Merlyn Carter Airport on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Merlin ( cy, Myrddin, kw, Marzhin, br, Merzhin) is a mythical figure prominently featured in the legend of

The name "Merlin" is derived from the Brythonic ''

The name "Merlin" is derived from the Brythonic ''

Therefore, Geoffrey's account of Merlin Ambrosius' early life is based on the story from the ''Historia Brittonum''. Geoffrey added his own embellishments to the tale, which he set in

Therefore, Geoffrey's account of Merlin Ambrosius' early life is based on the story from the ''Historia Brittonum''. Geoffrey added his own embellishments to the tale, which he set in  Nikolai Tolstoy hypothesized that Merlin is based on a historical personage, probably a 6th-century

Nikolai Tolstoy hypothesized that Merlin is based on a historical personage, probably a 6th-century

Sometime around the turn of the following 13th century,

Sometime around the turn of the following 13th century,  As the Arthurian myths were retold, Merlin's prophetic aspects were sometimes de-emphasised in favour of portraying him as a wizard and an advisor to the young Arthur, sometimes in struggle between good and evil sides of his character, and living in deep forests connected with nature. Through his ability to change his shape, he may appear as a "wild man" figure evoking that of his prototype Myrddin Wyllt, as a civilized man of any age, or even as a talking animal. In the ''Perceval en prose'' (also known as the Didot ''Perceval'' and too attributed to Robert), where Merlin is the initiator of the Grail Quest and cannot die until the end of days, he eventually retires after Arthur's downfall by turning himself into a bird and entering the mysterious '' esplumoir'', never to be seen again. In the Vulgate Cycle's version of ''Merlin'', his acts include arranging consummation of Arthur's desire for "the most beautiful maiden ever born," Lady Lisanor of Cardigan, resulting in the birth of Arthur's illegitimate son

As the Arthurian myths were retold, Merlin's prophetic aspects were sometimes de-emphasised in favour of portraying him as a wizard and an advisor to the young Arthur, sometimes in struggle between good and evil sides of his character, and living in deep forests connected with nature. Through his ability to change his shape, he may appear as a "wild man" figure evoking that of his prototype Myrddin Wyllt, as a civilized man of any age, or even as a talking animal. In the ''Perceval en prose'' (also known as the Didot ''Perceval'' and too attributed to Robert), where Merlin is the initiator of the Grail Quest and cannot die until the end of days, he eventually retires after Arthur's downfall by turning himself into a bird and entering the mysterious '' esplumoir'', never to be seen again. In the Vulgate Cycle's version of ''Merlin'', his acts include arranging consummation of Arthur's desire for "the most beautiful maiden ever born," Lady Lisanor of Cardigan, resulting in the birth of Arthur's illegitimate son

Viviane's character in relation with Merlin is first found in the ''Lancelot-Grail'' cycle, after having been inserted into the legend of Merlin by either de Boron or his continuator. There are many different versions of their story. Common themes in most of them include Merlin actually having the prior prophetic knowledge of her plot against him (one exception is the Spanish Post-Vulgate ''Baladro'' where his foresight ability is explicitly dampened by sexual desire) but lacking either ability or will to counteract it in any way, along with her using one of his own spells to rid of him. Usually (including in ''Le Morte d'Arthur''), having learnt everything she could from him, Viviane will then also replace the eliminated Merlin within the story, taking up his role as Arthur's adviser and court mage. However, Merlin's fate of either demise or eternal imprisonment, along with his destroyer or captor's motivation (from her fear of Merlin and protecting her own virginity, to her jealously for his relationship with Morgan), is recounted differently in variants of this motif. The exact form of his either prison or grave can be also variably a cave, a hole under a large rock (as in ''Le Morte d'Arthur''), a magic tower, or a tree.Loomis, Roger Sherman (1927).

Viviane's character in relation with Merlin is first found in the ''Lancelot-Grail'' cycle, after having been inserted into the legend of Merlin by either de Boron or his continuator. There are many different versions of their story. Common themes in most of them include Merlin actually having the prior prophetic knowledge of her plot against him (one exception is the Spanish Post-Vulgate ''Baladro'' where his foresight ability is explicitly dampened by sexual desire) but lacking either ability or will to counteract it in any way, along with her using one of his own spells to rid of him. Usually (including in ''Le Morte d'Arthur''), having learnt everything she could from him, Viviane will then also replace the eliminated Merlin within the story, taking up his role as Arthur's adviser and court mage. However, Merlin's fate of either demise or eternal imprisonment, along with his destroyer or captor's motivation (from her fear of Merlin and protecting her own virginity, to her jealously for his relationship with Morgan), is recounted differently in variants of this motif. The exact form of his either prison or grave can be also variably a cave, a hole under a large rock (as in ''Le Morte d'Arthur''), a magic tower, or a tree.Loomis, Roger Sherman (1927).

Celtic Myth and Arthurian Romance

'. Columbia University Press. These are usually placed within the

Merlin: Texts, Images, Basic Information

Camelot Project at the

Timeless Myths: The Many Faces of Merlin

BBC audio file

of the "Merlin" episode of ''

Introduction

an

(the

''Of Arthour and of Merlin''

translated and retold in modern English prose, the story from Edinburgh, National Library of Scotland MS Advocates 19.2.1 (the Auchinleck MS) (from the Middle English of the Early English Text Society edition: O D McCrae-Gibson, 1973, ''Of Arthour and of Merlin'', 2 vols, EETS and Oxford University Press) {{Authority control Arthurian characters Druids English folklore Fictional astronomers Fictional characters who use magic Fictional characters with neurological or psychological disorders Fictional depictions of the Antichrist Fictional half-demons Fictional humanoids Fictional offspring of rape Fictional prophets Fictional owls Fictional shapeshifters Fictional wizards Holy Grail Legendary Welsh people Literary archetypes by name Male characters in film Male characters in literature Male characters in television People whose existence is disputed Supernatural legends

King Arthur

King Arthur ( cy, Brenin Arthur, kw, Arthur Gernow, br, Roue Arzhur) is a legendary king of Britain, and a central figure in the medieval literary tradition known as the Matter of Britain.

In the earliest traditions, Arthur appears as a ...

and best known as a mage

Mage most commonly refers to:

* Mage (paranormal) or magician, a practitioner of magic derived from supernatural or occult sources

* Mage (fantasy) or magician, a type of character in mythology, folklore, and fiction

*Mage, a character class in s ...

, with several other main roles. His usual depiction, based on an amalgamation of historic and legendary figures, was introduced by the 12th-century British author Geoffrey of Monmouth

Geoffrey of Monmouth ( la, Galfridus Monemutensis, Galfridus Arturus, cy, Gruffudd ap Arthur, Sieffre o Fynwy; 1095 – 1155) was a British cleric from Monmouth, Wales and one of the major figures in the development of British historiograph ...

. It is believed that Geoffrey combined earlier tales of Myrddin

Myrddin Wyllt (—"Myrddin the Wild", kw, Marzhin Gwyls, br, Merzhin Gueld) is a figure in medieval Welsh legend. In Middle Welsh poetry he is accounted a chief bard, the speaker of several poems in The Black Book of Carmarthen and The Red Bo ...

and Ambrosius

Ambrosius or Ambrosios (a Latin adjective derived from the Ancient Greek word ἀμβρόσιος, ''ambrosios'' "divine, immortal") may refer to:

Given name:

*Ambrosius Alexandrinus, a Latinization of the name of Ambrose of Alexandria (before 21 ...

, two legendary Briton

British people or Britons, also known colloquially as Brits, are the citizens of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, the British Overseas Territories, and the Crown dependencies.: British nationality law governs mod ...

prophets with no connection to Arthur, to form the composite figure called Merlinus Ambrosius ( cy, Myrddin Emrys, br, Merzhin Ambroaz).

Geoffrey's rendering of the character became immediately popular, especially in Wales

Wales ( cy, Cymru ) is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is bordered by England to the Wales–England border, east, the Irish Sea to the north and west, the Celtic Sea to the south west and the ...

. Later writers in France and elsewhere expanded the account to produce a fuller image, creating one of the most important figures in the imagination and literature of the Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire a ...

.

Merlin's traditional biography casts him as an often-mad being born of a mortal woman, sired by an incubus

An incubus is a demon in male form in folklore that seeks to have sexual intercourse with sleeping women; the corresponding spirit in female form is called a succubus. In medieval Europe, union with an incubus was supposed by some to result in t ...

, from whom he inherits his supernatural powers and abilities, most commonly and notably prophecy

In religion, a prophecy is a message that has been communicated to a person (typically called a ''prophet'') by a supernatural entity. Prophecies are a feature of many cultures and belief systems and usually contain divine will or law, or prete ...

and shapeshifting

In mythology, folklore and speculative fiction, shape-shifting is the ability to physically transform oneself through an inherently superhuman ability, divine intervention, demonic manipulation, Magic (paranormal), sorcery, Incantation, ...

. Merlin matures to an ascendant sagehood and engineers the birth of Arthur through magic and intrigue. Later authors have Merlin serve as the king's advisor and mentor until his disappearance from the tale, leaving behind a series of prophecies foretelling the events yet to come. A popular story from the French prose cycles describes Merlin being bewitched and forever sealed or killed by his student known as the Lady of the Lake

The Lady of the Lake (french: Dame du Lac, Demoiselle du Lac, cy, Arglwyddes y Llyn, kw, Arloedhes an Lynn, br, Itron al Lenn, it, Dama del Lago) is a name or a title used by several either fairy or fairy-like but human enchantresses in the ...

after falling in love with her, with a local legend claiming him buried in the magical forest of Brocéliande

Brocéliande, earlier known as Brécheliant and Brécilien, is a legendary enchanted forest that had a reputation in the medieval European imagination as a place of magic and mystery. Brocéliande is featured in several medieval texts, mostly r ...

. Other texts variously describe his retirement or death.

Name

The name "Merlin" is derived from the Brythonic ''

The name "Merlin" is derived from the Brythonic ''Myrddin

Myrddin Wyllt (—"Myrddin the Wild", kw, Marzhin Gwyls, br, Merzhin Gueld) is a figure in medieval Welsh legend. In Middle Welsh poetry he is accounted a chief bard, the speaker of several poems in The Black Book of Carmarthen and The Red Bo ...

'', the name of the bard

In Celtic cultures, a bard is a professional story teller, verse-maker, music composer, oral historian and genealogist, employed by a patron (such as a monarch or chieftain) to commemorate one or more of the patron's ancestors and to praise t ...

who was one of the chief sources for the later legendary figure. Geoffrey of Monmouth

Geoffrey of Monmouth ( la, Galfridus Monemutensis, Galfridus Arturus, cy, Gruffudd ap Arthur, Sieffre o Fynwy; 1095 – 1155) was a British cleric from Monmouth, Wales and one of the major figures in the development of British historiograph ...

Latinised the name to ''Merlinus'' in his works. Medievalist Gaston Paris

Bruno Paulin Gaston Paris (; 9 August 1839 – 5 March 1903) was a French literary historian, philologist, and scholar specialized in Romance studies and medieval French literature. He was nominated for the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1901, 19 ...

suggests that Geoffrey chose the form ''Merlinus'' rather than the expected ''*Merdinus'' to avoid a resemblance to the Anglo-Norman Anglo-Norman may refer to:

*Anglo-Normans, the medieval ruling class in England following the Norman conquest of 1066

* Anglo-Norman language

**Anglo-Norman literature

* Anglo-Norman England, or Norman England, the period in English history from 10 ...

word ''merde'' (from Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power of the ...

''merda'') for feces

Feces ( or faeces), known colloquially and in slang as poo and poop, are the solid or semi-solid remains of food that was not digested in the small intestine, and has been broken down by bacteria in the large intestine. Feces contain a relati ...

. A more plausible suggestion is that 'Merlin' is an adjective and that consequently we should be speaking of "The Merlin", from the French ''merle'' meaning " blackbird", or that the "many names" deriving from Myrddin stem from the cy, myrdd: myriad.Dames, Michael. ''Merlin and Wales: A Magician's Landscape'', 2004. Thames & Hudson Ltd. Other suggestions derive the name Myrddin from Celtic languages, including that of a combination of *''mer'' ("mad") and the Welsh ''dyn'' ("man"), to mean "madman". In his ''Myrdhinn, ou l'Enchanteur Merlin'' (1862), La Villemarqué wished to derive the form ''Marz n'' from ''marz'', the Breton word for "miracle"; Villemarqué furthermore associated it with the marte, a type of fairy being from the French folklore.

Clas Myrddin or ''Merlin's Enclosure'' is an early name for Great Britain

Great Britain is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean off the northwest coast of continental Europe. With an area of , it is the largest of the British Isles, the largest European island and the ninth-largest island in the world. It is ...

stated in the Third Series of Welsh Triads

The Welsh Triads ( cy, Trioedd Ynys Prydein, "Triads of the Island of Britain") are a group of related texts in medieval manuscripts which preserve fragments of Welsh folklore, mythology and traditional history in groups of three. The triad is a ...

. Celticist A. O. H. Jarman suggests that the Welsh name ' () was derived from the toponym ''Caerfyrddin'', the Welsh name for the town known in English as Carmarthen

Carmarthen (, RP: ; cy, Caerfyrddin , "Merlin's fort" or "Sea-town fort") is the county town of Carmarthenshire and a community in Wales, lying on the River Towy. north of its estuary in Carmarthen Bay. The population was 14,185 in 2011, ...

.Koch, ''Celtic Culture'', p. 321. This contrasts with the popular folk etymology

Folk etymology (also known as popular etymology, analogical reformation, reanalysis, morphological reanalysis or etymological reinterpretation) is a change in a word or phrase resulting from the replacement of an unfamiliar form by a more famili ...

that the town was named after the bard. The name Carmarthen is derived from the town's previous Roman

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

*Rome, the capital city of Italy

*Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*''Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a letter ...

name Moridunum, in turn derived from Celtic Brittonic

Brittonic or Brythonic may refer to:

*Common Brittonic, or Brythonic, the Celtic language anciently spoken in Great Britain

*Brittonic languages, a branch of the Celtic languages descended from Common Brittonic

*Britons (Celtic people)

The Br ...

''moridunon'', "sea fortress".

Medieval legend

Geoffrey and his sources

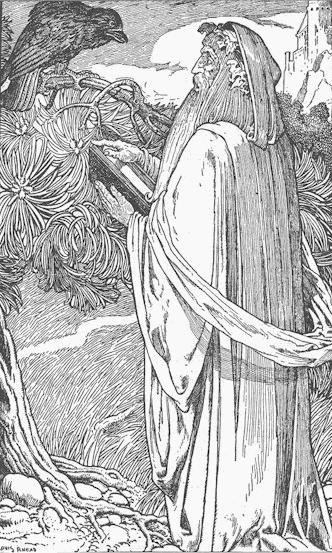

Geoffrey's composite Merlin is based mostly on the North Brythonic poet and seerMyrddin Wyllt

Myrddin Wyllt (—"Myrddin the Wild", kw, Marzhin Gwyls, br, Merzhin Gueld) is a figure in medieval Welsh legend. In Middle Welsh poetry he is accounted a chief bard, the speaker of several poems in The Black Book of Carmarthen and The Red Bo ...

, that is "Myrddin the Wild" (known as Merlinus Caledonensis or Merlin Sylvestris in later texts influenced by Geoffrey). Myrddin's legend has parallels with a Welsh and Scottish story of the mad prophet Lailoken

Lailoken (aka Merlyn Sylvester) was a semi-legendary madman and prophet who lived in the Caledonian Forest in the late 6th century. The ''Life of Saint Kentigern'' mentions "a certain foolish man, who was called ''Laleocen''" living at or near the ...

(Laleocen), and with ''Buile Shuibhne

''Buile Shuibhne'' or ''Buile Suibne'' (, ''The Madness of Suibhne'' or ''Suibhne's Frenzy'') is a medieval Irish tale about Suibhne mac Colmáin, king of the Dál nAraidi, who was driven insane by the curse of Saint Rónán Finn. The insanity ma ...

'', an Irish tale of the wandering insane king Suibihne mac Colmáin (Sweeney).Markale, J (1995). Belle N. Burke (trans) ''Merlin: Priest of Nature''. Inner Traditions. . (Originally ''Merlin L'Enchanteur'', 1981.) In Welsh poetry, Myrddin was a bard driven mad after witnessing the horrors of war, who fled civilization to become a wild man of the wood in the 6th century. He roams the Caledonian Forest, until cured of his madness by Kentigern (Saint Mungo

Kentigern ( cy, Cyndeyrn Garthwys; la, Kentigernus), known as Mungo, was a missionary in the Brittonic Kingdom of Strathclyde in the late sixth century, and the founder and patron saint of the city of Glasgow.

Name

In Wales and England, this s ...

). Geoffrey had Myrddin in mind when he wrote his earliest surviving work, the ''Prophetiae Merlini

The ''Prophetiæ Merlini'' is a Latin work of Geoffrey of Monmouth circulated, perhaps as a ''libellus'' or short work, from about 1130, and by 1135. Another name is ''Libellus Merlini''.

The work contains a number of prophecies attributed to ...

'' ("Prophecies of Merlin", c. 1130), which he claimed were the actual words of the legendary poet, however revealing little about Merlin's background.

Geoffrey was also further inspired by Emrys (Old Welsh

Old Welsh ( cy, Hen Gymraeg) is the stage of the Welsh language from about 800 AD until the early 12th century when it developed into Middle Welsh.Koch, p. 1757. The preceding period, from the time Welsh became distinct from Common Brittonic ...

: ''Embreis''), a character based in part on the 5th-century historical figure of the Romano-British

The Romano-British culture arose in Britain under the Roman Empire following the Roman conquest in AD 43 and the creation of the province of Britannia. It arose as a fusion of the imported Roman culture with that of the indigenous Britons, a ...

war leader Ambrosius Aurelianus

Ambrosius Aurelianus ( cy, Emrys Wledig; Anglicised as Ambrose Aurelian and called Aurelius Ambrosius in the ''Historia Regum Britanniae'' and elsewhere) was a war leader of the Romano-British who won an important battle against the Anglo-Sa ...

. When Geoffrey included Merlin in his next work, ''Historia Regum Britanniae

''Historia regum Britanniae'' (''The History of the Kings of Britain''), originally called ''De gestis Britonum'' (''On the Deeds of the Britons''), is a pseudohistorical account of British history, written around 1136 by Geoffrey of Monmouth. I ...

'' (c. 1136), he supplemented his characterisation by attributing to Merlin stories concerning Ambrosius, taken from one of his primary sources, the early 9th-century ''Historia Brittonum

''The History of the Britons'' ( la, Historia Brittonum) is a purported history of the indigenous British (Brittonic) people that was written around 828 and survives in numerous recensions that date from after the 11th century. The ''Historia Bri ...

'' attributed to Nennius

Nennius – or Nemnius or Nemnivus – was a Welsh monk of the 9th century. He has traditionally been attributed with the authorship of the ''Historia Brittonum'', based on the prologue affixed to that work. This attribution is widely considered ...

. In Nennius' account, Ambrosius was discovered when the British king Vortigern

Vortigern (; owl, Guorthigirn, ; cy, Gwrtheyrn; ang, Wyrtgeorn; Old Breton: ''Gurdiern'', ''Gurthiern''; gle, Foirtchern; la, Vortigernus, , , etc.), also spelled Vortiger, Vortigan, Voertigern and Vortigen, was a 5th-century warlord in ...

attempted to erect a tower at Dinas Emrys

Dinas Emrys () is a rocky and wooded hillock near Beddgelert in Gwynedd, north-west Wales. Rising some above the floor of the Glaslyn river valley, it overlooks the southern end of Llyn Dinas in Snowdonia.

Little remains of the Iron Age hillfo ...

. More than once, the tower collapsed before completion. Vortigen's wise men advised him that the only solution was to sprinkle the foundation with the blood of a child born without a father. Ambrosius was rumoured to be such a child. When brought before the king, Ambrosius revealed that below the foundation of the tower was a lake containing two dragons battling into each other, representing the struggle between the invading Saxons

The Saxons ( la, Saxones, german: Sachsen, ang, Seaxan, osx, Sahson, nds, Sassen, nl, Saksen) were a group of Germanic

*

*

*

*

peoples whose name was given in the early Middle Ages to a large country (Old Saxony, la, Saxonia) near the Nor ...

and the native Celtic Britons

The Britons ( *''Pritanī'', la, Britanni), also known as Celtic Britons or Ancient Britons, were people of Celtic language and culture who inhabited Great Britain from at least the British Iron Age and into the Middle Ages, at which point th ...

. Geoffrey retold the story in his ''Historia Regum Britanniæ'', adding new episodes that tie Merlin with King Arthur

King Arthur ( cy, Brenin Arthur, kw, Arthur Gernow, br, Roue Arzhur) is a legendary king of Britain, and a central figure in the medieval literary tradition known as the Matter of Britain.

In the earliest traditions, Arthur appears as a ...

and his predecessors. Geoffrey stated that this Ambrosius was also called "Merlin", therefore Ambrosius Merlinus, and kept him separate from Aurelius Ambrosius.

Therefore, Geoffrey's account of Merlin Ambrosius' early life is based on the story from the ''Historia Brittonum''. Geoffrey added his own embellishments to the tale, which he set in

Therefore, Geoffrey's account of Merlin Ambrosius' early life is based on the story from the ''Historia Brittonum''. Geoffrey added his own embellishments to the tale, which he set in Carmarthen

Carmarthen (, RP: ; cy, Caerfyrddin , "Merlin's fort" or "Sea-town fort") is the county town of Carmarthenshire and a community in Wales, lying on the River Towy. north of its estuary in Carmarthen Bay. The population was 14,185 in 2011, ...

, Wales (Welsh: Caerfyrddin). While Nennius' "fatherless" Ambrosius eventually reveals himself to be the son of a Roman consul

Consul (abbrev. ''cos.''; Latin plural ''consules'') was the title of one of the two chief magistrates of the Roman Republic, and subsequently also an important title under the Roman Empire. The title was used in other European city-states throug ...

, Geoffrey's Merlin is begotten by an incubus

An incubus is a demon in male form in folklore that seeks to have sexual intercourse with sleeping women; the corresponding spirit in female form is called a succubus. In medieval Europe, union with an incubus was supposed by some to result in t ...

demon on a daughter of the King of Dyfed

Prior to the Conquest of Wales, completed in 1282, Wales consisted of a number of independent kingdoms, the most important being Gwynedd, Powys, Deheubarth (originally Ceredigion, Seisyllwg and Dyfed) and Morgannwg (Glywysing and Gwent). Boun ...

(Demetae

The Demetae were a Celtic people of Iron Age and Roman period, who inhabited modern Pembrokeshire and Carmarthenshire in south-west Wales, and gave their name to the county of Dyfed.

Classical references

They are mentioned in Ptolemy's ''Geograp ...

, today's South West Wales

South West Wales is one of the regions of Wales consisting of the unitary authorities of Swansea, Neath Port Talbot, Carmarthenshire and Pembrokeshire.

This definition is used by a number of government agencies and private organisations including ...

). Usually, the name of Merlin's mother is not stated, but is given as Adhan in the oldest version of the Prose ''Brut'', the text also naming his grandfather as King Conaan. The story of Vortigern's tower is the same; the underground dragons, one white and one red, represent the Saxons and the Britons, and their final battle is a portent of things to come. At this point Geoffrey inserted a long section of Merlin's prophecies, taken from his earlier ''Prophetiae Merlini''. He told two further tales of the character. In the first, Merlin creates Stonehenge

Stonehenge is a prehistoric monument on Salisbury Plain in Wiltshire, England, west of Amesbury. It consists of an outer ring of vertical sarsen standing stones, each around high, wide, and weighing around 25 tons, topped by connectin ...

as a burial place for Aurelius Ambrosius, bringing the stones from Ireland. In the second, Merlin's magic enables the new British king Uther Pendragon

Uther Pendragon (Brittonic) (; cy, Ythyr Ben Dragwn, Uthyr Pendragon, Uthyr Bendragon), also known as King Uther, was a legendary King of the Britons in sub-Roman Britain (c. 6th century). Uther was also the father of King Arthur.

A few m ...

to enter into Tintagel Castle

Tintagel Castle ( kw, Dintagel) is a medieval fortification located on the peninsula of Tintagel Island adjacent to the village of Tintagel (Trevena), North Cornwall in the United Kingdom. The site was possibly occupied in the Romano-British pe ...

in disguise and to father his son Arthur with his enemy's wife, Igerna (Igraine

In the Matter of Britain, Igraine () is the mother of King Arthur. Igraine is also known in Latin as Igerna, in Welsh as Eigr (Middle Welsh Eigyr), in French as Ygraine (Old French Ygerne or Igerne), in ''Le Morte d'Arthur'' as Ygrayne—often ...

). These episodes appear in many later adaptations of Geoffrey's account. As Lewis Thorpe

Lewis Guy Melville Thorpe FRSA FRHistS (5 November 1913 – 10 October 1977)''UK and Ireland, Obituary Index, 2004-2018'' was a British philologist and translator. He was married to the Italian scholar and lexicographer Barbara Reynolds.

After ...

notes, Merlin disappears from the narrative subsequently. He does not tutor and advise Arthur as in later versions.

Geoffrey dealt with Merlin again in his third work, ''Vita Merlini

''Vita Merlini'', or ''The Life of Merlin'', is a Latin poem in 1,529 hexameter lines written around the year 1150. Though doubts have in the past been raised about its authorship it is now widely believed to be by Geoffrey of Monmouth. It tel ...

'' (1150). He based it on stories of the original 6th-century Myrddin, set long after his time frame for the life of Merlin Ambrosius. Geoffrey asserts that the characters and events of ''Vita Merlini'' are the same as told in the ''Historia Regum Britanniae''. Here, Merlin survives the reign of Arthur, about the fall of whom he is told by Taliesin

Taliesin ( , ; 6th century AD) was an early Brittonic poet of Sub-Roman Britain whose work has possibly survived in a Middle Welsh manuscript, the '' Book of Taliesin''. Taliesin was a renowned bard who is believed to have sung at the courts ...

. Merlin spends a part of his life as a madman in the woods and marries a woman named Guendoloena (a character inspired by the male Gwenddoleu ap Ceidio

Gwenddoleu ap Ceidio (died c. 573) or Gwenddolau was a Brythonic king who ruled in Arfderydd (now Arthuret). This is in what is now south-west Scotland and north-west England in the area around Hadrian's Wall and Carlisle during the sub-Roman p ...

). He eventually retires to observing stars from his house with seventy windows in the remote woods of Rhydderch. There, he is often visited by Taliesin and by his own sister Ganieda (Geoffrey's character based on Myrddin's sister Gwenddydd), who has become queen of the Cumbrians

Yr Hen Ogledd (), in English the Old North, is the historical region which is now Northern England and the southern Scottish Lowlands that was inhabited by the Brittonic people of sub-Roman Britain in the Early Middle Ages. Its population sp ...

and is also endowed with prophetic powers.

Nikolai Tolstoy hypothesized that Merlin is based on a historical personage, probably a 6th-century

Nikolai Tolstoy hypothesized that Merlin is based on a historical personage, probably a 6th-century druid

A druid was a member of the high-ranking class in ancient Celtic cultures. Druids were religious leaders as well as legal authorities, adjudicators, lorekeepers, medical professionals and political advisors. Druids left no written accounts. Whi ...

living in southern Scotland. His argument was based on the fact that early references to Merlin describe him as possessing characteristics which modern scholarship (but not that of the time the sources were written) would recognize as druidical, the inference being that those characteristics were not invented by the early chroniclers, but belonged to a real person. If so, the hypothetical Merlin would have lived about a century after the hypothetical historical Arthur. A late version of the ''Annales Cambriae

The (Latin for ''Annals of Wales'') is the title given to a complex of Latin chronicles compiled or derived from diverse sources at St David's in Dyfed, Wales. The earliest is a 12th-century presumed copy of a mid-10th-century original; later ed ...

'' (dubbed the "B-text", written at the end of the 13th century) and influenced by Geoffrey, records for the year 573, that after "the battle of Arfderydd

The Battle of Arfderydd (also known as Arderydd) was fought, according to the Annales Cambriae, in 573. The opposing armies are variously given in a number of Old Welsh sources, perhaps suggesting a number of allied armies were involved. The main ...

, between the sons of Eliffer and Gwenddolau son of Ceidio; in which battle Gwenddolau fell; Merlin went mad." The earliest version of the ''Annales Cambriae'' entry (in the "A-text", written c. 1100), as well as a later copy (the "C-text", written towards the end of the 13th century) do not mention Merlin. Myrddin/Merlin furthermore shares similarities with the shamanic bard figure of Taliesin, alongside whom he appears in the Welsh Triads and in ''Vita Merlini'', as well as in the poem "Ymddiddan Myrddin a Thaliesin" ("The Conversation between Myrddin and Taliesin") from ''The Black Book of Carmarthen

The Black Book of Carmarthen ( cy, Llyfr Du Caerfyrddin) is thought to be the earliest surviving manuscript written solely in Welsh. The book dates from the mid-13th century; its name comes from its association with the Priory of St. John the E ...

'', which was dated by Rachel Bromwich

Rachel Bromwich (30 July 1915 – 15 December 2010) born Rachel Sheldon Amos, was a British scholar. Her focus was on medieval Welsh literature, and she taught Celtic Languages and Literature in the Department of Anglo-Saxon, Norse and Celtic at ...

as "certainly" before 1100, that is predating ''Vita Merlini'' by at least half century while telling a different version of the same story. According to Villemarqué, the origin of the legend of Merlin lies with the French figure of Saint Martin of Tours

Martin of Tours ( la, Sanctus Martinus Turonensis; 316/336 – 8 November 397), also known as Martin the Merciful, was the third bishop of Tours. He has become one of the most familiar and recognizable Christian saints in France, heralded as the ...

.

Later developments

Sometime around the turn of the following 13th century,

Sometime around the turn of the following 13th century, Robert de Boron

Robert de Boron (also spelled in the manuscripts "Roberz", "Borron", "Bouron", "Beron") was a French poet of the late 12th and early 13th centuries, notable as the reputed author of the poems and ''Merlin''. Although little is known of him apart f ...

retold and expanded on this material in ''Merlin

Merlin ( cy, Myrddin, kw, Marzhin, br, Merzhin) is a mythical figure prominently featured in the legend of King Arthur and best known as a mage, with several other main roles. His usual depiction, based on an amalgamation of historic and le ...

'', an Old French

Old French (, , ; Modern French: ) was the language spoken in most of the northern half of France from approximately the 8th to the 14th centuries. Rather than a unified language, Old French was a linkage of Romance dialects, mutually intelligib ...

poem presenting itself as the story of Merlin's life as told by Merlin himself to the author. Only a few lines of what is believed to be the original text have survived, but a more popular prose version had a great influence on the emerging genre of Arthurian-themed chivalric romance

As a literary genre, the chivalric romance is a type of prose and verse narrative that was popular in the noble courts of High Medieval and Early Modern Europe. They were fantastic stories about marvel-filled adventures, often of a chivalric k ...

. In Robert's account, as in Geoffrey's ''Historia'', Merlin is created as a demon spawn, but here explicitly to become the Antichrist

In Christian eschatology, the Antichrist refers to people prophesied by the Bible to oppose Jesus Christ and substitute themselves in Christ's place before the Second Coming. The term Antichrist (including one plural form) 1 John ; . 2 John . ...

intended to reverse the effect of the Harrowing of Hell

In Christian theology, the Harrowing of Hell ( la, Descensus Christi ad Inferos, "the descent of Christ into Hell" or Hades) is an Old English and Middle English term referring to the period of time between the Crucifixion of Jesus and his re ...

. The infernal plot is thwarted when a priest (and the story's narrator) named is contacted by the child's mother. Blaise immediately baptizes the boy at birth, thus freeing him from the power of Satan and his intended destiny. The demonic legacy invests Merlin (already able to speak fluently even as a newborn) with a preternatural knowledge of the past and present, which is supplemented by God, who gives the boy a prophetic knowledge of the future. The text lays great emphasis on Merlin's power to shapeshift

In mythology, folklore and speculative fiction, shape-shifting is the ability to physically transform oneself through an inherently superhuman ability, divine intervention, demonic manipulation, sorcery, spells or having inherited the ...

, on his joking personality, and on his connection to the Holy Grail

The Holy Grail (french: Saint Graal, br, Graal Santel, cy, Greal Sanctaidd, kw, Gral) is a treasure that serves as an important motif in Arthurian literature. Various traditions describe the Holy Grail as a cup, dish, or stone with miracul ...

, the quest for which he foretells. Inspired by Wace

Wace ( 1110 – after 1174), sometimes referred to as Robert Wace, was a Medieval Norman poet, who was born in Jersey and brought up in mainland Normandy (he tells us in the ''Roman de Rou'' that he was taken as a child to Caen), ending his care ...

's ''Roman de Brut

The ''Brut'' or ''Roman de Brut'' (completed 1155) by the poet Wace is a loose and expanded translation in almost 15,000 lines of Norman-French verse of Geoffrey of Monmouth's Latin ''History of the Kings of Britain''. It was formerly known as ...

'', an Anglo-Norman Anglo-Norman may refer to:

*Anglo-Normans, the medieval ruling class in England following the Norman conquest of 1066

* Anglo-Norman language

**Anglo-Norman literature

* Anglo-Norman England, or Norman England, the period in English history from 10 ...

adaptation of Geoffrey's ''Historia'', ''Merlin'' was originally a part of a cycle of Robert's poems telling the story of the Grail over the centuries. The narrative of ''Merlin'' is largely based on Geoffrey's familiar tale of Vortigern's Tower, Uther's war against the Saxons, and Arthur's conception. What follows is a new episode of the young Arthur's drawing of the sword from the stone, an event orchestrated by Merlin. Merlin also earlier instructs Uther to establish the original order of the Round Table

The Round Table ( cy, y Ford Gron; kw, an Moos Krenn; br, an Daol Grenn; la, Mensa Rotunda) is King Arthur's famed table in the Arthurian legend, around which he and his knights congregate. As its name suggests, it has no head, implying that e ...

, after creating the table itself. The prose version of Robert's poem was then continued in the 13th-century ''Merlin Continuation'' or the ''Suite de Merlin'', describing King Arthur's early wars and Merlin's role in them, as he predicts and influences the course of battles. He also helps Arthur in other ways, including providing him with the magic sword Excalibur

Excalibur () is the legendary sword of King Arthur, sometimes also attributed with magical powers or associated with the rightful sovereignty of Britain. It was associated with the Arthurian legend very early on. Excalibur and the Sword in th ...

through a Lady of the Lake

The Lady of the Lake (french: Dame du Lac, Demoiselle du Lac, cy, Arglwyddes y Llyn, kw, Arloedhes an Lynn, br, Itron al Lenn, it, Dama del Lago) is a name or a title used by several either fairy or fairy-like but human enchantresses in the ...

. Here too Merlin's shapeshifting powers feature prominently.

The extended prose rendering became the foundation for the ''Lancelot-Grail

The ''Lancelot-Grail'', also known as the Vulgate Cycle or the Pseudo-Map Cycle, is an early 13th-century French Arthurian literary cycle consisting of interconnected prose episodes of chivalric romance in Old French. The cycle of unknown authors ...

'', a vast cyclical series of Old French prose works also known as the Vulgate Cycle. Eventually, it was directly incorporated into the Vulgate Cycle as the ''Estoire de Merlin'', also known as the Vulgate ''Merlin'' or the Prose ''Merlin''. A further reworking and continuation of the Prose ''Merlin'' was included within the subsequent Post-Vulgate Cycle

The ''Post-Vulgate Cycle'', also known as the Post-Vulgate Arthuriad, the Post-Vulgate ''Roman du Graal'' (''Romance of the Grail'') or the Pseudo-Robert de Boron Cycle, is one of the major Old French prose cycles of Arthurian literature from th ...

as the Post-Vulgate ''Suite du Merlin'' or the Huth ''Merlin''. All these variants have been adapted and translated into several other languages, and further modified. Notably, the Post-Vulgate ''Suite'' (along with an earlier version of the Prose ''Merlin'') was the main source for the opening part of Thomas Malory

Sir Thomas Malory was an English writer, the author of '' Le Morte d'Arthur'', the classic English-language chronicle of the Arthurian legend, compiled and in most cases translated from French sources. The most popular version of '' Le Morte d' ...

's English-language compilation work ''Le Morte d'Arthur

' (originally written as '; inaccurate Middle French for "The Death of Arthur") is a 15th-century Middle English prose reworking by Sir Thomas Malory of tales about the legendary King Arthur, Guinevere, Lancelot, Merlin and the Knights of the Rou ...

'' that formed a now-iconic version of the legend. Compared to his French sources, Malory limited the extent of the negative association of Merlin and his powers, relatively rarely being condemned as demonic by other characters such as King Lot

King Lot , also spelled Loth or Lott (Lleu or Llew in Welsh), is a British monarch in Arthurian legend. He was introduced in Geoffrey of Monmouth's influential chronicle ''Historia Regum Britanniae'' that portrayed him as King Arthur's brother- ...

. Conversely, Merlin seems to be inherently evil in the so-called non-cyclic ''Lancelot'', where he was born as the "fatherless child" from not a supernatural rape of a virgin but a consensual union between a lustful demon and an unmarried beautiful young lady, and was never baptized. The Prose ''Lancelot'' further relates that, after growing up in the borderlands between Scotland (Pictish lands) and Ireland (Argyll

Argyll (; archaically Argyle, in modern Gaelic, ), sometimes called Argyllshire, is a historic county and registration county of western Scotland.

Argyll is of ancient origin, and corresponds to most of the part of the ancient kingdom of ...

), Merlin "possessed all the wisdom that can come from demons, which is why he was so feared by the Bretons and so revered that everyone called him a holy prophet and the ordinary people all called him their god."

As the Arthurian myths were retold, Merlin's prophetic aspects were sometimes de-emphasised in favour of portraying him as a wizard and an advisor to the young Arthur, sometimes in struggle between good and evil sides of his character, and living in deep forests connected with nature. Through his ability to change his shape, he may appear as a "wild man" figure evoking that of his prototype Myrddin Wyllt, as a civilized man of any age, or even as a talking animal. In the ''Perceval en prose'' (also known as the Didot ''Perceval'' and too attributed to Robert), where Merlin is the initiator of the Grail Quest and cannot die until the end of days, he eventually retires after Arthur's downfall by turning himself into a bird and entering the mysterious '' esplumoir'', never to be seen again. In the Vulgate Cycle's version of ''Merlin'', his acts include arranging consummation of Arthur's desire for "the most beautiful maiden ever born," Lady Lisanor of Cardigan, resulting in the birth of Arthur's illegitimate son

As the Arthurian myths were retold, Merlin's prophetic aspects were sometimes de-emphasised in favour of portraying him as a wizard and an advisor to the young Arthur, sometimes in struggle between good and evil sides of his character, and living in deep forests connected with nature. Through his ability to change his shape, he may appear as a "wild man" figure evoking that of his prototype Myrddin Wyllt, as a civilized man of any age, or even as a talking animal. In the ''Perceval en prose'' (also known as the Didot ''Perceval'' and too attributed to Robert), where Merlin is the initiator of the Grail Quest and cannot die until the end of days, he eventually retires after Arthur's downfall by turning himself into a bird and entering the mysterious '' esplumoir'', never to be seen again. In the Vulgate Cycle's version of ''Merlin'', his acts include arranging consummation of Arthur's desire for "the most beautiful maiden ever born," Lady Lisanor of Cardigan, resulting in the birth of Arthur's illegitimate son Lohot

The Knights of the Round Table ( cy, Marchogion y Ford Gron, kw, Marghekyon an Moos Krenn, br, Marc'hegien an Daol Grenn) are the knights of the fellowship of King Arthur in the literary cycle of the Matter of Britain. First appearing in lit ...

from before the marriage to Guinevere

Guinevere ( ; cy, Gwenhwyfar ; br, Gwenivar, kw, Gwynnever), also often written in Modern English as Guenevere or Guenever, was, according to Arthurian legend, an early-medieval queen of Great Britain and the wife of King Arthur. First ment ...

. But fate

Destiny, sometimes referred to as fate (from Latin ''fatum'' "decree, prediction, destiny, fate"), is a predetermined course of events. It may be conceived as a predetermined future, whether in general or of an individual.

Fate

Although often ...

cannot always be changed: the Post-Vulgate Cycle has Merlin warn Arthur of how the birth of his other son will bring great misfortune and ruin to his kingdom, which then becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy

A self-fulfilling prophecy is a prediction that comes true at least in part as a result of a person's or group of persons' belief or expectation that said prediction would come true. This suggests that people's beliefs influence their actions. ...

. Eventually, long after Merlin is gone, his advice to dispose of the baby Mordred

Mordred or Modred (; Welsh: ''Medraut'' or ''Medrawt'') is a figure who is variously portrayed in the legend of King Arthur. The earliest known mention of a possibly historical Medraut is in the Welsh chronicle ''Annales Cambriae'', wherein he ...

through an event evoking the Biblical Massacre of the Innocents leads to the deaths of many, among them Arthur.

The earliest English verse romance concerning Merlin is ''Of Arthour and of Merlin

''Of Arthour and of Merlin'', or ''Arthur and Merlin'', is an anonymous Middle English verse romance giving an account of the reigns of Vortigern and Uther Pendragon and the early years of King Arthur's reign, in which the magician Merlin plays ...

'', which drew from the chronicles and the Vulgate Cycle. In English-language medieval texts that conflate Britain

Britain most often refers to:

* The United Kingdom, a sovereign state in Europe comprising the island of Great Britain, the north-eastern part of the island of Ireland and many smaller islands

* Great Britain, the largest island in the United King ...

with the Kingdom of England

The Kingdom of England (, ) was a sovereign state on the island of Great Britain from 12 July 927, when it emerged from various Anglo-Saxon kingdoms, until 1 May 1707, when it united with Scotland to form the Kingdom of Great Britain.

On 1 ...

, the Anglo-Saxon enemies against whom Merlin aids first Uther and then Arthur tend to be replaced by the Saracen

upright 1.5, Late 15th-century German woodcut depicting Saracens

Saracen ( ) was a term used in the early centuries, both in Greek and Latin writings, to refer to the people who lived in and near what was designated by the Romans as Arabia Pe ...

s or simply just invading pagans. Some of the many Welsh works predicting the Celtic revenge and victory over the Saxons have been also reinterpreted as Merlin's (Myrddin's) prophecies, and later used by propaganda of the Welsh-descent king Henry VIII of England

Henry VIII (28 June 149128 January 1547) was King of England from 22 April 1509 until his death in 1547. Henry is best known for his six marriages, and for his efforts to have his first marriage (to Catherine of Aragon) annulled. His disa ...

in the 16th century. The House of Tudor

The House of Tudor was a royal house of largely Welsh and English origin that held the English throne from 1485 to 1603. They descended from the Tudors of Penmynydd and Catherine of France. Tudor monarchs ruled the Kingdom of England and it ...

, which traced their lineage directly to Arthur, interpreted the prophecy of King Arthur's return figuratively as concerning their ascent to the throne of England that they sought to legitimise following the Wars of the Roses

The Wars of the Roses (1455–1487), known at the time and for more than a century after as the Civil Wars, were a series of civil wars fought over control of the English throne in the mid-to-late fifteenth century. These wars were fought bet ...

.

Many other medieval works dealing with the Merlin legend include an unusual story of the 13th-century ''Le Roman de Silence

''Le Roman de Silence'' is an octosyllabic verse Old French ''roman'' in the Picard dialect, dated to the first half of the 13th century. It is the only work attributed to ''Heldris de Cornuälle'' (Heldris of Cornwall, an Arthurian pseudonym). Du ...

''. The ''Prophéties de Merlin'' (c. 1276) contains long prophecies of Merlin (mostly concerned with 11th to 13th-century Italian history and contemporary politics), some by his ghost after his death, interspersed with episodes relating Merlin's deeds and with assorted Arthurian adventures in which Merlin does not appear at all. It pictures Merlin as a righteous seer chastising people for their sins, as does the 13th-14th Italian story collection ''Il Novellino'' which draws heavily from it. Even more political Italian text was Joachim of Fiore

Joachim of Fiore, also known as Joachim of Flora and in Italian Gioacchino da Fiore (c. 1135 – 30 March 1202), was an Italian Christian theologian, Catholic abbot, and the founder of the monastic order of San Giovanni in Fiore. According to the ...

's ''Expositio Sybillae et Merlini'', directed against Frederick II, Holy Roman Emperor

Frederick II (German language, German: ''Friedrich''; Italian language, Italian: ''Federico''; Latin: ''Federicus''; 26 December 1194 – 13 December 1250) was King of Sicily from 1198, King of Germany from 1212, King of Italy and Holy Roman Em ...

whom the author regarded as the Antichrist. The earliest Merlin text written in Germany was Caesarius of Heisterbach Caesarius of Heisterbach (ca. 1180 – ca. 1240), sometimes erroneously called, in English, Caesar of Heisterbach, was the prior of a Cistercian monastery, Heisterbach Abbey, which was located in the Siebengebirge, near the small town of Oberdolle ...

's Latin ''Dialogus Miraculorum'' (1220). Ulrich Füetrer

Ulrich Füetrer or Füterer (before 1450 - between 1496 and 1500) was a German writer, painter, and sculptor.

Born in Landshut before 1450 (some sources state 1430 as the year of his birth), Ulrich Füetrer went to the Latin school in that city ...

's 15th-century ''Buch der Abenteuer'', in the section based on Albrecht von Scharfenberg Albrecht von Scharfenberg (fl. 1270s) was a Middle High German poet, best known as the author of ''Der jüngere Titurel'' ("The Younger Titurel") since his two other known works, ''Seifrid de Ardemont'' and ''Merlin'', are lost. Linguistic evidence ...

's lost ''Merlin'', presents Merlin as Uter's father, effectively making his grandson Arthur a part-devil too. Merlin's unnamed daughter appears in the First Continuation of ''Perceval, the Story of the Grail

, original_title_lang = fro

, translator =

, written = between 1182 and 1190

, country =

, language = Old French

, subject = Arthurian legend

, genre = Chivalric romance

, for ...

'' to guide Perceval

Percival (, also spelled Perceval, Parzival), alternatively called Peredur (), was one of King Arthur's legendary Knights of the Round Table. First mentioned by the French author Chrétien de Troyes in the tale ''Perceval, the Story of the ...

towards the Grail Castle.

Tales of Merlin's end

In the prose chivalric romance tradition, Merlin has a major weakness that leads him to his relatively early doom: young beautiful women of ''femme fatale

A ''femme fatale'' ( or ; ), sometimes called a maneater or vamp, is a stock character of a mysterious, beautiful, and seductive woman whose charms ensnare her lovers, often leading them into compromising, deadly traps. She is an archetype of ...

'' archetype. His apprentice is often Arthur's half-sister Morgan le Fay

Morgan le Fay (, meaning 'Morgan the Fairy'), alternatively known as Morgan , Morgain /e Morg e, Morgant Morge , and Morgue namong other names and spellings ( cy, Morgên y Dylwythen Deg, kw, Morgen an Spyrys), is a powerful ...

. In the ''Prophéties de Merlin'', he also tutors with Sebile

Sebile, alternatively written as Sedile, Sebille, Sibilla, Sibyl, Sybilla, and other similar names, is a mythical medieval queen or princess who is frequently portrayed as a fairy or an enchantress in the Arthurian legends and Italian folklore. ...

and two other witch queens and the Lady of the Isle of Avalon (Dama di Isola do Vallone); the others who have learnt sorcery from Merlin include the Wise Damsel in the Italian ''Historia di Merlino'', and the male wizard Mabon in the Post-Vulgate ''Merlin Continuation'' and the Prose ''Tristan''. While Merlin does share his magic with his apprentices, his prophetic powers cannot be passed on. As for Morgan, she is sometimes depicted as Merlin's lover and sometimes as just an unrequited love

Unrequited love or one-sided love is love that is not openly reciprocated or understood as such by the beloved. The beloved may not be aware of the admirer's deep and pure affection, or may consciously reject it. The Merriam Webster Online Dic ...

interest. Contrary to the many modern works in which they are archenemies, Merlin and Morgan are never opposed to each other in any medieval tradition, other than Morgan forcibly rejecting him in some texts; in fact, his love for Morgan is so great that he even lies to the king in order to save her in the Huth ''Merlin'', which is the only instance of him ever intentionally misleading Arthur. Instead, Merlin's eventual undoing comes from his lusting after another of his female students: the one often named Viviane, among various other names and spellings, including Malory's (or really his editor Caxton's) now-popular form Nimue (originally Nymue). She is also called a fairy

A fairy (also fay, fae, fey, fair folk, or faerie) is a type of mythical being or legendary creature found in the folklore of multiple European cultures (including Celtic, Slavic, Germanic, English, and French folklore), a form of spirit, ...

(French ''fee'') like Morgan and described as a Lady of the Lake (the "chief Lady of the Lake" in case of Malory's Nimue). Malory's telling of this episode would later become a major inspiration for Romantic authors and artists of the 19th century.

Viviane's character in relation with Merlin is first found in the ''Lancelot-Grail'' cycle, after having been inserted into the legend of Merlin by either de Boron or his continuator. There are many different versions of their story. Common themes in most of them include Merlin actually having the prior prophetic knowledge of her plot against him (one exception is the Spanish Post-Vulgate ''Baladro'' where his foresight ability is explicitly dampened by sexual desire) but lacking either ability or will to counteract it in any way, along with her using one of his own spells to rid of him. Usually (including in ''Le Morte d'Arthur''), having learnt everything she could from him, Viviane will then also replace the eliminated Merlin within the story, taking up his role as Arthur's adviser and court mage. However, Merlin's fate of either demise or eternal imprisonment, along with his destroyer or captor's motivation (from her fear of Merlin and protecting her own virginity, to her jealously for his relationship with Morgan), is recounted differently in variants of this motif. The exact form of his either prison or grave can be also variably a cave, a hole under a large rock (as in ''Le Morte d'Arthur''), a magic tower, or a tree.Loomis, Roger Sherman (1927).

Viviane's character in relation with Merlin is first found in the ''Lancelot-Grail'' cycle, after having been inserted into the legend of Merlin by either de Boron or his continuator. There are many different versions of their story. Common themes in most of them include Merlin actually having the prior prophetic knowledge of her plot against him (one exception is the Spanish Post-Vulgate ''Baladro'' where his foresight ability is explicitly dampened by sexual desire) but lacking either ability or will to counteract it in any way, along with her using one of his own spells to rid of him. Usually (including in ''Le Morte d'Arthur''), having learnt everything she could from him, Viviane will then also replace the eliminated Merlin within the story, taking up his role as Arthur's adviser and court mage. However, Merlin's fate of either demise or eternal imprisonment, along with his destroyer or captor's motivation (from her fear of Merlin and protecting her own virginity, to her jealously for his relationship with Morgan), is recounted differently in variants of this motif. The exact form of his either prison or grave can be also variably a cave, a hole under a large rock (as in ''Le Morte d'Arthur''), a magic tower, or a tree.Loomis, Roger Sherman (1927). Celtic Myth and Arthurian Romance

'. Columbia University Press. These are usually placed within the

enchanted forest

In folklore and fantasy, an enchanted forest is a forest under, or containing, enchantments. Such forests are described in the oldest folklore from regions where forests are common, and occur throughout the centuries to modern works of fantasy. ...

of Brocéliande

Brocéliande, earlier known as Brécheliant and Brécilien, is a legendary enchanted forest that had a reputation in the medieval European imagination as a place of magic and mystery. Brocéliande is featured in several medieval texts, mostly r ...

, a legendary location often identified as the real-life Paimpont forest

Paimpont Forest (french: Forêt de Paimpont, br, Koad Pempont), also known as Brocéliande Forest (french: Forêt de Brocéliande), is a temperate forest located around the village of Paimpont in the department of Ille-et-Vilaine in Brittany, ...

in Brittany.

Niniane, as the Lady of the Lake student of Merlin is known as in the ''Livre d'Artus'' continuation of ''Merlin'', is mentioned as having broken his heart prior to his later second relationship with Morgan, but here the text actually does not tell how exactly Merlin did vanish, other than relating his farewell meeting with Blaise. In the Vulgate ''Lancelot'', which predated the later Vulgate ''Merlin'', she (aged just 12 at the time) makes Merlin sleep forever in a pit in the forest of Darnantes, "and that is where he remained, for never again did anyone see or hear of him or have news to tell of him." In the Post-Vulgate ''Suite de Merlin'', the young King Bagdemagus

Bagdemagus (pronounced /ˈbægdɛˌmægəs/), also known as Bademagu(s/z), Bagdemagu, Bagomedés, Baldemagu(s), Bandemagu(s), Bangdemagew, Baudemagu(s), and other variants (such as the Italian ''Bando di Mago'' or the Hebrew ''Bano of Magoç''), ...

(one of the early Knights of the Round Table

The Knights of the Round Table ( cy, Marchogion y Ford Gron, kw, Marghekyon an Moos Krenn, br, Marc'hegien an Daol Grenn) are the knights of the fellowship of King Arthur in the literary cycle of the Matter of Britain. First appearing in lit ...

) manages to find the rock under which Merlin is entombed alive by Niviene, as she is named there. He communicates with Merlin, but is unable to lift the stone; what follows next is supposedly narrated in the mysterious text ''Conte del Brait'' (''Tale of the Cry''). In the ''Prophéties de Merlin'' version, his tomb is unsuccessfully searched for by various parties, including by Morgan and her enchantresses, but cannot be accessed due to the deadly magic traps around it, while the Lady of the Lake comes to taunt Merlin by asking did he rot there yet. One notably alternate version having a happier ending for Merlin is contained within the ''Premiers Faits'' section of the ''Livre du Graal'', where Niniane peacefully confines him in Brocéliande with walls of air, visible only as a mist to others but as a beautiful yet unbreakable crystal tower to him (only Merlin's disembodied voice can escape his prison one last time when he speaks to Gawain

Gawain (), also known in many other forms and spellings, is a character in Arthurian legend, in which he is King Arthur's nephew and a Knight of the Round Table. The prototype of Gawain is mentioned under the name Gwalchmei in the earliest ...

on the knight's quest to find him), where they will then spend almost every night together as lovers. Besides evoking the final scenes from ''Vita Merlini'', this particular variant of their story also mirrors episodes found in some other texts, wherein Merlin either is an object of one-sided desire by a different amorous sorceress who too (unsuccessfully) plots to trap him or it is actually Merlin himself who traps an unwilling lover with his magic.

Unrelated to the legend of the Lady of the Lake, other purported sites of Merlin's burial include a cave deep inside Merlin's Hill ( cy, Bryn Myrddin), outside Carmarthen

Carmarthen (, RP: ; cy, Caerfyrddin , "Merlin's fort" or "Sea-town fort") is the county town of Carmarthenshire and a community in Wales, lying on the River Towy. north of its estuary in Carmarthen Bay. The population was 14,185 in 2011, ...

. Carmarthen is also associated with Merlin more generally, including through the 13th-century manuscript known as the '' Black Book'' and the local lore of Merlin's Oak

Merlin's Oak, also known as the Old Oak, ''Querecus Robur,'' and ''Priory Oak,'' is an oak tree that once stood on the corner of Oak Lane and Priory Street in Carmarthen, South Wales. Merlin's Oak is associated with the legend of Merlin in the l ...

. In North Welsh tradition, Merlin retires to Bardsey Island

Bardsey Island ( cy, Ynys Enlli), known as the legendary "Island of 20,000 Saints", is located off the Llŷn Peninsula in the Welsh county of Gwynedd. The Welsh name means "The Island in the Currents", while its English name refers to the "Islan ...

( cy, Ynys Enlli), where he lives in a house of glass ( cy, Tŷ Gwydr) with the Thirteen Treasures of the Island of Britain

The Thirteen Treasures of the Island of Britain (Welsh: ''Tri Thlws ar Ddeg Ynys Prydain'') are a series of items in late-medieval Welsh tradition. Lists of the items appear in texts dating to the 15th and 16th centuries.Jones, Mary"Tri Thlws a ...

( cy, Tri Thlws ar Ddeg Ynys Prydain). One site of his tomb is said to be Marlborough Mound

Marlborough Mound is a Neolithic monument in the town of Marlborough in the English county of Wiltshire. Standing 19 metres tall, it is second only to the nearby Silbury Hill in terms of height for such a monument. Modern study situates the con ...

in Wiltshire

Wiltshire (; abbreviated Wilts) is a historic and ceremonial county in South West England with an area of . It is landlocked and borders the counties of Dorset to the southwest, Somerset to the west, Hampshire to the southeast, Gloucestershire ...

, known in medieval times as ''Merlebergia'' (the Abbot of Cirencester

Cirencester (, ; see below for more variations) is a market town in Gloucestershire, England, west of London. Cirencester lies on the River Churn, a tributary of the River Thames, and is the largest town in the Cotswolds. It is the home of ...

wrote in 1215: "Merlin's tumulus gave you your name, Merlebergia"). Another site associated with Merlin's burial, in his 'Merlin Silvestris' aspect, is the confluence

In geography, a confluence (also: ''conflux'') occurs where two or more flowing bodies of water join to form a single channel. A confluence can occur in several configurations: at the point where a tributary joins a larger river (main stem); o ...

of the Pausalyl Burn and River Tweed

The River Tweed, or Tweed Water ( gd, Abhainn Thuaidh, sco, Watter o Tweid, cy, Tuedd), is a river long that flows east across the Border region in Scotland and northern England. Tweed cloth derives its name from its association with the R ...

in Drumelzier

Drumelzier (), is a village and civil parish on the B712 in the Tweed Valley in the Scottish Borders.

The area of the village is extensive and includes the settlements of Wrae, Stanhope, Mossfennan and Kingledoors. To the north is Broughton an ...

, Scotland. The 15th-century ''Scotichronicon

The ''Scotichronicon'' is a 15th-century chronicle by the Scottish historian Walter Bower. It is a continuation of historian-priest John of Fordun's earlier work '' Chronica Gentis Scotorum'' beginning with the founding of Ireland and thereby ...

'' tells that Merlin himself underwent a triple-death, at the hands of some shepherds of the under-king Meldred Meldred is a character who appears in literary accounts of post-Roman Britain. He is identified as a chieftain in part of what is now southern Scotland for a period in the 6th Century. A twelfth century text references a petty king named ''Meldredu ...

: stoned and beaten by the shepherds, he falls over a cliff and is impaled on a stake, his head falls forward into the water, and he drowns. The fulfilment of another prophecy, ascribed to Thomas the Rhymer

Sir Thomas de Ercildoun, better remembered as Thomas the Rhymer (fl. c. 1220 – 1298), also known as Thomas Learmont or True Thomas, was a Scottish laird and reputed prophet from Earlston (then called "Erceldoune") in the Borders. Thomas ...

, came about when a spate of the Tweed and Pausayl occurred during the reign of the Scottish James VI and I

James VI and I (James Charles Stuart; 19 June 1566 – 27 March 1625) was King of Scotland as James VI from 24 July 1567 and King of England and Ireland as James I from the union of the Scottish and English crowns on 24 March 1603 until ...

on the English throne: "When Tweed and Pausayl meet at Merlin's grave, / Scotland and England one king shall have."

Modern culture

Merlin and stories involving him have continued to be popular from theRenaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) , from , with the same meanings. is a period in European history marking the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and covering the 15th and 16th centuries, characterized by an effort to revive and surpass ideas ...

to the present day, especially since the renewed interest in the legend of Arthur in modern times. As noted by Arthurian scholar Alan Lupack, "numerous novels, poems and plays centre around Merlin. In American literature

American literature is literature written or produced in the United States of America and in the colonies that preceded it. The American literary tradition thus is part of the broader tradition of English-language literature, but also inc ...

and popular culture

Popular culture (also called mass culture or pop culture) is generally recognized by members of a society as a set of practices, beliefs, artistic output (also known as, popular art or mass art) and objects that are dominant or prevalent in a ...

, Merlin is perhaps the most frequently portrayed Arthurian character." Diverging from his traditional role in the legends, Merlin is sometimes portrayed as a villain, as in Mark Twain

Samuel Langhorne Clemens (November 30, 1835 – April 21, 1910), known by his pen name Mark Twain, was an American writer, humorist, entrepreneur, publisher, and lecturer. He was praised as the "greatest humorist the United States has p ...

's humorous novel ''A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court

''A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court'' is an 1889 novel by American humorist and writer Mark Twain. The book was originally titled ''A Yankee in King Arthur's Court''. Some early editions are titled ''A Yankee at the Court of King Arth ...

'' (1889). According to Peter H. Goodrich in ''Merlin: A Casebook:''

Merlin's primary characteristics continue to be recalled, refined, and expanded today, continually encompassing new ideas and technologies as well as old ones. The ability of this complex figure to endure for more than fourteen centuries results not only from his manifold roles and their imaginative appeal, but also from significant, often irresolvable tensions or polarities ..between beast and human (Wild Man), natural and supernatural (Wonder Child), physical and metaphysical (Poet), secular and sacred (Prophet), active and passive (Counselor), magic and science (Wizard), and male and female (Lover). Interwoven with these primary tensions are additional polarities that apply to all of Merlin's roles, such as those between madness and sanity, pagan and Christian, demonic and heavenly, mortality and immortality, and impotency and potency.In 2011, Merlin was one of eight British magical figures that were commemorated on a series of UK postage stamps issued by the

Royal Mail

, kw, Postya Riel, ga, An Post Ríoga

, logo = Royal Mail.svg

, logo_size = 250px

, type = Public limited company

, traded_as =

, foundation =

, founder = Henry VIII

, location = London, England, UK

, key_people = * Keith Williams ...

. Things named in honour of the legendary figure have included the asteroid 2598 Merlin

2598 Merlin, provisional designation , is a carbonaceous Dorian asteroid from the central regions of the asteroid belt, approximately 16 kilometers in diameter. It was discovered on 7 September 1980, by American astronomer Edward Bowell at Lowell ...

, the metal band Merlin

Merlin ( cy, Myrddin, kw, Marzhin, br, Merzhin) is a mythical figure prominently featured in the legend of King Arthur and best known as a mage, with several other main roles. His usual depiction, based on an amalgamation of historic and le ...

, and the literary magazine ''Merlin

Merlin ( cy, Myrddin, kw, Marzhin, br, Merzhin) is a mythical figure prominently featured in the legend of King Arthur and best known as a mage, with several other main roles. His usual depiction, based on an amalgamation of historic and le ...

''.

See also

*Garab Dorje

Garab Dorje (c. 665) () was the first human to receive direct transmission teachings from Vajrasattva. Garab Dorje then became the teacher of the ''Ati Yoga'' (Tib. Dzogchen) or Great Perfection teachings according to Tibetan buddhist and Nyingma ...

, also said to have been conceived by a nun without a human father

* Merlin's Cave

Merlin's Cave is a cave located beneath Tintagel Castle, south-west of Boscastle, Cornwall, England. It is long, passing completely through Tintagel Island from Tintagel Haven on the east to West Cove on the west. It is a sea cave formed by m ...

, a location under Tintagel Castle

Notes

References

Bibliography

* *External links

Merlin: Texts, Images, Basic Information

Camelot Project at the

University of Rochester

The University of Rochester (U of R, UR, or U of Rochester) is a private research university in Rochester, New York. The university grants undergraduate and graduate degrees, including doctoral and professional degrees.

The University of Roc ...

. Numerous texts and art concerning Merlin

Timeless Myths: The Many Faces of Merlin

BBC audio file

of the "Merlin" episode of ''

In Our Time In Our Time may refer to:

* ''In Our Time'' (1944 film), a film starring Ida Lupino and Paul Henreid

* ''In Our Time'' (1982 film), a Taiwanese anthology film featuring director Edward Yang; considered the beginning of the "New Taiwan Cinema"

* ''In ...

''

*Prose ''Merlin''Introduction

an

(the

University of Rochester

The University of Rochester (U of R, UR, or U of Rochester) is a private research university in Rochester, New York. The university grants undergraduate and graduate degrees, including doctoral and professional degrees.

The University of Roc ...

TEAMS Middle English text series) edited by John Conlea, 1998. A selection of many passages of the prose Middle English translation of the ''Vulgate Merlin'' with connecting summary. The sections from "The Birth of Merlin to "Arthur and the Sword in the Stone" cover Robert de Boron's ''Merlin''

''Of Arthour and of Merlin''

translated and retold in modern English prose, the story from Edinburgh, National Library of Scotland MS Advocates 19.2.1 (the Auchinleck MS) (from the Middle English of the Early English Text Society edition: O D McCrae-Gibson, 1973, ''Of Arthour and of Merlin'', 2 vols, EETS and Oxford University Press) {{Authority control Arthurian characters Druids English folklore Fictional astronomers Fictional characters who use magic Fictional characters with neurological or psychological disorders Fictional depictions of the Antichrist Fictional half-demons Fictional humanoids Fictional offspring of rape Fictional prophets Fictional owls Fictional shapeshifters Fictional wizards Holy Grail Legendary Welsh people Literary archetypes by name Male characters in film Male characters in literature Male characters in television People whose existence is disputed Supernatural legends