelation to Compilation: A Comparative Study with the Old and New Testaments'', p. 29. UK Islamic Academy. .

Migration to Medina

A delegation, consisting of the representatives of the twelve important clans of Medina, invited Muhammad to serve as chief arbitrator for the entire community; due to his status as a neutral outsider. There was fighting in Yathrib: primarily the dispute involved its Arab and Jewish inhabitants, and was estimated to have lasted for around a hundred years before 620. The recurring slaughters and disagreements over the resulting claims, especially after theBattle of Bu'ath

A battle is an occurrence of combat in warfare between opposing military units of any number or size. A war usually consists of multiple battles. In general, a battle is a military engagement that is well defined in duration, area, and for ...

in which all clans were involved, made it obvious to them that the tribal concept of blood-feud and an eye for an eye

"An eye for an eye" ( hbo, עַיִן תַּחַת עַיִן, ) is a commandment found in the Book of Exodus 21:23–27 expressing the principle of reciprocal justice measure for measure. The principle exists also in Babylonian law.

In Roman c ...

were no longer workable unless there was one man with authority to adjudicate in disputed cases.Watt, ''The Cambridge History of Islam'', p. 39. The delegation from Medina pledged themselves and their fellow-citizens to accept Muhammad into their community and physically protect him as one of themselves.

Muhammad instructed his followers to emigrate to Medina, until nearly all his followers left Mecca. Being alarmed at the departure, according to tradition, the Meccans plotted to assassinate Muhammad. With the help of Ali

ʿAlī ibn Abī Ṭālib ( ar, عَلِيّ بْن أَبِي طَالِب; 600 – 661 CE) was the last of four Rightly Guided Caliphs to rule Islam (r. 656 – 661) immediately after the death of Muhammad, and he was the first Shia Imam ...

, Muhammad fooled the Meccans watching him, and secretly slipped away from the town with Abu Bakr. By 622, Muhammad emigrated to Medina, a large agricultural oasis

In ecology, an oasis (; ) is a fertile area of a desert or semi-desert environmentmuhajirun

The ''Muhajirun'' ( ar, المهاجرون, al-muhājirūn, singular , ) were the first converts to Islam and the Islamic prophet Muhammad's advisors and relatives, who emigrated with him from Mecca to Medina, the event known in Islam as the '' Hij ...

'' (emigrants).

Establishment of a new polity

Among the first things Muhammad did to ease the longstanding grievances among the tribes of Medina was to draft a document known as the Constitution of Medina, "establishing a kind of alliance or federation" among the eight Medinan tribes and Muslim emigrants from Mecca; this specified rights and duties of all citizens, and the relationship of the different communities in Medina (including the Muslim community to other communities, specifically theJew

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""T ...

s and other "Peoples of the Book

People of the Book or Ahl al-kitāb ( ar, أهل الكتاب) is an Islamic term referring to those religions which Muslims regard as having been guided by previous revelations, generally in the form of a scripture. In the Quran they are ident ...

"). The community defined in the Constitution of Medina, ''Ummah

' (; ar, أمة ) is an Arabic word meaning "community". It is distinguished from ' ( ), which means a nation with common ancestry or geography. Thus, it can be said to be a supra-national community with a common history.

It is a synonym for ' ...

'', had a religious outlook, also shaped by practical considerations and substantially preserved the legal forms of the old Arab tribes.

The first group of converts to Islam in Medina were the clans without great leaders; these clans had been subjugated by hostile leaders from outside. This was followed by the general acceptance of Islam by the pagan population of Medina, with some exceptions. According to Ibn Ishaq

Muḥammad ibn Isḥāq ibn Yasār ibn Khiyār (; according to some sources, ibn Khabbār, or Kūmān, or Kūtān, ar, محمد بن إسحاق بن يسار بن خيار, or simply ibn Isḥaq, , meaning "the son of Isaac"; died 767) was an 8 ...

, this was influenced by the conversion of Sa'd ibn Mu'adh

Saʿd ibn Muʿādh ( ar, سعد ابن معاذ) () was the chief of the Aws tribe in Medina and one of the prominent companions of the Islamic Prophet Muhammad (peace be upon Him). He died shortly after the Battle of the Trench.

Family

Sa'd wa ...

(a prominent Medinan leader) to Islam. Medinans who converted to Islam and helped the Muslim emigrants find shelter became known as the '' ansar'' (supporters). Then Muhammad instituted brotherhood between the emigrants and the supporters and he chose Ali

ʿAlī ibn Abī Ṭālib ( ar, عَلِيّ بْن أَبِي طَالِب; 600 – 661 CE) was the last of four Rightly Guided Caliphs to rule Islam (r. 656 – 661) immediately after the death of Muhammad, and he was the first Shia Imam ...

as his own brother.

Beginning of armed conflict

Following the emigration, the people of Mecca seized property of Muslim emigrants to Medina. War would later break out between the people of Mecca and the Muslims. Muhammad deliveredQuran

The Quran (, ; Standard Arabic: , Quranic Arabic: , , 'the recitation'), also romanized Qur'an or Koran, is the central religious text of Islam, believed by Muslims to be a revelation from God. It is organized in 114 chapters (pl.: , sing.: ...

ic verses permitting Muslims to fight the Meccans. According to the traditional account, on 11 February 624, while praying in the Masjid al-Qiblatayn

The Masjid al-Qiblatayn ( ar, مسجد القبلتين, lit=Mosque of the Two Qiblas), also spelt Masjid al-Qiblatain, is a mosque in Medina believed by Muslims to be the place where the final Prophets and messengers in Islam, Islamic prophet, ...

in Medina, Muhammad received revelations from God that he should be facing Mecca rather than Jerusalem during prayer. Muhammad adjusted to the new direction, and his companions praying with him followed his lead, beginning the tradition of facing Mecca during prayer.

Muhammad ordered a number of raids to capture Meccan caravans, but only the 8th of them, the Raid of Nakhla, resulted in actual fighting and capture of booty and prisoners. In March 624, Muhammad led some three hundred warriors in a raid on a Meccan merchant caravan. The Muslims set an ambush for the caravan at Badr. Aware of the plan, the Meccan caravan eluded the Muslims. A Meccan force was sent to protect the caravan and went on to confront the Muslims upon receiving word that the caravan was safe. The Battle of Badr

The Battle of Badr ( ar, غَزْوَةُ بَدِرْ ), also referred to as The Day of the Criterion (, ) in the Qur'an and by Muslims, was fought on 13 March 624 CE (17 Ramadan, 2 AH), near the present-day city of Badr, Al Madinah Provin ...

commenced. Though outnumbered more than three to one, the Muslims won the battle, killing at least forty-five Meccans with fourteen Muslims dead. They also succeeded in killing many Meccan leaders, including Abu Jahl

ʿAmr ibn Hishām al-Makhzūmī ( ar, عمرو بن هشام المخزومي), (570 – 13 March 624), also known as Abu Jahl (lit. 'Father of Ignorance'), was one of the Meccan polytheist pagan leaders from the Quraysh known for his opposition ...

. Seventy prisoners had been acquired, many of whom were ransomed.Lewis (2002), p. 41.Rodinson (2002), pp. 168–69. Muhammad and his followers saw the victory as confirmation of their faith and Muhammad ascribed the victory to the assistance of an invisible host of angels. The Quranic verses of this period, unlike the Meccan verses, dealt with practical problems of government and issues like the distribution of spoils.

The victory strengthened Muhammad's position in Medina and dispelled earlier doubts among his followers. As a result, the opposition to him became less vocal. Pagans who had not yet converted were very bitter about the advance of Islam. Two pagans, Asma bint Marwan of the Aws Manat tribe and Abu 'Afak

Abu 'Afak ( Arabic: أبو عفك, died c. 624) was a Jewish poet who lived in the Hijaz region (today Saudi Arabia). Abu 'Afak did not convert to Islam and was vocal about his opposition to Muhammad. He became a significant political enemy o ...

of the 'Amr b. 'Awf tribe, had composed verses taunting and insulting the Muslims. They were killed by people belonging to their own or related clans, and Muhammad did not disapprove of the killings. This report, however, is considered by some to be a fabrication. Most members of those tribes converted to Islam, and little pagan opposition remained.

Muhammad expelled from Medina the Banu Qaynuqa

The Banu Qaynuqa ( ar, بنو قينقاع; he, בני קינוקאע; also spelled Banu Kainuka, Banu Kaynuka, Banu Qainuqa, Banu Qaynuqa) was one of the three main Jewish tribes living in the 7th century of Medina, now in Saudi Arabia. The g ...

, one of three main Jewish tribes, but some historians contend that the expulsion happened after Muhammad's death. According to al-Waqidi

Abu `Abdullah Muhammad Ibn ‘Omar Ibn Waqid al-Aslami (Arabic ) (c. 130 – 207 AH; c. 747 – 823 AD) was a historian commonly referred to as al-Waqidi (Arabic: ). His surname is derived from his grandfather's name Waqid and thus he became fa ...

, after Abd-Allah ibn Ubaiy

ʿAbd Allāh ibn 'Ubayy ibn Salūl ( ar, عبد الله بن أبي بن سلول), died 631, was a chieftain of the Khazraj tribe of Medina. Upon the arrival of the Islamic prophet Muhammad, Ibn Ubayy seemingly became a Muslim, but Muslim tradi ...

spoke for them, Muhammad refrained from executing them and commanded that they be exiled from Medina. Following the Battle of Badr, Muhammad also made mutual-aid alliances with a number of Bedouin tribes to protect his community from attacks from the northern part of Hejaz.

Conflict with Mecca

The Meccans were eager to avenge their defeat. To maintain economic prosperity, the Meccans needed to restore their prestige, which had been reduced at Badr. In the ensuing months, the Meccans sent ambush parties to Medina while Muhammad led expeditions against tribes allied with Mecca and sent raiders onto a Meccan caravan.Abu Sufyan

Sakhr ibn Harb ibn Umayya ibn Abd Shams ( ar, صخر بن حرب بن أمية بن عبد شمس, Ṣakhr ibn Ḥarb ibn Umayya ibn ʿAbd Shams; ), better known by his '' kunya'' Abu Sufyan ( ar, أبو سفيان, Abū Sufyān), was a prominent ...

gathered an army of 3000 men and set out for an attack on Medina.Lewis (1960), p. 45.

A scout alerted Muhammad of the Meccan army's presence and numbers a day later. The next morning, at the Muslim conference of war, a dispute arose over how best to repel the Meccans. Muhammad and many senior figures suggested it would be safer to fight within Medina and take advantage of the heavily fortified strongholds. Younger Muslims argued that the Meccans were destroying crops, and huddling in the strongholds would destroy Muslim prestige. Muhammad eventually conceded to the younger Muslims and readied the Muslim force for battle. Muhammad led his force outside to the mountain of Uhud (the location of the Meccan camp) and fought the Battle of Uhud

The Battle of Uhud ( ar, غَزْوَة أُحُد, ) was fought on Saturday, 23 March 625 AD (7 Shawwal, 3 AH), in the valley north of Mount Uhud.Watt (1974) p. 136. The Qurayshi Meccans, led by Abu Sufyan ibn Harb, commanded an army of 3,000 ...

on 23 March 625. Although the Muslim army had the advantage in early encounters, lack of discipline on the part of strategically placed archers led to a Muslim defeat; 75 Muslims were killed, including Hamza

Hamza ( ar, همزة ') () is a letter in the Arabic alphabet, representing the glottal stop . Hamza is not one of the 28 "full" letters and owes its existence to historical inconsistencies in the standard writing system. It is derived from ...