Marine Food Chain on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Compared to terrestrial environments, marine environments have

Compared to terrestrial environments, marine environments have

The fourth trophic level consists of

The fourth trophic level consists of

At the base of the ocean food web are single-celled algae and other plant-like organisms known as

At the base of the ocean food web are single-celled algae and other plant-like organisms known as  Among the phytoplankton are members from a phylum of bacteria called cyanobacteria. Marine cyanobacteria include the smallest known photosynthetic organisms. The smallest of all, ''

Among the phytoplankton are members from a phylum of bacteria called cyanobacteria. Marine cyanobacteria include the smallest known photosynthetic organisms. The smallest of all, ''

File:phytopla.gif, Phytoplankton

File:Noctiluca scintillans unica.jpg, Dinoflagellate

File:Diatoms through the microscope.jpg, Diatoms

In oceans, most

The second trophic level (

The second trophic level (

File:Tomopteriskils.jpg, Segmented worm

File:Hyperia.jpg, Tiny shrimp-like crustaceans

File:Squidu.jpg, Juvenile planktonic squid

Together,

Together,

"The secret lives of jellyfish: long regarded as minor players in ocean ecology, jellyfish are actually important parts of the marine food web"

''Nature'', 531(7595): 432-435. Hays, G.C., Doyle, T.K. and Houghton, J.D. (2018) "A paradigm shift in the trophic importance of jellyfish?" ''Trends in ecology & evolution'', 33(11): 874-884. That view has recently been challenged. Jellyfish, and more generally

; Marine invertebrates

; Fish

*

; Marine invertebrates

; Fish

*

File:Humpback lunge feeding.jpg,

File:WhalePump.jpg,

There has been increasing recognition in recent years that

There has been increasing recognition in recent years that

;Viruses

;Viruses

For pelagic ecosystems, Legendre and Rassoulzadagan proposed in 1995 a continuum of trophic pathways with the herbivorous food-chain and

For pelagic ecosystems, Legendre and Rassoulzadagan proposed in 1995 a continuum of trophic pathways with the herbivorous food-chain and

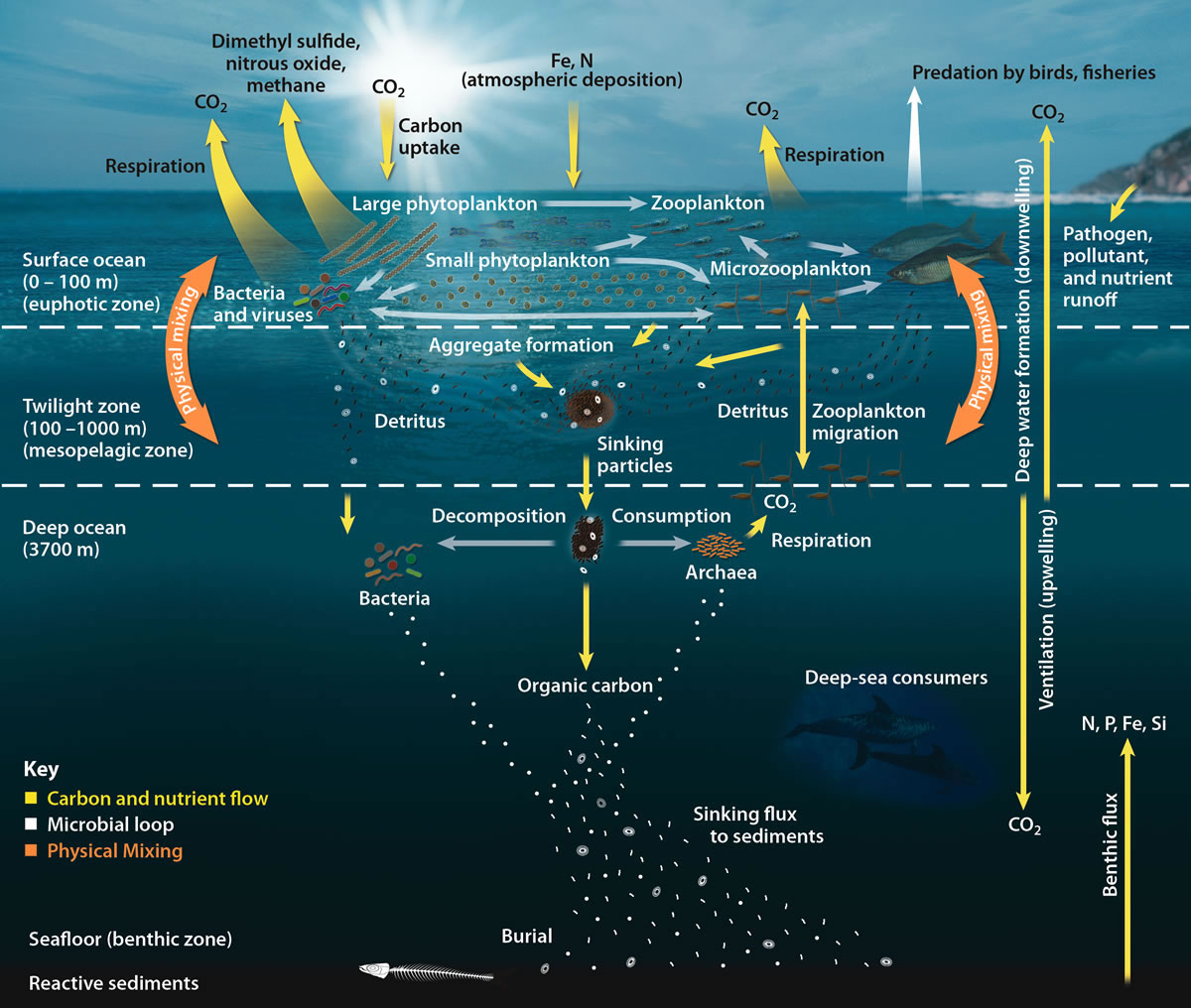

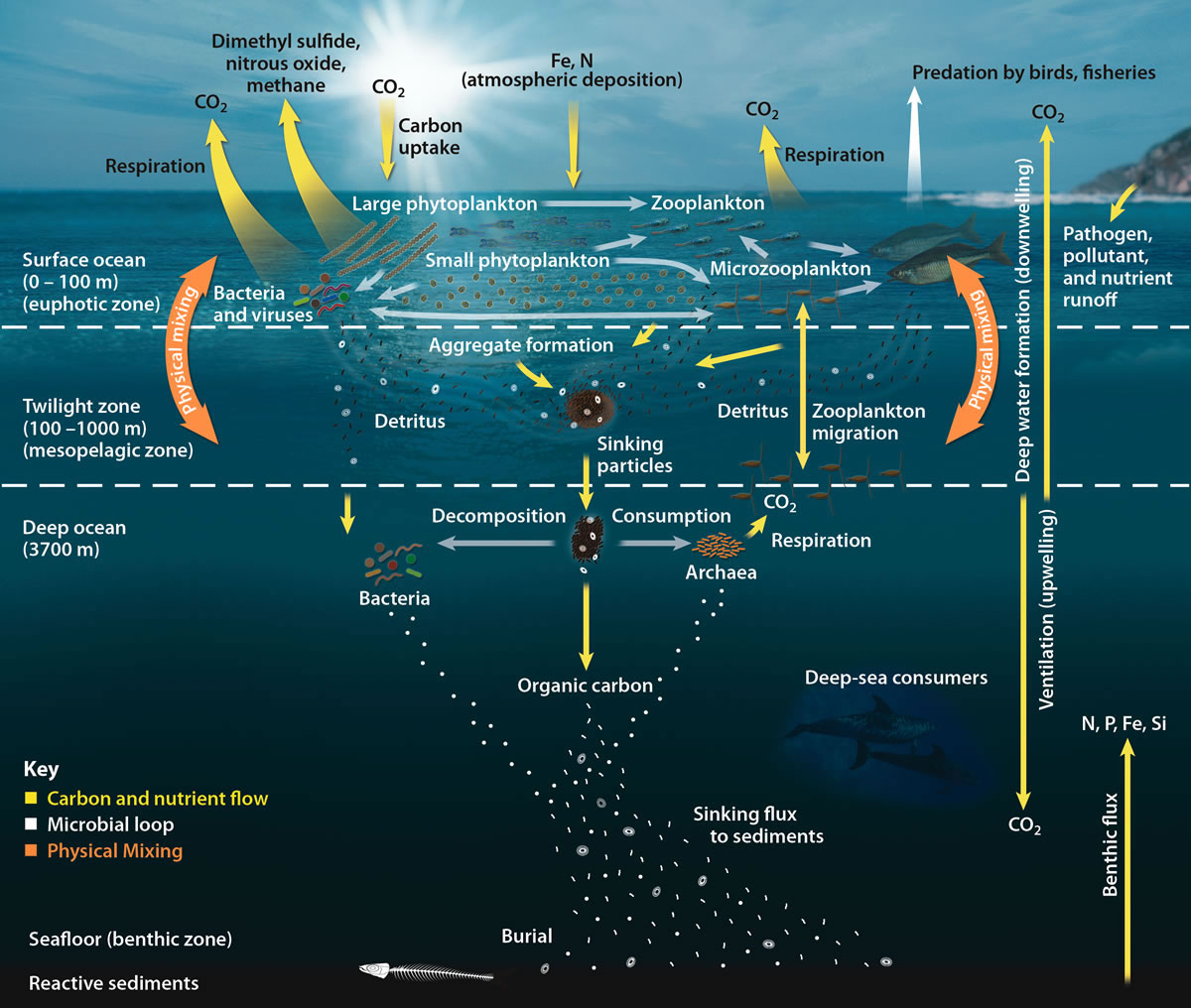

File:Export Processes in the Ocean from Remote Sensing.jpg, Pelagic food web and the

File:Mesopelagic species impact on global carbon budget.png, Impact of mesopelagic species on the global carbon budget

DVM = diel vertical migration NM = non-migration

File:Sigmops bathyphilus1.jpg, Mesopelagic

Scientists are starting to explore in more detail the largely unknown twilight zone of the

Scientists are starting to explore in more detail the largely unknown twilight zone of the

Enter the twilight zone: scientists dive into the oceans’ mysterious middle

''Nature News''. . According to a 2017 study,

Fish in the twilight cast new light on ocean ecosystem

''The Conversation'', 10 February 2014.

''The New York Times'', 29 June 2015. * Mesopelagic fishes - Malaspina circumnavigation expedition of 2010.

Ocean floor (

Ocean floor (

In the diagram above on the right: (1) ammonification produces and NH4+ and (2) nitrification produces NO3− by NH4+ oxidation. (3) under the alkaline conditions, typical of the seabird feces, the is rapidly volatised and transformed to NH4+, (4) which is transported out of the colony, and through wet-deposition exported to distant ecosystems, which are eutrophised. The phosphorus cycle is simpler and has reduced mobility. This element is found in a number of chemical forms in the seabird fecal material, but the most mobile and bioavailable is

In the diagram above on the right: (1) ammonification produces and NH4+ and (2) nitrification produces NO3− by NH4+ oxidation. (3) under the alkaline conditions, typical of the seabird feces, the is rapidly volatised and transformed to NH4+, (4) which is transported out of the colony, and through wet-deposition exported to distant ecosystems, which are eutrophised. The phosphorus cycle is simpler and has reduced mobility. This element is found in a number of chemical forms in the seabird fecal material, but the most mobile and bioavailable is

''Climate Change 2001: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability: Contribution of Working Group II to the Third Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change''

Page 807, Cambridge University Press. Both Arctic and Antarctic pelagic food webs have characteristic energy flows controlled largely by a few key species. But there is no single generic web for either. Alternative pathways are important for resilience and maintaining energy flows. However, these more complicated alternatives provide less energy flow to upper trophic-level species. "Food-web structure may be similar in different regions, but the individual species that dominate mid-trophic levels vary across polar regions". ; Arctic

The Arctic food web is complex. The loss of sea ice can ultimately affect the entire food web, from algae and plankton to fish to mammals. The

; Arctic

The Arctic food web is complex. The loss of sea ice can ultimately affect the entire food web, from algae and plankton to fish to mammals. The  ; Antarctic

; Antarctic

File:Ice planet and antarctic jellyfish (crop).jpg, Antarctic jellyfish '' Diplulmaris antarctica '' under the ice

File:Phaeocystis.png, Colonies of the alga '' Phaeocystis antarctica'', an important phytoplankter of the Ross Sea that dominates early season blooms after the sea ice retreats and exports significant carbon.

File:Fragilariopsis kerguelensis.jpg, The

Modified text was copied from this source, which is available under

Modified text was copied from this source, which is available under

Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

Microorganisms are at the heart of Arctic and Antarctic food webs. These polar environments contain a diverse range of

{{multiple image

, align = right

, image1 = Sea star at low tide.jpg

, width1 = 166

, alt1 =

, caption1 = The

{{multiple image

, align = right

, image1 = Sea star at low tide.jpg

, width1 = 166

, alt1 =

, caption1 = The  How starfish changed modern ecology

How starfish changed modern ecology

– ''Nature on PBS'' , footer_background = #e4e4e4 The concept of a

Toward an understanding of community resilience and the potential effects of enrichments to the benthos at McMurdo Sound, Antarctica

pp. 81–96 in Proceedings of the Colloquium on Conservation Problems Allen Press, Lawrence, Kansas. who applied it to certain members of marine Sea otters versus urchins

Sea otters versus urchins

– ''Pew'' , footer_background = #e4e4e4 The concept of the

In order to sustain the proper functioning of ecosystems, there is a need to better understand the simple question asked by Lawton in 1994: What do species do in ecosystems? Since ecological roles and food web positions are not independent, the question of what kind of species occupy various of network positions needs to be asked. Since the very first attempts to identify keystone species, there has been an interest in their place in food webs. First they were suggested to have been top predators, then also plants, herbivores, and parasites. For both community ecology and conservation biology, it would be useful to know where are they in complex trophic networks.

An example of this kind of

In order to sustain the proper functioning of ecosystems, there is a need to better understand the simple question asked by Lawton in 1994: What do species do in ecosystems? Since ecological roles and food web positions are not independent, the question of what kind of species occupy various of network positions needs to be asked. Since the very first attempts to identify keystone species, there has been an interest in their place in food webs. First they were suggested to have been top predators, then also plants, herbivores, and parasites. For both community ecology and conservation biology, it would be useful to know where are they in complex trophic networks.

An example of this kind of

{{further, Auxotrophy, Mixotrophy

Cryptic interactions, interactions which are "hidden in plain sight", occur throughout the marine planktonic foodweb but are currently largely overlooked by established methods, which mean large‐scale data collection for these interactions is limited. Despite this, current evidence suggests some of these interactions may have perceptible impacts on foodweb dynamics and model results. Incorporation of cryptic interactions into models is especially important for those interactions involving the transport of nutrients or energy.

The diagram illustrates the material fluxes, populations, and molecular pools that are impacted by five cryptic interactions:

{{further, Auxotrophy, Mixotrophy

Cryptic interactions, interactions which are "hidden in plain sight", occur throughout the marine planktonic foodweb but are currently largely overlooked by established methods, which mean large‐scale data collection for these interactions is limited. Despite this, current evidence suggests some of these interactions may have perceptible impacts on foodweb dynamics and model results. Incorporation of cryptic interactions into models is especially important for those interactions involving the transport of nutrients or energy.

The diagram illustrates the material fluxes, populations, and molecular pools that are impacted by five cryptic interactions:

''Stability and Complexity in Model Ecosystems''

Princeton University Press, reprint of 1973 edition with new foreword. {{ISBN, 978-0-691-08861-7.Pimm SL (2002

''Food Webs''

University of Chicago Press, reprint of 1982 edition with new foreword. {{ISBN, 978-0-226-66832-1. A

{{multiple image

, align = right

, direction = horizontal

, header = Marine producers use less biomass than terrestrial producers

, header_align =

, footer =

, footer_align =

, footer_background =

, background color =

, width1 = 200

, image1 = Prochlorococcus marinus (cropped).jpg

, alt1 =

, caption1 = The minute but ubiquitous and highly active bacterium

{{multiple image

, align = right

, direction = horizontal

, header = Marine producers use less biomass than terrestrial producers

, header_align =

, footer =

, footer_align =

, footer_background =

, background color =

, width1 = 200

, image1 = Prochlorococcus marinus (cropped).jpg

, alt1 =

, caption1 = The minute but ubiquitous and highly active bacterium

billion tonnes per year ! Total plant biomass

billion tonnes ! Turnover time

years , - , style="background:rgb(110,110,170); color:white;", {{center, Marine , {{center, 45–55 , {{center, 1–2 , {{center, 0.02–0.06 , - , style="background:rgb(110,110,170); color:white;", {{center, Terrestrial , {{center, 55–70 , {{center, 600–1000 , {{center, 9–20 {{clear left

Aquatic producers, such as planktonic algae or aquatic plants, lack the large accumulation of

{{clear left

Aquatic producers, such as planktonic algae or aquatic plants, lack the large accumulation of  {{clear

{{clear

{{further, Human impact on marine life

;Overfishing

;Acidification

{{further, Human impact on marine life

;Overfishing

;Acidification

''ScienceDaily''. 9 January 2018. "...increased temperatures reduce the vital flow of energy from the primary food producers at the bottom (e.g. algae), to intermediate consumers (herbivores), to predators at the top of marine food webs. Such disturbances in energy transfer can potentially lead to a decrease in food availability for top predators, which in turn, can lead to negative impacts for many marine species within these food webs... "Whilst climate change increased the productivity of plants, this was mainly due to an expansion of cyanobacteria (small blue-green algae)," said Mr Ullah. "This increased primary productivity does not support food webs, however, because these cyanobacteria are largely unpalatable and they are not consumed by herbivores. Understanding how ecosystems function under the effects of global warming is a challenge in ecological research. Most research on ocean warming involves simplified, short-term experiments based on only one or a few species." {{clear

{{clear

Compared to terrestrial environments, marine environments have

Compared to terrestrial environments, marine environments have biomass pyramid

An ecological pyramid (also trophic pyramid, Eltonian pyramid, energy pyramid, or sometimes food pyramid) is a graphical representation designed to show the biomass or bioproductivity at each trophic level in a given ecosystem.

A ''pyramid of e ...

s which are inverted at the base. In particular, the biomass of consumers (copepods, krill, shrimp, forage fish) is larger than the biomass of primary producer

Primary or primaries may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media Music Groups and labels

* Primary (band), from Australia

* Primary (musician), hip hop musician and record producer from South Korea

* Primary Music, Israeli record label

Work ...

s. This happens because the ocean's primary producers are tiny phytoplankton

Phytoplankton () are the autotrophic (self-feeding) components of the plankton community and a key part of ocean and freshwater ecosystems. The name comes from the Greek words (), meaning 'plant', and (), meaning 'wanderer' or 'drifter'.

P ...

which grow and reproduce rapidly, so a small mass can have a fast rate of primary production

In ecology, primary production is the synthesis of organic compounds from atmospheric or aqueous carbon dioxide. It principally occurs through the process of photosynthesis, which uses light as its source of energy, but it also occurs through c ...

. In contrast, many significant terrestrial primary producers, such as mature forests, grow and reproduce slowly, so a much larger mass is needed to achieve the same rate of primary production.

Because of this inversion, it is the zooplankton

Zooplankton are the animal component of the planktonic community ("zoo" comes from the Greek word for ''animal''). Plankton are aquatic organisms that are unable to swim effectively against currents, and consequently drift or are carried along by ...

that make up most of the marine animal biomass

Biomass is plant-based material used as a fuel for heat or electricity production. It can be in the form of wood, wood residues, energy crops, agricultural residues, and waste from industry, farms, and households. Some people use the terms biom ...

. As primary consumer

A herbivore is an animal anatomically and physiologically adapted to eating plant material, for example foliage or marine algae, for the main component of its diet. As a result of their plant diet, herbivorous animals typically have mouthpart ...

s, zooplankton are the crucial link between the primary producers (mainly phytoplankton) and the rest of the marine food web (secondary consumer

A carnivore , or meat-eater (Latin, ''caro'', genitive ''carnis'', meaning meat or "flesh" and ''vorare'' meaning "to devour"), is an animal or plant whose food and energy requirements derive from animal tissues (mainly muscle, fat and other sof ...

s).

If phytoplankton dies before it is eaten, it descends through the euphotic zone

The photic zone, euphotic zone, epipelagic zone, or sunlight zone is the uppermost layer of a body of water that receives sunlight, allowing phytoplankton to perform photosynthesis. It undergoes a series of physical, chemical, and biological pro ...

as part of the marine snow

In the deep ocean, marine snow (also known as "ocean dandruff") is a continuous shower of mostly organic detritus falling from the upper layers of the water column. It is a significant means of exporting energy from the light-rich photic zone to ...

and settles into the depths of sea. In this way, phytoplankton sequester about 2 billion tons of carbon dioxide into the ocean each year, causing the ocean to become a sink of carbon dioxide holding about 90% of all sequestered carbon. The ocean produces about half of the world's oxygen and stores 50 times more carbon dioxide than the atmosphere.

An ecosystem cannot be understood without knowledge of how its food web determines the flow of materials and energy. Phytoplankton autotrophically produces biomass by converting inorganic compound

In chemistry, an inorganic compound is typically a chemical compound that lacks carbon–hydrogen bonds, that is, a compound that is not an organic compound. The study of inorganic compounds is a subfield of chemistry known as '' inorganic chemi ...

s into organic

Organic may refer to:

* Organic, of or relating to an organism, a living entity

* Organic, of or relating to an anatomical organ

Chemistry

* Organic matter, matter that has come from a once-living organism, is capable of decay or is the product o ...

ones. In this way, phytoplankton functions as the foundation of the marine food web by supporting all other life in the ocean. The second central process in the marine food web is the microbial loop

The microbial loop describes a trophic pathway where, in aquatic systems, dissolved organic carbon (DOC) is returned to higher trophic levels via its incorporation into bacterial biomass, and then coupled with the classic food chain formed by ph ...

. This loop degrades marine bacteria

Marine prokaryotes are marine bacteria and marine archaea. They are defined by their habitat as prokaryotes that live in marine environments, that is, in the saltwater of seas or oceans or the brackish water of coastal estuaries. All cellula ...

and archaea, remineralise

In biogeochemistry, remineralisation (or remineralization) refers to the breakdown or transformation of organic matter (those molecules derived from a biological source) into its simplest inorganic forms. These transformations form a crucial link ...

s organic and inorganic matter, and then recycles the products either within the pelagic food web or by depositing them as marine sediment

Marine sediment, or ocean sediment, or seafloor sediment, are deposits of insoluble particles that have accumulated on the seafloor. These particles have their origins in soil and rocks and have been transported from the land to the sea, mai ...

on the seafloor.

Food chains and trophic levels

Food web

A food web is the natural interconnection of food chains and a graphical representation of what-eats-what in an ecological community. Another name for food web is consumer-resource system. Ecologists can broadly lump all life forms into one ...

s are built from food chain

A food chain is a linear network of links in a food web starting from producer organisms (such as grass or algae which produce their own food via photosynthesis) and ending at an apex predator species (like grizzly bears or killer whales), d ...

s. All forms of life in the sea have the potential to become food for another life form. In the ocean, a food chain typically starts with energy from the sun powering phytoplankton

Phytoplankton () are the autotrophic (self-feeding) components of the plankton community and a key part of ocean and freshwater ecosystems. The name comes from the Greek words (), meaning 'plant', and (), meaning 'wanderer' or 'drifter'.

P ...

, and follows a course such as:

phytoplankton → herbivorous zooplankton → carnivorous zooplankton →filter feeder Filter feeders are a sub-group of suspension feeding animals that feed by straining suspended matter and food particles from water, typically by passing the water over a specialized filtering structure. Some animals that use this method of feedin ...→ predatory vertebrate

Phytoplankton

Phytoplankton () are the autotrophic (self-feeding) components of the plankton community and a key part of ocean and freshwater ecosystems. The name comes from the Greek words (), meaning 'plant', and (), meaning 'wanderer' or 'drifter'.

P ...

don't need other organisms for food, because they have the ability to manufacture their own food directly from inorganic carbon, using sunlight as their energy source. This process is called photosynthesis

Photosynthesis is a process used by plants and other organisms to convert light energy into chemical energy that, through cellular respiration, can later be released to fuel the organism's activities. Some of this chemical energy is stored i ...

, and results in the phytoplankton converting naturally occurring carbon into protoplasm

Protoplasm (; ) is the living part of a cell that is surrounded by a plasma membrane. It is a mixture of small molecules such as ions, monosaccharides, amino acid, and macromolecules such as proteins, polysaccharides, lipids, etc.

In some defin ...

. For this reason, phytoplankton are said to be the primary producer

Primary or primaries may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media Music Groups and labels

* Primary (band), from Australia

* Primary (musician), hip hop musician and record producer from South Korea

* Primary Music, Israeli record label

Work ...

s at the bottom or the first level of the marine food chain. Since they are at the first level they are said to have a trophic level

The trophic level of an organism is the position it occupies in a food web. A food chain is a succession of organisms that eat other organisms and may, in turn, be eaten themselves. The trophic level of an organism is the number of steps it i ...

of 1 (from the Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

''trophē'' meaning food). Phytoplankton are then consumed at the next trophic level in the food chain by microscopic animals called zooplankton.

Zooplankton

Zooplankton are the animal component of the planktonic community ("zoo" comes from the Greek word for ''animal''). Plankton are aquatic organisms that are unable to swim effectively against currents, and consequently drift or are carried along by ...

constitute the second trophic level in the food chain, and include microscopic one-celled organisms called protozoa

Protozoa (singular: protozoan or protozoon; alternative plural: protozoans) are a group of single-celled eukaryotes, either free-living or parasitic, that feed on organic matter such as other microorganisms or organic tissues and debris. Histor ...

as well as small crustacean

Crustaceans (Crustacea, ) form a large, diverse arthropod taxon which includes such animals as decapods, seed shrimp, branchiopods, fish lice, krill, remipedes, isopods, barnacles, copepods, amphipods and mantis shrimp. The crustacean gro ...

s, such as copepod

Copepods (; meaning "oar-feet") are a group of small crustaceans found in nearly every freshwater and saltwater habitat. Some species are planktonic (inhabiting sea waters), some are benthic (living on the ocean floor), a number of species have p ...

s and krill

Krill are small crustaceans of the order Euphausiacea, and are found in all the world's oceans. The name "krill" comes from the Norwegian word ', meaning "small fry of fish", which is also often attributed to species of fish.

Krill are consid ...

, and the larva

A larva (; plural larvae ) is a distinct juvenile form many animals undergo before metamorphosis into adults. Animals with indirect development such as insects, amphibians, or cnidarians typically have a larval phase of their life cycle.

Th ...

of fish, squid, lobsters and crabs. Organisms at this level can be thought of as primary consumer

A herbivore is an animal anatomically and physiologically adapted to eating plant material, for example foliage or marine algae, for the main component of its diet. As a result of their plant diet, herbivorous animals typically have mouthpart ...

s.

In turn, the smaller herbivorous zooplankton are consumed by larger carnivorous zooplankters, such as larger predatory protozoa and krill

Krill are small crustaceans of the order Euphausiacea, and are found in all the world's oceans. The name "krill" comes from the Norwegian word ', meaning "small fry of fish", which is also often attributed to species of fish.

Krill are consid ...

, and by forage fish

Forage fish, also called prey fish or bait fish, are small pelagic fish which are preyed on by larger predators for food. Predators include other larger fish, seabirds and marine mammals. Typical ocean forage fish feed near the base of the ...

, which are small, schooling

A school is an educational institution designed to provide learning spaces and learning environments for the teaching of students under the direction of teachers. Most countries have systems of formal education, which is sometimes compulsor ...

, filter-feeding

Filter feeders are a sub-group of suspension feeding animals that feed by straining suspended matter and food particles from water, typically by passing the water over a specialized filtering structure. Some animals that use this method of feedin ...

fish. This makes up the third trophic level in the food chain.

The fourth trophic level consists of

The fourth trophic level consists of predatory fish

Predatory fish are hypercarnivorous fish that actively prey upon other fish or aquatic animals, with examples including shark, billfish, barracuda, pike/muskellunge, walleye, perch and salmon. Some omnivorous fish, such as the red-bellied pir ...

, marine mammal

Marine mammals are aquatic mammals that rely on the ocean and other marine ecosystems for their existence. They include animals such as Pinniped, seals, Cetacea, whales, Sirenia, manatees, sea otters and polar bears. They are an informal group, ...

s and seabird

Seabirds (also known as marine birds) are birds that are adapted to life within the marine environment. While seabirds vary greatly in lifestyle, behaviour and physiology, they often exhibit striking convergent evolution, as the same envir ...

s that consume forage fish. Examples are swordfish

Swordfish (''Xiphias gladius''), also known as broadbills in some countries, are large, highly migratory predatory fish characterized by a long, flat, pointed bill. They are a popular sport fish of the billfish category, though elusive. Swordfi ...

, seals

Seals may refer to:

* Pinniped, a diverse group of semi-aquatic marine mammals, many of which are commonly called seals, particularly:

** Earless seal, or "true seal"

** Fur seal

* Seal (emblem), a device to impress an emblem, used as a means ...

and gannet

Gannets are seabirds comprising the genus ''Morus'' in the family Sulidae, closely related to boobies.

Gannets are large white birds with yellowish heads; black-tipped wings; and long bills. Northern gannets are the largest seabirds in the ...

s.

Apex predators, such as orca

The orca or killer whale (''Orcinus orca'') is a toothed whale belonging to the oceanic dolphin family, of which it is the largest member. It is the only extant species in the genus '' Orcinus'' and is recognizable by its black-and-white ...

s, which can consume seals, and shortfin mako shark

The shortfin mako shark (; ; ''Isurus oxyrinchus''), also known as the blue pointer or bonito shark, is a large mackerel shark. It is commonly referred to as the mako shark, as is the longfin mako shark (''Isurus paucus''). The shortfin mako c ...

s, which can consume swordfish, make up a fifth trophic level. Baleen whale

Baleen whales ( systematic name Mysticeti), also known as whalebone whales, are a parvorder of carnivorous marine mammals of the infraorder Cetacea ( whales, dolphins and porpoises) which use keratinaceous baleen plates (or "whalebone") in th ...

s can consume zooplankton and krill directly, leading to a food chain with only three or four trophic levels.

In practice, trophic levels are not usually simple integers because the same consumer species often feeds across more than one trophic level. For example a large marine vertebrate may eat smaller predatory fish but may also eat filter feeders; the stingray

Stingrays are a group of sea rays, which are cartilaginous fish related to sharks. They are classified in the suborder Myliobatoidei of the order Myliobatiformes and consist of eight families: Hexatrygonidae (sixgill stingray), Plesiobatid ...

eats crustacean

Crustaceans (Crustacea, ) form a large, diverse arthropod taxon which includes such animals as decapods, seed shrimp, branchiopods, fish lice, krill, remipedes, isopods, barnacles, copepods, amphipods and mantis shrimp. The crustacean gro ...

s, but the hammerhead

Hammerhead may refer to:

* The head of a hammer

Fiction

* Hammerhead (comics), a Marvel Comics foe of Spider-Man

* ''Hammerhead'' (film), a 1968 film based on the novel by James Mayo

* '' Hammerhead: Shark Frenzy'' a 2005 TV movie starring ...

eats both crustaceans and stingrays. Animals can also eat each other; the cod

Cod is the common name for the demersal fish genus '' Gadus'', belonging to the family Gadidae. Cod is also used as part of the common name for a number of other fish species, and one species that belongs to genus ''Gadus'' is commonly not c ...

eats smaller cod as well as crayfish

Crayfish are freshwater crustaceans belonging to the clade Astacidea, which also contains lobsters. In some locations, they are also known as crawfish, craydids, crawdaddies, crawdads, freshwater lobsters, mountain lobsters, rock lobsters, ...

, and crayfish eat cod larvae. The feeding habits of a juvenile animal, and, as a consequence, its trophic level, can change as it grows up.

The fisheries scientist Daniel Pauly

Daniel Pauly is a French-born marine biologist, well known for his work in studying human impacts on global fisheries and in 2020 was the most cited fisheries scientist in the world. He is a professor and the project leader of the Sea Around Us ...

sets the values of trophic levels to one in primary producers and detritus

In biology, detritus () is dead particulate organic material, as distinguished from dissolved organic material. Detritus typically includes the bodies or fragments of bodies of dead organisms, and fecal material. Detritus typically hosts commu ...

, two in herbivores and detritivores (primary consumers), three in secondary consumers, and so on. The definition of the trophic level, TL, for any consumer species is:

::

where is the fractional trophic level of the prey ''j'', and represents the fraction of ''j'' in the diet of ''i''. In the case of marine ecosystems, the trophic level of most fish and other marine consumers takes value between

2.0 and 5.0. The upper value, 5.0, is unusual, even for large fish, though it occurs in apex predators of marine mammals, such as polar bears and killer whales. As a point of contrast, humans have a mean trophic level of about 2.21, about the same as a pig or an anchovy.

By taxon

Primary producers

At the base of the ocean food web are single-celled algae and other plant-like organisms known as

At the base of the ocean food web are single-celled algae and other plant-like organisms known as phytoplankton

Phytoplankton () are the autotrophic (self-feeding) components of the plankton community and a key part of ocean and freshwater ecosystems. The name comes from the Greek words (), meaning 'plant', and (), meaning 'wanderer' or 'drifter'.

P ...

. Phytoplankton are a group of microscopic autotroph

An autotroph or primary producer is an organism that produces complex organic compounds (such as carbohydrates, fats, and proteins) using carbon from simple substances such as carbon dioxide,Morris, J. et al. (2019). "Biology: How Life Works", ...

s divided into a diverse assemblage of taxonomic group

In biology, a taxon (back-formation from ''taxonomy''; plural taxa) is a group of one or more populations of an organism or organisms seen by taxonomists to form a unit. Although neither is required, a taxon is usually known by a particular nam ...

s based on morphology

Morphology, from the Greek and meaning "study of shape", may refer to:

Disciplines

*Morphology (archaeology), study of the shapes or forms of artifacts

*Morphology (astronomy), study of the shape of astronomical objects such as nebulae, galaxies, ...

, size, and pigment type. Marine phytoplankton mostly inhabit sunlit surface waters as photoautotroph Photoautotrophs are organisms that use light energy and inorganic carbon to produce organic materials. Eukaryotic photoautotrophs absorb energy through the chlorophyll molecules in their chloroplasts while prokaryotic photoautotrophs use chlorophyll ...

s, and require nutrients such as nitrogen and phosphorus, as well as sunlight to fix carbon and produce oxygen. However, some marine phytoplankton inhabit the deep sea, often near deep sea vent

A hydrothermal vent is a fissure on the seabed from which geothermally heated water discharges. They are commonly found near volcanically active places, areas where tectonic plates are moving apart at mid-ocean ridges, ocean basins, and hotspot ...

s, as chemoautotrophs which use inorganic electron sources such as hydrogen sulfide

Hydrogen sulfide is a chemical compound with the formula . It is a colorless chalcogen-hydride gas, and is poisonous, corrosive, and flammable, with trace amounts in ambient atmosphere having a characteristic foul odor of rotten eggs. The und ...

, ferrous iron

In chemistry, iron(II) refers to the element iron in its +2 oxidation state. In ionic compounds (salts), such an atom may occur as a separate cation (positive ion) denoted by Fe2+.

The adjective ferrous or the prefix ferro- is often used to s ...

and ammonia

Ammonia is an inorganic compound of nitrogen and hydrogen with the formula . A stable binary hydride, and the simplest pnictogen hydride, ammonia is a colourless gas with a distinct pungent smell. Biologically, it is a common nitrogeno ...

.

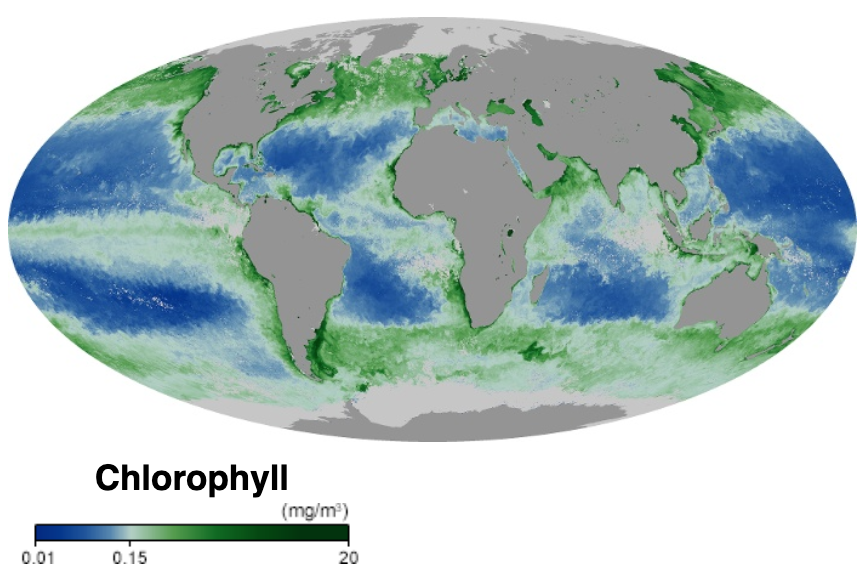

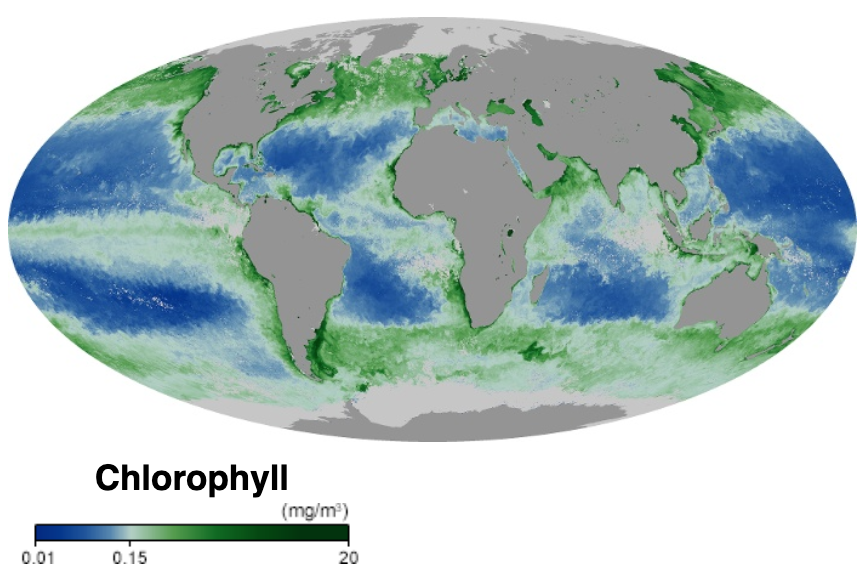

Marine phytoplankton form the basis of the marine food web, account for approximately half of global carbon fixation and oxygen production by photosynthesis and are a key link in the global carbon cycle. Like plants on land, phytoplankton use chlorophyll

Chlorophyll (also chlorophyl) is any of several related green pigments found in cyanobacteria and in the chloroplasts of algae and plants. Its name is derived from the Greek words , ("pale green") and , ("leaf"). Chlorophyll allow plants to ...

and other light-harvesting pigments to carry out photosynthesis

Photosynthesis is a process used by plants and other organisms to convert light energy into chemical energy that, through cellular respiration, can later be released to fuel the organism's activities. Some of this chemical energy is stored i ...

, absorbing atmospheric carbon dioxide to produce sugars for fuel. Chlorophyll in the water changes the way the water reflects and absorbs sunlight, allowing scientists to map the amount and location of phytoplankton. These measurements give scientists valuable insights into the health of the ocean environment, and help scientists study the ocean carbon cycle

The oceanic carbon cycle (or marine carbon cycle) is composed of processes that exchange carbon between various pools within the ocean as well as between the atmosphere, Earth interior, and the seafloor. The carbon cycle is a result of many inter ...

.

Among the phytoplankton are members from a phylum of bacteria called cyanobacteria. Marine cyanobacteria include the smallest known photosynthetic organisms. The smallest of all, ''

Among the phytoplankton are members from a phylum of bacteria called cyanobacteria. Marine cyanobacteria include the smallest known photosynthetic organisms. The smallest of all, ''Prochlorococcus

''Prochlorococcus'' is a genus of very small (0.6 μm) marine cyanobacteria with an unusual pigmentation ( chlorophyll ''a2'' and ''b2''). These bacteria belong to the photosynthetic picoplankton and are probably the most abundant photosyn ...

'', is just 0.5 to 0.8 micrometres across. In terms of individual numbers, ''Prochlorococcus'' is possibly the most plentiful species on Earth: a single millilitre of surface seawater can contain 100,000 cells or more. Worldwide there are estimated to be several octillion

Two naming scales for large numbers have been used in English and other European languages since the early modern era: the long and short scales. Most English variants use the short scale today, but the long scale remains dominant in many non-En ...

(1027) individuals. ''Prochlorococcus'' is ubiquitous between 40°N and 40°S and dominates in the oligotroph

An oligotroph is an organism that can live in an environment that offers very low levels of nutrients. They may be contrasted with copiotrophs, which prefer nutritionally rich environments. Oligotrophs are characterized by slow growth, low rates o ...

ic (nutrient poor) regions of the oceans. The bacterium accounts for about 20% of the oxygen in the Earth's atmosphere.

primary production

In ecology, primary production is the synthesis of organic compounds from atmospheric or aqueous carbon dioxide. It principally occurs through the process of photosynthesis, which uses light as its source of energy, but it also occurs through c ...

is performed by algae

Algae ( , ; : alga ) are any of a large and diverse group of photosynthetic, eukaryotic organisms. The name is an informal term for a polyphyletic grouping that includes species from multiple distinct clades. Included organisms range from ...

. This is a contrast to on land, where most primary production is performed by vascular plants

Vascular plants (), also called tracheophytes () or collectively Tracheophyta (), form a large group of land plants ( accepted known species) that have lignified tissues (the xylem) for conducting water and minerals throughout the plant. They a ...

. Algae ranges from single floating cells to attached seaweeds

Seaweed, or macroalgae, refers to thousands of species of macroscopic, multicellular, marine algae. The term includes some types of ''Rhodophyta'' (red), '' Phaeophyta'' (brown) and '' Chlorophyta'' (green) macroalgae. Seaweed species such a ...

, while vascular plants are represented in the ocean by groups such as the seagrass

Seagrasses are the only flowering plants which grow in marine environments. There are about 60 species of fully marine seagrasses which belong to four families ( Posidoniaceae, Zosteraceae, Hydrocharitaceae and Cymodoceaceae), all in the ...

es and the mangrove

A mangrove is a shrub or tree that grows in coastal saline or brackish water. The term is also used for tropical coastal vegetation consisting of such species. Mangroves are taxonomically diverse, as a result of convergent evolution in several ...

s. Larger producers, such as seagrasses and seaweed

Seaweed, or macroalgae, refers to thousands of species of macroscopic, multicellular, marine algae. The term includes some types of ''Rhodophyta'' (red), ''Phaeophyta'' (brown) and ''Chlorophyta'' (green) macroalgae. Seaweed species such as ke ...

s, are mostly confined to the littoral

The littoral zone or nearshore is the part of a sea, lake, or river that is close to the shore. In coastal ecology, the littoral zone includes the intertidal zone extending from the high water mark (which is rarely inundated), to coastal areas ...

zone and shallow waters, where they attach to the underlying substrate and are still within the photic zone

The photic zone, euphotic zone, epipelagic zone, or sunlight zone is the uppermost layer of a body of water that receives sunlight, allowing phytoplankton to perform photosynthesis. It undergoes a series of physical, chemical, and biological pro ...

. But most of the primary production by algae is performed by the phytoplankton.

Thus, in ocean environments, the first bottom trophic level is occupied principally by phytoplankton

Phytoplankton () are the autotrophic (self-feeding) components of the plankton community and a key part of ocean and freshwater ecosystems. The name comes from the Greek words (), meaning 'plant', and (), meaning 'wanderer' or 'drifter'.

P ...

, microscopic drifting organisms, mostly one-celled

A unicellular organism, also known as a single-celled organism, is an organism that consists of a single cell, unlike a multicellular organism that consists of multiple cells. Organisms fall into two general categories: prokaryotic organisms an ...

algae

Algae ( , ; : alga ) are any of a large and diverse group of photosynthetic, eukaryotic organisms. The name is an informal term for a polyphyletic grouping that includes species from multiple distinct clades. Included organisms range from ...

, that float in the sea. Most phytoplankton are too small to be seen individually with the unaided eye

Naked eye, also called bare eye or unaided eye, is the practice of engaging in visual perception unaided by a magnification, magnifying, Optical telescope#Light-gathering power, light-collecting optical instrument, such as a telescope or micr ...

. They can appear as a (often green) discoloration of the water when they are present in high enough numbers. Since they increase their biomass mostly through photosynthesis they live in the sun-lit surface layer (euphotic zone

The photic zone, euphotic zone, epipelagic zone, or sunlight zone is the uppermost layer of a body of water that receives sunlight, allowing phytoplankton to perform photosynthesis. It undergoes a series of physical, chemical, and biological pro ...

) of the sea.

The most important groups of phytoplankton include the diatoms and dinoflagellate

The dinoflagellates (Greek δῖνος ''dinos'' "whirling" and Latin ''flagellum'' "whip, scourge") are a monophyletic group of single-celled eukaryotes constituting the phylum Dinoflagellata and are usually considered algae. Dinoflagellates are ...

s. Diatoms are especially important in oceans, where according to some estimates they contribute up to 45% of the total ocean's primary production. Diatoms are usually microscopic

The microscopic scale () is the scale of objects and events smaller than those that can easily be seen by the naked eye, requiring a lens or microscope to see them clearly. In physics, the microscopic scale is sometimes regarded as the scale be ...

, although some species can reach up to 2 millimetres in length.

Primary consumers

The second trophic level (

The second trophic level (primary consumer

A herbivore is an animal anatomically and physiologically adapted to eating plant material, for example foliage or marine algae, for the main component of its diet. As a result of their plant diet, herbivorous animals typically have mouthpart ...

s) is occupied by zooplankton

Zooplankton are the animal component of the planktonic community ("zoo" comes from the Greek word for ''animal''). Plankton are aquatic organisms that are unable to swim effectively against currents, and consequently drift or are carried along by ...

which feed off the phytoplankton

Phytoplankton () are the autotrophic (self-feeding) components of the plankton community and a key part of ocean and freshwater ecosystems. The name comes from the Greek words (), meaning 'plant', and (), meaning 'wanderer' or 'drifter'.

P ...

. Together with the phytoplankton, they form the base of the food pyramid that supports most of the world's great fishing grounds. Many zooplankton are tiny animals found with the phytoplankton in ocean

The ocean (also the sea or the world ocean) is the body of salt water that covers approximately 70.8% of the surface of Earth and contains 97% of Earth's water. An ocean can also refer to any of the large bodies of water into which the wo ...

ic surface waters, and include tiny crustacean

Crustaceans (Crustacea, ) form a large, diverse arthropod taxon which includes such animals as decapods, seed shrimp, branchiopods, fish lice, krill, remipedes, isopods, barnacles, copepods, amphipods and mantis shrimp. The crustacean gro ...

s, and fish larvae and fry

Fry, fries, Fry's or frying may refer to:

Food and cooking

* Frying, the cooking of food in hot oil or fat

** French fries, deep-fried potato strips

** Frying pan, cookware for frying

Businesses and organizations

* Fry (racing team), a Britis ...

(recently hatched fish). Most zooplankton are filter feeder

Filter feeders are a sub-group of suspension feeding animals that feed by straining suspended matter and food particles from water, typically by passing the water over a specialized filtering structure. Some animals that use this method of feedin ...

s, and they use appendages to strain the phytoplankton in the water. Some larger zooplankton also feed on smaller zooplankton. Some zooplankton can jump about a bit to avoid predators, but they can't really swim. Like phytoplankton, they float with the currents, tides and winds instead. Zooplanktons can reproduce rapidly, their populations can increase up to thirty percent a day under favourable conditions. Many live short and productive lives and reach maturity quickly.

The oligotrich

The oligotrichs are a group of ciliates, included among the spirotrichs. They have prominent oral cilia

The cilium, plural cilia (), is a membrane-bound organelle found on most types of eukaryotic cell, and certain microorganisms known as ...

s are a group of ciliate

The ciliates are a group of alveolates characterized by the presence of hair-like organelles called cilia, which are identical in structure to eukaryotic flagella, but are in general shorter and present in much larger numbers, with a differen ...

s which have prominent oral cilia

The cilium, plural cilia (), is a membrane-bound organelle found on most types of eukaryotic cell, and certain microorganisms known as ciliates. Cilia are absent in bacteria and archaea. The cilium has the shape of a slender threadlike projecti ...

arranged like a collar and lapel. They are very common in marine plankton communities, usually found in concentrations of about one per millilitre. They are the most important herbivores in the sea, the first link in the food chain.

Other particularly important groups of zooplankton are the copepod

Copepods (; meaning "oar-feet") are a group of small crustaceans found in nearly every freshwater and saltwater habitat. Some species are planktonic (inhabiting sea waters), some are benthic (living on the ocean floor), a number of species have p ...

s and krill

Krill are small crustaceans of the order Euphausiacea, and are found in all the world's oceans. The name "krill" comes from the Norwegian word ', meaning "small fry of fish", which is also often attributed to species of fish.

Krill are consid ...

. Copepod

Copepods (; meaning "oar-feet") are a group of small crustaceans found in nearly every freshwater and saltwater habitat. Some species are planktonic (inhabiting sea waters), some are benthic (living on the ocean floor), a number of species have p ...

s are a group of small crustacean

Crustaceans (Crustacea, ) form a large, diverse arthropod taxon which includes such animals as decapods, seed shrimp, branchiopods, fish lice, krill, remipedes, isopods, barnacles, copepods, amphipods and mantis shrimp. The crustacean gro ...

s found in ocean and freshwater

Fresh water or freshwater is any naturally occurring liquid or frozen water containing low concentrations of dissolved salts and other total dissolved solids. Although the term specifically excludes seawater and brackish water, it does in ...

habitats

In ecology, the term habitat summarises the array of resources, physical and biotic factors that are present in an area, such as to support the survival and reproduction of a particular species. A species habitat can be seen as the physical ...

. They are the biggest source of protein in the sea, and are important prey for forage fish. Krill

Krill are small crustaceans of the order Euphausiacea, and are found in all the world's oceans. The name "krill" comes from the Norwegian word ', meaning "small fry of fish", which is also often attributed to species of fish.

Krill are consid ...

constitute the next biggest source of protein. Krill are particularly large predator zooplankton which feed on smaller zooplankton. This means they really belong to the third trophic level, secondary consumers, along with the forage fish.

Together,

Together, phytoplankton

Phytoplankton () are the autotrophic (self-feeding) components of the plankton community and a key part of ocean and freshwater ecosystems. The name comes from the Greek words (), meaning 'plant', and (), meaning 'wanderer' or 'drifter'.

P ...

and zooplankton

Zooplankton are the animal component of the planktonic community ("zoo" comes from the Greek word for ''animal''). Plankton are aquatic organisms that are unable to swim effectively against currents, and consequently drift or are carried along by ...

make up most of the plankton

Plankton are the diverse collection of organisms found in water (or air) that are unable to propel themselves against a current (or wind). The individual organisms constituting plankton are called plankters. In the ocean, they provide a cr ...

in the sea. Plankton is the term applied to any small drifting organism

In biology, an organism () is any life, living system that functions as an individual entity. All organisms are composed of cells (cell theory). Organisms are classified by taxonomy (biology), taxonomy into groups such as Multicellular o ...

s that float in the sea (Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

''planktos'' = wanderer or drifter). By definition, organisms classified as plankton are unable to swim against ocean currents; they cannot resist the ambient current and control their position. In ocean environments, the first two trophic levels are occupied mainly by plankton

Plankton are the diverse collection of organisms found in water (or air) that are unable to propel themselves against a current (or wind). The individual organisms constituting plankton are called plankters. In the ocean, they provide a cr ...

. Plankton are divided into producers and consumers. The producers are the phytoplankton (Greek ''phyton'' = plant) and the consumers, who eat the phytoplankton, are the zooplankton (Greek ''zoon'' = animal).

Jellyfish

Jellyfish and sea jellies are the informal common names given to the medusa-phase of certain gelatinous members of the subphylum Medusozoa, a major part of the phylum Cnidaria. Jellyfish are mainly free-swimming marine animals with umbrella- ...

are slow swimmers, and most species form part of the plankton. Traditionally jellyfish have been viewed as trophic dead ends, minor players in the marine food web, gelatinous organisms with a body plan

A body plan, ( ), or ground plan is a set of morphological features common to many members of a phylum of animals. The vertebrates share one body plan, while invertebrates have many.

This term, usually applied to animals, envisages a "bluepri ...

largely based on water that offers little nutritional value or interest for other organisms apart from a few specialised predators such as the ocean sunfish

The ocean sunfish or common mola (''Mola mola'') is one of the largest bony fish in the world. It was misidentified as the heaviest bony fish, which was actually a different species, '' Mola alexandrini''. Adults typically weigh between . The sp ...

and the leatherback sea turtle

The leatherback sea turtle (''Dermochelys coriacea''), sometimes called the lute turtle or leathery turtle or simply the luth, is the largest of all living turtles and the heaviest non-crocodilian reptile, reaching lengths of up to and weights ...

.Hamilton, G. (2016"The secret lives of jellyfish: long regarded as minor players in ocean ecology, jellyfish are actually important parts of the marine food web"

''Nature'', 531(7595): 432-435. Hays, G.C., Doyle, T.K. and Houghton, J.D. (2018) "A paradigm shift in the trophic importance of jellyfish?" ''Trends in ecology & evolution'', 33(11): 874-884. That view has recently been challenged. Jellyfish, and more generally

gelatinous zooplankton

Gelatinous zooplankton are fragile animals that live in the water column in the ocean. Their delicate bodies have no hard parts and are easily damaged or destroyed. Gelatinous zooplankton are often transparent. All jellyfish are gelatinous zoopla ...

which include salp

A salp (plural salps, also known colloquially as “sea grape”) or salpa (plural salpae or salpas) is a barrel-shaped, planktic tunicate. It moves by contracting, thereby pumping water through its gelatinous body, one of the most efficient ...

s and ctenophore

Ctenophora (; ctenophore ; ) comprise a phylum of marine invertebrates, commonly known as comb jellies, that inhabit sea waters worldwide. They are notable for the groups of cilia they use for swimming (commonly referred to as "combs"), and ...

s, are very diverse, fragile with no hard parts, difficult to see and monitor, subject to rapid population swings and often live inconveniently far from shore or deep in the ocean. It is difficult for scientists to detect and analyse jellyfish in the guts of predators, since they turn to mush when eaten and are rapidly digested. But jellyfish bloom in vast numbers, and it has been shown they form major components in the diets of tuna

A tuna is a saltwater fish that belongs to the tribe Thunnini, a subgrouping of the Scombridae ( mackerel) family. The Thunnini comprise 15 species across five genera, the sizes of which vary greatly, ranging from the bullet tuna (max le ...

, spearfish

Spearfish may refer to:

Places

*Spearfish, South Dakota, United States

*North Spearfish, South Dakota, United States

*Spearfish Formation, a geologic formation in the United States

Biology

* ''Tetrapturus'', a genus of marlin containing spear ...

and swordfish

Swordfish (''Xiphias gladius''), also known as broadbills in some countries, are large, highly migratory predatory fish characterized by a long, flat, pointed bill. They are a popular sport fish of the billfish category, though elusive. Swordfi ...

as well as various birds and invertebrates such as octopus

An octopus ( : octopuses or octopodes, see below for variants) is a soft-bodied, eight- limbed mollusc of the order Octopoda (, ). The order consists of some 300 species and is grouped within the class Cephalopoda with squids, cuttlefis ...

, sea cucumber

Sea cucumbers are echinoderms from the class Holothuroidea (). They are marine animals with a leathery skin and an elongated body containing a single, branched gonad. Sea cucumbers are found on the sea floor worldwide. The number of holothu ...

s, crabs and amphipods. "Despite their low energy density, the contribution of jellyfish to the energy budgets of predators may be much greater than assumed because of rapid digestion, low capture costs, availability, and selective feeding on the more energy-rich components. Feeding on jellyfish may make marine predators susceptible to ingestion of plastics."

Higher order consumers

; Marine invertebrates

; Fish

*

; Marine invertebrates

; Fish

* Forage fish

Forage fish, also called prey fish or bait fish, are small pelagic fish which are preyed on by larger predators for food. Predators include other larger fish, seabirds and marine mammals. Typical ocean forage fish feed near the base of the ...

: Forage fish occupy central positions in the ocean food web

A food web is the natural interconnection of food chains and a graphical representation of what-eats-what in an ecological community. Another name for food web is consumer-resource system. Ecologists can broadly lump all life forms into one ...

s. The organisms it eats are at a lower trophic level

The trophic level of an organism is the position it occupies in a food web. A food chain is a succession of organisms that eat other organisms and may, in turn, be eaten themselves. The trophic level of an organism is the number of steps it i ...

, and the organisms that eat it are at a higher trophic level. Forage fish occupy middle levels in the food web, serving as a dominant prey to higher level fish, seabirds and mammals.

* Predator fish

Predatory fish are hypercarnivorous fish that actively prey upon other fish or aquatic animals, with examples including shark, billfish, barracuda, pike/muskellunge, walleye, perch and salmon. Some omnivorous fish, such as the red-bellied pira ...

* Ground fish

; Other marine vertebrates

In 2010 researchers found whales carry nutrients from the depths of the ocean back to the surface using a process they called the whale pump

Whale feces, the excrement of whales, has a significant role in the ecology of the oceans, and whales have been referred to as "marine ecosystem engineers". Nitrogen released by cetacean species and iron chelate is a significant benefit to the ...

. Whales feed at deeper levels in the ocean where krill

Krill are small crustaceans of the order Euphausiacea, and are found in all the world's oceans. The name "krill" comes from the Norwegian word ', meaning "small fry of fish", which is also often attributed to species of fish.

Krill are consid ...

is found, but return regularly to the surface to breathe. There whales defecate a liquid rich in nitrogen and iron. Instead of sinking, the liquid stays at the surface where phytoplankton

Phytoplankton () are the autotrophic (self-feeding) components of the plankton community and a key part of ocean and freshwater ecosystems. The name comes from the Greek words (), meaning 'plant', and (), meaning 'wanderer' or 'drifter'.

P ...

consume it. In the Gulf of Maine the whale pump provides more nitrogen than the rivers.

Humpback whale

The humpback whale (''Megaptera novaeangliae'') is a species of baleen whale. It is a rorqual (a member of the family Balaenopteridae) and is the only species in the genus ''Megaptera''. Adults range in length from and weigh up to . The hum ...

s lunge from below to feed on forage fish

File:Gannet (Morus bassana), Belmont - geograph.org.uk - 529175.jpg, Gannets

Gannets are seabirds comprising the genus ''Morus'' in the family Sulidae, closely related to boobies.

Gannets are large white birds with yellowish heads; black-tipped wings; and long bills. Northern gannets are the largest seabirds in th ...

plunge dive from above to catch forage fish

Microorganisms

There has been increasing recognition in recent years that

There has been increasing recognition in recent years that marine microorganism

Marine microorganisms are defined by their habitat as microorganisms living in a marine environment, that is, in the saltwater of a sea or ocean or the brackish water of a coastal estuary. A microorganism (or microbe) is any microscopic living ...

s play much bigger roles in marine ecosystems than was previously thought. Developments in metagenomics

Metagenomics is the study of genetic material recovered directly from environmental or clinical samples by a method called sequencing. The broad field may also be referred to as environmental genomics, ecogenomics, community genomics or micr ...

gives researchers an ability to reveal previously hidden diversities of microscopic life, offering a powerful lens for viewing the microbial world and the potential to revolutionise understanding of the living world. Metabarcoding dietary analysis techniques are being used to reconstruct food webs at higher levels of taxonomic resolution

DNA barcoding is a method of species identification using a short section of DNA from a specific gene or genes. The premise of DNA barcoding is that by comparison with a reference library of such DNA sections (also called "sequences"), an indiv ...

and are revealing deeper complexities in the web of interactions.

Microorganism

A microorganism, or microbe,, ''mikros'', "small") and ''organism'' from the el, ὀργανισμός, ''organismós'', "organism"). It is usually written as a single word but is sometimes hyphenated (''micro-organism''), especially in olde ...

s play key roles in marine food webs. The viral shunt

The viral shunt is a mechanism that prevents marine microbial particulate organic matter (POM) from migrating up trophic levels by recycling them into dissolved organic matter (DOM), which can be readily taken up by microorganisms. The DOM recy ...

pathway is a mechanism that prevents marine microbial particulate organic matter

Particulate organic matter (POM) is a fraction of total organic matter operationally defined as that which does not pass through a filter pore size that typically ranges in size from 0.053 to 2 millimeters.

Particulate organic carbon (POC) is ...

(POM) from migrating up trophic level

The trophic level of an organism is the position it occupies in a food web. A food chain is a succession of organisms that eat other organisms and may, in turn, be eaten themselves. The trophic level of an organism is the number of steps it i ...

s by recycling them into dissolved organic matter

Dissolved organic carbon (DOC) is the fraction of organic carbon operationally defined as that which can pass through a filter with a pore size typically between 0.22 and 0.7 micrometers. The fraction remaining on the filter is called partic ...

(DOM), which can be readily taken up by microorganisms. Viral shunting helps maintain diversity within the microbial ecosystem by preventing a single species of marine microbe from dominating the micro-environment. The DOM recycled by the viral shunt pathway is comparable to the amount generated by the other main sources of marine DOM.

In general, dissolved organic carbon

Dissolved organic carbon (DOC) is the fraction of organic carbon operationally defined as that which can pass through a filter with a pore size typically between 0.22 and 0.7 micrometers. The fraction remaining on the filter is called partic ...

(DOC) is introduced into the ocean environment from bacterial lysis, the leakage or exudation of fixed carbon from phytoplankton (e.g., mucilaginous exopolymer from diatoms), sudden cell senescence, sloppy feeding by zooplankton, the excretion of waste products by aquatic animals, or the breakdown or dissolution of organic particles from terrestrial plants and soils. Bacteria in the microbial loop

The microbial loop describes a trophic pathway where, in aquatic systems, dissolved organic carbon (DOC) is returned to higher trophic levels via its incorporation into bacterial biomass, and then coupled with the classic food chain formed by ph ...

decompose this particulate detritus to utilize this energy-rich matter for growth. Since more than 95% of organic matter in marine ecosystems consists of polymeric, high molecular weight

A molecule is a group of two or more atoms held together by attractive forces known as chemical bonds; depending on context, the term may or may not include ions which satisfy this criterion. In quantum physics, organic chemistry, and bioch ...

(HMW) compounds (e.g., protein, polysaccharides, lipids), only a small portion of total dissolved organic matter

Dissolved organic carbon (DOC) is the fraction of organic carbon operationally defined as that which can pass through a filter with a pore size typically between 0.22 and 0.7 micrometers. The fraction remaining on the filter is called partic ...

(DOM) is readily utilizable to most marine organisms at higher trophic levels. This means that dissolved organic carbon is not available directly to most marine organisms; marine bacteria introduce this organic carbon into the food web, resulting in additional energy becoming available to higher trophic levels.

;Viruses

;Viruses

Virus

A virus is a wikt:submicroscopic, submicroscopic infectious agent that replicates only inside the living Cell (biology), cells of an organism. Viruses infect all life forms, from animals and plants to microorganisms, including bacteria and ...

es are the "most abundant biological entities on the planet", particularly in the oceans which occupy over 70% of the Earth’s surface. The realisation in 1989 that there are typically about 100 marine viruses

Marine viruses are defined by their habitat as viruses that are found in marine environments, that is, in the saltwater of seas or oceans or the brackish water of coastal estuaries. Viruses are small infectious agents that can only replica ...

in every millilitre of seawater gave impetus to understand their diversity and role in the marine environment. Viruses are now considered to play key roles in marine ecosystems by controlling microbial community dynamics, host metabolic status, and biogeochemical cycling

A biogeochemical cycle (or more generally a cycle of matter) is the pathway by which a chemical substance cycles (is turned over or moves through) the biotic and the abiotic compartments of Earth. The biotic compartment is the biosphere and ...

via lysis of hosts.

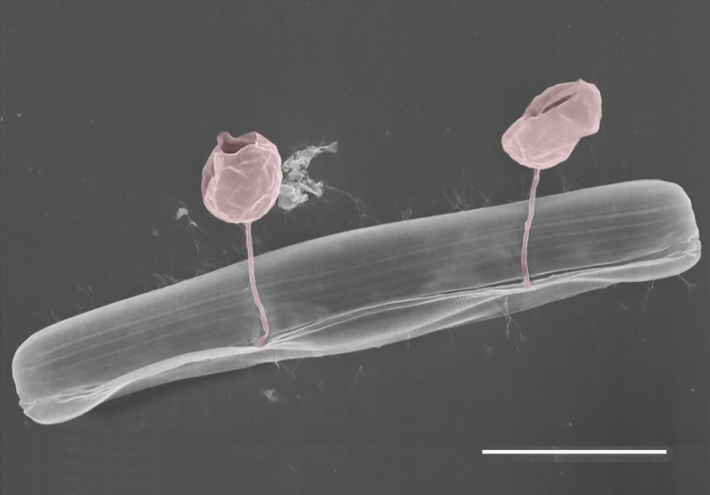

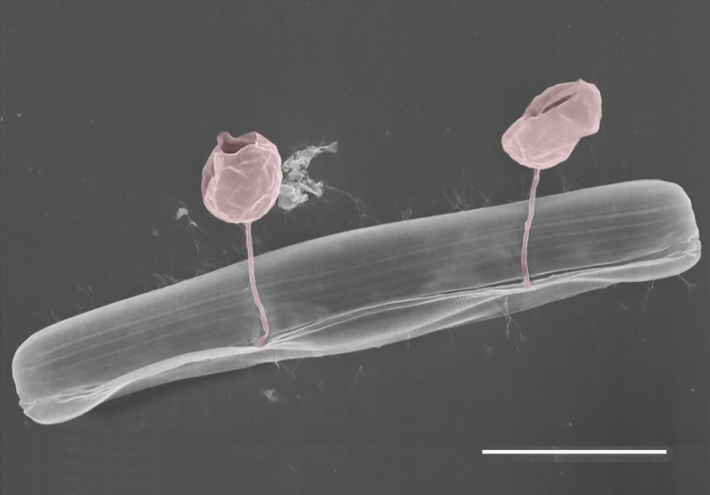

A giant marine virus CroV

''Cafeteria roenbergensis virus'' (CroV) is a giant virus that infects the marine bicosoecid flagellate ''Cafeteria roenbergensis'', a member of the microzooplankton community.

History

The virus was isolated from seawater samples collected from ...

infects and causes the death by lysis

Lysis ( ) is the breaking down of the membrane of a cell, often by viral, enzymic, or osmotic (that is, "lytic" ) mechanisms that compromise its integrity. A fluid containing the contents of lysed cells is called a ''lysate''. In molecular bio ...

of the marine zooflagellate ''Cafeteria roenbergensis

''Cafeteria roenbergensis'' is a small bacterivorous marine flagellate. It was discovered by Danish marine ecologist Tom Fenchel and named by him and taxonomist David J. Patterson in 1988. It is in one of three genera of bicosoecids, and the ...

''. This impacts coastal ecology because ''Cafeteria roenbergensis

''Cafeteria roenbergensis'' is a small bacterivorous marine flagellate. It was discovered by Danish marine ecologist Tom Fenchel and named by him and taxonomist David J. Patterson in 1988. It is in one of three genera of bicosoecids, and the ...

'' feeds on bacteria found in the water. When there are low numbers of ''Cafeteria roenbergensis

''Cafeteria roenbergensis'' is a small bacterivorous marine flagellate. It was discovered by Danish marine ecologist Tom Fenchel and named by him and taxonomist David J. Patterson in 1988. It is in one of three genera of bicosoecids, and the ...

'' due to extensive CroV infections, the bacterial populations rise exponentially. The impact of CroV

''Cafeteria roenbergensis virus'' (CroV) is a giant virus that infects the marine bicosoecid flagellate ''Cafeteria roenbergensis'', a member of the microzooplankton community.

History

The virus was isolated from seawater samples collected from ...

on natural populations of ''C. roenbergensis'' remains unknown; however, the virus has been found to be very host specific, and does not infect other closely related organisms. Cafeteria roenbergensis is also infected by a second virus, the Mavirus virophage

''Mavirus'' is a genus of double stranded DNA virus that can infect the marine phagotrophic flagellate '' Cafeteria roenbergensis'', but only in the presence of the giant '' CroV'' virus (''Cafeteria roenbergensis''). The genus contains only ...

, which is a satellite virus

A satellite is a subviral agent that depends on the coinfection of a host cell with a helper virus for its replication. Satellites can be divided into two major classes: satellite viruses and satellite nucleic acids. Satellite viruses, which a ...

, meaning it is able to replicate only in the presence of another specific virus, in this case in the presence of CroV. This virus interferes with the replication of CroV, which leads to the survival of ''C. roenbergensis'' cells. Mavirus

''Mavirus'' is a genus of double stranded DNA virus that can infect the marine phagotrophic flagellate ''Cafeteria roenbergensis'', but only in the presence of the giant '' CroV'' virus (''Cafeteria roenbergensis''). The genus contains only on ...

is able to integrate into the genome of cells of ''C. roenbergensis'', and thereby confer immunity to the population.

Fungi

By habitat

Pelagic webs

For pelagic ecosystems, Legendre and Rassoulzadagan proposed in 1995 a continuum of trophic pathways with the herbivorous food-chain and

For pelagic ecosystems, Legendre and Rassoulzadagan proposed in 1995 a continuum of trophic pathways with the herbivorous food-chain and microbial loop

The microbial loop describes a trophic pathway where, in aquatic systems, dissolved organic carbon (DOC) is returned to higher trophic levels via its incorporation into bacterial biomass, and then coupled with the classic food chain formed by ph ...

as food-web end members. The classical linear food-chain end-member involves grazing by zooplankton on larger phytoplankton and subsequent predation on zooplankton by either larger zooplankton or another predator. In such a linear food-chain a predator can either lead to high phytoplankton biomass

Biomass is plant-based material used as a fuel for heat or electricity production. It can be in the form of wood, wood residues, energy crops, agricultural residues, and waste from industry, farms, and households. Some people use the terms biom ...

(in a system with phytoplankton, herbivore and a predator) or reduced phytoplankton biomass (in a system with four levels). Changes in predator abundance can, thus, lead to trophic cascade Trophic cascades are powerful indirect interactions that can control entire ecosystems, occurring when a trophic level in a food web is suppressed. For example, a top-down cascade will occur if predators are effective enough in predation to reduce t ...

s. The microbial loop end-member involves not only phytoplankton, as basal resource, but also dissolved organic carbon

Dissolved organic carbon (DOC) is the fraction of organic carbon operationally defined as that which can pass through a filter with a pore size typically between 0.22 and 0.7 micrometers. The fraction remaining on the filter is called partic ...

. Dissolved organic carbon is used by heterotrophic bacteria for growth are predated upon by larger zooplankton. Consequently, dissolved organic carbon is transformed, via a bacterial-microzooplankton loop, to zooplankton. These two end-member carbon processing pathways are connected at multiple levels. Small phytoplankton can be consumed directly by microzooplankton.

As illustrated in the diagram on the right, dissolved organic carbon is produced in multiple ways and by various organisms, both by primary producers and consumers of organic carbon. DOC release by primary producers occurs passively by leakage and actively during unbalanced growth during nutrient limitation. Another direct pathway from phytoplankton to dissolved organic pool involves viral lysis

Lysis ( ) is the breaking down of the membrane of a cell, often by viral, enzymic, or osmotic (that is, "lytic" ) mechanisms that compromise its integrity. A fluid containing the contents of lysed cells is called a ''lysate''. In molecular bio ...

. Marine viruses

Marine viruses are defined by their habitat as viruses that are found in marine environments, that is, in the saltwater of seas or oceans or the brackish water of coastal estuaries. Viruses are small infectious agents that can only replica ...

are a major cause of phytoplankton mortality in the ocean, particularly in warmer, low-latitude waters. Sloppy feeding by herbivores and incomplete digestion of prey by consumers are other sources of dissolved organic carbon. Heterotrophic microbes use extracellular enzymes to solubilize particulate organic carbon

Particulate organic matter (POM) is a fraction of total organic matter operationally defined as that which does not pass through a filter pore size that typically ranges in size from 0.053 to 2 millimeters.

Particulate organic carbon (POC) is ...

and use this and other dissolved organic carbon resources for growth and maintenance. Part of the microbial heterotrophic production is used by microzooplankton; another part of the heterotrophic community is subject to intense viral lysis and this causes release of dissolved organic carbon again. The efficiency of the microbial loop depends on multiple factors but in particular on the relative importance of predation and viral lysis to the mortality of heterotrophic microbes.

biological pump

The biological pump (or ocean carbon biological pump or marine biological carbon pump) is the ocean's biologically driven sequestration of carbon from the atmosphere and land runoff to the ocean interior and seafloor sediments.Sigman DM & GH ...

. Links among the ocean's biological pump and pelagic food web and the ability to sample these components remotely from ships, satellites, and autonomous vehicles. Light blue waters are the euphotic zone

The photic zone, euphotic zone, epipelagic zone, or sunlight zone is the uppermost layer of a body of water that receives sunlight, allowing phytoplankton to perform photosynthesis. It undergoes a series of physical, chemical, and biological pro ...

, while the darker blue waters represent the twilight zone.

DVM = diel vertical migration NM = non-migration

bristlemouth

The Gonostomatidae are a family of mesopelagic marine fish, commonly named bristlemouths, lightfishes, or anglemouths. It is a relatively small family, containing only eight known genera and 32 species. However, bristlemouths make up for their l ...

s may be the most abundant vertebrates on the planet, though little is known about them.

File:Bathykorus bouilloni.jpg, Gelatinous predators like this narcomedusan consume the greatest diversity of mesopelagic prey

Scientists are starting to explore in more detail the largely unknown twilight zone of the

Scientists are starting to explore in more detail the largely unknown twilight zone of the mesopelagic

The mesopelagic zone (Greek μέσον, middle), also known as the middle pelagic or twilight zone, is the part of the pelagic zone that lies between the photic epipelagic and the aphotic bathypelagic zones. It is defined by light, and begins a ...

, 200 to 1,000 metres deep. This layer is responsible for removing about 4 billion tonnes of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere each year. The mesopelagic layer is inhabited by most of the marine fish biomass

Biomass is plant-based material used as a fuel for heat or electricity production. It can be in the form of wood, wood residues, energy crops, agricultural residues, and waste from industry, farms, and households. Some people use the terms biom ...

.Tollefson, Jeff (27 February 2020Enter the twilight zone: scientists dive into the oceans’ mysterious middle

''Nature News''. . According to a 2017 study,

narcomedusae

Narcomedusae is an order of hydrozoans in the subclass Trachylinae. Members of this order do not normally have a polyp stage. The medusa has a dome-shaped bell with thin sides. The tentacles are attached above the lobed margin of the bell with ...

consume the greatest diversity of mesopelagic prey, followed by physonect

Physonectae is a suborder of siphonophores. In Japanese it is called ().

Organisms in the suborder Physonectae follow the classic Siphonophore body plan. They are almost all pelagic, and are composed of a colony of specialized zooids that ori ...

siphonophore

Siphonophorae (from Greek ''siphōn'' 'tube' + ''pherein'' 'to bear') is an order within Hydrozoa, which is a class of marine organisms within the phylum Cnidaria. According to the World Register of Marine Species, the order contains 175 species ...

s, ctenophore

Ctenophora (; ctenophore ; ) comprise a phylum of marine invertebrates, commonly known as comb jellies, that inhabit sea waters worldwide. They are notable for the groups of cilia they use for swimming (commonly referred to as "combs"), and ...

s and cephalopod

A cephalopod is any member of the molluscan class Cephalopoda ( Greek plural , ; "head-feet") such as a squid, octopus, cuttlefish, or nautilus. These exclusively marine animals are characterized by bilateral body symmetry, a prominent head, ...

s. The importance of the so called "jelly web" is only beginning to be understood, but it seems medusae, ctenophores and siphonophores can be key predators in deep pelagic food webs with ecological impacts similar to predator fish and squid. Traditionally gelatinous predators were thought ineffectual providers of marine trophic pathways, but they appear to have substantial and integral roles in deep pelagic food webs. Diel vertical migration