Gottfried Wilhelm (von) Leibniz . ( – 14 November 1716) was a German

polymath

A polymath ( el, πολυμαθής, , "having learned much"; la, homo universalis, "universal human") is an individual whose knowledge spans a substantial number of subjects, known to draw on complex bodies of knowledge to solve specific pro ...

active as a

mathematician

A mathematician is someone who uses an extensive knowledge of mathematics in their work, typically to solve mathematical problems.

Mathematicians are concerned with numbers, data, quantity, structure, space, models, and change.

History

On ...

,

philosopher

A philosopher is a person who practices or investigates philosophy. The term ''philosopher'' comes from the grc, φιλόσοφος, , translit=philosophos, meaning 'lover of wisdom'. The coining of the term has been attributed to the Greek th ...

,

scientist

A scientist is a person who conducts Scientific method, scientific research to advance knowledge in an Branches of science, area of the natural sciences.

In classical antiquity, there was no real ancient analog of a modern scientist. Instead, ...

and

diplomat

A diplomat (from grc, δίπλωμα; romanized ''diploma'') is a person appointed by a state or an intergovernmental institution such as the United Nations or the European Union to conduct diplomacy with one or more other states or internati ...

. He is one of the most prominent figures in both the

history of philosophy

Philosophy (from , ) is the systematized study of general and fundamental questions, such as those about existence, reason, knowledge, values, mind, and language. Such questions are often posed as problems to be studied or resolved. Some ...

and the

history of mathematics

The history of mathematics deals with the origin of discoveries in mathematics and the mathematical methods and notation of the past. Before the modern age and the worldwide spread of knowledge, written examples of new mathematical developments ...

. He wrote works on

philosophy

Philosophy (from , ) is the systematized study of general and fundamental questions, such as those about existence, reason, knowledge, values, mind, and language. Such questions are often posed as problems to be studied or resolved. Some ...

,

theology

Theology is the systematic study of the nature of the divine and, more broadly, of religious belief. It is taught as an academic discipline, typically in universities and seminaries. It occupies itself with the unique content of analyzing the ...

,

ethics

Ethics or moral philosophy is a branch of philosophy that "involves systematizing, defending, and recommending concepts of right and wrong behavior".''Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy'' The field of ethics, along with aesthetics, concerns m ...

,

politics

Politics (from , ) is the set of activities that are associated with making decisions in groups, or other forms of power relations among individuals, such as the distribution of resources or status. The branch of social science that studies ...

,

law

Law is a set of rules that are created and are enforceable by social or governmental institutions to regulate behavior,Robertson, ''Crimes against humanity'', 90. with its precise definition a matter of longstanding debate. It has been vario ...

,

history

History (derived ) is the systematic study and the documentation of the human activity. The time period of event before the History of writing#Inventions of writing, invention of writing systems is considered prehistory. "History" is an umbr ...

and

philology

Philology () is the study of language in oral and writing, written historical sources; it is the intersection of textual criticism, literary criticism, history, and linguistics (with especially strong ties to etymology). Philology is also defin ...

. Leibniz also made major contributions to

physics

Physics is the natural science that studies matter, its fundamental constituents, its motion and behavior through space and time, and the related entities of energy and force. "Physical science is that department of knowledge which r ...

and

technology

Technology is the application of knowledge to reach practical goals in a specifiable and reproducible way. The word ''technology'' may also mean the product of such an endeavor. The use of technology is widely prevalent in medicine, science, ...

, and anticipated notions that surfaced much later in

probability theory

Probability theory is the branch of mathematics concerned with probability. Although there are several different probability interpretations, probability theory treats the concept in a rigorous mathematical manner by expressing it through a set o ...

,

biology

Biology is the scientific study of life. It is a natural science with a broad scope but has several unifying themes that tie it together as a single, coherent field. For instance, all organisms are made up of cells that process hereditary i ...

,

medicine

Medicine is the science and practice of caring for a patient, managing the diagnosis, prognosis, prevention, treatment, palliation of their injury or disease, and promoting their health. Medicine encompasses a variety of health care pract ...

,

geology

Geology () is a branch of natural science concerned with Earth and other astronomical objects, the features or rocks of which it is composed, and the processes by which they change over time. Modern geology significantly overlaps all other Ear ...

,

psychology

Psychology is the scientific study of mind and behavior. Psychology includes the study of conscious and unconscious phenomena, including feelings and thoughts. It is an academic discipline of immense scope, crossing the boundaries betwe ...

,

linguistics

Linguistics is the scientific study of human language. It is called a scientific study because it entails a comprehensive, systematic, objective, and precise analysis of all aspects of language, particularly its nature and structure. Linguis ...

and

computer science

Computer science is the study of computation, automation, and information. Computer science spans theoretical disciplines (such as algorithms, theory of computation, information theory, and automation) to Applied science, practical discipli ...

. In addition, he contributed to the field of

library science

Library science (often termed library studies, bibliothecography, and library economy) is an interdisciplinary or multidisciplinary field that applies the practices, perspectives, and tools of management, information technology, education, and ...

: while serving as overseer of the Wolfenbüttel library in Germany, he devised a cataloging system that would have served as a guide for many of Europe's largest libraries. Leibniz's contributions to this vast array of subjects were scattered in various

learned journal

An academic journal or scholarly journal is a periodical publication in which scholarship relating to a particular academic discipline is published. Academic journals serve as permanent and transparent forums for the presentation, scrutiny, and d ...

s, in tens of thousands of letters and in unpublished manuscripts. He wrote in several languages, primarily in Latin, French and German, but also in English, Italian and Dutch.

As a philosopher, he was one of the greatest representatives of 17th-century

rationalism

In philosophy, rationalism is the epistemological view that "regards reason as the chief source and test of knowledge" or "any view appealing to reason as a source of knowledge or justification".Lacey, A.R. (1996), ''A Dictionary of Philosophy' ...

and

idealism

In philosophy, the term idealism identifies and describes metaphysical perspectives which assert that reality is indistinguishable and inseparable from perception and understanding; that reality is a mental construct closely connected to ide ...

. As a mathematician, his greatest achievement was the development of the main ideas of

differential and integral calculus

Calculus, originally called infinitesimal calculus or "the calculus of infinitesimals", is the mathematical study of continuous change, in the same way that geometry is the study of shape, and algebra is the study of generalizations of arith ...

,

independently of

Isaac Newton

Sir Isaac Newton (25 December 1642 – 20 March 1726/27) was an English mathematician, physicist, astronomer, alchemist, theologian, and author (described in his time as a "natural philosopher"), widely recognised as one of the grea ...

's contemporaneous developments, and mathematicians have consistently favored

Leibniz's notation

In calculus, Leibniz's notation, named in honor of the 17th-century German philosopher and mathematician Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, uses the symbols and to represent infinitely small (or infinitesimal) increments of and , respectively, just a ...

as the conventional and more exact expression of calculus.

However, it was only in the 20th century that Leibniz's

law of continuity

The law of continuity is a heuristic principle introduced by Gottfried Leibniz based on earlier work by Nicholas of Cusa and Johannes Kepler. It is the principle that "whatever succeeds for the finite, also succeeds for the infinite". Kepler used ...

and

transcendental law of homogeneity

In mathematics, the transcendental law of homogeneity (TLH) is a heuristic principle enunciated by Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz most clearly in a 1710 text entitled ''Symbolismus memorabilis calculi algebraici et infinitesimalis in comparatione potent ...

found a consistent mathematical formulation by means of

non-standard analysis

The history of calculus is fraught with philosophical debates about the meaning and logical validity of fluxions or infinitesimal numbers. The standard way to resolve these debates is to define the operations of calculus using epsilon–delta ...

. He was also a pioneer in the field of

mechanical calculators

Mechanical may refer to:

Machine

* Machine (mechanical), a system of mechanisms that shape the actuator input to achieve a specific application of output forces and movement

* Mechanical calculator, a device used to perform the basic operations of ...

. While working on adding automatic multiplication and division to

Pascal's calculator, he was the first to describe a

pinwheel calculator

A pinwheel calculator is a class of mechanical calculator described as early as 1685, and popular in the 19th and 20th century, calculating via wheels whose number of teeth were adjustable. These wheels, also called pinwheels, could be set by usin ...

in 1685 and invented the

Leibniz wheel

A Leibniz wheel or stepped drum is a cylinder with a set of teeth of incremental lengths which, when coupled to a counting wheel, can be used in the calculating engine of a class of mechanical calculators. Invented by Leibniz in 1673, it was used ...

, used in the

arithmometer

The arithmometer (french: arithmomètre) was the first digital mechanical calculator strong enough and reliable enough to be used daily in an office environment. This calculator could add and subtract two numbers directly and could perform lon ...

, the first mass-produced mechanical calculator. He also refined the

binary number

A binary number is a number expressed in the base-2 numeral system or binary numeral system, a method of mathematical expression which uses only two symbols: typically "0" (zero) and "1" ( one).

The base-2 numeral system is a positional notatio ...

system, which is the foundation of nearly all digital (

electronic

Electronic may refer to:

*Electronics, the science of how to control electric energy in semiconductor

* ''Electronics'' (magazine), a defunct American trade journal

*Electronic storage, the storage of data using an electronic device

*Electronic co ...

,

solid-state

Solid state, or solid matter, is one of the four fundamental states of matter.

Solid state may also refer to:

Electronics

* Solid-state electronics, circuits built of solid materials

* Solid state ionics, study of ionic conductors and their use ...

,

discrete logic

A logic gate is an idealized or physical device implementing a Boolean function, a logical operation performed on one or more binary inputs that produces a single binary output. Depending on the context, the term may refer to an ideal logic gate, ...

)

computer

A computer is a machine that can be programmed to Execution (computing), carry out sequences of arithmetic or logical operations (computation) automatically. Modern digital electronic computers can perform generic sets of operations known as C ...

s, including the

Von Neumann architecture

The von Neumann architecture — also known as the von Neumann model or Princeton architecture — is a computer architecture based on a 1945 description by John von Neumann, and by others, in the ''First Draft of a Report on the EDVAC''. The ...

, which is the standard design paradigm, or "

computer architecture

In computer engineering, computer architecture is a description of the structure of a computer system made from component parts. It can sometimes be a high-level description that ignores details of the implementation. At a more detailed level, t ...

", followed from the second half of the 20th century, and into the 21st. Leibniz has been called the "founder of computer science".

In

philosophy

Philosophy (from , ) is the systematized study of general and fundamental questions, such as those about existence, reason, knowledge, values, mind, and language. Such questions are often posed as problems to be studied or resolved. Some ...

and

theology

Theology is the systematic study of the nature of the divine and, more broadly, of religious belief. It is taught as an academic discipline, typically in universities and seminaries. It occupies itself with the unique content of analyzing the ...

, Leibniz is most noted for his

optimism

Optimism is an attitude reflecting a belief or hope that the outcome of some specific endeavor, or outcomes in general, will be positive, favorable, and desirable. A common idiom used to illustrate optimism versus pessimism is a glass filled wi ...

, i.e. his conclusion that our world is, in a qualified sense, the

best possible world that

God

In monotheism, monotheistic thought, God is usually viewed as the supreme being, creator deity, creator, and principal object of Faith#Religious views, faith.Richard Swinburne, Swinburne, R.G. "God" in Ted Honderich, Honderich, Ted. (ed)''The Ox ...

could have

created, a view sometimes lampooned by other thinkers, such as

Voltaire

François-Marie Arouet (; 21 November 169430 May 1778) was a French Age of Enlightenment, Enlightenment writer, historian, and philosopher. Known by his ''Pen name, nom de plume'' M. de Voltaire (; also ; ), he was famous for his wit, and his ...

in his

satirical

Satire is a genre of the visual, literary, and performing arts, usually in the form of fiction and less frequently non-fiction, in which vices, follies, abuses, and shortcomings are held up to ridicule, often with the intent of shaming or e ...

novella

A novella is a narrative prose fiction whose length is shorter than most novels, but longer than most short stories. The English word ''novella'' derives from the Italian ''novella'' meaning a short story related to true (or apparently so) facts ...

''

Candide

( , ) is a French satire written by Voltaire, a philosopher of the Age of Enlightenment, first published in 1759. The novella has been widely translated, with English versions titled ''Candide: or, All for the Best'' (1759); ''Candide: or, The ...

''. Leibniz, along with

René Descartes

René Descartes ( or ; ; Latinized: Renatus Cartesius; 31 March 1596 – 11 February 1650) was a French philosopher, scientist, and mathematician, widely considered a seminal figure in the emergence of modern philosophy and science. Mathem ...

and

Baruch Spinoza

Baruch (de) Spinoza (born Bento de Espinosa; later as an author and a correspondent ''Benedictus de Spinoza'', anglicized to ''Benedict de Spinoza''; 24 November 1632 – 21 February 1677) was a Dutch philosopher of Portuguese-Jewish origin, b ...

, was one of the three great early modern

rationalists

In philosophy, rationalism is the epistemological view that "regards reason as the chief source and test of knowledge" or "any view appealing to reason as a source of knowledge or justification".Lacey, A.R. (1996), ''A Dictionary of Philosophy ...

. His philosophy also assimilates elements of the

scholastic tradition, notably the assumption that some substantive knowledge of reality can be achieved by reasoning from first principles or prior definitions. The work of Leibniz anticipated modern

logic

Logic is the study of correct reasoning. It includes both formal and informal logic. Formal logic is the science of deductively valid inferences or of logical truths. It is a formal science investigating how conclusions follow from premises ...

and still influences contemporary

analytic philosophy

Analytic philosophy is a branch and tradition of philosophy using analysis, popular in the Western world and particularly the Anglosphere, which began around the turn of the 20th century in the contemporary era in the United Kingdom, United Sta ...

, such as its adopted use of the term "

possible world

A possible world is a complete and consistent way the world is or could have been. Possible worlds are widely used as a formal device in logic, philosophy, and linguistics in order to provide a semantics for intensional logic, intensional and mod ...

" to define

modal notions.

Biography

Early life

Gottfried Leibniz was born on July 1 1646, toward the end of the

Thirty Years' War

The Thirty Years' War was one of the longest and most destructive conflicts in European history

The history of Europe is traditionally divided into four time periods: prehistoric Europe (prior to about 800 BC), classical antiquity (80 ...

, in

Leipzig

Leipzig ( , ; Upper Saxon: ) is the most populous city in the German state of Saxony. Leipzig's population of 605,407 inhabitants (1.1 million in the larger urban zone) as of 2021 places the city as Germany's eighth most populous, as wel ...

,

Saxony

Saxony (german: Sachsen ; Upper Saxon: ''Saggsn''; hsb, Sakska), officially the Free State of Saxony (german: Freistaat Sachsen, links=no ; Upper Saxon: ''Freischdaad Saggsn''; hsb, Swobodny stat Sakska, links=no), is a landlocked state of ...

, to

Friedrich Leibniz

Friedrich Leibniz (or Leibnütz; 1597–1652) was a Lutheran lawyer and a notary, registrar and professor of moral philosophy within Leipzig University.Brandon C. Look. Gregory Brown (Professor at University of Houston). Ariew, Roger. ''G. W. ...

and Catharina Schmuck. Friedrich noted in his family journal:

In English:

Leibniz was baptized on 3 July of that year at

St. Nicholas Church, Leipzig

The St. Nicholas Church (german: Nikolaikirche) is one of the major churches of central Leipzig, Germany (in Leipzig`s district Mitte). Construction started in Romanesque style in 1165, but in the 16th century, the church was turned into a Got ...

; his godfather was the

Lutheran

Lutheranism is one of the largest branches of Protestantism, identifying primarily with the theology of Martin Luther, the 16th-century German monk and reformer whose efforts to reform the theology and practice of the Catholic Church launched th ...

theologian . His father died when he was six years old, and from that point on, Leibniz was raised by his mother.

Leibniz's father had been a Professor of Moral Philosophy at the

University of Leipzig

Leipzig University (german: Universität Leipzig), in Leipzig in Saxony, Germany, is one of the world's oldest universities and the second-oldest university (by consecutive years of existence) in Germany. The university was founded on 2 Decemb ...

, and the boy later inherited his father's personal library. He was given free access to it from the age of seven. While Leibniz's schoolwork was largely confined to the study of a small

canon

Canon or Canons may refer to:

Arts and entertainment

* Canon (fiction), the conceptual material accepted as official in a fictional universe by its fan base

* Literary canon, an accepted body of works considered as high culture

** Western can ...

of authorities, his father's library enabled him to study a wide variety of advanced philosophical and theological works—ones that he would not have otherwise been able to read until his college years. Access to his father's library, largely written in

Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power of the ...

, also led to his proficiency in the Latin language, which he achieved by the age of 12. At the age of 13 he composed 300

hexameters

Hexameter is a metrical line of verses consisting of six feet (a "foot" here is the pulse, or major accent, of words in an English line of poetry; in Greek and Latin a "foot" is not an accent, but describes various combinations of syllables). It w ...

of

Latin verse

The history of Latin poetry can be understood as the adaptation of Greek models. The verse comedies of Plautus, the earliest surviving examples of Latin literature, are estimated to have been composed around 205-184 BC.

History

Scholars conven ...

in a single morning for a special event at school.

In April 1661 he enrolled in his father's former university at age 14,

and completed his

bachelor's degree

A bachelor's degree (from Middle Latin ''baccalaureus'') or baccalaureate (from Modern Latin ''baccalaureatus'') is an undergraduate academic degree awarded by colleges and universities upon completion of a course of study lasting three to six ...

in Philosophy in December 1662. He defended his ''Disputatio Metaphysica de Principio Individui'' (''Metaphysical Disputation on the Principle of Individuation''),

[Arthur 2014, p. x.] which addressed the

principle of individuation The principle of individuation is a criterion that individuates or numerically distinguishes the members of the kind for which it is given, that is by which we can supposedly determine, regarding any kind of thing, when we have more than one of them ...

, on 9 June 1663. Leibniz earned his

master's degree

A master's degree (from Latin ) is an academic degree awarded by universities or colleges upon completion of a course of study demonstrating mastery or a high-order overview of a specific field of study or area of professional practice. in Philosophy on 7 February 1664. In December 1664 he published and defended a

dissertation ''Specimen Quaestionum Philosophicarum ex Jure collectarum'' (''An Essay of Collected Philosophical Problems of Right''),

arguing for both a theoretical and a pedagogical relationship between philosophy and law. After one year of legal studies, he was awarded his bachelor's degree in Law on 28 September 1665. His dissertation was titled ''De conditionibus'' (''On Conditions'').

In early 1666, at age 19, Leibniz wrote his first book, ''

De Arte Combinatoria

The ''Dissertatio de arte combinatoria'' ("Dissertation on the Art of Combinations" or "On the Combinatorial Art") is an early work by Gottfried Leibniz published in 1666 in Leipzig. It is an extended version of his first doctoral dissertation, wr ...

'' (''On the Combinatorial Art''), the first part of which was also his

habilitation

Habilitation is the highest university degree, or the procedure by which it is achieved, in many European countries. The candidate fulfills a university's set criteria of excellence in research, teaching and further education, usually including a ...

thesis in Philosophy, which he defended in March 1666.

''De Arte Combinatoria'' was inspired by

Ramon Llull

Ramon Llull (; c. 1232 – c. 1315/16) was a philosopher, theologian, poet, missionary, and Christian apologist from the Kingdom of Majorca.

He invented a philosophical system known as the ''Art'', conceived as a type of universal logic to pro ...

's ''

Ars Magna'' and contained a

proof of the existence of God

The existence of God (or more generally, the existence of deities) is a subject of debate in theology, philosophy of religion and popular culture. A wide variety of arguments for and against the existence of God or deities can be categorized ...

, cast in geometrical form, and based on the

argument from motion

A cosmological argument, in natural theology, is an argument which claims that the existence of God can be inferred from facts concerning causation, explanation, change, motion, contingency, dependency, or finitude with respect to the universe o ...

.

His next goal was to earn his license and Doctorate in Law, which normally required three years of study. In 1666, the University of Leipzig turned down Leibniz's doctoral application and refused to grant him a Doctorate in Law, most likely due to his relative youth. Leibniz subsequently left Leipzig.

Leibniz then enrolled in the

University of Altdorf

The University of Altdorf () was a university in Altdorf bei Nürnberg, a small town outside the Free Imperial City of Nuremberg. It was founded in 1578 and received university privileges in 1622 and was closed in 1809 by Maximilian I Joseph of Ba ...

and quickly submitted a thesis, which he had probably been working on earlier in Leipzig. The title of his thesis was ''Disputatio Inauguralis de Casibus Perplexis in Jure'' (''Inaugural Disputation on Ambiguous Legal Cases'').

Leibniz earned his license to practice law and his Doctorate in Law in November 1666. He next declined the offer of an academic appointment at Altdorf, saying that "my thoughts were turned in an entirely different direction".

As an adult, Leibniz often introduced himself as "Gottfried

von

The term ''von'' () is used in German language surnames either as a nobiliary particle indicating a noble patrilineality, or as a simple preposition used by commoners that means ''of'' or ''from''.

Nobility directories like the ''Almanach de Go ...

Leibniz". Many posthumously published editions of his writings presented his name on the title page as "

Freiherr

(; male, abbreviated as ), (; his wife, abbreviated as , literally "free lord" or "free lady") and (, his unmarried daughters and maiden aunts) are designations used as titles of nobility in the German-speaking areas of the Holy Roman Empire ...

G. W. von Leibniz." However, no document has ever been found from any contemporary government that stated his appointment to any form of

nobility

Nobility is a social class found in many societies that have an aristocracy (class), aristocracy. It is normally ranked immediately below Royal family, royalty. Nobility has often been an Estates of the realm, estate of the realm with many e ...

.

1666–1676

Leibniz's first position was as a salaried secretary to an

alchemical

Alchemy (from Arabic: ''al-kīmiyā''; from Ancient Greek: χυμεία, ''khumeía'') is an ancient branch of natural philosophy, a philosophical and protoscientific tradition that was historically practiced in China, India, the Muslim world, ...

society in

Nuremberg

Nuremberg ( ; german: link=no, Nürnberg ; in the local East Franconian dialect: ''Nämberch'' ) is the second-largest city of the German state of Bavaria after its capital Munich, and its 518,370 (2019) inhabitants make it the 14th-largest ...

. He knew fairly little about the subject at that time but presented himself as deeply learned. He soon met

Johann Christian von Boyneburg

Johann Christian von Boyneburg (April 12, 1622 - December 8, 1672) was a German politician.

Life

Johann Christian von Boyneburg was born into a family whose members had often been in the official Hessian state service. His father was the counci ...

(1622–1672), the dismissed chief minister of the

Elector

Elector may refer to:

* Prince-elector or elector, a member of the electoral college of the Holy Roman Empire, having the function of electing the Holy Roman Emperors

* Elector, a member of an electoral college

** Confederate elector, a member of ...

of

Mainz

Mainz () is the capital and largest city of Rhineland-Palatinate, Germany.

Mainz is on the left bank of the Rhine, opposite to the place that the Main (river), Main joins the Rhine. Downstream of the confluence, the Rhine flows to the north-we ...

,

Johann Philipp von Schönborn

Johann Philipp von Schönborn (6 August 1605 – 12 February 1673) was the Archbishop-Elector of Mainz (1647–1673), the Bishop of Würzburg (1642–1673), and the Bishop of Worms (1663–1673).

Life

Johann Philipp was born in ...

. Von Boyneburg hired Leibniz as an assistant, and shortly thereafter reconciled with the Elector and introduced Leibniz to him. Leibniz then dedicated an essay on law to the Elector in the hope of obtaining employment. The stratagem worked; the Elector asked Leibniz to assist with the redrafting of the legal code for the Electorate. In 1669, Leibniz was appointed assessor in the Court of Appeal. Although von Boyneburg died late in 1672, Leibniz remained under the employment of his widow until she dismissed him in 1674.

Von Boyneburg did much to promote Leibniz's reputation, and the latter's memoranda and letters began to attract favorable notice. After Leibniz's service to the Elector there soon followed a diplomatic role. He published an essay, under the pseudonym of a fictitious Polish nobleman, arguing (unsuccessfully) for the German candidate for the Polish crown. The main force in European geopolitics during Leibniz's adult life was the ambition of

Louis XIV of France

, house = Bourbon

, father = Louis XIII

, mother = Anne of Austria

, birth_date =

, birth_place = Château de Saint-Germain-en-Laye, Saint-Germain-en-Laye, France

, death_date =

, death_place = Palace of Versa ...

, backed by French military and economic might. Meanwhile, the

Thirty Years' War

The Thirty Years' War was one of the longest and most destructive conflicts in European history

The history of Europe is traditionally divided into four time periods: prehistoric Europe (prior to about 800 BC), classical antiquity (80 ...

had left

German-speaking Europe

This article details the geographical distribution of speakers of the German language, regardless of the legislative status within the countries where it is spoken. In addition to the German-speaking area (german: Deutscher Sprachraum) in Europe, ...

exhausted, fragmented, and economically backward. Leibniz proposed to protect German-speaking Europe by distracting Louis as follows. France would be invited to take

Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a transcontinental country spanning the northeast corner of Africa and southwest corner of Asia via a land bridge formed by the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediter ...

as a stepping stone towards an eventual conquest of the

Dutch East Indies

The Dutch East Indies, also known as the Netherlands East Indies ( nl, Nederlands(ch)-Indië; ), was a Dutch colony consisting of what is now Indonesia. It was formed from the nationalised trading posts of the Dutch East India Company, which ...

. In return, France would agree to leave Germany and the Netherlands undisturbed. This plan obtained the Elector's cautious support. In 1672, the French government invited Leibniz to Paris for discussion, but the plan was soon overtaken by the outbreak of the

Franco-Dutch War

The Franco-Dutch War, also known as the Dutch War (french: Guerre de Hollande; nl, Hollandse Oorlog), was fought between France and the Dutch Republic, supported by its allies the Holy Roman Empire, Spain, Brandenburg-Prussia and Denmark-Nor ...

and became irrelevant. Napoleon's

failed invasion of Egypt in 1798 can be seen as an unwitting, late implementation of Leibniz's plan, after the Eastern hemisphere colonial supremacy in Europe had already passed from the Dutch to the British.

Thus Leibniz went to Paris in 1672. Soon after arriving, he met Dutch physicist and mathematician

Christiaan Huygens

Christiaan Huygens, Lord of Zeelhem, ( , , ; also spelled Huyghens; la, Hugenius; 14 April 1629 – 8 July 1695) was a Dutch mathematician, physicist, engineer, astronomer, and inventor, who is regarded as one of the greatest scientists of ...

and realised that his own knowledge of mathematics and physics was patchy. With Huygens as his mentor, he began a program of

self-study

Autodidacticism (also autodidactism) or self-education (also self-learning and self-teaching) is education without the guidance of masters (such as teachers and professors) or institutions (such as schools). Generally, autodidacts are individu ...

that soon pushed him to making major contributions to both subjects, including discovering his version of the differential and integral

calculus

Calculus, originally called infinitesimal calculus or "the calculus of infinitesimals", is the mathematical study of continuous change, in the same way that geometry is the study of shape, and algebra is the study of generalizations of arithm ...

. He met

Nicolas Malebranche

Nicolas Malebranche ( , ; 6 August 1638 – 13 October 1715) was a French Oratorian Catholic priest and rationalist philosopher. In his works, he sought to synthesize the thought of St. Augustine and Descartes, in order to demonstrate the ...

and

Antoine Arnauld

Antoine Arnauld (6 February 16128 August 1694) was a French Catholic theologian, philosopher and mathematician. He was one of the leading intellectuals of the Jansenist group of Port-Royal and had a very thorough knowledge of patristics. Contem ...

, the leading French philosophers of the day, and studied the writings of

Descartes and

Pascal

Pascal, Pascal's or PASCAL may refer to:

People and fictional characters

* Pascal (given name), including a list of people with the name

* Pascal (surname), including a list of people and fictional characters with the name

** Blaise Pascal, Fren ...

, unpublished as well as published. He befriended a German mathematician,

Ehrenfried Walther von Tschirnhaus

Ehrenfried Walther von Tschirnhaus (or Tschirnhauß, ; 10 April 1651 – 11 October 1708) was a German mathematician, physicist, physician, and philosopher. He introduced the Tschirnhaus transformation and is considered by some to have been the ...

; they corresponded for the rest of their lives.

When it became clear that France would not implement its part of Leibniz's Egyptian plan, the Elector sent his nephew, escorted by Leibniz, on a related mission to the English government in London, early in 1673. There Leibniz came into acquaintance of

Henry Oldenburg

Henry Oldenburg (also Henry Oldenbourg) FRS (c. 1618 as Heinrich Oldenburg – 5 September 1677), was a German theologian, diplomat, and natural philosopher, known as one of the creators of modern scientific peer review. He was one of the for ...

and

John Collins John Collins may refer to:

Arts and entertainment

* John Collins (poet) (1742–1808), English orator, singer, and poet

* John Churton Collins (1848–1908), English literary critic

* John H. Collins (director) (1889–1918), American director an ...

. He met with the

Royal Society

The Royal Society, formally The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, is a learned society and the United Kingdom's national academy of sciences. The society fulfils a number of roles: promoting science and its benefits, re ...

where he demonstrated a calculating machine that he had designed and had been building since 1670. The machine was able to execute all four basic operations (adding, subtracting, multiplying, and dividing), and the society quickly made him an external member.

The mission ended abruptly when news of the Elector's death (12 February 1673) reached them. Leibniz promptly returned to Paris and not, as had been planned, to Mainz. The sudden deaths of his two patrons in the same winter meant that Leibniz had to find a new basis for his career.

In this regard, a 1669 invitation from Duke

John Frederick of

Brunswick to visit Hanover proved to have been fateful. Leibniz had declined the invitation, but had begun corresponding with the duke in 1671. In 1673, the duke offered Leibniz the post of counsellor. Leibniz very reluctantly accepted the position two years later, only after it became clear that no employment was forthcoming in Paris, whose intellectual stimulation he relished, or with the

Habsburg

The House of Habsburg (), alternatively spelled Hapsburg in Englishgerman: Haus Habsburg, ; es, Casa de Habsburgo; hu, Habsburg család, it, Casa di Asburgo, nl, Huis van Habsburg, pl, dom Habsburgów, pt, Casa de Habsburgo, la, Domus Hab ...

imperial court.

In 1675 he tried to get admitted to the

French Academy of Sciences

The French Academy of Sciences (French: ''Académie des sciences'') is a learned society, founded in 1666 by Louis XIV of France, Louis XIV at the suggestion of Jean-Baptiste Colbert, to encourage and protect the spirit of French Scientific me ...

as a foreign honorary member, but it was considered that there were already enough foreigners there and so no invitation came. He left Paris in October 1676.

House of Hanover, 1676–1716

Leibniz managed to delay his arrival in Hanover until the end of 1676 after making one more short journey to London, where Newton accused him of having seen his unpublished work on calculus in advance. This was alleged to be evidence supporting the accusation, made decades later, that he had stolen calculus from Newton. On the journey from London to Hanover, Leibniz stopped in

The Hague

The Hague ( ; nl, Den Haag or ) is a city and municipality of the Netherlands, situated on the west coast facing the North Sea. The Hague is the country's administrative centre and its seat of government, and while the official capital of ...

where he met

van Leeuwenhoek

Antonie Philips van Leeuwenhoek ( ; ; 24 October 1632 – 26 August 1723) was a Dutch microbiologist and microscopist in the Golden Age of Dutch science and technology. A largely self-taught man in science, he is commonly known as " the ...

, the discoverer of microorganisms. He also spent several days in intense discussion with

Spinoza

Baruch (de) Spinoza (born Bento de Espinosa; later as an author and a correspondent ''Benedictus de Spinoza'', anglicized to ''Benedict de Spinoza''; 24 November 1632 – 21 February 1677) was a Dutch philosopher of Portuguese-Jewish origin, b ...

, who had just completed his masterwork, the ''

Ethics

Ethics or moral philosophy is a branch of philosophy that "involves systematizing, defending, and recommending concepts of right and wrong behavior".''Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy'' The field of ethics, along with aesthetics, concerns m ...

''.

In 1677, he was promoted, at his request, to Privy Counselor of Justice, a post he held for the rest of his life. Leibniz served three consecutive rulers of the House of Brunswick as historian, political adviser, and most consequentially, as librarian of the

ducal

Duke is a male title either of a monarch ruling over a duchy, or of a member of royalty, or nobility. As rulers, dukes are ranked below emperors, kings, grand princes, grand dukes, and sovereign princes. As royalty or nobility, they are ranked ...

library. He thenceforth employed his pen on all the various political, historical, and

theological

Theology is the systematic study of the nature of the divine and, more broadly, of religious belief. It is taught as an academic discipline, typically in universities and seminaries. It occupies itself with the unique content of analyzing the ...

matters involving the House of Brunswick; the resulting documents form a valuable part of the historical record for the period.

Leibniz began promoting a project to use windmills to improve the mining operations in the Harz Mountains. This project did little to improve mining operations and was shut down by Duke Ernst August in 1685.

Among the few people in north Germany to accept Leibniz were the Electress

Sophia of Hanover

Sophia of Hanover (born Princess Sophia of the Palatinate; 14 October 1630 – 8 June 1714) was the Electress of Hanover by marriage to Elector Ernest Augustus and later the heiress presumptive to the thrones of England and Scotland (later Grea ...

(1630–1714), her daughter

Sophia Charlotte of Hanover

Sophia Charlotte of Hanover (30 October 1668 – 1 February 1705) was the first Queen consort in Prussia as wife of King Frederick I. She was the only daughter of Elector Ernest Augustus of Hanover and his wife Sophia of the Palatinate. Her eld ...

(1668–1705), the Queen of Prussia and his avowed disciple, and

Caroline of Ansbach

, father = John Frederick, Margrave of Brandenburg-Ansbach

, mother = Princess Eleonore Erdmuthe of Saxe-Eisenach

, birth_date =

, birth_place = Ansbach, Principality of Ansbach, Holy Roman Empire

, death_date =

, death_place = St James's Pala ...

, the consort of her grandson, the future

George II George II or 2 may refer to:

People

* George II of Antioch (seventh century AD)

* George II of Armenia (late ninth century)

* George II of Abkhazia (916–960)

* Patriarch George II of Alexandria (1021–1051)

* George II of Georgia (1072–1089)

* ...

. To each of these women he was correspondent, adviser, and friend. In turn, they all approved of Leibniz more than did their spouses and the future king

George I of Great Britain

George I (George Louis; ; 28 May 1660 – 11 June 1727) was King of Great Britain and Ireland from 1 August 1714 and ruler of the Electorate of Hanover within the Holy Roman Empire from 23 January 1698 until his death in 1727. He was the first ...

.

The population of Hanover was only about 10,000, and its provinciality eventually grated on Leibniz. Nevertheless, to be a major courtier to the House of

Brunswick was quite an honor, especially in light of the meteoric rise in the prestige of that House during Leibniz's association with it. In 1692, the Duke of Brunswick became a hereditary Elector of the

Holy Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire was a Polity, political entity in Western Europe, Western, Central Europe, Central, and Southern Europe that developed during the Early Middle Ages and continued until its Dissolution of the Holy Roman Empire, dissolution i ...

. The British

Act of Settlement 1701

The Act of Settlement is an Act of the Parliament of England that settled the succession to the English and Irish crowns to only Protestants, which passed in 1701. More specifically, anyone who became a Roman Catholic, or who married one, bec ...

designated the Electress Sophia and her descent as the royal family of England, once both King

William III William III or William the Third may refer to:

Kings

* William III of Sicily (c. 1186–c. 1198)

* William III of England and Ireland or William III of Orange or William II of Scotland (1650–1702)

* William III of the Netherlands and Luxembourg ...

and his sister-in-law and successor,

Queen Anne, were dead. Leibniz played a role in the initiatives and negotiations leading up to that Act, but not always an effective one. For example, something he published anonymously in England, thinking to promote the Brunswick cause, was formally censured by the

British Parliament

The Parliament of the United Kingdom is the supreme legislative body of the United Kingdom, the Crown Dependencies and the British Overseas Territories. It meets at the Palace of Westminster, London. It alone possesses legislative supremacy ...

.

The Brunswicks tolerated the enormous effort Leibniz devoted to intellectual pursuits unrelated to his duties as a courtier, pursuits such as perfecting calculus, writing about other mathematics, logic, physics, and philosophy, and keeping up a vast correspondence. He began working on calculus in 1674; the earliest evidence of its use in his surviving notebooks is 1675. By 1677 he had a coherent system in hand, but did not publish it until 1684. Leibniz's most important mathematical papers were published between 1682 and 1692, usually in a journal which he and

Otto Mencke

Otto Mencke (; ; 22 March 1644 – 18 January 1707) was a 17th-century German philosopher and scientist.

Work

Mencke obtained his doctorate at the University of Leipzig in August 1666 with a thesis entitled: ''Ex Theologia naturali – De A ...

founded in 1682, the ''

Acta Eruditorum

(from Latin: ''Acts of the Erudite'') was the first scientific journal of the German-speaking lands of Europe, published from 1682 to 1782.

History

''Acta Eruditorum'' was founded in 1682 in Leipzig by Otto Mencke, who became its first editor, ...

''. That journal played a key role in advancing his mathematical and scientific reputation, which in turn enhanced his eminence in diplomacy, history, theology, and philosophy.

The Elector

Ernest Augustus commissioned Leibniz to write a history of the House of Brunswick, going back to the time of

Charlemagne

Charlemagne ( , ) or Charles the Great ( la, Carolus Magnus; german: Karl der Große; 2 April 747 – 28 January 814), a member of the Carolingian dynasty, was King of the Franks from 768, King of the Lombards from 774, and the first Holy ...

or earlier, hoping that the resulting book would advance his dynastic ambitions. From 1687 to 1690, Leibniz traveled extensively in Germany, Austria, and Italy, seeking and finding archival materials bearing on this project. Decades went by but no history appeared; the next Elector became quite annoyed at Leibniz's apparent dilatoriness. Leibniz never finished the project, in part because of his huge output on many other fronts, but also because he insisted on writing a meticulously researched and erudite book based on archival sources, when his patrons would have been quite happy with a short popular book, one perhaps little more than a

genealogy

Genealogy () is the study of families, family history, and the tracing of their lineages. Genealogists use oral interviews, historical records, genetic analysis, and other records to obtain information about a family and to demonstrate kins ...

with commentary, to be completed in three years or less. They never knew that he had in fact carried out a fair part of his assigned task: when the material Leibniz had written and collected for his history of the House of Brunswick was finally published in the 19th century, it filled three volumes.

Leibniz was appointed Librarian of the

Herzog August Library

The Herzog August Library (german: link=no, Herzog August Bibliothek — "HAB"), in Wolfenbüttel, Lower Saxony, known also as ''Bibliotheca Augusta'', is a library of international importance for its collection from the Middle Ages and ear ...

in

Wolfenbüttel

Wolfenbüttel (; nds, Wulfenbüddel) is a town in Lower Saxony, Germany, the administrative capital of Wolfenbüttel District. It is best known as the location of the internationally renowned Herzog August Library and for having the largest c ...

,

Lower Saxony

Lower Saxony (german: Niedersachsen ; nds, Neddersassen; stq, Läichsaksen) is a German state (') in northwestern Germany. It is the second-largest state by land area, with , and fourth-largest in population (8 million in 2021) among the 16 ...

, in 1691.

In 1708,

John Keill

John Keill FRS (1 December 1671 – 31 August 1721) was a Scottish mathematician, natural philosopher, and cryptographer who was an important defender of Isaac Newton.

Biography

Keill was born in Edinburgh, Scotland on 1 December 1671. His f ...

, writing in the journal of the Royal Society and with Newton's presumed blessing, accused Leibniz of having plagiarised Newton's calculus. Thus began the

calculus priority dispute which darkened the remainder of Leibniz's life. A formal investigation by the Royal Society (in which Newton was an unacknowledged participant), undertaken in response to Leibniz's demand for a retraction, upheld Keill's charge. Historians of mathematics writing since 1900 or so have tended to acquit Leibniz, pointing to important differences between Leibniz's and Newton's versions of calculus.

In 1711, while traveling in northern Europe, the Russian

Tsar

Tsar ( or ), also spelled ''czar'', ''tzar'', or ''csar'', is a title used by East Slavs, East and South Slavs, South Slavic monarchs. The term is derived from the Latin word ''Caesar (title), caesar'', which was intended to mean "emperor" i ...

Peter the Great

Peter I ( – ), most commonly known as Peter the Great,) or Pyotr Alekséyevich ( rus, Пётр Алексе́евич, p=ˈpʲɵtr ɐlʲɪˈksʲejɪvʲɪtɕ, , group=pron was a Russian monarch who ruled the Tsardom of Russia from t ...

stopped in Hanover and met Leibniz, who then took some interest in Russian matters for the rest of his life. In 1712, Leibniz began a two-year residence in

Vienna

en, Viennese

, iso_code = AT-9

, registration_plate = W

, postal_code_type = Postal code

, postal_code =

, timezone = CET

, utc_offset = +1

, timezone_DST ...

, where he was appointed Imperial Court Councillor to the

Habsburg

The House of Habsburg (), alternatively spelled Hapsburg in Englishgerman: Haus Habsburg, ; es, Casa de Habsburgo; hu, Habsburg család, it, Casa di Asburgo, nl, Huis van Habsburg, pl, dom Habsburgów, pt, Casa de Habsburgo, la, Domus Hab ...

s. On the death of Queen Anne in 1714, Elector George Louis became King

George I of Great Britain

George I (George Louis; ; 28 May 1660 – 11 June 1727) was King of Great Britain and Ireland from 1 August 1714 and ruler of the Electorate of Hanover within the Holy Roman Empire from 23 January 1698 until his death in 1727. He was the first ...

, under the terms of the 1701 Act of Settlement. Even though Leibniz had done much to bring about this happy event, it was not to be his hour of glory. Despite the intercession of the Princess of Wales, Caroline of Ansbach, George I forbade Leibniz to join him in London until he completed at least one volume of the history of the Brunswick family his father had commissioned nearly 30 years earlier. Moreover, for George I to include Leibniz in his London court would have been deemed insulting to Newton, who was seen as having won the calculus priority dispute and whose standing in British official circles could not have been higher. Finally, his dear friend and defender, the Dowager Electress Sophia, died in 1714.

Death

Leibniz died in

Hanover

Hanover (; german: Hannover ; nds, Hannober) is the capital and largest city of the German state of Lower Saxony. Its 535,932 (2021) inhabitants make it the 13th-largest city in Germany as well as the fourth-largest city in Northern Germany ...

in 1716. At the time, he was so out of favor that neither George I (who happened to be near Hanover at that time) nor any fellow courtier other than his personal secretary attended the funeral. Even though Leibniz was a life member of the Royal Society and the

Berlin Academy of Sciences, neither organization saw fit to honor his death. His grave went unmarked for more than 50 years. He was, however, eulogized by

Fontenelle, before the

French Academy of Sciences

The French Academy of Sciences (French: ''Académie des sciences'') is a learned society, founded in 1666 by Louis XIV of France, Louis XIV at the suggestion of Jean-Baptiste Colbert, to encourage and protect the spirit of French Scientific me ...

in Paris, which had admitted him as a foreign member in 1700. The eulogy was composed at the behest of the

Duchess of Orleans

Duke is a male title either of a monarch ruling over a duchy, or of a member of royalty, or nobility. As rulers, dukes are ranked below emperors, kings, grand princes, grand dukes, and sovereign princes. As royalty or nobility, they are ranked ...

, a niece of the Electress Sophia.

Personal life

Leibniz never married. He complained on occasion about money, but the fair sum he left to his sole heir, his sister's stepson, proved that the Brunswicks had, by and large, paid him well. In his diplomatic endeavors, he at times verged on the unscrupulous, as was all too often the case with professional diplomats of his day. On several occasions, Leibniz backdated and altered personal manuscripts, actions which put him in a bad light during the

calculus controversy.

He was charming, well-mannered, and not without humor and imagination. He had many friends and admirers all over Europe. He identified as a

Protestant

Protestantism is a Christian denomination, branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Reformation, Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century agai ...

and a

philosophical theist. Leibniz remained committed to

Trinitarian Christianity

The Christian doctrine of the Trinity (, from 'threefold') is the central dogma concerning the nature of God in most Christian churches, which defines one God existing in three coequal, coeternal, consubstantial divine persons: God the Fa ...

throughout his life.

Philosopher

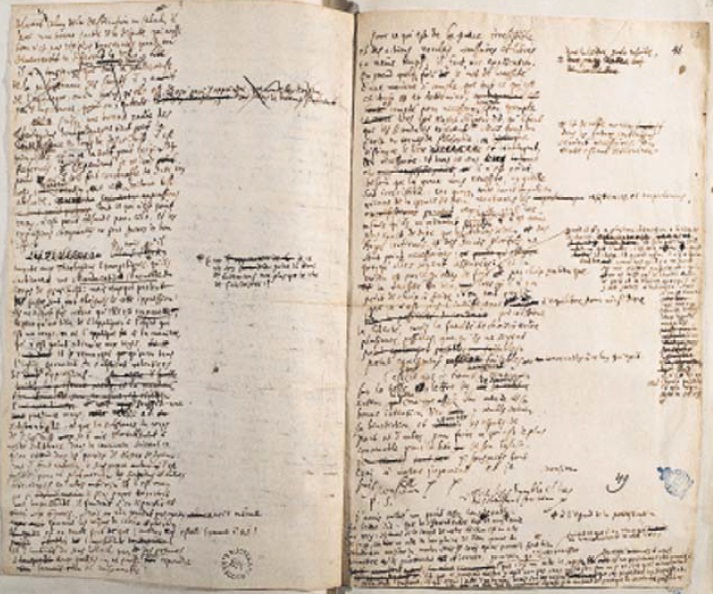

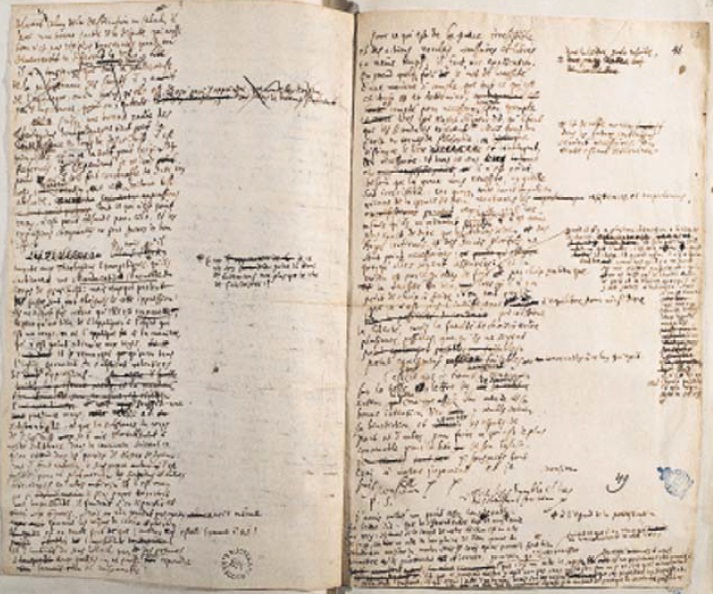

Leibniz's philosophical thinking appears fragmented, because his philosophical writings consist mainly of a multitude of short pieces: journal articles, manuscripts published long after his death, and many letters to many correspondents. He wrote only two book-length philosophical treatises, of which only the ''Théodicée'' of 1710 was published in his lifetime.

Leibniz dated his beginning as a philosopher to his ''

Discourse on Metaphysics

The ''Discourse on Metaphysics'' (french: Discours de métaphysique, 1686) is a short treatise by Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz in which he develops a philosophy concerning physical substance, motion and resistance of bodies, and God's role within the ...

'', which he composed in 1686 as a commentary on a running dispute between

Nicolas Malebranche

Nicolas Malebranche ( , ; 6 August 1638 – 13 October 1715) was a French Oratorian Catholic priest and rationalist philosopher. In his works, he sought to synthesize the thought of St. Augustine and Descartes, in order to demonstrate the ...

and

Antoine Arnauld

Antoine Arnauld (6 February 16128 August 1694) was a French Catholic theologian, philosopher and mathematician. He was one of the leading intellectuals of the Jansenist group of Port-Royal and had a very thorough knowledge of patristics. Contem ...

. This led to an extensive and valuable correspondence with Arnauld; it and the ''Discourse'' were not published until the 19th century. In 1695, Leibniz made his public entrée into European philosophy with a journal article titled "New System of the Nature and Communication of Substances". Between 1695 and 1705, he composed his ''

New Essays on Human Understanding

''New Essays on Human Understanding'' (french: Nouveaux essais sur l'entendement humain) is a chapter-by-chapter rebuttal by Gottfried Leibniz of John Locke's major work ''An Essay Concerning Human Understanding''. It is one of only two full-lengt ...

'', a lengthy commentary on

John Locke

John Locke (; 29 August 1632 – 28 October 1704) was an English philosopher and physician, widely regarded as one of the most influential of Age of Enlightenment, Enlightenment thinkers and commonly known as the "father of liberalism ...

's 1690 ''

An Essay Concerning Human Understanding

''An Essay Concerning Human Understanding'' is a work by John Locke concerning the foundation of human knowledge and understanding. It first appeared in 1689 (although dated 1690) with the printed title ''An Essay Concerning Humane Understand ...

'', but upon learning of Locke's 1704 death, lost the desire to publish it, so that the ''New Essays'' were not published until 1765. The ''

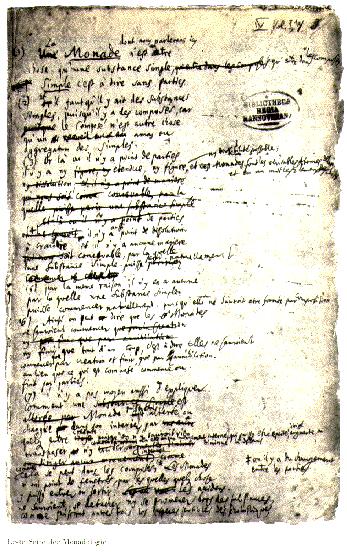

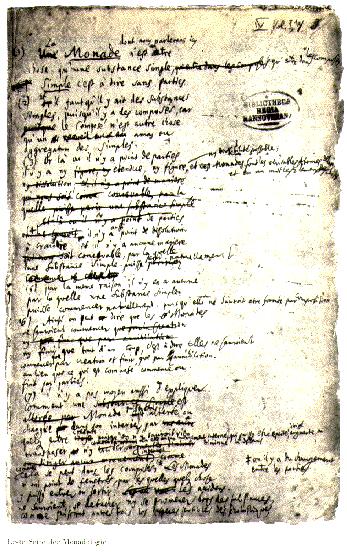

Monadologie

The ''Monadology'' (french: La Monadologie, 1714) is one of Gottfried Leibniz's best known works of his later philosophy. It is a short text which presents, in some 90 paragraphs, a metaphysics of simple substance theory, substances, or ''monad ...

'', composed in 1714 and published posthumously, consists of 90 aphorisms.

Leibniz also wrote a short paper, "Primae veritates" ("First Truths"), first published by

Louis Couturat

Louis Couturat (; 17 January 1868 – 3 August 1914) was a French logician, mathematician, philosopher, and linguist. Couturat was a pioneer of the constructed language Ido.

Life and education

Born in Ris-Orangis, Essonne, France. In 1887 he ...

in 1903 (pp. 518–523) summarizing his views on

metaphysics

Metaphysics is the branch of philosophy that studies the fundamental nature of reality, the first principles of being, identity and change, space and time, causality, necessity, and possibility. It includes questions about the nature of conscio ...

. The paper is undated; that he wrote it while in Vienna in 1689 was determined only in 1999, when the ongoing critical edition finally published Leibniz's philosophical writings for the period 1677–90. Couturat's reading of this paper was the launching point for much 20th-century thinking about Leibniz, especially among

analytic philosophers

Analytic philosophy is a branch and tradition of philosophy using analysis, popular in the Western world and particularly the Anglosphere, which began around the turn of the 20th century in the contemporary era in the United Kingdom, United Sta ...

. But after a meticulous study of all of Leibniz's philosophical writings up to 1688—a study the 1999 additions to the critical edition made possible—Mercer (2001) begged to differ with Couturat's reading; the jury is still out.

Leibniz met

Spinoza

Baruch (de) Spinoza (born Bento de Espinosa; later as an author and a correspondent ''Benedictus de Spinoza'', anglicized to ''Benedict de Spinoza''; 24 November 1632 – 21 February 1677) was a Dutch philosopher of Portuguese-Jewish origin, b ...

in 1676, read some of his unpublished writings, and has since been suspected of appropriating some of Spinoza's ideas. While Leibniz admired Spinoza's powerful intellect, he was also forthrightly dismayed by Spinoza's conclusions, especially when these were inconsistent with Christian orthodoxy.

Unlike Descartes and Spinoza, Leibniz had a thorough university education in philosophy. He was influenced by his

Leipzig

Leipzig ( , ; Upper Saxon: ) is the most populous city in the German state of Saxony. Leipzig's population of 605,407 inhabitants (1.1 million in the larger urban zone) as of 2021 places the city as Germany's eighth most populous, as wel ...

professor

Jakob Thomasius

Jakob Thomasius ( la, Jacobus Thomasius; 27 August 1622 – 9 September 1684) was a German academic philosopher and jurist. He is now regarded as an important founding figure in the scholarly study of the history of philosophy. His views were e ...

, who also supervised his BA thesis in philosophy.

[Arthur 2014, p. 13.] Leibniz also eagerly read

Francisco Suárez

Francisco Suárez, (5 January 1548 – 25 September 1617) was a Spanish Jesuit priest, philosopher and theologian, one of the leading figures of the School of Salamanca movement, and generally regarded among the greatest scholastics after Thomas ...

, a Spanish

Jesuit

, image = Ihs-logo.svg

, image_size = 175px

, caption = ChristogramOfficial seal of the Jesuits

, abbreviation = SJ

, nickname = Jesuits

, formation =

, founders ...

respected even in

Lutheran

Lutheranism is one of the largest branches of Protestantism, identifying primarily with the theology of Martin Luther, the 16th-century German monk and reformer whose efforts to reform the theology and practice of the Catholic Church launched th ...

universities. Leibniz was deeply interested in the new methods and conclusions of Descartes, Huygens, Newton, and

Boyle

Boyle is an English, Irish and Scottish surname of Gaelic, Anglo-Saxon or Norman origin. In the northwest of Ireland it is one of the most common family names. Notable people with the surname include:

Disambiguation

*Adam Boyle (disambiguation), ...

, but viewed their work through a lens heavily tinted by scholastic notions. Yet it remains the case that Leibniz's methods and concerns often anticipate the

logic

Logic is the study of correct reasoning. It includes both formal and informal logic. Formal logic is the science of deductively valid inferences or of logical truths. It is a formal science investigating how conclusions follow from premises ...

, and

analytic and

linguistic philosophy

__notoc__

Linguistic philosophy is the view that many or all philosophical problems can be solved (or dissolved) by paying closer attention to language, either by reforming language or by better understanding our everyday language. The former pos ...

of the 20th century.

Principles

Leibniz variously invoked one or another of seven fundamental philosophical Principles:

*

Identity

Identity may refer to:

* Identity document

* Identity (philosophy)

* Identity (social science)

* Identity (mathematics)

Arts and entertainment Film and television

* ''Identity'' (1987 film), an Iranian film

* ''Identity'' (2003 film), ...

/

contradiction

In traditional logic, a contradiction occurs when a proposition conflicts either with itself or established fact. It is often used as a tool to detect disingenuous beliefs and bias. Illustrating a general tendency in applied logic, Aristotle's ...

. If a proposition is true, then its negation is false and vice versa.

*

Identity of indiscernibles

The identity of indiscernibles is an ontological principle that states that there cannot be separate objects or entities that have all their properties in common. That is, entities ''x'' and ''y'' are identical if every predicate possessed by ''x'' ...

. Two distinct things cannot have all their properties in common. If every predicate possessed by x is also possessed by y and vice versa, then entities x and y are identical; to suppose two things indiscernible is to suppose the same thing under two names. Frequently invoked in modern logic and philosophy, the "identity of indiscernibles" is often referred to as Leibniz's Law. It has attracted the most controversy and criticism, especially from corpuscular philosophy and quantum mechanics.

*

Sufficient reason. "There must be a sufficient reason for anything to exist, for any event to occur, for any truth to obtain."

*

Pre-established harmony

Gottfried Leibniz's theory of pre-established harmony (french: harmonie préétablie) is a philosophical theory about causation under which every " substance" affects only itself, but all the substances (both bodies and minds) in the world never ...

. "

e appropriate nature of each substance brings it about that what happens to one corresponds to what happens to all the others, without, however, their acting upon one another directly." (''Discourse on Metaphysics'', XIV) A dropped glass shatters because it "knows" it has hit the ground, and not because the impact with the ground "compels" the glass to split.

*

Law of Continuity

The law of continuity is a heuristic principle introduced by Gottfried Leibniz based on earlier work by Nicholas of Cusa and Johannes Kepler. It is the principle that "whatever succeeds for the finite, also succeeds for the infinite". Kepler used ...

. ''

Natura non facit saltus

''Natura non facit saltus''Alexander Baumgarten, ''Metaphysics: A Critical Translation with Kant's Elucidations'', Translated and Edited by Courtney D. Fugate and John Hymers, Bloomsbury, 2013, "Preface of the Third Edition (1750)"p. 79 n. d " au ...

''

[Gottfried Leibniz, ''New Essays'', IV, 16: "''la nature ne fait jamais des sauts''". ''Natura non-facit saltus'' is the Latin translation of the phrase (originally put forward by ]Linnaeus

Carl Linnaeus (; 23 May 1707 – 10 January 1778), also known after his ennoblement in 1761 as Carl von Linné Blunt (2004), p. 171. (), was a Swedish botanist, zoologist, taxonomist, and physician who formalised binomial nomenclature, the ...

' ''Philosophia Botanica

''Philosophia Botanica'' ("Botanical Philosophy", ed. 1, Stockholm & Amsterdam, 1751.) was published by the Swedish naturalist and physician Carl Linnaeus (1707–1778) who greatly influenced the development of botanical taxonomy and systematics ...

'', 1st ed., 1751, Chapter III, § 77, p. 27; see also Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

The ''Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy'' (''SEP'') combines an online encyclopedia of philosophy with peer-reviewed publication of original papers in philosophy, freely accessible to Internet users. It is maintained by Stanford University. Eac ...

"Continuity and Infinitesimals"

and Alexander Baumgarten

Alexander Gottlieb Baumgarten (; ; 17 July 1714 – 27 MayJan LekschasBaumgarten Family'' 1762) was a German philosopher. He was a brother to theologian Siegmund Jakob Baumgarten (1706–1757).

Biography

Baumgarten was born in Berlin as the ...

, ''Metaphysics: A Critical Translation with Kant's Elucidations'', Translated and Edited by Courtney D. Fugate and John Hymers, Bloomsbury, 2013, "Preface of the Third Edition (1750)"

p. 79 n.d.

" aumgartenmust also have in mind Leibniz's "''natura non-facit saltus'' ature does not make leaps ( NE IV, 16)."). A variant translation is "''natura non-saltum facit''" (literally, "Nature does not make a jump")

Extract of page 289

) (literally, "Nature does not make jumps").

*

Optimism

Optimism is an attitude reflecting a belief or hope that the outcome of some specific endeavor, or outcomes in general, will be positive, favorable, and desirable. A common idiom used to illustrate optimism versus pessimism is a glass filled wi ...

. "God assuredly always chooses the best."

*

Plenitude The principle of plenitude asserts that the universe contains all possible forms of existence. Arthur Lovejoy, a historian of ideas, was the first to trace the history of this philosophically important principle explicitly. Lovejoy distinguishes ...

. Leibniz believed that the best of all possible worlds would actualize every genuine possibility, and argued in ''Théodicée'' that this best of all possible worlds will contain all possibilities, with our finite experience of eternity giving no reason to dispute nature's perfection.

Leibniz would on occasion give a rational defense of a specific principle, but more often took them for granted.

Monads

Leibniz's best known contribution to

metaphysics

Metaphysics is the branch of philosophy that studies the fundamental nature of reality, the first principles of being, identity and change, space and time, causality, necessity, and possibility. It includes questions about the nature of conscio ...

is his theory of

monads, as exposited in ''

Monadologie

The ''Monadology'' (french: La Monadologie, 1714) is one of Gottfried Leibniz's best known works of his later philosophy. It is a short text which presents, in some 90 paragraphs, a metaphysics of simple substance theory, substances, or ''monad ...

''. He proposes his theory that the universe is made of an infinite number of simple substances known as monads. Monads can also be compared to the corpuscles of the

mechanical philosophy

The mechanical philosophy is a form of natural philosophy which compares the universe to a large-scale mechanism (i.e. a machine). The mechanical philosophy is associated with the scientific revolution of early modern Europe. One of the first expos ...

of René Descartes and others. These simple substances or monads are the "ultimate units of existence in nature". Monads have no parts but still exist by the qualities that they have. These qualities are continuously changing over time, and each monad is unique. They are also not affected by time and are subject to only creation and annihilation. Monads are centers of

force

In physics, a force is an influence that can change the motion of an object. A force can cause an object with mass to change its velocity (e.g. moving from a state of rest), i.e., to accelerate. Force can also be described intuitively as a p ...

; substance is force, while

space

Space is the boundless three-dimensional extent in which objects and events have relative position and direction. In classical physics, physical space is often conceived in three linear dimensions, although modern physicists usually consider ...

,

matter

In classical physics and general chemistry, matter is any substance that has mass and takes up space by having volume. All everyday objects that can be touched are ultimately composed of atoms, which are made up of interacting subatomic partic ...

, and

motion

In physics, motion is the phenomenon in which an object changes its position with respect to time. Motion is mathematically described in terms of displacement, distance, velocity, acceleration, speed and frame of reference to an observer and mea ...

are merely phenomenal. It is said that he anticipated

Albert Einstein

Albert Einstein ( ; ; 14 March 1879 – 18 April 1955) was a German-born theoretical physicist, widely acknowledged to be one of the greatest and most influential physicists of all time. Einstein is best known for developing the theory ...

by arguing, against Newton, that

space

Space is the boundless three-dimensional extent in which objects and events have relative position and direction. In classical physics, physical space is often conceived in three linear dimensions, although modern physicists usually consider ...

,

time

Time is the continued sequence of existence and events that occurs in an apparently irreversible succession from the past, through the present, into the future. It is a component quantity of various measurements used to sequence events, to ...

, and motion are completely relative as he quipped,

"As for my own opinion, I have said more than once, that I hold space to be something merely relative, as time is, that I hold it to be an order of coexistences, as time is an order of successions."

[See H. G. Alexander, ed., ''The Leibniz-Clarke Correspondence'', Manchester: Manchester University Press, pp. 25–26.] Einstein, who called himself a "Leibnizian" even wrote in the introduction to

Max Jammer

Max Jammer (מקס ימר; born Moshe Jammer, ; April 13, 1915 – December 18, 2010), was an Israeli physicist and philosopher of physics. He was born in Berlin, Germany. He was Rector and Acting President at Bar-Ilan University from 1967 to 1 ...

's book ''Concepts of Space'' that Leibnizianism was superior to Newtonianism, and his ideas would have dominated over Newton's had it not been for the poor technological tools of the time; it has been argued that Leibniz paved the way for Einstein's

theory of relativity

The theory of relativity usually encompasses two interrelated theories by Albert Einstein: special relativity and general relativity, proposed and published in 1905 and 1915, respectively. Special relativity applies to all physical phenomena in ...

.

Leibniz's proof of God can be summarized in the ''

Théodicée

(from French: ''Essays of Theodicy on the Goodness of God, the Freedom of Man and the Origin of Evil''), more simply known as , is a book of philosophy by the German polymath Gottfried Leibniz. The book, published in 1710, introduced the term ...

''.

Reason is governed by the

principle of contradiction

In logic, the law of non-contradiction (LNC) (also known as the law of contradiction, principle of non-contradiction (PNC), or the principle of contradiction) states that contradictory propositions cannot both be true in the same sense at the sa ...

and the

principle of sufficient reason

The principle of sufficient reason states that everything must have a reason or a cause. The principle was articulated and made prominent by Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, with many antecedents, and was further used and developed by Arthur Schopenhau ...

. Using the principle of reasoning, Leibniz concluded that the first reason of all things is God.

All that we see and experience is subject to change, and the fact that this world is contingent can be explained by the possibility of the world being arranged differently in space and time. The contingent world must have some necessary reason for its existence. Leibniz uses a geometry book as an example to explain his reasoning. If this book was copied from an infinite chain of copies, there must be some reason for the content of the book. Leibniz concluded that there must be the "''monas monadum''" or God.

The

ontological

In metaphysics, ontology is the philosophical study of being, as well as related concepts such as existence, becoming, and reality.

Ontology addresses questions like how entities are grouped into categories and which of these entities exis ...

essence of a monad is its irreducible simplicity. Unlike atoms, monads possess no material or spatial character. They also differ from atoms by their complete mutual independence, so that interactions among monads are only apparent. Instead, by virtue of the principle of

pre-established harmony

Gottfried Leibniz's theory of pre-established harmony (french: harmonie préétablie) is a philosophical theory about causation under which every " substance" affects only itself, but all the substances (both bodies and minds) in the world never ...

, each monad follows a pre-programmed set of "instructions" peculiar to itself, so that a monad "knows" what to do at each moment. By virtue of these intrinsic instructions, each monad is like a little mirror of the universe. Monads need not be "small"; e.g., each human being constitutes a monad, in which case

free will

Free will is the capacity of agents to choose between different possible courses of action unimpeded.

Free will is closely linked to the concepts of moral responsibility, praise, culpability, sin, and other judgements which apply only to actio ...

is problematic.

Monads are purported to have gotten rid of the problematic:

* interaction between

mind

The mind is the set of faculties responsible for all mental phenomena. Often the term is also identified with the phenomena themselves. These faculties include thought, imagination, memory, will, and sensation. They are responsible for various m ...

and matter arising in the system of

Descartes;

* lack of

individuation

The principle of individuation, or ', describes the manner in which a thing is identified as distinct from other things.

The concept appears in numerous fields and is encountered in works of Leibniz, Carl Gustav Jung, Gunther Anders, Gilbert Sim ...

inherent to the system of

Spinoza

Baruch (de) Spinoza (born Bento de Espinosa; later as an author and a correspondent ''Benedictus de Spinoza'', anglicized to ''Benedict de Spinoza''; 24 November 1632 – 21 February 1677) was a Dutch philosopher of Portuguese-Jewish origin, b ...

, which represents individual creatures as merely accidental.

Theodicy and optimism

The ''

Theodicy

Theodicy () means vindication of God. It is to answer the question of why a good God permits the manifestation of evil, thus resolving the issue of the problem of evil. Some theodicies also address the problem of evil "to make the existence of ...

'' tries to justify the apparent imperfections of the world by claiming that it is

optimal among all possible worlds. It must be the best possible and most balanced world, because it was created by an all powerful and all knowing God, who would not choose to create an imperfect world if a better world could be known to him or possible to exist. In effect, apparent flaws that can be identified in this world must exist in every possible world, because otherwise God would have chosen to create the world that excluded those flaws.