John Sherman (May 10, 1823October 22, 1900) was an American politician from

Ohio

Ohio () is a state in the Midwestern region of the United States. Of the fifty U.S. states, it is the 34th-largest by area, and with a population of nearly 11.8 million, is the seventh-most populous and tenth-most densely populated. The sta ...

throughout the

Civil War

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies ...

and into the late nineteenth century. A member of the

Republican Party

Republican Party is a name used by many political parties around the world, though the term most commonly refers to the United States' Republican Party.

Republican Party may also refer to:

Africa

*Republican Party (Liberia)

* Republican Part ...

, he served in both houses of the

U.S. Congress

The United States Congress is the legislature of the federal government of the United States. It is Bicameralism, bicameral, composed of a lower body, the United States House of Representatives, House of Representatives, and an upper body, ...

. He also served as

Secretary of the Treasury

The United States secretary of the treasury is the head of the United States Department of the Treasury, and is the chief financial officer of the federal government of the United States. The secretary of the treasury serves as the principal a ...

and

Secretary of State. Sherman sought the Republican presidential nomination three times, coming closest

in 1888, but was never chosen by the party.

Born in

Lancaster, Ohio

Lancaster ( ) is a city in Fairfield County, Ohio, in the south-central part of the state. As of the 2020 census, the city population was 40,552. The city is near the Hocking River, about southeast of Columbus and southwest of Zanesville. It is ...

, Sherman later moved to

Mansfield, Ohio

Mansfield is a city in and the county seat of Richland County, Ohio, United States. Located midway between Columbus and Cleveland via Interstate 71, it is part of Northeast Ohio region in the western foothills of the Allegheny Plateau. The city ...

, where he began a law career before entering politics. Initially a

Whig, Sherman was among those

anti-slavery

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the movement to end slavery. In Western Europe and the Americas, abolitionism was a historic movement that sought to end the Atlantic slave trade and liberate the enslaved people.

The Britis ...

activists who formed what became the Republican Party. He served three terms in the House of Representatives. As a member of the House, Sherman traveled to

Kansas

Kansas () is a state in the Midwestern United States. Its capital is Topeka, and its largest city is Wichita. Kansas is a landlocked state bordered by Nebraska to the north; Missouri to the east; Oklahoma to the south; and Colorado to the ...

to investigate

the unrest between pro- and anti-slavery partisans there. He rose in party leadership and was nearly elected

Speaker

Speaker may refer to:

Society and politics

* Speaker (politics), the presiding officer in a legislative assembly

* Public speaker, one who gives a speech or lecture

* A person producing speech: the producer of a given utterance, especially:

** In ...

in

1859

Events

January–March

* January 21 – José Mariano Salas (1797–1867) becomes Conservative interim President of Mexico.

* January 24 ( O. S.) – Wallachia and Moldavia are united under Alexandru Ioan Cuza (Romania since 1866, final u ...

. Sherman was elected to the Senate

in 1861. As a senator, he was a leader in financial matters, helping to redesign the United States'

monetary system

A monetary system is a system by which a government provides money in a country's economy. Modern monetary systems usually consist of the national treasury, the mint, the central banks and commercial banks.

Commodity money system

A commodity m ...

to meet the needs of a nation torn apart by civil war. He also served as the Chair of the Senate Agriculture Committee during his 32 years in the Senate. After the war, he worked to produce legislation that would restore the nation's credit abroad and produce a stable,

gold-backed currency at home.

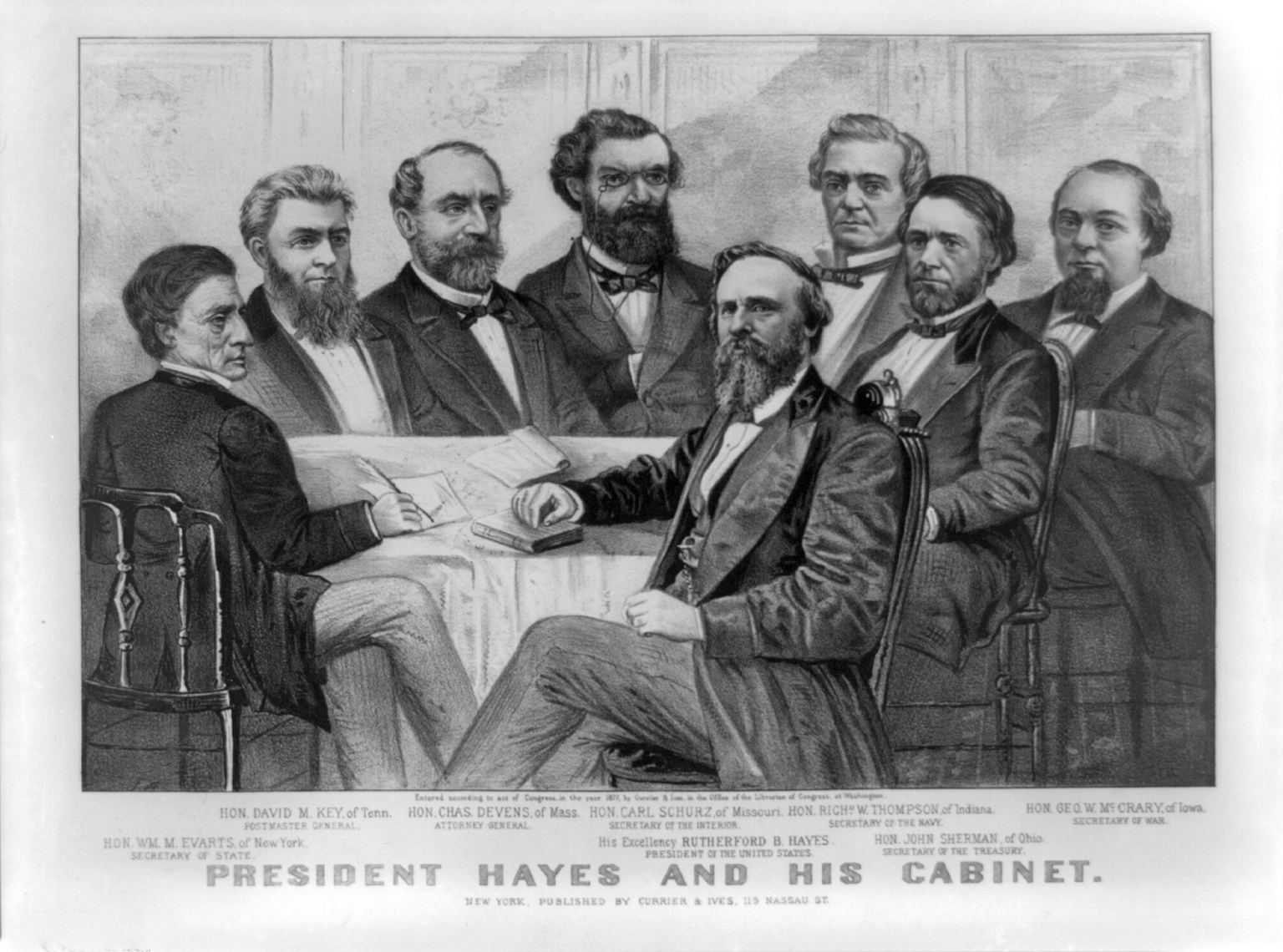

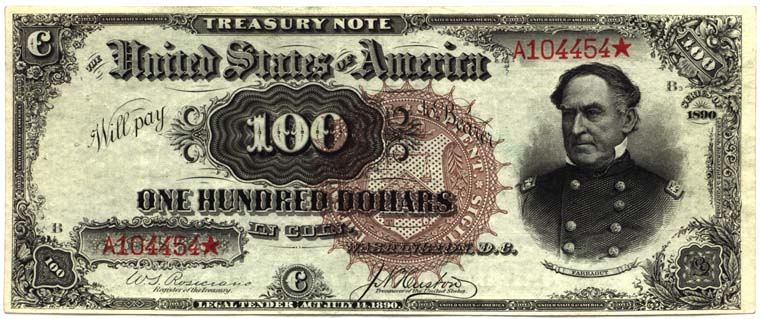

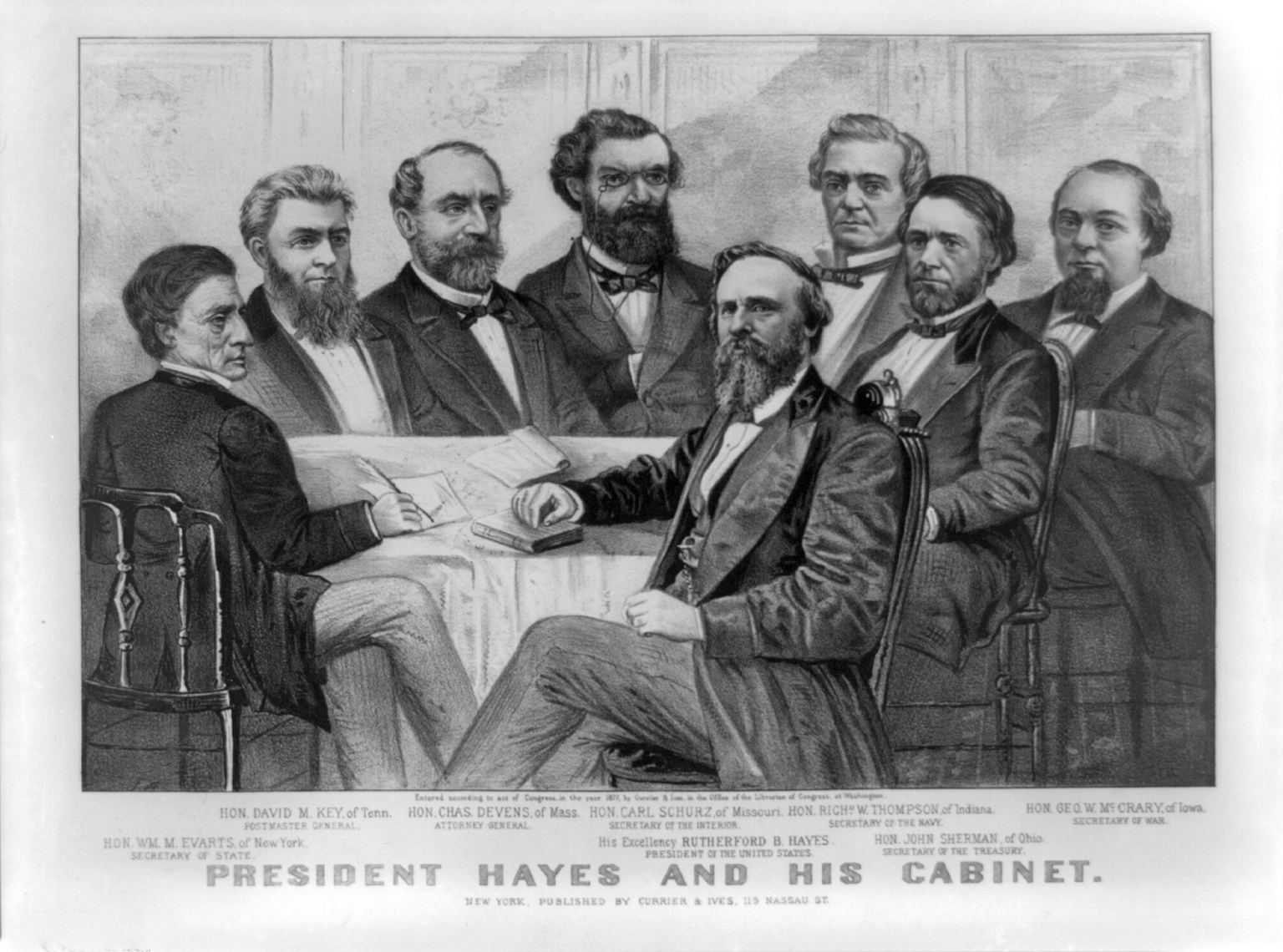

Serving as Secretary of the Treasury in the administration of

Rutherford B. Hayes

Rutherford Birchard Hayes (; October 4, 1822 – January 17, 1893) was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 19th president of the United States from 1877 to 1881, after serving in the U.S. House of Representatives and as governor ...

, Sherman continued his efforts for financial stability and solvency, overseeing an end to wartime

inflationary Inflationism is a heterodox economic, fiscal, or monetary policy, that predicts that a substantial level of inflation is harmless, desirable or even advantageous. Similarly, inflationist economists advocate for an inflationist policy.

Mainstream ec ...

measures and a return to gold-backed money. He returned to the Senate after his term expired, serving there for a further sixteen years. During that time he continued his work on financial legislation, as well as writing and debating laws on

immigration

Immigration is the international movement of people to a destination country of which they are not natives or where they do not possess citizenship in order to settle as permanent residents or naturalized citizens. Commuters, tourists, and ...

,

business competition law, and the regulation of

interstate commerce

The Commerce Clause describes an enumerated power listed in the United States Constitution ( Article I, Section 8, Clause 3). The clause states that the United States Congress shall have power "to regulate Commerce with foreign Nations, and among ...

. Sherman was the principal author of the

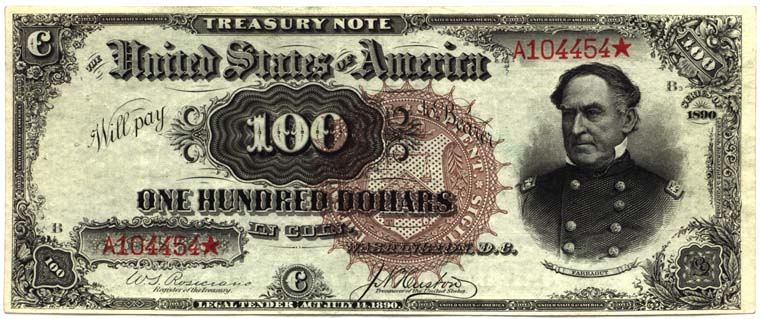

Sherman Antitrust Act

The Sherman Antitrust Act of 1890 (, ) is a United States antitrust law which prescribes the rule of free competition among those engaged in commerce. It was passed by Congress and is named for Senator John Sherman, its principal author.

Th ...

, which was signed into law by President

Benjamin Harrison

Benjamin Harrison (August 20, 1833March 13, 1901) was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 23rd president of the United States from 1889 to 1893. He was a member of the Harrison family of Virginia–a grandson of the ninth pr ...

in 1890. In 1897, President

William McKinley

William McKinley (January 29, 1843September 14, 1901) was the 25th president of the United States, serving from 1897 until his assassination in 1901. As a politician he led a realignment that made his Republican Party largely dominant in ...

appointed him Secretary of State. Failing health and declining faculties made him unable to handle the burdens of the job, and he retired in 1898 at the start of the

Spanish–American War

, partof = the Philippine Revolution, the decolonization of the Americas, and the Cuban War of Independence

, image = Collage infobox for Spanish-American War.jpg

, image_size = 300px

, caption = (clock ...

. Sherman died at his home in Washington, D.C., in 1900 at age 77.

His brothers included

William Tecumseh Sherman

William Tecumseh Sherman ( ; February 8, 1820February 14, 1891) was an American soldier, businessman, educator, and author. He served as a general in the Union Army during the American Civil War (1861–1865), achieving recognition for his com ...

, a

United States Army general;

Charles Taylor Sherman

Charles Taylor Sherman (February 3, 1811 – January 1, 1879) was a United States district judge of the United States District Court for the Northern District of Ohio.

Education and career

Born on February 3, 1811, in Norwalk, Connecticut, Sher ...

, a federal judge in Ohio; and

Hoyt Sherman

Major Hoyt Sherman (November 21, 1827 – January 25, 1904), a member of the prominent Sherman family, was an American banker.

Biography

Hoyt Sherman was born in 1827 in Lancaster, Ohio, the son of Charles R. Sherman, Judge of the Ohio S ...

, an Iowa banker.

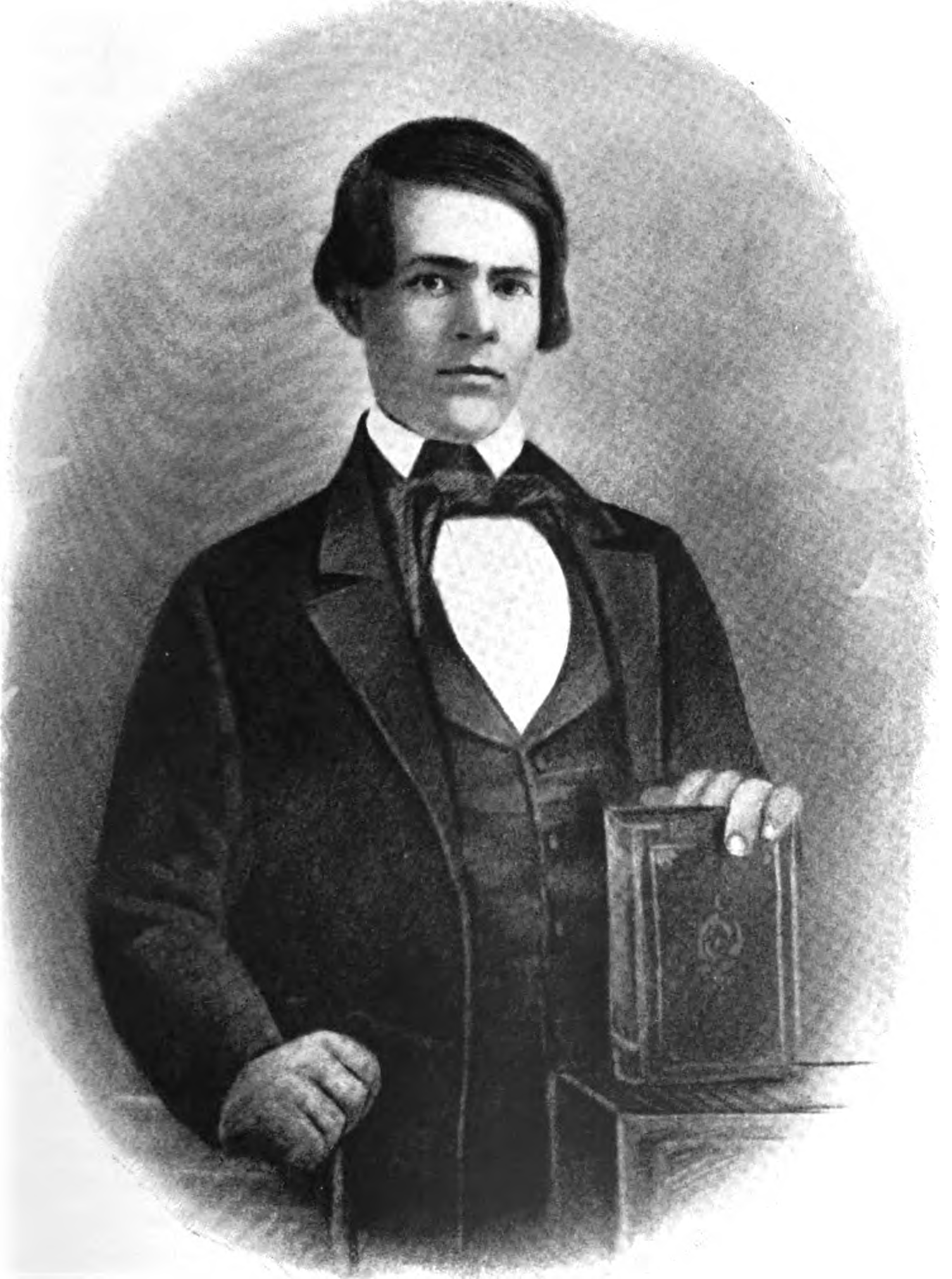

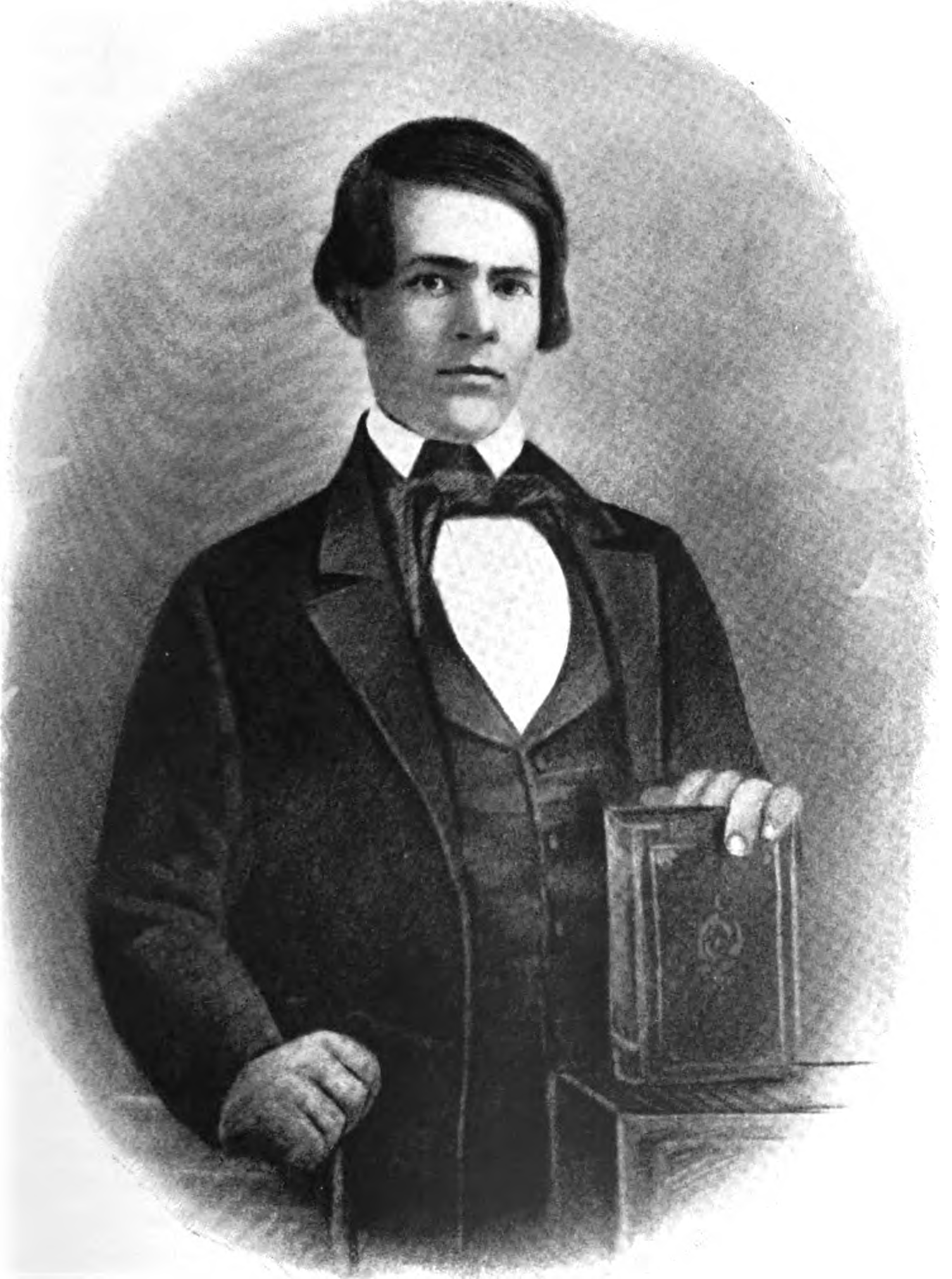

Early life and education

Sherman was born in

Lancaster, Ohio

Lancaster ( ) is a city in Fairfield County, Ohio, in the south-central part of the state. As of the 2020 census, the city population was 40,552. The city is near the Hocking River, about southeast of Columbus and southwest of Zanesville. It is ...

, to

Charles Robert Sherman

Charles Robert Sherman (c. September 26, 1788 – June 24, 1829) was an American lawyer and public servant. Of his 11 children, four became prominent public figures during and after the civil war.

Life and career

Sherman was born in Norwalk ...

and his wife, Mary Hoyt Sherman, the eighth of their 11 children. John Sherman's grandfather,

Taylor Sherman

Taylor Sherman (September 5, 1758 – May 14, 1815) was a member of the Connecticut House of Representatives from Norwalk in the sessions of May 1794, May 1795, and May 1796.

Sherman was born in Woodbury, Connecticut on September 5, 1758. He ...

, a Connecticut lawyer and judge, first visited Ohio in the early nineteenth century, gaining title to several parcels of land before returning to Connecticut. After Taylor's death in 1815, his son Charles, newly married to Mary Hoyt, moved the family west to Ohio. Several other Sherman relatives soon followed, and Charles became established as a lawyer in Lancaster. By the time of John Sherman's birth, Charles had just been appointed a justice of the

Supreme Court of Ohio

The Ohio Supreme Court, Officially known as The Supreme Court of the State of Ohio is the highest court in the U.S. state of Ohio, with final authority over interpretations of Ohio law and the Ohio Constitution. The court has seven members, a ...

.

Sherman's father died suddenly in 1829, leaving his mother to care for 11 children. Several of the oldest children, including Sherman's older brother

William Tecumseh Sherman

William Tecumseh Sherman ( ; February 8, 1820February 14, 1891) was an American soldier, businessman, educator, and author. He served as a general in the Union Army during the American Civil War (1861–1865), achieving recognition for his com ...

, were fostered with nearby relatives, but John and his brother

Hoyt Hoyt may refer to:

Places Canada

*Hoyt, New Brunswick

United States

*Hoyt, Colorado

*Hoyt, Kansas

*Hoyt, West Virginia

*Hoyt, Wisconsin

*Hoyt Peak, a mountain in Yellowstone National Park, Wyoming

Other uses

*Hoyt (name)

*Hoyt Archery, a bow manu ...

stayed with their mother in Lancaster until 1831. In that year, Sherman's father's cousin (also named John Sherman) took Sherman into his home in

Mount Vernon, Ohio

Mount Vernon is a city in Knox County, Ohio, United States. It is located northeast of Columbus. The population was 16,990 at the 2010 census. It is the county seat of Knox County.

History

The community was platted in 1805, and named after Mo ...

, where he enrolled in school. The other John Sherman intended for his namesake to study there until he was ready to enroll at nearby

Kenyon College

Kenyon College is a private liberal arts college in Gambier, Ohio. It was founded in 1824 by Philander Chase. Kenyon College is accredited by the Higher Learning Commission.

Kenyon has 1,708 undergraduates enrolled. Its 1,000-acre campus is se ...

, but Sherman disliked school and was, in his own words, "a troublesome boy". In 1835, he returned to

his mother's home in Lancaster. Sherman continued his education there at a local academy where, after being briefly expelled for punching a teacher, he studied for two years.

In 1837, Sherman left school and found a job as a junior

surveyor

Surveying or land surveying is the technique, profession, art, and science of determining the terrestrial two-dimensional or three-dimensional positions of points and the distances and angles between them. A land surveying professional is ca ...

on construction of improvements to the

Muskingum River

The Muskingum River (Shawnee: ') is a tributary of the Ohio River, approximately long, in southeastern Ohio in the United States. An important commercial route in the 19th century, it flows generally southward through the eastern hill country o ...

. Because he had obtained the job through

Whig Party patronage

Patronage is the support, encouragement, privilege, or financial aid that an organization or individual bestows on another. In the history of art, arts patronage refers to the support that kings, popes, and the wealthy have provided to artists su ...

, the election of a

Democratic governor in 1838 meant that Sherman and the rest of his surveying crew were discharged from their jobs in June 1839. The following year, he moved to

Mansfield

Mansfield is a market town and the administrative centre of Mansfield District in Nottinghamshire, England. It is the largest town in the wider Mansfield Urban Area (followed by Sutton-in-Ashfield). It gained the Royal Charter of a market tow ...

to

study law in the office of his older brother,

Charles Taylor Sherman

Charles Taylor Sherman (February 3, 1811 – January 1, 1879) was a United States district judge of the United States District Court for the Northern District of Ohio.

Education and career

Born on February 3, 1811, in Norwalk, Connecticut, Sher ...

. He was admitted to the

bar

Bar or BAR may refer to:

Food and drink

* Bar (establishment), selling alcoholic beverages

* Candy bar

* Chocolate bar

Science and technology

* Bar (river morphology), a deposit of sediment

* Bar (tropical cyclone), a layer of cloud

* Bar (u ...

in 1844 and joined his brother's firm. Sherman quickly became successful at the practice of law, and by 1847 had accumulated property worth $10,000 and was a partner in several local businesses. By that time, Sherman and his brother Charles were able to support their mother and two unmarried sisters, who now moved to a house Sherman purchased in Mansfield. In 1848, Sherman married Margaret Cecilia Stewart, the daughter of a local judge. The couple never had any biological children, but adopted a daughter, Mary, in 1864.

Around the same time, Sherman began to take a larger role in politics. In 1844, he addressed a political rally on behalf of the Whig candidate for president that year,

Henry Clay

Henry Clay Sr. (April 12, 1777June 29, 1852) was an American attorney and statesman who represented Kentucky in both the U.S. Senate and House of Representatives. He was the seventh House speaker as well as the ninth secretary of state, al ...

. Four years later, Sherman was a delegate to the

Whig National Convention where the eventual winner

Zachary Taylor

Zachary Taylor (November 24, 1784 – July 9, 1850) was an American military leader who served as the 12th president of the United States from 1849 until his death in 1850. Taylor was a career officer in the United States Army, rising to th ...

was nominated. As with most conservative Whigs, Sherman supported the

Compromise of 1850

The Compromise of 1850 was a package of five separate bills passed by the United States Congress in September 1850 that defused a political confrontation between slave and free states on the status of territories acquired in the Mexican–Ame ...

as the best solution to the growing sectional divide. In 1852, Sherman was again a delegate to the

Whig National Convention, where he supported the eventual nominee,

Winfield Scott

Winfield Scott (June 13, 1786May 29, 1866) was an American military commander and political candidate. He served as a general in the United States Army from 1814 to 1861, taking part in the War of 1812, the Mexican–American War, the early s ...

, against rivals

Daniel Webster

Daniel Webster (January 18, 1782 – October 24, 1852) was an American lawyer and statesman who represented New Hampshire and Massachusetts in the U.S. Congress and served as the U.S. Secretary of State under Presidents William Henry Harrison, ...

and incumbent

Millard Fillmore

Millard Fillmore (January 7, 1800March 8, 1874) was the 13th president of the United States, serving from 1850 to 1853; he was the last to be a member of the Whig Party while in the White House. A former member of the U.S. House of Represen ...

, who had become president following Taylor's death.

House of Representatives

Sherman moved north to

Cleveland

Cleveland ( ), officially the City of Cleveland, is a city in the U.S. state of Ohio and the county seat of Cuyahoga County. Located in the northeastern part of the state, it is situated along the southern shore of Lake Erie, across the U.S. ...

in 1853 and established a law office there with two partners. Events soon interrupted Sherman's plans for a new law firm, as the passage of the

Kansas–Nebraska Act

The Kansas–Nebraska Act of 1854 () was a territorial organic act that created the territories of Kansas and Nebraska. It was drafted by Democratic Senator Stephen A. Douglas, passed by the 33rd United States Congress, and signed into law by ...

in 1854 inspired him (and many other anti-slavery Northerners) to take a more involved role in politics. That Act, the brainchild of Illinois Democrat

Stephen A. Douglas

Stephen Arnold Douglas (April 23, 1813 – June 3, 1861) was an American politician and lawyer from Illinois. A senator, he was one of two nominees of the badly split Democratic Party for president in the 1860 presidential election, which wa ...

, opened the two named

territories

A territory is an area of land, sea, or space, particularly belonging or connected to a country, person, or animal.

In international politics, a territory is usually either the total area from which a state may extract power resources or an ...

to slavery, an implicit repeal of the

Missouri Compromise

The Missouri Compromise was a federal legislation of the United States that balanced desires of northern states to prevent expansion of slavery in the country with those of southern states to expand it. It admitted Missouri as a Slave states an ...

of 1820. Intended to quiet national agitation over slavery by shifting the decision to local settlers, Douglas's Act instead inflamed anti-slavery sentiment in the North by allowing the possibility of slavery's expansion to territories held as free soil for three decades. Two months after the Act's passage, Sherman became a candidate for

Ohio's 13th congressional district

The 13th congressional district of Ohio is represented by Representative Tim Ryan. Due to reapportionment following the 2010 United States Census, Ohio lost its 17th and 18th congressional districts, necessitating redrawing of district lines. F ...

. A local convention nominated Sherman over two other candidates to represent what was then called the

Opposition Party

Parliamentary opposition is a form of political opposition to a designated government, particularly in a Westminster-based parliamentary system. This article uses the term ''government'' as it is used in Parliamentary systems, i.e. meaning ''th ...

(later to become the

Republican Party

Republican Party is a name used by many political parties around the world, though the term most commonly refers to the United States' Republican Party.

Republican Party may also refer to:

Africa

*Republican Party (Liberia)

* Republican Part ...

). The new party, a fusion of

Free Soilers

The Free Soil Party was a short-lived coalition political party in the United States active from 1848 to 1854, when it merged into the Republican Party. The party was largely focused on the single issue of opposing the expansion of slavery into ...

, Whigs, and anti-slavery Democrats, had many discordant elements, and some among the former group thought Sherman too conservative on the slavery question. Nevertheless, they supported him against the incumbent Democrat,

William D. Lindsley

William Dell Lindsley (December 25, 1812 – March 11, 1890) was a one-term U.S. Representative from Ohio from 1853 to 1855.

Biography

Born in New Haven, Connecticut, Lindsley attended the common schools.

He moved to Buffalo, New York, in 1832 ...

. Democrats were defeated across Ohio that year, and Sherman was elected by 2,823 votes.

Kansas Territory

When the

34th United States Congress

The 34th United States Congress was a meeting of the legislative branch of the United States federal government, consisting of the United States Senate and the United States House of Representatives. It met in Washington, D.C., from March 4, 1855, ...

convened in December 1855, members opposed to Democratic President

Franklin Pierce

Franklin Pierce (November 23, 1804October 8, 1869) was the 14th president of the United States, serving from 1853 to 1857. He was a northern Democrat who believed that the abolitionist movement was a fundamental threat to the nation's unity ...

(most of them Northerners) held the majority in the House, while the Democrats retained their majority in the Senate. That House majority, however, was not fully unified, with some members adhering to the new anti-Nebraska party, and others loyal to the new nativist

American

American(s) may refer to:

* American, something of, from, or related to the United States of America, commonly known as the "United States" or "America"

** Americans, citizens and nationals of the United States of America

** American ancestry, pe ...

(or "Know-Nothing") party. The Know Nothings were also fractious, with some former Whigs and some former Free Soilers in their ranks. The result was a House that was unable to elect a speaker for two months. When they finally agreed on the election of

Nathaniel Banks

Nathaniel Prentice (or Prentiss) Banks (January 30, 1816 – September 1, 1894) was an American politician from Massachusetts and a Union general during the Civil War. A millworker by background, Banks was prominent in local debating societies, ...

of Massachusetts, the House quickly turned to the matter of Kansas. Preventing

the expansion of slavery to Kansas was the one issue that united Banks's fragile majority, and the House resolved to send three members to investigate the situation in that territory; Sherman was one of the three selected.

Sherman spent two months in the territory and was the primary author of the 1,188-page report filed on conditions there when they returned in April 1856. The report explained what anti-administration members already feared: that the principle of local control was being seriously undermined by the

invasion of Missourians who, while not intending to settle there, used violence to coerce the Kansans to elect pro-slavery members to the territorial legislature. The House took no action on the reports, but they were widely distributed as campaign documents. That July, Sherman proposed an amendment to an army appropriation act to bar use of federal troops to enforce the acts of the Kansas territorial legislature, which many now viewed as an illegitimate body. The amendment narrowly passed the House, but was removed by the Senate; the House ultimately agreed to the change. In spite of this defeat, however, Sherman had achieved considerable prominence for a freshman representative.

Lecompton and Financial Reform

Sherman was re-elected in 1856, defeating his Democratic opponent, Herman J. Brumback, by 2,861 votes. The Republican candidate for president,

John C. Frémont

John Charles Frémont or Fremont (January 21, 1813July 13, 1890) was an American explorer, military officer, and politician. He was a U.S. Senator from California and was the first Republican nominee for president of the United States in 1856 ...

, carried Ohio while

losing the national vote to the Democrat,

James Buchanan

James Buchanan Jr. ( ; April 23, 1791June 1, 1868) was an American lawyer, diplomat and politician who served as the 15th president of the United States from 1857 to 1861. He previously served as secretary of state from 1845 to 1849 and repr ...

. When the

35th Congress

The 35th United States Congress was a meeting of the legislative branch of the United States federal government, consisting of the United States Senate and the United States House of Representatives. It met in Washington, D.C. from March 4, 1857, ...

assembled in December 1857, the anti-Nebraska coalition—now formally the Republicans—had lost control of the House, and Sherman found himself in the minority. The sectional crisis had also deepened in the past year. In March 1857, the

Supreme Court

A supreme court is the highest court within the hierarchy of courts in most legal jurisdictions. Other descriptions for such courts include court of last resort, apex court, and high (or final) court of appeal. Broadly speaking, the decisions of ...

issued its decision in ''

Dred Scott v. Sandford

''Dred Scott v. Sandford'', 60 U.S. (19 How.) 393 (1857), was a landmark decision of the United States Supreme Court that held the U.S. Constitution did not extend American citizenship to people of black African descent, enslaved or free; t ...

'', holding that Congress had no power to prevent slavery in the territories and that blacks—whether free or enslaved—could not be citizens of the United States. In December of that year, in an election boycotted by free-state partisans, Kansas adopted the pro-slavery

Lecompton Constitution

The Lecompton Constitution (1859) was the second of four proposed constitutions for the state of Kansas. Named for the city of Lecompton where it was drafted, it was strongly pro-slavery. It never went into effect.

History Purpose

The Lecompton Co ...

and petitioned Congress to be admitted as a slave state. Buchanan urged that Congress take up the matter, and the Senate approved a bill to admit Kansas. Sherman spoke against the Kansas bill in the House, pointing out the evidence of fraud in the elections there. Some of the Northern Democrats joined with a unanimous Republican caucus to defeat the measure. Congress agreed to a compromise measure, by which Kansas would be admitted after another referendum on the Lecompton Constitution. The electorate rejected slavery and remained a territory, a decision Sherman would later call "the turning point of the slavery controversy".

Sherman's second term also saw his first speeches in Congress on the country's financial situation, which had been harmed by the

Panic of 1857

The Panic of 1857 was a financial panic in the United States caused by the declining international economy and over-expansion of the domestic economy. Because of the invention of the telegraph by Samuel F. Morse in 1844, the Panic of 1857 was ...

. Citing the need to pare unnecessary expenditures in light of diminished revenue, Sherman especially criticized Southern senators for adding appropriations to the House's bills. His speech attracted attention and was the start of Sherman's focus on financial matters, which would continue throughout his long political career.

House Leadership

The voters returned Sherman to office for a third term during 1858. After a brief special session in March 1859, the

36th Congress

The 36th United States Congress was a meeting of the legislative branch of the United States federal government, consisting of the United States Senate and the United States House of Representatives. It met in Washington, D.C. from March 4, 1859 ...

adjourned, and Sherman and his wife went on vacation to Europe. When they returned that December, the situation was similar to that of four years earlier: no party had an absolute majority. Republicans held 109 seats, Democrats 101, and the combination of

Oppositionists and

Know Nothing

The Know Nothing party was a nativist political party and movement in the United States in the mid-1850s. The party was officially known as the "Native American Party" prior to 1855 and thereafter, it was simply known as the "American Party". ...

s 27. Again, sectional tension had increased while Congress was in recess, this time due to

John Brown John Brown most often refers to:

*John Brown (abolitionist) (1800–1859), American who led an anti-slavery raid in Harpers Ferry, Virginia in 1859

John Brown or Johnny Brown may also refer to:

Academia

* John Brown (educator) (1763–1842), Ir ...

's

raid on Harpers Ferry, Virginia. The election for Speaker of the House promised to be contentious. This time, Sherman was among the leading candidates, receiving the second-largest number of votes on the first ballot, with no candidate receiving a majority. The election for Speaker was sidetracked immediately by a furor over an anti-slavery book, ''

The Impending Crisis of the South

''The Impending Crisis of the South: How to Meet It'' is an 1857 book by Hinton Rowan Helper, who declares himself a proud Southerner. It was written mostly in Baltimore, but it would have been illegal to publish it there, as he pointed out. It wa ...

'', written by

Hinton Rowan Helper

Hinton Rowan Helper (December 27, 1829 – March 9, 1909) was an American Southern critic of slavery during the 1850s. In 1857, he published a book that he dedicated to the "nonslaveholding whites" of the South. '' The Impending Crisis of the S ...

and endorsed by many Republican members. Southerners accused Sherman of having endorsed the book, but he protested that he had only endorsed its use as a campaign tool and had never read it. After two months of balloting, no decision had been reached. After their attempts to adopt a plurality rule failed, Sherman accepted that he could not be elected, and withdrew. Republicans then shifted their support to

William Pennington

William Pennington (May 4, 1796 – February 16, 1862) was an American politician and lawyer. He was the 13th governor of New Jersey from 1837 to 1843. He served one term in the United States House of Representatives, during which he served as ...

, who was elected on the forty-fourth ballot.

Pennington assigned Sherman to serve as chairman of the

Committee on Ways and Means

The Committee on Ways and Means is the chief tax-writing committee of the United States House of Representatives. The committee has jurisdiction over all taxation, tariffs, and other revenue-raising measures, as well as a number of other program ...

, where he spent much of his time on appropriations bills, while cooperating with his colleague

Justin Smith Morrill

Justin Smith Morrill (April 14, 1810December 28, 1898) was an American politician and entrepreneur who represented Vermont in the United States House of Representatives (1855–1867) and United States Senate (1867–1898). He is most widely remem ...

on the passage of what became known as the

Morrill Tariff. The Morrill Tariff raised

duties

A duty (from "due" meaning "that which is owing"; fro, deu, did, past participle of ''devoir''; la, debere, debitum, whence "debt") is a commitment or expectation to perform some action in general or if certain circumstances arise. A duty may ...

on imports to close the deficit that had resulted from falling revenues. It also had the effect of encouraging domestic industries, which appealed to the former Whigs in the Republican party. Sherman spoke in favor of the bill, and it passed the House by a vote of 105 to 64. The tariff bill would likely have died in the Senate, but the withdrawal of Southern members at the start of the Civil War allowed the

rump

Rump may refer to:

* Rump (animal)

** Buttocks

* Rump steak, slightly different cuts of meat in Britain and America

* Rump kernel, software run in userspace that offers kernel functionality in NetBSD

Politics

*Rump cabinet

* Rump legislature

* Ru ...

Senate to pass the bill in the 36th Congress final session, and President Buchanan signed it into law in February 1861. Likewise, Sherman supported a bill admitting Kansas as a free state that passed in 1861.

Sherman was renominated for Congress in 1860 and was active in

Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation thro ...

's campaign for president, giving speeches on his behalf in several states. Both were elected, with Sherman defeating his opponent,

Barnabas Burns

Barnabas Burns (June 29, 1817 – October 13, 1883) was an Ohio lawyer, businessman, and politician.

Burns was born in Fayette County, Pennsylvania, in 1817, the youngest of three children of Andrew and Sarah (Caldwell) Burns. Burns's fathe ...

, by 2,864 votes. He returned to Washington for the

lame duck session

A lame-duck session of Congress in the United States occurs whenever one Congress meets after its successor is elected, but before the successor's term begins. The expression is now used not only for a special session called after a sine die adjou ...

of the 36th Congress. By February 1861, seven states had reacted to Lincoln's election by

seceding from the Union. In response, Congress passed a constitutional amendment proposed by Representative

Thomas Corwin

Thomas Corwin (July 29, 1794 – December 18, 1865), also known as Tom Corwin, The Wagon Boy, and Black Tom was a politician from the state of Ohio. He represented Ohio in both houses of Congress and served as the 15th governor of Ohio and the ...

of Ohio. Known today as the

Corwin Amendment

The Corwin Amendment was a proposed amendment to the United States Constitution that was never adopted. It would shield "domestic institutions" of the states from the federal constitutional amendment process and from abolition or interference by ...

, it was an attempt to forge a compromise to keep the remaining slave states in the Union and entice the seceded states to return. Corwin's legislation would have preserved the ''status quo'' on slavery and prohibited any future amendment granting Congress power to interfere with slavery in the states. Sherman voted for the amendment, which passed both houses of Congress and was sent to the states for ratification. Few states ratified it, and the passage of the

Thirteenth Amendment in 1865, outlawing slavery, rendered the compromise measure moot.

Senate

Lincoln took office on March 4, 1861. Among his first acts was to nominate Senator

Salmon P. Chase

Salmon Portland Chase (January 13, 1808May 7, 1873) was an American politician and jurist who served as the sixth chief justice of the United States. He also served as the 23rd governor of Ohio, represented Ohio in the United States Senate, a ...

of Ohio to be

Secretary of the Treasury

The United States secretary of the treasury is the head of the United States Department of the Treasury, and is the chief financial officer of the federal government of the United States. The secretary of the treasury serves as the principal a ...

. Chase resigned his Senate seat on March 7, and after two weeks of indecisive balloting, the

Ohio Legislature

The Ohio General Assembly is the state legislature of the U.S. state of Ohio. It consists of the 99-member Ohio House of Representatives and the 33-member Ohio Senate. Both houses of the General Assembly meet at the Ohio Statehouse in Columbus ...

elected Sherman to the vacant seat. He took his seat on March 23, 1861, as the Senate had been called into

special session

In a legislature, a special session (also extraordinary session) is a period when the body convenes outside of the normal legislative session. This most frequently occurs in order to complete unfinished tasks for the year (often delayed by confli ...

to deal with the secession crisis. The Senate that convened at the start of the

37th Congress

The 37th United States Congress was a meeting of the legislative branch of the United States federal government, consisting of the United States Senate and the United States House of Representatives. It met in Washington, D.C. from March 4, 1861, ...

had a Republican majority for the first time, a majority that grew as more Southern members resigned or were expelled. In April, Sherman's brother William visited Washington to rejoin the army, and the brothers went together to the White House to meet Lincoln. Lincoln soon called for 75,000 men to enlist for three months to put down the rebellion, which William Sherman thought too few and too short a duration. William's thoughts on the war greatly influenced his brother, and John Sherman returned home to Ohio to encourage enlistment, briefly serving as an unpaid

colonel

Colonel (abbreviated as Col., Col or COL) is a senior military officer rank used in many countries. It is also used in some police forces and paramilitary organizations.

In the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries, a colonel was typically in charge of ...

of Ohio Volunteers.

Financing the Civil War

The

Civil War

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies ...

expenditures quickly strained the government's already fragile financial situation and Sherman, assigned to the

Senate Finance Committee

The United States Senate Committee on Finance (or, less formally, Senate Finance Committee) is a standing committee of the United States Senate. The Committee concerns itself with matters relating to taxation and other revenue measures generall ...

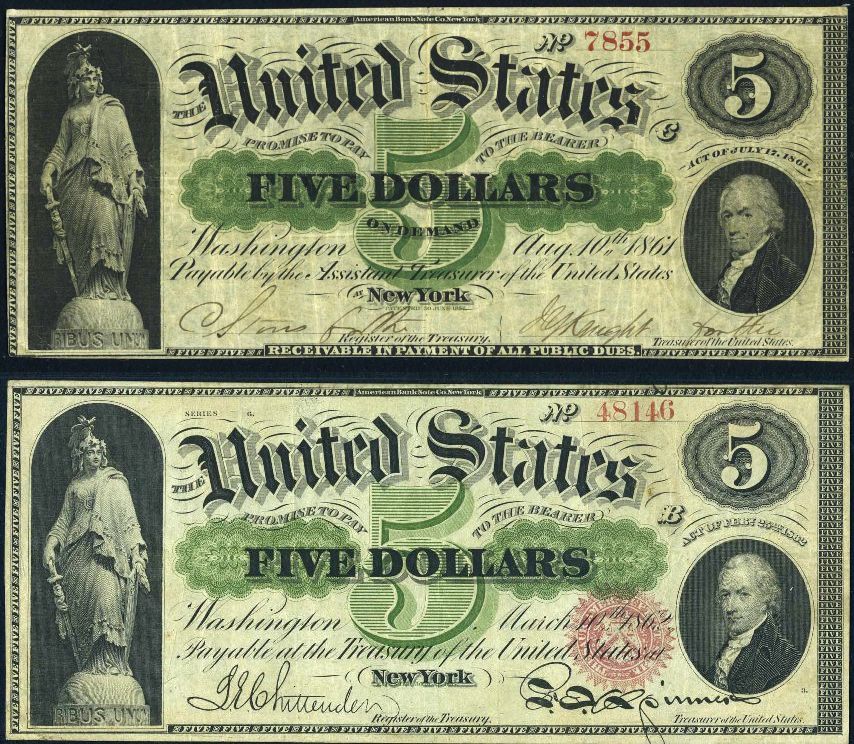

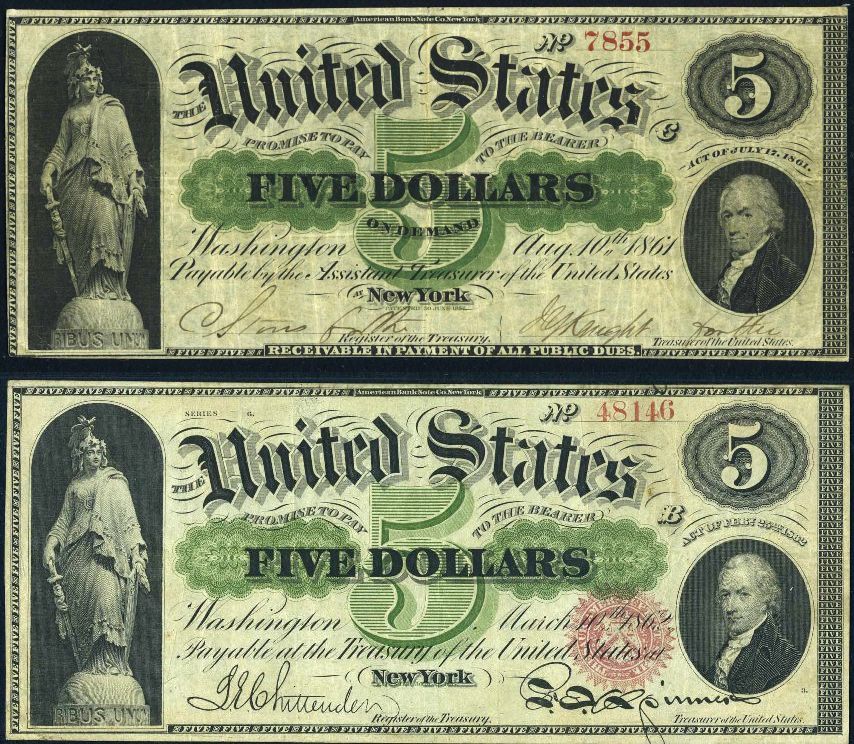

, was involved in the process of increasing the revenue. In July 1861, Congress authorized the government to issue

Demand Note

A Demand Note is a type of United States paper money that was issued between August 1861 and April 1862 during the American Civil War in denominations of 5, 10, and 20 . Demand Notes were the first issue of paper money by the United States ...

s, the first form of paper money issued directly by the United States government. The notes were redeemable in specie (''i.e.'', gold or silver coin) but, as Sherman would note in his memoirs, they did not solve the revenue problem, as the government did not have the coin to redeem the notes should they all be presented for payment. To solve this problem, Chase asked for and Congress authorized the issuance of $150 million in

bonds, which (as banks purchased them with gold) replenished the treasury. Congress also sought to increase revenue when they passed the

Revenue Act of 1861

The Revenue Act of 1861, formally cited as Act of August 5, 1861, Chap. XLV, 12 Stat. 292', included the first U.S. Federal income tax statute (seSec.49. The Act, motivated by the need to fund the Civil War, imposed an income tax to be "levied, c ...

, which imposed the first federal

income tax

An income tax is a tax imposed on individuals or entities (taxpayers) in respect of the income or profits earned by them (commonly called taxable income). Income tax generally is computed as the product of a tax rate times the taxable income. Tax ...

in American history. Sherman endorsed the measure, and even spoke in favor of a steeper tax than the one imposed by the Act (3% on income above $800), preferring to raise revenue by taxation than by borrowing. In August, the special session closed and Sherman returned home to Mansfield to promote military recruitment again.

When Congress returned to Washington in December 1861, Sherman and the Finance Committee continued their attempts to fix the deepening financial crisis caused by the war. The financial situation had continued to worsen, resulting that month in banks suspending specie payments—that is, they refused to redeem their

banknote

A banknote—also called a bill (North American English), paper money, or simply a note—is a type of negotiable instrument, negotiable promissory note, made by a bank or other licensed authority, payable to the bearer on demand.

Banknotes w ...

s for gold. Gold began to disappear from circulation. With the 500,000 soldiers in the field, the government was spending the then-unheard-of sum of $2 million per day. Sherman understood that "a radical change in existing laws relating to our currency must be made, or ... the destruction of the Union would be unavoidable ..." Secretary Chase agreed and proposed that the

Treasury Department issue

United States Note

A United States Note, also known as a Legal Tender Note, is a type of paper money that was issued from 1862 to 1971 in the U.S. Having been current for 109 years, they were issued for longer than any other form of U.S. paper money. They were k ...

s that were redeemable not in specie but in 6% government bonds. The bills would be "lawful money and a legal tender in the payment of all debts". Nothing but gold and silver coin had ever been legal tender in the United States, but Congress yielded to the wartime necessities, and the resulting

First Legal Tender Act

Legal tender is a form of money that courts of law are required to recognize as satisfactory payment for any monetary debt. Each jurisdiction determines what is legal tender, but essentially it is anything which when offered ("tendered") in pa ...

passed both the House and the Senate. The Act limited the notes (later known as "greenbacks") to $150 million, but two subsequent Legal Tender Acts that year expanded the limit to $450 million. The idea of making paper money legal tender was controversial, and

William Pitt Fessenden

William Pitt Fessenden (October 16, 1806September 8, 1869) was an American politician from the U.S. state of Maine. Fessenden was a Whig (later a Republican) and member of the Fessenden political family. He served in the United States House o ...

of Maine, chairman of the Senate Finance Committee, was among many who opposed the proposal. Sherman disagreed and spoke in favor of the idea. He defended his position as necessary in his memoirs, saying "from the passage of the legal tender act, by which means were provided for utilizing the wealth of the country in the suppression of the rebellion, the tide of war turned in our favor".

Reform of the nation's financial system continued in 1863 with the passage of the

National Banking Act of 1863

The National Banking Acts of 1863 and 1864 were two United States federal banking acts that established a system of national banks, and created the United States National Banking System. They encouraged development of a national currency backed by ...

. This Act, first proposed by Chase in 1861 and introduced by Sherman two years later, established a series of nationally chartered private banks that would issue

banknotes

A banknote—also called a bill (North American English), paper money, or simply a note—is a type of negotiable instrument, negotiable promissory note, made by a bank or other licensed authority, payable to the bearer on demand.

Banknotes w ...

in coordination with the Treasury, replacing (though not completely) the

system of state-chartered banks then in existence. Although the immediate purpose was to fund the war, the National Bank Act was intended to be permanent, and remained the law until 1913. A 10% tax on state banknotes passed in 1865 to encourage the shift to a national bank system. Sherman agreed with Chase wholeheartedly and hoped that state banking would be eliminated. Sherman believed the state-by-state system of regulation was disorderly and unable to facilitate the level of borrowing a modern nation might require. He also believed the state banks were unconstitutional. Not all Republicans shared Sherman's views, and when the Act eventually passed the Senate, it was by a narrow 23–21 vote. Lincoln signed the bill into law on February 25, 1863.

Slavery and Reconstruction

Besides his role in financial matters, Sherman also participated in debate over the conduct of the war and goals for the post-war nation. Sherman voted for the

Confiscation Act of 1861

The Confiscation Act of 1861 was an act of Congress during the early months of the American Civil War permitting court proceedings for confiscation of any of property being used to support the Confederate independence effort, including slaves.

...

, which allowed the government to confiscate any property being used to support the

Confederate

Confederacy or confederate may refer to:

States or communities

* Confederate state or confederation, a union of sovereign groups or communities

* Confederate States of America, a confederation of secessionist American states that existed between 1 ...

war effort (including slaves) and for the act

abolishing slavery in the District of Columbia. He also voted for the

Confiscation Act of 1862

The Confiscation Act of 1862, or Second Confiscation Act, was a law passed by the United States Congress during the American Civil War. Section 11 of the act formed the legal basis for President Abraham Lincoln's Emancipation Proclamation.

Natur ...

, which clarified that slaves "

confiscated

Confiscation (from the Latin ''confiscatio'' "to consign to the ''fiscus'', i.e. transfer to the treasury") is a legal form of seizure by a government or other public authority. The word is also used, popularly, of spoliation under legal forms, o ...

" under the 1861 Act were freed. In 1864, Sherman voted for the

Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution

The Thirteenth Amendment (Amendment XIII) to the United States Constitution abolished slavery and involuntary servitude, except as punishment for a crime. The amendment was passed by the Senate on April 8, 1864, by the House of Representative ...

, abolishing slavery. After some effort, it passed Congress and was ratified by the states the next year.

When the session ended, Sherman campaigned in Indiana and Ohio for

Lincoln's reelection. In 1865, he attended

Lincoln's second inauguration, then traveled to Savannah, Georgia to meet with his brother William, who had arrived there after his army's

march to the sea. Sherman returned home to Mansfield in April, where he learned of

Lincoln's assassination

On April 14, 1865, Abraham Lincoln, the 16th president of the United States, was assassinated by well-known stage actor John Wilkes Booth, while attending the play ''Our American Cousin'' at Ford's Theatre in Washington, D.C.

Shot in the head ...

just days after the

Confederate surrender. He was again in Washington for the

Grand Review of the Armies

The Grand Review of the Armies was a military procession and celebration in the national capital city of Washington, D.C., on May 23–24, 1865, following the Union victory in the American Civil War (1861–1865). Elements of the Union Army in the ...

and then returned home until December, when the

39th Congress

The 39th United States Congress was a meeting of the legislative branch of the United States federal government, consisting of the United States Senate and the United States House of Representatives. It met in Washington, D.C. from March 4, 1865, ...

assembled. There had been no special session that summer, and President

Andrew Johnson

Andrew Johnson (December 29, 1808July 31, 1875) was the 17th president of the United States, serving from 1865 to 1869. He assumed the presidency as he was vice president at the time of the assassination of Abraham Lincoln. Johnson was a Dem ...

, Lincoln's successor, had taken the lead on

Reconstruction

Reconstruction may refer to:

Politics, history, and sociology

*Reconstruction (law), the transfer of a company's (or several companies') business to a new company

*''Perestroika'' (Russian for "reconstruction"), a late 20th century Soviet Union ...

of the conquered South, to the consternation of many in Congress. Sherman and Johnson had been friendly, and some observers hoped that Sherman could serve as a liaison between Johnson and the party's "Radical" wing. By February 1866, however, Johnson was publicly attacking these

Radical Republican

The Radical Republicans (later also known as " Stalwarts") were a faction within the Republican Party, originating from the party's founding in 1854, some 6 years before the Civil War, until the Compromise of 1877, which effectively ended Reco ...

s, who demanded harsh punishment of the rebels and federal action to assist the freedmen. The following month Johnson vetoed the proposed

Civil Rights Act of 1866

The Civil Rights Act of 1866 (, enacted April 9, 1866, reenacted 1870) was the first United States federal law to define citizenship and affirm that all citizens are equally protected by the law. It was mainly intended, in the wake of the Amer ...

, which had passed Congress with overwhelming numbers. Sherman joined in re-passing the bill over Johnson's veto. That same year, Sherman voted for the

Fourteenth Amendment, which guaranteed equal protection of the laws to the freedmen. It became law in 1868.

By then, Johnson had made himself the enemy of most Republicans in Congress, including Sherman. Sherman, a moderate, took the side of the Radicals in voting for the

Tenure of Office Act, which passed over Johnson's veto in 1867—but in debating the

First Reconstruction Act, he argued against disenfranchising Southern men who had participated in the rebellion. The latter bill, amended to remove that provision, also passed over Johnson's veto. The continued conflict between Johnson and Congress culminated in

Johnson's impeachment by the House in 1868. After a trial in the Senate, Sherman voted to convict, but the total vote was one short of the required two-thirds majority, and Johnson continued in office. Writing later, Sherman said that although he "liked the President personally and harbored against him none of the prejudice and animosity of some others," he believed Johnson had violated the Tenure of Office Act and accordingly voted to remove him from office.

With

Ulysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant (born Hiram Ulysses Grant ; April 27, 1822July 23, 1885) was an American military officer and politician who served as the 18th president of the United States from 1869 to 1877. As Commanding General, he led the Union Ar ...

elected to the Presidency

in 1868, Congress had a more willing partner in Reconstruction. The

40th Congress's lame duck session passed the

Fifteenth Amendment, which guaranteed that the right to vote could not be restricted because of race; Sherman joined the two-thirds majority that voted for its passage. The

41st Congress

The 41st United States Congress was a meeting of the legislative branch of the United States federal government, consisting of the United States Senate and the United States House of Representatives. It met in Washington, D.C. from March 4, 1869, ...

passed the

Enforcement Act of 1870

The Enforcement Act of 1870, also known as the Civil Rights Act of 1870 or First Ku Klux Klan Act, or Force Act (41st Congress, Sess. 2, ch. 114, , enacted May 31, 1870, effective 1871) was a United States federal law that empowered the President ...

to enforce its civil rights Amendments among a hostile Southern population. That Act, written by

John Bingham

John Armor Bingham (January 21, 1815 – March 19, 1900) was an American politician who served as a Republican representative from Ohio and as the United States ambassador to Japan. In his time as a congressman, Bingham served as both assist ...

of Ohio to mirror the Fourteenth Amendment, created penalties for violating another person's constitutional rights. The next year, Congress passed the

Ku Klux Klan Act

The Enforcement Act of 1871 (), also known as the Ku Klux Klan Act, Third Enforcement Act, Third Ku Klux Klan Act, Civil Rights Act of 1871, or Force Act of 1871, is an Act of the United States Congress which empowered the President to suspend t ...

, which strengthened the Enforcement Act by allowing federal trials and federal troops to be used. Sherman voted in favor of both Acts, which had Grant's support.

Post-war finances

With the financial crisis abated, many in Congress wanted the greenbacks to be withdrawn from circulation. The public had never seen greenbacks as equivalent to specie, and by 1866 they circulated at a considerable discount, although their value had risen since the end of the war.

Hugh McCulloch

Hugh McCulloch (December 7, 1808 – May 24, 1895) was an American financier who played a central role in financing the American Civil War. He served two non-consecutive terms as U.S. Treasury Secretary under three presidents. He was originally ...

, the Treasury Secretary under Lincoln and Johnson, believed the notes were an emergency measure only and thought they should be gradually withdrawn. McCulloch proposed a bill, the

Contraction Act, to convert some of the greenbacks from notes redeemable in bonds to interest-bearing notes redeemable in coin. Most Senate Finance Committee members had no objection, and Sherman found himself alone in opposition to it, believing that withdrawing greenbacks from circulation would contract the money supply and harm the economy. Sherman instead favored leaving the existing notes in circulation and letting the growth in population catch up to the growth in money supply. He suggested an amendment that would instead just allow the Treasury to redeem the notes for lower-interest bonds, now that the government's borrowing costs had decreased. Sherman's amendment was voted down, and the

Contraction Act passed; greenbacks would be gradually withdrawn, but those still circulating would be redeemable for the high-interest bonds as before. In his memoirs, Sherman called this law "the most injurious and expensive financial measure ever enacted by Congress," as the continued high-interest payments it required "added fully $300,000,000 of interest" to the

national debt

A country's gross government debt (also called public debt, or sovereign debt) is the financial liabilities of the government sector. Changes in government debt over time reflect primarily borrowing due to past government deficits. A deficit oc ...

.

The Ohio legislature reelected Sherman to another six-year term that year, and when (after a three-month vacation in Europe) he resumed his seat he again turned to the greenback question. Public support for greenbacks had grown, especially among businesspeople who thought withdrawal would lead to lower prices. When a bill passed the House suspending the authority to retire greenbacks under the

Contraction Act, Sherman supported it in the Senate. It passed the Senate 33–4, and became law in 1868.

In

the next Congress, among the first bills to pass the house was the

Public Credit Act of 1869

The Public Credit Act of 1869 in the USA states that bondholders who purchased bonds to help finance the Civil War (1861 – 1865) would be paid back in gold. The act was signed on March 18, 1869, and was mainly supported by the Republican Part ...

, which would require the government to pay bondholders in gold, not greenbacks. The 1868 election campaign had seen the Democrats proposing to repay the bondholders (mostly supporters of the Union war effort) in paper; Republicans favored gold, as the bonds had been purchased with gold. Sherman agreed with his fellow Republicans and voted with them to pass the bill 42-13. Sherman continued to favor wider circulation of the greenback when he voted for the

Currency Act of 1870 The Currency Act of 1870 (41st Congress, Sess. 2, ch. 252, , enacted July 12, 1870) maintained greenbacks issued during the American Civil War at their existing level, about $356 million, neither contracting them nor issuing more. It replaced $45 m ...

, which authorized an additional $54 million in United States Notes. Sherman was also involved in debate over the

Funding Act of 1870

The Funding Act of 1870 (41st Congress, Sess. 2, ch. 256, , enacted July 14, 1870) was an Act of Congress to re-fund the national debt. It allowed the exchange of high interest, short-term floating bonds bearing lower interest and terms of up to ...

. The Funding Act, which Sherman called "

e most important financial measure of that Congress," refunded the national debt. The bill as Sherman wrote it authorized $1.2 billion of low-interest rate bonds to be used to purchase the high-rate bonds issued during the war, to take advantage of the lower borrowing costs brought about by the peace and security that followed the Union victory. The Act was the subject of considerable debate over the exact rates and amounts, but once the differences were ironed out, it passed by large majorities in both houses. While Sherman was unhappy with the compromises (especially the extension of the bonds' term to 30 years, which he believed too long), he saw the bill as an improvement over the existing conditions and urged its passage.

Coinage Act of 1873

The Ohio Legislature elected Sherman to a third term in 1872 after then-governor

Rutherford B. Hayes

Rutherford Birchard Hayes (; October 4, 1822 – January 17, 1893) was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 19th president of the United States from 1877 to 1881, after serving in the U.S. House of Representatives and as governor ...

declined the invitation of several legislators to run against Sherman. Sherman returned to his leadership of the Finance Committee, and the issues of greenbacks, gold, and silver continued into the next several congresses. Since the early days of the republic, the United States had minted both gold and silver coins, and for decades the ratio of value between them had been set by law at 16:1. Both metals were subject to "free coinage"; that is, anyone could bring any amount of silver or gold to the

United States Mint

The United States Mint is a bureau of the Department of the Treasury responsible for producing coinage for the United States to conduct its trade and commerce, as well as controlling the movement of bullion. It does not produce paper money; tha ...

and have it converted to coinage. The ratio was bound to be imperfect, as the amount of gold and silver mined and the demand for it around the world fluctuated from year to year; as a metal's market price exceeded its legal price, coins of that metal would disappear from circulation (a phenomenon known as

Gresham's law

In economics, Gresham's law is a monetary principle stating that "bad money drives out good". For example, if there are two forms of commodity money in circulation, which are accepted by law as having similar face value, the more valuable co ...

). Before the Civil War, gold circulated freely and silver disappeared, and while silver dollars were legal tender, Sherman wrote that "

though I was quite active in business ... I do not remember at that time to have ever seen a silver dollar". The issuance of greenbacks had pushed debate over gold-silver ratios to the background as coins of both metals disappeared from the nation's commerce in favor of the new paper notes, but as the dollar became stronger in peacetime and the national debt payments were guaranteed to be paid in specie, Congress saw the need to update the coinage laws.

Grant's Treasury Secretary,

George S. Boutwell

George Sewall Boutwell (January 28, 1818 – February 27, 1905) was an American politician, lawyer, and statesman from Massachusetts. He served as Secretary of the Treasury under U.S. President Ulysses S. Grant, the 20th Governor of Massachuse ...

, sent Sherman (who was by now Senate Finance Committee Chairman) a draft of what would become the

Coinage Act of 1873

The Coinage Act of 1873 or Mint Act of 1873, was a general revision of laws relating to the Mint of the United States. By ending the right of holders of silver bullion to have it coined into standard silver dollars, while allowing holders of go ...

. The list of legal coins duplicated that of the previous coinage act, leaving off only the silver dollar and two smaller coins. The rationale given in the Treasury report accompanying the draft bill was that to mint a gold dollar and a silver dollar with different intrinsic values was problematic; as the silver dollar did not circulate and the gold did, it made sense to drop the unused coin. Opponents of the bill would later call this omission the "Crime of '73," and would mean it quite literally, circulating tales of widespread bribery of Congressmen by foreign agents. Sherman emphasized in his memoirs that the bill was openly debated for several years and passed both Houses with overwhelming support and that, given the continued circulation of smaller silver coins at the same 16:1 ratio, nothing had been "demonetized," as his opponents claimed. Silver was still legal tender, but only for sums up to five dollars. On the other hand, later scholars have suggested that Sherman and others wished to demonetize silver for years and move the country onto a

gold-only standard of currency—not for some corrupt gain, but because they believed it was the path to a strong, secure currency.

In switching to what was essentially a gold standard, the United States joined a host of nations around the world that based their currencies on gold alone. But in doing so, these nations exacerbated the demand for gold as opposed to silver which, combined with more silver being mined, drove the cost of gold up and silver down. The result was not apparent immediately after the Coinage Act's passage, but by 1879 the ratio between the price of gold and that of silver had risen from 16.4:1 to 18.4:1; by 1896 it was 30:1. The ultimate effect was more expensive gold, which meant lower prices and deflation for other goods. The deflation made the effects of the

Panic of 1873

The Panic of 1873 was a financial crisis that triggered an economic depression in Europe and North America that lasted from 1873 to 1877 or 1879 in France and in Britain. In Britain, the Panic started two decades of stagnation known as the "Lon ...

worse, making it more expensive for debtors to pay debts they had contracted when currency was less valuable. Farmers and laborers, especially, clamored for the return of coinage in both metals, believing the increased money supply would restore wages and property values, and the divide between pro- and anti-silver forces grew in the decades to come. Writing in 1895, Sherman defended the bill, saying that, barring some international agreement to switch the entire world to a

bimetallic standard

Bimetallism, also known as the bimetallic standard, is a monetary standard in which the value of the monetary unit is defined as equivalent to certain quantities of two metals, typically gold and silver, creating a fixed rate of exchange betwee ...

, the United States dollar should remain a gold-backed currency.

Resumption of specie payments

At the same time as he sought to reform the coinage, Sherman worked for "resumption"—the policy of resuming specie payment on all bank notes, including the greenbacks. The idea of withdrawing the greenbacks from circulation altogether had been tried and quickly rejected in 1866; the notes were, as Sherman said, "a great favorite of the people". The economic turmoil of the Panic of 1873 made it even more clear that shrinking the money supply would be harmful to the average American. Still, Sherman (and others) desired an eventual return to a single circulating medium: gold. As he said in an 1874 speech, "a specie standard is the best and the only true standard of all values, recognized as such by all civilized nations of our generation". If greenbacks were not to be withdrawn from circulation, therefore, they must be made equal to the gold dollar.

While Sherman stood against printing additional greenbacks, as late as 1872 he remained a proponent of keeping existing greenbacks backed by bonds in circulation. Over the next two years, Sherman worked to develop what became the

Specie Payment Resumption Act The Specie Payment Resumption Act of January 14, 1875 was a law in the United States that restored the nation to the gold standard through the redemption of previously-unbacked United States Notes and reversed inflationary government policies promo ...

. The Act was a compromise. It required gradual reduction of the maximum value of greenbacks allowed to circulate to $300 million and, while earlier drafts had allowed the Treasury the choice between paying in bonds or coin, the final version of the Act required payment in specie, starting in 1879. The bill passed on a party-line vote in the lame duck session of the

43rd Congress

The 43rd United States Congress was a meeting of the legislative branch of the United States federal government, consisting of the United States Senate and the United States House of Representatives. It met in Washington, D.C. from March 4, 1873, ...

, and President Grant signed it into law on January 14, 1875.

Election of 1876

After the close of the session, Sherman returned to Ohio to campaign for the Republican nominee for governor there, former governor Rutherford B. Hayes. The issue of specie payments was debated in the campaign, with Hayes endorsing Sherman's position and his Democratic opponent, incumbent Governor

William Allen William Allen may refer to:

Politicians

United States

*William Allen (congressman) (1827–1881), United States Representative from Ohio

*William Allen (governor) (1803–1879), U.S. Representative, Senator, and 31st Governor of Ohio

*William ...

, in favor of increased circulation of greenbacks redeemable in bonds. Hayes won a narrow victory and was soon mentioned as a possible presidential candidate in 1876. The controversy over resumption carried into the presidential election. The Democratic platform that year demanded repeal of the Resumption Act, while the Republicans nominated Hayes, whose position in favor of a gold standard was well known. The

election of 1876 was very close, and the electoral votes of several states were

ardently disputed until mere days before the new president was to be inaugurated. Louisiana was one of the states in which both parties claimed victory, and Grant asked Sherman and a few other men to go to

and ensure the party's interests were represented.

Sherman, by this time thoroughly displeased with Grant and his administration, nonetheless took up the call in the name of party loyalty, joining

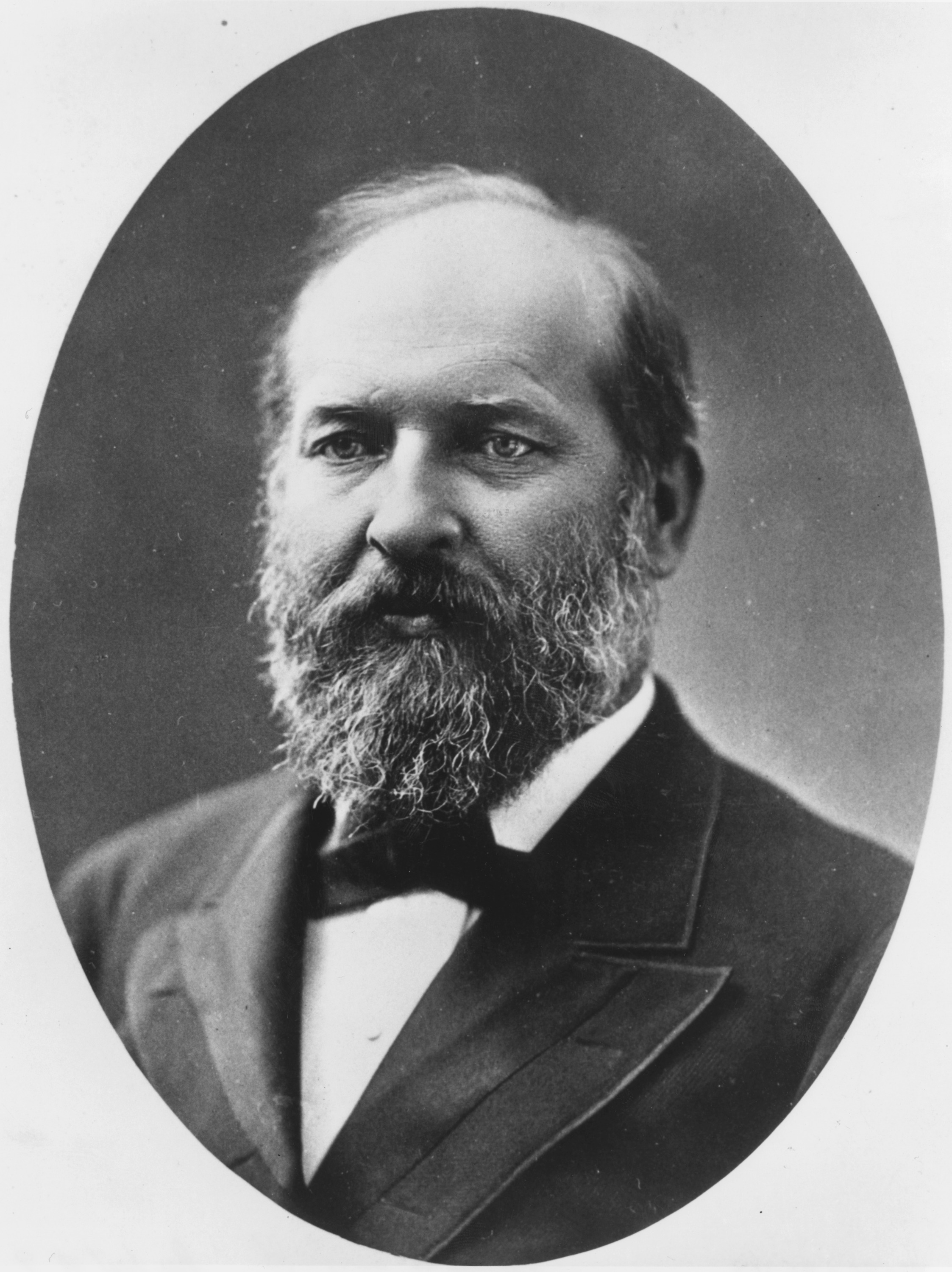

James A. Garfield

James Abram Garfield (November 19, 1831 – September 19, 1881) was the 20th president of the United States, serving from March 4, 1881 until his death six months latertwo months after he was shot by an assassin. A lawyer and Civil War gene ...

,

Stanley Matthews

Sir Stanley Matthews, CBE (1 February 1915 – 23 February 2000) was an English footballer who played as an outside right. Often regarded as one of the greatest players of the British game, he is the only player to have been knighted while stil ...

, and other Republican politicians in Louisiana a few days later. The Democrats likewise sent their politicos, and the two sides met to observe the elections return board arrive at its decision that Hayes should be awarded their state's electoral votes. This ended Sherman's direct role in the matter, and he returned to Washington, but the dispute carried over until a bipartisan election commission was convened in the capital. A few days before Grant's term would end, the commission narrowly decided in Hayes's favor, and he became the 19th President of the United States.

Secretary of the Treasury

Sherman's financial expertise and his friendship with Hayes made him a natural choice for Treasury Secretary in 1877. Like Grant before him, Hayes had not consulted party leaders about his cabinet appointments, and the Senate took the then-unusual step of referring all of them to committee. Two days later, senators approved Sherman's nomination after an hour of debate, and he began lobbying his former colleagues to approve the other nominations, which they eventually did. Hayes and Sherman became close friends in the next four years, taking regular carriage rides together to discuss matters of state in private. In the Treasury, as in the Senate, Sherman was confronted with two tasks: first, to prepare for specie resumption when it took effect in 1879; second, to deal with the backlash against the diminution of silver coinage.

Preparing for specie resumption

Sherman and Hayes agreed to stockpile gold in preparation for the exchange of greenbacks for specie. The Act remained unpopular in some quarters, leading to four attempts to repeal it in the Senate and fourteen in the House—all unsuccessful. By this time, public confidence in the Treasury had grown to the extent that a dollar in gold was worth only $1.05 in greenbacks. Once the public was confident that they could redeem greenbacks for gold, few actually did so; when the Act took effect in 1879, only $130,000 out of the $346,000,000 outstanding dollars in greenbacks were redeemed. Greenbacks were now at parity with gold dollars, and the nation had, for the first time since the Civil War, a unified monetary system.

Bland–Allison Act

Sentiment against the Coinage Act of 1873 gained strength as the economy worsened following the Panic of 1873. Democratic Representative

Richard P. Bland

Richard Parks Bland (August 19, 1835 – June 15, 1899) was an American politician, lawyer, and educator from Missouri. A Democrat, Bland served in the United States House of Representatives from 1873 to 1895 and from 1897 to 1899,

representing ...

of Missouri proposed a bill that would require the United States buy as much silver as miners could sell the government and strike it into coins, a system that would increase the money supply and aid debtors. In short, silver miners would sell the government metal worth fifty to seventy cents and receive back a silver dollar. The pro-silver idea cut across party lines, and

William B. Allison

William Boyd Allison (March 2, 1829 – August 4, 1908) was an American politician. An early leader of the Iowa Republican Party, he represented northeastern Iowa in the United States House of Representatives before representing his state in t ...

, a Republican from Iowa, led the effort in the Senate. Allison offered an amendment in the Senate requiring the purchase of two to four million dollars per month of silver, but not allowing private deposit of silver at the mints. Thus the

seignorage

Seigniorage , also spelled seignorage or seigneurage (from the Old French ''seigneuriage'', "right of the lord (''seigneur'') to mint money"), is the difference between the value of money and the cost to produce and distribute it. The term can be ...

, or the difference between the face value of the coin and the worth of the metal contained within it, accrued to the government's credit, not private citizens. The resulting Bland–Allison Act passed both houses of Congress in 1878. Hayes feared that the act would cause

inflation

In economics, inflation is an increase in the general price level of goods and services in an economy. When the general price level rises, each unit of currency buys fewer goods and services; consequently, inflation corresponds to a reductio ...

through the expansion of the money supply that would be ruinous to business. Sherman's opinion was more complicated. He knew that silver was gaining popularity, and opposing it might harm the party's candidates in the 1880 elections, but he also agreed with Hayes in wanting to avoid inflation.

Sherman pressured his friends in the Senate to defeat the bill, or to limit it to production of a larger silver dollar, which would actually be worth 1/16th its weight in gold. These efforts were unsuccessful, but Allison's amendment made the bill less financially risky. Sherman thought Hayes should sign the amended bill but did not press the matter, and the President vetoed it. "In view of the strong public sentiment in favor of the free coinage of the silver dollar", he later wrote, "I thought it better to make no objections to the passage of the bill, but I did not care to antagonize the wishes of the President." Congress overrode Hayes's veto and the bill became law. The effects of the Bland–Allison Act were limited: the premium on gold over silver continued to grow, and financial conditions in the country continued to improve.

Civil service reform

Hayes took office determined to reform the system of civil service appointments, which had been based on the

spoils system

In politics and government, a spoils system (also known as a patronage system) is a practice in which a political party, after winning an election, gives government jobs to its supporters, friends (cronyism), and relatives (nepotism) as a reward ...

since

Andrew Jackson

Andrew Jackson (March 15, 1767 – June 8, 1845) was an American lawyer, planter, general, and statesman who served as the seventh president of the United States from 1829 to 1837. Before being elected to the presidency, he gained fame as ...

was president forty years earlier. Sherman was not a civil service reformer, but he went along with Hayes's instructions. The foremost enemy of reform—and Hayes—was New York Senator

Roscoe Conkling

Roscoe Conkling (October 30, 1829April 18, 1888) was an American lawyer and Republican Party (United States), Republican politician who represented New York (state), New York in the United States House of Representatives and the United States Se ...

, and it was to Conkling's spoilsmen that Hayes first turned his attention. At Hayes's direction, Sherman ordered

John Jay

John Jay (December 12, 1745 – May 17, 1829) was an American statesman, patriot, diplomat, abolitionist, signatory of the Treaty of Paris, and a Founding Father of the United States. He served as the second governor of New York and the first ...

to investigate the

New York Custom House

The United States Custom House, sometimes referred to as the New York Custom House, was the place where the United States Customs Service collected federal customs duties on imported goods within New York City.

Locations

The Custom House ...

, which was stacked with Conkling's appointees. Jay's report suggested that the New York Custom House was so overstaffed with political appointees that 20% of the employees were expendable.

Hayes issued an

executive order

In the United States, an executive order is a directive by the president of the United States that manages operations of the federal government. The legal or constitutional basis for executive orders has multiple sources. Article Two of th ...

that forbade federal office holders from being required to make campaign contributions or otherwise taking part in party politics.

Chester A. Arthur

Chester Alan Arthur (October 5, 1829 – November 18, 1886) was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 21st president of the United States from 1881 to 1885. He previously served as the 20th vice president under President James A ...

, the

Collector of the Port of New York

The Collector of Customs at the Port of New York, most often referred to as Collector of the Port of New York, was a federal officer who was in charge of the collection of import duties on foreign goods that entered the United States by ship at t ...

, and his subordinates

Alonzo B. Cornell

Alonzo Barton Cornell (January 22, 1832 – October 15, 1904) was a New York politician and businessman who was the 27th Governor of New York from 1880 to 1882.

Early years

Cornell was born in Ithaca, New York, on January 22, 1832. He was ...

and

George H. Sharpe

George Henry Sharpe (February 26, 1828 – January 13, 1900) was an American lawyer, soldier, United States Secret Service, Secret Service officer, diplomat, politician, and Member of the Board of General Appraisers.

Sharpe was born in 1828, in ...

, all Conkling supporters, refused to obey the president's order. Sherman agreed with Hayes that the three had to resign, but he made clear in a letter to Arthur that he had no personal grudge against the Collector. In September 1877, Hayes demanded the three men's resignations, which they refused to give. He submitted appointments to the Senate for confirmation as their replacements but the Senate's Commerce Committee, which Conkling chaired, voted unanimously to reject the nominees.

During a congressional recess in July 1878, Hayes finally sacked Arthur and Cornell (Sharpe's term had expired) and appointed replacements. When Congress reconvened, Sherman pressured his former Senate colleagues to confirm the President's replacement nominees, which they did after considerable debate. Jay and other reformers criticized Sherman the next year when he traveled to New York to speak on Cornell's behalf in his

campaign for governor of New York. Sherman replied that it was important that the Republican party win the election there, despite their intra-party differences. His friendliness may also have related, as Arthur's biographer

Thomas C. Reeves