Joachim von Ribbentrop on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

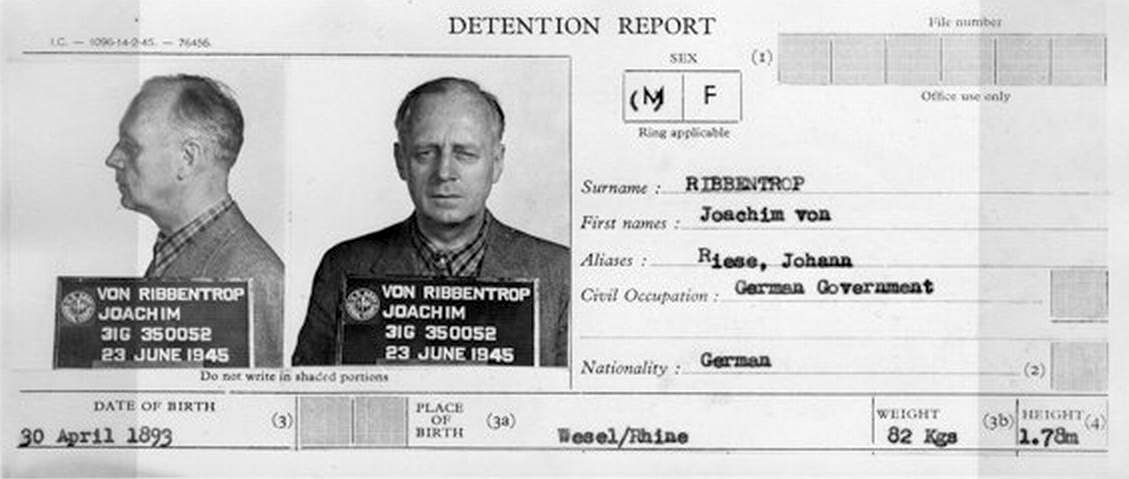

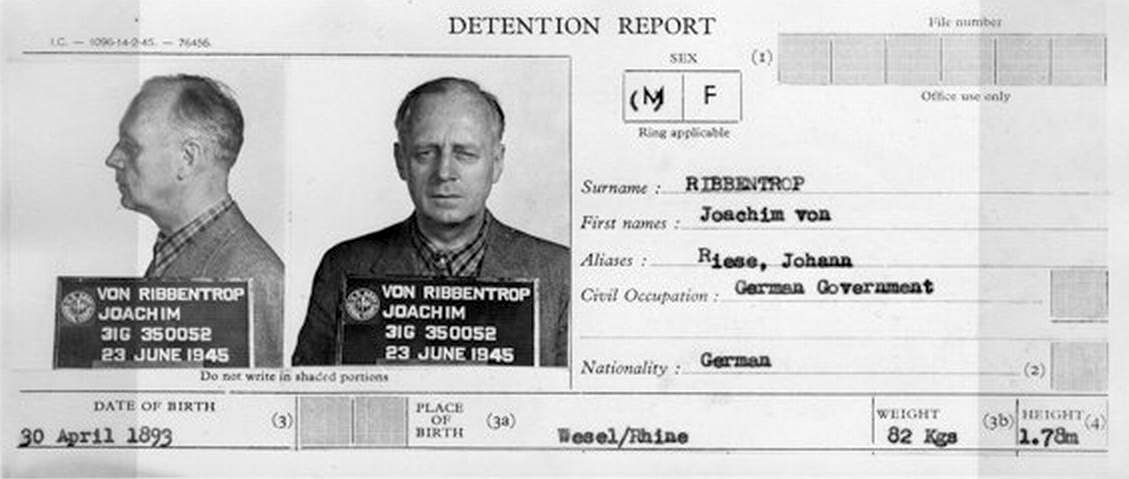

Ulrich Friedrich Wilhelm Joachim von Ribbentrop (; 30 April 1893 – 16 October 1946) was a German politician and diplomat who served as

p. 708

The Anti-Comintern Pact in November 1936 marked an important change in German foreign policy. The Foreign Office had traditionally favoured a policy of friendship with the

The Anti-Comintern Pact in November 1936 marked an important change in German foreign policy. The Foreign Office had traditionally favoured a policy of friendship with the

In early 1938, Hitler asserted his control of the military-foreign policy apparatus, in part by sacking Neurath. On 4 February 1938, Ribbentrop succeeded Neurath as Foreign Minister. Ribbentrop's appointment has generally been seen as an indication that German foreign policy was moving in a more radical direction. In contrast to Neurath's cautious and less bellicose nature, Ribbentrop unequivocally supported war in 1938 and 1939.Bloch, p. 195.

Ribbentrop's time as Foreign Minister can be divided into three periods. In the first, from 1938 to 1939, he tried to persuade other states to align themselves with Germany for the coming war. In the second, from 1939 to 1943, Ribbentrop attempted to persuade other states to enter the war on Germany's side or at least to maintain pro-German neutrality. He was also involved in

In early 1938, Hitler asserted his control of the military-foreign policy apparatus, in part by sacking Neurath. On 4 February 1938, Ribbentrop succeeded Neurath as Foreign Minister. Ribbentrop's appointment has generally been seen as an indication that German foreign policy was moving in a more radical direction. In contrast to Neurath's cautious and less bellicose nature, Ribbentrop unequivocally supported war in 1938 and 1939.Bloch, p. 195.

Ribbentrop's time as Foreign Minister can be divided into three periods. In the first, from 1938 to 1939, he tried to persuade other states to align themselves with Germany for the coming war. In the second, from 1939 to 1943, Ribbentrop attempted to persuade other states to enter the war on Germany's side or at least to maintain pro-German neutrality. He was also involved in

Ernst von Weizsäcker, the State Secretary from 1938 to 1943, opposed the general trend in German foreign policy towards attacking the

Ernst von Weizsäcker, the State Secretary from 1938 to 1943, opposed the general trend in German foreign policy towards attacking the  Before the Anglo-German summit at Berchtesgaden on 15 September 1938, the British Ambassador, Sir Nevile Henderson, and Weizsäcker worked out a private arrangement for Hitler and Chamberlain to meet with no advisers present as a way of excluding the ultrahawkish Ribbentrop from attending the talks.Bloch, p. 193. Hitler's interpreter, Paul Schmidt, later recalled that it was "felt that our Foreign Minister would prove a disturbing element" at the Berchtesgaden summit. In a moment of pique at his exclusion from the Chamberlain-Hitler meeting, Ribbentrop refused to hand over Schmidt's notes of the summit to Chamberlain, a move that caused much annoyance on the British side. Ribbentrop spent the last weeks of September 1938 looking forward very much to the German-Czechoslovak war that he expected to break out on 1 October 1938. Ribbentrop regarded the

Before the Anglo-German summit at Berchtesgaden on 15 September 1938, the British Ambassador, Sir Nevile Henderson, and Weizsäcker worked out a private arrangement for Hitler and Chamberlain to meet with no advisers present as a way of excluding the ultrahawkish Ribbentrop from attending the talks.Bloch, p. 193. Hitler's interpreter, Paul Schmidt, later recalled that it was "felt that our Foreign Minister would prove a disturbing element" at the Berchtesgaden summit. In a moment of pique at his exclusion from the Chamberlain-Hitler meeting, Ribbentrop refused to hand over Schmidt's notes of the summit to Chamberlain, a move that caused much annoyance on the British side. Ribbentrop spent the last weeks of September 1938 looking forward very much to the German-Czechoslovak war that he expected to break out on 1 October 1938. Ribbentrop regarded the  In the aftermath of Munich, Hitler was in a violently anti-British mood caused in part by his rage over being "cheated" out of the war to "annihilate" Czechoslovakia that he very much wanted to have in 1938 and in part by his realisation that Britain would neither ally itself nor stand aside in regard to Germany's ambition to dominate Europe.Weinberg 1980, pp. 506–507. As a consequence, Britain was considered after Munich to be the main enemy of the ''Reich'', and as a result, the influence of ardently Anglophobic Ribbentrop correspondingly rose with Hitler.

Partly for economic reasons, and partly out of fury over being "cheated" out of war in 1938, Hitler decided to destroy the rump state of

In the aftermath of Munich, Hitler was in a violently anti-British mood caused in part by his rage over being "cheated" out of the war to "annihilate" Czechoslovakia that he very much wanted to have in 1938 and in part by his realisation that Britain would neither ally itself nor stand aside in regard to Germany's ambition to dominate Europe.Weinberg 1980, pp. 506–507. As a consequence, Britain was considered after Munich to be the main enemy of the ''Reich'', and as a result, the influence of ardently Anglophobic Ribbentrop correspondingly rose with Hitler.

Partly for economic reasons, and partly out of fury over being "cheated" out of war in 1938, Hitler decided to destroy the rump state of

French-German Non-Aggression pact

Ribbentrop had conversations with French Foreign Minister Georges Bonnet, which Ribbentrop later claimed included a promise that France would recognize all of Eastern Europe as Germany's exclusive sphere of influence.

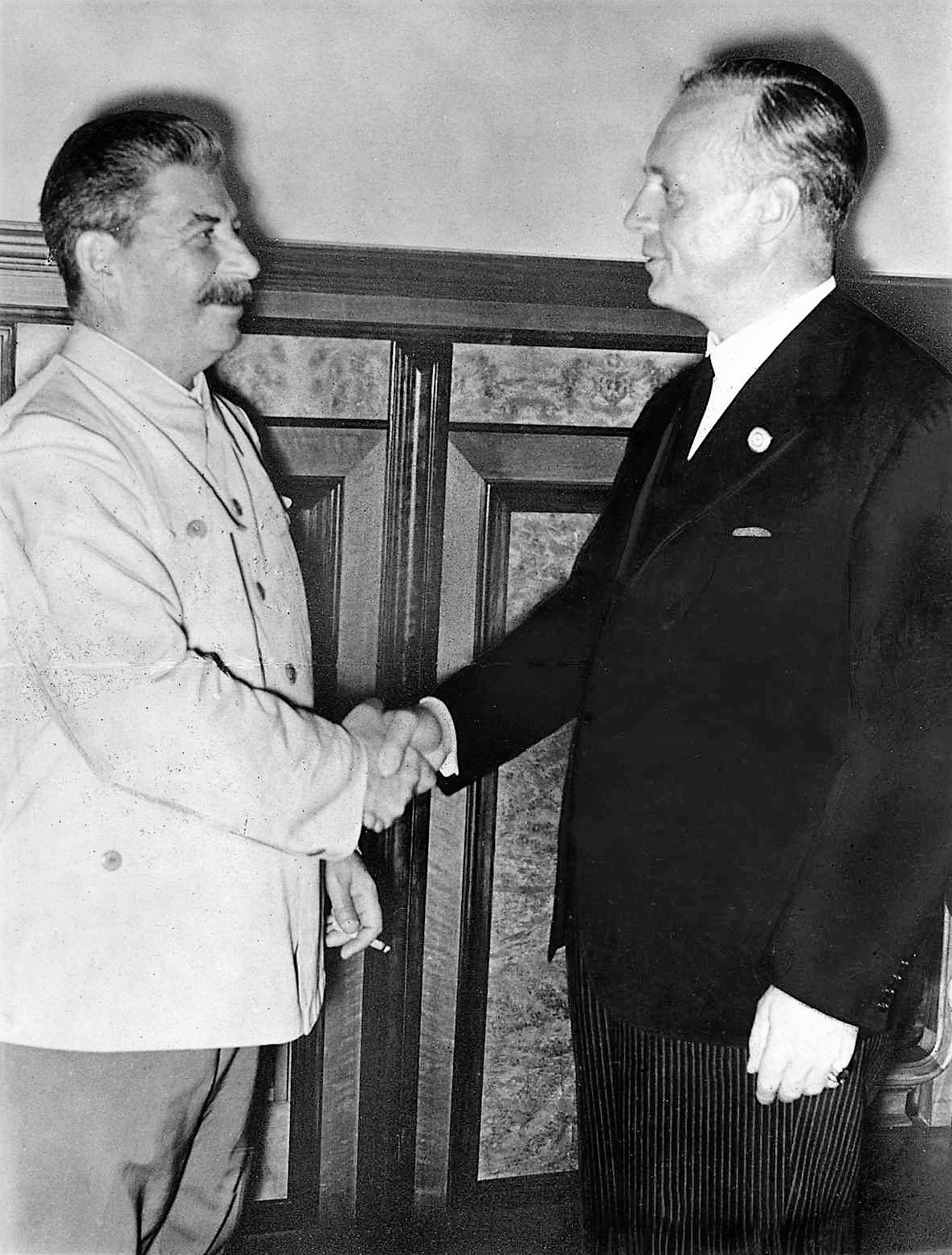

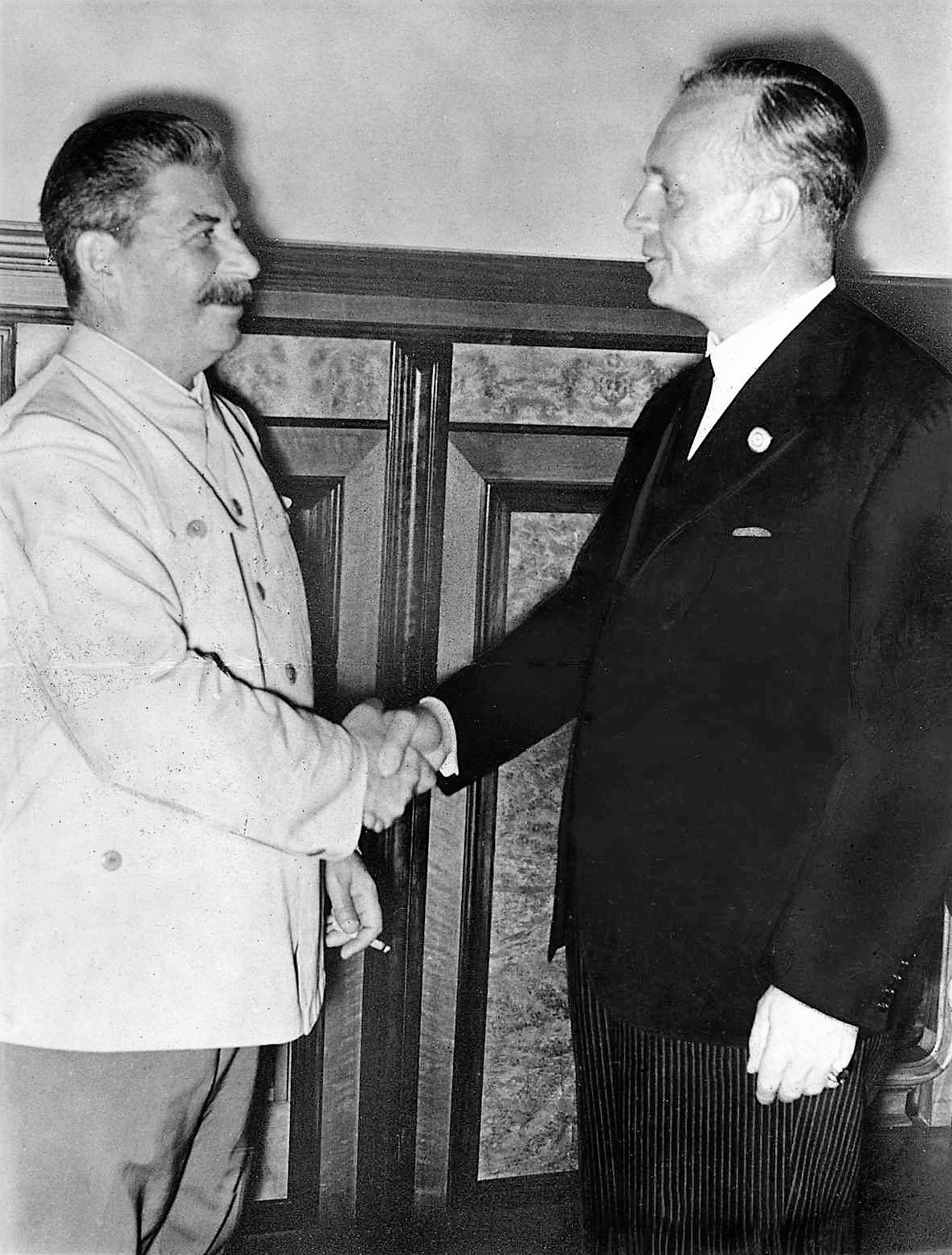

Ribbentrop played a key role in the conclusion of a Soviet-German non-aggression pact, the

Ribbentrop played a key role in the conclusion of a Soviet-German non-aggression pact, the  The signing of the Non-Aggression Pact in Moscow on 23 August 1939 was the crowning achievement of Ribbentrop's career. He flew to Moscow, where, over the course of a thirteen-hour visit, Ribbentrop signed both the Non-Aggression Pact and the secret protocols, which partitioned much of Eastern Europe between the Soviets and the Germans. Ribbentrop had expected to see only the Soviet Foreign Commissar Vyacheslav Molotov and was most surprised to be holding talks with

The signing of the Non-Aggression Pact in Moscow on 23 August 1939 was the crowning achievement of Ribbentrop's career. He flew to Moscow, where, over the course of a thirteen-hour visit, Ribbentrop signed both the Non-Aggression Pact and the secret protocols, which partitioned much of Eastern Europe between the Soviets and the Germans. Ribbentrop had expected to see only the Soviet Foreign Commissar Vyacheslav Molotov and was most surprised to be holding talks with  On the night of 30–31 August 1939, Ribbentrop had an extremely heated exchange with British Ambassador Sir Nevile Henderson, who objected to Ribbentrop's demand, given at about midnight, that if a Polish plenipotentiary did not arrive in Berlin that night to discuss the German "final offer", the responsibility for the outbreak of war would not rest on the ''Reich''. Henderson stated that the terms of the German "final offer" were very reasonable but argued that Ribbentrop's time limit for Polish acceptance of the "final offer" was most unreasonable, and he also demanded to know why Ribbentrop insisted upon seeing a special Polish plenipotentiary and could not present the "final offer" to Ambassador Józef Lipski or provide a written copy of the "final offer". The Henderson–Ribbentrop meeting became so tense that the two men almost came to blows. The American historian Gerhard Weinberg described the Henderson–Ribbentrop meeting:

On the night of 30–31 August 1939, Ribbentrop had an extremely heated exchange with British Ambassador Sir Nevile Henderson, who objected to Ribbentrop's demand, given at about midnight, that if a Polish plenipotentiary did not arrive in Berlin that night to discuss the German "final offer", the responsibility for the outbreak of war would not rest on the ''Reich''. Henderson stated that the terms of the German "final offer" were very reasonable but argued that Ribbentrop's time limit for Polish acceptance of the "final offer" was most unreasonable, and he also demanded to know why Ribbentrop insisted upon seeing a special Polish plenipotentiary and could not present the "final offer" to Ambassador Józef Lipski or provide a written copy of the "final offer". The Henderson–Ribbentrop meeting became so tense that the two men almost came to blows. The American historian Gerhard Weinberg described the Henderson–Ribbentrop meeting:

As World War II continued, Ribbentrop's once-friendly relations with the SS became increasingly strained. In January 1941, the nadir of the relations between the SS and the Foreign Office was reached when the Iron Guard attempted a coup in Romania. Ribbentrop supported Marshal Ion Antonescu's government and

As World War II continued, Ribbentrop's once-friendly relations with the SS became increasingly strained. In January 1941, the nadir of the relations between the SS and the Foreign Office was reached when the Iron Guard attempted a coup in Romania. Ribbentrop supported Marshal Ion Antonescu's government and  In late 1940 and early 1941, Ribbentrop strongly pressured the

In late 1940 and early 1941, Ribbentrop strongly pressured the  Despite his opposition to Operation Barbarossa and a preference to concentrate against Britain, Ribbentrop began a sustained effort on 28 June 1941, without consulting Hitler, to have Japan attack the Soviet Union.Hillgruber, p. 91. But Ribbentrop's motives in seeking to have Japan enter the war were more anti-British than anti-Soviet. On 10 July 1941 Ribbentrop ordered General Eugen Ott, the German Ambassador to Japan to:

As part of his efforts to bring Japan into Barbarossa, on 1 July 1941, Ribbentrop had Germany break off diplomatic relations with Chiang Kai-shek and recognized the Japanese-puppet government of Wang Jingwei as China's legitimate rulers.Bloch, p. 344. Ribbentrop hoped that recognizing Wang would be seen as a coup that might add to the prestige of the pro-German Japanese Foreign Minister Yōsuke Matsuoka, who was opposed to opening American-Japanese talks. Despite Ribbentrop's best efforts, Matsuoka was sacked as foreign minister later in July 1941, and the Japanese-American talks began.

After the war, Ribbentrop was found to have had culpability in

Despite his opposition to Operation Barbarossa and a preference to concentrate against Britain, Ribbentrop began a sustained effort on 28 June 1941, without consulting Hitler, to have Japan attack the Soviet Union.Hillgruber, p. 91. But Ribbentrop's motives in seeking to have Japan enter the war were more anti-British than anti-Soviet. On 10 July 1941 Ribbentrop ordered General Eugen Ott, the German Ambassador to Japan to:

As part of his efforts to bring Japan into Barbarossa, on 1 July 1941, Ribbentrop had Germany break off diplomatic relations with Chiang Kai-shek and recognized the Japanese-puppet government of Wang Jingwei as China's legitimate rulers.Bloch, p. 344. Ribbentrop hoped that recognizing Wang would be seen as a coup that might add to the prestige of the pro-German Japanese Foreign Minister Yōsuke Matsuoka, who was opposed to opening American-Japanese talks. Despite Ribbentrop's best efforts, Matsuoka was sacked as foreign minister later in July 1941, and the Japanese-American talks began.

After the war, Ribbentrop was found to have had culpability in

As the war went on, Ribbentrop's influence waned. Because most of the world was at war with Germany, the Foreign Ministry's importance diminished as the value of diplomacy became limited. By January 1944, Germany had diplomatic relations only with Argentina, Ireland, Vichy France, the

As the war went on, Ribbentrop's influence waned. Because most of the world was at war with Germany, the Foreign Ministry's importance diminished as the value of diplomacy became limited. By January 1944, Germany had diplomatic relations only with Argentina, Ireland, Vichy France, the

''Fascist Ideology''

London: Routledge, 2000 . * Lukes, Igor, and Erik Goldstein (eds.). ''The Munich Crisis, 1938: Prelude to World War II''. London: Frank Cass Inc, 1999. . * * Messerschmidt, Manfred "Foreign Policy and Preparation for War" from '' Germany and the Second World War'',

''The Origins of the Second World War''

Manchester University Press: Manchester, United Kingdom, 2001 . * Shirer, William L. (1960). ''The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich''. New York:

online

* Rich, Norman. ''Hitler's War Aims: Ideology, the Nazi State, and the Course of Expansion'' Vol. 1. (WW Norton, 1973). * Rich, Norman. ''Hitler's war aims: The establishment of the new order'' vol 2 (WW Norton, 1974)

The Trial of German Major War Criminals

access date 1 July 2006. *, in German {{DEFAULTSORT:Ribbentrop, Joachim Von 1893 births 1946 deaths 20th-century German politicians Ambassadors of Germany to the United Kingdom Articles containing video clips Executed people from North Rhine-Westphalia Foreign Ministers of Germany Foreign relations of Nazi Germany German Protestants German people convicted of crimes against humanity German people convicted of the international crime of aggression Grand Crosses of the Order of Saint Stephen of Hungary Holocaust perpetrators Members of the Reichstag of Nazi Germany Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact Nazi Germany ministers Nazi Party officials Nazi Party politicians Nobility in the Nazi Party People executed by the International Military Tribunal in Nuremberg People executed for crimes against humanity People from Wesel People from the Rhine Province Prussian Army personnel Recipients of the Iron Cross (1914), 1st class Joachim von SS-Obergruppenführer World War II political leaders German Army personnel of World War I

Minister of Foreign Affairs

A foreign affairs minister or minister of foreign affairs (less commonly minister for foreign affairs) is generally a cabinet minister in charge of a state's foreign policy and relations. The formal title of the top official varies between coun ...

of Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

from 1938 to 1945.

Ribbentrop first came to Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Nazi Germany, Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his death in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the le ...

's notice as a well-travelled businessman with more knowledge of the outside world than most senior Nazis and as a perceived authority on foreign affairs. He offered his house Schloss Fuschl for the secret meetings in January 1933 that resulted in Hitler's appointment as Chancellor of Germany. He became a close confidant of Hitler, to the disgust of some party members, who thought him superficial and lacking in talent. He was appointed ambassador to the Court of St James's, the royal court of the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the European mainland, continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotlan ...

, in 1936 and then Foreign Minister of Germany in February 1938.

Before World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

, he played a key role in brokering the Pact of Steel (an alliance with Fascist Italy

Fascism is a far-right, authoritarian, ultra-nationalist political ideology and movement,: "extreme militaristic nationalism, contempt for electoral democracy and political and cultural liberalism, a belief in natural social hierarchy and the ...

) and the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact

The Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact was a non-aggression pact between Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union that enabled those powers to partition Poland between them. The pact was signed in Moscow on 23 August 1939 by German Foreign Minister Joachim von Ri ...

(the Nazi–Soviet non-aggression pact). He favoured retaining good relations with the Soviets, and opposed the invasion of the Soviet Union. In late 1941, due to American aid to Britain and the increasingly frequent "incidents" in the North Atlantic between U-boats and American warships guarding convoys to Britain, Ribbentrop worked for the failure of the Japanese-American talks in Washington and for Japan to attack the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 U.S. state, states, a Washington, D.C., federal district, five ma ...

.Bloch, p. 345. He did his utmost to support a declaration of war on the United States after the attack on Pearl Harbor

The attack on Pearl HarborAlso known as the Battle of Pearl Harbor was a surprise military strike by the Imperial Japanese Navy Air Service upon the United States against the naval base at Pearl Harbor in Honolulu, Territory of Hawa ...

.Bloch, pp. 346–347. From 1941 onwards, Ribbentrop's influence declined.

Arrested in June 1945, Ribbentrop was convicted and sentenced to death at the Nuremberg trials for his role in starting World War II in Europe and enabling the Holocaust

The Holocaust, also known as the Shoah, was the genocide of European Jews during World War II. Between 1941 and 1945, Nazi Germany and its collaborators systematically murdered some six million Jews across German-occupied Europe; ...

. On 16 October 1946, he became the first of the Nuremberg defendants to be executed

Capital punishment, also known as the death penalty, is the State (polity), state-sanctioned practice of deliberately killing a person as a punishment for an actual or supposed crime, usually following an authorized, rule-governed process to ...

by hanging

Hanging is the suspension of a person by a noose or ligature strangulation, ligature around the neck.Oxford English Dictionary, 2nd ed. Hanging as method of execution is unknown, as method of suicide from 1325. The ''Oxford English Dictionary' ...

.

Early life

Joachim von Ribbentrop was born inWesel

Wesel () is a city in North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany. It is the capital of the Wesel district.

Geography

Wesel is situated at the confluence of the Lippe River and the Rhine.

Division of the city

Suburbs of Wesel include Lackhausen, Obrigh ...

, Rhenish Prussia, to Richard Ulrich Friedrich Joachim Ribbentrop, a career army officer, and his wife Johanne Sophie Hertwig.

From 1904 to 1908, Ribbentrop took French

French (french: français(e), link=no) may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to France

** French language, which originated in France, and its various dialects and accents

** French people, a nation and ethnic group identified with Franc ...

courses at Lycée Fabert in Metz

Metz ( , , lat, Divodurum Mediomatricorum, then ) is a city in northeast France located at the confluence of the Moselle and the Seille rivers. Metz is the prefecture of the Moselle department and the seat of the parliament of the Grand Est ...

, the German Empire's most powerful fortress. A former teacher later recalled Ribbentrop "was the most stupid in his class, full of vanity and very pushy". His father was cashiered from the Prussian Army in 1908 for repeatedly disparaging Kaiser Wilhelm II for his alleged homosexuality, and the Ribbentrop family was often short of money.

For the next 18 months, the family moved to Arosa, Switzerland, where the children continued to be taught by French and English private tutors, and Ribbentrop spent his free time skiing and mountaineering.

Following the stay in Arosa, Ribbentrop was sent to Britain for a year to improve his knowledge of English.

Fluent in both French

French (french: français(e), link=no) may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to France

** French language, which originated in France, and its various dialects and accents

** French people, a nation and ethnic group identified with Franc ...

and English, young Ribbentrop lived at various times in Grenoble

lat, Gratianopolis

, commune status = Prefecture and commune

, image = Panorama grenoble.png

, image size =

, caption = From upper left: Panorama of the city, Grenoble’s cable cars, place Saint- ...

, France and London

London is the capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary dow ...

, before travelling to Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, covering over , making it the world's second-largest country by tota ...

in 1910.

He worked for the Molsons Bank

The Molson Bank (sometimes labeled Molsons Bank) was a Canadian bank founded in Montreal, Quebec, by brothers William (1793–1875) and John Molson, Jr. (1787–1860), the sons of brewery magnate John Molson.

History

In 1850, it was constitute ...

on Stanley Street Stanley Street may refer to:

Streets:

*Stanley Street, Brisbane

*Stanley Street, East Sydney

*Stanley Street, Hong Kong

*Stanley Street, Liverpool

* Stanley Street (Montreal)

* Stanley Street, Singapore

In fiction:

*Stanley Street, the prime setti ...

in Montreal

Montreal ( ; officially Montréal, ) is the second-most populous city in Canada and most populous city in the Canadian province of Quebec. Founded in 1642 as '' Ville-Marie'', or "City of Mary", it is named after Mount Royal, the triple- ...

, and then for the engineering firm M. P. and J. T. Davis on the Quebec Bridge reconstruction. He was also employed by the National Transcontinental Railway, which constructed a line from Moncton to Winnipeg

Winnipeg () is the capital and largest city of the province of Manitoba in Canada. It is centred on the confluence of the Red and Assiniboine rivers, near the longitudinal centre of North America. , Winnipeg had a city population of 749 ...

. He worked as a journalist in New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the most densely populated major city in the U ...

and Boston

Boston (), officially the City of Boston, is the capital city, state capital and List of municipalities in Massachusetts, most populous city of the Commonwealth (U.S. state), Commonwealth of Massachusetts, as well as the cultural and financ ...

but returned to Germany to recover from tuberculosis

Tuberculosis (TB) is an infectious disease usually caused by ''Mycobacterium tuberculosis'' (MTB) bacteria. Tuberculosis generally affects the lungs, but it can also affect other parts of the body. Most infections show no symptoms, in w ...

. He returned to Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, covering over , making it the world's second-largest country by tota ...

and set up a small business in Ottawa

Ottawa (, ; Canadian French: ) is the capital city of Canada. It is located at the confluence of the Ottawa River and the Rideau River in the southern portion of the province of Ontario. Ottawa borders Gatineau, Quebec, and forms the core ...

importing German wine and champagne.Bloch, p. 7. In 1914, he competed for Ottawa's famous Minto ice-skating team and participated in the Ellis Memorial Trophy tournament in Boston in February.

When the First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fig ...

began later in 1914, Ribbentrop left Canada, which as part of the British Empire

The British Empire was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It began with the overseas possessions and trading post ...

was at war with Germany, and found temporary sanctuary in neutral United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 U.S. state, states, a Washington, D.C., federal district, five ma ...

.Bloch, p. 8. On 15 August 1914, he sailed from Hoboken, New Jersey

Hoboken ( ; Unami: ') is a city in Hudson County in the U.S. state of New Jersey. As of the 2020 U.S. census, the city's population was 60,417. The Census Bureau's Population Estimates Program calculated that the city's population was 58, ...

, on the Holland-America ship ''The Potsdam'', bound for Rotterdam

Rotterdam ( , , , lit. ''The Dam on the River Rotte'') is the second largest city and municipality in the Netherlands. It is in the province of South Holland, part of the North Sea mouth of the Rhine–Meuse–Scheldt delta, via the ''"N ...

, and on his return to Germany enlisted in the Prussian 12th Hussar Regiment.

Ribbentrop served first on the Eastern Front, then was transferred to the Western Front Western Front or West Front may refer to:

Military frontiers

*Western Front (World War I), a military frontier to the west of Germany

*Western Front (World War II), a military frontier to the west of Germany

*Western Front (Russian Empire), a majo ...

. He earned a commission and was awarded the Iron Cross. In 1918, 1st Lieutenant Ribbentrop was stationed in Istanbul

Istanbul ( , ; tr, İstanbul ), formerly known as Constantinople ( grc-gre, Κωνσταντινούπολις; la, Constantinopolis), is the List of largest cities and towns in Turkey, largest city in Turkey, serving as the country's economic, ...

as a staff officer. During his time in Turkey

Turkey ( tr, Türkiye ), officially the Republic of Türkiye ( tr, Türkiye Cumhuriyeti, links=no ), is a list of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country located mainly on the Anatolia, Anatolian Peninsula in Western Asia, with ...

, he became a friend of another staff officer, Franz von Papen.

In 1919, Ribbentrop met Anna Elisabeth Henkell ("Annelies" to her friends), the daughter of a wealthy Wiesbaden wine producer. They were married on 5 July 1920, and Ribbentrop began to travel throughout Europe as a wine salesman. He and Annelies had five children together. In 1925, his aunt, Gertrud von Ribbentrop, adopted him, which allowed him to add the nobiliary particle '' von'' to his name.

Early career

In 1928, Ribbentrop was introduced toAdolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Nazi Germany, Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his death in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the le ...

as a businessman with foreign connections who "gets the same price for German champagne as others get for French champagne". Wolf-Heinrich Graf von Helldorff, with whom Ribbentrop had served in the 12th Torgau Hussars in the First World War, arranged the introduction. Ribbentrop and his wife joined the Nazi Party

The Nazi Party, officially the National Socialist German Workers' Party (german: Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei or NSDAP), was a far-right political party in Germany active between 1920 and 1945 that created and supported t ...

on 1 May 1932. Ribbentrop began his political career by offering to be a secret emissary between Chancellor of Germany Franz von Papen, his old wartime friend, and Hitler.Turner, p. 70. His offer was initially refused. Six months later, however, Hitler and Papen accepted his help.

Their change of heart occurred after General Kurt von Schleicher ousted Papen in December 1932. This led to a complex set of intrigues in which Papen and various friends of president Paul von Hindenburg negotiated with Hitler to oust Schleicher. On 22 January 1933, State Secretary Otto Meissner

Otto Lebrecht Eduard Daniel Meissner (13 March 1880, Bischwiller, Alsace – 27 May 1953, Munich) was head of the Office of the President of Germany from 1920 to 1945 during nearly the entire period of the Weimar Republic under Friedrich Ebert ...

and Hindenburg's son Oskar met Hitler, Hermann Göring, and Wilhelm Frick

Wilhelm Frick (12 March 1877 – 16 October 1946) was a prominent German politician of the Nazi Party (NSDAP), who served as Reich Minister of the Interior in Adolf Hitler's cabinet from 1933 to 1943 and as the last governor of the Protectorate ...

at Ribbentrop's home in Berlin's exclusive Dahlem district. Over dinner, Papen made the fateful concession that if Schleicher's government were to fall, he would abandon his demand for the Chancellorship and instead use his influence with President Hindenburg to ensure Hitler got the Chancellorship.

Ribbentrop was not popular with the Nazi Party's '' Alte Kämpfer'' (Old Fighters); they nearly all disliked him. British historian Laurence Rees described Ribbentrop as "the Nazi almost all the other leading Nazis hated". Joseph Goebbels

Paul Joseph Goebbels (; 29 October 1897 – 1 May 1945) was a German Nazi politician who was the '' Gauleiter'' (district leader) of Berlin, chief propagandist for the Nazi Party, and then Reich Minister of Propaganda from 1933 to ...

expressed a common view when he confided to his diary that "Von Ribbentrop bought his name, he married his money and he swindled his way into office". Ribbentrop was among the few who could meet with Hitler at any time without an appointment, however, unlike Goebbels or Göring.

During most of the Weimar Republic

The German Reich, commonly referred to as the Weimar Republic,, was a historical period of Germany from 9 November 1918 to 23 March 1933, during which it was a constitutional federal republic for the first time in history; hence it is also r ...

era, Ribbentrop was apolitical and displayed no antisemitic prejudices.Bloch, pp. 16, 20–21. A visitor to a party Ribbentrop threw in 1928 recorded that Ribbentrop had no political views beyond a vague admiration for Gustav Stresemann, fear of Communism, and a wish to restore the monarchy. Several Berlin

Berlin is Capital of Germany, the capital and largest city of Germany, both by area and List of cities in Germany by population, by population. Its more than 3.85 million inhabitants make it the European Union's List of cities in the European U ...

Jewish businessmen who did business with Ribbentrop in the 1920s and knew him well later expressed astonishment at the vicious antisemitism he later displayed in the Nazi era, saying that they did not see any indications he had held such views. As a partner in his father-in-law's champagne firm, Ribbentrop did business with Jewish bankers and organised the Impegroma Importing Company ("Import und Export großer Marken") with Jewish financing.''Current Biography 1941''p. 708

Early diplomatic career

Background

Ribbentrop became Hitler's favourite foreign-policy adviser, partly by dint of his familiarity with the world outside Germany but also by flattery and sycophancy.Rees, p. 93. One German diplomat later recalled, "Ribbentrop didn't understand anything about foreign policy. His sole wish was to please Hitler". In particular, Ribbentrop acquired the habit of listening carefully to what Hitler was saying, memorizing his pet ideas and then later presenting Hitler's ideas as his own, a practice that much impressed Hitler as proving Ribbentrop was an ideal Nazi diplomat. Ribbentrop quickly learned that Hitler always favoured the most radical solution to any problem and accordingly tendered his advice in that direction as a Ribbentrop aide recalled:When Hitler said "Grey", Ribbentrop said "Black, black, black". He always said it three times more, and he was always more radical. I listened to what Hitler said one day when Ribbentrop wasn't present: "With Ribbentrop it is so easy, he is always so radical. Meanwhile, all the other people I have, they come here, they have problems, they are afraid, they think we should take care and then I have to blow them up, to get strong. And Ribbentrop was blowing up the whole day and I had to do nothing. I had to break – much better!"Another factor that aided Ribbentrop's rise was Hitler's distrust of and disdain for Germany's professional diplomats. He suspected that they did not entirely support his revolution. However, the Foreign Office diplomats loyally served the government and rarely gave Hitler grounds for criticism.Jacobsen, p. 59, in ''The Third Reich''. The Foreign Office diplomats were ultranationalist, authoritarian and antisemitic. As a result, there was enough overlap in values between both groups to allow most of them to work comfortably for the Nazis.Trevor-Roper, Hugh "Hitler's War Aims" from ''Aspects of the Third Reich'', H. W. Koch (ed.), London: Macmillan, 1985, pp. 241–242. Nonetheless, Hitler never quite trusted the Foreign Office and was on the lookout for someone to carry out his foreign policy goals.

Undermining Versailles

The Nazis and Germany's professional diplomats shared a goal in destroying theTreaty of Versailles

The Treaty of Versailles (french: Traité de Versailles; german: Versailler Vertrag, ) was the most important of the peace treaties of World War I. It ended the state of war between Germany and the Allied Powers. It was signed on 28 June 1 ...

and restoring Germany as a great power. In October 1933, German Foreign Minister Baron Konstantin von Neurath presented a note at the World Disarmament Conference

The Conference for the Reduction and Limitation of Armaments, generally known as the Geneva Conference or World Disarmament Conference, was an international conference of states held in Geneva, Switzerland, between February 1932 and November 193 ...

announcing that it was unfair that Germany should remain disarmed by Part V of the Versailles treaty and demanded for the other powers to disarm to Germany's level or to rescind Part V and allow Germany ''Gleichberechtigung'' ("equality of armaments"). When France rejected Neurath's note, Germany stormed out of the League of Nations

The League of Nations (french: link=no, Société des Nations ) was the first worldwide Intergovernmental organization, intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by ...

and the World Disarmament Conference. It all but announced its intention of unilaterally violating Part V. Consequently, there were several calls in France for a preventive war to put an end to the Nazi regime while Germany was still more-or-less disarmed.Bloch, pp. 40–41.

However, in November, Ribbentrop arranged a meeting between Hitler and the French journalist Fernand de Brinon, who wrote for the newspaper ''Le Matin''. During the meeting, Hitler stressed what he claimed to be his love of peace and his friendship towards France. Hitler's meeting with Brinon had a huge effect on French public opinion and helped to put an end to the calls for a preventive war. It convinced many in France that Hitler was a man of peace, who wanted to do away only with Part V of the Versailles Treaty.

Special Commissioner for Disarmament

In 1934, Hitler named Ribbentrop Special Commissioner for Disarmament. In his early years, Hitler's goal in foreign affairs was to persuade the world that he wished to reduce the defence budget by making idealistic but very vague disarmament offers (in the 1930s, disarmament described arms limitation agreements).Bloch, p. 56. At the same time, the Germans always resisted making concrete arms-limitations proposals, and they went ahead with increased military spending on grounds that other powers would not take up German arms-limitation offers. Ribbentrop was tasked with ensuring that the world remained convinced that Germany sincerely wanted an arms-limitation treaty, but he ensured that no such treaty was ever developed. On 17 April 1934, French Foreign MinisterLouis Barthou

Jean Louis Barthou (; 25 August 1862 – 9 October 1934) was a French politician of the Third Republic who served as Prime Minister of France for eight months in 1913. In social policy, his time as prime minister saw the introduction (in July ...

issued the so-called "Barthou note", which led to concerns on the part of Hitler that the French would ask for sanctions against Germany for violating Part V of the Versailles treaty. Ribbentrop volunteered to stop the rumoured sanctions and visited London and Rome.Craig, p. 422. During his visits, Ribbentrop met with British Foreign Secretary Sir John Simon

John Allsebrook Simon, 1st Viscount Simon, (28 February 1873 – 11 January 1954), was a British politician who held senior Cabinet posts from the beginning of the First World War to the end of the Second World War. He is one of only three peop ...

and Italian dictator Benito Mussolini

Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini (; 29 July 188328 April 1945) was an Italian politician and journalist who founded and led the National Fascist Party. He was Prime Minister of Italy from the March on Rome in 1922 until his deposition in ...

and asked them to postpone the next meeting of the Bureau of Disarmament in exchange for which Ribbentrop offered nothing in return other than promising better relations with Berlin. The meeting of the Bureau of Disarmament went ahead as scheduled, but because no sanctions were sought against Germany, Ribbentrop could claim a success.

Dienststelle Ribbentrop

In August 1934, Ribbentrop founded an organization linked to the Nazi Party called the ''Büro Ribbentrop'' (later renamed the ''Dienststelle Ribbentrop''). It functioned as an alternative foreign ministry. The ''Dienststelle Ribbentrop'', which had its offices directly across from the Foreign Office's building on the Wilhelmstrasse in Berlin, had in its membership a collection of ''Hitlerjugend'' alumni, dissatisfied businessmen, former reporters, and ambitiousNazi Party

The Nazi Party, officially the National Socialist German Workers' Party (german: Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei or NSDAP), was a far-right political party in Germany active between 1920 and 1945 that created and supported t ...

members, all of whom tried to conduct a foreign policy independent of and often contrary to the official Foreign Office. The Dienststelle served as an informal tool for the implementation of the foreign policy of Hitler, consciously bypassing the traditional foreign policy institutions and diplomatic channels of the German Foreign Office. However, the Dienststelle also competed with other Nazi party units active in the area of foreign policy, such as the foreign organization of the Nazis ( NSDAP/AO) led by Ernst Bohle and Nazi Party office of foreign affairs (APA) led by Alfred Rosenberg

Alfred Ernst Rosenberg ( – 16 October 1946) was a Baltic German Nazi theorist and ideologue. Rosenberg was first introduced to Adolf Hitler by Dietrich Eckart and he held several important posts in the Nazi government. He was the head ...

. With the appointment of Ribbentrop to the Minister of Foreign Affairs in February 1938, the Dienststelle itself lost its importance, and about a third of the staff of the office followed Ribbentrop to the Foreign Office.

Ribbentrop engaged in diplomacy on his own, such as when he visited France and met Foreign Minister Louis Barthou

Jean Louis Barthou (; 25 August 1862 – 9 October 1934) was a French politician of the Third Republic who served as Prime Minister of France for eight months in 1913. In social policy, his time as prime minister saw the introduction (in July ...

.Bloch, p. 52. During their meeting, Ribbentrop suggested for Barthou to meet Hitler at once to sign a Franco-German non-aggression pact. Ribbentrop wanted to buy time to complete German rearmament by removing preventive war as a French policy option. The Barthou-Ribbentrop meeting infuriated Konstantin von Neurath, since the Foreign Office had not been informed.

Although the ''Dienststelle Ribbentrop'' was concerned with German relations in every part of the world, it emphasised Anglo-German relations, as Ribbentrop knew that Hitler favoured an alliance with Britain. As such, Ribbentrop greatly worked during his early diplomatic career to realize Hitler's dream of an anti-Soviet Anglo-German alliance. Ribbentrop made frequent trips to Britain, and upon his return he always reported to Hitler that most British people longed for an alliance with Germany. In November 1934, Ribbentrop met with George Bernard Shaw, Sir Austen Chamberlain, Lord Cecil and Lord Lothian. On the basis of Lord Lothian's praise for the natural friendship between Germany and Britain, Ribbentrop informed Hitler that all elements of British society wished for closer ties with Germany. His report delighted Hitler, causing him to remark that Ribbentrop was the only person who told him "the truth about the world abroad". Because the Foreign Office's diplomats were not so sunny in their appraisal of the prospects for an alliance, Ribbentrop's influence with Hitler increased.Craig, p. 425. Ribbentrop's personality, with his disdain for diplomatic niceties, meshed with what Hitler felt should be the relentless dynamism of a revolutionary regime.

Ambassador-plenipotentiary at large

Hitler rewarded Ribbentrop by appointing him ''Reich'' Minister Ambassador-Plenipotentiary at Large. In that capacity, Ribbentrop negotiated the Anglo-German Naval Agreement (AGNA) in 1935 and theAnti-Comintern Pact

The Anti-Comintern Pact, officially the Agreement against the Communist International was an anti-Communist pact concluded between Nazi Germany and the Empire of Japan on 25 November 1936 and was directed against the Communist International ( ...

in 1936.

Anglo-German Naval Agreement

Neurath did not think it possible to achieve the Anglo-German Naval Agreement. To discredit his rival, he appointed Ribbentrop head of the delegation sent to London to negotiate it. Once the talks began, Ribbentrop issued an ultimatum toSir John Simon

John Allsebrook Simon, 1st Viscount Simon, (28 February 1873 – 11 January 1954), was a British politician who held senior Cabinet posts from the beginning of the First World War to the end of the Second World War. He is one of only three peop ...

, informing him that if Germany's terms were not accepted in their entirety, the German delegation would go home. Simon was angry with that demand, and walked out of the talks. However, to everyone's surprise, the next day the British accepted Ribbentrop's demands, and the AGNA was signed in London on 18 June 1935 by Ribbentrop and Sir Samuel Hoare, the new British Foreign Secretary. The diplomatic success did much to increase Ribbentrop's prestige with Hitler, who called the day the AGNA was signed "the happiest day in my life". He believed it marked the beginning of an Anglo-German alliance, and ordered celebrations throughout Germany to mark the event.

Immediately after the AGNA was signed, Ribbentrop followed up with the next step that was intended to create the Anglo-German alliance, the '' Gleichschaltung'' (co-ordination) of all societies demanding the restoration of Germany's former colonies in Africa. On 3 July 1935, it was announced that Ribbentrop would head the efforts to recover Germany's former African colonies. Hitler and Ribbentrop believed that demanding colonial restoration would pressure the British into making an alliance with the ''Reich'' on German terms. However, there was a difference between Ribbentrop and Hitler: Ribbentrop sincerely wished to recover the former German colonies, but for Hitler, colonial demands were just a negotiating tactic. Germany would renounce its demands in exchange for a British alliance.

=Anti-Comintern Pact

= The Anti-Comintern Pact in November 1936 marked an important change in German foreign policy. The Foreign Office had traditionally favoured a policy of friendship with the

The Anti-Comintern Pact in November 1936 marked an important change in German foreign policy. The Foreign Office had traditionally favoured a policy of friendship with the Republic of China

Taiwan, officially the Republic of China (ROC), is a country in East Asia, at the junction of the East and South China Seas in the northwestern Pacific Ocean, with the People's Republic of China (PRC) to the northwest, Japan to the northea ...

, and an informal Sino-German alliance had emerged by the late 1920s.Bloch, p. 81.Craig, p. 432. Neurath very much believed in maintaining Germany's good relations with China and mistrusted the Empire of Japan

The also known as the Japanese Empire or Imperial Japan, was a historical nation-state and great power that existed from the Meiji Restoration in 1868 until the enactment of the post-World War II 1947 constitution and subsequent for ...

. Ribbentrop was opposed to the Foreign Office's pro-China orientation and instead favoured an alliance with Japan. To that end, Ribbentrop often worked closely with General Hiroshi Ōshima, who served first as the Japanese military attaché and then as ambassador in Berlin, to strengthen German-Japanese ties, despite furious opposition from the Wehrmacht and the Foreign Office, which preferred closer Sino-German ties.

The origins of the Anti-Comintern Pact went back to mid-1935, when in an effort to square the circle between seeking a ''rapprochement'' with Japan and Germany's traditional alliance with China, Ribbentrop and Ōshima devised the idea of an anticommunist alliance as a way to bind China, Japan and Germany together. However, when the Chinese made it clear that they had no interest in such an alliance (especially given that the Japanese regarded Chinese adhesion to the proposed pact as way of subordinating China to Japan), both Neurath and War Minister Field Marshal

Field marshal (or field-marshal, abbreviated as FM) is the most senior military rank, ordinarily senior to the general officer ranks. Usually, it is the highest rank in an army and as such few persons are appointed to it. It is considered a ...

Werner von Blomberg persuaded Hitler to shelve the proposed treaty to avoid damaging Germany's good relations with China. Ribbentrop, who valued Japanese friendship far more than that of the Chinese, argued that Germany and Japan should sign the pact without Chinese participation. By November 1936, a revival of interest in a German-Japanese pact in both Tokyo and Berlin led to the signing of the Anti-Comintern Pact in Berlin. When the Pact was signed, invitations were sent to Italy, China, Britain and Poland to join. However, of the invited powers, only the Italians would ultimately sign. The Anti-Comintern Pact marked the beginning of the shift on Germany's part from China's ally to Japan's ally.

=Veterans' exchanges

= In 1935, Ribbentrop arranged for a series of much-publicised visits of First World War veterans to Britain, France and Germany.Bloch, p. 65. Ribbentrop persuaded the Royal British Legion and many French veterans' groups to send delegations to Germany to meet German veterans as the best way to promote peace. At the same time, Ribbentrop arranged for members of the ''Frontkämpferbund'', the official German World War I veterans' group, to visit Britain and France to meet veterans there. The veterans' visits and attendant promises of "never again" did much to improve the "New Germany's" image in Britain and France. In July 1935, Brigadier Sir Francis Featherstone-Godley led the British Legion's delegation to Germany. The Prince of Wales, the Legion's patron, made a much-publicized speech at the Legion's annual conference in June 1935 that stated that he could think of no better group of men than those of the Legion to visit and carry the message of peace to Germany and that he hoped that Britain and Germany would never fight again. As for the contradiction between German rearmament and his message of peace, Ribbentrop argued to whoever would listen that the German people had been "humiliated" by the Versailles Treaty, Germany wanted peace above all and German violations of Versailles were part of an effort to restore Germany's "self-respect". By the 1930s, much of British opinion had been convinced that the treaty was monstrously unfair and unjust to Germany, so as a result, many in Britain, such as Thomas Jones, Deputy Secretary to the Cabinet, were very open to Ribbentrop's message that European peace would be restored if only the Treaty of Versailles could be done away with.Ambassador to the United Kingdom

In August 1936, Hitler appointed Ribbentropambassador

An ambassador is an official envoy, especially a high-ranking diplomat who represents a state and is usually accredited to another sovereign state or to an international organization as the resident representative of their own government or sov ...

to the United Kingdom with orders to negotiate an Anglo-German alliance. Ribbentrop arrived to take up his position in October 1936. Ribbentrop's time in London was marked by an endless series of social gaffes and blunders that worsened his already-poor relations with the British Foreign Office.

Invited to stay as a house guest of the 7th Marquess of Londonderry at Wynyard Hall in County Durham, in November 1936, he was taken to a service in Durham Cathedral

The Cathedral Church of Christ, Blessed Mary the Virgin and St Cuthbert of Durham, commonly known as Durham Cathedral and home of the Shrine of St Cuthbert, is a cathedral in the city of Durham, County Durham, England. It is the seat of ...

, and the hymn '' Glorious Things of Thee Are Spoken'' was announced. As the organ played the opening bars, identical to the German national anthem, Ribbentrop gave the Nazi salute and had to be restrained by his host.

At his wife's suggestion, Ribbentrop hired the Berlin interior decorator Martin Luther

Martin Luther (; ; 10 November 1483 – 18 February 1546) was a German priest, theologian, author, hymnwriter, and professor, and Augustinian friar. He is the seminal figure of the Protestant Reformation and the namesake of Luther ...

to assist with his move to London and help realise the design of the new German embassy that Ribbentrop had built there (he felt that the existing embassy was insufficiently grand). Luther proved to be a master intriguer and became Ribbentrop's favourite hatchet man.Bloch, p. 107.

Ribbentrop did not understand the limited role in government exercised by 20th-century British monarchs. He thought that King Edward VIII, Emperor of India, could dictate British foreign policy if he wanted. He convinced Hitler that he had Edward's support, but that was as much a delusion as his belief that he had impressed British society. In fact, Ribbentrop often displayed a fundamental misunderstanding of British politics and society. During the abdication crisis in December 1936, Ribbentrop reported to Berlin that it had been precipitated by an anti-German Jewish-Masonic-reactionary conspiracy to depose Edward, whom Ribbentrop represented as a staunch friend of Germany, and that civil war would soon break out in Britain between supporters of Edward and those of Prime Minister Stanley Baldwin

Stanley Baldwin, 1st Earl Baldwin of Bewdley, (3 August 186714 December 1947) was a British Conservative Party politician who dominated the government of the United Kingdom between the world wars, serving as Prime Minister of the United Kingd ...

. Ribbentrop's civil war predictions were greeted with incredulity by the British people who heard them. Duke Carl Alexander of Württemberg had told the Federal Bureau of Investigation

The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) is the domestic intelligence and security service of the United States and its principal federal law enforcement agency. Operating under the jurisdiction of the United States Department of Justice, ...

that Wallis Simpson, Edward's lover and a suspected Nazi sympathizer, had slept with Ribbentrop in London in 1936; had remained in constant contact with him; and had continued to leak secrets.

Ribbentrop had a habit of summoning tailors from the best British firms, making them wait for hours and then sending them away without seeing him but with instructions to return the next day, only to repeat the process. That did immense damage to his reputation in British high society, as London's tailors retaliated by telling all their well-off clients that Ribbentrop was impossible to deal with. In an interview, his secretary Reinhard Spitzy stated, "He ibbentropbehaved very stupidly and very pompously and the British don't like pompous people". In the same interview, Spitzy called Ribbentrop "pompous, conceited and not too intelligent" and stated he was an utterly insufferable man to work for.

In addition, Ribbentrop chose to spend as little time as possible in London to stay close to Hitler, which irritated the British Foreign Office immensely, as Ribbentrop's frequent absences prevented the handling of many routine diplomatic matters. (''Punch

Punch commonly refers to:

* Punch (combat), a strike made using the hand closed into a fist

* Punch (drink), a wide assortment of drinks, non-alcoholic or alcoholic, generally containing fruit or fruit juice

Punch may also refer to:

Places

* Pun ...

'' referred to him as the '' "Wandering Aryan"'' for his frequent trips home.)Bloch, pp. 125–127. As Ribbentrop alienated more and more people in Britain, '' Reichsmarschall'' Hermann Göring warned Hitler that Ribbentrop was a "stupid ass". Hitler dismissed Göring's concerns: "But after all, he knows quite a lot of important people in England." That remark led Göring to reply "''Mein Führer'', that may be right, but the bad thing is, they know ''him''".

In February 1937, Ribbentrop committed a notable social gaffe by unexpectedly greeting George VI

George VI (Albert Frederick Arthur George; 14 December 1895 – 6 February 1952) was King of the United Kingdom and the Dominions of the British Commonwealth from 11 December 1936 until his death in 1952. He was also the last Emperor of I ...

with the "German greeting", a stiff-armed Nazi salute: the gesture nearly knocked over the King, who was walking forward to shake Ribbentrop's hand at the time. Ribbentrop further compounded the damage to his image and caused a minor crisis in Anglo-German relations by insisting that henceforward all German diplomats were to greet heads of state by giving and receiving the stiff-arm fascist salute. The crisis was resolved when Neurath pointed out to Hitler that under Ribbentrop's rule, if the Soviet ambassador were to give the Communist clenched-fist salute, Hitler would be obliged to return it. On Neurath's advice, Hitler disavowed Ribbentrop's demand that King George receive and give the "German greeting".

Most of Ribbentrop's time was spent demanding that Britain either sign the Anti-Comintern Pact or return the former German colonies in Africa. However, he also devoted considerable time to courting what he called the "men of influence" as the best way to achieve an Anglo-German alliance. He believed that the British aristocracy comprised some sort of secret society that ruled from behind the scenes, and that if he could befriend enough members of Britain's "secret government" he could bring about the alliance. Almost all of the initially-favourable reports Ribbentrop provided to Berlin about the alliance's prospects were based on friendly remarks about the "New Germany" that came from British aristocrats such as Lord Londonderry and Lord Lothian. The rather cool reception that Ribbentrop received from British Cabinet ministers and senior bureaucrats did not make much of an impression on him at first.Waddington, p. 58. This British governmental view, summarised by Robert, Viscount Cranborne, Parliamentary Under-Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs

The Parliamentary Under-Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs is a vacant junior position in the British government, subordinate to both the Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs and since 1945 also to the Minister of State for Foreign Affair ...

, was that Ribbentrop always was a second-rate man.

In 1935, Sir Eric Phipps, the British Ambassador to Germany, complained to London about Ribbentrop's British associates in the Anglo-German Fellowship. He felt that they created "false German hopes as in regards to British friendship and caused a reaction against it in England, where public opinion is very naturally hostile to the Nazi regime and its methods". In September 1937, the British Consul in Munich

Munich ( ; german: München ; bar, Minga ) is the capital and most populous city of the German state of Bavaria. With a population of 1,558,395 inhabitants as of 31 July 2020, it is the third-largest city in Germany, after Berlin and Ha ...

, writing about the group that Ribbentrop had brought to the Nuremberg Rally, reported that there were some "serious persons of standing among them" but that an equal number of Ribbentrop's British contingent were "eccentrics and few, if any, could be called representatives of serious English thought, either political or social, while they most certainly lacked any political or social influence in England". In June 1937, when Lord Mount Temple, the Chairman of the Anglo-German Fellowship, asked to see Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain

Arthur Neville Chamberlain (; 18 March 18699 November 1940) was a British politician of the Conservative Party who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from May 1937 to May 1940. He is best known for his foreign policy of appeasem ...

after meeting Hitler in a visit arranged by Ribbentrop, Robert Vansittart, the British Foreign Office's Permanent Under-Secretary of State

A permanent secretary (also known as a principal secretary) is the most senior civil servant of a department or ministry charged with running the department or ministry's day-to-day activities. Permanent secretaries are the non-political civil se ...

, wrote a memo stating that:

The P.M.After Vansittart's memo, members of the Anglo-German Fellowship ceased to see Cabinet ministers after they went on Ribbentrop-arranged trips to Germany. In February 1937, before a meeting with the Lord Privy Seal, Lord Halifax, Ribbentrop suggested to Hitler for Germany, Italy and Japan to begin a worldwide propaganda campaign with the aim of forcing Britain to return the former German colonies in Africa.Hildebrand, p. 48. Hitler turned down the idea, but nonetheless during his meeting with Lord Halifax, Ribbentrop spent much of the meeting demanding for Britain to sign an alliance with Germany and to return the former German colonies. The German historian Klaus Hildebrand noted that as early as the Ribbentrop–Halifax meeting the differing foreign policy views of Hitler and Ribbentrop were starting to emerge, with Ribbentrop more interested in restoring the pre-1914 German ''Imperium'' in Africa than the conquest of Eastern Europe. Following the lead of Andreas Hillgruber, who argued that Hitler had a ''Stufenplan'' (stage by stage plan) for world conquest, Hildebrand argued that Ribbentrop may not have fully understood what Hitler's ''Stufenplan'' was or that in pressing so hard for colonial restoration, he was trying to score a personal success that might improve his standing with Hitler. In March 1937, Ribbentrop attracted much adverse comment in the British press when he gave a speech at the Leipzig Trade Fair in Leipzig in which he declared that German economic prosperity would be satisfied "through the restoration of the former German colonial possessions, or by means of the German people's own strength."Bloch, p. 128. The implied threat that if colonial restoration did not occur, the Germans would take back their former colonies by force attracted a great deal of hostile commentary on the inappropriateness of an ambassador threatening his host country in such a manner. Ribbentrop's negotiating style, a mix of bullying bluster and icy coldness coupled with lengthy monologues praising Hitler, alienated many. The American historian Gordon A. Craig once observed that of all the voluminous memoir literature of the diplomatic scene of 1930s Europe, there are only two positive references to Ribbentrop.Craig, p. 419. Of the two references, General Leo Geyr von Schweppenburg, the German military attaché in London, commented that Ribbentrop had been a brave soldier in World War I, and the wife of the Italian Ambassador to Germany, Elisabetta Cerruti, called Ribbentrop "one of the most diverting of the Nazis". In both cases, the praise was limited, with Cerruti going on to write that only in Nazi Germany was it possible for someone as superficial as Ribbentrop to rise to be a minister of foreign affairs, and Geyr von Schweppenburg called Ribbentrop an absolute disaster as ambassador in London. The British historian/television producer Laurence Rees noted for his 1997 series '' The Nazis: A Warning from History'' that every single person interviewed for the series who knew Ribbentrop expressed a passionate hatred for him. One German diplomat, Herbert Richter, called Ribbentrop "lazy and worthless", while another, Manfred von Schröder, was quoted as saying Ribbentrop was "vain and ambitious". Rees concluded, "No other Nazi was so hated by his colleagues". In November 1937, Ribbentrop was placed in a highly-embarrassing situation since his forceful advocacy of the return of the former German colonies led British Foreign Secretaryrime Minister Rime may refer to: * Rime ice, ice that forms when water droplets in fog freeze to the outer surfaces of objects, such as trees Rime is also an alternative spelling of "rhyme" as a noun: *Syllable rime, term used in the study of phonology in lin ...should certainly not see Lord Mount Temple – nor should the S cretaryof S ate We really must put a stop to this eternal butting in of amateurs – and Lord Mount Temple is a particularly silly one. These activities – which are practically confined to Germany – render impossible the task of diplomacy.

Anthony Eden

Robert Anthony Eden, 1st Earl of Avon, (12 June 1897 – 14 January 1977) was a British Conservative Party politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1955 until his resignation in 1957.

Achieving rapid pro ...

and French Foreign Minister Yvon Delbos to offer to open talks on returning the former German colonies in return for which the Germans would make binding commitments to respect their borders in Central and Eastern Europe. Since Hitler was not interested in obtaining the former colonies, especially if the price was a brake on expansion into Eastern Europe, Ribbentrop was forced to turn down the Anglo-French offer that he had largely brought about.Bloch, p. 146. Immediately after turning down the Anglo-French offer on colonial restoration, Ribbentrop, for reasons of pure malice, ordered the ''Reichskolonialbund'' to increase the agitation for the former German colonies, a move that exasperated both the Foreign Office and the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

As the Italian Foreign Minister, Count Galeazzo Ciano, noted in his diary in late 1937, Ribbentrop had come to hate Britain with all the "fury of a woman scorned". Ribbentrop and Hitler, for that matter, never understood that British foreign policy aimed at the appeasement

Appeasement in an international context is a diplomatic policy of making political, material, or territorial concessions to an aggressive power in order to avoid conflict. The term is most often applied to the foreign policy of the UK governme ...

of Germany, not an alliance with it.

When Ribbentrop traveled to Rome in November 1937 to oversee Italy's adhesion to the Anti-Comintern Pact, he made clear to his hosts that the pact was really directed against Britain. As Ciano noted in his diary, the Anti-Comintern Pact was "anti-Communist in theory, but in fact unmistakably anti-British". Believing himself to be in a state of disgrace with Hitler over his failure to achieve the British alliance, Ribbentrop spent December 1937 in a state of depression and, together with his wife, wrote two lengthy documents for Hitler that denounced Britain. In the first report to Hitler, which was presented on 2 January 1938, Ribbentrop stated that "England is our most dangerous enemy". In the same report, Ribbentrop advised Hitler to abandon the idea of a British alliance and instead embrace the idea of an alliance of Germany, Japan and Italy to destroy the British Empire

The British Empire was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It began with the overseas possessions and trading post ...

.Michalka 1985, pp. 271–273.

Ribbentrop wrote in his "Memorandum for the ''Führer''" that "a change in the status quo in the East to Germany's advantage can only be accomplished by force" and that the best way to achieve it was to build a global anti-British alliance system.Hillgruber, pp. 64–65. Besides converting the Anti-Comintern Pact into an anti-British military alliance, Ribbentrop argued that German foreign policy should work to "winning over all states whose interests conform directly or indirectly to ours." By the last statement, Ribbentrop clearly implied that the Soviet Union should be included in the anti-British alliance system he had proposed.

Foreign Minister of the ''Reich''

In early 1938, Hitler asserted his control of the military-foreign policy apparatus, in part by sacking Neurath. On 4 February 1938, Ribbentrop succeeded Neurath as Foreign Minister. Ribbentrop's appointment has generally been seen as an indication that German foreign policy was moving in a more radical direction. In contrast to Neurath's cautious and less bellicose nature, Ribbentrop unequivocally supported war in 1938 and 1939.Bloch, p. 195.

Ribbentrop's time as Foreign Minister can be divided into three periods. In the first, from 1938 to 1939, he tried to persuade other states to align themselves with Germany for the coming war. In the second, from 1939 to 1943, Ribbentrop attempted to persuade other states to enter the war on Germany's side or at least to maintain pro-German neutrality. He was also involved in

In early 1938, Hitler asserted his control of the military-foreign policy apparatus, in part by sacking Neurath. On 4 February 1938, Ribbentrop succeeded Neurath as Foreign Minister. Ribbentrop's appointment has generally been seen as an indication that German foreign policy was moving in a more radical direction. In contrast to Neurath's cautious and less bellicose nature, Ribbentrop unequivocally supported war in 1938 and 1939.Bloch, p. 195.

Ribbentrop's time as Foreign Minister can be divided into three periods. In the first, from 1938 to 1939, he tried to persuade other states to align themselves with Germany for the coming war. In the second, from 1939 to 1943, Ribbentrop attempted to persuade other states to enter the war on Germany's side or at least to maintain pro-German neutrality. He was also involved in Operation Willi

Operation Willi was the German code name for the unsuccessful attempt by the SS to kidnap Prince Edward, Duke of Windsor in July 1940 and induce him to work with German dictator Adolf Hitler for either a peace settlement with Britain, or a r ...

, an attempt to convince the former King Edward VIII to lobby his brother, now the king, on behalf of Germany. Many historians have suggested that Hitler was prepared to reinstate the Duke of Windsor as king in the hope of establishing a fascist Britain. If Edward would agree to work openly with Nazi Germany, he would be given financial assistance and would hopefully come to be a "compliant" king. Reportedly, 50 million Swiss francs were set aside for that purpose. The plan was never realised.

In the final phase, from 1943 to 1945, he had the task of trying to keep Germany's allies from leaving her side. During the course of all three periods, Ribbentrop met frequently with leaders and diplomats from Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical ...

, Japan, Romania

Romania ( ; ro, România ) is a country located at the crossroads of Central, Eastern, and Southeastern Europe. It borders Bulgaria to the south, Ukraine to the north, Hungary to the west, Serbia to the southwest, Moldova to the east, a ...

, Spain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = '' Plus ultra'' ( Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem = (English: "Royal March")

, ...

, Bulgaria

Bulgaria (; bg, България, Bǎlgariya), officially the Republic of Bulgaria,, ) is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the eastern flank of the Balkans, and is bordered by Romania to the north, Serbia and North Mac ...

, and Hungary

Hungary ( hu, Magyarország ) is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Spanning of the Carpathian Basin, it is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine to the northeast, Romania to the east and southeast, Serbia to the south, Croa ...

. During all of that time, Ribbentrop feuded with various other Nazi leaders. As time went by, Ribbentrop started to oust the Foreign Office's old diplomats from their senior positions and replace them with men from the ''Dienststelle''. As early as 1938, 32% of the offices in the Foreign Ministry were held by men who previously served in the ''Dienststelle''.

One of Ribbentrop's first acts as Foreign Minister was to achieve a total volte-face in Germany's Far Eastern policies. Ribbentrop was instrumental in February 1938 in persuading Hitler to recognize the Japanese puppet state

A puppet state, puppet régime, puppet government or dummy government, is a state that is ''de jure'' independent but ''de facto'' completely dependent upon an outside power and subject to its orders.Compare: Puppet states have nominal sover ...

of Manchukuo

Manchukuo, officially the State of Manchuria prior to 1934 and the Empire of (Great) Manchuria after 1934, was a puppet state of the Empire of Japan in Manchuria from 1932 until 1945. It was founded as a republic in 1932 after the Japanese in ...

and to renounce German claims upon its former colonies in the Pacific, which were now held by Japan. By April 1938, Ribbentrop had ended all German arms shipments to China and had all of the German Army officers serving with the Kuomintang

The Kuomintang (KMT), also referred to as the Guomindang (GMD), the Nationalist Party of China (NPC) or the Chinese Nationalist Party (CNP), is a major political party in the Republic of China, initially on the Chinese mainland and in Tai ...

government

A government is the system or group of people governing an organized community, generally a state.

In the case of its broad associative definition, government normally consists of legislature, executive, and judiciary. Government ...

of Chiang Kai-shek recalled, with the threat that the families of the officers in China would be sent to concentration camps if the officers did not return to Germany immediately.Bloch, p. 179. In return, the Germans received little thanks from the Japanese, who refused to allow any new German businesses to be set up in the part of China they had occupied and continued with their policy of attempting to exclude all existing German and all other Western businesses from Japanese-occupied China. At the same time, the end of the informal Sino-German alliance led Chiang to terminate all concessions and contracts held by German companies in Kuomintang China.

Munich Agreement and Czechoslovakia's destruction

Ernst von Weizsäcker, the State Secretary from 1938 to 1943, opposed the general trend in German foreign policy towards attacking the

Ernst von Weizsäcker, the State Secretary from 1938 to 1943, opposed the general trend in German foreign policy towards attacking the First Czechoslovak Republic

The First Czechoslovak Republic ( cs, První československá republika, sk, Prvá česko-slovenská republika), often colloquially referred to as the First Republic ( cs, První republika, Slovak: ''Prvá republika''), was the first Czechoslo ...

and feared that it might cause a general war that Germany would lose. Weizsäcker had no moral objections to the idea of destroying Czechoslovakia but opposed only the timing of the attack. He favoured the idea of a "chemical" destruction of Czechoslovakia in which Germany, Hungary and Poland would close their frontiers to destabilise Czechoslovakia economically. He strongly disliked Ribbentrop's idea of a "mechanical" destruction of Czechoslovakia by war, which he saw as too risky. However, despite all of their reservations and fears about Ribbentrop, whom they saw as recklessly seeking to plunge Germany into a general war before the ''Reich'' was ready, neither Weizsäcker nor any of the other professional diplomats were prepared to confront their chief.

Before the Anglo-German summit at Berchtesgaden on 15 September 1938, the British Ambassador, Sir Nevile Henderson, and Weizsäcker worked out a private arrangement for Hitler and Chamberlain to meet with no advisers present as a way of excluding the ultrahawkish Ribbentrop from attending the talks.Bloch, p. 193. Hitler's interpreter, Paul Schmidt, later recalled that it was "felt that our Foreign Minister would prove a disturbing element" at the Berchtesgaden summit. In a moment of pique at his exclusion from the Chamberlain-Hitler meeting, Ribbentrop refused to hand over Schmidt's notes of the summit to Chamberlain, a move that caused much annoyance on the British side. Ribbentrop spent the last weeks of September 1938 looking forward very much to the German-Czechoslovak war that he expected to break out on 1 October 1938. Ribbentrop regarded the

Before the Anglo-German summit at Berchtesgaden on 15 September 1938, the British Ambassador, Sir Nevile Henderson, and Weizsäcker worked out a private arrangement for Hitler and Chamberlain to meet with no advisers present as a way of excluding the ultrahawkish Ribbentrop from attending the talks.Bloch, p. 193. Hitler's interpreter, Paul Schmidt, later recalled that it was "felt that our Foreign Minister would prove a disturbing element" at the Berchtesgaden summit. In a moment of pique at his exclusion from the Chamberlain-Hitler meeting, Ribbentrop refused to hand over Schmidt's notes of the summit to Chamberlain, a move that caused much annoyance on the British side. Ribbentrop spent the last weeks of September 1938 looking forward very much to the German-Czechoslovak war that he expected to break out on 1 October 1938. Ribbentrop regarded the Munich Agreement

The Munich Agreement ( cs, Mnichovská dohoda; sk, Mníchovská dohoda; german: Münchner Abkommen) was an agreement concluded at Munich on 30 September 1938, by Germany, the United Kingdom, France, and Italy. It provided "cession to Germany ...

as a diplomatic defeat for Germany, as it deprived Germany of the opportunity to wage the war to destroy Czechoslovakia that Ribbentrop wanted to see. The Sudetenland issue, which was the ostensible subject of the German-Czechoslovak dispute, had been a pretext for German aggression. During the Munich Conference, Ribbentrop spent much of his time brooding unhappily in the corners.Bloch, p. 196. Ribbentrop told the head of Hitler's Press Office, Fritz Hesse, that the Munich Agreement was "first-class stupidity.... All it means is that we have to fight the English in a year, when they will be better armed.... It would have been much better if war had come now". Like Hitler, Ribbentrop was determined that in the next crisis, Germany would not have its professed demands met in another Munich-type summit and that the next crisis to be caused by Germany would result in the war that Chamberlain had "cheated" the Germans out of at Munich.

In the aftermath of Munich, Hitler was in a violently anti-British mood caused in part by his rage over being "cheated" out of the war to "annihilate" Czechoslovakia that he very much wanted to have in 1938 and in part by his realisation that Britain would neither ally itself nor stand aside in regard to Germany's ambition to dominate Europe.Weinberg 1980, pp. 506–507. As a consequence, Britain was considered after Munich to be the main enemy of the ''Reich'', and as a result, the influence of ardently Anglophobic Ribbentrop correspondingly rose with Hitler.

Partly for economic reasons, and partly out of fury over being "cheated" out of war in 1938, Hitler decided to destroy the rump state of

In the aftermath of Munich, Hitler was in a violently anti-British mood caused in part by his rage over being "cheated" out of the war to "annihilate" Czechoslovakia that he very much wanted to have in 1938 and in part by his realisation that Britain would neither ally itself nor stand aside in regard to Germany's ambition to dominate Europe.Weinberg 1980, pp. 506–507. As a consequence, Britain was considered after Munich to be the main enemy of the ''Reich'', and as a result, the influence of ardently Anglophobic Ribbentrop correspondingly rose with Hitler.